Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned by the HTA programme as project number 08/101/01. The contractual start date was in May 2009. The draft report began editorial review in April 2011 and was accepted for publication in June 2011. As the funder, by devising a commissioning brief, the HTA programme specified the research question and study design. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Hockenhull et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

It has been suggested that worldwide incidents of violence account for more than 1.6 million deaths each year. 1 However, the proportion of personal violence resulting in death is only a fraction of personal violence or of violent assaults overall. In this introductory chapter we consider what we mean when we use the term ‘violence’ and examine the extent of violence in both the world and, specifically, the British context. Finally, the nature of the association between violence and mental disorder is explored.

The definition of violence

In a general sense, many would consider violence to consist of the use of physical force that is intended to hurt or injure another person. 2 However, arguably this rather simplistic and limited conceptualisation ignores the more insidious effects of non-physical violence, such as threats, intimidation and the self-directed violence of suicidal behaviour. It has been suggested that there may be several approaches to the definition of violence,3 although at present there is no widely held agreement on which of these is most appropriate. In this document we have adopted the broad conception offered by the World Health Organization (WHO), which has defined violence as ‘The intentional use of physical force or power, threatened or actual, against oneself, another person, or against a group or community, that either results in or has a high likelihood of resulting in injury, death, psychological harm, maldevelopment or deprivation’. 4

This definition includes threats, intimidation, neglect and physical, sexual and psychological abuse, as well as acts of self-harm and suicidal behaviour. Furthermore, it conceives of violence in terms of its outcomes on health and well-being rather than, for example, its characteristics as a construct that is purely culturally determined. 5

A number of attempts have been made to formulate a typology of violence. Krug et al. ,4 for example, suggested three broad categories: self-directed, interpersonal and collective violence. For our purposes here we propose to focus on only the second of these. This category, interpersonal violence, incorporates intimate partner violence, child abuse and stranger assaults, whether sexual or not. Excluded from this are acts of collective violence committed as a concomitant of war, terrorism or gang conflict.

The extent of violence

Determining the extent of serious violence at a global level is particularly problematic. Important among the range of obstacles to this is variation in the willingness and capacity of different governments and agencies to collect, and then make available, reliable data. The statistics that do exist indicate that global violence-related deaths in the year 2000 (the most recent year for which data exist) included 520,000 homicides, with rates being several times higher in low- to middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. 4 In absolute terms, death by homicide or suicide is considerably more likely among males, especially those aged 15–44 years, than among any other age/gender demographic grouping. 4 Comparable data for non-fatal violence are not available, as the true extent of this can be determined only by self-report, which is necessarily unreliable because much violence is likely to go unreported to the authorities or untreated by medical personnel. However, it seems reasonable to conclude that the true degree of violence will far outstrip nationally recognised figures for homicide. 6

In England and Wales, provisional data indicate that in the year 2008–9, 648 incidents of homicide were recorded in police figures, which represents the lowest level in 20 years. The most recent evidence from the British Crime Survey (BCS) and from police figures (crimes reported to the police) indicates that non-fatal violent crime remained essentially stable in the year 2008–9 compared with the previous year, with statistically non-significant reductions of between 4% and 6%. 7 In fact, BCS data suggest that the trend in all violence has gradually fallen year on year from a peak in 1995–6 to a current level that is 49% lower than this. 7 Nevertheless, the English Department of Health has identified the short-term management of violence as a key priority and supported development of clinical practice guidelines. 8

Perhaps ongoing public concern about the level of person-to-person violence serves to retain violence at the top of the political agenda, no doubt partly because acts of violence against the person account for approximately 20% of total crime, as recorded in police figures and reported by the BCS, respectively. 7 Domestic violence (DV) in particular has come to be regarded as a key priority of the British government, which recently set out its National Domestic Violence Delivery Plan for 2008–9. 9 This document makes it clear that in England and Wales in the year 2008–9 DV accounted for 14% of all violent incidents and had more repeat victims than any other crime. Violence towards staff working in the NHS has also come to be seen as a significant element in the government agenda, with 12% of staff reporting physical violence from patients or their relatives in the previous 12 months. 10 The government response to concerns about violence in adult psychiatric inpatient settings and hospital emergency departments has been to develop guidelines and other initiatives to improve the short-term management of this behaviour. 11

Although our focus in this document is principally on the perpetrators of violence, it is worth noting that, overall, 3% of adults in England and Wales have experienced a violent crime in the preceding year, with men being twice as likely as women to have been victims of some form of violence. 7 However, victim statistics are unlikely to present a true picture of the full extent of violence, as victim surveys tend to show lower rates of reporting for violence than for other types of crimes. 12,13

The association of violence with mental disorder

As many as 10 years ago it was observed that the number of homicides in England and Wales committed by persons with serious mental disorders had steadily declined over a 38-year period. 14 Despite this, acts of violence committed by people with mental illness remain a matter of continuing major concern to the public, as well as to service providers and policy-makers. 15

Recent large-scale reviews suggest that some diagnosed mental disorders, notably schizophrenia and other psychoses, are associated with an increased risk of violence. Fazel et al. 16 reviewed 20 studies with an aggregate sample of 18,423 individuals and, after discounting the influence of concurrent substance abuse, found an odds ratio (OR) of 2.1 for the relationship between active schizophrenia and violence. Douglas et al. 17 reviewed a total of 204 studies, subsuming 166 independent samples, and concluded that ‘… psychosis was reliably and significantly associated with an approximately 49–68% increase in the odds of violence relative to the odds of violence in the absence of psychosis’ (p. 687). Although this is clearly a substantial increase, it should also be noted that ‘the average effect size for psychosis … is comparable to numerous individual risk factors’ found in other research (p. 693). Furthermore, there was considerable heterogeneity in the findings surveyed. For example, approximately 25% of the effect sizes obtained were < 0 (with a mean OR of 0.73), whereas another 25% were large (above a mean OR of 3.30).

Violence reduction interventions

The mental health and criminal justice systems provide an important environment for the management and treatment of violence and for the prevention of future violence when the person is in the community. This review will examine the evidence base for a wide range of pharmacological, psychosocial and organisational interventions that have been used to deal with the problem of violence.

For the purpose of this report, an intervention is considered to be any explicitly defined action or set of actions taken by a practitioner with the aim of reducing the potential for violence by a specified individual. This definition incorporates a huge range of potential interventions18,19 with varying degrees of evidence supporting them, and a number of distinctions can be introduced in order to organise the field. One distinction is whether an intervention is based on a view of violence as secondary and symptomatic of an underlying problem or whether it is an intervention explicitly and primarily targeting violence as the problem. Most interventions designed to reduce antisocial personality disorder ‘globally’, for instance, would expect reductions in violent behaviour as a result of success in improving the person’s way of generally relating with the world. The review presented here includes both primary and secondary interventions, but includes only the former group when there is some assessment of violent behaviour as an outcome.

A further distinction must be drawn between short-term and long-term violence reduction interventions. Some interventions, such as rapid tranquillisation and verbal de-escalation, are designed for the prompt control and management of imminent violence involving highly aroused and disordered patients,11 whereas many others are delivered over longer time periods, up to a period of years for some milieu therapies, and are designed as treatments dealing with underlying causes rather than temporary or short-term symptom management. These long-term structured therapeutic interventions tend to be delivered in relatively low-arousal settings aimed at preventing future violence in inpatient, prison or community settings.

The range of factors underlying violent behaviour is very wide, ranging from genetic and biochemical influences to cultural forces, and the interplay between these factors in any particular act of violence is extremely complex. Given the complex causal pathways for any violent act, interventions have been developed to operate at numerous different levels ranging across neurological, psychological and social processes. Most studies consider an intervention operating at only one of these levels, whereas most health practice involves multimodal interventions where, for instance, drug treatment is combined with psychological techniques within a particular social milieu. This disparity between research and real world practice should be borne in mind when examining the evidence base.

With regard to pharmacological interventions, there are no drugs designed specifically to reduce violence per se. Haloperidol and lorazepam have been recommended for rapid tranquillisation in emergency situations11 and clozapine, among other second-generation antipsychotic drugs (e.g. olanzapine), has been reported to be effective in reducing violence associated with psychosis over longer time periods. 20 In the results of a systematic review,21 there is support for the use of benzodiazepines, combined, if necessary, with antipsychotic drugs, as part of a longer-term maintenance regime for people with mental health problems who are acting aggressively as part of their disorder.

Psychosocial interventions can be targeted at the individual or may be delivered as part of a therapeutic milieu. At the individual level, most interventions, and certainly most evidence-based interventions, are based on cognitive behavioural principles designed to change the person’s thinking style and interpretation of situations in which conflict may arise. The most well-articulated approaches within this family are Aggression Replacement Therapy22 and the variants of anger management. 23 Individual-level psychological interventions may also be based on psychodynamic or humanistic principles (e.g. Doctor and Nettleton24), but these are less well evaluated.

Beyond these individually targeted interventions, therapeutic communities and milieus have been used to generate therapeutic change through immersion of the violent individual into a particular culture that reinforces non-violent behaviour and encourages confrontation with antisocial behaviour. 25 Similarly, some interventions in traditional mental health units (i.e. outwith therapeutic communities) are environmental and cultural, in that their delivery is mediated through a third party. For instance, the human environment of a ward may be changed by training all staff in proactive de-escalation strategies26 or the physical environment may be adjusted. 27

An important methodological issue is deciding whether an intervention is a cause or an effect. Certain short-term management approaches (e.g. seclusion of an agitated person in a locked room) are interventions (i.e. an independent variable) as defined above but may also be a proxy measure (i.e. a dependent variable), as they may indicate the failure of more long-term interventions. As a general rule in this review, reactive management strategies – such as seclusion and restraint – are considered as dependent variables, whereas proactive strategies such as de-escalation are considered as interventions, even although they are equally short term. Part of the justification for this is that reactive strategies are often the target themselves of interventions designed to reduce reliance on them. 28 It is acknowledged, however, that this distinction is difficult to maintain with complete consistency.

A distinction can be drawn between complex and non-complex interventions. Non-complex interventions, such as pharmacological and dietary approaches, are relatively simple in terms of the relationship between exposure to the intervention and changes in behaviour. The drug is targeted at one specific physical system and if, all other things being equal, it changes behaviour then the causal mechanism and its efficacy can be more easily established. Complex interventions are considered to be those that consist of several components, each of which may make a contribution to the success of the intervention. 29 They are also recognised to be operating within the complex social system of a ward, prison or organisation. There is a growing recognition that traditional methods used to evaluate non-complex interventions and which prioritise the randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are severely limited in evaluating complex interventions.

Rationale for the review

The scope of the review presented here is deliberately wide. We have noted above the complexity of the phenomenon of violence, but there are benefits from casting the net as widely as possible and looking for consistent patterns across populations. Two populations are covered by the review as a reflection of the need to integrate the insights that can be gained from clinical and criminological research. These populations (people with an Axis 1 or 2 diagnosis and people who have committed an indictable offence, regardless of whether they have been found guilty or not) often overlap and often move between the criminal justice and mental health systems. 30 For similar reasons, the review encompasses interventions delivered both in institutions (i.e. hospitals, prisons and their variants) and outside in the community as part of an outpatient or community offender management programme.

After 20 years of sustained activity in this area, the primary research literature is now very large, yet the evidence base for making clinical and policy decisions is often bemoaned as inadequate. 31 The quality of the evidence base is certainly poor considering the vast number of studies and reviews that have been published in the last decade,32 largely because of a combination of methodological difficulties and lack of focus characteristic of the unusually rapid development of interest in the field. A number of systematic reviews have been conducted to summarise and integrate the findings from the literature and these provide evidence on a number of specific areas. However, inevitably these reviews tend to focus on a specific intervention, for example second-generation antipsychotic drugs33 and/or a specific outcome (e.g. reoffending) in various special populations (e.g. sex offenders). This review will instead adopt a more comprehensive approach by aiming to capture research on all interventions relating to a broad range of violence-related outcomes among a wide mental health and criminal justice population. In this way it is anticipated that the fragmented clinical and criminological literatures can be reintegrated to the mutual benefit of practitioners and researchers in both settings. 34

Other reviews

This review was conducted in the context of a number of other reviews of research on evaluations of violence reduction interventions by various teams around the world (for a survey of those pertaining to the field of criminal justice, see McGuire35,36). Given the breadth of the inclusion criteria adopted for the review here, 17 of these reviews are most relevant to the focus adopted here. However, these previous reviews cover specific populations and treat them distinctly, whereas the review reported below attempts to integrate the literature across these distinct groups. Four of the reviews focus exclusively on younger offenders in the age range of 12–21 years;37–40 seven address the problem of sexual offending;41–47 one deals with DV;48 one includes both adolescent and adult samples;49 and four are focused on studies of individuals diagnosed with personality disorders. 50–53

The broadest review was a meta-analysis (MA) by Dowden and Andrews. 49 This subsumed a range of studies that included mixed samples of adult and adolescent offenders and target offence behaviours, including general violence, sexual and domestic assaults. These authors found 34 evaluations of interventions to reduce violence, yielding 52 effect-size tests. Approximately 70% of the included studies focused primarily on work with adults. Unfortunately, they do not report separate outcome data for the two age groups. The overall mean effect size (r) was relatively low at +0.07, although there was enormous heterogeneity in the findings: effect sizes ranged from a low of –0.22 to a high of +0.63. The effect size for interventions based on the risk–need–responsivity model54 was better than the overall mean, at +0.12. This corresponds to recidivism rates of 44% for experimental and 56% for control groups. Possibly the most notable finding to emerge from this review was evidence of a close correspondence between the number of criminogenic needs targeted in interventions and the associated effect size: a correlation coefficient of 0.69 (p < 0.001).

