Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/01/02. The contractual start date was in September 2007. The draft report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Goodacre et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Asthma is a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways characterised by reversible airflow obstruction and bronchospasm. An acute asthma exacerbation (commonly referred to as an asthma attack) is characterised by shortness of breath, wheezing and chest tightness. Acute asthma was responsible for 55,259 emergency admissions and 153,877 bed-days in England in 2011–12,1 and many more emergency department (ED) attendances.

Management of acute asthma

The management of acute asthma in the UK NHS is subject to guidance issued by the British Thoracic Society (BTS) and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). 2 The severity of an acute asthma attack is categorised on the basis of presenting clinical characteristics into near-fatal, life-threatening, severe, moderate and brittle asthma. Patients with any features of life-threatening or severe asthma are referred to hospital for emergency treatment.

Prehospital and ED treatment of acute asthma in adults includes supplemental oxygen therapy, oral or parenteral steroids (prednisolone or hydrocortisone), nebulised β2-agonist bronchodilators (salbutamol or terbutaline) and nebulised ipratropium bromide. Patients are admitted to hospital if they have any feature of a life-threatening or near-fatal attack or any feature of a severe attack persisting after initial treatment. Patients whose peak flow is greater than 75% best or predicted 1 hour after initial treatment may be discharged from the ED unless they meet any of the following criteria, when admission may be appropriate: persistent significant symptoms; concerns about compliance; living alone/socially isolated; psychological problems; physical disability or learning difficulties; previous near-fatal or brittle asthma; exacerbation despite adequate dose steroid tablets prepresentation; presentation at night; or pregnancy.

Magnesium sulphate in acute asthma

Magnesium is an essential mineral nutrient that is present in every cell of every organism. Magnesium-dependent enzymes appear in virtually every metabolic pathway but notably, magnesium ions block calcium channels and, thus, affect nerve and muscle activity. Magnesium sulphate has an established therapeutic role in pre-eclampsia,3 torsade de pointes4 and hypomagnesaemia. 5 Its use has also been explored in ventricular arrhythmias other than torsade de pointes,6 cardiac arrest,7 myocardial infarction,8 atrial fibrillation9,10 and acute asthma. 11

The use of magnesium sulphate in acute asthma is based on possible smooth muscle relaxation and anti-inflammatory action. It can be given via the intravenous (i.v.) or nebulised route and may have a role augmenting treatment in a therapeutic ‘gap’ between the immediate action of nebulised bronchodilators and the delayed action of steroids. Doses of 1.2–2 g have been evaluated in acute severe asthma,11 although doses of 4–6 g can be used in other conditions. 3 The dose of nebulised magnesium sulphate is limited by the need to avoid administering a hypertonic nebulised solution and concurrent therapeutic need for nebulised β2-agonist. The maximum dose is therefore 500 mg per nebuliser.

Evidence for intravenous magnesium sulphate in acute asthma

Intravenous magnesium sulphate has been compared with placebo in five meta-analyses,11–15 two of which analysed adults separately from children. 11,14 The meta-analyses included a total of 15 randomised trials,16–30 nine of which were undertaken in adults. 16–24 The trials of adults used a bolus dose of either 1.2 g or 2.0 g of magnesium sulphate, given over 20–30 minutes. Only one trial followed the bolus dose with an infusion. 18

The most recent meta-analysis11 included all nine adult trials. 16–24 A variety of methods were used to measure pulmonary function, therefore these outcomes were pooled by calculating a standardised mean difference (SMD). The pooled relative risk (RR) for hospital admission after treatment with i.v. magnesium sulphate was 0.91 [95% confidence Interval (CI) 0.78 to 1.07; p = 0.27] and the pooled SMD in pulmonary function was 0.15 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.29; p = 0.035). The authors concluded that treatment with i.v. magnesium sulphate was associated with a modest improvement in pulmonary function, but the clinical significance of this effect was uncertain. Although there was no significant effect on hospital admission, the summary estimate included a potentially important reduction in admissions of up to 22%. Existing evidence was therefore insufficient to either recommend i.v. magnesium sulphate as standard treatment for acute severe asthma or rule out a potentially valuable role.

One further trial (n = 63) of i.v. magnesium sulphate has been published since the most recent meta-analysis was undertaken. 31 The trial reported a significant effect on predicted forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) at 120 minutes (62.84% vs. 56.7%; mean difference = 6.07; 95% CI 1.87 to 10.62; p < 0.01) and fewer patients admitted to hospital in the intervention group (2/30 vs. 9/30). Addition of these data to the most recent meta-analysis resulted in a pooled SMD of 0.35 (95% CI 0.06 to 0.64; p = 0.02) and a pooled RR for hospital admission of 0.85 (95% CI 0.68 to 1.06; p = 0.14).

Evidence for nebulised magnesium sulphate in acute asthma

Nebulised magnesium sulphate has been compared with placebo in three meta-analyses11,32,33 and eight randomised trials,34–41 of which five were undertaken in adults,34–38 two in children39–40 and one in a mixed population. 41 The most recent meta-analysis11 was the only one to report trials of adults and children separately. The trial with a mixed population was analysed with the trials of adults. The dose of magnesium sulphate used ranged from 95 to 500 mg, given up to four times, with doses every 20 to 30 minutes. The pooled RR for hospital admission after treatment with nebulised magnesium sulphate was 0.66 (95% CI 0.44 to 1.00; p = 0.048) and the pooled SMD in pulmonary function was 0.20 (95% CI –0.02 to 0.42; p = 0.076). Although the effect of nebulised magnesium sulphate on hospital admissions just reached significance, most of the admissions in this analysis were in one trial,36 and the effect was not consistent across the other trials. The authors concluded that the existing evidence was inadequate to either support nebulised magnesium sulphate as standard treatment for acute severe asthma or rule out a potentially valuable role.

Comparison between intravenous and nebulised magnesium sulphate

No previous trials have compared i.v. with nebulised magnesium sulphate.

Limitations of the existing evidence for intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate

The existing evidence for both i.v. and nebulised magnesium sulphate suggests a potentially worthwhile effect on pulmonary function and hospital admissions, but estimates of effect are imprecise and include the possibility of either no clinically worthwhile effect or a substantial effect. Furthermore, the existing evidence is subject to the following limitations:

-

Most previous trials were relatively small and powered to detect changes in pulmonary function rather than hospital admission.

-

Even if meta-analysis suggests a statistically significant difference in pulmonary function it is not clear whether such changes are important to patients or affect their clinical outcome.

-

Factors such as publication bias may influence selection of studies into meta-analysis, leading to overestimates of effectiveness. It has been noted that 35% of subsequent large trials conflict with the results of a previous meta-analysis. 42

-

The clinically important change in admission rate in patients with severe asthma identified in the meta-analysis by Rowe et al. 12 was based on post-hoc subgroup analysis.

-

No previous trials have included a head-to-head comparison of nebulised with i.v. magnesium sulphate.

Current use of intravenous and nebulised magnesium sulphate in the National Health Service

Current BTS/SIGN guidelines for the management of acute asthma2 state that there is limited evidence that, in adults, magnesium sulphate has bronchodilator effects and, although experience suggests that magnesium sulphate is safe when given by the i.v. or nebulised route, trials comparing these routes of administration are awaited. The guidelines suggest considering giving a single dose of i.v. magnesium sulphate to patients with acute severe asthma who have not had a good initial response to inhaled bronchodilator therapy or who have life-threatening or near-fatal asthma. Similar advice is provided by guidelines used in the USA. 43

A postal survey of the use of magnesium sulphate in the treatment of acute asthma in the ED was undertaken in the UK in 2009. 44 The lead clinician of each ED was mailed a survey asking about the use of magnesium sulphate in his or her department and 180 out of 251 responded (72%). Magnesium sulphate was reportedly used in 93% of the EDs, mostly because it was expected to relieve breathlessness (70%) or reduce critical care admissions (51%). Most departments used magnesium sulphate for patients with acute severe asthma (84%) and life-threatening exacerbations (87%), with 68% stating they would give the drug if there was no response to repeated nebulisers. In comparison, nebulised magnesium sulphate was used in only two EDs (1%). The main reason given for not administering via a nebuliser was insufficient evidence (51%). The authors commented that the reported use of i.v. magnesium sulphate was more extensive than current guidelines or available evidence appeared to support.

Research objectives

We aimed to measure the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of i.v. and nebulised magnesium sulphate in acute severe asthma and, thus, determine whether or not either should be standard first-line treatment for patients presenting to the ED with acute severe asthma.

We planned to test the following specific hypotheses:

-

intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate will reduce the proportion of patients who require admission at initial presentation or during the following week

-

intravenous or nebulised magnesium sulphate will improve patient assessment of their breathlessness over 2 hours after initiation of treatment.

We also planned to measure the effect of i.v. or nebulised magnesium sulphate on:

-

length of hospital stay and use of high-dependency unit (HDU) or intensive care unit (ICU)

-

mortality, adverse events and use of respiratory support

-

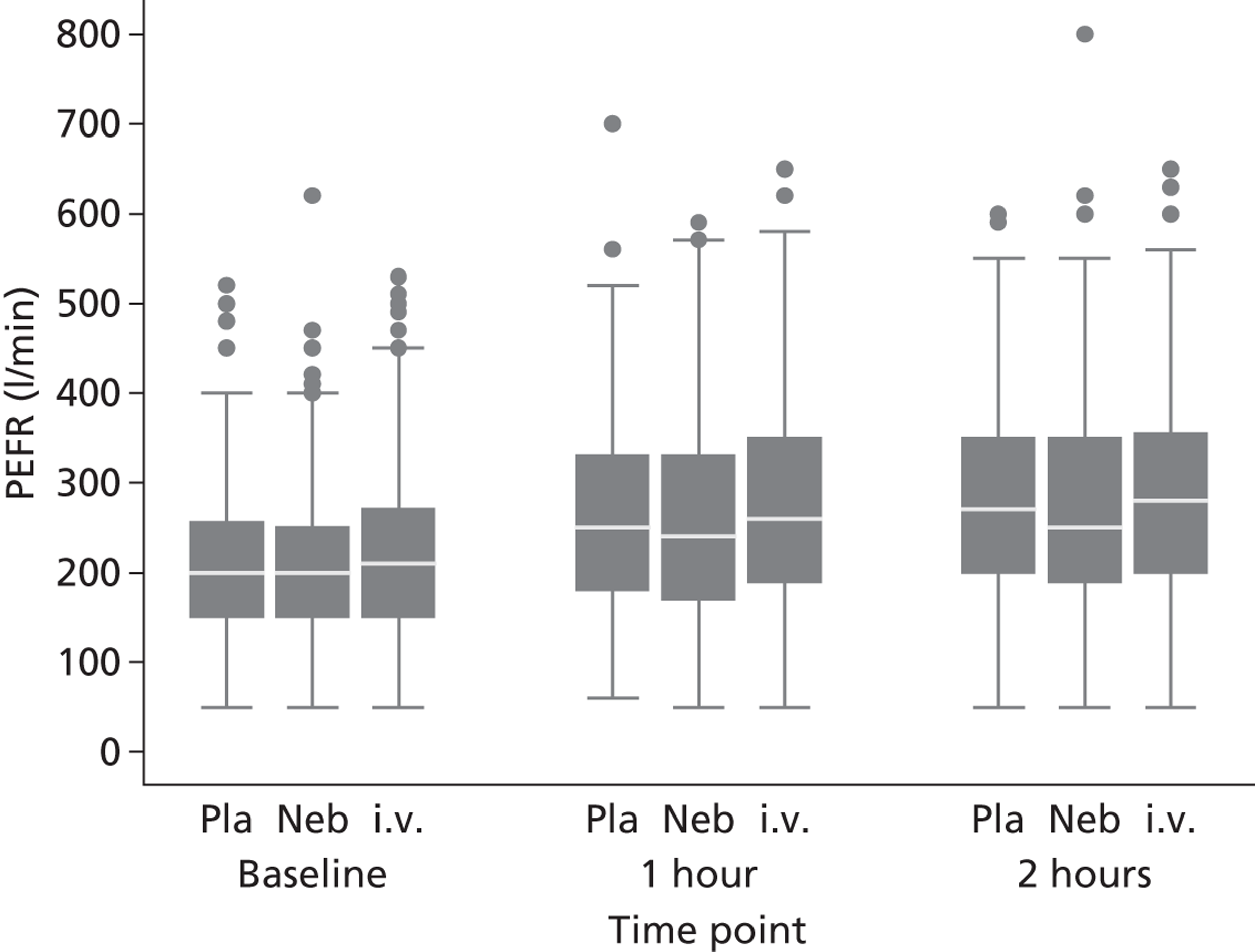

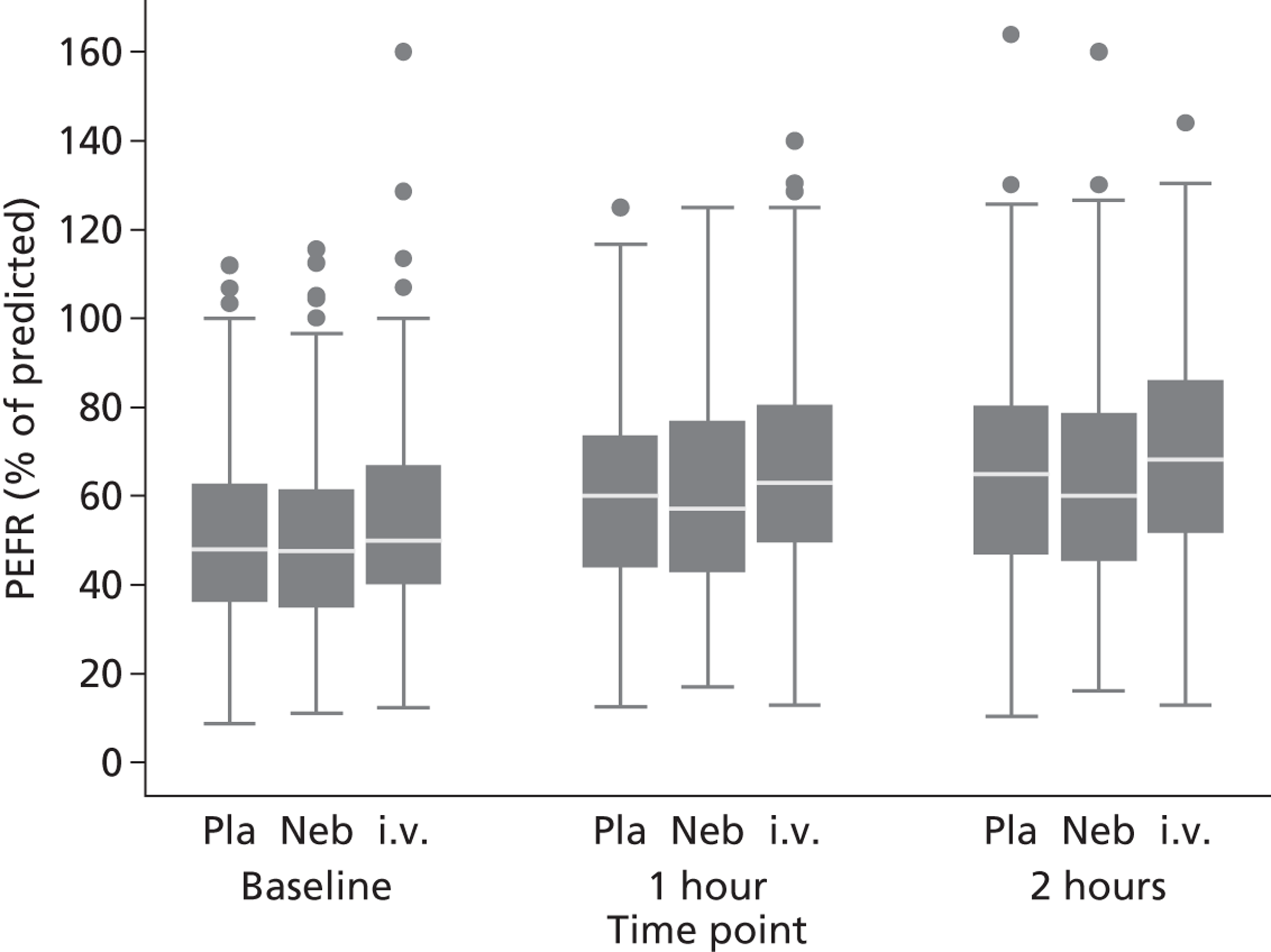

change in peak expiratory flow rate (PEFR) and physiological variables after initial treatment

-

patient-reported health utility

-

patient satisfaction with care

-

use of health and social services over the following month

-

time taken by patients off work

-

health and social care costs and productivity losses.

