Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/08. The contractual start date was in February 2009. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in October 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Pandor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Head injuries account for over 700,000 emergency department (ED) attendances every year in England and Wales1 (with about 20% of head-injured patients being admitted to hospital for further assessment and treatment),2 and are responsible for a significant proportion of the ED workload. In the UK, 70–88% of all people who sustain a head injury are male, 10–19% are aged ≥ 65 years and 40–50% are children. 1 The severity of head injury is directly related to the mechanism and cause. 2 Most minor head injuries (MHIs) in the UK result from falls (22–43%), assault (30–50%) or road traffic accidents (25%). 1 Alcohol may also be involved in up to 65% of adult head injuries. Motor vehicle accidents (MVAs) account for most fatal and severe head injuries. 3 There are, however, marked variations in aetiology across the UK, particularly by age, gender, area of residence and socioeconomic status. 3–5

Injury severity can be classified according to the patient’s consciousness level, as measured on the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) when they present to the emergency care services. Most patients (90%) present with a minor injury (GCS 13–15), whereas 10% present with either moderate (GCS 9–12) or severe (GCS 3–8) head injury. 6 Patients with a MHI are conscious and responsive, but may be confused or drowsy. Initial management of MHI may involve identification and treatment of other injuries, or first aid for scalp bruising or bleeding, but MHIs are typically isolated so initial treatment is limited to analgesia and reassurance.

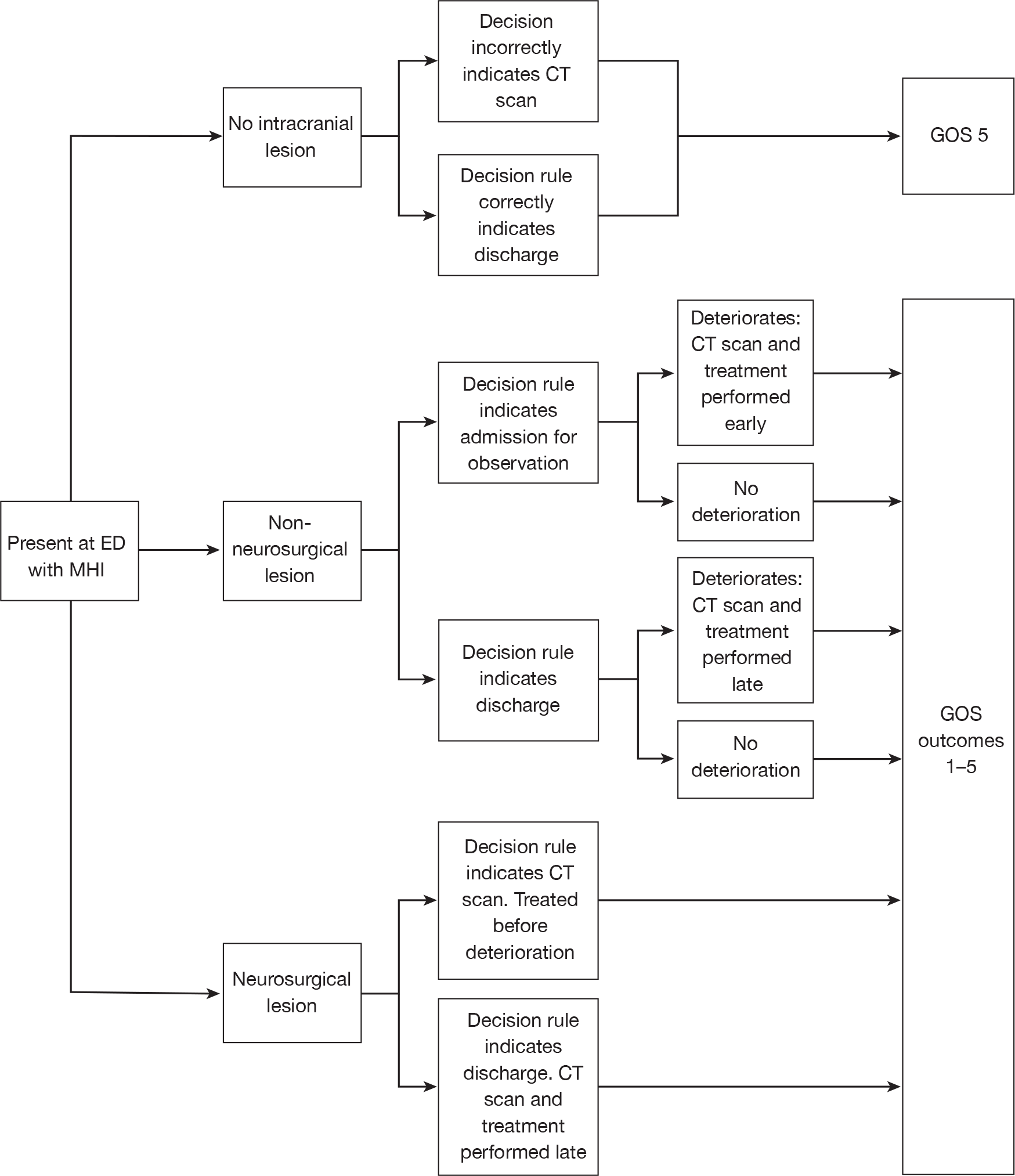

The main challenge in the management of MHI is identification of the minority of patients with significant intracranial injury (ICI), especially those who require urgent neurosurgery. Head injury can result in a range of intracranial lesions, including extradural or subdural haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral contusion or intracerebral haematoma. Although patients with intracranial lesions often present with moderate or severe head injury according to their GCS, some present with apparently MHI. Subsequent progression of the intracranial lesion can result in a decreasing consciousness level, brain damage, disability and even death.

Early identification of an intracranial lesion can reduce the risk of brain damage and death. First, some intracranial lesions (typically extradural haematoma) can rapidly expand if untreated, leading to raised intracranial pressure, brain damage and death. Emergency neurosurgery to evacuate the haematoma and relieve increased pressure can allow most patients to make a full recovery,7–11 whereas delayed neurosurgery is associated with poorer outcomes. 11,12 Second, a proportion of patients with an ICI that does not require urgent neurosurgery (i.e. a non-neurosurgical injury, such as an intracerebral haematoma) will subsequently deteriorate and require critical care support and/or neurosurgery. These patients may have better outcomes if they are admitted to hospital and managed in an appropriate setting. 13 We have defined the former group as having ‘neurosurgical’ injuries and the latter as having ‘non-neurosurgical’ injuries. However, it should be recognised that our definition is based upon the emergency treatment required rather than all subsequent treatment. Many patients with injuries that we define as having ‘non-neurosurgical’ injuries will benefit from general neurosurgical care and may require later neurosurgical interventions.

Outcome from head injury can be assessed using the Glasgow Outcome Score (GOS). The scale has the following categories:

-

dead

-

vegetative state – unresponsive and unable to interact with environment

-

severe disability – able to follow commands, but unable to live independently

-

moderate disability – able to live independently, but unable to return to work or school

-

good recovery – able to return to work or school.

The scale has subsequently been extended to eight categories by subdividing the severe disability, moderate disability and good recovery categories into upper and lower divisions [known as the extended GOS (GOS-E)].

Most patients with MHI have no intracranial lesion (or at least no lesion detectable by currently used imaging modalities) and will make a good recovery, although post-traumatic symptoms, such as headaches, depression and difficulty concentrating, are relatively common and often underestimated. There is some evidence that early educational intervention can improve these symptoms,14–17 but this does not rely upon initial diagnostic management. Most patients with a MHI and a neurosurgical or non-neurosurgical intracranial lesion will make a good recovery with appropriate timely treatment, although a significant proportion will suffer disability or die. 7–11,18 Failure to provide appropriate timely treatment appears to be associated with a higher probability of disability or death. 11,12

The incidence of death from head injury is estimated to be 6–10 per 100,000 population per annum. 2 This low incidence is owing to most patients having MHI with no significant intracranial lesion and the good outcomes associated with ICI in patients presenting with MHI when treated appropriately. However, when death or disability does occur following MHI, it often affects young people and, therefore, results in a substantial loss of health utility and years of life. As such outcomes are potentially avoidable, clinicians typically have a low threshold for investigation.

Current service provision

Patients with MHI present to the ED, where a doctor or nurse practitioner will assess them and, if appropriate, arrange investigation. Clinical assessment may consist of an unstructured assessment of the patient history and examination or may use a structured assessment to combine features of the clinical history and examination in a clinical decision rule. Investigations include skull radiography and computerised tomography (CT) of the head. After assessment and investigation, patients may be discharged home, admitted to hospital for observation or referred for emergency neurosurgery. The aim of diagnostic management is to identify as many patients with ICI as possible (particularly those with neurosurgical injury), while avoiding unnecessary investigation or hospital admission for those with no significant ICI.

Guidelines for managing head injury in the NHS were drawn up by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) in 200319 and revised in 2007. 1 These guidelines use clinical decision rules to determine which patients should receive CT scanning and which should be admitted to hospital. Similar guidelines from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) are used in Scotland. 20

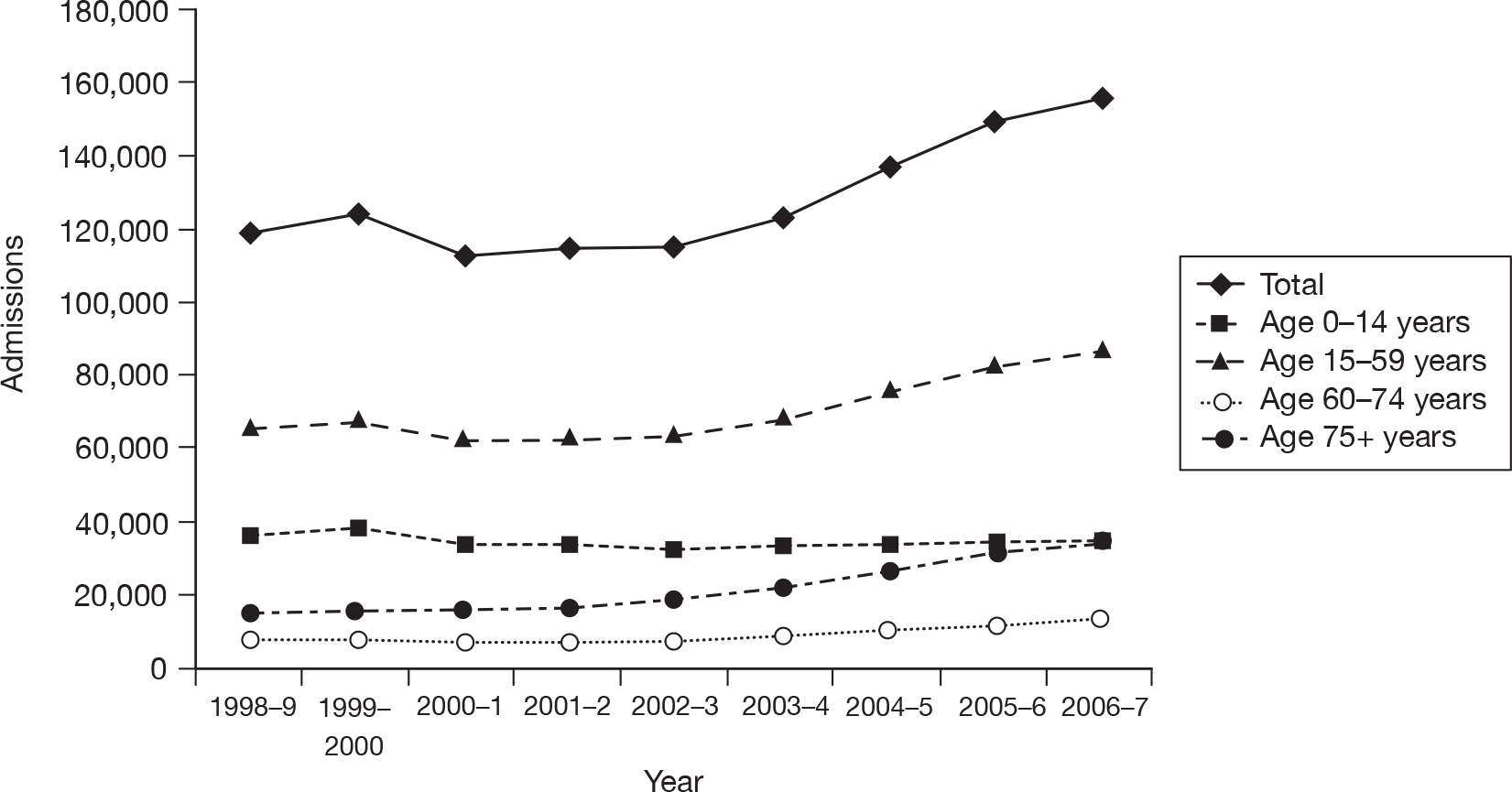

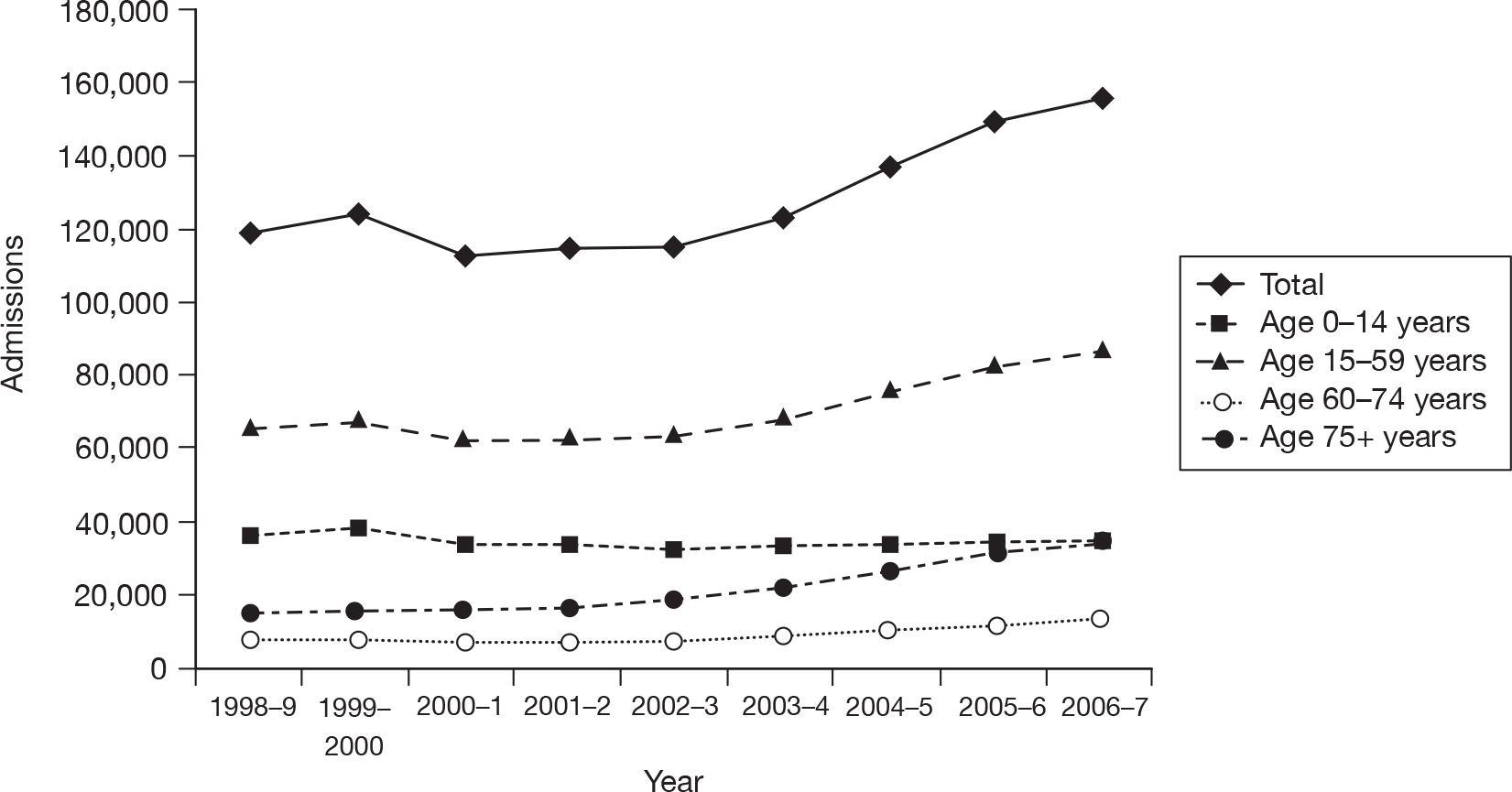

The NICE guidelines were based upon a literature review and expert consensus. Cost-effectiveness analysis was not used to develop the guidelines, but was used to explore the potential impact on health service costs. The guidelines were expected to reduce the use of skull radiography, increase the use of CT scanning and reduce hospital admissions, thus reducing overall costs. Data from a number of studies have since confirmed that more CT scans and less skull radiography are being performed. 21–23 However, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) for England show that the annual number of admissions for head injury increased from 114,769 in 2001–2 to 155,996 in 2006–7. As average length of stay remained relatively constant, bed-days increased from 348,032 in 2001–2 to 443,593 in 2006–7. Figure 1 shows that the increase in admissions has been seen in adults rather than in children. 24

FIGURE 1.

Head injury admissions in England, 1998–2007.24

These data suggest that the annual costs of admission for head injury have increased from around £170M to £213M since the guidelines were introduced.

The increase in admissions could be indirectly due to the NICE guidance. If, for example, clinicians were ordering more CT scans, but lacked the ability to interpret them or access to a radiological opinion then this could result in more admissions. However, changes in NHS emergency care occurring around 2003 other than NICE guidance could have been responsible for the increase in admissions. For example, the introduction of a target limiting the time spent in the ED to 4 hours could have resulted in patients being admitted to hospital rather than undergoing prolonged assessment in the ED. Furthermore, a general trend away from surgical specialties and towards emergency physicians in the responsibility for MHI admissions may have changed the threshold for hospital admission.

Description of technology under assessment

Diagnostic strategies for MHI include clinical assessment, clinical decision rules, skull radiography, CT scanning and biochemical markers. Clinical assessment can be used to identify patients with an increased risk of ICI and select patients for imaging or admission. A recent meta-analysis of 35 studies reporting data from 83,636 adults with head injury25 found that severe headache (relative risk 2.44), nausea (2.16), vomiting (2.13), loss of consciousness (LOC) (2.29), amnesia (1.32), post-traumatic seizure (PTS) (3.24), old age (3.70), male gender (1.26), fall from a height (1.61), pedestrian crash victim (1.70), abnormal GCS (5.58), focal neurology (1.80) and evidence of alcohol intake (1.62) were all associated with intracranial bleeding. A similar analysis of 16 studies reporting data from 22,420 children with head injury25 found that focal neurology (9.43), LOC (2.23) and abnormal GCS (5.51) were associated with intracranial bleeding.

