Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/503/10. The contractual start date was in December 2007. The draft report began editorial review in April 2012 and was accepted for publication in October 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Powell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Acute asthma continues to be one of the main reasons for acute hospital admission in children, and accounts for much morbidity, anxiety, stress, and time off school and work for the families of children with asthma. 1 The Department of Health has targeted respiratory disease as an area for improved management. 2 The British Thoracic Society and Scottish Intercollegiate Guideline Network (BTS/SIGN)3 have developed an evidence-based guideline for the management of asthma. It offers comprehensive guidance on the acute and chronic management of asthma in children and adults, but the document highlights the paucity of good information to guide the management of a number of clinical situations. Nowhere is this more striking than in the management of acute asthma, for which the recommended treatment for children (< 16 years old) differs markedly from that for adults (≥ 16 years) in those who are unresponsive to initial standard treatment – a reflection of the evidence base in the different age groups.

The guideline recommends that the initial management in children is inhaled β2-agonists and ipratropium and systemic corticosteroids. This is similar to the initial management in adults. Oxygen saturation of < 92% while breathing room air at presentation is noted to be an indicator of more severe asthma, as is oxygen saturation of < 92% at 20 minutes after inhaled β2-agonists. For children of > 5 years of age who do not respond to initial treatment, it is recommended that clinicians consider intravenous bronchodilator therapy – initially, salbutamol followed by a continuous infusion, then intravenous aminophylline followed by infusion. There is little evidence for an intravenous bronchodilator of choice. Furthermore, although the guideline recognises that intravenous magnesium sulphate (MgSO4) is a safe treatment for patients with acute asthma, with no side effects up to doses of 100 mg/kg, it concedes that its place in management is not yet established. MgSO4 is not recommended for children aged ≤ 5 years. The BTS guidelines3 recommend intravenous MgSO4 in the initial management of severe acute asthma in adults but, as there is a lack of evidence in children, it is not currently recommended as first-line intravenous treatment in paediatric care. 3 There are no current paediatric recommendations concerning nebulised MgSO4.

There is clear evidence that MgSO4 has bronchodilator effects in acute asthma. 4 The BTS guidelines state that experience suggests that intravenous and the nebulised routes are both safe ways of administering MgSO4 in adults. Further trial results are awaited in adults. 5 A single dose of intravenous MgSO4 of a dose of 1.2–2 g in an infusion over 20 minutes is safe and effective improving lung function in adults with acute severe asthma. Safety and efficacy at higher dosages in adults have not been assessed. There is some concern about higher doses causing muscle weakness and respiratory failure. Nebulised MgSO4 in doses of 135–1152 mg in combination with β2-agonists shows a trend towards reduction in the number of hospital admissions and is mentioned as a possible treatment in adults. 6,7 In marked contrast with the paediatric recommendations, intravenous aminophylline and intravenous β2-agonists have limited use in adults, with recommendations that these interventions are reserved for ventilated patients and those in extremis. 3 The final recommendation from BTS/SIGN3 is that more studies are needed regarding the route, frequency and dose in adults for MgSO4. The recommendations from the Cochrane review of 20056 and the 2007 systematic review by Mohammed and Goodacre4 are that more studies are needed in both adults and children to identify exactly how MgSO4 (intravenous or inhaled) should be used.

Rationale

Mechanisms

The use of MgSO4 for acute asthma was first described in 1936, and since then there has been increasing evidence for its use in adults and children with asthma. 3 There are a number of proposed mechanisms for its actions. In vitro studies demonstrate an inhibitory effect of MgSO4 on contraction of bronchial smooth muscle, and the release of acetylcholine in cholinergic nerve terminals and of histamine from mast cells. 6 There is evidence that MgSO4 may act as an anti-inflammatory agent by inhibiting the neutrophil respiratory burst in adults with asthma. 8 The main effect of MgSO4 is that it blocks the calcium ion influx to the smooth muscles of the respiratory system9 and bronchodilatation occurs.

Clinical evidence for magnesium sulphate as a bronchodilator

Intravenous magnesium sulphate

The Acute Asthma and Magnesium Study Group has demonstrated the efficacy of intravenous MgSO4 in severe acute asthma in adults. 10 In a multicentre randomised placebo-controlled trial of 248 adults with acute asthma and a forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) of < 30% predicted, intravenous administration of 2 mg of MgSO4 as an adjunct to the standard therapy resulted in significant benefit in FEV1 of nearly 5%. The effect appeared greatest in those with the most severe asthma, with a difference of 10% in FEV1 between MgSO4- and placebo-treated groups, thus the recommendations set out in the BTS guidelines. 3 A Cochrane review of intravenous treatment with MgSO411 supports this evidence and recommendation. Intravenous administration of MgSO4 requires careful monitoring because peripheral vasodilatation and systolic hypotension can occur in association with flushing, nausea and venous phlebitis at the site of infusion. Consequently, interest has grown in the use of nebulised MgSO4 in acute asthma.

Nebulised magnesium sulphate

Nebulised MgSO4 does not appear to act as a bronchodilator in subjects with stable chronic asthma. 12,13 However, in acute exacerbations in subjects between the age of 12 and 60 years with moderate to severe acute asthma, the response to nebulised MgSO4 appears to be of similar magnitude as the response to salbutamol, as defined by changes in peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR). 14

Initial therapeutic trials of nebulised MgSO4 administered as an adjunct to nebulised salbutamol gave conflicting results in adults. In a small study of 35 adults, Nannini et al. demonstrated a significantly greater improvement in PEFR at 20 minutes after administration in patients receiving nebulised MgSO4 in addition to nebulised salbutamol than with nebulised isotonic saline and salbutamol. 15 A report in adults with severe acute asthma with an FEV1 of < 30% of that predicted, 30 minutes after initial administration of salbutamol via a nebuliser, demonstrated a significant benefit in FEV1 for those receiving MgSO4 compared with isotonic saline. 16 In contrast, Bessmertny et al. could show no evidence of benefit in 74 adults with moderately severe asthma. 17

The most recent Cochrane review of nebulised MgSO4 examined only six randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving a total of 296 patients. 6 Four studies15–18 compared nebulised MgSO4 plus a β2-agonist with a β2-agonist plus placebo, and two studies14,19 compared MgSO4 with a β2-agonist alone. Three15–17 of the six studies14–19 involved adults exclusively: those by Bessmertny et al. (18–65 years),17 Hughes (16–65 years)16 and Nannini et al. (> 18 years). 15 Of the remaining three studies,14,18,19 one included a mix of adult and paediatric patients aged 12–60 years14 and there were two paediatric studies18,19 that included patients aged 5–17 years.

The two paediatric studies18,19 that used nebulised MgSO4 both have methodological deficits. However, the results of the studies show that nebulised MgSO4 appears to have a similar bronchodilator effect in acute asthma in childhood, although the magnitude and duration may not be as great as salbutamol when directly compared. 19 There appears to be an additive effect when inhaled MgSO4 is combined with salbutamol. 18

Meral19 examined two groups of 20 children with mean ages of 10.6 years and 11 years (range 8–13 years) with a severe exacerbation of asthma. In a RCT, patients received either 2 ml of MgSO4 (280 mmol/l, tonicity 258 mOsm, pH 6.7) nebulised over 15–20 minutes or inhaled salbutamol (note: no salbutamol was given in the MgSO4 group). Clinical score and PEFR were measured at 5, 15, 30, 60, 180, 240 and 360 minutes after treatment. Lung function at 5, 60 and 360 minutes was significantly greater in the salbutamol group. 19 This study19 had an unclear randomisation and blinding procedure, had a questionable outcome measure (owing to the lack of reproducibility and reliability of PEFR) and unclear inclusion and exclusion criteria. 20

Mahajan et al. 18 included 62 patients, aged 5–17 years, with severe acute asthma in a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Using FEV1 at 10 and 20 minutes after treatment and admission rates as outcomes along with a clinical score, they administered 2.5 ml of isotonic MgSO4 (6.3% solution) with salbutamol (2.5-mg nebule) or salbutamol with normal saline. One dose of the study medication was used and they demonstrated a significant improvement in FEV1 at 10 and 20 minutes after treatment with MgSO4 and salbutamol combined. 18

The overall conclusions from this review were that the use of nebulised inhaled MgSO4 in addition to β2-agonists in the treatment of an acute asthma exacerbation appears to have benefits with respect to improved pulmonary function [standard mean difference (SMD) 0.23 [95% confidence interval (CI) – 0.03 to 0.50]; four studies]. 6 The benefit was significantly greater in more severe asthma exacerbations [SMD 0.55 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.98)] but overall there were insufficient data, particularly in children, to make firm recommendations. Most importantly, there were no adverse events (AEs) reported and so the other important conclusion was that nebulised MgSO4 treatment was safe. 5 Thus, conclusions regarding treatment with nebulised MgSO4 were difficult to draw.

Mohammed and Goodacre4 completed a systematic review in 2007 and identified three more studies involving nebulised MgSO4. There were no new exclusively paediatric publications. There was one new adult study by Kokturk et al. 21 in 2005 (18–60 years) and two studies22,23 including mixed populations of adults and adolescents: Aggarwal et al. 22 (13–60 years) and Drobina et al. 23 (12–60 years). These three studies21–23 contributed a further 236 patients bringing the overall total to 532.

Kokturk et al. 21 examined 26 patients (18- to 60-year-olds) in a randomised, single-blinded trial. They examined PEFR up to 240 minutes post randomisation and admissions as their main outcomes of interest. They examined moderate to severe exacerbations and compared MgSO4 (2.5 ml of 6.3%) and salbutamol (2.5 ml) with saline as placebo and salbutamol. This small study21 suggested there is no benefit to be gained from adding MgSO4 to salbutamol in terms of PEFR or number of hospital admissions.

Aggarwal et al. 22 went on to study 100 patients (aged 13–60 years). The mean age of the patients studied was 46 years in both the intervention and the control group, which would suggest that the study was unlikely to have contained many adolescents. The authors examined PEFR up to 120 minutes post randomisation and admissions as the main outcomes and looked at severe to life-threatening acute asthma. They compared nebulised salbutamol (1 ml) with nebulised MgSO4 (1 ml of 500 mg), three doses in 1 hour, with saline and distilled water as placebo. The patients were randomised using a random number table and the study was double-blind. The investigators found no difference in outcomes between the two groups and concluded that there is no therapeutic benefit to be gained from adding MgSO4 to the standard treatment regimen. 22 Drobina et al. 23 (findings published in abstract only) examined 110 patients (12–60 years) with mild to severe asthma, again using PEFR and admissions as the primary outcomes. The intervention group received 150 mg of MgSO4 (0.3 ml of 50% MgSO4) added to each nebulised dose of medication. The control group received nebulised treatments of salbutamol 0.5% (5 mg/ml) combined with 0.5 mg of ipratropium bromide 0.02% inhalation solution. This study showed no evidence of an effect of adding MgSO4 on the above outcomes. 23

These further three studies21–23 with 236 patients thus found no evidence of an effect. Based on these findings, along with those of the other six studies, the reviewers concluded, that, in adolescents and adults, there is only weak evidence that the use of nebulised MgSO4 has an effect on respiratory function [SMD 0.17 (95% CI – 0.02 to 0.36); p = 0.09] or hospital admission [relative risk (RR) 0.68 (95% CI 0.46 to 1.02); p = 0.06]. These effects were clearly weaker that the results from the 2005 Cochrane review. 6 The reviewers felt able to draw an overall conclusion of the paediatric evidence based on the two paediatric studies. They concluded that there was no evidence of a significant effect of the addition of MgSO4 to standard treatment on respiratory function [SMD – 0.26 (95% CI – 1.49 to 0.98); p = 0.69] or hospital admission [RR 2.0 (95% CI 0.19 to 20.93); p = 0.56]. This conclusion did not differ significantly from the results of the Cochrane review in 2005. 6 Assessment of the risk of outcome reporting bias in the latest systematic review4 led to a sensitivity analysis adjusting for the suspected bias; the results24 suggested that the conclusions of the review were robust to this problem.

Risks and benefits

Risks

All six studies14–19 reported in the Cochrane review reported no serious adverse events (SAEs) in either arm. 6 The risk of SAEs was low in the studies comparing (1) MgSO4 with β2-agonists [risk difference (RD) 0.00 (95% CI – 0.11 to 0.11)] and (2) MgSO4 with a β2-agonist to a β2-agonist alone (RD 0.00; 95% CI – 0.03 to 0.03). The risk of SAEs was low and appeared to be even lower in patients treated with MgSO4 – either alone [RD – 0.17 (95% CI – 0.41 to 0.06)] or in combination with β2-agonists (RD – 0.09; 95% CI – 0.24 to 0.06). In the three extra papers in the Mohammed review,4 Aggarwal et al. 22 and Kokturk et al. 21 reported no significant AEs and Drobina et al. 23 made no comment (see Appendix 1, Table 38).

A systematic review (not published) of the adverse effects of inhaled MgSO4 in children was undertaken by the University of Liverpool for this study and identified two studies,25,26 not included in the Cochrane review,6 containing at most 18 further children. There were no reported AEs (see Table 1). These extra studies were not RCTs of MgSO4 during an acute asthma attack but they did report the effects of administering nebulised MgSO4, thus AEs could be examined. 25,26

In the MAGNET pilot study (Ashtekar et al. ;27 EudraCT no. 2004-003825-29), a total of 25 eligible patients were identified for inclusion into the study over a 3-month period. Of these, 17 gave informed consent to be randomised to receive nebulised magnesium or placebo in addition to salbutamol and ipratropium. All individuals received the treatment to which they were randomised. Seven patients who were randomised to active treatment and 10 patients to placebo. MAGNET27 found that there were no differences between the two groups when comparing the median Asthma Severity Score (ASS)28–30 after three nebulised treatments and the area under the curve (AUC) analysis of the ASS for the six time points. 27 There were insufficient numbers to make a significant comment about the efficacy of nebulised MgSO4 from the pilot study, the main aim of which was to test recruitment, administration and outcome assessment feasibility.

Two children (both of whom received MgSO4) had mild AEs. One child had transient facial flushing and, although asymptomatic, a blood pressure reading appeared low. The blood pressure was immediately remeasured and was then normal. Another child had transient tingling of the fingers. 27

Benefits

As described in detail above, five studies14–16,18–19 showed a benefit to using nebulised MgSO4 in some preparation, whereas four studies17,21–23 showed no benefit. There was heterogeneity between trials regarding study design, dose given, intervention comparison, primary outcomes and exclusion criteria (see Appendix 1, Tables 37–39), There was a non-statistically significant improvement in pulmonary function between patients whose treatments included nebulised MgSO4 in addition to β2-agonists [SMD 0.23 (95% CI – 0.03 to 0.50), four studies] and hospitalisations were similar between the groups [RR 0.69 (95% CI 0.42 to 1.12), three studies]. Subgroup analyses demonstrated statistically significant differences in lung function improvements with nebulised MgSO4 in addition to a β2-agonist in patients with severe exacerbations of their asthma [SMD 0.55 (95% CI 0.12 to 0.98)].

However, only one study16 reported the effect of three doses of MgSO4 nebulised with salbutamol in patients with severe asthma. In the study reported by Hughes,16 three nebulised treatments of MgSO4 mixed with salbutamol were given at 30-minute intervals to adults with severe asthma, and resulted in a twofold greater increase in FEV1 than the same dose of salbutamol administered with isotonic saline nebuliser solution; this enhanced bronchodilator response was associated with a significant reduction in hospital admission rates [RR 0.61 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.99), p = 0.04]. Only one study23 had used nebulised ipratropium bromide as well as salbutamol as standard treatment,23 which is certainly the current recommendation from the BTS for children and for adults. 3

The University of Liverpool systematic review also investigated the efficacy of nebulised MgSO4 in children. The findings are summarised in Table 1.

| Study | AEs in MgSO4 group | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|

| Rolla 198725 | Measured: not stated | No difference in lung function |

| Reported: no mention of AE in results/discussion | Improvement in airway responsiveness | |

| Rolla 198826 | Measured: not stated | Inhaled doses of > 0.1 mmol led to improvement in bronchial hyper-responsiveness |

| Reported: ‘no patient experienced side effects’ | ||

| Meral 199619 | Measured: ‘subjects were evaluated for possible adverse effects’ | PEFR: MgSO4 group better after 5 minutes, then back to pre-Mg measurement by 6 hours. Control group had sustained improvement at 6 hours. At 6 hours control group PEFR was better than magnesium group. Respiratory distress score: no difference between groups |

| Reported: in discussion – ‘No adverse reaction in either group as the heart rate and blood pressure did not change’ | ||

| Mangat 199814 | Measured: blood pressure, arrhythmia; hyporeflexia, respiratory depression | Patients treated with nebulised MgSO4 improved in terms of bronchodilatation and Fischl score.31 However, this effect was not significantly different to that of the group given nebulised salbutamol |

| Reported: (not stated whether these occurred in adults or children) – one transient hypotension (spontaneously resolved); no hyporeflexia | Note: the study report does not report the paediatric results separately from the adult results | |

| Mahajan 200418 | Measured: tremors, headaches, nausea, vomiting, hyporeflexia | FEV1 absolute: improvement at 10 minutes significantly better than in control group (p < 0.03); at 20 minutes no difference between groups |

| Reported: ‘none of the patients in either group showed any side effects’ | FEV1% predicted: no difference between groups |

At the beginning of recruitment to MAGNETIC, this was the current published evidence. We have currently completed a further update of the Cochrane review6 using the Cochrane review methodology, and this has now been published. 32 At the time of this report there were a total of 16 published studies of randomised controlled study design in acute asthma, with a total of 838 patients (439 subjects who had completed an intervention with MgSO4 and 399 who were control subjects in studies). The seven studies27,33–38 published since Mohammed 2007, or earlier studies not included in Mohammed's systematic review, are three studies involving adults exclusively;33–35 one study including adults and paediatric patients;36 two studies that enrolled children27,37 and, one study38 in which the age of participants was not stated. The data from these studies will be discussed in Chapter 5 of this report. The features of these 16 studies14–19,21–23,27,33–38 are presented in Appendix 1 in three tables but they are clearly heterogeneous in study design, population examined, intervention administered and outcomes measured.

Thus there is a need for a large study examining the addition of nebulised MgSO4 in children with acute severe asthma compared with standard treatment in a placebo-controlled double-blind randomised manner. MAGNETIC is a randomised placebo-controlled multicentre trial of the use of nebulised MgSO4 in severe acute asthma in childhood in patients who show a poor response to maximal conventional aerosol treatment.

