Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/25/02. The contractual start date was in May 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2010 and was accepted for publication in September 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

DWP has been an occasional advisor to the Nucleus™ Corporation (parent company of Entific® Medical Systems/Cochlear™), has had several research grants from the Nucleus Corporation, and runs a surgical training course annually for the company for which he is paid a fee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Colquitt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Aim and background

Aim

The aim of this report is to synthesise the evidence assessing the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bone-anchored hearing aids (BAHAs) for people who are bilaterally deaf.

The evaluation will consider BAHAs compared with conventional hearing aids, ear surgery and the unaided condition, and the use of unilateral or bilateral BAHAs. If the systematic review of economic evaluations shows that there are no appropriate good-quality economic evaluations, an economic model relevant to the UK setting is to be developed. The study aims to identify areas where further research is required.

Description of underlying health problem

Deafness and hearing loss can be described as mild, moderate, severe or profound (Table 1), and are defined according to the quietest sound a person can hear across a range of frequencies. The greater this threshold is, measured in units of decibels hearing level (dB HL), the worse the hearing loss is. Hearing loss that occurs in both ears is described as bilateral, and may be the same or different in each ear. Single-sided (unilateral) deafness is excluded from this evaluation.

| Audiometric descriptor1 | Hearing threshold level (dB)a |

|---|---|

| Mild hearing loss | 20–40 |

| Moderate hearing loss | 41–70 |

| Severe hearing loss | 71–95 |

| Profound hearing loss | > 95 |

Normal hearing occurs when sound waves travel through the external, middle and inner ear and are translated into nerve impulses, which are interpreted by the brain. The external ear acts as a sound-collecting funnel, with the passing sound waves causing the eardrum to vibrate. These vibrations (sound waves) are then passed on by the eardrum to three small bones (ossicles) in the middle ear, which amplify the vibrations and pass them on to the cochlea (inner ear). Movement of tiny hair-like cells in the fluid-filled cochlea convert the sound waves into nerve impulses, which are transmitted to the brain by the auditory nerve. Disturbances at any point in this pathway can cause hearing loss.

The main types of hearing loss are sensorineural loss and conductive loss,2 and the presence of both types is referred to as mixed hearing loss. Sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) is caused by damage to the outer or inner hair cells of the cochlea or the auditory nerve. 3 SNHL involves a loss of both the ability to detect quiet sound (acuity) and the ability to make sense of sound (discrimination) and is the most common form of hearing loss in more developed countries4 (approximately 90%). 3,5 It is often attributed to natural deterioration with ageing and prolonged noise exposure. 3 SNHL can have almost any frequency configuration and extent (from mild to profound).

Conductive hearing loss (CHL) involves a loss of acuity only and is the result of damage or blockage in the outer or middle ear due to a variety of causes such as infection, fluid (otitis media with effusion), ostosclerosis (growth of extra bone tissue) or trauma/damage to the eardrum. CHL may be caused by congenital abnormalities, which can affect any or all of the outer and middle ear structures,6 or may be part of a syndrome such as Treacher Collins, Crouzon, branchio-oto-renal or Goldenhar syndrome. 7 It can also occur following mastoid surgery or in Down syndrome8,9 (although SNHL can also occur with Down syndrome). The most common cause of CHL in children is otitis media with effusion and although this hearing loss is often only temporary,10 it may be permanent in a very small number of cases. 6 CHL is most commonly of a flat frequency configuration, and its maximum extent can only be that of the contribution of the conductive pathway to audition [40–50 decibels (dB)].

A less common type of hearing loss is neural deafness, caused by the absence of, or damage to, the auditory nerve. This type of hearing loss does not benefit from sound amplification as the nerve is unable to pass on any or enough sound information,2 and is therefore not considered further in this review.

The majority of people with hearing loss benefit from conventional air conduction hearing aids (ACHAs). These aids receive, amplify and transmit sound down the ear canal to the cochlea and are fitted behind the ear, in the ear or in the ear canal. However, people with an obstructed conduction process (via air) are unable to benefit fully or at all from ACHAs. For those with an infected ear, ACHAs may prevent adequate ventilation of the ear and thereby exacerbate the infection, whereas congenital abnormality or atresia of the pinna (external ear) may prevent an ACHA being fitted. 6 Some people with CHL can be treated with surgery in the form of repairing perforated eardrums, reconstruction or stapedectomy (surgical removal of the stapes ossicle of the middle ear),3,6,10 but for those for whom surgery is not an option, bone conduction hearing aids (BCHAs) may be an alternative.

Conventional BCHAs use a vibrator pressed firmly against the skin of the skull via a spring headband or special spectacles to conduct sound directly through the bone to the cochlea of the inner ear, bypassing the impaired or diseased external or middle ear. 11 However, BCHAs are associated with a number of drawbacks: they are uncomfortable to wear owing to the pressure needed to apply the device effectively and can cause skin irritations and headaches; they have poor aesthetics and are difficult to hide; and speech recognition can be affected by insecure positioning or shifting of the transducer and by the attenuation of sound by tissue layers between the vibrator and the skull. 12–14

An alternative type of hearing aid which utilises bone conduction (BC) is the BAHA, where contact with the skull is maintained by a surgical implant. It should be noted that the term ‘Baha®’ is a registered trademark of Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions AB, a Cochlear™ group company; however, reference to BAHA in this report applies to all such BC devices and not to the manufacturer, supplier or trade name. BAHAs are used to help people with conductive or mixed hearing loss who cannot benefit from conventional hearing aids or from ear surgery, or in some cases as an alternative to surgery (stapedectomy). BAHAs have undergone a number of developments since they were first introduced in 1977, and are discussed in further detail in Description of BAHAs.

Epidemiology of hearing loss

Although an understanding of the epidemiology of hearing loss is key to the assessment of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a technology and to the subsequent development of guidance on its provision and use, limited research has been undertaken. 15 Assessments of the epidemiology of hearing loss have tended to focus on retrospective cohort studies of its prevalence and have been limited in the type of hearing loss considered. They often use surrogate measures of prevalence such as use of health services, rather than population-based studies, resulting in the potential to underestimate needs. In addition, studies have tended to be affected by differences in the methods for assessing and diagnosing hearing loss (e.g. self-assessment) and variations in definitions and classification of hearing loss (including arbitrary nature of thresholds). Several studies have been undertaken within the UK and elsewhere and those most relevant to this evaluation are discussed in the following section. As there is little evidence focusing on CHL, the epidemiology of hearing loss in general is discussed to give some context to this evaluation.

Prevalence of hearing loss

Children

The prevalence of hearing loss in children has been assessed in several population-based surveys within the UK and elsewhere. These studies have shown variations in prevalence, with rates differing depending on the type of loss, its severity, temporal factors and its aetiology. Within the UK a series of retrospective studies (population surveys) has been undertaken by the Medical Research Council Institute for Hearing Research, providing prevalence data for several cohorts within cities, regions and nationally. In a retrospective survey of providers of health and educational services to children with a hearing loss conducted in 1995, Fortnum and Davis16 assessed the prevalence of permanent hearing loss [≥ 40 dB HL averaged over 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kilohertz (kHz)] in children resident in the Trent Health Region (UK) who were born between 1985 and 1990. They found an overall prevalence of permanent hearing loss of 1.33 cases per 1000 live births. For those with severe hearing loss (70–94 dB HL) the prevalence was 0.28 per 1000 and for profound hearing loss (≥ 95 dB HL) 0.31 per 1000. Congenital hearing loss was more prevalent than acquired hearing loss, accounting for 1.12 cases per 1000 live births (Table 2). Fortnum and Davis found that SNHL was more common than purely conductive loss. 16 The prevalence of congenital and acquired SNHL (≥ 40 dB HL) was 1.27 per 1000 live births compared with 1.33 per 1000 for all hearing losses. The higher prevalence of impairments that were congenital compared with acquired, and of sensorineural compared with conductive impediments, was evident for different levels of severity of hearing loss (see Table 2).

| Study | Hearing loss (kHz) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Moderate | Severe | Profound | ||

| Fortnum and Davis 199716 | (≥ 40 dB HL) | (40–69 dB HL) | (70–94 dB HL) | (≥ 95 dB HL) | |

|

Retrospective cohort survey Population: children born in Trent health region 1985–90, survey 1995 Outcome: prevalence per 1000 live births (95% CI) |

