Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a project commissioned by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC-NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’. To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and publish the findings in the HTA monograph series, if supported by NIHR funds.

Declared competing interests of authors

At the time that this research was conducted some of the research team at York and Brunel served on NICE Appraisal Committees (KC, SP, LL and SG), some of whom are also members of the NICE Decision Support Unit (KC, SP). York also provides analysis for the NICE appraisal process as one of a number of Evidence Review Groups.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2012. This work was produced by Claxton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to NETSCC.

2012 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and overview

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) is increasingly making decisions about health technologies close to licence through the single technology assessment (STA) process. Inevitably these decisions are being made when the evidence base to support these technologies is least mature and when there may be substantial uncertainty surrounding their cost-effectiveness, including their effectiveness and potential for harms. In these circumstances further evidence may be particularly valuable as it would lead to better decisions that improve patient outcome and/or reduce resource costs. However, a decision to approve a technology will often have an impact on the prospects of acquiring further evidence to support its use. This is because, once positive guidance has been issued, the incentives for manufacturers to conduct research are limited. Also, the clinical community is unlikely to regard further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) to be ethical once positive guidance provides access with a funding mandate. Therefore, the decision to approve a technology should account for both the potential benefits of access to a cost-effective technology and the potential costs to future NHS patients in terms of the value of evidence that may be forgone by early adoption. The general issue of balancing the value of evidence about the performance of a technology and the value of access to a technology can be seen as central to a number of policy questions. Establishing the key principles of what assessments are needed for ‘only in research’ (OIR) or ‘approval with research’ (AWR) recommendations, as well as how these assessments should be made, will enable them to be addressed in an explicit and transparent manner.

The Medical Research Council (MRC) and National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Methodology Research Programme recently funded the Universities of York and Brunel to undertake research to help inform when NICE should recommend the use of health technologies only in the context of an appropriately designed programme of evidence development (see Appendix 5). The NICE Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal1 states that ‘the Appraisal Committee may recommend that particular interventions are used within the NHS only in the context of research’. It indicates that four issues should be considered by the Appraisal Committee when recommending further research. These are (1) whether or not the intervention is reasonably likely to benefit patients and the public, (2) how easily the research can be set up or whether or not it is already planned or in progress, (3) how likely the research is to provide further evidence and (4) whether or not the research is good value for money.

The aims of this research are to:

-

establish the key principles of what assessments are needed to inform an OIR or AWR recommendation

-

evaluate previous NICE guidance in which OIR or AWR recommendations were either made or considered, and examine the extent to which the key principles from (1) are evident

-

evaluate a range of alternative options to establish the criteria, additional information and/or analyses that could be made available to help the assessments needed to inform an OIR or AWR recommendation

-

provide a series of final recommendations, with the involvement of key stakeholders, establishing both the key principles and associated criteria that might guide OIR and AWR recommendations, identifying what, if any, additional information or analyses might be included in the NICE technology appraisal process and how such recommendations might be more likely to be implemented through publically funded and sponsored research.

The relevance of this work to NICE has been evaluated through a series of two workshops involving key stakeholders, including members of NICE and its Advisory Committees (including lay members and members of other NICE programmes), patient representatives, manufacturers, and research and NHS commissioners, as well as relevant academics. Establishing the key principles of what assessments are needed to inform OIR or AWR recommendations requires a critical review of a diverse literature on principles and policy and previous NICE guidance (see Chapters 2 and 4); the development of a coherent conceptual framework (see Chapter 3, Key principles and assessments needed and Changes in prices and evidence); and consideration of whether or not such principles conflict with established ethical principles and the social value judgements adopted by NICE (see Chapter 3, Social value judgements and ethical principles).

The first workshop took place in September 2010 and considered four main topics:

-

the relevance to NICE of existing literature

-

whether or not the key principles and assessment that have been identified provide useful guidance on when OIR and AWR might be considered

-

the insights from a detailed review of previous NICE guidance

-

whether or not the proposed methods to inform assessment and criteria to select case studies are suitable.

Relevant summaries of the key issues were provided in the form of briefing documents that covered these four topics. These documents, which formed the basis for the workshop presentations and related group discussions, as well as a summary of feedback and list of participants, are available at www.york.ac.uk/che/research/teehta/workshops/only-in-research-workshop/.

The primary output of this workshop was a set of principles and explicit criteria (a sequence of assessments and decisions) to support OIR and AWR recommendations. This sequence of assessments (an algorithm) can be summarised as a simple 7-point checklist, which was subsequently applied to a series of four case studies. Each case study examines how each of the assessments might be made based on the type of evidence and analysis currently provided in NICE technology appraisals and how these assessments might be better informed with a range of additional information and/or analyses.

The second workshop took place in June 2011 and considered:

-

whether or not the revised algorithm of assessments and the associated checklist has identified the key judgements that need to be made when considering OIR and AWR guidance

-

based on the application of this checklist to the series of case studies, whether or not such assessments can be made based on existing information and analysis provided to NICE and in what circumstances could additional information and/or analysis be useful

-

what implications this more explicit assessment of OIR and AWR might have for policy (e.g. NICE guidance and drug pricing), the process of appraisal (e.g. greater involvement of research commissioners) and methods of appraisal (e.g. should additional information, evidence and analysis be required).

Relevant summaries of the key issues were provided in the form of briefing documents that covered these three topics. These documents, which formed the basis for the workshop presentations and related group discussions, as well as a summary of feedback and list of participants, is available at www.york.ac.uk/che/research/teehta/workshops/only-in-research-workshop/.

The primary output of this workshop was a list of possibilities that NICE might choose to take forward in the next revision of the Guide to the Methods of Technology Appraisal1 and how this might inform the formulation of guidance in the other NICE programmes. It might also suggest how a consideration of uncertainty and the need for evidence might influence value-based pricing and the impact of patient access schemes on OIR and AWR guidance.

The main report is intended to be accessible to a wide audience, providing intuitive explanations of why certain assessments are important and illustrating how they might be informed using examples. Notes have been used extensively, especially in Chapters 3 and 5, to provide explanatory detail without adding undue complexity to the exposition in the main text (see Notes). The main report is accompanied by (1) supporting material for each chapter (see Appendices 1–5), (2) a technical appendix (see Appendix 6), which provides a more formal treatment of why, in principle, each type of assessment is important, (3) full details of the analysis undertaken for each of the four case studies referred to in Chapter 5 of the main report (see Appendices 7–10) and (4) a series of technical notes (see Appendix 11) that deal with some conceptual and analytical details that are common to the case studies reported in Appendices 7–10.

The main report is organised as follows. The results of a critical review of policy, practice and literature in this area are presented in Chapter 2, supported by material in Appendix 1. The key principles and the sequence of assessments needed are presented in Chapter 3, supported by Appendix 2 and critically the technical appendix (see Appendix 6), which provides more formal treatment of the issues. A review of NICE technology appraisal guidance is presented in Chapter 4, supported by material in Appendix 3. The checklist of assessment needed and its application to the four case studies using a range of additional information and analysis is reported in Chapter 5. Chapter 5 is supported by material in Appendix 4 and critically by the full details of the analysis undertaken for each case study, reported in Appendices 7–10, and the series of technical notes in Appendix 11. Finally, Chapter 6 briefly draws together some of the possible implications for policy, process and methods of appraisal, distinguishing those issues directly relevant to the NICE remit and those that might be most relevant to other public bodies and stakeholders. Chapter 6 draws on the feedback provided at the second workshop, which has been summarised and is available online (see above).

Chapter 2 Critical review of policies, practice and literature

Aims and objectives

There is a growing and diverse literature on OIR/AWR2–5 and on when decisions to adopt a technology should be delayed. 6,7 There is also considerable variation in the terminology used across this literature, which reflects the different decision contexts, not all of which are relevant to NICE. There is a need to critically review this literature to distil any common themes and core principles relevant to the NICE context. The main purpose of the review is to help to inform the development of a unifying conceptual framework within which these themes and principles can be located and understood. This, in turn, will enable a consistent and clear terminology to be established which will assist clarity in subsequent policy debates and may provide NICE with useful definitions and terminology that can be used in communicating its guidance, considerations and methods. The specific aims of the review were:

-

to review alternative terminologies and taxonomies used to describe and classify approaches to OIR/AWR and to establish their relevance to the NICE context

-

to identify any common themes and principles discussed in relation to OIR/AWR.

Methods

The existing literature on OIR and AWR is only partly represented in traditionally published papers; much is located in policy and discussion documents. The diversity in these sources was reflected in the range of search strategies employed, covering (1) traditional published literature, (2) grey literature and (3) policy and discussion documents. In addition, relevant interest groups and policy websites were searched, reference lists of previous reviews8 were checked, separate citation searches were performed using key references and discussions were held with our Advisory Group. In reviewing the results of the systematic search and selecting relevant studies for inclusion, a relatively inclusive approach was adopted. Case study examples of AWR/OIR were not searched for explicitly; instead the focus of the searches was to identify relevant methodological papers. Case study examples comprising a significant discussion of methodological issues were, however, included in the review.

A summary of the search strategies are discussed under the relevant subheadings below. Full details of the separate searches are reported in Appendix 1.

Traditional published literature

A traditional systematic search was undertaken in MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, EconLit and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) based on appropriate search terms informed by key publications to identify relevant literature. 8 An iterative approach was used in the development of search terms and strategies incorporating ‘pearl-growing’ techniques through additional citation and reference searching of key publications and discussions with our Advisory Group. Searches were restricted to documents produced from 1999 onwards as the use of OIR and AWR policies is a relatively recent process and so it is not expected that any relevant references will be identified before this date.

To test the performance of the search strategy, records initially identified from the case for support and citations contained within those documents and articles were cross-referenced with the results identified from the searches (capture–recapture method). In doing this it was concluded that the final search strategy identified all of the records it would be likely to identify, that is, those accessible from traditional (non-grey literature) sources.

Grey literature searches

Additional searches of grey literature were also undertaken using a similar approach reported in the review by Stafinski et al. 8 The following grey literature databases were searched: the New York Academy of Medicine Grey Literature Report and the IDEAS database (Department of Economics, University of Connecticut). A similar set of key words as for the review of the traditional published literature was used for the grey literature searches, with some modifications because of the different recording mechanisms operated by the grey literature databases. Searches were again restricted to documents produced from 1999 onwards.

Policy and discussion documents

The third element of the search was based on policy and discussion documents. Although the focus of the search related to UK policy and discussion documents, documents from key international organisations were also included. Relevant international organisations and websites were identified in conjunction with our Advisory Group. A number of policy documents were also identified from those referenced in the case for support and from the reference lists of key papers. 9–12 A number of additional organisation websites were searched for relevant documents. Where possible, web searches were restricted to documents produced from 1999 onwards for consistency with the other search elements.

Other sources

The final element of the search considered a variety of other sources including relevant interest groups [e.g. the Health Technology Assessment international (HTAi) interest subgroup on conditional coverage and evidence development for promising technologies and the Programs for Assessment of Technology in Health (PATH) website containing publications relating to the programme of conditionally funded field evaluations (CFEEs) in Ontario], other reviews,8 references suggested by our Advisory Group and additional searches based on citations of papers identified from earlier stages.

Literature search results

A summary of the search results is provided in the following sections. Full details of the results and a summary of included references are reported in Appendix 1.

Identified references

In total, 59 references were included in the review; 43 of these were journal articles,2–5,8,13–50 11 were policy documents (eight UK and three non-UK)9–12,22,51–56 and five were based on presentation slides or discussion documents. 56–60

Of the 43 journal articles, the majority are academic ‘think pieces’ on issues relating to OIR and AWR with additional responses to previous articles. 5,13–16 Although a number of the journal articles provide a discussion of many of the general issues relating to the use of OIR and AWR,2,3,17–24 a smaller proportion explicitly address the issue of terminology and/or provide a taxonomy of OIR/AWR types (n = 11). The majority of the journal articles discuss specific issues relating to OIR/AWR implementation, most commonly in relation to evidence collection and design (n = 41). These issues are often illustrated in the context of specific case study applications such as the positron emission tomography register or the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT). A relatively large number of these articles also discuss ethical issues and social value judgements relating to the implementation of OIR/AWR policies (n = 20) and issues of investment and reversal costs (n = 21).

The 11 policy documents91–112,22,51–56 identified are from UK and non-UK sources. From the UK, relevant documents are produced by HM Treasury,9 the Department of Health,52 the House of Commons Health Committee,10 NICE and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ),51 NICE Citizens Council,11 NHS Scotland,53 the Office of Fair Trading (OFT)12 and the Office of Life Sciences. 54 Outside of the UK, relevant documents identified are all produced by US organisations: the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS),55 the Health Industry Forum56 and the National Health Policy Forum. 22 In many of these policy documents OIR and AWR are typically discussed as part of a wider general health policy theme as opposed to being the central issue under consideration. Only a small number22,51,55 offer any insights into terminology and/or taxonomies relating to OIR/AWR. Over half (n = 7) present general issues of OIR/AWR and specific issues most commonly related to evidence collection. Issues of investment and reversal costs, changing prices and ethical issues/social value judgements are covered to a lesser extent in the policy documents.

The final five references included are presentation slides or discussion documents. 56–60 These are all widely cited in the OIR and AWR literature. None of these references discusses terminology or taxonomies of OIR/AWR types. Instead they again focus on general themes of OIR/AWR, with some discussing specific issues such as evidence collection.

Summary of the key issues for practice and policies for ‘only in research’ and ‘approval with research’ schemes

The following sections discuss the main findings in line with the key objectives of the review.

Review of terminology and taxonomies of ‘only in research’/‘approval with research’ schemes

Multiple definitions of OIR- and AWR-type schemes are reported in the literature. These are commonly provided within a broader consideration of conditional coverage or risk-sharing schemes. Despite the variation in terminology that exists, a number of common themes emerge. Most notably, the use of OIR/AWR is commonly defined as providing an alternative to a binary accept/reject decision for policy-makers in situations in which the technology does not appear to meet the standard criteria for reimbursement, predominantly because of uncertainty surrounding the existing evidence base and when additional data collection could reduce this uncertainty. 21 The emphasis placed on uncertainty and the specific role that the collection/generation of additional evidence plays in reducing existing uncertainty is what distinguishes OIR/AWR schemes from the broader range of conditional coverage or risk-sharing approaches,25 in which the focus is to shift the burden of uncertainty onto another party (usually the manufacturer) rather than to collect information to reduce this uncertainty for future decisions. 4,24

In considering how to appropriately define and categorise OIR/AWR schemes, it is important to consider what particular terms mean in their various contexts. In the context of NICE, OIR is the term used when a recommendation is made to restrict an approval decision to only those patients who subsequently receive the intervention as part of a well-designed programme of research. OIR has been available as a formal policy option since the inception of NICE52 and provides an important additional option to accept and reject decisions. 3

In contrast to an OIR recommendation, the use of AWR does not necessarily limit coverage to those participating in the clinical study or registry. Hence, the distinction between OIR and AWR is primarily the degree of coverage that each confers for reimbursement purposes. Although AWR is not currently a formal policy option available to NICE, it is able to issue specific research recommendations as part of any guidance and can link this to the timing of any reappraisal. Consequently, AWR represents a valid option for consideration. Importantly, both OIR and AWR strategies are distinct from general recommendations for further research made as part of the appraisal process, in which no link to generating evidence as a condition of coverage is made. However, given the current directives and remit of NICE, the research recommendations issued as part of an AWR decision are not a mandatory requirement of approval. As a result, inevitably there exists some uncertainty following an AWR recommendation over whether or not the stated research recommendations will actually be conducted.

Although slightly different definitions and terminology are applied in the broader literature relating to OIR and AWR schemes, they are relatively similar in their meaning. For example, in the USA, the term ‘coverage with evidence development’ (CED) is often used as a catch-all term for OIR- and AWR-type schemes. Sections 1862(a)(1)(A) and (1)(E) of the Social Security Act provide statutory provision for the CMS to issue both OIR- and AWR-type coverage decisions involving the collection of additional evidence in registries or clinical trials, through national coverage determinations (NCDs). CMS describes two related but distinct processes: coverage with appropriate determination (CAD) and coverage with study participation (CSP). 55 As with OIR and AWR, these separate forms of CED are also closely linked to the level of coverage. CMS may issue a CAD to determine that patients receiving the treatment meet the conditions specified in the NCD. As part of this they may request more data. CSP allows coverage of certain items or services for which the evidence is not adequate to support full coverage and for which further data would be of benefit. Coverage may be extended to patients enrolled in a clinical research study. To recommend a CSP the evidence should assure basic safety, there should be high potential to provide significant benefit and there may be significant barriers to conducting clinical trials. Consequently, CSP would fit with OIR as it currently exists in the UK and CAD is closer to an AWR-type scheme.

Another example of the use of CED as a catch-all term for OIR/AWR schemes is the conditionally funded field evaluations (CFFEs) conducted in Ontario, Canada. These are recommended on the basis of a Health Technology Policy Analysis undertaken by the Medical Advisory Secretariat for the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee, which may conclude that there is not enough evidence to support uptake and diffusion of the technology. In these circumstances, coverage for a technology is provided conditional upon additional data being collected to specifically address residual uncertainty to better inform evidence-based decision-making. Primarily, the impetus for conducting a CFFE is a lack of evidence on transferability of evidence to a particular jurisdiction and/or its effectiveness or cost-effectiveness within particularly subgroups. 17,20 There are, however, reasons to recommend a CFFE on the basis of any decision uncertainty regarding the quality of evidence, safety data and cost-effectiveness. 20 In practice, coverage is sometimes restricted during the course of the field evaluation to only those patients participating in the study (e.g. the use of positron emission tomography scanners), that is, akin to an OIR recommendation; however, in other instances, hospitals can still purchase technologies and provide services through global budgets during the period of evaluation, thus appearing less restrictive than an OIR recommendation. Although this implicitly suggests that separate coverage schemes are considered when a CFFE is commissioned, there appears to be no formal distinction made within existing policy documents and other published literature between different types of schemes and also no discussion of the specific factors that might influence the degree of coverage. Instead, the type of scheme and degree of coverage appear to be determined on a case-by-case basis.

As well as any commonalities between CED and OIR/AWR schemes, there also appear to be similarities in terms of the challenges faced in successfully undertaking these schemes. In the UK, an OIR scheme can be recommended by NICE when appraising health technologies, but it also has potential in public health, diagnostics and devices. However, following an OIR recommendation, there are no formal arrangements to develop the research study required to reduce uncertainties. 3 NICE does not hold a budget to commission research so unless it is publically funded by research commissioners it will be undertaken only if manufacturers conduct it, with the NHS contributing excess treatment costs. The lack of co-ordination also makes it difficult to ensure an update of the recommendation following production of new evidence. 3 In the USA, although the CMS will cover the costs of a trial or registry associated with a CSP decision, there is currently no Medicare-specific funding mechanism for the additional data collection under CAD and hence there exists similar uncertainty concerning who will be responsible for paying for the additional data collection under CAD.

Although there have been several previous attempts to develop taxonomies,8,21,23,25 none of these has been focused specifically on OIR/AWR schemes and typically these are presented as part of a broader categorisation of conditional coverage and risk-sharing schemes. For example, in the taxonomy developed by Carlson et al. ,25 conditional coverage schemes are divided into CED and conditional treatment continuation schemes. Within CED, two subtypes are presented – OIR and ‘only with research’ (OWR) – with OWR similar to the term AWR used in this report. However, a more detailed consideration of OIR/AWR schemes and the potential for further subtypes within these schemes has not been previously explored in existing taxonomies.

General issues of ‘only in research’/‘approval with research’ schemes

There are many issues that need to be resolved to enable the successful implementation of an OIR or AWR scheme both generally and also within the specific constraints of NICE. 11 Central to this is the need to clarify the objectives of these schemes and the relevant criteria for their use. However, the critical review identified only limited discussion on the specific circumstances under which an OIR or AWR scheme may be an appropriate policy option. 9,10,51 The lack of any clear guidance has led to concerns expressed over ambiguity regarding their use26,57 and that OIR is currently being used as a ‘polite no’ by NICE. 11 Importantly, these concerns are not restricted to the use of OIR/AWR schemes by NICE. The general lack of clarity on the principles and criteria for using these schemes is reflected in many commentators’ views that the development and use of schemes internationally has appeared to be rather ad hoc to date. 57 Such concerns clearly highlight the importance of developing a clear set of principles for the use of OIR/AWR by NICE.

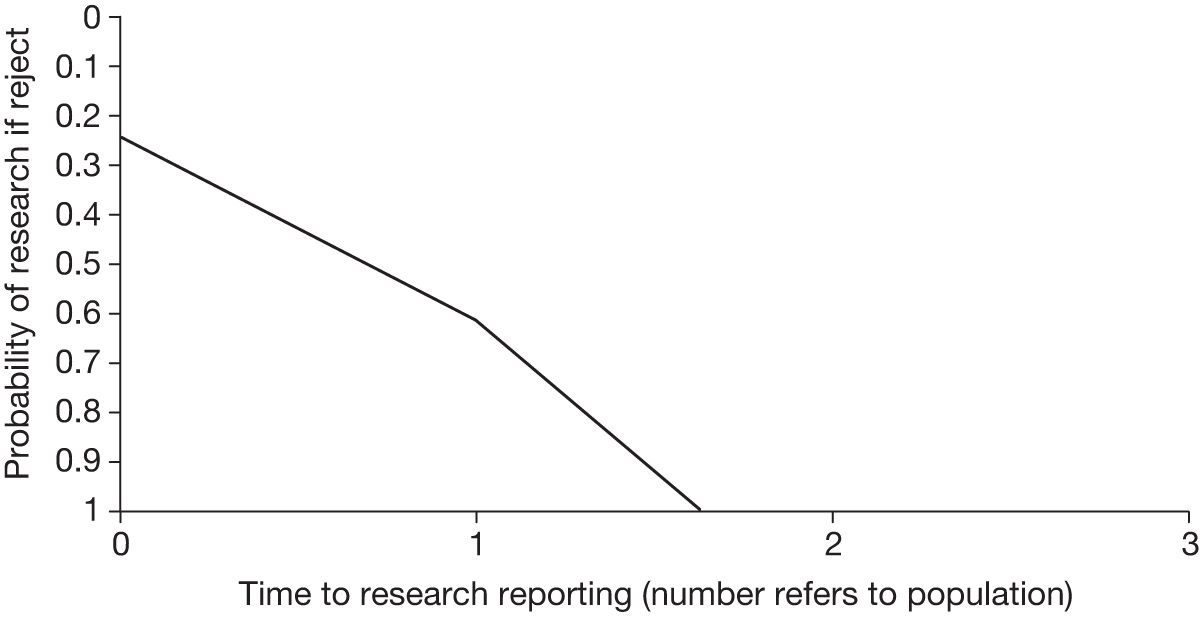

Although the majority of existing policy documents related to NICE are not explicit about the rationale and principles for the use of OIR and AWR in the UK, the report from the NICE Citizens Council11 on the use of OIR does describe the particular circumstances that the Council thought should be taken into account when NICE considers whether or not to issue OIR recommendations. These circumstances include:

-

Whether at least one appropriate, relevant study is:

-

– planned (e.g. the study will definitely start within 6 months of the guidance publication date)

-

– in progress (e.g. recruitment to the study is open and is expected to last at least 1 year beyond the guidance publication date) or

-

– could be established quickly (analysis in Chapter 5 explores the impact of the time taken for research to report).

-

-

Whether or not the question addressed by the study will contribute to reducing the uncertainties identified during the preparation of NICE guidance.

-

Whether or not the research is feasible (in terms of numbers of patients, recruitment, etc.) and is likely to deliver results within an appropriate time period.

-

Whether or not a fully supportive decision would lead to significant irrecoverable fixed costs of implementation (the impact of these types of cost are explored in Chapter 3, Technologies with significant irrecoverable costs and Chapter 5, Point 2: Are there significant irrecoverable costs?).

-

Whether a fully supportive decision, instead of an OIR recommendation, would lead to the termination of research in progress or prevent new research from beginning and thus have a negative impact on future collection of relevant information.

-

Whether or not it is realistic to hope that research can be carried out to the satisfaction of NICE. Factors to be considered include the timeliness of the research, potential number of patients able to participate in research, the pace of the current research and the precise nature of the questions to be answered.

In setting out a clear rationale and set of principles for the use of OIR/AWR, NICE will also be able to work towards identifying which technologies may be suitable for such policies. Ideally they should be those with potential net benefit but also some degree of uncertainty. 4 It has also been argued that these schemes could also be used to ‘fast track’ particular treatments. 26 However, in addition to their role in new and emerging technologies,3 other commentators have also stressed their potential use for established interventions to inform recommendations for increased investment or for disinvestment. 5

In addition to the rationale and principles, there are also numerous practical issues that need to be resolved for the successful use of such policies. The recent lung volume reduction surgery case study highlighted a number of challenges for OIR/AWR, in particular significant opposition from the clinical community, the significant level of funding required, the length of time required to complete data collection and limited access for patients in remote areas. As a result of the multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme, the importance of interagency collaboration, achieving consensus on acceptable quality of evidence, external peer review, predefined clinical benefit and determining who pays for treatment was also apparent. There also remain other important challenges, including the need to ensure that research is actually conducted and is fit for purpose, as well as ensuring that the process is undertaken in a legal, ethical and acceptable manner. 51 Another important consideration is that these schemes need to be designed in order to develop appropriate incentives to produce evidence in a timely fashion and strategies need to be put into place to ensure that the research is actually carried out.

Within the UK, the importance of interagency collaboration has been highlighted as a key issue in ensuring the success of OIR/AWR schemes. In particular, the Cooksey report9 recommended that arrangements between the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme and NICE should be formalised so that recommendations for the use of interventions in the context of clinical studies can be operationalised.

Specific issues of ‘only in research’/‘approval with research’

As well as the more general issues that need to be resolved to ensure the effective use of OIR/AWR policy options, there are a number of specific issues that need to be addressed.

Evidence collection

Acquiring appropriate evidence following an OIR or AWR policy is of paramount importance. 25 Without an appropriately designed and conducted study, it is likely that little will be achieved in terms of reducing the uncertainty that led to the use of such policies in the first instance. OIR and AWR policies allow evidence to be generated specifically to inform decisions, a role not intended for traditional regulatory trials. 5 This raises a number of issues and potential challenges related to the design and funding of further research studies. First, there is currently very little in the way of formalised arrangements following an OIR/AWR recommendation in many countries. 18,28 One exception to this are CFFEs conducted in Ontario, which have a specific funding stream (albeit modest) covering the evaluation by PATH and additional monies for the fieldwork itself. However, in many instances this budget is not sufficient to cover the full costs of a CFFE and therefore other avenues must be explored, such as cost-sharing. 17,20

A key issue identified in determining the success of these schemes is the development of working partnerships between stakeholders (clinical community, decision-makers and manufacturers). 3 Related to this is the issue of obtaining funding for OIR/AWR studies and establishing who pays for the research. In relation to NICE, it has been recommended that the relevant study should be either planned or currently in progress, or alternatively that a new study could be established quickly. 11 Without secure funding the research may never be undertaken and thus the uncertainties leading to an OIR/AWR recommendation will remain.

The design of the OIR/AWR study will ultimately determine its success23 and some of the failures of existing schemes have been attributed to inappropriately designed studies. 57 Perhaps the most important consideration emerging from the literature is the issue of which type of study is most appropriate for an OIR/AWR scheme. 51 OIR/AWR research (unlike licensing research) is not confined to RCTs and, depending on the source of uncertainties, other types of evidence may be sufficient. 29 The choice of study is ultimately context specific and related to the source of uncertainty; however, it may also be influenced by factors such as cost and availability of suitable patients, collaborating clinical centres and potential ethical considerations. Good routine data capture mechanisms have a potentially crucial role to play in the feasibility of any scheme18 and the development of health informatics could greatly reduce the cost of evidence. 18,55 Whichever study type is chosen, Tunis and Whicher30 argue that discussion regarding the study design should not take place when the decision is made over who should pay for the study as this imposes restrictions. 30 Clarification is also needed on how the evidence collected as a result of a OIR/AWR policy will be used in an updated coverage decision31 and also how many data are enough to inform subsequent decisions. 29

Important lessons can be learnt from previous studies commissioned as part of an OIR or AWR policy. The multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme has been heavily criticised by many. 26 Despite its intention to reduce uncertainty23 associated with the use of the disease-modifying drug therapies beta-interferon and glatiramer acetate in the UK NHS, the exclusion of a control group from the study has meant that it is difficult to determine effectiveness. Similarly, the Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Registry failed to provide the CMS with data required to answer questions regarding patient survival. 56 Another widely cited example, a trial of lung volume reduction surgery (NETT),5,22,27,28,32,33,57,58 is looked on favourably by some32,57 but has also been criticised for taking too long5 and for not addressing the uncertainties relevant for decision-making. A number of implications for future studies were also noted, in particular the importance of interagency collaboration, achieving consensus on acceptable quality of evidence, external peer review, predefined clinical benefit, determining who pays for treatment and establishing longer-term follow-up. 27

Investment and reversal costs

Investment and reversal costs have also been identified as relevant considerations in the existing literature. In particular, NICE needs to determine whether a fully supportive decision (as opposed to OIR) would lead to significant irretrievable costs of implementation and if it would lead to termination of ongoing research or prevent future research. 11 Gafni and Birch14 also highlight the need to consider what an intervention that has been subjected to a CED scheme is displacing before any assessment of potential cost savings through such schemes can be made.

There is also an ongoing challenge of disinvesting in technologies that have previously been approved. 18 Withdrawing coverage is logistically and politically difficult and it is considered more difficult to reverse a ‘yes’ than a ‘no’. 24 Although no clear consensus has emerged on how these costs could be factored into the decision-making process, it has been suggested that these could be based on formal options analysis. 29

Changing prices

Although discounting list prices can be thought of as an example of a risk-sharing agreement,23 depending on how the OIR/AWR system operates, it may also lead the manufacturer to reconsider the pricing of the technology. Allowing prices to change as part of an OIR/AWR scheme also further extends the options available to decision-makers. Evidence generated as part of an OIR/AWR clinical study may also lead to a change in price if NICE believes that there is significant new evidence that will affect a drug’s value. Something similar was observed with the multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme. Depending on the results observed, potential adjustments to the price of the drugs will be made at intervals to achieve an agreed cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) of no more than £36,000. 23 The wider coverage associated with the multiple sclerosis risk-sharing scheme meant that it was necessary to have an upfront agreement on price changes following provision of evidence. It is not clear, however, to what extent changing prices will reduce uncertainty regarding the coverage decision.

Ethical issues

The potential ethical issues arising from the use of OIR/AWR schemes is another important theme emerging from the existing literature. For OIR, the issue of compulsory participation is often raised as a concern. Also, because of practical arrangements under OIR, treatments may not be available in all areas, causing geographical inequalities. 34 If a RCT is commissioned following an OIR recommendation, this raises a greater issue in terms of participation than a simple registry. These access issues in relation to an OIR policy linked to a clinical trial can be somewhat remedied by a large-scale geographically diverse trial with broad inclusion criteria. 22

In addition, it has been argued that denying access to a treatment demonstrated to be effective (however uncertain) is unethical. Patient advocacy groups may also be unwilling to accept this policy especially if the treatment is considered to be safe and efficacious. 24 These issues have important implications for both the design and the successful conduct of research and hence are considered in more detail in later sections.

Summary

The critical review identified a number of important themes and principles in relation to the use of OIR/AWR schemes. However, much of the existing literature is relatively discursive and there is a need to provide a set of principles and to establish an analytical framework to help guide and develop appropriate criteria for the use of OIR/AWR schemes by NICE.

Chapter 3 What assessments are needed?

Since an important objective of the NHS is to improve health outcomes across the population it serves, a technology can be regarded as valuable if its approval is expected to increase overall population health. The resources available to the NHS must be regarded as fixed (certainly by NICE) and so it is not sufficient to establish that a technology is more effective (the health benefits compensate for any potential harms) than the alternative interventions available, because approving a more costly technology will displace other health-care activities that would have otherwise generated improvements in health for other patients. 62 Therefore, even if a technology is expected to be more effective, the health gained must be compared with the health expected to be forgone elsewhere as a consequence of additional NHS costs, that is, a cost-effective technology will offer positive net health effects (NHEs). 63–65 A social objective of health improvement and an ethical principle that all health impacts are of equal significance, whether they accrue to those who might benefit from the technology or other NHS patients, is an established starting point for the NICE appraisal process (see Social value judgements and ethical principles). 1

An assessment of expected cost-effectiveness or NHEs relies on evidence about effectiveness, impact on long-term overall health and potential harms, as well as the costs that fall on the NHS budget together with some assessment of what health is likely to be forgone as a consequence (the cost-effectiveness threshold). 66 Such assessments are inevitably uncertain and, without sufficient and good-quality evidence, subsequent decisions about the use of technologies will also be uncertain and there will be a chance that the resources committed by the approval of a new technology may be wasted if the expected positive NHEs are not realised. Equally, rejecting a new technology will risk failing to provide access to a valuable intervention if the NHEs prove to be greater than expected. Therefore, if the social objective is to improve overall health for both current and future patients then the need for and value of additional evidence is an important consideration when making decisions about the use of technologies. 67–69

This is even more critical once it is recognised that the approval of a technology for widespread use might reduce the prospects of conducting the type of research that would provide the evidence needed. 70 In these circumstances there will be a trade-off between the NHEs for current patients from early access to a cost-effective technology and the health benefits for future patients from withholding approval until valuable research has been conducted. A key ethical question arising from this trade-off is whether or not the health impacts for future patients should be considered and regarded as of similar significance to impacts on current patients (see Social value judgements and ethical principles). 24

Because publically funded research also consumes valuable resources that could have been devoted to patient care, or other more valuable research priorities, there are a number of trade-offs that must be made. In making these trade-offs consideration also needs to be given to uncertain events in the near or distant future, which may change the value of the technology and the need for evidence. 71 In addition, implementing a decision to approve a new technology is, in general, not a costless activity and may commit resources that cannot subsequently be recovered if the guidance changes in the future. 6,7,72 For example, there may be costs associated with implementing guidance or training health-care professionals, or other investment costs associated with equipment and facilities. 73,74 The irrecoverable nature of these costs can have particular influence on a decision to approve a technology if new research is likely to report or other events may occur in the future (e.g. the launch of new technologies or changes in the price of existing technologies).

The primary purpose of this chapter is to provide a non-technical exposition of the conceptual framework, developed more formally in Appendix 6, which identifies the key principles and assessments that are needed when considering both approval and research decisions. The first section outlines the key principles and the different types of assessment needed and how each sequence might lead to different categories of guidance. The next section, Changes in prices and evidence, examines how guidance might change if there are changes in the effective price of the technology or evidence. The following section, Social value judgements and ethical principles, highlights the social values and ethical principles associated with OIR and AWR. a Importantly, within this chapter we do not presuppose how the assessments ought to be made because there are a range of different types of additional information, evidence and methods of analysis that might be useful. These alternatives are examined in Chapter 5 where they are more fully explored and evaluated through four case studies.

Key principles and assessments needed

The key principles and assessments fall into four broad areas:

-

expected cost-effectiveness and population NHEs (including benefits, harms and NHS costs)

-

the need for evidence and whether or not the type of research required can be conducted once a technology is approved for widespread use

-

whether or not there are sources of uncertainty that cannot be resolved by research but only over time

-

whether or not there are significant (opportunity) costs that will be committed and cannot be recovered once the technology is approved.

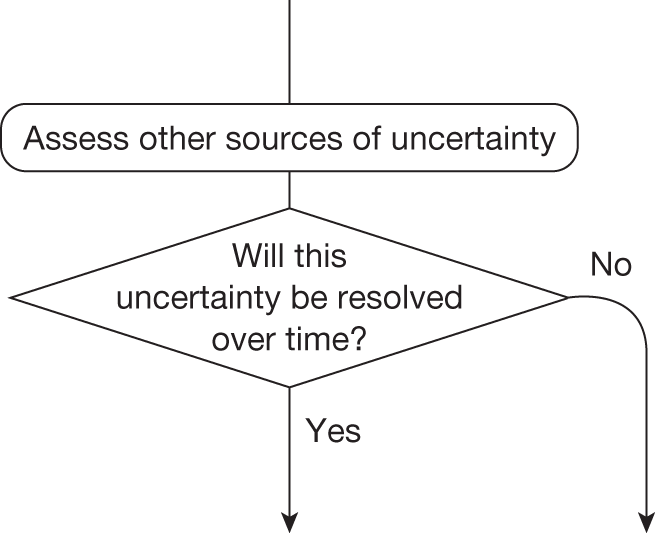

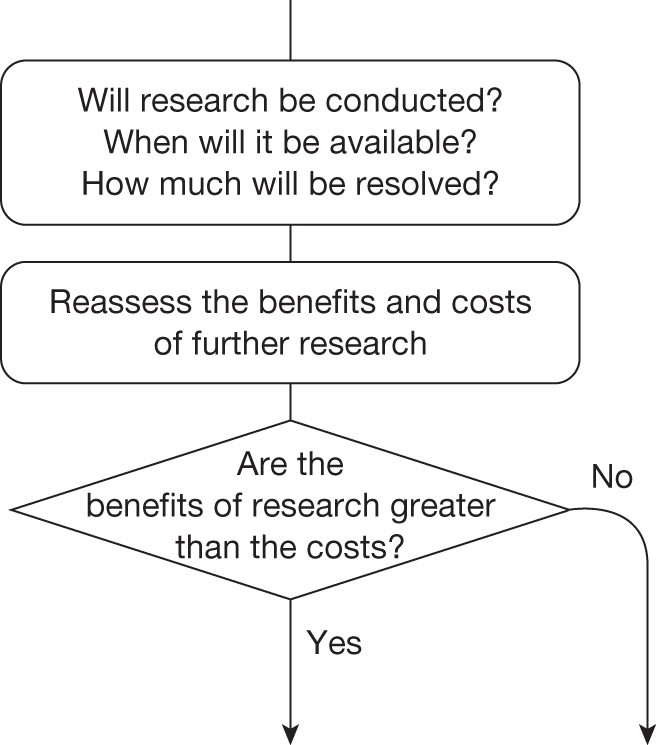

Guidance will depend on the combined effect of all of these assessments because they influence whether the benefits of research are likely to exceed the costs and whether any benefits of early approval are greater than withholding approval until additional research is conducted or other sources of uncertainty are resolved.

