Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/37/04. The contractual start date was in September 2008. The draft report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in November 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Stallard holds other grants paid to his institution from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and has received funding to speak at the Excellence in Paediatrics Conference in Istanbul in December 2012. Glyn Lewis has grants/grants pending to his institution from the NIHR, Medical Research Council, Wellcome Trust, and US National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism that are relevant to this work and has received funding to speak at the Austrian Society of General Practice and Family Medicine conference, Vienna, in 2012. Abigail Millings is currently employed by Ultrasis UK Ltd and has stock options with her employer. All other authors declare (1) no financial support for the submitted work from anyone other than their employer; (2) no financial relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; (3) no spouses, partners or children with relationships with commercial entities that might have an interest in the submitted work; and (4) no non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Stallard et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Depression is common in adolescents, with cumulative rates indicating that up to 20% of young people will suffer at least one clinically depressive episode by the age of 18 years. 1 Adolescent depression causes significant impairment, impacts on developmental trajectories, interferes with educational attainment and increases the risk of attempted and completed suicide as well as major depressive disorder in adulthood,2–5 yet it often remains unrecognised and untreated. 6,7 Depression in adolescence is an important public health issue and there has been growing interest in the development of preventative and early interventions. Systematic reviews of programmes designed to reduce symptoms of depression in adolescents have noted considerable variability in results but remain supportive of prevention and early intervention approaches delivered in schools. 8,9 However, significant methodological shortfalls, limited follow-up and absence of attention control or placebo comparisons have been noted as important omissions in previous studies10 and the cost-effectiveness of school-based depression prevention programmes has not yet been established.

Several evaluations have been carried out of depression prevention programmes based on cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) principles, including the Penn Resiliency Programme,11,12 Coping with Stress,13 Problem Solving for Life,14 FRIENDS,15 Resourceful Adolescent Programme (RAP)16 and other CBT programmes. 17 Although a number of studies have demonstrated short-term reduction in symptoms of depression, there is often an absence of long-term follow-up and where this is present effects typically diminish after 6 months. 1,10,18–20 Given the limited evidence of long-term gains for depression preventative interventions, it is possible that additional booster sessions could be useful in maintaining short-term benefits. Furthermore, active interventions need to be compared with appropriate controls, including placebo conditions, to account for non-specific treatment effects and spontaneous recovery. 1,8,9,18

Cognitive–behavioural therapy-based depression prevention programmes have been delivered as indicated (selective or targeted) interventions to adolescents with elevated symptoms of depression21,22 or as universal interventions to whole populations. 16,23 A meta-analytic review of school-based depression prevention programmes revealed that indicated programmes typically have larger effects than universal approaches. 9 However, indicated preventative interventions do not provide any input to low-risk children that would prevent symptoms developing and they encounter significant recruitment problems that severely limit their reach and potential impact. 11,21,24 Universal prevention programmes provide an alternative pragmatic approach, increasing reach (recruitment rates of 67–88% reported), reducing possible negative effects of stigma and labelling and resulting in lower rates of dropout. 13,14,16,25 Thus, although universal approaches might have a marginally smaller effect on symptoms of depression for individuals, they can potentially reduce far more disorders in the population as a whole. 26 The question of who delivers school-based interventions also needs to be considered, as depression prevention programmes that are led by trained facilitators typically have larger effects than those led by teachers. 9

Of the evaluated universal depression prevention programmes, the RAP appears particularly promising. Three studies have demonstrated a reduction in symptoms of depression relative to a control group post intervention, and all have demonstrated good reach (> 70% of the eligible population) and low attrition (< 10%),16,24,25 although sustained effects at long-term follow-up (12 months) were not assessed in two of these studies. 24,25 The largest of these studies was a multisite randomised controlled effectiveness trial in Australia of RAP involving 2664 students from 12 schools. 24 Of the ‘at-risk’ students, 49.1% in the RAP condition moved into the healthy category post intervention compared with 35.3% in the control group. This difference was maintained at 12-month follow-up and qualitative feedback indicated a high level of skills usage in the RAP group. 24

The current project aimed to undertake a pragmatic trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of a universally delivered classroom-based CBT depression prevention programme implemented under everyday conditions in the UK school context. To maximise the potential for effectiveness, an efficacious programme was selected (RAP), booster sessions were offered, and the programme was delivered by trained professionals external to the school. To overcome the methodological limitations of previous studies, classroom-based CBT was compared with usual Personal, Social and Health Education (PSHE) curriculum and attention control PSHE groups, and a long-term follow-up (12 months) was included.

Objectives

-

Examine the effectiveness of classroom-based CBT in reducing symptoms of depression in high-risk adolescents (aged 12–16 years) 12 months from baseline compared with the usual school curriculum and an attention control group.

-

Examine the effectiveness of classroom-based CBT compared with the control groups on the secondary outcomes on symptoms of depression, negative thoughts, self-esteem and anxiety (6 and 12 months from baseline).

-

Undertake secondary subgroup analysis to investigate effect modification on symptoms of depression (6 and 12 months from baseline) according to sex, age and baseline report of school connectedness, bullying, self-harm, and alcohol and drug use.

-

Assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in terms of reduction in symptoms of depression, health-related quality of life and cost–utility (6 and 12 months from baseline).

-

Undertake a process evaluation to assess factors associated with adherence, acceptability and sustainability of the intervention (post intervention).

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The study was a pragmatic cluster randomised controlled trial comparing three arms: classroom-based CBT, attention control PSHE and usual PSHE (Table 1). The programmes were delivered universally to whole classes of young people during lessons when they would usually be following the school PSHE curriculum. However, the focus of the evaluation was on assessing the effect upon students who had consistent elevated levels of depressive symptoms (‘high risk’) at screening and baseline assessments.

| Trial arm | Content | Delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Classroom-based CBT | The RAP, a focused CBT programme | Two facilitators (leading sessions) |

| Attention control PSHE | Usual school PSHE curriculum | One member of school staff (leading sessions) plus two facilitators |

| Usual PSHE | Usual school PSHE curriculum | One member of school staff |

A pilot phase was carried in one school in the South West region during the 2008–9 academic year. A further eight schools took part in the main trial, with interventions delivered during the 2009–10 academic year.

Ethical approval and consent

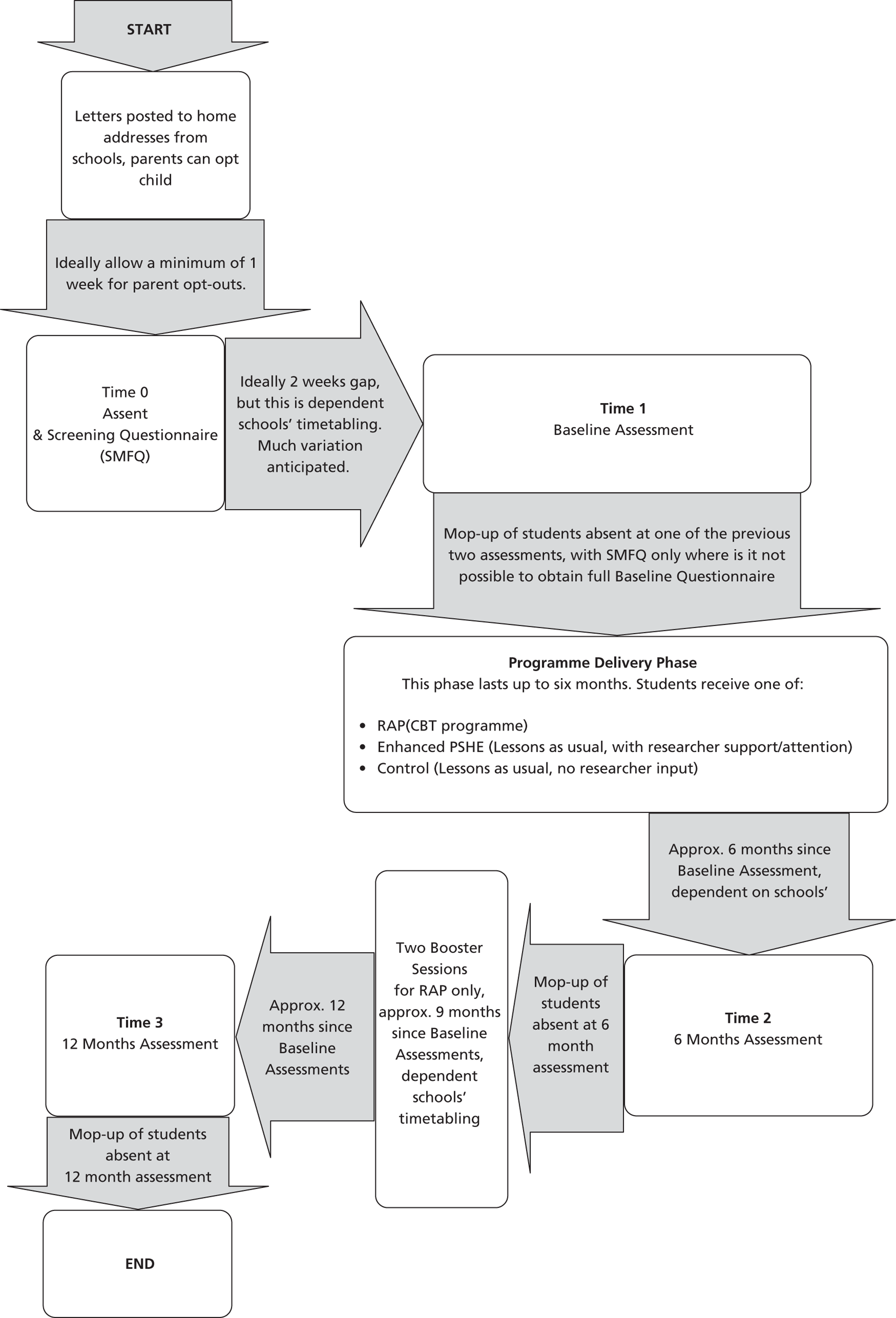

The study was approved by the University of Bath School for Health Research Ethics Approval Panel (14 November 2007). Consent/assent involved three stages: interested schools were required to opt in to the study; parents/carers of all eligible students were sent information and invited to opt out if they did not wish their child to complete the project assessments; and, finally, young people were required to opt in and provide written consent if they were willing to complete the assessments.

Participants and procedure

Sample size

The study was powered to detect a difference of two points in mean Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ) scores at 12-month follow-up between classroom-based CBT and each of the control arms. The pilot study provided estimates of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs; 0.025), mean year group size (n = 203), consent rate (84%) and SMFQ standard deviation (SD; 4.9) in the target population. Based on 80% consent, 80% retention and 20% of children being classified as high risk, a mean cluster size for analysis of 26 high-risk participants per year group was anticipated, requiring a minimum of 22 year groups to detect a difference of two points with 80% power and 2.7% Dunnett-correction two sided alpha.

