Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 06/79/01. The contractual start date was in March 2008. The draft report began editorial review in July 2010 and was accepted for publication in February 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Lewis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Research is needed to identify the most clinically effective and cost-effective management strategies for sciatica. Many treatment modalities for sciatica have been evaluated in placebo-controlled trials (or usual care used as the comparator), and the evidence relating to the direct comparison of numerous treatment modalities is missing. Previous systematic reviews have found evidence for the clinical effectiveness of invasive treatments such as epidural steroid injection (ESI), chemonucleolysis and lumbar discectomy, but found insufficient evidence to advise bed rest, keeping active, analgesia, intramuscular steroid injection or traction. None of the reviews made indirect comparisons across separate trials or examined cost-effectiveness. Previous economic evaluations that have been conducted vary quite considerably, and their value is limited to the perspective and setting for which they were undertaken. We undertook a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the different management strategies for sciatica, which tries to address some of these issues. We have also developed a decision-analytic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of different treatment modalities from the UK NHS perspective.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

-

To undertake a systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different management strategies for sciatica.

-

To synthesise the results using meta-analyses and a mixed treatment comparison (MTC) method.

-

To construct an appropriate decision-analytic model to estimate costs per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained for each treatment strategy.

Chapter 3 Background

Definition of sciatica

Sciatica is a symptom defined as unilateral, well-localised leg pain with a sharp, shooting or burning quality that approximates to the dermatomal distribution of the sciatic nerve down the posterior lateral aspect of the leg, and normally radiates to the foot or ankle. It is often associated with numbness or paraesthesia in the same distribution. 1,2 The symptom of sciatica is used by clinicians in different ways. Some refer to any leg pain referred from the back as sciatica, others prefer to restrict its use to pain originating from the lumbar nerve root. Some authors prefer to use the term ‘lumbar nerve root pain’ to distinguish it from referred leg pain. 3

Epidemiology of sciatica

The lack of clarity in the definition of sciatica persists in the epidemiological literature. In the UK, the prevalence of ‘sciatica suggesting a herniated lumbar disc’ has been reported as 3.1% in men and 1.3% in women. 4 However, like most surveys, this study did not use strict criteria to diagnose sciatica. A large population survey in Finland which did found a lifetime prevalence of 5.3% in men and 3.7% in women. 5 Sciatica accounts for < 5% of the cases of lower back pain presenting to primary care. 3 Some cohort studies have found that most cases resolve spontaneously, with 30% of patients experiencing persistent troublesome symptoms at 1 year, 20% out of work and 5–15% requiring surgery. 6,7 However, another cohort found that 55% still had symptoms of sciatica 2 years later, and 53% after 4 years (which included 25% who had recovered after 2 years, but had relapsed again by 4 years). 8 As the sciatica becomes more chronic (> 12 weeks), or with recurrent episodes, it becomes less responsive to treatment. 9 Effective treatment for patients with acute or subacute sciatica is therefore important in order to prevent patients developing a more chronic condition that is resistant to treatment and likely to incur high health-care and socioeconomic costs. The cost of sciatica to society in the Netherlands in 1991 was estimated at US$128M for hospital care, US$730M for absenteeism and US$708M for disablement. 10

Pathological mechanism

Sciatica caused by lumbar nerve root pain usually arises from a prolapsed intervertebral disc, but also from spinal stenosis, or surgical scarring as well as other aetiologies such as trauma and tumours. 6 It was initially thought to occur predominantly as a result of compression of the nerve root,11 leading to neural ischaemia, oedema (which would, in turn, lead to chronic inflammation), scarring and perineural fibrosis. However, it is now known that symptoms can occur in the absence of direct nerve root compression, possibly as a result of release of proinflammatory factors from the damaged disc. Pain occurs because of chronic, repetitive firing of the inflamed nerve root. 12,13 Referred leg pain occurs because pain fibres from paraspinal structures and from the leg converge on interneurons in the spinal cord and brain, so that nociceptive input from painful paraspinal tissues is perceived as leg pain.

Clinical diagnosis

It has been claimed that nerve root pain can be distinguished from referred leg pain because it is unilateral, radiates below the knee, results in leg pain that is worse than the back pain, can be aggravated by coughing or sneezing and has a segmental distribution. Important clinical signs include provocation tests for dural irritation, such as a limited straight leg raise (SLR) reproducing the leg pain, and compromised nerve root function leading to reduced power, sensation or reflexes in one nerve root. 3 A systematic review of the diagnostic value of history and physical examination in nerve root pain found that pain distribution was the only useful item in the history. The SLR test was the only sensitive sign in the physical examination, but had poor specificity; the crossed SLR test was the only specific sign, but had poor sensitivity. 14 However, another review found that there was no standard SLR procedure, no consensus on interpretation of results, no evidence of intra- and inter-observer reliability and its predictive value in lumbar intervertebral disc surgery was unknown. 15

Treatments

A variety of surgical and non-surgical treatments have been used to treat sciatica and have been the subject of previous systematic reviews, the findings of which are summarised below. However, none of the reviews examined the cost-effectiveness of the various treatment modalities.

Bed rest and advice to stay active

Most cases resolve spontaneously and, traditionally, bed rest has been advised. A Cochrane systematic review of bed rest16 found that there was high-quality evidence of little or no difference in pain or functional status between bed rest and staying active; moderate-quality evidence of little or no difference in pain intensity between bed rest and physiotherapy, but small improvements in functional status with physiotherapy; and moderate-quality evidence of little or no difference in pain intensity or functional status between 2–3 and 7 days’ bed rest. A Cochrane systematic review of advice to keep active reviewed the same trials comparing bed rest with activity and came to the same conclusions. Although there is no evidence to advise bed rest for sciatica, there is also very little evidence of any benefit of keeping active. 16

Analgesia

Most patients will obtain analgesic medication either on prescription or purchased ‘over the counter’ from their pharmacist. A systematic review of the conservative treatment for sciatica identified three randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that compared non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with a placebo tablet and found no evidence of efficacy. 17

Intramuscular steroids

Part of the mechanism of production of nerve root pain is the release of proinflammatory factors from damaged discs, so administration of intramuscular corticosteroid steroid injections to reduce inflammation of the nerve root has a theoretical basis. The systematic review of conservative treatment for sciatica identified two RCTs comparing steroid injections with a placebo injection and found no evidence of efficacy. 17

Traction

Traction is used relatively frequently to treat sciatica in North America, but less frequently in the UK, Ireland and the Netherlands. 18,19 A Cochrane systematic review found strong evidence that there was no significant difference between either continuous or intermittent traction versus placebo, sham or other treatments. 20

Epidural steroids

Introduction of corticosteroids into the epidural space is a commonly used treatment for lumbar nerve root pain, with the rationale of reducing nerve root inflammation. It was performed on 47,665 occasions in the NHS in England in 2005–6. 21 Systematic reviews of ESIs have reached conflicting conclusions with regard to their efficacy compared with placebo and their effectiveness compared with other treatments. 17,22–24

Spinal manipulation

The systematic review of conservative treatment for sciatica identified two RCTs of spinal manipulation. One found that manipulation was more effective than placebo, and another found no difference compared with manual traction, exercises or corset. 17

Chemonucleolysis

Chemonucleolysis is a technique that is now rarely used. It attempts to decrease the volume of a disc herniation by reducing the amount of material contained within the nucleus pulposus by injecting the enzyme chymopapain. A systematic review of lumbar discectomy and percutaneous treatments identified three RCTs that compared chymopapain with placebo injection, and reported that symptom relief was greater in the group that received chymopapain. 25

Lumbar discectomy

Between 5% and 15% of patients with lumbar nerve root pain are treated with surgery,6,7 usually involving a lumbar discectomy. In 2005–6, 8683 lumbar discectomies were performed in the NHS in England. 21 A Cochrane systematic review of surgery for lumbar disc prolapse26 found 40 RCTs and two quasi-randomised controlled trials (Q-RCTs), but only four RCTs comparing discectomy with conservative management, which suggested a temporary benefit in clinical outcomes at 1 year, but no difference at longer-term follow-up. Meta-analyses showed that surgical discectomy produced better clinical outcomes than chemonucleolysis, which was better than placebo. The review concluded that there was considerable evidence of the clinical effectiveness of discectomy for carefully selected patients with sciatica caused by lumbar disc prolapse that fails to resolve with conservative management. Serious complications from lumbar disc surgery are uncommon, with one study25 reporting a mortality rate of 0.3% an infection rate of 3% and 4% requiring an intraoperative transfusion. Surgery failed to relieve symptoms in 10–20% of the cases. 25

Other treatments

A number of other treatments that have not been included in previous systematic reviews, for example complementary therapies such as acupuncture, will be included in this review.

Pattern of treatments

Overall, there is no close correlation between symptom severity and pathology in sciatica. Increasing distance between onset and effective treatment has an unfavourable influence on symptoms and disability. Although there is reason to suppose that a stepped-care approach to sciatica could be helpful, the application of the various available treatments depends more on availability, clinician preference and socioeconomic variables than on patient needs. In practice, some patients will recover under an analgesic cocktail while on a waiting list, some will be offered surgery as a first-line intervention, and yet others will receive a combination of treatments in no particular order. With few exceptions, it would appear that the patients receiving differing treatments are clinically indistinguishable.

Chapter 4 Evidence synthesis: methods

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

The review was undertaken according to the methodology reported in the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) report Undertaking systematic reviews of research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for those carrying out or commissioning reviews27 and the Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. 28 Studies examining clinical effectiveness and those evaluating cost-effectiveness were reviewed separately. (The review protocol is presented in the appendices.)

Literature search

The following databases were searched for published, semi-published and grey literature. Full details of the search strategies are reported in Appendix 1. Initial searches took place in June 2008 and were then updated in December 2009, with databases searched from inception to the date of the search:

-

MEDLINE

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

OLDMEDLINE

-

EMBASE

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

-

Allied and Complimentary Medicine Database (AMED)

-

British Nursing Index

-

Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)

-

PsychINFO

-

Inspec

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Database

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

System for Information on Grey Literature In Europe (SIGLE)

-

Science Citation Index

-

Social Science Citation Index (SSCI)

-

Index to Scientific & Technical Proceedings (ISTP)

-

Physiotherapy Evidence Database (PEDro)

-

BIOSIS

-

National Research Register (NRR)

-

National Institute for Health’s ClinicalTrials.gov database

-

CenterWatch Clinical Trials Listing Service

-

Current Controlled Trials (CCT)

-

World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) this collects weekly data from:

-

– Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry

-

– ClinicalTrials.gov

-

– International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN) and monthly data from:

-

– Chinese Clinical Trial Registry

-

– Clinical Trials Registry – India

-

– German Clinical Trials Register

-

– Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials

-

– Japan Primary Registries Network

-

– Sri Lanka Clinical Trials Registry

-

– The Netherlands National Trial Register

-

-

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry

-

Clinical Trials Search.

The bibliographies of previous systematic reviews and included studies were screened to identify further relevant studies.

Management of references

The results of the searches were entered onto the reference management software E[sc]ndnote[/sc] (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicate records removed. Articles written in a language other than English were translated whenever possible. Multiple publications arising from the same study were identified, grouped together and represented by a single reference.

Inclusion and exclusion of studies

Selection criteria

Study design

Studies using any of the following study designs were considered for inclusion: RCTs, Q-RCTs, non-RCTs, cohort studies (with concurrent or historical controls), case–control studies, before and after studies and full economic evaluations as defined by Drummond et al. 29 and The Cochrane handbook. 28

Patient population

Studies involving adults with sciatica or lumbar nerve root pain diagnosed clinically or confirmed by imaging were eligible. The essential clinical criterion was leg pain worse than back pain. Other clinical criteria which support the diagnosis include unilateral leg pain, pain radiation below the knee, pain aggravated by coughs/sneezes, segmental distribution of pain, pain induced by provocation tests (e.g. impaired SLR) and reduced power, sensation or reflexes in one nerve root. Studies that included participants with low back pain were included only if the findings for patients with sciatica were reported separately; studies in which the results were not reported separately for sciatica were excluded. Studies of sciatica caused by specific conditions such as spinal stenosis or discogenic pain were only included if it was documented that leg pain was worse than back pain. If imaging was used it had to demonstrate evidence of nerve root irritation. Studies of sciatica caused by a tumour were excluded.

Interventions

Any intervention or comparator used to treat sciatica was included. Treatments were categorised using the system reported in Table 1. Inactive control represents placebo or sham treatment used within the study setting and could include sham traction or placebo epidural.

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Treatment category | Category codea | Type of treatment |

| Inactive control | Inactive control | A |

Placebo Sham treatment No treatment |

| Non-invasive | Usual/conventional care | B |

Usual care Conventional care Non-surgical treatment GP care |

| Invasive – surgical | Disc surgery | C |

Discectomy Microdiscectomy Automated percutaneous discectomy Nucleoplasty Laser discectomy Disc sequestrectomy Laminectomy Surgical decompression |

| Invasive – non-surgical | Epidural/intradiscal injections (includes spinal nerve block) | D |

Caudal epidural Segmental epidural Intradiscal injections Facet joints injections Intraforaminal injections Spinal nerve root block |

| Invasive – non-surgical | Chemonucleolysis | E |

Chymopapain Collagenase Ozone |

| Non-invasive | Non-opioids | F |

Oral, i.v. or intramuscular Steroids COX-2 inhibitors NSAIDs Paracetamol Muscle relaxants Neuropathic pain treatment |

| Invasive – surgical | Intraoperative interventions | G | |

| Non-invasive | Traction | H | Mechanical traction |

| Non-invasive | Manipulation | I |

Manipulation Chiropractic Osteopathic McKenzie |

| Non-invasive | Alternative | J |

Acupuncture Feldenkrais Muscle energy Reiki therapy Energy work Magnets |

| Non-invasive | Active PT/exercise therapy | K |

Flexibility Strengthening Conditioning Stabilisation |

| Non-invasive | Passive PT | L |

Ultrasound/phonophoresis Iontophoresis Heat/ice Massage Therapeutic touch Interferential Electrical stimulation techniques (TENS/PENS) Laser |

| Non-invasive | Biological agents | M | Anti-TNFs (and other antibody related interventions) |

| Non-invasive | Activity restriction | N | Bed rest |

| Non-invasive | Opioids | O | Oral, i.v. or intramuscular opioids |

| Non-invasive | Education/advice | P |

Back school Home exercise instruction Coping skills training Vocational counselling Activities of daily living (ALD) |

| Invasive + non-invasive | Mixed treatments | Q | Combination of different physical therapies and advice, etc. |

| Invasive – non-surgical | Others | R |

Peripheral nerve block Spinal cord stimulation (level 2, code Q) Radiofrequency lesioning (level 2, code S) |

Outcome measures

All relevant patient-based outcome measures such as pain, disability, functional status, adverse effects, health status, quality of life (QoL), analgesic use, operation rates, health utility, return to work, health-service use and costs were considered for inclusion in the review. Biochemical outcomes and biomechanical measurements (e.g. change in disc space) were excluded. Although all relevant outcome measures were extracted, because of the high volume of studies and time constraints, only those covered by the following important patient-centred outcome9 domains were included in the analysis of clinical effectiveness: global effect, pain intensity, condition-specific outcome measures (CSOMs) (Table 2) and adverse event data. This means that the outcomes health status, QoL, analgesic use, operation rates, health utility, return to work, health-service use and costs have not been analysed in the clinical effectiveness section of the review.

| Measure | Interpretation |

|---|---|

| Global effect | |

| MacNab criteria | Excellent, good, fair, poor |

| Global perceived effect (GPE) | Complete recovery to vastly worse |

| Patient perceived overall improvement | Various ordinal or dichotomous scales |

| Physician perceived overall improvement | Various ordinal or dichotomous scales |

| Proportion of patients below a threshold on a specific scale | |

| Proportion of patients free of pain | |

| Sciatica bothersomeness | Higher score indicates greater bothersomeness |

| Pain intensity outcomes | |

| Visual analogue scale (VAS) | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Bergquist-Ullman and Larson, pain index (B-U&LPI) | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Numerical rating scale (NRS) | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Likert scale | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Low back pain rating scale (LBRS) (pain subscale) | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| McGill Pain Questionnaire (subscales: VAS, present pain inventory) | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score (pain subscale) | Lower score indicates greater pain |

| Roland–Morris annotated thermometer | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Von Korff pain intensity | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| Pain diagram | Higher score indicates greater pain |

| CSOMs | |

| Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ) (including modified versions) | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Revised RMDQ | Lower score indicates greater disability |

| Oswestry Disability Index (ODI, also referred to as Oswestry Low Back Pain Disability Questionnaire) [including modified versions, e.g. Modified Oswestry Disability Index (MODEMS)] | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score | Lower score indicates greater disability |

| Low back outcome score (LBOS) | Lower score indicates greater disability |

| Dallas Pain Questionnaire (subscales: daily activities, work and leisure activities, anxiety-depression and sociability) | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Low back pain rating scale (LBRS) (subscales: pain, activity of daily living and physical function) | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| North American Spine Society (NASS) instrument score (subscales: neurogenic symptoms score and pain and disability score) | Lower score indicates greater disability |

| Symptom scoring system | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Waddell Disability Index | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Sciatica index | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Funktionsfragebogen Hannover (FFbH) | Lower score indicates greater disability |

| Core Outcome Measures Index (COMI) | Higher score indicates greater disability |

| Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QDS) | Higher score indicates greater disability |

Assessing relevancy of included studies

Two reviewers independently screened the titles and abstracts identified by the electronic searches for relevance. Potentially relevant studies were ordered and assessed for inclusion, using the criteria reported above, by two independent reviewers. Disagreements during both stages were resolved by discussion or if necessary taken to a third reviewer.

Data extraction

Data were extracted using predefined forms developed on a Microsoft A[sc]ccess[/sc] database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Separate forms were used for clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies. Data were extracted by one reviewer and checked for accuracy, against the original paper, by a second independent reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer if necessary.

Data extracted for clinical effectiveness studies included study location and setting, description of study population (including method of diagnosis and previous treatment), type of intervention and control used, how allocation was performed, outcome measures used and results (such as final means, change scores and proportions) with sufficient information, such as standard errors (SEs), significance levels and confidence intervals (CIs), in order to estimate missing standard deviations (SDs) wherever possible. When necessary, the results and the measures of dispersion were approximated from figures in the reports. Data for both continuous and binary outcomes were extracted based on the number of patients included in the analysis. Where possible, reported findings based on intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis were used. However, we did not recalculate findings based on the ITT principle, e.g. using worst- or best-case scenario for missing variables, as we believed we would be unlikely to have data on crossovers. For studies in which arm-level data were not available, but the mean difference between arms and associated SE had been reported, these were extracted and used in the synthesis instead. Additionally, if studies reported the mean difference between arms adjusted for baseline values, e.g. using analyses of covariates (ANCOVA), these were also extracted.

Data extraction for cost-effectiveness studies included the following: type of economic evaluation, specific details about the interventions being compared, study population, time period, measures of effectiveness, direct costs (medical and non-medical), productivity costs, resource use, currency, results and details of any decision modelling and sensitivity analysis.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was undertaken by two independent reviewers with differences being resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer if necessary. Data relating to quality assessment were recorded in an Access database.

For clinical effectiveness studies, the quality of both trials and observational studies was assessed using the same checklist based on the one used by the ‘Back Review Group’ of the Cochrane Collaboration for RCTs30 and the one developed by the Hamilton Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) team for quantitative studies (which includes both comparative observational studies and RCTs). 31 The checklist is presented in Appendix 2. The criteria cover selection bias and confounding, detection bias, performance bias and attrition bias. Criteria relating to external validity have also been added.

The quality of the economic evaluations was assessed according to an updated version of the checklist developed by Drummond et al. 29 (see Appendix 2). The checklist reflects the criteria for economic evaluation detailed in the methodological guidance developed by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). For studies based on decision models, the critical appraisal was based on the checklist developed by Weinstein et al. 32 (see Appendix 2).