Chapter 2 Methods

The 3Mg trial was a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, three-arm, randomised trial and economic analysis of i.v. or nebulised magnesium sulphate in acute severe asthma. The trial took place in 34 EDs in England and Scotland.

Recruitment and allocation of participants

Adults (age over 16 years) attending the ED with acute severe asthma were recruited to the trial. Acute severe asthma was defined as acute asthma with one or more of the following: PEFR < 50% of best or predicted; respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute; heart rate > 110 beats per minute; or inability to complete sentences in one breath. The percentage of best or predicted PEFR was calculated using the patient’s recent best PEFR (within 2 years) if it was known. If the recent best PEFR was not known, the predicted PEFR from age and height charts was used. This approach is recommended in BTS/SIGN guidance2 and was used to calculate all estimates of the percentage of best or predicted PEFR used in the trial. For convenience we use the term ‘% predicted PEFR’ to encompass all such estimates.

The following individuals were excluded:

-

patients with life-threatening features, defined as one or more of the following: oxygen saturation < 92% despite supplemental oxygen; silent chest; cyanosis; poor respiratory effort; bradycardia; arrhythmia; hypotension; exhaustion; coma; or confusion

-

patients with a contraindication to either nebulised or i.v. magnesium sulphate: pregnancy; hepatic or renal failure; heart block; or known hypermagnesaemia

-

patients who were unable to provide written or verbal consent

-

previous participants in the 3Mg trial

-

patients who had received i.v. or nebulised magnesium sulphate in the 24 hours prior to attendance at the ED.

The final exclusion criterion was added as a protocol amendment during the trial.

Anonymised basic details (age, sex, time and date of ED attendance) were collected from all potentially eligible patients to allow completion of a CONsolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart. Patients were identified by ED medical staff, who completed a patient recruitment form (see Appendix 1) to verify that the patient met the eligibility criteria and to record that consent was taken prior to randomisation. Eligible patients were initially given a brief information sheet with details of the study design, trial treatments and potential side effects (see Appendix 2). When their condition permitted, they were given a full information sheet with further details on trial processes and requirements (see Appendix 3). All patients were required to give consent before being recruited to the trial. If the patient’s condition permitted, full written consent was taken before recruitment using the Research Ethics Committee (REC)-approved consent form (see Appendix 4). If not, verbal consent was obtained from the patient, recorded on the consent form and written consent requested as soon as the patient’s condition improved. No provisions were made for personal or professional legal representation or for recruitment before consent. Therefore, any patient unable to provide written or verbal consent was excluded from the trial. Both oral and written consent were taken in the presence of a witness who also signed the consent form, in addition to the person taking consent.

Once eligibility had been confirmed and consent acquired, the participants were randomly allocated to a treatment group. The recruiting clinician accessed a web-based randomisation system or automated telephone hotline provided by the Sheffield Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) in partnership with epiGenesys (a University of Sheffield subsidiary software development company) and participants were allocated to a numbered treatment pack kept in the ED. The randomisation system only revealed the allocated pack number after patient details had been recorded and the patient irreversibly entered into the trial. A simple randomisation sequence was used in the first 20 hospitals open to recruitment, as planned in the protocol. 45 However, recruitment rates were lower than anticipated and, therefore, additional hospitals were opened to recruitment. To reduce the risk of random imbalances in the number allocated to each arm of the trial, blocked randomisation (block sizes of four or six), stratified by hospital, was used for subsequent centres. To avoid the risk of subversion of the randomisation process in these hospitals, decisions regarding the randomisation sequence were made independently by the CTRU and were not communicated to the investigators.

Each treatment pack contained an i.v. infusion and nebuliser solutions, either of which could be active treatment or placebo. Participants, hospital staff and research staff were all blind to allocated treatment, unless the formal unblinding procedure was undertaken. An emergency unblinding (code-break) procedure was in place to enable hospital staff to reveal the allocation of treatment when it was essential to know for their on-going clinical care whether or not the patient had received magnesium sulphate. A 24-hour unblinding service was available via the randomisation system (online or telephone), which immediately provided treatment allocation to the site and automatically alerted the study team and local principal investigator (PI) by e-mail that a participant had been unblinded. In case the online and telephone systems were unavailable, emergency unblinding envelopes were also prepared by the pharmacy production unit according to the randomisation schedule and stored with the investigational medicinal products (IMPs) at site. Tamper stickers were checked regularly to ensure that envelopes had not been opened and were returned, still sealed, to the central study team to ensure full accountability. If an envelope was opened it was reported to the study team and recorded as a participant unblinding.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to one of three treatment arms. Each patient received one i.v. and one nebulised treatment (consisting of three nebuliser vials given consecutively). The i.v. infusions and nebuliser vials were prepared as apparently identical solutions, with identical primary packaging and labelling to ensure blinding. Blinded treatment packs were assembled and labelled with a participant number in accordance with a randomisation schedule supplied by the CTRU. The three treatment arms are shown in Table 1.

| Treatment arm | Intravenous infusion | Nebulisers |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | i.v. magnesium sulphate, 8 mmol (2 g) in 100 ml of water for injections, adjusted to isotonicity with sodium chloride, given over 20 minutes | 7.5-ml vial of 0.9% saline, given three times 20 minutes apart |

| 2 | i.v. 0.9% saline, 100 ml given over 20 minutes | 7.5-ml vial of 2 mmol (500 mg) magnesium sulphate, given three times 20 minutes apart |

| 3 | i.v. 0.9% saline, 100 ml given over 20 minutes | 7.5-ml vial of 0.9% saline, given three times 20 minutes apart |

All three groups received standard therapy at the discretion of the treating physician, but guided by BTS/SIGN guidelines2 and the 3Mg Clinical Protocol (see Appendix 5). Recommended standard therapy included supplemental oxygen, nebulised salbutamol, nebulised ipratropium bromide and oral prednisolone, administered during recruitment, followed by up to 5 mg of salbutamol added to each trial nebuliser. The BTS/SIGN guidelines2 do not recommend magnesium sulphate, but suggest that i.v. use should be considered in patients with life-threatening features or those with severe asthma who do not respond to treatment. We, therefore, did not prohibit the use of magnesium sulphate outside the trial or recommend its use in patients unresponsive to treatment. During the trial we identified the occasional use of magnesium sulphate at an early stage of treatment of patients without life-threatening features. We therefore added an additional exclusion criteria that patients must not have received magnesium sulphate in the previous 24 hours before entry into the study.

Patients were managed in the ED and data collected until 2 hours after randomisation. At this point, if not already undertaken, a final disposition decision (hospital admission or discharge) was made.

Outcome measures

Two primary outcomes were specified in the trial protocol:

-

The health service primary outcome – the proportion of patients admitted to hospital, either after ED treatment or at any time over the subsequent week.

-

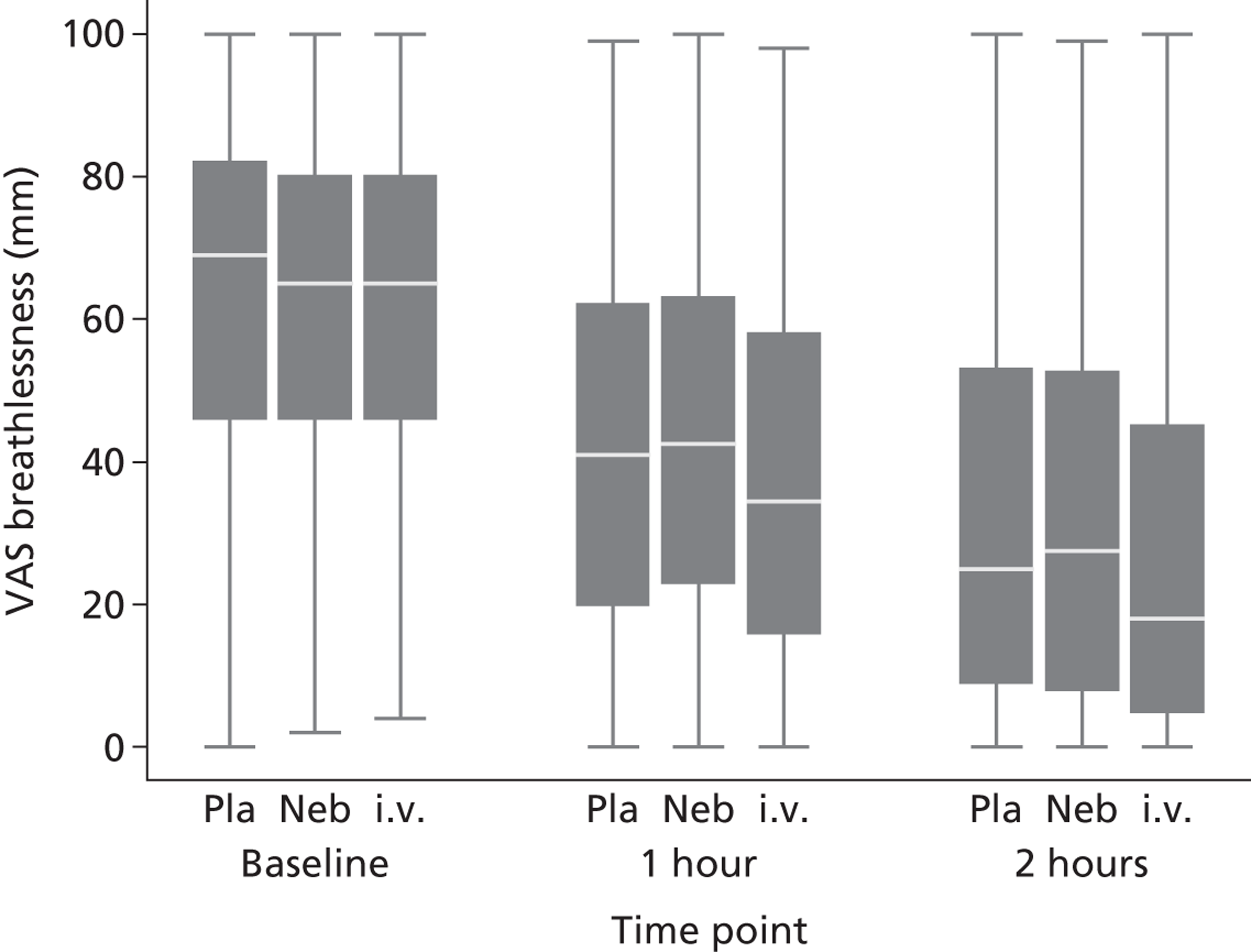

The patient-centred primary outcome – the patient’s visual analogue scale (VAS) for breathlessness over 2 hours after initiation of treatment.