Sexual offences

Regarding the specific phenomenon of sexual violence, to date a total of seven reviews have been reported; not surprisingly there is considerable overlap between these reviews, although they varied in their breadth of compass, their thoroughness and, in some cases, selected subdivisions of the field were the primary focus of interest. 41–47 The most comprehensive MA of this field46 synthesised findings from 69 studies, covering a cumulative sample of 22,181 participants, and included both medical and psychosocial treatments. From these findings Lösel and Schmucker46 were able to compute a total of 80 effect-size tests. A majority (60%) of the studies consisted of non-equivalent group designs, equivalence was assumed for a further 19, seven used statistical controls and six involved random allocation. Mean effect sizes across interventions, expressed as ORs, were +1.70 for reductions in sexual recidivism, equivalent to a 37% reduction relative to comparison samples; +1.90 for violent recidivism (44% reduction); and +1.67 for general recidivism (31% reduction). The largest effects were for physical treatments (surgical castration, eight studies, OR = 15.34; hormonal medication, six studies, OR = 3.08). Some psychosocial interventions achieved significant effects (behavioural, seven studies, OR = 2.19; cognitive behavioural, 35 studies, OR = 1.45), whereas others (insight-oriented and therapeutic community approaches) had ORs that were not significantly different from 1. The mean effect size for cognitive behavioural methods is lower than the OR of 1.67 found in another review of sex offender treatment that focused solely on psychologically based interventions. 44

Personality disorders

Personality disorder is a specific clinical phenomenon, which, in certain manifestations, can be relevant to violent behaviour. Two reviews have been reported of offenders with personality disorders, but neither is a systematic review nor has used statistical integration methods, because of the small number of studies that were located. Salekin50 reviewed a series of 42 outcome studies; however, only eight involved group comparison designs, and many others were single case reports, so although the latter may be clinically instructive, any firmer conclusions must remain tentative at present. Of those studies that could be regarded as more robust, there were five studies of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) incorporating a cumulative sample of 246 individuals. There were high-effect sizes on intermediate outcome variables for several therapeutic approaches, including CBT, personal construct therapy, and other approaches which ‘ addressed patients’ thoughts about themselves, others and society. Thus, they tended to directly treat some psychopathic traits’ (p. 93). 50 Salekin50 also observed that there was a strong association between effect size and duration and intensity of treatment: interventions lasting < 6 months were less likely to produce benefits than longer ones. Where attendance was maintained for > 1 year, or delivered at a rate of more than four sessions per week, a considerably higher fraction of the samples benefitted.

Addressing the controversial question of whether those individuals assessed as ‘psychopaths’ are untreatable, or (as reported by an earlier study) could potentially be made worse by treatment, Tanasichuk and Wormith51 found only three studies that compared treated and untreated samples. They located an initial total of 21 studies yielding 50 effect-size estimates (cumulative sample n = 5550). In comparisons between those designated as psychopaths and samples of non-psychopaths, the former consistently showed higher general, violent and sexual recidivism, more antisocial behaviour, higher levels of substance abuse, and spent significantly less time in treatment. In the three studies where comparisons were possible between treated and untreated psychopaths, there were no significant differences in general or violent recidivism; other types of comparisons were not feasible given the available data. However, contrary to the findings of some earlier research there was no evidence that treatment made psychopaths worse.

Recent National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidance (NICE. Antisocial personality disorder: treatment, management and prevention. NICE clinical guideline 77. 2009. URL: www.nice.or.uk/CG77) with regard to the management of antisocial personality disorder warns against the routine use of pharmacological interventions for the disorder overall or for aggression associated with it, and notes that there is insufficient evidence to justify the use of any specific medication, although appropriate medications may be used for treatment of comorbid conditions. To address problems such as impulsivity, interpersonal difficulties and antisocial behaviour associated with antisocial personality disorder, psychological interventions such as group-based CBT (e.g. ‘reasoning and rehabilitation’ programme) are recommended instead.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a second major diagnostic category that has been seen as linked to an increased risk of violent behaviour. A recent Cochrane review52 of 27 pharmacotherapy trials indicated that pharmacotherapy had some beneficial but differential effects on all aspects of the disorder. The affective dysregulation element, for instance, which is clearly relevant to aggressive propensities, was improved through treatment with haloperidol, aripiprazole, olanzapine and mood stabilisers. Other attempts to synthesise the evidence in this area (e.g. Herpertz et al. 53) are inconclusive about the efficacy of pharmacotherapy on the specific aggressive aspects of BPD. As with antisocial personality disorder, recent NICE guidance (NICE. Antisocial personality disorder: treatment, management and prevention. NICE clinical guideline 77. 2009. URL: www.nice.or.uk/CG77) recommends avoiding pharmacological treatment for the core disorder or its associated behaviours (other than for short-term crisis management), while highlighting the potential benefits of psychological interventions. No specific theoretical approach is indicated as long as there is some explicit orientation to the therapy, which is shared with the service user.

Domestic violence/partner abuse

This review also included the specific phenomenon of DV in order to enable comparisons to be made between this and the related violence fields. There is one MA of methods or strategies designed to reduce DV, consisting (almost overwhelmingly) of assaults by males on female partners. Babcock et al. ,48 examined findings from 22 studies yielding (after elimination of outliers) 36 effect size tests; 17 of the studies were quasi-experiments and the remaining five were ‘true’ experimental designs. The overall conclusion of Babcock et al. 48 (p. 1044) was that ‘… there is great room for improvement in our batterers’ treatment interventions’ and it is widely recognised that this remains possibly the largest single area in which, to date, effective methods of intervention have not yet been firmly identified.

Young offenders

Although the focus below is on violence by adults (aged > 16 years) there is some overlap with previous reviews of young offenders as the definition of young offenders can include those up to the age of 21 years. The largest of the previous reviews focused on young offenders is that of Lipsey and Wilson,37 who integrated findings from a total of 200 studies, 117 of interventions based in the community and 83 of interventions based in residential or custodial settings. All of these studies were with adjudicated offenders or with young people with adjustment problems, but not diagnosed with mental disorders. Intervention programmes in the ‘most consistently effective’ category were found to have an average impact in reducing recidivism by 40% in community settings and 30% in custodial settings. 37

A later review by Garrido and Morales38 is essentially an updated version of portions of the Lipsey and Wilson37 review, combining studies carried out in the period up to 2006 but including only studies with ‘chronic delinquents’ detained in institutions. Covering a related but separate area of research, Wilson et al. 39 reviewed studies of methods designed to reduce aggression in schools. Addressing a more specific question, McCart et al. 40 compared the relative effectiveness of behavioural parent training and CBT in reducing aggression and other antisocial behaviour among young people < 18 years old; they found 41 studies of the former and 30 of the latter.

Findings from all of these reviews showed on average positive outcome effects and the authors report analyses of the relative effectiveness of different interventions and the roles of moderator variables where possible. However, in all of these reviews a majority of the studies that were included consisted of quasi-experimental designs, with only a fairly small proportion using randomisation.

Previous review

The review reported here is an update of one part of an existing review. In 2002 the Department of Health commissioned the Liverpool Violence Research Group (LiVio) to complete a broad-ranging systematic review of interventions and risk assessment strategies for the management of violence in a widely defined population (offenders, people with mental health problems and offenders with mental health problems). The aim was to provide a picture of the literature that was broad enough to inform future improvements in research, policy and clinical practice, while strictly adhering to the main criteria for high-quality reviews. The original review55 covered publications released between 1955 and 2001 (with partial update to 2004) on a population that consisted of (1) adult offenders (> 17 years) with or without a mental disorder; (2) adults with a diagnosable mental disorder but no offences; and (3) adults in the general population exhibiting indictable acts of aggression without actual indictment (e.g. DV). Substance abuse alone was not deemed sufficient to constitute a diagnosis of mental disorder. Any pharmacological, psychological or other intervention targeted at the individual patient/offender and delivered individually or in small groups was included. Organisational interventions (e.g. ward-level changes) that did not report individualised outcomes were excluded. Changes on any outcome measure that was an actual or proxy assessment of aggression (e.g. observed aggression, self-reported hostility) were included. There were no exclusions based on design, language or publication format.

Search strategy and selection of studies

The primary method used to identify studies meeting the above criteria was to conduct (1) a detailed search of 31 electronic databases from their point of inception to December 2004; (2) a hand-search of 42 specialist research journals covering the period January 1990 to December 2000; and (3) a consultation exercise with a specified list of 50 active international violence researchers.

In total, 228,182 citations of relevance to human aggression were retrieved. Of these, 41,886 citations related, broadly speaking, to risk or intervention. Of the material meeting the broad review inclusion criteria, just over 1000 citations reported on empirical research, with aggression being the sole or main focus for nearly 90% of the reported studies. In line with the rapid expansion noted in the literature, the majority of empirical studies identified (85%) were written or published from 1980 onwards. An executive summary of the findings from the review can be found at www.liv.ac.uk/fmhweb/MRD%2012%2034%20Final%20Report.doc.

The final report55 has had significant influence on national policy in England and was formerly flagged on the website of the Department of Health/Ministry of Justice (England) National Risk Management Programme. 56 It also formed the basis for a set of national best practice guidelines on risk management57 and national policy guidance on selection of risk assessment tools. 58

Update of the review

This update uses the same search strategy and the same databases were searched where possible. The four senior reviewers involved in the original review were also involved in this update and are referred to in this document as ‘expert reviewers’.

Owing to the size of the original review it was decided that the update would be split into two distinct elements: this intervention review and, secondly, a review of risk assessment approaches with the same population (to be published at a later date). It is important to emphasise that the two processes are closely linked. Estimates of predictive validity from a risk assessment tool are of little use on their own if they are not used to design and target effective interventions. The structured clinical (or professional) judgement approach59 is important in this context, as this approach is recognised as encouraging practitioners to focus on risk management and flexibility in choosing appropriate interventions.

Research question

Which interventions are the most effective in reducing violence and which key variables are associated with a significant outcome?

Chapter 2 Methods

This review was conducted by a large team of reviewers, with varying numbers working on the review at any particular stage. The searches were conducted by two reviewers, application of stage one inclusion criteria by 11 reviewers, stage two inclusion criteria by seven reviewers, data extraction and cross-checking by nine reviewers, extraction of statistical outcomes by five ‘expert’ reviewers (four of whom had been involved in the original review).

Search strategy

The search strategy (see example in Table 54) used in the original review was rerun on the 19 databases shown in Table 1. The first database to be searched was PsycINFO and the searches were run in April 2008. The last database to be searched was SIGLE (System for Information on Grey Literature In Europe) and the searches we carried out in November 2008. Where it was possible to limit searches, they were initially run without limits and then rerun limited to children or animals or editorials. These hits were then removed from the first run. This method was used so that papers that had not been indexed on a term, for example ‘humans’, were not missed when running the searches.

| Database | Limits used |

|---|---|

| PsycINFO (CSA) | Animals, editorials, childhood (birth to 12 years) |

| MEDLINE (Ovid) | (Animals or (“newborn infant (birth to 1 month)” or “infant (1 to 23 months)” or “preschool child (2 to 5 years)” or “child (6 to 12 years)”) or editorial) |

| CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) | Animals or (“newborn infant (birth to 1 month)” or “infant (1 to 23 months)” or “preschool child (2 to 5 years)” or “child (6 to 12 years)”) or editorial) |

| AMED (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database) | None |

| British Nursing Index/Royal College of Nursing | None |

| IBSS (International Bibliography of the Social Sciences) | None |

| ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)/International ERIC | None |

| The Cochrane Library (Cochrane reviews, other reviews, clinical trials, methods studies, technology assessments, economic evaluations) | None |

| Web of Science [Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE), Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Art and Humanities Citation Index (A&HCI)] | Document type=(bibliography or editorial material or letter) |

| Sociological abstracts/SocioFile | None |

| Social Services Abstracts | None |

| EconLit (American Economic Association’s electronic bibliography) | None |

| British Humanities Index Online | None |

| Elsevier Science Direct | None |

| ProQuest (dissertations and theses) | None |

| ASLIB (index to theses) (searched on screen) | None |

| C2-SPECTR | None |

| Emerald Fulltext | None |

| SIGLE (searched on screen) | None |

As the searches were run, citations were imported into Endnote XIV® (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) sequentially. Owing to the limitations of Endnote, duplicate references were deleted first electronically and then manually.

