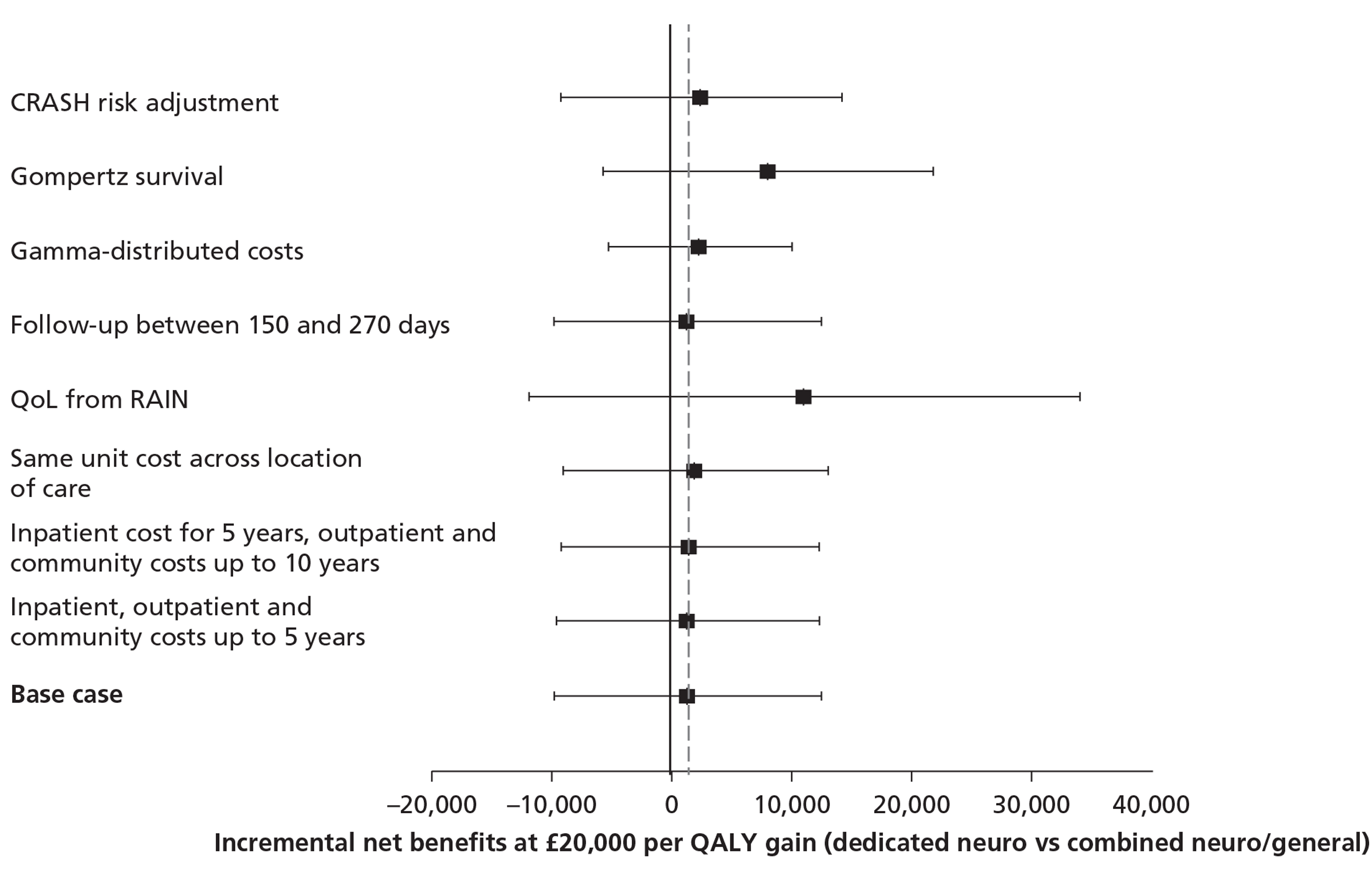

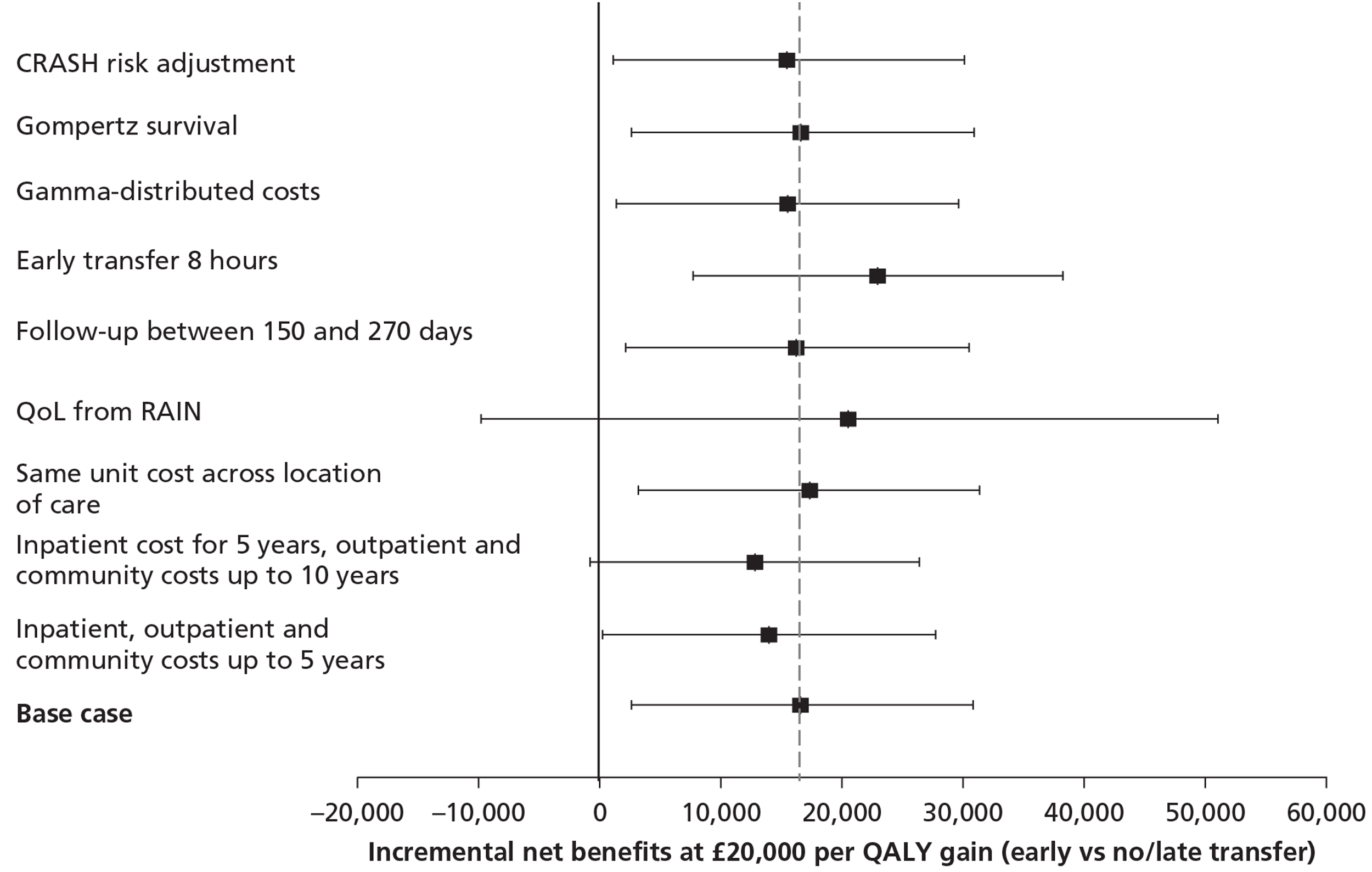

Notes

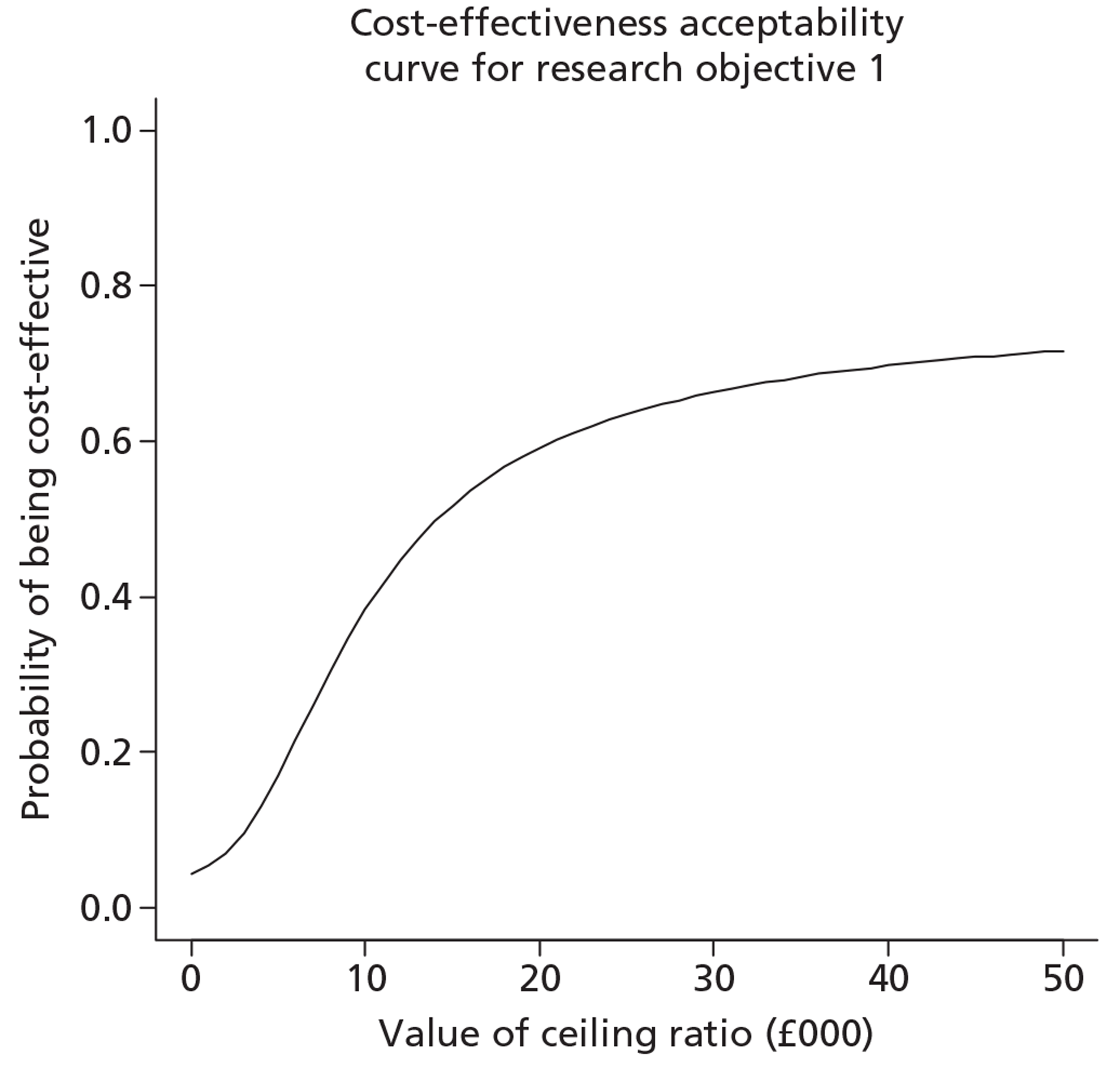

Article history paragraph text

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/37/29. The contractual start date was in November 2008. The draft report began editorial review in March 2012 and was accepted for publication in July 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

DKM is a paid consultant or member of a Data Monitoring Committee for Solvay Ltd, GlaxoSmithKline Ltd, Brainscope Ltd, Ornim Medical, Shire Medical and Neurovive Ltd. His institution receives payment for a registered patent for a new positron emission tomography ligand assessing mitochondrial function

Permissions

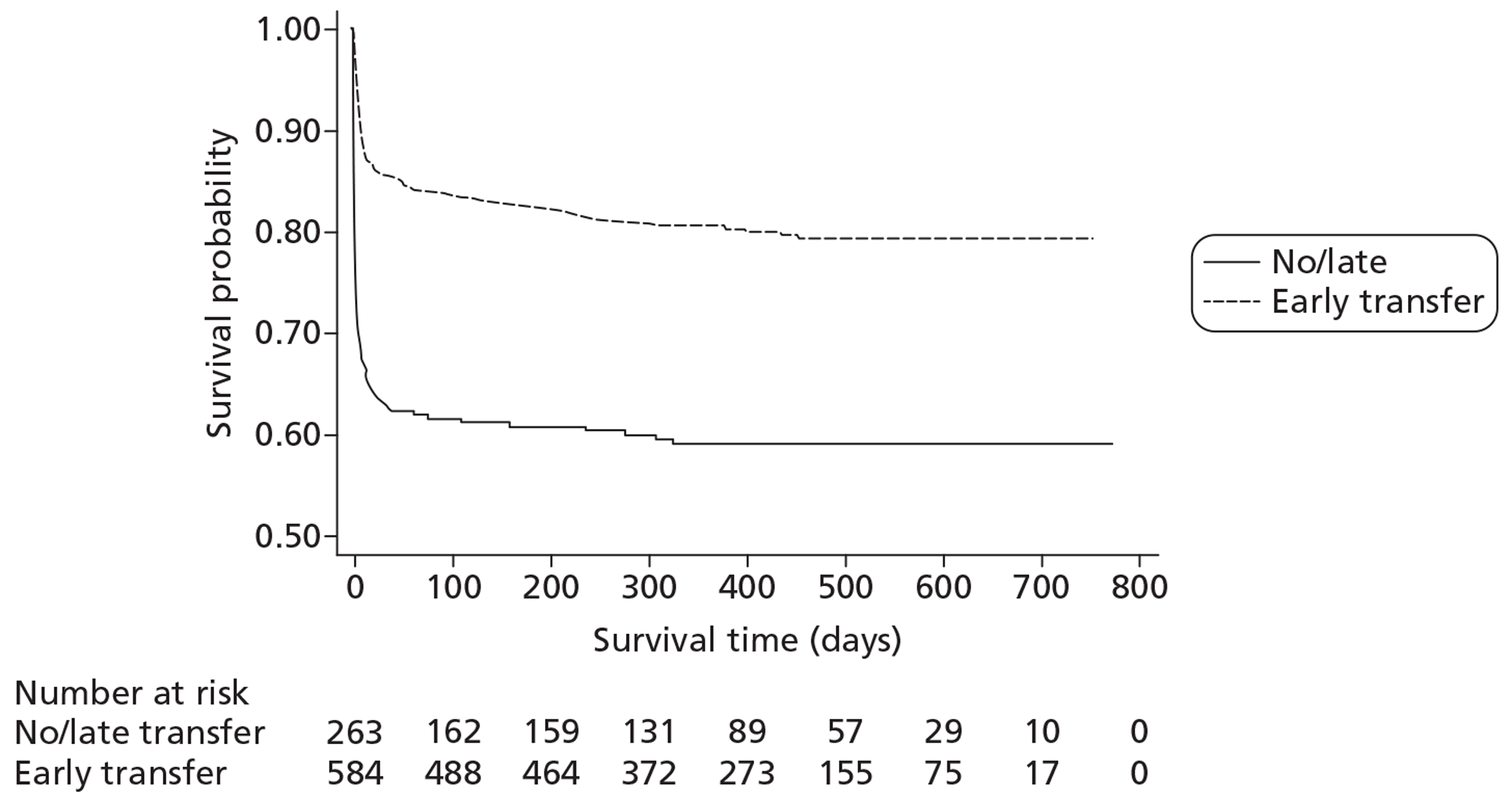

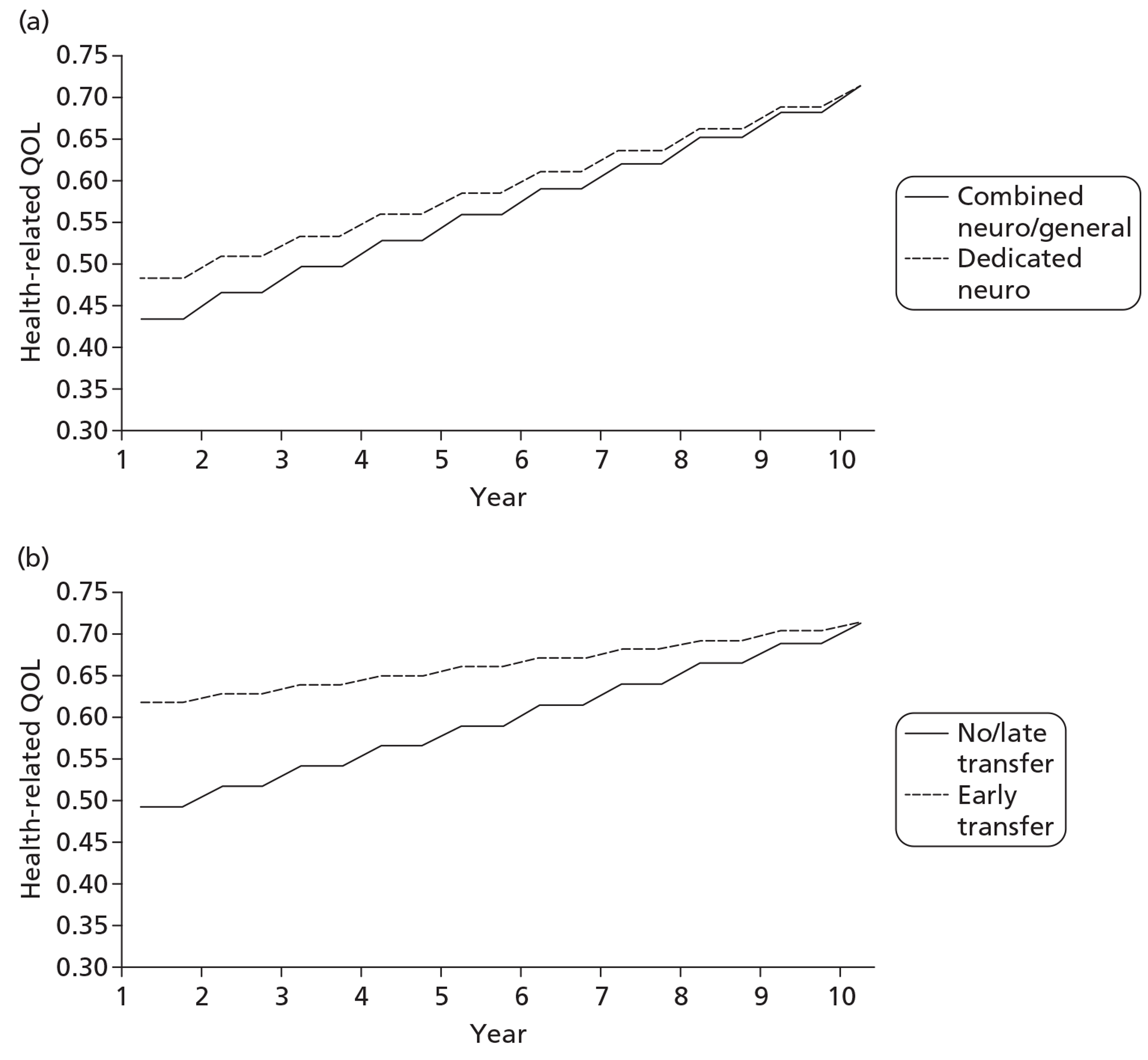

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Harrison et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Risk prediction models have been in established use in adult general critical care units for > 30 years, since the publication of the original Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) model in 1981. 1 In the UK, the first large-scale validation of a risk prediction model was the Intensive Care Society's APACHE II study in Britain and Ireland (1987–9). 2,3 This study produced recalibrated coefficients for the APACHE II model, and led, in 1994, to the formation of the Intensive Care National Audit and Research Centre (ICNARC) and the Case Mix Programme (CMP), the national clinical audit of adult general critical care units in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. ICNARC has continued to pioneer developments in risk prediction in the CMP, most recently through the validation and recalibration of a number of general risk prediction models4 and subsequent development of a new model – the ICNARC model. 5

Unlike adult general critical care, no data are routinely collected in the NHS for risk-adjusted comparison of outcomes from neurocritical care. Consequently, a number of dedicated neurocritical care units currently participate in the CMP. However, there are significant limitations to using models developed and validated for general critical care for patients receiving neurocritical care. Using a spectrum of measures for calibration and discrimination, risk prediction models – successfully developed and validated for adult admissions to general critical care units – showed significant departure from perfect calibration in admissions with head injuries to adult general and dedicated neurocritical care units. 6 The inclusion and handling within general risk models of variables of specific prognostic importance in acute traumatic brain injury (TBI) is often poor. 6 For example, the APACHE II model assumes that any patient who is sedated for the entire first 24 hours in the critical care unit is deemed neurologically normal, which is unlikely to be correct for TBI patients and has led to that the use of pre-sedation values of the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) for such patients. 7 The only general model to take any account of changes detected on computerised tomography (CT) scan is the Mortality Prediction Model (MPM) II, and the inclusion of CT information in this model is limited to the presence of an intracranial mass effect. Furthermore, all risk prediction models for adult general critical care use an outcome of mortality at discharge from acute hospital, which is not considered adequate for neurocritical care when longer-term (e.g. 6-month) mortality and, importantly, functional outcome are more valid. 8

Although a large number of risk prediction models for TBI exist, a systematic review found that most models are limited by being based on small samples of patients, having poor methodology, and rarely being validated on external populations. 9 Despite the more recent development of models based on larger, more representative data sources,10 these models require further prospective validation, and potentially recalibration, before they can be applied with confidence for research and audit in neurocritical care in the NHS.