All cases | ||||

| Congenital and acquired | 1.33 (1.22 to 1.45) | 0.74 (0.65 to 0.83) | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.35) | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.37) | |

| Congenital | 1.12 (1.01 to 1.23) | 0.64 (0.56 to 0.73) | 0.23 (0.19 to 0.29) | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.30) | |

| Permanent SNHL | |||||

| Congenital and acquired | 1.27 (1.16 to 1.39) | 0.68 (0.61 to 0.78) | 0.28 (0.23 to 0.34) | 0.31 (0.26 to 0.37) | |

| Congenital | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.17) | 0.59 (0.52 to 0.68) | 0.23 (0.18 to 0.28) | 0.24 (0.20 to 0.30) | |

| Fortnum et al. 200117 | (≥ 40 dB HL) | (41–70 dB HL) | (71–95 dB HL) | (> 95 dB HL) | |

|

Retrospective cohort survey Population: children born in the UK 1980–95, survey 1998 Outcome: prevalence per 1000 live births (95% CI) |

Children aged 3 years |

0.91 (0.85 to 0.98) 1.07 (1.03 to 1.12) |

0.45 (0.40 to 0.50) 0.60 (0.54 to 0.66) |

0.20 (0.17 to 0.24) 0.22 (0.21 to 0.24) |

0.26 (0.22 to 0.29) 0.27 (0.26 to 0.29) |

| Children aged 9–16 years |

1.65 (1.62 to 1.68) 2.05 (2.02 to 2.08)a |

0.89 (0.86 to 0.91) 1.21 (1.18 to 1.24)a |

0.35 (0.33 to 0.36) 0.41 (0.40 to 0.42)a |

0.39 (0.38 to 0.41) 0.44 (0.43 to 0.44)a |

|

| Fortnum et al. 200218 | (≥ 40 dB HL) | (41–70 dB HL) | (71–95 dB HL) | (> 95 dB HL) | |

|

Retrospective cohort survey Population: children born in the UK 1980–95, survey 1998 Outcome: percentage of total study population with aetiology |

Total known aetiology | 50.6 | 47.7 | 50.9 | 57.5 |

| Genetic | 20.2 | 18.3 | 20.8 | 24.1 | |

| Syndromal | 9.5 | 11.6 | 6.6 | 7.4 | |

| Prenatal | 4.1 | 2.4 | 5.2 | 6.8 | |

| Perinatal | 8.0 | 7.4 | 11.4 | 6.7 | |

| Postnatal | 6.9 | 5.3 | 6.3 | 11.3 | |

| Other | 1.9 | 2.8 | 0.6 | 1.2 | |

| MacAndie et al. 200319 | (≥ 40 dB HL) | ||||

|

Retrospective cohort survey Population: children born in the UK 1985–94, survey 2000 Outcome: prevalence per 1000 live births |

All | 1.23 | |||

| Congenital | 1.09 | ||||

Fortnum and colleagues17 undertook a similar study to estimate the prevalence of permanent bilateral hearing loss (greater than 40 dB averaged over pure-tone threshold of 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz in the better hearing ear) in children born between 1980 and 1995 who were resident in the UK in 1998. The retrospective survey of all health and educational providers for hearing-impaired children identified 17,160 cases, finding a prevalence of 0.91 per 1000 live births for children aged 3 years and a prevalence of 1.65 per 1000 for those aged 9–16 years (data for children aged 4–8 years were not provided numerically). Adjustment of these rates for underascertainment resulted in an increase to 1.07 and 2.05 per 1000 live births for children aged 3 years and 9–16 years, respectively. When comparing the prevalence by the severity of hearing loss, rates were higher among those children with a moderate loss than among those with a severe or profound loss. Some 0.45 per 1000 children aged 3 years and 0.89 per 1000 children aged 9–16 years had a hearing loss of 41–70 dB HL compared with 0.20 per 1000 and 0.35 per 1000 for children aged 3 years and 9–16 years, respectively, for a loss of 71–95 dB HL (severe) and 0.26 per 1000 and 0.39 per 1000 for children aged 3 years and 9–16 years, respectively, for a loss of ≥ 95 dB HL (profound).

Comparisons between the studies in the Trent health region and the UK showed limited difference between the prevalence rates when cohorts were matched for age. In the Trent health region the overall prevalence rate was 1.33 per 1000 [95% confidence interval (CI) 1.22 to 1.45] for children born in the period 1985–90 compared with 1.44 per 1000 (95% CI 1.41 to 1.48) for children born in the period 1988–93 in the UK survey. Similar prevalence rates were evident when comparing the different severities of hearing loss. In the Trent health region prevalence rates were 0.74 (95% CI 0.65 to 0.83) for moderate, 0.28 (95% CI 0.23 to 0.35) for severe and 0.31 (95% CI 0.26 to 0.37) for profound hearing loss compared with 0.80 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.82) for moderate, 0.29 (95% CI 0.28 to 0.31) for severe and 0.34 (95% CI 0.32 to 0.35) for profound hearing loss in the UK study.

Fortnum and colleagues18 assessed the annual prevalence of hearing loss and profound hearing loss among children born between 1980 and 1995 in the UK to see if there were any temporal patterns. They found that the prevalence of hearing loss increased from 634 cases in 1980 to 1342 cases in 1987, declining to 669 cases in 1995. The proportion of children with profound hearing loss has ranged from 31.5% of children with hearing loss in 1980 to 20.4% in 1989.

Fortnum and colleagues18 compared the aetiology for the different levels of severity of hearing loss. It was evident that for around 50% of all children with hearing loss, the cause was not known or specified. For all hearing losses, 20.2% were genetic, 9.5% syndromal, 8.0% perinatal, 6.9% postnatal and 4.1% prenatal. When comparing the aetiology for the different severities of hearing loss it was evident that there were significant differences. Fortnum and colleagues found that children with moderate hearing loss were more likely to have an unknown aetiology than those with severe loss (moderate 52.3%, severe 49.1%, profound 42.5%, p < 0.001) or a syndromal aetiology (moderate 11.6%, severe 6.6%, profound 7.4%, p < 0.001). Also, severely impaired children were more likely to have a perinatal cause (moderate 7.4%, severe 11.4%, profound 6.7%, p < 0.001) and profoundly impaired children to have a genetic (moderate 18.3%, severe 20.8%, profound 24.1%, p < 0.001), prenatal (moderate 2.4%, severe 5.2%, profound 6.8%, p < 0.001) or postnatal aetiology (moderate 5.3%, severe 6.3%, profound 11.3%, p < 0.001) than the other groups.

Similar prevalence rates for hearing loss were shown by MacAndie and colleagues19 in a retrospective study in Greater Glasgow (UK). The study focused on children born between 1985 and 1994 who were identified from the Educational Audiology database. Of the 105,517 live births in Greater Glasgow between 1985 and 1994, 130 children had a permanent hearing loss (≥ 40 dB HL), which equates to an incidence of 1.23 cases per 1000 live births. Some 116 children had a congenital hearing loss (1.09 per 1000 live births), with only 14 children having a hearing loss that was postnatally acquired or progressive. When assessing the aetiology of bilateral hearing loss, MacAndie and colleagues found that 31% of children had a family history of congenital hearing loss, 12% craniofacial syndrome, 15% had an admission to neonatal intensive care unit that may have contributed to their hearing loss, 7% had a postnatal infection, 3% a prenatal infection and 28% had an unknown or uncategorised aetiology.

Adults

Davis20 surveyed the prevalence of hearing loss among a cohort of 35,330 people within four cities in the UK between 1980 and 1986. The study found that 16.1% of people aged 17–80 years had mild (≥ 25 dB HL), 3.9% moderate (≥ 45 dB HL) and 1.1% severe (≥ 65 dB HL) hearing loss in both ears. The prevalence of bilateral hearing loss was shown to increase with age. Prevalence rates for moderate bilateral loss increased from 0.2% for those aged 17–30 years to 1.1% for 31- to 40-year-olds, 1.7% for 41- to 50-year-olds, 4.0% for 51- to 60-year-olds, 7.4% for 61- to 70-year-olds and 17.6% for 71- to 80-year-olds. Similar variations by age group were evident for those people with a severe bilateral hearing loss, although the prevalence rates were approximately a quarter of those for people with moderate hearing loss. For those with severe bilateral loss the rates varied from less than 0.1% for those aged 17–30 years to 0.7% for 31- to 40-year-olds, 0.3% for 41- to 50-year-olds, 0.9% for 51- to 60-year-olds, 2.3% for 61- to 70-year-olds and 4.0% for 71- to 80-year-olds.

Davis20 assessed the effects of age, sex, occupational group and occupational noise on hearing loss through logistic regression analysis. The prevalence of hearing loss (≥ 45 dB HL) was shown to significantly increase with a person’s age [odds ratios (OR) 7.6 (p < 0.05) for 41–50 years; 17.3 (p < 0.005) for 51–60 years; 32.1 (p < 0.005) for 61–70 years; 95.4 (p < 0.005) for 71–80 years], occupation [OR 2.2 (p < 0.005) for manual occupations] and exposure to occupational noise [OR 2.3 (p < 0.01) for ≥ 91 dB(A) equivalent continuous sound level (Leq].

