Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 05/516/06. The contractual start date was in February 2007. The draft report began editorial review in February 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Snowdon et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

If randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are to generate a sound evidence base to support the care of sick children and to improve survival and disability rates in settings where children are most at risk then the critically ill – who are most at risk of death and disability – are the clear target population for inclusion in research. This is especially the case in some of the trials conducted in neonatal and paediatric intensive care (NIC/PIC) settings. In such trials, comparison of mortality rates between intervention arms is a central analytical strategy. This reflects an explicit understanding that, given the severity of the condition of many of the children in the target population, some of those enrolled do not survive their illness or their clinical circumstances. It is the work of the trial to determine the effect that an intervention might have on a range of outcomes, including mortality. Whether mortality rates are lowered, raised or unaffected by a given intervention is considered at a group level, but behind the collective mortality rates are individual families who make the decision to enrol their child in a trial and whose child does not survive.

The last decade has witnessed a highly co-ordinated response in the UK to the shortfall in research evidence for many paediatric medicines and clinical interventions, which was acknowledged around the turn of the century. 1–3 The establishment of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Medicines for Children Research Network (MCRN) to provide an infrastructure for UK research in this field, and the attendant development and expansion of Local Research Networks (LRNs) throughout the UK, is intended to encourage and facilitate paediatric research. Along with the aim of encouraging more high-quality trials comes an increase in the number of families who will be involved in clinical research. It is important that the ways in which those families are cared for in the context of the research to which they give their consent are also of a high standard and, where possible, evidence based. Although there has been some empirical consideration of the perspectives of parents on trials involving their children, much of the work carried out so far has focused on aspects of the decision-making process for trial entry and has predominantly involved parents of children who have survived.

The forms of communication and the means of support that trial teams and their clinician representatives might offer to the bereaved families of research participants can be considered as being as much a part of trial processes and methods as the information leaflets, enrolment discussions and consent forms that were used when their child was entered into a trial. The management of bereavement subsequent to trial enrolment has been almost completely overlooked, however, and has rarely been the focus of empirical study. It is of concern that so little is known about the possible views and experiences of bereaved parents and those involved in their care in the trial context, especially as their particular contribution to clinical research is so important to medical progress. Without research that describes the perspectives of these central players, it is not possible to know whether current trial-related practice is appropriate and whether it meets their needs. It is important to find out exactly how parents, in all their variety, wish to be treated and what subsequent relationships, if any, they wish to have with research. It is also important to consider the views of clinicians who act as intermediaries between trial teams and parents. Other trial team members, such as non-clinical investigators, managers, statisticians and trial advisors, do not necessarily have contact with bereaved parents, but their views and the decisions that they make about the science and the day-to-day conduct of a trial may shape parental experiences overtly or subtly, directly or over time. Understanding how trial teams respond to bereavement and why they do so in particular ways, and how bereaved parents view their experiences and how they would like to be treated, is a complex task given the range of individuals whose views must be considered, and the variety of views and responses that are likely to exist in this very sensitive setting.

In 2006 the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funded the BRACELET (Bereavement and RAndomised ControlLEd Trials) study in order to generate information and insights into death and bereavement in this context, and to consider methods for research into this area. BRACELET was the first study to specifically focus on the complex and sensitive issues raised when death and bereavement occur in the context of RCTs.

This multidimensional study was conducted in two phases:

-

The quantitative phase (Phase I) sought to ascertain the numbers of babies and children who had been enrolled in NIC/PIC in a given period, the number who had survived and the number who died. By identifying the proportion and distribution of deaths in these trials, this component of the study would provide a valuable overview of the field, as well as giving a sense of the size of the population of parents whose babies and children have died subsequent to their enrolment in a trial. It would also provide a sound base from which to move on to the second qualitative phase of the study. Phase I of the study has been published4 (see Appendix 1 ).

-

The qualitative phase (Phase II) sought to examine how death in a trial setting is handled and experienced by parents, clinicians and trial teams, and to explore how they feel possible needs for communication and support, relating to bereavement, might be addressed.

The BRACELET study was also designed as a methodological study, focusing on two main aspects: methods to support the future running of trials involving children where deaths are expected, and methods for conducting qualitative research in this area, based on the experiences of carrying out Phase II of BRACELET. Given the lack of precedent for research in this area, BRACELET was planned as a feasibility study, determining the extent to which such sensitive research is possible, and assessing the value of the data produced. It aimed to consider the challenges of identifying a research population appropriate to the field of study, as well as how to inform and recruit potential participants, and how to conduct interviews in relation to such a sensitive topic. The plan for Phase II was also to test the value of flexible options for participation. As a scene-setting study working with potentially vulnerable populations, it was important to consider both the challenges of responding to bereavement as an element of clinical trial practice and developing methodological guidance for the conduct of future empirical work on this topic.

