Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a project commissioned/managed by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC–NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’.

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HTA journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

LL, YY, AT and JB are members of the EuroQol Group (a non-profit making organisation responsible for the development of EQ-5D). LL is a member of the Board of the EuroQol Group and Brunel University receives reimbursement for her time. JB developed the SF-6D and the University of Sheffield receives reimbursement for its commercial use. LL is a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Technology Appraisal Committee.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Longworth et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report addresses a range of important methodological issues arising from the use of generic and condition specific measures of health-related quality of life (HRQL) in the decision-making of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). It describes a series of studies undertaken to address the key questions of how to determine whether a generic measure of HRQL is valid for use in calculating quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), what to do when the generic measure is not available (and specifically the use of ‘mapping’ techniques) and examines a new approach to dealing with situations where the generic measure is found to miss important components of HRQL for specific conditions (i.e. the use of ‘bolt-on’ dimensions). The rest of this chapter describes the rationale for looking at these questions and presents the key objectives of the research.

Background

Generic preference-based measures (GPBMs) of HRQL are commonly used in the economic evaluation of health interventions. These instruments have many advantages, including that they can incorporate the impact of treatment or ill health on a multidimensional scale and can be combined with data on survival in the form of QALYs. Furthermore, they facilitate comparisons between interventions and across conditions, which is important if there is a need for consistency in decision-making between interventions or if there is a need to compare with a common benchmark or cost-effectiveness threshold. The questionnaires can usually be easily administered to patients for self-completion and the data can incorporate a reflection of the value associated with different levels of health (usually based on values from members of the general population).

In the UK, NICE has specified that Health Technology Assessments (HTAs) submitted to its Technology Appraisal programme should be based on an incremental cost per QALY framework and recommends the use of the EQ-5D as the preferred GPBM. 1 The EQ-5D descriptive classification consists of five dimensions of health: mobility, self-care, usual activities, anxiety/depression, and pain/discomfort. 2 In the older and most commonly used version, each dimension of health has three levels of severity; however, a new five-level version has recently been published. 3 The 3-level version can describe 243 unique health states, to which a preference value can be assigned based on a set of values obtained from a large UK general population survey. 4

The decision by NICE to recommend the EQ-5D was, in part, a pragmatic decision. 5 It is now widely recognised that the various GPBMs produce different values,6–8 and this can be problematic for an organisation wanting to make consistent, transparent and predictable decisions. The GPBMs, including EQ-5D, have been criticised for being insensitive or failing to capture important aspects of health. 9,10 While NICE recommends the use of the EQ-5D for its HTAs, in its Guide to the methods of technology appraisal,1 it recognises that the EQ-5D may not be an appropriate measure for all conditions. 1 NICE requests evidence to show that EQ-5D is inappropriate for the condition of interest; however, it does not specify areas where EQ-5D is inappropriate, nor does it provide criteria to determine when a measure is appropriate for a particular condition or treatment.

The first section of this report will describe a systematic assessment of the appropriateness of the EQ-5D and other commonly used GPBMs in four broadly defined health conditions using the criteria of reliability, validity and responsiveness. This assessment uses established psychometric methods but is complicated by the absence of a gold standard measure of HRQL with which to compare the GPBMs. It is not possible to definitively determine whether the generic measures are inappropriate; it still requires an element of judgement. A generic measure may legitimately show no overall change in HRQL in contrast with a disease-specific measure because they are measuring different constructs. For example, a condition-specific measure may show improvements in some symptoms, but the overall impact on HRQL may be weakened as a result of new symptoms or side effects from treatment. However, judgements can be made transparently and systematically based on the totality of the evidence available. The reviews presented here draw on published research and established psychometric methods to establish the performance of the GPBMs.

In addition to acknowledging that the EQ-5D may not always be appropriate, the NICE Guide to the methods of technology appraisal 1 also acknowledges that EQ-5D data may not always be available. This may be for a variety of reasons, such as planning the economic evaluation after the trial design, concerns about obtaining data directly from patients and concerns about the views of regulators regarding non-significant differences in HRQL between treatments. In these circumstances NICE suggests incorporating data from other measures of health through the use of ‘mapping’. ‘Mapping’ (sometimes referred to as ‘cross-walking’) describes a method by which values obtained from GPBMs, such as EQ-5D, can be predicted from other measures or indicators of health. 11,12 No specific guidance is provided on the best methods of mapping other than to state that it must be based on empirical analysis and the methods must be clearly described. In 2013, recommendations on the use of mapping were described;13 however, these acknowledge that there is limited evidence to provide clear guidelines on many aspects of mapping, in particular the most appropriate model specifications. A recent review of mapping functions showed use of a range of different models including linear models, tobit models, censored least absolute deviation (CLAD), two-part models (TPMs) and response mapping to predict quality of life (QoL). 11 Studies also report a variety of methods to assess model and predictive performance including predicted mean and standard deviation (SD), median, Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), R 2, pseudo-R 2, mean estimates across severity groups, root-mean-square error (RMSE) and mean square error. A further issue in mapping is uncertainty, which is typically ignored. There is uncertainty in utility measure weights, the mapping coefficients, the choice of coefficients and the choice of model and these have not been addressed in the literature.

The second section of this report aims to establish the most appropriate model specifications for mapping based on two separate data sets. The analysis draws on the results of the systematic reviews reported in Chapter 2 and focuses on conditions where the EQ-5D measure has been found to be appropriate based on the published evidence. An exploratory analysis demonstrates how the uncertainty in the estimates can be better incorporated into analyses.

The third section of the report examines an alternative method for dealing with the situations when the EQ-5D has been demonstrated to be inappropriate for a given condition owing to insensitivity or failing to cover an important dimension of HRQL. One option could be to use alternative GPBMs, but, as discussed above, this leads to a lack of comparability in the estimates compared with the standard EQ-5D approach and also may not cover missing dimension(s). Recently, there has been growing interest to explore an alternative approach by developing preference-based measures from existing and validated condition-specific measures of HRQL (for a full review of this approach, see the HTA monograph by Brazier et al. 14 and for recent examples, see papers by Yang et al. 15,16). This approach can offer a useful solution in some situations. There have, however, been concerns raised that these condition-specific preference-based measures also produce very different values to the GPBMs and so may compromise comparability17 and these differences may continue to arise even when the methods of valuation are designed to be similar with GPBMs. 14

One possible solution to this problem is to not use comparable methods of valuation only, but also to keep the health state classification systems as similar as possible through the development of ‘bolt-on’ items to the EQ-5D or the GPBM of interest. Bolt-ons are dimensions that can be appended to another instrument and to which utility values can be attributed to the health states described by the instrument with the bolt-on. Previous research has examined the impact of modifying the EQ-5D descriptive system to include additional dimensions of health. 18,19 Krabbe et al. 18 valued EQ-5D health states including a ‘cognition’ dimension of health and found that it significantly impacted upon health state values. 18 More recently, Yang et al. 19 developed a ‘sleep’ dimension to add to the EQ-5D but found that it did not significantly impact on values. 19 The value of any potential ‘bolt-on’ dimension to EQ-5D depends crucially on whether its inclusion significantly impacts on the values given to the EQ-5D health states. The design and complexity of ‘bolt-on’ valuation studies will depend on how the values of the bolt-on levels are affected by the EQ-5D states accompanying it and whether the inclusion of the bolt-on items has a significant impact on the values given to the EQ-5D dimensions. Furthermore, the methods of bolt-on development and valuation are not well developed. Two studies are described in this report to develop potential bolt-ons to the EQ-5D, to quantify the impact they have on EQ-5D values and to assess the implications of this for future bolt-on developments. In undertaking this, a full valuation model is provided for one of the EQ-5D bolt-ons.

Aims and objectives of the report

The overall aim of the study was to develop methods for systematically incorporating information from condition-specific measures into the NICE decision-making framework. Specifically, the project had three related objectives:

-

To examine whether the EQ-5D and other commonly used generic HRQL measures are appropriate for use in calculating QALYs for NICE decision-making in selected specific conditions.

-

To develop mapping functions to predict EQ-5D data from condition-specific or clinical measures, to compare alternative model specifications and to conduct an exploratory analysis around the incorporation of uncertainty in the predicted estimates.

-

To investigate the development and valuation of bolt-ons to expand the EQ-5D descriptive system for those conditions in which the EQ-5D is not appropriate.

The results from the analysis to meet the first objective are used to inform the second and third objectives. Mapping will not be successful if the measure to be predicted does not adequately capture HRQL; therefore, only those conditions where the EQ-5D is found to be appropriate (objective 1) are considered to inform the mapping analyses (objective 2). Conversely, those conditions found to be not adequately captured by EQ-5D (objective 1) are the focus of the analyses of bolt-on measures (objective 3).

Chapter 2 A systematic review of the psychometric properties of generic preference-based measures of health in four conditions

Introduction

The aim of the review reported in this chapter was to assess the reliability, validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D, Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3) and SF-6D for measuring HRQL in four broadly defined conditions: visual disorders, hearing disorders, skin conditions and cancer.

The three GPBMs focused on (EQ-5D, HUI3 and SF-6D) were chosen to represent commonly used GPBMs of HRQL in NICE Technology Appraisals. 20 Specifically, as noted previously, the EQ-5D is recommended as the preferred measure by NICE and is the most commonly used measure in its Technology Appraisals. 1,20 The HUI3 was chosen as it is commonly used internationally and is the second most frequently used in NICE Technology Appraisals. 20 The SF-6D was also chosen as it has properties considered important by NICE (as a validated and generic measure of HRQL that also has a set of UK general population values elicited using a choice based method). In addition, the SF-6D questionnaire was derived from the short form questionnaire-36 dimensions (SF-36), which is widely used in clinical trials.

The four conditions were chosen to represent areas where the EQ-5D measure may not be appropriate based on previous published research21–24 or concerns reported during the development of NICE Technology Appraisals. 25,26 Previous research has reported that the generic instruments, particularly the EQ-5D, do not adequately capture changes in health as a result of visual or hearing loss, but findings are mixed. 21–23,24 In addition, the measurement of HRQL in these conditions has been the subject of debate within NICE Technology Appraisals of treatments for these conditions. 25,26 The appraisals of treatments for skin conditions by NICE have frequently relied upon data from condition-specific measures in analyses rather than directly using generic measures of HRQL. Finally, the condition for which treatments are most frequently appraised by NICE is cancer. There have been suggestions that generic measures, such as the EQ-5D, may not adequately reflect the effects of cancer and related treatments that are considered important to patients (e.g. fatigue); however, a comprehensive review of the evidence has not been previously reported. A similar review has been conducted to examine the appropriateness of the EQ-5D in mental health as part of another Medical Research Council (MRC) funded project. 27,28

The rest of this chapter discusses the methods used for the systematic literature reviews, the findings and results for the four conditions, each discussed separately, and finally a brief discussion and conclusion is provided.

Methods

The generic preference-based measures

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D describes HRQL in terms of five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression. 2 Each dimension is usually described in terms of three levels of severity, although a version with five levels has recently been published. 3 The health classification system for the three-level version describes 243 health states and a tariff of values for each health state is available for several countries, including the UK. The UK value set was obtained from valuations provided by 3395 members of the general population using the time trade-off (TTO) valuation method. 4,29

SF-6D

Derived from the SF-36 and Short Form questionnaire-12 dimensions (SF-12) health questionnaires, the SF-6D has six dimensions (physical functioning, role limitation, social functioning, bodily pain, mental health and vitality) and each dimension has four to six severity levels. 6,30 Any patient who completes the SF-36 or the SF-12 can be uniquely classified according to the SF-6D. The health classification system of SF-6D describes a total of 18,000 health states and a tariff of values for each health state is available for several countries, including the UK. The UK value set was obtained from valuations provided by 611 members of the general population using the standard gamble (SG) valuation method. 30

Health Utilities Index Mark 3

Health Utilities Index is a group of GPBMs for measuring comprehensive health status and HRQL, including Health Utilities Index Mark 1(HUI1), Health Utilities Index Mark 2 (HUI2) and HUI3. HUI3 has nine dimensions (vision, hearing, speech, ambulation/mobility, pain, dexterity, self-care, emotion and cognition) and each dimension has three to six levels. The health classification system of HUI3 describes almost a million unique health states and a tariff of values for each health state is available for Canada. The Canadian value set was obtained from valuations provided by 504 members of the general population using the visual analogue scale (VAS) and SG valuation methods. 31

Search strategy and data identification

The search strategy aimed to identify relevant journal papers providing evidence on the reliability, validity and responsiveness of EQ-5D, HUI3 or SF-6D in the following four clinical conditions: vision disorders, hearing impairments, skin disorders and cancer.

Four separate search strategies were developed, one for each of the conditions. The search strategies were developed following consultation with experts in information resources and health economics. An iterative approach to the searches was adopted. The strategies consisted of a broad search to identify studies reporting the use of the GPBMs in patients with each of the four clinical conditions. The search included both free text and controlled terms. Free text words included ‘euroqol’, ‘hui3’, ‘sf6d’ (all with alternative spellings). Condition-specific terms were also included (see Appendix 2 for the full searches used). The following electronic databases were searched: BIOSIS (1969 to 2010), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) (1982 to 2010), Cochrane Library comprising the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Methodology Register, NHS Economic Evaluations Database (NHS EED) (1991 to 2010), EMBASE (1980 to 2010), MEDLINE (in process and non-indexed to 2010), PsycINFO (1806 to 2010) and Web of Science (1900 to 2010).

In addition, a database of studies held on the website of the EuroQol Group32 was searched to check for any missing papers reporting EQ-5D and to check that the search strategies were identifying relevant papers. Comparable databases for the SF-6D and HUI3 are not available. The search strategies are presented in Appendix 2 .

The inclusion criteria were that (1) the study reported dimensions and/or index values for at least one of the generic instruments EQ-5D, HUI3 or SF-6D and (2) the study reported another measure of QoL [including VAS or EuroQol VAS (EQ-VAS), TTO, SG direct valuation of QoL or another utility measure] or a measure of clinical severity/symptoms that would enable an assessment of validity, responsiveness or reliability.

The condition-specific inclusion criteria were that the studies reported the above data for people with one of the following conditions: vision disorders, hearing disorders, skin disorders or cancer.

There was no restriction relating to the type of study or type of condition within the overall definitions. Owing to resource limitations, only English language studies were reviewed.

Data extraction

Data were extracted from the studies using a standardised set of forms developed for this study after reviewing forms used for similar studies in other disease areas. 27 The data extracted included general characteristics of the study and participants, instruments used in the study, methods and results used in the study for assessment of reliability, construct validity and responsiveness. Data extraction for the different clinical conditions was undertaken by one member of the research team and summarised using items presented in Table 1 .

| General | Author name, year |

| Country where the study took place | |

| Type of disease/disorder | |

| Disease/treatment stage | |

| Treatment (if any) | |

| Study design | |

| Participant characteristics | Number of participants |

| Age (mean and range) | |

| Gender (percentage of males) | |

| Ethnicity | |

| Missing data, including reasons for non-completion if given | |

| Valuation and descriptive methods | Descriptive systems |

| Tariff or source of value sets | |

| Mean values (SD, range) | |

| Direct valuations used | |

| Condition-specific HRQL measures used | |

| Clinical measures used | |

| Qualitative questions asked | |

| Missing data of measures completion | |

| Reliability | Methods |

| Results | |

| Validity | Methods |

| Results | |

| Responsiveness | Methods |

| Results |

Data analysis

Assessment of quality and relevance

For the review, of most importance was the relevance of the study in terms of the patient population and inclusion of evidence to establish the psychometric performance of the generic measures. Studies including a mixed population of patients (i.e. with various conditions) were only included if they reported health-related utility values or dimension responses for subgroups of patients with one of the four specific conditions being evaluated. Nevertheless, a judgment regarding the risk of bias for each study was determined by reviewing the methods of patient recruitment and noting any missing data reported (either study drop-outs or incomplete questionnaires). Studies were not required to be specifically designed to assess validity, responsiveness or reliability, provided that they reported data in sufficient detail to allow an assessment of these traits. The intention of the assessment of quality was not to exclude relevant studies, but to highlight any concerns about quality when findings were interpreted.

Assessment of reliability

The reliability of a measure is defined as its ability to reproduce results when measurements are repeated on an unchanged population,33 or the comparability of responses across different assessors (for example, patient and proxy report). Reliability can be measured by retesting and reporting either the correlation or difference between estimates. In some circumstances, no change in health status may be expected over time and, subsequently, the values obtained using the measures may be stable. These results were interpreted as evidence of the reliability and stability of instruments. Other assessments of reliability included assessments of inter-rater reliability based on a comparison of responses given by multiple people completing the questionnaire on the patients' behalf. When considering the results of inter-rater comparisons, it is important to note that all of the GPBMs have been designed for self-completion and to report self-assessed HRQL. Therefore, perfect agreement between the intended respondents and their proxies may not be expected. Finally studies reporting internal consistency were also included as assessed through multitrait analysis.

Assessment of construct validity

Validity is defined as how well an instrument measures what it was intended to measure. More specifically, for the GPBMs, whether the dimensions adequately cover the key determinants of health-related utility. Criterion validity is determined by comparing an instrument to an established gold standard; however, a gold standard with which to benchmark HRQL measures against does not exist. Therefore, it is necessary to assess the validity of measures of health-related utility using measures that have evidence of construct validity for that condition, which establishes if patterns in scores confirm constructs or hypotheses about expected patterns.

We assessed the construct validity of the GPBMs using the ‘known-group’ method. The known-group method compares the values obtained from the GPBMs between groups of patients who are expected to differ [qualitatively or statistically using t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA)] in the construct measured by the indicator used to define the groups. The known groups in this context are often defined according to clinical severity using other measures. It should be noted that the usefulness of these comparisons can be limited by sample size, particularly as studies are usually not powered to detect differences according to preference-based measures. In addition, consideration must be given to the appropriateness of the clinical measure and the groups defined by it, and exogenous factors that may influence HRQL. For instance, groups defined solely by the presence of a biomarker may have no impact on HRQL. If patients have a number of comorbidities, then these may have a greater impact on HRQL than the condition of interest. Known groups can also be defined using a case–control analysis in which comparison is between patient and general public population, or defined on the basis of other aspects such as age, gender or countries. However, a more stringent test is to define known groups based on different levels of condition severity (for example, by using a clinical indicator).

We also examined convergent validity, which is a type of construct validity. Convergent validity is defined as the extent to which one measure correlates with another measure of the same or similar concept. In this review, we examined the extent to which the EQ-5D, SF-6D or HUI3 correlate with other measures of QoL or clinical severity. Correlation was defined as ‘low’ if correlation coefficient was < 0.3, ‘moderate’ if between 0.3 and 0.5 and ‘strong’ if > 0.5. Correlations need to be interpreted with caution as it is not always clear how strong the relationship between the generic and condition-specific indicators should be. Furthermore, we interpreted estimation of regression between GPBMs and other measures as another indication of a correlation, focusing on whether some measures were significant predictors of others.

Assessment of responsiveness

Responsiveness assesses the ability of an instrument to measure a change in health-related utility over time. As with construct validity, the measurement of responsiveness is difficult as there is no gold standard measure with which to compare. Nevertheless, we assessed the responsiveness of health-related utility measures by comparing change in health-related utility measured over a period of time in which health status is expected to change (e.g. before and after an intervention) with the change demonstrated by another measure of health. For inclusion in the assessment of responsiveness, the comparator measure must have demonstrated a change in health. We did not review data from studies outside of the review relating to responsiveness of the comparator measures. Good evidence of responsiveness is considered where the GPBM shows statistically significant change in health (e.g. t-test) shown by other measures or clinical indicators. Weaker evidence of responsiveness is considered where the same trend of change is shown but the change is not statistically significant. When responsiveness indices for estimates of health-related utility are reported [e.g. effect size (ES) or standard response mean], they were compared with other measures. ES is the mean change in score of a measure between two different time points divided by the SD of the score at baseline. Standardised response mean is the mean change score of a measure between two different time points divided by the SD of the change score. As for the tests of validity, it is important to consider whether the measures of health change that are being used to assess responsiveness are valid. In addition, it is important to consider whether other health changes not directly related to the condition could have impacted upon health-related utility (e.g. side effects of treatment).

Presentation and analysis

Data for each of the four conditions are presented separately. Information on the study design, participant characteristics and the measures included are reported. Within each of the broadly defined conditions, there is a range of underlying aetiologies with different symptoms. The results for visual disorders, skin diseases and cancers are therefore presented for subgroups defined according to type of condition. Subgroups are not presented for hearing impairments as the studies were mainly defined according to the presence or absence of hearing loss and/or extent of hearing loss. For each condition, a summary table is presented which reports an overview of the conclusions drawn from each paper for each of the types of assessment.

Results

Vision

Search results: vision

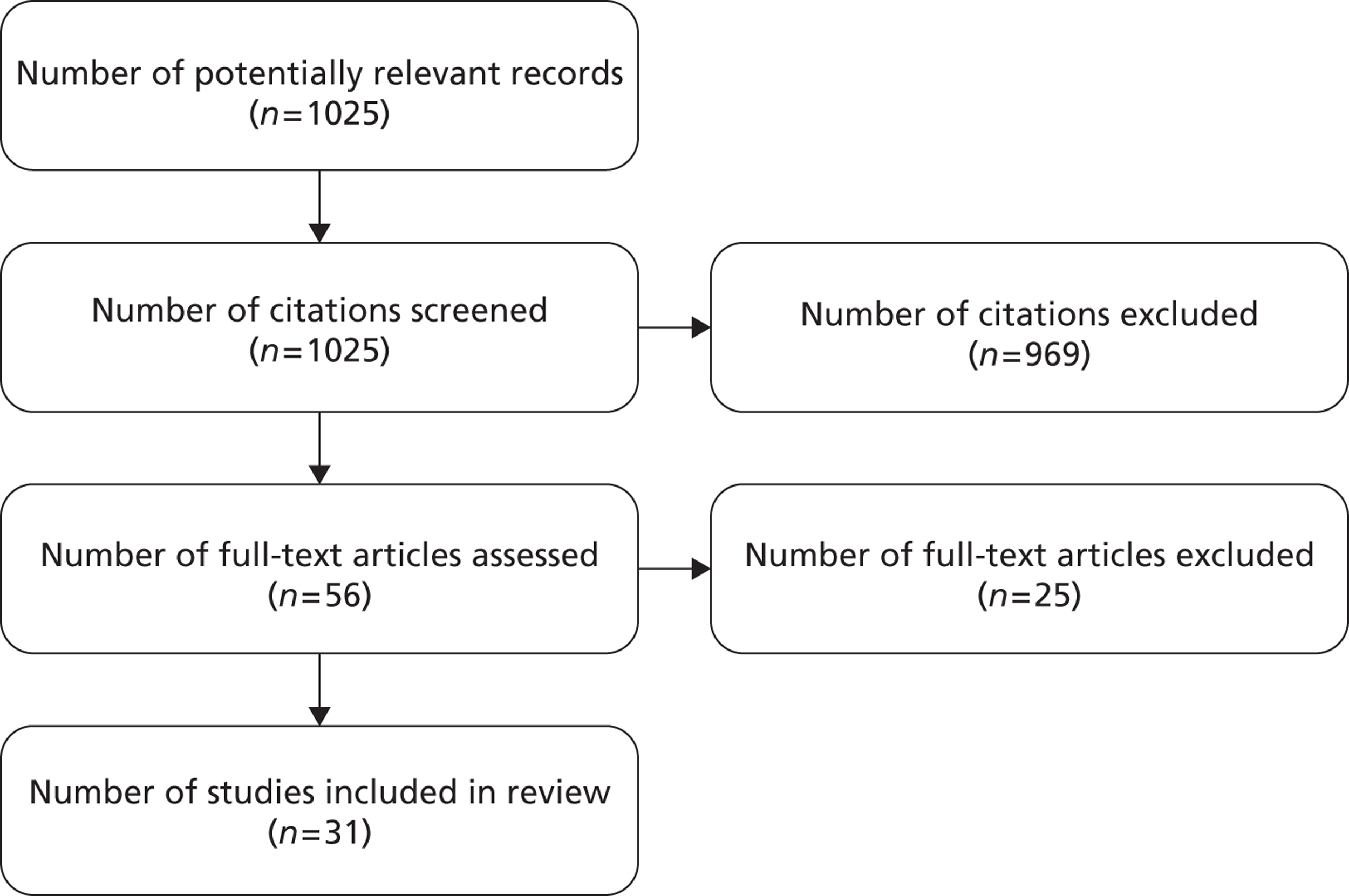

Bibliographic searching was completed in August 2010 and total of 1025 potentially relevant papers were identified. Abstracts and titles for all papers were screened to identify papers meeting the inclusion criteria; 969 records were excluded and full papers were ordered for the remaining 56 records. After reviewing the full papers, 25 were excluded and a total of 31 papers were included in the review. A flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies: vision.

Quality assessment: vision

A range of recruitment procedures were reported. Some were retrospective analyses of data sets with predetermined inclusion criteria,34–36 some were case–control analyses,37–39 and the majority were cross-sectional observational studies. 22,34,36,40–52 The only randomised controlled trial (RCT) had well-defined inclusion criteria. 53 Response rates for questionnaires ranged from 33% to 96%, with completion rates of longitudinal studies > 85% in all but one study50 (range 52–98%). No study was excluded after the assessment of quality.

Study design and patients' characteristics: vision

Summary characteristics of the 31 studies are presented in Table 2 . Thirty of the 31 studies were observational studies22,34,36–39,40–52,54–64 and the remaining study was a RCT. 53 The studies were conducted in different countries including the UK, the USA and Canada and some were multicountry studies. The studies identified included a wide range of visual disorders. Five studies were in patients with glaucoma,34,44–46,54 seven studies were in patients with age-related macular degeneration (AMD),22,43,47–49,55,56 eight studies included patients with cataracts,36–39,53,57–59 two studies were on patients with diabetic retinopathy,42,50 three were on patients with conjunctivitis51,60,61 and the remaining studies included people with various other visual conditions. 40,41,52,62,63,64

| Study reference grouped by condition (author, year) | Country | Disease/treatment stage | Sample size | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glaucoma | ||||

| Aspinall et al., 200844 | UK | Glaucoma and no other ocular comorbidity | 72 | Cross-sectional |

| Kobelt et al., 200645 | Sweden | Ocular hypertension or open-angle glaucoma | 109 | Cross-sectional |

| Mittmann et al., 200134 | Canada | Glaucoma – a subset from a study on a range of chronic conditions | 137 | Cross-sectional |

| Montemayor et al., 200146 | Canada | Chronic open-angle glaucoma, normal-pressure glaucoma or suspected glaucoma with treatment | 224 | Cross-sectional |

| Thygesen et al., 200854 | Multiple | Late-stage primary open-angle glaucoma | 162 | Case review |

| AMD | ||||

| Cruess et al., 200747 | Canada | Neovascular AMD | 67 | Cross-sectional |

| Espallargues et al., 200522 | UK | Wet or dry AMD | 209 | Cross-sectional |

| Kim et al., 201055 | Korea | – | 625 | Cohort |

| Lotery et al., 200748 | UK | Bilateral subfoveal neovascular-AMD | 75 | Cross-sectional |

| Payakachat et al., 200949 | Multiple | Wet AMD | 154 | Cross-sectional |

| Ruiz-Moreno et al., 200856 | Spain | Bilateral neovascular AMD | 89 | Prospective case–control |

| Soubrane et al., 200743 | Multiple | Neovascular AMD | 401 | Cross-sectional |

| Cataracts | ||||

| Asakawa et al., 200836 | Canada | With or without other comorbidities | 911 | Cross-sectional |

| Black et al., 200957 | UK | First or second eye | 860 | Prospective cohort |

| Conner-Spady et al., 200558 | Canada | – | 253 | Cohort |

| Datta et al., 200853 | UK | Bilateral cataracts in participants over 70 years of age | 289 | Secondary analysis of RCT |

| Jayamanne et al., 199959 | UK | First Eye | 144 | Prospective |

| Polack et al., 200737 | Kenya | – | 196 | Case–control |

| Polack et al., 200838 | Bangladesh | – | 217 | Case–control |

| Polack et al., 201039 | Philippines | Participants over 50 years of age | 401 | Case–control |

| Diabetic retinopathy | ||||

| Lloyd et al., 200842 | UK | Diabetic retinopathy due to diabetes | 122 | Cross-sectional |

| Smith et al., 200850 | USA | Type 2 diabetes | 401 | Cross-sectional |

| Conjunctivitis | ||||

| Pitt et al., 200460 | UK | – | 310 | Cohort |

| Rajagopalan et al., 200551 | Multiple | Non-Sjögren’s keratoconjunctivitis or Sjögren’s syndrome | 210 | Cross-sectional |

| Smith et al., 200561 | Spain | – | 401 | Cohort |

| Other visual disorders | ||||

| Boulton et al., 200640 | UK | Vision impairment or blindness in children | 100 | Cross-sectional |

| Clark et al., 200862 | Australia | Postcataract surgery endophthalmitis | 49 | Cohort |

| Kempen et al., 200363 | USA | Cytomegalovirus retinitis in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome | 961 | Prospective cohort |

| Langelaan et al., 200741 | Netherlands | Low-vision patients | 120 | Cross-sectional |

| Quinn et al., 200464 | USA | Retinopathy of prematurity | 244 | Cohort |

| van Nispen et al., 200952 | Netherlands | Vision impairment in older people | 296 | Observational |

The inclusion criteria varied across the studies reviewed within each of the specific conditions. Some studies reported that patients were identified through case notes, but no more details are provided. It was noted whether AMD was bilateral or unilateral and wet or dry, whether cataracts were present in the first or second eye and whether glaucoma was primary or multiple. Sample sizes also varied across studies, ranging from 4962 to 961. 63 One study40 included children with a mean age of 6 years and used HUI3. The authors reported that the HUI system had been used in a previous study of young children with a range of impairments similar to those included in their study, although it should be noted that this did not refer specifically to the HUI3 at that time. All other studies included adult patients and the AMD studies included patients over 70 years.