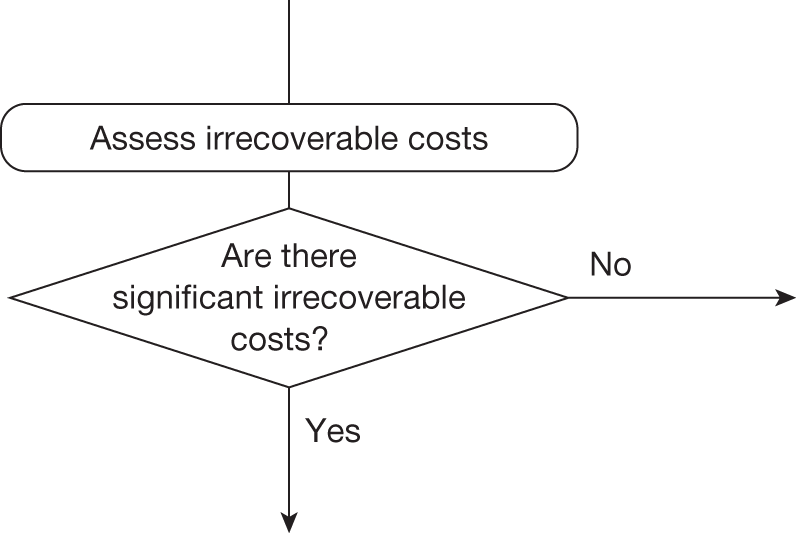

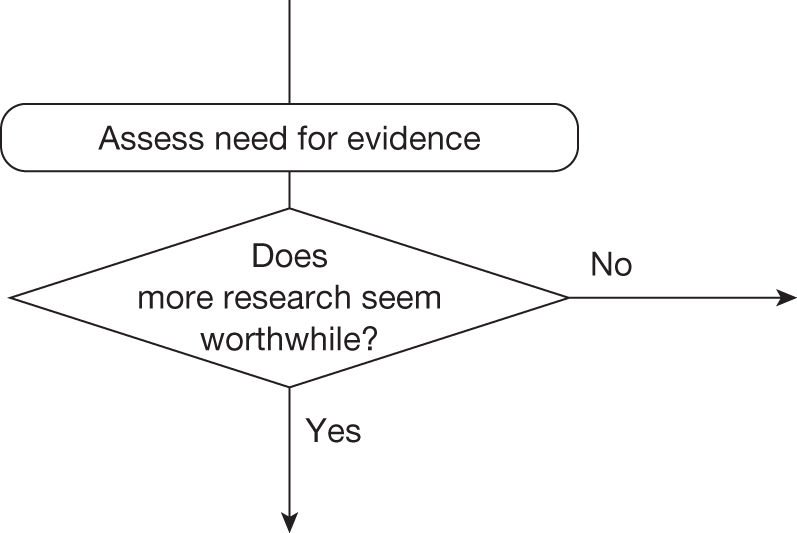

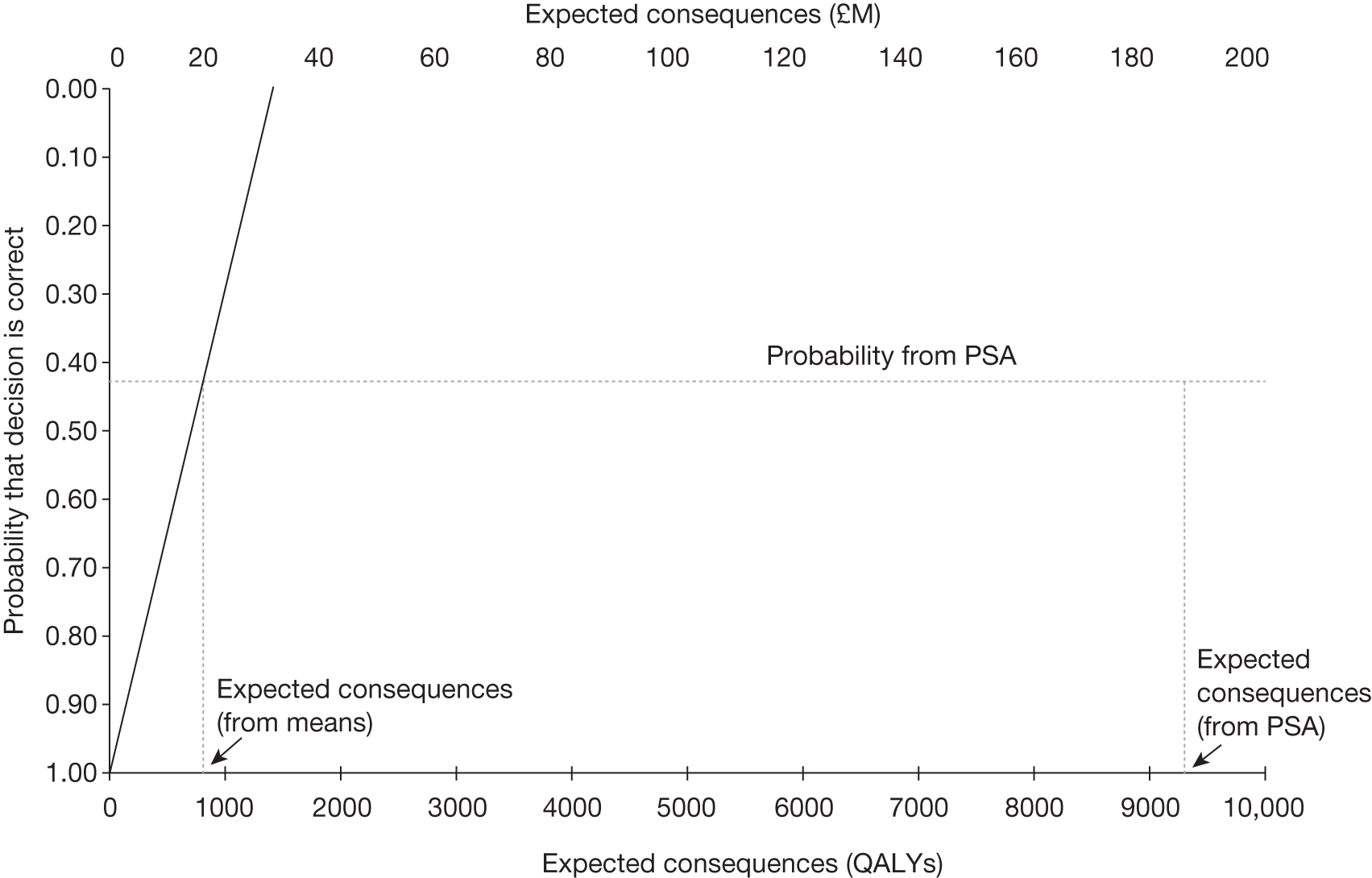

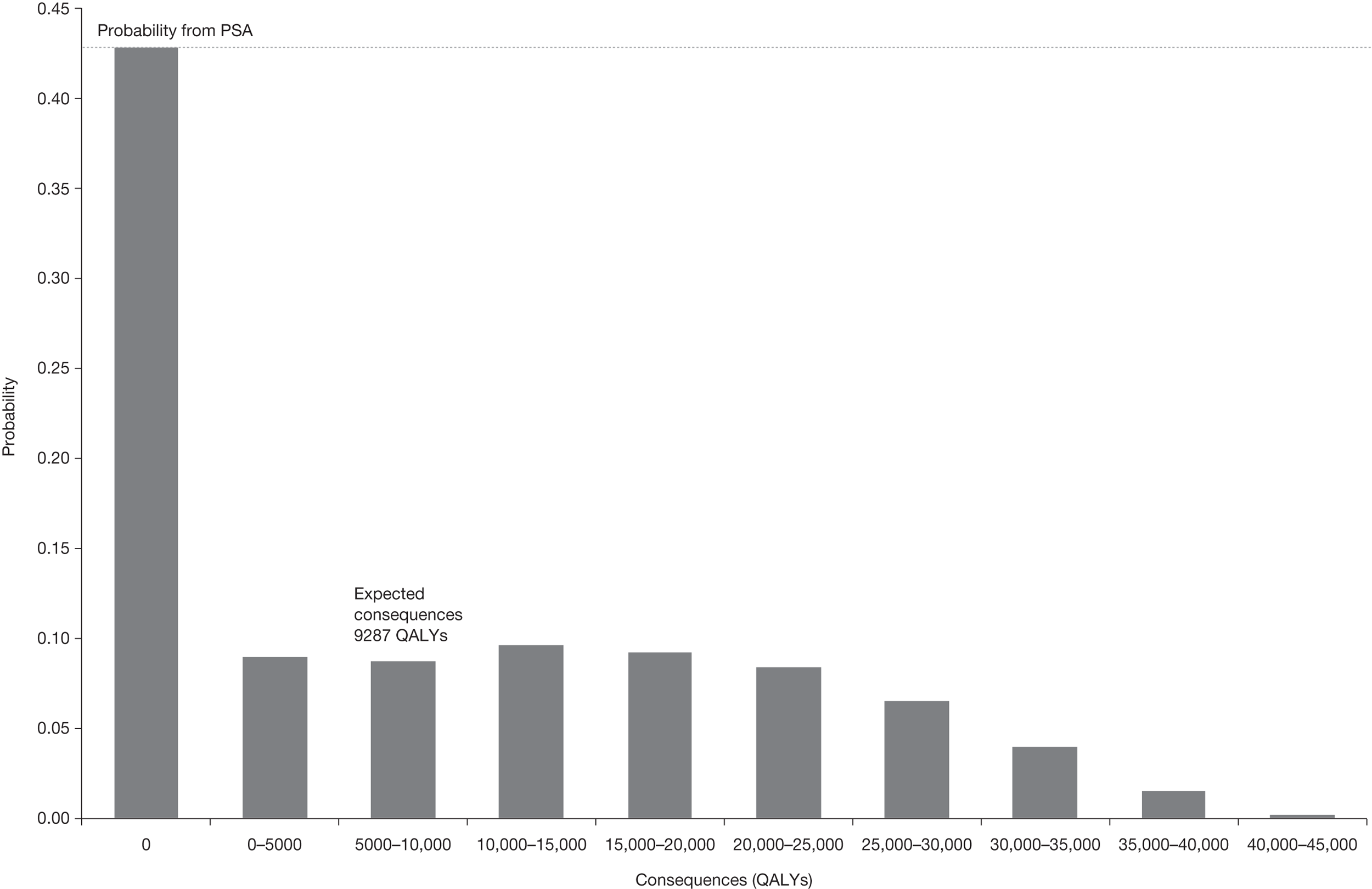

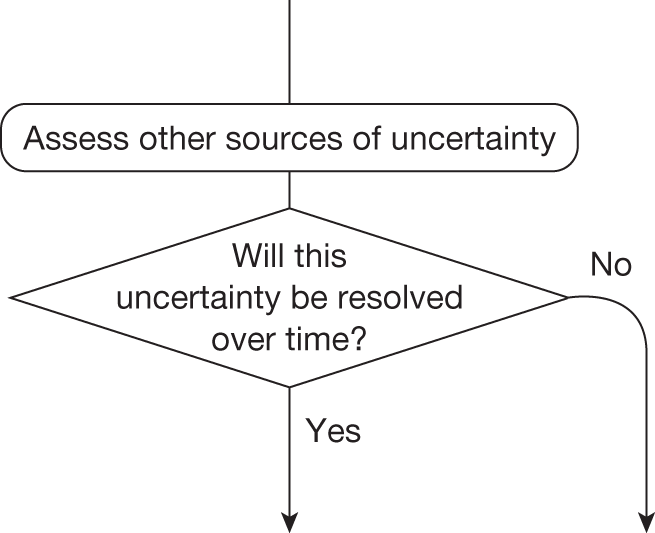

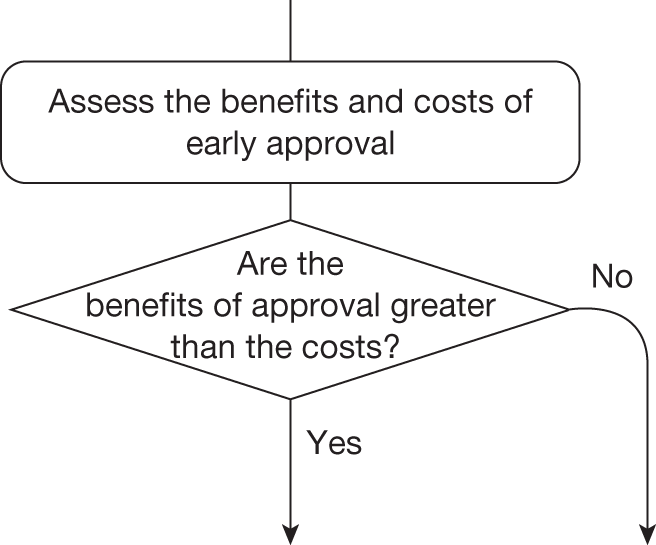

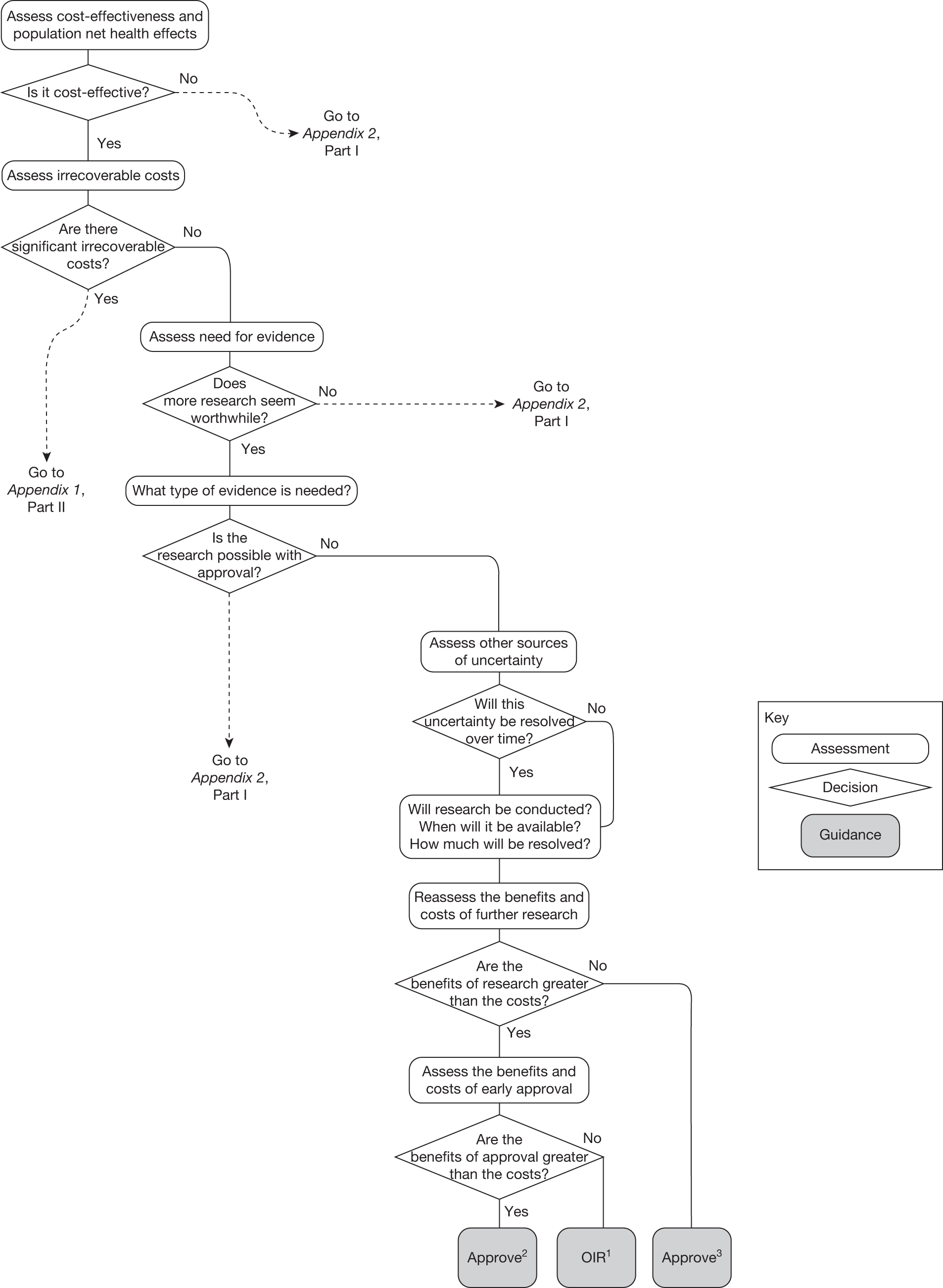

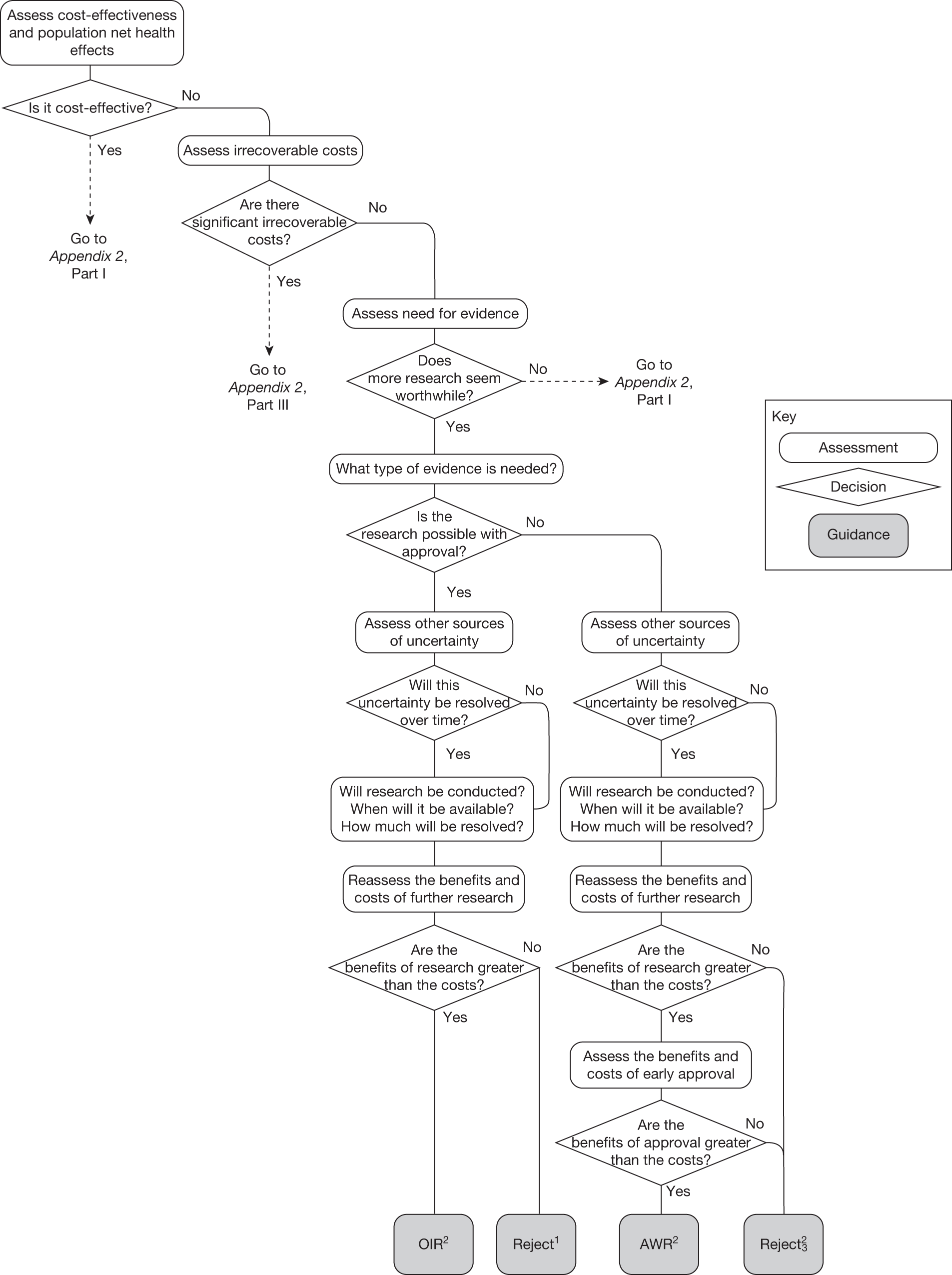

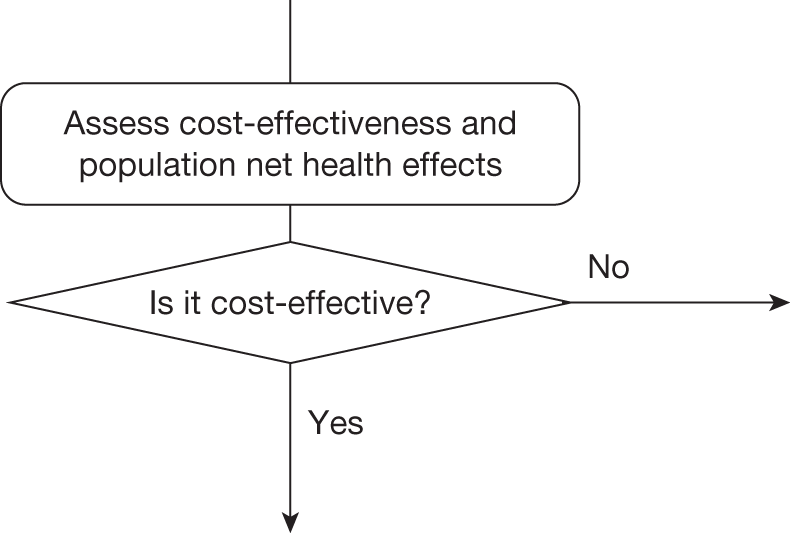

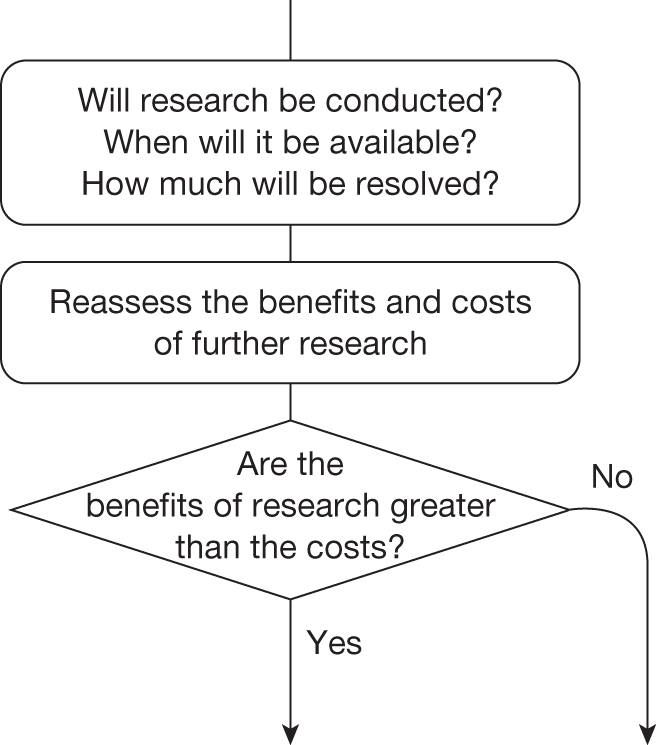

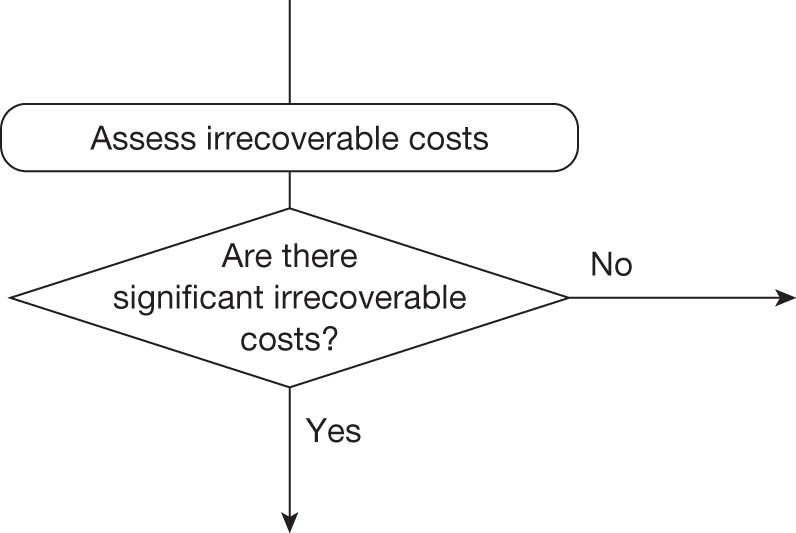

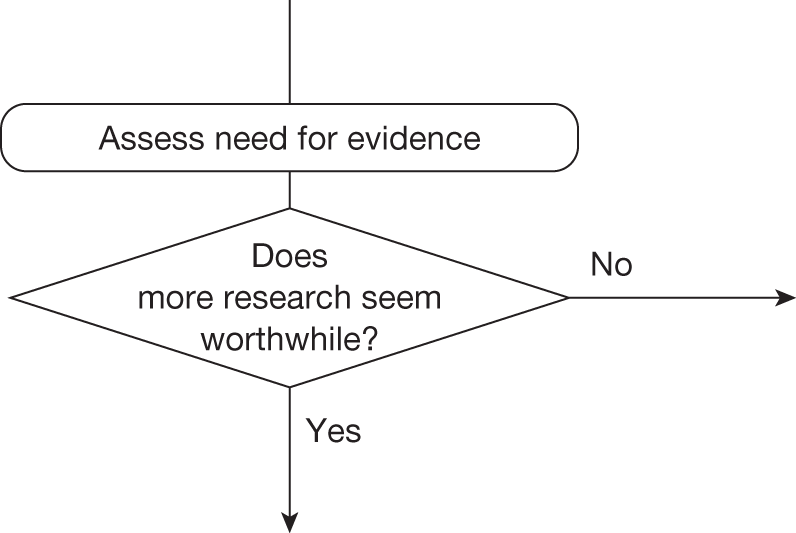

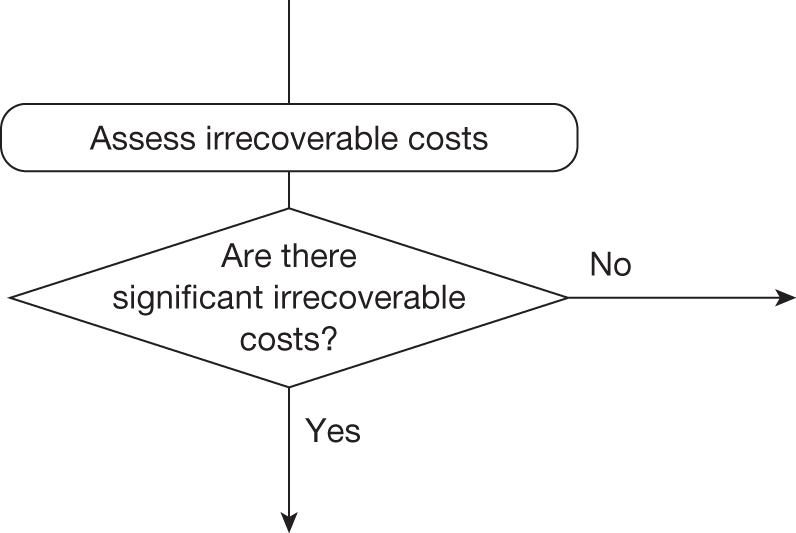

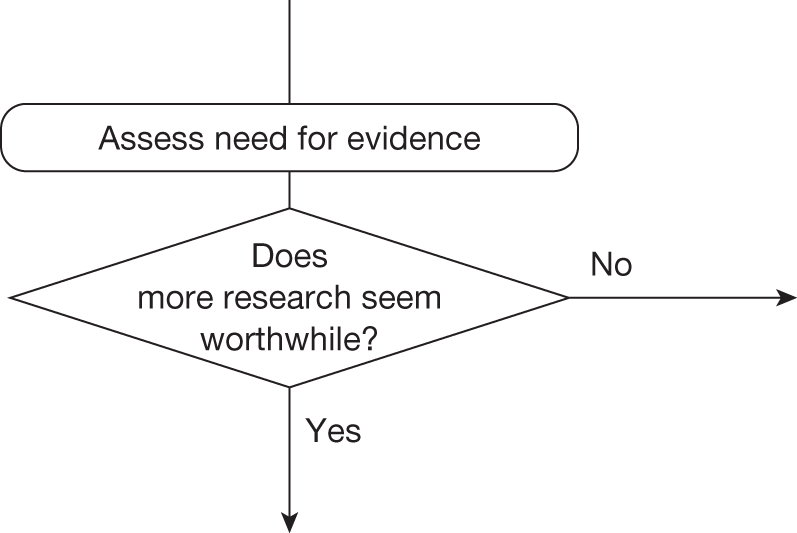

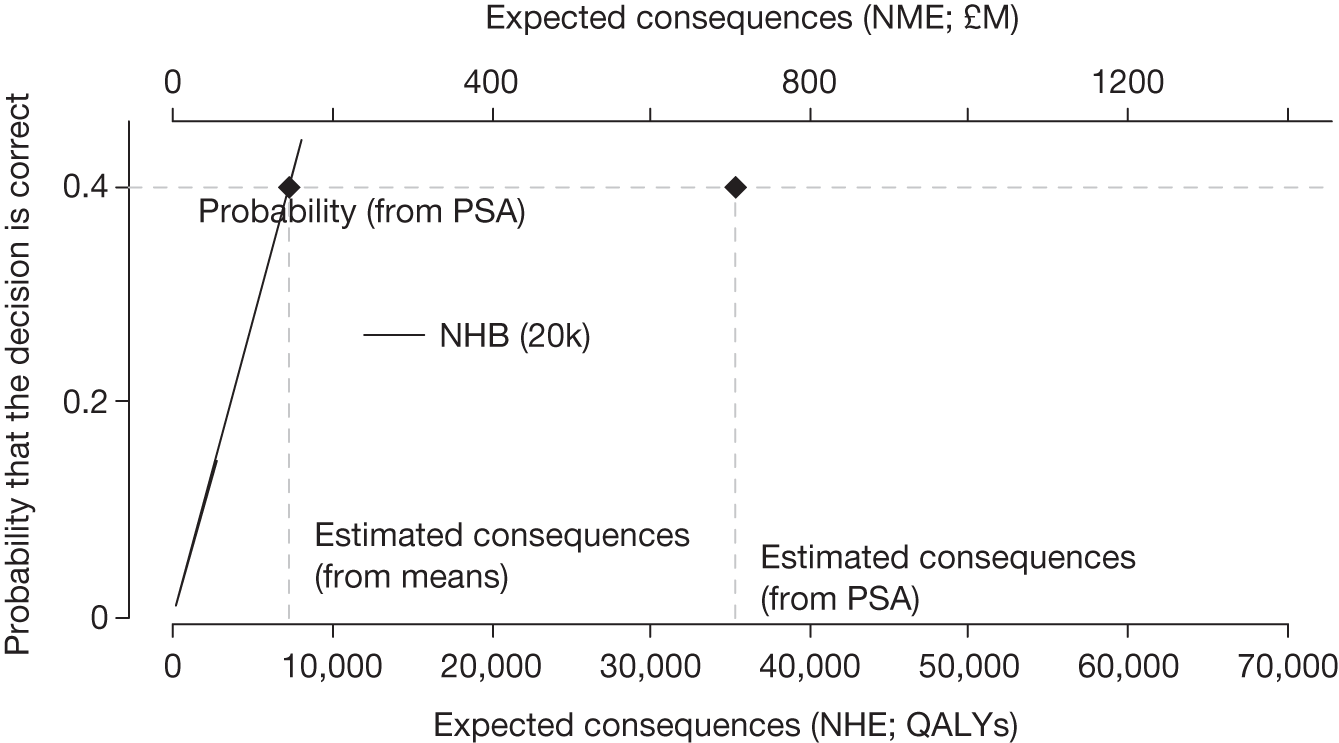

This can be complex because these different considerations interact. For example, the effect of irrecoverable costs will depend on the need for additional research and will also influence whether research is worthwhile. The sequence of assessments, decisions and resulting guidance can be represented by a flow chart or algorithm. Although such a representation is an inevitable simplification of the necessary trade-offs it helps to (1) identify how different guidance might be arrived at, (2) indicate the order in which assessments might be made, (3) identify how similar guidance might be arrived at through different combinations of considerations and (4) identify how guidance might change (e.g. following a reduction in price) and when it might be reviewed and decisions reconsidered. The complete algorithm is complex (reported in Appendix 2 for completeness), representing the sequences of assessments and associated decisions, each leading to a particular category and type of guidance. However, the key decision points in the algorithm, reflecting the main assessments and judgements required during appraisal, can be represented as a simple 7-point checklist (see Chapter 5, A checklist of assessment).

Four broad categories of guidance are represented within the algorithm and include ‘approve’, ‘AWR’, ‘OIR’ and ‘reject’. Each of the categories is further subdivided and numbered to indicate the different types of apparently similar guidance that could arise from different considerations. ‘Delay’ is not considered a particularly useful category because NICE always has the opportunity to revise its guidance, that is, a decision to reject can always be revised but it is only with hindsight that reject might appear to be delayed approval. The distinction made between assessment and decision reflects the NICE appraisal process: first, critically evaluate the information, evidence and analysis (an assessment), which can then assist the judgements (decisions) that are required in appraisal when formulating guidance.

Technologies without significant irrecoverable costs

Some element of cost that once committed by approval cannot be subsequently recovered is almost always present. However, the significance of these types of costs depends on their scale relative to expected population NHEs associated with the technology as well as the nature of subsequent events (see Technologies with significant irrecoverable costs and Chapter 5, Point 2: Are there significant irrecoverable costs?). 75 In this section we consider the relatively simple sequence of assessments and decisions which lead to guidance for those technologies that are not judged to have ‘significant’ irrecoverable costs associated with approval.