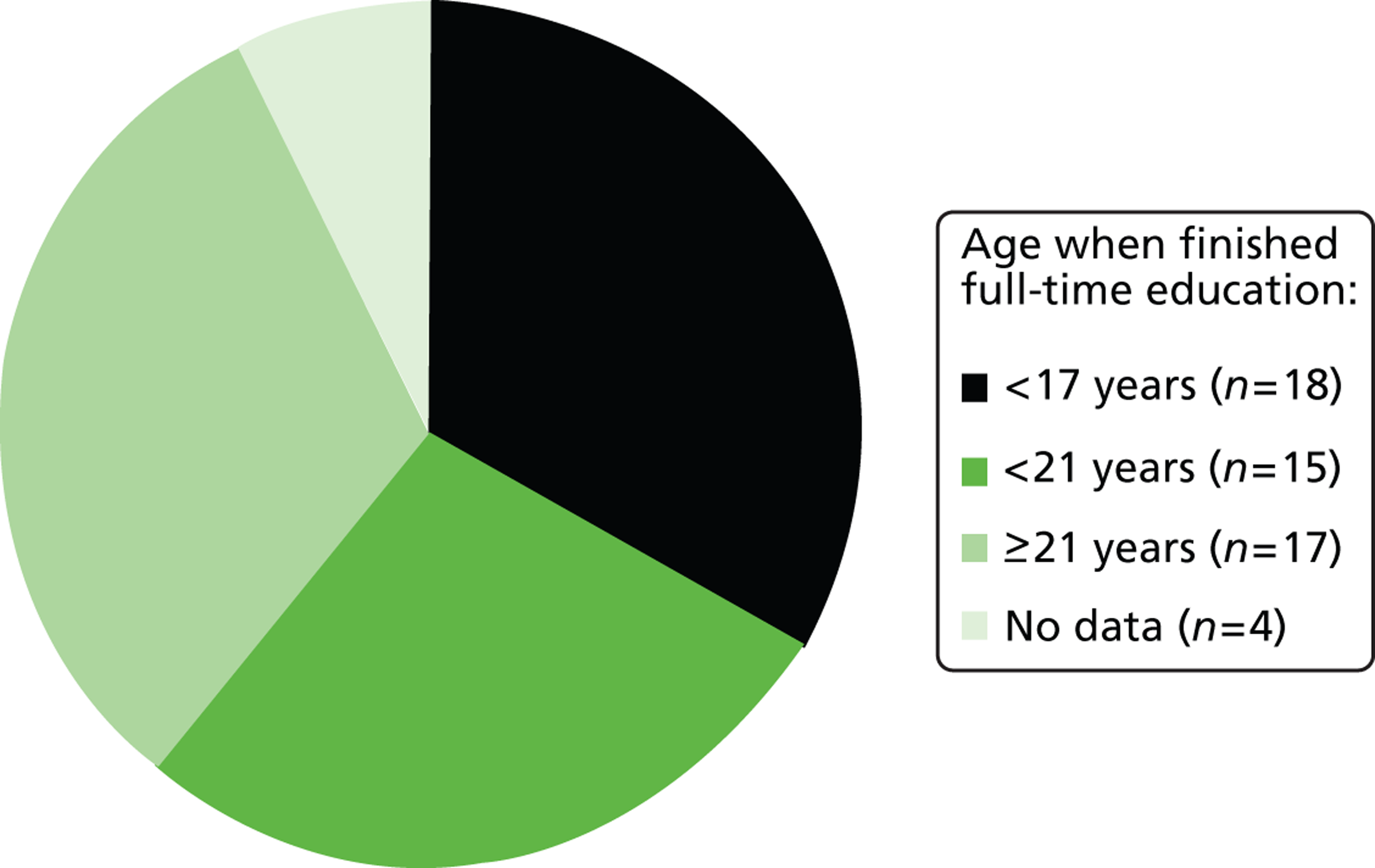

Thus, the empirical and methodological dimensions of BRACELET were closely tied, and were considered by the research team to be of equal importance.

The BRACELET study was carried out over the 6-year period 2007–12, a reflection of the multidimensional, multimethod work needed to gain insight into this underexplored field of research. The structure of this report reflects the three main bodies of work involved. After an introduction to the topic (see Chapter 2 ), the methods and the findings from the study are presented in three main sections and a concluding chapter as shown below:

-

Section A Quantitative survey of clinical trials and clinical centres (see Chapter 3 )

-

Section B Qualitative study of bereavement-related practice and experiences in neonatal clinical trials (see Chapters 4–9 )

-

Section C Methodological evaluation of tools and approaches to recruitment and participation in the BRACELET study (see Chapter 10 )

-

Conclusions Implications for practice and research (see Chapter 11 ).

This division of the three main components of the study suggests three discrete areas and emphasises their different methodological approaches. In fact there was much overlap and cross-fertilisation of ideas across the different areas of the study, with the insights gained in one area shaping methodological choices and guiding reflection in other areas. In the final methodological section of this report the benefits accrued from taking a mixed-method approach are considered (see Chapter 10 ).

Although BRACELET is a wide-ranging, multimethod, multidisciplinary study, it is intended to be the first step in gaining some insight into the range of experiences and responses to bereavement that might be encountered. It was not designed to explain fully the phenomenon of bereavement subsequent to RCT enrolment in NIC/PIC trials, but to provide methodological foundations upon which further research would build to refine understanding with examination of different situations, settings, practices and interventions, in paediatrics as well as in other settings in which bereavement can be a salient issue.

Chapter 2 Related research and research plan

Related research

The BRACELET study was developed in order to describe and explicate a specific and underexplored area of clinical trials practice, but much of the ground to be covered is not entirely new research territory. Although there has been little research on death subsequent to trial enrolment, the reactions of clinicians and parents to their experience in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs) and paediatric intensive care units (PICUs), including experiences of death in these setting, have been described by researchers from a wide range of disciplinary perspectives and have been the focus of a number of reviews. Bereavement care packages offered by attendant clinicians in NICUs have been described in a growing literature (see Harvey and colleagues5 for a review). Clinician and parental views of their involvement in RCTs is another burgeoning area of research. Although this broad body of available data provides a helpful empirical contextual base for BRACELET, consideration of the gaps in this literature points to important shortfalls to be addressed. An overview is provided below.

Experiences in neonatal intensive care units and paediatric intensive care units

A number of studies describe responses to NIC and PIC (for a review of qualitative studies of parental experiences of NICU stay, see Obeidat and colleagues;6 for a review of ongoing sequelae for parents after PICU stay, see Nelson and Gold7). They amply demonstrate that the intensive care unit (ICU) is an extraordinarily stressful environment for the adults concerned: for parents of neonates,8–12 when admission takes place shortly after birth, and for parents of older babies and children,13–16 when an admission may be the result of chronic or acute illness, trauma or violence. It can also be a challenging professional environment,17–22 but clinicians build up expertise over time and often develop strategies to deal with and manage difficult situations. 23

Death in the NICU or PICU can bring with it a number of very difficult experiences for parents in addition to the loss of their child, such as end-of-life decision-making,24–30 the experience of withdrawal of care and the impact of lingering death,31,32 loss of a multiple (e.g. a twin or triplet)28 and multiple losses,33 and the need to consider post-mortem examinations34 (for a review of studies of end-of-life decision-making in the NICU see Eden and Callister;32 for decision-making more generally in the PICU, see Madrigal and colleagues35). Studies of parental experiences of death in the ICU suggest that they value clear information given around the time of their child’s death,36 appreciate acts of kindness from ICU staff in their bereavement,37 and often want further contact with ICU clinicians. 38 When death occurs, clinicians can find their own emotional resources being strained. 39–42 They can be confronted with situations that challenge their own ethical positions and stretch their capacity to cope. 19,43–45 Research also shows that despite the difficulties, caring for the needs of parents in these circumstances can be a valued and satisfying aspect of clinical work. 46,47

Participation in neonatal and paediatric intensive care trials

Decisions about whether or not to enrol an infant or a child into a trial involve discussions between parents and recruiting clinicians, and the outcome of their discussion sets in train the experiences of interest here. All parties therefore have relevant insights of interest and value, and a substantial literature exists on the subject of clinical research involving babies and children (see Shilling and colleagues48 for a review). There are, however, a number of biases and gaps in relation to intensive care trials. The views of parents are better represented than those of clinicians, with only a small number of papers describing the research-related experiences and views of intensivists who have responsibility for recruiting to NIC trials,49–51 and there is a dearth of research specifically assessing the views of clinicians involved in PIC trials. Although parental involvement in PIC trials is similarly limited, with few examples identified,52,53 parents’ experiences and views of NIC trials have been relatively well studied: we have identified 21 papers. 49,51,54–72 Many of these papers focus on issues at the ‘front end’ of trials, such as comprehension, decision-making and views of enrolment in more than one trial. They highlight areas of potential difficulty around enrolment for parents with responsibility for proxy decision-making, while also dealing with the stresses and strains of having a sick child, as well as the admission to ICU. They also suggest the importance of parental responsibility as parents seek to make good decisions in relation to the care of their child, and reluctance for others to make that decision for them. There are few data that describe the ongoing experience of being involved in a NIC trial, or later responses after discharge or death when time has passed and parents’ thoughts about a trial may be worked through away from the ICU. Notably data are available to describe parents’ ongoing views and interest in feedback of trial results, which usually occurs some years after recruitment, but only for parents whose child has survived. 56 Whether bereaved parents are similarly interested in the outcome of a trial, or whether they have left this part of their experience in the past and do not wish to have the subject raised, is simply not known.