Recruitment of schools

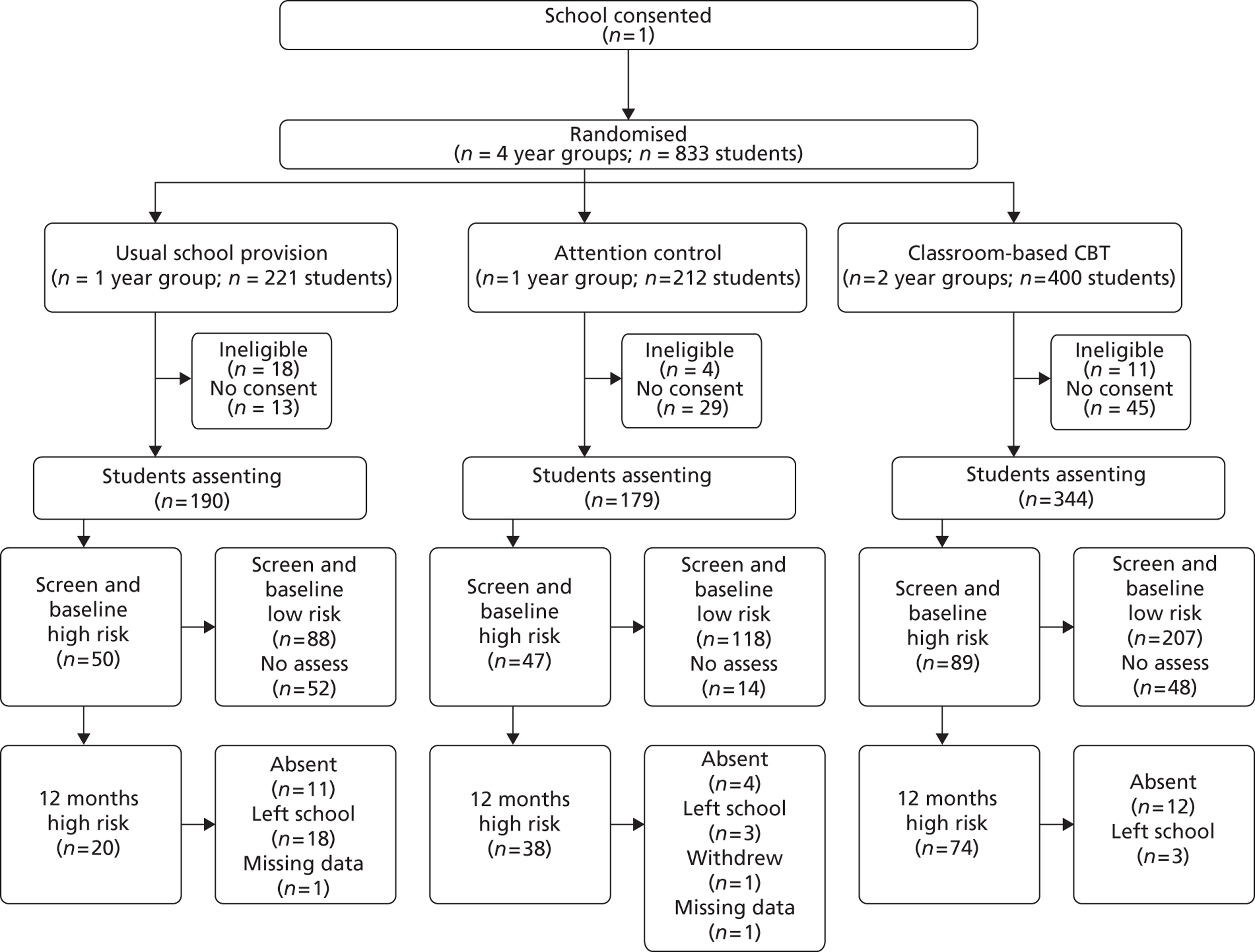

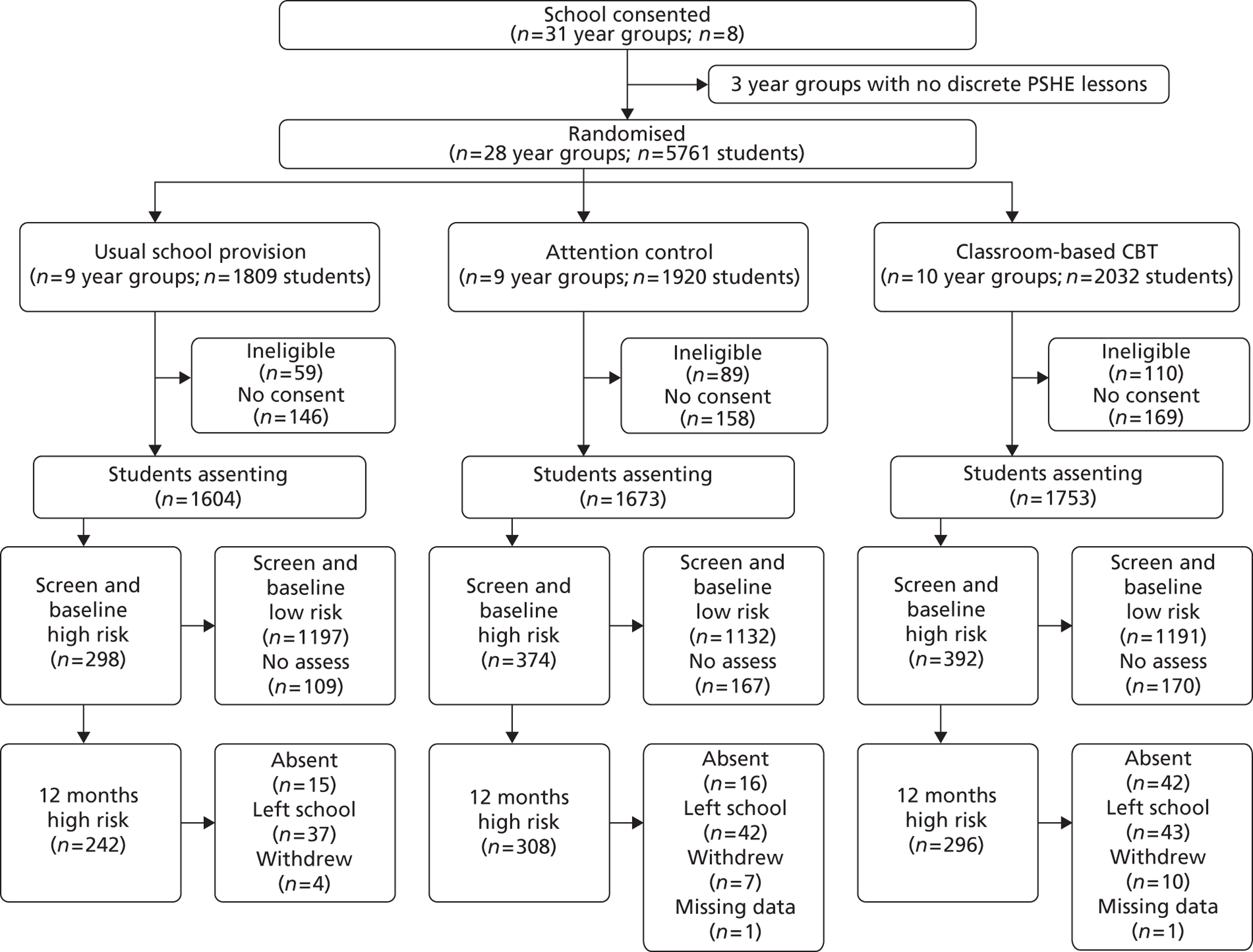

Information about the project was sent to 66 non-denominational comprehensive secondary schools in Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, Wiltshire, Nottingham City and Nottinghamshire County. Schools that expressed an interest were contacted by the research team and a face-to-face meeting was arranged to discuss the project. Nine schools were recruited: one for the pilot study and eight for the main trial. In the participating schools, three year groups could not be included as they did not have discrete PSHE lessons. Therefore, 28 year groups were included in the randomisation process for the main trial. Details of participant flow are provided in Figure 1 (pilot study) and Figure 2 (main trial).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram: pilot trial participant flow.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram: main trial participant flow.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Interventions were provided during the school day as part of the school PSHE curriculum. All children were eligible unless they did not attend PSHE lessons (e.g. if they were away from school on long-term sickness absence, were withdrawn from PSHE for religious reasons or were educated elsewhere). Young people and their carers were contacted if they were identified as possibly clinically depressed during assessments (i.e. in the highest 2–3% of SMFQ scores). They were provided with information on how to seek further help should they require it, but these young people continued to participate in the programmes running in the school as usual.

Classification of the high-risk group

The target group for the effectiveness analysis were those who were at high risk of depression, that is those who had elevated and persistent symptoms of depression assessed using the SMFQ. 27 Those with scores of ≥ 5 at both screening and baseline assessments were classified as high risk.

Procedure for individual assessments with young people

Assessments were carried out at four time points: screening (SMFQ only), baseline, and 6 and 12 months from baseline. Some variation in assessment intervals occurred to fit around school holidays, examinations and other events. Mean times between assessments were baseline to 6 months = 176 days (SD 34.2); 6 months to 12 months = 181 days (SD 35.8); and baseline to 12 months = 359 days (SD 20.4). There was no difference between trial arms for the interval between time points for primary analysis (baseline to 12 months).

Assessments with young people were self-completed in schools during lesson time in sessions that were led by the research team. Following the pilot study, we anticipated that there would be differential dropout for the year 11 students who had left school by the time of their 12-month follow-up. To maximise response rates in this group in the main trial, any year 11 students who had stayed on for year 12 were assessed in school after 12 months. Those who had left school were contacted by post and/or e-mail (contact details and permission were obtained at 6-month assessment) and offered an option of filling in the questionnaire online and an incentive of entry to a prize draw (the prize was a gift voucher: 10 of £10 and 20 of £5 were available).

Randomisation

Year groups were randomly allocated on a 1 : 1 : 1 basis once all schools had been recruited. Balance between trial arms with respect to number of classes, number of students, PSHE frequency and scheduling of PSHE lessons within the school was achieved by calculating an imbalance statistic28 of all possible allocation sequences, restricted to those in which every school had at least one year group allocated to classroom-based CBT. Using a computer random numbers generator, a statistician with no other involvement in the study randomly selected one sequence from a subset of 100 with the most desirable balance properties.

Interventions

Classroom-based cognitive–behavioural therapy: the Resourceful Adolescent Programme UK

The RAP is a manualised depression prevention programme designed for use with groups of young people aged 12–15 years. It is based on a CBT model and interpersonal therapy principles. CBT recognises the importance of negative thoughts and low self-worth/image in the onset and maintenance of depression. These are actively targeted with core treatment components including psycho-education, identifying and challenging negative/dysfunctional thoughts, identifying personal strengths (thereby enhancing self-esteem/image), managing social problems, and learning to problem solve. Students complete their own workbook and group leaders have a detailed manual specifying key learning points and objectives.

For this study, the RAP was modified for use in the UK (RAP-UK). The content, key messages and goals were consistent with the original RAP, but the structure and method of delivery were revised to fit in with the UK education system. The key elements of RAP-UK – personal strengths, helpful thinking, keeping calm, problem solving, support networks and keeping the peace – are organised into nine sessions, each approximately 50–60 minutes long. RAP-UK was designed with a flexible method of delivery in mind to ensure that it could fit into a busy school timetable while retaining the key elements of the programme. Two additional booster sessions were offered to schools approximately 6 months after the initial programme had been completed. These provided an opportunity to review RAP-UK skills and to practise applying them to current difficulties. RAP-UK was delivered by two trained facilitators external to the school.

Attention control Personal, Social and Health Education

The attention control PSHE intervention involved similar time and contact with external providers to classroom-based CBT, but did not include the active components of the CBT intervention. The school delivered its usual PSHE curriculum, but the class teacher was joined by two facilitators from outside the school who assisted with delivering the lessons and engaging with young people. This controlled for the non-specific effects of interventions that are considered important in studies of depression. 29 As with classroom-based CBT, delivery of attention control PSHE was designed around nine 50- to 60-minute sessions, with flexibility to fit in with existing school PSHE programmes.

Usual Personal, Social and Health Education

‘Usual PSHE’ was the usual school PSHE curriculum provided by the school staff and did not involve any external input from the research team.

Programme facilitators

Facilitators had completed at least an undergraduate degree and had experience of working with young people and/or in a health-care setting. They were employed on a sessional basis. Different facilitators delivered the classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE interventions to minimise therapist contamination. Facilitators received initial training, which covered the identification and management of mental health concerns, group management techniques and training in delivering their specific intervention. This was usually carried out with groups of new staff over 2 or 3 days, with condensed one-to-one training provided for staff joining at different points in the year as required. During the course of delivery, regular separate supervision groups were provided for classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE facilitators. Teachers were present in all PSHE sessions and remained responsible for managing class behaviour.

Outcome measures: individual assessments with young people

Assessments completed by young people focused on the following areas: psychological functioning, social relationships, risk behaviours, health-care resource usage and sociodemographics. A copy of the questionnaire is provided in Appendix 1 and additional details on these measures are included in the trial protocol (see Appendix 2).

Primary outcome

The SMFQ27 is a 13-item scale derived from the 33-item Mood and Feelings Questionnaire. 30 Each item consists of a simple statement (e.g. ‘I didn't enjoy anything at all’), which is rated as being ‘true’ (scores 2), ‘sometimes true’ (scores 1) or ‘not true’ (scores 0). The SMFQ correlates well with other measures of depression and has good test–retest reliability, and higher scores are associated with fulfilling diagnostic criteria for clinical depression. 31–33

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were the personal failure subscale of the Children's Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS),34 Rosenberg Self-Esteem Inventory,35 Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS),36 School Connectedness Scale,37 Attachment Questionnaire for Children38 and items relating to bullying (Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire39), self-harm, cannabis use, use of other ‘street drugs’ (e.g. amphetamines, LSD, ecstasy, cocaine, ketamine, crack, heroin), and alcohol use over the last 6 months.

Resource and service use

As part of their standard assessments, all participants were asked to complete the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions40 (EQ-5D: a standardised measure of quality of life/health outcome) and a modified self-report version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 41 The CSRI is widely used and has been adapted across the child and adult age range and for different services. 41 The wording and presentation of the questions were simplified and pilot tested for clarity and ease of completion by the younger age group during the pilot phase of this trial. The modified CSRI (see Appendix 2) retrospectively assessed time off school; receipt of mental health or other health services; educational support; antipsychotropic medication (i.e. antidepressants or others); and social work/care services over a 6-month period. The specific service use information recorded in the assessment for each type of service use is summarised in Table 2.

| Types of service use | Details recorded | Notes or limits |

|---|---|---|

| Overnight hospital stays | Reason for stay and number of days in hospital | For up to three stays |

| A&E visits | Number of visits, reasons for visits | Up to three reasons |

| Hospital outpatient appointments | Number of visits, reasons for visits | Up to three reasons |

| Visits to the GP | Number of visits, number of visits for worry anxiety or unhappiness | |

| ‘Seen anyone else for psychological problems (such as worry, anxiety or unhappiness)’ | Number of times seen (for each of nurse at GP's practice, school nurse, counsellor, child mental health service, child psychologist, social worker or ‘someone else, please say who’) | |

| Taking medication (for anxiety or depression) | Name of medicine, how long taken | Up to two medicines |

Sociodemographic data

Basic demographic data were collected (sex, age, who you usually live with, ethnicity). The Family Affluence Scale42 was used as an indicator of socioeconomic status.

Process evaluation

The process evaluation followed the RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy/effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance) framework. 43 Data were collected on attendance and attrition for classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE by programme facilitators. An independent observer attended 5% of classroom-based CBT sessions to assess treatment fidelity. Feedback was gathered from teachers, young people and facilitators using questionnaires and qualitative interviews.

Feedback questionnaires

Twenty per cent of classes were asked to complete evaluation questionnaires post intervention. This included a series of 11-point Likert scales (0–10), asking students about engagement and usefulness of the PSHE programmes. All teachers involved with classroom-based CBT were invited to complete evaluation questionnaires, where they rated on the following five-point Likert scales (0–4): quality of organisation of the programme; relevance to young people; age appropriateness; extent to which they thought the programme would help young people with their mood and dealing with challenges in day-to-day life; whether or not the number of sessions was appropriate; and how likely they would be to continue with the programme in the future. Facilitators were asked to rate on the following five-point scales (0–4): the adequacy of training and supervision; how much they enjoyed delivering the programme; how challenging they had found it; how much they thought it would make a difference to young people's mental health; and student engagement.

Qualitative evaluation

Purposive sampling was used for the focus groups with young people to ensure that a range of views was captured across schools, year groups and sexes. There was a combination of same- and mixed-sex groups to allow for variations in discussion influenced by group composition. In total, 42 young people (19 male and 23 female) participated across seven focus groups, with all year groups being represented at least once.

The school link person (either the PSHE coordinator or a member of the senior management team) and any other teachers involved in the trial at each school were invited to provide feedback via either interviews or focus groups. Members of school staff (four male and eight female) participated across seven interviews or focus groups. For focus groups with facilitators, 39 individuals (6 male and 33 female) participated across six groups (separate groups for classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE facilitators).

Semi-structured topic guides were used to gather the qualitative feedback, focusing on overall views of RAP, individual sessions (what worked and what did not), delivery, pupils' perceptions and maintenance of RAP (including likelihood of continuing the programme, giving consideration to cost and resources). Summary cards of RAP sessions and RAP manuals were provided to facilitate discussion. Interviews also captured general feedback on the trial, attention control PSHE, views on how PSHE is delivered in schools in general and any other comments. Focus groups were facilitated by a researcher and a co-facilitator/note-taker.

Analysis: pilot study

The aims of the pilot study were to establish whether or not the trial protocol was feasible in terms of reach and acceptability, gather data to check the sample size calculation for the main trial and trial the programmes and assessment procedure. The analysis focused on participant flow (recruitment and retention), descriptive analysis of change in symptoms over the course of the study, success in delivering sessions as intended and adherence/attrition and brief thematic analysis of feedback from students and teachers on acceptability.

Analysis: main trial

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata 11 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Descriptive statistics were used to assess the balance between the trial arms at baseline. Effects on the primary outcome (SMFQ at 12-month follow-up) were assessed by intention to treat without imputation. In order to take appropriate account of the hierarchical nature of the data, multivariable mixed-effects regression was used to compare mean SMFQ at 12 months for classroom-based CBT with attention control PSHE and usual PSHE, with adjustment for baseline SMFQ and randomisation variables. In a secondary analysis, further adjustment was made for variables that were imbalanced between the trial arms at baseline. These analyses were repeated for secondary outcomes.