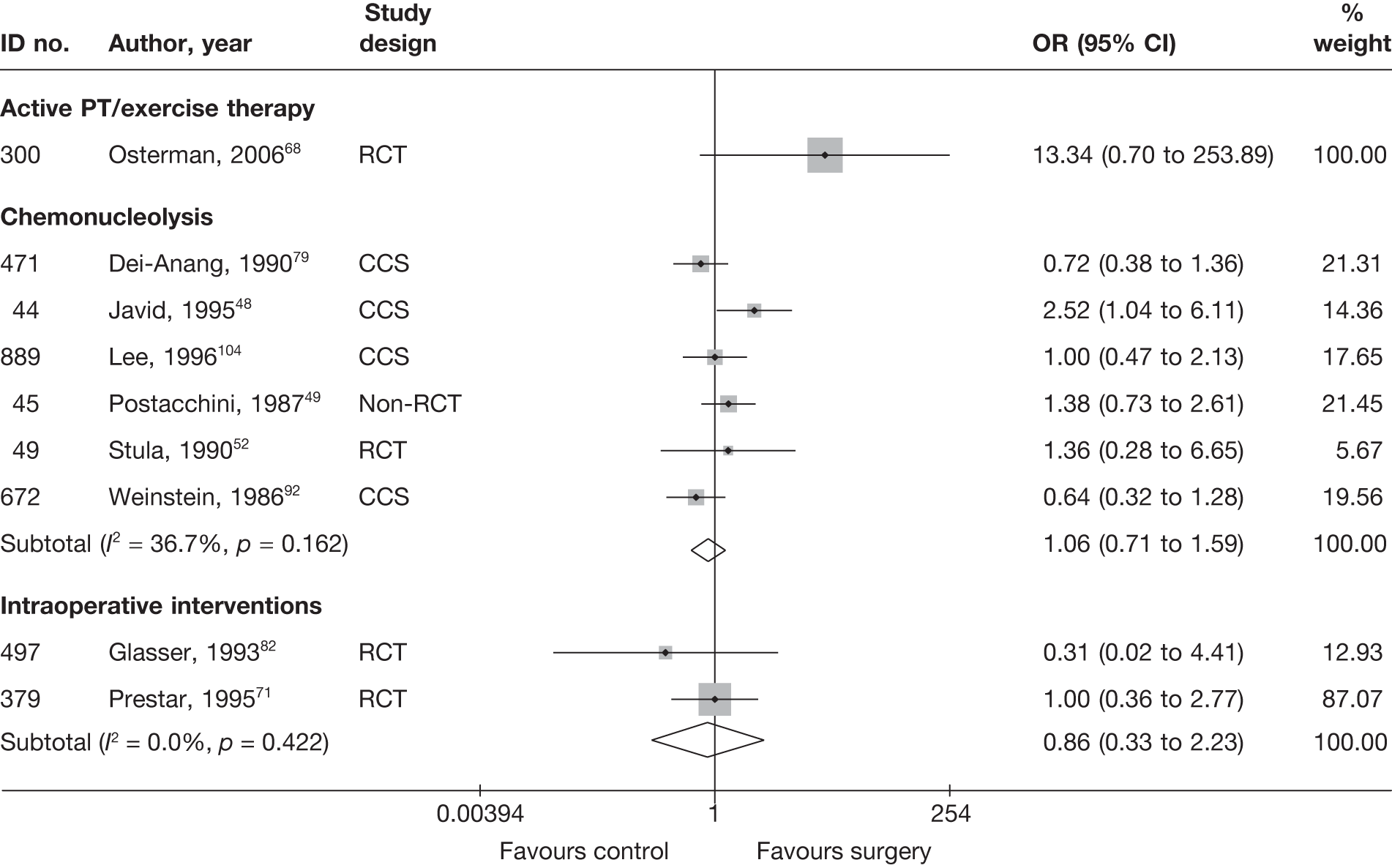

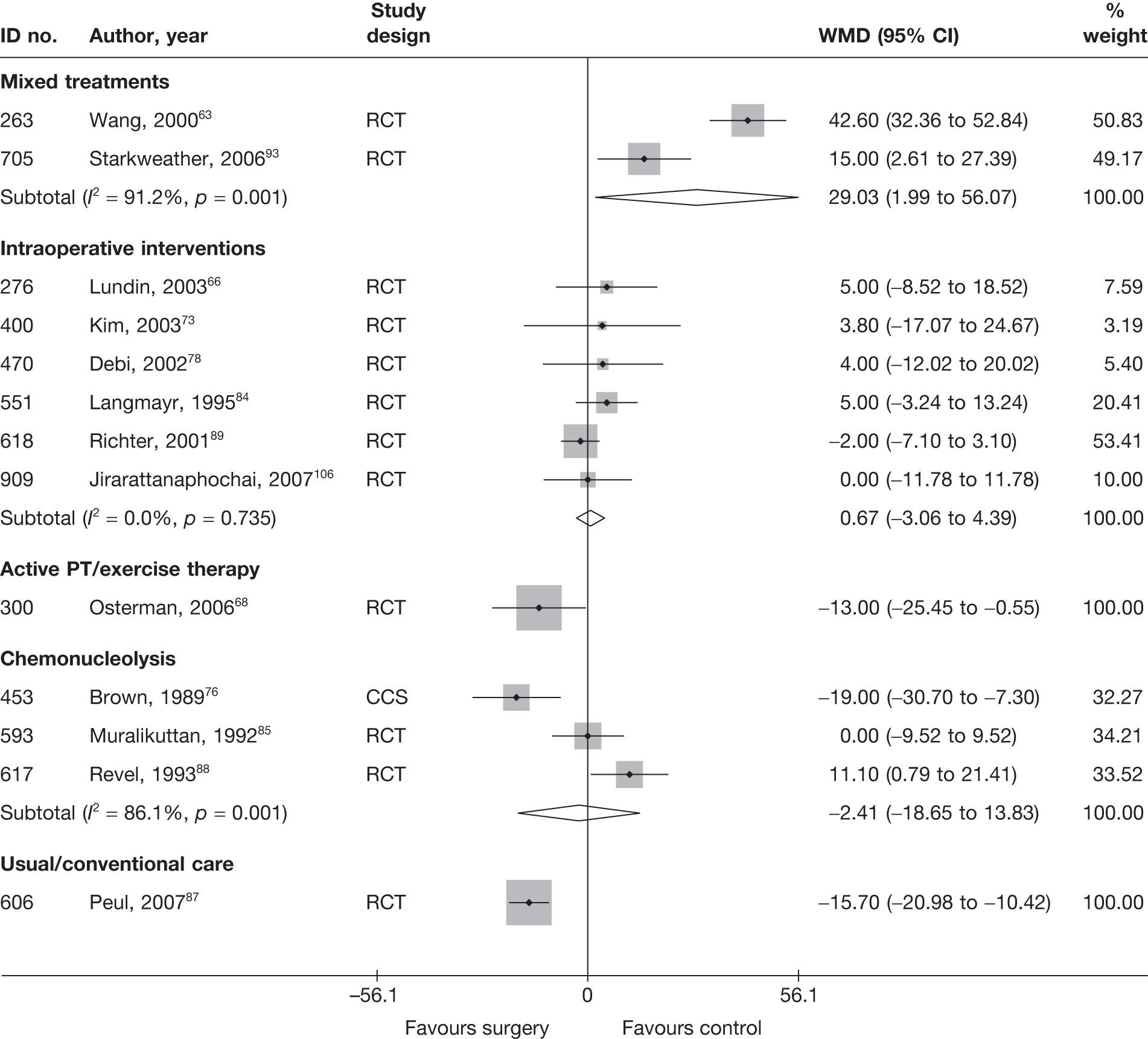

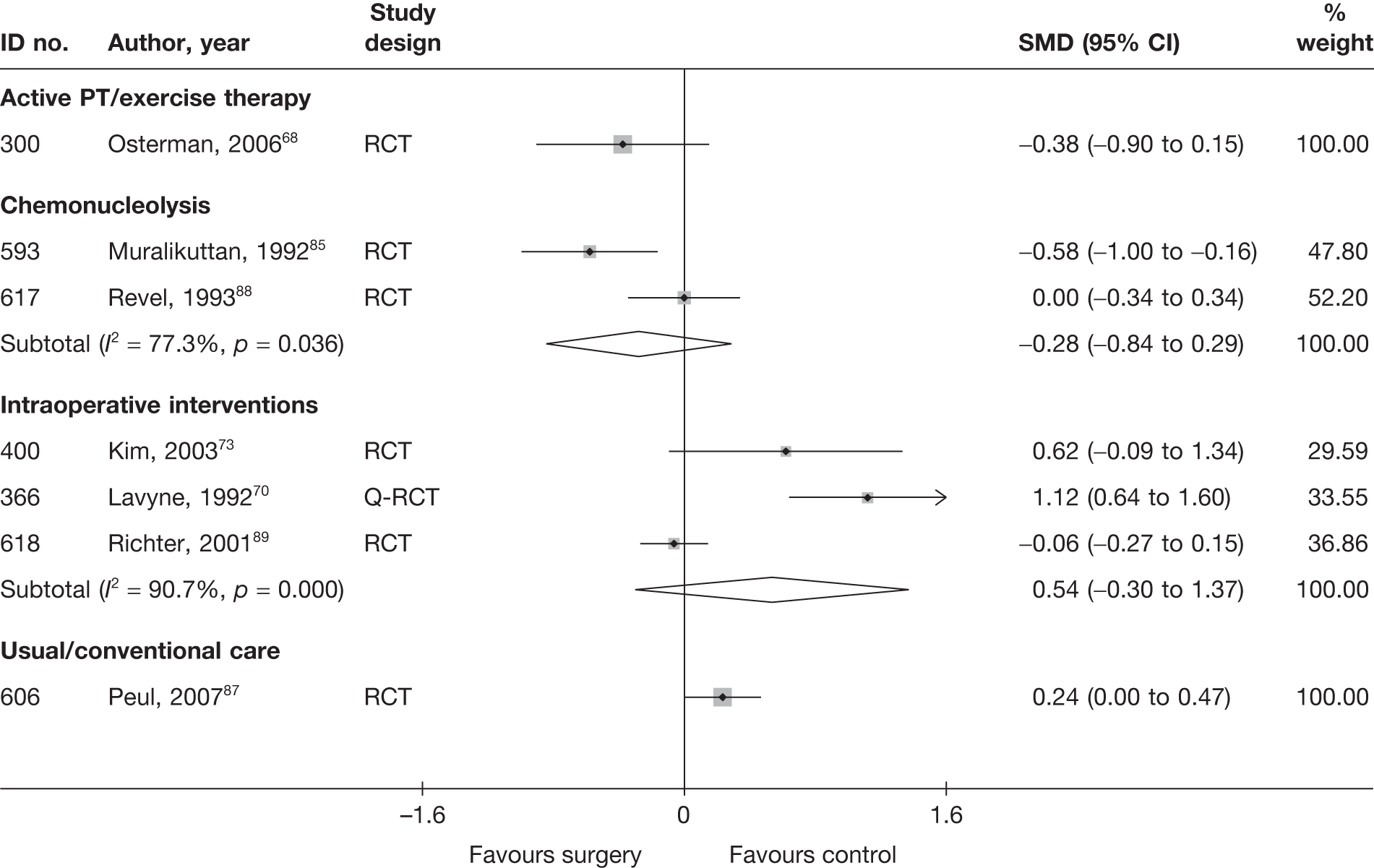

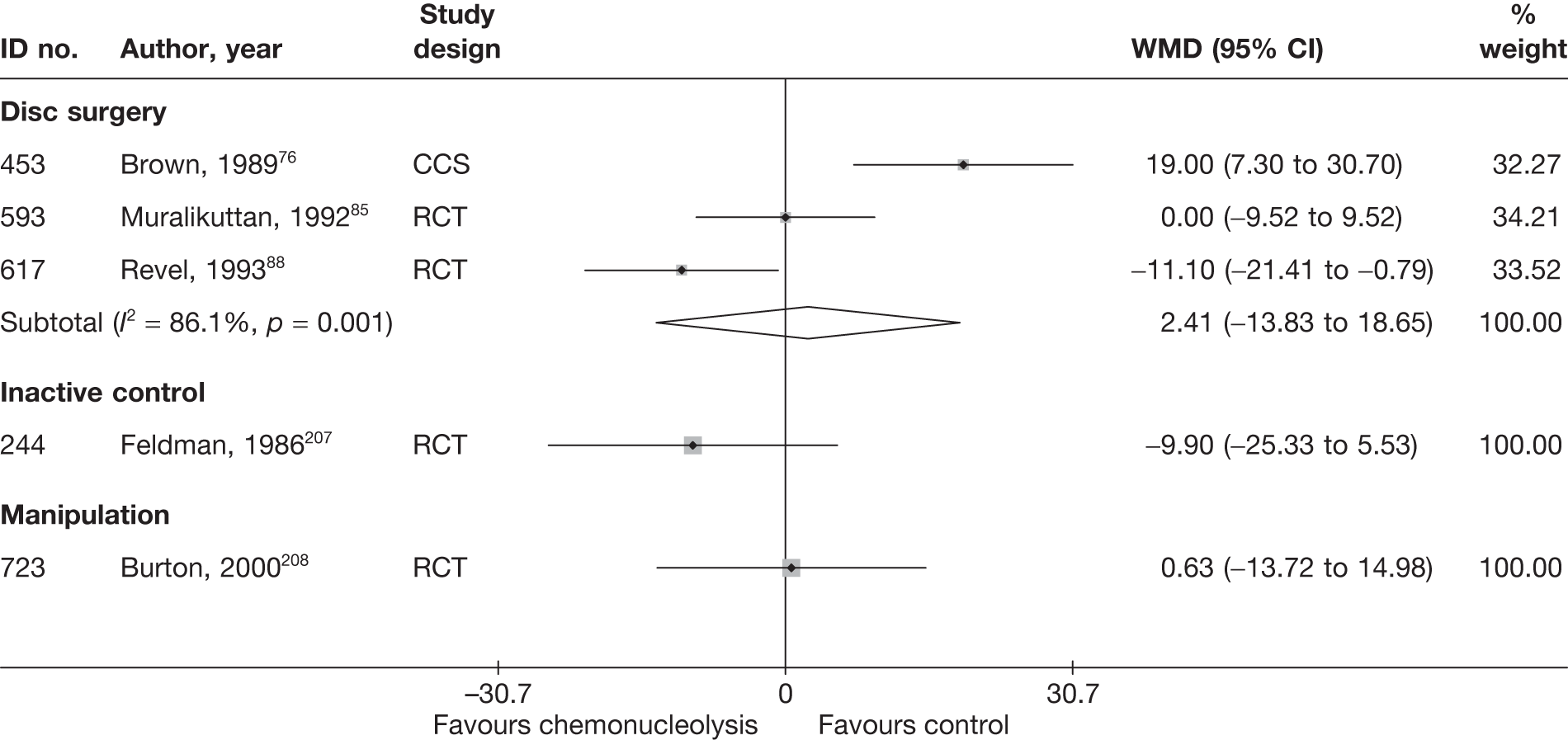

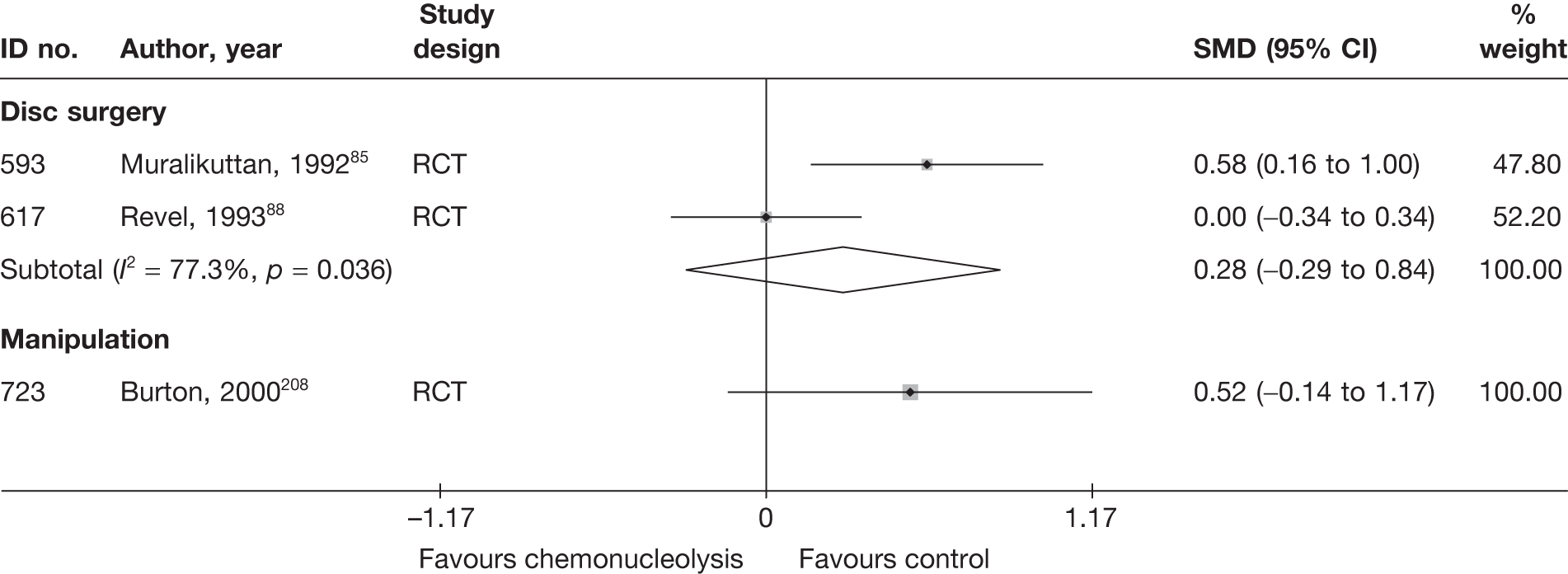

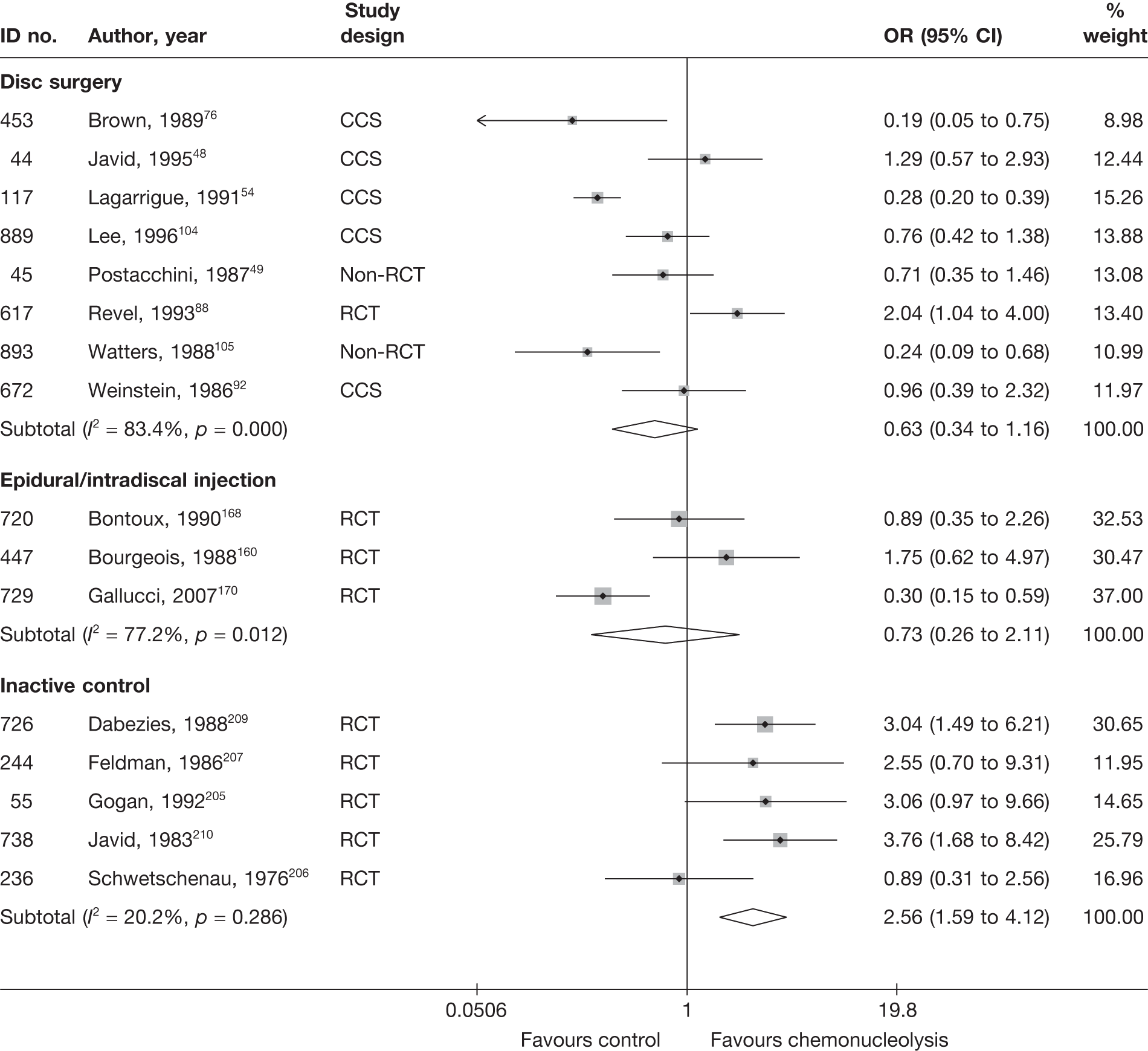

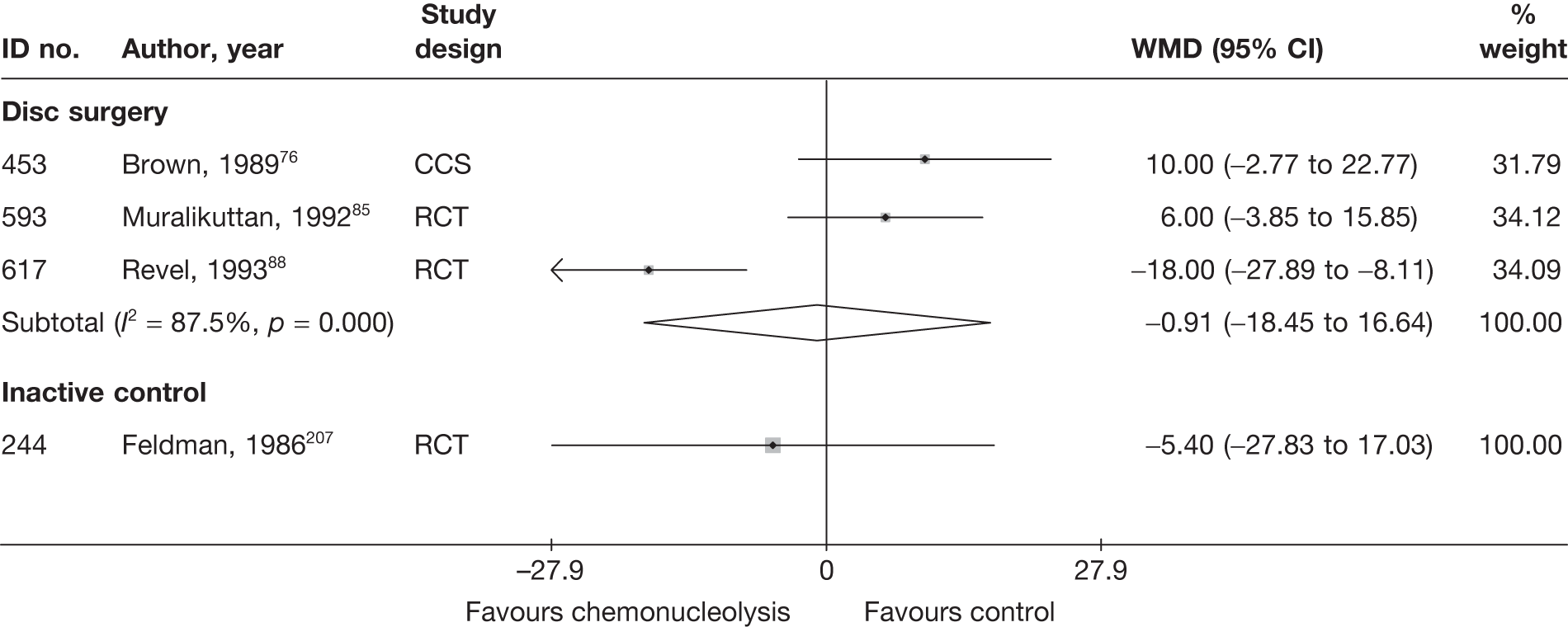

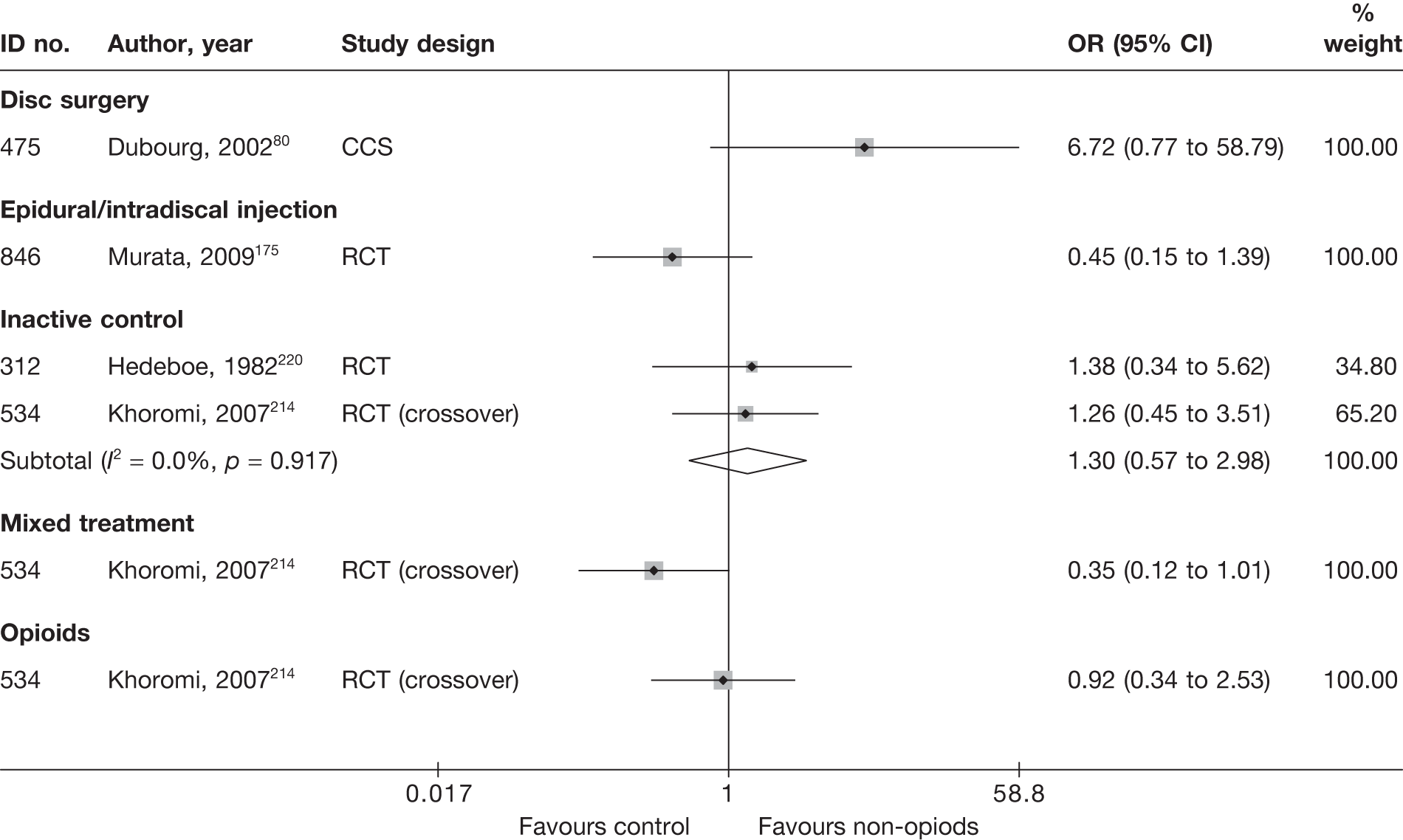

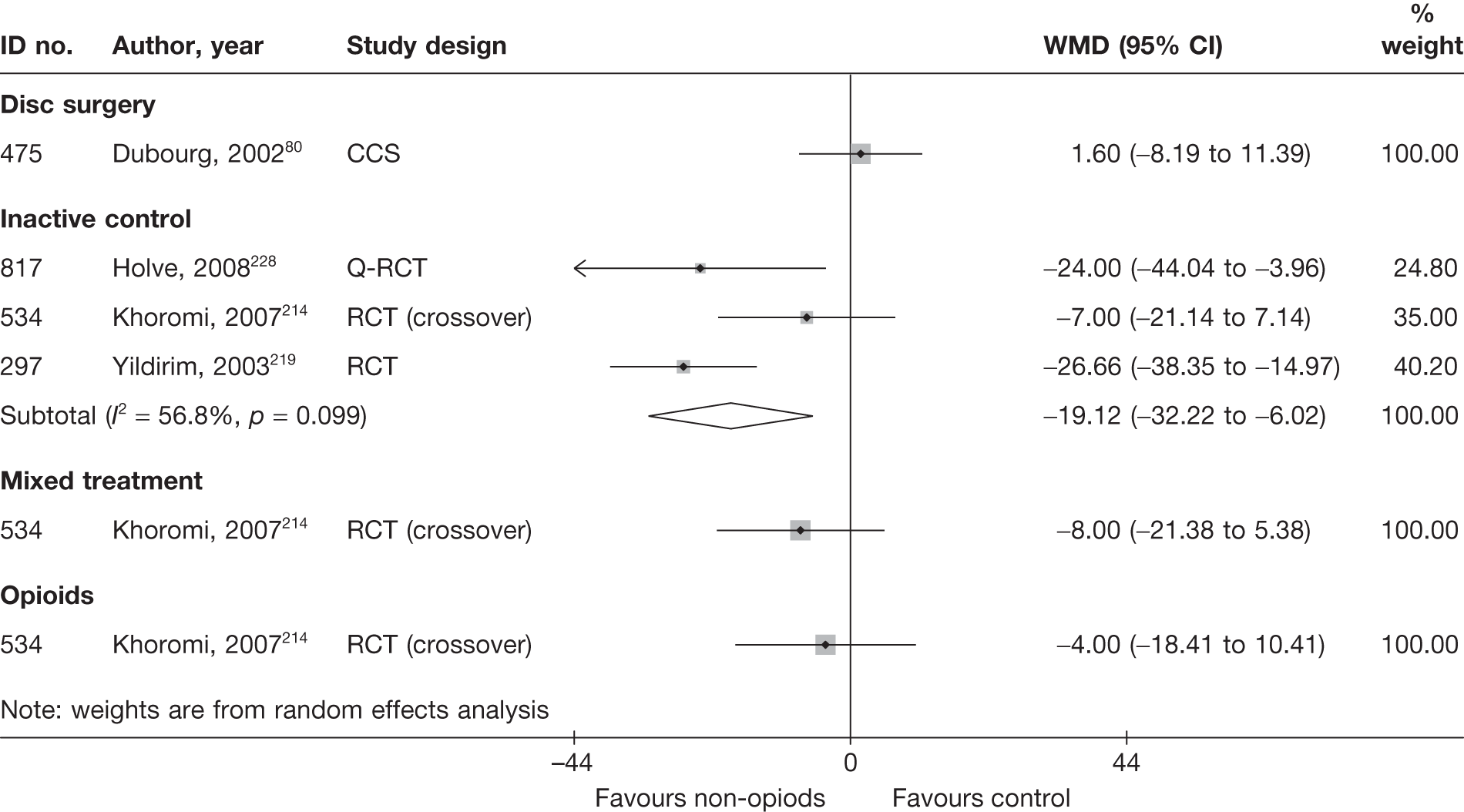

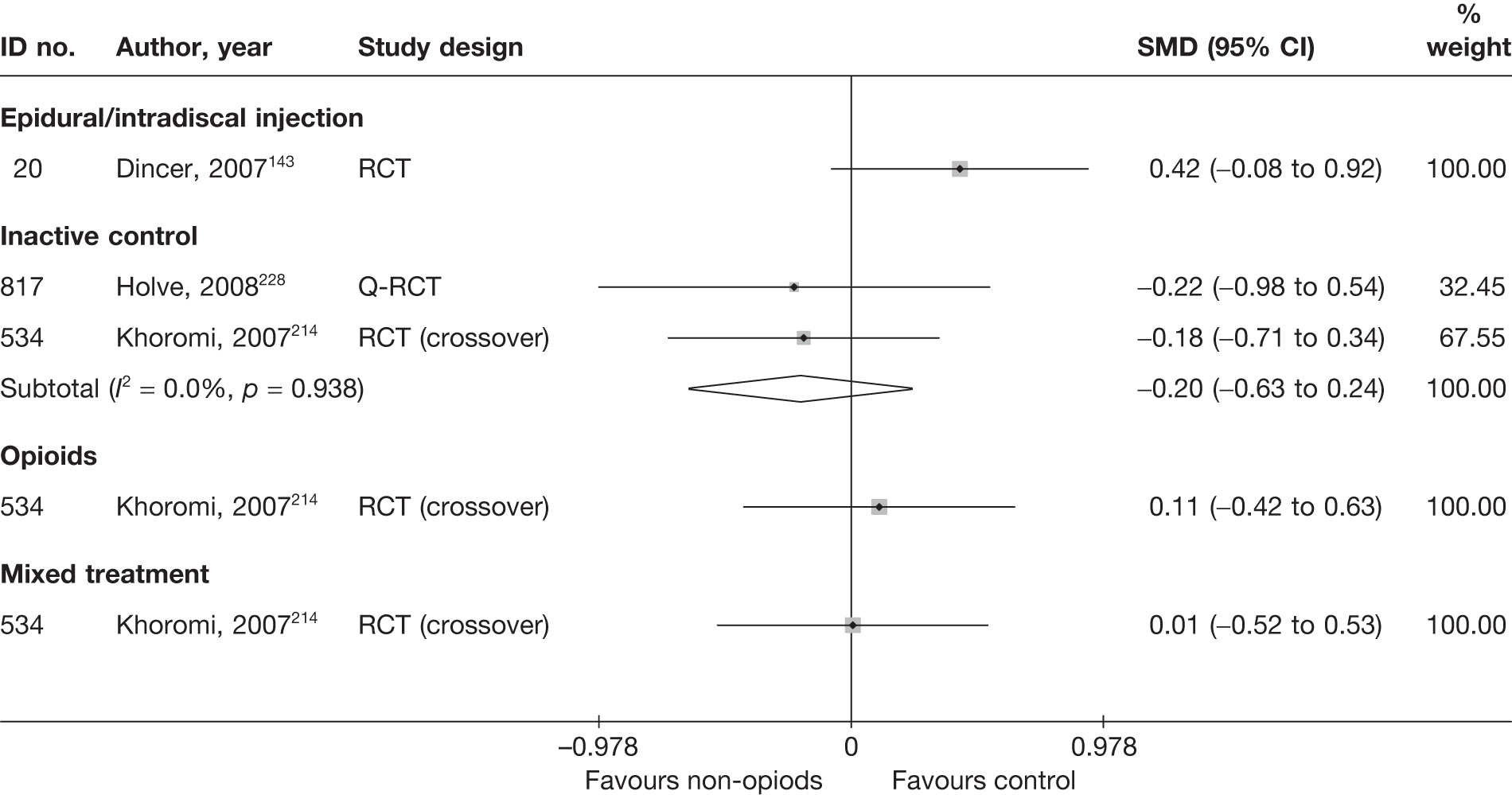

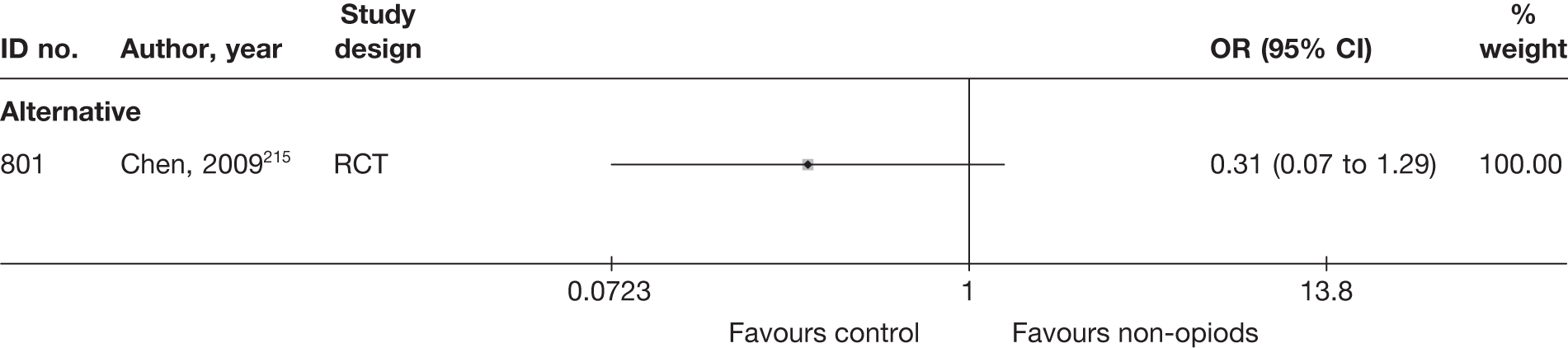

Methods of analysis/synthesis

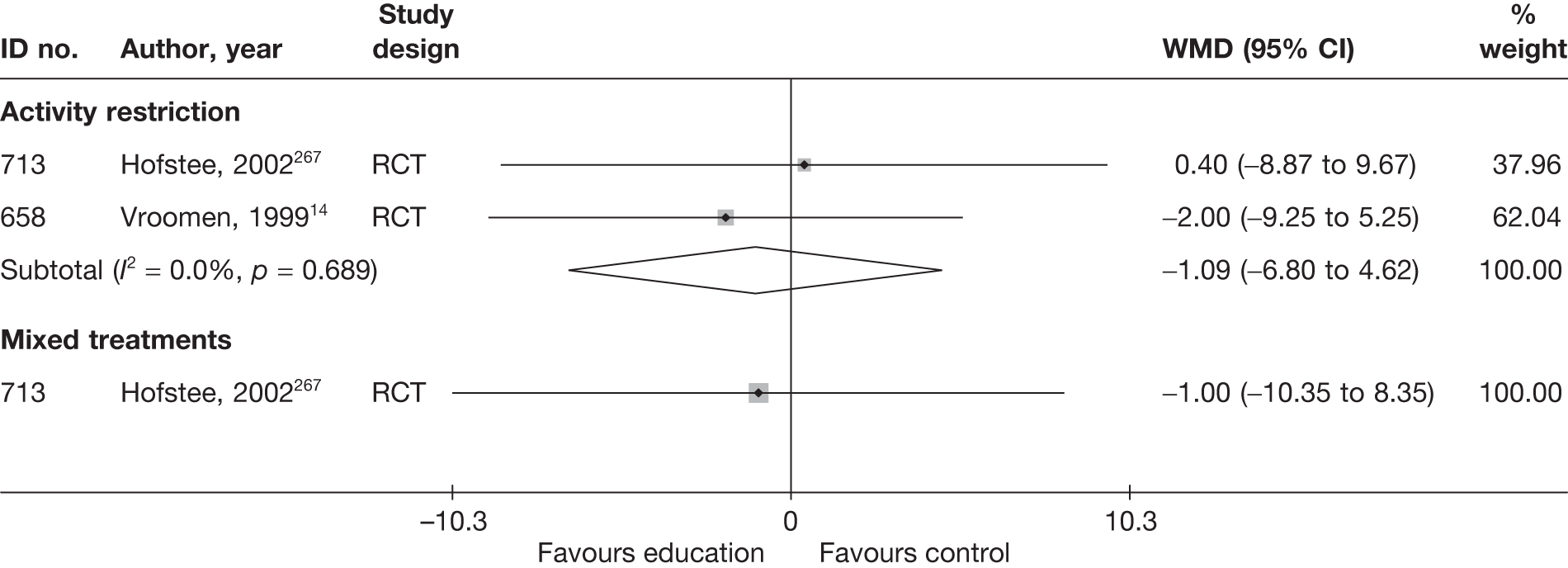

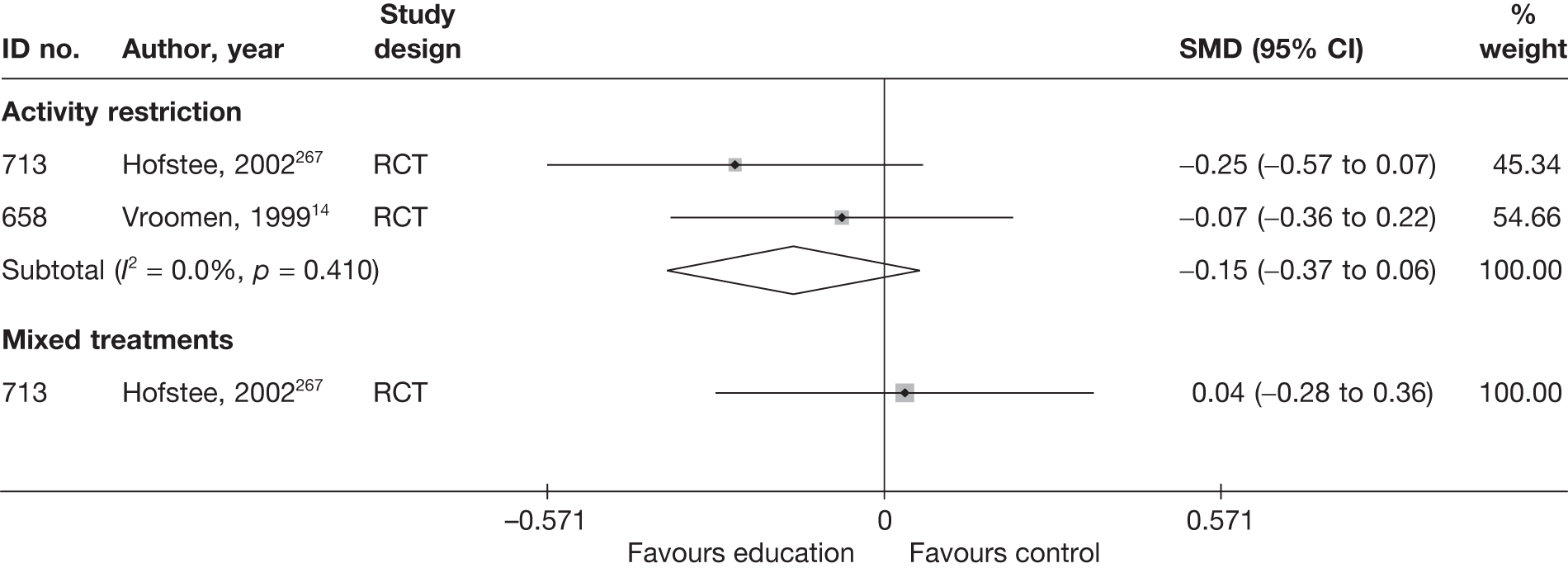

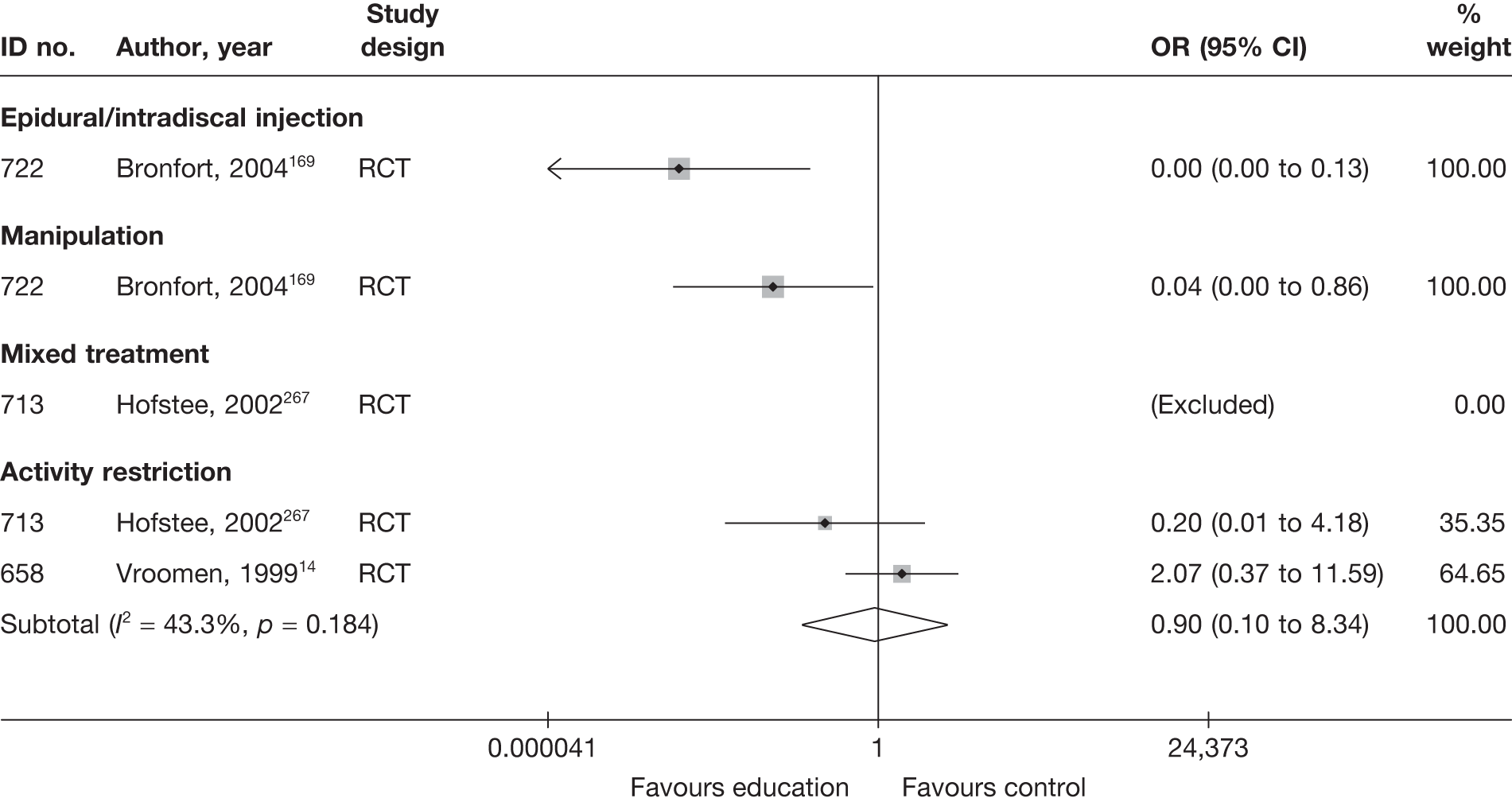

Treatments were categorised according to the system reported in Table 1. Pair-wise (standard) meta-analyses were initially conducted followed by MTC analysis. These were based on the three main outcome domains: global improvement (including absence of pain), reduction in pain intensity (measured using a continuous scale) and improvement in function based on a composite CSOM. Where feasible, the data were analysed according to chronicity of sciatica (acute ≤ 3 months; chronic > 3 months). The global effect was synthesised as binary data, pain intensity and the composite CSOM as continuous data.

Missing study-level outcome data, where feasible, were dealt with by deriving/imputing replacement values. Where mean values were unavailable but the medians were reported, the latter were used instead (i.e. medians were assumed to be equal to means). Where possible, SDs were estimated from SEs, 95% CIs or p-values, using methods reported in The Cochrane handbook,33 and for median values,using the interquartile range (IQR). If SDs for baseline values were available, then these were substituted for missing SDs. Finally, for studies that did not report sufficient data to derive the SDs, these were imputed using the weighted mean,34 which was calculated separately for each intervention category.

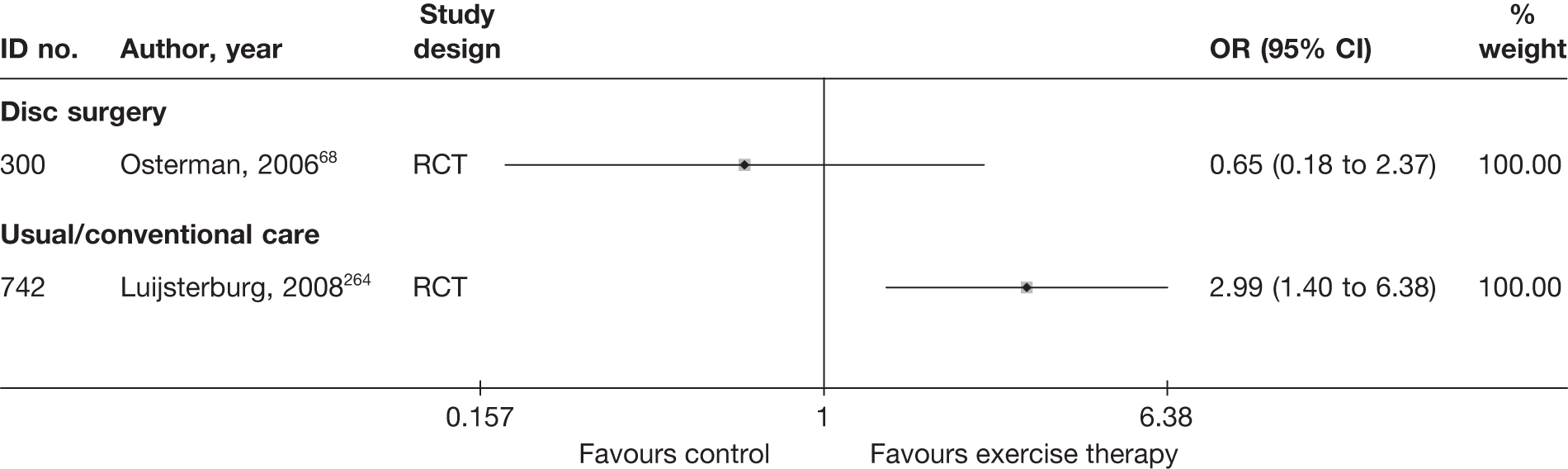

Global effect (including the absence of pain)

When this outcome was reported in an ordinal format, this was converted into binary data (e.g. improved, not improved, absence of pain, presence of pain). For studies that used ordinal scales, where little improvement (or similar terms) was a central category or grouped with unchanged, the data for patients in this group were classified as not improved. Where both treatment success and failure were reported, treatment success was used. Where treatment failure was reported on its own, the data were converted to treatment success. Where studies reported both overall improvement (sometimes based on a number of scales) and improvement in pain (categorical data), the data on overall improvement were used. For studies that reported both physician- and patient-perceived global effect, the data for patients’ perceived effect were used, as this is considered to be the most useful; if the study reported only physician’s assessment, then this was used.