Technologies expected to be cost-effective

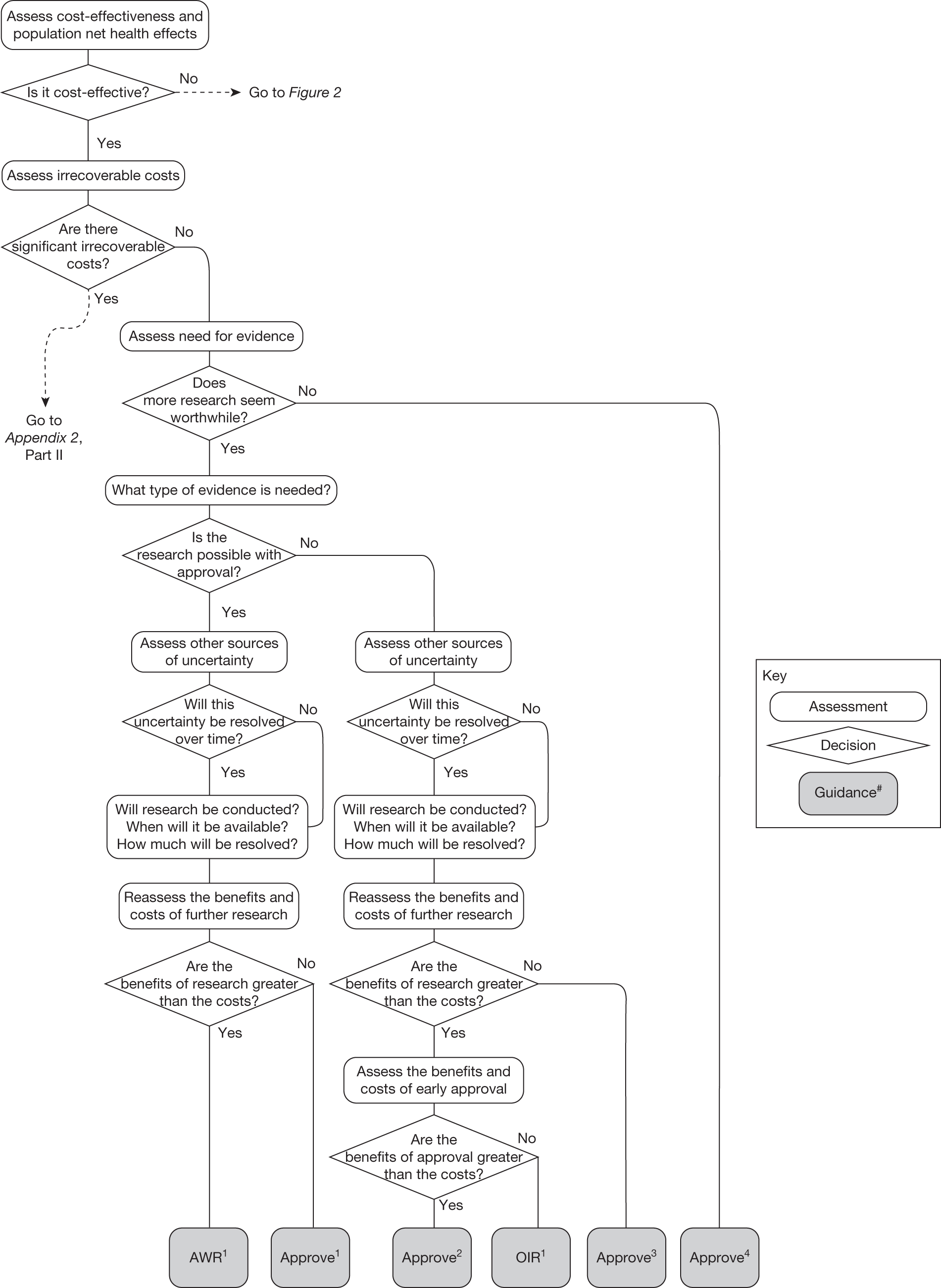

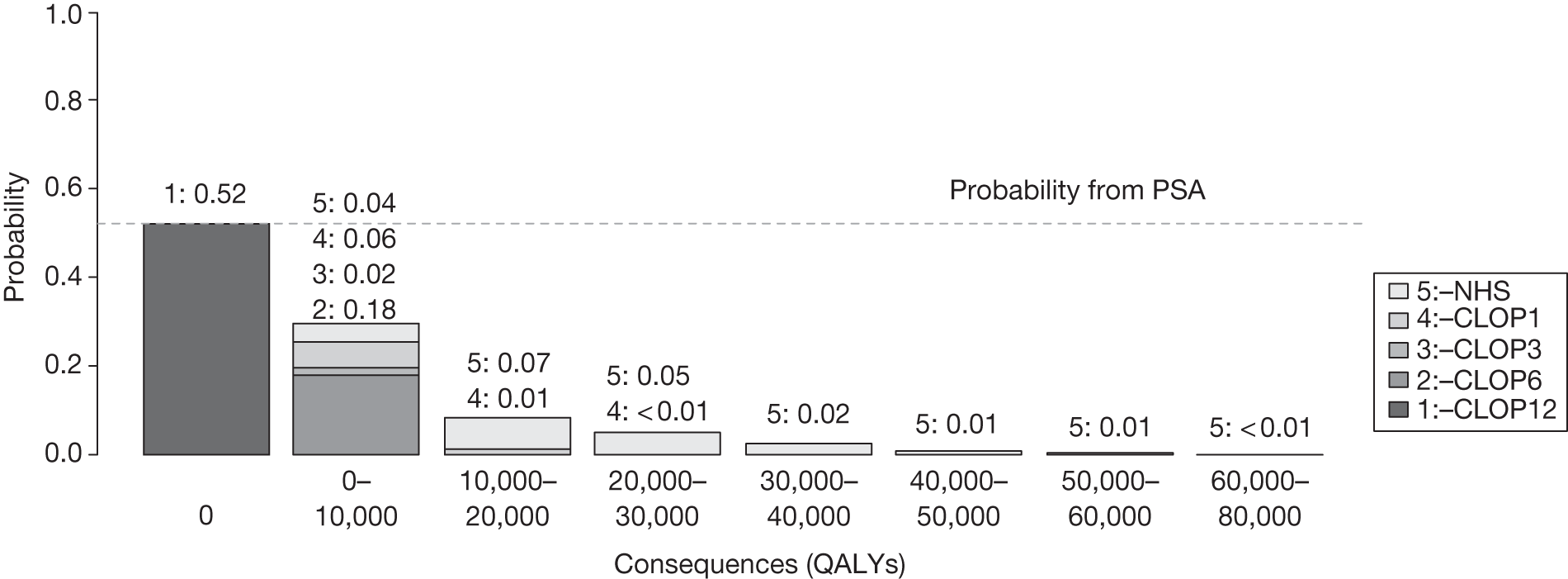

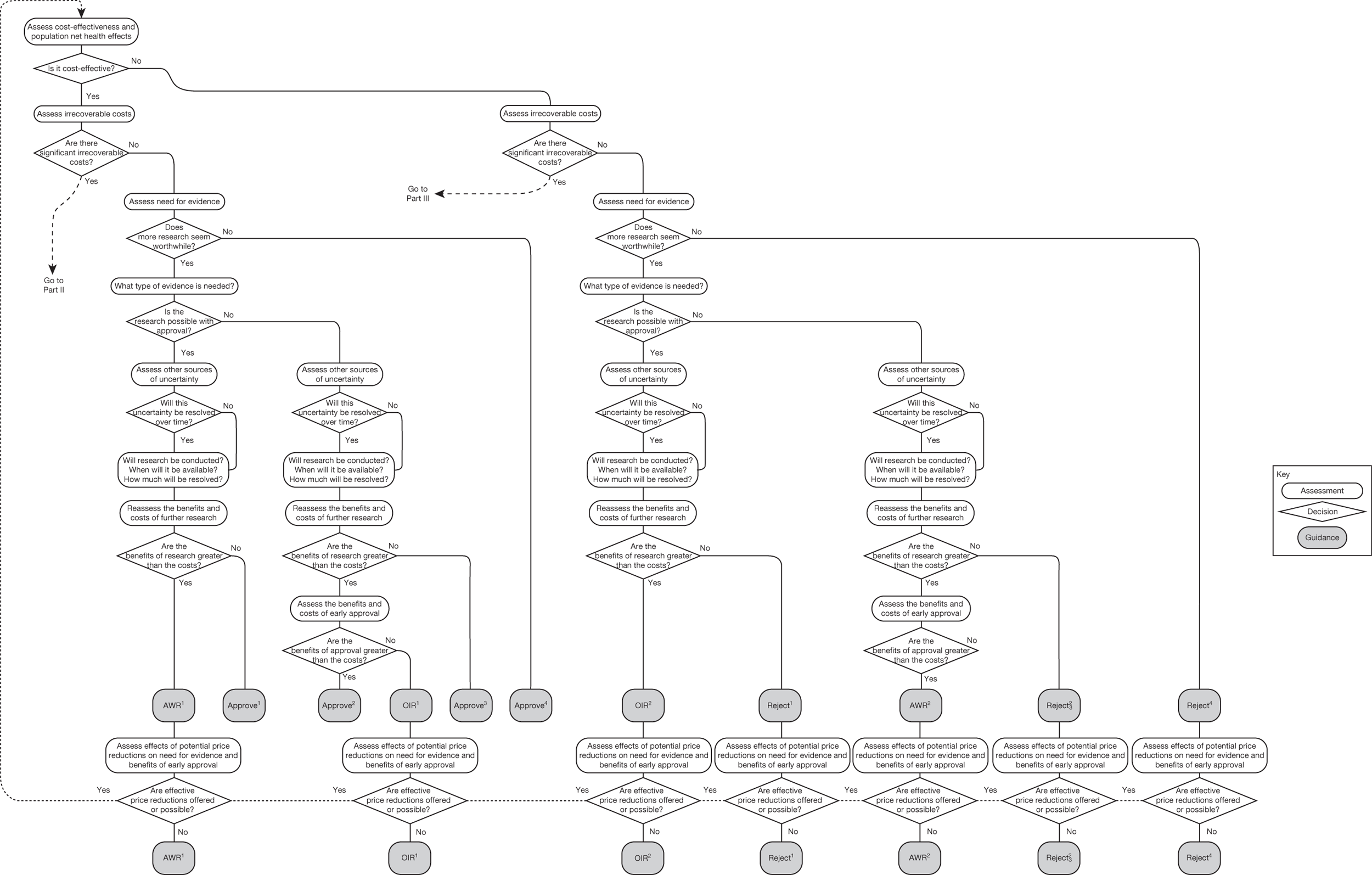

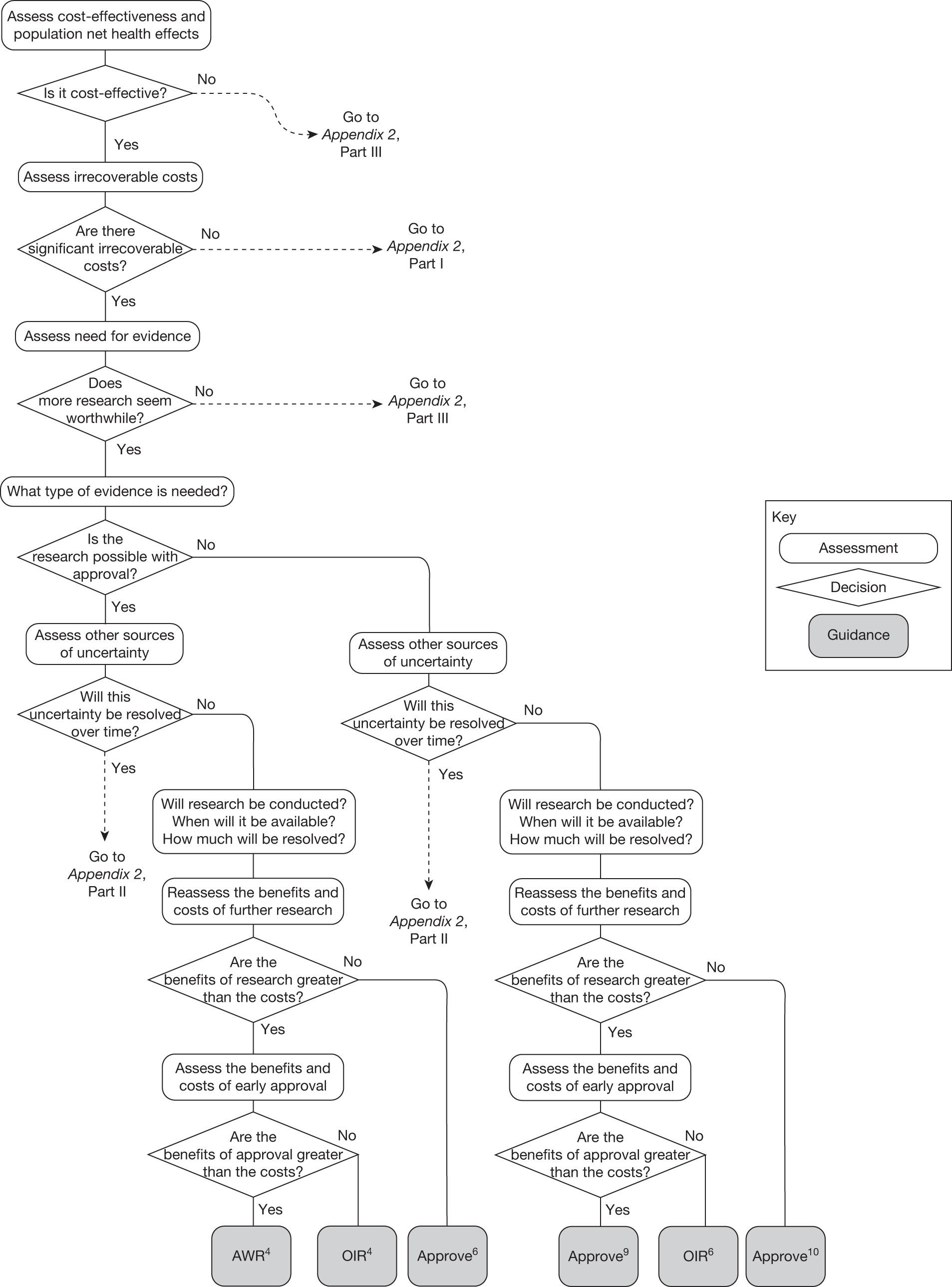

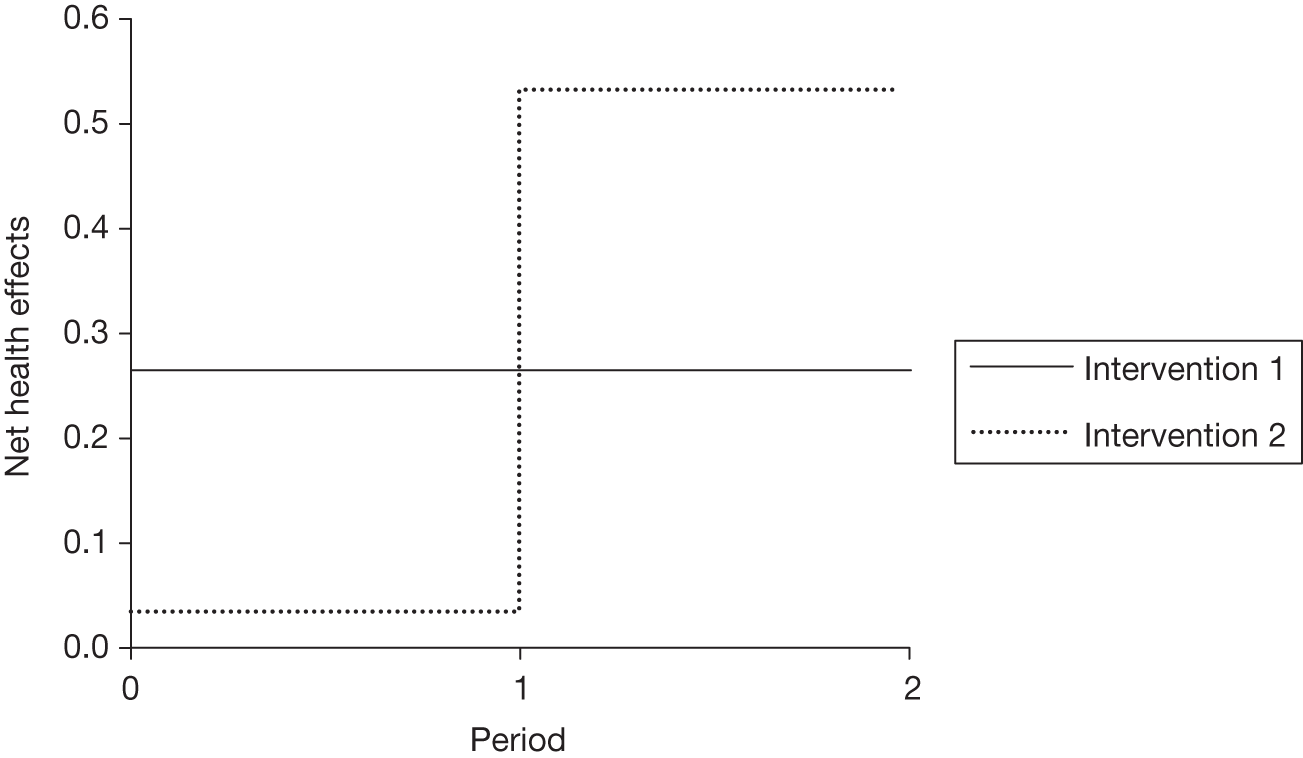

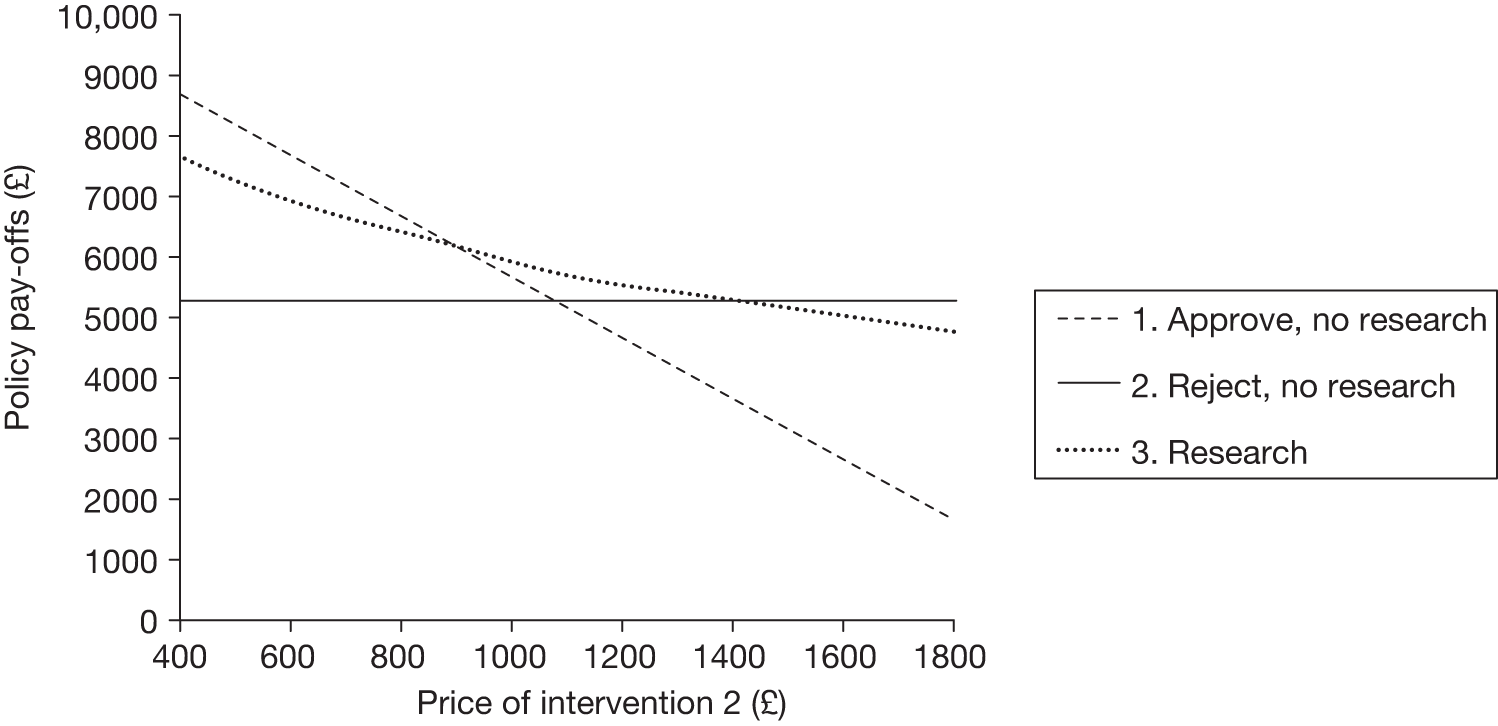

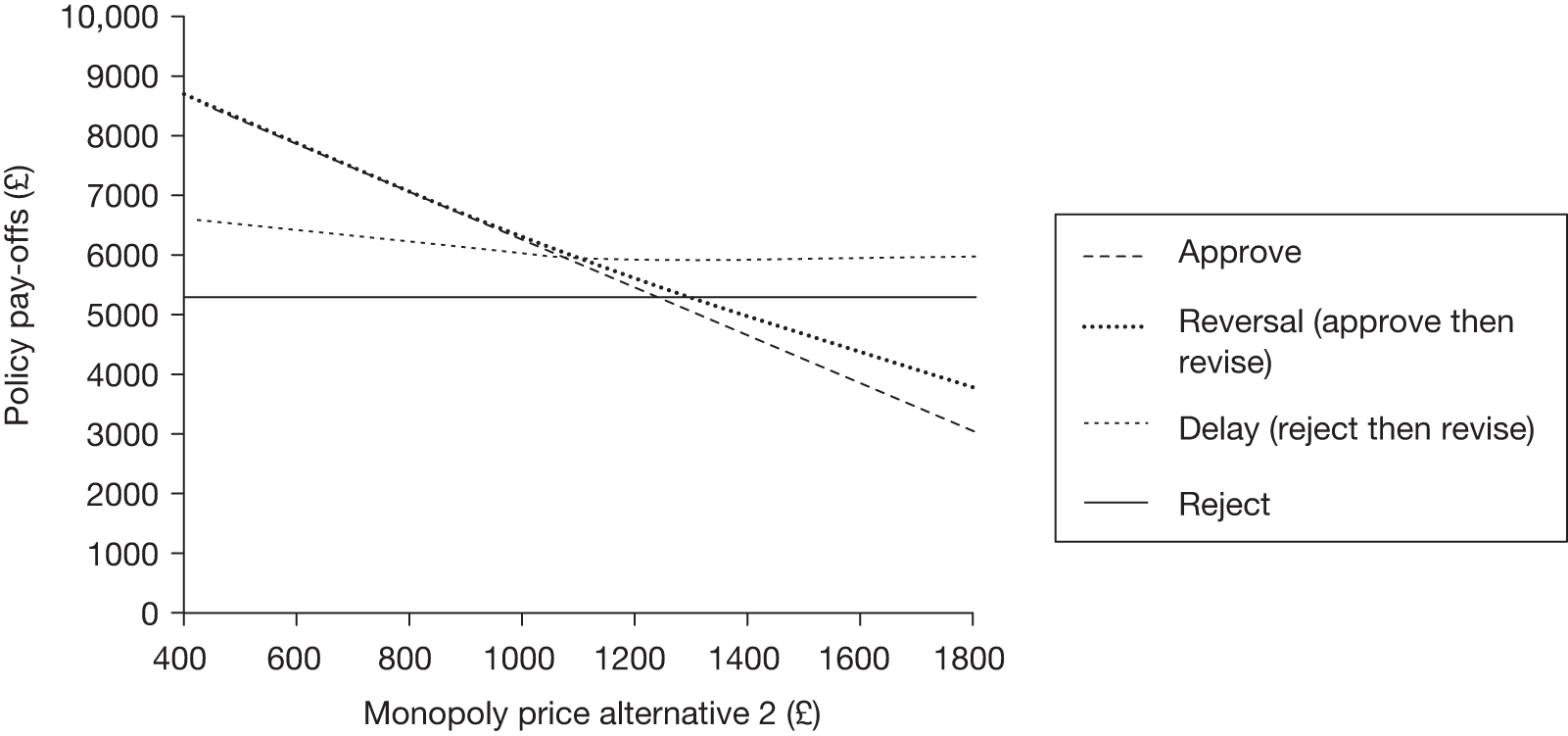

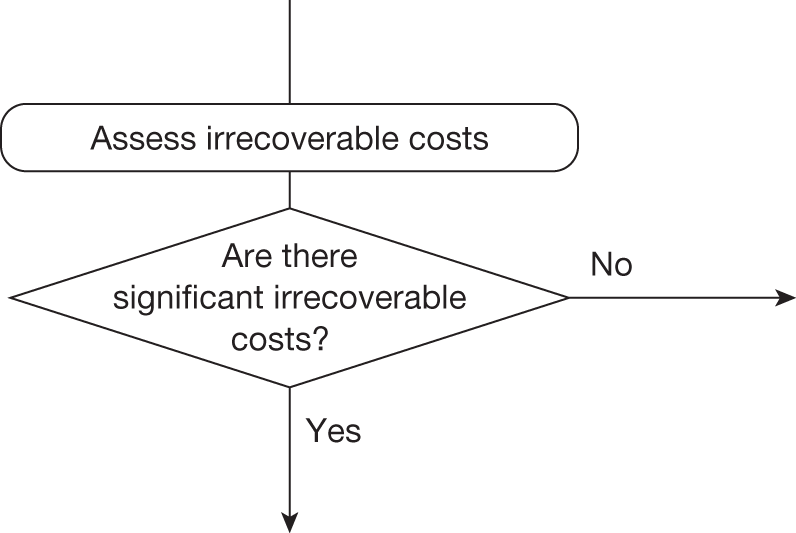

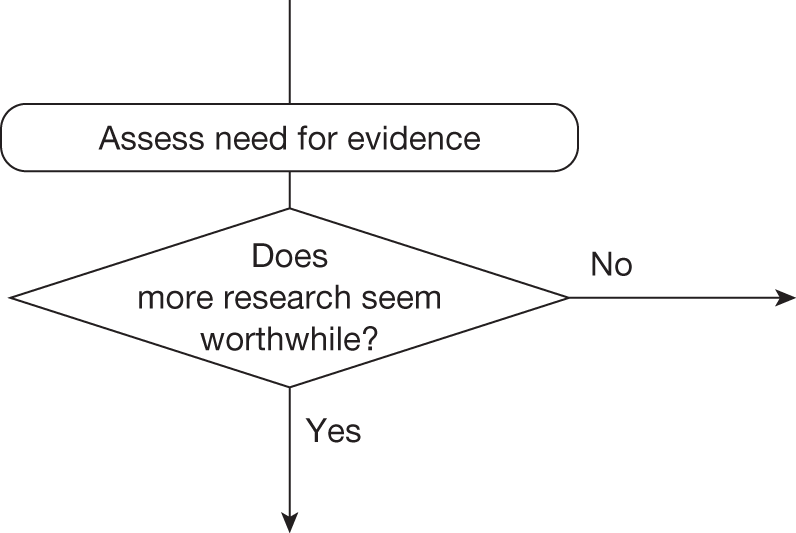

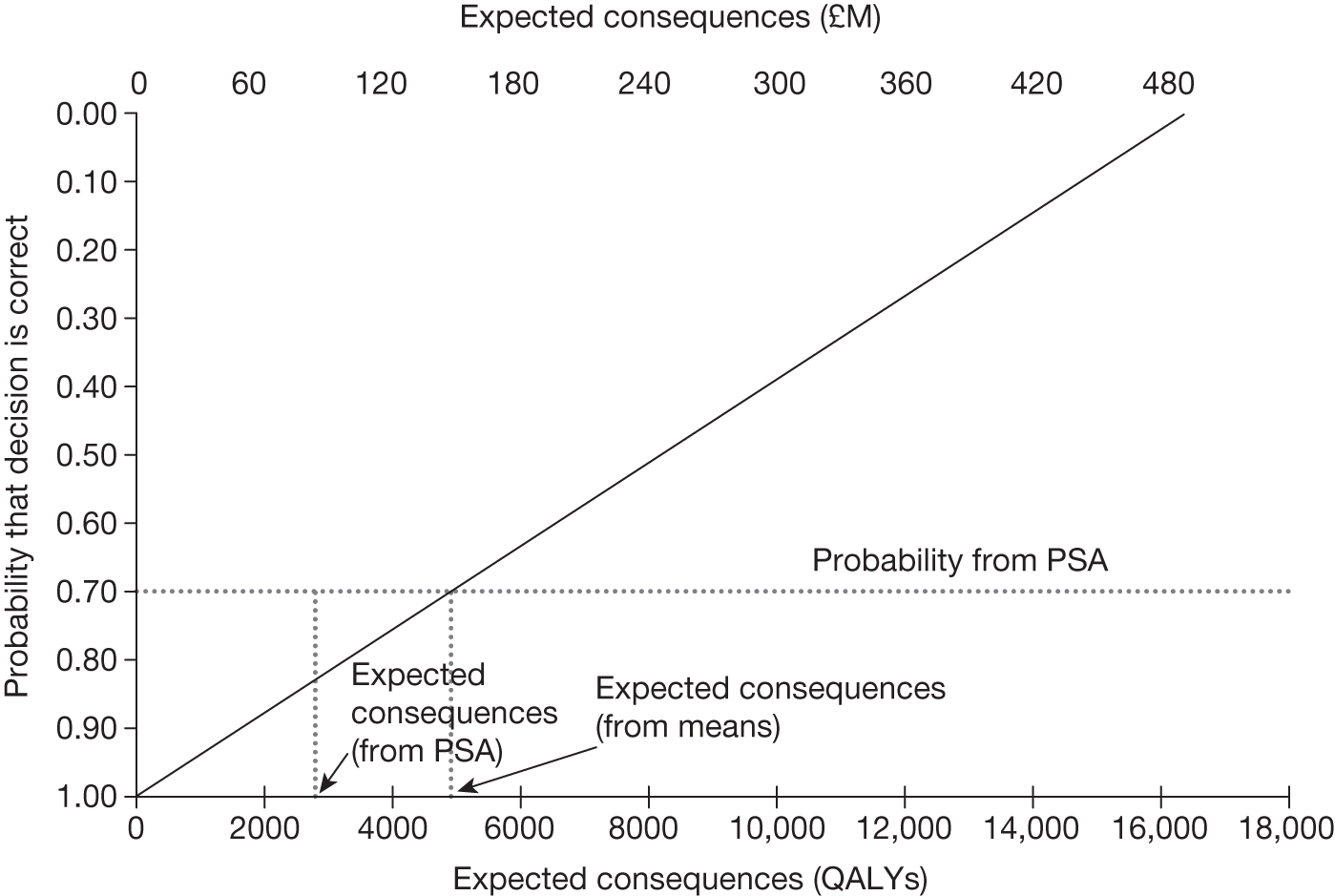

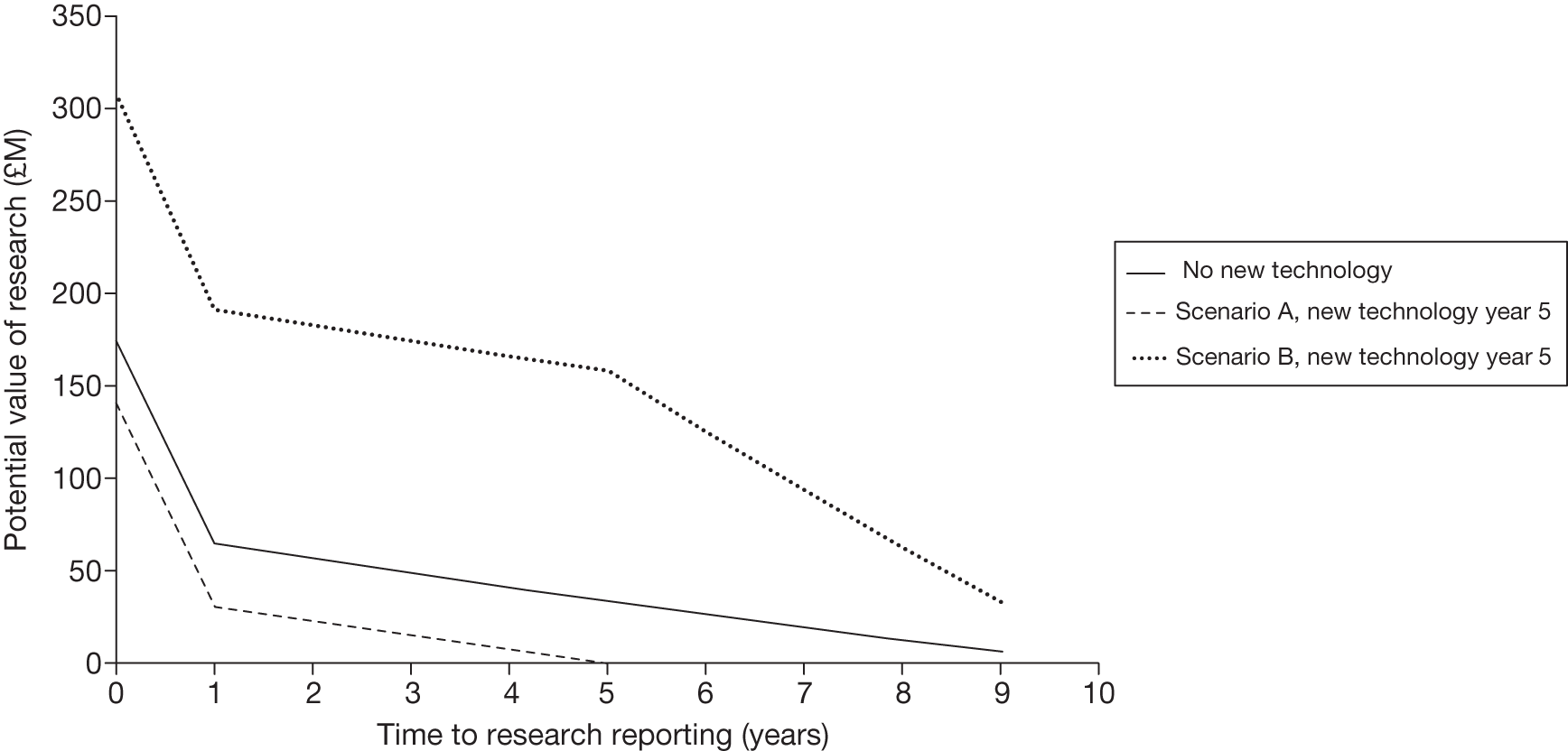

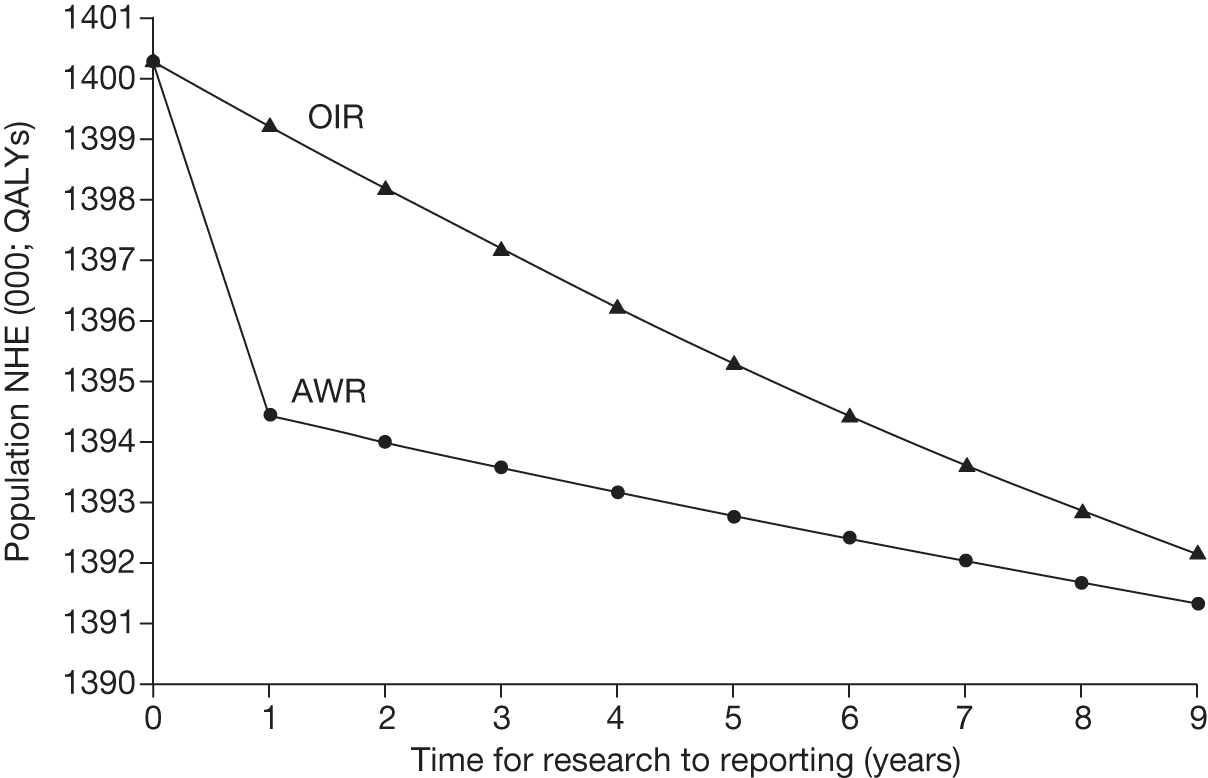

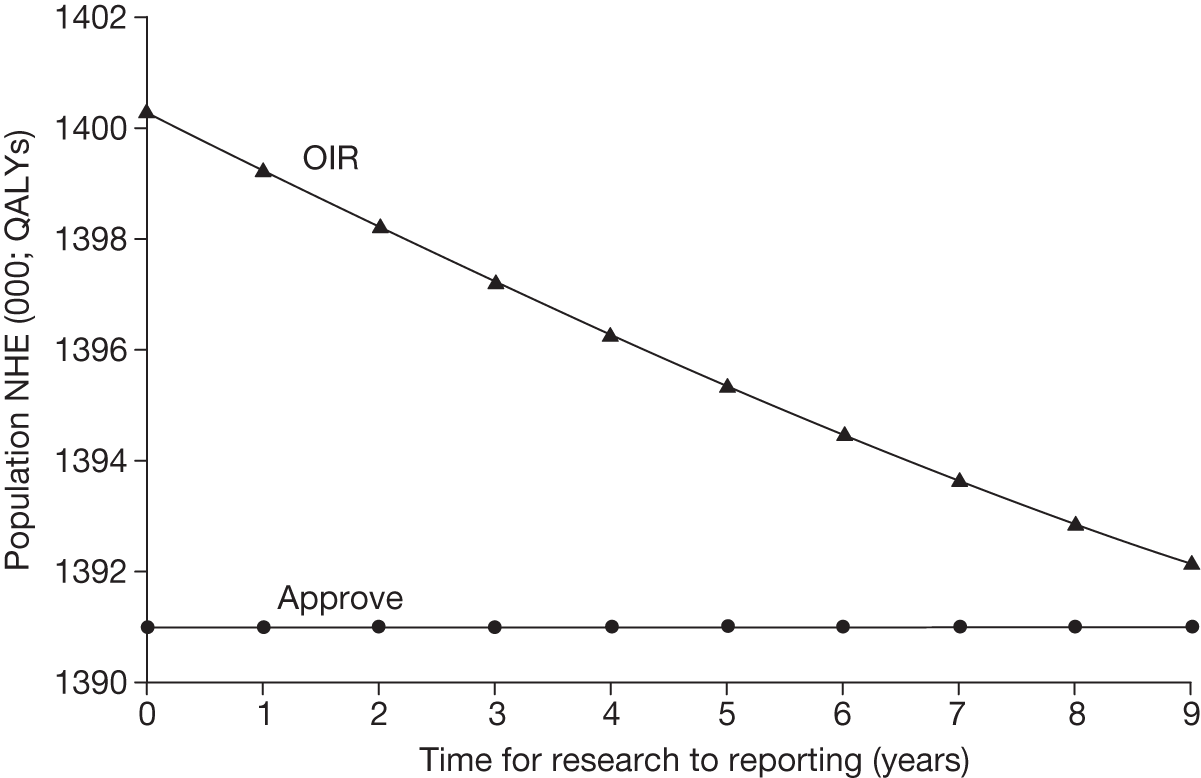

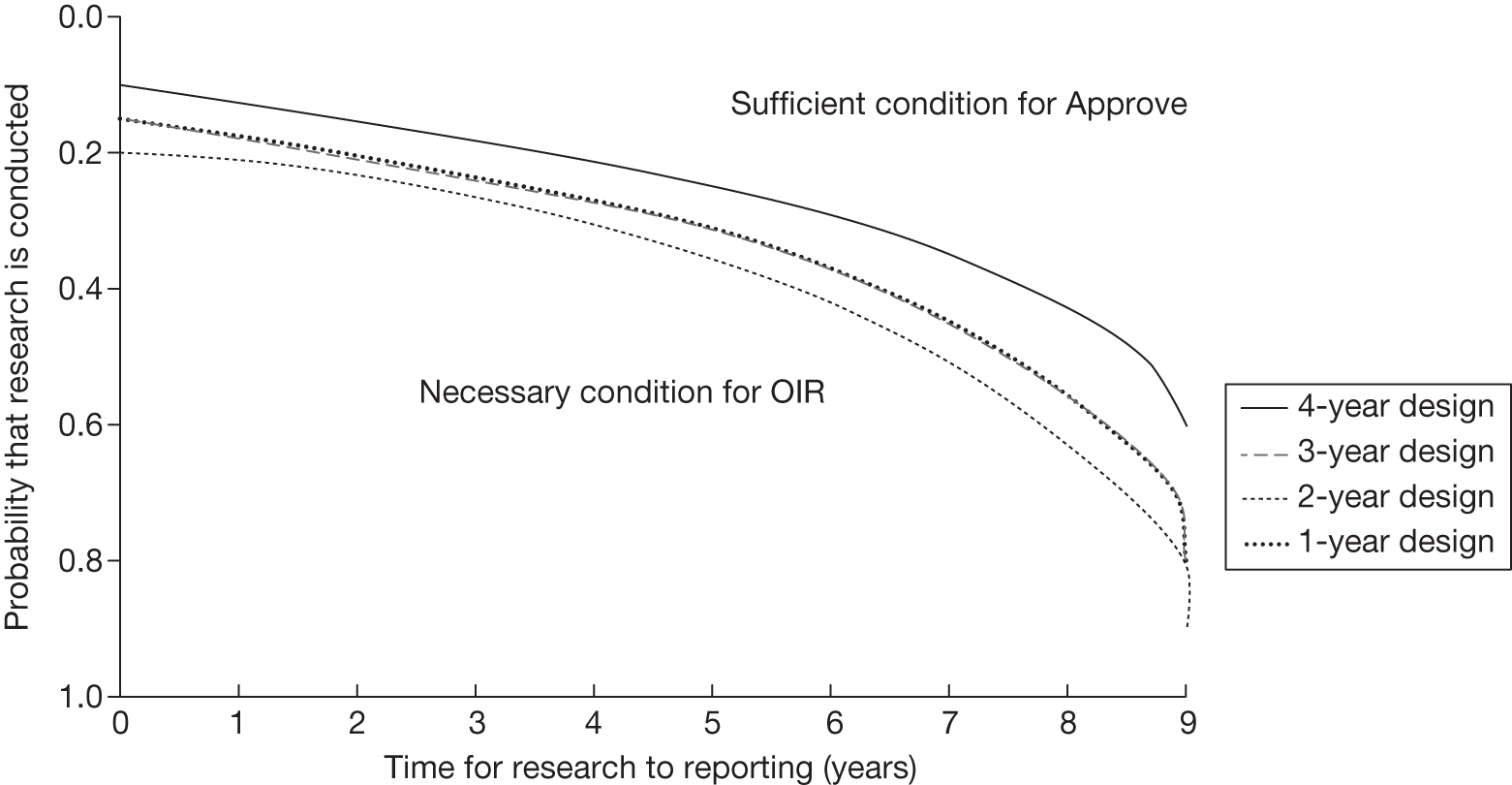

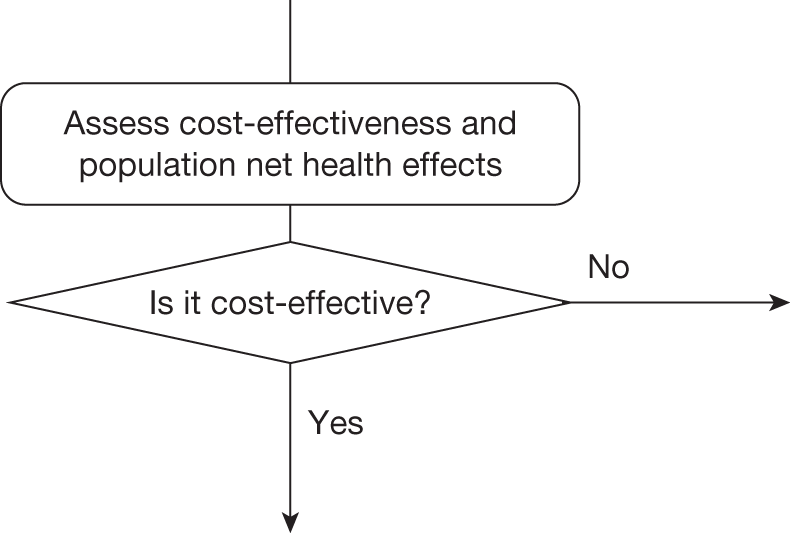

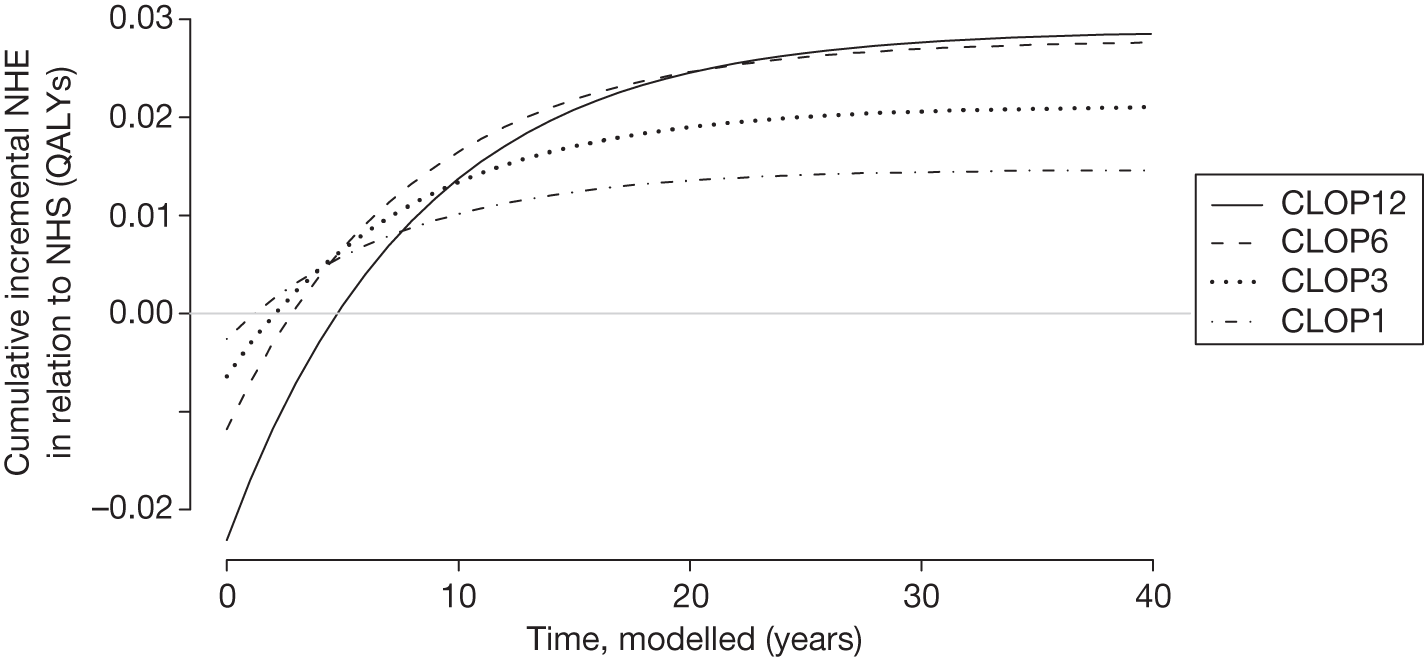

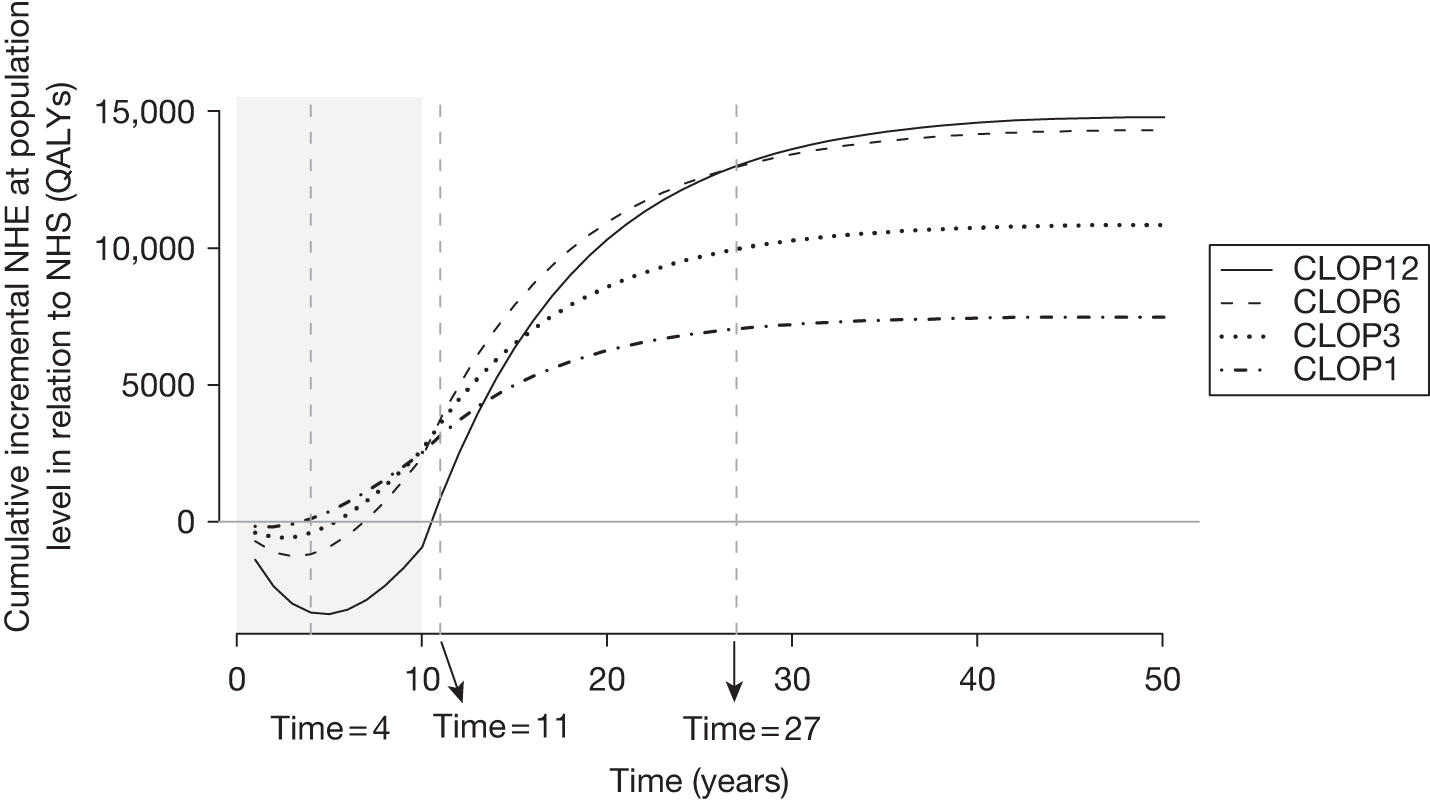

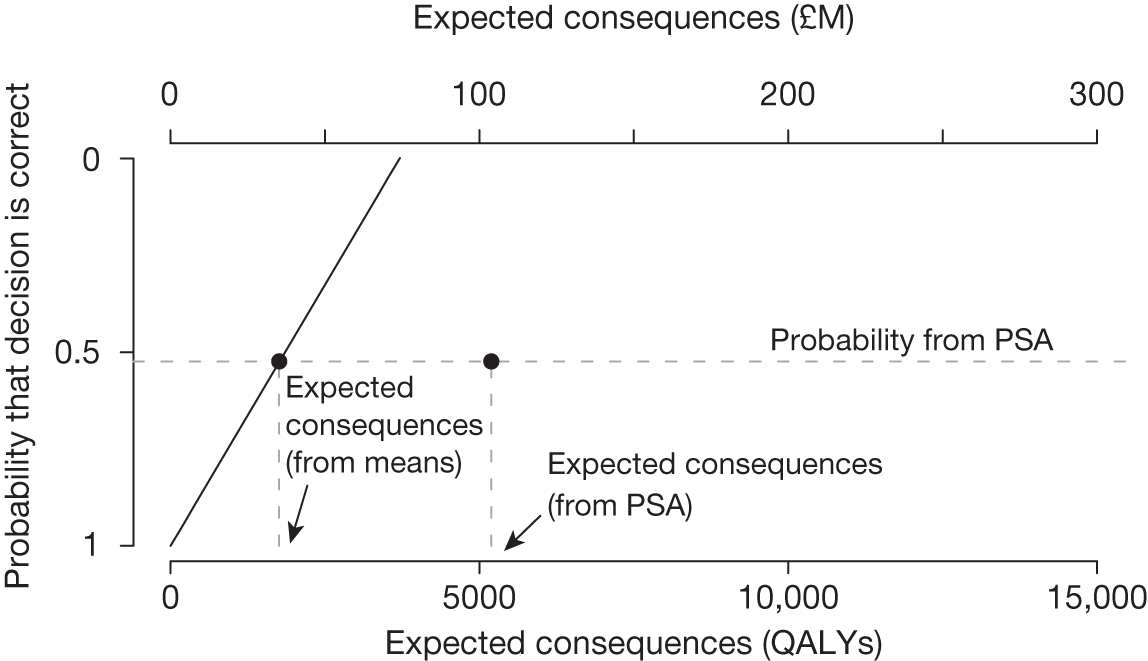

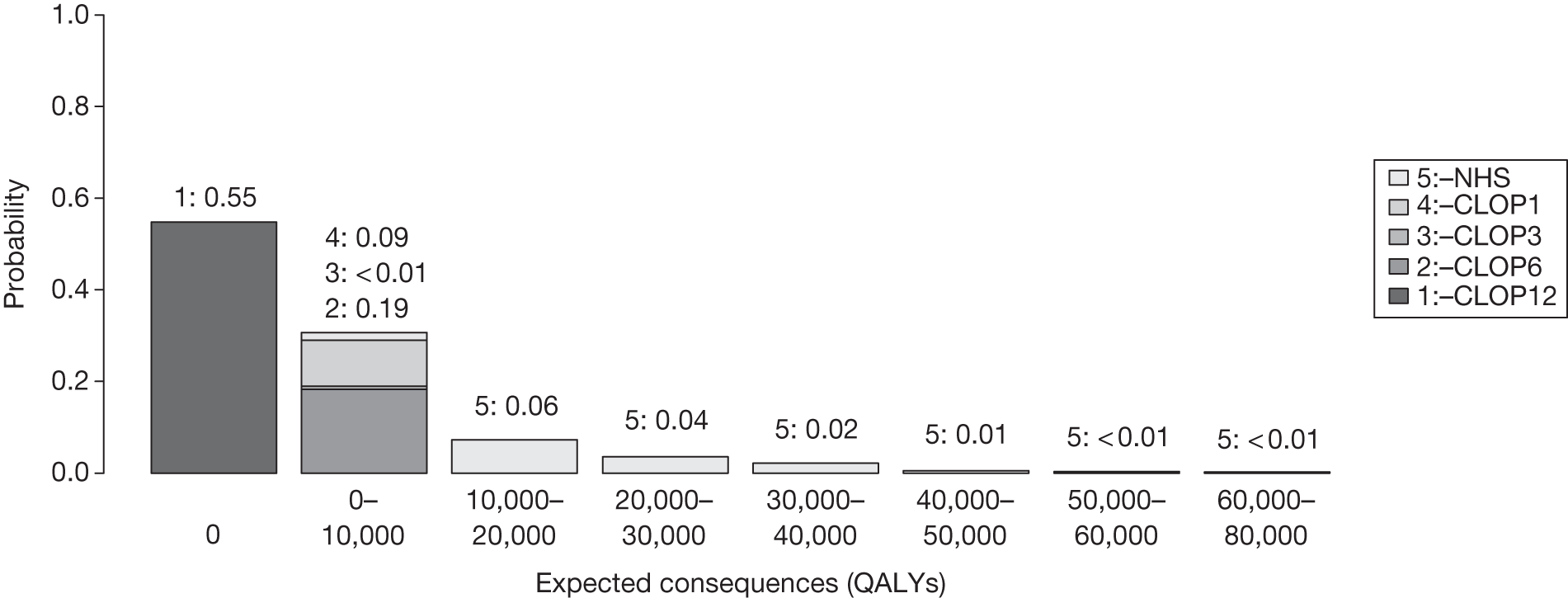

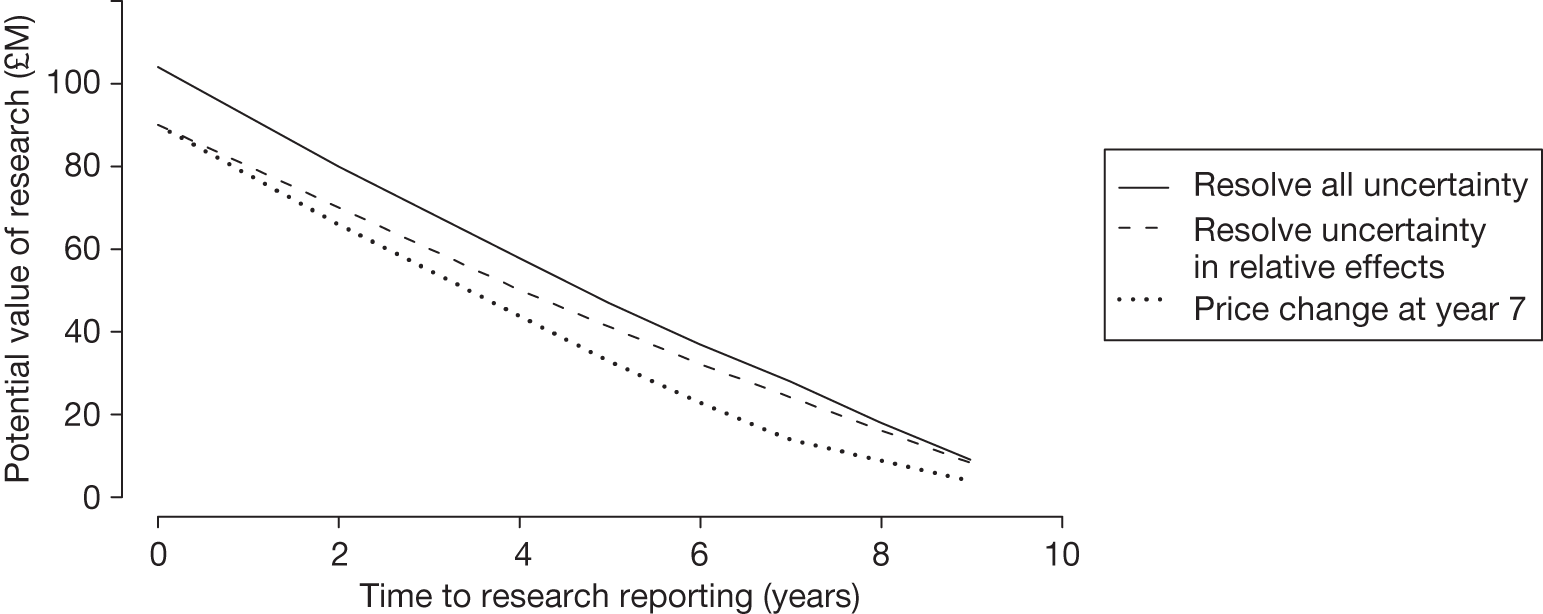

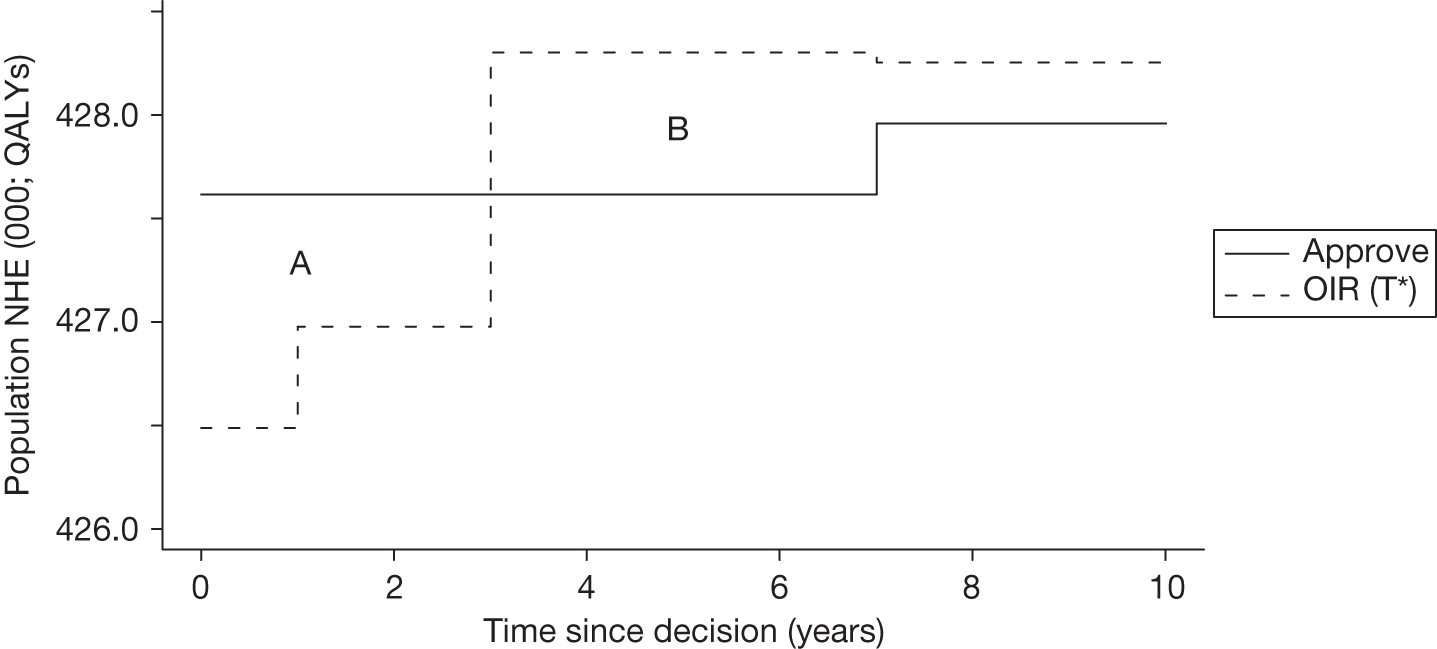

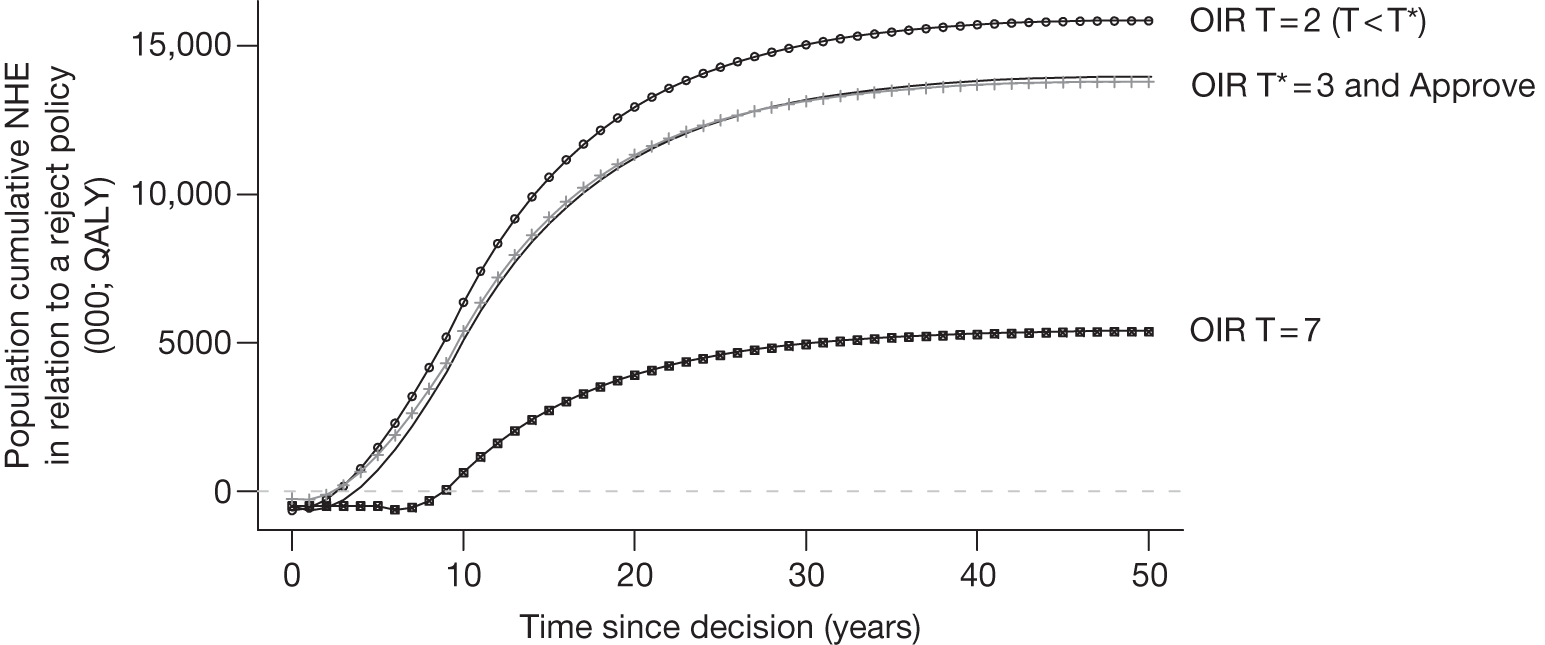

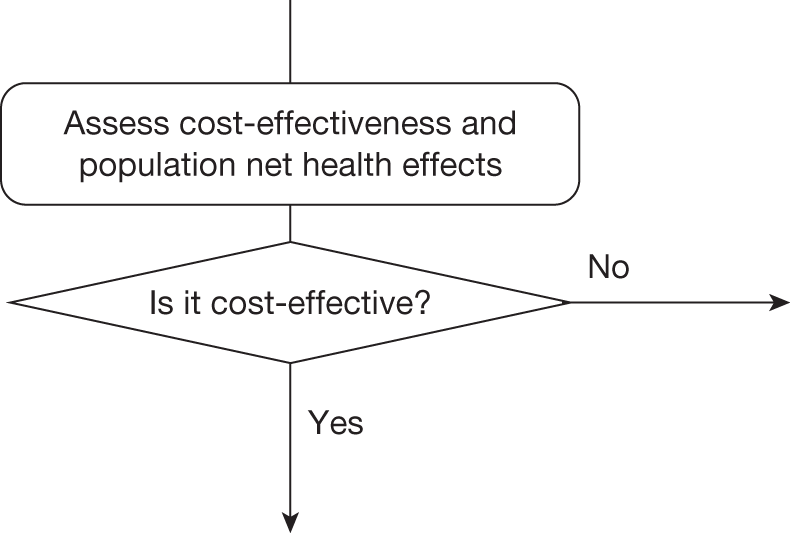

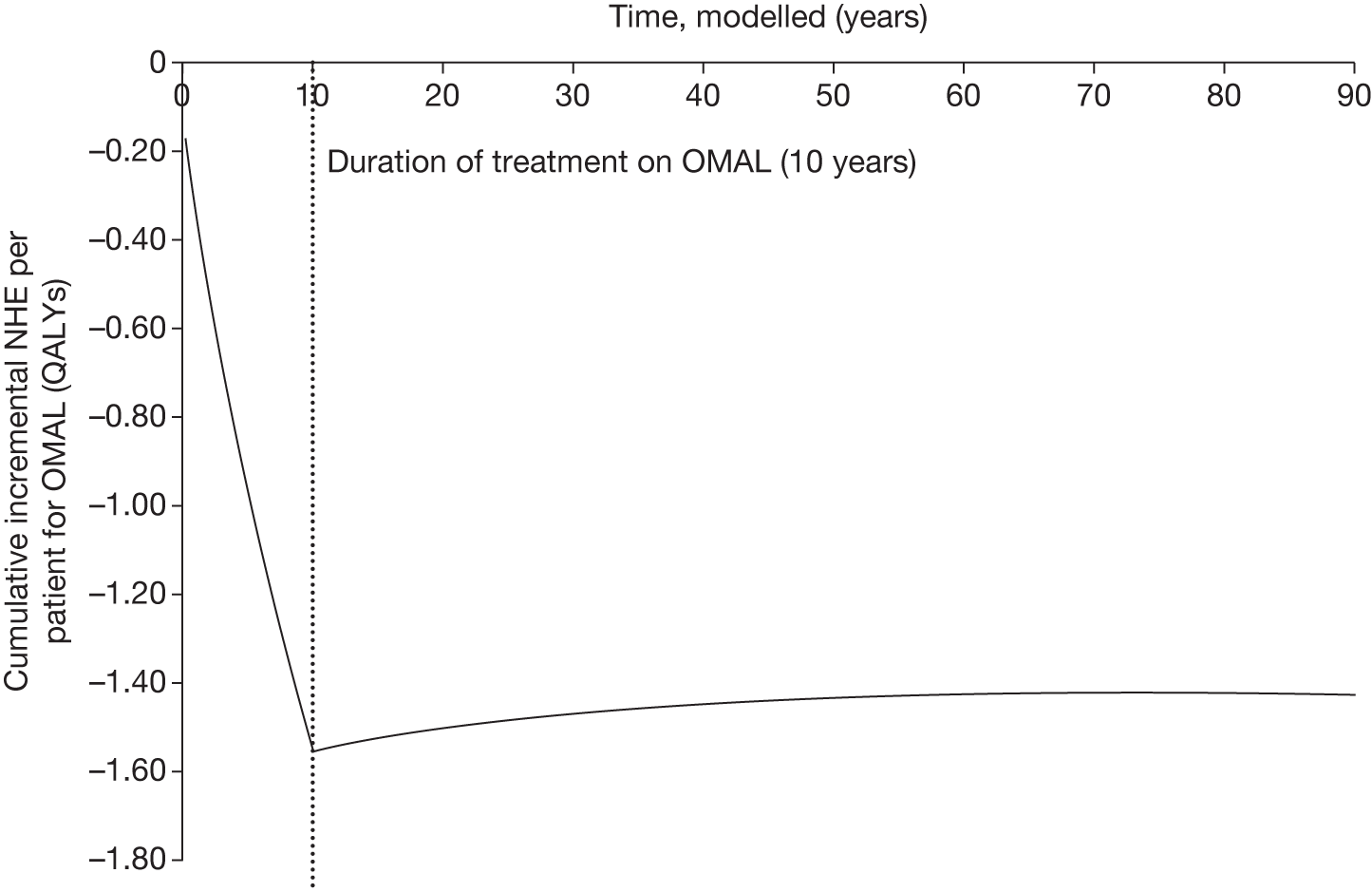

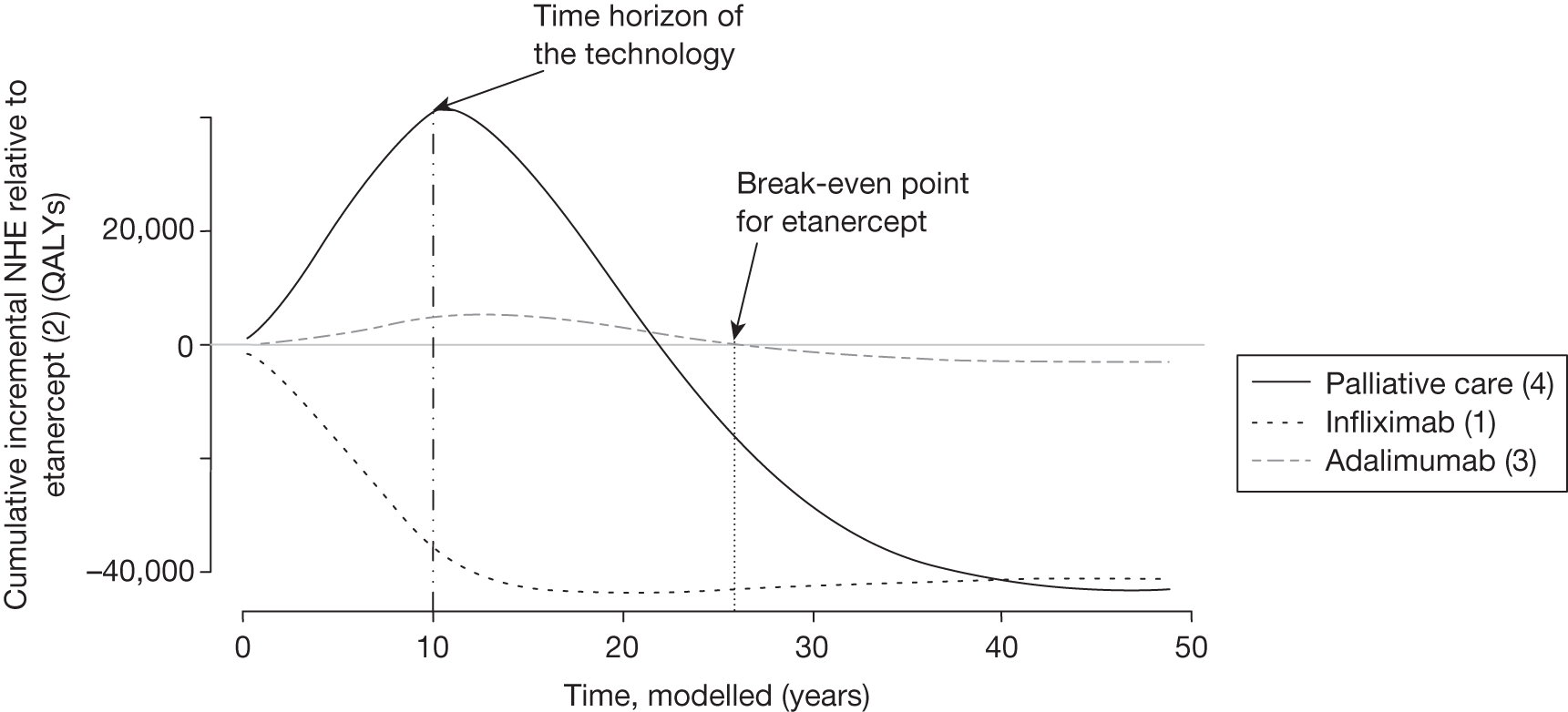

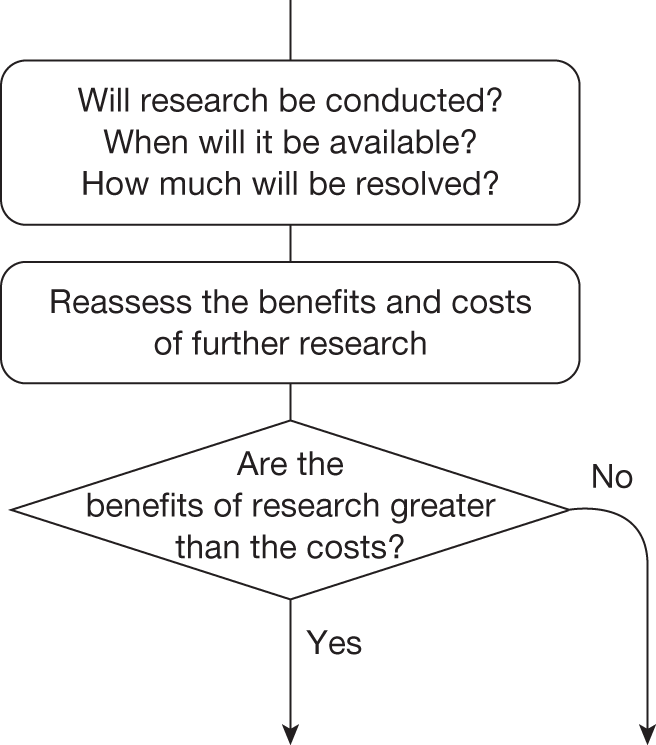

The sequence of assessments and decisions, which ultimately leads to guidance, starts with cost-effectiveness and the expected impact on population NHEs, that is, where existing NICE appraisal currently ends. This is an assessment of expected cost-effectiveness, that is, ‘on average’, based on the balance of the evidence and analyses currently available. It will include an assessment of effectiveness and potential for harms as well as NHS costs (see NICE’s Guide to Methods of Technology Appraisal1). Any assessment may be very uncertain with the scale and consequences of uncertainty assessed subsequently when considering the need for additional evidence. The sequence of assessments and decisions (judgements required) is illustrated in Figure 1. This demonstrates that an assessment of cost-effectiveness is only a first step and does not itself inevitably lead to a particular category of guidance. For example, a technology that might on balance be expected to be cost-effective might nevertheless receive OIR guidance if the additional evidence that is needed cannot be acquired if the technology is approved.

FIGURE 1.

Algorithm for technologies expected to be cost-effective.

Need for evidence

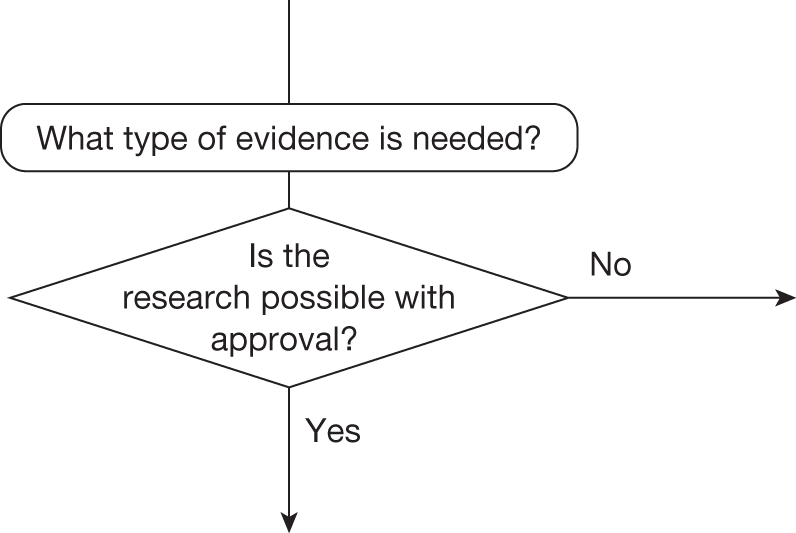

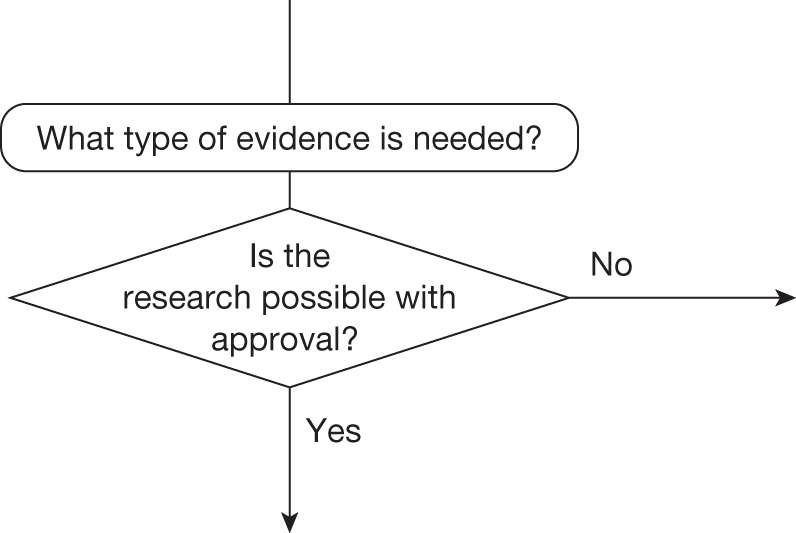

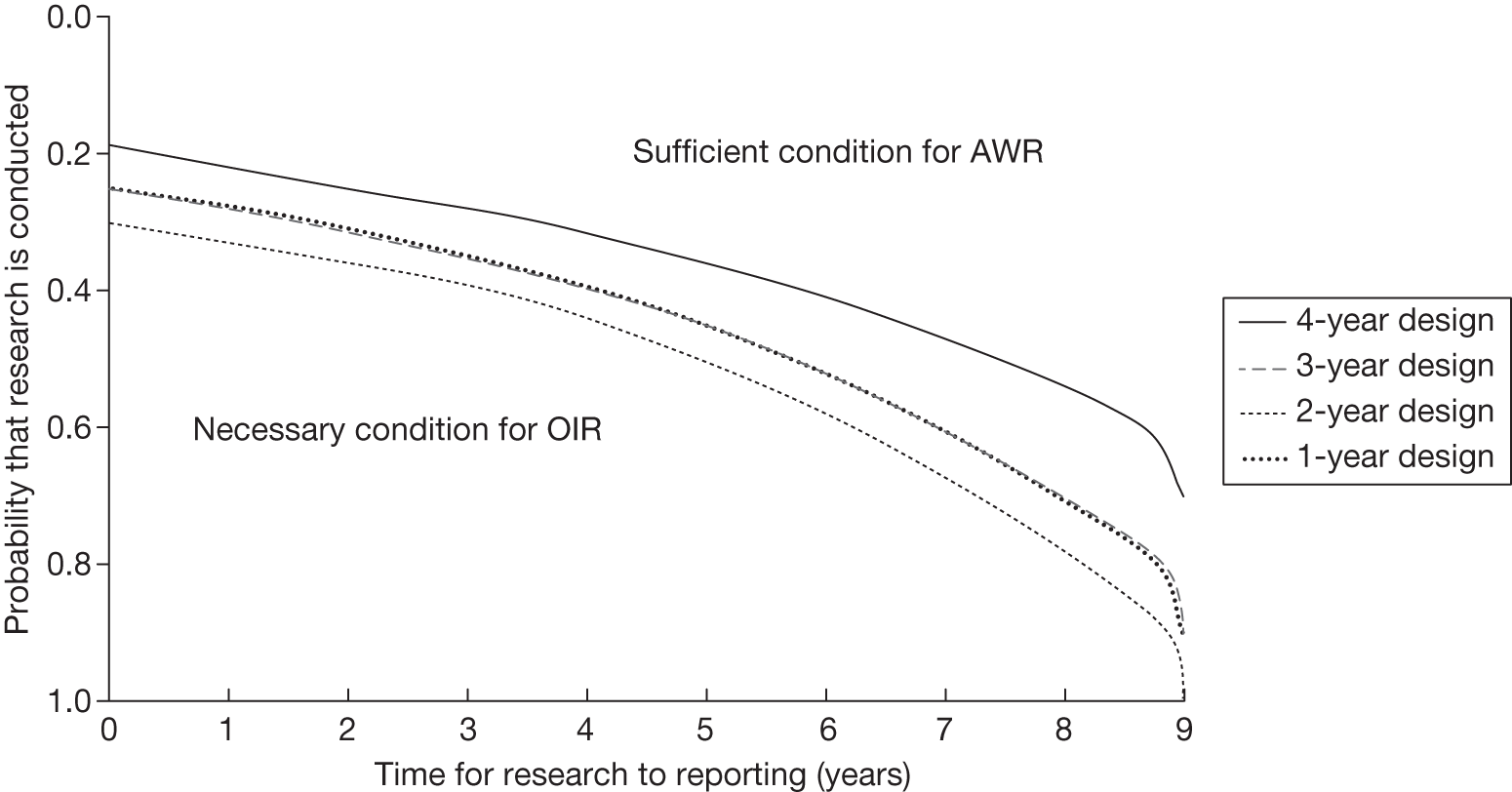

Some initial assessment of the need for further evidence and a decision about whether or not further research might be potentially worthwhile is important because a ‘no’ at this point can avoid further and complex assessments, for example a technology offering substantial and well-evidenced health benefits at modest additional cost is likely to exhibit little uncertainty about whether or not the expected population NHEs are positive. In these circumstances, further research may not even be potentially worthwhile (i.e. the opportunity costs of conducting this research exceed its potential value) and so guidance to approve could be issued on the basis of existing evidence and at the current price of the technology (e.g. ‘Approve4’ in Figure 1). If additional evidence is needed and further research might be worthwhile, then further assessments and decisions are required before guidance can be issued. Critically, some assessment is required of the type of evidence that is needed and whether or not the type of research required to provide it is likely to be conducted if approval is granted. 29