Measures used in studies: vision

Table 3 summarises the measures that have been used in the 31 studies included in the review. For the three GPBMs of interest, the EQ-5D was reported in 27 studies22,37–39,41–63 and therefore was the most commonly utility measure, six studies reported the HUI322,34,36,40,42,64 and only one study reported the SF-6D. 22 Ten studies also reported direct valuations of patients' own health states using methods such as the TTO or VAS. 22,44,45,51,58–63 Twenty-three studies reported visual acuity (VA)22,34,37–39,41–50,52–55,58,61,63,64 to indicate visual severity. In addition, various patient-reported visual-specific QoL measures were used.

| Study reference grouped by condition (author, year) | GPBM | Direct valuation | Rating scale | Condition specific HRQL instruments | Clinical severity | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | SF-6D | HUI3 | TTO | VAS | VFQ-20/25 | VF-14/4D | RQLQ | VFA | IDEEL | VA | |

| Glaucoma | |||||||||||

| Aspinall et al., 200844 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kobelt et al., 200645 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Mittmann et al., 200134 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Montemayor et al., 200146 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Thygesen et al., 200854 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| AMD | |||||||||||

| Cruess et al., 200747 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Espallargues et al., 200522 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Kim et al., 201055 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lotery et al., 200748 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Payakachat et al., 200949 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ruiz-Moreno et al., 200856 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Soubrane et al., 200743 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cataracts | |||||||||||

| Asakawa et al., 200836 | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Black et al., 200957 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Conner-Spady et al., 200558 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Datta et al., 200853 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Jayamanne et al., 199959 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Polack et al., 200737 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Polack et al., 200838 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Polack et al., 201039 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Diabetic retinopathy | |||||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 200842 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Smith et al., 200850 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Conjunctivitis | |||||||||||

| Pitt et al., 200460 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Rajagopalan et al., 200551 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Smith et al., 200561 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Other visual disorders | |||||||||||

| Boulton et al., 200640 | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Clark et al., 200862 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kempen et al., 200363 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Langelaan et al., 200741 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Quinn et al., 200464 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| van Nispen et al., 200952 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Reliability: vision

No tests of reliability were performed on the generic preference-based measures.

Known-group analysis and convergent validity: vision

Known-group analysis was performed in 24 studies:22,34,36–45,47–51,54,56,60–64 20 for EQ-5D,22,37–39,41–45,47–51,54,56,60–63 five for HUI3,34,36,40,42,64 but no studies for SF-6D. In six of the studies, groups were defined by VA, or by contrast sensitivity, and mean estimates of utility for each defined group were provided. 22,41–43,54,61 The remaining 25 studies had either a case–control design, had different conditions or did not define levels of severity.

Nine of the 31 studies reviewed provide evidence on correlation or regression between GPBMs with either each other or with visual measures. 22,37,38,44,46,50,52–54 Eight studies report evidence of convergent validity in EQ-5D compared with a visual measure,37,38,44,46,50,52–54 with Espallargues et al. 22 also reporting correlations across EQ-5D, SF-6D and HUI3. Details of the data are summarised in Appendix 3 and below by type of vision disorder.

Glaucoma

Three studies of people with glaucoma allowed a known-group analysis for EQ-5D where groups were defined by severity of vision problems. 44,45,54 The studies by Aspinall et al. 44 and Kobelt et al. 45 found that EQ-5D utility values decreased with increasing glaucomatous damage but were not statistically significant. The study by Thygesen et al. 54 defined three groups on the basis of the Snellen score and the ordering of mean utility values were consistent and statistically significant. No such data were available for HUI3 or SF-6D by severity groups. However, one paper reported HUI3 in a case–control study, which showed an appropriate and significant difference in HUI3 values between the cases and controls. 34

Three studies reported correlation statistics for EQ-5D with VA in patients with glaucoma. 44,46,54 Aspinall et al. 44 reported moderate and statistically significant correlations for the EQ-5D measure and the mobility, self-care and anxiety dimensions. The study by Thygesen et al. 54 also showed a significant correlation between VA and EQ-5D. However, Montemayor et al. 46 reported low and non-significant correlations for EQ-5D with VA.

Age-related macular degeneration

In studies of people with AMD, all seven22,43,47–49,55,56 papers provided evidence to allow an assessment of construct validity of the EQ-5D. Of these, five22,43,48,49,55 differentiated between groups based on severity of vision disorder and three43,47,56 included assessments of cases against controls. Three studies defined visual severity groups: two22,43 in terms of levels of VA and the other55 based on whether they had unilateral or bilateral AMD. Soubrane et al. 43 showed inconsistency with the mean estimates, with normal VA having a worse mean utility when compared with mild, moderate, severe and near blind utility values. The anxiety dimension of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) was also inconsistent between the normal and mild VA groups, but this inconsistency was not shown in the Visual Function Questionnaire-25 (VFQ-25). The study did, however, report a significant difference of utility values between those with neovascular AMD and the control group. Kim et al. 55 found a statistically significant difference in EQ-5D values between those with unilateral and bilateral AMD. Espallargues et al. 22 found a consistent relationship between VA and contrast sensitivity with HUI3, SF-6D, TTO and VAS but not EQ-5D.

Of the three case–control studies, two found that EQ-5D showed an appropriate and statistically significant reduction in HRQL for people with AMD compared with general population controls. 43,56 One reported a difference that was not a statistically significant difference, but the difference was in the appropriate direction. 47

Three studies provided correlation statistics between generic and visual measures in patients with AMD and all showed poor correlation of EQ-5D with other measures. 22,47,48 Espallergues et al. 22 found that the VAS, TTO, HUI3 and SF-6D were all significantly correlated with both VA and contrast sensitivity. However, they did not find significant correlations for EQ-5D with VA or contrast sensitivity.

Cataracts

Four36–39 of the seven37–39,53,57–59 studies in patients with cataracts provided evidence to allow an assessment of the construct validity of the EQ-5D37–39 and HUI3. 36 Three case–control studies conducted in different countries by Polack et al. 37–39 found that there were significant differences in EQ-5D between cases and controls, and found that cases were likely to report a significant difference across all dimensions (except pain dimension in Polack et al. 38). However, Polack et al. 39 reported an inconsistent association between EQ-5D and VA.

One study reported HUI3 values for cases and controls and identified a statistically significant and appropriate difference between the two groups. 36

Four studies provided evidence of the convergent validity of the EQ-5D with VA. 37–39,53 Polack et al. 37–39 tested associations between EQ-5D and VA, with one study finding that poorer VA was associated with higher odds of reporting any problem with all EQ-5D dimensions apart from anxiety. 37 The other two studies found no significant associations between VA and EQ-5D dimensions, apart from a borderline association with self-care. 38,39 Datta et al. 53 did not find significant correlations for EQ-5D with VA.

Diabetic retinopathy

Two studies reported EQ-5D identifying a statistically significant difference between the two extreme groups; however, the differences between neighbouring groups were not significant and frequently inconsistent. 42,50 In the study by Lloyd et al. 42 the inconsistencies were also shown in VAS ratings of patients' own health and the HUI3. This may be the result of small sample size or, as the authors speculate, it may be the result of a loss of independence of the participants when they reach that level of severity. 42

Smith et al. 50 fitted a linear regression and found visual angle to be a predictor of EQ-5D utility values. They also fitted a non-parametric ordinal logistic regression and this estimated that any degree of visual impairment would result in an increased likelihood of reporting non-perfect utility values.

Conjunctivitis

All three studies allowed an assessment of construct validity of the EQ-5D in people with conjunctivitis. Two were case–control studies and showed a statistically significant difference between cases and controls. 60,61 One study demonstrated a difference between groups defined according to severity. 51 Within the dimensions of the EQ-5D, the study by Pitt et al. 60 found the pain dimension to be the only dimension to show a statistical difference. However, Smith et al. 61 reported a significant difference across all dimensions except mobility. No studies provided evidence on the construct validity of the HUI3 or SF-6D.

No papers reported on convergent validity of the measures in patients with conjunctivitis.

Other visual conditions

The remaining six studies were in unique visual conditions. 40,41,52,62–64 Three of these studies allowed an assessment of the construct validity of the EQ-5D41,62,63 and two of the HUI3. 40,64 Clark et al. 62 and Kempen et al. 63 reported an appropriate, but non-significant, difference in the EQ-5D between the control group and those with endophthalmitis and cytomegalovirus, respectively. Langelaan et al. 41 undertook a study on visually impaired patients and identified an appropriate, but non-significant, difference in the EQ-5D between low and high visual field groups, but an inconsistent and non-significant difference in the EQ-5D between low- and high-VA groups.

Boulton et al. 40 and Quinn et al. 64 found the HUI3 identified statistically significant and appropriate differences between groups of patients with unspecified blindness/visual impairment.

A study by van Nispen et al. 52 reported a multivariate regression analysis of data from older patients with visual impairment. They found that worsening VA was a significant risk factor for a lower EQ-5D value.

Responsiveness

Only three studies reported responsiveness of the utility measures in visual disorders ( Appendix 4 ). 55,57,58 Kim et al. 55 reported a statistically significant improvement in both the Visual Function Questionnaire (4 dimension) (VF-4D) and the EQ-5D after photodynamic therapy in patients with AMD. Black et al. 57 reported a statistically significant improvement in both the Visual Function Questionnaire (14 item) (VF-14) and the EQ-5D postcataract surgery, although the latter was relatively small. Conner-Spady et al. 58 reported a statistically significant improvement in the Visual Function Assessment (VFA) and VA post cataract surgery, but the subsequent mean improvements in EQ-VAS and EQ-5D were small and not statistically significant. This may suggest that the EQ-5D is not responsive in this population; however, it should be recognised that the study was not initially powered to identify statistically significant changes and a mean improvement was identified. In addition, the VAS did not change from pre to post treatment; therefore, the treatment may not significantly impact on HRQL.

Summary of results for visual review

The 31 studies included in this review show a worsening of utility values as visual impairment increased in many though not all studies. The magnitude and statistical significance of the association varied between different GPBMs of HRQL. Table 4 shows an overview of performance of utility measures in visual impairment.

| Study reference grouped by measure (author, year) | Known group (severity) | Known group (case–control) | Known group (other) | Responsiveness | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conditions | Consistent evidence | Significant | Consistent evidence | Significant | Consistent evidence | Significant | Correlation | Consistent evidence | Significant | Reliability | |

| EQ-5D | |||||||||||

| Aspinall et al., 200844 | Glaucoma | ✓ | ✗ | Moderate | |||||||

| Kobelt et al., 200645 | Glaucoma | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Montemayor et al., 200146 | Glaucoma | ✓ (low) | |||||||||

| Thygesen et al., 200854 | Glaucoma | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Cruess et al., 200747 | AMD | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

| Lotery et al., 200748 | AMD | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |||||||

| Payakachat et al., 200949 | AMD | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Ruiz-Moreno et al., 200856 | AMD | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Soubrane et al., 200743 | AMD | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Espallargues et al., 200522 | AMD | ✗ | ✗ | Low | |||||||

| Kim et al., 201055 | AMD | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Datta et al., 200853 | Cataracts | ✗ | |||||||||

| Polack et al., 200737 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Polack et al., 200838 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |||||||

| Polack et al., 201039 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | |||||||

| Conner-Spady et al., 200558 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Black et al., 200957 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 200842 | Diabetic retinopathy | Mixed evidence | Mixed evidence | ||||||||

| Smith et al., 200850 | Diabetic retinopathy | Mixed evidence | Mixed evidence | ✓ | |||||||

| Pitt et al., 200460 | Conjunctivitis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rajagopalan et al., 200551 | Conjunctivitis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Smith et al., 200561 | Conjunctivitis | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Clark et al., 200862 | Other | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Kempen et al., 200363 | Other | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Langelaan et al., 200741 | Other | Mixed evidence | Mixed evidence | ||||||||

| van Nispen et al., 200952 | Other | ✓ | |||||||||

| HUI3 | |||||||||||

| Mittmann et al., 200134 | Glaucoma | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Asakawa et al., 200836 | Cataracts | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lloyd et al., 200842 | Diabetic retinopathy | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Boulton et al., 200640 | Other | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Quinn et al., 200464 | Other | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Espallargues et al., 200522 | AMD | Low to moderate | |||||||||

| SF-6D | |||||||||||

| Espallargues et al., 200522 | AMD | Low to moderate | |||||||||

The largest amount of evidence was found for the EQ-5D compared with the other generic measures and the results were mixed. Nearly all studies showed significant differences between patients with the condition and a control group. Studies comparing EQ-5D scores across severity groups were more mixed, with the majority of studies showing little or no difference between groups defined by clinical measures of visual impairment. No studies allowed an assessment of reliability for any of the measures. There were just three studies on responsiveness. and all were in the form of before-and-after studies of an intervention. 55,57,58 These identified changes consistent with an effective intervention, but differences were statistically significant in only two of three studies. 55,57 The assessment of convergent validity was also concerning, with half of the studies not demonstrating a statistically significant correlation with clinical measures. While there was less evidence for the HUI3, all but one study42 demonstrated good validity; no studies assessed responsiveness. There was very limited evidence on the SF-6D in patients with visual impairment.

Hearing

Search results: hearing impairment

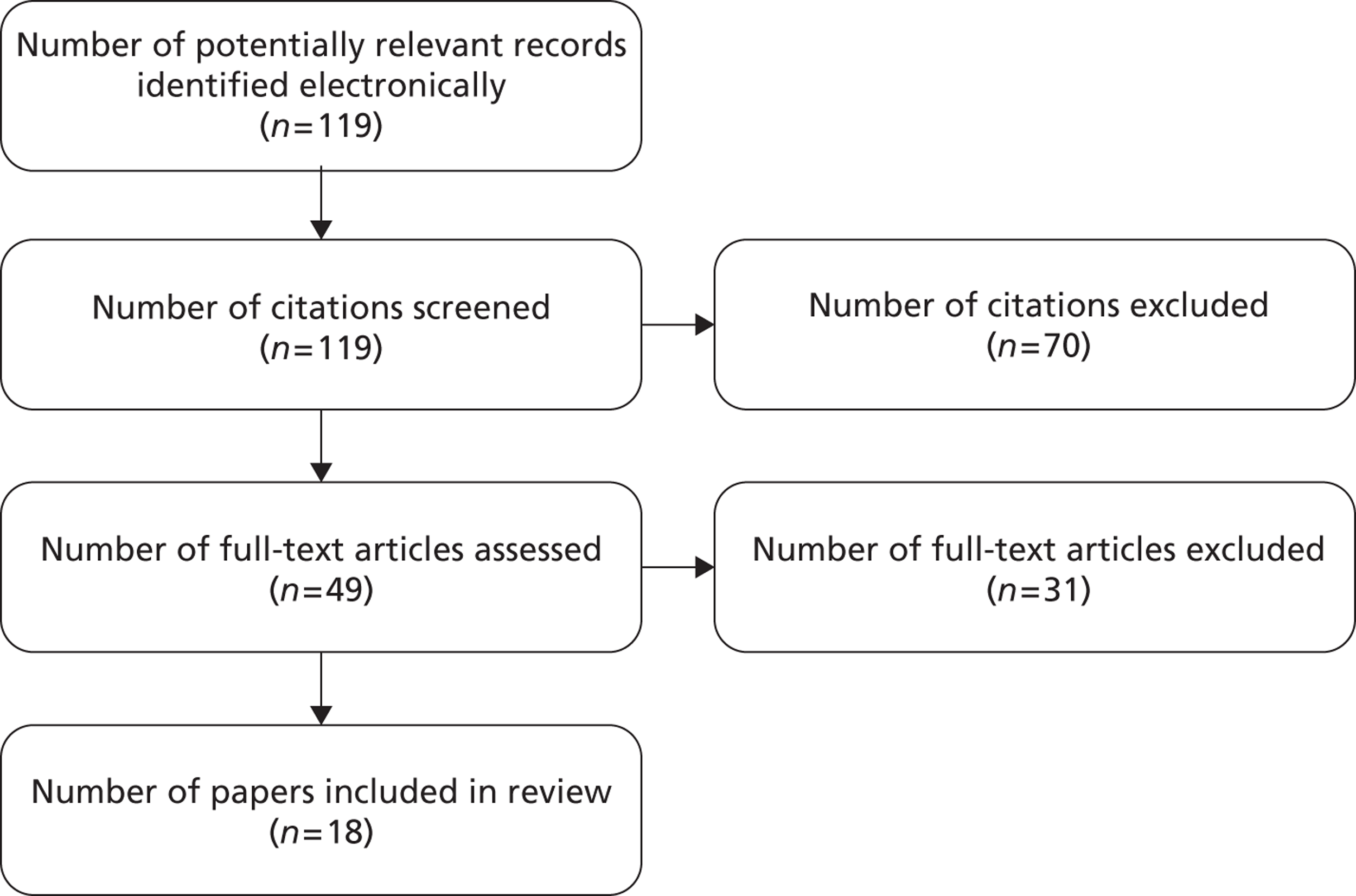

Bibliographic searching was completed in July 2010. The search strategy identified 119 articles. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 70 papers were excluded. Forty-nine papers were reviewed in full, and a further 31 were excluded and 18 papers were included in the final review. A flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies: hearing impairment.

