Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the National Coordinating Centre for Research Methodology (NCCRM), and was formally transferred to the HTA programme in April 2007 under the newly established NIHR Methodology Panel. The HTA programme project number is 06/90/12. The contractual start date was in May 2002. The draft report began editorial review in November 2010 and was accepted for publication in July 2011. The commissioning brief was devised by the NCCRM who specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Nicky Britten and Catherine Pope have both run workshops using some material from this research. Some have charged attendance fees and generated a small surplus which was paid to their universities. They have not received any personal payment for these workshops. Catherine Pope also co-authored a textbook entitled Synthesising qualitative and quantitative health evidence: a guide to methods, which contains material about metaethnography and cites the research on which this report is based. Pandora Pound was training to be an acupuncturist while also conducting this research and currently practises as an acupuncturist.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Campbell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Although it is widely acknowledged that science is cumulative, people have only very recently begun to acknowledge that scientists have a responsibility to cumulate scientifically.

Chalmers et al. 1

Evidence-based medicine and a science of synthesis

Recognition of the need for research syntheses has existed for over two centuries,1 but a ‘science of synthesis’ has been slow to advance. In the field of health care, much of the momentum for the development of methods of synthesis has come from the move towards evidence-based medicine: a shift that has had a variety of antecedents. One was apprehension about the rapidity of technological change and the impossibility of individual clinicians reading and appraising all the journal articles relevant to their specialty. 2 Another factor was unease about the quality of primary research testing the effectiveness of clinical and health-care interventions. 3 Foremost, however, was recognition that all the best available scientific evidence should primarily inform clinical decision-making and that changes in medical practice should not simply rely on expert opinion.

Narrative literature reviews have been the traditional method for bringing together existing knowledge in a particular area. From the mid-1980s onwards, however, a number of questions about the adequacy of this method for compiling research evidence on health-care interventions were raised. The narrative review was criticised for being unscientific and, as a consequence, it was suggested ‘the results and conclusions would often be susceptible to and reflect the biases of the reviewer’. 4 In addition, seminal studies such as that by Antman et al. 5 provided powerful demonstrations of the value of a systematic approach to all the components of a review including the selection of studies for inclusion, the appraisal of the quality of the research and the application of relevant statistical methods for pooling data from a number of studies. Using meta-analysis to synthesise randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence about the effectiveness of treatments in preventing death following heart attack, and contrasting this with expert recommendations in textbooks and review articles, these authors showed that some treatments were still being promoted when there was clear evidence that they were harmful, and that thrombolytic drugs were still not being recommended for use by more than half of clinical experts 13 years after cumulative meta-analyses showed them to be highly effective in reducing mortality. 5

In the late 1980s, international collaborations of researchers, responding both to Archie Cochrane’s6 championing of the value of the RCT in health-care evaluation and to his stinging criticism of health-care professionals’ failure to use scientific evidence as the primary basis for making choices about which preventive measures, diagnostic tests and treatments to use, began to publish the first systematic reviews of health care. Foremost among these was a two-volume publication containing hundreds of reviews about different aspects of the care of women and infants during pregnancy and childbirth. 7 There were two notable features of this review. Firstly, it was acknowledged that there would be different audiences for such reviews, and so a much shorter, more accessible, summary was also published. 8 Secondly, it was recognised that such a review would need to be regularly updated and that electronic publishing could facilitate this requirement. Rapid adoption of systematic reviews followed this pioneering work and global systematic reviewing networks have gradually developed, with the Cochrane Collaboration being the best known.

Health technology assessment

By the late 1990s, with the systematic review firmly established as a scientific method for bringing together findings from quantitative studies of effectiveness, interest was beginning to shift towards how qualitative data could be brought into the evidence base and a ‘science of synthesis’ developed for qualitative research. Whereas bringing together research information on effectiveness, costs and acceptability has always been fundamental to the health technology assessment (HTA) enterprise, the use of qualitative research methods within HTA has been a more recent development. In the mid-1990s, the HTA Methodology programme commissioned a review of the literature on the use of qualitative research methods in HTA, which noted that application of conventional systematic review methodology to qualitative research presented both philosophical and practical challenges. 9 Following publication of this report, the HTA recognised that further work was required to enable ‘users of qualitative research to be able to both appraise and to synthesise qualitative studies in a rigorous, replicable and formalised way’. 10

Synthesis of qualitative research

The possibility of synthesising qualitative research immediately raises a range of important epistemological, methodological and practical questions. The most fundamental of these is what ‘synthesis’ means in this context. Strike and Posner11 have suggested that ‘synthesis is usually held to be activity or the product of activity where some set of parts is combined or integrated into a whole… [Synthesis] involves some degree of conceptual innovation, or the invention or employment of concepts not found in the characterization of the parts as means of creating the whole’. Thus, synthesis of qualitative research could be envisaged as the bringing together of findings on a chosen theme, the results of which should, in conceptual terms, be greater than the sum of parts. This implies that qualitative synthesis would go beyond the description and summarising usually associated with a narrative literature review, as it would involve conceptual development and would be distinct from a quantitative meta-analysis in that it would not simply entail the aggregation of findings from individual, high-quality research studies. Qualitative synthesis should involve reinterpretation but, unlike secondary analysis, it would be based on published findings rather than primary data.

The impetus for developing methods of qualitative synthesis has arisen from recognition of the importance of qualitative evidence in complementing quantitative research and in particular its ability to provide a more complete understanding of phenomena, especially in terms of processes involved in the organisation and provision of services and influences on behaviours. 12 Another driver has been acknowledgement that the considerable expansion of the qualitative research literature over recent years has produced little accumulated understanding, highlighting a need to bring together isolated studies. 13 Thus, if qualitative research is to be made accessible to health policy-makers and planners, in a manageable form, then developing and evaluating methods of qualitative synthesis, as in this project, would seem to be an important and timely endeavour.

Despite recognition of the potential value of qualitative synthesis, it is a contentious enterprise. From a social science perspective, the notion of qualitative research synthesis best agrees with what is termed a ‘subtle realist’ position. This stance maintains that phenomena exist independently of the investigators’ claims about them, but also acknowledges the possibility of multiple, non-competing valid descriptions and explanations of the same phenomena. Subtle realism, therefore, enables the different constructions people make of reality to be studied, without accepting that particular beliefs are true; thus, qualitative synthesis can be regarded as potentially promoting such understanding. By contrast, an extreme relativist or radical constructionist perspective is based on a belief that reality is only what we make it and it is therefore not possible to have any knowledge of phenomena apart from our own experience of them. The aim of qualitative research arising from within this influential tradition is to describe unique particularities and present an ideographic account. The process of synthesis could thus be regarded as destroying the integrity of individual studies in the pursuit of some unattainable more ‘complete’ or ‘true’ account. As Sandelowski et al. 13 explained, from this perspective the summary of qualitative findings is regarded as thinning out the desired thickness of particulars, which may therefore ‘lose the vitality, viscerality, and vicariism (sic) of the human experiences represented in the original studies’. From a radical constructionist perspective, the aim of qualitative research is to produce fit descriptions of unique cases and leave it to the reader to engage in ‘naturalistic generalisation’ using these individual descriptions. However, as Hammersley14 observed, in practice it is rare for researchers not to hint at general conclusions from the unique cases that they study.

There are no standard or agreed methods for conducting syntheses of qualitative research. The review presented in Chapter 2 of this report illustrates a number of possible methods that have been identified and applied. Meta-ethnography, developed and used first in educational research, is one approach. 15 It involves taking relevant empirical studies to be synthesised, reading them repeatedly and noting down key concepts (interpretive metaphors). These key concepts are the raw data for the synthesis. Noblit and Hare15 suggested that the process by which a synthesis is achieved is one of translation. This entails examining the key concepts in relation to others in the original study and across studies. The way of translating key concepts or interpretive metaphors from one study to another involves an idiomatic rather than a word-for-word translation. The purpose of the translation is to try to derive concepts that can encompass more than one of the studies being synthesised. The synthesised concepts may not have been explicitly identified in any of the original empirical studies. As perhaps the best developed method for synthesising qualitative data, and one which clearly had its origins in the interpretive paradigm from which most methods of primary qualitative research evolved, this was the method selected for evaluation in this HTA project.

Prior to the research reported on here, this research group had undertaken a pilot synthesis of four papers concerned with the lay meanings of medicines, which demonstrated that it was possible to use meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative research. 16 A feasibility study followed that included the formative evaluation of a set of criteria for assessing qualitative research studies followed by a synthesis of selected studies on patient experiences of diabetes mellitus. 17 This second pilot synthesis proved to be successful and illuminating; as none of the research papers included it in contained any references to each other, it demonstrated the need for primary researchers to search and read the existing literature more carefully and indicated that it would be helpful to bring the findings of qualitative research together. This second synthesis also confirmed the effectiveness of meta-ethnography as a method of synthesis. In addition, a practical method of qualitative research assessment and data extraction evolved from it. However, this process required further testing and evaluation before it could be recommended for widespread adoption by those undertaking HTA, as a number of important questions remained to be answered, for example, in terms of the selection of studies, how many studies can be included and how reproducible syntheses are. It is this more detailed evaluation that is the subject of this report.

Aims and objectives

Aim

To appraise and synthesise qualitative health research for HTA using a meta-ethnographic approach.

Objectives

Primary

-

To conduct, using the meta-ethnographic method, syntheses of qualitative research studies in two applied health-care contexts:

-

living with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) (patient experiences of a chronic illness)

-

lay beliefs about medicine-taking in chronic disease.

-

-

To test a modified version of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)18 criteria for appraising qualitative research for appropriateness, ease of use and inter-reviewer agreement.

-

To evaluate the reproducibility of the meta-ethnographic method of synthesis.