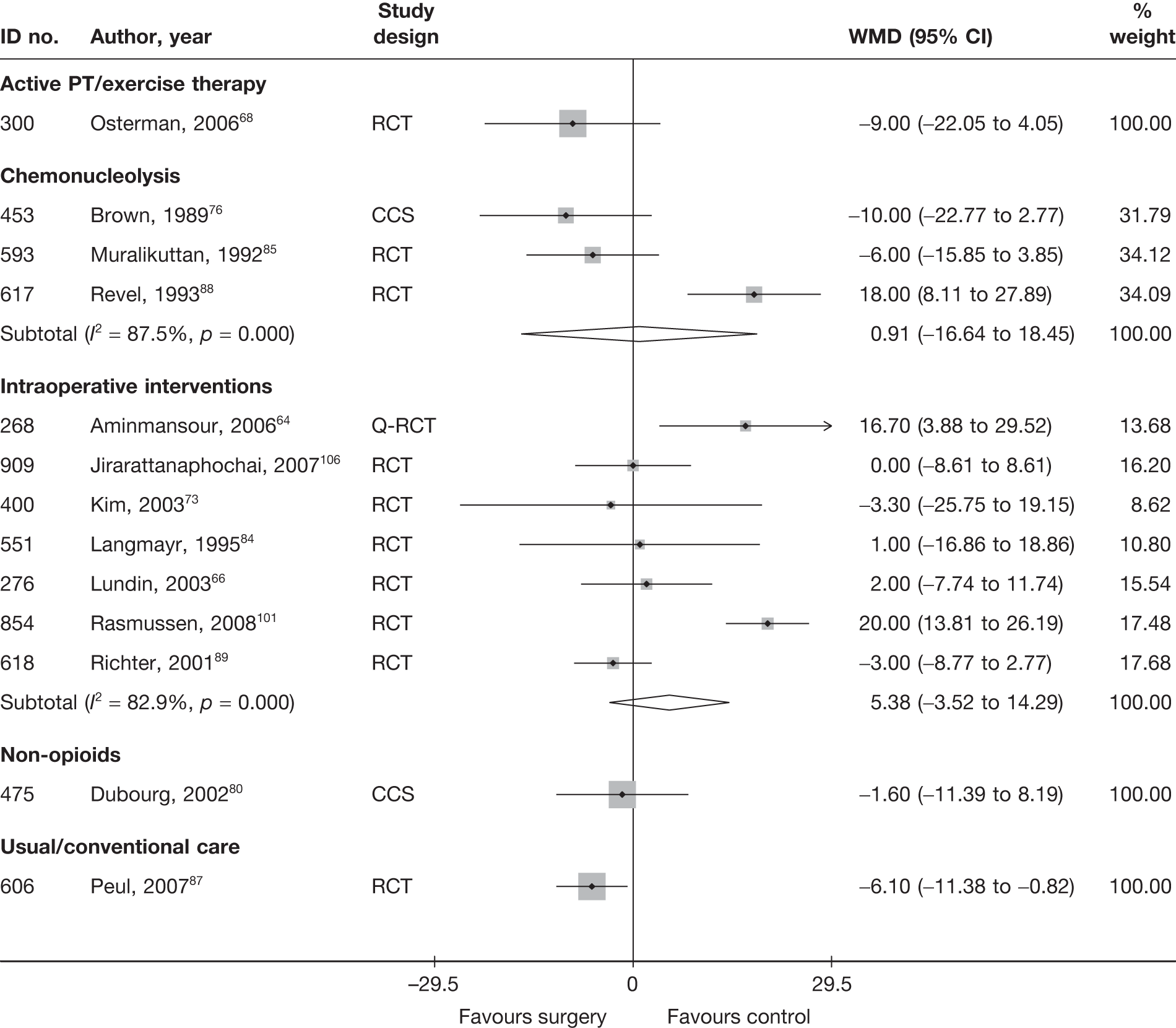

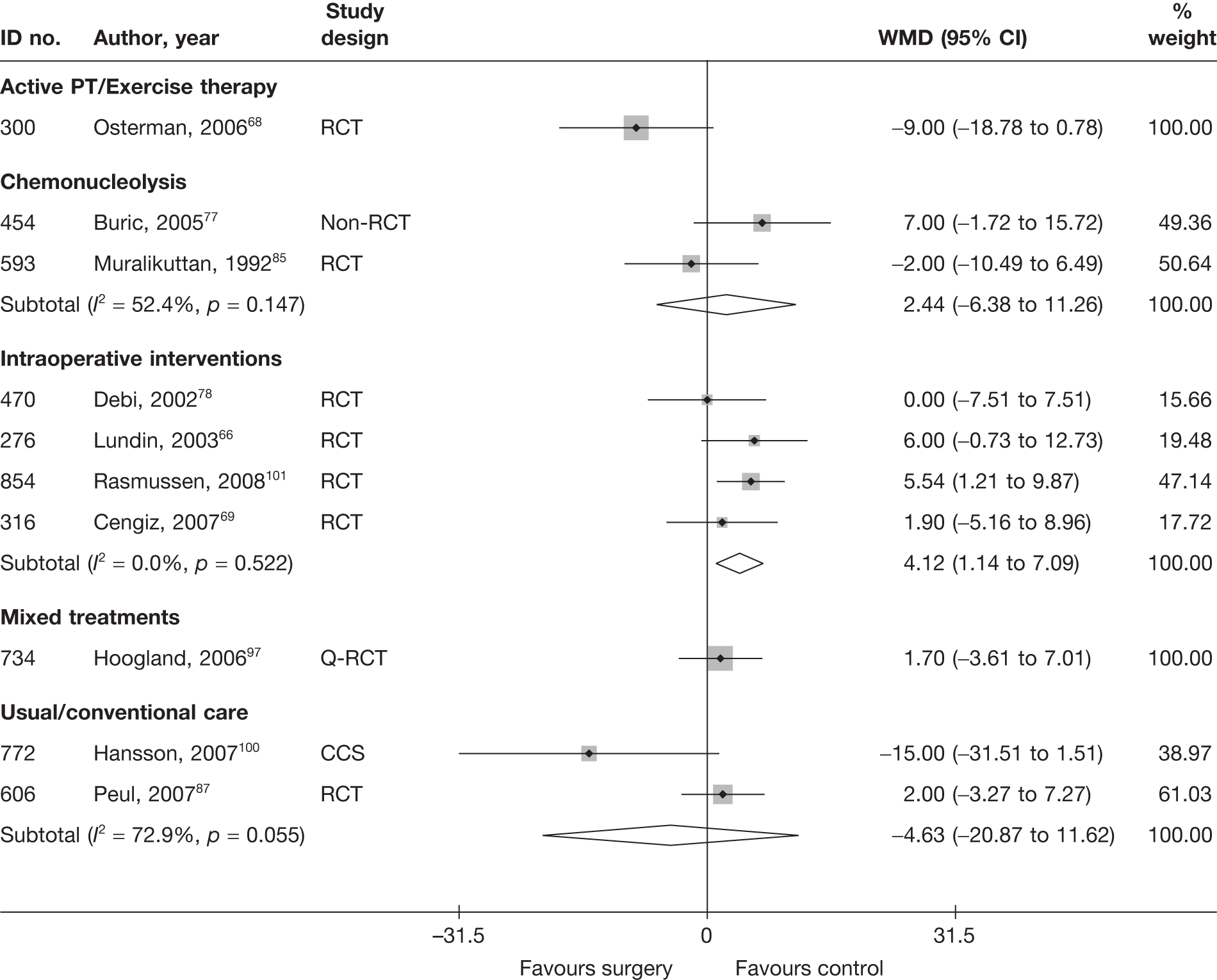

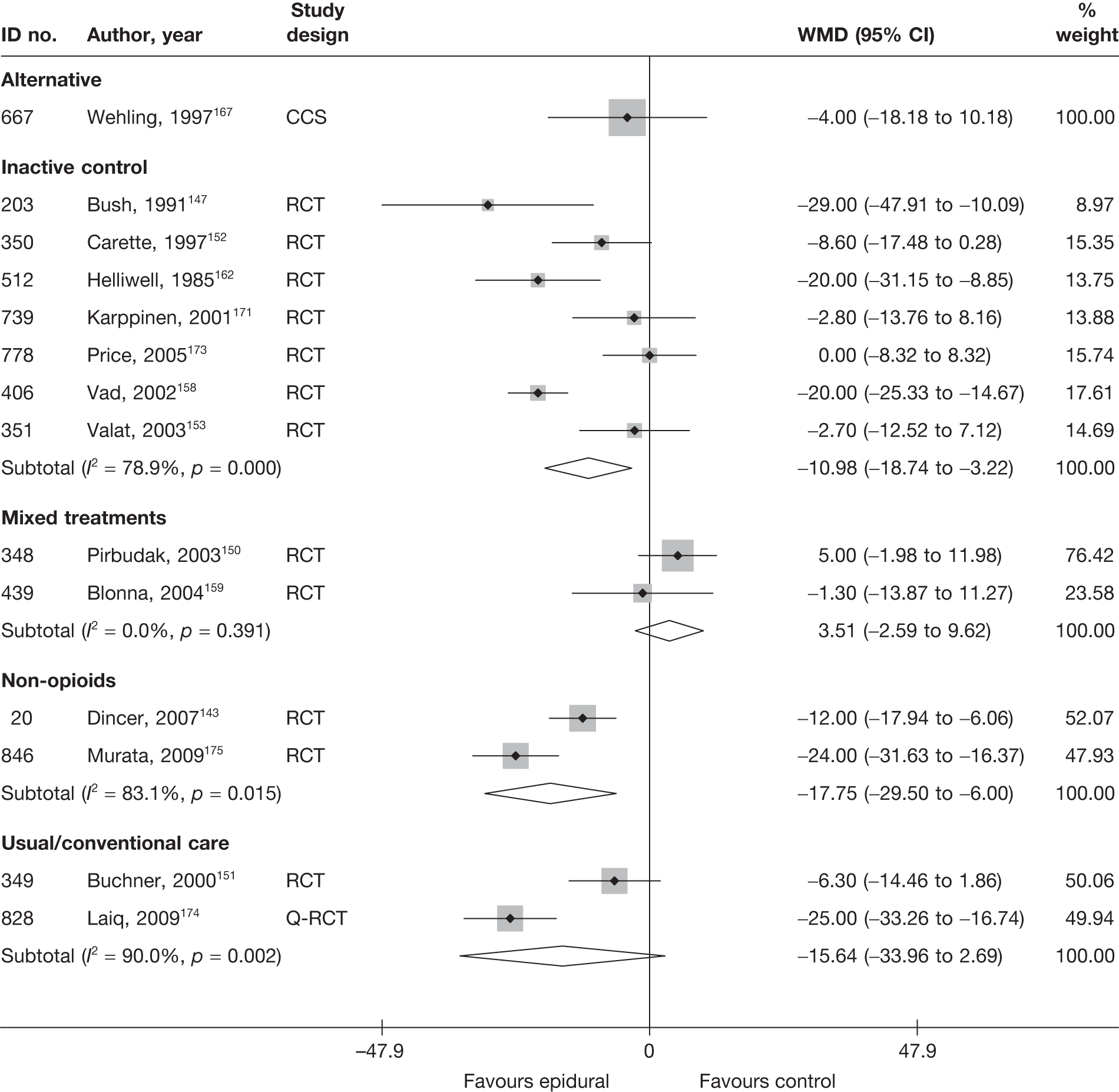

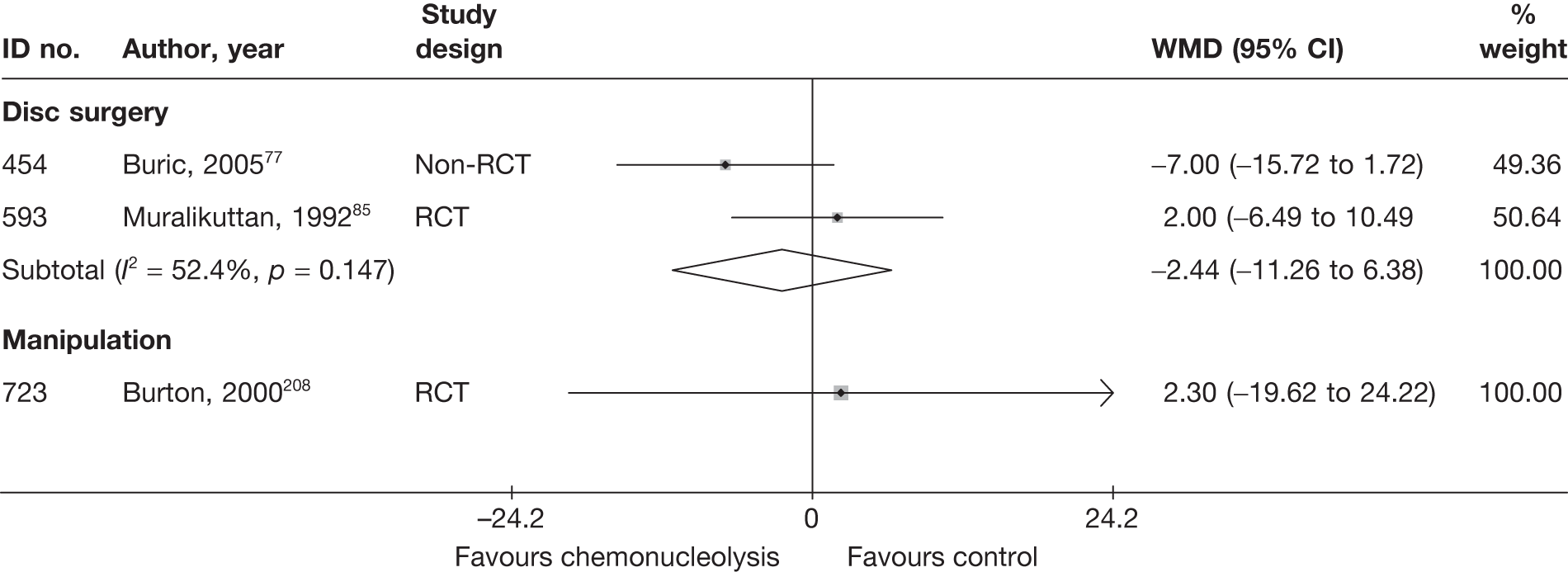

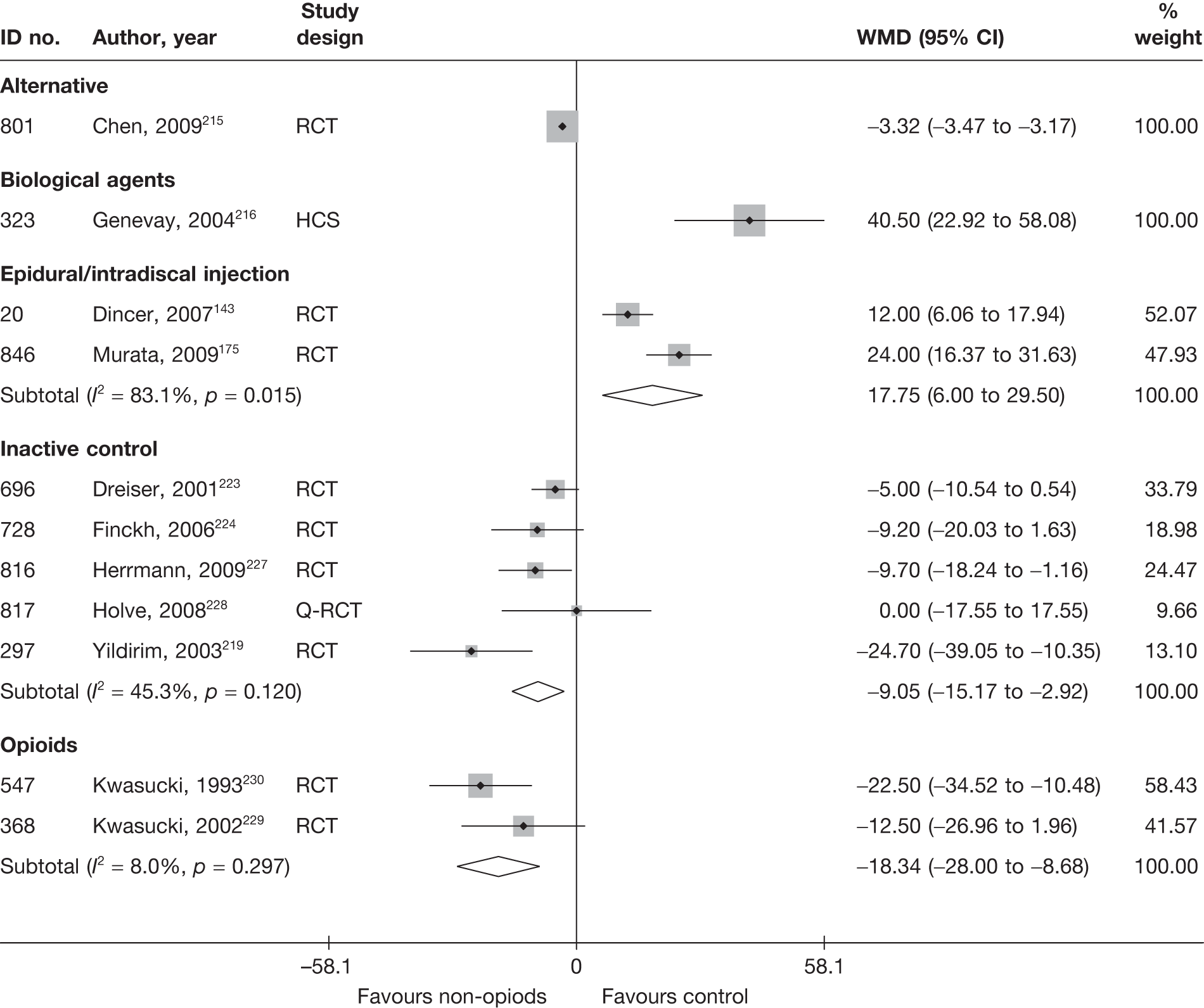

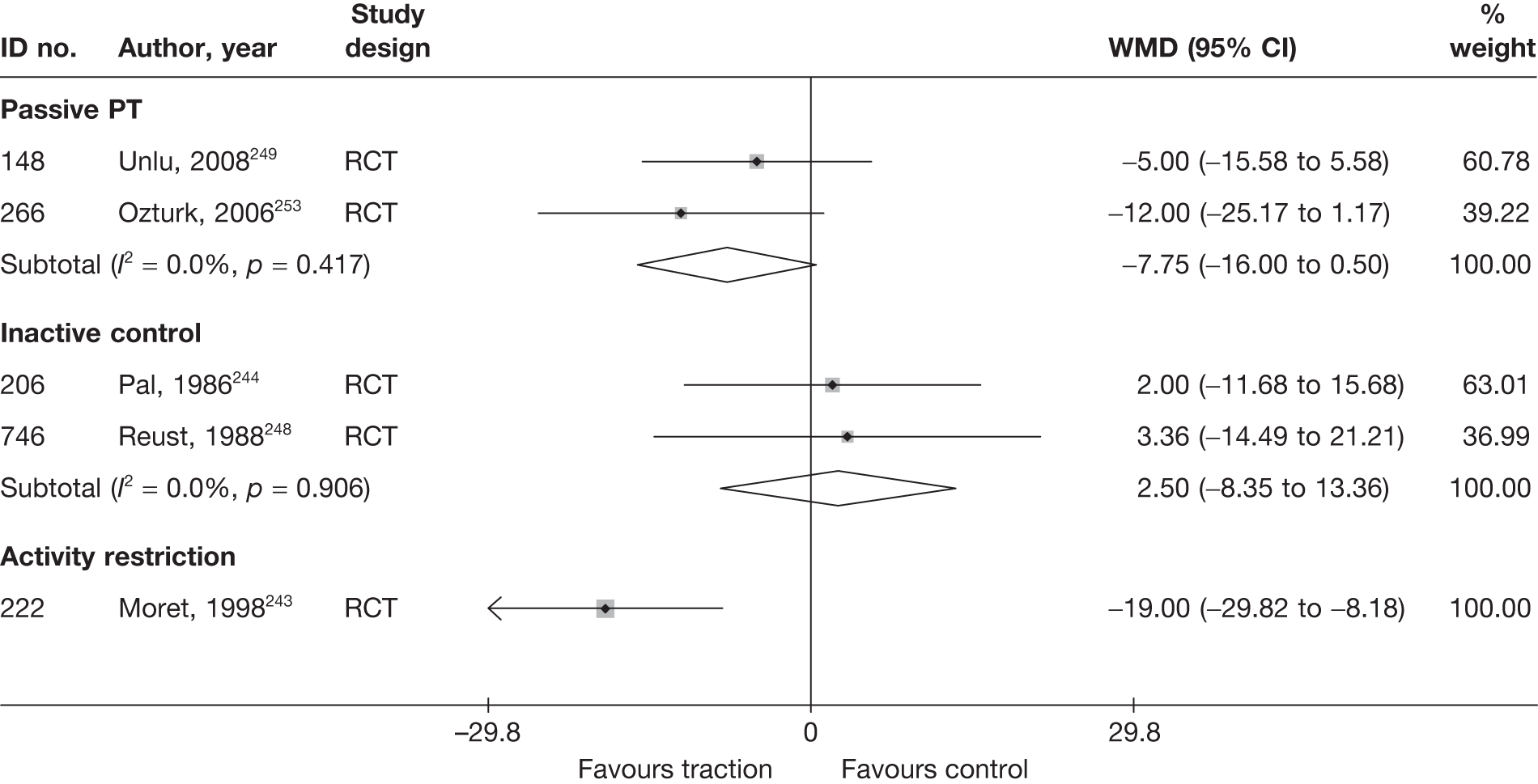

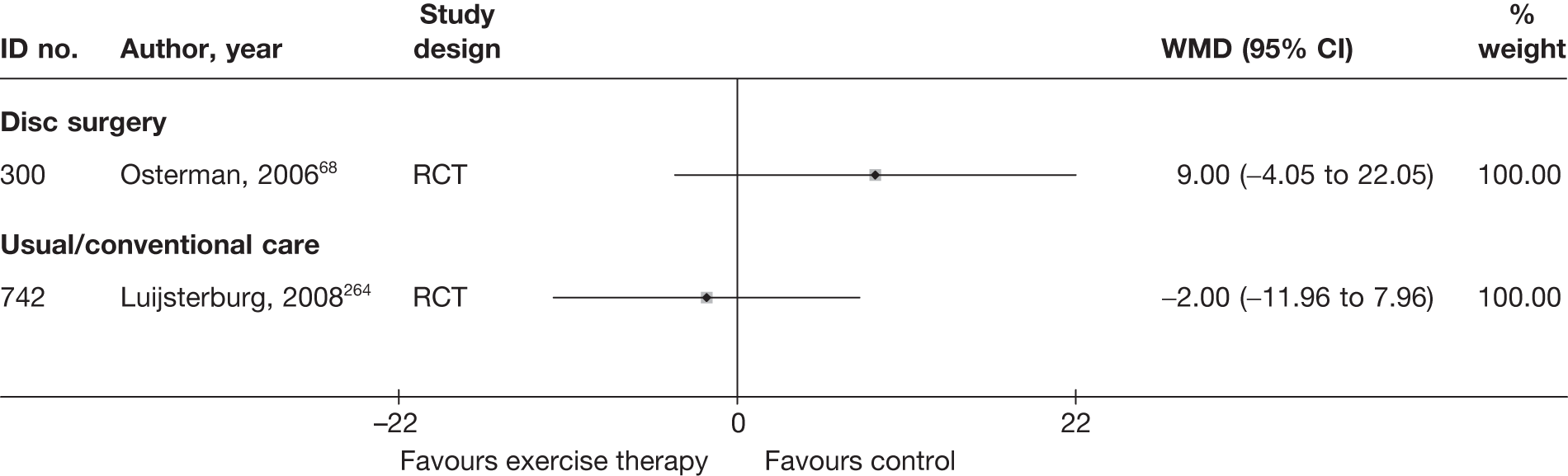

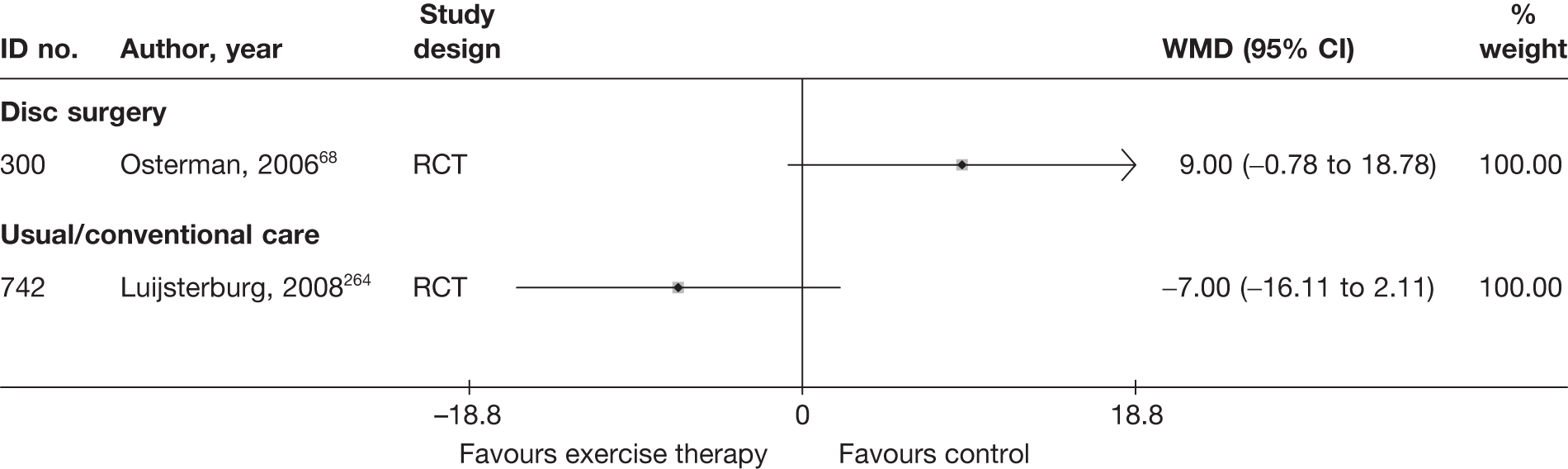

Pain intensity (based on a continuous scale)

Most of the studies reporting pain intensity used a visual analogue scale (VAS) to measure pain, with a mixture of both final mean and change scores reported. Studies were pooled using weighted mean difference (WMD). Studies that measured pain intensity on a similar continuous scale were also included, with the data converted to a scale of 0–100. Other types of pain measures were excluded as their inclusion would have necessitated using standardised mean differences (SMDs), where both final and change scores could not be used. Multiple and different locations of the pain were assessed across the studies. We included a pain assessment from only one site from each study using the following preference hierarchy: leg pain (preferred), then overall pain, and then back pain.

