Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 10/122/01. The protocol was agreed in October 2011. The assessment report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in December 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

David Wilson undertakes clinical practice in cement augmentation of the spine in both the NHS and the private sector.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Stevenson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Aetiology

Osteoporosis is a systemic skeletal disease characterised by low bone mass and microarchitectural deterioration of bone tissue, with a consequent increase in bone fragility and susceptibility to fracture. 1 A definition of osteoporosis has been developed based on bone mineral density (BMD), as this can be measured with precision and accuracy. This defines osteoporosis in terms of the T-score, which is the number of standard deviations (SDs) by which the individual’s BMD, as measured by dual X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) at the lumbar spine, hip (total hip or femoral neck) and forearm, differs from the average BMD of healthy young women. The BMD osteoporosis threshold proposed for Caucasian women is a T-score of 2.5 SD or more below that average (i.e. a T-score of ≥–2.5); a T-score of between 1 and 2.5 SD below that average (i.e. –1 to –2.5) indicates osteopenia. 2

The clinical significance of osteoporosis lies not in low BMD per se but in the fractures that may occur as a consequence of low BMD: without a fracture, a person suffering from osteoporosis will not suffer morbidity. Fractures are considered to be osteoporotic if they occur in a person with low BMD as a result of little or no trauma – the equivalent of a fall from standing height or lower. 3 Vertebral fractures are among the most common osteoporotic fractures. The risk of such fractures approximately doubles with each SD decrease in lumbar spine BMD. 4 However, as the occurrence of a vertebral compression fracture (VCF), even if asymptomatic, increases the risk of further VCFs by at least fourfold independently of BMD, there appears to be another aspect of bone fragility which is not measured by bone densitometry. 4 Research in women with post-menopausal osteoporosis indicates that, in the absence of antiosteoporotic medication such as bisphosphonates, once a VCF has occurred the risk of a subsequent VCF occurring within 1 year is about 19% [95% confidence interval (CI) 13.6% to 24.8%]. 5 Although about one-quarter of VCFs result from falls, most are associated with routine daily activities such as bending or lifting light objects. 6

In vertebral fracture, or vertebral compression fracture (these terms are used interchangeably within the literature), the vertebra is compressed, leading to a reduction in its height and potentially also to abnormal curvature of the spine (kyphosis). However, there is no universally accepted definition of a VCF. Definitions which depend on a reduction in the height of an individual vertebral body, whether relative or absolute, are restricted in their utility by the need for an earlier image against which to identify the change; they are therefore most commonly used in research studies. The same is true of the most widely accepted definition of VCF, Genant’s semiquantitative method, which classifies changes in vertebral body shape in terms of reductions in overall height and area. 7 In the absence of an earlier image, the reduction in vertebral height may be assessed by comparison with an adjacent undeformed vertebra. VCFs which are identified only on radiographs taken for research, population screening, or other purposes are termed radiographic or morphometric fractures.

Some osteoporotic VCFs are diagnosed clinically, usually when a person presents with back pain and a subsequent radiograph is interpreted as showing a fracture to a vertebral body. However, accurate clinical diagnosis of a new VCF may be confounded by the high prevalence of back pain from other causes, by changes in vertebral morphology which are either longstanding or due to causes other than fracture, or by non-standardised interpretation of spinal radiographs. 8 The evidence from clinical trials in which VCFs are identified radiographically suggests that about two-thirds of VCFs are not brought to clinical attention. 9 This may be because the fractures are associated with no, or only mild, symptoms, or because any symptoms present are attributed to another cause, such as muscle strain. 10 Previously unreported fractures might be identified only when they have caused kyphosis and obvious loss of height. 11 However, kyphosis also occurs in osteoporotic women without VCFs, and in these women it is presumably due to non-skeletal factors such as poor muscle tone and loss of disc height by degenerative spondylosis. 12

Research has shown that women with previously unreported vertebral deformities which are found incidentally during population screening are substantially more likely to have chronic back pain and functional difficulties than women without vertebral deformities. However, women with clinically diagnosed fractures are more likely to report symptoms than those whose fractures are detected only by population screening. 10 Only those patients who present to health care professionals with clinical VCFs and severe pain are likely to be considered for percutaneous vertebroplasty (PVP) or balloon kyphoplasty (BKP). Cummings and Melton4 have suggested that fewer than 10% of radiographically detected fractures – that is to say at most one-third of clinical fractures – are severe enough to require hospital admission. However, patients with fractures of such symptomatic severity are presumably those who are most likely to be offered PVP or BKP.

Osteoporotic VFCs may be due to primary or secondary osteoporosis. Primary osteoporosis is defined as osteoporosis that is not associated with any other illness; it is generally associated with ageing and is particularly common in post-menopausal women. Secondary osteoporosis may be related to certain medical conditions (e.g. hyperthyroidism, malabsorption and extreme dieting) or to prolonged steroid therapy. 13 Most osteoporotic VCFs occur in women with primary post-menopausal osteoporosis. However, because of the increase in chronic steroid use, the incidence of VCFs due to secondary osteoporosis is increasing. 14

The short-term impact of vertebral compression fractures

Clinical VCFs can cause considerable acute pain, which may be persistent. This pain is exacerbated by movement and reduced by rest, and may therefore limit mobility;14,15 consequently, patients with particularly severe cases may require hospitalisation. 16 Radiculopathy (pressure on, or other damage to, the nerve root) is not uncommon, and may cause either unilateral or bilateral pain radiating along the affected nerve. 15 Such acute pain is intense at the fracture site and usually lasts 4–6 weeks. This is illustrated by data from the VERTOS II study;17 the study inclusion criteria specified that participants should have had back pain for no more than 6 weeks, and 53% (229/431) of people who initially appeared to be eligible for randomisation became ineligible during the course of the screening process (i.e. in less than 6 weeks from pain onset) because of spontaneous pain relief.

However, in some patients the acute pain associated with a VCF is followed by chronic pain. This often occurs either when one vertebra is particularly severely compressed or when multiple vertebrae are fractured. 18 It may be predominantly caused not by the fracture itself but by strain on muscles and ligaments secondary to kyphosis, and therefore tends not to respond to the management strategies used for acute pain (rest, activity modification, and local and/or systemic analgesics) but may be better addressed through exercise. 10

Investigators have sought means of differentiating patients in whom pain following VCF is likely to resolve relatively quickly from those who are likely to develop chronic pain. Klazen et al. 19 studied conservatively treated patients with a radiographically diagnosed VCF who had had pain for no more than 2 weeks. By 6 months, the mean pain score had decreased significantly (i.e. by 50% or more) from baseline, but no significant decrease was seen between 6 and 23 months; thus, 63% of patients (22/35) had significant pain relief at 6 months, but the proportion had increased only to 69% (25/36) at 23 months. The patients could be divided into two categories: in those with significant pain relief at 23 months, a rapid decline in pain in the first 6 months continued more slowly thereafter, whereas in those without significant pain relief at 23 months, after a small decrease in pain in the first 6 months, there was no further decrease in pain, which might even increase. None of the recorded baseline factors (age, sex, number of VCFs at baseline, conservative therapy frequencies, grade of VCF, or pain medication) predicted significant pain relief at 6 or 23 months, but a high pain score at 6 months predicted no significant pain relief at 23 months [odds ratio (OR) 0.254, 95% CI 0.293 to 0.938, p = 0.030]. However, in a study of osteoporotic post-menopausal women with acute back pain, Lyritis et al. found that those with radiological evidence of a fully collapsed vertebra which was considered responsible for the pain had pain which was severe (9 ± 0.2 on a scale of 0–10) but of short duration (4–8 weeks). By contrast, women with radiological evidence of only a mild fracture, or with no radiological signs of fracture, had on average three attacks of pain, representing gradual fracture progression; thus, the intensity of the pain was less (6 ± 1.8) and the initial attack was of shorter duration, but the time to final resolution was longer (6–20 months). 11

The picture is complicated by the fact that it can be difficult to determine the precise date of occurrence of a VCF. In some cases, following the sudden onset of back pain, conventional radiographs cannot identify a vertebral deformity but scintigraphic imaging may identify a ‘hot spot’ which appears as a typical compression fracture on subsequent radiographs; in other cases, the patient may be identified as having an acute vertebral fracture when the deformity may in fact be seen on earlier radiographs. Moreover, the occurrence of additional episodes of pain associated either with new fractures or with the progression of the original deformity may make it difficult to determine the duration of pain associated with a specific fracture. 10

The longer-term impact of vertebral compression fractures

Patients who have suffered one VCF are not only at risk of developing chronic pain but also at increased risk of suffering another VCF. They are thus also at risk of long-term morbidity caused by the back pain and progressive loss of height and kyphosis associated with multiple fractures, and this in turn may lead to a loss of mobility which will exacerbate the underlying osteoporosis and increase the risk of future fractures. 6

People who have suffered a VCF have higher mortality rates than people of the same age who do not have VCFs. van Staa et al. 20 used data from the General Practice Research Database to compare observed and expected survival in England and Wales in men and women aged 65 and over following vertebral fracture. As these fractures had been recorded in the patients’ medical records, presumably most if not all were clinical rather than radiographic; given the age group being studied, it seems likely that the majority were osteoporotic. A statistically significant excess of mortality was seen in both sexes for up to 5 years following a fracture, but the effect appeared more marked in men than in women ( Table 1 ).

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed | Expected | Observed | Expected | |

| At 3 months | 87.8% | 97.9% | 94.3% | 98.4% |

| At 12 months | 74.3% | 91.8% | 86.5% | 93.6% |

| At 5 years | 42.1% | 64.4% | 56.5% | 69.6% |

It has been suggested that the primary reason for the excess mortality associated with VCFs is the impact on lung function;16 abdominal dysfunction associated with kyphosis may also be a contributory factor. 21 Research has shown that pulmonary function is significantly reduced in patients with primary osteoporosis and vertebral fracture, but not in patients with chronic low back pain without evidence of manifest spinal osteoporosis22 or in healthy control subjects of the same age. 23 A significant association has been found between the number of vertebral fractures and decline in lung function. 24 However, the increased risk of death may also be due, at least in part, to the co-existence of serious underlying diseases in many individuals with VCF. 25 Thus, research carried out in Sweden found that hospitalisation for vertebral fracture (including traumatic fracture) in men and women aged 50 or over was associated with an increase in the relative risk of death compared with the age- and sex-matched population. However, as the risk was particularly high in the younger individuals and decreased with age, it was suggested that this phenomenon might be related to the impact of trauma injuries or other significant comorbidities and secondary causes of osteoporosis. 26 It is also possible that the complications associated with long-term opioid analgesic use, such as respiratory depression, anorexia, and bowel obstruction associated with constipation, contribute to excess mortality.

Similarly, in the USA, a retrospective study was carried out in all residents of Rochester, MN, who had been diagnosed with one or more clinical vertebral fractures between 1985 and 1989; the maximum follow-up appears to have been 5 years, and the mean around 2.4 years. This study found that survival was significantly impaired in the short to medium term in the 276 patients who experienced fracture following mild to moderate trauma (defined as less than or equal to a fall from standing height), and whose fractures were not associated with primary or metastatic cancer or localised bone disease. The most commonly reported causes of death in such patients were cardiovascular diseases (43% – mainly coronary artery disease) and malignancies (18%); the mortality due to coronary artery disease or stroke was not higher than expected, but mortality due to cancer and other causes was elevated. However, relative survival data were presented for all people with clinical vertebral fractures (i.e. including fractures associated with severe trauma or in areas of bone affected by primary or metastatic cancer or localised bone disease). Cooper et al. 27 note that the gradual divergence of observed from expected survival suggests that the impaired survival is unlikely to result from the vertebral fracture per se, but is more likely to be due to an indirect association with comorbid conditions which lead to an increased risk of death, with the fractures simply representing a marker of increased frailty.

In 1991, Browner et al. 28 published data from the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) indicating that, in elderly women, osteopenia was associated with an elevated risk of non-trauma mortality, especially deaths from stroke. Subsequently, analysis of data from the FIT trial29 found that, in primarily healthy post-menopausal Caucasian women with osteoporosis or osteopenia, the age-related relative risk of dying following a clinical vertebral fracture was 8.64 (95% CI 4.45 to 16.74). Despite the fact that only 122 women died during the follow-up period of 3 to 4 years (99 before suffering a fracture at any site, and only 11 following a vertebral fracture), the risk was clearly elevated (although the CIs were wide) and remained virtually unchanged when adjusted individually for other factors (hypertension, smoking, physical activity, health status, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hip BMD). All 11 deaths following a clinical vertebral fracture occurred within 1 year of that fracture. However, the authors note that the elevated risk of death following clinical vertebral fracture may reflect an ascertainment bias, whereby women with more medical conditions and poorer health are more likely to receive a diagnosis of clinical vertebral fracture because they would be under greater medical surveillance. They also note that they were unable to estimate whether a death following a fracture was due to the fracture itself or to an underlying medical condition. Consequently, clinical vertebral fractures may be a marker for increased mortality rather than being independently linked to an increased risk of death. 30

Incidence and/or prevalence

As Cummings and Melton4 have noted, it is difficult to establish the total incidence and prevalence of VCFs both because of the lack of a universally accepted definition of VCF and because a substantial proportion of VCFs do not come to clinical attention. However, although structural deformity associated with VCFs might lead to serious morbidity and mortality, it is currently only symptomatic fractures which come to clinical attention that are candidates for PVP or BKP in the UK, and thus only the incidence of clinically diagnosed fractures is relevant to the current technology assessment. Therefore, we have not evaluated the possibility of the early use of BKP to address sagittal balance.

The prevalence of VCFs varies from country to country, and a number of factors – including environment, genetics, availability of diagnostic tests and willingness of radiologists to report fractures – are likely to play a part. 6 It is therefore important, for the current technology assessment, to identify the incidence of clinically diagnosed VCFs specific to England and Wales. However, as Ström et al. 31 note, data on the incidence of clinical vertebral fractures are not available for the UK. Holroyd et al. 6 have recently estimated that there are 2188 hospital admissions per year in England and Wales for vertebral fractures in patients aged 45 and over. While it is not fully clear what data were used to inform this estimate, the most likely source appears to be the UK General Practice Research Database, which Ström et al. 32 have suggested is likely to incorporate substantial under-reporting of clinical VCFs. Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data, which relate to hospital admissions and outpatient attendances, appear to provide the most reliable data relating to clinical fractures of sufficient severity to be considered for vertebral augmentation. However, Synthes33 and Medtronic34 have produced incompatible estimates based on HES data:

-

Synthes have estimated, on the basis of 2010–11 HES data, that 20,908 patients per year are diagnosed with osteoporotic VCF in the UK. 33 As the most recent available statistics35 indicate that the population of England and Wales is approximately 89% of that of the UK as a whole, Synthes’ estimate suggests that approximately 18,600 patients in England and Wales are diagnosed with osteoporotic VCF each year; presumably only a proportion of these will then be hospitalised as a result of osteoporotic VCF.

-

Medtronic reported HES data indicating that in 2008–9, 2009–10 and 2010–11, approximately 24,000 patients per year in England and Wales were hospitalised for osteoporotic VCF, while in 2010–11 the total number of patients admitted to hospital for osteoporotic VCFs, vertebral fatigue or collapsed fractures was 27,051. 34

Thus, Medtronic’s estimate appears to be substantially higher than that of Synthes.

In their sponsor submission, Johnson & Johnson36 estimated the number of patients per annum in England and Wales who were hospitalised with debilitating pain from osteoporotic VCFs using data from Dr Foster Intelligence, which routinely collects and analyses data from NHS hospitals in England (http://drfosterintelligence.co.uk). On this basis, 7073 patients a year were identified as potential candidates for vertebral augmentation. This figure appears to apply to England alone, but this is not wholly clear. It is substantially lower than the figures put forward by Synthes and Medtronic; the submission indicates that this is owing to the exclusion of patients with diagnoses other than osteoporosis (e.g. malignancy or trauma),36 thus making it more relevant to the decision problem.

The School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR) model uses data on the incidence of vertebral fractures drawn from a different source, a large-scale prospective Scottish study. 37 The figures from this study were the basis for a clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness model which has been used in previous National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) assessments of osteoporosis interventions. These are UK-specific data and explicitly report vertebral fracture rates rather than relying on estimating these from hip fracture incidence data.

Impact of health problem

Significance for patients in terms of ill health (burden of disease)

The significance for patients of VCF falls into three main categories:

-

pain

-

physical changes and impairment

-

psychosocial decline. 10

These will be discussed in turn below. However, it should be noted that the categories are not entirely independent: pain contributes to physical impairment, and both pain and physical impairment contribute to psychosocial decline. 10

Pain

Vertebral compression fractures are associated with both acute and chronic pain. Acute pain typically lasts for several weeks or months until the fracture heals. It varies widely in severity, and at worst is described as intolerable; however, it may respond to analgesics. By contrast, chronic pain, which can develop when kyphosis causes strain on muscles and ligaments, often does not respond to analgesics, but may respond to exercises which increase the tone and strength of the back muscles. 10,38

In a small case–control study, Lyles et al. 39 found that pain, as measured by the West Haven-Yale Pain Inventory, was significantly worse in women with VCFs than in matched control subjects (p = 0.001).

Physical and functional outcomes

Vertebral compression fractures, and in particular multiple fractures, are associated with decreases in stature and progressive kyphosis which cause loss of lung volume and loss of appetite. 10,24 In the USA, a prospective cohort study of women aged 65 or over found that severe kyphosis was related to pulmonary deaths [hazard ratio (HR) 2.6, 95% CI 1.3 to 5.1]. 40 However, Ettinger et al. 41 found that, in a sample of 610 white women aged 65 to 91, despite greater spinal curvature and height loss, the 10% with the most severe thoracic kyphosis did not report significantly greater back pain or back-related disability, or consider themselves to have poorer health, than the other women.

Vertebral fracture can also lead to a loss of spinal mobility, which causes problems with the activities of daily living. If the fracture is accompanied by acute pain which limits physical activity, this may lead to muscle weakness which may in turn contribute to chronic pain. 10 The rate of decline in BMD also appears to decrease with physical inactivity, and may decrease by as much as 40% during bed rest or post-fracture recovery, thus greatly increasing the risk of subsequent fractures. 10

The preservation of independence in elderly community-living individuals depends substantially on the extent to which they are able to perform everyday activities such as shopping and preparing meals. 42 A number of studies have found an association between symptomatic VCF and problems with such activities. In small studies, Cook et al. 43 found that over 80% of post-menopausal women with a diagnosis of chronic back pain due to osteoporotic VCF reported problems with physical functioning and activities of daily living, while Lyles et al. 39 found that women with two or more confirmed VCFs were significantly more likely than age- and race-matched control subjects with equivalent comorbid conditions to report pain and difficulty in performing functional activities, and to say that their health problems interfered with their daily activities (p = 0.002). Moreover, a population survey of 1010 white community-dwelling Californian women aged 55 and over found that those with clinically diagnosed osteoporotic VCFs were significantly more likely to report difficulty in activities such as lifting, shopping and cooking meals than women without known vertebral fractures [adjusted ORs 3.42 (95% CI 1.23 to 9.50), 5.20 (95% CI 1.61 to 16.78) and 6.93 (95% CI 1.55 to 30.99) respectively]. 44 The SOF,42 a prospective US study of 9704 ambulatory white women aged 65 and over, also found that a history of clinically diagnosed VCF was strongly predictive of impaired function (age-adjusted OR 2.32, 95% CI 1.89 to 2.86). Finally, Ryan45 found that 60% of women with symptomatic VCF attending a specialist bone clinic reported disturbed sleep; there was a significant association between sleep disturbance and the severity of vertebral deformities (p < 0.05). However, Ettinger et al. 46 found that women aged 55 to 75 with moderate to severe vertebral deformities were no more likely to require help at home because of their back than were similar women without vertebral deformities.

Psychosocial outcomes

Ross10 has identified four categories of psychosocial problem associated with osteoporosis. These relate to:

-

quality of life

-

fears, anxiety and depression

-

self-esteem

-

social support and roles.

However, he notes that these categories often overlap.

Quality of life

In people with osteoporotic fracture, quality of life can deteriorate quickly, even when physical function is not drastically affected, if changes in physical appearance, fear of fracture, and impediments to social function cause loss of self-esteem. 10 While most of the relevant research has been performed in post-menopausal women, men with VCFs and primary or secondary osteoporosis attending a UK hospital bone clinic scored much more highly in all six domains of the Nottingham Health Profile than age-matched or elderly male control subjects; the difference was particularly marked for energy, pain and physical mobility. The physical mobility scores indicated greater disability in men with secondary osteoporosis than in those with primary osteoporosis (p < 0.05). 47

Fears, anxiety and depression

Symptomatic VCFs are associated with fears, anxiety and depression, which may relate to fear of future fractures, fear of loss of independence, and a feeling of hopelessness resulting from being told to avoid activities such as bending, twisting and lifting heavy items, without being given advice on how to compensate. 10 Although post-menopausal women with a single VCF retain a good quality of life, once they have more than one fracture their quality of life is adversely affected by high levels of anxiety largely caused by fear of future fractures. 38 Such anxiety often leads to inactivity, which in turn can exacerbate BMD loss and declines in physical fitness, thus increasing the risk of falling. 10,38

In a small case–control study, Lyles et al. 39 found that psychiatric symptoms, as measured by the Hopkins Symptom Checklist Revised (SCL-90-R), were significantly worse in women with VCFs (p = 0.043) than in matched control subjects; however, there was no significant difference in depression as measured by the Beck Depression Inventory (p = 0.129). Cook et al. 43 found that emotional problems were common in post-menopausal women with chronic back pain due to VCF: 82% reported fear of falling, while 66% reported frustration and 53% reported anger. Unfortunately, this study did not include a control group of similar women without chronic back pain due to VCF.

Self-esteem

Vertebral compression fractures may lead to height loss, spinal deformity and abdominal protrusion, which adversely affect self-image and self-confidence, and to functional limitations which may lead to a loss of self-esteem by limiting independence and the ability to participate in social activities. 38 Even relatively mild chronic pain may cause discomfort which discourages participation in social activities that involve sitting or standing for extended periods. Moreover, spinal curvature and height loss may make it difficult or impossible to sit or stand erect, causing problems with conversation and other activities. 10 Cook et al. 43 found that over 50% of post-menopausal women with a diagnosis of chronic back pain due to osteoporotic VCF reported problems with leisure/social activities. However, in a small case–control study, Lyles et al. 39 found that women with VCFs and matched control subjects did not differ significantly in self-esteem as measured by the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (p = 0.731).

Social support and social roles

The pain and physical impairment caused by VCFs can undermine the reciprocity involved in interpersonal relationships by reducing the ability to provide help and support to family and friends, while potentially increasing the need for assistance with activities of daily living and other personal care. If people are obliged to give up work, domestic, recreational or sexual activities because of the limitations on their physical and functional abilities, they may also be deprived of their social roles. 38 The impact may be severe even if the activities in question do not seem to others to be demanding; the inability to stand or sit for extended periods may limit involvement in social events, leading to an inability to fulfil the social roles that form an important source of self-esteem, and thus to a severe reduction in quality of life. 10

Significance for the National Health Service

Osteoporotic VCFs are associated with significant morbidity, mortality and health and social care costs. 40,48 In a large UK-based study, Puffer et al. 49 found that, compared with matched control subjects, women diagnosed with osteoporotic VCFs had significantly more general practitioner (GP) consultations (difference 4.69, 95% CI 4.35 to 5.03, p < 0.001), referrals (difference 0.51, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.58, p < 0.001) and hospital admissions (difference 1.77, 95% CI 1.63 to 1.91, p < 0.001) in the year following diagnosis. The rate of GP consultations, referrals and hospital admissions were also significantly higher in the year prior to diagnosis (all, p < 0.001). Based on these figures, Puffer et al. 49 estimated difference in costs per patient of £1015 and £1598 for pre- and post-diagnosis years respectively. Furthermore, it was found that patients with VCFs had a significantly greater utilisation of pharmacological treatments in the year following diagnosis, with the largest difference being in the prescription of bisphosphonates (difference 52.71%, 95% CI 49.37% to 56.01%, p < 0.001). The total additional cost of pharmacological treatment per patient was estimated to be £97.37 per year. 49

Nevertheless, there are several reasons to interpret these estimates with caution. As noted above, people diagnosed with osteoporotic VCFs are more likely to have significant comorbidities requiring medical care. Hence, it is difficult to establish whether or not additional resource usage arises directly from the VCF. Furthermore, although only 30% of VCFs come to medical attention,50 undiagnosed VCFs are also likely to be associated with greater service use owing to the association of VCFs with excess morbidity and mortality. 51 The limitations VCFs can place on participation and, consequently, on patient well-being are highly significant issues with respect to care provision. 52

Measurement of disease

Osteoporotic VCF is identified by diagnosing both osteoporosis and vertebral fracture. The generally accepted approach to osteoporosis diagnosis is by the measurement of BMD. The presence of osteoporosis is assessed by converting an individual patient’s BMD into a measure known as the T-score, that is to say the number of SDs from healthy young adults matched for ethnicity and sex. A T-score ≤ –2.5 is widely accepted as the diagnostic threshold. 53 A meta-analysis has shown that the predictive value of a 1 SD decrease in bone mass for osteoporotic fractures was roughly similar to that of a 1 SD increase in blood pressure for stroke, and more than a 1 SD increase in serum cholesterol concentration for cardiovascular disease. 54 Methods of assessing BMD include single-photon and X-ray absorptiometry of the forearm and heel, DXA, and dual photon absorptiometry of the lumbar spine, proximal femur, whole body or particular regions thereof, and quantitative computed tomography of the spine or appendicular sites. 2

A number of methods have been proposed for identifying vertebral fractures. A widely used approach is the semiquantitative technique first described by Genant and colleagues,7 which also indicates fracture severity. This approach utilises pre-defined thresholds for fracture severity, based on perceived reductions in vertebral height and area. Hence, vertebral bodies can be classed as normal (grade 0), mildly deformed (grade 1: reduction between 20–25% in anterior, middle, and/or posterior height and a reduction of area of 10–20%), moderately deformed (grade 2: reduction between 25–40% in anterior, middle, and/or posterior height and a reduction of area of 20–40%), and severely deformed (≥ 40% reduction in any height and area). This grading system has demonstrated good to excellent intra- and inter-observer agreement, and similar estimates of incidence to quantitative morphometric measurements of vertebral height loss. 7 Common measures of angular deformity include kyphotic wedge angle, sagittal index and measures of sagittal balance, in particular lateral radiographs measuring the relationship between the C7 and S1 vertebrae (these are discussed in more detail in Chapter 2, Decision problem).

Current service provision

Management of disease

Traditionally, VCFs have been treated with optimal pain management (OPM). Bed rest is often required for 1–2 weeks until the acute pain begins to subside, and therefore hospitalisation may be necessary. 15 Pain relief is generally achieved with oral analgesics: narcotics can be effective for fracture pain, while non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDs) may relieve pain of inflammation and muscle spasm associated with VCF. 55 Calcitonin (Miacalcic®, Novartis) has also been shown to have a strong analgesic effect on patients with acute osteoporotic VCFs. 56 Patients who develop radicular pain as a result of compression of the nerve root may also require a nerve-root block or epidural injection of steroid and an anaesthetic. If such pain becomes chronic, other medications such as antidepressants, anticonvulsants and alpha-2-agonists may be required. 55 External immobilisation (back bracing or casting) may also be used to reduce pain and promote appropriate posture, although this strategy carries the risk of muscle tone loss. 55 Antiosteoporotic medication should be prescribed to reduce the risk of further vertebral fractures. 15,16

In order to prevent further bone loss, mobilisation should begin as soon as the acute pain begins to subside, and spine extension exercises may be used to strengthen the back muscles. 15 Muscle spasms associated with acute VCFs may be treated with muscle relaxants and heat treatment; massage and physiotherapy may also be required by patients with kyphosis. 57 Patients should also receive walking aids and education about ways to avoid pain in activities of daily living. 55

However, many patients complain of progressive pain and progressive functional limitation and loss of mobility despite conservative management. Thus, 75% of patients (n = 107) who were admitted to a Swedish emergency unit with a painful acute VCF and received conservative treatment reported persistent back pain at 12 months. 58 Moreover, conservative management cannot prevent kyphotic deformity. 59

In theory, open surgery with internal fixation may be performed in patients whose pain does not resolve with conservative management. However, such surgery is rarely undertaken in osteoporotic patients because the poor bone quality reduces the likelihood of achieving good results, while comorbidities in this patient group increase the risks associated with surgery. 60 Consequently, open surgery is generally performed only in patients with neurological deficits61 in whom the balance of risks and benefits differs from that in patients without such deficits.

Optimal pain management is associated with an increased risk of complications of bed rest [e.g. pneumonia, deep-vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism62], side effects of medication, admissions to nursing home and death. 63 Narcotic analgesics may lead to debilitating side effects, in particular cognitive impairment, nausea and constipation, while NSAIDs are associated with gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, gastritis and ulcers. 55 Injected calcitonin may cause side effects such as nausea and flushing,56 while nasal calcitonin is mainly associated with rhinitis and nasal symptoms. 64 Additional medications which may be used for chronic pain are also associated with a range of side effects. 55 Even in the absence of such severe adverse events, extended bed rest and the use of back bracing or casting may be problematic for many older patients: bed rest may result in loss of bone density and muscle mass, and braces are often poorly tolerated. 19

Current service cost

Medtronic35 reference Ström32 as estimating the cost of treatment of a vertebral fracture in the UK to be approximately 2756 euros in the first year. However, Ström gets this figure from Stevenson et al. 65 Medtronic also reference Swedish data that the total cost is almost as high as the cost of treatment of a hip fracture, with lower initial hospital costs offset by higher community and informal care costs between 12 and 18 months. 66

Synthes state that HES data for the last 12 months (apparently for the UK rather than England and Wales) recorded that 6375 patients (undifferentiated, i.e. not all osteoporotic) who had no surgical intervention (excluding facet injection or analgesia) occupied 78,923 bed days, with an average length of stay of 12.38 days; a further 698 patients received surgical treatment (PVP or BKP with or without stent), with an average length of stay of 7.5 days for PVP and 5.9 days for BKP. 33 In their submission, Medtronic indicated that the average inpatient stay associated with BKP was 5.1 days,34 while Johnson & Johnson identified the average length of stay as 3.24 days for PVP and 4.48 days for BKP,36 with these values provided by Dr Foster Intelligence. The longer lengths of stay identified by Medtronic include patients receiving vertebral augmentation for trauma or malignancy. 34

The assessment group note that a recent review of the cost-effectiveness of vitamin K compared with alendronate used a cost of a vertebral fracture in the first year of £2981. 67 This estimate was based on 2006 costs, which had been inflated by 8% to meet expected 2008 costs.

Variation in services and/or uncertainty about best practice

There is no single standard of best practice care provision for people with osteoporotic VCFs because treatment needs can vary substantially according to age, BMD loss, mobility and broader life conditions. Hence, care packages tailored to individual needs have been recommended by a number of authors. 68–70 However, the general aim of rehabilitation is to restore mobility, reduce pain and minimise the incidence of new VCFs. Barriers to adequate treatment in older people with osteoporosis include polypharmacy, comorbidities and cognitive impairment. Therefore, prevention of pain, disability, and functional decline should be pursued with these constraints in mind. 69

Analgesic treatment varies according to pain severity and patient-level contraindications. The need for back-pain relief can typically be met with acetaminophen, and supplementary codeine for breakthrough pain. 71,72 In cases of more severe and persistent pain, narcotic analgesics may be required for satisfactory pain reduction. While short-term use of these drugs is unlikely to lead to adverse events, undesirable side effects, in particular delirium and constipation, tend to be more pronounced in frail older people. 69 NSAIDs are often prescribed to treat low back pain; however, these drugs have been linked to gastrointestinal side effects. Chronic use of NSAIDs is also known to pose a risk of potentially fatal gastroduodenal bleeding. 73

A number of physical approaches to pain relief may also be beneficial for people with osteoporotic VCFs, although their efficacy remains moot. Back bracing is often used to minimise postural flexion and paraspinal muscle spasm, and to facilitate bone healing. 74 While there is moderate evidence that lumbar supports are effective for the treatment of general back pain,75 their effectiveness in osteoporotic VCFs remains poorly understood. 76 Moreover, chronic use of braces may lead to weakening of the paravertebral muscles and increased pain. 77 There is limited evidence that massage and superficial heat and cold therapy reduces general back pain, although evidence is lacking for the effectiveness of either treatment in osteoporotic VCFs specifically. 78,79

Owing to their role in skeletal homeostasis, calcium and vitamin D are widely viewed as the first line in osteoporosis treatment. However, while higher doses of vitamin D may be associated with greater benefits, this effect is yet to be confirmed. 80 Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis found that calcium supplements without co-prescribed vitamin D led to an increased risk of myocardial infarction. 81 Until recently, hormone replacement therapy (HRT) was widely used to treat women with osteoporosis. A meta-analysis of RCTs comparing the risk of VCFs in women treated with HRT compared with placebo found a risk reduction of approximately 33% in the HRT cohort. 82 However, HRT has been linked to a number of adverse events, including a 2.3% increase in the relative risk of breast cancer and an association with venous and pulmonary thromboembolism. 83 While these adverse events are linked only with current or recent use, they nevertheless suggest that HRT should be prescribed with caution. 83

One possibility explored in a recent non-randomised cohort study84 was the use of local anaesthetic and facet joint injection to control VCF-related back pain. Wilson et al. 85 performed facet joint injections under fluoroscopic guidance with lidocaine 1% and bupivacaine 0.5% to anaesthetise the affected area. Approximately one-third of the treated cohort (21 of 61) responded well to the intervention, which led these investigators to hypothesise that facet joint injections may be effective among patients in whom pain does not arise directly from the VCF but from biomechanical effects of the VCF occurring elsewhere in the spine. Anecdotally, the use of this approach prior to more invasive techniques is now widespread in the UK, and indeed is explicitly recommended by some NHS trusts. However, its long-term effectiveness is yet to be assessed.

Relevant national guidelines

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has issued Interventional Procedure Guidelines (IPGs) on the use of vertebroplasty and balloon kyphoplasty:

-

NICE IPG 12,86 issued in 2003, states that PVP may be considered for the provision of pain relief in patients with severe painful osteoporosis with loss of height and/or compression fractures of the vertebral body only if their pain is refractory to more conservative treatment. 86

-

NICE IPG 166,87 issued in 2006, states that BKP may be considered in patients with VCFs whose condition is refractory to medical therapy and in whom there is continued vertebral collapse and severe pain.

Both guidelines stipulate that the procedure should only be undertaken:

-

by clinicians trained to an appropriate level of expertise

-

following discussion by a specialist multidisciplinary team which includes a radiologist and a spinal surgeon

-

where there are arrangements for good access to a spinal surgery service.

Description of technologies under assessment

Summary of intervention

Percutaneous vertebroplasty

Percutaneous vertebroplasty is a procedure in which bone cement [such as polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA), glass polymers, hydroxyapatite or calcium compound] is injected into a fractured vertebra with the intention of reducing the pain caused by bone rubbing on bone and strengthening the bone so that it is unlikely to fracture further. 57 PVP is most commonly performed in the thoracic and lumbar vertebrae, and only occasionally in the cervical spine. 14 It is additional, rather than an alternative, to conventional therapy. 57

Percutaneous vertebroplasty is performed under radiological guidance using fluoroscopy. 88,89 It is usually performed using conscious sedation and local anaesthesia of the skin, subcutaneous tissue and the periosteum of the vertebral body into which the needle is to be introduced. 89 Sedation or light general anaesthesia is used in the majority of cases, with decisions being based on patient-level contraindications and anaesthetist preferences. 90 After adequate infiltration of local anaesthetic, a small skin incision is made and a disposable bone biopsy needle or trocar needle is placed centrally in the vertebral body using an image-guided safe access route. This may be done bilaterally through the pedicles, oblique across one pedicle or lateral oblique through the base of the pedicle. Under constant screening, it is advanced through the pedicle into the vertebral body with the aid of a light orthopaedic hammer. 14 An 11- or 13-gauge needle is used. 91 The cement is then injected very slowly, again under constant fluoroscopic screening, and the injection is stopped immediately if the cement begins to spread into a blood vessel or towards the posterior cortical margin. 18 To achieve optimal vertebral filling, two trocars may be used, one on either side of the midline. 90 The procedure may last from 45 minutes to 1 hour, depending on the number of vertebrae being treated. 14 Some centres perform computed tomography (CT) scanning at the end of the procedure to assess the distribution of cement and identify any complications. 14

At the end of the procedure, the patient remains on the operating table until the cement within the vertebral body has set. 16 This usually took about 20 minutes with earlier generations of bone cement. 92 However, setting time has been substantially reduced in recent years. For example, Goto et al. 93 compared the setting time of PMMA with bone cements containing micron-sized titania particles, and found a setting time of 11 minutes in a commercially available PMMA-based cement (Osteobond, Zimmer, Warsaw, IN). Glass-based polymers can set within 2 to 3 minutes. 94 The patient should then be kept in the recumbent position, with monitoring of vital signs and neurological evaluations every 15 minutes for the first hour and then every 30 minutes for the next 2 hours. 16 The initial mobilisation should be supervised by qualified staff. 14

Percutaneous vertebroplasty may be done as a day case if the patient’s general health and social circumstances are appropriate. 90 However, in exceptional cases an overnight stay may be required. 14 Prophylactic intravenous antibiotics may be used both before and after the procedure; some operators limit their use to patients with immunodeficiency. 14 Non-steroidal or steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs may be used for 2–4 days after vertebroplasty to minimise any inflammatory reaction to the heat generated by the polymerisation of the bone cement. 16 This is unlikely to apply to glass polymer-based bone cements, which do not have the same exothermic reaction upon mixing.

A number of bone cements are available for carrying out PVP, and decisions can be based on patient needs and operator preferences. The high-viscosity Confidence Spinal Cement System™ (DePuy Synthes, Indianapolis, IN, USA) is marketed by Johnson & Johnson, and carries an average cost of £1546 per operation (see also section 6.2). Low-viscosity cements are also available to purchase at prices that are lower than that of high-viscosity PMMA cement. The list price for such cements were obtained through NICE, and on clinical advice it was estimated that the costs using lower-viscosity cements, incorporating injection kit, needles cement and assorted consumables, would be in the region of £660, £720 and £780 for one-, two- and three-level procedures respectively. However, our clinical expert estimated that 15% of cases are more complex and would require Cortoss® cement (Stryker, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), collation or thicker cement, while younger patients would need bone-absorbable cement. It was assumed that the added cost of these complex cases would add slightly over £100 to the average cost of an operation resulting in an assumed cost of £800 per low-viscosity cement PVP procedure. Given that the estimate includes a component for using higher-viscosity cement, the price used within the analysis could be equated to a strategy where low-viscosity cement is used within the majority of patients, while higher-viscosity cements are used in a small proportion where the clinician believes that this is appropriate. In addition to the cements themselves, operating equipment, including bone biopsy or special trocar needles and vacuum cement mixing systems, is required.

Percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty

Percutaneous BKP is a variant of PVP in which one or two balloon-like devices (also known as tamps) are inserted bilaterally into the vertebral body. These balloons are slowly inflated until they reach their highest achievable volume, in order to restore vertebral body height (VBH). The balloons are then deflated and removed, leaving a cavity which is filled with bone cement; because of the existence of the cavity, the cement may be injected at a lower pressure than that used for PVP. 35

Sedation is based on practical considerations, such as patient-level contraindications. Some patients receive general anaesthetic and remain in hospital overnight for observation. 91 However, BKP may be done as a day case if the patient’s general health and social circumstances are appropriate. 90

Although there is no apparent reason why BKP should differ from PVP in terms of pain relief, it has some potential additional benefits. Medtronic suggest that the creation of a cavity of known volume into which cement may be injected results in a lower risk of leakage and consequent complications. 34 Furthermore, introduction of the balloon provides the potential for restoring vertebral height and thus correcting deformity. However, neither of these potential benefits has a good evidence base. There is no evidence of a higher complication rate in PVP, as most cement leakages remain asymptomatic. In addition, to be effective in restoring vertebral height and reducing kyphosis, BKP should be performed within a few weeks of fracture; thereafter, although a cavity will still be created within the vertebra, fracture healing is likely to prevent restoration of vertebral height. 95

In the UK, the device required for BKP is marketed by Medtronic as a single-use sterile pack containing two Kyphon® Xpander™ inflatable bone tamps and associated accessories, at a list price of £2600.50. 34 The components of the Medtronic KYPHON BKP kit obtained the CE mark in May 1999, while various components of the Kyphopak – the Osteo Introducers, Balloon, and Bone Fillers – obtained the CE mark in 2001, 2003 and 2002 respectively. 34 The bone cement included in the kit, Kyphon® ActivOs™ Bone Cement with Hydroxyapatite,96 is a PMMA cement to which hydroxyapatite (a calcium compound believed to promote osseointegration) has been added. 97 Kyphon® also produces two alternative cements for use in kyphoplasty: Kyphon® KyphOs FS™ Calcium Phosphate Bone Substitute and Kyphon® HV-R™ Bone Cement (all products are registered to Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA). 96

Balloon kyphoplasty with stenting (stentoplasty)

Balloon kyphoplasty with stenting seeks to overcome a problem inherent in simple PBK, namely that, because of pressure on the vertebra, some of the height restored by the fully inflated balloons may be lost after they are deflated and removed and before the cement is injected. A laboratory comparison of stenting compared with kyphoplasty found that most of the height gained in BKP appeared to be lost after the balloon was deflated. 98 In stentoplasty, a small balloon catheter surrounded by a metal stent is inserted into the vertebral body using a minimally invasive percutaneous approach under radiographic guidance and either local or general anaesthetic. The balloon catheter is then inflated with liquid, under pressure, to create a cavity in which the stent is expanded. The balloon catheter is then deflated and withdrawn but the stent is left in position within the vertebra and maintains the height of the cavity into which high-viscosity PMMA bone cement is then injected. The injected cement hardens within 1 hour, and the patient may then be mobilised. 33

The use of a vertebral body balloon (VBB), an optional site preparation device, is recommended: it enables the operator to identify the feasibility of cavity creation and full expansion of the stents. 33

Synthes market a vertebral body stenting system, which consists of a vertebral body stent catheter, an inflation system, a VBS access kit and an optional VBB catheter. The balloons included in the VBS and VBB catheters are said to be considerably more rigid than current kyphoplasty balloons and therefore less likely to herniate through the fracture. 33

Facet joint injection

Facet joint injections involve the administration of anti-inflammatory steroids and local anaesthetic to facet joints with focal tenderness. They are usually performed on an outpatient basis without sedation. Prior to the procedure, the patient lies in prone position while the operator palpates the back in order to localise the pain. Once identified, the skin and subcutaneous tissue surrounding the affected area are infiltrated with 1% lidocaine. Then, fluoroscopic or CT imaging is used to identify the posterior part of the joint and a 20- or 22-gauge needle is directed vertically into the joint space until bone cartilage is reached. 99 A long-acting steroid such as triamcinolone, methylprednisolone or betamethasone is administered to the joint, along with 0.5% bupivacaine to anaesthetise the area. 100

Although we did not directly assess the clinical effectiveness of facet joint injections for treating painful osteoporotic VCFs, the procedure is noted here because it is emerging as a possible treatment for a subgroup of patients in whom pain and functional impairment arises not from the VCF per se but from the impact of the VCF on other spinous processes. Ryan et al. 101 found that facet joints may be an important site of pain for people with osteoporotic VCFs, and, more recently, a cohort study by Wilson et al. (n = 61 treated patients)84 found that problems with the facet joint may account for back pain in approximately one-third of patients with osteoporotic VCFs. On the basis of their data, Wilson et al. suggested that the apparently high placebo response seen in the ‘sham’ treated cohorts in two recent RCTs102,103 may in fact have been a response to the local anaesthetic by patients whose pain was an indirect consequence of a VCF. Hence, in our cost-effectiveness model, a hypothetical scenario controlling for the potential influence of this patient subgroup has been included.

Bone cement

Percutaneous vertebroplasty and BKP are traditionally performed using PMMA, a low-viscosity acrylic bone cement, to which a radio-opaque substance such as barium, tantalium or tungsten sulphate has been added to facilitate visualisation during the procedure. 14 It is prepared by mixing a liquid component containing the monomer, accelerator and inhibitor with a powder containing the polymer, radio-opacifier and initiator. The heat that is released during the subsequent polymerisation process while the cement is hardening in situ may cause local damage to bone or other tissues. 104 However, in PVP and BKP, such damage may not be entirely detrimental. PMMA appears to have analgesic properties quite apart from those caused by the effect of the stability provided by the cement within the weakened vertebrae. The reason for such analgesic properties remains unclear, but one possibility is that it destroys or damages local nerve endings as a result of both the toxic effects of the free monomers of PMMA and the heat caused by the cement polymerisation. 14 However, we are not aware of any evidence to suggest that cements that do not generate heat are any less effective.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA)104 states that PMMA is contraindicated in the presence of active or incompletely treated infection at the site where the cement is to be applied. It also notes that hypotensive reactions have been noted between 10 and 165 seconds after its application; as these have lasted from 30 seconds to over 5 minutes, and some have progressed to cardiac arrest, the FDA recommends that patients should be monitored carefully for any changes in blood pressure during and immediately following the application of the cement. Other reported adverse events include pyrexia due to allergy to the cement. In addition, the FDA notes that the heat released while the cement is hardening in situ may damage bone or other tissues surrounding the implant. 105

The FDA also notes that caution is required in preparing and handling PMMA: excessive exposure to the concentrated monomer vapours may produce irritation of the respiratory tract, eyes and possibly the liver; contact lens wearers should not be near or involved in mixing PMMA. 104 However, newer manufacturer kits, such as the PLACOS® bone cement (Zimmer, Hanau, Germany), provide vacuum cement mixing tools to avoid this issue.

The newer composite cement bisphenol-A-glycidyl dimethacrylate (bis-GMA) resin (Cortoss) is more viscous than PMMA and consequently easier to handle. It does not contain the volatile monomers which may be the cause of cardiovascular and respiratory adverse events with PMMA. It is stronger than PMMA, and cures at a lower temperature, reducing the risk of thermal damage and setting more rapidly. It is also inherently opaque, and therefore does not need to be mixed with a toxic radio-opaque material. 14 The bioactive Cerament™ bone analogue cement (Bonesupport, Lund, Sweden) also has radio-opaque properties which obviates this requirement.

Follow-up required

It has been suggested that, following discharge, patients who have undergone PVP should be recalled for evaluation 1 day, 1 week and 1 month after treatment. 92 However, this appears to reflect US practice, and according to our clinical expert (DW) in the UK it would be more normal for a patient to receive a follow-up telephone call at 1 week after discharge and a clinical consultation at 1 month after.

Setting

Percutaneous vertebroplasty and BKP should be performed in a sterile environment which allows fluoroscopic imaging of the thoracolumbar spine. 18 The use of an interventional radiology suite rather than an operating theatre has been recommended because fixed fluoroscopic equipment offers better imaging quality than a mobile C-arm. 16 PVP and BKP should be performed only in hospitals which have adequate neurosurgical backup to deal with potentially serious complications. 14

Equipment required

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) equipment is requisite to screen all patients who are considered for PVP or BKP, in order to identify the fracture, assess its age, define its anatomy, assess the posterior vertebral body wall and exclude other causes of back pain. However, CT scanning may be used instead when MRI is unsafe (e.g. in patients with pacemakers). CT equipment is also required if there are any doubts regarding the intactness of the posterior vertebral wall. 16 Fluoroscopic imaging equipment is also required for use during the procedure.

Personnel involved

As stipulated in the NICE guidance,86,87 PVP and BKP should be performed only by clinicians trained to an appropriate level of expertise (for historic reasons, PVP and BKP have most commonly been performed by interventional radiologists). An anaesthetist should preferably be present to monitor sedation even when the procedure is performed under local anaesthesia. 14

Place in the treatment pathway

Percutaneous vertebroplasty and BKP are usually offered as a last resort to people with symptomatic VCFs in whom alternative treatments have not been successful. 89,106 An Australian review has noted that, while people with recent painful VCFs are potential candidates for either PVP or BKP, PVP is not appropriate for people with VCFs which cause symptoms such as pain or breathlessness due to a hunched posture, and who require structural correction for functional kyphotic deformity which is neither congenital nor due to trauma; such patients are potential candidates for either BKP or surgical stabilisation of the fracture with or without fusion of the vertebrae. 57

Criteria for treatment

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance indicates that PVP and BKP should be limited to patients whose pain is refractory to more conservative treatment;86,87 for BKP, there is an additional requirement that they should have continued vertebral collapse and severe pain. 87

Recent guidance from the Cardiovascular and Interventional Radiology Society of Europe (CIRSE) states that PVP is indicated in patients with ‘painful osteoporotic VCF refractory to medical treatment’. It defines failure of medical treatment as ‘minimal or no pain relief with the administration of physician-prescribed analgesics for 3 weeks or achievement of adequate pain relief with only narcotic dosages that induce excessive intolerable sedation, confusion, or constipation’. 16 The CIRSE guidelines further note that PVP may be considered within days of painful fracture if the patient is at high risk of complications resulting from immobility (e.g. thrombophlebitis, DVT, pneumonia or pressure ulcer). 16

Contraindications

The CIRSE guidelines list the following absolute contraindications to PVP:

-

asymptomatic vertebral body compression fracture

-

patient improving on medical treatment

-

osteomyelitis, discitis or active systemic infection

-

uncorrectable coagulopathy

-

allergy to bone cement or opacification agents

-

prophylaxis in osteoporotic patients. 16

Relative contraindications in osteoporotic patients include:

-

radicular pain

-

fracture of the posterior column (which increases the risk of cement leak)

-

spinal canal stenosis

-

lack of surgical backup and monitoring facilities. 16

These contraindications appear to be equally applicable to BKP.

Although neurological symptoms are not an absolute contraindication to PVP or BKP, in patients with such symptoms great care should be taken to avoid cement extravasation as this may exacerbate any pre-existing nerve compression. 90 Thus, prior to PVP/KP, a detailed examination should be performed to detect any neurological compromise and exclude other causes of pain such as degenerative spondylosis. Physical examination is important to accurately localise the symptomatic vertebra, especially in the presence of multiple fractures. 14

Identification of important subgroups

A number of authors have suggested that only patients with acute VCFs (≤ 6 weeks’ duration) are likely to benefit from PVP or BKP. 107,108 However, the clinical experience of rapid and dramatic post-procedural reductions in pain is likely to be confounded by the rapid healing of the fracture itself. This was suggested by the recruitment pattern in the recent VERTOS II trial, in which more than half of initially eligible participants became ineligible prior to enrolment owing to spontaneous pain reduction. 17 Furthermore, Rad and Kallmes109 presented a retrospective analysis of 321 single-level PVP procedures. These were stratified into acute (≤ 6 weeks), subacute (> 6 to ≤ 24 weeks) and chronic (> 24 weeks) fractures, and absolute and proportional pain reductions were compared between the three groups. There was no strong correlation between fracture acuity and pain relief. Hence, vertebral augmentation may be better used to treat people with chronic pain refractory to more conservative measures. 85,110

It has also been suggested that PVP is effective in specifically selected patients with more severe pain. 108 However, the evidence for this claim is unconvincing. Pain is a subjective experience mediated by various psychosocial factors111 and is consequently open to confounding influences and difficult to objectively assess. A strong placebo response due to positive expectations among persons with severe pain could not therefore be ruled out as a cause of apparent effectiveness. Indeed, a recent meta-analysis of individual patient data (IPD) from two operative placebo with local anaesthesia (OPLA)-controlled trials of PVP110 found that post-procedural pain reduction was unrelated to baseline pain severity.

It is possible that vertebral augmentation should be pursued only with those whose pain and functional impairments arise directly from the VCF rather than as indirect consequences thereof. Wilson et al. 84 found that one-third of patients who were eligible for PVP (n = 21 of 61 treated patients) responded favourably to a facet joint injection. It may be that the pain in this group was mediated by overload on the facet joints adjoining the fractured vertebral body, which could therefore be treated successfully with a less invasive procedure.

Current usage in the National Health Service

On the basis of data from Dr Foster Intelligence, Johnson & Johnson have estimated that, between April 2010 and March 2011, 473 vertebroplasties and 225 kyphoplasties were performed for osteoporotic VCF. 36 These figures appear to apply to England alone.

Medtronic reported, on the basis of HES data for 2009/10/11, that 487 patients in England and Wales were treated with PVP and 466 with BKP, for osteoporotic VCF;34 it is not clear whether this is figure relates to the 2-year period or to the average for 1 year.

Synthes note that HES data for 2010–11 indicate that 698 patients in the UK underwent either PVP or BKP with or without stent for osteoporotic VCF. 33

Anticipated costs associated with the intervention

A formal report on the likely costs associated with each analysis is contained in the cost-effectiveness section.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The assessment will address the question ‘What is the long-term efficacy, safety and cost-effectiveness of percutaneous vertebroplasty and percutaneous balloon kyphoplasty (with or without vertebral body stenting) as a treatment for osteoporotic vertebral compression fractures?’

Interventions

Percutaneous vertebroplasty or BKP with or without vertebral body stenting, performed under general or local anaesthesia.

Population including subgroups

The relevant population is adults of any age and either sex with painful osteoporotic VCFs. If the evidence permits, consideration will be given to subgroups defined by:

-

time from fracture to treatment

-

presence of fracture-related deformity before treatment

-

receipt of inpatient care before treatment.

People with malignancy-related vertebral fractures and those with neuropathy in the absence of osteoporotic compression fractures are not included the scope of this assessment.

Relevant comparators

The comparators specified in the protocol (see Appendix 1 ) are the interventions themselves and non-invasive management (including no treatment in people who cannot tolerate the relevant active comparator interventions). Injection of local anaesthesia to the affected vertebral body is also considered a relevant comparator, as this has been used as a ‘sham’ intervention in double-blind, OPLA-controlled trials of PVP. Moreover, our clinical advisor (DW) suggested that administration of local anaesthesia with facet joint injection is now routinely offered in the UK as a minimally invasive intervention before patients are considered for vertebral augmentation.

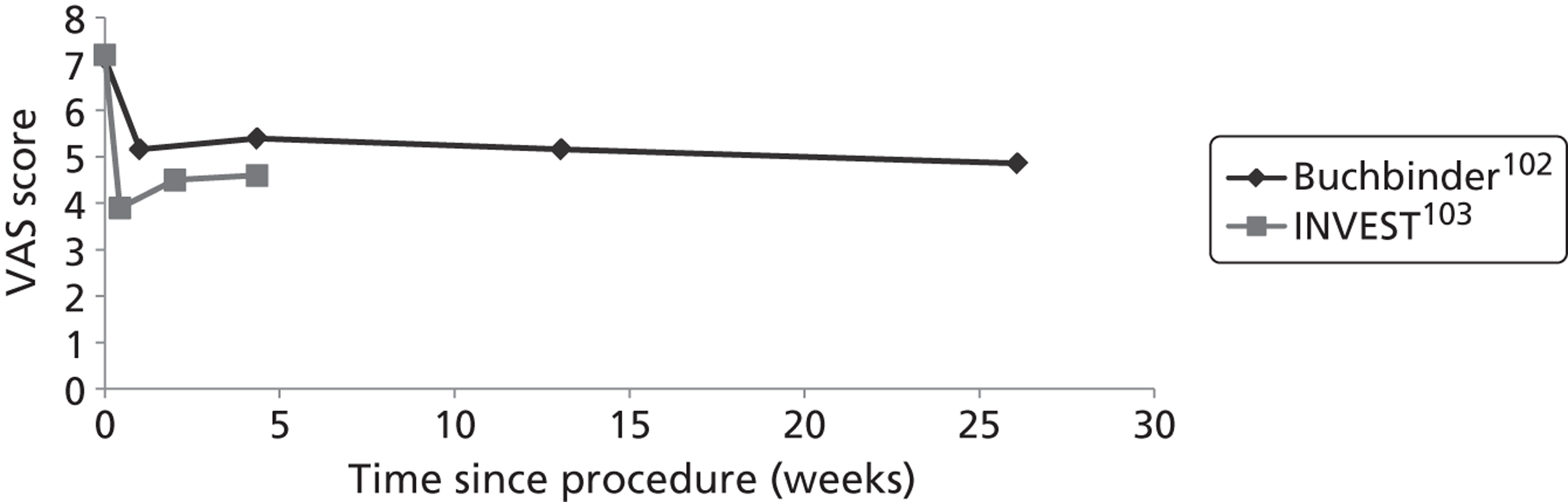

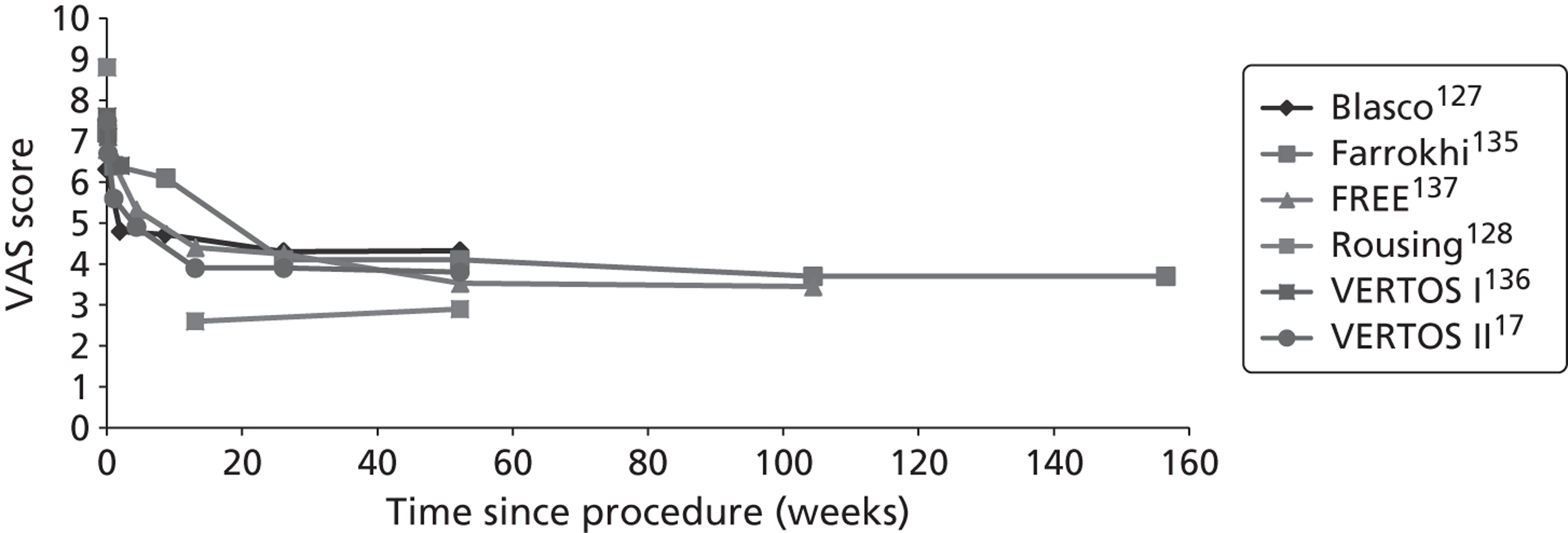

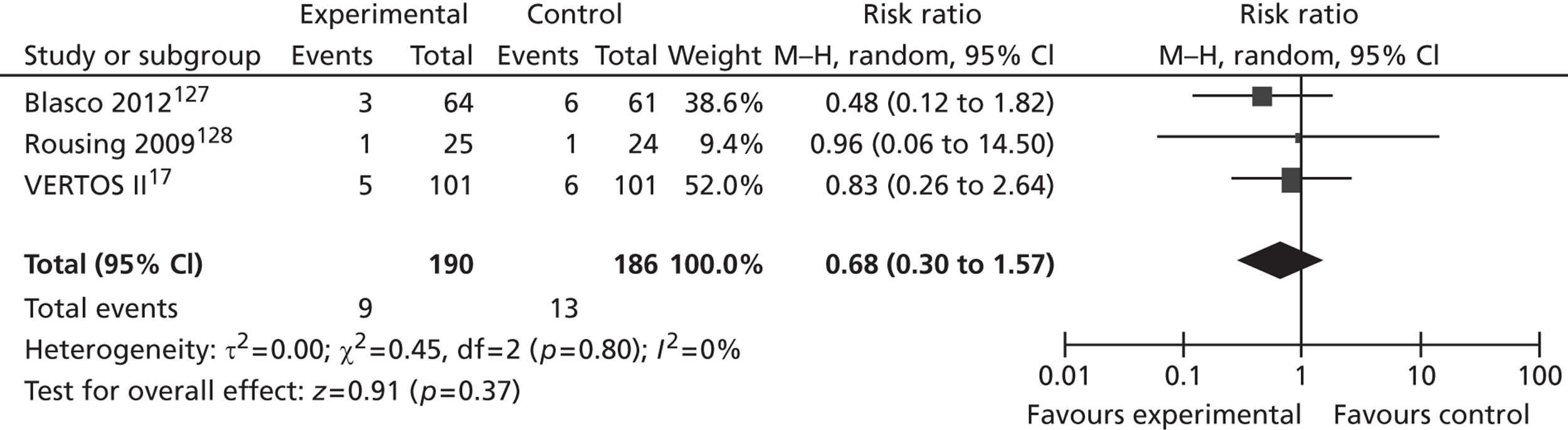

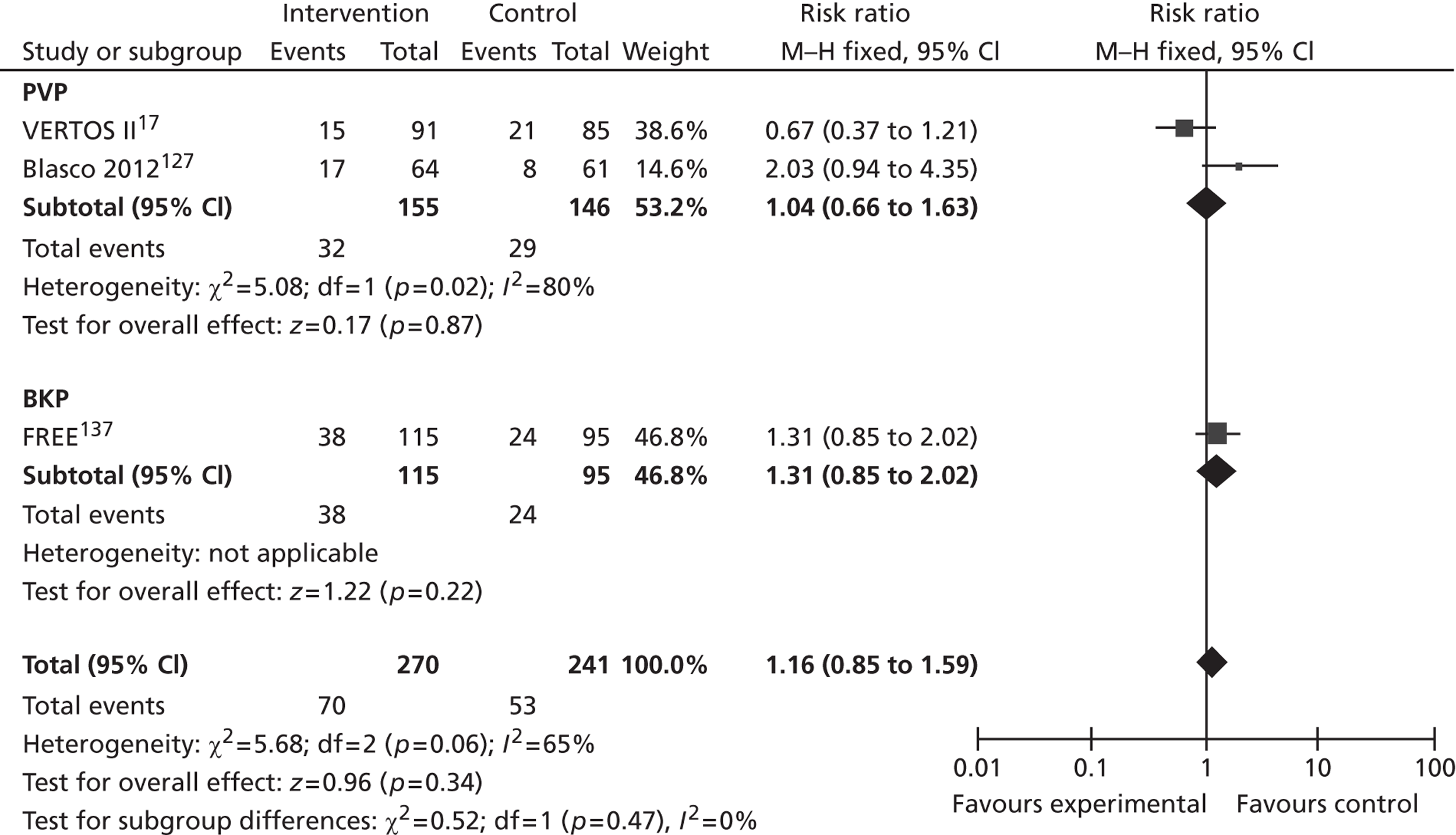

Both the Buchbinder102 and INVEST103 studies used what they describe as a ‘sham’ intervention for the control procedure. The procedure in each of these trials involved infusion of lidocaine 1% into the skin to numb the affected area. The INVEST trial also infiltrated the periosteum of the pedicles with 0.25% bupivacaine. Both trials then mimicked vertebroplasty through physical cues such as pressure to the back and opening of the methacrylate monomer to simulate the smell associated with PMMA preparation. In this review, it was decided that, rather than sham, these procedures would be described as ‘operative placebo with local anaesthesia’ (i.e. OPLA). This term was chosen because of the ongoing debate as to whether or not these procedures actually constitute a sham intervention. A number of authors have argued that the local anaesthetic may have had specific mechanisms of efficacy for long-term pain reduction107,112,113 and, indeed, some empirical evidence is available to support this possibility. 84,114 Conversely, some practitioners have proposed that, owing to the relatively low volumes of cement used in the Buchbinder and INVEST trials, the comparison was effectively placebo versus placebo. 115

Therefore, it was also viewed as important to highlight the possibility of a high placebo response to these interventions, which could be much greater than the response associated with vertebral augmentation. This may be strongly influenced by the elaborate rituals required in any operative procedure. According to Kaptchuk, healing rituals comprise ‘compelling multi-sensory dramas involving evocation, enactment, embodiment and evaluation’. 116 In surgical procedures, these rituals encompass the interventionist’s language and dress, the hospital setting in which they are performed, and the lived experience of being anaesthetised and undergoing the intervention. In short, each dimension of the surgical ritual implies a scientifically derived and culturally sanctioned process designed to move the patient from an ‘ill’ to a ‘well’ state. Such rituals enhance suggestibility and so heighten the probability of a favourable outcome. 117 Consequently, it has been argued that researchers must take these suggestive effects into account, particularly when considering trials that measure subjective outcomes such as pain. 117

There is no gold standard for non-invasive management: the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons considers the strength of the evidence for the various non-invasive treatment options (such as physiotherapy, analgesia and the use of antiosteoporotic agents such as a bisphosphonate or strontium ranelate) to be generally weak to inconclusive, although they provide a recommendation of moderate strength for the short-term use of calcitonin. 118

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

-

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

-

Back-specific functional status/mobility.

-

Pain/analgesic use.

-

Vertebral body height and angular deformity.

-

Incidence of new vertebral fractures.

-

Progression of treated fracture.

Secondary outcomes

-

All-cause mortality.

-

Symptomatic and asymptomatic leakage of cement (e.g. into adjacent intervertebral discs).

-

Peri-procedural balloon rupture.

-

Postoperative complications (including infection).

-

Other adverse events.

The majority of the primary outcomes take the form of continuous or quasi-continuous outcomes (e.g. pain measured on a 0–10 scale), whereas the secondary clinical outcomes are binary outcomes (e.g. the number of patients who suffer a given complication). Continuous outcomes can be compared in terms of:

-

the difference between the mean scores in the intervention and control groups at a specified point in time

-

the difference between the change in mean score in each group between two specified points in time (e.g. immediately before and 1 month after treatment).

To ensure that a continuous outcome measures a real difference between the intervention and control groups following the intervention, either the pre-intervention score for that outcome must have been identical in both groups or any pre-intervention differences must be minimised or controlled for through statistical adjustment. For this reason, we have presented continuous outcomes in terms of changes from baseline rather than as results at specified points in time.

While it is easy to determine whether or not any of these differences in outcome are statistically significant, it is less apparent whether or not they are also clinically relevant – in other words, whether or not they represent differences which the patients would recognise as beneficial. For this reason, research has been conducted for some outcome measures to attempt to quantify the smallest change in score that reflects a change in symptom which can be considered clinically relevant: this is termed the minimal clinically important difference (MCID). It should be noted that the proposed MCID values were for individual rather than group changes; in a trial, individual patients may show clinically important improvements even though the between-group difference in means is less than the MCID. 119 Nonetheless, the MCID provides a useful means of assessing whether or not, on average, an intervention is likely to be associated with greater clinical benefit than the control treatment.

Key issues

Research has shown that many patients with acute radiographically diagnosed VCF who receive conservative treatment report a reduction in pain of 50% or more by 6 months. 19 Because of the self-limiting nature of the condition, it is therefore crucial that outcomes are assessed in terms of the difference between the mean changes from baseline in the intervention and control groups in a randomised trial, and not in terms of the mean change from baseline in a single group of patients who have received the intervention.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this review is to systematically evaluate and appraise the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PVP and BKP in reducing pain and disability in people with osteoporotic VCFs in England and Wales.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing clinical effectiveness and safety

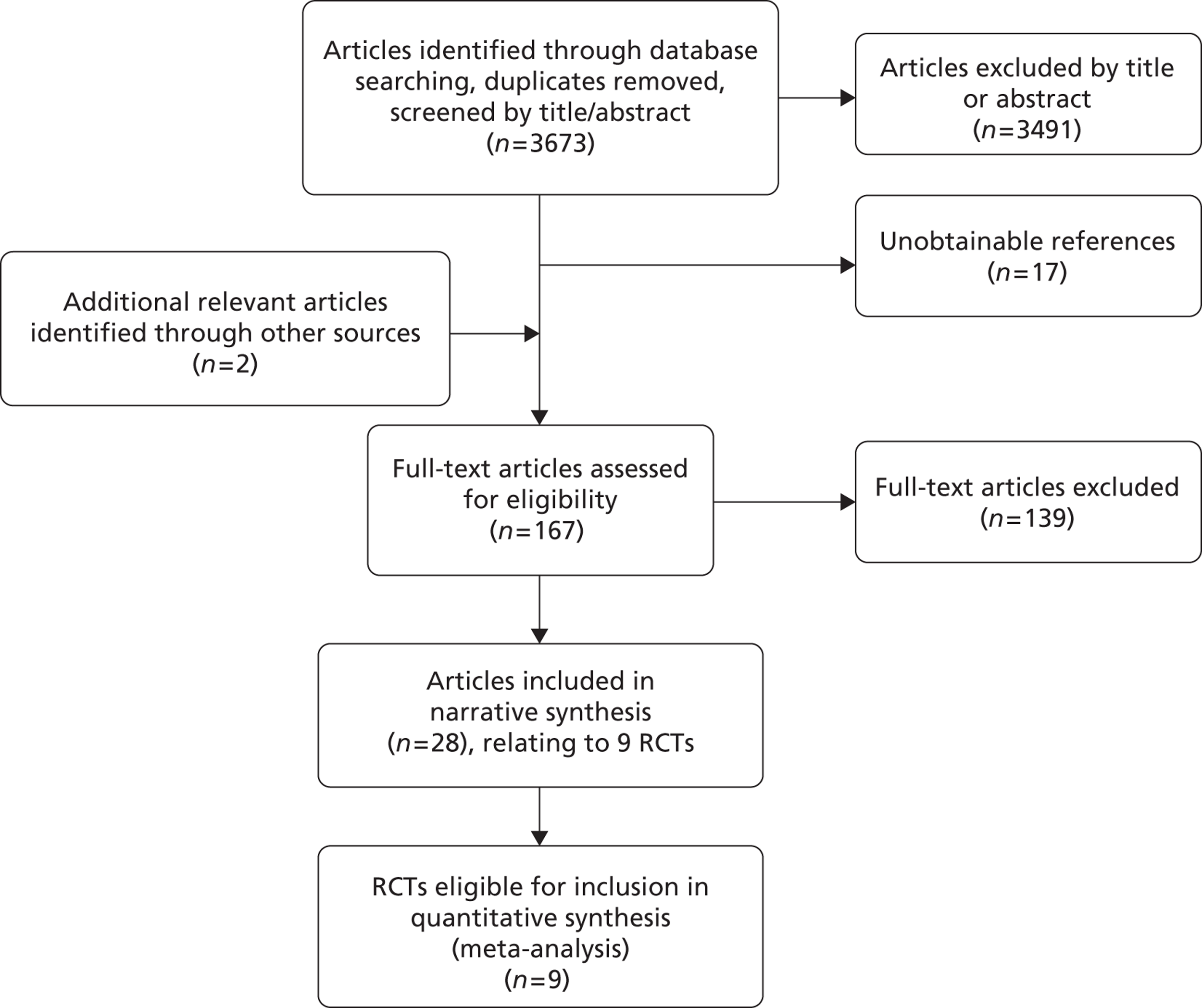

A systematic review was undertaken according to the recommendations of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Identification of studies

Extensive searches were undertaken with the aim of comprehensive retrieval of studies of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness relating to the research question.

The search strategy comprised the following main elements:

-

searching of electronic databases listed below

-

scrutiny of bibliographies of retrieved papers and previous systematic reviews

-

contact with experts in the field.

Electronic searches

The searches aimed to systematically identify all literature relating to the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of PVP and BKP as treatments for osteoporotic compression fractures in men and women of all ages. A comprehensive database of relevant published and unpublished articles was constructed using Reference Manager software (Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA).

Sources searched

The following electronic databases were searched from inception to 22 November 2011: MEDLINE (Ovid); MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); EMBASE; EconLit; The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCTR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Health Technology Assessment (HTA) databases; and Science Citation Index (SCI).

Search terms

The search strategy was developed in collaboration with the information specialist. Search terms included ‘vertebroplasty’, ‘kyphoplasty’, and a broad variety of related clinical terms (e.g. ‘bone void fill*’, ‘vertebral* and augmentation*) in order to obtain a wide scope. No bibliographic filters were used. Vocabulary around vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty is limited and, therefore, few synonyms were available. The searches were simple with an emphasis on sensitivity, utilising both keywords and MeSH/thesaurus terms where available. The MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Appendix 2 . Search strategies for the other databases are available on request.

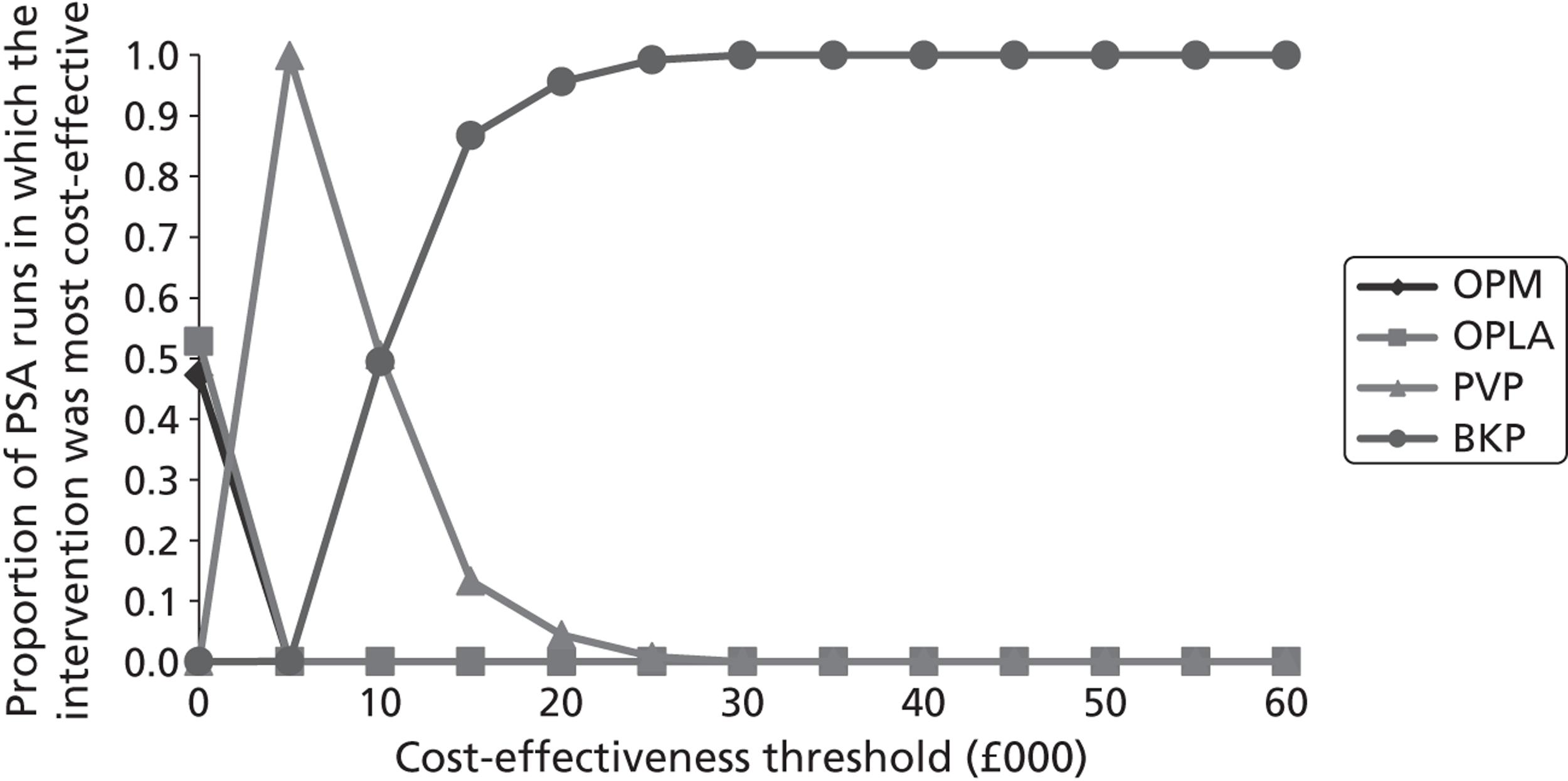

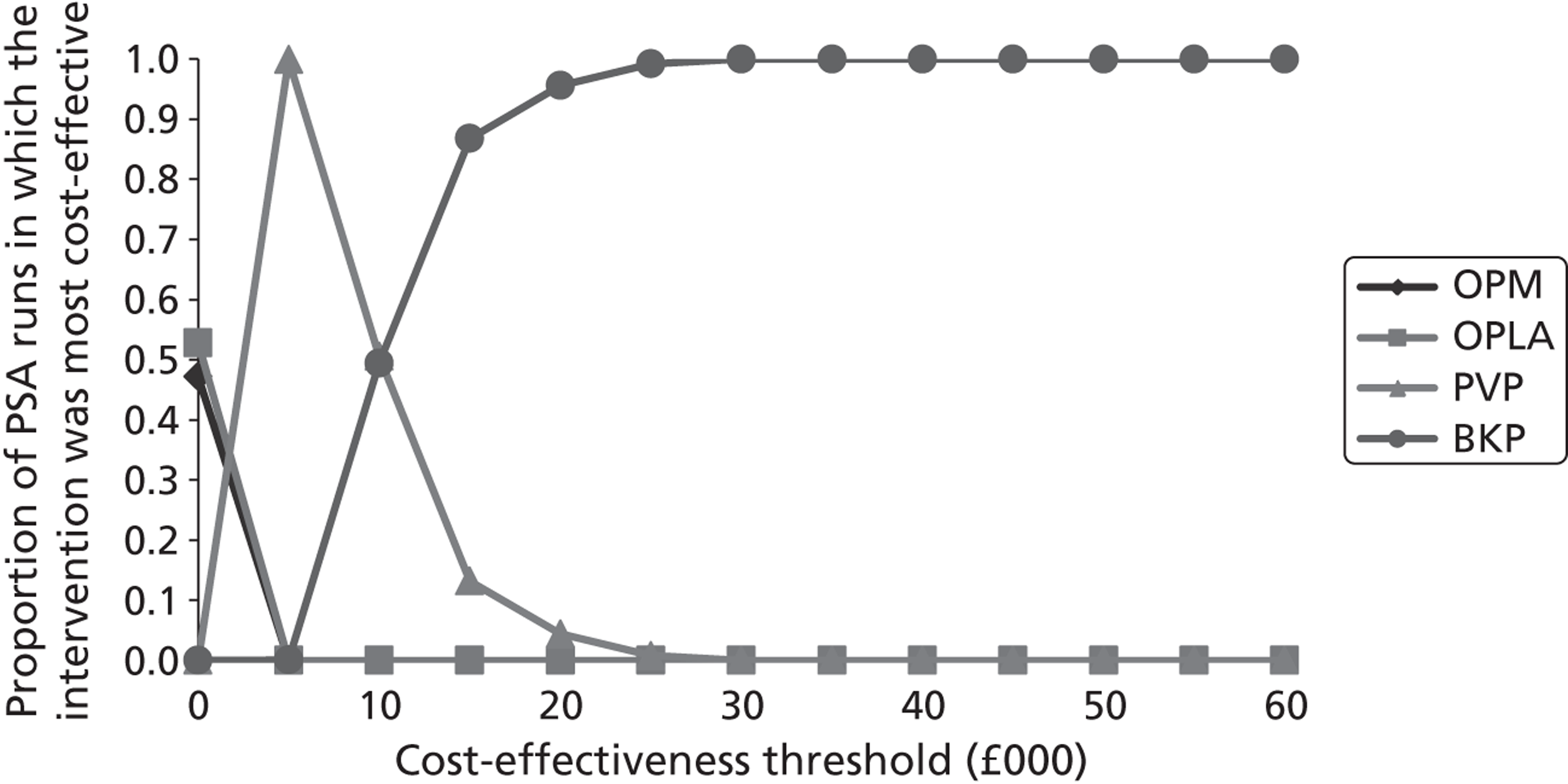

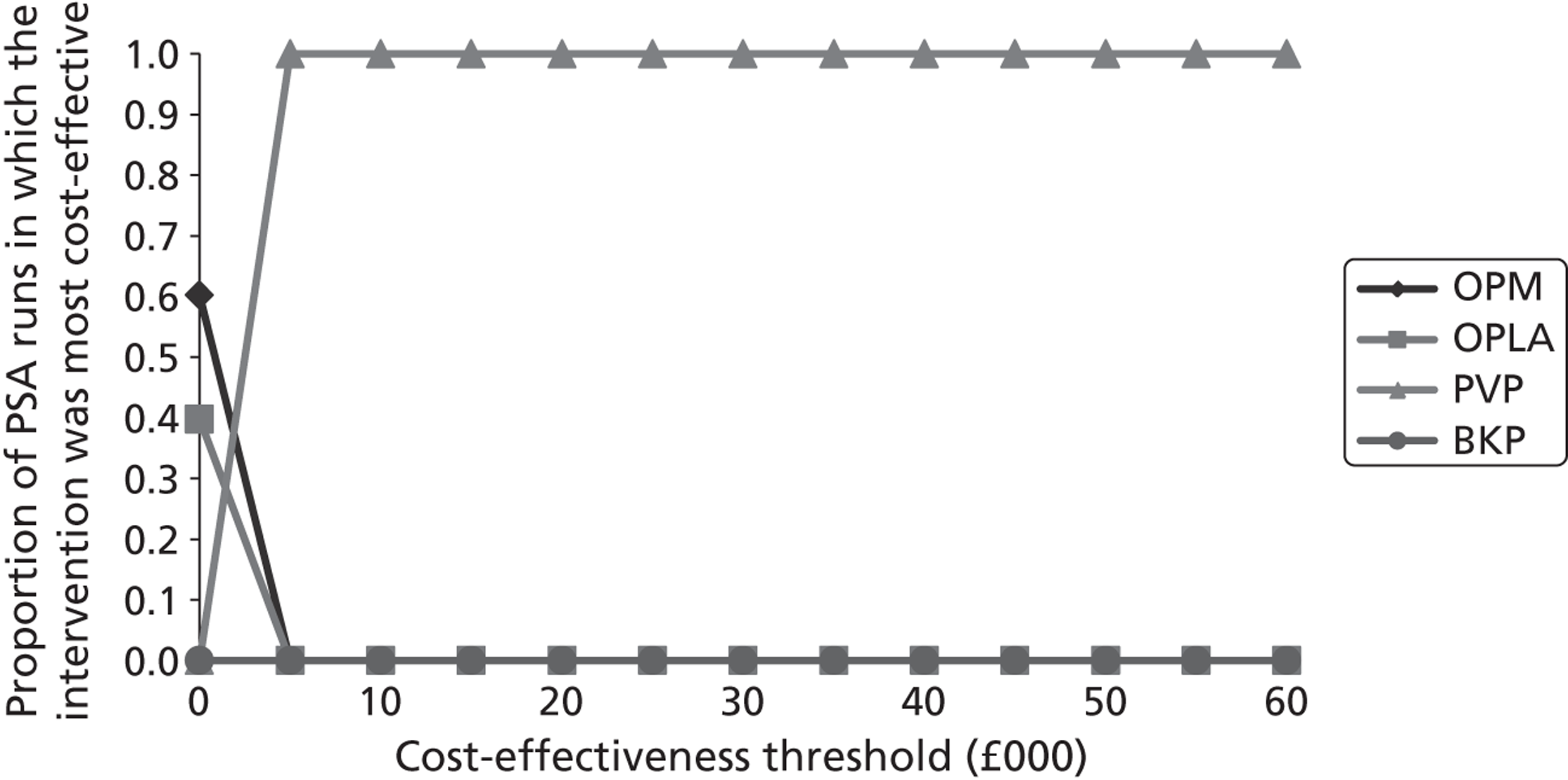

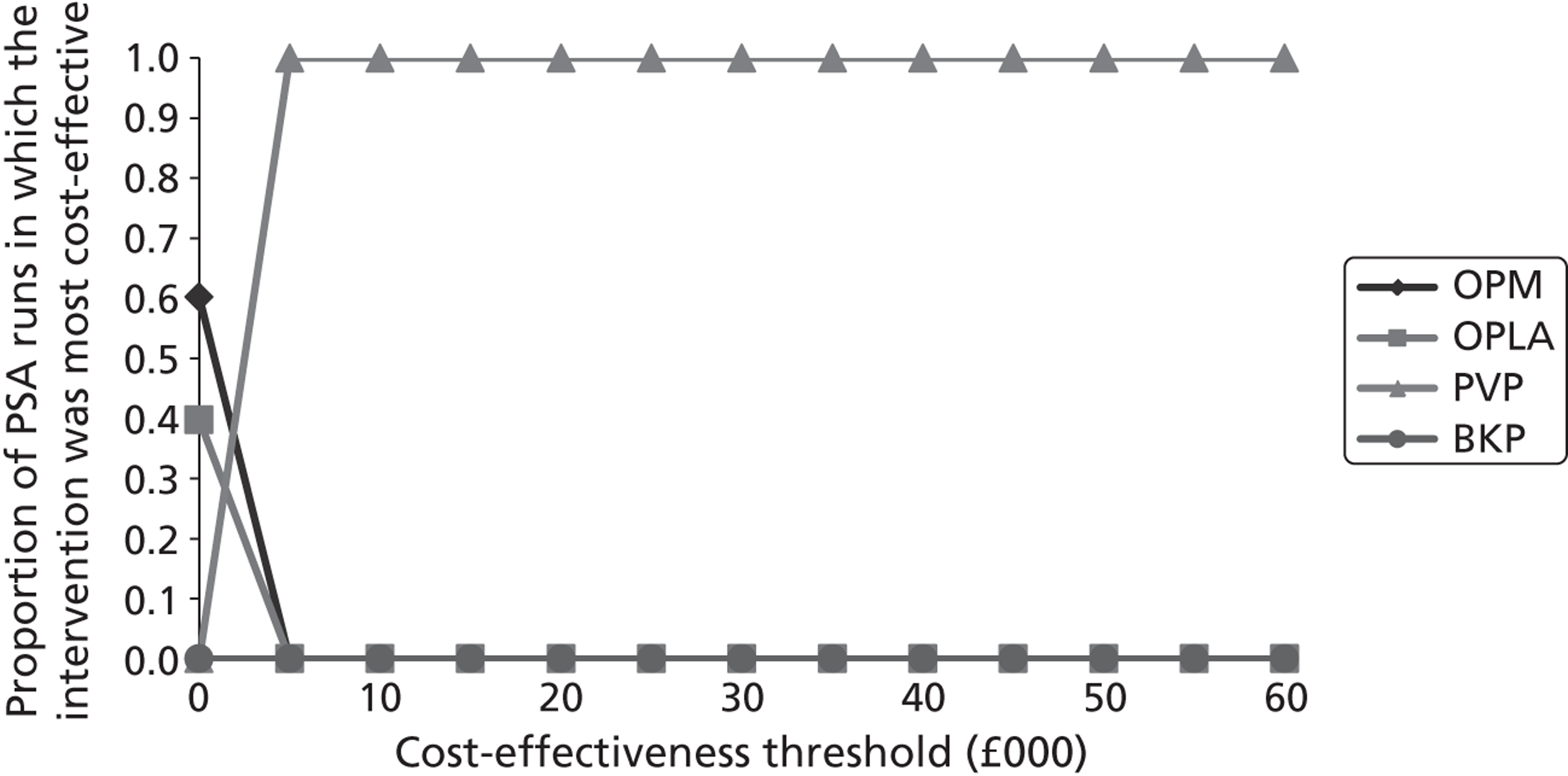

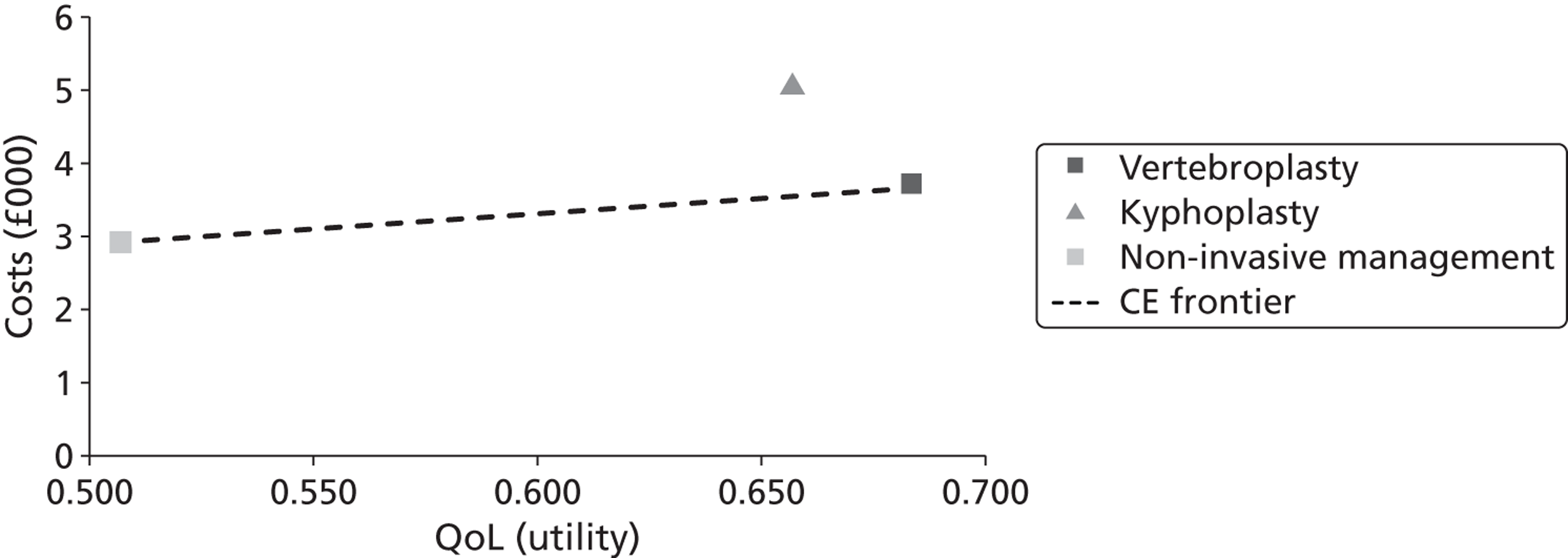

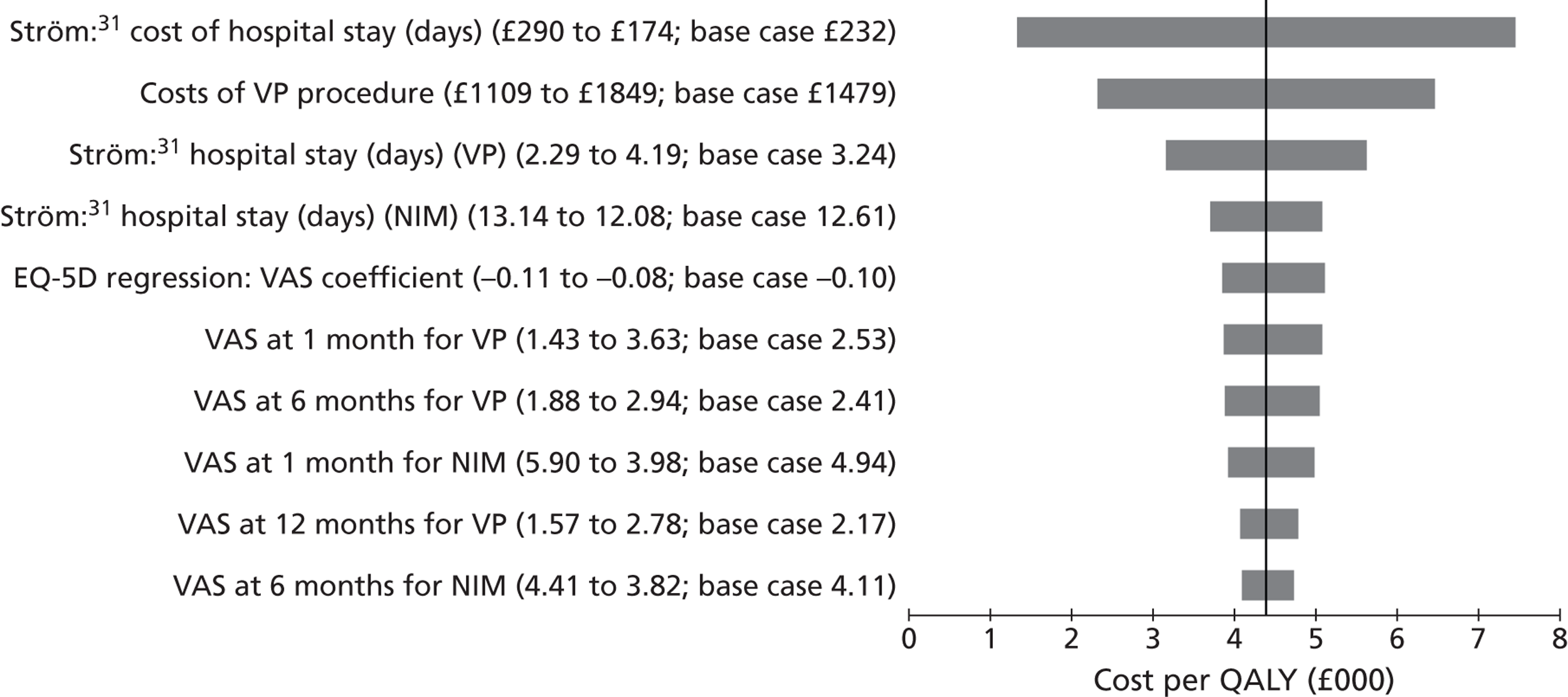

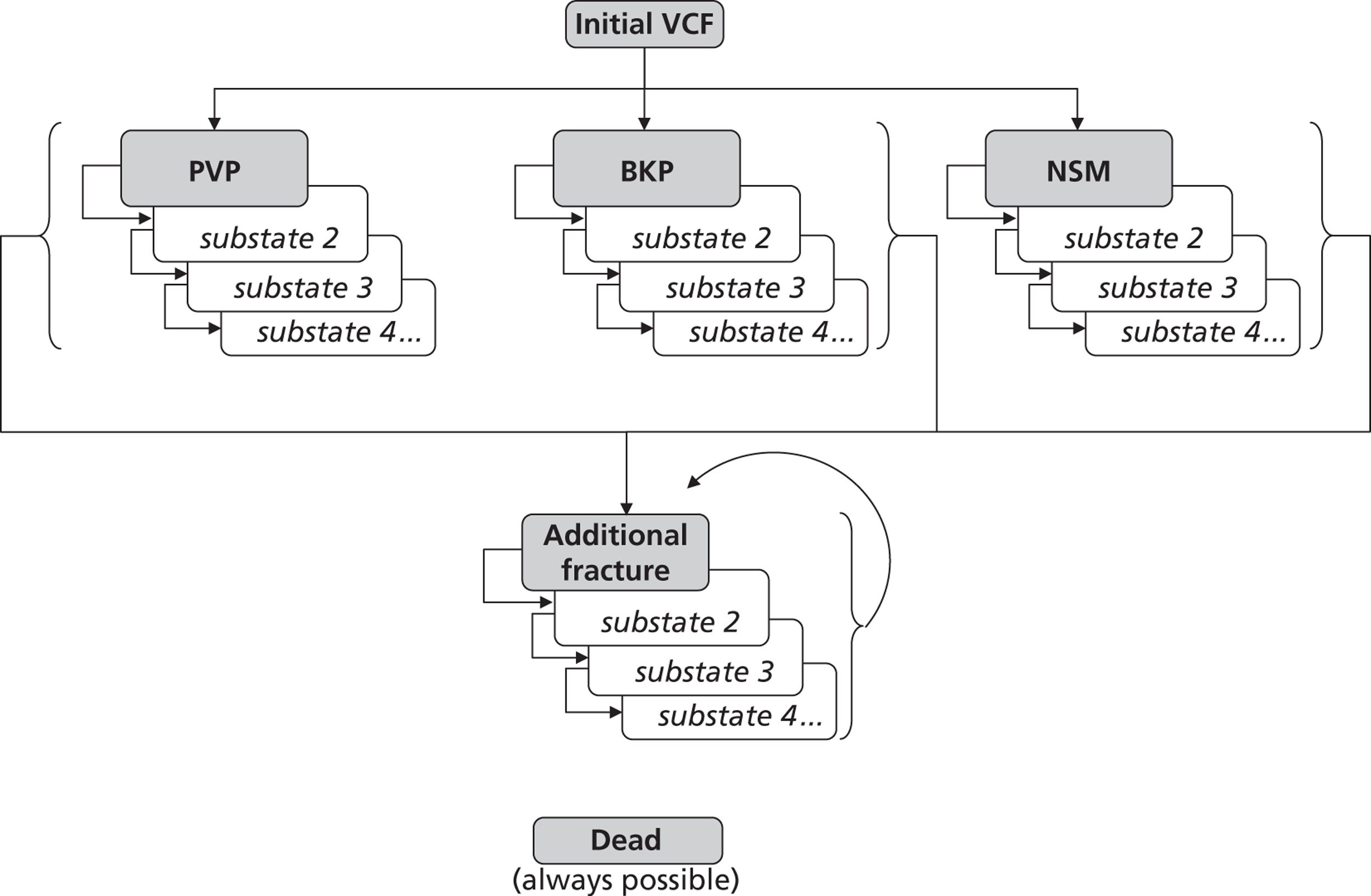

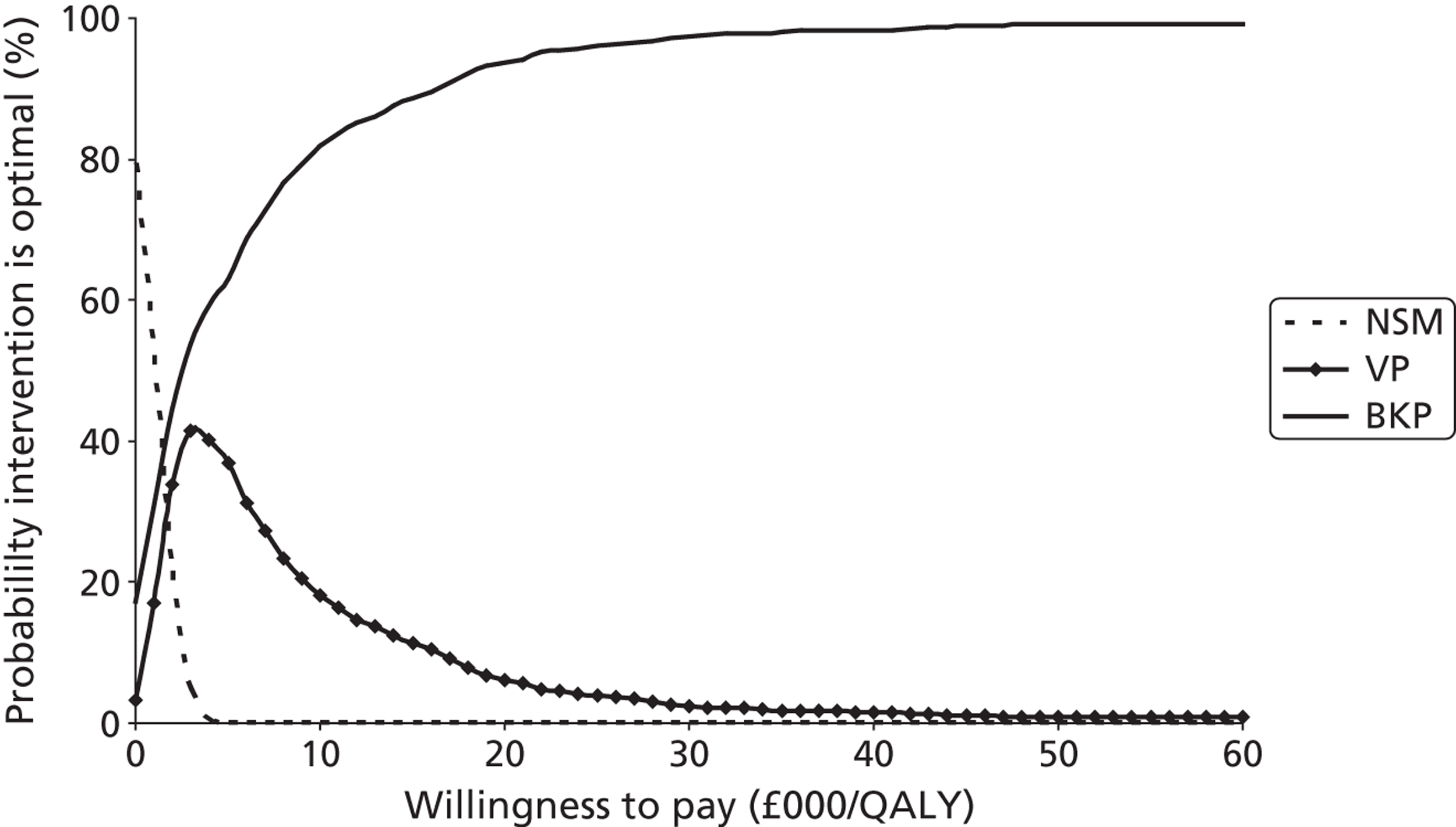

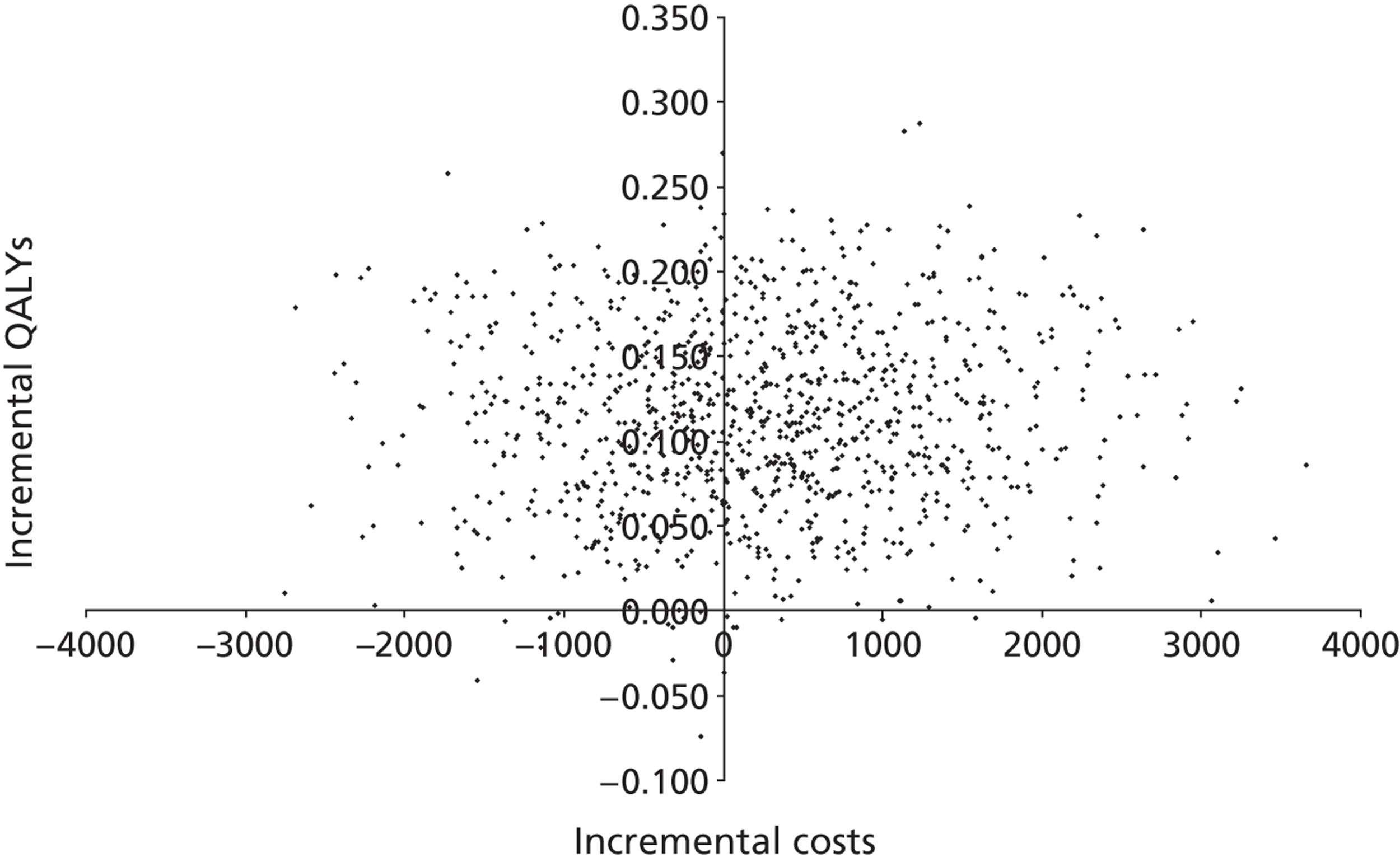

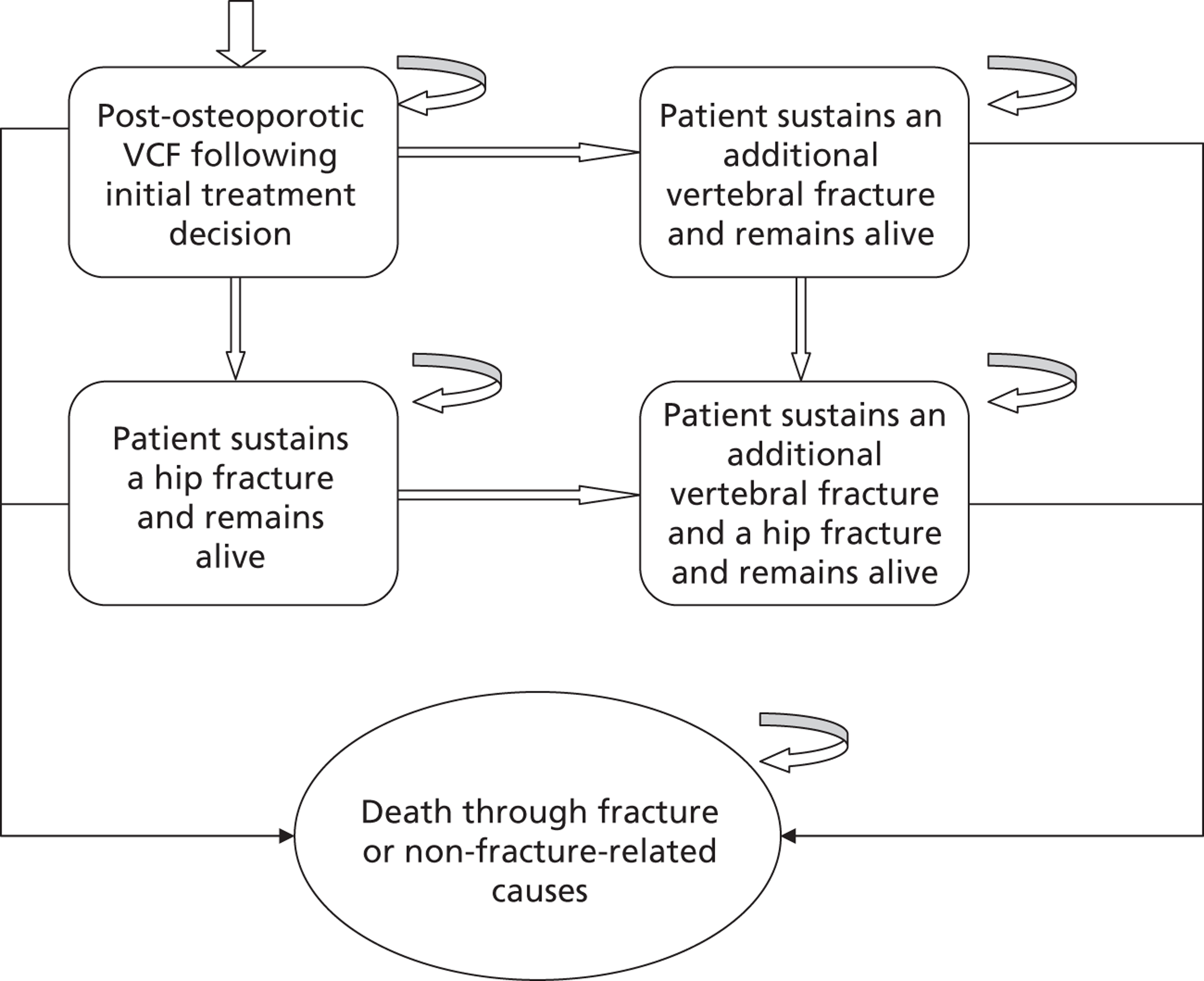

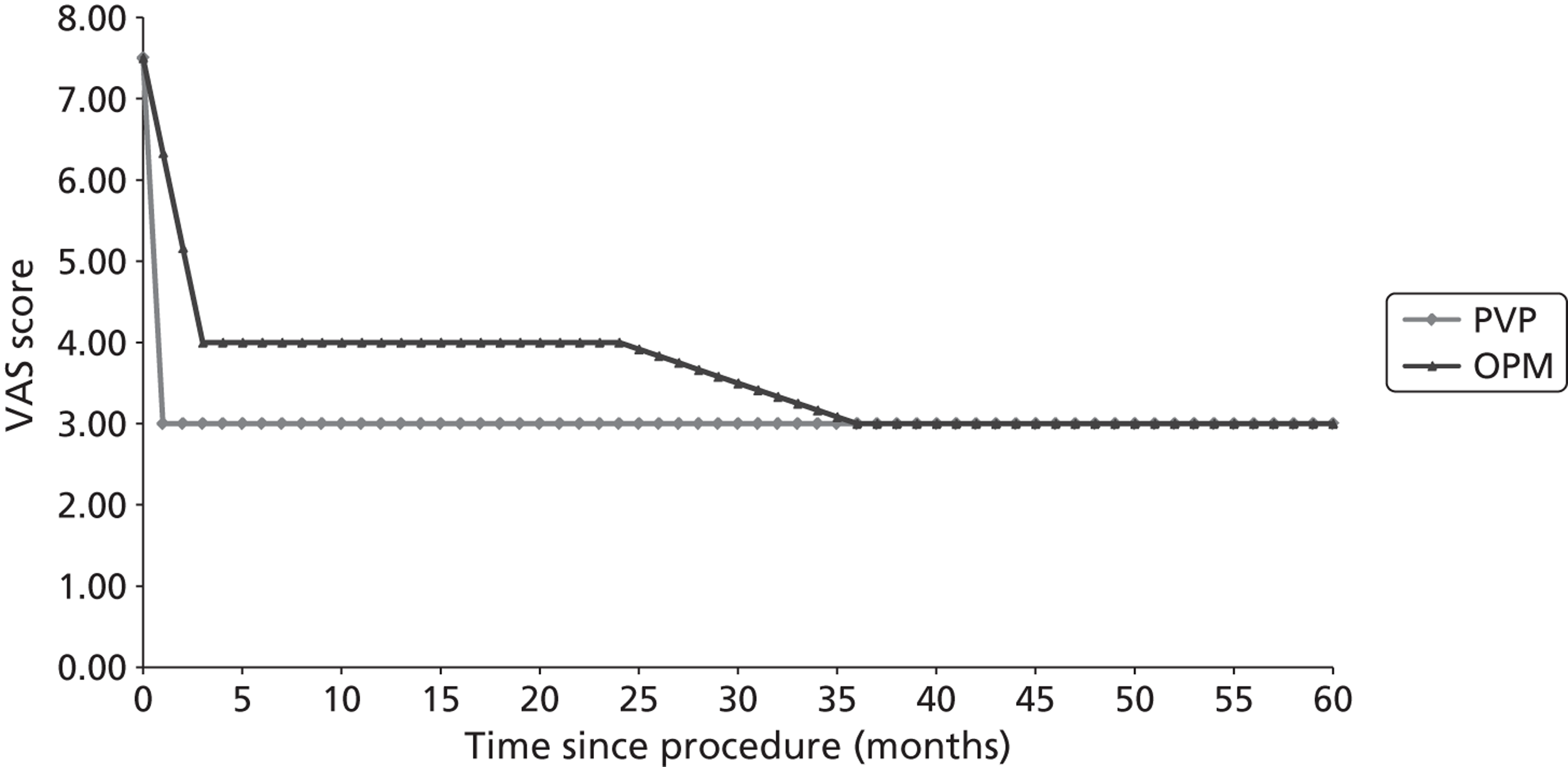

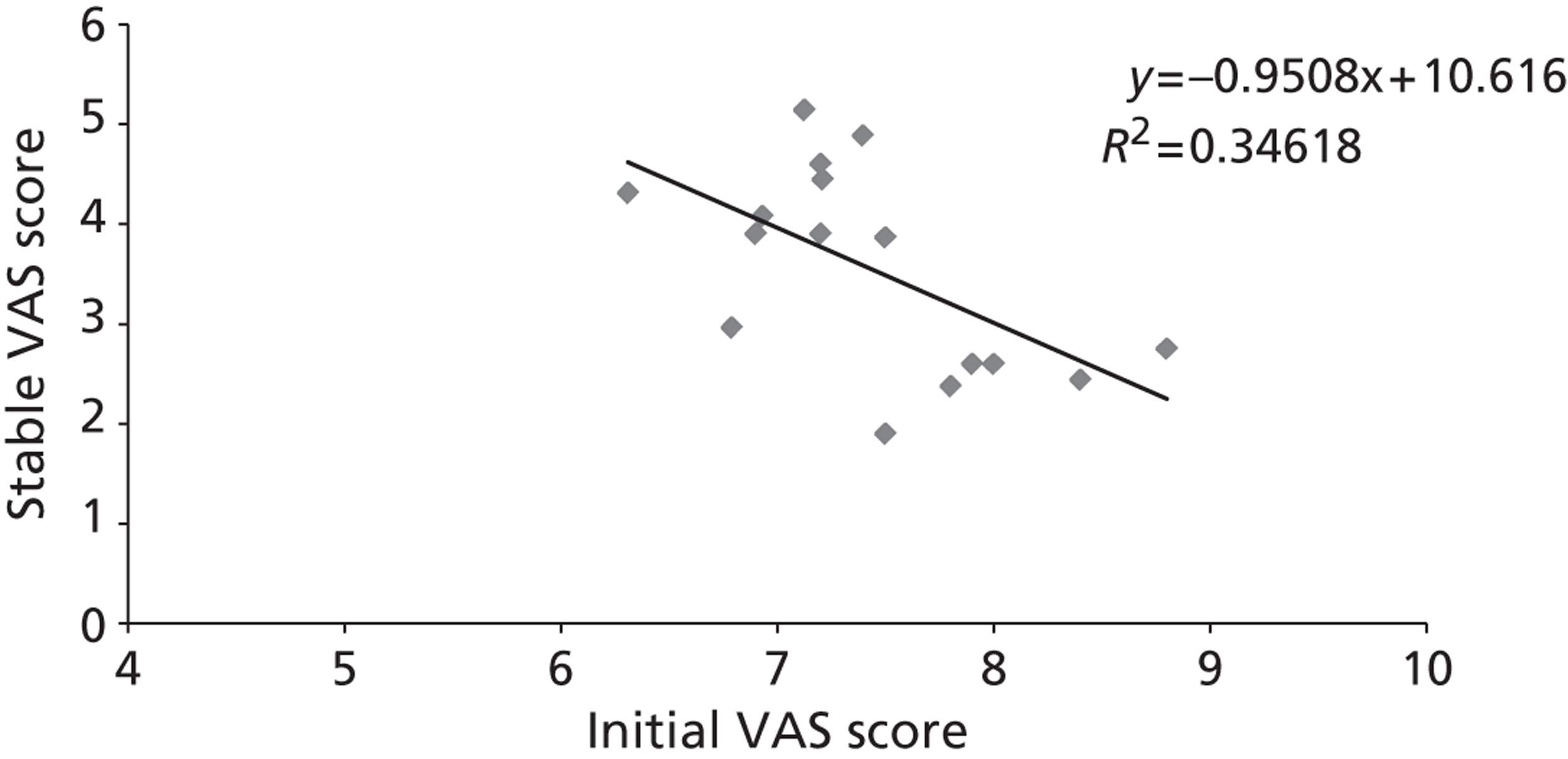

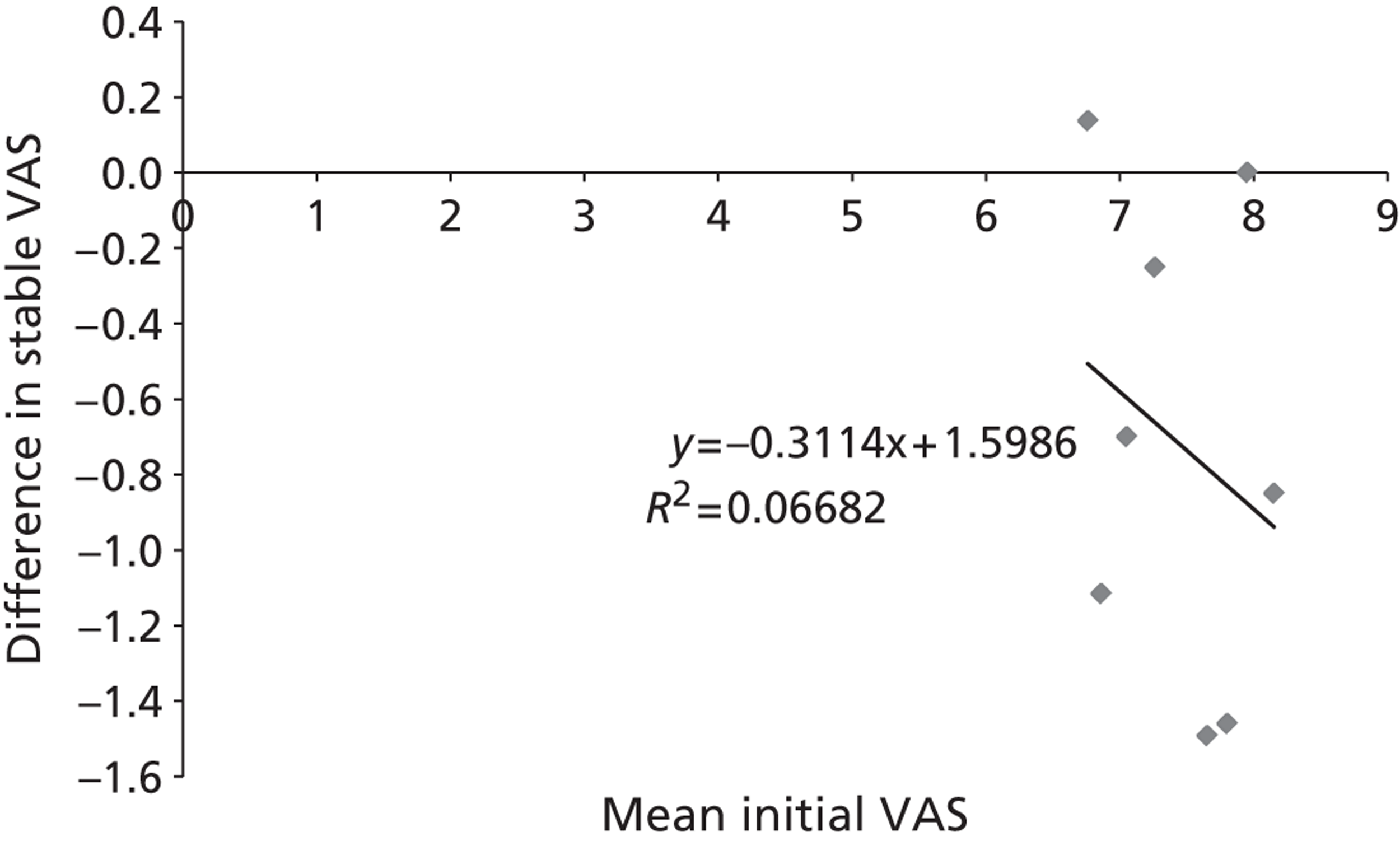

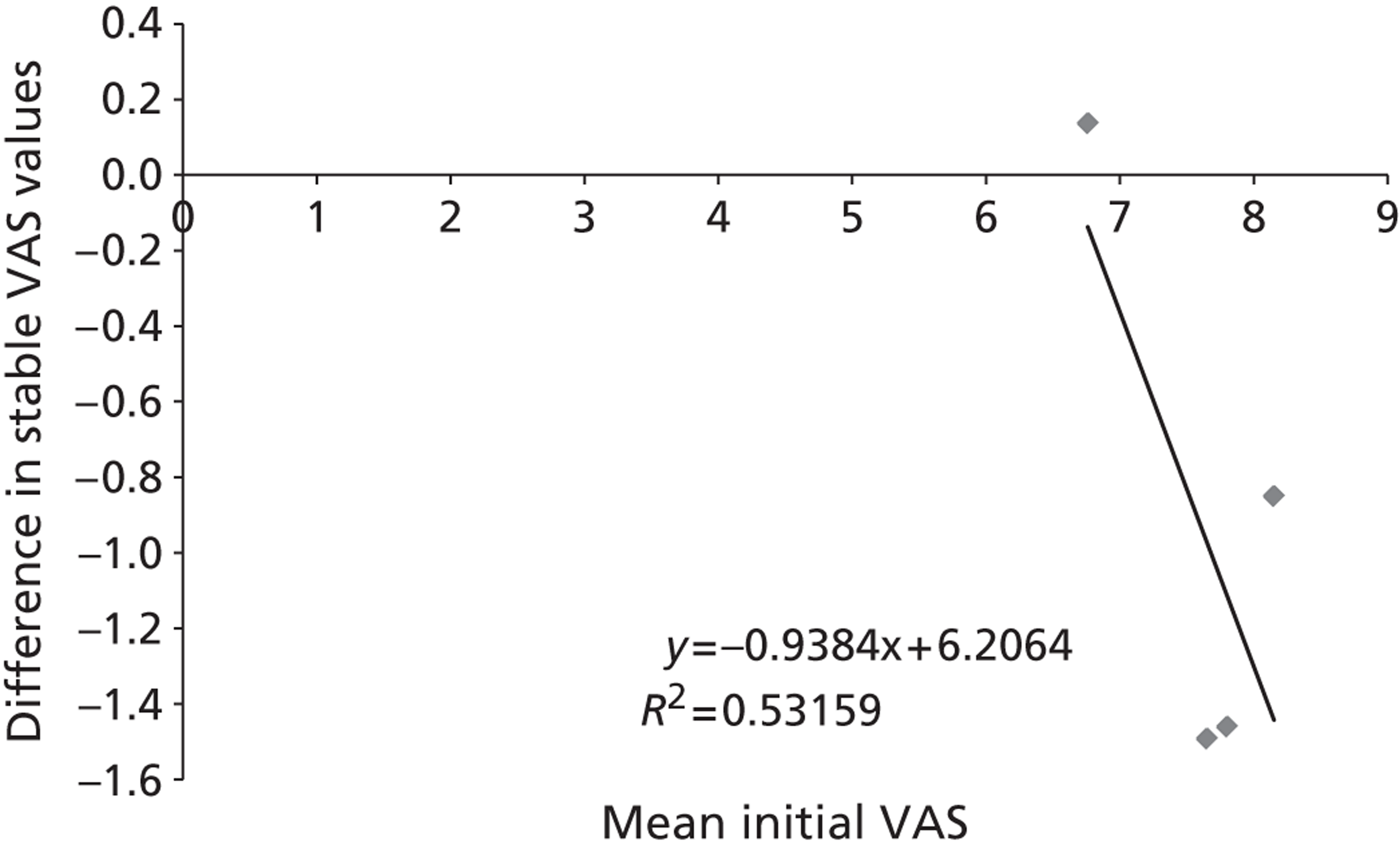

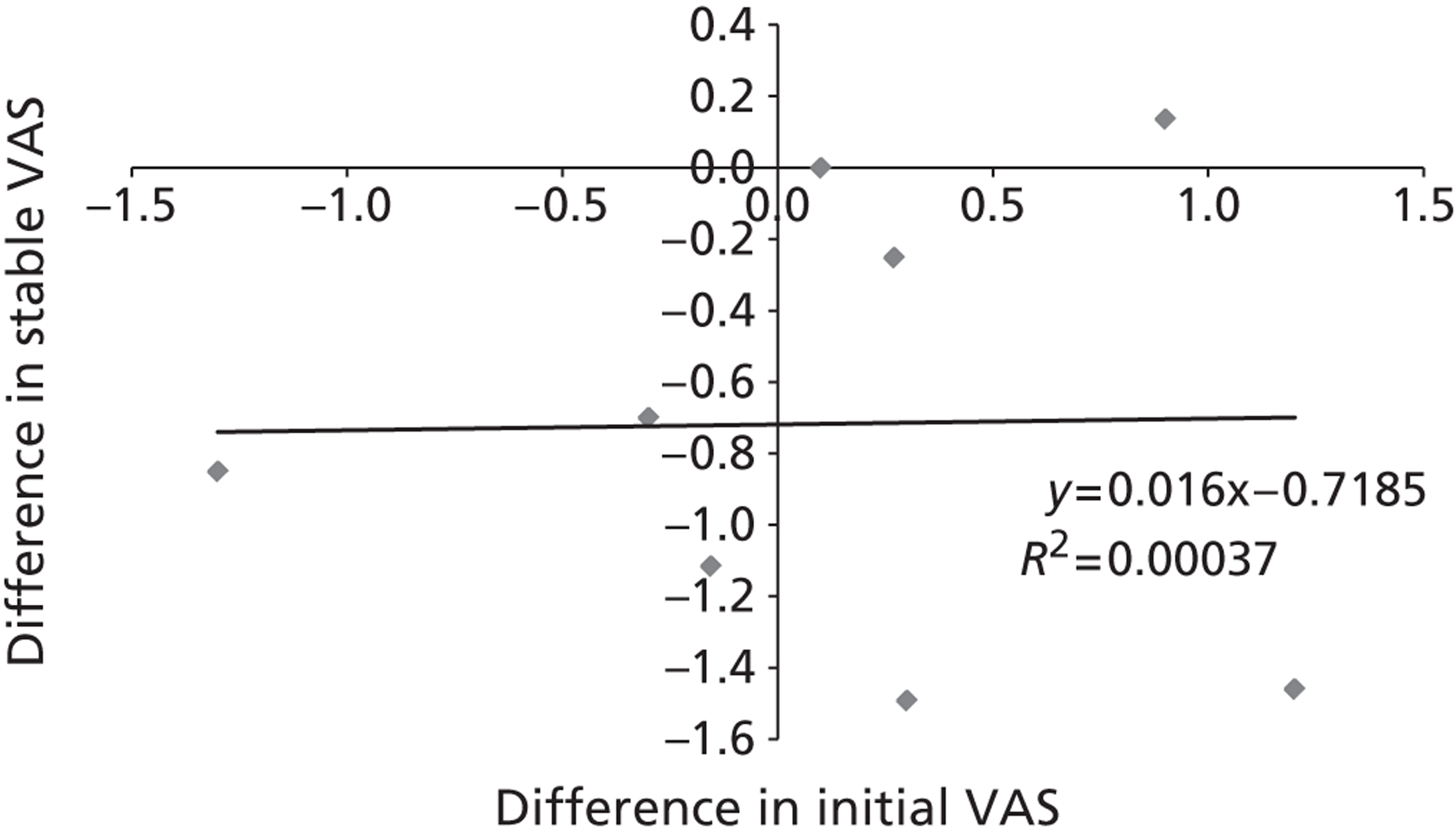

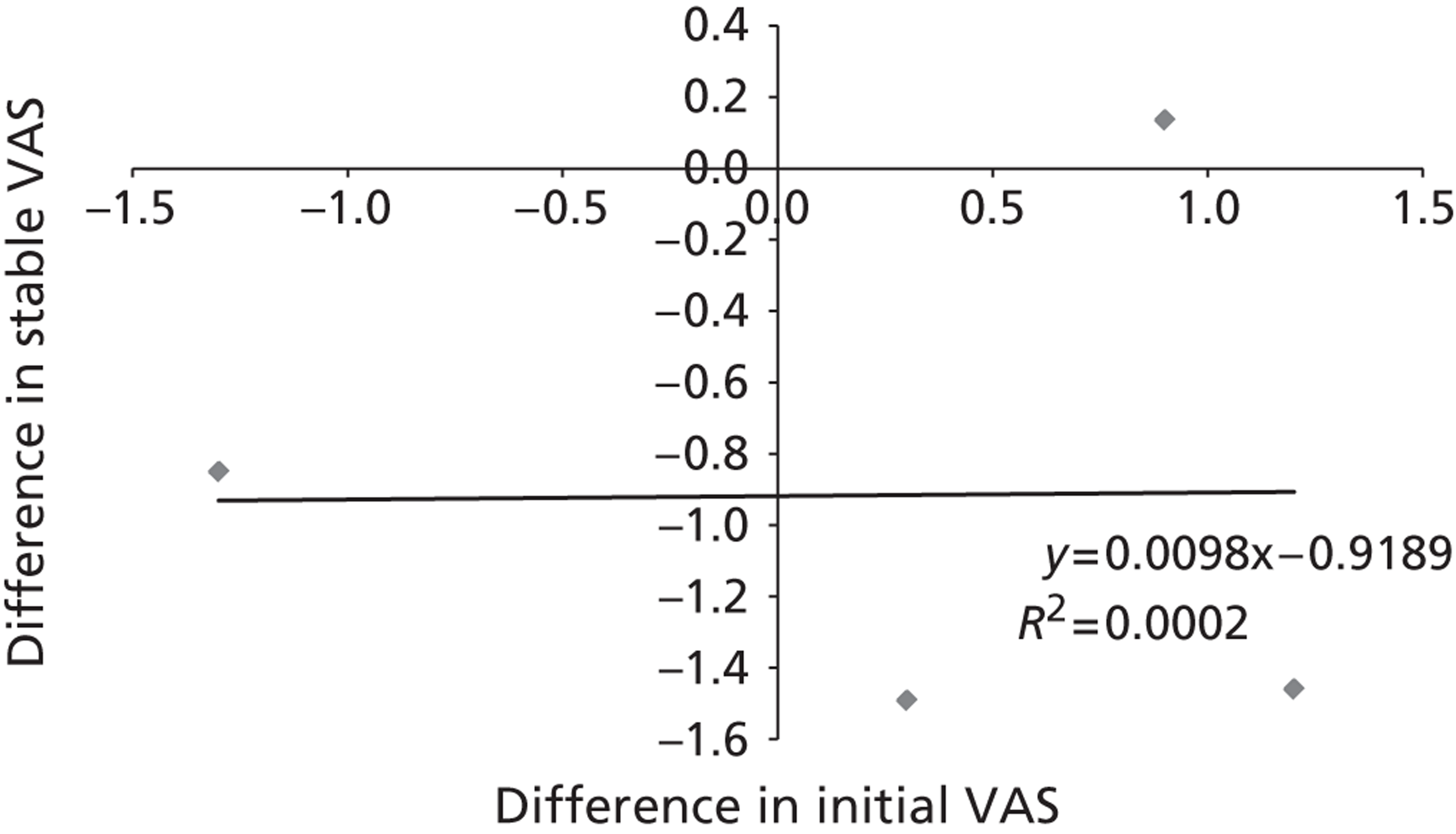

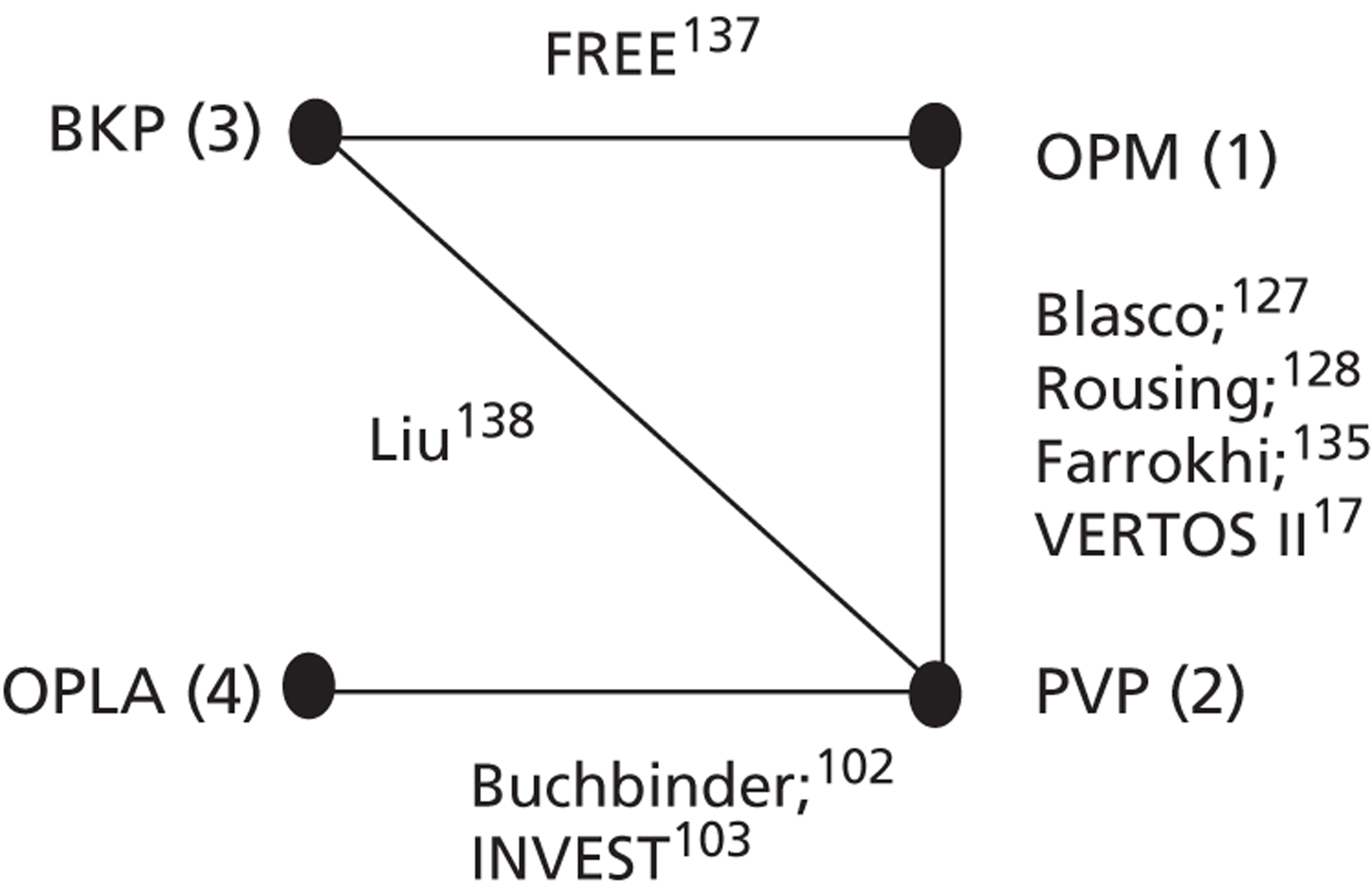

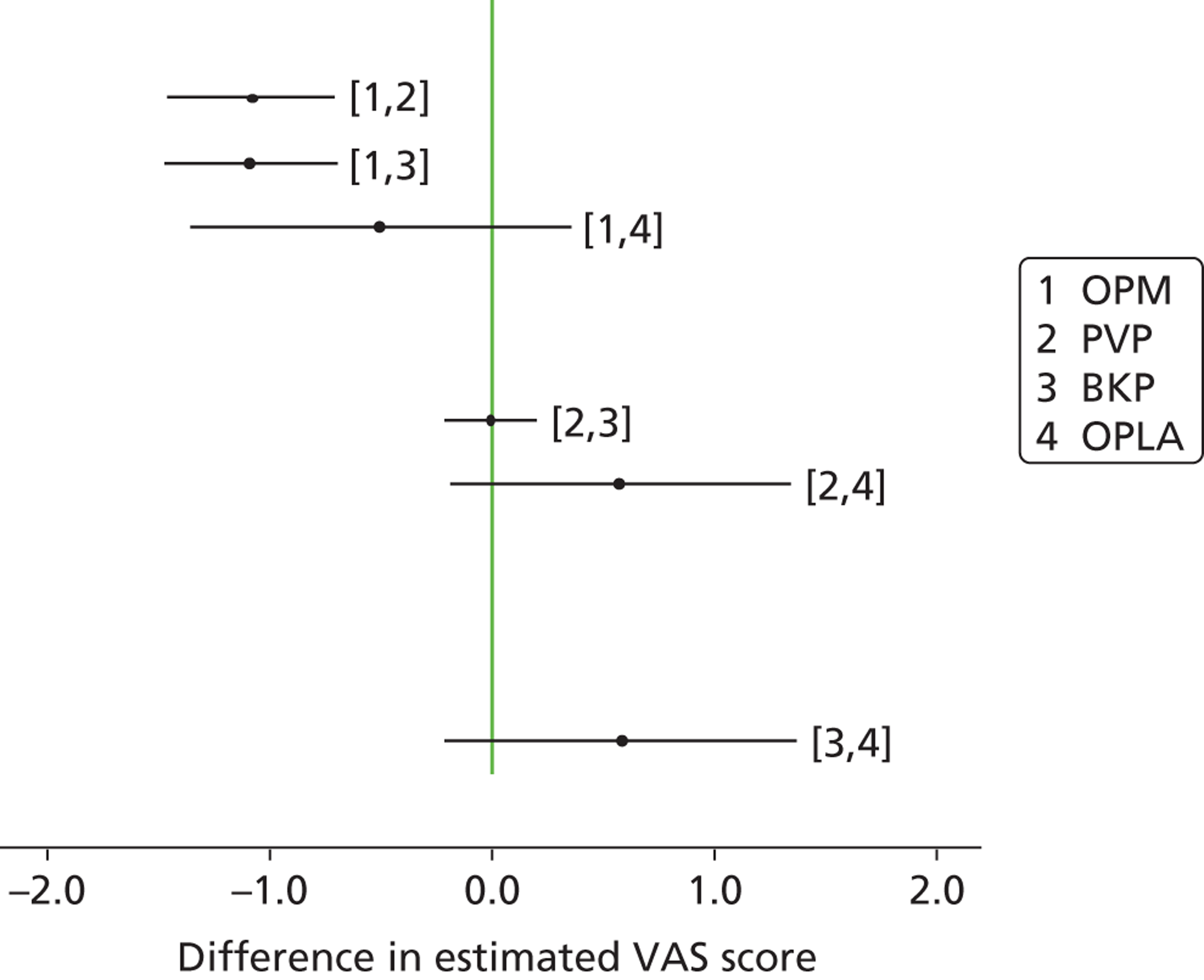

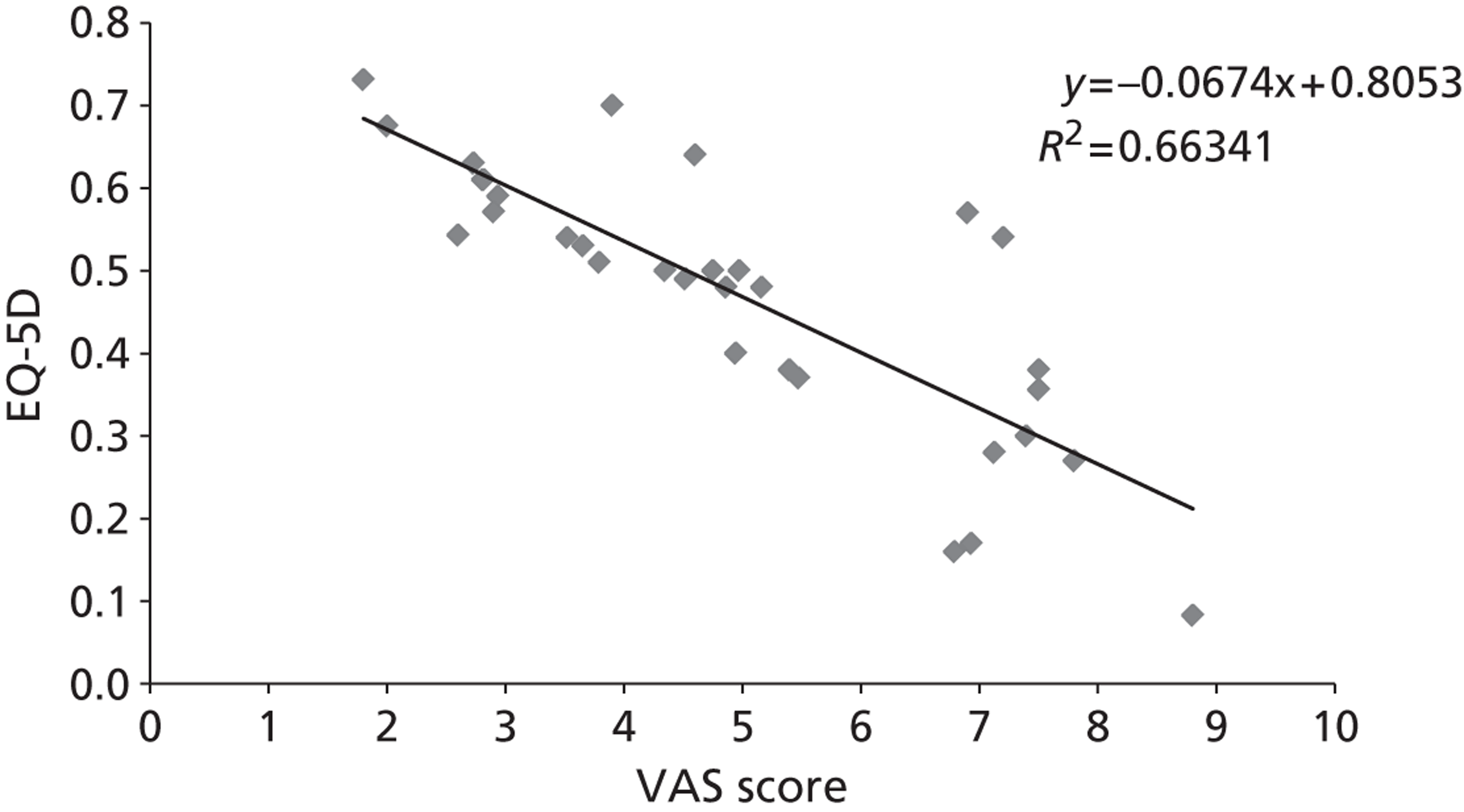

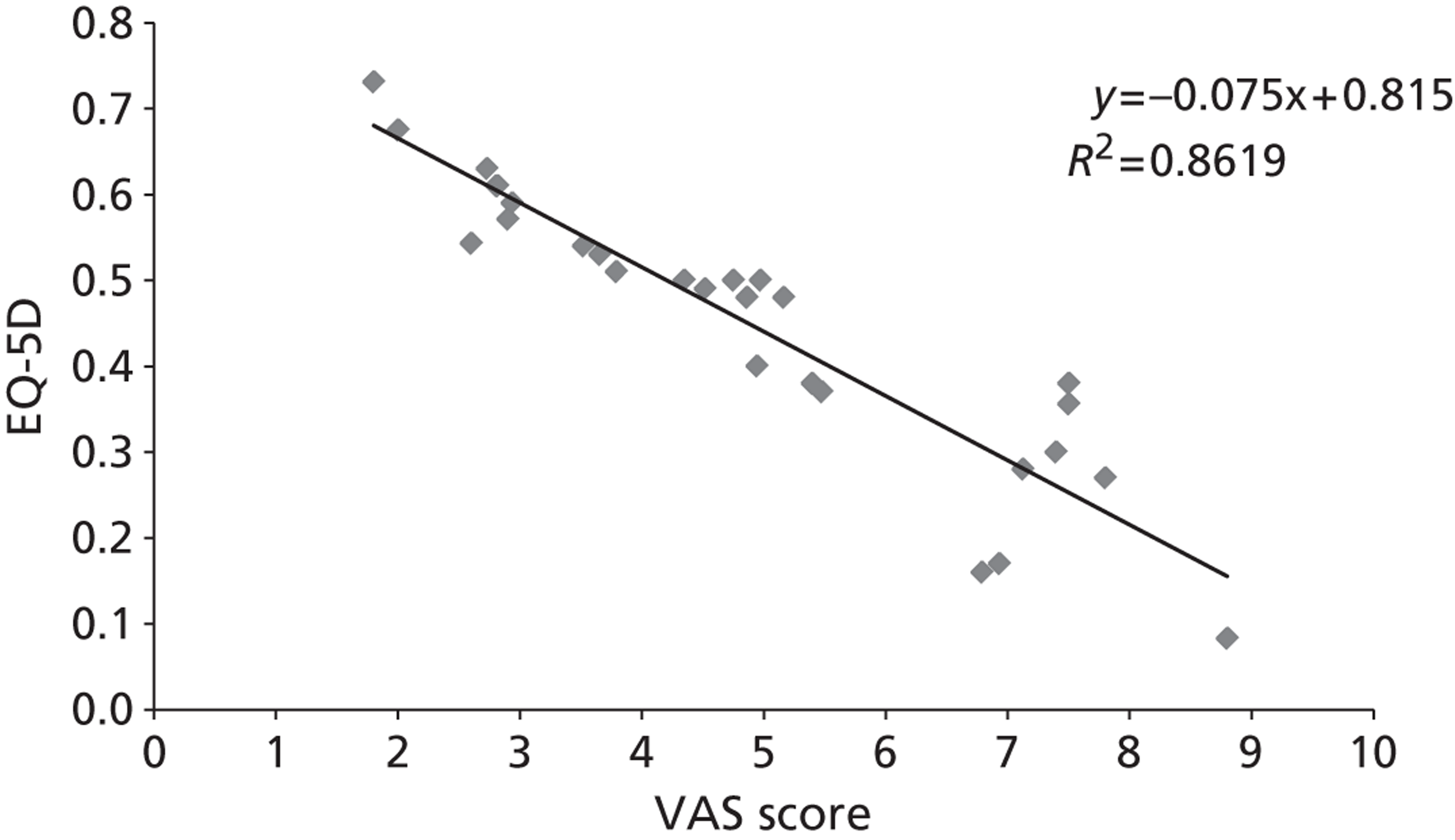

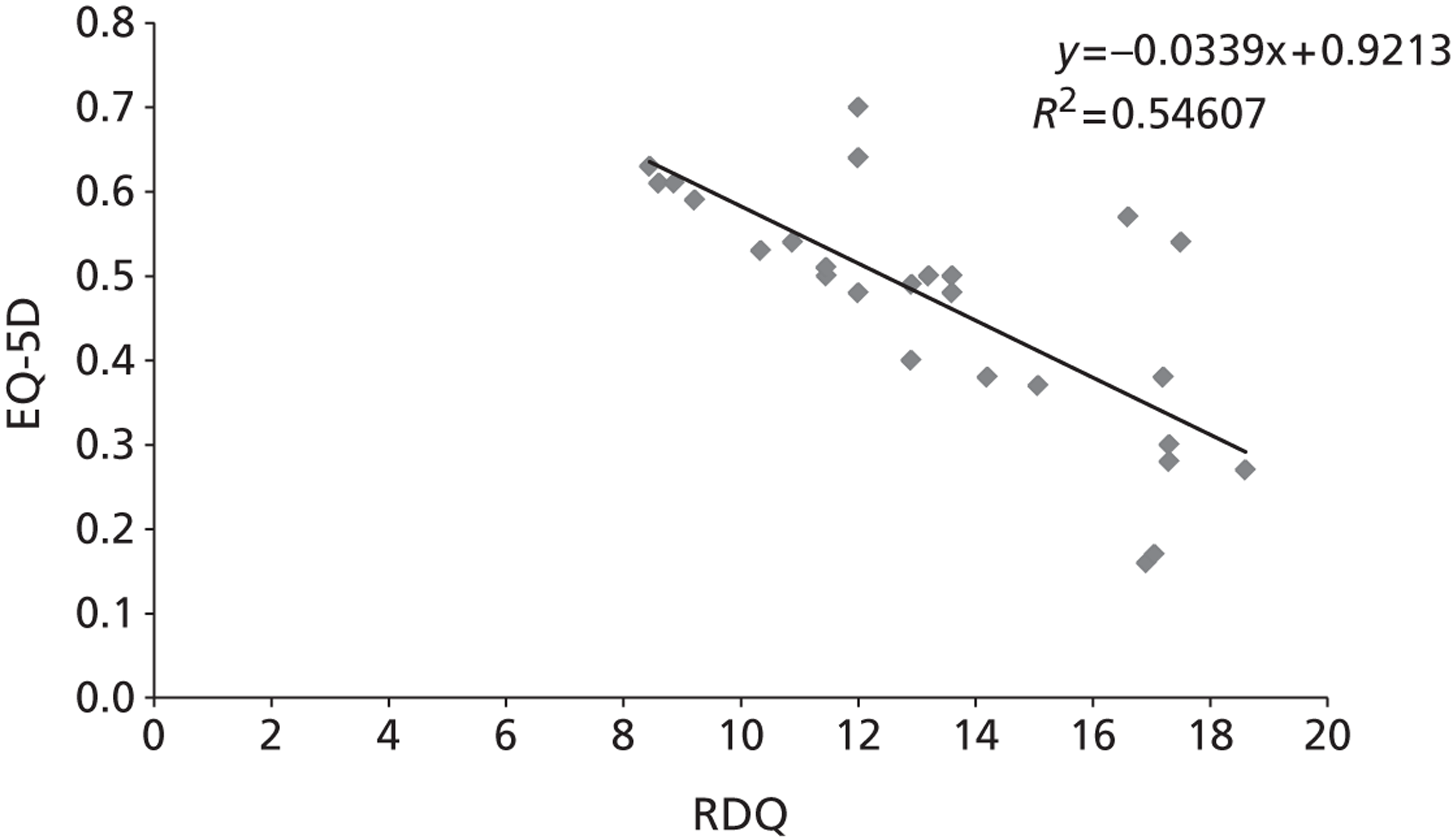

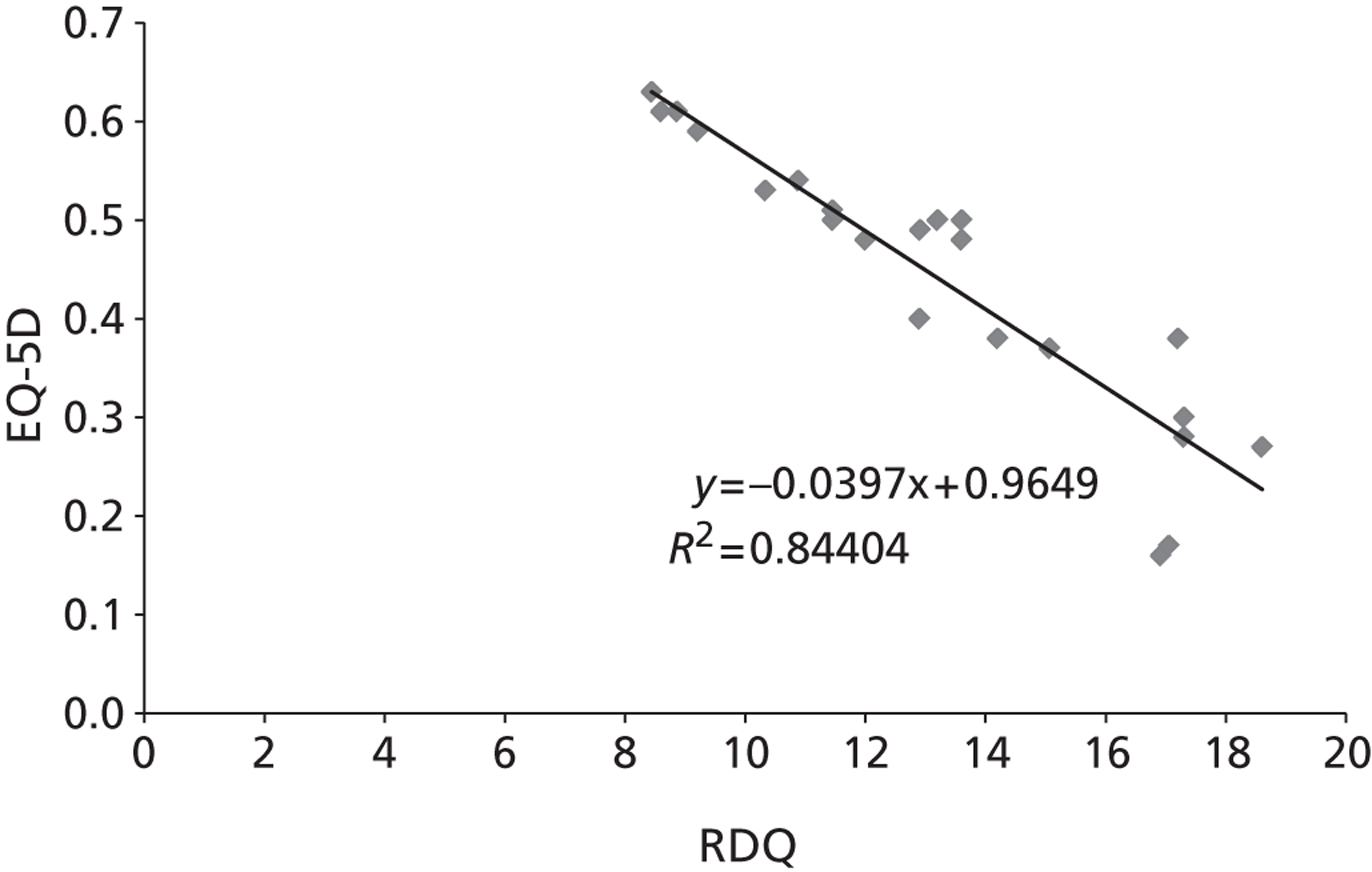

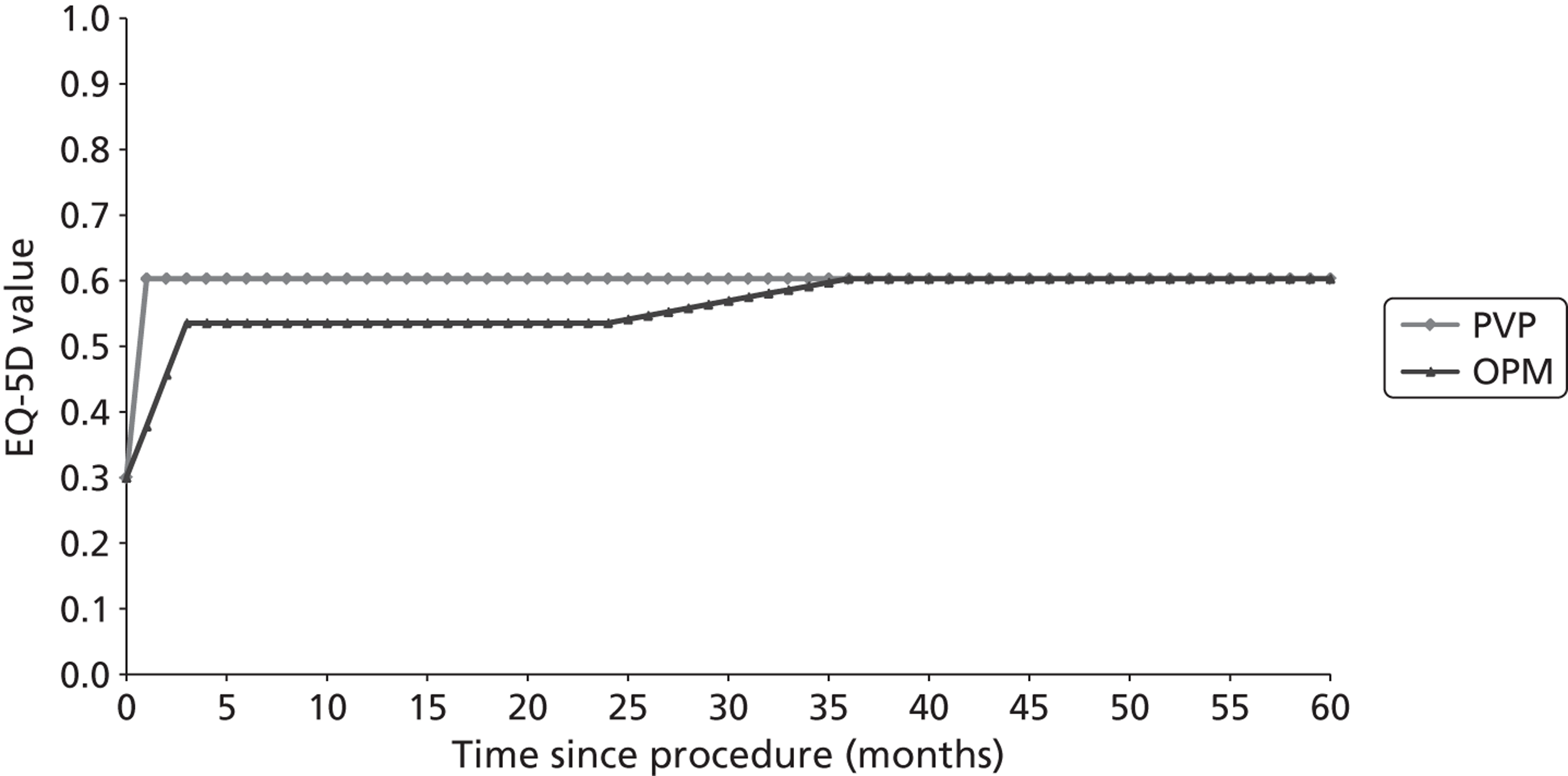

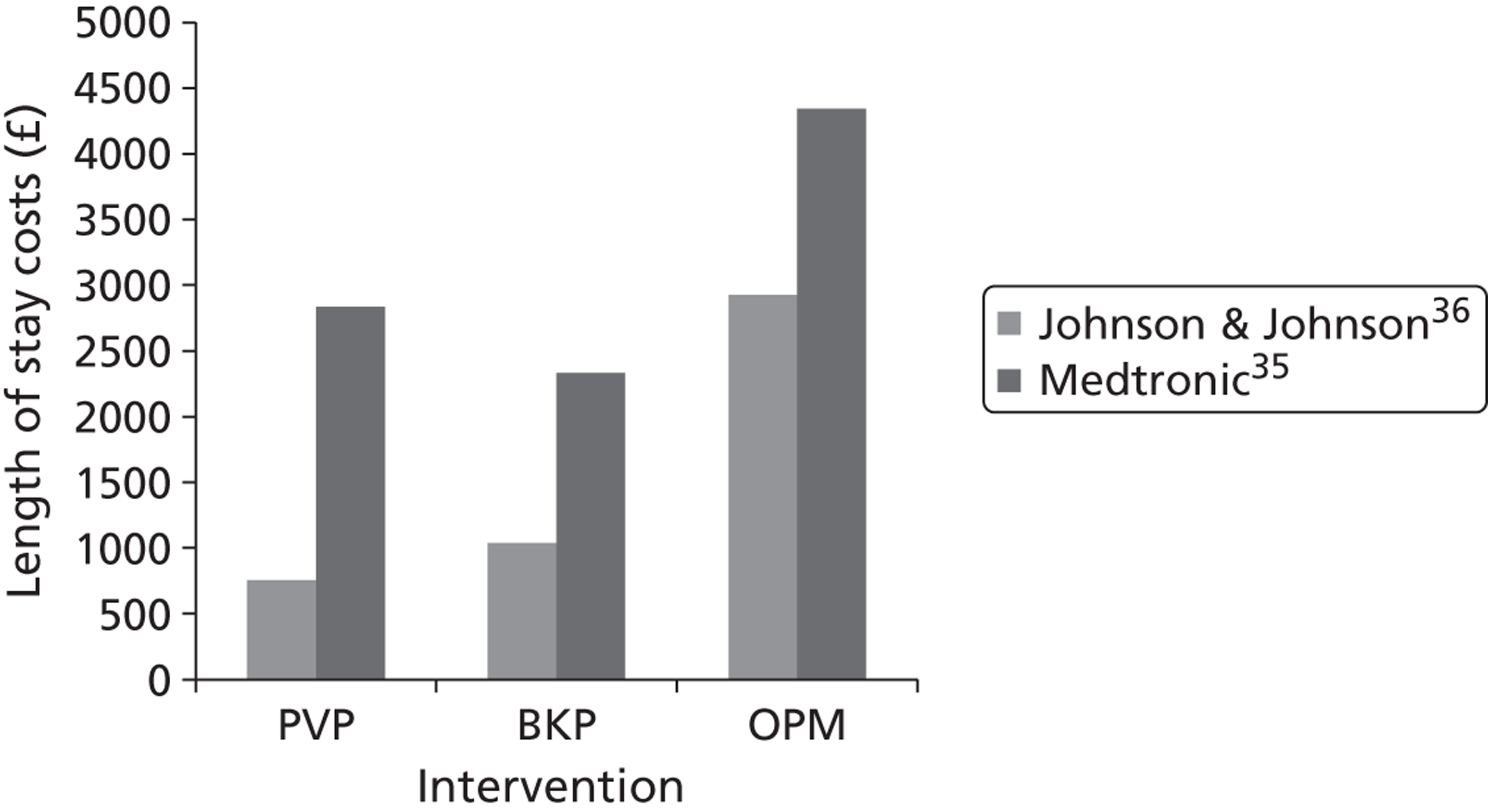

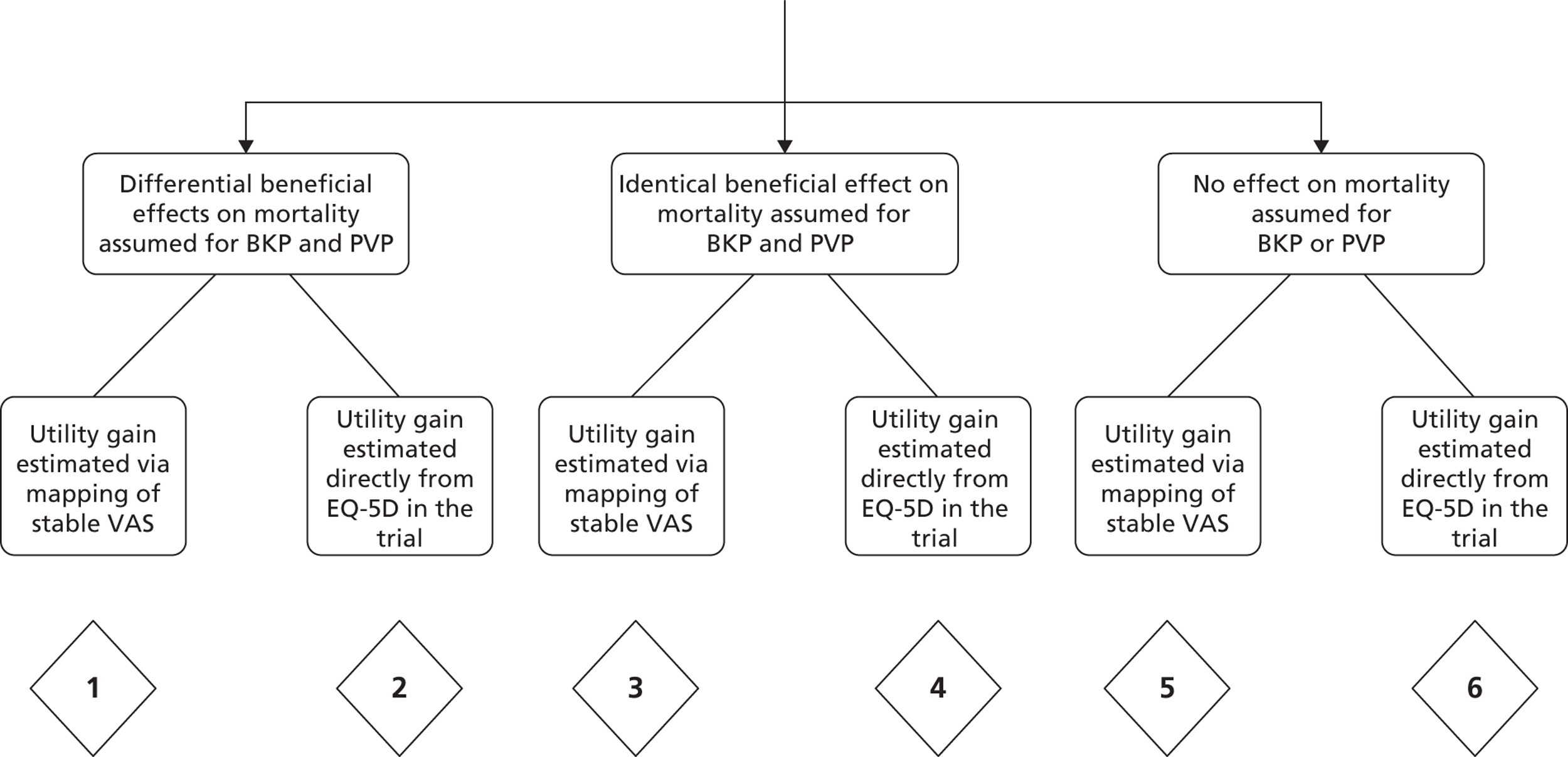

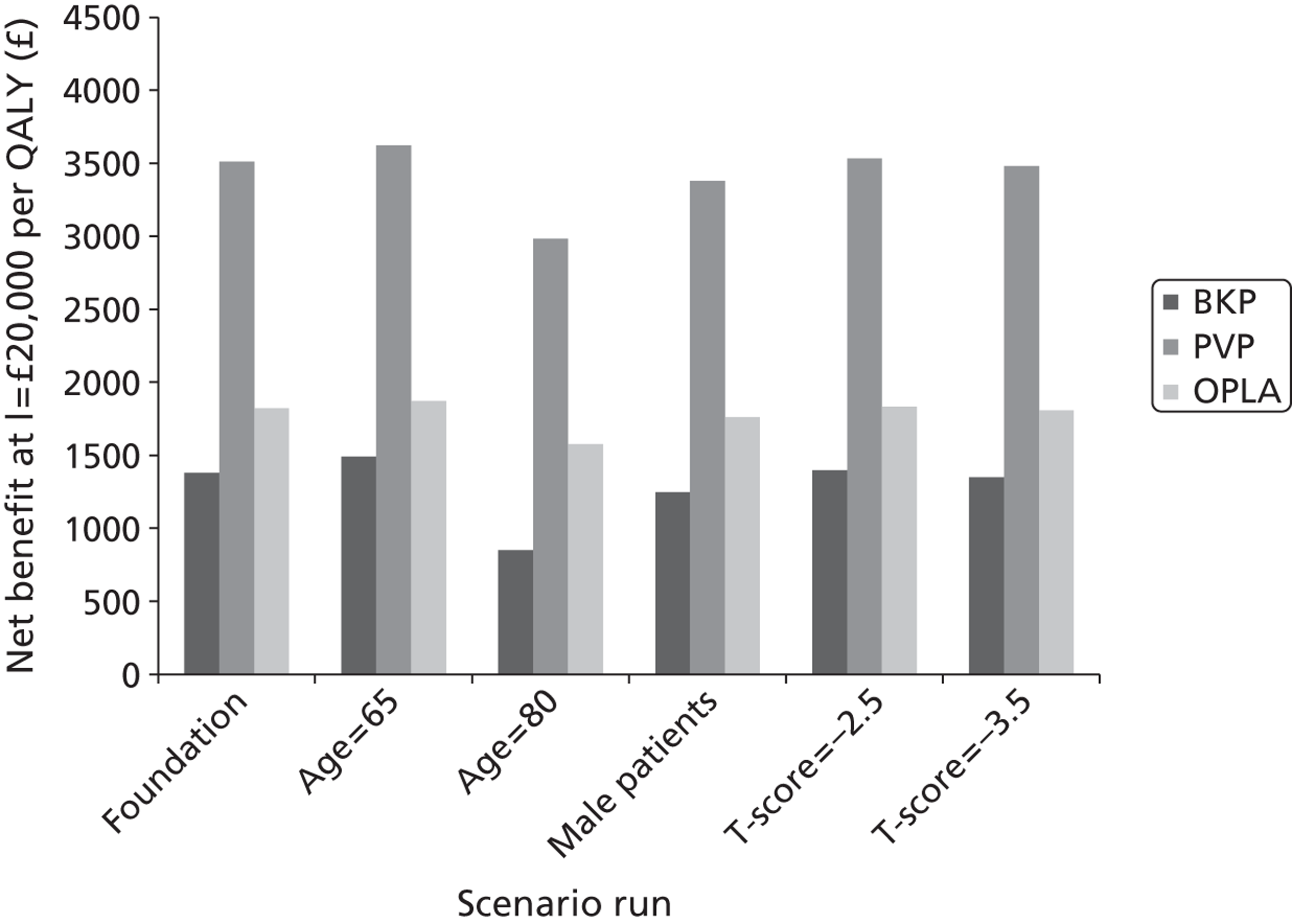

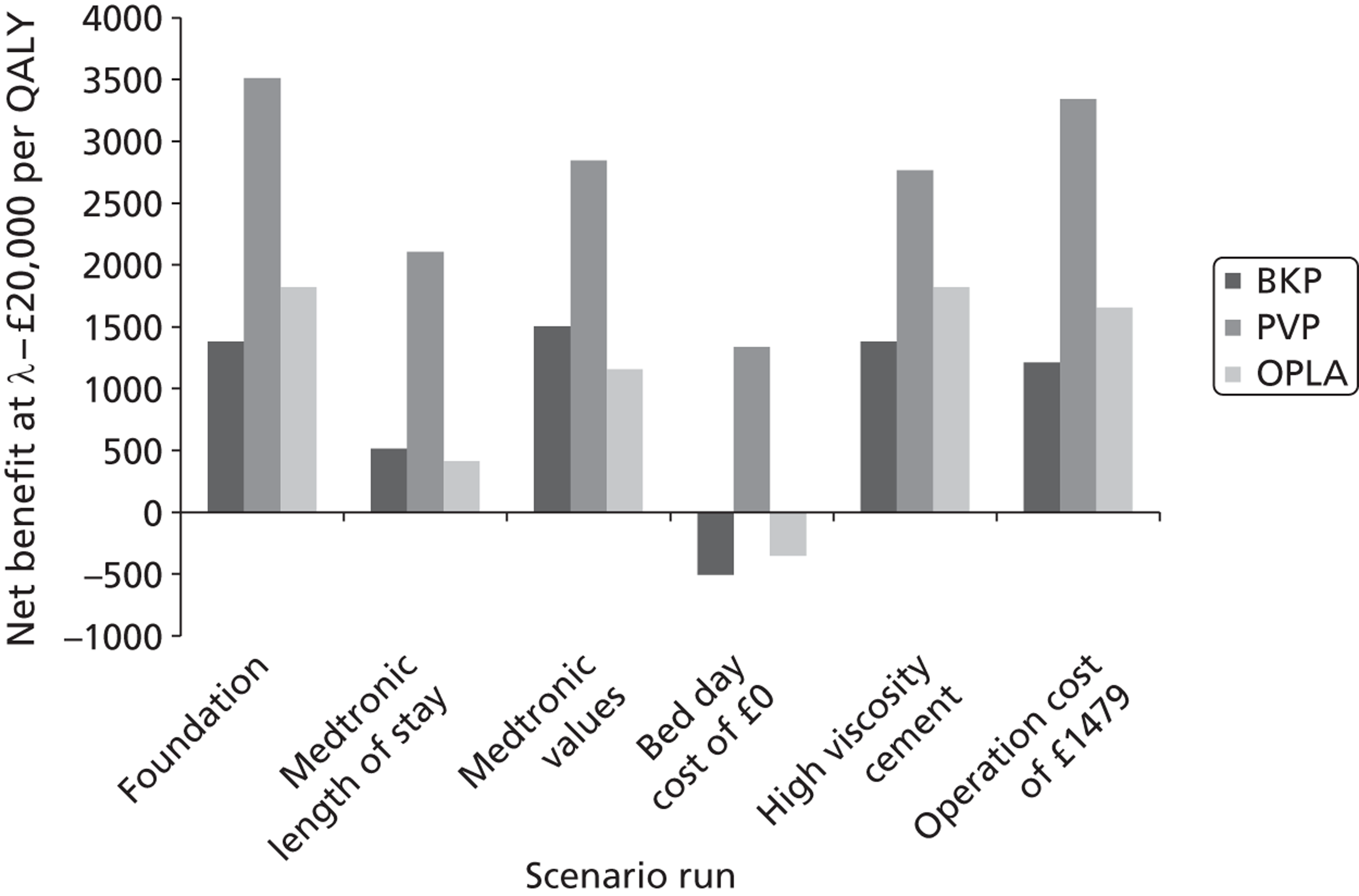

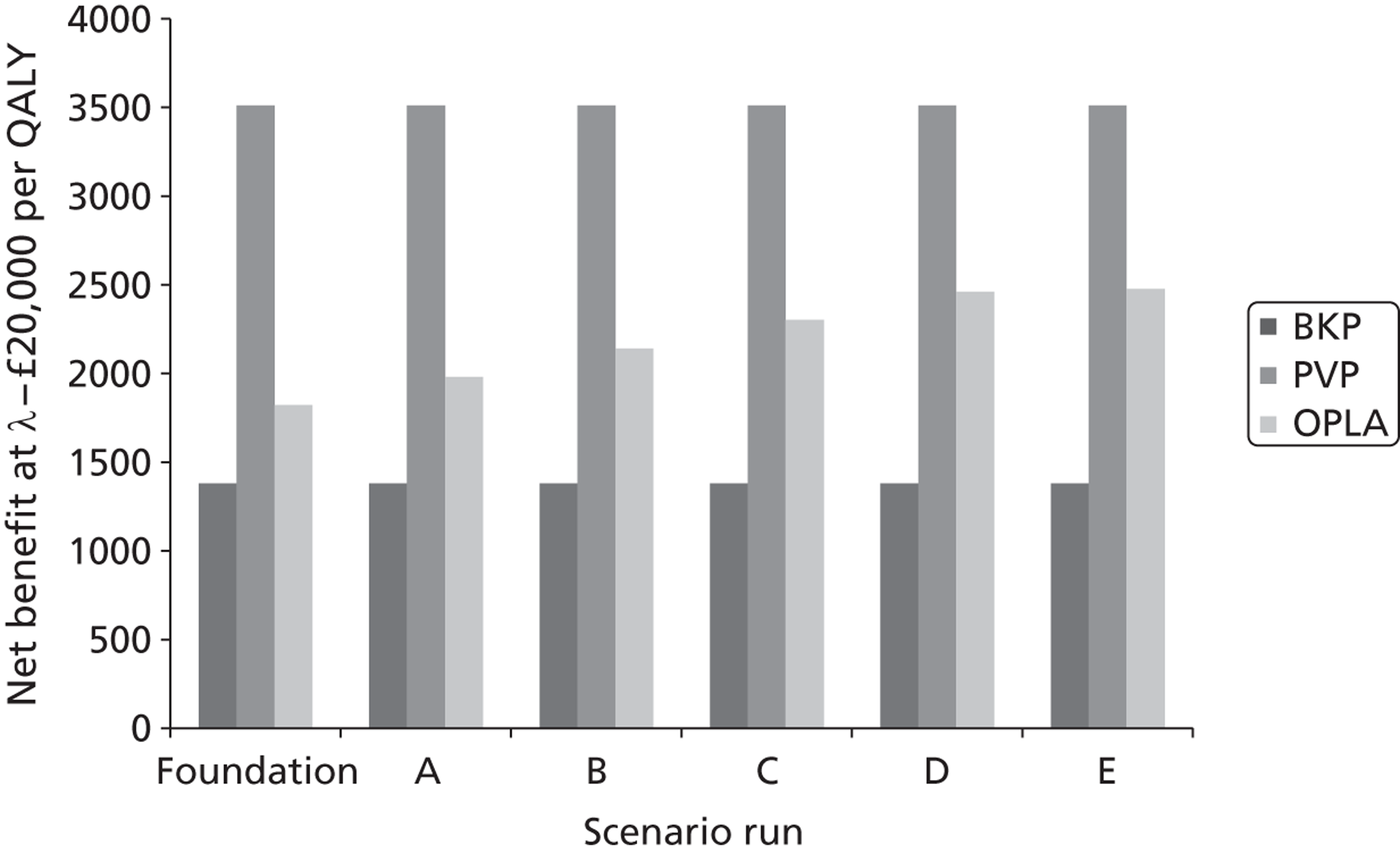

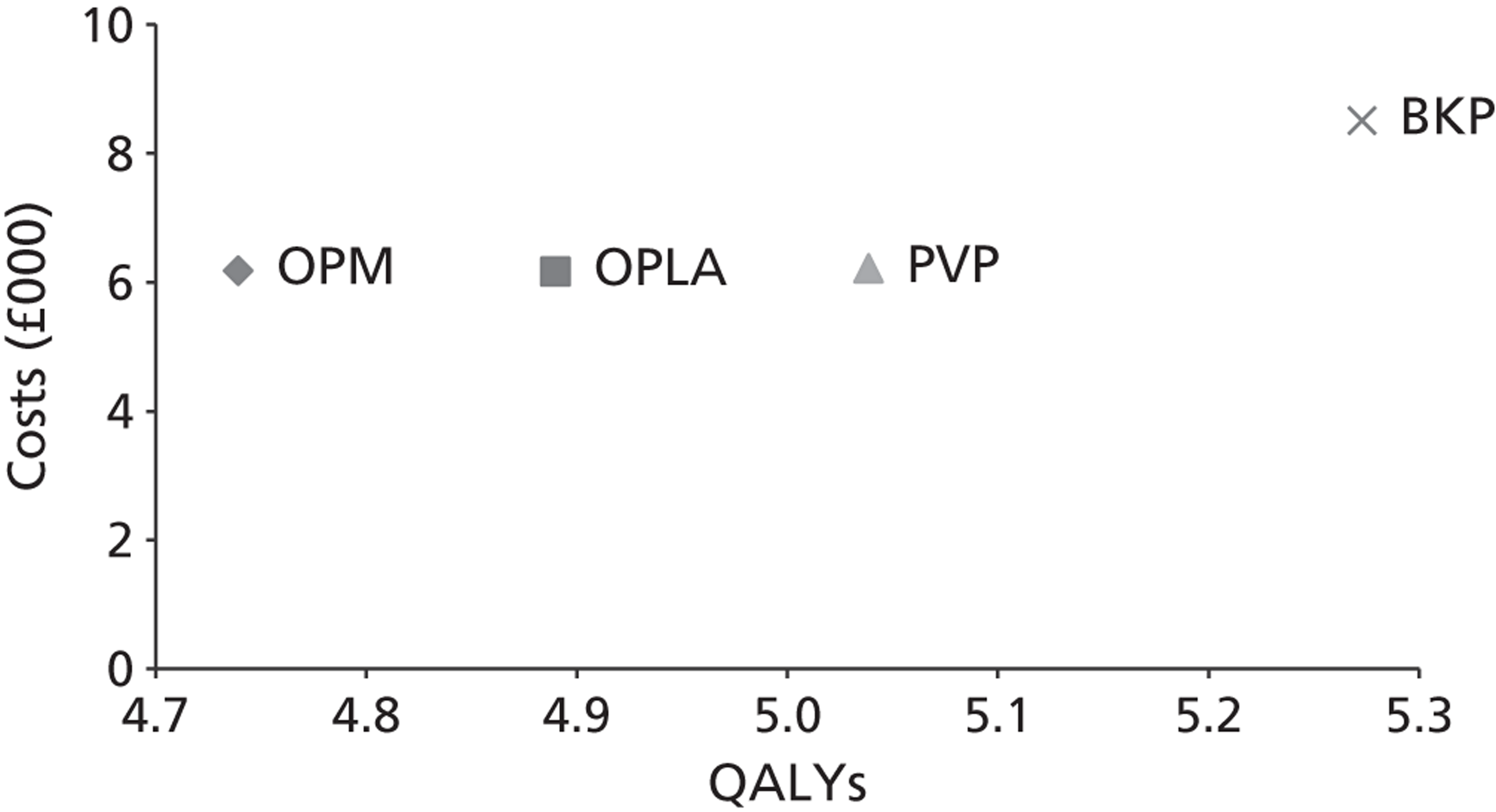

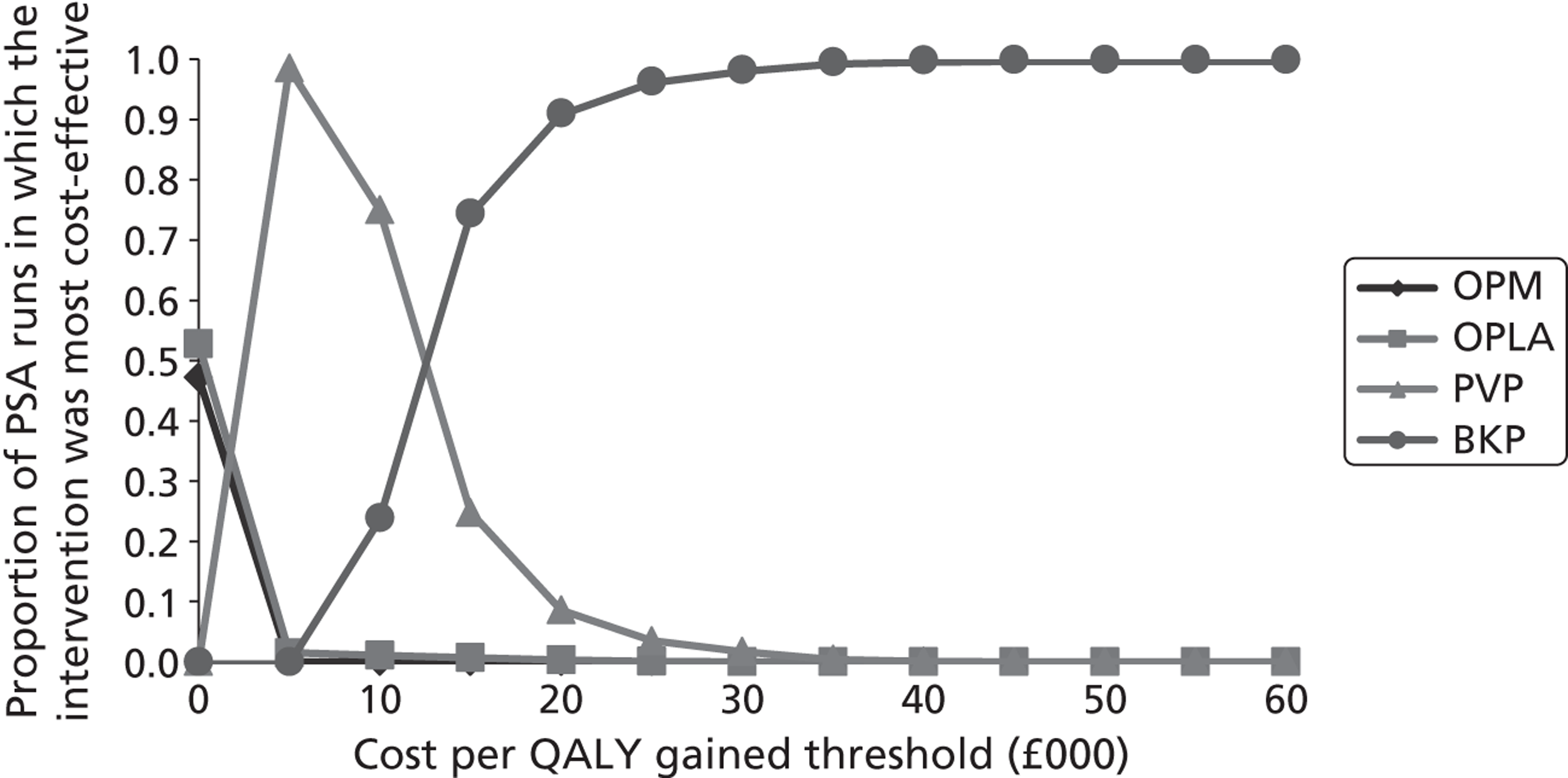

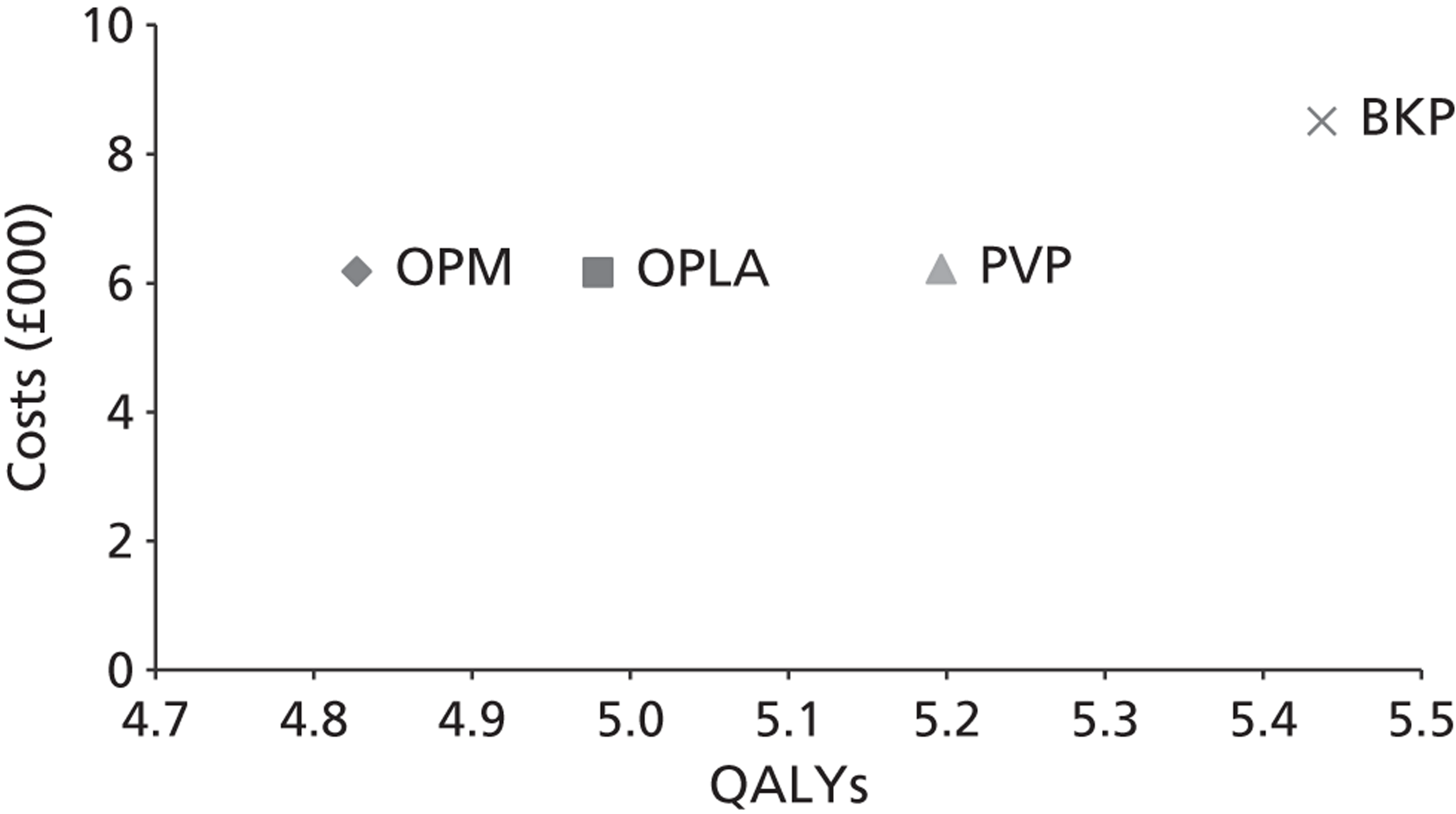

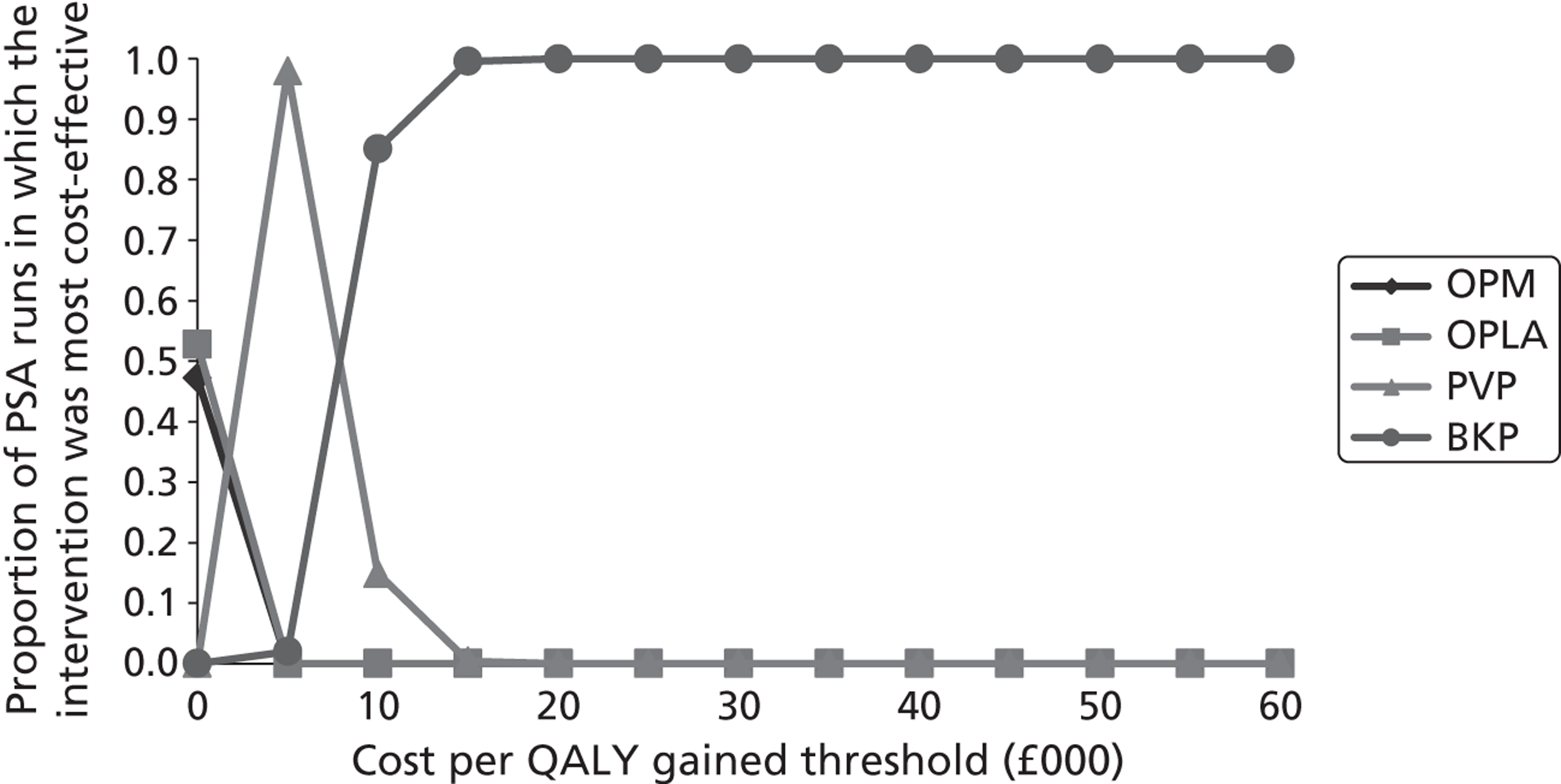

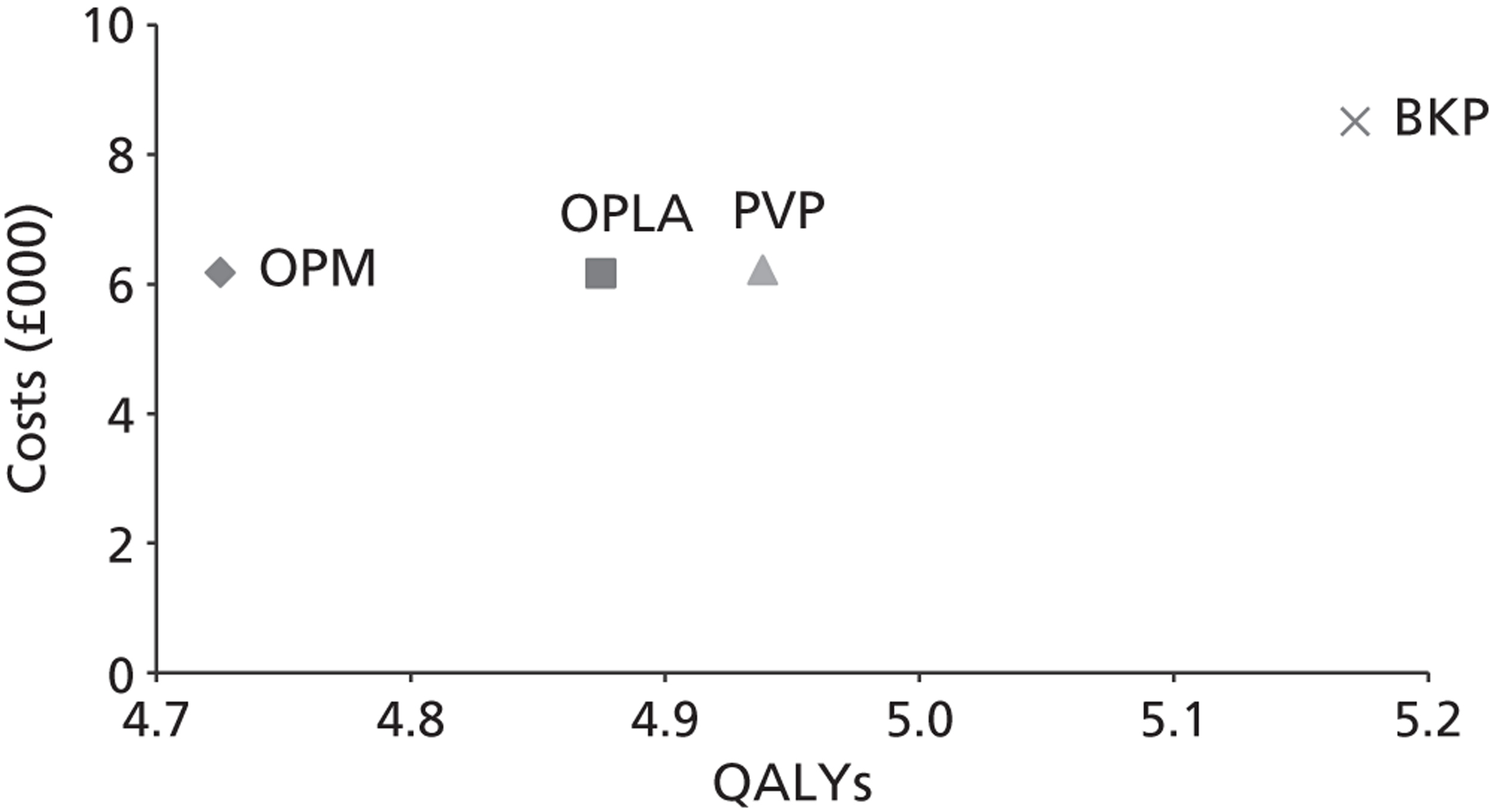

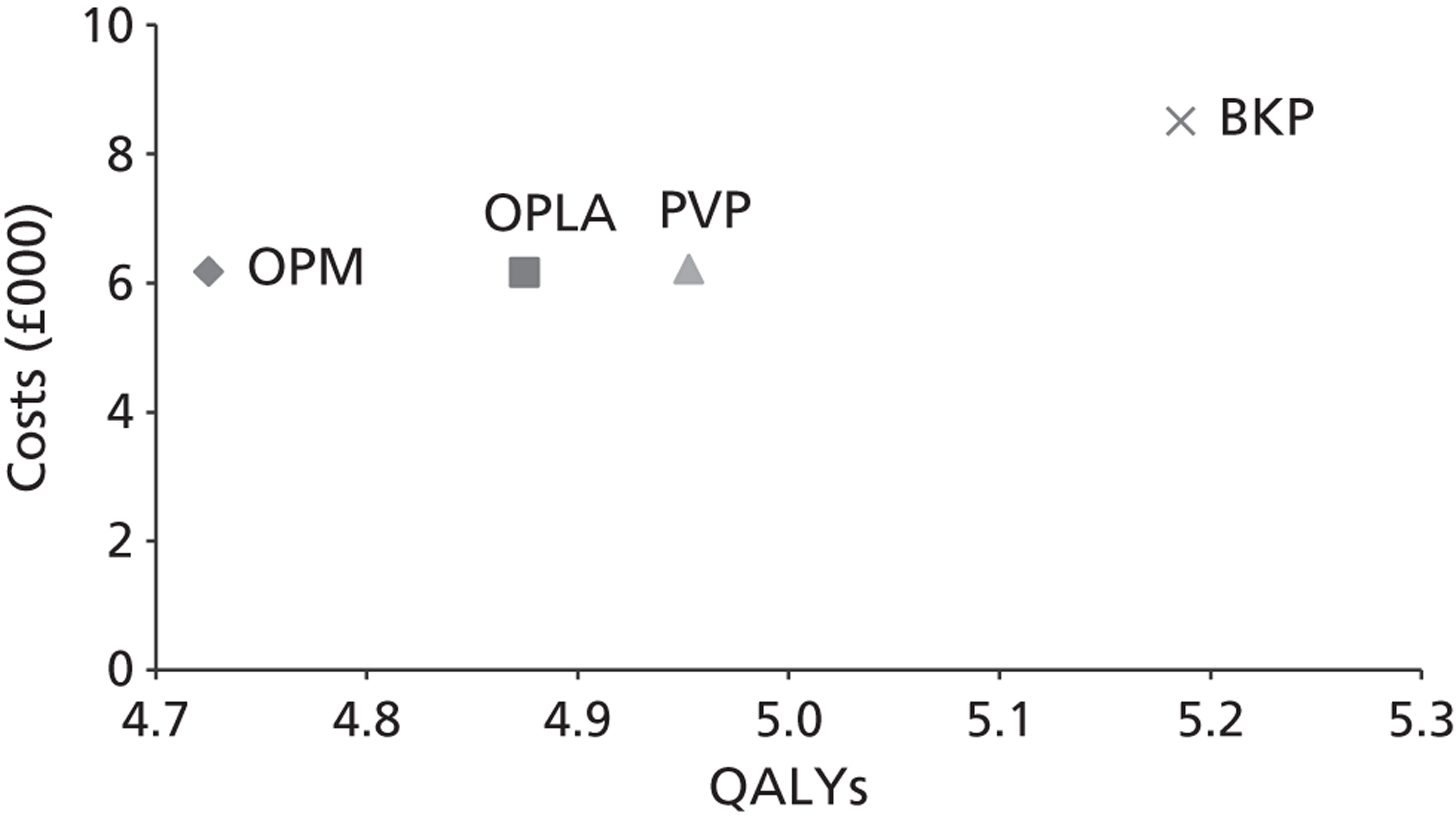

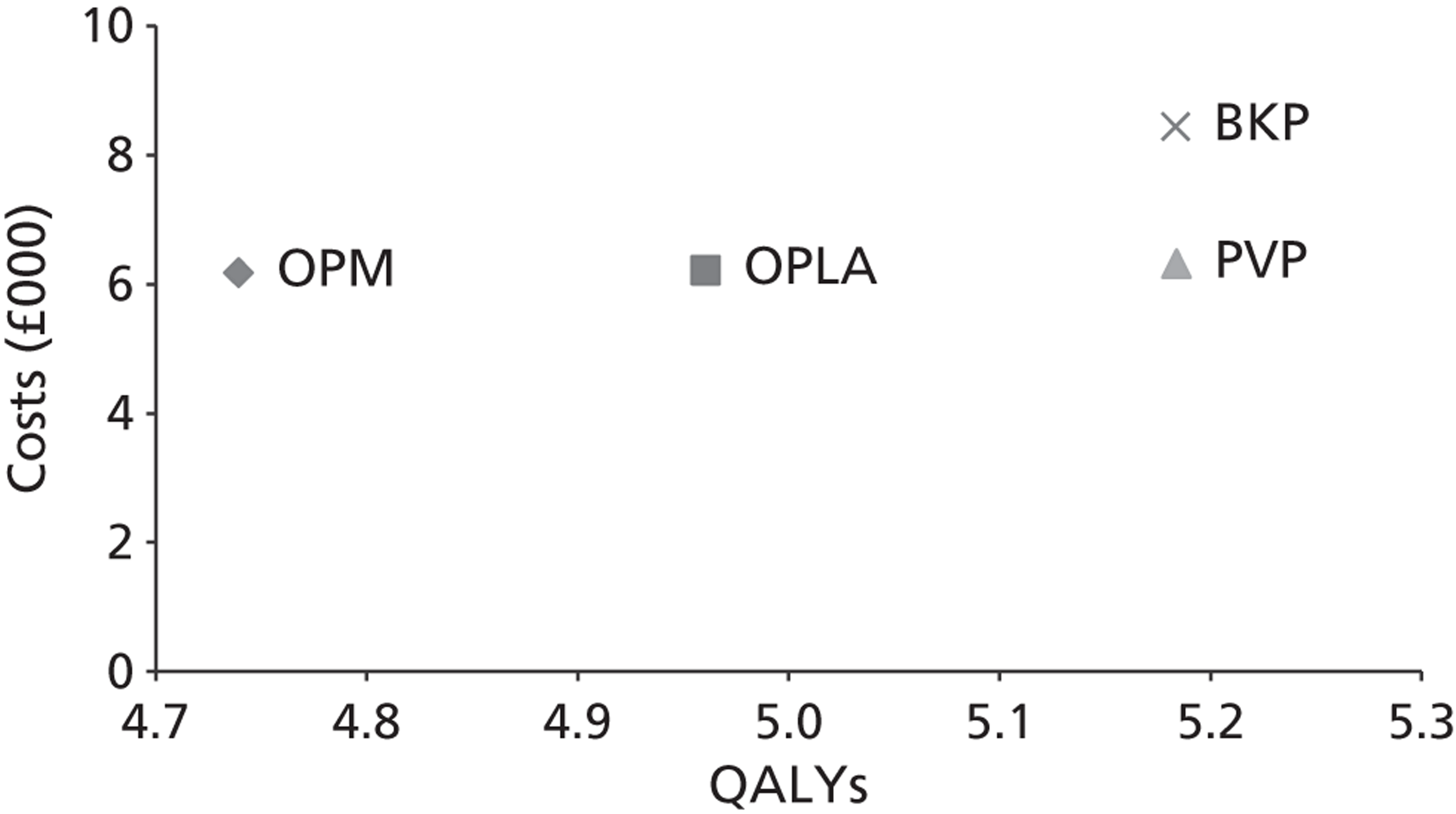

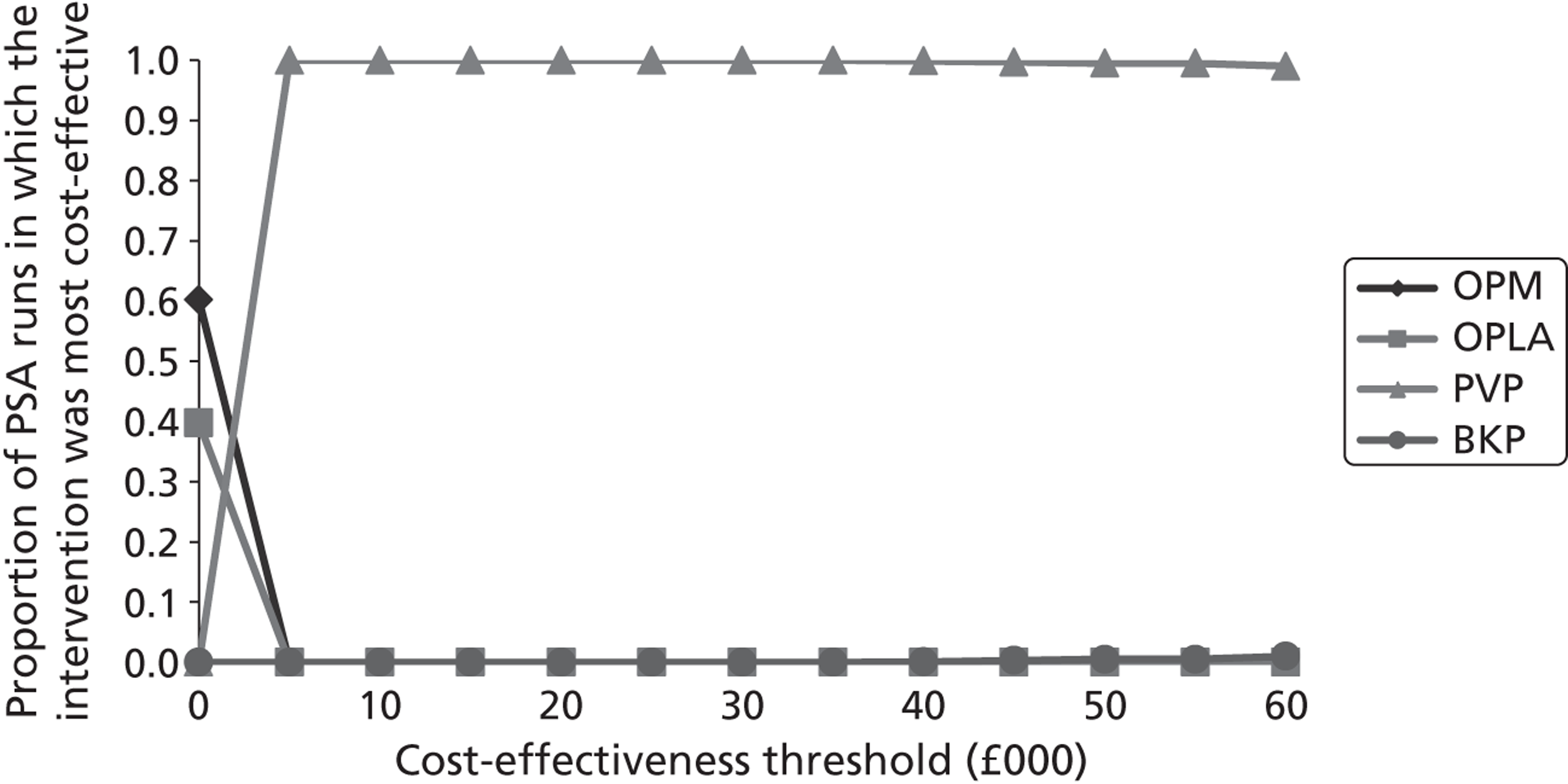

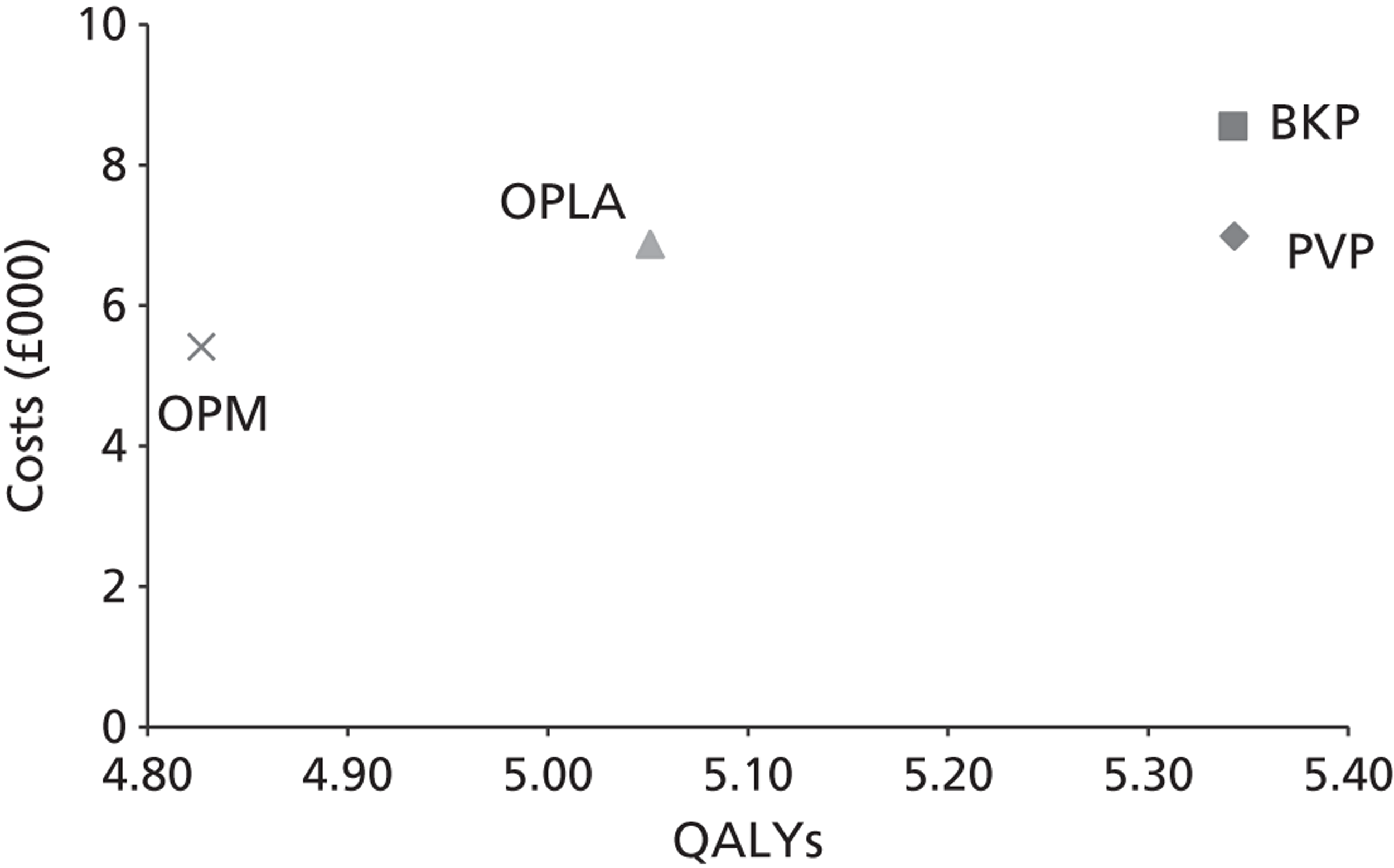

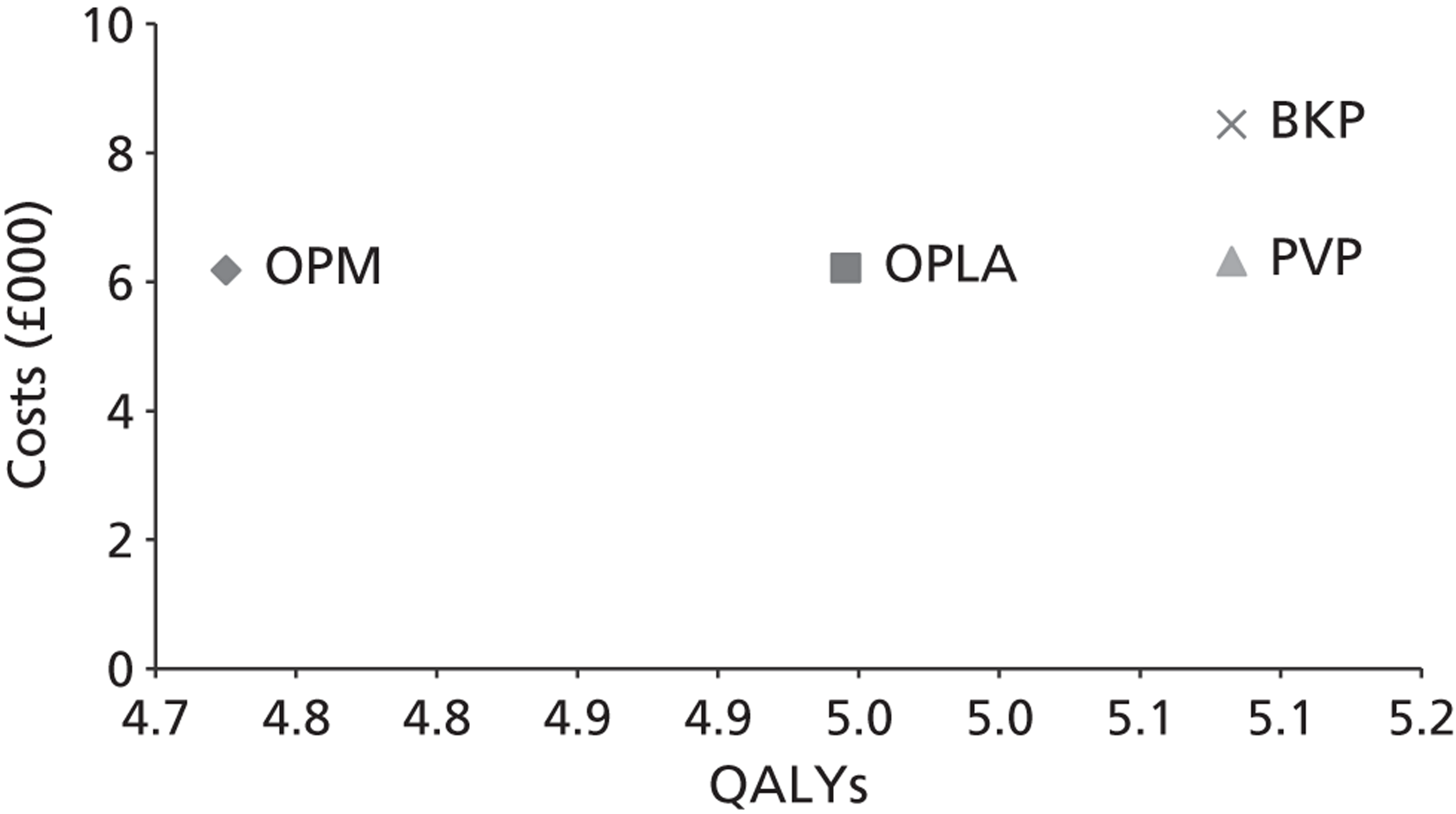

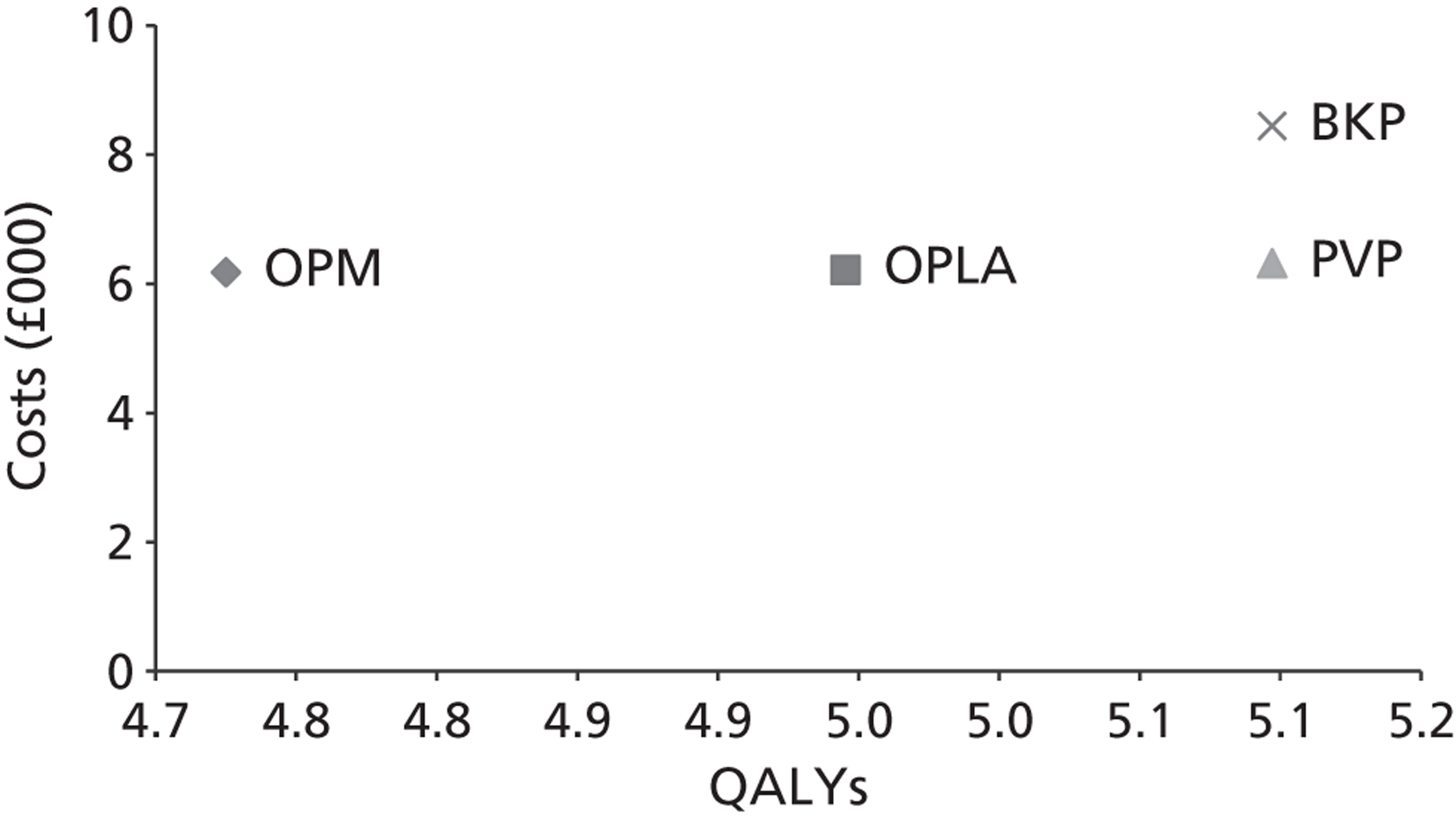

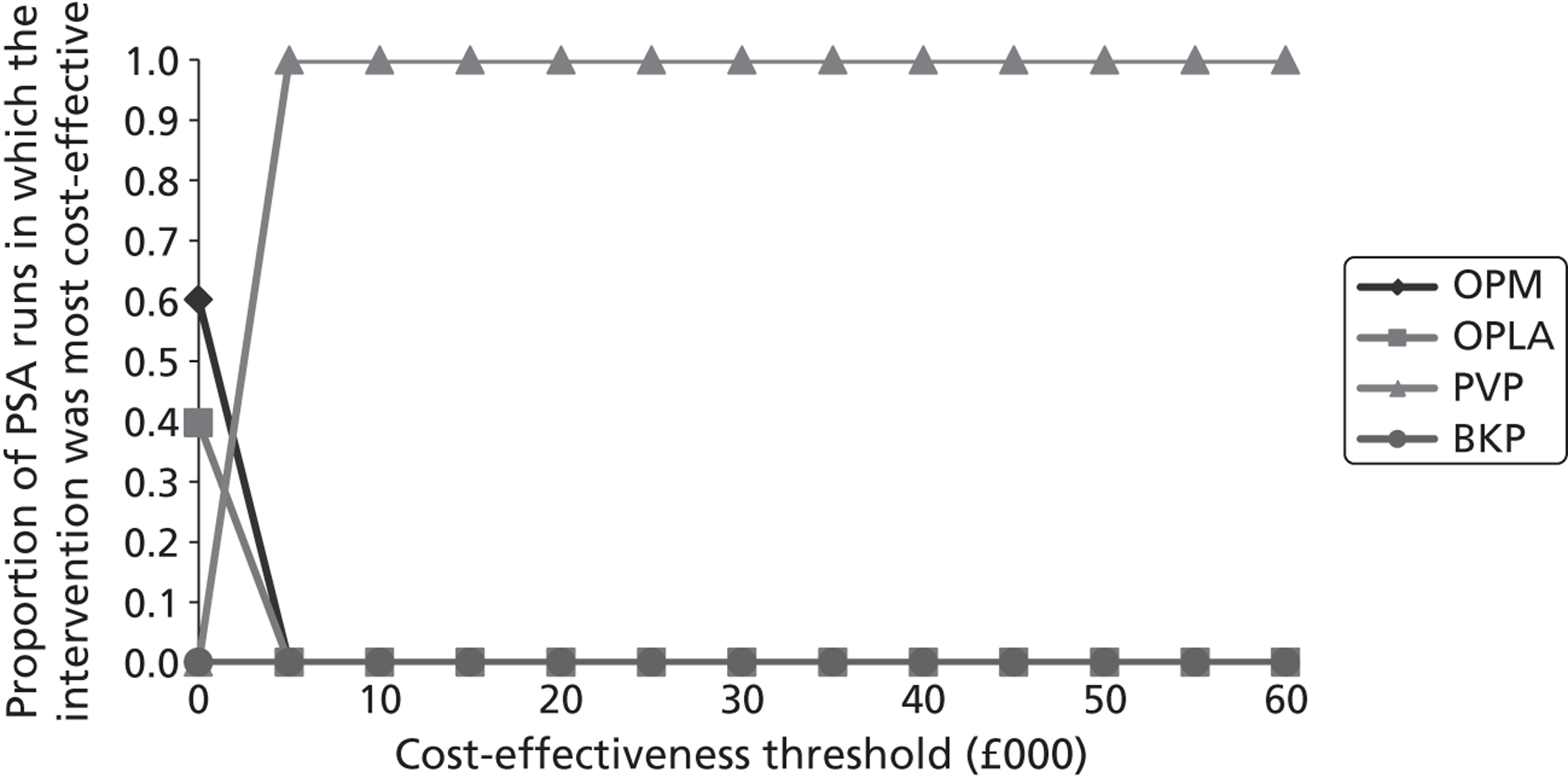

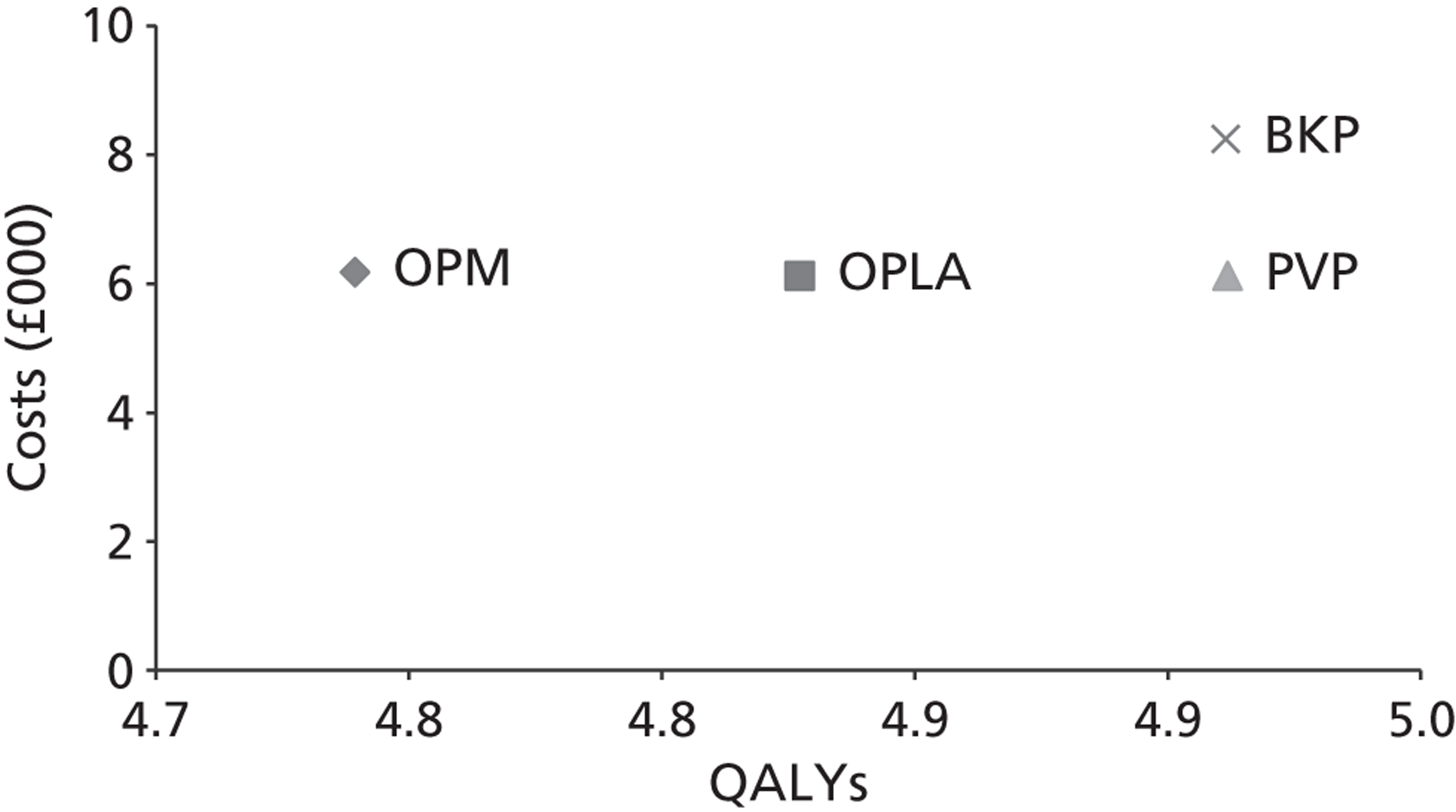

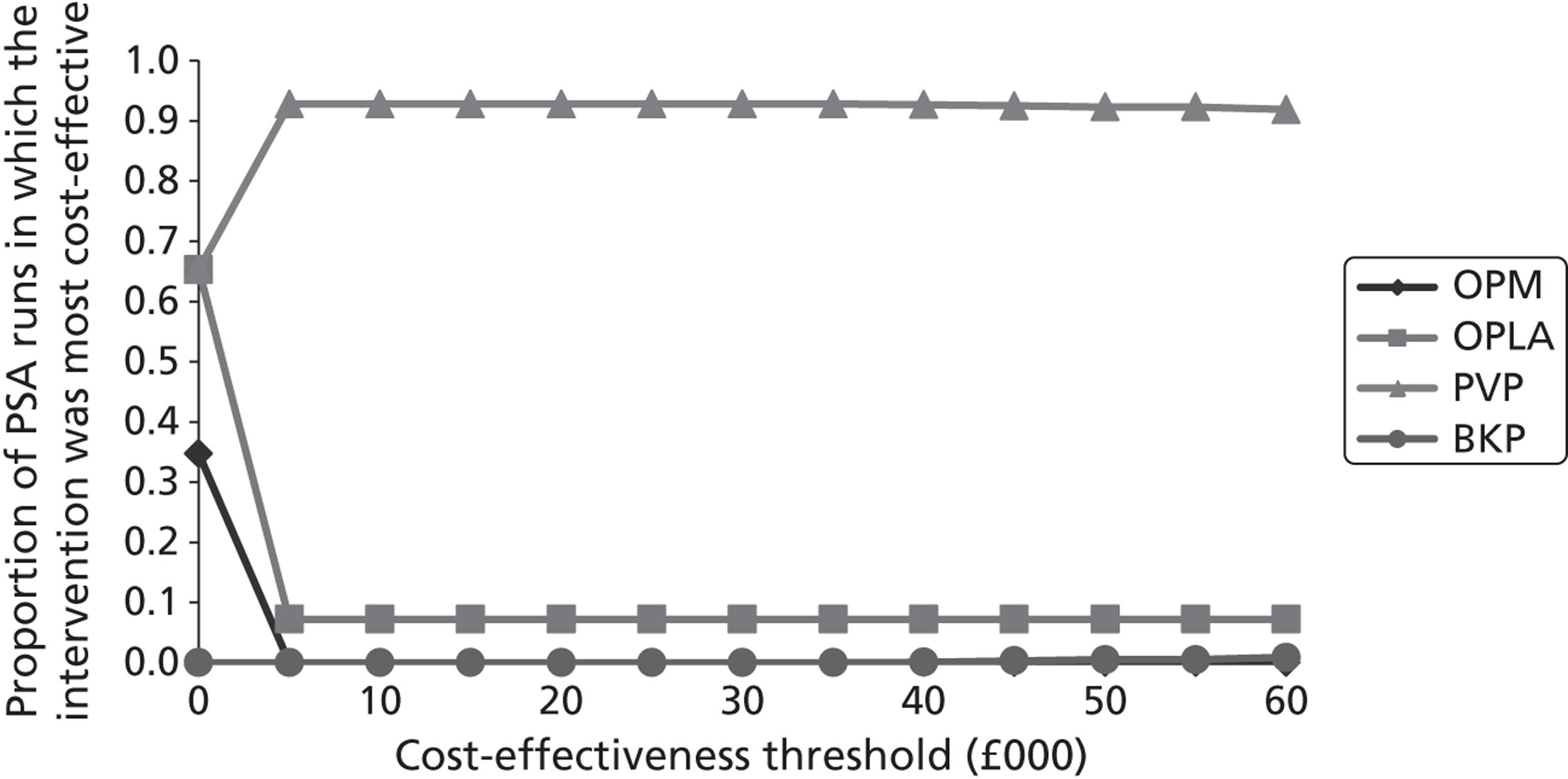

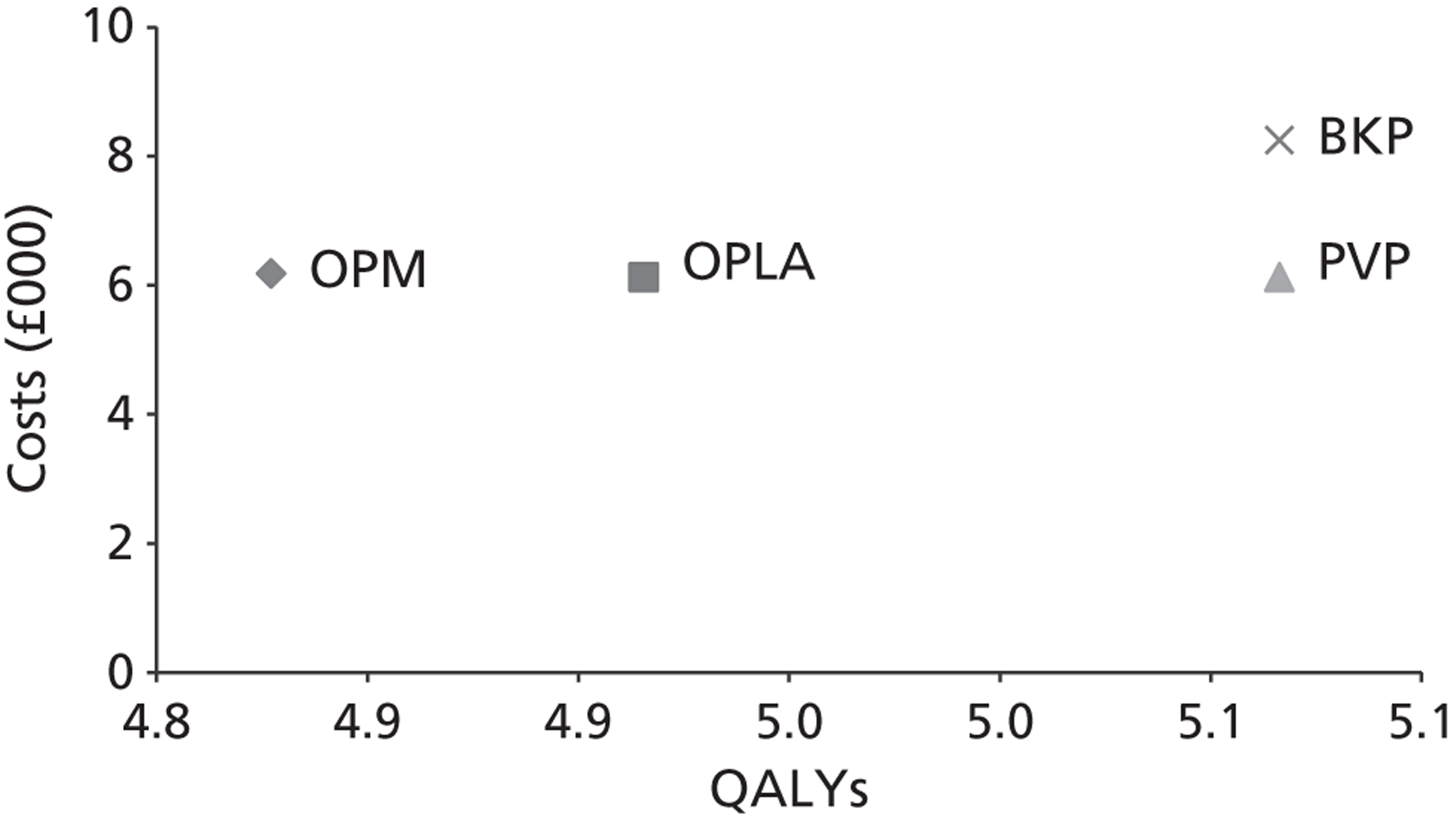

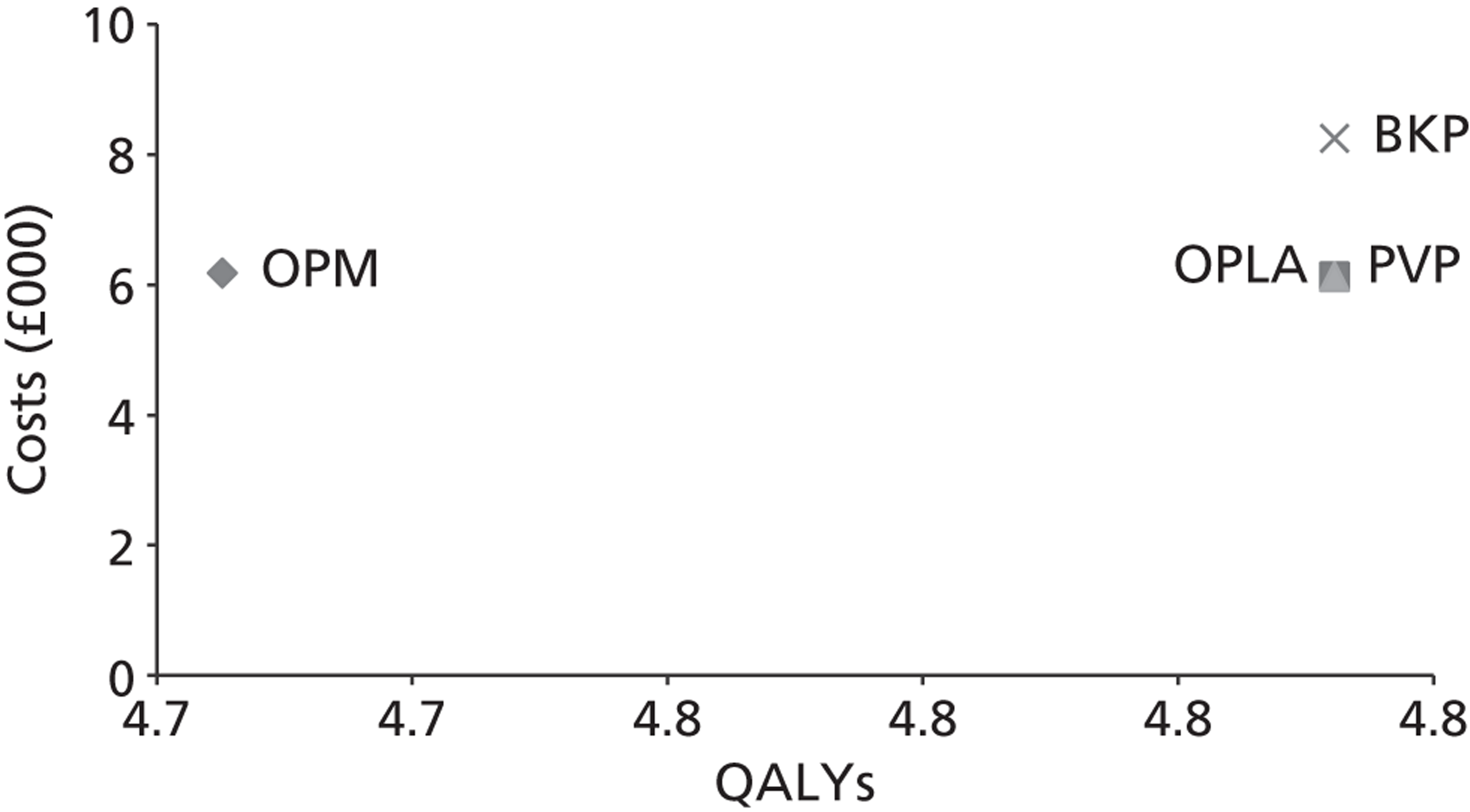

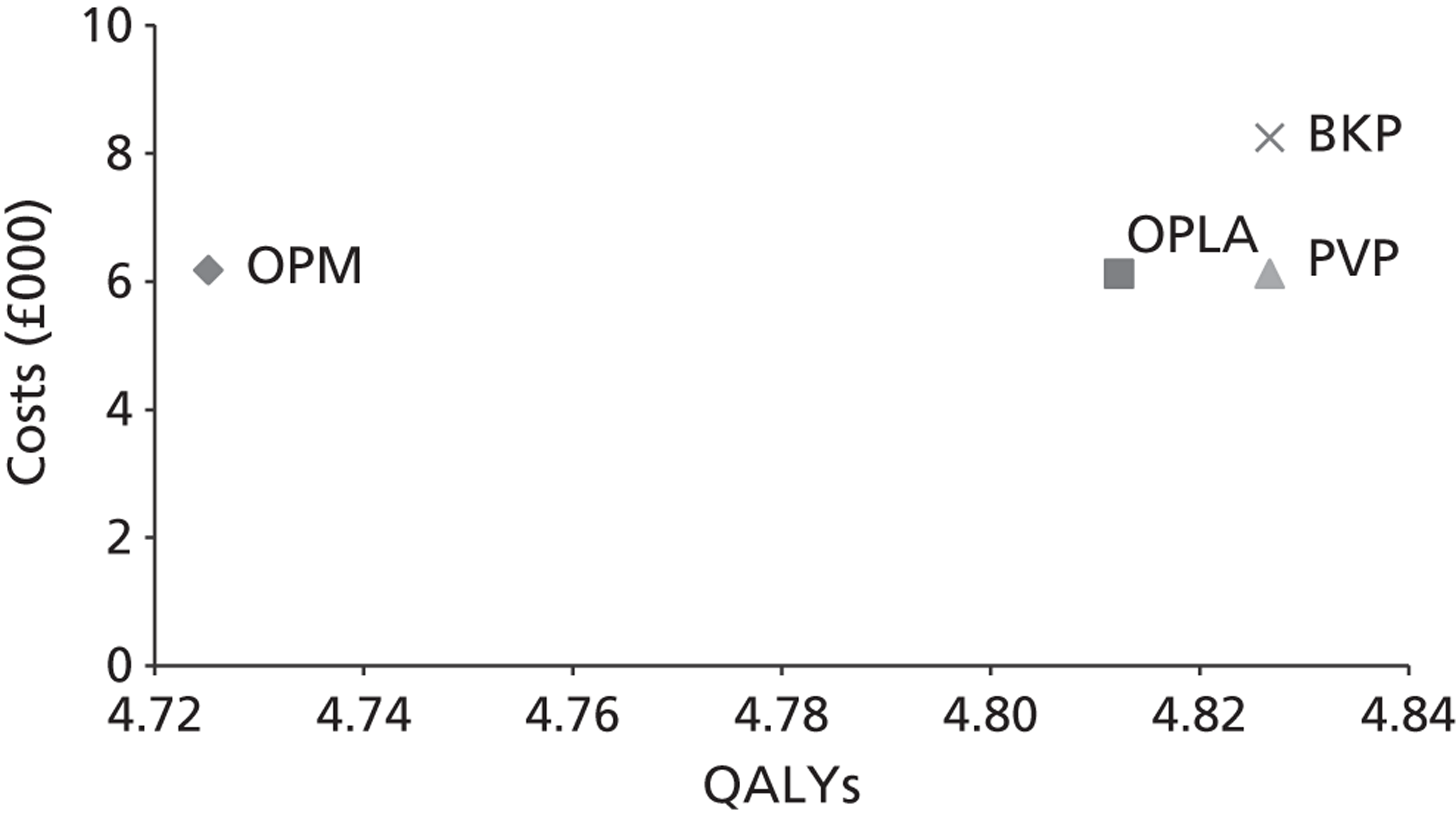

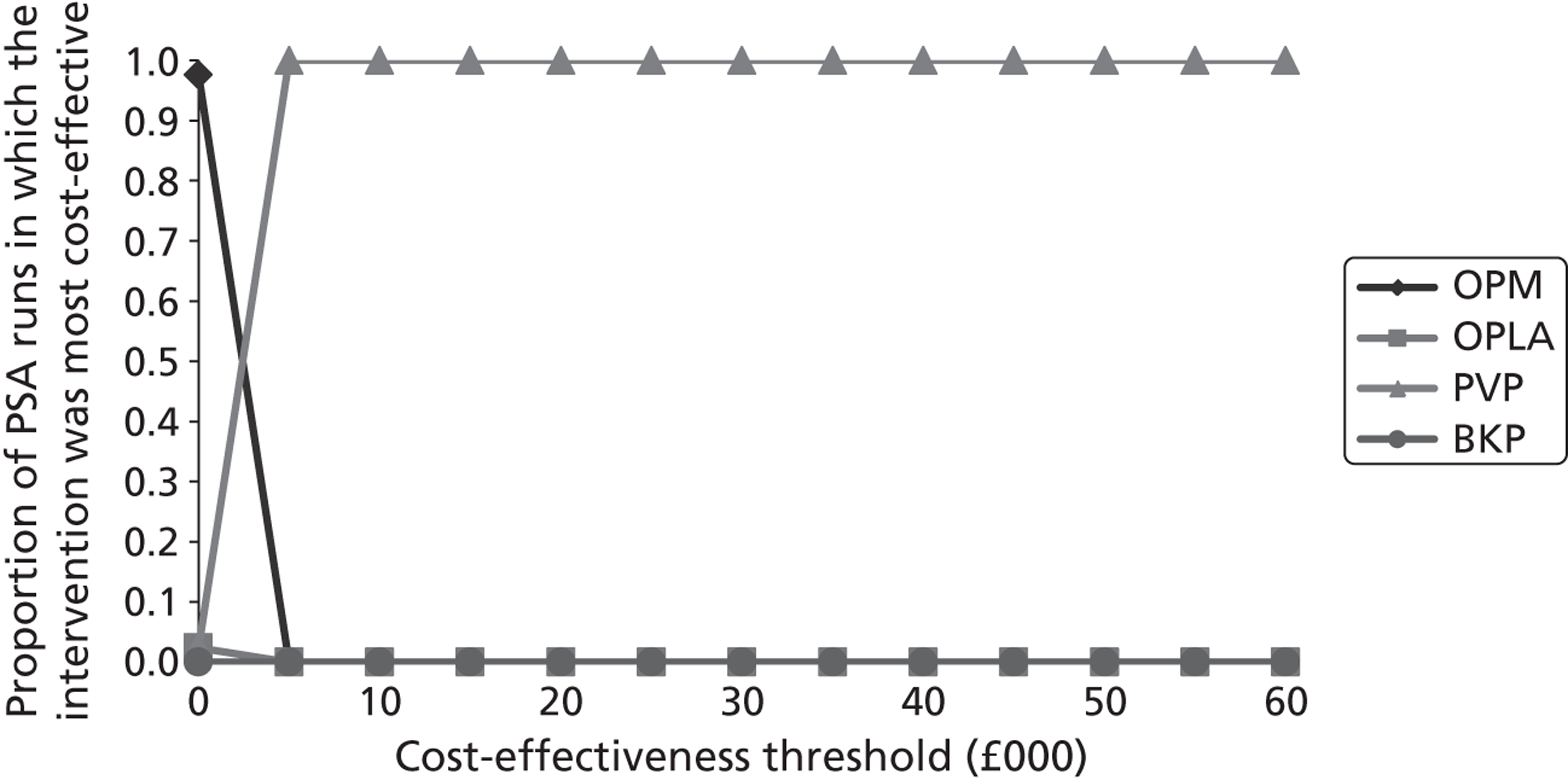

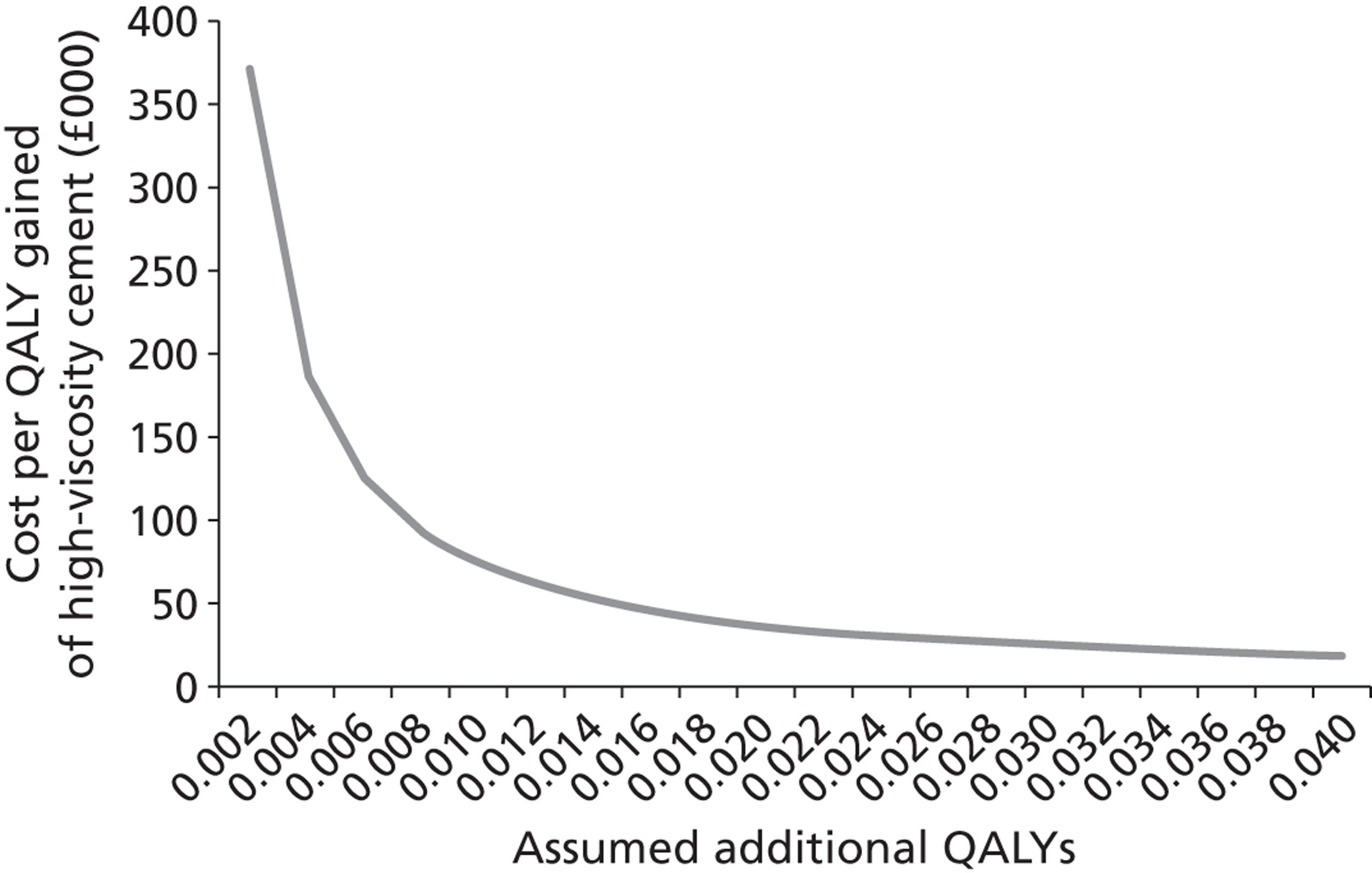

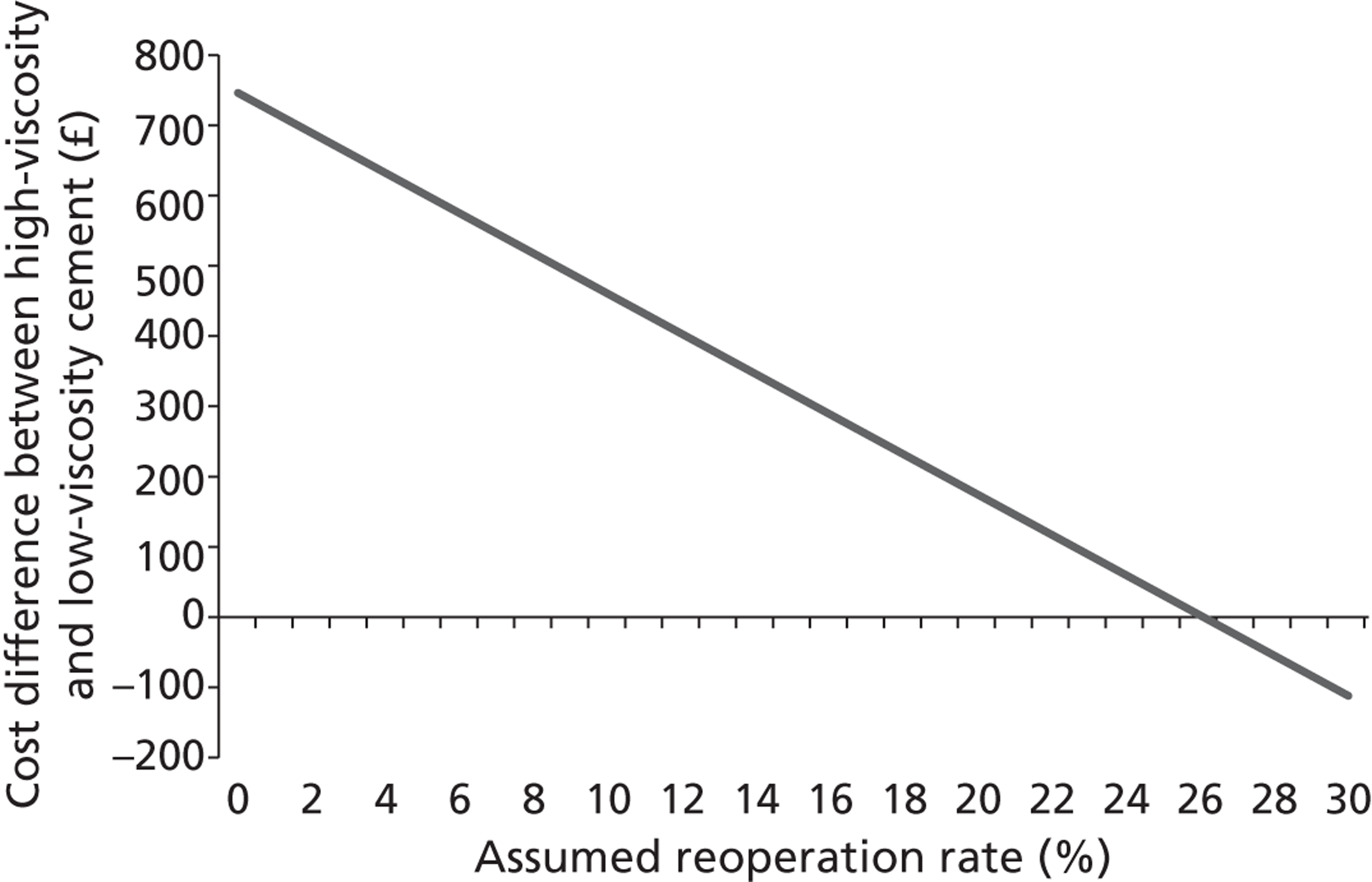

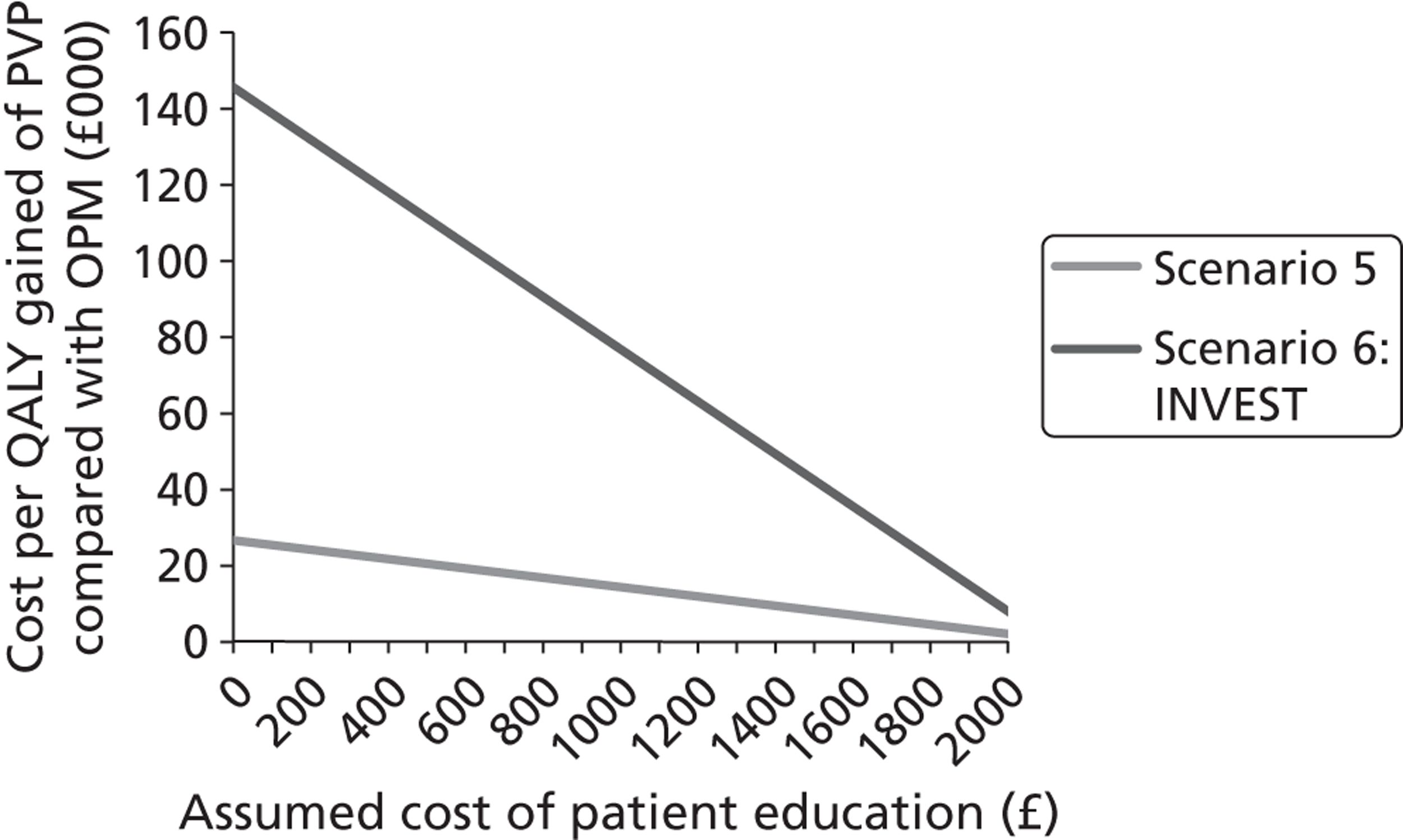

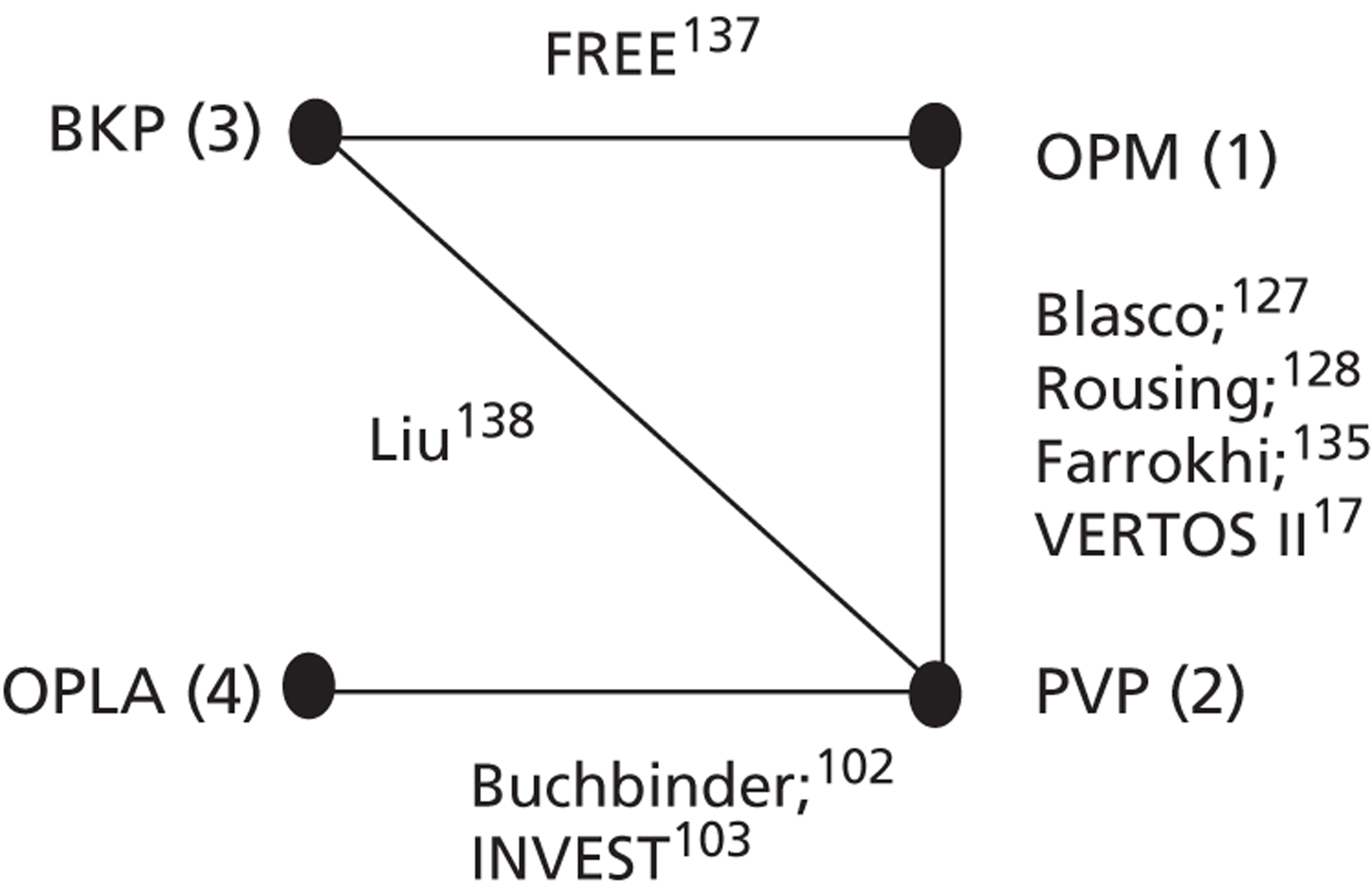

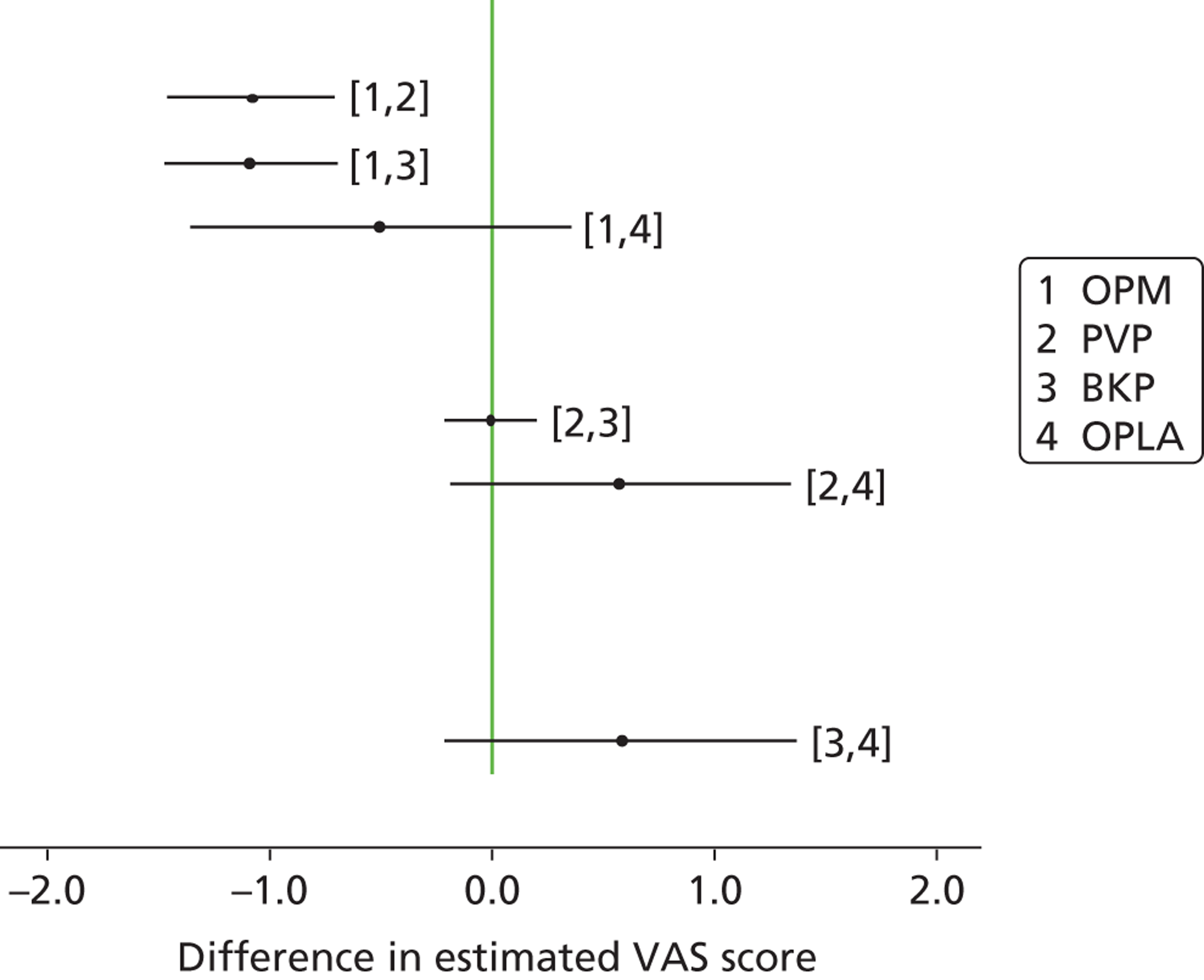

Search restrictions