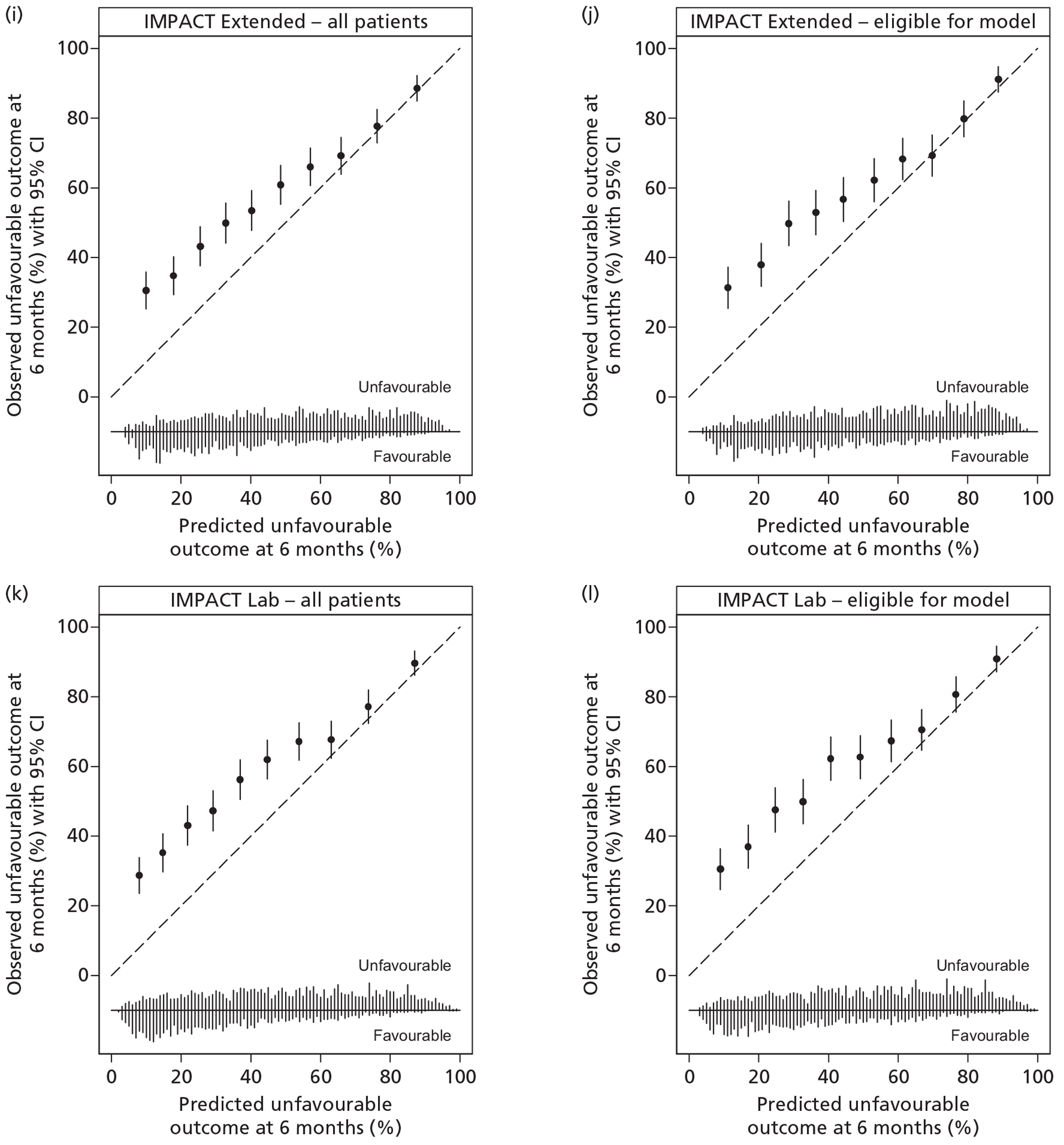

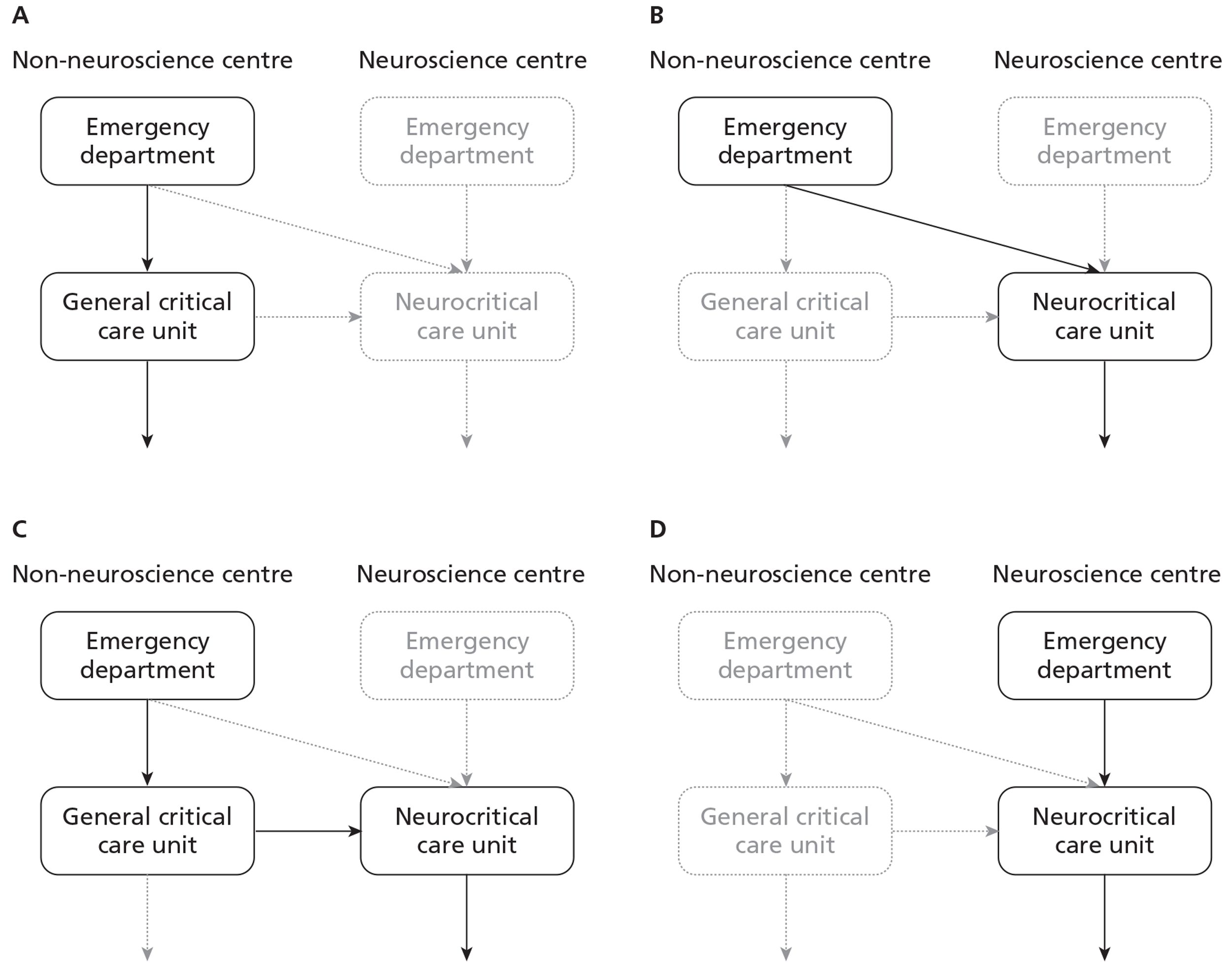

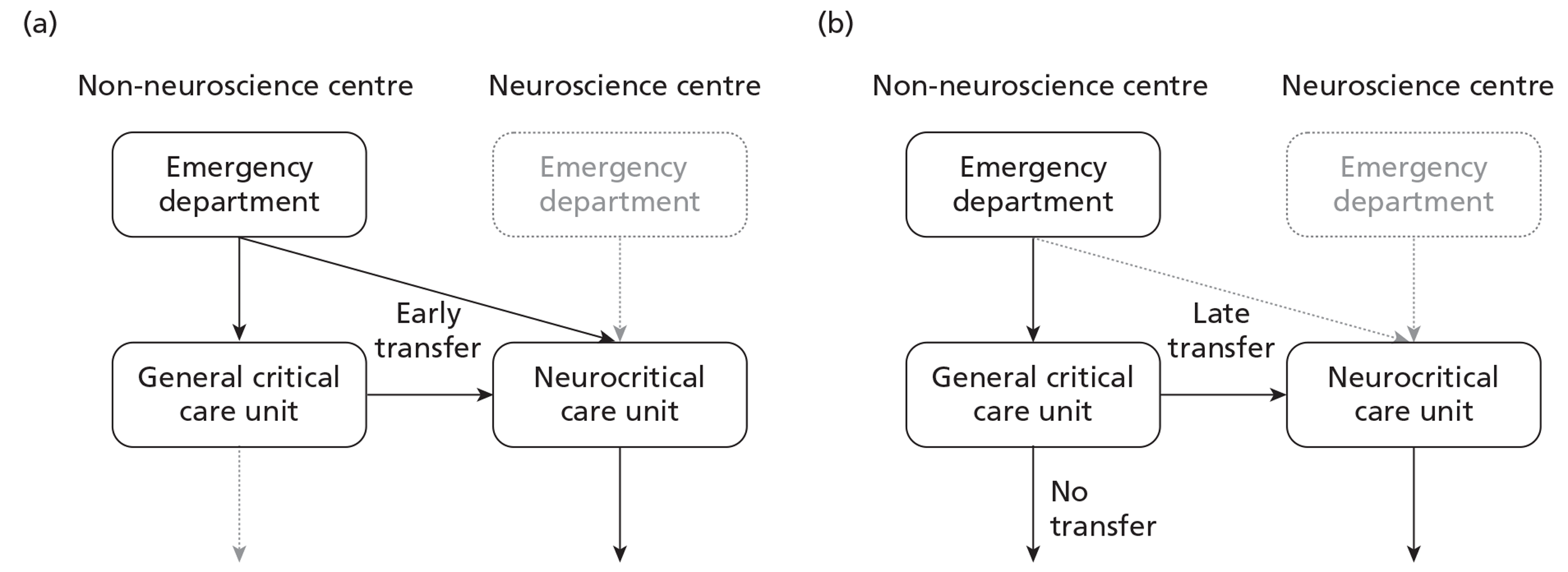

In the NHS, adult patients with TBI are rarely managed by a single service. They are usually managed by a succession of services from first contact to definitive critical care and the latter is not always within in a dedicated neurocritical care unit within a neuroscience centre. Despite guidelines recommending that all patients with severe TBI be treated within a neuroscience centre,11 many (particularly those without surgically remedial lesions) are currently neither treated in nor transferred to one. A combination of geography, bed availability, local variation and clinical assessment of prognosis can often determine the location of definitive critical care for an adult patient with TBI. The Neurocritical Care Stakeholder Group, established to offer expert advice to Department of Health and Commissioners, indicated in its audit report that, within the NHS, only 67% of beds that are ring-fenced for neurocritical care were in dedicated neurocritical care units and that neurocritical care unit occupancy rates exceeded 90% (especially for Level 3 beds). 12 Most neurocritical care for adult patients with TBI was delivered either in dedicated neurocritical care units (42%) or in combined neuro/general critical care units within a neuroscience centre (35%). However, despite clear guidelines and the progressive regionalisation of neurosurgical care since 1948, 23% of patients with TBI were treated in general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre.

Local critical care consultant opinion indicated that at least 83% of these patients required transfer to a neuroscience centre. No data were available, or are routinely collected even in 2012, within the NHS for risk-adjusted comparisons.

Where adult patients with TBI should be optimally managed is an important question for the NHS, in terms of both outcomes and costs. Belief and limited evidence has underpinned the establishment, and continuing expansion, of dedicated, neurocritical care facilities in the UK13,14 but no formal evaluation has been undertaken. Increased centralisation has been hypothesised to improve outcomes through concentration of knowledge and expertise, higher volumes of patients and greater adherence to evidence-based protocols. Recent research has suggested benefit from managing severe head injury in specialist centres;15,16 however, the results are inconclusive owing to lack of adjustment for all known confounders, no data on costs of care, and having follow-up data only to hospital discharge. The existing research also does not address the issue of dedicated compared with combined critical care units within neuroscience centres. A key issue for policy-makers is whether the additional initial costs of more specialised care are justified by subsequent reductions in morbidity costs and/or improvements in patient outcomes. Although conventional randomised controlled trial (RCT) methodology may be impractical in this setting, the presence of variation in the way services are organised and delivered can allow them to be compared using observational methods. This is possible only if a valid, reliable, appropriate and accurate risk prediction model exists.

The Risk Adjustment In Neurocritical care (RAIN) study was originally conceived in 2001. At its inaugural meeting in February 2007, the newly formed Neurocritical Care Network (NCCNet), a network of units and staff providing neurocritical care to patients in both dedicated and general units, identified establishing a risk prediction model to investigate and evaluate the location and outcomes of care for adult patients with TBI as their first, and top, priority. It was recognised that this aim could only be achieved through validation of an accurate risk prediction model for adult patients with TBI and the RAIN study was therefore adopted by NCCNet.

The primary aims of the RAIN study were to validate risk prediction models for acute TBI in the setting of neurocritical care in the NHS, and to use these models to evaluate the optimum location and comparative costs of neurocritical care in the NHS. Specific, detailed objectives to achieve these aims were to:

-

identify, from the literature, the existing risk prediction models for acute TBI most likely to be applicable to a neurocritical care setting, and identify a full list of variables required in order to be able to calculate these models (see Chapter 2)

-

collect complete, valid and reliable data for the variables identified above for consecutive adult admissions with TBI to dedicated neurocritical care units within a neuroscience centre, combined neuro/general critical care units within a neuroscience centre and general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre within the NHS (see Chapter 3)

-

describe the case mix of these patients and their survival, neurological outcome and quality of life (QOL) at 6 months following the TBI (see Chapter 4)

-

undertake a prospective, external validation of existing models for adult patients with TBI admitted to critical care, to identify the strengths and weaknesses of each model, and, if possible, to identify the best model to use for risk adjustment in this setting (see Chapter 5)

-

describe and compare adjusted outcomes and cost-effectiveness of care for adult admissions with TBI between dedicated neurocritical care units within a neuroscience centre, combined neuro/general critical care units within a neuroscience centre and general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre within the NHS (see Chapter 6)

-

make recommendations for policy and practice within the NHS (see Chapter 7).

Chapter 2 Selection of risk prediction models for critically ill patients with acute traumatic brain injury

Introduction

This chapter reports the process that was undertaken to select the most appropriate risk prediction models for external validation in the RAIN study. The aim was to identify the models most likely to be applicable in a neurocritical care setting in the NHS.

Methods

Selection of candidate risk prediction models was conducted in two phases. First, a systematic review of the literature was conducted to identify existing risk prediction models for acute TBI that are most likely to be applicable to a critical care setting and to identify the variables required to be able to calculate these models. Second, eligible models identified by the systematic review were reviewed by the RAIN Study Steering Group (see Acknowledgements) to determine if there were any relevant models that had been missed and to select the most appropriate models for external validation in the RAIN study.

Perel et al. 9 previously conducted a systematic review to identify and assess existing risk prediction models for TBI. 9 The first stage of the systematic review therefore was to update the existing review to identify relevant risk prediction models that had been published since 2006. The second stage was to assess the eligibility of studies previously identified by Perel et al. 9 and by the updated searches for the RAIN study.

Search strategy

The electronic search strategy was based on that used by Perel et al. 9 (see Appendix 1) and was performed using EMBASE (incorporating MEDLINE) to identify eligible studies, published in English, from 2006 to 2008, which (1) gave an overall prognostic estimation by combining the predictive information from at least two variables – studies could develop new prognostic models (derivation studies) or evaluate previous ones (validation studies); (2) used variables collected before hospital discharge, which were therefore considered as predictors; (3) included patients of any age; (4) included patients with any type or severity of TBI; and (5) predicted any outcome, such as neurological impairment, disability, survival, etc. There was no time restriction for the evaluation of outcomes. Three search themes were combined: ‘traumatic brain injury’; ‘brain/coma/consciousness/craino/skull’; and ‘prognosis/predicts’. One reviewer (GPr) examined titles, abstracts and keywords of records identified by the electronic database searches for eligibility. The full text of all potentially eligible papers was obtained and independently assessed by two reviewers (GPr and DAH) for eligibility using the pre-defined inclusion criteria described above. Disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer (KMR). The reference lists of all full-text papers reviewed were checked for any additional potentially eligible studies.

The studies previously identified by Perel et al. 9 and by the updated searches were then independently assessed by two reviewers (GPr and DAH) for eligibility for the RAIN study. Studies were eligible for inclusion if they (1) were based on adult (> 16 years) populations; (2) had a sample size of greater than 500 patients in either the development or validation data set; (3) aimed to evaluate outcome regardless of care received during the hospital stay; and (4) were UK based or multicentre. Disagreement was resolved by a third reviewer (KMR).

Assessment of methodological quality

There is no gold standard tool for quality assessment of either RCTs or observational studies. Assessment of the methodological quality of studies eligible for the RAIN study was conducted using the same approach as Perel et al. 9 considering two domains: (1) internal validity, which refers to systematic error and is related to the study design and (2) external validity, which refers to the generalisability of the study and whether the results can be extrapolated to other populations and settings. Eighteen questions related to internal and external validity were considered for each of the studies, as follows:

Internal validity

-

Did the study have adequate follow-up?

-

Was a discussion included about the rationale to include predictors?

-

Were the predictive variables clearly defined?

-

Were the outcomes predicted valid?

-

Were missing data adequately managed?

-

Was an adequate strategy performed to build the multivariable model?

-

Were interactions between the variables examined?

-

Were the continuous variables handled appropriately?

-

Were there > 10 events per variable included?