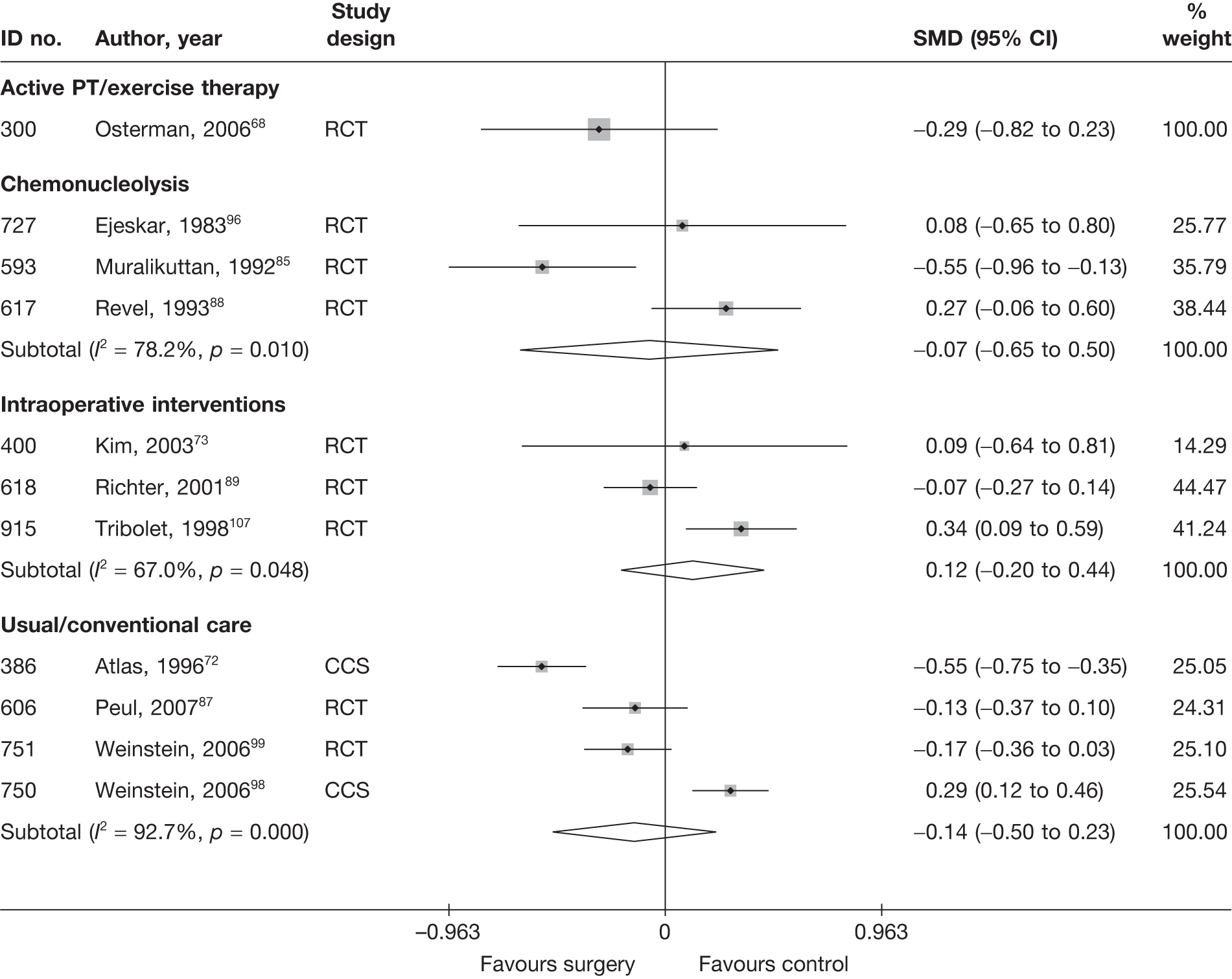

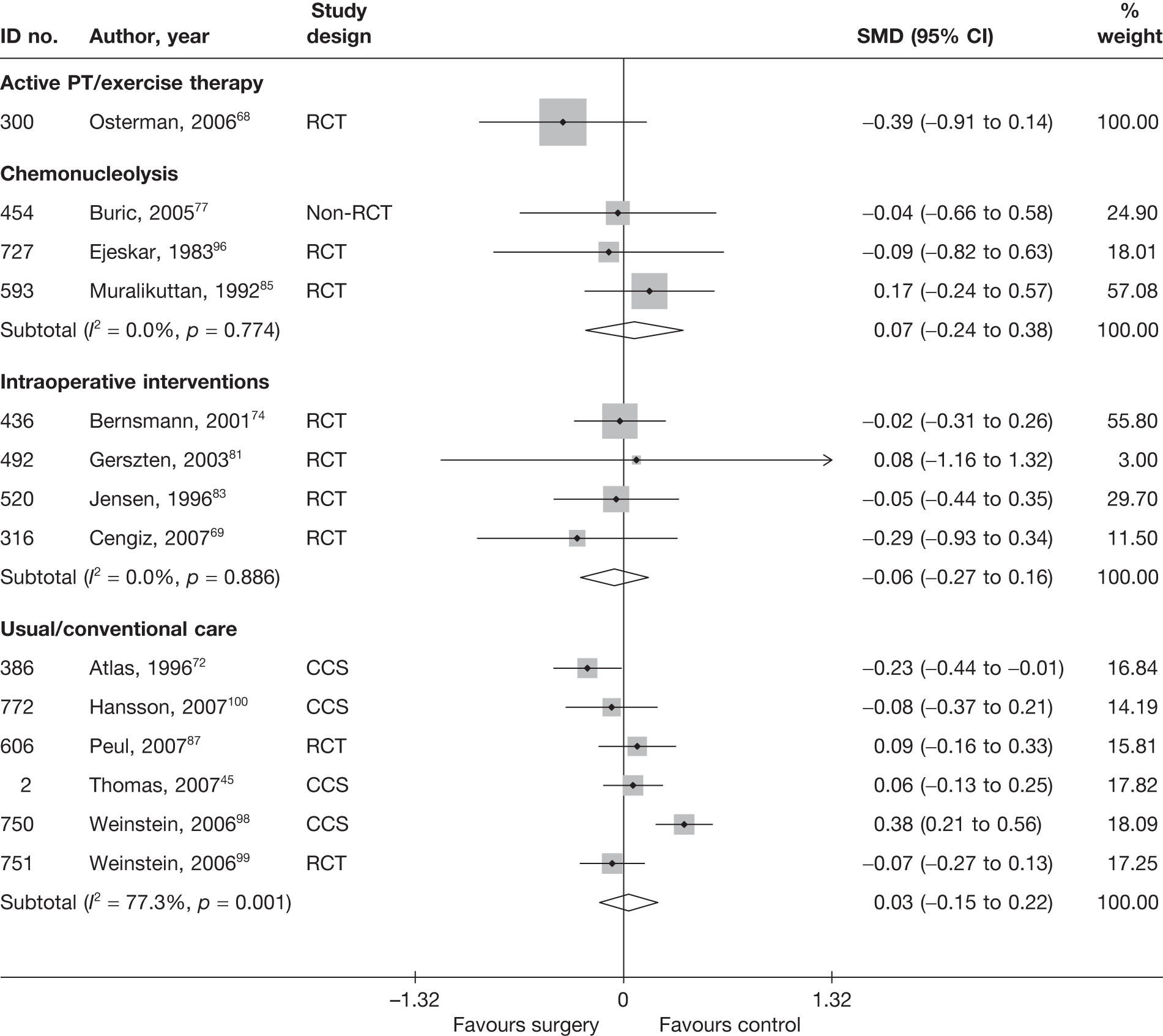

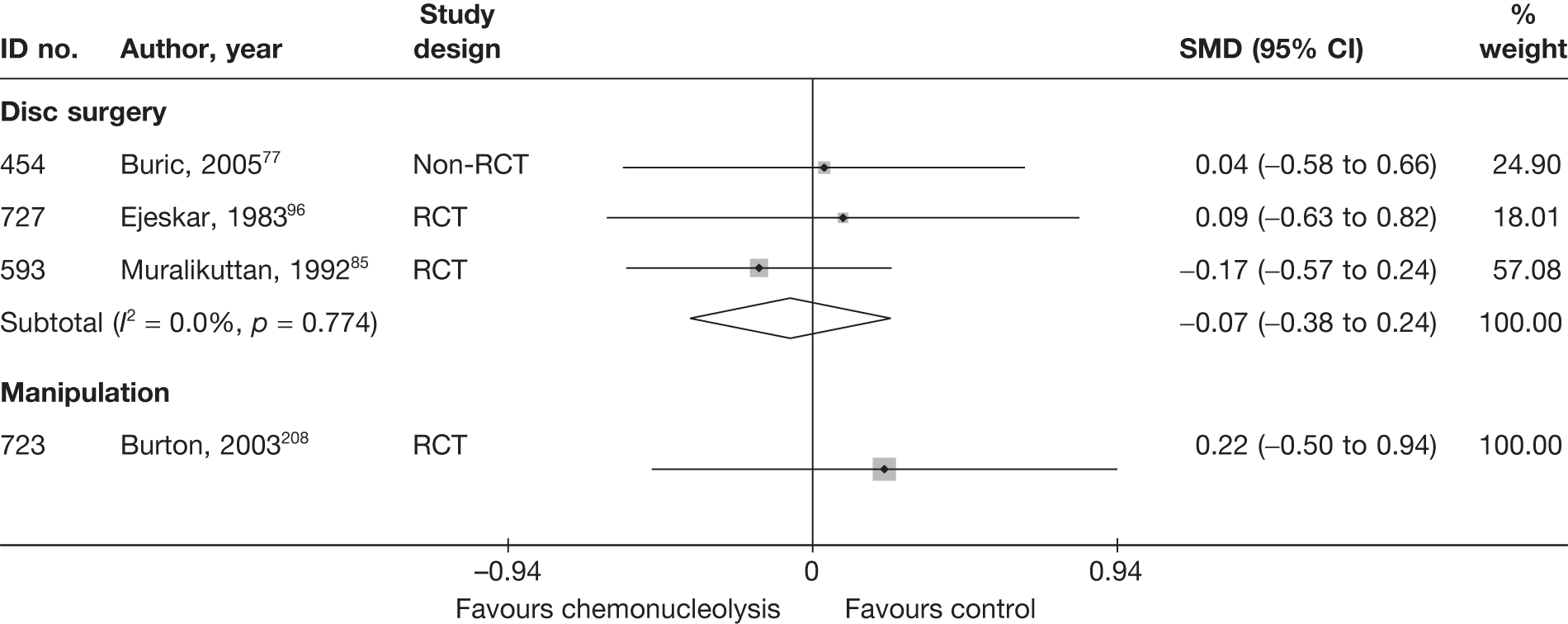

Condition-specific outcome measures

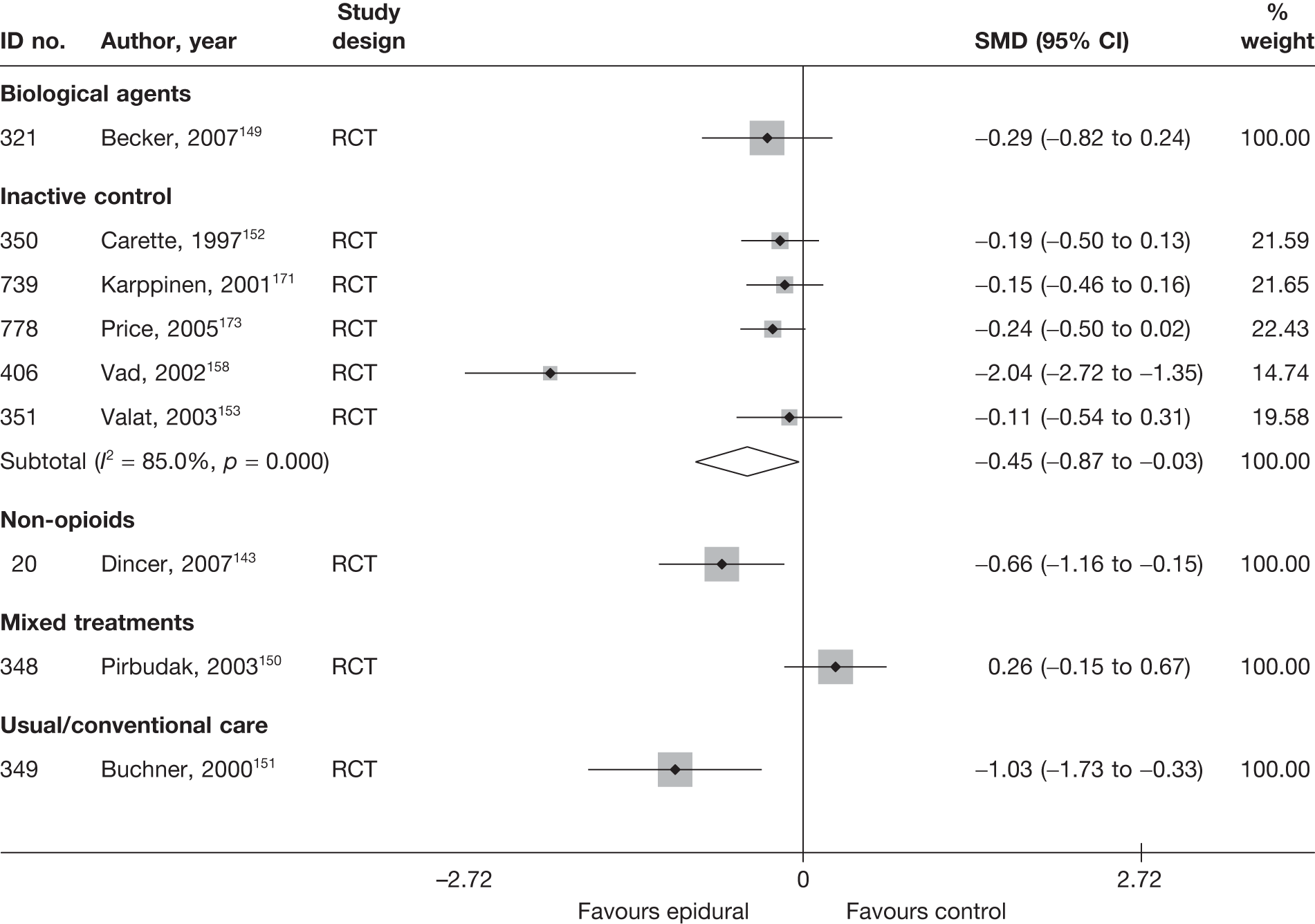

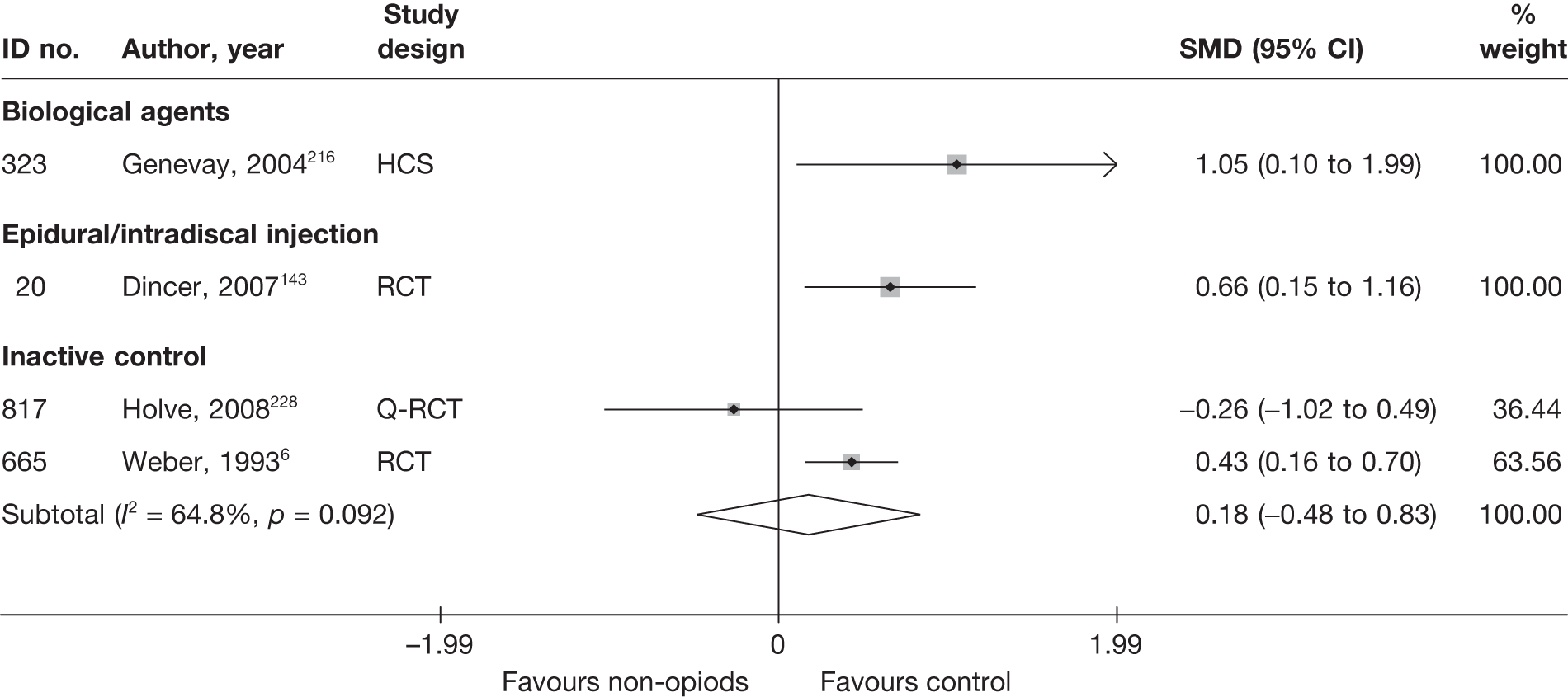

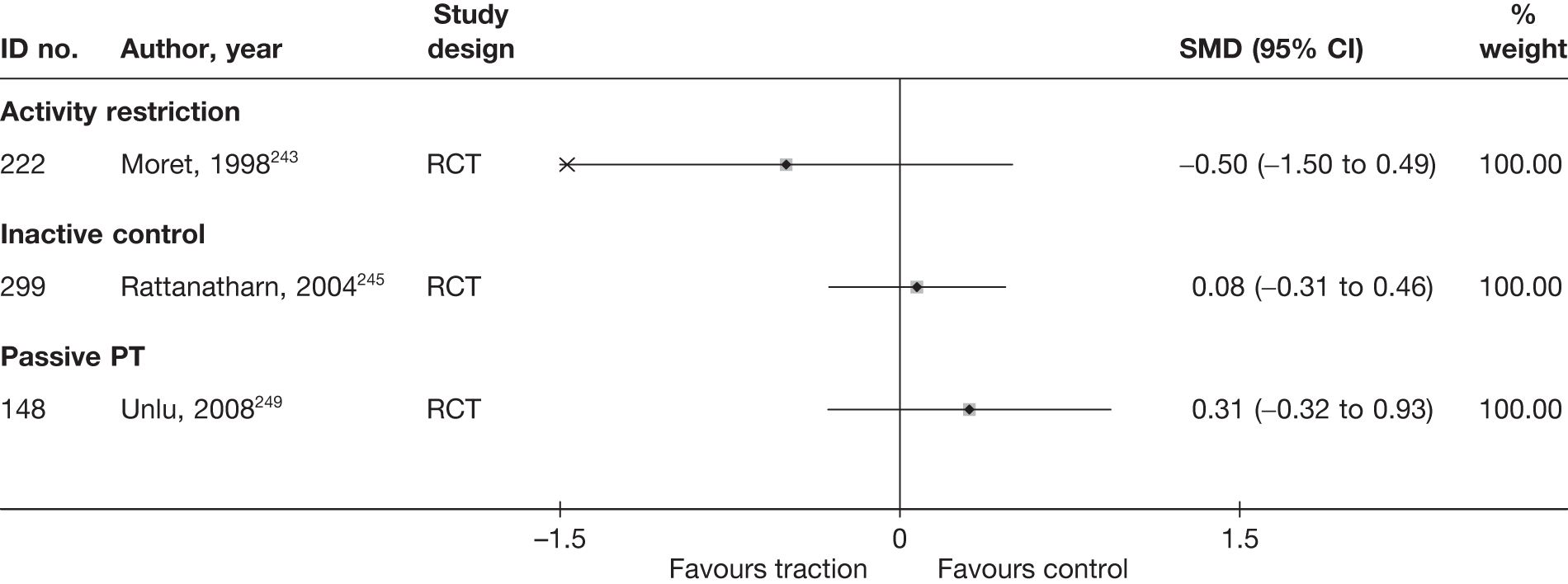

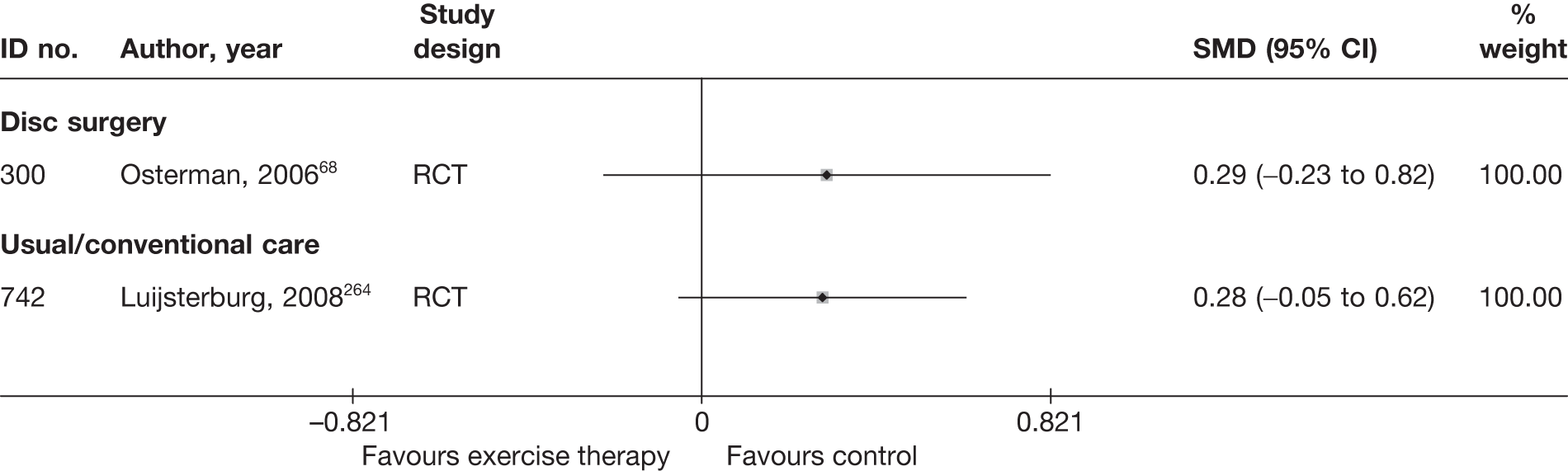

The included studies used a number of different scales to measure condition-specific functional status. The Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire (RMDQ)35 and the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI)36 are the most widely used CSOMs for sciatica studies,37 and an expert panel has recommended the use of either in lower back pain research. 35 The RMDQ was designed, and is more widely used, in primary care settings; the ODI was designed, and is more widely used, in secondary care. Both show some evidence of criterion and construct validity. The RMDQ is the more frequently cited and is more responsive than the ODI, which in turn has better test–retest reliability. 36 The RMDQ has undergone Rasch analysis to examine item separation, which found that all but four of the items contributed to a single underlying construct, but several items in the middle of the disability hierarchy were too similar and there were insufficient items at the upper and lower extremes. 38 The ODI has not undergone Rasch analysis, but like the RMDQ shows evidence of ceiling and floor effects. There are also different versions of the ODI following its adaptation by different groups. 39

To enable synthesis, the data were combined using a SMD. We had initially intended using change scores. In order to impute change from baseline SDs for studies that report only baseline and final means, it is necessary to include an estimate of the correlation between baseline and follow-up values for individuals. This entails estimating the correlation coefficient from (other) studies in the synthesis that reported SDs for baseline, final and change from baseline. 40 However, when doing this we found the average correlation to be ≤ 0.5 for most treatment categories, which means that there is little advantage over using final means. Some studies report findings for more than one CSOM scale, but results from only one scale from each study were used in the analyses, based on the following preference hierarchy: RMDQ,41 ODI,42 Quebec Back Pain Disability Scale (QDS), others.

Standard pair-wise meta-analyses

Data were analysed according to three follow-up periods: short (≤ 6 weeks), medium (6 weeks to 6 months) and long (> 6 months). Where studies reported findings for multiple follow-up intervals within a single follow-up period, the data relating to the duration closest to the upper limit were used.