For SMFQ, repeated-measures mixed-effects regression models were used to investigate convergence/divergence between trial arms over time. Preplanned subgroup analyses44 were carried out using interaction terms in the regression models between the randomised arm and the following baseline variables: symptom severity (SMFQ score 5–10, ≥11); self-harm (no/yes); alcohol and/or drug misuse (no/yes); year group (8–11); and family affluence.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the potential effect of missing data using multiple imputation chained equation methods,45 with the imputation model including all variables associated with absence of primary outcome at 12 months. Variance at class and school level was investigated by including these in the multilevel models. Neither of these sensitivity analyses made any material difference to the primary results and therefore the data presented are those from two-level (individual and year group) models based on observed data only.

Finally, the effect of actual attendance at allocated lessons was examined by estimating the compiler-average causal effect (CACE) using instrumental variable regression,46 weighted using inverse probability weights constructed using baseline SMFQ scores, randomised group and ‘adherence’ (defined as attendance at ≥ 60% of sessions).

Qualitative analysis

Interviews and focus groups were digitally audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The transcripts were thematically analysed, broadly following the guidelines of Braun and Clarke. 47 Transcripts were coded using NVivo 9 (QSR International, Southport, UK) software. A predefined, broad and descriptive coding framework was developed to enable the generation of initial codes. Each coding unit was coded exclusively into just one category as this allows very clearly defined coding categories to be developed. 48 Three members of the research team independently coded three randomly selected transcripts. Inter-rater reliabilities calculated using NVivo 9 revealed coding agreement ranging from 78% to 100%, indicating satisfactory consistency of interpretation. Any coding inconsistencies were resolved by discussion and consensus. The remaining 14 transcripts were then divided between the researchers and coded using the same framework. Data were then reviewed by the researchers and the themes were redefined as required. The emergent inductively coded themes were examined for consensus and conflict across the different participant groups.

Economic analysis

The service and resource use and cost-effectiveness analysis was carried out according to current best practice methods for conducting economic evaluation alongside trials,49 and specifically alongside cluster randomised controlled trials. 50

The unit costs applied to different types of health service use and for visits to different types of professionals or services because of anxiety or depression are provided in Table 3. The two main sources for the unit costs were the Department of Health's National Schedule of Reference Costs51 [for primary care trusts (PCTs) and NHS trusts combined] and the Personal Social Services Research's Unit Costs of Health and Social Care52 (hourly costs of patient or client contact for various types of health or social care professional).

The service/resource use data were checked and cleaned manually where required. Reported reason(s) for inpatient stays were assessed as being either elective or non-elective and relevant unit costs were applied (see Table 3). For a small minority (< 1%) of participants who reported taking medication for anxiety or depression, the information provided on medication names and on how long they had been taken was too unreliable to use as a basis for estimating these costs (e.g. where young people simply recorded ‘dunno’ or ‘can't remember’, or stated that they used ‘paracetamol’, other over-the-counter medications or herbal remedies, which would have no cost implications for the NHS) and was therefore excluded from further analysis.

The classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE programmes were costed using detailed project records of resource use. This included the paid time of facilitators delivering the programme, the cost of their training, travel costs, printing costs of course booklets, and an apportionment of the cost of recruiting schools. All costs were calculated as either the amount of resource used multiplied by a unit cost or the total amount incurred over the trial period divided by the number of pupils in participating classes, number of sessions delivered or number of schools, depending on the level at which the cost was incurred.

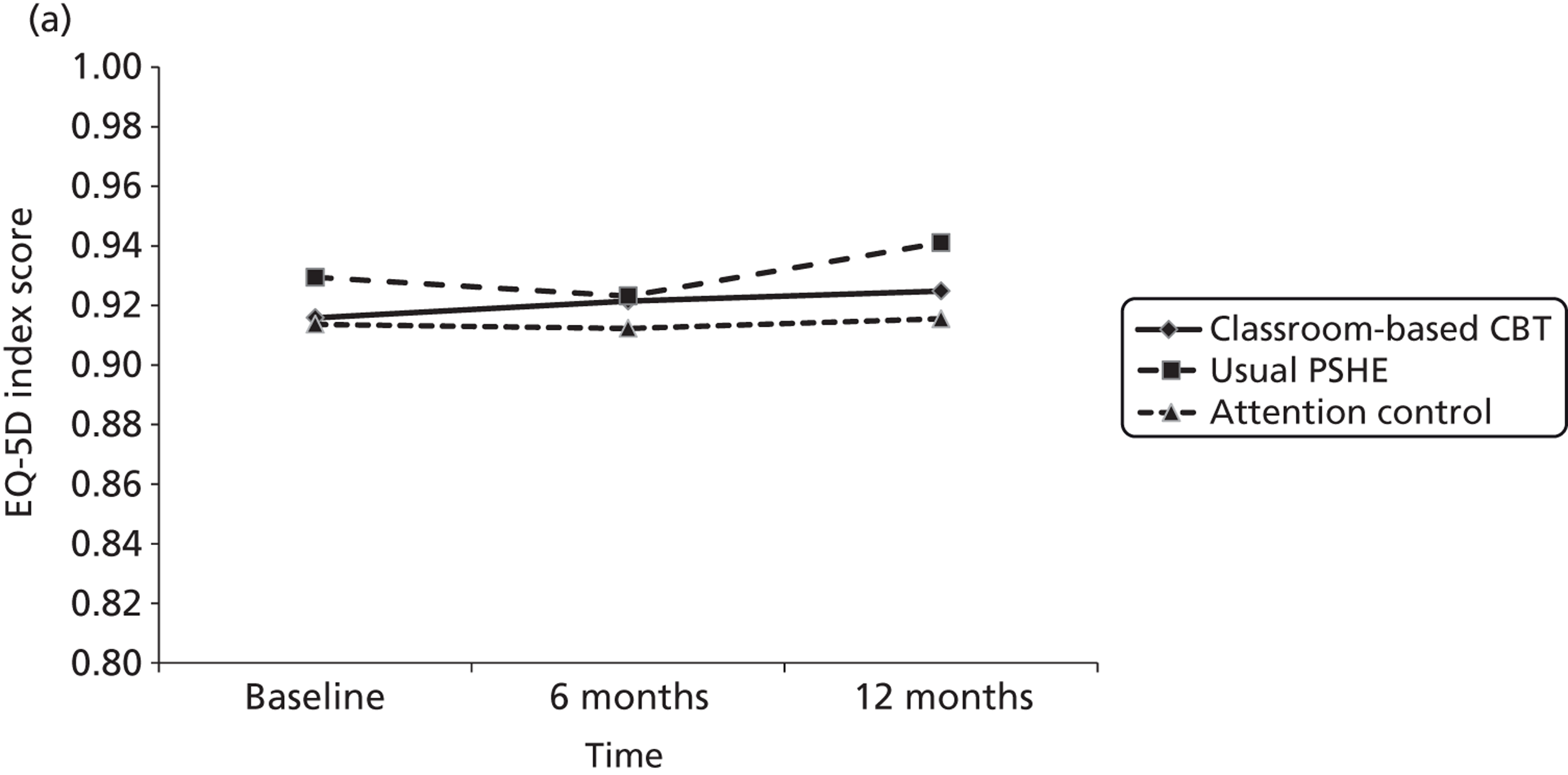

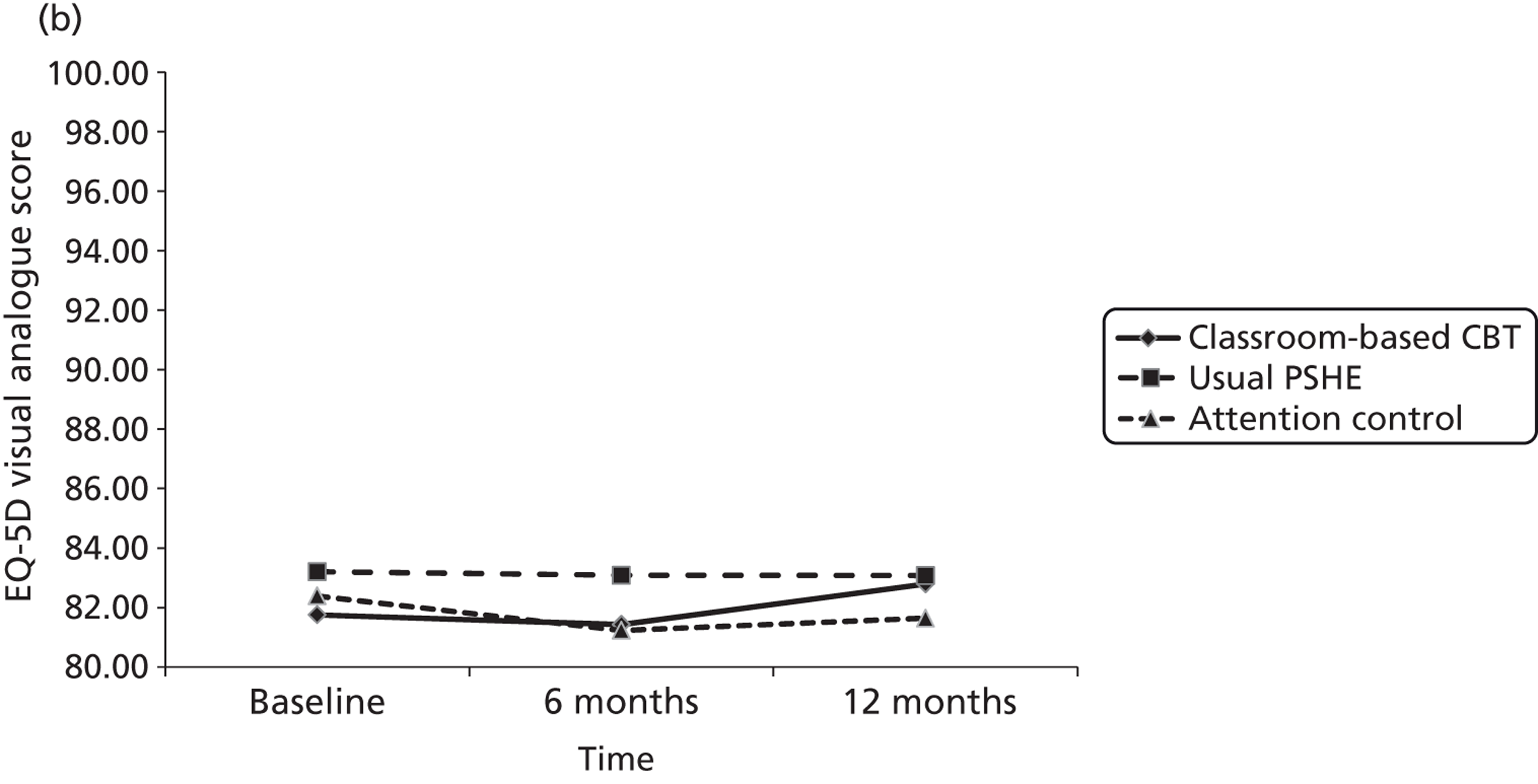

Cleaning and correction of resource use and EQ-5D data and calculation of service use costs were conducted using PASW Statistics 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Models for analysing incremental cost-effectiveness were fitted using Stata 12.0 software. Two cost-effectiveness analyses were conducted, the first using the SMFQ score and the second using quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) based on responses to the EQ-5D questionnaire. Derivation of the per-person QALYs from baseline to 12 months involved calculating the social preference weight (or utility) for all those who completed the EQ-5D at each of the three time points, estimating the ‘area under the curve’ between baseline and 6 months and between 6 months and 12 months and summing them. QALYs were therefore calculated only for students who had complete EQ-5D data at all three time points. The social preference weights for the EQ-5D were from a representative sample survey of the UK general population in 1993. 53

| Question numbers | Resource type and unit | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6–11 | Inpatient stays – elective | 781 per day | NSRC2009–10c |

| 6–11 | Inpatient stays – non-elective short stay (1 day/night) | 520 per day | NSRC2009–10c |

| 6–11 | Inpatient stays – non-elective long stay (> 1 day/night) | 386 per day | NSRC2009–10c |

| 13–16 | A&E attendances | 103 | NSRC2009–10 A&E services not leading to admitted (sheet: TPCTA and EMSNA) |

| 18–21 | Hospital outpatient clinics | 99 | NSRC2009–10 face-to-face outpatient appointments (weighted average, consultant and non-consultant led, first attendance and follow-ups) |

| 23 and 24 | Visit to GP | 32 | UC2010 Section 2.8 (11.7-minute consultation)a |

| 25a | GP practice nurse consultation | 10 | UC2010 Section 10.6 (nurse GP practice, per consultation)a |

| 25b | School nurse time (per hour) | 64 | UC2010 (community nurse, per hour with patient, £16 per 15-minute appointment)a |

| 25c | Counsellor (per hour)b | 44 | UC2010 Section 2.14 (counselling services in primary medical care, per hour with patient or per contact hour)a |

| 25d | Child mental health service (per hour)b | 48 | UC2010 (mental health nurse, per hour with patient)a |

| 25e | Child psychologist (per hour)b | 81 | UC2010 Section 9.5 (clinical psychologist, per hour with patient)a |

| 25f | Social worker (per hour)b | 53 | UC2010 Section 11.3 [social worker (children), per hour with client]a |

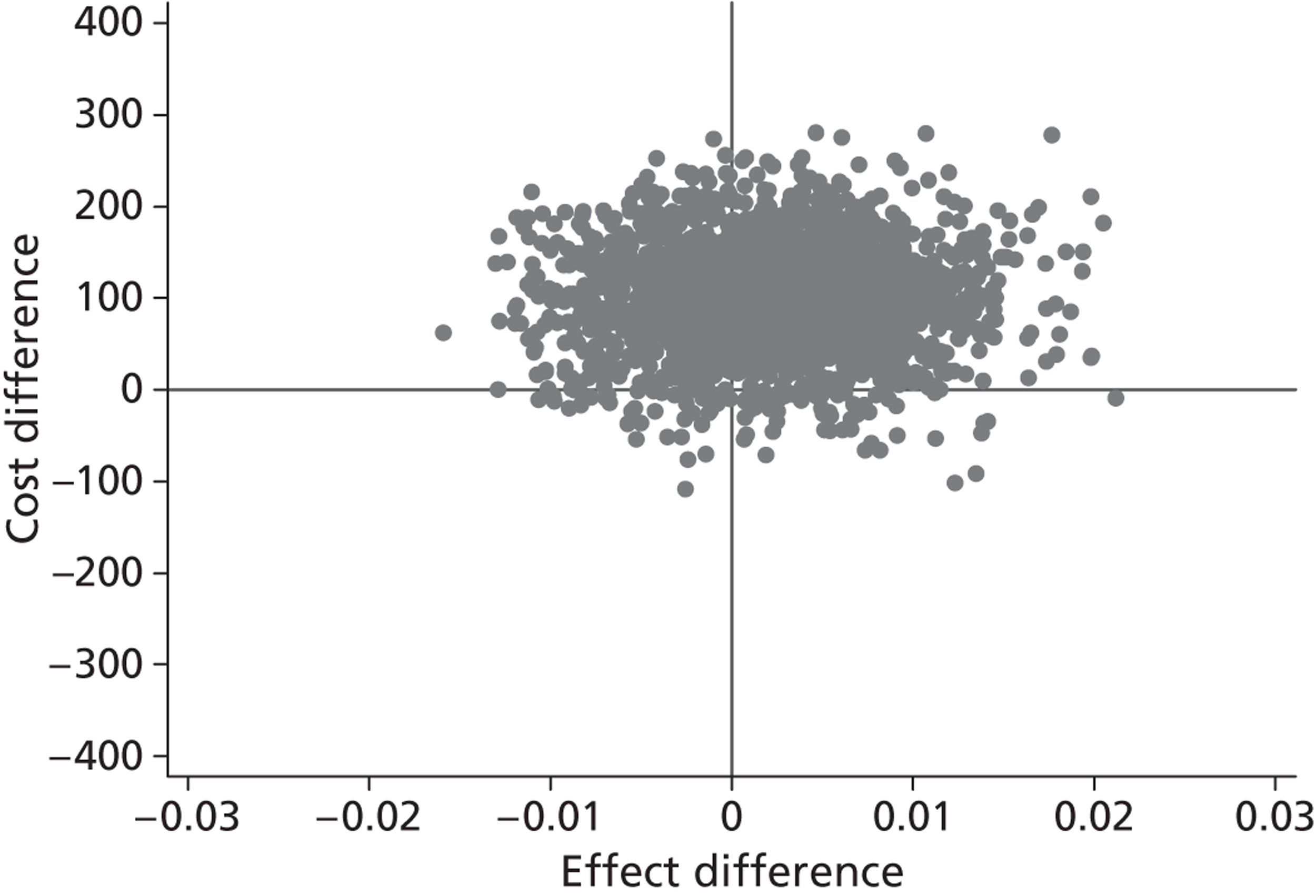

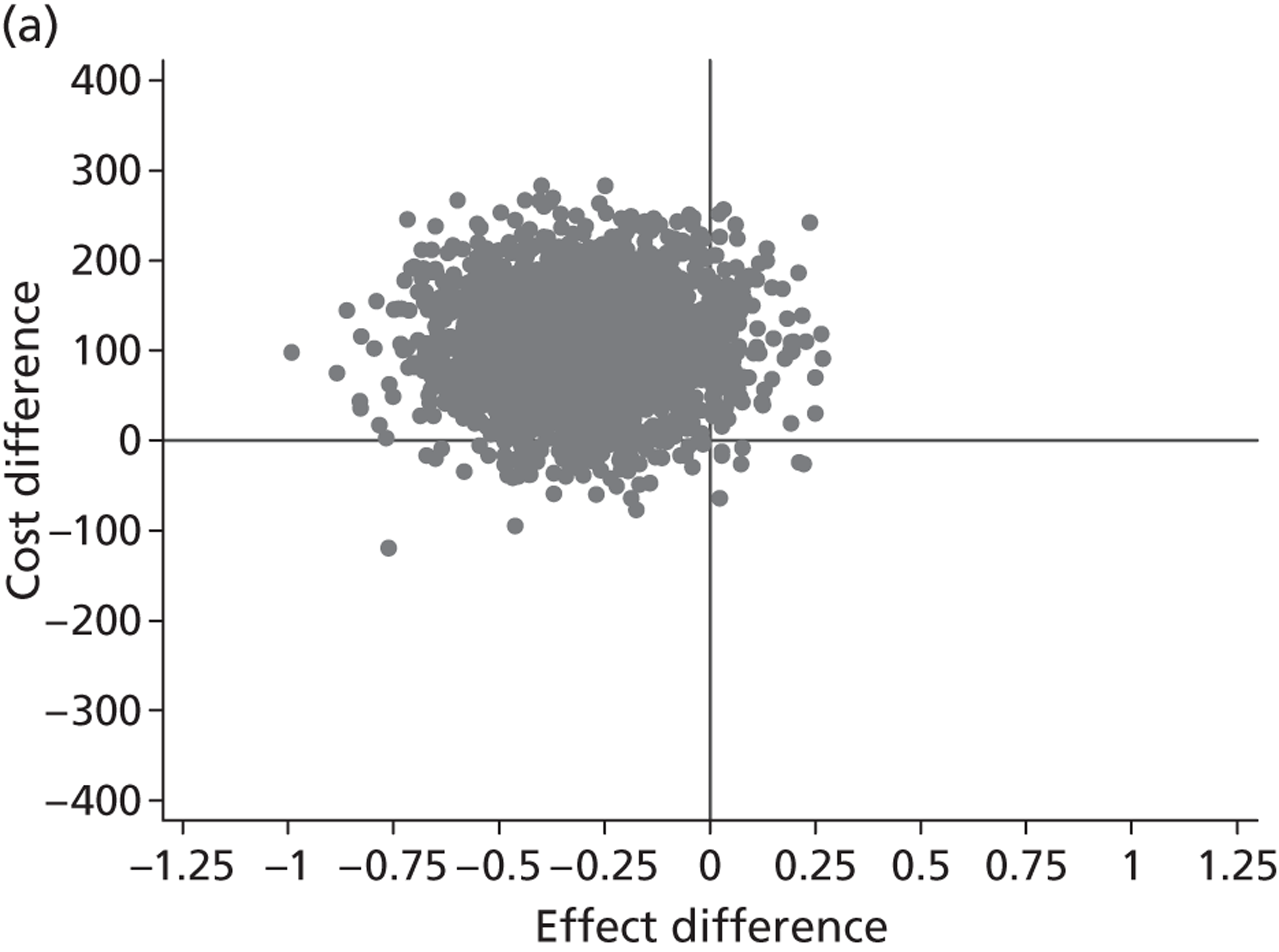

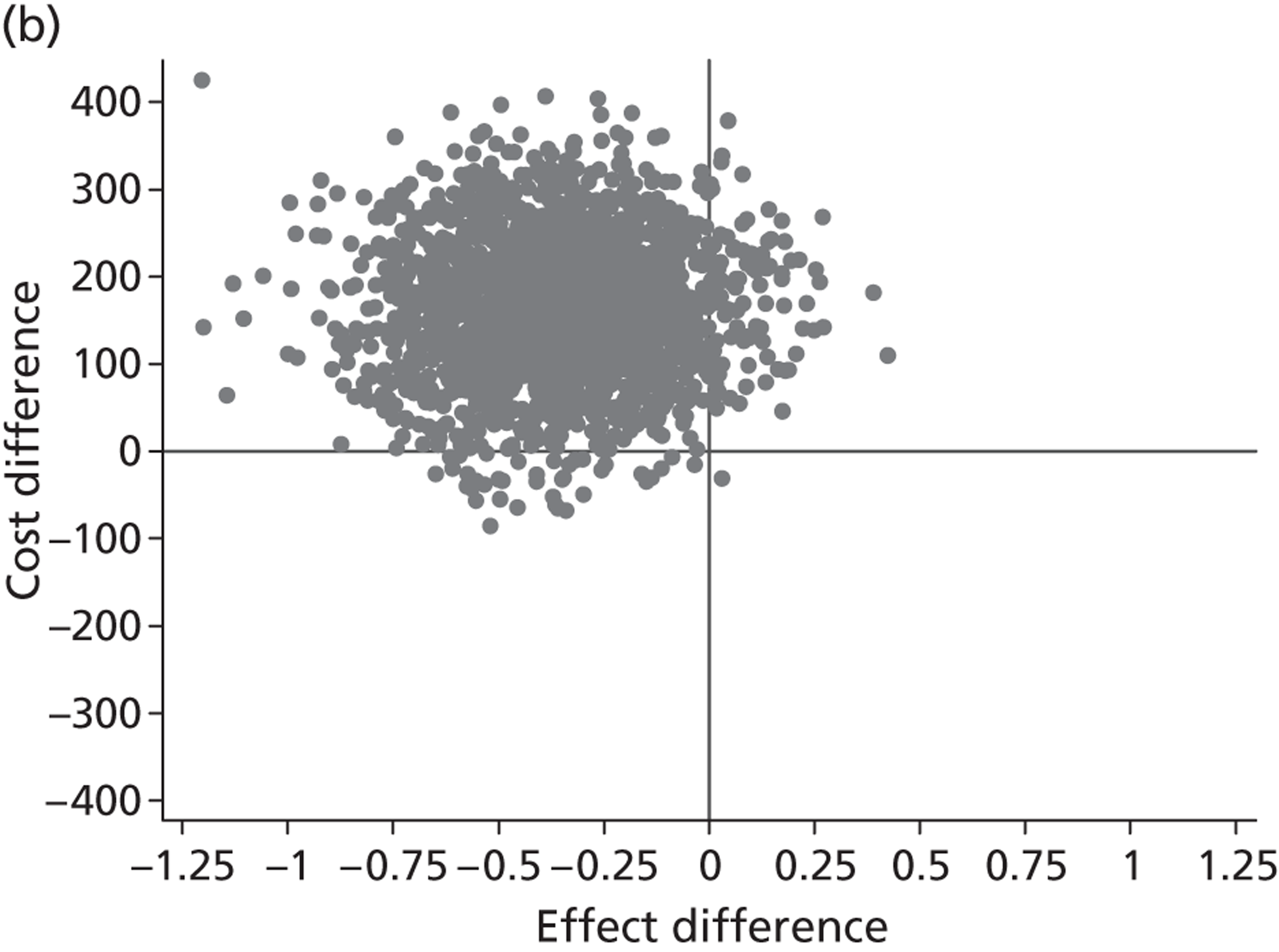

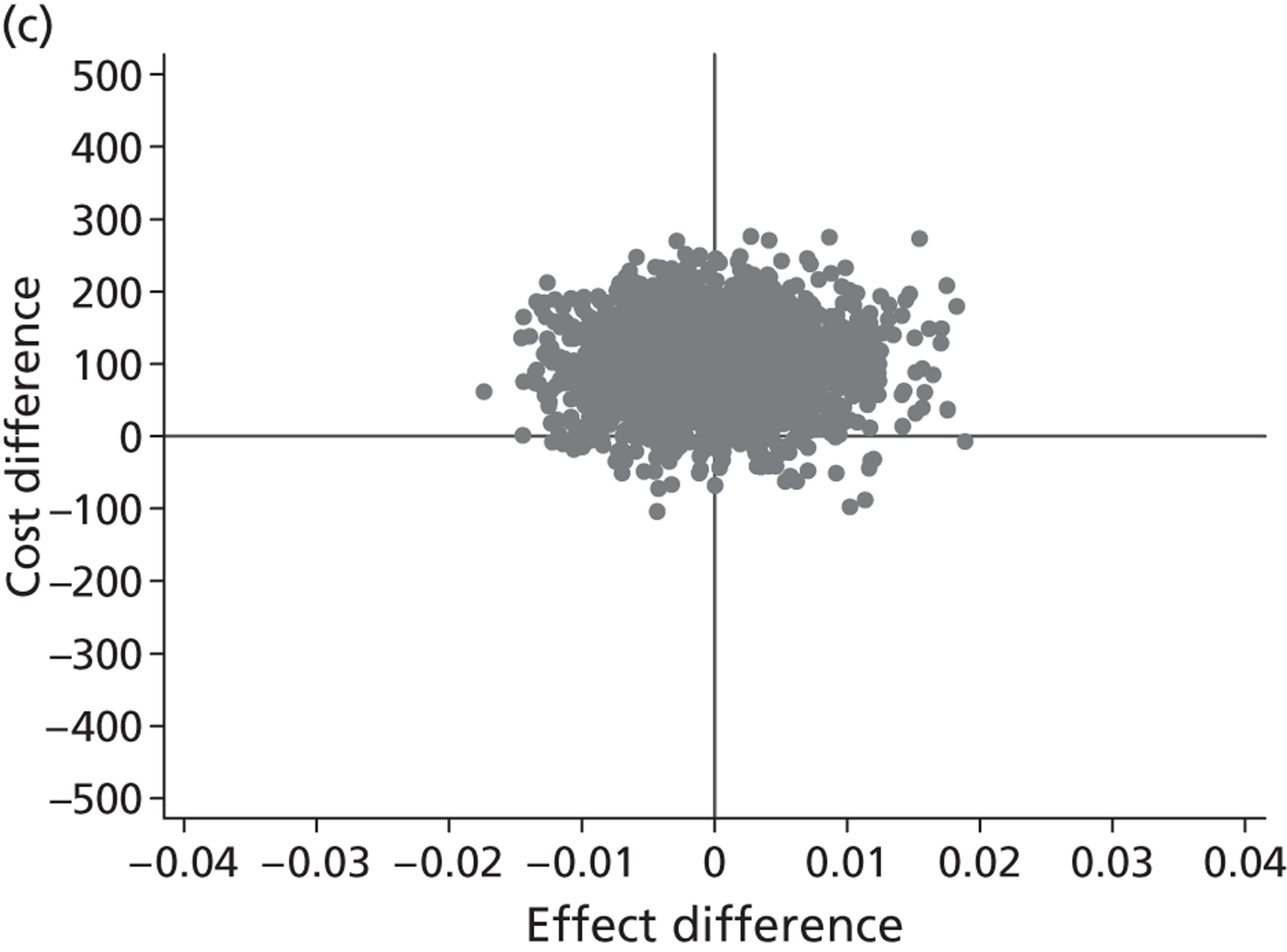

Incremental costs, incremental effects and, where relevant, incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs) were estimated, comparing each of the classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE trial arms with usual PSHE. The incremental cost per unit decrease in the SMFQ score (as lower scores on the SMFQ indicate better outcome) and the incremental cost per unit QALY increase were estimated. Both unadjusted and adjusted analyses (adjusting for site, mode of delivery, number of students and number of classes) were carried out. The incremental cost per unit decrease in SMFQ was additionally adjusted for SMFQ score at baseline.