The gap at the intersection

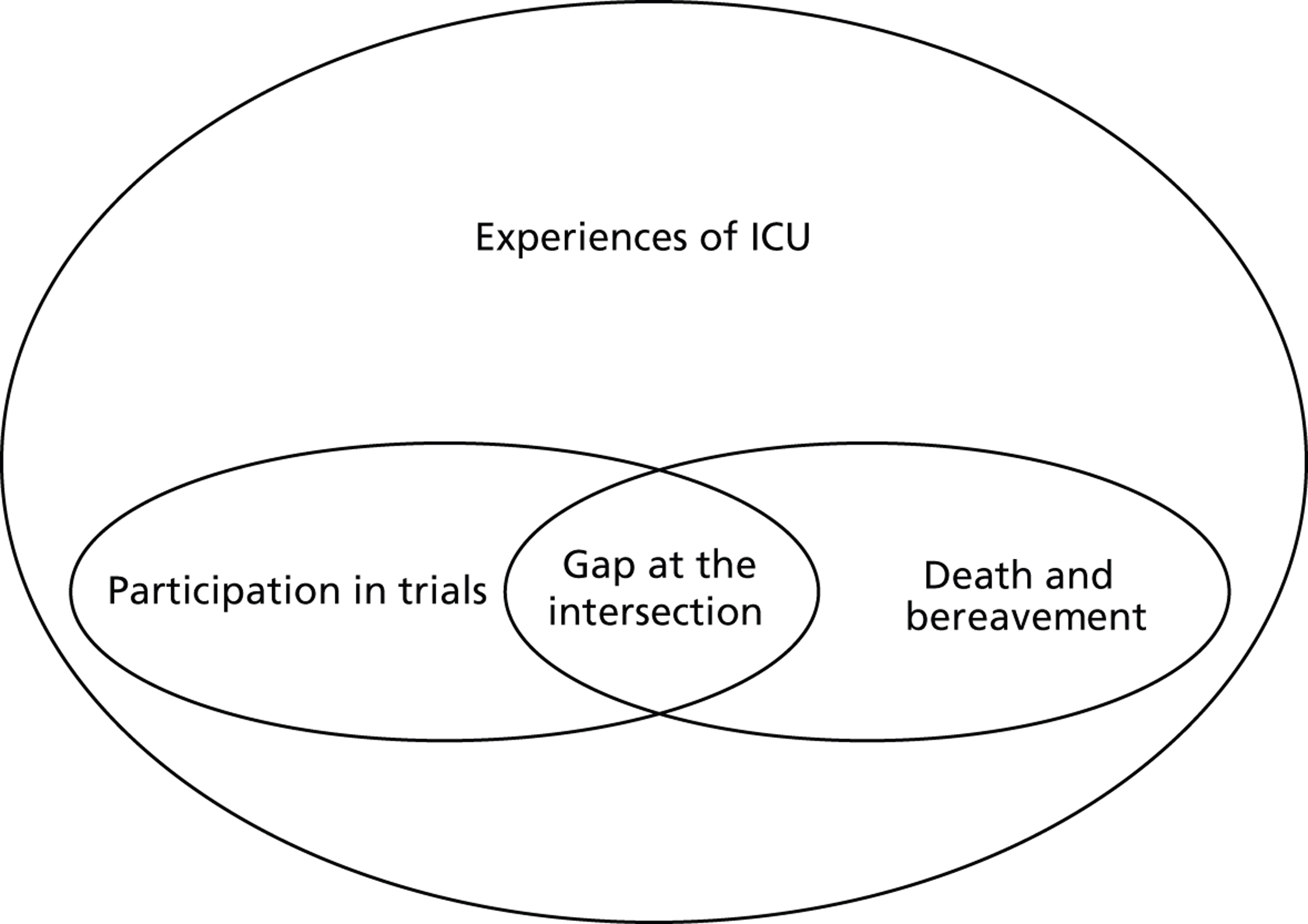

It is notable that despite the availability of overlapping bodies of literature on parenting and bereavement in the ICU, and on participation in ICU trials, the intersection of the three has been left unattended. In fact the knowledge sets that have built up have done so as if there were no common ground between bereavement and trial participation ( Figure 1 ). Even with the passage of time since BRACELET was funded to address this shortfall, there is still very little research available that describes the experiences of parents whose baby was enrolled in a NIC or PIC trial and subsequently died, or which explores whether the decision to enrol adds, positively or negatively, to the experiences of the families and clinicians involved. There is nothing to give an indication of how bereaved parents would like to be treated in relation to their links with a trial, or what might be appropriate practice and what might not. We found no editorials or opinion papers reflecting on this issue, and no practice-based papers in which clinicians describe how they handle this situation. This gap in research is in sharp contrast with the attention received by other elements of clinical trials practice, such as recruitment strategies and informed consent procedures.

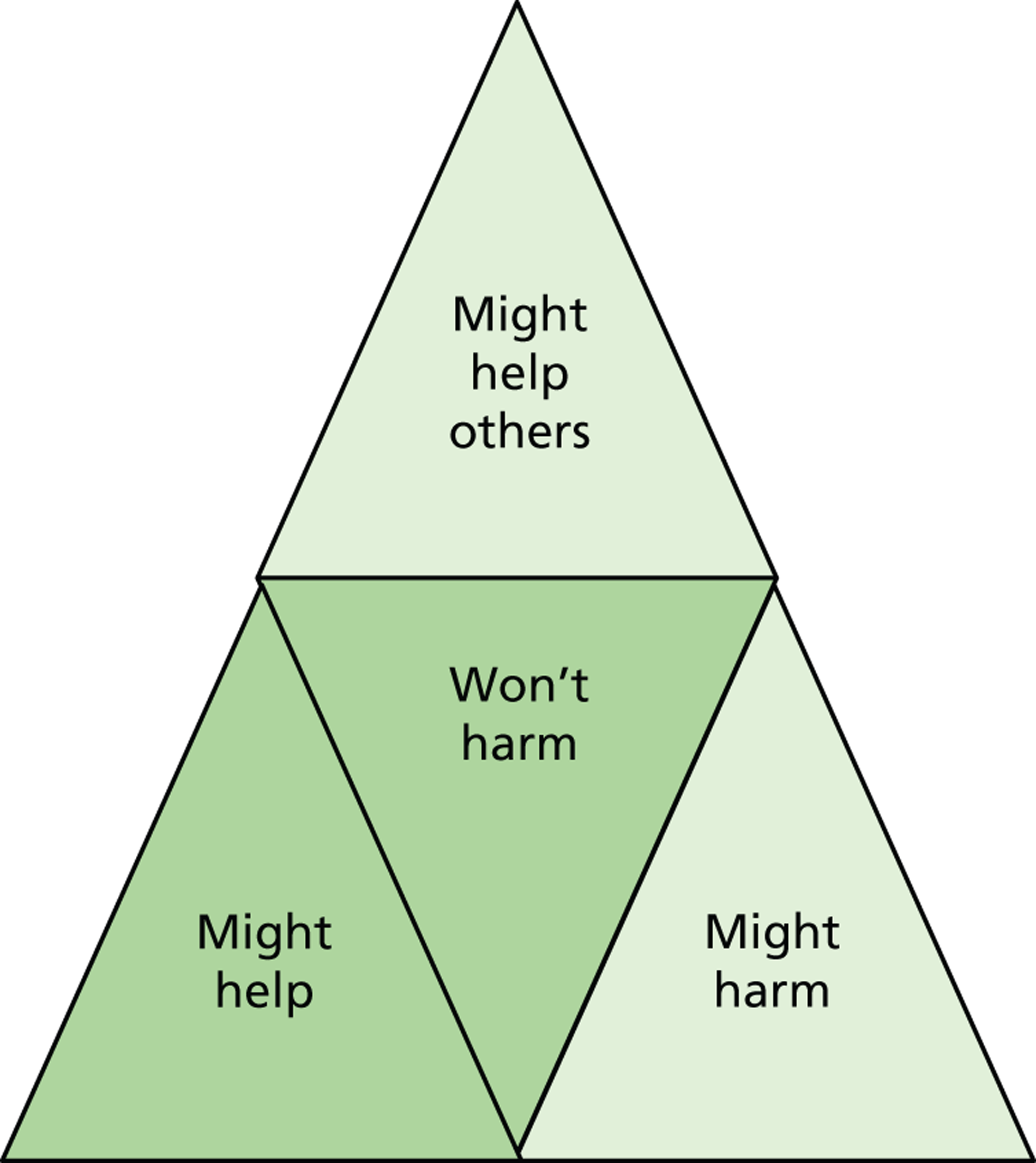

FIGURE 1.