Secondary

-

To complete a review of the methods available for appraising and synthesising qualitative research.

-

To document the effectiveness of different elements in the search strategies in identifying relevant qualitative research studies.

Content of this report

This report continues in Chapter 2 with a review of the methods of qualitative synthesis. We did not complete a review of methods of appraisal as two other projects commissioned by other bodies at a similar time had such a review within their remit. 19,20 To avoid unnecessary duplication, we focused our efforts on reviewing methods for the synthesis of qualitative research. Chapter 3 describes the literature searching strategies employed in the two meta-ethnographic syntheses undertaken. An evaluation of the methods of appraisal used in the syntheses is reported in Chapter 4. The precise methods used to conduct the syntheses are described in Chapter 5 together with an assessment of the reproducibility of the meta-ethnographic method. The two syntheses are presented in Chapters 6 and 7. Chapter 8 contains a discussion of all the issues raised by this evaluation of meta-ethnography, and a number of conclusions are drawn about its value as a method of qualitative synthesis and its potential role in HTA.

Chapter 2 Methods of qualitative synthesis

The relative inattention towards integrating qualitative findings stands in sharp contrast to the considerable attention given to the development of techniques for conducting syntheses of quantitative research.

Sandelowski et al. 13

Introduction

Methods for the synthesis of qualitative research have been slow to develop, as the above quote suggests, but a number have emerged in recent years. These methods are still evolving, but are doing so in the shadow of widely used and well-developed methods for quantitative research synthesis. The result is that there is sometimes an expectation or assumption that qualitative syntheses will proceed in a manner similar to their quantitative counterparts, despite the very obvious differences between the quantitative and qualitative research traditions. This chapter begins by considering the distinctions between different types of research syntheses before going on to review methods of qualitative synthesis.

One of the confusing features of the research synthesis literature is that the terms ‘review’ and ‘synthesis’ are often used interchangeably,21 yet a distinction can be made between these two activities. A process of review can be said to be one of seeking out, sifting through, reading, appraising and describing relevant research evidence. The synthesis of evidence, on the other hand, involves a process of extracting data from individual research studies and interpreting and representing them in a collective form. According to this distinction, conventional literature reviews are generally reviews, whereas systematic reviews usually combine elements of review and synthesis.

Within systematic reviews, Hammersley14 identified three types of synthesis: aggregative (involving the accumulation and generalisation of evidence); comparative or replicative (determining the extent to which different sources of evidence reinforce each other by comparison between sources); and developmental (overarching theory development). Although these have evolved within a quantitative research tradition, Hammersley14 suggested that none of these types of synthesis is incompatible with qualitative synthesis. Hammersley14 also suggested convenience mapping synthesis as a fourth category. This category drew on Howard Becker’s notion of a mosaic of different studies being put together in order to see the bigger picture, with each study providing a context for the next.

Noblit and Hare (p. 15)15 also made a distinction between integrative reviews, in which data from different studies are pooled or aggregated, and interpretive reviews, which bring together the findings from different studies using induction and interpretation to gain deeper understandings of a particular phenomenon. They noted how integrative reviews require an etic approach (working with a pre-existing frame of reference), thereby enabling the aggregation of findings by ensuring that there is ‘a basic comparability between phenomena’. 15 Drawing on work by Spicer,22 interpretative reviews were contrastingly characterised as using an emic approach with concepts and explanatory frameworks emerging through a process of induction.

This chapter examines the assumptions and procedures of different methods of synthesising qualitative research drawing on the framework proposed by Hammersley14 as a means of distinguishing different methods of qualitative synthesis. Particular attention is given to Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography, as this forms the main approach to qualitative synthesis employed in the health field and is the focus of this report. Methods for the formal integration and synthesis of quantitative and qualitative studies are beyond the scope of this report and have been considered in detail elsewhere. 21,23,24

Types of qualitative synthesis

Methods of qualitative synthesis are at an early stage of development and considerable methodological work is ongoing, particularly within health and educational research. The rapid expansion of the field has resulted in a lack of standard terminology, with the terms ‘meta-ethnography’, ‘meta-interpretation’, ‘meta-analysis’, ‘narrative synthesis’, ‘meta-synthesis’ and other descriptors being widely used to describe similar approaches. Conversely, the same terms are frequently employed to describe different approaches. This suggests a need to look beyond labels when searching and reviewing this area of work and for developing an agreed terminology.

The term ‘synthesis’ also has varying meanings and fuzzy boundaries in relation to qualitative research and involves a range of activities. At present, there is no single agreed classification of different types of qualitative synthesis and different authors adopt varying frameworks. Based on their main aims and approaches to synthesis, this chapter identifies the different types of synthesis that may be undertaken in relation to qualitative studies (i.e. secondary data) as numeric, narrative and interpretive (Box 1). In practice, however, these different methods may overlap and can be viewed as forming part of a continuum that ranges from numeric syntheses at one end to interpretive approaches based on a qualitative paradigm at the other. Some forms of secondary analysis of primary data across studies can also be regarded as a form of qualitative synthesis.

Case survey method

Bayesian methods

Narrative synthesisNarrative review

Thematic analysis

Cross-case analysis

Interpretive synthesisMeta-ethnography

Meta-study

Grounded theory

Realist synthesis

Primary data Secondary data analysisAggregative synthesis

It seems paradoxical to begin this review of methods for synthesising qualitative research with numeric approaches. Nevertheless, a variety of methods have been proposed for converting data from qualitative research studies into a quantitative form for the purposes of analysis and synthesis. An early example is Yin’s25 case survey method, which was developed for the synthesis of case studies based on a qualitative or mixed-method approach. This method involves the initial application of a closed-ended coding instrument to each qualitative case study to abstract and record relevant data. The collective data from these codes are then tallied and analysed in much the same way as traditional survey data. Examples are analyses by Yin25 and colleagues of citizen participation in urban services26 and of innovations in urban services. 27,28 This approach to the synthesis of qualitative data mimics quantitative meta-analysis in which findings (usually from individual RCTs) are aggregated in order to have sufficient statistical power to detect a cause and effect relationship between a particular treatment and specific health outcomes. 28

Current interest in combining qualitative and quantitative syntheses has led to other types of numeric methods, with a key example being the Bayesian synthesis of qualitative and quantitative evidence. This involves pooling of the data and is illustrated by Roberts et al. ’s29 investigation of childhood immunisation and the probable effects of a variety of factors on uptake. Their approach involved the initial extraction of factors influencing the uptake of childhood immunisation identified from qualitative studies. These factors were then classified in terms of broader descriptive categories (e.g. ‘lay beliefs’ was used to capture such concepts as ‘parents’ beliefs’ and ‘opinions of parents and other family members about the value of immunisation’). Rankings of the relative importance of each factor by each reviewer yielded a probability of that factor being important in determining uptake. These factors were then combined with evidence from the quantitative data to form a posterior probability that each factor identified (e.g. lay beliefs) was important in determining uptake of immunisation. This synthesis, therefore, provided a more complete enumeration of factors associated with the uptake of immunisation through combining quantitative and qualitative studies. Bayes factor methods were then employed to compare two possible meta-regression models in explaining the log-odds of immunisation uptake for each possible factor. This approach forms an important attempt to combine qualitative and quantitative evidence using numeric methods and pooling data, but like other numeric methods is mainly concerned with what Hammersley14 identified as aggregative purposes in terms of the accumulation and generalisation of evidence.

Other approaches to the systematic analysis/synthesis of studies derive from Miles and Huberman’s30 cross-case techniques, which involve developing summary tables based on content analysis and noting commonalities and differences between studies.

Narrative synthesis

The aims of narrative synthesis are generally to achieve an aggregation of findings or check the comparability and replication of findings, based on narrative rather than numeric methods. A narrative synthesis may also lead to new insights and form the basis for further interpretive analysis and conceptual development, although this is not the primary focus.

There are two broad approaches to qualitative narrative synthesis. One is based on the traditional literature review and involves the use of informal but critical and reflective methods. This approach, lately described as ‘narrative review’,20 unusually aims to provide a commentary and summary of the main features and findings of a body of literature using methods that are not explicitly pre-defined and transparent. This method has been distinguished from ‘narrative synthesis’, which employs more transparent and systematic methods to identify studies, assess study quality and synthesise the findings. It usually involves a form of thematic analysis to identify the main, recurrent or most important themes in the literature, thus allowing the findings of studies to be summarised and grouped. Examples of narrative syntheses include McNaughton’s31 review of research reports describing the home-visiting practice of public-health nurses to identify common elements and differences between studies, and Finfgeld’s32 review of studies to better clarify how individuals overcome drug and alcohol problems without participating in 12-step-type self-help groups or formal treatment.

Narrative synthesis is an approach that has evolved largely from within the quantitative systematic reviewing tradition. Indeed, the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York University33 now encourages reviewers to first undertake a ‘descriptive or non-quantitative synthesis’ of studies to be included in a review, in other words a narrative synthesis, to help them think about what the ultimate method of synthesis should be. In order to further assist this development, a report has recently been compiled to provide detailed guidance on how to undertake narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. 34

Interpretive synthesis

This is generally regarded as ‘the’ approach to the synthesis of qualitative research, and has as its specific aim the achievement of the developmental goal of qualitative synthesis in terms of producing interpretations that go beyond individual studies and thus contribute to conceptual and theoretical development in the field14 and accords with Strike and Posner’s11 notion of qualitative synthesis as achieving ‘conceptual innovation’ or the ‘invention or employment of concepts not found in the characterization of the parts as a means of creating the whole’ (p. 346). The output is, therefore, a new interpretation or theory that goes beyond the findings of any individual study.