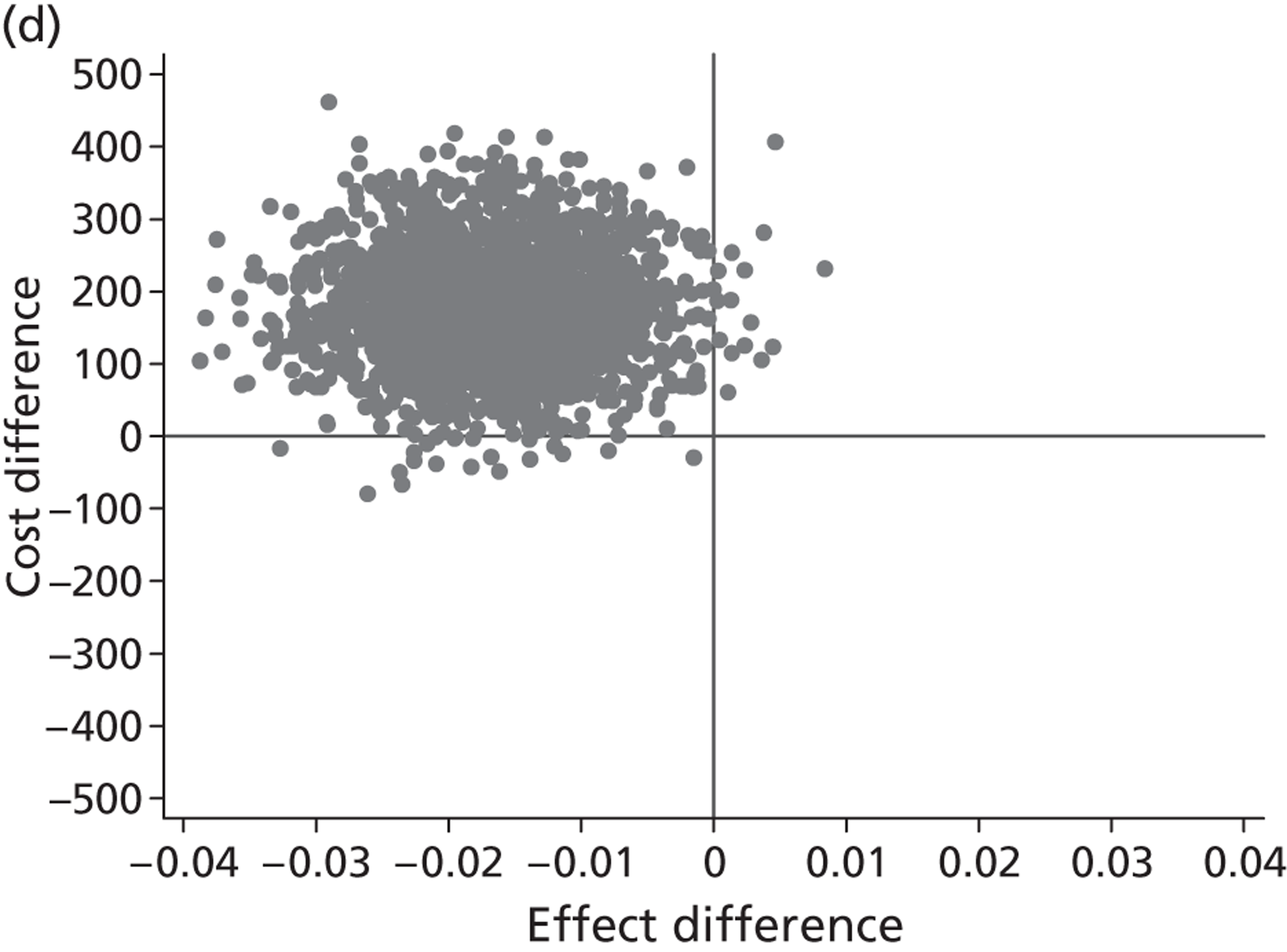

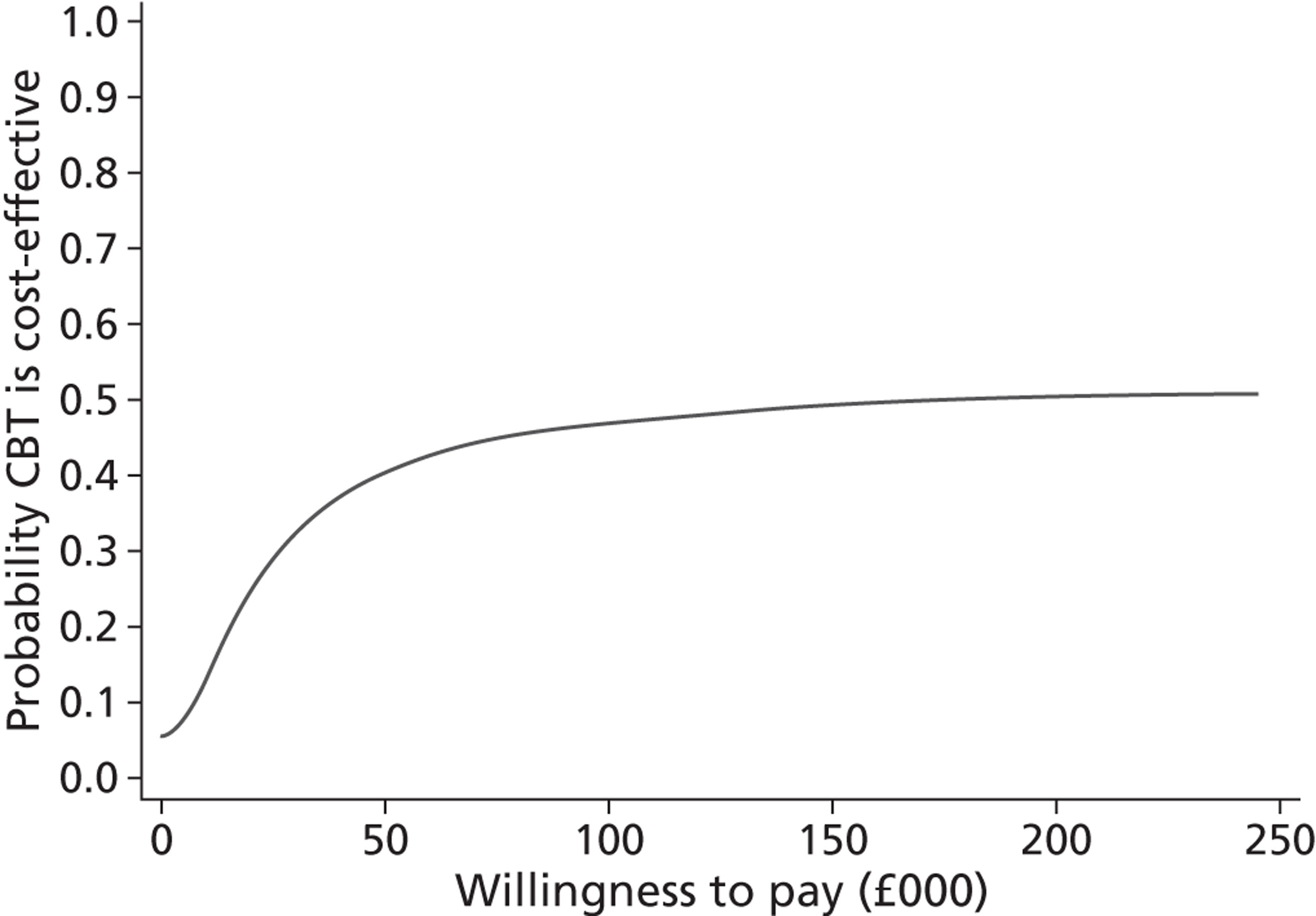

Random effects bivariate linear regression models54 were fitted to model cost and effectiveness (SMFQ or QALY) simultaneously, allowing for correlation within clusters and correlation between cost and effectiveness score within participants. Estimates of the mean difference in costs and corresponding standard error, the mean difference in effect and corresponding standard error and (indirectly via the variance–covariance matrix of the regression coefficients) the correlation between the mean cost difference were obtained from these models. Where the ICER was in the north-east quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane (i.e. intervention has both higher costs and greater effectiveness than control), Fieller's method was applied to obtain a parametric estimate of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the ICER and construct the cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC). 49 The degrees of freedom (df) for these calculations (implemented in Stata using the ‘fielleri’ and ‘accepti’ commands) were based on the number of clusters.

For all adjusted analyses, the joint distribution of the difference in costs and effects was displayed using a scatterplot with 2000 cost–effect data pairs generated parametrically (using simulation) from a bivariate normal distribution based on the estimates from the random effects bivariate regression model used to model the cost and effect outcomes. The parametric scatterplots were similar to those generated using a non-parametric bootstrap approach and so, for consistency, we present only the former. Note that because the cost of the intervention must be apportioned across all participants in a given trial arm, both the SMFQ- and QALY-based cost-effectiveness results are based on the whole sample with valid cost and outcome data (i.e. not just those assessed as high risk as in the primary effectiveness analysis). Given the short time horizon, neither costs nor outcomes were discounted to present values.

Chapter 3 Results: pilot study

Altogether, 326 and 387 girls agreed to participate in the pilot study (89.1% of the eligible population). Ninety-two per cent of those who completed the baseline assessment were retained at 6 months and 80.2% were retained at 12 months. Details of participant flow by trial arm are provided in Figure 1.

Symptom change

A decrease in SMFQ scores was observed across all trial arms in the high-risk group from the baseline assessment to the 12-month follow up (F = 7.55, df 1; p < 0.01). However, the pilot study was not powered to assess between group differences on the primary outcome measure (SMFQ).

Feasibility of intervention delivery

Classroom-based CBT was provided to students in school years 8 and 10. All nine RAP-UK sessions were delivered to 15 classes, with the remaining class receiving eight sessions. A total of 137 (95.2%) RAP-UK sessions were delivered as intended by two facilitators, with the other seven sessions being led by one facilitator. A total of seven sessions were unexpectedly cancelled owing to adverse weather (n = 2), early school closure (n = 1), bank holidays (n = 1), examinations (n = 1), a school project day (n = 1) and PSHE itself being cancelled (n = 1). Of the 409 eligible children in years 8 and 10, only nine (2.2%) failed to attend any RAP-UK sessions. Of these, five had either been excluded from or moved school before the sessions started. Approximately half (n = 188; 46.0%) attended all nine sessions, with 357 (87.3%) attending seven or more sessions.

Classroom-based CBT facilitators rated the coverage of self-esteem, emotional awareness and positive thinking over the course of the programme significantly higher (p < 0.05) than the attention control PSHE facilitators, who gave the highest ratings to the coverage of topics traditionally covered in PSHE (i.e. bullying, smoking, drugs, alcohol, sex education, ethical issues, diversity, religion and citizenship). There was no significant difference between the groups in the specific focus on depression, although classroom-based CBT facilitators rated the direct focus on mental health more highly.

Acceptability of the classroom-based cognitive–behavioural therapy programme (Resourceful Adolescent Programme UK)

Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with 19 students (nine from year 8 and 10 from year 10) who took part in the classroom-based CBT (RAP-UK). Overall, feedback was positive. Students liked the content, the positive focus and the way in which the individual sessions built upon each other. The accompanying workbook was liked by most of the younger students, but some of the older students thought that it was pitched at too young a level. Some students expressed a preference for more ‘hands-on’ activities, role plays and discussions. A number of students also felt that the video clips were outdated or unclear. The sessions that students found most helpful were those focusing on problem solving, emotional recognition, the connection between thoughts and feelings, thought checking and relaxation. Those that focused on identifying and changing unhelpful thoughts were seen as repetitive and the support network session was considered by some to be too long.

A focus group was undertaken with the eight teachers whose classes received the classroom-based CBT. Initially, teachers were concerned about addressing mental health in a group, but they felt reassured by the end of the programme. Teachers were generally positive about the programme facilitators and the way in which assessments were conducted. They felt that some of the concepts in RAP-UK were memorable for themselves as well as for the students, such as negative thinking traps and ‘snowballing’. It was felt that the benefits of the programme might not be obvious immediately, but that the skills students acquired could be useful when they encountered problems later in their lives. Teachers liked the content of the programme, but at times felt it was pitched more towards the younger students (year 8) and may not have stretched the most able students. Teachers also raised concerns about the ability of less able students to engage with the classroom-based CBT.

Disruptive student behaviour in classes was a major issue, particularly if students became disengaged. The ability of facilitators to manage student behaviour came to light, with additional support from other members of staff in the classroom being viewed as essential, particularly when working with large classes and managing small group activities. Teachers felt that the sessions were sometimes repetitive and had many ideas about how sessions could be more interactive and engaging, such as making the graphics in the workbooks more age appropriate, updating some of the materials (particularly the video clips) and using more practical tasks in addition to the discussions.

The feedback from teachers and young people was used to revise RAP-UK by condensing some of the sessions, adding more interactive tasks, modifying the workbook so that it was more age appropriate (e.g. using photos instead of cartoons, changing the colour scheme and font) and updating multimedia materials.

Chapter 4 Results: main trial

Reach and attrition

Participant flow for the main trial is shown in Figure 2.

A summary of the demographic profile of the eight participating schools compared with national averages is presented in Table 4.

| School | Pupils in trial (n) | White (%)55 | Special needs without statements (%)55 | Overall absence (%)56 | Persistent absence (%)56 | Achieving five A*–C GCSE passes including level 2 English and maths (%)57 | Eligible for free school meals (%)55 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 710 | 63.8 | 20.2 | 5.4 | 2.7 | 69 | 11.9 |

| 2 | 623 | 89.7 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 7.7 | 61 | 7.0 |

| 3 | 835 | 93.2 | 17.9 | 6.5 | 5.1 | 55 | 9.5 |

| 4 | 783 | 95.3 | 6.9 | 6.1 | 2.8 | 75 | 2.5 |

| 5 | 848 | 77.6 | 36.0 | 11.1 | 13.8 | 36 | 31.2 |

| 6 | 530 | 83.5 | 10.5 | 4.7 | 1.7 | No year 11 | 3.3 |

| 7 | 534 | 92.8 | 10.1 | 7.7 | 6.2 | 47 | 7.6 |

| 8 | 167 | 98.7 | 19.7 | 7.9 | 7.4 | 48 | 9.2 |

| Total trial | 5030 | 85.5 | 16.8 | 7.3 | 6.0 | 56.7 | 11.2 |

| UK national average | NA | 81.2 | 19.7 | 6.9 | 4.4 | 50 | 15.4 |

The study cohort had a greater percentage of white students, were more academically able and had fewer students eligible for free school meals than the national average.

Altogether, 2563 boys and 2467 girls agreed to participate (91.4% of the eligible population). Of the 5030 participants, 1064 (21.2%) were classified as high risk. These had been allocated to usual PSHE (n = 298), attention control PSHE (n = 374) or classroom-based CBT (n = 392). Valid primary outcome data at 12 months were available for usual PSHE (n = 242; 81%), attention control PSHE (n = 308; 82%) and classroom-based CBT (n = 296; 76%).

