Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 06/404/02. The contractual start date was in May 2008. The draft report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris Williams has been a past president of the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP), a workshop leader and an author of various book and online self-help resources addressing depression. He is Director of Five Areas Ltd, which licenses cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) self-help and training resources. Wilem Kuyken is co-founder of the Mood Disorders Centre, teaches nationally and internationally on CBT, and has co-authored a cognitive therapy book (Collaborative Case Conceptualization, published by Guilford Press). Anne Garland is clinical lead for the Nottingham Specialised Depression Service, principal investigator to the CLAHRC-NDL (Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care – Nottinghamshire, Derbyshire and Lincolnshire)-funded Depression Study, a past president of the BABCP, a CBT workshop leader, both nationally and internationally, and author of texts on depression.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Wiles et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Plain English summary

Many patients with depression who are prescribed antidepressants by their doctor do not get better after 6 weeks of treatment. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) is a type of ‘talking therapy’ that has been shown to help patients with previously untreated depression but there is little evidence about its effectiveness as a ‘next-step’ treatment for those patients whose depression has not responded to medication. To answer this question we studied 469 patients with depression who had been taking antidepressants for at least 6 weeks and who had not got better. All continued with usual care from their general practitioner, including medication, but half (234) received CBT in addition. We followed up participants for 1 year and found that those who had CBT as well as usual care were approximately three times more likely to have fewer depressive symptoms than those in the usual-care group. The treatment was good value for money over the 12 months. Participants sometimes found therapy to be a challenging and difficult process, but felt that the techniques learned from CBT helped them better manage their depression. This study has provided high-quality evidence that receiving CBT, in addition to continuing on antidepressants as part of usual care, is an effective treatment for patients with depression who have not got better on medication alone.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Depression is ranked among the top five contributors to the global burden of disease, and by 2030 is predicted to be the leading cause of disability in high-income countries. 1 Antidepressants are often the first-line treatment for depression and the number of prescriptions for antidepressants has risen dramatically in recent years in the UK2 and elsewhere. 3,4 Over 46 million prescriptions were issued in England in 2011, at a cost of more than £270M. 5 However, the recent STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) study found that only one-third of patients responded fully to pharmacotherapy and that half did not experience at least a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms following 12–14 weeks of antidepressant medication. 6 The reasons for this non-response are complex but include (1) intolerance to medication; (2) treatment resistance (when an adequate dose and duration of treatment has been given) and (3) non-adherence to the treatment regime (both in terms of adherence to medication and failure to attend follow-up). Under-treatment of depression is also a recognised problem. 7 The high prevalence of depression means that effective interventions have the potential to substantially impact on the economic cost of this condition (to the NHS, patients and society). 8

Defining treatment resistance

It is important to separate treatment resistance from a lack of tolerance of medication. For the latter, the clinician’s ‘next step’ would be to switch the patient to a different antidepressant to find one that could be tolerated and determine the outcome for an adequate trial of such medication before seeking alternative treatment options based on the problem of resistance.

Many definitions of treatment resistance have been proposed. These definitions cover a broad spectrum ranging from failure to respond to at least 4 weeks of antidepressant medication given at an adequate dose9 to classification systems based on non-response to multiple courses of treatment. 10,11 Irrespective of the definition used, it is clear that treatment-resistant depression (TRD) has a considerable impact on individuals, health services and society.

In the 2004 depression guidelines,12 the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) defined TRD as failure to respond ‘to two or more antidepressants given sequentially at an adequate dose for an adequate time’, but this could include individuals who have failed to respond to two different antidepressants that have the same pharmacological action. More recent guidance advocates that general practitioners (GPs) should reconsider treatment options if there has been little or no response after 4–6 weeks of antidepressant medication. 13 Options for the ‘next-step’ treatment include increasing the dose of medication, switching to a different antidepressant (either within or across pharmacological class) or augmentation with another pharmacological or psychological treatment. 13 However, there is currently little evidence to guide management after the initial 6 weeks of treatment. Hence for the research reported here we propose a more inclusive definition of TRD, directly relevant to UK primary care, given the uncertainty about what course of action to recommend to patients who have not responded to at least 6 weeks of antidepressant medication. These patients will be heterogeneous in terms of prior treatment, but all will have not responded to at least 6 weeks’ medication, thus ensuring trial results are generalisable.

Existing evidence on the management of treatment-resistant depression

The evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating pharmacological and psychological interventions for patients with TRD was summarised up to January 2001. 14 This systematic review included all studies in which patients with unipolar depression had not responded to at least 4 weeks of antidepressant medication at an adequate dose. Despite the broad inclusion criteria, the authors concluded that there was little evidence to guide the management of this patient group. Augmentation of pharmacotherapy was the most common treatment approach for such patients, but the RCTs were very small and of poor methodological quality and hence no precise treatment effects could be obtained. At that time, no RCTs had examined a psychological intervention for TRD. In December 2004, NICE published guidelines for the management of depression suggesting that ‘the combination of antidepressant medication with [face-to-face] cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) should be considered’ for patients with TRD. 12 However, this report acknowledged ‘significant limitations to the current evidence base’ [grade B evidence (no RCTs)]12 and there are few data on what constitutes ‘usual care’ for this patient group.

A review on the evidence for the effectiveness of psychological interventions for adults with TRD is currently being prepared for publication in The Cochrane Library (www.thecochranelibrary.com). In short, despite 10 years having elapsed since the earlier publication by Stimpson et al. ,14 the evidence base for this area remains weak. Three small studies (n < 50) of CBT have been published. One was our pilot study (n = 25) for the present CoBalT (Cognitive behavioural Therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care patients with treatment resistant depression) RCT. 15 The second (n = 44) examined the effect of augmentation with CBT among partial responders to antidepressants16 and the third study (n = 36), conducted among inpatients, was published only as a conference abstract. 17 Neither of the last two studies included a group who remained on antidepressants in order to evaluate the effectiveness of CBT as an adjunct to antidepressant medication (comparators: lithium augmentation16 and augmentation with supportive therapy17).

The REVAMP (Research Evaluating the Value of Augmenting Medication with Psychotherapy) trial18 recruited patients with chronic depression (defined as persistent depressive symptoms for > 2 years), who had not responded or only partially responded to 12 weeks of antidepressant medication. However, they found no difference in depression outcomes (symptoms, ‘response’ or ‘remission’) between those who switched to the next step in a medication algorithm and those who received psychotherapy [cognitive behavioural analysis system of psychotherapy (CBASP) or brief supportive psychotherapy (BSP)], and no difference in outcomes between the two different psychotherapies (CBASP vs. BSP). 18

The large US STAR*D study recruited 2876 patients with depression, and invited those who failed to respond to up to 14 weeks’ treatment with citalopram (Celexa®, Forest Laboratories Inc.) to take part in a RCT of various treatment options, including switching or augmenting with either antidepressants or CBT. 19–21 However, the STAR*D RCT included patients who could not tolerate citalopram, as well as those who were treatment resistant. This makes it difficult to apply the findings to clinical practice because, in practice, the clinician would try to find an antidepressant that the patient could tolerate and prescribe this for an appropriate interval at an adequate dose before deciding that the patient was treatment resistant and seeking alternative treatment options. However, more importantly, in STAR*D there was no comparison group of patients who continued on citalopram, so the effect of augmenting antidepressant medication with CBT as a ‘next-step’ treatment option cannot be ascertained from the STAR*D RCT. Given frequent patient preference for ‘talking therapy’,22 the lack of evidence of effectiveness of psychological interventions in this patient group is an important deficit. Furthermore, it is important that such trials are conducted in the UK, as data from other countries may not generalise to UK primary care owing to differences in health services and the clinical characteristics of patients presenting therein. Moreover, the UK needs information on cost-effectiveness that can be applied to the NHS. While it has become more commonplace for an economic evaluation to run alongside a RCT, this has not been the case historically. There are currently few data on the cost-effectiveness of CBT interventions. Those that exist relate to CBT for relapse prevention23 or CBT delivered in ‘real time’ over the internet using an instant messaging service. 24 Other reports on cost-effectiveness of CBT, for example, Durham et al. ,25 are confined to different patient populations (anxiety/psychosis) and varied CBT interventions (including low-intensity interventions comprising, on average, four sessions with a contact time of just 2.6 hours) and cannot be generalised more widely.

Ongoing studies

There are two small studies of CBT for TRD that are registered as ongoing on the clinical trials registers [‘www.controlled-trials.com’ and ‘www.clinicaltrials.gov’, searched 21 February 2013 (search terms: CBT/cognitive therapy and depression)]. The first, a UK-based study, aimed to recruit 24 patients from secondary care to determine the effectiveness of CBT compared with usual care for TRD (ISRCTN53305823). The study commenced in 2006 but was not completed owing to unexpected staffing changes (Stephen Barton, Newcastle University, 14 March 2012, personal communication). In addition, a US pilot study (n = 30) aimed to examine the effectiveness of CBT and desipramine compared with medication alone in outpatients with TRD (NCT00000376: anticipated start/end dates: 03/1996–02/1999). Although the anticipated end date of the trial was given as February 1999, no results have been published to date.

In addition, there are a number of ongoing studies of other psychological interventions for patients with TRD. For example, the Tavistock Adult Depression Study is examining the effectiveness of 60 sessions of weekly psychoanalytic psychotherapy compared with usual care in 90 patients with TRD (www.tavistockandportman.nhs.uk/adultdepressionstudy, ISRCTN40586372). The REFRAMED trial (www.reframed.org.uk, anticipated start/end dates: 1 January 2012 to 1 September 2014; ISRCTN85784627) is evaluating the effectiveness of Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (DBT) for TRD. A Canadian study (NCT01141426), currently in set-up, will evaluate the effectiveness of intensive short-term dynamic psychotherapy (ISTDP) compared with usual care in patients with an inadequate response to at least 6 weeks’ antidepressant medication. Others are recruiting to a RCT to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a specialist expert mood disorder team for refractory unipolar depressive disorder (NCT01047124). 26 CBT will be provided as part of the treatment offered by this specialist team to secondary care patients. Finally, the PATH-D study (NCT01021254) will examine the effectiveness of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) compared with a health-enhancement programme for patients with TRD.

Cognitive behavioural therapy for treatment-resistant depression

Many patients with depression express a preference for ‘talking therapies’,22 and some have estimated a need for 250 psychological treatment centres. 8 In England,27,28 and elsewhere,29,30 there have been initiatives to improve access to psychological therapies. CBT is the most widely available structured psychotherapy for depression in specialist mental health services in the NHS, and has been shown to be more effective than other psychotherapies in improving outcome in depression. 31 Nonetheless, although CBT is an effective treatment for previously untreated episodes of depression,31 this evidence is not specific to patients with TRD. Yet, in practice in the NHS, CBT is often reserved for those who have not responded to pharmacotherapy in primary care (i.e. those who are treatment resistant). The roll-out of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) project27,28,32,33 means that it is important (and timely) to examine the effectiveness of CBT for patients with TRD.

Cognitive behavioural therapy has been proposed as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy in patients with TRD. Although there is currently no evidence for the effectiveness of CBT in this group, there are indications that psychological treatments may be effective. In patients with residual depressive symptoms, who were randomised to receive CBT (16 sessions over 20 weeks), the relapse rate was significantly reduced (after 68 weeks) compared with usual care. 34 This benefit was lost fully only 3–4 years after the end of treatment. 35 There is also an increasing literature on the use of combination therapy for depression, which suggests that there is a small benefit of combination therapy compared with medication alone in reducing depressive symptoms,36,37 although the evidence base for patients with TRD is lacking. Furthermore, others have noted some benefit of combined treatment for those with chronic depression (defined as at least 2 years’ duration). For example, Keller et al. 38 found that the combination of nefazodone (now withdrawn) and psychotherapy was more effective than either component alone in reducing depressive symptoms after 12 weeks.