The research gap.

The lack of specific research in this area, as well as the exclusion of bereaved parents from more general research on participation, means that their voice, whether or not it is distinct from those of other parents, does not inform the evidence base for how to carry out a well-conducted RCT. The voice of the parents of survivors stands for all. As an example, Morley and colleagues63 considered parents’ views of participation in multiple trials. The choice to recruit parents to this study in the third week of their baby’s life meant that parents who had been invited to enrol their baby into more than one trial and were subsequently bereaved were unable to give their views. Their views may or may not differ from parents of surviving babies, but the evidence to sanction recruitment to multiple studies is put forward without exploration of this possibility. This is not at all unusual. In some studies it is stated that bereaved parents were actively excluded from research samples, either because this could have been upsetting to them58 or no reason was given. 49,68 This bias in the evidence base seems to have gone almost unnoticed, and passes largely without remark other than an early comment on the absence of bereaved parents in one of our studies: ‘For perfectly understandable ethical reasons . . . bereaved parents were not included in Snowdon’s study . . . however, if approached sensitively, many are helped by discussing related events and their feelings, so that there may in fact be no “ethical no-go-zone” preventing research in this area.’73

Few papers other than our own include bereaved parents in their samples; only three of the 20 studies listed above do so and in each they constitute a small minority of their sample. 61,64,71 We know of only two papers,74,75 a paired set of our own and both from the same study, in which intensivists74 and parents75 have been asked to consider in detail particular issues involved in bereavement and research. Although these papers relate specifically to neonatal trial-related post-mortems, and involve only 11 interviews with 18 bereaved parents (a subsample from a larger study), we were able to gain insights from the views and experiences these parents described. Even in this relatively small subsample there was variety and range, from those who felt that enrolment into a trial was an almost insignificant part of their experience, to others where it complicated and added a difficult element to their baby’s death. The study included one couple who were very pleased to have contributed to research, feeling that it was an important and helpful positive element in a dire situation. Another couple described how horrified they were to learn of allocation to a control group, and how they were left with the persistent feeling that their baby had been deprived of a treatment and so died without every effort being made on her behalf. 76 (This last case is presented in detail in Snowdon and colleagues.)76

Although there are limitations to these data, they are useful in suggesting that separate and dedicated study of bereavement in this context is appropriate. They also suggest that parental responses to ICU trials after the death of a child may, like the experience of bereavement itself, be highly varied, reflecting both parental differences in experiences and reactions, but also changing responses to bereavement over time. Some parents may be keen for further contact with a trial/clinical team after the death of their child, to gain further information, clarification of events and possibly for feedback of the results of the trial to which they contributed; others may shun any such contact.

The views of parents of survivors cannot simply be taken as universal accounts of ICU trial participation, nor should they. The availability of research on the impact of death in the ICU, on experiences at the time and on the long-term effects, suggests that research with bereaved parents on delicate and sensitive topics is possible and is informative. It is the particular combination of bereavement and trial participation that appears to have so far placed this population of parents beyond the scope of research into their views of this aspect of their ICU experience, meaning that recommendations or decisions about practice based on current literature are made on the basis of the views of parents of survivors only. Research on parents of survivors is clearly important as they form the majority of the parents involved, but bereaved parents may differ in terms of circumstances, experiences and views and these differences may inform and shape their reactions to trials. The experience of being invited to take part in a trial is part of a larger narrative of their child’s condition and care. A parent whose child does not survive may have a different set of prior experiences to those whose child recovers. If their child is already severely compromised and at high risk of death, they may be asked to consider trial participation with a different set of expectations and assumptions, and may be more likely to have made their decision in crisis. Reactions to a trial may be forged in the possibility of imminent and then actual bereavement, and any research that considers the views of parents must acknowledge the possible ongoing effects of their child’s death on their subsequent views.

If we are to use research data to inform practice in NIC and PIC trials then a more nuanced account of responses to research is needed. Such an account needs to draw on the views of the different parties involved to gain purchase on the broader responses to death in the context of a trial, and this, in turn, needs to be placed in the context of clinical trials practice in the UK. Addressing the research deficit in relation to bereaved parents, and the views of those who design and implement the trials in which they are involved, marks an important step towards that aim.

Plan of research

The bodies of work described above suggest something of the complexity of considering experiences of trial participation and bereavement. These experiences are part of a larger narrative set of pregnancy, birth, critical illness, care, research and death. They involve the interplay of many individuals, all with different roles, responsibilities and views, yet studies that consider the views and experiences of those involved in trials often look at a group in isolation, such as recruiting clinicians or participants and/or their proxies, and their views are often divorced from the larger context of the trials involved.

There are clearly challenges for any research study that seeks to rigorously explore and fairly represent this situation. The BRACELET study was designed and funded as a substantial first step in addressing the shortfall in knowledge identified here, as a foundation study aiming to tap the multifaceted, multilayered elements of this phenomenon.

The starting point for the study was the likelihood that a range of perspectives on bereavement in trials might exist and that these must be understood within the larger context of trials, their recruiting centres and trials-related practice, as well as with reference to the close detail of the roles played within a trial. It was therefore necessary to look beyond the views of single groups and to consider the topic of bereavement in trials in relation to both the infrastructure of trials-based research and to the role-related infrastructure of individual trials. How to carry out such a study in the light of the sensitivities that surround this topic, in ways that are acceptable to participants and that produce sound data, was also an important consideration.

This yielded a study in three parts using multiple methods to serve its different but overlapping aims. The structure and components of the study are described below.

Phase I: the quantitative component

An essential prerequisite to considering bereavement and trials was to ascertain the magnitude and distribution of mortality post-trial enrolment. This part of BRACELET therefore aimed to determine:

-

trial activity in UK NICUs and PICUs

-

the number and proportion of deaths among babies and children participating in NIC and PIC trials

-

variation in mortality across units, and across trials

-

whether any provision was made for bereavement within trials.*

*Key elements of these data were published during the course of The BRACELET study (Snowdon and colleagues4). The methods of data collection and findings are presented in the following chapters in more detail.

Phase II

Phase II involved both a qualitative and a methodological component, which, together, were intended to open up a new and important field of enquiry, considering throughout the factors that facilitate and impede further research in such a sensitive and difficult area. The aim was not to fully explicate the phenomenon of bereavement subsequent to trial enrolment but to generate new data that would produce important insights and generate further questions for the clinical and trials communities. With this in mind, the specific objectives of Phase II of the study were as follows.