For all participants, the median percentage of sessions attended was 89% (quartiles 67–100) in the classroom-based CBT group and 100% (quartiles 88–100) in the attention control PSHE group, with 80% of those in the classroom-based CBT group and 95% of the attention control PSHE groups attending at least 60% of sessions. One year group (n = 199) was withdrawn from classroom-based CBT after four sessions because of school closures in adverse weather. When this year group was removed from analysis, the median percentage of classroom-based CBT sessions attended was 89% (quartiles 78–100), with 92.2% attending at least 60% of sessions. For the high-risk participants, the median percentage of sessions attended was 88% (quartiles 67–100) in the classroom-based CBT arm and 89% (quartiles 78–100) in the attention control PSHE arm. The percentage of participants attending more than 60% of sessions was 80% and 93% in the classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE groups, respectively. Details were not collected on PSHE attendance in the usual PSHE arm.

Balance between trial arms

Characteristics of high-risk individuals at baseline were well balanced between trial arms, apart from alcohol, street drug and cannabis use and bullying others, which were reported by fewer participants in the usual PSHE group (Table 5).

The proportion of high-risk participants within the arms was also slightly higher in the classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE arms than in the usual PSHE arm (22.4%, 22.4% and 18.6%, respectively) (Table 6).

| Variable | Level | High-risk group (N = 1064) | All participants (N = 5030) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (n = 298) | Classroom-based CBT (n = 392) | Attention control PSHE (n = 374) | Usual PSHE (n =1604) | Classroom-based CBT (n = 1753) | Attention control PSHE (n = 1673) | ||

| Sex | Male | 101 (33.9) | 132 (33.7) | 135 (36.1) | 834 (52.0) | 880 (50.2) | 849 (50.7) |

| Female | 197 (66.1) | 260 (66.3) | 239 (63.9) | 770 (48.0) | 873 (49.8) | 824 (49.3) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 246 (86.6) | 314 (87.7) | 286 (81.7) | 1275 (86.1) | 1372 (86.7) | 1271 (83.6) |

| Non-white | 38 (13.4) | 44 (12.3) | 64 (18.3) | 205 (13.9) | 210 (13.3) | 250 (16.4) | |

| Living situation | Mother and father | 149 (53.4) | 186 (52.0) | 189 (53.7) | 981 (66.9) | 972 (62.2) | 1019 (67.1) |

| Parent and partner | 46 (16.5) | 64 (17.9) | 69 (19.6) | 193 (13.2) | 224 (14.3) | 189 (12.4) | |

| Single parent | 73 (26.2) | 96 (26.8) | 87 (24.7) | 262 (17.9) | 343 (22.0) | 283 (18.6) | |

| Other | 11 (3.9) | 12 (3.4) | 7 (2.0) | 30 (2.0) | 23 (1.5) | 29 (1.9) | |

| Year group | 8 | 112 (37.6) | 66 (16.8) | 79 (21.1) | 569 (35.5) | 470 (26.8) | 374 (22.4) |

| 9 | 89 (29.9) | 81 (20.7) | 102 (27.3) | 469 (29.2) | 384 (21.9) | 541 (32.3) | |

| 10 | 17 (5.7) | 153 (39.0) | 144 (38.5) | 179 (11.2) | 583 (33.3) | 562 (33.6) | |

| 11 | 80 (26.8) | 92 (23.5) | 49 (13.1) | 387 (24.1) | 316 (18.0) | 196 (11.7) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | Years | 13.9 (1.2) | 14.4 (1.0) | 14.1 (1.0) | 13.9 (1.2) | 14.1 (1.1) | 14.0 (1.0) |

| Trial arm | 6 months | 12 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | |

| Usual PSHE (n = 1495) | ||||

| Risk status | ||||

| Low (n = 1197) | 929/1110 (83.7%) | 181/1110 (16.3%) | 890/1040 (85.6%) | 150/1040 (14.4%) |

| High (n = 298) | 77/264 (29.2%) | 187/264 (70.8%) | 104/242 (43.0%) | 138/242 (57.0%) |

| Classroom-based CBT (n = 1583) | ||||

| Risk status | ||||

| Low (n = 1191) | 886/1090 (81.3%) | 204/1090 (18.7%) | 821/994 (82.6%) | 173/994 (17.4%) |

| High (n = 392) | 83/330 (25.2%) | 247/330 (74.8%) | 106/296 (35.8%) | 190/296 (64.2%) |

| Attention control (n = 1506) | ||||

| Risk status | ||||

| Low (n = 1132) | 839/1022 (82.1%) | 183/1022 (17.9%) | 789/954 (82.7%) | 165/954 (17.3%) |

| High (n = 374) | 78/341 (22.9%) | 263/341 (77.1%) | 90/308 (29.2%) | 218/308 (70.8%) |

Implementation

Classroom-based cognitive–behavioural therapy delivery

The classroom-based CBT arm included 79 classes. Intervention delivery was adapted to fit in with the existing structure of PSHE delivery within schools, with all programmes covering the core content and key tasks. The RAP-UK programme used was delivered in weekly lessons to 41 classes, while 22 classes had fortnightly lessons and 16 classes had other formats (project days or condensed programme over 3 weeks). All nine sessions were delivered to 71 classes, while four classes had a condensed eight-session programme and four classes had a seven-session programme. The RAP-UK programme was terminated after the fourth session for a whole year group (eight classes) in one school. This was due to disruption caused by adverse weather, which led to several days of school closure. Owing to competing priorities (i.e. making up time for examined subjects), the school was unable to complete the programme.

The additional RAP-UK booster sessions offered were completed by 40 of the classroom-based CBT classes. Of those classes that did not complete the boosters, eight were those that had terminated the programme at session 4, 16 classes were originally in year 11 so either had left school or were not doing PSHE the following academic year, eight classes had moved from year 10 to year 11 and no longer did PSHE, and one year group opted not to complete the booster sessions. Therefore, a total of 832 young people in the classroom-based CBT group (47.8%) attended at least one RAP-UK booster session to refresh and consolidate their skills approximately 6 months after completing the core programme.

Facilitators

Classroom-based CBT was delivered by 39 facilitators, while 35 people facilitated the attention control PSHE sessions. Classroom-based CBT was led by two facilitators, as intended, in 94.3% of sessions, with 5.7% being led by a single facilitator. There were two facilitators present at 83.1% of attention control PSHE sessions with 16.9% being attended by a single facilitator. To fit in with school timetables, a large number of facilitators were required as whole year groups or even whole schools received PSHE at the same time in some cases. This meant recruiting, training and managing a much larger team of facilitators than was originally anticipated. This had an impact on cost as well as causing operational difficulties with cover for staff absences/sickness and ensuring that the facilitators had sufficient regular working hours to make the posts viable.

Treatment fidelity

Of the 36 classroom-based CBT sessions observed to assess intervention fidelity, 31 covered all the core tasks, with at least 75% of core tasks being covered in the remaining five sessions. Differences in facilitator ratings of lesson content for classroom-based CBT versus attention control PSHE were examined using one-way analysis of variance and indicated that the classroom-based CBT focused more on self-esteem, emotional awareness and positive thinking, and less on topics traditionally covered in PSHE, i.e. sex education, ethical issues, diversity, religion and citizenship (all p < 0.05). There was no difference between classroom-based CBT and attention control PSHE in facilitators' views of student engagement with lessons.

High-risk participants: primary outcome (Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire)

There was a decrease in symptoms of depression between baseline and 12 months for the high-risk group overall (F = 158.8, df 1, p < 0.001). However, there was no evidence of an effect of classroom-based CBT on SMFQ at 12 months relative to attention control PSHE or usual PSHE (see Table 5). The 95% CIs for the adjusted treatment difference excluded the predefined clinically important difference of two points. Likewise, there was no evidence of an effect of classroom-based CBT when compared with usual PSHE on continuous SMFQ score at 6 months (Table 7).

| Time point | Usual PSHE, mean (SD) | Classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE adjusted difference from baseline (95% CI) | Classroom-based CBT, mean (SD) | Classroom-based CBT vs. attention control adjusted difference from baseline (95% CI) | Attention control PSHE, mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 10.56 (4.93) | NA | 10.64 (4.91) | NA | 10.60 (4.67) |

| 12 months | 6.81 (5.70) (n = 242) | 0.97 (−0.34 to 2.28); p = 0.067 | 8.22 (6.45) (n = 296) | −0.63 (−1.99 to 0.73); p = 0.249 | 8.50 (5.88) (n = 308) |

| 6 months | 8.61 (6.01) (n = 264) | 0.56 (−0.41 to 1.53); p = 0.259 | 9.22 (6.39) (n = 330) | −0.35 (−1.38 to 0.68); p = 0.505 | 9.44 (5.84) (n = 341) |

Further adjustment for variables that were imbalanced at baseline indicated that classroom-based CBT may have had a small but potentially harmful effect compared with usual PSHE (1.21, 95% CI 0.11 to 2.30, p = 0.031).

There was some evidence of a beneficial effect of classroom-based CBT when compared with attention control PSHE at 12 months for SMFQ as a binary outcome (which indicates the odds of being reclassified as ‘low risk’ at follow-up) (Table 8).

| Usual PSHE: 12 months, n (%) | Classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE, adjusted OR (95% CI) | Classroom-based CBT: 12 months, n (%) | Classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE, adjusted OR (95% CI) | Attention control PSHE: 12 months, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104/242 (43.0) | 0.85 (0.58 to 1.26); p = 0.429 | 106/296 (35.8) | 1.64 (1.08 to 2.51); p = 0.021 | 90/308 (29.2) |

Repeated-measures mixed-effects analyses showed no effect of classroom-based CBT over time for SMFQ score (classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE interaction coefficient −0.17, 95% CI −1.40 to 1.06, p = 0.785; classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE interaction coefficient 0.72, 95% CI −0.59 to 2.03, p = 0.282). The effect of classroom-based CBT in high-risk participants was not modified by any of the predefined subgroups we examined (Table 9). A post hoc interaction analysis showed no modification of effect by sex.

| Variable | Level | Classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE | Classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interaction (95% CI) | p-value | Interaction (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| SMFQ | 5–10 | Reference | 0.583 | Reference | 0.778 |

| 11+ | 0.56 (−1.44 to 2.55) | −0.27 (−2.14 to 1.60) | |||

| Self-harm thoughts | Yes | 0.52 (−1.48 to 2.53) | 0.607 | 0.15 (−1.73 to 2.03) | 0.880 |

| Self-harm behaviour | Yes | 0.52 (−1.69 to 2.73) | 0.644 | −1.35 (−3.38 to 0.68) | 0.192 |

| Alcohol use | Yes | −0.75 (−3.05 to 1.55) | 0.522 | −1.10 (−3.22 to 1.02) | 0.308 |

| Street drug use | Yes | −4.37 (−11.38 to 2.65) | 0.222 | −2.71 (−6.78 to 1.37) | 0.193 |

| Cannabis use | Yes | −1.95 (−5.37 to 1.46) | 0.263 | −2.30 (−5.08 to 0.48) | 0.105 |

| Year group | 8 | Reference | 0.832 | Reference | 0.212 |

| 9 | −1.64 (−6.44 to 3.16) | −1.95 (−6.41 to 2.50) | |||

| 10 | −2.44 (−7.83 to 2.95) | −1.83 (−5.32 to 1.66) | |||

| 11 | −1.59 (−6.64 to 3.47) | −5.33 (−10.55 to −0.11) | |||

| Sex | Female | −0.02 (−2.03 to 1.99) | 0.981 | 0.87 (−1.02 to 2.76) | 0.365 |

| Age | −0.32 (−1.39 to 0.75) | 0.559 | −0.81 (−1.90 to 0.28) | 0.144 | |

| Family Affluence Scale | −0.45 (−1.11 to 0.21) | 0.183 | −0.02 (−0.68 to 0.64) | 0.945 | |

High-risk participants: secondary outcomes

In the high-risk group, there was some evidence of a potentially harmful effect of classroom-based CBT relative to usual PSHE for CATS personal failure scores at 12 months (adjusted difference 1.95, 95% CI 0.25 to 3.66). However, there was also evidence of a potentially beneficial effect of classroom-based CBT on RCADS depression at 12 months compared with usual PSHE (adjusted difference 0.64, 95% CI 0.06 to 1.21) and on self-harm thoughts at 6 months compared with attention control PSHE [odds ratio (OR) 0.58, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.97]. Details of adjusted differences, adjusted ORs and CIs for analysis of the secondary outcomes are provided in Tables 10 and 11.

In repeated-measures regression analysis, no effect of classroom-based CBT over time was observed for any of the secondary outcomes in either high-risk participants or all participants.

| Variable | Usual PSHE | Adjusted OR (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Classroom-based CBT | Adjusted OR (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Attention control PSHE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%), | Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%) | Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%) | |||

| Bullying others | 80 (28.88) | 77 (30.08) | 41 (18.06) | 0.66 (0.42 to 1.05), 1.29 (0.75 to 2.23) | 96 (26.82) | 73 (23.25) | 55 (20.83) | 0.79 (0.47 to 1.32), 0.96 (0.55 to 1.69) | 118 (33.71) | 88 (26.51) | 57 (20.50) |

| Self-harming thoughts | 147 (53.07) | 111 (43.53) | 90 (38.96) | 0.92 (0.58 to 1.45), 1.06 (0.69 to 1.63) | 197 (55.18) | 142 (45.08) | 123 (46.42) | 0.58 (0.35 to 0.97), 0.93 (0.59 to 1.46) | 189 (54.15) | 167 (50.76) | 126 (45.00) |

| Self-harming behaviour | 77 (27.70) | 69 (27.17) | 51 (22.17) | 0.92 (0.56 to 1.51), 1.18 (0.71 to 1.99) | 106 (29.86) | 95 (30.16) | 77 (29.39) | 0.93 (0.55 to 1.58), 1.00 (0.56 to 1.74) | 109 (31.23) | 105 (32.31) | 71 (25.54) |

| Alcohol misuse | 77 (28.00) | 81 (31.89) | 70 (30.57) | 0.89 (0.54 to 1.46), 1.44 (0.84 to 2.47) | 112 (31.28) | 108 (34.73) | 105 (39.33) | 1.00 (0.60 to 1.68), 1.26 (0.72 to 2.20) | 97 (27.95) | 109 (33.33) | 99 (35.61) |

| Street drug misuse | 7 (2.55) | 10 (3.94) | 13 (5.70) | 0.93 (0.26 to 3.38), 1.22 (0.43 to 3.44) | 25 (7.00) | 18 (5.79) | 20 (7.55) | 1.47 (0.47 to 4.68), 2.93 (1.00 to 8.61) | 16 (4.58) | 15 (4.55) | 12 (4.30) |

| Cannabis misuse | 30 (10.87) | 31 (12.35) | 44 (19.30) | 1.18 (0.58 to 2.42), 0.67 (0.36 to 1.27) | 53 (14.85) | 57 (18.15) | 65 (24.34) | 0.94 (0.45 to 1.97), 1.30 (0.70 to 2.42) | 63 (17.95) | 66 (20.06) | 55 (19.57) |