The reference lists of relevant reviews identified at inclusion were searched for additional relevant references.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The identified citations were assessed for inclusion through two stages. The criteria used were those used in the previous review and are shown in Table 2.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

| Active diagnosis of mental illness, learning disability or personality disorder or | Participants are members of the general public, with no identified mental illness and no recorded violent offence and no evidence of having committed an act of violence that would constitute an indictable offence |

| Substance abuse (including alcohol abuse) in isolation from any other diagnosis of mental illness is not to be defined for the purposes of the review as an active diagnosis of mental illness | |

| Substance abuse (including and separately specified as alcohol abuse) is to be identified in relation to participant characteristics for the purposes of data extraction, as it is identified in primary studies | |

| Offender (person subject to penal sanction) or | |

| Person(s) known to have committed one or more acts of aggression constituting an indictable offence (whether or not an indictment has been made) | |

| Aged ≥ 17 years | Aged ≤ 16 years |

| Any intervention specifically identified as being evaluated with the intention of preventing violent behaviour or | Interventions focused solely on reducing or preventing target behaviours other than aggression towards others |

| Implemented with the immediate intention of preventing violent behaviour (e.g. ‘naturalistic’ evaluation in a clinical setting) | |

| Interventions must be targeted at the individual level | Studies that evaluate the impact of broad-based local or national population-level initiatives and which also fail to evaluate outcomes (compared with outcome criteria) at the individual level are to be excluded |

| Studies that have a focus on a main target behaviour which is not other-directed aggression (the target behaviour may be self-directed aggression), but which do include an evaluation of the association between exposure to an intervention and rates of other-directed aggression as a subsidiary focus are to be included | |

| Studies that evaluate the impact of broad-based local or national population-level initiatives and which also fail to evaluate outcomes (compared with outcome criteria) at the individual level are to be excluded | |

| For example, a study evaluating the impact of a binge drinking campaign on aggression, which evaluated outcomes purely by noting changes in population rates of violence across time would be excluded; a study evaluating the same intervention but reporting outcomes based on the same set of individuals with behaviour evaluated before and after the initiative would be included. The key point is that the specific individuals being assessed need to be evaluated at outcome | |

| Interventions may include, but are not restricted to, pharmacological, physical, psychological, environmental, or training initiatives | |

| Interventions include both ‘single dose’ and complex ‘multiple dose’ or ‘multifactorial’ interventions | |

| Studies that have a focus on a main target behaviour which is not other-directed aggression (the target behaviour may be self-directed aggression), but which do include an evaluation of the intervention on other-directed aggression as a subsidiary focus are to be included | Studies focused solely on self-directed aggression, including self-harm and suicidal behaviours are to be excluded |

| Any institutional setting/location | Setting/location of any study is not to be regarded as grounds for excluding that study |

| Any community setting/location | |

| Community-based ‘institutional’ settings, such as outpatient clinics, A&E, private practice clinics, etc., are also to be included | |

| Studies conducted at ‘remote’ locations, for example studies evaluating interventions conducted by telephone or in writing, are also to be included | |

| Any design explicitly measuring outcomes following an intervention meeting the above criteria | No attempt at any sort of empirical approach likely to elicit at least an association between dependent variables and outcomes should such exist |

| No clear identification of an intervention taken as either the main or as a subsidiary focus of the study | |

| Directly observed physical or verbal aggression by person(s) with an identified mental illness | No evaluation of outcomes |

| Aggressive behaviour (as defined for the population groups considered), not either a main or subsidiary outcome of the evaluation | |

| Directly observed physical aggression (meeting criteria for indictment) by members of the general public or current/previous offenders | |

| Proxy measures of the above (including but not restricted to: self or other report of the above categories of behaviour, including reports established via clinical records; official records of offence and conviction; psychometric and other scale-based outcomes of mentations or behaviours directly relevant to aggression, for example BPRS measures of ‘hostility’) | |

| Outcome evaluation must be based on individual-level data | Evaluations based on ‘non-attributable’ rates and other summary data are to be excluded: |

| ‘Collective’ acts of aggression, such as terrorism, ‘gang’ violence, organised violent crime, football violence, drug feuds, etc., are excluded from consideration by the review where the focus of the study is on the phenomenon as a collective behaviour; studies focused specifically on individual behaviour within these contexts should be included | |

| Evaluation of both imminent and non-imminent (future) violence is included within the review | Directly observed or proxy-evaluated aggressive behaviour (as defined for the population groups considered) is not either a main or subsidiary outcome of the evaluation |

Inclusion stage one

At stage one inclusion, six reviewers independently applied the inclusion criteria to 200 citations and a Cohen’s kappa (Fleiss–Cuzick extension) was calculated [κ = 0.63 (SE = 0.019), z (for k = 0) = 34.24, p < 0.0001]. Each new reviewer who joined the team was required to look at 100 citations that had previously been looked at by a reviewer and a > 80% agreement had to be reached. At this stage an ‘inclusive’ attitude was taken, i.e. where there was doubt a citation was included. Given the high level of agreement and the inclusive approach, further citations were screened by only 1 of the 11 reviewers.

If a citation was excluded then it was possible to mark the citation as either a review that needed the reference list checked (‘check’) or a paper of particular interest that should be obtained (‘obtain’).

Acquiring papers

Electronic copies of papers were then downloaded where possible by the University of Liverpool’s interlibrary loans team. Where electronic copies were not available, paper copies were either obtained from the University of Liverpool’s library or through interlibrary loans at the British Library.

Inclusion stage two

At stage two, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to the full papers identified from stage one. To aid with this a Microsoft Access database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was developed using a front page form with drop-down menus and tick boxes. It was at this stage that included papers were categorised into each of the two reviews: intervention or both risk and intervention. Furthermore, studies not reporting any statistical analysis, mainly due to qualitative designs, were excluded from the review though retained for future analysis.

As a quality control measure, all seven of the reviewers applied the inclusion criteria to 50 papers and a Kappa score was calculated [Cohen’s kappa (Fleiss–Cuzick extension): κ = 0.62 (standard error, SE = 0.032) z (for k = 0) = 19.46, p < 0.0001]. Investigation of individual pairs of inter-rater agreement (Table 3) revealed that one reviewer (G) had poorer reliability scores owing to being more inclusive than other reviewers. Therefore, it was decided that there was high enough agreement to continue with single reviewer application of inclusion criteria.

| A | B | C | D | E | F | G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 1 | 0.618 | 0.86 | 0.753 | 0.66 | 0.711 | 0.55 |

| B | 1 | 0.537 | 0.702 | 0.685 | 0.57 | 0.421 | |

| C | 1 | 0.683 | 0.684 | 0.684 | 0.68 | ||

| D | 1 | 0.571 | 0.628 | 0.477 | |||

| E | 1 | 0.523 | 0.59 | ||||

| F | 1 | 0.355 | |||||

| G | 1 |

Quality assessment

Owing to the diverse nature of the papers included in this review, no appropriate methodological quality assessment tool was identified. Therefore, variables pertinent to quality assessment were extracted as part of the full data extraction process (see Data extraction) and frequencies calculated where appropriate. Where there were available data, the effect of the quality of studies was explored in MAs.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out independently by nine reviewers, with regular meetings to co-ordinate activity and to explicitly cross-check extracted data. Data from each study relating to study design, type of intervention and whether or not a statistically significant outcome was reported were extracted into a predefined Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) database.

The Spss database was based on the one used in the original review and included both free-text variables, number variables and drop-down menus. The reviewers were then trained in its use and a pilot extraction conducted. Relevant changes were made and reviewers retrained. This process was repeated until the final version was agreed. Ongoing support was also given to reviewers in the form of a crib sheet covering each variable and an electronic forum was set up so that reviewers could post any queries that the expert reviewers could then answer.

Each paper was printed off and marked as data pertaining to the basic aspects of the study were extracted into the Spss database. The data extracted were then cross-checked by another reviewer using the marked paper and any disagreements were noted in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. The two reviewers then discussed disagreements and where no consensus could be found a third reviewer adjudicated.

Papers included in the intervention review were then given to one of the expert reviewers to extract outcome data in an Excel spreadsheet. Intervention arm and resultant statistics were loaded, with multiple lines per study. In particular, specific data were extracted on dependent variable means and standard deviations (SDs) together with statistical test values, confidence intervals (CIs) and probability levels when study groups (treatment vs control and/or baseline vs end point) were compared. This level of analysis had not been attempted in the original review. Subgroup analyses were not extracted where an included full analysis was reported. The outcome extraction for any RCTs identified was then cross-checked and any discrepancies settled with a third party.

Descriptive data

Details of key variables pertaining to quality, trial characteristics, participant characteristics, and intervention characteristics are tabulated and are discussed in Chapter 3, along with comparisons of the characteristics of RCT and non-RCT studies. Where appropriate, differences between RCTs and non-RCTs were investigated with either a chi-squared test or Mann–Whitney U-test (kurtosis and skewness tests reported).

Statistical methods

In Chapter 4, the key variables, as discussed in the descriptive section above, are explored in terms of their role in explaining the variance in whether a study reported a statistical significant result or not. These subgroup analyses should be seen as hypothesis generating rather than providing conclusive answers.

Bivariate and multivariate analyses

Bivariate analyses

A series of bivariate analyses using either a chi-squared test (for dichotomous data) or Spearman’s rho test (for continuous data) were conducted to explore possible sources of variance in whether or not a study reported a statistically significant result.

Multivariate analyses

A binary logistic regression was conducted, with categorical variables coded as ‘dummy’ (0/1, with 0 as the baseline category) and ‘whether or not a statistically significant outcome in favour of the primary intervention arm was established’ as the dependent variable (also coded 0/1). With no specific direction of effect or composite weighting in mind, the ‘ENTER’ method of adding variables to the model was used.

Selection of studies for analyses

Studies were selected for inclusion in these analyses if they provided statistical data suited to extraction and statistical analyses and reported data on statistical significance.

Where an individual study contributed more than one comparison to the data set, we selected for inclusion the main comparison focused on by the authors or, where comparisons appeared to be of equal weight, the comparison which provided the most substantive evaluation of effect (e.g. the comparison using the longest follow-up interval). This ensured, as far as possible, independence between the data points included in the MAs.