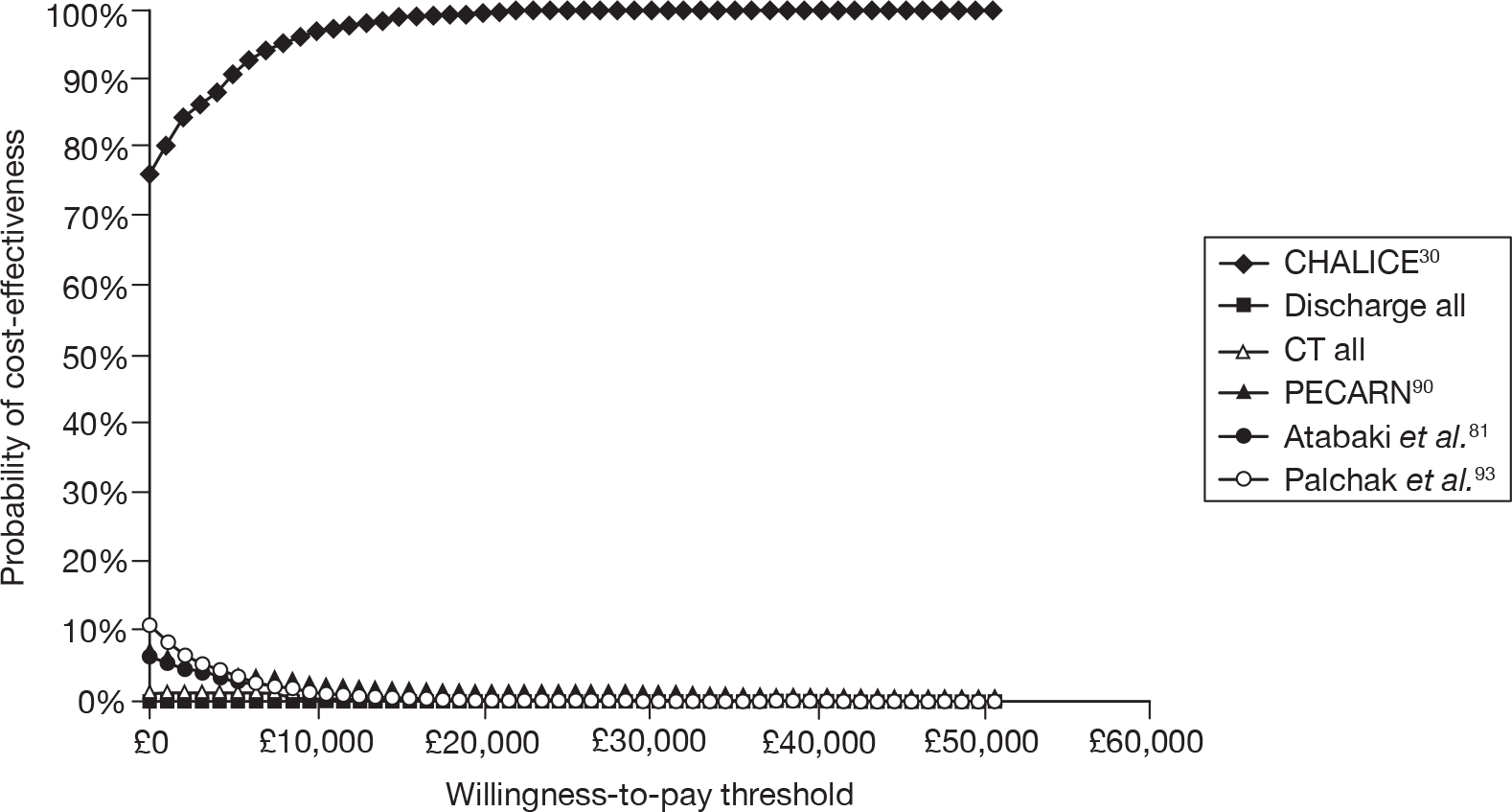

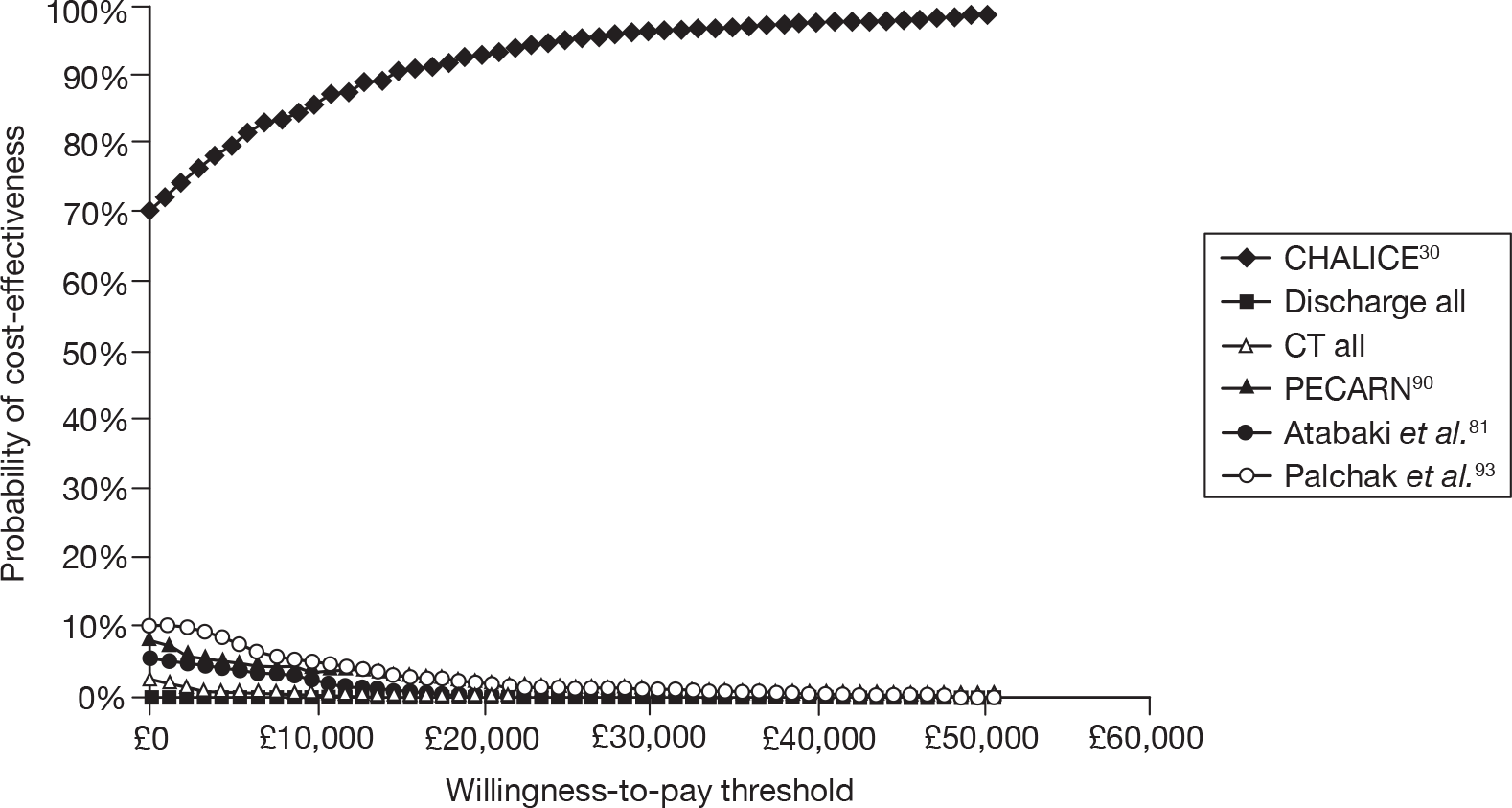

Clinical features have been combined in a number of studies to develop a structured clinical decision rule. Initially, clinical decision rules were developed to determine which patients should be admitted to hospital for observation. More recently, clinical decision rules have been developed to determine which patients should receive CT scanning. A systematic review undertaken for the NICE guidance19 identified four studies of four different clinical decision rules. The studies of the Canadian CT Head Rule (CCHR) criteria26 and the New Orleans Criteria (NOC) rule27 were both high quality, applicable to the NHS and reported 100% sensitivity for the need for neurosurgical intervention. Of the other two studies, one28 reported poor sensitivity and one29 was not applicable to the NHS. On this basis, the NICE guidance adapted the CCHR for use in the NHS and recommended this for adults and children, effectively as the NICE clinical decision rule. 19 In 2007, the guidance was updated1 to recommend using a rule developed specifically for children – the Children’s Head injury Algorithm for the prediction of Important Clinical Events (CHALICE) rule30 – although a modified version of the original rule continued to be recommended for adults.

Skull radiography can identify fractures that are associated with a substantially increased risk of intracranial bleeding, but cannot identify intracranial bleeding itself. Skull radiography is therefore used as a screening tool to select patients for investigation or admission, but not for definitive imaging. A meta-analysis31 found that skull fracture detected on a radiograph had a sensitivity of 38% and specificity of 95% for intracranial bleeding. More recent meta-analyses in adults25 and children32 reported relative risks of 4.08 and 6.13, respectively, for the association between skull fracture and intracranial bleeding. The NICE guidance only identifies a very limited role for skull radiography and use in the NHS has decreased accordingly. 21–23

Computerised tomography scanning definitively shows significant bleeding and a normal CT scan effectively excludes a significant bleed at the time of scanning. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can detect some lesions that are not evident on CT,33 but arguably none that is of clinical importance and certainly none that influences early management. CT can therefore be considered as a reference standard investigation for detecting injuries of immediate clinical importance. Liberal use of CT scanning will minimise the risk of missed ICI. However, this has to be balanced against the cost of performing large numbers of CT scans on patients with no ICI and the potential for harm from radiation exposure, particularly in children.

Hospital admission and observation may be used to identify intracranial bleeding by monitoring the patient for neurological deterioration. Although commonly used in the past, the effectiveness of this approach has not been studied extensively and has the disadvantage that neurosurgical intervention is delayed until after patient deterioration has occurred. Hospital admission and observation are usually used selectively, based upon clinical assessment or skull radiography findings. As with CT scanning, the use of hospital admission involves a trade-off between the benefits of early identification of patients who deteriorate owing to ICI and the costs of hospital admission for patients with no significant ICI.

Studies have compared CT-based strategies to skull radiography and/or admission to conclude that CT-based strategies are more likely to detect intracranial bleeding and less likely to require hospital admission. 34,35 Both cost analyses based upon randomised controlled trial (RCT) data36 and economic modelling37 suggest that a CT-based strategy is cheaper. However, admission-based strategies may be an inappropriate comparator for cost-effectiveness analyses because they appear to be expensive and of limited effectiveness, particularly if applied unselectively.

More recently, the role of biochemical markers for the identification of brain injury has been investigated. The focus of these research efforts has been on a rule-out test, of high sensitivity and negative predictive value, such that patients with a negative test can be discharged without the radiation exposure associated with CT scanning. The most widely researched biomarker is the astroglial cell S100 calcium-binding protein beta subunit (S100B). Although it has been identified in non-head-injured patients,38 following isolated head injury a measurable concentration less than the currently used cut-off of 0.1 µg/l measured within 4 hours of injury39 has been linked to negative CT scans with a sensitivity of 96.8% and specificity of 42.5%. So far, inconsistency of sensitivity and specificity results has limited its widespread application. The question of clinical applicability and cost-effectiveness has also yet to be addressed adequately. Other biochemical markers, such as neuron-specific enolase (NSE), dopamine and adrenaline, have been studied but less extensively and without validation or consistent results, rendering it impossible to draw any evidence-based conclusions about their utilisation.

Chapter 2 Research questions

Rationale for the study

The diagnostic management of MHI, particularly the use of CT scanning and hospital admission, involves a trade-off between the benefits of early accurate detection of ICI and the costs and harms of unnecessary investigation and admission for patients with no significant ICI. Clinical assessment, particularly if structured in the form of a decision rule, can be used to select patients for CT scanning and/or admission. Selective use of investigations or admission can reduce resource use, but may increase the risk of missed pathology. Cost-effectiveness analysis is therefore necessary to determine what level of investigation represents the most efficient use of health-care resources.

Although primary research can provide accurate estimates of the cost-effectiveness of alternative strategies, it can only compare a limited number of alternatives and is often restricted by ethical and practical considerations. Economic modelling allows comparison of a wide range of different strategies, including those that might currently be considered impractical or unethical, but may be revealed to be appropriate alternatives. Economic modelling is also a much cheaper and quicker way of comparing alternative strategies than primary research, so it can be used to identify which alternatives are most promising and where uncertainty exists and, thus, where primary research is best focused.

Economic modelling needs to be based upon systematic synthesis of robust and relevant data. We therefore planned to systematically review the literature to identify studies that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, decision rules and diagnostic tests used in MHI and studies that compared the outcomes of different diagnostic management strategies. These data could then be used to populate an economic model that estimated the costs and outcomes of potential strategies for managing patients with MHI and identify the optimal strategy for the NHS.

We limited our study to the diagnosis of acute conditions arising from MHI (the accuracy of tests for identifying acute injuries and the costs and benefits of identifying and treating acute injuries). Chronic subdural haematoma can develop weeks after MHI with an initially normal CT scan. As diagnosis and management of this condition occurs after initial presentation, it is more appropriately analysed as part of a separate decision-making process that is beyond the scope of this review. Similarly, we did not explore issues related to diffuse brain injury or persistent symptoms related to mild traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The overall aim was to use secondary research methods to determine the most appropriate diagnostic management strategy for adults and children with minor (GCS 13–15) head injury in the NHS. More specifically, the objectives were:

-

To undertake systematic reviews to determine (1) the diagnostic performance of published clinical decision rules for identifying ICI (including the need for neurosurgery) in adults and children with MHI; (2) the diagnostic accuracy of individual clinical characteristics for predicting ICI (including the need for neurosurgery) in adults and children with MHI; and (3) the comparative effectiveness of different diagnostic management strategies for MHI in terms of process measures (hospital admissions, length of stay, time to neurosurgery) or patient outcomes.

-

To use a cross-sectional survey and routinely available data to describe current practice in the NHS, in terms of guidelines and management strategies used and hospital admission rates.

-

To develop an economic model to (1) estimate the cost-effectiveness of diagnostic strategies for MHI, in terms of the cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained by each strategy; (2) identify the optimal strategy for managing MHI in the NHS, defined as the most cost-effective strategy at the NICE threshold for willingness to pay per QALY gained; and (3) identify the critical areas of uncertainty in the management of MHI, where future primary research would produce the most benefit.

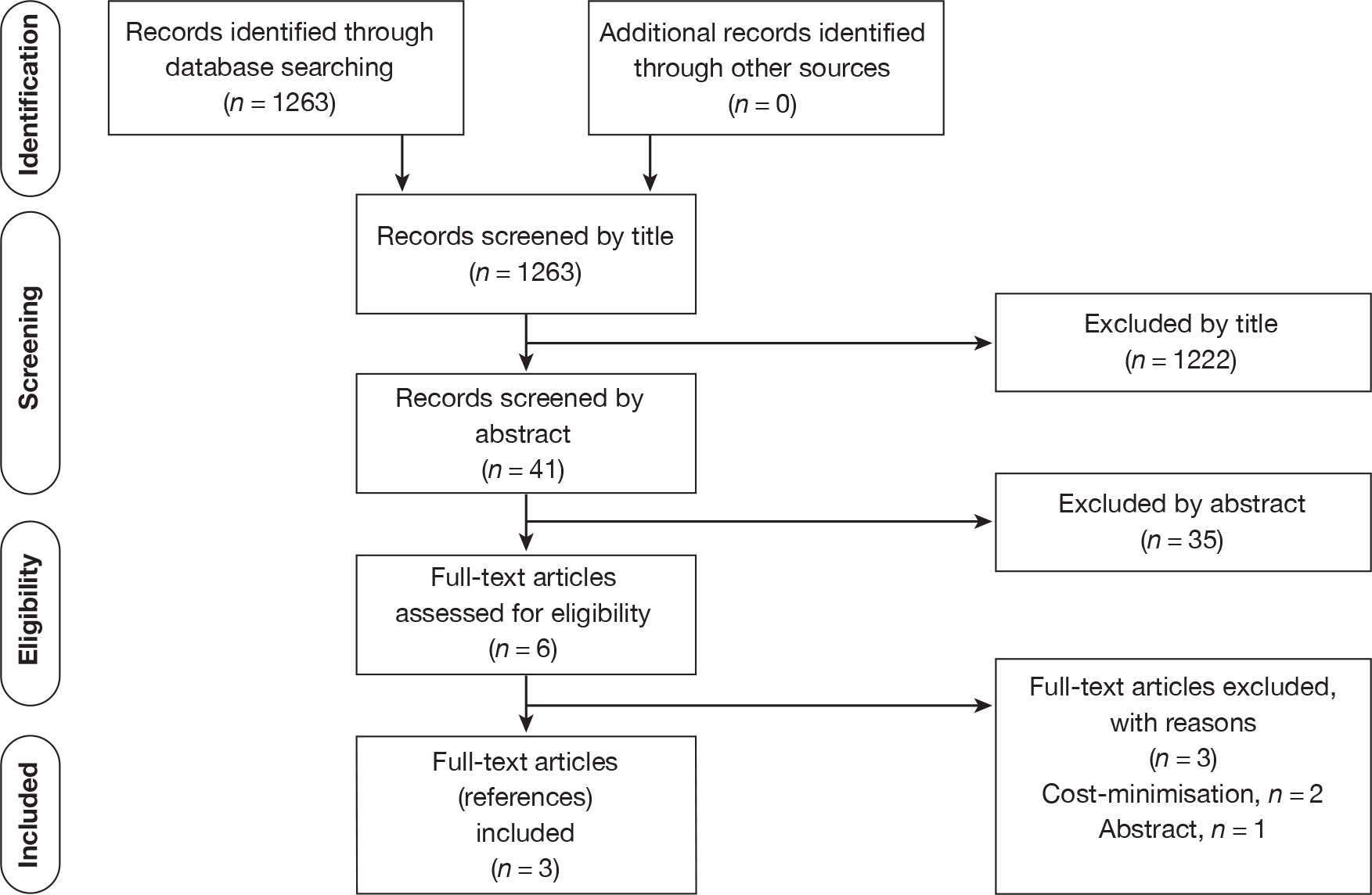

Chapter 3 Assessment of diagnostic accuracy

A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis (where appropriate) was undertaken to evaluate the diagnostic performance of clinical decision rules and to measure the diagnostic accuracy of key elements of clinical assessment for identifying intracranial injuries in adults and children with MHI.

The systematic review and meta-analysis was undertaken in accordance with the guidelines published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) for undertaking systematic reviews40 and the Cochrane Diagnostic Test Accuracy Working Group on the meta-analysis of diagnostic tests. 41,42

Methods for reviewing diagnostic accuracy

Identification of studies

Electronic databases

Studies were identified by searching the following electronic databases:

-

MEDLINE (via OvidSP) 1950 to March 2010

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via OvidSP) 1950 to March 2010

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCO) 1981 to April 2009

-

EMBASE (via OvidSP) 1980 to April 2009

-

Web of Science (WoS) [includes Science Citation Index (SCI) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (CPCI)] [via Web of Knowledge (WoK) Registry] 1899 to April 2009

-

Cochrane Central Registry of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2009)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (via Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2009)

-

NHS Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (via Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2009)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (via Cochrane Library Issue 2, 2009)

-

Research Findings Register (ReFeR)

-

National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) databases

-

International Network of Agencies for Health Technology Assessment (INAHTA)

-

Turning Research Into Practice (TRIP) database.

Sensitive keyword strategies using free text and, where available, thesaurus terms using Boolean operators and database-specific syntax were developed to search the electronic databases. Synonyms relating to the condition (e.g. head injury) were combined with a search filter aimed at restricting results to diagnostic accuracy studies (used in the searches of MEDLINE, CINAHL and EMBASE). Date limits or language restrictions were not used on any database. All resources were searched from inception to April 2009. Updated searches to March 2010 were conducted on the MEDLINE databases only. An example of the MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Appendix 1.

Other resources

To identify additional published, unpublished and ongoing studies, the reference lists of all relevant studies (including existing systematic reviews) were checked and a citation search of relevant articles [using WoK’s SCI and Social Science Citation Index (SSCI)] was undertaken to identify articles that cite the relevant articles. In addition, systematic keyword searches of the world wide web (WWW) were undertaken using the Copernic Agent™ Basic (version 6.12; Copernic, Quebec City, QC, Canada) meta-search engine and key experts in the field were contacted.

All identified citations from the electronic searches and other resources were imported into and managed using the Reference Manager bibliographic software version 12.0 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion of potentially relevant articles was undertaken using a three-step process. First, two experienced systematic reviewers (APa and SH) independently screened all titles and excluded any citations that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria (i.e. non-human, unrelated to MHI). Second, the list of included abstracts that were identified as possibly relevant by title (or when uncertainty existed) was divided equally between two pairs of authors (comprising an experienced reviewer and a clinical expert – APa and APi, respectively, or SH and SG, respectively) and assessed independently by each reviewer for inclusion. The full manuscript of all potentially eligible articles that were considered relevant by either pair of authors was obtained, where possible. Third, two review authors (APa and SH) independently assessed the full-text articles for inclusion. This was then checked by two clinical experts (SG and APi) separately. Blinding of journal, institution and author was not performed. Any disagreements in the selection process (within or between pairs) were resolved through discussion and included by consensus between the four reviewers. The relevance of each article for the diagnostic accuracy review was assessed according to the following criteria.

Study design

All diagnostic cohort studies (prospective or retrospective) with a minimum of 20 patients were included. Case–control studies (i.e. studies in which patients were selected on the basis of the results of their reference standard test) were excluded.

Reviews of primary studies were not included in the analysis, but were retained for discussion and identification of additional studies. The following publication types were excluded from the review: animal studies, narrative reviews, editorials, opinions, non-English-language papers and reports in which insufficient methodological details are reported to allow critical appraisal of the study quality.

Population

All studies of adults and children (of any age) with MHI (defined as patients with a blunt head injury and a GCS of 13–15 at presentation) were included. Studies of patients with moderate or severe head injury (defined as patients with a GCS of ≤ 12 at presentation) or no history of injury were excluded. Studies that recruited patients with a broad range of head injury severity were included only if > 50% of the patients had MHI.

Index test

Any test for ICI. This included clinical assessment (e.g. history, physical examination, clinical observation), laboratory testing (e.g. biochemical markers) or application of a clinical decision rule (defined as a decision-making tool that incorporates three or more variables obtained from the history, physical examination or simple diagnostic tests). 43

Target condition

The target conditions of this review were:

-

the need for neurosurgical intervention (defined as any ICI seen on CT or MRI scanning that required neurosurgery)

-

any ICI (defined as any intracranial abnormality detected on CT or MRI scan due to trauma).

Reference standard

The following reference standards were used to define the target conditions:

-

CT scan

-

combination of CT scan and follow-up for those with no CT scan

-

MRI scan.

Computerised tomography scanning is the diagnostic reference standard for detecting intracranial injuries that require immediate neurosurgical intervention, as well as those that require in-hospital observation and medical management. 1 Despite considerable variability in the use of CT scanning,44,45 performing a CT scan on all patients with MHI is costly and exposes most patients with normal CT scan to unnecessary radiation. 46 Therefore, CT scanning or follow-up for those not scanned was also deemed to be an acceptable reference standard.

Magnetic resonance imaging is considered to be more sensitive than CT scanning in detecting acute traumatic ICI in patients with MHI (i.e. can detect some lesions that are not evident on CT). 33 However, the lesions that are detected on MRI as opposed to CT are not likely to influence early neurosurgical management39 and its widespread use is constrained by costs, availability and accessibility issues. 39 Nevertheless, it can still be regarded as an appropriate reference standard.

Outcomes

Sufficient data to construct tables of test performance [numbers of true-positives (TPs), false-negatives (FNs), false-positives (FPs) and true-negatives (TNs) or sufficient data to allow their calculation]. Studies not reporting these outcomes were identified, but not incorporated in the analyses.

Data abstraction strategy

Data abstraction was performed by one reviewer (SH) into a standardised data extraction form and independently checked for accuracy by a second (APa). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers and, if agreement could not be reached, a third or fourth reviewer was consulted (SG and APi). Where multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study. The authors of the studies were contacted to provide further details in cases where information was missing from the articles.

The following information was extracted for all studies when reported: study characteristics (author, year of publication, journal, country, study design and setting), participant details (age, gender, percentage with MHI, GCS, inclusion and exclusion criteria), test details, reference standard details, prevalence of each outcome [clinically significant ICI and need for neurosurgery (including definitions)] and data for a two-by-two table (TP, FN, FP, TN). Where a study presented several different versions of a clinical decision rule (i.e. developed during the derivation phase), all test performance data were extracted. However, the analyses considered data from only the rule endorsed by the authors or the rule derived for the most appropriate outcome.