A number of approaches to the conduct of interpretive synthesis have been developed. These include meta-ethnography, meta-study, critical interpretive synthesis, realist synthesis and grounded formal theory. Each of these approaches is examined in detail in Approaches to interpretive synthesis, but a general feature is that the synthesis builds interpretation from original studies by firstly identifying interpretations offered by the original researchers (second-order constructs) and, secondly, enabling the development of new interpretations (third-order constructs) that go beyond those offered in individual primary studies.

Secondary data analysis

This approach is concerned with the analysis and interpretation of primary (i.e. ‘raw’) data rather than the findings of published studies. Secondary data analysis may be regarded as a form of interpretive synthesis if it fulfils two requirements: it involves multiple qualitative data sets rather than a single data set; and the aim is to provide a new perspective or conceptual focus rather than to undertake an additional in-depth or subset analysis of existing data.

There are currently only a few examples of secondary analysis of multiple qualitative data sets. These have mainly involved the re-analysis by researchers of their own data. An example is Bloor and MacIntosh’s35 study of techniques of client resistance to surveillance based on two earlier studies they conducted. Interest in the secondary analysis of qualitative data is growing, and the capacity to undertake such work is considerably enhanced by the establishment by the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC’s) UK Data Archive of an archive of data from qualitative studies.

Secondary analysis of qualitative data raises a number of ethical and methodological issues, including issues of consent in relation to the reuse of another researcher’s data for a different purpose,36,37 and methodological questions such as the effects of distance from the data collection and of possible variations in study design on interpretation. 38 It is likely that the greater availability of qualitative data sets and increasing interest in secondary analysis will lead to new protocols and strategies to address these issues, thus, enhancing this approach to the synthesis of qualitative research.

Approaches to interpretive synthesis

This section provides a more detailed consideration of four approaches to interpretive synthesis: meta-ethnography, meta-study, grounded formal theory and realist synthesis.

Meta-ethnography

Noblit and Hare’s15 method of meta-ethnography was published in 1988 and is described as ‘an attempt to develop an inductive and interpretive form of knowledge synthesis’. Noblit and Hare15 developed meta-ethnography in response to the perceived failure of a synthesis of five ethnographic studies of educational desegregation that were undertaken to convey information to policy-makers. This educational synthesis took an aggregative, thematic approach that involved abstracting data and isolating factors in each study that appeared to be responsible for the failure of schools to desegregate. This process of abstraction de-emphasised the uniqueness of each site. The context therefore merely became a confounding variable in the search for common findings rather than contributing to an explanation of these findings. As a result, the synthesis did not provide researchers or policy-makers with an understanding of what went wrong and what could be done about it. Noblit and Hare15 aimed to overcome these limitations through developing a distinct method for the synthesis of qualitative studies that was informed by Turner’s39 theory of social explanation and is interpretive rather than aggregative. As they stated:

The nature of interpretive explanation is such that we need to construct an alternative to the aggregative theory of synthesis entailed in integrative research reviews and meta-analysis and be explicit about it.

Noblit and Hare15 (p. 18)

This aim of constructing adequate interpretive explanations required developing a way of ‘reducing’ and deriving understanding from multiple cases, accounts, narratives or studies while retaining the sense of the account. Noblit and Hare15 were themselves ethnographers who were concerned with long-term intensive studies that employed observation, interviews and documents, and termed the approach that they developed ‘meta-ethnography’. However, they described meta-ethnography as being applicable to qualitative research generally and as forming ‘a rigorous procedure for deriving substantive interpretations about any set of ethnographic or interpretive studies’ (p. 9). Noblit and Hare15 also noted that their particular approach was ‘a’ meta-ethnography and that it formed ‘but one of many possible approaches’ (p. 25).

Noblit and Hare15 identified seven phases in undertaking meta-ethnography (Box 2), but observed that in practice these phases may occur in parallel and overlap. The phases broadly correspond with other methods of synthesis, but differ in the assumptions and procedures involved. One difference is that the sample for research is purposively selected in relation to the topic of interest (and may involve maximum variation sampling), rather than being exhaustive. This reflects the general approach of qualitative methods and the aim of achieving interpretive explanation. A second difference is that the interpretations and explanations contained in the original studies are treated as data through the selection and analysis of key ‘metaphors’ (i.e. the themes, perspectives or concepts revealed by qualitative studies), with the aim of reducing accounts while preserving the sense of the account. Preparation for comparison between studies requires listing and juxtaposing the key metaphors, phases, ideas and/or concepts used in each account but retaining, as far as possible, the terminology used by the authors to remain faithful to the original meanings (phase 4). A third difference is that comparison between studies involves processes of ‘translation’, with the metaphors/concepts and their interrelationships in one account being compared with those in another account. This process of translation is idiomatic and focuses on translating the meaning of the text rather than a literal translation, with the aim of preserving original meanings and contextualisation. Noblit and Hare15 identified three possible types of relationship that guide translation and subsequent synthesis:

-

Reciprocal: when studies are about similar things, they can be synthesised as direct translations (i.e. in an iterative fashion each study is translated into the metaphors of the others – see Chapter 5 for a detailed description and illustration of this process). ‘These reciprocal translations may reveal that the metaphors of one study are better than those of others in representing both studies, or that some other set of metaphors not drawn from these studies seems reasonable.’ Noblit and Hare15 pointed out that the ‘uniqueness of studies may not make it possible for a single set of metaphors to adequately express the studies’, in which case more is often learned from the process of translation than from the metaphors alone.

-

Refutational: this is undertaken when studies refute each other. It requires a more elaborate set of translations ‘involving’ translations of both the ethnographic account and the refutations to examine the implied relationship between competing explanations.

-

Lines-of-argument: many studies suggest a lines-of-argument or inference about some larger issue or phenomenon. This involves first translating studies into each other and then constructing an interpretation (‘lines-of-argument’) that may serve to reveal what was hidden in individual studies (discovering a ‘whole’ among a set of parts). This is achieved through the use of the comparison and theory generation aspects of grounded theory as described by Glaser and Straus,40 and involves the detailed study of differences and similarities among studies to be synthesised with the aim of producing an integrated scheme and new interpretive context.

Phase 1: Getting started – ‘identifying an intellectual interest that qualitative research might inform’. This may be changed/modified as interpretive accounts are read.

Phase 2: Describing what is relevant to initial interest – an exhaustive search for relevant accounts can be undertaken followed by selection of research relevant to the topic of interest (they observe that employing all studies of a particular setting often yields trite conclusions).

Phase 3: Reading the studies – the repeated reading and noting of metaphors is required and continues as the synthesis develops.

Phase 4: Determining how the studies are related – the task of putting together the studies requires creating a list of key metaphors, phrases, ideas or concepts (and their relations) used in each account, and juxtaposing them. This leads to initial assumptions about relations between studies.

Phase 5: Translating the studies into one another – the metaphors and/or concepts in each account and their interactions are compared with the metaphors and/or concepts and their interactions in other accounts. These translations are one level of meta-ethnographic synthesis.

Phase 6: Synthesizing translations – ‘the various translations can be compared with one another to determine if there are types of translation or if some metaphors/concepts are able to encompass those of other accounts. In these cases, a second level of synthesis is possible, analysing types of competing interpretation and translating them into each other’ to produce a new interpretation/conceptual development.

Phase 7: Expressing the synthesis – for the proposed synthesis to be communicated effectively it needs to be expressed in a medium that takes account of the intended audience’s own culture and so uses concepts and language they can understand.

How translations are synthesised (phase 6), and the product of this process, depends on how studies relate to each other. Both translation and synthesis involve a continuous comparative analysis of texts until a comprehensive understanding of the phenomena is realised and the synthesis is then complete. Noblit and Hare15 did not specify this process in detail, but regarded it as akin to the general processes of qualitative research. The main difference is that the ‘data’ of meta-ethnography are the substance of several qualitative studies.

The final stage of meta-ethnography is ‘expressing the synthesis’ or communicating with an audience. This was given considerable emphasis by Noblit and Hare,15 who stated that ‘the worth of any synthesis is in its comprehensibility to some audience’ (p. 82). They described the needs of the audience (e.g. researchers, policy-makers) as influencing both the form and substance of the synthesis. Some understanding of the audience’s culture is therefore required to ensure that the translation of studies for the synthesis uses intelligible concepts to inform the final presentation of synthesis. They observed that if the data are inadequate or if the audience cannot see the connection between data and the argument then the study becomes unbelievable. Comprehensibility and believability are thus central to determining worth.

Noblit and Hare’s15 approach to meta-ethnography was based on a literary tradition of interpretivism and was, therefore, driven by a desire to achieve adequate interpretive explanations rather than by technical interests. This means that the authors were critical of the emphasis given by some qualitative researchers to the explicitness of processes employed to analyse data and refer to what Marshall41 described as the ‘bureaucratization of data analysis’. 15 Instead they emphasised the fluidity and interpretive aspects, and described the conduct of meta-ethnography as an ongoing process in which substantive interests may change as the synthesis proceeds. Similarly, translations were regarded as emergent and interactive, with the stages of translation and synthesis often interweaving rather than forming distinct phases.

Noblit and Hare15 illustrated the methods of meta-ethnography using brief excerpts of material from educational studies. Following publication of their monograph, there has been considerable interest in the application of meta-ethnography to a variety of fields including education, public policy and health. The greatest number of recent meta-ethnographic syntheses have come from nursing, reflecting the large number of qualitative studies in nursing and the particular interests and contributions of schools of nursing in the USA and Canada.

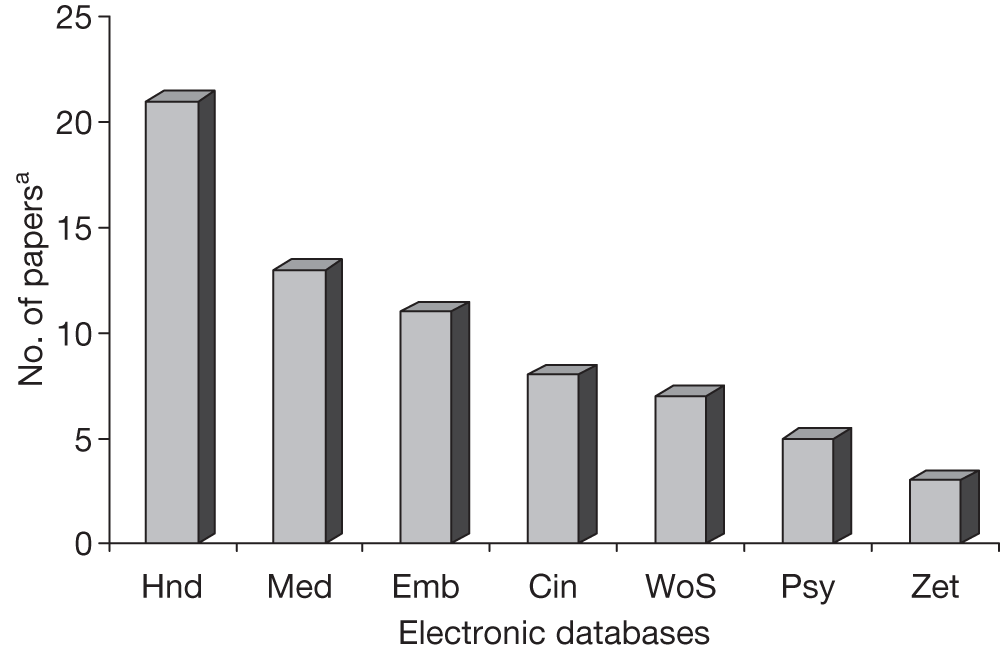

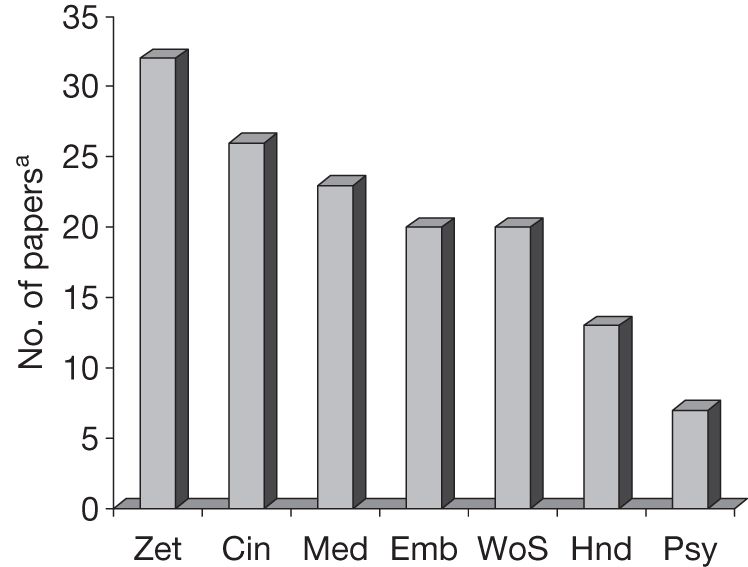

The present review involved a search for examples of meta-ethnography and other methods of interpretive synthesis in the health field. This initially involved a computer search undertaken in spring 2003 and updated in the summer of 2006 using MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, Web of Science (Social Science Citation Index and Science Citation Index), PsychINFO and Zetoc (British Library’s Electronic Table of Contents) electronic databases. A simple search strategy was used that combined the term ‘qualitative research’ with the terms ‘meta analysis’, ‘meta synthesis’, ‘meta ethnography’, ‘systematic review’, ‘data synthesis’ and ‘meta study’. Hyphenated terms (e.g. meta-ethnography) were also used. Further syntheses were identified via a published textbook of methods of qualitative meta-synthesis42 and later compared with Finfgeld’s43 review. However, the aim was not so much to achieve an exhaustive list as to identify representative syntheses using meta-ethnography and to examine their practical applications.

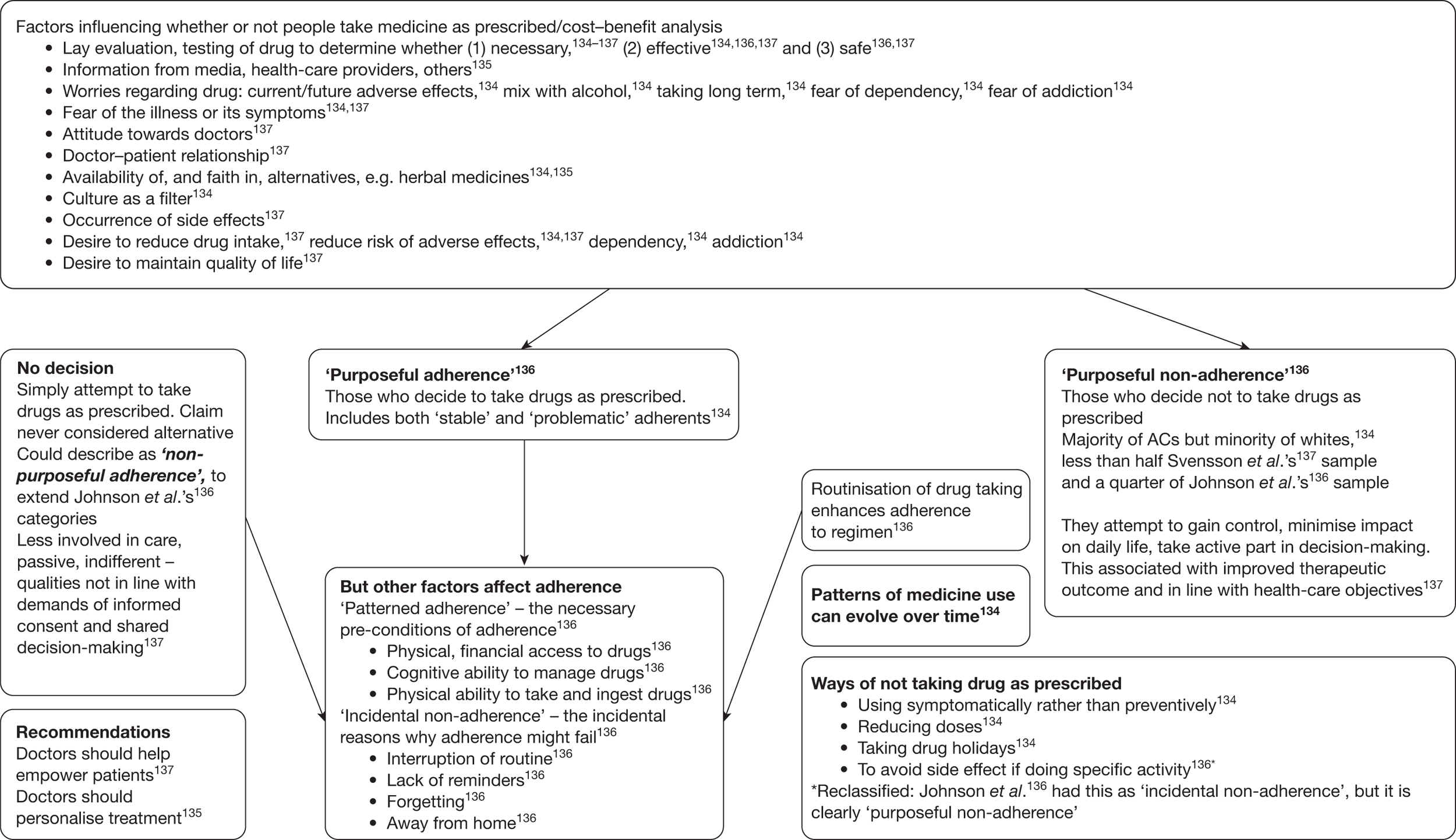

A total of 41 reports were identified that appeared to be qualitative syntheses. 16,17,44–82 The authors used various terms to describe the methods employed and occasionally used more than one term. We therefore broadly grouped syntheses according to what appeared to be their main approach. Syntheses employing meta-ethnography prior to the beginning of the present project demonstrated the potential value of this approach in producing conceptual developments. This is illustrated by the development of a wellness–illness model,61 a model of caring,74 models of diabetes management17,70 and explanations of states and behaviours such as moral distress among nurses, non-adherence among patients, the experience of post partum depression and help-seeking behaviours (Table 1). The studies included in these syntheses mainly collected data through interviews with only a few including focus groups or observational methods. They also exhibited a limited variety of theoretical perspectives, reflecting the dominant approaches to qualitative research in the field of health and illness.

| Authors and title | Number of reports included | Authors’ description | Appraisal criteria | Main concepts/explanations | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-ethnography | |||||

|

Britten et al. , 200216 Using meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative research: a worked example |

Four papers, arbitrarily chosen (included three by authors) | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Developed a line of argument that accounts for patients’ medicine-taking behaviour and communication with health professionals in different settings based on notions of self-regulation and selective disclosure | Aimed to assess benefits of meta-ethnography through a worked example |

|

Campbell et al. , 200317 Evaluating meta-ethnography: a synthesis of qualitative research on lay experiences of diabetes and diabetes care |

10 reports, purposively selected | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography |

Questions from CASP18 Two papers excluded because of methods and one because of an overlap with another paper |

Identified a model of diabetes management involving strategic non-compliance which was associated with being in control of diabetes, ‘coping’, achieving a balance between quality of life and illness, improved glucose levels and a feeling of well-being | Aimed to provide a formative assessment of meta-ethnography and of a qualitative assessment tool |

|

Feder et al. , 200644 Women exposed to intimate partner violence: expectations and experiences when they encounter health-care professionals: a meta-analysis of qualitative studies |

29 articles, computer search | Meta-analysis of qualitative studies. Use of Schulz et al.’s3 framework of constructs for meta-analysis. Meta-ethnography method used by Campbell et al.,17 and first used by Noblit and Hare15 | No | Use of first-, second- and third-order constructs to identify desirable characteristics of health-care professionals in consultations in which partner violence is raised | Table of third-order constructs in terms of recommendations to health-care providers by stage of interaction with abused women |

|

Smith et al. , 200545 Delay in presentation of cancer: a synthesis of qualitative research on cancer patients’ help-seeking experiences |

32 papers, computer search | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Use of second- and third-order constructs. Similarities in help-seeking in patients with different cancer types. Key concepts were recognition and interpretation of symptoms, and fear of consultation. Fear of embarrassment and fear of cancer. Patient’s gender and the sanctioning of help-seeking were important factors in prompt consultation | Provides international overview through the systematic synthesis of a diverse group of small-scale qualitative studies |

|

Walter et al. , 200446 Lay understanding of familial risk of common chronic diseases: a systematic review and synthesis of qualitative research |

11 qualitative articles, computer search and reference lists |

Meta-analysis using meta-ethnographic methods and drawing on Schulz et al. 3 Three stages: first-order constructs (key concepts from each article); second-order constructs (translating first-order constructs); third-order constructs (synthesising second-order constructs to produce overarching concepts) |

Articles assessed using appraisal scoring system (CASP). None excluded | Second-order constructs included diseases running in my family; experiencing a relative’s illness; personal mental models; personalising vulnerability; and control of familial risk. Led to three main third-order constructs: salience; personalising process; and personal sense of vulnerability | Identifies third-order constructs for health professionals to explore with patients that may improve the effectiveness of communication about disease risk and management |

| Meta-synthesis | |||||

|

Attree, 200547 Parenting support in the context of poverty: a meta-synthesis of the qualitative evidence |

12 studies, search methods not given | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnographic methods to produce meta-synthesis of findings | Quality appraised using checklist that drew on earlier models of assessing qualitative research: Popay et al.,83 Seale,84 Mays and Pope,85 CASP,18 Spencer et al.19 Studies graded A–D. A–C grades were included | Systematic review of qualitative studies of low-income parents to explore informal and formal support networks. Two main themes were found: informal and formal support | Difficult to identify any of the key components of a meta-ethnography, e.g. reciprocal translation, refutation or lines-of-argument |

|

Barroso and Sandelowski, 200448 Substance abuse in HIV-positive women |

74 reports, search methods not given | Qualitative meta-synthesis of studies | No | Qualitative meta-synthesis of studies containing information on abuse among HIV-positive women. Three main themes found: diagnosis as a turning point; complications of motherhood for dually diagnosed women; and benefits of recovery – beyond stopping substance abuse | Constructs trajectory that describes events of women’s lives with regard to substance abuse and its intersection with HIV infection |

|

Barroso and Powell-Cope, 200049 Meta-synthesis of qualitative research on living with HIV infection |

21 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis | Burns86 standards: led to ‘some exclusions’ | Identified importance of finding meaning in HIV infection/AIDS which led to being able to establish human connectedness, focusing on the self, negotiating health care and dealing with stigma. Those for whom HIV infection had shattered meaning were unable to establish a framework for coping |

Conducted a post-review validity check on a random sample of a further 33 studies published 1996–8 to determine that their metaphors were still valid in these studies Many extracts of interviews with HIV-positive people |

|

Beck, 200250 Mothering multiples: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research |

Six qualitative studies, computer search | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Synthesis produced five themes: bearing the burden; riding the emotional roller coaster; lifesaving support; striving for maternal justice; and acknowledging individuality | Synthesis conducted to illustrate the method |

|

Beck, 200251 Post partum depression: a meta-synthesis |

18 studies, computer search | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Identified four overarching themes with their subsumed metaphors in relation to the experience of post partum depression: incongruity between expectations and reality of motherhood; spiralling downward; pervasive loss; and making gains. Coping involved seeking professional help, adjusting unrealistic expectations and regaining control in their lives | Described the end product as a comprehensive and thickly descriptive account that is the foundation for theory development |

|

Carrol, 200452 Nonvocal ventilated patients’ perceptions of being understood |

12 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis following Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Found five overarching themes and divided them into two groups: characteristics of non-vocal ventilated patients’ communication experience; type of nursing care desired by non-vocal patients in order to be understood | Data translated into second-order interpretations, but not constructed into third-order interpretations |

|

Clemmens, 200353 Adolescent motherhood: a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies |

18 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis following Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Five metaphors were found: reality of motherhood brings hardship; living in the two worlds of adolescence and motherhood; motherhood as positively transforming; baby as stabilising influence; and supportive context as turning point for future. Clinical implications of study | |

|

Coffey, 200654 Parenting a child with chronic illness: a meta-synthesis |

11 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis following Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Two of the 11 studies were triangulated. Seven themes were found: living worried; staying in the struggle; carrying the burden; survival as a family; bridge to the outside world; critical times; and taking charge | |

|

Coffman M, 200455 Cultural caring in nursing practice: a meta-synthesis of qualitative research |

13 studies, computer search | Meta synthesis following Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Findings reduced to six overall themes: connecting with the client; cultural discovery; the patient in context; in their world, not mine; roadblocks; and the cultural lens | |

|

Evans and FitzGerald, 200256 The experience of physical restraint: a systematic review of qualitative research |

Four qualitative studies, computer search | Using meta-ethnography Noblit and Hare;15 meta-synthesis Jenson and Allen;61 content analysis (Suikkala and Leino-Kilpi87). Identify the key themes and compare these across studies | Locally developed tool to appraise: methodology; clear descriptions; adequate result information; information supported by exemplars from study participants | Summarises current evidence on the experience of being physically restrained, and the experience of having a relative subject to restraint in an acute or residential care facility | References a number of approaches to qualitative synthesis, but does not seem to apply them |

|

Finfgeld-Connett, 200557 Clarification of social support |

47 studies, computer search (3 linguistic analyses and 44 qualitative studies) | Meta-synthesis. Use of the Template Verification and Expansion Model (Finfgeld88) of concept development, based on meta-synthesis of findings from qualitative studies and linguistic analyses to inductively clarify and expand existing conceptual models and triangulate findings | No | Aimed to clarify the concept of social support. Findings placed in a matrix organised by Walker and Avant’s89 broad concept analysis categories: antecedents, critical attributes and consequences. Three themes found: types of social support; attributes of social support; and antecedents of social support | |

|

Finfgeld-Connett, 200658 Meta-synthesis of presence in nursing |

18 studies, computer search (14 qualitative studies and 4 linguistic-concept analyses) | Finfgeld’s43 meta-synthesis methods. Grounded theory (Strauss and Corbin90) | No | Presence is an interpersonal process that is characterised by sensitivity, holism, intimacy, vulnerability and adaptation to unique circumstances. Created chart: ‘process of presence’ | |

|

Goodman, 200559 Becoming an involved father of an infant |

10 articles, computer search | Meta-synthesis using Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Fathers of infants experienced four phases: entering with expectations and intentions; confronting reality; creating one’s role of involved father; and reaping rewards. Implications for theory development, research and clinical practice are discussed | |

|

Howell and Brazil, 200560 Reaching common ground: a patient-family-based conceptual framework of quality EOL care |

Seven studies, computer search | Descriptive meta-synthesis in systematic review. Linking metaphors in a Venn diagram, Miles and Huberman30 | Excluded if inductive reasoning not used/lack of evidentiary support. Sandelowski and Barroso’s91 typology used for classifying studies on the basis of their interpretive analysis to determine their methodological comparability | Found eight themes: pain and symptom control; dying process not prolonged; prepared for death; support of family or friends; supported decision-making; spiritual support and meaning; holistic and individualised care; death in a supportive environment in location of choice | Grounded theory methods were used for developing metaphors and themes in four studies; unspecified content analysis was described in the remaining studies |

|

Jensen and Allen, 199461 A synthesis of qualitative research on wellness–illness |

112 studies, search methods not given (included 63 dissertations and theses) | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography and grounded theory | No | Derived overall model of wellness–illness based on lived experience involving abiding vitality (when one is healthy); transitional harmony (experience of unity disrupted by disease); rhythmical connectedness (disease results in detachment or disconnection from oneself, others and environment); unfolding fulfilment; active optimism; and reflective transformation | |

|

Kärkkäinen et al. , 200562 Documentation of individualized patient care: a qualitative metasynthesis |

14 research reports, computer search | Qualitative meta-synthesis | Data management followed Gadamer’s hermeneutic empirical theory:a a new understanding of investigated matter occurs when a concept conveyed by the studied text by means of hermeneutic dialogue is added to the researchers view. Results of analysed articles can be interpreted in a different way | Three themes emerged that affected the content of nursing-care documentation: reflecting the demands on an organisation; reflecting nurses attitudes and duties; and reflecting patients’ involvement in their care | |

|

Kennedy et al. , 200363 An exploration meta-synthesis of midwifery practice in the United States |

Six studies, search methods not given | Meta-synthesis | No | Four themes identified, conceptually arrayed into a helix model to portray their dynamic and overlapping nature: the term midwife as an instrument of care; the woman as a partner in care; alliance in midwifery care; and the environment in the process of midwifery care | Uses some of the stages in meta-ethnography as described by Noblit and Hare15 |

|

Kylma, 200564 Despair and hopelessness in the context of HIV infection – a meta-synthesis on qualitative research findings |

Five qualitative studies by the same author, computer search | Meta-synthesis method: extraction, comparing extracted factors, coding, gathering categories together | No | Despair consists of two subprocesses – downwards and upwards. Downwards: being stuck in a situation, losing perspective. Upwards: fighting against sinking, rising up | Five studies were all by the same author |

|

Kylma, 200565 Dynamics of hope in adults living with HIV infection/AIDS: a substantive theory |

Five articles by the same author, computer search | Meta-synthesis: read articles, extraction, comparing extracted factors, coding, gathering categories together | No | Dynamically altering balance between interconnected hope, despair and hopelessness based on folding and unfolding possibilities with regard to the dynamics of hope in dealing with the changing self and life with HIV infection/AIDS | Five grounded theory studies – all by the same author |

|

Lefler and Bondy, 200466 Women’s delay in seeking treatment with myocardial infarction: a meta-synthesis |

48 reports, computer search (39 descriptive studies, 4 experimental in design, 5 used qualitative methodology) | Meta-synthesis of the literature using Cooper’s92 five stages: problem formation; data collection; data evaluation; analysis and interpretation; and presentation of results | Articles representing opinions/discussions were excluded | Three factors explain why women delay in seeking treatment: clinical; sociodemographic; and psychosocial | |

|

Meadows-Oliver, 200367 Mothering in public: a meta-synthesis of homeless women with children living in shelters |

18 studies, search methods not given | Meta-synthesis | No | Six reciprocal translations of homeless mothers caring for children in shelters: becoming homeless; protective mothering; loss; stressed and depressed; survival strategies; and strategies for resolution | Uses some of the stages in meta-ethnography as described by Noblit and Hare15 |

|

Nelson, 200368 Transition to motherhood |

Nine studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis | No | Two processes inherent in maternal transition were identified: engagement, and growth and transformation. In addition, five thematic categories identified signifying areas of disruption present in the maternal transition: commitment; daily life; relationships; work; and self | |

|

Nelson, 200269 A meta-synthesis mothering other-than-normal children |

12 studies, search methods not given | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No (three exclusions as not qualitative and two not relevant) | 13 themes/metaphors reduced to four steps common to the mothering experience: becoming a mother of a disabled child, negotiating a new kind of mothering, dealing with daily life; and the process of acceptance/denial | |

|

Paterson et al. , 199870 Adapting to and managing diabetes |

43 papers (38 studies), computer search | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Identifies ‘balance’ as the main metaphor in the experience of diabetes, and examines process and requirements for learning to balance | Use of prior organising framework: Curtin and Lubkin93 conceptualisation of the experience of chronic illness. Several methods used to achieve trustworthiness including other members of team reviewing/agreeing analysis; identifying negative/disconfirming cases; testing rival hypotheses |

|

Roux et al. , 200271 Inner strength in women: meta-synthesis of qualitative findings in theory development |

Five studies, search methods not given | Meta-synthesis using Walker and Avant.89 Meta-synthesis used is similar to qualitative analysis or constant comparison, the selected literature was read, reread and examined for patterns of similarities among study findings that could be categorised or grouped together | No | ‘Conceptual model of inner strength in women revealed in the following constructs: knowing and searching; nurturing through connection; dwelling in a different place by recreating the spirit within; healing through movement in the present; and connecting with the future by living a new normal’71 | |

|

Sandelowski et al. , 200472 Stigma in HIV-positive women |

93 studies, search methods not given | Meta-synthesis. Worked inductively to create a taxonomy to depict the conceptual range of findings | No | Key findings included pervasiveness of both felt and enacted stigma; gender-linked intensification of HIV infection-related stigma; and unending work and care of stigma management | |

|

Sandelowski and Barroso, 200573 The travesty of choosing after positive prenatal diagnosis |

17 studies, computer search | Meta-summary techniques included the calculation of frequency effect sizes, used to aggregate findings. Meta-synthesis techniques included the reciprocal translation of concepts (Noblit and Hare15 used to interpret the findings) | No | Emphasis in findings is on the termination of pregnancy following positive diagnosis. The thematic emphasis is on the dilemmas of choice and decision-making. For couples, positive prenatal diagnosis was an experience of chosen losses and lost choices | |

|

Sherwood, 199774 Meta-synthesis of qualitative analyses of caring: defining a therapeutic model of nursing |

16 studies, search methods not given | Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | Burns86 and Roberts and Burke94 applied to each study. None excluded | Developed a therapeutic model of caring that identifies relationships between caregivers and receivers of care in producing therapeutic outcomes (involves the interaction context, nurses’ knowledge and nurses’ response patterns) | Consultation with two independent caring experts to validate the findings |

|

Steeman et al. , 200675 Living with early-stage dementia: a review of qualitative studies |

33 articles (28 studies), computer search, manually searched reference lists | Meta-synthesis aimed at an integrative interpretation of findings from single qualitative studies to synthesise a more substantive description of the phenomenon43,95,96 | Studies meeting inclusion criteria were appraised using Sandelowski and Barrosso97 guide for qualitative research | Living with dementia is described from the stage at which a person discovers the memory impairment, through the stage of being diagnosed with dementia, to that of the person’s attempts to integrate the impairment into everyday life | |

|

Swartz, 200576 Parenting preterm infants: a meta-synthesis |

10 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis. Use of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Five themes of parenting preterm infants emerged: adapting to risk; protecting fragility; preserving the family; compensating for the past; and cautiously affirming the future. Clinical implications | |

|

Varcoe et al. , 200377 Health-care relationships in context: an analysis of three ethnographies |

Three reports (based on own studies) | Qualitative meta-data analysis influenced by Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography | No | Importance of ‘moral distress’ for nurses due to experience of structural and personal constraints (e.g. excessive workloads, absence of interdisciplinary team rounds, conflict between team members and conflict with patients and families) and may lead to coercive practices | All studies conducted within 5-year period in four acute hospitals in same geographical location in western Canada. Studies based on different theoretical perspectives |

|

Werner, 200278 Human response outcomes influenced by nursing care |

42 studies, computer search | Meta-synthesis | No | Use of Loomis and Wood’s98 model of the seven human response systems which has three dimensions: health and illness; human-response systems; and nursing clinical decision-making. Findings organised into categories: physical human responses influenced by nurse caring; emotional human responses influenced by nurse caring; cognitive human responses influenced by nurse caring; family human responses influenced by nurse caring; social human responses influenced by nurse caring; spiritual human responses influenced by nurse caring | |

| Meta-studies | |||||

|

Paterson et al. , 200379 Embedded assumptions in qualitative studies of fatigue |

35 primary research reports, computer search | Meta-study (analysis in three stages): meta-data analysis, meta-method and meta-theory. Synthesis is a creative interpretation of the primary research to produce new and expanded understandings of the phenomenon under study | No | Four key assumptions found in the data: fatigue as exclusively attributed to disease; fatigue as a unitary phenomenon across human experiences; fatigue as inherently and necessarily problematic; and fatigue as isolated from the context in which it occurs | |

|

Paterson, 200180 The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness |

292 studies that met inclusion criteria from 1000 computer and manual search and professional networks | Meta-study including meta-ethnography |

Yes Burns standards86 |

Depicts people with chronic illness as shifting between illness and wellness in the foreground. Also identifies major factors leading to shift to illness in the foreground and process of ‘bouncing back’ to wellness in the foreground | Data synthesised to create model |

|

Thorne and Paterson, 199881 Shifting images of chronic illness |

158 reports that met inclusion criteria from 400 identified, computer and manual search (included dissertations) | Meta-study |

Yes Burns standards86 |

Describes shifting conceptualisations of individuals with chronic illness and parallel shifts in conceptualisations of health-care relationships appropriate to chronic illness from client-as-patient to client-as-partner | |

| Critical interpretative synthesis | |||||

|

Dixon Woods et al. , 200682 Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups |

119 papers, computer search, websites, reference chaining, contacting experts | Development and use of the method of CIS. Identified their method as reciprocal translational analysis; refutational syntheses and lines of argument synthesis | NHS National Electronic Library for Health for the evaluation of qualitative research, to inform judgements on the quality of papers. 20 excluded on grounds of being ‘fatally flawed’ | Created synthesis including critique of utilisation as a measure of access; candidacy; identification of candidacy; navigation; permeability of services; appearances at health services; adjudications; offers and resistance; operating conditions; and the local production of candidacy | |

Altogether we identified six syntheses that were clearly labelled as employing the methods of meta-ethnography. These included two papers on preliminary work published by the present team;16,17 a synthesis of 43 papers concerned with the experience of diabetes;70 a meta-ethnographic synthesis by Smith et al. 45 examining cancer patients’ help-seeking experiences; a synthesis by Feder et al. 44 of health-care professionals’ interactions with women in violent relationships; and another by Walter et al. 46 which was concerned with lay understandings of familial risk in common cancers.

The largest group of qualitative syntheses that we identified were labelled as meta-synthesis. Qualitative meta-synthesis was defined by Sandelowski et al. 13 as ‘the theories, grand narratives, generalizations, or interpretative translations produced from the integration or comparisons of qualitative synthesis’. Meta-synthesis, thus, seems to be, in effect, another term for qualitative synthesis and one that is not identified with any particular method. Many of the syntheses included within this category cited Noblit and Hare15 and claimed to be using meta-ethnographic methods, but what seemed to distinguish this group of studies from those labelling themselves explicitly as meta-ethnographies was that the latter group adhered more closely to the approach described by Noblit and Hare,15 included a smaller number of studies (maximum of 32) and, in general, achieved a higher degree of conceptual development. Meta-study and critical interpretative synthesis, which have their origins in meta-ethnography, are more recent developments and to date have been used only by their creators. The general tendency among all these syntheses was not to formally assess the quality of the research prior to synthesis. Where this did occur it was liable to result in just a couple of exclusions or in none at all. The reports of most syntheses aimed to draw out the implications for policy-makers and practitioners, but there was little evidence of wider policy/practitioner responses to these findings and assessment of worth in these terms.

The next section considers a development of Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography through its use as one aspect of a wider meta-study.

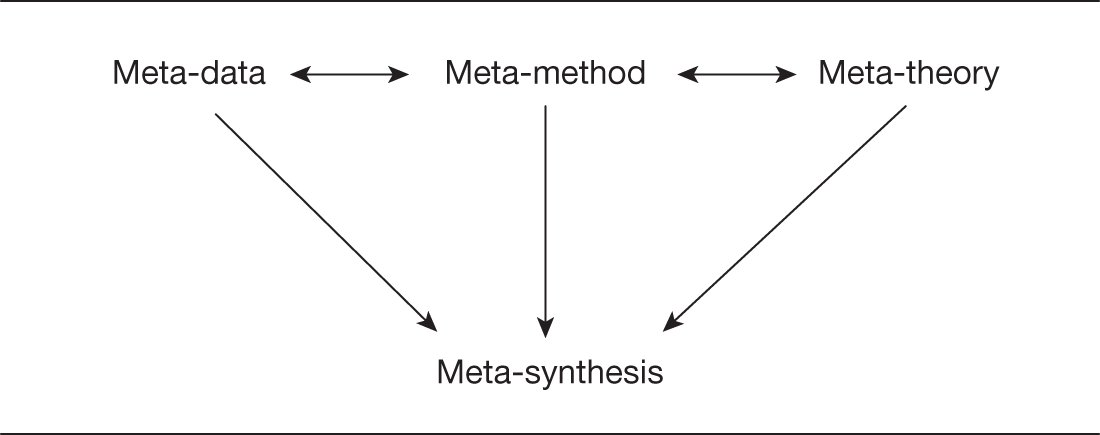

Meta-study

Paterson et al. 42 described an approach to synthesis that incorporates Noblit and Hare’s15 meta-ethnography as part of a meta-study. 70 Meta-study aims to go beyond meta-ethnography (or other methods of what they term meta-data analysis), as Paterson and colleagues do not regard meta-ethnography as giving sufficient attention to the way that theories and methods shape knowledge and confer meaning on findings. The enlarged framework of meta-study that Paterson and colleagues present derives from earlier sociological work that was concerned about understanding the ways in which theoretical, methodological or societal contexts shape reported results and bodies of knowledge. They draw particularly on the writings of Ritzer99 and of Zhao,100 who introduced the term meta-study and described its components: meta-data analysis (study of the processed data based on meta-ethnography or other methods of data analysis), meta-method (study of the appropriateness and rigour of particular methods used in the research studies and the implications of a range of epistemologically sound approaches for emerging data and interpretations) and meta-theory (analysis of the philosophical, cognitive and theoretical perspectives underlying the research that influences emerging data and interpretations). Paterson et al. 42 described each of these components as providing a unique angle of vision from which to deconstruct and interpret a body of qualitatively derived knowledge about a particular phenomenon, and suggests that meta-synthesis ‘… brings back together those ideas that have been taken apart or deconstructed in these three analytic meta-study processes’ (p. 13). Meta-synthesis, therefore, represents ‘the creation of a new interpretation of a phenomenon that accounts for the data, method and theory by which the phenomenon has been studied by others’ (p. 13) (Figure 1).

Paterson et al. 42 outlined the assumptions and methods for conducting a meta-study in their book, Meta-study of qualitative health research,42 and illustrated this in terms of the conduct of their own synthesis of the subjective experience of chronic illness. 70,101 Their initial phase of meta-data analysis was based on the methods of meta-ethnography, but whereas Noblit and Hare15 focused on the in-depth study of a small number of cases, Paterson et al. ’s42 synthesis began with the identification of close to 1000 reports, books, dissertations and research articles published during a 16-year period. These initial publications were reduced to 292 through assessment of their relevance to the review and appraisal of the sampling, data analysis and interpretation that was undertaken using Burns’86 standards for qualitative research. This appraisal involved at least three members of the team reviewing each report and reaching a consensus. Paterson et al. 42 stated that the number of studies was not reduced further as they regarded this number as necessary to achieve all components of the meta-study. The decision to include such a large number of studies required a systematised approach to meta-ethnography (i.e. meta-data analysis component) and was undertaken by the use of coded categories of themes, patterns, processes, etc. This was followed by a computer-based analysis in much the same way as the analysis of the original primary data. The use of computer software also facilitated comparisons between different groups (e.g. whether or not the disease was considered terminal, the method of sampling, gender, etc.). Paterson et al. 42 acknowledged that the handling of large numbers of reports in this way meant that there was an element of context stripping at this level, although their overall aim was to achieve greater contextualisation through finally integrating the different elements of a meta-synthesis (see Figure 1).

Although Paterson et al. 42 provided a clear and fairly detailed description of their approach to meta-data analysis, the stages of meta-method and meta-theory are less fully developed (particularly meta-theory). They also gave little guidance as to how the three components were to be integrated in the final stage of the meta-synthesis. Indeed, in terms of achieving the synthesis, they stated that they ‘… resist definitive procedural steps and encourage instead a dynamic and iterative process of thinking, interpreting, creating, theorising, and reflecting’. 42

Paterson et al. ’s42 own experience of conducting a meta-study has been their work on the subjective experience of chronic illness. 101 They acknowledged that the vast size of this undertaking presented considerable demands of organisation and data management, as well as requiring much time and a large team of researchers. What they termed the meta-data analysis component led to the depiction of the shifting perspective experienced by people with chronic illness from ‘wellness’ in the foreground to ‘illness’ in the foreground and the factors responsible for this shift and ‘bouncing back’. 80 Their attempt to achieve a meta-synthesis based on the three components of meta-study has not, however, led to a major new understanding of chronic illness, although they described the changes that have occurred in the conceptualisation of chronic illness over time. The approach they adopted to meta-synthesis also raises issues of practicability, with considerable time and resources required by the processes involved in first deconstructing and then reconstructing and synthesising the distinct components of meta-study; their own study involved seven researchers who contributed time over several years. Nevertheless, their work is important in its emphasis on the need for syntheses to take account of wider contextual factors, including the influence of theories and methods on the questions addressed and the interpretations developed. This is of particular importance in relation to the syntheses of studies conducted over a long time period and involving a broad area of research, as with Paterson et al. ’s42 own study of chronic illness. Their work also draws attention to the importance of meta-theory in terms of the study of the influence of cognitive, philosophical and theoretical perspectives on the questions addressed and interpretations as an aspect of study in its own right to complement more empirical data-based approaches.

Critical interpretive synthesis

More recently, Dixon-Woods et al. 102 used meta-ethnography to synthesise the diverse quantitative and qualitative literature on access to health care by vulnerable groups. In doing so, they suggest that it was necessary to introduce a number of innovations that were judged to be of sufficient substance to produce what they regard as a new methodological approach that they titled critical interpretive synthesis.

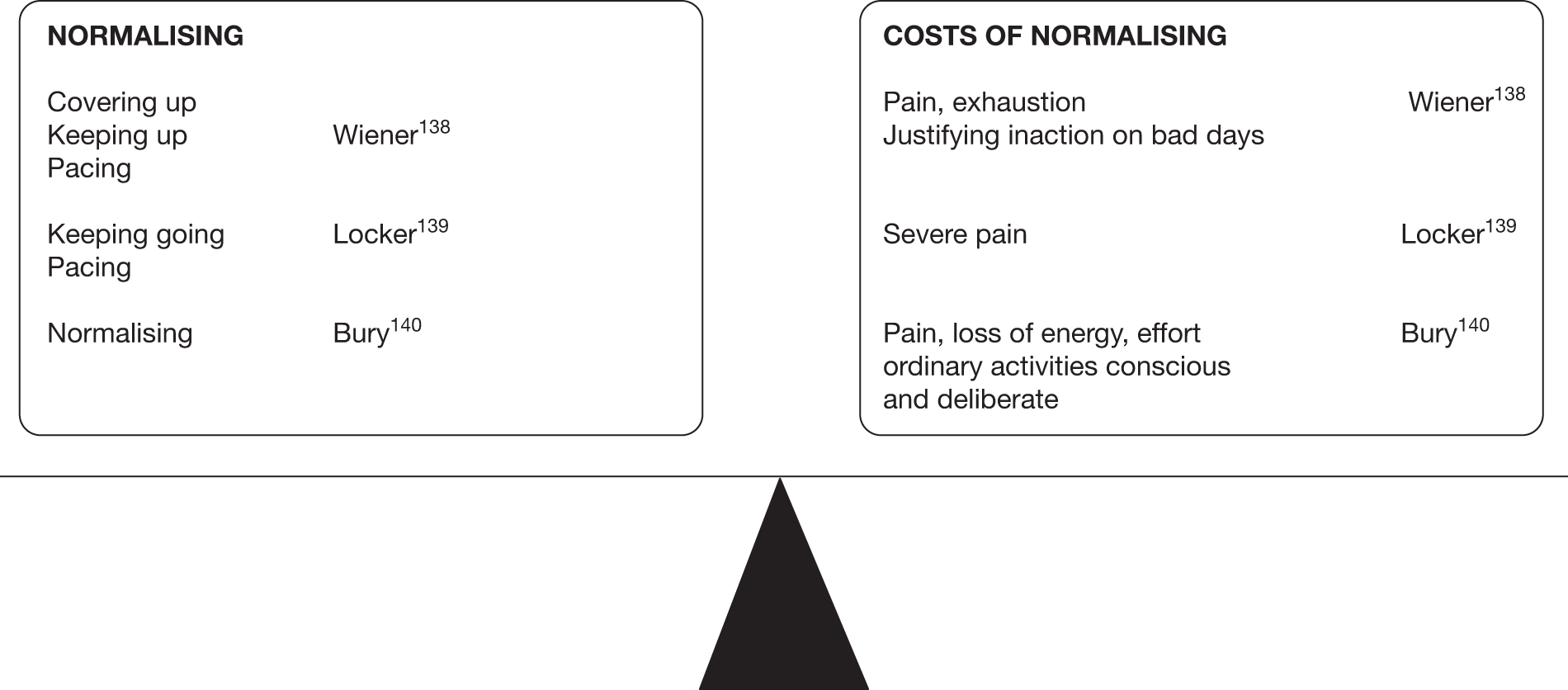

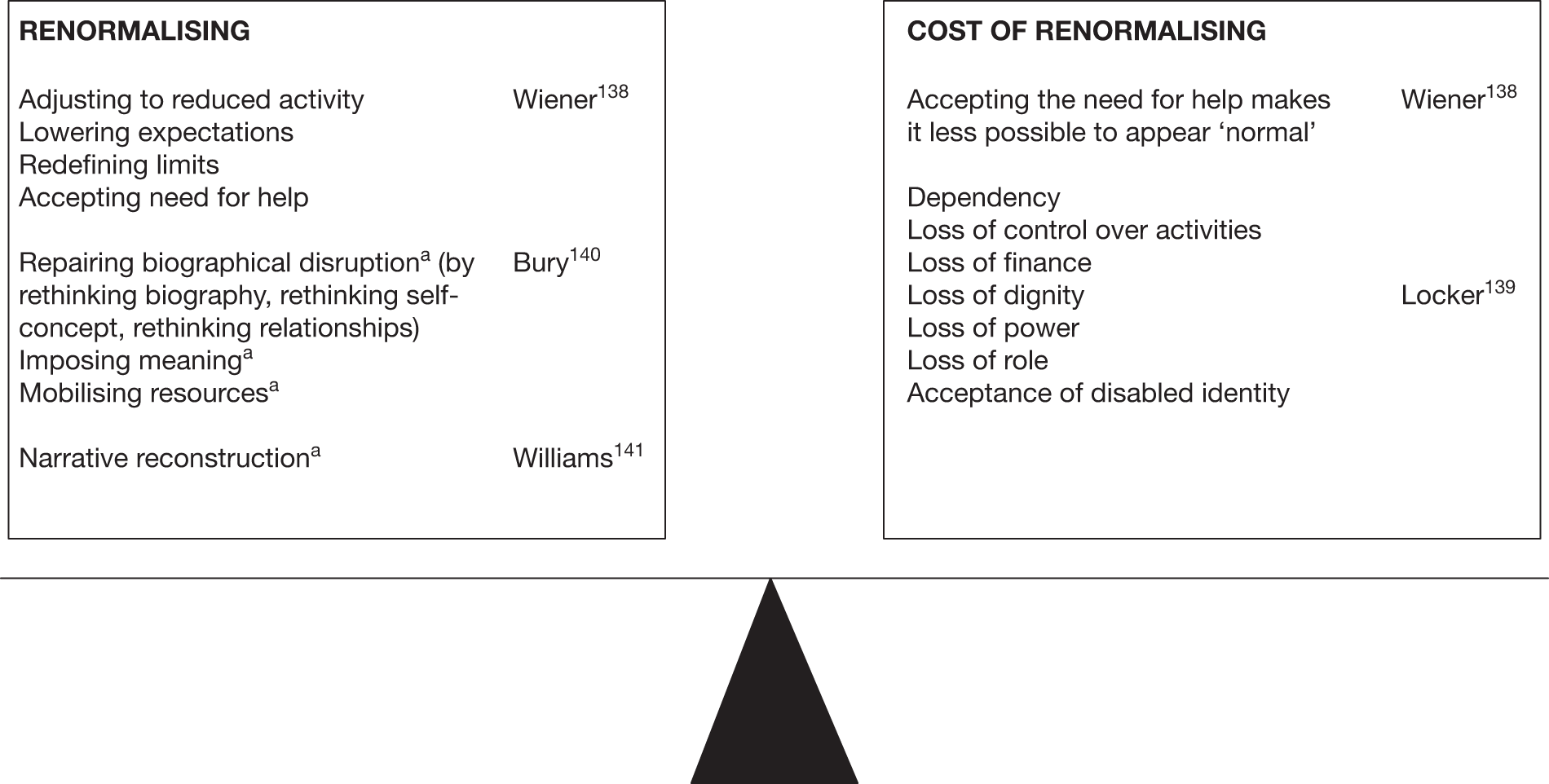

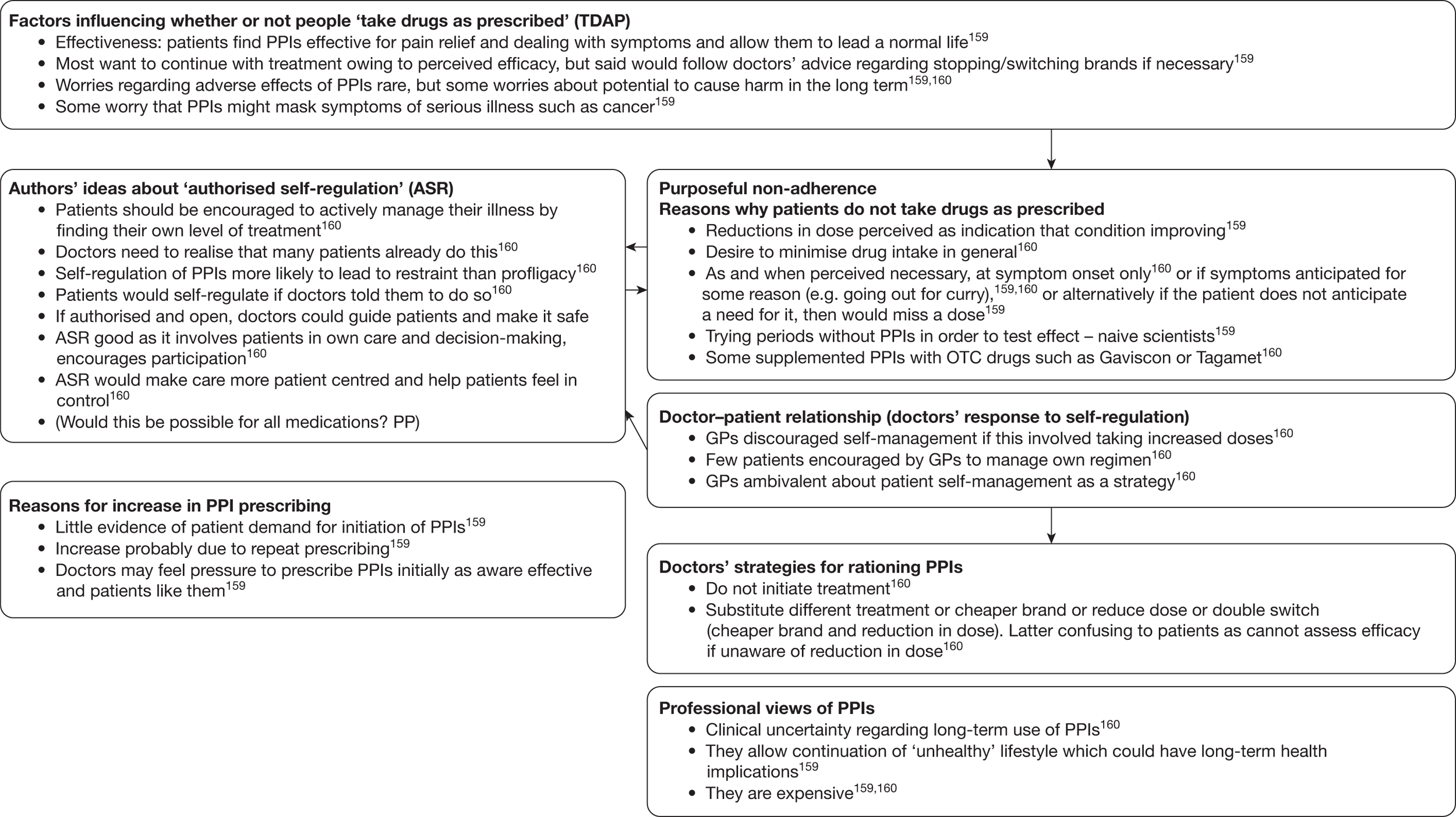

This synthesis was truly innovative in that it used meta-ethnography to synthesise a wide range of different paper types including primary quantitative, primary qualitative, mixed methods, editorial, review and theoretical papers. Books and reports were also included. Dixon-Woods et al. , citing Glaser and Strauss,40 present a compelling argument for there being no reason in principle why interpretive syntheses should not include different forms of evidence. The end result was that six syntheses were produced. The first was a synthesis that set out ‘a general taxonomic framework within which the literature on access to health care can usefully be organised’. 102 The remaining five syntheses comprised interpretive syntheses of access to health care for specific vulnerable groups (socioeconomically disadvantaged people, people of minority ethnicity, children and young people, and older people) and a synthesis examining the effects of gender. These syntheses led to a substantial number of findings and specific recommendations for policy and practice. In addition, concepts of candidacy and the porosity or permeability of services were proposed as useful aids to understanding access to health care. Candidacy was characterised as the processes of negotiation between people and health-care providers by which people’s eligibility for health care is established. Service porosity signalled ease of use and the number of qualifications for candidacy: the more porous a service the more comfortable it is for people to use and the fewer the qualifications required for candidacy. 102