| Variable | Usual PSHE | Adjusted difference (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Classroom-based CBT | Adjusted difference (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Attention control PSHE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | |||

| CATS | 12.20 (9.28) | 10.16 (9.52) | 8.18 (8.68) | 1.20 (−0.39 to 2.78), 1.95 (0.25 to 3.66) | 12.40 (9.21) | 11.51 (10.53) | 10.48 (10.00) | 0.71 (−1.03 to 2.45), 0.29 (−1.48 to 2.07) | 13.35 (8.99) | 11.64 (9.87) | 10.63 (9.94) |

| Self-esteem | 15.88 (4.80) | 16.58 (5.22) | 17.39 (5.34) | 0.02 (−0.81 to 0.85), 0.12 (−0.81 to 1.05) | 15.54 (4.70) | 16.33 (5.39) | 16.93 (5.65) | 0.13 (−0.76 to 1.02), −0.13 (−1.12 to 0.87) | 15.36 (4.38) | 16.02 (4.38) | 16.68 (5.25) |

| General anxiety | 5.74 (2.87) | 5.55 (2.96) | 4.67 (3.05) | 0.16 (−0.34 to 0.66), 0.41 (−0.15 to 0.97) | 5.92 (2.84) | 5.63 (2.96) | 5.18 (3.12) | −0.00 (−0.54 to 0.53), −0.24 (−0.82 to 0.35) | 5.77 (2.86) | 5.76 (3.08) | 5.40 (2.91) |

| Separation anxiety | 2.26 (2.19) | 1.94 (2.36) | 1.65 (2.17) | 0.15 (−0.25 to 0.54), 0.04 (−0.37 to 0.44) | 2.27 (2.26) | 2.07 (2.50) | 1.98 (2.34) | 0.11 (−0.31 to 0.53), −0.18 (−0.60 to 0.25) | 2.35 (2.31) | 2.12 (2.56) | 2.09 (2.45) |

| Social phobia | 6.64 (3.24) | 6.11 (3.17) | 5.72 (3.31) | 0.24 (−0.27 to 0.76), 0.34 (−0.26 to 0.93) | 6.87 (3.33) | 6.39 (3.43) | 6.26 (3.57) | 0.27 (−0.27 to 0.82) 0.02 (−0.60 to 0.64) | 6.58 (3.22) | 6.34 (3.52) | 6.34 (3.48) |

| Panic | 4.15 (3.19) | 3.85 (3.48) | 3.17 (3.23) | 0.25 (−0.28 to 0.77), 0.25 (−0.31 to 0.81) | 4.35 (3.17) | 4.25 (3.48) | 3.79 (3.49) | 0.11 (−0.44 to 0.66), −0.25 (−0.84 to 0.34) | 4.14 (3.16) | 4.05 (3.34) | 3.59 (3.18) |

| Depression | 5.27 (2.83) | 4.69 (3.19) | 4.06 (3.26) | 0.24 (−0.28 to 0.75), 0.64 (0.06 to 1.21) | 5.64 (2.88) | 5.20 (3.39) | 4.94 (3.32) | −0.10 (−0.65 to 0.46), −0.02 (−0.65 to 0.60) | 5.47 (3.10) | 5.10 (3.25) | 4.83 (3.19) |

| RCADS | 24.07 (10.69) | 22.11 (11.59) | 19.27 (11.64) | 1.07 (−0.81 to 2.95), 1.48 (−0.64 to 3.59) | 25.04 (10.80) | 23.42 (12.22) | 22.16 (12.38) | 0.23 (−1.76 to 2.23), −0.60 (−2.88 to 1.67) | 24.29 (11.01) | 23.39 (12.23) | 22.27 (11.74) |

| School connectedness | 26.22 (6.19) | 25.82 (6.76) | 26.84 (6.94) | 0.11 (−0.86 to 1.08), 0.42 (−0.70 to 1.55) | 25.36 (6.20) | 25.85 (6.85) | 26.18 (6.80) | 0.25 (−0.78 to 1.29), 0.57 (−0.65 to 1.80) | 25.17 (6.04) | 25.29 (6.36) | 25.94 (6.64) |

All participants: primary outcome (Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire)

Including all participants in the analysis, there was no evidence of an effect of classroom-based CBT on SMFQ score at 12 months (classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE 0.27, 95% CI −0.08 to 0.62; classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE −0.01, 95% CI −0.42 to 0.39) or an effect of classroom-based CBT on SMFQ score over time (classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE interaction coefficient −0.04, 95% CI −0.47 to 0.40, p = 0.869; classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE 0.04, 95% CI −0.39 to 0.48, p = 0.848).

In the subgroup analysis (Table 12), there was some suggestion of a beneficial effect of classroom-based CBT compared with both control groups in those who used ‘street drugs’ (classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE interaction coefficient −4.62, 95% CI −8.14 to −1.11; classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE interaction coefficient −3.41, 95% CI −5.82 to −0.99), but of a possible harmful effect compared with usual PSHE among those who reported self-harm behaviour (interaction coefficient 1.57, 95% CI 0.37 to 2.78).

| Variable | Level | Classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE | Classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interactiona | p-value | Interactiona | p-value | ||

| SMFQ | < 5 | Reference | 0.069 | Reference | 0.117 |

| 5–10 | −0.01 (−0.88 to 0.85) | −0.81 (−1.65 to 0.02) | |||

| 11+ | 1.35 (0.19 to 2.51) | −0.64 (−1.76 to 0.47) | |||

| Self-harm thoughts | Yes | 0.86 (−0.00 to 1.71) | 0.051 | −0.31 (−1.12 to 0.50) | 0.457 |

| Self-harm behaviour | Yes | 1.57 (0.37 to 2.78) | 0.010 | −0.47 (−1.56 to 0.60) | 0.393 |

| Alcohol use | Yes | −0.39 (−1.28 to 0.51) | 0.400 | −0.57 (−1.49 to 0.35) | 0.225 |

| Street drug misuse | Yes | −4.62 (−8.14 to −1.11) | 0.010 | −3.41 (−5.82 to −0.99) | 0.006 |

| Cannabis misuse | Yes | −0.18 (−1.61 to 1.25) | 0.800 | −1.33 (−2.64 to −0.02) | 0.047 |

| Year group | 8 | Reference | 0.892 | Reference | 0.994 |

| 9 | 0.23 (−1.36 to 1.82) | 0.03 (−1.44 to 1.50) | |||

| 10 | 0.48 (−1.06 to 2.03) | −0.11 (−1.28 to 1.06) | |||

| 11 | 0.56 (−1.21 to 2.33) | −0.12 (−2.14 to 1.89) | |||

| Sex | Female | −0.09 (−0.73 to 0.55) | 0.780 | −0.26 (−0.90 to 0.38) | 0.428 |

| Age | 0.20 (−0.17 to 0.56) | 0.294 | −0.00 (−0.41 to 0.41) | 0.998 | |

| Family Affluence Scale | −0.21 (−0.45 to 0.04) | 0.100 | 0.07 (−0.19 to 0.32) | 0.619 | |

All participants: secondary outcomes

Among all participants, there was some evidence of a beneficial effect of classroom-based CBT on bullying status at 12 months when compared with attention control PSHE (OR 0.69, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.94) and on cannabis use at 6 months (OR 0.56, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.82) and 12 months (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.48 to 0.93) when compared with usual PSHE. However, there was also evidence that classroom-based CBT was less useful than usual PSHE for panic symptoms at 6 and 12 months, less useful than attention control PSHE for panic symptoms at 6 months and less useful than usual PSHE for CATS personal failure scores at 6 months and general anxiety at 12 months. Full details of adjusted differences, ORs and 95% CIs for this analysis are provided in Tables 13 and 14.

| Variable | Usual care | Adjusted difference (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Classroom-based CBT | Adjusted difference (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Attention control PSHE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | Baseline, mean (SD) | 6 months, mean (SD) | 12 months, mean (SD) | |||

| SMFQ | 3.55 (4.73) | 3.60 (4.78) | 3.21 (4.50) | 0.22 (−0.09 to 0.53), 0.27 (−0.08 to 0.62) | 4.11 (4.95) | 4.24 (5.37) | 3.95 (5.44) | 0.06 (−0.30 to 0.42), −0.01 (−0.42 to 0.39) | 3.90 (4.81) | 4.28 (5.22) | 4.00 (5.21) |

| CATS | 4.07 (6.68) | 3.98 (6.53) | 3.47 (6.09) | 0.51 (0.06 to 0.96), 0.52 (−0.00 to 1.03) | 4.62 (7.08) | 4.86 (7.89) | 4.45 (7.68) | 0.40 (−0.13 to 0.94), 0.07 (−0.52 to 0.66) | 4.72 (7.14) | 4.82 (7.57) | 4.44 (7.44) |

| Self-esteem | 21.44 (5.23) | 21.42 (5.52) | 21.74 (5.43) | −0.07 (−0.39 to 0.24), 0.07 (−0.30 to 0.44) | 20.97 (5.41) | 20.97 (5.57) | 21.48 (5.71) | −0.15 (−0.52 to 0.22), 0.08 (−0.34 to 0.50) | 20.88 (5.31) | 20.97 (5.72) | 21.31 (5.74) |

| General anxiety | 3.11 (2.61) | 3.31 (2.70) | 2.93 (2.65) | 0.12 (−0.07 to 0.30), 0.23 (0.01 to 0.44) | 3.47 (2.71) | 3.66 (2.86) | 3.36 (2.96) | 0.05 (−0.17 to 0.26), −0.00 (−0.25 to 0.24) | 3.19 (2.74) | 3.54 (2.88) | 3.34 (2.86) |

| Separation anxiety | 1.06 (1.56) | 1.03 (1.81) | 0.89 (1.67) | 0.06 (−0.07 to 0.18), 0.04 (−0.10 to 0.19) | 1.21 (1.72) | 1.17 (1.89) | 1.06 (1.93) | 0.07 (−0.07 to 0.22), −0.04 (−0.20 to 0.12) | 1.21 (1.81) | 1.15 (1.89) | 1.12 (1.96) |

| Social phobia | 3.83 (2.88) | 4.10 (2.89) | 4.09 (2.93) | −0.03 (−0.22 to 0.16), −0.12 (−0.35 to 0.10) | 4.19 (3.09) | 4.32 (3.14) | 4.16 (3.27) | 0.11 (−0.12 to 0.33), −0.13 (−0.39 to 0.13) | 4.06 (2.99) | 4.36 (3.17) | 4.33 (3.25) |

| Panic | 1.63 (2.36) | 1.72 (2.49) | 1.49 (2.27) | 0.27 (0.10 to 0.43), 0.30 (0.12 to 0.49) | 1.90 (2.51) | 2.16 (2.74) | 1.95 (2.77) | 0.27 (0.07 to 0.46), 0.19 (−0.03 to 0.40) | 1.77 (2.39) | 1.96 (2.64) | 1.77 (2.52) |

| Depression | 2.17 (2.50) | 2.25 (2.56) | 2.07 (2.53) | 0.03 (−0.14 to 0.20), 0.15 (−0.05 to 0.35) | 2.62 (2.71) | 2.62 (2.81) | 2.54 (2.99) | −0.05 (−0.25 to 0.15), 0.10 (−0.14 to 0.33) | 2.44 (2.73) | 2.62 (2.86) | 2.40 (2.87) |

| RCADS | 11.80 (9.55) | 12.37 (9.88) | 11.48 (9.56) | 0.38 (−0.24 to 1.01), 0.52 (−0.23 to 1.28) | 13.33 (10.30) | 13.89 (10.85) | 13.08 (11.61) | 0.43 (−0.31 to 1.16) 0.06 (−0.81 to 0.94) | 12.63 (10.74) | 13.63 (10.81) | 12.96 (10.94) |

| School connectedness | 31.04 (6.11) | 30.07 (6.42) | 30.48 (6.33) | −0.05 (−0.45 to 0.35), 0.13 (−0.34 to 0.60) | 30.22 (6.29) | 29.63 (6.63) | 30.02 (6.77) | −0.12 (−0.58 to 0.34), 0.21 (−0.33 to 0.76) | 30.19 (6.39) | 29.27 (6.61) | 29.73 (6.79) |

| Variable | Usual PSHE | Adjusted OR (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Classroom-based CBT | Adjusted OR (95% CI):a 6 months, 12 months | Attention control PSHE | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%) | Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%) | Baseline, n (%) | 6 months, n (%) | 12 months, n (%) | |||

| SMFQ (< 5, ≥ 5) | 410 (26.61) | 399 (27.29) | 313 (22.93) | 1.07 (0.87, 1.32), 1.13 (0.91, 1.41) | 533 (32.09) | 495 (32.23) | 408 (29.10) | 0.91 (0.73, 1.15), 0.85 (0.67, 1.08) | 489 (30.91) | 493 (33.27) | 431 (31.39) |

| Bullying others | 215 (14.79) | 223 (15.58) | 161 (12.44) | 0.92 (0.72, 1.17), 0.91 (0.69, 1.20) | 258 (16.57) | 246 (16.67) | 178 (13.60) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.14), 0.69 (0.51, 0.94) | 312 (20.74) | 265 (18.48) | 209 (16.28) |

| Self-harm thoughts | 254 (17.43) | 259 (18.15) | 228 (17.52) | 0.84 (0.65, 1.08), 0.94 (0.73, 1.20) | 315 (20.27) | 274 (18.58) | 254 (19.36) | 0.78 (0.58, 1.05), 1.02 (0.78, 1.33) | 311 (20.66) | 304 (21.16) | 261 (20.17) |

| Self-harm behaviour | 113 (7.76) | 134 (9.42) | 110 (8.47) | 0.98 (0.72, 1.34), 1.20 (0.88, 1.65) | 162 (10.43) | 163 (11.06) | 161 (12.28) | 0.95 (0.67, 1.36), 1.34 (0.92, 1.95) | 160 (10.62) | 176 (12.32) | 139 (10.79) |

| Alcohol misuse | 294 (20.28) | 361 (25.26) | 370 (28.53) | 0.86 (0.68, 1.08), 0.87 (0.69, 1.10) | 328 (21.13) | 358 (24.34) | 375 (28.67) | 1.08 (0.82, 1.42), 1.00 (0.77, 1.30) | 247 (16.54) | 309 (21.64) | 316 (24.61) |

| Street drug misuse | 14 (0.97) | 28 (1.96) | 30 (2.31) | 1.18 (0.61, 2.30), 0.93 (0.50, 1.71) | 48 (3.10) | 45 (3.05) | 51 (3.89) | 1.48 (0.77, 2.86), 1.17 (0.65, 2.11) | 29 (1.93) | 41 (2.86) | 39 (3.02) |

| Cannabis misuse | 100 (6.89) | 143 (10.05) | 167 (12.88) | 0.56 (0.38, 0.82), 0.70 (0.48, 0.93) | 160 (10.33) | 159 (10.77) | 190 (14.48) | 0.71 (0.47, 1.07), 1.12 (0.79, 1.58) | 144 (9.59) | 169 (11.79) | 154 (11.96) |

Complier average causal effect

The instrumental variable analysis in high-risk participants did not alter the conclusions of the primary analysis for classroom-based CBT compared with attention control PSHE (adjusted difference −0.82, 95% CI −1.79 to 0.14; p = 0.093). However, the evidence was strengthened in that mean SMFQ score at 12 months in the classroom-based CBT group was higher (i.e. more symptoms of low mood) than in the usual PSHE group, although not exceeding clinically important levels (adjusted difference 1.43, 95% CI 1.22 to 1.64; p < 0.001).

