Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/228/01. The contractual start date was in April 2009. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in November 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programmespecified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draftdocument. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Kaltenthaler et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Historical perspective

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is an independent organisation that is part of the NHS and is responsible for providing guidance on the promotion of good health and the prevention and treatment of ill health to the population of England and Wales. The establishment of NICE in 1999 was the natural extension and institutionalisation of the process of using clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence to inform clinical practice decisions. One of the key components of NICE’s work involves technology appraisals, which lead to recommendations on the use of new and existing medicines and treatments within the NHS, such as medicines and medical devices among others. NICE technology appraisal guidance is mandatory in the NHS in England and Wales, giving NICE the potential to decrease variation in the provision of care across the nations.

The processes used to establish NICE guidance on technology appraisals are based on the internationally accepted models of reviewing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence. These include a rigorous and systematic approach to identifying, evaluating and synthesising the available evidence (clinical and economic data) carried out by groups of academic researchers (assessment groups) aided by submissions from the involved manufacturers of the technologies. The result of this synthesis is then considered by a carefully selected group of clinicians, health economists, statisticians and patients. This group, the Appraisal Committee (AC), is responsible for weighing all of the available evidence, including submissions from manufacturers, patients and expert groups, to make recommendations regarding the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of various technologies and produce guidance to direct care in the NHS. This is known as the multiple technology appraisal (MTA) process. In addition to this process for the evaluation of evidence, opportunity is also provided for interested parties to appeal against the AC decisions.

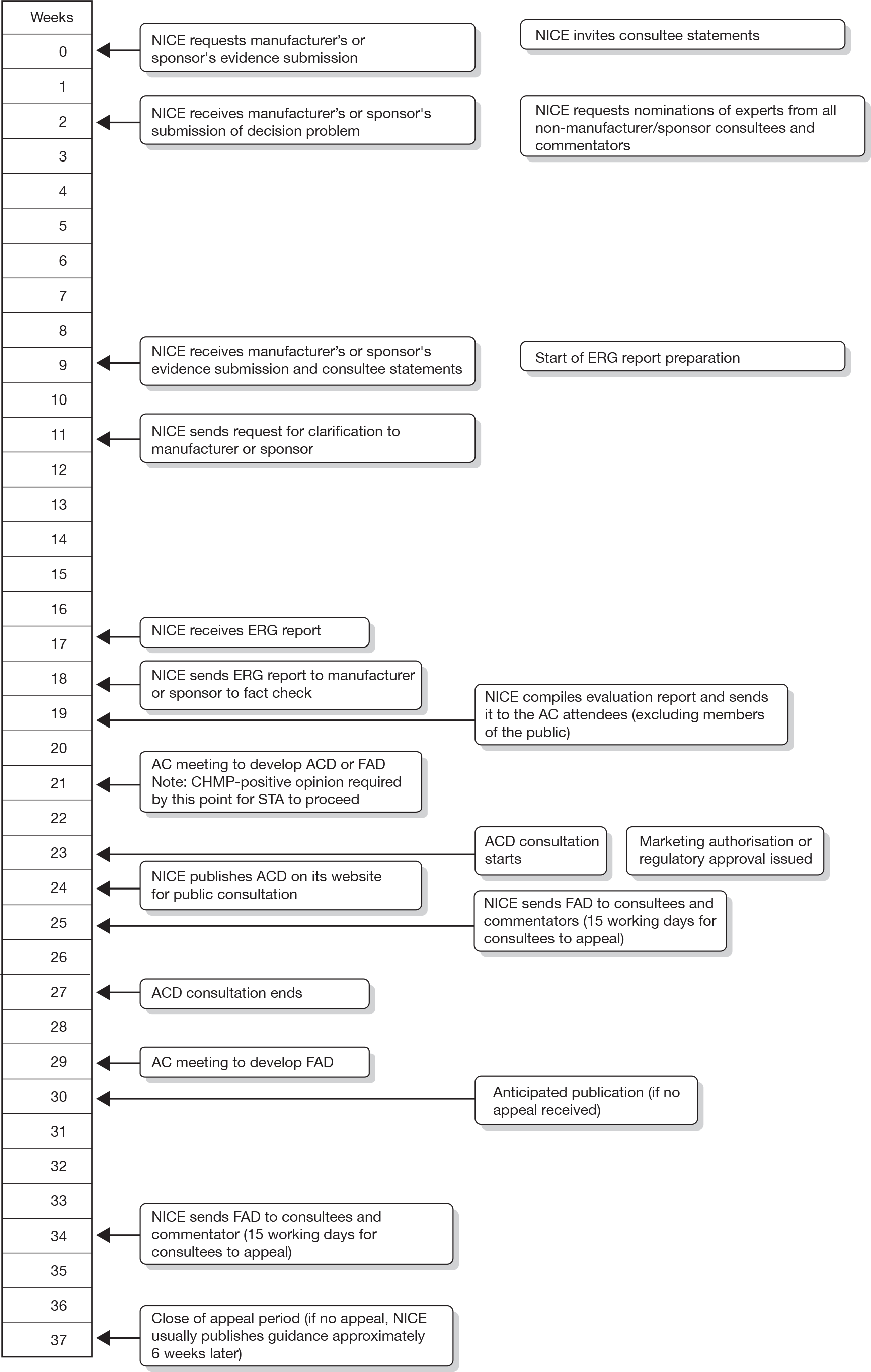

A more rapid process became a political imperative and the newer single technology appraisal (STA) process was introduced in 2005. The STA process was specifically designed to appraise a new technology for a single indication, although there may be more than one comparator; most importantly, the STA process was designed to examine evidence in a more timely fashion than the MTA process so that guidance for new products was produced as close to their launch into the NHS as possible. The STA process differs from the MTA process in that the manufacturer’s submission (MS) to NICE forms the principal source of evidence for decision-making. The MS is expected to contain an evaluation of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the technology using decision-analytic approaches as outlined in the STA methods guidelines developed by NICE. 1 The timescales from time of referral of the appraisal to production of the final appraisal documentation (FAD) are intended to be much shorter for STAs, around 34 weeks compared with 51 weeks for an MTA. Initially, scoping workshops (which are an opportunity for consultees and commentators to discuss the scope and important issues related to it) did not take place for STAs; however, this has changed and scoping workshops now take place for both MTAs and STAs.

Further changes to both the MTA and the STA processes occurred in 2009, related to what has come to be known as ‘end-of-life’ criteria and technology pricing. End-of-life criteria affect the use of life-extending treatments licensed for terminal illnesses (survival < 24 months) affecting small numbers of patients, so that treatments that may have been previously ruled out as not sufficiently cost-effective for routine use in the NHS might now be recommended for use. This change, implemented within a very time-limited consultation process, is based on the assumption that the last few months of life are in fact worth more than ‘ordinary’ life and therefore there should be a willingness to pay that is higher than in other technologies. The exact amount of this extra value was not stipulated in the final policy document. 2 A second change to the technology appraisal processes took place as a result of the new Pharmaceutical Price Regulation Scheme (PPRS), launched in January 2009, which allows manufacturers to submit proposals for Patient Access Schemes (PASs) and flexible pricing schemes. 3 These schemes have the potential to lengthen the STA process. Finally, manufacturers are now invited to participate in, and contribute to, the AC meetings.

Description of the single technology appraisal process

The STA process is divided into stages. Initially, provisional topics are identified. NICE manages the topic selection process on behalf of the Department of Health (DH) and works with the DH to develop a draft scope for each topic, which defines the disease, the patients and the technology covered by the appraisal and the questions it aims to answer. Consultees and commentators are then requested to comment on the draft scope and a scoping workshop is held to discuss key issues relating to the scope. The DH formally refers topics to NICE and the STA timelines are then set. Figure 1 shows the STA process timeline from formal referral through to the issuing of NICE guidance.

FIGURE 1.

Single technology appraisal process timeline (from NICE guide to the STA process3). ACD, appraisal consultation document; CHMP, Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use.

Manufacturers are invited to prepare their submission to NICE using a standard report template. Extensive guidance for manufacturers is provided in the NICE guide to the methods for technology appraisal. 1 The MS is expected to include a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness evidence for the technology under consideration, as well as a cost-effectiveness analysis. External independent Evidence Review Groups (ERGs) are based in academic centres and are charged with the task of critically appraising the MS to identify strengths, weaknesses and gaps in the evidence presented. The resultant ERG reports are then considered as a part of the evidence considered by the AC. Little guidance has been provided outlining the approaches ERG teams should take. ERG teams are expected to critically appraise the MS to determine whether the evidence presented is:

-

relevant to the issue under consideration in terms of patient groups, comparators, perspective and outcomes

-

complete (all relevant evidence must be identified)

-

inclusive of all study design information (including the type of study, the circumstances of its undertaking and the selection of outcomes and costs) and inclusive of all intention to treat patients

-

fit for purpose [contributing to an overall assessment of the clinical benefit and quality of life (QoL), preferably in such units that allow comparison of the benefits from different technologies and between different patient groups].

In addition, the ERG team must critically appraise the MS to ensure that the analyses and modelling presented by the manufacturer are methodologically sound and minimise any bias. Models must be replicable, have face validity (be plausible) and be open to external scrutiny.

Within the STA process, there are no resources for the ERG to produce an independent systematic review or cost-effectiveness model. The current ERG report template is attached as Appendix 1. Currently, NICE works with the following ERGs (three new ERGs will join these seven teams from April 2011):

-

Health Economics Research Unit and Health Services Research Unit, University of Aberdeen

-

Liverpool Reviews and Implementation Group (LRiG), University of Liverpool

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) and Centre for Health Economics (CHE), University of York

-

Peninsula Technology Assessment Group (PenTAG), Peninsula Medical School, Universities of Exeter and Plymouth

-

School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield

-

Southampton Health Technology Assessment Centre (SHTAC), University of Southampton

-

West Midlands Health Technology Assessment Collaboration (WMHTAC), Department of Public Health and Epidemiology, University of Birmingham.

The process of requesting further information from the manufacturer following submission was not included in the original plan for the conduct of an STA. However, it very soon became apparent that such a mechanism was required, as the ERGs identified aspects of the submissions that were unclear or where further information was required. The process of the clarification letter was implemented and is now standard practice. The ERG is requested to submit any clarification questions for the manufacturer within 10 working days of receiving the MS. NICE contributes additional questions and sends the letter on to the manufacturer who has 10 working days to respond. The format of the letter has evolved over time and more recent letters follow a consistent format developed by NICE that separates out clinical and economic clarification issues.

The AC meets to consider the evidence presented by the manufacturer and also the critique of the evidence by the ERG and makes recommendations to NICE. There are currently four ACs. If the AC’s provisional recommendations are more restrictive than the terms of the marketing authorisation for the technology under appraisal then an appraisal consultation document (ACD) is produced and consultees and commentators are invited to comment on the ACD. The AC meets again to consider these comments and aims to produce the FAD, which forms the basis of the guidance that NICE will issue to the NHS in England and Wales. However, instead, the AC may issue another ACD inviting further comments from consultees and commentators, which are, again, considered by the AC to produce the FAD.

Both ACDs and FADs may have more than one decision within the same document; for example, for different subgroups of patients different decisions may be made. An appeal may be launched up to 15 working days after the FAD has been issued and guidance is not published until an appeal decision has been made by the appeal panel.