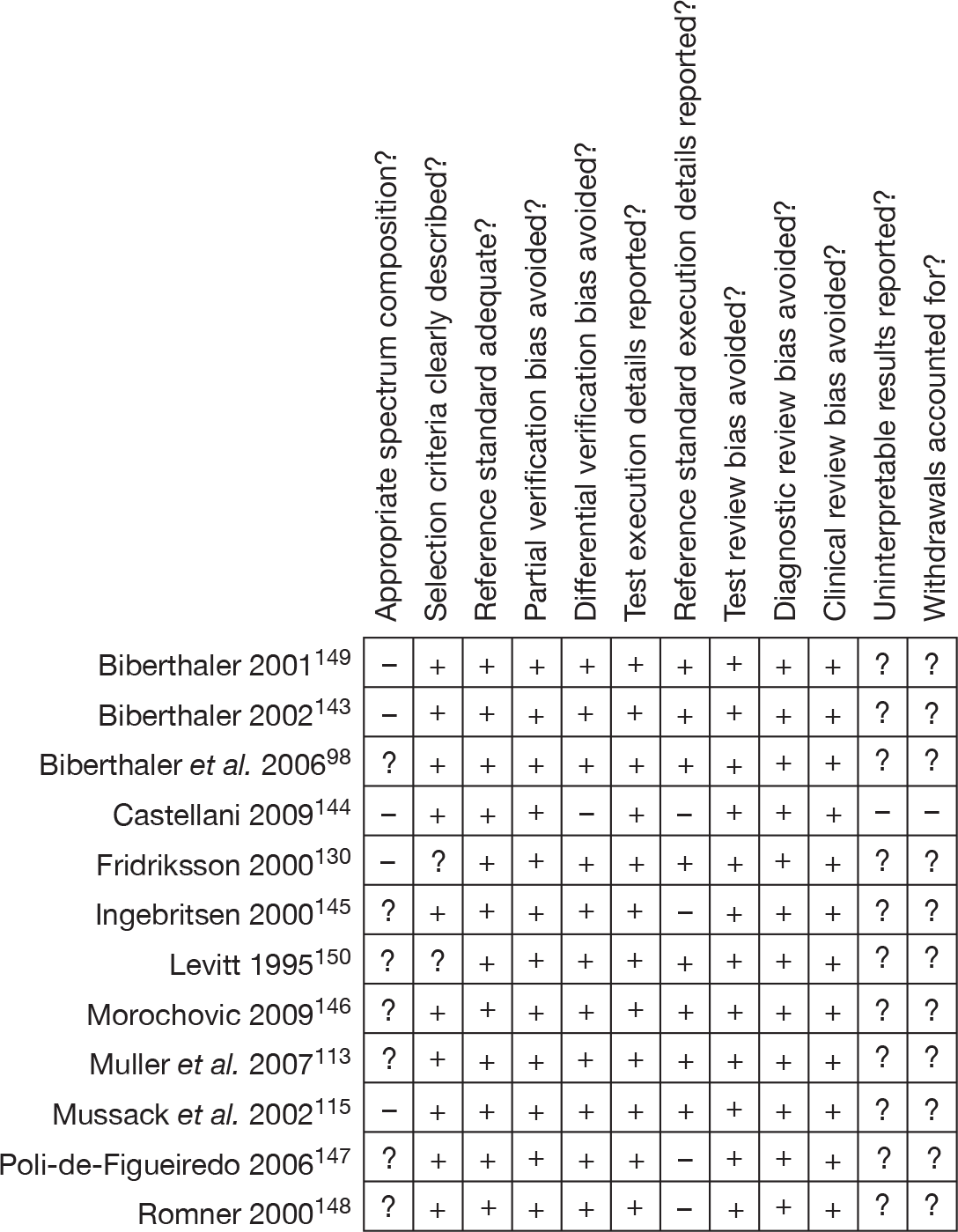

Quality assessment strategy

The methodological quality of each included study was assessed by one reviewer (SH) and checked by another (APa) using a modified version of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS) tool47 (a generic, validated, quality assessment instrument for diagnostic accuracy studies). In case of doubt, a third and fourth reviewer (SG and APi) were consulted.

The quality assessment items in QUADAS include the following: spectrum composition, description of selection criteria and reference standard, disease progression bias (this item was not applicable to this review as the reference standard was defined as CT or MRI within 24 hours of admission), partial and differential verification bias, test and reference standard review bias, clinical review bias, incorporation bias (this item was not applicable to this review as the reference standard was always independent of the index test), description of index and reference test execution, study withdrawals and description of indeterminate test results. For studies reporting decision rules, three items relating to the reference standard (adequacy of reference standard, partial and differential verification bias) were included twice, once for each target condition. For studies reporting clinical characteristics, these items were included once and scored negatively if either reference standard was inadequate. Study quality was assessed with each item scored as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unclear’. A summary score estimating the overall quality of an article was not calculated as the interpretation of such summary scores is problematic and potentially misleading. 48,49 Further details on the modified version of the QUADAS tool are provided in Appendix 2.

Methods of data synthesis

Indices of test performance were extracted or derived from data presented in each primary study of each test. Two-by-two contingency tables of TP cases, FN cases, FP cases and TN cases were constructed. Data from cohorts of children were analysed separately. Data from cohorts of adults, mixed cohorts and cohorts with no clear description of the age range included were analysed together.

