Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/53/33. The contractual start date was in April 2010. The draft report began editorial review in May 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Matata et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

The majority of cardiac surgery is performed as on-pump surgery with the support of a heart and lung machine commonly termed cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB). 1 Although recent evidence shows that off-pump coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is associated with lower in-hospital mortality and complication rates than on-pump CABG, the long-term morbidity outcomes are comparable. 1

Patients undergoing on-pump cardiac surgery have an increased risk of developing major organ dysfunctions. 2 Two mechanisms that may contribute to postoperative organ dysfunction with on-pump cardiac surgery have been postulated. Firstly, on-pump surgery induces a significant haemodilution that has a deleterious effect on oxygen transport throughout tissues. 3 Haemodilution occurs as a result of the use of 1–2 litres of priming solution, which is added into the perfusion circuit. The combination of this ‘pump prime’ and subsequent cardioplegia may, in some cases, rapidly add a total of 2–3 litres to the patient's fluid balance. The consequence of this haemodilution is increased extravascular water, which is common during the onset of multiple organ dysfunctions, particularly in the heart, lungs and brain. 3 Secondly, on-pump cardiac surgery is associated with the development of the so-called ‘post-bypass systemic inflammatory response syndrome’ (SIRS), characterised by an onset of a capillary leak syndrome akin to septic shock. 2–4 Although the increased capillary permeability often subsides within 12–24 hours, it presents a major challenge for the critical care physician in the immediate postoperative period, during which time it is important to maintain adequate intravascular fluid volumes without inducing overhydration and tissue oedema. 3 It is well recognised that such perioperative complications lead to increased hospital stay and mortality, and eventually to increased cost of health care. 4–7 Mortality has remained high despite the use of different renal replacement therapies in these patients in the postoperative phase and after hospital discharge. 8

For patients with pre-operative moderate renal impairment, on-pump surgery often may lead to further deterioration of kidney function. 9 It is known that pre-operative mild kidney impairment is an independent predictor of long-term postoperative risk of death. 10–12 It is estimated that up to 20% of patients undergoing cardiac surgery have pre-existing renal insufficiency, typically with a creatinine value of > 132 µmol/l. 13 An increasing body of evidence suggests that inflammatory factors and oxidant stress play significant roles in the pathogenesis of coronary artery disease in patients with underlying end-stage kidney disease. 14 It is therefore reasonable to expect that patients with renal impairment and elevated oxidative stress are at increased risk of complications after cardiac surgery. 14,15

Several strategies have been used to manage perioperative kidney impairment. Theoretically, strategies that optimise the delivery of renal oxygen may be effective. 16–23 Interestingly, pharmacological interventions that increase renal blood flow or decrease renal oxygen consumption have not proved successful. 16–22 On the other hand, several non-pharmacological strategies related to the management of the CPB circuit have been shown to have some potential to reduce renal injury by the mechanism of avoiding excessive haemodilution and the need for red cell transfusion. 23 Strategies such as extracorporeal leucodepletion and haemofiltration during CPB appear to show some promise, although the extent of clinical efficacy is not clear. 23 Newer developments in surgical techniques, such as minimally invasive surgery which avoids the manipulation of the ascending aorta, can also reduce kidney complications. 23

Although there is evidence from a variety of sources24–26 that early filtration soon after on-pump surgery is beneficial for patients who have pre-operative renal impairment, there is a deficit of previous work on the clinical impact of intraoperative haemofiltration (haemofiltration applied during on-pump surgery). The Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the Society of Cardiovascular Anaesthesiologists' blood conservation practice guidelines27 also recommend that the existing evidence, designated IIb(a) (p. 948), is insufficient to reach a consensus as to whether or not intraoperative haemofiltration is significantly beneficial. It was therefore concluded that there was need for large randomised trials or meta-analyses. 27 A recent meta-analysis of small randomised trials on zero-balanced ultrafiltration (Z-BUF) by Zhu et al. 28 failed to show an apparent improvement in postoperative recovery predominantly because of heterogeneity in the statistical results and presumably because of the small sample sizes involved. In contrast, an earlier randomised trial that recruited 192 patients29 demonstrated that both intraoperative haemofiltration and steroids attenuated the inflammatory response, but only haemofiltration reduced time to tracheal extubation for adults after CBP. Previous non-randomised studies also demonstrated that Z-BUF removes inflammatory mediators. 30,31 A non-randomised study32 also demonstrated that haemofiltration during CPB attenuates postoperative anaemia, thrombocytopenia and hypoalbuminaemia, and may thus reduce postoperative bleeding and decrease postoperative pulmonary complications. Further evidence from a non-randomised study also demonstrated that intraoperative haemofiltration protected renal function. 13 In another setting,33 combined use of balanced ultrafiltration and modified ultrafiltration was shown to be effective at concentrating blood, modifying the increase of some harmful inflammatory mediators, and attenuating lung oedema and inflammatory pulmonary injury, thus mitigating the impairment of pulmonary function. However, none of these studies has investigated the impact of intraoperative haemofiltration in a subgroup of patients with pre-operative kidney impairment. In view of the evidence that has shown the potential advantages of haemofiltration during cardiopulmonary bypass, we hypothesised that intraoperative haemofiltration could form the basis for a reduction in intensive care unit (ICU) stay, perioperative complications and overall length of hospital stay for patients with pre-operative kidney impairment, hence the objective of this pilot study. In addition, there is currently no evidence to suggest that haemofiltration when applied to patients during the period of the operation may have an impact on the postoperative cost of care and clinical renal impairment outcomes.

In summary, there is an absence of past trial data from randomised trials to inform practice on whether or not the use of intraoperative haemofiltration during on-pump CABG surgery is clinically efficacious in protecting vulnerable kidneys and whether or not the treatment strategy is cost-effective. We hypothesised that the initiation of intraoperative haemofiltration using high-volume fluid exchange during cardiopulmonary bypass in patients with pre-operative impaired renal function effectively reduces overall length of ICU stay and limits progression of renal impairment. We therefore sought to conduct a pilot randomised clinical trial to assess the issues that might impact on conducting a larger definitive multicentre trial. In addition, we sought to assess the safety of the procedure, and to evaluate whether or not intraoperative haemofiltration had any impact on certain cardiac outcomes. These outcomes assessed would include duration of ICU stay for patients with significant pre-operative renal impairment [estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 ml/minute and > 15 ml/minute), ability to improve renal outcomes or protect vulnerable kidneys, and projected health economic outcome measures.

Trial aims and rationale

This pilot study had the primary objective of assessing the feasibility of randomising 60 coronary artery bypass surgery patients, with impaired kidney function, in 6 months within a single-centre for intraoperative haemofiltration in order to investigate the likelihood of recruitment into the main definitive study and explore issues that may impact on recruitment, such as the likely patient numbers, staff requirements, barriers to recruitment, and suitability and reliability of the outcome measures selected.

Specifically, as renal impairment is one of the major complications for patients undergoing cardiac operations, the results would be useful in giving a preliminary indication of the impact that the procedure has on health-care pathways such as length of stay in the ICU and the total overall hospital stay. Furthermore, the results of the pilot trial would be useful to guide us on whether or not a definitive randomised trial could address the underlying concerns about the costs and clinical benefits of using intraoperative haemofiltration.

These outcomes may be beneficial in influencing clinical decision-making and potentially help to achieve cost savings within the NHS.

A definitive randomised trial on the application of intraoperative haemofiltration may also provide information as to whether or not this technique can increase capacity by freeing more ICU bed-days (wherever the care is carried out) and reducing ward stay, consequently allowing more operations to be performed in the same amount of time. In addition, a definitive randomised trial may provide information on the number of potential cases where permanent renal damage or end-stage chronic renal failure could be averted by this strategy, hence saving on long-term use of NHS resources.

Trial objectives

As other previous large randomised trials had not based their inclusion criteria on the basis of pre-existing kidney impairment, the study design is limited by the absence of past trial data that could be used as a reference. In order to overcome these limitations, we first made a decision to conduct a pilot trial with an embedded feasibility study with the following objectives:

-

to assess the feasibility of randomising 60 on-pump CABG surgery patients with impaired kidney function in 6 months within a single centre for intraoperative haemofiltration; that is, to investigate the likely recruitment rates and issues that may impact on recruitment into the study

-

to assess the suitability and reliability of chosen outcome measures; and

-

to investigate the likelihood of recruitment into the main definitive study and explore issues that may impact conducting such a study, for example staff requirements, barriers to recruitment, and suitability and reliability of the outcome measures selected.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial setting

This single-centre pilot randomised trial was carried out at the Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital NHS Foundation Trust between November 2010 and March 2012. Institutional, Ethics and National Competent Authority [Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)] approvals were obtained prior to commencement of recruitment.

Trial design

This was a pilot, open-label, single-centre randomised trial comparing outcomes of on-pump CABG surgery with or without the use of intraoperative haemofiltration. The secondary feasibility outcomes of the pilot trial included the assessment of the ratio of patients randomised to those screened as eligible; the incidence of crossover between the randomised treatment groups; and the accuracy of data collection assessed by a 20% source data verification check. In addition, this pilot study sought to identify the likely barriers to effective recruitment into a main definitive trial, and whether or not the outcome measures and data collection methods were appropriate and reliable.

Selection of patients

Patients scheduled to undergo isolated CABG surgery were identified daily by the research nurse from the cardiac surgery referrals database and from the operation lists. Patients were screened by the research nurse for impaired kidney function, indicated by an eGFR of < 60 ml/minute adjusted for 1.73 m2 of body surface area in accordance with the US National Kidney Foundation guidelines. 34 On occasion, participating surgeons would also screen patients for eligibility in their outpatient clinics and then alert the research nurse to obtain consent. Most elective patients were screened for eligibility 1–2 weeks before admission to hospital for surgery, via the pre-investigation outpatient clinics. Patients who gave informed consent were recruited into the study. Patients who were admitted to hospital via the urgent or interhospital transfer pathways were screened in hospital wards 1–2 days before their operation. Renal dysfunction was assessed pre-operatively on the basis of reduced eGFR determined within a 4-week window before the operation. eGFR was selected because it takes into account that patients can have significant reduction in clearance while having normal plasma creatinine.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Consenting men and women with impaired kidney function were included if they were ≥ 18 years old and were scheduled to have elective or urgent on-pump isolated CABG surgery. Patients were excluded if they were undergoing redo surgery, surgery on the great vessels (aortic surgery) or valve surgery; had significant impaired liver function [serum bilirubin > 60 µmol/l or international normalised ratio (INR) > 2 without anticoagulation]; had severe/end-stage renal failure (i.e. eGFR < 15 ml/minute); or were on dialysis. In addition, they were excluded if they could not give informed consent, had a malignancy or were known to be pregnant.

