Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/25/02. The contractual start date was in February 2009. The draft report began editorial review in November 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jeff Breckon has delivered consultancy and training services on behalf of Sheffield Hallam University relating to motivational interviewing in health care.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Goyder et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Regular physical activity is associated with reductions in all-cause mortality, risk of cardiovascular disease and some types of cancer. 1–3 Frequent exercise has a role in both the prevention and the management of hypertension, type 2 diabetes and obesity as well as a variety of mental health conditions. 4–6 However, most of the UK population do not attain levels of physical activity sufficient to confer such benefits. 7 For the last 10 years, a key Department of Health policy objective has been encouraging the population to undertake a total of at least 30 minutes of at least moderate intensity physical activity on 5 or more days of the week. 8

Brief interventions delivered in primary care can increase physical activity levels and are recommended as effective and cost-effective interventions by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 9,10 However, the evidence base largely consists of studies with short-term follow-up post intervention and that use self-reported increases in physical activity by trial participants as a primary outcome. Maintenance of recommended physical activity levels is understood to be essential to achieve the reported health benefits. As a result, NICE identified that further research was warranted on the long-term sustainability of such treatment effects. 10 At the time, the few studies that had followed participants over the long term suggested that approximately half of those who initiate a physical activity programme relapse and return to their previous sedentary lifestyle within 6 months. 11

In the last 6 years, since the publication of the original NICE guidance in March 2006 recommending the use of brief interventions in primary care to encourage physical activity,10 a number of additional primary studies and relevant systematic reviews have been published. These recent reviews of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence are further discussed in Chapter 8 (see Other recent evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ‘brief’ and ‘booster’ interventions for increasing and sustaining physical activity). The availability of further evidence on the use of brief interventions has led to the initiation of a programme to update the original NICE guidance and this new guidance was published in May 2013. 12

In the meantime, the Sheffield physical activity booster trial was funded and undertaken to address one of the major gaps in the evidence base identified by the original NICE guidance. 10

The booster trial was designed to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of motivational interviewing (MI) ‘booster’ interventions to help previously sedentary people maintain recently increased physical activity levels acquired following a brief intervention. MI13 is one of the behaviour change interventions recommended by NICE for health promotion. 14

The brief intervention involved provision of an interactive DVD based on a MI approach that is directive, is person centred and replicates the style of other successful behaviour change programmes and was underpinned by the theoretical construct of self-determination theory. 15,16 All interventions were delivered by trained facilitators whose competence was independently assessed using a treatment fidelity framework to ensure consistent delivery. 17,18

Chapter 2 Methods

Methods for the main trial

This report is concordant with the extension of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement to improve the reporting of pragmatic trials. 19 An internal pilot trial, conducted between May 2009 and March 2010 and focusing on feasibility outcomes, is reported elsewhere. 20 The final protocol can be found in Appendix 1 and a table of changes made to the protocol over the course of the project is presented in Appendix 2.

Participants

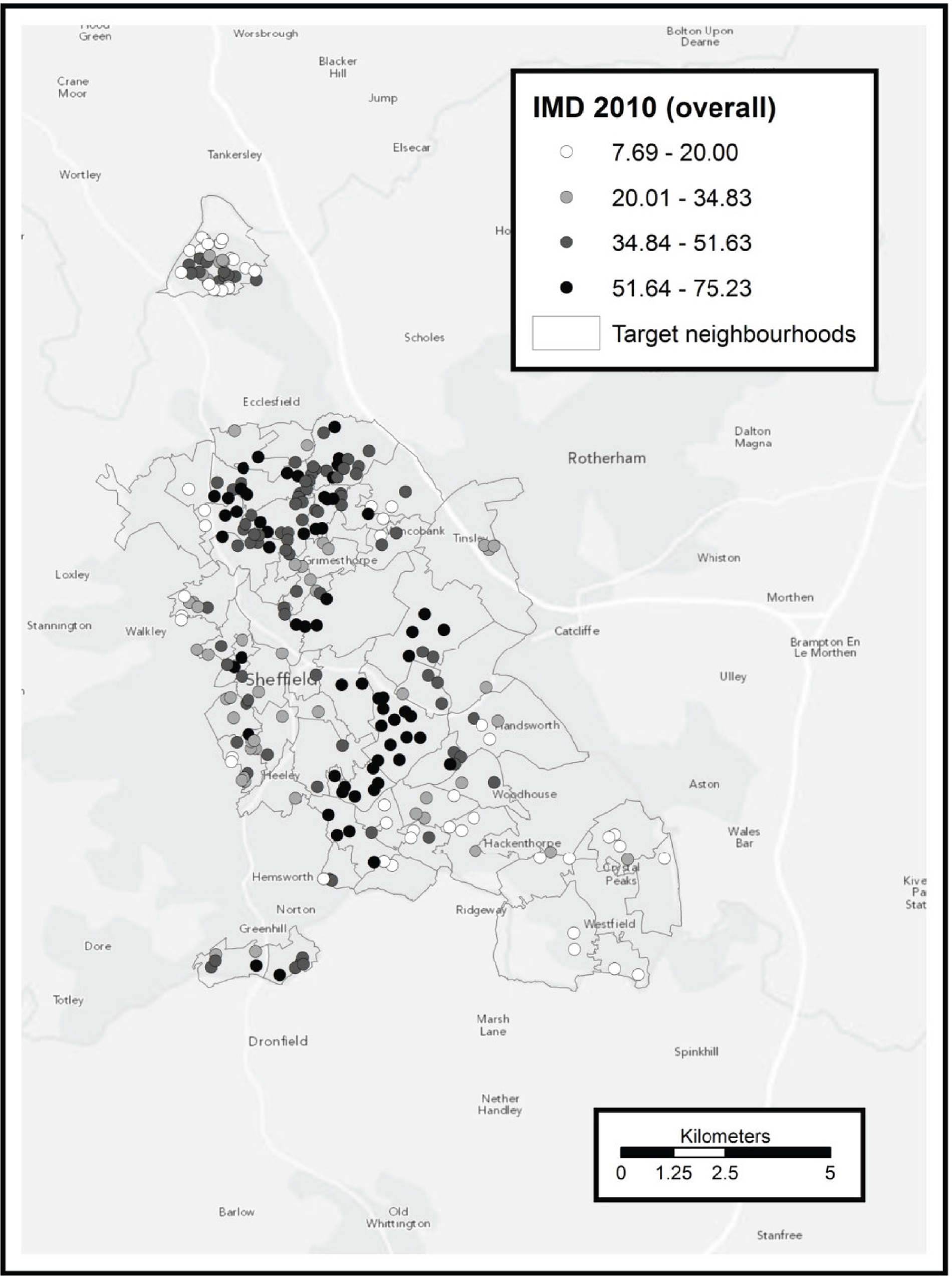

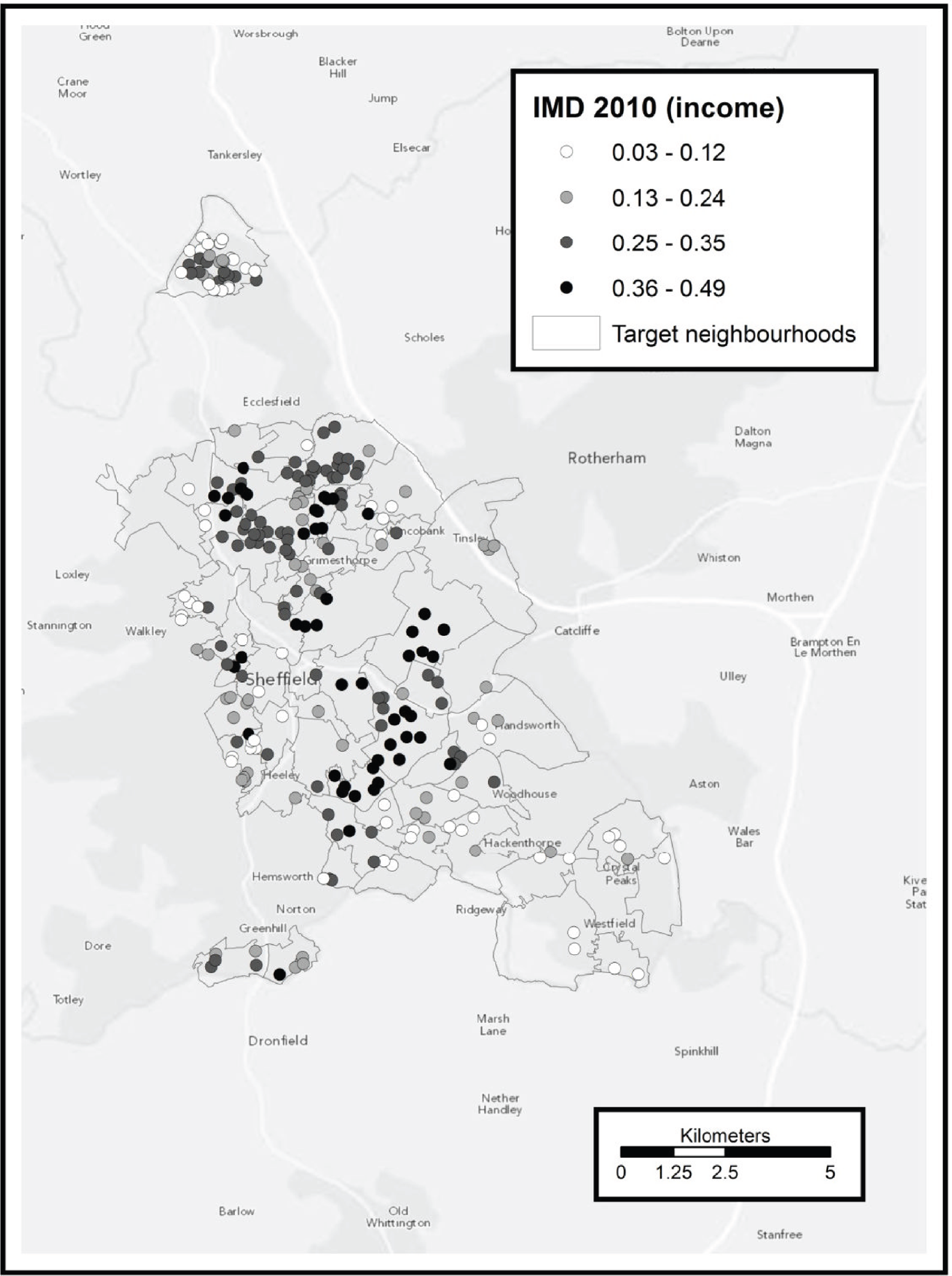

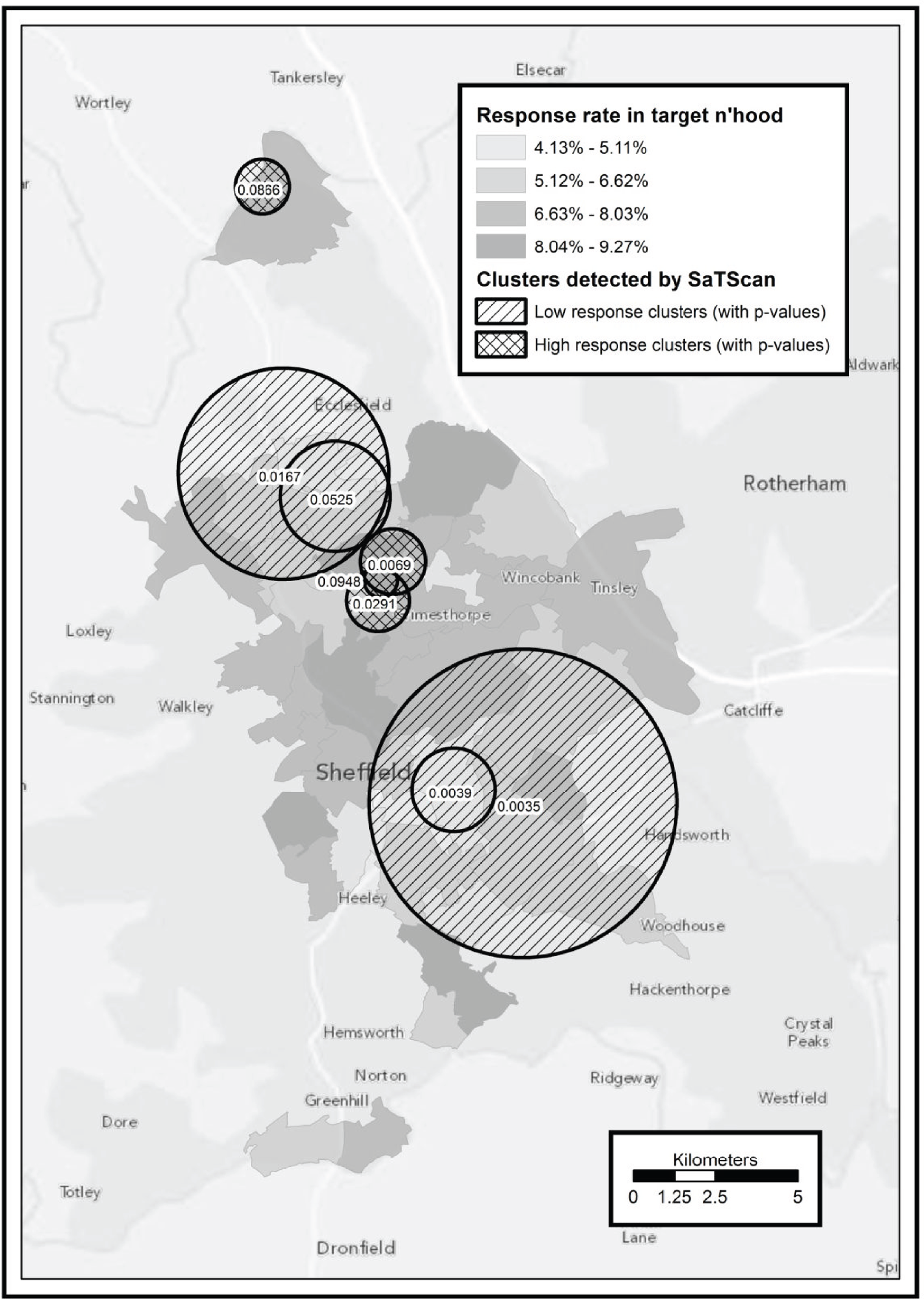

To identify potentially eligible study candidates we worked with NHS Sheffield (Sheffield Primary Care Trust), the health service organisation responsible for commissioning health services for the local population (until April 2013). Between May 2009 and June 2011 NHS Sheffield sent letters with postage-paid reply cards to 70,388 people inviting them to enrol in a programme to help them become more physically active. Six general practices were also given a total of 305 marked recruitment packs to distribute. These packs were identical to those sent from NHS Sheffield with the exception that the covering letter was not personalised. An unknown number of packs were also given to four community centres to be distributed by health trainers and health champions. Mail-outs and responses were allocated to output areas (OAs) according to the National Statistics Postcode Look-up table [November 2010 version; see http://geoconvert.mimas.ac.uk/help/documentation/10nov/nspd-version-notes-november-2010.pdf (accessed 21 November 2013)]. The response rate for each OA was calculated as the total number of allocated responses divided by the total number of allocated mail-outs. We performed a post hoc analysis to investigate whether response rate was related to population transience. Transience rate was calculated using information obtained from the 2001 census (small area statistics, Table CAS008), specifically the outgoing population divided by the outgoing population plus the static population. 21 An unweighted Spearman’s rank correlation test between response rate and transience was performed in R version 2.15.0. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; see www.R-project.org/).

The physical activity programme involved a ‘brief intervention’ combining an interactive DVD and area-specific written information about local facilities and opportunities for physical activity. The DVD was developed by a team at Sheffield Hallam University using MI principles, which are consistent with NHS guidance on physical activity and behaviour change interventions. 10,14 The content and development of this DVD are provided more fully in Appendix 1.

Research assistants (RAs) telephoned respondents and administered the Scottish Physical Activity Questionnaire (SPAQ). 22 Those eligible to receive the brief intervention (DVD and information sheet) were (1) residents of the 55 most economically deprived neighbourhoods in the city of Sheffield (out of 100), (2) those aged 40–64 years and (3) those not achieving the recommended activity level (30 minutes of moderate activity on at least 5 days) assessed using the SPAQ and wishing to have support to become more active. RAs telephoned those sent a DVD 3 months later to assess their eligibility for participation in the trial. Eligible candidates (4) had increased their physical activity level by at least 30 minutes of moderate or vigorous activity per week (assessed using the SPAQ) over the 3-month brief intervention (DVD) period and (5) were capable of giving written informed consent for trial participation. Individuals with chronic conditions who could benefit from physical activity were not excluded unless their condition significantly impaired their ability to exercise.

The validated SPAQ contains a series of questions assessing physical activity behaviour over the previous 7 days and also asks whether or not this level of weekly activity is typical. When observed weekly activity was reported as atypical, SPAQ asks participants to clarify what constitutes a more typical week in terms of an increased or reduced number of minutes of physical activity. Before and after the brief intervention period the RAs were asked to interpret the observed minutes of physical activity (as assessed using SPAQ) and to include any additional minutes of activity that were felt to be typical for study candidates who reported that the previous week had been atypical.

Interventions

Candidates who were assessed as eligible during the telephone assessment described in the previous section were invited to attend a baseline assessment at a community venue. Those who consented were randomly allocated (see Randomisation and blinding) to one of three groups:

-

a ‘full booster’ group receiving two face-to-face physical activity consultations provided in a MI style, 1 and 2 months after randomisation

-

a ‘mini booster’ group receiving two telephone-based physical activity consultations provided in a MI style, 1 and 2 months after randomisation

-

a control group who received no intervention after randomisation.

Both booster interventions are fully described in the study protocol, which can be found in Appendix 1. The full booster involved two face-to-face consultations, intended to last between 20 and 30 minutes, which took place in community venues. The consultations replicated a brief MI method designed for time-limited consultations in medical settings and which had already been successfully employed to change health-related behaviours. 23,24 During the full booster consultations, strategies were worked through at a pace dictated by the participant and the menu used to structure information exchange without being prescriptive.

The mini booster involved two physical activity MI consultations delivered by telephone, each intended to last approximately 20 minutes. The telephone consultations followed a script of known efficacy that has been implemented in previous physical activity promotion studies delivered by members of this research team. 25,26 It is thought that telephone counselling can provide an alternative to face-to-face contact that is relatively inexpensive in time and financial terms. 14 In previous studies in adult populations, telephone-based approaches have increased physical activity participation at 6 months compared with no telephone support and to a greater extent than standard reading materials. 27,28

Objectives

The primary objective of the main study, a parallel-group randomised controlled trial (RCT), was to determine if physical activity assessed using an Actiheart device (CamNtech Ltd, Cambridge, UK) 3 months after randomisation (6 months after a brief intervention) increases in participants allocated to two intervention groups (receiving two booster physical activity consultations, delivered in a MI style, either by telephone or face to face) compared with participants allocated to a control group (receiving no further contact after the baseline assessment). Secondary objectives were to:

-

determine whether physical activity 9 months after randomisation (12 months after the brief intervention) is significantly increased in participants allocated to the two intervention groups compared with participants allocated to the control group

-

compare physiological measures of fitness (12-minute walk test29) and self-reported physical activity (SPAQ instrument) between allocated groups

-

compare health-related quality of life (HRQoL), resource use (including health and social care contacts) and economic costs between allocated groups

-

investigate whether the impact of the intervention may be modified by gender, ethnicity or the types of physical activity undertaken (including use of community facilities for physical activity)

-

undertake a process evaluation to identify, using both quantitative and qualitative methods, psychosocial and environmental factors that may mediate or modify the effectiveness of the intervention.

Outcomes

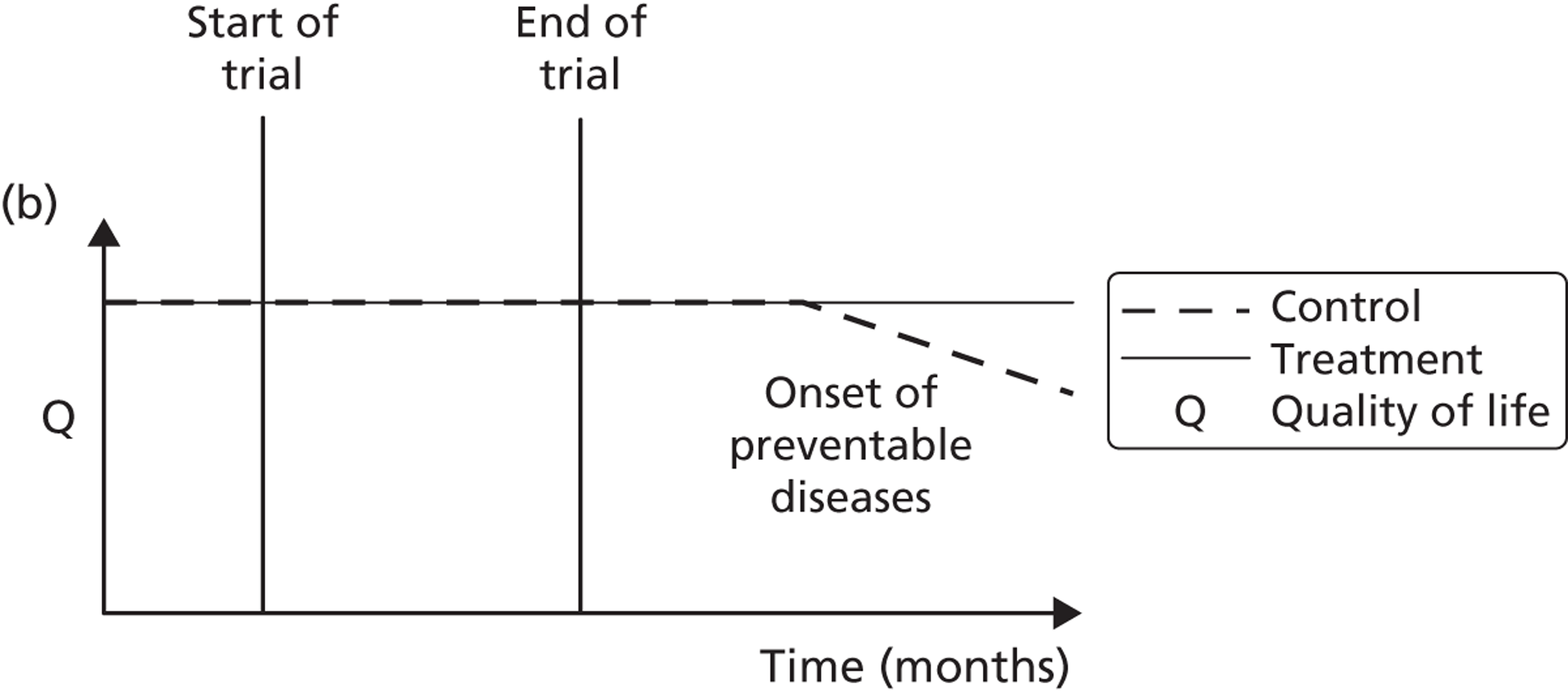

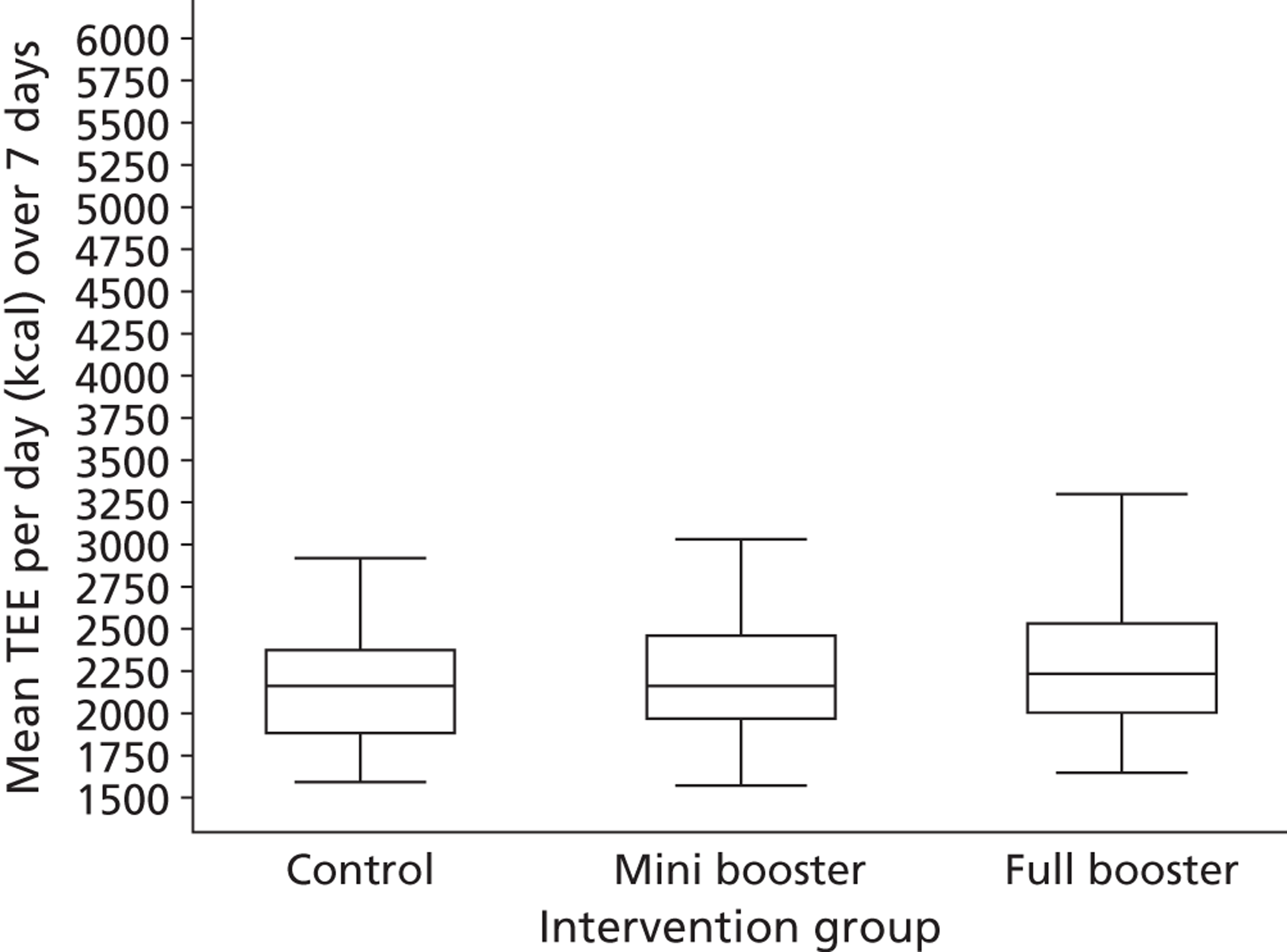

Table 1 shows the timing of assessments and interventions, all made at community venues. The primary end point was the level of physical activity measured at 3 months post randomisation using Actiheart [specifically, the mean total energy expenditure (TEE) in kcal per day over a 1-week period]. Secondary end points were:

-

objective measures of physical activity including:

-

TEE in kcal per day from 7-day accelerometry and heart rate monitoring using Actiheart (at 9 months)

-

physical activity counts (PACs) per week

-

minutes of moderate/vigorous physical activity per day

-

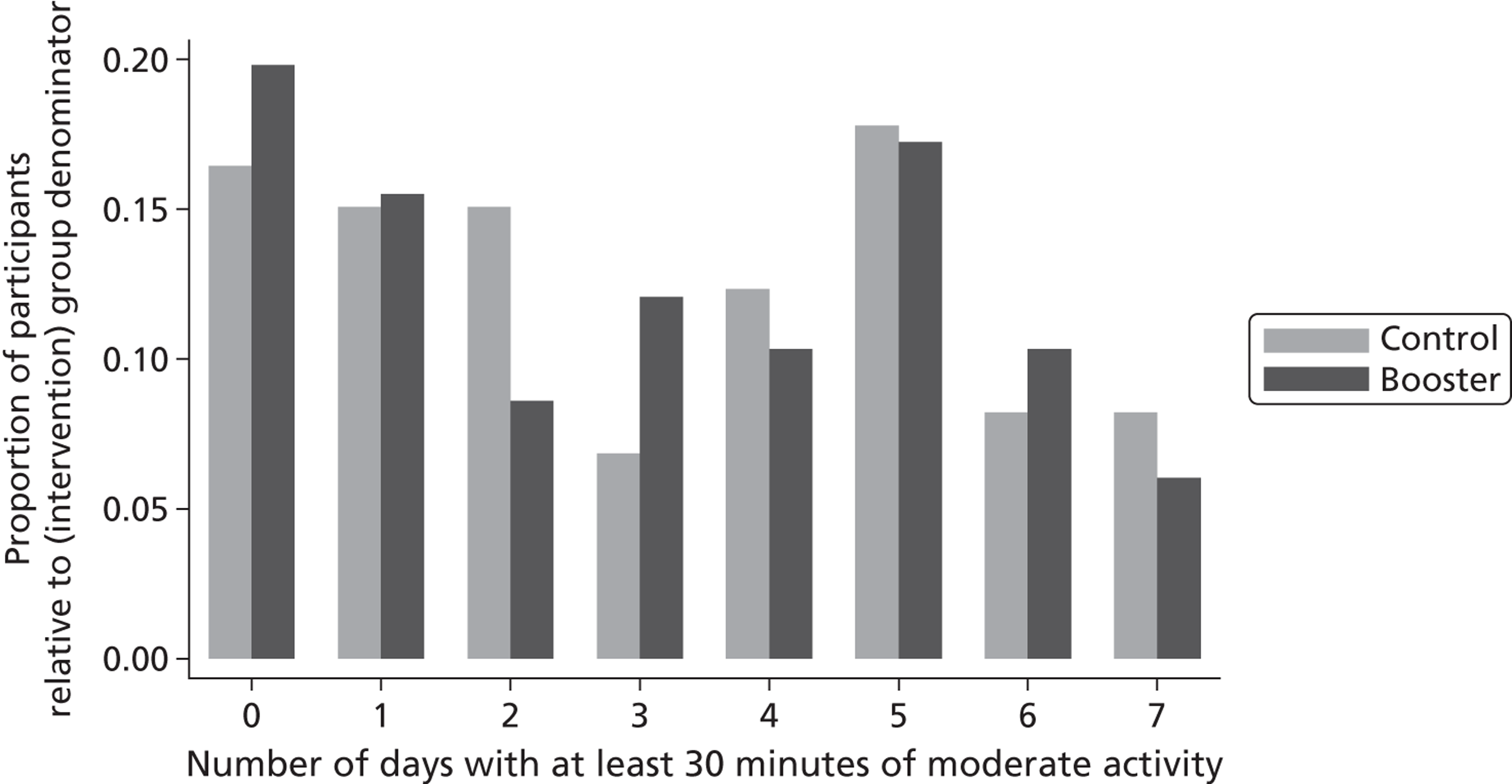

meeting the current physical activity recommendation of at least 30 minutes per day (continuous or in bouts of at least 10 minutes of at least moderate intensity) for at least 5 days a week (yes or no)

-

-

self-reported moderate or strenuous physical activity using the SPAQ, which records type and duration of activities in the previous week

-

HRQoL using the Sheffield version of the 16-item Short Form health survey instrument (SF-12v2 plus 4)

-

self-reported use of community facilities for physical activity

-

self-reported health and social care contacts (see Methods for the health economic analysis for the analysis plan)

-

self-determination using the Behavioural Regulation in Exercise Questionnaire (BREQ-2)30

-

body weight and height [to allow calculation of body mass index (BMI)]

-

physiological measure of fitness (12-minute walk test).

| Assessment/intervention | Minus 3 months | Minus 2 months | Minus 1 month | ∼ Minus 1 week | Baseline | 1 month | 2 months | 3 months | 9 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brief intervention screening checklist | ✓ | ||||||||

| SPAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Brief intervention questionnaire 1 | ✓ | ||||||||

| DVD (if eligible) | ✓ | ||||||||

| DVD usage assessment/advice | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Booster trial screening checklist | ✓ | ||||||||

| Participant information sheet | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Participant consent form | ✓ | ||||||||

| BREQ-2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Booster trial questionnaire 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Questionnaire 3 (SF-12v2 plus 4) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Height and weight | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Randomisation | ✓ | ||||||||

| Booster intervention (booster groups only) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 12-minute walk test | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| 7-day accelerometry | ✓ | ✓ |

The primary outcome was measured at 3 months post randomisation whereas the secondary outcomes were measured at 3 and 9 months post randomisation.

A decision was made to abandon the analysis of self-reported physical activity based on a questionnaire adopted from the HTA-funded Exercise Evaluation Randomised Trial (EXERT) trial. 31 This was because completion errors remained high even after repeat training of those administering it. The decision to abandon the use of this form was made in consultation with the trial steering committee and the HTA programme manager and the EXERT team and is fully documented elsewhere. 32

Sample size

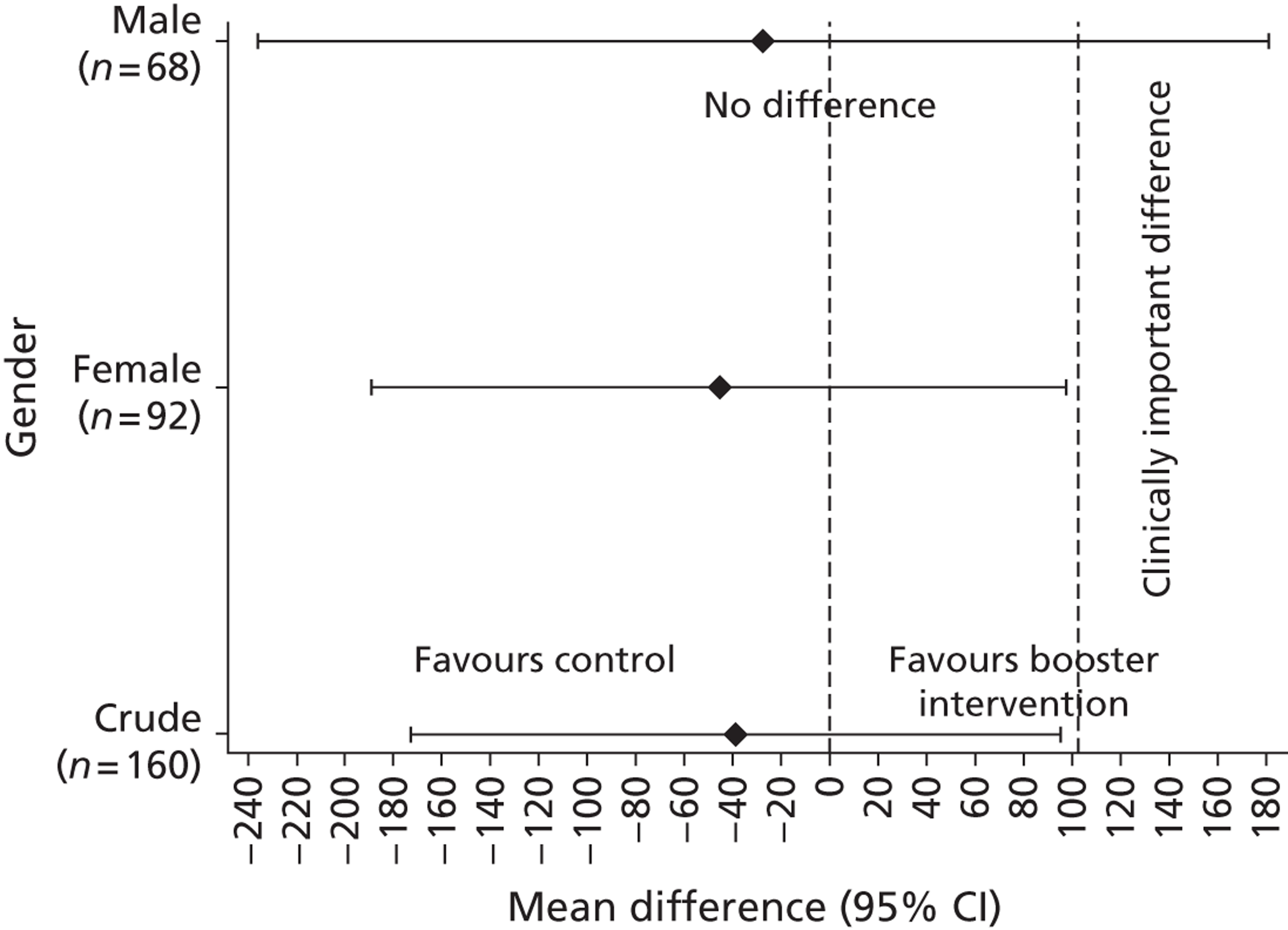

The sample size was originally based on a primary outcome that was subsequently superseded by the use of Actiheart, that is, a physical activity measure based on the mean physical activity levels from the 7-day accelerometric assessment (recorded as counts per week) at 3 months post randomisation (6 months after initial contact). Before progression to the main trial, an internal pilot was undertaken to estimate the variability of the outcomes and the minimum clinically important difference (MCID) based on one-third of the standard deviation (SD) of the primary outcome from the observed data and power estimation (conditional on the initial proposed sample size of 600 subjects). From the feasibility phase, the estimated effect size based on one-third of the SD was 34,464.7 PACs per week and 101.5 kcal per day TEE. 32 When re-estimating the sample size using data from an internal pilot study the revised sample size estimate either stays the same or increases (it cannot be less than the original estimate). 33,34

Assuming a mean difference in TEE of 101.5 kcal per day between the intervention group and the control group as the smallest difference of clinical and practical importance that is worth detecting, then with 450 subjects (300 intervention, 150 control) the trial was originally determined to have 92% power to detect this mean difference or greater between the ‘booster’ arm and the control arm (assuming a SD of 304.6 kcal per day) as statistically significant at the 5% (two-sided) significance level using a two independent samples t-test. With 300 subjects in the booster intervention (150 mini booster, 150 full booster) the trial would also have had approximately 82% power to detect a similar mean difference in TEE of 101.5 kcal per day between the two booster arms as statistically significant at the 5% (two-sided) significance level using a two independent samples t-test. Assuming an approximate 25–35% loss to follow-up by 3 months post randomisation, we proposed to recruit and randomise 200 subjects per intervention group to give a total sample size of 600 participants, giving the study power of between 87% and 92% to detect a mean difference in TEE of 101.5 kcal per day.

Randomisation and blinding

A Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) statistician, not on the trial team, used a simple randomisation procedure to generate the randomisation sequence, with each participant having a one-third probability of being allocated to one of the three intervention arms. We used a block size of 200 with no stratification. Eligible participants were randomised to one of the three arms using a central web-based randomisation service delivered by Sheffield CTRU after patient eligibility and informed consent were confirmed by a RA. Participants and outcome assessors were not blind to treatment allocation because of the practical nature of the intervention. However, the primary outcome was objectively assessed using the Actiheart device. Most other outcomes were self-reported. Study statisticians and the principal investigator were blinded to the treatment allocation codes until after the final analysis.

Statistical methods

Analysis population

The intention-to-treat (ITT) data set included all participants who were randomised according to randomised treatment assignment (ignoring anything that happened after randomisation, including non-compliance, protocol deviations and withdrawals); participants also had to have a valid 3-month post-randomisation Actiheart accelerometry measurement of physical activity.

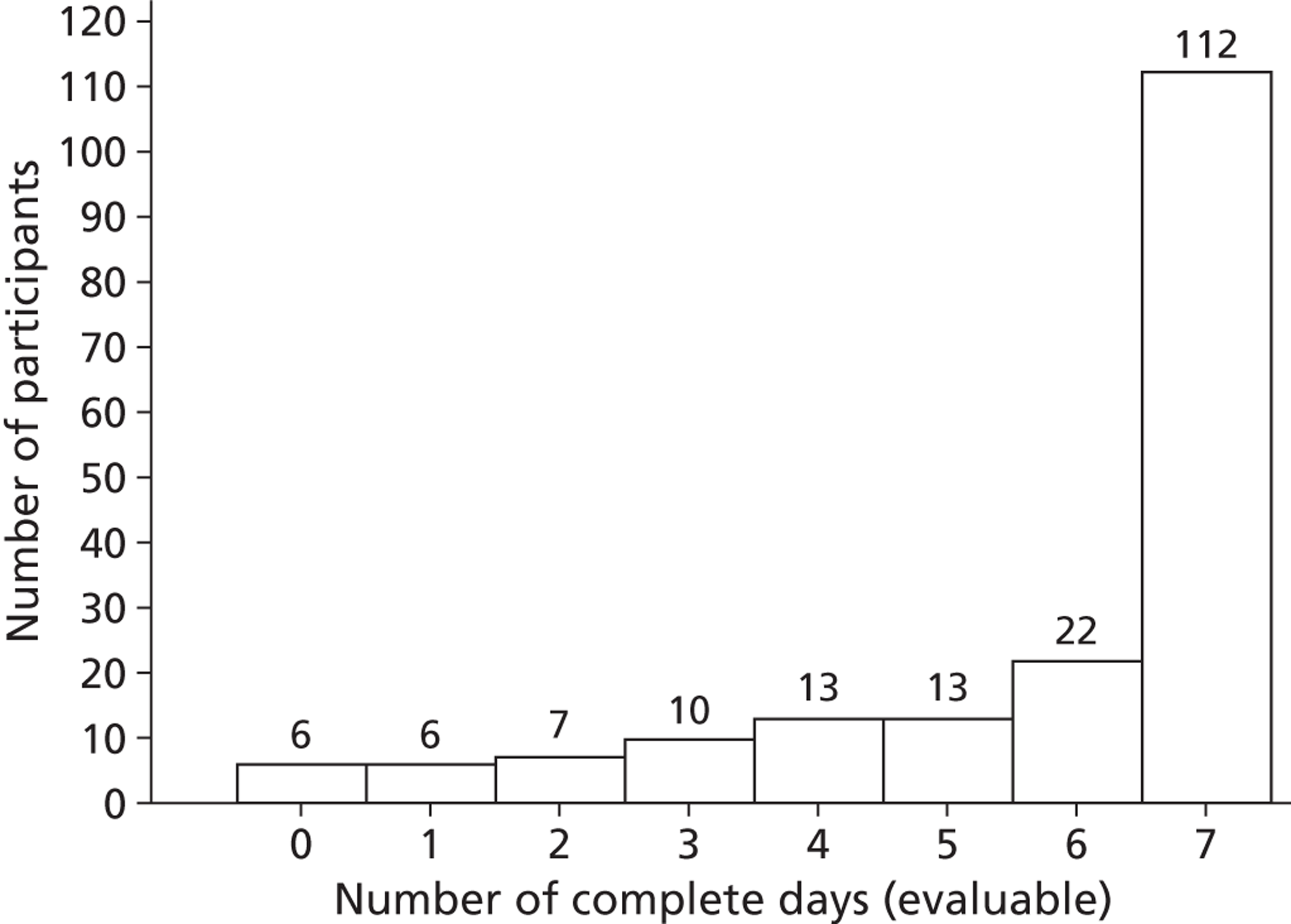

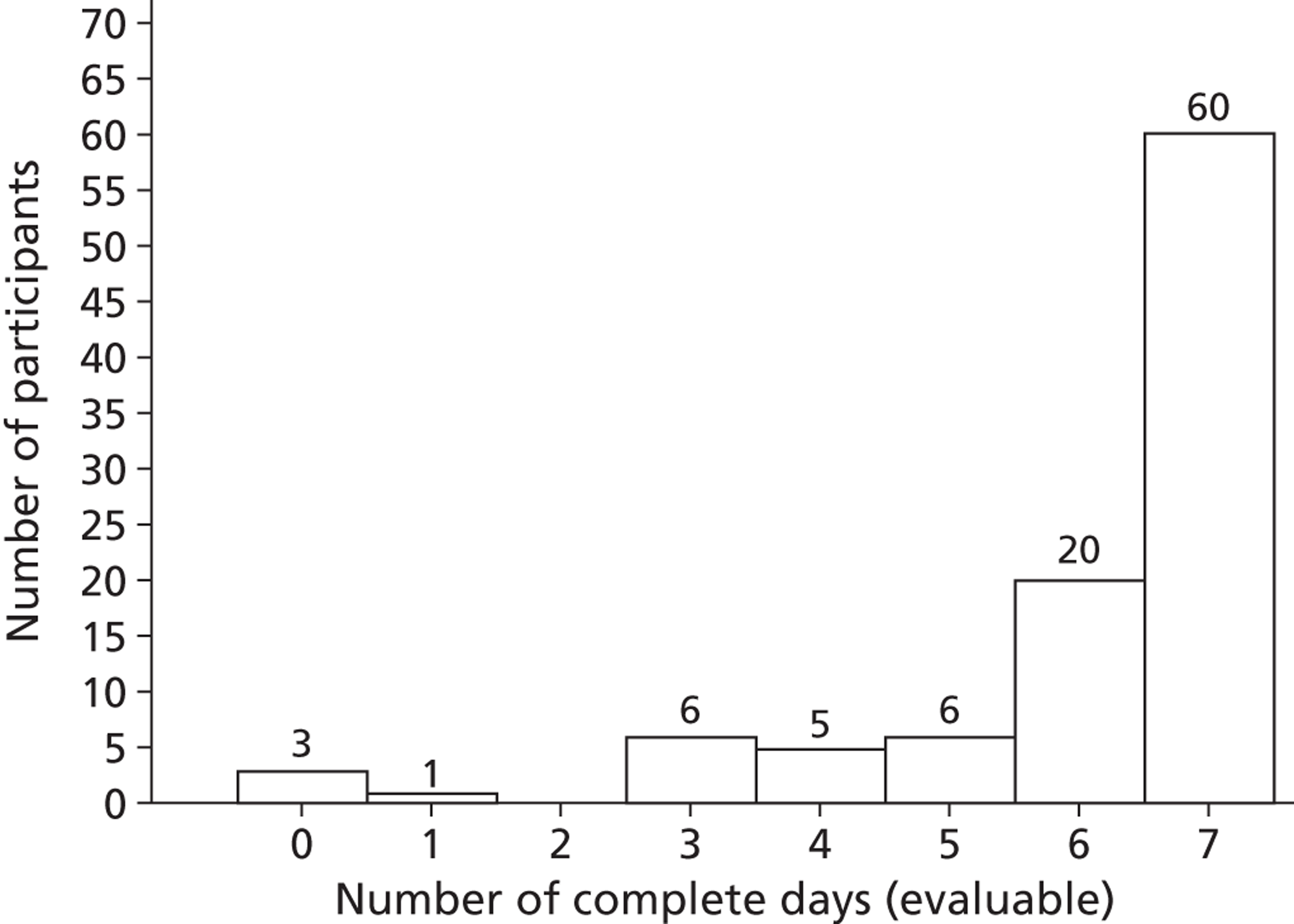

A valid Actiheart accelerometry measurement was defined as having at least 4 complete days (of the 7 days) of measurements of physical activity. We used the ‘auto-fill’ option on the Actiheart to minimise the amount of missing data. The ‘auto-fill’ option fills the gaps, of up to 2 hours, with the average value calculated from the recorded portion of the same day. 35 If the device identified > 2 continuous hours of missing data then, even using the ‘auto-fill’ option, this was classified as an incomplete day. When data were obviously missing because the participant had taken the accelerometer off to sleep, imputation of ‘sleeping’ values was employed by using the mean values during sleeping times. The decision about which data were missing as a result of ‘sleeping’ was made by study team members blind to the treatment allocation. After discussion with the trial management group and steering committee, incomplete days were classified as having > 1000 minutes (16.7 hours) of lost or missing activity per day as measured by the Actiheart. Although the manufacturers assert that there should be no issue with missing data, few studies report the majority of participants returning complete data sets. A brief review of published studies shows that a ‘complete day’ of Actiheart data is typically considered to be 500–600 minutes of recording. 36,37 Although many studies do not report the thresholds used, in the absence of advice from the manufacturers or definitive studies to determine the optimal threshold, researchers must determine an appropriate cut point to maximise both data validity and participant inclusion.

In addition to the ITT set, two other data sets were analysed as part of the sensitivity analysis. A complete cases data set was a subset of the ITT data set that included randomised participants with all 7 complete days of physical activity measurements at 3 months post randomisation. A per-protocol data set was defined as including those who received the intended two booster sessions (either face to face or by telephone) among participants in the booster intervention arm. Participants who did not receive the booster sessions as intended were excluded from this data set. Additional data sets were also analysed for the primary outcome as part of the sensitivity analysis assuming different missing mechanisms using regression and multiple imputation approaches.

Handling incomplete days or missing daily counts measurements

Exploratory analysis of potential risk factors associated with not having evaluable data (at least 4 complete days of Actiheart data) was undertaken using logistic regression. Spaghetti plots stratified by intervention arm were also used to explore the missing pattern of the primary end point with respect to the measurements during days of the week. To achieve 80% reliability with respect to activity counts and time spent in moderate to vigorous activity in adults, at least 3–4 days (of the 7 days) of activity monitoring are required. 38,39 In this regard, the primary outcome measure (mean TEE in kcal per day) was calculated as the mean TEE over 7 days among those with at least 4 complete days of evaluable Actiheart data.

The primary method to deal with missing data on the secondary outcome, activity counts per week, was to scale up complete observed daily measurements to 7 days using the following formula:

where PAC7i is the new standardised physical activity measurement for 7 days for participant i. The number of PACs per day was calculated by multiplying PACs per minute by 1440 (24 hours in a day multiplied by 60 minutes in an hour). This approach was used for patients who have at least 4 complete days measured after imputation using ‘auto-fill’ and ‘sleeping’ time as described earlier.

Statistical analysis

Multiple logistic and linear regression was used to compare the baseline characteristics [i.e. gender, ethnicity, employment status, age, BMI, weight, height, SF-12v2 plus 4 physical component summary score (PCS), SF-12v2 plus 4 mental component summary score (MCS), Relative Autonomy Index (RAI) of the BREQ-2, and SPAQ change scores] of the completers (≥ 4 days of valid Actiheart data at 3 months post randomisation) and non-completers (< 4 days). An interaction term was included in the regression model to see whether the characteristics of the completers and non-completers were different between the booster and the control groups. The purpose was to explore whether the missing data mechanism was related to the intervention or whether there are observed characteristics that might predict whether or not a randomised participant would have valid and complete Actiheart data at 3 months post randomisation.

For sensitivity analysis, multiple imputation was used to obtain a complete data set for the primary outcome by filling incomplete daily measurements. Twenty multiple imputation data sets were created and we imputed, at most, 3 incomplete days of the week per participant (among those with at least 4 complete days). The multiple imputation model took into account participants’ baseline characteristics (such as age, gender, weight, height, HRQoL and BMI) and longitudinal time sequence as well as total physical activity at baseline and 3 months before randomisation. In addition, for participants with at least 1 complete day of the outcome measure, multiple imputation was also used to impute the missing daily measurements as part of further sensitivity analysis using the same multiple imputation model as described above but imputing at most 6 incomplete days of the week per participant.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline demographic characteristics and physical measurements were summarised and assessed for comparability between the booster and the control arms. 40–42 Age, weight (mass), height (stature), BMI, SPAQ change score, BREQ-2 RAI dimension score and SF-12v2 plus 4 PCS and MCS scores were presented on a continuous scale. For these continuous variables, summary statistics such as the minimum, maximum, mean, SD, median and interquartile range (IQR) were presented. Numbers of observations used with number and percentages in each category are presented for categorical variables (e.g. gender, marital status, ethnicity and stage of change). Summary statistics are presented by treatment group and assessed for comparability. No statistical significance testing has been carried out to test baseline imbalances between the intervention arms but any noted differences are descriptively reported. 43,44

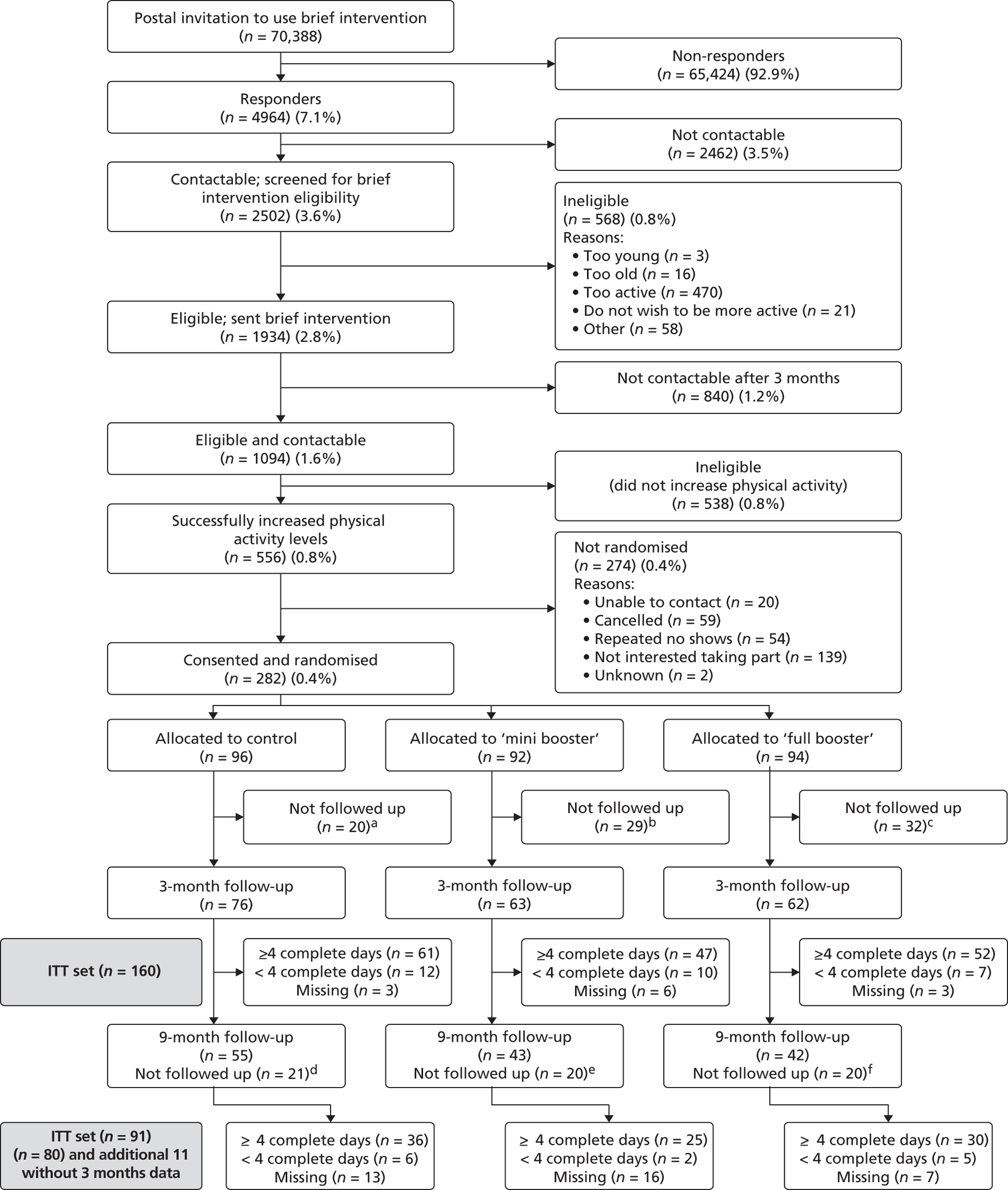

Data completeness

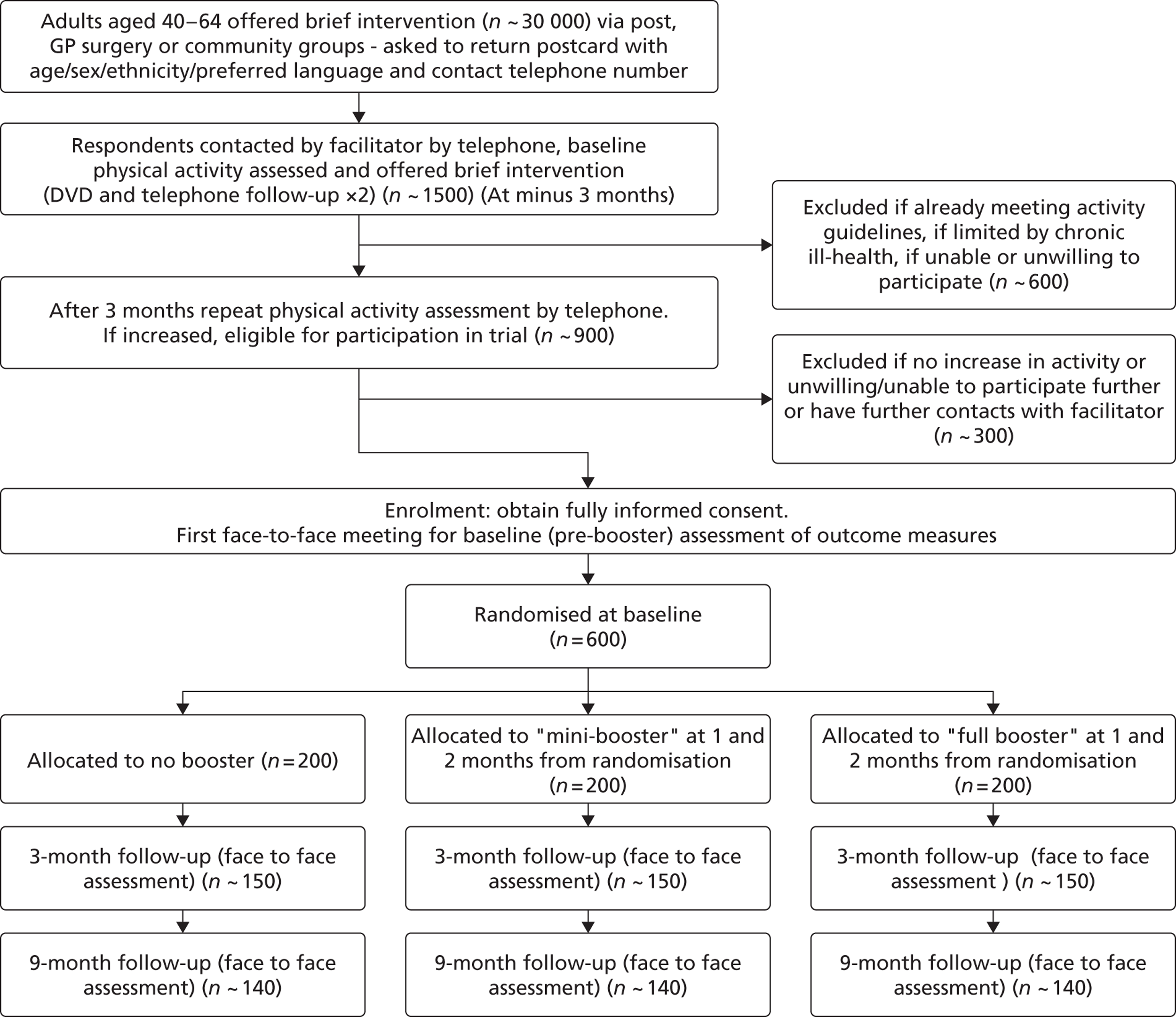

Reporting of data completeness is an integral part of clinical trial reporting. Hence, summaries of data completeness are shown on a CONSORT flow chart from participants’ enrolment, during follow-up and at the end of the trial. Data completeness is based on the primary outcome (mean TEE in kcal per day) and having a valid measurement at 3 and 9 months post randomisation.

Effectiveness analyses

The primary aim was to compare the intervention group (full or mini booster) with the control group (no booster). The primary comparison was between the mean physical activity levels from the accelerometer (mean TEE in kcal per day) in the two ‘booster’ arms combined compared with the mean physical activity levels in the control arm at 3 months post randomisation. This difference in means between the intervention group and the control group was compared using a two independent samples t-test; a 95% confidence interval (CI) for estimated mean difference between the groups was also calculated and reported with its associated p-value. The research hypothesis was that the booster intervention groups will have greater levels of physical activity than the control group. In all of the analyses the control group was treated as the reference for comparisons.

An adjusted analysis using multiple regression was also conducted to estimate the effect of the intervention adjusted for baseline covariates (such as age, gender, HRQoL, BMI and SPAQ at baseline and 3 months before randomisation). The ordinary least squares adjusted regression coefficient for the intervention effect was presented and reported with its associated 95% CI and p-value.

A secondary objective of the study was to compare the effect of the two interventions (full booster vs. mini booster) at 3 months post randomisation using the primary outcome, mean TEE per day. Therefore, we repeated the above analysis to compare the effects of the full and mini booster interventions.

The analysis outlined above for the primary outcome was also repeated for the main secondary outcome, PACs per week at 3 months post randomisation, and for the TEE and PAC outcomes at 9 months post randomisation.

Analysis of secondary outcomes

The following continuous secondary outcome measures were assessed at 3 and 9 months post randomisation:

-

PCS, MCS and Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) scores from the SF-12v2 plus 4

-

average minutes per day spent on moderate activity [3–6 metabolic equivalents of task (METs)]

-

average minutes per day spent on vigorous activity (> 6 METs)

-

average minutes per day spent on moderate and vigorous activity (≥ 3 METS)

-

BREQ-2 dimensions (amotivation, external regulation, introjected regulation, identified regulation, intrinsic regulation, RAI)

-

BMI

-

distance walked (in minutes) during a 12-minute walk test.

Mean outcomes were compared between the combined booster groups and the control group using two analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) multiple regression models: a simple model that adjusted for the baseline value of the outcome only and a more complex model that adjusted for several covariates including age, gender, BMI, total minutes of physical activity at 3 months and 1 week before randomisation and the baseline outcome measurement. The mean differences in outcomes between the groups and their associated 95% CI and p-value from the two models were reported.

Secondary binary categorical outcomes were the number and proportion maintaining (or increasing) their weekly duration of physical activity (based on the self-reported SPAQ) and the number and proportion meeting the current recommendations of at least 30 minutes of moderate physical activity (MET level ≥ 3) on at least 5 days of the week. We compared these outcomes between the booster groups and the control group at 3 and 9 months post randomisation using a continuity-corrected chi-squared test; 95% CIs for the estimated differences in proportions between the booster groups and the control group were also calculated. 45

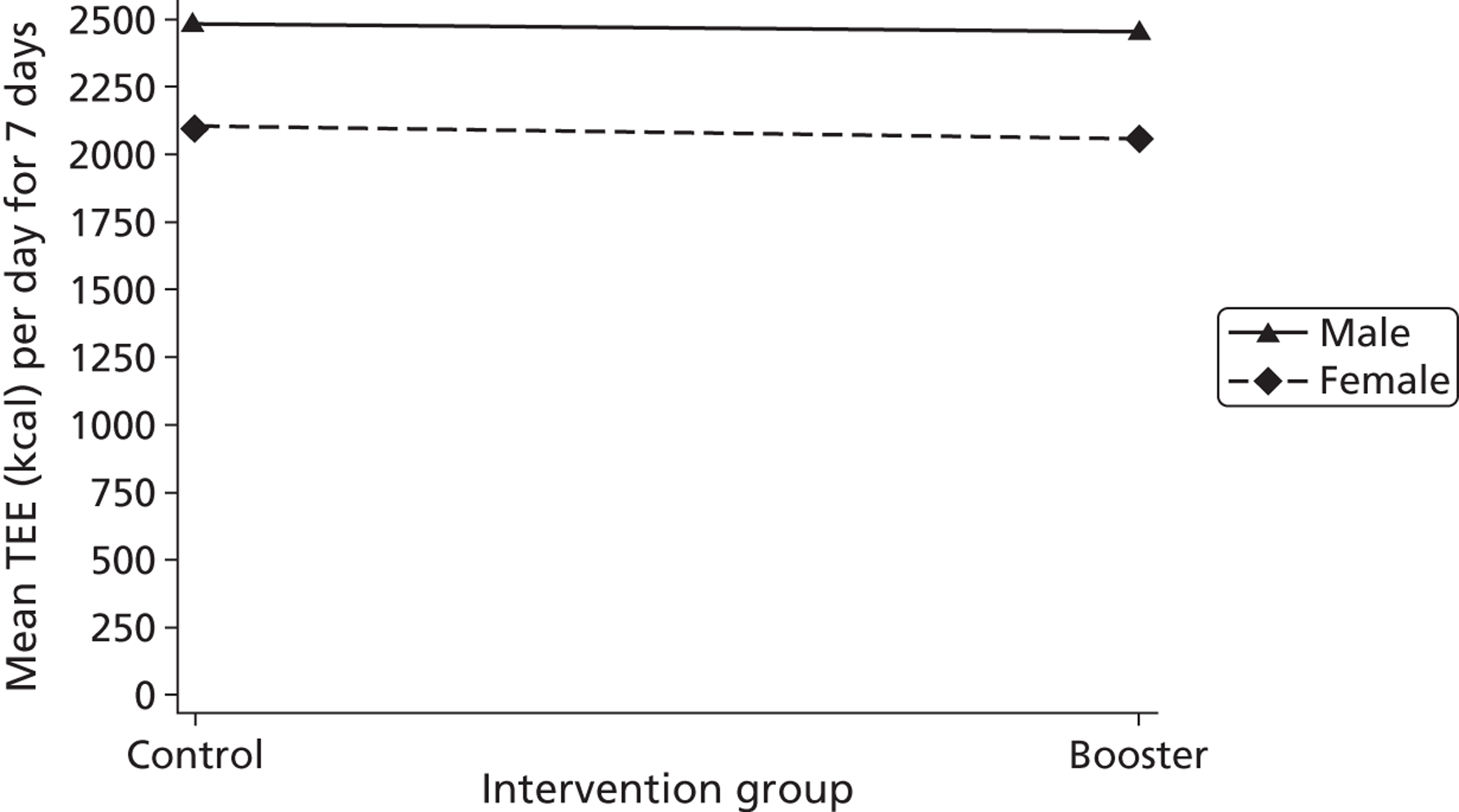

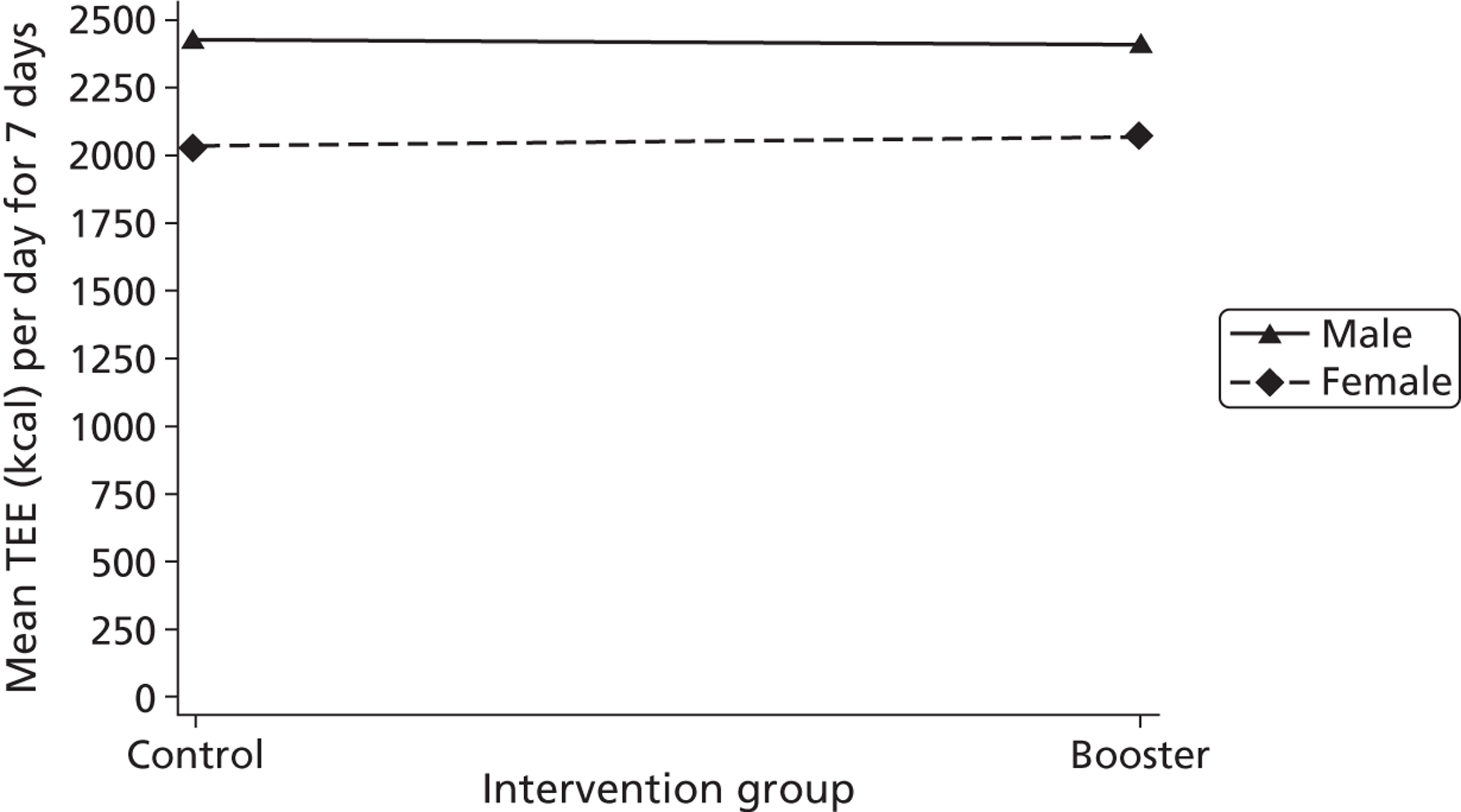

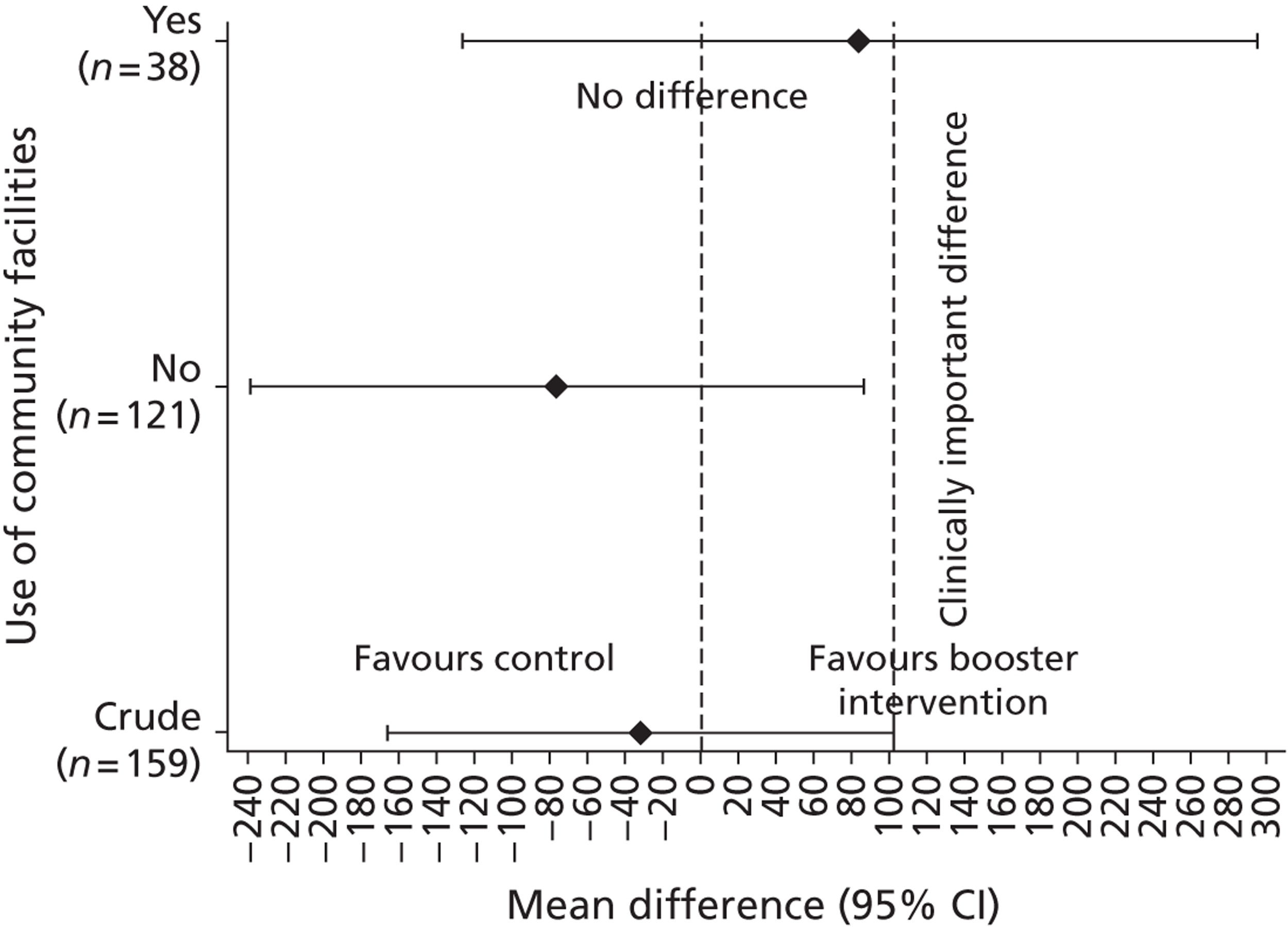

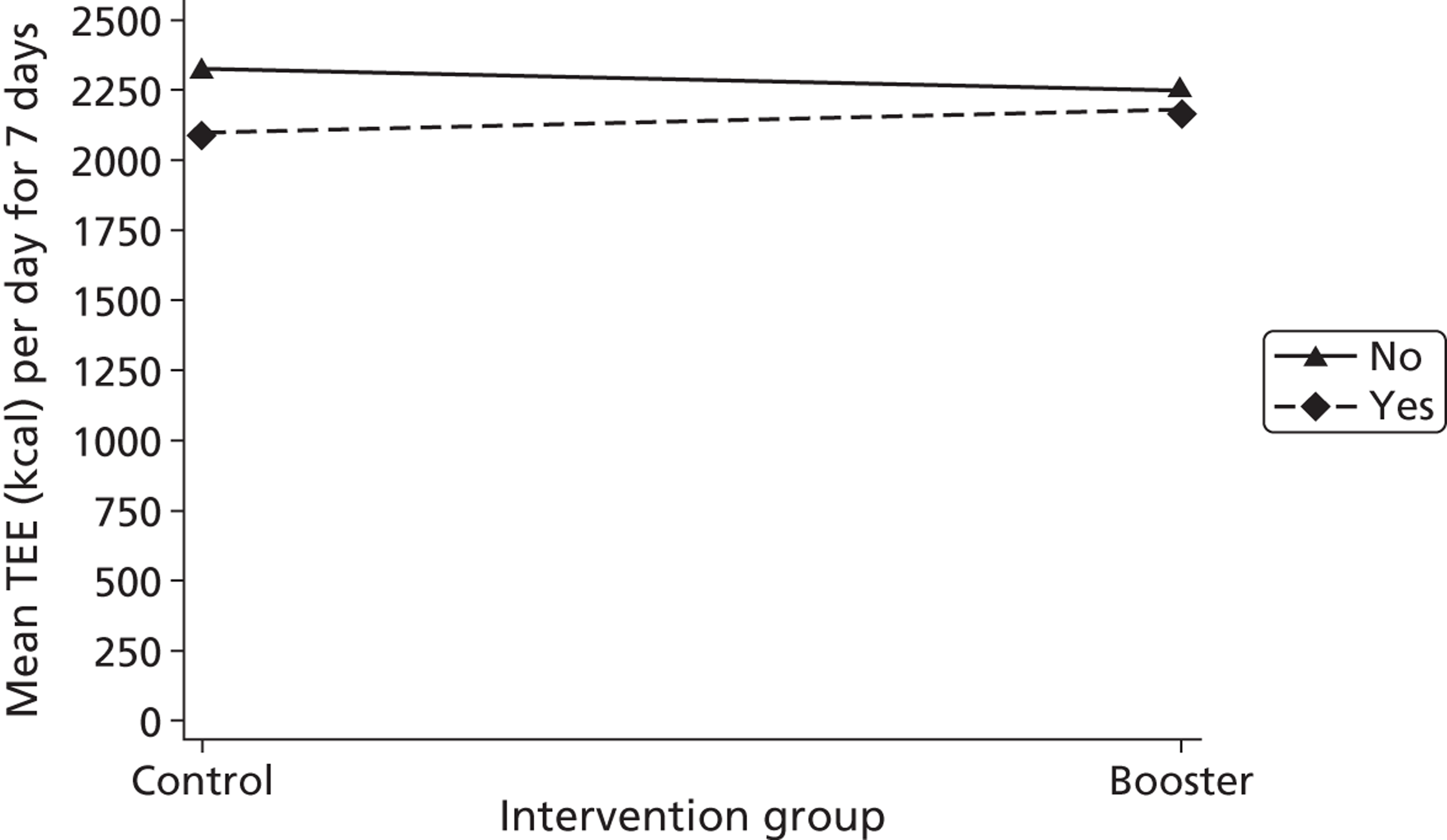

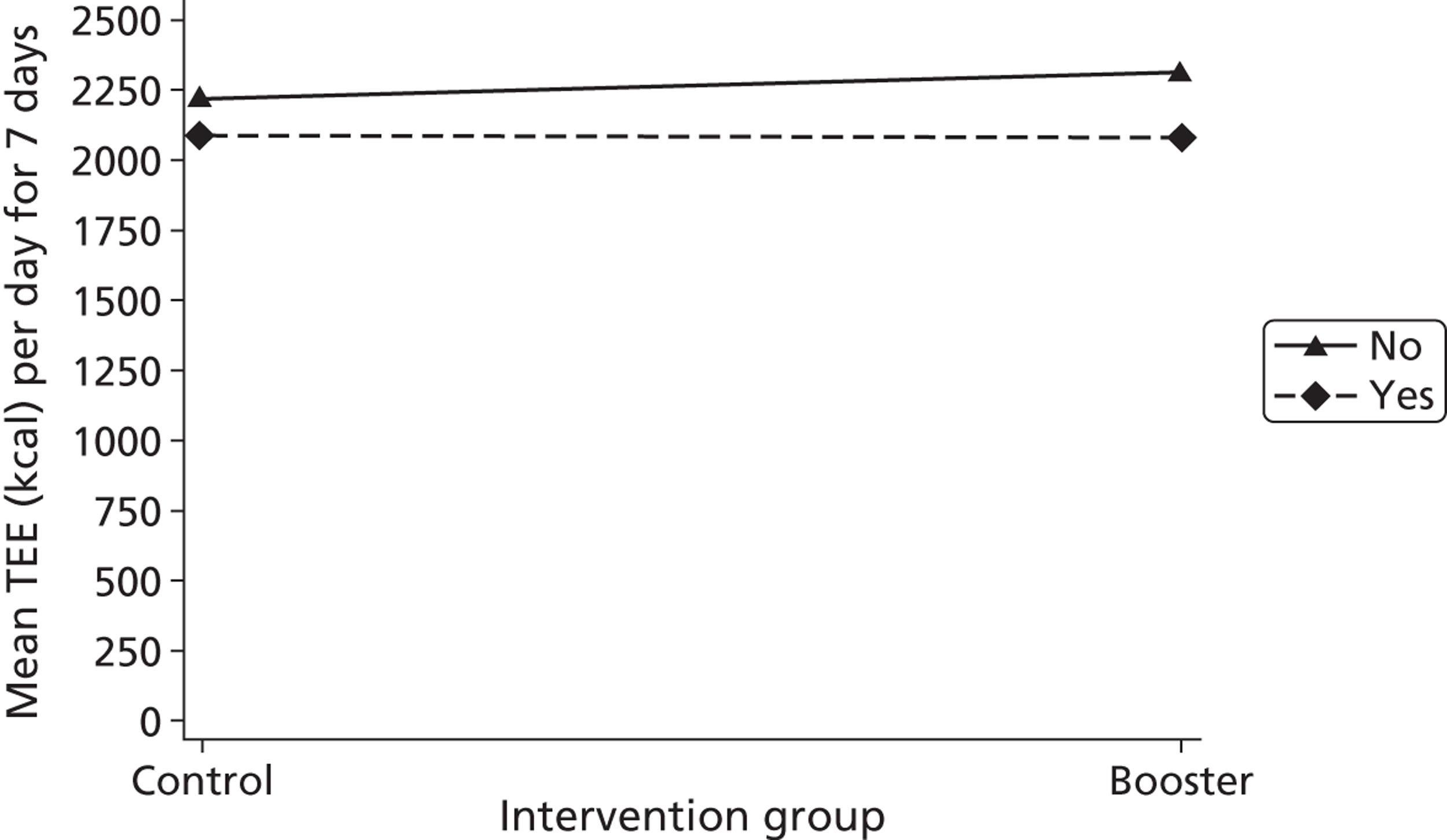

Gender, ethnicity and access to community facilities (self-reported use of community facilities vs. no use of community facilities) were predefined as subgroups that we wished to test for evidence of effectiveness in an exploratory analysis. An additional post hoc exploratory subgroup evaluation was undertaken to assess the impact of the timing of the initial mail-out (summer/spring vs. winter/autumn). The exploratory subgroup analysis used multiple linear regression with the primary outcome, the mean TEE (per day) levels from the Actiheart at 3 months post randomisation, as the response. We used an statistical test for interaction between the randomised intervention group and the subgroup to directly examine the evidence for the treatment effect of the combined booster groups varying between subgroups. 43,46,47 Subgroup analyses were performed regardless of the statistical significance of the overall intervention effect (booster vs. control). The model below was used to assess the interaction:

A graphical plot of mean profile subgroups with intervention group was used to display the interaction effect. 48

Methods for the process evaluation

The aim of the process evaluation was to (1) assess how acceptable and appropriate participants found the intervention and (2) identify psychosocial and environmental factors that may modify the effectiveness of the intervention. The study contained two components: (1) a survey by postal questionnaire, incorporating closed and open questions, and (2) a semistructured interview conducted individually face to face or over the telephone, depending on the preference of each participant.

Our methodological and theoretical approach is that adopted by Snape and Spencer,49 characterised by a subtle realism, interpretivism and pragmatism: we understand our subject matter through participants’ contextually situated perspectives; we strive for neutrality and objectivity during data collection and analysis and we attempt to be as transparent as possible as we move beyond the data during interpretation to serve the needs of policy-makers.

Survey

Survey questionnaires were sent to participants before their 3-month research assessment and they were asked to completed the questionnaire before the assessment and return it in a sealed envelope. If the survey was not completed participants were asked if they would be willing to complete it at the 3-month research assessment, after which the participant sealed it in an envelope and handed it back to the RA. Because of delays in regulatory approvals, questionnaires were sent out from April 2010 only and the first 47 randomised participants were not invited to complete it.

The survey questionnaire asked participants about the type and location of physical activity that they had undertaken during the previous 3 months, reasons for staying physically active, factors that influenced their physical activity behaviour and social support from significant others. The versions of the questionnaire sent to participants in the full and mini booster arms of the trial also contained questions on the intervention received. Participants were asked why they chose to participate; their preferred format for such an intervention; their expectations of the intervention and the extent to which these were met and whether they found the intervention easy, convenient, non-judgemental and non-confrontational. Participants were also asked their opinion about the amount of contact time with the project worker, the extent to which they felt encouraged to set their own goals for physical activity and the extent to which they felt that the intervention had helped them to resolve their barriers to physical activity, expand their knowledge of physical activity, increase their awareness of local facilities and opportunities and increase their confidence to stay active. Finally, participants were asked whether they had become more physically active than they were before participating and what had helped them achieve this. The questionnaire sent to those in the full booster arm of the trial can be found in Appendix 4. The questionnaires distributed to the mini booster and control arms are available from the team on request.

In-depth interviews

Those receiving a booster intervention who also responded to the survey questionnaire (see Survey) were given the option of participating in an in-depth interview. Because of the poor response there was no scope for purposive sampling; as a result, we interviewed a sample comprising all of the 26 people who volunteered. We did not elicit reasons for declining a research interview. Three RAs performed the interviews: Andrew Hutchison PhD (male) and Kimberly Horspool MSc and Sue Kesterton MSc (both female). KH and SK had both studied qualitative research techniques as part of their MSc but were novice interviewers. AH was more experienced having conducted a number of qualitative research interviews as part of his doctoral research. None of the interviewers delivered the intervention to the interviewees but interviewers may have been involved in collecting baseline data for the RCT component from some interviewees. Interviewees would have known that interviewers were on the research team and were from Sheffield Hallam University and may have associated them with exercise science and delivery of the intervention. The interviewers were asked to withhold their own opinions and to make it clear that this interview was separate from the intervention motivational interviews. No field notes were taken and no repeat interviews were undertaken.

Semistructured interviews lasted between 9 and 32 minutes (median 21 minutes) and were conducted over the telephone or face to face in a quiet room at a community venue, according to each participant’s choice. For most interviews no one was present except for the participant and the researcher. In one case a participant chose to conduct the interview on a mobile phone and, for part of the time, in a public place.

A topic guide was provided to interviewers (see Appendix 5); this was not pilot tested. This guide included questions on participants’ levels, choice and prioritisation of physical activity as well as the benefits and costs associated with staying physically active. It also included questions on participants’ experiences of the booster sessions and why they had or had not helped them to stay active and why participants felt that the booster sessions were or were not a good way to give them the support that they needed.

Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment or correction. Daniel Hind conducted the initial data analysis in NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Southport, UK) using a constant comparative method to identify themes. We used a ‘framework’ approach to analysis in which a priori and emergent themes were identified using the following stages: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, mapping and interpretation (charting was not undertaken). 50 For instance, a theme of a priori interest was the perceived effectiveness of the booster sessions; subthemes within this category were derived inductively from familiarisation with the transcripts. 50,51 The results were used to explore insights into the mechanisms that may have contributed towards the quantitative findings and to identify any other emerging issues or factors that may have influenced the uptake of the boosters and which had not previously been documented. 52 Data saturation was achieved53 with no substantively new themes emerging in the last 10 interview transcripts. Participants were not asked to provide feedback on the themes.

Having indexed transcripts using our own thematic framework, we undertook a rapid review of the literature to find existing frameworks to evaluate dimensions of (1) prior conditions experienced by the participants; (2) barriers to and facilitators of adoption of new behaviours or technologies; and (3) the acceptability/appropriateness of the interventions. For prior conditions (see Chapter 4, Prior conditions) we used dimensions described by Rogers (p. 172). 54 We adopted, with modifications, the dimensions of the Motivators of and Barriers to Health-Smart Behaviors Inventory, developed by Tucker and colleagues55 (see Chapter 4, Barriers to physical activity and Physical activity: motivators). Our dimensions of intervention acceptability are based on those described by Nastasi and Hitchcock56 (see Chapter 4, Motivational interviewing: perceived effectiveness, Motivational interviewing: consistency with perspectives or world views, Motivational interviewing: perceived feasibility and Motivational interviewing: perceived importance).

Methods for the fidelity study

Background

Although a small number of studies assessing the efficacy of physical activity counselling have reported the content, frequency and duration of training of those delivering the physical activity counselling intervention, the majority do not, and it is not uncommon for most clinical trials to fail to even report the content of the counselling intervention. 57,58

Although physical activity counselling based on MI has been rolled out across the UK through the Let’s Get Moving education programme,59 it remains unclear whether those delivering the training and those delivering the intervention to patients are doing so according to the approach intended. This failure to embed assessments of competence has raised questions over the value of short-term workshops with little or no ongoing supervision and professional practice reflection. It is clear that programmes such as this offer a potentially valuable additional education framework but few studies are currently being published that have clearly assessed the fidelity of those delivering the intervention.

It has therefore been suggested that behavioural interventions should clearly report (1) the content of or elements of the intervention, (2) the characteristics of those delivering the intervention, (3) the characteristics of the recipients, (4) the setting [e.g. Physical Activity Referral Scheme (PARS)], (5) the mode of delivery (e.g. face to face or by telephone), (6) the intensity and contact time (e.g. number of sessions) and (7) participant adherence to delivery protocols. 60 The booster trial embedded these principles into its design along with treatment fidelity frameworks intended to provide standardisation of the behavioural intervention without losing innovation and flexibility within the two intervention arms. 17,18 Furthermore, the action planning and maintenance phases in both experimental arms used behaviour change techniques, as recommended by Michie and colleagues,60 which are thought to enhance self-regulation towards change. The assessment of the existing competence and subsequent training of those delivering the MI interventions was evidence based and built on recent reviews of training in MI. 61

Motivational interviewing content and delivery

The MI component was delivered by RAs trained by a member of the Motivational Interviewing Network of Trainers and followed existing frameworks for MI in physical activity contexts. 62,63 The key phases and content of the intervention are provided in Table 2 and follow the phases of MI. 64 The relational aspect (or ‘spirit’) of MI is pivotal to the approach and emphasises participant ‘autonomy’ as opposed to ‘imposing authority’; ‘evocation’ rather than ‘education’; and ‘collaboration’ instead of ‘confrontation’. Once underpinned with the relational approach, the technical skills of MI were delivered, which included open-ended questions, affirmations, reflective listening and summarising. 13 Those delivering the intervention received 6 days of formal training over the first 12 months of the study in addition to follow-up supervision for the remainder of the study using audio recordings for reflective feedback.

| MI content | MI phase |

|---|---|

| Opening exchange/agenda setting | Engagement |

| Decisional balance | Focusing |

| Importance of change (agreed target behaviour) | Evoking |

| Readiness to change (agreed target behaviour) | |

| Action planning | Planning |

| Maintenance phase | Maintenance |

Treatment fidelity assessment and methods

To ensure that the criteria for treatment fidelity were met, those delivering the MI physical activity booster interventions (RAs) were assessed for their competence in delivering MI before and throughout the intervention period. The assessment of practitioner competence used was the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) assessment. 65 Minimum practitioner levels will be based on the levels of ‘competence’ as stated in the MITI coding system. To account for practitioner competence ‘drift’ (post training), follow-up reviews of practitioner MI competence were carried out at appropriate intervals (approximately every 9 months).

The MITI assessment was used to measure the interventionist application of key facets of MI, which included ‘global ratings’ of evocation, collaboration, autonomy/support, direction and empathy. In addition, ‘behaviour counts’ were recorded, which included giving information, MI adherent behaviours (e.g. asking permission, affirming, emphasising personal control), MI non-adherent behaviours (e.g. advising, confronting, directing), open compared with closed questions and simple and complex reflections. The calculations for MITI were based on existing standards,65 as seen in Table 3.

| Clinician behaviour count or summary score thresholds | Beginner proficiency | Competency |

|---|---|---|

| Global clinician ratings (average) | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| Reflection to question ratio (R : Q) | 1 | 2 |

| Per cent open questions (% OQ) | 50 | 70 |

| Per cent complex reflections (% CR) | 40 | 50 |

| Per cent MI adherent (% MIA) | 90 | 100 |

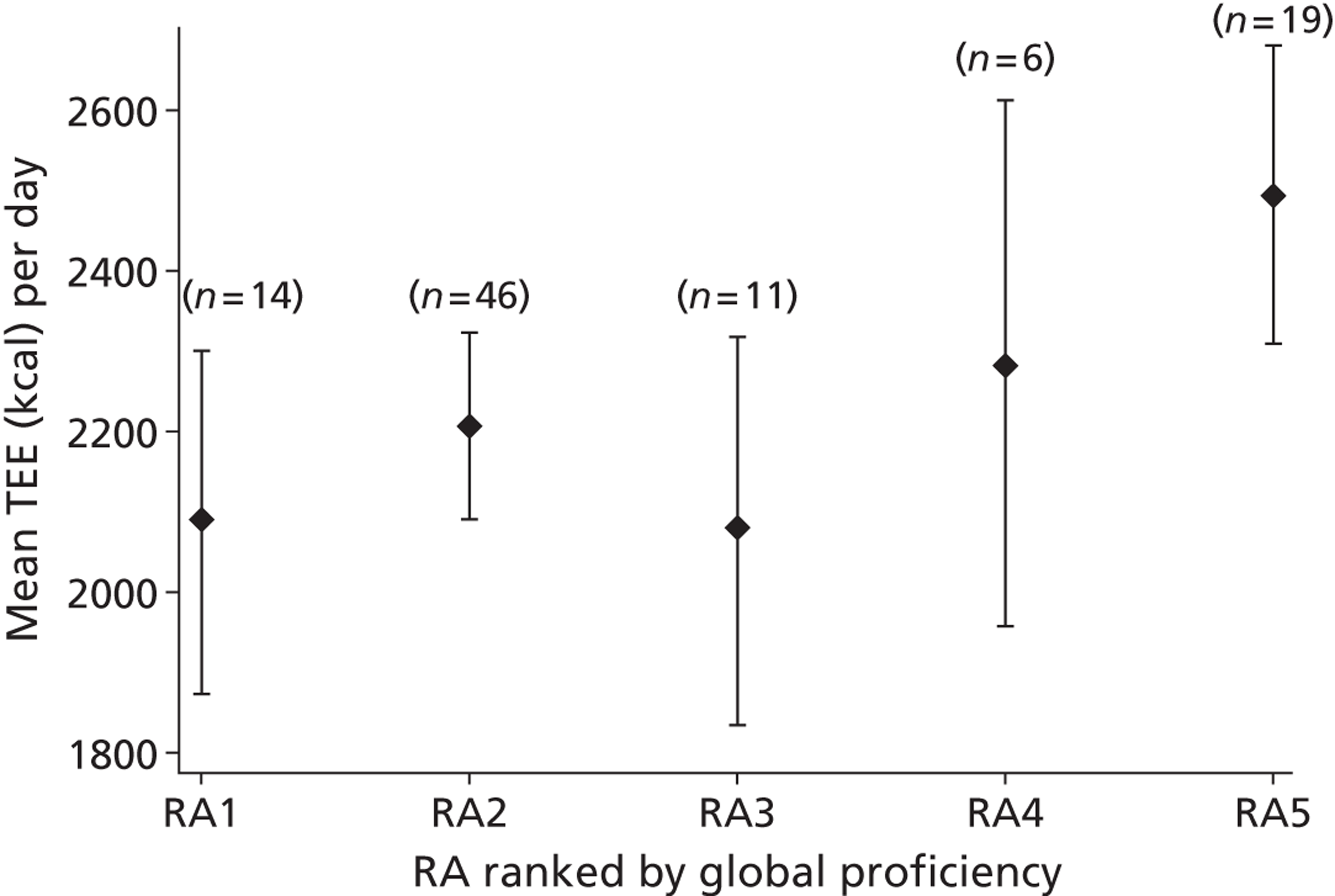

The relationship between motivational interviewing fidelity and levels of physical activity: statistical methods

We employed analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test the null hypothesis that physical activity measured by mean TEE at 3 months was the same across all of the RAs who delivered the MI intervention. We plotted the means of mean TEE with their associated 95% CIs stratified by the RA who delivered the MI intervention to show how physical activity varies across RAs ranked by their global proficiency ratings. A further ANOVA model was fitted with RAs with the same global proficiency rating grouped together. We dropped from the analysis RAs who delivered very few sessions. In addition, for the few sessions in which MI was delivered by two RAs, we allocated the session to the RA who delivered more sessions.

Methods for the geographical information systems study

Aim

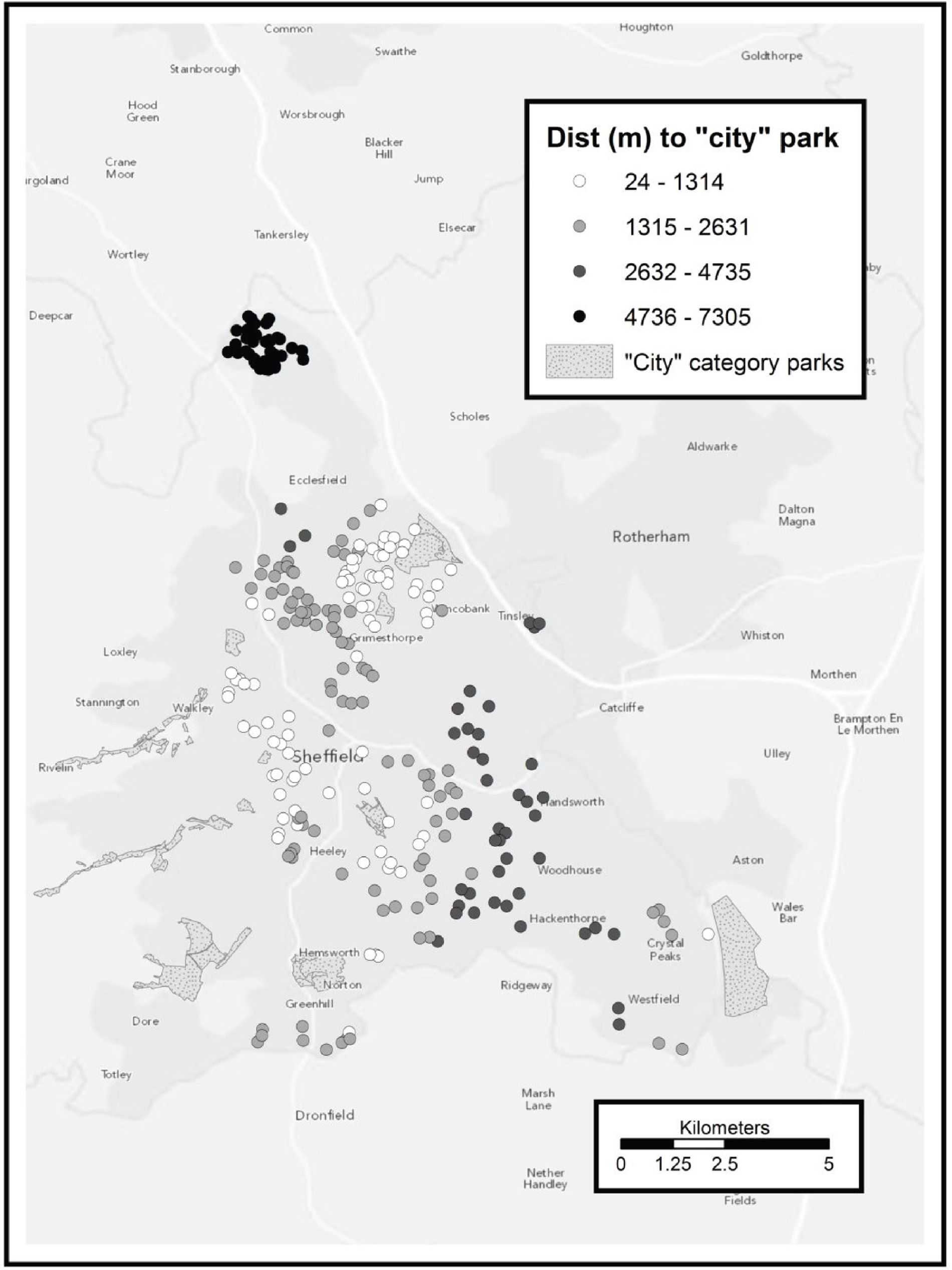

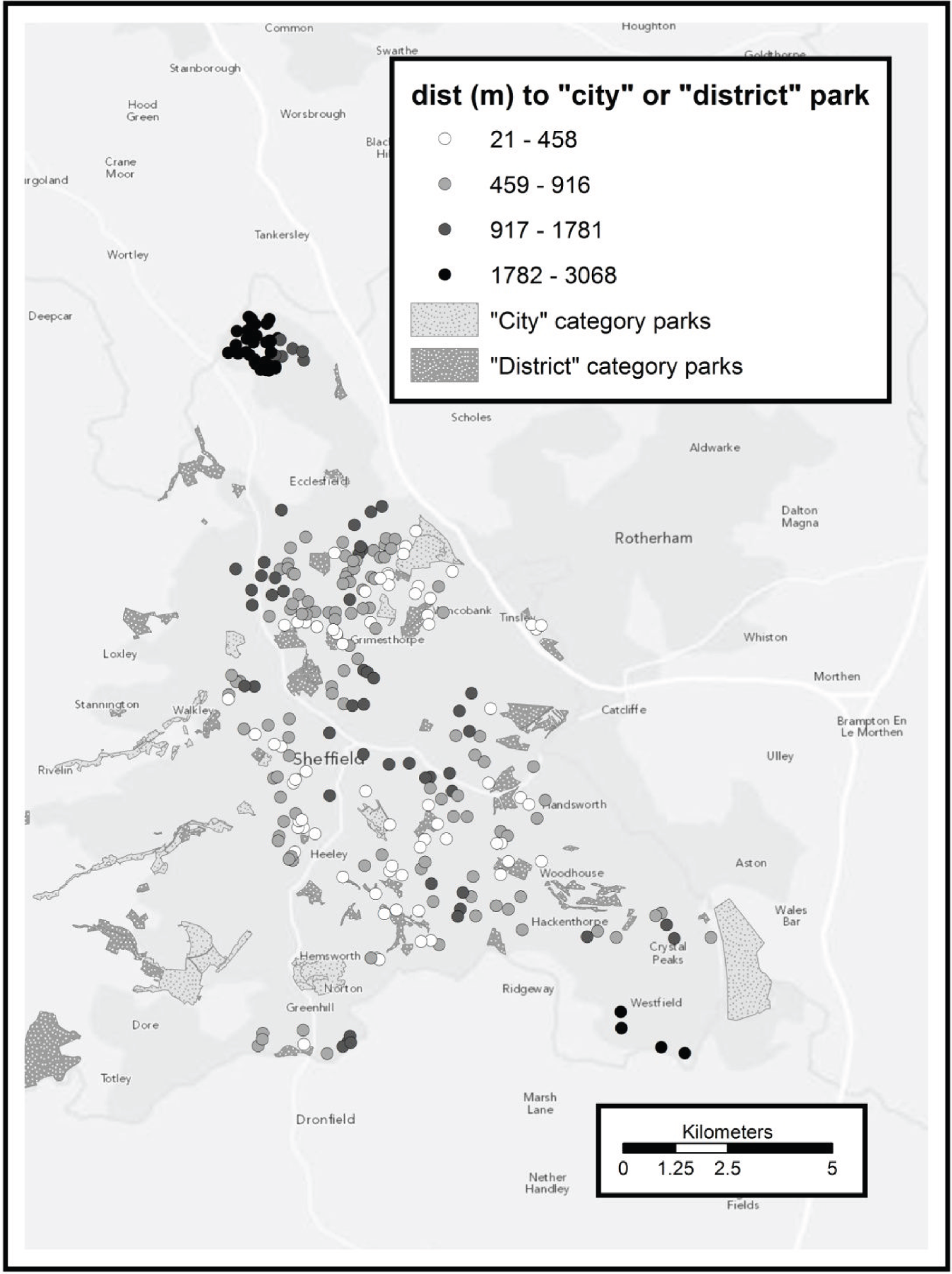

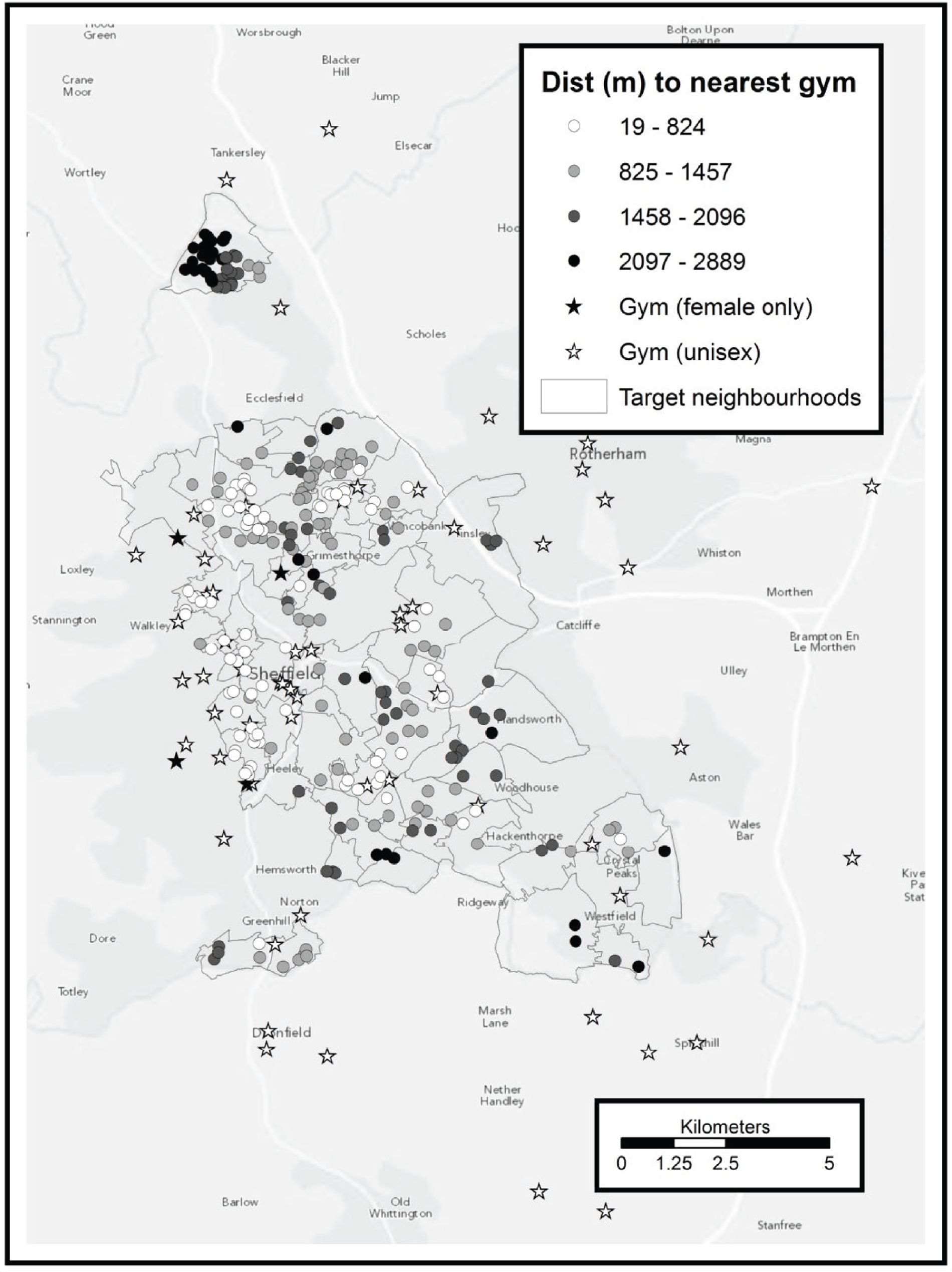

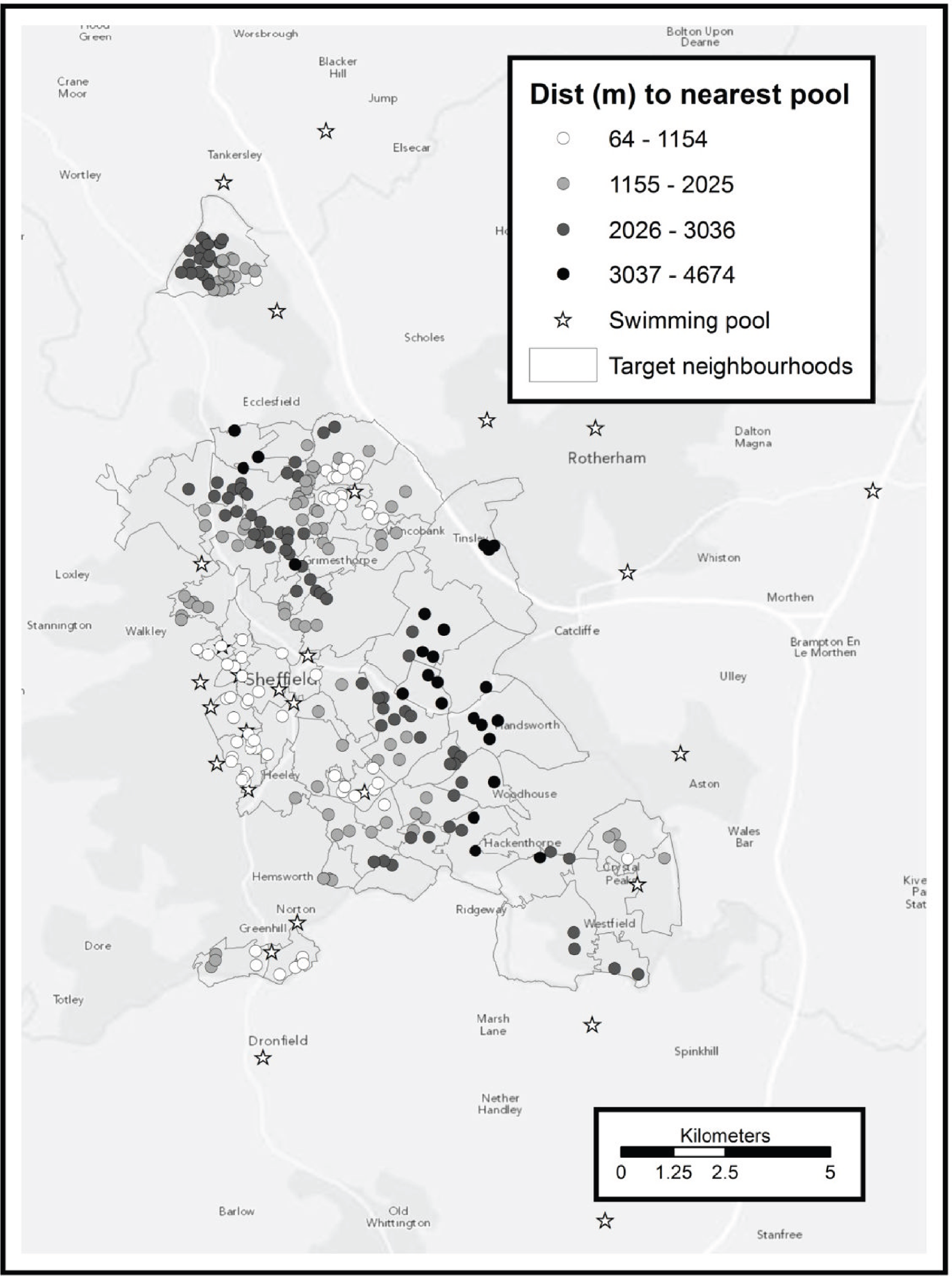

The aim of this substudy was to explore whether access to green space and leisure facilities influenced the effectiveness of the intervention. We used network distance analysis to produce a set of variables for each of the 282 trial participants, which represents his or her pedestrian access to municipal green space and any relevant leisure facilities.

Network distance analysis

Euclidean (straight line) distance is the simplest measure of distance between two points. However, in a city it is rarely possible to follow a straight line between two points. Moreover, rivers, railway lines and sometimes roads force pedestrians to take routes that may deviate considerably from a straight line. To gauge the realistic walking distance between two points in a city, it is necessary to build a network representation of the pedestrian-accessible routes within the city and surrounding area. The shortest route between any two points on the network can then be calculated mathematically.

The most labour-intensive step is creating the network. The Integrated Transport Network™ (ITN) in OS MasterMap® [Ordnance Survey, Southampton, UK; see www.ordnancesurvey.co.uk/oswebsite/products/os-mastermap/itn-layer/index.html (accessed 10 October 2012)], can be used for this purpose, but unfortunately it is not possible to download a single portion of the ITN covering all of Sheffield and the surrounding area. Instead, we downloaded the data for this area from OpenStreetMap (see www.openstreetmap.org). In a certain respect, OpenStreetMap is actually more useful to us than the ITN; it is created (in part) by local volunteers, walking on foot and recording data with global positioning system (GPS) devices, and therefore provides information on pedestrian access that is more detailed than a typical OS map.

Roads and footpaths, etc. in OpenStreetMap are stored in a simple vector format that makes it relatively easy to extract the information required to build a network. The only problem is that the labelling of pedestrian accessibility for roads (especially trunk roads) is not consistent and is occasionally inaccurate. It was therefore necessary to manually exclude the following sections of road:

-

A61 Dronfield bypass

-

Sheffield Parkway

-

Mosborough Parkway

-

A57 (section linking Mosborough Parkway to the M1)

-

A616 Stocksbridge bypass

-

Park Square roundabout

-

Tinsley roundabout and Tinsley viaduct.

Crossing points for non-pedestrian roads, for example bridges and underpasses, are well detailed in OpenStreetMap.

Although the shortest distance between points within the network can be calculated very accurately, there is the potential for error when calculating the network distance between features that do not lie within the network. Unfortunately, the centroids of postcode areas, and the polygons representing municipal green space boundaries, do not lie within the network. Here it is necessary to spatially ‘join’ these features to an appropriate point on the network. This is best done manually; however, because of the large amount of work that this would require it was necessary to automate the joining process, as follows.

Each postcode centroid was linked to the closest point on the network and the Euclidean distance between the centroid and the network point added to the network distance.

Each green space polygon was linked to all network points falling inside it, with the minimum network distance to any of these points deemed to be the minimum network distance to the polygon itself. As pedestrian entry points to green space are well detailed in OpenStreetMap, this means that the network distance mostly takes the entry points into account.

The major limitation of the automated joining process is that sometimes the network point that the feature is linked to is not always the most appropriate. For example, a postcode area may include adjacent houses that face onto different streets so that an address may be attributed to a network point on a street from which there is actually no access to the property. Similarly, for green space, points on the network outside the green space polygon may sometimes be closer to the actual entry points than those inside the polygon. This can result in network distance errors of ≥ 100 m, in some cases substantially more if the difference in network distance between the automated choice of point and the optimum choice of point is large. Fortunately, very large anomalies appear only in rural areas where the road network is sparse and therefore were not a significant concern in this analysis.

Green space measures

All municipal green spaces in Sheffield were considered, excluding certain types of land use inappropriate for exercise. Sheffield City Council classifies these spaces as ‘city’, ‘district’ or ‘local’ according to their catchment areas. We used ‘city’ as a proxy for high-quality space and ‘district’ as a proxy for medium-quality space in terms of attractiveness. Local spaces were too ubiquitous for a meaningful spatial analysis. Of municipal green spaces belonging to other authorities, only Rother Valley Country Park was included (designated high quality).

Digitised boundary data for municipal green spaces in Sheffield were provided by the Sheffield City Council Parks and Countryside team. As well as boundary information, these data included a classification of the usage and catchment area categorisation of each space. These are explained fully in a Sheffield City Council Parks and Countryside report66 but are summarised here as follows:

-

Usage type:

-

parks

-

gardens

-

sports sites (e.g. tennis courts)

-

playing fields

-

playgrounds

-

playground/open space

-

woodlands

-

moorland/heathland

-

open spaces

-

allotments

-

churchyards/cemeteries

-

other site types – specified:

-

golf courses

-

farms

-

show grounds

-

depots

-

ancillary sites to other leisure facilities (e.g. car parks).

-

-

-

Catchment area categorisation:

-

city wide

-

district (up to 1.3 km)

-

local (up to 0.4 km).

-

We decided to disregard the following usage types: playgrounds (because our participants are middle-aged), allotments (as nearby allotments are relevant only to the minority of local residents who rent them), churchyards/cemeteries (less likely to be appropriate places for exercise), farms, depots and ancillary sites.

Inclusion of the catchment area categorisation information is more problematic than inclusion of usage type as it is not clear on what research, if any, it is based. However, disregarding the categorisation is equally problematic as ‘local’ municipal green space is ubiquitous. For example, our preliminary study considered all municipal green spaces in Sheffield of the appropriate usage type and the size of a football pitch or greater and found very few postcodes in the city that were further than 1 km from such a space, with roughly 50% falling within 500 m and roughly 30% falling within 300 m. This tallies with the findings of Barbosa and colleagues. 67 Also, most distances > 500 m fell in the most affluent parts of the city, which were not included in the booster trial (this also tallies with the findings of Barbosa and collegaues67). Because of random errors inherent in our network distance measurements (see Network distance analysis), such small network distances would contain an unacceptable amount of uncertainty. It was also felt that it was important for us to take some account of the attractiveness of municipal green spaces.

Therefore, we decided to make use of the catchment area categorisation as a proxy for the quality/attractiveness of the space, using an ordinal scale in which citywide represents the highest quality, district represents medium quality and local represents the lowest quality. Disregarding all green spaces with unsuitable usage types (see earlier) we measured the shortest network distance to:

-

high-quality municipal green spaces of appropriate types

-

high- or medium-quality municipal green spaces of appropriate types.

We excluded Sheffield’s three municipal golf courses; these have citywide catchment areas but this is clearly based on their attraction as a leisure facility (as defined in leisure facility measures) offering golf, rather than as a green space, and the booster participant questionnaire responses indicated that very few participants played golf.

One potential problem with using the green space data for Sheffield is that many of the booster participants live on the edge of the city and could be using municipal green spaces belonging to surrounding authorities (Barnsley Metropolitan Borough Council, Rotherham Metropolitan Borough Council, Derbyshire County Council or North East Derbyshire District Council). This was a matter of sufficient concern for us to request green space boundary data from these authorities. However, because of the green belt around Sheffield, there are actually few important municipal green spaces belonging to these authorities that are close to the borders of Sheffield. The exception to this is Rotherham, with the two conurbations forming a continuous urban area. However, this area is heavily industrialised and there are few important municipal green spaces. One very important exception is Rother Valley Country Park, which borders south-east Sheffield; a boundary polygon for this park was added manually to the set of green spaces having a citywide catchment area.

All green space measures in this study are shortest distance measures. So far we have decided not to use a gravity model for green space as the need to include an arbitrary distance decay parameter would be a potential source of bias. However, this remains an option for future work. Regarding the more sophisticated floating catchment area gravity model, this may actually be inappropriate for green space: unlike a capacity-constrained service such as a health practitioner, a green space that is heavily used (and thus full of people) may be more attractive and more likely to be perceived as appropriate for recreational exercise or as a walking route than one that is less well used.

Leisure facility measures

Leisure facilities, as distinct from green spaces, are defined here as places where a physical activity is facilitated by some kind of organisation, usually in return for payment. For example, we define a tennis club as a leisure facility but an unsupervised tennis court within a park as part of a green space. Similarly, a publicly accessible playing field is considered a green space rather than a leisure facility, unless it is part of a sports club. Data on leisure facilities are easier to collect than data on green spaces because leisure facilities can be treated as point locations. Even though these facilities may cover a large area, there is usually an office where people must go to pay, and this is typically also the building to which the address of the facility relates. Therefore, noting the limitations of geocoding accuracy explained in Network distance analysis, it is credible to use the postcode centroid of the facility’s address as a point location.

The chief problems in collecting data on leisure facilities were twofold:

-

deciding which types of leisure facility were relevant to the booster participants

-

ensuring that all leisure facilities of these types, located within a reasonable distance of the study area, were included.

To address the first point we had the benefit of the questionnaires completed by the booster participants (see Outcomes and Survey). These data suggest that the main physical activities relevant to the participants were walking, gardening, swimming and gym-based activities. Walking relates to municipal green space rather than leisure facilities and gardening relates to neither, so we considered only leisure facilities offering a gym and/or swimming.

To address the second point we used the Sport England online ‘active places’ database,68 which provides an authoritative list of sports facilities, with each facility listed as offering one or more types of activity. Two of these types of facilities, ‘health and fitness suite’ and ‘swimming pool’, correspond directly to gyms and swimming respectively. The postcode of each facility is also included on the database, as is an indicator of how the public can access the facility (those open only to sports clubs or community associations, rather than individuals, were excluded). For each facility postcode we calculated the network distance to every other postcode within Sheffield, and for each Sheffield postcode we recorded the shortest network distance to:

-

a unisex gym

-

a female-only gym

-

a swimming pool.

As with green space, we did not implement any of the more sophisticated ‘gravity’ models for leisure facilities. The basic gravity model is additive, meaning that having three gyms a 500-m network distance from one’s home would be scored three times better than having one gym 500 m away. This is clearly inappropriate as gyms are often paid for on a membership basis, and it is unlikely that a participant would join several gyms. Although swimming may be offered on a pay-per-session basis more frequently than gym facilities, it is still questionable whether having three local pools is exactly three times better than having one local pool.

Here, the floating catchment area gravity model is potentially more useful than the basic gravity model as it links the usefulness of local facilities to local demand. 69 A gym may be less desirable if it is frequently crowded and one has to wait to use particular exercise machines, and the same may also apply to lane swimming in pools. In this context having multiple local facilities can be beneficial, as greater provision of facilities means that they are less likely to be crowded. Unfortunately, the problem with interpreting this model is determining local demand; although the size of the local population can be easily obtained from census data, people often choose leisure facilities close to where they work rather than where they live, so using population data could be misleading, particularly in the city centre.

Given these issues, and for consistency in the analysis methods, we have used straightforward minimum distance analysis.

With leisure facilities there is also the issue of affordability. Some facilities are expensive and may not be realistically accessible to the more deprived communities targeted by the booster recruitment strategy. However, pricing information is not included in the Sport England database and it was not possible within the timescale of this project to obtain pricing information separately for each facility. Restricting the analysis to municipal facilities was considered but in Sheffield some privately run leisure facilities are less expensive than municipal ones. It is therefore important to recognise that affordability may be an additional barrier to accessing local leisure facilities, even when they are geographically close, which this analysis does not address.

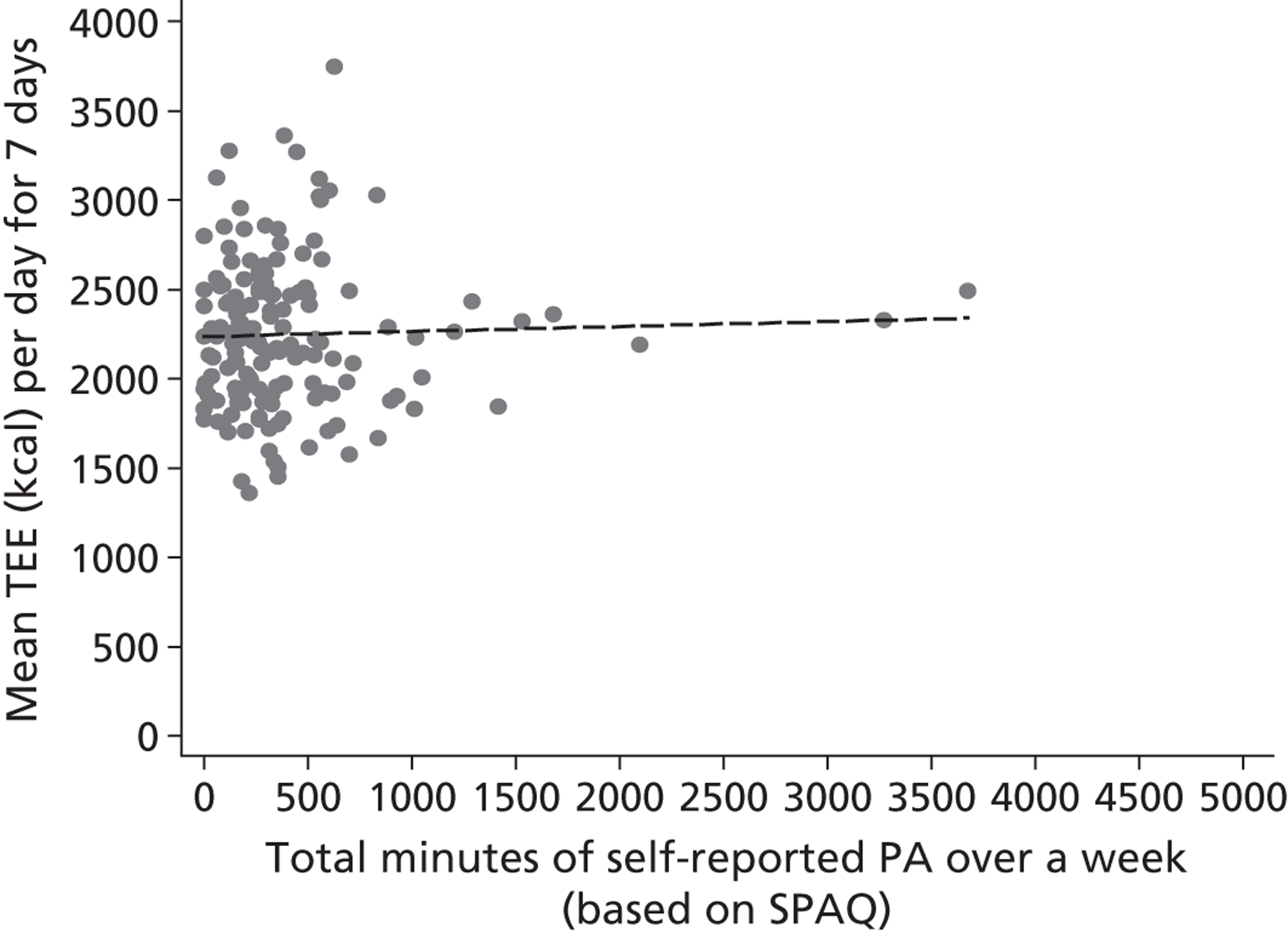

Statistical methods

We constructed crude scatter plots of mean TEE per day (kcal) at 3 months against potential moderators generated from the geographical information systems (GIS) analysis and other continuous baseline potential moderators to explore any univariable linear relationships. In addition, we stratified these plots by intervention arm to explore whether the univariable linear relationships were consistent within the intervention arms. Univariable linear regression models were fitted with amount of physical activity measured by mean TEE per day (kcal) as the response and potential moderator as an explanatory variable to explore whether a potential moderator was a predictor of physical activity at 3 months.

To explore the moderation effect, we fitted multivariable linear regression models on the same response variable with intervention group, potential moderator and interaction between treatment group and potential moderator as explanatory variables (as given by Equation 3). Plots of the fitted regression line stratified by booster treatment group were constructed to explore any potential interactions. In addition, hypothesis testing on the interaction term was also undertaken using Equation 3 to test the moderation effect of GIS variables on physical activity. Variables were classified as being moderators of physical activity if they had a significant interaction effect with treatment at 3 months.

Methods for the health economic analysis

Introduction

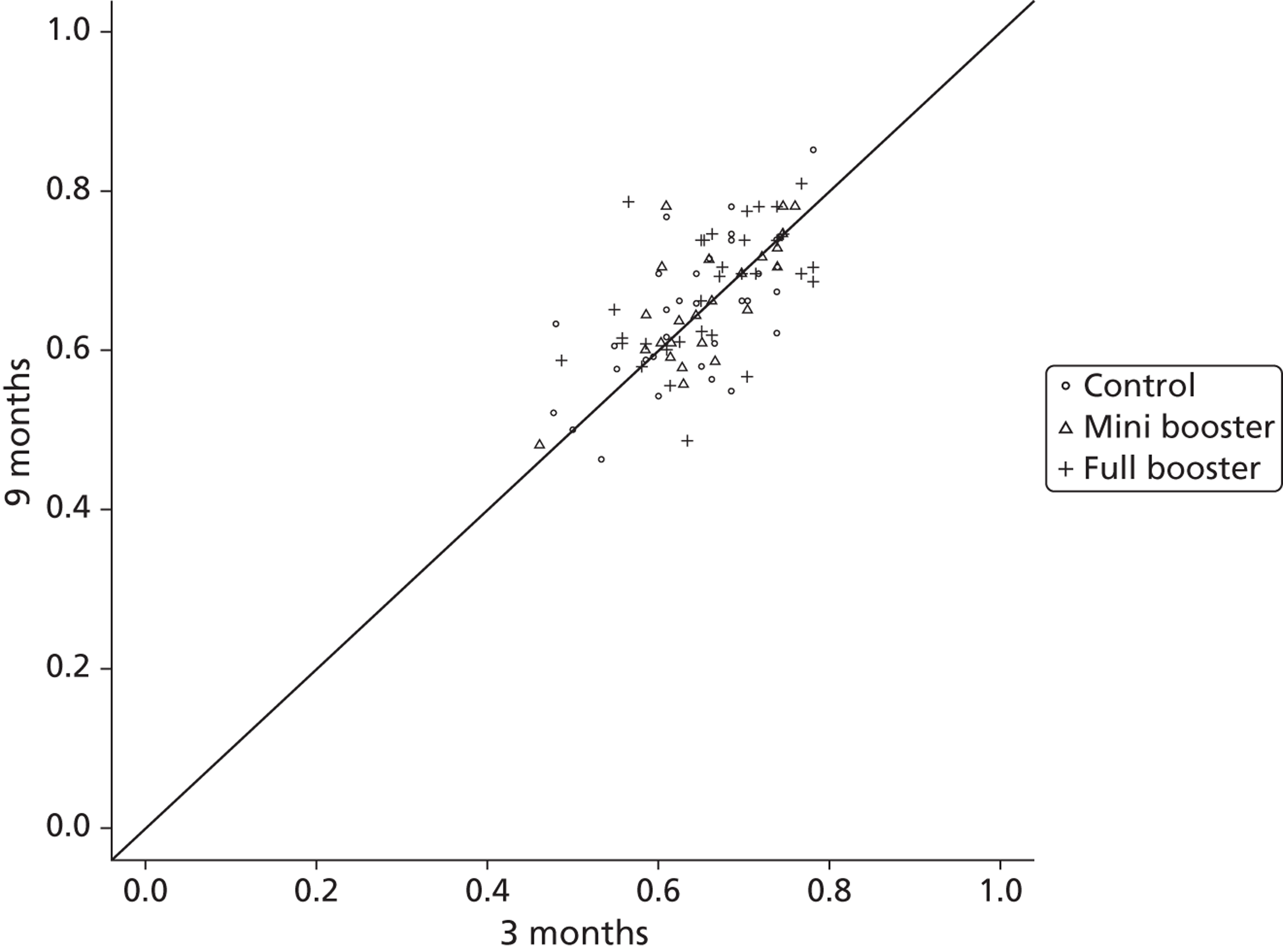

As part of the trial data collection, participants answered questions on their use of NHS facilities at 3 months and 9 months post randomisation. Participants also completed the SF-12v2 plus 4 HRQoL questionnaire, allowing SF-6D HRQoL scores at 3 and 9 months to be produced. 70 Together with an estimate of the intervention cost, such data allow a simple estimate of the effect of the intervention on mean HRQoL and average cost to be produced by comparing costs and utility scores at the end of the intervention with those before the intervention.

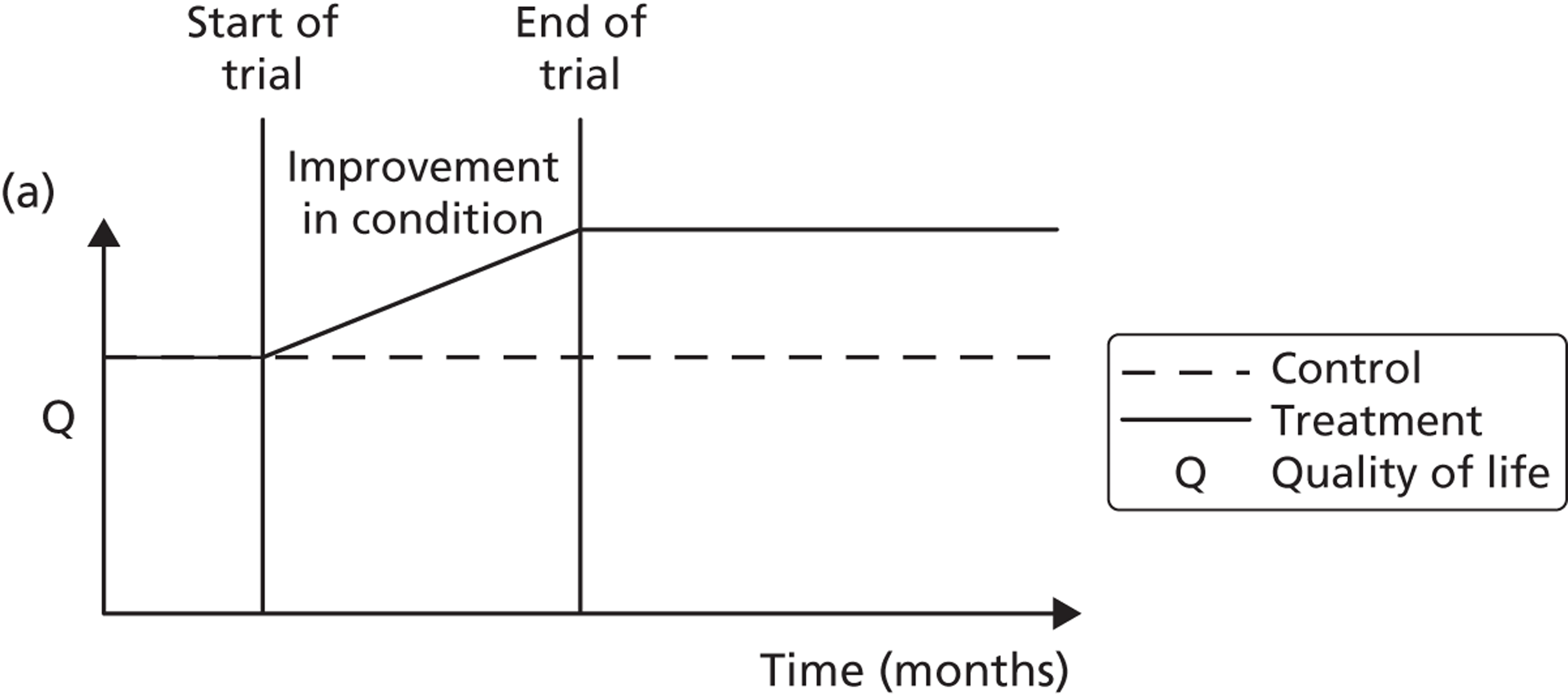

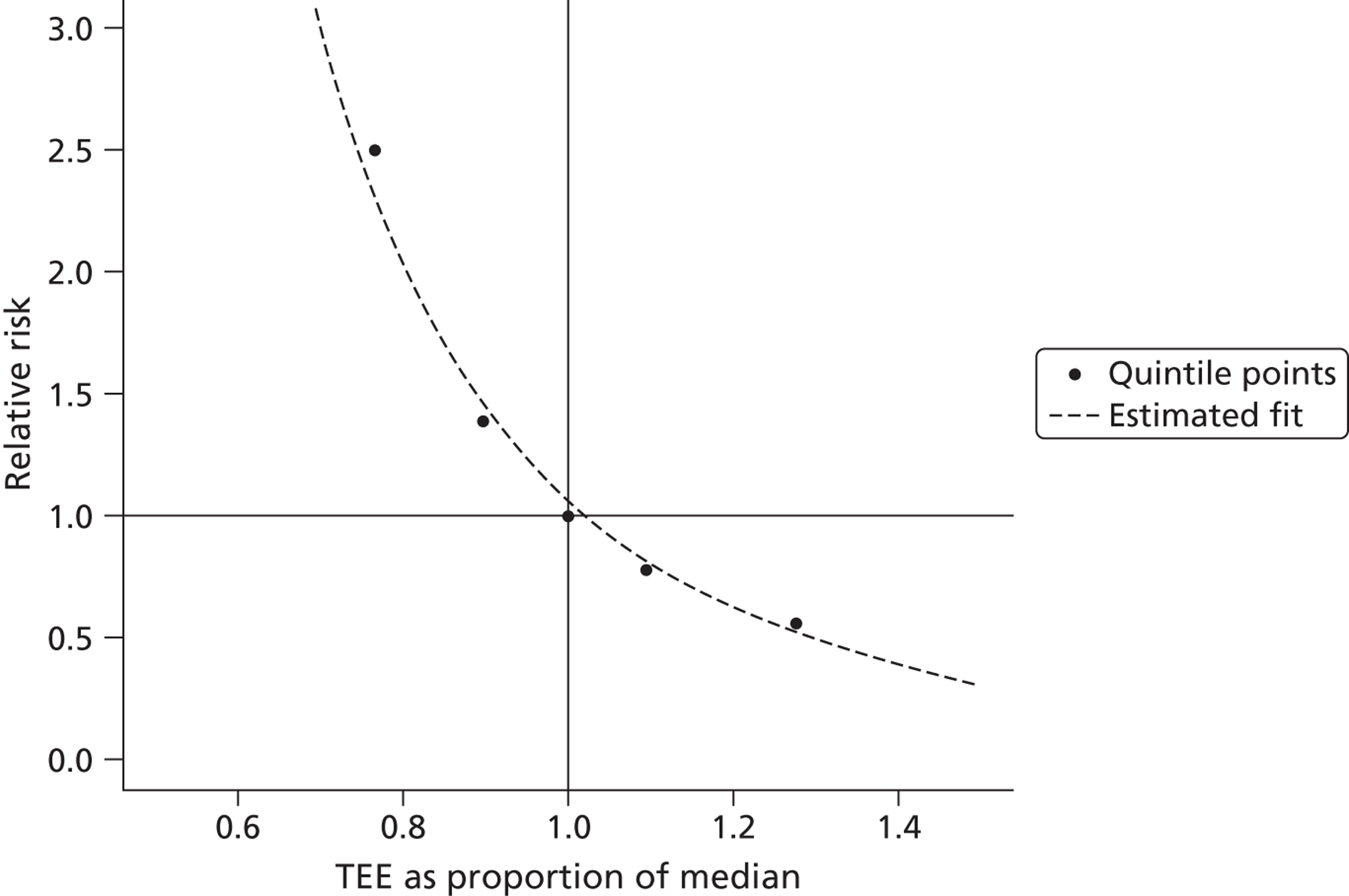

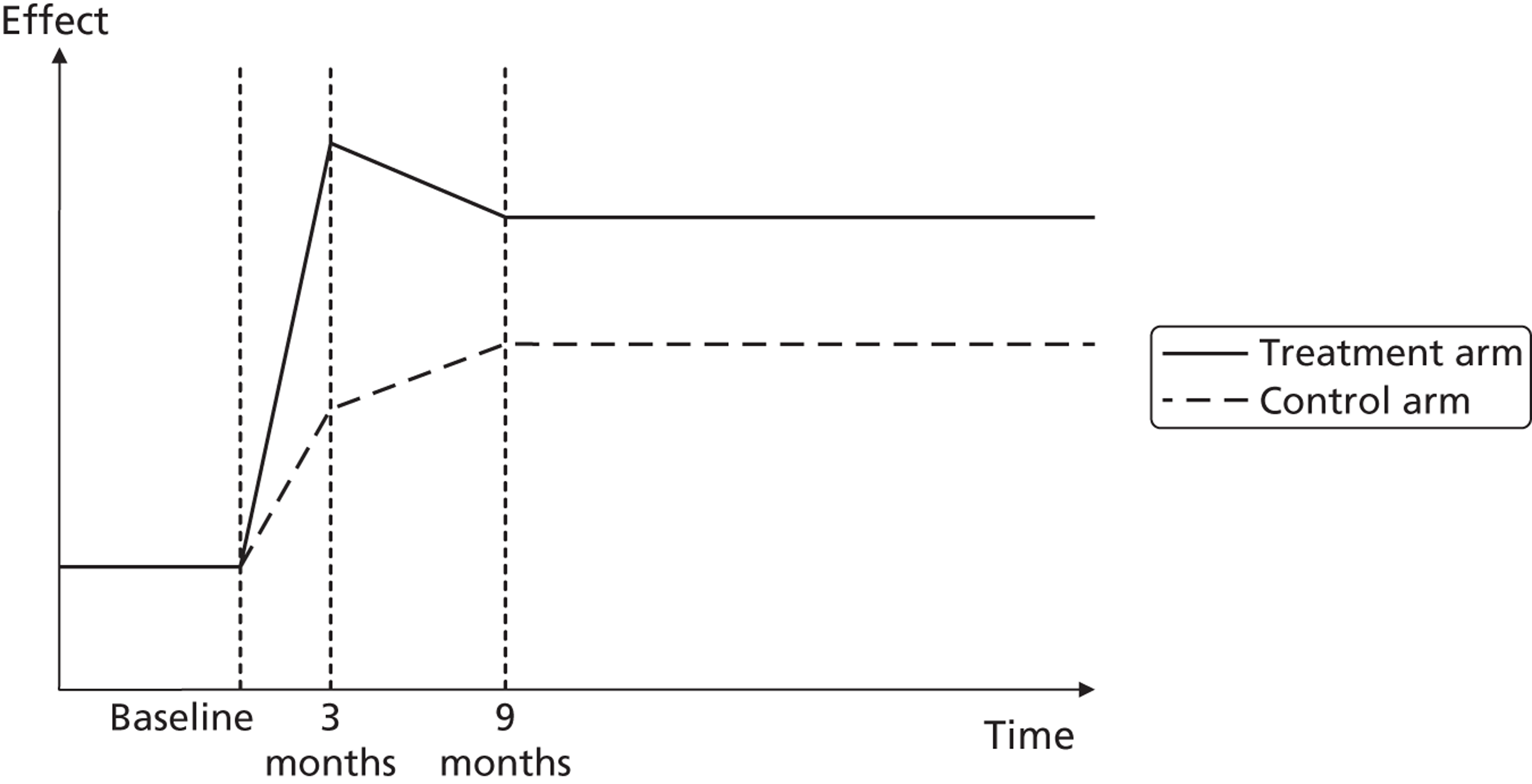

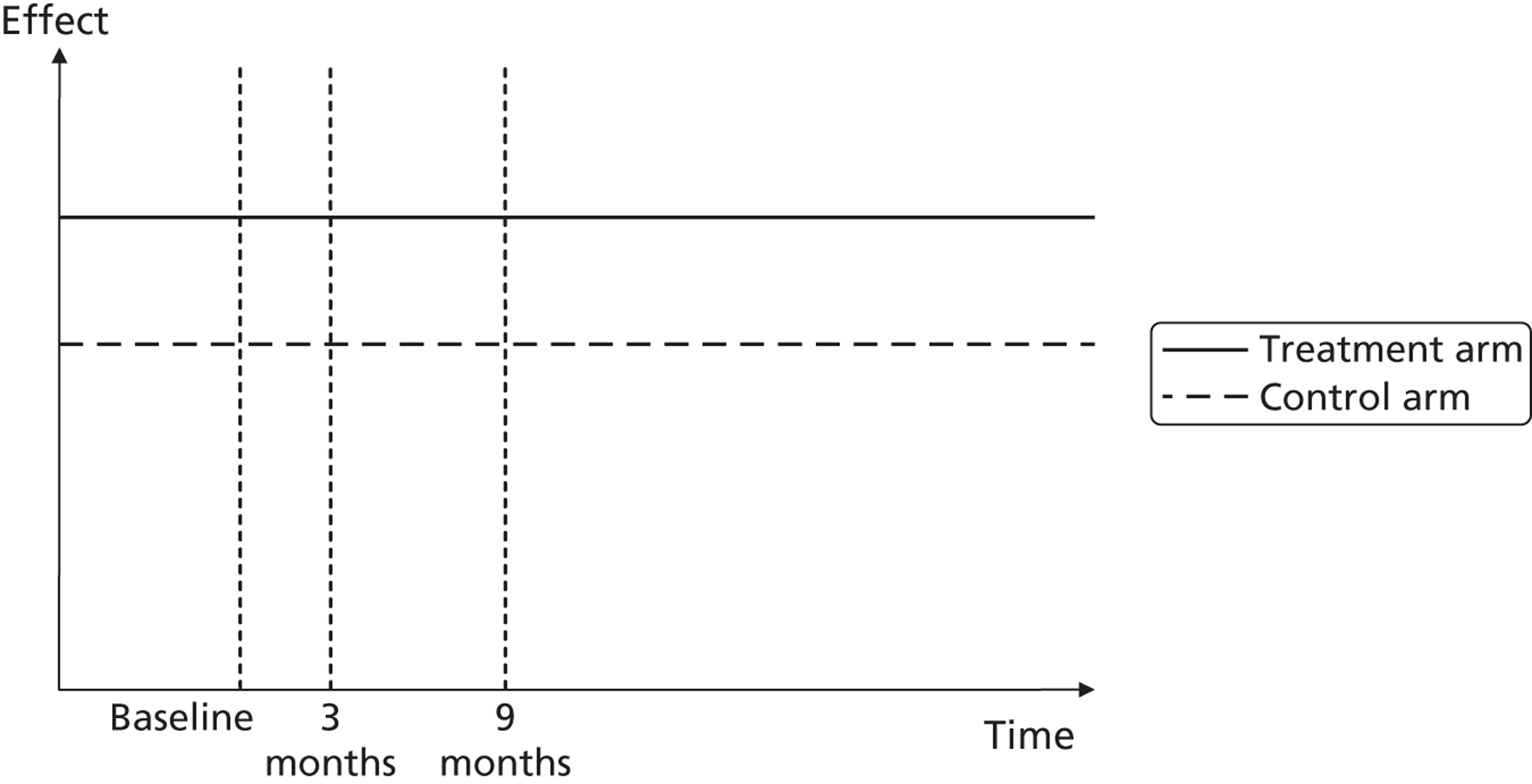

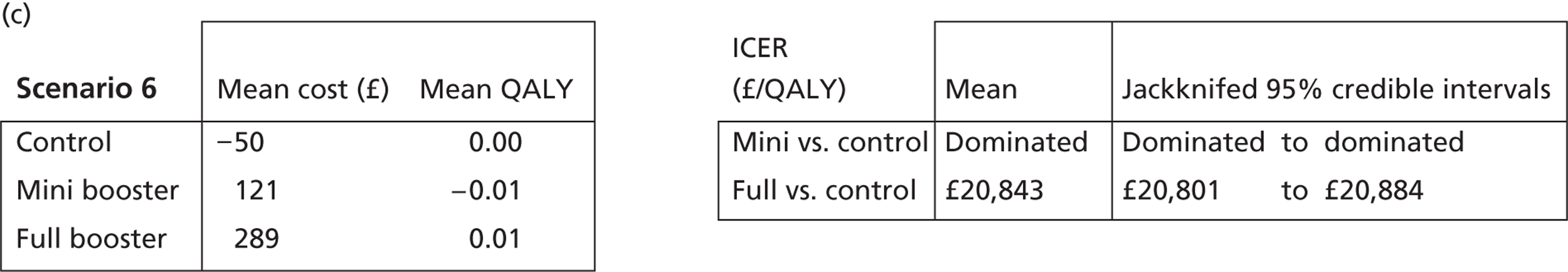

A potential problem with using this approach in the case of the booster intervention is illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 1a illustrates a typical pharmaceutical RCT. The patient population is recruited on the basis of suffering from a particular disease, which has a progressive effect on their HRQoL. The intervention reduces disease progression and so a difference in HRQoL emerges between the intervention arm (dashed line) and the control arm (solid line) by the end of the trial. Figure 1b indicates the potential effect on HRQoL of a lifestyle intervention. Both the control arm and the intervention arm are generally in good health initially but because of low levels of physical activity both are at an increased risk of developing a range of diseases and conditions related to sedentary behaviour. As the intervention is not intended to modify a disease but instead modify a lifestyle factor that predisposes people over the long term to increased morbidity and mortality risks, a straightforward comparison of before-and-after levels of resource use and HRQoL may be misleading as it may have been too soon for the mediating effect of physical activity on health to have become apparent.

FIGURE 1.

Timing of HRQoL benefits. (a) Curative intervention; and (b) preventative public health intervention.

For this reason, the cost-effectiveness of the interventions was assessed using two distinct modelling approaches. Alongside a short-term model comparing participants’ self-reported HRQoL and NHS resource use at 3 and 9 months, a long-term epidemiological model was also developed in which differences in the primary physical activity measure recorded in the trial, TEE, were mapped onto effects on mortality reported in epidemiological literature. This approach better allows the complex mediating effects of physical activity on health to be formally represented but also increases the dependence of the modelling results on strong assumptions about this physical activity–health relationship.

In the rest of this section overviews of the methods used to produce the two models are provided.

Cost-effectiveness modelling overview

Two types of cost-effectiveness model were developed, which used different approaches and sources of data to estimate the health effect, in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), of the interventions. Both types of model are described in more detail below.

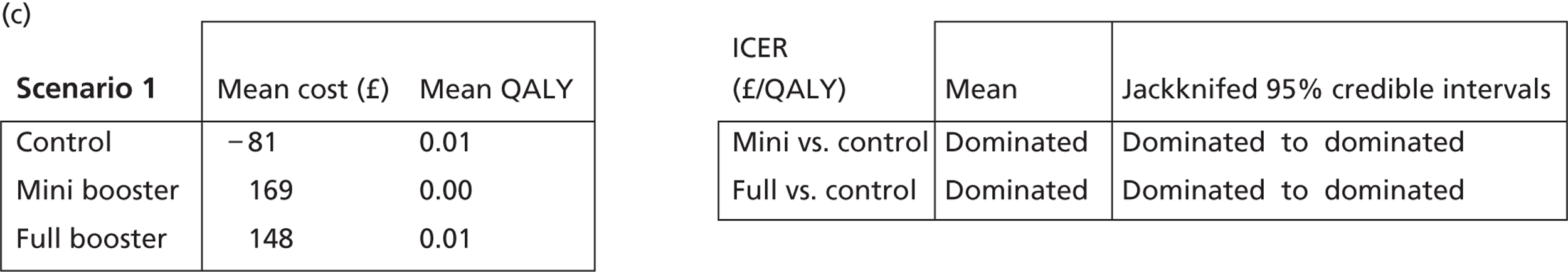

Short-term questionnaire-based model

A short-term cost-effectiveness model has been constructed that incorporates trial-based estimates of the effect of the two interventions – mini booster and full booster – on participants’ use of NHS resources during the trial period. It also uses trial-based estimates of the effect of the interventions on participant utility using responses from participants who completed the SF-12v2 plus 4 HRQoL questionnaire at baseline and 9 months. 70 Approximate costs of the interventions are also incorporated in the model alongside the estimates of the effect of the interventions on resource use.

Resource use data collected and used

Data were collected at randomisation and at the end of the trial on participant use of NHS facilities. This included all face-to-face and telephone consultations with general practitioners (GPs) and other primary care staff, attendance at hospital accident and emergency (A&E) facilities, use of hospital outpatient facilities, number of hospital day cases and number and duration of hospital stays. With these data it is possible to produce an estimate of the effect of the intervention on resource use from an NHS perspective. Uncertainty in the true frequency with which each type of NHS resource was accessed was represented using a Dirichlet distribution with a non-informative prior of 0.5 added to each cell count.

For each trial arm – control, mini booster and full booster – the number of times that each participant had been to A&E, used hospital outpatient facilities, been a hospital day case and stayed overnight in hospital was recorded at both randomisation and up to 9 months later. Along with the reason for each resource use event, the number of times that type of resource was accessed for that reason was also recorded. For example, some participants may stay 2 nights in a hospital for a particular reason, others may have three hospital day appointments for another reason. What is of interest from a resource use perspective is the number of resource use units – such as nights in hospitals, day appointments, A&E admissions – rather than number of events. For this reason the number of resource use units of each resource use type was calculated by multiplying the number of resource units represented by an event by the frequency of each event. Costs for each type of resource use unit were estimated from a standard source71 to produce estimates of the cost of each type of resource use at the start and end of the trial and in each trial arm. These were divided by the number of participants in each arm to produce an estimated cost per participant.

Estimating costs from a societal perspective

These data were also used to provide estimates of the effect of different health conditions from a broader, societal perspective, which are presented as separate analyses. From this broader perspective, each use of a NHS facility was assumed to incur an additional cost. This additional cost was calculated as the national minimum wage for older people of working age multiplied by an assumed amount of time that it would take a patient to make use of each particular service type. The number of working hours foregone in making use of each type of NHS resource is shown in Table 4.

| Resource type | Assumed working hours foregone |

|---|---|

| Visit to A&E | 15 (2 days) |

| Hospital day case | 7.5 (1 day) |

| Hospital outpatient | 7.5 (1 day) |

| Hospital overnight stay | 7.5 (1 day) |

| GP telephone consultation | 1 |

| Visit to GP surgery | 3.75 (half a day) |

Although a significant proportion of the patient population was close to, or older than, retirement age and so may not be expected to be in full-time employment, the same opportunity costs were applied to all patients. This is to account for the societal value of services that people who are not in employment can be assumed to provide to friends and family, such as looking after children, home maintenance, looking after pets and so on. Each of these services can be bought and so has a market value at or above minimum wage. These simplifying assumptions are more likely to overestimate than underestimate the true societal costs and so could be considered an upper range of the cost-effectiveness of the interventions from a societal perspective.

Estimating health-related quality of life

Responses from participants who completed the SF-12v2 plus 4 questionnaire were used to derive an SF-6D utility score. 70 Differences in differences between an intervention arm and the control arm are used to produce an estimate of the incremental effect of each intervention on participant utility over this period.

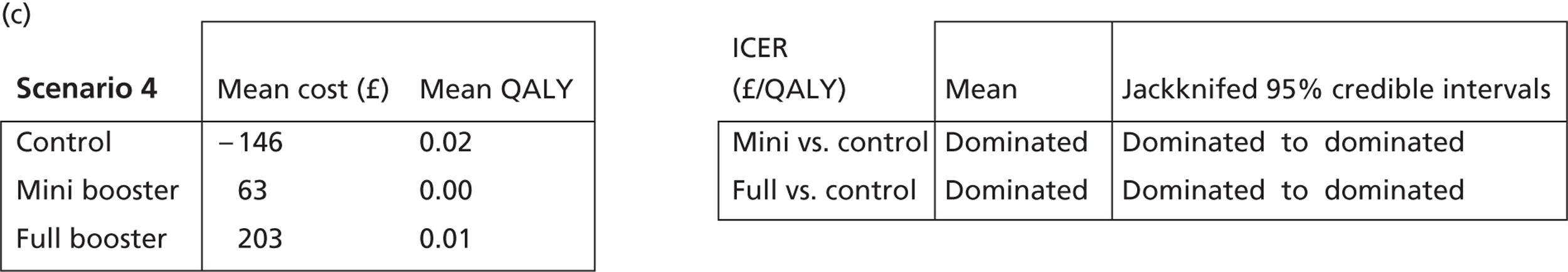

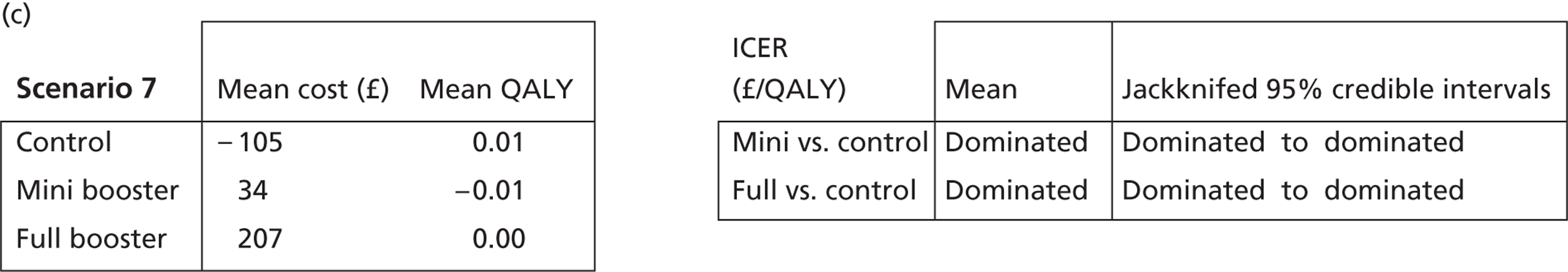

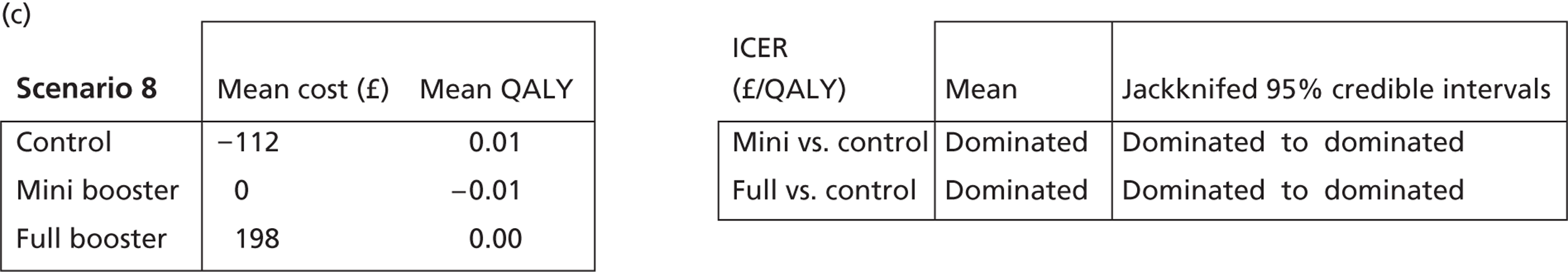

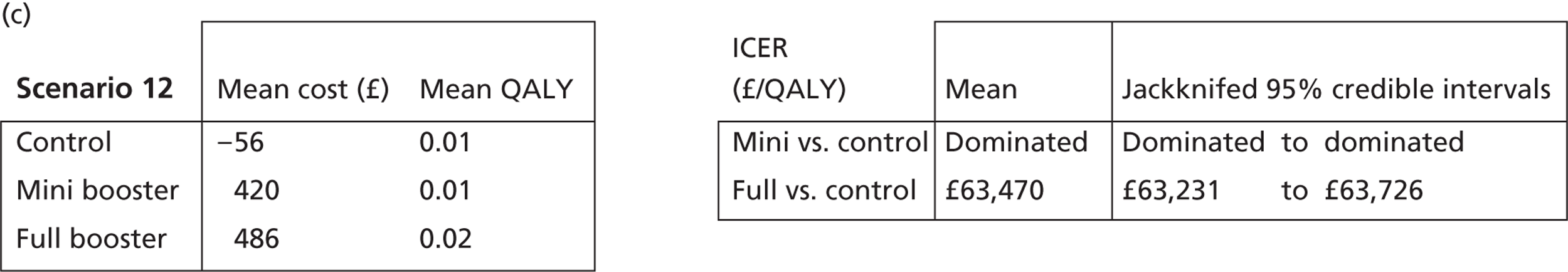

Deterministic results

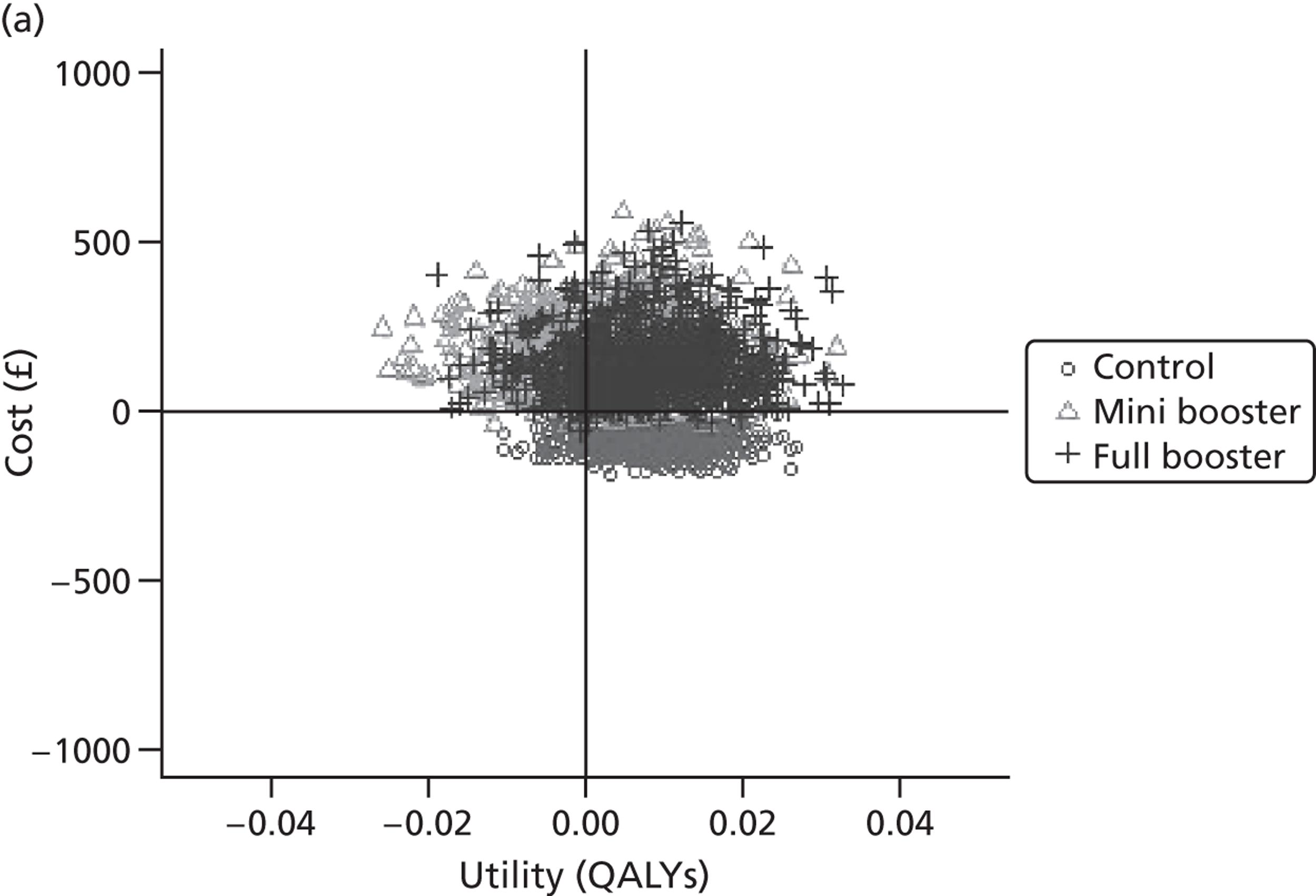

A version of the model is presented that provides a single best estimate of the mean incremental cost and mean incremental QALY gain for both the mini booster and full booster interventions. These best estimates combine resource use and utility values estimated from trial data with approximate intervention costs elicited from report authors involved in conducting the interventions. These estimates are somewhat approximate and are intended more to be illustrative than authoritative. The effect of the high level of uncertainty in these estimates on decision uncertainty is explored through probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA).

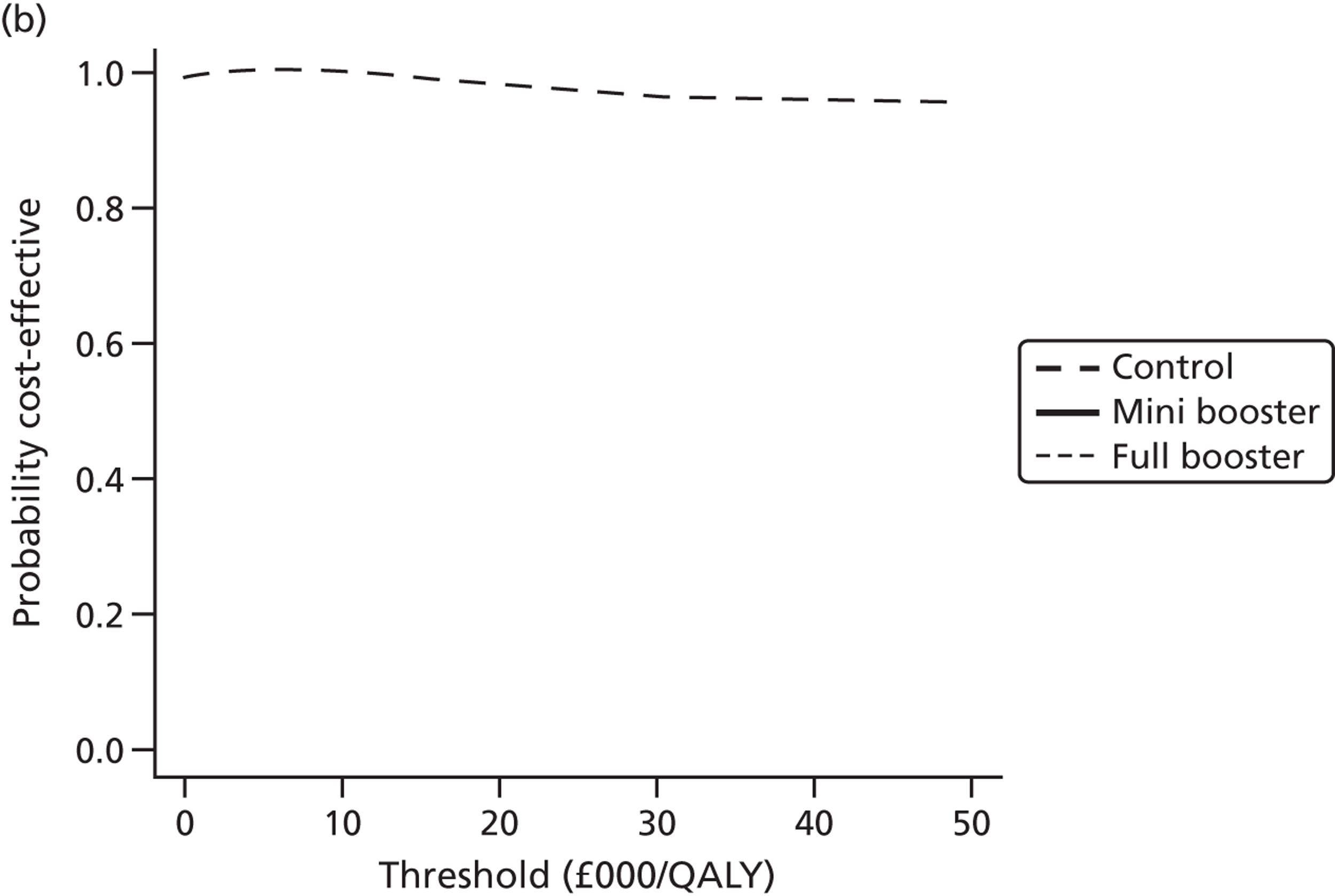

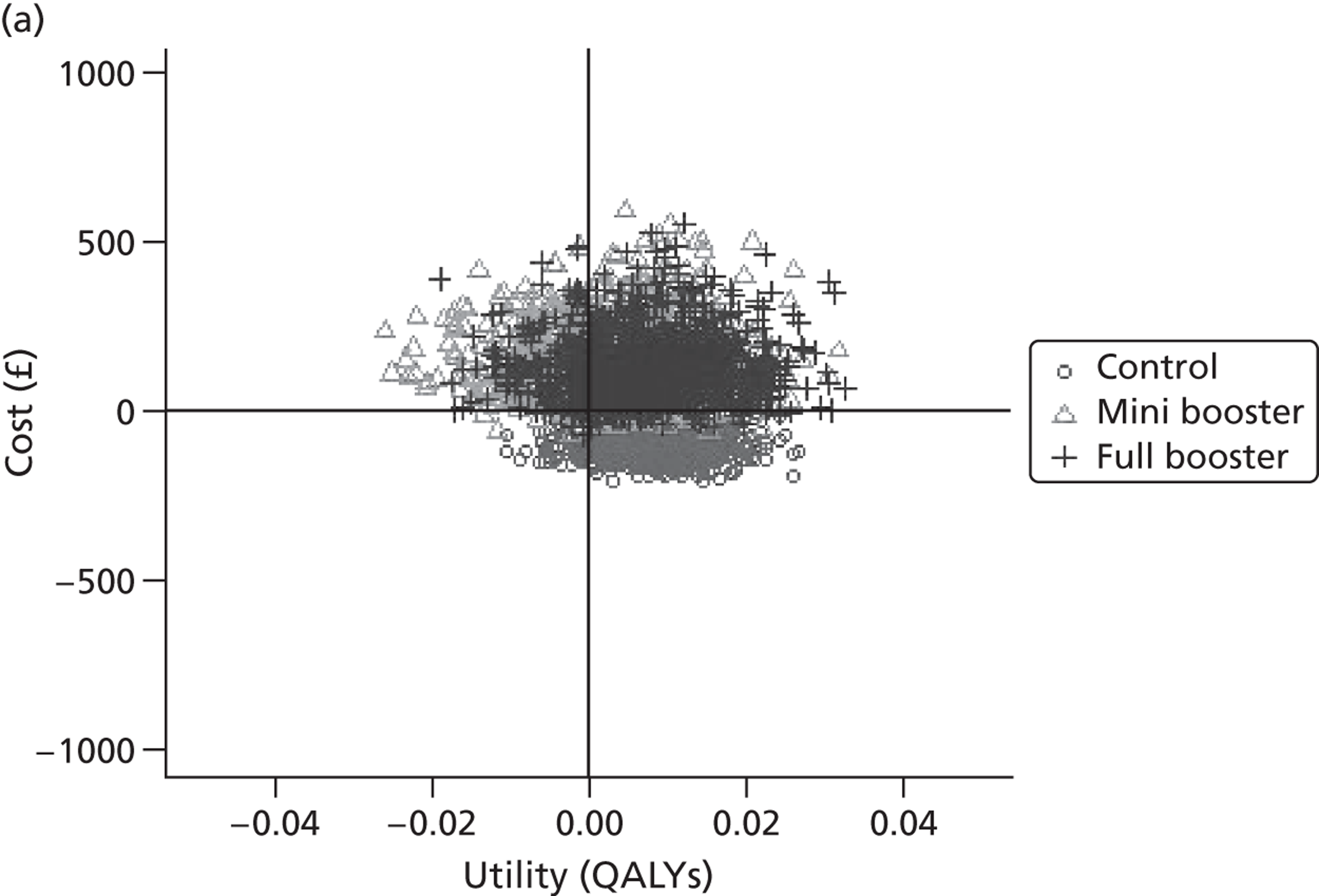

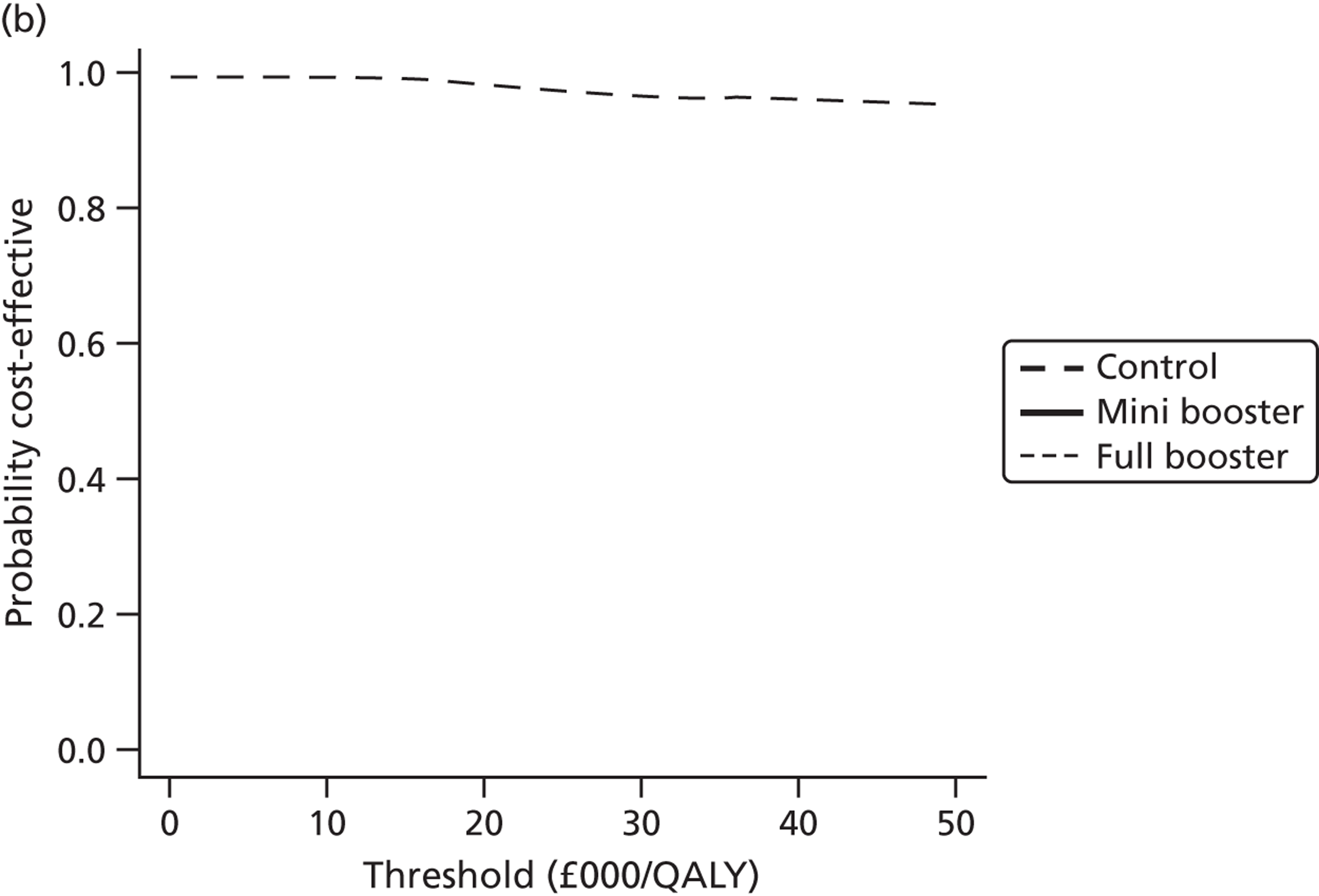

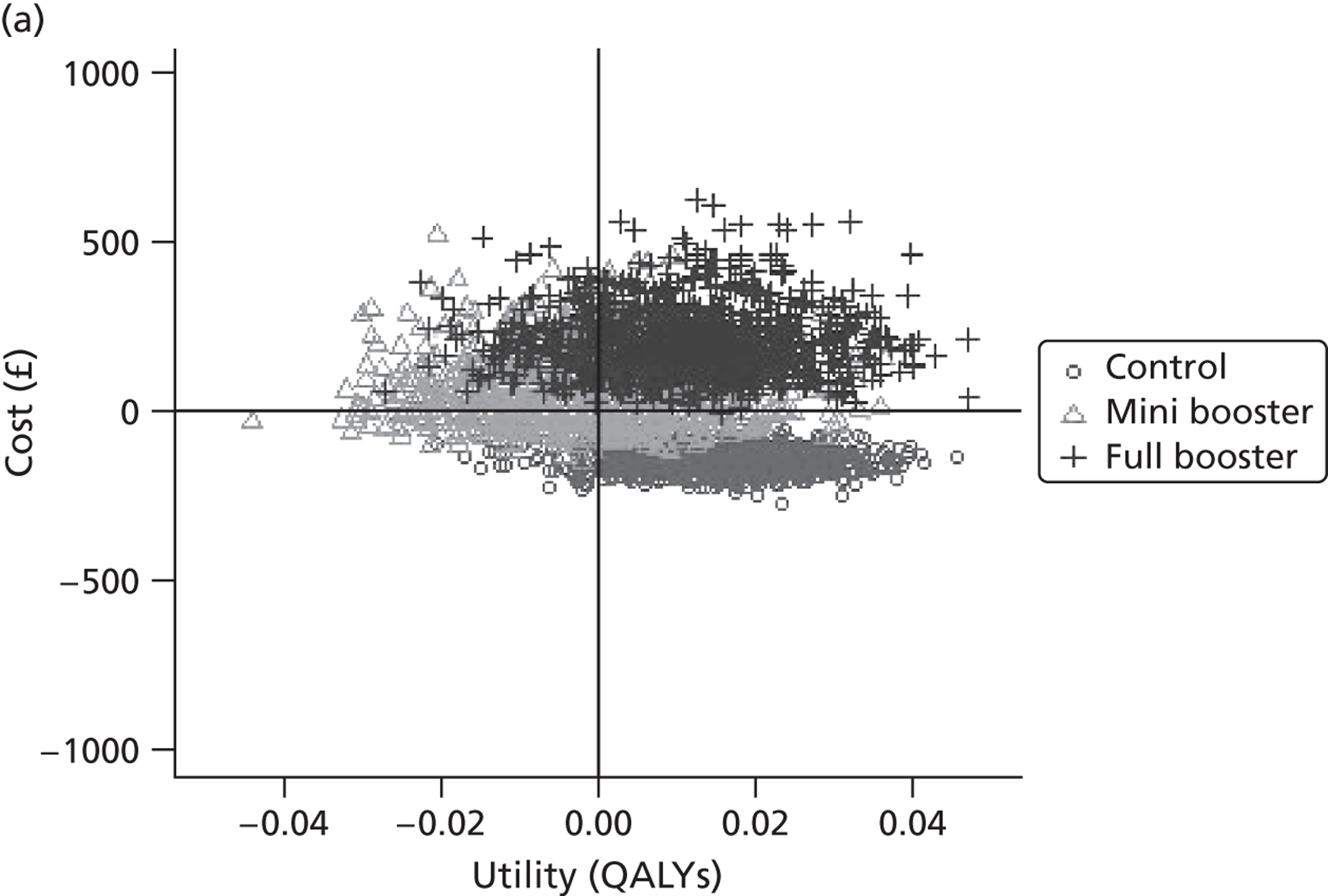

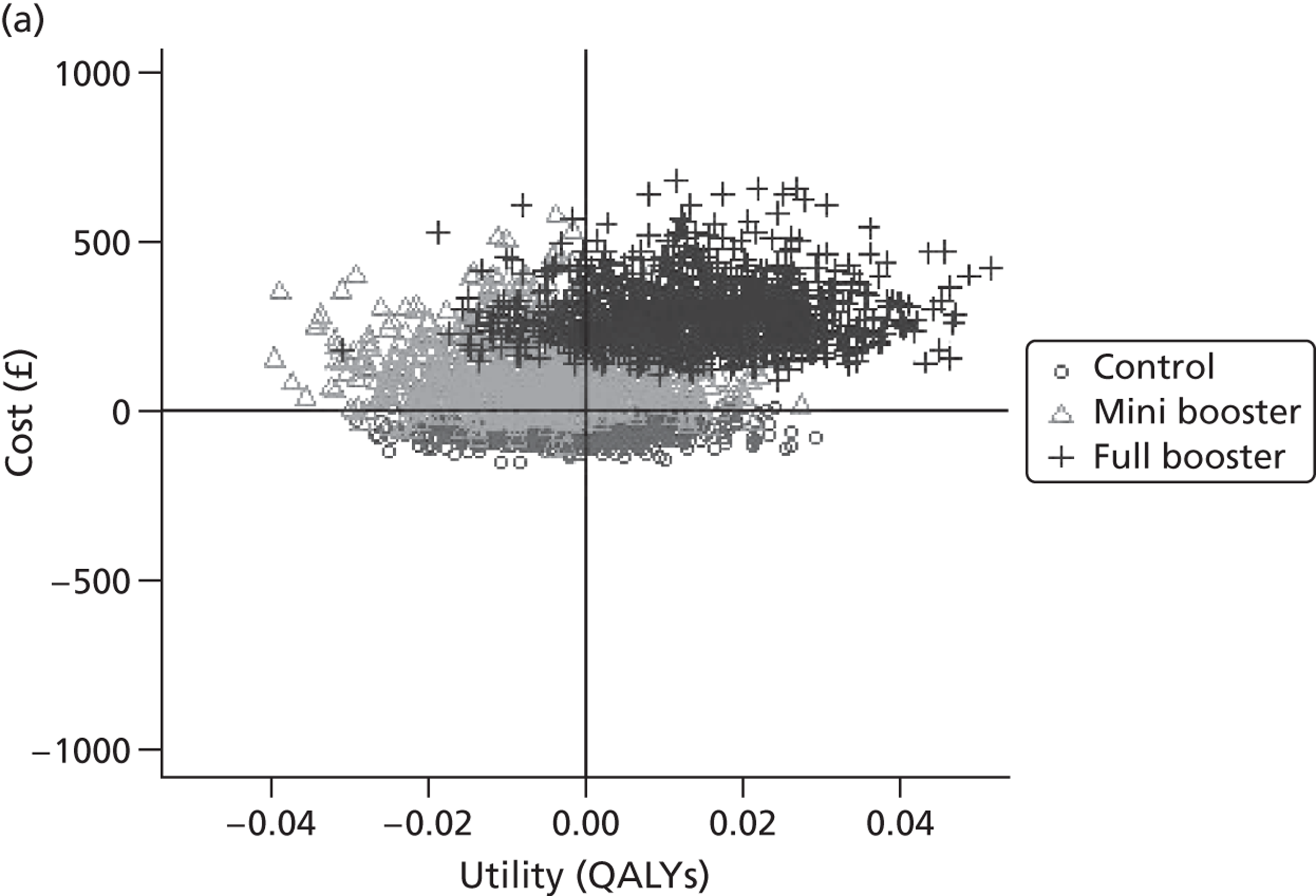

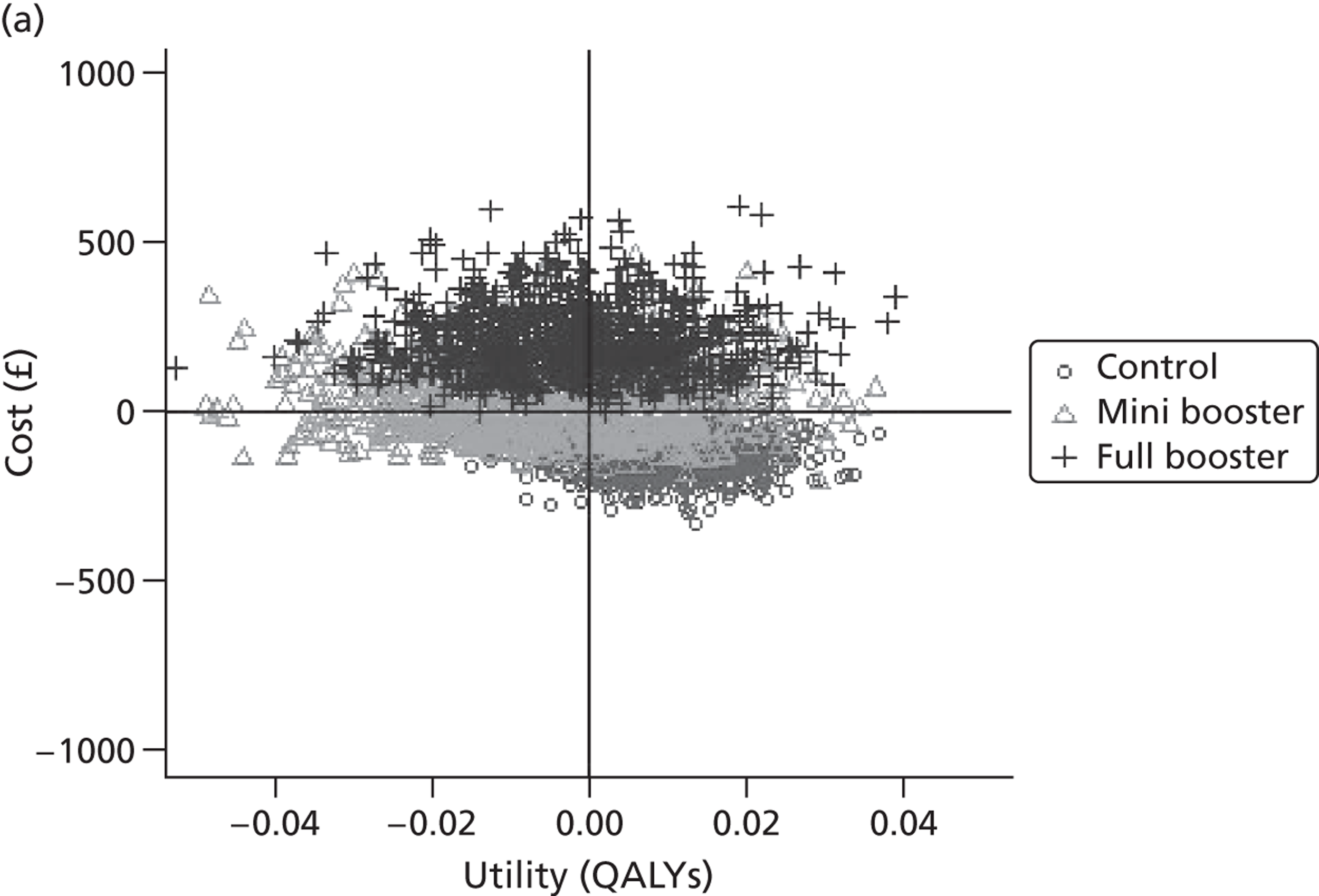

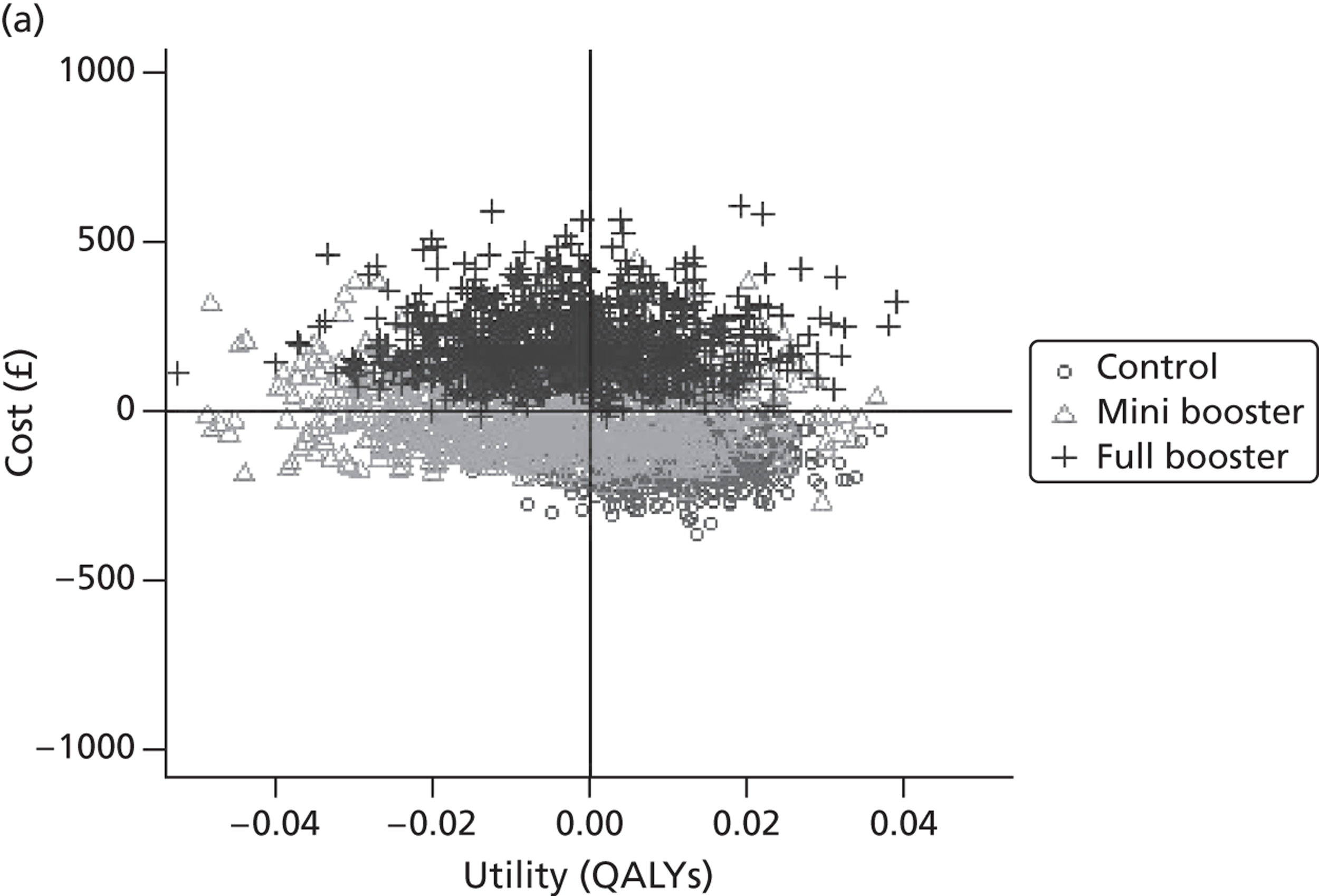

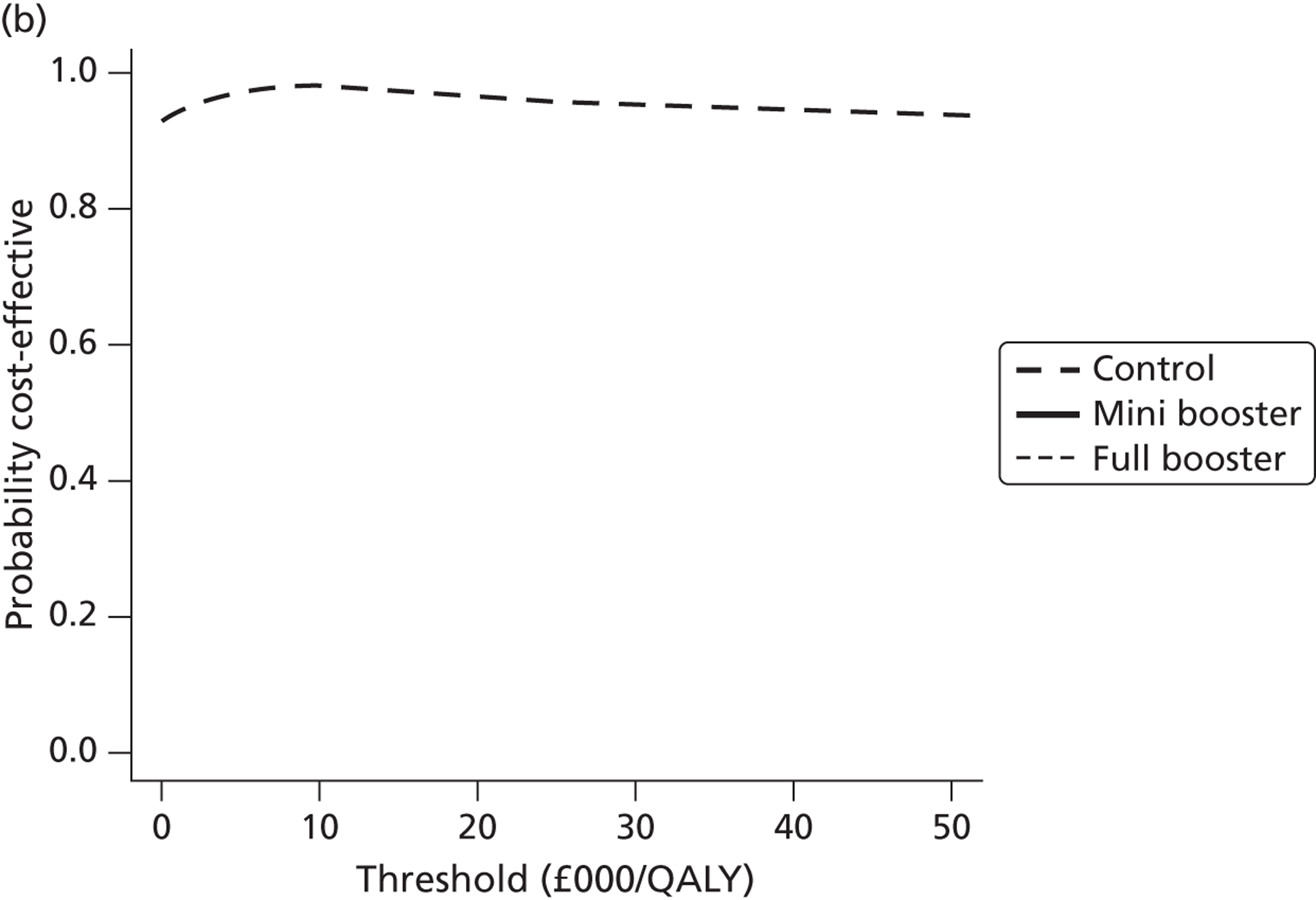

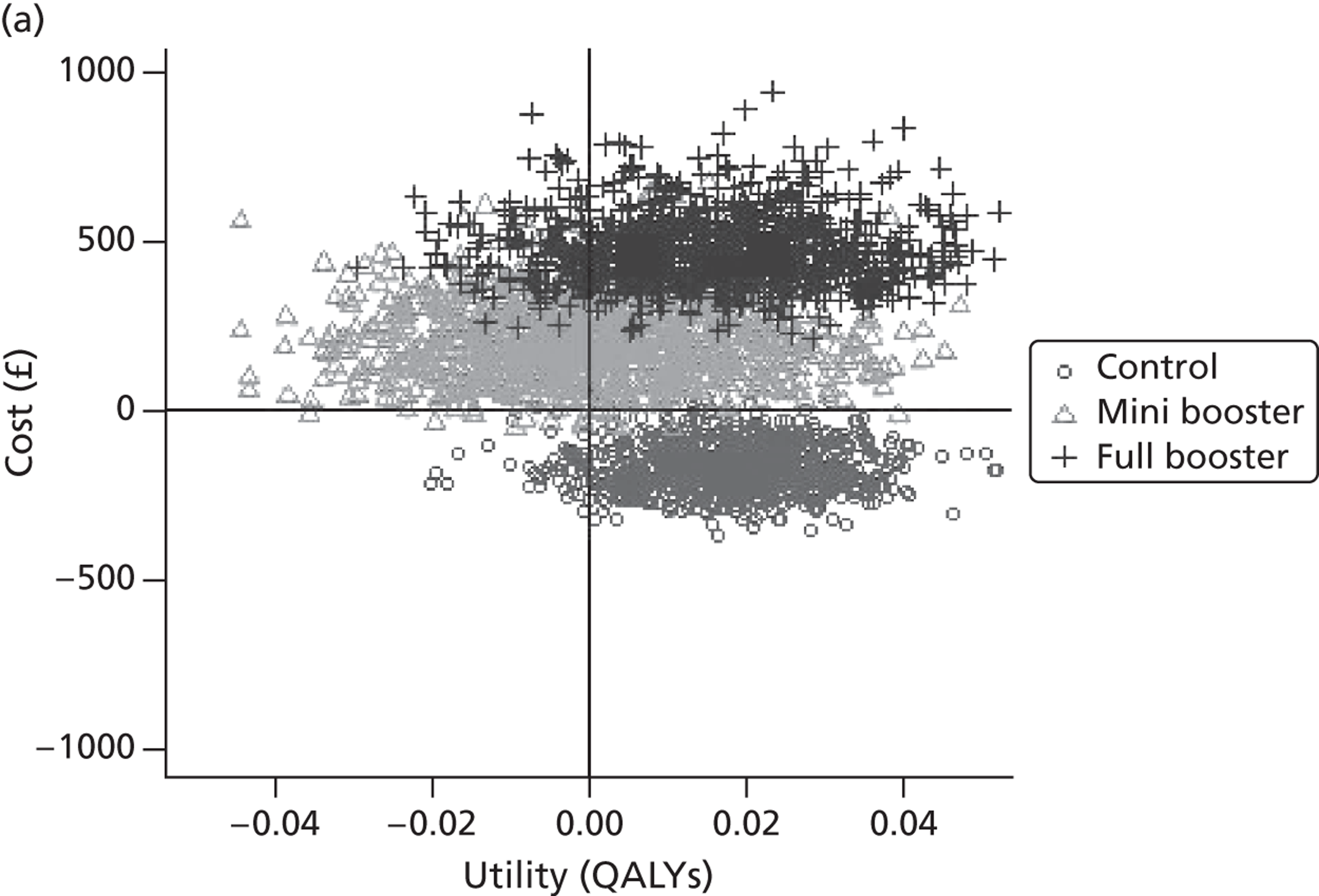

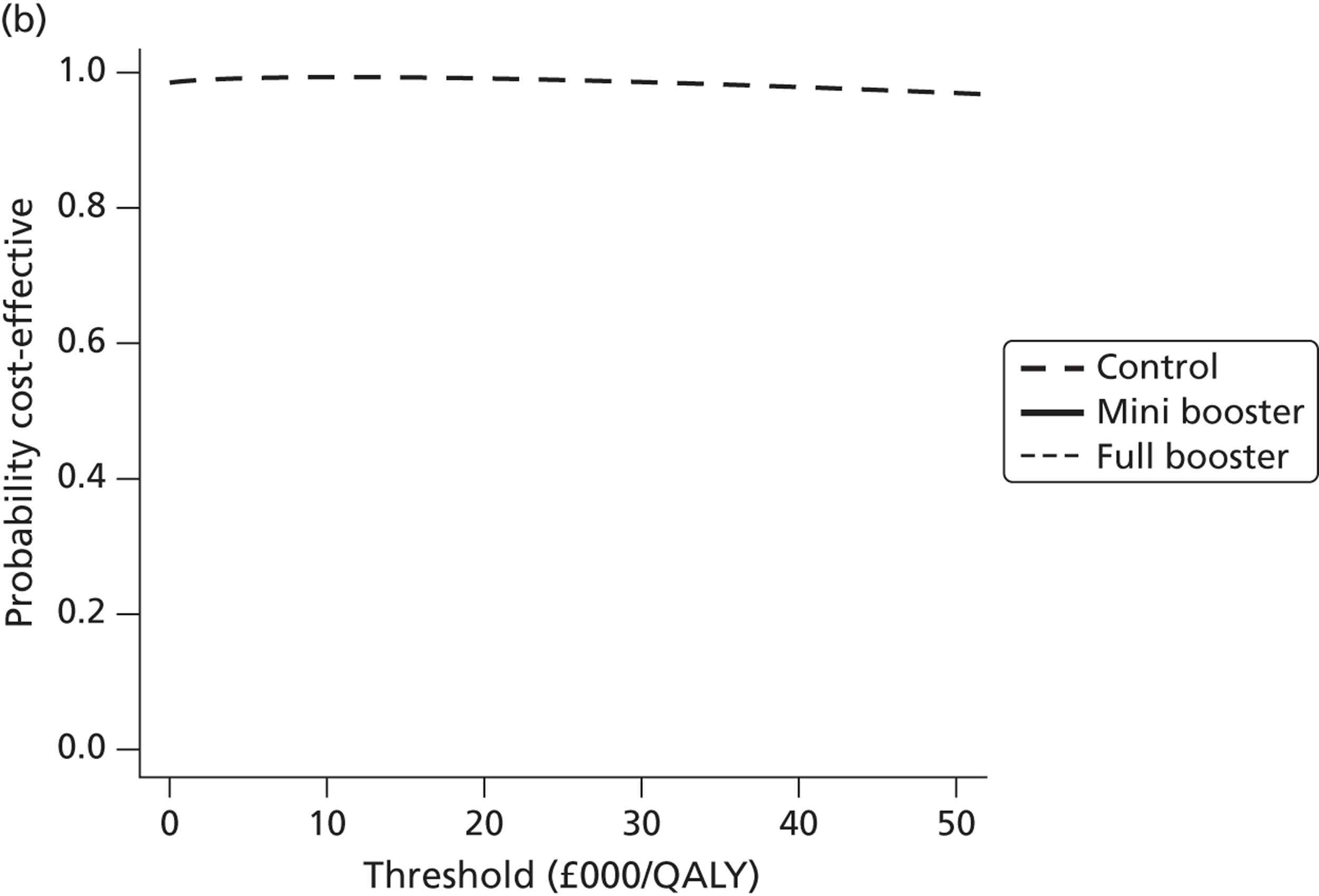

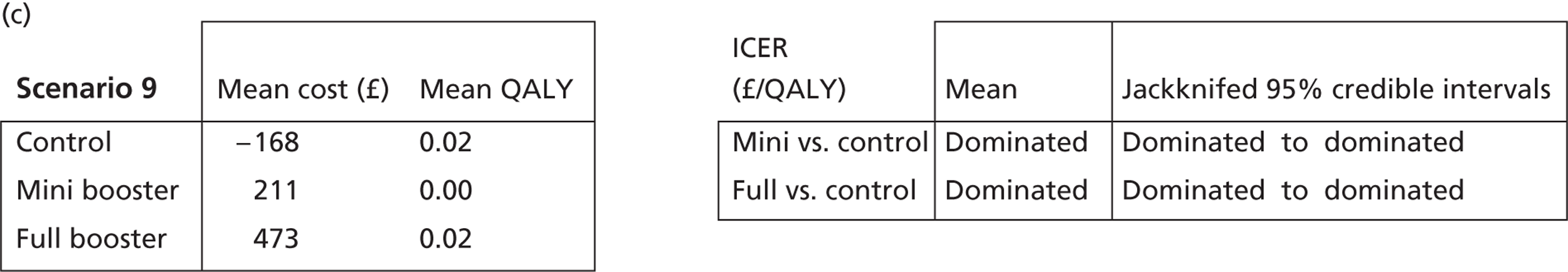

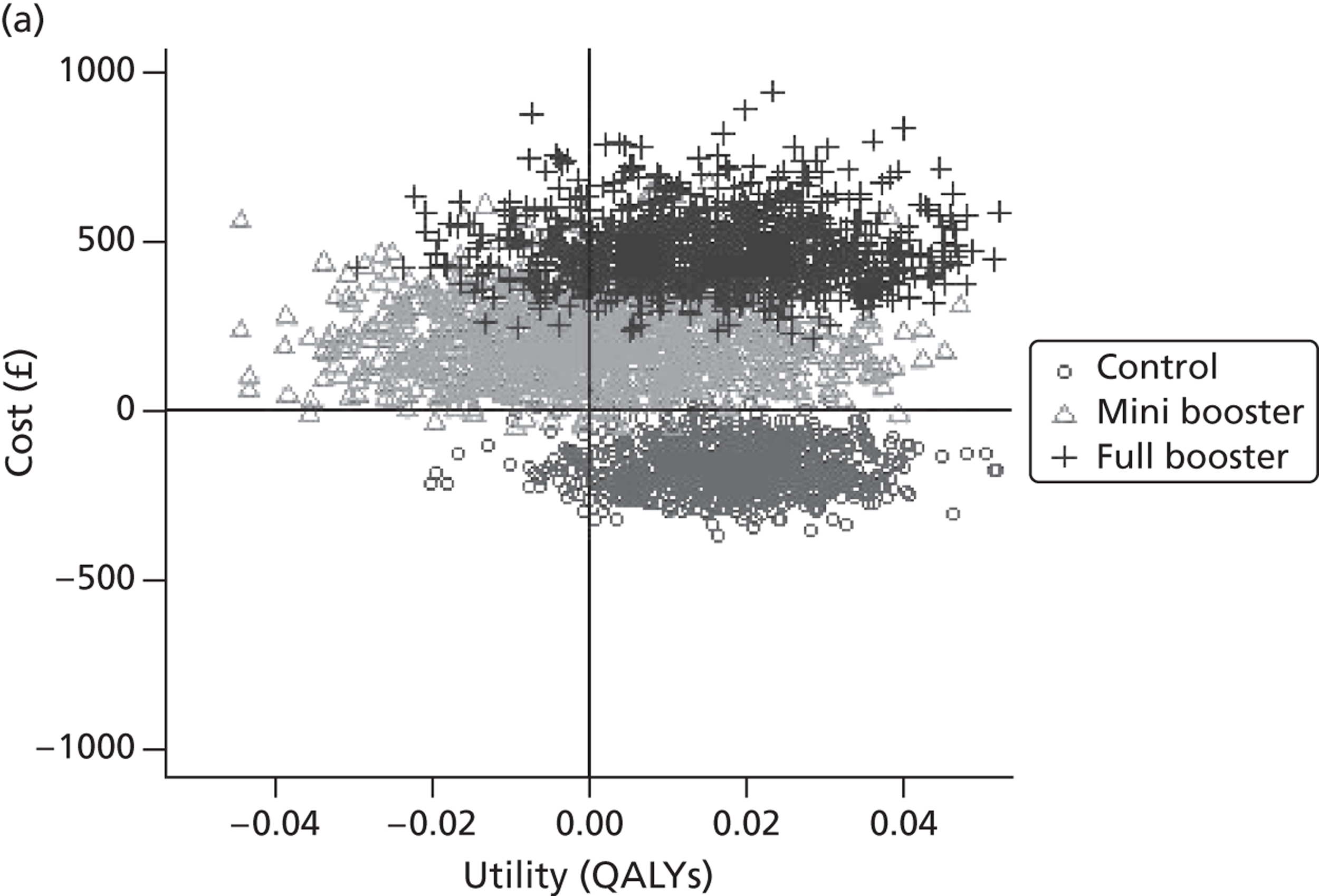

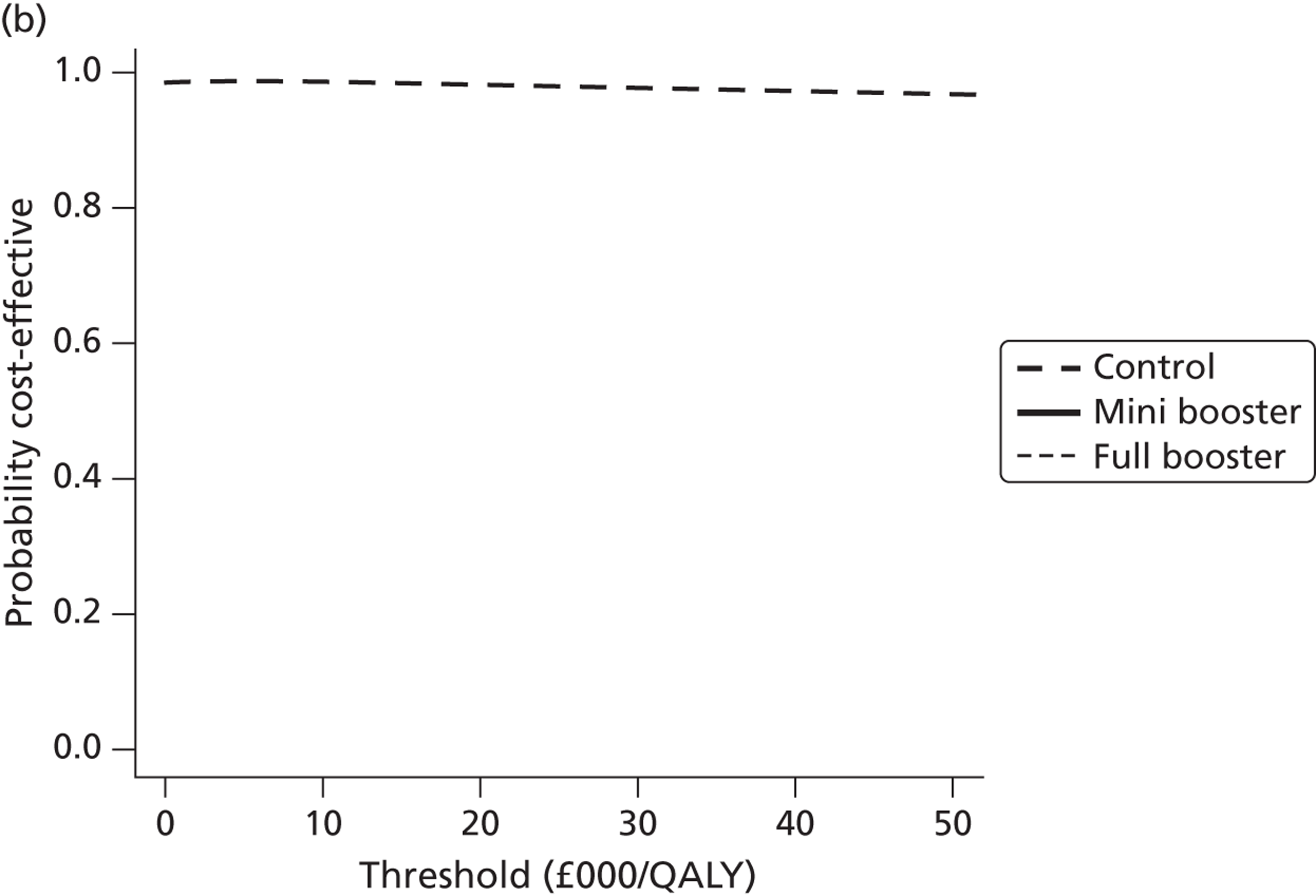

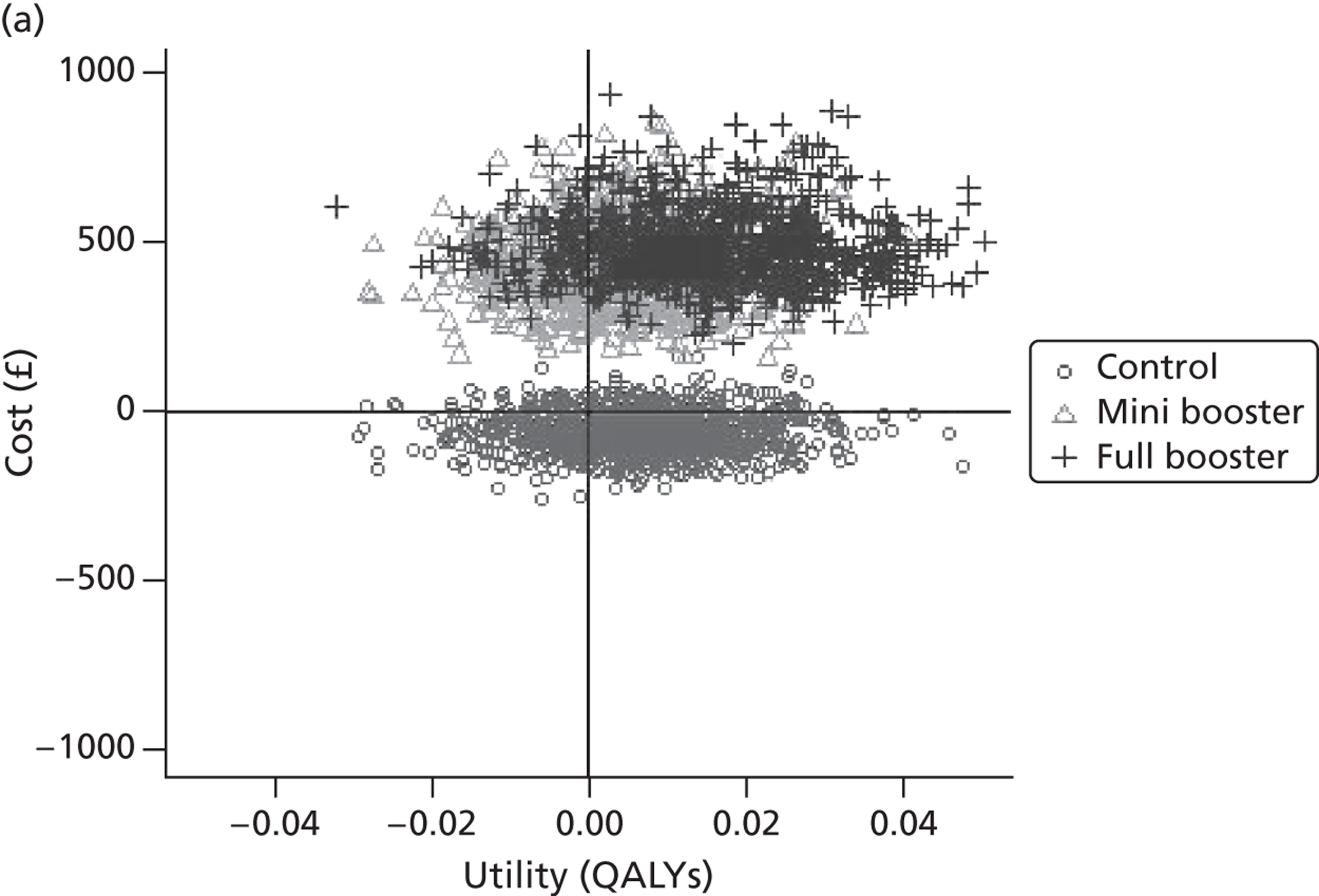

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis

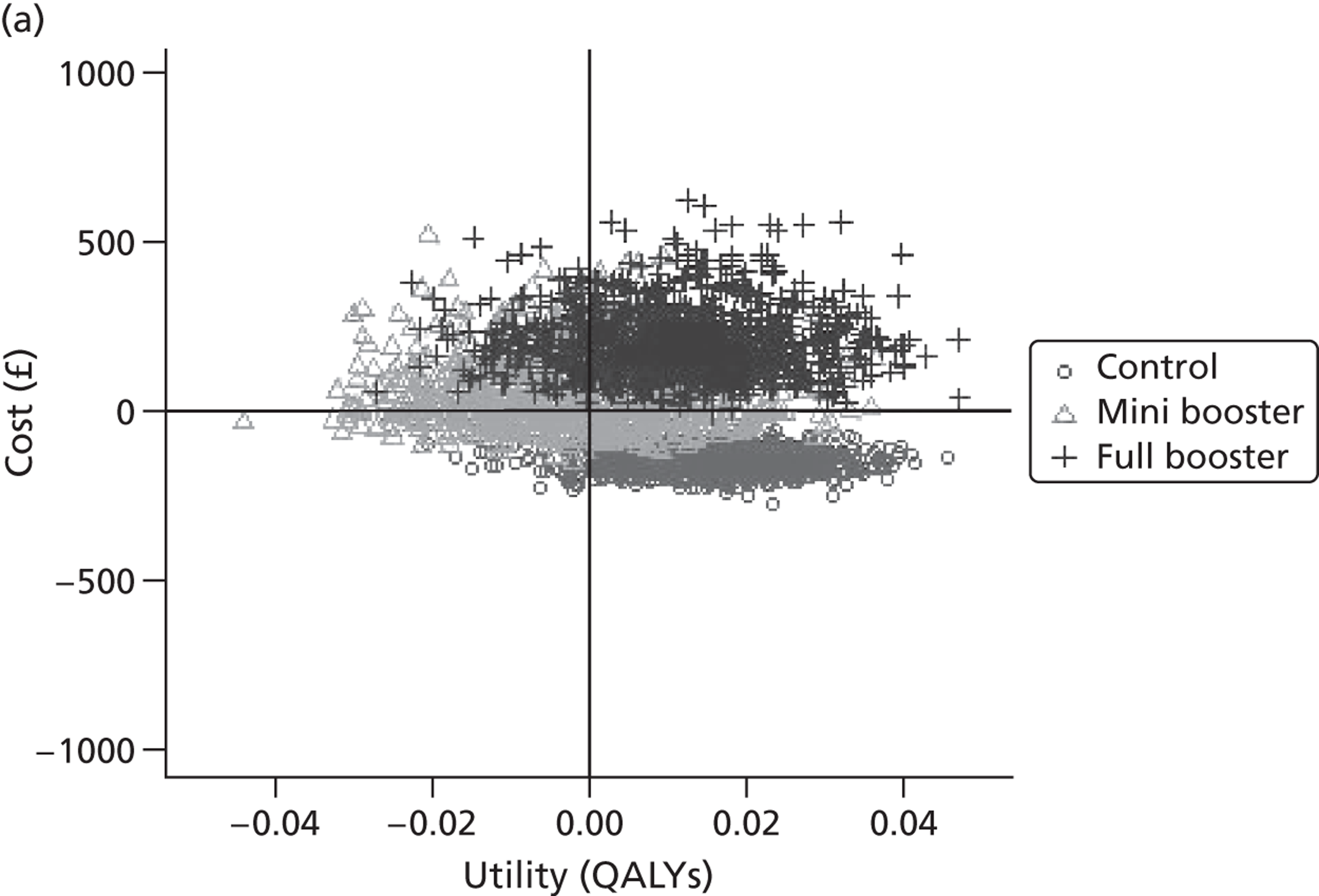

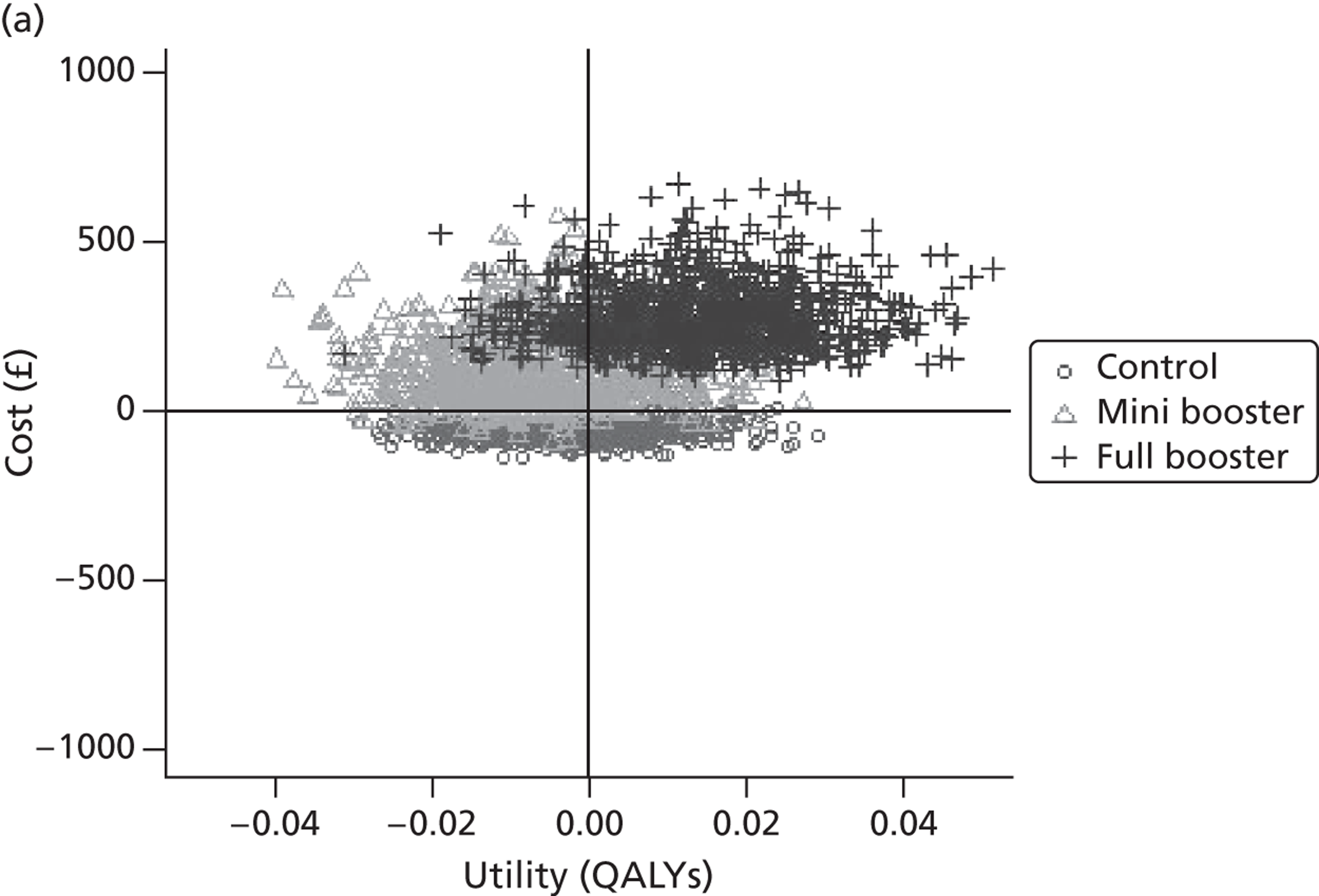

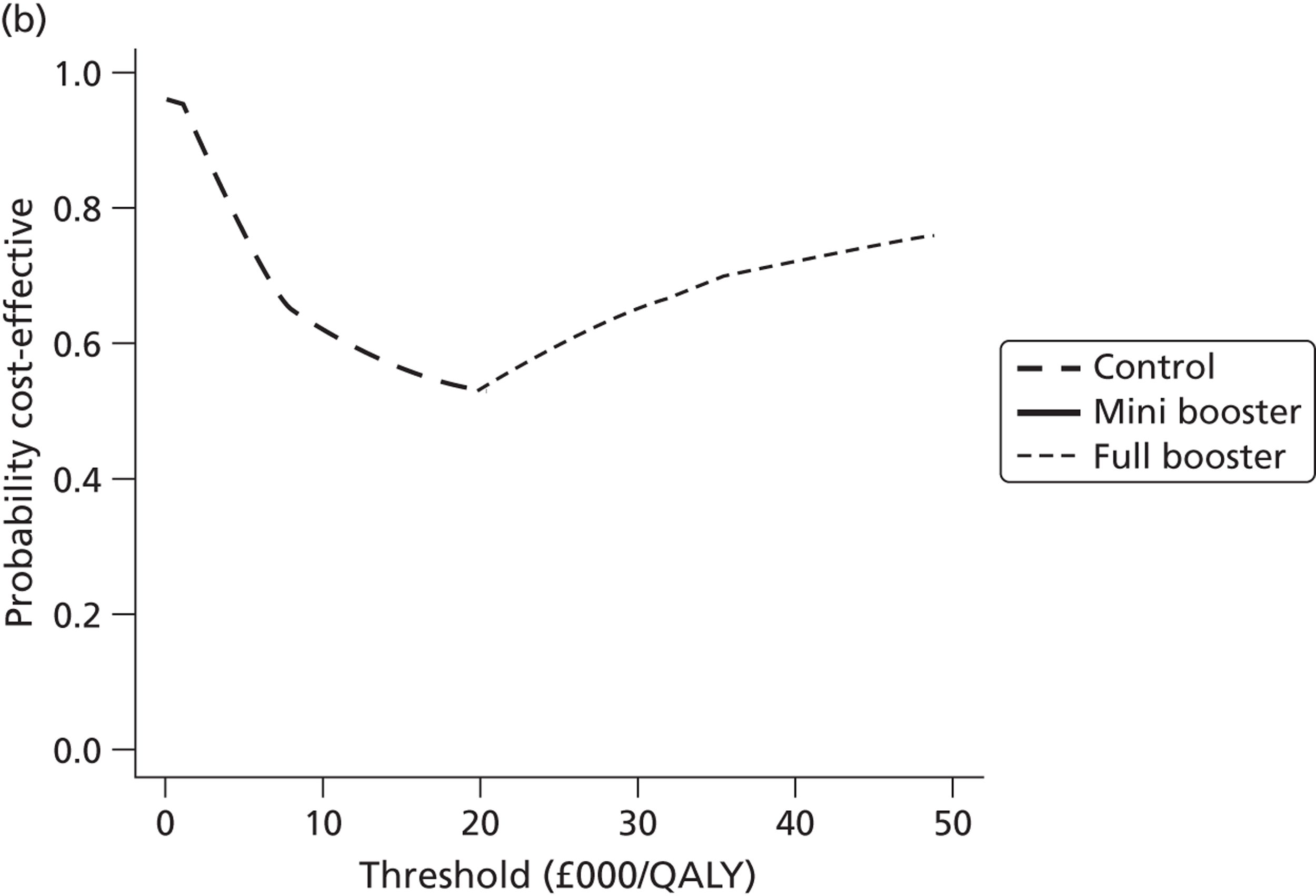

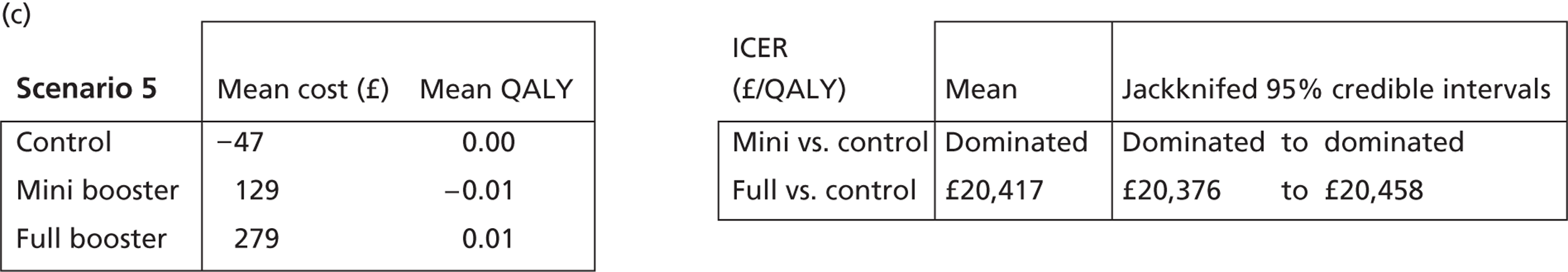

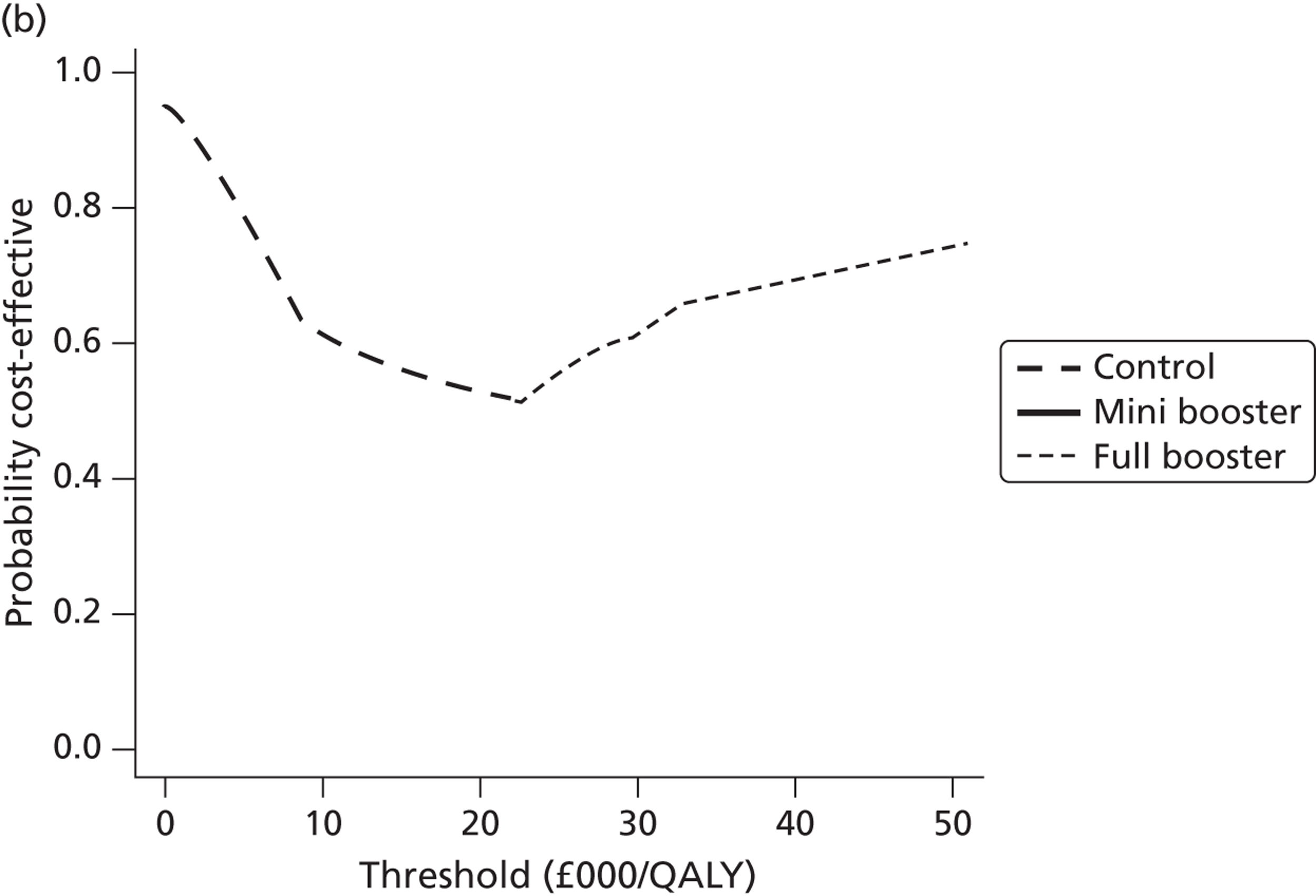

Within PSA, instead of a single best estimate of the incremental cost and QALY gain of each intervention being used, the effect of uncertainty around these values was assessed by drawing 1000 plausible values from joint distributions of the mean costs and mean QALYs of each intervention. These are shown on scatterplots, with different plotting symbols representing estimates from different arms.

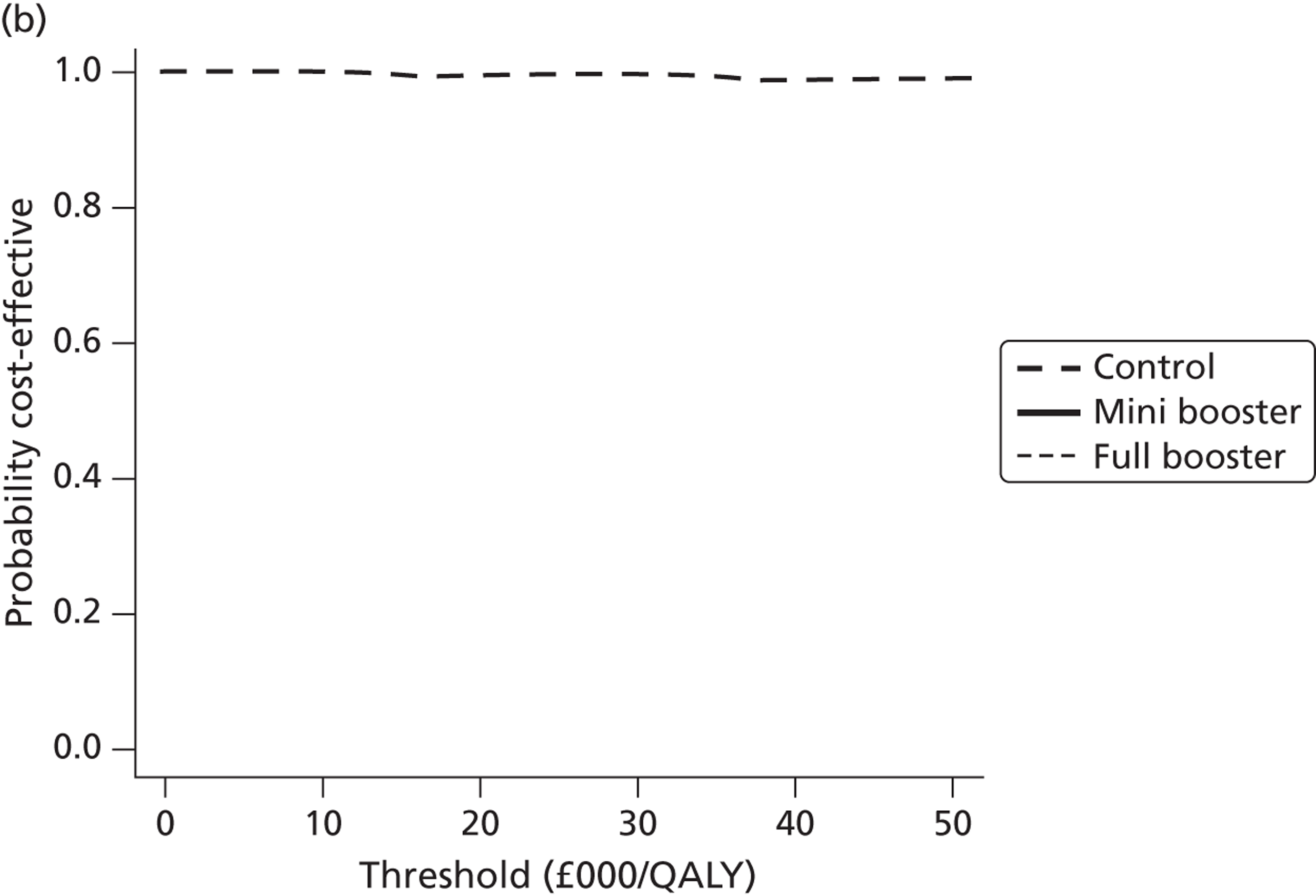

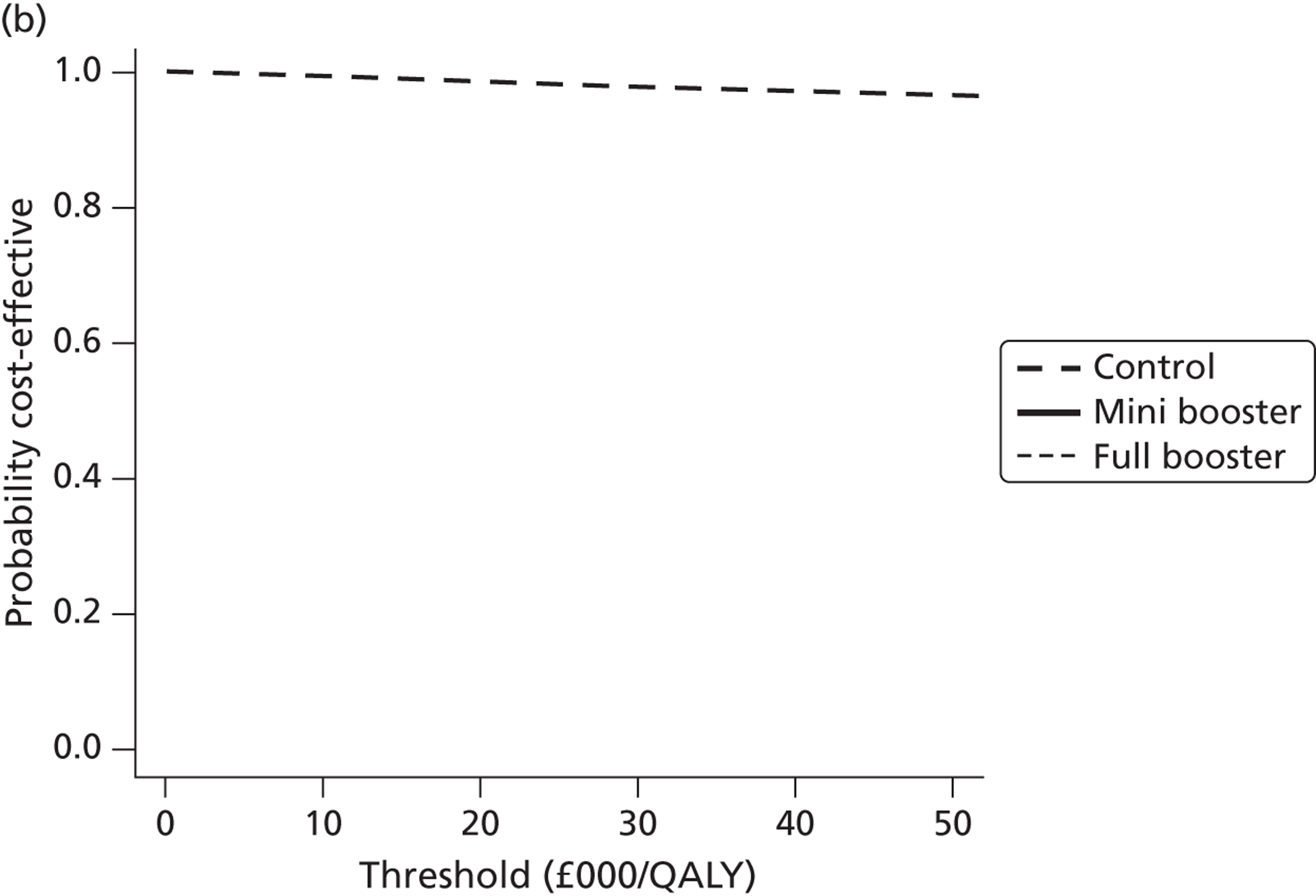

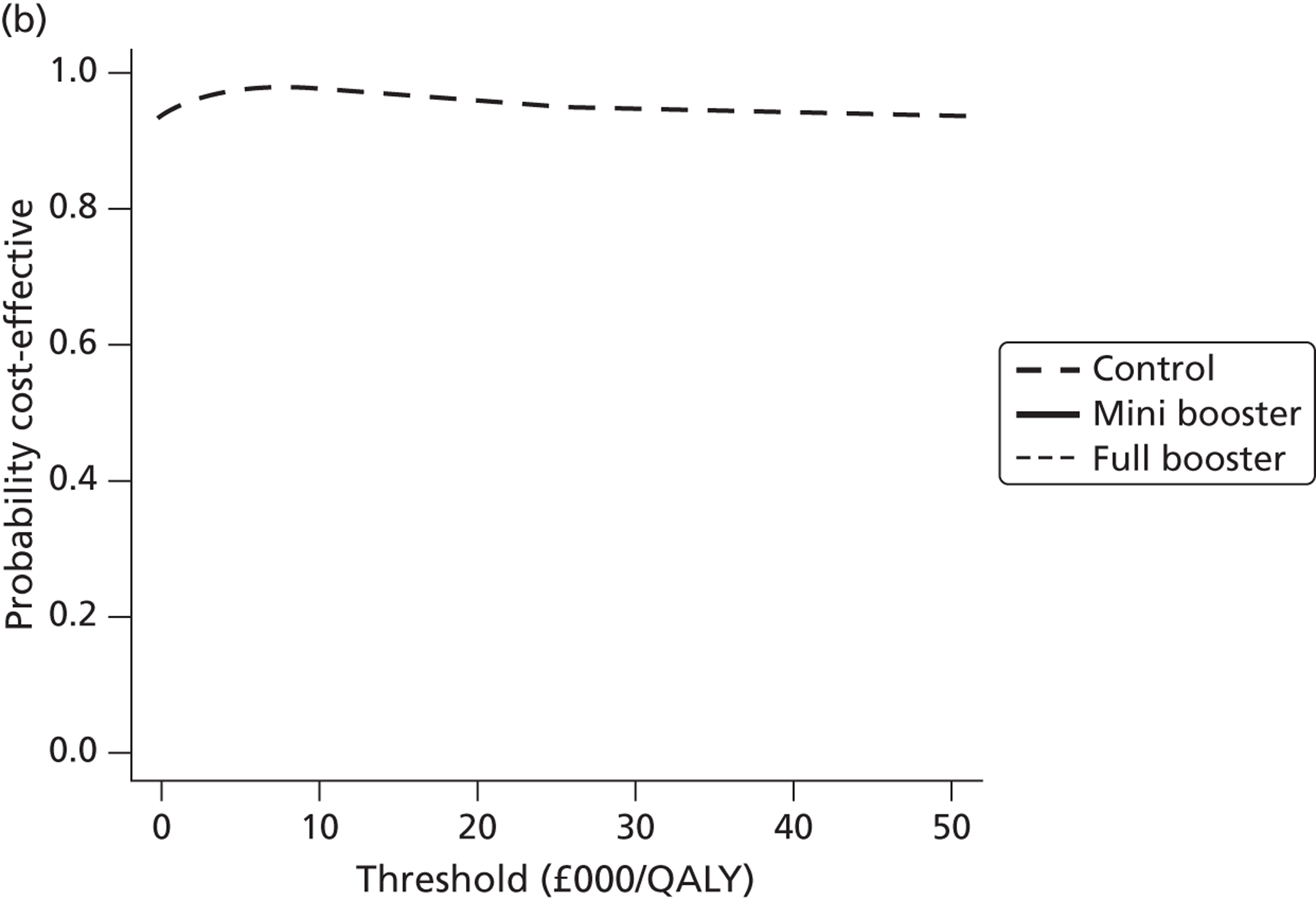

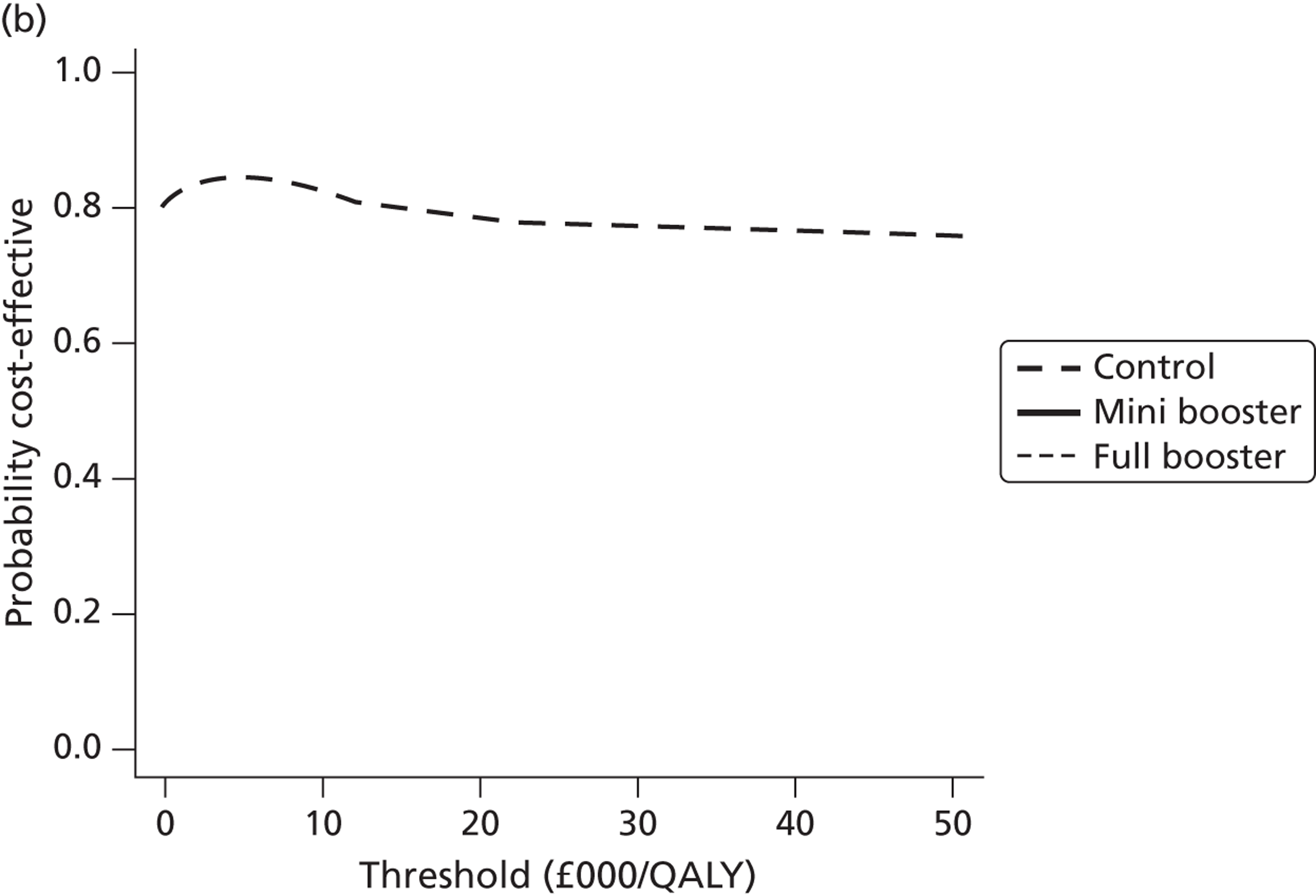

Cost-effectiveness acceptability frontiers

Cost-effectiveness acceptability frontiers (CEAFs) were used to translate the joint incremental cost and incremental QALY estimates (‘scatter’) produced from the PSA into an indication of decision uncertainty. This involved calculating the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) implied by each joint estimate of incremental cost and incremental QALYs and identifying the proportion of ICERs that are below a given willingness-to-pay threshold (λ). The horizontal axis of a CEAF indicates how the proportion of ICER estimates below the threshold varies across different values of λ. Within this analysis, the range of λ values considered was between £0 and £50,000 per QALY. CEAFs differ from cost-effectiveness acceptability curves in that only the option estimated to be optimal, that is, with the greatest net mean benefit, is plotted.

Long-term epidemiological model

As stated previously, interpretation of the short-term cost-effectiveness model can be problematic as the intervention is preventative rather than curative and the participants are not selected from a population characterised by a particular disease. Because of this, it may be more valid to consider the effect of the intervention over a much longer time horizon than the trial duration and to assume that any potential QALY benefits of the intervention are mediated through the clinically measurable health benefits of increased physical activity. This is the rationale for presenting a long-term epidemiologically based model alongside the short-term questionnaire-based model described in the previous section. Unfortunately, adopting this approach requires making a number of strong assumptions about how the physical activity measures recorded within the trial translate into an impact on population health. The long-term model was an individual sampling model constructed in the R statistical programming language (version 2.14.2). The approach taken to develop this model, together with the assumptions made, are described in the following section.

Populating a hypothetical cohort of individuals

As the population who participated and were eligible for the intervention were drawn from a fairly general working age population, an individual sampling model was constructed to represent variability in terms of age and gender of the population at baseline. After discussion amongst project members, it was decided that the age distribution of the hypothetical population considered in the long-term model should be drawn from the age distribution of the booster trial participants rather than the population eligible for the trial. This is because trial participants did not appear to be uniformly drawn from the population eligible to participate but were disproportionately drawn from the upper end of the age range eligible to participate. For simplicity, it was assumed that trial participants were drawn equally from both genders.

Hypothetical population size

Within these analyses, the size of the simulated cohort was selected to be 500,000 individuals. Increasing the number of individuals sampled in the simulation will lead to greater stability in estimates of mean effect but will substantially increase the computing time that models need to run.

Defining and simulating the ongoing mortality hazard in the simulated population

Once the hypothetical cohort of individuals was constructed, the aim was to simulate their clinical experiences over their lifetime. Beginning at their initial age, the probability that they die in the following year was estimated using Office for National Statistics (ONS) life table data. 72 If they survive the following year, their age is increased by 1 year and the probability of them dying in the following year is updated to reflect their new age. The mathematical model involves applying this process iteratively for each of the individuals in the cohort until death, producing a series of simulated initial ages and ages at death. Table 5 provides a simple illustration of this:

| Person number | Initial age (years) | Gender | Age at death (years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | Male | 82 |

| 2 | 45 | Male | 75 |

| 3 | 59 | Female | 84 |

| 4 | 48 | Female | 90 |

| 5 | 52 | Male | 86 |

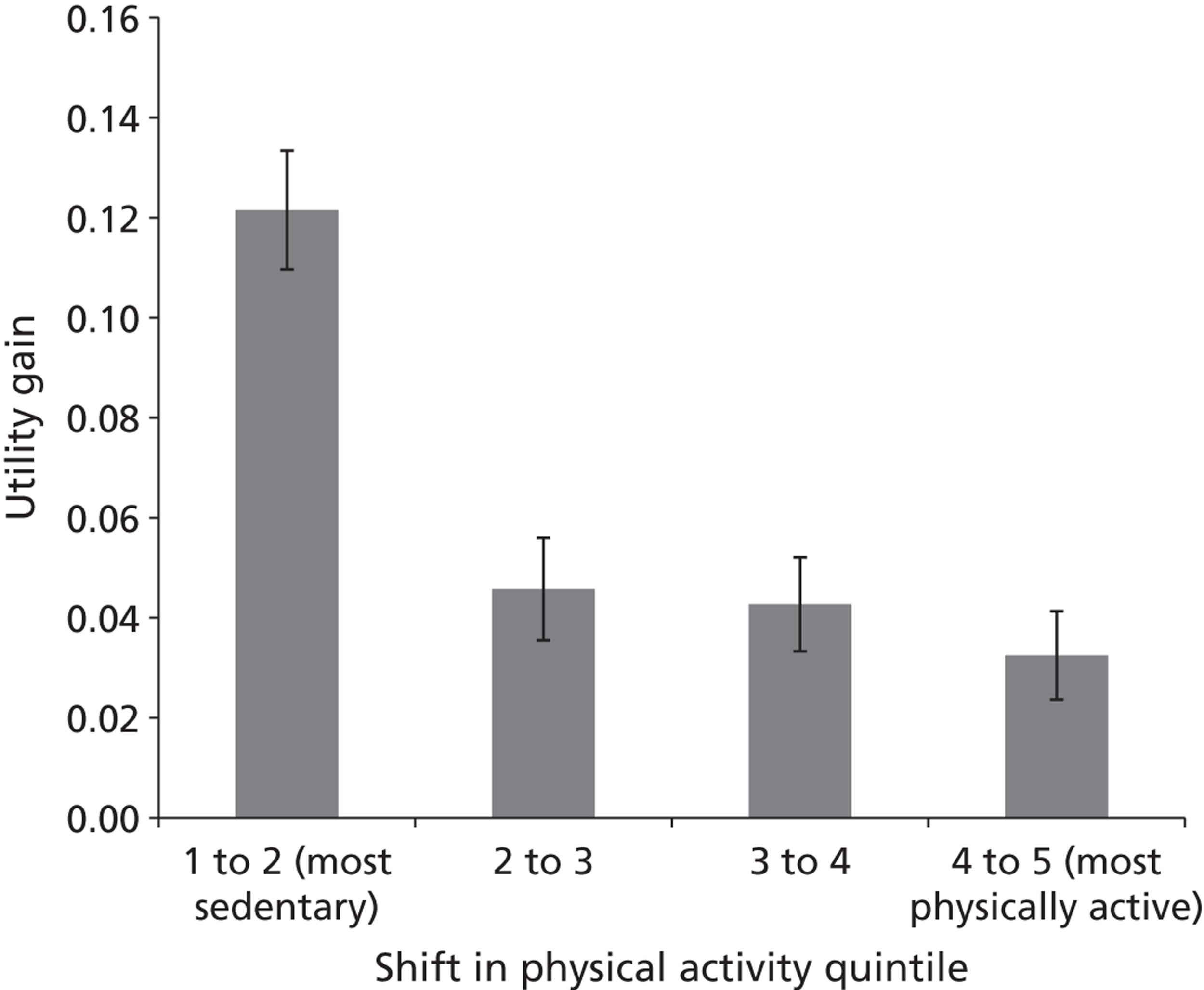

Calculating quality-adjusted life-years

The purpose of simulating each individual 1 year at a time is to estimate the accrual of QALYs over the life course. Recent work by the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) at the University of Sheffield has indicated that the QALYs associated with living another year differ according to the age and gender of the patient and to reflect this it has produced a regression equation that allows age- and gender-adjusted QALYs to be calculated. 73 This equation has been used within the mathematical model to produce more accurate estimates. Each additional year lived by a simulated individual therefore results in an increment to the number of QALYs accrued by that individual but this amount differs each year according to this equation.

In adjusting QALYs according to the age and gender of an individual, the different levels of morbidity that typically affect people at different ages and which differentially affect men compared with women are implicitly accounted for and so the model incorporates morbidity effects alongside mortality effects. For simplicity, however, it was assumed that different levels of physical activity do not have a mediating effect on the degree of morbidity that an individual experiences relative to other people of the same age and gender.

Discounting

As is standard practice in UK-based health-care economic modelling, QALYs gained are discounted at a rate of 3.5% per annum. 74

Assumptions about the longevity of the effect of the intervention

An intention of the long-term model was to represent a plausible decline in physical activity levels in the years following the trial, returning to baseline levels for participants in each of the three trial arms after 2 years. As baseline levels of physical activity were not recorded using Actiheart, three alternative scenarios using the long-term model were used. One scenario used the 9-month activity levels relative to the 3-month activity levels and two other scenarios compared differences between arms at 3 months and 9 months post randomisation. The implications of these different assumptions about the appropriate comparators are discussed below, see Problems with inferring causal effects from the data.

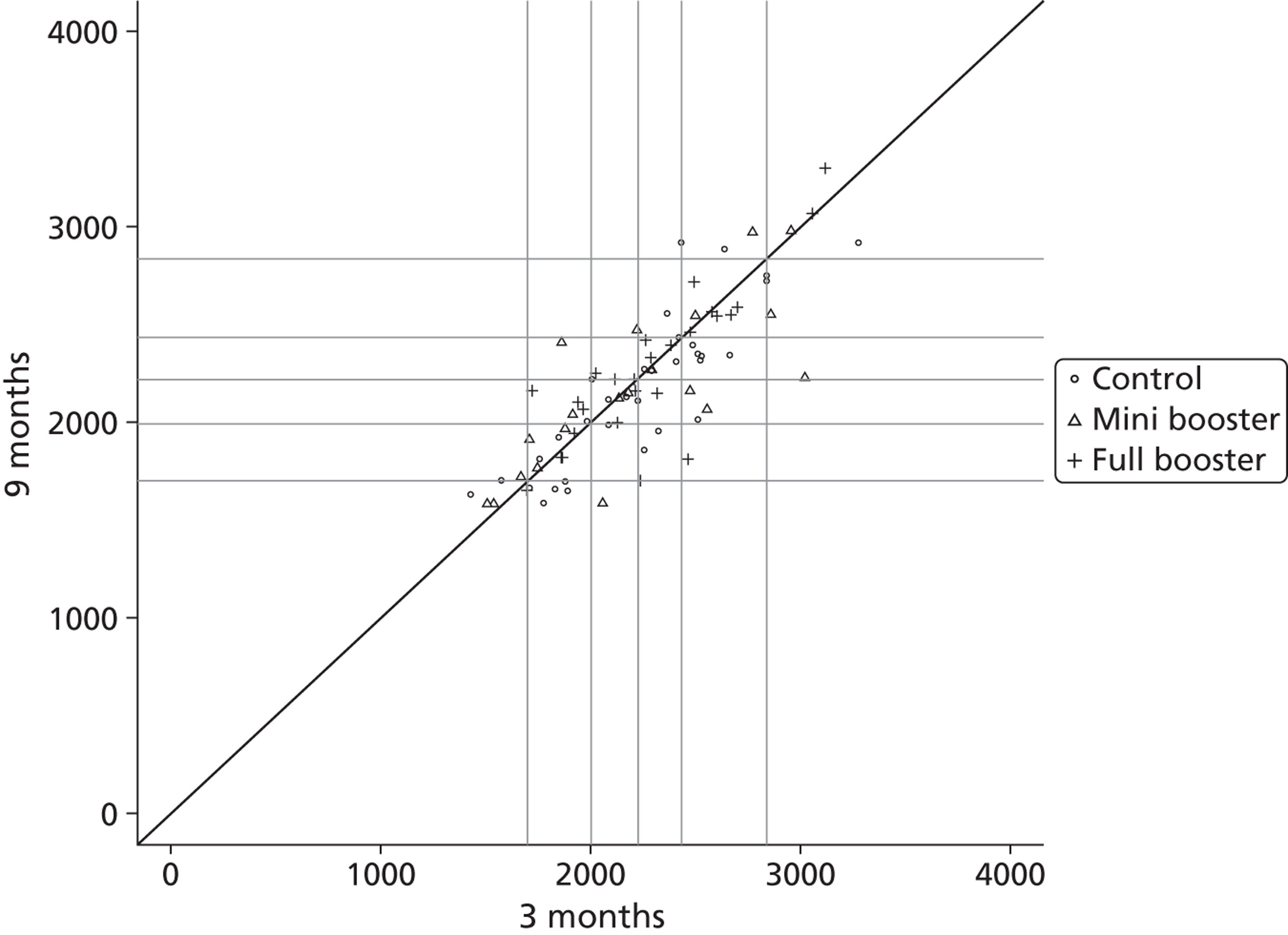

Assumptions about the causal relationship between physical activity and mortality hazards

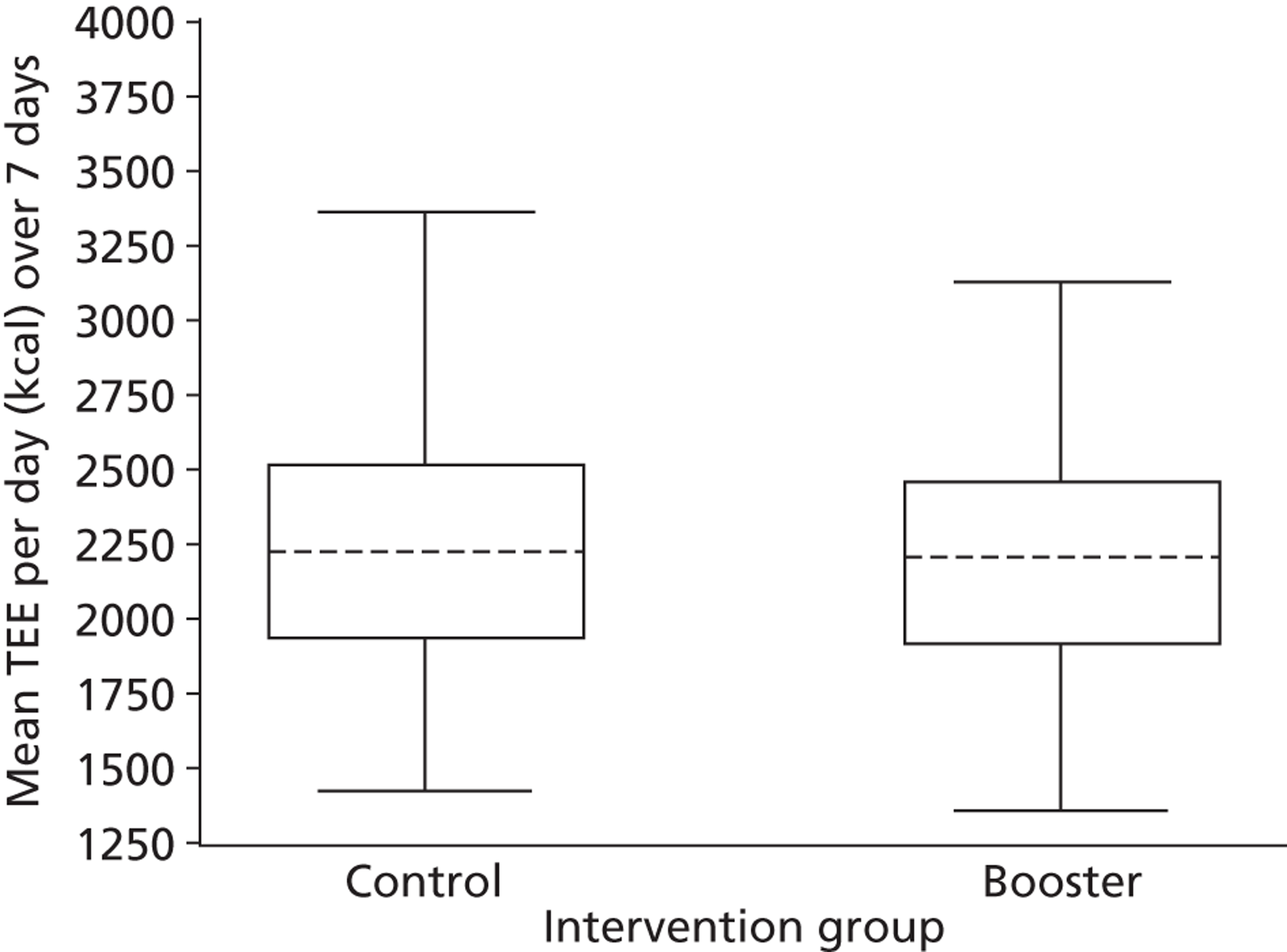

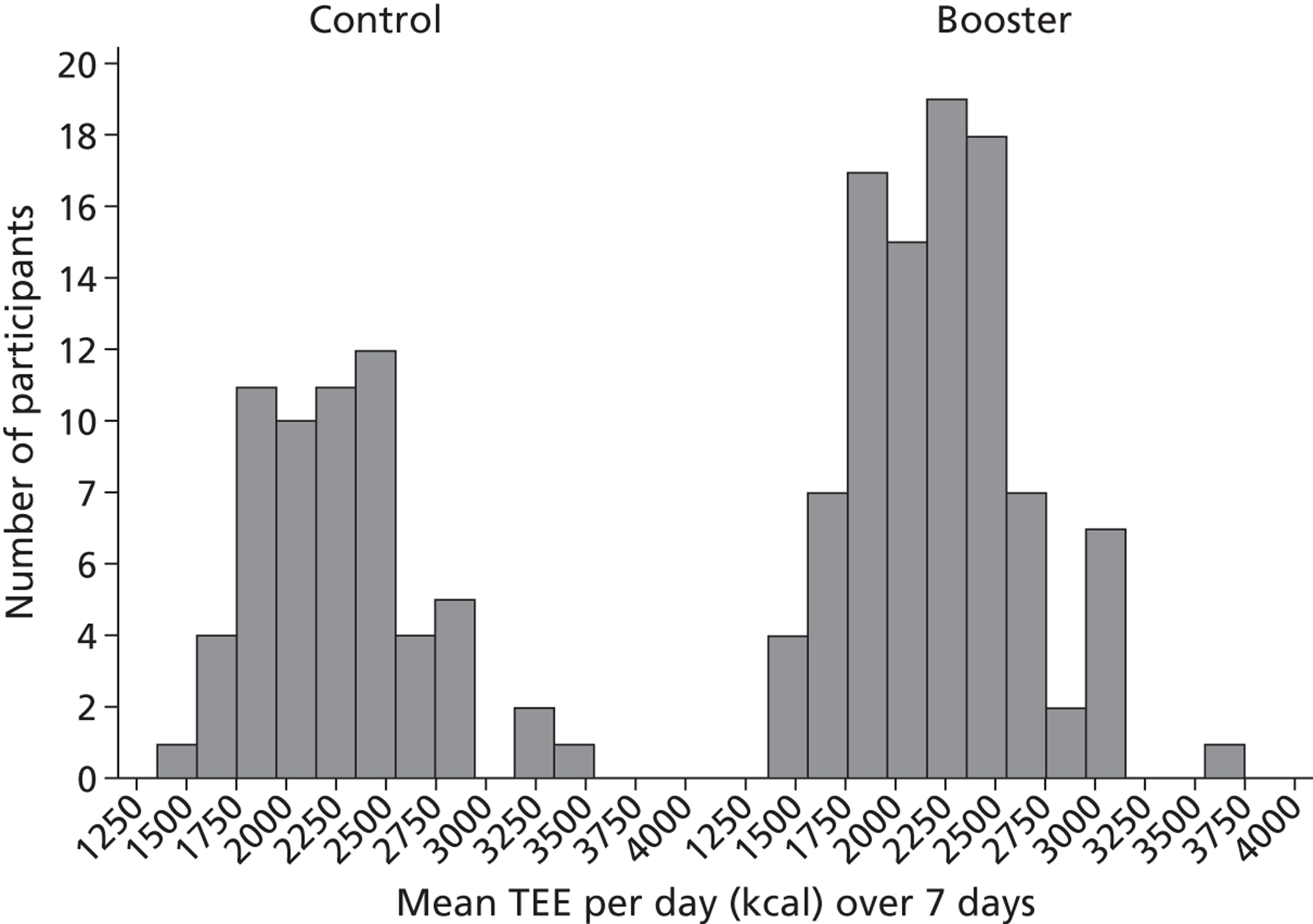

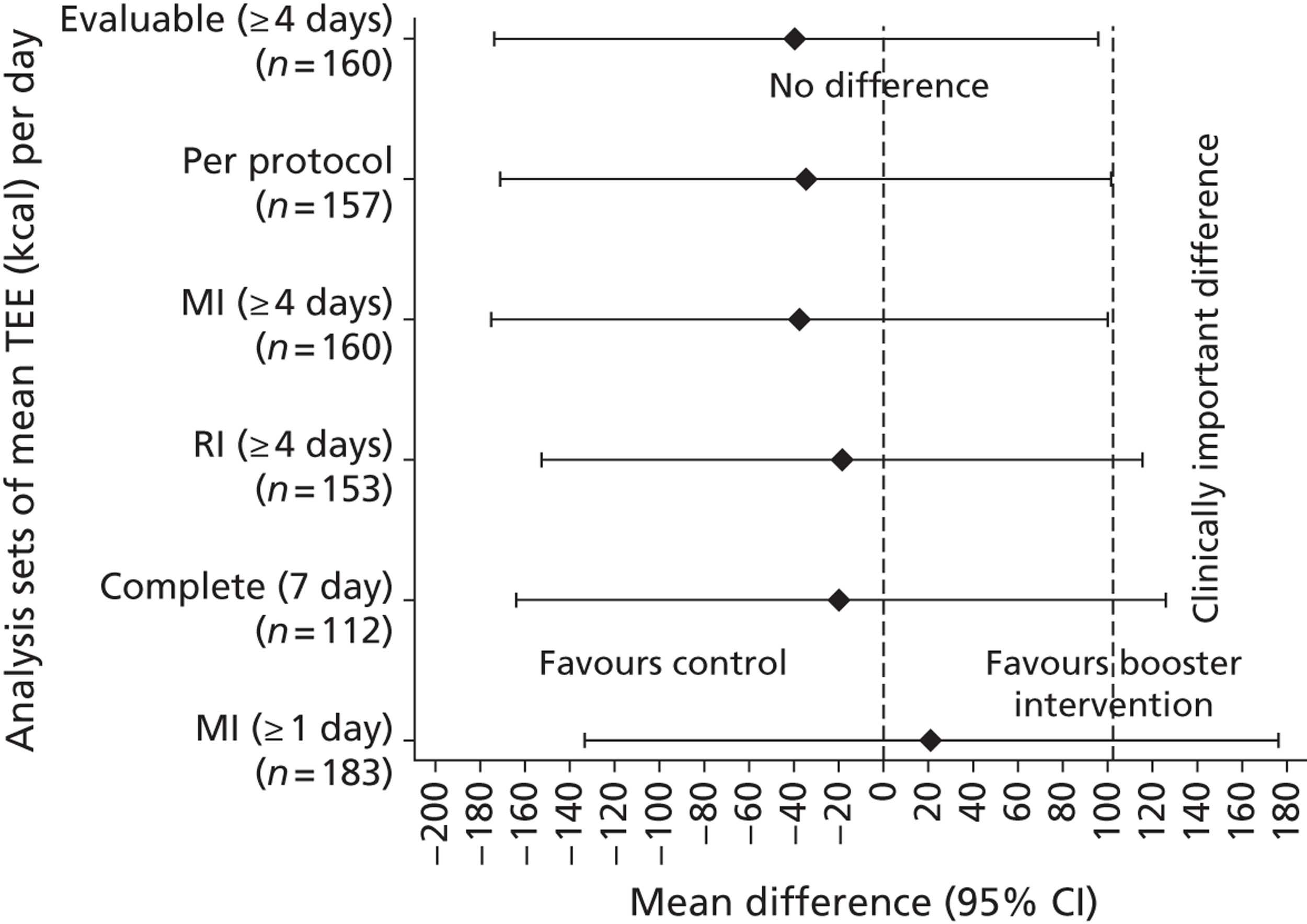

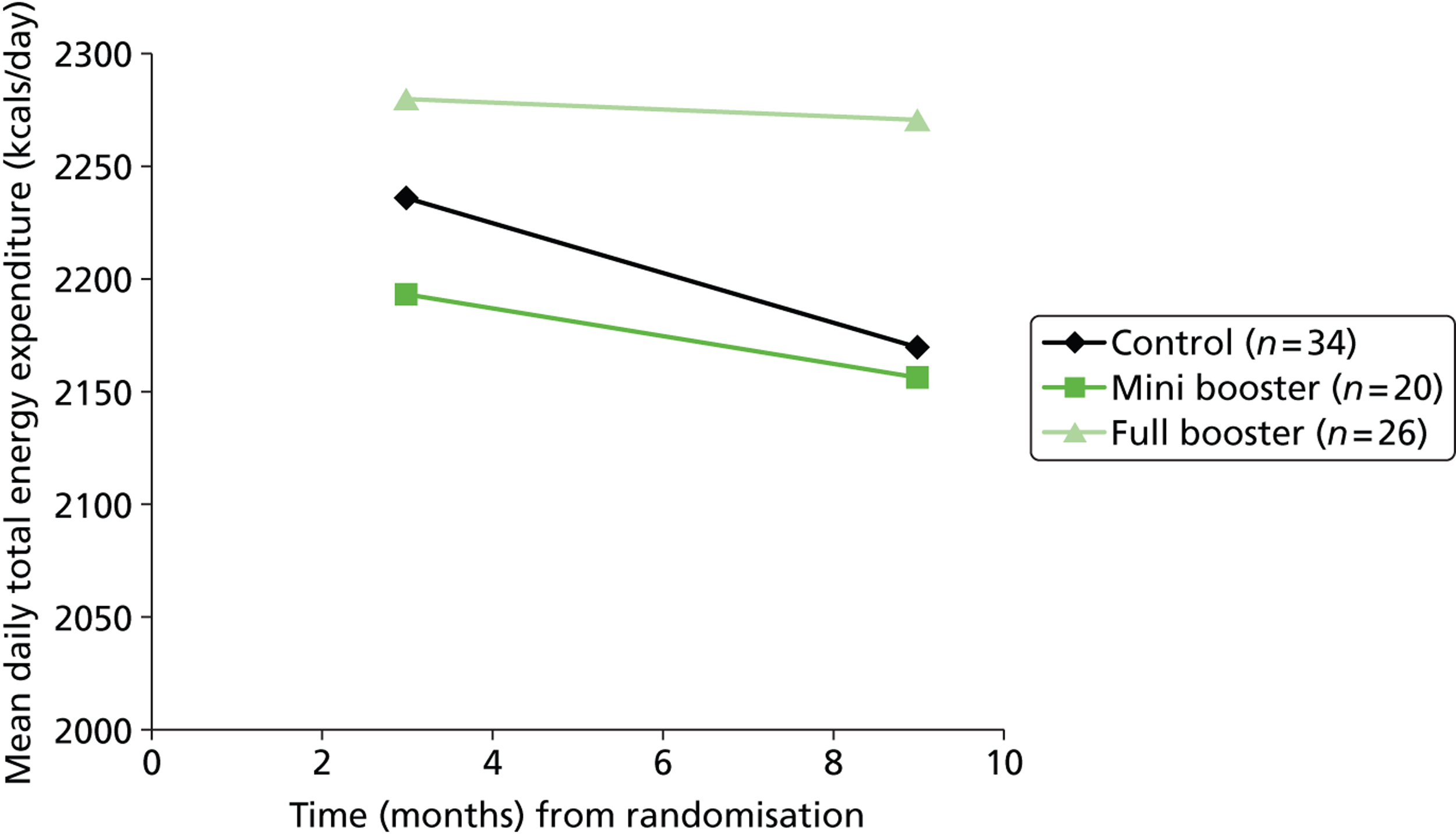

A number of sources of epidemiological research exist which suggest that a monotone relationship exists between how physically active people of working age are and their all-cause mortality rates. 75–80 However, no source could be identified that related directly to the population eligible for the intervention (those aged between 40 and 64 years inclusive), those who participated in the intervention (who tended to be drawn disproportionately from the older ages within the pool of those eligible) or the particular physical activity measures recorded by the Actiheart system.