When the STA process was initially introduced, concerns were raised that it may represent a less robust process for producing guidance on the use of health technologies than the MTA process. 4 Concerns have also been raised regarding the need for consistency and transparency of methods used to critically appraise the MS as part of the STA process.

The NICE Decision Support Unit (DSU) is a collaboration of UK universities that is commissioned by NICE to provide research and training to support the NICE technology appraisal process. Occasionally, the DSU is requested to provide additional analysis to enable the AC to reach a decision. The NICE DSU reviewed the STA process in 20085 and looked at the first 10 STAs only. The report highlighted the potential for inconsistencies between ERGs in terms of the content of their reports. This report takes a broader perspective and provides an in-depth analysis of components of the STA process, which have changed significantly since the earlier report by the DSU.

Aims and objectives

The aims of this study were to review the methods currently used by ERG teams to critically appraise MSs within the NICE STA process and to provide recommendations on approaches that could be considered in the future. An additional aim was to map the STA process to date. There were five primary objectives:

-

to provide a map of the STA process to date

-

to identify current approaches to critical appraisal of MSs by ERGs

-

to identify recurring themes in clarification letters sent to manufacturers

-

to provide recommendations for possible alternative approaches to be used in the critical appraisal process

-

to revise the current ERG report template.

Chapter 2 describes the mapping of the STA process to date, Chapter 3 covers the documentary and thematic analysis of 30 ERG reports and Chapter 4 explores the issues identified in the 21 clarification letters. Chapter 5 includes a description of the process used to modify the ERG report template, as well as recommendations for approaches to be considered in the development of ERG reports.

The protocol for this project stated that telephone interviews would be undertaken with members of the ERGs who had worked on STAs. However, subsequently a Technology Assessment Services Collaboration (InterTASC) workshop to discuss the STA process was arranged and several issues were discussed during this meeting in April 2010. Key points debated during the workshop have been integrated into the discussion and conclusion sections of this report.

Chapter 2 Mapping exercise

Methods

Data collection

All STAs that had been identified by NICE up to, and including, March 2009 were included in the mapping exercise. The list of STAs was provided by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC). A mapping tool was devised using a Microsoft Excel 2003 spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and is attached as Appendix 2. The tool was designed to collect information on a range of topics from each STA.

The mapping tool/spreadsheet was piloted by two reviewers (EK and AB) on nine STAs. Following the pilot, amendments were made. These included standardising data entry and insertion of comment boxes where clarification of the data was required.

The majority of the data for each STA was obtained from the NICE guidance website. 6 Three reviewers (DP, AB and EK) extracted the data. After data extraction was completed a sample of nine STAs was taken and data were checked by a second reviewer (DP, EK or AB) who had not completed the initial data collection in order to verify that data extraction had been undertaken in a consistent manner by all reviewers. Where data were not available on the NICE website, for example referral date in some cases or the date of ERG report submission, the information was requested from NETSCC.

Data analysis

Data analysis was completed in Excel. The majority of analyses involved calculating frequencies for each topic considered in the mapping tool/spreadsheet. This was used, for example, to calculate the number of STA projects that were completed, in progress, suspended or terminated. The number of working days for the following time periods were calculated and then the values were divided by five to calculate the number of working weeks:

-

referral date to FAD, i.e. total length of project

-

date of commencement (date of final scope) to FAD, i.e. total length of ‘active’ project

-

referral date to final scope date

-

date of manufacturer report submission to ERG report submission

-

date of ERG report submission to first AC

-

date between first AC and second AC

-

date between second AC and FAD.

The exact date (day/month/year) was not provided on documents such as the final scope and FAD. The date was usually provided only in month/year format on the documents and an exact date of upload was provided on the NICE website. Where the month of issue differed on the scope or FAD document from the month stated on the NICE website for the document upload, the month listed on the document was used and the 28th day of the month was chosen as the ‘exact date’ in order to perform analyses between the different stages in the STA project timeline. Where the month agreed between the document and date of upload on the NICE website, the exact date listed as the upload date on the NICE website was used. For either scenario, these decisions meant that the analyses would underestimate, rather than overestimate, the time taken between stages in the STA process. Similarly, when the exact date of referral provided by NETSCC was not available, the 28th day of the month that the STA was referred was selected for each referral date. Simple descriptive statistics, such as calculating the mean and range, were applied where appropriate.

The NICE disease categories to which STA topics were allocated were obtained from the NICE website and the numbers within each category were tabulated. Information on DSU involvement and appeals was obtained from the NICE website and the information summarised in a narrative synthesis. The number of suspended or terminated appraisals was tabulated and reasons summarised. A completed STA was defined as an STA that had received a final decision (FAD) from NICE on the technology being considered. STAs that had previously received a final decision from NICE but which was subsequently withdrawn were not included in the completed STA category.

Results

Single technology appraisals by characteristics

Ninety-five STAs had been identified in the NICE appraisal process since the STA programme began in 2005 up to, and including, March 2009 as per the list provided by NETSCC.

Topic area

Single technology appraisals are categorised by topic on the NICE website. There are 21 topic categories. Table 1 shows the categorisation of topics identified in the mapping exercise. Some topics are listed under more than one category, for example ‘pemetrexed for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer’7 is listed under cancer and respiratory. Thirty-one STAs were listed in more than one category. The majority of topics were cancer topics. Under the cancer category, some STAs, such as those concerning satraplatin for hormone-refractory prostate cancer and capecitabine for advanced pancreatic cancer, were not listed on the NICE website and the topic category was assigned on the basis of the title of the appraisal by the authors of this report.

| STA topics in NICE disease categories | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Cancer | 46 |

| Musculoskeletal | 15 |

| Digestive system | 13 |

| Respiratory | 11 |

| Cardiovascular | 9 |

| Therapeutic procedures | 7 |

| Skin | 7 |

| Central nervous system | 5 |

| Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic | 4 |

| Infectious diseases | 3 |

| Blood and immune system | 2 |

| Gynaecology, pregnancy and birth | 2 |

| Eye | 1 |

| Injuries, accidents and wounds | 1 |

| Mental health and behavioural conditions | 1 |

| Public health | 1 |

| Urogenital | 1 |

| Diagnostic procedures | 0 |

| Ear and nose | 0 |

| Mouth and dental | 0 |

| Surgical procedures | 0 |

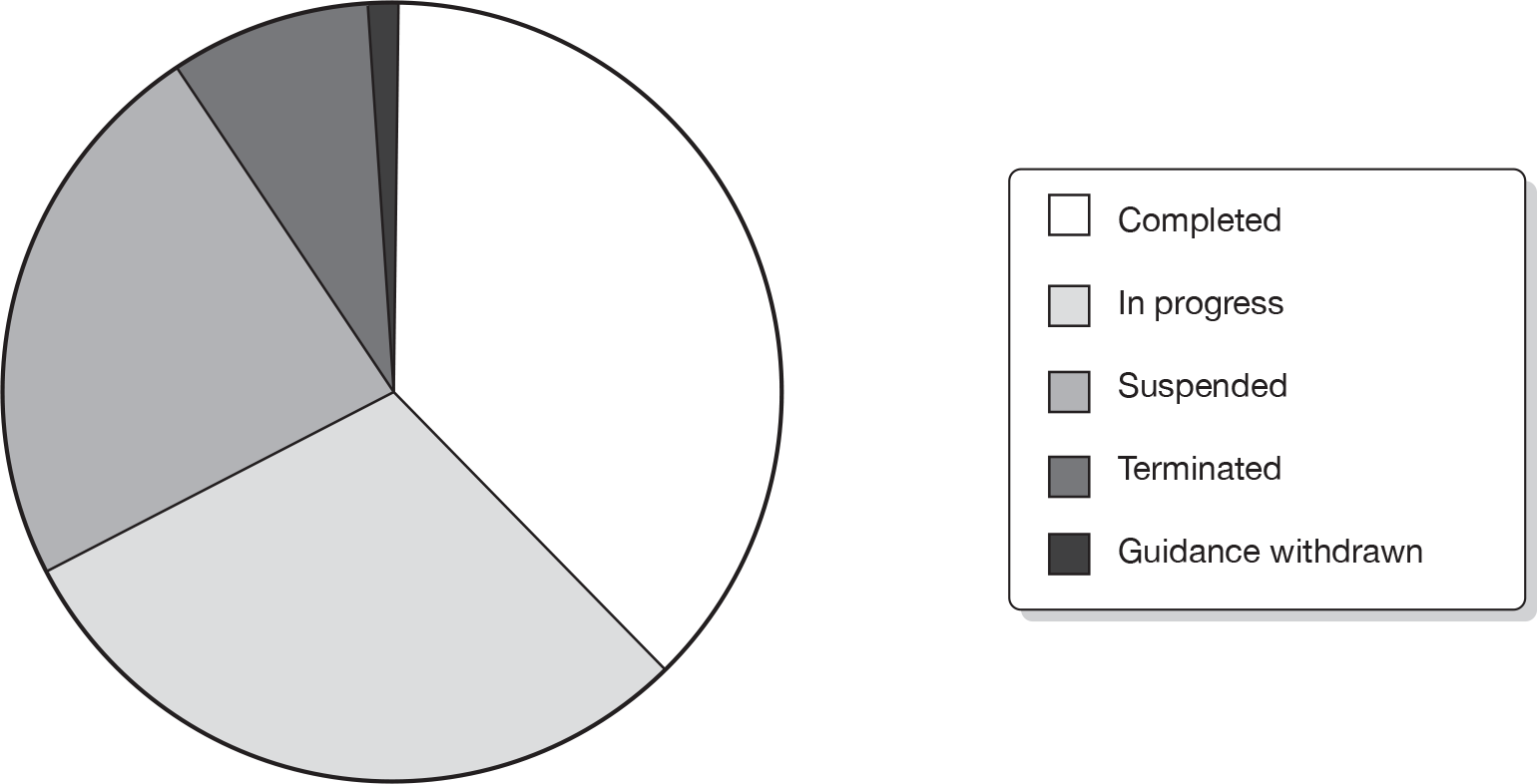

Single technology appraisal report and project status

Of the 95 STAs identified, 36 were categorised as completed STAs (38%), 28 were in progress (29%), 22 (23%) had been suspended, eight terminated (8%) and one had been completed but subsequently the guidance was withdrawn (1%). Three of the 95 STAs (satraplatin for hormone-refractory prostate cancer, etanercept for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents and rimonabant for type 2 diabetes mellitus) had passed through the topic selection process but were not referred to NICE. See Figure 2 for STA project status.

FIGURE 2.

Single technology appraisal project status.