For the qualitative component:

-

to start to address the shortfall that exists on the subject of bereavement subsequent to trial enrolment by initiating enquiry into this new research territory

-

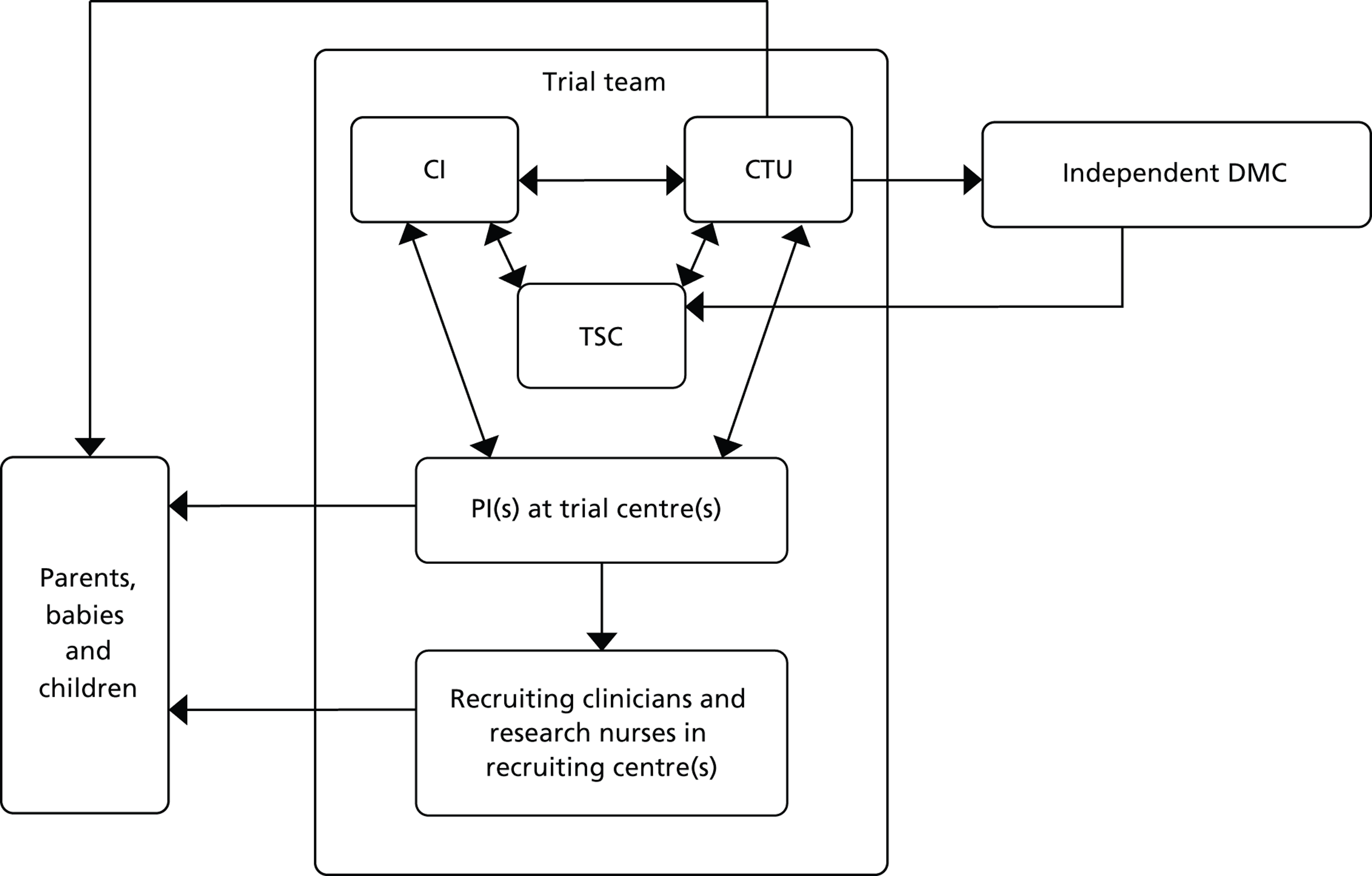

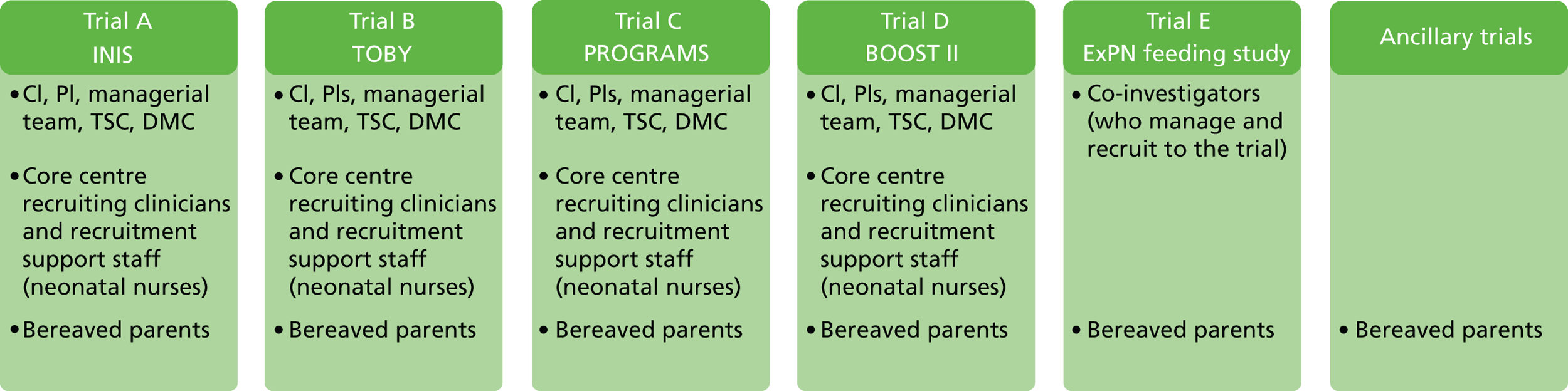

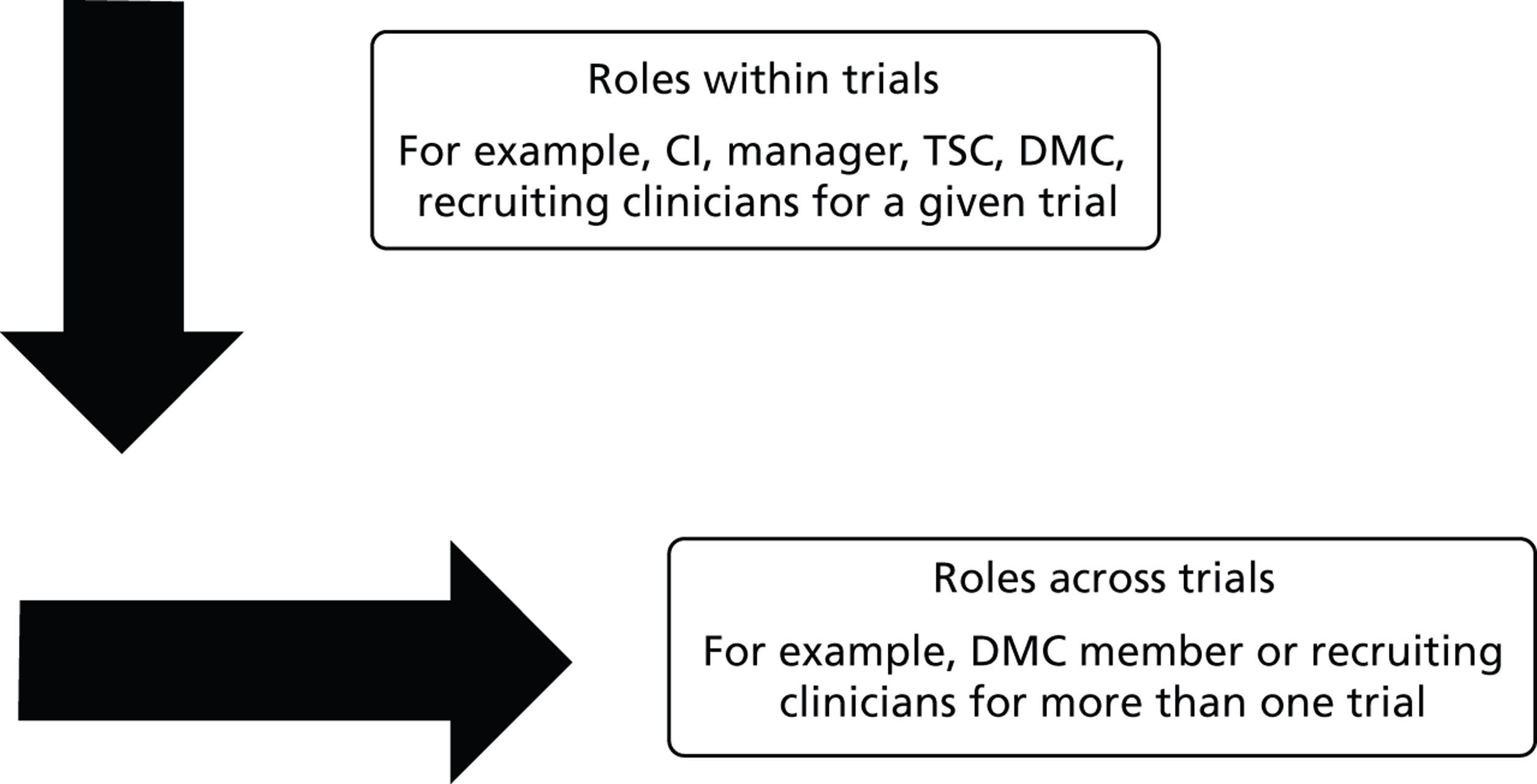

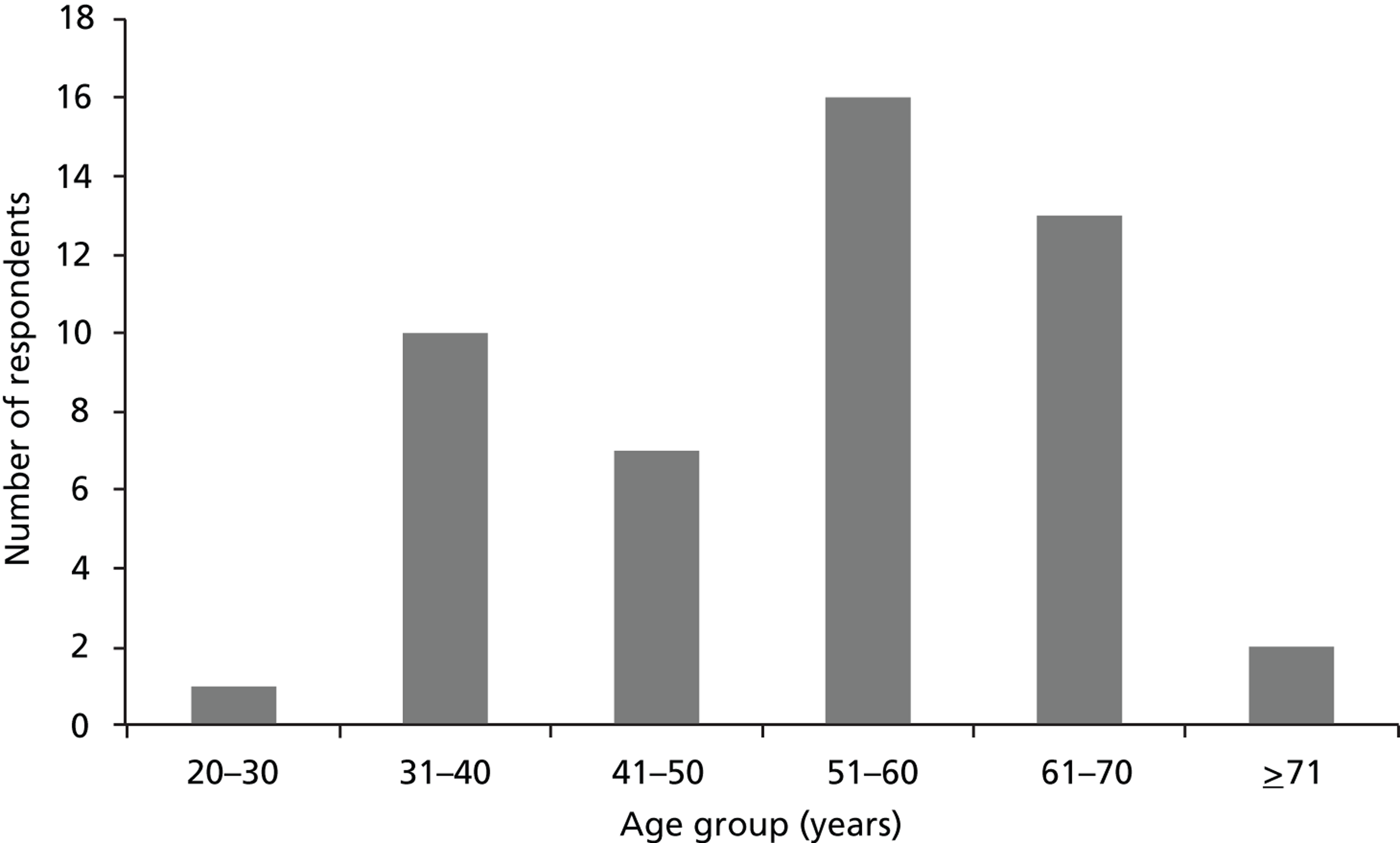

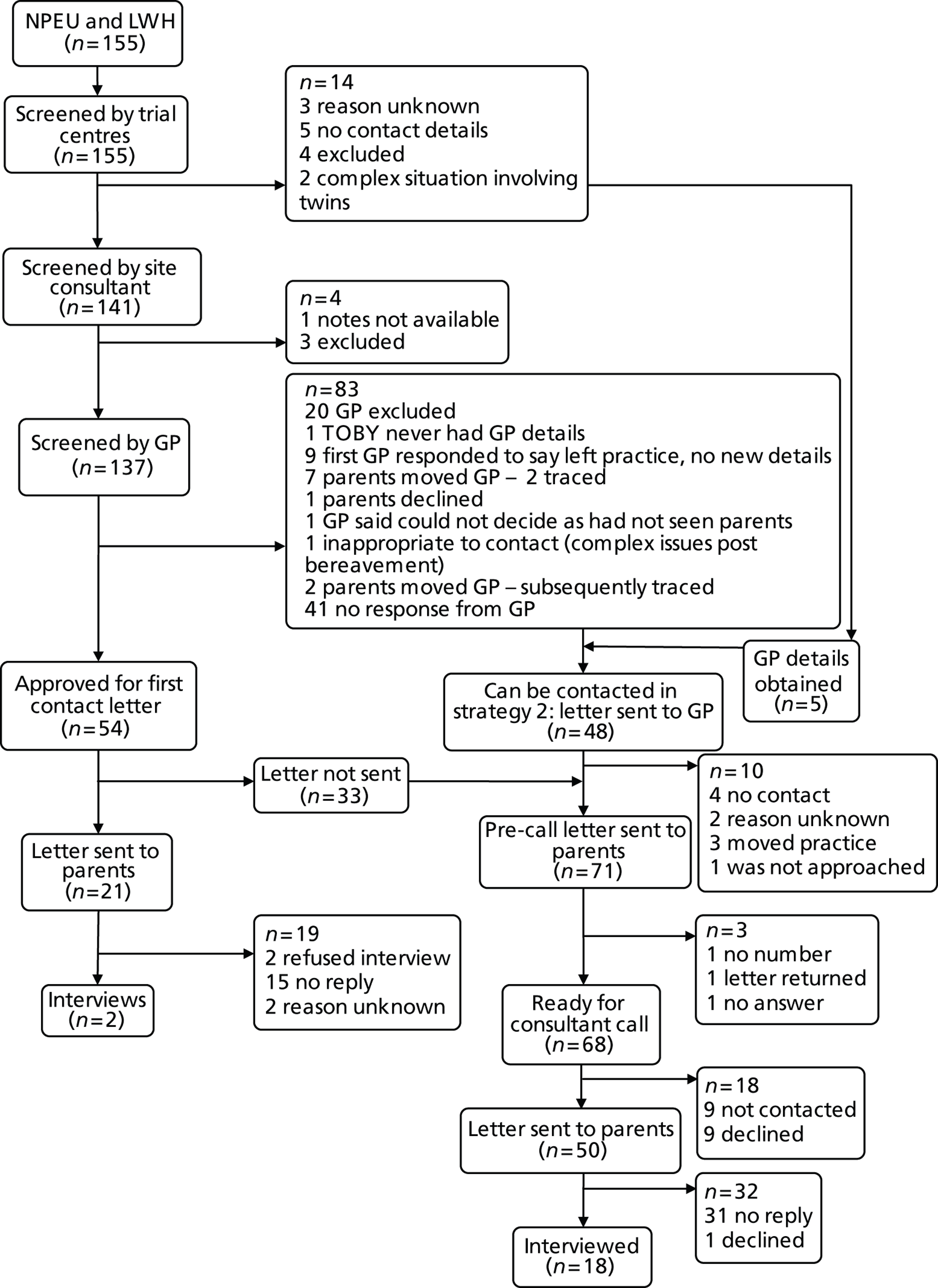

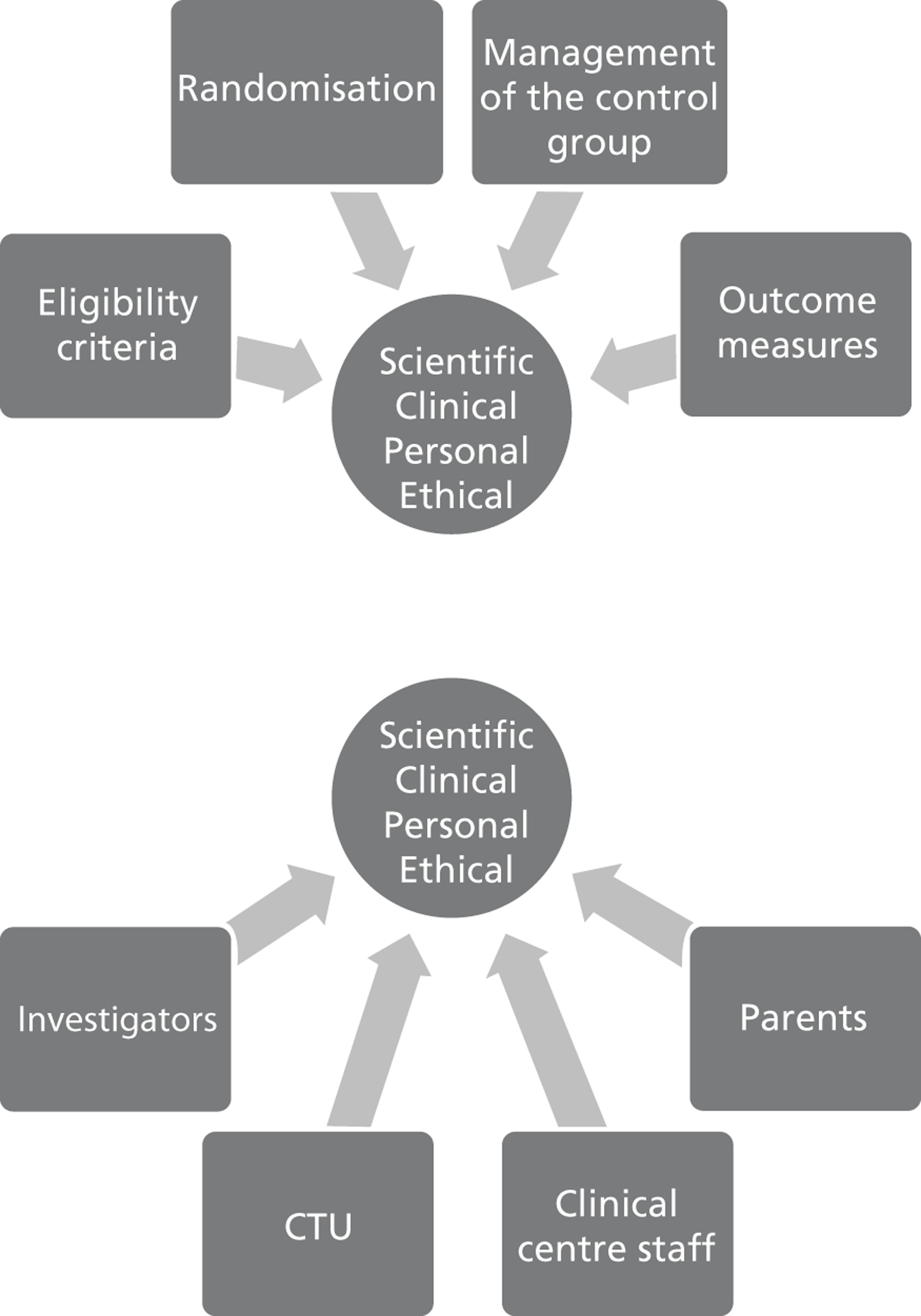

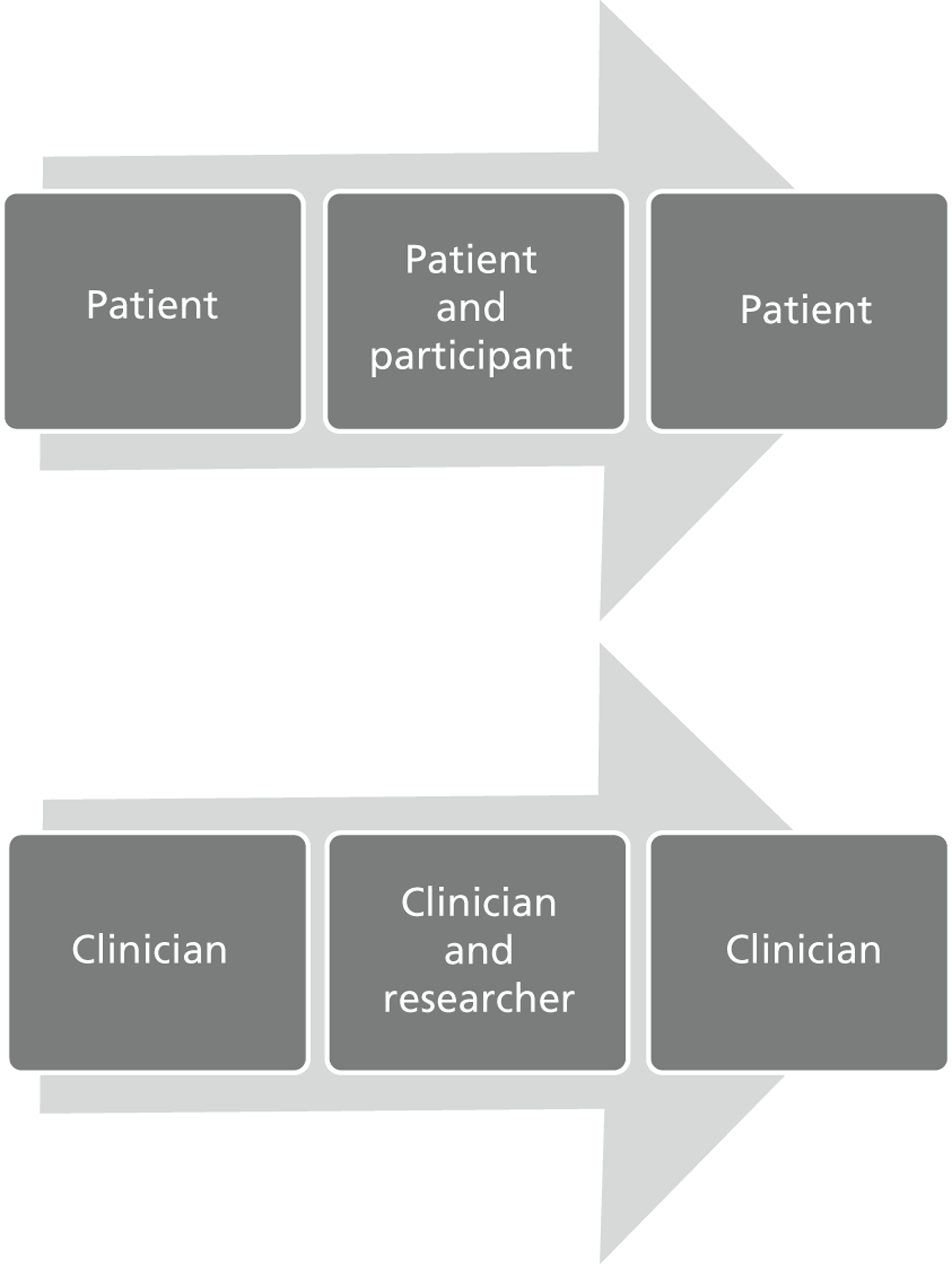

to start to delineate the relevance of trial enrolment to bereavement in this context, by describing and exploring the experiences and views of key people involved in NIC and