Lee and colleagues21 assessed the prevalence of self-reported hearing loss among adults (107,100 White and 17,904 African-American people aged ≥ 18 years) in the USA using the National Centre for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey between 1986 and 1995 (annual survey of approximately 50,000 civilian households). The annual age-adjusted rates for ‘some hearing impairment’ and ‘severe bilateral impairment’ were higher among Whites than among African Americans. The rates for ‘some hearing impairment’ ranged from 11.0% to 12.7% for Whites and from 5.9% to 8.5% for African Americans. The prevalence of ‘severe bilateral impairment’ was lower for both groups, with rates ranging from 0.7% to 1.1% for Whites and from 0.1% to 0.5% for African Americans. Although the rates varied temporally during the 10 years, there were no significant upward or downward trends in prevalence.

Unsurprisingly, analysis of the prevalence of ‘any hearing impairment’ among different age groups showed that the older age groups had a higher prevalence of impairment. This was evident for both the White and African American groups, although the prevalence was higher for all age groups among Whites than among African Americans. Comparison of the prevalence of impairment for the different age groups during the 10-year period showed limited variation for all the age groups in the White population and among the 18–39, 40–49, 50–59 and 60–69 years age groups in the African-American population. In contrast, the 70–79 and ≥ 80 years age groups in the African-American population showed considerable variation, although there were no discernible trends in the prevalence data.

Estimates of burden of hearing loss in England and Wales

Using the studies of the prevalence of hearing loss and population estimates for England and Wales,16,17,19,22,23 it is possible to provide a provisional estimate of the burden of bilateral hearing loss in England and Wales (Table 3). These estimates should be interpreted with caution owing to the differences in the nature of the studies and the classifications of hearing loss used. Estimates of the prevalence of bilateral hearing loss among children in England and Wales indicate that there could be between 900 and 1000 children in each annual birth cohort with a bilateral hearing loss of ≥ 40 dB HL. Although the majority of children would have a moderate hearing loss of 41–70 dB HL, around 400 would have either a severe (71–95 dB HL) or profound loss (≥ 95 dB HL). It was evident that the majority of impairments among children would be congenital in origin, accounting for hearing impairment in around 750–775 children per annual birth cohort in England and Wales. 16,19 Most of these congenital hearing impairments are thought to be permanent sensorineural (approximately 730 per annual birth cohort). 16 It was estimated that among adults in England and Wales there would be around 1.6 million people aged 17–80 years with a hearing loss of ≥ 45 dB, with around a quarter of these having a loss of ≥ 65 dB (Table 4). Around 60% (275,000) of those with a hearing loss ≥ 65 dB HL would be aged 60–80 years.

| Severity of hearing loss | Range of prevalence of bilateral hearing loss (rate per 1000 live births)16,17 | Range of estimated number of children with a bilateral hearing loss in England and Walesa |

|---|---|---|

| Moderate (41–70 dB) | 0.74–0.80 | 511–552 |

| Severe (71–95 dB) | 0.28–0.29 | 193–200 |

| Profound (≥ 95 dB) | 0.31–0.34 | 214–235 |

| All impairments (≥ 40 dB) | 1.33–1.44 | 918–994 |

| Age group (years) | Population in England and Wales (mid-2008) (000s)23 | Prevalence of bilateral hearing loss (%)20 | Estimated number of people with hearing loss in England and Wales | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Severity of loss | Severity of loss | ||||

| ≥ 45 dB | ≥ 65 dB | ≥ 45 dB | ≥ 65 dB | ||

| 17–30 | 10,186.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 20,372 | 10,186 |

| 31–40 | 7516.0 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 82,676 | 52,612 |

| 41–50 | 7907.4 | 1.7 | 0.3 | 134,426 | 23,722 |

| 51–60 | 6563.6 | 4.0 | 0.9 | 262,544 | 59,072 |

| 61–70 | 5411.4 | 7.4 | 2.3 | 400,444 | 124,462 |

| 71–80 | 3718.8 | 17.6 | 4.0 | 654,509 | 148,752 |

| Total | 41,303.3 | 3.9 | 1.1 | 1,610,829 | 454,336 |

Impact of hearing loss

For those people with hearing loss who identify with the ‘Deaf community’ (people whose first or preferred language is British Sign Language), being deaf is seen as part of their total identity and not as a deficiency. 24 However, deafness and hearing loss can have a profound effect on individuals and have been associated with a range of negative consequences, including educational and employment disadvantages, social isolation and stigmatisation. 25,26 According to a report by the World Health Organization, hearing loss is the second leading cause globally of ‘years lived with disability’ and has a larger non-fatal burden than alcohol use disorders. 26 The impact of hearing loss is influenced by the severity of the loss and age at onset. Deafness present at birth or during early childhood (the pre-lingual period) has considerable effects on speech acquisition and cognitive and psychosocial development. 27 Deafness acquired post-lingually requires the individual to adopt new communication strategies and often an entirely different lifestyle,24 and can result in isolation and compromised quality of life (QoL). 27 Hearing loss affects not only individuals, but also the people around them such as family and co-workers. 28 These people have to put more effort into communication with the individual, for example speaking more slowly and with better articulation, turning their face to allow lip-reading and moving closer. 28 As a consequence, there is a risk that people will make less contact and the individual will become more isolated.

Early hearing loss delays the development of basic auditory skills, including auditory detection, discrimination, recognition, comprehension and attention, which negatively affects the child’s ability to learn and use an auditory–oral language system. 29 Difficulties with the rules of language, the meaning of words and the use of language in social contexts lead to comprehension, expressive communication and learning problems, and can result in reduced academic achievement. 29 In contrast, a number of studies have shown that children with hearing loss who are raised by parents with hearing loss often have psychosocial advantages over those who are born to hearing families, as they grow up in an environment where communication is naturally dependent on visual, not oral, cues. 24

A recent study used both parent-report and videotaped data from 116 severely and profoundly deaf and 69 hearing preschool-age children, and demonstrated that hearing-impaired children displayed more behaviour problems and greater difficulties with oral language, parent–child communication and sustained attention than hearing children. 30 High rates of behavioural and emotional problems and a high rate of social maladjustment according to general population norms were also found by a cross-sectional study of 84 children and adolescents (age 2–18 years) attending schools for the deaf. 31 According to parents’ descriptions, children were socially isolated and not participating in structured activities. Similar results were demonstrated by a study in Upper Austria to evaluate mental health and QoL in a representative sample of deaf pupils with a bilateral impairment of at least 40 dB, from both mainstream schools and a school for the hearing impaired. 32 Using the strengths and difficulties questionnaire,33 deaf children scored higher for conduct, emotional and peer problems than children from a normative sample, though differences were less marked for hyperactivity/inattention. Whereas parents of deaf children had a generally positive view of their child’s QoL, deaf children provided a more complex picture, stressing areas of dissatisfaction.

A non-systematic review of mild bilateral hearing loss described studies demonstrating that many children with even mild hearing loss do not perform at expected academic levels, especially in the areas of vocabulary, reading comprehension and language use, and that they expend more effort in listening to speech in quiet and in the presence of background noise than children with normal hearing. 34 The author suggests that children with even a relatively mild degree of bilateral hearing loss may exert more energy than their normal-hearing peers to listen in a classroom setting, leaving them with less energy or attention capacity for processing what they hear, taking notes and other activities required of school children. 34

There is evidence to suggest that the effects of hearing loss in adults differ according to age group. For example, a large Norwegian health-screening survey examined the association between hearing loss, measured by pure-tone audiometry, and self-report symptoms of mental health and well-being in a normal population sample of over 50,000 people aged between 20 and 101 years. 35 The survey found a moderate but clear effect of hearing loss on anxiety, depression, self-esteem and well-being among young and middle-aged people. The strongest effects were found for depression and self-esteem among young men; however, the effects were almost absent among elderly people.

These findings are supported by a recent cross-sectional study which used the internet to determine both hearing status and self-reported psychosocial health in 1511 adults aged 18–70 years. 36 Hearing status was assessed using the ‘National Hearing test’, an online speech-in-noise screening test (also available via telephone) that has been implemented in the UK and the Netherlands. The study found significant associations between hearing status and distress, somatisation, depression and loneliness, but not between hearing status and self-efficacy or anxiety. For every dB signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) reduction in hearing status, the odds for developing moderate or severe depression increased by 5%, and the odds for developing severe or very severe loneliness increased by 7%. The study also found that different age groups exhibit different associations between hearing status and psychosocial health; increased loneliness was an issue for the 18–29 years group and the 40- to 49-year-olds had the greatest number of significant associations (distress, somatisation, self-efficacy, depression and anxiety), but in the 60–70 years group none of the adjusted associations reached statistical significance. The authors suggest that the differences in age groups could be due to differences in the time of onset of hearing loss, in the use of health care, or in the way hearing loss is regarded; it may be considered as part of the normal ageing process by older adults,36 whereas younger people may suffer from being different in terms of not being fully able to function as expected for people of their age. 35 Nevertheless, hearing loss can still affect the lives of older adults, as demonstrated by a population-based longitudinal study of 2688 participants aged 53–97 years. 37 This study used pure-tone audiometry to assess hearing loss, and reported a significant association between severity of hearing loss and reduced QoL.