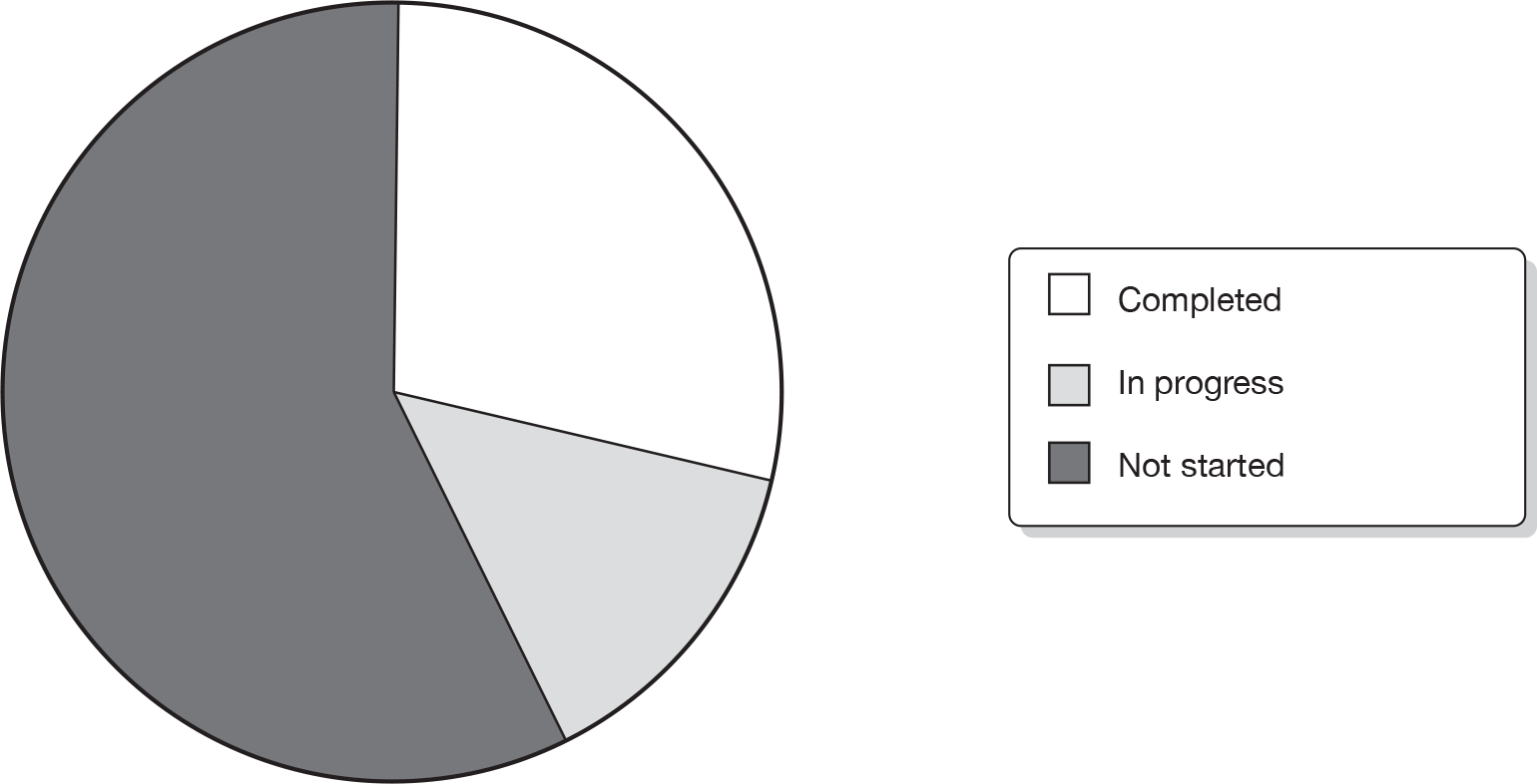

Of the 28 in-progress STAs, eight had completed ERG reports, four had ERG reports not yet completed and 16 ERG reports had not yet commenced (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Evidence Review Group report status.

Of the 31 STAs that had been suspended or terminated or had their guidance withdrawn, three ERG reports had been completed. For two of these appraisals (mifamurtide for osteosarcoma and romiplostim for thrombocytopenic purpura) the appraisals were suspended due to delays in drug launch. For the third appraisal (rimonabant for type 2 diabetes mellitus) the guidance was withdrawn.

Manufacturer

Sixty-four STAs had a named manufacturer, while the remaining 31 did not have a manufacturer reported on the NICE website, usually because the STA process for those topics was still in the early stages. Twenty-seven manufacturers have been involved in the STA process to date. Table 2 lists manufacturers and the numbers of STAs they have been involved in.

| Manufacturer | No. of STAs |

|---|---|

| Roche Products Ltd | 12 |

| Schering-Plough Ltd | 6 |

| Bristol-Meyers Squibb Pharmaceuticals Ltd | 5 |

| Eli Lilly & Co | 4 |

| GlaxoSmithKline | 3 |

| Merck Serono | |

| Sanofi-aventis | |

| Abbott Laboratories Ltd | 2 |

| AstraZeneca | |

| Boehringer Ingelheim | |

| Celgene | |

| Janssen-Cilag | |

| Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd | |

| Pfizer Ltd | |

| Archimedes | 1 |

| Amgen | |

| Basilea Medical | |

| Bayer | |

| Bayer Schering Pharma | |

| Biogen | |

| Gilead Sciences | |

| IDM Pharma | |

| Ipsen Ltd | |

| PharmaMar | |

| Schering Health Care Ltd | |

| UCB | |

| Wyeth Pharmaceuticals |

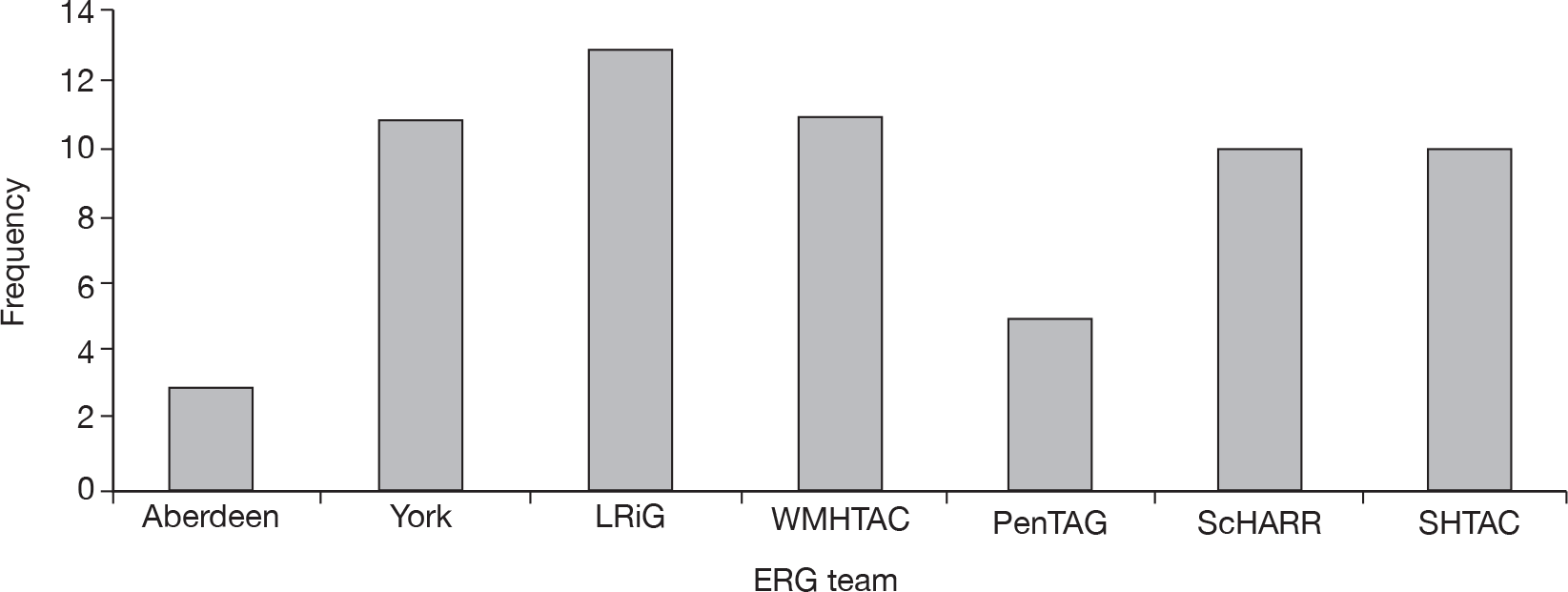

Evidence Review Group team

Sixty-three of the STAs had been assigned an ERG team. Five teams undertook 10 or more ERG reports and the remaining two teams undertook three and five reports (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Evidence Review Group teams.

Decision process in completed and in-progress single technology appraisals

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios reported

Thirty-six completed STAs and seven in-progress STAs contained figures for the base-case incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) reported by the manufacturer within their submission. Thirty-three completed STAs and seven in-progress STAs included figures for base-case ICERS reported by the ERG within their report.

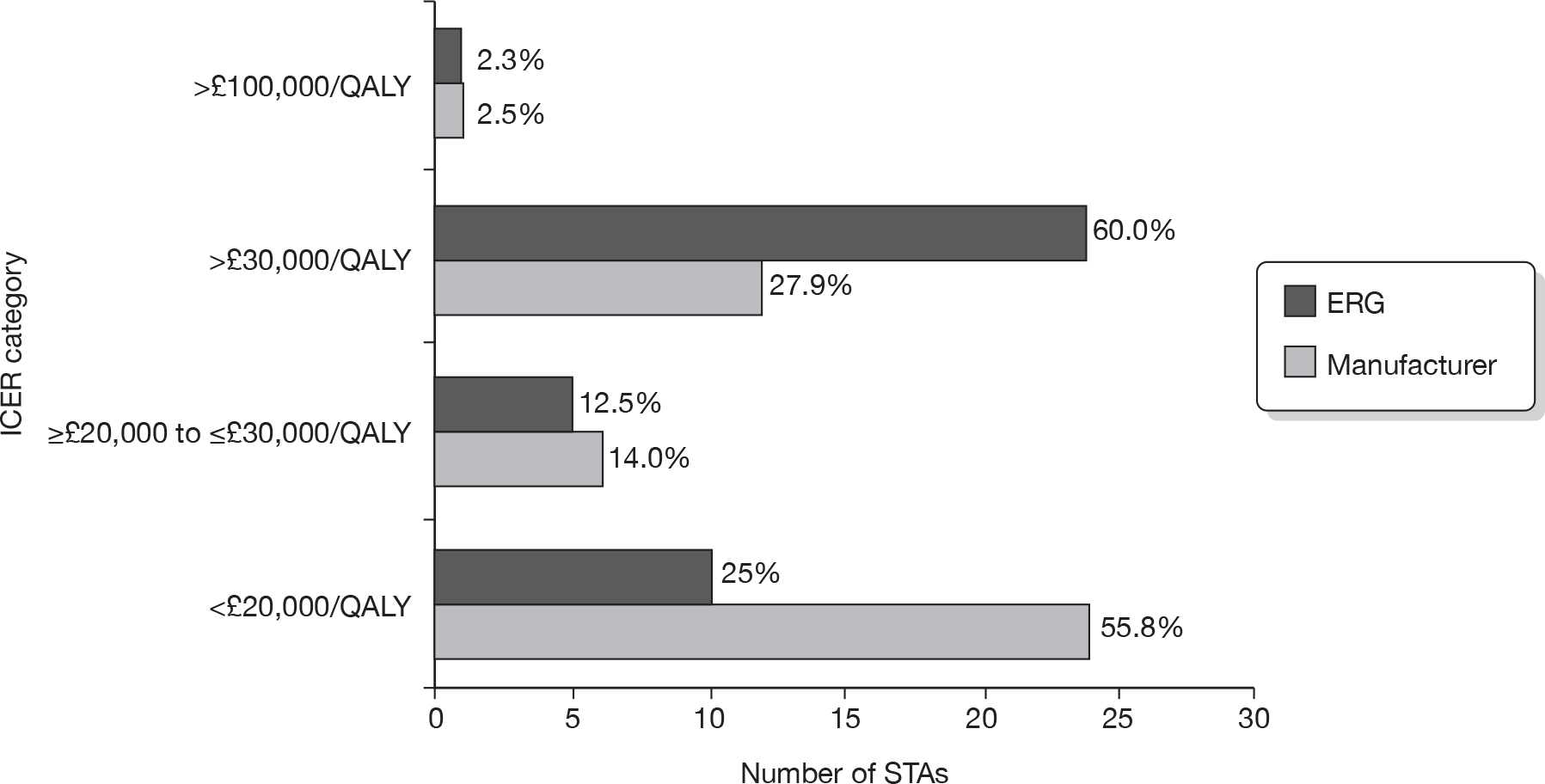

Significant differences were seen when the manufacturer and ERG base-case ICERs were compared. The manufacturer base-case ICERs were > £30,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) in 13 cases and < £30,000 per QALY in 30 cases. In contrast, the ERG base-case ICERS were reported as > £30,000 per QALY in 25 cases and < £30,000 per QALY in 15 cases (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Base-case ICERs reported by ERG and manufacturer.