Objective

Primary objective

Does nebulised MgSO4, used as an adjunct to nebulised salbutamol and ipratropium bromide for 1 hour in children with severe asthma, result in a clinical improvement compared with nebulised salbutamol, ipratropium bromide and placebo?

Secondary objectives

Does nebulised MgSO4, used as an adjunct to nebulised salbutamol and ipratropium bromide for 1 hour in children with severe asthma, compared with nebulised salbutamol, ipratropium bromide and placebo, have an effect on:

-

(a) clinical outcomes in terms of additional treatment/management while in hospital, and length of stay (LOS) in hospital

-

(b) patient outcomes in terms of quality of life (QoL), time off school and health-care resource usage over the following month

-

(c) parent outcomes in terms of time off work over the following month

-

(d) costs and cost-effectiveness for the NHS and Personal Social Services and, more broadly, for society?

Chapter 2 Methods

Objective

The objective of the MAGNETIC trial was to assess whether the addition of magnesium to standard treatment for acute severe asthma in children resulted in a clinical improvement compared with standard treatment alone.

Design

This was designed as a prospective, controlled, double-blind, multicentre RCT comparing the effects of nebulised MgSO4 with placebo for children presenting to secondary care with an acute severe asthma exacerbation.

Participants

Using the Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN), 30 centres were identified. The network now covers most regions in England. Adding the Northern Ireland Research Network, the Scottish MCRN and the one site in Wales (Cardiff), we established (via an initial feasibility study) that each centre would be likely to able to recruit sufficient patients with severe acute asthma for the numbers required for the study. These centres all received patients with acute asthma into their unit's unscheduled care service and this may be in the form of a visit to emergency department (ED) or a children's assessment unit (CAU) or both. The patient inclusion and exclusion criteria for the MAGNETIC trial were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

Potential participants for the study could be between the ages of 2 years and 16 years. They could have had a previous history and diagnosis of asthma and be on treatment but could also be patients who have presented for the first time with acute asthma as per BTS/SIGN definitions. 3 Subjects could be recruited in either an ED or a CAU in secondary care. The main clinical definition for inclusion was severe acute asthma as defined by the BTS/SIGN guidelines. 3

For children of ≥ 6 years, severe acute asthma is based on at least one of the following criteria being met:

-

(a) oxygen saturations of < 92% while breathing room air

-

(b) too breathless to talk

-

(c) heart rate of > 120 beats per minute (b.p.m.)

-

(d) respiratory rate of > 30 breaths per minute

-

(e) use of accessory neck muscles.

For children aged 2–5 years, severe acute asthma is based on at least one of the following criteria being met:

-

(a) oxygen saturations of < 92% while breathing room air

-

(b) too breathless to talk

-

(c) heart rate of > 130 b.p.m.

-

(d) respiratory rate of > 50 breaths per minute

-

(e) use of accessory neck muscles.

Exclusion criteria

-

(a) Co-existing respiratory disease, such as cystic fibrosis or chronic lung disease of prematurity.

-

(b) Severe renal disease.

-

(c) Severe liver disease.

-

(d) Known pregnancy.

-

(e) Known previous reaction to magnesium.

-

(f) Inability to give informed consent.

-

(g) Previous randomisation into the MAGNETIC trial.

-

(h) Life-threatening symptoms.

-

(i) Current or previous (in the 3 months preceding screening) involvement with a trial of a medicinal product.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to receive nebulised salbutamol 2.5 mg (aged 2–5 years) or 5 mg (aged ≥ 6 years) and ipratropium bromide 0.25 mg mixed with either 2.5 ml of isotonic MgSO4 (250 mmol/l, tonicity 289 mOsm; 151 mg per dose) or 2.5 ml of isotonic saline on three occasions at approximately 20-minute intervals. There is currently no specific agreed dose of MgSO4 for use in children. 4 The MgSO4 dose for this study was chosen based on the doses described in the published paper by Hughes in 2003,16 as they were shown to be effective and safe in acute asthma in an adult population. 16 The magnesium solution needs to be isotonic as hypertonic and hypotonic solutions may cause bronchoconstriction. 16 The doses used in the published paediatric studies were both isotonic [Meral,19 2 ml of isotonic MgSO4 (280 mmol/l, tonicity 258 mOsm, 116 mg/dose); Mahajan et al. ,18 2.5 ml of isotonic (6.3%) MgSO4, 145 mg/dose)]. The frequency of the dosing was based on the three doses of bronchodilators (salbutamol and ipratropium) in the first hour of treatment as recommended by BTS,3 with the MgSO4 or placebo added. Use of various doses is described in the clinical effectiveness literature (see Appendix 1 and discussion in Chapter 5).

Study procedures

Patients were identified on presentation to EDs or CAUs and assessed against the study inclusion criteria. If they fulfilled the severity criteria as defined by the BTS definition,3 the Yung ASS was recorded. 30 Patients were then given a nebuliser containing salbutamol and/or ipratropium bromide (variations allowed; as per site routine clinical practice) and parents/guardians were then approached and asked for their informed consent.

Following this initial nebuliser the patient was re-assessed against the inclusion criteria and the ASS recorded again. Patients were eligible for randomisation provided at least one of the inclusion criteria of the severe asthma BTS definition3 were met and informed consent had been obtained from the parent and if appropriate assent from the child.

Patients were randomised to receive either 2.5 ml of isotonic MgSO4 (250 mmol/l, tonicity 289 mOsm; 151 mg per dose) or 2.5 ml of isotonic saline via nebuliser on three occasions at approximately 20-minute intervals. Each nebuliser also contained salbutamol 2.5 mg (children aged 2–5 years) or 5 mg (children aged ≥ 6 years) and ipratropium bromide 0.25 mg in both the active and placebo groups. It was planned that as soon as they were randomised then the treatment would start.

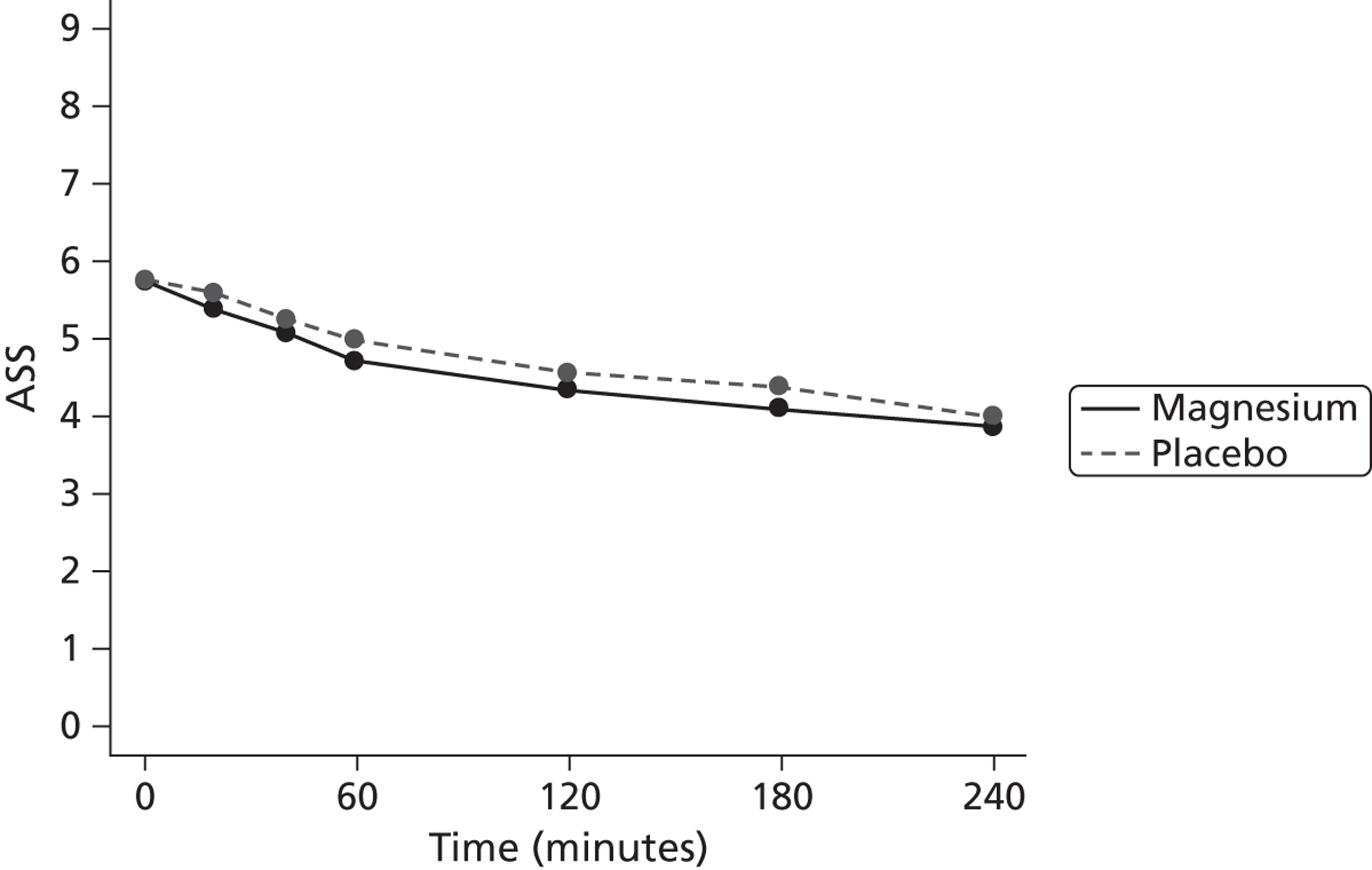

The ASS was measured at approximately 20 (T20, after first treatment nebuliser), 40 (T40, after second treatment nebuliser), 60 (T60, after third treatment nebuliser), 120, 180 and 240 minutes post randomisation. AEs, concomitant medication, oxygen saturation, respiratory rate and blood pressure were also recorded at these assessment points.

Following the conclusion of 4-hour follow-up, AEs were monitored and data collection continued until discharge from hospital to assess secondary outcome measures. Parents and patients (if aged ≥ 5years) were contacted by the research team and asked to complete postal questionnaires 1 month after their hospital visit in order to collect health-related QoL and health economics data. The schedule of study procedures is shown in Table 2, see below.

| Procedures | Screening | Randomisationa | Minutes post randomisation: | During admission | Before discharge | 1-month follow-up | Premature discontinuation | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 | 40 | 60 | 120 | 180 | 240 | ||||||||

| Signed consent form | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Assessment of eligibility criteria | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||||

| Yung ASS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Assignment to study treatment | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Review of medical history | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||||

| Review of concomitant medications | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Study interventionb | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Blood pressure, SaO2, respiration rate | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| PedsQL™ Asthma Module | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| EQ-5D | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Health economics questionnaires | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Physical examination | Complete | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Symptom-directed | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | (✗) | ||||

| Assessment of AEs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||

Procedures for assessment

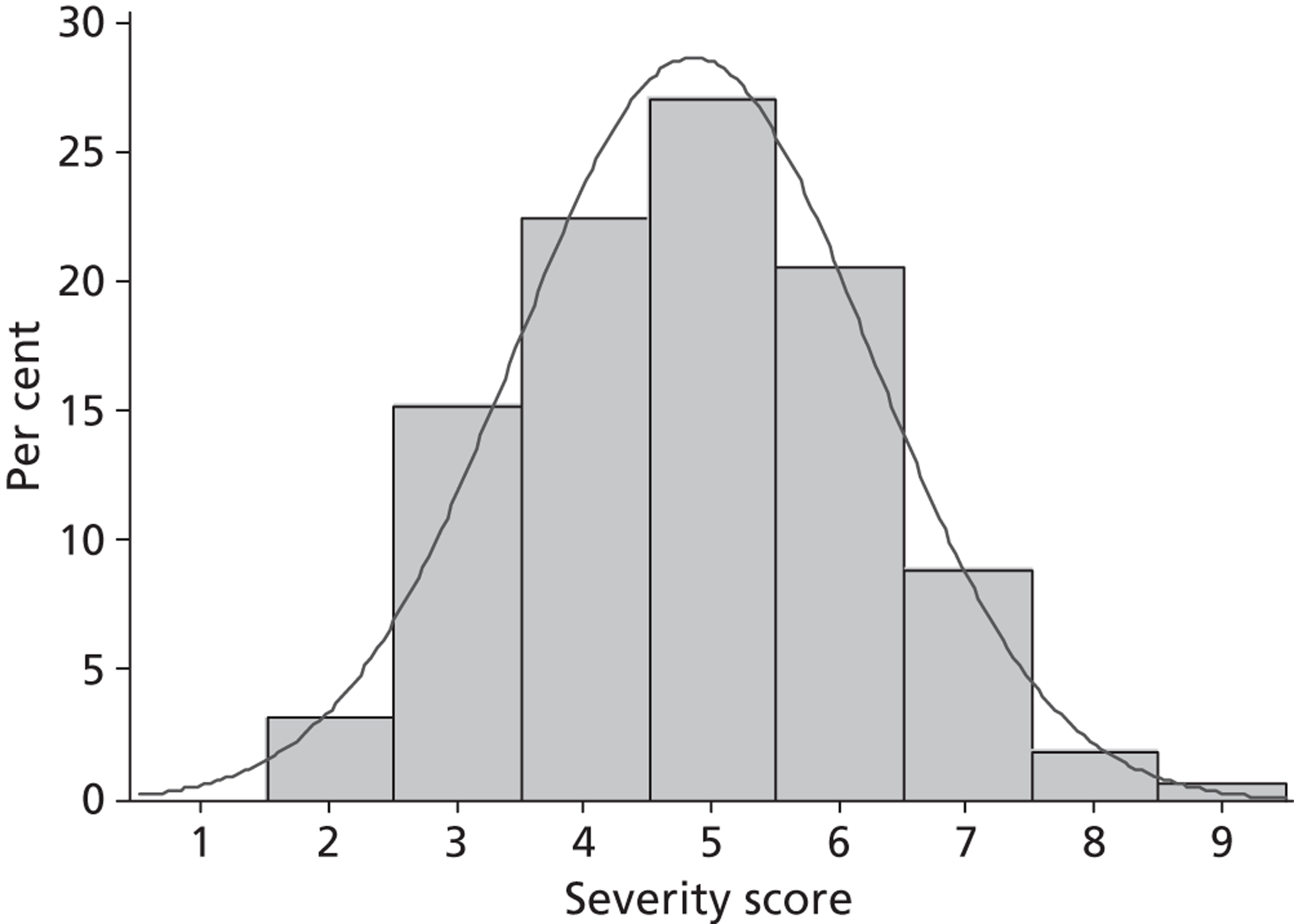

Efficacy

Asthma severity was assessed using a validated score, the Yung ASS,28–30 which comprises three clinical signs: wheezing, accessory muscle use and heart rate. Each component has a minimal score of zero and a maximum of 3. The total score is a sum of each component, giving a minimum score of zero and a maximum of 9. The score has been validated as a measure of asthma severity in children including the younger age group, has been demonstrated to be reproducible and reliable,29 with good interobserver agreement, and correlates well with oxygen saturation and FEV1. 30 This score is clinically easy to use and involves some of the standard assessments, used routinely by medical and nursing staff while managing children with acute asthma. The ASS assessment was carried out by a clinician or by a nurse who was appropriately trained to make the necessary observations in the opinion of the principal investigator for that site.

Safety

Patient status was monitored for 4 hours post randomisation. Oxygen saturation, respiratory rate and blood pressure were recorded twice during screening, approximately 20, 40 and 60 minutes post randomisation, and follow-up checks at 120, 180 and 240 minutes post randomisation. The research team were prompted to check for AEs at each assessment point, by reviewing physiological parameters such as blood pressure and asking about known side effects, for example facial flushing. AEs were followed up until discharge from hospital.

Health economics and quality of life

The case report form (CRF) used by the clinical team at each site recorded each child's NHS resource use from randomisation to discharge from hospital. The 1-month follow-up postal questionnaire collected QoL [Paediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL™) Asthma Module and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaires] and health economics (NHS and non-NHS) data from discharge to 1 month post randomisation (see Appendices 2 and 9).