Current service provision

In the UK, babies are screened for hearing loss as part of the NHS Newborn Hearing Screening Programme (within 26 days) and further monitoring and tests can confirm any diagnosis of hearing loss. Although there is no national school-based hearing screening programme in the UK, a 2007 survey found that most areas (over 90% of state schools) apply a hearing test at school entry,38 and the UK National Screening Committee recommended in 2006 that screening for hearing loss in school-age children should continue. 38 Those whose hearing loss develops during later childhood or adulthood generally present to their general practitioner, who will undertake tests and refer on to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) department for assessment and treatment if necessary. In many cases people are referred on to an audiology department, where treatment is the supply of a hearing aid.

As described previously, there are different hearing aid options available to those with deafness, including ACHs, BCHAs and BAHAs. In the UK NHS, most ACHAs are now digital and the types prescribed are typically behind-the-ear types; hearing aids that sit in the ear are less often prescribed in the NHS but people may purchase their own privately. For those with congenital hearing loss, or who cannot wear ACHAs owing to infection, BCHAs can be used. However, as discussed previously, they can be uncomfortable and so many people do not use them in all situations, and some prefer not to use them at all. In some cases of bilateral deafness surgical procedures (such as stapedectomy) are considered and can lead to improved hearing, but for many there are no surgical options. In these instances BAHAs may be considered.

Bone-anchored hearing aids are available on the NHS, but are usually fitted at a specialised centre rather than in a local ENT department. 2 In general, a referral for a BAHA will come to a specialist centre from an ENT surgeon; however, in some cases an audiologist will make this referral. In either situation, an audiological assessment to ascertain suitability for a BAHA will be made. Thereafter, BAHA availability can depend on local reimbursement policies (see Variation in services below). Follow-up visits are required to assess if the healing process and BAHA fixture are satisfactory. There are currently 89 BAHA centres in the UK, with around 10 more planned. 39

Quality standards in BAHAs for children and young people suggest that a child with a significant hearing loss must be provided with suitable amplification soon after diagnosis, prior to the referral to the BAHA service. 6 For some children, an ACHA may be tried in the first instance, although where a chronic CHL is present, BCHAs should always be considered, tried and evaluated and children should be provided with the opportunity to be referred for assessment to the BAHA service. 6 Until the child is old enough for BAHA surgery, a BAHA® Softband (Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions, Sydney, Australia) may be used. This is an elastic band with a BAHA sound processor connected to a plastic snap connector disc sewn into the band. The plastic snap connector disc is held against the skin behind the ear, or at another bony location of the skull, through the pressure from the band, and works in the same way as a conventional bone conductor.

Variation in services

The number of BAHAs in use is unknown as there are no formal records, but it is thought that there are about 6000–7000 BAHAs in current use in the UK (David Proops, Birmingham Children’s NHS Hospital Trust, March 2010, personal communication). Services for BAHA users vary throughout the NHS and funding is not universally available. Primary care trusts (PCTs) differ in policy on the provision of BAHAs, the eligibility criteria for funding BAHAs and sometimes the number of aids funded. 40 For most children with bilateral hearing loss, PCTs will fund a unilateral BAHA as long as a range of criteria around the nature of the hearing loss, the indication and the social and psychological impact have been met. Few PCTs, however, will fund bilateral BAHAs. Furthermore, as stated previously, not all NHS hospitals have an audiology department or one that specialises in the fitting of BAHAs;2 therefore, people referred for BAHAs may have to travel a considerable distance for treatment. 41

Current service cost

Bone-anchored hearing aid funding is recovered on an individual cost-per-case basis via the PCT. 39 BAHAs are more costly than other hearings aids,42 with the sound processor having to be replaced every 3–5 years. 13 The NHS reference costs 2007/08,43 report that a day-case admission for one-stage insertion of fixture for a BAHA costs £1918. This does not include the cost of fixtures, surgical consumables and the BAHA sound processor, which are reimbursed separately, through a high-cost low-volume top-up payment. Prices from Cochlear UK suggest that the product cost for an implant, abutment and processor ranges from £2700 to £3800, this price being dependent on the type of processor used. The 2010 price list from Oticon Medical AB (William Demant Holding) gives a package deal (processor, implant and abutment) for the Ponto (Oticon Medical, Askim, Sweden) and Ponto Pro (Oticon Medical, Askim, Sweden) of £2654.64 and £2886.60, respectively. Prices for surgery, inpatient episode and internal device cost published by the Nottingham University Hospitals44 in 2007–8 were £2683 for adults and £1588 for children. Additional maintenance costs amounted to £3800 in the first year, reducing to £1250 annually, and these did not differ for adults or children. 44

People with BAHAs require lifelong rehabilitation. Every individual should be on a rolling maintenance programme, and therefore funding is required for ongoing maintenance and replacement. These costs, however, need to be considered in the light of the often considerable costs of hearing loss to the person, the NHS and wider society.

Description of BAHAs

Criteria for treatment

Bone-anchored hearing aids are indicated for people with conductive or mixed hearing loss who can benefit from amplification of sound. BAHAs are also indicated for unilateral sensorineural deafness, also known as single-sided deafness, which is beyond the scope of this report. Otological indications for BAHAs include:45

-

congenital malformation of the middle/external ear or microtia

-

chronically draining ear or other infective state that does not allow use of an ACHA (e.g. external otitis, draining mastoid activity)

-

patients with bilateral CHL due to ossicular disease (and not appropriate for surgical correction) or unable to be aided by conventional hearing aid devices.

Chronic suppurative otitis media and recurrent ear canal infections are the most common diagnoses for adults fitted with BAHAs, as these make it difficult to wear conventional ACHAs. 46 For children, the most common diagnoses are congenital ear malformations, with the BAHA often used instead of a conventional BCHA. 46 Bone thickness is critical for implant integration47 and is often insufficient in children under 4 years of age. 48 While it has been suggested that children as young as 3 years can be fitted with a BAHA,2 the devices are indicated for children aged ≥ 5 years. 49,50

Intervention

The BAHA consists of:

-

A permanent titanium implant (3–4 mm), which is surgically placed in the mastoid bone behind the ear, where it fuses with the living bone (osseointegration). The implant transfers sound vibrations to the functioning cochlea.

-

An abutment, which protrudes through the skin and connects the titanium implant to the sound processor, transferring sound vibrations.

-

A small sound processor, which picks up sound vibrations and transfers them to the abutment. The processor can be attached to the abutment and disconnected by the user. Some processors are at head level, although the more powerful are body worn.

Fitting a BAHA requires surgery and can involve either a one-stage or two-stage surgical procedure, with each stage taking around 1 hour. In the one-stage procedure, the implant and abutment are placed at the same time, whereas in the two-stage procedure, the abutment is fitted after a period of around 3 months in adults or 4–6 months in children to allow osseointegration (where bone fuses with the implant) to occur. 51 The advantage of one-stage surgery is that it requires only one surgical procedure, but it risks transmission of forces through the abutment to the fixture before osseointegration has occurred, resulting in a failure of osseointegration and loss of the fixture. The two-stage procedure is therefore most commonly used for young children, adults who may not be able to protect the abutment adequately (e.g. adults with learning difficulties) or adults with poor bone quality (e.g. irradiated bone following radiotherapy in cancer patients). The one-stage procedure is, however, being trialled in children in some centres and has been found to be safe for children as well as adults,52,53 and can be considered for the older child aged 14–16 years. Finally, the sound processor is connected to the abutment after a period of about 1 month. 54

Bone-anchored hearing aid surgery is generally uncomplicated. The most common potential side effects are soft tissue reactions (with poor hygiene being the most frequent reason for adverse skin reactions)55 and loss of fixture. 54 Failures in children tend to occur soon after implantation as, relative to the adult skull, the infant skull is lower in mineral and higher in water content. 49 Re-operation rates are more common in children than adults, for example a Health Technology Assessment review13 for the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care found that re-operation rates for tissue reduction or repositioning were generally under 10% for adults but as high as 25% for children. Similarly, an association between younger age and increasing adverse outcomes, such as requiring revision surgery or experiencing fixture loss, was reported by a UK review of 71 children with BAHAs. 54