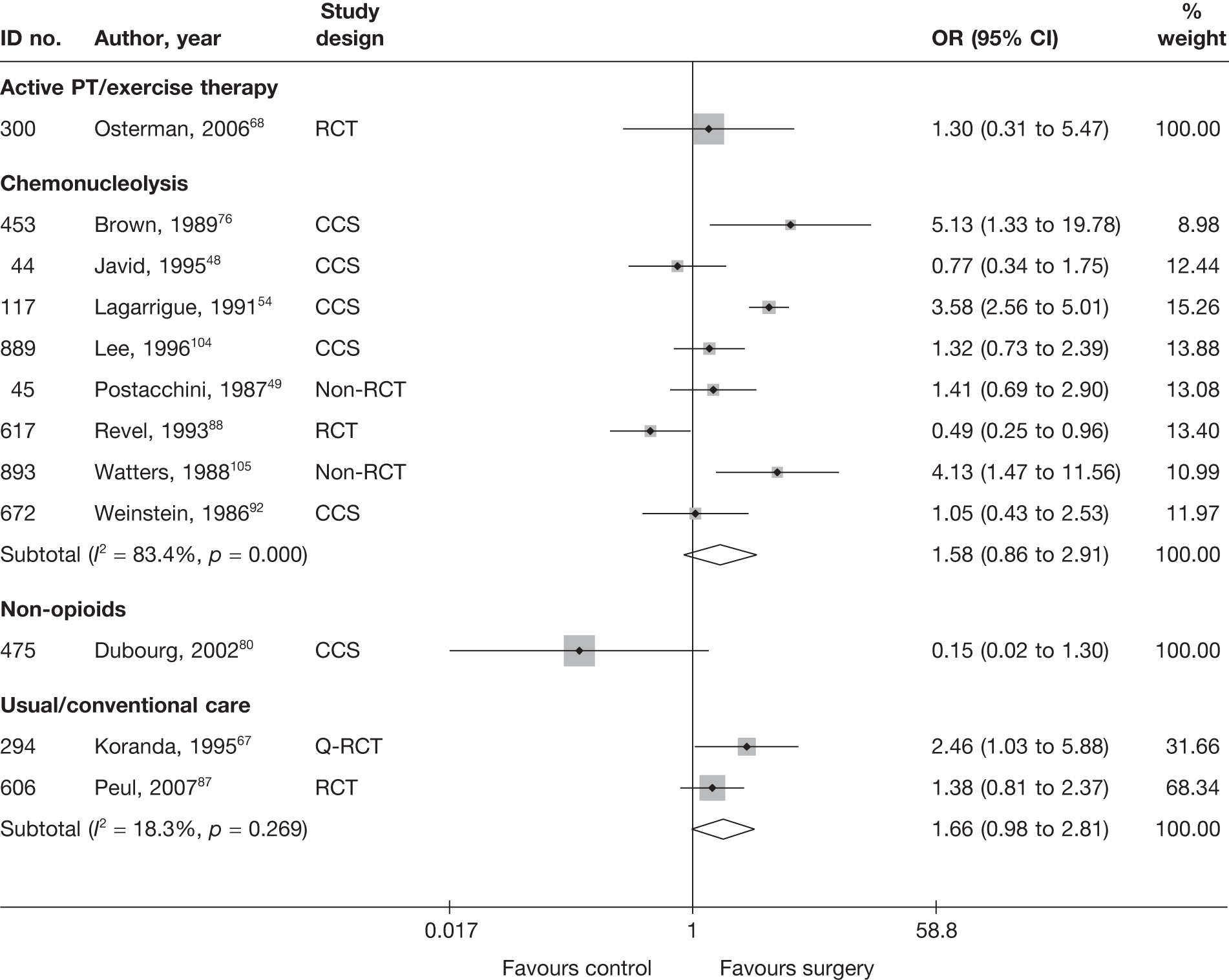

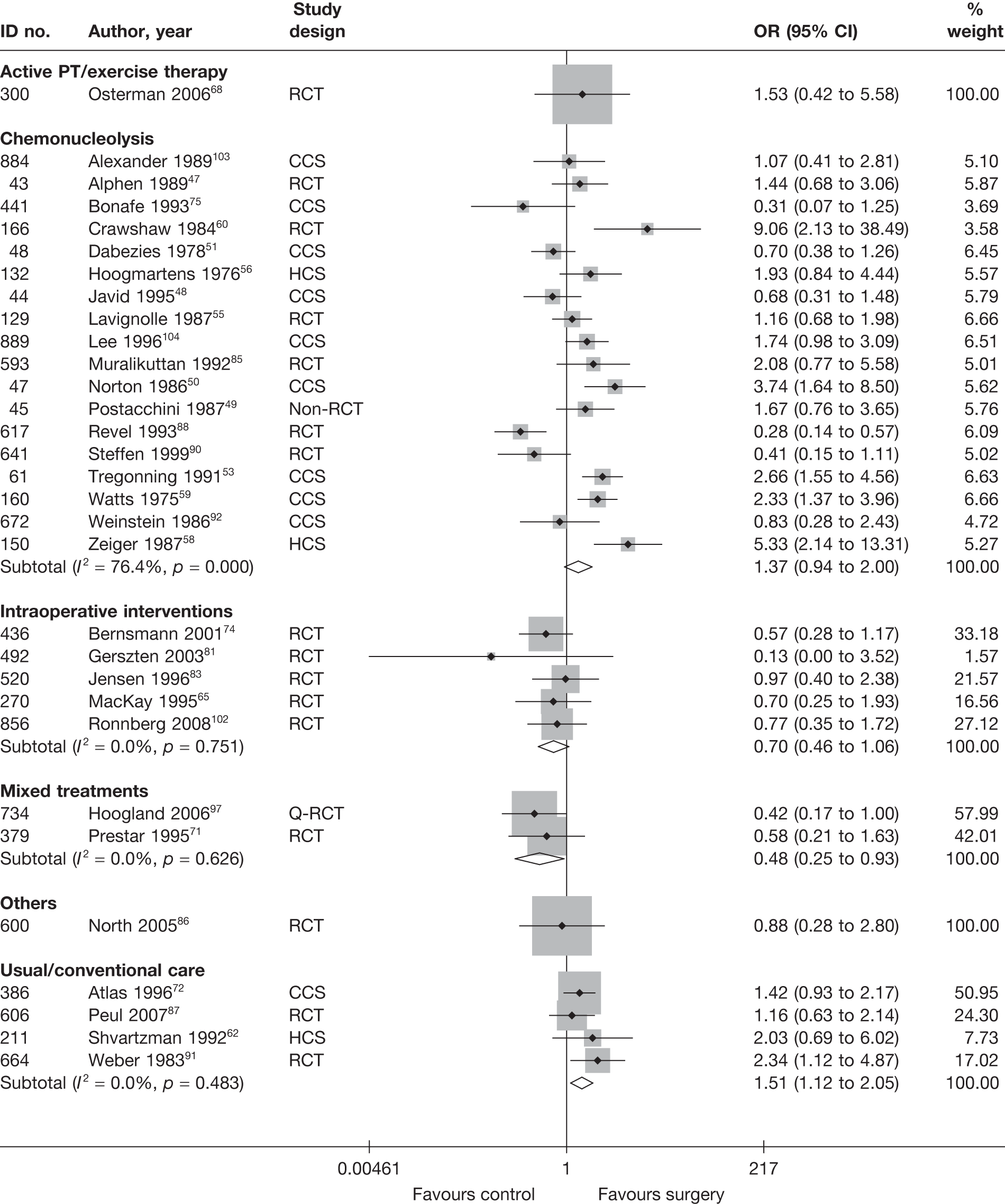

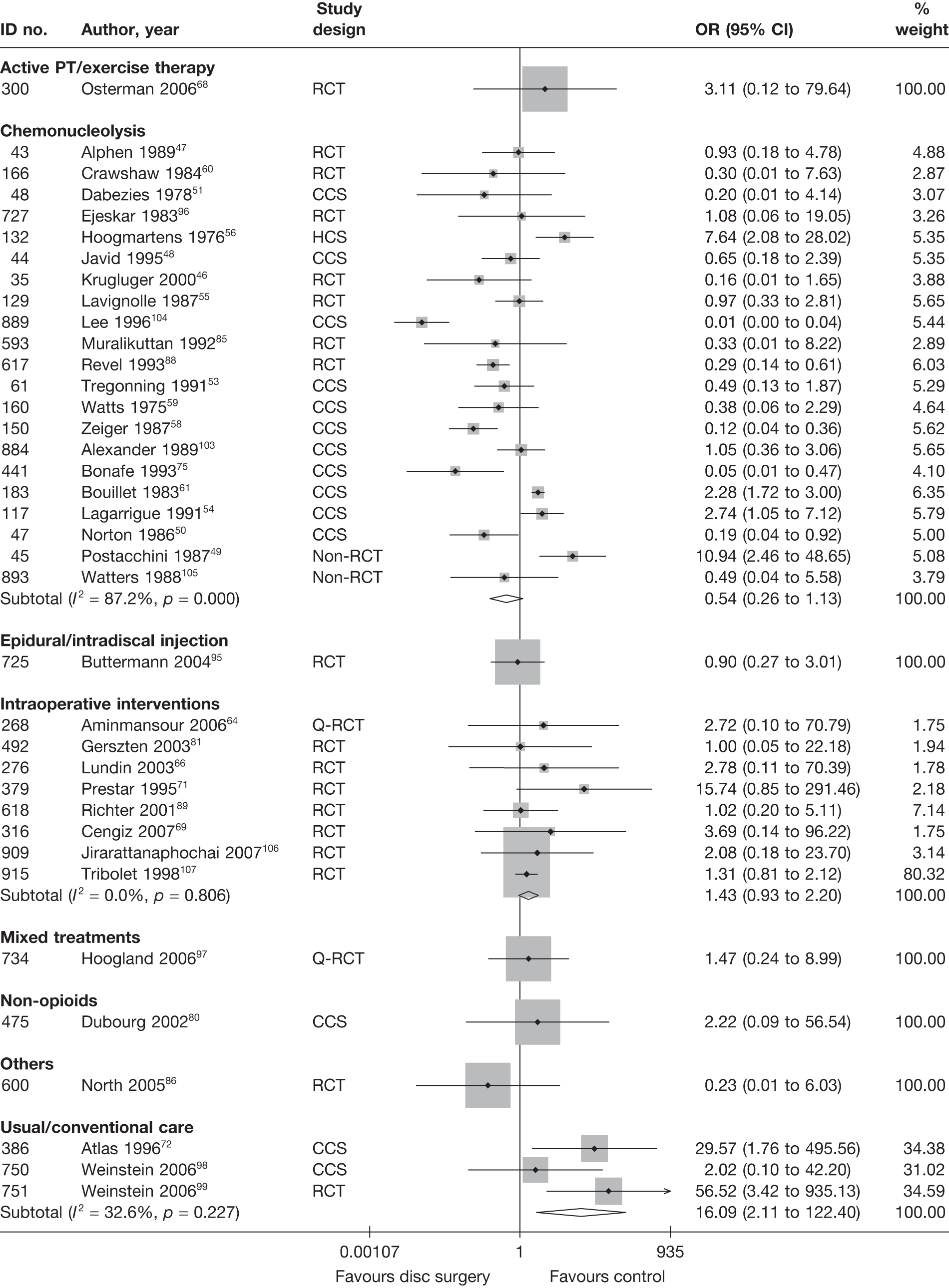

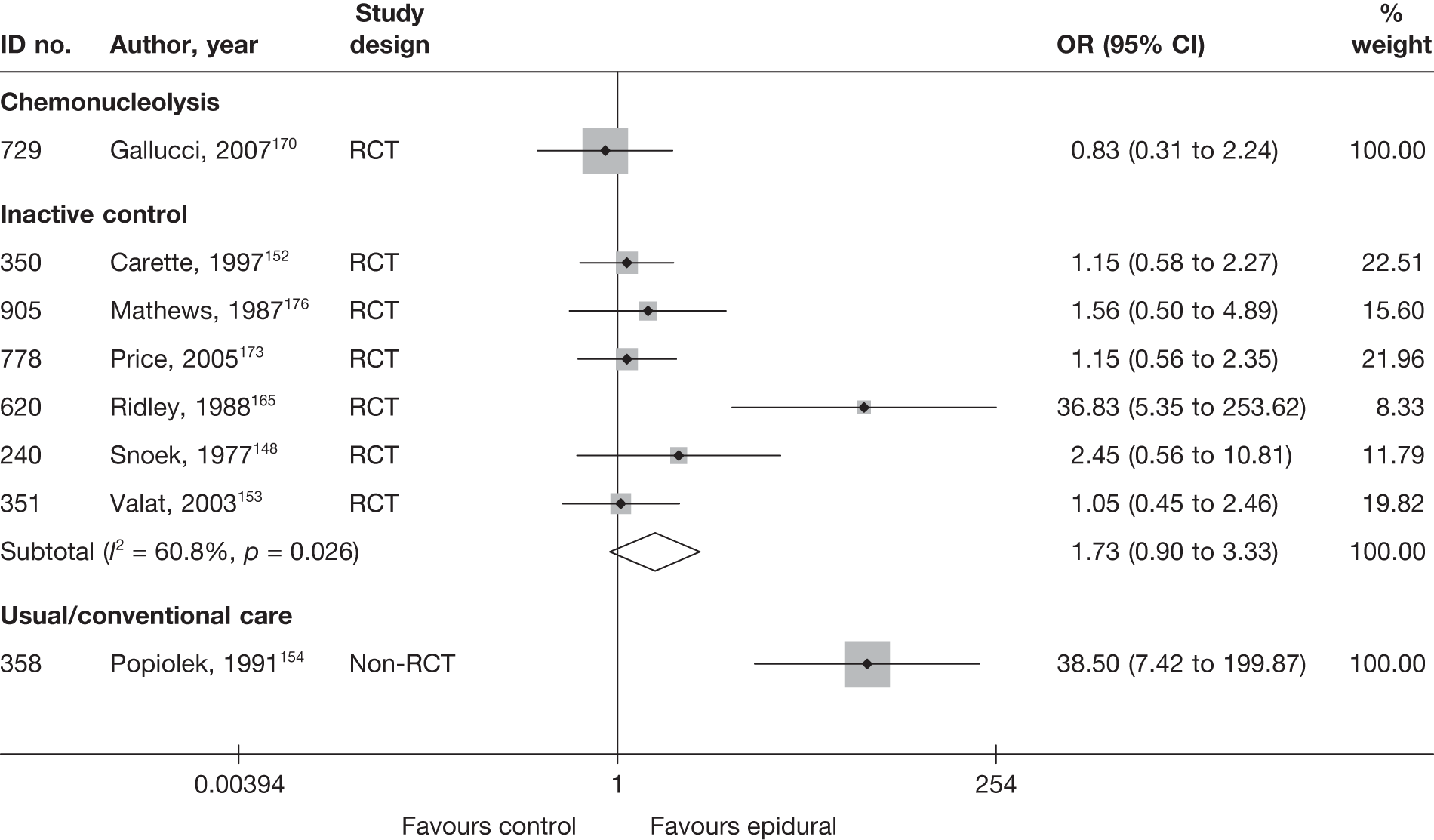

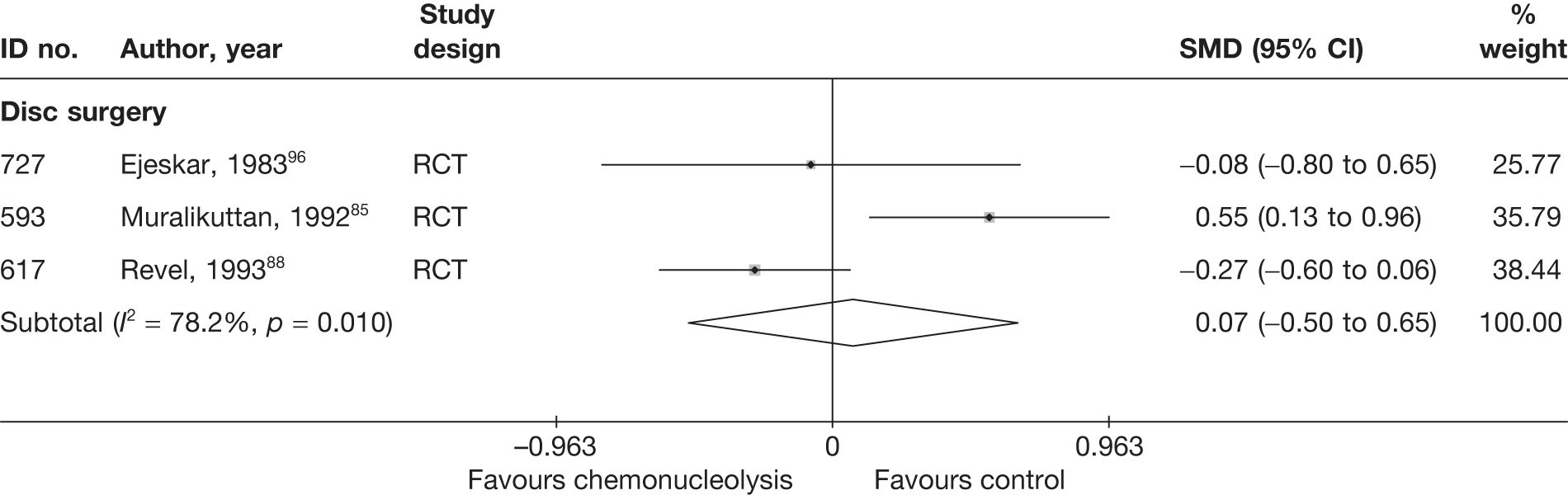

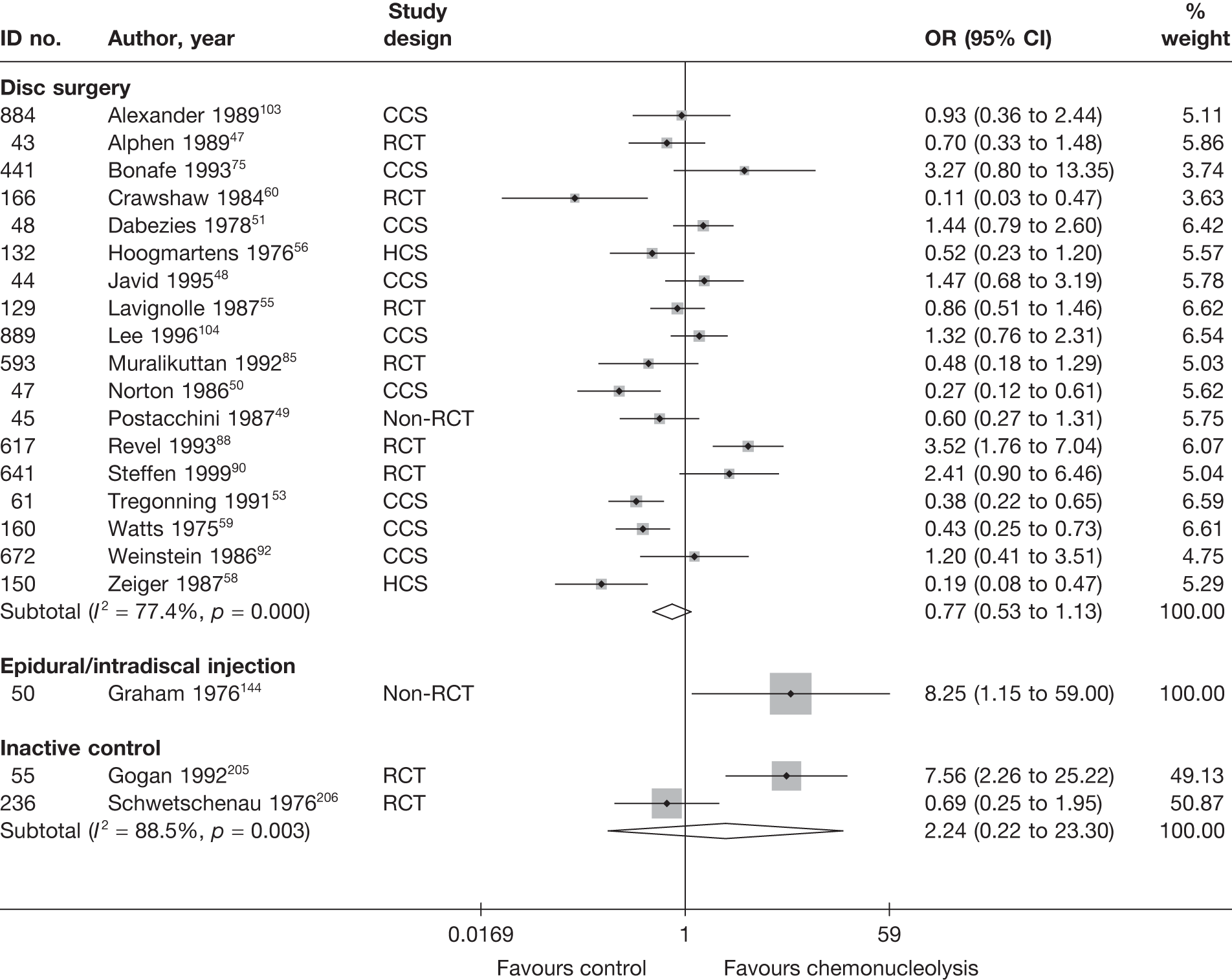

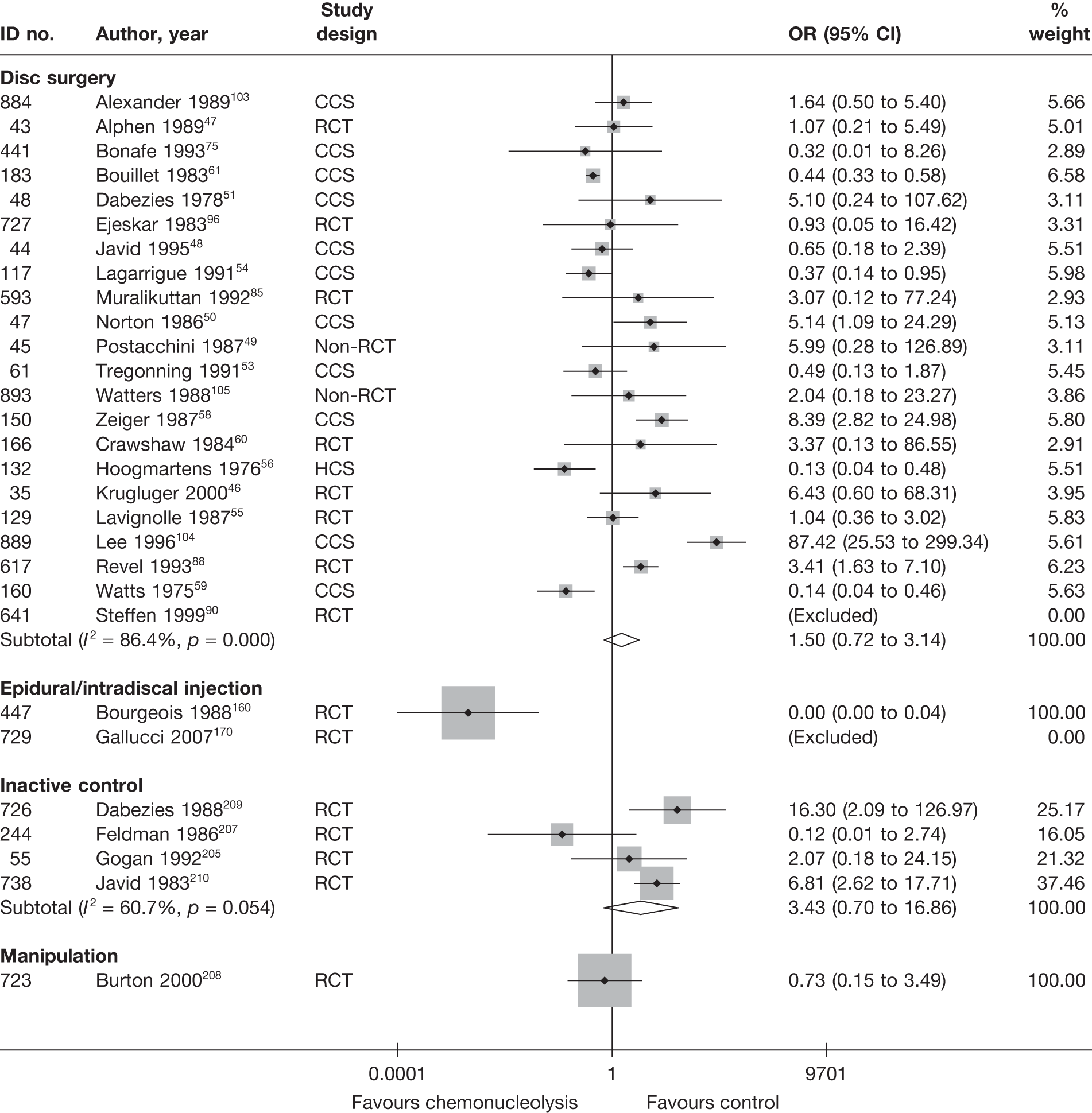

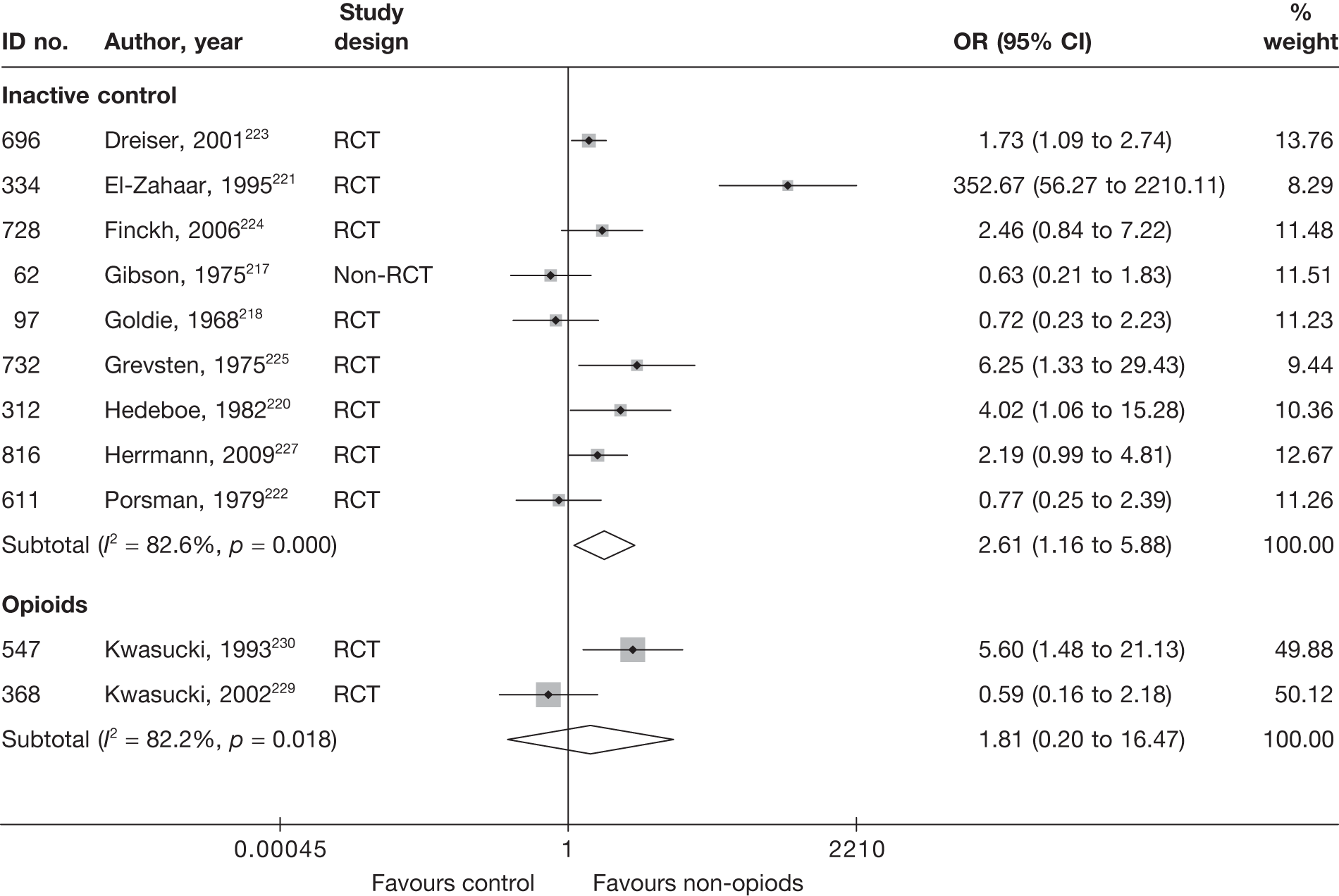

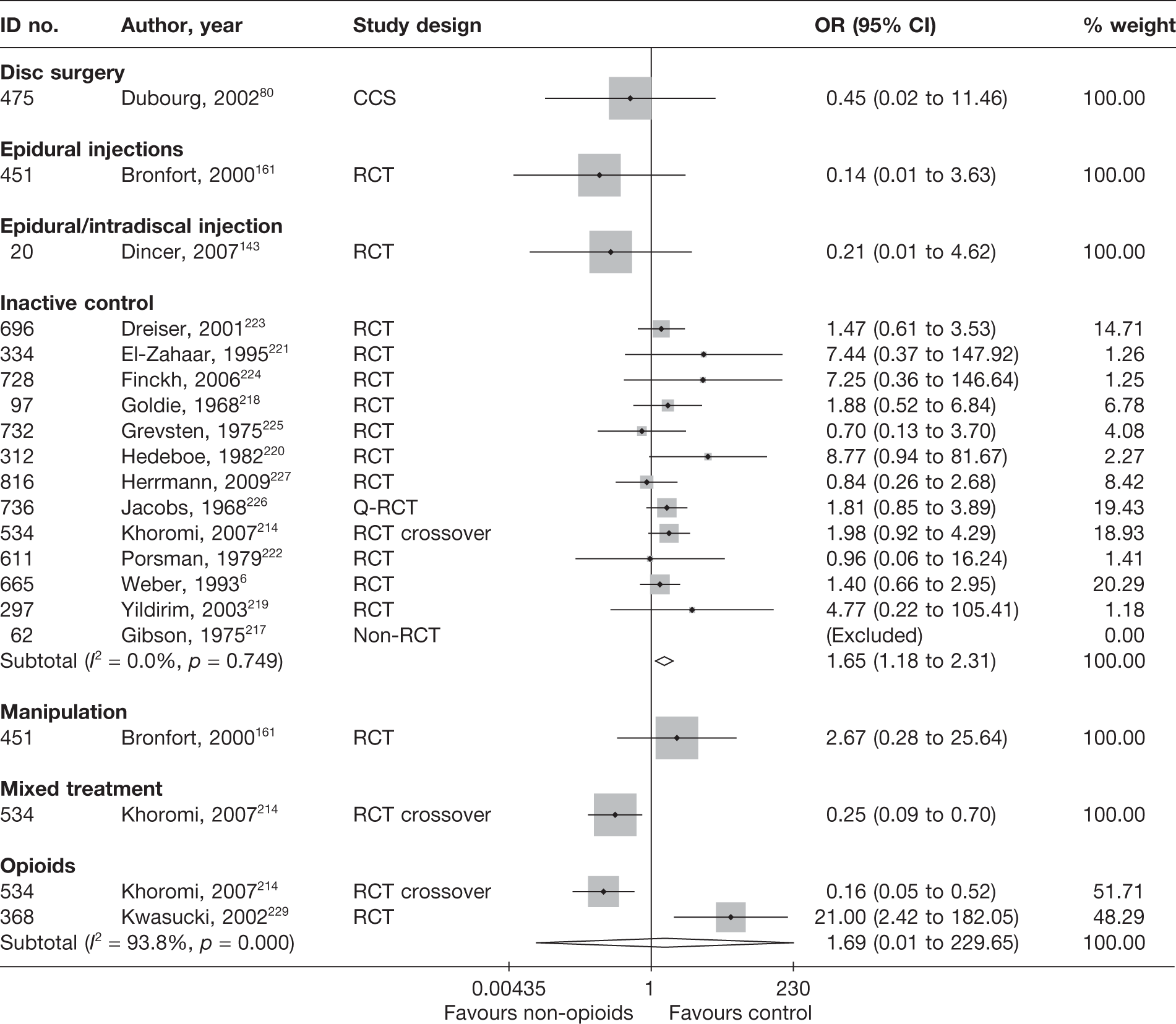

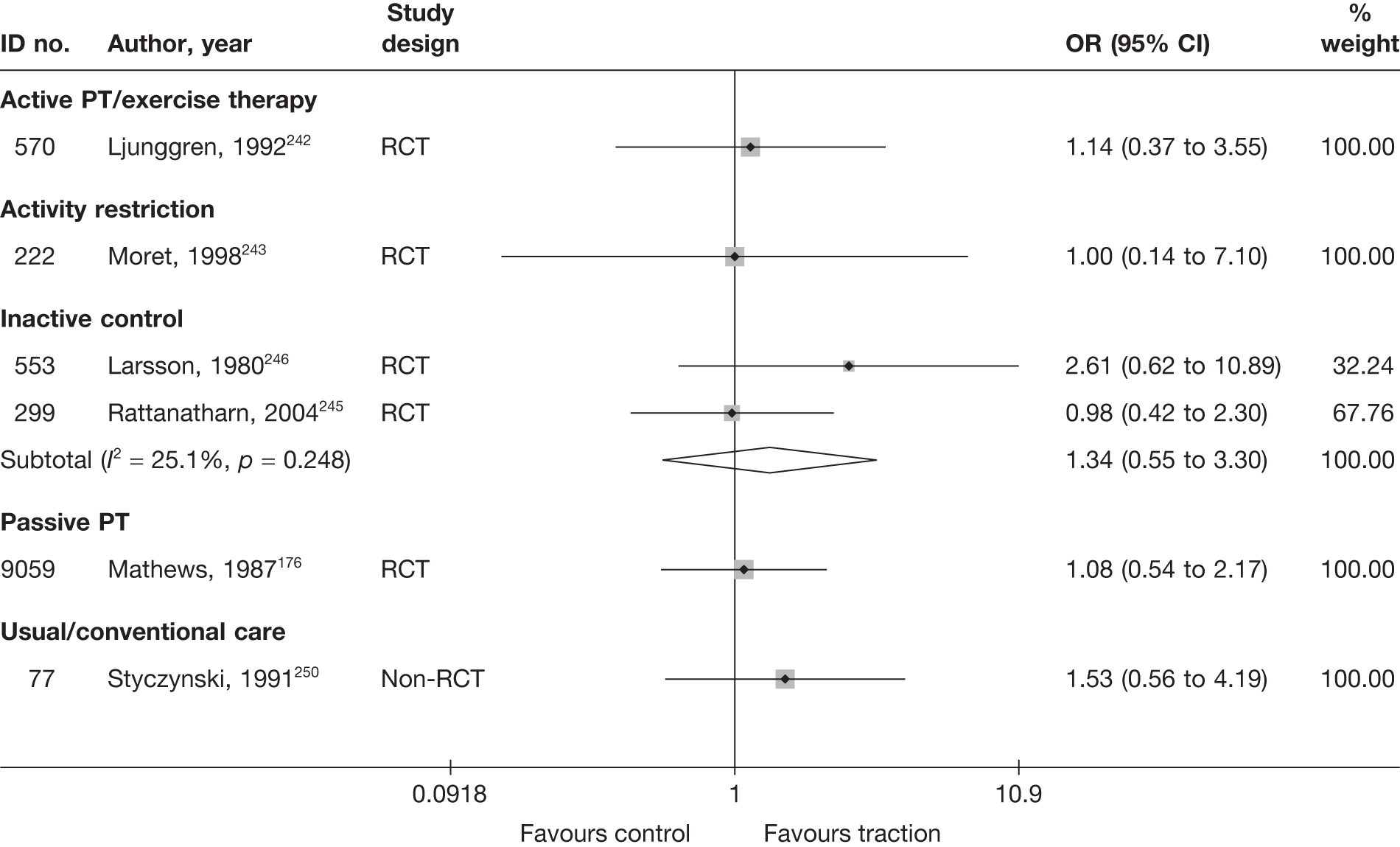

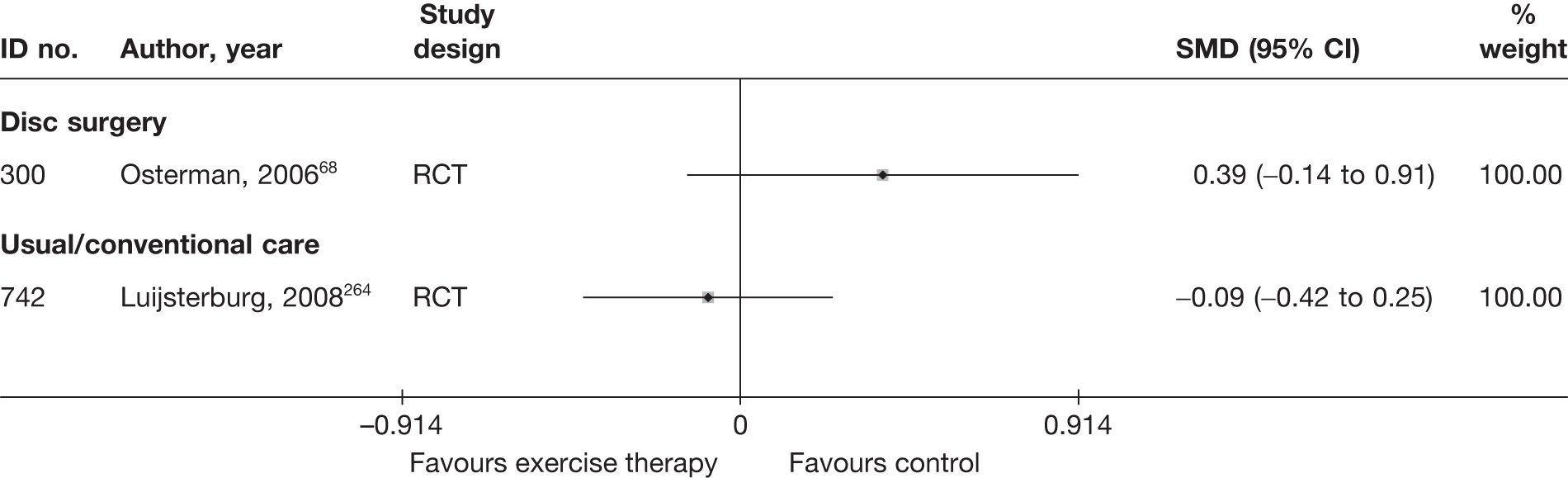

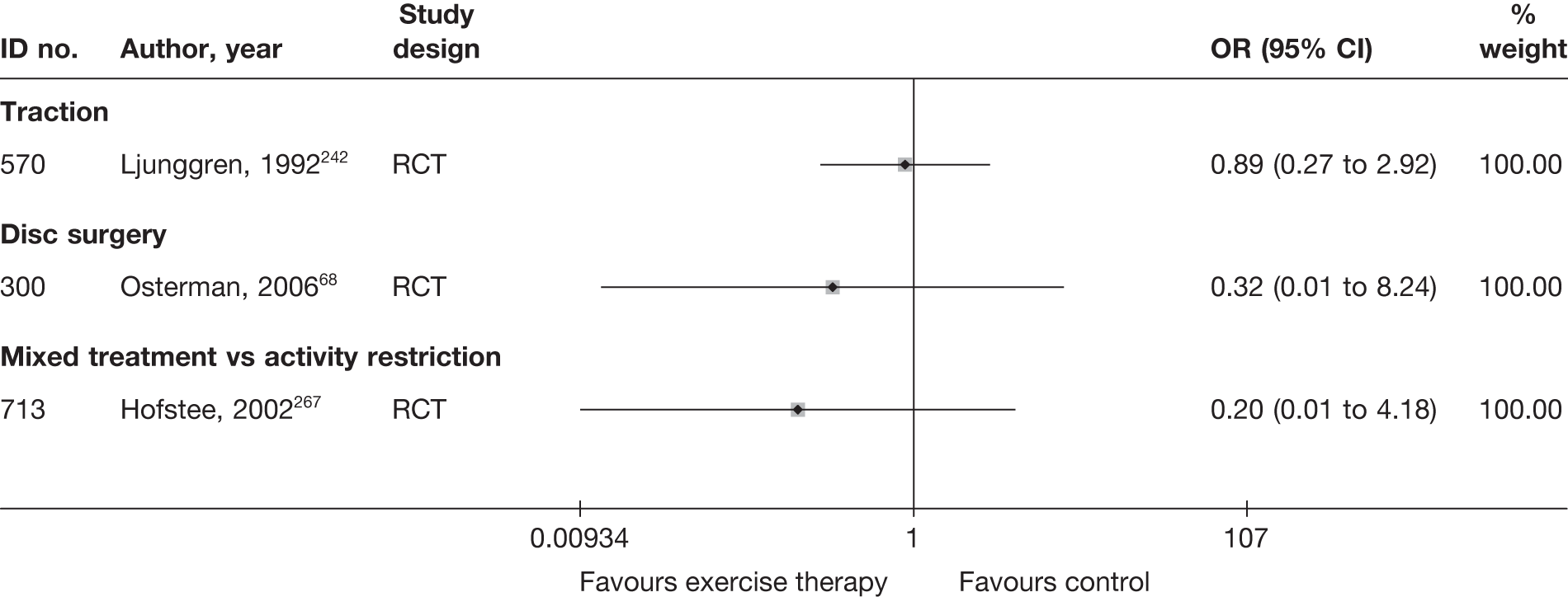

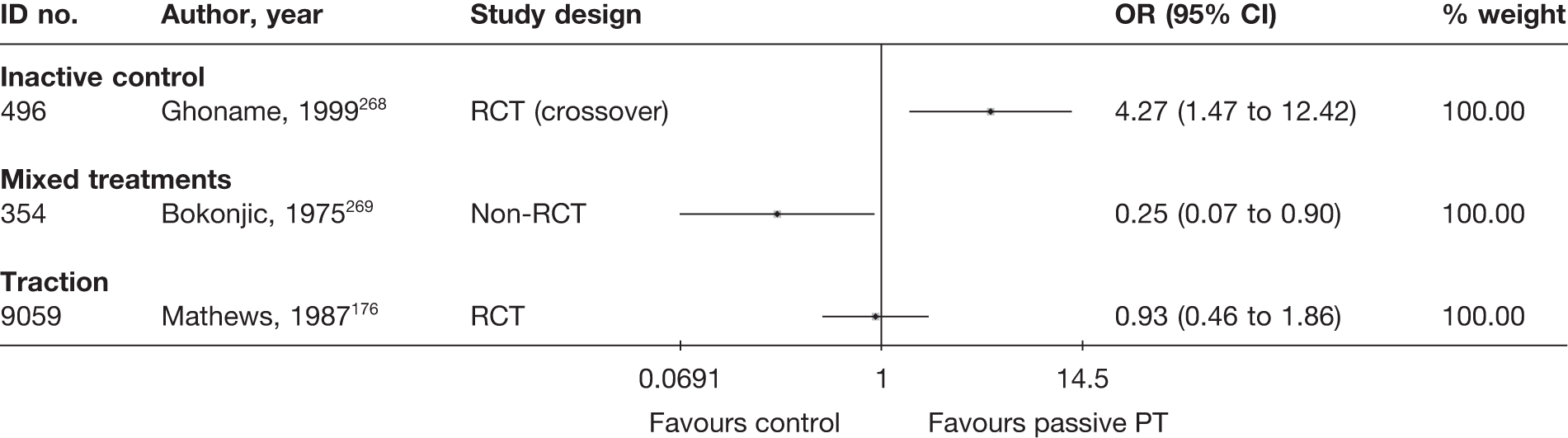

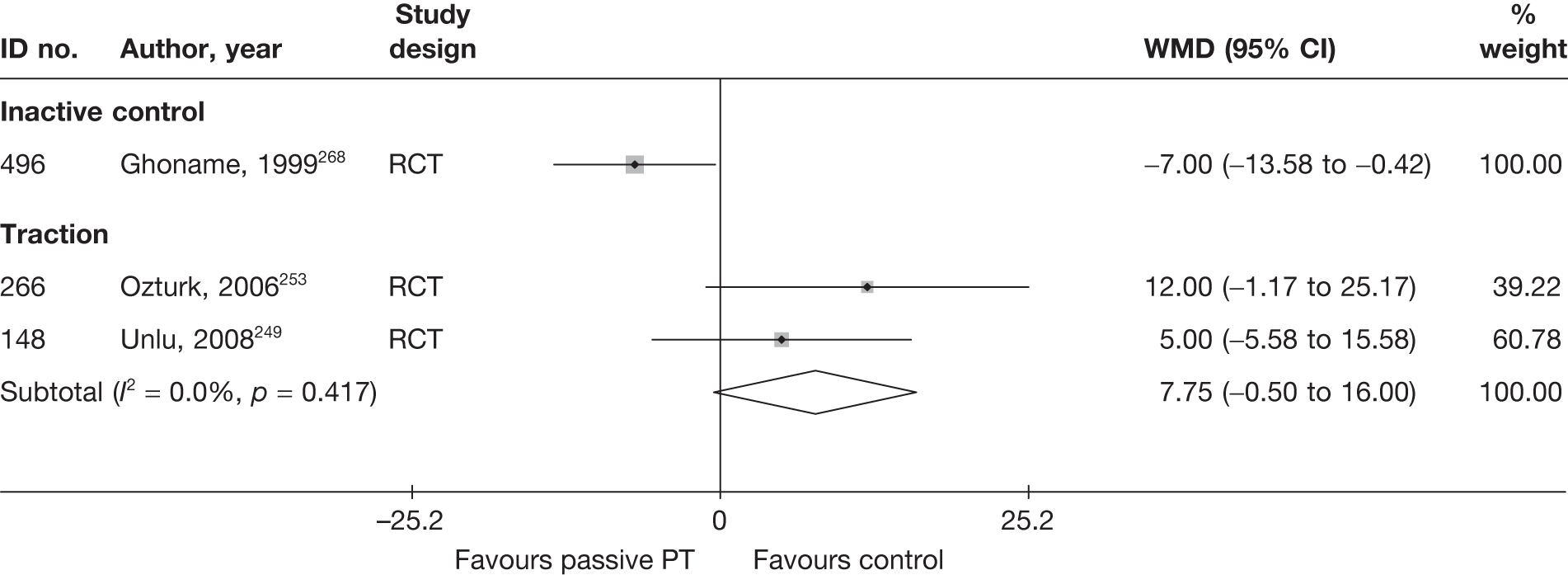

Results are presented in structured tables and forest plots, grouped according to the treatment category being evaluated (see Table 1). Studies were pooled using the random effects model43 in Stata (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with between-study heterogeneity examined using I2 and chi-squared statistics. [There were insufficient studies to use individual treatments (level 3) as separate meta-analyses.]

Although studies comparing different interventions that fell into the same category were included in the review, their findings are not reported here, e.g. studies comparing different types of surgery or different types of epidural injections.