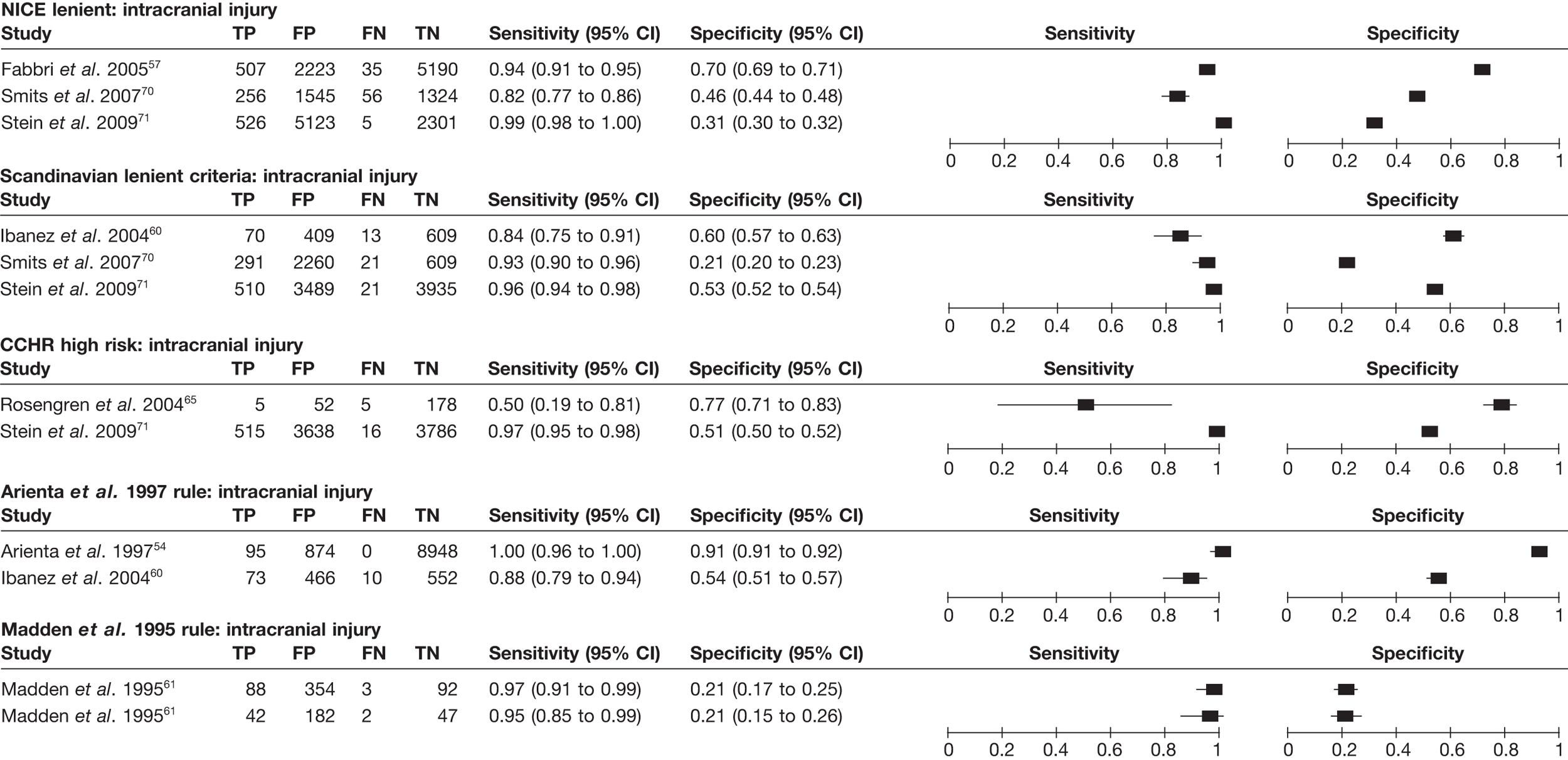

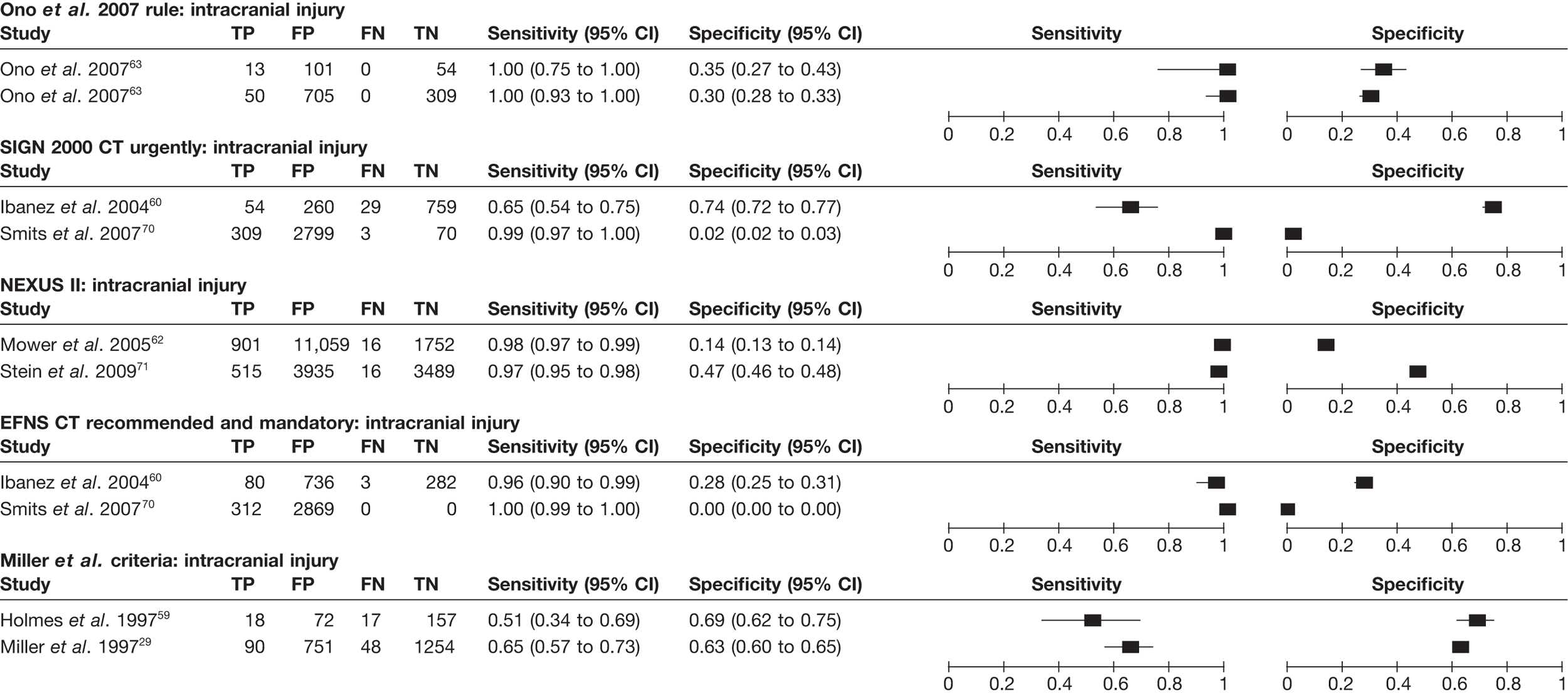

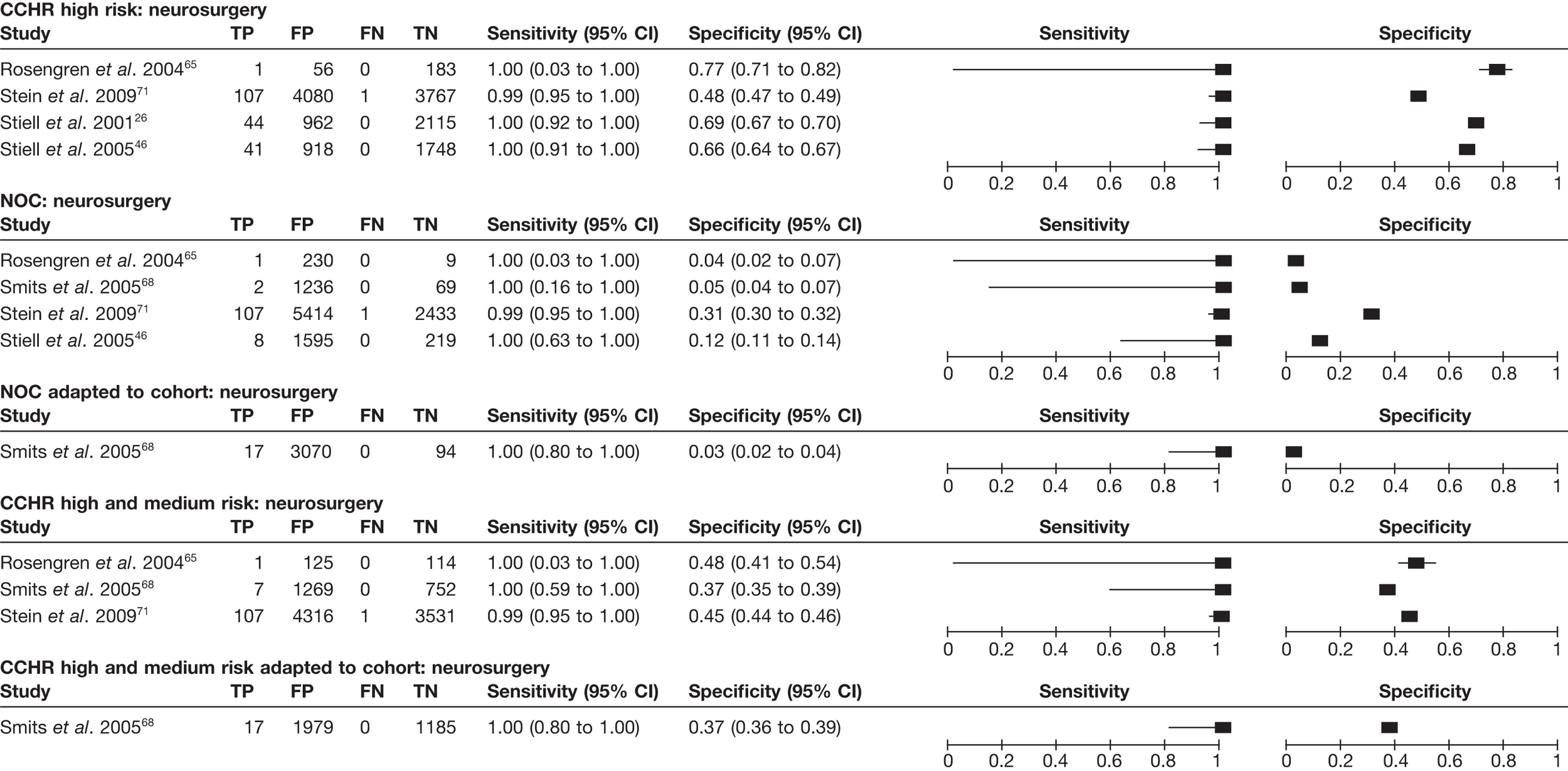

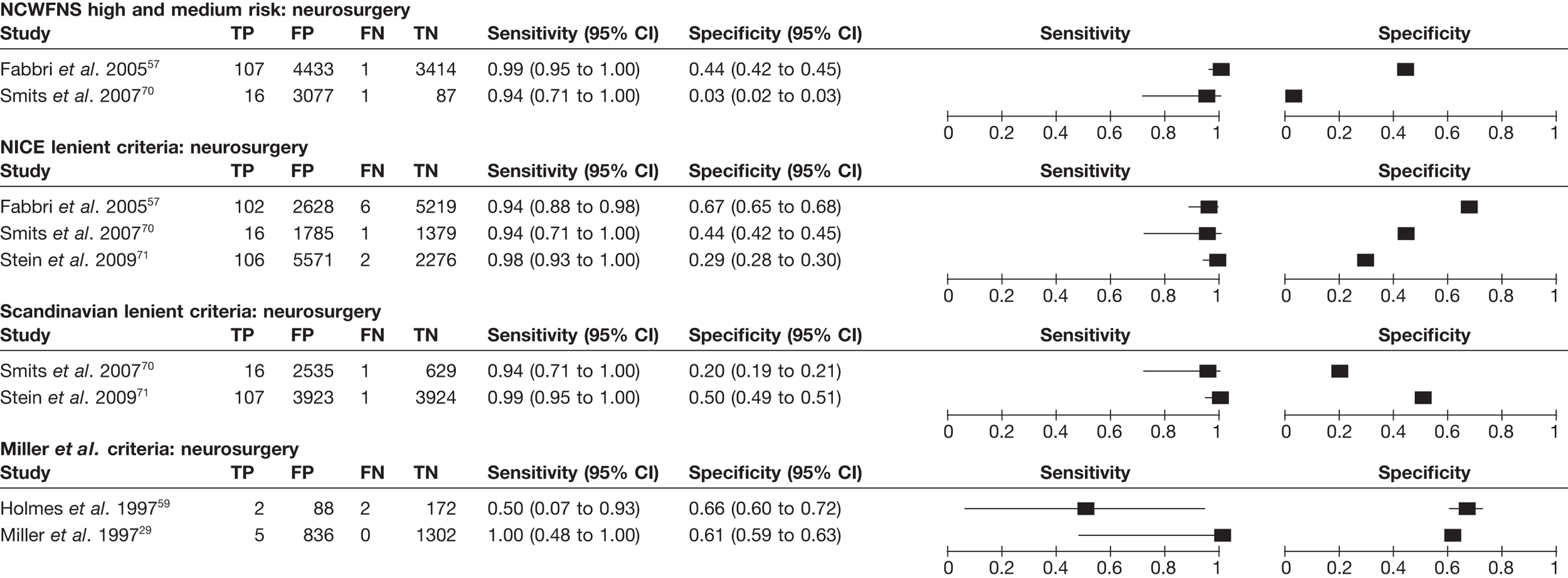

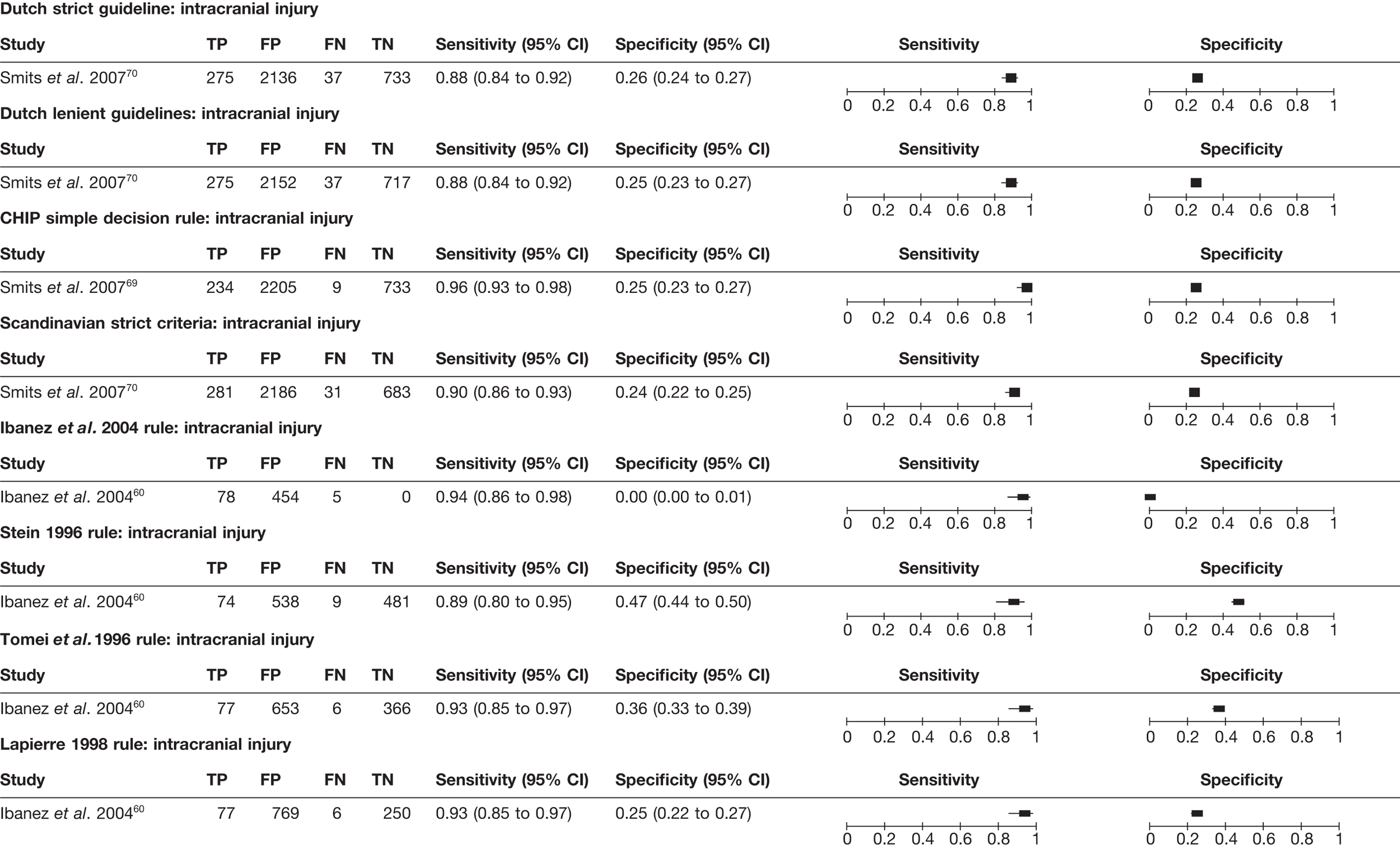

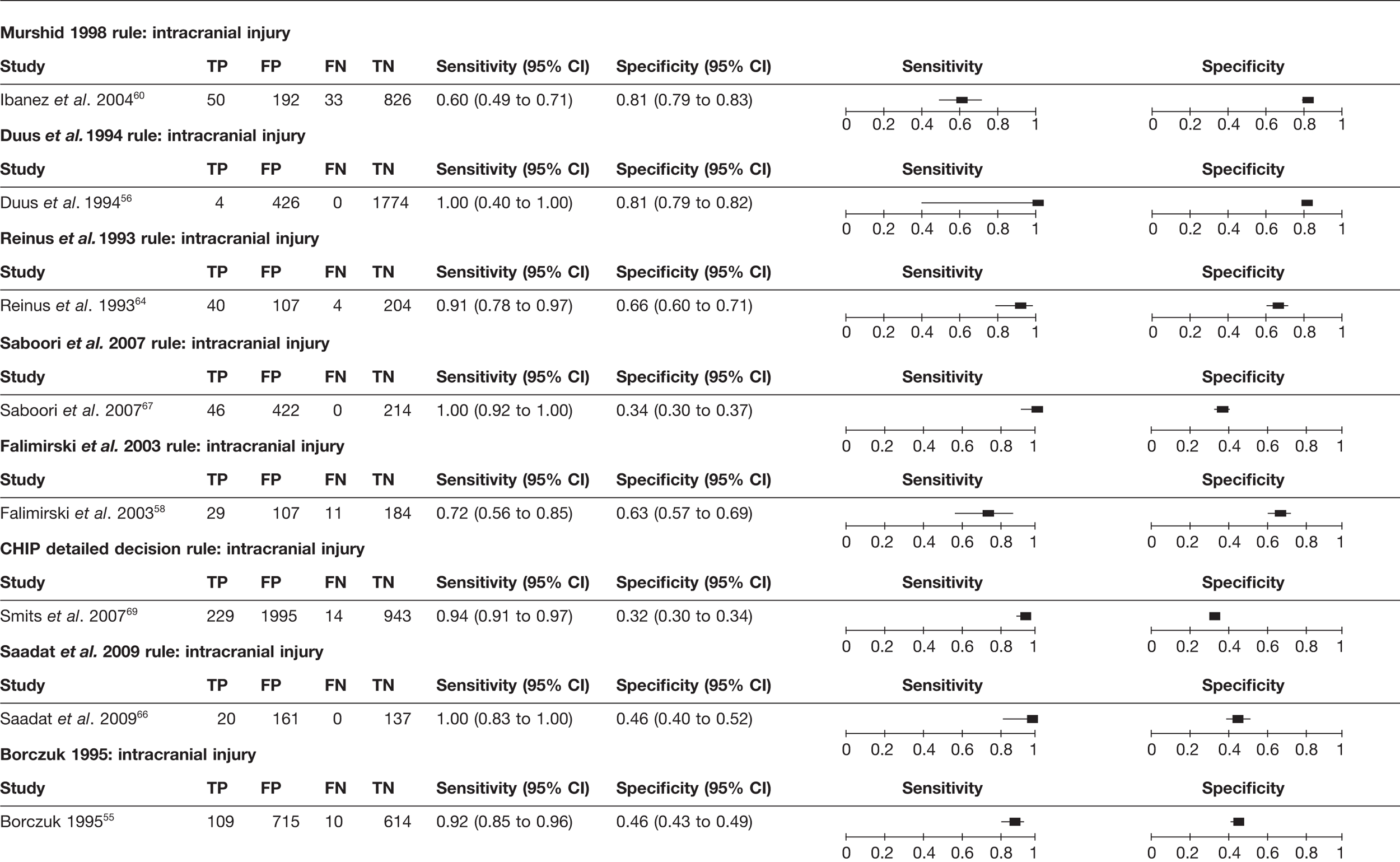

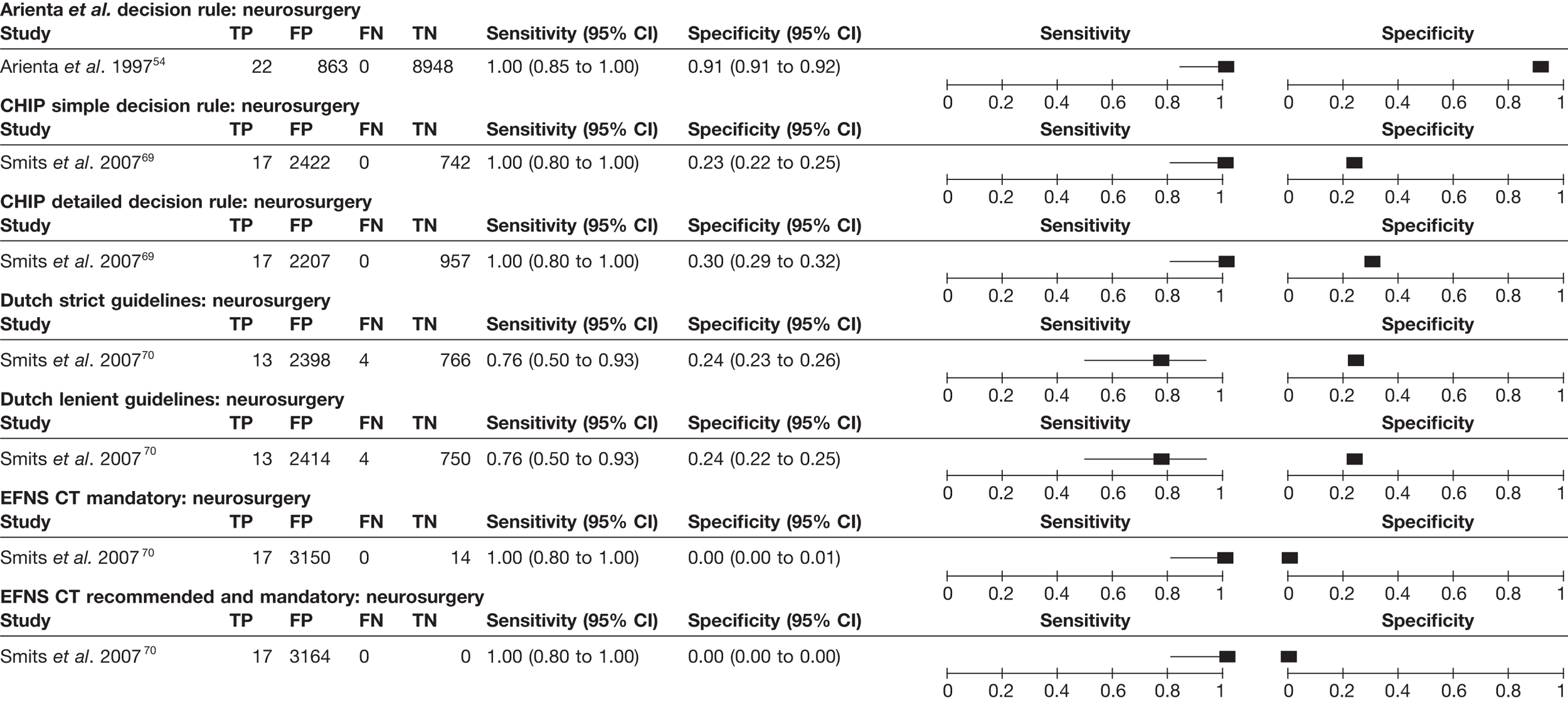

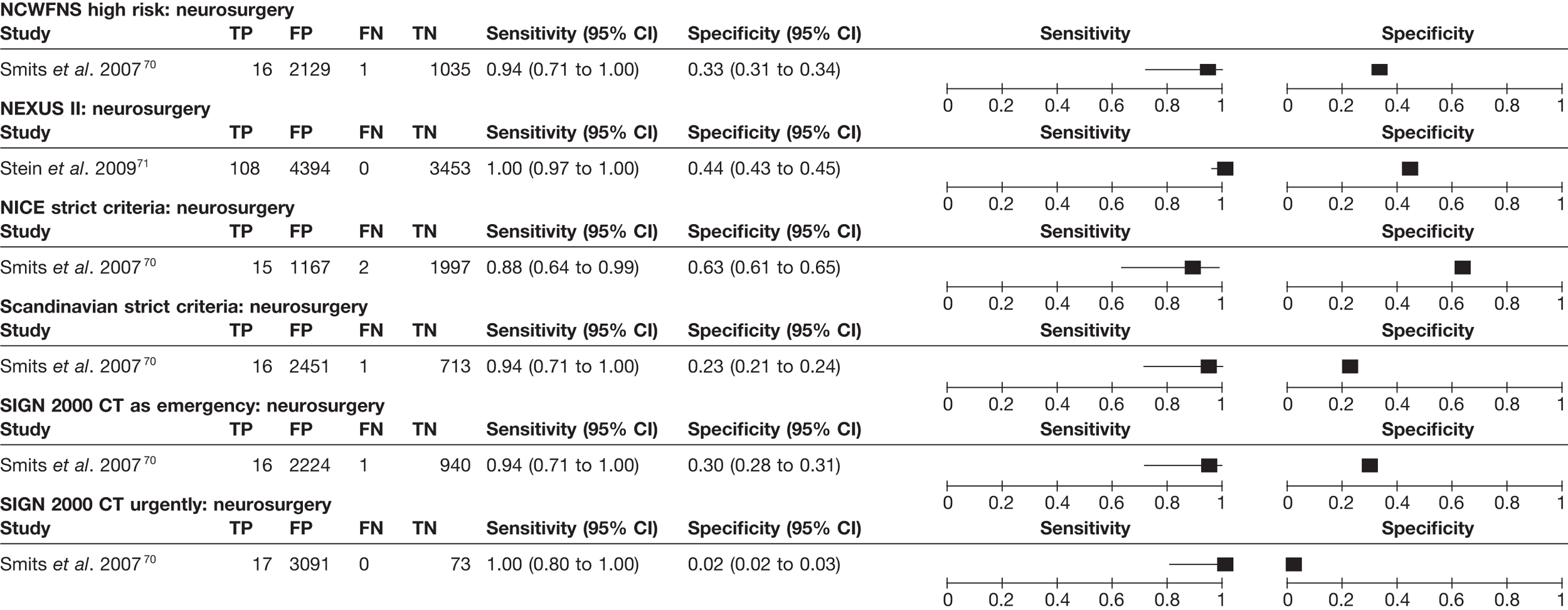

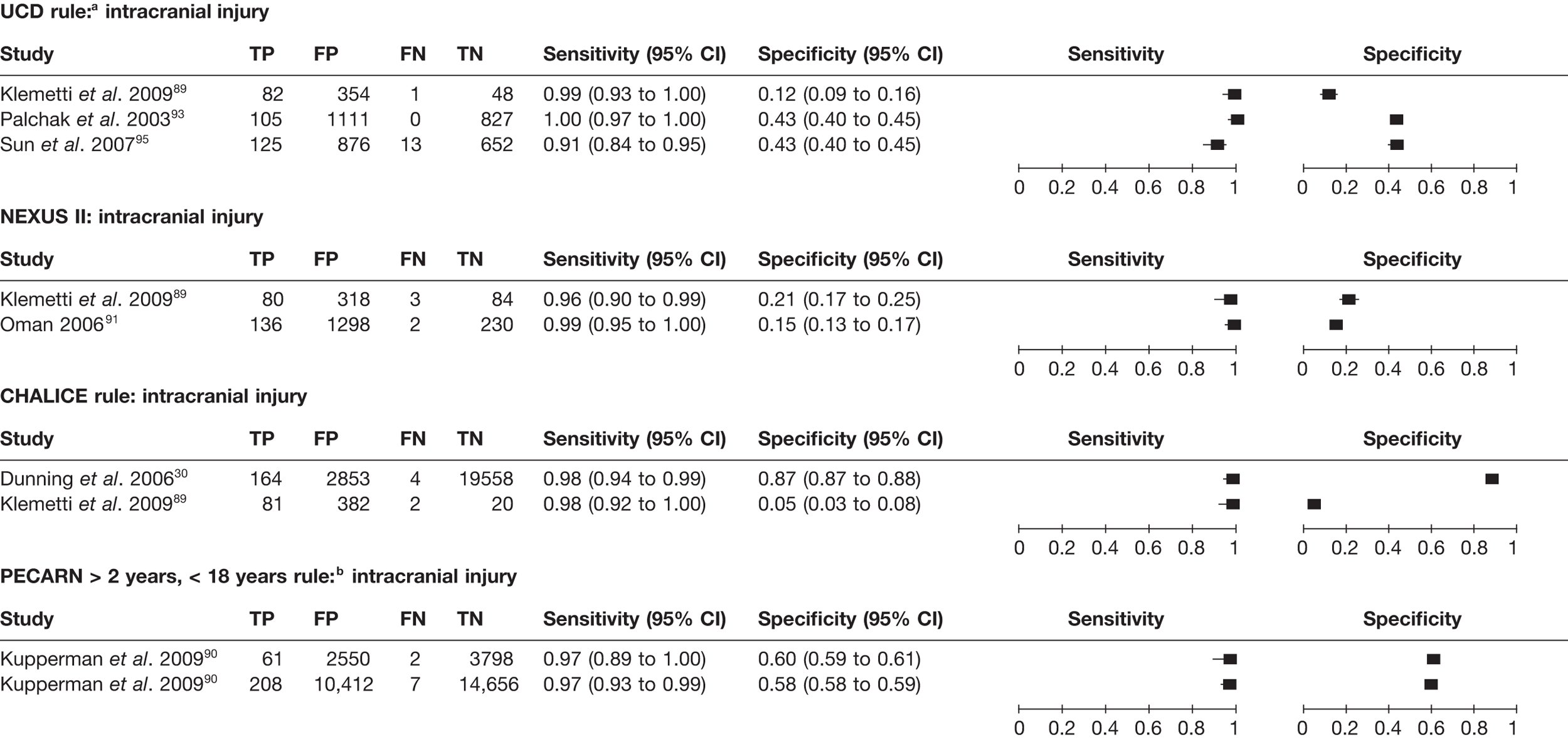

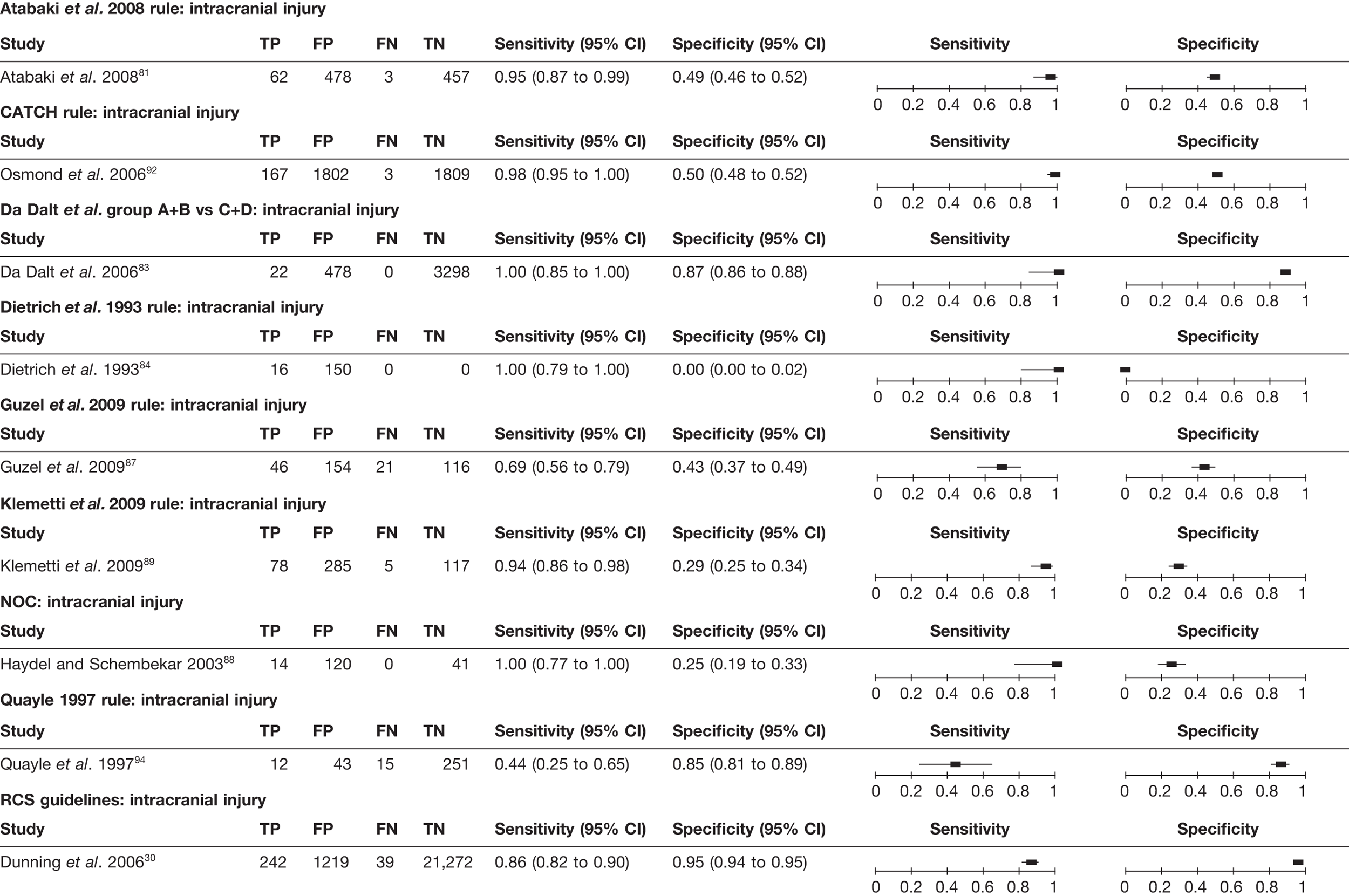

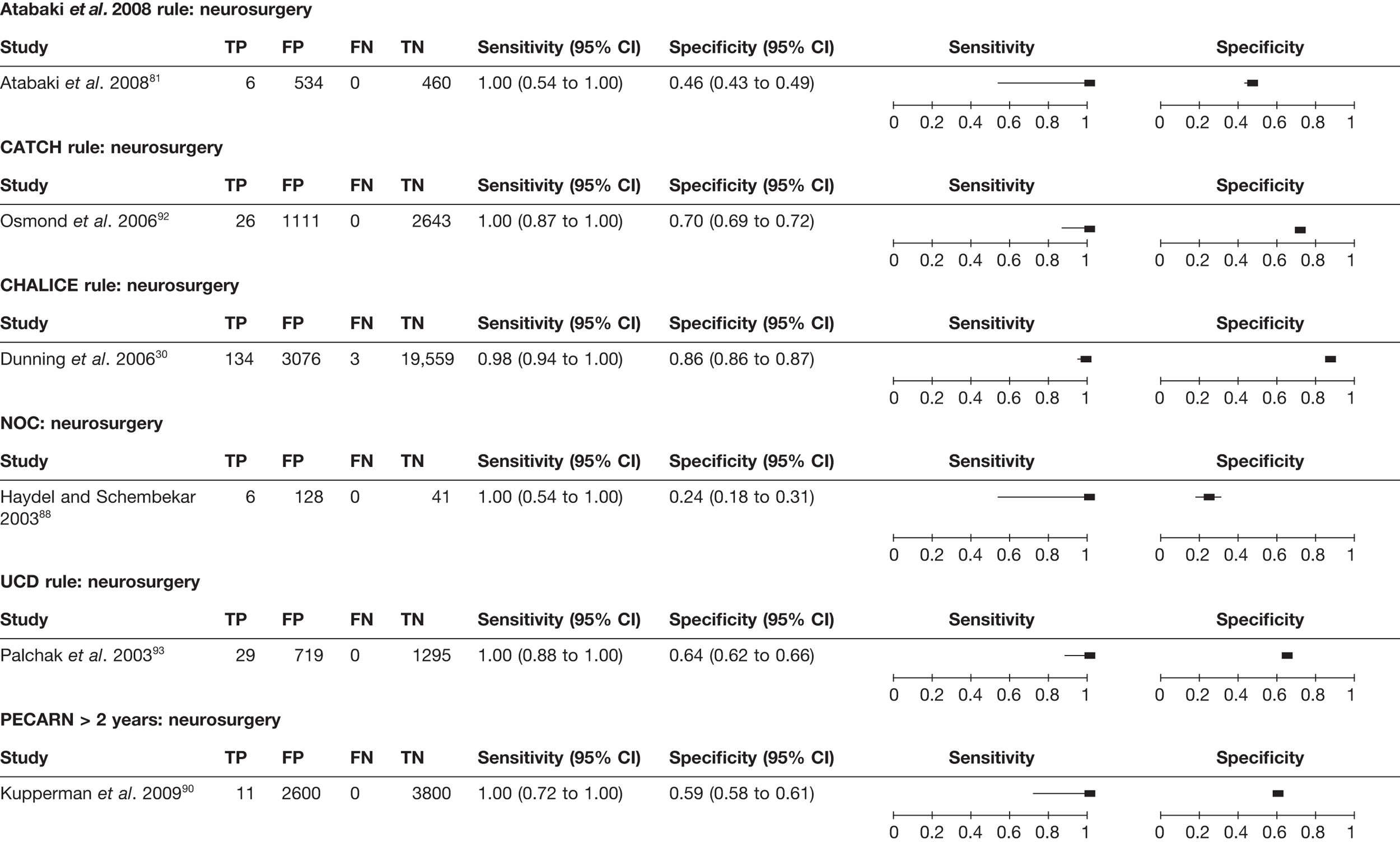

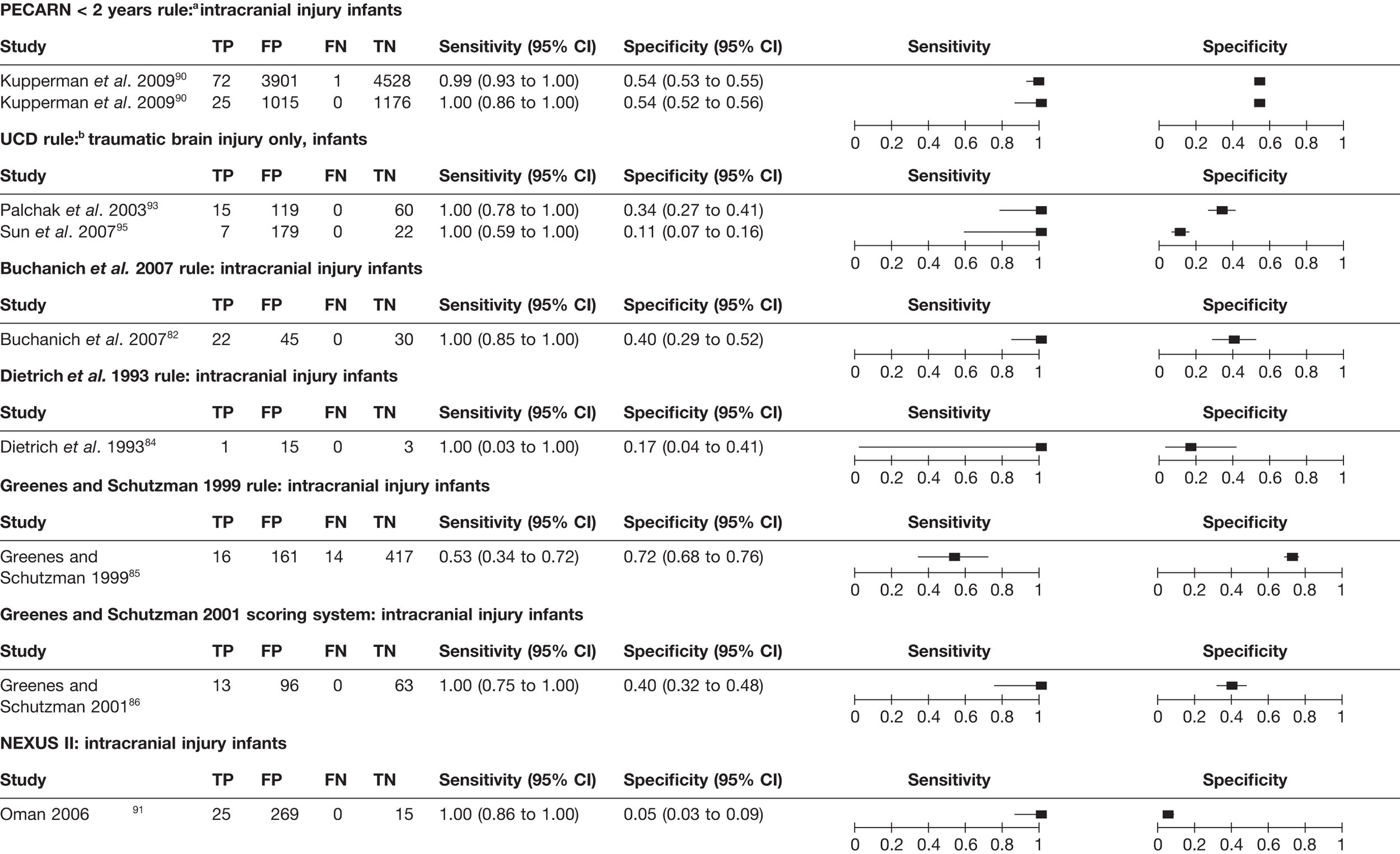

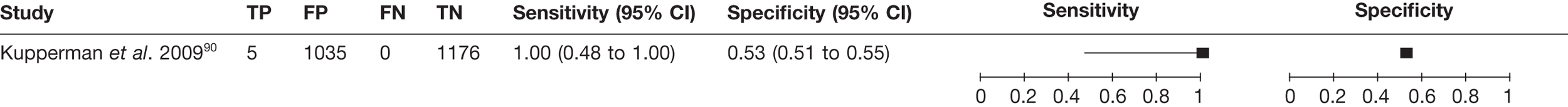

For the diagnostic performance of published clinical prediction rules (for diagnosing intracranial bleeding requiring neurosurgery or any clinically significant ICI), the data of the two-by-two tables were used to calculate sensitivity and specificity [and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each study]. We planned to undertake meta-analysis if there were a sufficient number of validation studies of the same rule in cohorts that were not markedly heterogeneous. However, after searches were completed it was apparent that no rule had been studied sufficiently to allow a meaningful meta-analysis. Therefore, results were presented in a narrative synthesis and illustrated graphically (forest plots) using the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager software (version 5.0; The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). 50

For the diagnostic accuracy of clinical assessment, a different approach was used. We selected clinical characteristics that had been defined in a reasonably homogeneous and clinically meaningful way. Where applicable, three different approaches were used to meta-analyse the data. If data from only one study were available, no meta-analyses were undertaken, and the analysis produced estimates of sensitivity, specificity, negative likelihood ratio (NLR) and positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and corresponding 95% CIs. The last were calculated assuming that the statistics were normally distributed on the logit scale (sensitivity, specificity) and on the logarithm scale (NLR, PLR).

The PLR is the proportion with the outcome (neurosurgery or ICI) given that the risk factor is ‘positive’, divided by the proportion without the outcome given that the risk factor is ‘positive’, i.e. the PLR is the odds of having the outcome, given a positive risk factor. By a similar argument, the NLR is the odds of having the outcome given a negative risk factor. 51 Thus, the PLR and NLR are two potentially useful clinical diagnostic measures, depending on whether or not a patient is risk factor positive or risk factor negative.

If there were data from two studies, a fixed-effects meta-analysis was conducted using the DerSimonian and Laird method,52 weighted by the inverse of study variance estimate, and, as before, estimates of sensitivity, specificity, NLR, PLR and corresponding 95% CI. Note, that the correlation between outcomes cannot be taken into account in this case as there were insufficient data.

For data from three or more studies, a full Bayesian meta-analysis was conducted. The bivariate random-effects method of Reitsma et al. 53 was used. The Bayesian approach was chosen because the between-studies uncertainty can be modelled directly, which is important in any random effects meta-analysis where there are small numbers of studies and potential heterogeneity. Correlation between sensitivity and specificity was modelled at the logit level and the correlation was modelled separately. In addition to the estimated sensitivity, specificity, NLR, PLR and corresponding 95% highest-density regions (HDRs), results also included estimated heterogeneity (Q) statistics and corresponding p-values for sensitivity and specificity, calculated using a fixed-effects approach.

Results of the review of diagnostic accuracy

This section presents the results of the following systematic reviews separately:

-

the diagnostic performance of published clinical decision rules for identifying ICI or the need for neurosurgery in adults and children with MHI (see Clinical decision rules)

-

the diagnostic accuracy of individual clinical characteristics for predicting ICI or the need for neurosurgery in adults and children with MHI (see Individual characteristics)

-

the diagnostic accuracy of various biochemical markers for predicting ICI or the need for neurosurgery in adults and children with MHI (see Biomarkers).

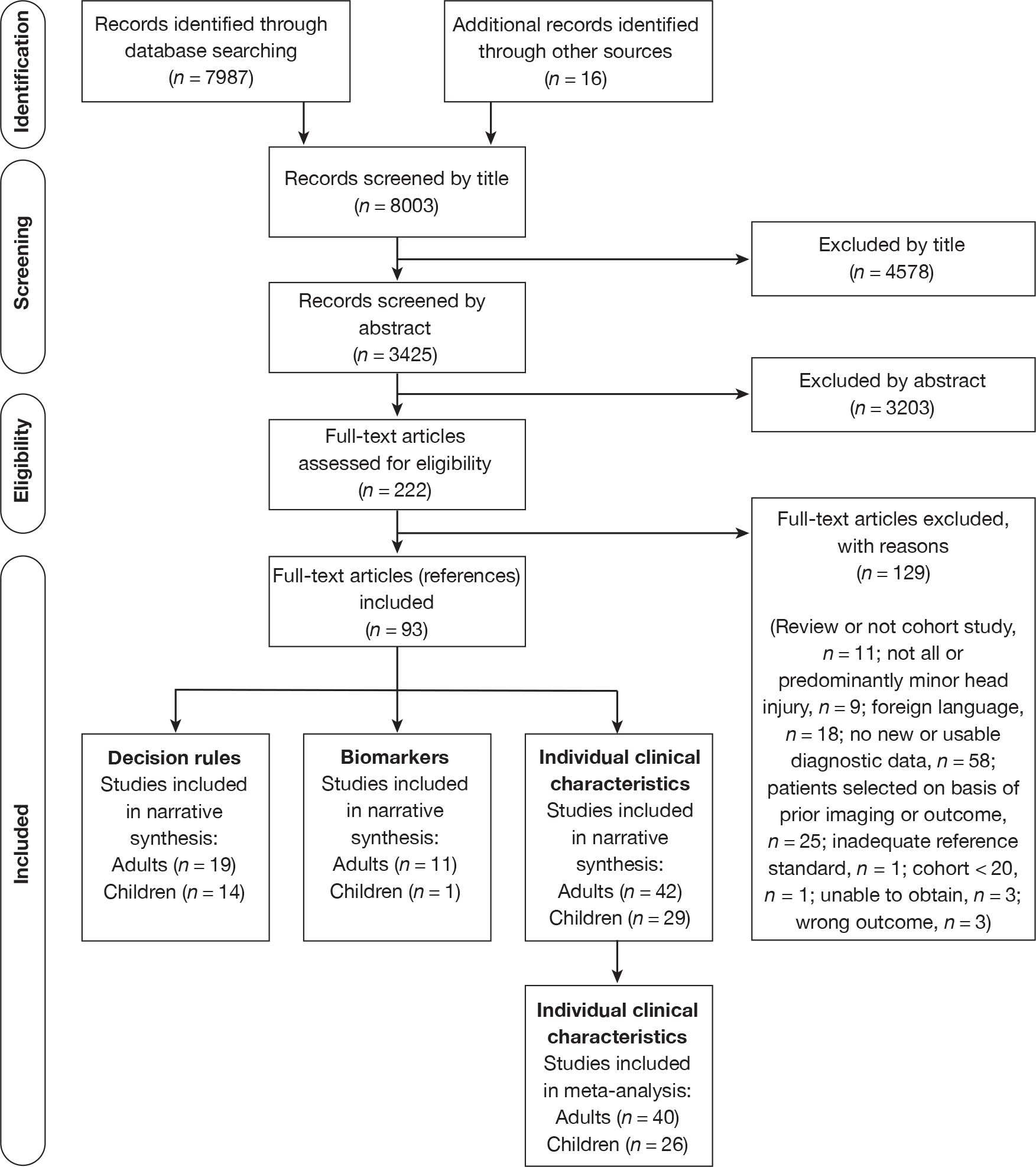

Studies included in the review

Overall, the literature searches identified 8003 citations. Of the titles and abstracts screened, 222 relevant full papers were retrieved and assessed in detail. A flow chart describing the process of identifying relevant literature can be found in Appendix 3. A total of 93 papers evaluating the diagnostic performance and/or accuracy of clinical decision rules, individual clinical characteristics (symptoms, signs and plain imaging) and biochemical markers met the inclusion criteria. Table 1 shows the number of studies included for each systematic review of diagnostic accuracy. Studies excluded from the review are listed in Appendix 4.

| Diagnostic review | No. of included studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Adults | Children and/or infants | |

| Clinical decision rules | 19 | 14 |

| Individual clinical characteristics | 42 | 29 |

| Biomarkers | 11 | 1 |

Clinical decision rules

Description of included studies

Adults

The design and patient characteristics of the 19 studies (representing 22 articles)26,27,29,46,54–71 that evaluated the diagnostic performance of clinical decision rules for identifying ICI or need for neurosurgery in adults with MHI are summarised in Table 2. Eight studies were from the USA,27,29,55,58,59,61,62,64 two each from Italy,54,57,71 Canada26,46 and the Islamic Republic of Iran,66,67 and one each from the Netherlands,68–70 Australia,65 Japan,63 Spain60 and Denmark. 56 Six were multicentre studies. 26,46,62,66–70 Cohorts ranged in size from 16863 to 13,728. 62 Fourteen studies derived a new rule. 26,27,29,54–56,60,61–64,66,67,69 Four studies46,57,60,68–71 reported validation results for more than one rule in the same cohort. Data were collected prospectively in 15 studies,26,27,29,46,56–63,66–71 of which participants were recruited consecutively in 13,26,27,29,56–60,62,63,66–71 as a convenience sample in one,46 and one did not report the method of participant recruitment. 61 The remaining four studies were retrospective. 54,55,64,65 Of the 19 studies, three reported both a derivation and a validation cohort,27,61,63 making a total of 22 different cohorts.

| Author, year | Rule(s) derived | Rule(s) validated | Country | Design | No. of patients, n | Mean or median age, years (range) | Prevalence of neurosurgery | Prevalence of ICI | CT as inclusion? (yes/no) | Male, n | Patients with MHI, n | Prevalence of GCS 15, n | Other significant inclusion criteria | Other significant exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arienta et al. 199754 | Arienta et al. 199754 | Italy | R | 9917 | NR | 24/9917 (0.2%) | 85/9917 (0.86%) | No | NR for this subgroup | 9917/9917 (100%) | 9833/9917 (99%) | ≥ 6 years of age. Presenting to the ED directly | Children < 6 years of age | |

| Borczuk 199555 | Borczuk 199555 | USA | R | 1448 | NR | 119/1448 (8.2%) | Yes | 999/1448 (68%) | 1448/1448 (100%) | 1211/1448 (83.6%) | ≥ 17 years of age. GCS ≥ 13, blunt head trauma, had CT scan | ≤ 16 years. Patients with penetrating cranial trauma | ||

| Duus et al. 199456 | Duus et al. 199456 | Denmark | P, Cs | 2204 | Mean: 23.7 (0 to 108) | 4/2204 (0.18%) | No | 1378/2204 (62.5%) | 2204/2204 (100%) | NR | MHI, able to walk and talk | Comatose, unable to identify themselves or unresponsive to pain | ||