In three ERG reports, a clear figure for the base-case ICER calculated by the ERG was not reported. 8–10 One ERG report stated that a £30,000-per-QALY threshold analysis was conducted (natalizumab for the treatment of adults with highly active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis8); one ERG report estimated two base-case ICERs of > £30,000 and > £100,000 per QALY (pemetrexed for the treatment of relapsed non-small cell lung cancer9); and one ERG report stated that the ERG was unable to provide revised ICERs (pemetrexed for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer10).

Appraisal consultation document decision

The AC can make various recommendations in the ACD. Obviously there can be a clear ‘yes’, a clear ‘no’ or a ‘minded’ opinion. A ‘minded’ opinion usually means that the AC is minded to say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ but that it requires further information, usually from the manufacturer, to make its decision at the subsequent AC meeting. There were 38 STAs with ACD decisions available on the NICE website (31 completed STAs and seven in-progress STAs). Nineteen had a ‘no’ recorded as the ACD decision, nine were recorded as ‘yes’ decisions and seven had ‘minded no’ decisions within the ACD (Table 3). Two STAs had both a ‘yes’ and a ‘minded no’ decision recorded within the ACD and one STA had both a ‘no’ and a ‘minded no’ recorded in the ACD.

| ACD decisiona | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Yes | 9 (23.7) |

| No | 19 (50.0) |

| ‘Minded no’ | 7 (18.4) |

| Yes and ‘minded no’ | 2 (5.3) |

| No and ‘minded no’ | 1 (2.6) |

| ACD not on website | 5 (N/A) |

Appraisal consultation documents were not made available on the NICE website for five completed STAs11–15 (trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer;11 varenicline for smoking cessation;12 dabigatran etexilate for the prevention of venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing elective hip and knee surgery;13 rituximab for the first-line treatment of low-grade follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma;14 and rivaroxaban for the treatment of venous thromboembolism15). However, ACDs are issued only if the AC recommendations are restrictive or if the manufacturer is requested to provide further clarification, and therefore ACDs are not issued for all STAs.

Two STAs had two ACDs, of which one had a ‘no’ decision recorded in its first ACD and then a ‘yes’ decision in the second ACD,16 and the other had a ‘no’ decision recorded in its first ACD and then a ‘yes’ decision with conditions in the second ACD. 17

Final appraisal determination decision

Thirty-six completed STAs and one in-progress STA had FAD decisions. Twenty-five STAs were recorded as ‘yes’ decisions, whereas 12 were recorded as ‘no’ decisions. Thirty-two STAs had both ACD and FAD documents available on the NICE website. Table 4 shows the initial ACD decision (taken from the first ACD if more than one ACD) and subsequent FAD decision in the 32 STAs with both ACDs and FADs. All ‘yes’ decisions and 10 out of 14 ‘no’ decisions remained the same between the ACD and FAD. ‘Minded no’ and ‘yes/minded no’ decisions within the ACDs almost always became ‘yes’ decisions within the FAD. The one exception was a ‘minded no’ to ‘no’ decision between the ACD and FAD. In this case, a subsequent appeal was upheld. After additional work was undertaken by the DSU, the AC met again and the ‘no’ decision in the FAD was subsequently changed to a ‘yes with conditions’ (erlotinib for the treatment of relapsed non-small cell lung cancer18).

| ACD decision | FAD decision ‘yes’ | FAD decision ‘no’ |

|---|---|---|

| Yes | 8 | 0 |

| No | 4 | 10 |

| ‘Minded no’ | 6 | 1 |

| Yes and ‘minded no’ | 2 | 0 |

| No and ‘minded no’ | 0 | 1 |

Project timeline (dates analyses)

Table 5 shows the breakdown of project timelines for the 36 completed STAs. Some of the analyses are based on fewer than 36 STAs as some of the data were missing, for example scope dates or AC dates.

| Date analysis | Mean (range) in working weeks |

|---|---|

| Referral date to FAD | 54.9 (30.4 to 131.0) |

| Final scope to FAD | 44.0 (26.2 to 122.2) |

| Referral date to scope | 15.3 (4.4 to 83) |

| MS to ERG report submission | 10.5 (8.2 to 23.8) |

| ERG report to first AC | 5.3 (3.4 to 11.2) |

| First AC to second AC | 10.4 (8.2 to 22) |

| Second AC to FAD | 8.2 (3.0 to 29.8) |

Referral date to final appraisal determination

The NICE STA process guide3 states on p. 18, in section 3.2.1, that the STA process begins ‘after NICE has received formal referral from the Secretary of State for Health’. However, no guidance is given with regards to the length of the STA project between the referral date and the FAD. Week 0 on the STA project timeline is when manufacturers are invited to complete an evidence submission or when the final scope is issued. The time from final scope to FAD should be 34 weeks or less, as stated in the 2009 STA process guide3 (when there is no appeal). In the original STA process guide (2006)19 this was stated to be 35 weeks.

The time period between the referral date and final scope date (i.e. week 0) ranges considerably between 4.4 and 83 working weeks (see Table 5). The length of the entire STA project was taken as the number of working weeks between the referral date and the FAD date. The mean number of working weeks between the referral date and the FAD in the 36 completed STAs was 54.9. This ranged considerably between 30.4 and 131.0 working weeks. The majority of completed STAs (27/36) took between 39 and 60 weeks to complete from their referral to FAD.

Final scope to final appraisal determination

The 35-week final scope to FAD time period for a completed appraisal was used in this analysis, as some of the STAs were completed before 2006. A 2-week grace period was added to allow for holiday periods and other delays, making the cut-off point 37 weeks for a completed, on-time STA. Scopes (and scoping workshops) were not part of the initial STA process and seven STAs did not have a final scope available on the NICE website. It was therefore not possible to calculate the time period between the issue of final scope and FAD in these seven STAs. Eight of the 29 STAs where it was possible to calculate time to completion were completed within 37 working weeks, i.e. 28% of STAs were completed within a period that could be considered ‘on time’ when the final scope date is taken as the start of the process and there is no appeal process. The mean number of working weeks between the final scope and FAD in the 36 completed STAs was 44.0. This ranged considerably from 26.2 to 122.2 weeks.

The scope to FAD period for 12 STAS was delayed between 2 and 5 weeks. Possible reasons made available on the NICE website for the 2- to 5-week delay were provided for two STAs only and included appraisal suspension (omalizumab for severe persistent allergic asthma20) and transfer from the 10th to the 12th wave (natalizumab for the treatment of adults with highly active relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis8). A third STA was recorded to have a 2- to 5-week delay between scope and FAD (docetaxel for adjuvant treatment of early breast cancer21). However, this STA had been transferred from the MTA to the STA process and thus the final scope date related to that of the original MTA (scopes were not initially provided for STAs). There did not appear to be any reasons provided on the NICE website as to why the remaining nine STAs were delayed between 2 and 5 weeks. However, it was noted that four of the STAs required extra work from the manufacturer22–25 (adalimumab for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriatic arthritis,22 rituximab for the treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis,23 rituximab for the treatment of recurrent or refractory stage III or IV follicular non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma,24 and entacavir for the treatment of chronic hepatitis B25) and extra work was undertaken by the ERG for one STA26 (cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic and/or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck26).

The scope to FAD period was delayed by > 5 weeks for two STAs,7,27 for which no apparent reasons were provided on the NICE website (ustekinumab for the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis27 and pemetrexed for the first-line treatment of locally advanced or metastatic non-small cell cancer7). A further seven STAs had scope to FAD periods delayed by > 10 weeks. Reasons for scope to FAD periods being delayed by > 10 weeks were provided for six of these STAs and included appeal proceedings (erlotinib – non-small cell lung cancer,18 abatacept,28 febuxostat29), additional work undertaken (erlotinib18), end-of-life consideration with production of two ACDs (lenalidomide16), first AC meeting cancelled owing to clarification of European regulatory timings (febuxostat29), timings reset at the request of the manufacturer to allow for the outcome of discussions with the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency to be incorporated in the MS (abatacept28), third and fourth AC meetings (cetuximab for colorectal cancer30) and a FAD returned with comments after the second AC (sunitinib31). There were no apparent reasons stated on the NICE website to explain why the scope to FAD period for the infliximab for ulcerative colitis32 STA was delayed by 14.2 weeks.

In addition, seven STAs are delayed and were still in progress at the time of data extraction (August 2009):

-

Topotecan for the treatment of recurrent and stage IVB carcinoma of the cervix (third AC meeting for end-of-life consideration). 33

-

Tocilizumab for the treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis (delay due to pricing issues, guidance delayed as a result). 34

-

Bevacizumab in combination with non-taxane chemotherapy within its licensed indications for the first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer (rescheduled to align with regulatory approval). 35

-

Trabectedin for the treatment of advanced metastatic soft tissue sarcoma (extension granted for manufacturer to meet full requirements of the STA process). 36

-

The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of erlotinib monotherapy for maintenance treatment of non-small cell lung cancer after previous platinum-containing chemotherapy (rescheduled to align with regulatory expectations). 37

-

The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of erlotinib in combination with bevacizumab for maintenance treatment of non-squamous advanced or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer after previous platinum-containing chemotherapy (rescheduled to align with regulatory expectations). 38

-

Rituximab for relapsed treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (delays due to variation to marketing authorisation). 39

If these delays had been taken into account then the overall time frame for the 95 STAs would have been lengthened.

Manufacturer submission to Evidence Review Group report submission

The appendix B document in the NICE STA process guide3 (p. 56) allows 8 weeks between the manufacturer report submission and ERG report submission. The NICE guidance also stipulates that ERG teams will be given a minimum of 8 weeks to complete the ERG report. Eighteen (50%) of the completed STA ERG reports were completed within 8–10 working weeks and a further 14 (39%) STA ERG reports were submitted 10–12 working weeks after receipt of the MS. The mean number of working weeks between the manufacturer report submission and ERG report submission in the 36 completed STAs was 10.5. This ranged considerably between 8.2 and 23.8 working weeks. The majority of STAs (32/36) took 8–12 working weeks between the manufacturer report submission and ERG report submission.

Evidence Review Group report submission to first Appraisal Committee

The first AC is scheduled to take place 4 weeks after the ERG report has been submitted, and this was the case for 5 out of the 36 completed STAs. The first AC meeting was 4–5 weeks after the ERG report submission in 15 STAs and 5–7 weeks in 13 STAs. The mean number of working weeks between the ERG report submission and first AC in the 36 completed STAs was 5.3. This ranged considerably between 3.4 and 11.2 working weeks.