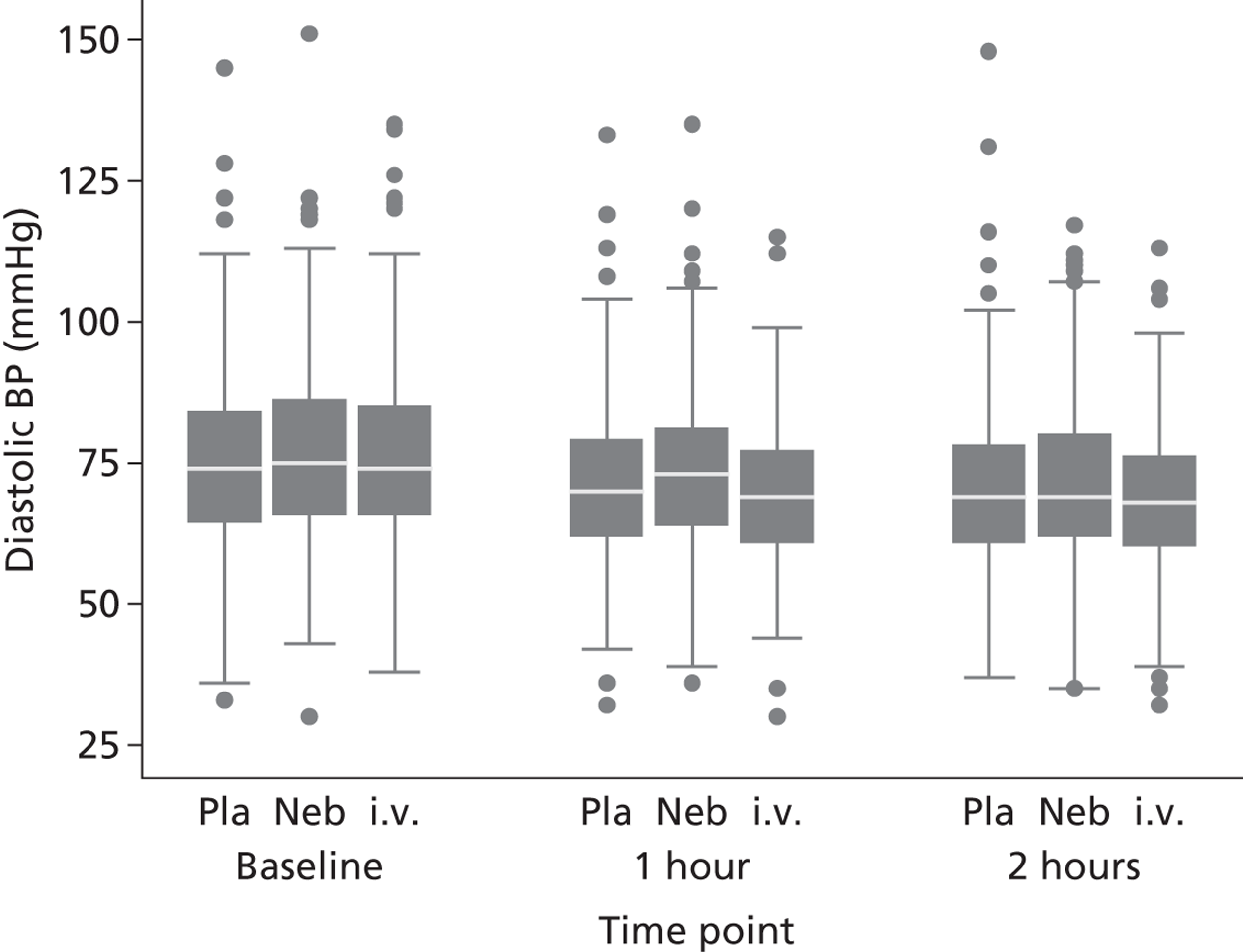

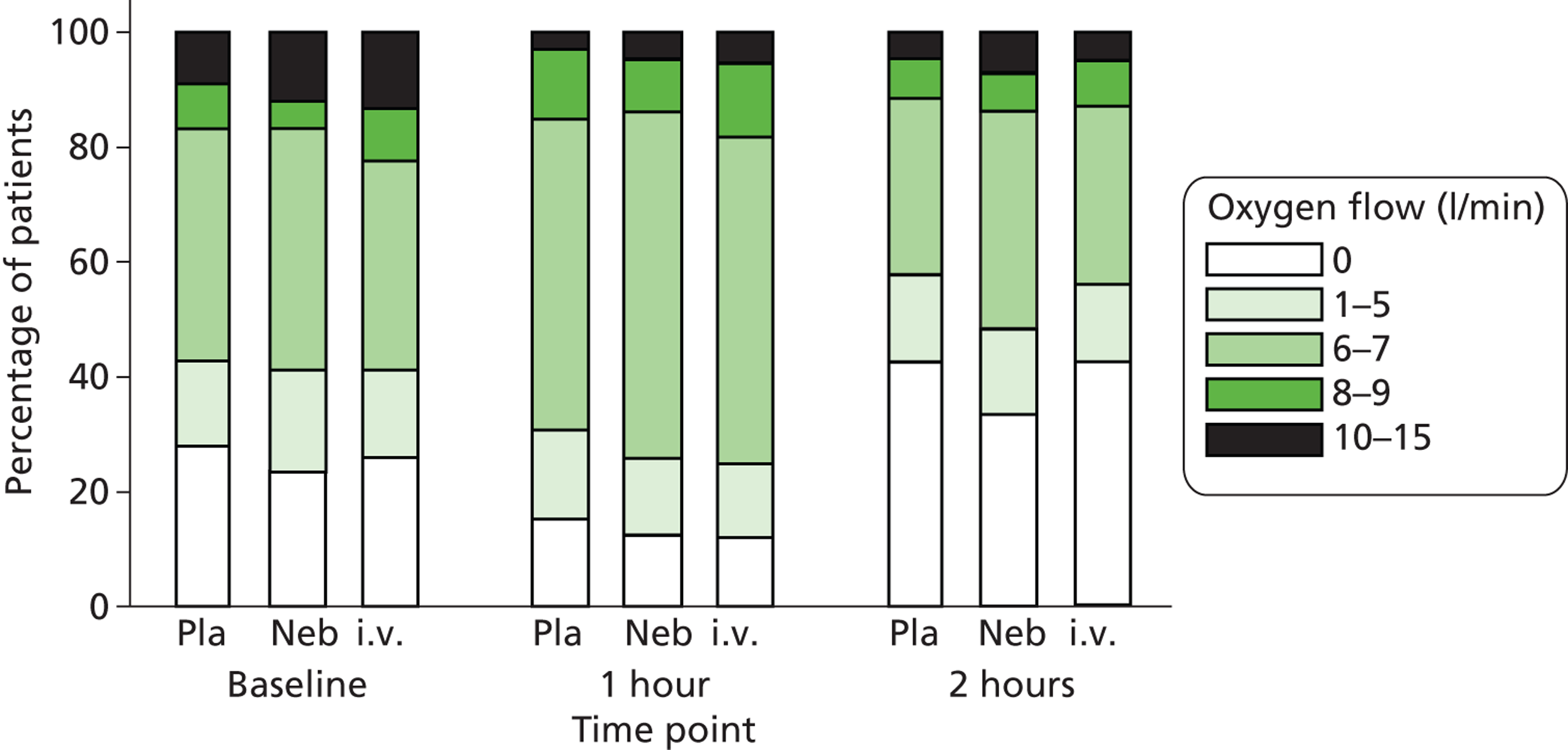

Secondary outcomes included mortality; adverse events; the use of ventilation or respiratory support; length of hospital stay; use of HDU or ICU; change in PEFR and physiological variables (oxygen saturation, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure) over 2 hours; quality of life at baseline and at 1 month [measured by European Quality of Life 5-Dimensions (EQ-5D)]; number of unscheduled health-care contacts (ED, walk-in centre or general practitioner attendances) over the subsequent month; and satisfaction with care.

The two primary outcome measures were selected to identify important changes in patient management and symptoms of asthma. The primary outcome of hospital admission included any admission over the following week, because this time period would encompass the expected duration of an asthma exacerbation and a typical course of associated treatment. Admission during this time therefore represented an overall failure of treatment, whereas admission later than 1 week was considered a separate episode.

The VAS and the Borg scale have both been used to measure breathlessness during exercise,46 but have only recently been tested in acute asthma. Kendrick et al. 47 showed that the Borg scale correlated with measures of respiratory function in a cohort of patients with asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, whereas Karras et al. 48 and Gupta et al. 49 showed correlation between the VAS and measures of respiratory function in cohorts with acute asthma. The study by Karras48 also showed that the mean VAS change among patients who reported their asthma to be ‘a little better’ after treatment was 22 mm on a 100-mm VAS and concluded that this represented a minimum clinically significant change. On the basis of these studies we concluded that the VAS was the best validated measure, offering a simple and reliable means of measuring symptomatic breathlessness in people with acute asthma, with an estimate of the minimum clinically significant change in VAS.

Outcomes were measured in two phases: (1) over 2 hours after randomisation and (2) at 1 month after attendance. During the first phase we measured variables that reflect patient response to emergency treatment, such as VAS, PEFR and physiological variables. During the second phase we measured variables that reflect the overall patient experience of an asthma attack and its subsequent treatment, such as adverse events, use of health services, satisfaction with care and quality of life.

Data collection and management

A recruitment form was completed for all patients attending the ED with acute severe asthma at participating sites. These data were used to complete the CONSORT flow chart and generate reports on non-recruited patients for discussion at management group meetings.

Clinical staff recorded baseline data, details of co-interventions and outcome data up to 2 hours after randomisation on the paper case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 6). Further data were collected up to 1 month after recruitment by research nurses using routine data sources and by patient self-completion questionnaire. A postal survey consisting of the EQ-5D, a health-care resource use questionnaire, and a patient satisfaction questionnaire was mailed to all participants who were alive and had not withdrawn from the trial 1 month after recruitment (see Appendices 7 and 8). A repeat mailing was undertaken for all non-responders at 2 weeks, with telephone completion of the EQ-5D attempted 2 weeks later for non-responders to either mailings. Patients who had not responded to mail or telephone contact by 8 weeks after study entry were recorded as lost to follow-up for questionnaire data.

Trial data were entered via web-based interface to a database developed in-house by the CTRU. The system, and its underlying database, resided on a server in Corporate Information and Computing Services at the University of Sheffield. Automated backups were made nightly. Prospect was accessed remotely via a secure web browser and all data transmissions were encrypted. Access was restricted by username and password (issued by the CTRU) and an automated audit trail recorded when (and by which user) records were created, updated or deleted. The profile of each user was set to allow only the appropriate information to be viewed and edited, e.g. site data inputters could only enter and view data about patients from their own sites. Quality control procedures were applied to validate the trial data. Error reports were generated where data clarification was required and data queries resolved by research nurses at sites. All activities were performed in accordance with Sheffield CTRU standard operating procedures (SOPs).

Proposed sample size

We planned to recruit 1200 participants, divided equally between the three trial arms (400 participants per arm). We anticipated that the hospital admission would be recorded for all participants, but that a proportion of cases would not have VAS measured. The sample size would therefore provide the following statistical power:

-

Proportion of patients admitted – assuming that 80% of patients with severe asthma are admitted after ED management, the study would have 90% power to detect a 10% absolute reduction in the proportion admitted (i.e. to 70%) for any pair of treatment groups compared (α = 0.05).

-

VAS breathlessness – assuming that the standard deviation on a 100-mm VAS is 3 cm, that 2.2 cm represents a minimum clinically significant difference48 and that 20% of participants will not have their VAS measured, the study would have 90% power to detect a 8-mm difference in a 100-mm VAS at 2 hours after treatment initiation (α = 0.05).

Statistical analysis

Analysis of coprimary outcomes

For the health service primary outcome, patients were considered to have been admitted if either (i) they had not been discharged within 4 hours and/or (ii) if they were recorded as having been readmitted at any point within 7 days following randomisation. The proportion admitted was analysed using logistic regression. We anticipated that data would be missing from only a very small proportion of the trial population (those withdrawing within a few hours of recruitment) and, therefore, planned only a complete case analysis.

For the patient-centred primary outcome, breathlessness was defined as the change in VAS from baseline to 2 hours and was analysed using linear regression. As both missing data and measurements outside the allotted time window were anticipated, the analysis plan proposed three analyses:

-

‘As is’ – complete case analysis, no adjustment is made for timing.

-

‘Imputed’– measurements more than ± 15 minutes from their scheduled time were adjusted by linear interpolation or extrapolation.

-

Multiple imputation by chained estimation. Missing 2-hour VAS scores (n = 108; 10%) were imputed based on age, sex, smoking status, previous admission for asthma, previous admission to ICU or HDU for asthma, time since last admission for asthma, baseline and 1-hour VAS, PEFR and heart rate over 2 hours’ observations, and status at 4 hours (i.e. discharged or admitted/awaiting decision).

Analysis was undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis. Patients were removed from analysis post randomisation only if recruitment was an unequivocal protocol violation (i.e. no consent had been recorded or if they had previously been recruited) or if the patient withdrew from the trial prior to any treatments having been administered. In all other cases, participants were analysed in accordance with the groups they were allocated to regardless of whether or not they actually completed their allocated treatment. A secondary, per-protocol analysis excluded participants who did not receive treatment, defined as a minimum nebulised dosage of 7.5 ml (the equivalent of one nebuliser) or 50 ml of i.v. volume (50% of the i.v. dose).

The primary and most of the secondary analyses included two covariates: treatment group and centre (hospital). For the purposes of the analysis, hospitals recruiting fewer than 10 patients in total were combined into one group for analyses in which centre was used as a covariate. The robustness of the findings to potential differences in baseline characteristics was assessed, in particular the initial breathlessness (VAS) and age.

We used Simes’ method,50 which is a modification of the Bonferroni method but has better power to adjust for multiplicity arising from having two primary outcomes. However, we did not adjust the CIs associated with the estimate of the treatment effect with each outcome. We tested the two hypotheses simultaneously through the analysis of variance. With three groups (A = nebuliser, B = i.v. and C = control) we had two degrees of freedom for analysis, which we split into two orthogonal contrasts (–2, +1, +1) to contrast both active treatments compared with control and (0, –1, +1) to contrast the active treatments.

Secondary outcomes

The length of hospital stay was analysed using a log-normal distribution, which allowed for interval censoring of non-admitted patients and right censoring of hospital duration among those still in hospital 30 days after randomisation. PEFR and physiological measures were analysed in the same manner as breathlessness. All secondary analyses were undertaken as complete case, intention-to-treat analyses.

Subgroup analyses

We prospectively defined three subgroup analyses, within which patients were stratified on the basis of:

-

Asthma severity, according to whether baseline PEFR (pretreatment PEFR as a percentage of predicted value) was above or below median baseline PEFR. A previous meta-analysis12 suggested that i.v. magnesium sulphate is more effective in patients with severe asthma.

-

Age, above or below 50 years. Older patients with a diagnosis of asthma are more likely to have chronic respiratory disease that may be less responsive to treatment with magnesium sulphate.

-

Treatment before arrival. We recruited patients on arrival at hospital, thus testing magnesium sulphate as a first-line treatment. However, some patients received prehospital treatment with nebulisers, thus making magnesium sulphate, in effect, a second-line treatment. Patients with severe asthma after receiving prehospital treatment are likely to have more severe asthma than those presenting without prehospital treatment.

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation took an approach consistent with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) reference case analysis. 51 The perspective taken was that of the NHS and personal social services. Health benefits were measured in quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) using the EQ-5D and the time horizon over which health benefits were derived was 30 days. Health benefit was also measured by assessing breathlessness on a 100-mm VAS at 1 and 2 hours after the initiation of study treatment. The data collected 2 hours after the initiation of treatment were used in the cost-effectiveness analysis.

The following resources were identified as being important and collected using either the CRF or patient-completed questionnaire:

-

trial medication

-

ICU – asthma related (days)

-

HDU – asthma related (days)

-

ward – asthma related (days)

-

ICU – non-asthma related (days)

-

HDU – non-asthma related (days)

-

ward – non-asthma related (days)

-

telephone health advice [e.g. general practitioner (GP), NHS Direct] (number of times used)

-

GP surgery consultations (number of times used)

-

GP home visits (number of times used)

-

nurse home visits (number of times used)

-

social worker visits (number of times used)

-

ED attendances (number of times used)

-

attendance at hospital as an outpatient (number of times used)

-

asthma-related concomitant medications: salbutamol, prednisolone, ipratropium bromide, salmeterol xinafoate/fluticasone propionate (Seretide®, GlaxoSmithKline), budesonide (Pulmicort®, AstraZeneca), montelukast, beclometasone dipropionate (Clenil® Modulite®, Chiesi Ltd), aminophylline, theophylline, hydrocortisone, tiotropium (Spiriva®, Boehringer Ingelheim Ltd), magnesium sulphate, salmeterol, ipratropium bromide/salbutamol (Combivent®, Boehringer Ingelheim) and terbutaline (Bricanyl®, AstraZeneca UK Ltd).

Inpatient stays and medications were collected via CRFs, with the remainder collected by patient questionnaire. Productivity loss as a consequence of the number of days patients took off work during the study was collected using the patient questionnaire and separate analyses were conducted excluding and including productivity loss.

Unit costs for medication were taken from the British National Formulary (BNF),5 with the implied dose being that of the most common recorded within the trial (Table 2). Other unit costs were derived primarily from NHS reference costs52 and the Personal Social Service Research Unit annual unit costs publication. 53 NHS reference costs were inflated to 2011/12 prices using the gross domestic product deflator (as the relevant Hospital and Community Health Services Index figure is not yet available). The costs of NHS Direct advice were estimated from an evaluation of this service54 and the costs of production losses were estimated using data from the Office for National Statistics. 55 These unit costs are shown in Table 3.

| Item of resource (medicationsa) | Route | Dose | Cost per doseb (£) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment arm 1 (2 mg of i.v. magnesium sulphate) | – | – | 7.39 |

| Treatment arm 2 (2 mg of nebulised magnesium sulphate) | – | – | 7.39c |

| Treatment arm 3 (saline) | – | – | 0 |

| Aminophylline | Oral | 1 × 225 mg | 0.04 |

| Aminophylline | i.v. | 2 × 10-ml ampoule | 1.56 |

| Beclometasone dipropionate | Inhaled | 2 × 100 µg | 0.07 |

| Combivent | Nebulised | 1 × 2.5 ml | 0.40 |

| Hydrocortisone | Oral | 1 × 20 mg | 1.53 |

| Hydrocortisone | i.v. | 2 × 100 mg | 2.16 |

| Ipratropium bromide | Nebulised | 1 × 500 µg | 0.37 |

| Ipratropium bromide | Inhaled | 2 × 20 µg | 0.05 |

| Magnesium sulphate | i.v. | 1 × 2 g | 7.39 |

| Methylprednisolone | Oral | 2 × 16 mg | 1.14 |

| Montelukast | Oral | 1 × 10 mg | 0.96 |

| Prednisolone | Oral | 8 × 5 mg | 0.35 |

| Pulmicort | Nebulised | 1 × 1 mg | 30.30 |

| Pulmicort | Inhaled | 1 × 200 µg | 0.12 |

| Salbutamol | i.v. | 1 × 5 mg | 0.19 |

| Salbutamol | Nebulised | 1 × 5 mg | 0.19 |

| Salbutamol | Inhaled | 2 × 100 mg | 0.02 |

| Salmeterol (Serevent®, GlaxoSmithKline) | Inhaled | 2 × 25 µg | 0.46 |

| Seretide | Inhaled | 2 × 250 µg | 0.60 |

| Terbutaline | Inhaled | 1 × 500 µg | 0.07 |

| Theophylline | Oral | 1 × 200 mg | 0.05 |

| Tiotropium | Inhaled | 1 × 18 µg | 1.06 |

| Item of resource | Cost per unit (£) | Year | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Telephone advice from NHS Direct | 25 | 2011/12 | 54 |

| GP surgery consultations | 37 | 2011/12 | 53 |

| GP home visits | 124 | 2011/12 | 53 |

| Nurse home visits | 37 | 2011/12 | 53 |

| Social worker visits | 108 | 2011/12 | 53 |

| ED attendance | 96 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| Outpatient visits – asthma related | 133 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| Inpatient days – asthma related | 358 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| Inpatient days – asthma and other related | 261 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| ICU days | 868 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| HDU days | 623 | 2011/12 | 52 |

| Days off work | 101 | 2011/12 | 55 |

Quality-adjusted life-years were calculated for each patient over the duration of the study using the EuroQoL tariff56 and by applying the trapezoidal rule based on data at baseline and at 30 days. The change from baseline in breathlessness 2 hours after the initiation of study treatment, as measured using a 100-mm VAS, was calculated for each patient. Reduction from baseline is defined as minus one times the change from baseline to reflect the fact that a reduction in breathlessness is a positive outcome.

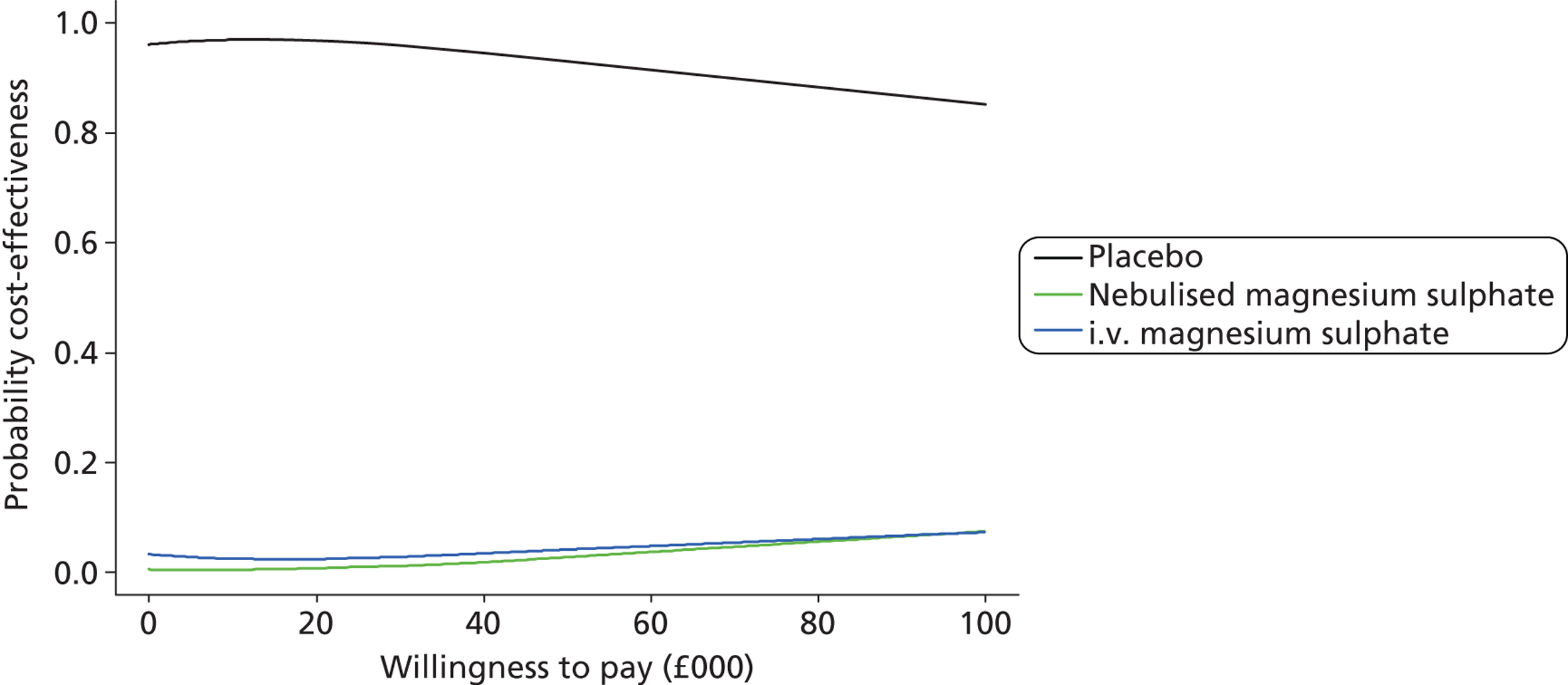

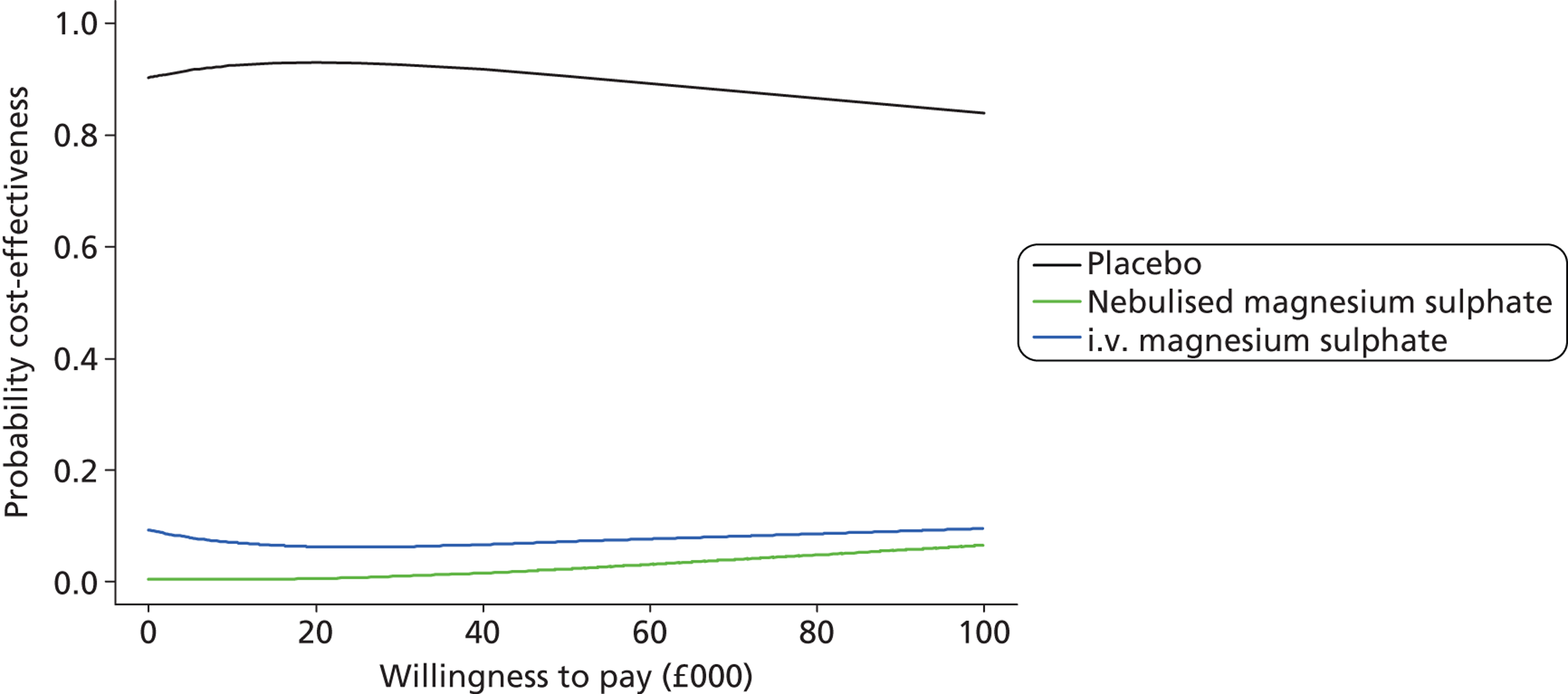

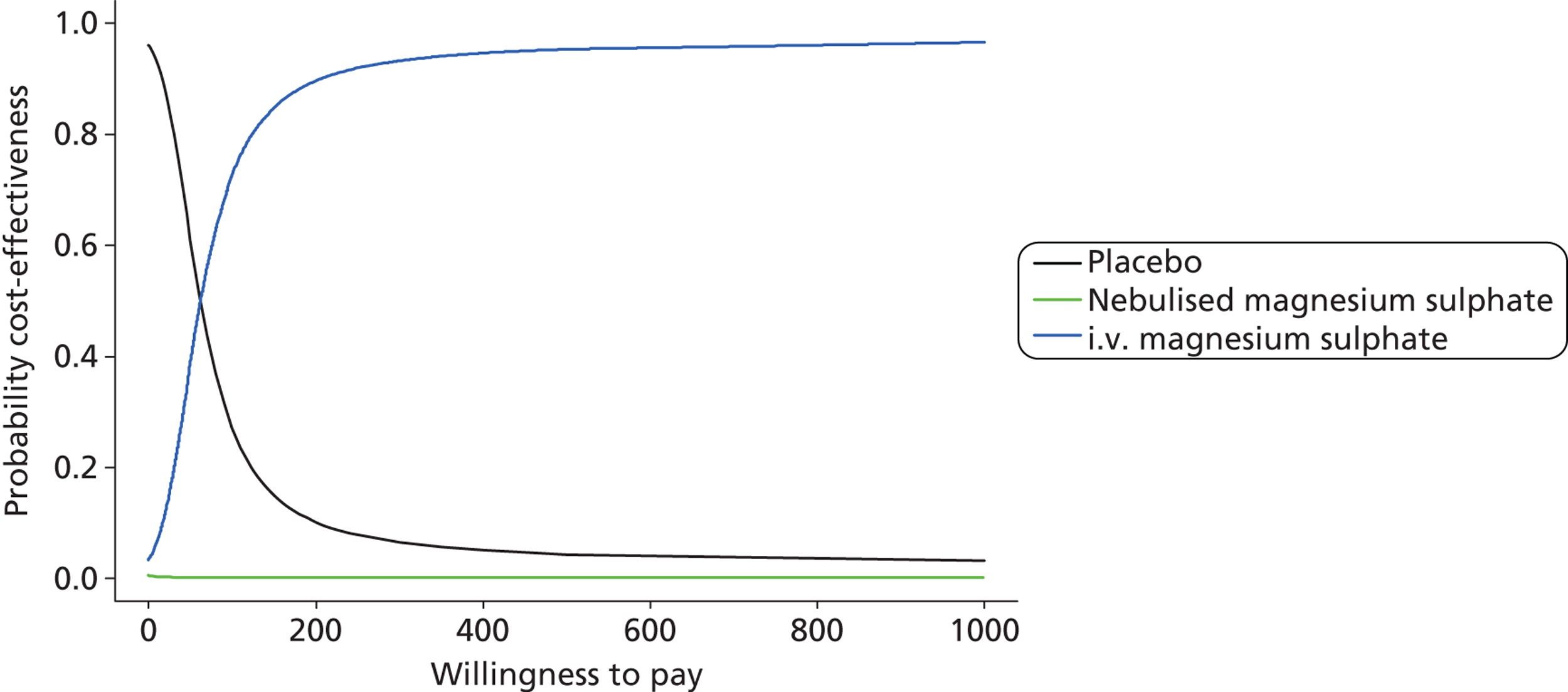

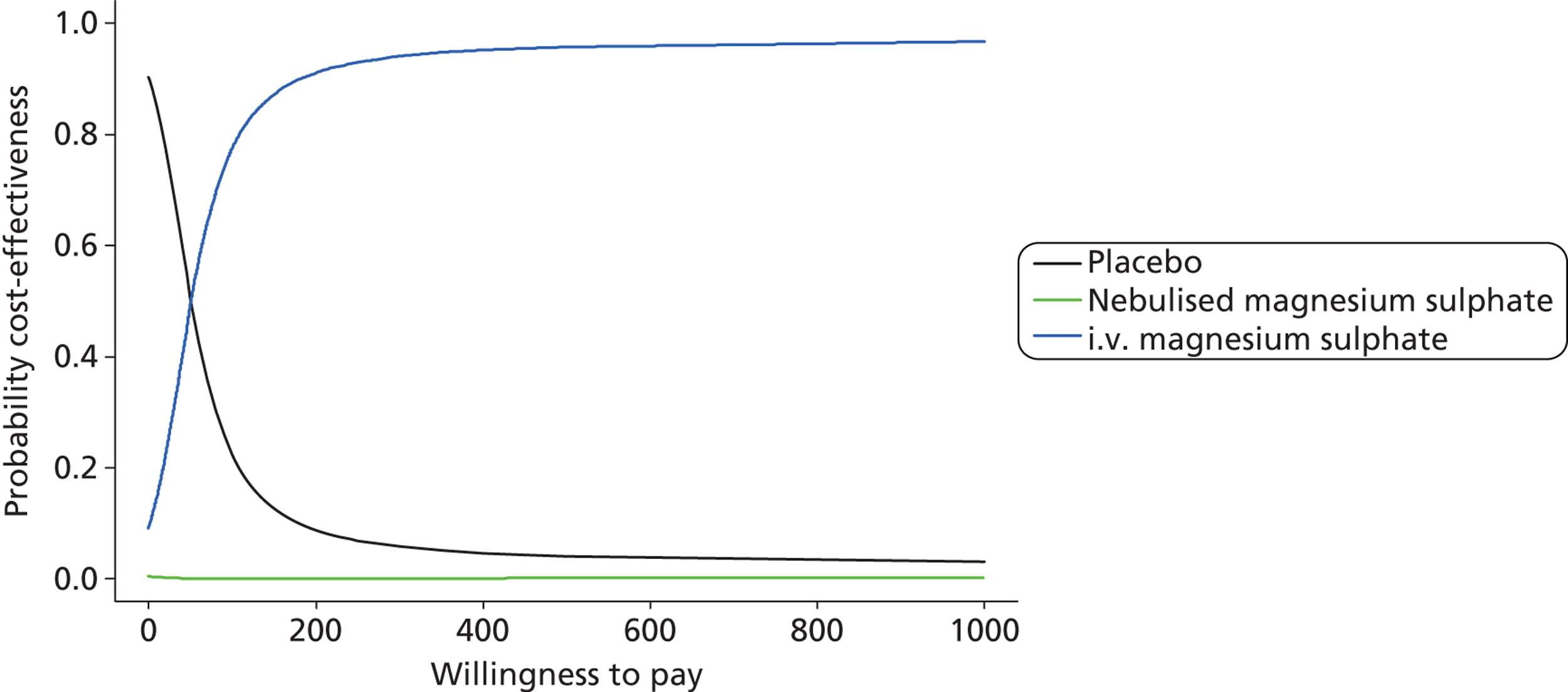

The primary analysis was a cost-effectiveness analysis using the QALYs associated with treatment. Additionally, the change from baseline in breathlessness 2 hours after the initiation of study treatment, as measured using a 100-mm VAS, was used as a secondary cost-effectiveness analysis. The focus of the analysis is on the probability that the intervention arms are cost-effective at funding thresholds of £20,000 and £30,000 per QALY. In addition, cost-effectiveness acceptability frontiers are presented over the range £0–100,000 per QALY. As with all cost-effectiveness analyses, it is necessary for the measure of effectiveness to be linear in the sense that the value of an incremental increase of E units of effectiveness is EK, where K is the value to the decision-maker of increasing effectiveness by one unit. Unlike QALYs, it is not clear how much value a decision-maker may give to a unit reduction in breathlessness on the VAS scale, but is likely to be much less than that for a QALY. Cost-effectiveness acceptability frontiers are presented over the range £0–1000 per unit reduction in breathlessness. Sensitivity analyses were performed incorporating production losses (i.e. time taken from paid employment).

Missing data were imputed using a single-value imputation approach. A multiple imputation algorithm was attempted but it failed to converge, possibly as a consequence of the large number of missing data associated with some outcome measures and the assumptions being made about their underlying probability distributions in the multiple imputation algorithm.

The analysis was initially planned to use bootstrapping, but this was replaced by an analysis using a Bayesian approach using a bivariate normal likelihood function for the effectiveness and total cost. 57 The bivariate normal likelihood function is justified by appealing to the central limit theorem, which says that for data from any underlying probability distribution with finite mean and variance, the distribution of the sample means will tend to be a normal distribution with sufficiently large sample sizes. This change was undertaken in advance of the analysis commencing.

The analysis was conducted using the freely available software WinBUGS 1.4.3 (Imperial College and Medical Research Council, UK). 58 Weak prior information was included in the analysis. The model converged very quickly but for accuracy and precision purposes the results are based on 100,000 Markov chain Monte Carlo iterations after a burn-in of 25,000 iterations.

With sample sizes as large as those in this study, the results are expected to be similar to what would have been generated using bootstrap or a more exact approach that specifically models the underlying distribution of the derived effectiveness and total cost data. Nevertheless, a benefit of this approach is that it allows a more direct interpretation about the probability associated with the parameters of interest (i.e. population mean incremental cost and effectiveness) and the probability of positive net benefit.

Predictors of unsuccessful treatment

To maximise the value of this project, we planned to undertake an additional analysis of trial data to identify factors that predicted unsuccessful treatment for acute severe asthma. Predicting unsuccessful treatment would be helpful for deciding which patients need asthma nurse review after discharge,59 which need hospital admission and which need HDU or ICU support. Currently these decisions are made largely on PEFR recordings,2 although it is not clear how useful these are as predictors of relapse.

Data collection for the trial included variables that may be potentially useful predictors of unsuccessful treatment, such as baseline and post-treatment PEFR, physiological variables, age, sex, smoking status, and previous hospital, HDU and ICU admissions. We examined the ability of these factors to predict unsuccessful treatment, defined at two levels: (1) need for critical care, i.e. HDU or ICU care, airway management, respiratory support or cardiopulmonary resuscitation or respiratory arrest, cardiac arrhythmia or death within 7 days of initial attendance; and (2) need for emergency medical treatment (including critical care) within 7 days of presentation, either by attendance at the ED or unscheduled inpatient review.

Models were fitted separately for the two definitions. For each, an initial screening phase assessed potential covariates, with those achieving a minimum significance level of p < 0.15 retained for the multivariable modelling. Outcomes were modelled using logistic regression. Continuous covariates (physiological variables, PEFR and age) were modelled using fractional polynomials,60 but the resultant model compared with two alternative functional forms (linear and quadratic) to assess whether or not a simpler model could achieve an adequate fit. Predictive ability was assessed by calculating the area under the receiver operator characteristic (AUROC) curve of the model. Internal validation was performed by two methods: (1) bootstrap validation, assessing the robustness of model covariates and (2) cross-validation. The model was fitted separately to the following subgroups defined by (i) seasonality (October–March vs. April–September), (ii) time period (2008–10 vs. 2011–12) and (iii) type of hospital (teaching vs. non-teaching). In each case the resultant models were assessed for consistency between the subgroups.

For each definition, three models were incrementally compared:

-

a model based solely on %PEFR at admission

-

a model using the best-fitting combination of baseline (pretreatment) physiological covariates

-

a model incorporating change in physiological measures over 2 hours, in addition to those used in model 2.

Ethical issues

The trial was undertaken in accordance with the Medicine for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 200461 and subsequent amendments, and was approved by the Scotland A REC. The main ethical issue was that patients with acute severe asthma may lack capacity to provide informed consent or the ability to complete a written consent form, yet the very nature of the trial required that recruitment should take place quickly in an emergency and include acutely ill patients. 62,63 We initially planned to use personal or professional legal representatives to provide proxy consent for patients lacking capacity. However, on the advice of the ethics committee this provision was dropped and only patients able to provide some form of consent were recruited to the trial. In addition to the person taking consent, a witness also had to sign the consent form to verify that the patient had capacity to give informed consent. It was felt that patients who were too ill to consent were likely to have life-threatening asthma and that excluding patients lacking capacity would not compromise validity.

Participants were therefore only recruited into the trial if they could provide written or verbal-informed consent. We used the following process for seeking consent, based on the Medicine for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004 and subsequent amendments, and taking into account the ethics committee review:

-

All patients were given emergency treatment with supplemental oxygen, salbutamol nebuliser and ipratropium bromide nebuliser while consent was being sought. Initial investigations, such as arterial blood gas sampling and chest radiography, continued simultaneously.

-

Potential participants were given a brief initial information sheet (see Appendix 2) and asked if they wished to consider participation in the trial.

-

Those patients that would consider participation were given further verbal information.

-

Potential participants who were able to express their consent and were able to complete the consent form (see Appendix 4) were asked to provide written consent.

-

Potential participants who were able to express their consent but unable to complete the consent form as a result of their acute illness were recorded on the consent form as having provided verbal consent.

-

If the potential participant was not competent to give written or verbal consent, then he or she was not recruited into the trial.

-

Every recruited participant was reviewed at regular intervals during their treatment. As soon as their condition improved, they were provided with the full information sheet (see Appendix 3). Those participants who had completed a written consent form were asked if they were happy to remain in the trial. Those participants who had not completed a written consent form were asked to do so.

The risks to participants in this trial were considered to be low. Magnesium sulphate has been used by i.v. and nebulised routes in a number of trials and, although unlicensed, has frequently been used in the treatment of acute severe asthma. It is also included as a possible treatment for acute asthma in BTS/SIGN guidelines. 2 Although minor side effects such as nausea or flushing are common, serious side effects (arrhythmias and coma) are uncommon. Potential participants were advised of these risks when they were invited to participate.

Research governance

The trial was conducted in accordance with Medical Research Council (MRC) Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice (GCP)64 and the Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) Regulations 2004. Sheffield Teaching Hospitals (STH) NHS Foundation Trust was the trial sponsor. The trial was an IMP trial covered by clinical trial regulations from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). A clinical trial authorisation was applied for and received from the MHRA. A site agreement between the sponsor, participating site, CTRU and University of Sheffield outlined responsibilities of all parties and was signed prior to commencement of recruitment at sites.

All clinicians responsible for recruiting patients to the trial were required to complete training in GCP. This presented substantial logistical barriers as, at the time the trial commenced, there was no requirement for GCP training as part of emergency medicine specialist training and there was a rapid turnover of doctors in emergency medicine. To address this we established GCP training on the emergency medicine specialist training curriculum, developed a GCP training package and made it available through the College of Emergency Medicine website, and promoted GCP training in the Emergency Medicine Journal. 65

Blinded treatment packs were manufactured in conjunction with the CTRU, initially by STH NHS Foundation Trust Pharmacy Production Unit at the Royal Hallamshire Hospital (RHH) and subsequently by Tayside Pharmaceuticals. All products were checked by a qualified person (QP) prior to release. The change to Tayside Pharmaceuticals was necessary as RHH did not maintain its manufacturer’s authorisation for IMPs, the manufacturer’s/importer’s licence (MIA), after the production of the first batch of IMPs. However, RHH continued to label the kits with a randomisation code in accordance with a randomisation schedule supplied by the CTRU and distribute kits to sites. This assembly service is permitted under the exemption for hospitals (regulation 37, UK SI 2004/1031). The pharmacy production units maintained an investigational medical products dossier (IMPD) (see Appendix 9) and relevant documentation.

Blinded treatment kits were manufactured, assembled and labelled as per European Commission Good Manufacturing Practice annex 13 requirements66 to enable the treatment to be identified and the batch source of the materials traced. Treatment kits consisted of a box containing an infusion bag and three nebuliser solution vials. Boxes carried an outer label identifying the trial and kit number. An unblinded kit number list and randomisation schedule (accessed via the online randomisation system using a pharmacy production unique username) allowed the RHH production unit to identify which arm of the trial each kit belonged to, and label the kits with a randomisation code. IMPs were supplied on a demand basis to the participating sites with minimal waste of materials. Treatment kit accountability logs were maintained by all parties (production units, CTRU, sites, hospital pharmacies), to allow full reconciliation of IMPs including assignment to patients.

Three committees were established to govern the conduct of the trial: the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), the independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and the Project Management Group (PMG). These committees functioned in accordance with Sheffield CTRU SOPs.

The TSC consisted of four independent members [Professor of Respiratory Medicine (as chairperson), statistician, consultant in emergency medicine, patient representative] and three members of the trial team (chief investigator, emergency medicine co-applicant on the grant and the project manager). The TSC supervised the trial and in particular, the progress of the trial, adherence to protocol, patient safety and consideration of new information. The TSC made the decisions on how to proceed with the trial following recommendations from the DMEC.

The DMEC consisted of an independent statistician, a respiratory consultant and an emergency medicine consultant. The principal duty of the DMEC was patient safety. The DMEC agreed a charter stating the intended interim analyses and stopping rules for the study, and made recommendations to the TSC and PMG. The DMEC could make recommendations to:

-

continue recruiting

-

stop the trial

-

continue, with modification to the protocol.

The PMG consisted of the chief investigator, co-applicants, project manager and co-ordinators, statistician, research nurses and sponsor representative. The role of this group was to oversee the day-to-day management of the trial.

Reporting of serious adverse events

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were reported in accordance with the 3Mg trial SAE reporting protocol and the sponsor’s (STH) SOP67 for reporting, managing and recording adverse events for STH studies. All SAEs occurring within 30 days of recruitment to the trial were reported immediately to the sponsor on learning of their occurrence. Site trial staff and delegated ED staff were responsible for recording all adverse events that were reported by the participant and making them known to the PI. An investigators’ brochure (IB) was maintained by the trial team as the reference safety information for reporting SAEs (see Appendix 10).

Magnesium sulphate is a naturally occurring compound that is a normal constituent of the human body and, since the trial involved administering magnesium sulphate over a single 1-hour period, it was expected that any effect on other medications would be limited to the first few hours after administration. Thus, the SAE reporting procedure for the 3Mg trial only recorded those concomitant medications given in the 48-hour period after the trial drug was administered.

Reporting of protocol violations and deviations

Protocol violations and deviations were reported in accordance with the 3Mg and STH protocol violation and deviation SOPs. The site research nurse was responsible for reviewing the participant CRF and ED notes after entry into the trial to determine if treatment was given in accordance with the protocol, consent was obtained correctly and by a suitably trained and delegated doctor, and that the patient met the eligibility criteria. Any suspected protocol violation or deviation was reported to the local PI and to the central 3Mg team. The chief investigator/CTRU reviewed and confirmed if the incident was a violation/deviation and reported to the sponsor. Participants continued to participate in the trial except if the patient had given no informed consent or if they have requested to be withdrawn from the study. Fully consented patients enrolled on the trial were followed up and analysed as per intention-to-treat analysis outlined in the 3Mg protocol (see Appendix 11).

Trial monitoring

Throughout the trial there was ongoing management and monitoring to ensure that the integrity of the data and the rights and well-being of participants were protected. Monitoring was completed both at site and at a central level, and regular reports were submitted to relevant parties.

Reporting

The trial team were required to submit annual reports on trial progress, data completion rates, and safety and protocol compliance to the MHRA and MREC; and 6-monthly reports to the funding body [National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme]. Reports were also prepared for all-trial oversight committees.

Site monitoring

On-site monitoring was performed before (prior to recruitment commencing at site), during (after third patient recruited and then annually) and after recruitment ended at a trial site. Monitors checked the following during site visits:

-

source data verification – data recorded on the CRFs against available source documents

-

SAEs/suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions – reported to the sponsor and followed up to resolution

-

resolution of data queries

-

investigator site file maintenance

-

training records for site staff (3Mg trial specific and GCP) and appropriate delegation of duties

-

IMP accountability and storage of IMPs in both ED and pharmacy

-

patient consent procedures

-

reporting of protocol deviations/violations.

Central data validation

Validation checks were built into the database which enabled validation reports to be generated monthly. Any missing values, values out of range or inconsistent with the data set were flagged. Queries were sent to sites and followed up to resolution prior to data lock. Data entry validation was completed on 5% of CRFs and questionnaires, queries resolved, and database entry error rates reviewed to assess if they were within acceptable limits.

Production of investigational medicinal product

Monitors independent of the study team checked QP-release certificates for all batches of product and verified that labelling with randomisation number had been done correctly according to the randomisation number and unblinded kit list.

During the trial we had to change the supplier of the IMPs. Initially the IMPs were supplied by the pharmacy production unit at RHH. However, this unit did not maintain a MIA licence and subsequently stopped fully supporting IMP trials during the trial, so we moved production to Tayside Pharmaceuticals. Labelling and distribution services remained the responsibility of the RHH pharmacy production unit.

Changes to the trial protocol

All changes to the trial protocol and study conduct were reviewed by the sponsor and submitted to the REC and MHRA for approval as appropriate. In summary, the following amendments were made:

-

prior to first participant recruitment:

-

change of sponsor from the University of Sheffield to STH NHS Foundation Trust

-

option for consent from a legal representative removed, written or oral informed consent must be obtained, as required by the REC

-

changes to statistical analysis plan to clarify that the primary analysis incorporated an adjustment for hospital; clarification that covariate adjusted analysis would be performed; subgroup analysis for asthma severity to be based on PEFR instead of VAS score (prior to recruitment commencing).

-

-

during trial recruitment:

-

changes to the number of recruiting sites and list of participating sites/PIs

-

minor changes to study documents for clarity or administrative purposes

-

changes to the storage requirements for the IMP, to allow storage at temperatures up to 30 °C

-

research alert page introduced as a study document to use at sites

-

IMPD and IB updates

-

option to telephone patients to collect EQ-5D data if no response from initial and reminder postal questionnaire

-

pharmacy production unit changed to Tayside Pharmaceuticals

-

addition of extra exclusion criteria – patients who have received i.v. or nebulised magnesium sulphate in the previous 24 hours prior to attendance at the ED

-

clarification that concomitant medications in SAE reports to be reported only for the period up to 48 hours post IMP administration

-

extension of recruitment period to 30 June 2012

-

change from ‘doctors will consent the patient’ to include the option for other health-care professionals to take consent.

-

Archiving

The site files and all study documentation were sent to the CTRU and archived according to the sponsor SOP for a period of 15 years. A log of all documents archived and a list of named individuals who can access the archive is kept by the CTRU.

Chapter 3 Results

Trial progress

The project started on 1 September 2007. Original recruitment predictions were based on the assumption of 12 hospitals recruiting one patient per centre per week for 2 years, with recruitment complete by the end of February 2010. The process of setting up the trial took much longer than anticipated and, after the start of recruitment at the first site, it took a further year until the original target of 12 recruiting sites was achieved. The main reasons for the delays were (a) slow progress in drawing up contracts between the sponsor and participating sites; (b) slow progress in securing NHS research governance approval at the participating sites; and (c) the time taken to provide GCP training for recruiting clinicians. Ethical approval, by contrast, was secured quickly and efficiently. The need to provide GCP training for emergency physicians was a specific problem for this trial. Owing to the acuity of the condition, patients could present to the ED at any time and we aimed to train as many emergency physicians as possible. There appeared to be no existing NHS infrastructure for supporting trials in emergency medicine, so we developed a GCP training package that was proportionate to the limited trial activities that the recruiting doctors were involved with and promoted it through the College of Emergency Medicine.

Patient recruitment

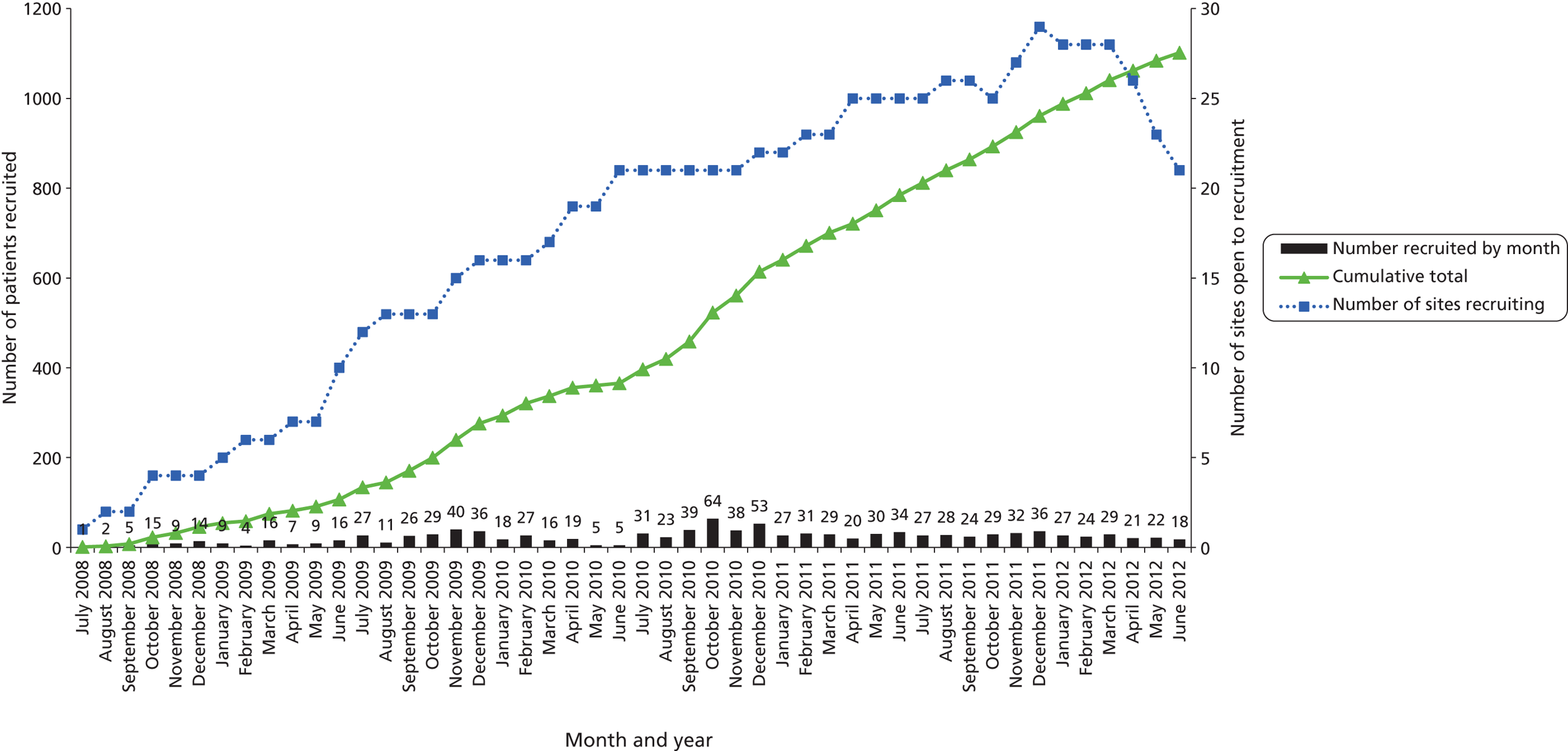

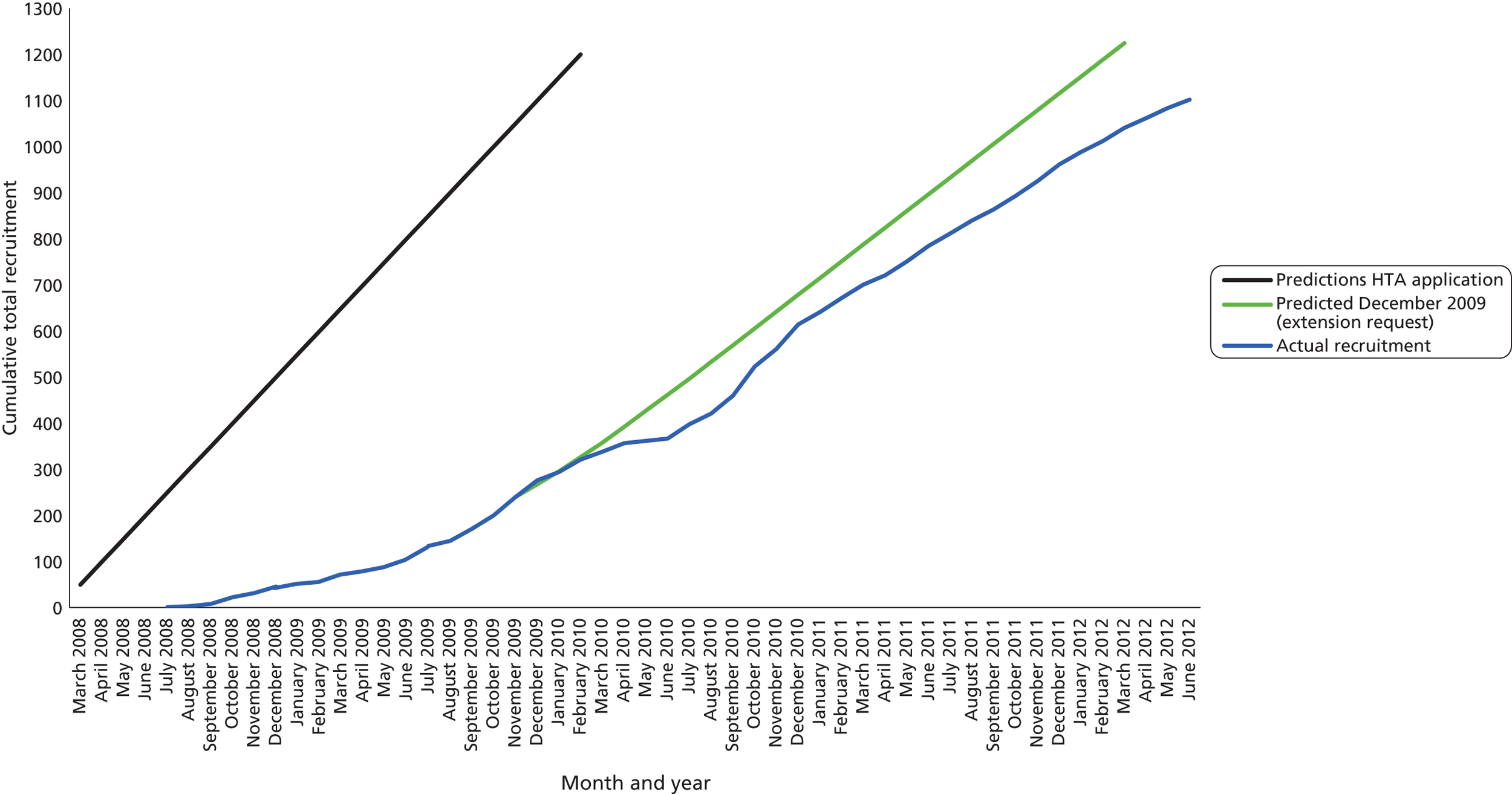

The trial opened to recruitment on 30 July 2008 and closed on 30 June 2012. A total of 1109 participants were recruited to the trial, 92% of the intended sample size of 1200. Figure 1 shows the number of patients recruited and the number of recruiting centres open per month, alongside the cumulative recruitment to the trial. Figure 2 shows the actual recruitment compared with the initial planned recruitment and subsequent revised recruitment plan.

FIGURE 1.

Number of recruiting centres and actual recruitment rates (30 July 2008–30 June 2012).

FIGURE 2.

Predicted vs. actual recruitment of participants.

Recruitment at the participating centres was slower than expected as a result of a combination of a lower than anticipated availability of eligible patients and difficulties in ensuring that GCP-trained staff were available to recruit. To address the shortfall in recruitment, we increased the number of sites and promotional activities. Later in the trial we replaced existing sites that were experiencing recruitment fatigue or had small numbers of eligible patients with new sites that we identified via the NIHR Injuries and Emergencies National Priority Group. We were granted a funded extension to the trial to continue recruitment until 30 June 2012.

Using data available at the time of the funded extension request (after 276 patients were recruited), we revised the recruitment predictions assuming that we would recruit, on average, 0.4 patients per site per week and adjusted this for the predicted number of sites that would be recruiting each month. At this stage, we predicted that we would reach the target number by March 2012. Mid-trial we had to change the IMP manufacturer, and recruitment to the trial had to be suspended between May and June 2010 as the new IMPs were not delivered as a result of a problem with the sterile production process. The seasonality of asthma usually meant that recruitment increased in the winter months, but the final winter season saw generally lower numbers of presenting patients. We kept a large proportion of the sites open to recruitment for an additional 3 months compared with the revised recruitment plan, staggering the close of sites to assist with scheduling close-out monitoring.

Non-recruited patients

During the trial we asked participating centres to record basic anonymised details of patients attending ED aged 16 years or over with acute severe asthma who were not recruited. These data were captured by a mixture of prospective screening by recruiting doctors and retrospective case note review by research nurses. Unfortunately, limited research nurse availability and service pressure in the ED prevented reliable collection of these data at some centres. Nevertheless, data were collected from a total of 3948 non-recruited patients attending at recruiting centres during the trial. Of these, 1165 patients were not identified by recruiting doctors because of a variety of administrative reasons (the ED was too busy, no GCP-trained doctors were available or no treatment packs were available) but were retrospectively identified by research nurses on the basis of information in the ED record. The remaining 2783 patients were identified prospectively, but excluded on the basis of ineligibility (n = 847), declining to participate (n = 200), inability to give consent (n = 21), administrative reasons as outlined above (n = 306) and other reasons (n = 201), while no reason was recorded for 89 patients. The patient characteristics recorded (age and sex) were not obviously different between those who did not take part and those who did (Table 4), with the possible exception of the subset who were eligible but unable to give consent.

| Patient classification | Age (years), mean (SD) | Sex, n (%) male |

|---|---|---|

| Recruited (N = 1109) | 36 (14) | 321 (30) |

| Not identified (N = 1165) | 36 (16) | 359 (31) |

| Ineligible (N = 847) | 37 (15) | 217 (26) |

| Declined to participate (N = 200) | 37 (16) | 62 (31) |

| Unable to give consent (N = 31) | 44 (19) | 11 (36) |

| Administrative reasons (N = 306) | 37 (15) | 94 (31) |

| Other (N = 201) | 38 (17) | 50 (25) |

| Not recorded (N = 89) | 35 (18) | 30 (33) |

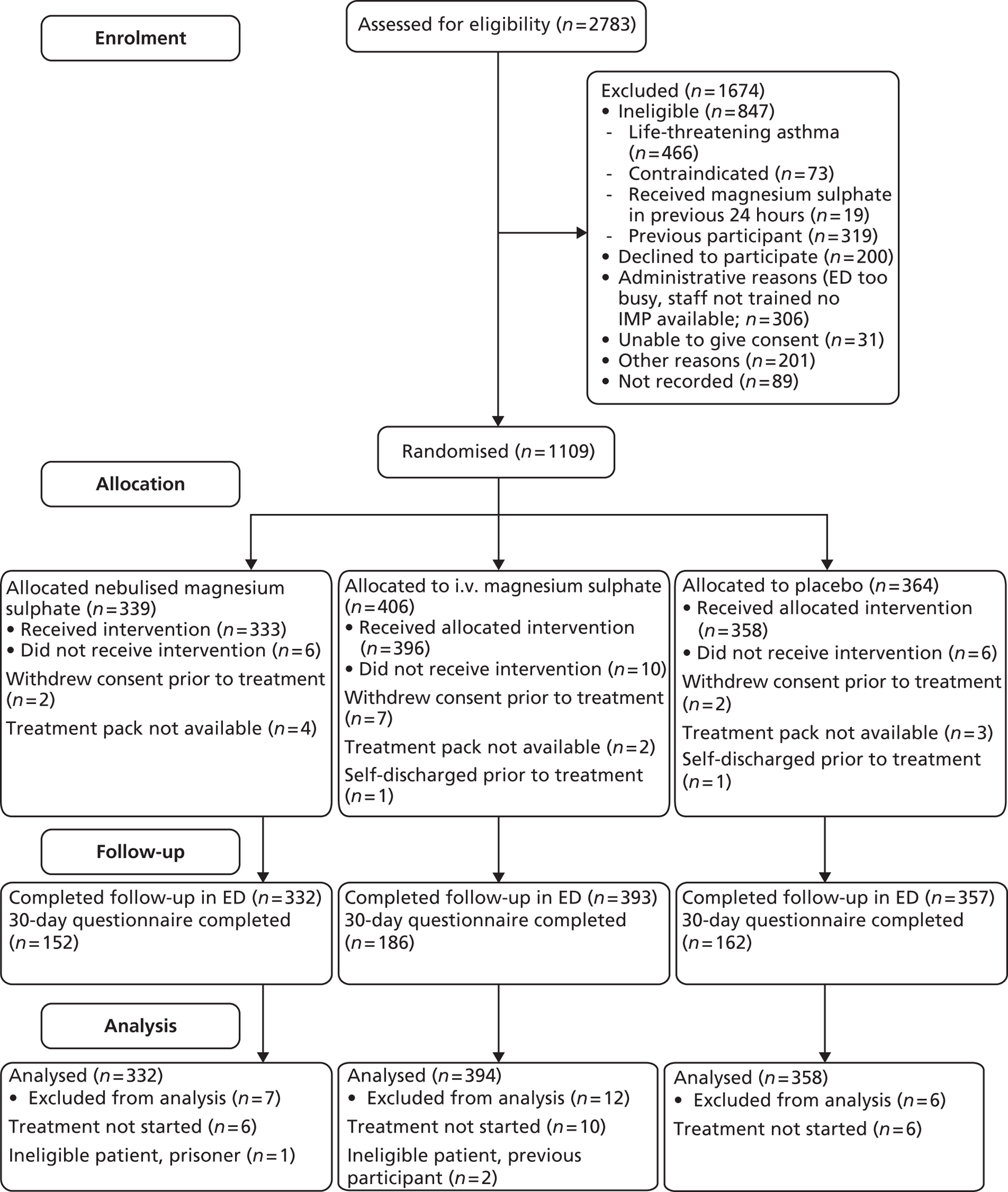

The trial population

The CONSORT flow chart (Figure 3) shows the flow of participants through the trial. Of the 1109 participants randomised, 25 were excluded from the analysis. Eleven patients received no medication and no data were collected after randomisation. These patients either withdrew consent prior to any medication being delivered or recruiting doctors had randomised them before taking consent and patients subsequently refused consent. Two patients self-discharged without being treated. There were nine occasions where the numbered medication pack was not available in the ED and no treatment was subsequently given. The remaining three patients received treatment but there were protocol violations and these patients should not have been recruited: two were subsequently found to be previous participants and one was a prisoner. All remaining 1084 patients were included in analyses according to intention-to-treat principles, regardless of whether or not they received any medication.

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow chart.

Protocol deviations which did not result in the participants being removed from analysis were also reported and reviewed at PMG meetings. A total of 203 protocol deviations were reported, which can be broadly categorised as follows: 42 deviations from the trial treatment protocol (randomised but trial treatment not commenced, treatment started but not completed or incorrect treatment), 143 consent not fully documented (no witness signature, verbal but not written consent, consent taken by a doctor without GCP training and/or not on delegation, log or tick boxes not completed), 15 administrative errors (prescription incorrectly completed, patient details recorded incorrectly, randomisation after treatment commenced or pack opened in error), and three screening assessment queries. The apparently high number of deviations can be attributed to the complexities of recruiting in an emergency setting and our requirement for sites to report any deviation from the protocol, however minor. Deviations from the consent procedure were reviewed to ensure that there was sufficient evidence that consent had been obtained before deciding if the participant should remain in the trial.

Table 5 summarises the recruitment and allocation of patients across the centres. Overall, 34 centres recruited to the study, of which 24 recruited 10 or more patients. The remaining centres were combined into one group for the purposes of all analyses. Table 6 shows the demographics and characteristics of the trial population. PEFR values reported in this table are predicted values. The actual baseline values are reported alongside the 1- and 2-hour values in Table 25. Patients were generally female (70%), white (90%) and relatively young (82% were below the age of 50 years). Overall, 64% of patients had previously been admitted to hospital for asthma, with the percentage being higher in the active two arms (68% nebulised, 66% i.v. and 59% placebo) and 14% of patients had previously been admitted to ITU. Where previous admissions had been recorded, around half had been admitted in the past year.

| Centre | Nebulised magnesium sulphate (n = 332) | Intravenous magnesium sulphate (n = 394) | Placebo (n = 358) | Total (n = 1084) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | 56 (17%) | 67 (17%) | 56 (16%) | 179 (17%) |

| Sheffield – Northern General Hospital | 30 (9%) | 41 (10%) | 35 (10%) | 106 (10%) |

| Royal United Hospital Bath | 25 (8%) | 29 (7%) | 23 (6%) | 77 (7%) |

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 17 (5%) | 23 (6%) | 17 (5%) | 57 (5%) |

| University Hospital of N. Staffordshire | 20 (6%) | 17 (4%) | 20 (6%) | 57 (5%) |

| Crosshouse Hospital | 18 (5%) | 15 (4%) | 19 (5%) | 52 (5%) |

| Bristol Frenchay Hospital | 13 (4%) | 17 (4%) | 18 (5%) | 48 (4%) |

| Barnsley Hospital | 14 (4%) | 14 (4%) | 18 (5%) | 46 (4%) |

| Plymouth – Derriford Hospital | 12 (4%) | 14 (4%) | 12 (3%) | 38 (4%) |

| York Hospital | 10 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 13 (4%) | 38 (4%) |

| Ayr Hospital | 9 (3%) | 12 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 31 (3%) |

| Royal Devon and Exeter Hospital | 12 (4%) | 8 (2%) | 11 (3%) | 31 (3%) |

| Bristol Royal Infirmary | 10 (3%) | 11 (3%) | 9 (3%) | 30 (3%) |

| Leicester Royal Infirmary | 9 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 14 (4%) | 30 (3%) |

| Kettering General Hospital | 9 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 29 (3%) |

| Lancaster Royal Infirmary | 8 (2%) | 16 (4%) | 5 (1%) | 29 (3%) |

| Derbyshire Royal Infirmary | 6 (2%) | 11 (3%) | 11 (3%) | 28 (3%) |

| Fife – Queen Margaret Hospital | 5 (2%) | 11 (3%) | 10 (3%) | 26 (2%) |

| Hull Royal Infirmary | 10 (3%) | 9 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 23 (2%) |

| Royal Alexandra Hospital – Paisley | 7 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 6 (2%) | 21 (2%) |

| University Hospital Coventry | 5 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 19 (2%) |

| Fife – Victoria Hospital | 5 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 15 (1%) |

| Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge | 3 (1%) | 6 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 13 (1%) |

| The Royal London Hospital | 3 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 11 (1%) |

| Southend University Hospital | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 9 (1%) |

| James Cook University Hospital – Middlesbrough | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Hairmyres Hospital | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Leeds Teaching Hospitals | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (1%) | 5 (< 1%) |

| Northampton General Hospital | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (1%) | 5 (< 1%) |

| Rotherham General Hospital | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 0 | 5 (< 1%) |

| Doncaster Royal Infirmary | 0 | 3 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 4 (< 1%) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 2 (1%) | 3 (< 1%) |

| Queens Medical Centre, Nottingham | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (< 1%) |

| Pinderfields Hospital | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 2 (< 1%) |

| Patient characteristic | Nebulised magnesium sulphate (n = 332) | Intravenous magnesium sulphate (n = 394) | Placebo (n = 358) | Total (n = 1084) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 36.5 (14.8) | 35.6 (13.1) | 36.4 (14.1) | 36.1 (14.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 35.0 (23–47) | 34.0 (25–44) | 34.5 (24–47) | 34.0 (24–46) |

| Min., max. | 16, 85 | 16, 84 | 16, 88 | 16, 88 |

| Sexa | ||||

| Male | 100 (30%) | 115 (29%) | 106 (30%) | 321 (30%) |

| Female | 232 (70%) | 279 (71%) | 252 (70%) | 763 (70%) |

| Ethnicitya | ||||

| White | 286 (86%) | 369 (94%) | 319 (89%) | 974 (90%) |

| Mixed | 2 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 5 (1%) | 8 (1%) |

| Asian or Asian British | 14 (4%) | 8 (2%) | 16 (4%) | 38 (4%) |

| Black or black British | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 11 (1%) |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (< 1%) |

| Not stated | 22 (7%) | 8 (2%) | 11 (3%) | 41 (4%) |

| Missing | 4 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 10 (1%) |

| Smoking statusa | ||||

| Never | 151 (45%) | 156 (40%) | 143 (40%) | 450 (42%) |

| Current | 98 (30%) | 138 (35%) | 127 (35%) | 363 (33%) |

| Previous | 72 (22%) | 95 (24%) | 81 (23%) | 248 (23%) |

| Missing | 11 (3%) | 5 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 23 (2%) |

| Predicted PEFR | ||||

| n | 324 | 389 | 346 | 1059 |

| Mean (SD) | 430.0 (118.8) | 431.8 (116.9) | 435.0 (110.8) | 432.3 (115.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 425.0 (350–500) | 435.0 (350–500) | 425.0 (350–500) | 425.0 (350–500) |

| Min., max. | 100, 700 | 140, 800 | 150, 790 | 100, 800 |

| Previous admissions with asthma | ||||

| At least one previous ITU admissiona | 56 (17%) | 61 (15%) | 39 (11%) | 156 (14%) |

| At least one previous admissiona | 226 (68%) | 260 (66%) | 213 (59%) | 699 (64%) |

| If yes, time since last admission with asthma (months) | ||||

| n | 221 | 256 | 208 | 688 |

| Mean (SD) | 42.0 (72.2) | 38.5 (69.5) | 40.8 (61.9) | 40.1 (68.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 12.0 (4–47) | 12.0 (4–37) | 17.0 (6–48) | 12.5 (4–47) |

| Min., max. | 3 days, 32 years | 1 day, 50 years | 1 day, 40 years | 1 day, 50 years |

| Entry criterion for acute severe asthmaab | ||||

| PEFR < 50% of best or predicted | 179 (54%) | 205 (52%) | 192 (53%) | 576 (53%) |

| Heart rate > 110 beats per minute | 213 (64%) | 251 (64%) | 218 (61%) | 682 (63%) |

| Respiratory rate > 25 breaths per minute | 178 (54%) | 227 (58%) | 204 (57%) | 609 (67%) |

| Unable to complete sentences in one breath | 138 (42%) | 159 (40%) | 139 (39%) | 436 (40%) |

| Baseline PEFRa | ||||

| < 33% predicted | 53 (16%) | 50 (13%) | 56 (16%) | 156 (15%) |

| 33–50% predicted | 112 (34%) | 116 (29%) | 116 (32%) | 344 (32%) |

| 50–75% predicted | 107 (32%) | 148 (38%) | 118 (33%) | 373 (34%) |

| ≥ 75% predicted | 36 (11%) | 61 (15%) | 37 (10%) | 134 (12%) |

| Not recorded | 24 (7%) | 19 (5%) | 31 (9%) | 74 (7%) |

Trial and other treatments given

Table 7 shows the concurrent medications given in the 24 hours prior to hospital attendance, in the ambulance and ED immediately prior to randomisation, and alongside trial treatments in the 4 hours immediately after randomisation. Most patients (88%) had used salbutamol in the 24 hours prior to attendance and one-third had taken prednisolone. Use of salbutamol (95%) and ipratropium bromide (72%) was typical in the ambulance or ED prior to randomisation, whereas 41% were given prednisolone and 21% hydrocortisone. Salbutamol, ipratropium bromide, prednisolone and hydrocortisone were also commonly given alongside trial treatments.

| Medication Usage | Nebulised magnesium sulphate (n = 332) | Intravenous magnesium sulphate (n = 394) | Placebo (n = 358) | Total (n = 1084) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Used medication 24 hours prior to attendance | 304 (92%) | 370 (94%) | 320 (89%) | 994 (92%) |

| Salbutamol | 293 (88%) | 350 (89%) | 309 (86%) | 952 (88%) |

| Prednisolone | 115 (35%) | 140 (36%) | 106 (30%) | 361 (33%) |

| Seretide | 58 (17%) | 54 (14%) | 62 (17%) | 174 (16%) |

| Ipratropium bromide | 42 (13%) | 58 (15%) | 47 (13%) | 147 (14%) |

| Pulmicort | 32 (10%) | 33 (8%) | 24 (7%) | 89 (8%) |

| Beclometasone (Clenil) | 25 (8%) | 23 (6%) | 22 (6%) | 70 (6%) |

| Montelukast | 15 (5%) | 12 (3%) | 14 (4%) | 41 (4%) |

| Amoxicillin | 9 (3%) | 13 (3%) | 12 (3%) | 34 (3%) |

| Salmeterol (Serevent) | 12 (4%) | 10 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 29 (3%) |

| Terbutaline (Bricanyl) | 8 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 8 (2%) | 25 (2%) |

| Theophylline | 8 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 22 (2%) |

| Tiotropium (Spiriva) | 7 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 7 (2%) | 19 (2%) |

| Hydrocortisone | 6 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 15 (1%) |

| Aminophylline | 7 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 14 (1%) |

| Formoterol (Oxis, AstraZeneca UK Ltd) | 5 (2%) | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 6 (1%) |

| Clarithromycin | 2 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 3 (< 1%) |

| Combivent | 0 | 2 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (< 1%) |

| Zarfirlukast | 2 (1%) | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 3 (< 1%) |

| Other | 5 (2%) | 4 (1%) | 6 (2%) | 15 (1%) |

| Given medication in ambulance or ED prerandomisation | 325 (98%) | 375 (95%) | 344 (96%) | 1044 (96%) |

| Salbutamol | 320 (96%) | 367 (93%) | 338 (94%) | 1025 (95%) |

| Ipratropium bromide | 241 (73%) | 279 (71%) | 259 (72%) | 779 (72%) |

| Prednisolone | 126 (38%) | 154 (39%) | 168 (47%) | 448 (41%) |

| Hydrocortisone | 71 (21%) | 86 (22%) | 69 (19%) | 226 (21%) |

| Combivent | 9 (3%) | 19 (5%) | 10 (3%) | 38 (4%) |

| Amoxicillin | 7 (2%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 13 (1%) |

| Amoxicillin trihydrate/potassium clavulanate (Augmentin, GlaxoSmithKline UK) | 2 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 9 (1%) |

| Clarithromycin | 1 (<1%) | 2 (1%) | 4 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Aminophylline | 2 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 3 (< 1%) |

| Magnesium sulphate | 0 | 0 | 3 (1%) | 3 (< 1%) |

| Theophylline | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 2 (< 1%) |

| Montelukast | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 1 (< 1%) |

| Pulmicort | 0 | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (< 1%) |

| Given medication 0–4 hours post randomisation | 180 (54%) | 195 (49%) | 182 (51%) | 557 (51%) |

| Salbutamol | 107 (32%) | 101 (26%) | 93 (26%) | 301 (28%) |

| Prednisolone | 64 (19%) | 62 (16%) | 54 (15%) | 180 (17%) |

| Ipratropium bromide | 59 (18%) | 50 (13%) | 53 (15%) | 162 (15%) |

| Hydrocortisone | 16 (5%) | 25 (6%) | 19 (5%) | 60 (6%) |

| Magnesium sulphate | 21 (6%) | 16 (4%) | 21 (6%) | 58 (5%) |

| Amoxicillin | 9 (3%) | 16 (4%) | 15 (4%) | 40 (4%) |

| Augmentin | 11 (3%) | 12 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 30 (3%) |

| Combivent | 7 (2%) | 13 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 27 (2%) |

| Clarithromycin | 7 (2%) | 9 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 25 (2%) |

| Aminophylline | 8 (2%) | 7 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 24 (2%) |

| Pulmicort | 2 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 6 (1%) |

| Seretide | 0 | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 2 (< 1%) |

| Theophylline | 1 (< 1%) | 1 (< 1%) | 0 | 2 (< 1%) |

| Other | 9 (3%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 15 (1%) |

Table 8 shows the proportion of patients receiving prednisolone or hydrocortisone at any point from 24 hours before attendance to 4 hours after randomisation. Around one-third of patients had taken corticosteroids in the 24 hours before attendance, 61% were given corticosteroids before randomisation and 21% after. Some patients were given additional corticosteroids in the ambulance or ED despite having taken corticosteroids in the previous 24 hours and, therefore, overall 95% of the trial population received corticosteroid therapy at some point from 24 hours prior to hospital attendance to 4 hours after randomisation. Table 9 shows the total dose of salbutamol given in the ambulance or ED prior to randomisation or up to 4 hours after randomisation. All but 10 patients (1%) received salbutamol at some point and 95% received salbutamol prior to randomisation, with a mean dose of 4.9 mg. Overall, it appears that there was adherence to BTS/SIGN guidance and substantial use of standard treatments that are known to be effective. 2

| Usage | Nebulised magnesium (n = 332) | Intravenous magnesium (n = 394) | Placebo (n = 358) | Overall (n = 1084) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any usage in or before ED | 316 (95%) | 372 (94%) | 344 (96%) | 1032 (95%) |

| Last 24 hours before attendance | 119 (36%) | 143 (36%) | 110 (31%) | 372 (34%) |

| Ambulance/ED pre randomisation | 191 (58%) | 236 (60%) | 231 (65%) | 658 (61%) |

| After randomisation 0–4 hours | 77 (23%) | 83 (21%) | 69 (19%) | 229 (21%) |

| Usage | Nebulised magnesium (n = 332) | Intravenous magnesium (n = 394) | Placebo (n = 358) | Overall (n = 1084) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usage in ambulance or ED | ||||

| Any usagea | 329 (99%) | 391 (99%) | 354 (99%) | 1074 (99%) |

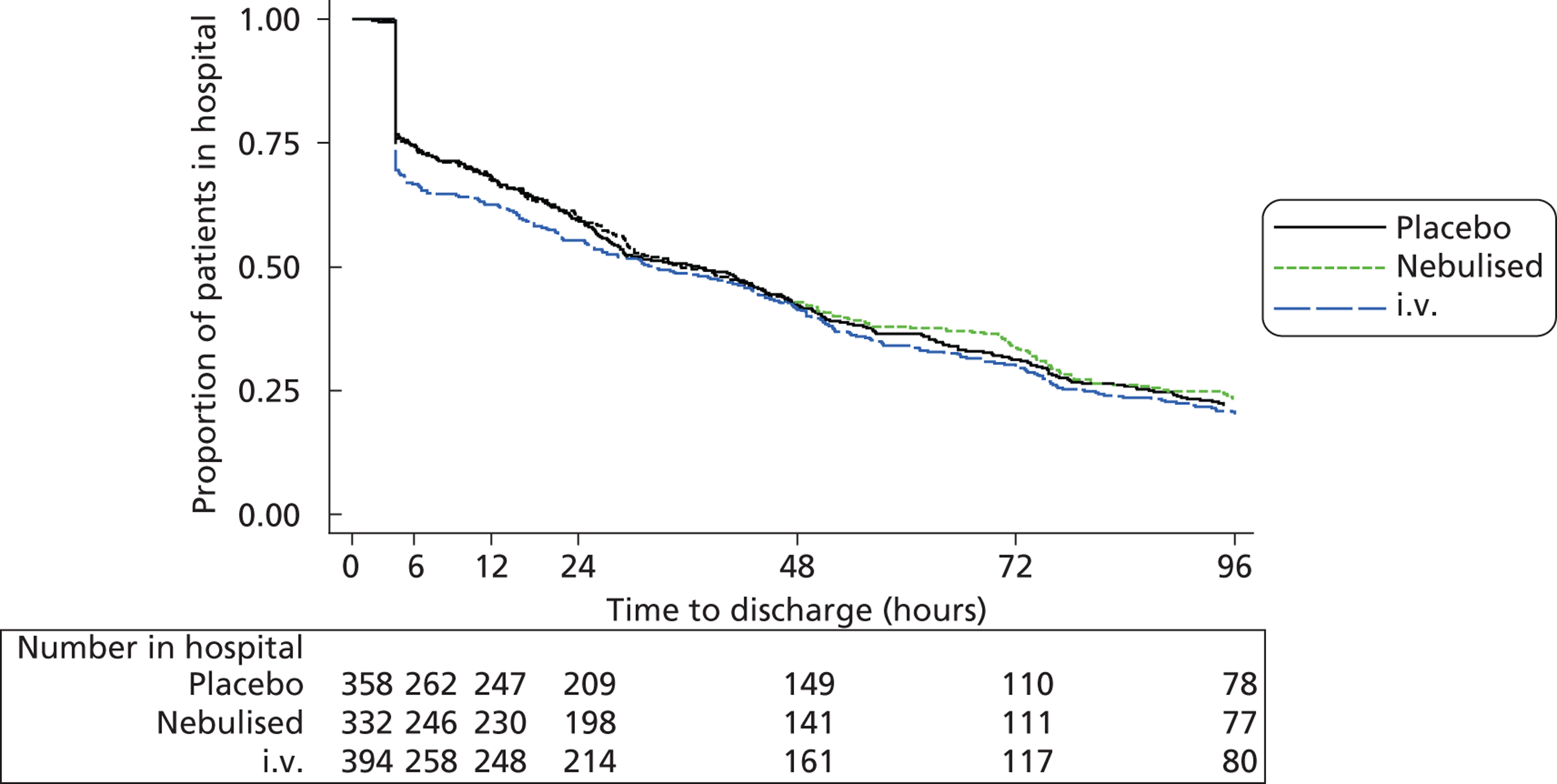

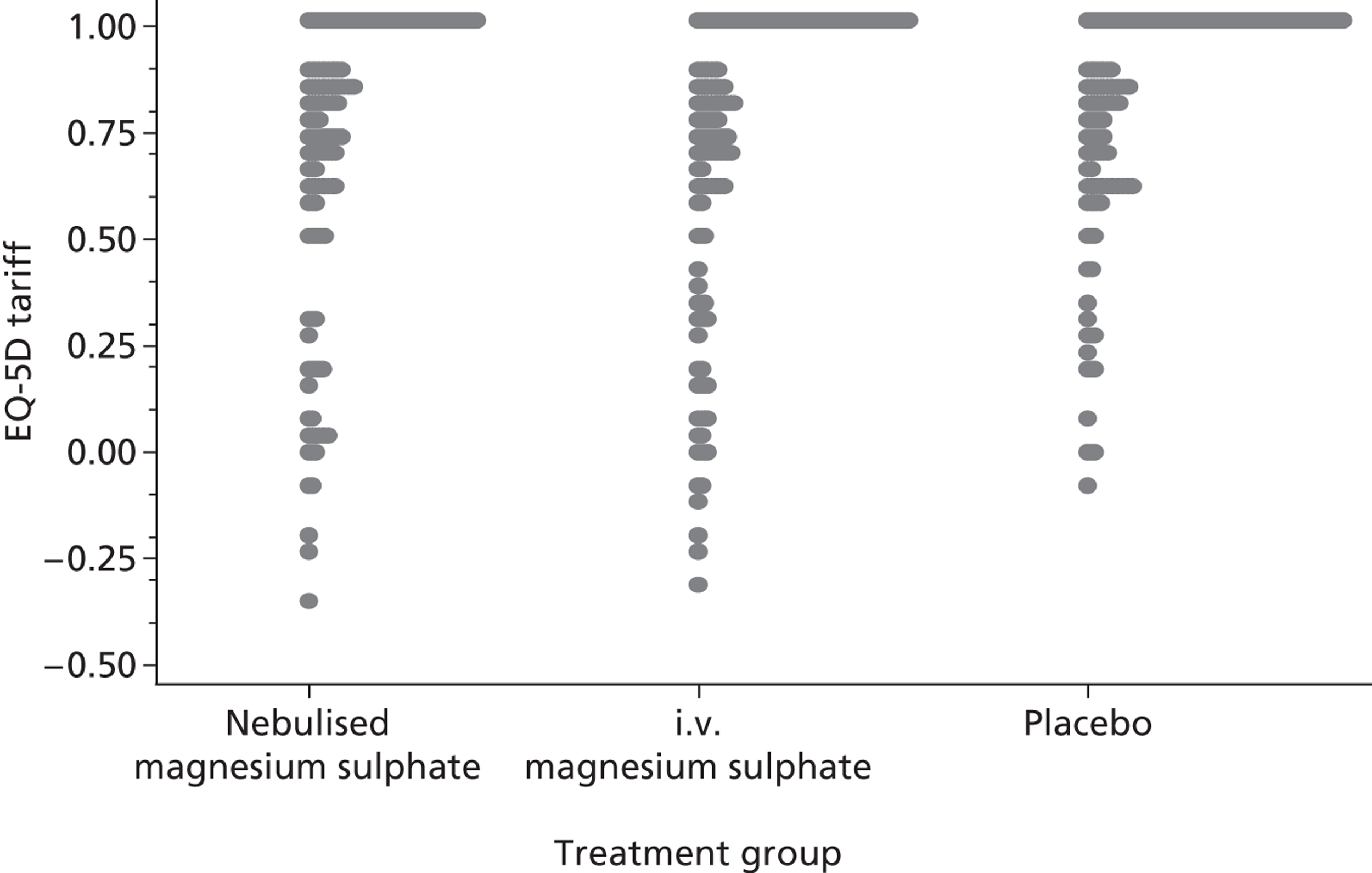

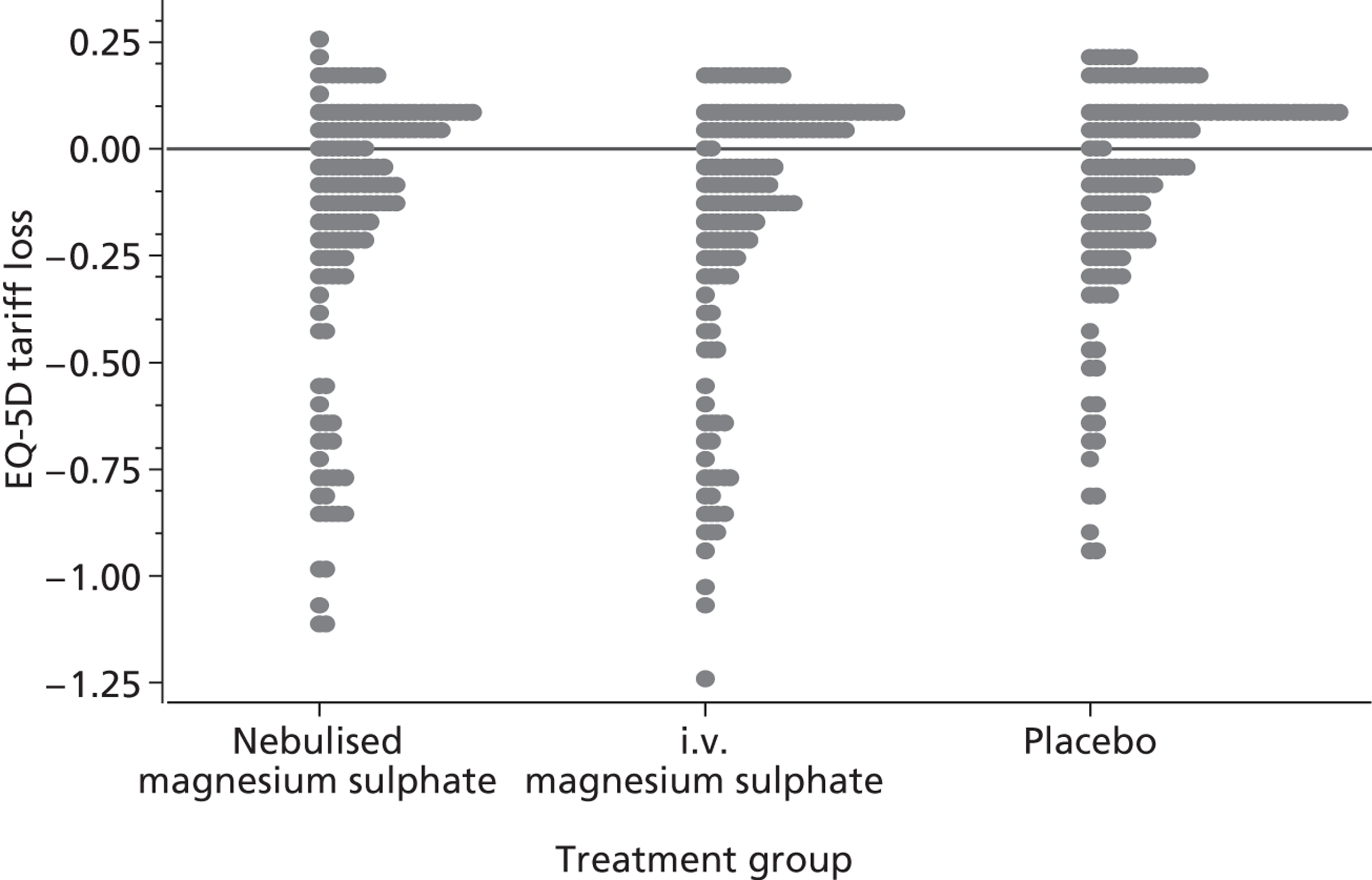

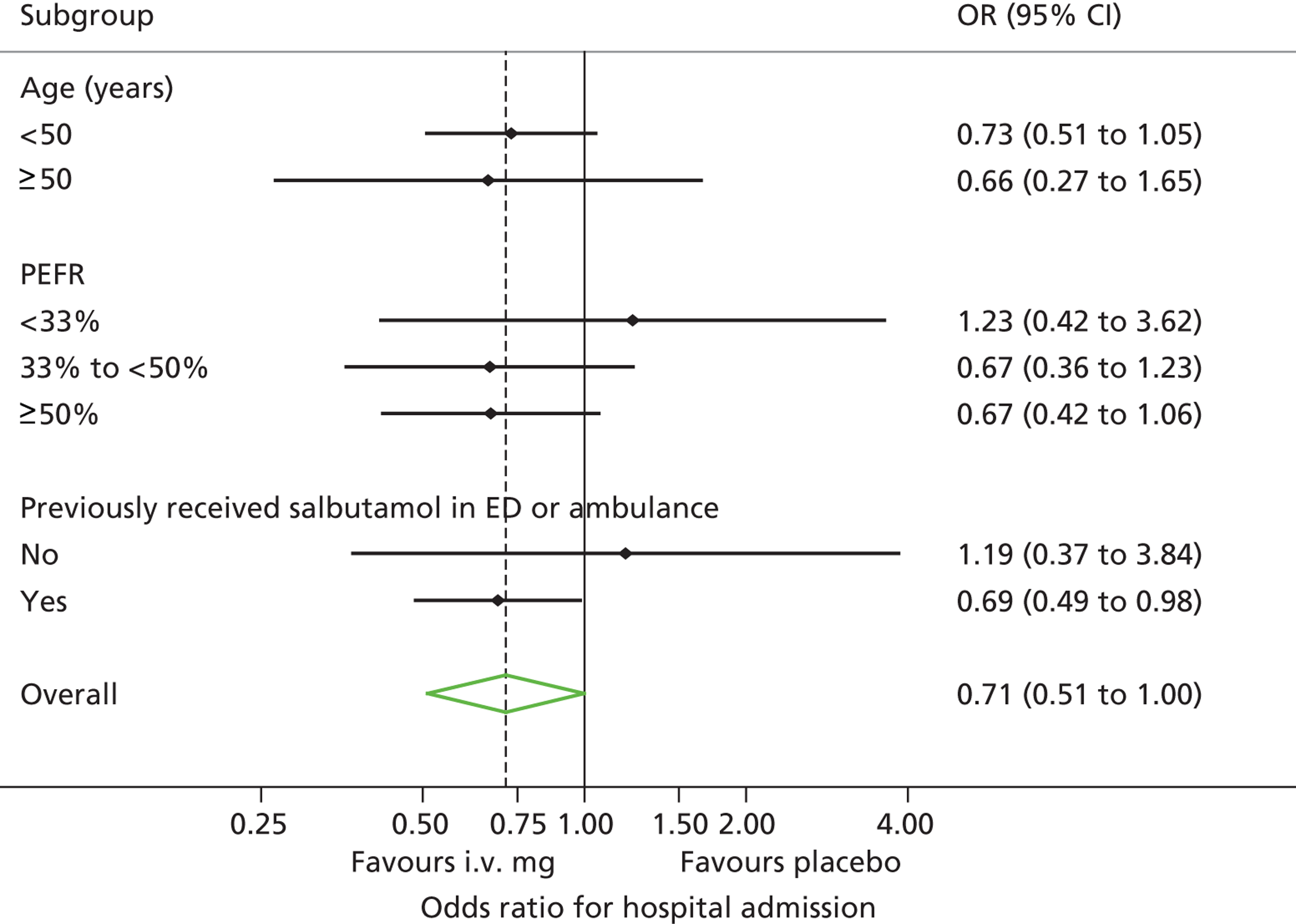

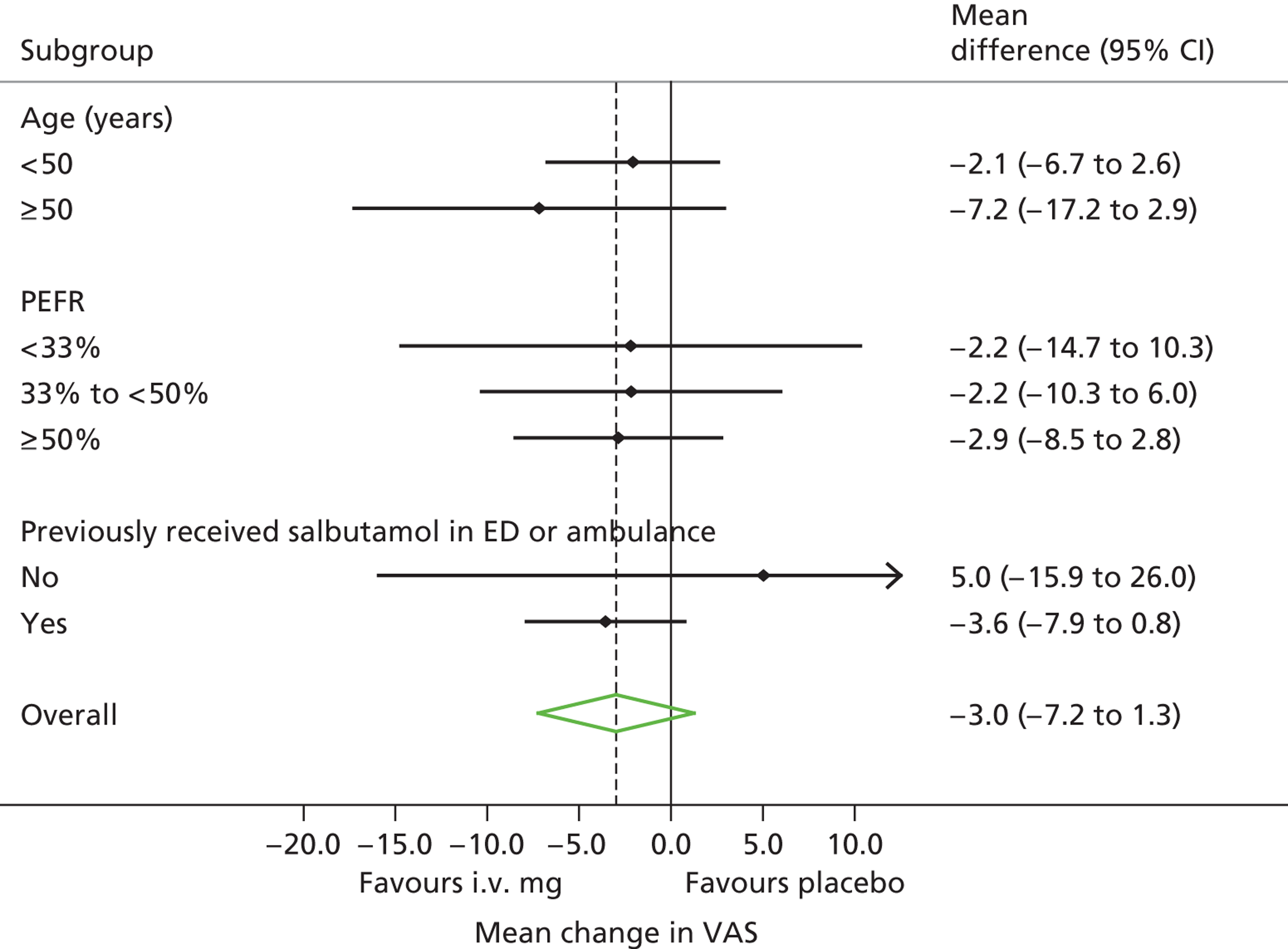

| Mean (SD) dose given (mg) | 8.7 (3.4) | 8.0 (3.4) | 8.2 (3.4) | 8.3 (3.4) |