Notes

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/02/01. The contractual start date was in February 2008. The draft report began editorial review in January 2012 and was accepted for publication in July 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Underwood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Care homes

The population of Britain, like that of other countries, is ageing. The biggest change for health and social care systems is the expansion in the number of the oldest old (aged ≥ 85 years). In mid-2010, there were 1,410,700 people aged ≥ 85 years in the UK1 – an increase from 600,000 in 1981. Increasing age is associated with increasing disability. This large burden of illness and disability inevitably places huge demands on health and social care services. One consequence of this is an increase in demand for long-term care for the oldest old, which, despite the increased emphasis on community care,2 will remain a necessary component of health and social care provision. 3,4

Even the most optimistic projections for increasing quantity and quality of care in the community leave society facing the prospect of greatly increased numbers of older people in care homes. 4 There are 18,000–19,000 care homes in England with a capacity of 450,000–469,000 places; the majority of places are residential, not involving specialist nursing care. 5,6 Nearly 90% of residents in care homes require care because of disability from long-term conditions, 72% have mobility problems, and 62% are described as confused. 7 Concerns exist about the standards of care received by care home residents. 6,8 Care standards introduced by the Care Quality Commission9 for all care homes in England and Wales in 2011 defined minimum standards of care. These include overriding principles including that residents will be told what is happening to them; that they will receive care and support to meet their needs; that they can expect to be safe; that they will be cared for by qualified staff; and that their care will be constantly checked. The care home business has some inherent instabilities. The Care Quality Commission's 2011 report6 on the state of health care and adult social care in England identified substantial potential for improving the quality of care homes. Even quite modest improvements in mental and physical health are likely to produce large relative increases in the number of quality-adjusted life-years available to this group, which has an extremely poor baseline level of health and life expectancy.

As much of this long-term care provision is in the private sector, and privately funded, one might question the National Health Service's interest in this area. The financial collapse of the Southern Cross Group in 2011, however, emphasises the over-riding role of the state in sponsoring an ostensibly private sector of the economy; what happens in care homes is everybody's business. 10 Large chains of care homes report that between 40% and 75% of their residents are state funded. 11

There is a clear need for more high-quality research to identify effective and cost-effective approaches that can improve the quality of life of care home residents. Because of the very large numbers of National Health Service patients in this sector, and their major health problems, it is an appropriate area for health services research.

Care home terminology

At the time this study was designed the terms residential home and nursing home were used to distinguish between residential facilities that did, or did not, provide nursing care. Since then, the terminology has changed to care homes with, or without, nursing. All of our study materials and our protocol papers used the old terminology. 12,13 The results of this study will be interpreted within the current terminology. Henceforth, we will use the terms care homes with, or without nursing, in preference to the terms residential home and nursing home except when the older terms are critical in understanding the work or when we are reporting work by others and use their original terminology.

Depression in care home residents

Untreated depression is a major cause of morbidity in older people, particularly in those who live in care homes. Up to 40% of care home residents meet criteria for significant depression on validated depression symptom scales. 14,15 Incidence rates for depression in care home residents are typically 6–12% per year for major depression,16–18 with persistence of depression among people already depressed also a major contributor to the burden of morbidity. 19

Multiple physical morbidities are expected in care home residents20 and there is often a lack of social interaction among those living in nursing homes. 21 There is good evidence that both functional impairment and loneliness are risk factors for depression in care home residents. 22

In many cases depression is not recognised by the care home staff or by the resident's general practitioner23–25 and, even if recognised, it is often not treated. 26 Using various depression identification methods, only between 15% and 27% of depressed residents were identified by staff in 30 UK care homes. 27 Evidence from the USA, in contrast, suggests substantial increases in the diagnosis of depression among nursing home residents28 and in the rates of prescription of antidepressants among nursing home residents. 28,29 This matters because depression is an important, independent predictor of adverse outcomes in older people. Among older people living in the community, depression is an independent predictor of both admission to care homes and death. 30–33 Furthermore, in care home residents, it is an independent predictor of more rapid cognitive decline,34 increased medical service use35 and death. 18,27 For people with dementia living in care homes, depressive symptoms are the most important single influence on their quality of life. 36 In care homes, the likelihood of persistence of depression has been shown to be between 45%18 and 63%. 35 Depression is therefore an important target for interventions within care homes.

Approaches to managing depression among care home residents include staff training in detection,25 multifaceted interventions involving highly qualified specialists,15 adaptations of cognitive behavioural therapy for care home populations,37 antidepressant medication and exercise. The evidence that exercise has a beneficial effect on depression in older people with dementia is limited. 38 Antidepressant medication has attractions and there is some evidence of increased use in care homes, especially in the USA. 28,29 Evidence for the efficacy of antidepressants remains modest in this patient group, whereas they have major potential for adverse events due to comorbidity20 and direct toxicity; for example, there is a twofold increase in falls in those taking tricyclic or selective serotonin re-uptake inhibitor (SSRI) antidepressants. 39 Reducing the burden of depression in care home residents, by using a conventional medical model of diagnosis and drug treatment, is likely to fail, at least in the UK, because of poor recognition, low intervention rates and the toxicity of medications. More generally there is a move away from drug treatment for mild/moderate depression. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines do not recommend drug treatment for mild depression; they suggest that drugs should be used only as part of a more holistic package of care for those with moderate depression. 40 Specifically for the elderly, the guidelines recommend that their poor physical state and social isolation should be addressed. 40 Interventions that may address these multiple requirements are therefore needed. Exercise shows promise as a non-drug intervention that may be helpful for depression.

Exercise/activity as treatment for depression

Evidence for the use of the structured exercise programme

Physical activity is ‘any bodily movement produced by skeletal muscles that results in caloric expenditure’. 41 Exercise is a subcategory of physical activity; it is planned, structured, repetitive and results in improvement or maintenance of one or more facets of physical fitness. There are several types of exercise, including aerobic exercise (submaximal, rhythmic, repetitive exercise of large muscle groups, during which the needed energy is supplied by inspired oxygen) and resistance exercise (any form of active exercise in which a dynamic or static muscular contraction is resisted by an outside force). 42

The endorphin hypothesis suggests that physical activity and exercise cause an increase in the release of ß-endorphins, believed to be related to a positive mood and an enhanced sense of well-being. 43 Although it was originally thought that these ß-endorphins could not cross the blood–brain barrier,44 the endogenous release of central opioids with strenuous exercise may directly account for the sensations of euphoria associated with this type of exercise. 45 Some of the endorphin-related effects may be elicited during aerobic physical activity via an increased discharge from the mechanosensitive nerve fibres within contracting skeletal muscles. 46,47 The level of these increases in endorphins also appears to be directly related to the use of more intense resistance exercise. 48

The monoamine hypothesis suggests that exercise leads to an increase in the availability of brain neurotransmitters (such as serotonin, dopamine and noradrenaline) that are often decreased in depression. 43,47 Exercise also appears to cause increases in levels of monoamines in the blood and urine, and may do so centrally. This theory is based on animal work, and the connection to central increases in monoamines following exercise in humans is as yet unproven. 43

Neurotrophins, especially brain-derived neurotrophic factor, can counteract the hippocampal atrophy that appears to be associated with the high plasma cortisol levels seen in stress and depression,49 and may make the brain more resistant to stress. Neurotrophins are a family of closely related proteins that control many aspects of survival, development and function of neurons in both the peripheral and central nervous system. 50 Exercise appears to activate cellular cascades, such as increases in brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression, which may be both time and intensity dependent. 51,52 Moderate intensity aerobic exercise for a period of 12 months may have the capacity to significantly increase hippocampal size in healthy older adults53 and there appear to be links between resistance exercise and mood changes via the brain-derived neurotrophic factor system,54 although the evidence for the direct effects of resistance exercise on brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels have so far been inconsistent. 55

Engaging in exercise may have the capacity to counteract common symptoms of depression, such as negative thought patterns, low self-esteem and anhedonia (the inability to gain pleasure from enjoyable experiences)56 through distraction, mastery experience,43,57 improvements in self-evaluation58,59 and a sense of achievement. 60 A further theoretical underpinning comes from the theories of positive psychology, considering the potential of exercise interventions to build on ‘virtues’ and ‘character strengths’, such as love of learning (mastery of new skills), bravery (not shrinking from challenge or difficulty) and hope (expecting the best and working to achieve it). 61

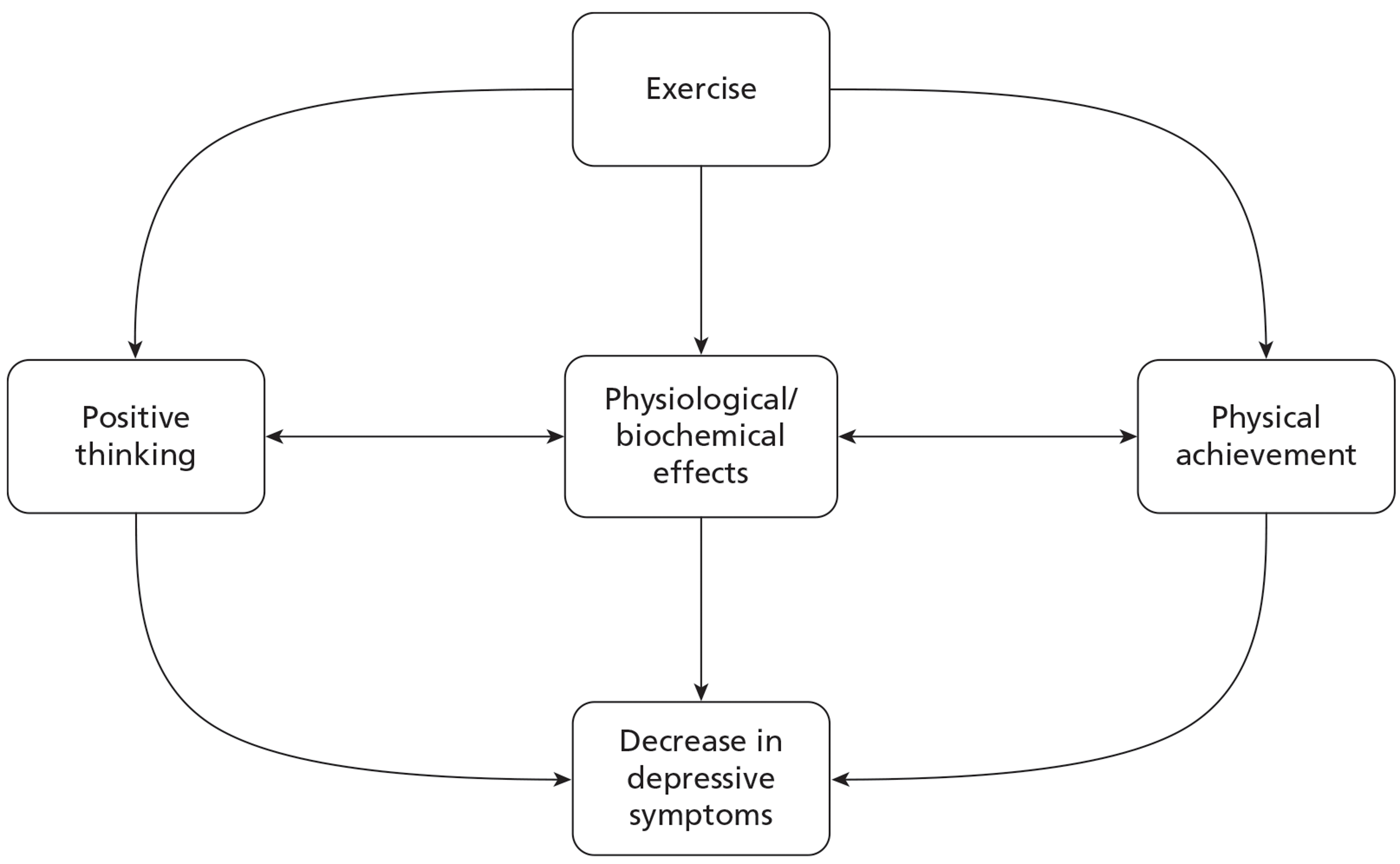

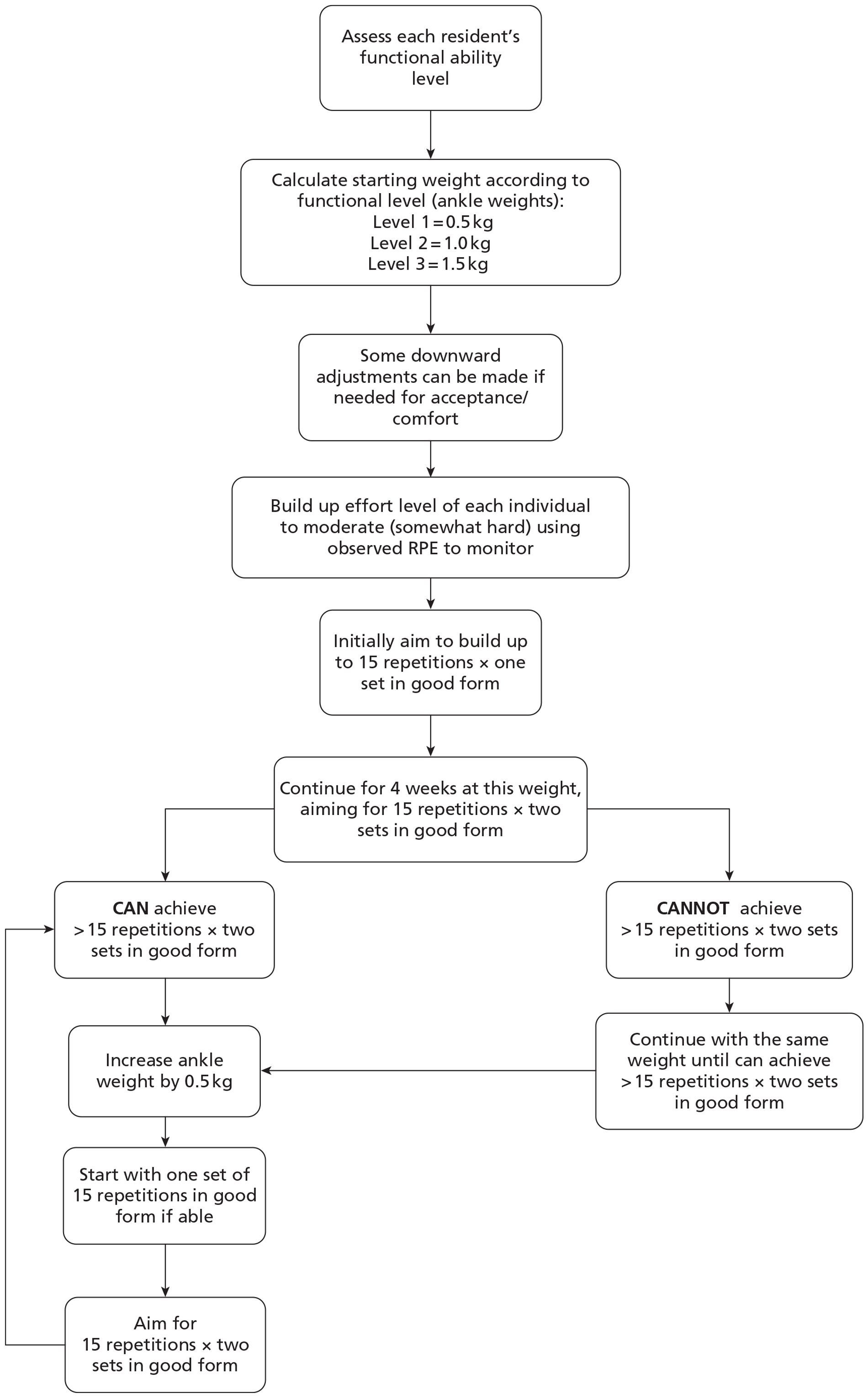

Based on our literature review we developed a theoretical model for how exercise might reduce depressive symptoms (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical model of effect of exercise on depressive symptoms.

A systematic review of the evidence for the effects of exercise and physical activity on depression in older people concluded that aerobic and resistance exercise are likely to be the most effective forms of exercise for decreasing depressive symptoms in this group. The review also found that interventions using moderate or high intensities of training appeared to be the most effective, signifying that there may be a dose–response effect. 62 A second review examined the evidence for the effect of physical activity and exercise interventions in older people with dementia and depression. It concluded that although there is no clear indication of effect on depressive symptoms or quality of life, there appears to be good potential for people with dementia to participate in physical activity and group exercise programmes, including the use of strength training and higher exercise intensities. 38

Exercise participation for older people with dementia

Kitwood's principles of ‘positive person work’ emphasises the need to understand people with dementia as individuals with very different experiences of life, and different needs, feelings, likes and dislikes63 (Box 1). The features of a person-centred dementia care approach are most likely to support well-being and enable any intervention to create the best possible effects.

Recognition To be acknowledged as a person, known by name, unique

Negotiation To be consulted about preferences, desires and needs, skills needed to take into account anxieties and insecurities

Collaboration Align on a shared task, person's own initiative and abilities are involved

Play To encourage development of spontaneity and self-expression

Timalation The use of interactions of which the prime modality is sensory, without the use of complex cognitive strategies, so that it provides contact, reassurance and pleasure while making few demands

Celebration To enable life to be experienced as intrinsically joyful

Relaxation To enable a person to relax in solitude or with others near them (considering that some people with dementia have strong social needs)

Validation To accept someone's subjective truth, and acknowledge that person's emotions and feelings

Holding To provide a safe psychological space, to help ‘hold’ someone psychologically or physically. This can help the person feel that there is hope that things will get better, and that there is someone who will stay with them however bad things (or they) get

Facilitation Where enabling merges into collaboration, to enable an interaction to get started and to amplify it. This requires great sensitivity to the possible meaning in a person's movements

Neurophysiology of dementia and motor control theory

Motor learning principles can further support maximum participation, success and adherence within both a physical activation programme and exercise groups. A person with dementia can face many challenges in processing visual, auditory, proprioceptive and somatosensory information, indicating the need to provide adequate time to achieve this processing, along with other props that might support their responses, such as the use of rhythm, familiar actions and tasks. 64,65

Because of the pattern of initial change in declarative or explicit memory and learning (for names and facts) among most people with dementia, the use of procedural or implicit memory stimulation and learning strategies (for processes and routines) can be very useful66,67 via the use of:

-

Preserved functions:

-

Repetition:

-

Procedural learning accumulates slowly through much repetition in varying circumstances, where the person (possibly unconsciously) begins to form rules associated with the task. 70

-

-

Feedback and demonstration:

-

The use of targeted feedback and demonstration is linked to classical conditioning and the formation of a predictive relationship between stimuli,68 which can further support the development of automatic responses to those stimuli.

-

Associated with these procedural learning strategies are specific training techniques:

-

Errorless learning:

-

Where multiple cues are provided to prevent errors and so enable success at every stage of a task. This is particularly useful in training people with memory losses, as it avoids the learning of the ‘error’ that might be encountered in ‘trial and error’ techniques, and is effective in promoting the mastery experiences mentioned previously. 71

-

-

Backward chaining:

-

Where a task is broken down into small, achievable parts, with assistance provided until the end of the task (e.g. guide each stage of ‘turn to sit’, but allow person to descend to sitting independently). This is also useful for people with cognitive impairment as it is more likely to promote success and mastery. 72–74

-

-

Functional approach:

-

Owing to the frequent involvement of the parietal cortex and the resultant presence of dyspraxia as a symptom of dementia, the functional approach can be a valuable tool. This employs the use of visual, verbal and physical prompting to support and enhance either the learning of new compensatory strategies or the regaining of previously learned skills. 75

-

Music can be used to increase the efficiency of exercise efforts with evidence indicating improved respiratory efficiency associated with the use of synchronous music, and improved running speeds associated with the use of motivational synchronous music. 76 Music may act as a cue to improve performance, especially in neurological conditions,77 as well as to support memory via the use of classical conditioning. 68 Music may also positively influence adherence via its influences on cerebral areas associated with arousal, emotions and reward,78,79 as well as the attainment of flow (a state of focused motivation/concentration). 76

A group format for structured exercise may offer the protective and positive effects associated with social activities on well-being and mental health. 80,81 Delivering exercise in groups is also likely to enhance adherence and may improve the cost-effectiveness of an intervention. 82,83

Theoretical concepts supporting the use of a whole-home approach

Older adults are more likely than any other age group to lead a sedentary lifestyle despite an awareness of the benefits of being physically active. They cite deterrent factors such as lack of interest, shortness of breath, joint pain, perceived lack of fitness and lack of energy. 84 Frail older adults with multiple comorbidities and high disability levels residing in care homes are even more likely to have very limited physical activity levels. 85,86 To influence the physical activity behaviour of as many residents as possible, and maximise exposure to the exercise sessions, any activity/exercise intervention should offer a variety of physical activity opportunities without placing unreasonable demands on care home staff.

A large number of factors create barriers to physical activity within care homes: resource limitations, perceived role boundaries, limited staff training opportunities and restricted access to appropriate health-care providers. 86–92 Hence, any intervention to increase exercise participation should include approaches to create the culture change needed to effectively address these barriers. 92,93

A whole-home intervention, using an organisational approach to encourage all residents and staff in efforts to increase the residents' level of physical activity, is more likely to achieve the positive effects sought than simply providing group exercise sessions. Such whole-home interventions need to consider the full range of physical, organisational and attitudinal barriers that may be encountered.

Cluster randomised trials in care homes

A systematic review identified 73 cluster randomised trials in residential facilities for the aged, of which 70 were conducted in care homes (Table 1). 94 The earliest trial identified was published in 1992. The trials randomised between 3 and 230 homes, and recruited between 49 and 10,558 participants. The review identified variable quality among the trials, with particularly low proportions accounting for clustering in the sample size calculations and reporting the intracluster correlation coefficients for the homes.

| Characteristics | Median | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|

| Year of publication | 2006 | 1992 | 2010 |

| No. of clusters randomised | 15 | 3 | 230 |

| Mean cluster size (participants per cluster) | 28 | 2 | 217 |

| No. of participants recruited | 352 | 49 | 10,558 |

| Country | No. | ||

| USA | 16 | ||

| UK | 16 | ||

| Netherlands | 9 | ||

| Canada | 6 | ||

| Sweden | 5 | ||

| Others | 18 | ||

| Type of outcome | |||

| Falls | 15 | ||

| Medication prescription | 13 | ||

| Quality of life | 9 | ||

| Mobility | 6 | ||

| Fractures | 5 | ||

| Others | 22 | ||

Most commonly, the trials focused on falls, use of medications, use of physical restraints or quality of life. Two trials focused on depression. There were 13 trials for which physical exercise formed part of the experimental intervention. Overall, the quality of these trials was varied (based on their potential for recruitment/identification bias of participants, and accounting for clustering in design and analyses). The nature of the exercise interventions was also very varied, ranging from gentle exercises based on activities of daily living (six trials) to balance and resistance exercises (seven trials). The frequency of the exercises ranged from once to thrice weekly (except for one trial on hand motor activity for 30 minutes, 5 days a week, during 6 weeks).

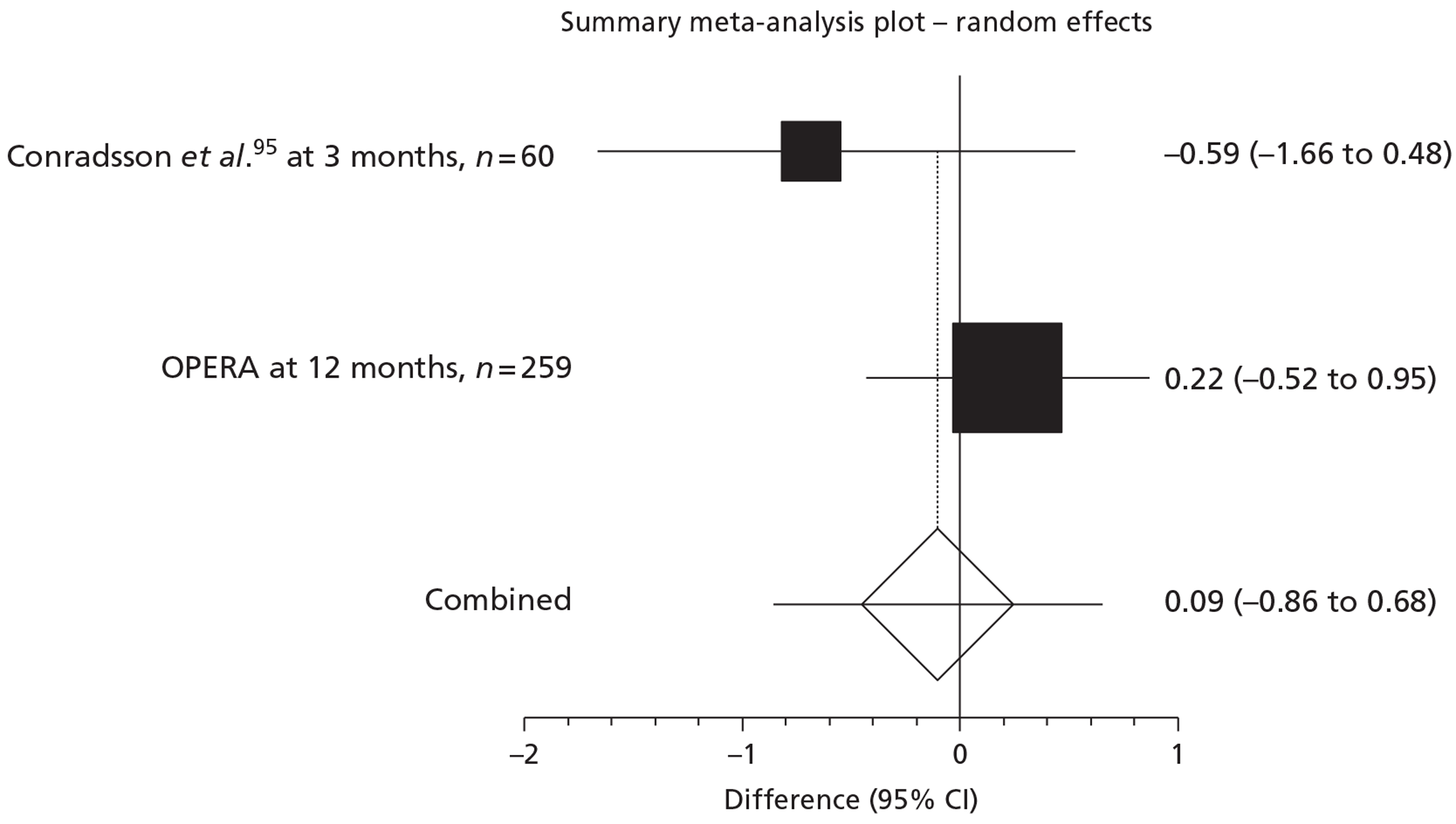

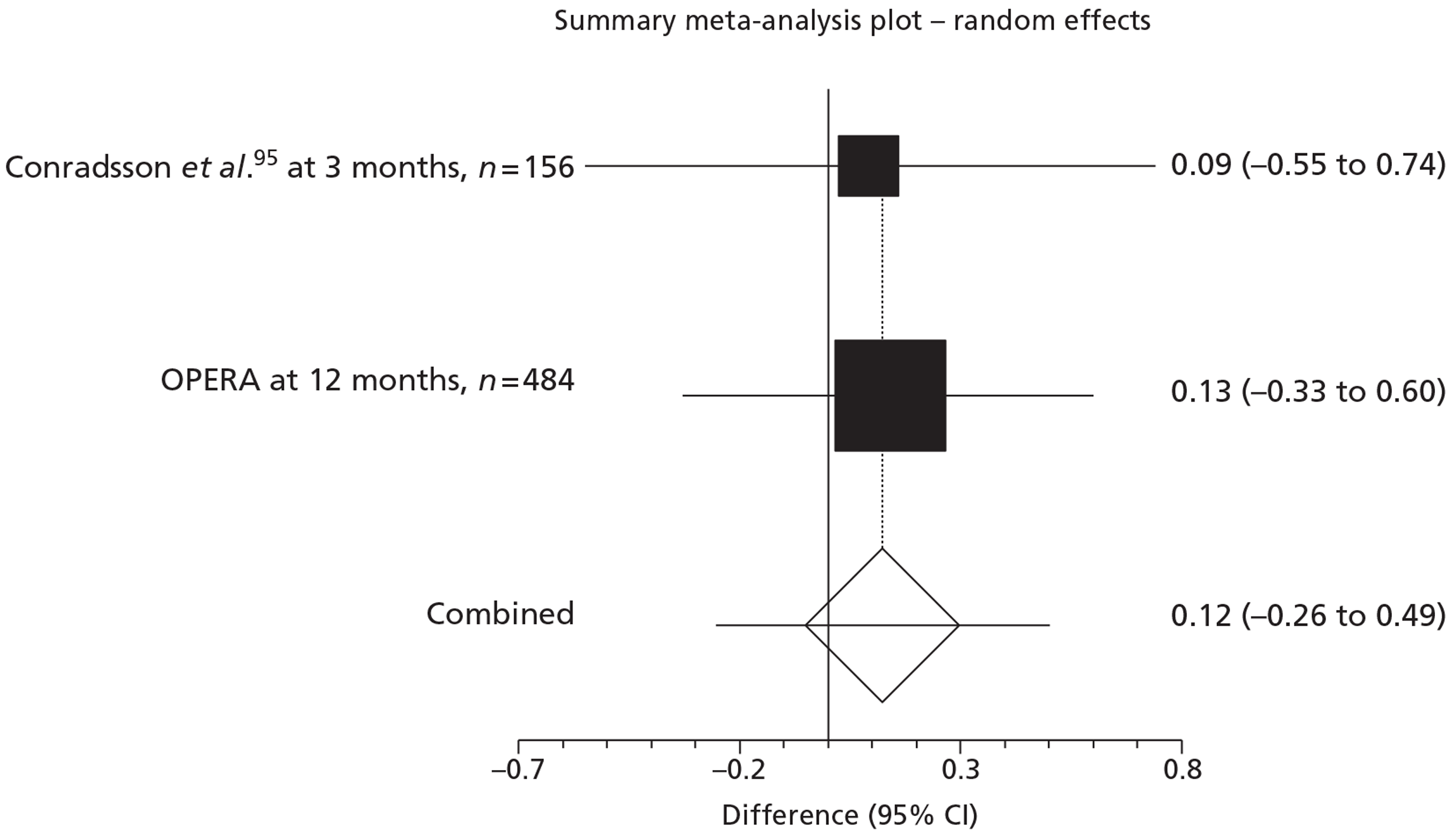

The outcomes of these exercise interventions included physical function, falls, quality of life and depressive symptoms. One trial95 tested the effect of a moderate-intensity functional exercise programme, of 3 months' duration. There was no evidence of effect of the intervention on depression. This trial,95 published after OPERA had completed recruitment, was too small, however, to exclude a positive effect from the intervention, particularly in those with depressive symptoms. 95

Ethical issues

Cluster randomised trials have become increasingly common in health service research for a range of pragmatic and methodological reasons. However, the nature of cluster randomised trials, where randomisation, and often also the intervention, is at the level of the cluster rather than the individual, means that the standard ethical requirement of informed consent from all research participants prior to participation cannot be achieved.

The diverse range of models for cluster randomised trials means that how researchers need to secure appropriate consent, while respecting the rights of research participants, is complex. 96–98 MacRae et al. 99 draw on the moral foundations of informed consent and international regulatory guidelines to offer a framework for consent in cluster randomised trials. 99 This includes justificatory reasons for waiver of consent, when consent to randomisation may not be necessary, and the level of information required to be provided following randomisation. When the unit of randomisation in a cluster randomised trial is a care home, the ‘cluster guardian’, who provides consent for participation in the study, will usually be the care home manager. The manager also acts as a gate keeper, controlling access to individual residents for recruitment. The importance of care home managers and staff in the recruitment of participants to research in care home settings has been noted previously. 100 Reasons for excluding access include the views of care home staff on the resident's capacity to consent, the resident's or their next of kin's (NOK's) physical frailty, and the value they place on their privacy. There is a difficult ethical balance to be struck by care home managers in protecting their residents' interests while not denying them the opportunity to participate in research if they wish.

A further difficulty in conducting research in care homes is the substantial number of residents who have a degree of cognitive impairment and who therefore may lack capacity to consent. Cognitive impairment, per se, is not determinative of whether or not a person has capacity to make a specific decision such as consenting or refusing to participate in a research project. There is no direct correlation between Mini Mental State Examination scores and capacity to consent,101 and there is considerable variability in judgements of the capacity of people with Alzheimer's disease to consent to research, even among experienced psychiatrists. 102 A key message from these studies would appear to be that researchers must take responsibility for assessing capacity of participants for their specific study, and recording the process and reasoning for their assessment. It is not clear from the literature that this is currently regarded as standard research practice. A systematic review of cluster randomised trials in care homes found that of the 46 papers that reported consent processes, three trials relied on the opinion of care home staff to assess capacity and seven assumed lack of capacity in all participants by virtue of being resident in a dementia specialist home. 94

Some potential research participants in care homes will clearly lack capacity to consent to take part in research. International research ethics guidelines permit research involving participants who lack capacity if specific criteria are met, for example that the risk of harm to the participant should be no more than slightly greater than that of ordinary medical care103 or that consent is given by a legal representative. 104

The Mental Capacity Act 2005105 requires researchers to consult with either a personal or nominated consultee to seek advice on whether or not the person who lacks capacity would have objected to taking part in the research if they were able to consent. Confusion among research ethics committees and researchers regarding this consultation process has been identified. 106,107 There are also concerns about the impact of this requirement on recruitment of participants who lack capacity to consent. Two UK studies that specified recruitment rates for care home residents through proxies or consultees reported levels of 61% and 41%, respectively. 100,108

In developing this study we identified several ethical issues:

-

the ethics of cluster randomisation and the role of care home managers as cluster guardians providing consent for participation in the study

-

recruitment and consent of individuals for assessments and data gathering in an institutional setting, including the role of home staff as gatekeepers

-

obtaining valid consent for individual participation in a population that will include a high number of cognitively impaired participants, including assessment of capacity to consent

-

the involvement of personal and nominated consultees in decisions about recruitment of residents who lacked capacity to consent

-

the challenges of fluctuating mental capacity throughout the study.

Process evaluations of complex interventions

The effectiveness of any intervention is only partly determined by the content of the intervention. The context in which it is delivered, including the process of delivery and the physical and social environment, has a major influence and should be considered. 109 Process evaluation involves an examination of the processes by which a programme or intervention is implemented. A number of authors have described the use of process evaluation in complex intervention trials, pointing out the value of being able to place findings into context, understanding both how the intervention was delivered and how the social, political and physical context impacted on its effectiveness. 109–111

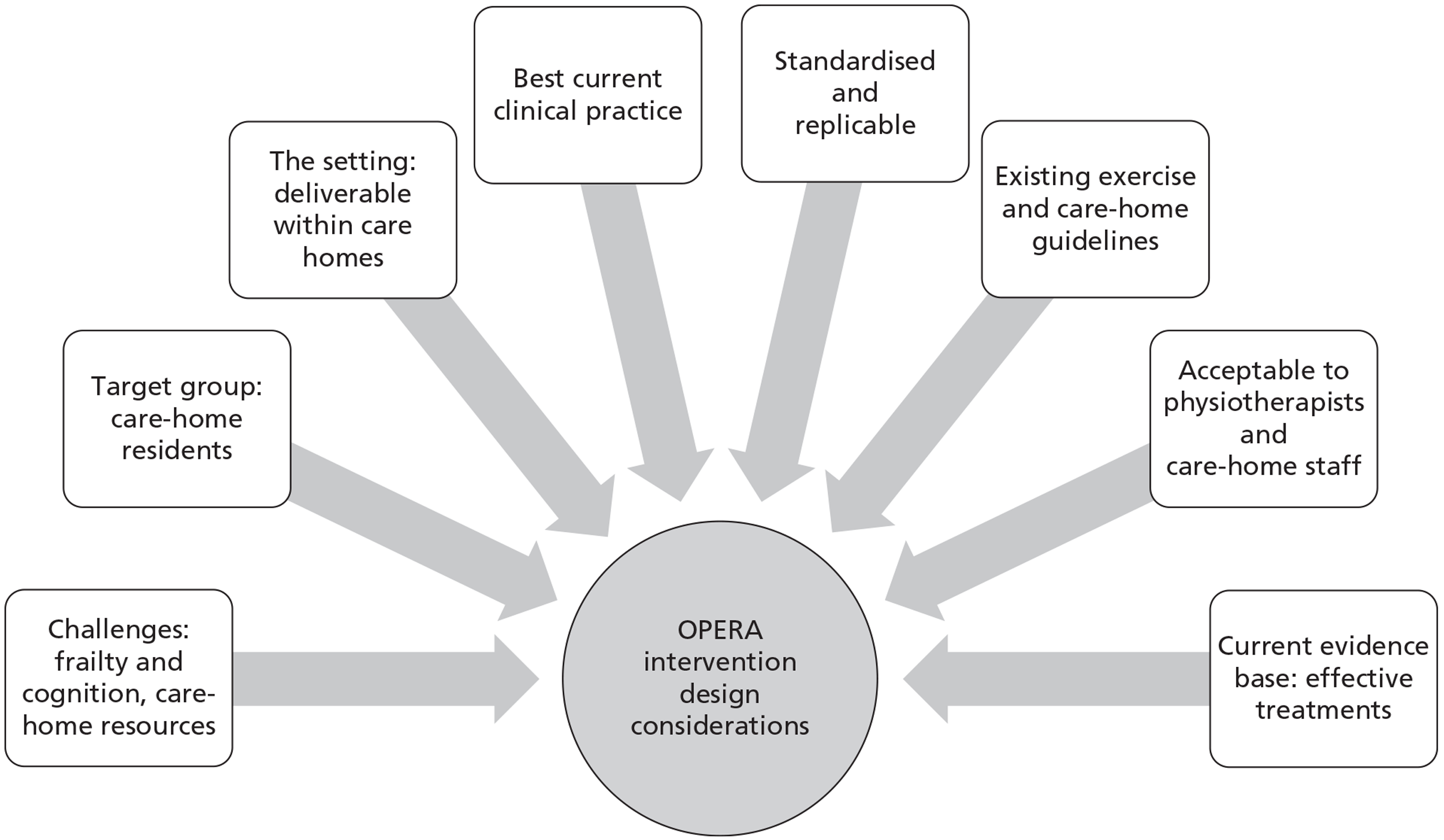

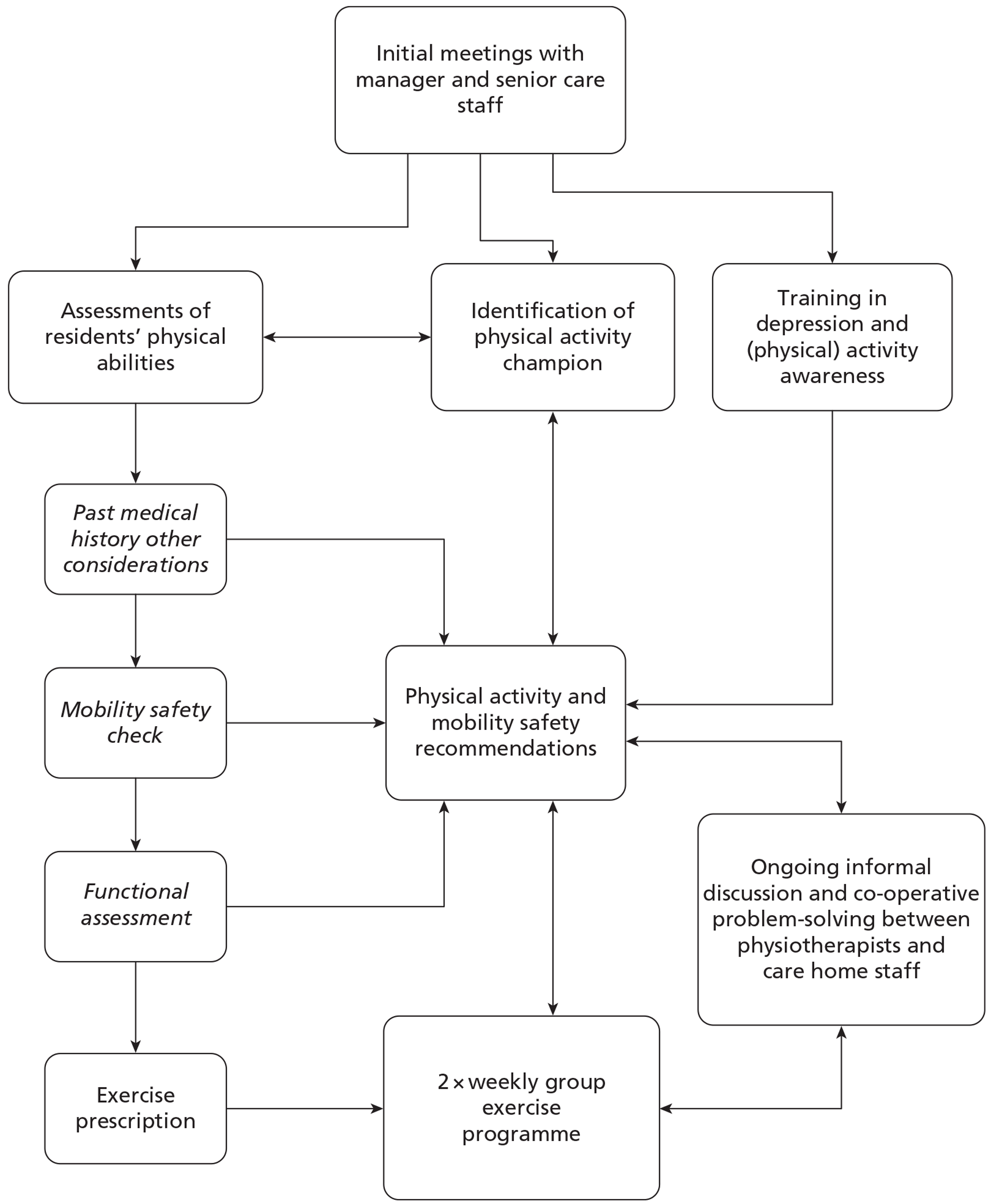

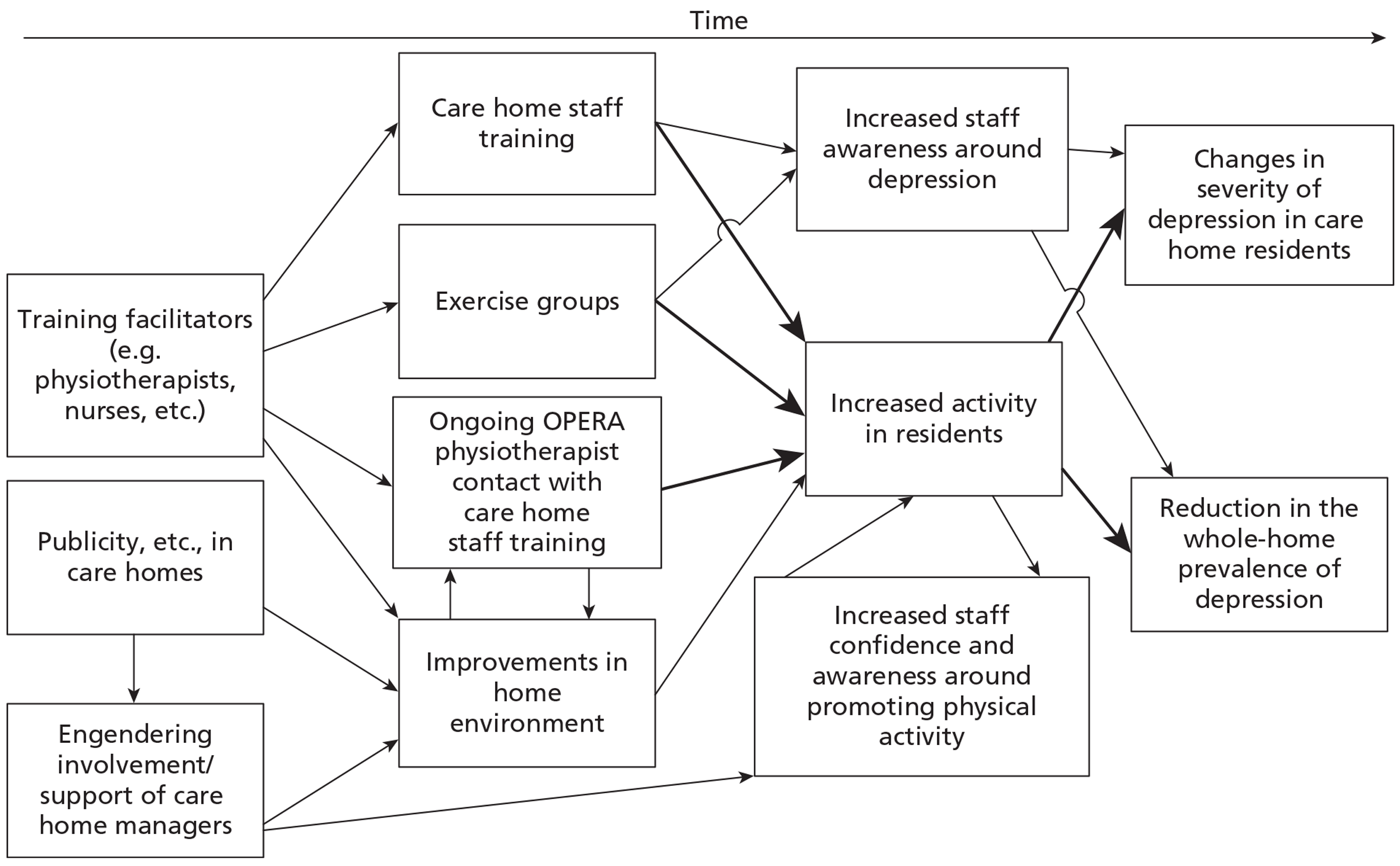

Aims and objectives of OPERA

The overall aim of the OPERA study was to evaluate the impact of a whole-home intervention, consisting of training for residential and nursing home staff backed up with a twice-weekly, physiotherapist-led exercise class on depressive symptoms in care home residents. Specifically, we sought to test the effect of the OPERA intervention on:

-

the prevalence of depression in those able to complete assessments 12 months after their homes were randomised (cross-sectional analysis)

-

the change in number of depressive symptoms 6 months after randomisation in those who were depressed at baseline (cohort analysis)

-

the change in the number of depressive symptoms in all residents 12 months after randomisation (cohort analysis).

In parallel with this effectiveness analysis, there was a cost-effectiveness analysis, a process evaluation of the study, an ethics substudy and a post-study evaluation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design considerations

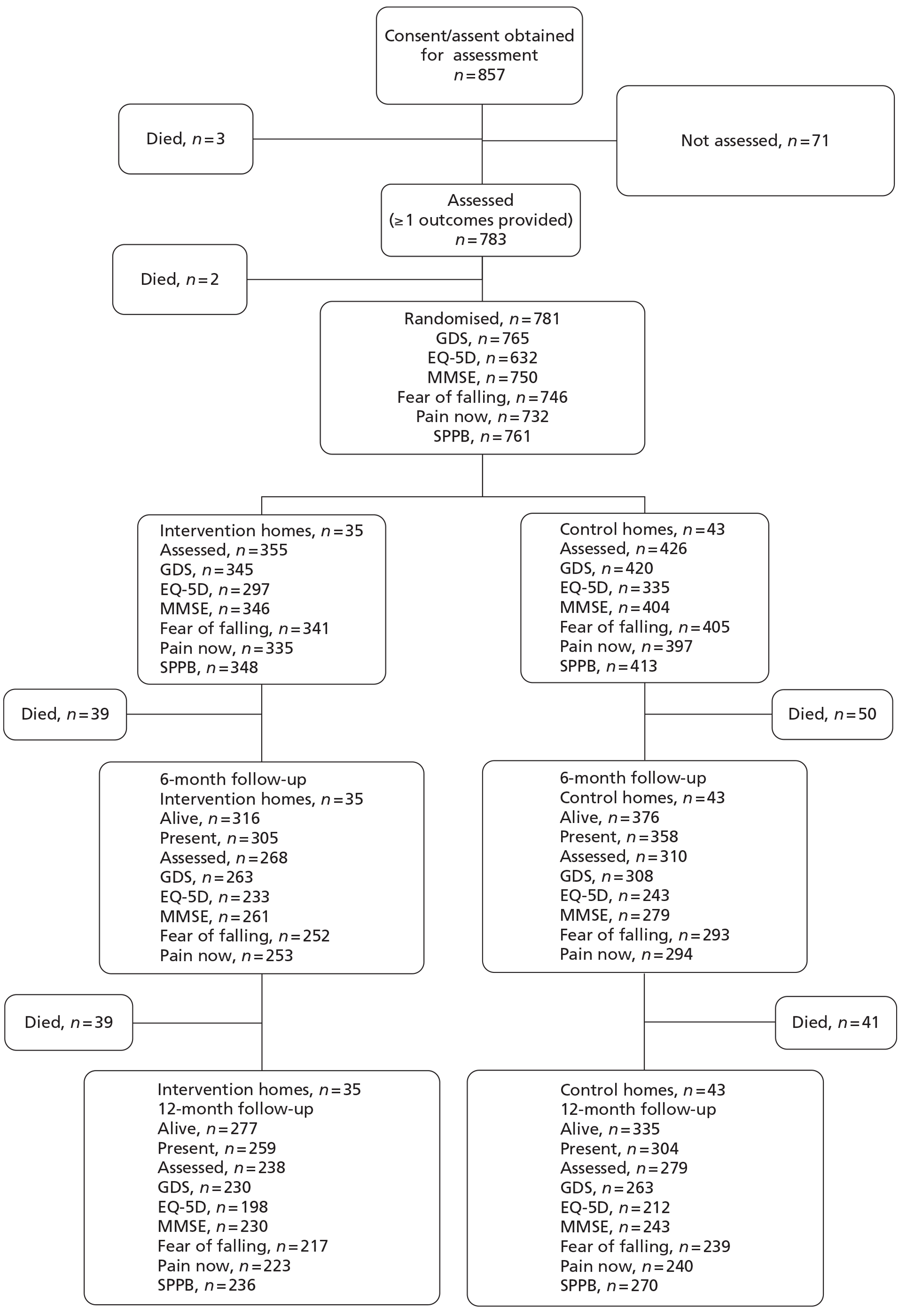

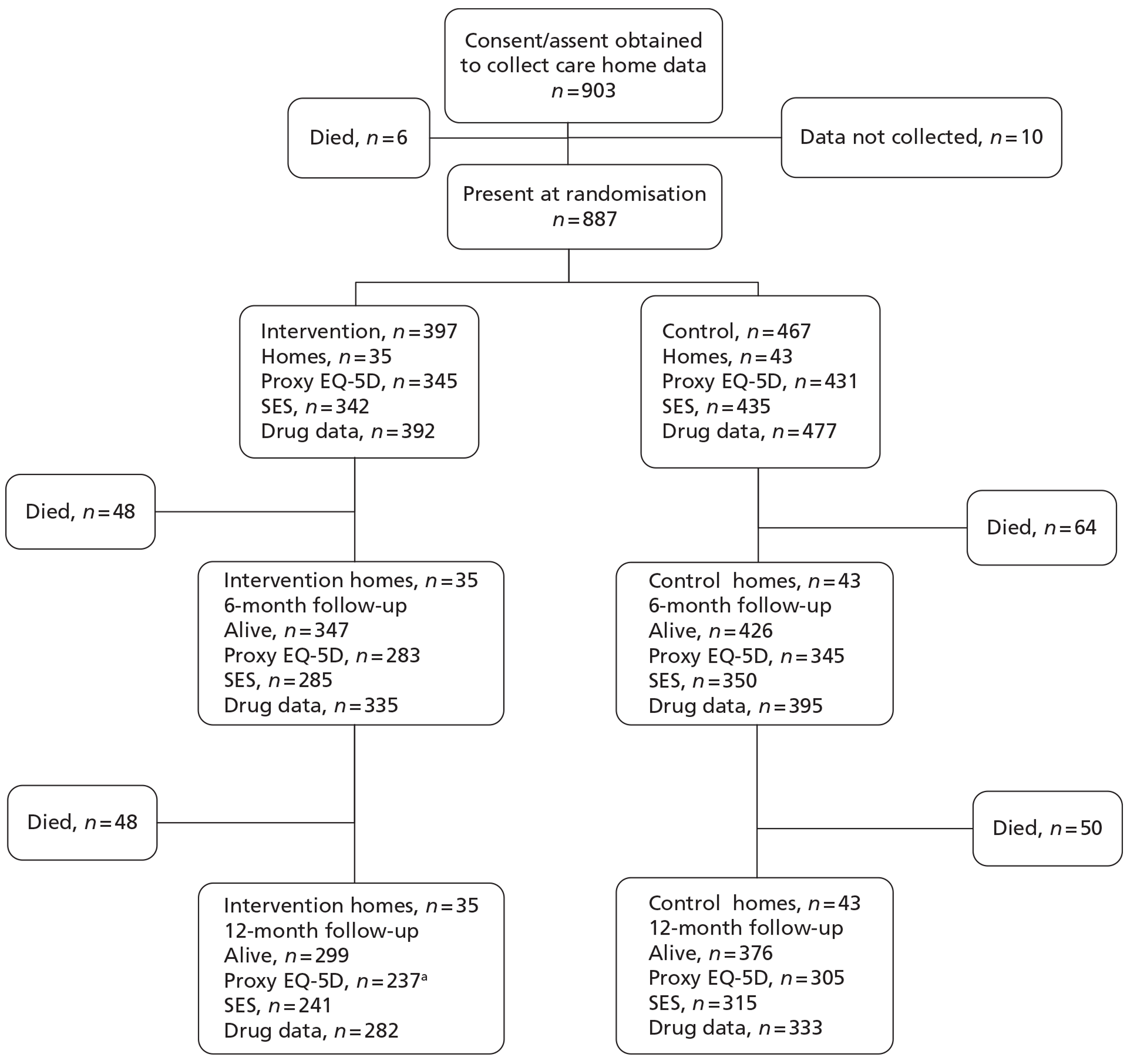

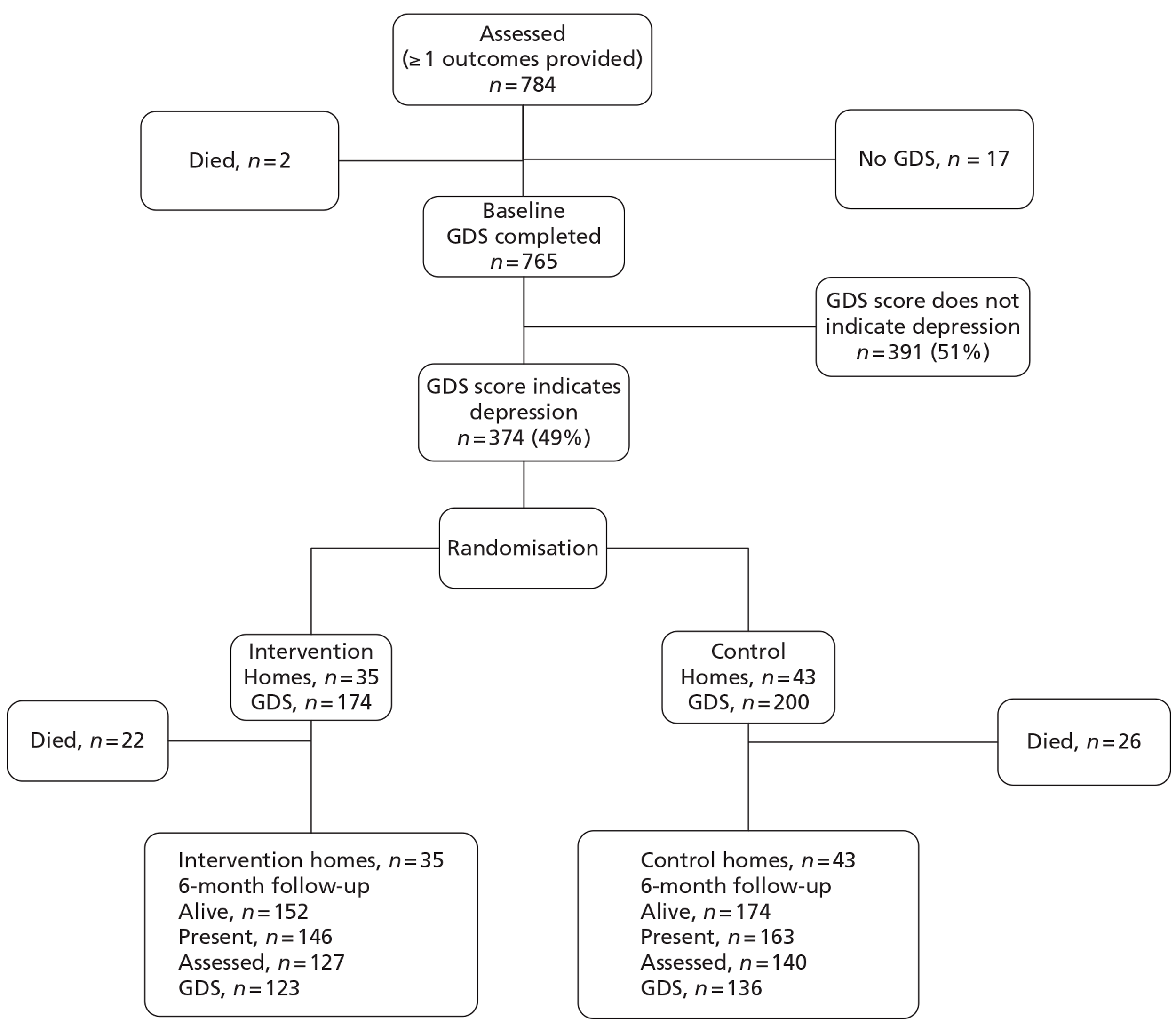

The focus of OPERA was on testing an intervention that could be implemented as part of routine health/social care. The original brief from the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme called for a cluster randomised trial of the effect of a programme of group exercise on the remission of depression in care home residents. An exercise intervention would be difficult to introduce into normal practice if it is to be available only to those who have been diagnosed with depression. This is because of the need to pre-screen residents for depression. It also may be less likely to be effective if only those who are depressed attend, as positive social interactions and peer modelling of maximal effort may contribute to effectiveness. If a positive approach to increasing exercise in the residents is built into the values of care home staff, the likelihood of a group exercise intervention having a positive effect will be maximised. We, therefore, chose to test a whole-home intervention, consisting of a training programme for care home staff backed up by a twice-weekly, physiotherapist-led exercise class. As all residents were exposed to the OPERA intervention, its effects, positive or negative, on mental and physical health, may affect both those who are depressed and those who are not depressed. Furthermore, there is a high turnover of care home residents, with many new residents also being exposed to the intervention. For these reasons measurement of outcomes on all residents is important. The potential for harm from the intervention meant that it was very important to collect data on all residents, not just those with depression. With an ongoing intervention any effects, positive and negative, will continue to accrue in the long term. Indeed, only if long-term beneficial effects can be demonstrated would it be appropriate to build such a programme into the work of care homes. The outcome of interest then becomes the prevalence of depression in all of those residents in the care home at the end of the study. This includes any new residents who joined the study after randomisation. Thus, our pragmatic primary outcome of interest was the proportion of care home residents who were depressed 12 months after their care home was randomised. Henceforth, we will refer to this as the cross-sectional analysis, recognising that this population includes participants who had been in the study for variable lengths of time. The term cohort analysis will be used when referring to our more explanatory primary outcomes of change in depressive symptoms, involving those residents who were present in the home, and who had provided data, prior to randomisation. Where appropriate, we refer specifically to the depressed cohort of residents, who were classified as depressed on the Geriatric Depression Scale-15. 112 Likewise, the results of secondary analyses are similarly reported as cross-sectional analysis and depressed cohort analysis.

We collected data from several sources:

-

Directly from the participants, henceforth assessment data.

-

Indirectly from the care homes and the National Health Service, henceforth care home data. This includes data collected from routine care home records, henceforth record data, and assessments by care home staff of participant's health state and social interaction, henceforth proxy data, and data from the Secondary Uses Services databases held by participating primary care trusts, and the National Health Service Medical Record Information Service, henceforth National Health Service data.

A participant in the OPERA study is anyone for whom we have consent/agreement to provide data; a resident is anyone living an OPERA home. Some participating residents might not have been present in the home at the time assessments were carried out, for example because they were in hospital. On occasion when referring to the group exercise sessions we refer to exercise group participation which is distinct from study participation.

Some participants did not complete face-to-face assessments, and thus did not provide assessment data, but they did provide care home data. The reasons for this were either that the relevant permissions (consent/assent) were not obtained to allow face-to face assessments, the participant was not present at the time assessments were done, or that when approached the residents were unable, or unwilling, to engage with the assessment process because they were cognitively impaired. A small number of participants agreed to provide assessment data but not to allow access to care home data.

In addition to those included in the cross-sectional analyses and the cohort analyses there are two further groups of residents who have contributed data to the study. Firstly, there are those who provided individual baseline data after their home was randomised but who did not provide data for the cross-sectional analysis; typically these were people who were only resident in the home for part of the year. This group contribute to the specific data on fracture rates. Secondly, as any harms from the intervention might also affect non-participants we collected some safety data from all residents.

Although the core of this study was a very simple trial to find out if exercise helps depression, there are a number of different populations contributing to the different analyses. Only by including these different populations are we able to give the full picture of how the intervention might affect care home residents. This added overall value to the study.

Pilot study

In the pilot study we tested the recruitment processes and refined the study interventions and process evaluation design prior to the main study.

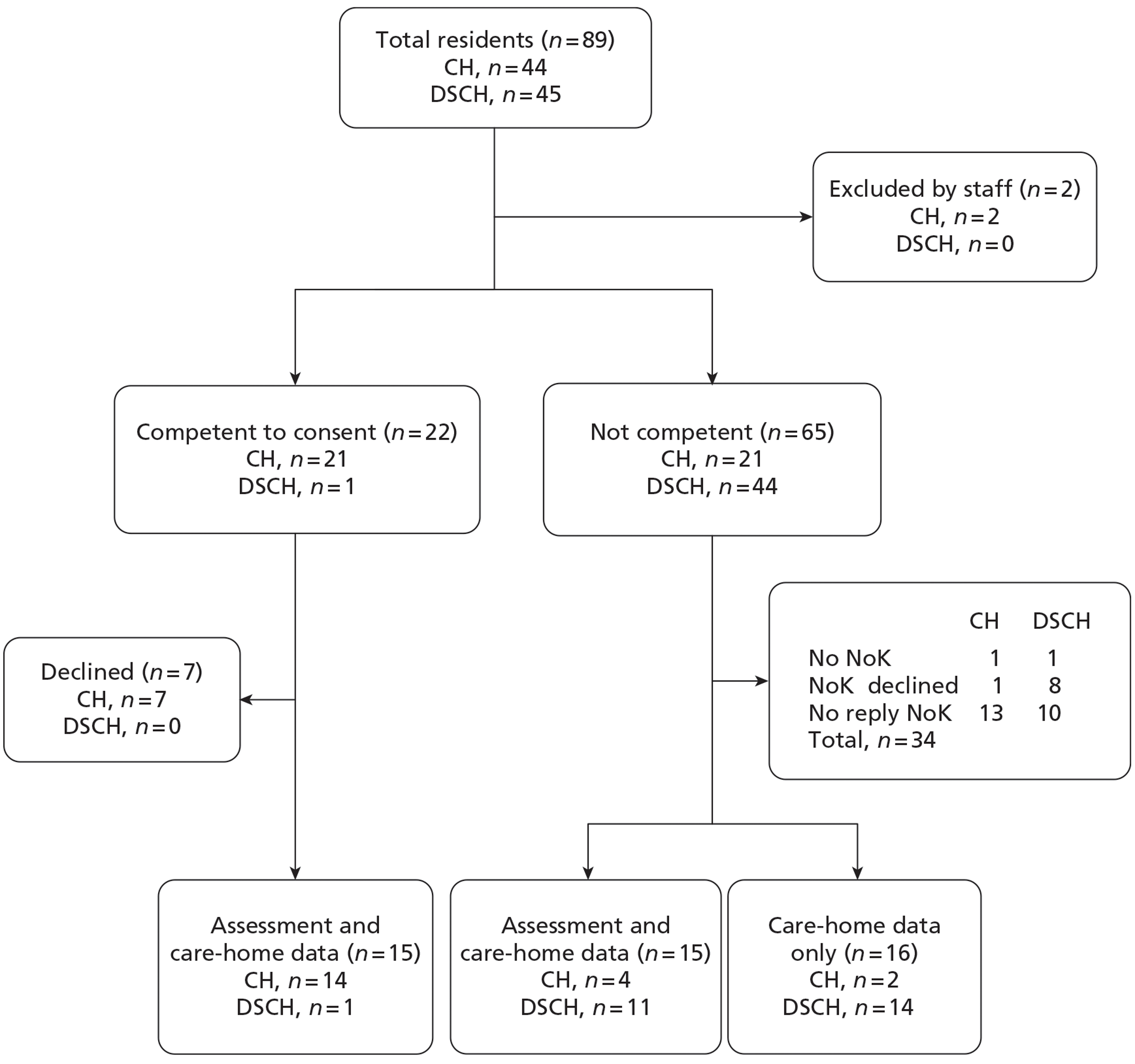

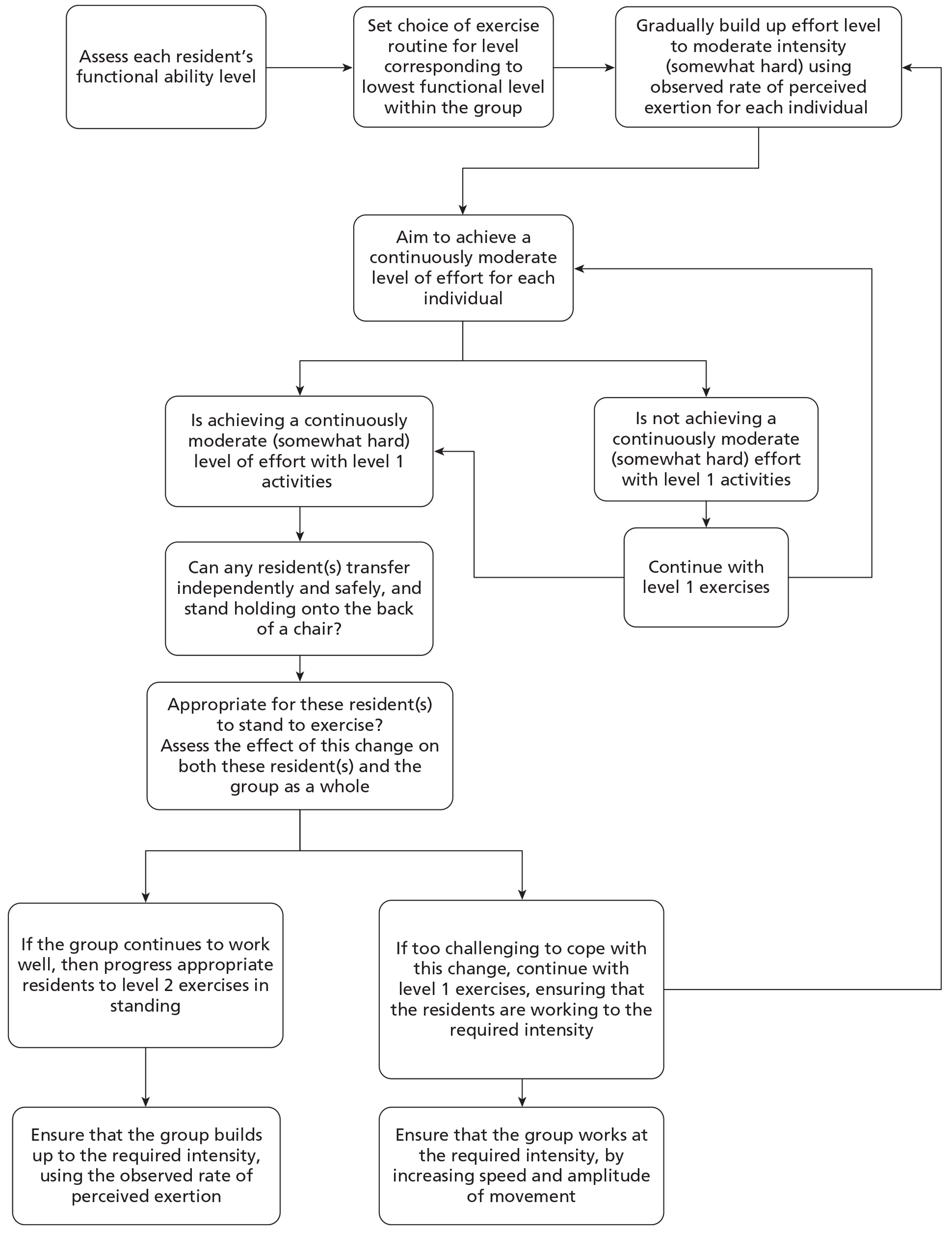

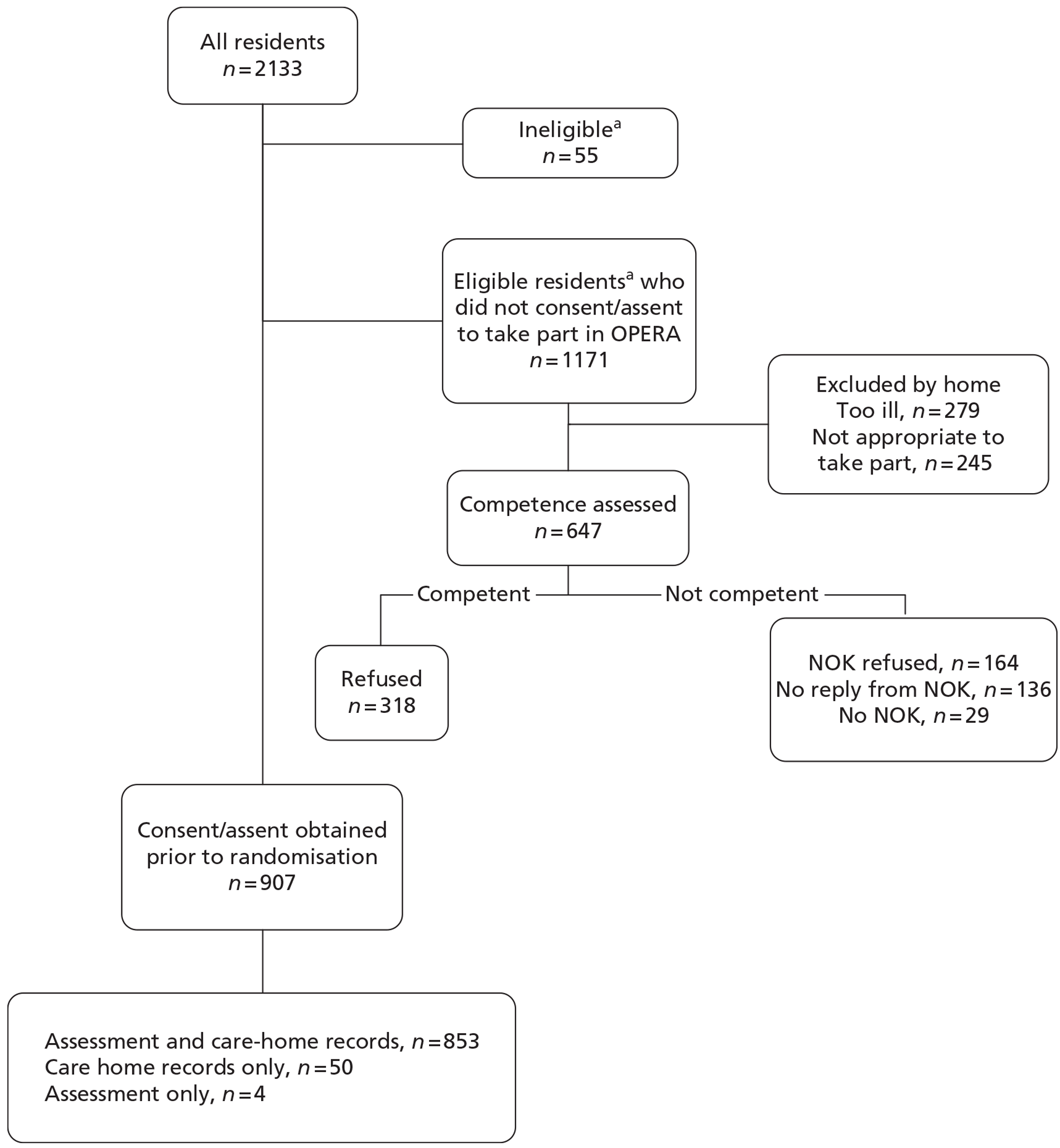

We recruited three local care homes in Coventry in June/July 2008: two residential care homes and one dementia specialist care home. The residential homes were selected to represent care homes in the locality, and the dementia specialist home to test the assessment procedures and exercise intervention with more cognitively impaired residents. We assessed recruitment flow for the three care homes to allow comparison of recruitment rates between the two residential homes and the dementia specialist home (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment in pilot homes. CH, care home; DSCH, dementia specialist care home.

There were 89 residents in the three care homes at the time of recruitment; staff excluded two residents because they were considered too ill to take part in the study. Half of residents in the two residential care homes were judged to have capacity to consent and one resident in the dementia specialist home. Fifteen residents gave consent to take part in the study assessments and permission for staff to collect data from their home records.

Twenty-three (37%) NOK did not respond to written request for assent and nine NOK did not want their relatives to take part in the study. Assent/agreement was obtained for 31 residents to take part in the study; however, 16 of these, when approached by the recruitment team, were unable to complete study assessments and provided access to care home data only. That 14 of these participants were resident in the dementia specialist home identified initial challenges in collecting assessment data from more cognitively impaired residents.

Following the recruitment phase of the pilot study a number of processes were revised:

-

Permission was approved by the ethics committee to contact NOK by telephone if no reply for assent/agreement had been received 2 weeks after the written request in an attempt to improve response rates.

-

Owing to difficulties experienced in recruiting residents from, and collecting the primary outcomes in, the dementia specialist home, the management team proposed re-evaluating the inclusion of dementia specialist homes in the main study.

Once potential participants were recruited to the pilot, we randomised the two residential care homes: one to the control intervention and one the exercise intervention. The dementia specialist care home was allocated the exercise intervention so that we could evaluate the feasibility of running the exercise groups for residents with moderate to severe cognitive impairment.

The exercise groups were well attended in the residential homes and dementia specialist home, and proved to be appropriate for residents with and without cognitive impairment. Following observation by a member of the process evaluation team and staff delivering the exercise groups, small changes were made to the physiotherapist assessments of residents and the format of the exercise groups.

The pilot study demonstrated that the depression awareness training (a component of both the control and active intervention, which is outlined in detail later) was well received by care home staff, and the format required very little change prior to the start of the main study.

Observation visits to the three care homes helped inform the development of the process evaluation protocol for the main study. The wide range of cognitive and physical abilities observed in the residents in the care homes identified the importance of developing an inclusive approach to recruitment to ensure that findings reflected the experiences of all residents. As a consequence of our observations in the pilot homes we felt that none of the planned outcome measures captured levels of activity or social engagement in the homes. We therefore decided to add the Social Engagement Scale as a secondary outcome measure. 113

Developing the process evaluation

The process evaluation pilot had two main aims: to inform (1) the development and implementation of both the whole-home intervention and the control intervention for the main study, and (2) the design of the process evaluation of the main study. We used a formative approach in the pilot phase to ensure that any problems were identified and addressed in the main study protocols and procedures. As part of the process evaluation of the pilot study, one researcher (DE) spent time in the three pilot study homes observing the research staff activity and talking to staff and residents. Although we aimed to conduct non-participant observation, it proved impossible to maintain non-participant observer status in this setting. The researcher was inevitably drawn into the activities in the home; residents became familiar with him and expected him to interact with them socially. We used both non-participant and participant observation in the main study process evaluation as these approaches are complementary. 114

Other challenges were identified in the pilot process evaluation13 and influenced our development of the process evaluation protocol including:

-

We were working with a vulnerable population with varying degrees of cognitive and physical abilities. We had to take care to be inclusive in our approach to ensure that our findings reflected the experiences of the whole population of the care homes.

-

In many homes space to carry out interviews in private was limited. We needed to establish standard operating procedures that as far as possible respected residents' right to privacy.

-

A normal day in a care home is structured with set times for meals, breaks, activities and drug rounds, which can leave little time for a researcher to engage with residents. During the pilot study, we found that there was often a narrow window of opportunity to engage in individual interviews. Residents tended to be more receptive in the mornings (a common finding in populations with a high prevalence of dementia), with many homes running activities at these times for this very reason. This coupled with prearranged interviews being cancelled when the resident was found to be asleep further narrowed the opportunities for carrying out interviews.

-

Observations and feedback from team members revealed that the process of recruiting participants and, in particular, gaining informed consent, took considerably longer than originally envisaged. During the pilot phase, a number of problems with the process of gaining consent were noted, including the content of the consent forms and the difficulties of ensuring that participants had given informed consent.

In a focus group with the recruiting team, to discuss issues in the process of gaining consent, the team reported finding the process challenging, and thought the consent form was too complex for residents. It took up to 20 minutes to complete the process for each individual resident, and some of the residents found the information difficult to understand and to retain. Those study recruitment staff who had carried out the assent/agreement process (with relatives of residents deemed unable to give informed consent) found it easier, with fewer tick boxes, making it simpler to complete. This led to the consent form being shortened to make it easier for residents to complete.

A number of other changes to the conduct of the main study were implemented as a result of the pilot study process evaluation, including changes to data collection forms. Other recommendations arising from the pilot process evaluation are described in Box 2.

Ensuring that the intervention homes were aware of what the exercise intervention entailed and the need for support from the staff

A review of the physiotherapist assessment of residents to reduce burden on physiotherapist

A review of the exercise sessions and the use of leg weights in the classes

A review of whether or not dementia specialist homes should be included, given the low numbers or residents who were able to complete the primary outcome measure, the Geriatric Depression Scale-15

As a result of the recommendations from the pilot study, amendments were made to the process evaluation protocol: nursing homes were included as a separate category in the sampling frame for case study homes and two focus groups (one for the recruiting team and one for the physiotherapists) were planned instead of individual interviews

Recruitment

Homes

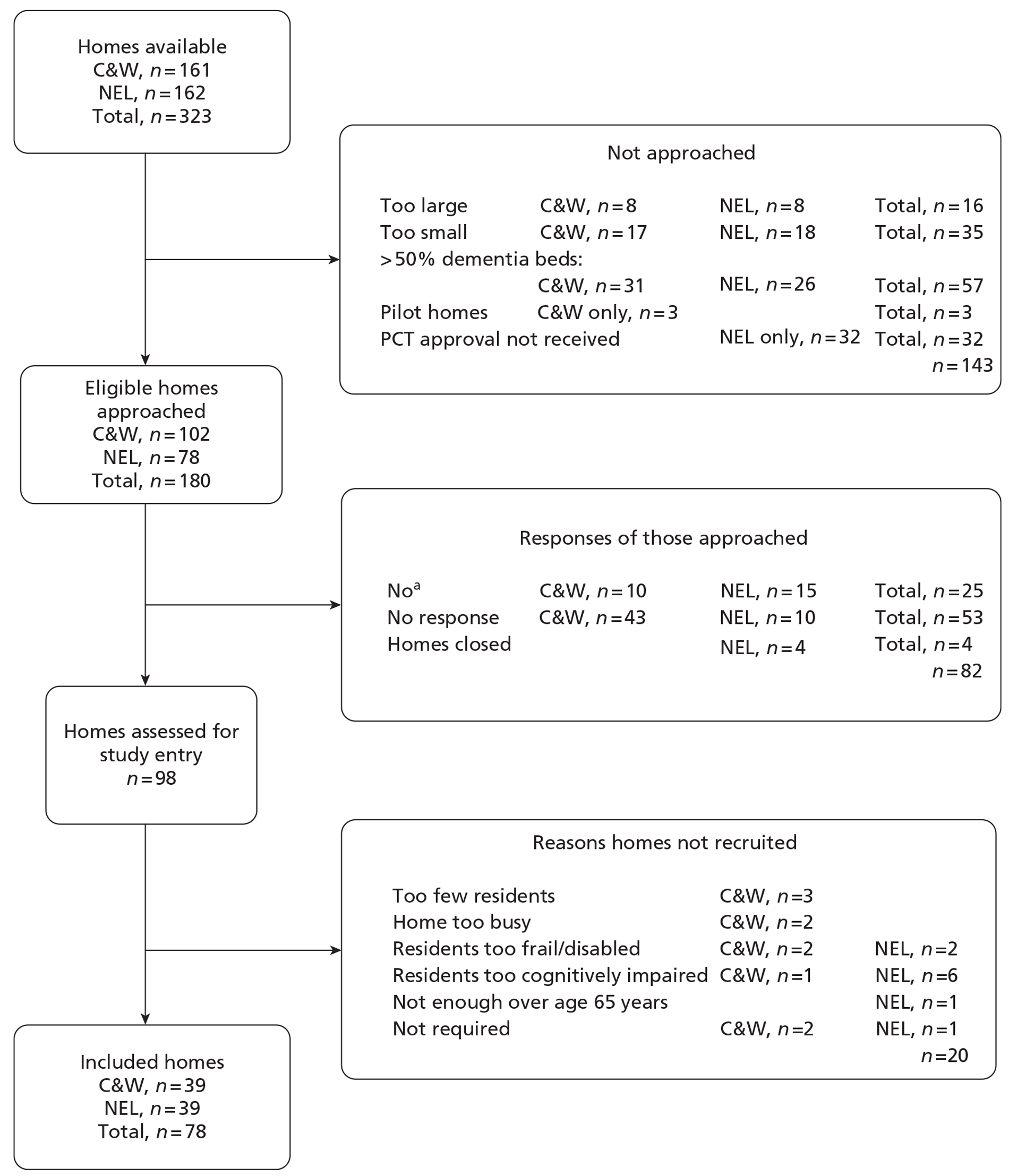

We recruited homes from two geographical locations: Coventry and Warwickshire (C&W) and north-east London (NEL). The practicalities of delivering the intervention meant that all care homes needed to be within reasonable travelling distance for the physiotherapists delivering the intervention: either Warwick Clinical Trials Unit for C&W or Barking & Dagenham Primary Care Trust's physiotherapy department for NEL. Together, these two locations provided a wide range of populations broadly representative of the social mix within the UK, ranging from prosperous rural South Warwickshire through to deprived multicultural urban communities in Coventry and NEL.

We identified all care homes within the relevant primary care trust areas (Barking & Dagenham, Coventry, Havering, Redbridge, Waltham Forest, Warwickshire and West Essex). Following primary care trust approval we approached all care homes with between 16 and 60 beds, but from 11 February 2009 increased the maximum number of beds to 70. Also, from this date we specified that a minimum of six residents needed to have been assessed to be included in the study; our lower limit for home size was based on being able to recruit a minimum of six participants from each home. We excluded smaller homes to ensure that we could collect, from each home, follow-up data from at least one resident with five or more depressive symptoms at baseline. We excluded larger homes because the reduced statistical power from larger clusters meant the additional time taken in recruitment and delivering the intervention was an inefficient use of available resources. With the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee we decided to exclude homes in which more than half of the beds were registered as dementia specialist beds. We took this decision because recruiting in the first dementia specialist home for the main study confirmed our observation from the pilot study, that too few residents in dementia specialist homes were able to provide data on the primary outcome measure. With the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee we changed our protocol to exclude these homes after the first of them had been randomised.

We approached, by post, all apparently eligible homes, apart from three in C&W included in our pilot study. Interested homes were then visited by a member of the recruitment team to assess their suitability. At this time homes were excluded if fewer than six residents were likely to be able to take part in the study; more than half of the residents had severe cognitive impairment; the majority of residents were non-English speaking; or, after discussion with the study team, the home felt they were too busy to participate. Towards the end of the study some interested homes were unable to participate because we had reached our target for home recruitment.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

-

permanent resident in the care home

-

aged ≥ 65 years

-

English speaker (for assessments).

Exclusion criteria:

-

terminal illness or too ill to be seen at the time of assessment

-

severe problems communicating (for assessments).

Many care home residents had multiple comorbidities, which meant that they would not be able to provide data for some, or all, of our assessments. The whole-home nature of our intervention meant, however, that all home residents would be exposed to the intervention regardless of their ability to provide data for our primary outcome or to participate in the exercise groups. For this reason we asked residents to give consent, or their NOK to give agreement, for us to collect assessment data directly from participants, and also to collect indirect care home data. Furthermore, any harms relating to the intervention would affect both participants and non-participants. For this reason we collected safety data (fractures and deaths) on all residents.

In some instances NOK had provided assent/agreement for us to assess a resident but upon approaching them the assessment was abandoned due to the resident being uncooperative or too cognitively impaired.

Ethical considerations

Obtaining appropriate valid consent from participants is essential to any research study and there are specific ethical concerns regarding consent in both cluster randomised trials and research conducted in care homes (see Chapter 1, Ethical issues). Many residents were likely to have substantial cognitive impairment and therefore may have lacked capacity to consent to taking part in a research study, which involves completing a series of assessments and allowing access to their records.

In the OPERA study the clusters were the care homes where the home managers not only acted as gatekeepers to individual residents, or their NOK, for the purposes of consent to the assessments, but were also the cluster guardians for the home giving consent for the home to participate, and actively participated in the whole-home intervention. 96

To ensure that participants had given valid consent particular attention needed to be paid to assessment of capacity during the information-giving process. We therefore developed a two-stage approach to gaining consent; first assessing capacity and at a second visit obtaining consent (see Obtaining consent, below). All of the research nurses and physiotherapists who were part of the recruitment team received specific training in assessment of capacity and taking consent by the study ethicist.

Enrolling participants who are unable to consent into a study is ethically problematic, as it can be difficult to argue that participation is necessarily in their best interests. For those residents who were unable to consent to take part in the assessment component of the study we followed the requirements of The Mental Capacity Act 2005,105 which provides the legal framework for involving people who lack capacity in medical research. Initially, the NOK was approached as the personal consultee, as defined in the Act, and if no personal consultee could be identified then a nominated consultee, as defined in the Act, was sought.

If the consultee agreed that the resident should take part in the study then the resident was enrolled as a participant. The process of setting up the study and obtaining ethics approval took place very soon after enactment of The Mental Capacity Act 2005, when researchers were still familiarising themselves with the practical implications of its requirements for research. As a result, our documentation referred to assent/agreement of the consultee to the resident taking part in the research. We are aware that there has been discussion in the literature about the initial failure of researchers and research ethics committees to fully understand the precise intention of the Act in this regard. 106

There has been a subsequent movement towards seeking a consultee's views about the likely wishes of the individual (the resident) about participating in the research, rather than their agreement on their behalf. Our own research practice has mirrored this development in thinking. However, as our study documentation, which had been subjected to ethical review, included the terms assent and agreement, we will continue to use these throughout this report to describe this research process.

Residents who lacked capacity to consent to take part in the research may still have been able to give consent, or refuse, to take part in an individual assessment. Therefore, at each assessment their consent or agreement was sought for that particular assessment. If at any time during the assessment a participant indicated that they did not want to take part their wishes were respected, whether or not they had formally consented or agreement had been provided by NOK.

Ethical review for the study was provided by the Joint University College London/University College London Hospital Committees on the Ethics of Human Research (Committee A), now known as Central London REC 4. The REC reference for the study is 07/Q0505/56. The Committee also approved 10 Substantial Amendments for the study.

Obtaining consent

At the first visit to the care home the care home manager, or delegated staff member, was asked to exclude any residents whom they felt it would be inappropriate to approach to take part in the study, for example those with a terminal illness. A specially trained research nurse or physiotherapist approached the remaining residents to tell them about the study and assess their capacity to give consent (stage 1). Those who, in the opinion of the recruitment team, lacked capacity to give consent to participate were not approached further; we did, however, approach their NOK. Residents not interested in taking part in the study were excluded.

Information sheets were given to residents who were considered competent to consent, and left in a prominent place so that they could discuss it with their relatives or friends. Large print or audio versions were available for those with visual impairment. Mutually agreed appointments were made for study assessments within about 1 week of the initial approach, giving residents time to consider taking part in the study.

Residents had the option to consent, or NOK had the option to give assent, either to the assessments, the use of care home data or to both. Residents (or NOK) could also consent (or assent) to the results of assessments being shared with the care home manager and their NOK, and/or their general practitioners being informed of their participation in the study. The research nurse/physiotherapist conducting the recruitment assessment checked that the resident had read, or otherwise availed themselves of, the information sheet and understood the broad nature of the study, and answered any questions that the resident had. In practice, family members were sometimes present for these discussions. Each statement on the consent form was discussed and initialled by the resident; if they were in agreement then the consent form was signed by the resident and witnessed by the research nurse. For those residents with sight impairment a member of the care home staff witnessed the consent process. The process of going through the information sheet and consent form and checking understanding provided a further check on the resident's capacity to consent (stage 2). If at this stage it was clear that the resident lacked capacity then the process was stopped and a personal consultee was approached.

Care homes wrote to the NOK of residents who lacked capacity to consent, enclosing information about the study and an expression-of-interest slip. Residents who were unable to communicate were identified by the care home manager at the initial meeting, and agreement was requested for access to care home data only. NOK who expressed an interest in their relative/friend taking part in the study were contacted by telephone to answer any queries and arrange for an assent form to be sent to them by post or to be completed with the research nurse at the care home.

If after 2 weeks there had been no response to the request from the initial letter the relatives were contacted by telephone. It had been anticipated that if a resident had no known NOK then an appropriate nominated person could be contacted as permitted by The Mental Capacity Act 2005. 105

We consulted with local social services departments and the Independent Mental Capacity Advocacy (IMCA); neither organisation felt able to provide this service. In view of the relatively small numbers of residents involved we decided not to explore other possibilities for a nominated consultee and therefore residents who were unable to give consent and who had no contactable NOK were not recruited.

Baseline data collection

Assessments were carried out in the resident's own room or an alternative quiet location in the care home in which the resident felt most comfortable. Assessment lasted between 30 and 60 minutes and the research nurse/physiotherapist administered the questionnaire instruments; Geriatric Depression Scale-15,112 Mini Mental State Examination,115 European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),116 fear of falling and current pain. They also did a brief physical assessment: the Short Physical Performance Battery. 117,118 The results were recorded on paper whilst with the resident, and entered directly on to a laptop computer after the assessment had finished. Assessments were terminated if the resident expressed any distress or desire to withdraw.

Wherever possible all baseline assessments were collected prior to randomisation. For a small number of residents the recruitment process was started prior to randomisation but consent/assent was not obtained until after randomisation. Data collection for these participants was then carried out as soon as possible after randomisation. These participants' data were not included in the cohort analysis but were included in safety analyses, and if present at the end of the study they were included in the cross-sectional analyses.

Where consent/agreement had been given we provided the care home manager with the resident's Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores and a brief interpretation/suggested action. Residents with Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores of 0–4 were considered to have no depression. It was suggested that residents with Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores of between 5 and 10 (moderate depression) were encouraged to take part in activities and be monitored by care home staff. Care home staff were encouraged to refer residents with Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores of between 11 and 15 (severe depressive symptoms) to their general practitioner or Community Mental Health Team. For those residents who were unable to complete all 15 questions (but did complete ≥ 10) we used an algorithm to calculate and report the score, based on proportion of positive replies from questions answered (see Appendix 1).

Residents recruited after randomisation

At the 3- and 6-month visits the care home manager was asked to identify any new permanent residents (see Follow-up, below). We did not do this at 9 months to ensure that all those contributing to the cross-sectional analyses had been exposed to the environment within the care home long enough to be exposed to at least 4 months of the environment of that home. If the resident was eligible and interested in taking part in the study, the research nurse/physiotherapist explained the study and assessed their capacity to give informed consent, allowing the resident at least 24 hours to consider taking part in the study. NOK of residents unable to give informed consent were contacted in the same manner as those approached prior to randomisation. All processes for data collection were the same as for participants recruited prior to randomisation (see Obtaining consent, above).

Care home data

We collected demographic data (age, sex, ethnicity, social class, age at leaving full-time education), comorbidities (cancer, stroke, dementia, depression, anxiety, osteoporosis, chronic lung disease, urinary incontinence) and data on length of residence from the care home records. Data on current medication use were obtained directly from residents' Medication Administration Record Sheets. The resident's key carer, or carer looking after them on the day of data collection, was asked to complete a proxy EQ-5D, Barthel Index and Social Engagement Scale (Table 2). 113,116,119

| Data collection | Time recruited | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | |

| Before randomisation and immediately post randomisation | Sociodemographic data, comorbidities, GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, SPPB, fear of falling, pain, Barthel Index, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications | |||

| 3 months | Proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | Sociodemographic data, comorbidities, GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, SPPB, fear of falling, pain, Barthel Index, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications | ||

| 6 months | GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, fear of falling, pain, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | Proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | Sociodemographic data, comorbidities, Barthel Index, GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, SPPB, fear of falling, pain, Barthel Index, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications | |

| 9 months | Proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, fear of falling, pain, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | Proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | Sociodemographic data, comorbidities, Barthel Index, GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, SPPB, fear of falling, pain, Barthel Index, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications |

| 12 months, end of study | GDS-15, MMSE, EQ-5D, SPPB, fear of falling, pain, proxy EQ-5D, SES, medications, fractures, deaths | |||

Follow-up

We did four cycles of follow-up in each home. Follow-up data were collected over several visits, at around 3, 6, 9 and 12 months after the home was randomised.

Follow-up data collection

At 6 and 12 months we sought to complete follow-up assessments on all residents from whom we had consent or agreement to take part in study assessments. The research nurse/physiotherapist confirmed with the care home manager that it was an appropriate time to approach the resident. Residents who agreed to take part in follow-up assessment completed the same questionnaire instruments as baseline apart from the physical assessment Short Physical Performance Battery, which was not administered at 6 months.

Residents who were known to have died or had moved from the home were reported to the study team by the care home manager at each visit. At 6 and 12 months residents who were in hospital, or too unwell at the time of assessment, were contacted within 1 month to see if they were now well enough to be assessed. Participants who had moved to another participating care home were contacted and assessed, at the time that assessments were being done in their original home. We were unable to follow-up participants who had moved to a non-participating home.

Care home data were collected for those for whom we had consent/agreement and who were present in the care home at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Medication use, visits by health-care professionals, outpatient appointments, accident and emergency (A&E) attendances, and hospital admissions were recorded. The resident's key carer, or carer looking after them on the day of data collection, was asked to complete a proxy EQ-5D and the Social Engagement Scale at the 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up visits.

Residents recruited after randomisation

Follow-up assessments were completed in the same manner as those recruited prior to randomisation with an assessment 6 months after they had joined the study. All participating new residents had an end of study assessment when their home came to the end of its 12-month study period. The majority of new residents were identified and recruited at 3- and 6-month follow-up visits to the care homes; a small number requiring assent from NOK were recruited at between 6 and 9 months post randomisation.

Evaluation of recruitment processes

As part of the process evaluation, recruitment processes, including home recruitment and recruitment of individual participants, were evaluated (see Process evaluation, below).

Independent observations of the process of consenting participants were carried out by the process evaluation research fellow. This involved shadowing the recruiting staff on a number of occasions and observing the consent and assessment process in different homes. Results of these observations are reported in the quality control section and are mentioned in the consent substudy section (see Ethics substudy, below).

Assessment

In light of the poor state of health of many of our study participants we used a parsimonious set of outcome assessments. For the cohort analyses we collected follow-up data, directly from participants, at 6 and 12 months after randomisation. A drug trial for the treatment of depression would expect maximal effect to be seen by 4 months. 40 If exercise were an effective treatment for depression we might expect a response in a similar time. However, there is a time lag between randomisation and participants gaining any benefits from the exercise programme because of the time taken to start changing the attitudes of the care home staff and to establish exercise groups as a regular routine in the care home. Anticipating that the intervention would be fully functional 2 months after randomisation, we did our first assessment 6 months after the home was randomised.

We originally intended to collect 6-month follow-up data just from those with five or more depressive symptoms (or equivalent) at baseline. Early in the study it became clear that the average cluster size was smaller than anticipated. In view of concerns about obtaining sufficient data for any 6-month analysis, and with the agreement of the Trial Steering Committee, we changed to collecting 6-month assessment data from all participants. We did not, however, have sufficient research nurse/physiotherapist capacity to also collect the Short Physical Performance Battery on all participants at 6 months and therefore did not include the 6-month physical assessment. For the cross-sectional analyses we included residents who had been in an OPERA care home for at least 3 months prior to the end-of-study (12-month) data collection.

At each assessment we started by collecting our primary outcome measure, the Geriatric Depression Scale-15, to maximise response rates in those who might not be able to complete the full assessment. 112 We had originally set an exclusion criterion of a Mini Mental State Examination score of < 10 for severe cognitive impairment, as we thought that those with lower scores would be unable to complete the Geriatric Depression Scale-15. 115 Experience in the pilot study was that we were collecting satisfactory Geriatric Depression Scale-15 scores prior to attempted completion of the Mini Mental State Examination. We therefore removed this exclusion criterion from the main study. This concurs with reports of successful completion of the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 in people with severe cognitive impairment. 120

Primary outcome measure

Our primary outcome measure was the Geriatric Depression Scale-15. 112 This brief instrument consists of 15 yes/no questions and has been well validated in care home populations. It avoids using potentially somatic features of depression that may be misleading in this age group, focusing more on mood and functional symptoms of depression. 121 It is one of the most widely used measures in this field. It is simple to complete, with 97% of cognitively intact nursing home residents producing analysable data, and showed high internal consistency in a large sample of US nursing home residents. 122 The Geriatric Depression Scale-15 can be interpreted as an indication of the presence/absence of depressive mood. A score of ≥ 5 appears to give the best sensitivity and specificity for presence/absence of depressive mood. 120,123 Nevertheless, the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 is not a substitute for a clinical diagnosis of depression. However, in this report we will refer henceforth to the presence of five or more depressive symptoms, or its equivalent, on the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 as depression (Table ). Some individuals completed fewer than 15 items on the Geriatric Depression Scale. The recommended score indicating depression is ‘5’ when 13 or more items are completed, ‘4’ when 12 or 11 items are completed and ‘3’ when 10 items are completed (see Table 3). When nine items or fewer were completed the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 score was set to missing. Henceforth the presence of the appropriate number of positive items is referred to as depression. The Geriatric Depression Scale-15 has been used as a continuous measure in other randomised controlled trials based in care homes. 95,124 We also use the Geriatric Depression Scale-15 as a continuous measure in some of our analyses.

| Responses to GDS | Score indicating depression |

|---|---|

| 15 | ≥ 5 |

| 14 | ≥ 5 |

| 13 | ≥ 5 |

| 12 | ≥ 4 |

| 11 | ≥ 4 |

| 10 | ≥ 3 |

Data collection

For the cohort study we collected Geriatric Depression Scale-15 and the other participant reported outcomes prior to randomisation and then at 6- and 12-month follow-up. For those joining the study after randomisation we collected these data at study entry, 6 months after study entry and/or at the end of the study.

Other participant reported outcomes

Health-related quality of life

The EQ-5D is a widely-used brief measure of health utility. 125–127 [The EQ-5D and proxy EQ-5D were used with the permission of the EuroQol Executive Office. All copyrights in the EQ-5D, its (digital) representations, and its translations exclusively in the EuroQol Group. The EQ-5D™ is a trade mark of the EuroQol Group.] It measures quality of life using questions in five domains, the EQ-5D, plus the EuroQol Visual Analogue Scale (thermometer). To reduce questionnaire load we used the EQ-5D as our overall measure of health-related quality of life and for our health economic analyses. It has been used satisfactorily in previous studies of nursing home residents. 127

Cognitive function

We measured cognitive function using the Mini Mental State Examination115 (The Mini Mental State Examination was used with permission of Psychological Assessment Resources Inc., which retains the copyright). The Mini Mental State Examination is the most widely used measure of cognitive impairment worldwide. 128 It is quick, validated in relevant populations, sensitive to change and allows comparisons to be made with other studies. There is a suggestion that exercise may have a direct effect on preventing cognitive decline. 129 This is therefore an important secondary outcome.

Fear of falling

Although there are grounds for optimism that exercise intervention of the type used in OPERA may reduce both falls and falls injury, there is a justifiable concern that, by encouraging residents to be more active, it might lead to an increase in falls. 130,131 Recording of falls within care homes is likely to be unreliable and within a cluster randomised trial of this nature it is prone to reporting bias. In community studies fear of falling has been shown to be an independent predictor of falls risk. 132 For this study we used a simple yes/ no question of fear of falling to make completion easier. Others have found, in similar populations, that many residents are unable to complete a scale for fear of falling. 133

Pain

The association between pain and depression in older people is well recognised. 134,135 Exercise may have a beneficial effect on pain in this population, independent of the beneficial effects it may have on depression. 33 We ascertained presence or absence of pain from the EQ-5D pain question. For those with pain we then assessed their current level of pain on a five-point ordinal scale, i.e. pain now: no pain, mild pain, moderate pain, severe pain, and pain as bad as it could be. For analysis we collapsed this into three groups: no pain, mild/moderate pain, and pain as severe or as bad as can be.

Physical assessment

Mobility

To assess the effect of the programme on mobility we used the Short Physical Performance Battery, which incorporates three essential aspects of physical function that should be improved by the exercise programme: static balance, lower limb strength and dynamic balance. 117 Because of the central importance of physical function to the ability to thrive, the Short Physical Performance Battery has been used extensively in trials and observational studies of older people. It has well-established and surprisingly strong relationships with a range of important public health outcomes, including onset and progression of disability, mortality and nursing home admission. 136 Testing procedures are standardised and timed. 117,118 A change in the Short Physical Performance Battery would indicate if the OPERA intervention has had an effect on its primary target of improving physical activity.

Data collection

For the cohort study we collected Short Physical Performance Battery prior to randomisation and at the end-of-study assessment. For those joining the study after randomisation, we collected these data at study entry and at the end of the study. In the original protocol we were planning to collect only 6-month outcome data on those who were depressed at baseline. As a sustained effect on mobility was the outcome of interest this was measured at study entry and end-of-study assessments only.

Proxy measures

We collected proxy data on all of those for whom we had permission to collect care home data. Thus, more proxy data are available on participants than data from the participant-completed measures.

Activities of daily living

At baseline only we collected data on activities of daily living in order to provide data on the severity of physical disability in our population. We used the Barthel Index, a widely used measure of activities of daily living. 119

Health-related quality of life

The use of proxy measures of the EQ-5D, where the proxy is asked to report on how they think the subject feels, is well established. 137 Many of our participants would be unable to satisfactorily complete the EQ-5D. In particular, the use of the EQ-5D Visual Analogue Scale (thermometer) is difficult for those with substantial cognitive impairment or visual impairment. The level of agreement between self-completed and proxy scores varies according to subjects' underlying illnesses and who the proxy is (family member or health-care professional). Agreement is better for the EQ-5D index score than the Visual Analogue Scale but varies across EQ-5D domains. Agreement is reasonable for people living with stroke and better for Parkinson's disease. 138,139 One study in dementia found an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.42 for the index score between health-care professionals and patients for EQ-5D index score in people suffering from dementia. 140 Whatever the absolute level of agreement between proxy and self-completed EQ-5D might be in individual cases, the proxy values should reliably identify changes in health state.

The calculation of quality-adjusted life-years requires multiple measures at different time points. It is likely that the health of a substantial proportion of participants will deteriorate over 12 months, reducing the proportion who can contribute to the health economic analysis. For this reason we collected proxy EQ-5D at each time point on all participants, even if they had satisfactorily completed an EQ-5D themselves. We asked carers to rate how he/she (the proxy) thought the resident would rate his/her own health-related quality of life if he/she (the resident) was able to communicate it (EQ-5D, proxy version 2). 137

Social engagement

Improving level of social engagement in care home residents through group activity and increased mobility is an alternate pathway through which the OPERA intervention might affect mood. Collecting data by direct observation across 78 homes would be impractical. For this reason we used the Social Engagement Scale, which is completed by carers to give an indication of the involvement of a resident in activities within a nursing or residential home. (The Social Engagement Scale is part of assessment instruments owned by interRAI, a non-profit corporation with central offices in the USA. However, use of these instruments in the UK is handled by an English affiliate led by Dr Iain Carpenter, University of Kent. Dr Carpenter kindly gave us permission to use this item.) The Social Engagement Scale uses six Minimum Data Set Resident Assessment Instrument items. 141 As part of the Minimum Data Set Resident Assessment Instrument the Social Engagement Scale is normally administered by direct observation of the resident by the researcher as well as asking the residents and care home staff. This was impractical in our study and the Social Engagement Scale was added to proxy measures completed by care staff. The items are scored with yes (1) or no (0) responses indicating the presence or absence of the behaviour in question. 113,142 Scores range from 0 to 6, with a higher score indicating higher levels of social engagement. For the purposes of reporting, individual scores were calculated and then grouped into low (scores of 0 or 1), medium (scores 2–4), and high social engagement (scores of 5 or 6).

Data collection

For the cohort analyses we collected proxy EQ-5D and proxy Social Engagement Scale prior to randomisation and then at 3-, 6-, 9- and 12-month follow-up. For those joining the study after randomisation we collected these data at study entry, and 3 and 6 months after study entry and/or at the end of the study.

Care home data

Participant characteristics.

We collected demographic data (age, sex, ethnicity, social class and age at leaving full-time education), comorbidities (cancer, stroke, dementia, depression, anxiety, osteoporosis, chronic lung disease, urinary incontinence) and data on length of residence and current medication from the care home records.

Medication

We collected data on all medications used over a 1-week period from the home records. We extracted the exact drug name (as written in care home records), preparation and dose used, plus the number of times any medication was actually administered over a 1-week period. We then used the prescription cost analysis database to attach a code to each unique preparation used. 143 In this way we were able to attach a cost to each individual preparation used, and to estimate total amount used of each individual drug listed in the British National Formulary. 144 Using the World Health Organization (WHO)-defined daily dose for each drug we were able to generate number of days of medication used by British National Formulary chapter and subchapter. 145

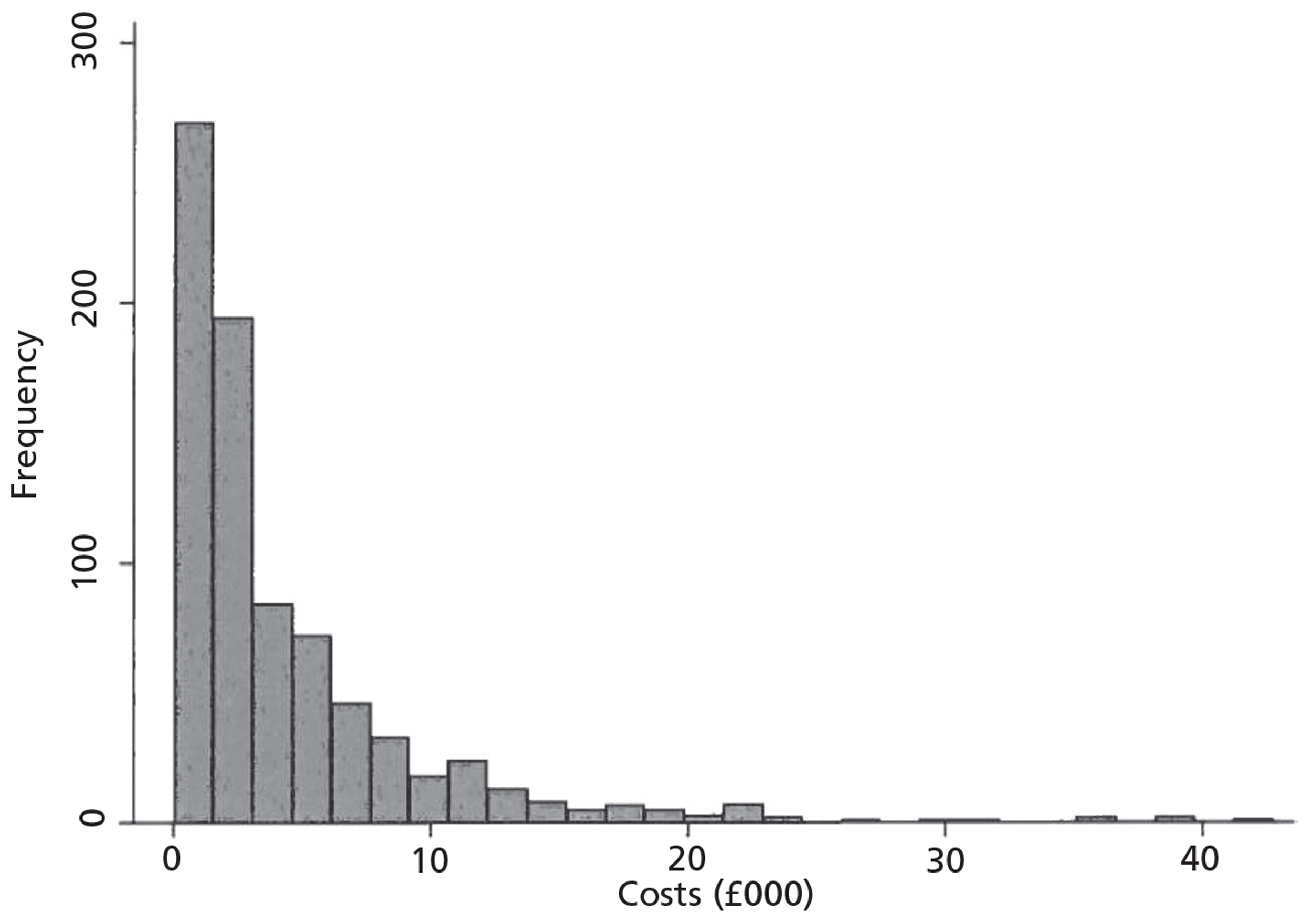

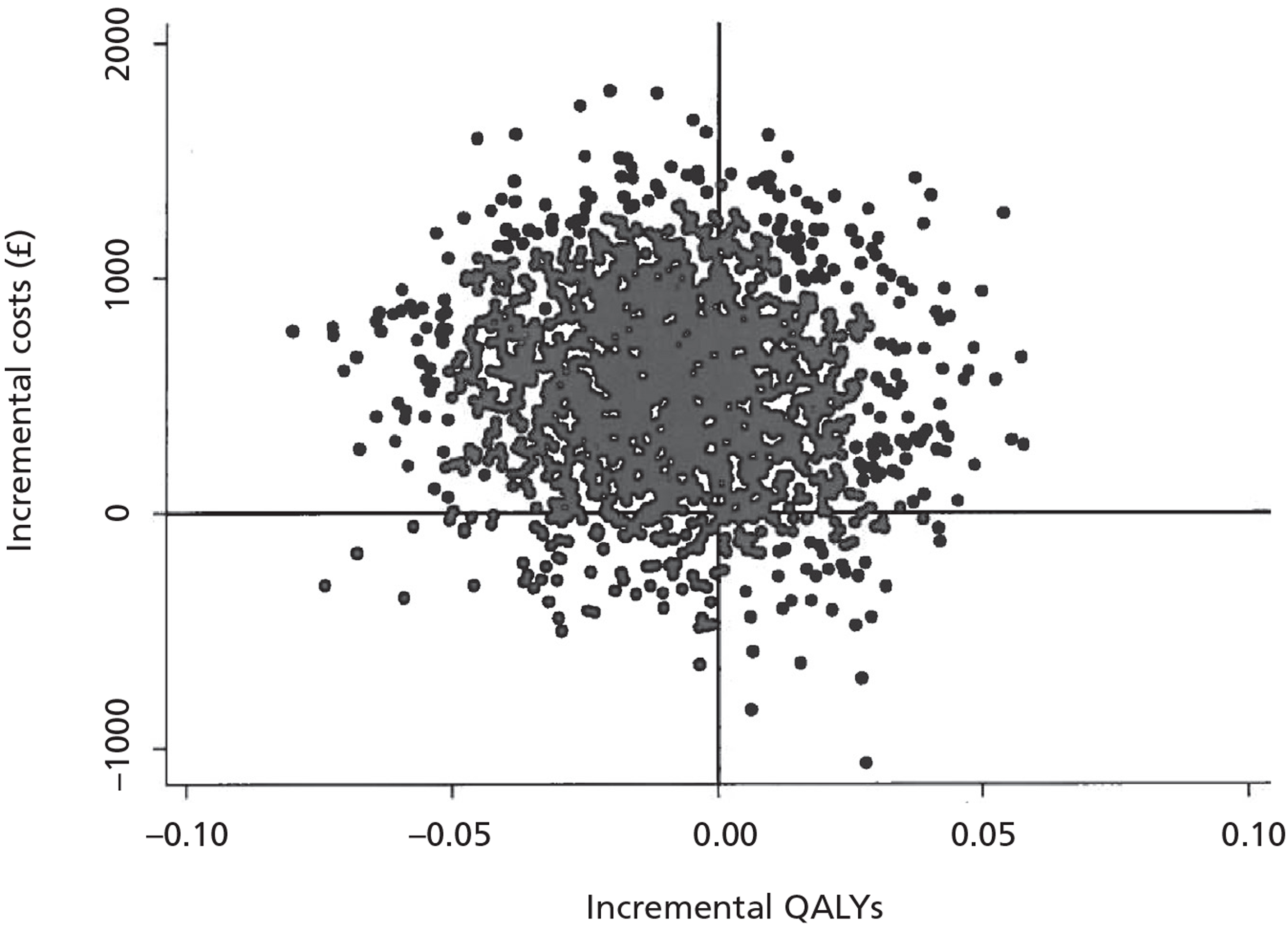

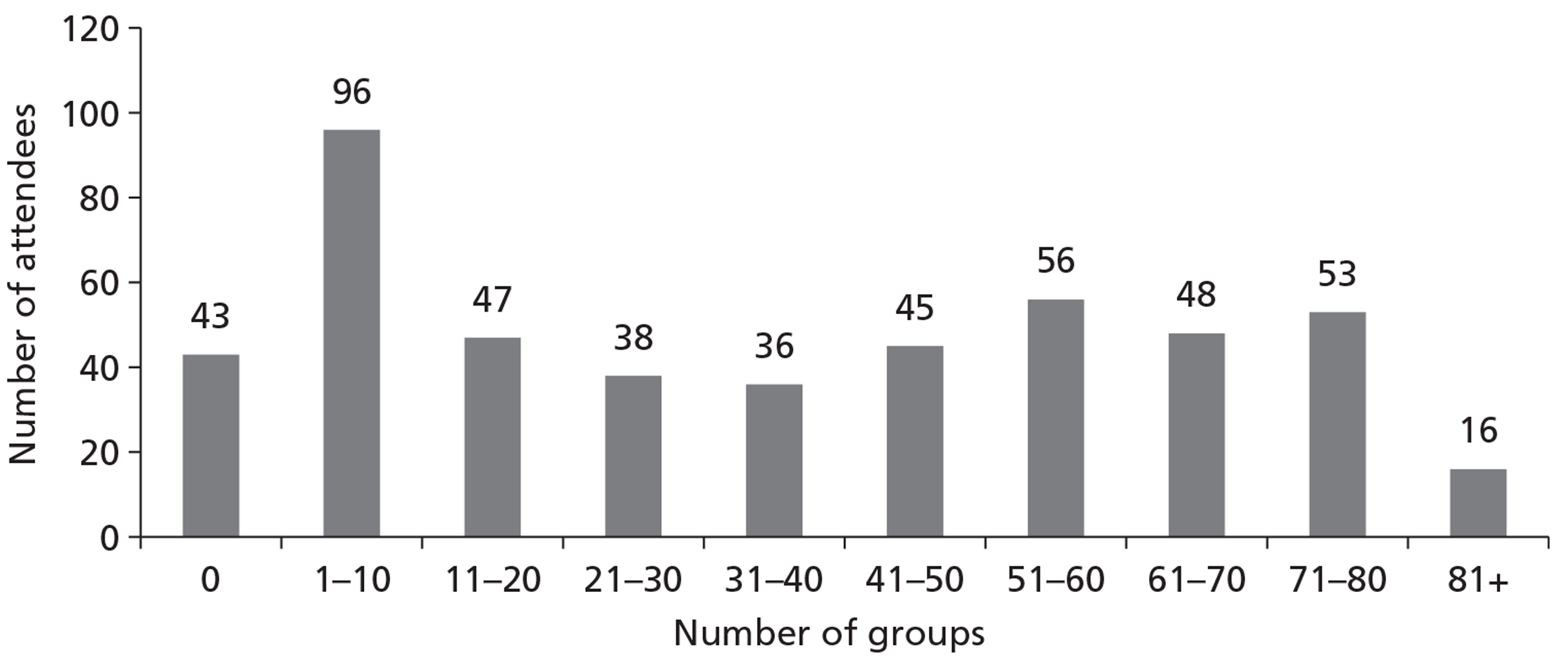

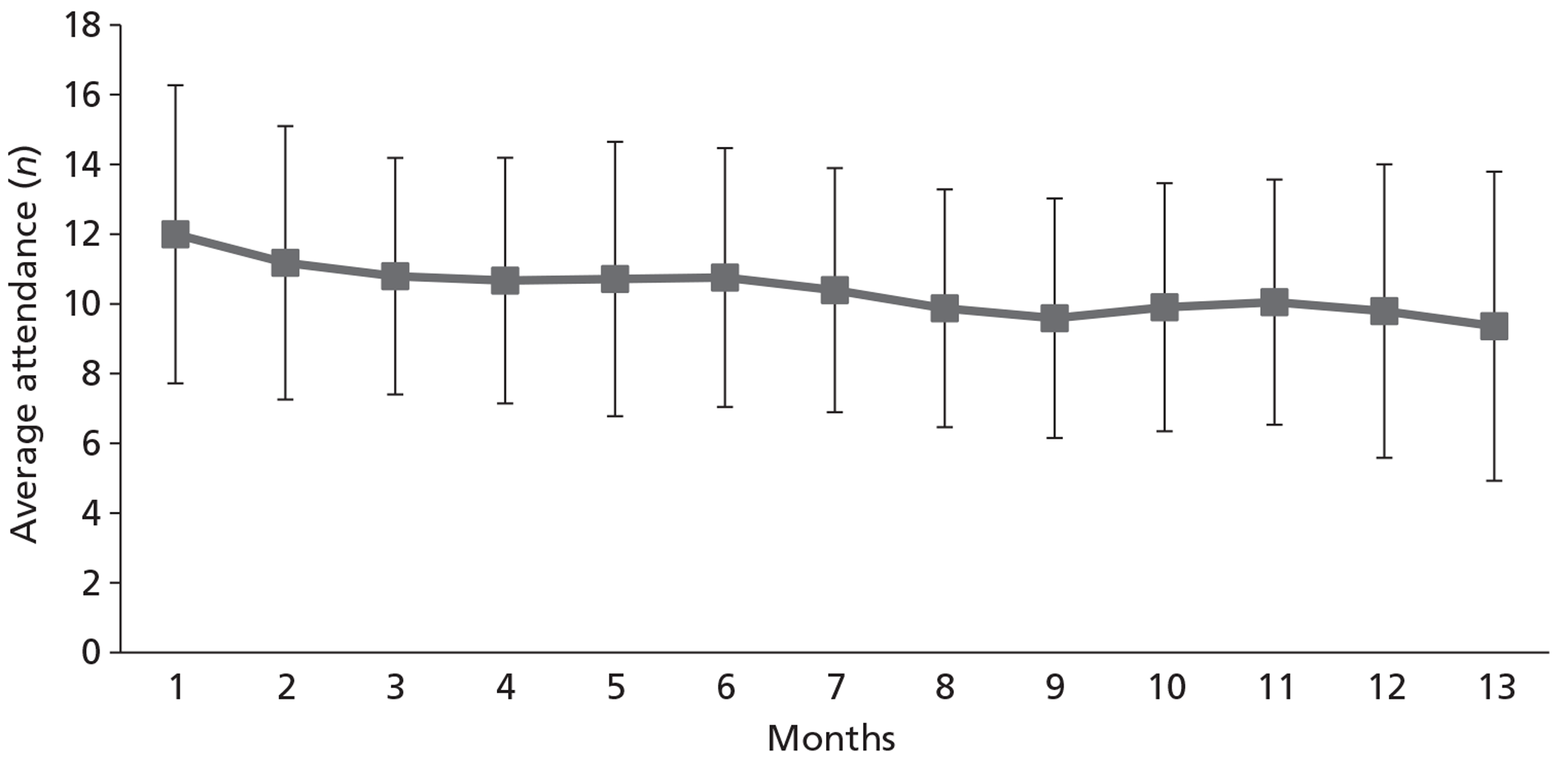

For some products estimating total usage from care home records was not possible. For example, the amount of topical preparation used at each administration is not recorded, and the degree of variability in recording of appliances and dressing between care homes meant that these data were not reliable.