Research is possible with approval

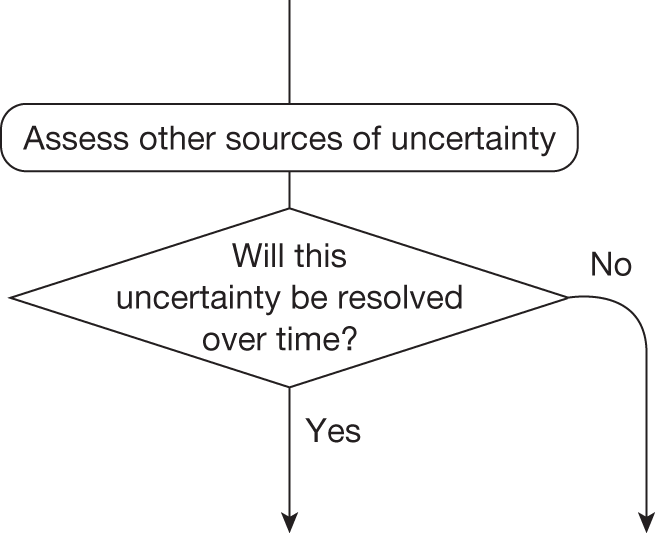

If research is possible with approval, some further assessment of the long-term benefits of research is required, including (1) the likelihood that the type of research needed will be commissioned by research funders or conducted by manufacturers, (2) how long until such research will be commissioned, recruit and successfully report and (3) how much of the uncertainty might be resolved by the type of research that is likely to be undertaken. 70 An assessment of other sources of uncertainty that will resolve only over time is also needed, for example changes in prices or the launch of new technologies. 71 These sources of uncertainty will influence the future benefits of research that could be undertaken as part of AWR. For example, even if the current benefits of research, which might be very likely to be undertaken, are considerable, if the price of the technology is likely to fall significantly before or shortly after the research reports, or if future innovation makes the current technology obsolete (or more effective), then the future benefits, once the research reports, might be very limited. In these circumstances it might be better to approve (rather than use a policy of AWR) and reconsider whether and what type of research is needed at a later date once these uncertainties have resolved. The judgement of whether the long-term benefits of research are likely to exceed its expected costs determines guidance, with ‘AWR1’ and ‘Approve1’ in Figure 1 dependent on ‘yes’ and ‘no’, respectively.

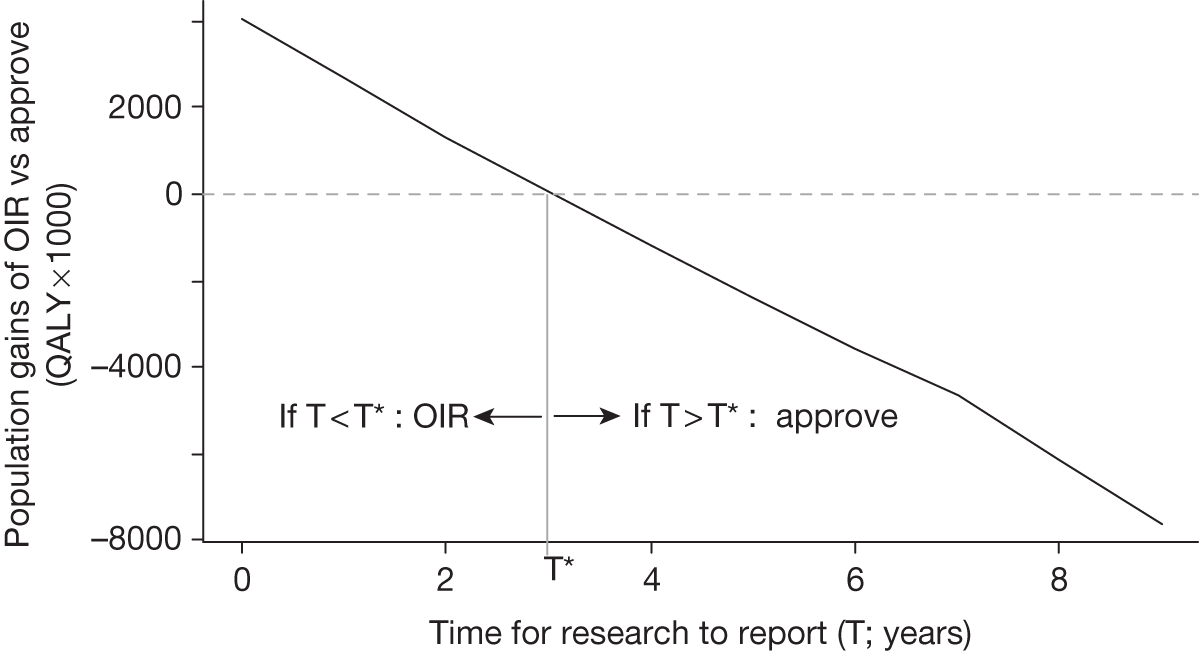

Research is not possible with approval

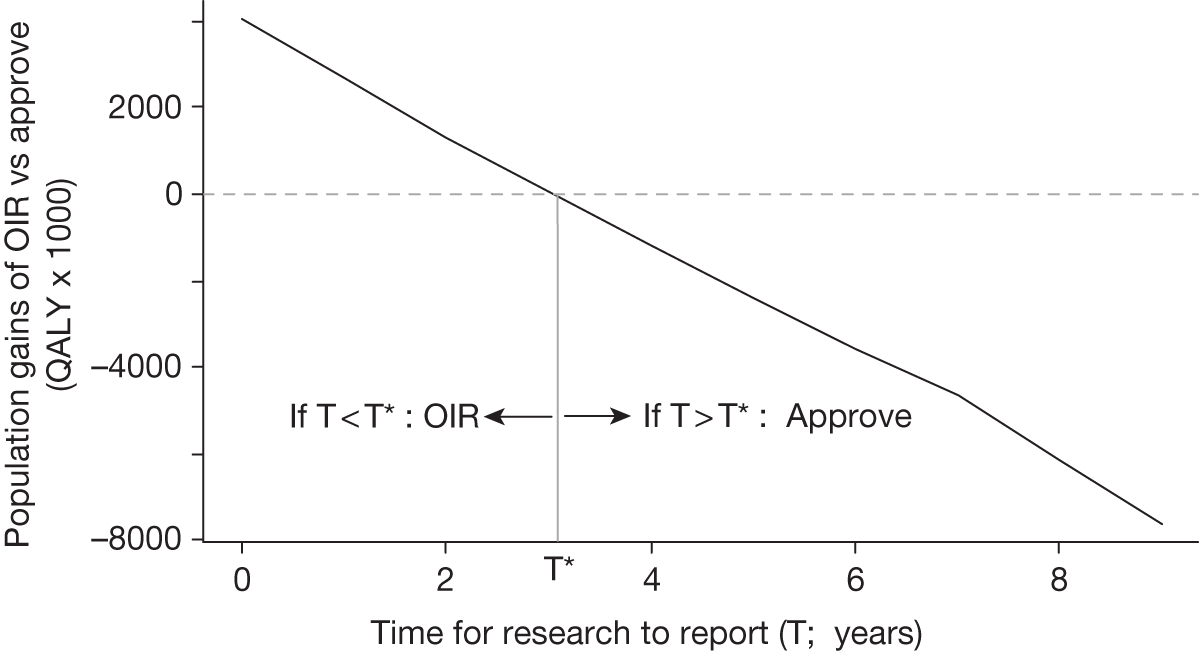

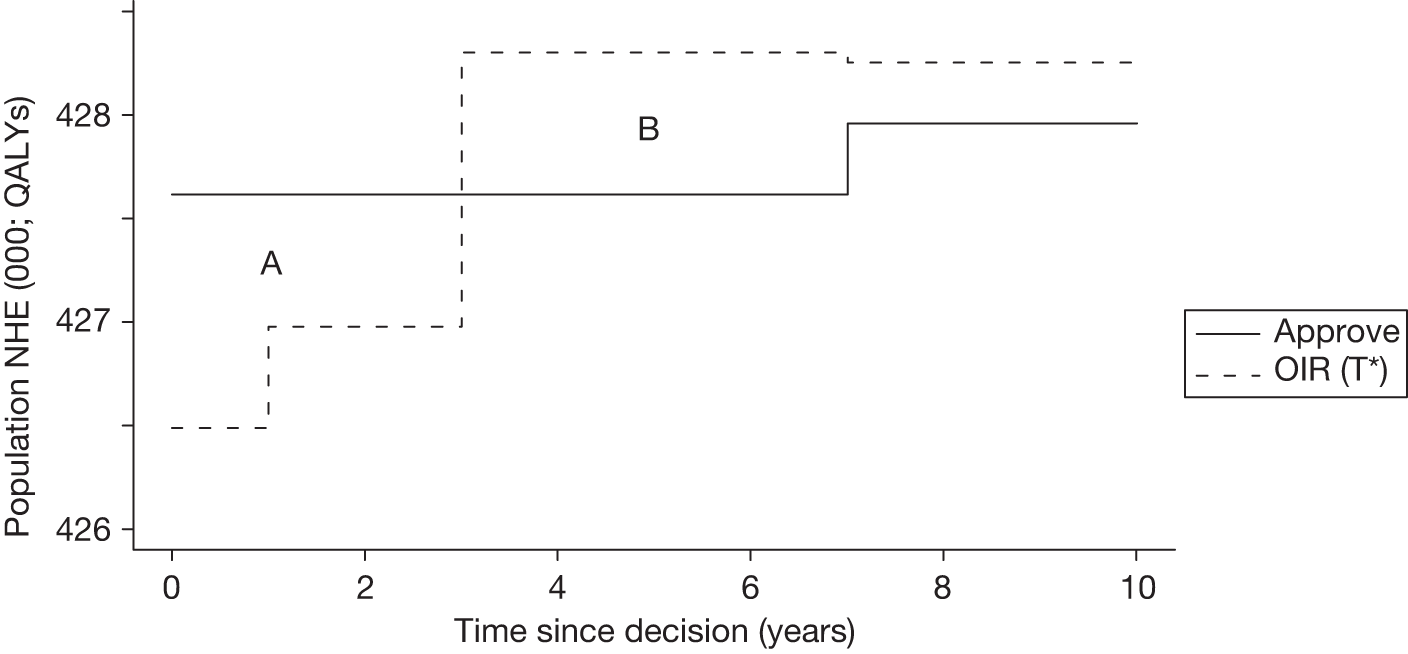

The type of research needed, for example RCTs, may not be possible once a technology is approved for widespread NHS use (because of ethical concerns, recruitment problems and limited incentives for manufacturers). In these circumstances the expected benefits of approval for current patients must be balanced against the benefits to future patients of withholding approval to allow the research to be conducted. Initially, the same assessment of the long-term value of the type of research that might be conducted if approval is withheld is still required. Similarly, the impact of other sources of uncertainty on the longer-term benefits of research is also needed. If the benefits of research are judged to be less than the costs (i.e. research is not worthwhile anyway), the technology can be approved based on current evidence and prices (‘Approve3’ in Figure 1). However, judging that research is worthwhile at this point is not sufficient for OIR guidance. In addition, an assessment of whether the benefits of early approval (expected population net benefits for current patients) are greater than the opportunity costs (the net benefit of the evidence likely to be forgone for future patients as a consequence of approval) is required. If the expected benefits of early approval are judged to be less than the opportunity costs then OIR guidance would be appropriate (‘OIR1’ in Figure 1). Alternatively, if the expected benefits of early access for current patients are judged to be greater than the opportunity costs for future patients then approval would be appropriate (‘Approve2’ in Figure 1). All of these assessments, including the benefits of early approval and the value of evidence, will change if the effective price of the technology is reduced (see Changes in effective prices).