Outcomes

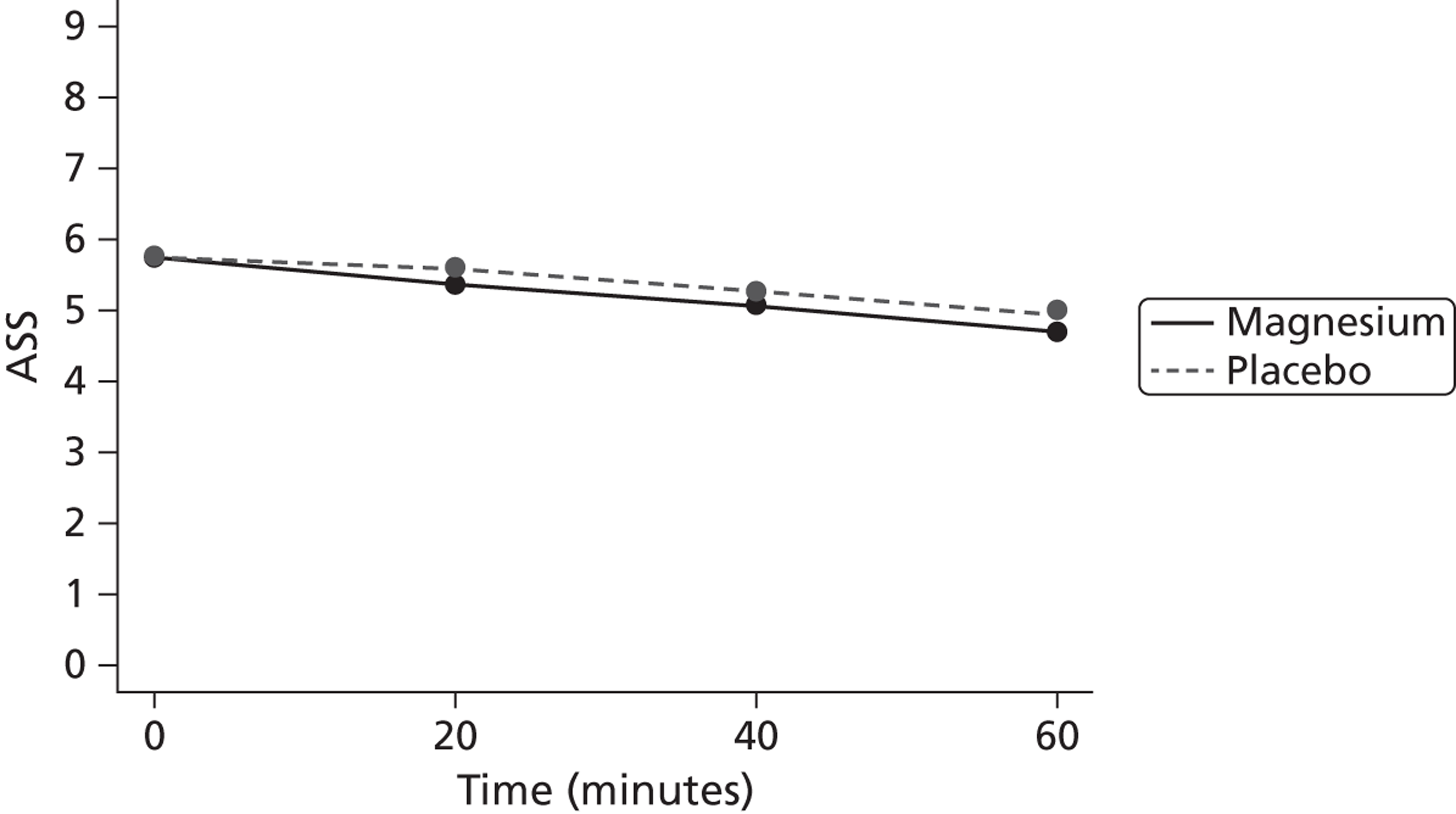

There are many and varied primary outcomes to choose from in acute asthma studies. 39 There are no agreed core outcomes for use in acute asthma studies in ether adult or paediatric studies, and so there is huge variation in the primary and secondary outcomes reported. 4,6 In the nebulised MgSO4 literature, numerous and varied outcomes (see Appendix 1, Table 38) are reported. Measurements of lung function in children recorded during an acute attack or in those in whom lung function has never previously been measured are too unreliable to use accurately. 40 Thus, an ASS appears to be a clinically relevant score to use in children to avoid the need for measuring lung function. The main problem is there are over 20 asthma severity scores39,41,42 all with different qualities. We chose the most validated and easiest to use – the Yung ASS. 30 The choice of the ASS is discussed further in Chapter 5. As there was evidence that the response to inhaled MgSO4 is within the first hour of treatment4,7,19 we decided to measure the primary outcome as the ASS at 60 minutes post treatment (T60) and then hourly up to 240 (T240) minutes post treatment to establish if there is a sustained effect. We also measured respiratory rate, heart rate, oxygen saturation in air and blood pressure as objective measurements. There are a number of secondary outcomes that we collected based on the most common secondary outcomes measured in acute asthma studies. 39 ‘Stepping down’ of treatment at 1 hour describes the decision to change from nebulisers to spacers, a proxy for the treating clinician making a judgement that the child is getting better having presented with severe exacerbation. In a study of 36 EDs in Australia including 720 patients with acute asthma, 50% of those with acute asthma who presented as a severe exacerbation improved sufficiently to be classified as to be moderate at 1 hour after treatment was started, thus potentially able to change from nebulisers to spacers. 43

Primary outcome

The primary end point was the ASS after 60 minutes of treatment. It was defined as ASS at T60.

Secondary outcomes

Clinical (during hospitalisation):

-

‘stepping down’ of treatment at 1 hour (the ‘stepping down’ of treatment at 1 hour is defined by the change to metered dose inhaler (MDI)/spacer combination only or no further treatment until discharge)

-

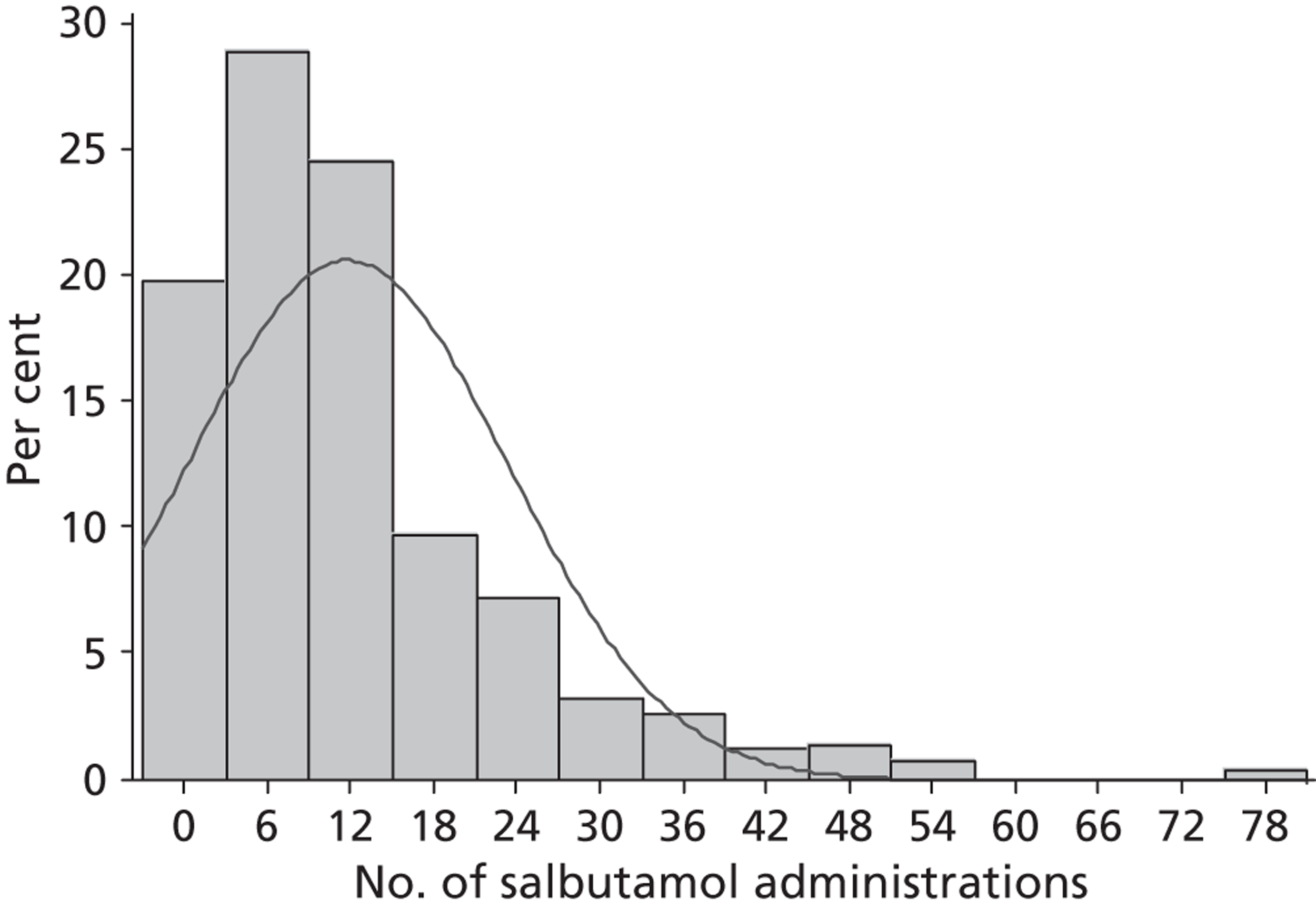

number and frequency of additional salbutamol administrations

-

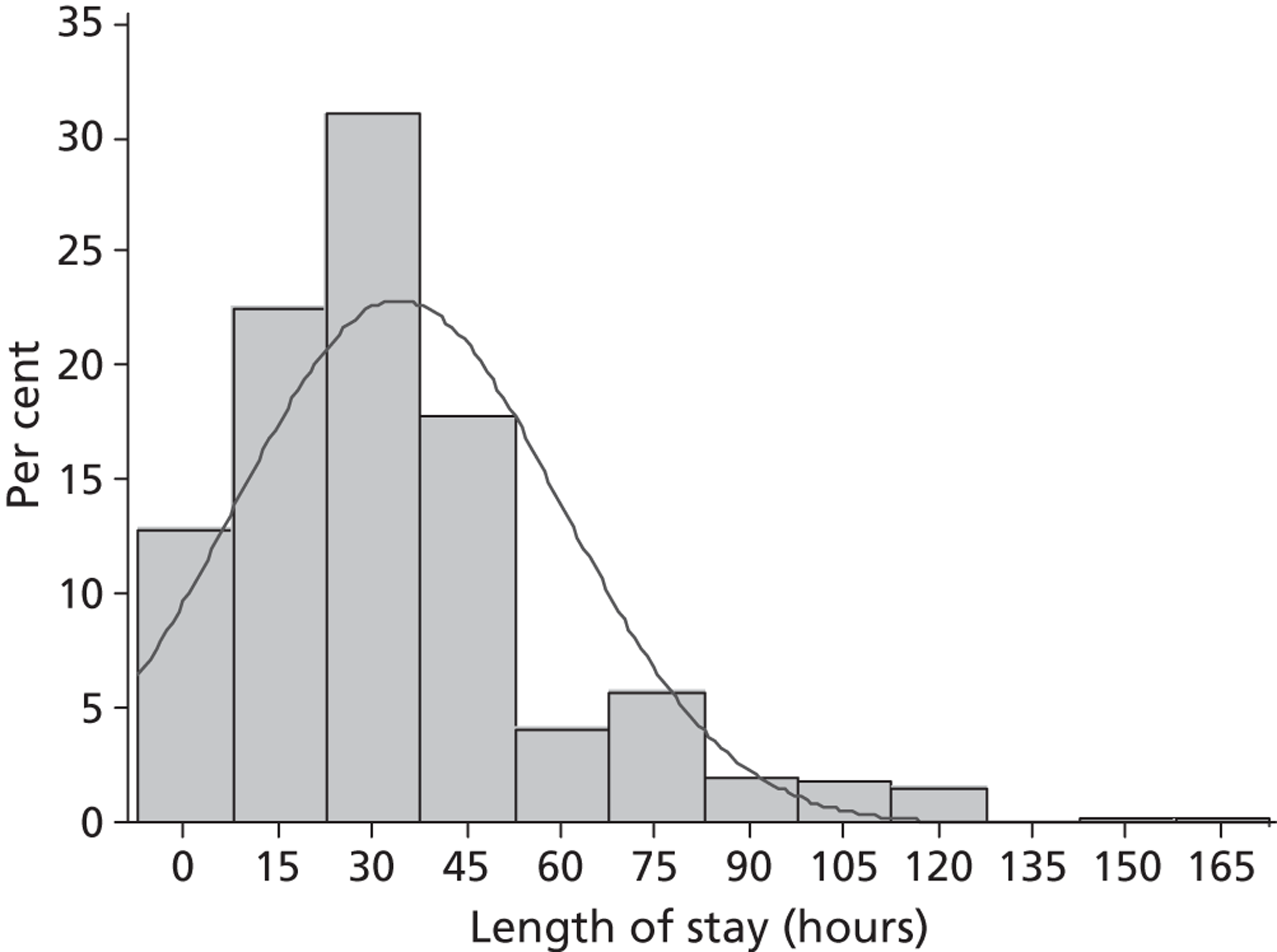

LOS in hospital

-

requirement for intravenous bronchodilator treatment

-

intubation and/or admission to a paediatric intensive care unit (PICU).

Patient and parental outcomes at follow-up (1 month):

-

paediatric QoL (PedsQL™ Asthma Module parental report for all children and self-completion if aged > 5 years, EQ-5D)

-

time off school/nursery for the child

-

health-care resource usage [e.g. general practitioner (GP) visits, additional prescribing]

-

time off work (related to child's illness).

Sample size calculation

In order to detect a difference between the two treatment groups at T60 of 0.5 points on the ASS at a 5% significance level with 80% power, 500 children were required to participate in the trial. This assumes a standard deviation (SD) = 1.95 based on a similar population in Australia. 30 The SD was estimated from the Cardiff pilot study (EudraCT no. 2004–003825–29) to be 1.7. We took the larger SD estimate in order to be conservative. The ASS can range from zero to 9. A difference of 0.5 was deemed by the research and Trial Management Group (TMG) members to be the minimum worthwhile clinically important difference to be detected. This sample size will also be sufficient to identify an increase in the number of children being ‘stepped down’ in terms of medication after 1 hour of treatment from 50–63% with 80% power at a 5% significance level. Sample size calculations were undertaken using nQuery Advisor software (Statistical Solutions, Saugus, MA, USA), version 4. 44

Randomisation and blinding

Randomisation lists were generated in Stata Statistical Software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), release 9, using block randomisation with random variable blocks length 2 and 4 and a 1 : 1 ratio of treatment allocation. Randomisation was stratified by centre. Treatment packs were identical in appearance and numbered in sequential order in the format XXXYYY (X = site code, Y = sequential number beginning with 001). Each pack contained three vials of 2.5 ml of MgSO4 or placebo, manufactured and quality controlled and QP released by St Mary's Pharmaceutical Unit, Cardiff, UK [MA (IMP) 35929] (IMP, Investigational Medicinal Product). Centres used their own stock of salbutamol and ipratropium bromide.

Data management

The data were recorded on standardised CRFs designed collaboratively by the TMG. These were returned to the MCRN CTU and the data entered on to a validated electronic study database [InferMed MACRO version 3 (InferMed, London)] by trained staff. Confirmation of patient recruitment was by receipt of a fully signed consent form. Each CRF was checked for adherence to the trial protocol and for missing and/or erroneous values. Discrepancies were queried with study sites to obtain the correct data or obtain reasons, where possible, for missing data/errors. Data entry accuracy checks were performed on 100% of primary outcome data, ‘LOS’, ‘admission to PICU/intubation’ and ‘need for IV treatment’. Checks were performed by a member of staff independent from the trial. Levels of missing data were monitored throughout and strategies developed to minimise occurrence; however; as much information as possible were collected about the reasons for missing data.

Statistical methods

Internal pilot

To ensure the appropriateness of the SD used in the sample size calculation it was planned to undertake an internal pilot after the first 30 children had been randomised and completed follow-up. This blinded internal pilot was not deemed to have any significant impact on the final analysis and no between-group comparisons were made. If the SD had been found to be smaller than that used in the sample size calculation, suggesting that fewer patients were required than initially proposed, then no action would be taken and the size of the study would remain as planned. If the SD was found to be larger than assumed, suggesting the need for more patients, then, on the advice of the Independent Data and Safety Monitoring Committee (IDSMC), the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) would have aimed to increase recruitment and consider implications for funding and existing resources.

Interim analysis

To estimate the effect of nebulised MgSO4 for the primary efficacy outcome, a single interim analysis adopting the Haybittle–Peto45 approach was planned after approximately 250 children had been randomised, with 99.9% CIs calculated for the effect estimate. This method was chosen to ensure that interim efficacy results would have to be extreme before early termination would be recommended in order to be convincing to the clinical community. The method also minimises controversy regarding interpretation of the results from estimation and hypothesis testing at the final analysis, and no inflation factor needs to be applied to the sample size using this approach.

Study statistical analysis plan

All analyses were conducted according to the statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Appendix 3), which provides a detailed and comprehensive description of the main, pre-planned analyses for the study. Analyses were performed with standard statistical software (SAS version 9.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) apart from joint modelling (undertaken as a sensitivity analysis for examining the effect of missing primary outcome data) that was undertaken using the R language, version 2.15.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) (http://cran.r-project.org/). The software for joint modelling (JoineR library; 2.13.0 version, the R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austina) has been validated through simulations in variety of settings representing different correlation patterns between longitudinal and survival processes. The main features of the SAP are summarised below.

The CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) flow diagram is used to summarise representativeness of the study sample and patient throughput in the trial. It was planned to collect screening data, and hence efforts were regularly made to encourage the return of screening logs.

Baseline characteristics are presented by treatment group and overall, with continuous variables summarised in terms of means (SD) or medians [interquartile range (IQR)] depending on the degree of skewness, and categorical variables presented in terms of numbers (%) per category. The intention-to-treat (ITT) principle is used with a two sided p-value of 0.05 (5% level) for statistical significance and 95% CIs for the relative treatment effect reported throughout.