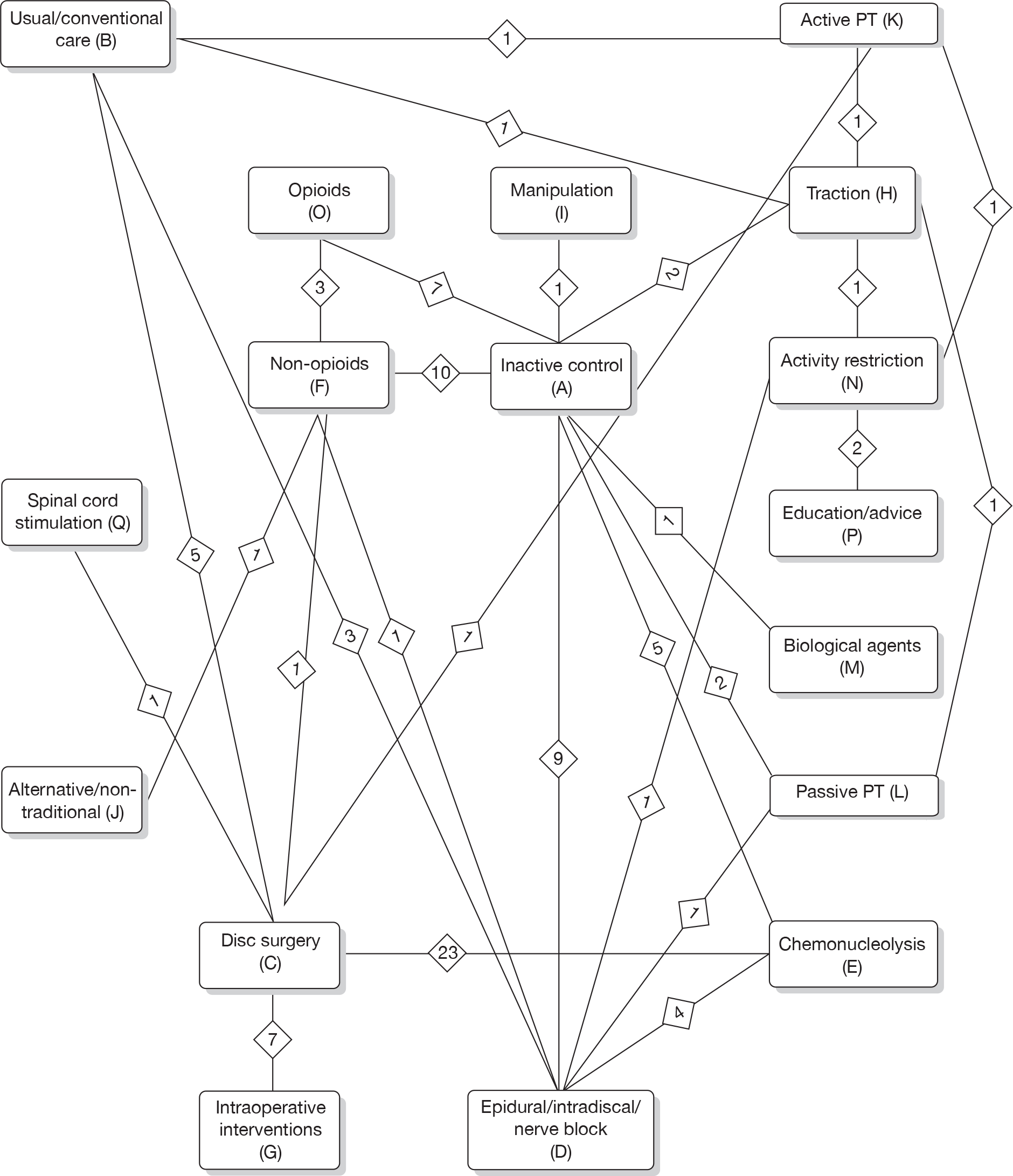

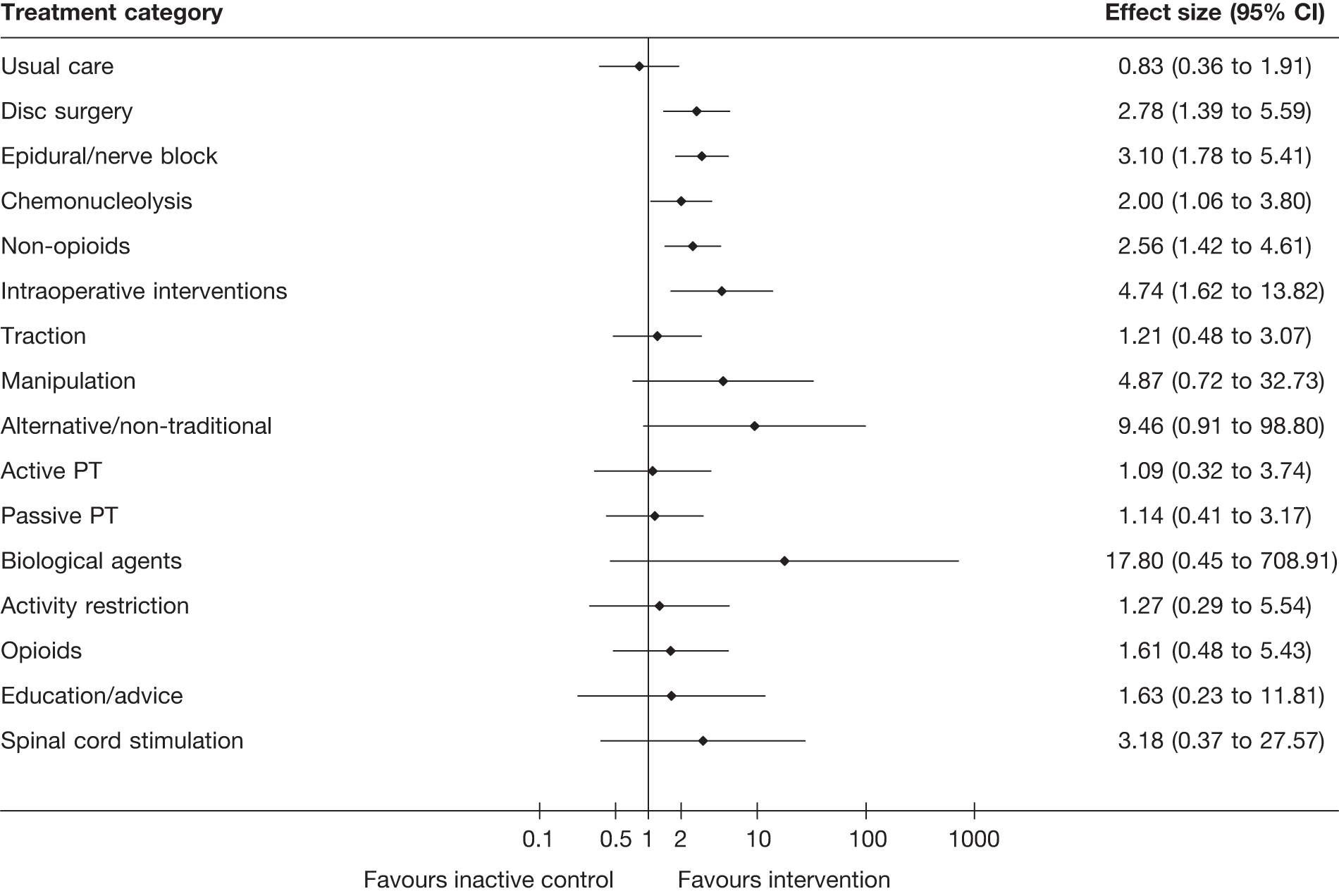

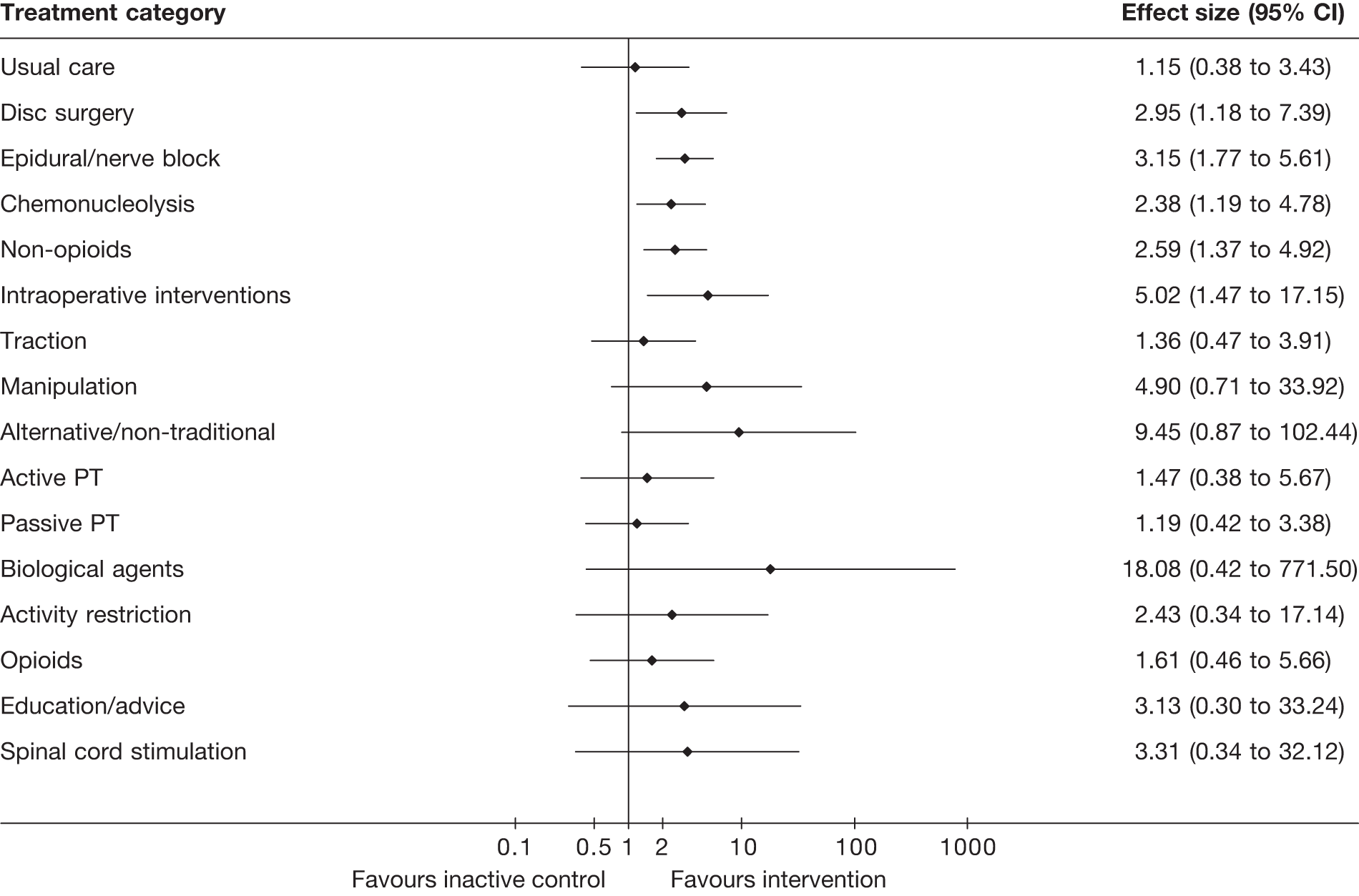

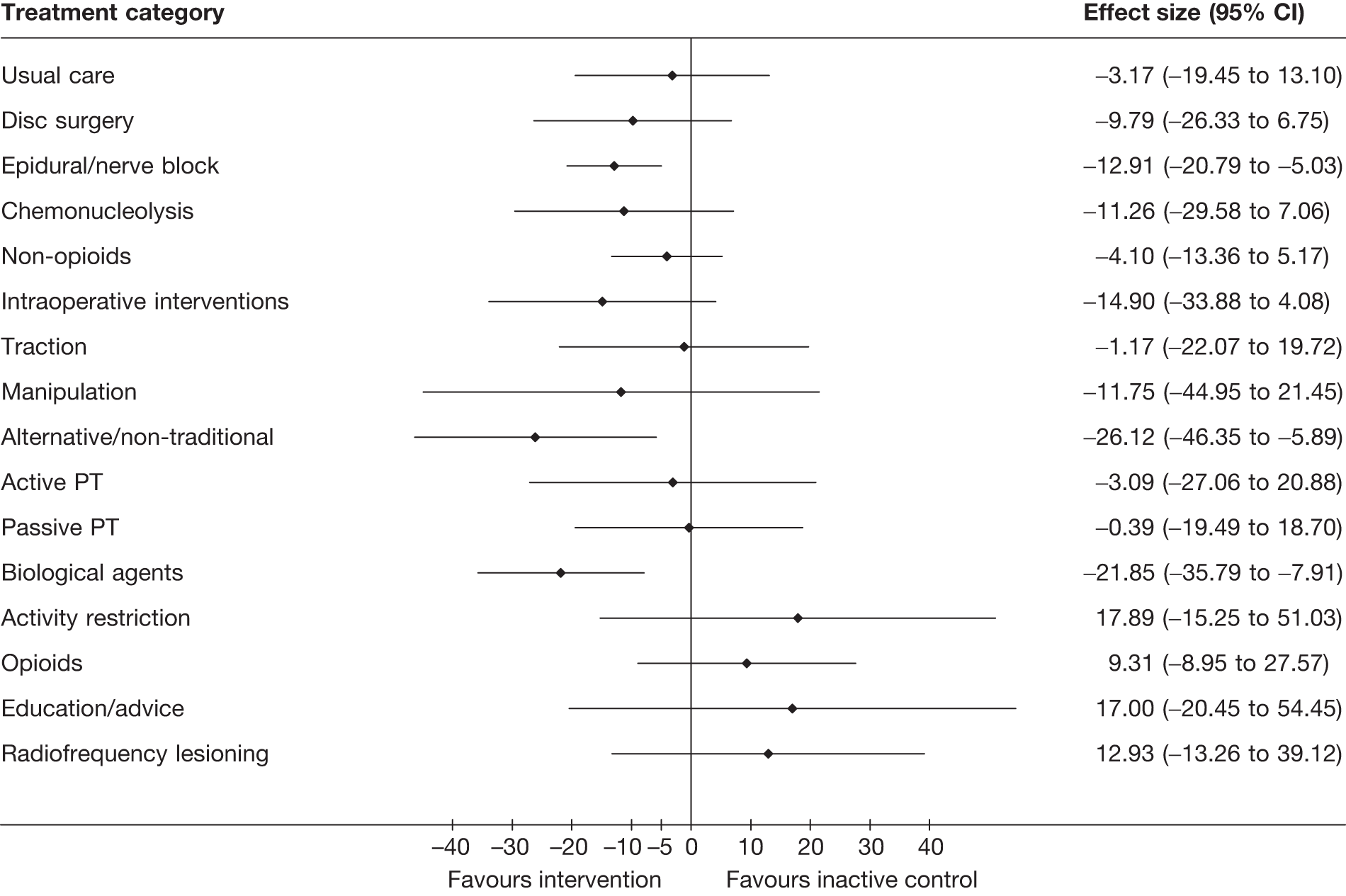

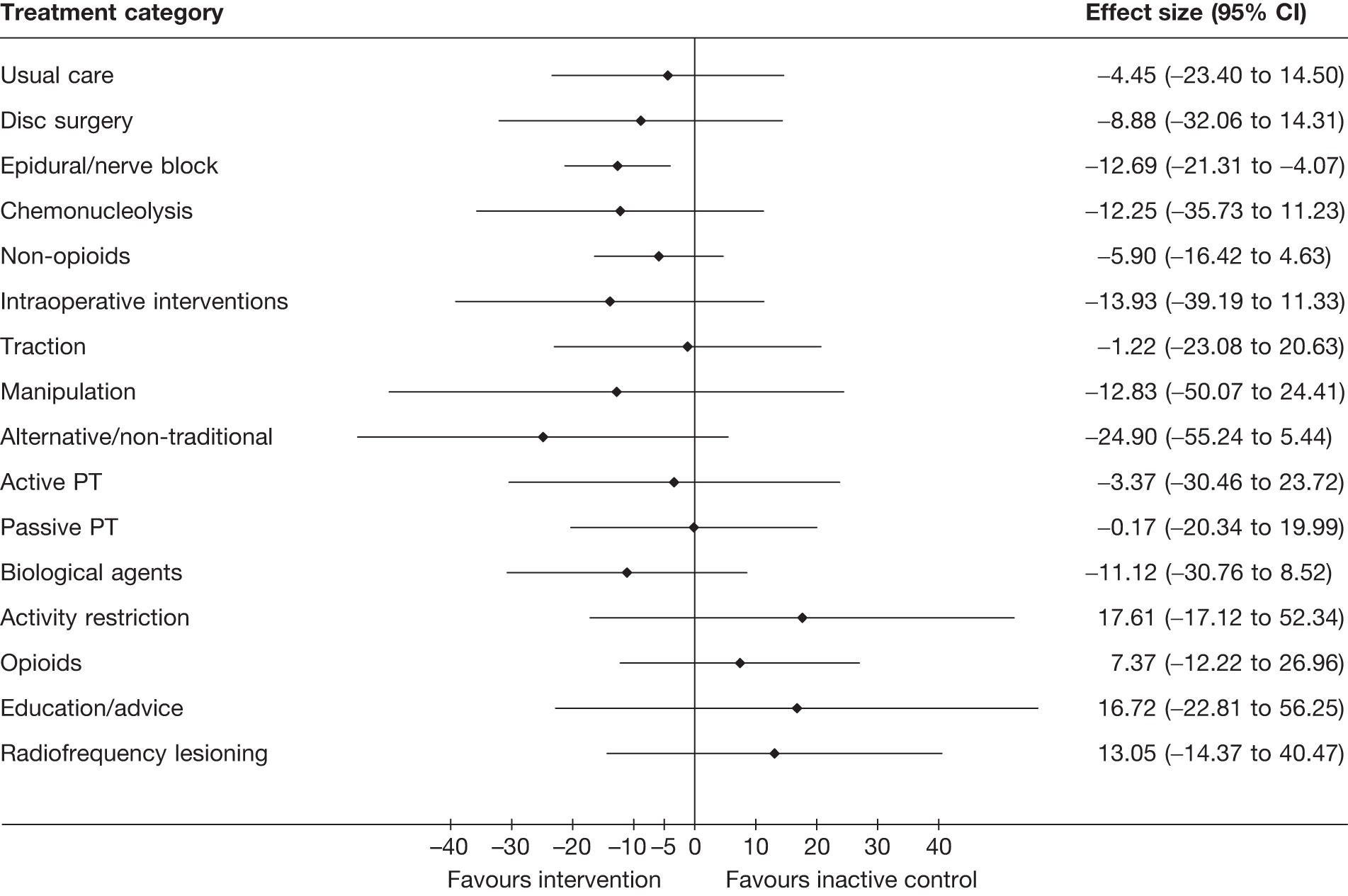

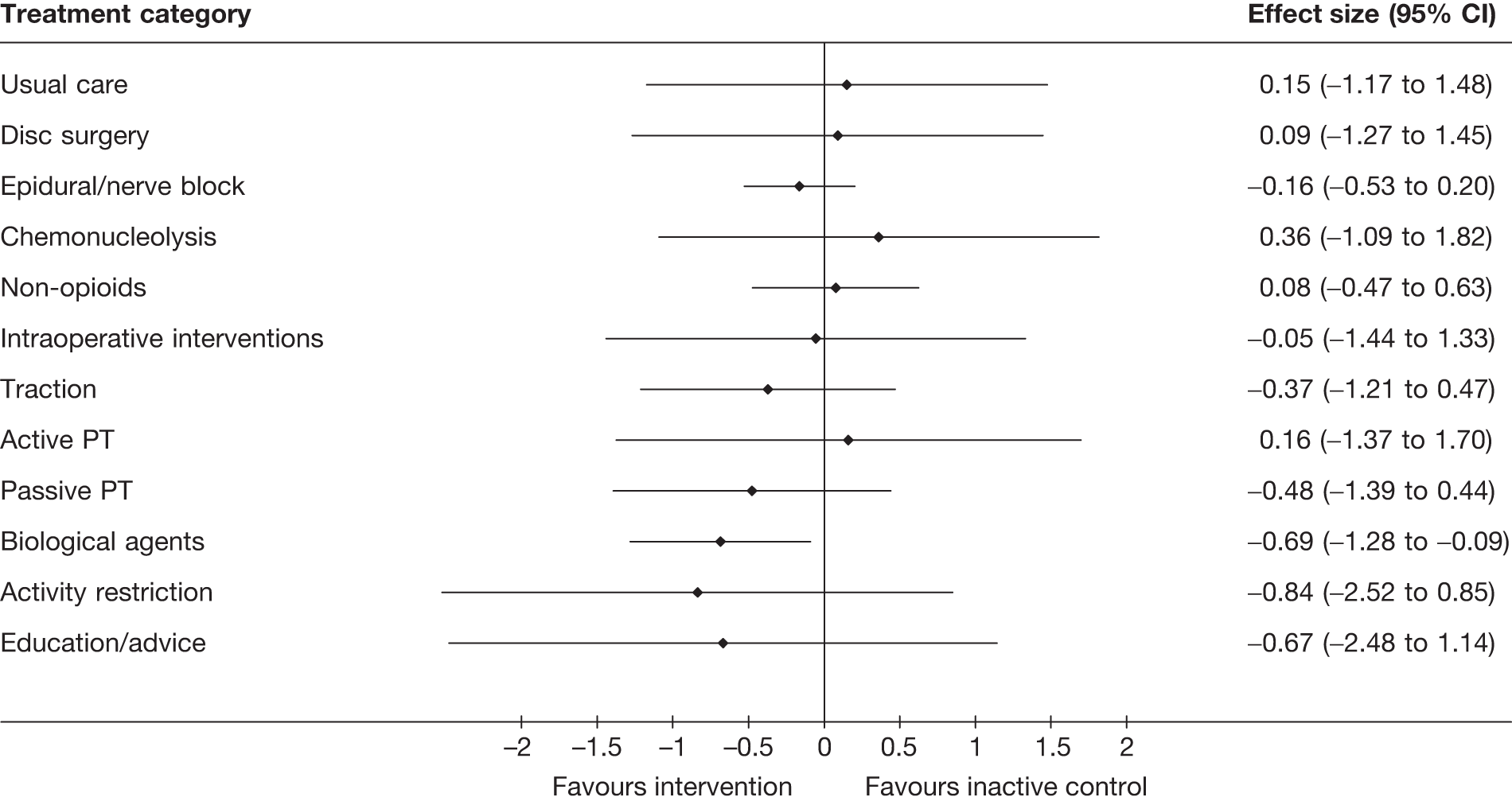

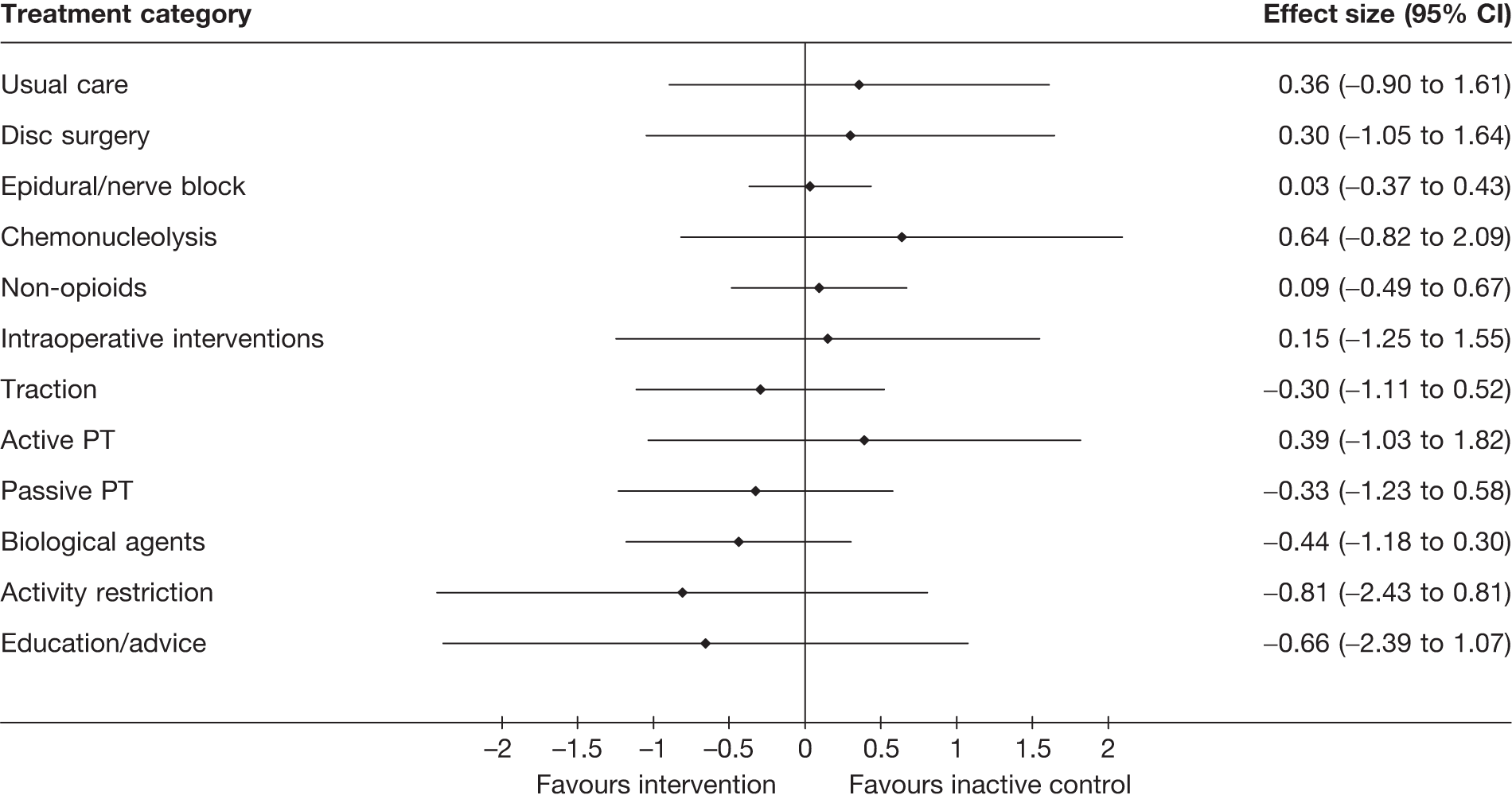

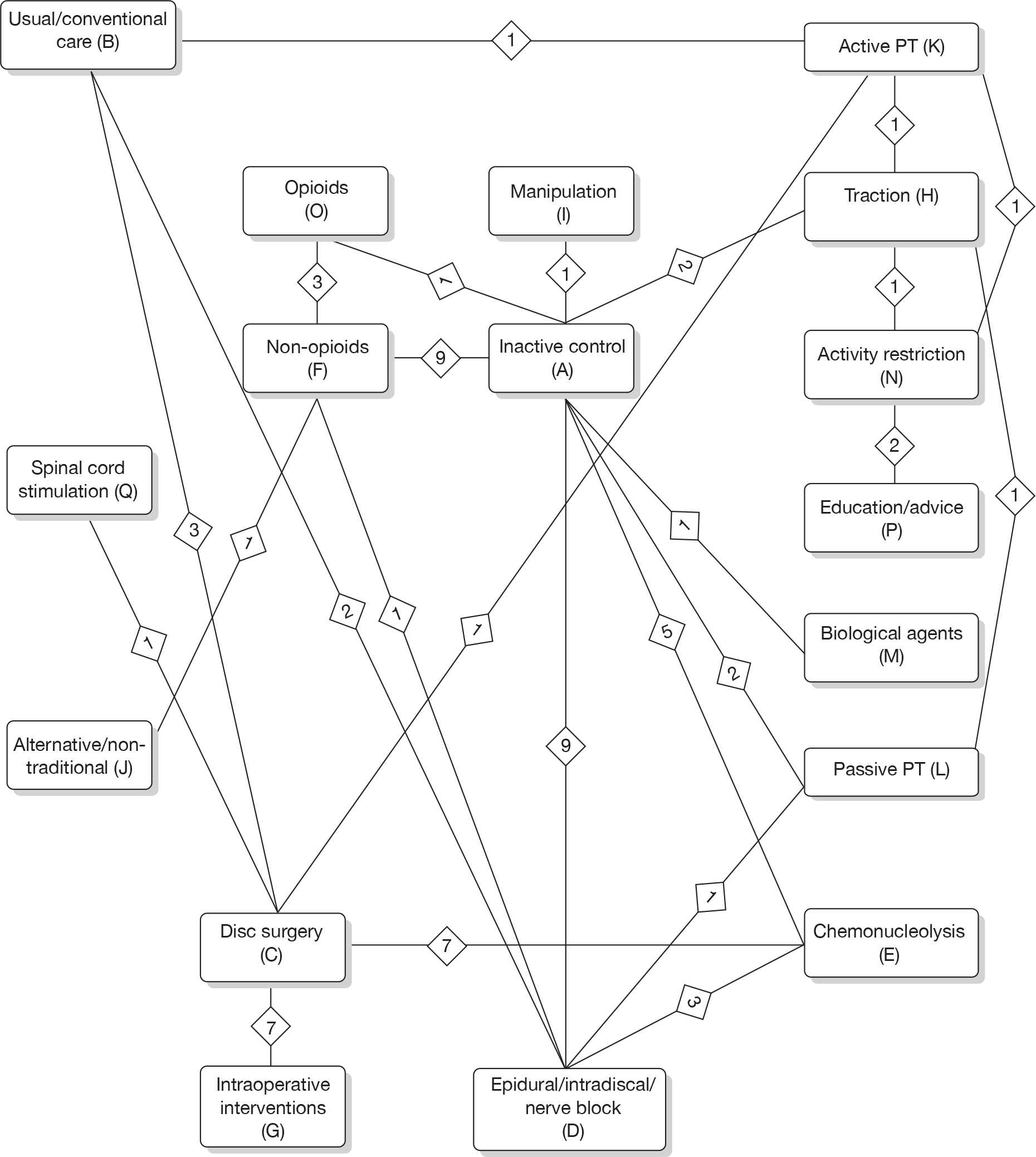

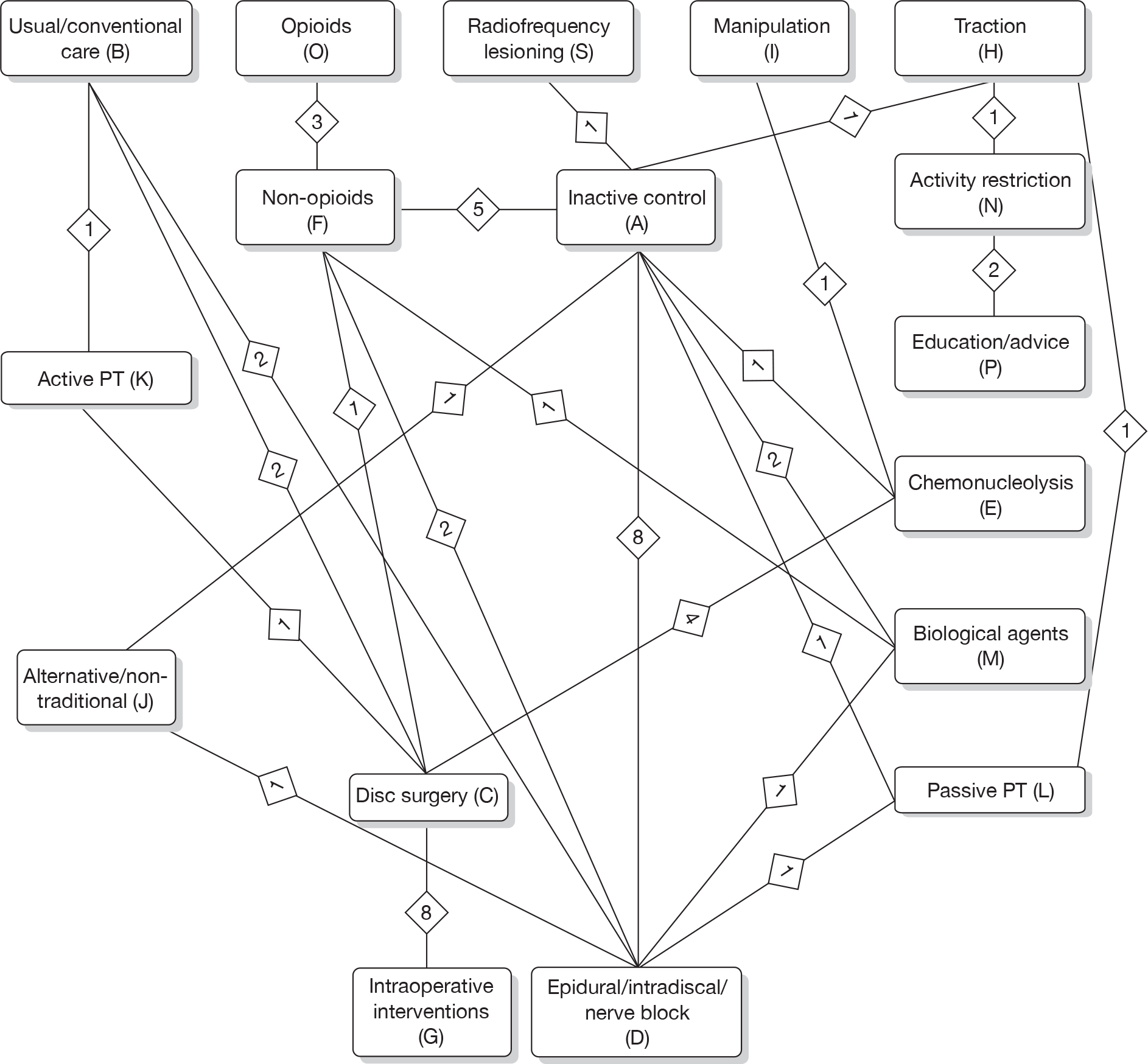

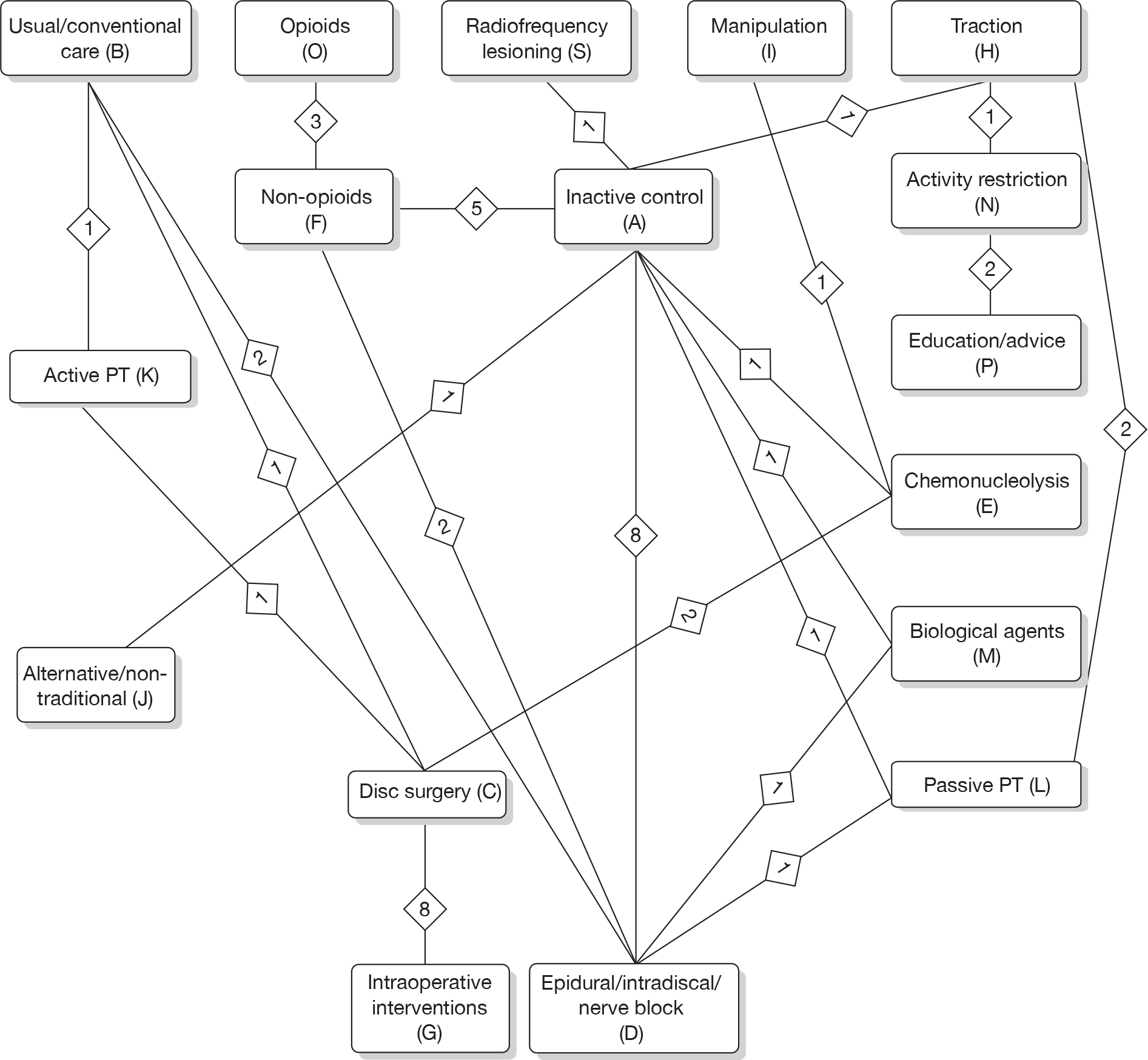

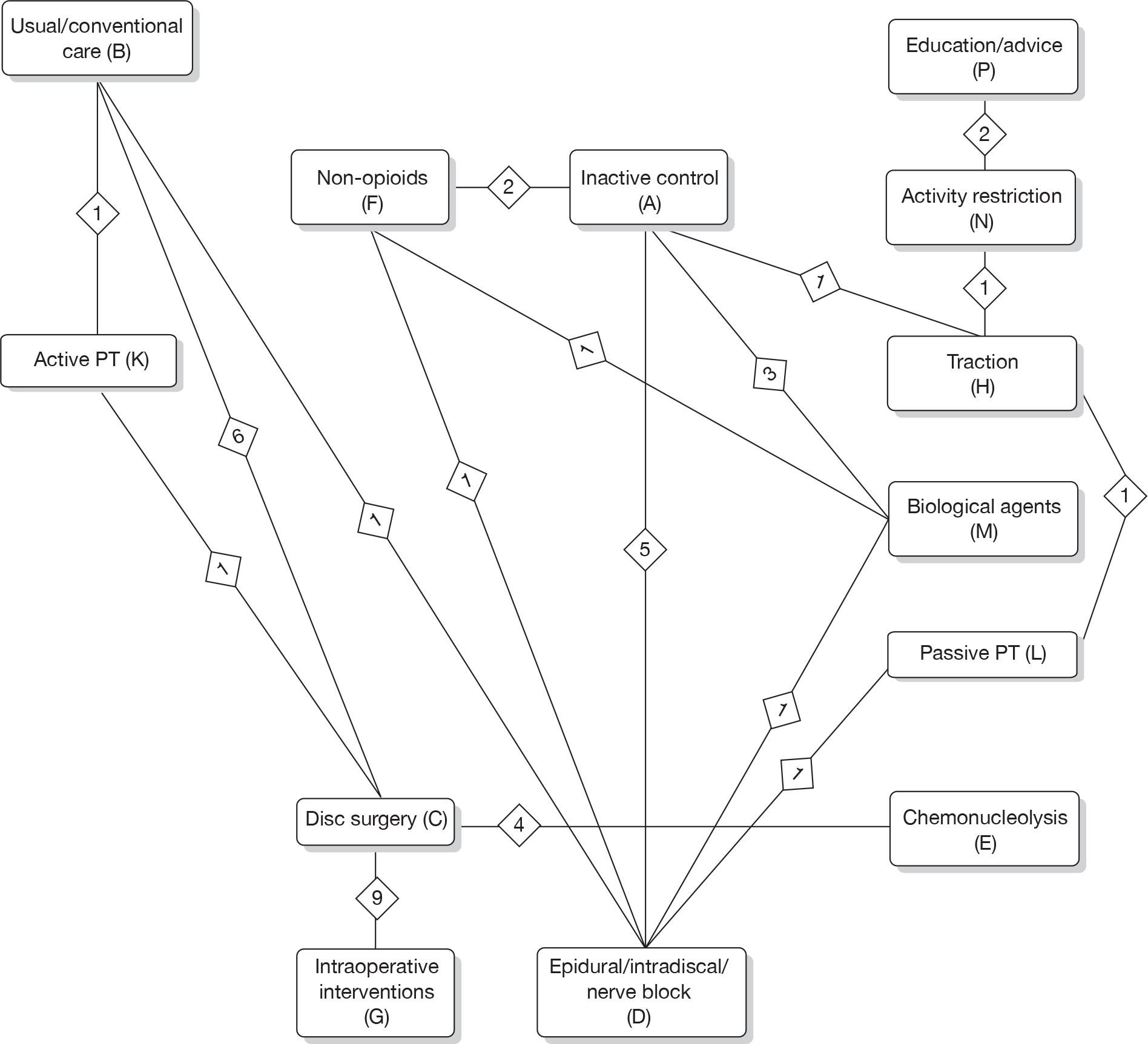

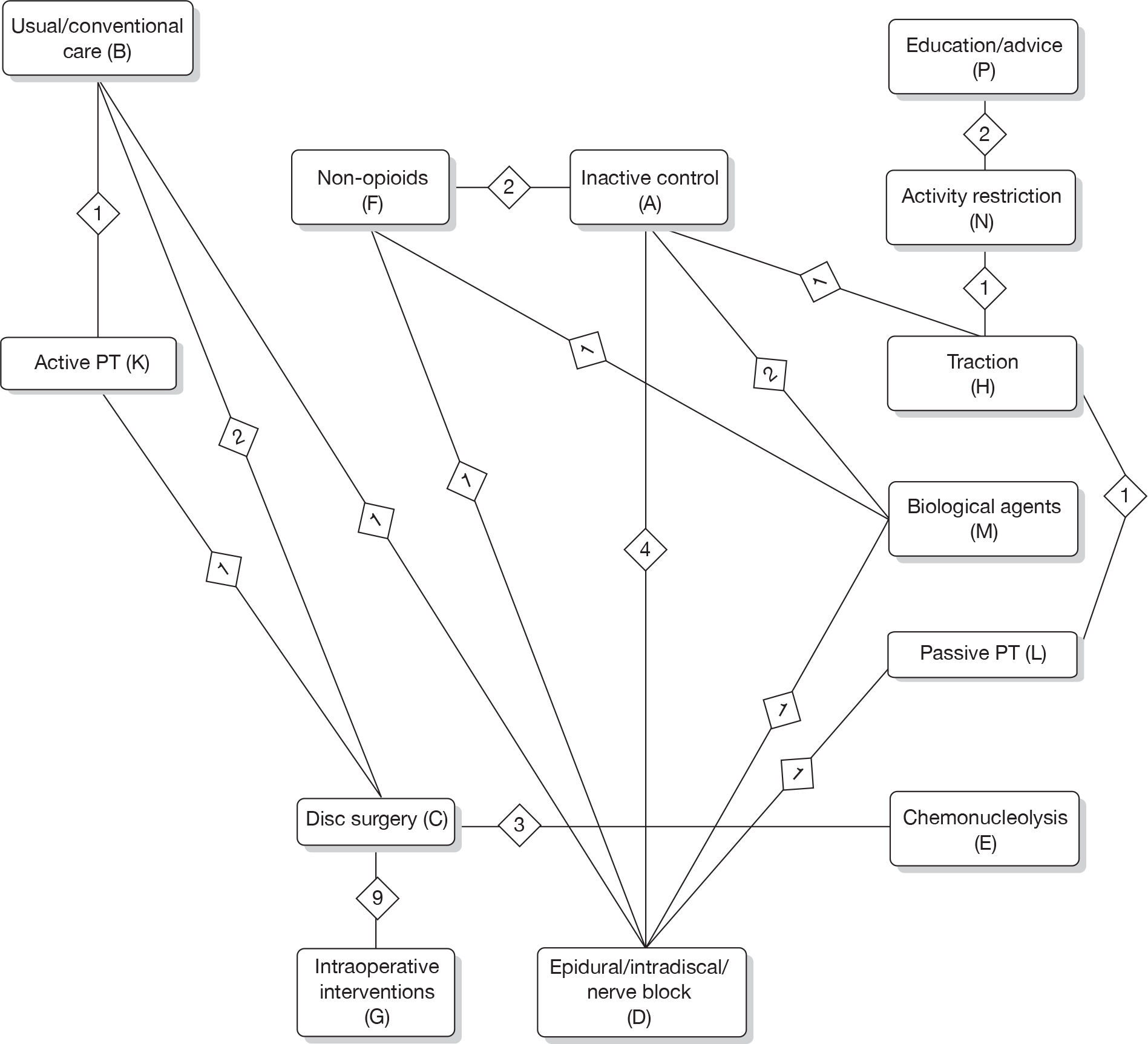

Mixed treatment comparison meta-analyses

Prior to performing the MTC we checked whether or not the included studies formed a closed network using level 2 treatment categorisations (see Table 1) [there were insufficient data to use individual (level 3) treatments as nodes]. Studies evaluating mixed treatments (or combination therapy) were excluded, because of the uncertainty regarding the extent of interaction between the combined interventions. For the MTC, only one time point was considered, with the findings from individual studies closest to 6 months’ follow-up used in the analyses. Analyses were conducted for global effect, pain intensity and CSOMs, for all study designs and after excluding observational studies and non-RCTs.