First Appraisal Committee to second Appraisal Committee

The second AC is scheduled to take place 8 weeks after the first AC. The mean number of working weeks between the first AC and second AC in the 36 completed STAs was 10.4. This ranged considerably between 8.2 and 22 working weeks. The time period between the first AC and second AC in two-thirds of completed STAs (24/36) was between 8 and 10 working weeks.

Second Appraisal Committee to final appraisal determination

The FAD is published (if no appeal is received) 10 weeks after the second AC meeting, although a second AC meeting is not held if an ACD is not produced at the first AC meeting. In all but four STAs this was achieved. The mean number of working weeks between the second AC and the FAD in the 36 completed STAs was 8.2 working weeks. This ranged considerably between 3 and 29.8 working weeks. The time period between the second AC and the FAD was 3–5 weeks in six STAs and 5–9 weeks in 20 STAs.

Extra work involved in the single technology appraisal process

Manufacturer

After the first AC meeting, in 11 out of 36 of the completed STAs and in one out of seven of the in-progress STAs, the manufacturer was requested to complete further work before the second AC meeting.

Evidence Review Group

Before the first AC meeting, in 5 out of 36 of the completed STAs and in three out of seven of the in-progress STAs, the ERG was requested to complete work in addition to the ERG report. After the first AC meeting, in 4 out of 36 of the completed STAs and in one out of seven of the in-progress STAs, the ERG was requested to complete further work before the second AC meeting.

Decision Support Unit involvement

Three STAs had involvement from the NICE DSU:

-

cetuximab for first-line treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer30

-

erlotinib for the treatment of relapsed non-small cell lung cancer18

-

lapatinib for breast cancer for use in women with previously treated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer. 40

In one of these STAs it appears that the decision of the AC changed from ‘no’ in the ACD to ‘yes’ with restrictions in the FAD (cetuximab30). For one of the STAs (erlotinib18) the decision changed from ‘minded no’ at ACD to ‘no’ at FAD; however, after additional work undertaken post appeal the decision was changed to ‘yes’ but with restrictions. For lapatinib,40 the decision remained ‘no’ at FAD although at the time of writing this STA is still ongoing.

End-of-life consideration

On 5 January 2009, NICE issued supplementary advice to be taken into account when appraising treatments which may be life-extending for patients with short life expectancy. 41 Four STAs16,26,33,40 have considered this supplementary advice: two completed STAs and two in-progress STAs. Lenalidomide for relapsed and/or refractory multiple myeloma (completed STA) recorded the first ACD decision as ‘no’, changing to ‘yes’ in the second ACD and FAD (requiring three ACs). 16 Cetuximab for the treatment of metastatic and/or recurrent squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (completed STA) recorded a ‘no’ decision within the ACD and FAD. 26 Lapatinib for breast cancer for use in women with previously treated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer (in-progress STA) recorded a ‘no’ decision within the ACD and FAD. 40 Following on from an appeal, this technology was put forward for end-of-life consideration. Topotecan for the treatment of recurrent and stage IVB carcinoma of the cervix (in-progress STA) recorded a ‘no’ in the ACD; the FAD decision is to be confirmed. 33

Appeals

In total, 8 out of the 36 completed appraisals in this analysis had an appeal. The appraisals were:

-

cetuximab in its licensed indications for refractory head and neck cancer26

-

erlotinib for the treatment of relapsed non-small cell lung cancer18

-

abatacept for the treatment of refractory rheumatoid arthritis28

-

trastuzumab as adjuvant therapy for early-stage breast cancer11

-

febuxostat for the management of hyperuricaemia in patients with gout29

-

lapatinib for breast cancer for use in women with previously treated, advanced or metastatic breast cancer40

-

pemetrexed for the treatment of relapsed non-small cell lung cancer42

-

bortezomib monotherapy for relapsed multiple myeloma. 17

Four of these appeals were dismissed (abatacept,28 trastuzumab,11 febuxostat29 and pemetrexed42). For three STAs – cetuximab,26 erlotinib18 and bortezomib17 – the appeals resulted in a change to NICE guidance. In all cases the decision became ‘yes’ with restrictions. At the time of writing, one STA (lapatinib40) was ongoing (March 2010).

Suspended/withdrawn/terminated single technology appraisals

Overall, 30 of the 95 STAs (32%) in this study were either suspended or terminated. Guidance was released and later withdrawn by NICE for one STA (rimonabant for the treatment of overweight and obese patients43).

Twenty-two STAs are listed as suspended. In two of these STAs, the ERG report had already been submitted when the appraisal was suspended. Reasons for suspension include the drug not yet launched (2), indication for the drug uncertain (1), regulatory or licensing issues (11), no MS received (1), further data awaited by manufacturer (3), referral to MTA process (1) and no reason given (3). Eight STAs are listed as terminated. Three STAs passed through topic selection but were not referred to NICE; two were terminated because no MS was received by NICE. No reasons were stated on the NICE website for the other three terminated STAs.

Record-keeping and consistency issues

Nearly all of the information used in this mapping analysis was obtained from the NICE website; therefore the information described in this report is a reflection of the record-keeping on the website and not necessarily an accurate reflection of what actually happened during the appraisal process. There are a number of issues regarding record-keeping and consistency requiring further discussion.

Dates

Full dates (day/month/year) were often not recorded within documents published on the website; often only the month and year were available and this made calculation of timings difficult. Where exact dates were not published within documents, such as the scope and FADs, we used the 28th of each month as the date of issue. Therefore, there is some inaccuracy and underestimation within these analyses.

There were also other inconsistencies with dates. Often the month of issue within the scope and FAD documents was not the same as the month stated on the website. Examples of this are romiplostim for the treatment of chronic immune or idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)44 and paclitaxel for the adjuvant treatment of early breast cancer. 45

Documentation

Some documents were missing from the NICE website, such as ACDs and final scopes. This could be due to the fact that initially scoping documents and ACDs were not part of the STA process and were later additions. In some appraisals there were two FAD documents and it was not always clear why.

Transparency and inconsistencies

Reasons for delays, suspensions or terminations are not always clear on the NICE website. As each appraisal does not have a unique identifying number, and there are several appraisals for the same drug within different conditions, it was sometimes difficult to find information on a specific appraisal.

Three STAs in this mapping exercise had passed through the topic selection process but were not referred to NICE: two of these are listed on the NICE website, although difficult to find, while one is not mentioned at all (etanercept for moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis in children and adolescents).

As described previously, there is inconsistency in the way STAs are categorised by topic. The terms ‘suspended’ and ‘terminated’ are not used consistently. NICE continues to monitor topics that are referred to it even if the appraisal has ended. STAs also occasionally have different titles within different documents relating to the same appraisal that occasionally caused confusion.

Discussion

Almost all of the necessary relevant documentation relating to each STA included in this mapping exercise was available on the NICE website. However, some information was difficult to locate and there was inconsistency in the details related to dates of topic referral. A guide for the public regarding where specific documentation is kept could be useful.

Within a relatively short time period NICE has dealt with 95 STA topics. Base-case ICERs reported by the ERGs were consistently higher than those reported by manufacturers. Extra analyses were requested of manufacturers in 28% of STAs, which translates to extra work for the ERGs. Not all of the extra work required of the ERGs was recorded on the NICE website.

Lack of consistency in recording referral dates meant it was difficult to calculate the total STA process timelines. However, it is noted that the length of time between referral date and final scope date can be substantial.

The majority (78%) of STAs in this study do not meet the established 35-week scope to FAD target. The delays are attributable not to delays in submission of ERG reports or the scheduling of AC meetings but to delays in other aspects of the process.

The first delay point relates to STAs that were suspended or terminated. We identified that 32% (30/95) of the topics were in this category, with a further seven marked as in progress but delayed. The vast majority of topics in these groups were stopped because of regulatory issues and/or non-submission by the manufacturers.

Suspended/terminated appraisals have significant resource implications. Each topic referred as part of the STA process includes a scoping workshop to which the appropriate stakeholders are invited to comment on the proposed scope for the STA. These meetings can involve as few as 10 people or as many as 30 and they take a half-day plus travel time for each participant. Delays can also occur further along in the process, resulting in substantial waste of resources.

The next delays occur after the first AC meeting. Although not always the case, requests for additional analysis from the manufacturer or the ERG have the potential to delay the second AC meeting and therefore the FAD. This is not a common occurrence but does happen. In addition, this subsequent analysis may require input from the DSU, additional AC meetings and subsequent consultation on further ACDs. These are all resource-intensive activities. Anecdotal evidence has been provided by one ERG indicating that one STA is now at its fifth AC meeting.

However, the longest delay in the process takes place when an appeal is made, usually by the manufacturer. This occurred in 22% (8/36) of completed appraisals included in this analysis, with one of these going on to judicial review. The appeal process is very time-consuming for all of those involved, although manufacturers are likely to take heart in the fact that half of the topics that went to appeal resulted in approval (although with restrictions) of their product.

The STA process is already complex and, looking to the future, is likely to become more so, and these complexities have potential to add even further delays to the release of guidance. The introduction of the consideration of end-of-life issues and PASs3 has the potential to extend the STA processes.

Chapter 3 Thematic analysis of Evidence Review Group reports

Methods

A documentary analysis of the first 30 ERG reports was undertaken. For this research we were exclusively interested in the content, rather than the context, of the reports. Attention was focused neither on the context within which the documents were produced nor on their subsequent impact on external decision-making processes, but rather on the content of the reports, making this a content analysis approach. Content analysis is a strategy ‘to identify consistencies and meanings’ in the text, with the aim of identifying patterns, themes and categories; the document is viewed as ‘a container of static and unchanging information’. 46 The 30 ERG reports were anonymised and are referred to in this report as numbers 1–30.

Data extraction was conducted by three team members (AB, CC, PF), using forms developed for this project and piloted on two ERG reports (see Appendix 4). The aim of the extraction was to retrieve data on key elements of the MSs, the processes undertaken by ERGs, and the strengths and weaknesses of the MSs. To address these first two issues, data were extracted on key elements, such as the number of trials included, whether or not a meta-analysis or sensitivity analysis (SA) was performed, and whether or not ERGs replicated submissions searches. These findings are presented as descriptive statistics (see Descriptive statistics from the 30 Evidence Review Group reports, below).

Second, data were extracted on the ERGs’ assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of MSs (see Thematic analysis results, below). These data consisted of text, i.e. statements or summaries by the ERG, so an appropriate form of analysis was applied. Thematic analysis was chosen as this method is grounded in the data and permitted the generation of a novel theoretical framework reflecting the ERGs’ assessments of the strengths and weaknesses of MSs to the STA process. 47 This method of synthesis is interpretive and the first stage is data reduction, i.e. to reduce statements, comments, quotations or findings to a single theme, which captures or reflects those data. This process was initially performed by one reviewer (CC) on the extractions of the strengths, weaknesses, key issues and uncertainties sections in the executive summaries of a random sample of 10 ERG reports. This section of the ERG report was chosen for the primary analysis because it should reflect most if not all of an ERG’s comments on the submission that appear elsewhere in the ERG report. If themes identified in this way were considered to be related then they were placed under a broader theme that captured them all; for example, ‘inappropriate analysis’ and ‘issues with data in the analysis’ were both placed within the broader theme of ‘processes’, and ‘population issues’ and ‘comparator issues’ within the broader theme of ‘satisfying objectives’. Definitions were developed for each theme in order to produce greater reliability in the coding of data, especially when this was carried out by more than one reviewer. Two members of the project team (RD and EK) then independently assessed whether these interpretations of the data were both credible and appropriate, and whether the themes identified reflected the data. This led to a small number of revisions: the relabelling of one theme, the reassignment of some data to different themes, and some further clarification of the themes’ definitions.