From clinical practice it is known that not all patients who are offered psychotherapy will complete the course. Although no figures specific to this patient group and intervention are available, it has been estimated that around 47% of individuals do not complete a course of psychotherapy. 39 Quantitative studies have suggested that non-completion is more common among those of lower socioeconomic background, but there are few other consistent predictors. 39 Importantly, as there has been little qualitative research in this area, there is only limited understanding of why patients adhere to psychotherapy or not, and, likewise, for the rationale behind their decisions. Researchers have used qualitative methods to explore people’s experiences of CBT40,41 and their work shows the value of listening to patients, particularly in relation to better understanding patients’ views on both the therapeutic process and outcomes of therapy. To our knowledge, to date no one has focused specifically on the views and experiences of patients with TRD who have received CBT.

Qualitative research methods are increasingly being used within RCTs to investigate patients’ experiences of participation and trial processes (e.g. how interventions are implemented and delivered42,43) and the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) recommends that both qualitative and quantitative methods are used to evaluate complex interventions. 44 Data collected during in-depth interviews or focus groups with trial participants can provide detailed insight into their experiences of the trial and intervention, and the extent to which they view a particular treatment as acceptable and effective. Such data can also illuminate possible reasons for the quantitative findings and give another viewpoint from which to evaluate the treatment being delivered.

Summary of rationale for randomised controlled trial

In summary, given the frequently expressed patient preference for talking therapies, the recent initiatives to widen access to ‘talking therapies’27–30 and the paucity of evidence for interventions for patients with TRD, there is clearly a need for a large-scale pragmatic RCT to examine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CBT as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, as a ‘next-step’ option for patients who have not responded to antidepressant medication. As indicated earlier, there are reasons to believe that a CBT intervention may be effective and such a trial would make a major contribution to the evidence base for the ‘next-step’ options for the treatment of depression. It is important that any such trial uses an inclusive definition of treatment resistance (based on non-response to at least 6 weeks of antidepressant medication) that is directly relevant to the manner in which depression is typically treated in UK primary care. 13

Given the high prevalence of depression in primary care, an effective intervention has the potential to have a substantial impact on the economic burden associated with this patient group. Currently, the lack of evidence means that clinicians are increasingly faced with a dilemma as to what action to recommend to patients who do not respond to antidepressants.

Research objectives

Amongst patients with TRD (defined as those who have significant depressive symptoms following at least 6 weeks’ treatment with antidepressant medication at an adequate dose) in primary care, to determine (1) the effectiveness of CBT in addition to pharmacotherapy in reducing depressive symptoms and improving quality of life over the following 12 months (compared with usual care that includes pharmacotherapy) and (2) the cost-effectiveness of this intervention. In addition, this study will incorporate a qualitative study to (1) explore patients’ views and experiences of CBT; (2) identify patients’ reasons for completing or not completing therapy and (3) describe ‘usual care’ for this patient group.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The CoBalT study was a multicentre, pragmatic RCT with two treatment groups: a usual-care group and an intervention group. The intervention consisted of 12–18 sessions of CBT in addition to usual care. For both groups, usual care included antidepressant medication as well as continued support and advice from the GP.

An economic evaluation was conducted alongside the RCT in order to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the intervention (see Chapter 4 ). The nested qualitative study is described in more detail (see Chapter 5 ). The trial protocol has been published. 45

Ethical approval and research governance

Ethical approval for the study was given by West Midlands Multicentre Research Ethics Committee – ref. no. NRES/07/H1208/60. Site-specific approvals were obtained from the relevant Local Research Ethics Committees and primary care trusts (PCTs)/health boards covering the three study sites (Bristol, Exeter and Glasgow). In addition, research governance approval was obtained from Avon & Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership NHS Trust, who were the employers of, and whose premises were used, on occasion, by the Bristol therapists. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN38231611). A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given in Table 1 .

| Description | Submitted | Approved |

|---|---|---|

| Original submission | 19 October 2007 | 26 February 2008 |

Amendment 1 (protocol v3)

|

12 March 2008 | 15 April 2008 |

Amendment 2 (protocol v4)

|

8 August 2008 | 3 September 2008 |

Amendment 3 (protocol v5)

|

30 September 2009 | 14 October 2009 |

Amendment 4 (protocol v6)

|

9 February 2010 | 28 April 2010 |

Amendment 5 (protocol v7)

|

17 July 2010 | 29 July 2010 |

Amendment 6 (protocol v8)

|

27 September 2010 | 10 October 2010 |

Amendment 7 (protocol v9)

|

10 May 2011 | 20 May 2011 |

Participants

The study sought to recruit patients with TRD from 73 general practices across the three centres.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients were those aged 18–75 years, who were currently taking antidepressant medication, and had done so for at least 6 weeks at an adequate dose [based on the British National Formulary (BNF: www.bnf.org.uk/bnf) and advice from psychopharmacology experts)] (see Appendix 1 ). In addition, it was necessary for eligible patients to have adhered to their antidepressant medication, score ≥ 14 on the Beck Depression Inventory, second version (BDI-II)46 and meet International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Edition (ICD-10), criteria for depression, assessed using the revised Clinical Interview Schedule (CIS-R). 47

It is difficult to measure adherence to medication. Therefore, our definition of treatment resistance was operationalised using the Morisky scale, a four-item self-report measure of adherence,48 which had previously been validated against electronic monitoring medication bottles. A score of ‘0’ (range 0–4) on this scale was indicative of at least 80% adherence. 49 Given the relatively long half-life of antidepressant medication, an additional item (‘Did you miss 2 days’ antidepressant tablets in a row?’ yes/no) was added to this scale to ensure that only individuals who had missed more than one consecutive dose were excluded.

Exclusion criteria

General practitioners were asked to exclude those patients who fulfilled any of the following exclusion criteria at the time of the record search:

-

patients who had bipolar disorder, psychosis or major alcohol or substance abuse problems

-

patients who were not able to complete the study questionnaires

-

patients who were currently receiving CBT or other psychotherapy or secondary care for depression, or who had received CBT in the past 3 years

-

women who were pregnant (women who became pregnant during the trial were able to continue to participate with consent and approval of their GP).

Patients who were currently taking part in another intervention study were excluded, although they were offered the opportunity to participate in CoBalT once their involvement in the other research study had ended. In addition, GPs excluded any patients whom they considered it would be inappropriate to invite.