| Fabbri et al. 2005;57 aStein et al. 200971 | CCHR,26 NCWFS,72 NICE,19 NOC,27 NEXUS II,62 Scandinavian73 | Italy | P, Cs | 7955 | Median: 44 | 108/7955 (1.4%, reported as 1.3%) | 542/7955 (6.8%) | No | 4415/7955 (55.5%) | 7955/7955 (100%) | 7426/7955 (93.4%) | ≥ 10 years. Acute MHI within 24 hours of injury | Unclear history, unstable vital signs, GCS < 14, penetrating injuries, voluntary discharge, reattendances | |

| Falimirski et al. 200358 | Falimirski et al. 200358 | USA | P, Cs | 331 | Mean: 39.21 (16 to 95) | 40/331 (12.1%) | No | 214/337 (65%) | 331/331 (100%) | 302/331 (91.2%) | ≥ 16 years of age. Blunt injury, witnessed LOC or amnesia, GCS 14–15 | GCS 13, or transferred with a CT scan | ||

| Haydel et al. 200027 | NOC27 | USA | P, Cs | 520 | Mean: 36 (3 to 97) | 36/520 (6.9%) | No | 338/520 (65%) | 520/520 (100%) | 520/520 (100%) | > 3 years of age. GCS 15, LOC/amnesia, normal by brief neurological examination, injury within last 24 hours | Declined CT, concurrent injuries that preclude CT | ||

| NOC27 | P, Csb | 909b | Mean: 36 (3 to 94)b | 57/909 (6.3%)b | Nob | 591/909 (65%)b | 909/909 (100%)b | 909/909 (100%)b | As above | As above | ||||

| Holmes et al. 199759 | Miller et al. 199729 | USA | P, Cs | 264 | Mean: 39.5 | 4/264 (1.5%) | 35/264 (13.3%, reported as 13.2%) | Yes | 181//264 (68.5%) | 264/264 (100%) | 0 (all GCS 14) | Closed head injury, evidence of LOC or amnesia after head trauma and GCS 14. Had CT scan | Delay in presentation > 4 hours after injury | |

| Ibanez and Arikan 200460 | Ibanez and Arikan 200460 | Stein 1996,74 Tomei et al. 1996,75 Arienta et al. 1997,54 Lapierre 1998,76 Murshid 1998,77 NOC,27 Scandinavian,73 SIGN 2000,78 NCWFNS,72 CCHR,26 EFNS79 | Spain | P, Cs | 1101 | Mean: 46.7 (15 to 99) | 83/1101 (7.5%) | No | 573/1101 (52%) | 1101/1101 (100%) | 978 (88.8%) | > 14 years. MHI (GCS 14 or 15), with or without LOC | Referrals from other hospitals | |

| Madden et al. 199561 | Madden et al. 199561 | USA | P, NR | 537 | NR | 91/537 (17%) | Yes | NR | NR | All | All patients with acute head trauma presenting to the ED with head CT | Patients who received facial CT scans without cerebral studies | ||

| Madden et al. 199561 | P, NRb | 273b | 44/273 (16.1%)b | Yesb | NRb | NRb | Allb | As aboveb | As aboveb | |||||

| Miller et al. 199729 | Miller et al. 199729 | USA | P, Cs | 2143 | NR | 5/2143 (0.2%) | 138/2143 (6.4%) | Yes | NR | 2143/2143 (100%) | 2143/2143 (100%) | Normal mental status, LOC/amnesia, CT after blunt head trauma. Within 24 hours of injury, < 2 hours prior to presenting to the ED | No exclusion criteria applied | |

| Mower et al. 200562 | NEXUS II62 | USA | P, Cs | 13,728 | NR | 917/13,728 (6.7%) | Yes | 8988/13,728 (66%) | NR | All | All ages. Had CT scan, acute blunt head trauma | Delayed presentation, penetrating trauma | ||

| Ono et al. 200763 | Ono et al. 200763 | Japan | P, Cs | 1064 | Mean: 46 | 50/1064 (4.7%) | No | 621/1064 (58.4%) | 1064/1064 (100%) | 912 (85.7%) | ≥ 10 years. With head injury, within 6 hours of injury, GCS ≥ 14 | Extremely trivial injury (scalp or facial wounds), those who refused examination | ||

| Ono et al. 200763 | NRb | 168b | NRb | 13/168 (7.7%)b | Nob | NRb | 168/168 (100%)b | NRb | As above (assumed) | As above (assumed) | ||||

| Reinus et al. 199364 | Reinus et al. 199364 | USA | R | 355 | Mean: 39 (15 to 93) | 44/355 (12.4%) | Yes | 234/373 (62.7%) | NR | NR | > 15 years of age. Referred for CT scan from ED for closed or penetrating trauma to the head | Patients referred only for evaluation of facial bone fractures | ||

| Rosengren et al. 200465 | CCHR26 | Australia | R | 240 | Mean: 38 (14 to 95) | 1/240 (0.42%) | 10/240 (4.17%) | Yes | 168/240 (70%) | 240/240 (100%) | 240/240 (100%) | Adults, history of blunt trauma, GCS 15, history of LOC or amnesia | None reported | |

| Saadat et al. 200966 | Saadat et al. 200966 | Saadat et al. 200966 | Islamic Republic of Iran | P,Cs | 318 | NR | 20/318 (6.3%) | No | 242/318 (76%) | 318/318 (100%) | 285 (89.5%) | 15–70 years old with blunt head trauma within 12 hours of presentation and GCS ≥ 13 | Opium-addicted, concurrent major injuries that necessitated specialised care, unstable, suspected of malingering, or refused to participate in the study | |

| Saboori et al. 200767 | Saboori et al. 200767 | Islamic Republic of Iran | P, Cs | 682 | Mean: 29 (6 to 85) | 46/682 (6.7%) | No | 534/682 (78.3%) | 682/682 (100%) | 682 (100%) | ≥ 6 years of age. GCS 15 | > 24 hours post injury, no clear history of trauma, obvious penetrating skull injury or obvious depressed fracture | ||

| Smits et al. 2005,68 2007,69 200770 | CHIP69 | CCHR,26 NOC,27 Dutch, NCWFNS,72 EFNS,79 NICE,19 SIGN,78 Scandinavian73 | Nether-lands | P, Cs | 3181 | Mean: 41.4 (16 to 102) | 17/3181 (0.5%) | 243/3181 (7.6%) | No | 2244/3181 (70.5%) | 3181/3181 (100%) | 2462/3181 (77.4%) | ≥ 16 years. Presentation < 24 hours, GCS score 13–14 at presentation, or GCS 15 and one risk factor | Concurrent injuries precluded head CT within 24 hours of injury, contraindications to CT scanning, transfer from another hospital |

| CCHR26 | P, Csc | 1307c | 2/1307 (0.15%)c | 117/1307 (9%)c | Noc | NRc | 1307/1307 (100%)c | NRc | Subset (GCS score 13–15, LOC, no neurological deficit, no seizure, no anticoagulation, age > 16 years) selected from original cohort | |||||

| NOC27 | P, Csc | 2028c | 7/2028 (0.3%)c | 205/2028 (10.1%)c | Noc | NRc | 2028/2028 (100%)c | NRc | Subset (GCS 15, LOC, no neurological deficit, age > 3 years) selected from original cohort | |||||

| Stiell et al. 200126 | CCHR26 | Canada | P, Cs | 3121 | Mean: 38.7 ± (16 to 99) | 44/3121 (1.41%) | 254/3121 (8.14%) | No | 2135/3121 (68.4%) | 3121/3121 (100%) | 2489/3121 (80%) | ≥ 16 years. Witnessed LOC or amnesia or disorientation and GCS ≥ 13 and injury in last 24 hours | < 16 years. Minimal injury, no history of trauma as primary event, penetrating injury, obvious depressed skull fracture, focal neurological deficit, unstable vital signs, seizure, bleeding disorder/anticoagulants, reassessment of previous injury, pregnant | |

| Stiell et al. 200546 | CCHR,26 NOC27 | Canada | P, Cv | 2707 | Mean: 38.4 (16 to 99) | 41/2707 (1.5%) | 231/2707 (8.5%) | No | 1884/2707 (69.6%) | 2707/2707 (100%) | 2049/2707 (75.7%) | As per Stiell et al. 200126 | As per Stiell et al. 200126 | |

| CCHR,26 NOC27 | P, Cvc | 1822c | Mean: 37.7 (16 to 99)c | 8/1822 (0.4%)c | 97/1822 (5.3%)c | 1246/1822 (68.4%)c | 1822/1822 (100%)c | Subset (GCS 15) |

Median prevalence of neurosurgical injury was 0.95% [interquartile range (IQR) 0.3% to 1.5%]. Median prevalence of ICI was 7.2% (IQR 6.3% to 8.5%). Variations in prevalence may be owing to differences in inclusion criteria, reference standards and outcome definitions. Participant inclusion ages ranged from > 3 years27 to adults aged ≥ 17 years,55 with five studies including all ages or not reporting an age limit. 29,56,59,61,62 In seven studies,29,55,59,61,62,64,65 patients were enrolled only if they had a CT scan and in nine studies26,27,29,46,55,58,59,65,68–70 patients were selected on the basis of clinical characteristics, such as amnesia or LOC at presentation, which, in some studies, were used as criteria for having a CT scan. Five studies defined MHI as GCS 14–1554,57,58,60,63,71 and included only patients presenting within this range. Four studies collected data only on those with GCS 15,27,29,65,67 one study collected data on GCS 14 only,59 two studies61,62 included data from all GCS categories and two did not report GCS status. 56,64 The remaining five studies26,46,55,66,68–70 included patients with GCS 13–15. Ten studies26,27,29,46,57,59,63,66–71 stated that they enrolled people who presented within 48 hours of injury, although the more usual figure was within 24 hours of injury.