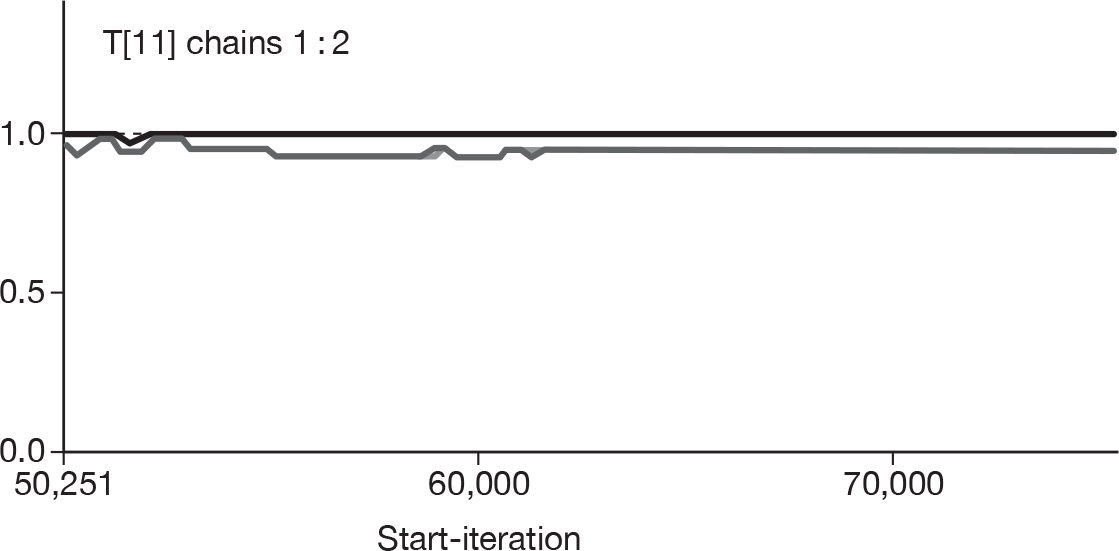

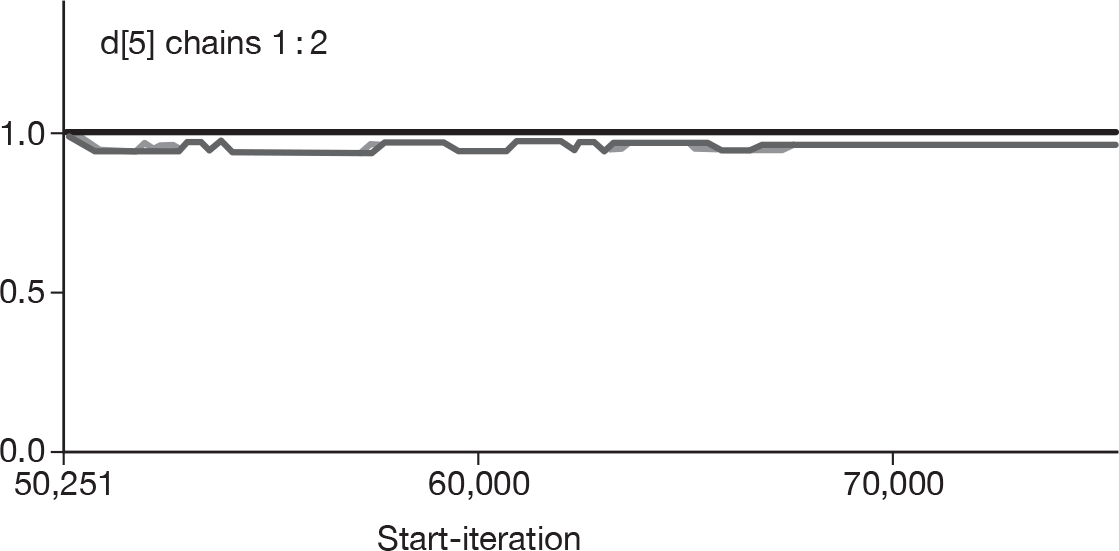

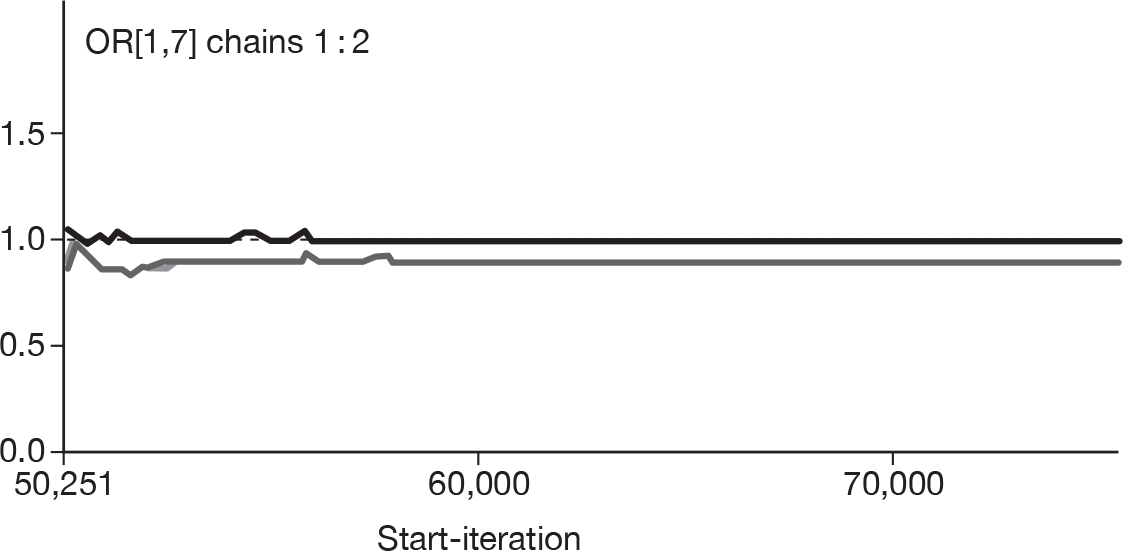

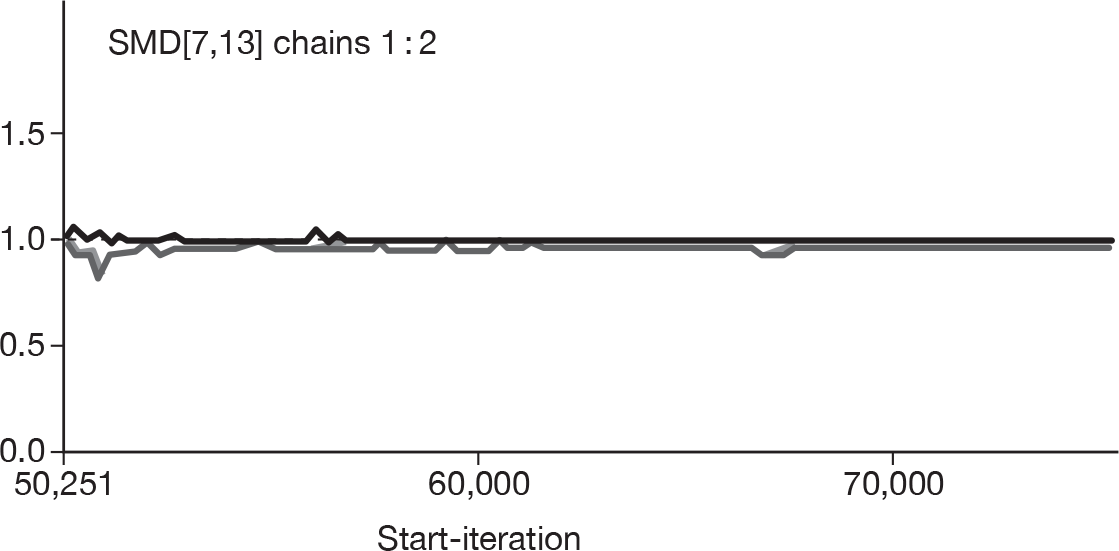

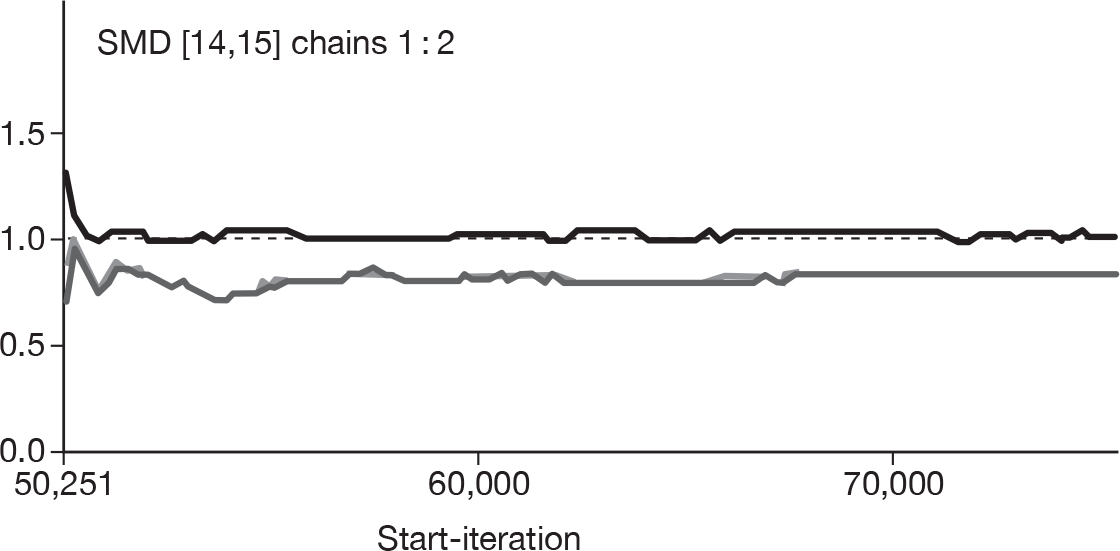

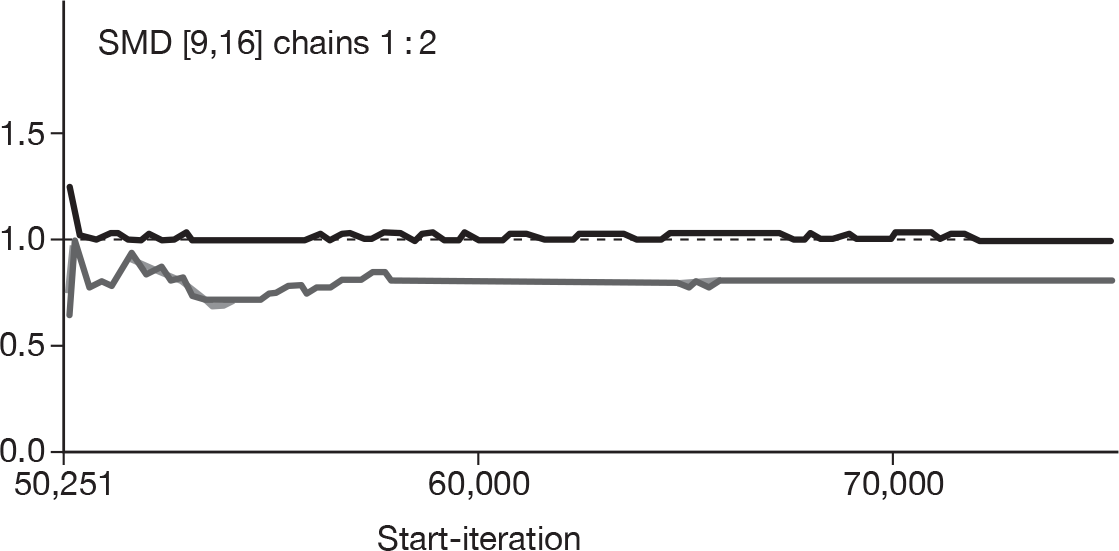

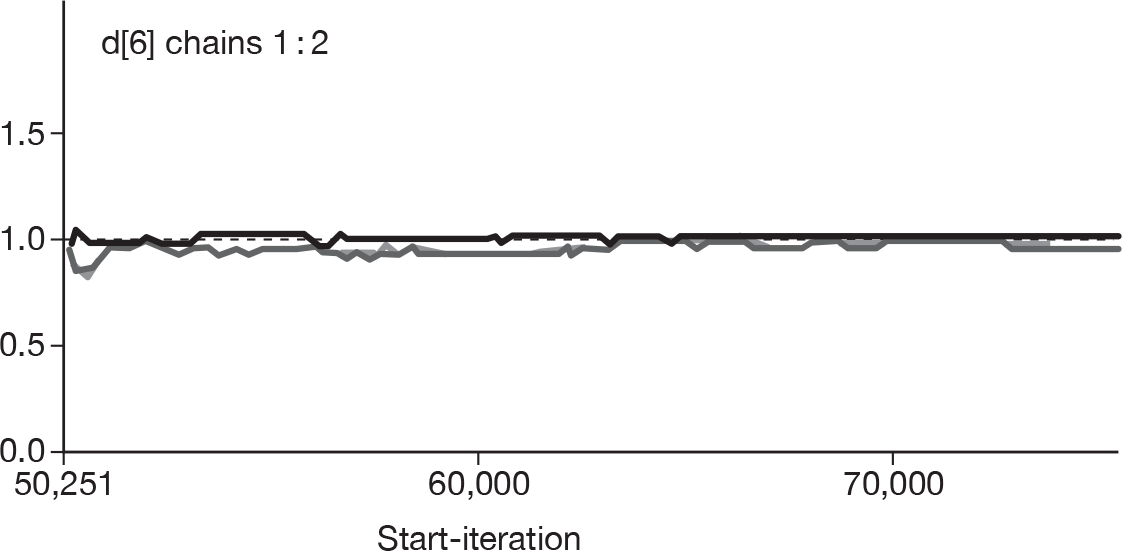

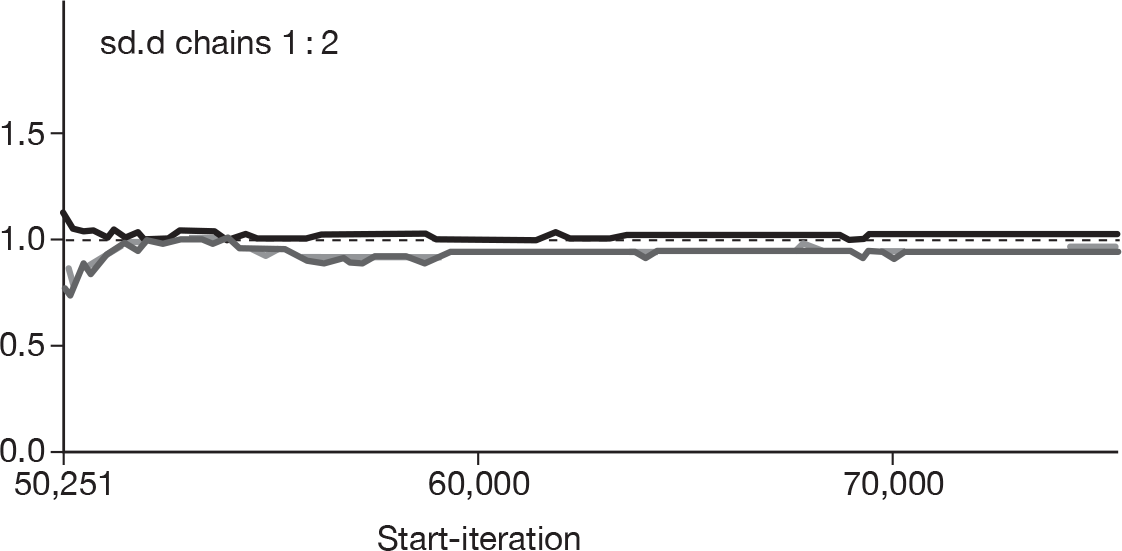

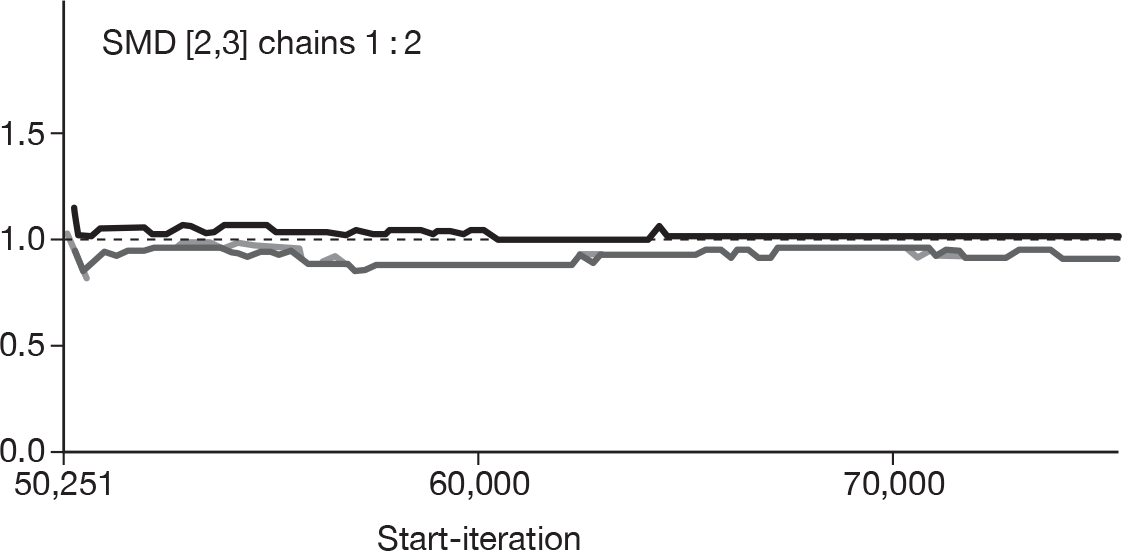

The analyses were performed by the Multi-parameter Evidence Synthesis Research Group in the Bayesian framework and the modelling computed with Markov chain Monte Carlo stimulation methods using Winbugs (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). The codes that were used are presented in the Appendix 3 and are based on those used elsewhere. 44 An inactive control was used as the reference treatment. In all cases, an initial burn-in of at least 50,000 stimulations was discarded and all the results presented are based on a further sample of at least 50,000 stimulations. Convergence was assessed using the Brooks–Gelman–Rubin diagnostic tool in Winbugs and the inspection of the auto-correlation and history plots. The model fit was checked by the global goodness of fit statistic, residual deviance. If the model is an adequate fit, it is expected that the residual deviance would be roughly equal to the number of unconditional data points.

The main parameters of interest in an MTC are the estimates of effects of treatments B, C, D, etc. relative to a baseline ‘treatment’ A (which is considered as a ‘nuisance’ variable). In our review, ‘usual care’ was a treatment category that we were interested in, and we therefore considered inactive control to be the most appropriate ‘baseline’ comparator. We also included treatment categories such as non-opioids, which could similarly be used as a baseline comparator if considering the use of usual care.

Analysis of covariates

Where 10 or more studies were included in the pair-wise meta-analyses described in Chapter 6, it had been our intention to evaluate the effect of study-level covariates (e.g. symptom duration used and study quality criteria such as adequate randomisation procedure, adequate allocation concealment, > 80% followed up and blind outcome assessment) on between-study heterogeneity using metaregression, but only one comparison (disc surgery vs chemonucleolysis for global effect at long-term follow-up) included sufficient studies. The possible effect of covariates such as study design, study quality and duration of symptoms on pooled results has been discussed when summarising the findings.

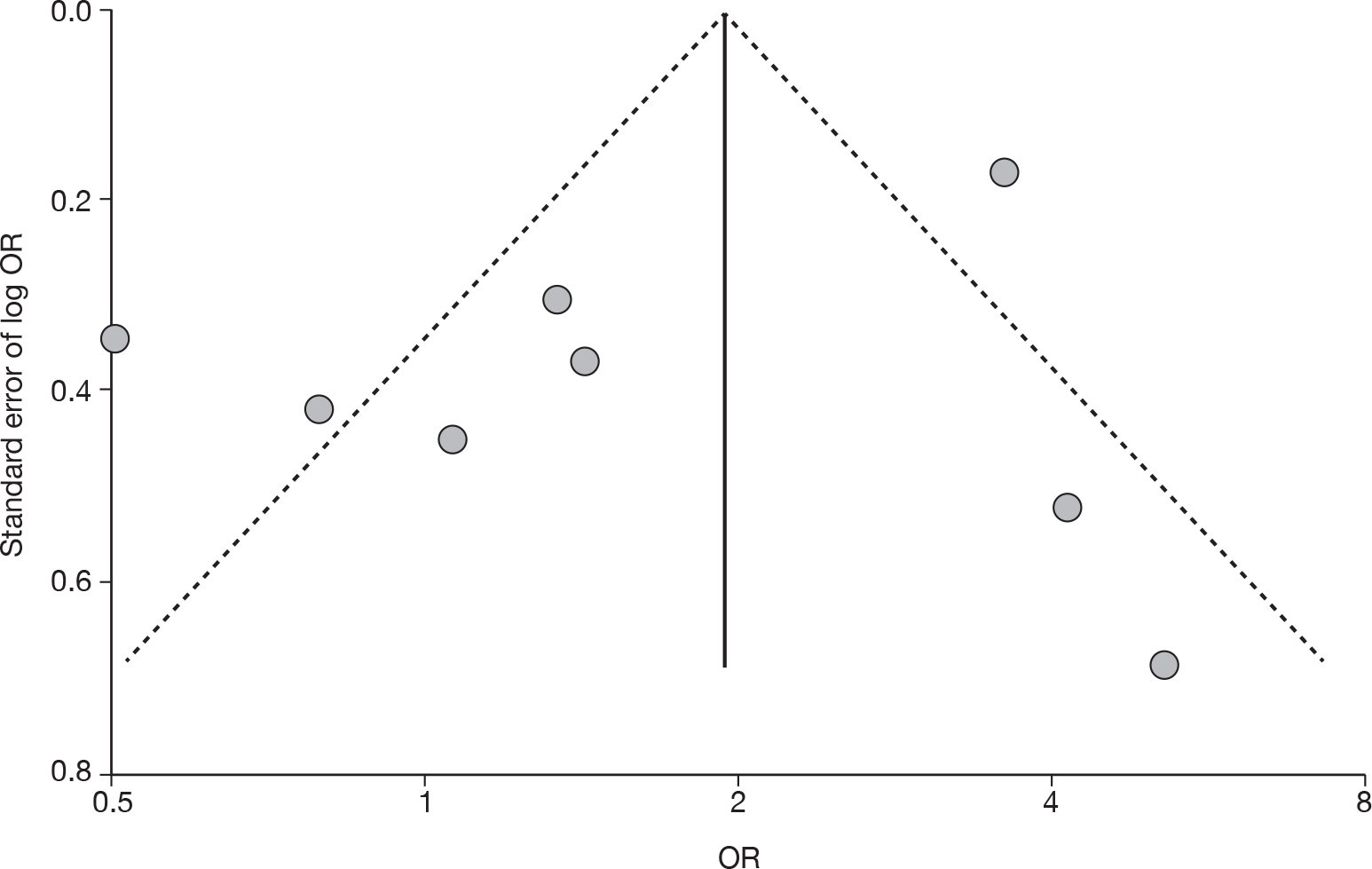

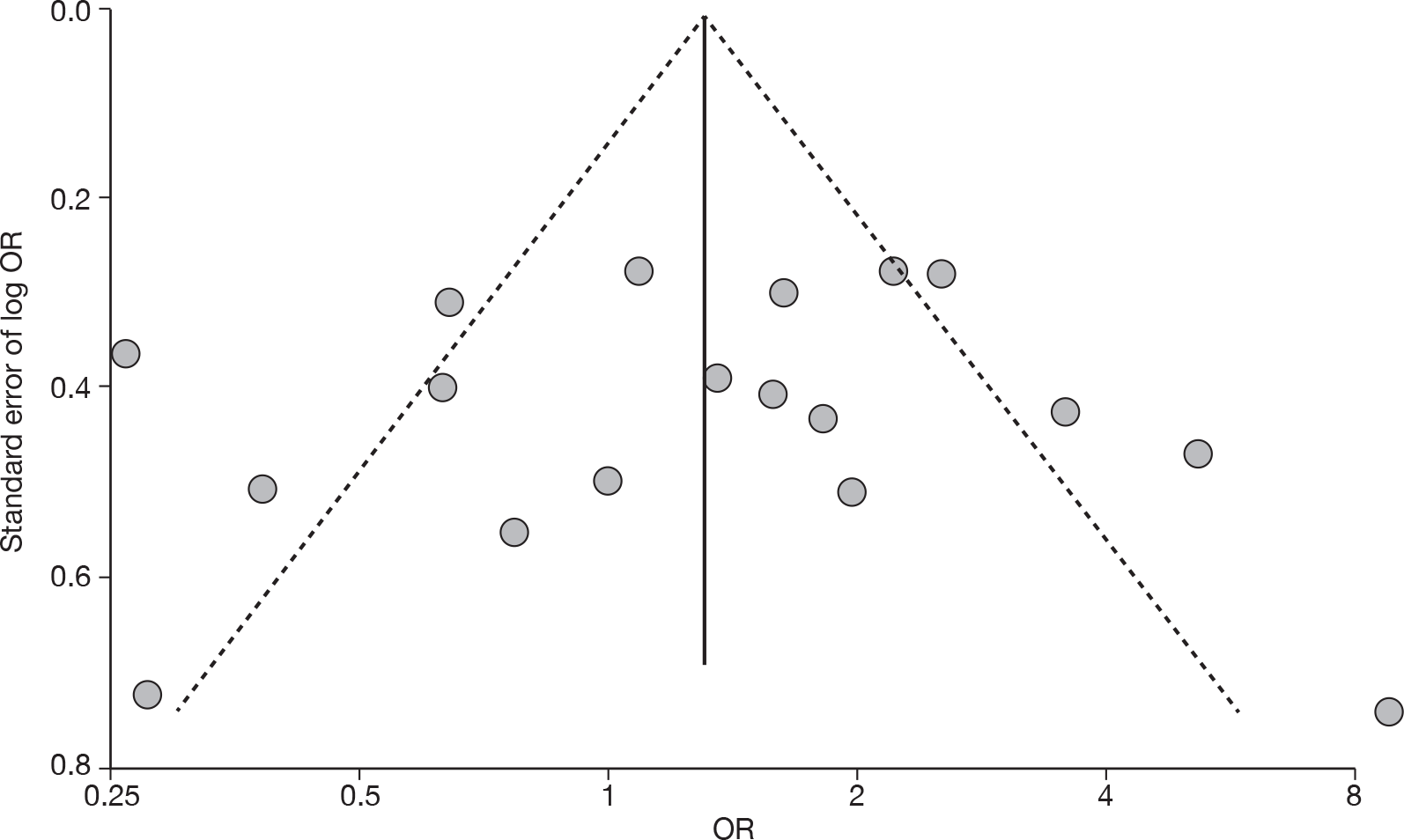

Publication bias

For all comparisons for which there were more than eight studies, funnel plots together with associated statistical tests were used to assess the potential publication bias.

Economic evaluations

Given the nature and lack of homogeneity between included economic evaluations, we performed a narrative review of the included studies and made overall conclusions. Details of each published economic evaluation, together with a critical appraisal of its quality, are presented in structured tables with a narrative summary. Where appropriate and where the data permitted, indications of the uncertainty underlying the estimation of the differential cost and effects of the alternative treatment options were summarised.

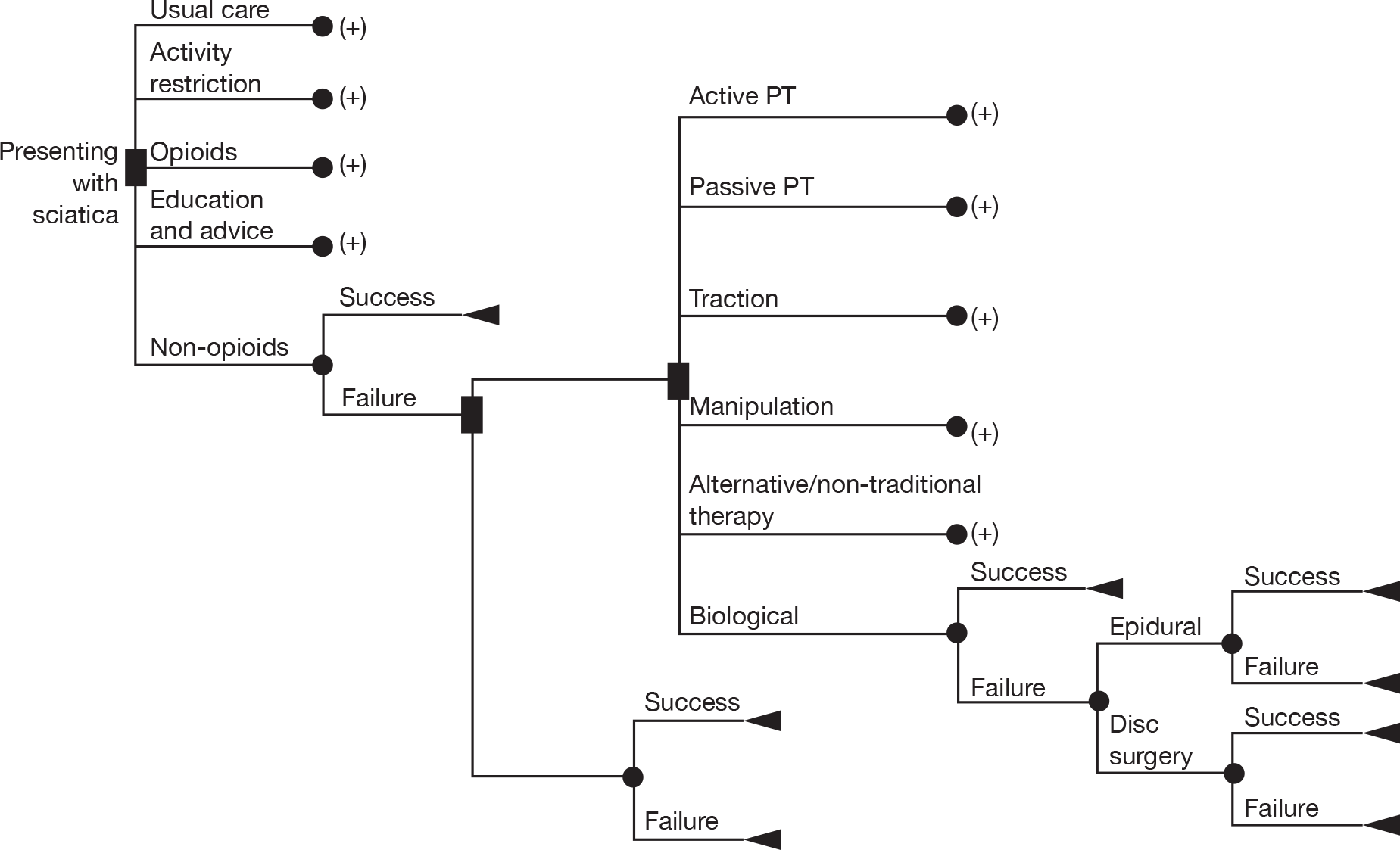

Economic model

The methods and results of the economic model are reported separately in Chapter 9.

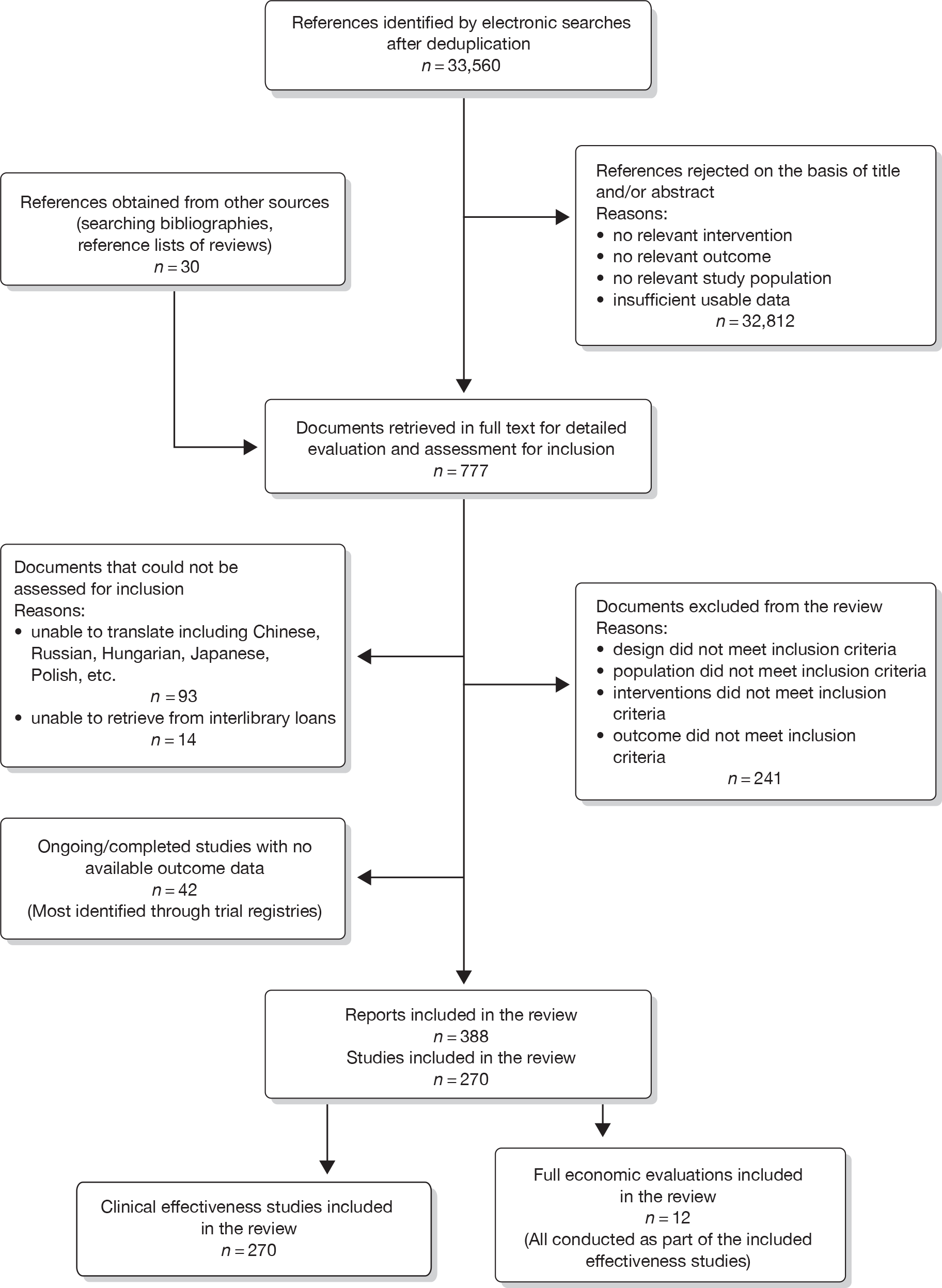

Chapter 5 Results of searches

The electronic searches identified 33,560 references and a further 30 references were identified by hand searching. Of these, 777 references were ordered and, after collating multiple publications, 270 studies that met the inclusion criteria were identified. These included 12 economic evaluations performed as part of the clinical effectiveness studies, but reported separately.

A flow diagram showing the number of references identified, retrieved and included in the review is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram showing the number of references identified, documents/studies retrieved for assessment and included in the review.

Forty-two ongoing or unpublished studies were identified while searching trial registries and are summarised in Appendix 4.

Seventeen (18%) out of 96 studies that reported data on CSOMs used more than one condition-specific outcome scale, five (5%) of which reported data on both RMDQ and ODI.

Chapter 6 Review of clinical effectiveness: results

The results of clinical effectiveness are presented for each intervention category separately, according to the order that interventions are listed in Table 1. Findings relating to usual care and inactive control are not reported separately (only as comparators for other interventions). Studies that evaluated mixed treatments are also not reported separately. Studies that compared interventions that fell under the same treatment category were included in the review as a whole, but their findings are not presented here. However, information on the type of interventions that they examined is presented (see Chapter 4, Standard pair-wise meta-analysis).