Multiple imputations and missing data

Multiple imputations of 12-month SMFQ score for high-risk participants had no effect on the main conclusions (Table 15).

| Number of multiple imputations | Adjusted difference (95% CI)a | |

|---|---|---|

| Classroom-based CBT vs. usual PSHE at 12 months | Classroom-based CBT vs. attention control PSHE at 12 months | |

| 0 | 0.97 (−0.07 to 2.01); p = 0.067 | −0.63 (−1.71 to 0.44); p = 0.249 |

| 20 | 0.85 (−0.19 to 1.88); p = 0.110 | −0.56 (−1.64 to 0.52); p = 0.308 |

Comparison of baseline characteristics for participants categorised as high risk showed that individuals with missing primary outcome data tended on average to be slightly older; not living with both parents; using alcohol and cannabis; and bullying others. Within the usual PSHE arm in particular, those with missing primary outcome data were more likely to be engaging in regular self-harm thoughts and behaviour (Tables 16–18).

| Variable | Level | Trial arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (N = 298) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 392) | Attention control PSHE (N = 374) | |||||

| Present (n = 242; 81%) | Missing (n = 56; 19%) | Present (n = 296; 76%) | Missing (n = 96; 24%) | Present (n = 308; 82%) | Missing (n = 66; 18%) | ||

| Sex | Male | 84 (34.7) | 17 (30.4) | 105 (35.5) | 27 (28.1) | 104 (33.8) | 31 (47.0) |

| Female | 158 (65.3) | 39 (69.6) | 191 (64.5) | 69 (71.9) | 204 (66.2) | 35 (53.0) | |

| Ethnicity | White | 198 (86.5) | 48 (87.3) | 245 (88.8) | 69 (84.1) | 239 (82.1) | 47 (79.7) |

| Non-white | 31 (13.5) | 7 (12.7) | 31 (11.2) | 13 (15.9) | 52 (17.9) | 12 (20.3) | |

| Living situation | Mother and father | 129 (57.3) | 20 (37.0) | 147 (53.8) | 39 (45.9) | 165 (56.1) | 24 (41.4) |

| Parent and partner | 36 (16.0) | 10 (18.5) | 49 (17.9) | 15 (17.6) | 56 (19.0) | 13 (22.4) | |

| Single parent | 53 (23.6) | 20 (37.0) | 69 (25.3) | 27 (31.8) | 66 (22.4) | 21 (36.2) | |

| Other | 7 (3.1) | 4 (7.4) | 8 (2.9) | 4 (4.7) | 7 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Year group | 8 | 100 (41.3) | 12 (21.4) | 59 (19.9) | 7 (7.3) | 74 (24.0) | 5 (7.6) |

| 9 | 82 (33.9) | 7 (12.5) | 62 (20.9) | 19 (19.8) | 93 (30.2) | 9 (13.6) | |

| 10 | 13 (5.4) | 4 (7.1) | 124 (41.9) | 29 (30.2) | 129 (41.9) | 15 (22.7) | |

| 11 | 47 (19.4) | 33 (58.9) | 51 (17.2) | 41 (42.7) | 12 (3.9) | 37 (56.1) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | Years | 13.7 (1.1) | 14.7 (1.2) | 14.3 (1.0) | 14.9 (0.9) | 13.9 (0.9) | 14.9 (1.0) |

| Variable | Trial arm, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (N = 298) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 392) | Attention control PSHE (N = 374) | ||||

| Present (n = 242; 81%) | Missing (n = 56; 19%) | Present (n = 296; 76%) | Missing (n = 96; 24%) | Present (n = 308; 82%) | Missing (n = 66; 18%) | |

| SMFQ | 10.5 (4.8) | 10.9 (5.4) | 10.6 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.9) | 10.8 (4.1) | 10.6 (4.8) |

| CATS | 12.0 (9.1) | 13.2 (10.2) | 11.9 (9.0) | 14.0 (9.7) | 12.9 (8.0) | 13.4 (9.2) |

| Self-esteem | 16.2 (4.7) | 14.7 (5.1) | 15.7 (4.8) | 15.1 (4.4) | 15.7 (4.3) | 15.3 (4.4) |

| General anxiety | 5.7 (2.9) | 5.7 (2.6) | 5.8 (2.8) | 6.4 (3.1) | 5.3 (2.4) | 5.9 (2.9) |

| Separation anxiety | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.1 (2.2) | 2.3 (2.3) | 2.3 (2.2) | 2.3 (1.9) | 2.4 (2.4) |

| Social phobia | 6.6 (3.2) | 6.7 (3.3) | 6.8 (3.4) | 7.0 (3.2) | 6.9 (3.1) | 6.5 (3.2) |

| Panic | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.3 (3.4) | 4.3 (3.2) | 4.5 (3.0) | 4.2 (2.8) | 4.1 (3.2) |

| Depression | 5.2 (2.8) | 5.5 (3.0) | 5.6 (2.9) | 5.9 (2.9) | 6.1 (3.2) | 5.3 (3.1) |

| RCADS | 24.0 (10.8) | 24.4 (10.3) | 24.7 (10.8) | 26.1 (10.7) | 24.9 (9.5) | 24.2 (11.3) |

| School connectedness | 26.2 (6.2) | 26.2 (6.2) | 25.2 (6.2) | 25.9 (6.1) | 26.2 (6.7) | 25.0 (5.9) |

| Variable | Level | Trial arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (N = 298) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 392) | Attention control PSHE (N = 374) | |||||

| Present (n = 242; 81%) | Missing (n = 56; 19%) | Present (n = 296; 76%) | Missing (n = 96; 24%) | Present (n = 308; 82%) | Missing (n = 66; 18%) | ||

| Self-harm thoughts | Never | 110 (48.7) | 20 (39.2) | 117 (42.7) | 43 (51.8) | 26 (46.4) | 134 (45.7) |

| Once or twice | 81 (35.8) | 21 (41.2) | 117 (42.7) | 27 (32.5) | 23 (41.1) | 109 (37.2) | |

| 3 or more times | 35 (15.5) | 10 (19.6) | 40 (14.6) | 13 (15.7) | 7 (12.5) | 50 (17.1) | |

| Self-harm behaviour | Never | 165 (72.7) | 36 (70.6) | 187 (68.8) | 62 (74.7) | 35 (62.5) | 205 (70.0) |

| Once or twice | 39 (17.2) | 11 (21.6) | 55 (20.2) | 13 (15.7) | 14 (25.0) | 48 (16.4) | |

| 3 or more times | 23 (10.1) | 4 (7.8) | 30 (11.0) | 8 (9.6) | 7 (12.5) | 40 (13.7) | |

| Alcohol consumption | Never drank alcohol | 69 (30.8) | 8 (15.7) | 70 (25.5) | 12 (14.5) | 9 (16.4) | 79 (27.1) |

| Once or twice | 99 (44.2) | 22 (43.1) | 126 (45.8) | 38 (45.8) | 26 (47.3) | 136 (46.6) | |

| More than 2–4 times a month | 49 (21.9) | 15 (29.4) | 59 (21.5) | 22 (26.5) | 13 (23.6) | 62 (21.2) | |

| More than once a week | 7 (3.1) | 6 (11.8) | 20 (7.3) | 11 (13.3) | 7 (12.7) | 15 (5.1) | |

| Street drug misuse | Never taken | 222 (98.7) | 46 (92.0) | 257 (93.8) | 75 (90.4) | 55 (98.2) | 278 (94.9) |

| Once or twice | 3 (1.3) | 2 (4.0) | 15 (5.5) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (1.8) | 14 (4.8) | |

| 2–4 times a month | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 2 (0.7) | 3 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| More than once a week | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Cannabis misuse | Never smoked | 207 (91.6) | 39 (78.0) | 243 (88.0) | 61 (75.3) | 36 (63.2) | 252 (85.7) |

| Once or twice | 14 (6.2) | 1 (2.0) | 21 (7.6) | 16 (19.8) | 17 (29.8) | 34 (11.6) | |

| 2–4 times a month | 5 (2.2) | 4 (8.0) | 7 (2.5) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.8) | 7 (2.4) | |

| More than once a week | 0 (0.0) | 6 (12.0) | 5 (1.8) | 3 (3.7) | 3 (5.3) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Bullying others | Never | 166 (73.5) | 31 (60.8) | 207 (75.5) | 55 (65.5) | 31 (54.4) | 201 (68.6) |

| Once or twice | 54 (23.9) | 20 (39.2) | 53 (19.3) | 22 (26.2) | 22 (38.6) | 77 (26.3) | |

| 2–3 times a month | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 9 (3.3) | 3 (3.6) | 2 (3.5) | 11 (3.8) | |

| Once a week | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (2.4) | 2 (3.5) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Several times a week | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.0) | |

Comparison of baseline characteristics for all participants showed that those individuals with missing primary outcome data tended on average to be slightly older; to be living with a single parent or parent and their partner; to score noticeably worse on the psychometric scales; to be regularly using alcohol, street drugs and cannabis; and to be regularly bullying others. Within the usual PSHE arm in particular, those with missing primary outcome data were more likely to be engaging in regular self-harm thoughts and behaviour (Tables 19–21).

| Trial arm | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Level | Usual PSHE (N = 1604) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 1753) | Attention control PSHE (N = 1673) | |||

| Present (n = 1365; 85%) | Missing (n = 239; 15%) | Present (n = 1402; 80%) | Missing (n = 351; 20%) | Present (n = 1373; 82%) | Missing (n = 300; 18%) | ||

| Sex | Male | 707 (51.8) | 127 (53.1) | 707 (50.4) | 173 (49.3) | 669 (48.7) | 180 (60.0) |

| Female | 658 (48.2) | 112 (46.9) | 695 (49.6) | 178 (50.7) | 704 (51.3) | 120 (40.0) | |

| Ethnicitya | White | 1085 (85.8) | 190 (88.4) | 1141 (88.2) | 231 (80.2) | 1074 (84.3) | 197 (79.8) |

| Non-white | 180 (14.2) | 25 (11.6) | 153 (11.8) | 57 (19.8) | 200 (15.7) | 50 (20.2) | |

| Living situationa | Mother and father | 874 (69.6) | 107 (50.7) | 828 (64.9) | 144 (50.2) | 898 (70.5) | 121 (49.0) |

| Parent and partner | 146 (11.6) | 47 (22.3) | 175 (13.7) | 49 (17.1) | 148 (11.6) | 41 (16.6) | |

| Single parent | 211 (16.8) | 51 (24.2) | 255 (20.0) | 88 (30.7) | 200 (15.7) | 83 (33.6) | |

| Other | 24 (1.9) | 6 (2.8) | 17 (1.3) | 6 (2.1) | 27 (2.1) | 2 (0.8) | |

| Year group | 8 | 529 (38.8) | 40 (16.7) | 432 (30.8) | 38 (10.8) | 346 (25.2) | 28 (9.3) |

| 9 | 440 (32.2) | 29 (12.1) | 322 (23.0) | 62 (17.7) | 468 (34.1) | 73 (24.3) | |

| 10 | 165 (12.1) | 14 (5.9) | 495 (35.3) | 88 (25.1) | 514 (37.4) | 48 (16.0) | |

| 11 | 231 (16.9) | 156 (65.3) | 153 (10.9) | 163 (46.4) | 45 (3.3) | 151 (50.3) | |

| Age, mean (SD) | Years | 13.7 (1.1) | 14.8 (1.2) | 13.9 (1.1) | 14.8 (1.0) | 13.8 (0.9) | 14.7 (1.1) |

| Variable | Trial arm, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (N = 1604) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 1753) | Attention control PSHE (N = 1673) | ||||

| Present (n = 1365; 85%) | Missing (n = 239; 15%) | Present (n = 1402; 80%) | Missing (n = 351; 20%) | Present (n = 1373; 82%) | Missing (n = 300; 18%) | |

| SMFQ | 3.3 (4.6) | 4.8 (5.5) | 3.9 (4.9) | 4.9 (5.2) | 3.8 (4.8) | 4.4 (4.8) |

| CATS | 3.8 (6.4) | 5.6 (8.1) | 4.2 (6.7) | 6.3 (8.3) | 4.6 (7.1) | 5.4 (7.2) |

| Self-esteem | 21.7 (5.1) | 19.7 (5.5) | 21.3 (5.3) | 19.6 (5.5) | 21.0 (5.3) | 20.0 (5.1) |

| General anxiety | 3.0 (2.6) | 3.6 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.6) | 3.9 (3.0) | 3.2 (2.8) | 3.3 (2.6) |

| Separation anxiety | 1.0 (1.5) | 1.3 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.7) | 1.2 (1.8) | 1.4 (1.9) |

| Social phobia | 3.7 (2.9) | 4.5 (3.0) | 4.1 (3.1) | 4.7 (3.2) | 4.0 (3.0) | 4.4 (3.0) |

| Panic | 1.5 (2.2) | 2.1 (2.9) | 1.8 (2.5) | 2.3 (2.7) | 1.7 (2.4) | 2.1 (2.4) |

| Depression | 2.0 (2.4) | 3.0 (3.1) | 2.5 (2.6) | 3.2 (2.9) | 2.3 (2.7) | 3.0 (3.0) |

| RCADS | 11.3 (9.3) | 14.5 (10.4) | 12.9 (10.2) | 15.3 (10.7) | 12.4 (10.3) | 14.1 (10.3) |

| School connectedness | 31.3 (6.0) | 29.3 (6.3) | 30.5 (6.2) | 28.9 (6.6) | 30.4 (6.3) | 29.3 (6.7) |

| Variable | Level | Trial arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usual PSHE (N = 1604) | Classroom-based CBT (N = 1753) | Attention control PSHE (N = 1673) | |||||

| Present (n = 1365; 85%) | Missing (n = 239; 15%) | Present (n = 1402; 80%) | Missing (n = 351; 20%) | Present (n = 1373; 82%) | Missing (n = 300; 18%) | ||