Definitions of outcomes and the reference standards used varied across studies (Table 3). If CT was not an inclusion criterion and was not performed on all then the reference standard used telephone follow-up and/or review of hospital records to identify clinically significant lesions. This method would not be expected to accurately identify all intracranial injuries and would potentially affect estimates of sensitivity and specificity. 80 Eight studies reported neurosurgery as an outcome. 26,29,46,54,57,59,65,68–71 The length of follow-up for neurosurgery varied from being not reported to up to 30 days after injury. The main difference in outcome definition for ICI involved the perception of clinical significance, with five cohorts defining this and 16 identifying any common acute lesion (listed in Table 3). Definitions of surgical lesions also varied, but most definitions included haematoma evacuation, elevation of depressed skull fracture and intracranial pressure monitoring.

| Author, year | Rule(s) tested | Definition of ICI | Reference standard used for ICI | Patients who had CT, n | Definition of need for neurosurgery | Reference standard used for need for neurosurgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arienta et al. 199754 | Arienta et al. 199754 | Intracranial lesion: not defined. Injuries listed include extradural haematoma, cortical contusion, subarachnoid haemorrhage, pneumocephalus, depressed fracture with contusion, intracerebral haematoma and subdural haematoma | CT scan or follow-up telephone call. Further details NR | 762/9917 (7.7%) | Neurosurgery or death | Retrospective chart review, telephone follow-up |

| Borczuk 199555 | Borczuk 199555 | ICI: abnormalities believed to be related to the trauma | CT scan | 1448/1448 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Duus et al. 199456 | Duus et al. 199456 | Intracranial complications: not defined |

If admitted: observation, CT scan if deteriorating level of consciousness and/or neurological signs If discharged: information sheet advising return if deterioration National Danish Patient Register checked for anyone diagnosed with appropriate ICD codes |

21/2204 (1%) | NA | NA |

| Fabbri et al. 2005;57 Stein et al. 200971 | CCHR,26 NCWFNS,72 NICE,19 NOC,27 Nexus II,62 Scandinavian73 |

Stein et al. 200971 – any lesion: surgical (intracranial haematoma large enough to require surgical evacuation) or non-surgical (other intracranial abnormality diagnosed on CT) Fabbri et al. 200557 – any post-traumatic lesion at CT within 7 days from trauma: depressed skull fracture, intracerebral haematoma/brain contusions, subarachnoid haemorrhage, subdural haematoma, epidural haematoma, intraventricular haemorrhage |

Patients were managed accord to NCWFS guidelines where low-risk patients sent home without CT, medium-risk patients given CT and observed for 3–6 hours if negative then discharged, high-risk patients given CT and observed 24–48 hours. All discharged with written advice of signs and symptoms with which they should return | 4177/7955 (52.5%) |

Stein et al. 200971 – surgical intracranial lesion: intracranial haematoma large enough to require surgical evacuation Fabbri et al. 2005:57 haematoma evacuation, skull fracture elevation within first 7 days of injury. Injuries after this period not considered in this analysis |

Assume hospital records |

| Falimirski et al. 200358 | Falimirski et al. 200358 | Significant ICI: not defined. Injuries recorded include subarachnoid haemorrhage, subdural haematoma, epidural haematoma, intracerebral haemorrhage, contusion, pneumocephaly, skull fracture | CT scan | 331/331 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Haydel et al. 200027 | NOC27 | ICI – presence of acute traumatic ICI: a subdural, epidural or parenchymal haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral contusion or depressed skull fracture | CT scan |

520/520 (100%) 909/909 (100%)a |

NA | NA |

| Holmes et al. 199759 | Miller et al. 199729 | Abnormal CT scan: any CT scan showing an acute traumatic lesion (skull fractures or intracranial lesions: cerebral oedema, contusion, parenchymal haemorrhage, epidural haematoma, subdural haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage or intraventricular haemorrhage) | CT scan: patients with abnormal CT scan followed to discharge; those with normal CT not studied further | 264/264 (100%) | Neurosurgery |

Patients with abnormal CT scan followed to discharge Those with normal CT not studied further |

| Ibanez and Arikan 200460 |

Ibanez and Arikan 2004,60 Stein 1996,74 Tomei et al. 1996,75 Arienta et al. 1997,54 Lapierre 1998,76 Murshid 1998,77 NOC,27 Scandinavian,73 SIGN 2000,78 NCWFNS,72 CCHR,26 EFNS79 |

Relevant positive CT scan: acute intracranial lesion, not including isolated cases of linear skull fractures or chronic subdural effusions | CT scan | 1101/1101 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Madden et al. 199561 | Madden et al. 199561 | Clinically significant scan: pathology related to trauma affecting the bony calvaria or cerebrum (including non-depressed skull fractures, excluding scalp haematomas, those with no bony skull or intracerebral pathology) | CT scan: scans examined for bony and soft tissue injury, herniation, pneumocephalus, penetrating injury and the size and location of any cortical contusions, lacerations or external axial haematomas |

537/537 (100%) 273/273 (100%)a |

NA | NA |

| Miller et al. 199729 | Miller et al. 199729 | Abnormal CT scan: acute traumatic intracranial lesion (contusion, parenchymal haematoma, epidural haematoma, subdural haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage) or a skull fracture | CT scan: within 8 hours of injury | 2143/2143 (100%) | Surgical intervention: craniotomy to repair an acute traumatic injury or placement of a monitoring bolt | Hospital records of those with positive CT scan followed until discharge |

| Mower et al. 200562 | NEXUS II62 | Significant ICI: any injury that may require neurosurgical intervention, (craniotomy, intracranial pressure monitoring, mechanical ventilation), lead to rapid clinical deterioration or result in significant long-term neurological impairment | CT scan | 13,728/13,728 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Ono et al. 200763 | Ono et al. 200763 | Intracranial lesion: not defined. Injuries listed include subdural and epidural haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage, contusion, pneumocephalus | CT scan |

1064/1064 (100%), 152/168 (90.5%)a |

NA | NA |

| Reinus et al. 199364 | Reinus et al. 199364 | CT outcome: intracalvarial abnormalities, either axial or extra-axial, which could not be shown to be chronic | CT scan | 355/355 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Rosengren et al. 200465 | CCHR26 | Clinically significant ICI: CT abnormalities not significant if patient neurologically intact and had only one of the following: solitary contusion < 5 mm in diameter, localised subarachnoid blood < 1 mm thick, smear subdural haematoma < 4 mm thick, isolated pneumocephaly, closed depressed skull fracture not through the inner table (as per Stiell et al. 2001)26 | CT scan | 240/240 (100%) | Neurological intervention: not defined | NR |

| Saadat et al. 200966 | Saadat et al. 200966 | Positive CT scan: skull fracture (including depressed, linear, mastoid, comminuted, basilar, and sphenoid fracture), intracranial haemorrhage (including epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, intraparenchymal and petechial haemorrhage), brain contusion, pneumocephalus, midline shift and the presence of an air–fluid level | CT scan | 318/318 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Saboori et al. 200767 | Saboori et al. 200767 | Intracranial lesion: all acute abnormal finding on CT |

Normal CT: discharged with advice to return if symptoms occur, 1-week follow-up call Abnormal CT: admission, treatment. Evaluation at 2 weeks and 1 month after discharge |

682/682 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Smits et al. 200568–70 | CCHR,26 NOC,27 Dutch, NCWFNS,72 EFNS,79 NICE,19 SIGN, 78 Scandinavian,73 CHIP69 |

Any neurocranial traumatic finding on CT: any skull or skull base fracture and any intracranial traumatic lesion Smits et al. 2007 (CHIP derivation) definition differs: any intracranial traumatic findings on CT that included all neurocranial traumatic findings except for isolated linear skull fractures |

CT scan |

3181/3181 (100%) 1307/1307 (100%)b |

Neurosurgery: a neurosurgical intervention was any neurosurgical procedure (craniotomy, intracranial pressure monitoring, elevation of depressed skull fracture or ventricular drainage) performed within 30 days of the event | Assume patient records |

| Stiell et al. 200126 | CCHR26 | Clinically important brain injury on CT: all injuries unless patient neurologically intact and had one of following: solitary contusion < 5 mm, localised subarachnoid blood < 1 mm thick, smear subdural haematoma < 4 mm thick, closed depressed skull fracture not through inner table |

1. CT scan ordered on basis of judgement of physician in ED or result of follow-up telephone interview 2. Proxy telephone interview performed by registered nurse (24.4%). For those whose responses did not warrant recall for a CT scan this was the only reference standard |

2078/3121 (67%) | Within 7 days: death due to head injury, craniotomy, elevation of skull fracture, intracranial pressure monitoring, intubation for head injury demonstrated on CT | Performance of neurosurgery as reported in patient records and 14-day follow-up telephone interview (interview 100% sensitive for need for neurosurgery) |

| Stiell et al. 200546 | CCHR,26 NOC27 | As per Stiell et al. 200126 | As per Stiell et al. 200126 |

2171/2707 (80.2%) 1378/1822 (75.6%)b |

As per Stiell et al. 200126 | As per Stiell et al. 200126 |

Children and infants

The design and patient characteristics of the 14 studies (representing 16 papers)30,81–95 that evaluated the diagnostic performance of clinical decision rules for identifying ICI or need for neurosurgery in children and/or infants with MHI are summarised in Table 4. Six studies82,84–86,90,91,93,95 recruited only infants or reported a subset of infants-only data. Eight studies were from the USA,82,84–6,88,90,91,93–95 one from the USA and Canada,81 and one each from Italy,83 the UK,30 Turkey,87 Finland89 and Canada. 92 Nine studies30,81–87,89,90,92–94 derived a new rule or rules and five validated existing rules. 30,88–91,95 Three studies both derived and validated rules. 30,89,90 Six studies30,81,83,90–92,95 were multicentre studies. Eleven studies30,81,83–86,88,90–95 were prospective, one of which used a convenience sample,81 seven83–86,88,91,92,94,95 of which recruited consecutive patients, and three30,90,93 did not report how the sample was recruited. Three further studies82,87,89 used retrospective data. Two studies30,90 were very large with cohorts over 20,000. The smallest study was 97 patients. 82

| Author, year | Rule(s) derived | Rule(s) validated | Country | Design | No. of patients, n | Mean or median age, years (range) | Prevalence of neurosurgery | Prevalence of ICI | CT as inclusion? (yes/no) | Male, n | Patients with MHI, n | Prevalence of GCS 15, n | Other significant inclusion criteria | Other significant exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atabaki et al. 200881 | Atabaki et al. 200881 | USA, Canada | P, Cv | 1000 | Mean: 8.9 years (NR) | 6/1000 (0.6%) | 65/1000 (6.5%) | Yes | 641/1000 (64.1%) | 1000/1000 (100%) | 852/1000 (85.2%) | Birth to 21 years. Closed head trauma, undergoing CT | Prior CT at referring hospital, GCS < 13 | |

| Buchanich 200782 | Buch-anich 2007 | USA | R | 97 | Mean: 15.2 months (NR) | 22/97 (22.7%) | No | 97/97(100%) | NR | < 3 years old. GCS 14–15 | Penetrating injuries, depressed skull fractures, intentional injuries, CT scan > 24 hours after injury | |||

| Da Dalt et al. 200683 | Da Dalt et al. 200683 | Italy | P, Cs | 3806 | NR | 22/3806 (0.6%) | No | 2315/3806 (60.8%) | NR | 14 or normal value for age; 3749/3800 (98.7%) | < 16 years, history of blunt head trauma of any severity | Admitted > 24 hours after trauma, open injuries, previous history of neurological disorders or bleeding diathesis | ||

| Dietrich et al. 199384 | Dietrich et al. 199384 | USA | P, Cs | 166a | NR for this subgroupa | 16/166 (9.64%)a | Yesa | NR for this subgroupa | NR for this subgroupa | NR for this subgroupa | ≥ 2 years to 20 years, head trauma, with CT scana | Unable to answer questions because of age or altered mental statusa | ||

| 71a | NR for this subgroupa | 3/71 (4.2%)a | Yesa | NR for this subgroupa | NR for this subgroupa | NR for this subgroupa | < 2 years, as abovea | As abovea | ||||||

| Dunning et al. 200630 | CHALICE30 | RCS guidelines96 | UK | P, NR | 22,772 | Mean: 5.7 (NR) | 137/22,772 (0.6%) | 168/22,579 (0.744%) | No | 14,767/22,772 (64.8%) | 22,298/22,772 (97.9%) | 21,996/22,772 (96.6%) | < 16 years. History/signs of injury to the head. LOC or amnesia was not a requirement | Refusal to consent to entry into the study |

| Greenes and Schutzman 1999,85 b200186 | Greenes and Schutzman 199985 | USA | P, Cs | 608 | Mean: 11.2 months ± 6.8 months (NR) | 63/608 (10%) | No | 344/608 (57%) | NR | NR | < 2 years. Head trauma (symptomatic and asymptomatic) | NR | ||

| bGreenes and Schutzman 200186 | 172b | Mean: 11.6 months (3 days to 23 months)b | 13/172 (7.6%)b | Yesb | NRb | 100% (assumed from inclusion criteria)b | NRb | Asymptomatic subset of above cohort. With head CT scanb | Symptomaticb patients with any of history of LOC, lethargy, irritability, seizures, three or more episodes of emesis, irritability or depressed mental status, bulging fontanelle, abnormal vital signs indicating increased intracranial pressure or focal neurological findings | |||||

| Guzel et al. 200987 | Guzel et al. 200987 | Turkey | R | 337 | NR | 67/337 (19.9%) | Yes (applied at data extraction stage) | 223/337 (66.2%) | 337/337 (100%) | 304/337 (90.2%), | < 16 years. GCS 13–15. Had CT (applied at data extraction stage) | > 16 years, moderate or severe head injury, no clear history of trauma, obvious penetrating skull injury, unstable vital signs, seizure before assessment, bleeding disorder/anticoagulants, reattendances | ||

| Haydel and Schembekar 200388 | Noc27 | USA | P, Cs | 175 | Mean: 12.8 (range NR) | 6/175 (3.4%) | 14/175 (8%) | Yes | 114/175 (67%) | 100% (assumed from inclusion criteria) | 175/175 (100%) | 5–17 years. Within 24 hours of injury, blunt trauma with LOC, non-trivial mechanism of injury, CT scan | Trivial injuries, refused CT, concurrent injuries precluded CT, irritable or agitated (GCS < 15) | |

| Klemetti et al. 200989 | Klemetti et al. 200989 | CHALICE,30 NEXUS II,62 UCD93 | Finland | R | 485 | NR | 83/485 (17.1%) | No | 313/485 (65%) | NR | NR | ≤ 16 years. Admitted to paediatrics (usually hospitalised even after MHI), history of head trauma. Patients identified by reference to discharge diagnosis | NR | |

| cKupperman et al. 200990 | cPECARN (≥ 2 years to < 18 years)90 | USA | P, NR | 25,283c | NR for this subsetc | 215/25,283 (0.9%)c | Noc | NRc | 25,283/25,283 (100%)c | 24,563/25,283 (97.2%)c | ≥ 2 years to < 18 years. Children presenting within 24 hours GCS ≥ 14c | Trivial injuries, penetrating trauma, known brain tumours, pre-existing neurological disorders, or neuroimaging before transfer. Coagulopathy, shunts, GCS < 14c | ||

| cPECARN (< 2 years)90 | 8502c | 73/8502 (0.9%)c | Noc | NRc | 8502/8502 (100%)c | 8136/8502 (95.7%)c | As above, < 2 yearsc | As abovec | ||||||

| PECARN (2 years to < 18 years)90 | 6411c | 11/6411 (0.2%)c | 63/6411 (1%)c | Noc | NRc | 6411/6411 (100%)c | 6248/6411 (97.5%)c | As for derivation cohortc | As for derivation cohortc | |||||

| PECARN (< 2 years)90 | 2216c | 5/2216 (0.2%)c | 25/2216 (1.1%)c | Noc | NRc | 2216/2216 (100%)c | 2124/2216 (95.8%)c | As for derivation cohortc | As for derivation cohortc | |||||

| dOman 2006;91 dSun et al. 200795 | dNEXUS II,62 UCD93 | USA | P, Cs | 1666d | NRd | 138/1666 (8.3%)d | Yesd | 1072/1666 (64%)d | NRd | NRd | < 18 years. Had CT scan (physicians discretion), acute blunt head traumad | Delayed presentation, without blunt trauma (penetrating trauma)d | ||

| dNEXUS II91 | 309d | 25/309 (8.1%)d | Yesd | 170/309 (55%)d | NRd | NRd | Subset of above, < 3 years of aged | As aboved | ||||||

| dUCD95 | 208d | 7/208 (3.4%)d | Yesd | NR for this subgroupd | NRd | NRd | Subset of above, < 2 years of aged | As aboved | ||||||

| Osmond et al. 200692 | CATCH for ICI,92 CATCH for Neurosurgery92 | Canada | P, Cs | 3781 | Mean: 9.2 (NR) | 27/3781 (0.7%) | 170/3781 (4.5%) | No | 2458 (65%) | 3781/3781 (100%) | 3414/3781 (90.3%) | ≤ 16 years. GCS 13–15, documented LOC, amnesia, disorientation, persistent vomiting or irritability (if ≤ 2 years of age)e | NR | |

| Palchak et al. 200393 | UCD (neurosurgery),93 UCD (intervention or brain injury)93 | USA | P, NR | 2043 | Mean: 8.3 ± 5.3 (10 days to 17.9 years) | 29/2043 (1.4%) | No | 1323/2043 (65%) | NR | GCS 14 or 15: 1859/2043 (91%) | < 18 years. History of non-trivial blunt head trauma with findings consistent with head trauma: LOC, amnesia, seizures, vomiting, current headache, dizziness, nausea or vision change or physical examination findings of abnormal mental status, focal neurological deficits, clinical signs of skull facture or scalp trauma | Trivial injuries, neuroimaging before transfer | ||

| UCD (TBI)93 | 1098 | NR for this subset | 39/1098 (3.6%) | Yes | NR for this subset | 1098/1098 (100%) | GCS 14 or 15: 1098/1098 (100%) | Subset of above cohort; GCS 14–15 and had CT scan only | As above | |||||

| UCD (TBI)93 | 194 | NR for this subset | 15/194 (7.73%) | Yes | NR for this subset | 194/194 (100%) | NR for this subset | Subset of above cohort (had CT scan GCS 14 or 15), ≤ 2 years | As above | |||||

| Quayle et al. 199794 | Quayle et al. 199794 | USA | P, Cs | 321 | Mean: 4 years 10 months (2 weeks to 17.75 years) | 27/321 (8.4%) | Yes |

189/321 (59%) |

NR | NR | < 18 years. Non-trivial injury: symptoms such as headache, amnesia, vomiting, drowsiness, LOC, seizure, dizziness or significant physical findings including altered mental status, neurological deficit and altered surface anatomy. Scalp laceration or abrasion in infants < 12 months, scalp haematoma in infants < 24 months | Trivial head injuries, penetrating head injuries |

The median value for the prevalence of neurosurgery was 1.2% (IQR 0.2% to 1.4%). The median value for the prevalence of ICI was 6.5% (IQR 1.0% to 9.8%). Cohorts were not similar in terms of inclusion and exclusion criteria. For studies of children, the upper age limit ranged between 1630,83,87,89,92 and 21 years,81 and the lower limit between 081 and 5 years. 88 For infants, the upper age limit was usually 2 years, but in one case was 3 years82 of age. Eight studies30,83–85,89,91,93–95 included all severities of head injury; six81,82,87,88,90,92 recruited those with MHI. Two of these studies reported results for a MHI subset of the larger cohort. 86,93 Five studies excluded those with trivial head injury and/or recruited only those with clinical characteristics consistent with head trauma. 88,90,92,93,94 Six studies81,84,87,88,91,94 included only those who had a CT scan and two reported a subset, all of whom underwent CT. 86,93 Selection of patients on the basis of having had a CT scan and exclusion on the basis of trivial injury or not presenting with clinical characteristics is likely to recruit a patient spectrum with greater risk of ICI.