The results are presented for overall recovery (global effect), pain intensity and back-specific functional status (CSOMs) at short-, medium- and long-term follow-up. The findings for any adverse effects that occurred during the study (overall follow-up) are also reported.

Details of the quality assessment of individual studies are presented in Appendix 5.

Disc surgery (including intraoperative interventions)

Intraoperative interventions have been considered as a separate intervention category to disc surgery in the MTC and are therefore treated the same here. Intraoperative interventions are supplemental procedures undertaken during surgery, such as the application of steroids or free fat grafts.

Description of disc surgery studies

Summary of interventions

A total of 97 studies evaluated disc surgery for sciatica. 45–141 Sixty-three of these studies compared disc surgery with an alternative type of intervention (including intraoperative). 45–107 The type of interventions being compared are listed in Table 3a. One of theses studies,46 which compared disc surgery with chemonucleolysis, did not include useable comparative data and reported only descriptive results for change from baseline for each group separately. One further study61 did not report any data on global effect, pain intensity or CSOMs.

| ID no. | Author, year | Study design | Treatment description | Control description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc surgery vs chemonucleolysis | ||||

| 884 | Alexander, 1989103 | CCS | Disc surgery (removal of protruding disc fragment only + free fat graft) | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (2000 U) |

| 43 | van Alphen, 198947 | RCT | Discectomy with emptying of disc space | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) |

| 441 | Bonafe, 199375 (French language) | CCS | Percutaneous automated nucleotomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) |

| 183 | Bouillet, 198361 | CCS | Conventional lumbar disc surgery | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain injections |

| 453 | Brown, 198976 | CCS | Disc surgery | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 453 | Brown, 198976 | CCS | Disc surgery | Collagenase chemonucleolysis |

| 454 | Buric, 200577 | Non-RCT | Standard microdiscectomy | Chemonucleolysis with ozone–oxygen mixture |

| 166 | Crawshaw, 198460 | RCT | Disc surgery | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) |

| 48 | Dabezies, 197851 | CCS | Laminectomy with or without fusion | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (2 ml) |

| 471 | Dei-Anang, 199079 (German language) | CCS | Percutaneous nucleotomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) or collagenase (600 U) |

| 727 | Ejeskar, 198396 | RCT | Discectomy with unilateral laminotomy and removal of disc hernia only | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (400 IU) |

| 132 | Hoogmartens, 197656 | HCS | Discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 44 | Javid, 199548 | CCS | Partial hemilaminectomy using magnification and fat graft | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (3000 IU) |

| 35 | Krugluger, 200046 | RCT | Automated percutaneous discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymodiactin (4000 U) |

| 117 | Lagarrigue, 199154 (French language) | CCS | Discectomy with minimal bony resection | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (2000–5000 U) |

| 129 | Lavignolle, 198755 (French language) | RCT |

Microscopic discectomy Unilateral limited interlaminar |

Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) |

| 889 | Lee, 1996104 (German language) | CCS | Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 889 | Lee, 1996104 (German language) | CCS | Percutaneous manual and laser discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 593 | Muralikuttan, 199285 | RCT | Standard discectomy with fenestration, disc space cleared | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (2000 U) |

| 47 | Norton, 198650 | CCS | Conventional surgical discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 45 | Postacchini, 198749 | Non-RCT | Disc excision using unilateral laminotomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (2 ml) |

| 617 | Revel, 199388 | RCT | Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy | Chemonucleolysis |

| 641 | Steffen, 199990 (German language) | RCT | Laser disc decompression | Chemonucleolysis with chymodiactin (2 ml) |

| 49 | Stula, 199052 (German language) | RCT | Conventional disc surgery | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (500 U) |

| 61 | Tregonning, 199153 | CCS | Fenestration or partial laminectomy removing extruded disc material | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 893 | Watters,1988105 | Non-RCT | Microdiscectomy with free fat graft over exposed dura | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4000 U) |

| 160 | Watts, 197559 | CCS | Discectomy with laminotomy and foraminotomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (4 mg) |

| 672 | Weinstein, 198692 | CCS | Discectomy | Chemonucleolysis with chymopapain |

| 150 | Zeiger, 198758 | CCS | Microdiscectomy with intraoperative injection into intervertebral space with steroid 125 mg methylprednisolone + morphine 4 mg used to reduce postoperative pain and morbidity | Chemonucleolysis with chymodiactin (2.5 ml) |

| Disc surgery vs epidural/intradiscal injection | ||||

| 725 | Buttermann, 200495 | RCT | Discectomy | Epidural injection of steroid betamethasone 10–15 mg up to three injections |

| Disc surgery vs exercise therapy | ||||

| 300 | Osterman, 200668 | RCT | Microdiscectomy and exercise therapy | Exercise therapy |

| Disc surgery vs intraoperative interventions | ||||

| 268 | Aminmansour, 200664 | Q-RCT | Discectomy with fenestration + distilled water injection | Discectomy with fenestration + 40 mg intravenous dexamethasone |

| 268 | Aminmansour, 200664 | Q-RCT | Discectomy with fenestration + distilled water injection | Discectomy with fenestration + 80 mg intravenous dexamethasone |

| 436 | Bernsmann, 200174 | RCT | Microdiscectomy with partial hemi-laminectomy, but no free fat graft | Microdiscectomy with partial hemi-laminectomy and free fat graft |

| 470 | Debi, 200278 | RCT | Lumbar discectomy with saline applied to exposed nerve route on a collagen sponge | Lumbar discectomy with steroid methylprednisolone 80 mg applied to exposed nerve route on a collagen sponge |

| 492 | Gerszten, 200381 | RCT | Sham irradiation prior to repeat surgical decompression (control group) | Irradiation prior to repeat surgical decompression (treatment group) |

| 497 | Glasser, 199382 | RCT | Microdiscectomy with partial hemilaminectomy and emptying of disc space only (group 3) | Microdiscectomy with partial hemilaminectomy, emptying of disc space and intraoperative steroid methylprednisolone 490 mg + local anaesthetic 30 ml bupivacaine (group 1) |

| 497 | Glasser, 199382 | RCT | Microdiscectomy with partial hemilaminectomy and emptying of disc space only (group 3) | Microdiscectomy with partial hemilaminectomy, emptying of disc space and intraoperative local anaesthetic 30 ml bupivacaine (group 2) |

| 520 | Jensen, 199683 | RCT | Flavectomy, partial laminectomy without free fat transplantation (group B) | Flavectomy, partial laminectomy with free fat transplantation (group A) |

| 909 | Jirarattanaphochai, 2007106 | RCT | Disc surgery + saline administered to nerve root + intramuscularly (placebo group) | Disc surgery + corticosteroid administration (80 mg of methylprednisolone sodium succinate) to nerve root + bupivacaine (30 ml 0.375%) intramuscularly (steroid group) |

| 400 | Kim, 200373 | RCT | Discectomy without Oxiplex®/SP Gel (FzioMed, CA, USA) | Discectomy with anti-adhesion barrier Oxiplex®/SP Gel |

| 551 | Langmayr, 199584 | RCT | Microdiscectomy plus intrathecal saline injection (placebo group) | Microdiscectomy with intrathecal steroid injection betamethasone (2 ml) (steroid group) |

| 366 | Lavyne, 199270 | Q-RCT | Microdiscectomy followed with epidural irrigation of saline | Microdiscectomy followed with epidural irrigation of steroid methylprednisolone 40 mg |

| 276 | Lundin, 200366 | RCT | Discectomy + saline (control group) | Discectomy + intramuscular, intravenous and fat graft soaked in steroids methylprednisolone 490 mg |

| 270 | MacKay, 199565 | RCT | Standard hemilaminotomy, limited discectomy, dura left uncovered | Standard hemilaminotomy, limited discectomy, dura covered with free fat graft |

| 270 | MacKay, 199565 | RCT | Standard hemilaminotomy, limited discectomy, dura left uncovered | Standard hemilaminotomy, limited discectomy, dura covered with gelfoam interposion membrane |

| 854 | Rasmussen, 2008101 | RCT | Patients received disc surgery only | Local application of 40 mg methylprednisolone following disc excision |

| 618 | Richter, 200189 | RCT | Microdiscectomy unilateral interlaminar without applying any gel | Microdiscectomy unilateral interlaminar with the application of ADCON-L gel (Gliatech Inc., OH, USA) |

| 856 | Ronnberg, 2008102 | RCT | Partial discectomy with no gel applied prior to closure of the wound | Partial discectomy and ADCON-L gel applied around the nerve root, thecal sac and posterior longitudinal ligament |

| 316 | Cengiz, 200769 | RCT | Disc surgery + no adhesion barrier | Disc surgery + anti-adhesion barrier ADCON-L |

| 316 | Cengiz, 200769 | RCT | Disc surgery + no adhesion barrier | Disc surgery + anti-adhesion barrier Healon GV |

| 915 | de Tribolet, 1998107 | RCT | Decompression of the affected nerve root. Type of surgery: laminectomy 4, laminotomy 25, hemilaminectomy 53, hemilaminotomy 58, foraminotomy 1. Incision was closed in a routine fashion. No gel applied | Decompression of the affected nerve root. Type of surgery: laminectomy 2, laminotomy 22, hemilaminectomy 49, hemilaminotomy 55, foraminotomy 0. Before closure 3–5 g of ADCON-L gel applied to nerve root |

| Disc surgery vs mixed treatments | ||||

| 734 | Hoogland, 200697 | Q-RCT | Endoscopic discectomy |

(Surgery + chemonucleolysis) Endoscopic discectomy and chemonucleolysis with chymopapain (1000 U) |

| 379 | Prestar, 199571 (German language) | RCT | Discectomy without preoperative, intraoperative or postoperative steroid |

(Surgery + non-opioids) Discectomy with preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative steroid dexamethasone 4–40 mg for 7 days |

| 705 | Starkweather, 200693 | RCT | Microdiscectomy and placebo medication |

(Surgery + non-opioids) Microdiscectomy and antidepressant medication – amitriptyline 75 mg for 7 days prior |

| 705 | Starkweather, 200693 | Non-RCT |

(An additional non-randomised group) Microdiscectomy with no intervention |

(Surgery + non-opioids) Microdiscectomy and antidepressant medication – amitriptyline 75 mg for 7 days prior |

| 263 | Wang, 200063 | RCT | Placebo acupuncture before and after surgery |

(Surgery + alternative) Classical acupuncture before or after surgery |

| Disc surgery vs non-opioids | ||||

| 475 | Dubourg, 200280 | CCS | Disc surgery (operative group) (various surgical techniques) | Non-operative intervention group. Some received steroids |

| 144 | Rossi, 199357 (Italian language) | Non-RCT | Percutaneous discectomy (groups Ia and IIa) | Oral dexamethasone 8 mg for 9 days, naproxen 500–1000 mg for 5 days (group Ib) |

| 144 | Rossi, 199357 (Italian language) | Non-RCT | Microdiscectomy (group 2b) | Oral dexamethasone 8 mg for 9 days, naproxen 500–1000 mg for 5 days (group Ib) |

| Disc surgery vs others | ||||

| 600 | North, 200586 | RCT | Re-operation with laminectomy, discectomy with our without fusion | Spinal cord stimulation group |

| Disc surgery vs usual/conventional care | ||||

| 716 | Alaranta, 199094 | CCS | Discectomy with partial laminectomy | Conservative treatment |

| 386 | Atlas, 199672 | CCS | Surgery most had open discectomy | Various non-surgical treatments |

| 772 | Hansson, 2007100 | CCS | Surgical treatment | Conservative non-surgical treatment. No further details |

| 294 | Koranda, 199567 (Czech language) | Q-RCT | Disc surgery | Conservative therapy |

| 606 | Peul, 200787 | RCT | Microdiscectomy | Conventional care control |

| 211 | Shvartzman, 199262 | HCS | Standard lumbar discectomy | Physical therapy at a local rehabilitation centre. No further details |

| 2 | Thomas, 200745 | CCS | Lumbar microdiscectomy with hemilaminotomy | Non-operative multidisciplinary care, no injections |

| 664 | Weber, 198391 | RCT | Discectomy | Bed rest, physiotherapy, analgesia |

| 750 | Weinstein, 200698 | CCS | Open or microdiscectomy (group S) | Non-operative treatment (usual care) |

| 751 | Weinstein, 200699 | RCT | Standard open or microdiscectomy (group S) | Non-operative treatment (usual care) |

Thirty-eight studies compared different types of disc surgery64,65,69,82,108–141 and five compared different intraoperative interventions64,65,69,82,141 (four of these studies were three-arm studies that also compared intraoperative interventions with disc surgery64,65,69,82). The types of surgical procedures being compared are listed in Table 3b, but the findings of these studies are not considered any further than this.

| ID no. | Author, year | Study design | Intervention type | Treatment description | Control type | Control description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilateral vs unilateral | ||||||

| 21 | Barlocher, 2000108 | CCS | Unilateral (microscope) | Unilateral fenestration with microdiscectomy | Bilateral (microscope) | Bilateral fenestration with microdiscectomy |

| 502 | Hagen, 1977128 | CCS | Bilateral | Discectomy with bilateral laminectomy and emptying of disc space (group1) | Unilateral | Discectomy with unilateral laminectomy and emptying of disc space (group 2) |

| Day case vs inpatient | ||||||

| 219 | Gonzalez-Castro, 2002117 | Q-RCT | Day-case | Conventional discectomy (fenestration) day-case surgery – disc space cleared, no microscope | Inpatient | Conventional discectomy (fenestration) inpatient stay – disc space cleared, no microscope |

| Disc surgery + fusion vs disc surgery alone | ||||||

| 66 | Takeshima, 2000109 | HCS | Disc surgery + fusion | Disc excision with posterolateral fusion (fusion group) | Disc surgery alone | Disc excision without fusion (non-fusion group) |

| 653 | Tria, 1987136 | HCS | Disc surgery + fusion | Laminectomy combined with spinal fusion | Disc surgery alone | Simple laminectomy |

| 673 | White, 1987138 | Non-RCT | Disc surgery + fusion | Discectomy with laminectomy plus fusion with internal fixation | Disc surgery alone | Simple laminectomy with no fusion |

| Discectomy + endplate curettage vs disc surgery alone | ||||||

| 430 | Balderston, 1991124 | CCS | Discectomy + endplate curettage | Lumbar discectomy combined with vertebral endplate curettage | Discectomy alone | Lumbar discectomy with laminectomy, but no endplate curettage |

| Endoscopic discectomy vs endoscopic discectomy | ||||||

| 680 | Yang, 2005140 | HCS | Endoscopic discectomy (without laser) | Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy | Endoscopic discectomy (laser decompression) | Percutaneous laser disc decompression |

| 164 | Righesso, 2007114 | RCT | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Open discectomy using magnification | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy |

| 402 | Ruetten, 2008121 | Q-RCT | Open discectomy (microscope) | Conventional microsurgical discectomy | Endoscopic discectomy (no microscope) | Full endoscopic interlaminar or transforaminal discectomy |

| 403 | Ryang, 2008122 | RCT | Open discectomy (microscope) | Standard open microdiscectomy | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Minimal access trocar microdiscectomy |

| 651 | Toyone, 2004135 | Non-RCT | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Standard open microdiscectomy with removal of herniated material only | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy |

| Endoscopic discectomy vs open discectomy | ||||||

| 460 | Chatterjee, 1995127 | RCT | Endoscopic discectomy | Automated percutaneous lumbar discectomy | Open discectomy | Microdiscectomy |

| 536 | Kim, 2007130 | CCS | Endoscopic discectomy (no microscope) | Targeted percutaneous transforaminal endoscopic discectomy | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Microscopic discectomy |

| 582 | Mayer, 1993131 | RCT | Endoscopic discectomy (no microscope) | Percutaneous endoscopic discectomy | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Microdiscectomy |

| 632 | Schizas, 2005132 | Non-RCT | Endoscopic discectomy (no microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Microdiscectomy |

| 327 | Shin, 2008119 | RCT | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy with partial hemilaminectomy | Open discectomy (microscope) | Microscopic discectomy with partial hemilaminectomy |

| 409 | Wu, 2006123 | CCS | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Standard open posterior lumbar discectomy |

| 459 | Zhang, 2007126 | Non-RCT | Endoscopic discectomy (microscope) | Microendoscopic discectomy | Open discectomy (no microscope) | Open lumbar discectomy |

| Extensive disc surgery vs limited disc surgery | ||||||

| 391 | Carragee, 2006120 | HCS | Open discectomy | Subtotal discectomy with removal of extruded fragments and emptying of disc space | Limited discectomy | Limited discectomy with removal of extruded fragments only |

| 525 | Kahanovitz, 1989129 | CCS | Extensive disc surgery (microscope) | Microdiscectomy (with an operating microscope) | Limited disc surgery (no microscope) | Limited unilateral discectomy without magnification |

| 643 | Striffeler, 1991133 | CCS | Limited discectomy (microscope) | Conservative microdiscectomy with removal of prolapsed disc, disc space irrigated | Extensive discectomy (microscope) | Standard microdiscectomy with emptying of disc space |

| 647 | Thome, 2005134 | RCT | Extensive discectomy (microscope) | Microdiscectomy with emptying of disc space | Limited discectomy (microscope) | Sequestrectomy with removal of herniated material only |

| Laser discectomy vs open discectomy | ||||||

| 116 | Lee, 2006111 | CCS |

Endoscopic discectomy (no microscope) Laser decompression |

Percutaneous endoscopic lumbar discectomy |

Open dicectomy (microscope) No laser |

Open lumbar microdiscectomy with partial hemilaminectomy |

| 165 | Tassi, 2006115 | HCS | Laser decompression | Percutaneous laser disc decompression | (Microscope) | Standard surgical microdiscectomy |

| Ligamentum flavum preservation vs ligamentum flavum excision | ||||||

| 69 | Aydin, 2002110 | HCS | Ligamentum flavum preservation (microscope) | Microdiscectomy with preservation of ligamentum flavum (group 1) | Ligamentum flavum excision (microscope) | Standard microdiscectomy with fenestration, foraminotomy, partial or total excision of ligamentum flavum (group 2) |

| Microscope vs no microscope | ||||||

| 432 | Barrios, 1990125 | CCS | Microscope | Standard discectomy with partial hemilaminectomy | No microscope | Microdiscectomy |

| 167 | Katayama, 2006116 | RCT | Microscope | Microdiscectomy without laminectomy, disc space emptied (group B) | No microscope | Macrodiscectomy with partial laminectomy, no microscope, disc space emptied (group A) |

| 143 | Kho, 1986113 (German language) | HCS | Microscope | Microdiscectomy | No microscope | Lumbar discectomy without microscope |

| 126 | Lagarrigue, 1994112 (French language) | RCT | Microscope | Microscopic lumbar discectomy | No microscope | Normal lumbar discectomy (without microscope) |

| 232 | Tullberg, 1993118 | RCT | Microscope | Microscopic surgery (micro-group) – disc space cleared | No microscope | Standard macrodiscectomy (without microscope) – disc space cleared |

| 654 | Tureyen, 2003137 | RCT | Microscope | Microdiscectomy with emptying of disc space (group A) | No microscope | Macrodiscectomy with laminectomy and emptying of disc space, no microscope (group B) |

| 674 | Wilson, 1981139 | HCS | Microscope | Microdiscectomy with evacuation of disc space, but no curettage of end plates | No microscope | Standard open discectomy with evacuation of disc space, but no curettage of end plates |

One further study142 compared disc surgery plus epidural (mixed treatments) with conventional care given while waiting for surgery. However, the study only reported health-care utilisation and employment-related outcomes.

Summary of study participants for disc surgery

Summary data for included participants are presented in Table 4. The number of participants included in the 61 studies that reported outcome data for global effect, pain or CSOMs ranged from 10 to 2749 (median 103). A similar number of studies included patients with chronic sciatica, or either chronic or acute sciatica, or did not report this information. Four studies62,68,80,87 included patients with acute sciatica, with a mean duration of symptoms ranging from 25.7 days80 to 68.5 days. 68 Four studies54,67,69,83 included some patients with spinal stenosis and 1068,74,83,95,97,98,99,101,103,107 included patients with sequestered or extruded discs. The diagnosis of sciatica, or the presence of herniated disc, was confirmed by imaging in 52 (85%) studies. Six studies49,66,74,92,95,105 included patients who had sciatica for the first time and seven studies50,57,63,72,80,81,83,86 included only patients with recurrent sciatica. The remaining studies included patients with either first-episode or recurrent sciatica, or did not report this information. The majority of studies (n = 40) included patients who had received previous treatment for their current episode of sciatica. Ten studies45,56,59,63,71,80,81,86,88,95 included patients who had received previous disc surgery and 32 studies included patients who had not.

| ID no. | Author, year | Study design | No. of patients | Mean age (years) | No. of men (%) | Symptom duration | Type of sciatica | Confirmed by imaging? | Recurrent episode | Included patients with stenosis? a | Included patients with sequestered disc (or extruded)?a | Any previous treatment for sciatica? | Any previous back surgery for sciatica? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc surgery vs chemonucleolysis | |||||||||||||

| 884 | Alexander, 1989103 | CCS | 100 | 33.5 (range 18–65) | 90 (90) | Mean 5.5 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 43 | van Alphen, 198947 | RCT | 151 | 34 (range 18–45) | 99 (66) | 55% < 6 months; 45% > 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 441 | Bonafe, 199375 (French language) | CCS | 40 | 46 (range 27–68) | 28 (70) | Mean 3 months (range several days to 15 months) | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 183 | Bouillet, 198361 | CCS | 2749 | NR | NR | Ranged from weeks to months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 453 | Brown, 198976 | CCS | 85 | 37.6 | 59 (69) | At least 3 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 454 | Buric, 200577 | Non-RCT | 45 | 45 (SD 14.2; range 19–77) | 23 (51) | Mean 203.9 days (SD 129.6; range 21 to > 365 days) | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 166 | Crawshaw, 198460 | RCT | 52 | 37 | NR | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 48 | Dabezies, 197851 | CCS | 200 | 39 | 132 (66) | NR | Nerve root pain and referred pain | No | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 471 | Dei-Anang, 199079 (German language) | CCS | 201 | NR | NR | NR | Nerve root pain | NR | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| 727 | Ejeskar, 198396 | RCT | 29 | 39.3 | 21 (72) | Mean 4.5 months (SD 3 months) | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 132 | Hoogmartens, 197656 | HCS | 97 | 35.5 | 48 (49) | 25–35 months | Nerve root pain | NR | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 44 | Javid, 199548 | CCS | 200 | 39 (range 17–81) | 134 (67) | Mean 7.2 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 35 | Krugluger, 200046 | RCT | 22 | 40 (range 24–60) | 16 (73) | Mean 7 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 117 | Lagarrigue, 199154 (French language) | CCS | 1085 | 42 (range 14–83) | 682 (63) | Mean 13.4 months | Nerve root pain | No | NR | Yes | No | Yes | NR |

| 129 | Lavignolle, 198755 (French language) | RCT | 358 | 41 (SD 12.03) | 225 (63) | NR | Nerve root pain | NR | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| 889 | Lee, 1996104 (German language) | CCS | 300 | 50% < 30; 25% > 40 | 213 (71) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 593 | Muralikuttan, 199285 | RCT | 92 | 35 (range 19–60) | 55 (60) | Mean 24 weeks | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 47 | Norton, 198650 | CCS | 105 | 40 (range 20–67) | 86 (82) | Mean 18.5 months (range 5 days–128 months) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No | No | Yes | No |

| 45 | Postacchini, 198749 | Non-RCT | 161 | NR | NR | Mean 8.75 months (range 1.2–36.0 months) | Nerve root pain and referred pain | Yes | First episode | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 617 | Revel, 199388 | RCT | 165 | 39 (SD 9; range 21–65) | 96 (68) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 641 | Steffen, 199990 (German language) | RCT | 69 | NR | NR | 10.6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 49 | Stula, 199052 (German language) | RCT | 69 | Range 22–54 | 57 (83) | < 1 year | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | Yes | No |

| 61 | Tregonning, 199153 | CCS | 268 | 40.4 (range 20–65) | 135 (68) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 893 | Watters,1988105 | Non-RCT | 100 | 36.5 | 59 (59) | Mean 13 weeks | Nerve root pain | Yes | First episode | No | No | NR | NR |

| 160 | Watts, 197559 | CCS | 274 | Range 24–62 | 55 (55) | NR | Nerve root pain and referred pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 672 | Weinstein, 198692 | CCS | 159 | 41 (range 28–57) | 64 (41) | Minimum period of 3 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | First episode | No | No | Yes | No |

| 150 | Zeiger, 198758 | CCS | 126 | NR | NR | 4 weeks or more | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| Disc surgery vs epidural | |||||||||||||

| 725 | Buttermann, 200495 | RCT | 100 | 40.5 (SD 12) | Mean 3.55 months (SD 2.75 months) | Nerve root pain | Yes | First episode | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| Disc surgery vs exercise therapy | |||||||||||||

| 300 | Osterman, 200668 | RCT | 57 | 38 (SD 7) | 34 (61) | Mean 68.5 days (SD 27 days) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | Yes | NR | No |

| Disc surgery vs intraoperative interventions | |||||||||||||

| 268 | Aminmansour, 200664 | Q-RCT | 61 | 38.5 (SD 10.4) | 35 (57) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| 436 | Bernsmann, 200174 | RCT | 200 | 43 (range 22–75) | 97 (52) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | First episode | No | Yes | NR | NR |

| 470 | Debi, 200278 | RCT | 70 | 41 (range 18–60) | 43 (70) | Mean 56 days (range 12–135 days) | Nerve root pain | NR | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 492 | Gerszten, 200381 | RCT | 10 | 42 | 5 (50) | Mean 3.5 years (range 1.5–10.0 years) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 497 | Glasser, 199382 | RCT | 32 | 46.1 (SD 3.66) | Within 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No | |

| 520 | Jensen, 199683 | RCT | 118 | Median 46 (range 19–75) | 53 (45) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No central stenosis but some had lateral stenosis | Yes | NR | No |

| 909 | Jirarattanaphochai, 2007106 | RCT | 103 | 52 (SD 11; range 21–79) | 48 (47) | NR | Nerve root pain | NR | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| 400 | Kim, 200373 | RCT | 35 | 43.5 (range 28–65) | 11 (31) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 551 | Langmayr, 199584 | RCT | 26 | 42 | 20 (77) | Median 35 days (range 14–150 days) | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 366 | Lavyne, 199270 | Q-RCT | 84 | 40 (range 17–70) | 57 (73) | Few days to several months | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 276 | Lundin, 200366 | RCT | 80 | 41.7 | 44 (55) | Mean 4.5 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | First episode | No | No | NR | No |

| 270 | MacKay, 199565 | RCT | 190 | 39 (range 14–79) | 106 (69) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | NR |

| 854 | Rasmussen, 2008101 | RCT | 200 | 42.5 (range 18–66) | 122 (61) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | Yes | Yes | NR |

| 618 | Richter, 200189 | RCT | 398 | 43 (range 30–65) | 221 (62) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 856 | Ronnberg, 2008102 | RCT | 128 | 39 (range 18–66) | 68 (53) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 316 | Cengiz, 200769 | RCT | 60 | 44.2 (SD 10.2) | 35 (58) | Mean 12.3 years (SD 9.2 years) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | Yes | No | NR | No |

| 915 | de Tribolet, 1998107 | RCT | 298 | 39.1 (SD 9.5) | 167 (56) | Not stated | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | Yes extruded and sequestered discs | Yes | No |

| Disc surgery vs mixed treatments | |||||||||||||

| 734 | Hoogland, 200697 | Q-RCT | 280 | 40.5 (range 18–60) | 186 (66) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 379 | Prestar, 199571 (German language) | RCT | 100 | 44.7 (range 26–76) | NR | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| 705 | Starkweather, 200693 | RCT | 70 | 45.5 (SD 11; range 21–65) | 40 (57) | 61% < 1 year; 39% > 1 year | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | NR |

| 263 | Wang, 200063 | RCT | 145 | 21–80 | 78 (59) | At least 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Disc surgery vs non-opioids | |||||||||||||

| 475 | Dubourg, 200280 | CCS | 67 | 48.8 (SD 13.9; range 28–81) | 42 (63) | Mean 25.7 days (SD 28.7 days) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | NR | Yes |

| 144 | Rossi, 199357 (Italian language) | Non-RCT | 40 | 42.5 (SD 10.5; range 20–65) | NR | < 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No | No | NR | NR |

| Disc surgery vs others | |||||||||||||

| 600 | North, 200586 | RCT | 60 | 50.2 (SD 13.3; range 26–76) | 30 (50) | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Disc surgery vs usual/conventional care | |||||||||||||

| 716 | Alaranta, 199094 | CCS | 357 (322 partial rhizography) | 39.6 | 179 (50) | Mean 3.6 months | Nerve root pain | No | NR | No | No extrusion | NR | No |

| 386 | Atlas, 199672 | CCS | 507 | 42 (range 18–85) | 322 (64) | 41% < 1 year; 1–24% 5 years; 35% > 5 years | Nerve root pain | No | Recurrent | No | No | Yes | No |

| 772 | Hansson, 2007100 | CCS | 184 | 43 (range 22–59) | 87 (47) | 20% < 1 week; 39% 1 week to 1 year; 42% > 1 year | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 294 | Koranda, 199567 (Czech language) | Q-RCT | 100 | NR | NR | NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | Yes | No | Yes | NR |

| 211 | Shvartzman, 199262 | HCS | 55 | 42.3 (SD 11.1; range 23–59) | 55 (100) | Patients presented with acute episode of sciatica, actual duration NR | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | Yes | No |

| 2 | Thomas, 200745 | CCS | 623 | 42.9 | 291 (59) | Mean 191.5 days (SD 195 days) | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | No | NR | Yes |

| 664 | Weber, 198391 | RCT | 126 | 41 (range 25–55) | 68 (54) | At least 14 days | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 751 | Weinstein, 200699 | RCT | 501 | 42 (SD 11.6) | 278 (59) | 79% < 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | Yes | Yes | No |

| 606 | Peul, 200787 | RCT | 283 | 42.6 (SD 9.8) | 186 (66) | Mean 9.5 weeks (range 6–12 weeks) | Nerve root pain | Yes | NR | No | No | NR | No |

| 750 | Weinstein, 200698 | CCS | 743 | 41.4 (SD 11.2) | 406 (56) | 77% < 6 months | Nerve root pain | Yes | Recurrent and first episode | No | Yes | Yes | No |

Summary of study design and quality for disc surgery studies

Summary information on study details are presented in Table 5. The full results of the quality assessment are presented in the Appendix 5. Just over half (33/62, 53%) of the disc surgery studies were RCTs, of which only two87,99 were good quality overall (comparing disc surgery with usual care). Four RCTs68,73,89,99 had used both adequate randomisation and allocation concealment (comparators included exercise therapy, intraoperative interventions and usual care). A further eight studies81,85–88,101,106,107 used adequate randomisation, but not allocation concealment (although two studies87,106 used sealed envelopes), and one study69 used adequate allocation concealment, but not randomisation. Two studies91,93 used sealed envelopes, but gave no further details on method of randomisation. Three studies45,47,87 had strong external validity.

| ID no. | Author, year | Study size | Overall follow-up | Study design | Adequate randomisation? | Allocation concealment? | Follow-up (%) | Blind outcome assessment? | Overall quality rating | Overall external validity rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disc surgery vs chemonucleolysis | ||||||||||

| 884 | Alexander, 1989103 | 100 | Mean 14 months; range 6–35 months | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 43 | van Alphen, 198947 | 151 | 12 months | RCT | Partial | Unclear | 80–100 | No | Moderate | Strong |

| 441 | Bonafe, 199375 (French language) | 40 | Mean 15 months; range 3–36 months | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 453 | Brown, 198976 | 85 | 3 months | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | Yes | Weak | Weak |

| 454 | Buric, 200577 | 45 | 18 months | Non-RCT | No | No | 80–100 | NA | Weak | Weak |

| 166 | Crawshaw, 198460 | 52 | 1 year | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Moderate |

| 48 | Dabezies, 197851 | 200 | 2 years | CCS | No | No | Can’t tell | No | Weak | Moderate |

| 471 | Dei-Anang, 199079 (German language) | 201 | 1 year | CCS | No | No | NA | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 727 | Ejeskar, 198396 | 29 | 1 year | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Moderate |

| 132 | Hoogmartens, 197656 | 97 | 58 months for discectomy and 38 months for chemonucleolysis | HCS | No | No | NA | NA | Weak | Moderate |

| 44 | Javid, 199548 | 200 | 1 year | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | No | Weak | Moderate |

| 35 | Krugluger, 200046 | 22 | 2 years | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 117 | Lagarrigue, 199154 (French language) | 1085 | Mean 17.2 months; range 12–4 months | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Moderate |

| 129 | Lavignolle, 198755 (French language) | 358 | Mean 25 months for surgery and 22 months for chemonucleolysis | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 889 | Lee, 1996104 (German language) | 300 | 1 year | CCS | No | No | Can’t tell | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 593 | Muralikuttan, 199285 | 92 | 1 year | RCT | Yes | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Moderate | Moderate |

| 47 | Norton, 198650 | 105 | At least 1 year | CCS | No | No | NA | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 45 | Postacchini, 198749 | 161 | Mean 2.9 years; range 20–38 months in chemonucleolysis. Mean 2.8 years; range 21–42 months in surgery | Non-RCT | No | No | 80–100 | No | Weak | Moderate |

| 617 | Revel, 199388 | 165 | 1 year | RCT | Yes | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Moderate | Weak |

| 641 | Steffen, 199990 (German language) | 69 | 1 year | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Yes | Weak | Weak |

| 49 | Stula, 199052 (German language) | 69 | Postoperative | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 61 | Tregonning, 199153 | 268 | 10 years | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | No | Weak | Moderate |

| 893 | Watters,1988105 | 100 | 3 years | Non-RCT | No | No | 80–100 | No | Weak | Weak |

| 160 | Watts, 197559 | 274 | 2 years | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 672 | Weinstein, 198692 | 159 | Mean 10.3 years; range 10.0–13.5 years | CCS | No | No | 80–100 | NA | Weak | Weak |

| 150 | Zeiger, 198758 | 126 | Range 6–46 months; average time from treatment to follow-up 18 months | CCS | No | No | NA | Yes | Weak | Weak |

| Disc surgery vs epidural | ||||||||||

| 725 | Buttermann, 200495 | 100 | 2–3 years | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | No | Moderate | Moderate |

| Disc surgery vs exercise therapy | ||||||||||

| 300 | Osterman, 200668 | 57 | 2 years | RCT | Yes | Yes | 80–100 | NA | Moderate | Weak |

| Disc surgery vs intraoperative interventions | ||||||||||

| 268 | Aminmansour, 200664 | 61 | 2 months | Q-RCT | No | No | 80–100 | Yes | Weak | Moderate |

| 436 | Bernsmann, 200174 | 200 | Median of 24.2 months after surgery | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Yes | Moderate | Weak |

| 470 | Debi, 200278 | 70 | 1 year | RCT | Unclear | Partial | 80–100 | No | Weak | Weak |

| 492 | Gerszten, 200381 | 10 | 1 year | RCT | Yes | Unclear | 80–100 | NA | Moderate | Weak |

| 497 | Glasser, 199382 | 32 | 1 month | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 520 | Jensen, 199683 | 118 | Median 376 days; range 276–501 days | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Yes | Moderate | Moderate |

| 909 | Jirarattanaphochai, 2007106 | 103 | 3 months | RCT | Yes | Partial | 80–100 | Yes | Moderate | Moderate |

| 400 | Kim, 200373 | 35 | 6 months | RCT | Yes | Yes | 80–100 | NA | Moderate | Weak |

| 551 | Langmayr, 199584 | 26 | 6 months | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Yes | Moderate | Moderate |

| 366 | Lavyne, 199270 | 84 | 6 weeks | Q-RCT | No | No | 80–100 | Unclear | Weak | Weak |

| 276 | Lundin, 200366 | 80 | 2 years | RCT | Unclear | Unclear | 80–100 | Yes | Moderate | Moderate |