The remaining textual data in the data extraction forms, i.e. from the strengths, weaknesses, key issues and uncertainties sections of the other 20 ERG reports, as well as all other textual data extracted from all 30 ERG reports relating to the MSs, were then coded using these agreed themes following a process akin to that outlined in framework analysis. 48 This was performed by two reviewers (CC and EK), each working on the data extracted from 15 of the ERG reports.

Results

Descriptive statistics from the 30 Evidence Review Group reports

Description of manufacturers’ submissions

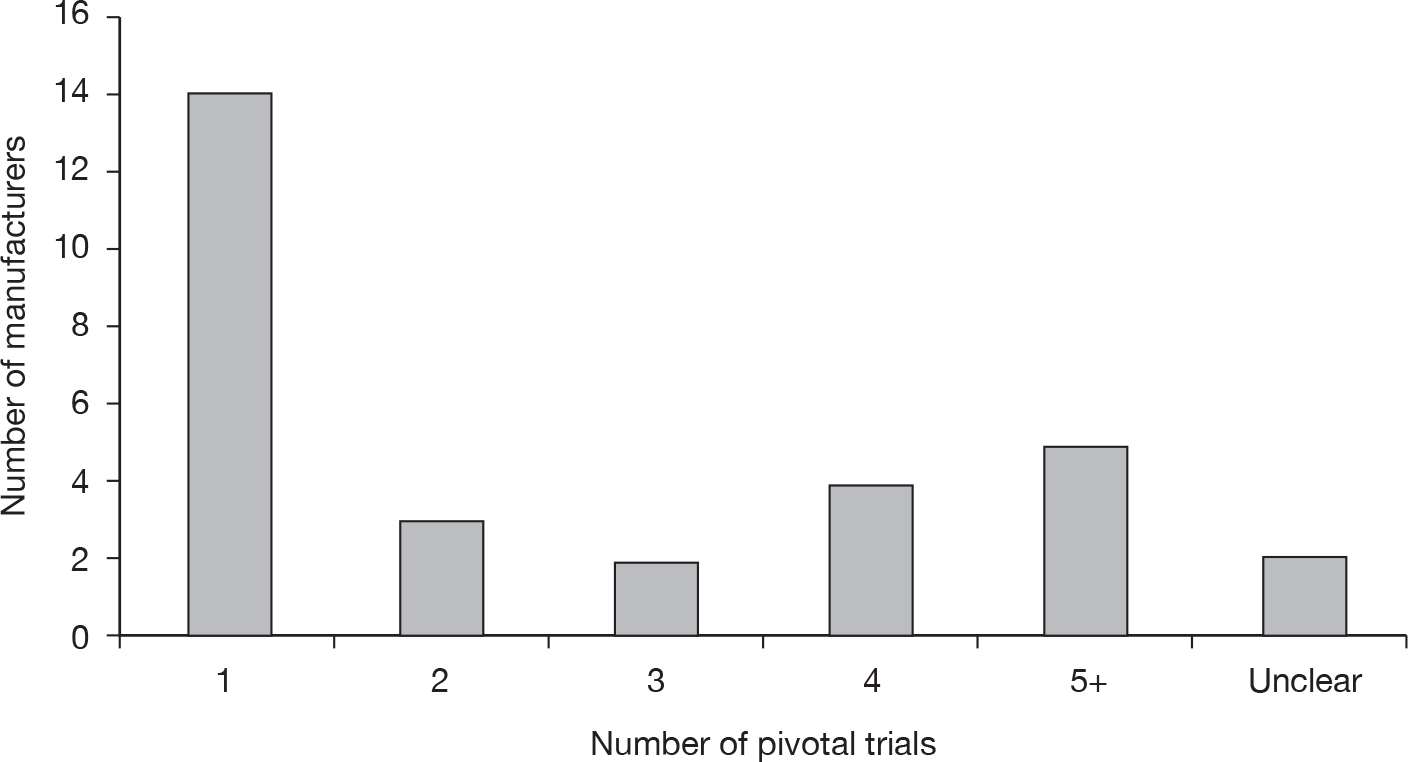

The numbers of pivotal trials included in the MSs are shown in Figure 6. Less than half of MSs included only one pivotal trial.

FIGURE 6.

Number of pivotal trials included by manufacturers.

Eight manufacturers (27%) included a meta-analysis in their submission, although as 14 out of 30 submissions included only one pivotal trial then a meta-analysis would not have been appropriate in these submissions. Nineteen manufacturers (63%) undertook an indirect comparison, 29 (97%) undertook SAs and 28 (93%) carried out probabilistic sensitivity analyses (PSAs).

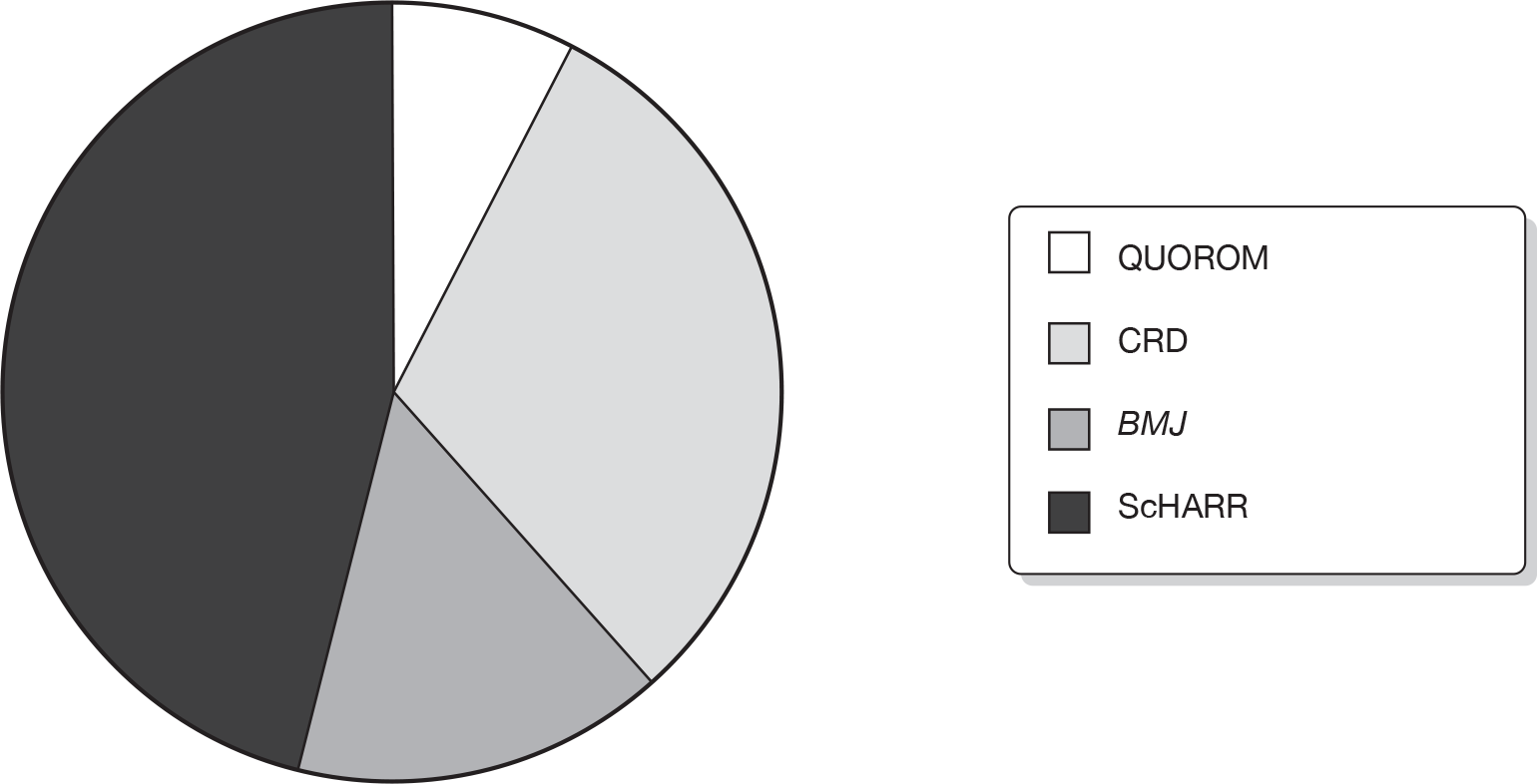

Description of Evidence Review Group approaches to critical appraisal of clinical evidence

In 26 (87%) ERG reports the team commented on the searches in the MS and 14 (47%) replicated the searches. Methods used to critically appraise the manufacturer’s systematic review were not always clear. Thirteen (43%) ERG reports stated that a published critical appraisal tool was used to assess the quality of the review. These included the QUOROM (quality of reporting of meta-analyses),49 CRD,50 BMJ (British Medical Journal)51 and ScHARR52 tools. Figure 7 shows the tools used in the 13 ERG reports reporting that published tools were used.

FIGURE 7.

Published tool used to appraise quality of manufacturer’s systematic review.