Quality assessment: hearing impairment

A range of study designs was reported in the studies included in the review. Three studies were cross-sectional65–67 but the majority were prospective or retrospective before-and-after studies. 21,23,68–78 Studies had well-defined inclusion/exclusion criteria for recruitment. For longitudinal studies, no study had extremely high levels of missing data and completion rates for patients in studies ranged from 60%68 to 100%. 66 The completion rates for the instruments included were usually high, ranging from 71%67 to 97%. 23 The reporting in these papers was reasonably clear. After quality assessment, no studies were excluded from the review.

Study characteristics: hearing impairment

The main characteristics of the 18 papers included in this review are shown in Table 5 . The two papers by Joore et al. 71,72 and the two papers by Joore73,74 reported the results of one specific study and, similarly, the two papers by Vuorialho et al. 77,78 reported a single study. In total, 14 separate studies were included in the review. The studies were undertaken in a range of countries, including the UK, the Netherlands, the USA, Canada and Finland. Some studies recruited patients with specific hearing problems, e.g. large vestibular aqueduct syndrome,23 but most were for defined the sample using clinical indicators such as the better ear unaided pure-tone average (PTA). As shown in Table 5 , the level of hearing loss varied between studies.

| Study reference (author, year) | Country | Hearing disorder | Treatments | Sample size (n) | Study design |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barton et al., 200521 | UK | Hearing impaired | Hearing aid (analogue and digital signal-processing) | 609 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Barton et al., 200665 | UK | Hearing impaired | Cochlear implant | 3272 | Cross-sectional |

| Damen et al., 200769 | Netherlands | Postlingual deafness | Cochlear implant | 83 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Grutters et al., 200723 | Netherlands | Hearing impaired | Hearing aid | 337 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Hol et al., 200470 | Netherlands | Conductive or mixed hearing loss | Bone-anchored hearing aid | 56 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Joore et al., 2002,71 2002,74 2003,72 200373 | Netherlands | First-time hearing-aid users | Hearing aid | 126 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Palmer et al., 199975 | Canada and USA | Severe to profound hearing impaired | Cochlear implant | 62 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Vuorialho et al. 2006,77 200678 | Finland | First-time hearing aid user over 60 | Hearing aid | 101 | Prospective before-and-after |

| Lee et al., 200679 | South Korea | Postlingual deafness | Cochlear implant | 26 | Retrospective before-and-after |

| Bichey et al., 200268 | USA | Large vestibular aqueduct syndrome | Cochlear implant and hearing aid | 20 | Retrospective before-and-after |

| Cheng et al., 200080 | USA | Profoundly deaf | Cochlear implant | 140 | Retrospective |

| Sach and Barton, 200776 | UK | Hearing impaired children | Unilateral cochlear implant | 222 | Retrospective before-and-after |

| Lovett et al., 201066 | UK | Profoundly deaf | Cochlear implant (bilateral and unilateral) | 50 | Cross-sectional |

| Smith-Olinde et al., 200867 | USA | Permanent childhood hearing loss | Cochlear implant | 146 | Cross-sectional |

The sample sizes of the studies reviewed ranged from 2068 to 3272. 65 Most studies had approximately 100 participants, but two studies only had approximately 20 participants. 68,79 Five studies included young children with hearing impairments (the mean age of the samples ranged from 7 to 9 years),66–68,76,80 and the remaining studies included adults, with most focusing on older adults over 60 years of age. The studies involving children used parents or caregivers as proxies to assess HRQL of children.

Measures: hearing impairment

Table 6 summarises the measures used in the 18 papers. 21,23,65–80 Eleven papers reported EQ-5D,21,23,70–74,76–79 10 reported HUI321,23,65–69,75,79,80 and one used the SF-6D21 (alongside EQ-5D and HUI3). Among those studies that used EQ-5D, most reported the EQ-5D index based on the tariff of UK population values. In two cases, it was unclear which tariff of population values had been used. 71,77 Three papers also reported responses on the EQ-5D dimensions alongside the utility values. 72–74 A total of 11 papers reported patients' rating of own health using VAS66,70–74,76–80 and two used TTO methods. 79,80 A total of seven studies employed self-reported hearing-specific HRQL measures66,69–71,74,77,78 and seven studies reported clinical indicators to indicate severity of hearing impairment,23,65,67–69,75,77 including PTA for the best or worst ear without hearing aid and speech identification tests.

| Study reference (author, year) | GPBMs | Direct valuation | Rating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | HUI3 | SF-6D | TTO | VAS | Hearing-specific measures | Clinical indicators | |

| Barton et al., 200521 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Barton et al., 200665 | ✓ | AHL | |||||

| Grutters et al., 200723 | ✓ | ✓ | BEPTA | ||||

| Lee et al., 200679 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Bichey et al., 200268 | ✓ | PTA | |||||

| aCheng et al., 200080 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Damen et al., 200769 | ✓ | NCIQ | NVA and AN test | ||||

| Lovett et al., 201066 | ✓ | ✓ | SSQ | ||||

| Palmer et al., 199975 | ✓ | NU-6; audiological mean score for CID sentence recognition | |||||

| Smith-Olinde et al., 200867 | ✓ | BEPTA | |||||

| Hol et al., 200470 | ✓ | EQ-VAS | HHDI | ||||

| Joore et al., 200271 | Index and responses | VAS and EQ-VAS | ADPI | ||||

| Joore et al., 200372 | Index and responses | VAS and EQ-VAS | |||||

| Vuorialho et al., 200677 | Index and responses | ✓ | HHIE-S | BEHL, SRT, WRS | |||

| Joore et al., 200373 | ✓ | VAS and EQ-VAS | |||||

| Joore et al., 200274 | ✓ | VAS and EQ-VAS | HHIE-S and hearing aid satisfaction/use | ||||

| Sach and Barton, 200776 | ✓ | EQ-VAS and QoL VAS | |||||

| Vuorialho et al., 2006b78 | ✓ | EQ-VAS | HHIE-S, hearing aid satisfaction | ||||

Reliability: hearing impairment

The review found little evidence on the reliability assessments of EQ-5D, HUI3 and SF-6D in hearing impairment. No papers reported test–retest experiments. Although not specifically for test–retest reliability purposes, one study71 reported EQ-5D responses and VAS indices at baseline and asked respondents to recall them 3 months after a hearing aid fitting. The authors did not find any significant difference between the baseline assessment and the recalled assessment of baseline health for EQ-5D.

Known-group analysis and convergent validity

Out of the 18 papers included in the review, seven papers provided information to enable an assessment of the validity of EQ-5D, HUI3 or SF-6D,23,65–68,75,76 although most studies were not designed to examine the validity of these measures. 23,65–68,75,76 The results are summarised in Appendix 5 .

Known-group analysis

Seven studies presented data to allow an assessment of known-group differences of HUI3 and EQ-5D where the groups were defined by the severity of hearing loss.

Using ANOVA, the study by Grutters et al. 23 demonstrated that EQ-5D failed to detect significant differences by hearing loss severity whereas HUI3 showed a difference. Sach and Barton76 found that EQ-5D differentiated the group with the most severe hearing loss but not groups defined by milder levels of deafness.

Barton et al. 65 reported that HUI3 mean scores were different between moderate, severe, profound and implanted groups but no statistical test was reported. Palmer et al. 75 showed that HUI3 showed significant difference between people with and without hearing aids at two follow-up time points. Similarly, HUI3 discriminated two groups of patients with cochlear implant and with normal hearing aids where the hearing loss of these two groups was different according to their PTA. 68 In a study comparing HUI3 and the quality of well-being scale (QWB) in hearing loss, both scores declined with the degree of hearing loss for children who did not have a cochlear implant with a much greater extent for HUI3 than QWB. 67 Another study found that the HUI3 differentiated between groups defined according to unilateral or bilateral implantation but this was not significant as suggested by the speech measure. 66 However, this finding was also reflected in the VAS measure and might reflect that the additional impact of bilateral implantation in this group and the sample size was small.

Convergent validity

Four studies presented data for an assessment of convergent validity of EQ-5D and HUI3. 21,23,65,69 HUI3 showed moderate correlation with two speech perception tests, which was consistent with a hearing specific QoL measure that also showed similar results. 69 Barton et al. 65 reported a regression analysis and showed that for cochlear implant (grouped by age at implantation and duration of use), the average of pure-tone air-conduction thresholds at different frequencies in the better hearing ear and gender were significant predictors of HUI3 in a large cross-sectional study. 65 Grutters et al. 23 reported a moderate correlation between EQ-5D and HUI3 and Barton et al. 21 reported strong correlations between EQ-5D, HUI3 and SF-6D in their study.

Responsiveness

Twelve papers21,23,66,69–72,74,77–80 involved a total of nine studies that provided adequate information to allow an assessment of responsiveness of EQ-5D, HUI3 and/or SF-6D (see Appendix 6 ).

Assessment of EQ-5D

Six studies reported evidence to assess the responsiveness of EQ-5D. 21,23,70–72,74,77–79 In most of these studies, no statistically significant changes before and after the hearing intervention were detected23,70–74,77,78 and the ES where reported were very low. However, for these studies, statistically significant improvements were shown in VAS scores or condition-specific measures or SF-36 social functioning domain.

Six studies reported the responsiveness of HUI3. 21,23,66,69,79,80 Grutters et al. 23 found that HUI2 and HUI3 detected statistically significant change after cochlear implant fitting. The study by Lee et al. 77 demonstrated that the increases in EQ-5D, VAS, HUI3 and QWB scores following cochlear implantation were all statistically significant. The results suggest that the EQ-5D was responsive in capturing larger improvements in hearing, as in the study by Lee et al. ,79 but was not able to capture the smaller levels of improvement shown in the study by Grutters et al. 23

Cheng et al. 80 found that the change in HUI3 overall score was higher than the change in both VAS and TTO scores after cochlear implant fitting, but all changes were statistically significant. Only the change in scores on the hearing and speech dimensions of HUI3 were significant and the change score was greatest for the hearing dimension, while scores on other dimensions were stable over time. Moderate correlations between the change scores of VAS, TTO and HUI3 were found.

Barton et al. 21 detected statistically significant differences (p < 0.001) between the changes in HUI3 and EQ-5D values and between the changes in HUI3 and SF-6D values, but not between the changes in EQ-5D and SF-6D values.

Summary and conclusion

Overall, the HUI3 was the most commonly used measure in the studies. In all six cases,23,65–68,75 the HUI3 detected a difference between groups defined by their severity of hearing impairment and four23,68,78,79 out of five23,66,69,79,80 cases detected statistically significant changes as a result of intervention ( Table 7 ). Differences picked up by the HUI3 were driven by the hearing dimensions and, in some cases, the speech and emotion dimensions. On the other hand, the findings of the review suggested relatively poor responsiveness of EQ-5D in this condition as, in five23,70–72,74,77,78 out of six cases,23,70–72,74,77–79 EQ-5D failed to detect change. The studies that allowed an assessment of known groups using the EQ-5D suggested it had only weak ability to discriminate difference between severity groups. Only one study involved the SF-6D; thus, the information is too limited to conclude on its performance. 21 No studies allowed an assessment of reliability to be made.

| Study reference grouped by measure (author, year) | Known group (severity) | Known group (case–control) | Known group (other) | Responsiveness | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consistent evidence | Significant | Consistent evidence | Significant | Consistent evidence | Significant | Correlation | Consistent evidence | Significant | Reliability | |

| EQ-5D | ||||||||||

| Grutters et al., 200723 | ✓ | ✓ | Moderate | ✗ | ✗ | |||||

| Sach and Barton, 200776 | Mixed evidence | Mixed evidence | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Lee et al., 200679 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hol et al., 200470 | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Joore et al., 2002a, 2002b, 2003a71,72,74 | Mixed evidence | ✗ | ||||||||

| Vuorialho et al., 2006a, 2006b77,78 | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Barton et al., 200521 | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||||

| HUI 3 | ||||||||||

| Barton et al., 200665 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Bichey et al., 200268 | ✓ | N/R | ||||||||

| Damen et al., 200769 | Moderate | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Grutters et al., 200723 | ✓ | ✓ | Moderate | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Lovett et al., 201066 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ||||||

| Palmer et al., 199975 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Smith-Olinde et al., 200867 | ✓ | N/R | ||||||||

| Lee et al., 200679 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Cheng et al., 200080 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Barton et al., 200521 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| SF-6D | ||||||||||

| Barton et al., 200521 | Strong | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

Skin conditions

Search results: skin conditions

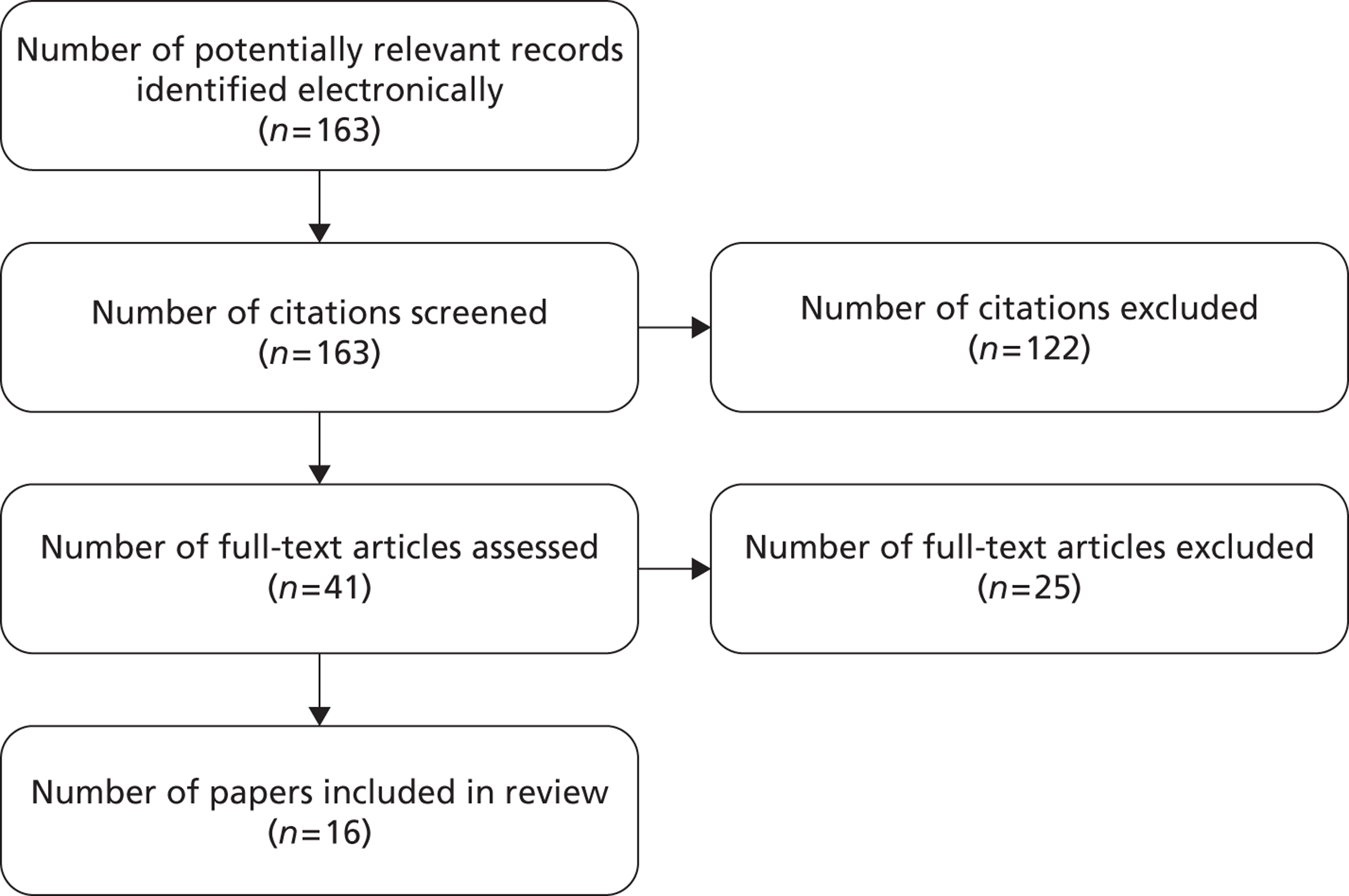

The bibliographic search was completed in September 2010. The search of electronic databases identified 161 records and two additional records were identified from the EuroQol Group website database. After reviewing titles and abstracts, 122 records were excluded. Forty-one papers were reviewed in full: a further 25 papers were excluded and 16 papers were included in the final review ( Figure 3 ).

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram showing selection of studies for skin review.

Quality assessment: skin conditions

Three types of study designs were observed in the review. Eleven studies were RCTs,81–91 four studies were cross-sectional92–95 and one was an uncontrolled before-and-after study. 96 The majority of studies provided clear inclusion and exclusion criteria, but two did not. 81,82 Six papers did not report completion rates82,83,87,88,92,96 and, among the 10 studies reporting this information, completion rates were reasonable or high (ranging from 70%84 to 97%). 94 The completion rates for specific measures (e.g. item non-response) were generally high (above 90%). 82,91,92,95 No study was excluded after the assessment of quality.

Study design and patients' characteristics: skin conditions

The main characteristics of the 16 papers included in this review are shown in Table 8 . 81–96 Studies were conducted in various European and American countries, with several multinational studies. All but four studies recruited patients with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis;82–88,92–96 the remaining studies recruited patients with acne,81 eczema,90 hidradenitis suppurativa89 or venous leg ulcers. 91 All studies included adults (mean age approximately 43 years), and male respondents accounted for 24–71% of the samples. Sample sizes ranged from 3291 to 27,994,95 with most studies including between 100 and 200 participants.

| Study reference grouped by condition (author, year) | Country | Treatment | Sample size | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis | ||||

| Bansback et al., 200683 | UK | Methotrexate with and without ciclosporin A | 72 | RCT |

| Brodszky et al., 201092 | Hungary | None | 183 | Cross-sectional |

| Christophers et al., 201093 | Multiple | None | 1660 | Cross-sectional |

| Daudén et al., 200984 | Multiple | Continuous vs. paused subcutaneously therapy | 720 | RCT |

| Van de Kerkhof 200482 | Multiple | Two-compound product (+ ointment vehicle, once daily), Two-compound product (twice daily), calcipotriol (Dovonex®, LEO) (twice daily), ointment vehicle (twice daily) | 828 | RCT |

| Luger et al., 200996 | Multiple | Continuous and paused etanercept therapy | 130 | Before-and-after |

| Reich et al., 200985 | Multiple | Etanercept | 720 | RCT |

| Revicki et al., 200894 | Multiple | Adalimumab (Humira®, AbbVie), methotrexate, placebo | 54 | Cross-sectional |

| Shikiar et al., 200695 | USA and Canada | Subcutaneously administered adalimumab vs. placebo | 27994 | Cross-sectional |

| Shikiar et al., 200786 | USA and Canada | Subcutaneously administered adalimumab vs. placebo | 142 | RCT |

| Weiss et al. 200287 | USA | N/R (only baseline data were reported) | 271 | RCT |

| Weiss et al. 200688 | USA | Topical therapy vs. combination clobetasol solution | 147 | RCT |

| Acne | ||||

| Klassen et al. 200081 | UK | Isotretinoin or antibiotic, hormonal, physical and topical treatments | 148 | RCT |

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | ||||

| Matusiak et al. 201089 | Poland | N/R | 233 | RCT |

| Hand eczema | ||||

| Moberg et al. 200990 | Sweden | N/R | 35 | RCT |

| Venous leg ulcers | ||||

| Walters et al. 199991 | UK | Compression bandaging in a community clinic setting vs. usual home-based care by district nursing services | 32 | RCT |

Measures used in studies: skin diseases

Table 9 summarises the measures that have been used in the 16 studies included in the review. Of the three GPBMs of interest, only those studies reporting EQ-5D were identified and included in the review. No studies reported data from SF-6D or HUI3. Fourteen studies also reported patients' valuation of their own health states using VAS. 81,82,84–89,90–92,94–96 Clinical indices were reported in studies to indicate severity of skin problems, including the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) by eight studies,85–88,92,94–96 Nail Psoriasis Severity Index (NAPSI) by one study,96 and the Acne Grade by one study. 81 Various generic measures [e.g. SF-36, Health Assessment Questionnaire – Disability Index (HAQ-DI), Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ)], skin-specific HRQL measures [e.g. Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI)], or symptom-specific HRQL measures (e.g. HADS, the Depression Inventory) were included in the studies (see Table 9 ).

| Study reference grouped by condition (author, year) | GPBMs | Direct valuation | Rating scale | Generic or condition specific HRQL instruments | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EQ-5D | SF-6D | HUI3 | TTO | VAS | SF-36 | DLQI | PASI | Others | |

| Plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis | |||||||||

| Bansback et al., 200683 | ✓ | HAQ-DI | |||||||

| Brodszky et al., 201092 | ✓ | ✓ (pain, global assessment) | ✓ | PsAQoL, HAQ, PASI, DAS28, BASDAI, swollen joint count, tender joint count, EQ-VAS, patient pain VAS, patient global assessment VAS | |||||

| Christophers et al., 201093 | ✓ | BSA, employment disadvantage questionnaires | |||||||

| Daudén et al., 200984 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | HADS, PSS, BSA, PGA | ||||

| Van de Kerkhof 200482 | ✓ | ✓ | Psoriasis Disability Index | ||||||

| Luger et al., 200996 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | HADS, SGA, PGA, BSA, NAPSI | |||

| Reich et al., 200985 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | FACIT-F, BSA | ||||

| Revicki et al., 200894 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Shikiar et al., 200695 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | PGA | |||

| Shikiar et al., 200786 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | PGA | |||

| Weiss et al., 200287 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SAPASI, SWLS | |||||

| Weiss et al., 200688 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | SAPASI, BSA | ||||

| Acne | |||||||||

| Klassen et al., 200081 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Acne grade | |||||

| Hidradenitis suppurativa | |||||||||

| Matusiak et al., 201089 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | BDI-SF, FACIT-F, QLES-Q, GQ 6-item scale, Hurley’s classification | |||||

| Hand eczema | |||||||||

| Moberg et al., 200990 | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Venous leg ulcers | |||||||||

| Walters et al., 199991 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | FAI, SF-MPQ, self-perceived transition question (item 2 of SF-36) with three scales: better, same and worse compared with 3 months earlier | |||||

Reliability: skin conditions

No study reported data on reliability of the three GPBMs.

Known-group analysis and convergent validity: skin conditions

Thirteen studies of patients with skin conditions provided sufficient evidence to allow assessment of known-group analysis and convergent validity of EQ-5D81–85,88–93,95,96 including: 12 known-group analyses82–86,88–93,96 and seven convergent validity analyses. 83,87,89–92,95 A summary of the findings is presented below. See Appendix 7 for details.

Plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis

Eight studies provided evidence of known-group validity for EQ-5D among people with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. 82–85,87,92,93,96 Three studies showed that EQ-5D was able to discriminate between severity groups on the basis of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis,93 treatments,84 pain and nail psoriasis. 96 Three case–control studies confirmed that EQ-5D can differentiate between people with psoriasis and the general population. 82,85,87 Brodszky et al. 92 found that the standard mean difference between groups measured by EQ-5D were comparably lower than measured with the Psoriatic Arthritis Quality-of-Life Scale (PsAQoL) or the HAQ; however, the groups were defined not according to severity aspects, but according to possible surrogate markers of severity such as admission to hospital or use of devices. 92

Good convergent validity of EQ-5D was found among people with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis in four studies. 83,88,92,95 Three studies showed moderate or strong correlation between EQ-5D and other generic or skin-specific measures. 87,92,95 Bansback et al. 83 suggested that the HAQ disability index was a significant predictor of EQ-5D.

Other skin conditions

Four studies had sufficient information to allow assessment of construct and convergent validity in various skin conditions. 81,89–91

In a case–control study, Klassen et al. 81 found that people with acne reported more problems on most EQ-5D dimensions than the general population. Among those with hidradenitis suppurativa, Matusiak et al. 89 found that significant differences according to the severity groups defined by Hurley's classification groups were suggested by EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, DLQI, the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form (BDI-SF) and other measures. Among patients with hand eczema, Moberg90 suggested that EQ-5D and EQ-VAS significantly differ between groups defined according to whether they have hand eczema groups, as well as age and gender. For venous leg ulcer patients, Walters et al. 91 reported small ESs for the EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, SF-36 and Frenchay Activities Index (FAI) for patients grouped on the basis of their initial leg ulcer size, current ulcer duration, maximum ulcer duration and age; however, the differences were statistically significant only for the EQ-5D, EQ-VAS, FAI and five subscales of the SF-36.

Among those with hidradenitis suppurativa, moderate correlation was reported between EQ-5D with DLQI and EQ-5D with Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy – Fatigue module (FACT-F). Moberg et al. 90 found strong correlation between EQ-5D and EQ-VAS among hand eczema patients, and, similarly, Walters et al. 91 found moderate to high correlations with SF-36 subscales.

Responsiveness: skin conditions

A total of 10 studies provided evidence to allow assessment of responsiveness of EQ-5D in skin diseases. 81,82,84–86,88,91,94–96 Among them, eight studies included people with psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis,82,84–86,88,94–96 one study included people with acne81 and one study focused on venous leg ulcers. 91 Ten studies examined changes of scores over time or after treatment,81,82,84–86,88,91,94–96 and two provided details of ES or standard response mean estimation. 81,91 One study checked the correlation between change scores of health measures with changes in clinical measures95 (see Appendix 8 ).

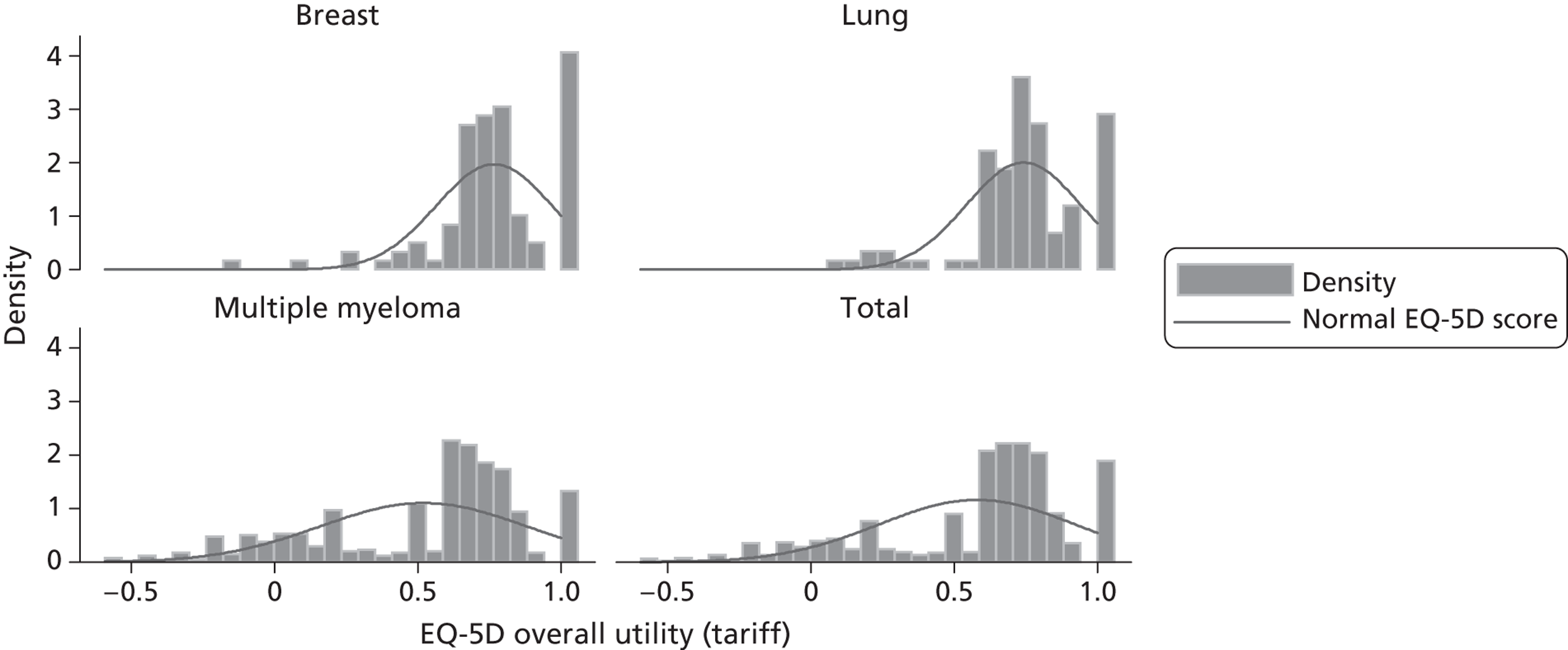

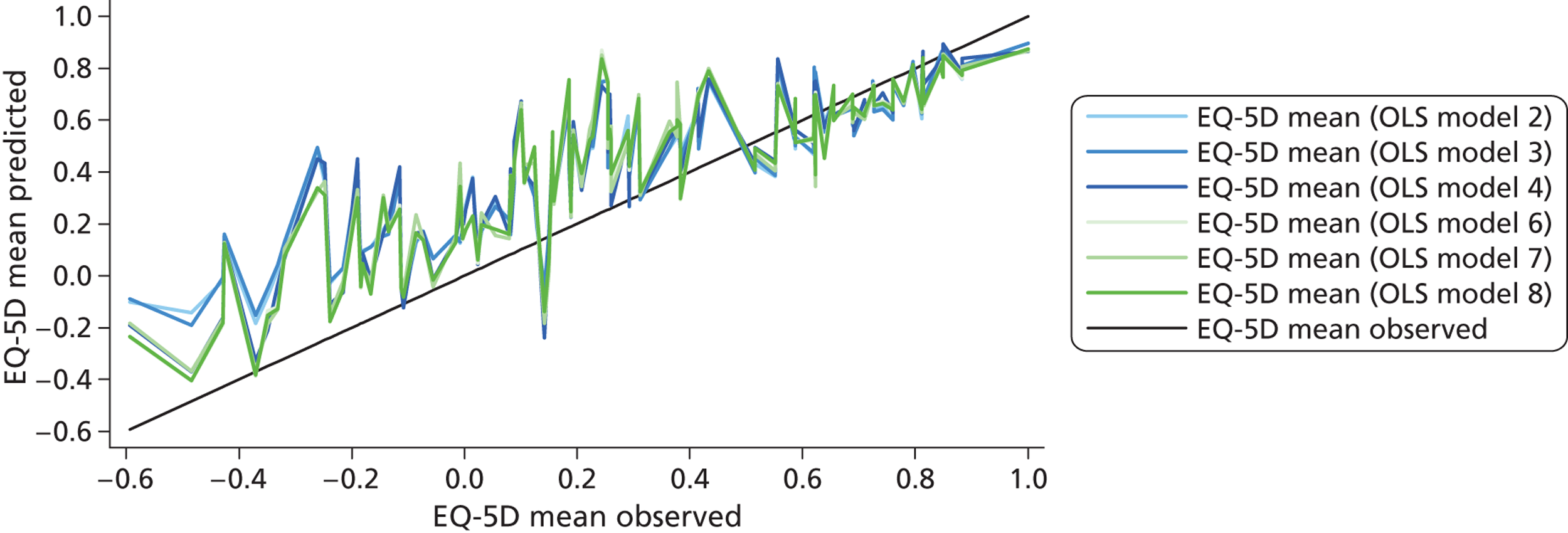

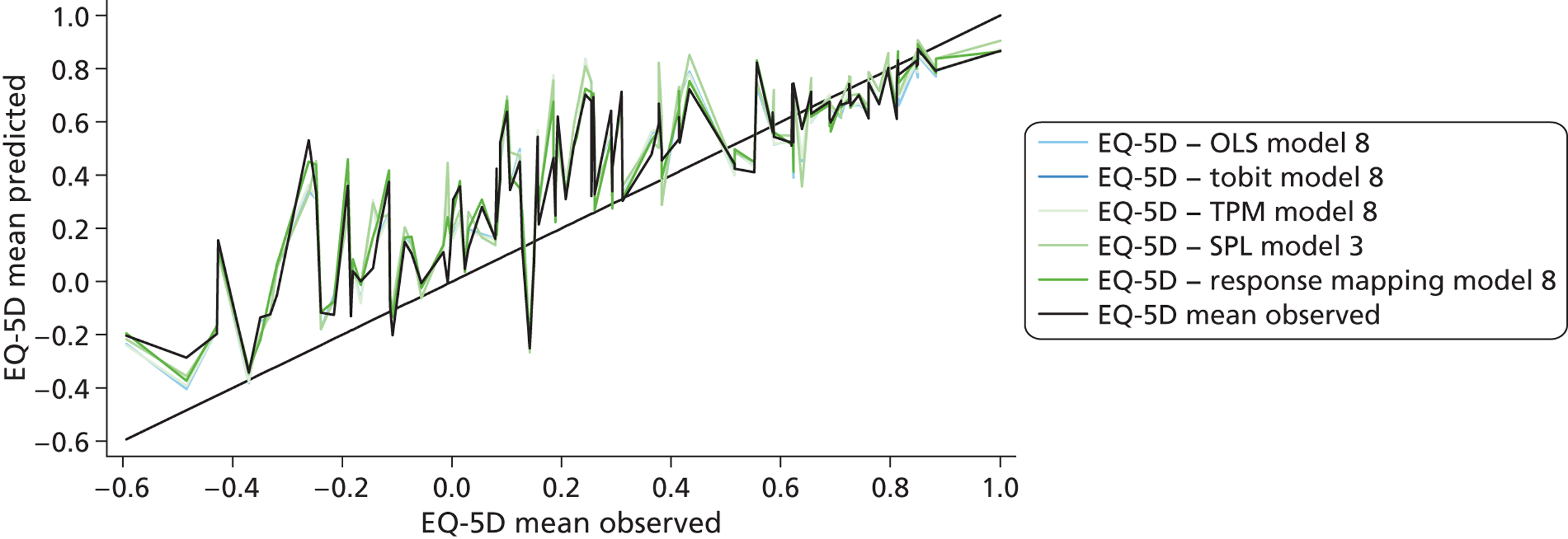

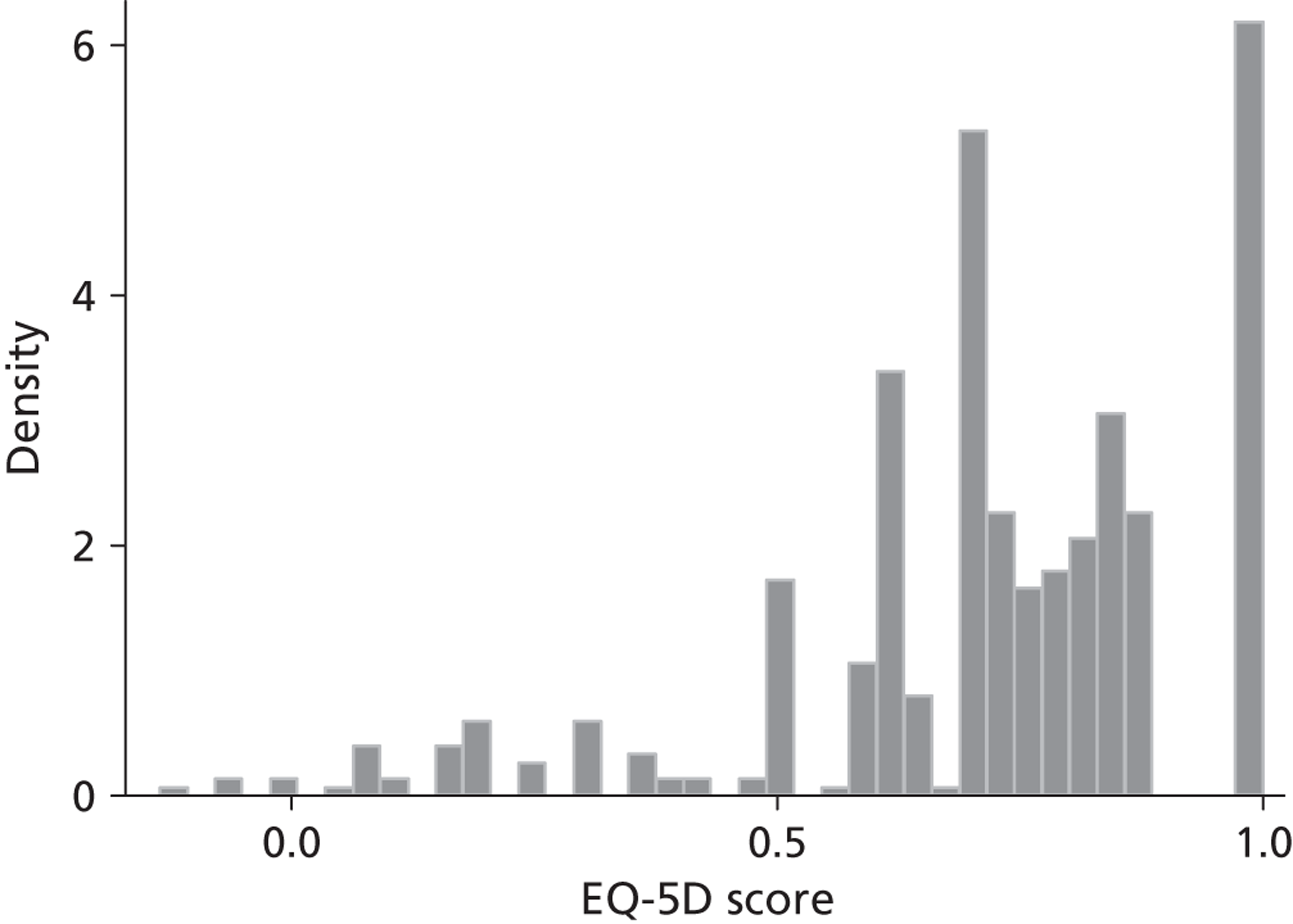

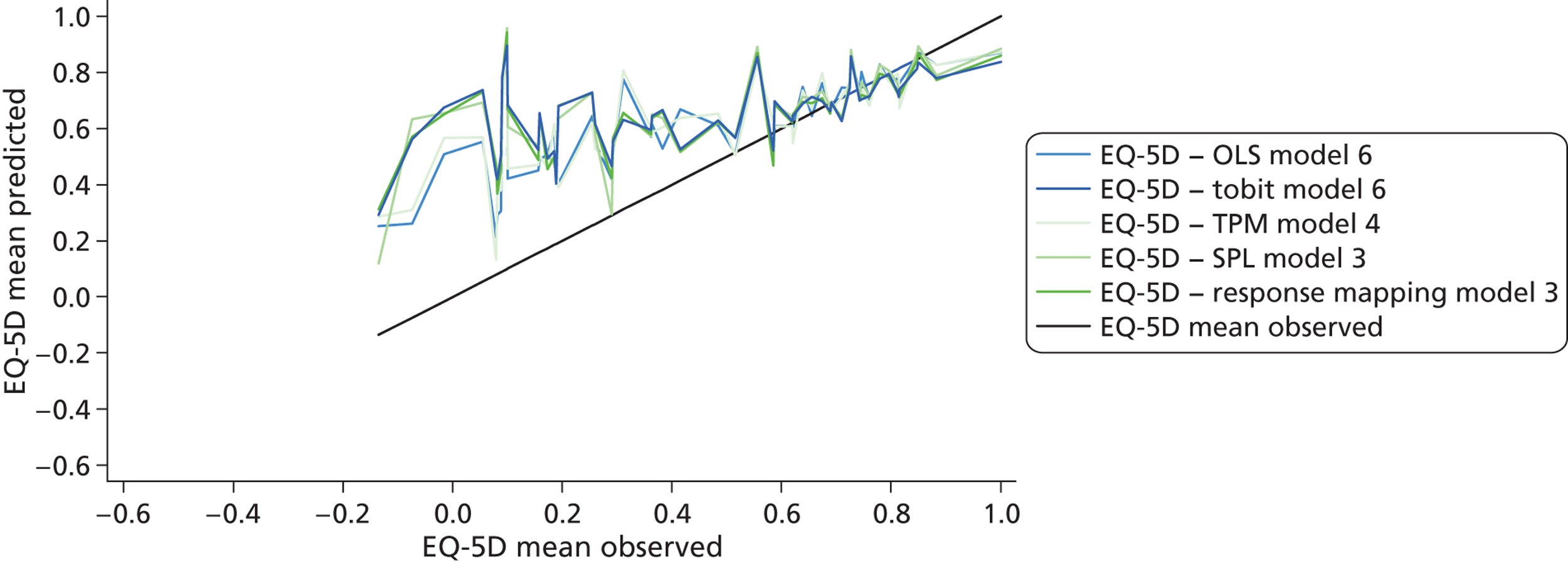

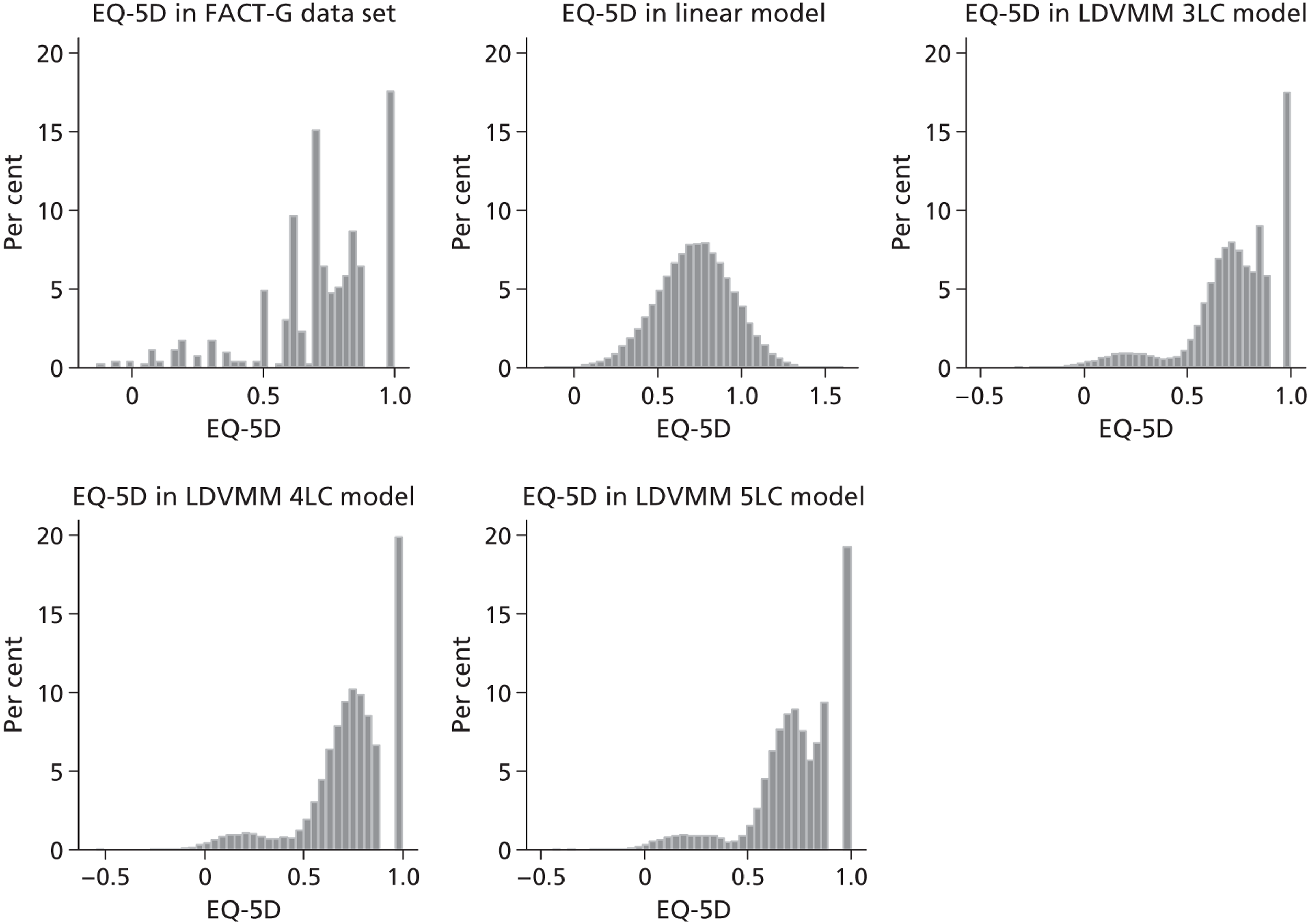

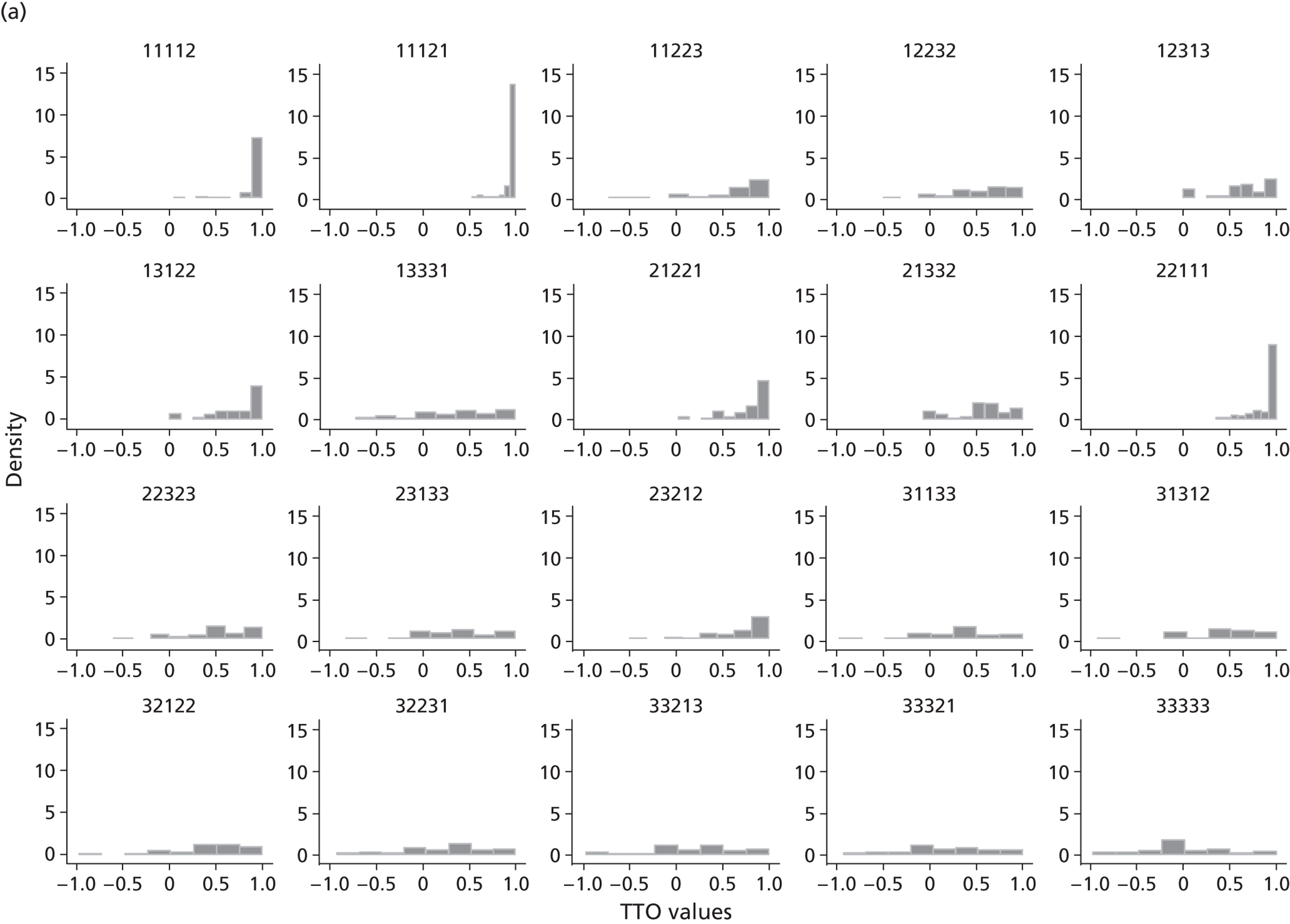

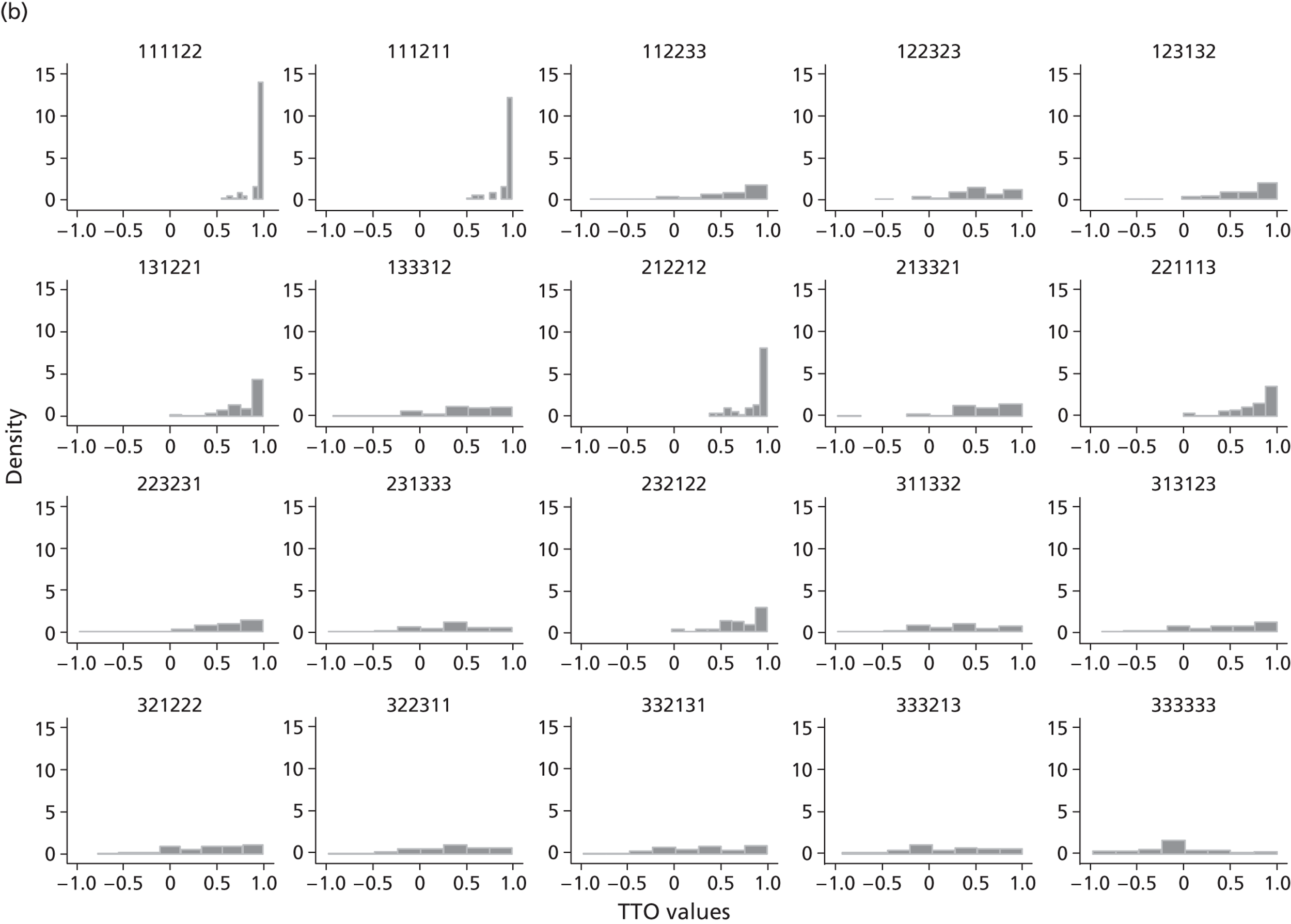

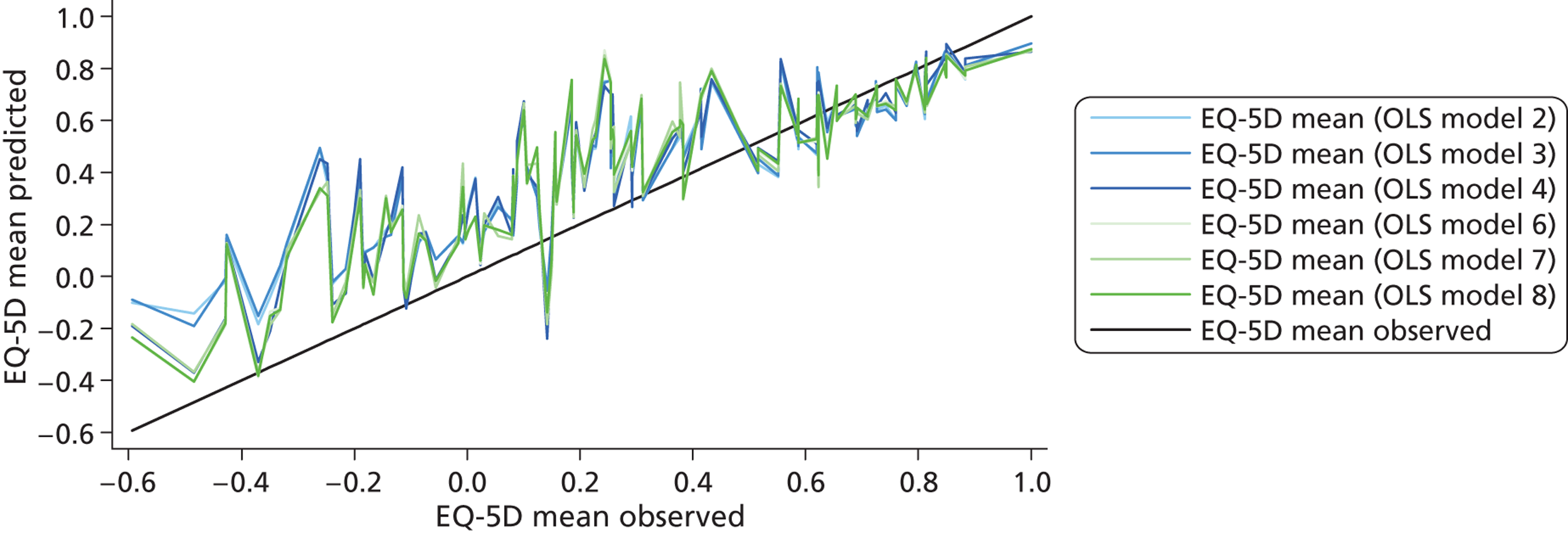

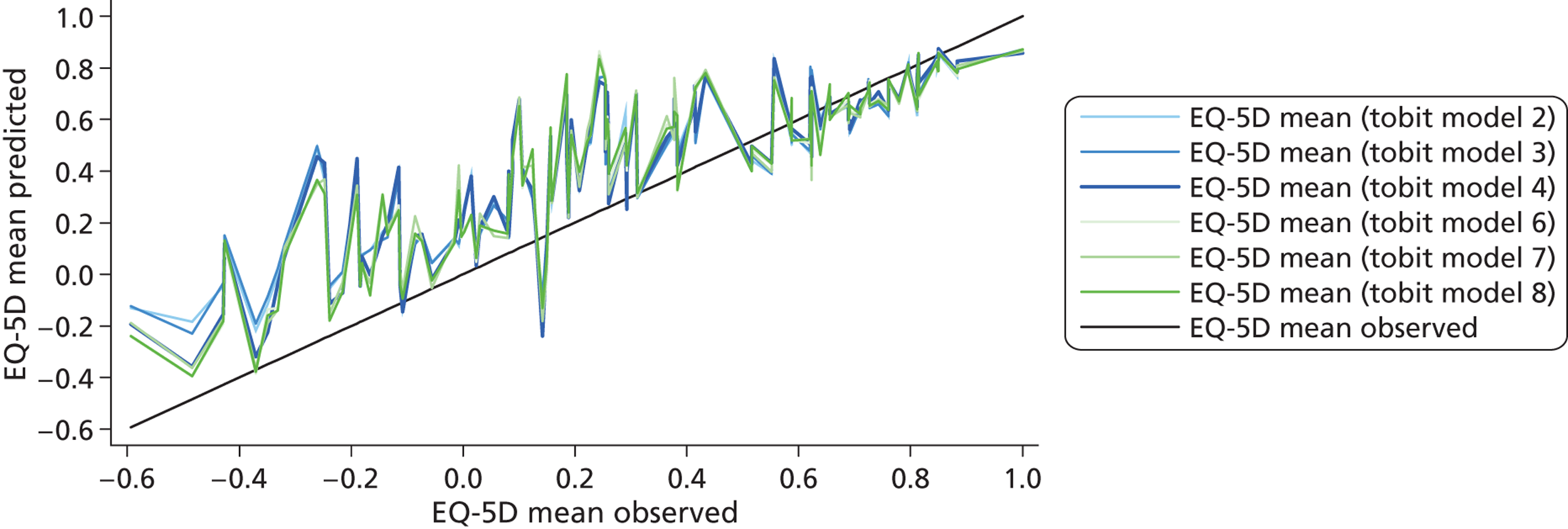

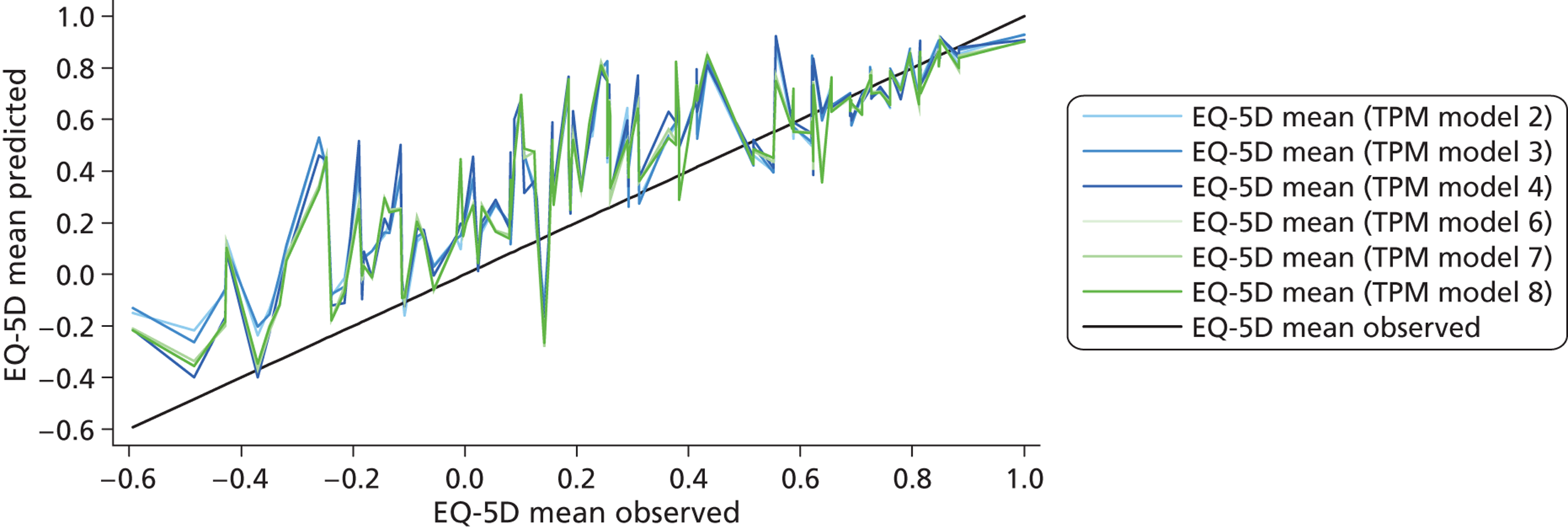

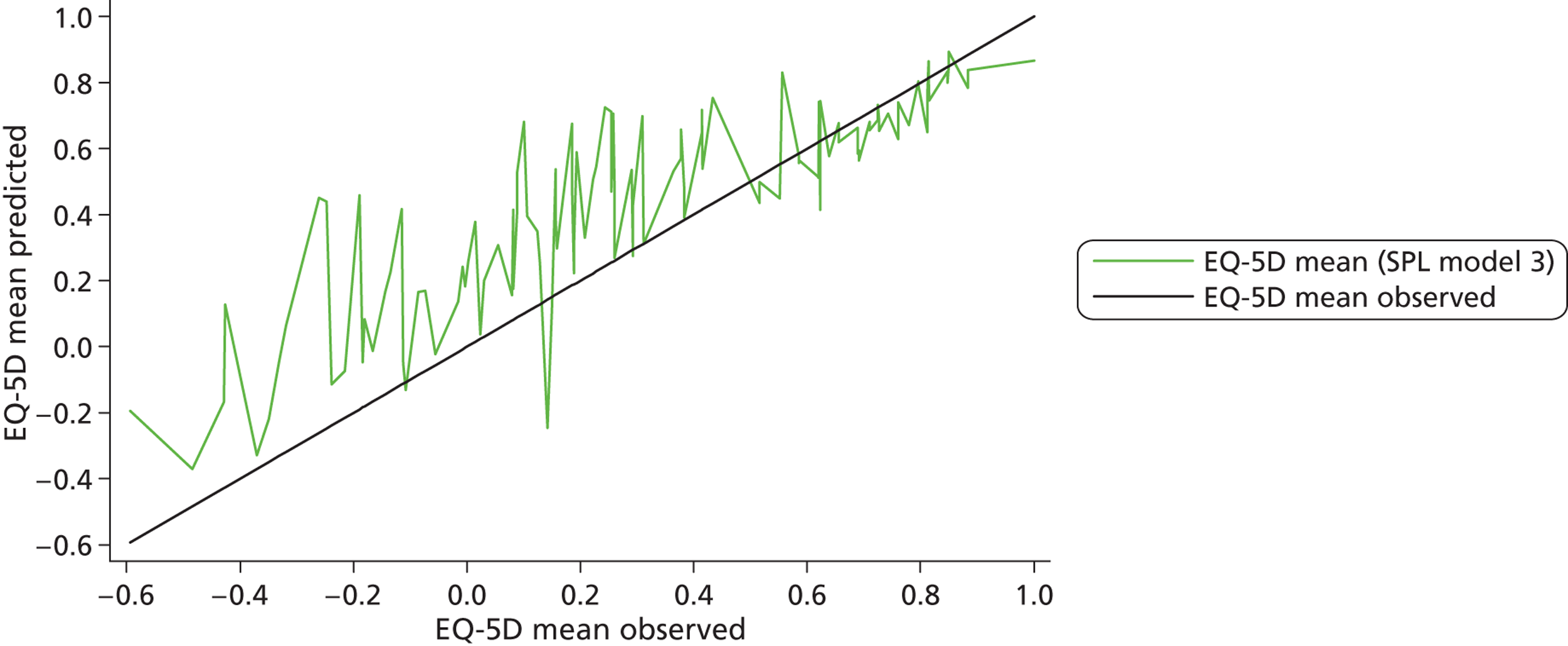

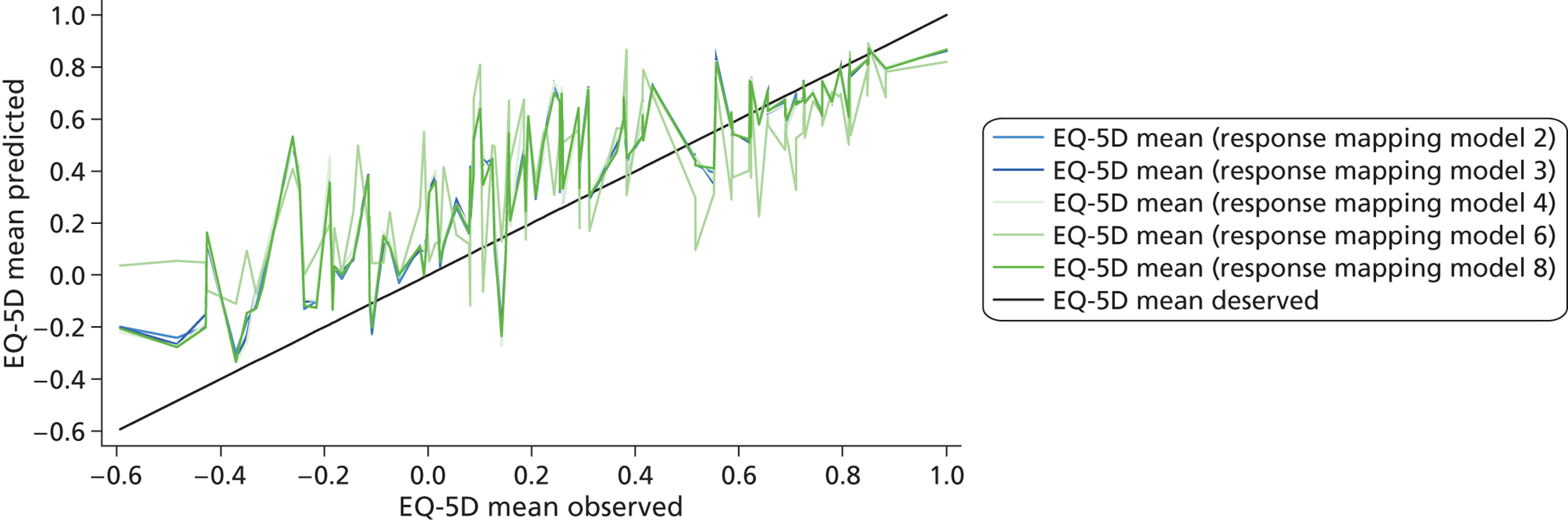

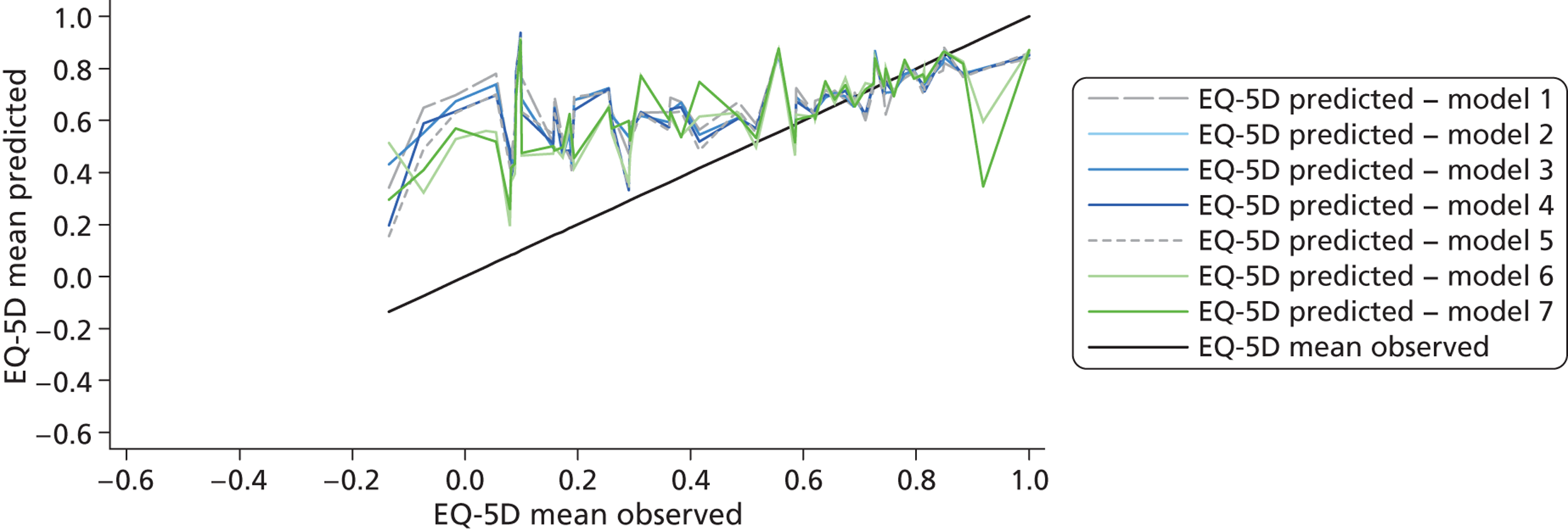

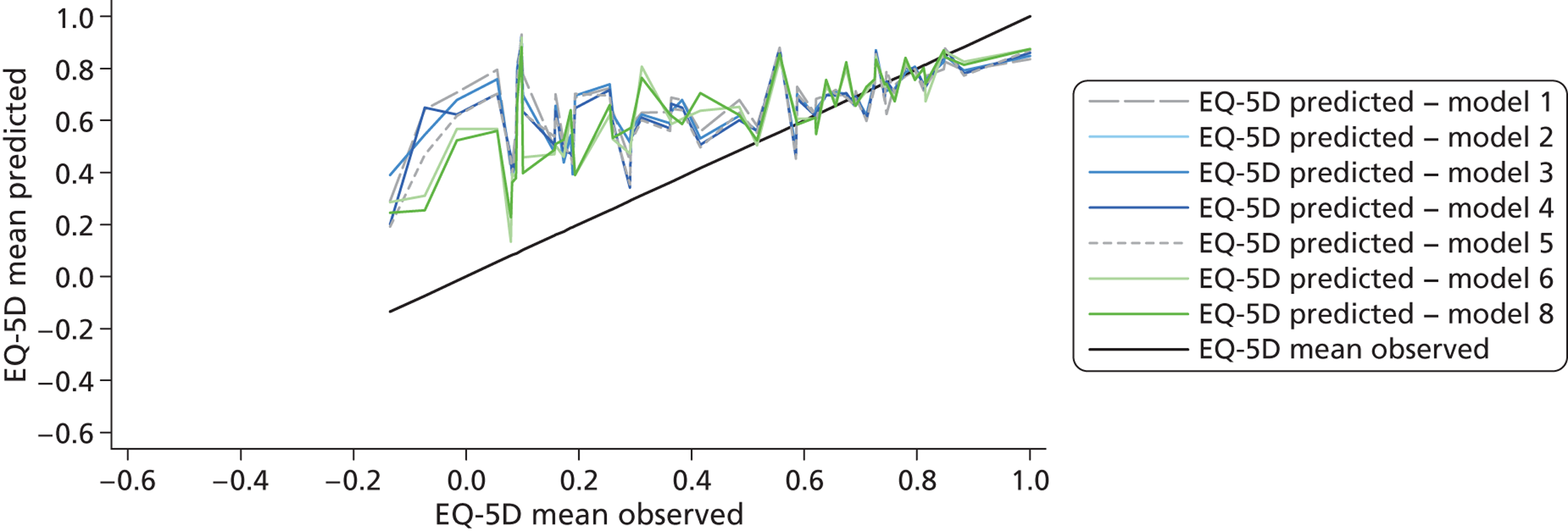

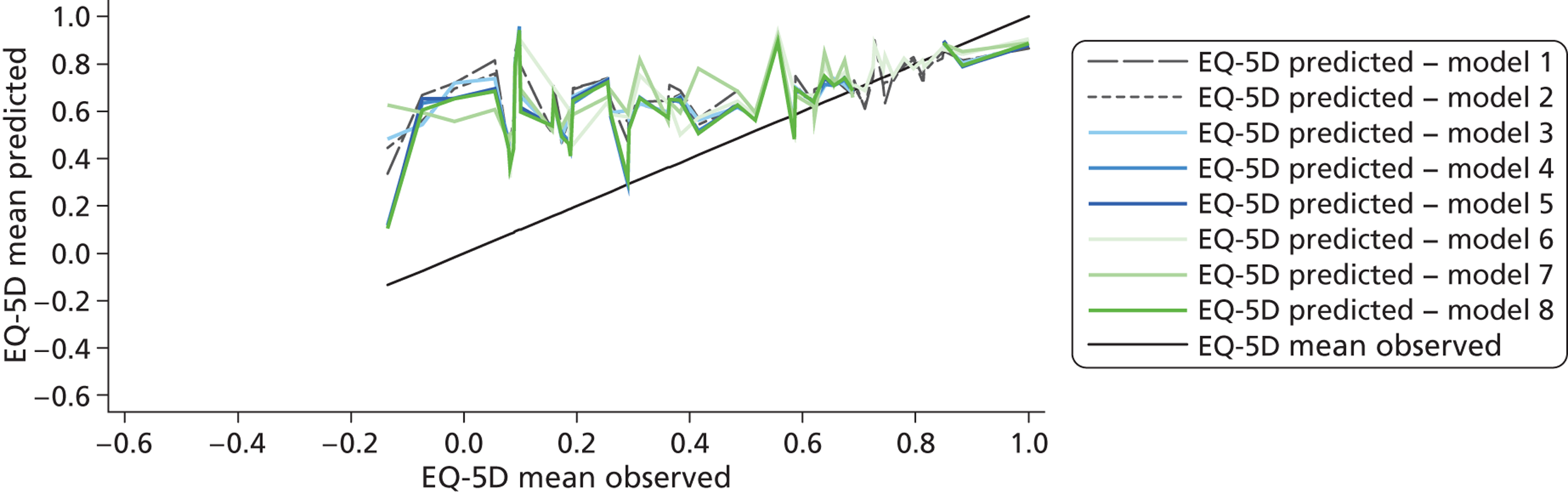

Plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis