Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 03/46/09. The contractual start date was in June 2005. The draft report began editorial review in June 2010 and was accepted for publication in October 2010. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Gregory et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction to the DEPICTED study

Diabetes

Diabetes is the third most common chronic disease in childhood, with 1–2 per 1000 children and adolescents in the UK receiving prescriptions of insulin in recent years (1998 and 2005). 1 Since 1989, the incidence has doubled, with a particularly marked increase noted in the preschool age group. 2 In childhood, the vast majority of affected children experience autoimmune-mediated destruction of their insulin-secreting pancreatic β-cells, which leads to insulin deficiency (type 1 diabetes). As a consequence of insulin deficiency, children develop raised blood glucose concentrations (hyperglycaemia), which lead to excess urinary losses (polyuria) and therefore increased thirst (polydipsia). In addition, insulin deficiency leads to uncontrolled breakdown of fat (lipolysis), as demonstrated by marked weight loss over relatively short time periods. Lipolysis in the presence of insulin deficiency results in ketosis, which, if uncontrolled, may lead to potentially life-threatening episodes of acute diabetic ketoacidosis. The presence of vomiting or development of ketoacidosis are common reasons for children with diabetes to require hospital admission. The acute metabolic consequences of insulin deficiency may be reversed or prevented by the administration of an insulin treatment.

Complications of diabetes

In the short term, excess insulin for requirements may cause hypoglycaemia (low blood glucose levels), which, if severe, may lead to loss of consciousness. By contrast, inadequate insulin therapy may cause symptoms similar to those at diagnosis (see above). In the longer term, chronically elevated blood glucose concentrations leads to an increased risk of clinical complications. In childhood, poor glycaemic control causes growth failure and pubertal delay, which may be reversible with improved clinical management including optimisation of insulin therapy. In the longer term, more serious and eventually irreversible microvascular complications arise. These include sight-threatening retinopathy and renal disease. Initially, renal disease is asymptomatic and detected by increased protein (albumin) excretion in the urine but, if untreated, will eventually deteriorate leading to renal failure and the need for dialysis. A further devastating complication is neuropathy, which may produce a range of symptoms such as impaired peripheral sensation and pain or gastrointestinal and genitourinary problems if the autonomic system is affected, resulting in major adverse effects on quality of life (QoL). In addition to the microvascular complications, macrovascular disease is common, with increased risks of myocardial infarction and strokes in later life. Microvascular and macrovascular complications are rarely seen in childhood, but occur with increasing frequency in young adult life. There is clear evidence, however, that the quality of blood glucose control through childhood is a significant risk factor for the development of many of these complications in later adult life. 3

Psychosocial aspects of diabetes

The management of diabetes is complex, requiring significant practical expertise to optimise outcomes and, unsurprisingly, may result in significant psychological difficulties for young people with diabetes and their families. Variations in blood glucose concentrations, particularly overnight, have been shown to affect mood and behaviour. 4 The difficulties of adhering to a practically demanding regimen may result in overdependence of children on their parents5 or adverse effects on behaviour, including an increase in suicidal thoughts. 6 For the family, managing childhood diabetes brings particular pressures, including the grief experienced by parents at diagnosis. 7 In relation to the challenges of the day-to-day management of the diabetes, problems may occur in communication between parent and child, and there is a risk of increased family conflict with the experience of frustration and guilt at failure to achieve optimal outcomes. 8 Existing psychological issues within families involving functioning, coping and interpersonal relationships may be exacerbated. Psychiatric and psychological problems (including eating disorders and effects on body image, etc., exacerbated by the inter-relationship with insulin and other aspects of diabetes management) are therefore unsurprisingly seen more commonly in young people with diabetes than in the non-diabetic population. 9,10

It is well recognised11 that psychosocial and educational influences play a key role in determining management outcomes in children with diabetes. For example, a large audit in Scotland has shown that throughout childhood family structure is associated with glycaemic control. 12 During adolescence, rapid physical change (puberty) leads to relative resistance to the effects of insulin. 13 Concurrent major developmental changes include increasing independence, emerging sexuality and increased stress from peer and academic pressures. These factors together are often associated with deteriorating glycaemic control. Knowledge and skills imparted by the diabetes teams are especially important tools for the child and their family to achieve optimal glycaemic control during this crucial period.

Diabetes management

The management of diabetes by patients and their family requires them to develop an understanding of the complex interaction of the effects of insulin, food and physical activity on blood glucose concentrations. Treatment of diabetes involves the regular administration of insulin, most commonly by two to four subcutaneous injections daily or through the use of an insulin pump, which provides a continuous infusion of insulin through a subcutaneously sited catheter. A healthy lifestyle is recommended, including regular physical activity and a diet that regulates carbohydrate and fat intake. To optimise diabetes management, it is recommended14 that the patient and his/her family develop a sophisticated understanding of the carbohydrate content of food so that the amount of insulin administered can be finely tuned (so-called ‘carbohydrate counting’). The efficacy of management is monitored in the short term by regular self-measurement (ideally four or more times daily) of blood glucose concentrations and in the longer term by monitoring (3–4 monthly) glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels in blood and regular review in paediatric diabetes clinics.

In the UK, clinical care is usually delivered by paediatric diabetes services established in secondary care. Such services require the multidisciplinary input of doctors with expertise in both paediatrics and childhood diabetes, nurse specialists who liaise between the clinic, the child’s home and school, dietitians, child psychologists, podiatrists and social workers. There also needs to be close collaboration between paediatric and adult services to ensure that as children progress through their teens arrangements are made for their care to be handed over from paediatric to adult services. This is a time when particular difficulties may be encountered by clinical services, as teenagers with diabetes take increasing responsibility for their self-management and also encounter the problems caused by increased insulin resistance during puberty. 15

Adherence to diabetes management

The aims of paediatric diabetes services are to support and educate children and their parents in the care of diabetes, to manage diabetes in a manner that optimises clinical outcomes and to prepare teenagers for young adult life by helping them to become increasingly independent in their self-management. Given the complexities of diabetes management described above, it is unsurprising that many children and their families struggle to adhere to optimal treatment strategies, resulting in adverse consequences for diabetes outcomes in both the short and longer term. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has recommended that parents and children be informed that the target for optimal HbA1c concentrations is values < 7.5%. 16 However, an audit of outcomes in 2002 for children treated in the UK demonstrated that, depending on age, only 14–20% of children cared for in clinical services in the UK achieve these outcomes. 17

The landmark Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT study) has shown that provision to a group of teenagers and young adults of very high levels of support from the multidisciplinary team to facilitate intensification of their diabetes treatment can produce dramatic improvements in blood glucose and HbA1c concentrations. 18 After a mean of 6.5 years’ follow-up, the group who received intensification of their diabetes management experienced – by comparison with the control group receiving conventional treatment – a reduction in their risk for the development of retinopathy of 76%, microalbuminuria of 39% and clinical neuropathy of 60%, albeit at a cost of a two- to threefold increase in severe hypoglycaemia. Subgroup analysis has shown similar benefits for the younger participants in this study. Interestingly, even after the discontinuation of the DCCT study when both arms experienced similar HbA1c concentrations, those who had undergone intensified therapy continued to experience a longer-term benefit of a reduced risk of developing diabetes-related complications, including a near 50% reduction in serious adverse cardiovascular disease event. 19–21

The challenge for paediatric diabetes clinical services, therefore, is how to facilitate patients and their families to make changes in their diabetes management that result in similar improvements in HbA1c level to those achieved in the DCCT study, with subsequent reduced risks of diabetes-related complications.

Behaviour change

Theories of health behaviour change (e.g. reasoned action theory, the health action process approach) and the research associated with them have clarified the need to look beyond a simple approach to adherence and change based upon the delivery of expert information. 22 As Marteau and Lerman23 have put it, ‘Just telling people they are at risk of developing a disease is rarely sufficient to change behaviour’. Two variables run through many of the theoretical models as predictors of health behaviour change: beliefs about the value of change and beliefs about one’s capacity to succeed (self-efficacy). Thus, for example, the efficacy of theory-based interventions such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) has largely been attributed to their capacity to enhance self-efficacy. 24 Using a skills-based approach to counselling has been found to be effective in a number of fields. 24. 25 So, too, brief interventions have been found to be effective in changing a number of risky health behaviours. 26

A second line of research has focused on how the therapeutic relationship either hinders or promotes motivation to change. For example, an early effort to understand the effective ingredients of motivational interviewing (MI)27 identified a correlation between confrontational interviewing and resistance, and between ‘change talk’ and behaviour change. 28 A meta-analysis of MI29 found consistent evidence for effectiveness in some (e.g. alcohol, drug use), but not in all behavioural domains. Interest in the field of diabetes among young people has also emerged. 30–33 One of the challenges in much of this research, however, has been to clarify exactly what elements of a complex method were used by the interventionists. It does appear that some of the principles of MI can be realised in brief health-care consultations, and that helping patients to clarify for themselves why and how they might change their behaviour (MI) can be more effective than brief advice-giving. 34,35 One recent development has been the first effort to integrate this method with CBT. 36 Put simply, this body of work calls attention to both the direction of consultations about change (towards enhancing coping skills) and the way patients are spoken to (eliciting motivation and solutions from them).