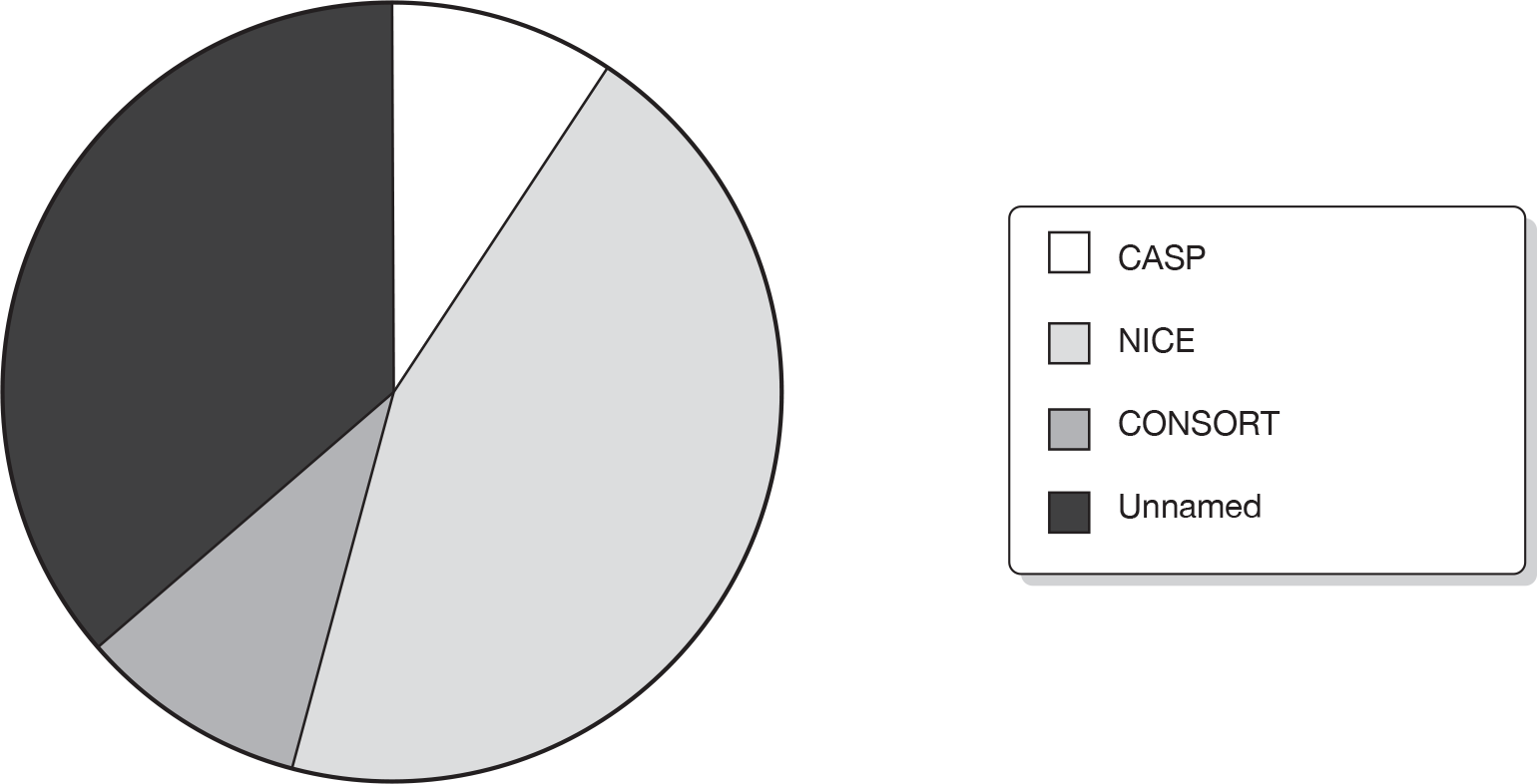

Only 11 (37%) used a published critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of the manufacturer’s included trials. In 12 (40%) methods for assessing the quality of the trials were unclear. Figure 8 shows the tools used in the 11 ERG reports reporting the use of a published tool, which included the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme),53 NICE1 and CONSORT (consolidated standards of reporting trials)54 checklists.

FIGURE 8.

Tools used in 11 ERG reports to assess trial quality.

In 11 (37%) ERG reports the team undertook additional analysis of the clinical data. Table 6 shows the reported number of clinicians used by the ERGs, either listed as an author or mentioned in the acknowledgement section in the 30 ERG reports.

| No. of clinicians | ERG reports |

|---|---|

| 0 | 1 (3%) |

| 1 | 10 (33%) |

| 2 | 11 (37%) |

| 3 | 1 (3%) |

| 4 or more | 4 (13%) |

| Unclear | 3 (10%) |

Description of Evidence Review Group approaches to critical appraisal of cost-effectiveness evidence

Sixteen (53%) of the ERG reports commented on the manufacturers’ searches for economic evidence and five (17%) replicated the searches. Only two (7%) of the ERG reports stated that a published tool was used to critically appraise the quality of included cost-effectiveness studies. In both cases the tool was the Drummond checklist. 55 Fourteen (47%) reports stated that the MS followed the NICE reference case1 (see Appendix 3). Table 7 shows the reported critique of the MSs in the ERG reports from the point of the view of items in the NICE reference case. Table 8 provides an overview of the elements used in the critique of the submitted model(s) by the ERGs. In the 30 ERG reports included in this study, 23 (77%) reported that extra cost-effectiveness analyses were undertaken. Table 9 shows the frequency of various approaches reported by the ERG teams to assess the models presented in the 30 MSs.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Perspective | ||

| Yes | 5 | 17 |

| No | 21 | 70 |

| Uncertain | 4 | 13 |

| Time horizon | ||

| Yes | 6 | 20 |

| No | 22 | 73 |

| Uncertain | 2 | 7 |

| Patient population | ||

| Yes | 13 | 43 |

| No | 14 | 47 |

| Uncertain | 3 | 10 |

| Choice of comparators | ||

| Yes | 12 | 40 |

| No | 15 | 50 |

| Uncertain | 3 | 10 |

| Choice of outcomes | ||

| Yes | 5 | 17 |

| No | 24 | 80 |

| uncertain | 1 | 3 |

| Costs | ||

| Yes | 19 | 63 |

| No | 11 | 37 |

| Uncertain | ||

| Alternative consideration of costs | ||

| Yes | 9 | 30 |

| No | 16 | 53 |

| Uncertain | 5 | 17 |

| Benefits | ||

| Yes | 16 | 53 |

| No | 13 | 43 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 3 |

| Alternative consideration of benefits | ||

| Yes | 9 | 30 |

| No | 15 | 50 |

| Uncertain | 6 | 20 |

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Choice of model structure | ||

| Yes | 14 | 47 |

| No | 15 | 50 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 3 |

| Health states | ||

| Yes | 9 | 30 |

| No | 20 | 67 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 3 |

| Sequencing of treatments | ||

| Yes | 4 | 13 |

| No | 9 | 30 |

| Uncertain | 16 | 53 |

| Incorporation of efficacy data | ||

| yes | 20 | 67 |

| no | 6 | 20 |

| uncertain | 4 | 13 |

| Incorporation of adverse events | ||

| Yes | 17 | 57 |

| No | 11 | 37 |

| Uncertain | 2 | 7 |

| Incorporation of survival data | ||

| Yes | 15 | 50 |

| No | 3 | 10 |

| Uncertain | 12 | 40 |

| Incorporation of QoL data | ||

| Yes | 18 | 60 |

| No | 11 | 37 |

| Uncertain | 1 | 3 |

| Mapping of health states | ||

| Yes | 6 | 20 |

| No | 4 | 13 |

| Uncertain | 20 | 67 |

| Replication of trial results | ||

| Yes | 10 | 33 |

| No | 4 | 13 |

| Uncertain | 16 | 53 |

| Type of continuity correction | ||

| Yes | 7 | 23 |

| No | 9 | 30 |

| Uncertain | 14 | 47 |

| Approach to discounting | ||

| Yes | 4 | 13 |

| No | 26 | 87 |

| Uncertain | ||

| Question | Response | Results | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Did the ERG comment on the methods used by the manufacturer to determine internal validity? | Yes | 17 | 57 |

| No | 9 | 30 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 4 | 13 | |

| Did the ERG comment on the transparency of the model? | Yes | 16 | 53 |

| No | 8 | 27 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 6 | 20 | |

| Did the ERG comment on the level of detail in the annotation to the model provided by the manufacturer? | Yes | 7 | 23 |

| No | 10 | 33 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 13 | 43 | |

| Did the ERG undertake additional economic analysis? | Yes | 23 | 77 |

| No | 7 | 23 | |

| Did the ERG run the manufacturer’s model with different parameter values? | Yes | 21 | 70 |

| No | 4 | 13 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 5 | 17 | |

| Did the ERG run the manufacturer’s model after making corrections to the model? | Yes | 12 | 40 |

| No | 8 | 27 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 10 | 33 | |

| Did the ERG carry out separate analysis of evidence to augment/replace aspects of the manufacturer’s submitted analysis? | Yes | 10 | 33 |

| No | 14 | 47 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 6 | 20 | |

| Did the ERG estimate revised ICERs as part of their additional analysis? | Yes | 20 | 67 |

| No | 2 | 7 | |

| Unclear/not stated | 8 | 27 | |

| How many economic advisors/economists did the ERG use? | 0 advisors | 20 | 67 |

| 1 advisor | 8 | 27 | |

| 2 advisors | 2 | 7 | |

Thematic analysis results

The thematic analysis generated a large number of themes. However, five broader themes emerged, under which themes related to one another could be meaningfully grouped. These five themes related to the ‘processes’ applied in the MSs; the ‘reporting’ of the submissions review and analysis processes (sometimes strong, sometimes poor); the ‘satisfaction of objectives’ by the submissions; the ‘reliability’ and ‘validity of the submissions’ findings; and the ‘content’ of the submissions (e.g. the amount and quality of evidence contained in the submissions). Numbers in parentheses refer to unique, anonymised identifiers relating to the ERG reports containing data that helped to generate that particular theme. The result was the creation of a framework of a priori themes with associated definitions (Table 10).

| Theme | Definition | Subthemes |

|---|---|---|

| Process | How various methodologies have been applied, e.g. in the performance of the review – searching, screening, extraction, appraisal; in the modelling – in the meta-analysis, in the performance of the review |

Conduct of review Conduct of modelling |

| Was an analysis performed? May include failure to include or perform all necessary analyses (e.g. in a model); inadequate conduct of the review or analysis | No or inadequate analysis | |

| Was the analysis method applied appropriate? May include inappropriate combining of data; inappropriate data being used to populate the model | Inappropriate analysis | |

| Issues concerning data used, especially in the modelling, including costs, parameters and assumptions | Issues with data used in analysis | |

| Reporting | Provision of sufficient or insufficient details about searching, selection, extraction, criteria, analyses performed and their rationale; descriptions and definitions provided in the Background section |

Adequate reporting Inadequate reporting |

| Satisfying objectives | Success or failure to answer question(s) set or for the submission to reflect the decision problem and its scope in terms of the target population, the intervention and its dose, relevant comparators and outcomes, and the NICE base case for the model |

Population issues Intervention issues Comparator issues Outcome issues NICE base case |

| Reliability and validity of findings | Excessive uncertainty surrounding results or model due to lack of evidence, bias within or across included trials or potential exaggerated effect of intervention; explicit concerns regarding validity |

Uncertainty due to absence of evidence Uncertainty due to possible bias or exaggerated effect |

| Findings reported as being reliable (as opposed to uncertain as above) and not uncertain | Reliability of findings | |

| Issues affecting external validity, e.g. specified differences between the trials and data and what exists in the UK, including population, dose, comparator, licensing, real-world/current practice; future developments that may change key parameters | External validity | |

| Content | Weaknesses or strengths inherent in the trial evidence. Amount – concerns issues with number of trials included (e.g. often only one); quality – concerns how good the included evidence is, e.g. very good or very poor? | Amount and quality of evidence |

Processes

The ‘processes’ theme emerged from five subthemes, which were interpretations of ERG comments on the conduct or performance of the reviewing and modelling in the submissions and, in particular, the conduct of the analyses. How well or how badly the manufacturer performed these key processes for the submission was a frequent source of criticism or comment within ERG reports. The five subthemes identified from the data were the conduct of both the review and the modelling processes; the inadequacy or inappropriateness of the analyses performed; and reported concerns with the data that were used in the analyses.

More than half of the ERG reports (17/30) explicitly criticised the conduct of the review, for example the quality of the searching, screening or quality assessment processes (1, 2, 5, 11, 13–17, 20, 27); the definition or application of inclusion criteria, especially for indirect comparisons (5, 7, 13, 15–17, 19, 20); the presence of errors in, or a failure to perform, meta-analyses (5, 16, 19); failure to control for confounders (6, 28) or perform a key subgroup analysis (28); or even the complete absence of a formal systematic review (9, 30). On some occasions, elements of the review process, such as searching and data extraction, prompted positive comments from an ERG (8, 10, 19, 20, 22, 25) or a statement that the review generally was reasonable or good (21, 26).