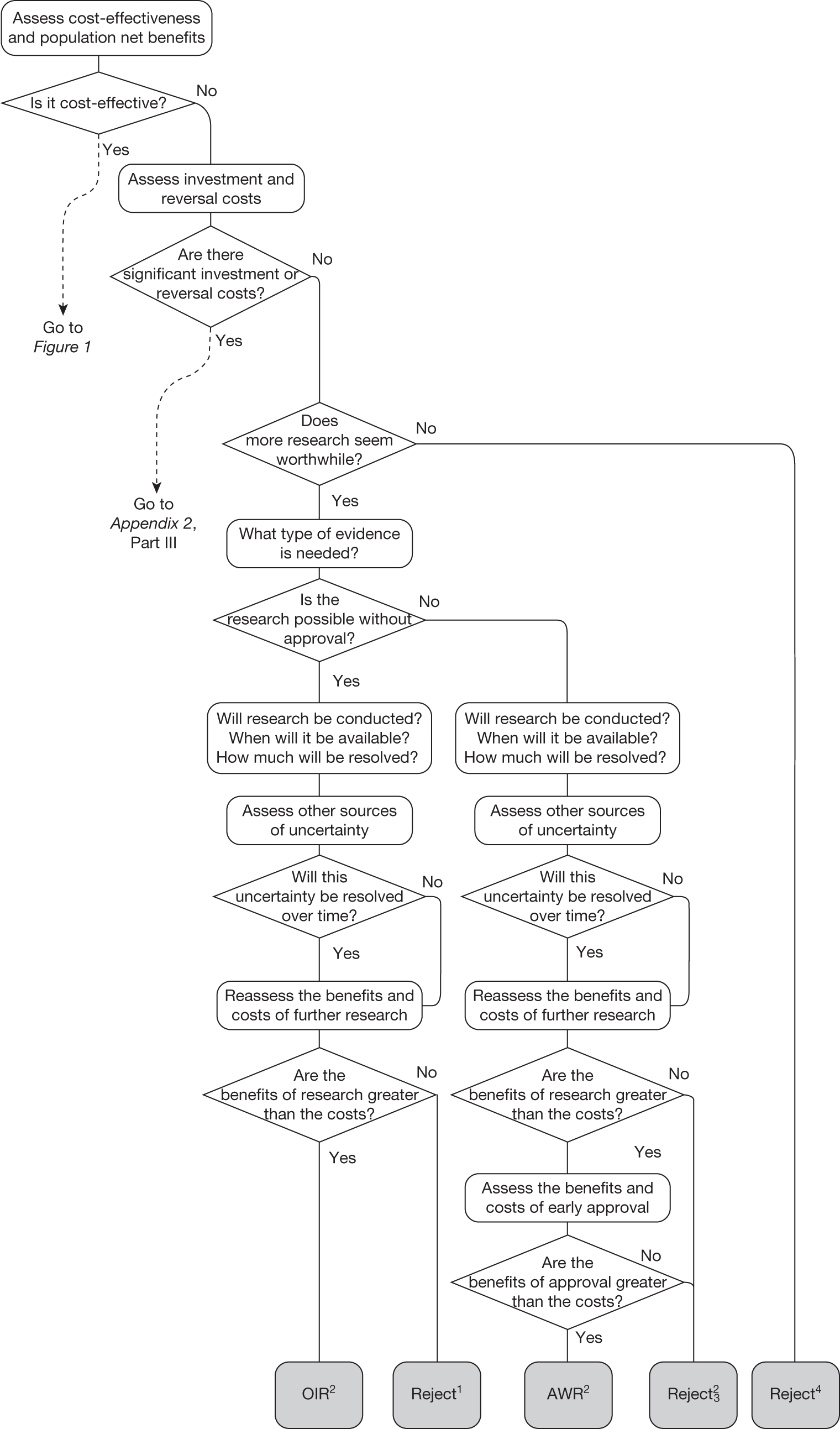

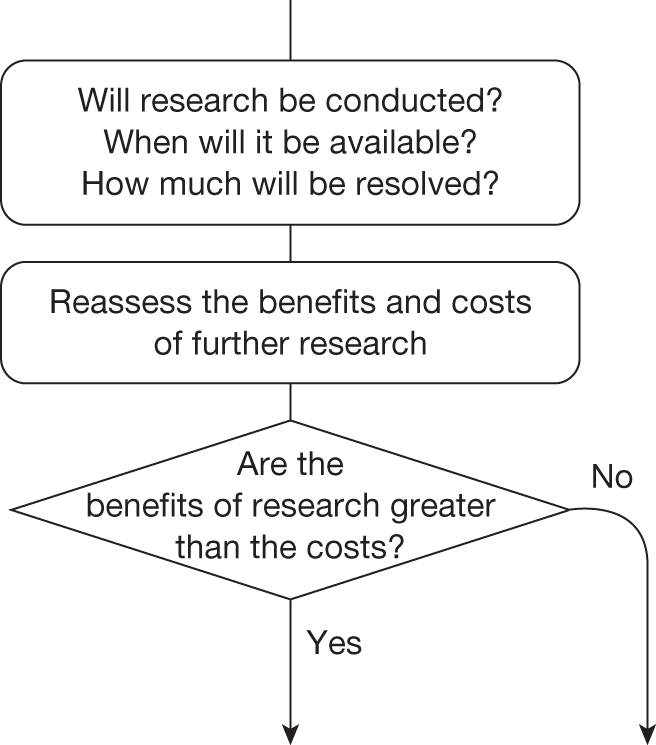

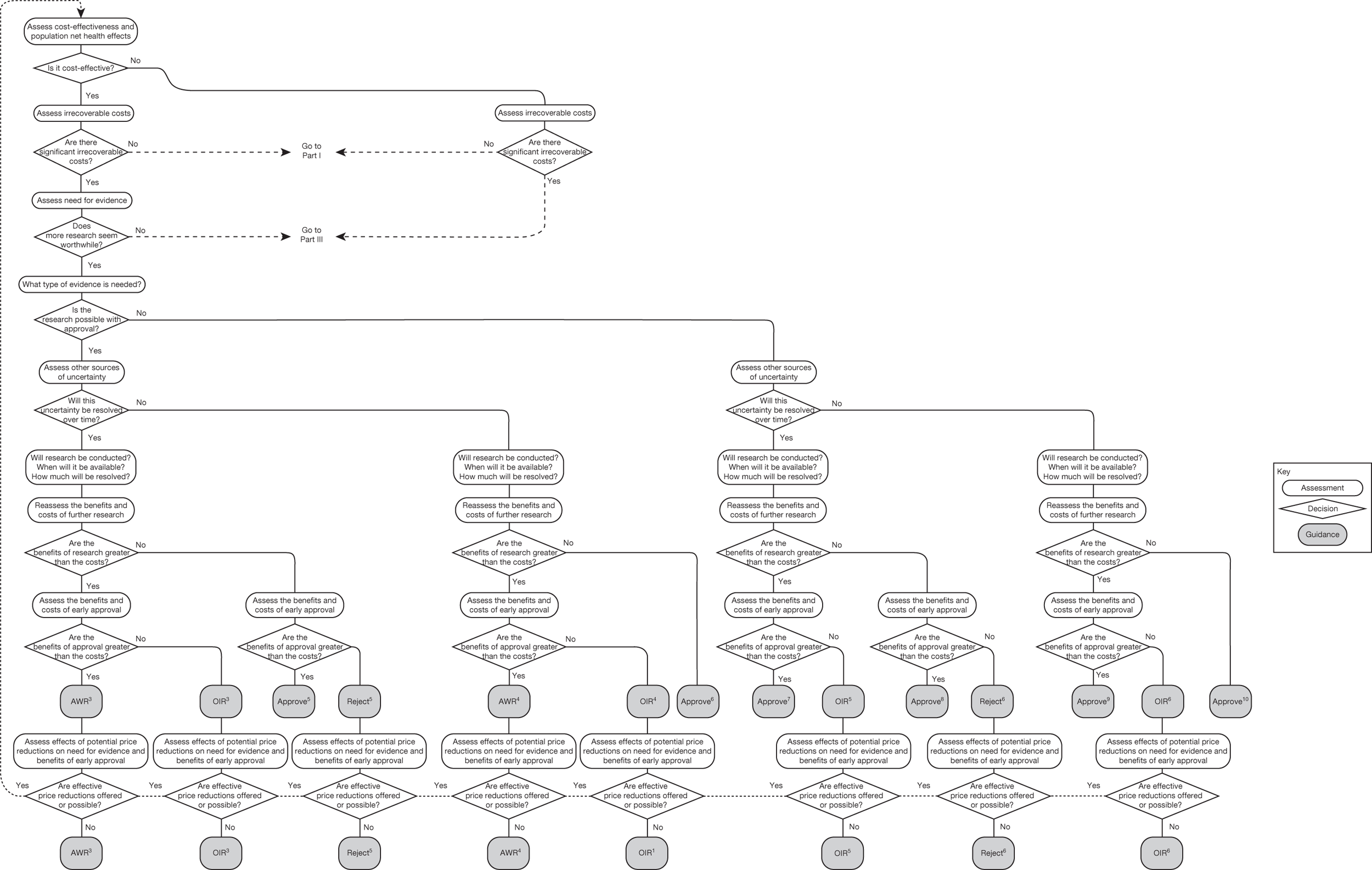

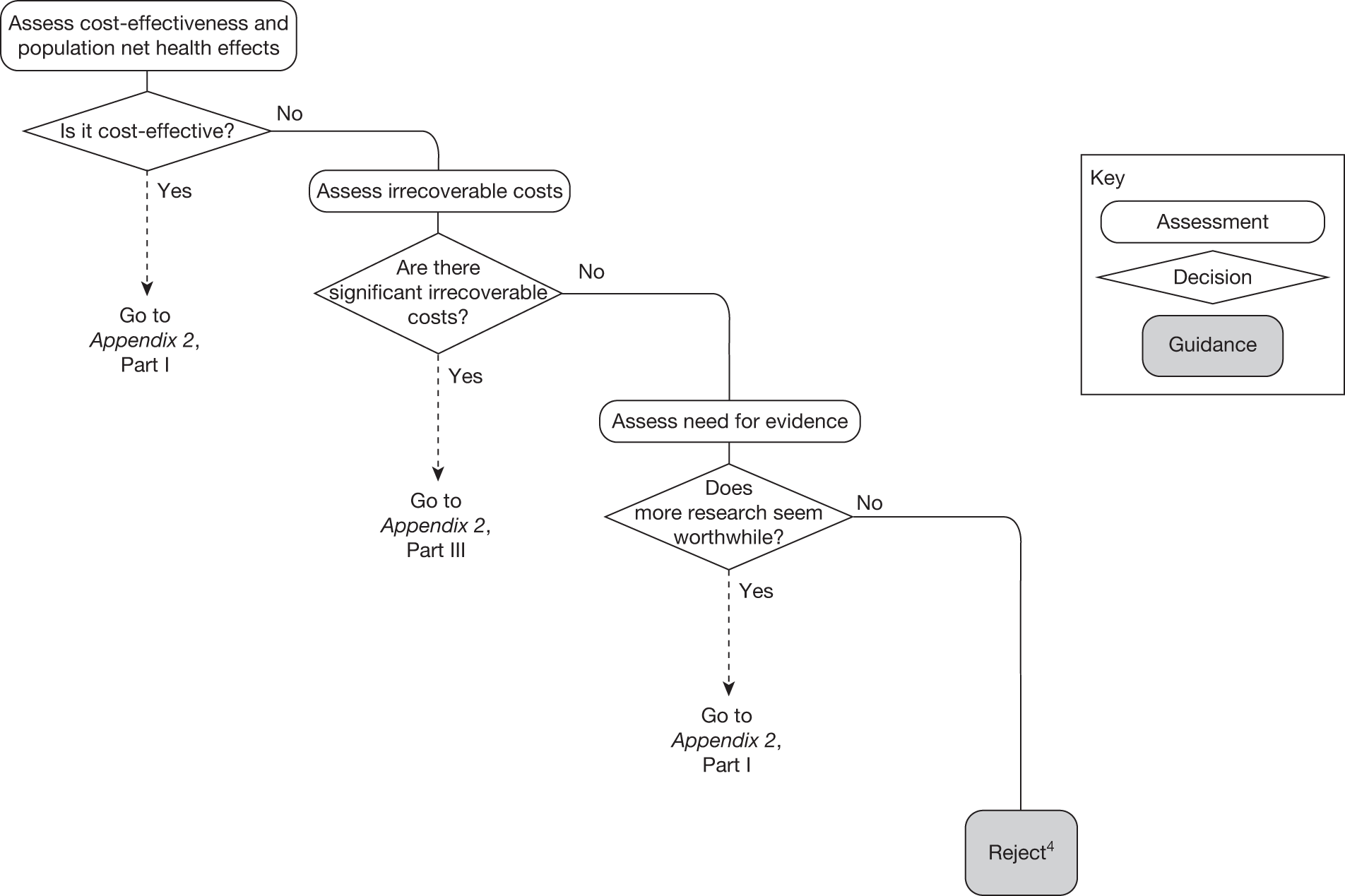

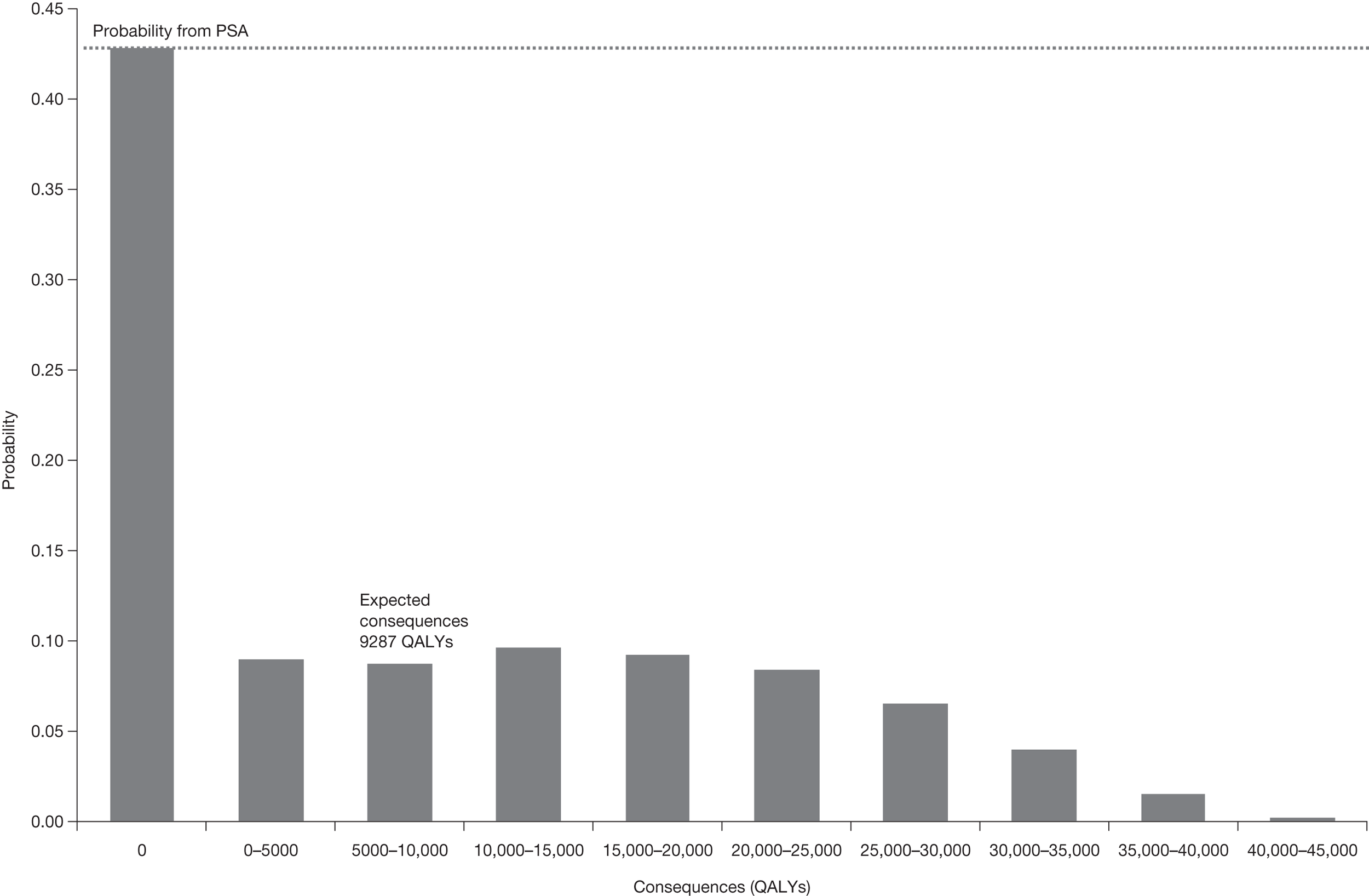

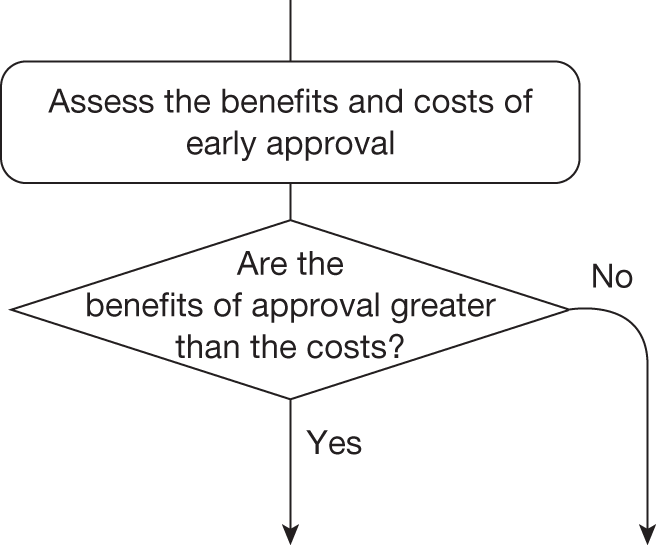

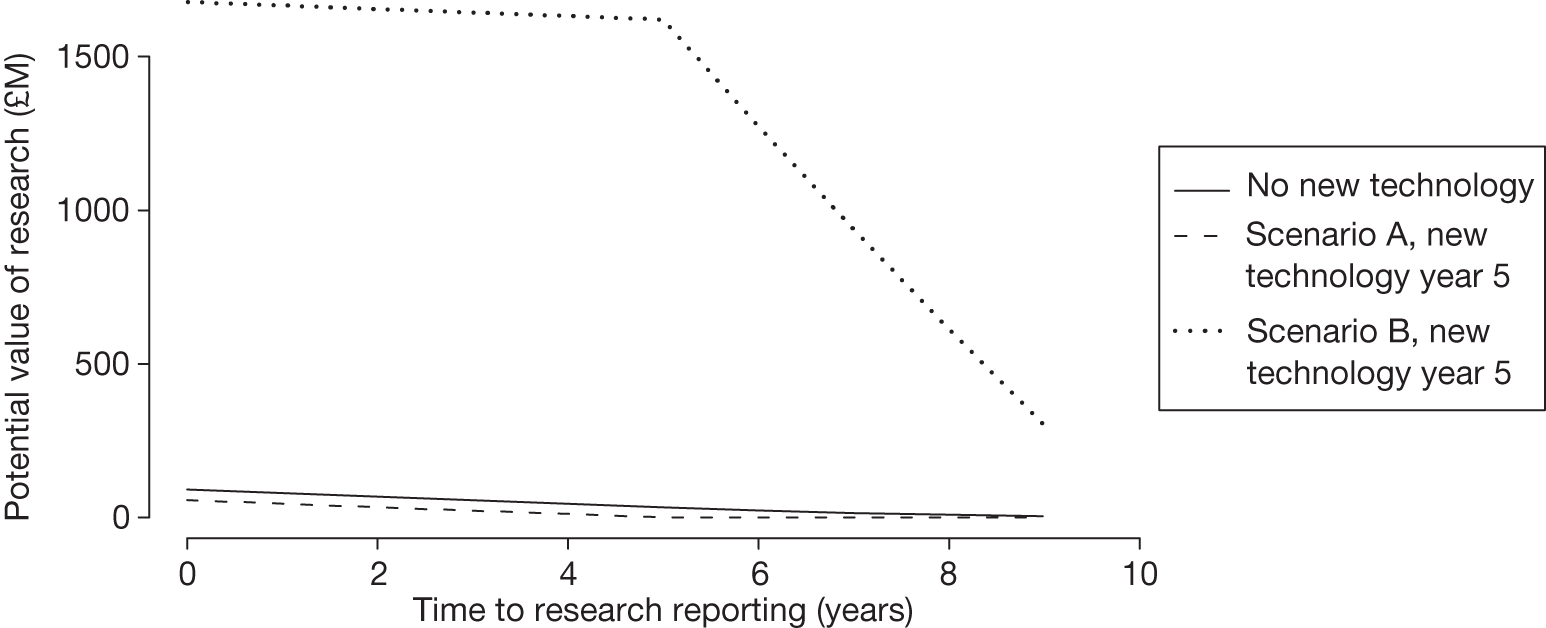

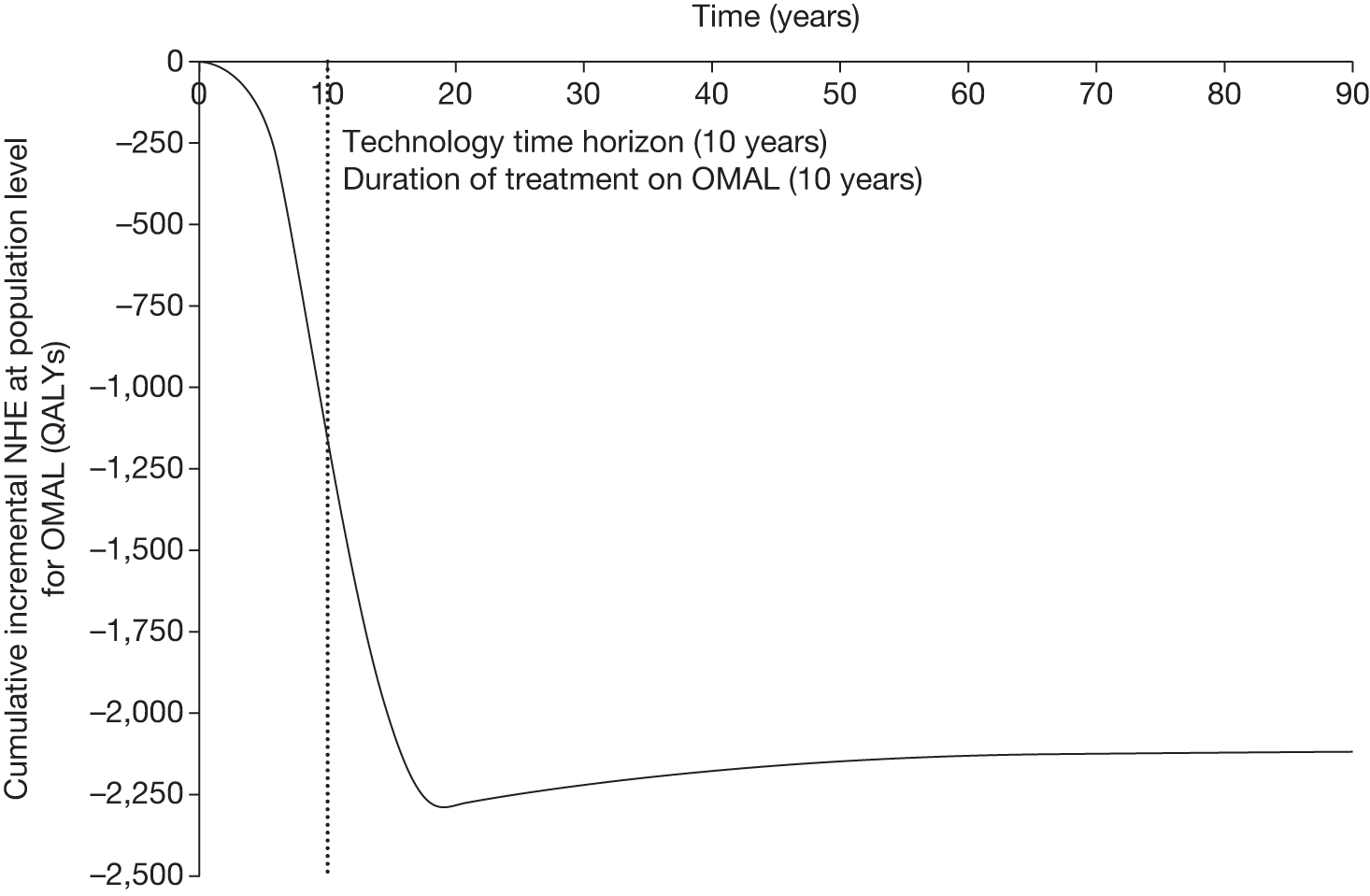

Technologies not expected to be cost-effective

A technology that is not expected to be cost-effective will, on balance, impose negative population NHEs if it is approved. These negative NHEs can arise because the technology may not be effective, the potential for harm exceeds any benefits and/or the additional NHS costs are not justified by the magnitude of the expected health benefits offered. In these circumstances approval can be ruled out, but which of the other categories of guidance might be appropriate will depend on subsequent assessments and decisions (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Algorithm for technologies not expected to be cost-effective.

Need for evidence

Any assessment will be uncertain, so it remains possible that a technology that is not expected to be cost-effective on the balance of existing evidence might offer positive NHEs. Therefore, the scale and consequences of this uncertainty must be considered to make an initial assessment of the need for additional evidence and whether additional research might, in principle, be worthwhile. If it is not then the technology can be rejected based on existing evidence and its current price (‘Reject4’ in Figure 2). Alternatively, if further research might be worthwhile then an additional assessment is required of whether the type of evidence and research that is needed can be conducted without approval.

Research is possible without approval

Generally, most types of research (including RCTs) will be possible without approval. Further assessment of the longer-term benefits of the type of research that is likely to be conducted, and when it might report, is required, including the impact of other sources of uncertainty that will resolve over time. If, following this reassessment, the expected benefits of research are judged to exceed the associated costs then OIR would be appropriate (‘OIR2’ in Figure 2). Alternatively, if the costs of research are likely to exceed the longer-term expected benefits then the technology should be rejected at this point (‘Reject1’ in Figure 2).

Research is not possible without approval

In some circumstances it is possible that certain types of evidence might be acquired only, or be more easily acquired (more quickly and at lower cost), once a technology is in widespread use, for example linking surrogates (specific to the technology) to longer-term health outcomes, longer-term and/or rare adverse events, greater understanding of learning and incremental improvements in the use of a technology, or identifying the particular types of patients that might benefit most. 76 In this less common situation, in which the type of research needed is not possible (or is significantly more costly) without approval, the same assessment of the longer-term benefits of research is required. If further research is judged not to be worthwhile following this reassessment, the technology can be rejected (‘Reject2’ in Figure 2). Alternatively, if research is judged worthwhile, an additional assessment of whether the benefits of approval exceed the costs is required. In this case, approval of a cost-ineffective technology would make the research possible, but will impose opportunity costs (negative expected population NHEs). The key question is whether the net benefits of the research exceed these opportunity costs. If they do not then the technology should be rejected even though research, had it been possible without approval, would have been worthwhile (‘Reject3’ in Figure 2). Alternatively, if the net benefits of research more than offset the opportunity costs then AWR would be appropriate even though the technology is expected to be cost-ineffective (‘AWR2’ in Figure 2).

Therefore, AWR guidance for technologies not expected to be cost-effective is certainly possible but is appropriate only in certain circumstances: (1) the type of research needed is not possible without approval, (2) the long-term benefits of the research are likely to exceed the expected costs and (3) the additional net benefits of such research exceed the opportunity costs of approving a cost-ineffective technology. More commonly, research might be possible but more costly without approval. In these circumstances, AWR guidance could be considered only if the additional costs of research without approval exceed the opportunity costs of approving a cost-ineffective technology.

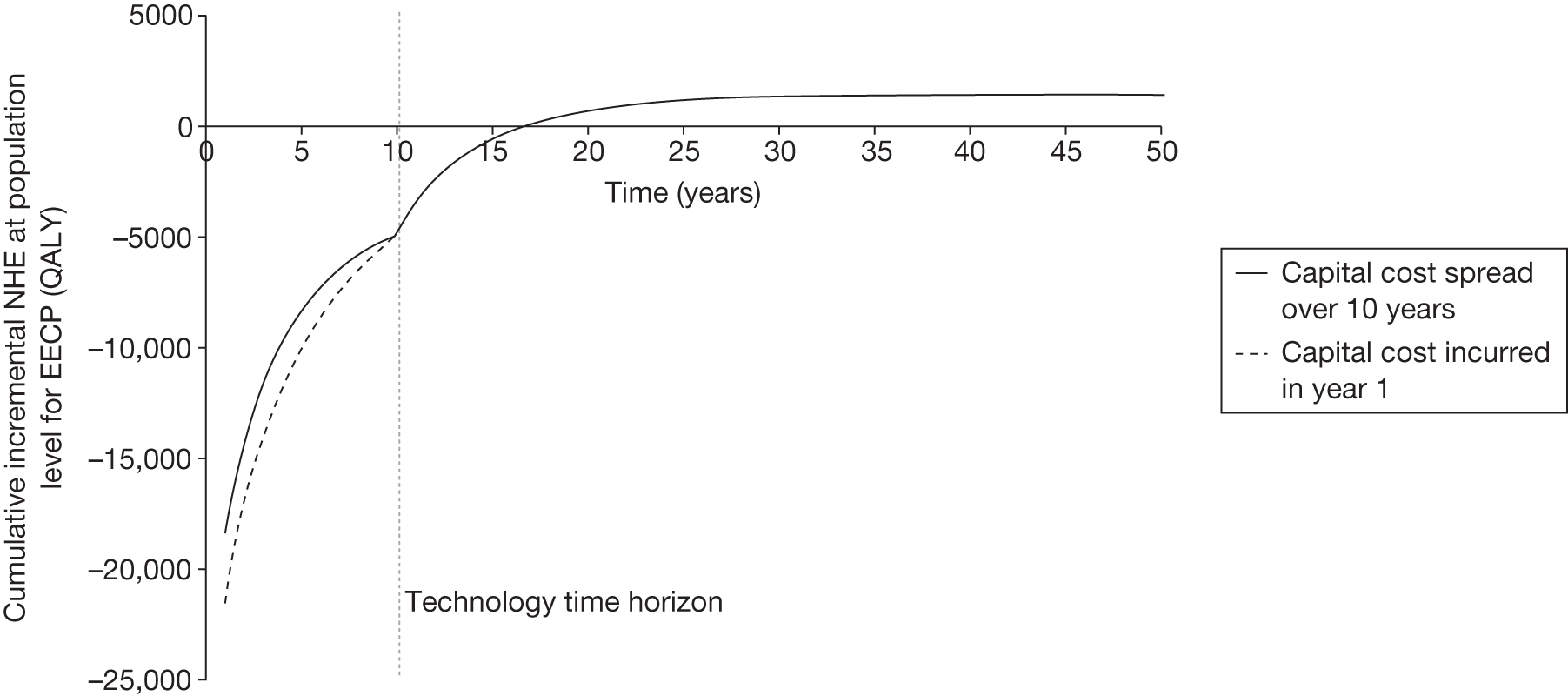

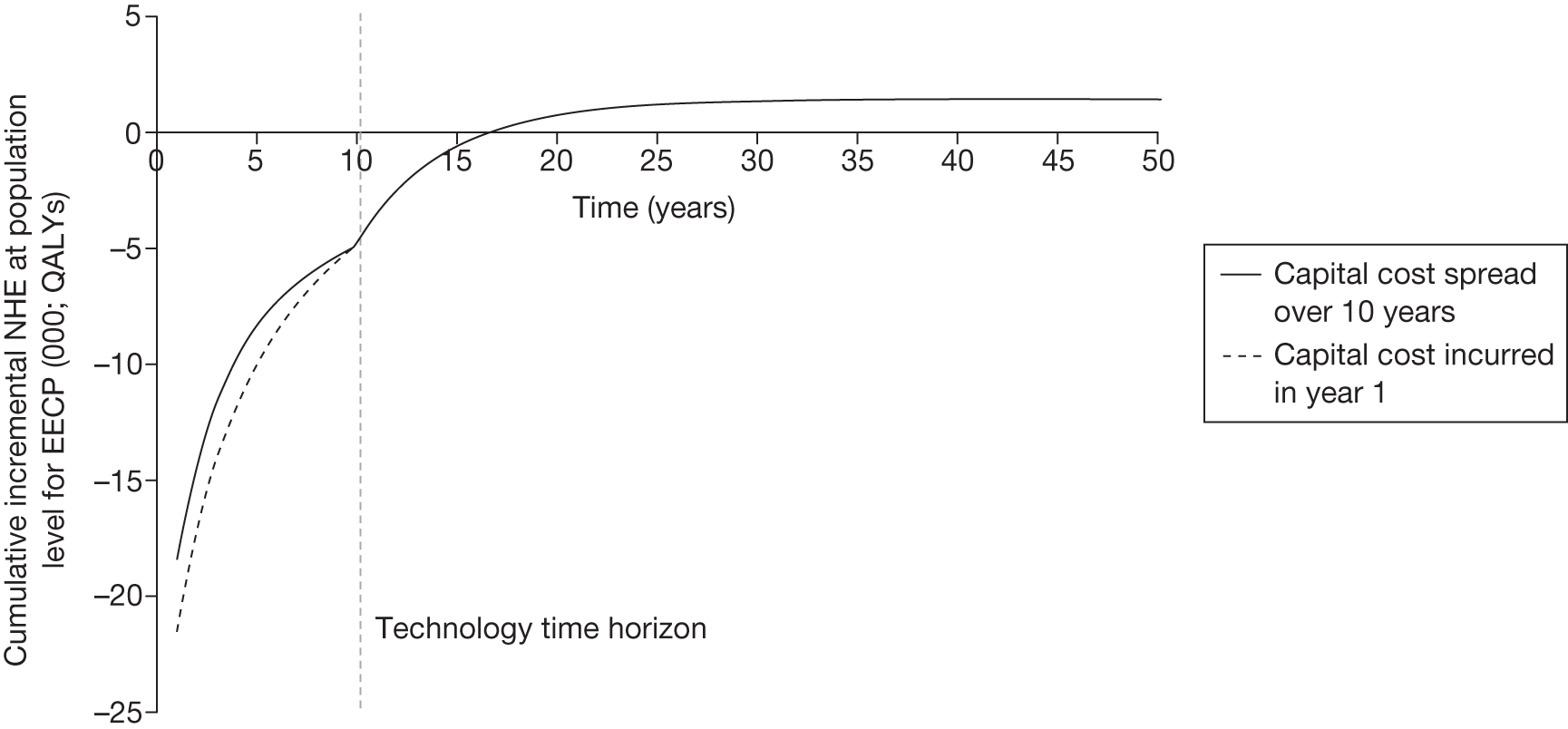

Technologies with significant irrecoverable costs

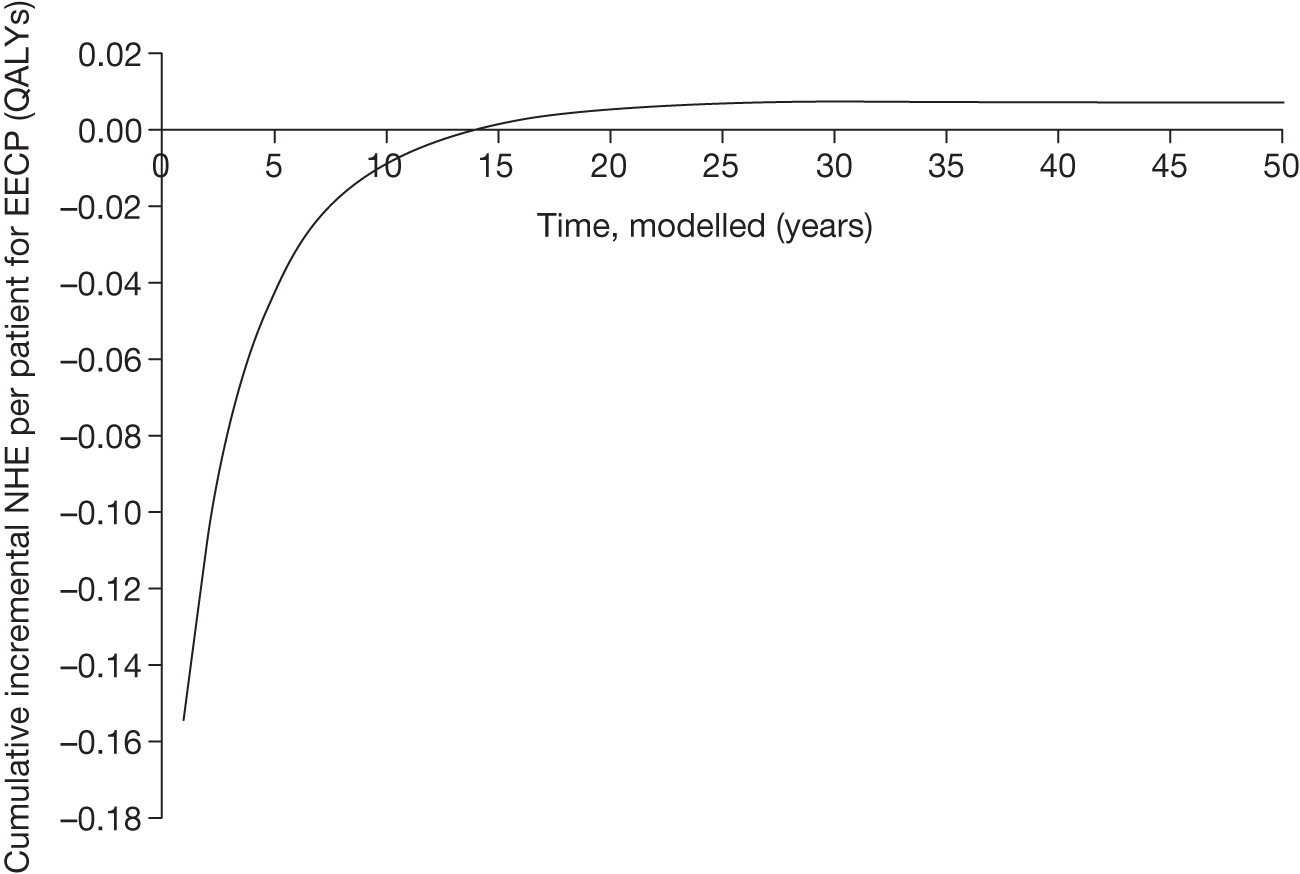

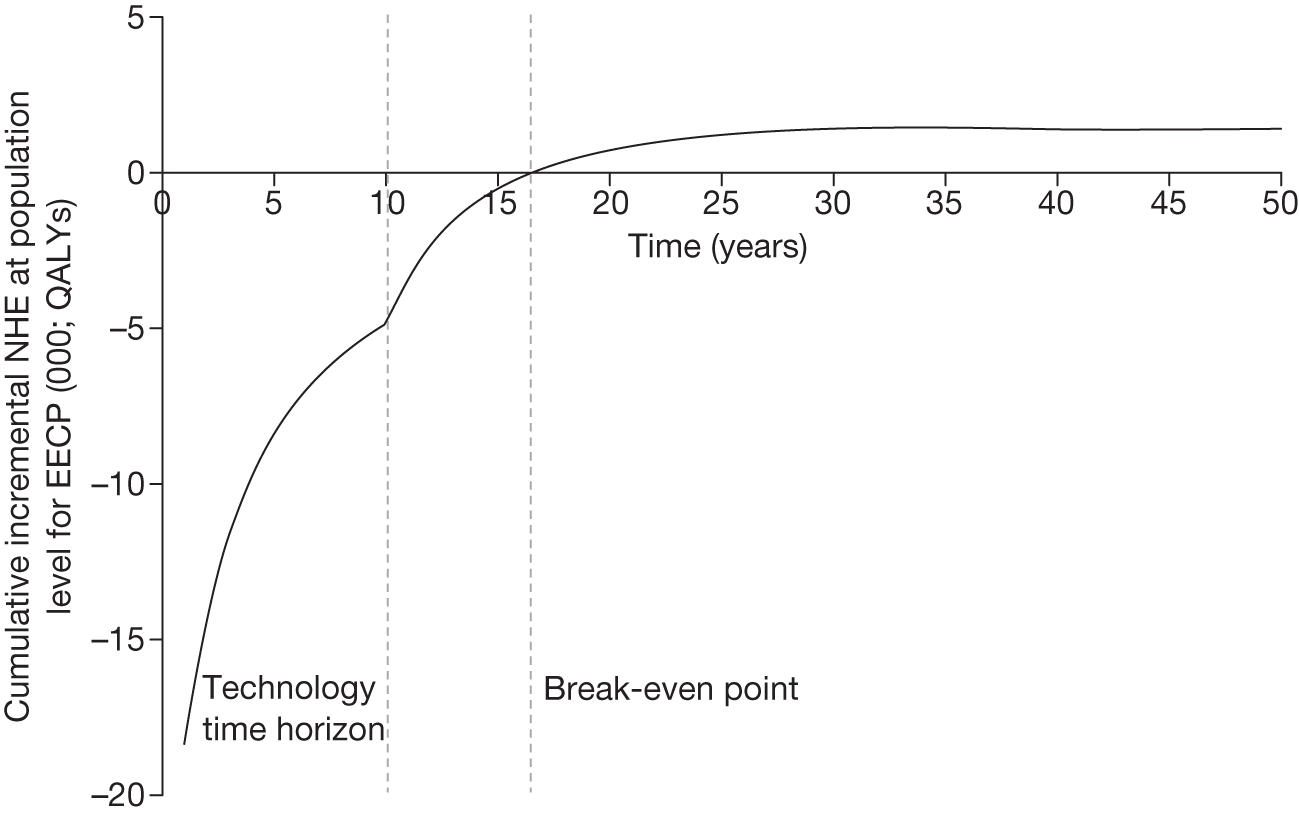

Irrecoverable costs are those that, once committed, cannot be recovered should guidance be revised at a later date. In most NICE appraisals these are included in the expected (per patient) cost of a technology. However, rarely is their potential additional impact explored when future events, such as research reporting or other sources of uncertainty resolving, might mean that guidance will be revised in the near or distant future. 6,72 These types of cost are commonly thought of as capital expenditure on equipment or facilities which have a life expectancy that extends beyond the current patient population. They might also include the resources required to implement guidance or to train staff to use a new health technology or a period of ‘learning’ during which NHEs are lower. Although these costs are incurred up front, they tend to be included in NICE assessments as if they are paid per patient treated over the lifetime of the equipment or facility. This common assumption will have no effect as long as guidance is certain not to change during this period. However, if it is possible that initial approval might be withdrawn at some point, then, although future patients will no longer use the technology, these upfront costs cannot be recovered (see Issues specific to ‘only in research’ recommendations). Therefore, in these circumstances it would be inappropriate to include these costs as if they were paid per patient treated (see Point 2: Are there significant irrecoverable costs?). The possibility that approve or AWR might be reconsidered after research reports, for example, and the impact that this would have on expected costs need to be considered before committing these types of capital costs, that is, it may be better to withhold approval and avoid commitment of resources until the uncertainty is resolved.