Psychoeducational interventions in diabetes

An NHS health technology assessment (HTA) systematic review of the effects of educational and psychosocial interventions for adolescents with diabetes, which led to the commissioning brief for this study, reported that there were no results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of psychoeducational interventions in the UK. 37 However, the review did identify an ongoing study evaluating the effects of MI on behaviour change in teenagers. 32 This trial was based on positive findings in a pilot study in children33 and an RCT involving adults with type 2 diabetes. 38,39 The review commented that small to medium-sized beneficial effects on a variety of diabetes management outcomes have been demonstrated mostly in North American studies. 40 It concluded that there is a need for well-designed clinical trials that recognise the inter-relatedness of various aspects of diabetes management and assess outcomes that are specifically targeted for change, at an appropriate time after the intervention. In particular, the review recommended that such research be developed by a consultation process with stakeholders including patients, their families, health-care professionals (HCPs) and health economists. The commissioning brief for this research project further refined these principles in that effort should be directed towards a generic intervention that does not require delivery by trained clinical psychologists, given their relative scarcity in paediatric diabetes services. 41

Overview of the DEPICTED study

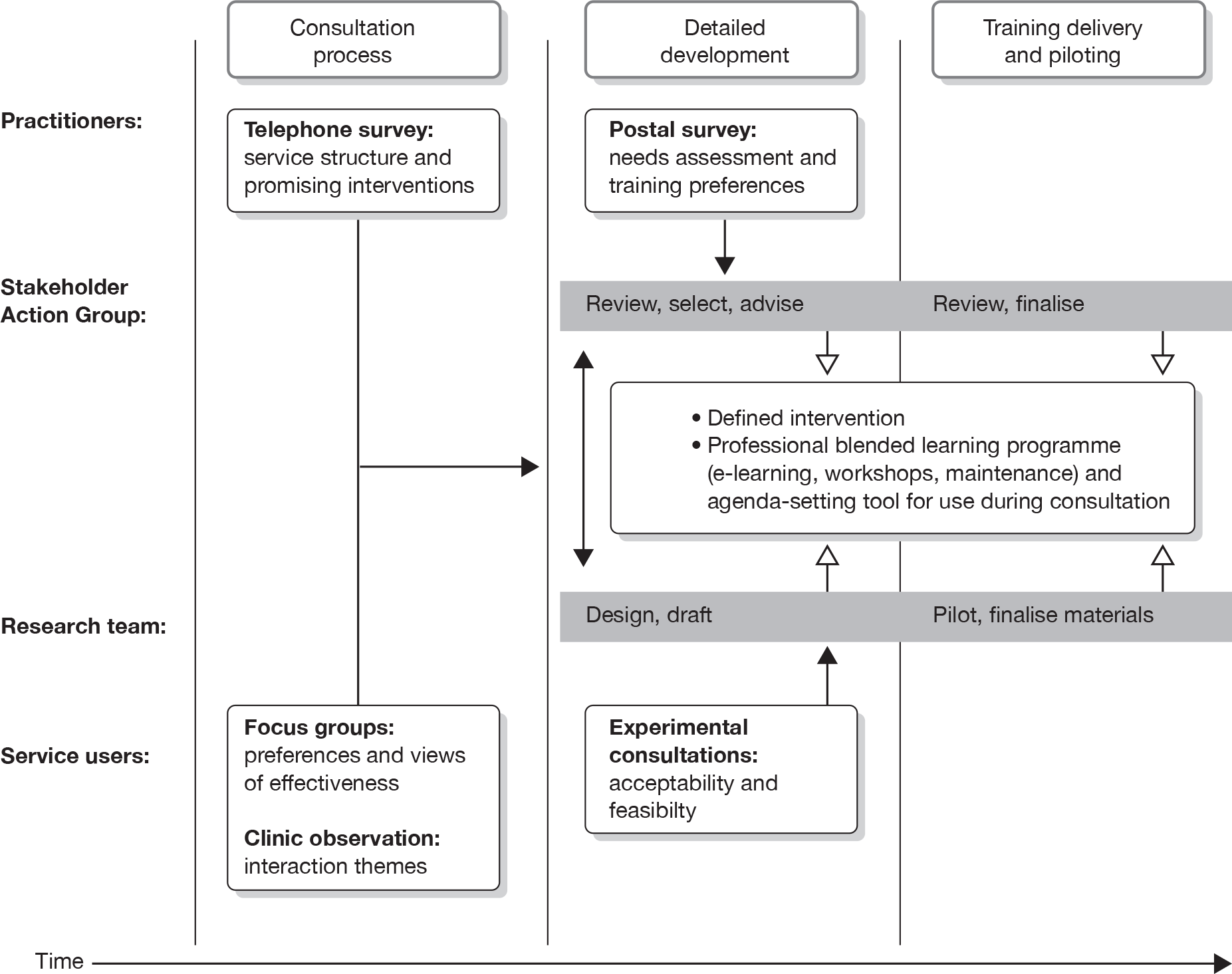

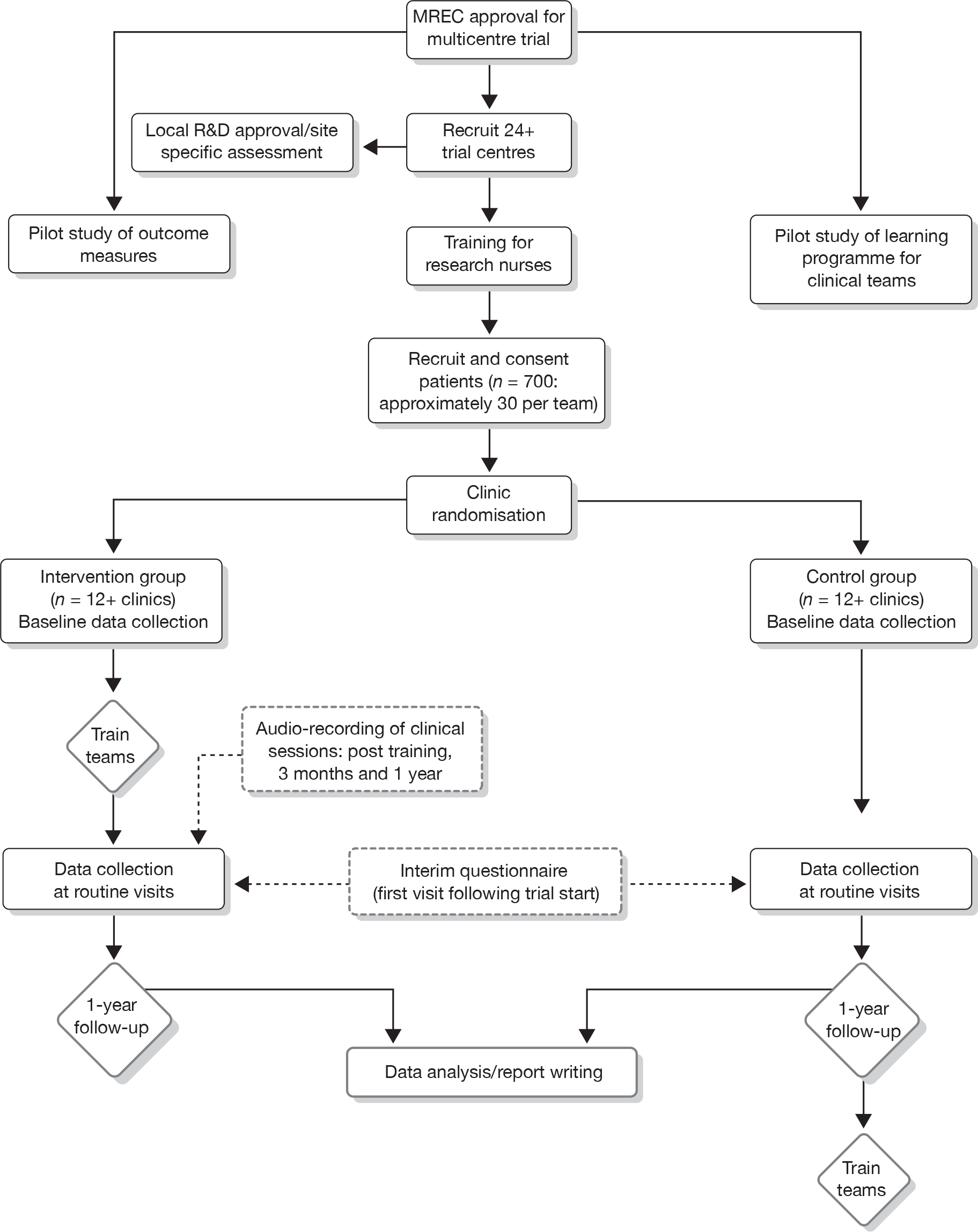

The study described in this report was delivered in two phases. The first phase involved six developmental components required to inform the development of the emerging intervention (health-care staff trained to modify their consultation approach to help them discuss behaviour change skilfully in their patients and families), and was followed by a second phase in which the intervention and training programme were trialled. This overview starts with a brief consideration of the issues relevant at the time to modelling and complex intervention development.

Modelling and complex intervention development

This research did not start out with a fixed position on the best psychosocial approach on which to base the intervention. However, a number of principles and conceptual aids were brought to the development process for consideration by the research team and associated stakeholders (Box 1).

The need to integrate behaviour change within routine clinical care encounters

Consideration and balancing of multiple behaviours

Matching intervention components to individual need

An intervention that addresses common clinical problems, delivered by non-specialist (i.e. psychologist) diabetes practitioners

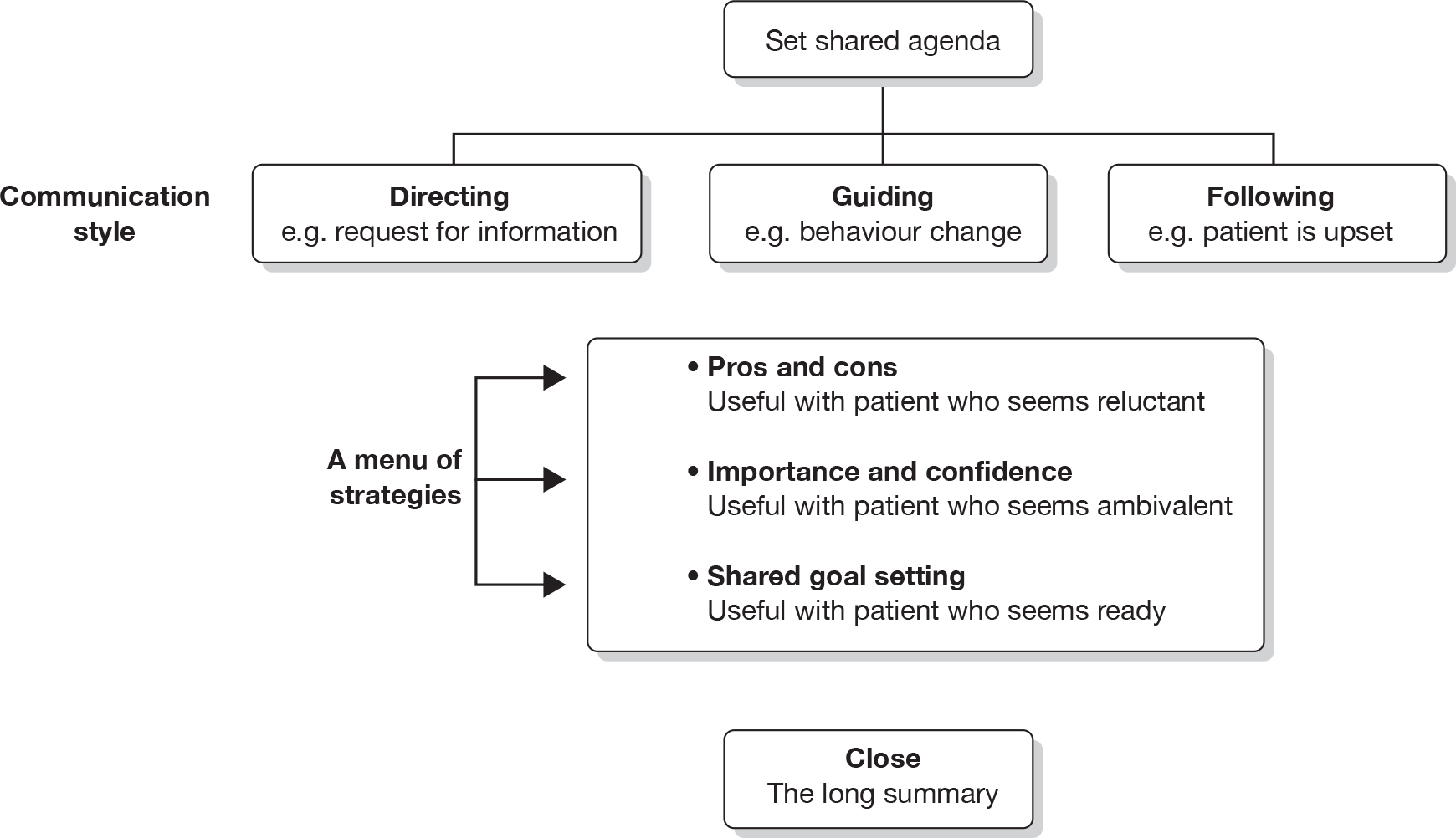

First, there was the need to integrate talk about lifestyle change, self-control and QoL with routine care when patients are at the receiving end of a range of medical and nursing interventions. Practitioners would need to find ways of moving between providing medical care on the one hand and ‘letting go responsibility’ on the other,39 to encourage children and teenagers to take control of their health with assistance from others. Of relevance, therefore, was a model developed by one of the co-applicants with practitioners in the coronary heart disease field, which described the value of moving flexibly between directing, listening and guiding communication styles when talking about behaviour change. 42