Evidence Review Group reports rarely commented explicitly positively on the approach taken in the submission to reviewing, modelling or analysis. However, half of all ERG reports (15/30) did pass positive comments on the appropriateness of the structure of the economic model presented or the reasonableness of the modelling approach taken (8, 9, 12, 14, 16–19, 21–23, 25–27, 30), albeit often with some criticism of certain elements of the model. Such weaknesses, highlighted in 20 ERG reports, included a failure to incorporate or capture adequate levels of uncertainty (1, 10, 17); calculation errors in the model requiring revision or correction (2, 3, 25); other technical, structural or design errors in the model or SA (4, 5, 7, 10, 11, 15, 17, 21, 22, 28, 30); and the failure to control for confounders (6) or queries over a key assumption (13), missing data (13, 17, 24, 29) or the absence of a SA (16).

The analyses performed by the manufacturers and reported in the submissions constitute another element of the effectiveness review process that was frequently critiqued by the ERGs. Criticisms of the inadequacies of the analyses presented consisted of the failure to address heterogeneity of trials (5); the failure to perform a relevant analysis, for example a meta-analysis or SA or PSA (6, 7, 16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 27); no validation of the model (6, 13); or the inadequate analysis of safety outcomes (15). However, it was not simply the failure to perform a necessary analysis, but rather the performance of an inappropriate analysis also, that generated criticism in 17 ERG reports, i.e. that the combination, pooling or comparison of effectiveness data was highly questionable (2, 7, 11, 17, 20, 21, 23–25) or that the methods used for the reported analysis (6, 8, 11, 13, 15, 20, 21, 27) or modelling (1, 5, 7, 29) were deemed to be inappropriate.

The other major criticism relating to analyses contained within submissions focused on issues with the data being used, especially the data used in the cost-effectiveness model. Two-thirds of ERG reports (20/30) contained such criticisms. These criticisms related to the efficacy data being used from both direct and indirect comparisons (8, 9, 14, 17, 18, 20, 23, 24); the cost data used (1, 5, 7, 18–20, 30); the utility or QoL data (1, 25, 27, 29, 30); the data on population, comparators, outcomes or various model parameters (5, 6, 8–10, 12, 18, 19, 23, 28); the use of unpublished data (23, 25, 29); and the data being used in the SAs or PSAs (7, 21). By contrast, the data used in the direct and indirect comparisons performed for the effectiveness review generated explicit criticism in only four ERG reports (5, 24, 25, 27).

Reporting

The ‘reporting’ theme was derived from explicit comments made in ERG reports on the quality of the manufacturers’ description of the conduct of both the reviewing and the modelling. Only in a small number of cases did ERGs make explicit, positive comments on the description of the technology or processes within MSs. Nine ERGs commented on the accuracy and adequacy of the background section provided in the submission (6–8, 10, 11, 13, 20, 27, 29), albeit in some cases stating that further information would still have been useful (11, 13, 20, 27). The reporting of the searches for the effectiveness review was praised in four ERG reports (3, 21–23) and the description of the model and its data sources in five ERG reports (21–23, 26, 29). One ERG specifically described good reporting of statistics (1), and another a well-reported multiple treatment comparison process (18).

It was far more common, however, for ERGs to perceive as inadequate the reporting or description of the processes being undertaken or the sources of data being used. A total of 26 out of 30 ERG reports described some form of inadequacy in the reporting of a submission. These included poor descriptions of the searches undertaken, prohibiting replication, for both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness reviews (2, 4–6, 8, 20, 26, 27); an explicit criticism in seven ERG reports regarding the lack of transparency of the clinical review processes generally, for both direct and indirect comparisons (e.g. screening, extraction and quality appraisal) (2, 5, 7, 11, 12, 20, 23); and, quite frequently, in eight ERG reports, inadequate reporting concerning the number of included studies and their characteristics for both clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness reviews (2, 4, 18, 19, 22–25). Five ERGs also considered the background section to be inadequate and lacking key information (14–16, 29, 30). The description of the analyses in submissions was also a major source of criticism, i.e. the failure to report data and data sources in full (1, 29, 30); the failure to describe all of the methods being used in direct (5, 20, 24, 27) or indirect comparisons (12, 17–19); the failure to provide adequate descriptions of the analyses more generally (6, 11, 18), and the poor reporting of included studies and data in tables (4, 5, 16). However, the submissions’ reporting of the cost-effectiveness model was the most common criticism by ERGs. Eleven submissions were deemed to be affected by such inadequacies as a failure to describe adequately the parameters or assumptions behind the model, the generation or source of various values, or the impact of bias from missing data (4, 11, 17–22, 27, 28, 30).

Satisfaction of objectives

The ‘satisfaction of objectives’ theme emerged from issues surrounding the relationship between the decision problem and whether, or how far, the elements of the decision problem were satisfactorily addressed in the MSs. The five subthemes identified under this theme relate to the objectives determined by the decision problem, i.e. the population, intervention, comparator, outcomes and the NICE base case.

Ten submissions were not criticised for the relevance of their included trial populations to the populations required by the scope, but 20 out of the 30 ERG reports did raise issues with the trial populations being presented and considered in the submission (1–3, 6, 7, 9–11, 15, 16, 18–22, 25–28, 30). These concerned differences between the population defined in the decision problem and the population being evaluated in the submissions’ trials (3, 9–11, 19, 20, 22, 25–27, 30); differences between the UK population and the trial population based on age, treatment or current practice (1, 2, 6, 7, 15, 27); differences between the licensed population and the trial population (9, 28); a failure to consider the effect of the treatment on different, relevant subgroups of patients (1, 7, 18, 19, 21, 30), including in the model (18); and, finally, problems with the definition of the population in the submission (16, 20, 26, 30), again including in the model (26).

The second major disparity between submissions and the requirements of the decision problem concerned the comparators. Twelve ERG reports found nothing to criticise in this regard, but 18 did raise various issues with the comparators considered in submissions. The principal issue involved a submission’s failure to consider one or more of the comparators designated in the decision problem, or the submission’s use of a combination of comparators not admitted in the decision problem: this was raised in 13 reports (1, 3–5, 7–9, 11, 13, 15, 17, 22, 30). In two cases, this issue was raised for the cost-effectiveness model too (8, 11). Three reports were concerned that the comparator being evaluated was not in use in the UK (6, 15, 26) or that a non-optimal dose of the comparator was being assessed (26), and two reports also identified problems with a lack of definition for the chosen comparator (25, 30). One submission reported a non-optimal treatment duration for the comparator in the model (28) and one conducted a mixed-treatment comparison (MTC) using comparators other than the principal comparator named in the scope (18).

By contrast, few ERGs reported a submission’s failure to satisfy the intervention or outcome elements of the decision problem. Twenty-one ERG reports found no problem with the intervention being evaluated in the submission. In nine instances the actual definition of the intervention was an issue, i.e. the inclusion or failure to include the intervention as combination therapy or monotherapy (1, 16, 18, 29, 30); differences between the trial interventions and UK practice (22, 26); differences between the licensed intervention and the trial intervention (3); and a specific instance where the dose being evaluated was an issue (11). Twenty-one reports (1–7, 9, 10, 12, 13, 18, 19, 21, 23–28, 30) also did not have any criticism to make of the outcomes presented in the submissions. The principal issue in the remaining reports concerned uncertainties regarding the appropriateness of the outcome being measured (8, 11, 14, 20, 22, 29). Otherwise, comments were limited to a lack of clarity on how QoL was being measured (14, 16), the inadequacy of the safety measures presented (15), a failure to report outcomes (17) or concerns about a trial’s lack of power to detect the secondary outcomes being presented (17).

The vast majority of the issues relating to the satisfaction of objectives were raised in the appraisal of the clinical effectiveness evidence. Very few, for example only those relating to the measurement of QoL as an outcome (14, 16), were issues raised principally or exclusively in the cost-effectiveness sections of the reports. In relation to satisfying objectives, the principal focus of the cost-effectiveness section concerned the submission’s failure or otherwise to satisfy the requirements of the NICE base case when developing the model. The majority of submissions appear to have adhered to the NICE base-case scenario and prompted no criticism: only eight ERGs reported either multiple deviations from the base case (23, 29) or specific deviations in relation to either the calculation of utilities (3, 5, 13) or the comparator (17, 20, 27).

Reliability and validity

The ‘reliability and validity’ theme emerged from four subthemes that were interpretations of ERG comments on the robustness or limitations of the submissions’ findings. The four subthemes are uncertainty due to the possibility of bias or an exaggerated estimate of effect; uncertainty due to the absence of evidence; the reliability (rather than uncertainty) of the findings; and external validity, i.e. how far the ERG considered the submission to be externally valid for the intended population and service.

The level of uncertainty surrounding the findings presented by the submissions was a frequent cause of criticism in ERG reports. A total of 27 out of 30 ERG reports (1–13, 15–18, 20–24, 26–30) stressed the presence of bias within the analyses, thus highlighting the lack of certainty surrounding the results presented in the submissions. The principal causes of uncertainty identified by ERGs concerned the possible exaggerated effect of the technology from the analysis (13, 15, 21, 27, 29), especially the relative efficacy of the technology versus relevant comparators (1, 5, 9, 11, 12, 23, 24); the safety of the technology (11); and uncertain levels of risk for different populations (30). These uncertainties within the clinical effectiveness analyses impacted on the models, which were also subject to other biases, such as uncertainties due to issues with the parameters or values in the model (3, 4, 6, 7, 15, 17, 20, 24, 28, 29); an exaggeration or overestimate of benefits or costs (1, 2, 8, 9, 18, 22, 23); excessive extrapolation from the data (2, 9, 16, 26); errors in the model itself (10, 13, 16); and uncertainty due to the model’s high degree of sensitivity to values or assumptions within the model (2, 5, 8, 12, 20, 21).

By contrast, few ERG reports stated that it was the lack of evidence rather than the quality of the evidence or its analysis that generated uncertainty in the submissions’ findings. Only seven ERG reports stated that the available trial evidence was insufficient to generate robust findings on follow-up or treatment duration (3, 4, 14, 16, 28), including survival in the model (1, 14). There was also uncertainty regarding relative efficacy of technologies as no head-to-head trial had been performed (3, 23, 30) or because the findings were based on only a single trial (21). ERG reports did sometimes also explicitly comment that the findings of the effectiveness or cost-effectiveness analyses were strong and reliable, but this was relatively infrequent. In seven reports, ERGs stated that the submission offered a convincing case for the technology (3, 5), an unbiased estimate of treatment effect (17–19) or a fair interpretation of the trial data (26, 28). In terms of the cost-effectiveness analysis, only three ERG reports considered that the submission presented a reasonable estimation of the cost-effectiveness of the technology versus relevant comparators (10), that the modelling of the costs of the technology appeared sound (15), or that the model was superior to previous published models (28).

Finally, the external validity of the submission’s findings was not criticised in 13 ERG reports, but was certainly queried explicitly by 17 ERG teams. These issues principally related to differences between the trial and UK populations (1, 6, 12, 15, 26, 27), including subgroups of UK patients likely to receive the treatment (7); differences between the treatment practices being evaluated in trials and clinical practice in the UK (2, 8, 14, 15, 22, 26) and those in Europe (5); or, simply, differences between the trials and ‘real-world’ clinical practice generally (10). One model was also criticised for not reflecting ‘real-world’ decisions (11), two others for using non-UK sources of data for the model (13, 16) and one ERG reported that the efficacy findings could not be extrapolated to all of the PSA populations (28).

Content