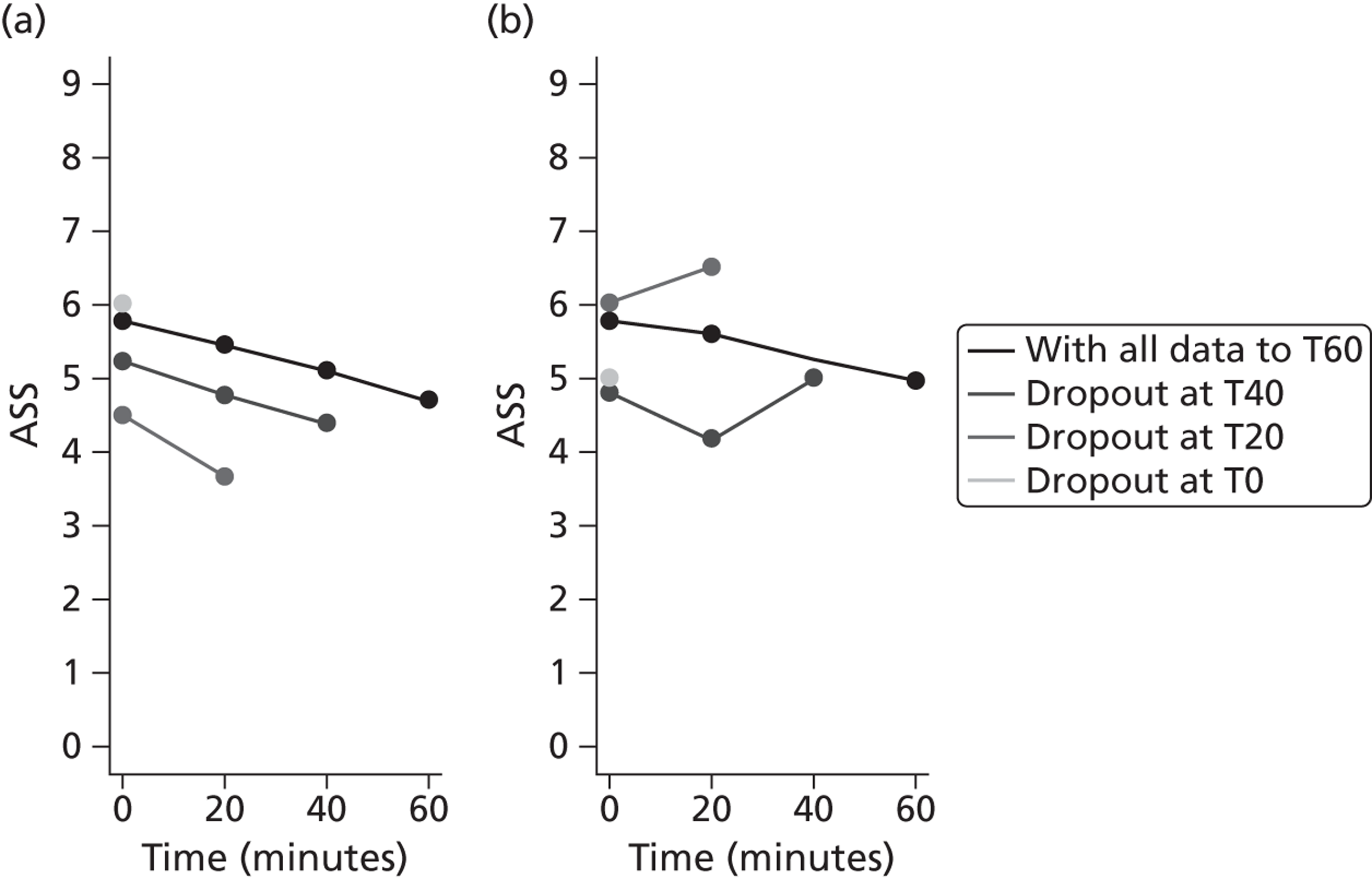

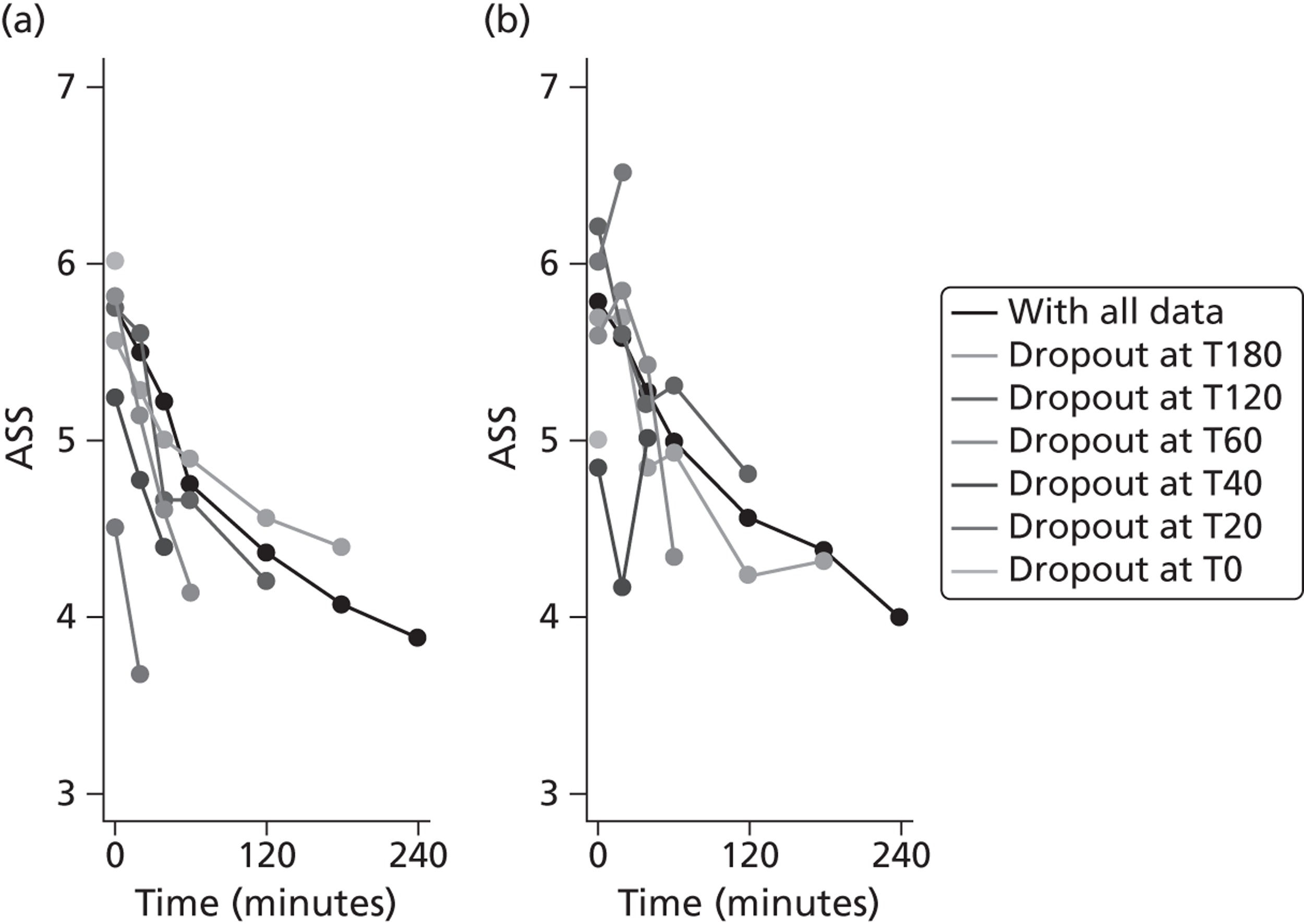

The primary outcome is presented with means and SDs at T60 for each treatment group. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) is used to present results adjusted for baseline ASS value. The reasons for missing primary outcome data are provided with the results of the sensitivity analyses which are used to investigate the robustness of the primary outcome results to missing data (see Appendix 5). The chief investigator classified the information on the reason for missing ASS data and was blind to the treatment group allocation. Key baseline characteristics for those with observed ASS at T60 are compared between treatment groups, and differences in key baseline characteristics between patients with observed and missing ASS at T60 are also investigated (see Appendix 5) to assess whether missingness affects the randomisation balance and plausibility of the missing completely at random (MCAR) assumption. Sensitivity analysis was also performed to examine a centre effect (see Appendix 6).

All continuous secondary outcomes that were non-normally distributed are summarised in terms of medians and IQR for each treatment group, and compared using the Mann–Whitney U-test. When a secondary outcome is categorical, the two treatment groups are compared using a chi-squared test.

The chief investigator classified information on the reason for PICU admission/intubation in terms of whether it was likely to be related to trial treatment, queries regarding whether children had stepped down at 1 hour, and AEs and SAEs, blind to treatment group allocation. A statistical test comparing the percentage of children suffering an AE in each arm has not been performed for two reasons: (1) this analysis would assume the AEs are of equal importance; and (2) no hypotheses on AEs were set out upfront before the blind had been broken.

Protocol amendments

Protocol amendments are summarised in Appendix 4. In summary, the main amendments following those made to obtain Multicentre Research Ethics Committee (MREC) and Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approval were to include additional principal investigators and participating centres. No major changes to the study procedures were made during the trial.

Health economics analysis plan

The economic evaluation aimed to assess the cost-effectiveness of nebulised MgSO4 in the management of severe acute asthma in children based on the data collected within the MAGNETIC trial.

Treating children with asthma is likely to have at least two economic research aspects, which both relate to clinical effectiveness. The first is the short-term side effects and relief from primary symptoms and direct consequences of the condition on costs and health-related QoL. The second is the medium- and long-term effects in terms of reduced disability and any medium- and long-term adverse reactions from treatment. This study focused on the short- and medium-term costs and consequences of nebulised MgSO4 in the management of severe acute asthma in children. The study protocol had allowed for extrapolation of costs and consequences over a longer time horizon if the results had demonstrated a difference in medium-term outcomes. This longer-term modelling would have been based on the natural history of the disease and additional evidence from the literature in the event that the trial yielded significant benefits for MgSO4.

The primary analysis (base case) took the perspective of the NHS and Personal Social Services46 and, consequently, the costs incurred by children's families or education services were excluded from the base-case analysis. A sensitivity analysis took a wider societal perspective that included broader economic costs, including costs incurred by children's families at the time of treatment and during the 4 weeks thereafter.

Two main analyses of incremental cost-effectiveness were conducted. The first analysis comprised a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) calculating the incremental cost per unit change in ASS after 60 minutes of treatment, whereas the second comprised a cost–utility analysis (CUA) calculating the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained through treatment.

Collection of resource-use data

Data were collected about all significant health service and broader societal resource inputs over the 1-month time horizon of the study (i.e. over the period between randomisation and 1 month post randomisation). These data were obtained through two principal means. First, the study CRFs captured all resource use related to the child's primary hospital attendance(s) including diagnosis and treatment as well as transfers between wards and hospitals. Specifically, individualised resource use was estimated for the resources associated with the primary ED/CAU attendance, admissions to inpatient wards [classified as PICU, high-dependency unit (HDU), general paediatric ward (GM)], duration of intubation during the hospital admission(s), duration of mechanical ventilation during the hospital admission(s), surgical procedures performed during the hospital admission(s), tests or investigations performed during the hospital admission(s), additional bronchodilator medication, concomitant medications, and resources associated with AEs. Duration of resource use for significant resource items during the ED/CAU attendance and hospital admission(s) was recorded. Second, economic questionnaires were posted to the main parent of each child approximately 1 month post randomisation. The questionnaires recorded the children's resource use during the period between completion of ED/CUA or hospital discharge and 1 month post randomisation (see Appendix 9). The data collected in the postal questionnaires recorded direct non-medical costs borne by parents and carers as a result of attending hospital with the child during their ED/CAU and/or hospital admission(s). These direct non-medical costs covered travel costs, child care costs, expenses incurred while in hospital, and other direct non-medical expenses. The parent-completed questionnaires also recorded the children's use of prescribed inhalers, other prescribed medicines, privately purchased over-the-counter medications, and non-hospital community health and social services, as well as their hospital outpatient attendances and hospital re-admissions (by type of ward). Finally, the parent-completed questionnaires recorded direct non-medical costs borne by parents and carers, as well as their self-reported lost earnings, as a result of the child's asthma during the period between completion of ED/CAU or hospital discharge and 1 month post randomisation. The 1-month economic questionnaire had been piloted among members of the lay panels of the MCRN to ascertain its acceptability, comprehension and reliability, and reminder letters were sent to parents to increase the response and completion rates. All resource-use data were entered directly from the postal questionnaires into the MACRO trial database, with in-built safeguards against inconsistent entries, and then verified by dual coding.

Valuation of resource-use cost data

Unit costs for resources used by children who participated in the study were obtained from a variety of primary and secondary sources, with the majority obtained from secondary sources. All unit costs used followed recent guidelines on costing health and social care services as part of an economic evaluation. 46,47 Where necessary, secondary information was obtained from ad hoc studies reported in the literature. Unit costs of hospital and community health-care costs were largely derived from national sources and took account of the cost of the health professionals' qualifications. 48 Some costs were valued using the NHS Reference Costs (2009–10), a catalogue of costs compiled by the Department of Health in England. 49 Drug costs were obtained from the British National Formulary (BNF). 50 Costs for individual preparations were used as well as costs for chemical entities, i.e. drugs were grouped by chemical entity and unit costs for these chemical entities were calculated (Prescription Cost Analysis 2010). 49 The values attached to direct non-medical costs borne by parents and carers and their lost earnings were those provided by the parents completing the 1-month economic questionnaire. Lost earnings were not valued if annual or compassionate leave was taken as a result of the child's health state. All costs were expressed in pounds sterling and valued at 2009–10 prices. None of the costs were inflated or deflated for use in the economic evaluation. For the base-case analyses, unit costs were combined with resource volumes to obtain a net cost per child covering all categories of hospital and community health and social services. In one of several sensitivity analyses, these costs were supplemented with the range of costs incurred by family members and carers in the course of treatment and follow-up (societal perspective adopted). Further details on the methods used to value resource use are provided in Appendix 2.

Calculation of utilities and quality-adjusted life-years

Parents of children aged ≥ 5 years were asked to describe their children's QoL at 1 month after participation in the MAGNETIC trial using the proxy version of the EuroQol EQ-5D instrument. 51 The EQ-5D is the generic, multiattribute, preference-based measure preferred by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for broader cost-effectiveness comparative purposes. 46 The EQ-5D consists of two principal measurement components. The first is a descriptive system, which defines health-related QoL in terms of five dimensions: ‘mobility’, ‘self care’, ‘usual activities’, ‘pain/discomfort’ and ‘anxiety/depression’. Responses in each dimension are divided into three ordinal levels coded: (1) no problems; (2) some or moderate problems; and (3) severe or extreme problems. A total of 243 health states are generated by the EQ-5D descriptive system. For the purposes of this study, the York A1 tariff was applied to each set of responses to the descriptive system to generate an EQ-5D utility score at 1 month for each child. 52 The York A1 tariff set was derived from a survey of the adult UK population (n = 3337), which used the time trade-off valuation method to estimate utility scores for a subset of 45 EQ-5D health states, with the remainder of the EQ-5D health states subsequently valued through the estimation of a multivariate model. 52 Resulting utility scores range from scores – 0.59 to 1.0, with ‘0’ representing death and ‘1’ representing full health. Utilities values of < 0 indicate health states worse than death. The second measurement component of the EQ-5D, the vertical visual analogue scale ranging from 100 (best imaginable health state) to 0 (worst imaginable health state), was not included in MAGNETIC.

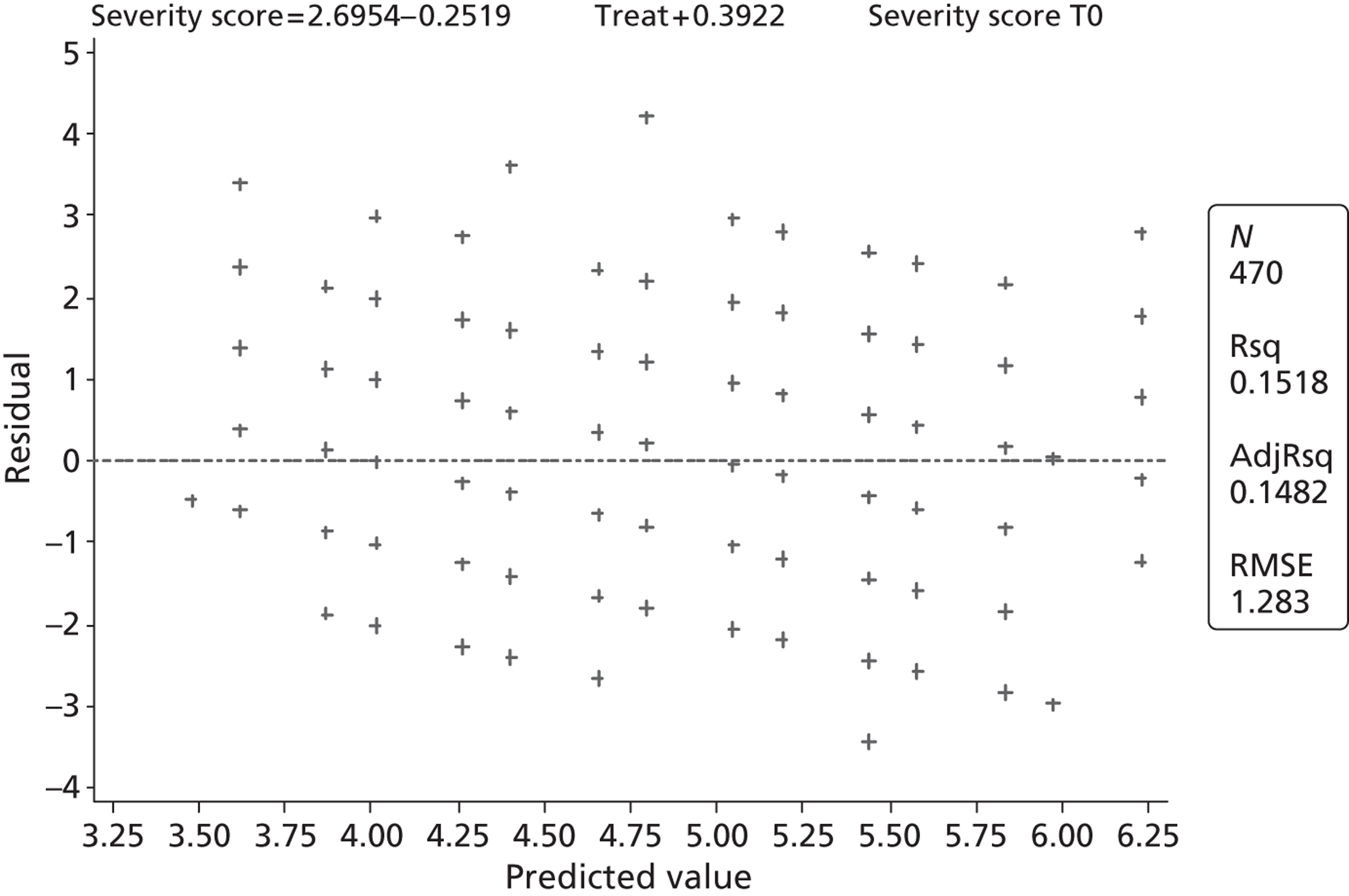

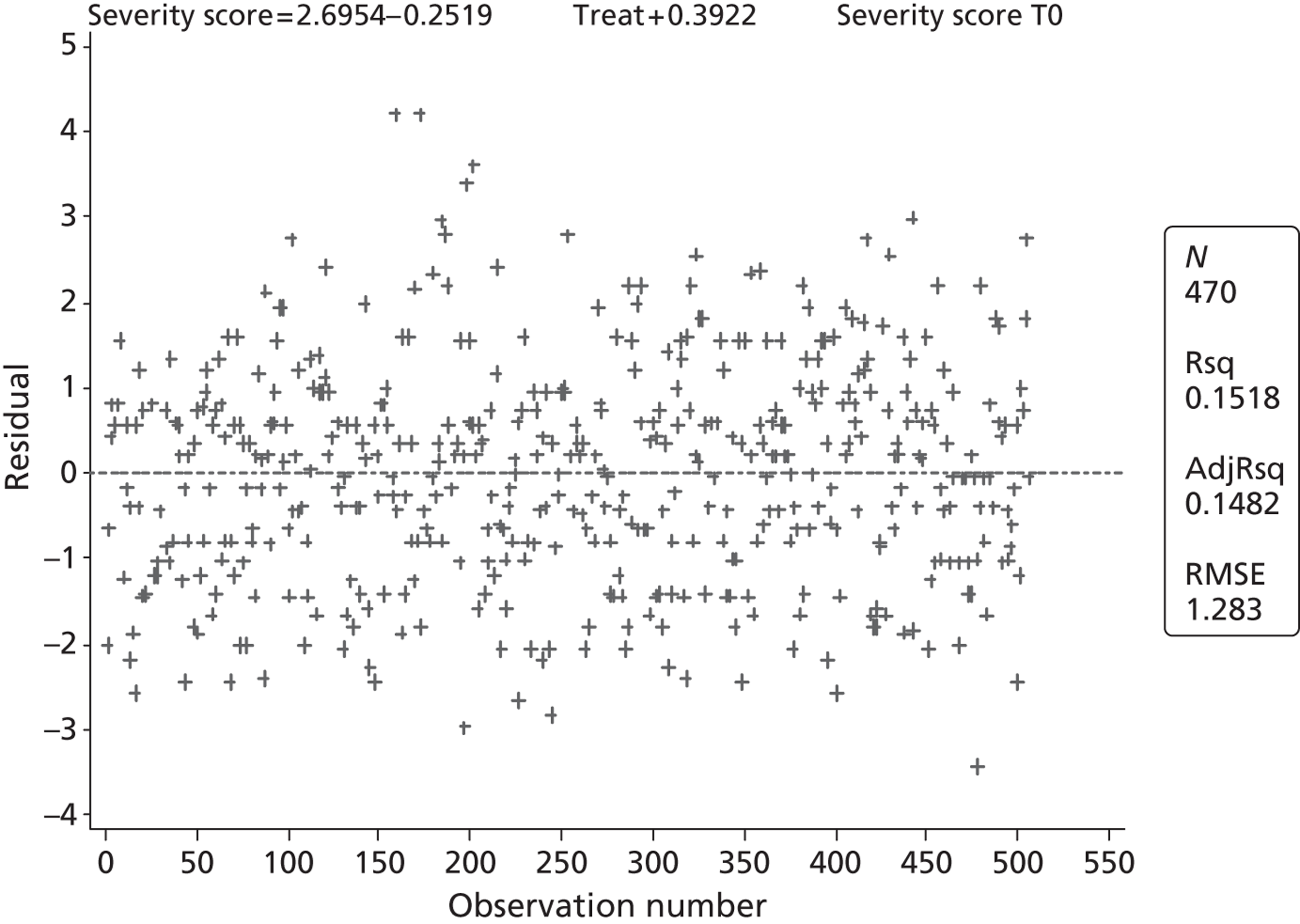

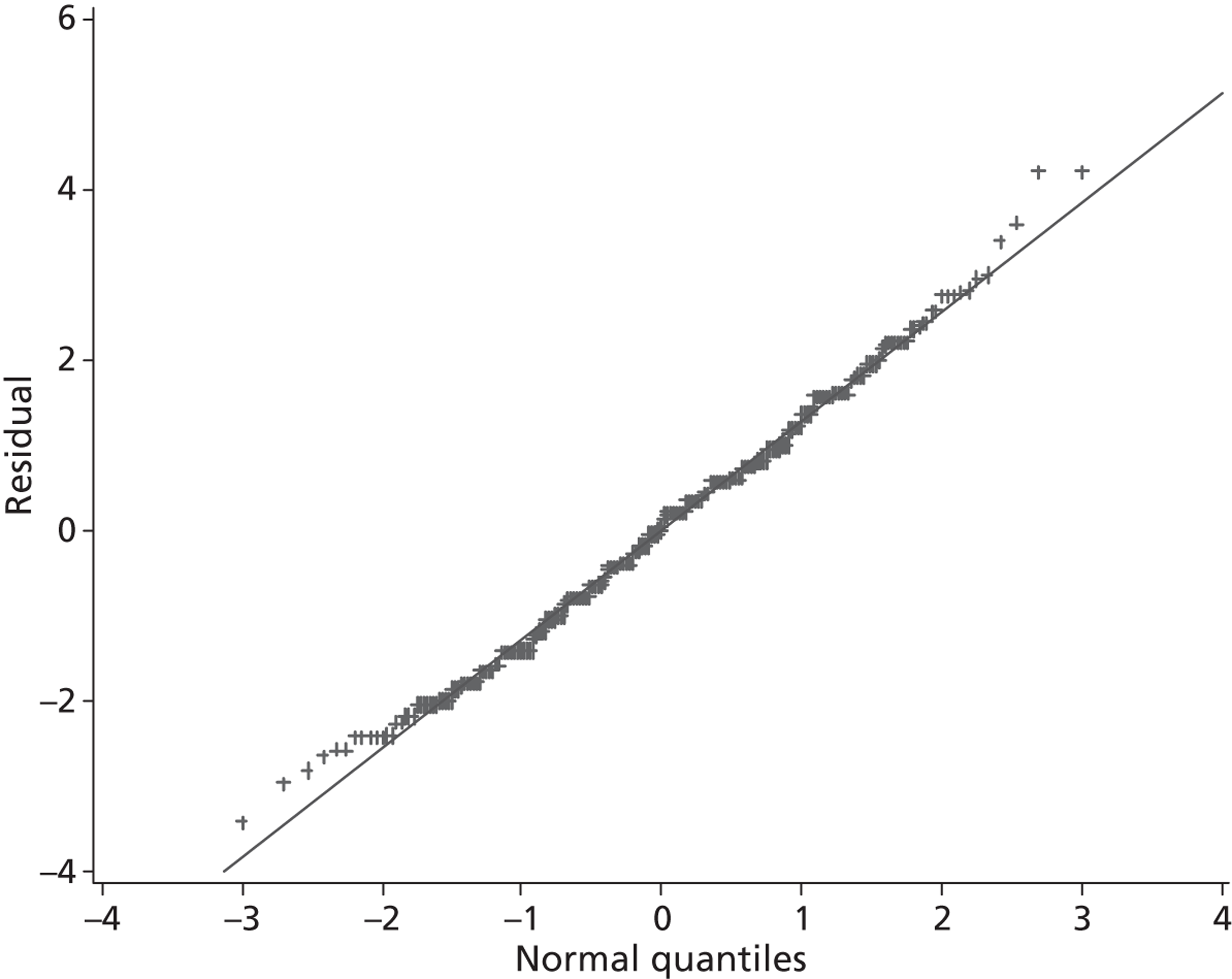

There is limited evidence of the psychometric properties of the EQ-5D in young children. 53 Consequently, analyses were conducted to ‘map’ or ‘cross-walk’ responses to the PedsQL™ Asthma Module on to EQ-5D utility scores. These mapping models were developed on the basis of data collected for 5- to 16-year-old children for whom both EQ-5D and PedsQL™ responses were available; the resulting mapping algorithms were used to estimate EQ-5D utility scores for 2- to 4-year-old children in MAGNETIC for whom the validated toddler module of the PedsQL™ Asthma Scales had been completed. A number of models were used to develop these mapping algorithms in keeping with current methodological guidance for mapping between non-preference-based and preference-based measures of health status. 54,55

Model 1: ordinary least squares using PedsQL™ total score

It was assumed that there was a linear relationship between the PedsQL™ total score and the EQ-5D utility score with a high score on the PedsQL™ correlated with a high score on the EQ-5D measure and vice versa. An ordinary least squares (OLS) model was used to examine the existence of such a relationship between the PedsQL™ total score and the EQ-5D utility score. The dependent variable, the EQ-5D utility score, was measured on its natural scale (i.e. – 0.594 to 1). The PedsQL™ total score was measured on a (0–100) scale. Covariates for age and gender were also included in the model.

Model 2: ordinary least squares using the PedsQL™ subscales

A simple model that includes the PedsQL™ total score may not be able to explain the variation between PedsQL™ and EQ-5D responses, as the relationship between the two may be more complex. The PedsQL™ total score can be broken down into four subscales: asthma symptoms, treatment problems, worry and communication; using information from these subscales may result in a model that provides a better fit. The simple OLS model can therefore be improved by using the four subscales of the PedsQL™ as independent variables in place of the PedsQL™ total score. As in model 1, the dependent variable (EQ-5D utility score) was measured on its natural scale and the PedsQL™ subscale scores were each measured on a (0–100) scale. Covariates for age and gender were also included in the model. We explored whether multicollinearity was present in our mapping model 2, which included PedsQL™ subscale scores and age and gender as explanatory variables. The mean variance inflation factor in this model was estimated at 1.72, well below the threshold value of 10 that is normally indicative of multicollinearity. Moreover, there is a now a wealth of evidence in the published literature confirming the four-factor conceptually derived measurement model for the PedsQL™ scales (www.pedsql.org).

Model 3: ordinary least squares using the PedsQL™ subscales with squared terms and interactions

A multiple OLS regression model was used to examine the relationship between the EQ-5D utility score and the four PedsQL™ subscale scores, squared subscale scores and interaction terms derived using the product of subscale scores. The dependent variable (EQ-5D utility score) was measured on its natural scale and the PedsQL™ subscale scores were measured on a (0–100) scale. The model was defined as:

where i = 1, 2, . . . , n represents individual respondents, j = 1, 2, . . . , and m represents the four different subscales. The dependent variable, y, represents the EQ-5D utility score, x represents the vector of PedsQL™ subscales, r represents the vector of squared terms, z represents the vector of interaction terms and εij represents the error term. This is an additive model that imposes no restrictions on the relationship between dimensions. The squared terms are designed to pick up non-linearities in the relationship between dimension scores and the EQ-5D utility score. The interaction terms are considered important as the dimensions are not additive. Covariates for age and gender were also included in this model.

The best-fitting model of the three was identified on the basis of the highest explanatory power in terms of the lowest Akaike information criterion (AIC) statistic. This model was used to make the EQ-5D predictions for the 2- to 4-year-old children in MAGNETIC. The accuracy of the predictions were tested by carrying out a within sample validation and the root-mean-squared error (RMSE) (a recommended measure of predictive ability) was calculated for each model. 54

Baseline utility data were not collected because trial participants were enrolled in ED/CUA with minimal data collection and concomitant concerns surrounding family intrusions at such a sensitive time. To estimate QALYs, it was necessary to impute baseline utility data based on secondary evidence. A physician panel made up of two respiratory nurses and a consultant mapped the ASS scores on to EQ-5D health states from which baseline utility scores were estimated. In the base-case analysis, ASS scores of 1–3 were mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 11111; ASS scores of 4–6 were mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 22222; and ASS scores of 7–9 were mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 33333. These mappings were varied as part of the sensitivity analyses (see Chapter 4 for details).

The number of QALYs accrued over the 1-month follow-up period was calculated using linear interpolation between the baseline and follow-up utility score. It is likely that children return to the EQ-5D health state reported at 1 month earlier than that time; however, it is acknowledged that this depends in part on the number of asthma attacks that have occurred since treatment. Consequently, the base-case analysis assumed that the EQ-5D health state had been achieved immediately following hospital discharge, while a sensitivity analysis applied linear interpolation of the utility scores over the follow-up period. In order to account for potential baseline imbalances between the trial groups, adjustments were made to the QALY estimates by simply subtracting each child's baseline utility value from their on-treatment utilities before calculating QALYs. This method effectively indexes the utilities relative to baseline.

Missing data

Multiple imputation was used to impute missing data and avoid biases associated with complete case analysis. 56 Missing data was a particular issue for costs and utility scores collected at the 1-month follow-up. The MICE (Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations) algorithm within R statistical software version 2.13 (R Development Core Team) was used to impute missing data for the following variables: total health and social care costs based on data combined from the CRFs and from parental questionnaires; total societal costs based on data combined from the CRFs and from parental questionnaires; QALY estimates based on linear interpolation, assuming that the health gain was achieved immediately following hospital discharge; and QALY estimates based on linear interpolation assuming that the health gain was achieved linearly over the follow-up period. Age, sex and treatment allocation were included as explanatory variables in the imputation models. Costs up to completion of ED/CUA attendance or hospital discharge were included as an additional explanatory variable in the models that imputed values for total health and social care costs and total societal costs over the 1-month time horizon. The ‘match’ option within ‘ice’ was used for utilities and costs as this algorithm is less dependent on assumptions of normality than default options. Five imputed data sets were generated.

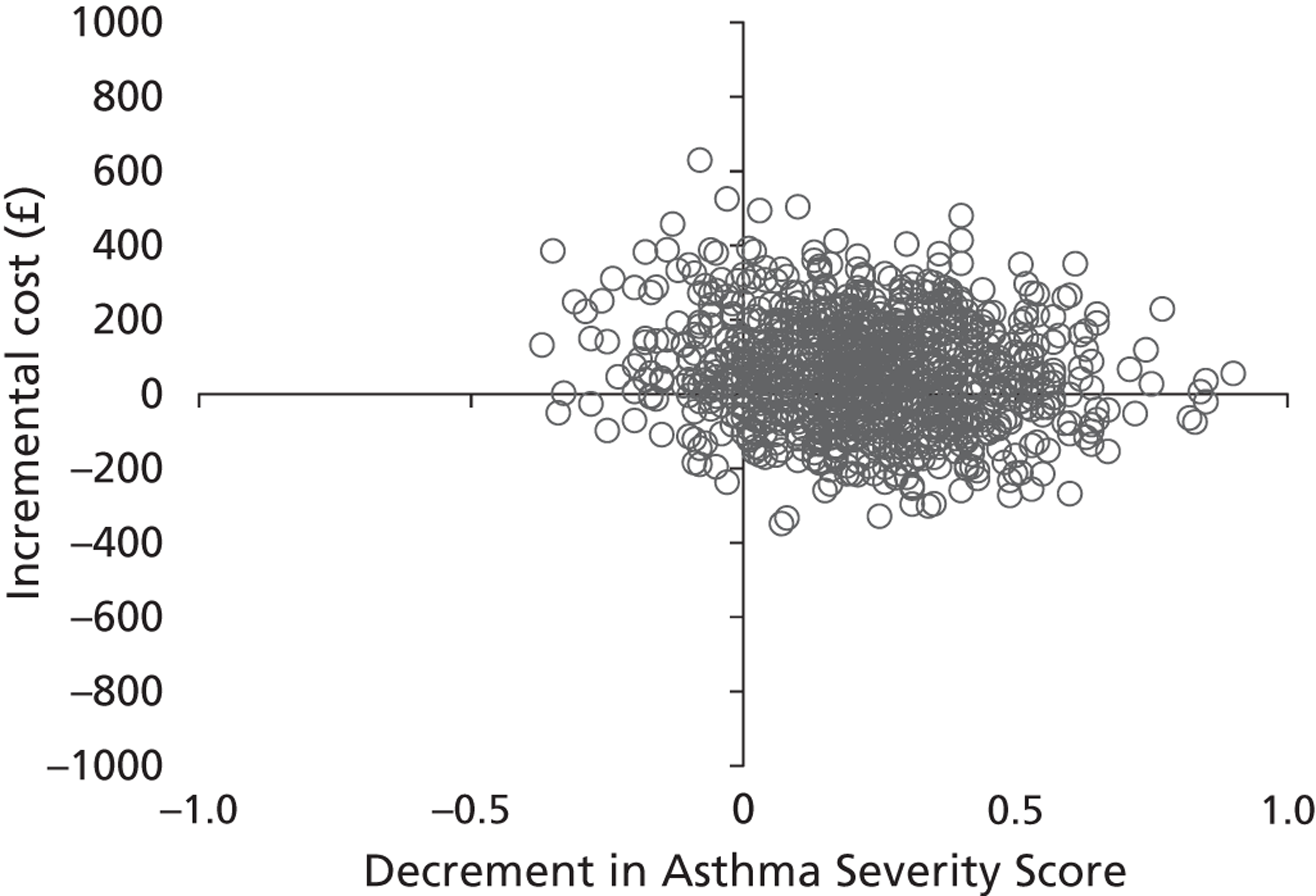

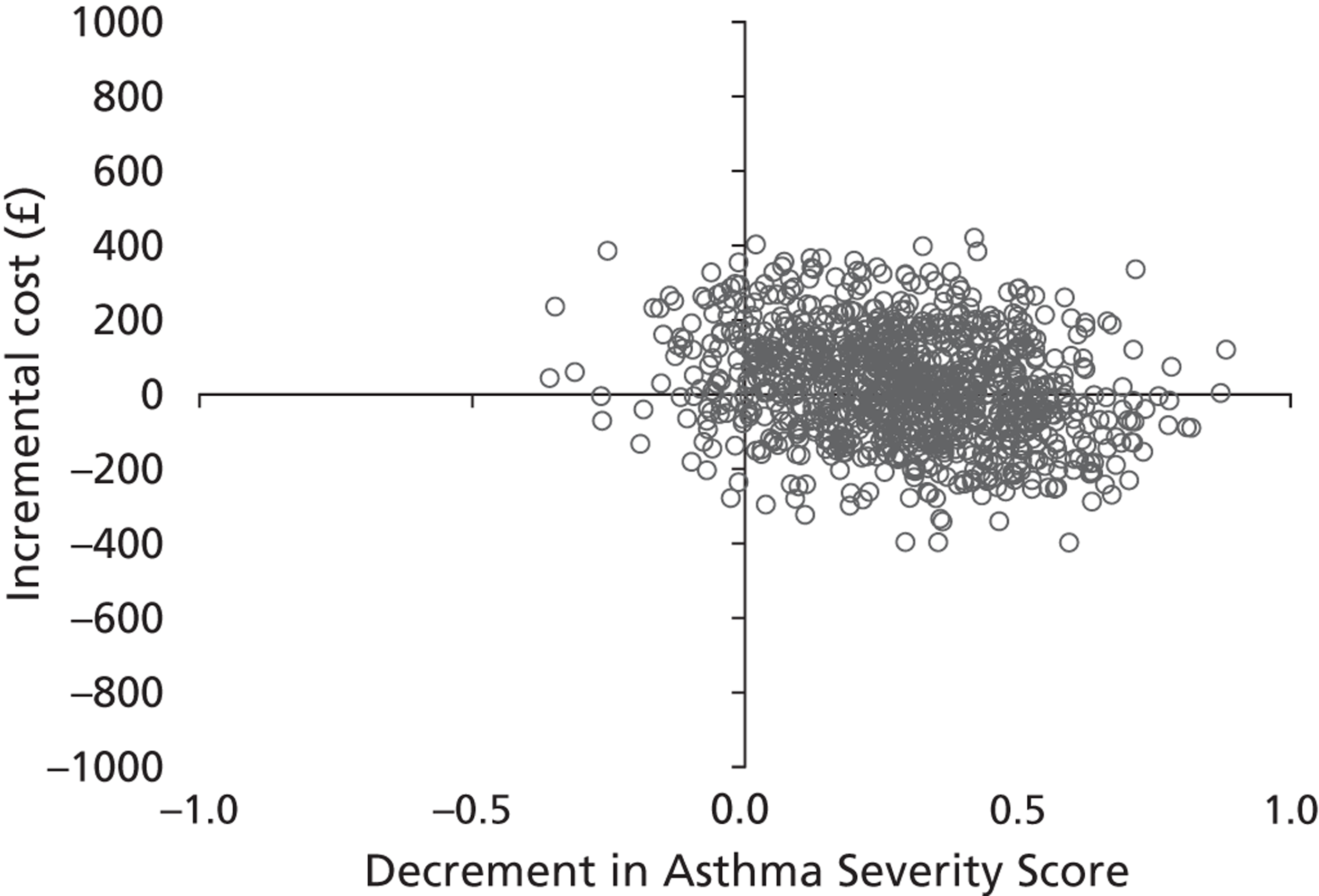

Cost-effectiveness analytic models

As described above, the primary clinical outcome measure for the study was ASS at T60. Assessment severity score data were collected both before (as part of screening) and during the trial (prior to randomisation and at T20, T40, T60 and when necessary thereafter). The assessment severity score at T60 was the primary clinical outcome pre-specified in the protocol and this was also used in the CEA. In the CEA, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the difference in average costs (ΔC) divided by the difference in average effects (ΔE) and expressed as the incremental cost per unit change in ASS at T60. A separate CUA was performed, the results of which were expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained. The time horizon for the measurement and valuation of costs and health outcomes within the CEA covered the period between randomisation and discharge from the ED/CUA or the hospital where the child was admitted to an inpatient ward immediately following ED/CUA attendance. The time horizon for the measurement and valuation of costs and health outcomes within the CUA covered the period between randomisation and 1 month post randomisation. No discounting of costs or benefits was applied as the time horizon was < 12 months.

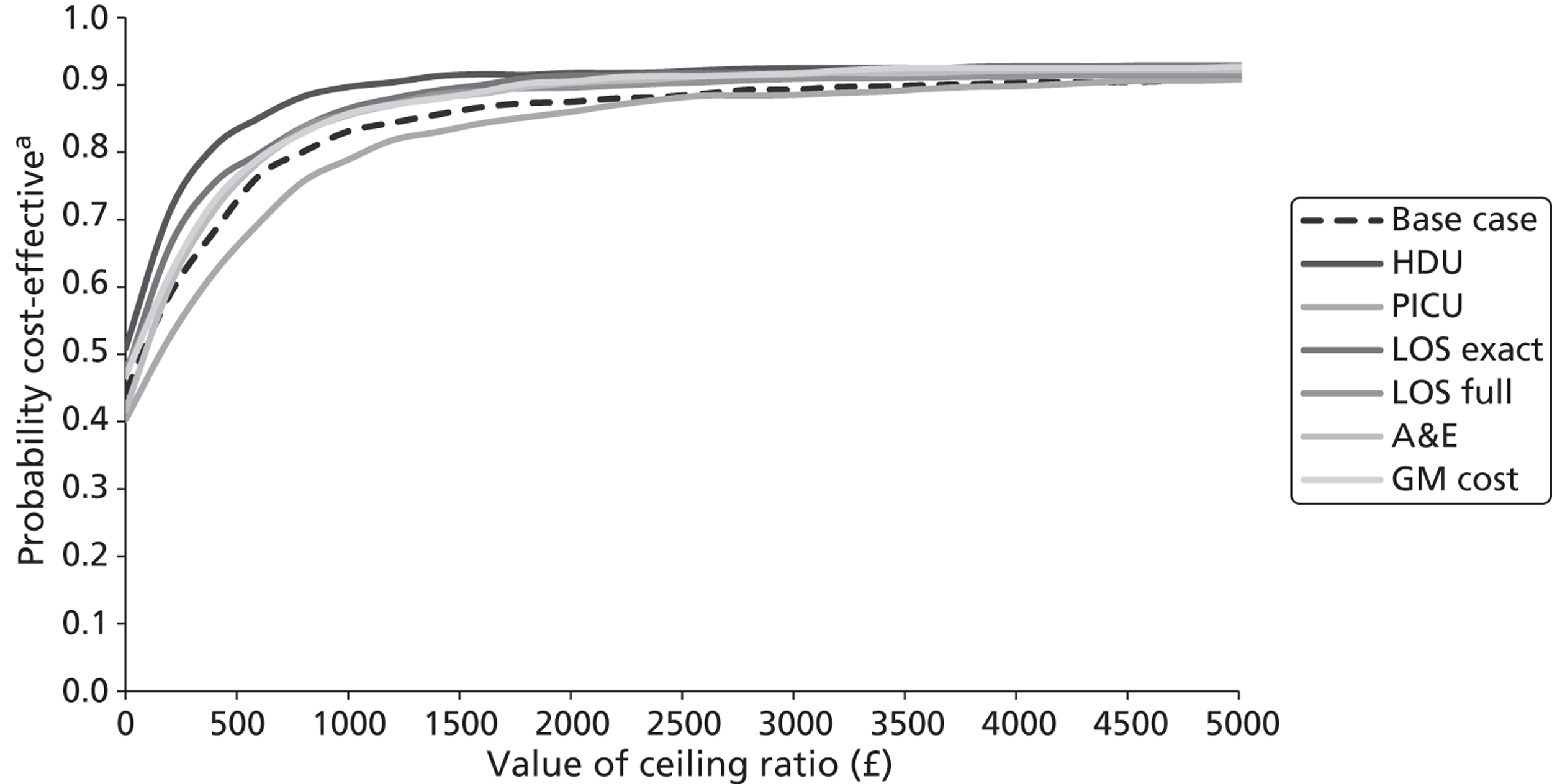

Independent-sample t-tests were used to test for differences in resource use, costs, utility scores and QALYs between treatment groups. All statistical tests were two-tailed. Multiple regression was used to estimate the differences in total cost between the magnesium and placebo groups and to adjust for potential confounders, including the covariates incorporated into the main clinical analyses. For the generalised linear model (GLM) on costs, a gamma distribution and identity link function was selected in preference to alternative distributional forms and link functions on the basis of its low AIC statistic.

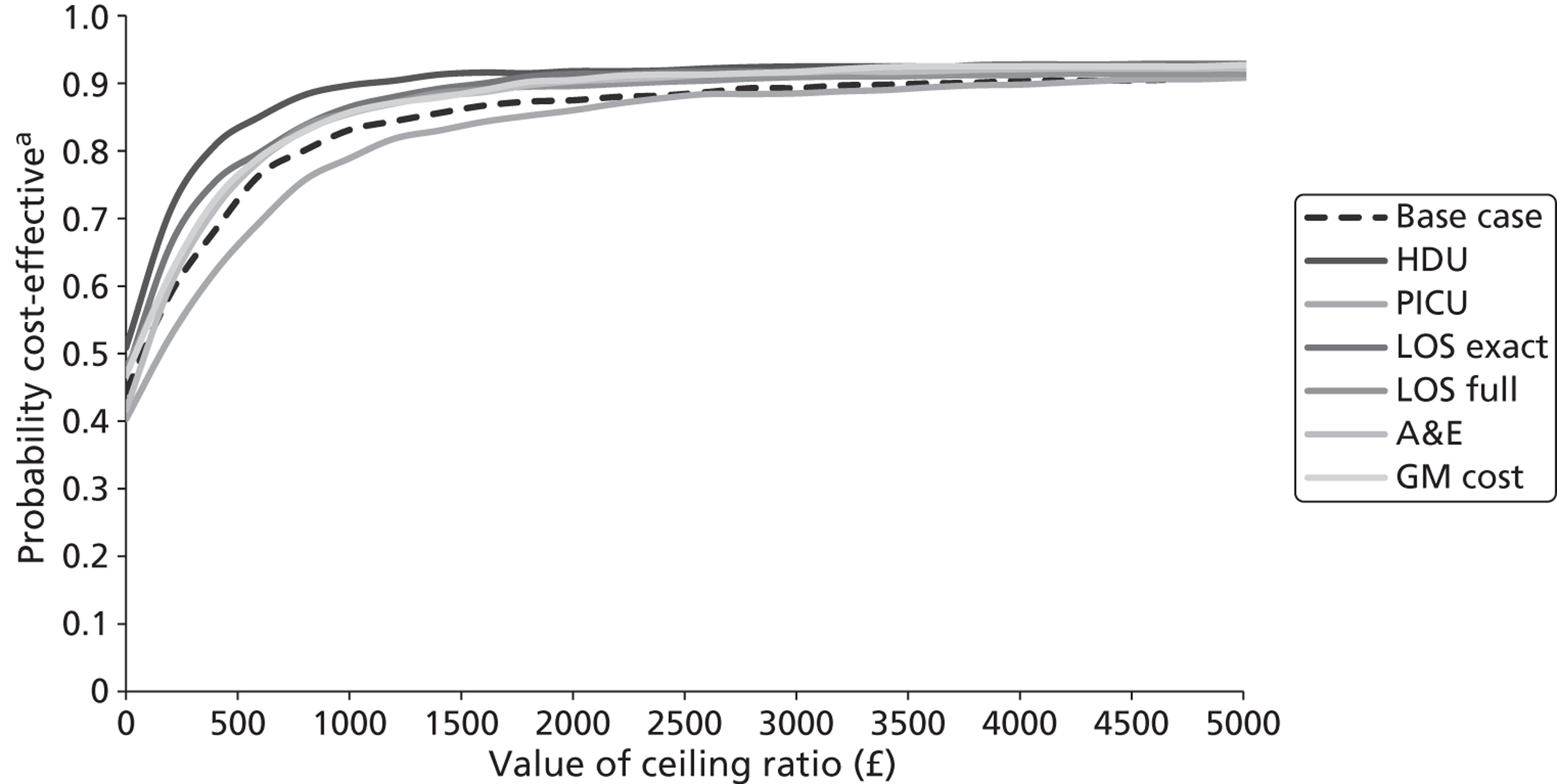

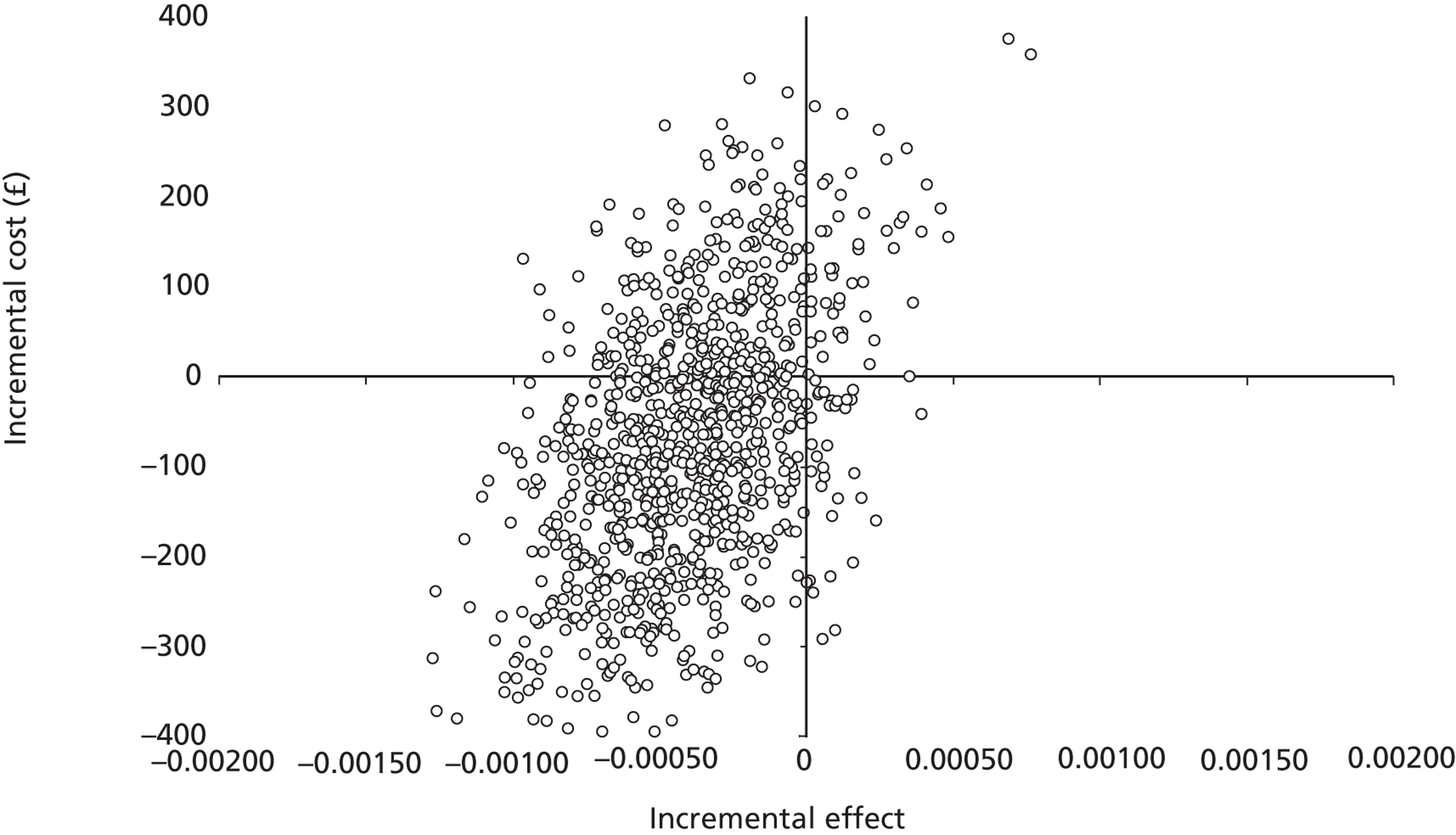

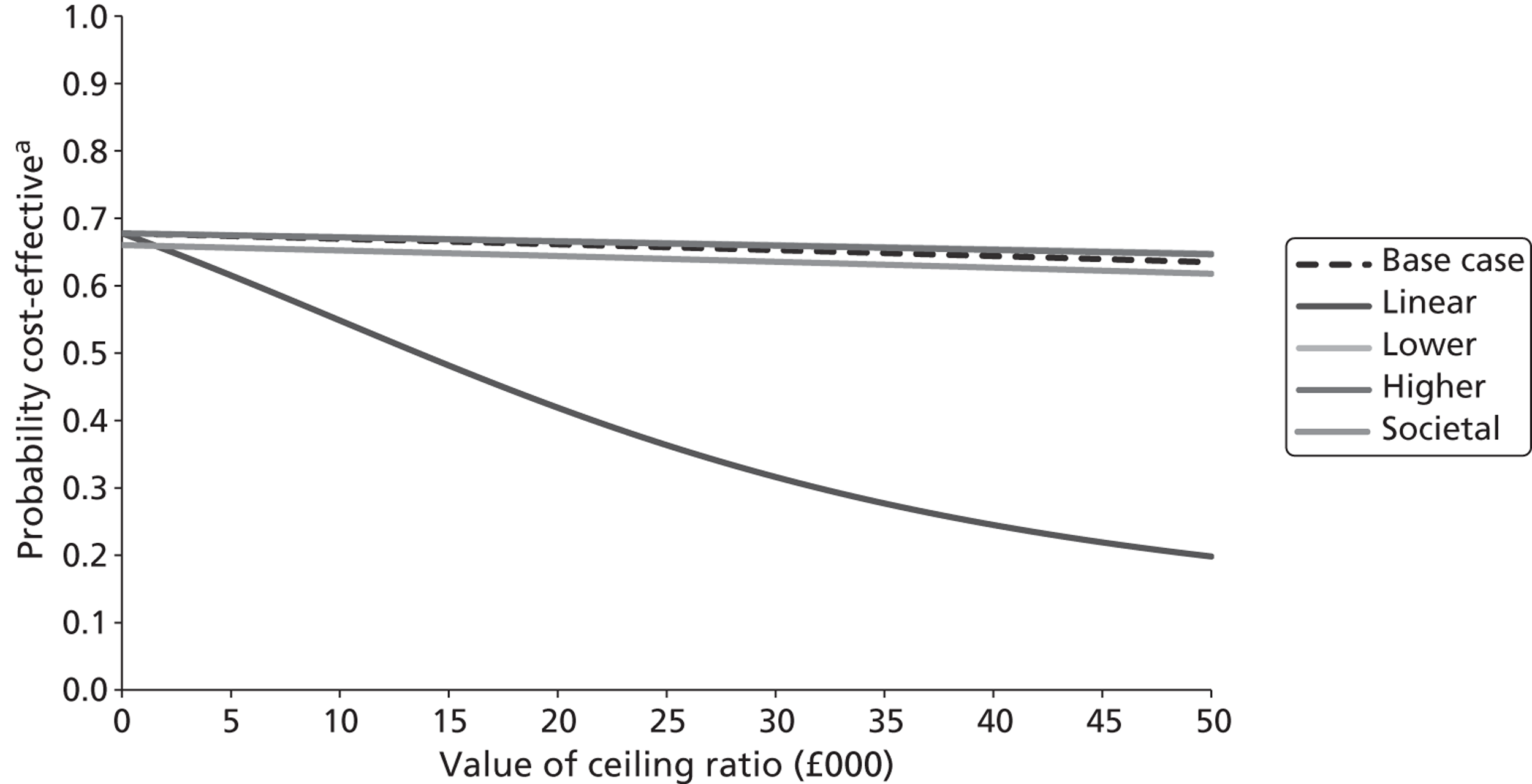

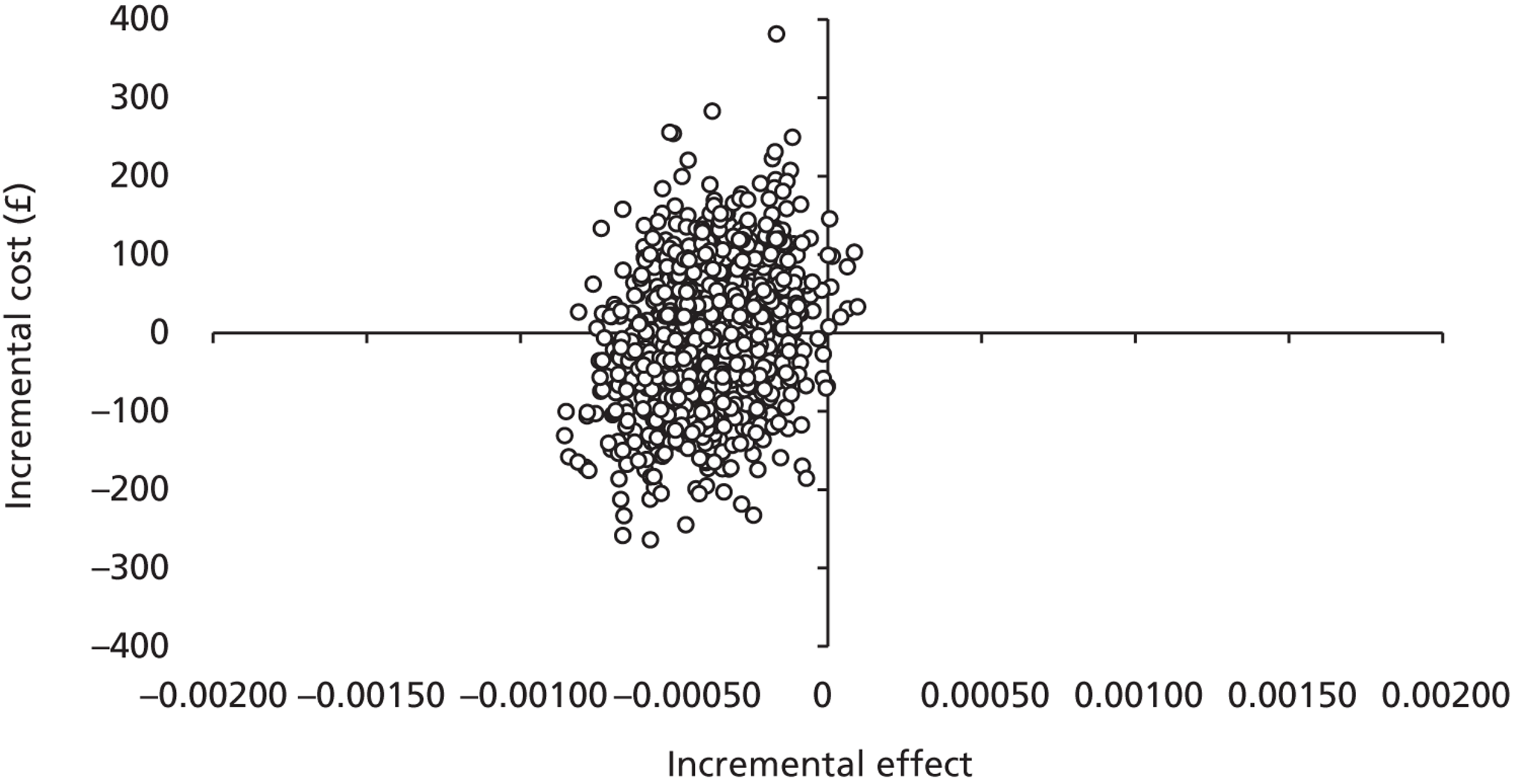

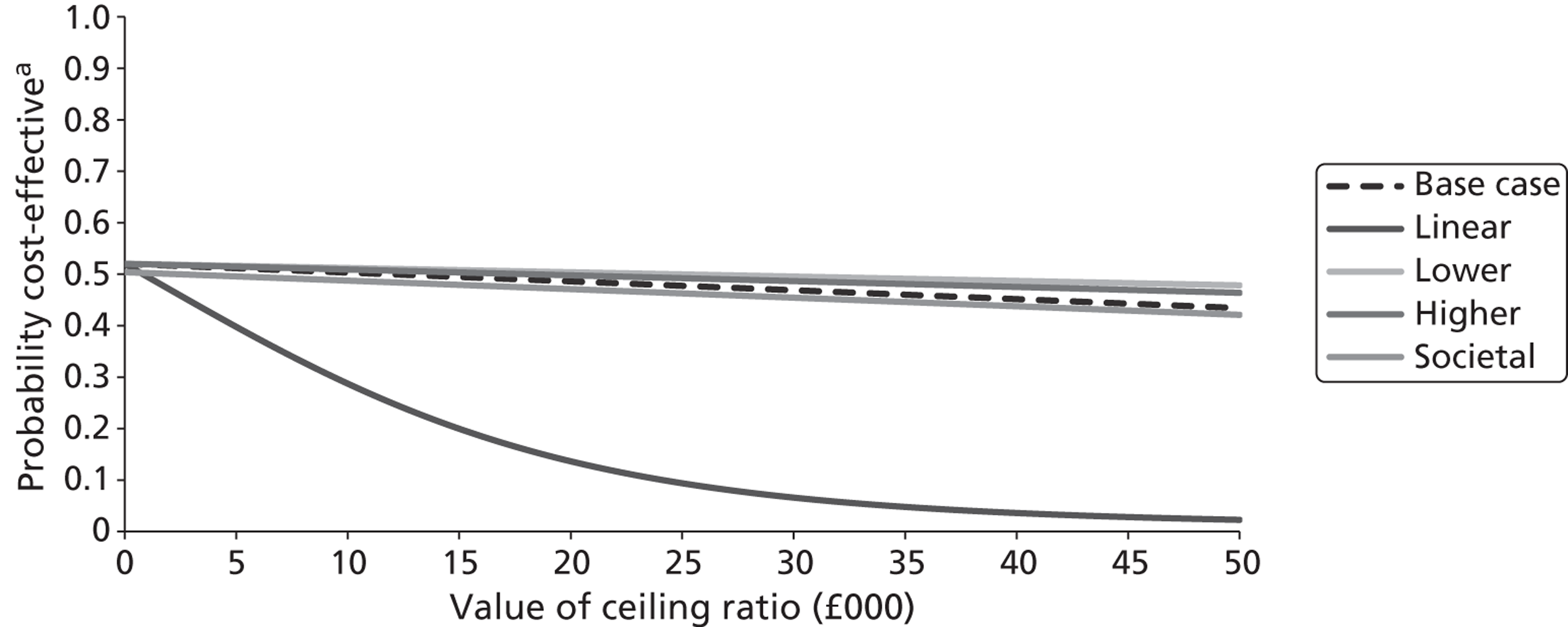

The five imputed data sets generated through multiple imputation were bootstrapped separately in Microsoft Excel 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and the results were subsequently combined56 to calculate standard errors (SEs) around mean costs and effects that incorporate uncertainty around imputed values as well as sampling variation. SEs were used to calculate 95% CIs around total and incremental costs, incremental effects and QALYs based on Student's t-distribution. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) showing the probability that magnesium is cost-effective relative to placebo at a range of ceiling ratios were generated, based on the proportion of bootstrap replicates (across all five imputed data sets) with positive incremental net benefits. 57,58 For the purposes of the CEA, incremental net benefit was defined as the unit reduction in ASS multiplied by the cost-effectiveness threshold for this clinical outcome minus the incremental cost, where the ceiling ratio (or cost-effectiveness threshold) represents the maximum society is willing or able to pay for each unit reduction in ASS. For the purposes of the CUA, incremental net benefit was defined as the incremental QALY gain multiplied by the ceiling ratio minus the incremental cost, where the ceiling ratio (or threshold) represents the maximum that society is willing or able to pay for each additional QALY. Unless otherwise stated, all statements about cost-effectiveness are based on a £20,000 per QALY gained threshold. The probability that magnesium is less costly or more effective than no treatment was based on the proportion of bootstrap replicates that had negative incremental costs or positive incremental health benefits (unit reduction in ASS for the purposes of the CEA: QALYs for the purposes of the CUA), respectively.

Several sensitivity analyses were undertaken to assess the impact of areas of uncertainty surrounding components of the economic evaluation. These included the following for purposes of the CEA: (1) performing a complete case (rather than multiple imputation) analysis, which limited the CEA to the children for whom complete information on both costs and ASS were available; (2) varying the per diem costs for inpatient stays in paediatric wards (PICU, HDU, GM); (3) assuming that part of a day spent by a child in an inpatient ward equated to a proportional period for costing purposes and that, consequently, the vacated inpatient bed would be filled immediately; (4) assuming that part of a day spent by a child in an inpatient ward equated to a full 24-hour period for costing purposes and that, consequently, the inpatient bed would not be filled until the end of that 24-hour period; and (5) varying the average cost of an ED/CUA attendance. The sensitivity analyses included the following for purposes of the CUA: (1) performing a complete case (rather than multiple imputation) analysis, which limited the CUA to the children for whom complete information on both costs and QALYs was available; (2) assuming linear interpolation of health utilities over entire follow-up period; (3) assuming baseline ASS scores mapped on to EQ-5D health states with lower utility scores than in the baseline analysis (ASS scores of 1–3 mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 11222; ASS scores of 4–6 mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 22333; and ASS scores of 7–9 were mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 33333); (4) assuming baseline ASS mapped on to EQ-5D health states with higher utility scores than in the baseline analysis (ASS of 1–3 mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 11111; ASS of 4–6 mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 22111; and ASS of 7–9 were mapped on to an EQ-5D health state of 33222); and (5) adopting a societal perspective rather than a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow and recruitment

Five hundred and eight children were randomised from 30 centres throughout the UK (one centre in Wales, two in Scotland, two in Northern Ireland and 25 in England).

The first child was recruited on 14 December 2008 and the last child was randomised on 21 March 2011. Table 3 shows all of the 30 recruiting centres, the date the site was initiated, the target recruitment, the number of participants randomised, the date of the first randomisation and the date of the last randomisation. All 30 centres randomised at least one participant.

Five further centres were at different stages of opening for recruitment at the end of the study (Royal Alexander Children's Hospital, Brighton; Fairfield Hospital, Bury; Leighton Hospital, Crewe; Whiston Hospital, Prescot, Liverpool; Morriston Hospital, Swansea; Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Belfast) but did not randomise any children.

Screening data

Sites were requested to prospectively record each potentially eligible child on a screening log and return this to the Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) on a monthly basis. The log recorded the time and date of presentation, whether or not the child was screened/eligible, and whether or not he/she was then randomised. Reasons for screen failures/non-randomisation were also requested.

Unfortunately, few centres complied, with the majority citing that collection of this information prospectively was too onerous for staff. In instances in which the logs were received, they were often sent sporadically and were poorly completed, not recording children who were missed for trial eligibility assessment.

Efforts were regularly made to encourage return [supported on one occasion by the MRCN local research networks (LRNs)], as screening information was the primary way to objectively assess barriers to recruitment in underperforming sites. Another option given was to record the information retrospectively by review of departmental records; however, again the majority of centres stated they did not have the resources to do this on a regular basis.

Recruitment rates

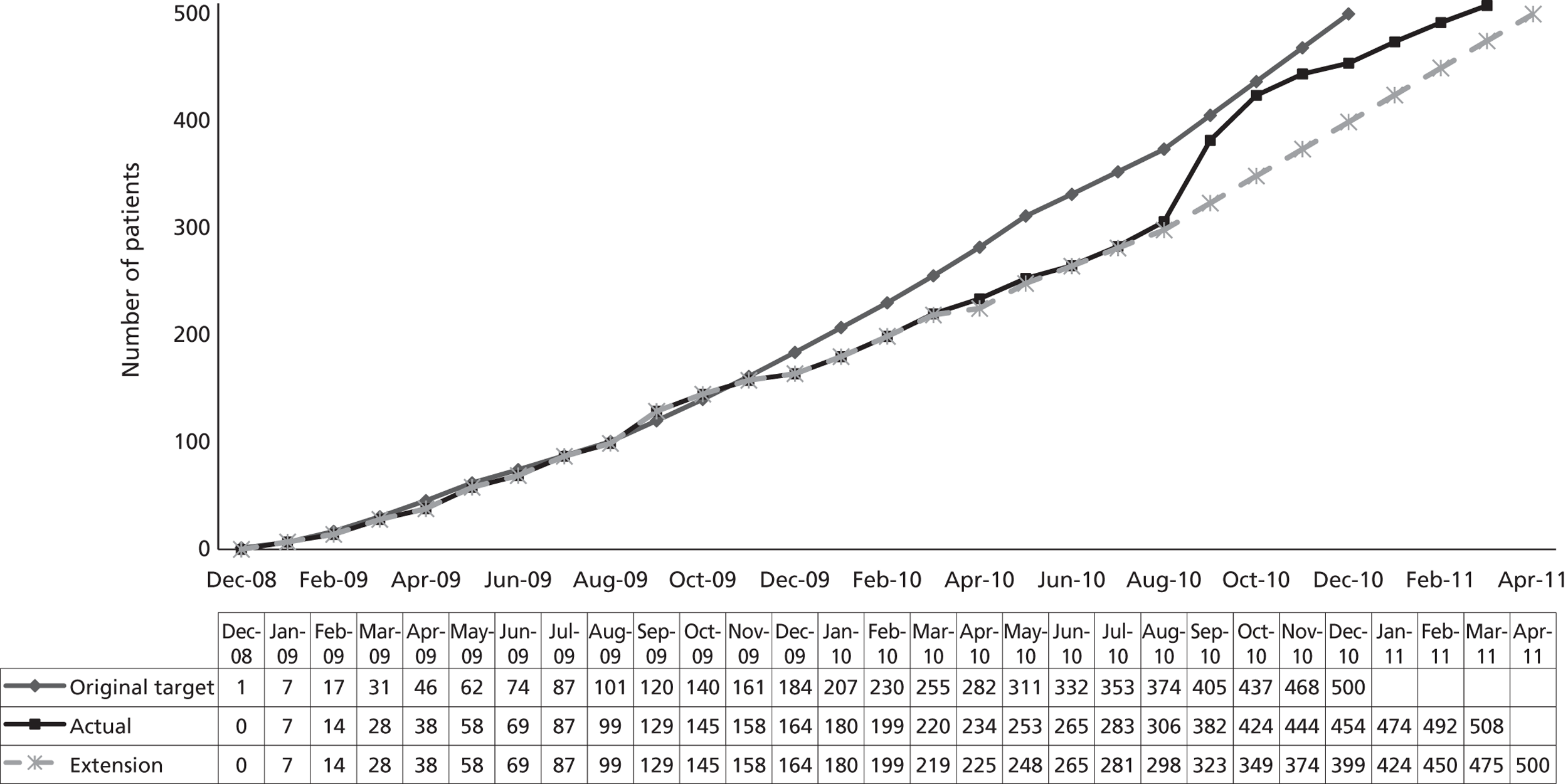

The study target sample size of 500 was expected to have been achieved within a 24-month recruitment period. The actual recruitment was somewhat slower than anticipated (Figure 1), being achieved within 28 months. Reasons for the slower than expected recruitment include the time taken to obtain approvals and undertake training at centres (specifically, good clinical practice training, required to consent children to the trial), rotation of middle-grade medical staff responsible for obtaining consent at many centres (again a training issue), and the seasonal fluctuations in asthma presentations.

The recruitment period of the trial was extended for 5 months in August 2010, and recruitment rates improved following intervention of the MCRN LRNs who conducted a feasibility survey to identify additional recruiting centres. Throughout the trial, at different stages of the study, the LRNs ran MAGNETIC promotions to keep up the profile of the study. For example, Nottingham invested extra resources to boost recruitment in March 2010 with the theme of MAGNETIC March.

FIGURE 1.

Expected vs. actual recruitment rates.

| Centre | Date site initiated | Target recruitment | No. randomised | Date of first randomisation | Date of final randomisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Thomas' Hospital | 4 December 2008 | 30 | 26 | 2 January 2009 | 17 March 2011 |

| Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital | 4 December 2008 | 30 | 33 | 5 January 2009 | 20 March 2011 |

| Derbyshire Children's Hospital | 17 December 2008 | 20 | 21 | 20 February 2009 | 17 January 2011 |

| Tameside General Hospital | 17 December 2008 | 10 | 3 | 14 January 2009 | 27 October 2009 |

| Leicester Royal Infirmary | 9 January 2009 | 20 | 20 | 23 July 2009 | 8 July 2010 |

| Royal Albert Edward Infirmary, Wigan | 9 January 2009 | 18 | 20 | 2 March 2009 | 25 February 2011 |

| Queens Hospital, Burton | 9 January 2009 | 20 | 21 | 13 February 2009 | 14 November 2010 |

| University Hospital of Wales | 9 January 2009 | 25 | 31 | 5 February 2009 | 18 January 2011 |

| Royal London Hospital | 9 January 2009 | 12 | 11 | 2 April 2009 | 21 November 2010 |

| Countess of Chester Hospital | 21 January 2009 | 16 | 26 | 30 July 2009 | 15 March 2011 |

| Macclesfield District General Hospital | 21 January 2009 | 25 | 28 | 17 February 2009 | 5 March 2011 |

| Royal Hospital for Sick Children, Glasgow | 29 January 2009 | 30 | 22 | 14 April 2009 | 21 December 2010 |

| Sheffield Children's Hospital | 29 January 2009 | 20 | 14 | 28 May 2009 | 19 November 2010 |

| Preston Royal Infirmary | 29 January 2009 | 14 | 12 | 4 August 2009 | 6 February 2011 |

| Bristol Royal Children's Hospital | 16 April 2009 | 30 | 37 | 27 April 2009 | 15 March 2011 |

| Queen's Medical Centre Nottingham | 6 May 2009 | 20 | 20 | 29 June 2009 | 22 November 2010 |

| Victoria Hospital Blackpool | 6 May 2009 | 17 | 7 | 26 June 2009 | 1 February 2011 |

| Ormskirk and District Hospital | 12 May 2009 | 20 | 30 | 5 June 2009 | 9 June 2011 |

| Wythenshawe Hospital | 16 September 2009 | 10 | 3 | 15 December 2009 | 6 December 2010 |

| Birmingham Children's Hospital | 2 October 2009 | 15 | 14 | 28 November 2009 | 23 February 2011 |

| University Hospital of North Staffordshire | 3 November 2009 | 18 | 19 | 28 January 2010 | 9 February 2011 |

| Craigavon Area Hospital | 14 November 2009 | 13 | 9 | 29 January 2010 | 24 January 2011 |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 18 January 2010 | 15 | 4 | 28 March 2010 | 11 May 2010 |

| Royal Aberdeen Children's Hospital | 1 April 2010 | 16 | 11 | 8 June 2010 | 27 January 2011 |

| University Hospital North Tees | 30 April 2010 | 18 | 17 | 22 May 2010 | 6 March 2011 |

| University Hospital Lewisham | 30 April 2010 | 15 | 14 | 30 May 2010 | 7 March 2011 |

| Altnagelvin Area Hospital | 9 June 2010 | 10 | 14 | 15 August 2010 | 2 February 2011 |

| Southampton General Hospital | 2 July 2010 | 10 | 6 | 29 July 2010 | 14 October 2010 |

| Royal Manchester Children's Hospital | 23 August 2010 | 10 | 10 | 27 August 2010 | 28 January 2011 |

| Royal Cornwall Hospital | 7 December 2010 | 8 | 5 | 9 February 2011 | 16 March 2011 |