A second conceptual and clinical challenge was the need to move beyond thinking about change as involving an isolated, single behaviour, a limitation in much of the theory of behaviour change in health psychology. The challenge was to help patients find a balance between multiple and inter-related health behaviours and lifestyle choices. 37,39,43 How to negotiate a complex behaviour change agenda would be one useful starting point in intervention development. 44

Thirdly, the possibility of targeting or matching interventions to the needs of patients would need to be borne in mind. Efforts to match interventions to patients in other fields45,46 have proved difficult; therefore, the feasibility of targeting would be a particular focus for the stakeholders to consider. Among the key targets might be interventions, for example, for different age groups or for talking to parents in a constructive way. Another view of targeting would be to regard this as something that happens not across interventions but within the consultation, as the practitioner shifts style and topic according to the needs of the patient. 47 To this end, there was some evidence for the acceptability and feasibility of using a targeting approach based on a flexible menu of strategies in which the practitioner and patient selected a topic according to need. 46,48 This intervention framework had been developed in efforts to train health-care professionals to use elements of MI, and an application among drug-abusing young people had produced promising results. 49 In the present context, however, it was not the intervention approach (MI) or content that might have been useful, but the use of a framework or methodology for targeting within the consultation based on a menu of topics for discussion.

Finally, the intervention development process would benefit from a clear understanding of who would be providing what and to whom. To this end a conceptual approach at the outset helped to distinguish between:

-

psychological therapy provided by a therapist, using a wide range of skills in a relatively long consultation

-

brief counselling provided by any health-care professional that involves setting aside some time, perhaps 10–15 minutes, to discuss specific issues of importance to the patient

-

psychosocial intervention as part of routine care and consultations; this third level of intervention required the use of a much narrower range of therapeutic skills, but carried the advantage of use in a relatively much large number of consultations.

The level of intervention in this research would fit within points (2) and (3) above, and its exact nature would emerge from the various developmental studies in the first phase of this research.

In summary, it was essential to move beyond the use of a simple model of compliance that assumed that patients merely need expert information to encourage behaviour change. Theory and research on behaviour change and development work already carried out clearly indicated that the dynamics of talk about behaviour change were more complex.

Phase I

Intervention development

The modelling stage in developing a complex intervention uses appropriate exploratory methods to identify and clarify the effective components of the intervention, as well as considering factors such as acceptability and feasibility. Modelling may also be used to better understand the processes operating with the normal (usual care) setting. 50 Phase I of this research would follow this guidance using a variety of research methods, and, combined with the review of the literature,37 would build on approaches found to be useful in development work in other areas. For example, patients would be used not only to understand the issues,51–53 but also to receive the emerging intervention and provide feedback. 34 We also planned that the emergent intervention once developed would be thoroughly documented. 48,54 Materials developed in the study for use by health-care professionals would draw heavily upon clinical examples (including lay study participants and practitioners), providing face validity to the intervention. Practitioners would also be part of the intervention development process; a survey of current practice and promising interventions would be accompanied by interviews with them51 and simulated consultations would be used to refine the intervention. 55

Practitioner training and skill acquisition/assessment

A similar approach would be required to develop an acceptable and feasible method for helping practitioners to learn new skills. Training practitioners to change their behaviour, to use a complex intervention of the kind described above, would clearly need to move beyond the delivery of guidelines for good practice56 or the production of a training manual. Even if the intervention was relatively simple when compared with specialist delivery of psychological therapy, some form of face-to-face training would probably be essential. The development work in phase I would seek to model a training programme that itself is acceptable and feasible for practitioners. Among the approaches to be used were:

-

surveys (telephone and postal) for establishing current practice and the acceptability of training options

-

provision of time for practitioners themselves to contribute the training outline via a specially constituted group of lay and professional stakeholders – the Stakeholder Action Group (SAG)

-

pilot training to refine its structure and content in the light of change in competencies and feedback from participants themselves.

Similar work among general practitioners has led to the development of what has been called context-bound learning,55,57 in which everyday clinical scenarios form the basis for learning new skills and for monitoring their use in practice.

The core research team would work with the SAG and other contributors to develop aspects of the intervention and training programme. For the latter, a resource that they could consider adopting was the use of simulated patients. Other available resources included an existing software architecture designed to host training content for health practitioners (Talking Sense, Cardiff University, Cardiff and Smile-On Ltd, London), which could be adapted to suit varying health or social-care settings.

If the intervention to be used involved face-to-face with patients, a measure of practitioner competence would be an essential adjunct to assessing the efficacy of training and for monitoring the quality of intervention delivery in the RCT. This project would utilise the team’s recent experience of developing an instrument to measure shared decision-making in primary care58 and another on the subject of behaviour change counselling in health-care settings. 59,60 It was expected that initial development work would commence in phase I, but would continue through the course of phase II.

Preparation for the randomised controlled trial

The modelling process informed the development of the intervention prior to the trial. Outcomes were to be compared with those arising from ‘control’ centres delivering ‘usual care’. The stakeholders and user consultation process would identify the most relevant established outcomes to be targeted by the intervention. In addition to the process for assessing professional performance just described, a survey for assessing patient and carer preferences within the consultation was developed in this phase. This included the identification of attributes for a discrete choice experiment (DCE) in collaboration with the SAG (described further in Chapter 6).

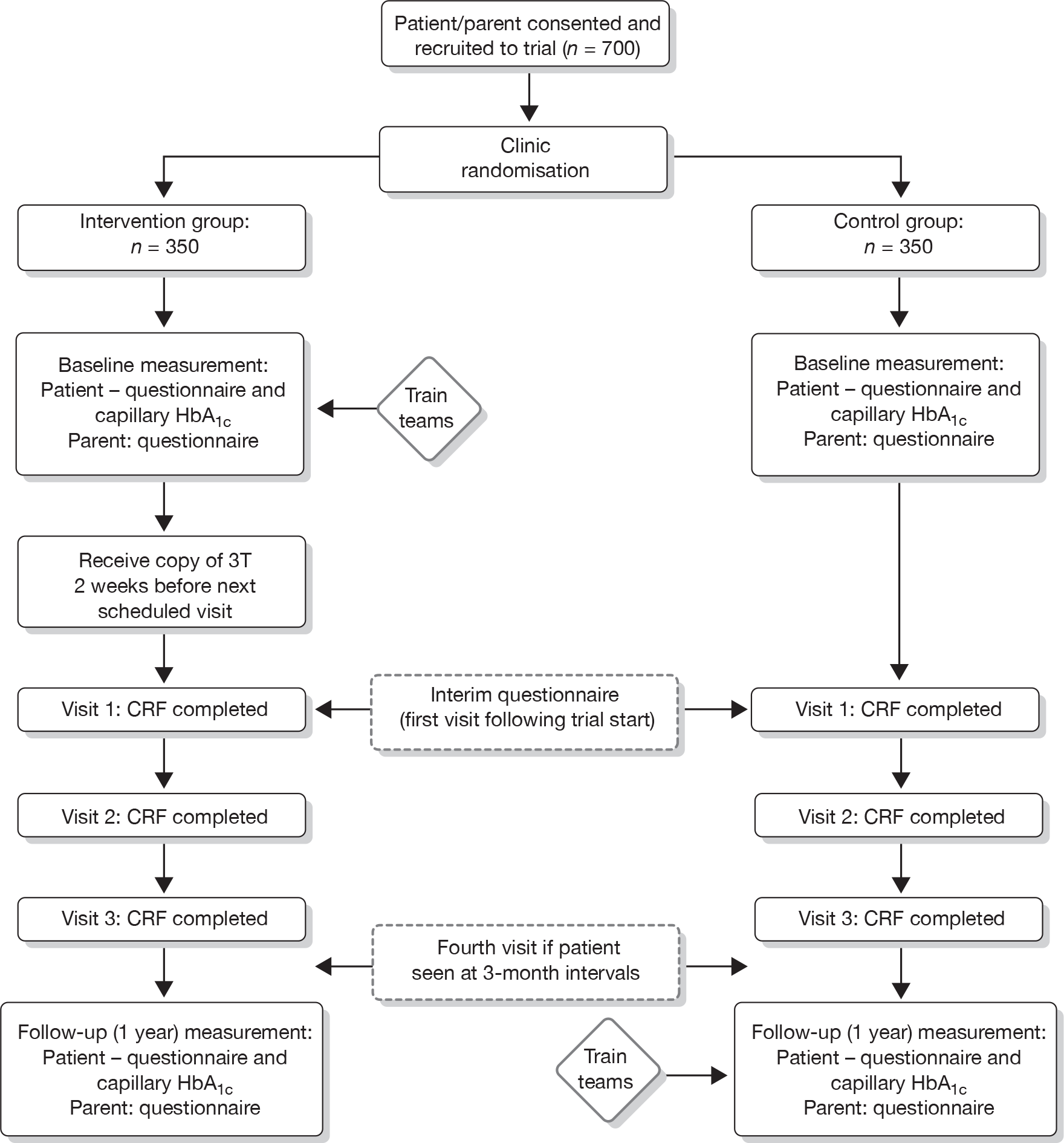

Phase II

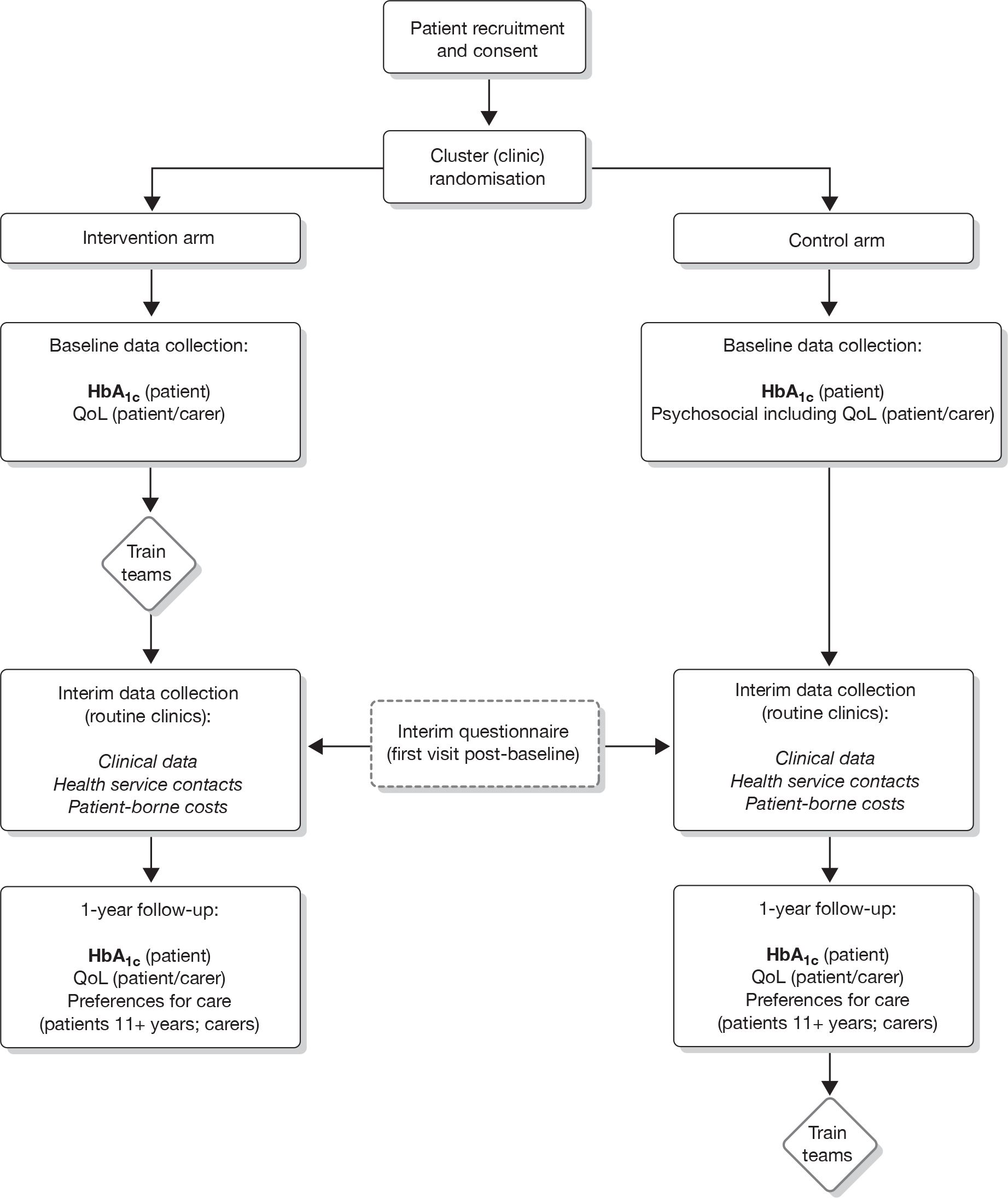

The effectiveness of the intervention developed in phase I would be assessed using a pragmatic cluster RCT design described more fully later in this report (see Chapters 8–13). The primary outcome in this trial was to be the change in blood HbA1c concentrations in patients with type 1 diabetes. Following a 12-month study period, comparisons between intervention and control groups would also include the following secondary outcomes.

Patients

-

Clinical measures such as body mass index (BMI).

-

Patient-reported outcomes, such as generic and specific QoL, self-care/management activities, perceptions of health-care providers and preferences for care.

-

Service usage measures, such as hospital admissions (particularly with ketoacidosis), attendance at diabetes clinic, other health service contacts.

Carers

-

Self Generic QoL, perceptions of health care provided and preferences for care.

-

Proxy Generic and specific QoL for the younger child, school absences.

Professionals

-

Performance of techniques taught during the training programme.

A cost-effectiveness analysis would be undertaken assessing costs against the primary outcome measure (levels of HbA1c).

Presentation of this report

The next six chapters present the component studies of the development phase of the DEPICTED (Development and Evaluation of a Psychosocial Intervention for Children and Teenagers Experiencing Diabetes) study. Chapter 2 presents the overarching methodological framework adopted for these studies and Chapters 3–6 report the individual studies. Chapter 7 describes how these were integrated within the intervention and training programme, which are also described in detail, and it also serves to summarise the body of work conducted in the developmental phase. Chapters 8–10 describe the introduction, methods and results of the trial, respectively. The DCE, which explores patient and carer preferences, is described in entirety in Chapter 11, whereas the trial process evaluation (PE) is presented in Chapter 12. Finally, the results from the DEPICTED study as a whole are discussed, with conclusions, in Chapter 13.

Chapter 2 Phase I of the DEPICTED study: overview and framework of developmental studies

In this first chapter describing the work conducted within the developmental phase of the DEPICTED study, we present an update of the existing evidence base and the theoretical rationale underpinning our approach. First, the previous HTA systematic review of the effects of educational and psychosocial interventions for adolescents with diabetes mellitus61 was updated. Second, we provide details of the MI approach, which underwrote many aspects of our developing intervention. Finally, we summarise the framework for our methodological approach.

Updating the systematic review

In 2001, the NHS research and development (R&D) HTA programme published a systematic review of the effects of educational and psychosocial interventions for adolescents with diabetes mellitus. 37 In summary, this review identified 62 studies, of which 25 were RCTs, mostly conducted in the USA (none from the UK). The mean (pooled) effect size was 0.37 for psychosocial outcomes and 0.33 for HbA1c with outliers (0.08 without outliers), suggesting that these interventions have small to medium beneficial effects on diabetes management outcomes. The authors concluded that future studies should be evaluated by assessing outcomes that the intervention specifically targets for changes, at an appropriate point in time post intervention to reflect the impact and durability of the intervention. The lack of cost-effectiveness analyses of published studies was highlighted.

When our study was initiated, we undertook an update to this systematic review. At the time of analysis of papers identified, similar structured and systematic review updates of the effectiveness of psychoeducational interventions in children with diabetes were published. 62–64 These published reviews identified largely similar manuscripts and drew similar conclusions to those that we were developing at that time and, therefore, we will draw largely upon their findings.

A further 27 papers had been published describing the evaluation of 24 psychoeducational interventions. 64 As before, routine clinical care seems to produce inadequate metabolic outcomes. Education seems most effective when integrated into routine care, where continued parental involvement65,66 and adolescent self-efficacy is encouraged. Although there was evidence of a methodological improvement in published trials, there was no evidence of improved effectiveness of the interventions. Although psychological interventions seemed more effective in children and adolescents than in adults,63 few studies have investigated the effectiveness of interventions in younger children and most trials remained underpowered to demonstrate modest, but clinically significant improvements in HbA1c level. An estimated sample size of 360 is required to show an HbA1c concentration difference of 0.5%, and a sample size of 350 is required to detect a small psychological effect size of 0.3 with 80% power. 64 Most psychological interventions were based around CBT and the limited understanding of the potential of MI in childhood diabetes32,33 was highlighted. 63 No specific psychoeducational intervention could be deemed superior to others. Specifically, there were no interventions that seemed effective when targeting those with poor glycaemic control, and concerns have been expressed62 that targeting only those demonstrating ‘readiness to change’ patterns of thinking may overestimate the effectiveness of certain interventions. 33

Hampson and colleagues37 concluded that agreement was required on appropriate, valid outcome measures for trials of psychoeducational interventions, but little progress has been made in this respect. The need to agree measures that include glycaemic control using common reference methodology, age-validated questionnaires for psychosocial variables and service utilisation and cost measures is clear. Unresolved issues include the relative importance of the content of the intervention as opposed to contact time with the interventionist and whether or not interventions should be combined with other efforts to intensify insulin therapy. 67 Given the increasing importance ascribed to education and the wider number of HCPs, including physicians, providing such education to patients and their families, the importance of understanding the role of self-efficacy, the principles of education and its delivery have been highlighted as priorities for training. 64 Future interventions should be theoretically grounded, with clearly described protocols to allow adequate analysis and reproduction62 and greater priority given to patient preferences. 63

Motivational interviewing

The starting point

When this research was awarded funding, there was consensus within the team that MI might inform the emergence of the intervention to be developed. This consensus was based on two features of MI: first, its purposeful focus on behaviour change, which seemed suited to the lifestyle challenges faced by children with type 1 diabetes and, second, its focus on using the professional relationship to enhance motivation for change.

These two features of MI lie at the centre of a method originally developed in the addictions field in the early 1980s as a form of psychotherapy. The central feature of this method is the use of empathic listening rather than confrontation when speaking to people struggling with ambivalence about behaviour change; specific listening techniques are developed to encourage clients to express their own arguments for change (phase I) and to formulate a plan of action that feels achievable (phase II). 27

Refinement of motivational interviewing for health-care settings

From its origins in the addictions field, MI was adapted and refined in a number of ways over the following 20 years. To begin with, attention focused on a series of research studies that examined the process and outcome of feeding back test results to people with drinking problems. Thus, for example, outcome was significantly better if these results were fed back in an empathic style compared with a more usual ‘confrontational’ style. 68 This led to the development of a four-session variant of MI called motivational enhancement therapy. Other research confirmed the importance of counsellor style on behaviour change outcomes. For example, in the delivery of behaviour therapy, counsellor empathy accounted for over two-thirds of the variance in outcome. 69 MI delivered prior to treatment (inpatient and outpatient), with adults and adolescents, produced better outcomes of subsequent treatment and also improved retention in treatment (see Miller and Rose70 for a review of this research).

By the mid-1990s the most striking refinement was in the development of brief forms of MI suitable for application in health-care and other settings. Development work and a series of outcome studies were published in a number of fields, for example among drinkers in a hospital setting,46 smokers in primary care34 and among adults with type 2 diabetes. 38

Among the innovations that emerged from this health-care development work were:

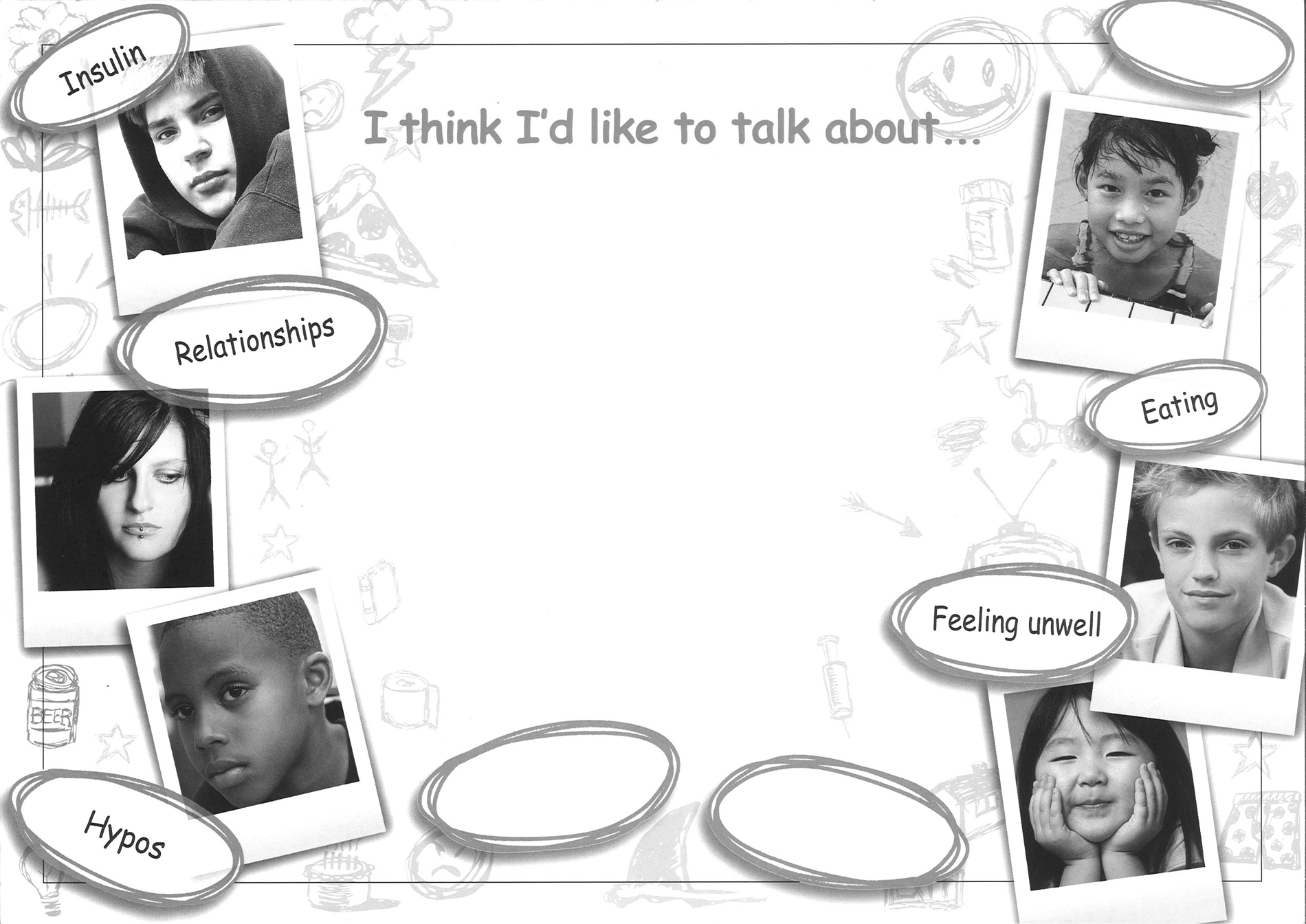

-

‘agenda-setting’ – tested in the diabetes field,39 this is a strategy for helping patients make choices about the kind of behaviour change on which they and the practitioner feel it is advisable to focus

-

the ‘elicit–provide–elicit’ sequence for exchanging information

-

the ‘pros and cons’ strategy for resolving ambivalence about behaviour change

-

the ‘importance and confidence’ strategy for conducting a rapid assessment of motivation to change, in which scaling questions are used to encourage patients to articulate why and how they might change.

Much of this work was documented in a practical text for clinicians,44 and the first systematic review of brief forms of MI in four behavioural domains was published in 2001. 71

By the time this research study was funded, two other significant developments had occurred: first, the research base had broadened, with four further reviews and meta-analyses confirming the effectiveness of MI in many settings and problem areas, although not all. 29,72–75 The last of these reviews embraced 72 randomised trials. The current record presents over 200 trials to date across a wide range of clinical settings. 70

A second, more recent, development was a conceptual one, designed to explain the link between MI and everyday practice. To this end, it was suggested that better practice in consultations about change might be promoted through a switch in style from directing to guiding,42 with MI being conceptualised simply as a refined form of the guiding style. As such, learning a guiding style in health-care consultations might provide the foundation for more specialist or complex MI practice.

Application of motivational interviewing in the diabetes field in Cardiff

On the initiation of this study, development work and position papers had earmarked MI as a potential intervention in the diabetes field. 44,61,76,77

Within the School of Medicine, Cardiff University, a Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded trial had examined the ability of general practitioners and nurses to use an agenda-setting chart to elicit meaningful changes areas from patients with type 2 diabetes. 38,39 Attention then turned to children with type 1 diabetes in a series of studies that led up to the current research project. Initially, an encouraging pilot feasibility study was conducted that explored the potential of counsellor-delivered MI for lowering HbA1c levels;33 this was followed by a larger randomised, multisite trial in which a nurse counsellor trained in MI produced significantly better outcomes than routine care supported by non-directive support counselling. 32 Of particular interest here was the use of agenda-setting in both of the above studies. Finally, a study by Viner and colleagues31 seemed to support the robustness of MI for adaptation in the diabetes field, leaving open the question of whether or not it was possible to adapt the method further for use by any clinician involved in the routine care of children with type 1 diabetes.

Some questions about motivational interviewing for the development phase

Among the questions about MI taken into the development phase of this research were the following:

-

What training experience and aspirations held by clinicians might lend themselves to which elements of MI?

-

What are the priorities of parents and children in consultations with clinicians, and how might these be blended with what elements of MI?

-

How feasible is it to train everyday diabetes practitioners in the finer arts of listening skills, apparently central to MI?57,70

-

How attractive is the idea of the guiding style to clinicians, parents and children?

-

Could the idea of ‘agenda-setting’ prove attractive to all participants involved?

Framework for the methodological approach

The approach of the team to the research development of the intervention mirrored many of the principles they felt could underpin the resulting clinical intervention itself. As a group of experts in the field, we felt we had some ideas that might be useful, but needed to explore how the target practitioners and patients would receive these ideas and what they would find useful.

These questions provided the starting point for the intervention development process, in which the systematic study of the views and experiences of clinicians would be brought to a multidisciplinary group of stakeholders that included parents and children. This stakeholder group would work with the research team to design the guiding principles and structure of an intervention that responded to the needs of all involved. Chapters 3–7 provide an account of this unfolding development process.

Chapter 3 Telephone survey of professionals: the challenges faced in meeting psychological needs in routine care

Introduction

This section is a description of a survey of practitioners, one of the stakeholder consultation activities designed to elicit information about their experiences of meeting psychosocial needs in clinical practice. The aims of the survey were to understand practitioners’ own assessment of challenges in delivering routine care and their existing approaches to encouraging behaviour change. This information would inform the development of the intervention and the training programme for teams.

Method

A random sample of 112 hospital centres stratified by region was selected from an augmented list of 216 UK hospitals (excluding Northern Ireland) providing services to children and young people with diabetes in the UK. 78 No more than one hospital per trust was selected for inclusion. Consultants (or nominated alternatives) responding positively to an initial postal approach were followed up by telephone interview.

A telephone interview schedule was developed by the research team with additional input from Diabetes UK. Survey domains covered included current and past service innovation and educational approaches, routine care provision, psychological support and clinic characteristics (Box 2).

Clinic characteristics (e.g. size, specialist nursing sessions, access to psychiatric and/or psychology support, routine clinic structure)

Past and present psychosocial support initiatives

Education programmes within the service

Target outcomes for children and adolescents

Main challenges in providing care

Gaining awareness of patients’ psychosocial needs

Current approaches to behaviour change

The survey was anchored on patients at least 12 months post diagnosis. The survey instrument was piloted in six interviews by two members of the research team with four local practitioners. The interview was planned for 20 minutes’ duration, included several open-ended items with standardised probes, and was audio-recorded with respondents’ verbal consent. Two interviewers completed the interviews.

Analysis

Responses to quantitative items were analysed and reported using percentages. Responses to key open-ended items were transcribed, analysed and coded according to emergent themes. A priori categories were not used. Coding of the narrative data was agreed by two researchers (HH and KB) who both independently coded three interviews and then the coding was completed by one researcher (HH) supported by the use of a Microsoft Access 2003 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Illustrative extracts will be used to support the description of emergent themes with the coding of ‘D’ for doctor and ‘N’ for nurse, followed by their identity number.

Results

Seventy (63%) practitioners responded to the initial approach and 51 clinicians completed the interview, of whom 22 (43%) were from teaching hospitals. Forty-four respondents (86%) were doctors and seven (14%) were nurses. Characteristics of responding practitioners and clinics are summarised in Table 1.

| Respondent | n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 35 (69) | |

| Female | 16 (31) | |

| Profession | ||

| Medical | 44 (86) | |

| Nursing | 7 (14) | |

| Previous training | ||

| Postgraduate communication skills | 16 (31) | |

| Psychology-based training | 15 (29) | |

| Clinic sizea | ||

| Mean (SD) no. of nursing sessions (per 100 clients) | ||

| Small (≤ 70) | 10 (20) | 15.7 (7.7) |

| Medium (71–150) | 25 (49) | 9.9 (6.0) |

| Large (> 150) | 15 (29) | 8.1 (7.7) |

| Psychology/psychiatry support | ||

| Mean (SD) no. of clients per service | ||

| Provided | 27 (53) | 151.4 (86.5) |

| Not provided | 23 (45) | 116.8 (79.3) |

The main responses to the four open questions are summarised in Box 3. The key themes to emerge are described in two sections: Challenges of providing care and Managing behaviour change.

Medical (e.g. low HbA1c levels, glycaemic control, growth)

Experiential (e.g. accepting diabetes as a way of life)

Behavioural (e.g. able to manage diabetes, school attendance)

How do you gain awareness of psychosocial need?Nurse contact with family

Physical symptoms (e.g. admissions)

School nurse

Team discussions

What are the main challenges of providing care?Integrating diabetes into everyday life

Managing diabetes in a family context

Imposition of a rigid lifestyle

Teenage rebellion

Overprotectiveness of young children

Communication about complications

How do you encourage behaviour change?Giving advice

Pointing out positives of change

Information about complications

Shared goal-setting

Discussing barriers to change

Individualised approach

Challenges of providing care

In considering the practitioners’ views of the challenges faced by teams in providing psychosocial care, the dominant theme was the issue of engagement and communication, but within this there were two key areas: the integration of diabetes into everyday life and meeting the needs of different ages.

Engagement and communication

The capacity to engage patients and their families with the process of, for example, self-care, clinic attendance, education, etc., was regarded as a significant challenge. This was related to the complexities of meeting the needs of families and different age groups, but it also encompassed communication skills including balancing different priorities, conveying health messages sensitively, and cultural and language issues. Respondents talked about dealing with educational and emotional issues: ‘engaging them and helping them to understand what diabetes is about and trying to get across the longer term for them without frightening them’ (N17).

There was variation in the amount of training and supervision respondents had received in communication skills: postgraduate generic communication skills training was the most common (16 practitioners, 31%) and two (4%) practitioners had received diabetes-specific communication skills training. Fifteen (29%) had received psychology-based training, of whom three (6%) had received diabetes-specific training and five (10%) had trained in behaviour change methods such as MI. Supervision by a mental health professional had been received by 12 practitioners.

Integrating diabetes into their everyday life

One of the key target outcomes identified by respondents was for diabetes to affect the patients ‘day-to-day as little as possible’ (N21). However, it was recognised that this presents a challenge of integrating the diabetes regime into the ‘very variable lifestyles’ (D1) of patients within the service. For example, one clinician stated ‘we are trying to impose quite a rigid lifestyle on individuals … it’s about the constraint of diabetes lifestyle’ (D16). This was also mentioned in relation to the family context, which clinicians identified as a specific challenge to providing care.

Meeting needs of different ages

Age was frequently mentioned as a factor, for example the ‘challenges of various age groups’ (D4) within their service and patients’ changing ‘developmental stages and educational needs’ (D4).

When working with families with younger children, practitioners raised the issue of parents’ ‘guilt complex’ (D5) and being ‘overprotective’ (D26). The most frequent age-related comments were in respect of working with teenagers (Box 4), referencing the impact of the peer group, their changing emotional relationship with diabetes and their need for independence.

‘A lot don’t want to know about their diabetes, its not top of their priority due to peer pressure’ (N31)

‘Difficulties with teenagers are the emotional factors, and if they’ve had it a long time, there can be an element of denial that they’ve got it, and sometimes going through a grieving reaction with their diabetes’ (D2)

‘They have ‘a feeling of omnipotence’ … it’ll never happen to me’ (D44)

‘The adolescent group want to try things and do things differently so they don’t comply’ (D18)

Managing behaviour change

When asked to describe their approaches to encouraging patients and families to change behaviour (Table 2), there were two broad categories of response: some were more focused on education and advice-giving using a didactic style, whereas others were more exploratory and included shared goal-setting. It was also recognised that each individual presents a unique set of issues and so the approach needs to be individualised. This question about encouraging behaviour change was one that some clinicians expressed difficulty in answering (5) and others (7) gave very vague responses, such as ‘through discussion’ (N31) or ‘it would take a week to go through all the possibilities, I don’t think I can say in a nutshell’ (D37) and did not elaborate further.

| Education and advice | ‘I try to motivate them to do better, pointing out their positive abilities, pointing out where they can do better and improve things’ (D4) |

| ‘Usually just to learn more about diabetes and the complications, not to the point to frighten them but you need to stress to them why it is important for them to do that’ (D18) | |

| Exploratory, including shared goal-setting | ‘My personal way of doing it is looking at what I think is ideal, or they think is ideal, then ask them what things they need to do to move in that direction, and how we could achieve it … what could be done, what are they willing to do rather than giving them a list of things that they haven’t agreed to and which they are very unlikely to do’ (D4) |

| ‘We discuss the situation and try and work out why it is difficult and try and come up with a workable solution specific to that family’ (D42) | |

| Individualised | ‘I think it depends on the individual family … it’s about anticipating those difficulties and giving them advice about trying to prevent that becoming a problem’ (D15) |

Discussion

Completing the survey engaged stakeholders in thinking about their services, the challenges they face in relation to providing routine care and their experience of facilitating behaviour change. The high rate of response to this survey demonstrated that this is an area that practitioners recognise as a priority. Respondents outlined the complexity of engaging patients and their families and the importance of communication skills in trying to meet the needs of many different ages, developmental stages and cultural backgrounds within a range of family contexts. They described using a combination of advice, education, listening and shared goal-setting to help encourage their patients to change.

From the responses it would seem that the clinicians were using the three core skills of asking, listening and informing in their communication. There was also implicit recognition that behaviour change is at the heart of the interaction: practitioners described trying to engage patients in making those shifts between the competing demands, yet that process of change was very difficult for the majority to conceptualise or articulate. In considering the most appropriate patient–practitioner interactional model for the intervention in DEPICTED, it had to be effective in addressing behaviour change and incorporate the practitioners’ existing key consultation skills. One model of communication with potential for improving practitioners’ confidence and skilfulness in dealing with behaviour change in routine consultations was to incorporate more of a guiding style into their consultations, encouraging patients to explore their own views of the behaviour and making their own decisions – an approach that has been shown to make change more likely. 42

Although many respondents had received communication skills training in various guises, it would seem that training in communication skills and behaviour change may have been too distant, too general, or not tailored to the context in which they work, to be of use in helping practitioners have a conceptual map of the work and tools available to enable them to function confidently.

The survey contributed significant information to help plan the training programme. It was clear that any intervention had to have a broad application that was flexible enough to respond to the differing needs of a very mixed patient population. It had to facilitate the balancing of the often different priorities of patient, family and practitioner in the consultation process. For practitioners to be able to grasp the relevance of any such training programme to behaviour change, the training needed to be conceptually clear and specific to the context of delivering clinical care within a paediatric diabetes service. By ensuring that the training was more context bound, with the focus on everyday scenarios that have meaning for the practitioners and with the communication skills aspects of training woven into the practice, the aim was to increase the relevance and retention of the information. 55 As well as giving guidance in relation to the development of the DEPICTED study, the findings of this survey underline the importance of the style of training at undergraduate and postgraduate levels across disciplines.

Chapter 4 Questionnaire survey of communication skills of health-care professionals in paediatric diabetes services

Introduction

The attitudes and experience of professionals in the UK in communicating with children and teenagers with diabetes and their families are unknown. For children and teenagers with type 1 diabetes, consultations are complicated by family dynamics and developmental issues. In the UK, notable attempts to train HCPs in communication skills have occurred in specialties such as oncology and general practice and have met with mixed success. 38,43,79,80 However, there is little published evidence regarding the acquisition and proficiency of communication skills of HCPs in paediatric disciplines. Staff involved in the management of child and adolescent obesity in the USA have reported low levels of self-perceived proficiency in the use of behavioural management strategies, delivering guidance in parenting strategies and in addressing family conflict. 81 This suggests that additional training would be beneficial in improving confidence and skills in these areas. This survey aimed to assess communication experiences, attitudes and training opportunities for HCPs to inform the development of the programme.

Blended learning approaches, which provide a mixture of learning opportunities, have been effective in delivering communication skills programmes. 79,82–84 More recent technological advances, such as CD-ROM (compact disc read-only memory) and web-based programmes, provide a flexible method of education delivery and have been used with some success to teach clinical communication skills. 85 However, such technologies have not been evaluated on a large scale in a multidisciplinary clinical environment in the UK and their potential acceptability to paediatric clinical staff is unknown. Despite the obvious advantages of e-learning (such as the potential to reach large numbers of learners), barriers to the use of e-learning in continuing professional development (such as lack of time and confidence) have been reported and may restrict such developments. 86. 87 However, the use of technology by HCPs in everyday practice is rapidly developing. It is possible that such problems may have been resolved and preferences for training may have moved to embrace such approaches. Therefore, this element of the developmental work also aimed to assess the perceived feasibility of and preferences for various methods of learning among staff working in paediatric diabetes services.

Methods

Sample

In April 2006, consultants from 67 paediatric diabetes services were asked to distribute questionnaires for completion by all doctors, nurses, dietitians, psychologists and other HCPs working in their paediatric diabetes teams. These consultants had previously taken part in the telephone survey reported in the previous chapter. Lead consultants for the services were clarified by telephone contact with listed services and were approached to participate. Sixty-seven consultants who had expressed an interest in taking part in the previous survey also agreed to be contacted in relation to this postal survey. Questionnaires were distributed to 383 professionals in total, including 150 doctors, 124 nurses, 77 dietitians and 32 psychologists or therapists.

Questionnaire

The survey covered three broad areas (1) previous experience in communication skills training and its delivery; (2) a scenario-based assessment of attitudes towards addressing different topics in routine consultations; and (3) perceived feasibility of different options for training delivery and skill maintenance. The overall content domain and individual items were developed by a research team comprising psychologists, communication skills trainers and clinical practitioners in paediatric diabetes, among others, and piloted with 11 practitioners working in two paediatric diabetes centres in south Wales. Consultants’ responses to a previous telephone survey of psychosocial service provision for children with diabetes also contributed to the content of the questionnaire.

Scenario-based assessments

To represent commonly encountered challenges within routine paediatric and adolescent diabetes practice, three clinical case scenarios were constructed for use in the questionnaire. Each scenario was constructed to contain clinically relevant medical and psychosocial topics (e.g. elevated levels of HbA1c, health-threatening behaviour), each of which then formed the basis of subsequent questions (Box 5). Respondents were asked to rate the importance they gave to addressing that topic within the consultation, and their confidence in addressing it. Respondents used a rating scale from 1 to 5, where a score of 1 represented ‘not at all important/confident’ and 5 ‘very important/confident’. These importance and confidence ratings were developed on the basis of behaviour change theory,44 with an aim to identify areas of training need and clinicians’ motivation to learn new skills. Scores across the three scenarios were combined to form aggregate ‘importance’ and ‘confidence’ summary scores for both ‘psychosocial’ and ‘medical’ topics. Internal consistency of the summary scores was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.

Emma, a 14-year-old girl, comes to see you with her mother. Her HbA1c result is 13.5% and she has lost 5 kg of weight since her last clinic visit. Her mother has told you in confidence that Emma has been feeling low lately and is concerned that Emma has been losing weight deliberately.

How much importance would you give to addressing the following topics?

How confident would you feel addressing these topics?

-

her loss in weight

-

her HbA1c result

-

her insulin regimen

-

her diet

-

her low mood

-

her mother’s concern about her weight

-

Emma’s views on life with diabetes

Respondents were asked to rate the feasibility of a variety of possible training options on a scale of 1–5, where 1 represented ‘not at all feasible’ and 5 ‘very feasible’. Options included traditional training, such as off-site workshops, as well as the applications of newer technology, such as internet ‘chat rooms’.

Follow-up procedure

If a questionnaire had not been received back from a centre within 3 weeks of distribution, the consultant was followed up by telephone to establish whether or not the questionnaires had been received, whether or not any further questionnaires were required and to encourage distribution and completion.

Data analysis

Data are presented as frequencies, means and medians. Differences in responses to scenarios were analysed using t-tests and analysis of variance (ANOVA). Standard deviations were adjusted to account for clustering of responses within services through inflation by the intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC). 88 Responses from services with just one team member in the sample were excluded from analyses of scenario responses to minimise distortion of the ICC (n = 11). Associations between variables were examined by calculating Pearson’s coefficient. For analyses of responses to all questions on previous experience of training in communication skills and the case scenarios, psychologists and other therapists were excluded from the analysis (n = 14). All data were analysed using Spss version 14.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Survey sample

In total, 266 completed questionnaires were received from 65 services – a response rate of 69.5%. Respondents included consultants, doctors in specialist training, dietitians, specialist diabetes and paediatric nurses, psychologists, psychotherapists, counsellors and play therapists (Table 3). The majority of respondents were female (74.1%). Respondents’ experience of working with children and teenagers with diabetes ranged from < 1 year to 44 years (median 9 years).

| Professional group | No. | Percentage | Median years’ experience in paediatric diabetes (25th, 75th percentiles) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doctor | 109 | 41.0 | 10 (5, 20) |

| Nurse | 91 | 34.2 | 11 (6, 16) |

| Dietitian | 50 | 18.7 | 5 (2.4, 10) |

| Psychology/other (therapist) | 14 | 5.3 | 4 (2.5, 8.5) |

| Not reported | 2 | 0.8 | |

| Total | 266 | 100 | 9 (4.5, 16) |

Previous training in communication skills

Almost one-quarter of nurses and 41 (16.4%) of all professionals had received no previous training in communication skills. One hundred and fifty-four (61.6%) professionals received training as an undergraduate, 122 (48.8%) had received postgraduate training and 70 (28.0%) had received specialist training, with a minority of dietitians having received training in behaviour change counselling techniques, such as MI (Table 4).

| Professional group | Training | Training in specialist communication skills | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None (%) | Undergraduate (%) | Postgraduate (%) | Diabetes specific (%) | MI (%) | CBT (%) | Family therapy (%) | Other counselling (%) | |

| Doctor | 15.5 | 53.2 | 67.9 | 14.0 | 4.5 | 0 | 1.9 | 4.7 |

| Nurse | 23.1 | 57.1 | 27.5 | 20.4 | 12.1 | 0 | 3.4 | 11.4 |

| Dietitian | 6.0 | 88.0 | 46.0 | 6.0 | 28.0 | 6.0 | 0 | 6.0 |

| All groups | 16.4 | 61.6 | 48.8 | 14.6 | 12.0 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 7.3 |

Importance and confidence ratings for communicating with patients

The internal consistency of aggregate scores was high for ‘confidence’ ratings (medical issues α = 0.91; psychosocial issues α = 0.83) and reasonable for ‘importance’ ratings (medical issues α = 0.81; psychosocial issues α = 0.69). Internal consistency of aggregate scores was optimised by excluding those topics not falling exclusively into a ‘medical’ or ‘psychosocial’ category, such as a girl’s weight.

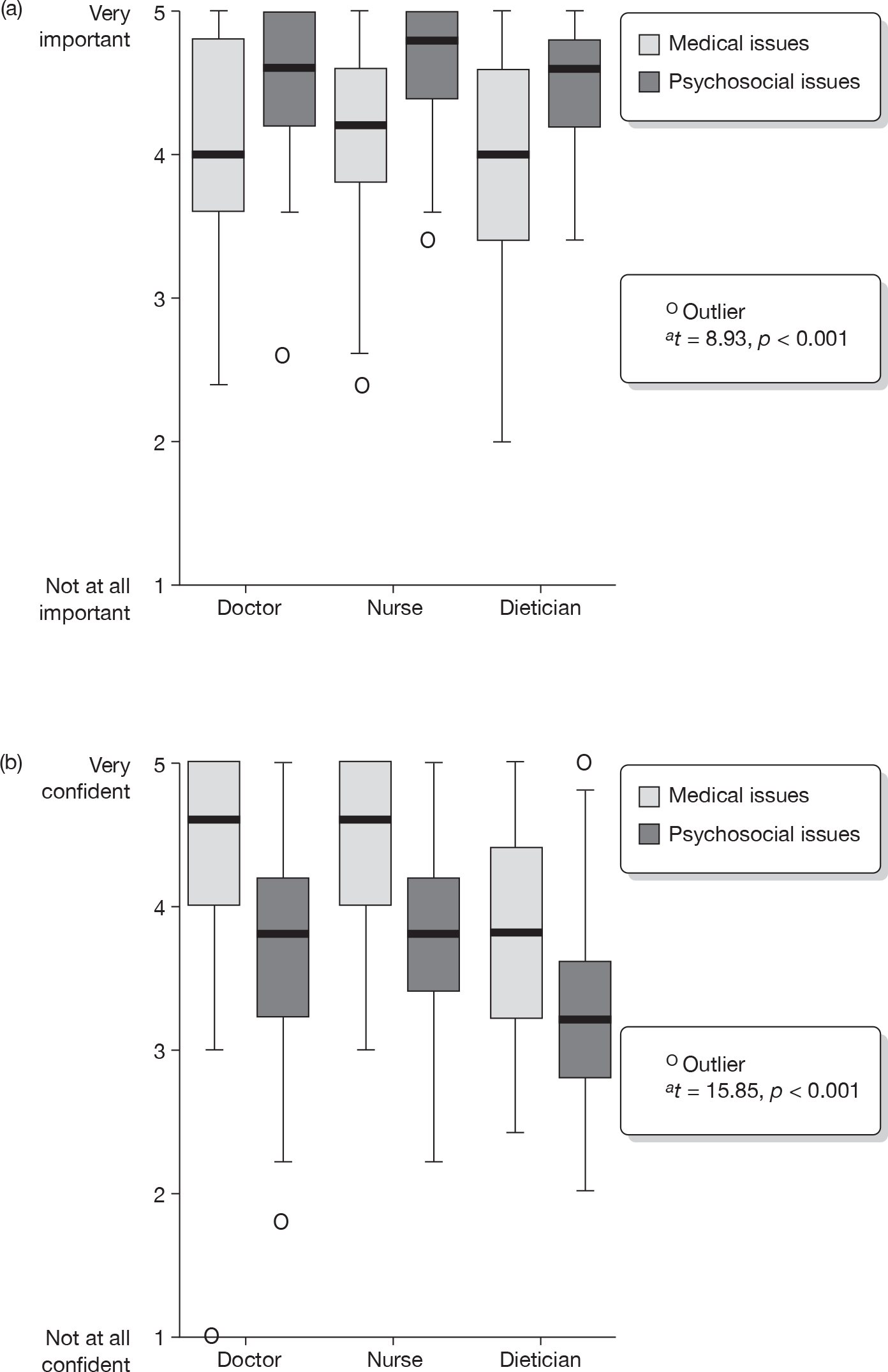

For the case scenarios presented, respondents rated both ‘medical’ and ‘psychosocial’ issues as either important or very important to address during routine consultations {mean [standard deviation (SD)] ratings 4.0 (0.68) and 4.5 (0.50), respectively}. Psychosocial issues were given higher importance ratings to address within a routine consultation than medical issues (t = 8.93, p < 0.001). Confidence to address medical issues was high [mean rating = 4.3 (0.66)], particularly among doctors and nurses, but confidence to address psychosocial issues was significantly lower across all disciplines [mean 3.5 (0.75), t = 15.85, p < 0.001; Figure 1)]. The biggest discrepancy between importance ratings for a specific topic and confidence ratings related to the topic of a teenage girl’s low mood (see Box 5). Other issues which respondents rated as ‘important’ or ‘very important’, but had less confidence to address included the impact of parental conflict on a young girl and talking about a teenage girl’s views of living with diabetes. Sixty-eight (27.0%) respondents said they would not consider addressing the impact of parental conflict on a young girl themselves (Table 5).

| Topic | Percentage rating as either ‘important’ or ‘very important’ | Mean (SDa) important rating (all) | Percentage rating as either ‘confident’ or ‘very confident’ | Mean (SDa) confident rating (all) | Percentage stating they would not attempt to address topic themselves | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Doctor | Nurse | Dietitian | All | Doctor | Nurse | Dietitian | All | Doctor | Nurse | Dietitian | |||

| A teenage girl’s … | ||||||||||||||

| HbA1c resultb | 75.2 | 78.0 | 72.5 | 74.0 | 4.1 (0.98) | 89.2 | 93.6 | 89.0 | 80.0 | 4.3 (0.77) | 1.2 | 0.9 | 0 | 4.0 |

| Insulin regimenb | 65.0 | 64.2 | 69.2 | 59.1 | 3.9 (1.03) | 80.0 | 93.6 | 86.8 | 80.0 | 4.1 (0.98) | 9.3 | 1.9 | 1.1 | 56.2 |

| Low moodc | 95.6 | 98.1 | 97.8 | 85.7 | 4.7 (0.56) | 42.8 | 47.7 | 46.1 | 26.0 | 3.3(1.10) | 14.9 | 18.5 | 8.9 | 18.0 |

| Views on life with diabetesc | 98.4 | 98.1 | 98.9 | 98.0 | 4.8 (0.46) | 66.8 | 69.7 | 76.9 | 42.0 | 3.7 (0.93) | 5.6 | 2.7 | 5.5 | 12.0 |

| A teenage boy’s … | ||||||||||||||

| HbA1c resultb | 70.1 | 72.6 | 72.5 | 62.0 | 4.0 (0.97) | 89.6 | 94.4 | 93.4 | 72.0 | 4.4 (0.80) | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0 | 6.0 |

| Insulin regimen (encouraging him to talk about)b | 81.9 | 85.0 | 85.7 | 70.0 | 4.3 (0.79) | 87.6 | 92.6 | 94.5 | 64.0 | 4.3 (0.78) | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 8.0 |

| Life at schoolc | 91.5 | 90.7 | 93.4 | 89.6 | 4.5 (0.69) | 77.5 | 72.2 | 89.0 | 68.0 | 4.0 (0.77) | 3.2 | 3.7 | 3.3 | 2.0 |

| Drinking behaviourc | 90.0 | 87.0 | 94.5 | 88.0 | 4.4 (0.69) | 69.9 | 63.8 | 81.3 | 62.0 | 3.9 (0.82) | 6.0 | 9.3 | 3.3 | 4.0 |

| A young girl’s … | ||||||||||||||

| HbA1c resultb | 76.5 | 80.5 | 79.8 | 62.0 | 4.0 (0.81) | 90.3 | 92.2 | 93.5 | 80.0 | 4.4 (0.80) | 0.8 | 0.9 | 0 | 2.0 |

FIGURE 1.

Importance (a) and confidence (b) ratings for medical and psychosocial issues. a, t-statistics are for the whole sample.

There were no interprofessional group differences in importance given to addressing psychosocial and medical topics within the consultation, but there were interprofessional differences in confidence, with dietitians expressing less confidence across all issues (F2,229 = 4.12, p = 0.018; Figure 1). Confidence ratings for addressing both medical and psychosocial issues were correlated with years of experience working in diabetes (r = 0.30 and r = 0.36, respectively, both p < 0.001). A weak correlation was found between importance ratings for addressing psychosocial issues and years’ experience working in diabetes (r = 0.15, p = 0.026). The correlation between importance ratings given to medical issues and years’ experience in diabetes was not significant (r = 0.13, p = 0.059). Those who had received specialist communication skills training, such as MI and CBT, reported slightly higher mean confidence ratings for psychosocial issues than those who had not received specialist training (mean = 3.8 and 3.6, respectively), although this difference was not statistically significant (t = 1.6, p = 0.103). No other differences were found between attitudes towards addressing psychosocial issues and previous communication skills training. There was some clustering of importance and confidence ratings within services, particularly for confidence ratings to address psychosocial issues (ICC = 0.08), indicating a tendency for members of the same team to self-rate in similar fashion. The same was true for importance ratings given to medical issues (ICC = 0.04).

Motivating factors for participating in a communication skills learning programme included helping patients talk about their needs more easily, helping to change patient behaviour and learning skills that can be used in life beyond diabetes care (80.0%, 79.2% and 72.8% of respondents agreed with these statements). A total of 19.6% of respondents expressed finding talking with patients sometimes quite difficult as a reason for participation. Agreement with this statement was correlated with fewer years’ experience working in diabetes (r = 0.15, p = 0.016).

Training delivery

Face-to-face training

The most common formats for communication skills training previously experienced by respondents were small-group discussions (n = 56, 21.0%), lectures (n = 19, 7.1%) and role play (n = 33, 12.4%). Respondents considered the most feasible options for training in communication skills to be meeting together as a team once per month for 30 minutes and attending a 1-day off-site workshop (Table 6). Attending a 3-day off-site workshop was rated unfeasible by 143 (54.1%) respondents.

| Training options | Percentage rating ‘feasible’ (scored 4 or 5) | Percentage rating ‘unfeasible’ (score 1 or 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Team meeting once per month | 77.3 | 6.9 |

| One-day off-site workshop | 64.8 | 12.5 |

| CD-ROM | 53.6 | 16.7 |

| Website | 56.4 | 16.6 |

| Three-day off-site workshop | 17.5 | 54.1 |

Technology-based training

Nine respondents reported experience of learning with video and audio materials and just one respondent had interacted with web-based materials. However, 149 (56.4%) respondents rated engaging with materials on a website as a feasible training option. Perceived barriers to accessing web-based material at work included lack of time (n = 143, 55.4%), lack of privacy or a busy office (n = 87, 33.9%), inconvenient location (n = 47, 18.5%) and slow internet connection (n =31, 12.2%). Few respondents considered insufficient computer skills and lack of interest to be barriers to either web-based or CD-ROM learning (n = 14, 5.5%, and n = 6, 2.4%, respectively). A total of 178 (66.3%) respondents reported that they would consider accessing web-based learning materials on their computer at home.

Practising skills

Discussing experiences with colleagues once per month and allowing an experienced coach or colleagues to observe and feed back on consultations were all rated as feasible options for encouraging skills in practice by most respondents. The least feasible option was discussing experiences with other practitioners on the internet, rated unfeasible by 154 (58.8%). Writing up reports of challenging consultations was rated unfeasible by one-quarter of respondents (Table 7).

| Learning activities | Percentage rating ‘feasible’ (4 or 5) | Percentage rating ‘unfeasible’ (1 or 2) |

|---|---|---|

| Discussing experiences with: | ||

| Colleagues (once per month) | 65.5 | 9.3 |

| A visiting coach | 62.2 | 11.9 |

| An experienced coach by e-mail | 53.4 | 22.9 |

| Other providers in a 1-day workshop | 44.3 | 24.1 |

| An experienced coach by telephone | 42.1 | 36.3 |

| Other providers in an internet ‘chat room’ | 17.0 | 58.8 |

| An experienced coach observing your consultations | 65.2 | 10.7 |

| A colleague observing your consultations | 65.0 | 13.4 |

| Audio-recording a consultation to reflect on yourself | 57.4 | 20.5 |

| Audio-recording a consultation to share with a coach | 57.8 | 18.4 |

| Audio-recording a consultation to share with colleagues | 49.4 | 20.3 |

| Writing up reports of challenging consultations | 46.0 | 25.3 |

Discussion

Although some professionals had undertaken specialist training in communicating with patients, almost one-quarter of nurses had received no such training and half of all professionals surveyed had received no training since graduating. Confidence among doctors and nurses to address medical issues in consultations involving young people with diabetes was high, but confidence to address psychosocial issues was significantly lower. Given that addressing psychosocial needs is perceived as important by both patients89 and professionals, these low confidence ratings reflect a training need and motivation to learn new skills among professionals working in paediatric diabetes and a gap in current care provision.

It is clear that some practitioners feel unprepared to address psychosocial challenges that are commonly found in practice, and it may be that some feel that it is outside their remit to do so. Referral to psychology services may be an answer for some patients with particularly pressing concerns, but access to such support is limited. 90 In many services, practitioners have little option but to address complex psychological and emotional topics themselves. The clustering of confidence and importance ratings found within individual services may be a reflection of differing ‘cultures’ and variations in the availability of specialist support. Establishing models of care to meet families’ psychological and emotional needs that are applied across services is therefore a priority.

High importance ratings given to addressing psychosocial issues, coupled with low confidence ratings, suggest a role for communication skills education to support routine care. In addition, reasons given by practitioners for participating in a communication skills learning programme demonstrate the clinical challenge of behavioural self-management in diabetes and emphasise the perceived importance of effective communication between family and professional.

Among the strengths of this study was the development of the survey instrument by a team of clinical and research professionals with a particular interest in training, enhancing both the face and content validity of the final survey instrument. Furthermore, the scenario-based assessments were developed on the basis of clinical experience and conceptually driven. This was borne out by the high level of internal consistency for three of the four resulting aggregate scales, with scores exceeding the benchmark Cronbach’s alpha of 0.7. 91 Similarly, associations found with other related variables, such as the positive relationships between confidence ratings and years of experience in diabetes, support the construct validity of these measures. Potential weaknesses of the study include the response rate and coverage of the survey. The sample of respondents may be biased towards professionals who are interested in, or seeking training in, communication skills. Therefore, caution should be taken before suggesting that these findings represent the attitudes and training needs of all staff working in paediatric diabetes. However, given that clinicians from approximately one-quarter of all services in the UK took part in the survey, the sample includes a significant proportion of professionals working with children and teenagers with diabetes in the UK.

What messages are there for training provision in this field from this part of the developmental work? There was support for multiple methods of delivery of a learning programme with monthly team-based learning activities rated as most feasible and support given for face-to-face learning, case reflection, colleague and coach observation, and feedback. Training within teams at regular intervals may prove a valuable method of learning, particularly in context. Given the lack of previous experience of online learning in communication skills, there was considerable support for the use of web-based or CD-ROM materials, although potential barriers – such as lack of time – continue to be reported. 85 Unlike previous findings,85,86 lack of skills was barely reported as a potential barrier to accessing web materials and is a likely reflection of the rapid increase in skills in and use of information technology by health professionals in everyday practice. Given potential barriers such as lack of time, electronically delivered learning programmes must ensure flexible delivery, minimal technical demands of the user, and timely support.

Chapter 5 Incorporating users’ experiences in the development of training materials for the DEPICTED study

Introduction

This section describes part of the preparation for the development of a clinical intervention to improve communication in clinic consultations, deliverable within the context of routine care by the diabetes team. As part of the development of this intervention, the DEPICTED team used focus group methodology to gather contextual information from children and young people with diabetes (and their parents or guardians) about the way diabetes affected their lives and how they felt the doctor–patient relationship worked for them in clinical encounters.

Methods

Focus group methods were adapted for paediatric settings, using previously published guidelines. 92,93 The discussion framework used in the focus group discussions is described in Box 6. These discussions aimed to enable participants to describe the issues that took prominence in their lives, their hopes and aspirations, how these were identified and dealt with by HCPs in the clinic setting, and what patients and families wanted from clinic consultations.

What’s the hardest thing about living with diabetes?

What would you most like to change about living with diabetes?

What’s most helpful about the diabetes clinic?

What would you most like to change about the diabetes clinic?

What is communication like with the clinic staff and how would you want it to be?

Six audio-recorded focus groups were comoderated by two non-clinical researchers. Potential participants (parents, children and young people), who were identified by a clinician working in a paediatric diabetes service, were sent information sheets and forms for consent to researcher contact. Same-gender and related-age-range discussion groups were arranged, as recommended by earlier research on conducting focus groups with children. 92 Participants were selected to achieve a range of treatment regimens (two, three or four injections per day – insulin pump), family structures (single- or two-parent families, siblings or parents with diabetes) and coping/treatment adherence (e.g. ‘doing well’ or ‘struggling’ from a clinician perspective). Children (aged 7–11 years) and young people (aged 12–16 years) with type 1 diabetes and their parents were invited to participate.

All potential participants expressing an interest in the study were telephoned a few days before the focus groups for the researchers to introduce themselves, reiterate the purpose and format of the groups, re-confirm their decision to participate and to respond to any questions. A specialist nurse from the paediatric diabetes service, familiar to the participants, greeted them on arrival, and was available after the discussions to answer any medical concerns that may have arisen. The specialist nurse was not present during the focus group discussions themselves. Written informed consent was taken before the focus groups started. All participants received refreshments on arrival and a £10 gift voucher as token appreciation. All parents, those participating and those accompanying their children/young people to the venue, completed an information sheet documenting their own age, occupation, family size, child’s age, duration of diabetes, other family members with diabetes and, for accompanying parents, how well they believed diabetes management was going at that time for their child.