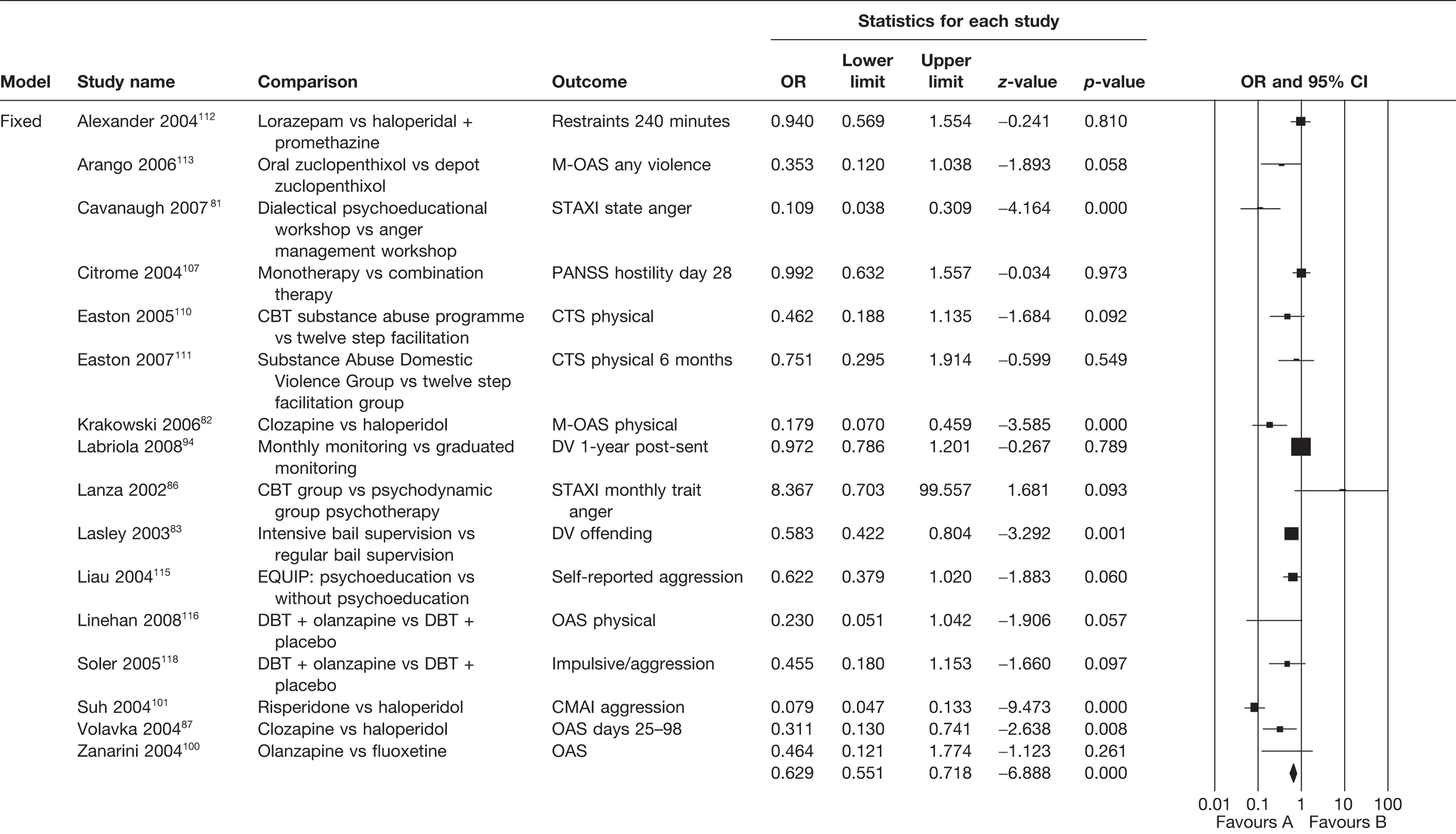

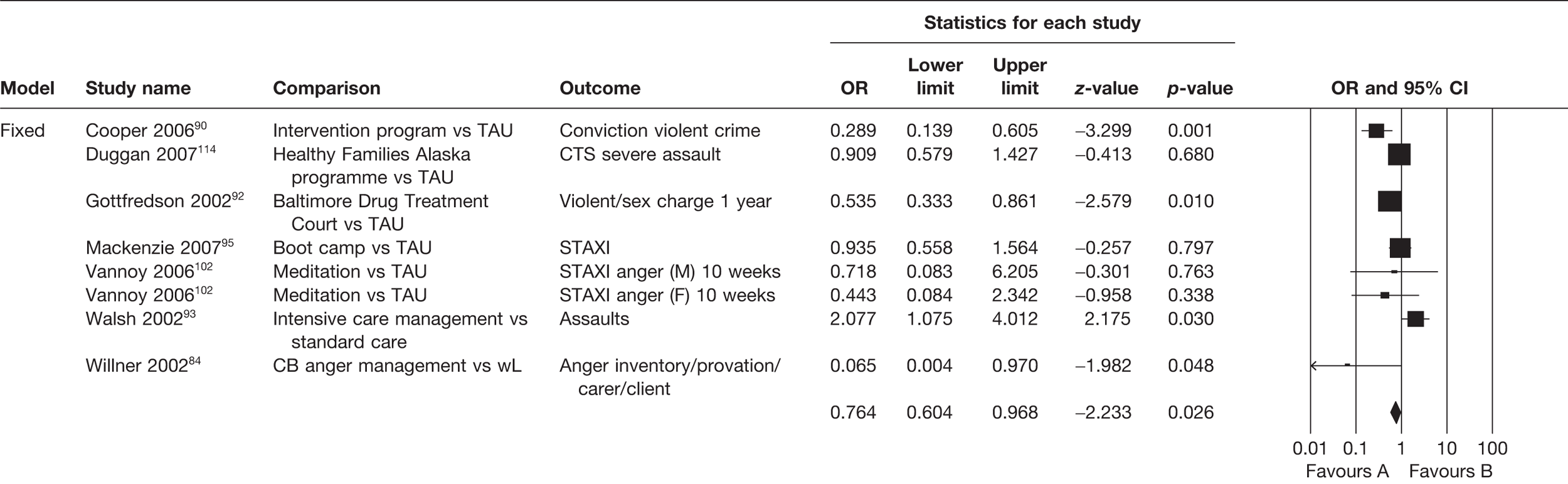

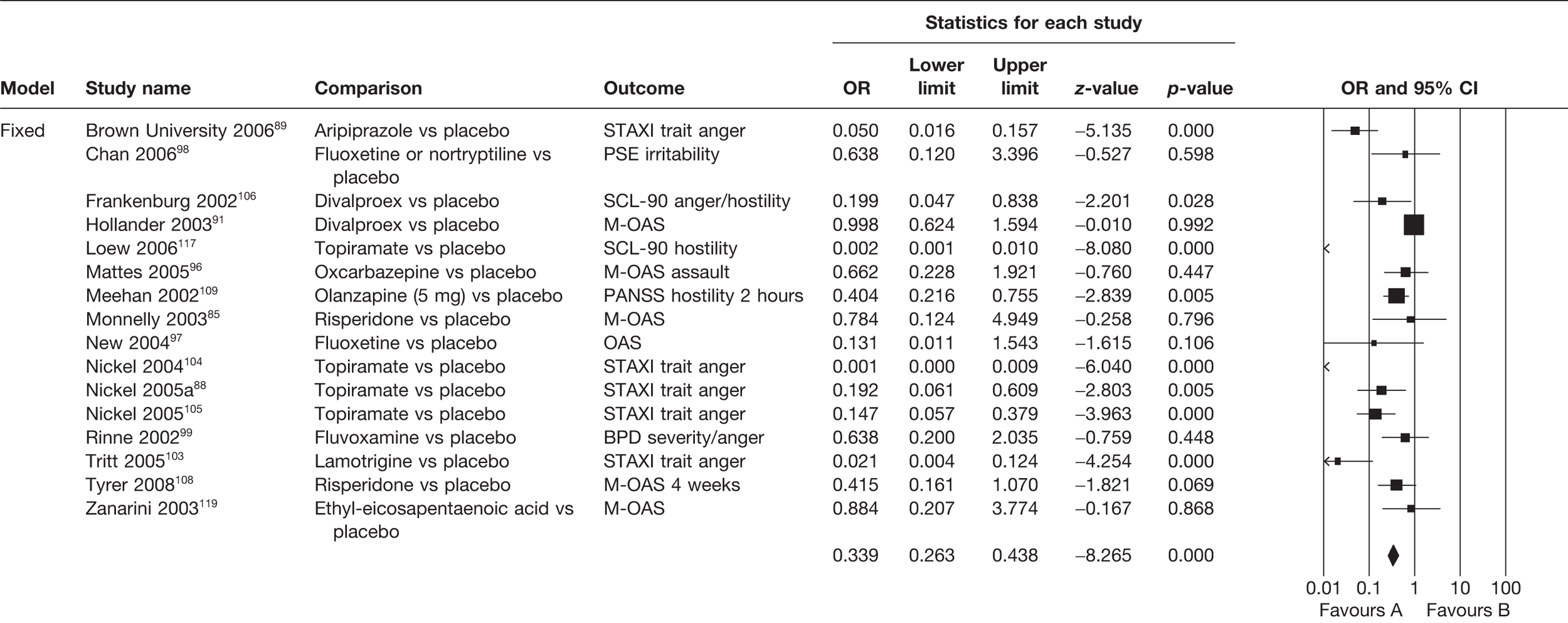

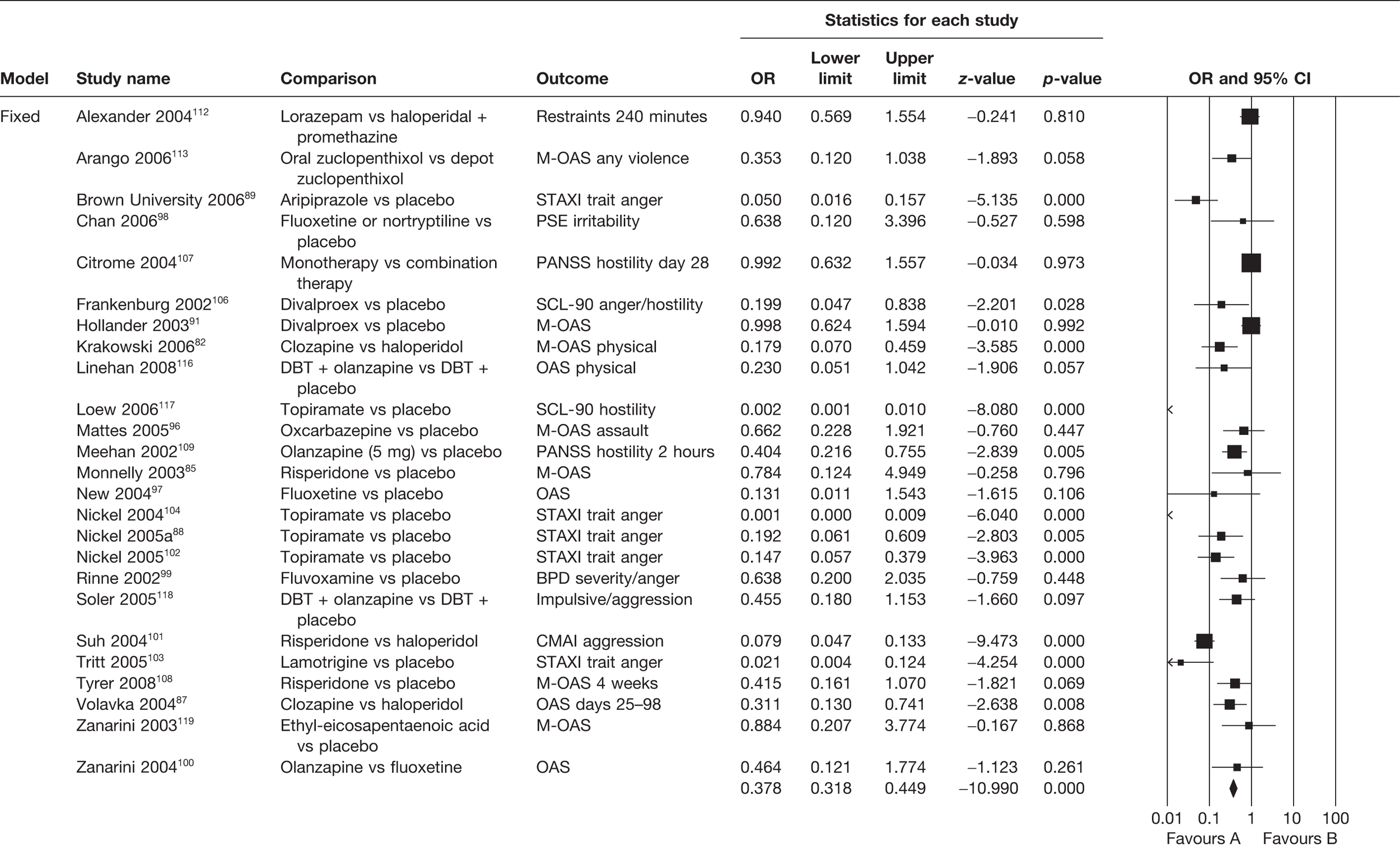

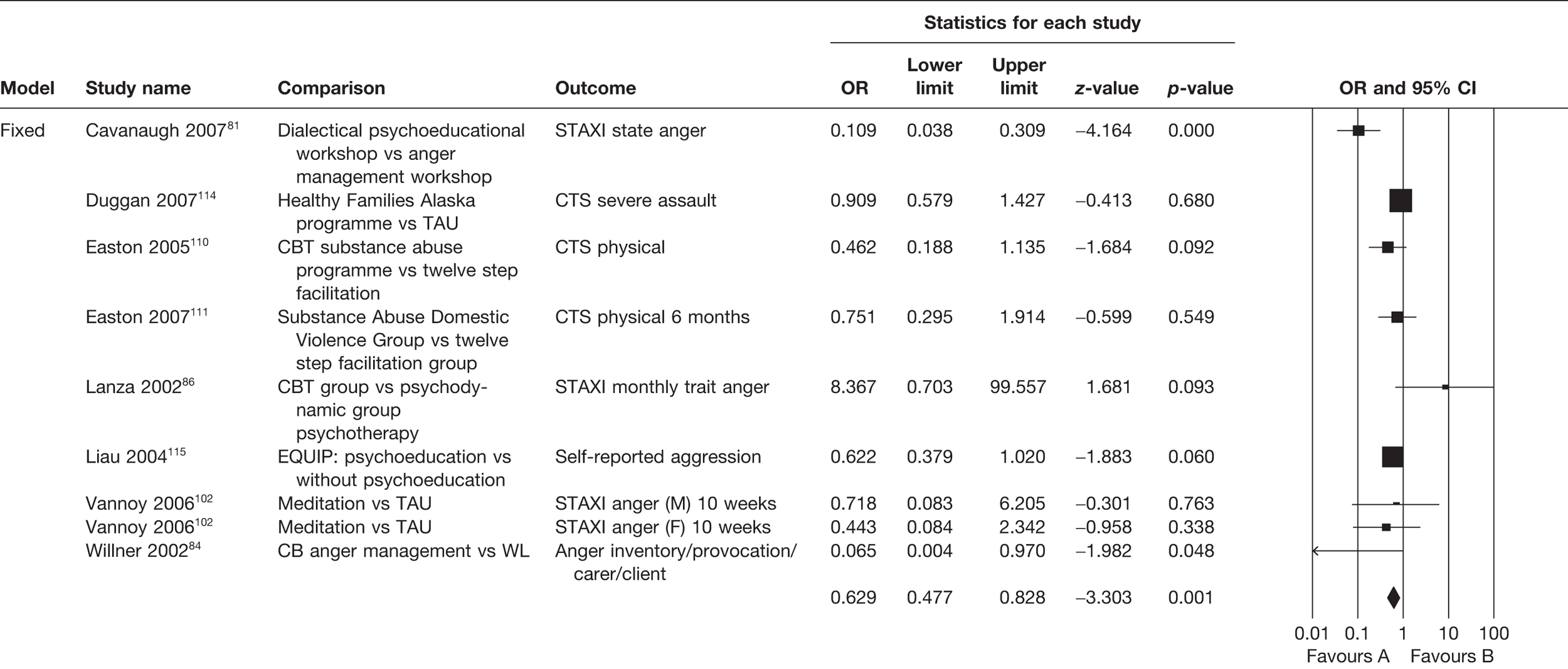

Meta-analysis

Selection of studies for meta-analysis

Studies were selected for inclusion into the MAs if they followed a RCT design and reported data that could be converted into ORs or risk ratios. Where an individual study contributed more than one comparison to the data set, we selected for inclusion the main comparison focused on by the authors or, where comparisons appeared to be of equal weight, the comparison that provided the most substantive evaluation of effect (e.g. the comparison using the longest follow-up interval). This ensured, as far as possible, independence between the data points included in the MA. Details of studies and outcomes selected for each MA are outlined in Appendix 3.