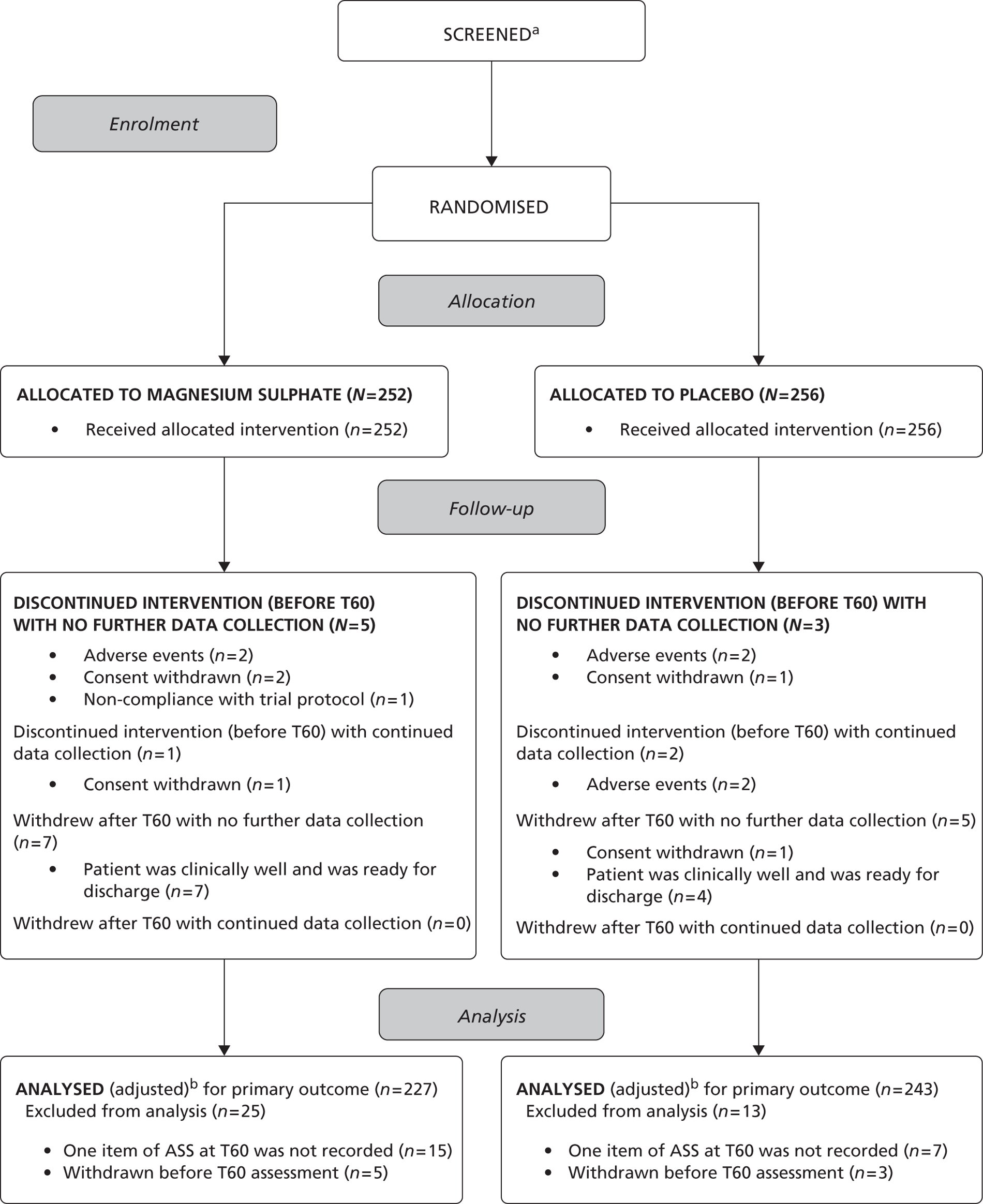

The flow of children

The flow of children through the trial is represented in the CONSORT flow diagram in Figure 2. Five hundred and eight children were randomised: 339 patients from EDs and 169 from paediatric assessment units (PAUs), 252 to the magnesium group and 256 to the placebo group.

In total, 13 children withdrew in the magnesium group; six children discontinued the intervention (withdrew before T60 assessment) and five out of six children did not provide data for the primary outcome analysis; seven children withdrew after T60 assessment and only one child continued to provide further data following withdrawal. In total, 10 children withdrew from the placebo group; five children discontinued the intervention (withdrew before T60 assessment) and three out of five did not provide data for the primary outcome analysis; five children withdrew after T60 assessment and none continued to provide further data following withdrawal. In total, 25 children on magnesium and 13 children on placebo did not have data to contribute to the analysis of the primary outcome. Consequently, 227 children were analysed for the primary outcome in the magnesium group, and 243 children were analysed for the primary outcome in the placebo group.

FIGURE 2.

Consort flow diagram. (a) Few centres complied, with the majority citing that collection of this information prospectively was too onerous for staff. In instances where the logs were received, they were often sent sporadically and were poorly completed and not recording children who were missed. (b) Analysed unadjusted for baseline ASS.

Baseline comparability of randomised groups

Table 4 shows that the baseline characteristics of the 508 randomised participants were similar, with no differences deemed clinically significant.

Participants ranged in age between 1 and 15 years, with the median age similar in both the treatment groups as well as their median age at asthma onset. There were no gender differences between the groups. There were also no differences in current treatment taken for their asthma, treatment given before presentation for the acute attack or previous admissions for acute asthma.

The mean ASS at baseline was almost identical in the two treatment groups. There were no physiological differences in presentation heart rate, respiratory rate or blood pressure or oxygen therapy required at admission.

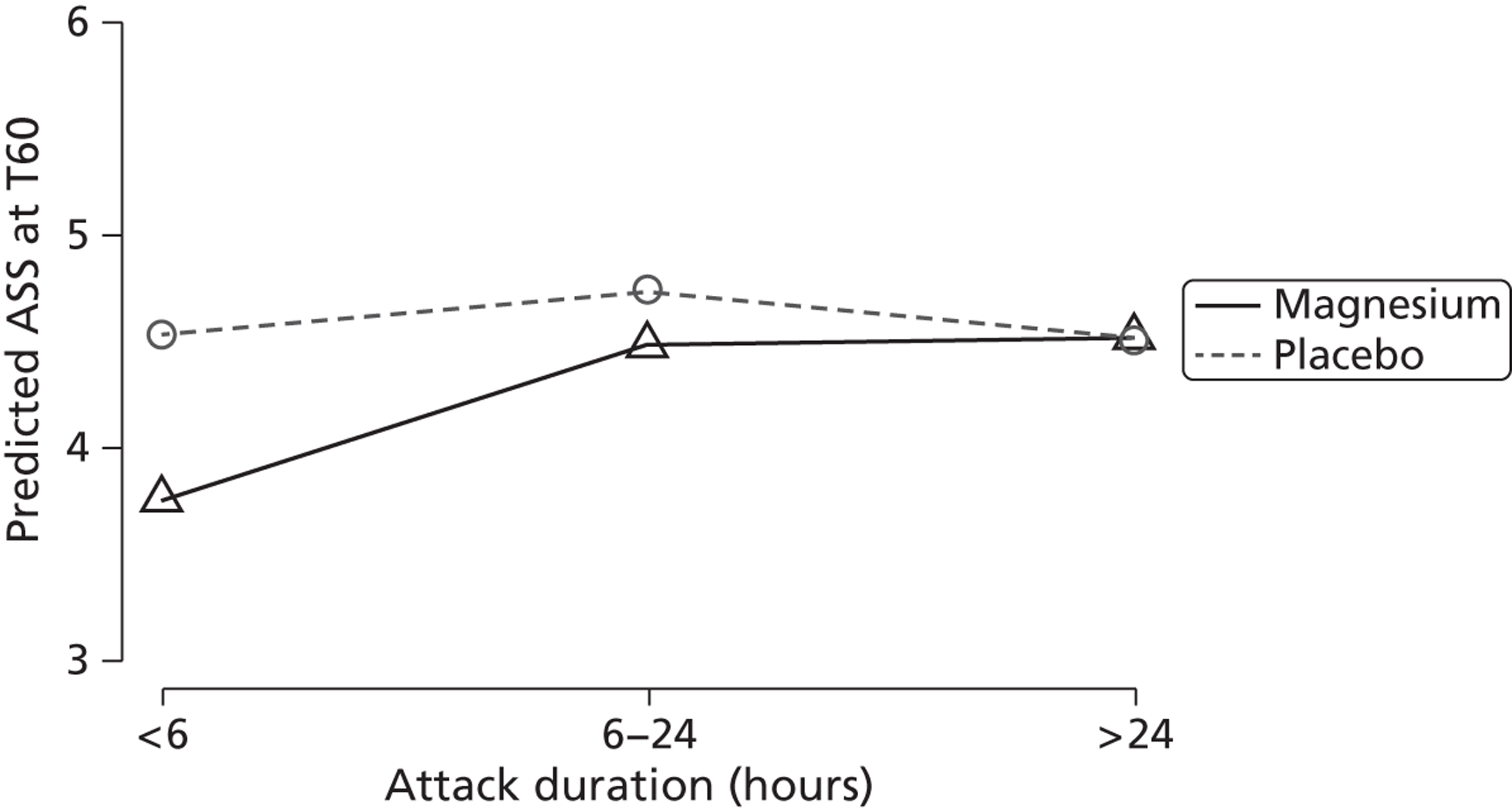

Most (69%) children were randomised between 0900 and 1700 hours. This is clearly when most of the research staff were around to recruit patients. There were three categories of duration of most recent asthma attack, with the most frequent duration being between 6 and 24 hours.

| Baseline characteristic | Magnesium (n = 252) | Placebo (n = 256) | Total (n = 508) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years): median (IQR), range | 4.0 (3.0–7.0), 2–15 | 4.0 (3.0–7.0), 1–15 | 4.0 (3.0–7.0), 1–15 |

| Male, n (%) | 143 (57) | 150 (59) | 293 (58) |

| Age (years) at asthma onset: | (n = 165) | (n = 168) | (n = 333) |

| Median (IQR), range | 2.0 (1.0–3.0), 0–11 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0), 0–10 | 2.0 (1.0–3.0), 0–11 |

| Undiagnosed, n (%) | 79 (31) | 76 (30) | 155 (31) |

| Missing, n (%) | 8 (3) | 12 (5) | 20 (4) |

| Time of day that randomisation occurred: n (%) | |||

| 0900–1700 | 181 (72) | 168 (66) | 349 (69) |

| 1700–2200 | 49 (19) | 59 (23) | 108 (21) |

| 2200–0900 | 22 (9) | 29 (11) | 51 (10) |

| ASS at baseline | (n = 248) | (n = 254) | (n = 502) |

| Mean (SD), range | 5.7 (1.3), 2–9 | 5.8 (1.4), 2–9 | 5.7 (1.4), 2–9 |

| Previous admissions for asthma: n (%) | (n = 250) | (n = 255) | (n = 505) |

| 0 | 101 (40) | 99 (39) | 200 (40) |

| 1–4 | 101 (40) | 95 (37) | 196 (39) |

| > 4 | 48 (20) | 61 (24) | 109 (21) |

| Duration of the most recent asthma attack: n (%) | (n = 251) | (n = 254) | (n = 505) |

| For the last few days | 54 (22) | 54 (21) | 108 (21) |

| For the last 24 hours | 162 (64) | 162 (64) | 324 (64) |

| For the last 6 hours or less | 35 (14) | 38 (15) | 73 (15) |

| Current asthma medication: n (%) (can be > 1) | |||

| Undiagnosed | 79 | 76 | 155 |

| Diagnosed | 173 | 180 | 353 |

| None | 7 (2) | 1 (0) | 8 (1) |

| Short-acting β2-agonists | 196 (51) | 207 (53) | 403 (52) |

| Inhaled corticosteroids | 106 (28) | 109 (28) | 215 (28) |

| Long-acting β2-agonists | 11 (3) | 19 (5) | 30 (4) |

| Long-acting β2-agonist/steroid combination | 15 (4) | 14 (4) | 29 (4) |

| Leukotriene receptor antagonists | 28 (7) | 28 (7) | 56 (7) |

| Oral steroids | 6 (2) | 2 (0) | 8 (1) |

| Othera | 8 (2) | 7 (2) | 15 (2) |

| Nothing ticked (V1 CRF)b | 5 (1) | 6 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Allergy history: n (%) (can be more than one) | |||

| None/nothing ticked | 118 (40) | 123 (39) | 241 (39) |

| Hay fever | 38 (13) | 61 (19) | 99 (16) |

| Eczema | 97 (33) | 91 (29) | 188 (31) |

| Food allergy | 41 (14) | 42 (13) | 83 (14) |

| Treatment received pre-admission: | |||

| Steroids only | 21 (8) | 25 (10) | 46 (9) |

| Nebulisers only | 68 (27) | 72 (28) | 140 (27) |

| Both steroids and nebulisers | 47 (19) | 55 (21) | 102 (20) |

| Yes, but neither steroids nor nebulisers | 20 (8) | 17 (7) | 37 (7) |

| Not known | 3 (1) | 10 (4) | 13 (3) |

| None | 79 (31) | 73 (29) | 152 (30) |

| Nothing ticked (V1 CRF) | 10 (4) | 3 (1) | 13 (3) |

| Other treatment missing (V1 CRF) | 4 (2) | 1 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Nebuliser received before randomisation: n (%) | (n = 250) | (n = 254) | (n = 504) |

| Salbutamol | 106 (42) | 101 (40) | 207 (41) |

| Salbutamol + ipratropium | 144 (58) | 150 (59) | 294 (58) |

| Not given | 0 (0) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

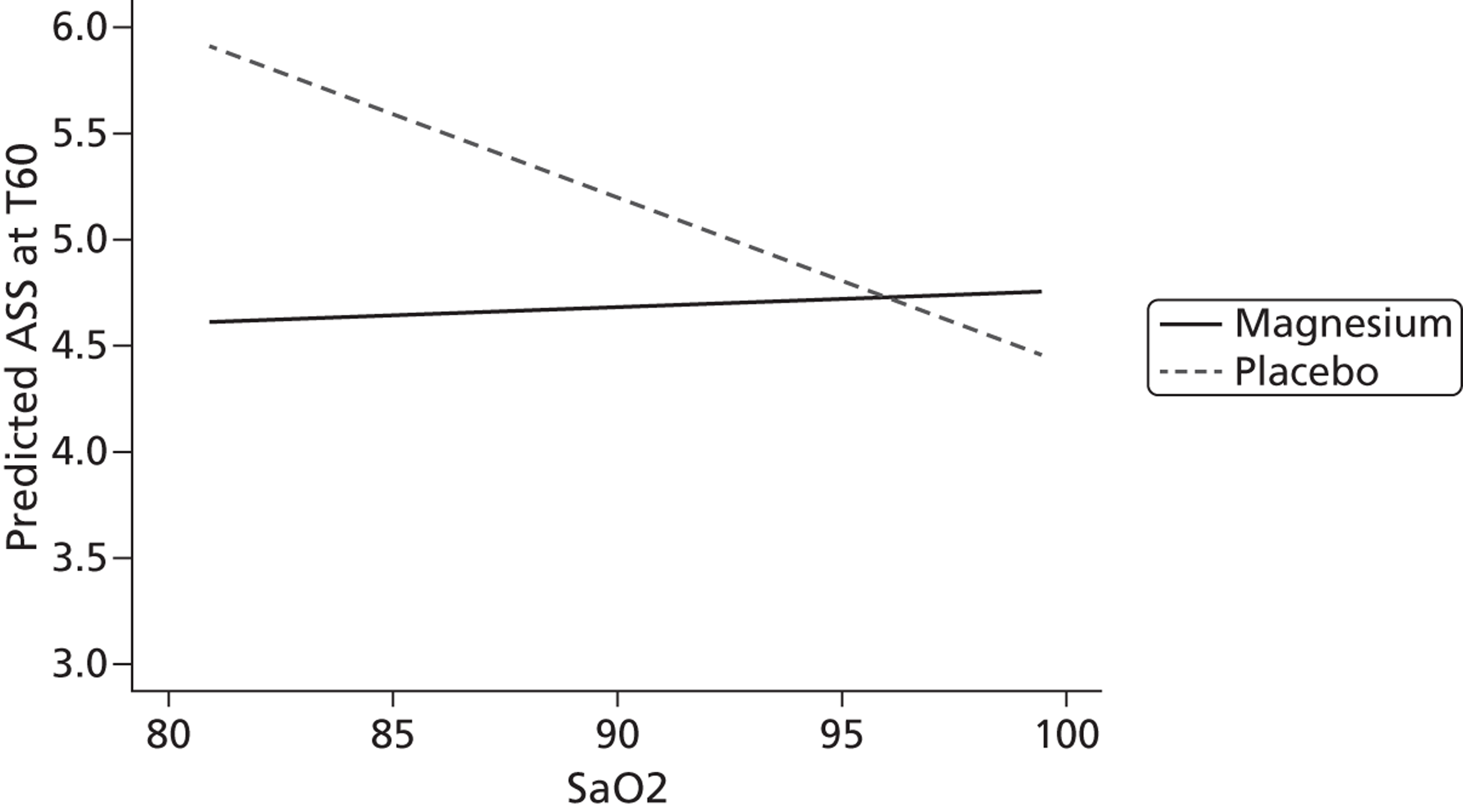

| SaO2 (%), mean (SD), range | (n = 250) | (n = 253) | (n = 503) |

| 93.8 (3.5), 84–100 | 93.4 (3.4), 81–100 | 93.6 (3.4), 81–100 | |

| Blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD), range | (n = 210) | (n = 211) | (n = 421) |

| Systolic | 109.5 (14.1), 62–163 | 112.7 (12.5), 70–172 | 111.1 (13.4), 62–172 |

| Diastolic | 65.5 (11.6), 30–105 | 66.3 (12.7), 34–123 | 65.9 (12.2), 30–123 |

| Respiratory rate (breaths per minute), mean (SD), range | (n = 247) | (n = 250) | (n = 497) |