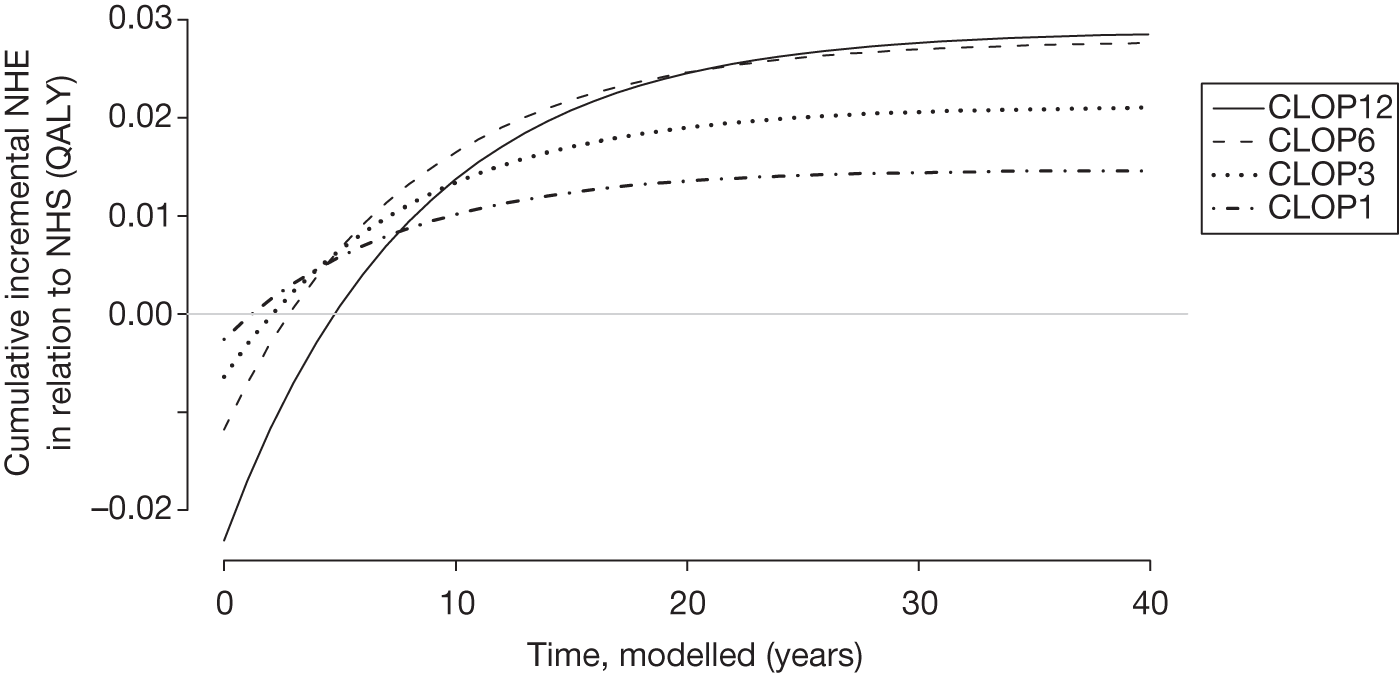

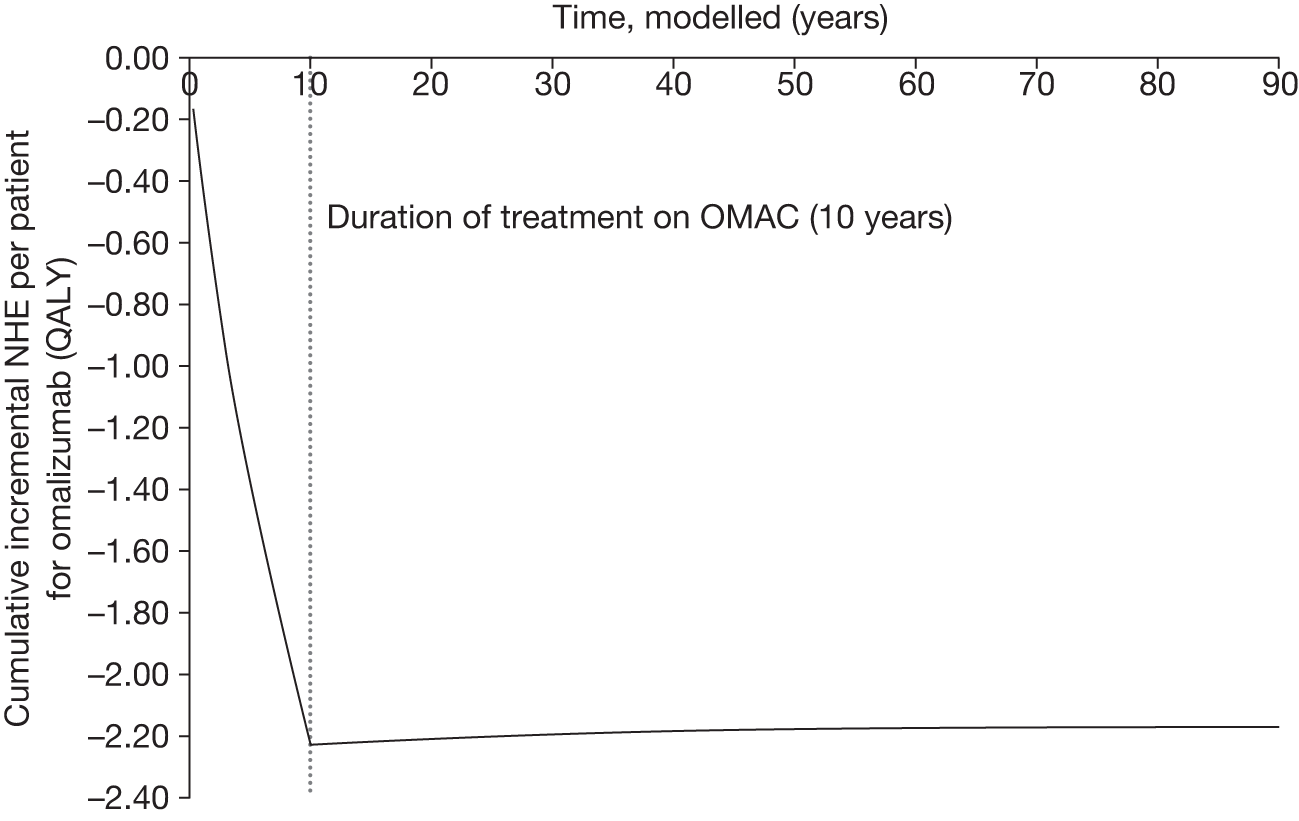

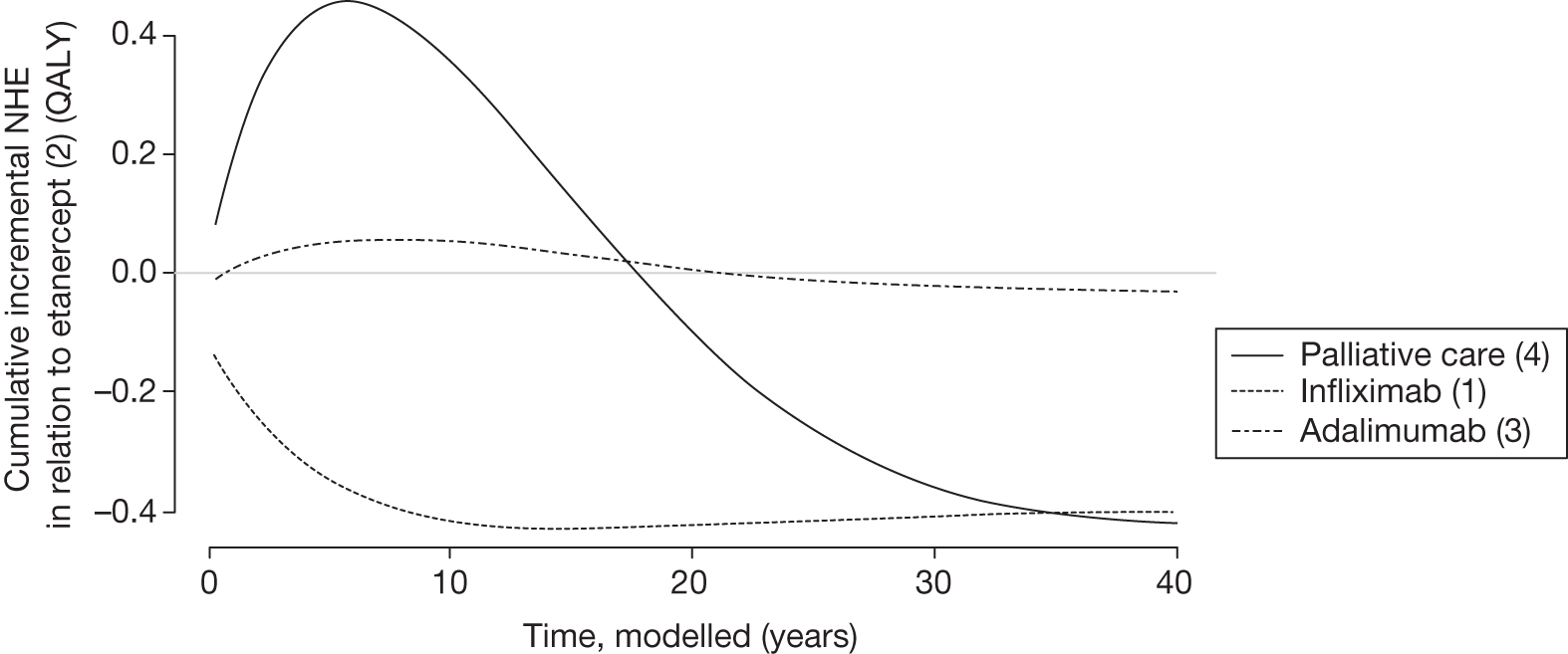

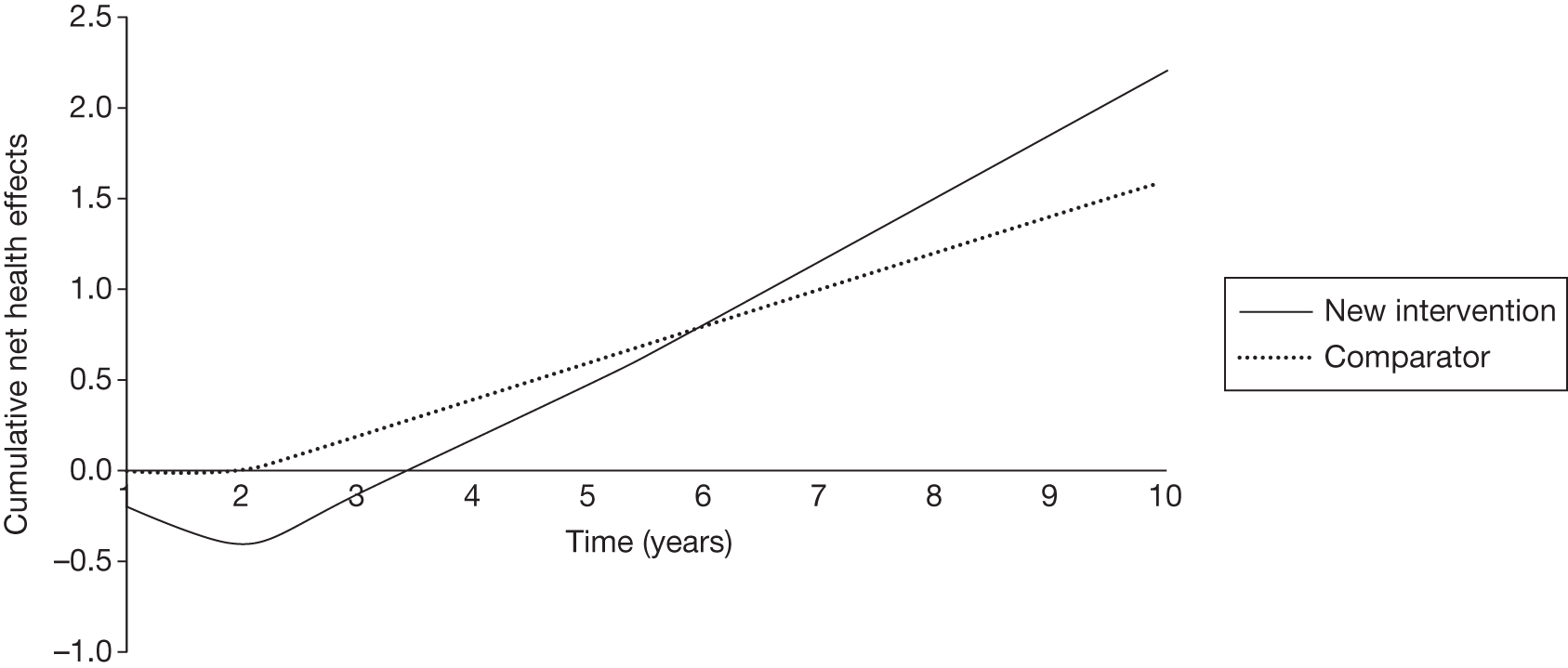

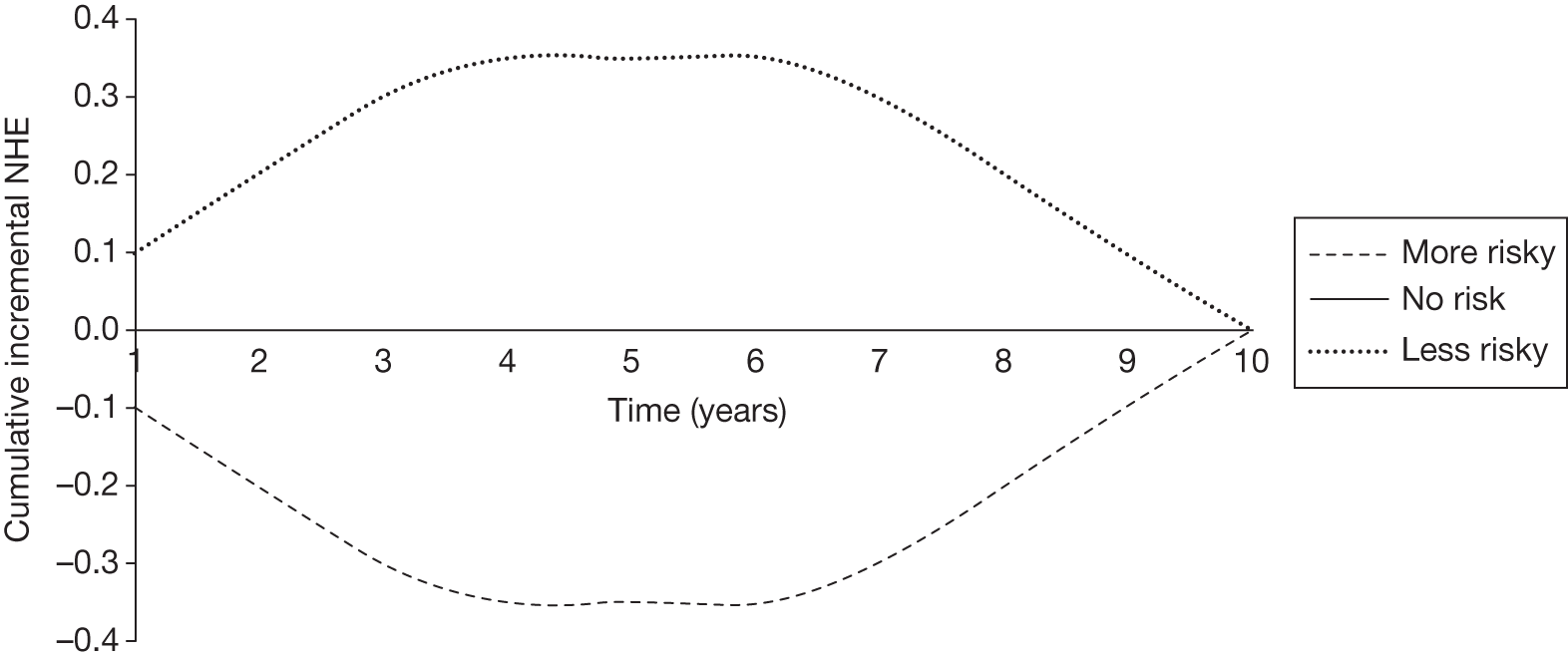

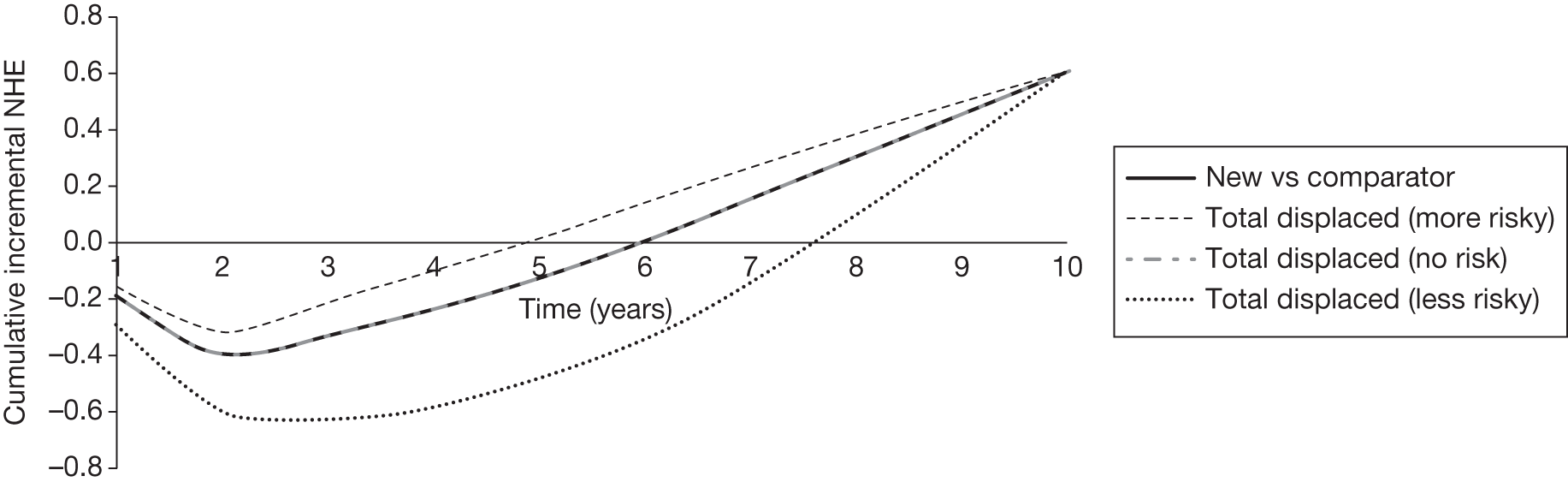

However, irrecoverable costs may be much more common. Even in the absence of capital investment in equipment and facilities, most new technologies offer a ‘risky investment profile’ for each patient treated. Generally they impose initial per patient treatment costs that exceed the immediate health benefits (see Point 1: Is it expected to be cost-effective?). These irrecoverable treatment costs are offset only by cost savings and health benefits in the longer run, that is, initially negative NHEs (losses) are only gradually compensated by later positive ones (gains). Therefore, a technology expected to be cost-effective may be expected to break-even, that is, when accumulated ‘gains’ compensate earlier ‘losses’, after some considerable time. If guidance is likely to change it is possible that initial losses will not be compensated by later gains and the expected additional NHEs will not be realised. 75 This type of investment profile becomes significant (has some influence on a decision to approve) if the decision to treat a presenting patient can be delayed until uncertainty is resolved (e.g. research reports or other events occur) because the commitment of irrecoverable opportunity costs (negative NHEs) can be avoided (see Point 2: Are there significant irrecoverable costs?). In these circumstances, OIR or reject avoids this commitment and preserves the option to approve the technology at a later date when its purchase by the NHS represents a ‘less risky investment’. 75,b

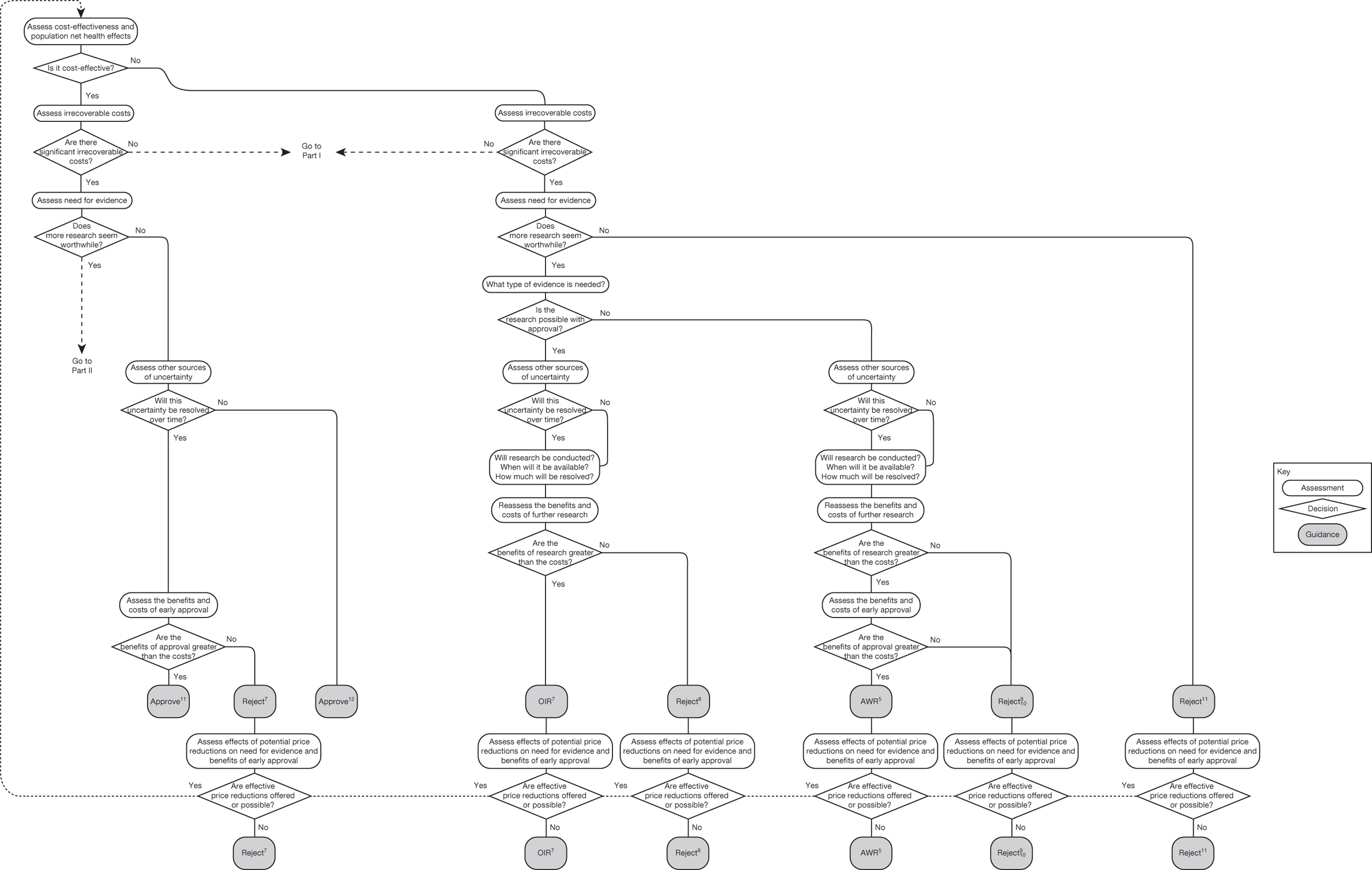

Although aspects of irrecoverable cost are almost always present, their potential significance also depends on their scale relative to expected population NHEs of the technology. Critically, their impact depends on the chance that guidance will be revised in the near or distant future as a result of new evidence becoming available or changes in prices and technologies. The full algorithm becomes more complex (see Figures 27 and 28 in Appendix 2) so here we focus on the key differences from the section on technologies without significant irrecoverable costs.

Technologies expected to be cost-effective

The presence of irrecoverable costs associated with a technology that is expected to be cost-effective will influence guidance and be regarded as ‘significant’ only if there are future events (research reporting or other sources of uncertainty resolving) that might change guidance. For example, if research is possible with approval and is expected to be worthwhile, AWR does not necessarily follow as previously (e.g. see ‘AWR1’ in Figure 1) because the impact of irrecoverable costs must also be considered. Now OIR may be more appropriate than AWR (e.g. the choice between ‘OIR4’ or ‘AWR4’ in Figure 27), even though the research would be possible with approval, because OIR avoids the commitment of irrecoverable costs until the results of research are known. This is especially so when there are also other sources of uncertainty that might resolve while the research is being conducted because they increase the chance that guidance will be revised (e.g. ‘OIR3’ or ‘AWR3’ in Figure 27).

If research is not possible with approval but is expected to be worthwhile, then OIR will be appropriate if the opportunity costs of early approval are judged to exceed the benefits (e.g. ‘OIR6’ rather than ‘Approve9’ in Figure 27). These opportunity costs will now also include the impact of irrecoverable costs when guidance might be changed as well as the value of evidence that will be forgone by early approval. Therefore, irrecoverable costs will tend to make OIR rather than approval more likely, particularly when there are other sources of uncertainty that might resolve while the research is being conducted (e.g. ‘OIR5’ rather than ‘Approve7’ in Figure 27).

If research is not judged worthwhile, approval does not necessarily follow as previously (e.g. ‘Approve1,3,4’ in Figure 26). Now the technology should be approved only if there are no other sources of uncertainty. If there are other sources of uncertainty, then an assessment of the benefits and costs of early approval is needed that takes account of irrecoverable costs and the risk that guidance might change in the future. Therefore, reject rather than approval is possible, even though a technology is expected to be cost-effective, because the decision to commit the irrecoverable costs can be reconsidered once the other sources of uncertainty have resolved (e.g. ‘Reject5,6’ in Figure 27).

Technologies not expected to be cost-effective

The presence of irrecoverable costs for technologies not expected to be cost-effective does not change the categories of guidance, or how they might be arrived at. However, it does mean that reject is more likely to be appropriate than AWR when research is not possible without approval (see ‘AWR5’ in Figure 28). This is because a decision to reject, although it may be revised to approve, generally does not commit irrecoverable costs. Although there may be resources associated with making sure subsequent approval is properly implemented, these costs are properly considered as an irrecoverable cost associated with approval (rather than a reversal cost of reject). There may be circumstances when implementing guidance to reject a technology also requires resources if it has already diffused into clinical practice. If these are significant they should be taken into account in the same way as other irrecoverable costs, tending to make AWR more likely to be appropriate.

Different types of guidance

Each sequence of assessment and decision leads to different categories and ‘types’ of guidance for technologies with differing characteristics, indications and target populations. The different ‘types’ of guidance illustrate how similar guidance might be arrived at in different ways, helping to identify the particular combinations of considerations that might underpin guidance, contributing to the transparency of the appraisal process. The possible categories and types of guidance are summarised in Table 1; the numbers in the body of the table refer to the numbered guidance in Figures 1 and 2 and the algorithm in Appendix 2 (see Figures 26–28).

| Type of guidance | No significant irrecoverable costs | Significant irrecoverable costs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Research not needed | Research possible with approval | Research not possible with approval | Research not needed | Research possible with approval | Research not possible with approval | |||||

| Benefits > costs | Benefits < costs | Benefits > costs | Benefits < costs | Benefits > costs | Benefits < costs | Benefits > costs | Benefits < costs | |||

| Technologies expected to be cost-effective | ||||||||||

| Approve (12) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11, 12 | 5, 6 | 7, 9 | 8, 10 | ||

| AWR (3) | 1 | 3, 4 | ||||||||

| OIR (5) | 1 | 3, 4 | 5, 6 | |||||||

| Reject (3) | 7 | 5 | 6 | |||||||

| Technologies not expected to be cost-effective | ||||||||||

| Approve (0) | ||||||||||

| AWR (2) | 2 | 5 | ||||||||

| OIR (2) | 2 | 7 | ||||||||

| Reject (8) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 9 | 10 | ||

The categories of guidance available to NICE have wider application than is reflected in previous guidance (see Chapter 4). For example, there are five different types of OIR that may be appropriate when a technology is expected to be cost-effective. Indeed, OIR may be appropriate even when research is possible with approval if there are significant irrecoverable costs. AWR can be considered only when research is possible with approval, but reject remains a possibility even for a cost-effective technology if there are irrecoverable costs. Therefore, the full range of categories of guidance (OIR and reject as well as AWR and approve) ought to be considered for technologies that, on the balance of existing evidence and current prices, are expected to be cost-effective.

It is only approval that can be ruled out if a technology is not expected to be cost-effective, that is, cost-effectiveness is necessary but not sufficient for approval but lack of cost-effectiveness is neither necessary nor sufficient for rejection. Although likely to be uncommon, there are circumstances when AWR may be appropriate even when a technology is not expected to be cost-effective (see Technologies without significant irrecoverable costs and Technologies expected to be cost-effective). More commonly the choice of appropriate guidance will be either reject or OIR. Importantly, which category of guidance will be appropriate depends only partly on an assessment of expected cost-effectiveness and hence this assessment should be regarded only as an initial step in formulating guidance. Guidance will depend on a number of other key assessments including (1) the need for evidence, (2) whether or not the type of research required is possible with approval, (3) the expected longer-term benefits and costs of the type of research likely to be conducted, (4) the impact of other sources of uncertainty that will resolve over time and (5) the significance of any irrecoverable costs.

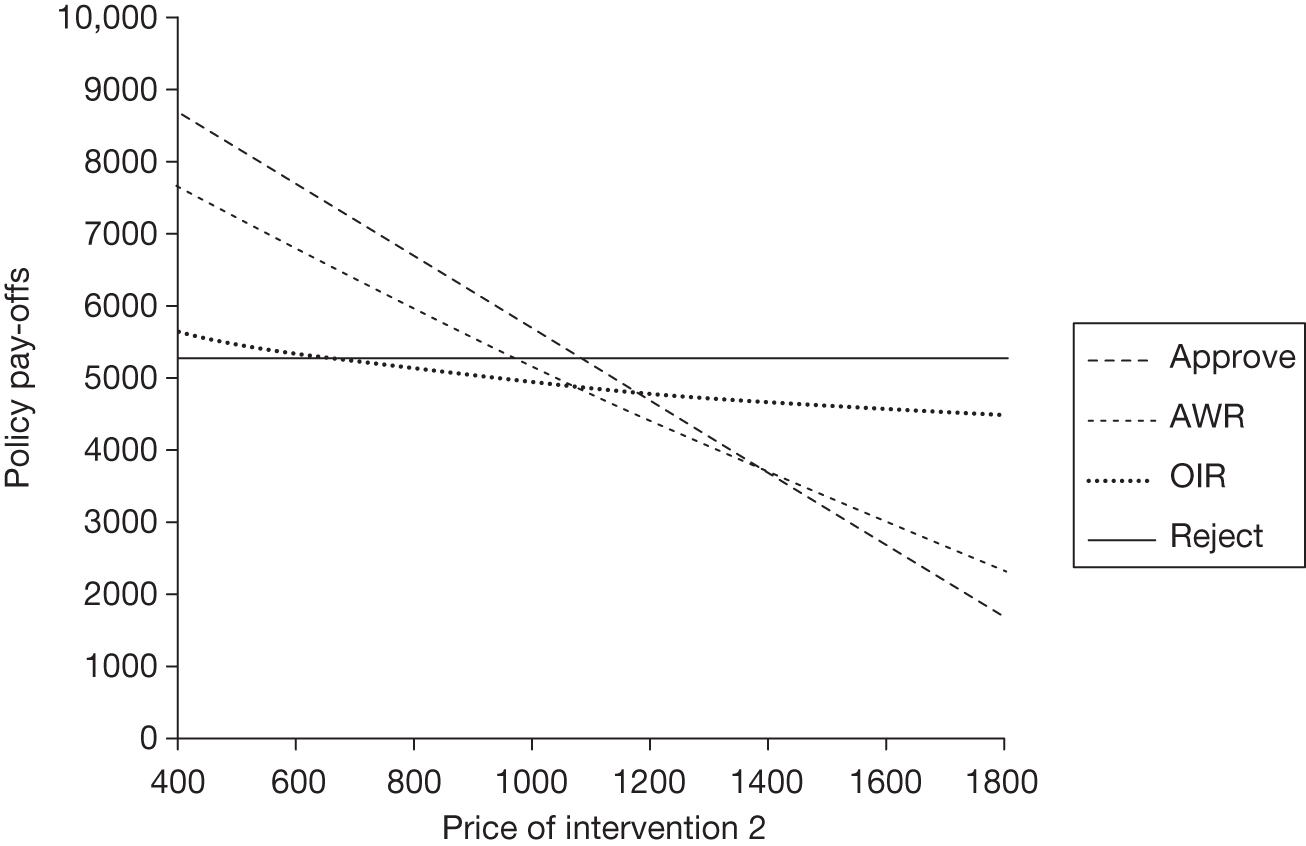

Changes in prices and evidence

The type of guidance that might be appropriate will be influenced by changes in the effective price of the technology, the type of evidence available to support its use and whether or not further research is likely to be undertaken, either by manufacturers or research commissioners, as a result of OIR or AWR guidance.

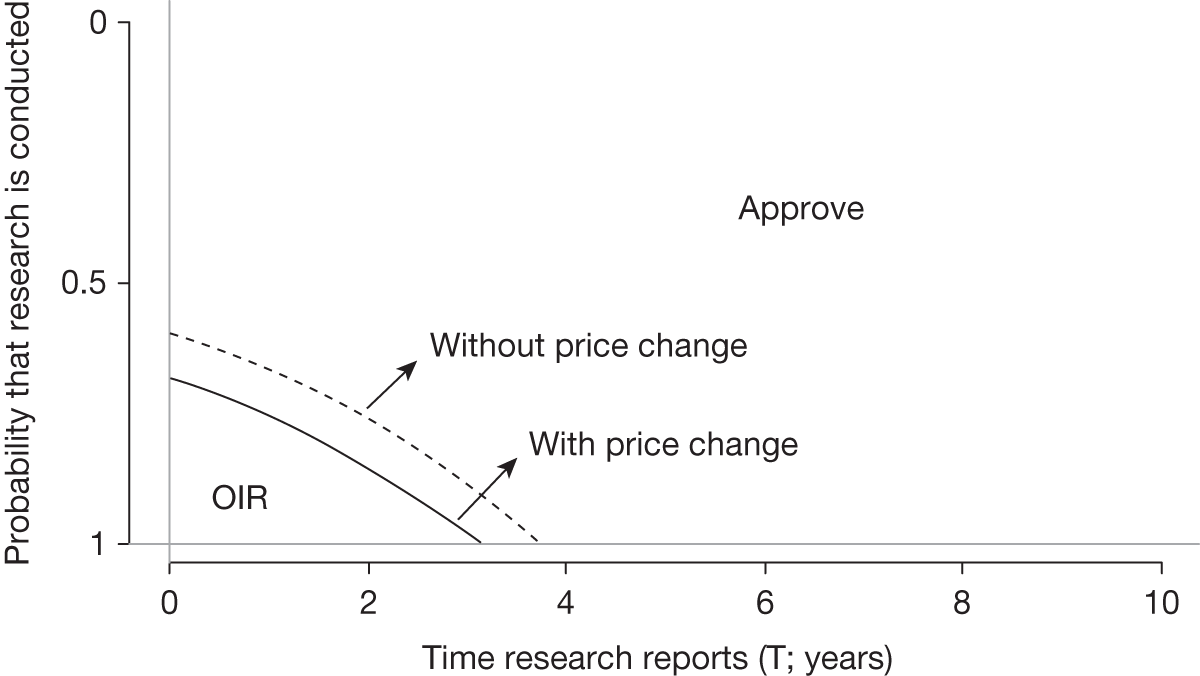

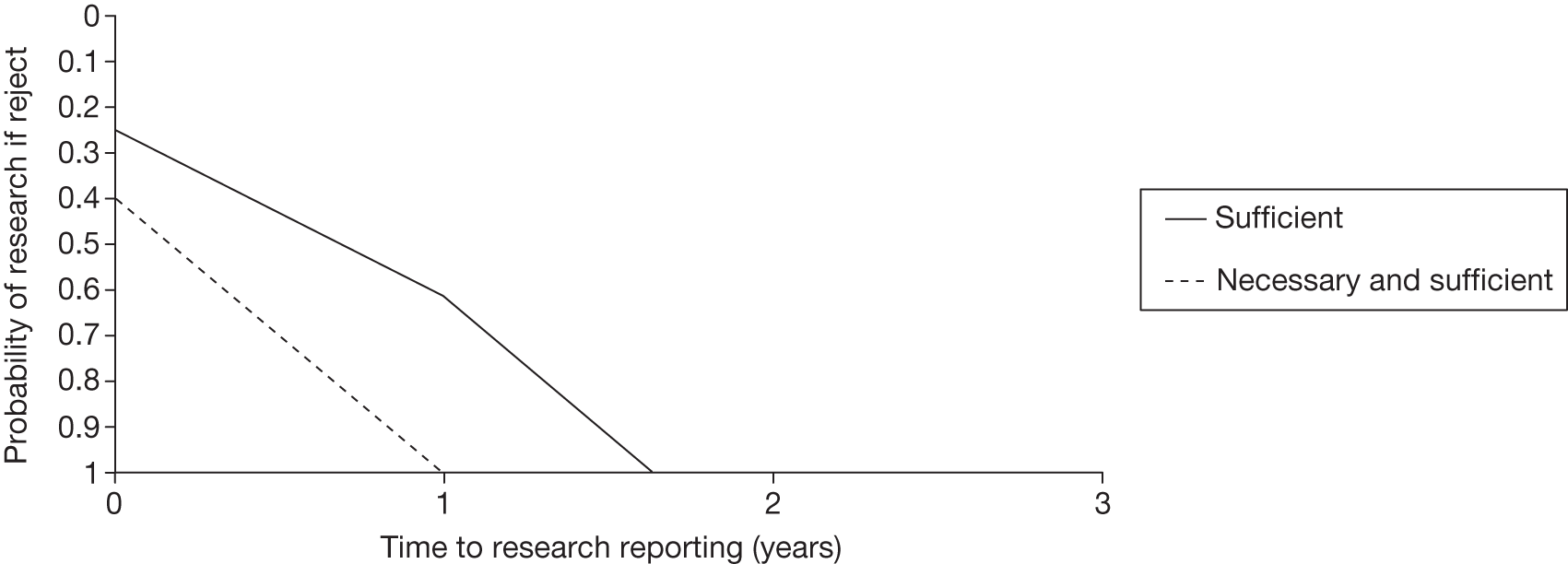

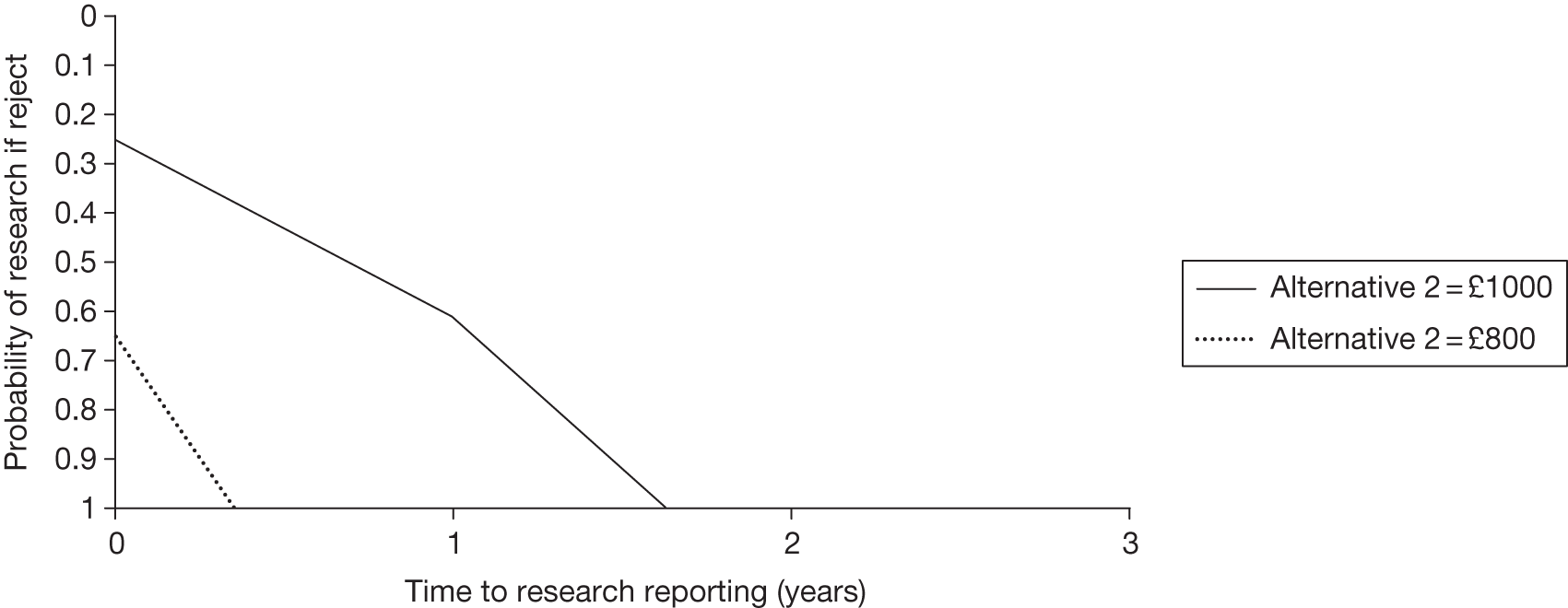

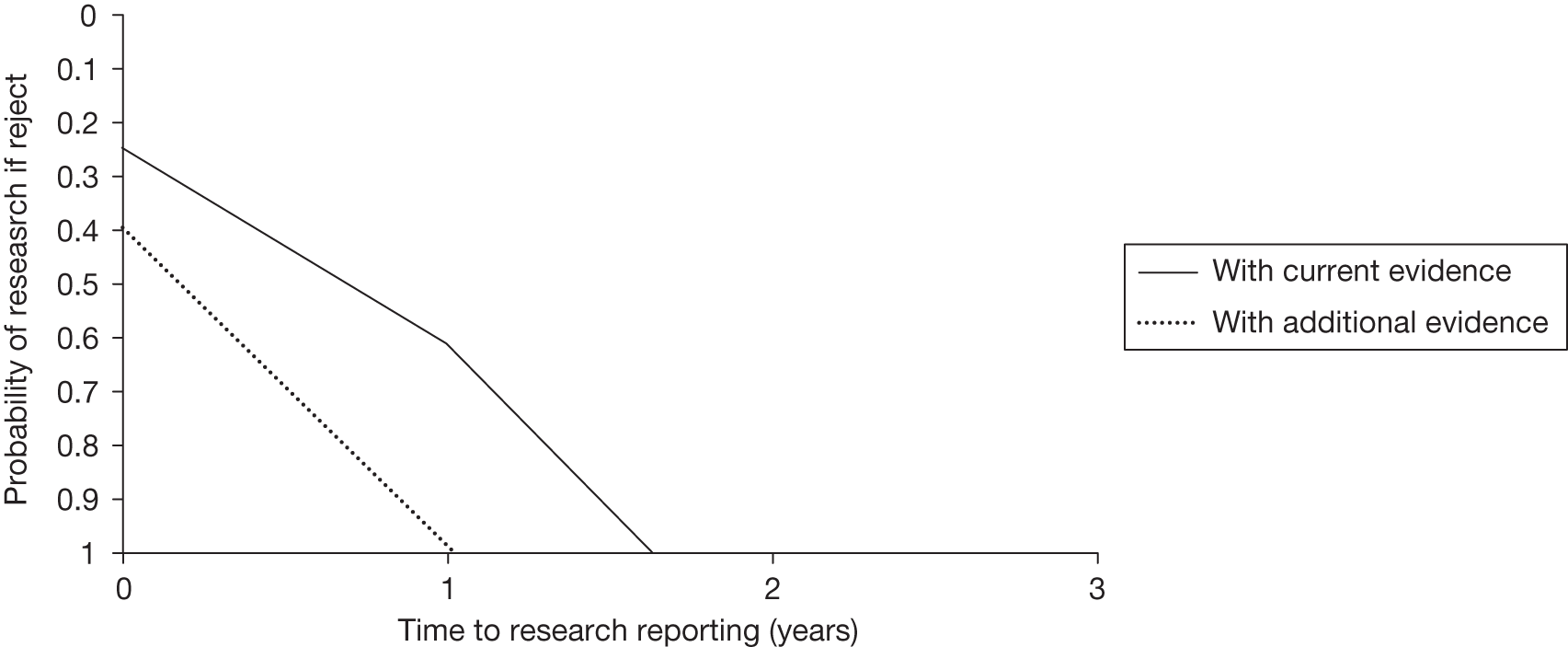

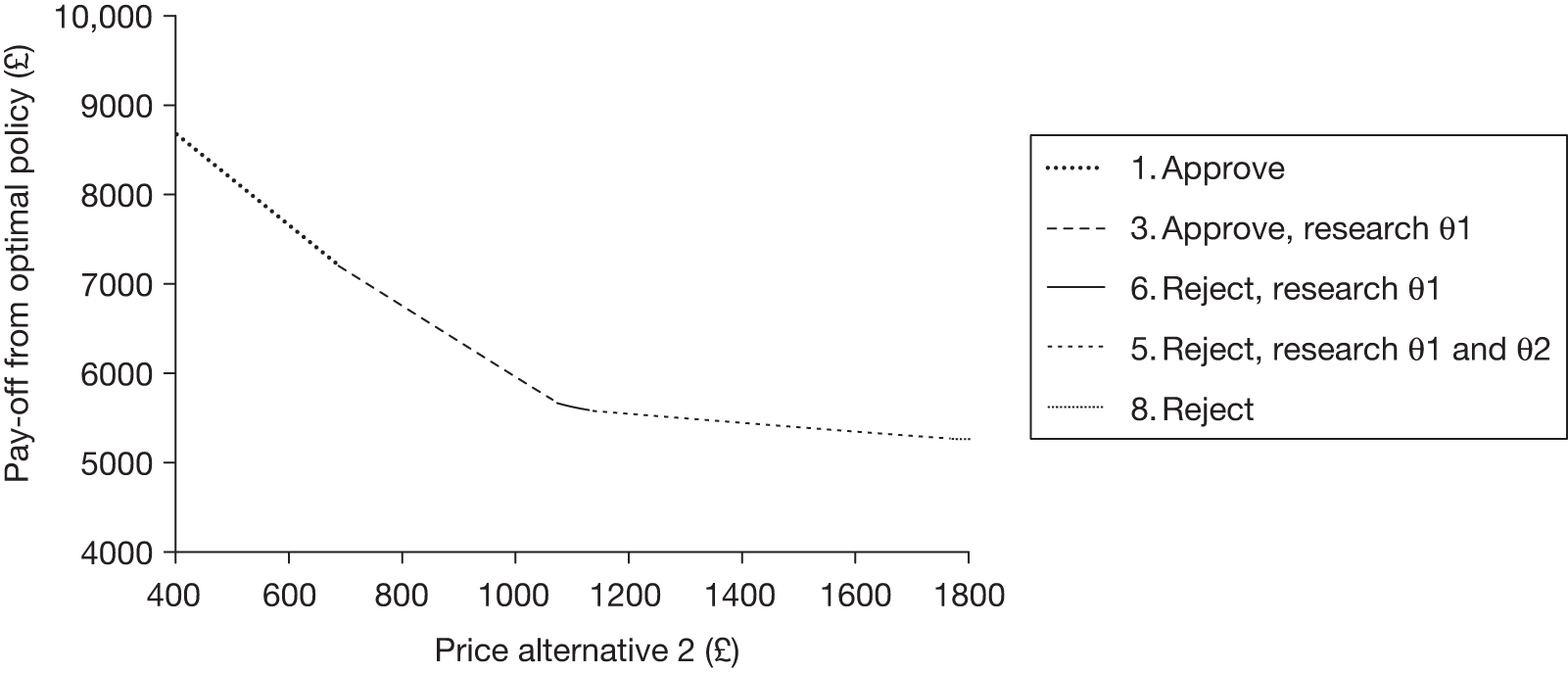

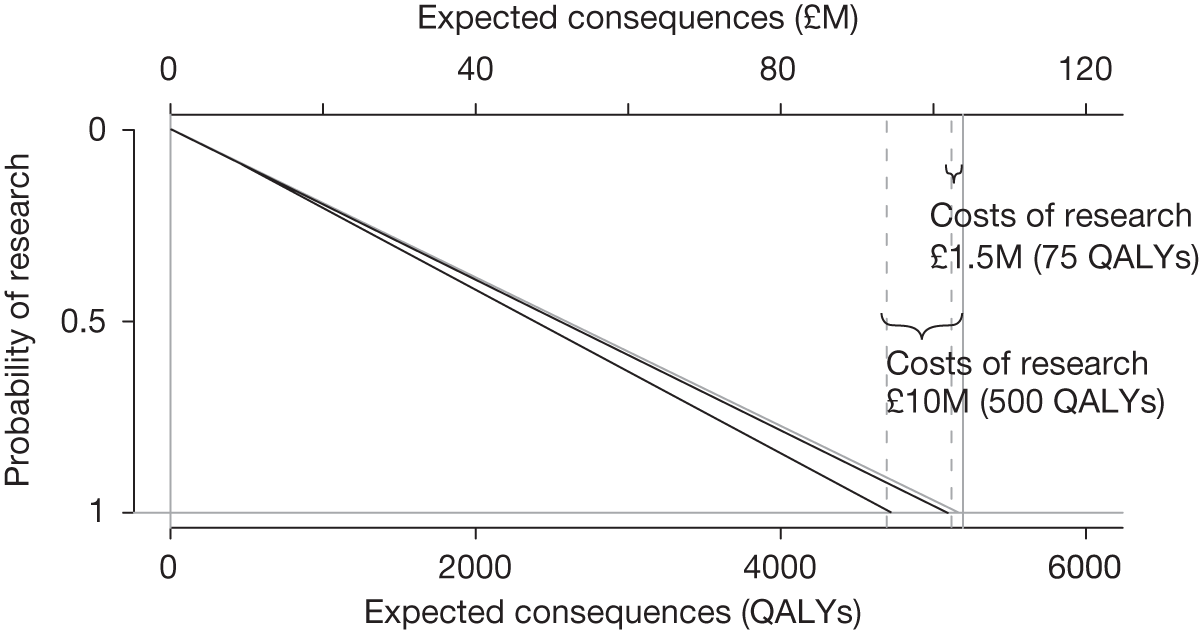

Changes in effective prices

Any change in the effective price of a technology, either through patient access schemes (which offer some form of discount that reduces NHS costs) or direct price changes (possibly negotiated though a future value-based pricing scheme), will affect key assessments and decisions, leading to different ‘paths’ through the algorithm, consequently changing the category of guidance that would be appropriate (Simon Walker, Centre for Health Economics, University of York, UK, July 2011, personal communication). 4,23 For example, provisional OIR guidance for a technology that is expected to be cost-effective might be revised to approve with a sufficient price reduction because the benefits of early approval will be greater and uncertainty about its cost-effectiveness and therefore the value of additional evidence will tend to be lower (e.g. from ‘OIR1’ to ‘Approve2’ in Figure 1). c Similarly, AWR might be revised to approve if the benefits of early approval now exceed the value of additional evidence (e.g. from ‘AWR1’ to ‘Approve2’ in Figure 1). d

Equally, provisional guidance to reject a technology that is not expected to be cost-effective might be revised to OIR if the reduction in price is not sufficient to make it cost-effective but makes the costs associated with a reject decision more uncertain and hence the value of research worthwhile (e.g. from ‘Reject1’ to ‘OIR2’ in Figure 2). e If the reduction in price is greater and sufficient to make the technology cost-effective, then guidance might be revised to AWR if research remains worthwhile and possible with approval (e.g. from ‘Reject1’ or ‘OIR2’ in Figure 2 to ‘AWR1’ in Figure 1). Clearly, with an even greater reduction in price, it is possible that provisional guidance to reject could be altered to early approval (e.g. ‘Approve1’ in Figure 1). Even if research is not possible with approval, a sufficient reduction in price could also lead to early approval (e.g. from ‘Reject1’ or ‘OIR2’ in Figure 2 to ‘Approve2,3,4’ in Figure 1). f

Therefore, consideration of the effect of price changes on OIR and AWR is needed when assessing the potential impact of patient access schemes and more direct price negotiation through value-based pricing. 65,77–79 It should be noted that, all other things being equal, the presence of significant irrecoverable costs will require greater reductions in effective price to achieve the same revision to a more permissive category of guidance.

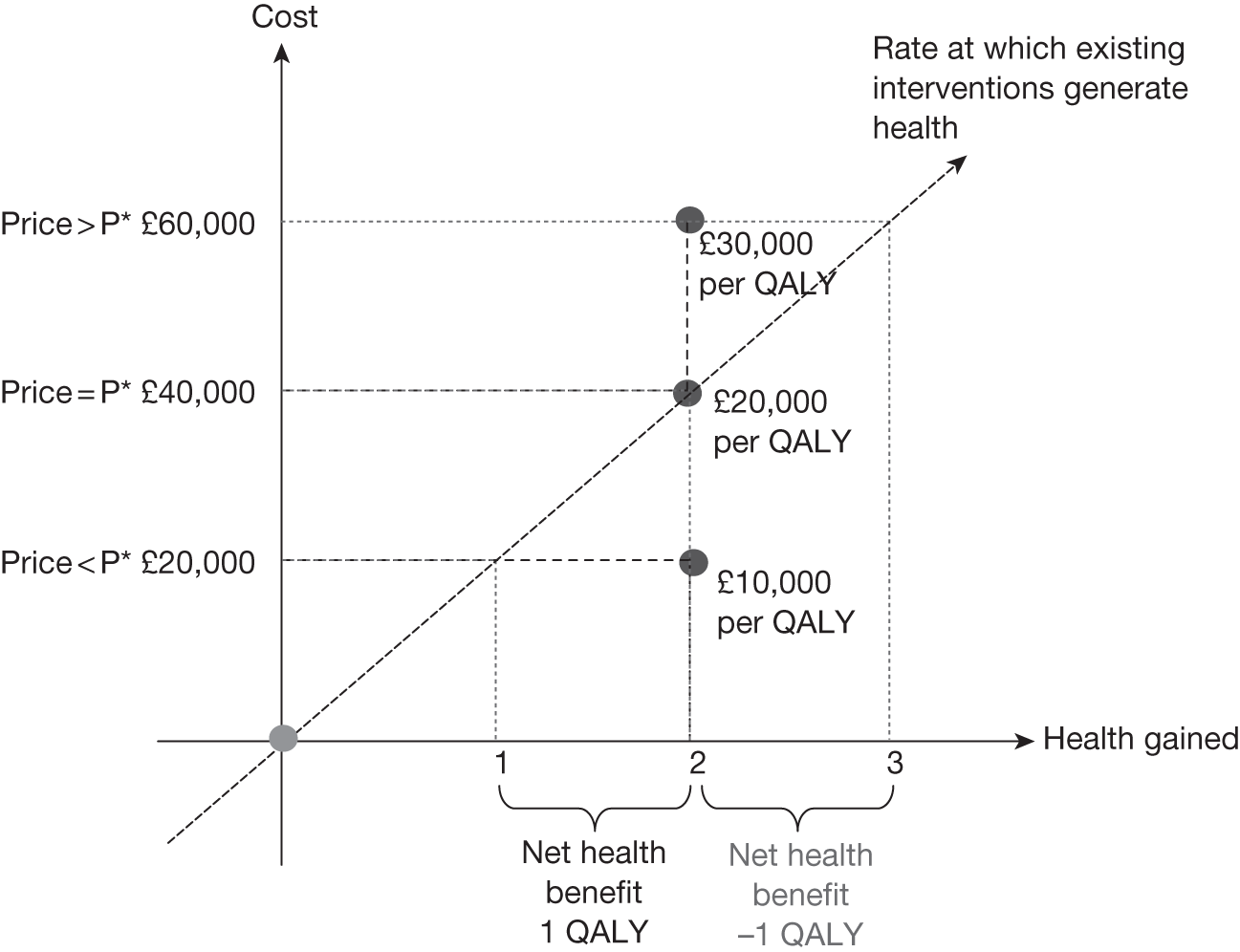

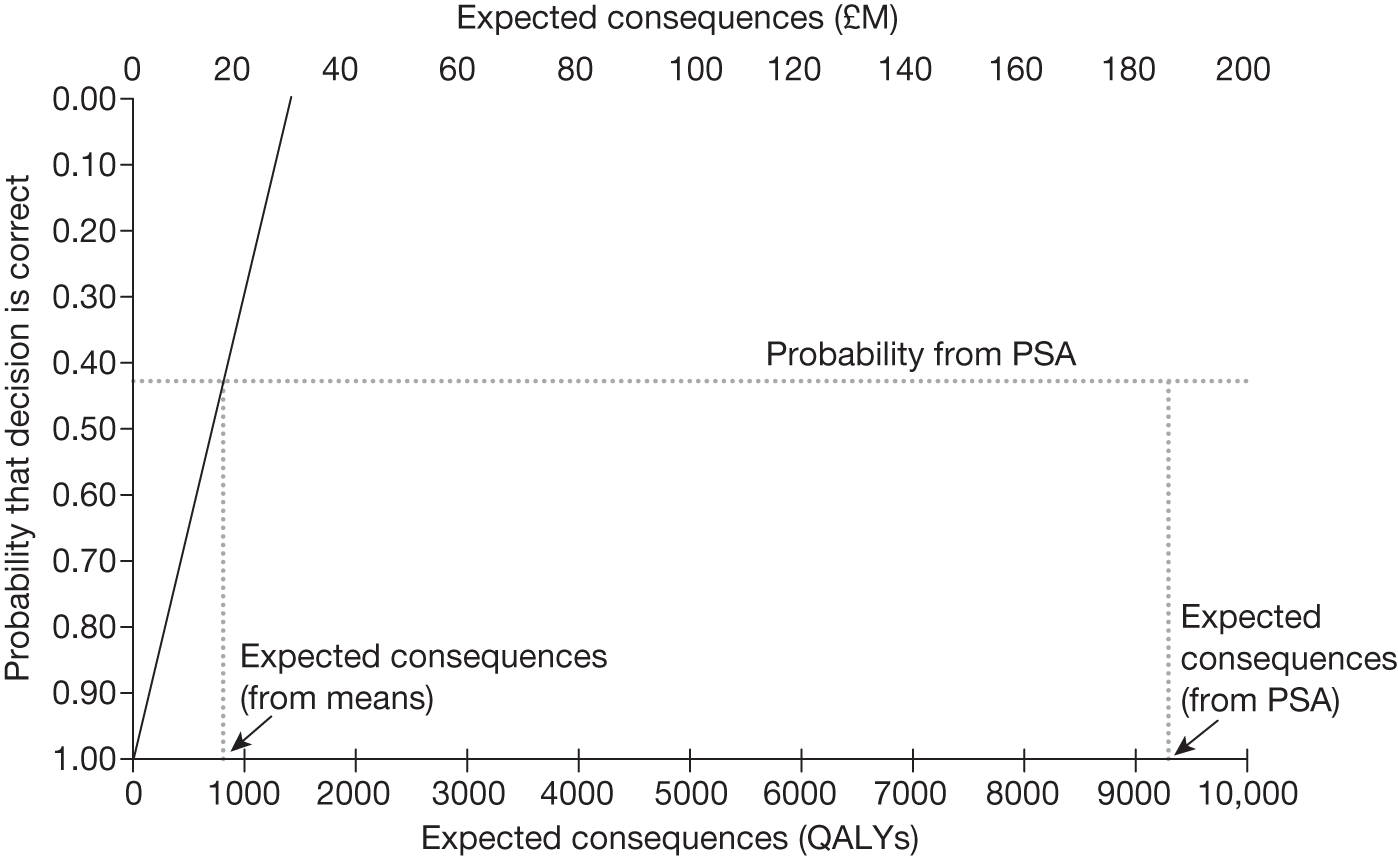

Threshold prices and value-based prices

The price at which the technology would just be expected to be cost-effective is commonly regarded as the value-based price for the technology, that is, the maximum price that the NHS can afford to pay without imposing negative health effects. 65,80 This single price describes the threshold for approve/reject decisions and would be the relevant threshold price when (1) OIR or AWR guidance is not available to the decision-maker or there is no uncertainty in cost-effectiveness or (2) the research, if needed, can be conducted with approval and (3) there are no irrecoverable costs. In all other circumstances there are a number of other threshold (value-based) prices. The number and value of these thresholds depends on the characteristics of the technology (the path through the algorithm); however, the threshold prices for approval will always be lower than the single approve/reject price based on expected cost-effectiveness.

For example, for a technology (without significant irrecoverable costs) for which research could be conducted without approval but not with it, there are two threshold prices: (1) the threshold that would move guidance from reject to OIR and (2) the threshold that would move guidance from OIR to approve. The latter will always be lower than the price that would move the same technology from reject to approve if OIR was excluded from consideration. If a technology also imposes significant irrecoverable costs then there may be more threshold prices. For example, when research can be conducted with or without approval there are three thresholds: (1) reject to OIR, (2) OIR to AWR and (3) AWR to approve. Again, (3) will be lower than the approve/reject threshold for the same technology if AWR was excluded from consideration. All other things being equal the presence of irrecoverable costs will tend to reduce the threshold price for approval.

Even in circumstances in which price negotiation becomes possible alongside NICE appraisal, it will be important to retain the OIR and AWR as available categories of guidance for two reasons. First, there is no guarantee that manufacturers will always agree to the lower price threshold that would lead to approval rather than OIR or AWR. Second, and possibly more importantly, there may be many circumstances when there is no effective price reduction that would make approval appropriate. g For example, reject or OIR guidance may still be appropriate even if the effective price of a technology is zero if there is substantial uncertainty about its effectiveness and/or potential for harms.