Effect sizes

Where possible, metrics were converted to ORs using equations provided by Lipsey and Wilson. 60 To provide a context in which to evaluate the relative impact implied by the mean effect sizes presented, effect sizes based on the standardised mean differences are also reported.

For each MA, both an fixed-effects model and a random-effects model were fitted, rather than assuming a priori that either was most appropriate.

Heterogeneity

To identify the indicative variance existing within various groupings of studies used in MA, we calculated both Q statistic and I2 estimates of heterogeneity for each MA performed. The rationale for providing two tests in this context was that the Q-statistic, although generally a reliable test of heterogeneity, fails to provide an estimate of the extent of heterogeneity. The I2-statistic can be used to evaluate the extent of heterogeneity, which is useful in exploring the likely impact on outcomes.

Where heterogeneity was present, data were re-evaluated by modelling the impact of the potential modifiers on both observed heterogeneity and on effect size outcomes. The potential impact of each modifier was explored using metric-appropriate statistics (analysis of variance, logistic and linear regression). Further MAs focused on studies identified as similar in respect of these key characteristics were then carried out to explore the mean effect sizes generated for a range of interventions within relevantly similar groupings.

Subgroup analyses on the following were also conducted to investigate heterogeneity: (1) type of comparison, for example single group designs, active treatment versus treatment as usual (TAU); (2) broad intervention groups, i.e. pharmacological, psychological and ‘other’; and (3) specific intervention groupings.

The exploration of potential modifiers that may account for the variation in outcome between studies was restricted to the variables that were reliably reported by the included studies. Taking into account the likely relevance of these to clinical practice and policy, sensitivity analyses were carried out for (1) clinically relevant factors; mental health status, age, sex and ethnicity and the setting in which the study was conducted; (2) type of outcome measure; and (3) study quality indicators, namely sample size, number lost to follow-up, blinding, length of follow-up baseline equivalence and whether an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was used.

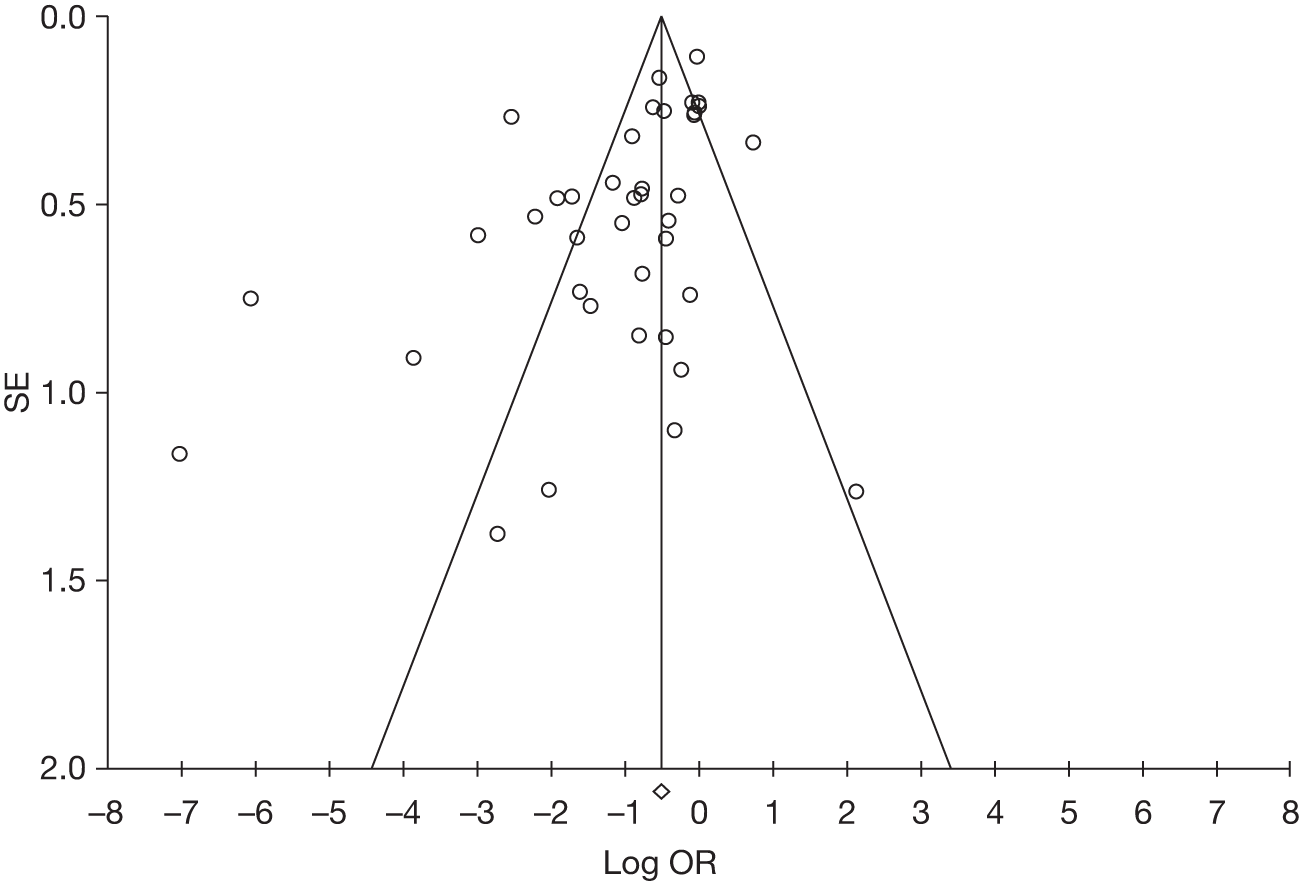

Publication bias

Publication bias was explored using a funnel plot,61 i.e. a scatterplot of effect size against sample size (or SE, which is expected to closely associate with sample size).

Advisory panel

As this review is part of a larger project Developing Evidence-based Guidelines for the Prevention of Violence in Mental Health Settings (EPOV) funded by the Department of Health, Research for Patient Benefit Programme (RfPB), the steering group for this larger project provided support and answered specific questions as the review progressed and commented on a draft of this report.

Chapter 3 Overview of the literature

Selection of included studies

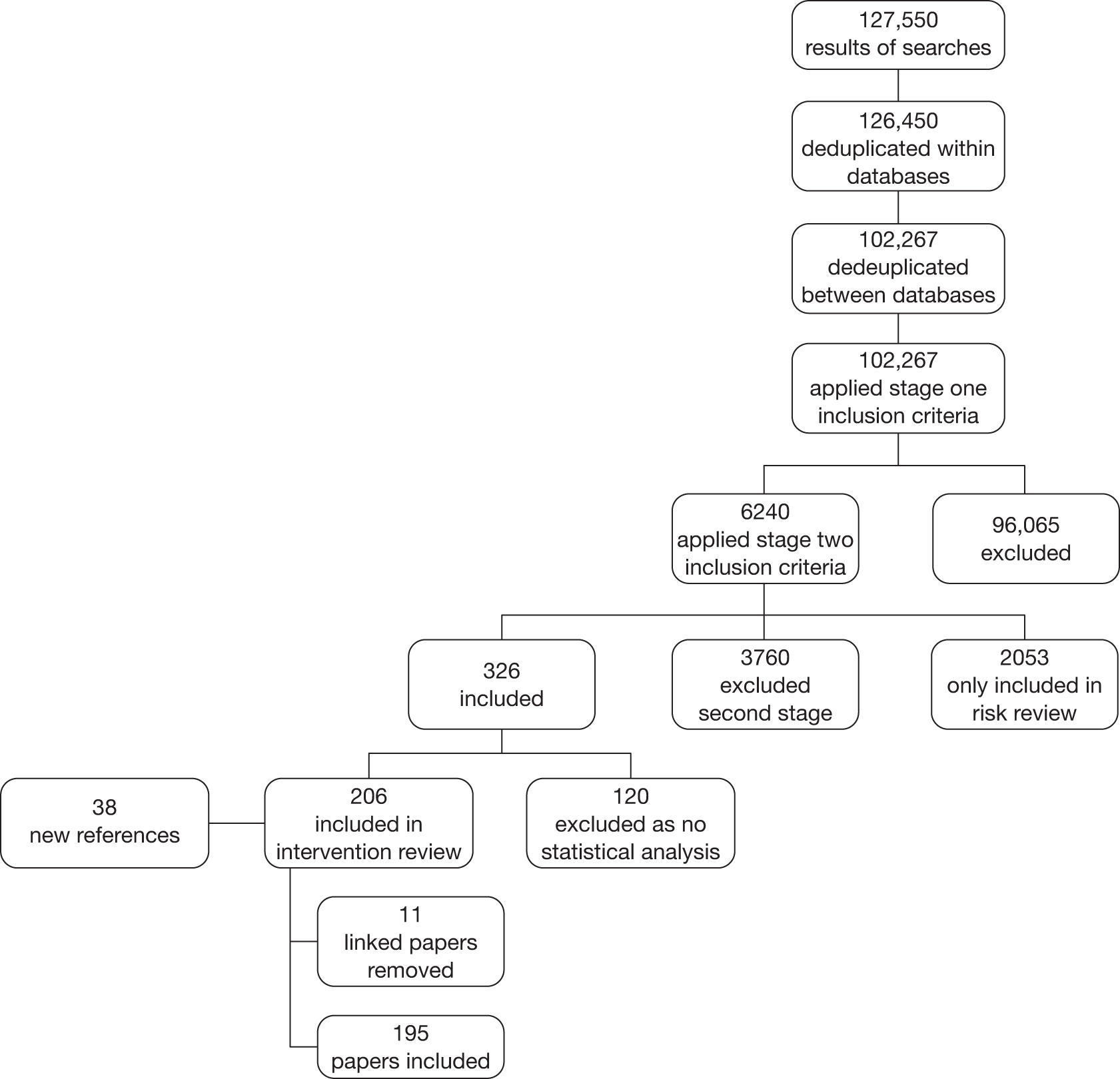

As shown in Figure 1, the electronic searches identified 127,550 citations. After deduplication, both within and between the databases, 102,267 citations had the inclusion criteria applied at stage one. This resulted in 96,077 citations being excluded, 246 of which were reviews.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of inclusion of studies.

As a result of searching the reference lists of the 246 reviews, an additional 38 references were identified. Therefore, a total of 6240 papers had the inclusion criteria applied at stage two.

The process of applying stage two inclusion criteria resulted in 3760 references being excluded from both the intervention and risk reviews and a further 2053 being included in the risk review only. The remaining 326 papers met the inclusion criteria for the intervention review and data were extracted. At data extraction, 120 of the 326 papers were identified as not reporting any statistical analysis, mainly because of qualitative designs, and were therefore excluded from the review. A further 11 papers were identified as reporting data that were reported in other included papers. The primary paper for each study was retained, with any additional data reported in the linked paper combined, while the linked paper itself was excluded. A list of included papers is shown in Appendix 1, Table 55, and a list of excluded papers available on request.

Of the 195 included papers, three included more than one study, resulting in 198 studies being data extracted. All of the following analyses will be reported by study rather than by paper.