Randomisation

Patients who fulfilled the inclusion and exclusion criteria and gave informed consent to participate in the study were randomised into either of the two study groups on the day prior to surgery as follows:

-

On-pump CABG surgery patients with eGFR < 60 ml/minute to receive haemofiltration during cardiopulmonary bypass (experimental group).

-

On-pump coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery patients with eGFR < 60 ml/minute not to receive haemofiltration during cardiopulmonary bypass (control group).

Treatment assignment was done online and was based on the block randomisation method using randomly varying block sizes of 2, 4 and 6 to ensure numerical balance between the groups. An independent statistician provided the randomisation tables. Each participant had an equal chance of being randomised to an experimental group of Z-BUF or a control group without intraoperative haemofiltration. Patients were stratified at the design stage on the basis of diabetes mellitus and the level of eGFR (eGFR between 15 and 40 ml/minute versus eGFR between 40 and 60 ml/minute). Only trial staff with a unique user identification and password could log on to the bespoke, encrypted database. The allocation was revealed only after unique patient data were entered. Access to any list of previously randomised patients or to case record forms was not permitted; only the research nurse had such access.

Treatment

Anaesthetic management was per consultant preference. All anaesthetics were opioid based with anaesthesia being induced with either a benzodiazepine (diazemuls or midazolam) or propofol (Diprivan®, AstraZeneca). Muscle relaxation was maintained with vecuronium (Norcuron®, Organon) and anaesthesia was maintained using isoflurane in oxygen/air. Depth of anaesthesia was continuously monitored in all patients using bispectral index monitoring. Inotrope requirements were at the discretion of the individual consultants but all inotropes used were recorded within the case record.

In all cases, CABG surgeries were performed through a median sternotomy. Following full anticoagulation with heparin given at an initial loading dose of 300 IU/kg, then as required to maintain an activated clotting time of 400–600 seconds, CPB was instituted using ascending aortic cannulation and a two-stage right atrial venous cannulation. A roller pump (Jostra HL-20) and hollow-fibre membrane oxygenator (commonly Jostra Quadrox or Sorin Apex) were used. The extracorporeal circuit was primed with 800–1400 ml of Hartmann's solution and 5000 IU of heparin. CPB was maintained with non-pulsatile flow with a minimum flow rate of 2.4 l/m2/minute at normothermia with temperature allowed to drift to 32 °C. Arterial line filtration was used in all cases. Shed blood was recycled using cardiotomy suction. Acid–base was managed with alpha stat control. Myocardial protection was based on surgical preferences, with a choice between intermittent cold blood and intermittent cold crystalloid cardioplegia (St Thomas' solution). The delivery route was antegrade only or antegrade followed by retrograde. Some surgeons preferred to complete all anastomoses proximal and distal while the aortic cross-clamp was still on. Others preferred to do the distal anastomoses with a partially occluding side-biting clamp on (once the aortic cross-clamp had been removed) and some used a variation of the above depending on the number of grafts and condition of the aorta. A standard 1.3 m2 haemoconcentrator set was used for intraoperative haemofiltration that was supplied by Chalice Medical, UK (www.chalicemedical.com). Heparin was reversed with protamine at 1 : 1 ratio on weaning off CPB.

Patients randomised to the control arm were operated on without ultrafiltration during CPB. Patients in the intervention arm were given a Z-BUF technique during CPB. Z-BUF was commenced from the time of establishment of safe CPB to just prior to the termination of CPB in patients randomised to the haemofiltration group. As fluid was removed from the circulation an equivalent amount of fluid, Accusol 35 (Baxter Healthcare Ltd, Deerfield, IL, USA), a balanced salt crystalloid solution, was added to the circulation to replace it; therefore, a fluid exchange occurred, removing potentially harmful metabolites and pro-inflammatory markers. The overall fluid balance was maintained at a relatively constant level.

During CPB, haemofiltration is a simple procedure where blood is drawn passively from the CPB circuit using the arterial pump pressure to drive the flow through the haemofilter. To prevent patient blood flow being compromised, the arterial pump rate is increased to compensate for the blood flow through the haemofilter. The hydrostatic pressure difference occurring across the haemofilter membrane, termed the transmembrane pressure (TMP), provides the driving force for filtration. TMP is a function of the average pressure within the blood path minus the pressure on the effluent side. TMP can be altered by modifying these variables. In this study a high filtration rate was achieved by using a high-pressure source for the inlet to the filter and, if necessary, modification of the pressure at the outlet and/or on the effluent side. The haemofilter blood contact surface was a 1.3 m2 through polysulfone (PS-Polypure, Allmed Medical GmbH, Pulsnitz, Germany) pre-set filter unit that was able to remove protein macromolecules to a molecular size of 30,000 Da. A minimum exchange of approximately 6000 ml/hour, which is a filtration rate of 100 ml/minute, could be maintained. Fluid removed was replaced with the equivalent volume of Accusol 35.

It was not possible to blind surgeons and other clinicians in the surgical theatre to noticing the presence of vacuum containers full of waste solution, which is indicative of the haemofiltration procedure, and therefore only patients and ICU staff were considered blinded to the intervention allocation. Discharge from ICU is based on nurse discharge guidelines, which are independent of ICU physicians and follow a scoring system, termed Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS),35 which ranges from 0 to 3. Nurses usually discharged patients from ICU when the MEWS was < 2.0 and only consultant cardiac surgeons/intensivists were authorised to discharge a patient from ICU when the total MEWS was > 3.0. All ICU staff remained blinded to whether or not a patient received intraoperative haemofiltration, in order to eliminate bias. Incidences such as infection, antibiotic usage, reoperation or reopening of the chest in ICU, postoperative anaemia, thrombocytopenia, hypoalbuminaemia, postoperative bleeding and postoperative pulmonary complications, which are potential confounding factors that determine ICU stay, were documented. In addition, to avoid any bias, the need for renal support postoperatively by haemofiltration followed hospital standard surgical guidelines as follows. Indications for postoperative haemofiltration were:

-

hyperkalaemia (potassium levels > 6.0 mmol/l)

-

metabolic acidosis of renal origin

-

anuria or oliguria: urine output of < 0.5 ml/kg/hour for > 6 hours (despite adequate filling and adequate cardiac output) resulting in clinically significant fluid overload. The value of 0.5 ml/kg/hour is commonly used to define oliguria in adults.

The choice of use of inotropes and the duration was left to the discretion of ICU clinicians. However, in our ICU only noradrenaline and adrenaline intravenous infusions, and on rare occasions enoximone, are used. The total number of inotropes and duration of usage was documented and summarised for each treatment group.

Follow-up data collection

Hospital follow-up started from the day of surgery and continued until hospital discharge or up to the 30th consecutive day of hospital stay before discharge. Patients were also monitored after hospital discharge and data were collected up to the follow-up clinic visit that took place 6–8 weeks later. All information was collected in structured case record forms (CRFs). A manual of operation documents containing relevant procedural instructions and definitions was produced. Data were entered into a secure password-protected bespoke database. Prospective monitoring of adverse and clinical events started at randomisation and continued until hospital discharge. Costs associated with each of the two pilot arms, postoperative renal replacement therapy, ICU stay, hospital ward stay and medications were estimated up until hospital discharge. Serious adverse and clinical events monitoring started at randomisation and continued until hospital discharge or up to 30 consecutive days of in-hospital stay.

Sample size

This pilot trial investigated whether or not it was feasible to randomise 60 patients in a period of 6 months at a recruitment rate of 10 patients per month from our centre. This complies with the previous recommendation for good practice that pilot randomised control trials should recruit a minimum number of 60 patients. 36 The objective was to use the results from this pilot data to calculate a more accurate sample size, trial duration and/or the number of recruiting centres that would be required for the main trial.

Outcome measures

Outcome measures were assessed for suitability for the main trial and whether or not they were reliably informative of the impact of intraoperative haemofiltration.

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was the frequency of duration of ICU stay > 3 days for patients with renal impairment. Total ICU length of stay as a continuous variable was also determined.

Secondary clinical outcome measures

Secondary clinical outcome measures were:

-

composite of perioperative incidences: bleeding (clinically defined significant loss of blood that needed transfusion of blood products), sepsis, death, arrhythmias, stroke and myocardial infarction

-

30-day mortality

-

need for postoperative continuous venovenous haemofiltration (CVVH) in the ICU: indications for requirement of postoperative CVVH adhered to standard surgical guidelines (i.e. onset of hyperkalaemia > 6.0 mmol/l; metabolic acidosis of renal origin; and anuria or oliguria) defined above

-

mechanical ventilation time

-

postoperative hospital stay; and

-

eGFR change from baseline at 6-week follow-up.

Secondary economic outcomes

Resource utilisation and key cost indicators associated with each of the two pilot arms, specifically ICU stay, hospital stay, postoperative renal replacement therapy, mechanical ventilation and medications, were estimated up until hospital discharge or up to 30 consecutive days' in-hospital stay. A health-related quality-of-life questionnaire, European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),37 was administered at hospital admission before surgery and at the 6-week follow-up hospital visit.

Adverse events

Adverse events occurring during the perioperative and follow-up periods were documented and reported. Typically, adverse events reported included complications such as anaemia, bleeding, pneumothorax, respiratory/chest infections, atelectasis, in-hospital deaths, gastrointestinal complications, pleural effusion, pulmonary oedema, reintubation, sepsis in ICU, cerebrovascular accidents, myocardial infarctions, cardiac arrests and heart blocks. Other complications that required the return of patients to theatre for reoperation, such as bleeding, tamponade and rewiring, were also included. Patients who developed acute renal failure (defined as eGFR decline of > 50% of the baseline value13) were managed by postoperative haemofiltration or other renal replacement therapies. Some patients also developed wound complications such as sternal dehiscence or infection (including sternal infections). In addition, arrhythmias such as atrial fibrillation were frequently observed and commonly treated with amiodarone infusion or in some cases by cardioversion shock.

Feasibility outcome measures

Barriers to recruitment to a larger full study were documented as observations made during the recruitment period of the trial. Reliability of data collection methods was monitored using a 13-point CRF validation check (see Appendix 1). Three audit clerks who were independent of the trial team performed this check. They randomly chose 12 CRFs and checked the data entry against the patient's clinical notes and the generic database.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were undertaken on the intention-to-treat basis and were carried out using the statistical package SSPS (PASW) version 18 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Summary statistics, including mean, median and frequencies, along with corresponding measures of variability such as standard deviation (SD) and confidence intervals (Cls), were used to describe demographic data, study outcomes and adverse events.

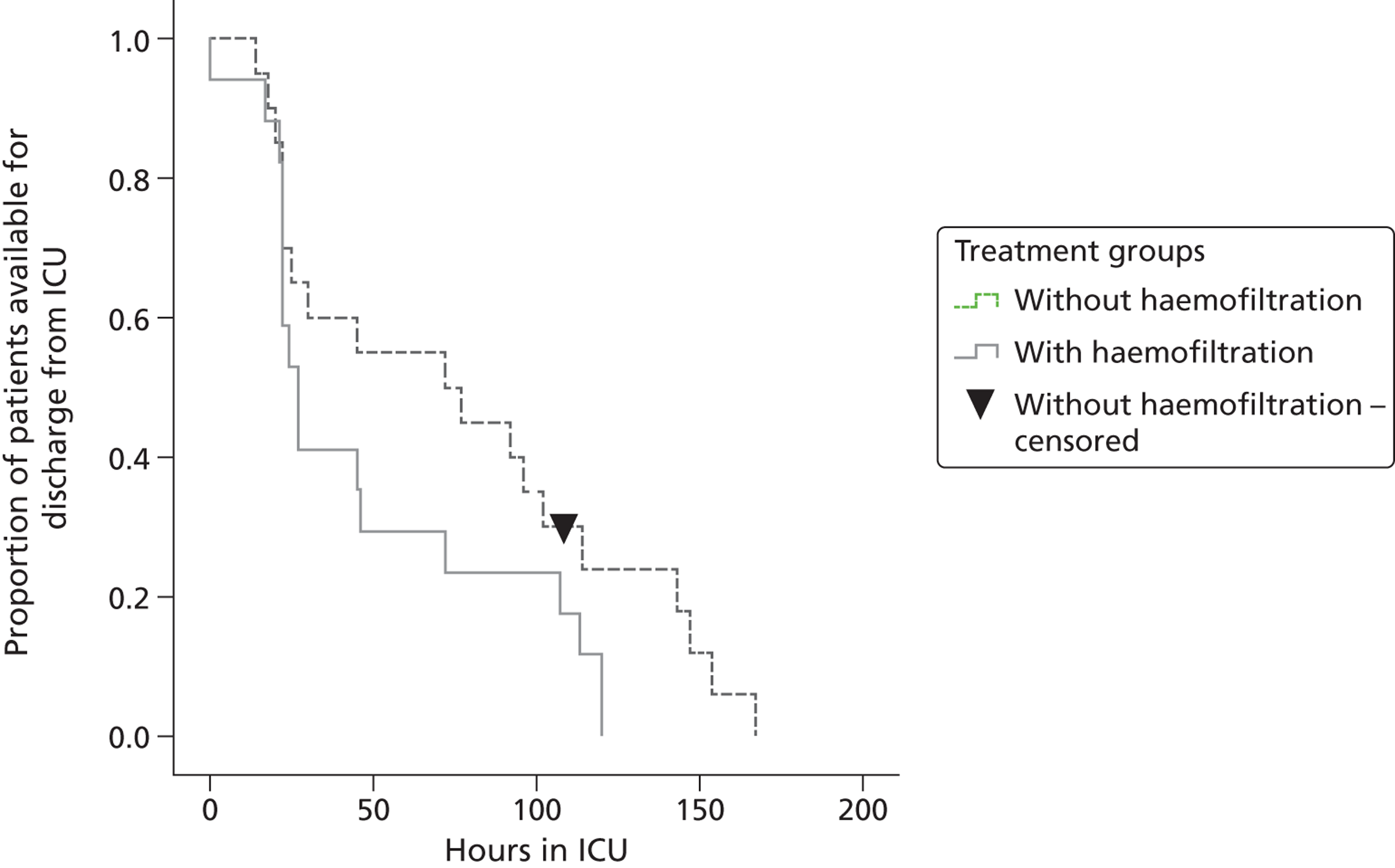

Time to discharge from ICU was described using a Kaplan–Meier plot.

Chapter 3 Results

Introduction

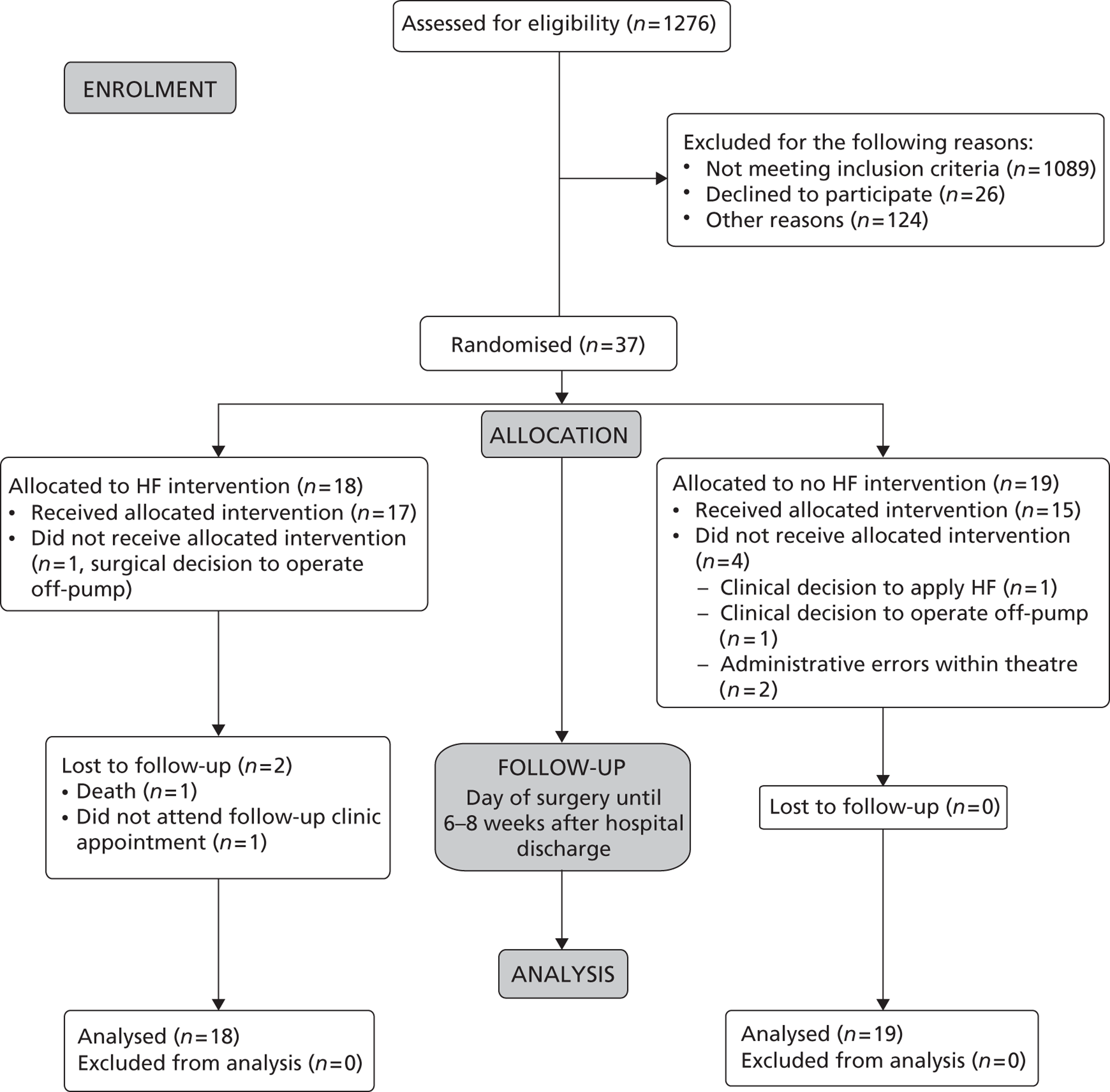

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram is included to describe the recruitment process in a participant flow chart (Figure 1). This is followed by demographic information, barriers to recruitment, summary findings, trial outcomes, trial adverse events, feasibility study outcomes and key findings.

The pilot trial was conducted over a period of 15 months (21 November 2010 to 30 March 2012). As shown in the CONSORT diagram, a total of 1276 patients were screened for eligibility, of whom 952 were excluded because their eGFR was ≥ 60 ml/minute. A further 137 were excluded, despite having eGFR < 60 ml/minute, because they were undergoing off-pump surgery (n = 103) or had planned combined valve replacement or other complex surgeries (n = 34), as summarised in Table 1. One hundred and seven out of 187 patients undergoing isolated on-pump CABG surgery with an eGFR of < 60 ml/minute met the inclusion criteria. Thirty-seven out of these 107 eligible patients consented and were successfully randomised into the trial arms, with a ratio of randomised to screened eligible patients of 3.5 : 10.

| Surgery types | Numbers of patients |

|---|---|

| Off-pump CABG | 103 |

| Aortic valve replacement/repair | 23 |

| Mitral valve replacement/repair | 7 |

| TAVI | 3 |

| Combined valve surgery | 1 |

| Total | 137 |

A total of 26 patients declined to participate (for religious or personal reasons), while 124 patients were lost to recruitment for other reasons. Reasons why eligible patients were not approached included patients being available for approach outside the hours the centre was staffed for recruitment, patients being unable to understand the study information, and the surgical decision to exclude patients because of clinical need. Patients were also excluded if they declined consent or if they were participating in another study such that it might have impacted on the outcomes of both protocols.

Participant flow chart

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials 2010 flow diagram.

Summary of the main reasons for not recruiting eligible patients

Eligible patients were not recruited largely for the following reasons:

-

Patients had an eGFR of > 60 ml/minute, or were undergoing off-pump surgery (n = 103) or combined surgeries/complex surgeries (n = 34): that is, combined CABG and valve surgery, valve replacement surgery, thoracic aneurysms, redo CABG surgery, transcatheter aortic valve implantation, thoracic surgery/bronchoscopy, pacemaker change, or sternal wire removal.

-

Recruitment was restricted to the research nurses' working week of Monday to Friday, 0900–1700 hours. Consequently, 36 patients who were potentially eligible for the trial could not be recruited because they were available for approach outside these hours.

-

Patients were screened but not included because of surgical decisions (n = 44).

-

eGFR was unknown at the time of a patient's hospital admission (n = 30).

-

Patients declined consent for religious or personal reasons (n = 26).

-

Patients were awaiting surgery at the close of trial recruitment (n = 14).

Demographic information

As shown in Table 2, patients had similar patterns of baseline demographic characteristics regardless of intervention.

| Variables | No-haemofiltration group (N = 19) | Haemofiltration group (N = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 6 (31.6) | 4 (22.2) |

| Male | 13 (69.4) | 14 (87.8) |

| Age, mean (SD) | 72.66 (7.33) | 72.12 (8.29) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White (British) | 18 (94.7) | 18 (100) |

| White (other) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Procedure, n (%) | ||

| Elective | 9 (47.4) | 11 (61.1) |

| Urgent | 10 (52.6) | 7 (48.9) |

| Family history of IHD, n (%) | ||

| No | 7 (36.8) | 7 (38.9) |

| Yes | 12 (63.2) | 11 (61.1) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | ||

| No | 4 (21.0) | 5 (27.8) |

| Yes | 15 (79.0) | 13 (72.2) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | ||

| No | 3 (21.0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Yes | 16 (79.0) | 15 (83.3) |

| Smoking, n (%) | ||

| Smokes cigars | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) |

| Never smoked | 7 (38.9) | 6 (33.3) |

| Ex-smoker | 11 (55.6) | 9 (50.0) |

| Current smoker | 1 (5.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| LV function (EF), n (%) | ||

| < 30% | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| 30–50% | 7 (36.8) | 3 (16.7) |

| > 50% | 12 (63.2) | 13 (72.2) |

| EuroSCORE, mean (SD) | 5.16 (2.67) | 5.17 (3.31) |

| Diabetic, n (%) | ||

| No | 13 (68.4) | 10 (55.6) |

| Yes | 6 (31.6) | 8 (44.4) |

| NYHA class, n (%) | ||

| No limitation | 3 (21) | 5 (27.8) |

| Slight limitation | 8 (31.5) | 9 (50) |

| Marked limitation | 6 (42) | 4 (22.2) |

| Inability to carry out any physical activity | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) |

| CCS class, n (%) | ||

| 0. No chest pain | 5 (26.3) | 8 (44.4) |

| I. Pain on moderate exertion | 1 (5.3) | 3 (16.7) |

| II. Slight limitation of normal activities | 9 (47.4) | 3 (16.7) |

| III. Marked pain limitation of ordinary activities | 2 (10.5) | 3 (16.7) |

| IV. Unstable: pain on any activity or rest pain | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.6) |

| eGFR (ml/minute) at screening, median (IQR) | 50.7 (7.3) | 49.9 (10.9) |

| Urea at screening (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 8.40 (2.18) | 8.40 (4.07) |

| Creatinine at screening (µmol/l), mean (SD) | 111.0 (29) | 113.5 (27) |

| Platelet counts × 109 at screening, median (IQR) | 197 (69) | 199 (52) |

| HCT at screening, median (IQR) | 38 (5.) | 37.5 (5) |

| Serum albumin at screening (g/l), mean (SD) | 42.0 (3.6) | 44.16 (3.0) |

Feasibility trial outcomes

Barriers to recruitment

One of the key objectives of the pilot trial was to obtain an understanding of the barriers to the recruitment of trial patients with an initial plan to recruit 60 patients in 6 months. However, only 37 participants were recruited over a period of 15 months. The recruitment of a relatively small number of patients during the trial period highlights some significant but not insurmountable barriers to recruitment in this setting.

The main barriers were as follows:

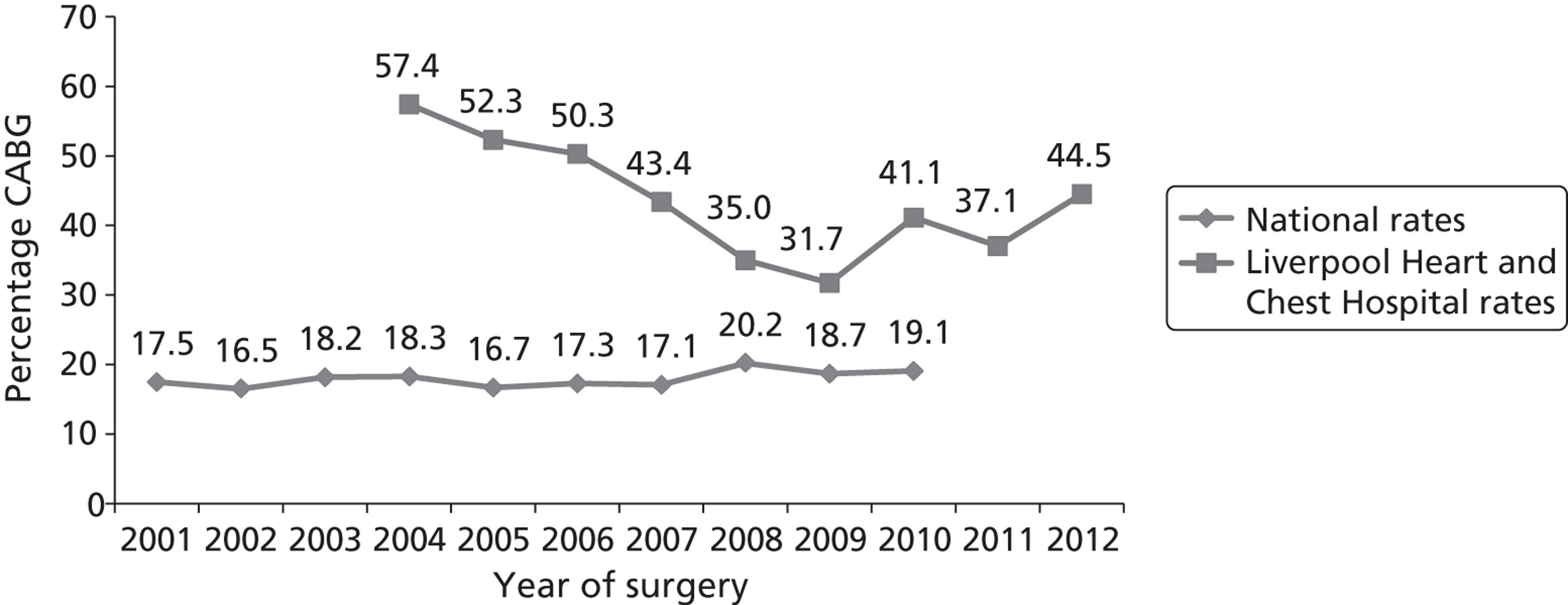

-

In our centre, up to 50% of coronary surgery is performed off-pump, a figure that is one of the highest in the UK, and this trial was recruiting on-pump CABG surgery patients only. Our figure demonstrates that 103 patients with pre-operative renal impairment underwent off-pump CABG surgery during the time frame of the trial.

-

Recruitment was restricted to research nurses' working week hours (Monday to Friday, 0900–1700 hours). Consequently, 36 patients who were potentially eligible for the trial could not be recruited outside of those hours because they were available for approach outside these hours.

-

Issues were encountered through the screening process for identifying prospective eligible patients. The primary inclusion criterion for the trial is the presence of mild to moderate impairment in kidney function as measured by eGFRs (< 60 ml/minute and > 15 ml/minute). In the cardiac surgery setting patients may be scheduled for CABG surgery through the elective route or be admitted into the hospital as an urgent case. It is particularly common in patients admitted as urgent cases that their eGFR values are often not documented in the case notes/clinical database or that blood samples are not taken until later on the day before surgery. Consequently, 30 patients who were eligible for this trial were not recruited.

-

Seasonal outbreaks of pandemic influenza and other infectious diseases occurred. In the winter of 2010–11, an outbreak of pandemic influenza led to the closure of all elective cardiac surgery from December 2010 to February 2011. In addition, an outbreak of norovirus within one surgical ward in January 2012 significantly reduced planned cardiac surgical activities for 2 weeks and only urgent cases were considered for operations during that time.

-

Protocol deviations and treatment crossovers arose. There were two protocol deviations and four crossovers. In three cases this was because of a necessary change in clinical strategy intraoperatively. Of the remaining cases, in two there were communication errors and in the last case eGFR had recovered to normal following the initial screening. Treatment fidelity for intraoperative haemofiltration was followed in all cases where the intervention was received in accordance with standard protocol Z-BUF, regardless of whether or not the patients were crossovers.

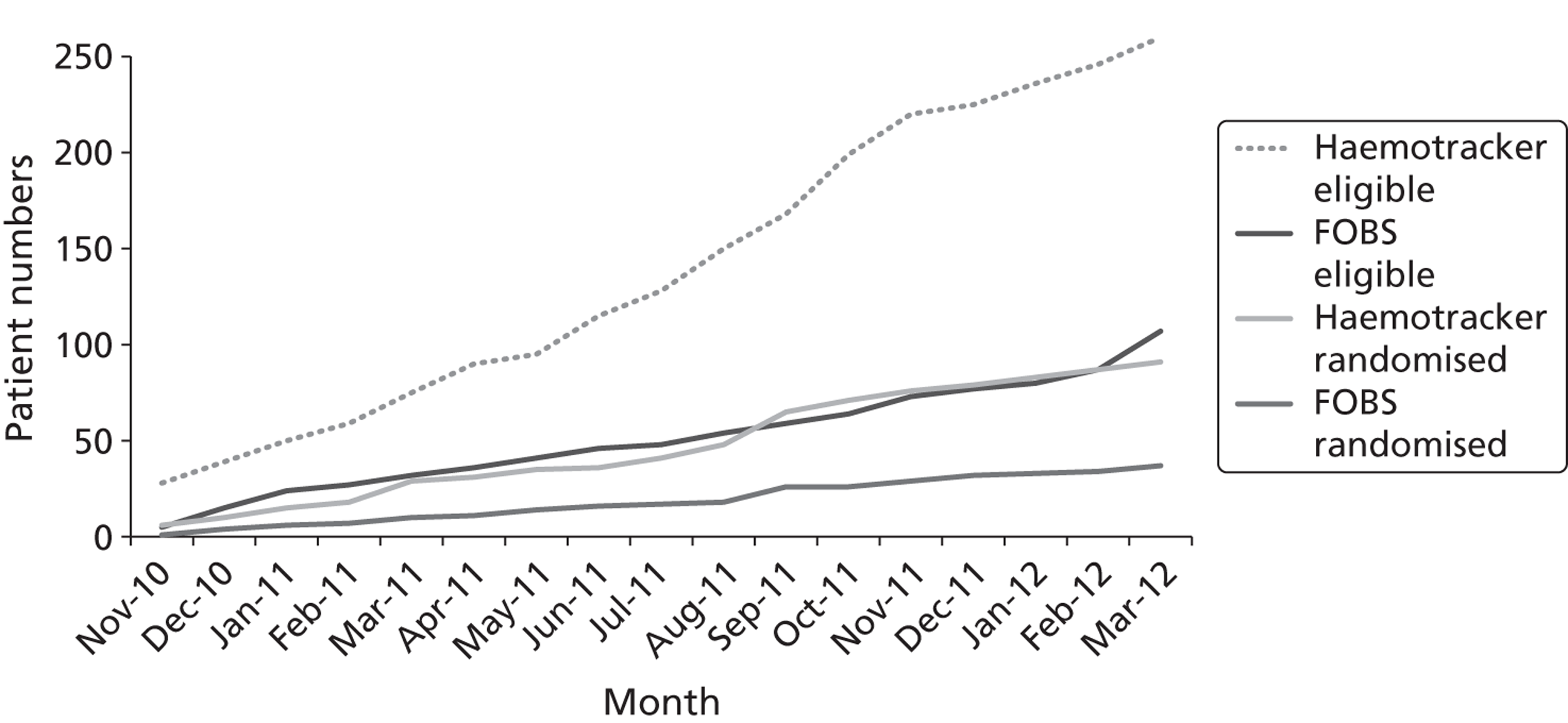

We have also observed that recruitment could be markedly increased if enrolment criteria were widened to include patients with impaired renal function undergoing other types of cardiac procedures, such as valves or combined valves and CABG surgery. This is based on observations from another ongoing trial (the Haemotracker trial, ISRCTN 48429978) in our centre, which is investigating the impact of intraoperative haemofiltration on oxidative stress for patients with impaired renal function undergoing all cardiac procedures. As shown in Figure 2, within a similar time frame 91 patients were consented and randomised into the Haemotracker trial compared with 37 patients in this trial [the filtration on bypass surgery (FOBS) trial]. If the criteria for the FOBS trial were extended to include all cardiac surgery and recruitment was optimised to all hours we estimate that we could meet a target of 35–50%.

FIGURE 2.

Comparison of recruitment rates for the Haemotracker and FOBS trials.

Reliability of data collection methods

Data were collected by one research nurse, starting from screening and continuing to follow-up. This research nurse also entered the data into the trial database. The accuracy and reliability of this method of data collection was assessed using a 13-point validation check form performed by three audit clerks independent of the trial. These individuals randomly chose four CRFs each and checked the recorded data against the patient clinical notes and the generic database. Twelve CRFs with a total of 9509 database fields were checked for completion and accuracy. This check revealed that 323 database fields (3.4%) were missing and also some information was outstanding from patients awaiting follow-up visits. In addition, no data entry errors were found. A future study could easily follow a similar kind of approach for data collection. However, we plan to work with a registered clinical trials unit in a future multicenter trial, and it is likely that they would have a more robust data collection and entry validation tool.

Reliability of outcome measures

The main clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness outcomes were assessed to establish whether or not they would be suitable for a future trial. The length of ICU stay days was considered more suitable as a primary outcome measure than ICU stay > or < 3 days. However, there is concern that the decision to discharge patients to a lower level of care could potentially be influenced by many reasons, such as acute shortage of ICU beds or availability of ward beds, rather than by a patient's speed of recovery. Time to tracheal extubation and blood transfusion requirements in theatre are outcome measures that could also be considered in a larger trial. However, these are limited by the issue of how to define the criteria for weaning ventilator support or for intraoperative transfusion. A future trial must consider putting in place clear criteria for addressing these concerns. Thirty-day mortality comparisons are likely to require large sample sizes in a future trial and therefore may not be appropriate as a primary outcome measure. Outcomes that seek to establish the level of renal impairment, including eGFR and urinary albumin–creatinine ratio, should be explored in a definitive trial. It would also be useful to explore the suitability of other biomarkers of renal impairment, such as urinary neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin levels, in a larger trial. Other non-clinical outcomes, such as condition-specific health-related quality of life (HRQL), might add value to the outcomes of a large randomised trial. We have demonstrated in this pilot trial that these can be collected effectively without due burden on the patient and with a > 90% completion rate.

Clinical outcome measures

The analysis was as per intention to treat and involved all patients who were randomised. Nineteen patients were randomised to the no-haemofiltration arm and 18 were randomised to the haemofiltration arm. One patient randomised to the no-haemofiltration arm died of gastrointestinal complications (intestine ischaemia) in ICU. Further investigation revealed that the patient had a high pre-operative risk of death reflected by his or her additive EuroSCORE of 10.

The trial arms were equally balanced in terms of age, sex, ethnicity, baseline eGFR, diabetes, whether urgent or elective procedure, family history of ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking status, left ventricular function, and additive EuroSCORE. In addition, there were similar trends in terms of baseline albumin/creatinine ratio, platelet counts, haematocrit, urea and creatinine.

Table 3 summarises the intraoperative outcomes, such as duration of CPB, cross-clamp time, transfusion needs, urine volume, inotropic support and intraoperative fluid balance. The results show that there was a trend towards a reduction in blood transfusion needs in theatre for the haemofiltration group but not in the postoperative period. Other intraoperative outcomes, such as CPB times and cross-clamp times, indicated that there is a trend for groups with haemofiltration to require longer duration; however, the small sample size limits us from drawing any firm conclusions.

| Variables | No-haemofiltration group | Haemofiltration group |

|---|---|---|

| CPB time (minutes), median (IQR) | 94.5 (34.5) | 100.5 (45.25) |

| Cross-clamp time (minutes), median (IQR) | 56 (25.5) | 64.5 (26.25) |

| Intraoperative blood transfusion needs (ml), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | 101 (263) | 22 (69) |

| Diabetic patients | 73 (179) | 55 (101) |

| Intraoperative inotropes, n/N (%) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | 2/13 (15.4) | 1/10 (10) |

| Diabetic patients | 2/6 (33.3) | 1/8 (12.5) |

| Urine volume (ml), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | 1556 (581) | 1414 (662) |

| Diabetic patients | 1708 (701) | 1320 (464) |

| Total intraoperative haemofiltration time (hours), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | NA | 1.16 (0.26) |

| Diabetic patients | NA | 1.41 (1.34) |

| Intraoperative fluid balance (ml), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | 1303 (513) | 1274 (511) |

| Diabetic patients | 1322 (392) | 1320 (464) |

Table 4 outlines changes in urea, creatinine, haematocrit (HCT) and serum albumin on admission to ICU, at 24 hours after ICU admission, and a day after ward admission compared with baseline values. The values indicate a similar pattern between the treatment groups. Interestingly, while the pattern of platelet counts increased in both groups, HCT levels and serum albumin were lower than baseline during and after the first 24 hours after surgery. In contrast, the patterns of creatinine and urea levels rose in both groups but the magnitude was slightly lower in the group who were given haemofiltration.

| Variables | Times | No-haemofiltration group | Haemofiltration group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Urea (mmol/l), mean (± SD) | Day of admission to ICU | – 1.61 (2.63) | – 2.11 (1.54) |

| 24 hours after admission to ICU | 0.45 (2.08) | – 0.52 (1.40) | |

| 1 day after admission to ward | 2.45 (2.79) | 0.73 (1.78) | |

| Creatinine (µmol/l), mean (± SD) | Day of admission to ICU | – 15.33 (29.99) | – 28.20 (22.97) |

| 24 hours after admission to ICU | 5.37 (21.76) | 5.22 (24.85) | |

| 1 day after admission to ward | 10.88 (35.61) | 1.73 (28.70) | |

| Platelet counts × 109 (mean ± SD) | 24 hours after admission to ICU | 4 (37) | 8.5 (35) |

| 1 day after admission to ward | 52 (109) | 24.5 (90) | |

| HCT (mean ± SD) | 24 hours after admission to ICU | – 2.11 (4.06) | – 1.60 (3.20) |

| 1 day after admission to ward | – 0.61 (3.95) | – 0.46 (3.79) | |

| On hospital discharge day | – 1.43 (4.79) | – 0.35 (4.66) | |

| Serum albumin (g/l), mean (± SD) | 24 hours after admission to ICU | – 14.88 (4.10) | – 16.39 (4.16) |

Table 5 summarises the postoperative clinical outcomes such as time to tracheal extubation, length of ICU stay, duration of hospital stay (days) and 30-day mortality. The length of ICU had an overall trend towards a reduced stay for patients who were given intraoperative haemofiltration. This trend was much more evident in patients with diabetes. The categorical variable of incidents of ICU stay < 3 days and the number of composite outcome measures were found to be less informative. A future trial should report on total hospital morbidity (a count of the number of hospital complications) instead of the composite outcome measure described in this pilot trial. Other outcomes also showed similar trends between the treatment groups.

| Variables | No-haemofiltration group | Haemofiltration group |

|---|---|---|

| Time to tracheal extubation (minutes) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients, median (IQR) | 435 (195) | 435 (653) |

| Diabetic patients, median (IQR) | 450 (311) | 525 (731) |

| Overall, mean (SD) | 498 (221) | 634 (397) |

| Length of ICU stay (days) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients, mean (95% CI) | 2.07 (0.97 to 3.16) | 2.12 (0.95 to 3.29) |

| Diabetic patients, mean (95% CI) | 4.88 (2.75 to 7.01) | 2.70 (0.65 to 4.75) |

| Overall, mean (SD) | 3.10 (2.19) | 2.17 (2.00) |

| Frequency of duration of ICU stay (categorical), n/N (%) | ||

| < 3 days | 10/19 (52.6) | 11/18 (61.1) |

| 3–10 days | 9/19 (47.4) | 7/18 (38.9) |

| Hours in CCU area, median (IQR) | 58.5 (99.0) | 27.0 (75.0) |

| Days in ward, median (IQR) | 5.0 (7.0) | 5.5 (5.0) |

| Number of composite outcomes, mean (SD) | 1.8 (1.3) | 2.5 (0.7) |

| Thirty-day mortality, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 19/19 (94.7) | 18/18 (100) |

| Yes | 1/19 (5.3) | 0/18 (0) |

| Haemostasis agents, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 15/19 (78.9) | 14/18 (77.8) |

| Yes | 4/19 (21.1) | 4/18 (22.2) |

| Postoperative blood transfusions, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 10/19 (52.6) | 7/18 (38.9) |

| Yes | 9/19 (47.4) | 11/18 (61.1) |

| Postoperative blood transfusion volume (ml), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic patients | 152 (316) | 264 (340) |

| Diabetic patients | 293 (227) | 243 (183) |

| Mediastinal blood loss, mean (95% CI) | 977 (754 to 1201) | 960 (679 to 1241) |

| Platelet counts × 109 at admission to ICU, median (IQR) | 150 (60) | 154 (76) |

| Platelet counts × 109 at 24 hours post operation, median (IQR) | 160 (48) | 154 (59) |

| HCT at admission to ICU, median (IQR) | 28.0 (4.0)a | 29.5 (3.0)b |

| HCT at 24 hours post operation in ICU, median (IQR) | 28.0 (4.0)a | 27.0 (3.0)b |

| Total number of postoperative inotropes given, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 6/19 (31.6) | 3/18 (16.7) |

| Yes | 13/19 (68.4) | 15/18 (83.3) |

| Duration of inotrope used (hours), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-adrenaline | 32 (32) | 30 (36) |

| Adrenaline | 7 (1) | 72 (34) |

| Duration of total inotropic support (hours), mean (SD) | ||

| Non-diabetic | 13 (69) | 16 (49) |

| Diabetic | 15 (18) | 24 (81) |

| Dopexamine, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 17/19 (84.2) | 17/18 (94.4) |

| Yes | 2/19 (15.8) | 1/18 (5.6) |

| Postoperative haemofiltration, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 18/19 (94.7) | 16/18 (88.9) |

| Yes | 1/19 (5.3) | 2/18 (11.1) |

| Metabolic acidosis, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 18/19 (94.7) | 18/18 (100) |

| Yes | 1/19 (5.3) | 0/18 (0) |

| Anuria/oliguria, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 18/19 (94.7) | 16/18 (88.9) |

| Yes | 1/19 (5.3) | 2/18 (11.1) |

| IABP, n/N (%) | ||

| No | 19/19 (100) | 17/18 (94.4) |

| Yes | 0/19 (0) | 1/18 (5.6) |

| eGFR (ml/minute) at 6 weeks' follow-up, median (IQR) | 49.0 (15)b | 54.5 (18)b |

The time taken to discharge 50% of the trial patients from ICU (median discharge time) was 27 (95% CI 20 to 132) hours for patients given haemofiltration compared with 72 (95% CI 1 to 142) hours for patients without haemofiltration. The cumulative number of patients in the two treatment groups leaving the ICU at any given time is presented in a Kaplan–Meier plot in Figure 3. The pattern in the two groups was similar for shorter periods of ICU stay of up to 50 hours. Beyond this time, fewer patients in the no-intraoperative haemofiltration group left the ICU relative to those who received intraoperative haemofiltration, who remained in the ICU for anything up to 150 hours.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier curves for days on ICU.

Postoperative renal function outcomes and need for postoperative renal replacement therapy

Urine outputs and fluid balances

We assessed the pattern of urine output and fluid balances during the postoperative period of up to 96 hours after surgery. Table 6 shows similar patterns of urine output between the groups during the perioperative period of up to 48 hours after surgery. The fluid balances showed different patterns between the patient groups and also for diabetic and non-diabetic patients during the perioperative period of up to 48 hours after surgery. After the first 48 hours a significant number of data were missing and therefore are not shown in Table 6. The reason for the incompleteness was the fact that most patients were well enough to be discharged from ICU into wards after 72 hours. In the wards most patients had their urine catheters taken out and were free to use toilets and take in fluids as they wished. Consequently, for some patients, urine outputs and fluid balances were not adequately monitored or documented by staff.

| Treatment allocations at randomisation | Diabetes | Urine output (ml), mean (SD) | Fluid balance (ml), mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 hours | 48 hours | 24 hours | 48 hours | ||

| Haemofiltration | No | 1308 (571) | 1980 (923) | 472 (650) | – 473 (1032) |

| No haemofiltration | No | 803 (458) | 1773 (632) | 1037 (648) | – 4 (459) |

| Haemofiltration | Yes | 1510 (509) | 1787 (957) | 1510 (509) | 1787 (957) |

| No haemofiltration | Yes | 1567 (537) | 1984 (355) | 864 (963) | – 16 (779) |

Postoperative acute renal failure

As summarised in Table 7, there were three patients who developed postoperative acute renal failure out of the 37 randomised patients. These three patients were given postoperative renal support [haemofiltration, dopexamine (Dopacard®, Cephalon) and furosemide infusions]. One non-diabetic patient with pre-operative eGFR of 29 ml/minute who was randomised to the no-intraoperative haemofiltration arm developed postoperative metabolic acidosis and anuria/oliguria. The patient was given postoperative haemofiltration for 67 hours and intravenous dopexamine and furosemide infusions for 107 hours. The second patient was diabetic and had a pre-operative eGFR of 50 ml/minute, was randomised and given intraoperative haemofiltration and then developed anuria/oliguria postoperatively. The patient was given postoperative haemofiltration for 19 hours together with intravenous furosemide infusions for < 1 hour. The third patient was non-diabetic with an eGFR of 25 ml/minute, was randomised to the intraoperative haemofiltration group and then developed postoperative anuria/oliguria and was given haemofiltration for 22 hours together with intravenous dopexamine for 7 hours in total. The pattern of the duration of postoperative haemofiltration appears to favour the use of intraoperative haemofiltration, although owing to the small numbers no definitive conclusion can be reached based on this observation.

| Patient no. | Treatment allocations at randomisation | Baseline eGFR | Diabetic | Time on postoperative haemofiltration (hours) | Time on intravenous dopexamine (hours) | Time on intravenous furosemide infusions (hours) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 009 | No haemofiltration | 29 | No | 68 | 107 | 17 |

| 021 | Haemofiltration | 25 | Yes | 22 | 7 | 0 |

| 026 | Haemofiltration | 50 | Yes | 19 | 0 | < 1 |

Changes in estimated glomerular filtration rate

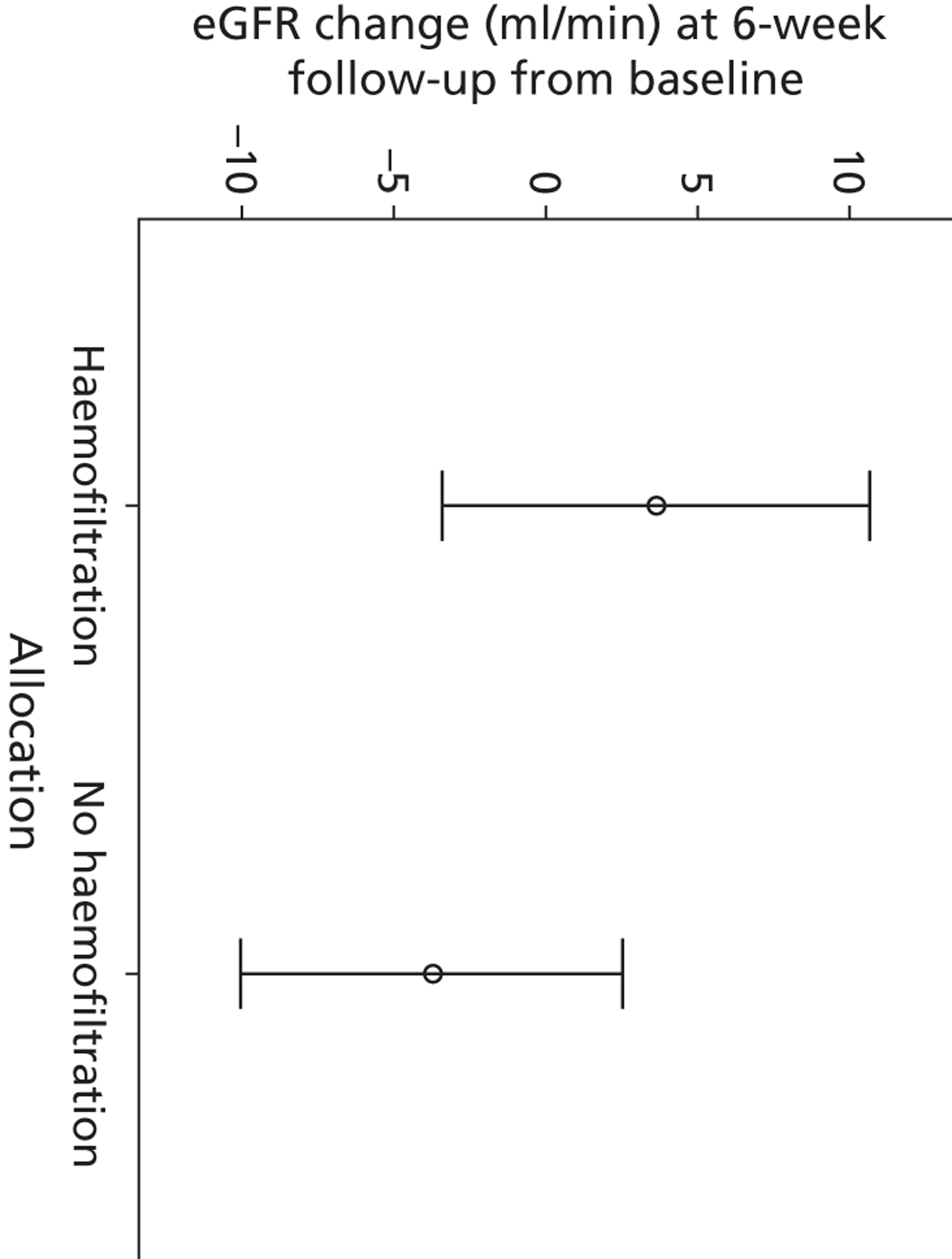

The difference in changes in eGFR between 6 weeks' follow-up and baseline values indicated a trend towards higher values for the haemofiltration group than the group without haemofiltration (Figure 4). Again, the sample size is too small to draw any conclusions from this.

FIGURE 4.

Mean eGFR change (95% CI) between baseline and at 6 weeks' follow-up.

Health-related quality-of-life measurement (European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions health scores)

Health-related quality-of-life questionnaires (EQ-5D) were administered to a sample of the patients (n = 20) as a late addition to the trial protocol to test the feasibility of reliably collecting informative data on changes on health within this cohort of patients. The EQ-5D consists of two elements: a visual analogue scale (VAS) and a questionnaire. The VAS asks patients to rate their health on a scale from 0 to 100. A score of 100 indicates the best HRQL and vice versa, with a score of 0 indicating the worst HRQL. The results are summarised in Table 8, showing a trend towards improved median HRQL for the haemofiltration group compared with the no-haemofiltration group. However, the small sample size rules out any definitive conclusions from these findings.

| Variables | No-haemofiltration group (n = 11) | Haemofiltration group (n = 12) |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-operative score, median (IQR) | 80 (23) | 75 (23) |

| Postoperative score, median (IQR) | 80 (25) | 83 (26) |

| Score differences, median (IQR) | 3 (10) | 18 (33) |

Trial adverse events

The trial adverse events are summarised in Table 9. The trial events adjudication panel confirmed that all reported adverse events were not due to the trial interventions. There was only one death, which occurred in a patient in the group without haemofiltration as a result of gastrointestinal complications (ischaemic gut).

| Variables | No-haemofiltration group (N = 19) | Haemofiltration group (N = 18) |

|---|---|---|

| In-hospital deaths, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Atelectasis, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | 2 (11.1) |

| Chest infections, n (%) | 5 (26.3) | 3 (6.7) |

| Sepsis in ICU, n (%) | 7 (36.8) | 4 (22.2) |

| Events requiring readmission, n (%) | ||

| Unstable sternum requiring rewiring/and need for blood transfusion in ICU | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural effusion and ICD insertion requiring postdischarge hospital readmission | 1 (5.3) | 3 (16.7) |

| Arrhythmias, n (%) | ||

| No | 10 (52.6) | 12 (66.7) |

| Asystole | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 6 (31.6) | 3 (16.7) |

| Bradycardia | 0 (0) | 2 (11.0) |

| Slow nodal rhythm | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Supraventricular tachycardia | 2 (10.5) | 1 (5.6) |

| Pulmonary oedema, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Pleural effusion, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Pneumothorax, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 0 (0) |

| Bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Tamponade, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Re-exploration, n (%) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| Anaemia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (11.1) |

| Thrombocytopenia, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (5.6) |

| Wound infections (including sternal), n (%) | 2 (10.6) | 0 (0) |

| Formal surgical reconstruction, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) |

| Gastrointestinal complications, n (%) | 2 (10.5) | 0 (0) |

Key findings

The potential barriers to recruitment were identified as the high volume of off-pump coronary surgery within our centre (37–45%), recruitment restricted to working hours of the week (0900–1700 hours, Monday to Friday), too narrow enrolment criteria, participation of some patients being restricted by the absence of eGFR values before hospital admission, and the threat of treatment crossovers. These barriers can be overcome in a larger trial by widening the inclusion criteria to other cardiac procedures besides CABG surgery. Priority could be given to centres with low off-pump/on-pump CABG ratios. In addition, there should be sufficient staff resources and support to all participating centres to ensure that recruitment activities are covered at all hours. Treatment crossovers and protocol deviations could be ameliorated by delaying randomisation until patients are as close to undergoing surgery as possible (randomising in theatre just before surgery begins). For patients admitted to hospital under the urgent or interhospital transfer pathway whose eGFR values are unknown, consent could be delayed until later on during the evening/night of the day of admission or the morning before surgery to allow time for the measurement to be determined in-house.

Twenty-seven per cent of the randomised participants were female, equally spread between the two study groups. Demographic factors such as age, ethnicity, and family history of ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, smoking and diabetes, as well as baseline eGFR and EuroSCORE, were similarly distributed between the two groups.

Data collection was sufficiently robust, with few errors detected. One exception is the data on urine outputs and fluid balances in the duration in excess of 48 hours after the operation, which were largely missing because a lot of this information was not documented in the case records. One typographical error was detected in an e-mail message sent out to theatre staff regarding a patient's treatment allocation. A future trial can avoid such errors by having in place a robust system that automatically generates e-mails to whoever is concerned regarding the treatment allocation. Some outcome measures were also more reliably informative than others, such as the continuous outcome measure of length of ICU stay which provides a better insight into the distribution pattern than the categorical variable of frequency of duration of ICU stay > 3 days, as highlighted in Table 5. The composite outcomes variable was also found to be less informative and therefore a broader outcome of the number of hospital complications would be preferable in a larger trial.

The application of intraoperative haemofiltration in this pilot trial was associated with a trend towards a reduced length of ICU stay, particularly for patients with diabetes. In addition, the number of adverse events showed a similar trend in both treatment arms, with no new complications observed that were different from those expected from major operations such as cardiac surgery.

Chapter 4 Economic analysis

Introduction

The focus of the economic analysis was entirely determined by the clinical objectives of the feasibility study, which were to assess the benefits of continuous haemofiltration for on-pump CABG patients in terms of ICU stay, hospital stay, composite perioperative incidents, mechanical ventilation, medications, and tests and procedures within the hospital environment. The economic assessment had three main aims: (1) to undertake an exploratory economic evaluation using the clinical and cost data collected during the feasibility study; (2) to assess the adequacy of the data collection tools; and (3) to discuss the economic methodological implications for a future study.

Exploratory economic evaluation

Framework

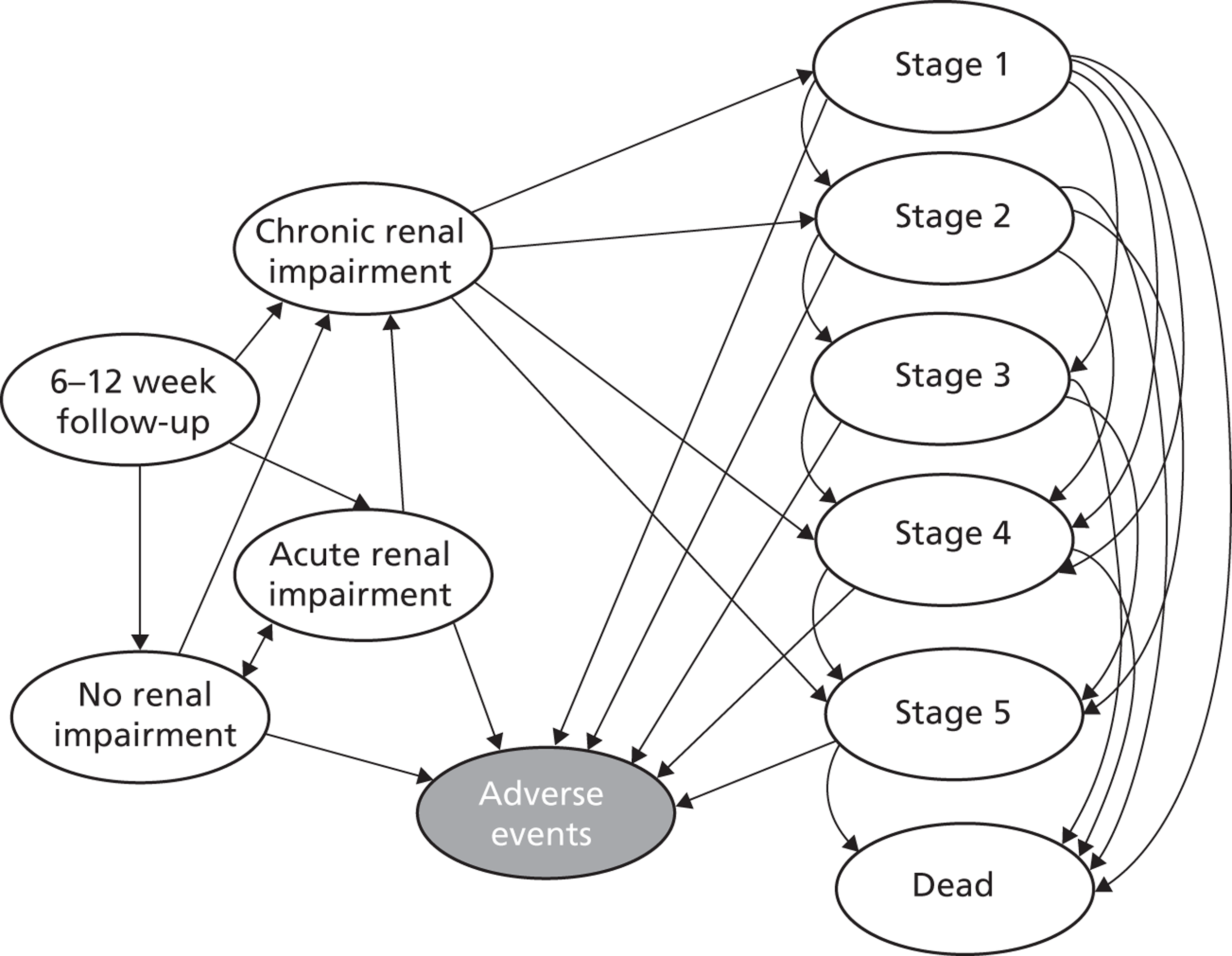

One of the key issues that needs to be considered is the type of framework to adopt for the economic analysis. Acute kidney injury is reported in the literature to occur in up to 30% of postcardiac surgery patients,27 leaving a large scope to provide benefit in terms of both clinical outcomes and costs. However, whether or not this will be seen in the feasibility analysis and for this particular patient group is uncertain.

The gold standard in economic analysis is cost–utility analysis, in which results are expressed cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). However, one aspect that needs to be explored within this pilot study is the feasibility of quality-of-life measurement tools in sensitively differentiating between the two groups of patients.

Methodology

The economic model aims to assess the quality of life and cost variation between the two groups and thus assess the incremental cost-effectiveness of using intraoperative haemofiltration during surgery. The perspective of the cost analysis is that of the NHS. The benefits included are quality of life in the form of the EQ-5D. No adverse events are considered although their occurrence, if the effects remain at follow-up, should be encompassed within the quality-of-life measurement within the EQ-5D.

Quality of life

A small sample of EQ-5D questionnaires was used with one measurement pre surgery and one post surgery as a late addition to the protocol whose follow-up is not yet complete for all patients at the time of producing this report. The sample with pre-admission and postdischarge values is 20 patients. The validity of any differences between the two groups depends on precision of the matching of the two treatment groups so that theoretically all patients are the same at the start of the trial. If this is the case then any variation in quality-of-life outcomes can be attributed to the use of haemofiltration within theatre.

The quality-of-life measure used in this study was the EQ-5D, which classifies 243 different health states with five different dimensions of health, each with its own level of severity. The EQ-5D is a generic measure and is the preferred method of the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE). NICE recommends the use of the weighted values from the EQ-5D questionnaire to be taken into consideration when evaluating health-care technologies.

The EQ-5D produces two estimates of quality of life. The VAS records the estimated quality of life of the individual who marks the scale. The answers to the EQ-5D questionnaire can be weighted according to the values generated by the UK population's preferences for each of the health states. In this pilot study we have considered both elements of the EQ-5D.

Costs

In order to assess the cost implications of the use of haemofiltration within theatre it is necessary to appropriately identify the resource use that differs between the two groups as a direct result of the change to treatment.

The key elements of resource use data that are utilised within the economic analysis concern the duration of hospital stay and what combination of ICU and ward days this stay consisted of, the use of haemofiltration, whether it was used within the theatre or in the ICU environment, and drugs prescribed specifically to aid renal function.

-

The costs of nursing time are not included for within theatres because no additional nursing support is required in order to facilitate the intraoperative haemofiltration, as this is performed by the perfusionists running the pump. Postoperatively, within the ICU, the nurse to patient ratio is already 1 : 1 and such nurses are trained to be able to use the haemofiltration machine.

-

The cost that has been allocated for 1 day on a ward is £264, which is the cost for the ward in which the patients are most likely to end up.

-

The cost of 1 day's stay in ICU has been divided by 24 and used alongside the number of hours that the patient stays within the ICU, in order to allow for more precision in the estimates. This does not, however, take into consideration the fact that staying in ICU for 1 hour during the night may in effect cost less as, for example, meals would not be necessary, or the fact that charges may have to be made for an entire day, even if the patient occupies the bed for only a short period of time.

-

The postoperative haemofiltration machine is estimated to last for 10 years. The number of patient hours over a 1-year period between November 2010 and October 2011 has been recorded as 1375 and used to calculate the number of hours of use of the haemofiltration machine over a 10-year period (13,750). The fixed cost of the purchase of the machine (£24,713) has, therefore, for the purpose of this analysis, been calculated as a cost per hour.

-

The cost of haemofiltration consumables within the theatre has been calculated at £63 per patient on average. This estimate is derived from the Liverpool Heart and Chest Hospital patients who receive intraoperative haemofiltration in theatre. The duration of the use of the intraoperative haemofiltration and the cost of consumables used are, however, unlikely to differ in this patient group. This does mean, however, that the cost of the use of haemofiltration within theatre does not currently take into consideration the duration of the filtration.

-

The costs of consumables used for postoperative haemofiltration within the ICU environment were estimated from the resource use of three patients similar to those in the trial. In order to estimate the consumables and other resources used within a full 24-hour period, costs were estimated and an average generated. In each case, although the full day of usage may have fallen part way through the treatment period, the cost of the initial set-up material (dialysis line, which is used for the duration of the treatment unless infection is suspected, and an aqua-set, which is changed every 72 hours) is included to most accurately represent what the costs of patients within the trial would be. As all the patients within the pilot study who required postoperative haemofiltration within the ICU were on the machine for less than 24 hours, the costs of consumables for the second day, when the initial set-up materials were not needed, did not need to be included.

-

The drug use that has been considered within the economic analysis regards only those drugs that specifically target renal function. Within the ICU, dopexamine is used intravenously. It is assumed that this drug is used for the duration of the period that the patient remains in the ICU and therefore drug costs (£19.80 per 24-hour period), along with the cost of saline solution (£4.27 per 24 hours), are allocated according to hours spent in the ICU.

-

In terms of drugs prescribed on discharge, furosemide, assumed at a dose of 20 mg, has been included in the costs (at £0.80 per pack of 28 × 20-mg tablets) when the patient was not already being prescribed the drug on admission. The furosemide prescription at follow-up has not been included in the cost analysis as it may be influenced by the variation in time until follow-up.

Short-term modelling

The economic analysis is largely focused on the data collected within the pilot study. The outcome of interest for the economic evaluation is HRQL as measured by the EQ-5D. This information can be used to calculate an incremental benefit of the use of intraoperative haemofiltration within cardiac surgery. The benefit of measuring quality of life post surgery but close to discharge from hospital is that it means that any effects of the surgery that last beyond the hospital stay and impact on quality of life will be picked up. While quality of life throughout a patient's stay may have varied somewhat, this may not be important over the longer term. On the other hand, what a postsurgery measurement close to discharge does not capture is the time that the individual has spent in hospital. This will be assessed to some extent within the costing element of the economic analysis; however, it means that those patients who have had to reside within the hospital for a longer period will not have their overall assessment of quality of life adjusted accordingly.

The EQ-5D follow-up scores could be adjusted to take into consideration the variation in follow-up time, which could vary between 6 and 12 weeks. Currently, the follow-up time is assumed to be similar in the two groups on average and therefore the quality-of-life change is compared unadjusted. Such adjustment would enable greater accuracy in the estimation of QALYs and would need to be considered in a further trial.

A study assessing the HRQL of chronic kidney disease patients was conducted in Japan. 38 The authors in that case also used the EQ-5D questionnaire along with eGFR and took into consideration some comorbidities including hypertension, diabetes and cardiovascular disease. In this case, patients were categorised as having cardiovascular disease if they had ischaemic or congestive heart disease or stroke in their record. EQ-5D values were produced for each of the five chronic kidney disease states with the subgroups mentioned above and analysed separately. These can be compared with the results obtained from the sample of patients in the pilot study, although it must be noted that the preference weights attached to the EQ-5D values are those of a Japanese population and therefore may differ from those within the UK population.

The clinical outcome of this pilot study is related to the number of days' ICU care that is required by each patient. This will be captured within the economic analysis as one of the costs to be compared between groups. The cost of the use of the filtration machine both within theatre and subsequently within the ICU will also be compared along with the costs of stay within a general ward and any drug use or additional nursing care that is necessary as a result of the renal impairment. The resource use at the individual level will have a cost attached to it and then the two groups can be compared.

Results

Quality of life

The EQ-5D consists of two elements: the VAS and a questionnaire. The VAS asks the patients to rate their health on a scale from 0 to 100. The results of this section are detailed below in Table 10.

| Groups | Pre operation | Post discharge | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| Non-haemofiltration | 75.11 (63.32 to 86.90) | 77.78 (67.39 to 88.16) | 2.67 (– 5.20 to 10.54) |

| Haemofiltration | 65.91 (50.23 to 81.59) | 80.82 (71.43 to 90.20) | 14.91 (3.87 to 25.95) |

The mean on admission differs by almost 10 points between the two groups; however, by follow-up this difference has narrowed to around 3 points. The mean difference between the two time points is also recorded in the table showing that the quality-of-life improvement is greater in patients who received haemofiltration.

The answers from the EQ-5D questionnaire can be converted into quality-of-life estimates based on the preferences of the UK population. These weights have been derived and used to generate the means for each group as shown in Table 11. The quality-of-life estimated preoperatively is slightly different between the two groups and this gap then widens at follow-up. The incremental benefit of using intraoperative haemofiltration, ceteris paribus, is 0.11 within the 0–1 range of the quality-of-life scale.

| Groups | Pre operation | Post discharge | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | Mean (95% CI) | |

| No haemofiltration | 0.77 (0.63 to 0.90) | 0.77 (0.68 to 0.87) | 0.01 (– 0.12 to 0.13) |

| Haemofiltration | 0.72 (0.54 to 0.90) | 0.84 (0.76 to 0.92) | 0.12 (– 0.06 to 0.29) |

The mean estimated quality of life of patients with chronic kidney disease in Japan who have cardiovascular disease is 0.826 (stage 3) and 0.843 (stage 4). 38 The improvement in quality of life from stage 3 to stage 4 is unexpected and may represent abnormalities in the sample used. It could, however, be a true reflection of quality of life within this group of patients. The quality of life of the patients within our pilot study is lower than that of the patients in the Japanese study. This could be simply due to the demographic differences between the people of Japan and the UK but may also be because the patients within this pilot study all are undergoing CABG surgery, and therefore the severity of their cardiovascular disease may be greater than that of the patients within the Japanese study sample.

Costs

Table 12 depicts the mean costs for each of the groups for those elements of resource use assumed to be directly influenced by the use of haemofiltration in theatre. The averages are for all patients for whom data were recorded.

| Groups | Haemofiltration | ICU hours | Dopexamine in ICU | Haemofiltration in ICU | Ward-days | Furosemide (28/20 mg) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No haemofiltration | 3.51 | 4614.58 | 6.69 | 13.95 | 2244.00 | 0.61 | 6883.30 |

| Haemofiltration | 56.46 | 3444.08 | 8.87 | 27.09 | 1667.37 | 0.46 | 5204.33 |

| Difference | 52.96 | – 1170.50 | 2.18 | 13.14 | – 576.63 | – 0.15 | – 1678.97 |

The largest average cost difference came from the duration of ICU stay, followed by the duration of stay on the ward. However, only three patients within the pilot study were prescribed dopexamine, and therefore this element may play a more significant role within a larger data set if the proportion of patients prescribed the drug was to increase. The total average cost per patient is 24% lower in those patients who received haemofiltration within theatre.

In such a small sample, the costs of exceptions to the protocol, such as the patient who was randomised to the no-haemofiltration arm but received haemofiltration in theatre, can make a difference to the overall cost-effectiveness analysis.

However, we had EQ-5D data for only 20 patients in total and thus, to be consistent, we used the costs from only these patients. This does not greatly affect costs; the incremental cost for haemofiltration now becomes –£1744 (Table 13).

| Groups | Haemofiltration | ICU hours | Dopexamine in ICU | Haemofiltration in ICU | Ward-days | Furosemide 28/20 mg | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No haemofiltration | 7.01 | 4937.50 | NA | NA | 2581.33 | 0.53 | 7526.38 |

| Haemofiltration | 51.62 | 4062.50 | 10.94 | 25.11 | 1632.00 | 0.58 | 5782.75 |

| Difference | 44.60 | – 875.00 | 10.94 | 25.11 | – 949.33 | 0.05 | – 1743.63 |

Subgroup analysis

One of the aims of the pilot trial was to stratify the patients into subgroups according to the presence or absence of diabetes, and kidney functioning levels. It would have been interesting to consider the patients by both their diabetes status and their eGFR ranges; however, owing to the small sample sizes, this was not possible. It is worth mentioning that in a larger trial it would be important to explore this aspect further as it may be possible to make predictions or acquire costs from the patient ranges.

Table 14 categorises the number of patients in each trial arm. As shown in Table 14 the numbers in each arm are relatively small, which means that the results may not be representative of the patient population of interest, hence a larger group of patients is required in a future trial.

| Groups | Patients in group (total) | Patients in group (with an EQ-5D result) |

|---|---|---|

| No haemofiltration | ||

| Diabetic | 7 | 2 |

| Non-diabetic | 11 | 7 |

| Haemofiltration | ||

| Diabetic | 7 | 2 |

| Non-diabetic | 12 | 9 |

The impact of diabetic/non-diabetic status on the cost analysis

Part of the study's aim was to stratify the patients where possible and then perform a cost analysis for the patient subgroups and in particular for those patients with or without diabetes. From this we added costs for each of the patients in their groups (as shown in Table 14) and then calculated as an average cost for each of these subgroups. However, one caveat to note at this point is that at such a small scale we can only discuss the patterns of trends shown from the average costs. Table 15 depicts the averages from the subgroup costings.

| Groups | Haemofiltration | ICU hours | Dopexamine in ICU area | Haemofiltration in ICU | Ward-days | Furosemide 28/20 mg | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No haemofiltration | |||||||

| Diabetic | 0 | 6830 | 0 | 0 | 2187 | 0.57 | 9018 |

| Non-diabetic | 5.74 | 3204 | 10.94 | 22.82 | 2280 | 0.64 | 5524 |

| Haemofiltration | |||||||

| Diabetic | 63.13 | 4437 | 6.88 | 34.07 | 1584 | 0.34 | 6125 |

| Non-diabetic | 52.58 | 2864 | 10.03 | 23.02 | 1716 | 0.53 | 4666 |

Table 15 has itemised the costs for diabetic and non-diabetic patients in both groups (non-haemofiltration and haemofiltration) in order to establish whether or not there are any trends. As shown in Table 15, in both groups the costs are greater for the diabetic patients than for the non-diabetic patients. The sample is too small to definitively say if there is a relationship between the two, although it is feasible that additional care is required for diabetic patients and this could be the reason for the increase in overall costs. Additionally, it is interesting to note that the length of time spent in ICU (and therefore the costs associated) for the diabetic groups, regardless of whether or not they had haemofiltration, was approximately twofold higher than for the non-diabetic patients. This too may relate to costs associated with diabetes as a disease although with such a small sample the evidence cannot be conclusive.