External validity

-

Was a description of the sample population reported?

-

Was there a clear explanation on how to estimate the prognosis provided?

-

Were measures of discrimination reported?

-

Were measures of calibration reported?

-

Were confidence intervals (CIs) reported?

-

Was the model validated?

-

Was the model internally validated?

-

Was the model externally validated?

-

Was the effect of the model established?

Expert review

All studies eligible for the RAIN study were then reviewed by the RAIN Study Steering Group to identify any additional studies, either published or ongoing, of relevance, and to select the most appropriate models for validation in a UK critical care setting.

Results

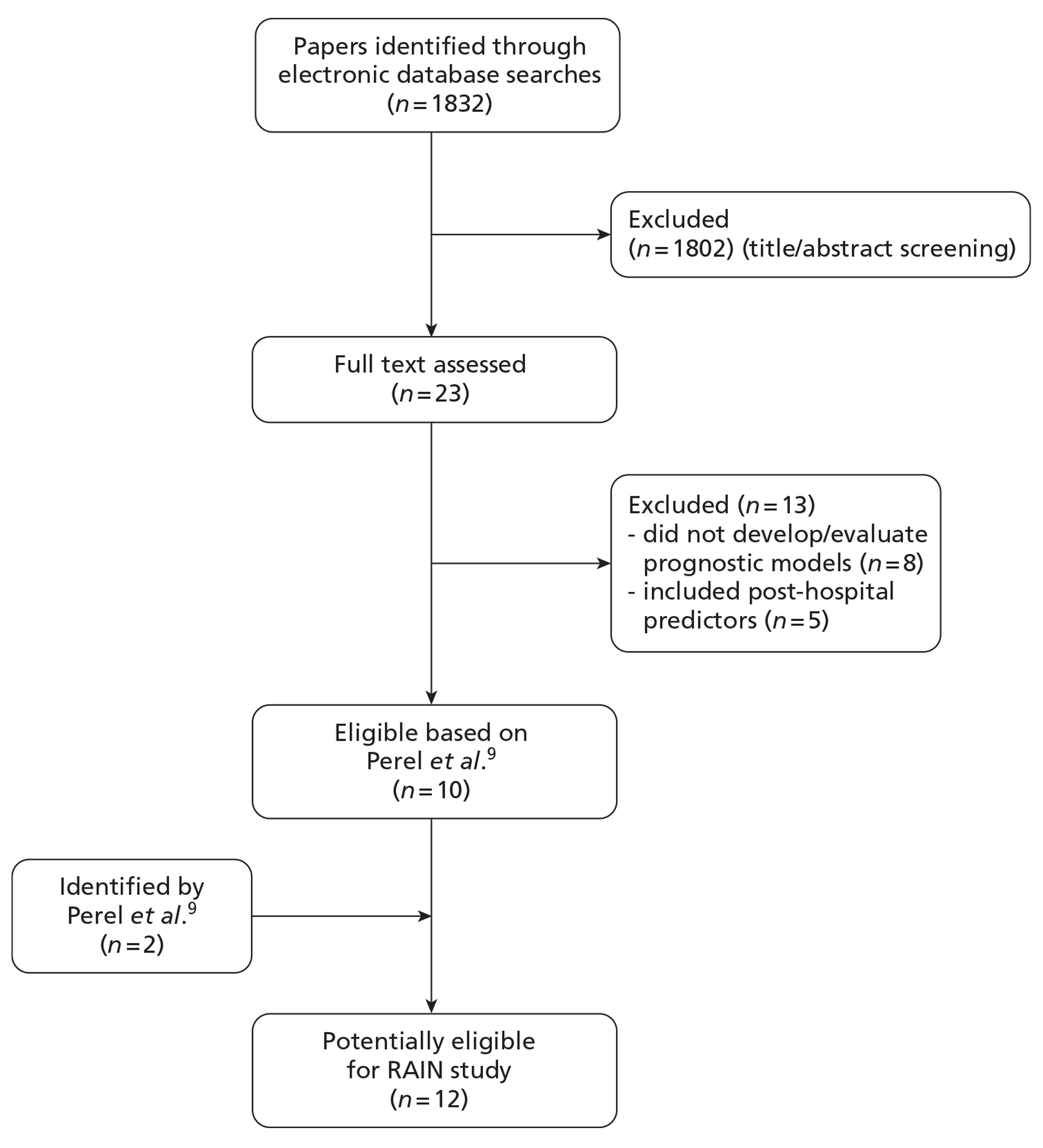

The electronic database searches identified a total of 1832 citations. After screening of titles and abstracts, 23 potentially eligible papers were identified for full-text review. 17–39 In addition, the electronic database searches identified seven review articles,40–46 the references lists of which did not identify any further potentially eligible papers. Of the 23 full-text papers reviewed, 13 were excluded because either they were not studies that had developed or evaluated prognostic models for TBI or they were prognostic models that included predictors measured after discharge from hospital (Figure 1).

A total of 53 studies reporting 102 models were identified by Perel et al. 9 However, of these, the authors considered the models developed by Signorini et al. 47 and Hukkelhoven et al. 48 to be the most clinically useful for patients from high-income countries with moderate and severe TBI, as they fulfilled the majority of the methodological requirements and showed acceptable performance in the external validation. They were also considered to be available in a user-friendly way. A total of 12 potentially eligible studies were therefore identified from Perel et al. 9 and from the updated searches (see Figure 1).

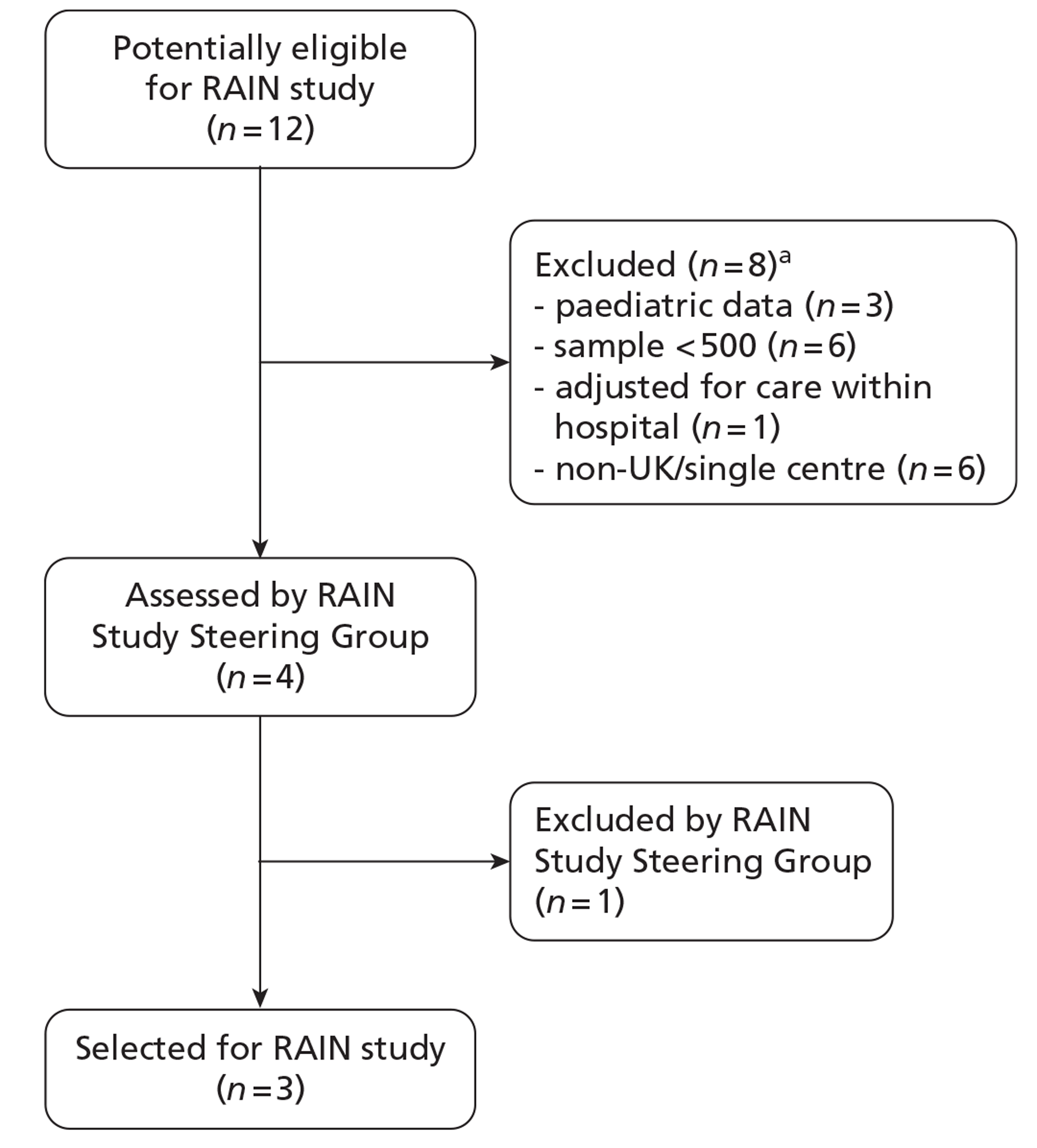

Of the 12 potentially eligible studies, eight did not fulfil the RAIN study eligibility criteria because the models had been developed in paediatric populations, were based on samples of fewer than 500 patients, adjusted for care received within hospital or had been conducted in a single-centre, non-UK setting (Figure 2). This resulted in four eligible studies for review by the RAIN Study Steering Group.

FIGURE 2.

Stage 2 of the selection process: selection of models for external validation in the RAIN study. (a) Studies were excluded for more than one reason.

Description of eligible studies

Four studies,30,35,47,48 reporting a total of 17 risk prediction models, met the RAIN study eligibility criteria. A brief description of each is given below and a summary is provided in Table 1.

| Model | Variables in model | Derivation sample | External validation | Outcome | Discrimination c-index (95% CI)a | Calibration, p-value from Hosmer-Lemeshow test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signorini et al. (1999)47 | ||||||||

| GCS score | Single-centre observational study (n = 372) | Single-centre observational study (n = 520) | Mortality at 1 year | 0.835 | < 0.001 | |||

| Pupil reactivity | ||||||||

| SS | ||||||||

| Haematoma | ||||||||

| Hukklehoven et al. (2005)48 | ||||||||

| Model | Age | Two multicentre RCTs (n = 2,269) | EBIC (n = 796) | Mortality at 6 months | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.89) | 0.42 | ||

| GCS motor score | TCDB (n = 746) | Mortality at 6 months | 0.89 (0.87 to 0.91) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Pupil reactivity | ||||||||

| Hypoxia | EBIC (n = 796) | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | 0.83 (0.80 to 0.86) | 0.05 | ||||

| Hypotension | ||||||||

| CT classificationb | ||||||||

| SAH | ||||||||

| MRC CRASH trial collaborators (2008)30 – CRASH models | ||||||||

| Basic model | Age | One multicentre RCT (n = 2185) | IMPACT database (n = 8509) | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | 0.81 | 0.70 | ||

| GCS score | ||||||||

| Pupil reactivity | ||||||||

| Major extracranial injuryc | ||||||||

| CT model | As above for Basic model plus: | One multicentre RCT (n = 1955) | IMPACT database (n = 8509) | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | 0.83 | 0.63 | ||

| Petechial haemorrhagesc | ||||||||

| Obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns | ||||||||

| SAH | ||||||||

| Midline shift | ||||||||

| Non-evacuated haematoma | ||||||||

| Steyerberg et al. (2008)35 – IMPACT models | ||||||||

| Core model | Age | IMPACT database (n = 8509) | CRASH tria (n = 6272) | Mortality at 6 months | 0.78 | – | ||

| GCS motor score | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | 0.78 | – | |||||

| Pupil reactivity | ||||||||

| Extended model | As above for core model plus: | IMPACT database (n = 6999) | CRASH tria (n = 6272) | Mortality at 6 months | 0.80 | – | ||

| Hypoxiac | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | 0.80 | – | |||||

| Hypotensionc | ||||||||

| CT classificationb | ||||||||

| SAH | ||||||||

| Extradural haemorrhagec | ||||||||

| Laboratory model | As above for Core and Extended models plus: | IMPACT database (n = 3554) | Not externally validated | Mortality at 6 months | – | – | ||

| Glucose | Unfavourable outcome at 6 months | – | – | |||||

| Haemoglobin | ||||||||

Signorini et al.

Signorini et al. 47 developed a risk prediction model in a cohort of consecutive patients admitted to a regional trauma centre with moderate or severe head injury (n = 372) between January 1989 and July 1991. The criteria for enrolment into the study were (1) age ≥ 14 years and (2) admission or last known GCS score of < 12, or of 13–15 with concomitant systemic injuries giving an injury severity score (ISS) of ≥ 16. The outcome assessed was mortality at 1 year. The variables included in the model are detailed in Table 1. The model was externally validated in a similar cohort of patients in the same centre accrued as part of an almost identical study between July 1991 and April 1996 (n = 520).

Hukkelhoven et al.

Hukkelhoven et al. 48 developed two risk prediction models using data from two multicentre RCTs: (1) the International Tirilazad trial (n = 1120) conducted in 40 centres in Europe, Israel and Australia from 1992 to 199449 and (2) the North America Tirilazad trial (n = 1149) conducted in 36 centres in the USA and Canada from 1991 to 1994. 50 Patients were included who (1) were aged ≤ 65 years; (2) had a total GCS score of < 9 or a total GCS score of 9–12 and an abnormal CT scan; (3) had a GCS motor score available; (4) had a CT scan available; and (5) had been admitted to hospital within 4 hours of the TBI. The outcomes assessed were mortality at 6 months and unfavourable outcome (death, vegetative state or severe disability) at 6 months, defined using the Glasgow Outcome Scale (GOS). The variables included in the models are detailed in Table 1. The model for mortality at 6 months was externally validated in two populations of patients: the core data survey conducted by the European Brain Injury Consortium (EBIC), which included 796 patients with severe or moderate TBI consecutively collected between February and April 1995 from 55 European centres in which the 6-month outcome assessment was routinely performed,51 and the Traumatic Coma Data Bank (TCDB), which contained data collected on 746 patients with non-penetrating severe TBI admitted to four centres in the USA between 1984 and 1988. 52 The model for unfavourable outcome at 6 months was externally validated in the EBIC data set only.

Medical Research Council CRASH trial collaborators

The Medical Research Council (MRC) Corticosteroid Randomisation After Significant Head injury (CRASH) trial collaborators30 developed eight risk prediction models using data from the MRC CRASH trial, a large international RCT which enrolled 10,008 patients between 1999 and 2004. 53–54 Risk models were developed for death at 14 days and unfavourable outcome at 6 months in patients with TBI in low-/middle- and high-income countries. The risk models that were eligible for the RAIN study were those developed using data from high-income countries (n = 2482). The outcome of interest for the RAIN study was unfavourable outcome at 6 months. Two models were developed: (1) the Basic model, which included only clinical and demographic variables, and (2) the CT model, which also included CT scan results. Patients were included who (1) were aged ≥ 16 years; (2) had a total GCS score of < 15; and (3) were within 8 hours of the TBI. The variables included in the model are detailed in Table 1. The models, with some modifications, were externally validated in a cohort of 8509 patients with moderate to severe TBI from the International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI [IMPACT (International Mission for Prognosis and Analysis of Clinical Trials in TBI)] database (described below). For validation of the Basic model, the ‘variable major extracranial injury’ was excluded, and for validation of the CT model, the ‘variable petechial haemorrhages’ was excluded, as these variables were not available in the validation sample.

Steyerberg et al.

Steyerberg et al. 35 developed three risk models using data from the IMPACT database,55 which includes data from eight RCTs and three observational studies conducted between 1984 and 1997. Patients were included who had a GCS score of < 13. The outcomes assessed were mortality and unfavourable outcome at 6 months. Three models were developed for each outcome: a Core model, an Extended model and a Laboratory model. The variables included in each of the models are detailed in Table 1. The Core model and a variant of the Extended model were validated using data from the CRASH trial (described above). For validation of the Extended model, the variables ‘hypoxia’, ‘hypotension’ and ‘extradural haemorrhage’ were excluded, as these were not available in the validation sample. It was not possible to externally validate the Laboratory model, as laboratory values were not recorded in the CRASH trial.

Assessment of methodological quality

The quality assessment of the four studies,30,35,47,48 using the criteria of Perel et al. ,9 is summarised in Table 2. Neither the MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 nor Steyerberg et al. 35 reported completeness of follow-up in their respective papers reporting development of the CRASH and IMPACT models. However, for the CRASH trial, a separate paper reporting the trial results indicated overall follow-up of 95% for GOS at 6 months,54 and a paper reporting the design of the IMPACT database indicated overall follow-up of 95% for GOS at 6 months (including last observation carried forward imputation of 18% of values from 3 months). 55

| Quality criteria, Perel et al. (2006)9 | Signorini et al. (1999)47 | Hukkelhoven et al. (2005)48 | MRC CRASH trial collaborators (2008)30 | Steyerberg et al. (2008)35 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal validity – study | |||||

| 1 | Did the study have adequate follow-up? | Yes (> 90%) | Yes (> 90%) | Yes (> 90%) | Yes (> 90%) |

| Internal validity – variables | |||||

| 2 | Was a discussion included about rationale to include the predictors? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Were the predictive variables clearly defined? | No | No | No | No |

| 4 | Were the outcomes predicted valid? | Yes (mortality) | Yes (mortality/GOS) | Yes (GOS) | Yes (mortality/GOS) |

| 5 | Were missing data adequately managed? | No (complete case analysis) | Yes (regression imputation) | No (complete case analysis) | Yes (multiple imputation) |

| Internal validity – analysis | |||||

| 6 | Was an adequate strategy performed to build the multivariable model? | Forward selection based on clinical criteria and completeness | Backward stepwise selection (p < 0.2) | p < 0.05 in full model | Partial R2 from previous analysis of same database |

| 7 | Were interactions between the variables examined? | Not reported | No | Noa | Yes |

| 8 | Were continuous variables handled appropriately? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Were > 10 events per variable included? | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| External validity | |||||

| 10 | Was the description of the sample reported? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 11 | Was it clearly explained how to estimate the prognosis? | Yes (nomogram) | Yes (simple score) | Yes (web calculator) | Yes (simple score, web calculator and spreadsheet) |

| 12 | Were measures of discrimination reported? | Yes (with CI) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 13 | Were measures of calibration reported? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 14 | Were CIs presented? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 15 | Was the model validated? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | Was the model internally validated? | No | Yes (bootstrap) | Yes (bootstrap) | Yes (cross-validation) |

| 17 | Was the model externally validated? | Yes | Yes | Yesb | Yes/noc |

| 18 | Was the effect of using the model established? | No | No | No | No |

All of the studies30,35,47,48 provided some justification for the predictors included in the models, reflecting a combination of an existing established relationship with outcome and ease of collection and use. However, none of the investigators reported clear definitions for the predictors. All of the studies30,35,47,48 used valid outcomes (mortality and/or GOS) in the models. Handling of missing data varied. In two studies,30,47 complete case analyses were used. The final number of patients included in the model of Signorini et al. 47 was not reported; however, 20% of patients were missing CT assessment alone and, therefore, a maximum of 80% of the original sample of 365 patients can have been used in fitting the final model. The MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 cited low levels of missing data as justification for their complete case approach; however, this approach resulted in only 88% of the original sample being included in the Basic model for high-risk countries and 79% in the CT model. In contrast, for the remaining two studies,35,48 statistical imputation methods were used, resulting in all patients being included in the final models. Hukkelhoven et al. 48 used regression imputation to impute the 4.8% of missing values, acknowledging that such an approach would slightly underestimate the true variability and Steyerberg et al. 35 used the gold standard method of multiple imputation.

In all four studies,30,35,47,48 risk prediction models were developed using logistic regression, although the approach to variable selection varied. Signorini et al. 47 used a form of forward stepwise selection but with the order of variables being added to the model based on a combination of data completeness and clinical criteria rather than statistical significance alone. Hukkelhoven et al. 48 fitted a full model and used backward stepwise selection to remove variables with p > 0.2. The MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 included variables in the final models if they were significant at the 5% level in a full multivariable model. Finally, Steyerberg et al. 35 based inclusion in their final models on partial Nagelkerke R2-values from a previous multivariable analysis of the same database. 57 The only authors who reported evaluating interactions between predictors were Steyerberg et al. ;35 however, it was unclear which, or how many, potential interactions were examined. All of the studies30,35,47,48 used continuous modelling for continuous variables, and all either included or considered some degree of non-linearity. The criterion of at least 10 events per predictor variable included in the modelling process was met by three of the four studies. 30,35,48 Signorini et al. 47 reported approximately eight events per predictor variable included in the model.

A description of the sample population, including important case mix variables, was reported for all four studies. 30,35,47,48 In addition, simple methods for calculating predictions, including a nomogram, simple clinical scores, web calculators and a spreadsheet calculator, were provided. Measures of discrimination were reported in all papers, although only Hukkelhoven et al. 48 included a CI on the c-index [area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve]. In all papers, calibration was summarised graphically and tested for perfect calibration with the Hosmer–Lemeshow test, with CIs reported on model estimates.

All models were validated either internally and/or externally as described above and summarised in Table 1. None of the models was evaluated for its effect in clinical practice.

Internal validation was performed by Hukkelhoven et al. 48 and the MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 using bootstrap methods, and by Steyerberg et al. 35 using cross-validation across the 11 separate study data sets comprising the IMPACT database. The model of Signorini et al. 47 was externally validated using data from a further 520 patients admitted to the same single centre. The models of Hukkelhoven et al. 48 were externally validated using data from approximately 1500 patients from observational registries. Modified versions of the CRASH models were validated using the IMPACT database. 30 The IMPACT Core models and modified versions of the IMPACT Extended models were validated in the CRASH trial data set; however, it was not possible to externally validate the IMPACT Lab models, as the CRASH trial did not record the required laboratory values. 35

Expert review

The RAIN Study Steering Group did not identify any further studies (either published or ongoing) that would be potentially eligible for the RAIN study. The four studies identified by the systematic review reported development and validation of 17 risk prediction models. Of these, 11 were potentially eligible for validation in the RAIN study; the models developed by the MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 for low-income countries and predicting mortality at 14 days were excluded. Following review by the RAIN Study Steering Group, 10 risk prediction models were selected for external validation in the RAIN study. The model developed by Signorini et al. 47 was excluded because the model was developed using data from a relatively small single-centre study with mortality at 1 year as the outcome. The remaining three studies were large multicentre studies, which considered functional outcome as well as mortality at 6 months. There was also concern about the data burden associated with the ISS included in the Signorini et al. model. 47

Discussion

Principal findings

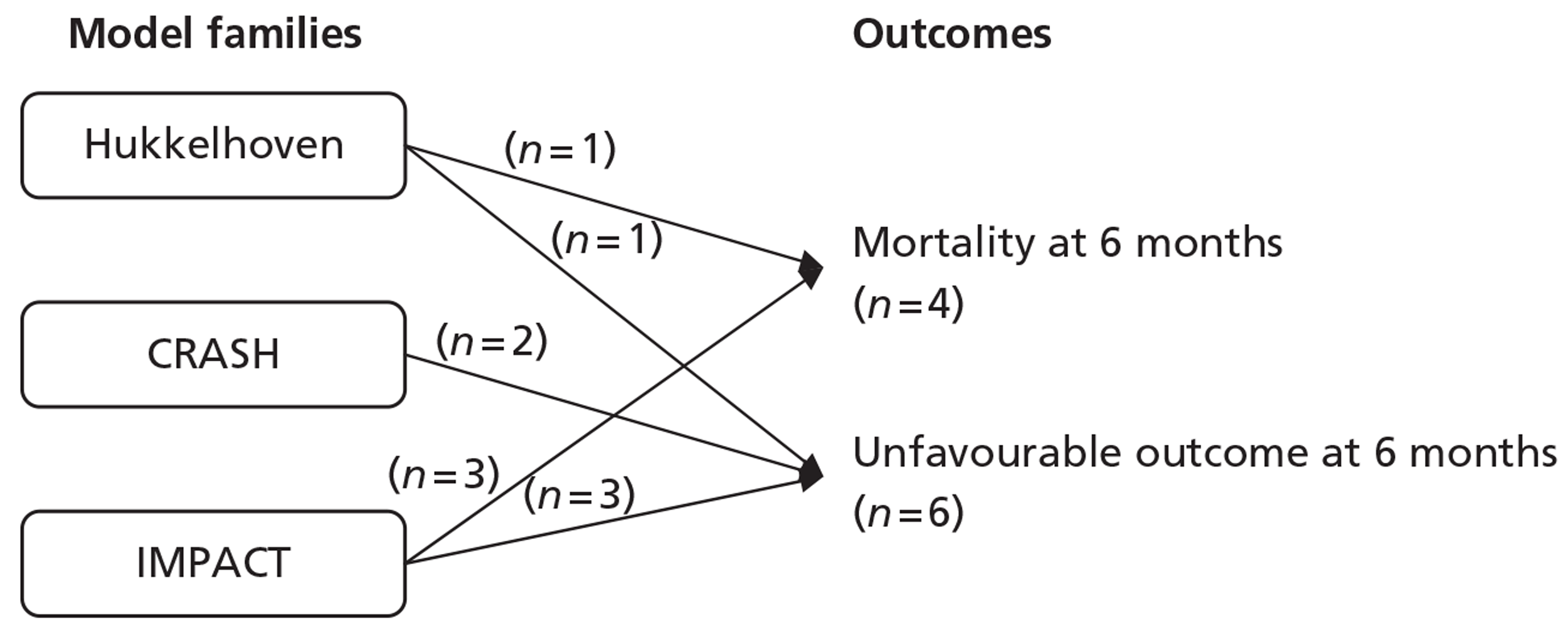

The systematic review of the literature identified four studies30,35,47,48 reporting development and validation of 17 risk prediction models for TBI. Of the 17 models, 11 were eligible for the RAIN study. Following assessment of their methodological quality and review by the RAIN Study Steering Group, 10 models, developed and validated in three studies,30,35,48 were selected for external validation in the RAIN study. Four models were developed for mortality at 6 months35,48 and six models were developed for unfavourable outcome, using the GOS, at 6 months. 30,35,48

The variables included across the 10 selected models were age, GCS score, GCS motor score, pupil reactivity, presence of major extracranial injury, hypoxia, hypotension, glucose, haemoglobin, Marshall CT classification,56 presence of traumatic subarachnoid haemorrhage (SAH), presence of extradural haematoma, presence of petechial haemorrhages, obliteration of the third ventricle or basal cisterns, midline shift and non-evacuation of haematoma. The outcomes assessed were mortality and unfavourable outcome, using the GOS, at 6 months.

Strengths and weaknesses

A major strength of this systematic review was being built on a previous, rigorous systematic review. 9 One of the strengths of the Perel et al. 9 review is that there was no restriction on the types of patients, i.e. any age and any severity of TBI, or on the setting. Interestingly, although the burden of trauma is much greater in low-income countries, only 2% of the models identified included patients from these countries. The MRC CRASH trial collaborators30 identified significant interactions between the country's income level and several predictors and so developed separate models for low-/middle-income countries and for high-income countries. Given that the RAIN study was seeking to validate prognostic models for use in a UK NHS setting, models developed for low-/middle-income countries were excluded.

There are some limitations to the systematic review. The original literature search by Perel et al. 9 was restricted to 1990 onwards. However, this was on the basis that changes in management and diagnostic technology in recent years means that prognostic models developed before 1990 are unlikely to be relevant for the current medical care of patients with TBI. In addition, only studies that explicitly combined at least two predictors were included, which means that studies that used multivariable analysis to investigate individual predictors but did not report an overall estimation were excluded. Similarly, studies that assessed clinical prediction rules considering more than one variable were excluded if they did not combine them.

Methodological quality of the risk prediction models

The original systematic review by Perel et al. 9 and the recent update reveal that a large number of prognostic models for TBI have been published. However, their methodological quality is relatively poor. Limitations include, small sample sizes (fewer than 10 events per variable), loss to follow-up rates in excess of 10%, inappropriate handling of missing data (i.e. not using statistical imputation methods), and rarely being validated in external populations. Perel et al. 9 reported that of the 102 models (in 53 studies) identified, they considered only the three models developed by Signorini et al. 47 and Hukkelhoven et al. 48 to be clinically useful for patients from high-income countries. All three models fulfilled the eligibility criteria for inclusion in the RAIN study. The updated search identified an additional eight models (from two studies30,35) that were also eligible. In general, the methodological quality of these 11 models was good. However, eight models35,48 were developed using data from multiple sources and may therefore be limited by differences between data sets in eligibility criteria, definitions of variables and timings of measurements. Although all of the studies included discussion about the rationale for including specific predictors, none reported clear definitions for predictive variables. In addition, there was variation in how missing data were handled: two of the four studies used regression or multiple imputation and two used complete case analysis on the basis that there were few missing data; however, this meant that for at least one of the models, only 79% of the original sample was included. 30

Of the 11 eligible models, 10 risk prediction models were selected by the RAIN Study Steering Group for validation in the RAIN study. 30,35,48 All were developed using some or all data from RCTs, which may limit their external validity. Even in large pragmatic RCTs, such as the CRASH trial,30 external validity may be affected by self-selection of centres and patients to participate in the trial, as well as the potential for patients enrolled in a trial (in both the active and control arms) to receive better standard of care than in usual clinical practice. 58,59 To assess whether a model is generalisable to other populations, it is important to conduct external validation. Of the 10 models, all except two were validated on patients from different centres. However, for four of the remaining eight models, a limitation was that some variables had to be excluded from the models for validation as they were not available in the validation sample. Therefore, only four of the 10 models – those by Hukkelhoven et al. 48 and the Core models from Steyerberg et al. 35 – have been externally validated without undergoing any modifications.

Summary

In summary, three families of risk prediction models including 10 individual models were identified that are most likely to be applicable to a UK critical care setting. 30,35,48 These models require further prospective validation, and potentially recalibration, before they can be applied with confidence in neurocritical care in the NHS.

Chapter 3 The Risk Adjustment In Neurocritical care study

Introduction

The systematic review of the literature identified three families of risk prediction models for acute TBI that were likely to be applicable to a neurocritical care setting. In order to externally validate these models and to use them to evaluate the optimum location and comparative costs of neurocritical care in the NHS, a prospective cohort study was undertaken in dedicated neurocritical care units, combined neuro/general critical care units within a neuroscience centre and general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre. Data were collected on consecutive adult patients admitted to critical care with suspected acute TBI. This chapter reports the RAIN study set-up from research governance, through design and development of the data set, recruitment of sites and patients, data management, and 6-month follow-up of neurological outcomes and QOL.

Methods

Research governance

The RAIN study was sponsored by ICNARC. The contract for the study was signed in December 2008 and, once the study co-ordinator was appointed, the process of completing research governance approvals commenced. Owing to the inclusion of adults with incapacity, two separate applications were made to the NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) for Wales, covering sites in England and Wales under the Mental Capacity Act 2005, and to the Scotland A REC, covering sites in Scotland under the Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000. Favourable opinions were received on 13 March 2009 (ref. 09/MRE09/10) and 30 March 2009 (ref. 09/MRE00/15), respectively.

In response to the unique problems faced by patients with acute TBI in critical care, we delayed the request for consent until 6 months after the TBI at the point of follow-up. At hospital/critical care unit admission these patients are often unconscious and their level of consciousness continues to vary during their stay in the critical care unit. Generally, treatment needs to be started urgently, so there is little time for health-care staff to adequately explain research studies to patients or their families. This is, of course, a stressful and emotional time for families. In view of these difficulties in gaining informed consent, an application was made to the National Information Governance Board (NIGB) Ethics and Confidentiality Committee (ECC) for support under Section 251 of the NHS Act 2006 for permission to hold sufficient patient identifiable data, prior to patient consent, in order for us to contact the patient at 6 months post TBI and gain their consent. Section 251 support, covering sites in England and Wales, was obtained on 4 August 2009 [ref. ECC 2–06(d)/2009]. For the two sites in Scotland, falling outside the remit of the NHS Act 2006, approval was sought from the Caldicott Guardian and was granted on 10 November 2009 and 25 March 2010.

Central Research and Development (R&D) approval was gained on 4 August 2009. Site-specific information (SSI) forms were submitted for each for each NHS Trust, with the last form submitted on 3 November 2009 and the final approval gained on 28 January 2010.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio details high-quality clinical research studies that are eligible for support from the NIHR CRN in England. The RAIN study was adopted on to the NIHR CRN Portfolio on 27 August 2009 (ref. 7349).

Changes to protocol

The initial RAIN study protocol submitted for approvals was Version 1.3 (21 January 2009). Amendments to the RAIN study follow-up documentation, not requiring changes to the study protocol, were submitted in March 2009, May 2009, July 2009 and November 2009, and approved by the RECs. A final non-substantial amendment to the Study Protocol (Version 1.4, 1 February 2011; see Appendix 2) was submitted in February 2011, clarifying explicitly that participating critical care units would be required to submit anonymised CT scans to the Wolfson Brain Imaging Centre (WBIC) at Addenbrooke's Hospital (University of Cambridge/Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) for the purpose of the substudy on inter-rater reliability of CT scan reporting.

Design and development of data set

The initial RAIN study data set was developed and produced by the RAIN study team from the original model publications. Definitions for some of the fields were refined through discussion and consultation with the clinical experts on the RAIN Study Steering Group. There were five elements to the data set: (1) characteristics of the patients and their injury; (2) risk factors for the selected risk prediction models; (3) location of care details, to describe and cost the patient journey in order to investigate the effect of location of neurocritical care; (4) short-term outcomes at discharge from critical care and acute hospital; and (5) contact details, to provide the information required for the 6-month follow-up.

To avoid duplication of data collection, the RAIN study was piggybacked on to the CMP in England and Wales and linked with data provided by the Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group (SICSAG) in Scotland. Both the CMP and SICSAG databases have been independently assessed to be of high quality against 10 criteria for coverage and accuracy by the Directory of Clinical Databases at docdat.ic.nhs.uk. Critical care units in England and Wales that were not participating in the CMP recorded all required fields within the RAIN study data set.

The publications reporting each risk prediction model, other associated publications and, where available, original study documentation relating to the data sources were examined for definitions for each field to be included in the data set. The definitions and, in particular, the time points for data collection were often not clearly defined and/or varied both between risk models and between different data sources used for the development of the same risk model. Clinical experts from the RAIN Study Steering Group also identified a small number of additional fields that they felt to be important predictors of outcome following TBI that were not included in any of the risk prediction models, the collection of which was considered valuable for informing future work in this area.

The full RAIN study data set and definitions are provided in Appendix 3. A brief summary is given below.

Characteristics

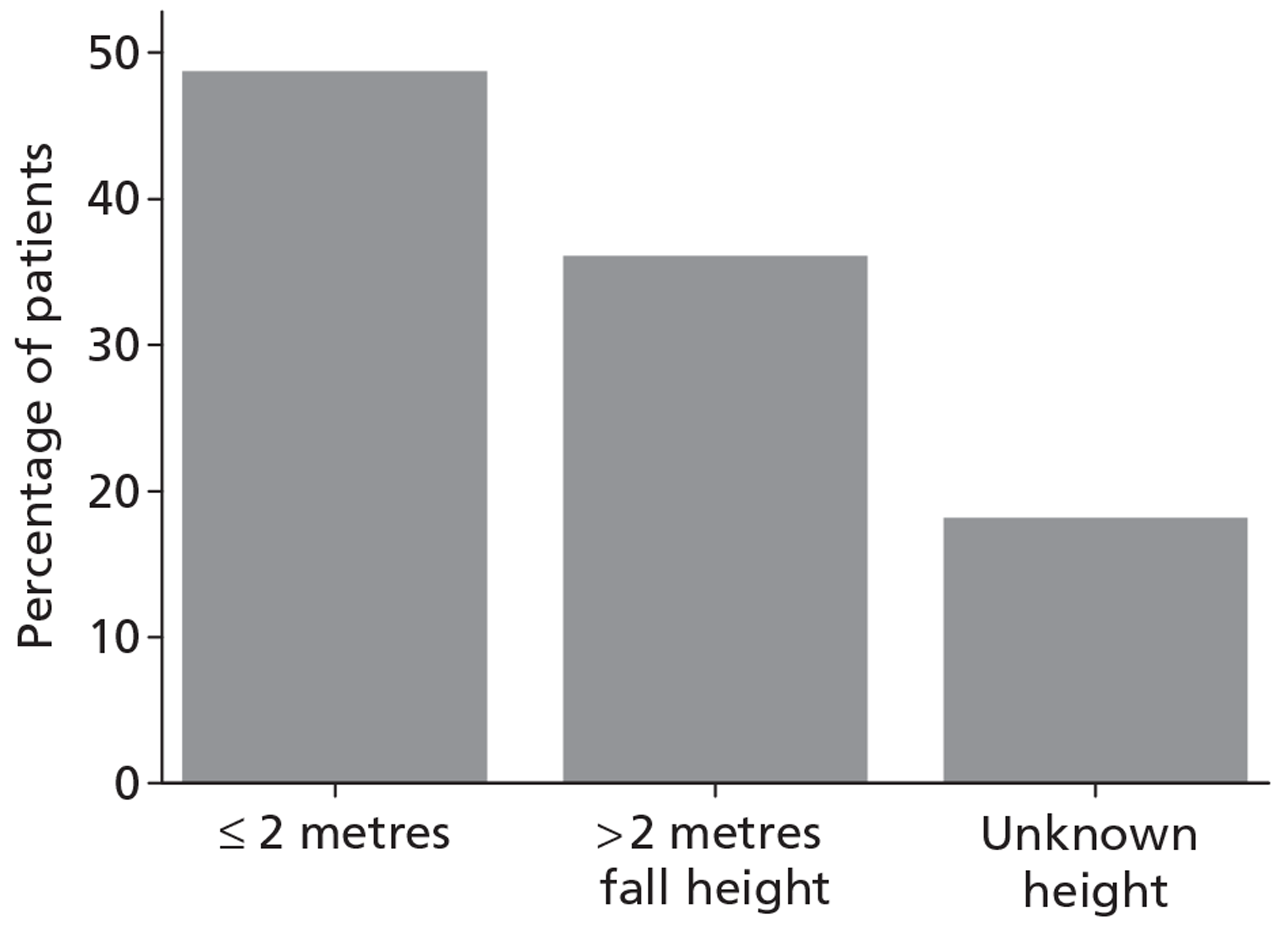

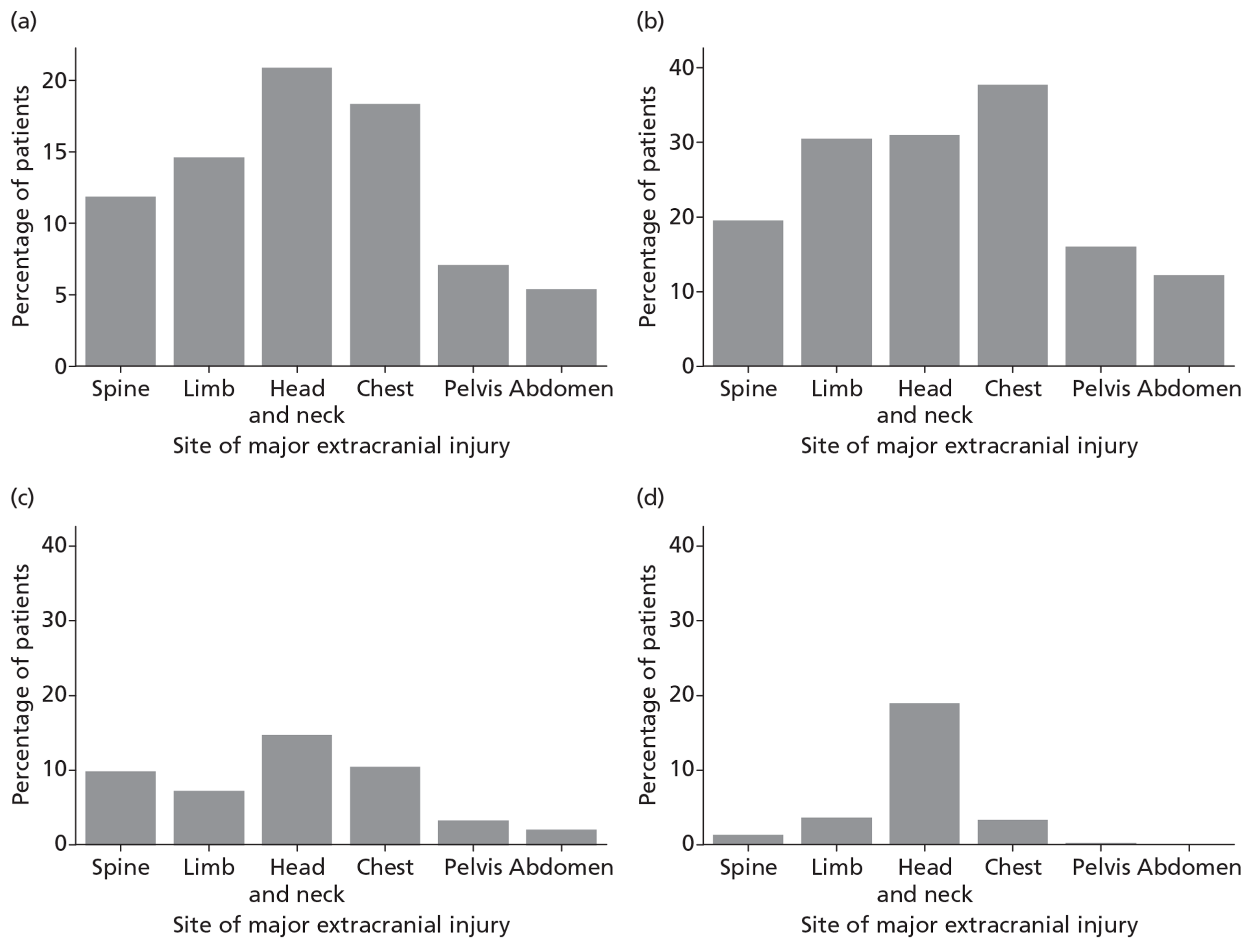

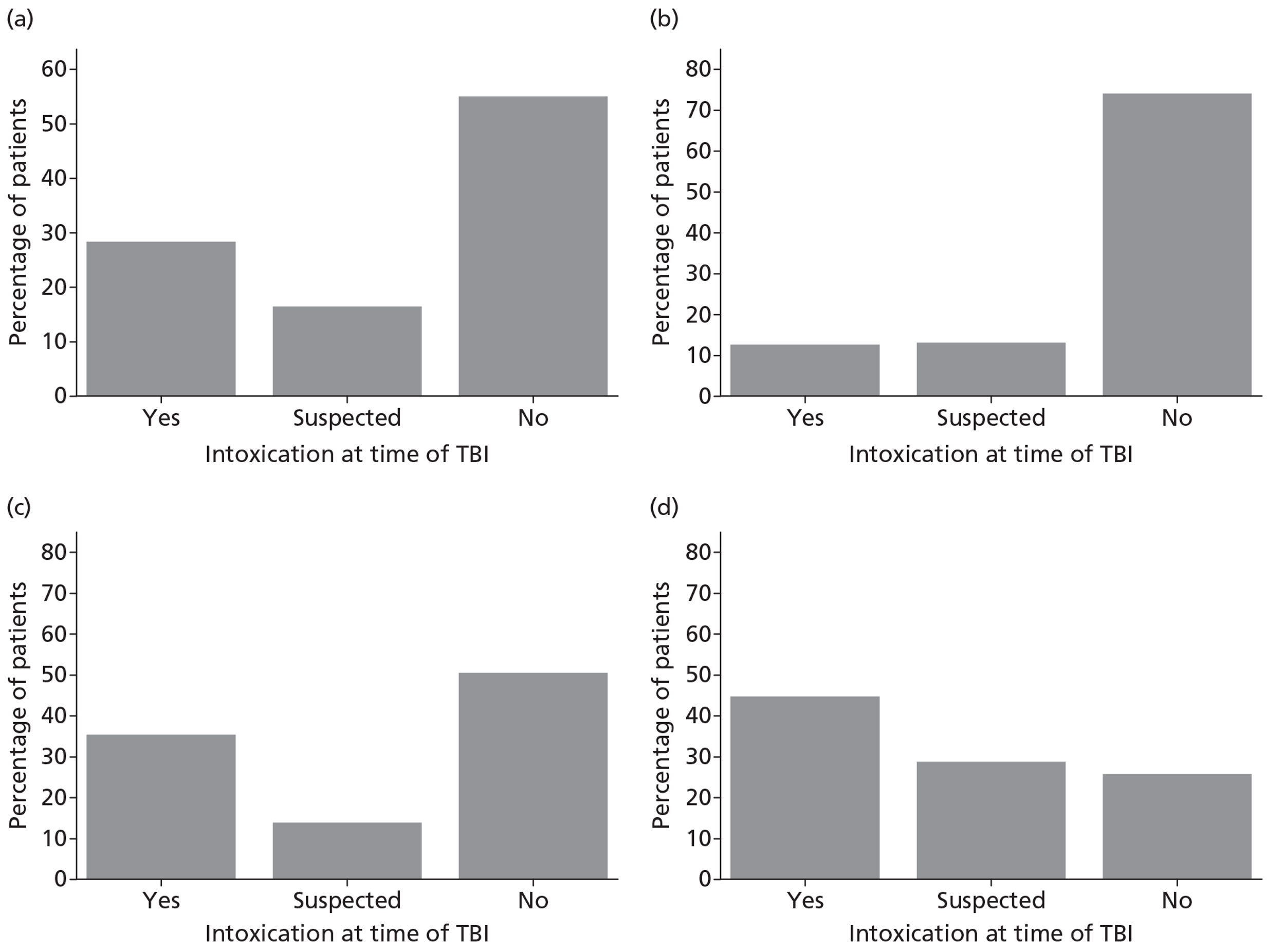

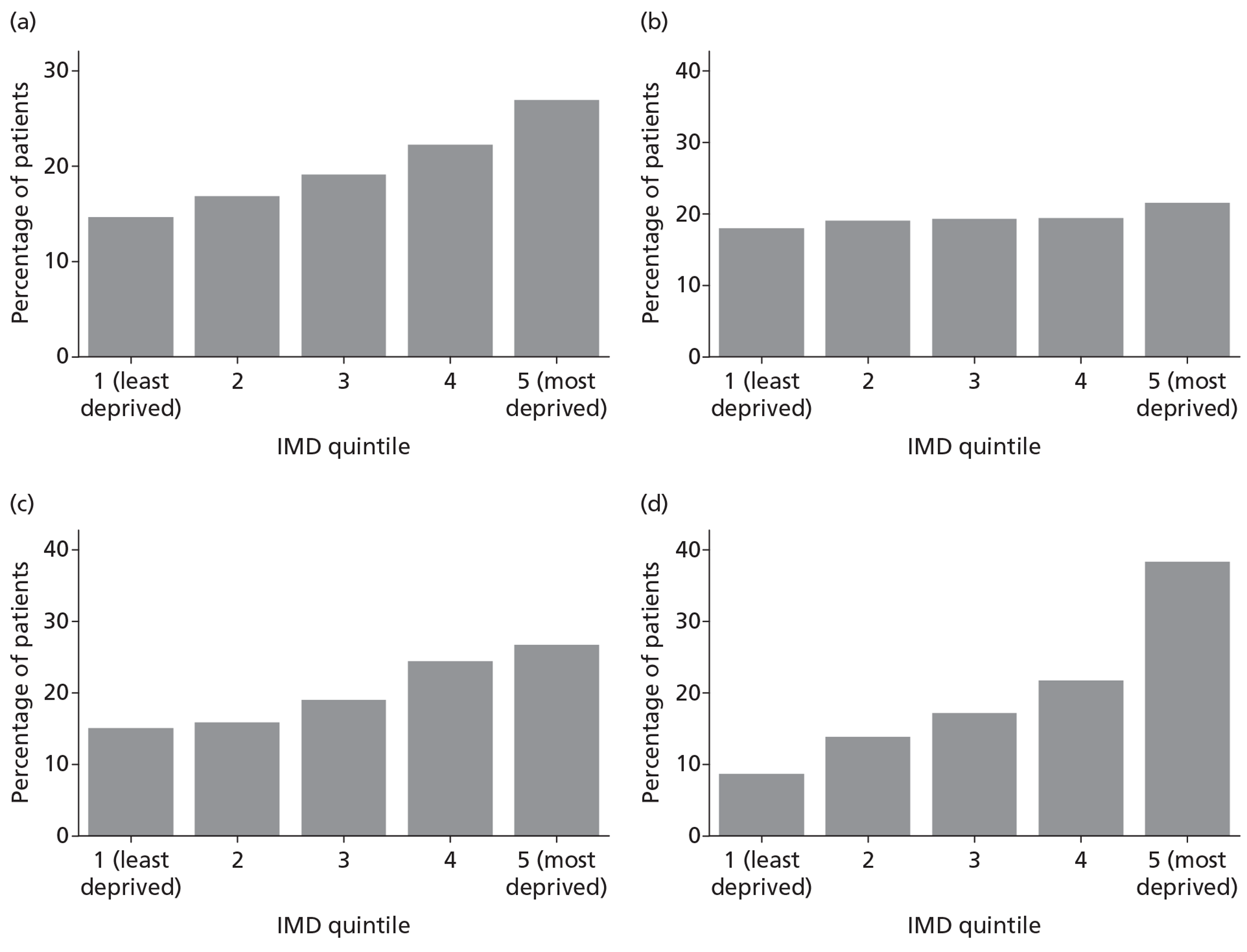

Patients were characterised by their age, sex, residential postcode (permitting linkage to small area deprivation statistics), residence prior to hospital admission and prior dependency. The injury was characterised by timing, cause, intoxication at the time of injury and presence, and site(s) of major extracranial injury.

Risk factors

Pupil reactivity and GCS score data were collected both pre-hospital (prior to attendance at first hospital) and at admission to the first hospital (within 12 hours of attendance at the first hospital). GCS score was collected additionally as the last value prior to sedation, and pupil reactivity at the point of admission to the critical care unit. CT scan data were evaluated based on the first CT scan performed after the TBI.

Location of care details

The patient journey prior to admission to the critical care unit was recorded using the immediate prior location and, for patients who were admitted from a more transient location (e.g. theatre, imaging, emergency department), their location prior to this. Data for resource use was based on the total numbers of calendar days of both organ support and levels of care as defined for the Department of Health Critical Care Minimum Data Set (CCMDS).

Short-term outcomes

Survival status at discharge from the critical care unit was recorded in the RAIN study for all admissions. For survivors, subsequent information on location following discharge (including critical care transfers), and outcomes at final discharge from critical care and acute hospital were also collected.

Contact details

The patient's full name, address and any telephone number(s) were included to permit the follow-up of patients by postal (or telephone) questionnaire at 6 months following the TBI. The patient's NHS number was included to ensure accurate linkage to national death registration using the ‘list cleaning’ service of the Medical Research Information Service (MRIS) at the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care. Name and contact details for the patient's general practitioner (GP) were included to confirm from the GP that the patient was still alive prior to sending the questionnaire.

Sample size calculation

We performed a simulation study to assess the power to detect a difference in the c-index (area under the ROC curve) between two different risk prediction models applied to the same population. Simulations were based on the following assumptions: the rate of unfavourable outcome (death or severe disability) at 6 months in the population will be 40% (based on the observed rate of unfavourable outcomes in high-income countries in the CRASH trial30 and consistent with the results of a regional audit in East Anglia60); statistical tests will be based on a two-sided p-value of p = 0.05; and the ability to detect, with 80% power, a 10% relative difference in c-index from the value of 0.83 observed for the CRASH model in the development sample. 30 A total of 17,500 data sets were simulated at different sample sizes using a binormal model61 and the empirical power was assessed at each sample size as the proportion of data sets in which a statistically significant difference was detected (see Appendix 2).

Based on these simulations, a sample size of 3100 patients was required for model validation. To allow for 8% loss to follow-up [based on the observed follow-up rates from the CRASH62 and Randomised Evaluation of Surgery with Craniectomy for Uncontrollable Evaluation of Intra-Cranial Pressure (RESCUEicp) RCTs63], we aimed to recruit 3400 patients.

Using data from the CMP database, we anticipated the rate of admission of adult patients following acute TBI to be approximately eight per unit per month for dedicated neurocritical care units, six per unit per month for combined neuro/general critical care units, and 0.5 per unit per month for general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre. We therefore aimed to recruit at least 12 dedicated neurocritical care units, 13 combined neuro/general critical care units and 30 general critical care units outside neuroscience centres to complete recruitment within 18 months.

Recruitment of sites and patients

Recruitment of sites

All neurocritical care units in the UK and adult general critical care units participating in the CMP were invited to participate in the RAIN study. Standalone high-dependency units (HDUs) were not eligible for participation in the study. The RAIN study was publicised to critical care units via the CMP, NCCNet, the Intensive Care Society and the UK Critical Care Trials Forum (UKCCTF).

Maintenance and motivation of sites

Regular contact was maintained with all participating critical care units during the course of the RAIN study. Newsletters were sent on a monthly to quarterly basis, depending on the stage of the study, to maintain motivation and encourage involvement by keeping data collectors informed of study progress. Newsletters were also used as an opportunity to clarify any data issues and remind local collaborators to enrol all eligible patients. The study co-ordinator maintained close contact with all sites by telephone and e-mail throughout the study and was available to answer queries.

Updates on study progress were also given at meetings of the CMP, NCCNet, the Neuroanaesthesia Society of Great Britain and Ireland and the UKCCTF in order to maintain the profile of the RAIN study in the critical care community. Regular updates on study progress were also provided to the NIHR Comprehensive CRN Critical Care Specialty Group. Members of the RAIN Study Steering Group also publicised the study at relevant conferences.

Recruitment of patients

All adult patients (defined as aged ≥ 16 years) admitted to participating adult critical care units following an actual or suspected TBI, and with a GCS score of < 15, following resuscitation, were identified.

Data management

Start-up meetings/data set familiarisation courses

The start-up meetings/data set familiarisation courses were 1-day events, at which the background, aims and rationale for the RAIN study were discussed with the collaborating clinicians, research nurses and data clerks. This was followed by a detailed explanation of the definition for each field in the data set with opportunities for questions and examples. At least one member of staff from each site was required to attend a RAIN study start-up meeting/data set familiarisation course to ensure that they understood the aims of the RAIN study and the precise rules and definitions of the data set. Each delegate was given a RAIN study Data Collection Manual to take back with them to their site for reference purposes.

The Data Collection Manual contained precise, standardised definitions for each field (see Appendix 3), along with data collection forms and flows (see Appendix 4), to guide them through the data collection process. The Data Collection Manual was regularly reviewed and new versions released to ensure clarity and to answer common queries.

Data entry and monitoring of recruitment

From the data collection forms, data were entered by members of the research team at participating sites on to a dedicated, secure, web-based data entry system (‘web portal’) developed and hosted by ICNARC. A guide to using the web portal was produced and sent to research staff to assist in data entry. Data Collection Manuals, flows and forms, definitions and error checking were also available from the web portal, either for download or built into the design.

Data management was an ongoing process. Data were monitored throughout the data collection period in order to ensure that the database was as complete as possible and the rate of recruitment was as expected to minimise the time between the end of data collection and the start of data analysis. For each site, the number of patients entered on to the web portal and the date the last patient was entered was monitored. Neurocritical care units were contacted if no patients had been admitted in one calendar month. General critical care units outside a neuroscience centre received monthly e-mails to remind them to monitor for eligible patients. Quarterly CMP data submissions were reviewed to identify any admissions recorded in the CMP with a reason for admission to that critical care unit that potentially indicated a TBI that had not been entered on to the RAIN web portal.

Every patient initially thought to have TBI was entered on to the RAIN web portal to ensure completeness of recruitment. However, any patient that was subsequently found to have a different cause for their neurological impairment (e.g. cerebrovascular accident) was excluded from analyses.

Data validation reports

Two data validation reports (DVRs) were sent regularly to participating critical care units. The purpose of the first DVR was to ensure complete data entry of the fields required for patient follow-up. This DVR was sent on a weekly to fortnightly basis and checked all patients reaching 4 weeks post TBI to ensure that complete identifiers and contact details (full name and postal address, contact telephone number, NHS number, date of birth and GP details) were available. Data collectors were asked to enter data, where missing, or confirm with the RAIN study team that data were unavailable.

The second DVR checked data accuracy. These checks identified any incomplete data (missing values) and inconsistent data (unusual, although not impossible, data that must be confirmed as correct by the data collectors) both within individual fields and across fields. Following receipt of a DVR, data collectors either updated/corrected the data on the web portal or responded to the RAIN study team to confirm the data were correct in order to clear queries.

Data linkage with the Case Mix Programme

RAIN study data were linked with the corresponding CMP data using the CMP admission number and checked using date of birth, sex, NHS number, date and time of admission to the critical care unit and status on discharge from the critical care unit. Any discrepancies between the two databases were resolved with the respective data collectors. Data linkage between the RAIN study database and CMP database was performed regularly, to ensure outcome data required for the 6-month follow-up of patients were available.

Data linkage with the Scottish Intensive Care Society Audit Group

RAIN study data were linked with the corresponding SICSAG data using the SICSAG Key (unique identifier) and checked using the age in years, sex, and date and time of admission to the critical care unit. Data linkage between the RAIN study database and SICSAG database was performed once at the end of the study.

External validation against the Trauma Audit and Research Network database

The Trauma Audit and Research Network (TARN; www.tarn.ac.uk) is the trauma registry for England and Wales with coverage of approximately 70% of trauma-receiving hospitals. For hospital sites in TARN with a critical care unit participating in the RAIN study, TARN provided data on the number of admissions to critical care associated with TBI as an external data source to verify the completeness of recruitment to the RAIN study.

Data linkage with death registration

The follow-up of patients was carefully monitored to prevent any potential distress to those who care for the patient from receiving a letter addressed to a deceased relative or partner. In order to obtain an outcome for patients at 6 months after acute TBI, the follow-up process started at 4.5 months to allow for the administrative processes. On a weekly basis, the status of any patient that had reached 4.5 months post TBI was checked on the web portal. A list of patients who were not indicated as ‘dead’ was then sent to the MRIS to confirm the mortality status of patients. Patients indicated as having died were logged and the follow-up process ended; all other patients started the 6-month follow-up process to ascertain their neurological outcome and QOL. At the end of the study, a final file was sent to the MRIS to confirm the final survival status of all patients in the RAIN study.

Six-month follow-up of neurological outcome and quality of life

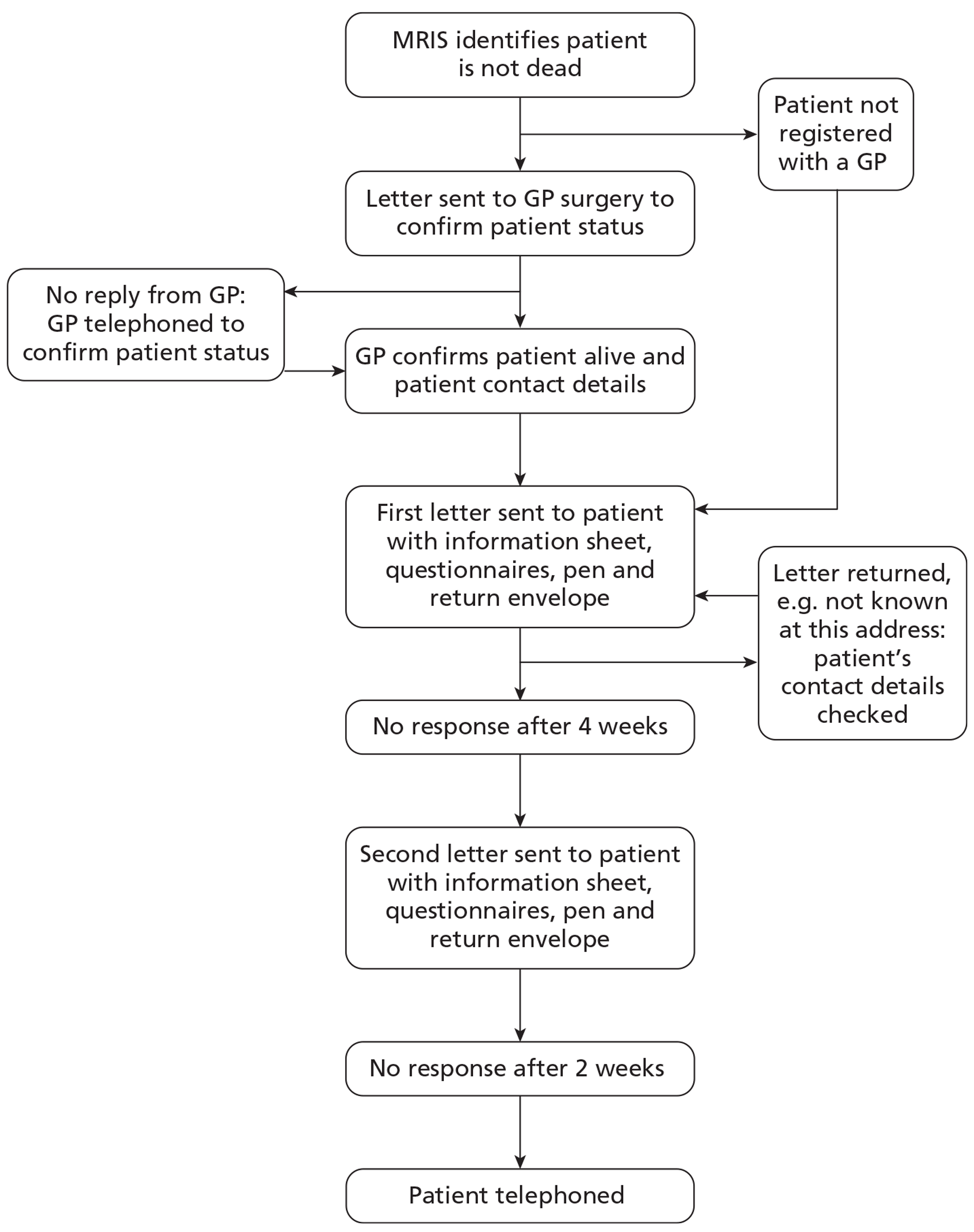

Patients identified as not having died at 4.5 months using data from the critical care unit and from MRIS followed the process shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Patient follow-up process.

Patient outcomes were collected centrally by the RAIN study team at ICNARC, using methods based on those undertaken in previous research studies, including the CRASH62 and RESCUEicp RCTs. 63 For patients registered with a general practice, their GP was sent a letter explaining the RAIN study and a form to complete to confirm that the patient had not died and to verify the patient's address. GPs could confirm the patient's status and address in a variety of ways: by returning the form by post or fax, completing a secure on-line response form or telephoning the RAIN study team. If no response was received, a follow-up telephone call was made to ensure the original information had been received. In cases where patients were not registered with a GP, REC approval allowed for them to be contacted directly. When informed that a patient was no longer registered with the GP contacted, attempts were made to ascertain the patient's current GP.

Patients were then sent, by post, an introductory letter, information sheet, consent form, questionnaires, freepost return envelope and pen (see Appendix 5), following best evidence-based practice to maximise response. 64 In instances where the patient was unable to consent, a boxed section on the letter addressing their carer asked them to offer what they feel would be the presumed will of the patient. Two questionnaires were included: the Your Health Questionnaire and the Health Services Questionnaire. The Your Health Questionnaire included the required questions to evaluate the European Quality of life (EuroQol) 5-dimension, 3-level version (EQ-5D-3L)65 and the Glasgow Outcome Scale – Extended (GOSE)66 measures. The EQ-5D-3L was included to enable the calculation of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as the best available global measure of health outcome. 67 The GOSE questionnaire is the most widely used measure of functional outcome following acute TBI,68 and has been used in most of the large, recent and ongoing RCTs. 54,63 Use of a postal questionnaire to collect the GOSE questionnaire responses has been found to have high reliability. 69 The Health Services Questionnaire included questions about the patients use of health services following discharge from acute hospital and was used to cost subsequent use of health services (see Chapter 6). Patients were asked to complete the consent form and questionnaires if they wished to take part in the RAIN study, or to return the questionnaires blank to indicate that they did not wish to take part. Non-responders were followed up with a second letter after 4 weeks, including the same enclosures as the original.

If no postal response was received after a further 2 weeks following the second letter, then patients were telephoned if contact details were available. A telephone interview template was used to explain the RAIN study and to ask for informed consent. In order not to overburden the interviewee, the telephone interview included only the GOSE questionnaire as the primary outcome for the RAIN study. Telephone calls were made at various times from Monday to Saturday between 0900 and 2030 hours to maximise the chances of contacting the patient.

Follow-up ended when a postal questionnaire was returned, either complete or blank, or when a telephone interview was completed or refusal obtained. When post was returned (e.g. not known at this address, no longer at this address, address inaccessible, etc.) the critical care unit and GP were contacted to check the address details and to elicit any updates to the patient information.

When patients were identified either as discharged to or subsequently moved to a care home, rehabilitation centre or another hospital, these institutions were contacted to establish the status of the patient and the most appropriate way to proceed with follow-up. If a patient had capacity to consent but required assistance in reading and/or completing the questionnaire then health-care professionals would often assist the patient. For those unable to consent, institutions advised on the most appropriate person to contact to gain consent. In cases in which a patient did not have the capacity to consent and either there was no next-of-kin or the next-of-kin was also unable to consent, where possible, an Independent Mental Capacity Advocate was identified.

When attempts to make contact by telephone were repeatedly unsuccessful, for example where telephone numbers would ring through to an answering service or a mobile telephone was continually switched off, and attempts had been made on various days and at various times of day over at least a month, and no alternative contact information was available, if an answering service was available, a message with information to contact the RAIN study team was left and if the call was not returned then the patient was considered lost to follow-up.

Data management of 6-month follow-up data

Two databases were set up for central data entry of questionnaire responses: one for the Your Health Questionnaire and one for the Health Services Questionnaire. Ambiguous responses (e.g. two boxes ticked, responses written instead of ticked, alterations made to questions, etc.) were initially left blank for subsequent review. Following data entry, all GOSE questionnaires with blank responses (except for those where responses were unnecessary for scoring, e.g. return to work for patients who were retired prior to the injury) were identified and manually reviewed to determine whether (1) the response was clearly indicated by the information available on the questionnaire (e.g. the word ‘yes’ or ‘very’ written next to a box rather than the box being ticked); (2) the response could be imputed with reasonable confidence from the other information on the questionnaire; or (3) there was insufficient information to assume a response. Changes to data owing to situations (1) or (2) were identified separately on the database, such that the data could be reanalysed with imputed GOSE responses excluded.

Glasgow Outcome Scale–Extended responses were used to assign each patient to a GOSE category based on their worst response using an algorithm supplied by the original developers of the postal questionnaire. Following guidelines for the application of the questionnaire,69,70 all of those assigned to the categories of upper or lower severe disability were reviewed if other responses appeared to contradict this categorisation (e.g. return to the same work as prior to the injury). In addition, all questionnaires for patients assigned to the category of pre-existing severe disability or severe disability not due to the injury were reviewed to confirm whether the questionnaire responses were consistent with this categorisation. When questionnaires were reviewed, the entire response to all questions, including the EQ-5D-3L when available, was used to assign the patient to the most appropriate GOSE category.

For a few patients, two separate responses were received (either two paper questionnaires or one paper questionnaire and one telephone interview). These were reviewed to determine the most appropriate questionnaire to use for the analysis, taking into account the respondent (patient preferred over family member preferred over carer), timing of the response (favouring responses closer to/after 6 months) and completeness of questionnaire (favouring more complete responses).

All questionnaire reviews were performed by two investigators with any areas of ambiguity or disagreement reviewed and discussed with a third.

Results

Recruitment of sites

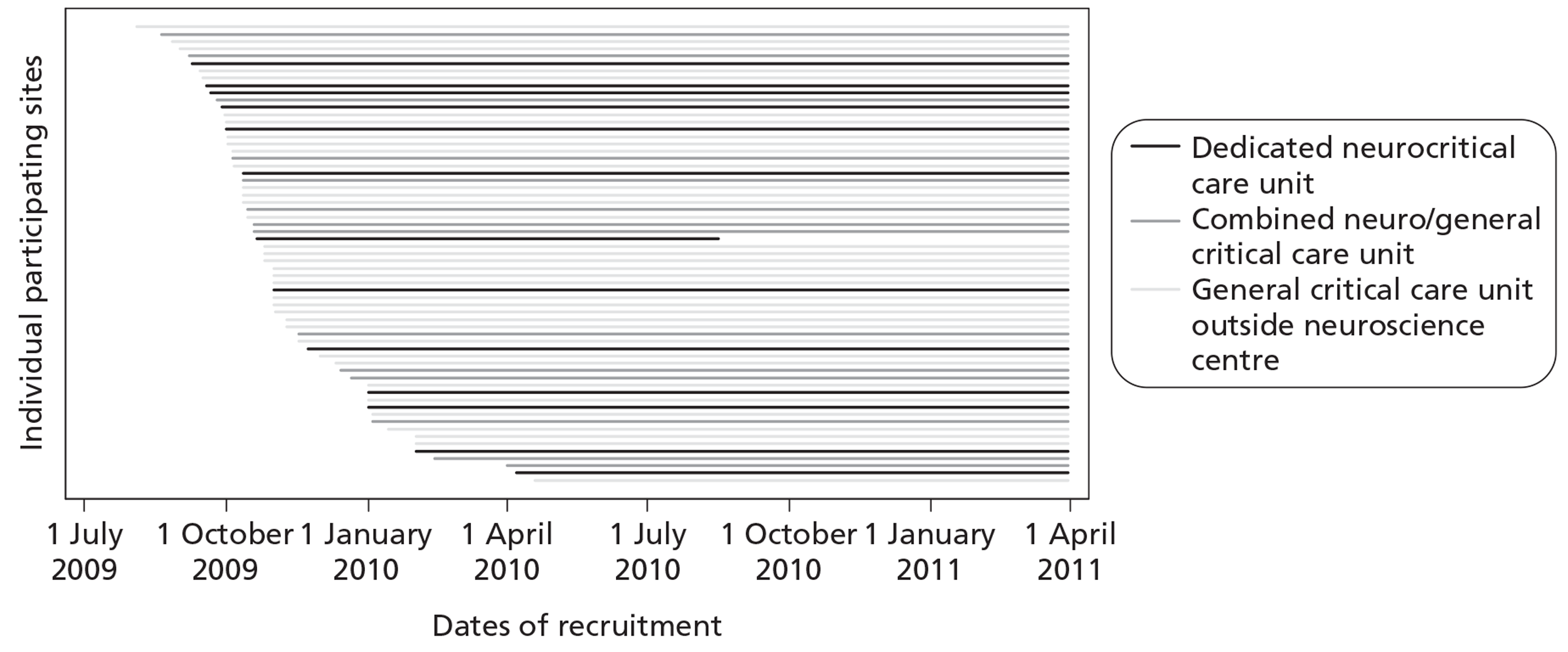

Recruitment of sites took place between December 2008 and December 2009. In total, 74 critical care units expressed an interest in taking part in the study and were sent an SSI form to complete. Of these, one neurocritical care unit was unable to take part owing to a conflicting, ongoing research study and a further four general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre did not reach the R&D submission stage. Local R&D approval was sought and gained for 69 critical care units. R&D approvals took a median of 68 days [interquartile range (IQR) 32 to 237] from submission of SSI form. R&D approval to start of RAIN study data collection took a median of 27 days (IQR 13 to 119). Two neurocritical care units withdrew, as they were unable to meet the study start date giving a total of 67 critical care units. This exceeded the recruitment targets with 13 dedicated neurocritical care units, 14 combined neuro/general critical units, four additional critical care units within a neuroscience centre (admitting overflow patients from the neurocritical care unit) and 36 general critical care units outside a neuroscience centre participating in the RAIN study (Table 3). One neurocritical care unit (and an additional critical care unit within the same neuroscience centre) withdrew from the study in August 2010 owing to research staffing shortages. All other critical care units collected data until March 2011 (Figure 4).

| Geographical region | Neuroscience centresa | Non-neuroscience centres | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number (%) in RAINb | Total number in region | Number (%) in RAIN | Total number in region | |

| UK | 27 (84) | 32 | 36 (16) | 223 |

| England | 23 (92) | 25 | 34 (19) | 180 |

| East Midlands SHA | 1 (100) | 1 | 4 (33) | 12 |

| East of England SHA | 1 (100) | 1 | 7 (41) | 17 |

| London SHA | 6 (86) | 7 | 3 (11) | 28 |

| North East SHA | 2 (100) | 2 | 2 (13) | 15 |

| North West SHA | 2 (67) | 3 | 6 (24) | 25 |

| South Central SHA | 2 (100) | 2 | 1 (9) | 11 |

| South East Coast SHA | 1 (100) | 1 | 2 (11) | 18 |

| South West SHA | 2 (100) | 2 | 3 (18) | 17 |

| West Midlands SHA | 3 (100) | 3 | 3 (16) | 19 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber SHA | 3 (100) | 3 | 3 (17) | 18 |

| Wales | 2 (100) | 2 | 2 (14) | 14 |

| Northern Ireland | 0 (0) | 1 | 0 (0) | 9 |

| Scotland | 2 (50) | 4 | 0 (0) | 20 |

FIGURE 4.

Recruitment timeline.

Each critical care unit was represented at a start-up meeting/data set familiarisation course. In total, seven start-up meetings/data set familiarisation courses were held between May 2009 and March 2010.

Recruitment of patients

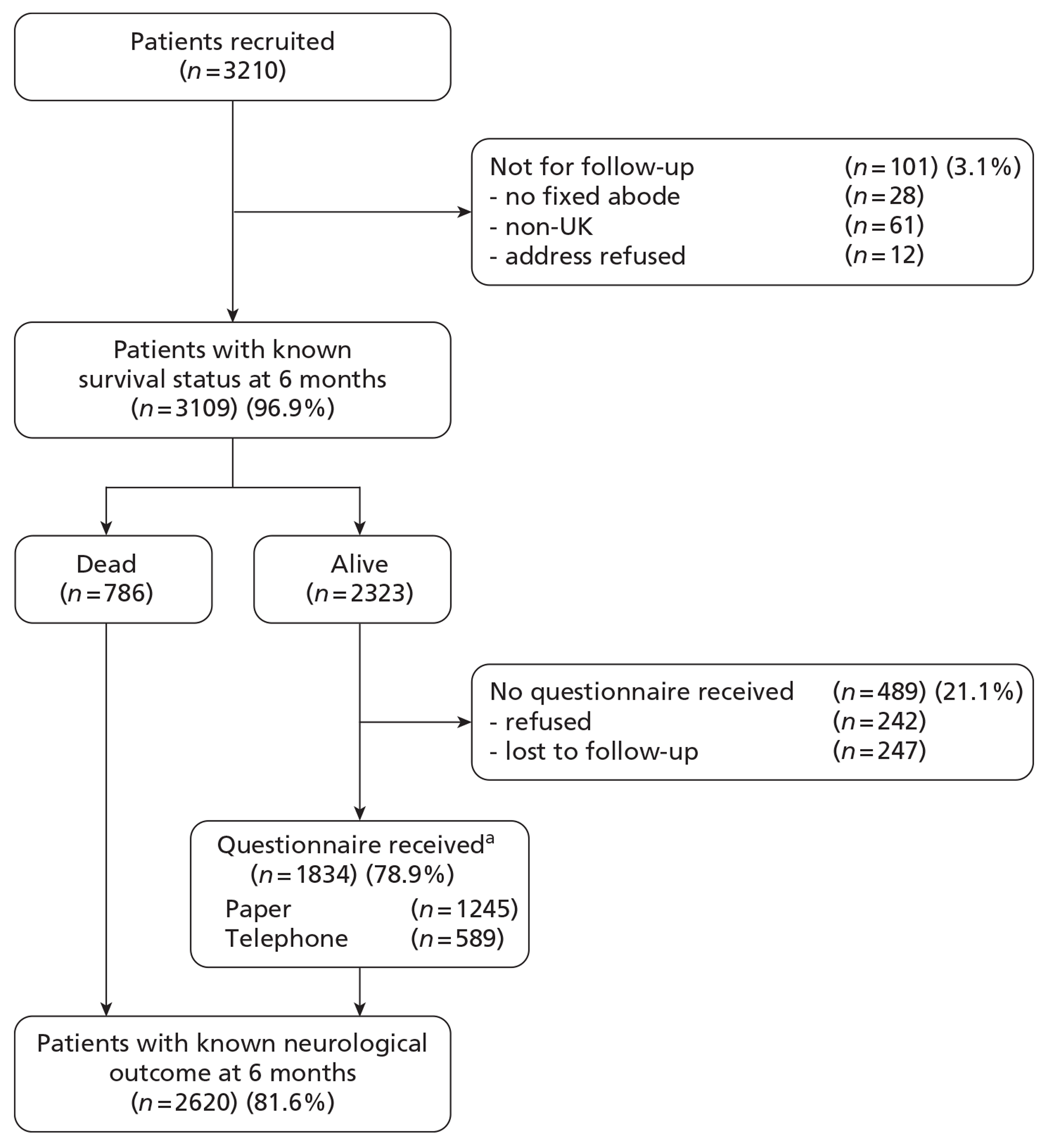

The first patient was recruited to the RAIN study on 19 August 2009 and patient recruitment continued until 31 March 2011. The final RAIN study data set contained a total of 3626 critical care unit admissions. After excluding multiple admissions of the same patient and patients who did not prove finally to have a TBI, 3210 patients remained (Figure 5). Of these, 28 patients were homeless, 61 were non-UK residents and for 12 patients (military) the address details were withheld, resulting in a cohort of 3109 patients (97%) that were followed up for 6-month survival by data linkage with death registrations.

FIGURE 5.

Patient flow. a, Paper questionnaire included full Your Health Questionnaire (GOSE and EQ-5D-3L) and Health Services Questionnaire; telephone questionnaire included GOSE only.

As a result of the regular feedback to critical care units participating in the CMP, four instances of a missed admission for TBI were identified after recruitment of patients had closed and these were, therefore, unable to be included in the study. There were also six admissions for which the research team at the unit was unable to confirm whether or not the patient had a TBI. Validation against figures from TARN indicated similar numbers of patients recruited to the RAIN study as reported through TARN. In some sites, the number of patients in the RAIN study exceeded the number reported to TARN by a small amount and, in other sites, the reverse was true, reflecting different definitions for TBI in the two projects.

Six-month follow-up of neurological outcome and quality of life

Of 2323 patients not reported as dead by MRIS, 242 (10%) refused follow-up and 247 (11%) were lost to follow-up (the first patient was recruited to the RAIN study on 19 August 2009 and patient recruitment continued until 31 March 2011).