Different sections of the report require different selections of studies, as described throughout the report. However, Table 4 summarises the number of studies for each level of analysis.

| Chapter | Section | Description | No. of studies | No. of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | Quality assessment; Study characteristics, Participant characteristics, Intervention characteristics | Descriptives | 198 | 728 |

| 3 | RCTs | RCTs | 51 | NA |

| 3 | Non-RCTs | 147 | NA | |

| 4 | Bivariate/multivariate analyses | 179 | 195 | |

| 5 | MAs | 40 | NA |

Quality assessment

Design of studies

Of 198 studies, 51 (25.8%) were RCTs, one-third (33.3%) were concurrent/cross-sectional group comparisons and 68 (34.3%) were before/after study comparisons. The remaining 13 studies were crossover comparisons, correlational studies and experimental case studies (Table 5).

| Study design | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| RCT | 51 | 25.8 |

| Concurrent/cross-sectional group comparison | 66 | 33.3 |

| Crossover comparison (n > 1) | 2 | 1 |

| Before-/after-study comparison (n > 1) | 68 | 34.3 |

| Correlational/single group no comparator | 8 | 4 |

| Experimental case study (n = 1 or set of Ns = 1) | 3 | 1.5 |

| Total | 198 | 100 |

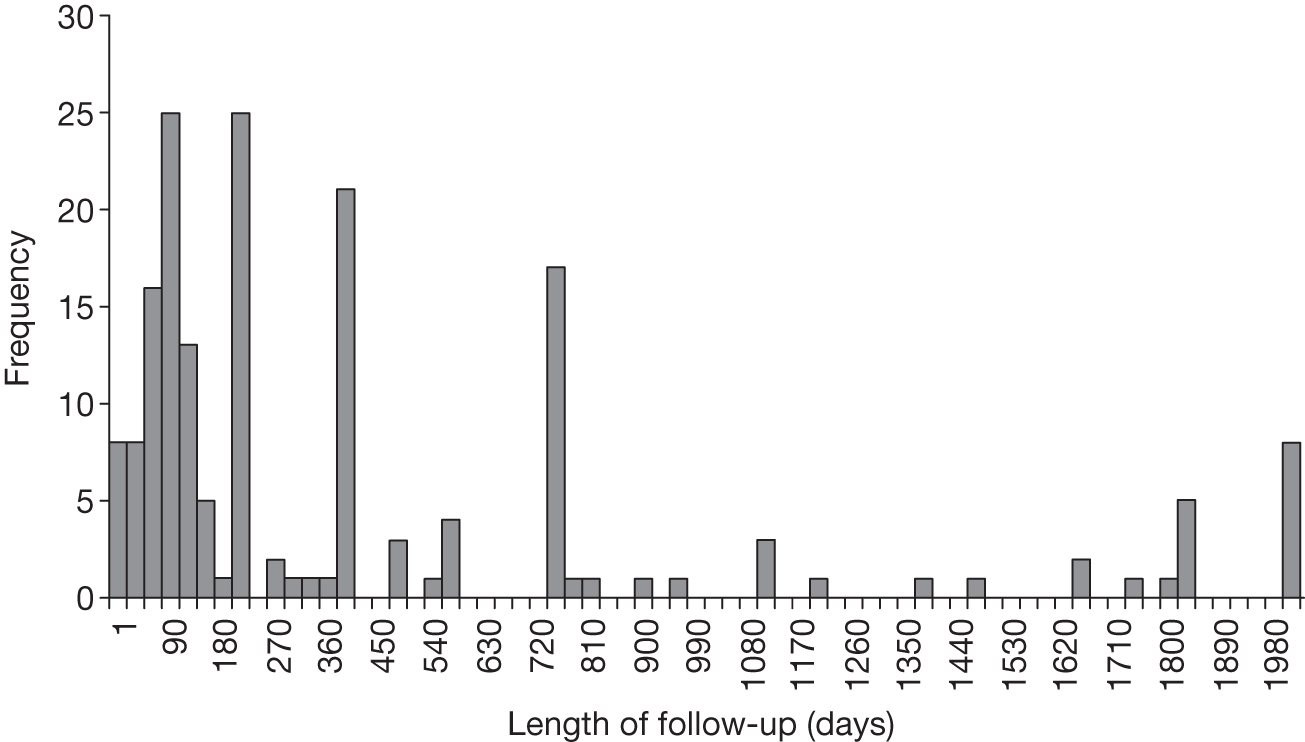

Length of follow-up

The maximum length of follow-up was reported by 179 studies and ranged from half an hour to 14 years, with the average length of follow-up being: mean = 524.26 days, median = 183.40 days and mode = 365 days (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Total length of follow-up in days.

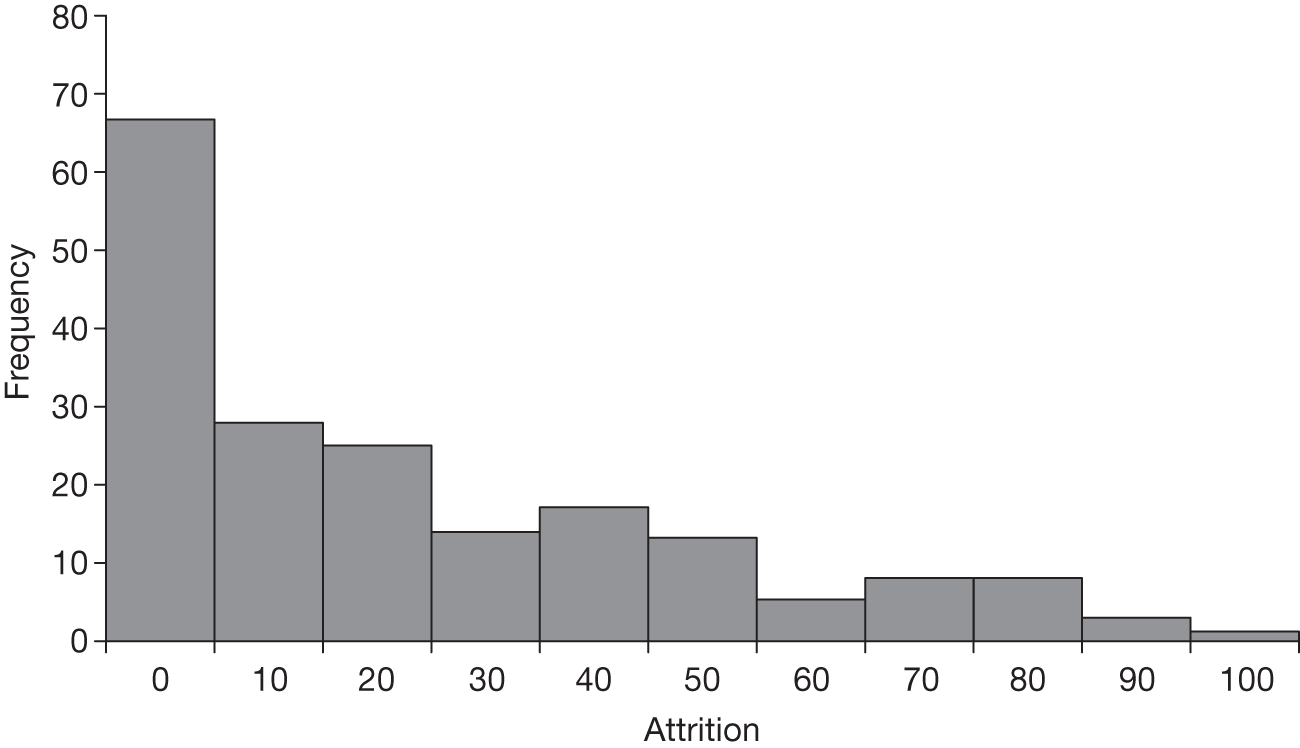

Attrition

Attrition was calculable for 189 of the studies: 67 (35.4%) reported no attrition and four (2.1%) more than 80% attrition (Figure 3). The mean attrition was 20.0% and the median was 9.9%.

FIGURE 3.

Attrition rates.

Intention to treat

The 198 studies included in the review reported on 728 comparisons. Of these, 31.9% were analysed on an ITT basis, 59.1% were not analysed on an ITT basis and 9.1% did not state whether they were ITT analysis or not (Table 6).

| ITT analysis | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| No | 430 | 59.1 |

| Yes | 232 | 31.9 |

| Not stated | 66 | 9.1 |

| Total | 728 | 100 |

Baseline equivalence

Of the 120 studies comparing different study groups, equivalent baseline measures of aggression were reported for 51 (42.5%) studies. A further 11 reported equivalence on some measures of aggression and 16 (13.3%) reported non-equivalence. Twenty studies reported the baseline levels of aggression for each group but did not compare them statistically and 22 (18.3%) did not report any baseline measure of aggression (Table 7).

| Equivalence of baseline measures of aggression | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, for all aggression outcome variables | 51 | 42.5 |

| Yes, for some aggression outcome variables | 11 | 9.2 |

| No | 16 | 13.3 |

| Unsure, no p-values stated | 20 | 16.7 |

| Not stated/unclear | 22 | 18.3 |

| Total | 120 | 100.0 |

Blinding

Given the nature of many of these studies it is not surprising that blinding was not stated in the majority of papers, as for practical reasons this is impossible to achieve when evaluating psychosocial interventions. Where it was stated, it was most frequently reported for patients and the interventionist, with 10.1% of patients not being blinded and 14.6% being blinded, and interventionists not being blinded in 12.1% of studies and blinded in 12.6% of studies (Table 8).

| Blinding | Patient | Interventionist | Assessor | Analyst | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| No | 20 | 10.1 | 24 | 12.1 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0.5 |

| Yes, i.e. explicitly stated | 29 | 14.6 | 25 | 12.6 | 16 | 8.1 | 3 | 1.5 |

| Partial | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 176 | 88.9 |

| Not stated/unclear | 126 | 63.6 | 128 | 64.6 | 156 | 78.8 | 17 | 8.6 |

| Not applicable | 23 | 11.6 | 21 | 10.6 | 18 | 9.1 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 198 | 100 | 198 | 100 | 198 | 100 | 198 | 100 |

| 198 | 99.9 | 198 | 99.9 | 198 | 100 | 198 | 100 | |

Study characteristics

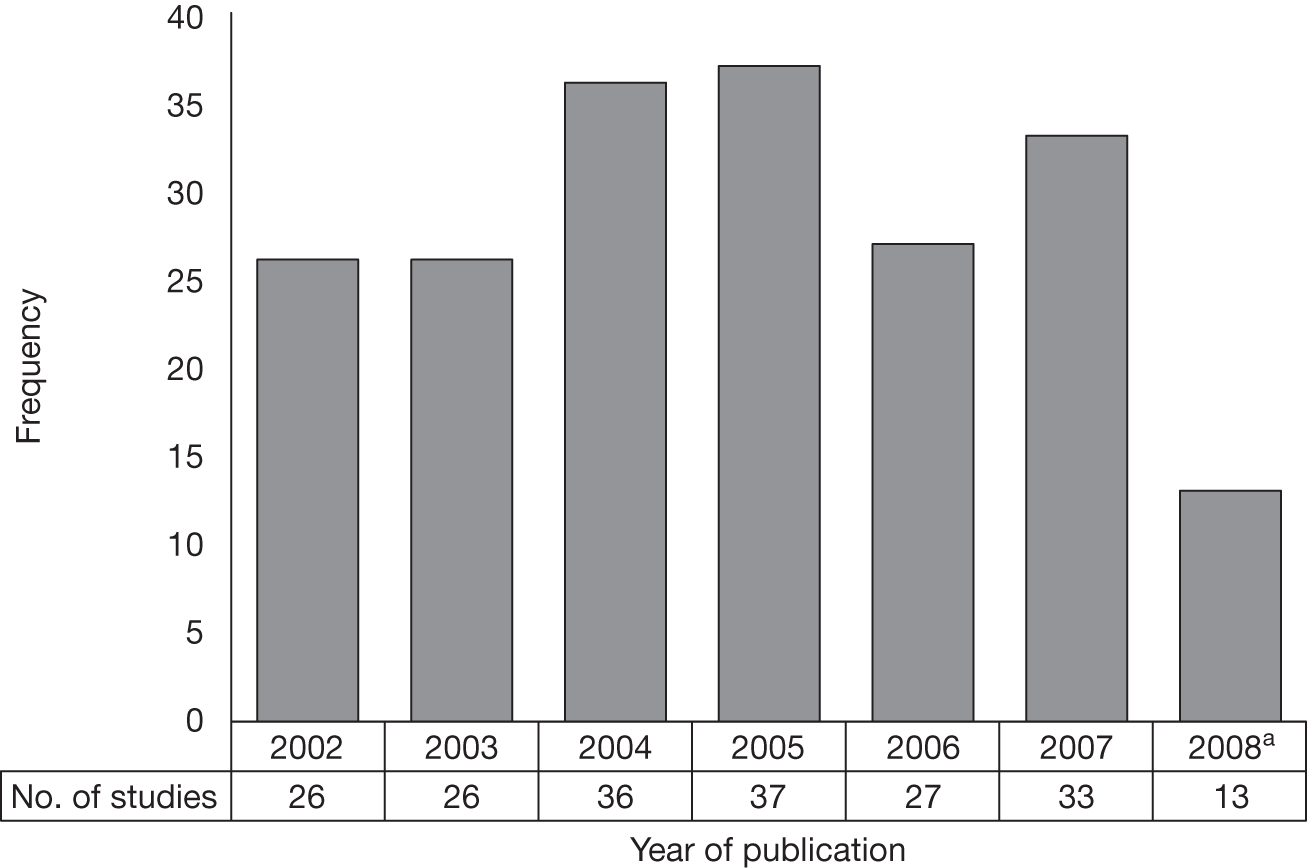

Number of studies

The number of studies published was relatively steady across the years, with an average of 32 papers being published each full year (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Number of studies by year of publication. a, The year 2008 was a partial year.

Country in which studies were conducted

Studies were conducted in 21 different countries, with only three studies being multinational, i.e. participants from more than one country. The majority of studies were conducted in the USA (55.1%), with the UK being the second most common location (10.6%), followed by Canada (6.6%) (Table 9).

| Country | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| USA | 109 | 55.1 |

| UK | 21 | 10.6 |

| Canada | 13 | 6.6 |

| Australia | 8 | 4.0 |

| Netherlands | 4 | 2.0 |

| Italy | 3 | 1.5 |

| Spain | 3 | 1.5 |

| Brazil | 2 | 1.0 |

| Germany | 2 | 1.0 |

| India | 2 | 1.0 |

| Israel | 2 | 1.0 |

| New Zealand | 2 | 1.0 |

| South Korea | 2 | 1.0 |

| Sweden | 2 | 1.0 |

| Belgium | 1 | 0.5 |

| China | 1 | 0.5 |

| Finland | 1 | 0.5 |

| Japan | 1 | 0.5 |

| Norway | 1 | 0.5 |

| Switzerland | 1 | 0.5 |

| Taiwan | 1 | 0.5 |

| Multinational | 3 | 1.5 |

| Not stated/unclear | 13 | 6.6 |

| Total | 198 | 100 |

Participant characteristics

Details of the characteristics of people included in the studies are shown below (see Tables 10–14 and Figures 5–7).

| Variable | n | Lower value (years) | Upper value (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 158 | 19.0 | 80.9 |

| SD | 118 | 1 | 15.9 |

| Median age | 8 | 29 | 43 |

| Minimum age | 71 | 13 | 65 |

| Maximum age | 70 | 32 | 97 |

| Population | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Mental disorder | 75 | 38 |

| Offender | 70 | 35 |

| Indictable offences | 29 | 15 |

| Forensic | 24 | 12 |

| Total | 198 | 100 |

| Diagnostic group | Mental disorder | Forensic | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder only | 10 | 13.3 | 1 | 4.2 | 11 | 11.1 |

| Dementia only | 4 | 5.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 4.0 |

| Personality disorder only | 18 | 24.0 | 2 | 8.3 | 20 | 20.2 |

| Other single mental health grouping | 25 | 33.3 | 9 | 37.5 | 34 | 34.3 |

| Mixed diagnostic groups | 17 | 22.7 | 11 | 45.8 | 28 | 28.3 |

| No specific diagnoses given | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Not stated/unclear | 1 | 1.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 1.0 |

| Total | 75 | 100 | 24 | 100 | 99 | 100 |

| Type of offence | Offender | Forensic | Indictable | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| General violence | 3 | 4.3 | 1 | 4.2 | 3 | 10.3 | 7 | 5.7 |

| Domestic violence | 31 | 44.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 65.5 | 50 | 40.7 |

| Sex offending | 16 | 22.9 | 7 | 29.2 | 0 | 0.0 | 23 | 18.7 |

| Mixed group of offences | 20 | 28.6 | 10 | 41.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 30 | 24.4 |

| Not stated/unclear | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 20.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 4.1 |

| Other indictable offences | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.2 | 7 | 24.1 | 8 | 6.5 |

| Total | 70 | 100 | 24 | 100 | 29 | 100 | 123 | 100 |

| Type of substance abuse | n | % | % of studies reporting on substance abuse (n = 86) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No substance abuse identified | 21 | 10.6 | 24.4 |

| Illicit drug use identified | 5 | 2.5 | 5.8 |

| Alcohol abuse identified | 3 | 1.5 | 3.5 |

| Both illicit drug use and alcohol abuse identified | 33 | 16.7 | 38.4 |

| Substance not specified | 24 | 12.1 | 27.9 |

| Not stated or unclear | 112 | 56.6 | NA |

| Total | 198 | 100 | 100 |

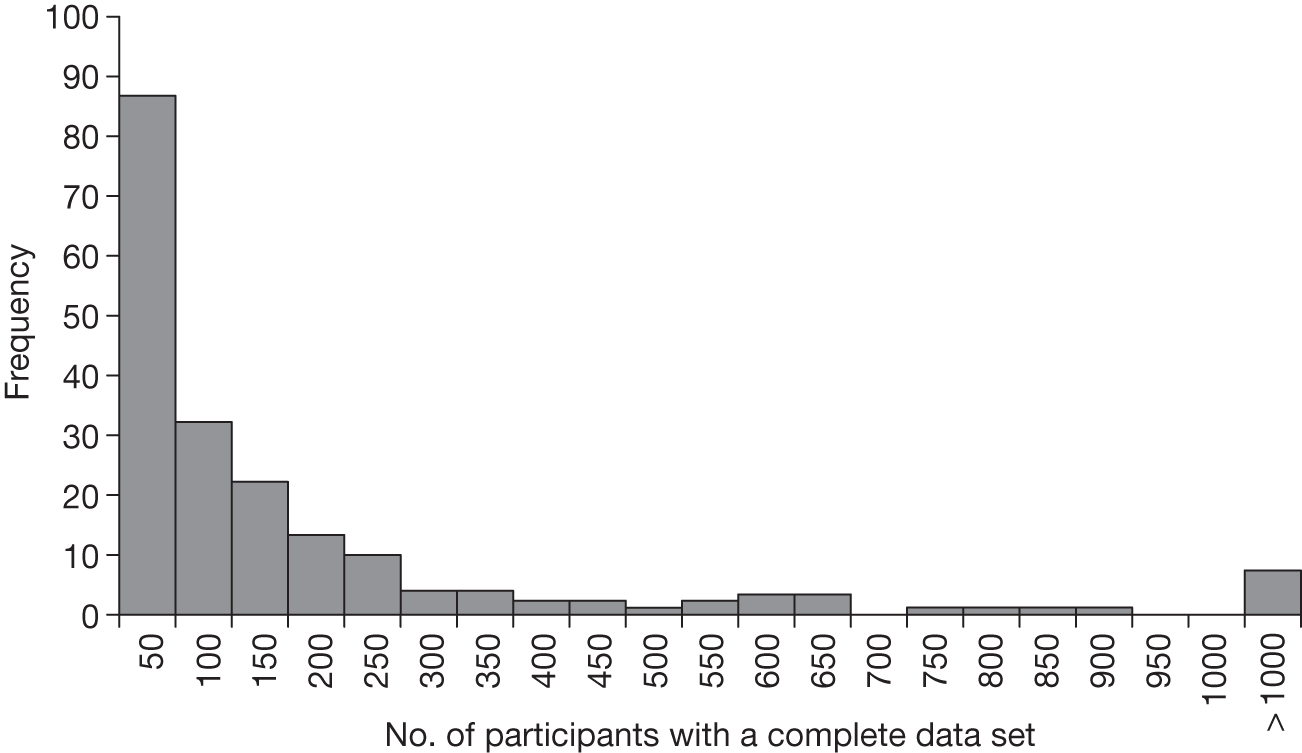

FIGURE 5.

Number of participants in complete data set.

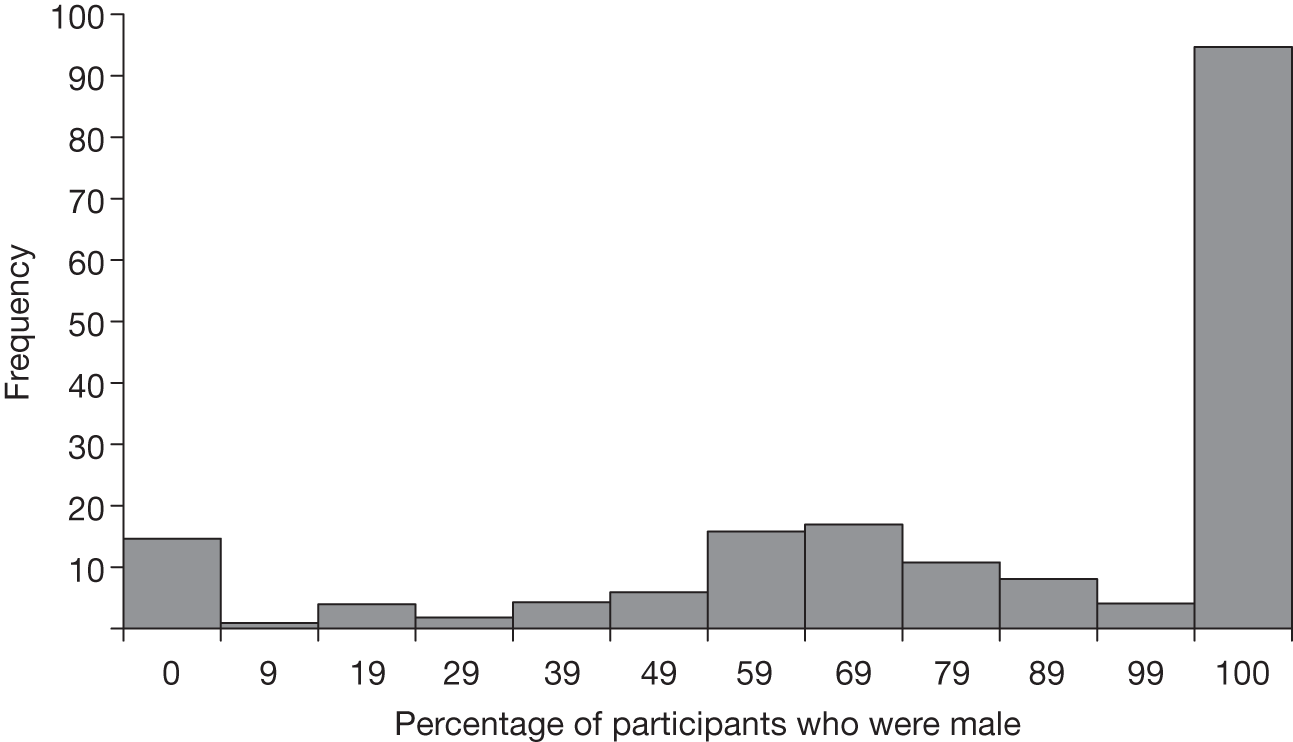

FIGURE 6.

Percentage of participants who were male.

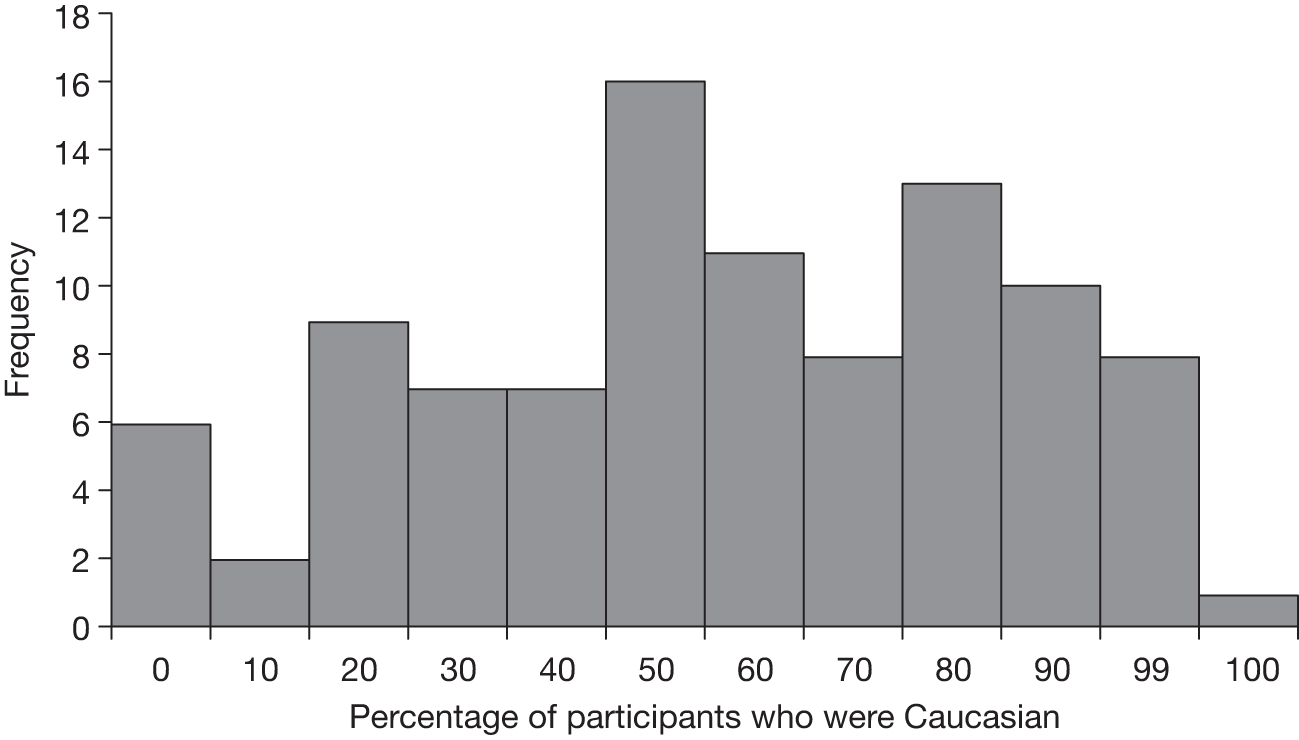

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of participants who were Caucasian.

Number of participants

The number of people approached to take part in the studies was reported in 94 (47.4%) of studies and ranged from 1 to 8325. The number of participants enrolled was reported in 191 (96.5%) of studies and ranged from 1 to 10,753. The number of participants at the end point of the study was reported in 196 (99.0%) of studies meaning that two studies failed to report the final number of participants in their study.

The studies reporting the final number of participants described a total of 51,258 individuals, the smallest study having one participant and the largest 10,753 participants (Figure 5). The majority (60%) of studies included ≤ 100 people.

Demographics of participants

The sex of participants was reported in 183 (92.4%) studies, with 95 (52%) studies including only males and 15 (8%) including only females. The percentage of males in the remaining studies ranged from 8% to 95% (Figure 6).

The average age of participants was reported in 166 studies (158 reported the mean age, four reported the median age and four reported both the mean and median age). The mean age ranged from 19 to 80.9 years, with SDs (reported by 118 studies) ranging from 1 to 15.9 years. The range of ages was reported by 70 studies (an additional study reported minimum age only). The minimum age of participants ranged from 13 and 65 years and the maximum age ranged from 32 to 97 years. Therefore, the youngest participant was 13 years and the oldest was 97 years (Table 10).

The percentage of participants who were described as Caucasian was reported in 98 studies, with six (6%) studies not including any Caucasian participants, and one study (1%) including only Caucasian participants. The percentage of Caucasian participants in the remaining studies ranged from 6% to 99% (Figure 7).

Population

Populations included in the review were either participants with a diagnosis of mental disorder, offenders, indictable offenders (i.e. those having committed indictable offences but not having been charged) or forensic participants (i.e. those with a diagnosis of mental disorder and offender/indictable offender status). The numbers of studies looking at each of these population types are shown in Table 11. Participants were mainly people with a mental disorder (38%) or offenders (35%), with those reported to have committed an indictable offence being studied in 15% of studies and offenders with a mental disorder (forensic) being included in 12% of cases.

Studies reporting on individuals with a diagnosis of a mental disorder (including forensic groups) reported a range of diagnostic groups, with patients defined as having an ‘other’ single mental health grouping being the most frequently reported (34%), followed by participants with a ‘mixed diagnosis’ (28%). Participants with personality disorders only were studied in 20% of the studies and participants with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder only were studied in 11% of the studies (Table 12).

There were differences between the diagnosis of participants in the mental disorder group and the forensic group. Almost half of the studies investigating forensic participants reported mixed diagnoses, and a further 37.5% reported participants with an ‘other single mental health grouping’. Participants with a specific mental health diagnosis were reported in only 3 out of the 24 forensic studies (12.5%), whereas 32 out of the 75 studies (42.6%) examining participants with just a mental disorder reported investigating participants with specific mental disorder diagnoses.

The index offences that participants had committed differed greatly between the three groups. Offender participants had been charged with predominantly DV (44.3%), followed by mixed group of offences (28.6%) and sex offending (22.9%). For studies including forensic participants, mixed groups of offences were more frequently reported (41.7%), followed by sex offending (29.2%). A further 20.8% of studies did not report what offences participants had committed.

As expected, in the indictable group, DV was the most reported offence type (65.5%), with other indictable offences being reported in 24.1% of studies (Table 13).

Substance abuse

Substance abuse by participants was poorly reported in most studies, with only 43.4% (86) of papers reporting whether current substance abuse was or was not identified. Of the 86 studies reporting on substance abuse, 21 (24.4%) reported no substance abuse, five (5.8%) identified drug abuse, three identified (3.5%) alcohol abuse and 33 (38.4%) both alcohol and drug abuse. A further 24 (27.9%) studies identified some form of substance abuse, but did not report on the nature, i.e. whether it was drugs or alcohol (Table 14).

Intervention characteristics

Types of interventions

Of the 198 studies, 74 (37.37%) were single-group designs and 124 (62.6%) compared two or more groups. Of the 124 using a comparator group, 29.8% compared two different types of treatment (head-to-head comparisons), 24.2% TAU, 14.5% a placebo, 12.9% compared subgroups of one treatment (e.g. completers vs non-completers) and 8.9% no treatment. The remaining seven studies used a historical control (3.2%) or self as a control (2.4%) (Table 15).

| Type of comparison | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Head to head | 37 | 29.6 |

| Historical control | 5 | 4.0 |

| Placebo | 18 | 14.4 |

| Self as control | 3 | 2.4 |

| Subgroup | 16 | 12.8 |

| TAU | 30 | 24.0 |

| No treatment | 11 | 8.8 |

| WL | 5 | 4.0 |

The types of intervention studied are shown in Tables 16 and 17. Half of included studies used a psychological intervention (50.5%) as the primary intervention, one-quarter used a pharmacological intervention (23.7%) and one-quarter another form of intervention (25.8%). The specific categories of intervention by comparison type are shown in Table 16 and the comparators used in head-to-head studies in Table 17.

| Primary intervention | Comparator group: n (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single group | Historical control | Placebo | Self as control | Subgroup | TAU | No treatment | WL | Head to head | |

| Behavioural/cognitive | 30 (40.5) | 1 (33.3) | 8 (50) | 10 (33.3) | 5 (45.5) | 4 (80) | 10 (27.0) | ||

| Other psychological therapy | 4 (5.4) | 1 (6.3) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (5.4) | |||||

| Substance abuse therapy | 2 (2.7) | ||||||||

| Domestic violence/batterer programmes | 10 (13.5) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (10) | 1 (20) | 1 (2.7) | ||||

| Case management model | 1 (20) | 2 (6.7) | |||||||

| Legal | 1 (1.4) | 2 (40) | 4 (13.3) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (2.7) | ||||

| Clozapine | 3 (8.1) | ||||||||

| Divalproex | 1 (1.4) | 2 (11.1) | 1 (6.3) | ||||||

| Fluoxetine | 2 (11.1) | ||||||||

| Fluvoxamine | 1 (1.4) | 1 (5.6) | |||||||

| Haloperidol | 1 (5.6) | 1 (2.7) | |||||||

| Lamotrigine | 1 (1.4) | 1 (5.6) | |||||||

| Lorazepam | 1 (5.6) | 1 (2.7) | |||||||

| Midazolam | 1 (2.7) | ||||||||

| Nefalzone | 1 (1.4) | ||||||||

| Olanzapine | 1 (5.6) | 4 (10.8) | |||||||

| Quetiapine | 2 (2.7) | ||||||||

| Risperidone | 2 (11.1) | 2 (5.4) | |||||||

| Topiramate | 4 (22.2) | ||||||||

| Ziprasidone | 1 (1.4) | 1 (2.7) | |||||||

| Zuclopenthixol | 1 (2.7) | ||||||||

| Other pharmacological | 4 (5.4) | 3 (16.7) | 1 (9.1) | 2 (5.4) | |||||

| Therapeutic communities | 1 (3.3) | ||||||||

| Multimodal programme | 7 (9.5) | 2 (40) | 5 (16.7) | 3 (27.3) | 3 (8.1) | ||||

| Other form of intervention | 9 (12.2) | 2 (66.7) | 3 (18.8) | 5 (16.7) | 4 (10.8) | ||||

| Total studies | 74 (100) | 5 (100) | 18 (100) | 3 (100) | 16 (100) | 30 (100) | 11 (100) | 5 (100) | 37 (100) |

| Primary intervention | Comparator group: n (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioural/cognitive | Other psychological therapy | Community therapy | Legal intervention | Multi-modal programme | Clozapine | Fluoxetine | Haloperidol | Olanzapine | Topiramine | Zuclopenthixol | Other pharmacological | Other form of intervention | Total | |

| Behavioural/cognitive | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (10.0) | 3 (30.0) | 10 (100) | ||||||||

| Other psychological therapy | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||

| Domestic violence/batterer programmes | 1 (100.0) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Legal | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Clozapine | 3 (100) | 3 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Haloperidol | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Lorazepam | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Midazolam | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Olanzapine | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 2 (50) | 4 (100) | ||||||||||

| Risperidone | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||

| Ziprasidone | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Zuclopenthixol | 1 (100) | 1 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Other pharmacological | 1 (50) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | |||||||||||

| Multimodal programme | 1 (33.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (100) | |||||||||||

| Other form of intervention | 4 (100) | 4 (100) | ||||||||||||

| Total | 5 (13.5) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 4 (10.8) | 1 (2.7) | 1 (2.7) | 7 (18.9) | 9 (24.3) | 37 (100) |

Psychological studies were more likely to use single-group comparisons and pharmacological studies head-to-head or placebo comparators. Where head-to-head studies were used, the same categories of intervention were compared, i.e. psychological interventions compared with another psychological intervention, and pharmacological interventions compared with another pharmacological intervention.

Setting

The start and end settings are shown in Table 18. The term ‘setting’ here refers to the location where the intervention is conducted and in the case of ‘community’ under what conditions, i.e. a probation order, or under the supervision of a mental health practitioner or neither (e.g. a person concerned about their propensity for violence who is offered a self-help intervention). The most frequently reported setting was community with people on probation (18.7%), followed by penal institutions (16.2%), community (14.6%) and community mental health (12.1%). The majority of studies (87.9%) had the same start and end setting. Of the 24 studies reporting different start and end settings, 12 were studies that started in penal institutions but ended in either the community or in mixed settings.

| Setting started in: | Setting follow-up ended in: | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forensic mental health | Penal institution, e.g. prison | Open inpatient hospital ward | Secure non-forensic inpatient ward | Nursing home | Community | Community: probation | Community mental health | A&E or psychiatric emergency service | Mixed settings | Other | Not stated or unclear | Total: n (%) | |

| Forensic mental health | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 12 (6.1) |

| Penal institution, e.g. prison | 0 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 32 (16.2) |

| Open inpatient hospital ward | 0 | 0 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 (8.1) |

| Secure non-forensic inpatient ward | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.5) |

| Nursing home | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (1.5) |

| Community | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 29 (14.6) |

| Community: probation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 37 (18.7) |

| Community mental health | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24 (12.1) |

| A&E or psychiatric emergency service | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (3.5) |

| Mixed settings | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 2 | 15 (7.6) |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 10 (5.1) |

| Not stated or unclear | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 10 (5.1) |

| Total n | 11 (5.6) | 20 (10.1) | 14 (7.1) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) | 36 (18.2) | 34 (17.2) | 25 (12.6) | 7 (3.5) | 22 (11.1) | 11 (5.6) | 12 (6.1) | 198 (100) |

When start settings for the interventions are examined by intervention type (Table 19), it can be seen that studies in a forensic mental health setting mainly studied behavioural and cognitive therapies (75.0%), as did penal institutions (56.3%), community (44.8%), mixed settings (33.3%) and other settings (40.0%), whereas community probation settings used DV programmes. Pharmacological interventions were the focus of the majority of studies in community mental health settings (58.0%), accident and emergency (A&E) settings (100%), mixed settings (33.3%) and studies where the setting was unclear or not stated (40.0%).

| Start setting | Intervention type | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological | Behavioural and cognitive therapies | Therapeutic community | DV programme | Other psychological intervention | Substance abuse | Case management | Legal | Multimodal | Other | Total | |

| Forensic mental health | 0 | 9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 12 |

| Penal institution, e.g. prison | 1 | 18 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 32 |

| Open inpatient hospital ward | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 6 | 16 |

| Secure non-forensic inpatient ward | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Nursing home | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Community | 4 | 13 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 29 |

| Community: probation | 1 | 10 | 0 | 11 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 3 | 37 |

| Community mental health | 14 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 24 |

| A&E or psychiatric emergency service | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Mixed settings | 5 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15 |

| Other | 2 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 10 |

| Not stated or unclear | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 10 |

| Total | 47 | 67 | 1 | 18 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 9 | 20 | 23 | 198 |

Level of intervention

The levels of interventions for each of the types of intervention are shown in Table 20. Pharmacological interventions were by design at an individual level, whereas the psychological interventions were generally at the small group level.

| Type of intervention | Level of intervention | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual | Small group | Ward or team | Hospital or institution | Population | Other | Mixed | Not stated/unclear | Total | |

| Behavioural and cognitive therapies | 5 | 45 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 67 |

| Therapeutic community | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| DV programme | 1 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 18 |

| Other psychological intervention | 1 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 |

| Substance abuse | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Case management | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |