Notes

Article history

The MRC-NIHR Methodology Research Programme funded the PRET project (Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff, MRC ref. G0901500), and the EuroQol Group funded the PRET-AS project (Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff – Additional Sample) as an extension to the PRET project with formal agreement from the MRC.

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HTA journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The PRET-AS component of this project was funded by the EuroQol Group as an extension to the PRET project, with formal agreement from the Medical Research Council. The EQ-5D and EQ-5D-5L are intellectual property of the EuroQol Group. JB, ND, LL and AT are members of the EuroQol Group, and therefore could have a potential conflict of interest. The research reported here was carried out independently, and the views expressed in this report are not those of the EuroQol Group. NB’s institution has received financial support from Pfizer Canada as a postdoctoral funding award.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Mulhern et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background to the Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff project

Introduction

Measuring cost-effectiveness

Health-care resources are limited and need to be allocated efficiently. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) was set up to help make better health-care resource allocation decisions. NICE bases its recommendations on cost-effectiveness analyses, with the quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) gained as the outcome measure. A QALY combines values for quality and quantity of life in a single figure, and allows the assessment of the effectiveness across interventions and treatments for different conditions using a common metric. This requires a value for the health-related quality of life (HRQL) or utility for a particular health state, which is then multiplied by the duration of the health state to calculate the number of QALYs. Utility values can be generated using generic preference-based measures of health, such as the EQ-5D.

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D1 is the preferred instrument to use to derive utility values to assess the HRQL impact of medical interventions. 2 The EQ-5D assesses HRQL across five dimensions (mobility, self care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) each with three response levels (no, some or extreme problems). Therefore, the entire descriptive system generates 243 health-state descriptions, each of which produces a utility value (known as the value set).

The current UK EQ-5D value set is based on the Measurement and Valuation of Health (MVH) study. This study used face-to-face interviews of a representative sample of the UK general population to value 45 hypothetical EQ-5D states using the preference elicitation method time trade-off (TTO). The results of the valuation study were modelled using regression to provide a utility score for all 243 health states (range of −0.594 to 1). 3 Utility scores are anchored on a 0–1 scale, where 1 is equivalent to full health, 0 to dead, and negative values to states worse than dead.

The UK EQ-5D value set is used for economic evaluations by a range of decision-makers and researchers. They are also used in a range of further applications, including population health surveys (e.g. the Health Survey for England); burden of disease studies; hospital inpatient surveys and the NHS Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) initiative. 4 However, there is the need for a new EQ-5D value set to be developed for the following reasons:

-

A five-level version of the EQ-5D, the EQ-5D-5L,5 has been developed (response categories: none, slight, moderate, severe, extreme/unable). This version generates a possible 3125 health states, and there is the need for a value set to be developed for the larger descriptive system so that the instrument can be used in the economic evaluation of new interventions and treatments.

-

It is possible that the preferences of the general population may have changed since the original MVH study was carried out in the 1990s.

-

Change in demography may mean that although individual preferences may not have changed, the composition of people across the country has changed, so that average preferences may have changed.

-

There has been recognition of the shortcomings of the MVH protocol used to generate the UK EQ-5D value set, in particular in regards to the valuation method used for states perceived by respondents as worse than dead.

-

There have been advances in health-state valuation methods, including the potential application of discrete choice experiments (DCEs) to derive utility values, by including duration as an attribute [discrete choice experiment incorporating duration (DCETTO)].

-

There have been advances in the administration modes available for valuation studies [e.g. using computer-assisted personal interviews (CAPIs) or online methods].

The ‘Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff project’ and ‘Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff project – Additional Sample’

The methods used for the generation of EQ-5D-5L population value sets needs to be up to date and informed by the latest understanding of the techniques used to value health states. The ‘Preparatory study for the Re-valuation of the EQ-5D Tariff project’ (PRET) is a methodological study that aims to contribute to the generation of EQ-5D-5L population value sets by exploring a range of methodological issues associated with a range of health-state valuation techniques, including TTO and DCETTO. The ‘PRET – Additional Sample’ (PRET-AS) study is an extension to PRET and allows further investigation into health-state valuation-related methods. This report will cover both projects.

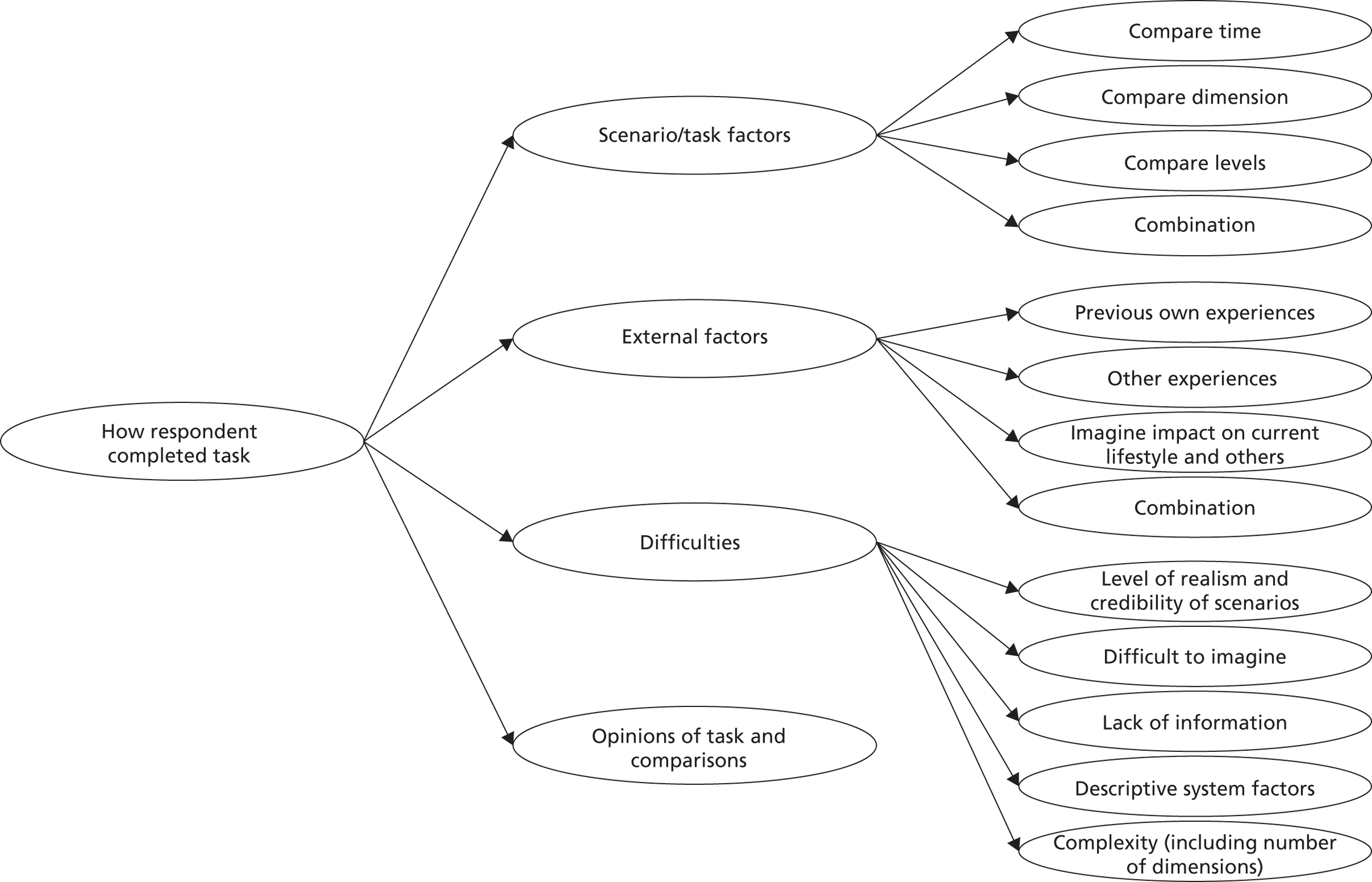

The PRET study is a methodological study that has four stages. In stage 1, a large scale online survey is carried out to explore a series of methodological issues related to health-state valuation using binary choice questions. PRET-AS is an extension of stage 1, and involves a further online survey investigating two binary choice techniques that can be used to generate utility values. In stage 2, a segment of the PRET stage 1 online survey is carried out in a face-to-face environment using CAPI to test the equivalence of responses to the valuation questions across different modes of administration. Stage 3 uses CAPI to investigate the strategies and processes used to answer health-state valuation questions based around DCETTO and TTO. Stage 4 uses in-depth cognitive interviews to investigate the completion of TTO and DCETTO in more detail.

The remainder of this chapter is organised as follows. In the Methods of health-state valuation considered in PRET section below, the health-state valuation techniques TTO and DCETTO are introduced. In the Issues with the design of health-state valuation studies considered in PRET and PRET-AS section, the methodological issues that need to be considered in the design of any health-state valuation study are outlined, with reference to the issues investigated in this study.

Sections of this chapter are reported in an online discussion paper6 (accessible at www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.165490!/file/1116.pdf).

Methods of health-state valuation considered in PRET

TTO

Time trade-off7 is a widely used method for valuing health-states valuation, and the MVH TTO protocol8 that was used to derive the EQ-5D value set1,3 has also been used to generate utility scores for condition-specific preference-based measures of health. 9–13

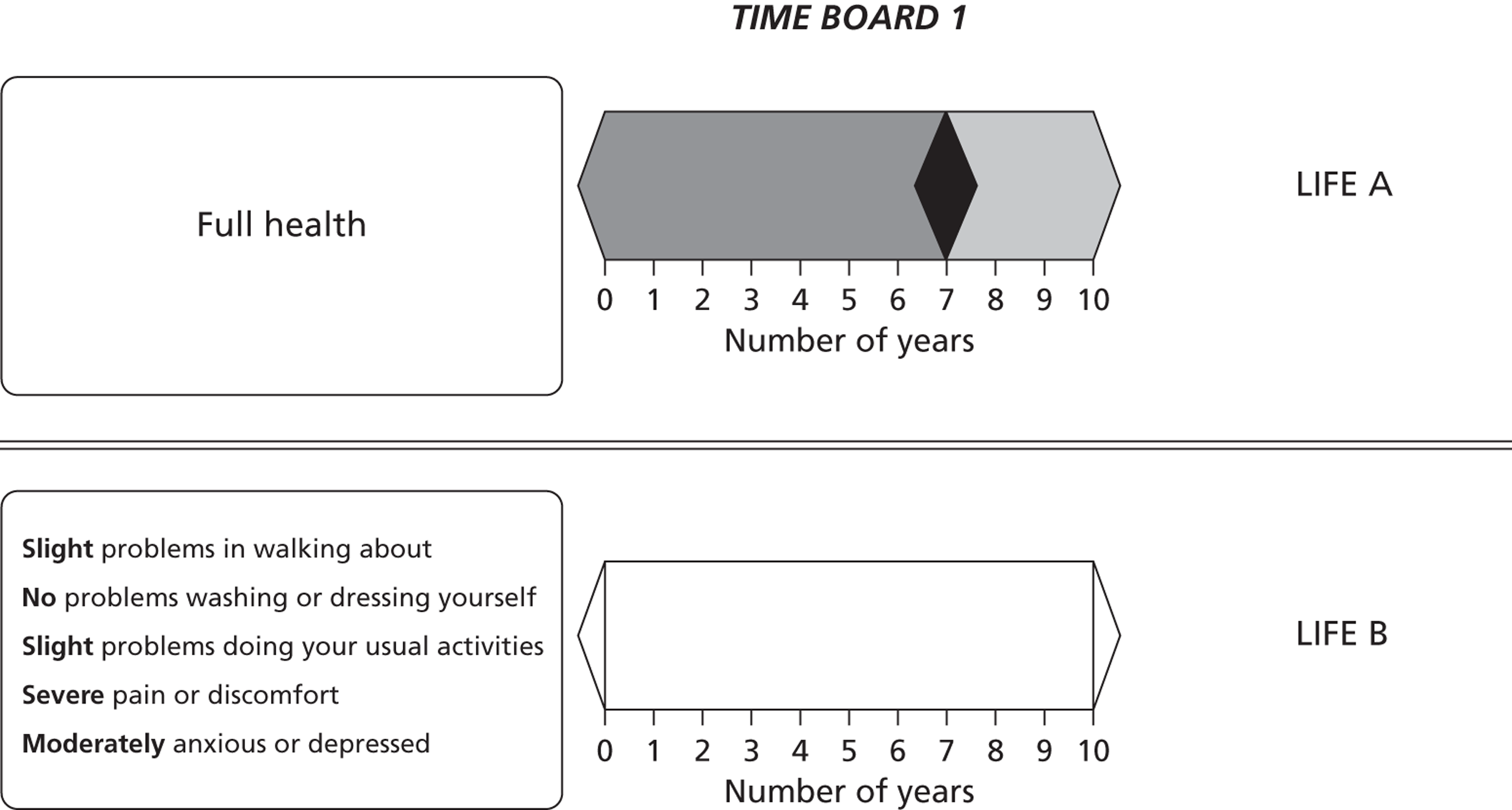

Time trade-off is an iterative cardinal technique that elicits a health-state value by asking respondents to trade off time in full health to avoid living in a hypothetical health state described by the classification system. The value is derived at the point where respondents are indifferent between the scenarios. The MVH TTO protocol used face-to-face interviews, and the task follows a set procedure to derive each utility value. First, respondents are asked whether they would prefer to live in health state (H) for 10 years, or to die immediately, or whether they were indifferent between the options. This established whether the health state was perceived as better than, worse than, or equal to being dead.

For states perceived as better than dead, respondents choose between (1) living in H for T years (usually 10) or (2) living in full health for X years (where X ≤ 10). The duration of full health (X) is varied iteratively until respondents are indifferent between the options. The value for H is then calculated as X/10. Typically, zero time preference is assumed.

For health states that are ‘worse than dead’, respondents are asked to consider a choice between (1) H for W years followed by full health for X years (where W + X = 10) after which they will die or (2) immediate death. Both years in full health, X, and years in the health state, W = 10 − X, are varied until respondents are indifferent between the two options. However, this may result in extreme values. For example, if a respondent is indifferent between (1) H for 3 months followed by full health for 9 years 9 months after which they die and (2) immediate death, this would suggest that the value of health is −0.25/9.75 = −39 on a scale on which ‘1’ = full health and ‘0’ = being dead. Traditionally, this has been regarded as unacceptable and arbitrary transformations have been applied. 3,14–16 Under the established convention, H is calculated as −X/10.

Regardless of whether the state is better or worse than being dead, the iterative process is susceptible to bias. This is because when people are asked two (or more) consecutive questions, the later question is not independent of the earlier question. For example, the response given to a TTO question where X is 3 years will be affected by the value of X used in the preceding question (e.g. whether it was 1 year or 5 years). The issue of biases caused by iterative questioning is a key topic in the literature on the monetary valuation of health but is under-researched in the literature on health-state valuations.

To estimate utility values for each health state defined by a classification system, the results of the TTO study are modelled using multivariate regression. The disutility coefficient for each severity level of each dimension is calculated using level 1 (no problem) as the baseline. Therefore, full health is anchored at 1, and the utility value for each overall health state is calculated by subtracting the disutility value for each dimension from 1.

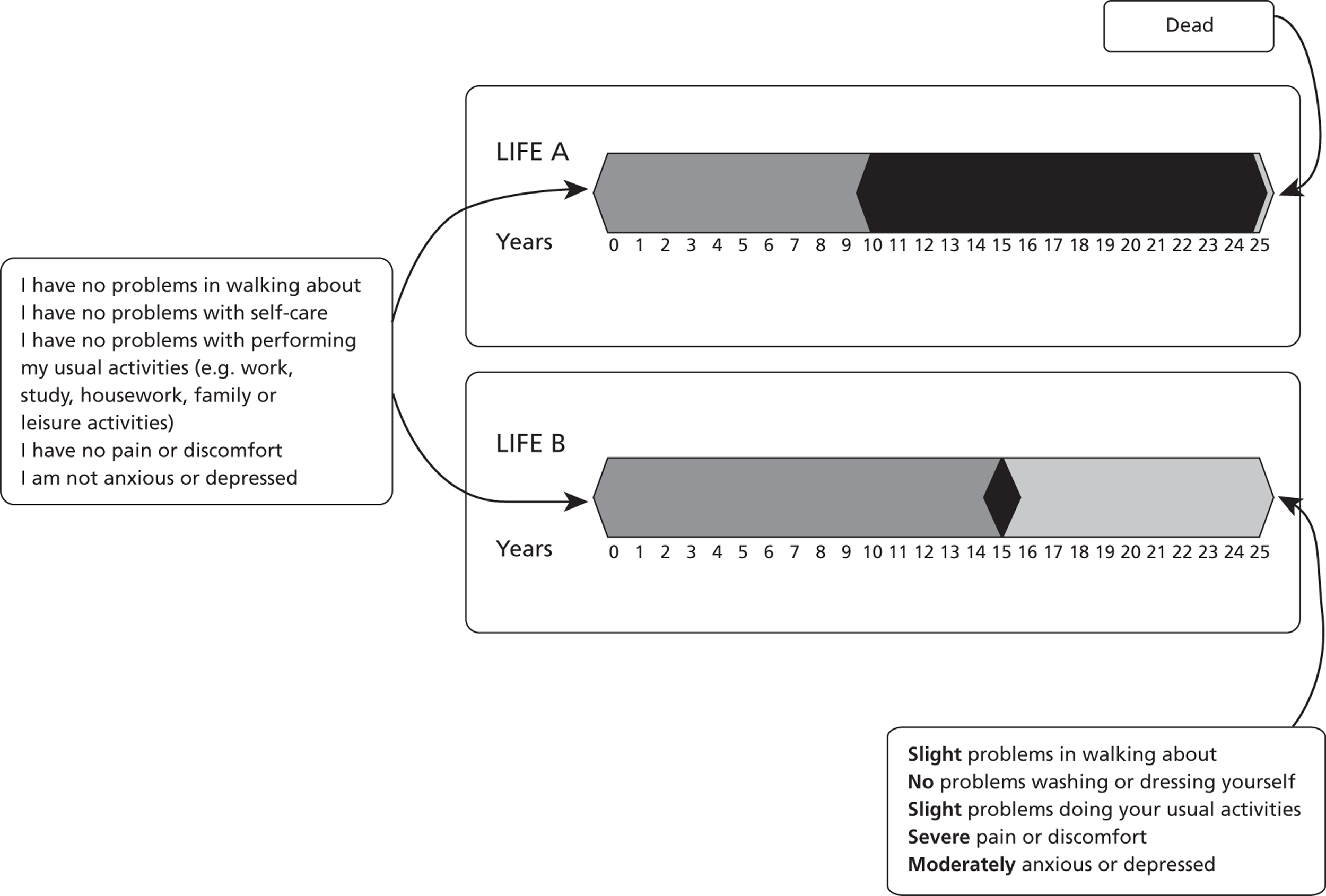

Lead time – time trade-off

A concern with the MVH TTO protocol above is the process used to value states worse than dead. 16–18 The following problems were identified with this procedure: (1) The method is not the same as the method for states better than dead; (2) time spent in health state H has become the decision variable, with the result that respondents are not valuing a specified time in the state (as is the case for states better than dead); and (3) the raw result is non-linear for the time spent in state H, such that as H approaches zero the index approaches negative infinity ( Figure 1 ) and, as is pointed out above, transformations used are arbitrary, and render the values incommensurable with those for states better than dead.

FIGURE 1.

Increase in health-state value as time in poor health decreases.

The lead time – time trade-off (LT-TTO) was devised to overcome these problems. In order to allow X to take negative values, LT-TTO appends a stretch of ‘lead time’ in full health before the usual TTO scenarios begin. For example, if lead time is 15 years, a LT-TTO question compares living in full health for 15 years followed by H for 10 years against living in full health for some duration between zero and (15 + X) years. If indifference is achieved at, say, 20 years in full health, then by removing the lead time this is the same as X = 5 in a TTO without lead time (20 − 15 = 5). If indifference is at 12 years in full health then this corresponds to a ‘negative duration’ (12 − 15 = −3). Note first that the value of living in H for 1 year is given by X/10, regardless of whether H is better or worse than dead, and, second, the calculation assumes that the size of T is unaffected by the addition of the lead time. 16

As can be seen, a lead time of 15 years against a duration of 10 years will allow LT-TTO to elicit values in the range [−1.5 to 1]. If the value of H is < −1.5 then a respondent will strongly prefer immediate death over the prospect of 15 years of lead time plus 10 years in state H. This is called ‘exhausting’ the lead time, and if the objective is to identify a point of indifference for all states for all respondents, it calls for a longer lead time (or a shorter duration). There have been a number of attempts to explore the optimal ratio of the lead time to the duration but a clear answer is yet to emerge. 19

DCEs

There is growing interest in using ordinal techniques such as DCE to generate health-state values. 20 DCEs generate ordinal preference data by asking respondents to indicate their preferred option from a set of health-state profiles (usually two profiles are presented), in which each profile is described in terms of attributes and levels. The results of the choice exercise are then modelled using regressions to generate a coefficient value for each level of each attribute, or dimension. DCE does not require the application of an iterative procedure, and therefore may be less cognitively demanding and avoid the bias associated with iterative procedures.

Discrete choice experiment assumes that preferences are measured on a ‘latent’ scale, and are directly unobservable, but can be modelled in terms of observed characteristic of each choice. As a result, the raw regression coefficients are also on a latent scale, with no direct meaning. Thus, to use DCE to generate utility values that can be used as the HRQL adjustment weights for the QALY, coefficients must be anchored on the full health–dead utility scale. This has typically been done using external values generated, for example, from a TTO exercise. 21 Recently, a method has been developed that avoids the need to use external values by incorporating duration as an attribute of the health-state profile, therefore interpreting DCE data as a TTO exercise (DCETTO). 22 To estimate utility values for health states, a regression model incorporating interaction terms between each level of the health-state dimensions and the duration attribute are estimated (see Chapter 8 , DCE TTO analysis, for more details). The approach has been tested using EQ-5D health states, and has been shown to be a feasible approach to deriving logical and consistent health-state values.

Issues with the design of health-state valuation studies considered in PRET and PRET-AS

In the design of health-state valuation studies, a range of key methodological issues that can impact on the validity and usability of the value sets derived need to be taken into account. These include:

-

Whose values to obtain?

-

What mode of administration to use?

-

What method of valuation to use?

-

How many, and which hypothetical health states to value?

-

The duration of each hypothetical health state?

Each is discussed in detail below, with reference to the issues investigated by PRET and PRET-AS.

Whose values?

The value sets for the three-level EQ-5D,3 and SF-6D,23,24 generic preference-based measures of health and a range of condition-specific measures9–13 are based on general population values, and this is recommended by NICE. 2 However, it is possible that the values given to hypothetical health states by the general population may differ from values given by patients, and there has been debate about whose values should be used. 25,26 Health state satisfaction and adaptation to the health state can be used as a proxy to test this issue as a recent study has demonstrated that if the general public can be informed about the extent to which patients are satisfied with their condition, the discrepancy in values may diminish. 27 PRET tests this further by incorporating a level of life satisfaction, health satisfaction, or adaptation into the health-state description. Alongside this, PRET also tests whether health-state values, which contain satisfaction levels, are influenced by the respondent’s level of satisfaction with their own health or life.

There is also a normative element to this debate, concerning whether general public values ought to be used over patient values. The use of general public values is typically justified with reference to the non-welfarist argument. This states that as the values are used for decision-making in a publicly funded health-care system, they should come from people as informed citizens, not from people as consumers. 28 The traditional approach to health-state valuation, and that used for the current EQ-5D MVH value set, has been to obtain valuations by asking respondents to imagine themselves in the health state. If an informed citizen perspective is taken then a different framing of the TTO question may be required to reflect that the respondent is valuing health states on behalf of other members of society. However, it is unclear what impact an alternative perspective will have on values. PRET investigates this by comparing responses using the standard individual perspective with two alternatives reflecting the citizen approach.

What mode of administration?

Face-to-face interviews with pen and paper questionnaires have been the most widely used method for collecting health-state valuation data using iterative techniques, and was the mode used for EQ-5D using TTO,3 and SF-6D using standard gamble (SG). 23,24 Advances in technology means that it is now also possible to carry out TTO studies using face-to-face CAPI, and this mode was used to derive EQ-5D population value sets for Australia29 and Denmark. 30 Health-state preferences have also been elicited using DCE in a face-to-face setting,21 and the feasibility of carrying out both TTO and DCETTO in an online setting has been investigated. 22

A comparison of the online and face-to-face delivery of TTO found that the responses differed by administration mode, with the online sample displaying more variation in response. 31 Tests of the person trade-off (PTO) valuation technique across online and CAPI administrations also found potential differences across modes. 32,33 Therefore, iterative health-state valuation tasks administered online may generate different results from face-to-face studies, but it is not clear whether the difference comes from the mode of administration or an interaction between the iterative task and the mode of administration. Furthermore, there are also concerns about potential differences in the characteristics of samples collected using face-to-face and online modes, and therefore the overall level of comparability.

The equivalence of responses to binary choice health-state valuation questions (which are amenable to online delivery) across administration modes has not been investigated. Therefore, one of the purposes of PRET was to carry out a head-to-head comparison of an online administration (in stage 1) and a CAPI administration (in stage 2) of an otherwise identical survey containing binary choice health-state valuation questions. A secondary aim is to investigate the similarities and differences of the samples recruited to each mode using the standard recruitment procedure utilised in studies of this kind.

What method of valuation?

As has been described above, there are a range of available techniques for the valuation of health states, and there is also the potential for new and innovative techniques to be developed in the future. The issues with each method need to be considered by those designing health-state valuation studies, as this may impact on the final value sets produced. Further work needs to be done to investigate a range of issues related to each technique described above (TTO, LT-TTO and DCETTO), and one of the aims of PRET is to further the knowledge base in this area, and therefore inform the choice of valuation technique for any health-state valuation exercise. This is described below.

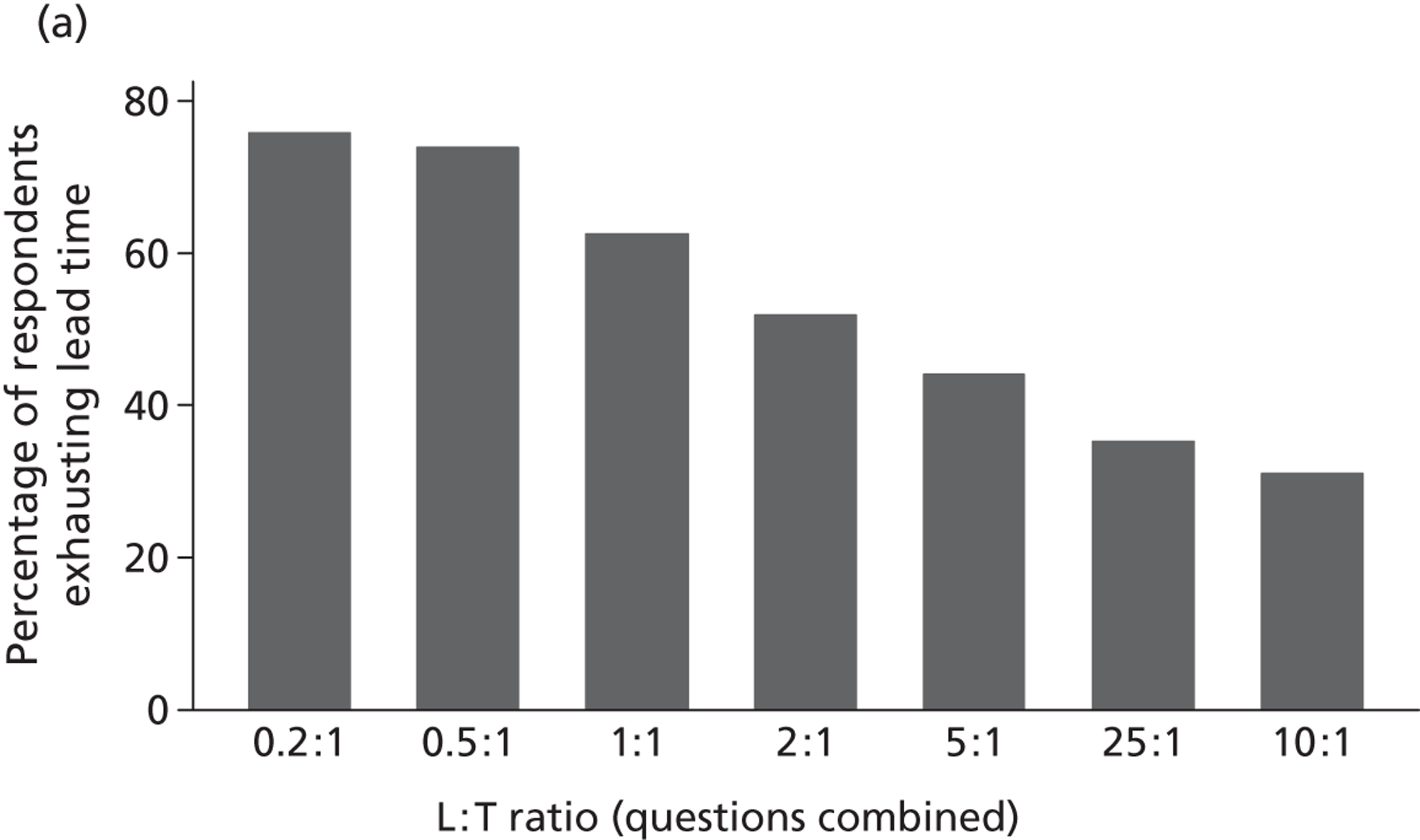

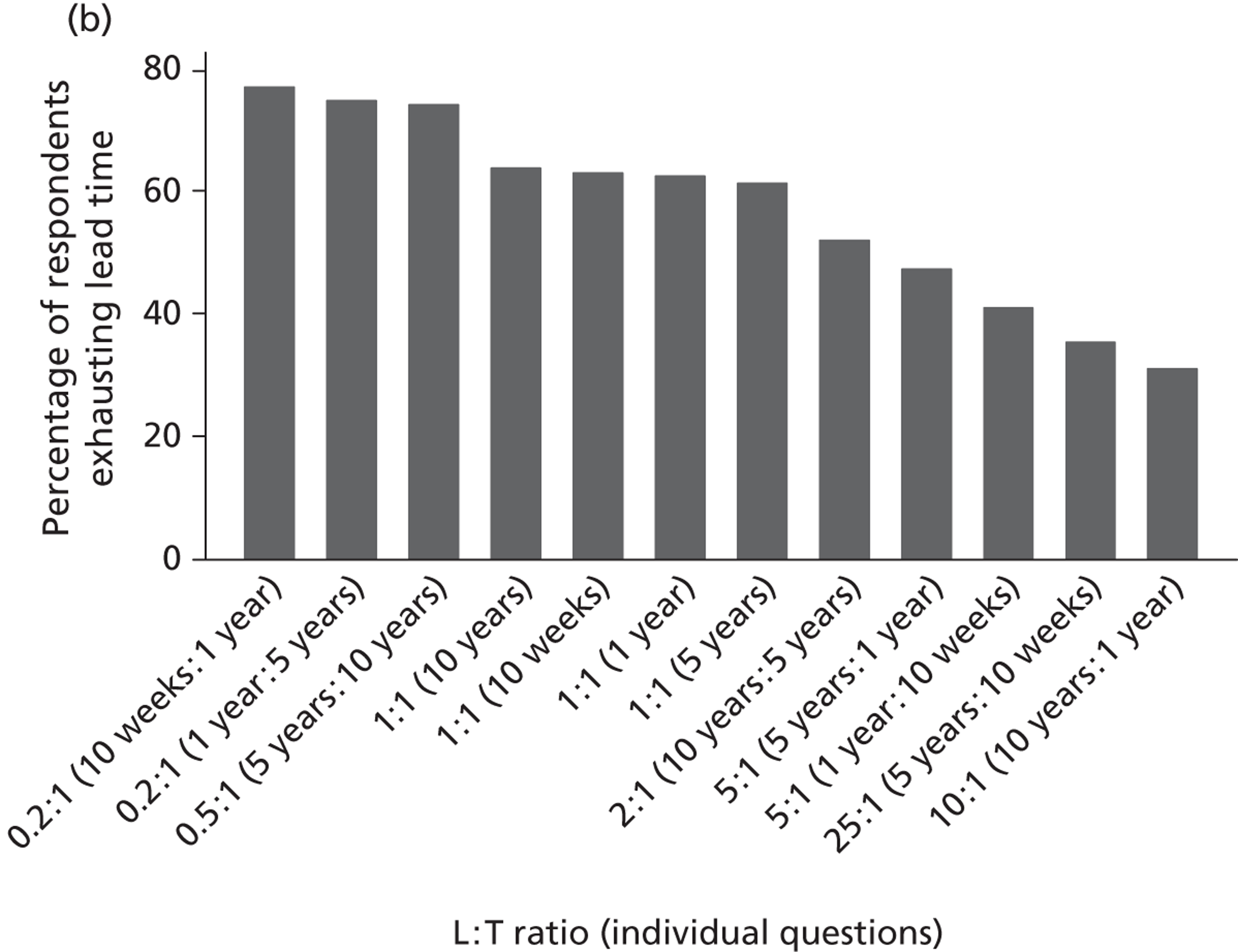

As was described above, MVH TTO protocol used to value the EQ-5D has problems regarding the procedure used to value states worse than dead, and this lead to the development of LT-TTO. Further investigation of the LT-TTO technique is required to identify the optimal length of the lead time used, particularly in very poor health states for which a number of respondents may use up or ‘exhaust’ all of the lead time. One of the objectives of PRET was to provide evidence on this issue. Moreover, another concern is that if the value of a health state depends on its timing and on a preceding health state, then the addition of lead time may distort the TTO value. PRET compares the values produced using binary choice versions of the original and LT-TTO methodologies described in Chapter 2 .

The DCETTO has been shown to be a feasible method for producing values for EQ-5D. However, further testing using a larger descriptive system, such as that found in EQ-5D-5L, is required to investigate the validity of the technique further. PRET and PRET-AS investigate these issues further. Following on from the development of DCETTO, it is possible that other binary choice techniques could be used to produce utility values anchored on the full health–dead scale, and this includes versions of both TTO and LT-TTO, in which one of the choices includes full health. Little is known about the acceptability of both the traditional iterative and new binary choice methods for deriving utility values, and also the ways in which respondents perceive, process and complete the tasks. One of the objectives of PRET is to investigate these issues using both CAPI techniques and detailed qualitative interviews, and this may inform the choice of valuation technique used in future studies.

How many, and which hypothetical health states to value?

The original three-level EQ-5D has 243 possible states. The current MVH TTO value set is based on direct valuations of 45 of these. However, the introduction of EQ-5D-5L means that there are now 3125 possible health states to model. Findings from the DCETTO questions included in PRET, and the modelling approach used to select questions for the study, may be used as prior information to assist in the selection of states and design of the revaluation study.

One aspect that needs to be considered in the design of DCETTO studies is the number of choices each participant can be asked to make. In a recent review, De Bekker-Grob and colleagues20 found that the mean number of choice sets per respondent in health-related DCEs is 14 and it has been suggested that including 8–16 choice tasks is good practice. 34 Furthermore, limited formal work has been done to establish the sample size requirements for DCEs, and PRET and PRET-AS investigate these issues further.

How long should each hypothetical state last?

The current MVH TTO value set is based on participants being asked to imagine each health state lasting for a duration of 10 years. However, the MVH also estimated TTO tariffs for different durations because there was a concern that the tariff values may be a function of the duration of the health state. There are four related issues, all of which are also relevant to DCETTO. 35 One is whether or not constant proportional time trade-off (CP-TTO) holds so that the utility associated with a marginal survival in a given health state remains constant regardless of the health state or the duration. It has been argued that for very severe states there may be a ‘maximal endurable time’ limit, beyond which the marginal benefit of survival diminishes. 36 The second issue is whether or not respondents use a positive temporal discount rate when valuing hypothetical health scenarios. 37–39 The third is the impact of life stage concerns in health-state valuations. If the duration of the state is too long then the scenarios will not be credible for older respondents and vice versa. Furthermore, depending on the duration, people may be thinking about life stage events rather than about the trade-off between longevity and quality of life.

The final issue is whether or not 10 years is the most relevant duration for NICE decision-making. If the issues highlighted above mean that the value of a state is a function of its duration then the revaluation of the EQ-5D may not be based on scenarios with a 10-year duration. The PRET stage 1 online survey examines the impact of varying duration on health-state preferences.

Format of report

The aim of this report is to describe in detail the methods used across the project, and present the results of each stage. Chapter 2 gives a broad overview of the methods used for the PRET stage 1 and PRET-AS online surveys, and presents the demographic characteristics of the respondent samples overall and by each question type. Chapters 3 – 8 report the results of the PRET and PRET-AS online surveys with each of the chapters reporting the findings relating to one of the methodological issues addressed by the online surveys; Chapter 9 reports the methods and results of stage 2; Chapter 10 the methods and results of stage 3, and Chapter 11 the methods and results of stage 4. Finally, Chapter 12 provides a general discussion and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 General overview of the PRET stage 1 and PRET-AS online surveys

Introduction

The aim of this chapter is to briefly outline the methodological issues addressed by the online surveys carried out in stage 1 of the PRET project and PRET-AS, and to describe the format, recruitment process and administration of the online surveys. Stage 1 of the PRET project used a large online survey to investigate a range of methodological factors relating to health-state valuation, using binary choice questions. PRET-AS was a second online survey that investigated two binary choice health-state valuation techniques that can be used to produce population tariffs on the full health–dead utility scale. The study design and questions used to investigate each of the methodological issues is described in detail in the subsequent chapters reporting the results. In the rest of this chapter, the second section describes the overall aims and objectives of the studies, and provides an overview of the methodological issues tested; the third section reports the general format of the surveys, and the recruitment and administration procedures used; and the fourth section reports overall response rates for each online survey.

The first three sections of this chapter are reported in an online discussion paper6 (accessible at www.shef.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.165490!/file/1116.pdf).

Aims and objectives and the methodological issues tested

PRET stage 1

The aim of the PRET stage 1 online survey was to test a range of methodological assumptions and questions related to health-state valuation, using health states based on EQ-5D-5L. This was done using binary choice questions based on TTO and DCE. The questions tested were:

-

whether health-state preferences are independent of duration (see Chapter 3 )

-

whether health-state preferences are independent of person perspective used (see Chapter 4 )

-

investigation of LT-TTO (see Chapter 5 )

-

whether health-state preferences are independent of lead time

-

to what extent respondents exhaust lead time under very poor health

-

-

whether the preferences of others’ health is independent of when health events take place (see Chapter 6 )

-

whether health-state preferences are independent of satisfaction in the state (see Chapter 7 )

-

whether DCETTO is feasible for EQ-5D-5L, and if so which states should be valued (see Chapter 8 ).

Issues 1–5 are methodological, and therefore the questions used to investigate this are not designed to produce utility values anchored on the full health–dead scale for EQ-5D-5L. Issue 6 uses a method that is designed to elicit utility values.

PRET-AS

The aim of PRET-AS was to investigate the feasibility of two binary choice question types that can be used to derive utility values anchored on the full health–dead utility scale. This was done by conducting an additional online survey of similar size to that in stage 1.

-

The first question type in PRET-AS was also used in the PRET stage 1 survey to investigate issue (6) and presents a DCE with an associated duration level using EQ-5D-5L health states. The results are presented alongside the findings from PRET stage 1 (see Chapter 8 ).

-

The second question type presented a binary choice version of LT-TTO using whole three-level EQ-5D health states. The results are presented alongside the findings from the PRET stage 1 LT-TTO investigation (see Chapter 5 ).

The methods used for the surveys are briefly described in the next six sections, and the study design to test each methodological question is described in detail in the relevant chapter.

Basic question format

Binary choice questions were used to investigate the methodological issues highlighted above. A single response to a binary choice question cannot identify the level of HRQL that an individual feels is right for a given health state, and this was not the aim of the majority of the questions used for the PRET project. However, by examining the distribution of responses of multiple respondents across different binary choice questions incorporating different attributes included in valuation tasks, the methodological issues highlighted above can be tested.

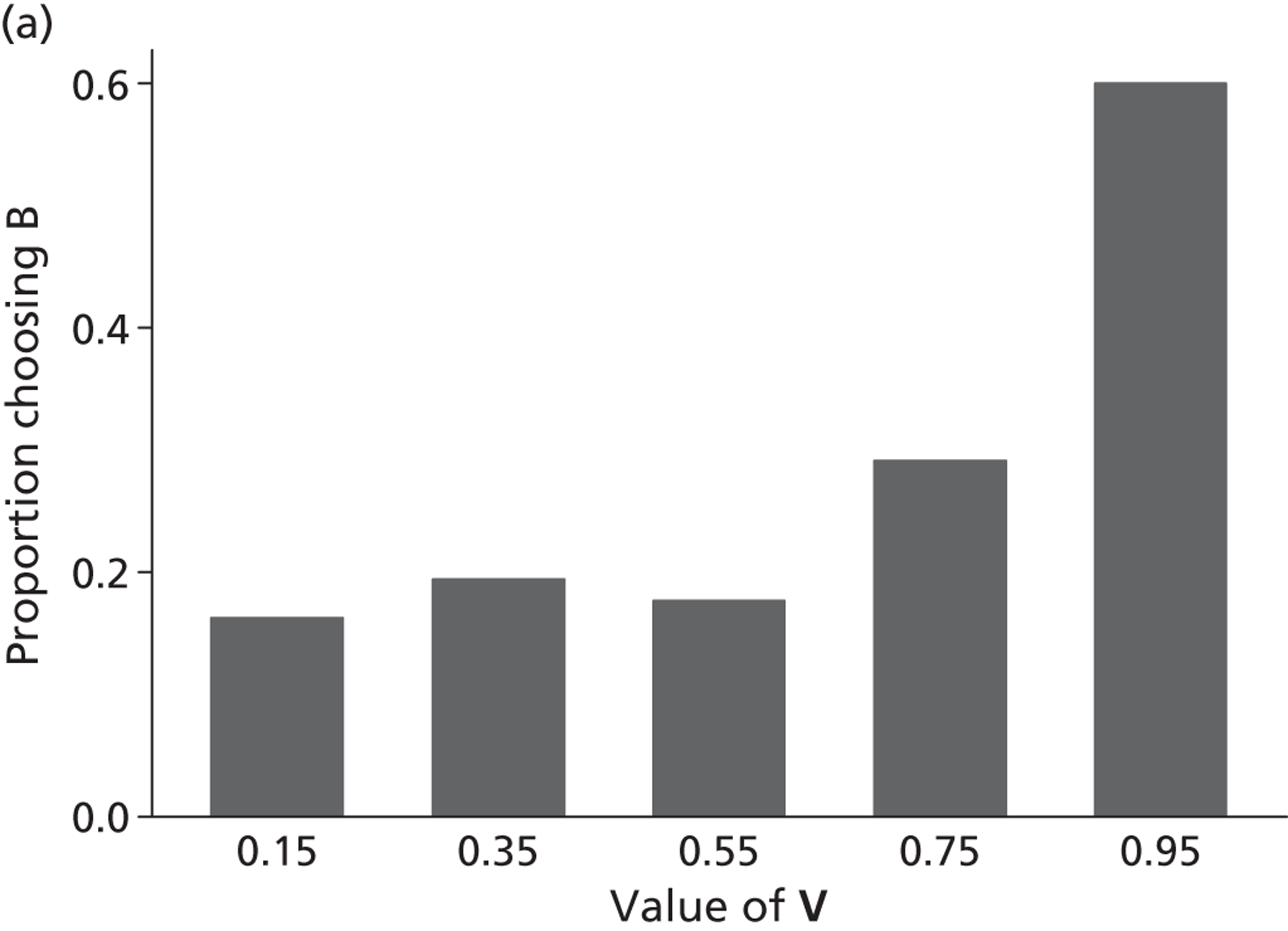

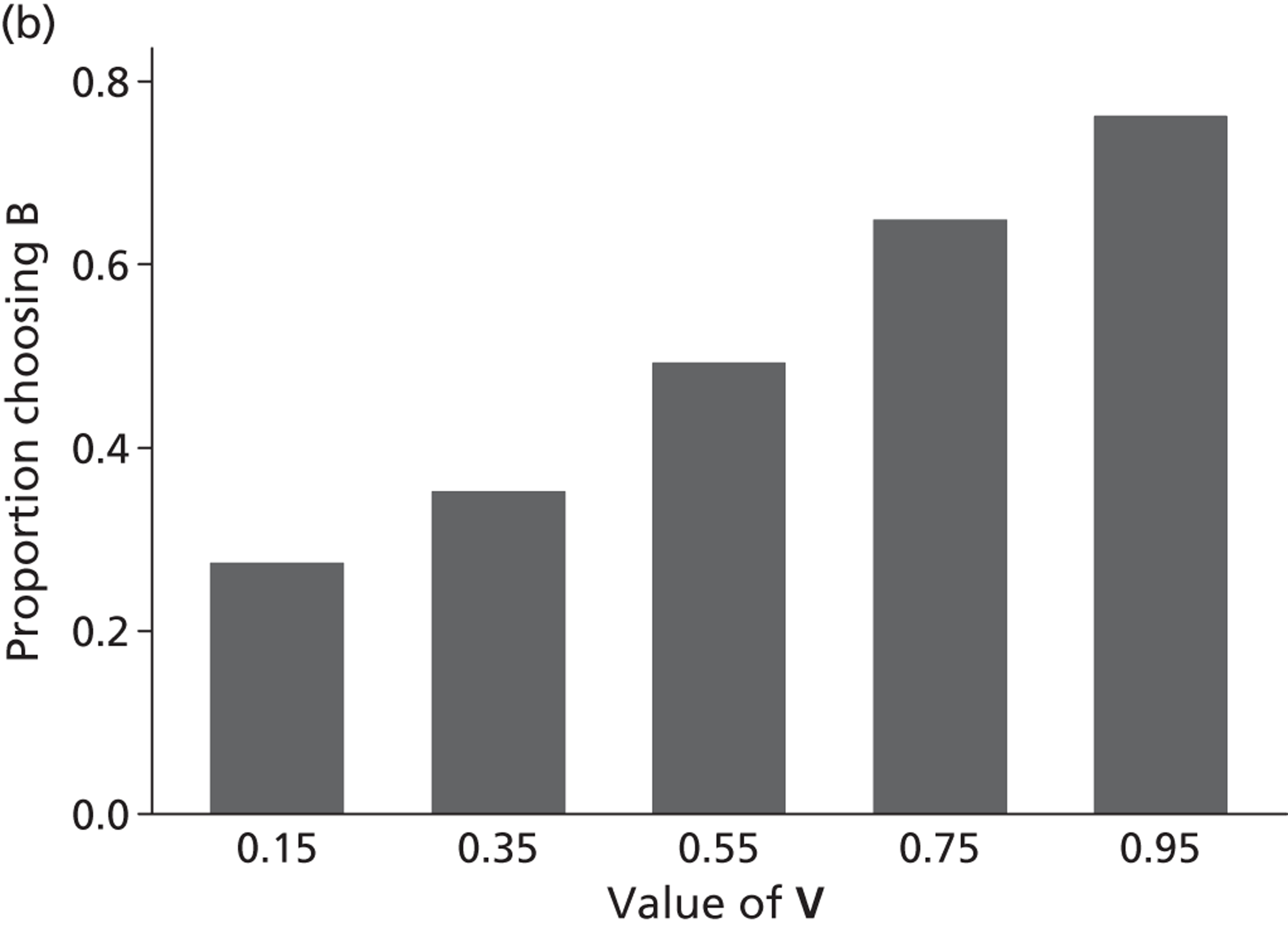

The most ‘basic’ sort of binary choice question used for PRET stage 1 was as follows:

-

[Scenario A]: you will in health state H for 10 years and die

-

[Scenario B]: you will live in full health for (V × 10) years and die (where V is a value between 0 and 1)

-

Which of the two scenarios do you think is better?

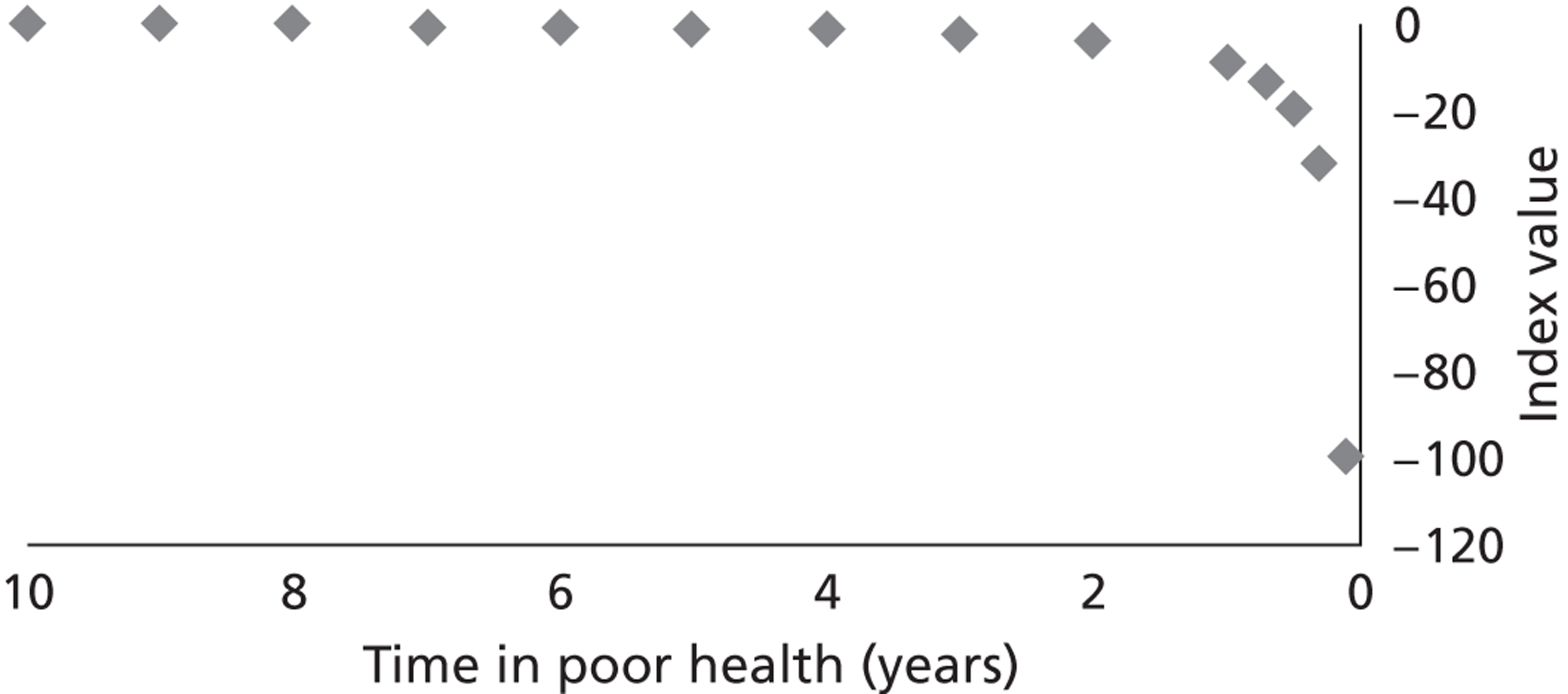

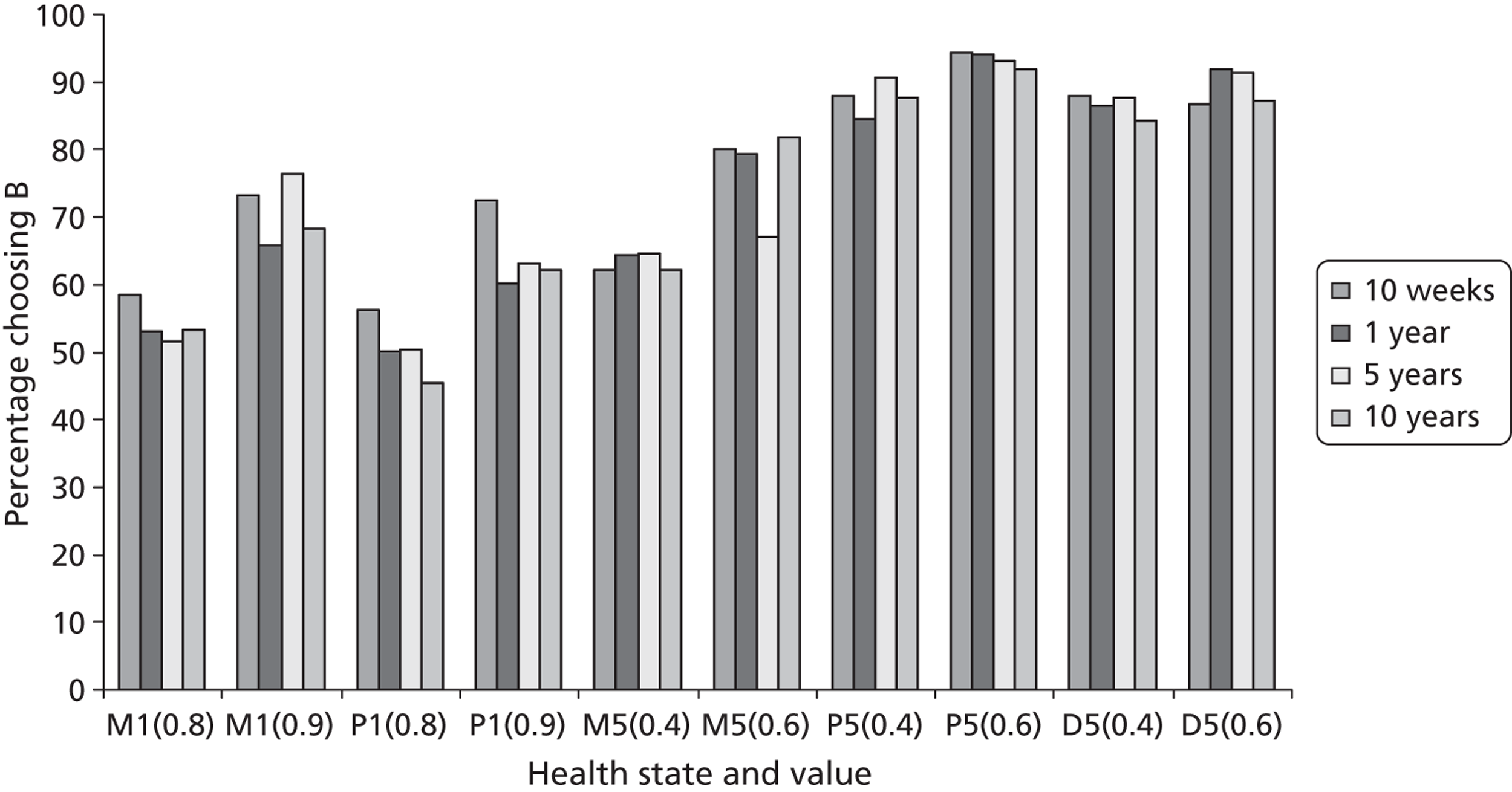

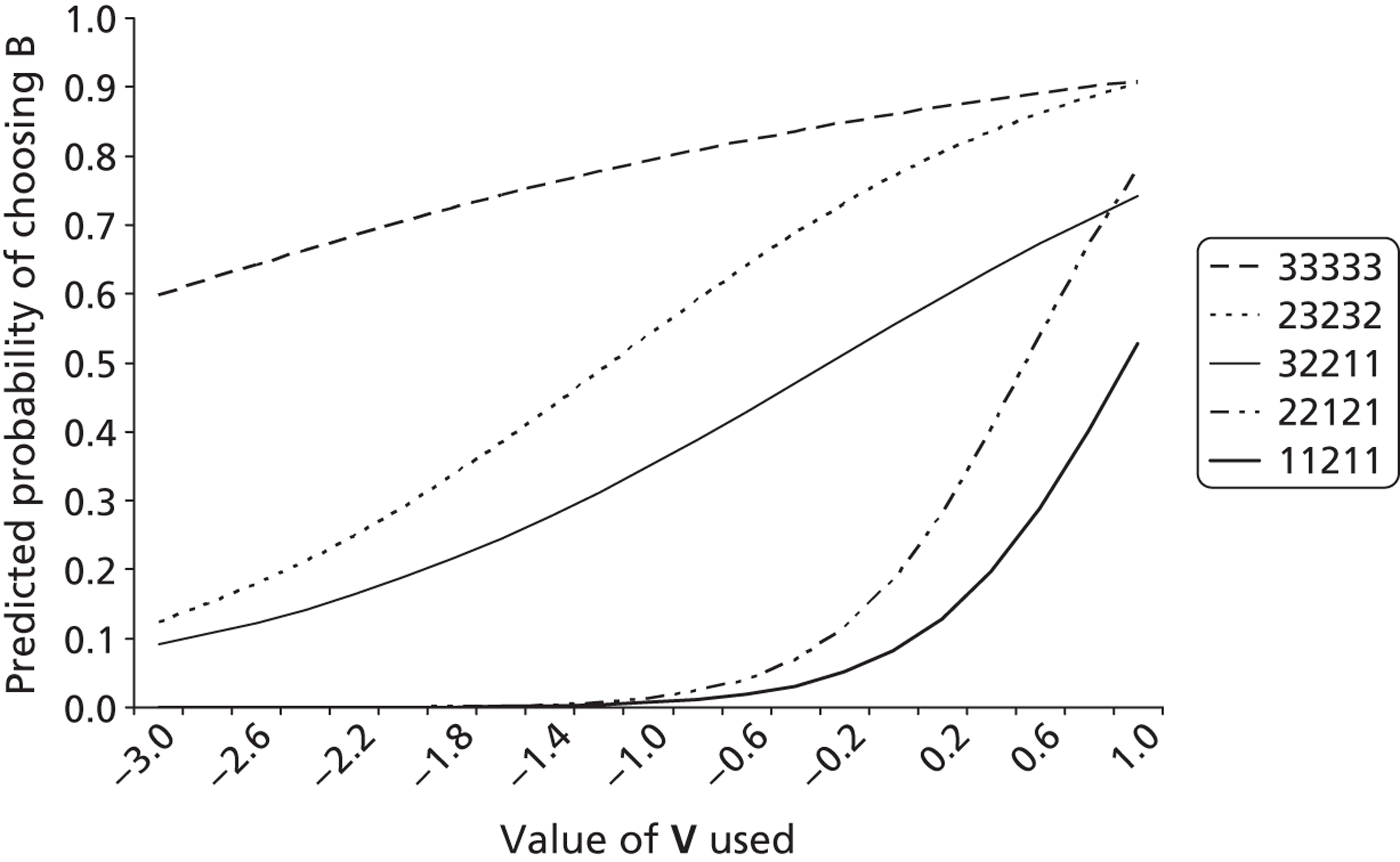

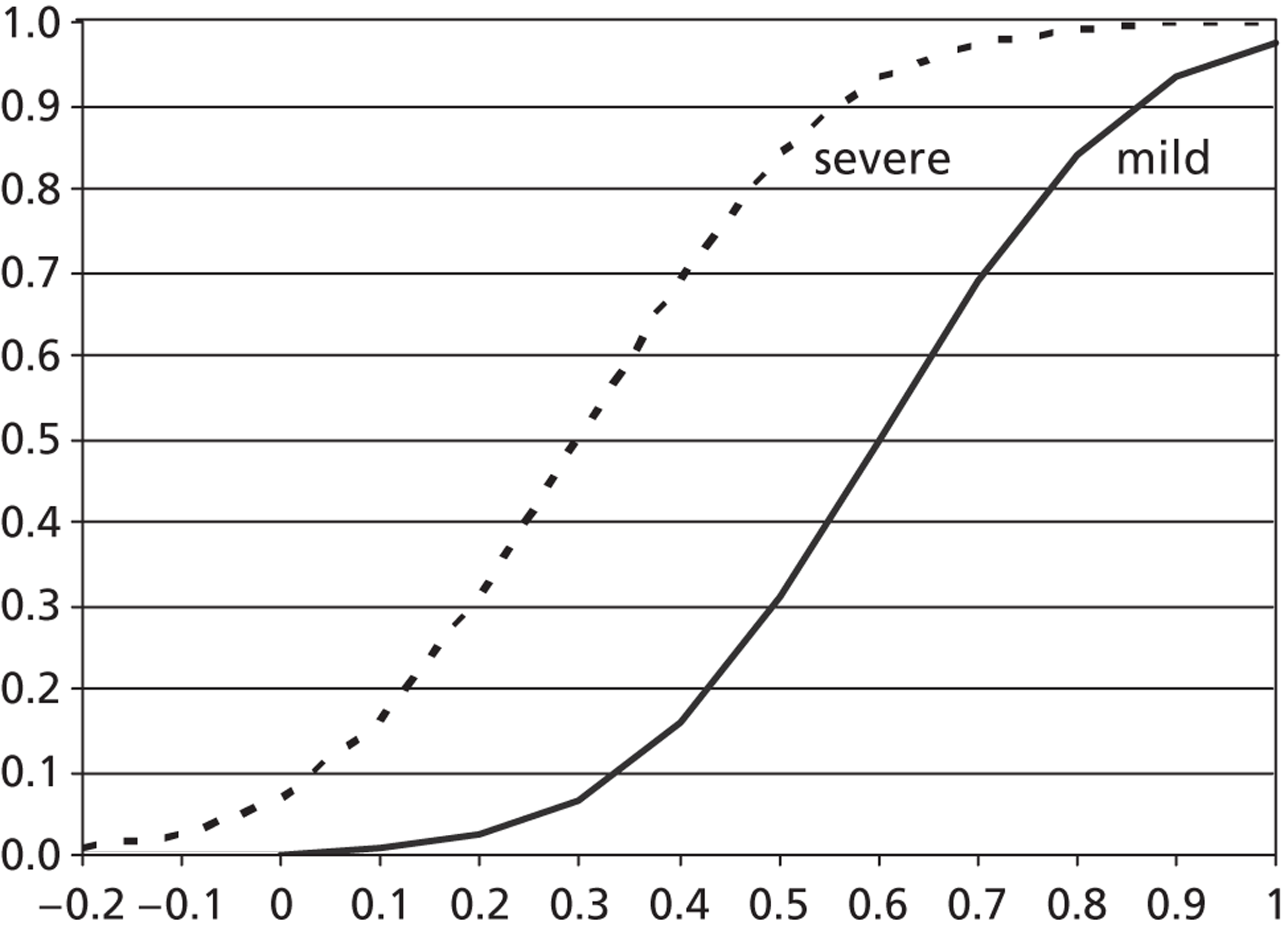

The value of V corresponds to the level of HRQL and was varied across different versions of the questions included in the surveys. If we assume that there is an unobserved genuine value of the health state, say V*, then a respondent will, in effect, assess the duration in full health given in scenario B in light of this value. Thus (errors permitting), they will choose B when V* < V. Figure 2 displays an illustrative example of two hypothetical states: ‘severe’ (with a lower V*; but we do not know where it lies) and ‘mild’ (with a higher V*). Along the horizontal axis is the value of V with 0 for dead and 1 for full health. Along the vertical axis is the proportion of people choosing to live in full health (i.e. scenario B), given the task above with different values of V. The curve indicates that, as V increases, the proportion of people who think the given health state is no better than V (namely V* < V) will increase and therefore more will choose scenario B. Now, suppose V is at 0.6. If the state H in the example above is the severe state then, from the curve, around 90% of observations can be expected to be for scenario B, and be consistent with V* > 0.6, but if state H is the mild state then around 50% can be expected to be for scenario B. In other words, given a value of V in a binary choice scenario, the proportion of respondents choosing scenario B will be a function of the value V* that respondents give to the state H (and any further relevant factors, explained below).

FIGURE 2.

The value of V and the proportion of respondents choosing scenario B (full health).

Thus the different scenarios used in the project were assessed in terms of the proportion of people choosing one scenario over the other. All binary choice scenarios included information about a health state, and the length of time lived in the state, followed by death.

Note that the binary questions used are a snapshot of one question from the conventional iterative TTO procedure. This is because the typical TTO exercise is a series of binary choice questions and involves changing V until the respondent is indifferent between the two scenarios. In fact, the procedure of TTO can be interpreted as a special case of DCE, in which scenario B always involves full health.

Question type summary

To investigate the methodological issues, eight types of binary choice questions were used, and these are summarised in Table 1 . PRET included question types I–VII, and PRET-AS included question types VII and VIII. The question types included one or more of the following parameters:

-

Single dimensions or full health states from EQ-5D-5L health states (H): see The hypothetical health states used.

-

Duration (T) lived in state H. PRET used durations of 10 weeks, 1 year, 5 years and 10 years.

-

Lead time stretches (L) in full health before (H) occurs, including 0, 10 weeks, 1 year, 5 years and 10 years.

-

Person perspective (P) that the hypothetical health states apply to. PRET used ‘you’, ‘somebody else like you’ and ‘somebody else’ perspectives.

-

Level of satisfaction with one’s own health or life (S). PRET used low health satisfaction, high health satisfaction, high life satisfaction, and ‘learnt to live with the health state’.

| Question type parameter | I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | VII |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| State of health (H) | CS | CS | CS | CS | CS | 55555 | 5L | 3L |

| Duration in full health (T) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | n/m | ✓ |

| Duration in H | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Lead time (L) | n/m | n/m | ✓ | ✓ | n/m | ✓ | n/m | ✓ |

| Person/perspective (P) | You | Other | You | Other | You | You | You | You |

| Satisfaction (S) | n/m | n/m | n/m | n/m | ✓ | n/m | n/m | n/m |

Each question type will be described in detail in the relevant chapter below. Each question type was used to investigate one (or more) of the PRET assumptions or PRET-AS methods. Question types I–VI were developed to assess methodological issues, and not to derive a utility tariff, whereas question types VII and VIII can be used for this purpose.

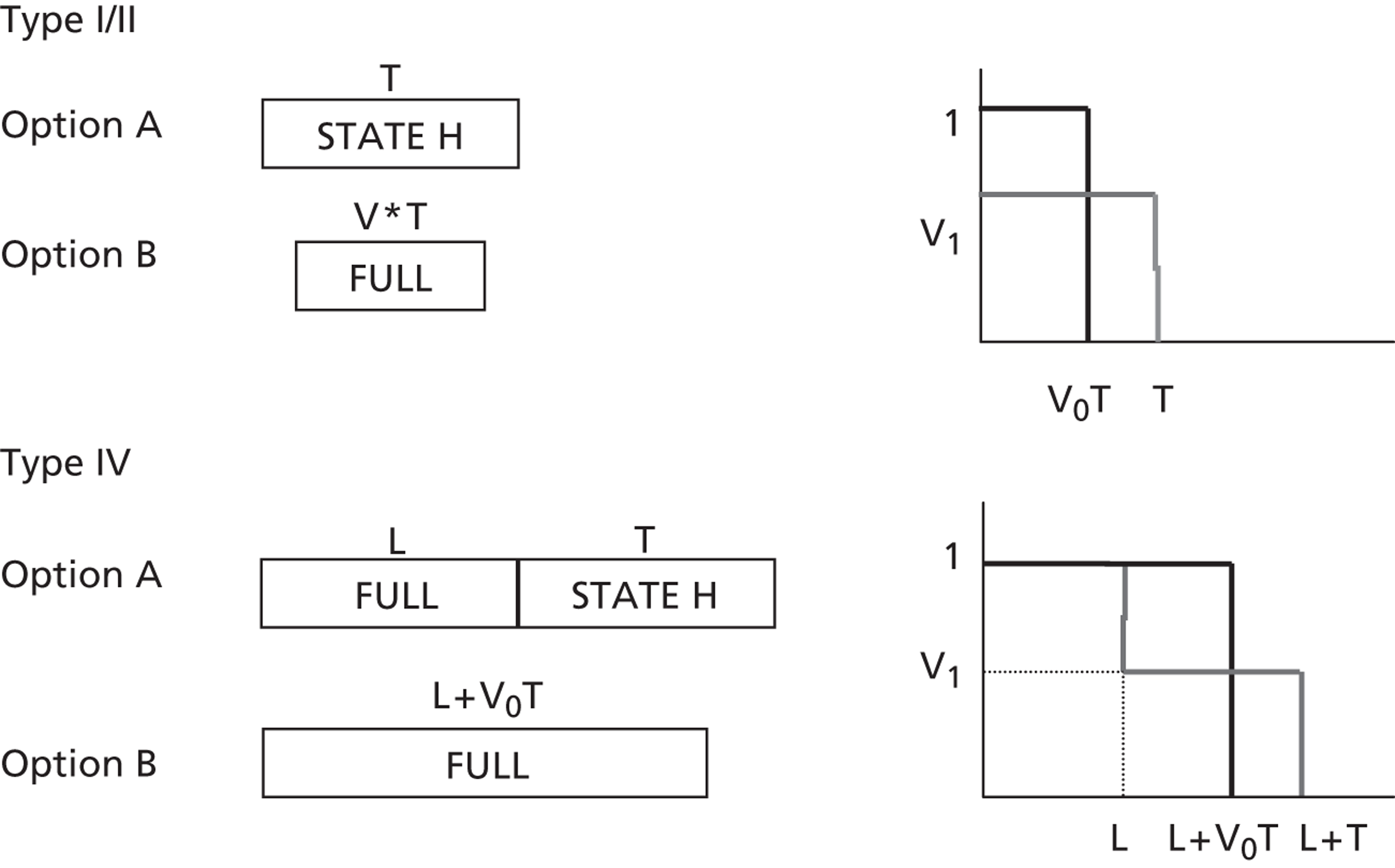

Question type I was used to investigate assumption 1 (health-state preferences are independent of duration, or an assessment of CP-TTO). It also provided a comparator question for question types II–V (which use the same question format but vary certain parameters to test the impact of the addition of these parameters); Question type II investigates question 2 (whether health-state preferences are independent of person perspective). Three question types are used for the investigation of LT-TTO: type III to investigate question 3a (whether health-state preferences are independent of lead time); type VI to investigate question 3b (the extent to which lead time is exhausted); and type VIII questions to investigate whether binary choice LT-TTO can be feasibly used to generate values on the utility scale (PRET-AS aim 2). Question type IV was used to investigate question 4 (whether the preferences for others’ health is independent of when health events take place, or an investigation of time preference); question type V investigated question 5 (whether health-state preferences are independent of satisfaction in the state); and question type VII was used to assess the feasibility of DCE with duration for producing utility values (PRET-AS aim 1).

The hypothetical health states used

Questions type I–V used the following five health dimensions adapted from EQ-5D-5L health states:

-

‘Slight problems walking about’ (level 2 of the mobility dimension from EQ-5D-5L state 21111).

-

‘Slight pain’ (level 2 of the pain dimension from EQ-5D-5L state 11121).

-

‘Unable to walk about’ (level 5 of the mobility dimension from EQ-5D-5L state 51111).

-

‘Extreme pain’ (level 5 of the pain/discomfort dimension using pain only from EQ-5D-5L state 11151).

-

‘Extreme depression’ (level 5 of the anxiety/depression using depression only from EQ-5D-5L state 11115).

For question types I–V, such corner states (CSs, with only one problem each) were chosen so that any variation across states could be linked to a single EQ-5D dimension, and to make the health scenarios easy to picture. The scenarios cover different aspects of health, and therefore enabled us to test the key methodological issues across different hypothetical health concerns. For the health states taken from the pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression dimensions, the questions only included either pain or depression. In order to reflect that the health states described had no problems (represented level 1) on the other EQ-5D dimensions, respondents were explicitly requested to assume that they have no other health problems other than those indicated. Two sets of V values were used: 0.8 and 0.9 for the two states involving level 2 (i.e. slight problems) and 0.4 and 0.6 for the three states involving level 5 (unable/extreme problems). These values were chosen in line with the MVH tariff values for the five comparable health states taken from the three-level version of EQ-5D. This was done to use V values near to the modelled indifference point from the MVH tariff to make the choices challenging. For the two mild states, the comparable MVH values were 0.850 (21111) and 0.796 (11121), and for the extreme states the comparable values were 0.213 (31111), 0.264 (11131) and 0.414 (11113).

Type VI questions used the worst possible state using EQ-5D-5L (state 55555), which is the most likely state to lead respondents to exhaust lead time.

For question type VII, whole EQ-5D-5L health states were used. This is because these question types investigate methods to produce values on the full health–dead utility scale for whole health-state descriptive systems, such as EQ-5D-5L.

For question type VIII, whole states from the three-level EQ-5D were used. The three-level version was used as we were assessing the feasibility of a new binary choice health-state valuation method, and the whole states used had also been used in previous research developing the LT-TTO method.

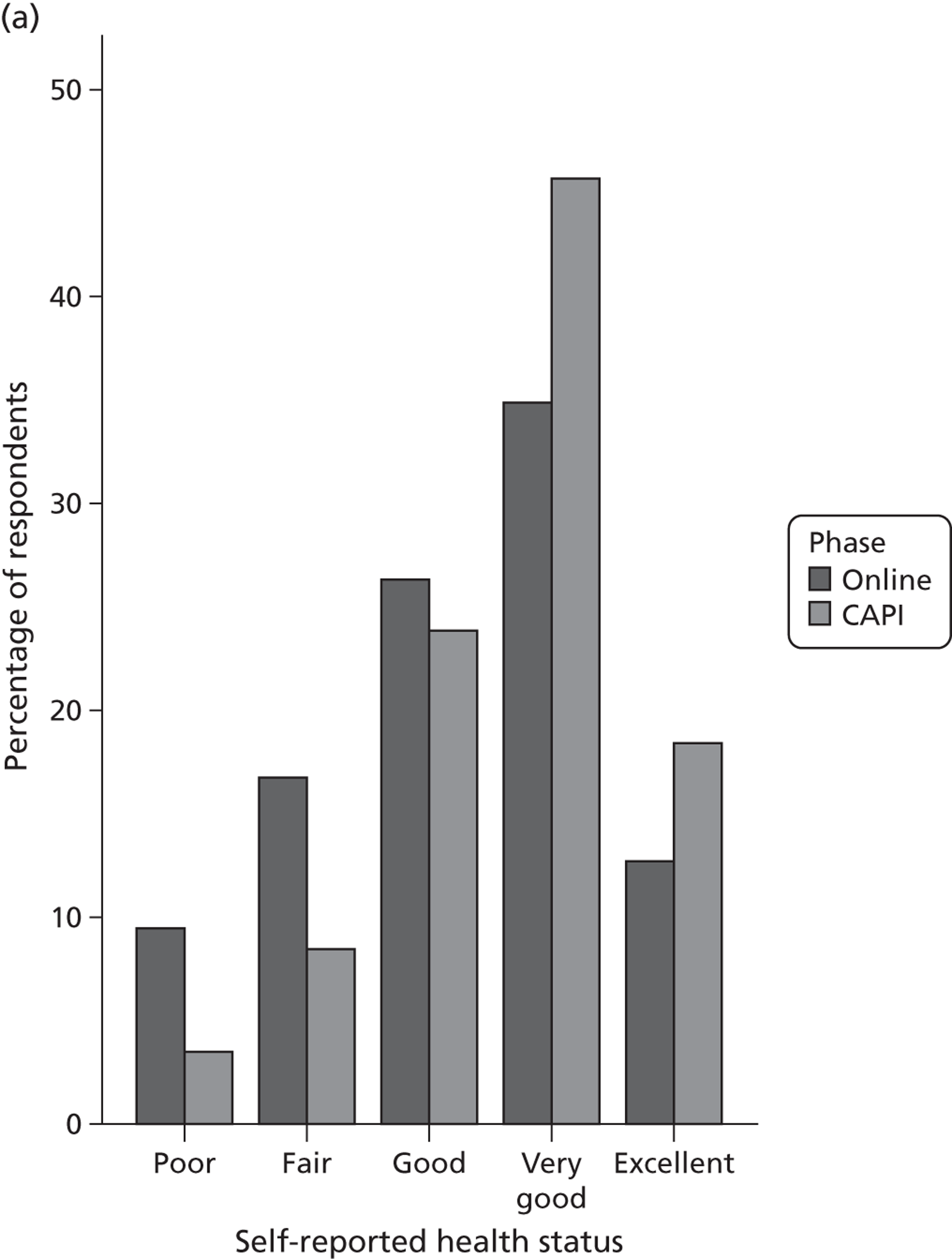

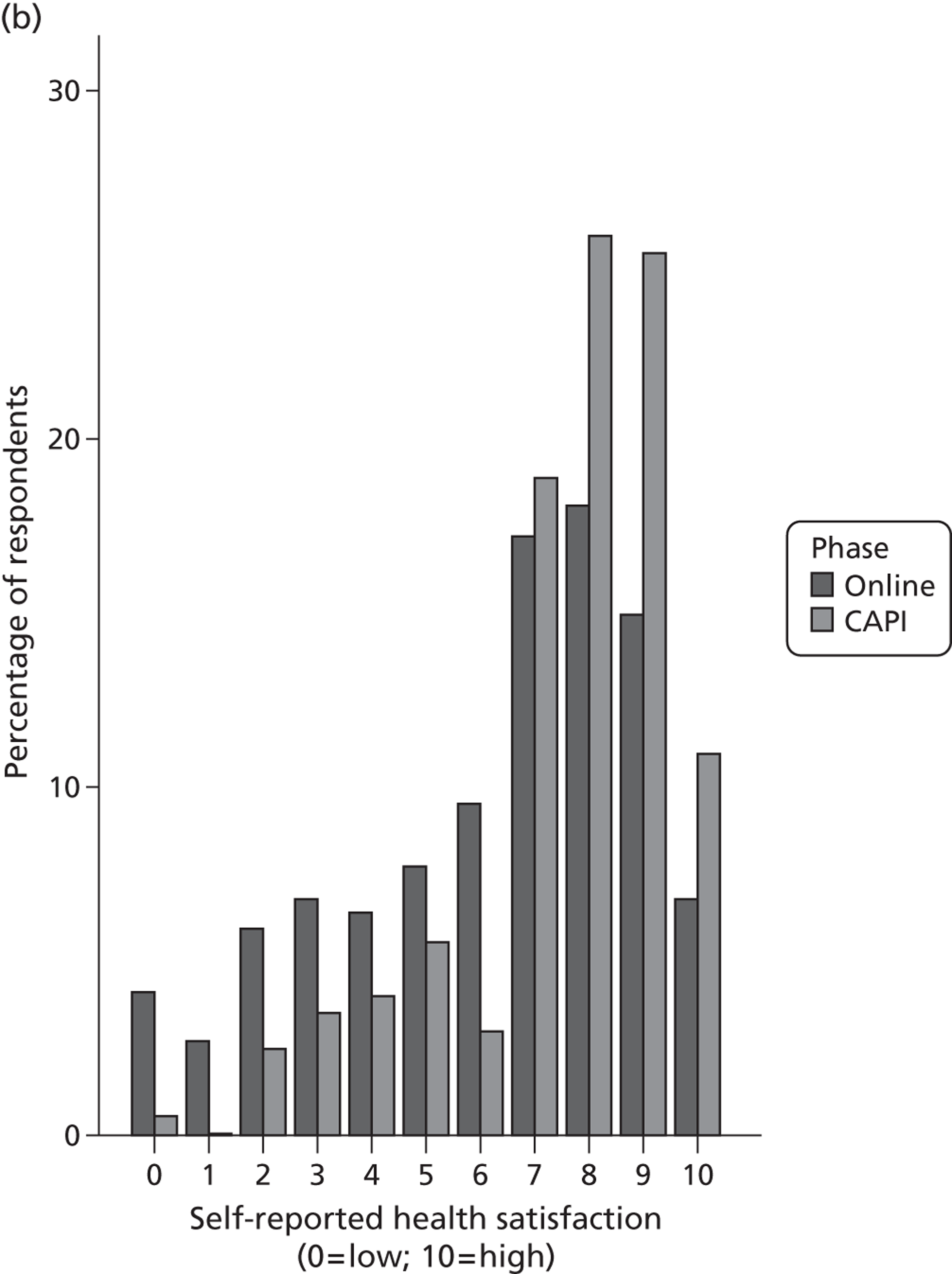

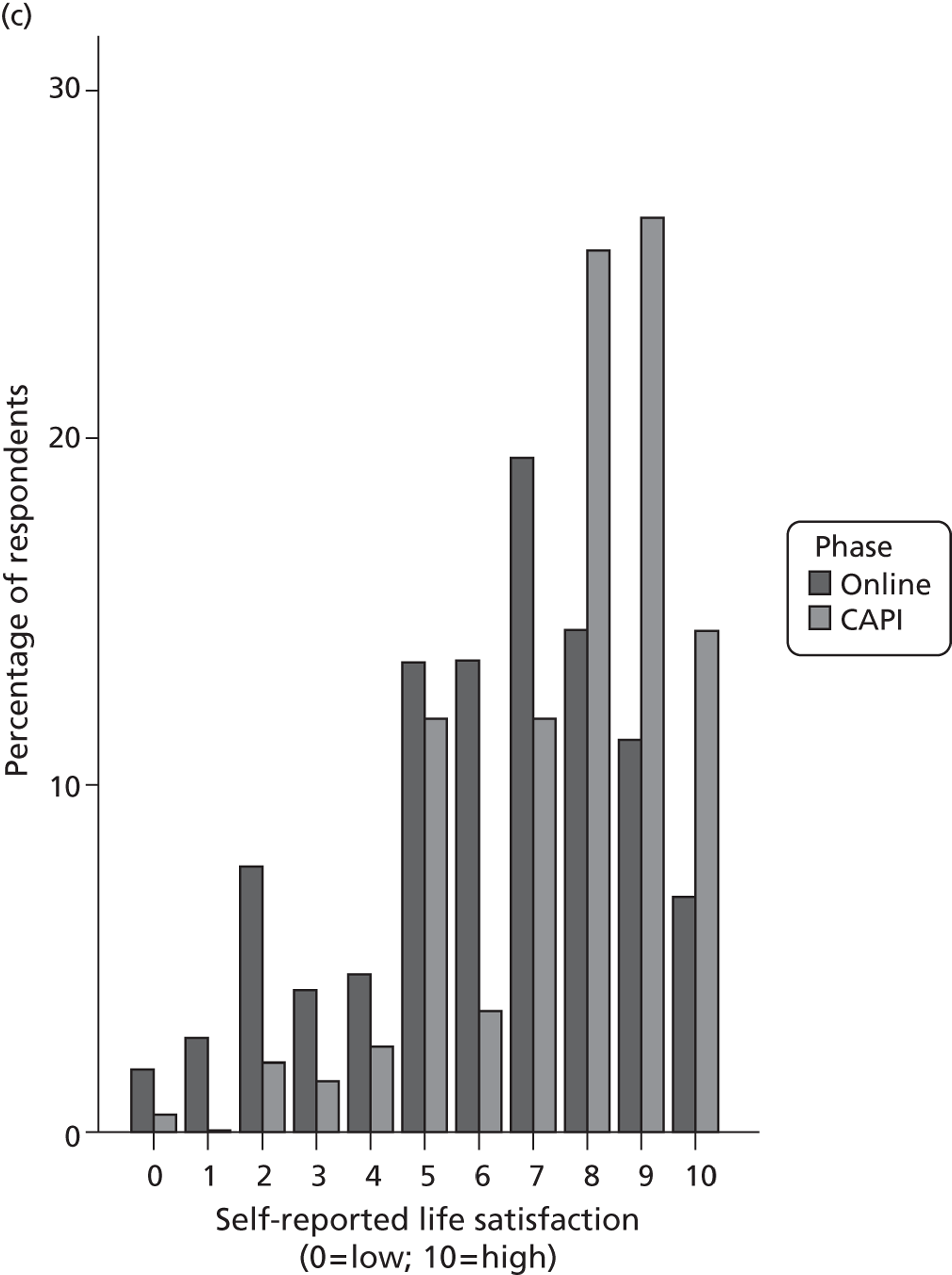

Survey completion process

Each survey began by providing a brief background explaining the purpose of the survey, and this was followed by a compulsory informed consent page. After consenting, respondents provided demographic information, including age, gender, marital status, employment status, whether they were educated past the minimum level, and whether they had a degree. Respondents answered questions about health status (on a five-point scale from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’); health satisfaction and life satisfaction [measured on a 10-point scale from ‘completely satisfied’ to ‘completely dissatisfied’, and known as SWBH (own health satisfaction) and SWBL (own life satisfaction), respectively], and the EQ-5D-5L. For half of the respondents these questions were followed by the experimental question modules. However, the other half of the respondents completed the self-report questions after the experimental modules. On the final page there was a free text box to enable respondents to provide their opinions on the survey, or any other relevant information (see Appendix 1 for screenshots from version 15 of the online survey).

Allocation of questions to questionnaire versions

PRET

The seven different question types were presented across three experimental modules:

-

Module 1 Five type I questions.

-

Module 2 Five questions specific to the questionnaire version (using question types II–VI).

-

Module 3 Two type VII questions.

Each respondent completed 12 binary choice questions and there were 15 versions of the online survey overall ( Table 2 describes the question types included in each survey). The ordering of the questions within each module was randomised. For 14 of the versions, module 2 consisted of five binary choice questions from one of types II, III, IV, V or VI. Therefore, respondents who completed these versions faced three question types each. However, for version 15, module 2 included one question each of types II, III, IV, V or VI. Therefore, respondents allocated to version 15 completed all seven question types. This was done so that we could compare the results for all question types across different modes of administration at stage 2 of the project (see Chapter 4 ).

| Group | Questions | No. of versions | Version names | Approximate n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Module 1 | Module 2 | Module 3 | ||||

| 1 | 5 × type I | 5 × type II | 2 × type VII | 3 (12 subversions) | V1/V2/V3 | 600 |

| 2 | 5 × type I | 5 × type III | 2 × type VII | 3 (12 subversions) | V4/V5/V6 | 600 |

| 3 | 5 × type I | 5 × type IV | 2 × type VII | 3 (12 subversions) | V7/V8/V9 | 600 |

| 4 | 5 × type I | 5 × type V | 2 × type VII | 2 (8 subversions) | V10/V11 | 400 |

| 5 | 5 × type I | 5 × type VI | 2 × type VII | 3 (12 subversions) | V12/V13/V14 | 600 |

| 6 | 5 × type I | 1 × type II/III/IV/V/VI | 2 × type VII | 1 (4 subversions) | V15 | 200 |

Furthermore, there were 60 subversions of the survey (each of the 15 versions has four subversions) for module 3. This enabled 120 DCETTO pairs to be allocated across the 60 subversions (i.e. two per subversion).

PRET-AS

The PRET-AS respondents completed either 15 type VII questions across three experimental modules of five questions or 10 type VIII questions across two experimental modules of five questions.

Recruitment and the sample

PRET

Respondents were recruited from an existing commercial internet panel. Overall, approximately 3000 respondents were recruited into stage 1 of PRET across the 60 subversions of the online survey, with each version completed by a minimum sample size of 50. Respondents were sourced from an existing internet panel following set quotas for age across five age groups (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–65 years, although a handful of respondents reported that they were older than 65 years) and gender, in an attempt to recruit a sample that was representative of the UK general population in this age range. To recruit participants, invitations were sent out by e-mail. Respondents were screened out prior to starting the experimental questions if the relevant quota for age and gender was complete, or after completing the survey if they answered all of the survey questions in less than the minimum imposed time limit of 5 minutes. Those who successfully completed the survey received online points worth approximately £1.

The same recruitment procedures that were used for the PRET online survey was followed for PRET-AS, with approximately 1800 respondents across the 36 type VII question surveys and 1200 across the 27 type VIII surveys. We reduced the minimum completion times so that respondents were classified as non-completers if they completed the survey in < 3 minutes (and the time to complete the overall survey and each experimental question module was recorded).

Respondents entering the survey firstly completed the same demographic and self-reported health questions. They were then presented with information about the tasks. This included details about the EQ-5D-5L health dimensions, and instructions to imagine that they would experience each health state for the period shown without relief or treatment, that death would be very swift and completely painless, and that they would have no other health problems besides what was indicated. A practice task was then completed, followed by the valuation questions.

Respondent characteristics

Tables 3 and 4 present the characteristics of the respondents to the PRET and PRET-AS online surveys overall, and in comparison with the UK general population using census data. 40 Respondents who completed the PRET online survey were not invited to take part in the PRET-AS online survey. Following recommendations in Dolan and Metcalfe,41 we merge levels of SWBH and SWBL into the following categories: ‘low’ if 0–5; ‘medium’ if 6–7; ‘high’ if 8–9; and ‘very high’ if 10. This is because those scoring ‘10’ display different characteristics than those that might be expected – for example they tend to be older and less healthy.

| Characteristic | General populationa | Invited | Non-responders | Respondersb | Responder, non-completerb | Completers | Type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | II | III | IV | V | VI | VII | |||||||

| n | 34,892 | 27,142 | 7750 | 4591 | 3159 | 3159 | 829 | 847 | 849 | 645 | 873 | 3159 | |

| Age, years | |||||||||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.2 | 37.2 | 37 | 39.0 (13.6) | 37.4 (13.2) | 40.8 (13.8) | 40.8 (13.8) | 39.4 (13.7) | 41.0 (13.5) | 39.9 (13.9) | 42.5 (14.0) | 41.7 (13.8) | 40.8 (13.8) |

| Range | 18–64 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–74 | 18–65 | 18–64 |

| Age category, years (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| 18–24 | 14 | 5882 (16.9) | 17 | 1232 (18.2) | 744 (20.5) | 488 (15.4) | 488 (15.4) | 146 (17.6) | 123 (14.5) | 147 (17.3) | 90 (14) | 123 (14.1) | 488 (15.4) |

| 25–34 | 23 | 8377 (24.0) | 23 | 1849 (27.3) | 1064 (29.4) | 785 (24.9) | 785 (24.9) | 214 (25.8) | 209 (24.7) | 232 (27.3) | 147 (22.8) | 204 (23.4) | 785 (24.9) |

| 35–44 | 24 | 10,222 (29.3) | 32 | 1256 (18.5) | 698 (19.3) | 558 (17.7) | 558 (17.7) | 157 (18.9) | 166 (19.6) | 133 (15.7) | 109 (16.9) | 149 (17.0) | 558 (17.7) |

| 45–54 | 22 | 6682 (19.2) | 18 | 1391 (20.5) | 673 (18.6) | 718 (22.8) | 718 (22.8) | 188 (22.7) | 196 (23.2) | 194 (22.9) | 129 (20) | 213 (24.4) | 718 (22.8) |

| 55–65 | 17 | 3727 (10.7) | 18 | 1046 (15.4) | 442 (12.2) | 604 (19.2) | 604 (19.2) | 124 (15.0) | 153 (18.1) | 143 (16.8) | 169 (26.2) | 185 (21.2) | 604 (19.2) |

| Male (n, %) | 47 | 22,452 (64.3) | 69 | 3273 (48.1) | 1833 (50.3) | 1440 (45.6) | 1440 (45.6) | 368 (44.4) | 372 (43.9) | 401 (47.2) | 278 (43.1) | 444 (49.2) | 1440 (45.6) |

| Employment (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| In employment | 62 | NA | NA | 3612 (53.1) | 1928 (52.9) | 1684 (53.3) | 1684 (53.3) | 444 (53.6) | 443 (52.3) | 467 (55.0) | 343 (53.3) | 468 (53.7) | 1684 (53.3) |

| Student | 7 | NA | NA | 728 (10.7) | 446 (12.2) | 282 (8.9) | 282 (8.9) | 96 (11.6) | 78 (9.2) | 73 (8.6) | 52 (8.1) | 67 (7.7) | 282 (8.9) |

| Not in employment | 31 | NA | NA | 1202 (17.7) | 614 (16.8) | 1193 (37.8) | 1193 (37.8) | 289 (34.9) | 326 (38.5) | 309 (36.4) | 249 (42.1) | 338 (38.7) | 1193 (37.8) |

| Marital status (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| Married/partner | 53 | NA | NA | 3613 (53.1) | 1858 (51.0) | 1755 (55.6) | 1755 (55.6) | 439 (52.9) | 486 (57.3) | 450 (53.0) | 366 (56.8) | 492 (56.3) | 1755 (55.6) |

| Single | 47 | NA | NA | 3191 (46.9) | 1788 (49.0) | 1403 (44.4) | 1403 (44.4) | 390 (47.1) | 361 (42.7) | 399 (47.0) | 186 (28.88) | 381 (43.7) | 1403 (44.4) |

| Education (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| Education after minimum age | NA | NA | NA | 6115 (76.0) | 2796 (76.7) | 2273 (75.1) | 2273 (75.1) | 628 (75.7) | 634 (74.9) | 659 (77.6) | 482 (74.8) | 643 (73.7) | 2273 (75.1) |

| Educated to degree level | 22 | NA | NA | 2702 (39.9) | 1491 (41.2) | 1211 (38.4) | 1211 (38.4) | 310 (37.4) | 321 (37.9) | 363 (42.7) | 250 (38.8) | 311 (35.6) | 1211 (38.4) |

| Time taken to complete, minutes (mean, SD) | |||||||||||||

| Overall | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.01 (4.6) | 9.01 (4.6) | 8.74 (5.0) | 8.69 (4.4) | 8.61 (3.9) | 8.6 (4.7) | 8.52 (3.9) | 9.01 (4.6) |

| Module 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.15 (1.1) | 1.15 (1.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.15 (1.1) |

| Module 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.42 (1.4) | NA | 1.25 (1.1) | 1.48 (1.4) | 1.55 (1.6) | 1.4 (1.5) | 1.49 (1.4) | 1.42 (1.4) |

| Module 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.25 (1.2) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.25 (1.2) |

| Health status (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| Good | NA | NA | NA | 4306 (78.5) | 1942 (81.6) | 2364 (76.1) | 2364 (76.1) | 620 (74.8) | 647 (76.4) | 649 (76.4) | 497 (77.1) | 659 (75.5) | 2364 (76.1) |

| Poor | NA | NA | NA | 1179 (21.5) | 438 (18.4) | 741 (23.9) | 741 (23.9) | 209 (25.2) | 200 (23.6) | 200 (23.6) | 148 (23) | 214 (24.5) | 741 (23.9) |

| SWBH (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 537 (9.8) | 1470 (11.9) | 243 (7.8) | 243 (7.8) | 60 (7.2) | 59 (7.0) | 68 (8.03) | 64 (9.9) | 59 (6.8) | 243 (7.8) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 3140 (57.3) | 1334 (56.0) | 1806 (58.2) | 1806 (58.2) | 489 (58.9) | 503 (59.4) | 498 (58.7) | 366 (56.7) | 503 (57.6) | 1806 (58.2) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 1808 (33.0) | 752 (31.6) | 1056 (34.0) | 1056 (34.0) | 281 (33.9) | 285 (33.7) | 283 (33.3) | 215 (33.3) | 311 (35.6) | 1056 (34.0) |

| SWBL (n, %) | |||||||||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 491 (9.0) | 282 (11.9) | 209 (6.7) | 209 (6.7) | 43 (5.2) | 54 (6.3) | 51 (6.0) | 60 (9.3) | 60 (6.9) | 209 (6.7) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 3191 (58.2) | 1324 (55.6) | 1867 (60.1) | 1867 (60.1) | 495 (59.7) | 520 (61.4) | 531 (62.5) | 363 (56.3) | 528 (67.4) | 1867 (60.1) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 1803 (32.9) | 774 (32.5) | 1029 (33.1) | 1029 (33.1) | 402 (35.1) | 273 (32.2) | 268 (31.5) | 222 (34.4) | 285 (32.7) | 1029 (33.1) |

| Characteristic | General populationa | Invited | Non-responders | Respondersb | Responders, non-completersb | Completers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 5552 | 1039 | 4513 | 2714 | 1799 | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.2 | 38.8 | 39.1 | 39.4 (13.2) | 37.9 (12.8) | 40.4 (13.3) |

| Range | 18–64 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 |

| Age category, years (n, %) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 14 | 735 (13.2) | 4.1 | 431 (14.7) | 178 (15.8) | 253 (14.1) |

| 25–34 | 23 | 1093 (19.7) | 8.0 | 752 (25.7) | 322 (28.5) | 430 (23.9) |

| 35–44 | 24 | 2261 (40.7) | 78.1 | 663 (22.6) | 283 (25.0) | 380 (21.1) |

| 45–54 | 22 | 852 (15.3) | 6.3 | 615 (21.0) | 212 (18.8) | 403 (22.4) |

| 55–65 | 17 | 607 (10.9) | 3.5 | 468 (15.9) | 135 (11.9) | 333 (18.5) |

| Male (n, %) | 47 | 3425 (61.7) | 88.6 | 1499 (51.0) | 679 (59.6) | 820 (45.6) |

| Employment (n, %) | ||||||

| In employment | 62 | NA | NA | 1711 (70.3) | 669 (71.2) | 1042 (57.9) |

| Student | 7 | NA | NA | 261 (10.9) | 108 (11.5) | 153 (8.5) |

| Not in employment | 31 | NA | NA | 463 (19.0) | 163 (17.3) | 757 (42.1) |

| Marital status (n, %) | ||||||

| Married/partner | 53 | NA | NA | 1617 (55.9) | 598 (53.5) | 1019 (56.6) |

| Single | 47 | NA | NA | 1274 (44.1) | 520 (46.5) | 780 (43.4) |

| Education (n, %) | ||||||

| Education after minimum age | NA | NA | NA | 3.835 (85.0) | 2239 (76.8) | 1404 (78.0) |

| Educated to degree level | 22 | NA | NA | 1242 (42.6) | 1242 (55.5) | 762 (42.4) |

| Time taken to complete, minutes (mean, SD) | ||||||

| Overall | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 9.42 (5.4) |

| Module 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 2.00 (1.5) |

| Module 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.72 (1.7) |

| Module 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.55 (1.5) |

| Health status (n, %) | ||||||

| Good | NA | NA | NA | 1898 (78.4) | 516 (82.6) | 1384 (76.9) |

| Poor | NA | NA | NA | 524 (21.6) | 109 (17.4) | 415 (23.1) |

| SWBH (n, %) | ||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 196 (8.1) | 76 (12.2) | 120 (6.7) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 1436 (59.3) | 359(57.4) | 1077 (59.9) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 790 (32.6) | 190 (30.4) | 602 (33.5) |

| SWBL (n, %) | ||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 174 (7.2) | 63 (10.1) | 111 (6.2) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 1452 (60.0) | 370 (59.2) | 1082 (60.1) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 796 (32.9) | 192 (30.7) | 606 (33.7) |

Response process

PRET

Overall, 34,892 panel members were invited to take part in the PRET stage 1 online survey, and 7750 (22.2%) clicked the link to access the survey. Of those who entered the survey, 668 (8.6%) did not start the questions, 2158 (27.8%) dropped out during the survey, 1765 (22.8%) either completed the survey in less than the minimum time of 5 minutes or did not click the final page so were classified as non-completers, and 3159 (40.8%) fully completed the survey. The available demographics for responder and non-responder samples overall and across the VII question types are reported in Table 3 .

PRET-AS type VII

Overall, 5552 respondents were invited to take part, and 4513 (81%) respondents accessed the survey. Of these, 1183 (26% of those accessing the survey) were turned away because their quota was full, leaving 3330 (74%) to enter the survey. Of these, 1020 (31%) dropped out before reaching the DCETTO questions. Of the remaining 2310 who entered the DCETTO questions, 23, 50 and 33 dropped out during the first, second, and third modules, respectively. A further nine completed all of the DCETTO questions but failed to formally sign out from the survey and to be counted. Finally, 396 respondents (17% of those who started the DCETTO questions) were excluded because they completed the survey in less than the minimum time limit of 3 minutes. Therefore, 1799 respondents (40% of those accessing the survey) fully completed the whole survey in > 3 minutes. This amounts to 40% of those accessed the survey, 54% of those who entered and 78% of those who started the DCETTO questions. The available demographics for responder and non-responder samples are reported in Table 4 .

PRET-AS type VIII

Overall, 4696 respondents were invited, and 3570 (76.0%) accessed the survey. Of those who accessed the survey, 1035 (29.0%) did not start the questions, 658 (18.4%) dropped out during the LT-TTO survey, 677 (19.0%) either fully completed the survey in < 3 minutes or completed but did not click the final link so were classified as non-completers, and 1200 (33.6%) fully completed the survey in > 3 minutes. The available demographics for responder and non-responder samples are reported in Table 5 .

| Characteristic | General populationa | Invited | Non-respondersb | Responders | Responders, non-completers | Completers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 4696 | 1126 | 3570 | 2370 | 1200 | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 42.2 | 38.6 | 39.2 | 38.9 (12.8) | 37.3 (12.4) | 40.4 (13.1) |

| Range | 18–64 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 | 18–65 |

| Age category, years (n, %) | ||||||

| 18–24 | 14 | 638 (13.6) | 36 (3.5) | 428 (17.6) | 245 (19.8) | 183 (15.3) |

| 25–34 | 23 | 874 (18.6) | 60 (5.8) | 612 (25.1) | 334 (26.9) | 278 (23.2) |

| 35–44 | 24 | 2025 (43.1) | 856 (83.2) | 593 (24.3) | 319 (25.7) | 274 (22.9) |

| 45–54 | 22 | 712 (15.2) | 46 (4.5) | 490 (20.1) | 225 (18.2) | 265 (22.1) |

| 55–64 | 17 | 447 (9.5) | 31 (3.0) | 314 (12.9) | 116 (9.4) | 198 (16.5) |

| Male (n, %) | 47 | 2987 (63.6) | 945 (91.8) | 1297 (52.8) | 726 (57.9) | 571 (47.6) |

| Employment (n, %) | ||||||

| In employment | 62 | NA | NA | 1357 (55.7) | 748 (60.4) | 609 (50.8) |

| Student | 7 | NA | NA | 227 (9.3) | 113 (9.1) | 114 (9.5) |

| Not in employment | 31 | NA | NA | 854 (35.0) | 377 (30.5) | 591 (49.2) |

| Marital status (n, %) | ||||||

| Married/partner | 53 | NA | NA | 1350 (55.4) | 656 (53.0) | 694 (57.8) |

| Single | 47 | NA | NA | 1088 (44.6) | 582 (47.0) | 506 (42.2) |

| Education (n, %) | ||||||

| Education after minimum age | NA | NA | NA | 1801 (73.9) | 913 (73.8) | 888 (74.0) |

| Educated to degree level | 22 | NA | NA | 966 (39.7) | 526 (42.6) | 440 (36.7) |

| Time taken to complete, minutes (mean, SD) | ||||||

| Overall | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 7.41 (4.6) |

| Module 1 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.68 (1.4) |

| Module 2 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Module 3 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Health status (n, %) | ||||||

| Good | NA | NA | NA | 1617 (80.3) | 686 (84.1) | 932 (77.7) |

| Poor | NA | NA | NA | 397 (19.7) | 129 (15.9) | 268 (22.3) |

| SWBH (n, %) | ||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 155 (7.7) | 78 (9.5) | 77 (6.4) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 1238 (61.4) | 509 (62.2) | 729 (60.8) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 624 (31.0) | 231 (28.2) | 393 (32.8) |

| SWBL (n, %) | ||||||

| 10 | NA | NA | NA | 78 (7.1) | 44 (9.0) | 75 (6.3) |

| 6–9 | NA | NA | NA | 661 (59.8) | 292 (59.5) | 712 (59.3) |

| 1–5 | NA | NA | NA | 366 (33.1) | 155 (31.6) | 413 (34.4) |

Summary

The development of the EQ-5D-5L and advances in the techniques used for health-state valuation means that there is the need to derive a new population value set for use in cost-effectiveness analysis. The PRET and PRET-AS projects investigate a range of methodological issues relating to the health-state valuations. The methodological issues are assessed using binary choice questions administered online. The aim of this chapter was to briefly describe the methodological issues addressed in the PRET and PRET-AS online surveys, and to outline the surveys used and recruitment procedure. More detailed descriptions of the methods, results and discussion of each stage are included in Chapter 3 .

Chapter 3 Are health-state preferences independent of duration (assessing CP-TTO using type I questions)?

Introduction

Constant proportional time trade-off is a key assumption underlying the use of TTO health-state values in the generation of QALYs. CP-TTO assumes that the health-state values produced by TTO are the same irrespective of the duration assigned to the health state. If the assumption does not hold, health states may be valued differently, dependent on their duration.

Evidence both for and against42,43 CP-TTO has been found, and the research reported in this chapter aimed to test the assumption using a binary choice question incorporating a range of duration values (and associated time in full health) and health-state dimensions. This was done using the most ‘basic’ binary choice question type I used in PRET stage 1. The objectives of the analysis of this question type were twofold:

-

To provide a baseline or reference point for the PRET binary choice question design in terms of the frequencies of respondents choosing scenario B (shorter time in full health) across different combinations of state H , value V and duration T The results of this baseline question can then be compared with question types II–V which incorporate the same health dimensions and duration along with information about additional attributes. We also assess the impact of respondent characteristics on the scenario choice, and examine the logical consistency of responses.

-

To test the CP-TTO assumption If health-state preferences are independent of duration then, for a given combination of state H and value V, the distribution of respondents between the two scenarios should not be affected by duration T. Therefore, if the duration (10 × V) years in the basic scenario above was replaced with (5 × V) years, the proportion of people choosing each scenario at a given V should not differ (i.e. are health-state preferences independent of duration or a test of CP-TTO).

Methods

Question format and study design

The type I binary choice questions used the following format (and an example of how the question was presented in the survey is shown in Appendix 2 ).

-

[Scenario A]: You will live in health state H for T years and then die.

-

[Scenario B]: You will live in full health for (VT) years and then die.

-

Which scenario do you think is better?

The health state H was a ‘CS’ and used the following five health dimensions adapted from EQ-5D-5L health dimensions. CSs were used so that variation could be linked to a single dimension, and also to make the health scenarios easy to imagine. Respondents were instructed to assume that they have no other health problems other than those indicated in the scenario.

-

‘Slight problems walking about’ (level 2 of the mobility dimension from EQ-5D-5L state 21111).

-

‘Slight pain’ (a segment of level 2 of the pain dimension using pain only from EQ-5D-5L state 11121).

-

‘Unable to walk about’ (level 5 of the mobility dimension from EQ-5D-5L state 51111).

-

‘Extreme pain’ (a segment of level 5 of the pain/discomfort dimension using pain only from EQ-5D-5L state 11151).

-

‘Extreme depression’ (a segment of level 5 of the anxiety/depression using depression only from EQ-5D-5L state 11115).

Duration T took one of four values: 10 weeks, 1 year, 5 years and 10 years. The values were chosen as follows: 10 years for comparability with the ‘standard’ MVH TTO protocol, 5 and 1 years as intermediate whole-year values, and 10 weeks to test the maximum endurable time of the more severe CSs.

Two sets of V values were used: 0.8 and 0.9 for the two states using level 2 (i.e. slight), and 0.4 and 0.6 for the three states using level 5 (unable/extreme). V values of 0.4 and 0.8 are described as ‘V(low)’, and 0.6 and 0.9 as ‘V(high)’.

All 15 versions of the online survey included five type I questions as the first module presented to respondents, meaning that there were 75 ‘slots’ for this question type overall. Combining the five health states H, four dimension levels T, and two values for V used for type I questions resulted in a total of 40 possible combinations. Therefore, 35 of the combinations appeared twice in different versions of the online survey, with five (one for each health state) appearing once. The allocation of the question combinations across the different survey versions are displayed in Appendix 3 .

In addition, each respondent was given a question similar to a type I question, but tests for logical consistency. In this question, scenario A was dominated by scenario B: scenario A was to live for a shorter duration in worse health and scenario B was to live for a longer duration in full health. Thus, the logical answer is to choose B. If respondents were choosing randomly between A and B then around half of them would choose A. In other words, double the proportion of those choosing A for the logical consistency test question may be interpreted to represent the proportion of respondents who were not fully engaged.

Analysis

For question type I, the outcome of interest is the proportion of respondents selecting scenario B, which means preferring less time in full health over more time in worse health, and thus represents the proportion of respondents for whom the value of V* of state H is lower than the value of V used in the scenario pair. The proportions of those choosing scenario B were analysed across the different scenario attribute combinations and background characteristics. For type I questions, the proportion of respondents who violated logical dominance was also assessed.

The findings were tested for the overall sample, and also by splitting the sample into two groups based on the median time taken to complete question module 1 (which included five type I questions). Group 1 included those who completed the question module in less than the median time taken to complete the module, and group 2 included those who completed the module in more than or equal to the time taken to complete the module.

Probit regression was used to explore the significant impacts on choosing scenario B across each set of scenario attributes and background characteristics. The equation used is as follows:

where Pr represents probability, the β is are the estimated parameters, D represents the background characteristics of respondents, SWB represents self-reported satisfaction levels (SWB H and SWB L), X represents the properties of the health state using health state (H), duration (T), lead time in full health (L), person perspective (P), and satisfaction level (S), and the function Φ(.) is the distribution function of the standard normal distribution. Marginal effects are reported where, for example, a marginal effect of −0.1 for female indicates that being female reduces the probability of choosing scenario B by 10%. Statistical significance levels of both < 0.05 and < 0.1 were used.

Results

Demographics

As all respondents were given type I questions, the sample here consists of 3159 full survey completers who each completed five type I questions (of which one was a test of logical consistency). Therefore, the responses to the four logical questions generated 12,636 type I observations. Each combination of H, V and T was completed by either (approximately) 200 or 400 respondents. The characteristics of the sample are displayed in Table 3 .

Objective 1: descriptive analysis

Of the 3159 respondents, 200 (6%) failed the test of logical consistency (i.e. responded that they would rather live for less time in one of the five health states than a longer time in full health). Using bivariate analysis, there is a disproportionate number of males (chi-squared test; p = 0.001) – those whose education continued after minimum school leaving age (p = 0.012) and those in poorer self-reported general health (p = 0.015) – who failed the logical consistency test. Age, having a degree, and time taken were not associated with failing the logical consistency test. When assessing the proportions of respondents failing the logical consistency test across the two groups defined by the time taken to complete question module 1 described above (see Analysis), it was found that the proportion of respondents failing the test did not differ significantly between group 1 (n = 85, 5.5%) and group 2 (n = 115, 7.7%) (p = 0.06).

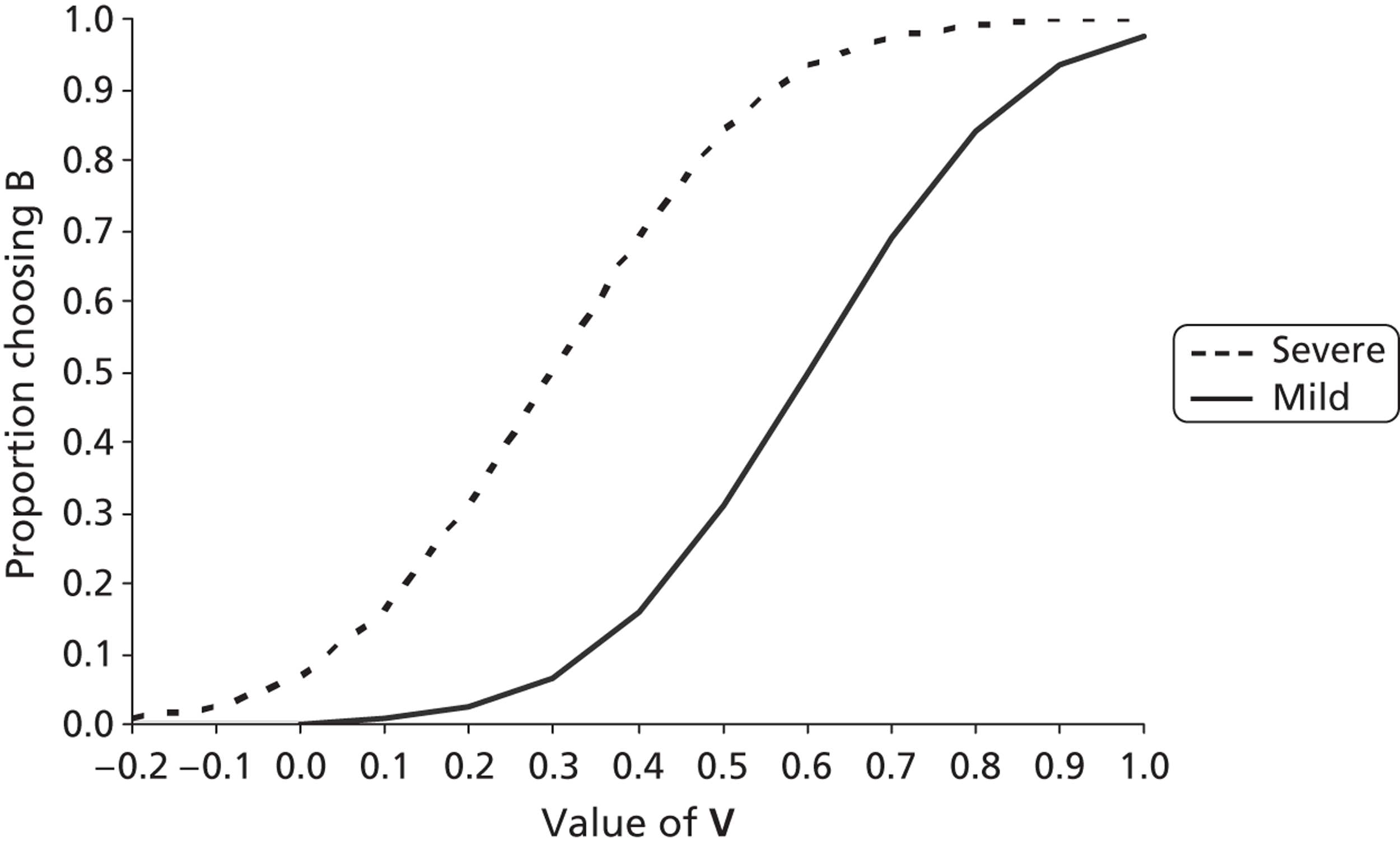

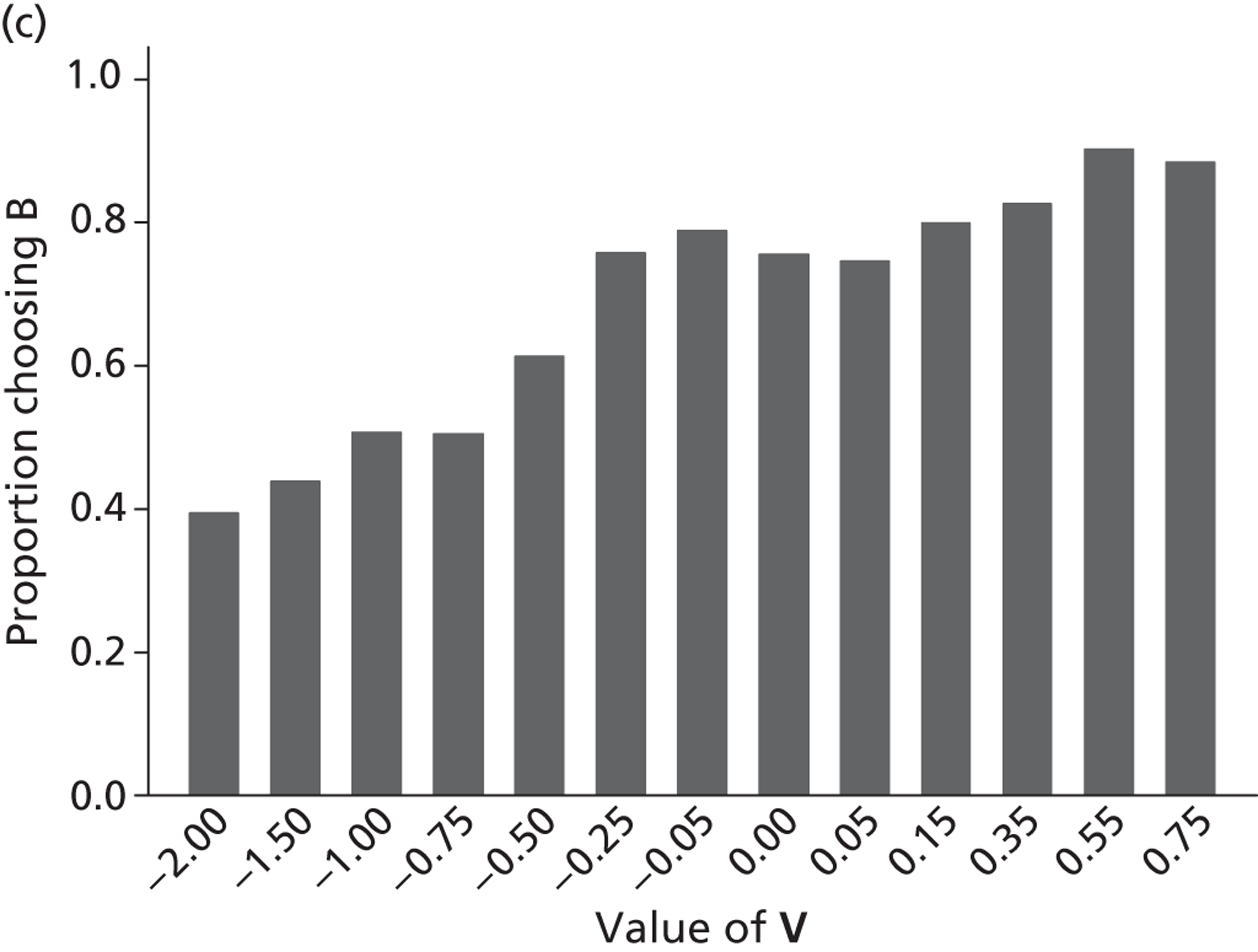

Based on the remaining four type I questions in module 1, Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of respondents choosing scenario B, broken down by the health-state dimension, duration of the health state, and the value used to generate the associated time in full health in scenario B. In other words, this was the proportion of respondents for whom the value used in the scenario (V) was larger than the value they perceive (V*) for the state. It should be noted that the majority of bars are > 50%, some of them as high as 90%. This suggests that the values of V used in the design of the question types may have been set lower (this is discussed in relation to all of the question types in Chapter 12 , Weaknesses of the project).

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of sample choosing scenario B (type I questions).

Within each health-state dimension, the proportion of respondents choosing B was higher when the value of V was larger. For example, the bars for ‘slight problems walking about’ with a high V value [M2(0.9)] are taller than the corresponding bars for ‘slight problems walking about’ with a lower V value [M2(0.8)] across the same duration of time spent in the health state. The exception (by a small margin) is for ‘extreme depression’ [D5(0.4)] and [D5(0.6)] with a duration of 10 weeks. Within each specific health problem (where a comparison is possible), the proportion choosing scenario B was always higher for the more severe state so that the bars for ‘unable to walk about’ (M5) are taller than corresponding bars for ‘slight problems walking about’ (M2), and the bars for ‘extreme pain’ (P5) are taller than the corresponding bars for ‘slight pain’ (P2). This demonstrates that respondents are more likely to choose the full health option when the state is severe. There does not seem to be a pattern to the proportions of respondents choosing scenario B across the four duration levels. For example, the bars for the 10-week duration scenarios tend to be taller than the corresponding bars for longer durations, but there are exceptions.

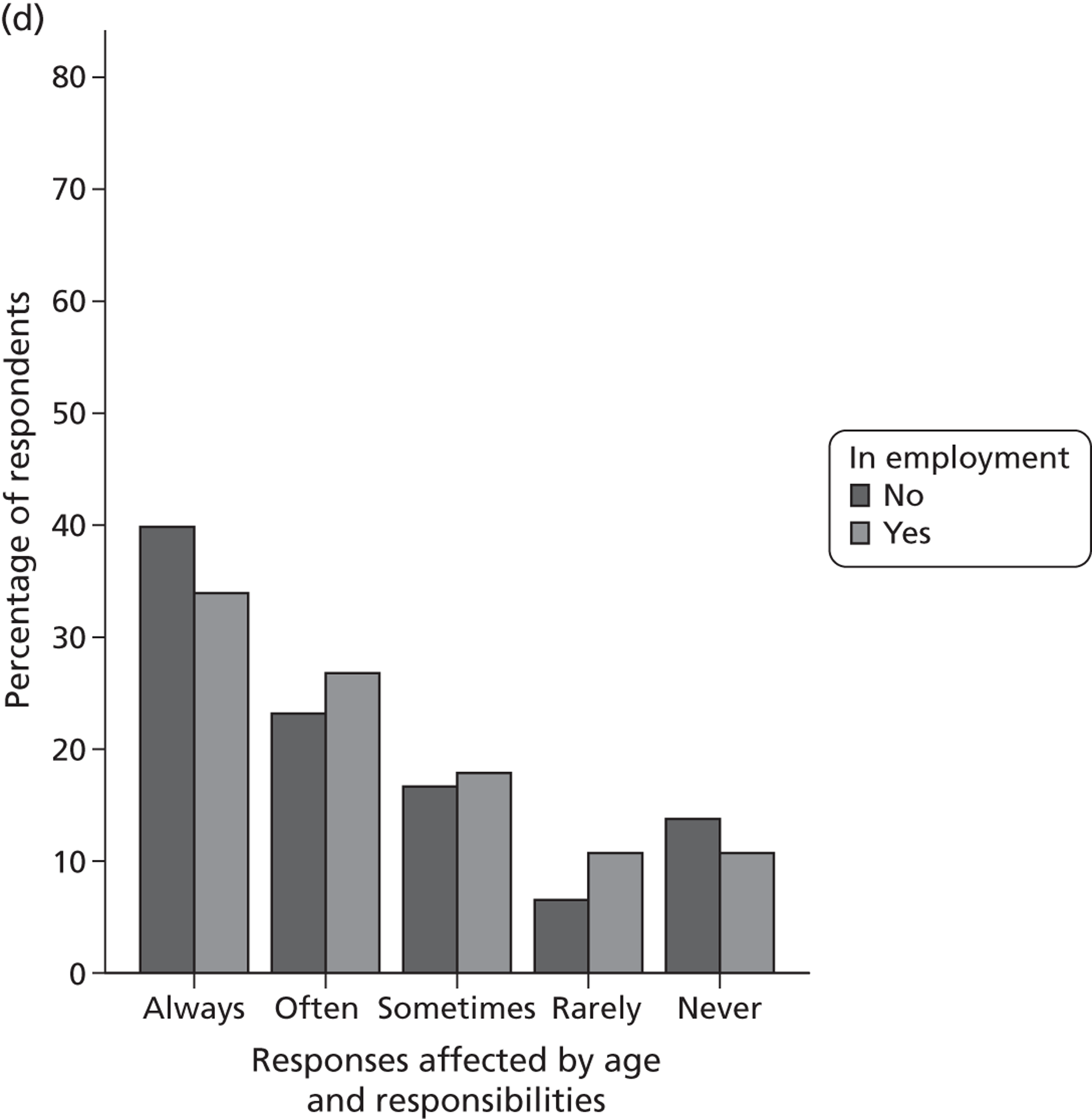

Table 6 summarises the results of a series of probit regressions explaining the propensity to choose scenario B (living in full health for a shorter period of time), without (models 1–5) and with (models 6–10) controlling for a series of covariates. As the distribution of data for own health in EQ-5D-5L is skewed, dummy variables indicating any problem in mobility, pain/discomfort or anxiety/depression were used. The models by state indicate that generally the higher the value of V, the higher the probability of choosing to live in full health for a shorter duration [although this is not significant for ‘extreme depression’ (D5)]. There were no covariates that affect the choice consistently across all states. Regarding the effect of respondents’ self-reported health in EQ-5D (models 6–10), the exercise finds that, controlling for duration and V value, having a mobility problem was associated with being less likely to choose scenario B (living for less time in full health) for the two mobility-based states (M2 and M5) and extreme pain (P5); having pain/discomfort was associated with being less likely to choose scenario B when the state is ‘slight problems in walking about’ (M2) and ‘slight pain’ (P2) but not ‘extreme pain’ (P5); and having anxiety/depression was associated with being less likely to choose scenario B when the state was ‘extreme depression’ (D5). This indicates that, to some extent, respondents who have experience of the health state they are valuing may be more likely to hypothetically associate it with a higher utility value.

| Scenario attributes/background characteristics | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | (10) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M2 | P2 | M5 | P5 | D5 | M2 | P2 | M5 | P5 | D5 | |

| V value (ref.: V low) | ||||||||||

| V high | 0.452*** | 0.359*** | 0.407*** | 0.352*** | NS | 0.482*** | 0.358*** | 0.412*** | 0.359*** | NS |

| Duration (ref.: 10 years) | ||||||||||

| 10 weeks | 0.154* | 0.273*** | NS | NS | NS | NS | 0.283*** | NS | NS | NS |

| 1 year | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| 5 years | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS |

| Marital status | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| Employment status | NS | NS | NS | NS | −0.043** | |||||

| Age category | −0.074*** | −0.055* | NS | 0.071* | NS | |||||

| General health | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| Health satisfaction | NS | NS | NS | 0.266** | NS | |||||

| Report problems on EQ-5D-5L | ||||||||||

| Mobility (score ≥ 2) | −0.261** | NS | −0.219** | −0.316** | NS | |||||

| Pain (score ≥ 2) | −0.125* | −0.302*** | NS | NS | NS | |||||

| Depression (score ≥ 2) | NS | NS | NS | NS | −0.275*** | |||||

| Constant | NS | NS | 0.366*** | 1.132*** | 1.017*** | 0.442*** | 0.273* | 0.506*** | 0.944*** | 1.071*** |

| n | 2533 | 2495 | 2550 | 2526 | 2532 | 2495 | 2461 | 2514 | 2493 | 2497 |

| Log-likelihood | −1656.551 | −1682.460 | −1541.726 | −740.201 | −951.307 | −1600.001 | −1636.980 | −1501.139 | −702.528 | −911.776 |

All of the state dummies were significant when pooling across states ( Table 7 ; model 11 without covariates, and model 12 with covariates). It suggests that ‘slight problems walking about’ (M2) was perceived as being worse than ‘slight pain’ (P2), and ‘unable to walk about’ (M5) was perceived as worse than ‘extreme depression’ (D5), which, in turn, was worse than ‘extreme pain’ (P5). As the values are clustered by the severity groups, the state coefficients cannot be compared across the mild states and the severe states. All duration and value dummies were significant. The dummy for the V value 0.9 was omitted as there was collinearity in the design (this is because all scenarios with M2 or P2 that do not use the value of 0.8 use 0.9). Having problems on the EQ-5D-5L dimensions of Mobility, Pain/discomfort, and Anxiety/depression were all significant in the pooled model, indicating that having existing health concerns impacts on the propensity to choose full health (p < 0.001).

| Scenario attributes/background characteristics | (11) | (12) |

|---|---|---|

| All states | All states | |

| State (ref.: M2) | ||

| P2 | −0.128*** | −0.124*** |

| M5 | −0.131** | −0.128** |

| P5 | 0.676*** | 0.688*** |

| D5 | 0.513*** | 0.524*** |

| V value (ref.: 0.4) | ||

| 0.6 | 0.311*** | 0.319*** |

| 0.8 | −0.392*** | −0.402*** |

| 0.9 | [Omitted] | [Omitted] |

| Duration (ref.: 10 years) | ||

| 10 weeks | 0.109** | 0.107** |

| 1 year | NS | NS |

| 5 years | NS | NS |

| Marital status | NS | |

| Employment status | NS | |

| Age category | −0.022* | |

| General health | NS | |

| SWBH | 0.104** | |

| Report problems on EQ-5D-5L | ||

| Mobility (score ≥ 2) | −0.163*** | |

| Pain (score ≥ 2) | −0.124*** | |

| Depression (score ≥ 2) | −0.081** | |

| Constant | 0.467*** | 0.673*** |

| n | 12,636 | 12,460 |

| Log-likelihood | −6591.027 | −6415.893 |

Objective 2: assessing assumption 1 – CP-TTO

The coefficients of interest for assessing CP-TTO are those for duration spent in the health state. The 10-year duration value is used as the reference as this is the value used in the ‘standard’ MVH TTO protocol. For the two milder states of ‘slight problems walking about’ (M2) and ‘slight pain’ (P2), the 10-week duration had a significantly positive effect relative to 10 years. However, durations of 1 year and 5 years were not significant (see Table 6 , model 1 for M2 and model 2 for P2). For the states ‘unable to walk about’ (M5, model 3) and ‘extreme pain’ (P5, model 4), none of the duration coefficients was significant. For ‘extreme depression’ (D5, model 5), the 5-year duration is significant. The same pattern of significance was found when covariates were controlled for (see Table 7 , models 6–10). In the model pooling across states, only the 10-week coefficient was significant (see Table 8 , model 11 without and model 12 with controlling for covariates). The positive coefficients indicate that the shorter duration value was associated with having higher preferences for the health state presented.

The above analysis demonstrates that whether or not CP-TTO holds depends on the dimension and severity of the state. In the case of D5, the pattern was not monotonic. It is somewhat surprising that the extreme (level 5) states, where one may have expected maximal endurable time to apply, have resulted in no significant duration coefficients. There also seems to be no pattern of interactions between the state, associated duration, V value and respondent characteristics.

Discussion

The type I questions used in this chapter are a snapshot of one iteration of the TTO procedure, and, as such, provide a comparator for the other question types which incorporate various attributes to the standard question to allow for the testing of the methodological issues introduced in Chapter 2 . A small number of respondents failed the test of logical consistency, indicating that they may not be paying full attention to the online survey or answering truthfully, although we cannot investigate the reasons in more detail. However, failing the logical consistency test does not seem to be related to the time taken to complete the type I questions, as there was no difference between those completing the module quickly and those taking longer to complete (defined in terms of the median time taken).

The questions also allow us to test the assumption of CP-TTO. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first attempt to assess CP-TTO using binary choice questions that are a snapshot of the TTO procedure. The findings are inconclusive: there is no clear pattern to the coefficient values across each duration level, which suggests that the relationship between CP-TTO and the state description and duration value is complex and needs further investigation. We do not produce strong evidence for or against the CP-TTO assumption. Therefore, it is not clear whether the value of a state is a function of its duration, and we cannot give clear guidance on the best duration values to use in future valuation studies. Furthermore, there are limits to what can be implied from the binary choice questions as a small range of V values were used in this study. This is discussed more generally in terms of all question types in Chapter 12 (see Weaknesses of the project) of this report.

Chapter 4 Are health-state preferences independent of person perspective (using type II questions)?

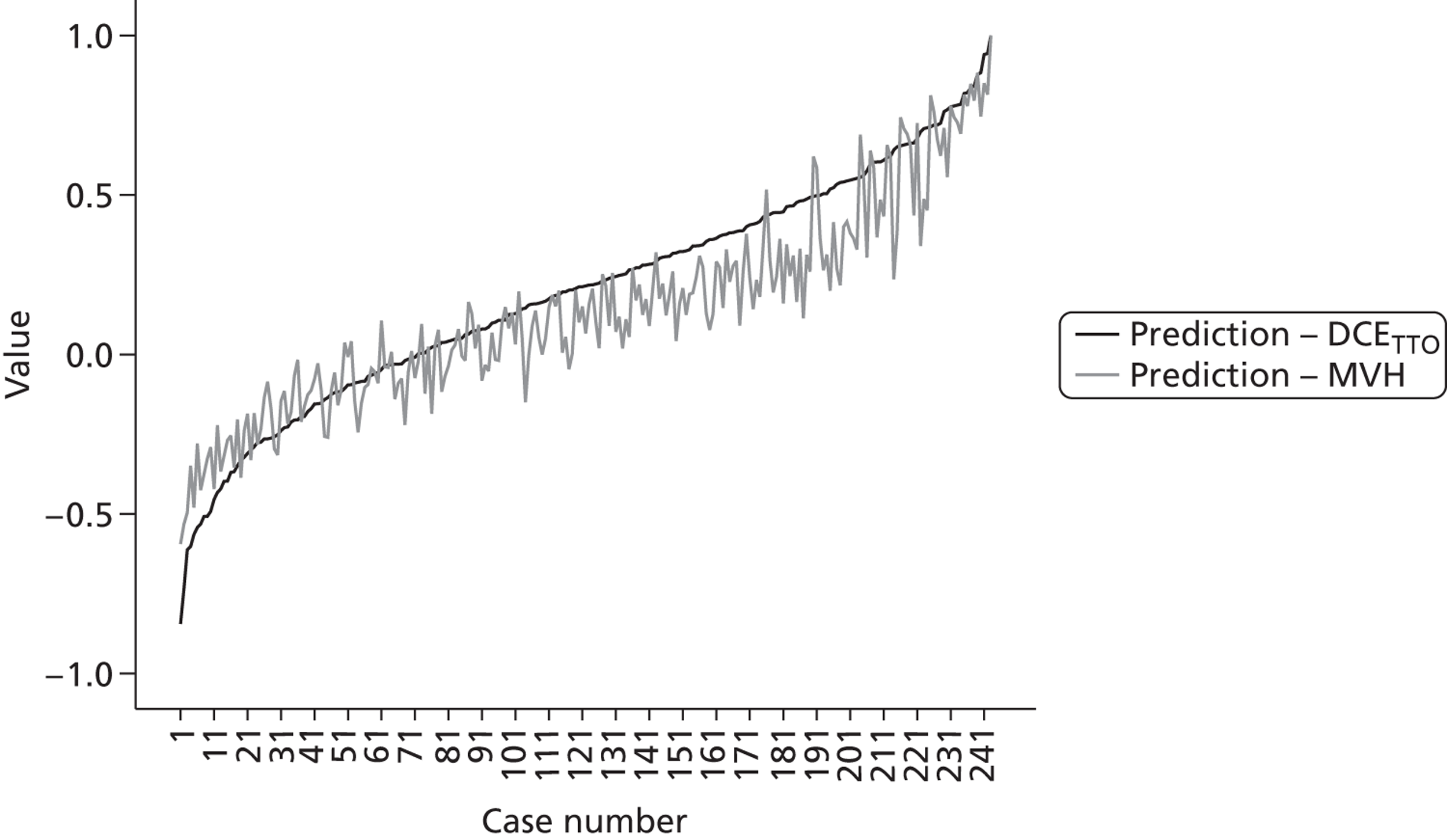

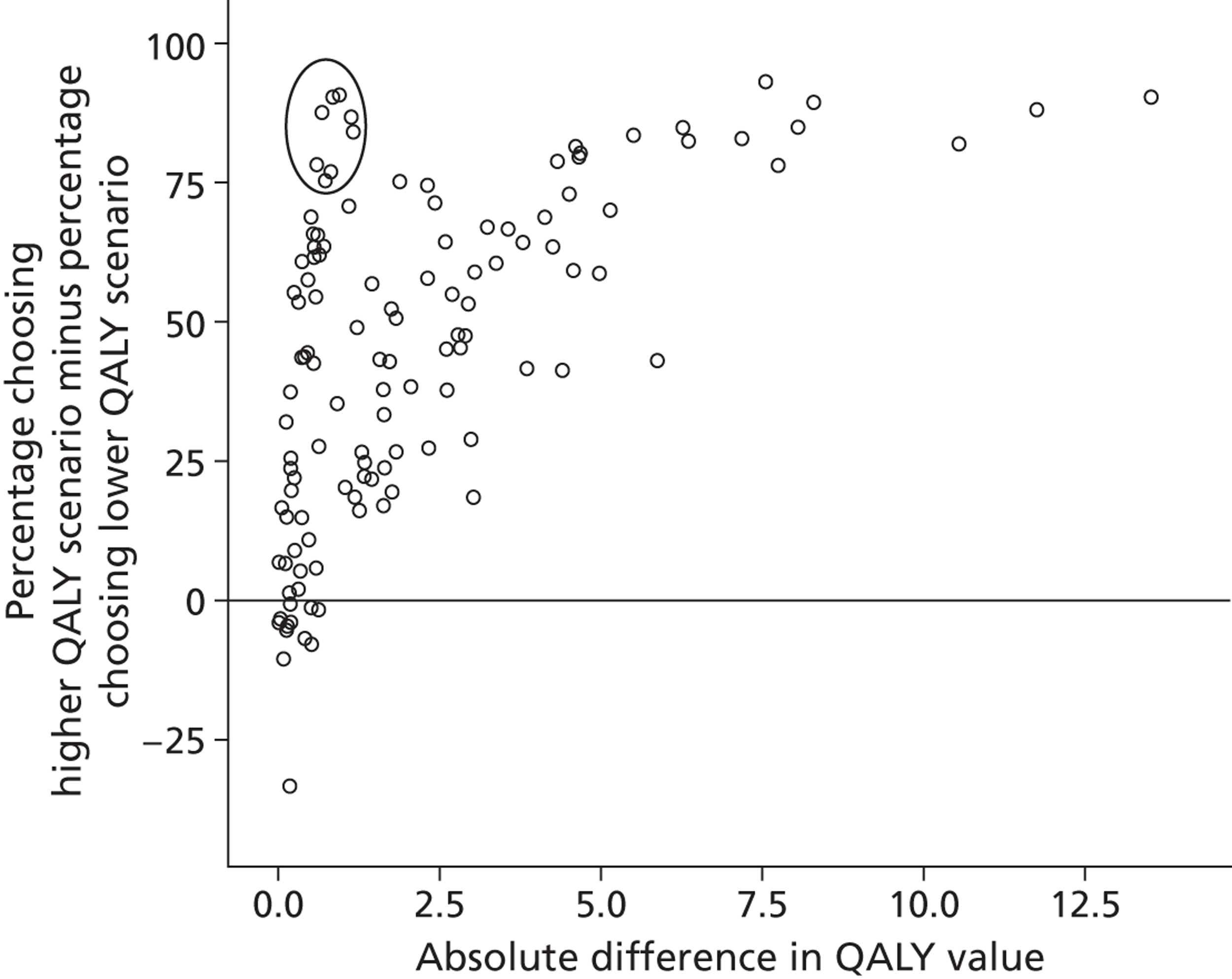

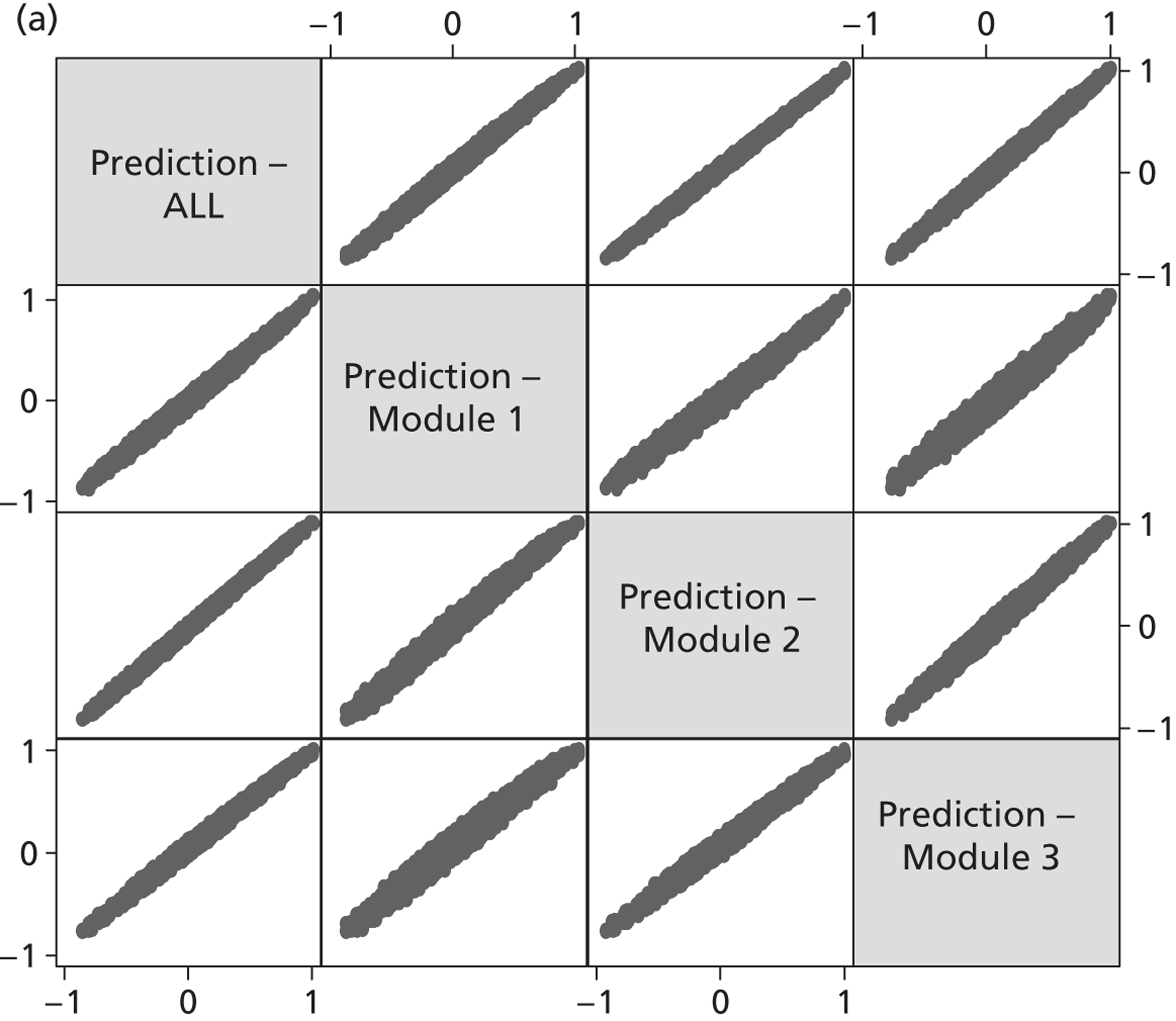

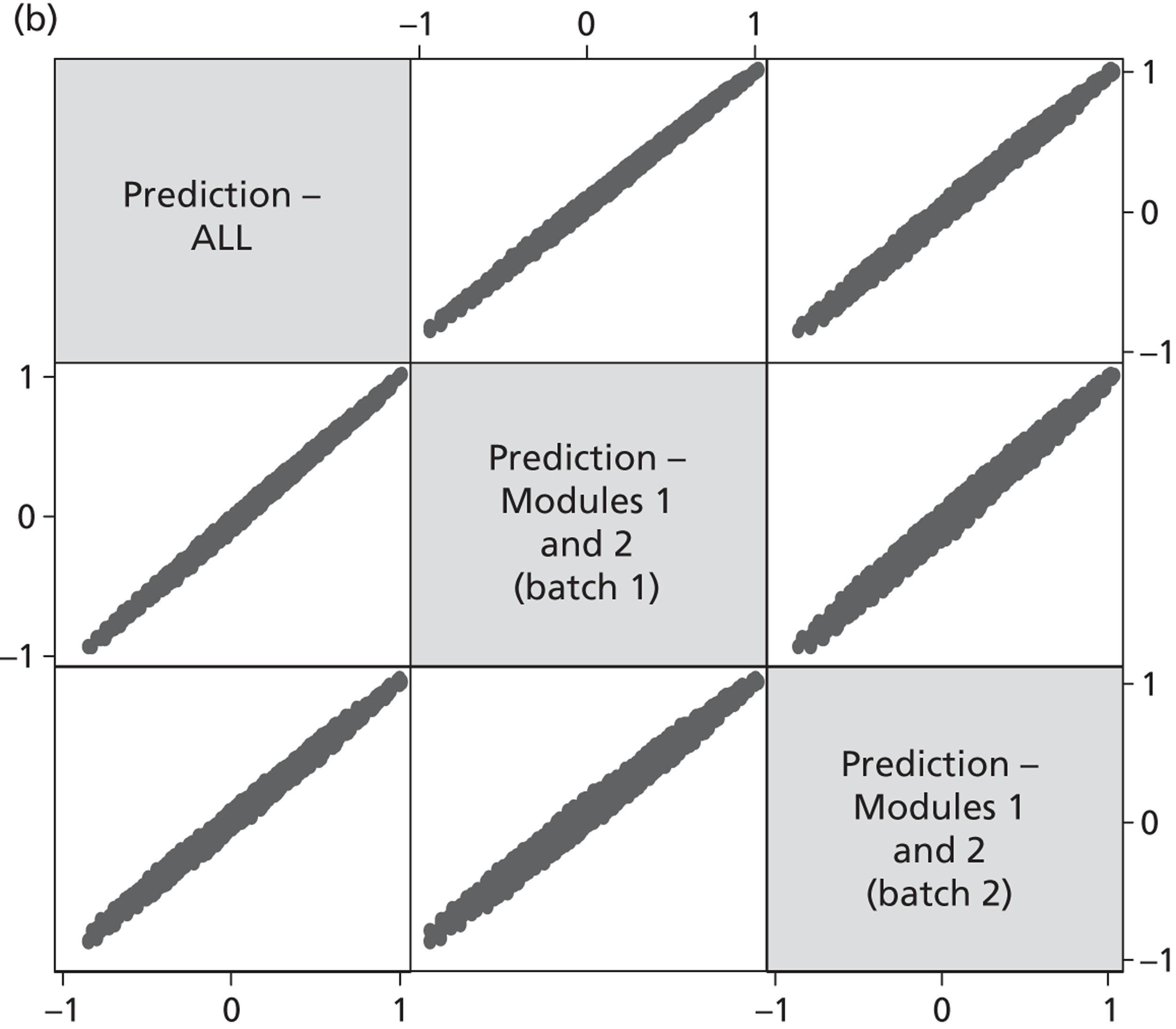

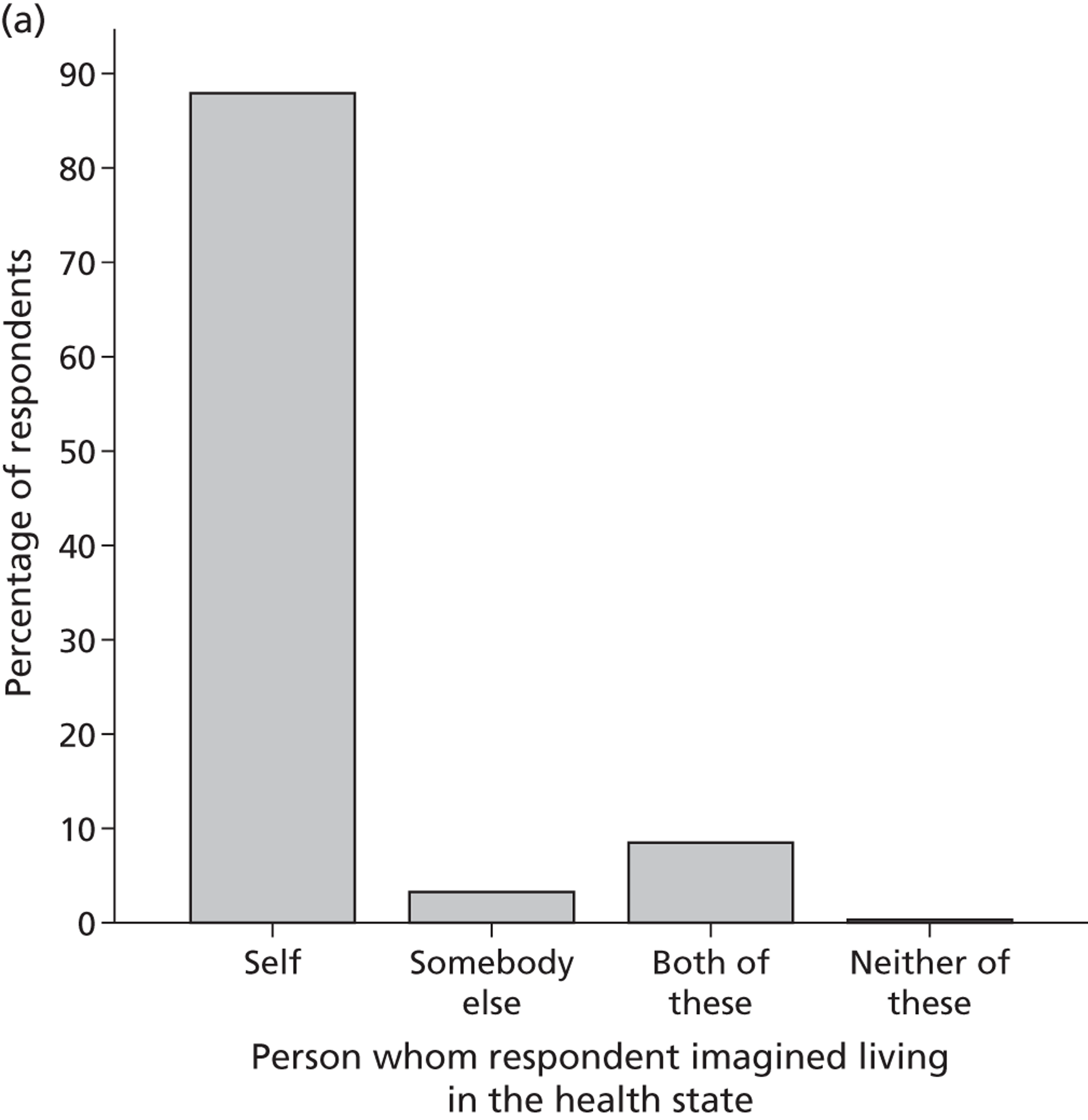

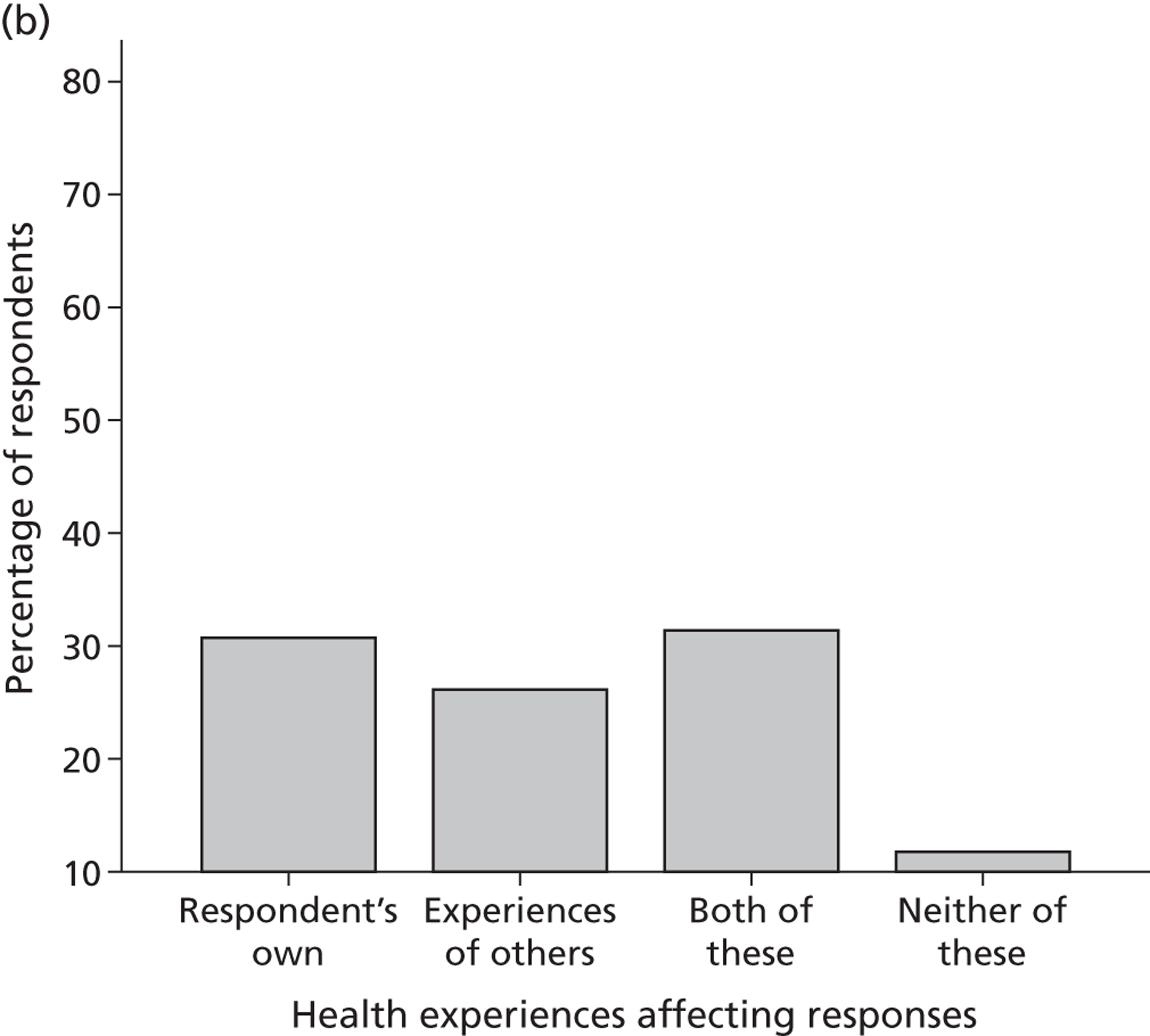

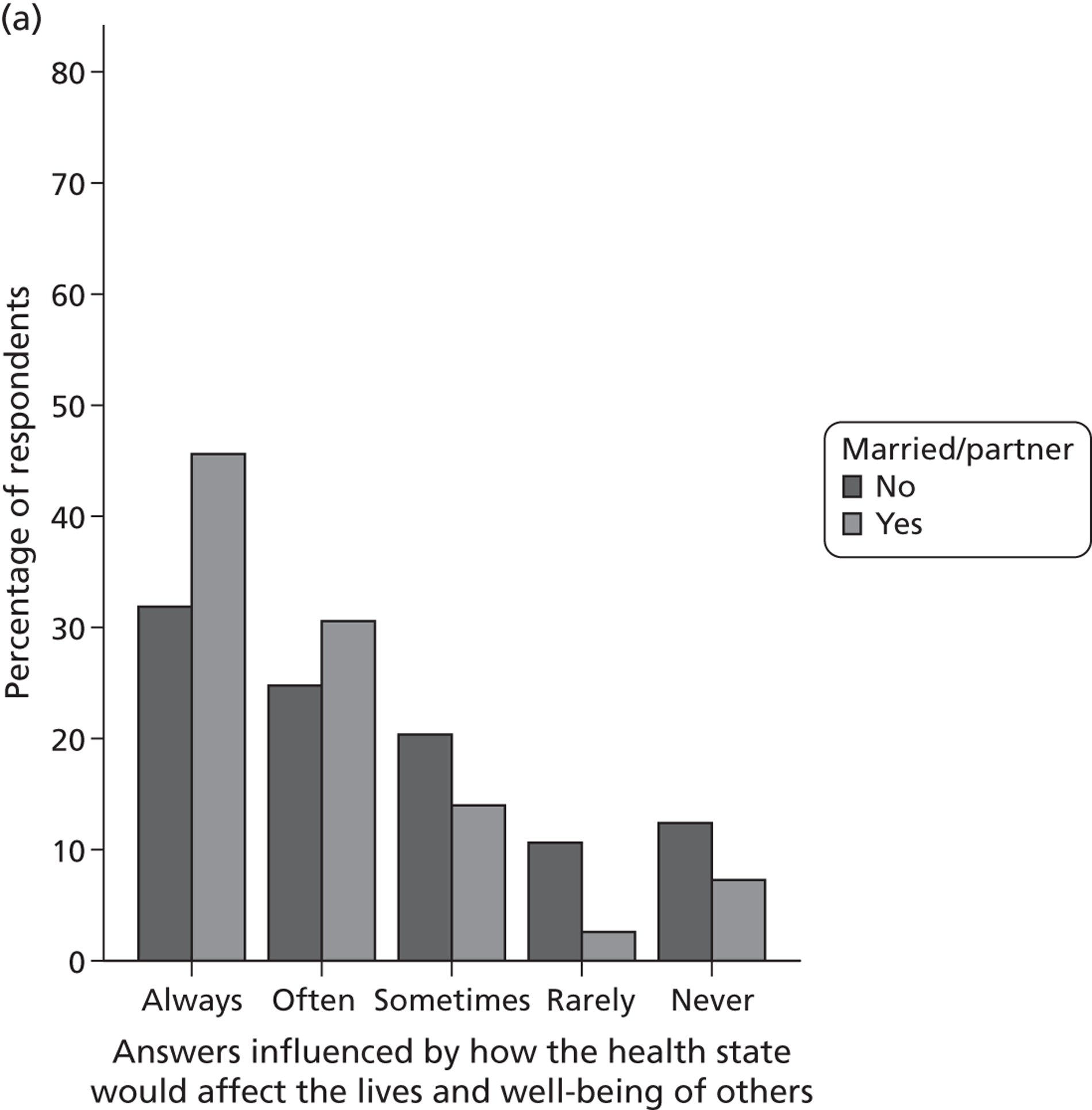

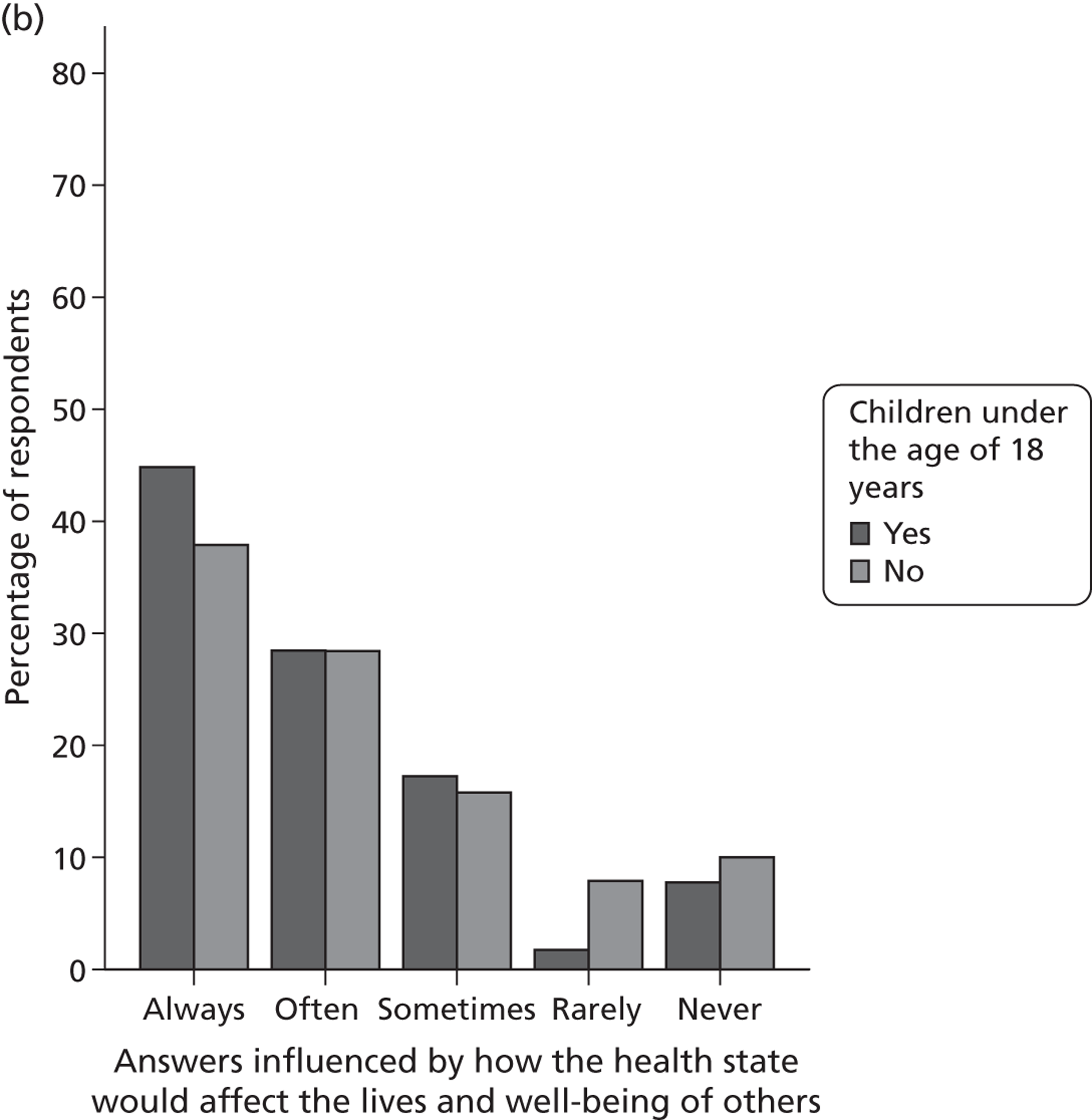

Introduction