Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Technology Assessment journal series contains a project commissioned/managed by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC–NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HTA journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Brazier was a developer of the SF-6D and Michael Barkham was a developer of the CORE-OM.

Disclaimer: This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Brazier et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

There has been a shift in mental health services from an emphasis on treatment focused on reducing symptoms based on a narrow notion of health and disease, to a more holistic approach which takes into consideration both well-being and functioning. 1,2 Mental health services in the UK, for example, are now including the routine assessment of patient-reported outcomes in psychological services [e.g. the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) initiative and the Department of Health’s Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) programme]. At the same time, there has been an increasing use of generic measures of health, such as the EQ-5D, SF-36® (and its derivatives) and HUI3 in the economic evaluation of health-care interventions. These generic preference-based measures produce health-state utility values on a scale from 0 to 1 in order to calculate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). These QALY calculations are used by policy-makers including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) to assess the cost-effectiveness of interventions in terms of their cost per QALY gained. 3–10 These generic measures of health are designed for both physical and mental health problems; however, some argue that they are not suitable for people with more severe mental health problems, including psychosis. 11,12

In this report we present the findings of a research project examining the appropriateness of these generic measures for assessing the impact of mental health problems on quality of life. This chapter begins by describing the EQ-5D and SF-36 (and its derivative, the preference-based SF-6D® index). It goes on to consider the different definitions of quality of life and the problems of measuring such a subjective concept, in order to provide a broader context for the work being presented in this report. It then considers how the key measurement concept of validity is approached in the literature before providing an overview of the research undertaken for the report.

Generic preference-based measures

Many agencies around the world (e.g. NICE) recommend assessing the efficiency of new health-care interventions in terms of their incremental (or extra) cost per QALY gained. 4–10 The QALY combines survival and health-related quality of life into a single measure of value. The number of QALYs is calculated by multiplying survival in life-years by a value assigned to those years, which is known as a health-state utility value. Full health has a value of 1 and states equivalent to being dead are given a value of 0, with states worse than dead being negative. 13 While the QALY was initially used mainly to assess the benefits of life-saving treatments such as coronary artery bypass graft,14 over time it has been applied to assess the benefits of interventions aimed primarily at improving quality of life rather than quantity, including interventions for people with mental health conditions. The purpose of using a measure such as the QALY is to inform comparisons not only between treatments, but also between programmes of care across physical and mental health conditions.

This report appraises two generic preference-based measures used to generate values for health-related quality of life (HRQoL) on the zero-to-one QALY scale, and considers whether or not they are appropriate in people with mental health problems. The most commonly used measures for valuing health states in order to generate QALYs are the generic preference-based measures of health, such as the EQ-5D,15 SF-6D,16 HUI317 and Quality of Well-Being Scale. 18 Generic preference-based measures have two parts: one is a classification for describing health across a set of dimensions or domains, and the second is an algorithm for assigning values to each health state defined by the classification. The EQ-5D, for example, has five dimensions, each with three levels that together define 243 possible health states. A respondent is assigned a health state through their completion of a short questionnaire in which they indicate the level best describing their health on each dimension. The scoring algorithm is provided by valuations obtained from members of the general public using a valuation technique. In the case of the EQ-5D, the valuation technique is called time trade-off (TTO), whereby respondents are asked how many years in full health are equivalent to a longer period in an ill-health state. 9 The focus for this report, however, is not the method of scoring per se, but the description of health used by these instruments, as this largely determines the appropriateness of their use in mental health.

The EQ-5D has been selected as the most widely used preference-based measure and the one that is preferred by NICE in health technology assessment submissions and the Department of Health PROMs programme. The SF-36 and its derivatives (the SF-12® and the preference-based SF-6D) have also been selected because the SF-36 is another widely used generic measure of health, and the SF-6D is accepted by a number of other agencies around the world. 3–10

EQ-5D

The EQ-5D questionnaire comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and anxiety/depression ( Table 1 ). These can be seen as a combination of physical functioning (mobility, self-care), mental health (depression and anxiety), social functioning (which may be included in usual activities) and symptoms (pain and discomfort). Respondents are asked to report their level of problems (no problems, some/moderate problems or extreme problem/unable to do) on each dimension to provide a position on the EQ-5D health-state classification system. Responses can be converted into one of 243 different health states [ranging from no problems on any of the dimensions (11111) to severe problems on all five dimensions (33333)], each with its own preference-based score. Preference-based scores are determined by eliciting strength of preference data, that is, by establishing which health states are preferred from a sample of the general public. Preferences are elicited using the TTO technique, which involves asking participants to consider the relative lengths of time in full health (i.e. number of life-years) they would be willing to sacrifice to avoid poorer health states. The scoring algorithm, or social tariff, for the UK is based on TTO responses of a random sample (n = 2997) of non-institutionalised adults. Values are anchored by ‘1’ representing full health and ‘0’ representing the state ‘dead’, with states ‘worse than death’ bounded by ‘−1’. Utility values from the UK EQ-5D tariff range from −0.59 to 1. 15 The EQ-5D is often administered with the EQ visual analogue scale (EQ-VAS), which asks respondents to indicate their health state on a rating scale from worst health imaginable to best imaginable.

| Dimension | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Mobility | 1 | No problems walking about |

| 2 | Some problems walking about | |

| 3 | Confined to bed | |

| Self-care | 1 | No problems with self-care |

| 2 | Some problems washing or dressing self | |

| 3 | Unable to wash or dress self | |

| Usual activities | 1 | No problems with performing usual activities (e.g. work, study, housework, family or leisure activities) |

| 2 | Some problems with performing usual activities | |

| 3 | Unable to perform usual activities | |

| Pain/discomfort | 1 | No pain or discomfort |

| 2 | Moderate pain or discomfort | |

| 3 | Extreme pain or discomfort | |

| Anxiety/depression | 1 | Not anxious or depressed |

| 2 | Moderately anxious or depressed | |

| 3 | Extremely anxious or depressed |

SF-36 and SF-12

The SF-36 is a generic health status profile measure consisting of eight dimensions of general health, bodily pain, physical functioning, role-physical, mental health, vitality, social functioning and role-emotional ( Table 2 ). 19,20 These eight dimensions produced separate scores by taking a simple summation of item responses and applying a linear transformation to place them onto a 0 to 100 scale. There is also an alternative normalised scoring system generating a mean normative score of 50, with 10 points representing a standard deviation (SD) in a normal population. Physical and mental health component summary scores (PCS and MCS) can also be generated from these dimension scores. 10 The SF-1211 is a shortened version of the SF-36, containing 12 SF-36 items, and also produces PCS and MCS scores. These measures are two of the most widely used generic measures of health and have been validated in many conditions and settings. However, the SF-36 and SF-12 cannot be used in their standard form in economic evaluation because the scoring method is not preference-based and, therefore, cannot be used to generate QALYs. Furthermore, they produce a profile of scores and cannot be combined with survival, so they provide no single measure of effectiveness required for assessing cost-effectiveness. For this reason, a preference-based measure called the SF-6D has been derived from the SF-36.

| Dimension | No. of items | Summary of content | No. of response choices | Range of response choice |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 10 | Extent to which health limits physical activities such as self-care, walking, climbing stairs, bending, lifting, and moderate and vigorous exercises | 3 | ‘Yes limited a lot’ to ‘no, not limited at all’ |

| Role limitations – physical | 4 | Extent to which physical health interferes with work or other daily activities, including accomplishing less than wanted, limitations in the kind of activities, or difficulty in performing activities | 2 | Yes/No |

| Bodily pain | 2 | Intensity of pain and effect of pain on normal work, both inside and outside the home | 5 and 6 | ‘None’ to ‘very severe’ and ‘not at all’ to ‘extremely’ |

| General health | 5 | Personal evaluation of health, including current health, health outlook, and resistance to illness | 5 | ‘All of the time’ to ‘none of the time’ |

| Vitality | 4 | Feeling energetic and full of life vs. feeling tired and worn out | 6 | ‘All of the time’ to ‘none of the time’ |

| Social functioning | 2 | Extent to which physical health or emotional problems interfere with normal social activities | 5 | ‘Not at all’ to ‘extremely’ and ‘All of the time’ to ‘none of the time’ |

| Role limitations – emotional | 3 | Extent to which emotional problems interfere with work or other daily activities, including decreased time spent on activities, accomplishing less and not working as carefully as usual | 2 | Yes/No |

| Mental health | 5 | General mental health, including depression, anxiety, behavioural–emotional control, general positive affect | 6 | ‘All of the time’ to ‘none of the time’ |

SF-6D

The SF-6D provides a means of translating the SF-36 or the SF-12 into a preference-based single index. 16,21 The SF-6D reduces the eight dimensions of the SF-36 to six: physical functioning, role limitations, social functioning, pain, mental health and vitality ( Table 3 ). Each dimension has four, five or six levels, giving a total of 18,000 possible health states. The values attached to each level and dimension generated by the classification system were derived from standard gamble valuations for a sample of 249 of these health states. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with a representative sample of 611 members of the UK population. 16 States were valued by asking respondents to choose between each of five SF-6D states (imagining they remained in those states for the rest of their lives), versus a gamble between the best and ‘pits’ health states. Respondents were then asked to value the worst state in relation to immediate death. The valuations for the SF-6D were derived from a linear random-effects model, and ranged from 0.29 to 1.0 (full health) (see www.shef.ac.uk/scharr/sections/heds/mvh/sf-6d). 16

| Dimension | Level | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Physical functioning | 1 | Your health does not limit you in vigorous activities |

| 2 | Your health limits you a little in vigorous activities | |

| 3 | Your health limits you a little in moderate activities | |

| 4 | Your health limits you a lot in moderate activities | |

| 5 | Your health limits you a little in bathing and dressing | |

| 6 | Your health limits you a lot in bathing and dressing | |

| Role limitations | 1 | You have no problems with your work or other regular daily activities as a result of your physical health or any emotional problems |

| 2 | You are limited in the kind of work or other activities as a result of your physical health | |

| 3 | You accomplish less than you would like as a result of emotional problems | |

| 4 | You are limited in the kind of work or other activities as a result of your physical health and accomplish less than you would like as a result of emotional problems | |

| Social functioning | 1 | Your health limits your social activities none of the time |

| 2 | Your health limits your social activities a little of the time | |

| 3 | Your health limits your social activities some of the time | |

| 4 | Your health limits your social activities most of the time | |

| 5 | Your health limits your social activities all of the time | |

| Pain | 1 | You have no pain |

| 2 | You have pain but it does not interfere with your normal work (both outside the home and housework) | |

| 3 | You have pain that interferes with your normal work (both outside the home and housework) a little bit | |

| 4 | You have pain that interferes with your normal work (both outside the home and housework) moderately | |

| 5 | You have pain that interferes with your normal work (both outside the home and housework) quite a bit | |

| 6 | You have pain that interferes with your normal work (both outside the home and housework) extremely | |

| Mental health | 1 | You feel tense or downhearted and low none of the time |

| 2 | You feel tense or downhearted and low a little of the time | |

| 3 | You feel tense or downhearted and low some of the time | |

| 4 | You feel tense or downhearted and low most of the time | |

| 5 | You feel tense or downhearted and low all of the time | |

| Vitality | 1 | You have a lot of energy all of the time |

| 2 | You have a lot of energy most of the time | |

| 3 | You have a lot of energy some of the time | |

| 4 | You have a lot of energy a little of the time | |

| 5 | You have a lot of energy none of the time |

What is ‘quality of life’?

The question addressed in this report is whether the EQ-5D or SF-6D are able to reflect the way mental health problems impact on the quality of people’s lives. Before addressing this question it is helpful to consider more broadly the way quality of life can be defined. Quality of life has been described as an amorphous concept for which there is no widely accepted theory or measurement instrument. 22 The area is bedevilled by the absence of any accepted gold standard. There are many different views or models of quality of life and the more influential ones in health include: objective indicators, needs satisfaction, subjective well-being, capabilities, psychological health and subjective health or HRQoL. These views are not independent and often overlap. This section provides a brief description of these different accounts in order to understand where EQ-5D and SF-36 fit into the literature, and to provide some background for interpreting some of the findings presented from the qualitative research reported in Chapters 5 and 6 .

Objective indicators

A tension exists in quality-of-life measurement over whether it should have a subjective or objective orientation. A more objective approach may place its emphasis on income, living conditions, access to resources, participation in occupational and social roles,23,24 or the presence or absence of a medical condition or symptom. While objective measures have an important place in the broader quality-of-life literature, within health there has been an increasing emphasis on the importance of the patient’s perspective and this has been assumed to imply a move away from objective measures. This has been partly because many of the commonly used objective indicators like income have been found to be only weakly related to well-being. It is also because objective indicators, by their nature, take a top-down, paternalistic approach, rather than reflecting what individuals might perceive to be important to their quality of life. There has been a similar movement in health care, with a move away from using clinical indicators to measure the outcome of health care towards a more user-focused approach using subjective measures of health and well-being.

Needs satisfaction

There has been a tradition of defining quality of life in terms of the extent to which human needs are met. This is based on Maslow’s25 hierarchy of needs necessary for human existence (e.g. food, drink and shelter, social and belonging, status and self-esteem and self-actualisation). Once the basic needs for food, drink and shelter are met, then human beings can look to fulfil higher needs such as control, autonomy, pleasure and self-realisation. 26,27 These have been found to correlate highly with life satisfaction. This approach continues to be influential in the development of measures, including recent work on an outcome measure for social care. 28

Subjective well-being

It can be argued that in the developed world, where basic needs have been met, a focus on objective or needs-based measures should be replaced by perceived well-being. 29 Economists in the 19th century saw utility as a cardinal indicator of happiness and this comes from the utilitarian Benthamite tradition concerned with maximising the happiness of the greatest number. 30 There has been something of a revival in using happiness and other measures of well-being in public policy in psychology and economics, such as through the work of Kahneman and others. 31 In its modern formulation, subjective well-being is seen to have two components. One is a hedonistic view based on how an individual feels in any given moment. It has typically been assessed using simple items asking people to rate their current level of happiness. 32 The second is a more evaluative concept based on a reflection on how satisfied we are with our lives, and this may include past and present happiness and future expectations, and embrace notions of self-fulfilment, realisation or actualisation. This has typically been assessed using items that ask people to rate how satisfied they are with their life and aspects of it. 33

The revival of subjective well-being in economics has in part been a response to criticisms of measures of benefit used by economists in economic evaluations such as the QALY. By the start of the 20th century, mainstream economics had moved away from an experiential view of utility to one based on preference satisfaction. 34 This is best seen in the marketplace where individuals make choices between goods and services on the basis of what they most desire. They are regarded as autonomous and perfectly informed individuals who will choose the mix of goods and services that maximises their well-being. Where such ‘revealed’ preferences are not available, as is often the case for health, respondents are asked to state strength of preference for different states of the world. This is a preference-based or decision-based notion of utility. However, there is a large body of evidence that consumers do not necessarily know what will maximise the well-being that they eventually experience. 31 While this debate has not been important in the general quality-of-life literature, it has been highly controversial in health economics since the EQ-5D and SF-6D are scored using the preferences of the general public. 35

Capabilities

The notion of capability was developed by Sen36 in response to what he regarded as the narrow perspective of economists in the way they assessed value. He argues that subjective well-being and preference-based utility both fail to consider all the factors that matter for informing public policy. Again, this is an economics-focused debate, but one that has important implications later in this report for the interpretation of qualitative data on what seems to matter to people with mental health problems (see Chapters 5 and 6 ).

Sen36 offers a framework for moving from the purchase of goods and services (including health care) to utility or well-being. He proposes that along the way individuals are transformed by the benefits of the goods or service; for example, a bicycle will confer improved functioning in terms of mobility. 36,37 Economics usually ignores the impact of what a person has on a person’s functioning, and focuses on utility as reflected in their choices. Sen takes it one step further for policy-making, as he argues that public policy is not concerned with functioning per se; so, in the case of the bike, public policy is concerned not with whether or not the person chooses to use the bike, but simply the fact that they are able to function in a particular way. This idea of capability offers someone the choice to be able to ‘do’ or to ‘be’. The object of public policy is to provide opportunities and not to make people do one thing or another. Sen accepts that for some basic capabilities this distinction between capability and functioning may not be important as individuals have little choice, but in large areas of public policy it will be important to separate out these concepts. 36

Sen did not prescribe a particular set of capabilities or a way to operationalise the concept. There have been attempts by others, with the most common being attempts by experts to construct a list of those functionings they think are important, covering basic capabilities through to higher-level issues around human rights and well-being. 38 These tend to be more like the objective lists described earlier and there has been little attempt to score them. In health economics, examples of capability measures include the recently developed ICECAP-O and ICECAP-A, though these use stated preferences to generate the scores. The items were developed from interviews with members of the general public, and attempts to capture the idea of capability by using terms such as ‘I am able to be . . .’ or ‘I can have . . .’. 39,40 Although there may be doubts about whether or not this is truly a measure of capability (including the way it uses preferences in the scoring), it is an important development in terms of going beyond health. This measure will be considered again in the light of the findings of this research in Chapter 6 .

Psychological well-being

This is a broad category of constructs that covers aspects of personality that include morale, self-esteem and self-concept, sense of coherence, self-efficacy, autonomy and control. This list often includes aspects of subjective well-being, but we have presented them separately as they can be seen as mediating variables rather than necessarily determining quality of life in their own right. Indeed, it has been proposed that there should be a model of quality of life based on these psychological factors and the way they explain variations in subjective well-being through cognitive mechanisms. 41,42 They clearly have an important role in the way people cope with and adapt to problems with their health. Knowledge of the precise mechanisms and the support for different models, however, are limited. It is interesting to note that these variables have also been found in measures of quality of life and capabilities as dimensions in their own right. 27,39,40

Health and health-related quality of life

There has been a separate tradition of measuring perceived health in health services research and health economics, and the EQ-5D and SF-36 have come out of this tradition. 43 Health can be seen as a part of quality of life, and is usually seen as narrower than quality of life. However, some definitions of health are very broad, such as the widely cited World Health Organization (WHO) statement, set out in its original constitution, that health is: ‘A state of complete physical, mental and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity’. 44 This too is a rather amorphous construct. The field is made more complicated by the idea of HRQoL, whereby the concern is not with health per se but those aspects of quality of life that are related to a person’s health. Given the central role of health in many people’s lives, this is likely to cover many different aspects of quality of life. A definition of HRQoL provided by researchers, representing what many people in the field mean by HRQoL, is: ‘A person’s subjective perception of the impact of health status, including disease and treatment, on physical, psychological and social functioning and well-being’. 45 This is also a broad definition, and as a result, the content of HRQoL measures varies widely and is no less wide-ranging in coverage than many measure purporting to measure quality of life; indeed, they are often wider.

Discussion of views of quality of life and their implications for this report

This section has demonstrated that there are many different and often competing views of quality of life: objective versus subjective accounts; what people do and feel versus capability; well-being versus psychological well-being (e.g. self-esteem, autonomy, choice and so forth); and narrow versus broader notions. No measure can capture all these elements and ultimately there is a value judgement to be made regarding what matters to policy-makers. It is also the case that these views are not entirely separable, so, for example, needs satisfaction covers objective aspects alongside those concerned with psychological well-being. In practice, measures often contain items from more than one of these views of quality of life. The EQ-5D, for example, covers negative aspects of well-being (i.e. depression and anxiety) and objective aspects such as mobility and self-care. Items of the SF-36 cover well-being (i.e. mental health and vitality), objective aspects (i.e. physical function) and psychological health (i.e. general health perception).

The lack of an agreed view or clear definition means that any attempt to measure quality of life and mental health-related quality of life is fraught with difficulty. This rules out the application of criterion validation in this field, whereby a measure is compared to some accepted gold standard. This has been a source of frustration for researchers and has led to some scepticism as to the value of trying to measure quality of life. 46 However, the primary aim of health services is to improve the quality (health related) and quantity of life, so it is imperative for policy-relevant research to have measures of what matters in the lives of people who use health services. The aim of this report is to examine the extent to which the EQ-5D and SF-36 achieve this through the application of qualitative and quantitative methods.

The appropriateness of the EQ-5D and SF-36 in mental health

Measures of health or HRQoL can be generic, or specific to a patient group defined in various ways (e.g. by a medical condition). The EQ-5D and SF-36 are generic measures that are intended to reflect a core set of domains relevant to all groups of patients (such as mobility, self-care or pain). The more specific measures cover a narrower set of domains and tend to be more symptoms-orientated. Mental health research has tended to be dominated by measures specific to mental health, such as the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder Assessment (GAD-7), General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-12), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Lancashire Quality of Life Scale, Health of the Nation Outcome Scales (HoNOS), Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure (CORE-OM), Camberwell Assessment of Need (CAN) and many more. Generic measures of health are rarely used in mental health research and this has been seen as a major limitation to conducting economic evaluations in mental health. 1 This has been either because these measures are not regarded as valid in the patient group or investigators are keen to keep patient burden down and prefer to use a more specific measure.

There has been some scepticism about the appropriateness of the EQ-5D in mental health, given that it has only one dimension specifically addressing mental health problems,11,47–49 though some have argued it is appropriate in common mental health conditions like depression. 50 Recent years have seen the development of preference-based condition-specific measures,51 including one for common mental health problems. 52 However, the pressure to use generic measures remains and has started to impact on the scales used in clinical studies and, most recently in the UK, in routine patient-reported outcome measurement. The appropriateness of a measure depends on meeting criteria such as reliability, validity and responsiveness. This report is concerned with bringing together quantitative and qualitative evidence on these criteria.

Assessing appropriateness

This report brings together important new evidence on the appropriateness of the two most widely used generic preference-based measures in mental health in the UK (the EQ-5D and SF-6D), and assesses whether or not it is necessary to adapt them in some way, or consider developing a new preference-based measure for mental health. It uses a combination of quantitative and qualitative evidence within the psychometric framework to assess the validity of the measures in mental health populations. 53,54

Validity

Validity is defined as the extent to which an instrument measures what it is intended to measure and is the core criterion for assessing psychometric performance. The problem for assessing validity is that there is not a gold standard for comparison, as the concept of quality of life, and, therefore, mental health-related quality of life, is fundamentally subjective. Nonetheless, various indirect ways of establishing validity have been developed in the health field and elsewhere, including content validity and construct validity. 55,56

Content validity ‘refers to the degree to which the content of the items reflects the content of the domains of interest’. 57 There are quantitative methods for assessing content validity, based on the extent of agreement between experts regarding the extent to which an item taps the domain. However, these techniques presuppose that the domains are known, which may not always be the case. To address this gap, researchers in the health field have increasingly been applying qualitative methods to obtain the views of people with a given condition to develop and validate the content of the instrument. 56 Indeed, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration58 regards this as an essential step in the process of validating a patient-reported outcome measure. Qualitative methods provide a depth of understanding that is rarely possible with conventional psychometric techniques. We obtained evidence on the appropriate content of a measure of the impact of mental health problems on quality of life by reviewing qualitative studies of people with mental health problems using in-depth interviews and focus groups. The findings were further tested by conducting in-depth interviews with mental health service users in order to obtain data on a broader range of mental health problems and to refine the emerging themes.

The more conventional approach to validation is to examine construct validation. This can be broken down into two types of tests: discriminant or known-group differences validity and convergent validity. Known-group validity requires data sets with indicators or measures of severity that can be used to define the groups. It should be noted that the usefulness of these tests is limited by sample size (especially as studies are usually not powered on a preference-based measure), the appropriateness of the clinical groups defined, and exogenous factors that may influence quality of life. For instance, groups may be defined by specific clinical symptoms such as mania, but whether or not these result in differences in quality of life is less clear. In mental health there is also the problem of comorbidities, whereby differences between groups may arise due to another condition (such as physical health problems or depression) rather than the one being considered (e.g. schizophrenia).

The other subset of construct validity examined in this report, convergent validity, is defined as the extent to which one measure correlates with another measure of what is purported to be a similar concept. This can be the extent to which generic measures correlate with each other and/or with measures of mental health, but again this depends on the extent to which the latter reflects genuine differences in quality of life.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness is the ability of an instrument to measure clinically significant changes in health over time and can be seen as another form of validity. Responsiveness is usually assessed statistically using measures such as the ‘effect size’ (where the mean change in score is divided by either the SD at baseline or the SD of the change). A common assumption in the assessment of responsiveness is that for a given health change, the measure with the largest effect size is the better measure. 59 Where the objective is to minimise sample size, this makes sense and maximises the ability to detect significant differences. For economic evaluation, this is less important and, instead, it is a case of establishing that the descriptive content is able to detect change of significance to service users. Related to this is the concept of precision, which is concerned with the ability of a measure to detect changes over the range experienced by patients being assessed. 53 This requires the items and levels of the domains to be well spread over the range of the measure.

The problem for assessing validity and the related responsiveness is that it is rarely possible to prove that a measure is valid or that it is not valid. The nature of the evidence is rarely that conclusive. It is more a question of bringing together evidence, both quantitative and qualitative, that either supports or refutes the claim of validity in comparison to other measures and indicators used in the field.

Outline of report

The aim of this research is to assess the appropriateness of the EQ-5D and the SF-36 (and its derivatives the SF-12 and the preference-based SF-6D) in people with mental health problems, in terms of their validity and responsiveness. These criteria are assessed using evidence from a range of different sources: the literature, a number of existing data sets and interviews with users. This research considers all the main groups of people with mental health problems, including those with common mental health problems (e.g. mild to moderate depression, anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder and panic disorders), severe and complex non-psychotic disorders (e.g. personality disorder), and schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. The ways the groups are defined is to a large extent determined by the literature being reviewed, the data available or, in the case of the interviews, by the way services for people with mental health problems are organised. Although we must adopt diagnostic and service groupings in parts of the report, such groupings are not mutually exclusive and, furthermore, many users have more than one diagnosis.

In all, there were four studies undertaken to examine the appropriateness of the measures, and a fifth study to estimate mapping functions between the EQ-5D and SF-6D and commonly used mental health-specific measures. Chapters 2 and 3 are concerned with the quantitative evidence on the construct validity (i.e. known-group differences and convergent validity) and responsiveness, with Chapter 2 presenting a systematic review of the existing literature on the EQ-5D and SF-36 across the main mental health conditions and Chapter 3 presenting new psychometric analyses of existing data sets. For those situations where the EQ-5D and/or SF-6D were found to be acceptable in terms of their psychometric properties, the next stage was to estimate mapping functions between those mental health-specific measures widely used in clinical studies and the two generic measures. This is presented in Chapter 4. Chapters 5 and 6 present qualitative evidence on the domains of quality of life that appear to be important to people with mental health problems in order to shed light on the validity of the content of these generic measures. Chapter 5 presents a review of previous qualitative research; although this evidence was helpful in starting to identify key themes on the impact of mental health problems on quality of life, it was limited in terms of the groups covered and by the topic guide used by the researchers. Therefore, in-depth interviews were carried out with mental health service users and a thematic analysis undertaken, and this is presented in Chapter 6 in order to provide the basis for reviewing the appropriateness of content of the generic measures.

Chapter 7 presents a brief overview of the findings of each study before discussing the main findings of this research, and presents the recommendations for further research and implications for policy.

Chapter 2 A systematic review of the validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D, SF-36, SF-12 and SF-6D in mental health

This chapter examines the validity and responsiveness of two generic preference-based measures of health (the EQ-5D and SF-6D) and two related generic non-preference-based measures (the SF-36 and SF-12) in populations with mental health problems. The assessment is based on a systematic review of studies reporting one or more of these measures alongside various condition-specific indicators of mental health that can be used to assess validity using known-group comparisons and convergence, and responsiveness to changes in health over time. It forms the first study presented in this report.

This review covers five mental health conditions: schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, personality disorders, depression and anxiety. Four separate systematic reviews were undertaken from one common search of the literature, with depression and anxiety reviewed together. This chapter presents the methods and an overview of the findings. The detailed findings with tables of results by study are available in published articles or in discussion paper form. 60–62

Methods

Selecting review studies

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they contained HRQoL data obtained using one or more of the instruments under study (SF-36, SF-12, SF-6D or EQ-5D) within the specified population of adults (aged ≥ 18 years) suffering from one of the five conditions. HRQoL data could be from descriptive systems (i.e. their items and dimensions) or health-state utility values generated by the EQ-5D or SF-6D, or the EQ-VAS. Studies whose primary focus was on individuals with alcohol and/or drug dependency were excluded whether or not those individuals had one of the five conditions. The outcomes had to include data that allowed measurement of the construct validity (i.e. known groups, convergent or discriminant) or the responsiveness of the HRQoL instrument(s). Responsiveness data had to be in the form of effect sizes, standardised response means (SRMs) or correlation with change scores on symptom measures. Studies that only provided data on other psychometric properties, such as reliability, face validity and content validity, were not included.

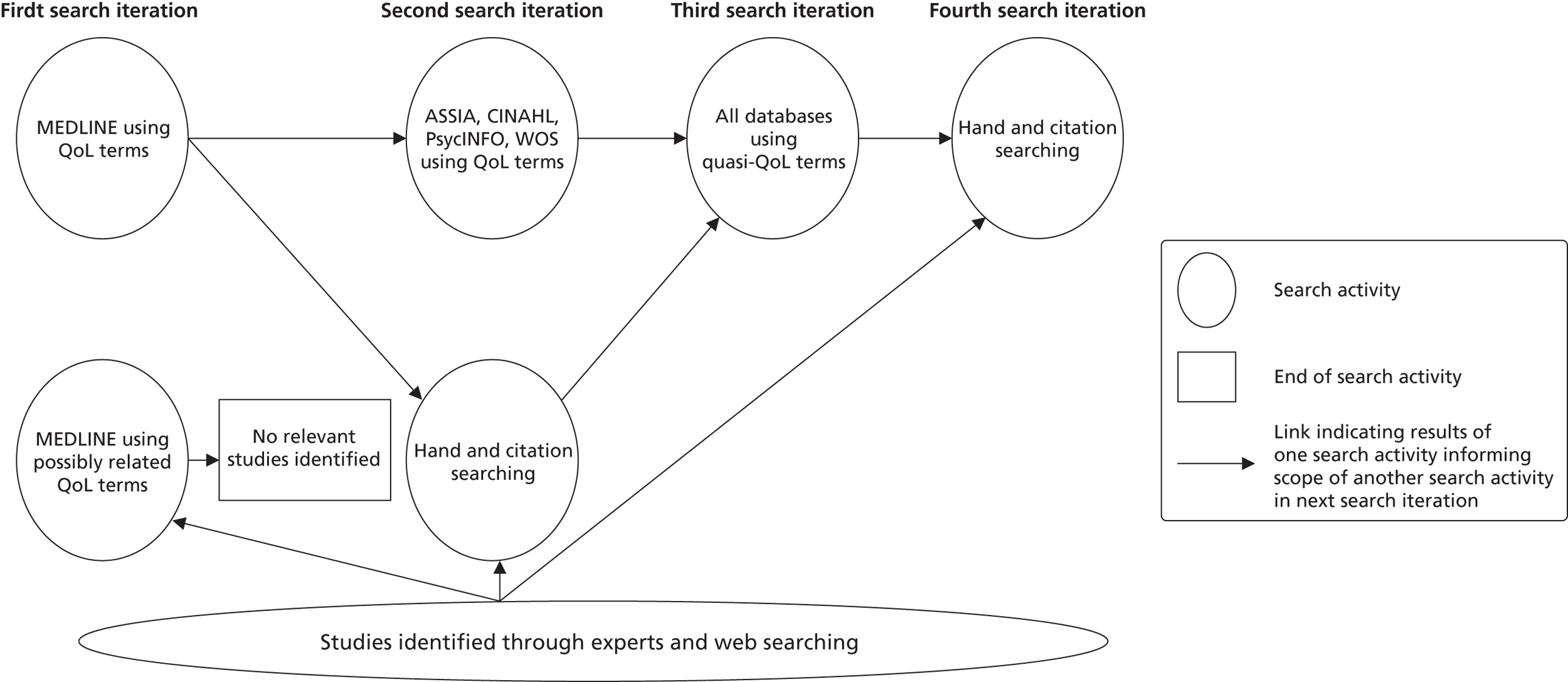

Identification of studies

A literature search was performed to identify relevant research for all mental health conditions being investigated within the wider review, using a database thesaurus and free text terms. Two sets of search terms were combined: terms for each of the four HRQoL measures and terms for each mental health condition (the search strategy is in Appendix 2 ). Ten databases were searched for published research from inception: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED), Health Technology Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE and Web of Science. Searches were limited to English language only but not by any date restriction. All searches were initially conducted in August 2009, though updates were undertaken for personality and bipolar disorders until March 2011, and for depression and anxiety until December 2010. The reference lists of relevant studies were searched for further papers.

Citations identified by the searching process were screened by one reviewer (DP or TP) using the inclusion criteria. The full texts of papers were retrieved for any titles or abstracts that appeared to satisfy the inclusion criteria, or for which inclusion or exclusion could not be definitely determined. The same inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to assess full-text papers and any queries over inclusion were resolved by discussion and consensus between two reviewers (DP and JB or TP and JB).

Data extraction

Data from all included trials were extracted using a form designed specifically for this review, and piloted on a sample of papers. Data extracted included: country of publication, type of disorder, study sample characteristics (numbers, age, sex), other measures used, mean scores on HRQoL measures, type and method of validity assessment, type and method of responsiveness assessment, and validity and responsiveness data. Extractions were performed by one reviewer (DP or TP). Where duplicate publications reported on similar data, the most complete and recent data were extracted.

Quality assessment

There is no formal method for assessing the quality of these studies (i.e. there are no quality assessment checklists), and thus we used the methods described by Fitzsimmons et al. 63 to evaluate HRQoL data in their systematic review on the use and validation of HRQoL instruments with older cancer patients. These included examining whether or not tests of statistical significance were applied, differences between treatment groups reported (where applicable, e.g. in known-group validity), clinical significance discussed and missing data documented. We also report on response and completion rates where these were provided.

Evidence synthesis and meta-analysis

Owing to the large degree of heterogeneity between studies (including types of study designs, HRQoL measure, population characteristics and methods of determining construct validity and responsiveness), it was not appropriate to perform meta-analysis. Analysis was by narrative synthesis and data were tabulated. All analyses were performed based on the HRQoL measure, with data analysis grouped by type of validity (convergent/discriminant or known groups) or responsiveness test used.

Defining validity and responsiveness

Validity and responsiveness were assessed using the definitions presented in Chapter 1 . For convergent validity, the strength of correlation between the two measures is calculated using statistical tests (e.g. Pearson’s product moment correlation or Spearman’s rank correlation). We have used the following categories for evidence of correlation: > 0.6 = very strong, ≥ 0.5 to < 0.6 = strong, < 0.5 to ≥ 0.3 = moderate, and < 0.3 = weak. Statistical significance is also attached to correlations (p < 0.05). Responsiveness can be measured in a number of ways by effect size statistics64 standardised in different ways, such as dividing through by the SD at baseline or SD of the change in scores over time (i.e. SRMs). Within this review, Cohen’s65 categories for magnitude of effect size were used: ≥ 0.80 = large, < 0.80 and ≥ 0.50 = moderate, and 0.30 to < 0.50 = small. As pointed out in Chapter 1 , these tests need to be used with some care as there is no gold standard and the application of these tests sometimes uses indirect indicators of the concept (e.g. symptoms rather than quality of life).

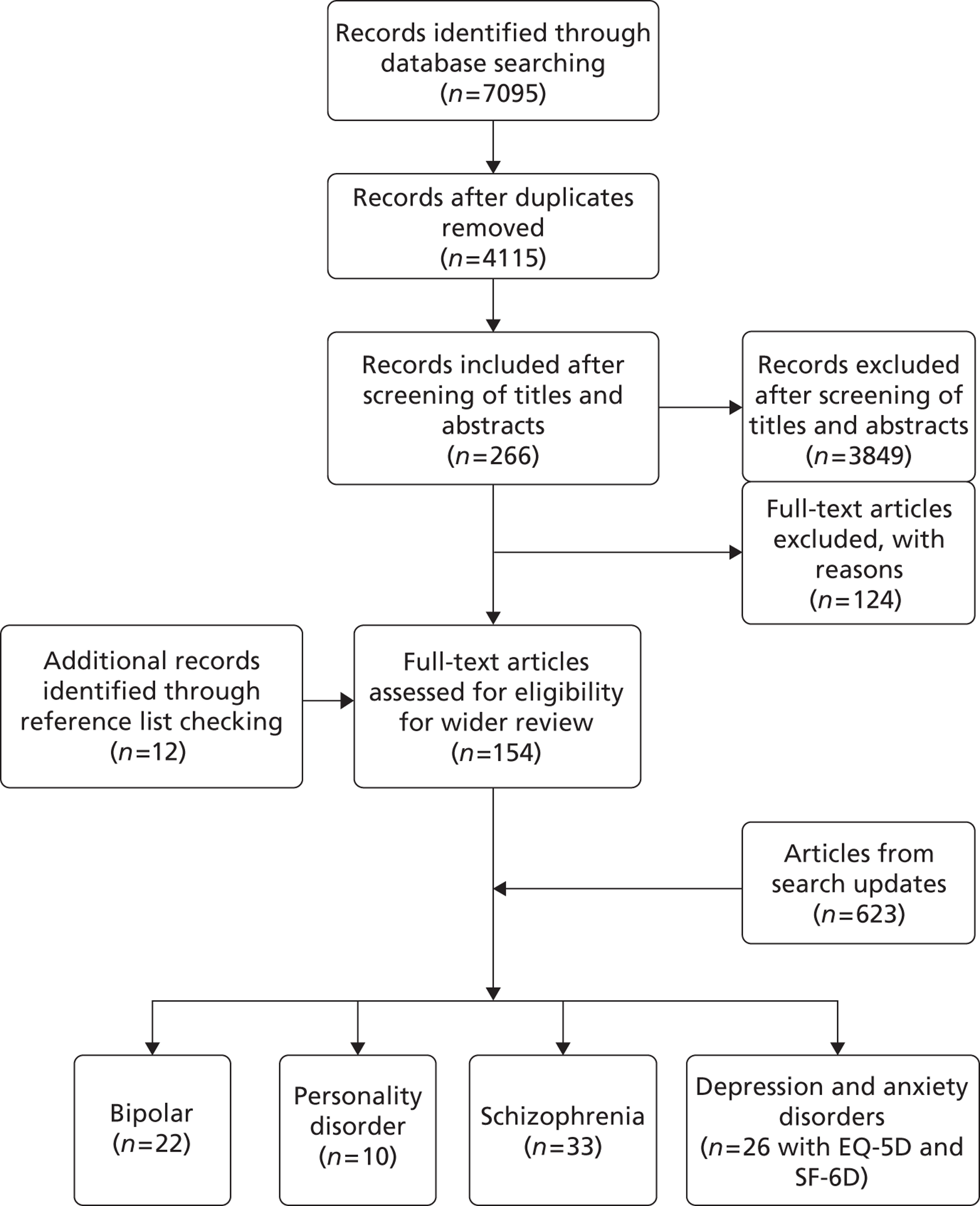

Study characteristics

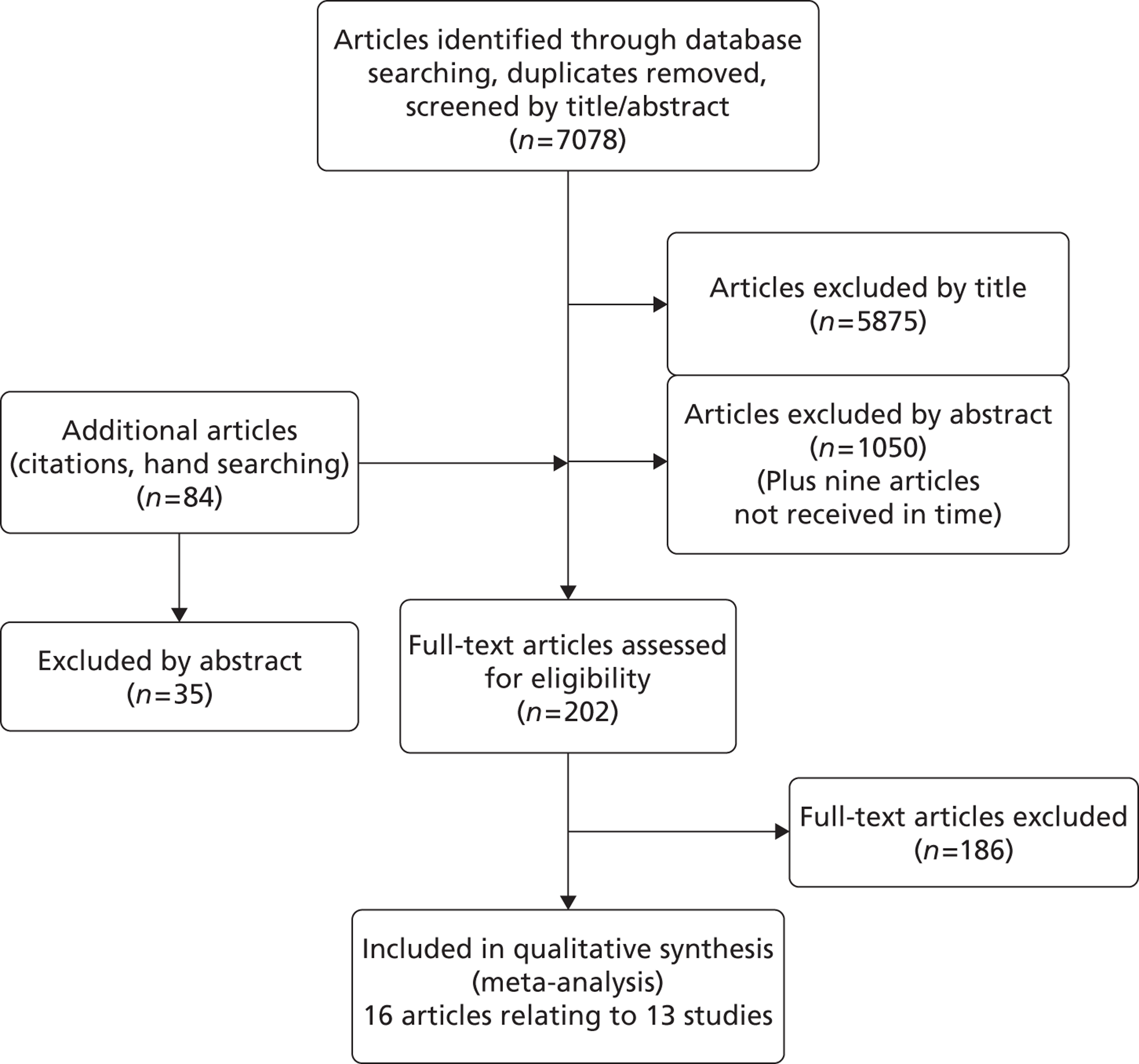

The initial search for studies for the wider review retrieved 4115 unique citations across the five mental health conditions ( Figure 1 ). Of these, 3849 were excluded at the title and abstract stage and 266 were examined in full text. From these, 154 studies were found that met the inclusion criteria. A further 12 studies were identified through reference list checking. Overall, the findings from 91 studies are discussed in this chapter for the five conditions. SF-36 and SF-12 studies were not ultimately included in the depression and anxiety review as a sufficiently large number of studies used the SF-6D to be able to extrapolate to these longer versions of the measure. Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of study identification and the characteristics of the studies reviewed by condition are presented in Appendix 2 .

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study identification.

Schizophrenia

Thirty-one studies were identified that provided data on the validity and/or responsiveness of the EQ-5D, SF-36, SF-12 or SF-6D within individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder or schizoaffective disorder (see Appendix 2 , Table 32 ). 48,66–95 Six studies were undertaken internationally across more than one country. 66–71 The numbers of participants in the studies with schizophrenia or related conditions ranged from 15 to 2657. Participants included males and females with a mean age of participants with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, reported in 21 of the 33 studies, ranging between 20.3 and 57.9 years. 48,68,70–73,75–80,82,84,86,88–91,94,95

All studies obtained HRQoL information from patients; seven of these studies compared patient HRQoL values with published general population ‘normative’ values,70–76 three compared HRQoL values with normal comparison participants that were recruited to the study77–79 and two used ‘norms’ from healthy participants who had taken part in large surveys. 80,96

Bipolar disorder

Twenty-two studies were identified that provided data on the validity and/or responsiveness of the generic HRQoL measures in bipolar disorder (see Appendix 2 , Table 33 ). 74,97–117 Nineteen studies74,97,98,102–117 contained data on the SF-36, one study involved the SF-12101 and four studies98–101 contained data on the EQ-5D. No studies were identified that examined the SF-6D in individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorder. The numbers of participants in the studies with bipolar disorder ranged from 30 to 1999. Participants included men and women. The mean age of participants with a bipolar disorder, reported in 19 of the 22 studies,97–103,106–117 ranged between 29.3 and 60.2 years.

All studies obtained HRQoL information from patients; six of these studies compared patient HRQoL values with ‘norms’ derived from published general population ‘normative’ values,48,76,80,81,96,118 three compared HRQoL values with normal comparison subjects that were recruited to the study74,79,82 and one study used ‘norms’ from healthy subjects taking part in large surveys. 83 Four studies investigated differences in HRQoL between mood groups in bipolar disorder. 75,84–86 Two of the four studies investigating the EQ-5D used general population preferences for EQ-5D health states to generate EQ-5D index values. 87,96

Personality disorder

In total, there were 10 studies reporting HRQoL data on patients with personality disorder. 96,119–128 Six studies looked at the EQ-5D,120,124–128 two at the SF-36119,121 and two at the SF-12 (corresponding to three articles). 96,122,123 No studies were found investigating the validity or responsiveness of the SF-6D in this patient group. Studies were undertaken in four countries. Nine96,119–128 of the 10 studies presented data for different personality disorders together. One study looked exclusively at individuals with borderline personality disorder. The numbers of individuals included within the studies that were diagnosed or screened as having one or more personality disorders ranged from 48 to 1708. Participants included males and females (proportions can be seen in Appendix 2 , Table 34 ). The mean age of participants with personality disorders, reported in 9 of the 10 studies, ranged between 29.4 and 45 years. 96,119–121,124–128

Two studies120,127 investigated the known-group validity of the EQ-5D, one study127 investigated the convergent validity of the EQ-5D and four studies124–126,128 investigated the responsiveness of the EQ-5D. Two studies119,121 investigated the known-group validity of the SF-36 and two studies96,122,123 investigated this property in the SF-12. One study119 investigated the responsiveness and convergent validity of the SF-36.

Depression and anxiety

Owing to the large number of studies reporting SF-36 and SF-12 data in this group, it was decided to focus on EQ-5D and SF-6D data. SF-36 and SF-12 are not preference-based and have been included in the other studies to give an indication of the likely performance of the derivative SF-6D. In all, there were 22 studies50,129–149 identified with data on the validity and/or responsiveness of the generic HRQoL measures in depression and anxiety for EQ-5D and SF-6D. Fourteen studies50,129,136–139,142–149 had data on the EQ-5D and seven130,131,133–135,140,141 contained data on the SF-6D. Studies were undertaken in at least 12 countries (a number covered Europe). The numbers of participants with depression and anxiety in these studies ranged from 44 to 3815. Participants included men and women with a mean age between 39.2 and 49 years of age.

Six studies139,142,144,147–149 investigated the known-group validity of the EQ-5D across severity groups, five studies129,136,137,143,145 reported convergent validity of the EQ-5D and 14 studies50,130–138,140,141,145,146 investigated the responsiveness of the EQ-5D. Two studies139,142 had known-groups differences in the SF-6D, three132,134,137 had convergent validity and two136,145 had responsiveness.

Quality of included studies

Most studies reported tests for statistical significance of the properties measured for difference between groups (e.g. known-group validity) and responsiveness to change over time. A minority of studies considered what constituted a clinically significant difference in HRQoL scores, by either providing a predefined value or discussing whether or not the results were clinically meaningful. There was little discussion or inclusion, however, of clinical significance defined in terms of patient perception, and thus, from the perspective of preference-based measures, the lack of patient preference undermines the concept of clinical significance. Most studies did not report missing HRQoL data. This has implications for the representativeness of these samples due to possible selection bias.

Results

Detailed findings with tables of results on the validity and responsiveness have been reported elsewhere. 60–62 This section summarises the results using a simple classification of the evidence: ✓ indicates results in support of validity or responsiveness and ✗ indicates an inconsistent or non-significant result. The results on validity have been divided into known-group differences across severity groups typically defined using symptoms, known differences against a normal case–control group and convergence with a measure of the condition.

Schizophrenia

The majority of the evidence (25 studies) examined the validity and responsiveness of the SF-36. 66,67,69–85,88,92–95 Although there appears to be strong evidence that the SF-36 is able to distinguish between general population norms and scores of people with schizophrenia (known-group validity), the evidence for convergent validity and responsiveness is less certain ( Table 4 ). Similar findings exist for the EQ-5D, with mixed evidence for the properties of convergent validity and responsiveness. Indeed, when strong associations were found between individual EQ-5D health-state dimensions (e.g. anxiety/depression or self-care) and symptom or functioning measures, this did not necessarily translate into comparable changes in overall EQ-5D index scores, i.e. health-state utility values. 48,90 There was some evidence that associations with measures of depression were comparatively stronger than those with symptom measures of schizophrenia [e.g. the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)]. 71,88–90

| Criterion | EQ-5D | SF-36 | SF-12 | SF-6D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGV: severity | ✓ | ✓ | None | None |

| KGV: case–control | None | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | None |

| Correlation | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✗ ✓ ✗ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✗ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✗ ✗ ✗ ✗ | None | ✓ |

| Responsiveness | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✗ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✗ ✗ ✗ | None | ✗ |

When testing associations between measures for convergent validity (or change scores in responsiveness), there are reasons to predict that stronger and more consistent correlations might exist between generic HRQoL measures and functioning [e.g. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF), Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS)] or mental health/schizophrenia-specific HRQoL [e.g. Quality of Life Scale for Schizophrenia (QLS)] measures than purely symptom-based measures such as the PANSS. By their very nature, symptom measures are measuring different concepts from HRQoL measures, so it might be reasonable to predict that it is less likely that a strong correlation might exist. A re-examination of the evidence, taking into account evidence for the type of measure used to assess convergent validity (symptom vs. functioning or HRQoL measures, subjective vs. objective measures), produced mixed results. Functioning and schizophrenia HRQoL measures did not fare much better than clinical and symptom-based measures, with four studies indicating strong evidence for convergent validity,82–84,86 and four indicating uncertain or no evidence of such a relationship. 69,81,88,89

Bipolar disorder

There was positive evidence that the SF-36 is a valid and responsive measure in bipolar disorder when individuals are in a depressed, euthymic or mixed state ( Table 5 ). There was little evidence available on the EQ-5D and SF-12 and none for the SF-6D. What evidence there is on the EQ-5D is mixed, with three tests supporting the validity of the EQ-5D in this group and three against it across four studies. 98–101

| Criterion | EQ-5D | SF-36 | SF-12 | SF-6D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGV: severity | ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✓✓ | ✓ | None |

| KGV: case–control | ✗ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ | None | None |

| Correlation | ✓ ✗ ✓ ✗ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ | ✓ | None |

| Responsiveness | None | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ | None | None |

It is unclear if these generic measures are valid in manic or hypomanic individuals. Only 7 out of 22 SF-36 studies included individuals in a manic or hypomanic state,74,99,101,104,106,110,117 and these suggest it is not a valid and responsive measure within this population. However, where studies examined convergent validity with clinical measures of mania, the numbers of patients in the manic or hypomanic mood state were too small to be meaningful. More generally, there is some concern around how to obtain reliable HRQoL ratings within bipolar disorder individuals in manic or hypomanic states as this relies on self-report.

Depression and anxiety

The SF-6D and EQ-5D demonstrate good construct validity and responsiveness for patients with depression ( Table 6 ). They can both distinguish between groups that are known to vary according to severity of depression, and across differences in quality of life of depressed patients. Both measures respond to clinical and quality-of-life improvement and deterioration. Indeed, in many cases they are more responsive than depression-specific measures (this may be due to the integrated nature of mental and physical health problems and potential simultaneous improvement in comorbid conditions).

| Criterion | EQ-5D | SF-6D |

|---|---|---|

| KGV: severity | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ |

| KGV: case–control | None | ✓ ✓ |

| Correlation | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ ✓ |

| Responsiveness | ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✗ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ ✓ |

The performance of the EQ-5D for patients with anxiety is a little more mixed. The measures were found to be more highly correlated with depression scales than with clinical anxiety scales in patients with anxiety.

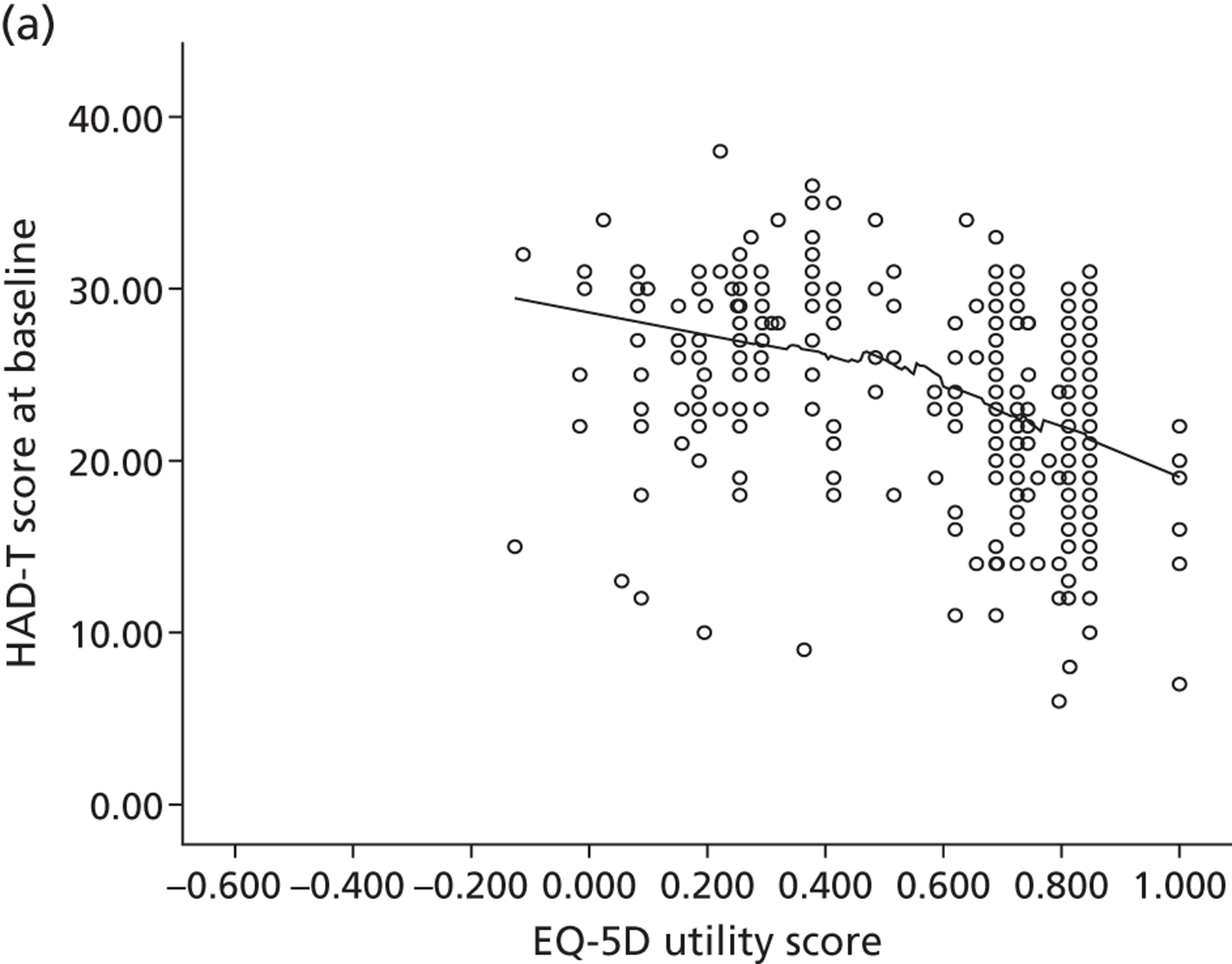

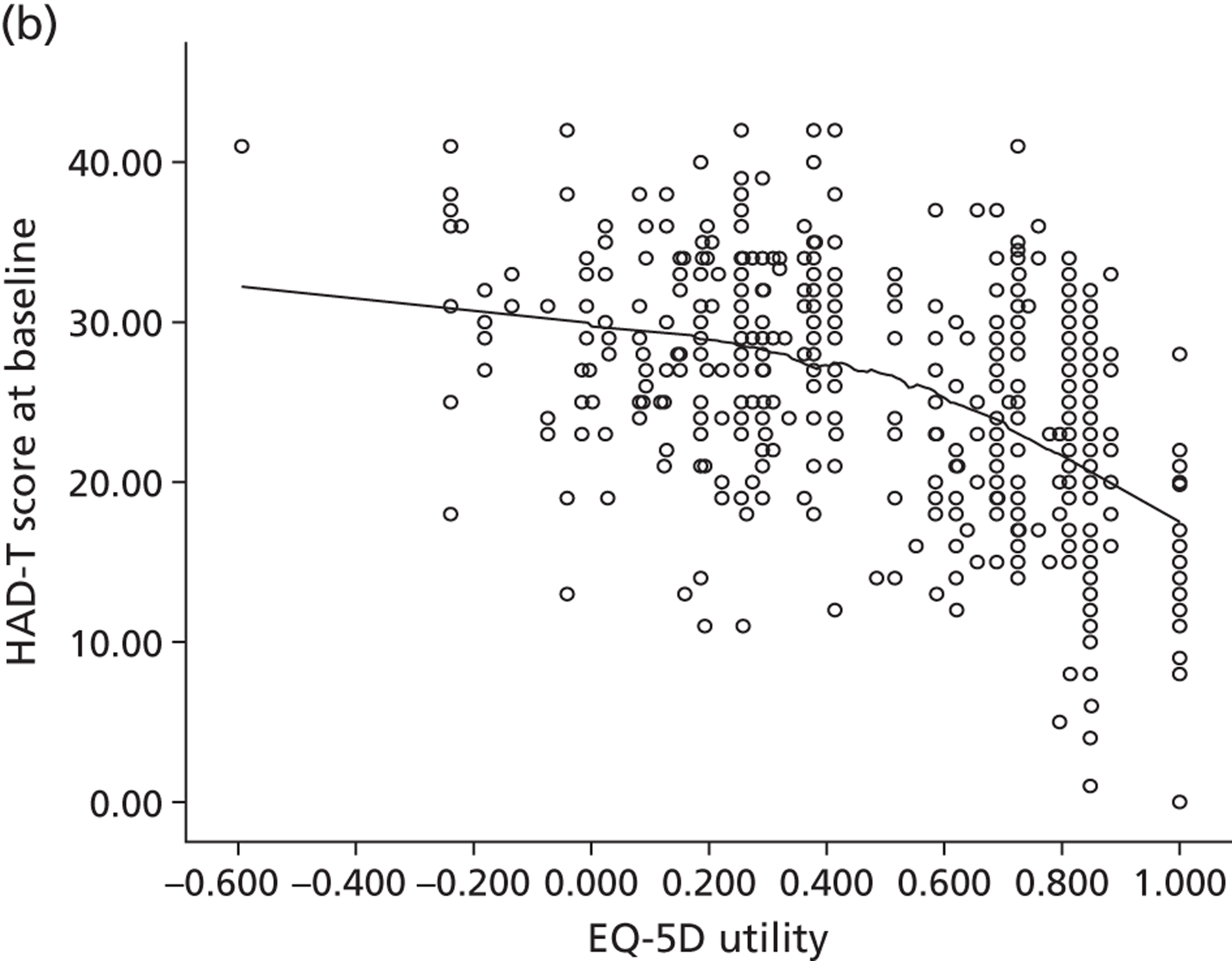

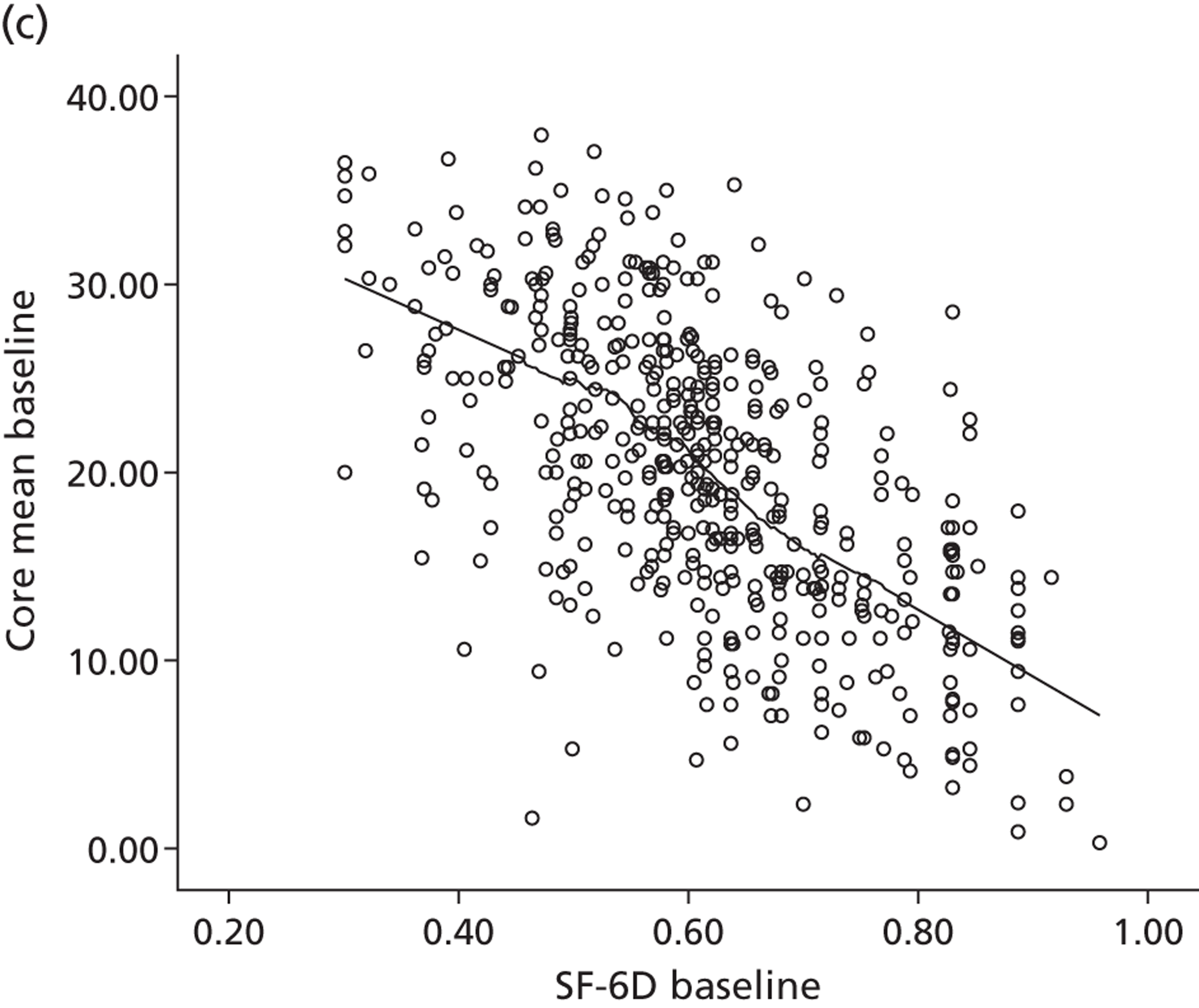

The relationship between the EQ-5D and the SF-6D reflects that found for other conditions. The EQ-5D shows a lower level of utility at the most severe end for depression, and the SF-6D shows equal or greater detriment at the milder end. The SF-6D identifies utility loss in patients that report full health on the EQ-5D, though patient averages for mild depression and anxiety are still able to show lower than normal population utility using the EQ-5D.

Personality disorder

The EQ-5D appears responsive in individuals with personality disorders ( Table 7 ). Data on other properties such as convergent and known-group validity were very limited. There was also little evidence on the SF-36 or SF-12 and none on the SF-6D. Nevertheless, the studies which did exist provided some positive evidence that the measures are valid for use in personality disorders. 100,102,107 An exception was Narud et al. ,119 who found that most dimensions on the SF-36 were not able to detect changes in patients in the same way as clinical measures. They concluded that this may be because some SF-36 dimensions are not relevant to HRQoL, so that, even if patients change clinically, this does not translate to a change in HRQoL.

| Criterion | EQ-5D | SF-36 | SF-12 | SF-6D |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| KGV: severity | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ ✓ | None |

| KGV: case–control | ✓ | ✓ ✓ | None | None |

| Correlation | ✓ | ✓ | None | None |

| Responsiveness | ✓ ✓ ✓ | ✓ | None | None |

Discussion

This review is the first to have comprehensively identified studies that report on the construct validity and responsiveness of these four generic HRQoL measures, and to tabulate and give a narrative synthesis of the findings. Overall, the evidence suggests that generic HRQoL measures are appropriate for patients with depression and personality disorder, but it is more mixed in relation to anxiety, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.

The findings for depression are encouraging, but there is a concern that this may be driving the differences between groups found for other conditions. For anxiety, the ability of generic preference-based measures to distinguish between subgroups of patients with anxiety may be driven by aspects of depression within anxiety disorder and the presence of comorbid depression. There was some evidence that associations with measures of depression were comparatively stronger than those with symptom measures of schizophrenia (e.g. the PANSS). 71,88–90 This may indicate that: (a) the generic HRQoL measures were only able to detect this component of HRQoL, or (b) depression is the only component of HRQoL within these groups of patients that is important within the context of HRQoL measurement. The issue is whether schizophrenia or anxiety has quality-of-life implications not adequately described by the five dimensions of the EQ-5D. It is also difficult to predict how HRQoL is affected by the manic or hypomanic states from the perspective of the individual with bipolar disorder. These non-depression consequences of these conditions are explored later in this report through qualitative interviews with patients.

The review has some limitations, resulting from the need to compromise on some elements of the review process because of the large scope of the project. Although the search for studies was reasonably comprehensive, it was limited to key databases and reference list checking of included studies, and study selection was undertaken by one reviewer. Ideally, further searching could be undertaken in trial registries, conference proceedings and by citation searching to make the search more comprehensive in terms of process. Study quality assessment has been pragmatic and focused on the elements that contribute to HRQoL analysis. The populations included in this review were heterogeneous in terms of the nature of their conditions, particularly for conditions such as schizophrenia and personality disorder where there are numerous subgroups, and not all studies provided detailed or uniform information on these characteristics. Such clinical variables clearly have an impact on HRQoL, and thus these factors will have had an impact upon the results of individual studies.

It is also difficult to draw any firm conclusions on the basis of this review, owing to the limited nature of much of the evidence in terms of the number of studies, the size of some of the studies and the heterogeneity within the conditions. There is very limited evidence of validity or responsiveness for the SF-12 and SF-6D, and though these are derivatives of the SF-36, their more limited item coverage (12 and 11, respectively) means that they may not perform as well. Therefore, further research needs to be directed towards demonstrating these properties for these instruments. To improve the evidence base, the next chapter will conduct further psychometric tests on existing data sets containing the EQ-5D and SF-6D. More evidence is also required on the validity and responsiveness of generic measures for older people with depression, as this group may be different from the younger adults typically found in published trials.

There is another general concern regarding whether or not it is reasonable to assess HRQoL when an individual is in a particular state, such as a manic or hypomanic state, as he or she may view the effect that the state had on his or her HRQoL very differently when not actually in that health state.

The findings are also limited by the measures used to establish validity and responsiveness. It is difficult to determine, in theory, how strongly correlated generic HRQoL measures should be with symptom and/or other clinical measures, and there is little guidance on what constitutes reasonable correlation. Indeed, it is impossible to prove validity of HRQoL instruments, as no ‘gold standard’ exists. Also, as discussed previously, where health dimensions and changes appear to have been missed by preference-based HRQoL measures, these may not actually be important to patients or valued by the general population. The former will be examined in the qualitative research reported in Chapters 5 and 6 .

The dominance of physical health in the EQ-5D may explain why it is not sensitive to differences in some mental health populations. 48 Although this does not seem to have been a problem in depression, it may account for the more mixed results in other conditions. There are also concerns that the descriptive systems of the generic measures are too narrow in terms of the dimensions they cover. Some of the questions raised are addressed later in this report using the findings of qualitative interviews of people with mental health problems, who can provide some insight into the shortcomings of the content of the descriptions contained in these generic measures (see Chapters 5 and 6 ).

Research needs to be directed towards developing robust methods of demonstrating validity and responsiveness for generic HRQoL measures. For known-group validity, the evidence discriminating between healthy and non-healthy individuals could be considered fairly crude; large differences should be obviously apparent between such groups. Therefore, research is required to test instruments in terms of the ability to reflect known-group differences using indicators of condition severity that are important to patients. For convergent validity, this might mean consideration of which measures to choose for assessment of strength of correlation, both by considering the type of measure (e.g. symptom functioning or HRQoL) and the nature of the measure (subjective or objective). Studies need to be explicit at their outset about the hypothesised associations when investigating validity and responsiveness. In addition, wherever studies investigate the feasibility of administering generic HRQoL measures alongside construct validity and responsiveness using quantitative and qualitative methods within this disease area, this will allow a greater overall understanding of which measures are useful within schizophrenia.

Conclusion

Despite the shortcomings identified in the evidence base, this review gives an overall picture of the validity and responsiveness of the EQ-5D and SF measures across mental health populations. It has shown a mixed picture, with the generic measures appearing to perform acceptably well in depression and personality disorder, but less well in anxiety, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. This has highlighted the need for further quantitative research, and the insights that can be gained from people regarding the content validity of the measures in terms of coverage of the dimensions of their life impacted upon by their mental health problems. The following chapters report both quantitative and qualitative studies that further investigate the validity of these measures.

Chapter 3 Assessing the psychometric performance of the EQ-5D and SF-6D using existing data sets

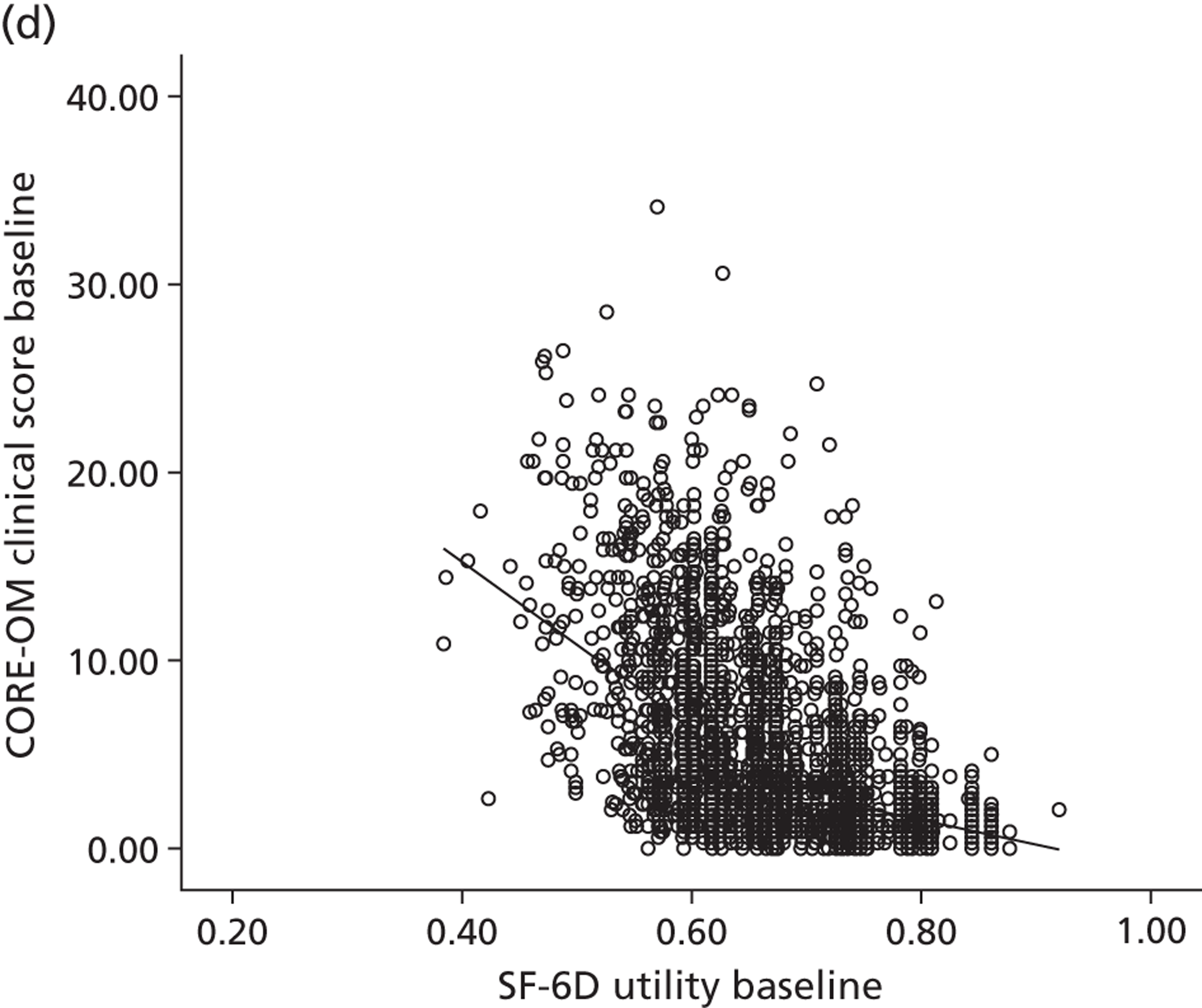

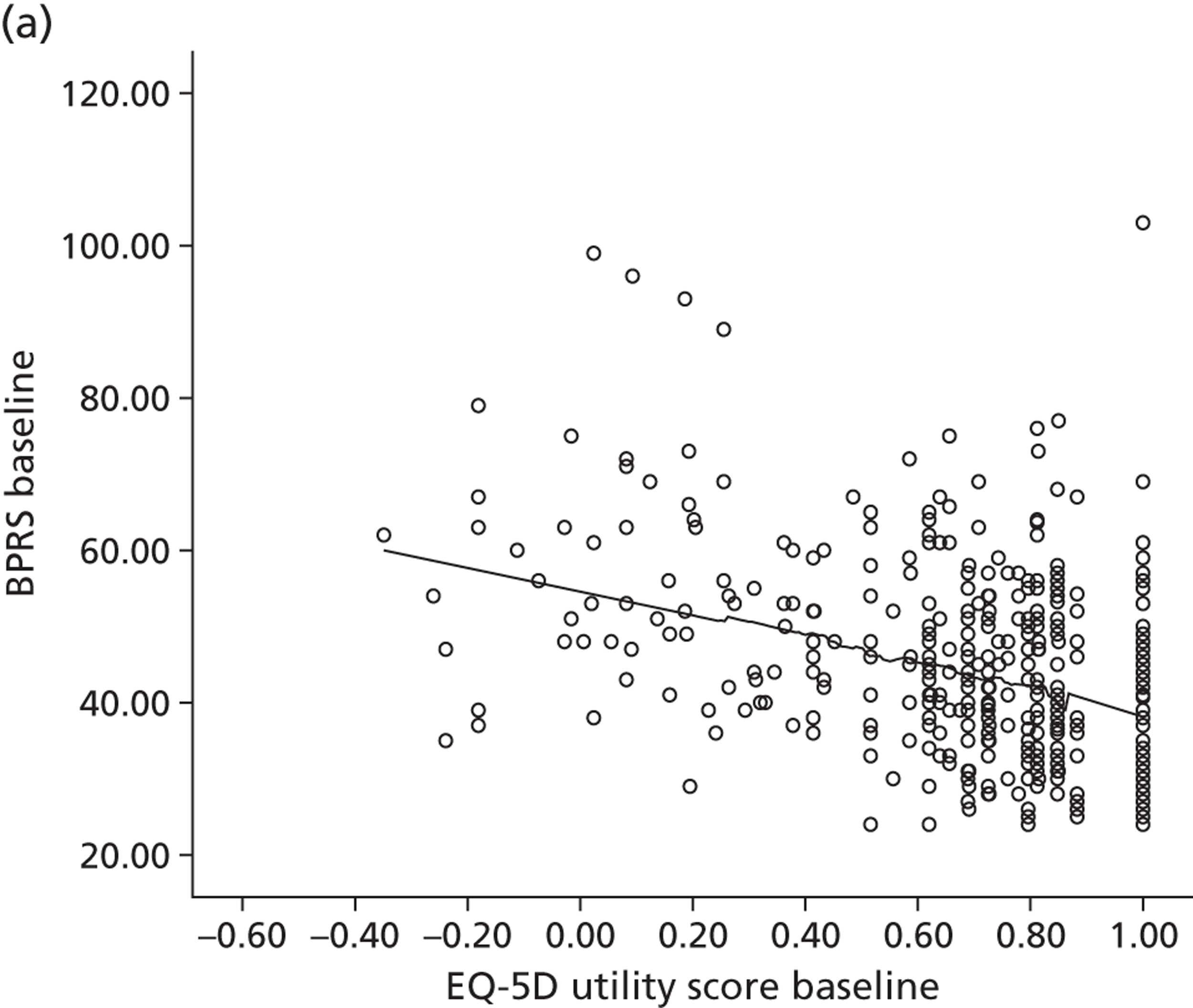

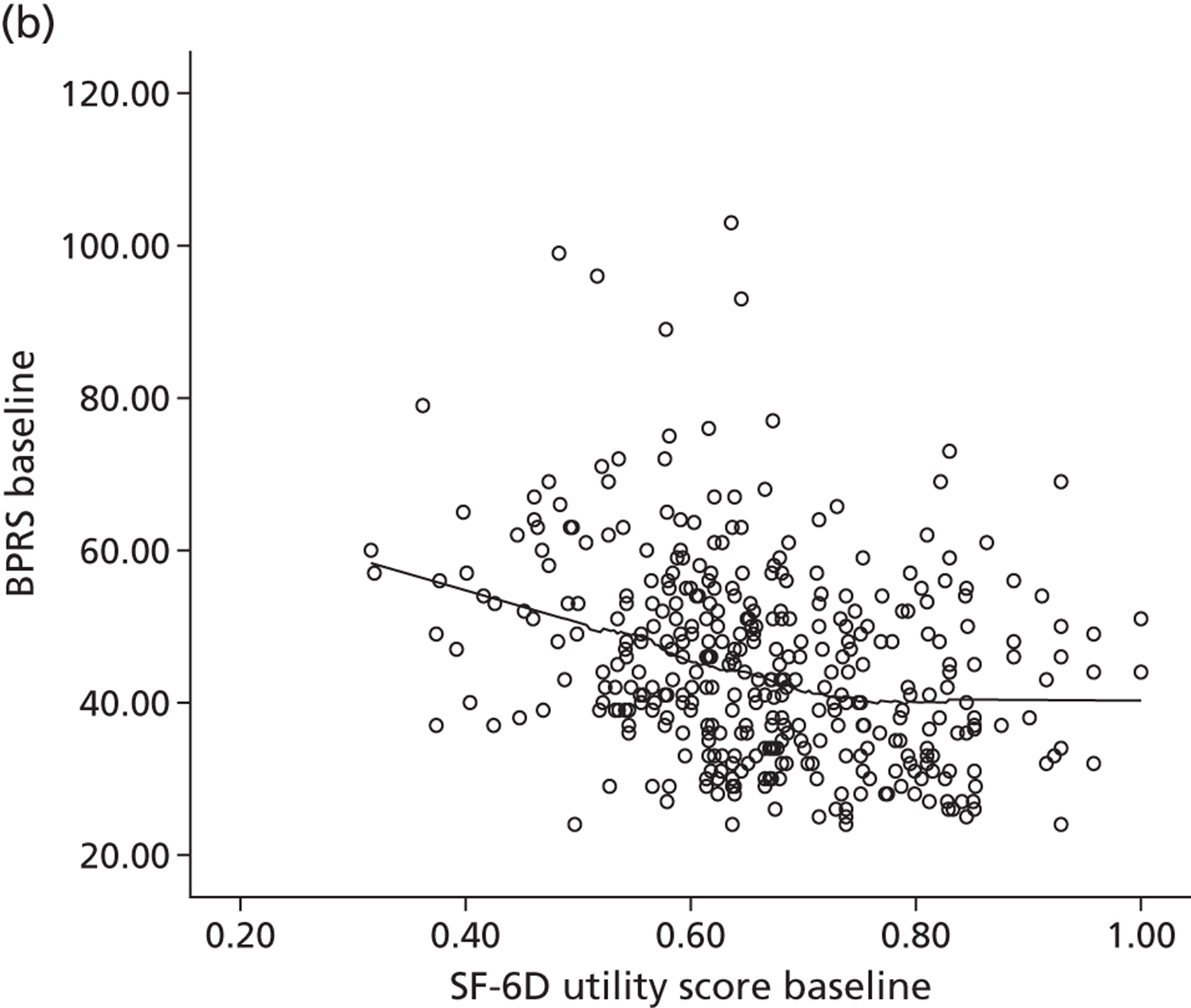

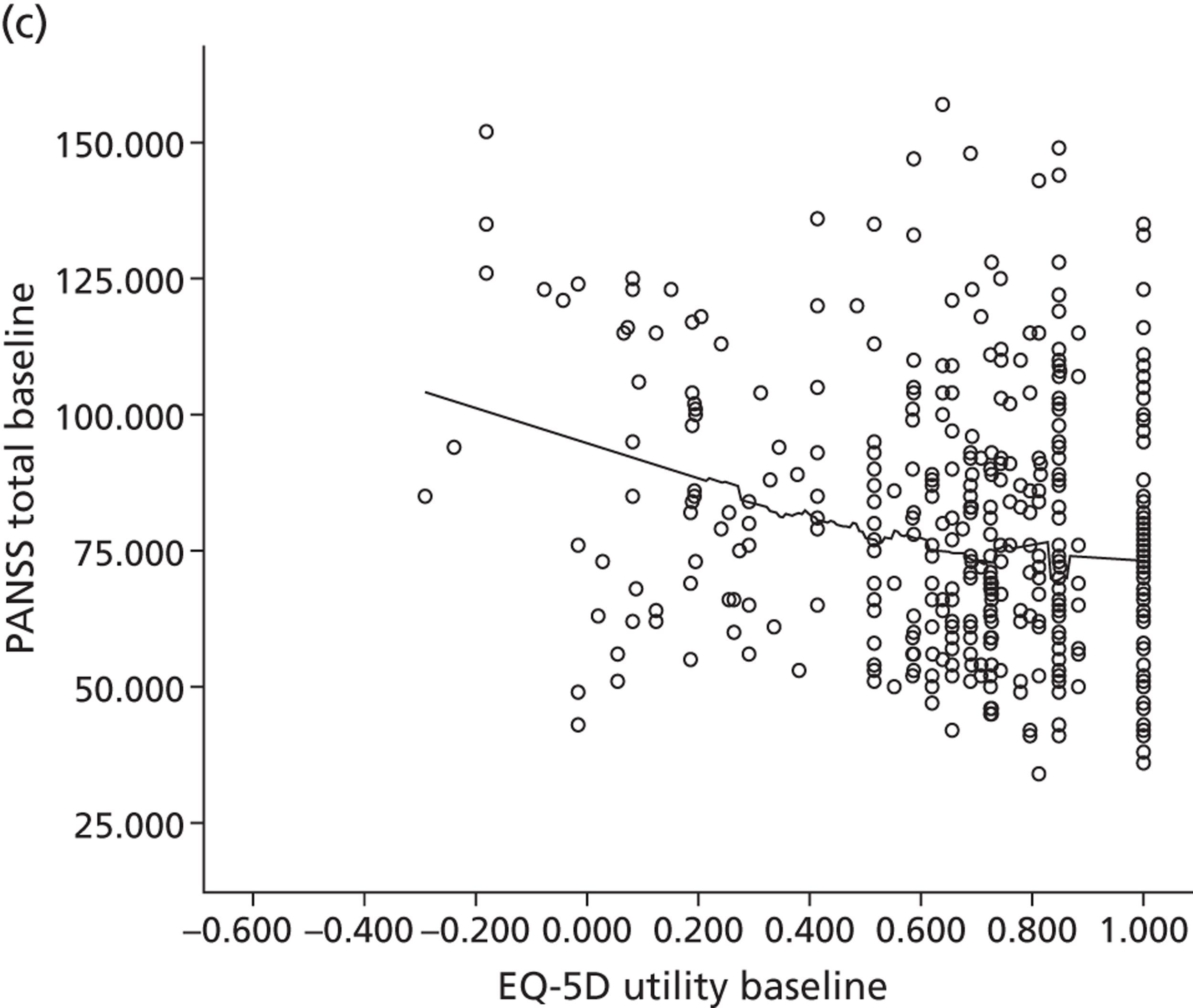

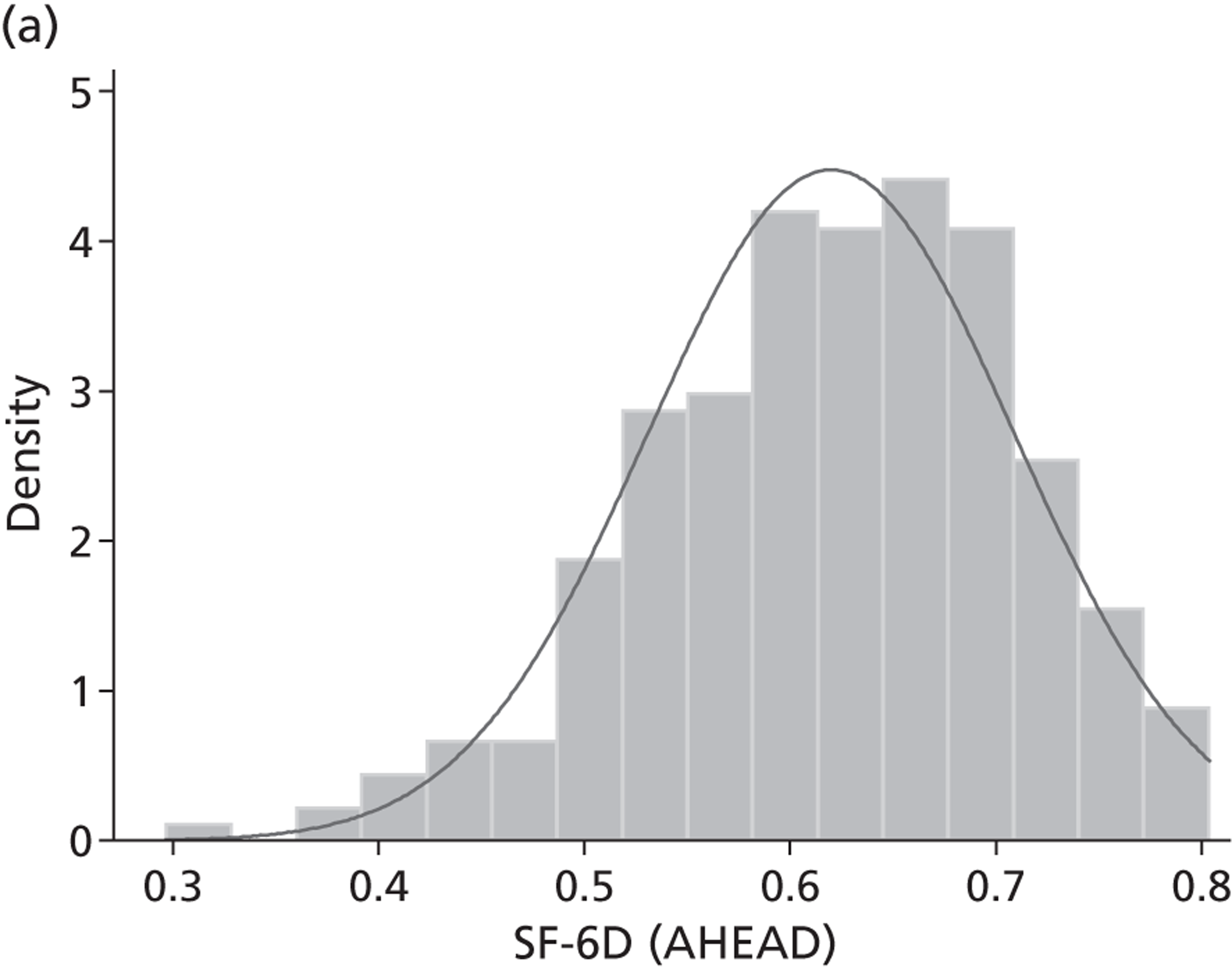

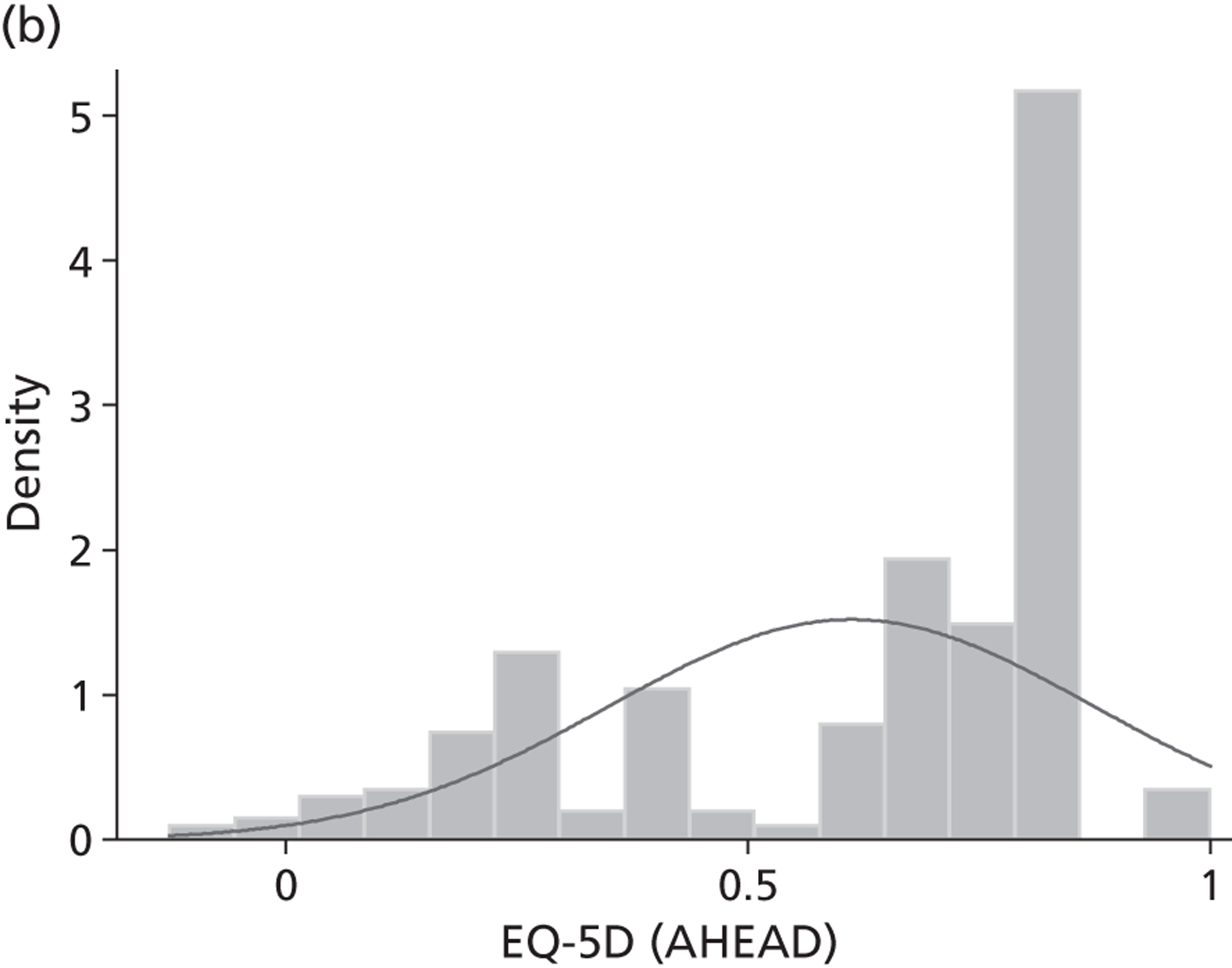

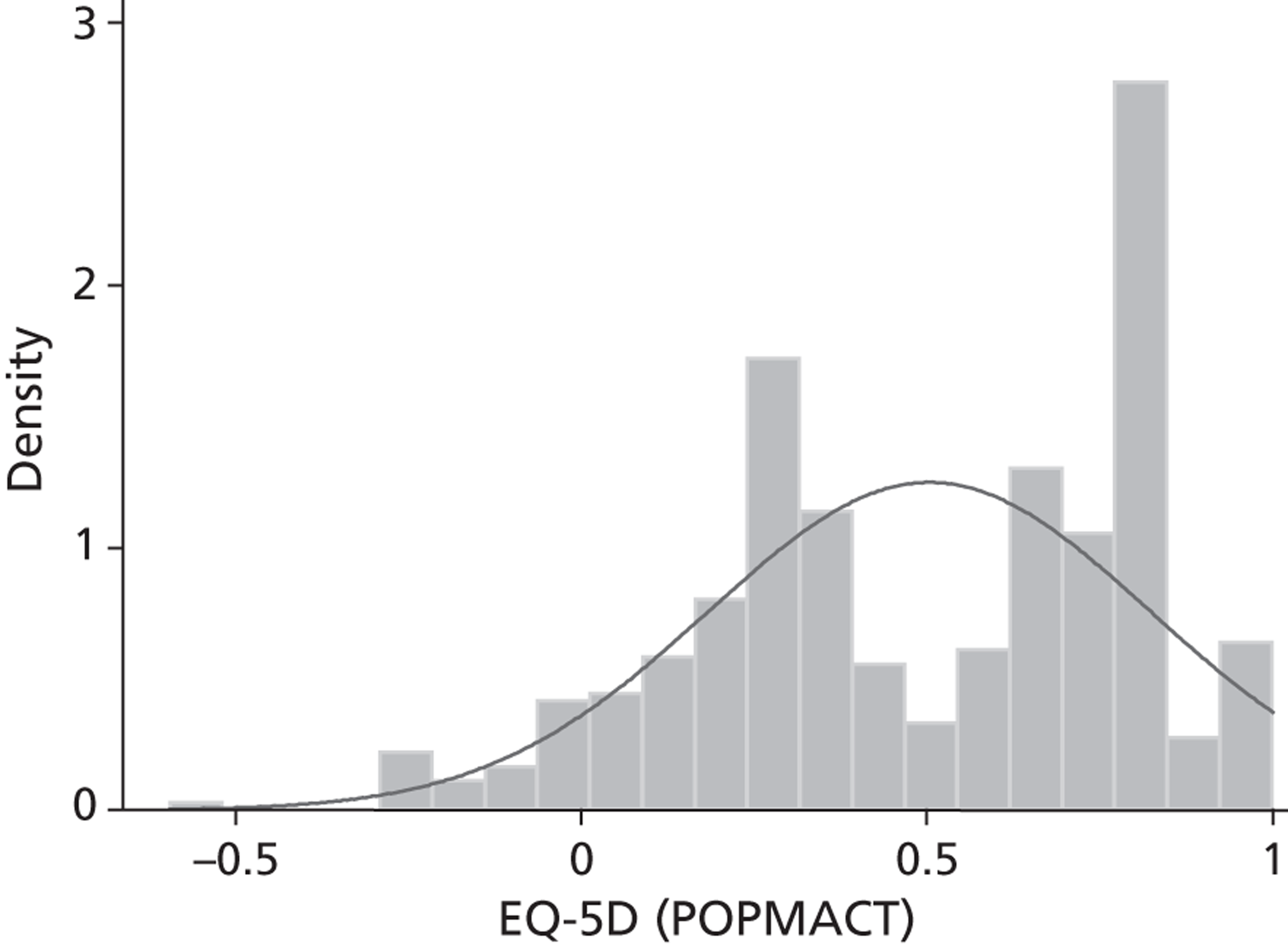

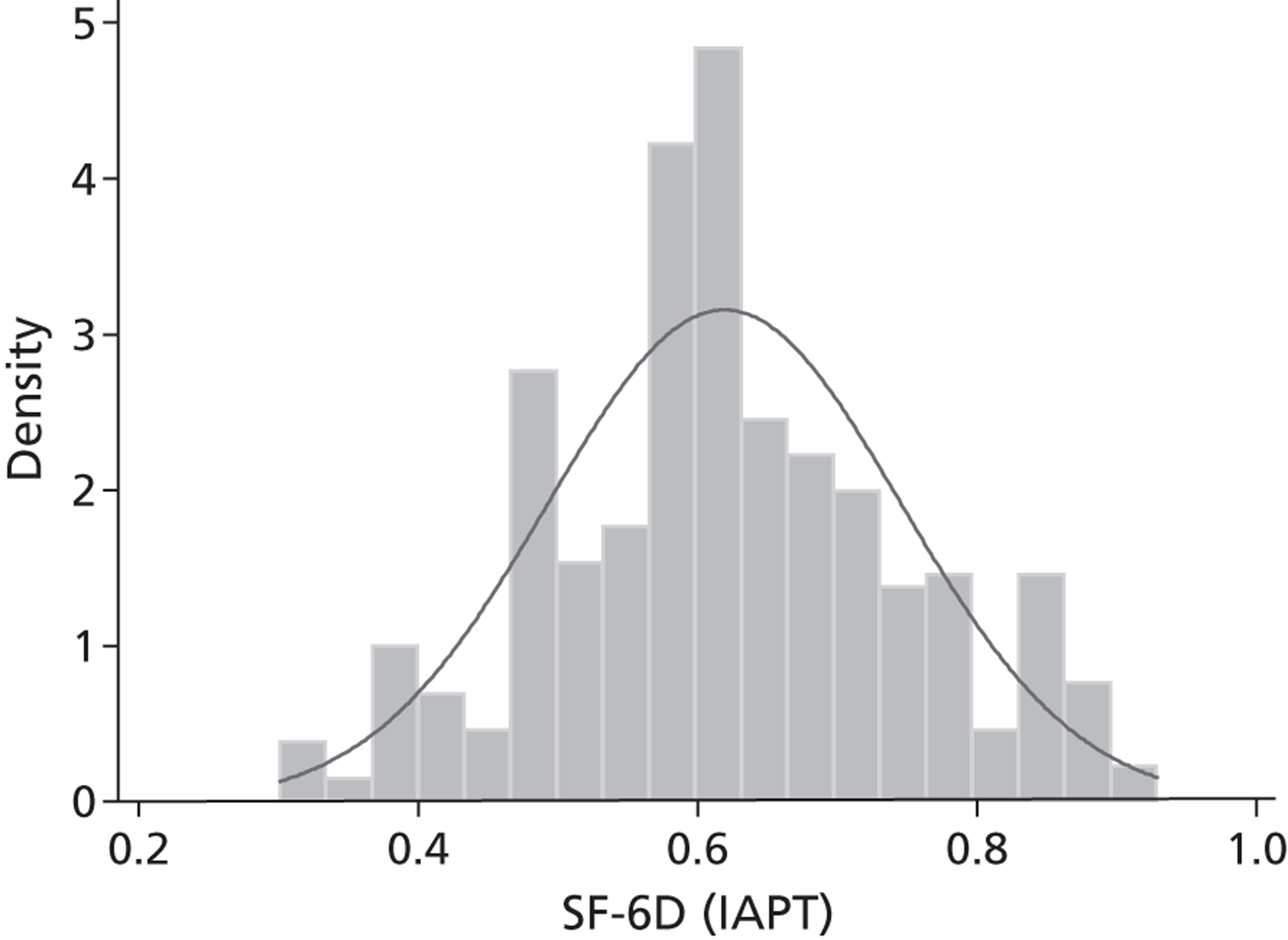

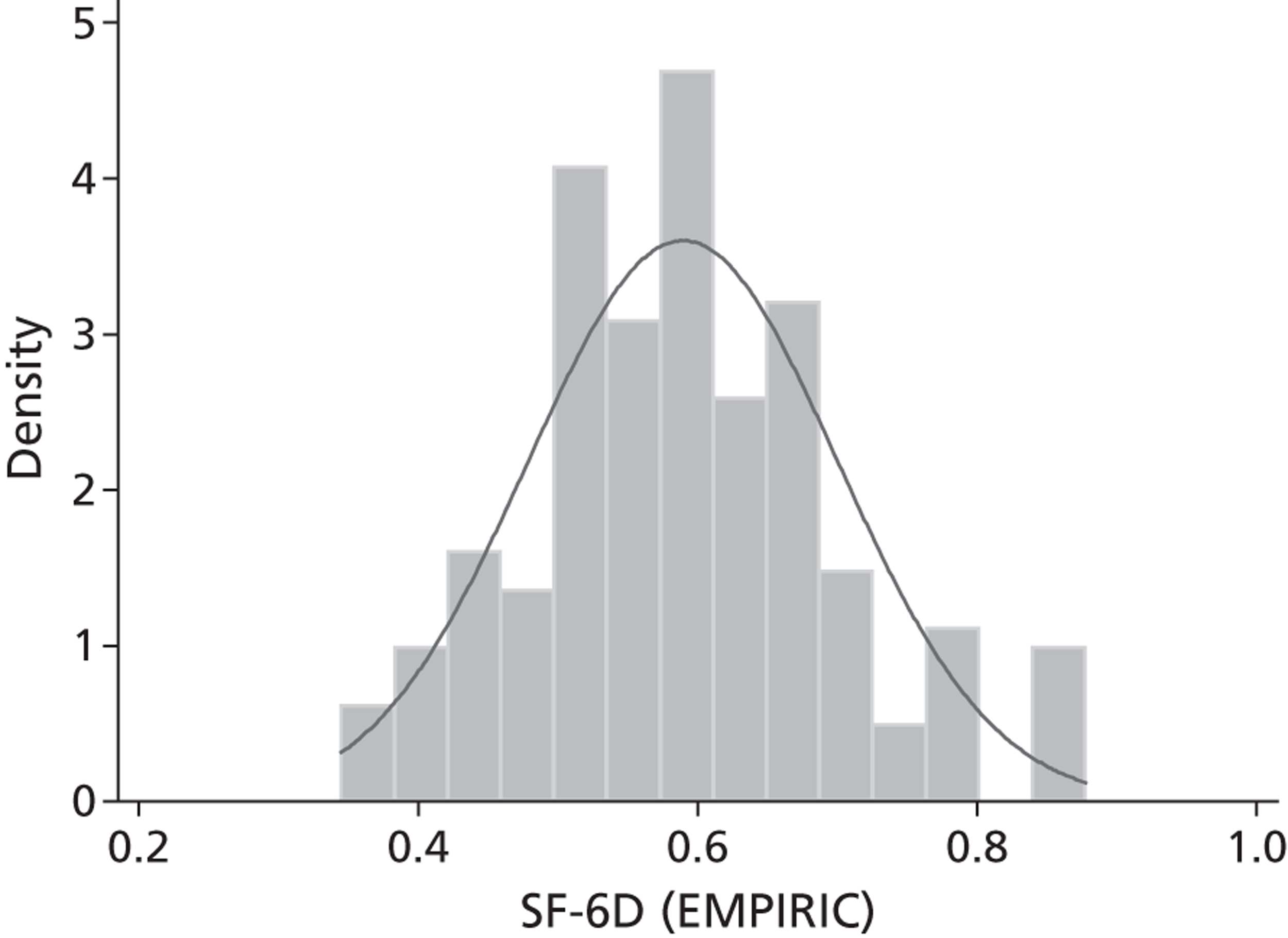

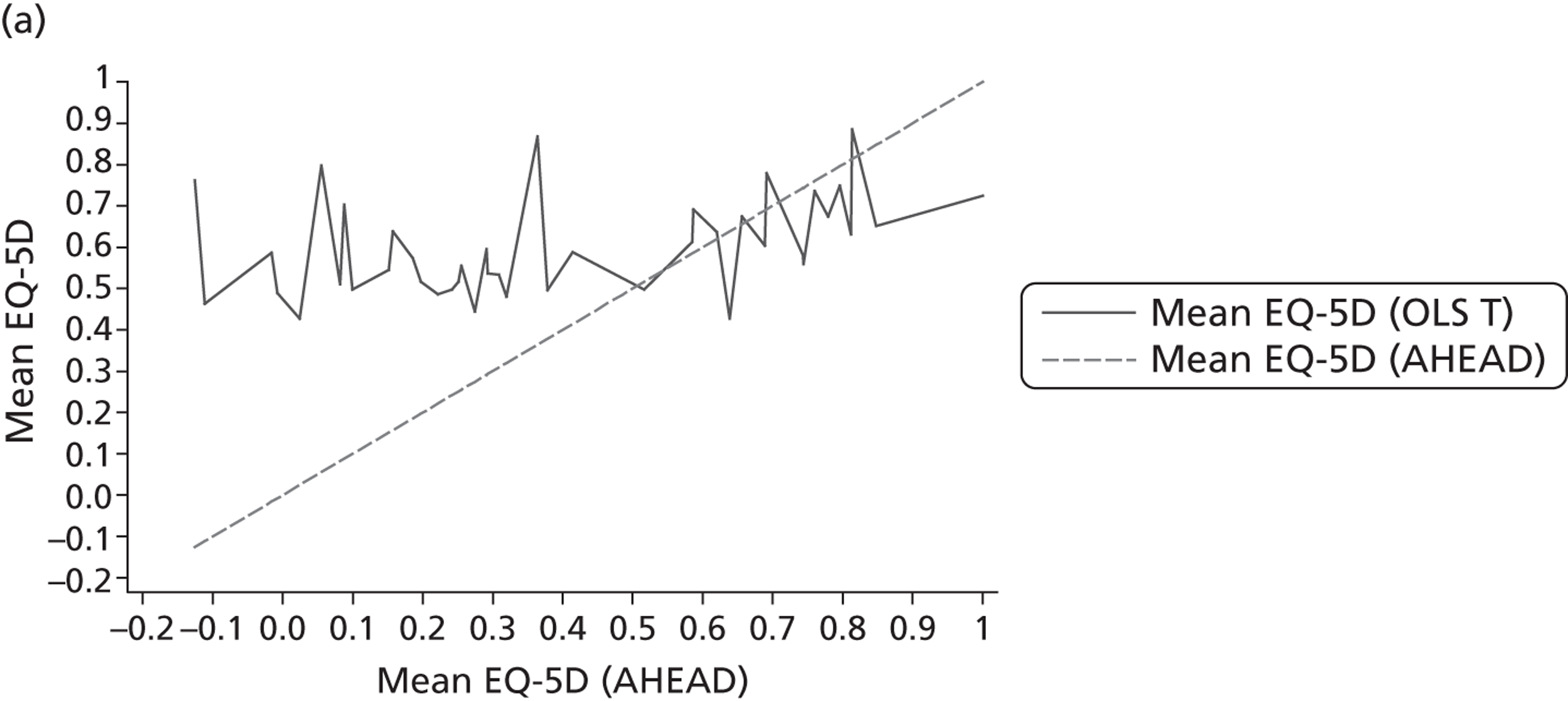

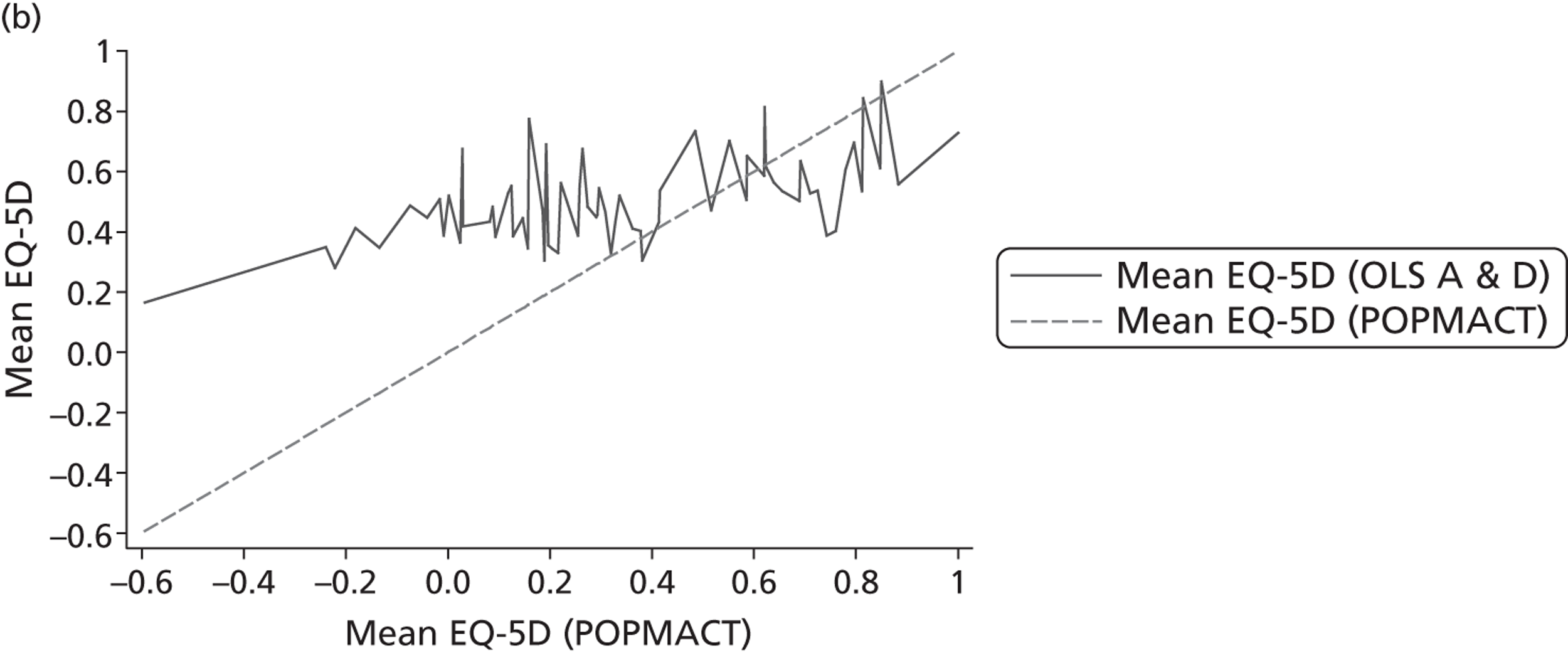

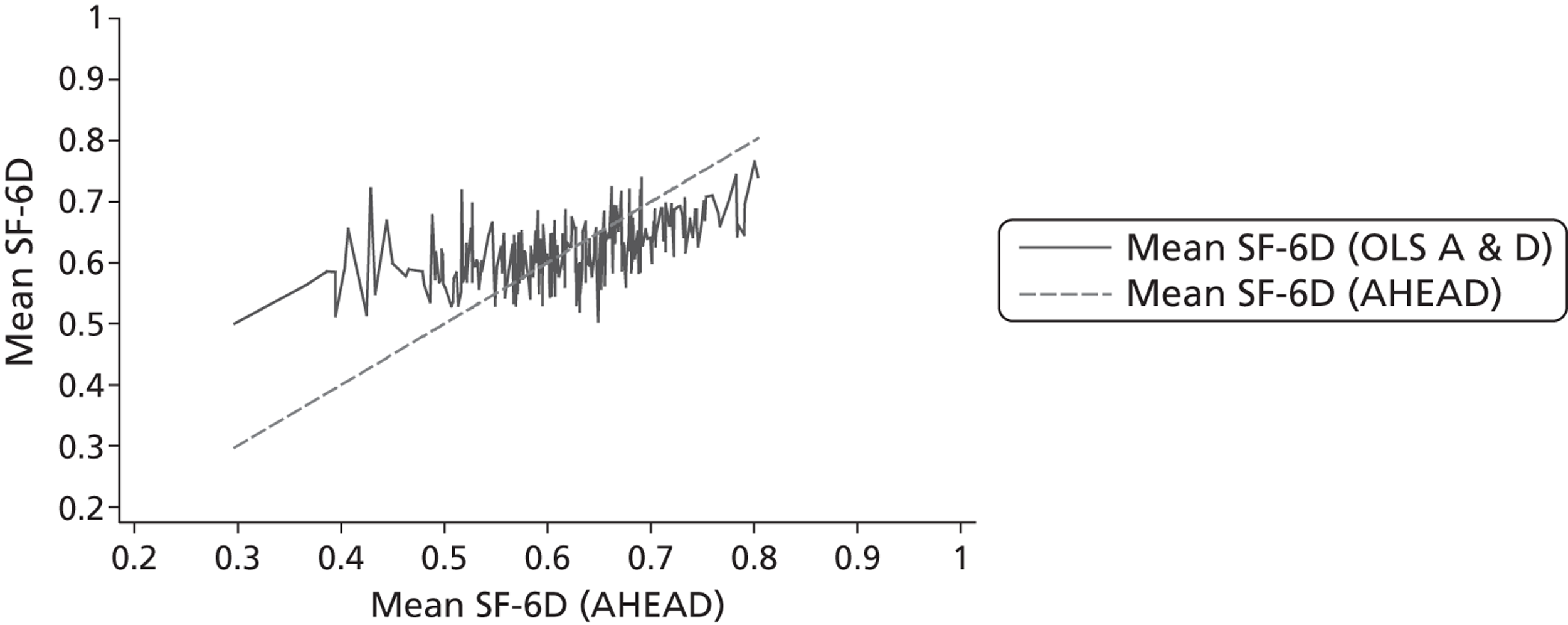

The review of psychometric evidence reported in the last chapter found mixed evidence on the performance of the EQ-5D and SF-36 (and its derivatives). The aim of the study reported in this chapter was to use existing data to supplement the psychometric evidence on both the EQ-5D and the SF-6D in samples of common mental health conditions, schizophrenia and personality disorder. The validity of the instruments and their responsiveness to change over time were assessed in comparison with widely used condition-specific outcome measures that have been validated for use in the mental health population, using existing data sets sourced from a range of studies. These data sets included 3512 people with common mental health problems (including depression and anxiety), 480 people with a mixed diagnosis of moderately severe common mental health problems and personality disorders leading to self-harm, and 1756 people with schizophrenia and other personality disorders. The analysis adds to the evidence base regarding the psychometric performance of the EQ-5D and SF-6D in mental health populations, providing information on the conditions in which the generic measures can be used and those for which improvements to the existing instruments and/or new measures are required.

Methods

Measures used in data sets

The EQ-5D and SF-6D were compared to one widely used and validated condition-specific measure within each data set. The measures used were restricted to those included in the data sets available. Table 8 displays the measures used in the analysis. Details of the two generic preference-based measures are presented in Chapter 1 . The condition-specific measures are described below.

| Data set | Description | Time points used | Generic measure | Condition-specific measure | Characteristics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (baseline) | Age (years), mean (SD) | Female (%) | |||||

| Common mental health conditions | |||||||

| Assessing Health Economics of Antidepressants (AHEAD)150 | RCT of the cost-effectiveness of antidepressants (three time points). Sample includes common mental health concerns – depression, MADD and phobias | Baseline 6 months 12 months |

EQ-5D | HADS | 327 | 43.1 (15.4) | 67.0 |

| Psychological Interventions for Postnatal Depression (PoNDER)151 | Study of two psychologically informed interventions for women with postnatal depression | Baseline 6 months 12 months |

SF-6D | CORE-OM | 2640 | 31.5 (5.1) | 100.0 |

| IAPT cohort study152 | Evaluation of the outcomes from two IAPT demonstration sites. Sample reports common mental health condition | Baseline 4 months 8 months |

SF-6D | CORE-OM | 527 | 40.9 (14.2) | 72.3 |

| Common mental health and personality disorders | |||||||

| The POPMACT study153 | RCT of MACT vs. TAU in recurrent self-harm. Sample includes patient with diagnoses of common mental health conditions and personality disorders leading to self-harm | Baseline | EQ-5D | HADS | 480 | 32.0 (11.2) | 67.9 |

| Schizophrenia | |||||||

| Quality of Life following Adherence Therapy (QUATRO)154 | Multicounty RCT of adherence therapy in patients with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia who needed continuing antipsychotic medication for at least 1 year from assessment, and had evidence of clinical instability in the year before assessment | Baseline 12 months |

EQ-5D SF-6D |

BPRS-E | 409 | 41.5 (11.5) | 59.9 |

| Multicentre study of Art Therapy In Schizophrenia: Systematic Evaluation (MATISSE)155 | RCT of group art therapy for people with a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia | Baseline 12 months |

EQ-5D | PANSS | 417 | 41.0 (11.5) | 33.3 |

| Schizophrenia and personality disorders | |||||||

| Study of Cost-Effectiveness of Personality disorder TREatment (SCEPTRE)120 | Dutch study of adult patients with personality disorders (UK EQ-5D tariff used for comparability) | Baseline 12 months |

EQ-5D | DSM-IV personality disorder category | 932 | 35.1 (9.8) | 68.1 |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)156 is a 14-item self-report measure that contains two seven-item subscales: depression (HADS-D) and anxiety (HADS-A). The total score for each dimension is 21 (items are scored 0–3) with high scores indicative of increased levels of anxiety and depression (a score of 8+ indicates a possible case, and a score of 11+ indicates a probable case). The overall score [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale – Total score (HADS-T)] is also used as a measure of global functioning. The HADS has been widely used across clinical groups and research settings,157 and there is evidence for its psychometric validity in comparison with other mental health158,159 and generic measures. 160 In this study, HADS was used to assess the psychometric performance of the EQ-5D in two separate samples of people with anxiety and depression.

Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation – Outcome Measure

The CORE-OM161–165 is a self-reported measure developed in the UK for routine use in psychological services at assessment and outcome. It comprises 34 items addressing domains of subjective well-being, symptoms (anxiety, depression, physical problems, trauma), functioning (general functioning, close relationships, social relationships) and risk (risk to self, risk to others). Items are scored on a 5-point, 0–4 scale. CORE clinical scores are computed as the mean of all completed items multiplied by 10 (range 0–40). This is so that clinically meaningful differences are represented by whole numbers. The psychometric validity of the CORE-OM in comparison to other widely used measures of mental health has been demonstrated. 166,167 In this study, the CORE-OM was used to assess the psychometric performance of the SF-6D in two separate samples of people with anxiety and depression.

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale – Expanded

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)168 was developed to assess symptom change in psychiatric inpatients and is one of the most widely used measures to assess psychotic and affective symptoms. The current study used the expanded version, the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale – Expanded (BPRS-E), which has 24 items developed for use in schizophrenia patients. The BPRS-E is administered using semistructured interviews and each of the 24 items has a possible score of 1 (not present) to 7 (extremely severe). Total scores range from 24 to 168 with higher scores indicating higher severity. The BPRS has been shown to be highly sensitive to change in psychiatric patients. 169 In this study, the BPRS-E was used to assess the psychometric performance of both the EQ-5D and SF-6D in a sample of people with schizophrenia.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

The PANSS was developed to evaluate positive, negative and other symptom dimensions in schizophrenia by combining the 18 items of the BPRS with the 12 items of the Psychopathology Rating Schedule with detailed instructions on completion by interview. It has 30 items which are scored from 1 (absent) to 7 (extreme) and result in 3 subscales: positive, negative and general psychopathology. 170,171 The PANSS is sensitive to changes in both positive and negative symptoms in patients. 169 The PANSS was used to assess the performance of the EQ-5D in a sample of people with schizophrenia.

Data sets

Identification of data sets

The systematic reviews reported in Chapter 2 examined the performance of generic preference-based measures in depression, anxiety and schizophrenia, and these reviews identified 91 studies. Corresponding authors of these studies were contacted and the data sets were requested for use in this study, and publicly available data sets were sourced. In total, 12 data sets were received (13% of those requested), and these were reviewed for acceptable condition-specific comparison measures or clinical indicators. Three data sets were excluded as they focused on general population samples, and two were excluded as they did not include a comparison measure of interest.

Seven data sets were selected for use in this study. Three included common mental health problem samples [Assessing Health Economics of Antidepressants (AHEAD), Psychological Interventions for Postnatal Depression (PoNDER) and IAPT]; one included mixed common mental health and personality disorder diagnoses (POPMACT); two included schizophrenia samples [Quality of Life following Adherence Therapy (QUATRO) and Multicentre study of Art Therapy In Schizophrenia: Systematic Evaluation (MATISSE)]; and one included schizophrenia and personality disorder [Study of Cost-Effectiveness of Personality disorder TREatment (SCEPTRE)] (see Table 8 ).

Common mental health problems data sets

The AHEAD study150 was a prospective randomised controlled trial (RCT) of the cost-effectiveness of tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and lofepramine. The sample (n = 327) consisted of patients recruited in a primary care setting who reported a range of common mental health concerns including depression, mixed anxiety and depressive disorders (MADD) and a number of phobias. The EQ-5D and HADS were collected at baseline and at six follow-up time points. In this study, baseline and two follow-up time points (6 months and 12 months) have been considered.

The PoNDER trial,151 which assessed two psychologically informed interventions for women with postnatal depression, was also selected. The sample used is those patients who completed the study at all time points (n = 2640). SF-6D and CORE-OM data were collected at baseline, 6 months, 12 months and 18 months, with the first three time points considered in this study.

The IAPT152 cohort study (n = 527 patients), which examined access to psychological therapies and associated outcomes for patients with mild to moderate depression and anxiety, was also selected. SF-6D and CORE-OM were administered at baseline, 4 months and 8 months.

Mixed common mental health and personality disorder diagnoses data set

The POPMACT study153,172 was a RCT of manual-assisted cognitive therapy versus treatment as usual in recurrent self-harm. The baseline sample was used in this study and consisted of patients presenting with recurrent deliberate self-harm (n = 480).

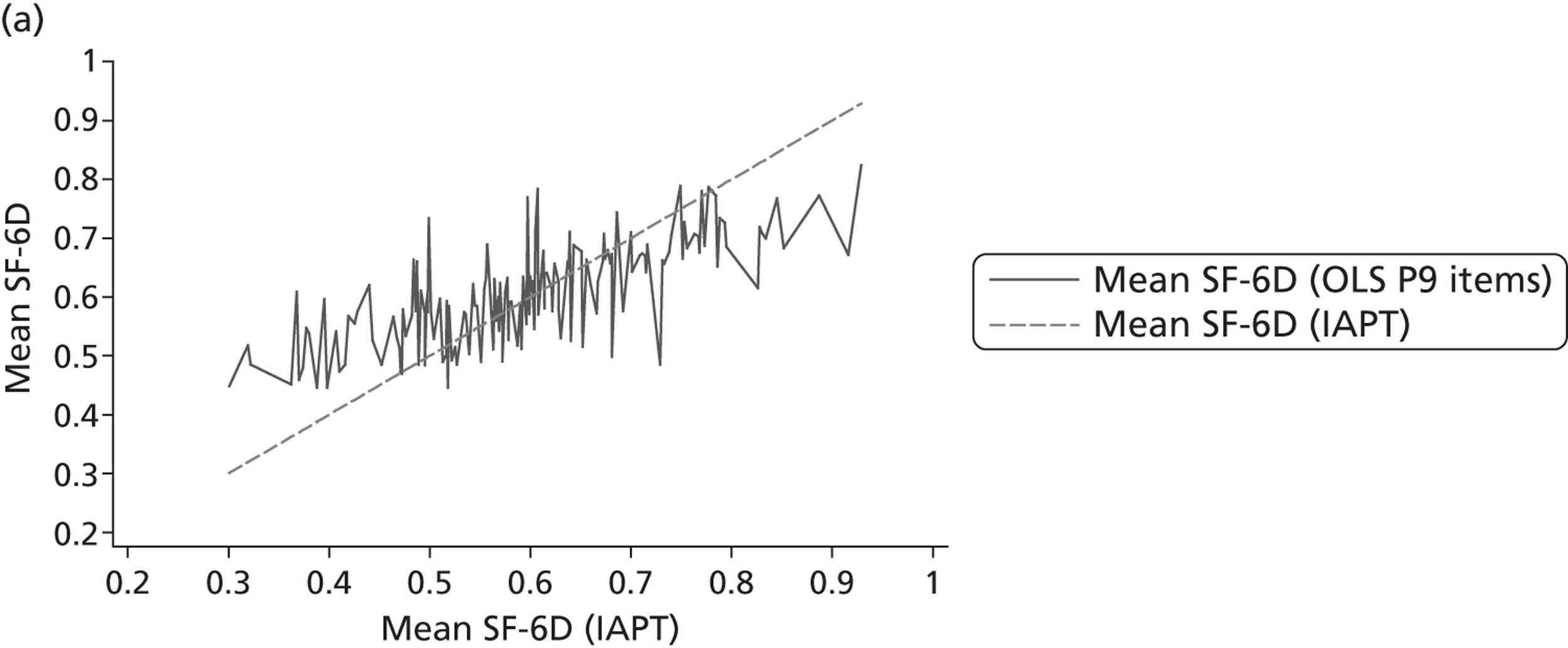

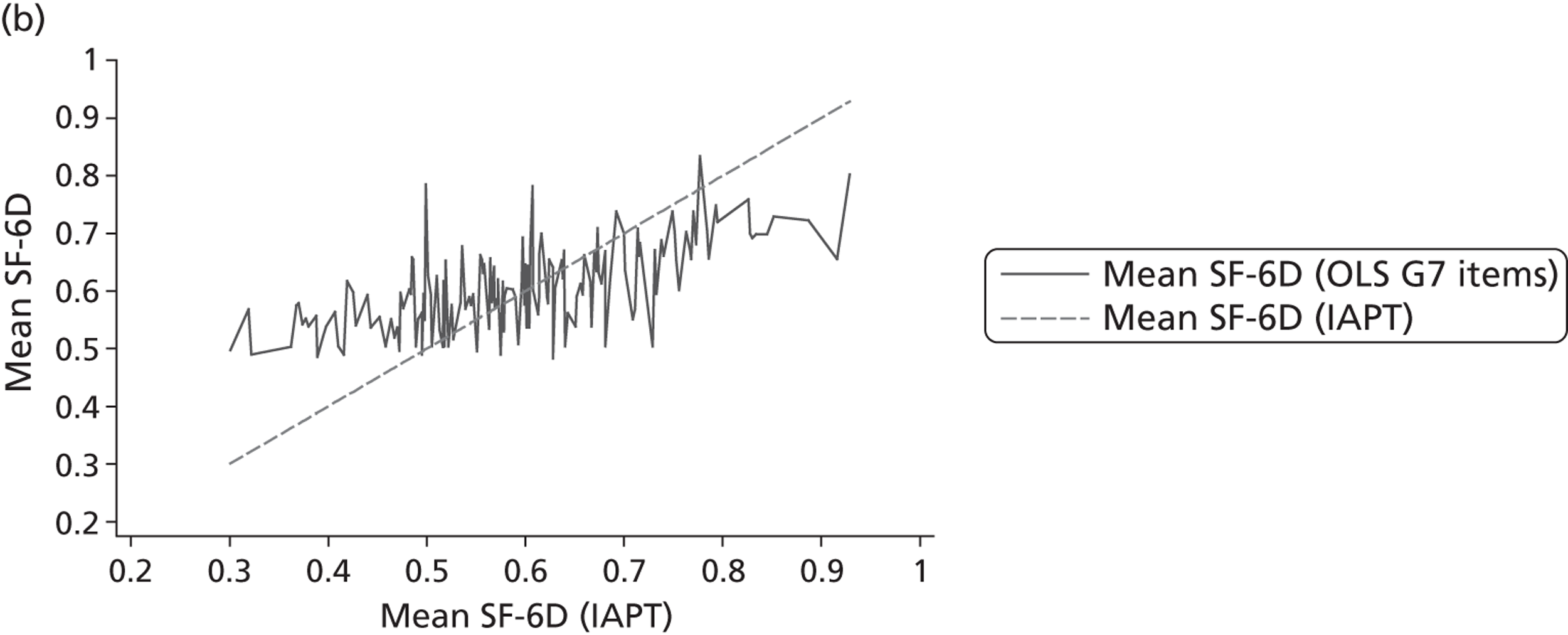

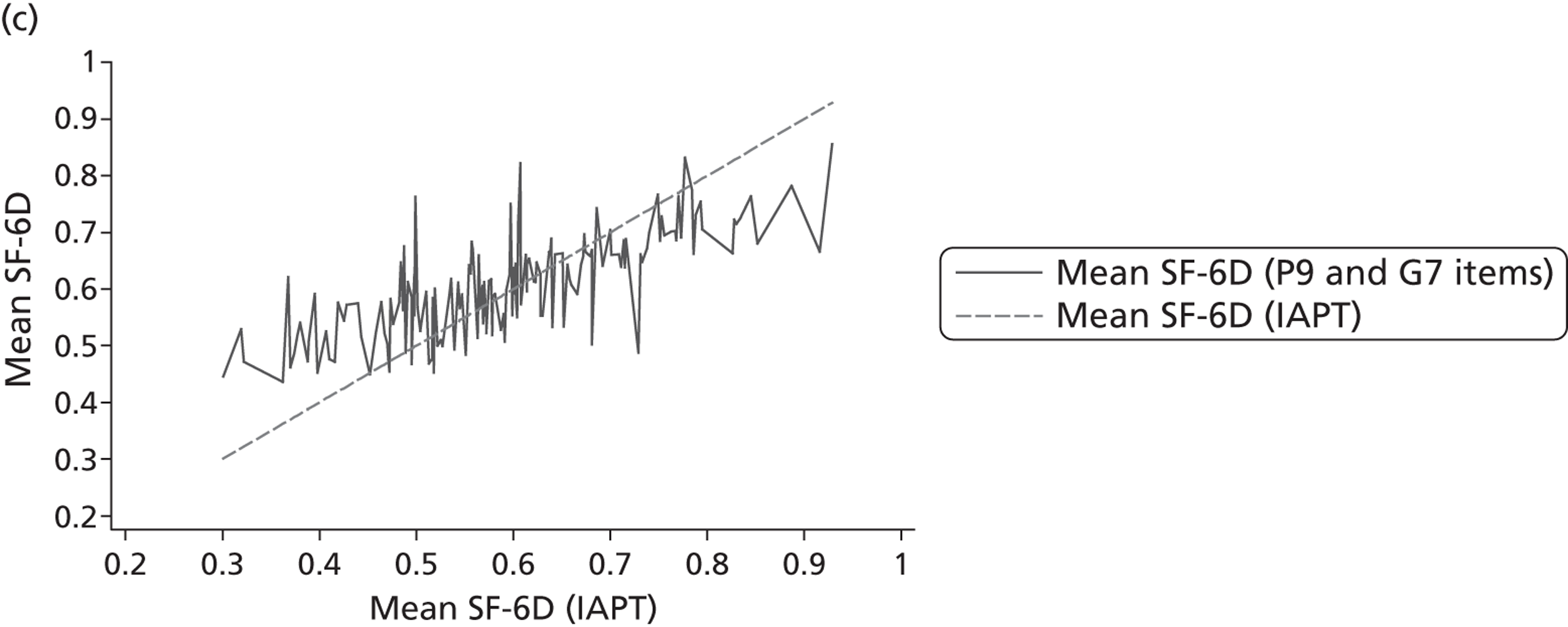

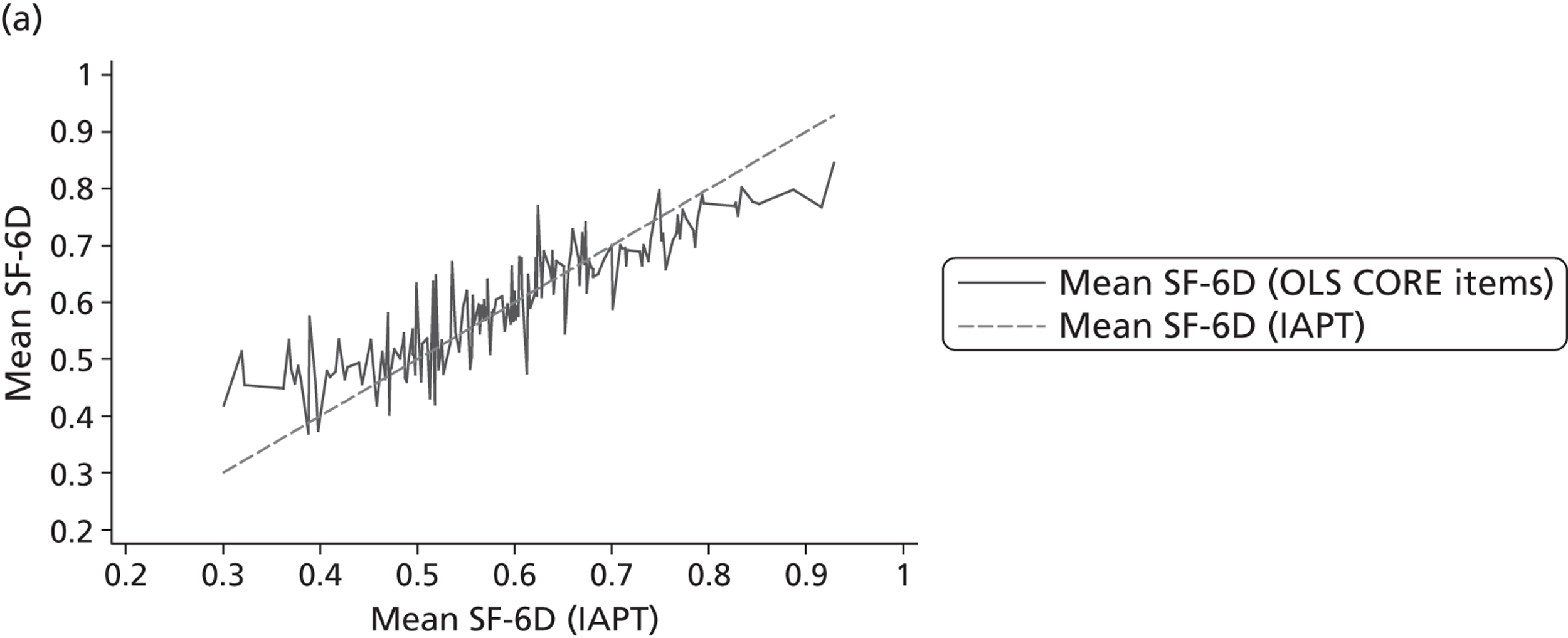

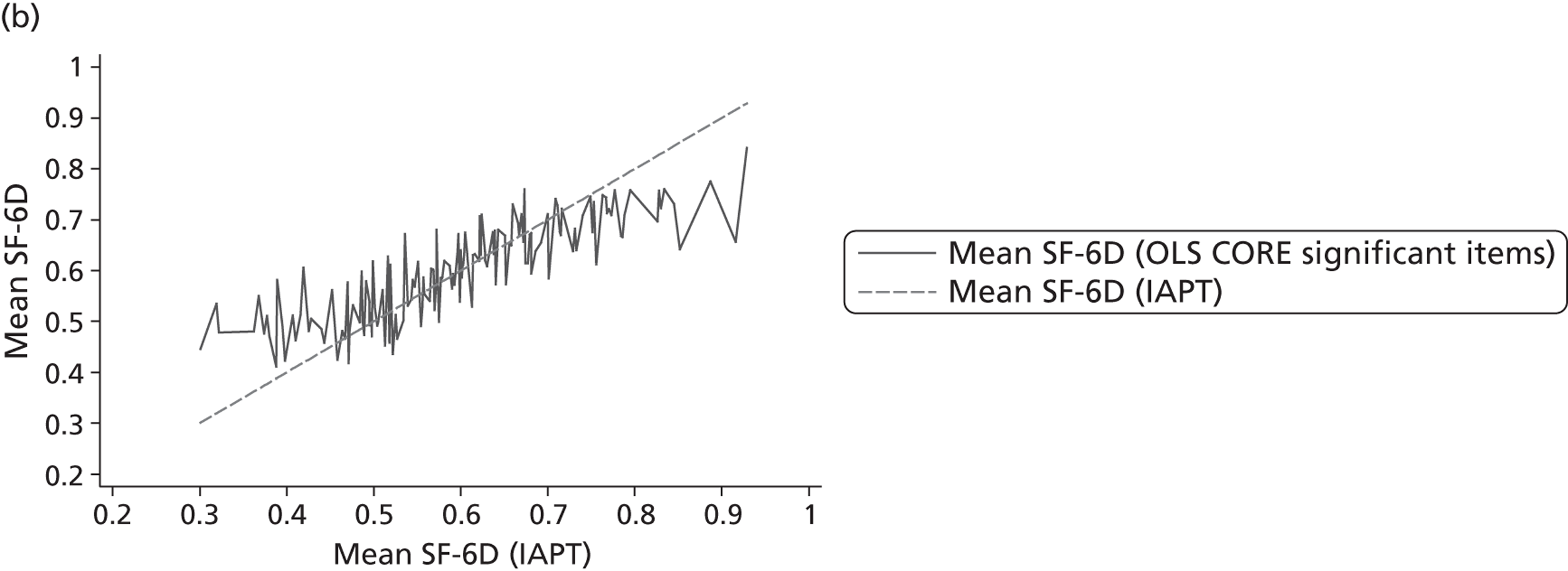

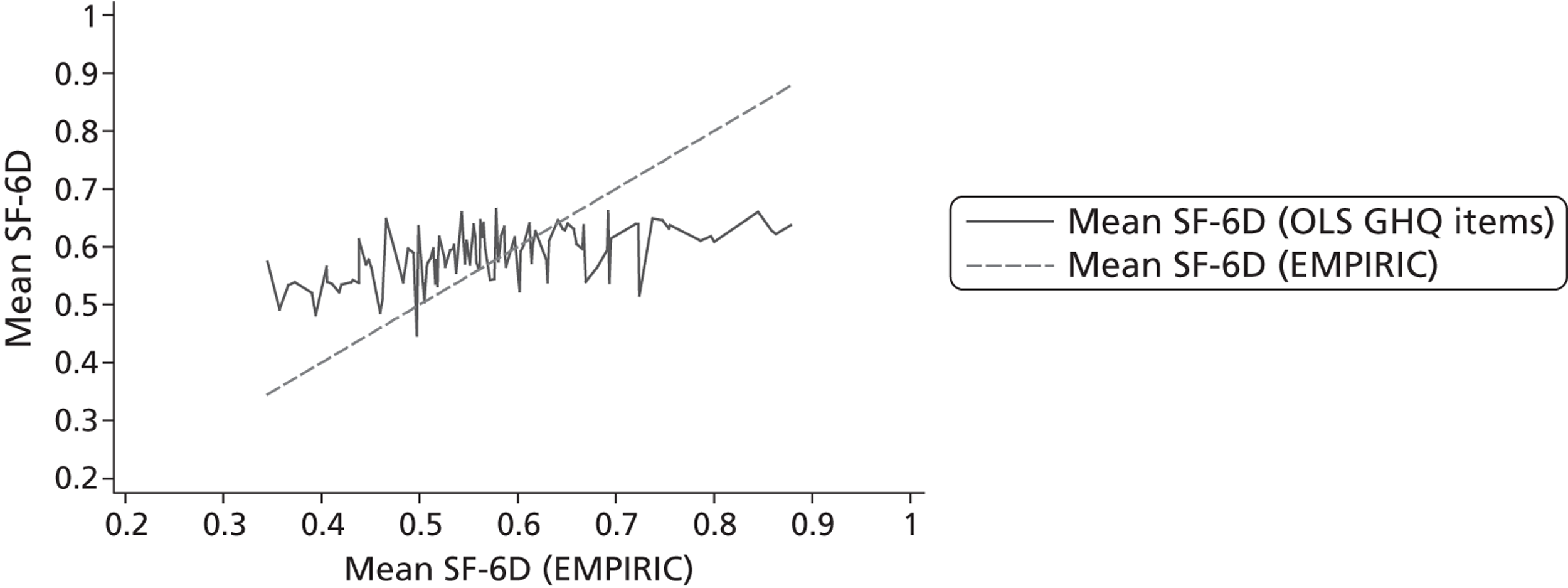

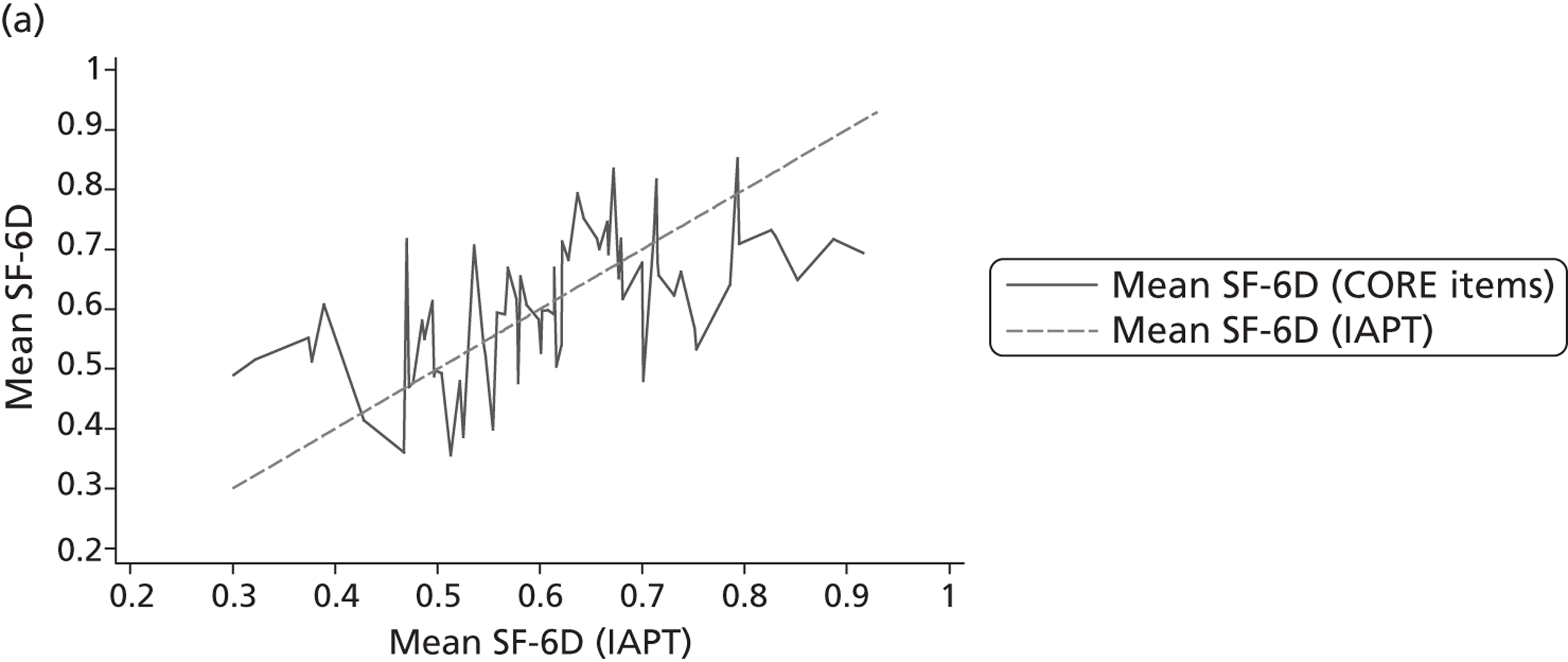

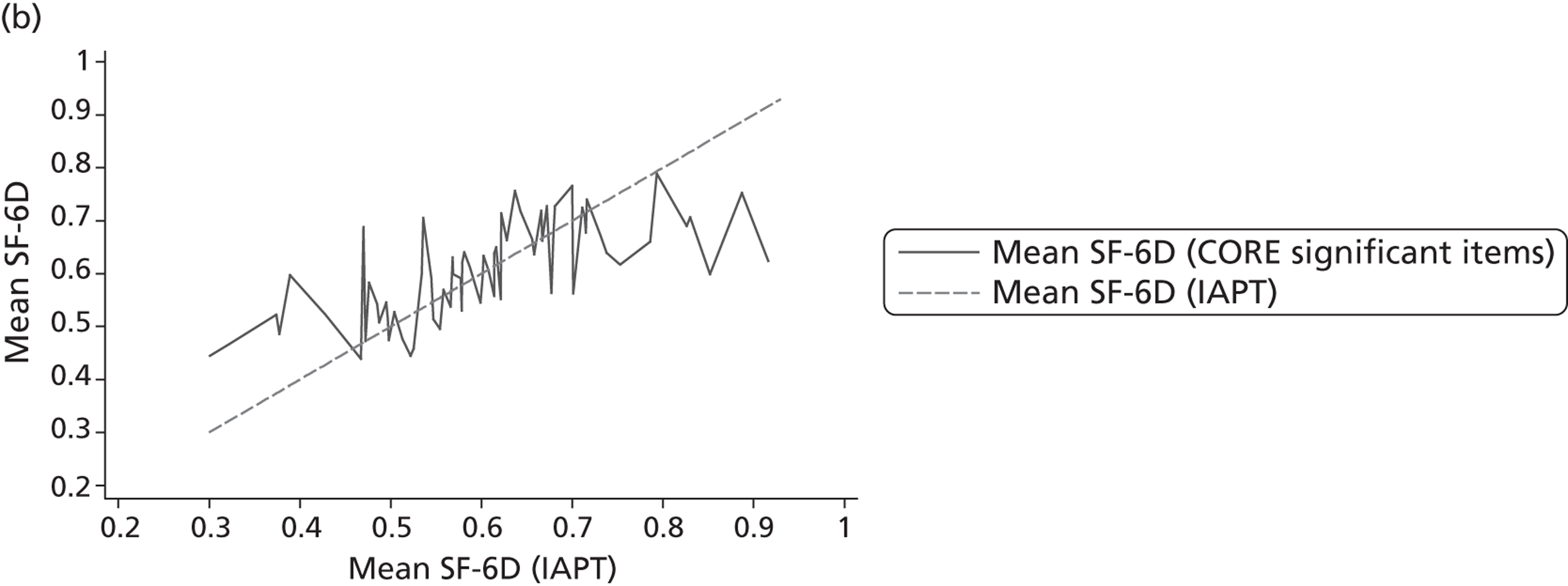

Schizophrenia data sets