Definitions of outcomes and the reference standards used varied across studies (Table 5). The predominant differences in outcome definition for ICI involve the perception of clinical significance, with four cohorts30,89–91,95 having this defined and the remaining ten studies81–88,92–94 failing to define a positive outcome or just identifying any common acute lesion. The reference standards used where CT was not possible for all, and was not an inclusion criterion, usually comprised telephone follow-up, review of hospital records or both. The length of follow-up for neurosurgery varied from being not reported to following up until discharge, which may not capture all neurosurgical procedures leading to inaccurate estimations of diagnostic accuracy. Definitions of surgical lesions also varied or were not reported, but most definitions included haematoma evacuation and intracranial pressure monitoring; only one mentioned elevation of skull fracture explicitly.

| Author, year | Rule(s) tested | Definition of ICI | Reference standard used for ICI | Patients who had CT, n | Definition of need for neurosurgery | Reference standard used for need for neurosurgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atabaki et al. 200881 | Atabaki et al. 200881 | ICI: subdural, epidural, subarachnoid, intraparenchymal and intraventricular haemorrhages as well as contusion and cerebral oedema | CT scan | 1000/1000 (100%) | Neurosurgery, including craniotomy, craniectomy, evacuation or intracranial pressure monitoring | Medical record review (unclear when performed) |

| Buchanich 200782 | Buchanich 200782 | ICI: intracranial haematoma, intracranial haemorrhage, cerebral contusion and/or cerebral oedema |

CT scan Follow-up questionnaire/telephone interview |

97/97 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Da Dalt et al. 200683 | Da Dalt et al. 200683 | ICI: identified on CT either at initial ER presentation or during any hospital admission or readmission |

CT scan obtained at discretion of treating physician All children discharged immediately from ER or after short observation received a follow-up telephone interview approximately 10 days later. Hospital records were checked for readmissions for 1 month after conclusion of study |

79/3806 (2%) | NA | NA |

| Dietrich et al. 199384 | Dietrich et al. 199384 | Intracranial pathology: epidural or subdural haematoma, cerebral contusions or lacerations, intraventricular haemorrhage pneumocephaly or cerebral oedema, with or without skull fracture | CT scan |

166/166 (100%) 71/71 (100%)a |

NA | NA |

| Dunning et al. 200630 | CHALICE,30 RCS guidelines96 | Clinically significant ICI: death as a result of head injury, requirement for neurosurgical intervention or marked abnormalities on the CT scan |

All patients treated according to RCS guidelines. This recommends admission for those at high risk and CT scan for those at highest risk Follow-up: all patients who were documented as having had a skull radiograph, admission to hospital, CT scan or neurosurgery were followed up |

744/22,772 (3.3%) | NR | NR, assume as for ICI |

| Greenes and Schutzman 1999,85 200186 | Greenes and Schutzman 1999,85 200186 |

Greenes and Schutzman 1999 85 ICI: acute intracranial haematoma, cerebral contusion and/or diffuse brain swelling evident on head CT Greenes and Schutzman 2001 86 ICI: cerebral contusion, cerebral oedema or intracranial haematoma noted on CT |

Greenes and Schutzman 199985 CT scan, follow-up calls, review of medical records Greenes and Schutzman 200186 CT scan |

188/608 (31%). 73 symptomatic patients did not receive CT85 |

NA | NA |

| Guzel et al. 200987 | Guzel et al. 200987 | Positive CT scan: definition NR | CT scan | 337/337 (100%) | NA | NA |

| Haydel and Schembekar 200388 | NOC27 | ICI on head CT: any acute traumatic intracranial lesion, including subdural epidural or parenchymal haematoma, subarachnoid haemorrhage, cerebral contusion or depressed skull fracture | CT scan | 175/175 (100%) | Need for neurosurgical or medical intervention in patients with ICI on CT | All patients with abnormal CT scan admitted and followed until discharge |

| Klemetti et al. 200989 | Klemetti et al. 2009,89 CHALICE,30 NEXUS II,62 UCD93 | Complicated or severely complicated head trauma: brain contusion, skull base fracture, skull fracture. Patients who required neurosurgical intervention, patients who succumbed, epidural haematoma, subdural haematoma, subarachnoid haematoma, intracerebral haematoma | Hospital records | 242/485 (49.9%) | NA | NA |

| Kupperman et al. 200990 | Kupperman et al. 200990 | Clinically important brain injury: death from TBI, neurosurgery, intubation for > 24 hours for TBI, or hospital admission of two nights or more associated with TBI on CT. Brief intubation for imaging and overnight stay for minor CT findings not included |

CT scans, medical records, and telephone follow-up. Those admitted: medical records, CT scan results Those discharged: telephone survey 7 to 90 days after the ED visit, and medical records and county morgue records check for those uncontactable |

9420/25,283 (37.3%)c 2632/8502 (31.0%)c 2223/6411 (34.7%)c 694/2216 (31.3%)c |

NR | NR for neurosurgery. Assume as for ICI |

| Oman 2006;91 aSun et al. 200795 | NEXUS II,62 UCD93 | Clinically important/significant ICI: any injury that may require neurosurgical intervention, lead to rapid clinical deterioration, or result in significant long-term neurological impairment | CT scan |

1666/1666 (100%)d 309/309 (100%)d 208/208 (100%)d |

NA | NA |

| Osmond et al. 200692 | CATCH92 | Brain injury |

CT scan 14-day telephone interview |

NR | Neurosurgery: craniotomy, elevation of skull fracture, intubation, intracranial pressure monitor and/or anticonvulsants within 7 dayse | NR |

| Palchak et al. 200393 | UCD93 | TBI identified on CT scan or TBI requiring acute intervention or intervention by one or more of: neurosurgical procedure, ongoing antiepileptic pharmacotherapy beyond 7 days, the presence of a neurological deficit that persisted until discharge from the hospital, or two or more nights of hospitalisation because of treatment of the head injury | CT or performance of intervention |

1271/2043 (62.2%) 1098/1098 (100%) 194/194 (100%) |

Need for neurosurgical intervention | NR |

| Quayle et al. 199794 | Quayle et al. 199794 | ICI: definition NR | CT scan | 321/321 (100%) | NA | NA |

Quality of included studies

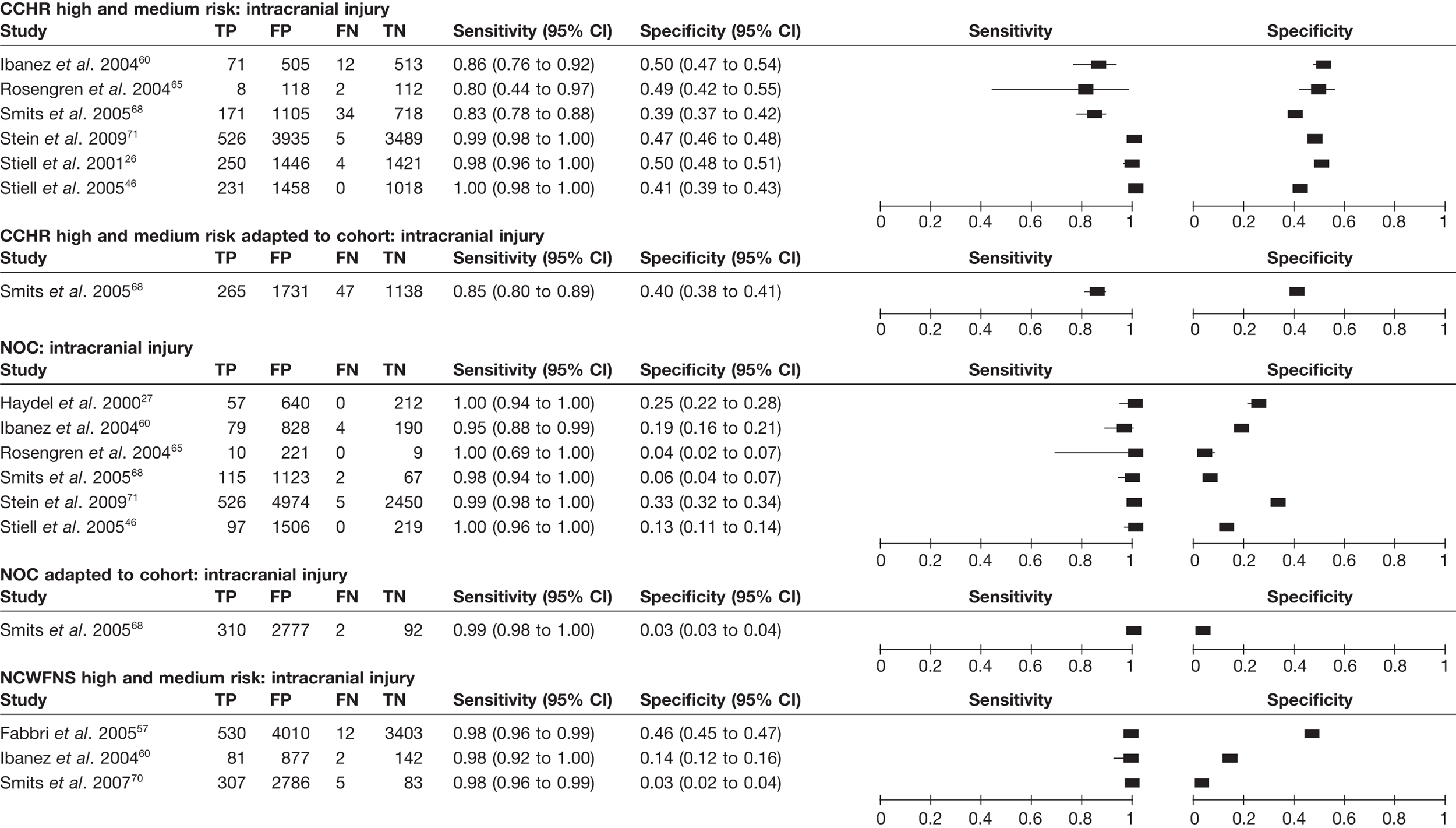

Adults

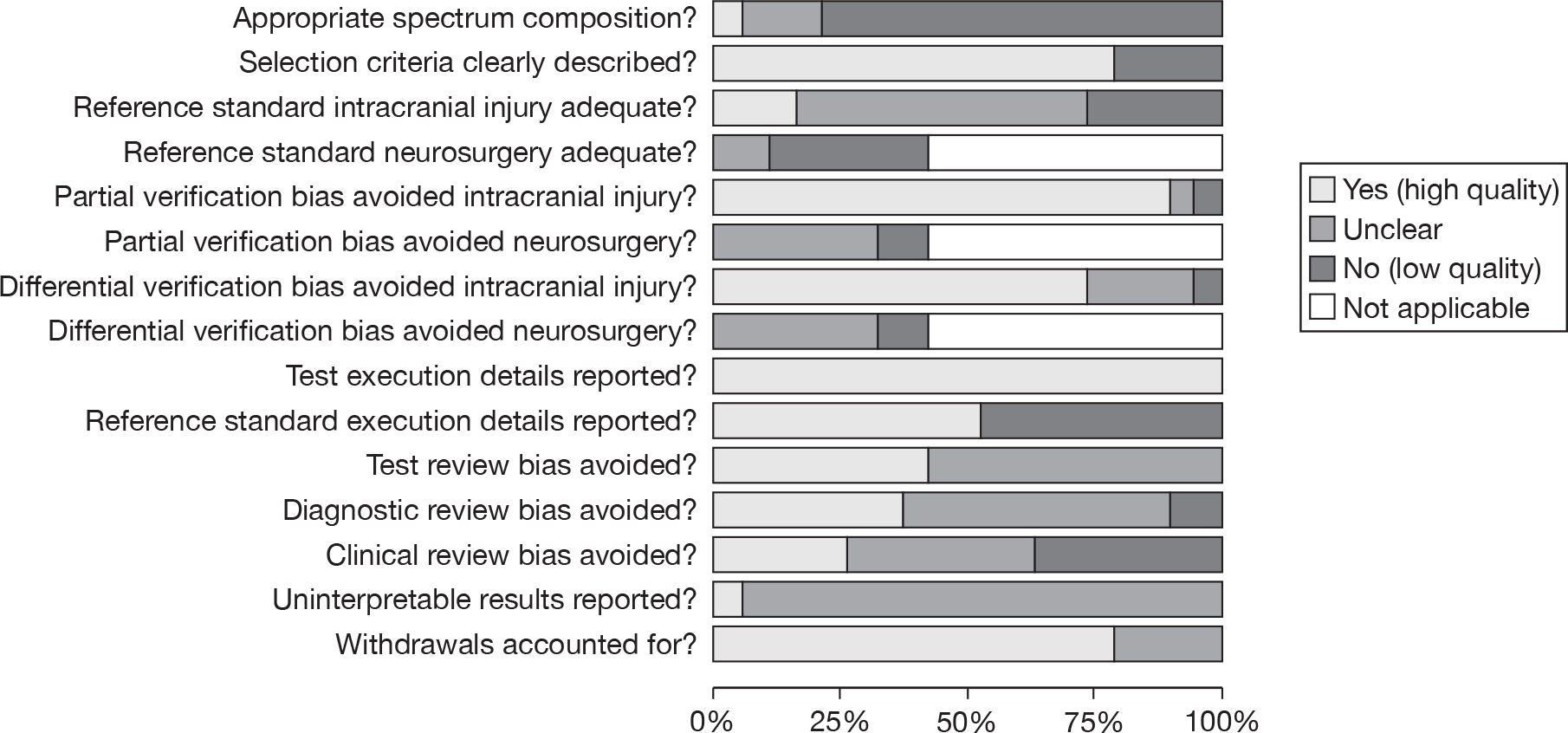

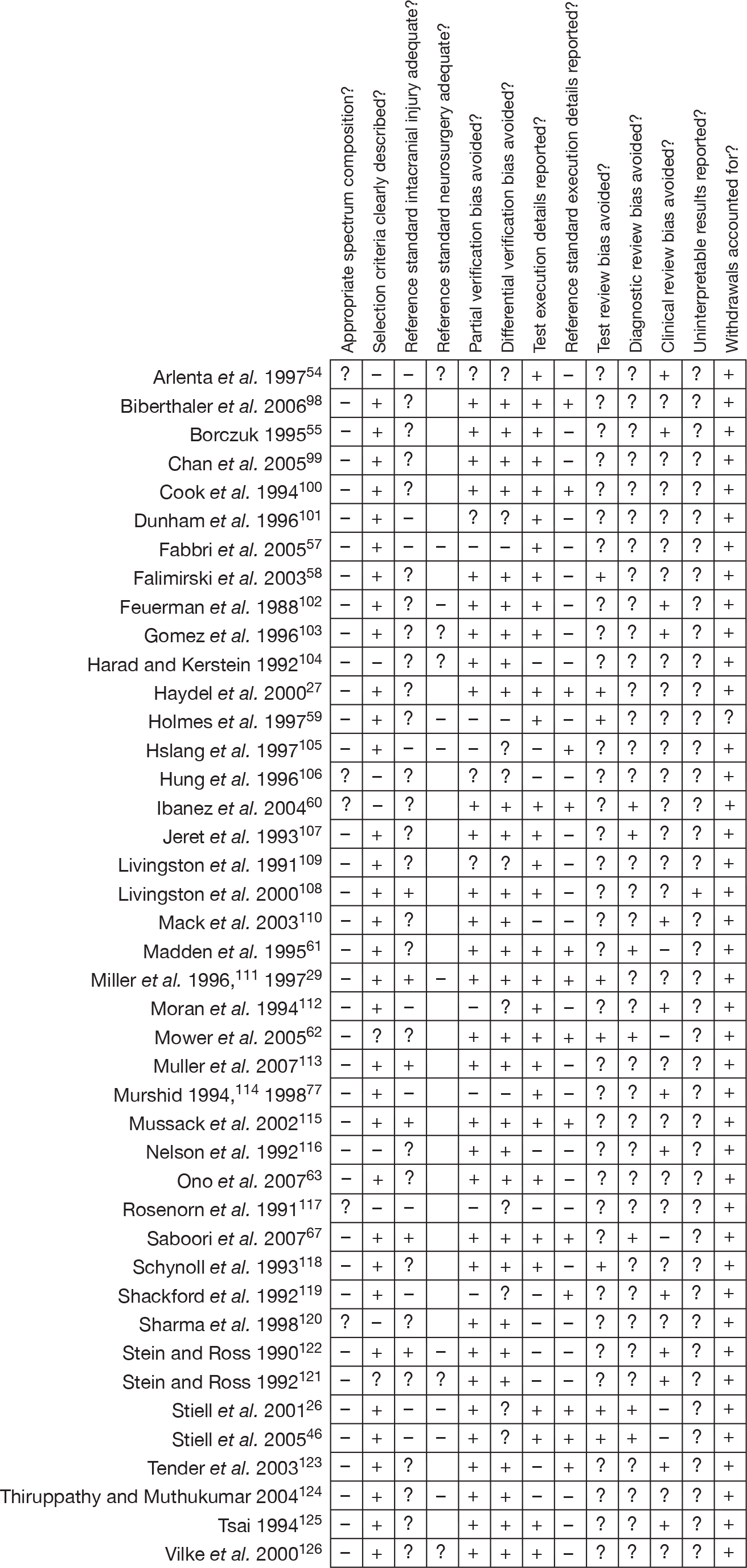

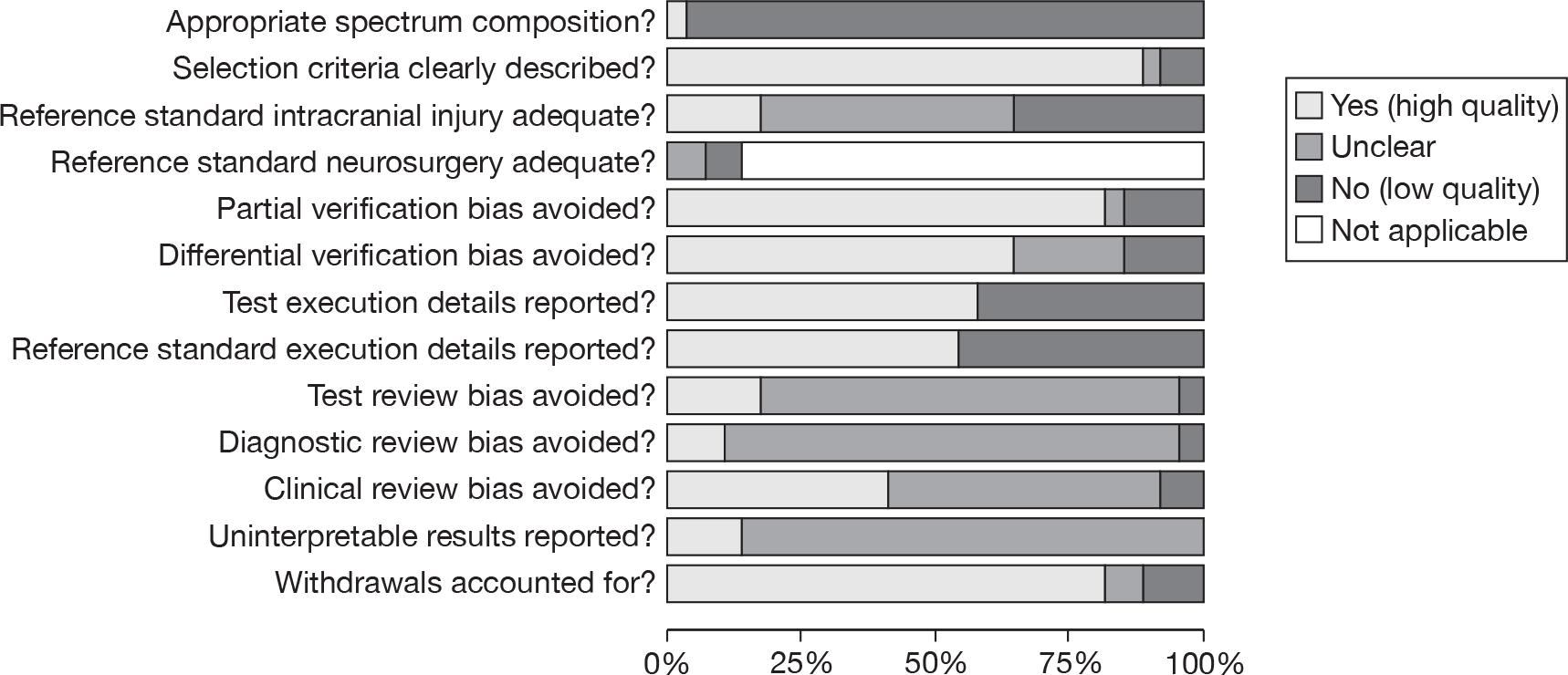

The methodological quality assessment of each included study is summarised in Figures 2 and 3. Overall, most of the included studies were well reported and generally satisfied the majority of the quality assessment items of the QUADAS tool, but with notable exceptions. 54–57,71 Despite poor reporting of the reference standards in most studies, the main source of variation was for patient spectrum, which will affect comparability across cohorts and application of conclusions to practice.

FIGURE 2.

Decision rules for adults with MHI – methodological quality graph. Review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

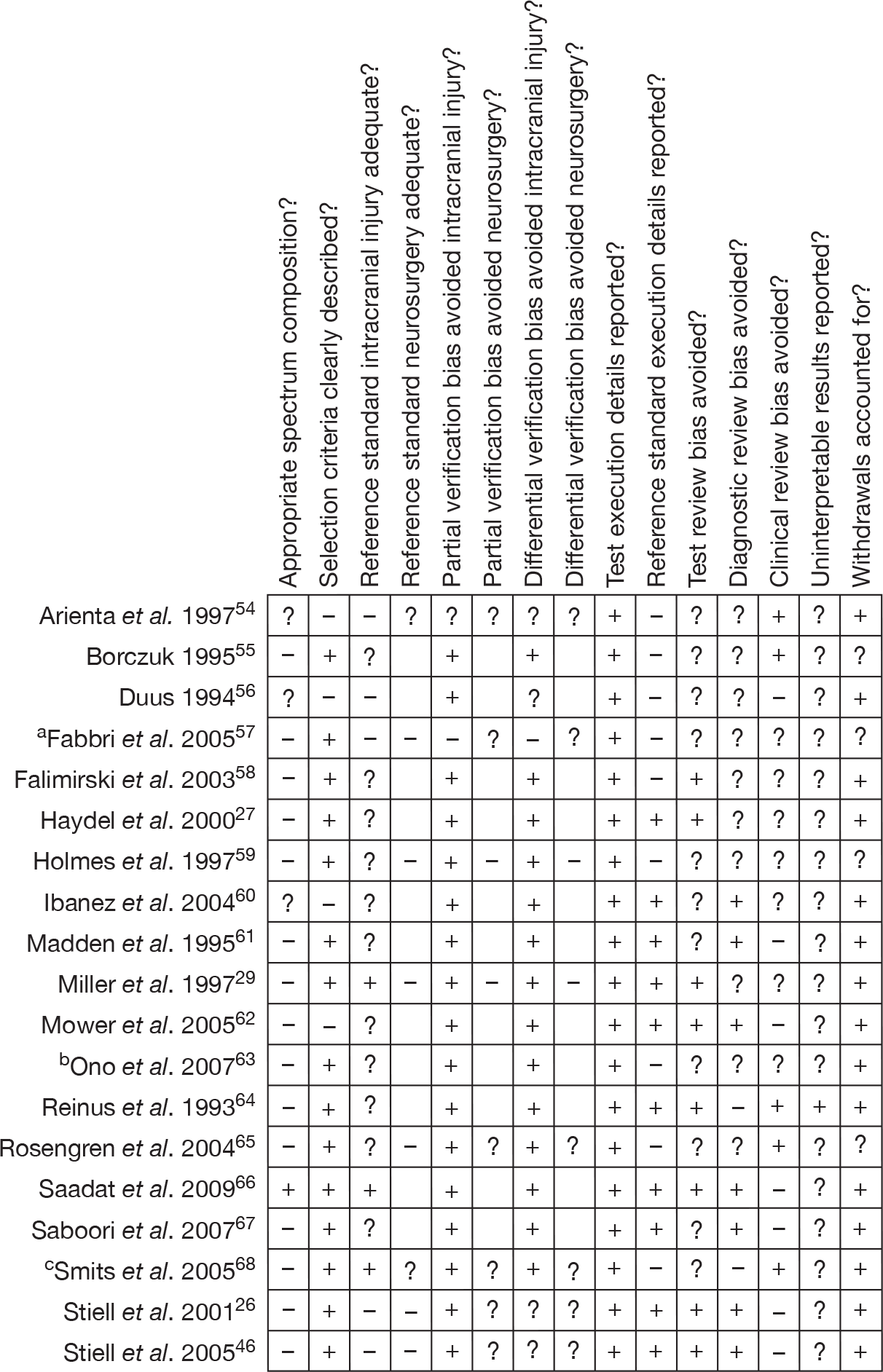

FIGURE 3.

Decision rules for adults with MHI – methodological quality summary. Review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study. Minus sign, negative score; plus sign, positive score; question mark, unclear whether item scores negatively or positively; blank space, not applicable. a, Data from Fabbri et al. 57 and Stein et al. 71 b, Ono et al. 63 recruited two separate cohorts for validation and derivation. The derivation cohort was treated differently for the ICI outcome: the reference standard was not adequate, it was unclear whether partial verification bias was avoided and differential verification bias was not avoided. c, Smits et al. 68–70

The spectrum of patients was appropriate in only one study,66 was unclear in three studies54,56,60 and did not completely match the desired patient spectrum in the remaining 15 studies, often because patients were selected on the basis of having a clinical characteristic at presentation (Table 2). Although 11 studies carried out CT in all participants,27,55,58–65,67 they did not state whether CT was performed within 24 hours and were therefore rated as unclear for the ICI reference standard quality assessment item. A further three cohorts performed CT on all participants within 24 hours and so scored well. 29,66,68–70 The remaining five studies did not perform CT in all participants and so scored negatively for this item. 26,46,54,56,57 The reference standard for neurosurgery was not reported for two studies54,68–70 and not considered adequate in the remaining six. 26,29,46,57,59,65,71 This was usually because not all patients were followed up.

Partial verification bias was largely avoided, with only two cohorts scoring unclear54 or negatively. 57,71 However, these two cohorts were large, and one reported results for a number of rules. 71 Partial verification bias may be more of an issue for the neurosurgery data as no cohort scored well. Differential verification bias for ICI may have affected results in the same large cohort reporting several rules. 57,71 Here participants received different reference standards according to clinical characteristics at presentation or the judgement of the treating physician. Criteria for CT were identical to the rule being tested in the case of the Neurotraumatology Committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies (NCWFNS)72 rule. In four cases26,46,54,56 it was unclear, although the majority avoided differential verification bias. For neurosurgery, it was unclear if differential verification bias was avoided in six cohorts26,46,54,57,65,68–71 and was scored negatively in two cohorts. 29,59

The execution of the index test was well described in all studies. The execution of the reference standards (either one or both) was not reported well in nine studies54–59,63,65,68 and scored negatively for this item. Diagnostic and test review biases may affect results as less than half of the studies scored well for blinding; the index test was interpreted blind in eight cases,26,27,29,46,58,62,64,66, but blinding status was unclear in 11. 54–57,59,60,61,63,65,67–70 The reference standard was interpreted blind in seven cases,26,46,60–62,66,67 and was not interpreted blind in two cases;64,68–70 blinding status was unclear in ten cases. 27,29,54–59,63,65 Studies were of mixed quality for clinical review bias, with almost equal numbers scoring in each quality category. Information about uninterpretable results was only given in one study,64 with all other studies scoring unclear for this item. Studies scored well for withdrawals, with only four studies55,57,59,65,71 scoring unclear because it was not apparent whether all patients were accounted for at the end of the study.

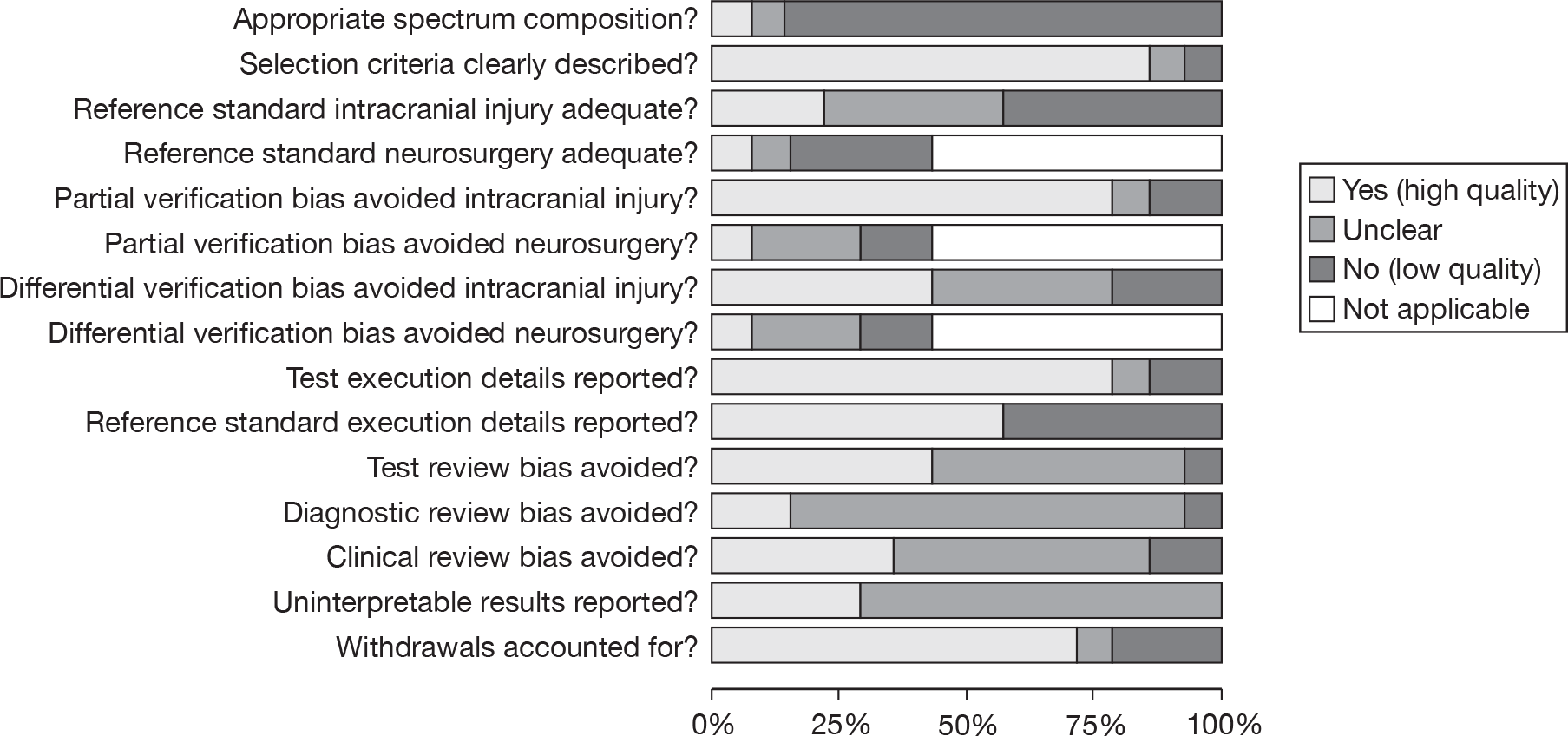

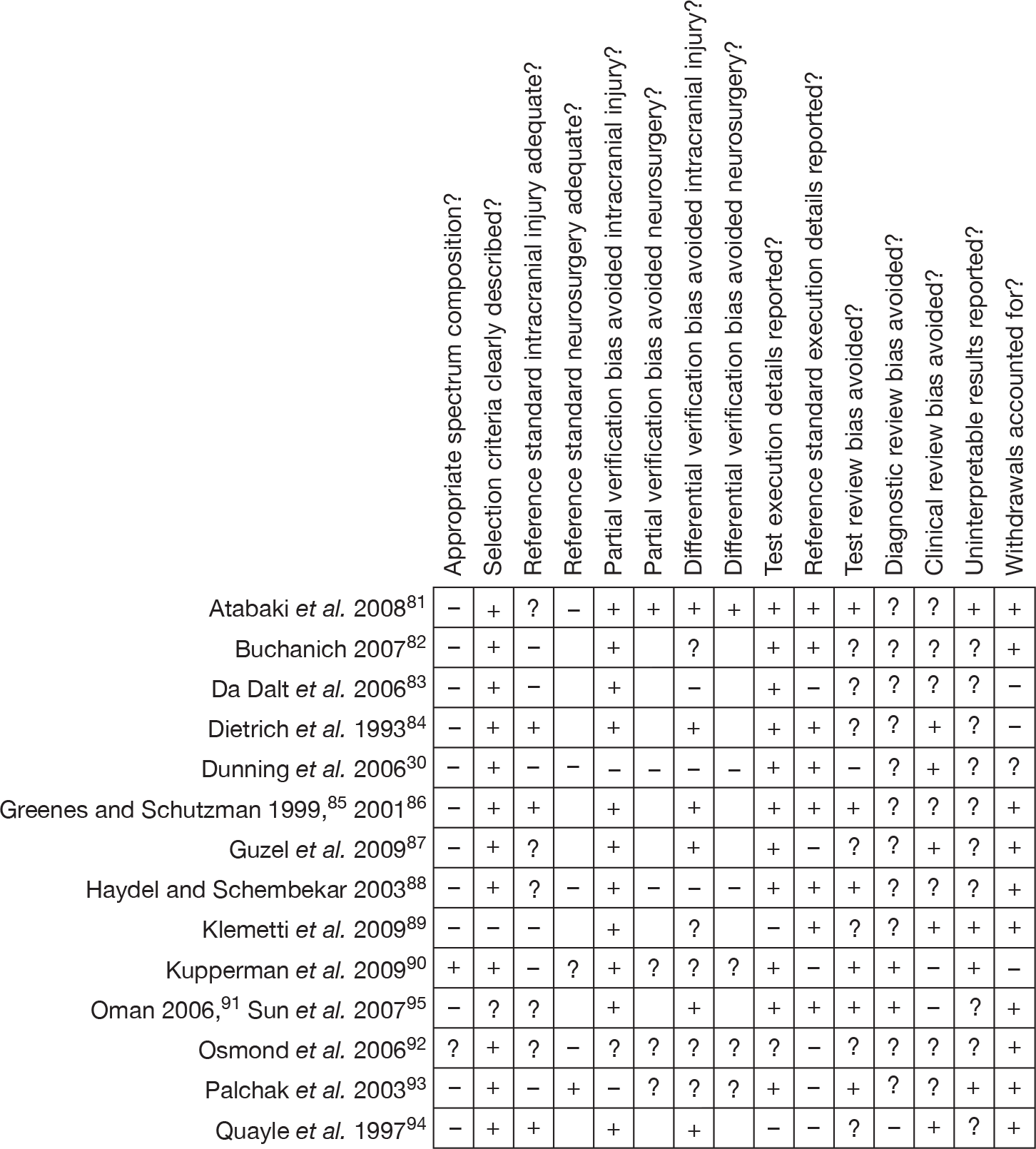

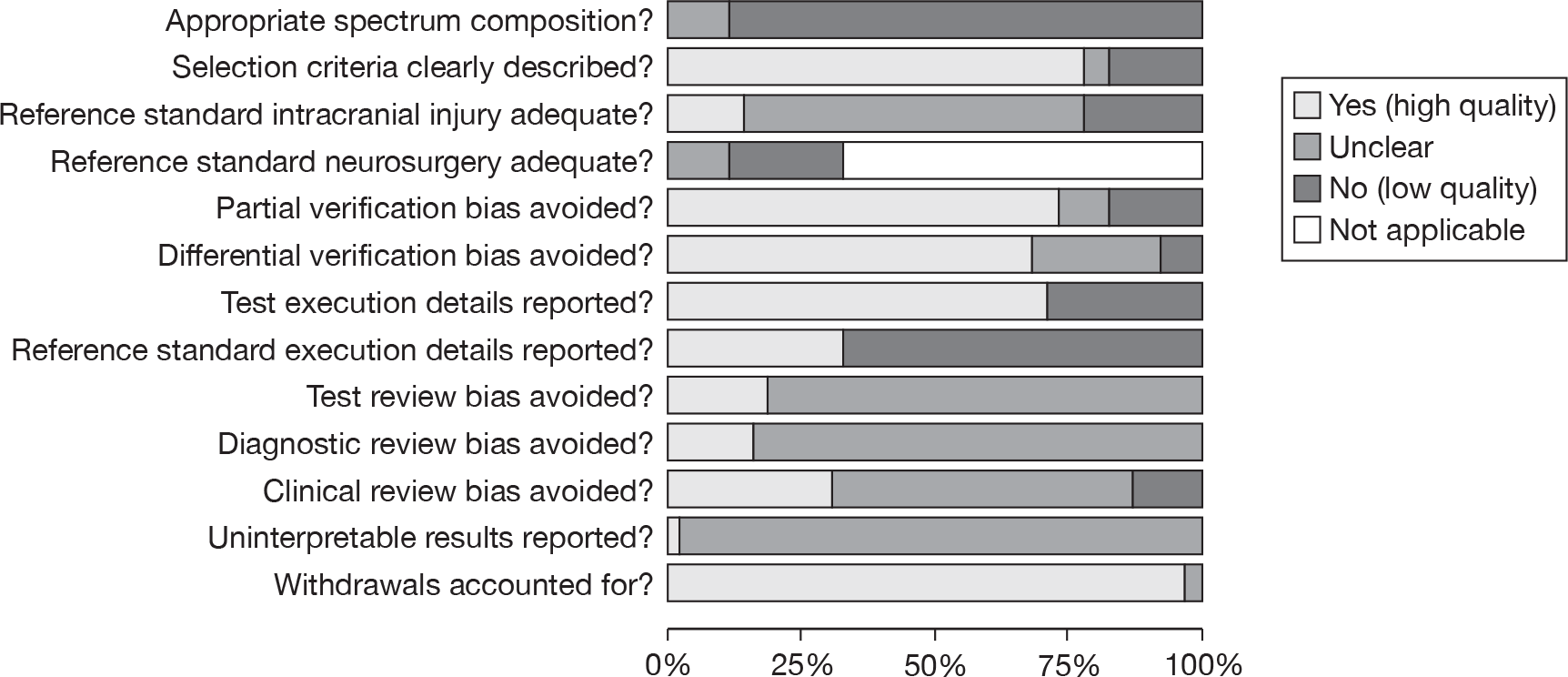

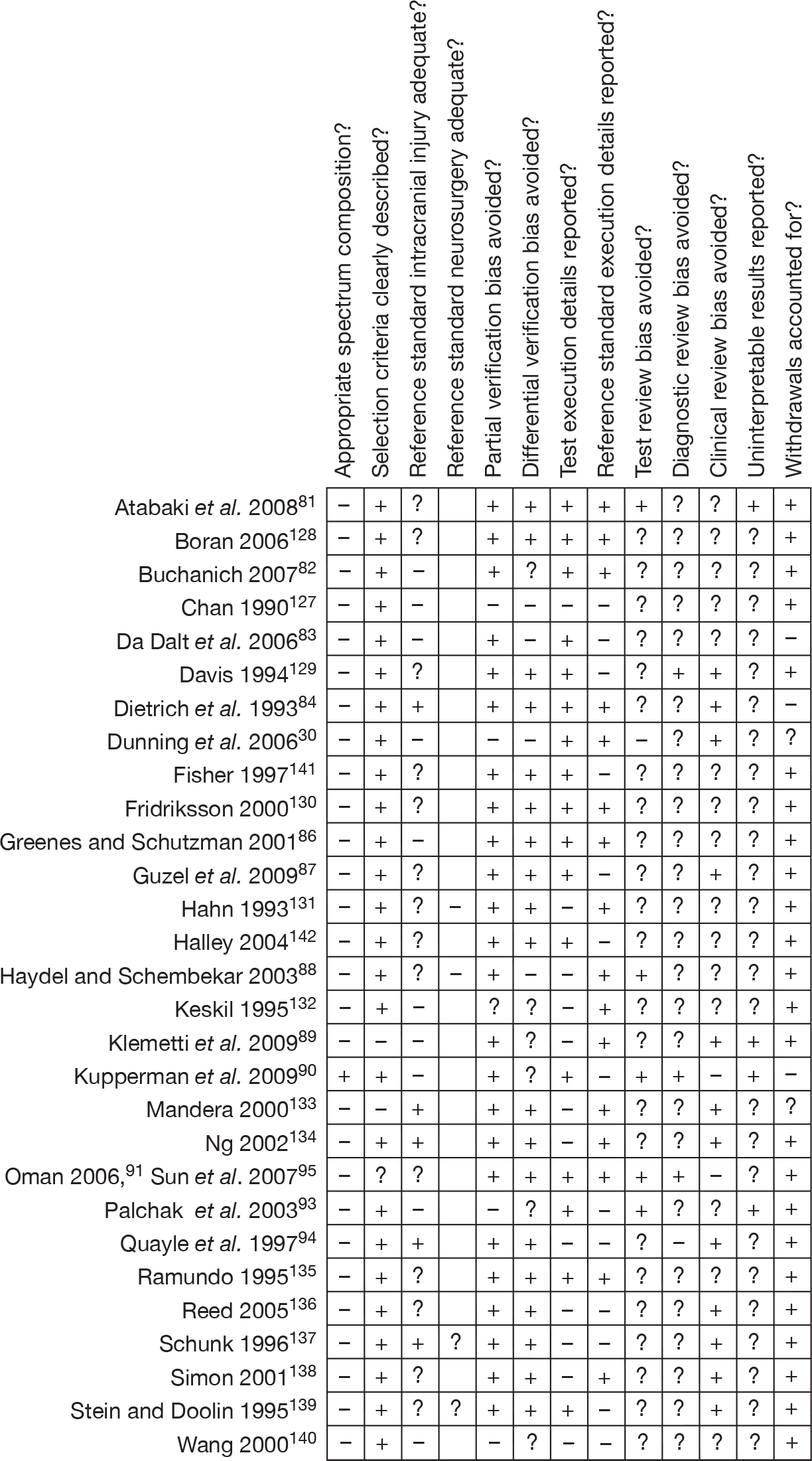

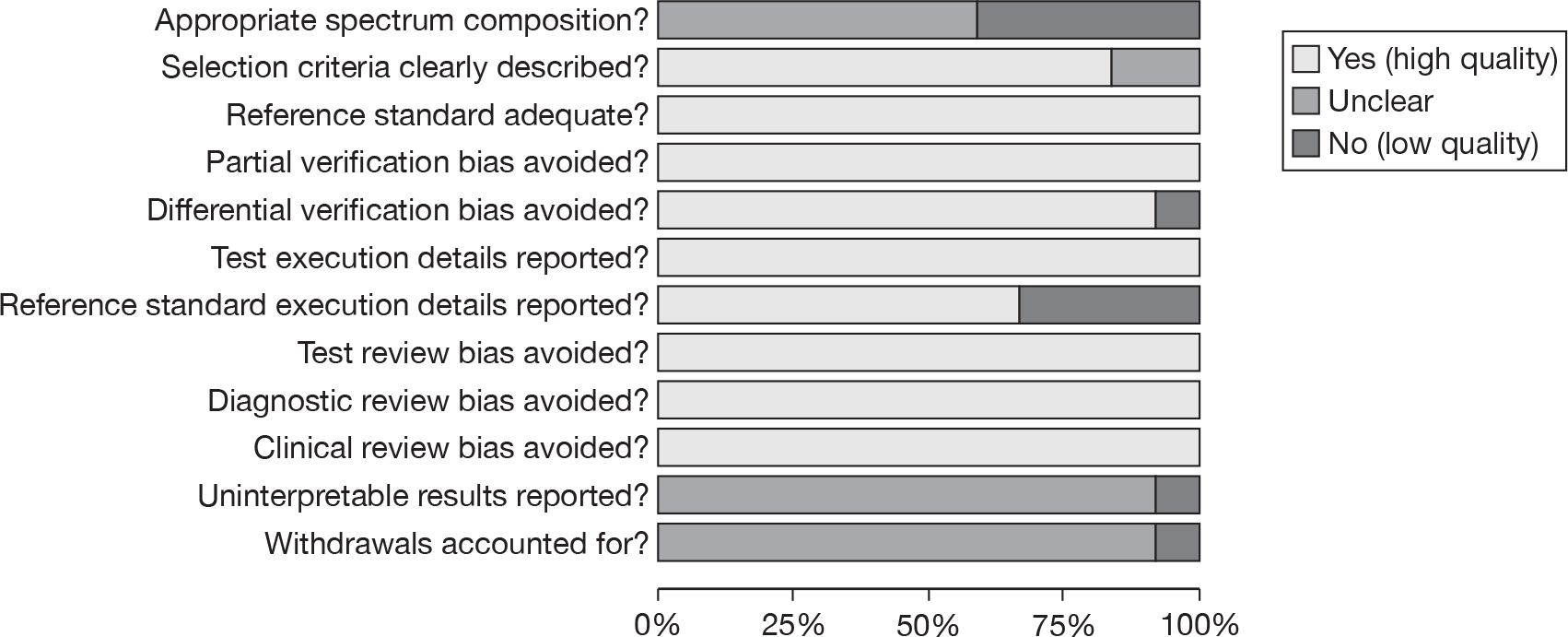

Children and infants

The methodological quality assessment of each included study is summarised in Figures 4 and 5. Overall, most of the included studies were poorly reported and did not satisfy the majority of the quality assessment items of the QUADAS tool. The study30 that scored the most negatives and fewest positives was also one of the two large cohorts (> 20,000), and consequently has the potential to influence the results. This study scored poorly mainly owing to the use of pragmatic reference standards.

FIGURE 4.

Decision rules for children and infants with MHI – methodological quality graph. Review authors’ judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

FIGURE 5.