Recruitment of participants

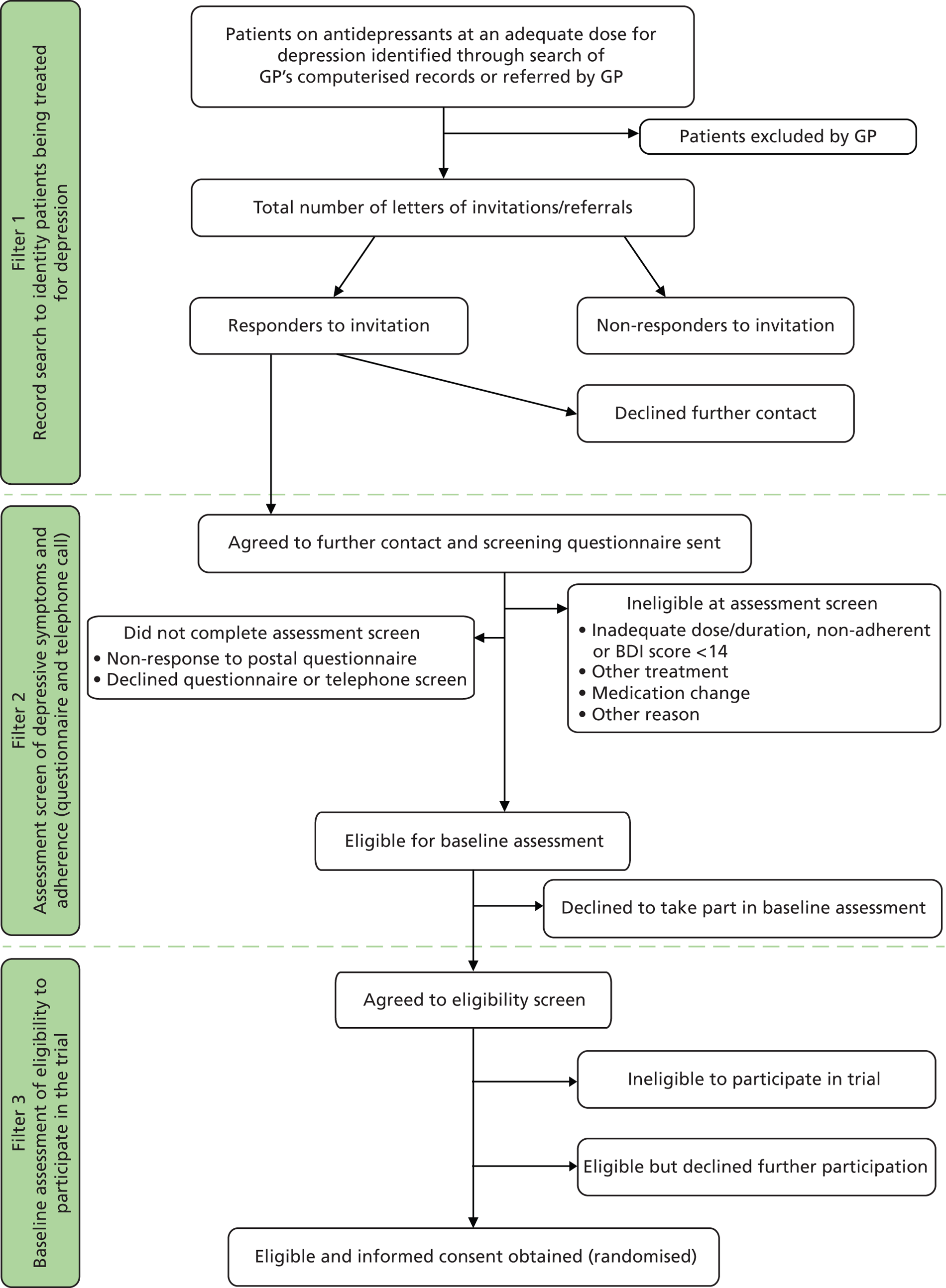

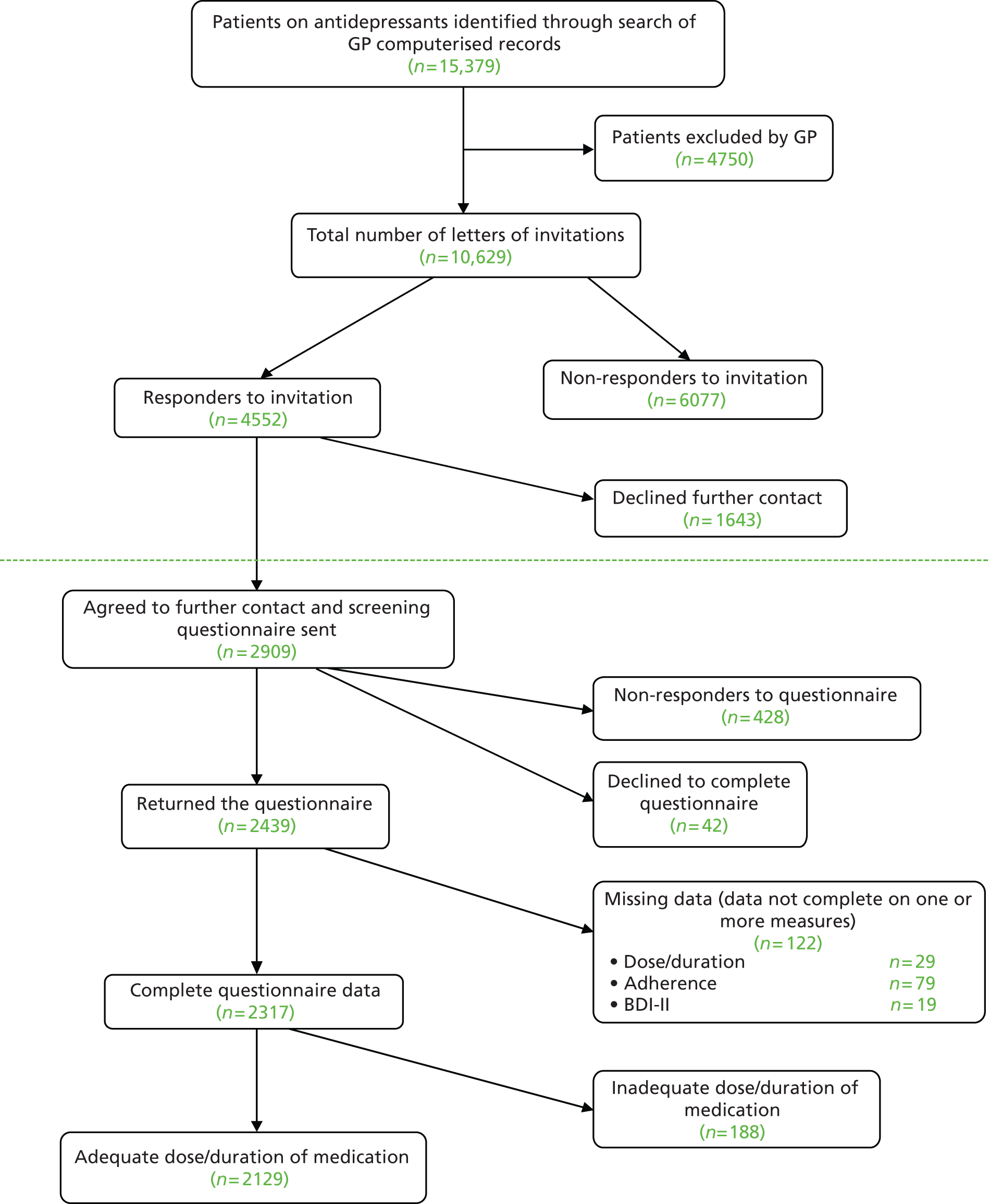

Eligible participants were identified using a three-stage process ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1.

CoBalT trial design.

Filter 1: search of general practitioner computerised records to identify patients being treated for depression

The search of GP computerised records identified all patients in the appropriate age range who had received repeated prescriptions for an antidepressant during the previous 4 months, and who were currently being prescribed an antidepressant medication at an adequate dose for depression.

General practitioners then screened this list of patients and excluded those who fulfilled any of the exclusion criteria listed above. A letter of invitation and brief information leaflet about the study was sent by the general practice to the remaining potential participants. This letter sought permission for the research team to contact them and to send a questionnaire asking about their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication. Patients replied directly to the study team, indicating whether or not they agreed to be contacted. One reminder was sent to those who did not respond to the initial letter of invitation.

On the reply slip, those who did not wish to participate were asked to indicate their age, gender and reason for non-participation. In addition, non-participants were asked to indicate their willingness to take part in a brief telephone interview to discuss their reasons for non-participation. This would provide more detailed insight into the reasons for non-participation and, in particular, the potential demand for CBT by this patient group.

Anonymised data on age and gender of those patients who were mailed an invitation to participate but who did not respond (or refused to participate when invited during the consultation) were collected to assess the generalisability of the study findings. GPs could also invite patients to take part in the study during a consultation. In such cases, the GP provided the patient with an information leaflet about the study and obtained permission from the patient to pass their contact details to the research team. The research team then mailed a questionnaire to the patient asking them about their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication (as earlier).

Filter 2: assessment of depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressants

All of those who agreed to be contacted by the research team (either in response to the postal invitation or to a direct invitation from their GP during the consultation) were sent a postal questionnaire. This questionnaire collected data on the following:

-

sociodemographic variables (age, gender, marital status, ethnicity, educational qualifications, employment status, home ownership and financial difficulties)

-

severity of depressive symptoms, using the BDI-II46

-

duration of antidepressant treatment, dose of medication and adherence to medication. 48

One reminder was sent to those individuals who did not return a completed postal questionnaire within 2 weeks.

Those who met the definition of TRD (based on severity of depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressants at an adequate dose for at least 6 weeks) were contacted by a researcher by telephone to ascertain their eligibility with respect to current/past psychological treatment and current secondary care for depression. Those who were not currently receiving (or scheduled to start) CBT or secondary care for their depression, and who had not received CBT in the past 3 years, were invited to attend a face-to-face appointment with a researcher to discuss participating in the trial and to assess their eligibility. The date, time and location of the baseline appointment were confirmed by letter. A detailed patient information leaflet and a leaflet that provided an introduction to CBT were also enclosed, and the patient was asked to read both of these prior to attending the baseline appointment.

Those who were currently receiving non-CBT therapy [e.g. computerised CBT (cCBT) or counselling] were given the option of being contacted again for a rescreen once their current treatment had finished. An ‘end of therapy’ date was taken and the patients were mailed a second postal screen after this point to assess whether they were eligible to participate in the trial.

Those who completed the screening process (postal questionnaire with or without telephone questionnaire), but were not eligible to participate, received a letter informing them of this and thanking them for taking part. The letter explained that their GP had also been informed and would continue to care for them as usual. The GP received a letter that explained that the patient was ineligible as they had not met one or more of the eligibility criteria, but that the GP could refer the patient back to the trial if these factors changed. If the patient had given permission in the postal questionnaire, the GP also received a report that gave more detail about the inclusion criteria that were/were not satisfied, as well as the individual’s score on the BDI-II.

Filter 3: baseline assessment

Baseline assessments to establish eligibility were conducted in the patients’ own home, at their GP surgery or at nearby NHS/university premises. Only those patients who fulfilled ICD-10 criteria (F32) for their current depressive episode (assessed using the CIS-R47), had a BDI-II score of ≥ 14 and who were continuing to take the prescribed antidepressants at an adequate dose were eligible to participate in the trial.

As well as completing the CIS-R and BDI-II in order to assess eligibility, the baseline assessment also collected information on life events, social support, smoking habits and use of alcohol. 50 Sociodemographic details were also recorded (age, gender, ethnicity, marital status), together with information on a number of socioeconomic markers (including employment status, housing situation, financial stress). Questions on post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (PC-PTSD:51 Primary Care Post-traumatic Stress Disorder) and personality (Big Five neuroticism scale52) were also collected at baseline. Additional measures such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),53 the Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment-7 items (GAD-754), panic (from the Brief Patient Health Questionnaire),55 the Short-Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12)56 and European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions-3 Levels (EQ-5D-3L)57 were collected at baseline and at subsequent follow-ups, as were measures of dysfunctional attitudes58 and metacognitive awareness59 (see Secondary outcomes, below, for more detail).

Prior to randomisation, participants were asked to indicate whether or not they had any preference for treatment (‘prefer CBT (in addition to usual care)’, ‘prefer usual care’ or ‘don’t mind’) and also asked about whether or not they thought that CBT would help them (based on a list of five response options: ‘CBT would definitely help me’; ‘CBT would probably help me’; ‘I don’t know if CBT would help me’; ‘CBT would probably not help me’; and ‘CBT would definitely not help me’). The latter information was used in an a priori subgroup analysis to examine the influence of patient expectation of effectiveness of the trial intervention on outcome.

If a patient was not eligible to take part in the trial, they were informed of this and thanked for their time. It was explained to them that their GP would also be informed and that a summary giving more detail about the inclusion criteria that were/were not fulfilled, and their depressive symptoms (scores on the BDI-II at postal screen and baseline) could be fed back to their GP, if they had given permission. If the patient was eligible to participate, the individual was asked whether or not they were happy to proceed and, if so, written informed consent was obtained.

Prior to the start of the baseline assessment, patients were asked to provide informed, written consent for the storage and processing of the data collected at the time of the assessment. This covered the data collected from both those who were found to be ineligible to participate in the trial as well as those who were eligible, thus enabling the trial to be reported in line with CONSORT (Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials) guidelines. 60 Those patients who were identified as eligible to participate in the trial were asked to provide additional informed, written consent for this purpose. The original signed and dated consent forms were held securely as part of the trial site file, with copies for both the participants and their GPs for their records.

Randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding

Randomisation was at the level of the individual, with eligible and consenting patients randomised at the end of their baseline assessment to one of two treatment groups: ‘Usual care’ or ‘Usual care plus CBT’. At the point of randomisation, all patients were taking antidepressants and had agreed with their GP to continue with such medication as part of their usual care.

To conceal the allocation of treatment from those conducting the research, randomisation of individual participants to one of the two treatment arms was undertaken using an automated telephone randomisation system that was administered remotely and used a computer-generated code. The randomisation service was provided by the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration-registered trials unit (www.bris.ac.uk/social-community-medicine/centres/brtc). Once the randomisation procedure had been completed, the outcome and further details about the allocated treatment was immediately communicated by the researcher to the participant. Given the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants, GPs, researchers or the CBT therapists to the treatment allocation.

Randomisation was stratified by centre (n = 3), with minimisation used to ensure balance in the following variables:

-

baseline BDI-II score (mild 14–19; moderate 20–28; severe ≥ 29)

-

whether the general practice had a counsellor (yes/no)

-

prior treatment with antidepressants (yes/no)

-

duration of their current episode of depression (< 1 year, 1–2 years, ≥ 2 years).

Minimisation with a probability weighting of 0.8 was used in order to reduce predictability. 61

Treatment group allocation

Eligible participants were randomised to either ‘usual care’ or ‘usual care plus CBT’.

Usual care

There were no restrictions on treatment options for patients randomised to be managed as usual by their GP. Patients could be referred for counselling or to secondary care (including for CBT) if it was deemed clinically appropriate by the GP. It was felt unethical to withhold the option of counselling or to restrict access to secondary care if the GP deemed it appropriate. Although the roll-out of IAPT services had improved access to psychological therapies in England, there could still be long waiting times (as is the situation in Scotland), so any such contamination was considered unlikely to substantially influence the primary outcome. Nonetheless, such treatments were recorded as part of the follow-up questionnaires.

Usual care plus cognitive behavioural therapy

Cognitive behavioural therapy manuals

Therapists used the seminal CBT depression treatment manuals. 62,63 Given that the study population had TRD, where appropriate therapists used elaborations on the manual designed to address treatment resistance. 64 The Moore and Garland manual64 emphasises approaches that overcome cognitive and behavioural avoidance, and formed the basis for the treatment manual used in an earlier MRC trial that examined the effectiveness of CBT for patients with residual depression. 34 The therapists were flexible in responding to problems raised by the patient, for example by targeting symptoms of anxiety using appropriate cognitive behavioural models if these were considered important. Emphasis was also given to formulating the psychopathology in terms of conditional beliefs.

Therapy: length and number of sessions

Details of those patients randomised to receive CBT were passed over to the therapy team based in each centre. The allocated therapist contacted the patient to arrange the first appointment at a mutually convenient time and place.

Patients randomised to CBT received a course of 12 sessions, with (up to) a further six sessions if deemed clinically appropriate by the therapist. Sessions typically lasted 50–60 minutes. Therapy usually took place in the patients’ GP surgery, or at nearby NHS premises. In a few exceptional cases the therapy took place at the patient’s home, or by telephone.

Therapists

As this was a pragmatic trial, we aimed to recruit therapists who were representative of CBT therapists working within NHS psychological therapy services, for example ‘high-intensity’ IAPT practitioners who had postgraduate CBT qualifications or equivalent experience, and were accredited (or eligible for accreditation) by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP: www.babcp.com).

Across the three sites, 11 therapists working part time [ranging from 0.1 full-time equivalent (FTE) to 0.8 FTE] delivered the therapy (Bristol n = 6; Exeter n = 3; Glasgow n = 2). Ten of the eleven (91%) therapists were female and the mean age of the therapists was 39.2 years [standard deviation (SD) 8.1, range 27–58 years]. The professional background of the therapists varied: four had a mental health nursing background, six were clinical psychologists and one had completed a MSc in Psychological Therapies. On average, the trial therapists had practised as a therapist for 9.7 years (SD 8.1; range 0 (newly qualified)–30). Before the trial, seven of the therapists had received formal CBT training (Masters or Postgraduate Certificate/Diploma) and two of these individuals completed a MSc in CBT during their employment with the study.

Training and supervision of therapists

There were four therapists employed at the start of recruitment, who received 4 days’ training with one of the authors of the manual designed to address treatment resistance (AG). 64 There were five additional training days (including 4 days with AG) over the course of the trial. All therapists attended at least one of these additional training days and received at least 1 day’s training, specific to the trial, from AG.

Therapists received weekly hourly supervision sessions (in groups of two or three) from an experienced therapist based at each centre. This arrangement met the standards for clinical supervision set out by the BABCP (defined as at least 1 hour per month: www.babcp.com/Accreditation/Practitioner/Practitioner_Accreditation.aspx) and the more stringent requirements set out by IAPT (at least 1 hour of individual supervision on a weekly basis for full-time staff: www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/iapt-supervision-guidance-revised-march-2011.pdf). Therapists in two sites were supervised by two of the principal investigators (Bristol, GL; Exeter, WK).

Fidelity to the cognitive behavioural therapy model

Therapy sessions were recorded, with the patient’s consent, using a digital voice recorder. Individual permission was sought to use these recordings for teaching and/or research purposes. A random sample of recordings was selected, and fidelity to the CBT model evaluated by three independent raters from the Oxford Cognitive Therapy Centre using a recognised CBT rating scale. 65 This evaluation was restricted to the recordings of the CBT sessions for the nine therapists who delivered the majority (97%) of the intervention. Assessment (session 1) and review sessions (final session for those who completed therapy) were excluded from the pool of potential sessions for selection, as these sessions are different and would not typically provide a demonstration of competence in CBT.

As three raters were undertaking this evaluation, the first step was to demonstrate inter-rater reliability in Cognitive Therapy Scale-revised (CTS-R) ratings. To ensure an approximately equal distribution between sessions sampled from earlier or later in therapy, one therapist was selected at random and one session selected at random from earlier/later sessions of therapy dependent on the frequency distribution of number of sessions. The remaining eight therapists were then ranked in terms of the number of patients allocated to them (thus including those who completed therapy as per the study protocol; those who withdrew from therapy; and those who were discharged for non-compliance). Four therapist pairs were then defined on the basis of caseload and within each therapist pair, a random number was generated to determine whether an earlier or later therapy session (selected at random) was evaluated. Across the nine therapists, this ensured an approximately equal distribution in the number of earlier and later sessions rated. This process generated one CTS-R rating for each of the nine therapists rated by three independent raters and these data were used to establish inter-rater reliability. If the audio-recording for the selected session was missing (either because the audio-file was missing or the patient withdrew consent for that session to be recorded) or incomplete (the recording failed for technical reasons) then an alternative session for the same patient was randomly selected from within the specified stratum (early/late). If there were no alternative sessions within the same stratum, another patient was selected at random and an early/late session sampled at random, as appropriate.

If there was a handover between therapists during the course of therapy and the selected session was one delivered by the second therapist then the nearest session delivered by the first therapist was selected for evaluation. This corresponded to the therapist who was listed as the allocated therapist and thus prevented sessions from any individual therapist being over-/under-sampled.

It was specified in advance that if at least ‘moderate’ reliability [intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) > 0.666] between the three raters was observed then each of the three raters would be asked to rate a further 18 sessions. For each of the nine therapists, six patients would be selected at random. A random number would be generated to determine whether an earlier or later therapy session (selected at random) should be evaluated for each of these six patients. This would result in three earlier and three later sessions being sampled for each of the nine therapists (giving a total of 54 sessions for evaluation). The procedure for selecting an alternate recording in the event of a missing/incomplete audio-recording or change in therapists, as outlined earlier, applied.

If there was insufficient inter-rater reliability (ICC ≤ 0.60) then each of the three raters would be asked to rate the same 18 sessions. In this case, one earlier and one later session would be selected at random for each of the nine therapists.

A mean CTS-R rating across all therapists is reported accounting for therapist caseload using sampling weights. For the 12-item CTS-R, a cut-point of ≥ 36 is deemed appropriate, equating to a mean item score of 3.0 ‘competent’. 65

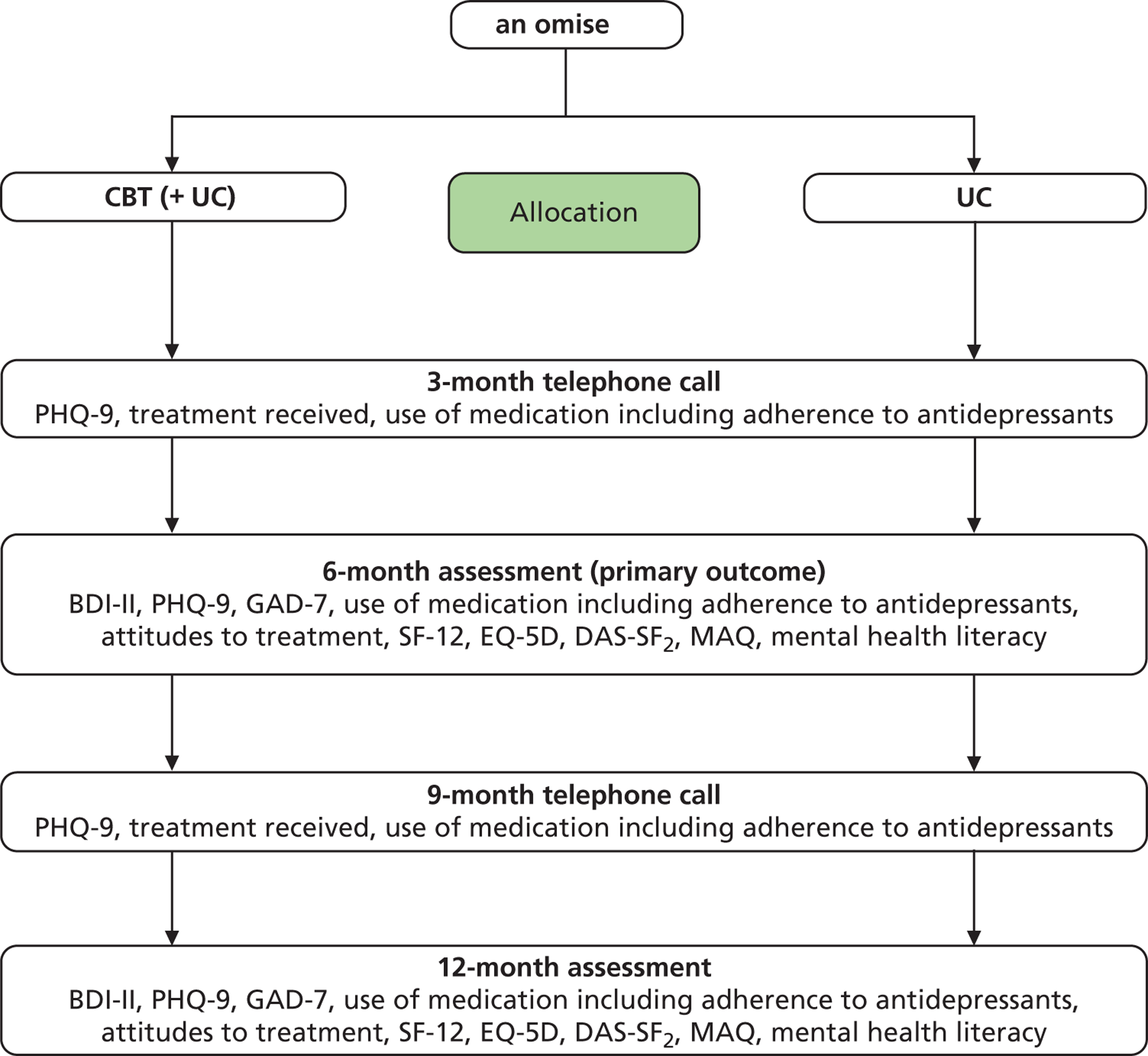

Follow-up

A flow chart outlining CoBalT follow-up procedures is provided in Figure 2 . Follow-up data collection took place at four time points: 3, 6, 9 and 12 months post randomisation. Measurement of the primary outcome took place at the 6-month follow-up, as it was expected that most of those in the intervention group would have attended all (or most) of their CBT sessions by this time. The 12-month follow-up was designed to enable the investigation of any longer-term effects on study outcomes.

FIGURE 2.

CoBalT trial follow-up stages and data collected. DAS-SF2, Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale-Short Form (version 2); MAQ, Metacognitive Awareness Questionnaire; UC, usual care.

To maximise response rates, wherever possible the researcher arranged to meet the patient at 6- and 12-month follow-up at the participant’s home, in their GP surgery or at university premises. A small number of participants chose to return the questionnaire(s) by post.

The 3- and 9-month follow-ups were conducted by telephone. These follow-ups were designed to maintain contact with participants and enable collection of brief outcome data in terms of depressive symptoms, use of antidepressant medication and receipt of other treatments.

Data collection and management

To standardise processes across the three centres and maximise data quality, researchers were trained to use detailed standard operating procedures for each stage of data collection. A number of cross-checks were routinely performed as a means of ensuring that any data inconsistencies arising from either baseline assessment or follow-up were identified and resolved at the earliest opportunity. Trial data were entered into a Microsoft Access 2003 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) at each centre, before being merged into one central database following the end of data collection. A range of data validation checks were carried out in both Microsoft Access and Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to minimise erroneous or missing data.

Measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was the BDI-II score at 6 months post randomisation – specifically a binary variable representing response defined as a reduction in depressive symptoms of at least 50% compared with baseline. A threshold of 50% improvement in symptoms is a widely used definition of improvement67 and used to compare treatment effects in the systematic review of interventions for TRD. 14

The BDI-II is a 21-item self-report instrument to measure the severity of depressive symptoms occurring over the previous 2 weeks and has been widely used in depression trials. The 21 items are rated on a four-point severity scale (0–3) and are summed to give a total score (range 0–63). A higher score on the BDI-II denotes more severe depression.

Secondary outcomes

The BDI-II was also completed at 12 months to assess the longer-term effect of the intervention. Secondary outcomes included the BDI-II as a continuous score, and a further binary version representing remission of symptoms (defined as a BDI-II score of < 10).

Other outcome measures included at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups assessments are listed below:

-

SF-12 (version 2) A 12-item Short Form Health Survey measuring quality of life. 56 The SF-12 is an abbreviated form of the SF-36 (Short Form questionnaire-36 items), a 36-item instrument for measuring subjective health status. It consists of 12 self-report items, selected from the SF-36. The CoBalT study used a revised version of the SF-12, the SF-12v2, which was introduced in 2002. The algorithms used to score data are dependent on the recall period. The CoBalT study used the acute (1-week recall) survey. Norm-based scores for the physical and mental subscales were calculated. Higher scores indicate better health and functioning.

-

PHQ-9 The Patient Health Questionnaire, a brief nine-item depression scale53 developed for use in a primary care setting. The questionnaire is designed to assess the patient’s mood over the previous 2 weeks and scores for each of the nine items range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Items are summed to give a total score (range 0–27), with a higher score denoting more severe depression.

-

GAD-7 The Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment – a measure of generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). 54 The GAD-7 is a brief self-report questionnaire designed to detect probable cases of GAD and to provide a measure of its severity as recalled over the previous 2 weeks. As with the PHQ-9, scores for each item range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Items are summed to give a total score (range 0–21), with a higher score denoting more symptoms of anxiety. The PHQ-9 and GAD-7 form part of the core IAPT outcome data set (www.iapt.nhs.uk/silo/files/iapt-outcome-framework-and-data-collection.pdf) and will enable comparison with national IAPT data.

-

Panic (Brief PHQ) The presence of panic disorder was measured using the panic module of the self-report version of the PRIME-MD questionnaire (Brief PHQ). 55 The measure consists of five items. The first item asks individuals to report whether or not they have experienced an anxiety attack within the last 4 weeks; if they have they are asked four further questions about their experience. Each question elicits a response of ‘Yes’ or ‘No’. The total number of panic items endorsed therefore ranges from 0 to 5.

-

EQ-5D-3L A standardised measure of health status developed by the EuroQol Group to provide a simple, generic measure of health for clinical and economic appraisal. 57 The EQ-5D-3L is used in CoBalT as a measure of health outcome for the economic evaluation. Scores were calculated using standard algorithms, with higher scores indicating better health.

Bespoke measures relating to patient’s treatment experience and mental health literacy were also recorded at 6 and 12 months.

Self-reported adherence to antidepressants was collected at each of the four time points. 48 With consent, data on antidepressant medication received (additional prescriptions, changes in dose and/or changes in the antidepressant prescribed) and other medications prescribed during the course of the study were recorded from GP records, together with details of consultations in primary care. Data on antidepressants prescribed during the year prior to entry to the study were also recorded, when consent was given to access medical records. Data on health care utilisation in primary and secondary care, private treatments, and complementary and alternative treatments were collected as part of the 6- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires and were used to inform the economic evaluation.

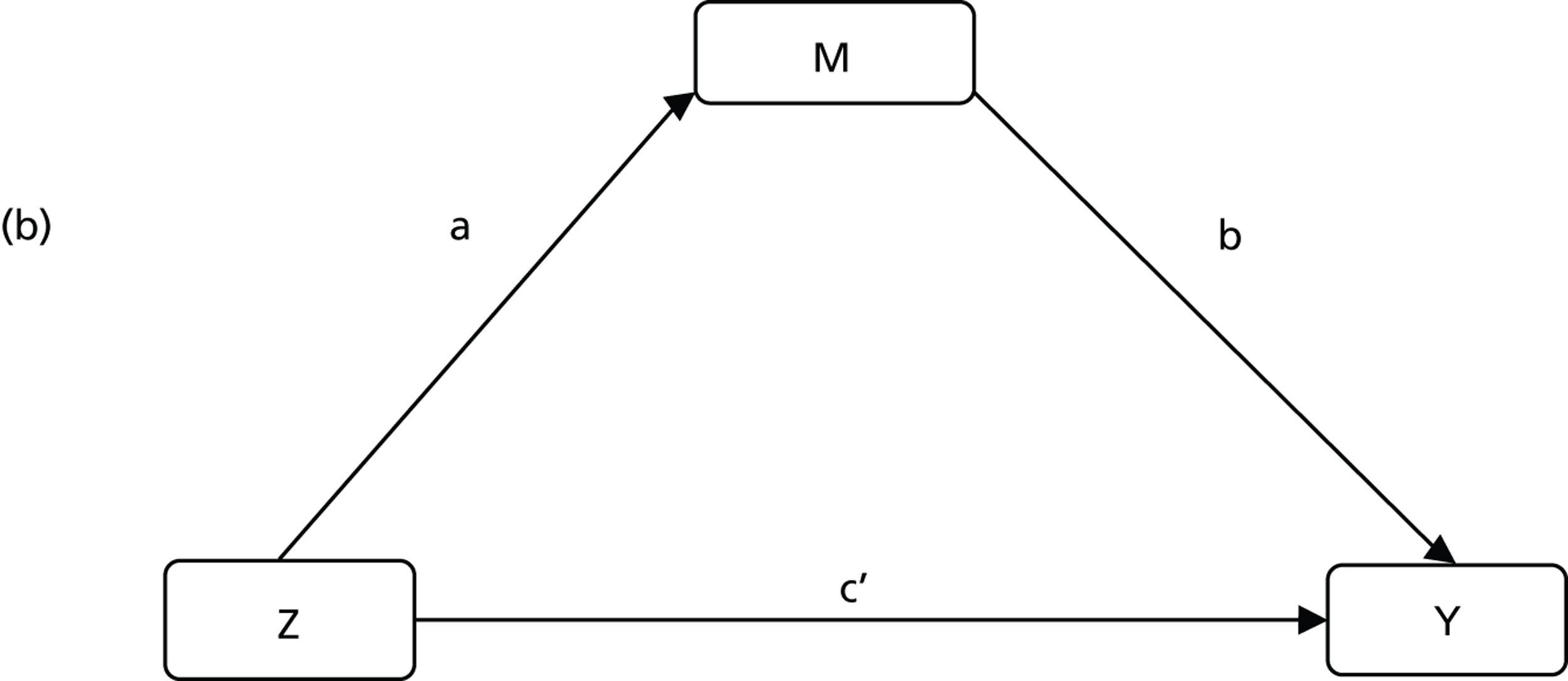

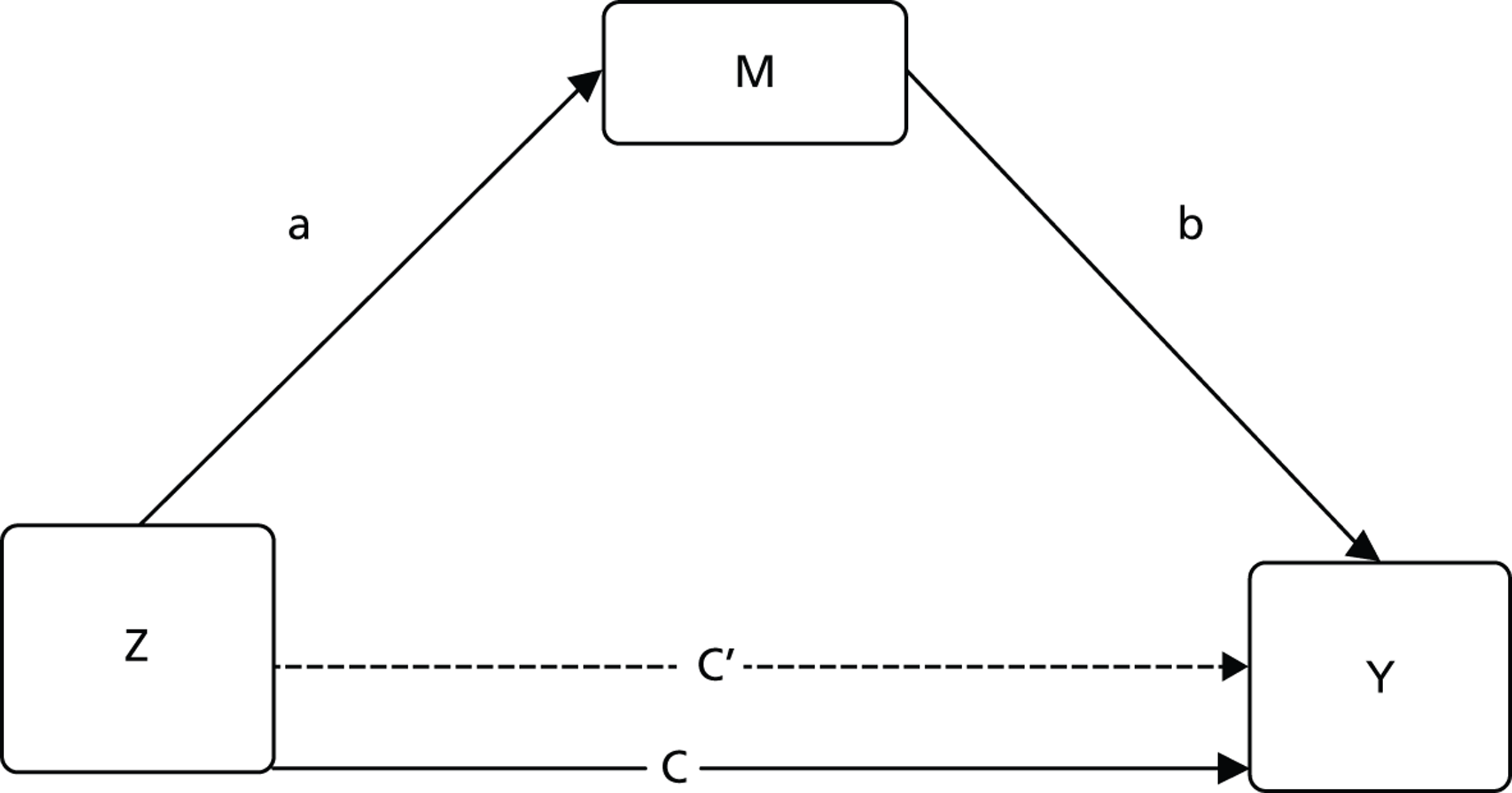

Process measures of dysfunctional attitudes and metacognitive awareness were also collected at the 6- and 12-month assessments:

-

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale-Short Form (version 2) (DAS-SF 2 ) The DAS-SF2 is a self-report questionnaire containing nine items that was developed from Weissman’s original Dysfunctional Attitude Scale,68 using item response analysis to provide an efficient and accurate assessment of dysfunctional attitudes among depressed individuals. 58

-

Metacognitive Awareness Questionnaire (MAQ) The MAQ59 assessed whether or not patients with depression view their negative thoughts as reflecting reality. The scale consists of nine self-report items and has the same seven-point response format as the Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale (DAS), with higher MAQ scores reflecting greater metacognitive awareness.

The brief telephone follow-ups at 3 and 9 months comprised the PHQ-9, use of antidepressant medication, including adherence to antidepressants48 and other treatments received.

Table 2 shows the measures and when they were collected.

| Concept | Measure | Time points | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | ||

| Sociodemographics | a | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Alcohol use | AUDIT-PC | ✓ | |||||

| ICD-10 diagnosis | CIS-R | ✓ | |||||

| Depression severity | BDI-II | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Depression severity | PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Adherence | Four-item Morisky scale | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Post-traumatic stress | PC-PTSD | ✓ | |||||

| Anxiety | GAD-7 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Panic | Brief PHQ-Panic | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Quality of Life | SF-12 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Economic evaluation | SF-6D | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Economic evaluation | EQ-5D-3L | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Dysfunctional attitudes | DAS-SF2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Metacognitive awareness | MAQ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Personality | Big Five (neuroticism subscale) | ✓ | |||||

| Mental health awareness | Bespoke questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Treatment experience | Bespoke questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

Handling missing items

For outcomes on the BDI-II, PHQ-9, GAD-7, DAS-SF2 and MAQ, the trial dealt with any missing data at an individual item level by adopting the following rule. If > 10% of the items were incomplete then the data collected on that measure for that participant were disregarded. However, if < 10% of items on a particular measure were missing, missing item(s) were imputed using the mean of the remaining items (rounded to an integer). Therefore, when an individual had completed 19 or 20 items for the primary outcome measure (BDI-II) then the remaining one or two items were imputed. For all other measures (PHQ-9, GAD-7, DAS-SF2, and MAQ) the 10% rule meant that only a single item would be imputed. Data were complete for the majority of the sample; the number of cases for which values were imputed are reported in Table 3 .

| Instrument | Maximum no. of items imputed | No. of cases in which imputation of individual items was undertaken | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | ||

| BDI-II | 2 | 0 | – | 1 | – | 5 |

| PHQ-9 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| GAD-7 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| DAS-SF2 | 1 | 0 | – | 0 | – | 2 |

| MAQ | 1 | 0 | – | 1 | – | 2 |

The scoring manuals for the SF-12 or EQ-5D-3L, which require the application of complex scoring algorithms, indicated that if any item was missing, the scale score should not be calculated. In the case of greater item non-response or missing follow-up data, sensitivity analyses were conducted using the method of multiple imputation by chained equation (MICE) to examine the impact of missing data on the main findings (see Sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of missing data, below).

Justification of sample size

To calculate the required sample size, we assumed that usual care would involve GPs acting in line with NICE guidance,12,13 i.e. increasing the dose of antidepressant, switching to another antidepressant or augmenting the medication. Data from the large US STAR*D study suggested that, among those who had not responded to up to 14 weeks treatment with citalopram, only 30% would ‘respond’ when their antidepressant medication was switched19 or augmented. 20

Original sample size calculation

The expected treatment effect for the CoBalT study was based upon systematic review evidence for the effectiveness of CBT,31 which concluded that there was a threefold increased odds of recovery for CBT compared with treatment as usual (TAU). 31 However, a reduced effect was expected given that this review did not focus specifically on patients with TRD. Therefore, the original sample size calculation for the CoBalT trial was based on detecting an odds ratio (OR) of 2 (or a difference of 16 percentage points between groups). Other trials of residual depression,34 or chronic depression,38 report effect sizes that are not dissimilar.

Thus, the original plan was to recruit 200 patients in each treatment group to yield 90% power to detect a difference between 30% and 46% response (defined as at least a 50% reduction in depressive symptoms) or an OR of 2, at a 2-sided 5% significance level. Allowing for 15% loss to follow-up at 6 months, the sample size was initially calculated to be 472.

Revised sample size calculation

However, a slightly delayed start to recruitment, a slightly lower than anticipated recruitment rate in one centre and difficulties matching recruitment rates to therapist capacity in two centres (to avoid a lengthy delay between randomisation and the start of therapy) necessitated a request for extended funding. This request was submitted in October 2009. A revised power calculation was presented as part of this application ( Table 4 ). The original power calculation was amended to reflect a reduced sample size of 432. This reduced sample size would have 87% power to detect the originally specified difference of 16 percentage points, and would have 90% power to detect a 17 percentage point difference in the binary ‘response’ outcome (between 30% and 47%).

| Sample size calculation | N randomised | n for primary analysis | Power to detect originally specified difference (%)a | Detectable difference with: | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 80% power | 90% power | ||||

| Original | 472 | 400 | 90 | 14 percentage points (30% vs. 44% = OR 1.84) | 16 percentage points (30% vs. 46% = OR 2.00) |

| Revised | 432 | 367 | 87 | 15 percentage points (30% vs. 45% = OR 1.89) | 17 percentage points (30% vs. 47% = OR 2.07) |

Statistical analysis

The analysis and reporting of this trial was undertaken in accordance with CONSORT guidelines. 60,69,70 All statistical analysis was undertaken in Stata 11.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), following a pre-defined analysis plan agreed with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). The primary comparative analyses between the randomised groups were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis without imputation of missing data.

Preliminary analyses

Descriptive statistics of the key sociodemographic and clinical variables were used to ascertain any marked imbalances at baseline, and to inform any additional adjustment of the primary and secondary analyses as appropriate.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis used logistic regression to compare the groups as randomised in terms of the primary (binary) BDI-II outcome at 6 months, adjusting for stratification and minimisation variables (the ‘design variables’: centre, baseline BDI-II score, access to a counsellor, prior treatment with antidepressants and duration of the current depressive episode), which included adjustment for the baseline measurement of the outcome (BDI-II score as a continuous variable). The ORs of ‘response’ in the intervention group compared with the usual-care group is presented along with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and the p-value for the comparison.

Secondary analyses

Secondary analyses of the primary outcome included additional adjustment for any prognostic variables demonstrating marked imbalance at baseline (ascertained using descriptive statistics). The BDI-II was also considered as a continuous outcome, with an associated increase in power. Secondary analyses were conducted for other outcomes measured at 6 and 12 months.

Repeated measures analyses were used to incorporate the outcome data from both 6 and 12 months post randomisation (or, in the case of the PHQ-9, from 6, 9 and 12 months) to examine whether or not any treatment effects were sustained or emerged later. This was tested formally by the introduction of an interaction between treatment group and time. In the absence of any time effect, repeated measures analyses generate an average effect size over the duration of follow-up. In all analyses, ORs (or regression coefficients for continuous outcomes), with 95% CIs and p-values, are reported.

Potential clustering by therapist

There is the potential for clustering by therapist within this trial, although clustering effects will operate in only one arm of the trial. Secondary analyses therefore used generalised linear and latent mixed models to obtain a fully specified heteroscedastic model (described in Roberts and Roberts71) to examine the influence of clustering by therapist on the results.

Subgroup analyses

Two subgroup analyses were specified a priori and were conducted by introducing an appropriate interaction term to the regression model for the primary outcome. This permitted investigation of any differential effects of treatment on outcome according to two predefined factors: (1) patient expectation of outcome (defined as three levels: ‘CBT would definitely help me’; ‘CBT would probably help me’; ‘I don’t know if CBT would help me/would probably not help me’) and (2) degree of treatment resistance [six levels based on duration of symptoms (< 1, 1–2, ≥ 2 years) and past treatment with antidepressant medication (yes/no)].

Sensitivity analyses to examine the impact of missing data

The pattern of missing data was investigated by identifying those variables recorded at baseline that were associated with ‘missingness’ of the primary outcome (BDI-II score) at p < 0.20 at either the 6-month follow-up and/or 12-month follow-up. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using the method of MICE72 to impute missing data (Stata ice procedure, version 1.9.5, dated 15 April 2011). The imputation model included all of those variables that were part of the substantive ITT model, together with the variables associated with missingness (as identified above) and all available measures of depressive symptoms (BDI-II and PHQ-9) and anxiety (GAD-7), irrespective of statistical significance. The baseline CIS-R score was also included in the imputation model as another marker of severity. Variables included in the imputation model were declared as continuous, binary, categorical or ordinal variables, as appropriate. The match procedure was used to handle non-normally distributed variables that could not be successfully transformed. In total, 25 data sets were generated and 10 switching procedures were used.

Treatment efficacy

Complier-Average Causal Effect (CACE) estimates73 for those who were viewed as ‘on track’ to receive the full course of CBT treatment at the time of the 6-month follow-up (defined as having completed nine or more sessions) were estimated using instrumental variables regression methods. As the primary outcome ‘response’ was a binary variable, a probit transformation was used, and the primary ITT analysis repeated on this transformed scale for comparison with the CACE estimates.

Complier-Average Causal Effect estimates were also determined for the longer-term outcome at 12-months. For the latter, those who had received ≥ 12 sessions were regarded as having received CBT in line with the treatment protocol.

The CACE methodology compares the outcomes for those who ‘complied’ with the intervention with a similar group of ‘would-be compliers’ from those randomised to usual care, thus avoiding the biases inherent in crude per-protocol analyses. The original definition of a ‘complier’ included those where the therapy goals were achieved in fewer than 12 sessions, as agreed between the patient and therapist. However, in practice, this included individuals who had an ‘agreed end’ of fewer than eight sessions, and thus a stricter definition was adopted, as outlined above.

Safety reporting and disclosure

Although CoBalT was not a Clinical Trial of an Investigational Medicinal Product (CTIMP), it was recognised that both psychopharmacology and psychotherapy have risks and benefits for patients. 74 Therefore, in accordance with good clinical practice the CoBalT team recorded and reported any serious adverse events to comply with the National Research Ethics Service annual safety report requirements of non-CTIMP trials.

In the case of CoBalT, GPs were responsible for the ongoing clinical care of participants. Therefore, researchers and therapists had a duty of care to ensure that the GP was aware of any suicidal ideation expressed by participants. Researchers were not clinically trained and therefore adhered to the study’s safety and disclosure policy and did not engage in any assessment of risk. This policy stated that if at any time the researcher believed that there was a significant suicide risk with a patient who was participating in the study (which had not been communicated to his/her GP), the researcher would ask the patient for their consent to pass this information on to their GP. If the patient refused, the researcher would consult the appropriate clinician (or nominated deputy) at the research site. This person would examine the patient’s data and, if it was considered necessary, would assess the patient. If it was concluded that there was a significant risk, the patient’s GP would be notified without the patient’s consent. The need to break confidentiality in situations where there was significant concern about harm to the individual (or others) was explained in the patient information leaflet.

It was expected that therapists would use their clinical judgement to assess the seriousness of risk and follow normal clinical procedures with respect to communicating disclosure to the participant’s GP.

Trial monitoring

The trial was independently supervised by a TSC, chaired by an academic psychiatrist. Other members included an independent statistician, another senior academic with trials experience, a service user, an observer from the funder [National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment], the chief investigator (NW), principal investigator (GL), Trial Statistician (TP) and the trial co-ordinator. The trial was also supervised by an independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee, chaired by an academic GP and also including a statistician and an academic clinical psychologist. Members of these committees are named in Acknowledgements.

Chapter 3 Results: clinical effectiveness

Practice details

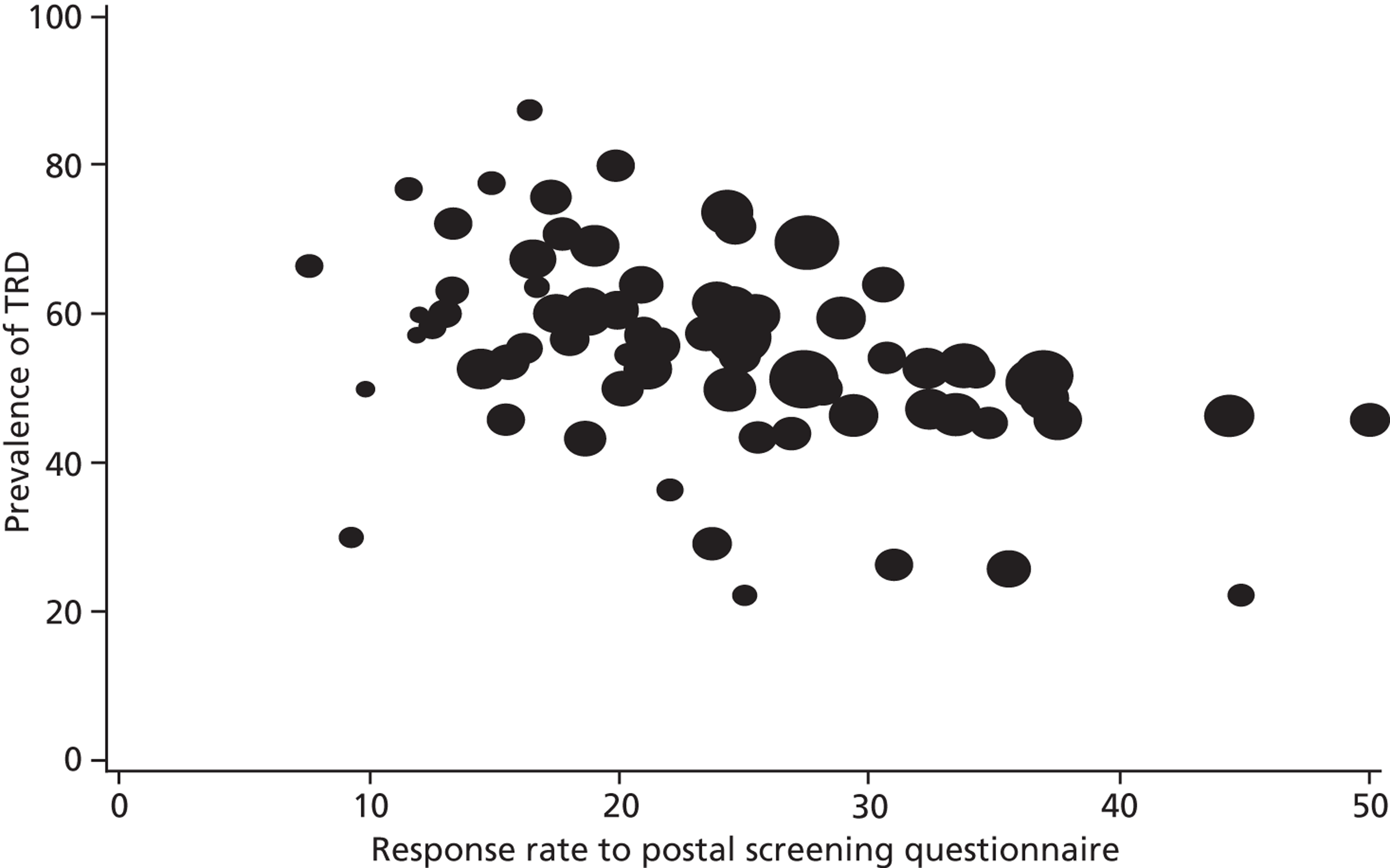

One hundred and six general practices across the three centres were approached to participate in the CoBalT study. Eighty-eight practices agreed to collaborate. Record searches were conducted and mailings sent out from 73 general practices. A summary of the practice characteristics for the 73 participating practices are presented in Table 5 . The average number of patients invited to participate in the study per practice was similar in all three centres, although the practices in Glasgow were smaller in size than the other two centres (Bristol and Exeter).

| Characteristic | Bristol | Exeter | Glasgow | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of practices | 26 | 22 | 25 | 73 |

| Practice list size: median (IQR) | 9435 (7400 to 12,026) | 7500 (6677 to 11,000) | 4281 (3200 to 6500) | 7400 (4286 to 10,368) |

| No. of full-time GPs per practice: mean (SD)a | 5.8 (2.3) | 5.1 (3.0) | 2.6 (1.3) | 4.5 (2.6) |

| No. of patients per practice | ||||

| Invited: median (IQR) | 158 (104 to 203) | 128 (96 to 157) | 143 (104 to 172) | 149 (98 to 180) |

| Screened: median (IQR) | 49 (36 to 57) | 38 (31 to 55) | 27 (17 to 37) | 37 (26 to 53) |

| Randomised: mean (SD) | 7.3 (4.4) | 7.3 (3.9) | 4.7 (2.2) | 6.4 (3.8) |

Flow of participants into the trial

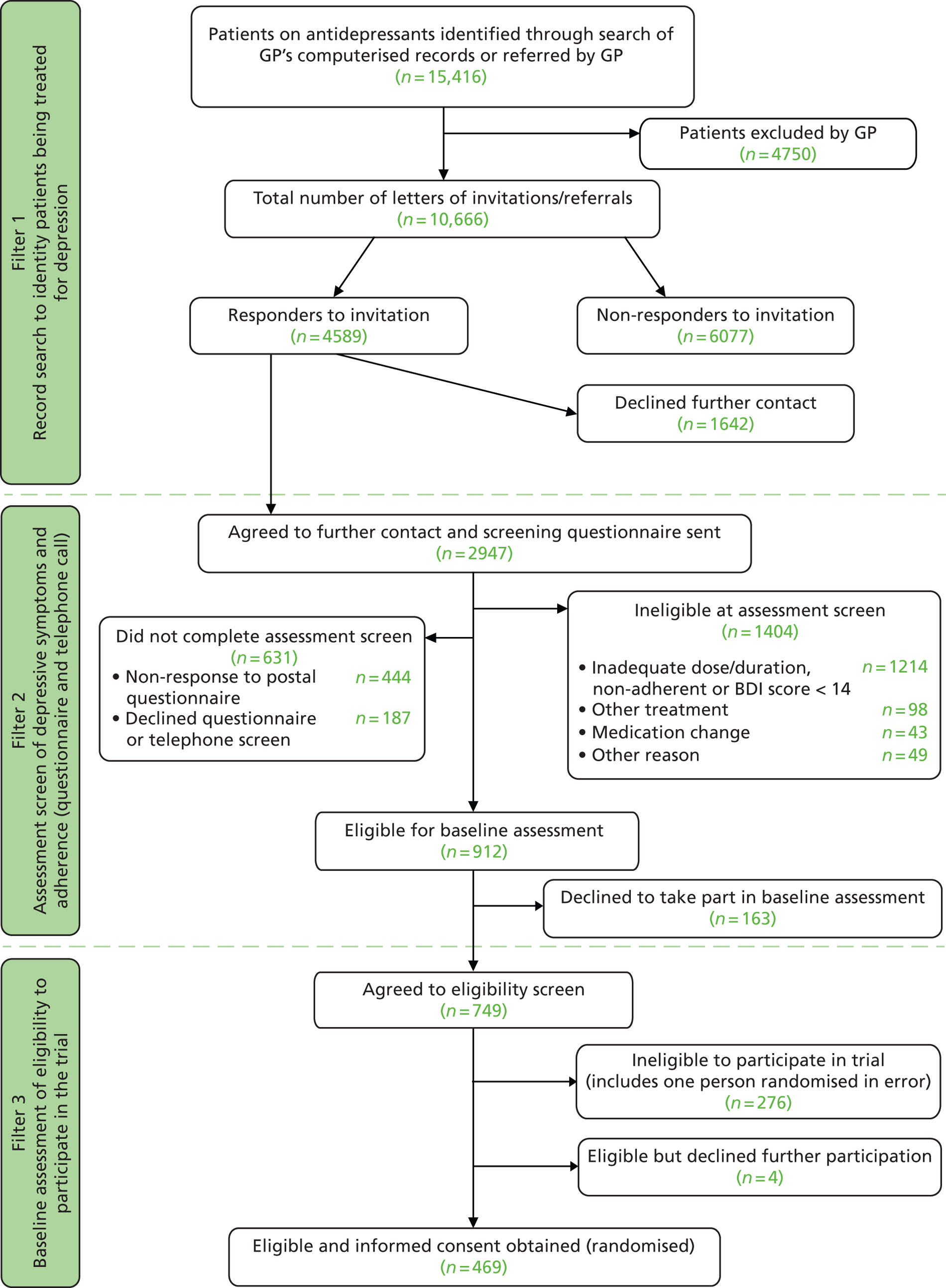

As it was not possible to easily identify those patients with TRD from general practice records, a screening process was used to firstly identify those patients being treated for depression (filter 1) and then assess their depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication (filter 2) in order to identify the target population who was potentially eligible to participate in the CoBalT trial. Potential participants were then invited to a baseline assessment with a researcher to establish eligibility (filter 3). The flow of participants through these three stages is described below. The screening process commenced in November 2009, and the final patient was randomised to the trial on 30 September 2010. All follow-up data were collected between March 2009 and 31 October 2011.

Search of general practitioner computerised records to identify patients being treated for depression

In total, 15,379 patients, aged 18–75 years, who had received repeated prescriptions for antidepressant medication over the previous 4 months and who were currently being prescribed antidepressants at an adequate dose for depression were identified through searches of the practice computerised records. A further 37 individuals were referred to the study directly by their GP. GPs excluded 4750 individuals who were ineligible ( Figure 3 – filter 1).

FIGURE 3.

Case CONSORT flow chart illustrating flow of participants into the CoBalT trial.

In all, 10,666 patients were mailed a letter of invitation to participate in the study asking for their permission for the research team to contact them or were invited to take part by their GP during the consultation. Of these, 4589 individuals (43.0%) responded to the letter of invitation, with the majority, 2947 (64.2%) agreeing for the research team to contact them (see Figure 3 – filter 1).

When available, information on age and gender was recorded from GP records. Older individuals were more likely to decline to participate [analysis of variance (ANOVA), p < 0.001]. Women were more likely to respond to the invitation to participate and to give permission for the research team to contact them (‘accepted invitation’) (chi-squared test: p = 0.001) ( Table 6 ).

Assessment of depressive symptoms and adherence to antidepressant medication

A screening questionnaire was mailed to 2947 potential participants (see Figure 3 – filter 2). In total, 631 individuals did not complete the assessment screen, either not responding to the postal questionnaire or declining to complete this questionnaire or the additional questions to assess eligibility asked over the telephone (see Figure 3 – filter 2). Older individuals were more likely to complete the assessment screening process (t-test: p = 0.007) ( Table 7 ). There was no evidence of a difference in gender between those who did or did not complete the assessment screen (chi-squared test: p = 0.13).

| N | Age | Female | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Mean | SD | n a | n | % | ||

| Did not complete screen | 631 | 599 | 46.8 | 13.3 | 615 | 455 | 74.0 |

| Completed assessment screen | 2316 | 2185 | 48.5 | 13.6 | 2244 | 1590 | 70.9 |

The primary aim of filter 2 was to identify those with TRD. A large number of respondents (n = 1214) were not eligible as their depression was below the threshold on the BDI-II (score of < 14) or they were not adhering to their antidepressant medication or did not meet the criteria for an adequate dose/duration of treatment (see Figure 3 – filter 2). In total, 912 participants were eligible to attend a baseline appointment with a researcher to establish an ICD-10 diagnosis of depression but 18% declined (see Figure 3 – filter 2). There were no differences in age or gender between those who did or did not agree to attend a baseline appointment ( Table 8 ) (t-test age: p = 0.48; chi-squared test gender: p = 0.37).

| Agreed to attend a baseline appointment with a researcher? | N | Age | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Mean | SD | n a | n | % | ||

| No (declined) | 163 | 154 | 50.7 | 13.3 | 155 | 113 | 72.9 |

| Yes (agreed) | 749 | 711 | 49.9 | 12.5 | 749 | 519 | 69.3 |

However, those who agreed to attend a baseline assessment were more highly educated than those who declined ( Table 9 ) (chi-squared test: p = 0.009).

| Agreed to attend a baseline appointment with a researcher? | N | n a | A-levels/Higher Grade or above | Other qualifications | No formal qualifications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| No (declined) | 163 | 160 | 58 | 36.3 | 53 | 33.1 | 49 | 30.6 |

| Yes (agreed) | 749 | 739 | 366 | 49.5 | 199 | 26.9 | 174 | 23.6 |

Baseline assessment of eligibility to participate in the randomised controlled trial

A total of 749 participants agreed to attend a face-to-face appointment with a researcher to discuss participating in the CoBalT trial, establish eligibility and obtain written informed consent (see Figure 3 – filter 3). The baseline assessment took place, on average (median), 34 days [interquartile range (IQR) 21–55] following completion of the screening questionnaire. Two hundred and seventy-six individuals were ineligible to participate (including one person who was randomised in error). The majority (n = 233) were ineligible because they did not meet ICD-10 criteria for depression. In total, 469 individuals were eligible to participate, gave written informed consent and were randomised (see Figure 3 – filter 3).

There were no differences between those who were and were not eligible to participate in the CoBalT trial in terms of age ( Table 10 ) (t-test: p = 0.20), although women were more likely to be eligible (chi-squared test: p = 0.02).

| Eligibility status | N | Age | Female | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n a | Mean | SD | n a | n | % | ||

| Eligible (including declined to participate) | 473 | 473 | 49.6 | 11.7 | 473 | 342 | 72.3 |

| Ineligible at baseline | 276 | 274 | 50.8 | 13.3 | 274 | 176 | 64.2 |

There were no differences in educational qualifications among those who were or were not eligible to participate in the trial ( Table 11 ) (chi-squared test: p = 0.12).

| Eligibility status | N | n a | A-levels/Higher Grade or above | Other qualifications | No formal qualifications | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |||

| Eligible (including declined to participate) | 473 | 467 | 218 | 46.7 | 131 | 28.1 | 118 | 25.3 |

| Ineligible at baseline | 276 | 272 | 148 | 54.4 | 68 | 25.0 | 56 | 20.6 |

Summary of recruitment by centre

A summary of the key recruitment statistics by centre is provided in Table 12 . Between 3000 and 4000 invitations were mailed out from each of the three centres. The percentage of patients who agreed for the research team to contact them was around 30% in both Bristol and Exeter. The percentage agreeing to be contacted was lower in Glasgow but, otherwise, the percentage completing the assessment screen, who were eligible to attend a baseline assessment and who were randomised, was similar in all three centres.

| Characteristic | Bristol | Exeter | Glasgow | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of practices | 26 | 22 | 25 | 73 |

| Invitations/GP referrals | ||||

| GP referrals | 13 | 19 | 5 | 37 |

| Total invitations | 4088 | 3066 | 3512 | 10,666 |

| No. returned | 1793 | 1607 | 1189 | 4589 |

| No. accepted | 1185 | 984 | 778 | 2947 |

| Percentage accepted | 29.0 | 32.1 | 22.2 | 27.6 |

| Assessment screen completed | 915 | 805 | 596 | 2316 |

| Percentage completing assessment screen | 77.2 | 81.8 | 76.6 | 78.6 |

| Eligible for baseline assessment | 369 | 313 | 230 | 912 |

| Percentage eligible | 40.3 | 38.9 | 38.6 | 39.4 |

| Baseline assessments | 313 | 251 | 185 | 749 |

| Randomisations | ||||

| No. | 190 | 161 | 118 | 469 |

| Percentage of baseline assessments | 60.7 | 64.1 | 63.8 | 62.6 |

| Average/month | 9.5/month, 20 months | 8.9/month, 18 months | 6.6/month, 18 months | 8.4/month |

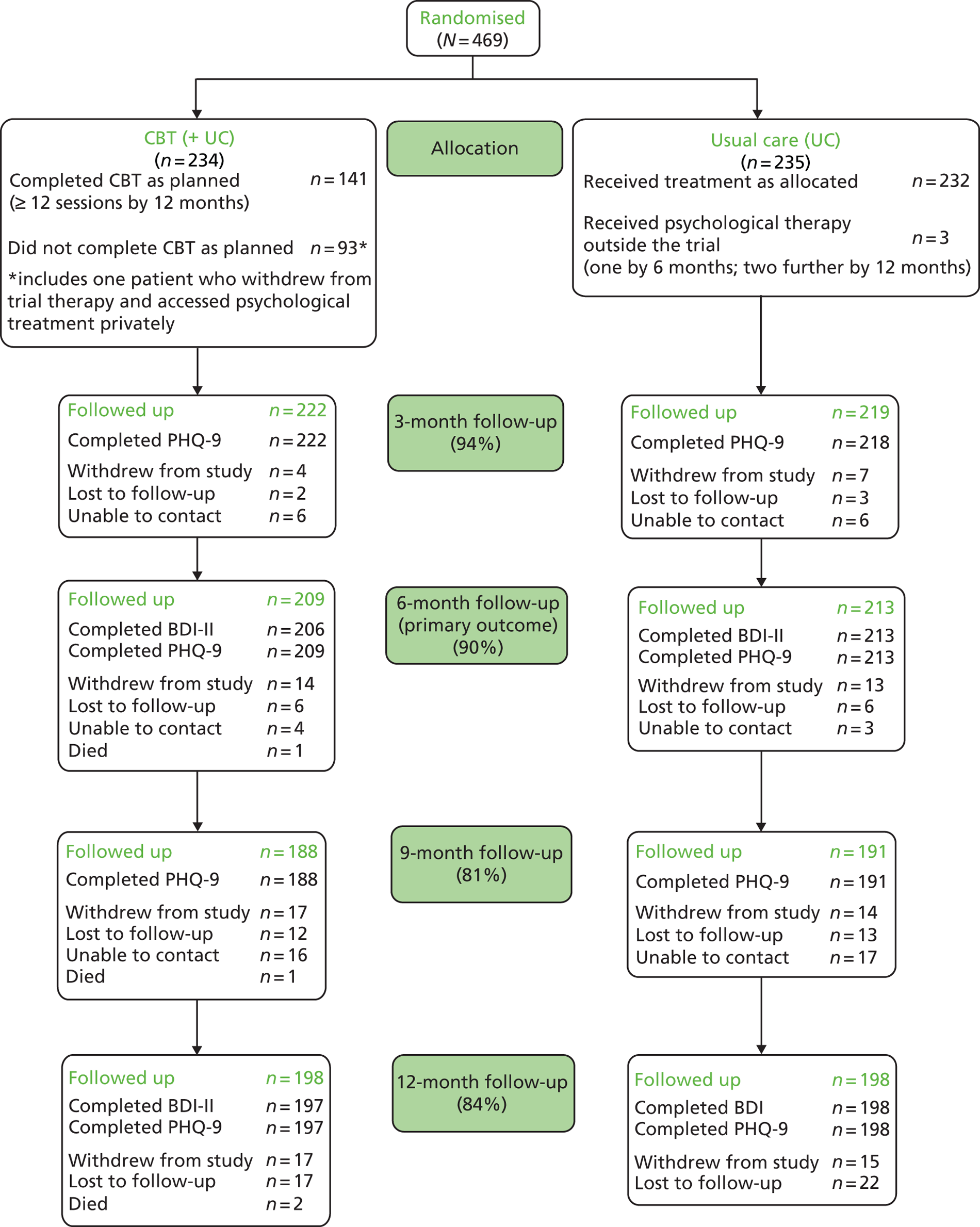

Follow-up of participants in the trial

Of the 469 randomised, 234 were allocated to receive CBT in addition to usual care and 235 were allocated to continue with usual care. All participants were taking antidepressant medication at the point of randomisation, with the expectation that this would continue as part of usual care for this patient group. The CONSORT flow diagram for the CoBalT trial is presented in Figure 4 . The number of individuals who withdrew from the study, were lost to follow-up or died is reported, as well as the number who could not be contacted at a particular follow-up but who were contacted later (‘unable to contact’ in Figure 4 ).

FIGURE 4.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart.

A summary of the follow-up rates by centre is given in Table 13 . Follow-up rates in Glasgow were lower than the other two centres. Part-way through recruitment, the Glasgow research team received additional support from the Scottish Mental Health Research Network (SMHRN), which enabled the research team to devote more resources to maximising the number of trial participants who were successfully contacted at the 12-month follow-up. This was prioritised over attaining a high follow-up rate at the brief 9-month telephone follow-up, hence explaining the lower follow-up rate at this time point. [The other two centres received additional support from the Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) from earlier in the study due to differences in the timing of the establishment of this network in England and Scotland.]

| Follow-up (months) | Bristol (n = 190) | Exeter (n = 161) | Glasgow (n = 118) | Total (n = 469) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| 3 | 180 | 94.7 | 157 | 97.5 | 104 | 88.1 | 441 | 94.0 |

| 6 | 176 | 92.6 | 156 | 96.9 | 90 | 76.3 | 422 | 90.0 |

| 9 | 166 | 87.4 | 152 | 94.4 | 61 | 51.7 | 379 | 80.8 |

| 12 | 164 | 86.3 | 150 | 93.2 | 82 | 69.5 | 396 | 84.4 |

Follow-up assessments were scheduled to take place at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months following randomisation. These time frames were not always achieved. However, the mean time to each follow-up was close to the target ( Table 14 ) and the vast majority of follow-up assessments were conducted within 2 months of the target (see Table 14 ).

| Follow-up (months) | n | Mean (months) | SD | Within x ± 2 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||||

| 3 | 441 | 3.1 | 0.4 | 437 | 99.1 |

| 6 | 422 | 6.4 | 0.7 | 406 | 96.2 |

| 9 | 379 | 9.1 | 0.4 | 376 | 99.2 |

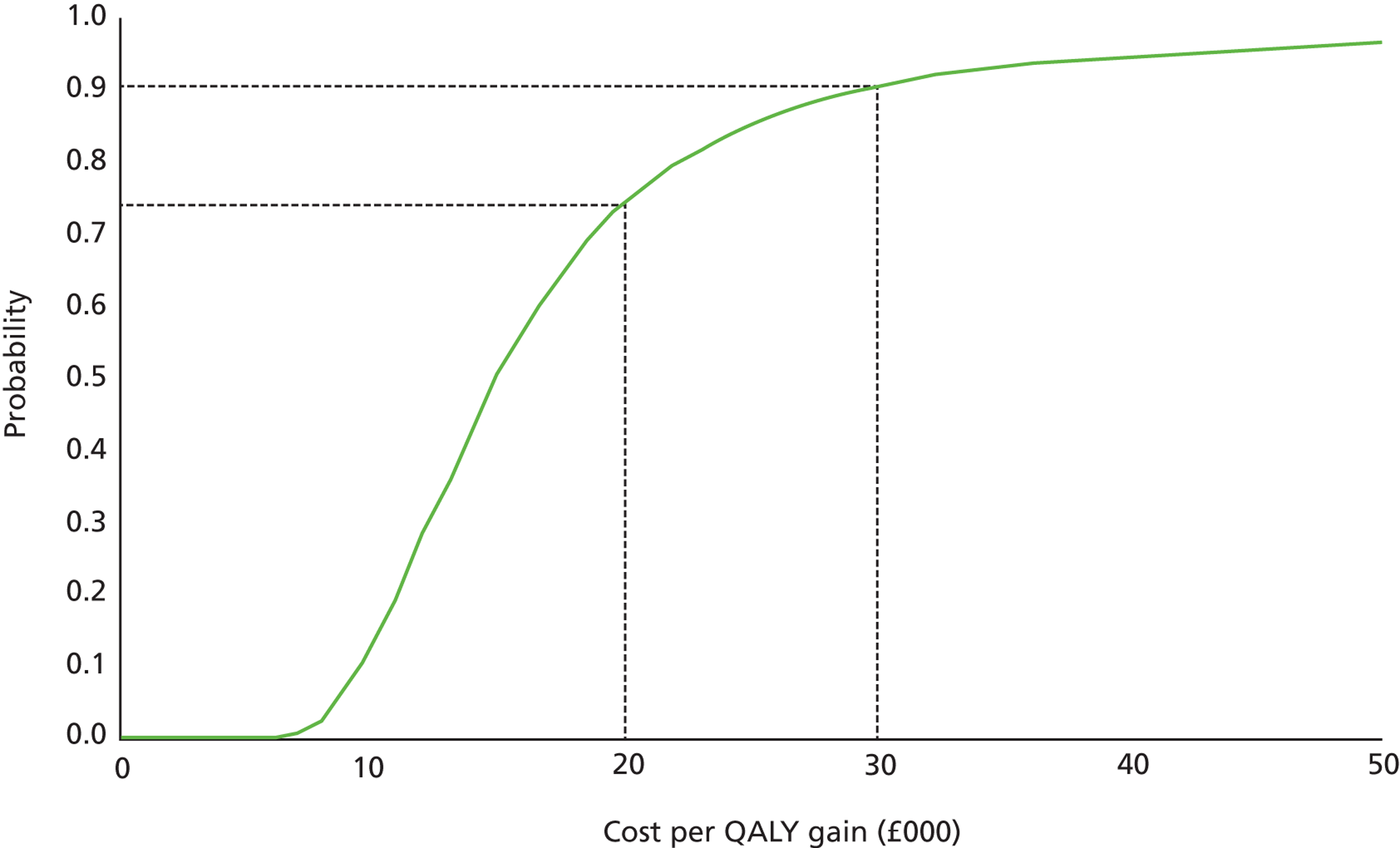

| 12 | 396 | 12.6 | 1.2 | 367 | 92.7 |