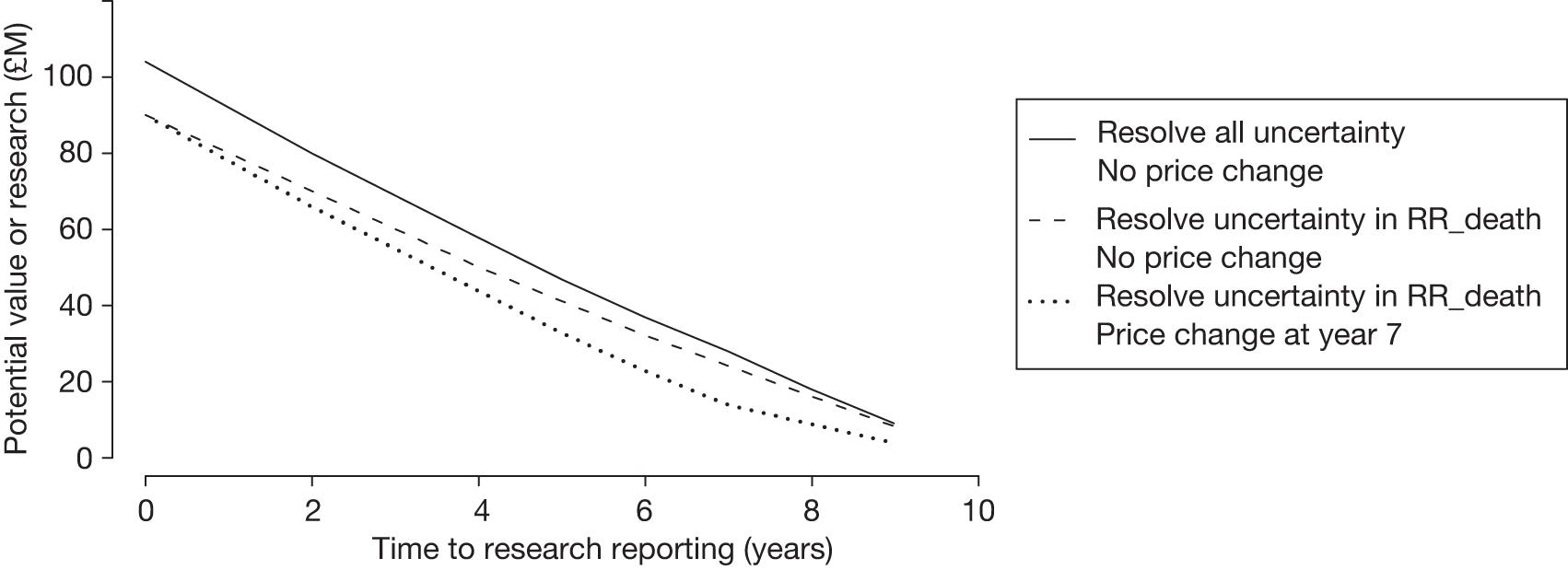

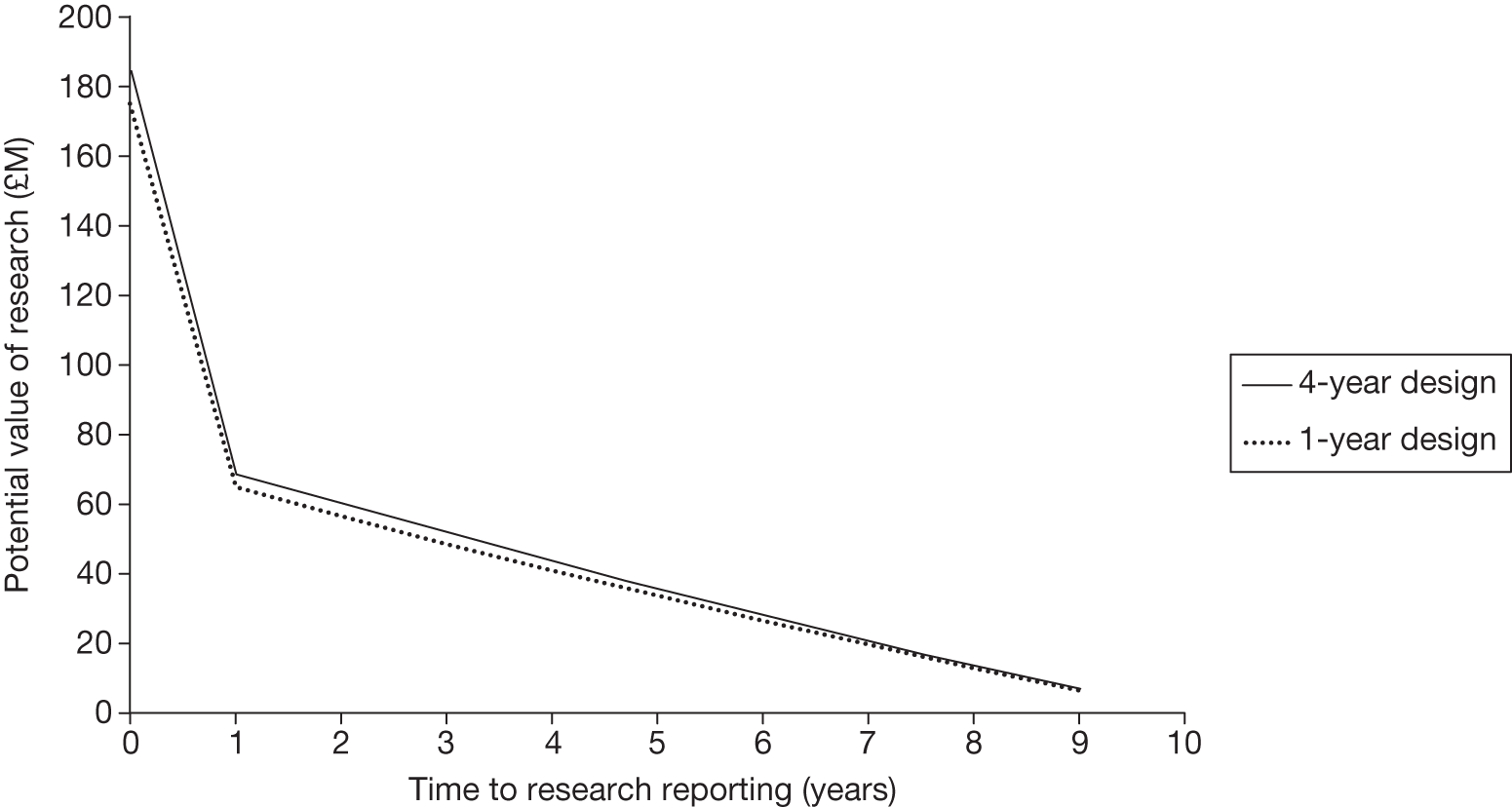

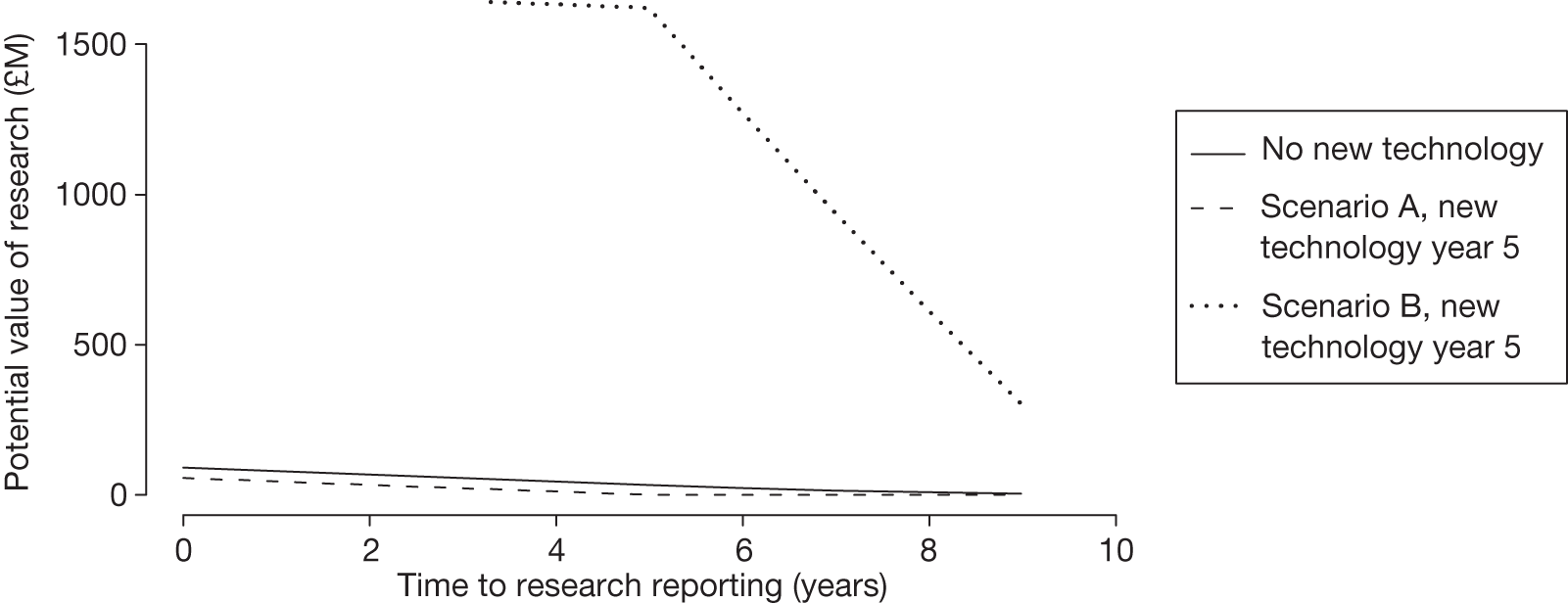

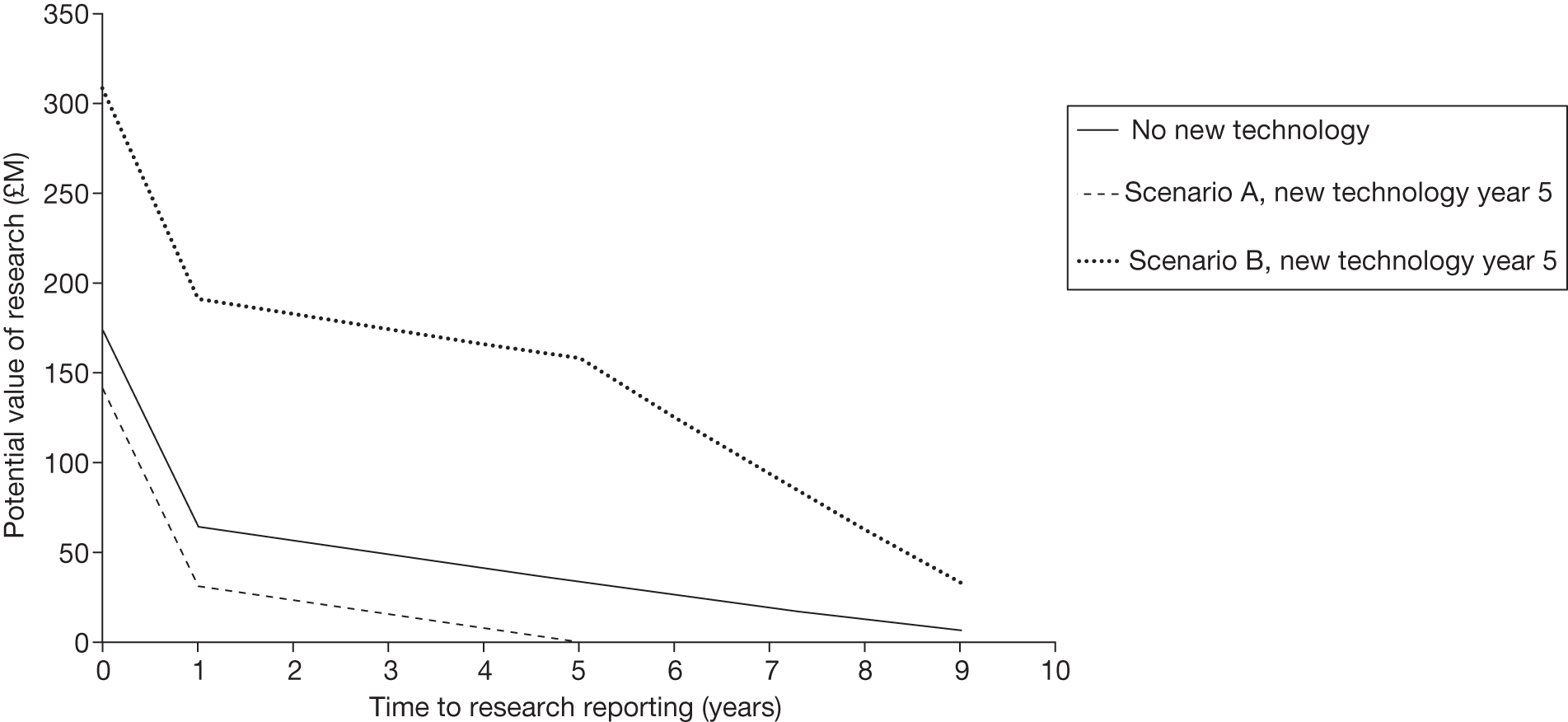

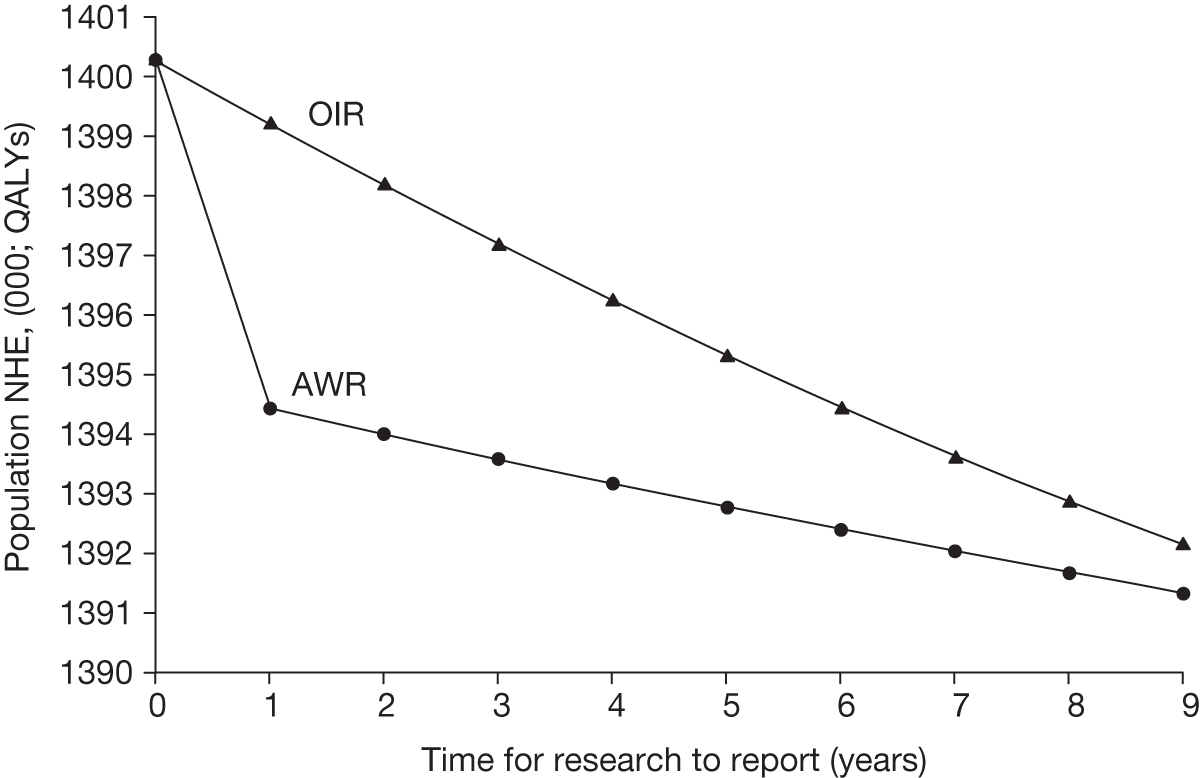

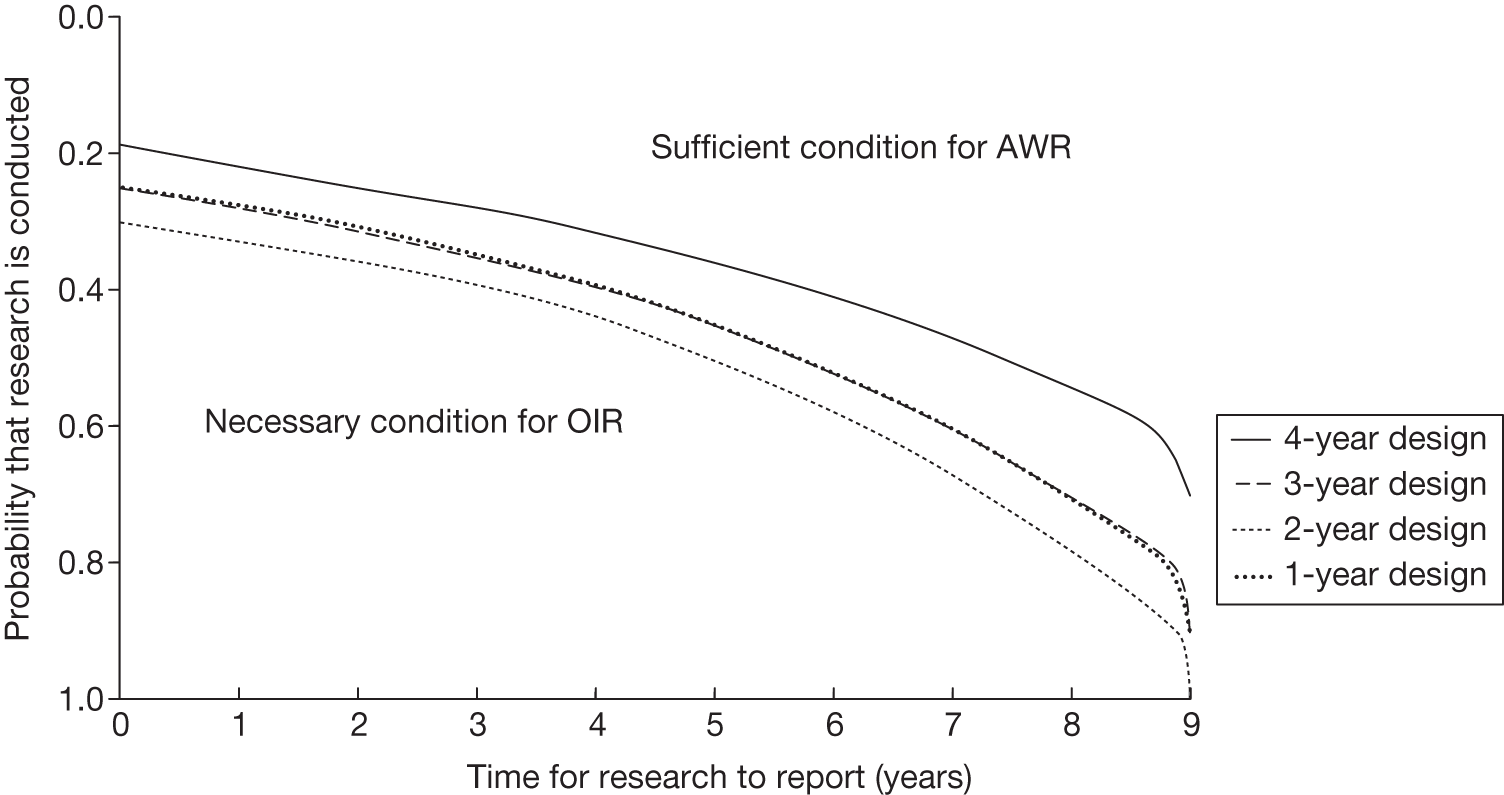

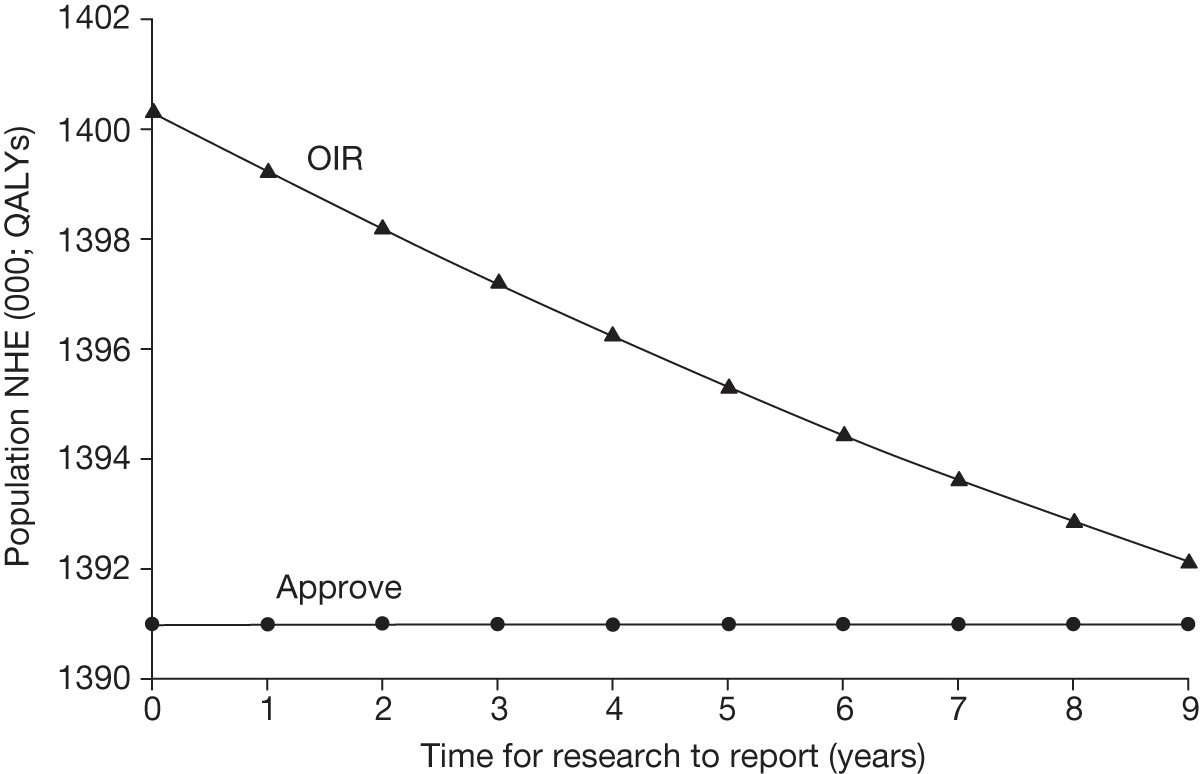

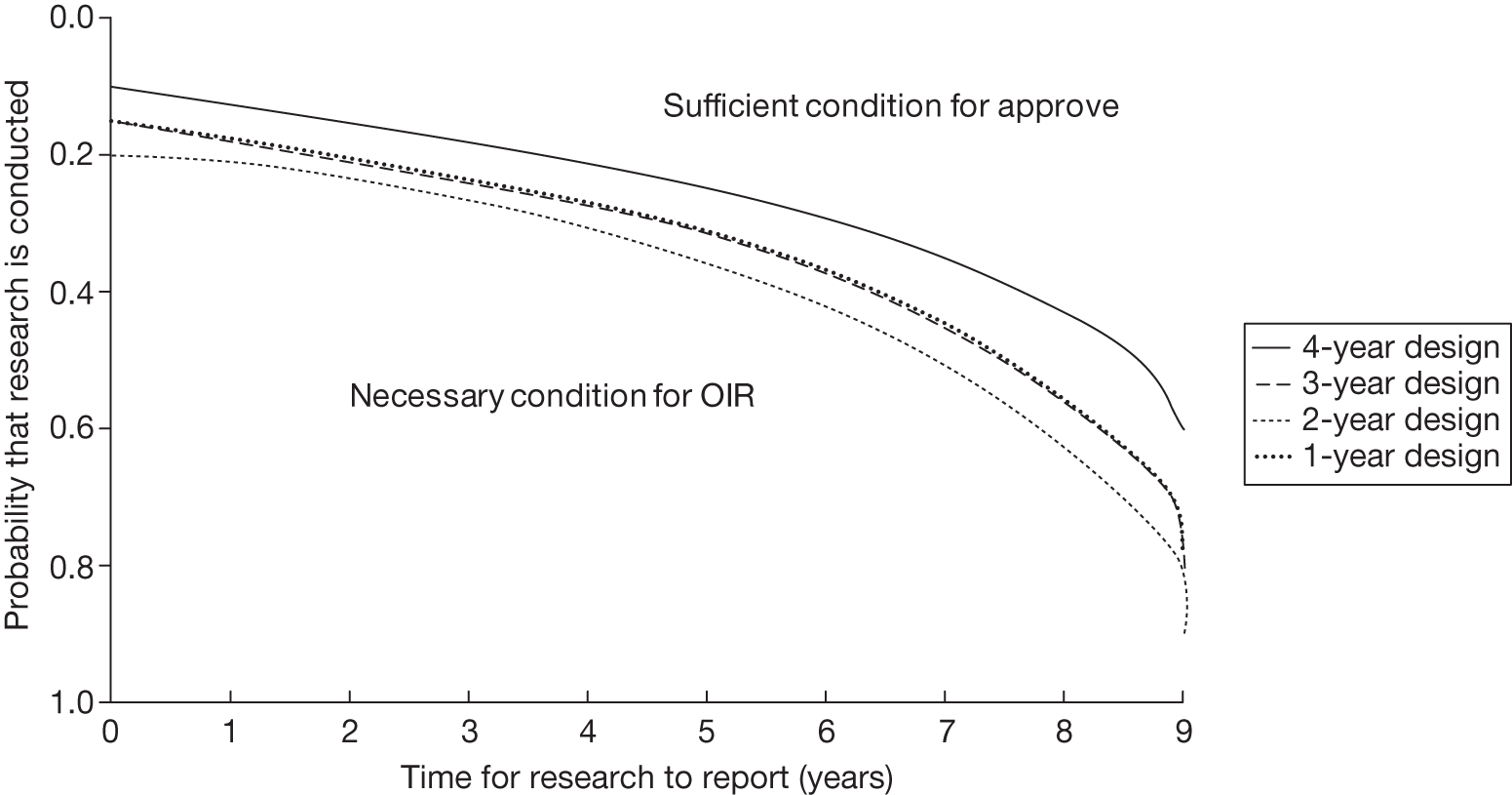

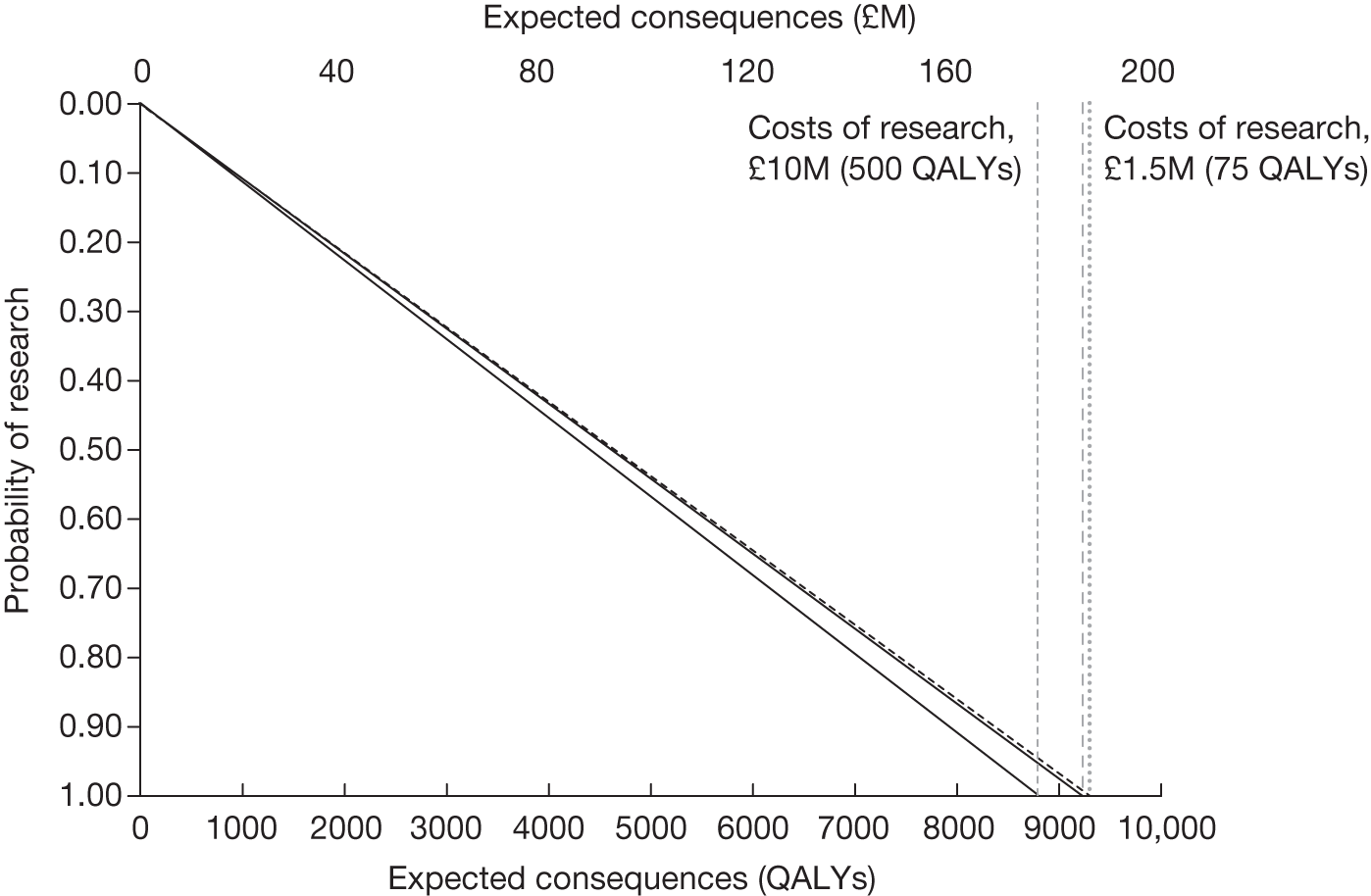

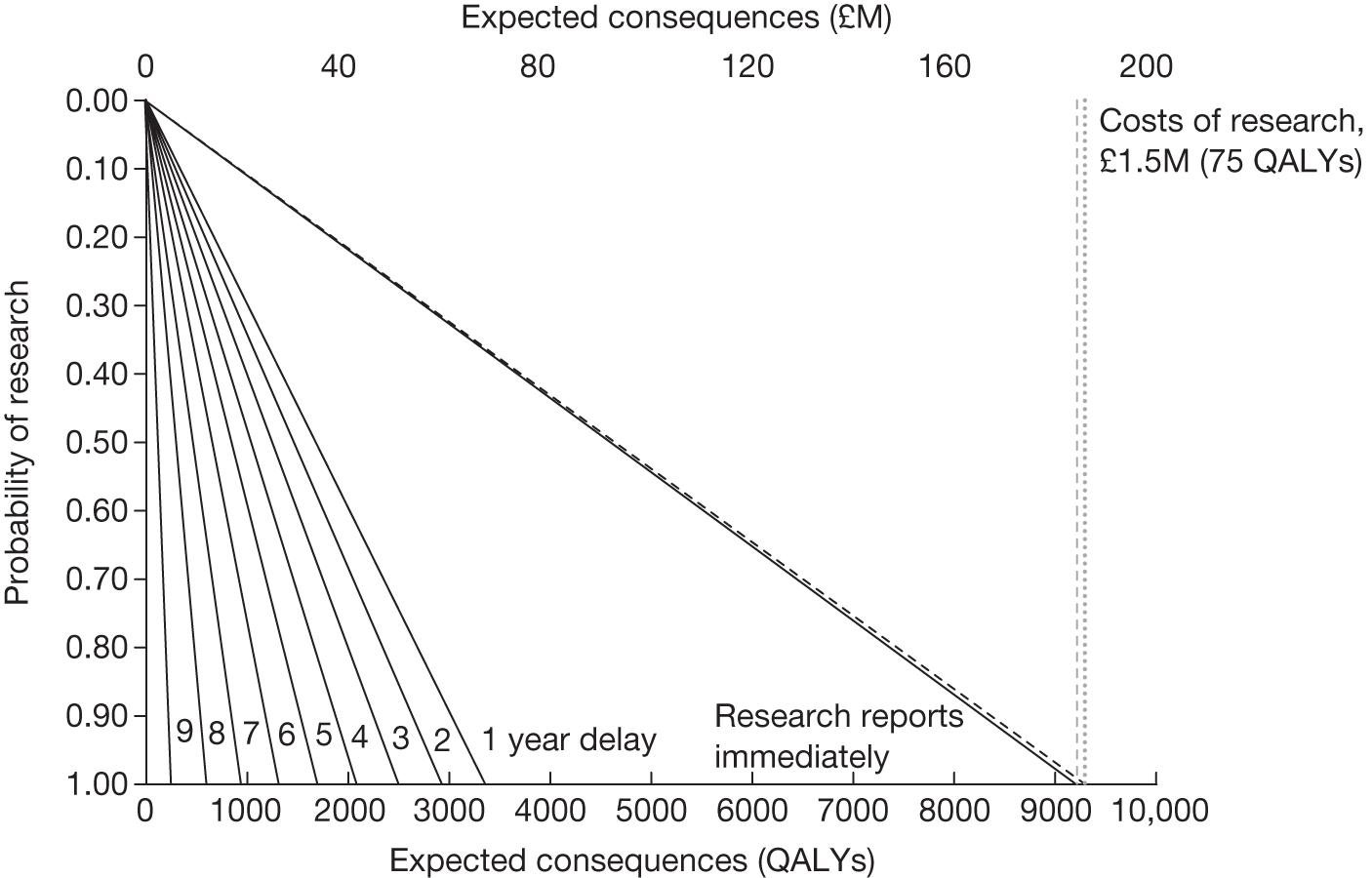

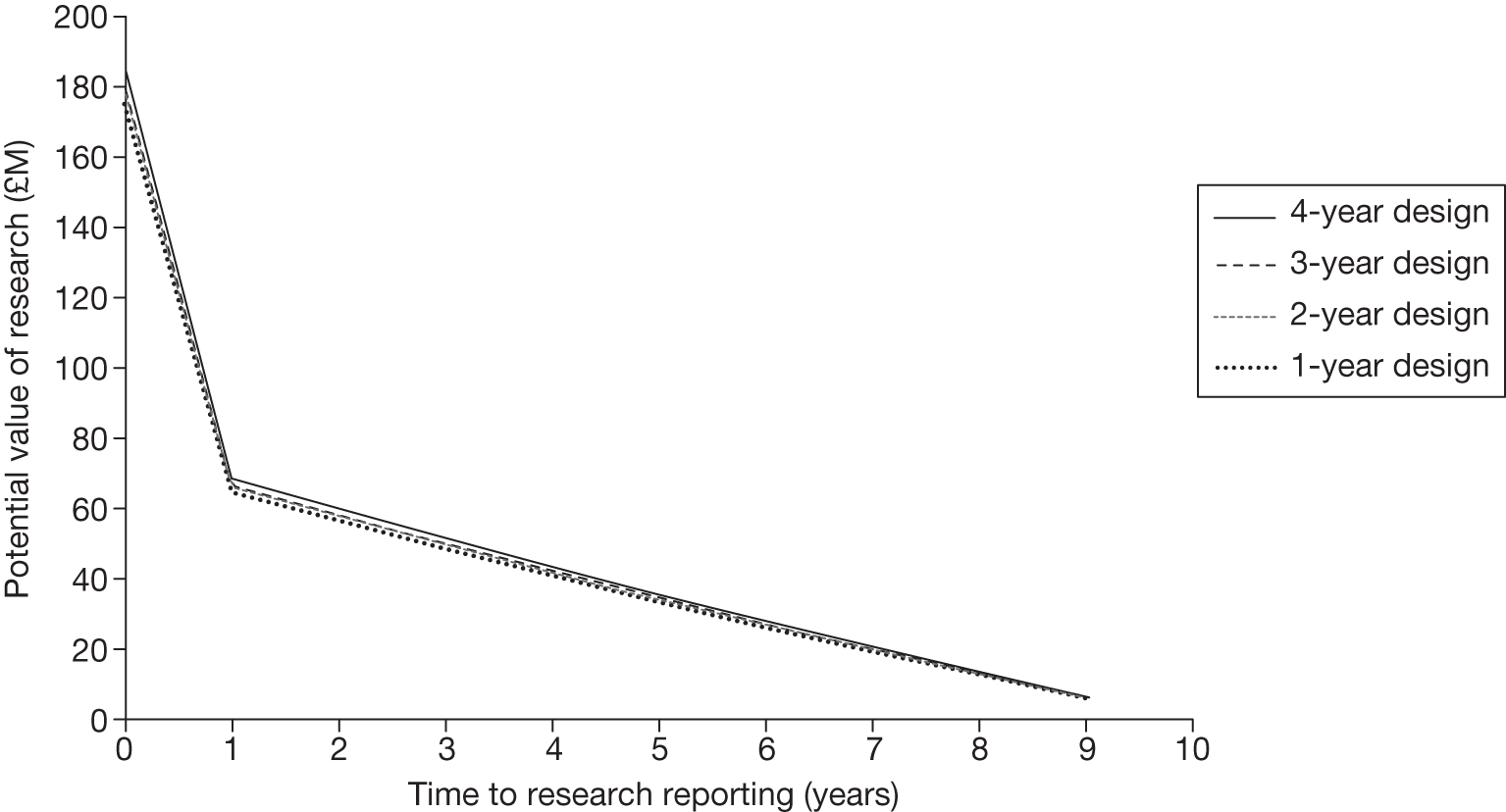

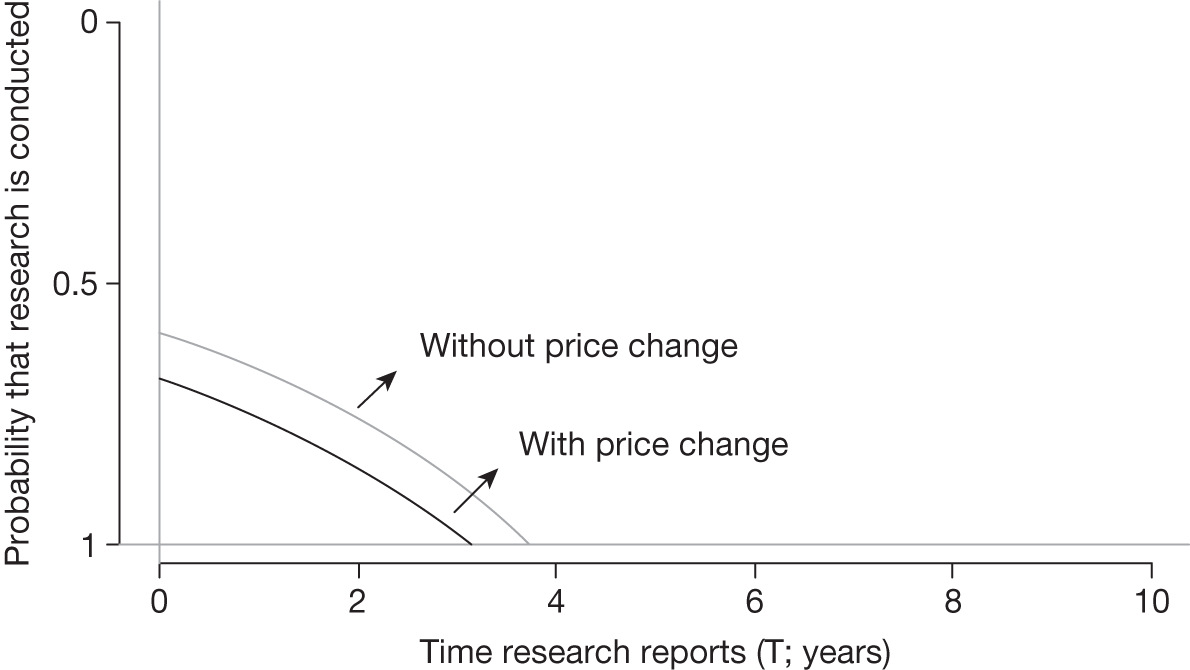

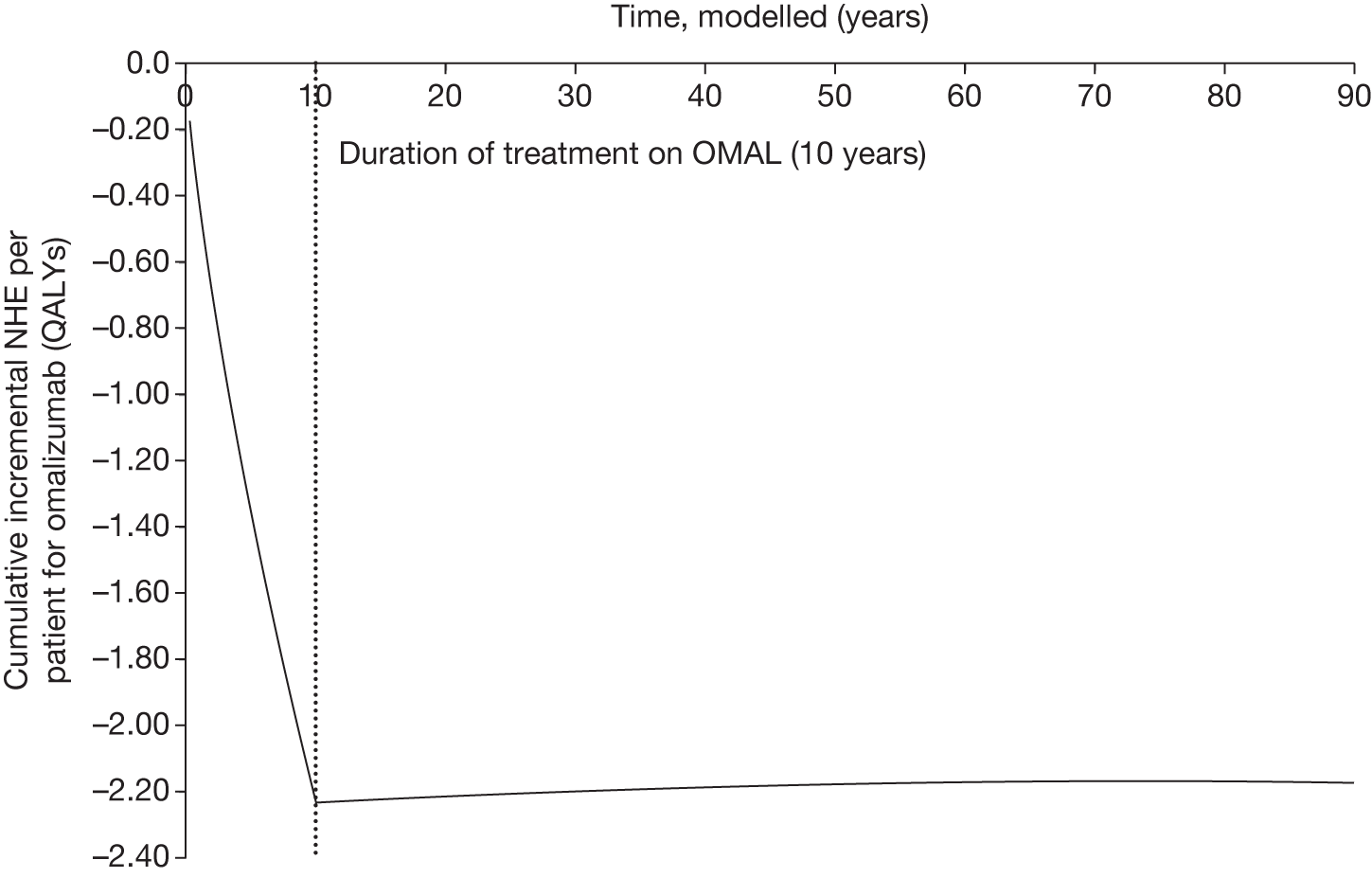

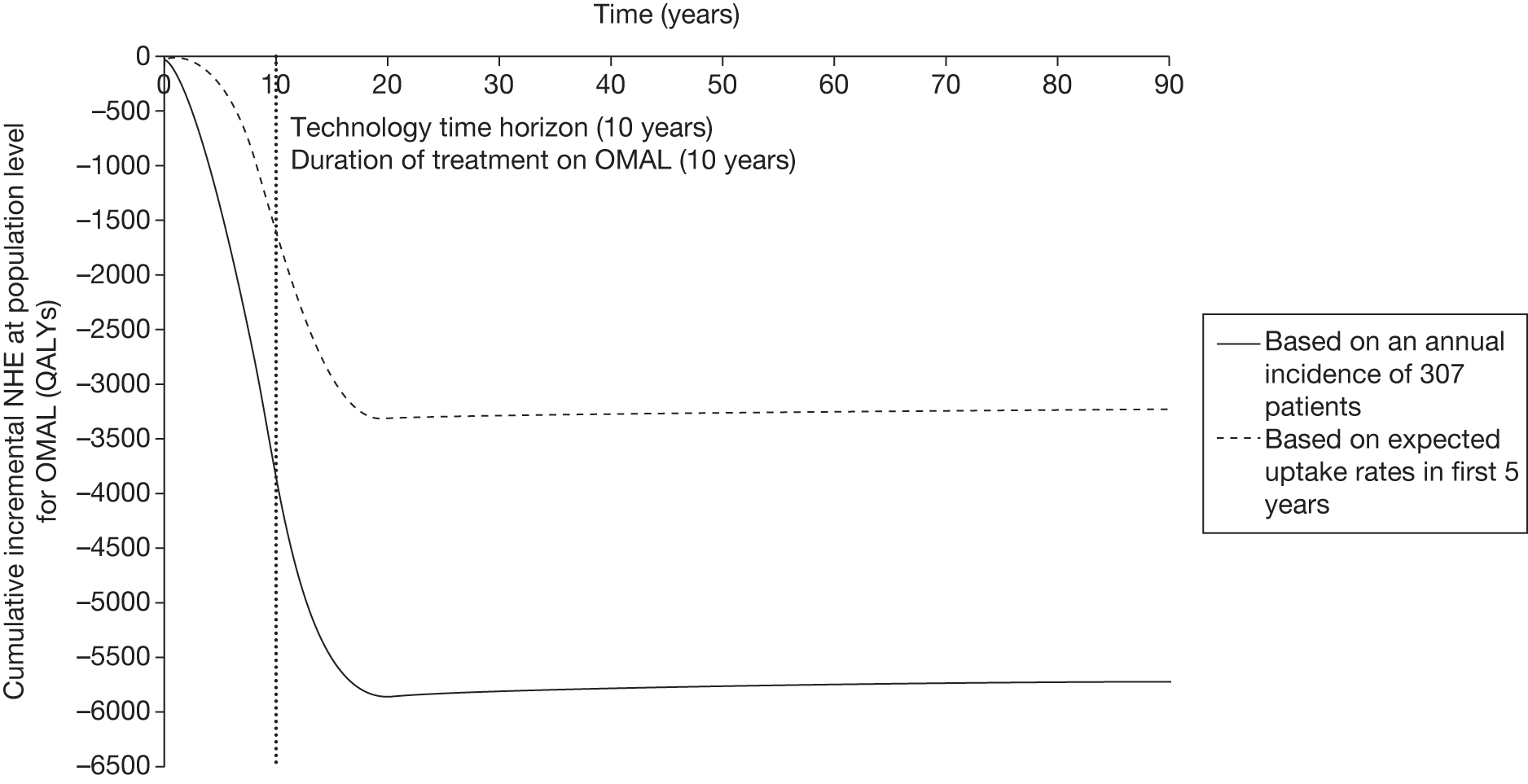

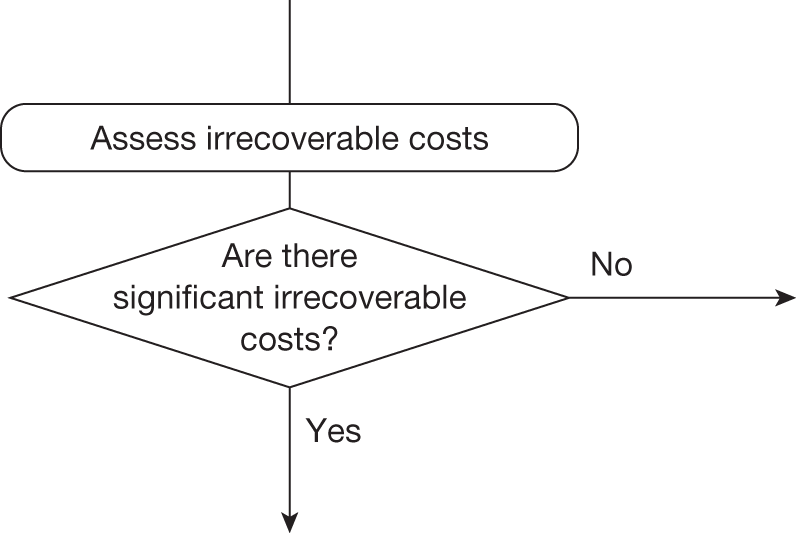

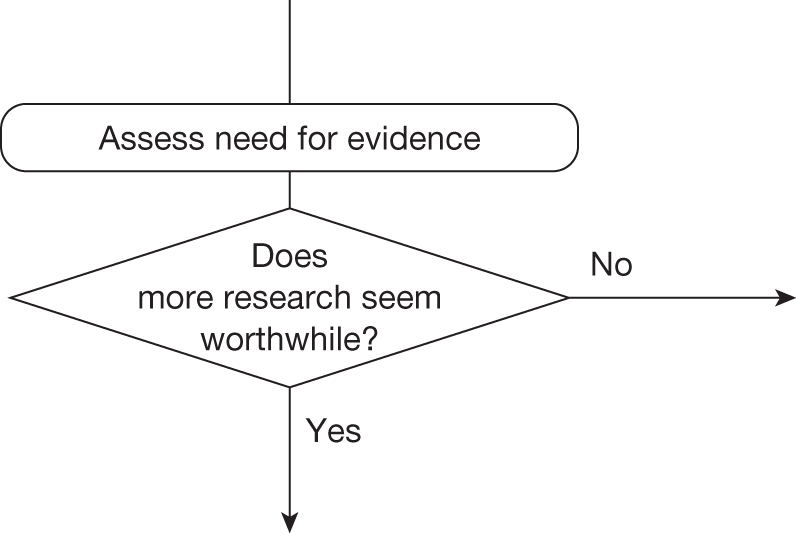

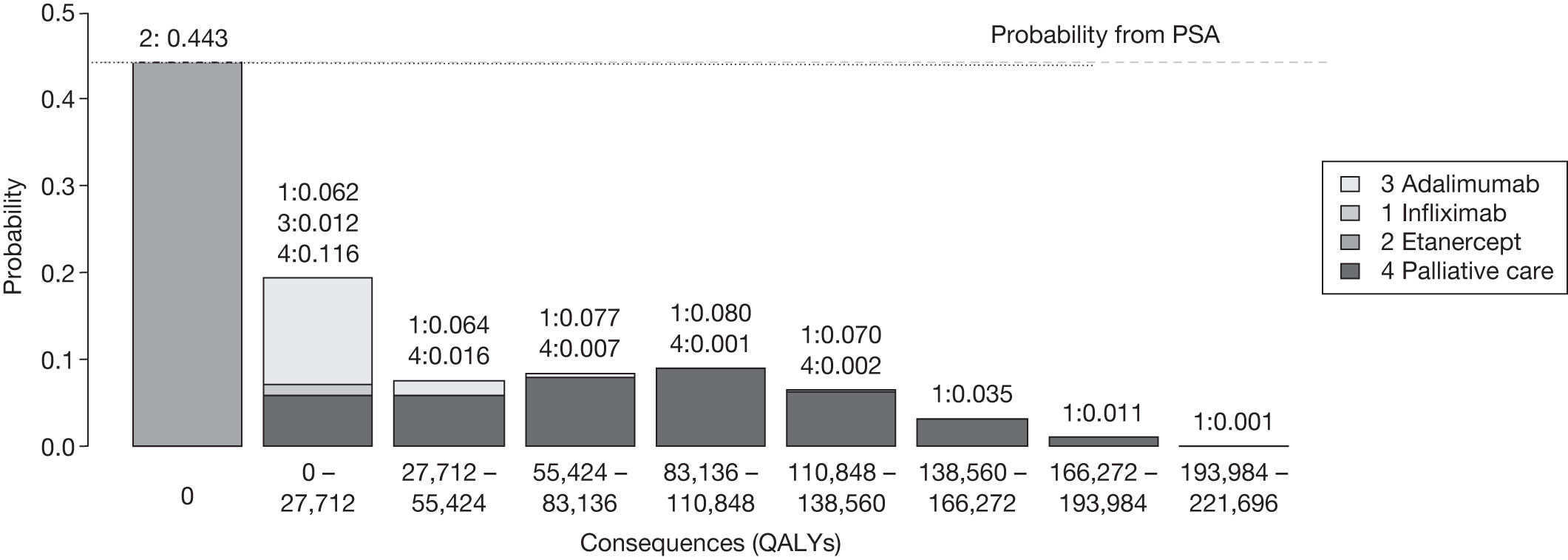

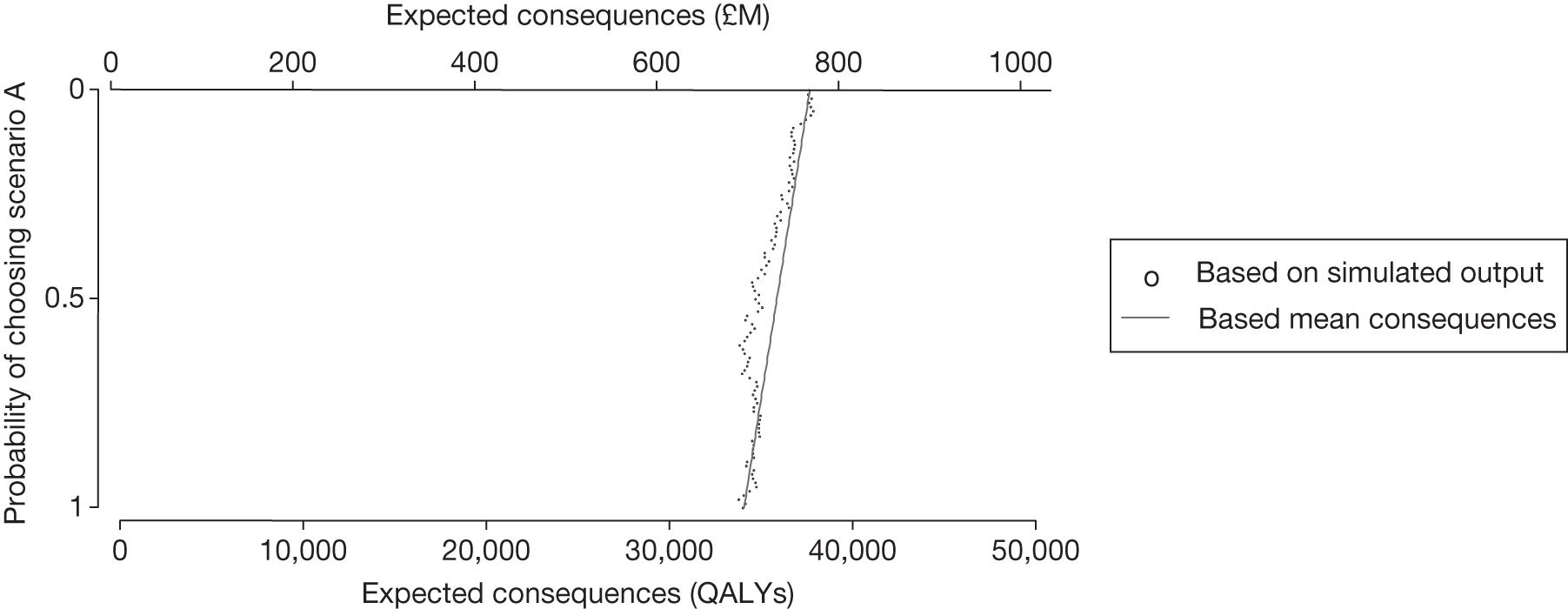

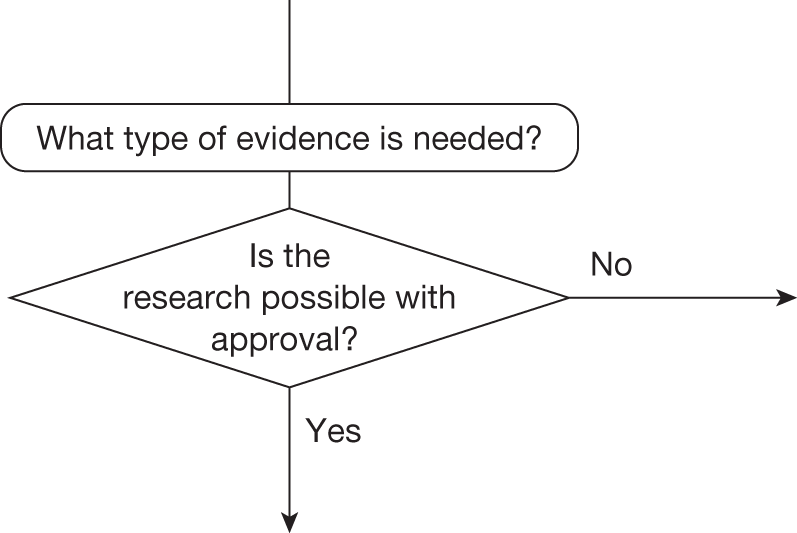

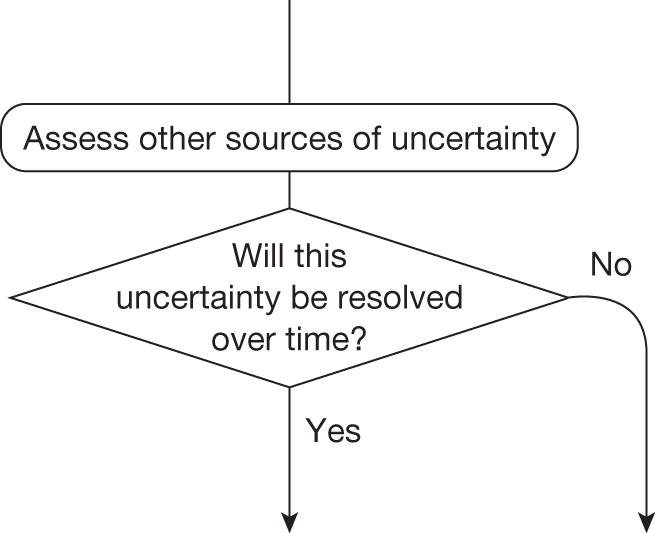

Incentives for evaluative research