A breakdown of the 242 patients for whom outcome data were refused is shown in Table 4. The majority of refusals (177, 73%) were by return of a blank questionnaire (from which no further information was available).

| Method of/reason for refusal | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Return of blank questionnaire | 177 |

| During telephone follow-up | 65 |

| By patient | 29 |

| Patient refused before study could be explained | 2 |

| Patient refused without giving reason | 23 |

| Patient found questionnaire distressing or confusing | 4 |

| By family member or carer | 36 |

| Family member could not determine whether relative was able to consent | 7 |

| Family member did not wish to answer on behalf of relative who was unable to consent | 9 |

| Family member or friend blocked access to a patient who would have had capacity to consent | 5 |

| Family member or carer informed us that patient did not wish to take part | 10 |

| Carer informed us that family member did not wish the patient to take part | 5 |

A breakdown of the 247 patients lost to follow-up is shown in Table 5. The largest number of patients lost to follow-up (122, 49%) were those with whom we were unable to make any contact, despite exhausting all options available to us. On four occasions, contact to a patient was blocked by their GP because the patient had not consented in advance, despite NIGB and REC approval for the follow-up process used in the study. Eight requests were received from GPs not to contact the patient or family, either on compassionate grounds or because the GP had spoken to the patient or family and they did not wish to be contacted, and on six occasions family members did not want us to contact their relative. All such requests were respected.

| Reason for loss to follow-up | Number of patients |

|---|---|

| Follow-up stopped by health-care professional | 20 |

| GP blocked access to patient because the patient had not consented in advance | 4 |

| GP requested we should not contact the patient or family | 8 |

| Health-care professional informed us patient was unable to consent and no next-of-kin available | 8 |

| Other reasons | 222 |

| Patient died after 6 months while attempts to make contact were ongoing | 21 |

| Family member informed us that patient had capacity to consent but did not want us to contact them | 6 |

| Patient or family member informed us that a postal questionnaire had been returned but this was never received | 26 |

| Patient or family member informed us that they had received a postal questionnaire but wished to consider the study and did not want to complete the questionnaire by telephone or be contacted again | 39 |

| Adequate communication prevented by poor understanding of English | 4 |

| Unable to contact the patient – prisoner | 4 |

| Unable to contact the patient or family despite repeated attempts | 122 |

| Processing errors | 5 |

| Incorrect data entry on web portal – patient reported to have died | 5 |

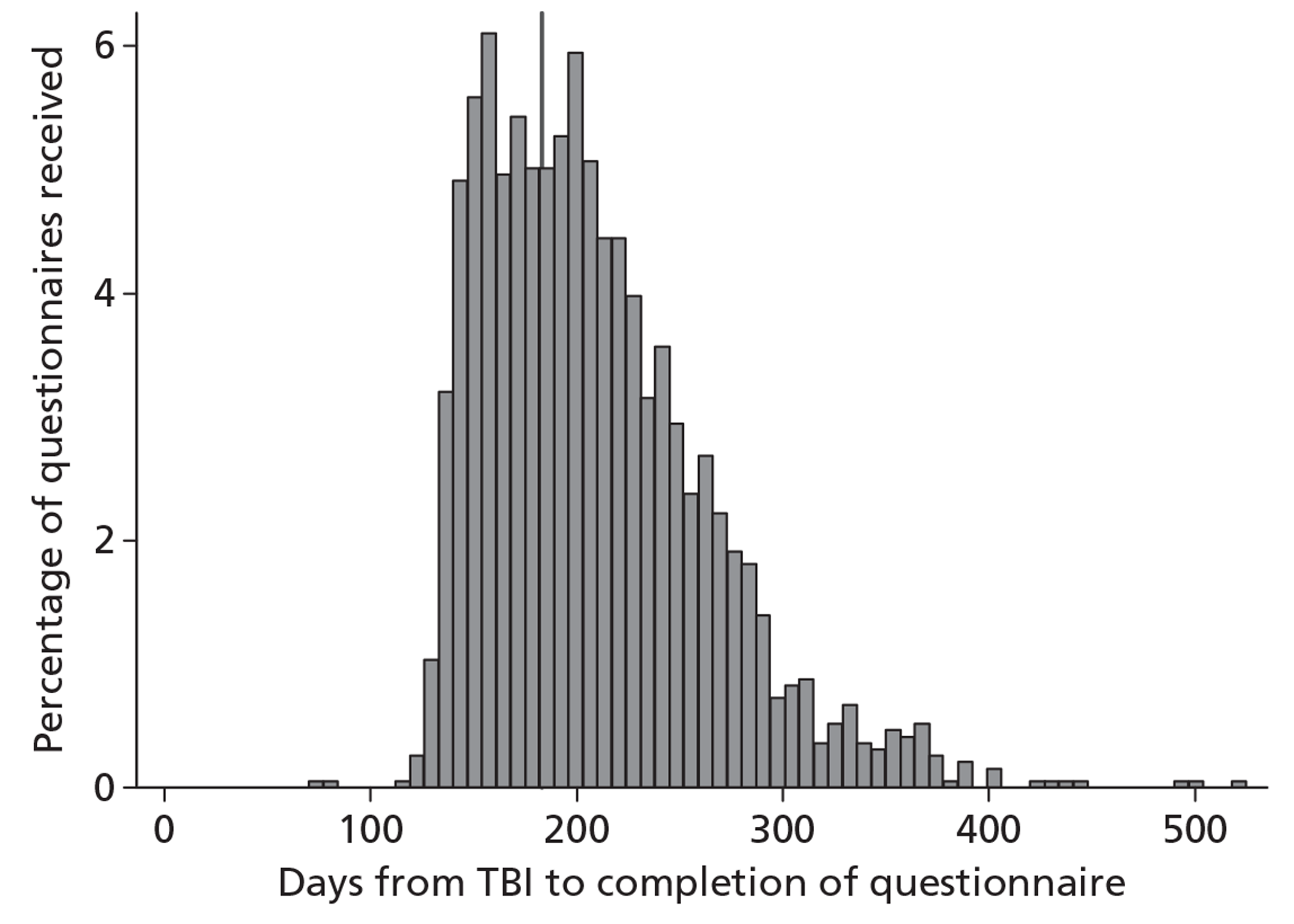

Questionnaires were completed a median of 199 days (IQR 166 to 239 days) after the TBI (Figure 6). Two questionnaires were received very early, owing to data entry errors in the date of TBI that were not identified until follow-up had commenced. There was an initial peak at around 160 days corresponding to postal questionnaires returned following the initial posting, a second peak at around 200 days corresponding to postal questionnaires returned following the second posting, and a subsequent heavy tail of the patients followed up by telephone that were often difficult to contact. A total of 30 patients were eventually contacted for the 6-month follow-up more than 1 year after their TBI.

FIGURE 6.

Distribution of days from TBI to completion of questionnaire. Vertical line indicates 6 months post TBI.

Discussion

Principal findings

The RAIN study has provided case mix data from the time of injury and presentation at hospital and outcomes data at 6 months following injury on a highly representative sample of patients receiving critical care following acute TBI in the UK.

Challenges in conducting the study

Patients with TBI present a challenging population for obtaining reliable, longer-term outcome data. The reasons for this are wide ranging and must be considered when discussing those who were lost to follow-up. Identifying the current location of the patient is not straightforward because of the frequent movement between hospitals and health-care institutions, entry into rehabilitation programmes and moving back to live with family and friends after TBI, as well as a relatively high proportion of homeless patients and those from overseas. Other challenges include ascertaining whether a patient has the capacity to consent and to accurately answer the questions. For example, in some instances, we were informed by health-care professionals or family that while the patient had the capacity to consent following the TBI they had tendencies to confabulate and that answers provided may not have been accurate.

Throughout the follow-up process, every effort was taken to avoid causing unnecessary distress to patients or their families. Following MRIS confirmation, for those registered with a GP, it was necessary to send a letter to confirm the patient's status. There were a small number of cases where the GP blocked contact with the patient or refused to provide the information because prior patient consent had not been obtained. This was despite GPs being fully informed, by letter and telephone, about the study and the governance and ethics approvals. There were also instances where the GP contacted the patient and the patient requested not to be contacted by the Study Team. This raises possible questions whether such patients were fully informed about the study. However, the benefits of contacting GPs do appear to outweigh these possible missed follow-ups. In 28 cases, patients were not reported as having died by MRIS but, on contacting the GP, were found to have died. Despite this being a relatively small number in comparison with the resources and time required to collect GP responses, the prevention of distress to these families by this intervention cannot be ignored. In cases where GPs requested that we did not contact the patient or family for compassionate reasons, this was respected. Despite the dual safeguards of checking for reported deaths both with MRIS and GPs, there were seven cases in which, on making contact with the family, we were informed the patient had recently died. It is inevitable, when following up a high-risk population, that such situations will occur, but it is the responsibility of the researcher to do everything possible to keep these to a minimum.

The use of postal questionnaires may have been a factor in our response rate. Twenty-six patient questionnaires were reported to have been posted by the patient or family but were never received and, once it appeared that undelivered mail could potentially be influencing response rates and fluctuations in the returns were noticed, Royal Mail was contacted. The registered freepost envelope presented a possible issue. Considering this, and research indicating that stamped addressed envelopes may improve response rates over reply-paid envelopes,64 we switched to using stamps during the course of the study. Additionally, when patients indicated during telephone follow-up that they had already returned a questionnaire by post, we requested that they also complete a telephone interview so that in the event the postal questionnaire was not received an outcome would still be available.

Chapter 4 Case mix and outcomes at 6 months for critically ill patients with acute traumatic brain injury

Introduction

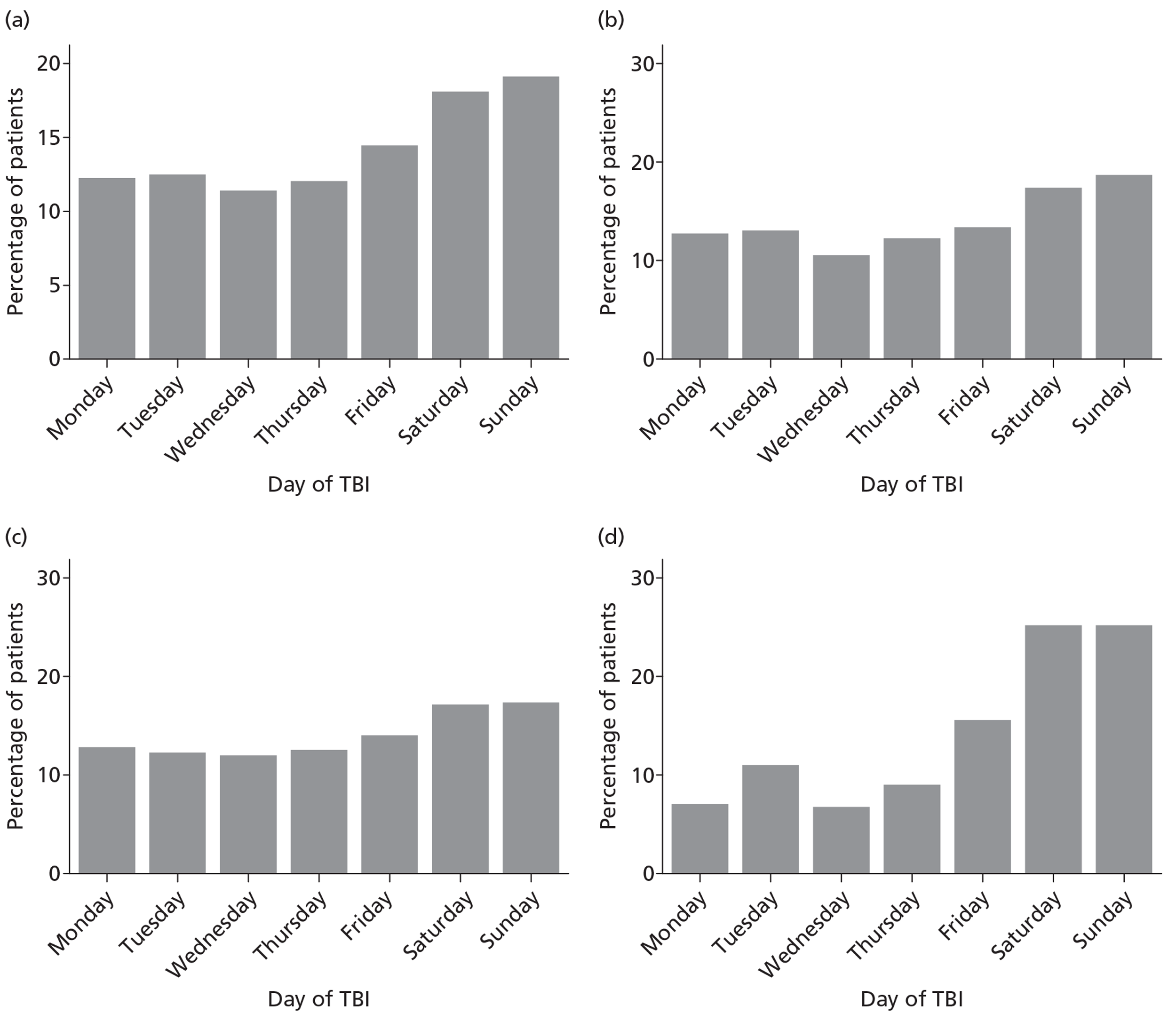

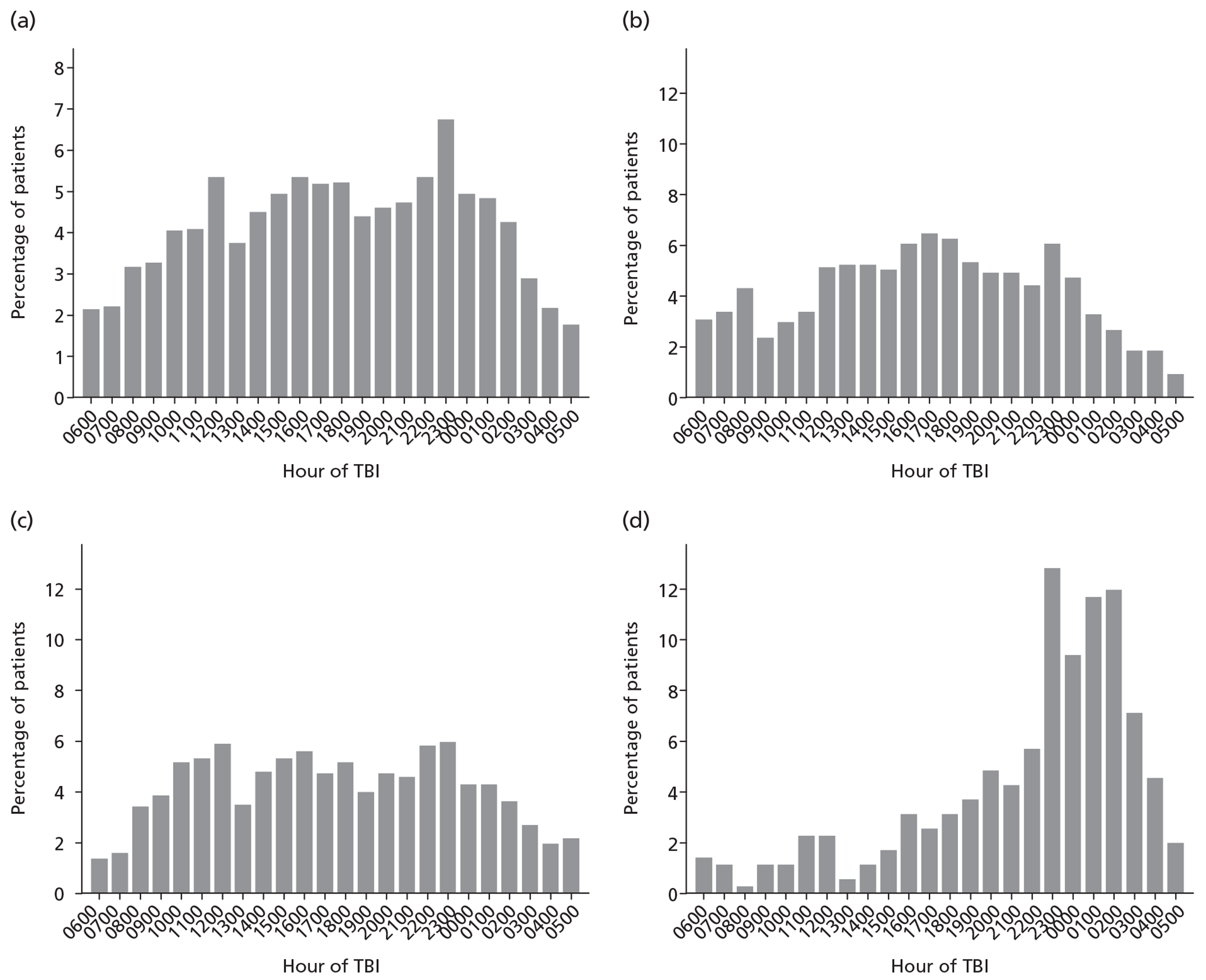

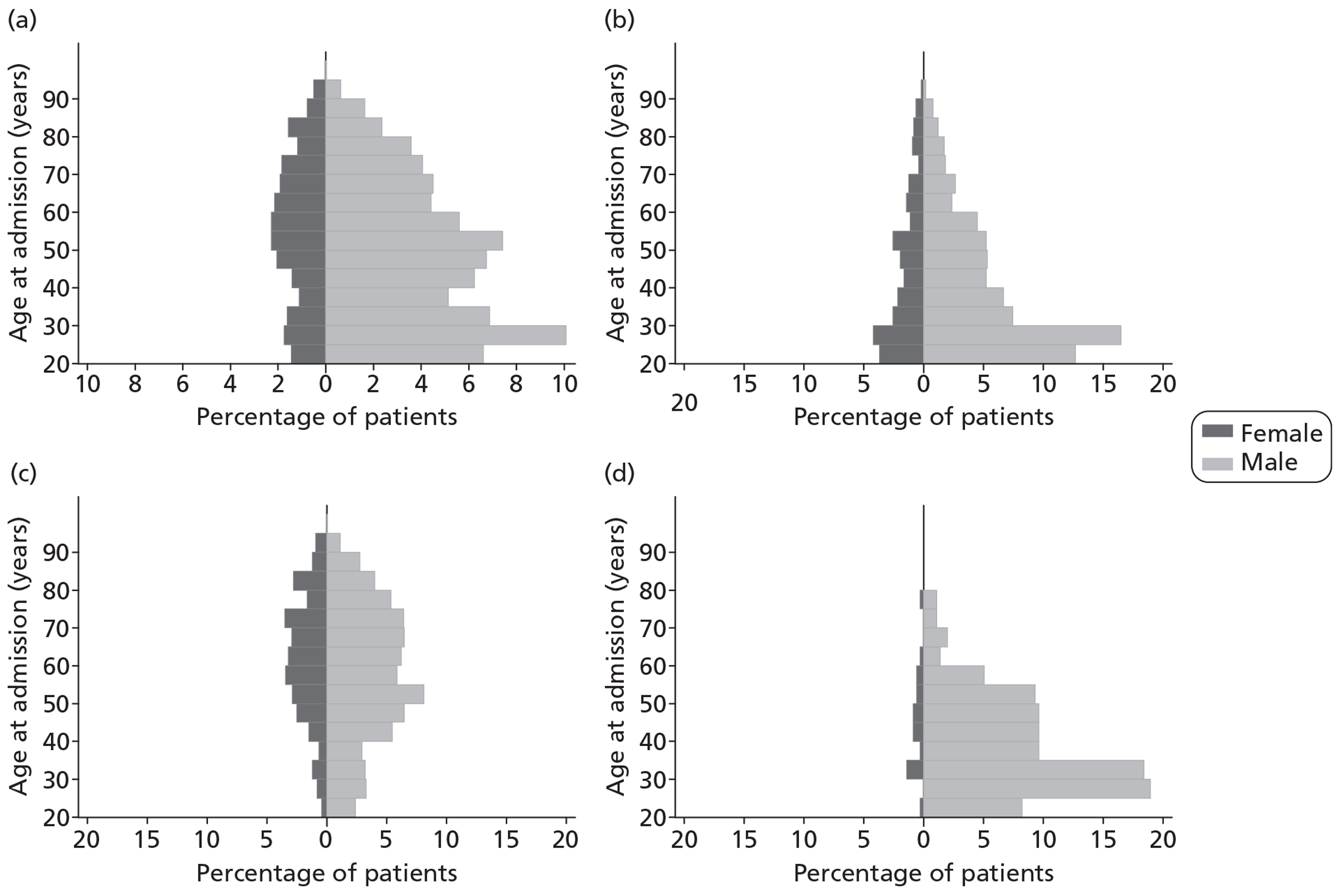

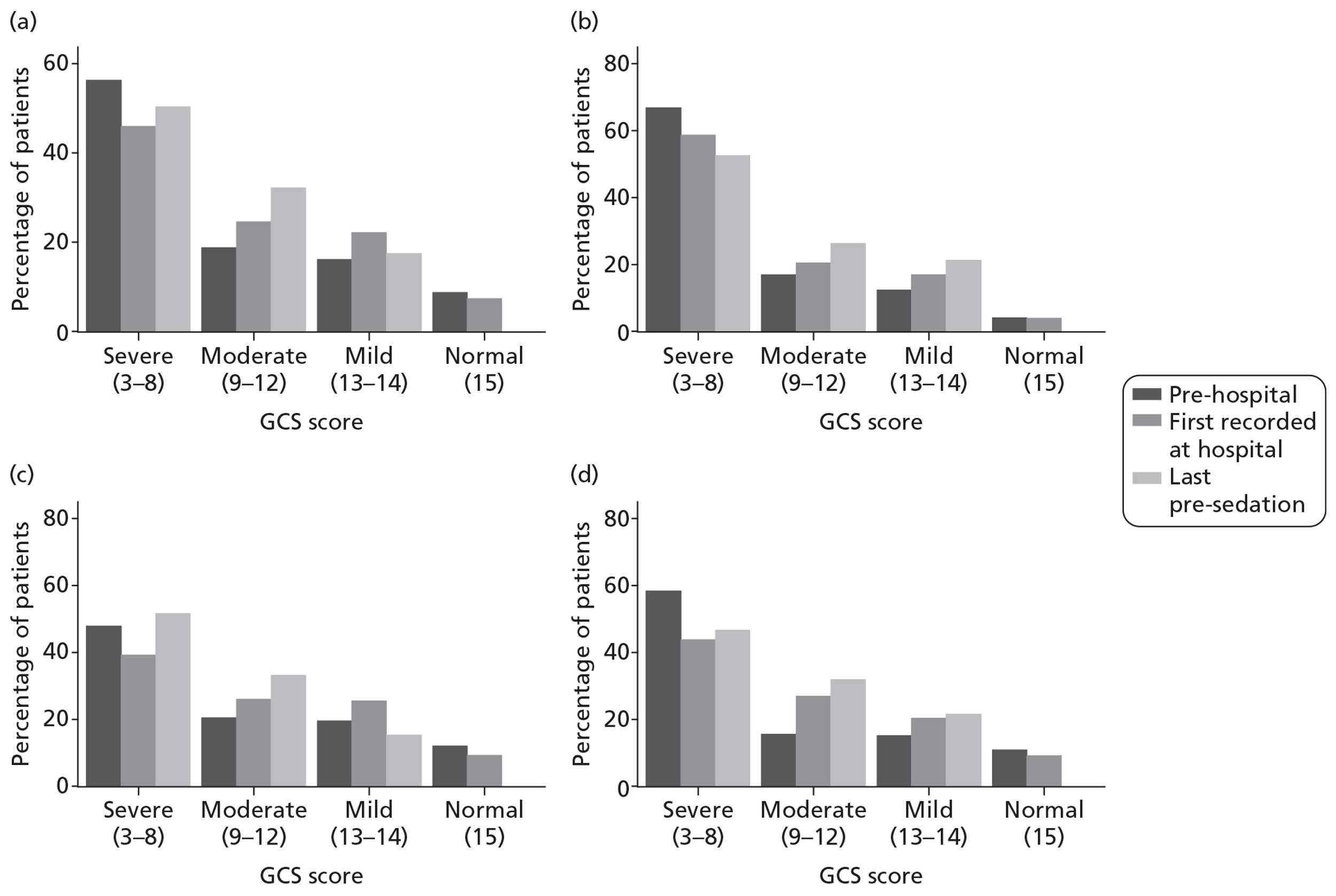

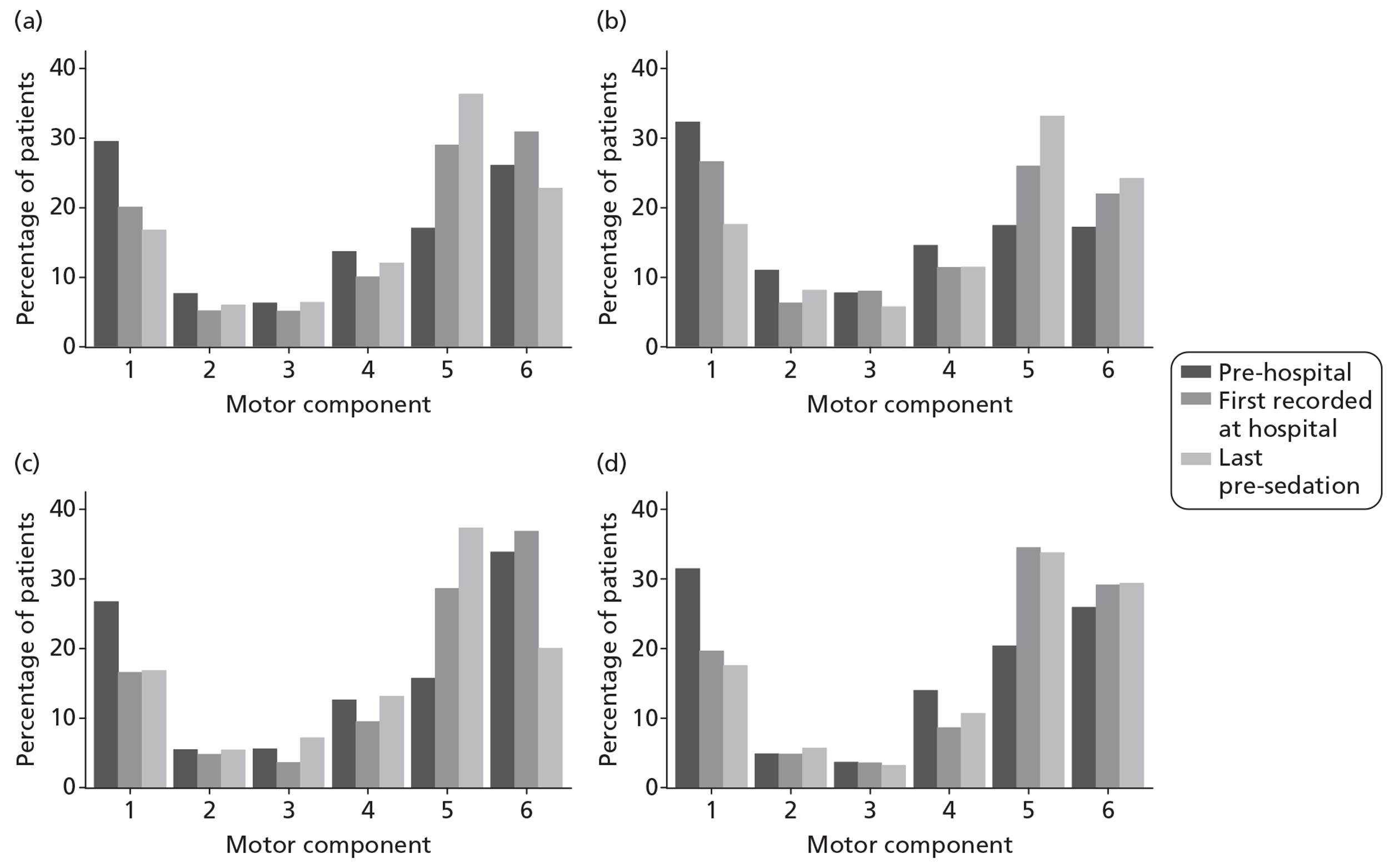

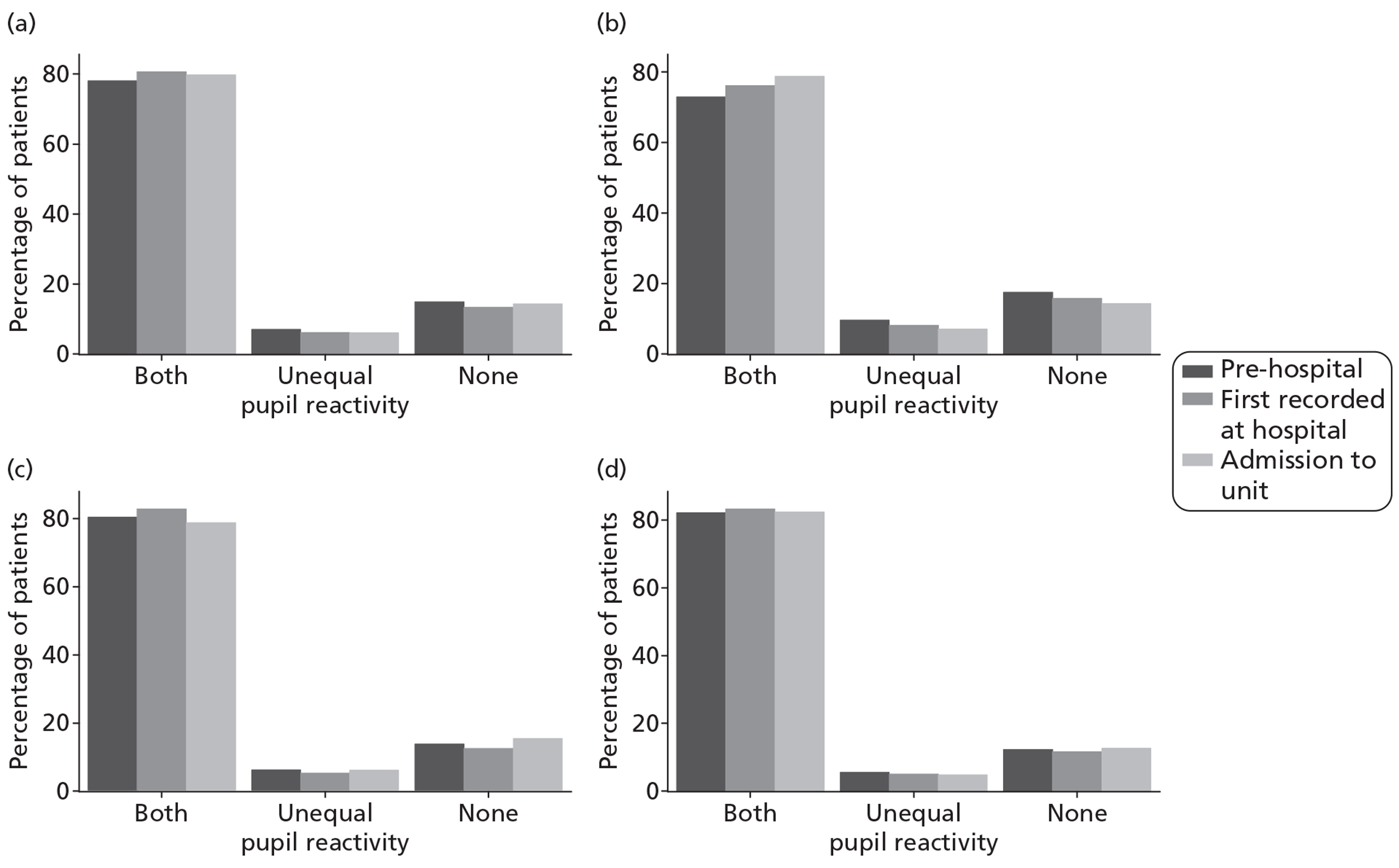

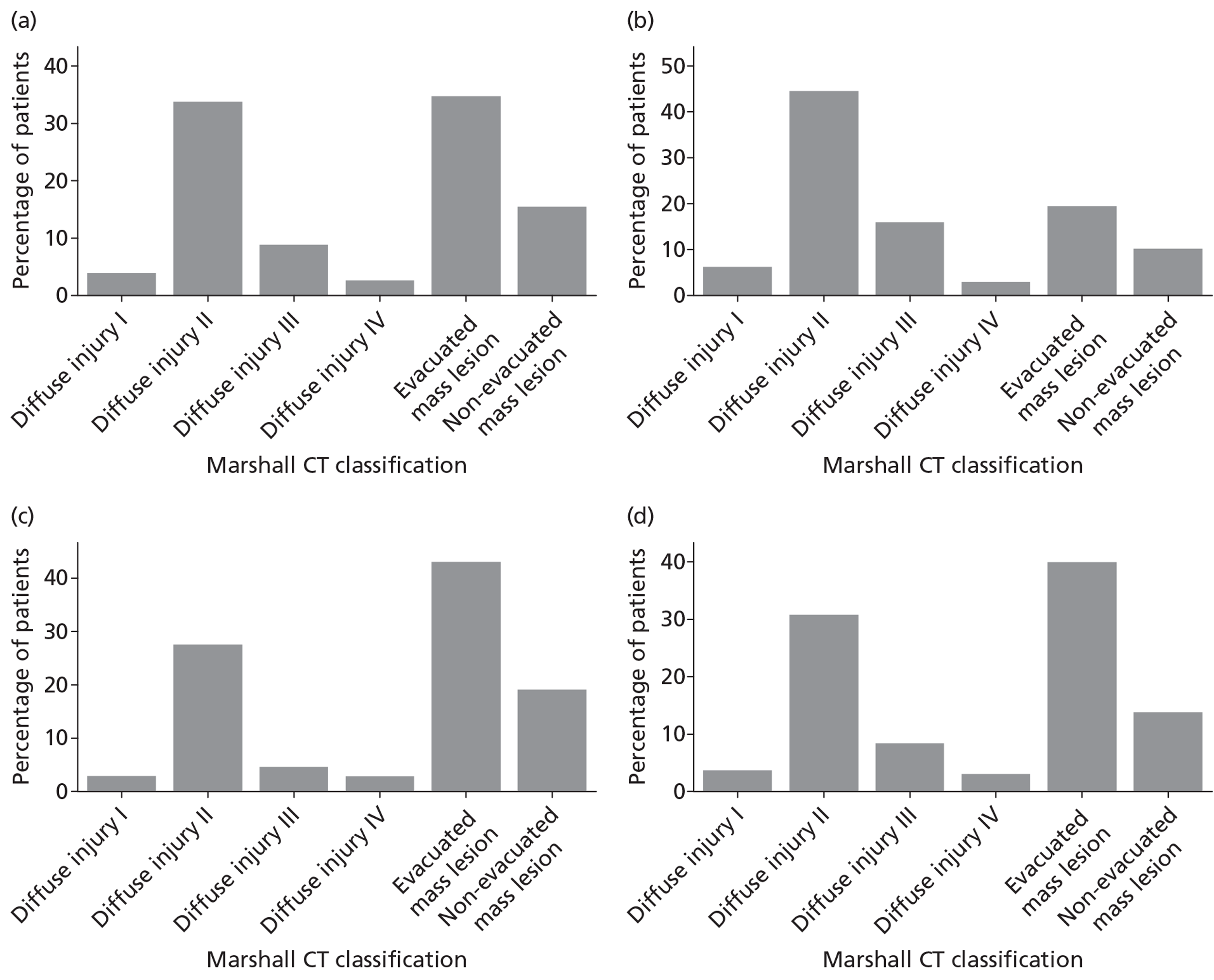

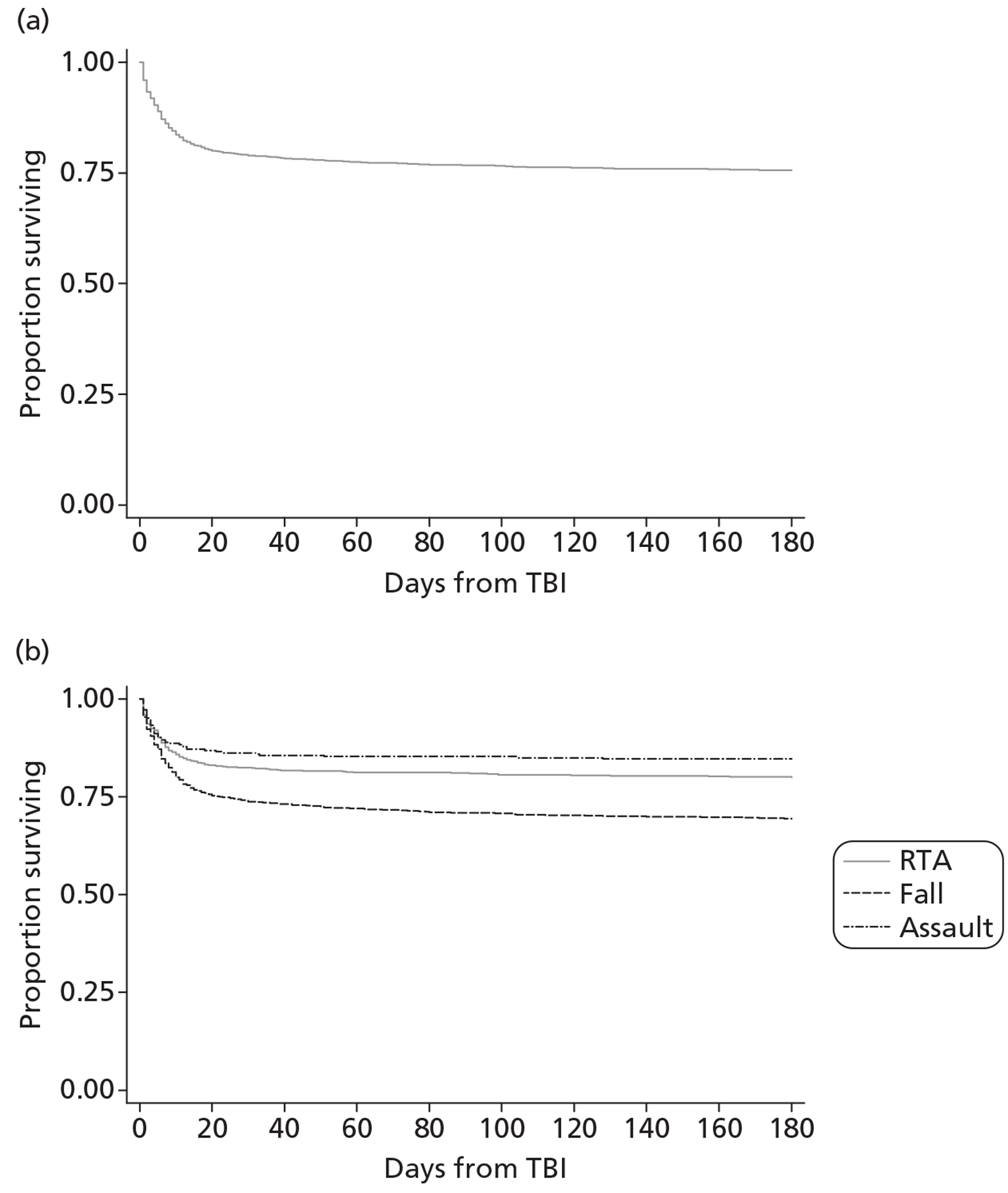

This chapter describes the case mix of patients in the RAIN study admitted to critical care units following acute TBI and their survival, neurological outcome and QOL at 6 months following TBI.