If trauma or failure of osseointegration occurs, a reserve or ‘sleeper’ implant may be fitted during the first procedure as a backup. This allows a new vibrating part to be fitted into the second implant as soon as a problem occurs with the first, without the need for a repeated first-stage procedure and subsequent 4- to 6-month wait for osseointegration to occur, during which time the individual would be without any hearing aid. It has been usual practice to fit the sleeper approximately 5 mm from the primary fixture; however, the sleeper is rarely needed and, as the bone is thinner, it is less likely to osseointegrate successfully. 57 For bilateral hearing loss it has been recommended that the sleeper should be placed on the contralateral side at the time of the primary surgery, where it is located in an optimum position and could be used if the decision is made to proceed to bilateral BAHA placement, reducing the number of procedures needed. 57

In the past the BAHA was fitted on just one side (unilaterally), which could be either the better hearing side if the two cochleae differ in acuity58 or the side preferred by the individual. The vibratory patterns of bone-conducted sound would suggest that one BAHA should be sufficient for good hearing amplification in bilateral hearing loss, as sound is transmitted to both the ipsilateral (same side) and contralateral (opposite side) cochleae. 59 However, it has been suggested that people with bilateral BAHAs benefit in terms of greater stimulation levels at the cochlea, better directional hearing and space perception, and better speech recognition in noise. 14,59–61 A potential advantage of this includes road safety, especially for children. A further benefit of bilateral BAHAs is that in the event of a problem with one side, for example an infected site or malfunctioning processor, the individual still has one functioning BAHA rather than being without any hearing aid while the problem is resolved. In a consensus statement from BAHA experts in 2005,42 bilateral application with thorough counselling was advocated in young children with severe congenital conductive hearing impairment.

However, the application of bilateral BAHAs is still debatable. Although the benefits of bilateral stimulation through air conduction (AC) are well established, the benefits with BC are less clear. One consequence of BC stimulation is crossover transmission, where the signal presented to one side of the head is transmitted to the contralateral cochlea. When bilateral stimulation occurs, the signals from each side are transmitted to both cochleae and thus interfere, potentially leading to the cancelling of the differences in signals arriving from the two ears and removing the benefits of binaural hearing. 62 The term binaural hearing ‘denotes our faculty for taking advantage from comparisons of the acoustic signals at the two ears’,63 implying the involvement of specialised brain processing that compares the neural correlates of the acoustic signals at the two ears. While empirical evidence suggests that some people with two BAHAs can use some available cues for localisation of sound, the processes remain unclear.

Past BAHA models

The BAHA technique was introduced in 1977, with the first BAHA device made by Branemark and Kuikka. 64 Since then, BAHAs have undergone a series of developments. The first generation of BAHAs, HC 100 (1981–6, Wennberg finmekanik),65 were serially produced but handmade. The second generation of BAHAs, HC 200 [1987–91, Nobel Biotech, Zurich, Switzerland (previously Nobelpharma, Göteborg, Sweden)],65 incorporated a number of improvements such as a damped transducer and a new amplifier system. A more powerful body-worn version, known as the Superbass HC 220 (1987–97, Nobel Biotech, Zurich, Switzerland/Nobelpharma, Göteborg, Sweden) was also developed for people with poorer nerve loss.

The third generation of BAHAs included the HC 300 (1987–97, Nobel Biotech, Zurich, Switzerland/Nobelpharma, Göteborg, Sweden), later named the Classic 300 (1991–9, Nobelpharma). 65 The first Cordelle (Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions, Sydney, NSW, Australia) (previously Mega base HC 380) was introduced in 1999, described as having the most powerful sound processor,50 with a functional gain that exceeded older BAHAs in higher (5–7 dB) and lower (10–15 dB) frequencies. 55 This was followed by the Compact (Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions, Sydney, NSW, Australia) (previously HC 360) in 2000. 65 Although the simple signal processing used by models such as the Classic 300 and the Compact benefitted users with CHLs, newer models use more complex signal processing schemes that also benefit users with sensorineural loss. 66 The third-generation BAHA devices marketed by Entific Medical Systems (now Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions AB) have US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) clearance and carry the CE mark. 67

The Xomed Audiant® (Xomed-Treace, Florida, FL, USA) was introduced in 1985 and manufactured by Xomed and Treace, but was never CE marked. 68 It was a transcutaneous type of BAHA, which used electromagnetic energy from an external processor. The Audiant did not perform well at lower frequencies and is no longer manufactured. 47

The above models are no longer sold in the UK and users should have received an upgrade to one of the devices described below.

Current BAHA models

There are six BAHA devices that are currently manufactured: four from Cochlear and two from Oticon Medical.

The Baha Divino™, Baha Intenso™ and Cordelle II™ were initially manufactured by Entific Medical Systems (Gothenburg, Sweden), which was acquired by the Cochlear Corporation in 2005. The Divino is described as being suitable for people with moderate-to-severe mixed hearing or symmetrical conductive loss [defined as ≤ 10 dB difference (pure-tone average, PTA) or ≤ 15 dB difference at individual frequencies]. Bilateral fitting is suitable for people with moderate-to-severe bilateral symmetrical conductive and/or mixed hearing loss. The processor’s digital technology and built-in directional microphone operate entirely at head level. 69

The Intenso device also has digital technology and operates entirely at head level. 69 It has a larger sound processor than the Divino and hence needs a larger battery. The device is indicated for people with mixed or conductive hearing loss with BC thresholds in the 0–45 dB range across speech frequencies. 70 It is also indicated for bilateral implantation in people with bilaterally symmetrical conductive or mixed hearing loss. The function gain of BC for both the Divino and the Intenso, defined as the difference between BC thresholds measured with a standard audiometer and aided sound field thresholds (expressed in dB HL), is between 5 and 10 dB. 71 The Divino is described as having good sound clarity with reduced feedback.

The Cordelle II reportedly offers even more amplification for people with a severe hearing loss and is on average 13 dB stronger than the discontinued Classic 300 model. It is indicated for CHL and mixed hearing loss, in individuals with average BC thresholds better than 45 dB (across 0.5, 1.2 and 3.0 kHz). It connects directly to external equipment such as television, MP3 players and hi-fi systems, without disconnecting the environmental microphone, and a built-in telecoil receiver allows wearers to connect to teleloop facilities. This device has a body-worn amplifier unit that powers an ear-level transducer. 69

The latest generation of devices from Cochlear and Oticon Medical are even more sophisticated. They are digital with computer-based fitting allowing adjustment to the person’s individual hearing requirements, whereas BAHAs such as the Divino are adjusted using a screwdriver. The devices also have improved quality and advanced features such as directionality.

The most recently launched BAHA sound processor by Cochlear is the BP100 (Cochlear Bone Anchored Solutions, Sydney, NSW, Australia). It is indicated for people with conductive and mixed hearing loss or single-sided sensorineural deafness and average BC thresholds of ≤ 45 dB (across 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 kHz). It is also indicated for bilateral implantation in people with bilaterally symmetric conductive or mixed hearing loss. The device is reported to offer improved audibility, sound quality and speech understanding owing to various automatic systems and has been attributed with a more than 25% improvement in speech understanding in noise. 72

The Ponto and Ponto Pro processors were released in the UK in autumn 2009 by Oticon Medical. The range complies with all European medical device regulatory requirements and has FDA approval. The processors are indicated for people with conductive and mixed hearing loss with an average BC threshold better than 45 dB HL (across 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 kHz), and for single-sided deafness with a PTA AC threshold of the hearing ear better than 20 dB HL (across 0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 3.0 kHz). Bilateral fitting is applicable for most people with a symmetrical BC threshold. The Pronto Pro model contains additional advanced features such as automatic multiband adaptive directionality, noise reduction and learning volume control.

Chapter 2 Methods for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol (see Appendix 1), which was sent to experts for comment. Although helpful comments were received relating to the general content of the research protocol, there were none that identified specific problems with the methodology of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Search strategy

A comprehensive search strategy was developed, tested and refined by an experienced information scientist. Separate searches were conducted to identify studies of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, QoL, resource use and costs, and epidemiology. Sources of information and search terms are provided in Appendix 2. The most recent search was carried out in November 2009.

A total of 19 electronic resources were searched: 13 databases listing published papers and abstracts and six databases listing ongoing studies. Searches were from database inception to the current date with no language restrictions. The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid); MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; EMBASE; The Cochrane Library including Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination including Health Technology Assessment Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and National Health Service Economic Evaluation Database; EconLit; Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (Web of Science); BIOSIS; Health Management Information Consortium; National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) CRN Portfolio; Current Controlled Trials; Clinical trials.gov; CenterWatch; Health Services Research Projects in Progress; and Computer Retrieval of Information on Scientific Projects. In addition, society websites and conferences were searched for recent abstracts and ongoing studies (see Appendix 2). Bibliographies of retrieved articles were checked for any additional references, and the expert advisory group and BAHA manufacturers were contacted to identify additional published and unpublished studies.

Inclusion and data extraction process

Studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness through a two-stage process using predefined and explicit criteria. The full literature search results were independently screened by two reviewers to identify all citations that possibly met the inclusion criteria. Full papers of relevant studies were retrieved and assessed independently by two reviewers using a standardised eligibility form. As far as possible, full papers or abstracts describing the same study were linked together, with the article reporting key outcomes designated as the primary publication.

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standard data extraction form and checked by a second reviewer. At each stage, any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness were assessed for potential eligibility by two health economists using predetermined inclusion criteria. Full papers were formally assessed for inclusion by one health economist with respect to their potential relevance to the research question.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality and the quality of reporting of the included clinical effectiveness studies were assessed following guidelines by Thomas and colleagues,73 which were modified to accommodate the types of studies included in this review (see Appendices 6–10). Quality criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, with any differences in opinion resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Quality assessment for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness was based on a checklist for economic evaluation publications74 and guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. 75

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants

-

Adults and children with bilateral deafness were included.

-

Single-sided deafness was excluded.

-

Studies reporting both bilateral and unilateral hearing loss were included only if the groups were reported separately or if the majority of participants had bilateral hearing loss.

Interventions

-

Bone-anchored hearing aids, consisting of a surgically implanted titanium fixture. Devices in current use and devices no longer manufactured were included. BAHAs could be fitted unilaterally or bilaterally.

Comparisons

-

Bone-anchored hearing aids versus:

-

– conventional hearing aids (ACHA or BCHA)

-

– unaided hearing

-

– ear surgery (tympanoplasty, myringoplasty, ossiculoplasty, stapedectomy and stapedotomy).

-

-

Unilateral versus bilateral BAHAs.

-

Studies comparing different BAHA models were excluded.

Outcomes

-

Hearing measures, aided hearing thresholds, speech recognition scores.

-

Validated measures of QoL and patient satisfaction.

-

Adverse events.

-

Measures of cost-effectiveness [i.e. cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), cost per life-year saved] and consequences in terms of health service resources.

Study design

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, studies were classified according to the criteria by Thomas and colleagues,73 with some adaptations to meet the requirements of this review. The following study designs were eligible:

-

randomised controlled trials (RCTs)

-

controlled clinical trials

-

prospective cohort analytic studies (two groups pre and post, i.e. assessments made before and after BAHA surgery in the intervention group and the control group)

-

prospective cohort one-group pre and post studies (no control group, assessments made before and after BAHA surgery)

-

cross-sectional ‘audiological comparison studies’ [no control group, assessments with intervention and comparator(s) made at one point in time, after BAHA surgery]

-

prospective case series (no comparator condition, outcomes reported with BAHA only).

Where evidence from different types of study design was identified for each of the above comparisons, only studies with the most rigorous designs were included. Where higher level evidence was limited to BAHA models no longer in current use, lower level evidence for models in current use (Divino, Intenso, Cordelle II, BP100, Ponto, Ponto Pro) was considered.

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were included only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

Only full economic evaluations, those reporting both costs and outcomes, were eligible for inclusion in the systematic review of cost-effectiveness evidence. Conference abstracts were not eligible for inclusion in the cost-effectiveness section.

Data synthesis

Studies of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were synthesised through a narrative review with full tabulation of the results of all included studies. It was considered inappropriate to combine the results of the studies in a meta-analysis owing to differences in the outcome measures and patient populations. Within Chapter 3, results are discussed according to the comparison to aid interpretation. Where studies report outcomes for more than one comparison (e.g. BAHA vs ACHA and BAHA vs unaided), these are discussed in each relevant section. Care should therefore be taken to avoid double-counting the BAHA data, which are repeated. This is noted where appropriate. Outcome measures are discussed throughout the review of clinical effectiveness as reported by the included studies, including the use of descriptions such as ‘improvement’ or ‘deterioration’. To aid interpretation of the data, lower hearing thresholds are considered to be ‘better’ than higher thresholds, but it is acknowledged that this is a simplistic approach and, while true in many cases, it may not necessarily be so. The methods for the economic model are described in Chapter 4, Southampton Health Technology Assessments Centre economic analysis.

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness results

Quantity and quality of research available

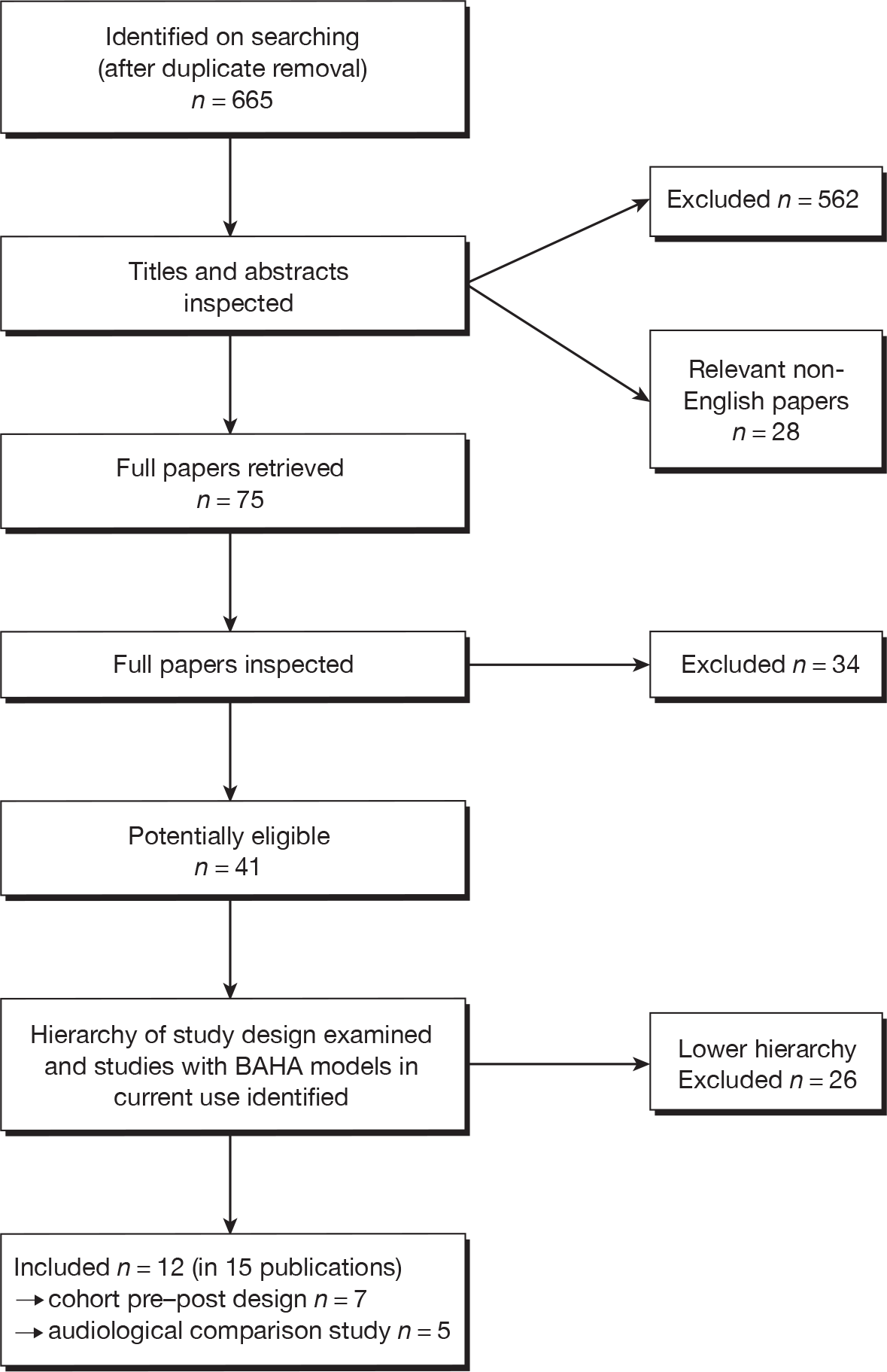

Searching identified 665 references after de-duplication. The number of references excluded at each stage of the systematic review is shown in Figure 1. Selected references which were retrieved but later excluded are listed in Appendix 3 with reasons for exclusion. Studies were often excluded for more than one reason; the most common reason being study design (16 studies), followed by outcomes (12 studies), intervention (six studies), comparator (10 studies) or participants (one study). Although not formally assessed, the level of agreement between reviewers for screening was good. Twenty-eight relevant non-English references were identified by the searches and can be seen in Appendix 4. After examination of the titles and English abstracts (where available) it was unclear whether or not any of these studies met the inclusion criteria, and none appeared to have a concurrent control group. Because it was anticipated the studies would add limited value to the review, and in view of limited resources, translation and full screening of the papers were not undertaken. Searches did not identify any eligible ongoing studies.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of identification of studies.

Forty-one potentially eligible studies were identified. After selecting the highest level of evidence available for each comparison (BAHA vs BCHA, ACHA, unaided hearing or ear surgery, unilateral vs bilateral BAHA) and checking the remaining studies for BAHA models in current use, 12 studies (in 15 publications) were included in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness. 59,60,66,76–87 The included studies were either one-group cohort pre and post studies or cross-sectional ‘audiological comparison’ studies (study design is discussed further in Quality assessment); no RCTs, controlled clinical trials or prospective cohort analytic studies were identified. Only two studies included BAHA models that are in current use. 66,76 A summary of the highest level of evidence available and the current availability of the BAHAs used (whether or not currently manufactured) for each comparison can be seen in Table 5. The remaining 26 lower evidence studies are listed in Appendix 5, and were described by reviewers as audiological comparison studies (using BAHAs no longer manufactured, 20 studies) or prospective case series with no comparator (six studies). No eligible studies comparing BAHAs with ear surgery were identified.

| Comparison | Highest level of evidence identified and current availability of BAHA (no. of studiesa) |

|---|---|

| BAHA vs BCHA | CPP and BAHA in current use: 0 |

| CPP and BAHA no longer manufactured: 477–82 | |

| ACS and BAHA in current use: 0 | |

| ACS and BAHA no longer manufactured: 14 (see Appendix 5) | |

| BAHA vs ACHA | CPP and BAHA in current use: 0 |

| CPP and BAHA no longer manufactured: 578–84 | |

| ACS and BAHA in current use: 176 | |

| ACS and BAHA no longer manufactured: 13 (see Appendix 5) | |

| BAHA vs unaided | CPP and BAHA in current use: 166 |

| CCP and BAHA no longer manufactured: 377,78,83 | |

| ACS and BAHA in current use: 0 | |

| ACS and BAHA no longer manufactured: 6 (see Appendix 5) | |

| BAHA vs ear surgery | 0 eligible studies |

| Unilateral vs bilateral | CPP and BAHA in current use: 0 |

| CPP and BAHA no longer manufactured: 0 | |

| ACS and BAHA in current use: 0 | |

| ACS and BAHA no longer manufactured: 459,60,85–87 |

Characteristics of included studies

BAHAs versus BCHA or ACHA

Study design

Seven studies (one study had three associated publications79–81) comparing BAHAs with conventional aids, either BCHAs,77 ACHAs76,83,84 or both (in separate subgroups),78–82 were included (Table 6, Appendices 6–8). Three of the studies also tested participants unaided77,78,83 (see BAHA versus unaided hearing). Six77–84 of the studies were described by reviewers as cohort pre- and post-studies (before and after studies) and either assessed BAHAs models that are no longer manufactured77–83 or did not report the model used (although this study was published in 1998 so is unlikely to have used a BAHA that is currently manufactured84). Only one study was identified that assessed a BAHA model in current use;76 this study compared the BAHA Intenso with an ACHA, and was described by reviewers as a cross-sectional audiological comparison study.

| Study | Intervention and timing of audiology | Participants indication and characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| BAHAs vs BCHA | ||

|

Béjar-Solar et al. 200077 Mexico Cohort pre–post |

One group: n = 11

|

Inoperable bilateral congenital microtia atresia. BC PTA ≥ 45 dB HL with 100% speech discrimination. Low socioeconomic background Age, mean years (range): 10 (5–17) Sex (M : F): 7 : 4 PTA thresholds (1.25–3.00 kHz), mean, dB HL: AC right ear 69, left ear 69; BC right ear 20, left ear 14; sound field PTA 64 |

| BAHA vs ACHA | ||

|

UK Cohort pre–post |

One group: n = 9

|

Otosclerosis. Average BC thresholds (0.5–4.0 kHz) < 40 dB HL for ear level BAHA, < 60 dB HL for body-worn Superbass Age, mean years (range): NR for study sample Sex (M : F): NR for study sample Average BC thresholds (0.5–4.0 kHz), dB HL: NR for study sample |

|

Flynn et al. 200976 Sweden Audiological comparison study |

One group: n = 10

|

Mixed hearing loss, no further details. Sensorineural component ≥ 25 dB HL plus air-bone gap > 30 dB Age, mean years (range): 59 (32–75) Sex (M : F): 5 : 5 PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz), mean dB HL (range): AC 77 (55–80); BC 41 (25–66) |

|

Netherlands Cohort pre–post |

One group: n = 34

|

Bilateral conductive or mixed hearing loss with chronic otitis. No audiological criteria stated Age, mean years (range): 48 (26–72) Sex (M : F): 12 : 22 PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz), mean dB HL (range):d AC 60 (25–90); BC 26 (6–46) |

| BAHA vs BCHA and ACHA (in separate subgroups) | ||

|

UK Cohort pre–post |

Four subgroups [previous aid AC or BC, aetiology congenital (CON) or CSOM]:

|

CSOM or congenital aetiology. Average BC thresholds (0.5–4.0 kHz) < 40 dB HL (ear level) or < 60 dB HL (body-worn), speech discrimination score ≥ 60% Age, mean years:e CSOM/ACHA 58; CSOM/BCHA 61; CON/ACHA 30; CON/BCHA 24 Sex (M : F): NR PTA thresholds (0.5–4.0 kHz), mean dB HL:e AC: CSOM/ACHA 58, CSOM/BCHA 65, CON/ACHA 70, CON/BCHA 60; BC: CSOM/ACHA 24, CSOM/BCHA 30, CON/ACHA 20, CON/BCHA 13 |

|

Netherlands Cohort pre–post |

Two subgroups (previous aid AC or BC):

|

Acquired conductive or mixed hearing loss, no further details Age, mean years (range): ACHA 47.9 (24–73), BCHA 62 (42–82) Sex (M : F): ACHA 12 : 24; BCHA 9 : 11 PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz), mean dB HL (range): AC: ACHA 63.2 (30–103), BCHA 76.5 (40–107); BC: ACHA 26.8 (9–51), BCHA 43.4 (17–63) |

|

cSnik et al. 1992,79 1994,80 199881 Netherlands Cohort pre–post |

Two subgroups (previous aid AC or BC):79

|

Recurrent otorrhoea. Severe mixed hearing loss with sensorineural components of 45–60 dB HL79 Age, mean (SD, range): (i) 60.6 (18.8, 34–84) years; (ii) 62 (13.9, 46–78) years Sex (M : F): NR PTA thresholds (frequencies NR), mean dB HL (SD, range):f,g AC (i) 91.1 (14.3, 70–108), (ii) 84.8 (12.3, 72–100); BC (i) 46.2 (12.6, 28 to > 62), (ii) 49.6 (7.3, 40–57) |

Four subgroups (previous aid AC or BC, current BAHA HC200 or HC220):80

|

Chronic otitis media/externa, aural atresia. Both normal to moderate and more severe SNHL80 Age, range: 10–77 (mean NR) years Sex (M : F): NR PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz) for BC, range dB HL: HC 200 (n = 42) 0–44; HC 220 (n = 16) 33–63 |

|

Two subgroups:81

|

Conductive or mixed binaural hearing loss, SNHL of ≤ 30 dB HL. No details of aetiology81 Age, range: 10–70 (mean 43) years Sex (M : F): NR PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 kHz), mean dB HL (range): AC 55 (30–90); BC 16 (0–28) |

|

| BAHA vs unaided (see also three studies from above: Béjar-Solar et al. 2000,77 Burrell et al. 199683 and Cooper et al. 199678) | ||

|

Kompis et al. 200766 Switzerland Cohort pre–post |

One group: n = 7

|

Bilateral CHL, some mild-to-moderate SNHL. No further details. All had at least 2 years’ experience with BAHAs Age, mean (range): 49 (19–66) years Sex (M : F): 3 : 4 PTA AC and BC thresholds: IPD presented in figure but could not be extracted |

| Unilateral vs bilateral BAHAs | ||

|

Netherlands Audiological comparison study |

One group: n = 25(HC 200 or Classic 300) Assessments at same session |

Recurrent otorrhoea, otitis externa, congenital atresia Age, mean (range): 44.3 (12–74) years Sex (M : F): 14 : 11 BAHA experience, mean (range):f unilateral 49.1 (18–105) months; bilateral 13.6 (3–105) months PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz), mean dB HL (SD, range): AC first fitted side 59.5 (13.7, 32–82),f second fitted side 63.6 (10.9, 38–82);f BC first fitted side 21.0 (10.7, –5 to 36);g second fitted side 21.9 (12.4, –8 to 48)g |

|

Dutt et al. 200286 UK Audiological comparison study |

One group: n = 11(Compact) Assessments at same session |

Treacher Collins syndrome, Goldenhar syndrome, bilateral: mastoid cavities, CON, chronic otitis media, microtia, acquired otosclerosis Age, mean (range):f 42.3 (22–54) years Sex (M : F): 3 : 9 (one patient chose not to participate) BAHA experience, mean (range):f unilateral 6.3 (3–12) years; bilateral 2.2 (1–5) years PTA AC and BC thresholds: NR |

|

Priwin et al. 200487 Sweden Audiological comparison study |

One group: n = 12(Compact and Classic 300) Assessments at same session |

Chronic otitis, otosclerosis, congenital ear canal atresia Age, mean (range):f 51.7 (27–68) years Sex (M : F): 3 : 9 BAHA experience, mean (range):f unilateral 14.3 (5.8–21) years; bilateral 6.8 (1–19.6) years PTA thresholds (0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz), mean dB HL (SD, range):f,g AC first fitted side 58.3 (15.3, 38–87), second fitted side 59 (20.7, 27–102); BC first fitted side 29.8 (15.2, 8–53),h second fitted side 30.9 (13.4, 7– 50) |

|

Priwin et al. 200759 Sweden Audiological comparison study |

Two groups:(Compact and Classic) Assessments at same session |

Majority had symmetrical maximal or near-maximal conductive bilateral hearing loss Age, mean (range): 11.3 (6–17) years Sex (M : F): 3 : 6 BAHA experience: at least 3 months (no further details) PTA (M4) thresholds (0.5, 1.0, 2.0 and 4.0 kHz) mean dB HL (SD): AC better ear 61.3 (15.5), worse ear 72.1 (12.1); BC better ear 14.1 (12.7); worse ear 13.8 (10.7) |

Post-operative assessment with the BAHA was undertaken after either 4–6 weeks79,80,84 or 6 months. 77,78,82 The post-operative duration was not reported in one study. 83 Participants in the cross-sectional audiological comparison study had ≥ 12 months experience with the BAHA before being assessed with a BAHA and an ACHA at the same time point. 76

Participants

The study from the Netherlands by Snik and colleagues79–81 was associated with three eligible publications, which had considerable overlap of participants. It appears that the participants who formed the BAHA HC 200 subgroup (n = 42) and the HC 220 subgroup (n = 16) in the 1994 study by Snik and colleagues80 were also reported in the 1998 study (BAHA HC 200, n = 41)81 and the 1992 study (BAHA HC 220, n = 12),79 respectively. Participants from another centre were also included in the 1992 study. To avoid double-counting of participants these three publications have been considered as one study with the appropriate publication referenced when discussed. It is not clear whether there is an overlap with the participants from the studies by Mylanus and colleagues84 or Hol and colleagues,82 which were also conducted by the same group in the Netherlands. There may also be some overlap of participants between two of the UK studies, which were undertaken by the Birmingham group, but again this is not clear. 78,83

The studies comparing BAHAs with conventional aids included participants with inoperable bilateral congenital microtia atresia,77 otosclerosis,83 chronic otitis media/externa or otorrhoea,78,79,81,84 aural atresia80 and congenital hearing loss. 78 Details of aetiology were not reported in the studies by Flynn and colleagues76 or Hol and colleagues. 82

All seven studies76–84 reported PTA thresholds for AC and/or BC, although the frequencies over which these were determined varied between the studies (see Table 6). Mean PTA thresholds for AC varied from 55 dB HL (range 30–90 dB HL) at 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz in the 1998 publication by Snik and colleagues81 to 91.1 dB HL [standard deviation (SD) 14.3, range 70–108 dB HL] (frequencies not reported) in the BCHA subgroup of the 1992 publication by Snik and colleagues. 79 Similarly, mean PTA thresholds for BC varied from 16 dB HL (range 0–28 dB HL) at 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 kHz in the 1998 publication by Snik and colleagues84 to 49.6 dB HL (SD 7.3, range 40–57 dB HL) (frequencies not reported) in the ACHA subgroup of the 1992 publication by Snik and colleagues. 79

One study included children only (age 5–17 years)77 and five studies76,78,79,82,84 included adults only (mean age from approximately 4378 to 5982 years). In the study by Snik and colleagues, two of the publications included children and adults (age range from 10 to 7081 or 7780 years), while the 1992 publication77 included adults only (age range 34–78 years). The proportion of men and women varied between those studies reporting characteristics of the study sample. 76,77,82,84

These studies are generalisable only to people with bilateral conductive or mixed hearing loss who had previously used either an ACHA or a BCHA.

Outcomes

Data were reported in a variety of ways in the studies. Five of the studies reported pure-tone or warble-tone average thresholds,76–78,83,84 and one study reported the average difference between warble-tone thresholds. 79 The range of frequencies over which these were assessed varied between the studies, and although in the USA it is mandatory to include 3 kHz, this is not required in Europe. One study did not report any audiological measures at follow-up. 82 Outcomes for speech audiometry included 100% speech audiometry discrimination with background noise at 65 dB HL,77 speech recognition threshold (level at which 50% of the presented phonemes were repeated properly by the participant)79 and speech discrimination score at 63 dB. 78,83 One study reported the speech-to-noise ratio with BAHAs and ACHAs,76 whereas two other studies reported only the change in speech-to-noise ratio81,84 or the change in speech reception threshold (SRT) in quiet. 81 The maximum phoneme score was reported by two studies. 79,84 One study reported the number of participants with a statistically significant change in the speech recognition in quiet score and speech-to-noise ratio score. 80 Accurate directional identification of location of a sound source was evaluated by one study. 78

Two studies77,82 reported using a validated measure of QoL, although limited details and data were reported in one of these. 77 The second study80 did not report any audiological measures, but presented before and after data from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36), European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) and the Hearing Handicap and Disability Index (HHDI). Five studies reported the results of subjective questionnaires on patient preference,77,81,83,84 satisfaction,78 comfort79,83 and opinions on speech recognition in noise and quiet,78–81 but none of these questionnaires appears to have been validated.

In five of the seven studies,76,78,80,81,83,84 some data were reported only in figures and had to be estimated by reviewers, which increases potential for error. In two of the studies,79,83 individual patient data without any summary statistics were reported for some outcomes, therefore means and SDs presented in this review for these studies were calculated by reviewers. Data estimated from figures or summary statistics calculated by reviewers are indicated in Tables 6, 8 and 10.

BAHA versus unaided hearing

Four studies included a comparison of BAHAs with unaided hearing (see Table 6 and Appendices 6–9). 66,77,78,83 Three of these studies have been described above, as they compared BAHAs with conventional aids but also reported outcomes unaided. The BAHAs used in these studies are no longer manufactured. Audiological assessment was undertaken 6 months post-operatively in two studies,77,78 but this was not reported in the other study. 83

A study by Kompis and colleagues66 was identified that compared BAHAs with the unaided condition and included a BAHA model in current use (BAHA Divino). This study is defined by reviewers as a pre and post cohort study, but differs from the other included studies as the participants had prior experience with BAHAs when tested unaided at baseline. The aim of the study was to compare the BAHA Divino with the BAHA Compact (this comparison did not meet the inclusion criteria of the review), and the participants had at least 2 years’ experience with a BAHA Compact or Classic 300 prior to the study. However, the study also assessed the unaided condition at baseline and then assessed the BAHA Divino after 3 months’ use, so these data were included in the systematic review (see Appendix 9).

Participants

Kompis and colleagues66 included participants described as having substantial bilateral CHL, some combined with mild-to-moderate SNHL. No details of aetiology were reported. PTA thresholds for AC and BC for each ear of individual participants were presented in figures in this study, but data could not be extracted. The participants in this study were adults with a mean age of 48.6 years. 66 The studies by Burrell and colleagues,83 Cooper and colleagues78 and Béjar-Solar and colleagues77 have already been described in BAHAs versus BCHA or ACHA.

The generalisability of the study by Kompis and colleagues66 may be limited to people with bilateral conductive or mixed hearing loss with previous experience of BAHAs.

Outcomes

Kompis and colleagues66 reported the average improvement in sound field pure-tone thresholds over all frequencies compared with unaided. Outcomes for speech audiometry included mean speech recognition threshold and speech recognition scores in quiet, and speech recognition in noise when noise was presented from the front or back. QoL was not reported. Outcomes reported by Burrell and colleagues,83 Cooper and colleagues78 and Béjar-Solar and colleagues77 have already been described in BAHAs versus BCHA or ACHA.

Data had to be estimated from figures by reviewers for the study by Kompis and colleagues;66 this is indicated in Tables 6 and 12.

Country

The study by Kompis and colleagues66 was conducted in Switzerland and, as described in BAHAs versus BCHA or ACHA, two studies were conducted in the UK78,83 and one in Mexico. 77

Funding

The BAHA Divinos used in the study by Kompis and colleagues66 were provided by Entific Medical Systems. The other three studies are reported in BAHAs versus BCHA or ACHA. 77,78,83

Unilateral versus bilateral BAHAs