PIC trials. The methodological starting point for this component of the BRACELET study was therefore to consider the typical structure of a multicentre trial, which involves a central trial team, comprising the chief investigator (CI), Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC), and the recruiting centre teams comprising principal investigators (PIs), recruiting clinicians and research nurses. Trials often work in conjunction with an independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), which advises but stands apart from the trial team. Although DMCs are not part of the trial team itself, DMC members are likely to have an important perspective of how a trial is run. This broad grouping was defined as one of the major populations of interest to BRACELET and, for convenience, the different roles involved were all considered under the generic term of ‘trial team.’ The other major population to consider was the bereaved parents whose children were enrolled in a trial ( Figure 2 )

-

to consider the similarities and differences in how bereavement is approached in the policies and practices of central trial teams and teams in recruiting centres. This information would allow for best practices to come to light and highlight any actions or omissions which the key people involved consider to be problematic.

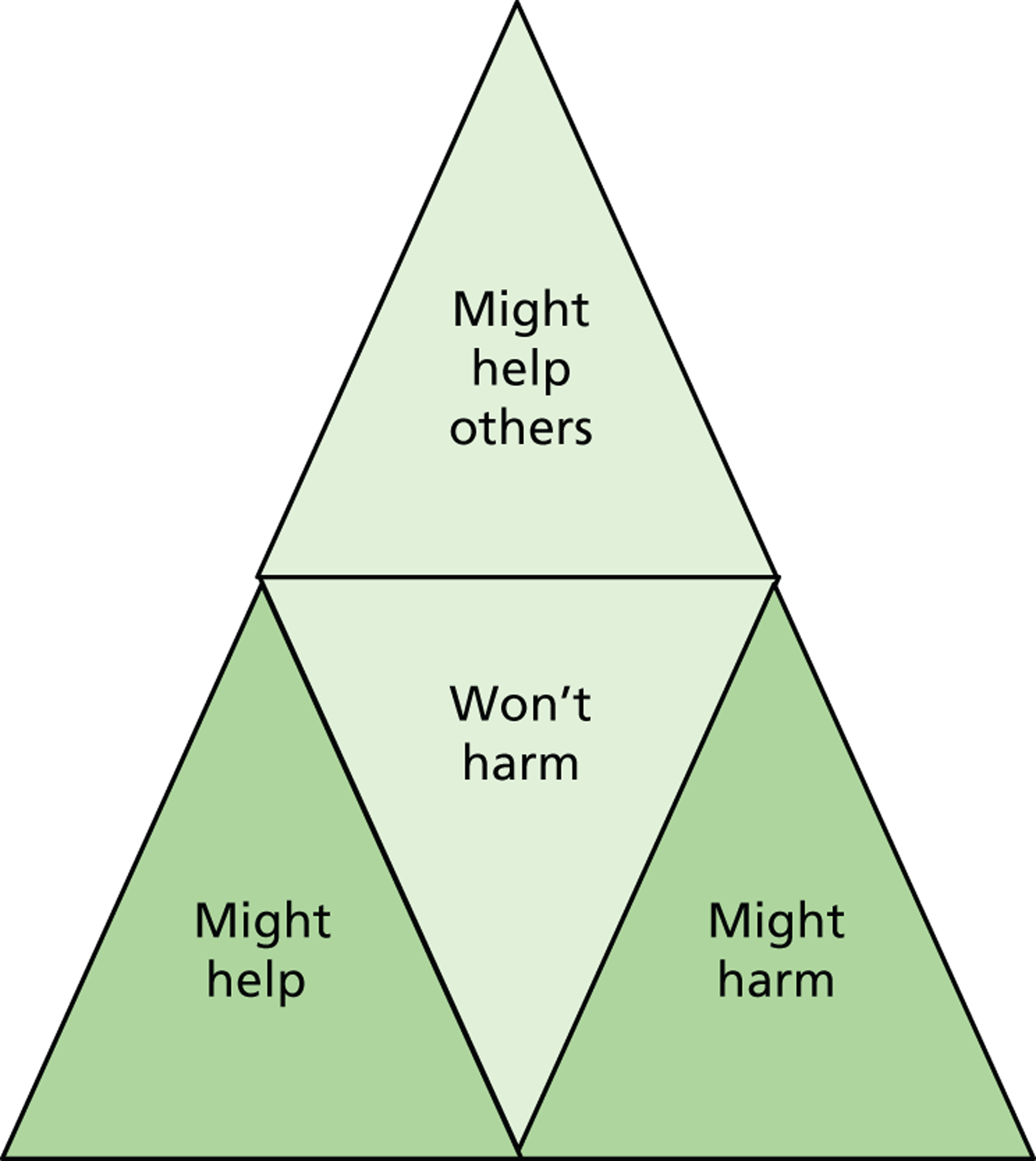

FIGURE 2.

Typical structure of a multicentre trial.

For the methodological component:

-

to act as an important foundation for future research, ascertaining the feasibility, and acceptability of research in this area, through reflection and through feedback from study participants

-

to consider and reflect on issues for future researchers encountered during the course of the research process such as, gaining trust and facilitating collaboration (trial teams and clinical centres), approaches to recruitment, the ethical and sensitive conduct of interviews and potential information and support needs post interview.

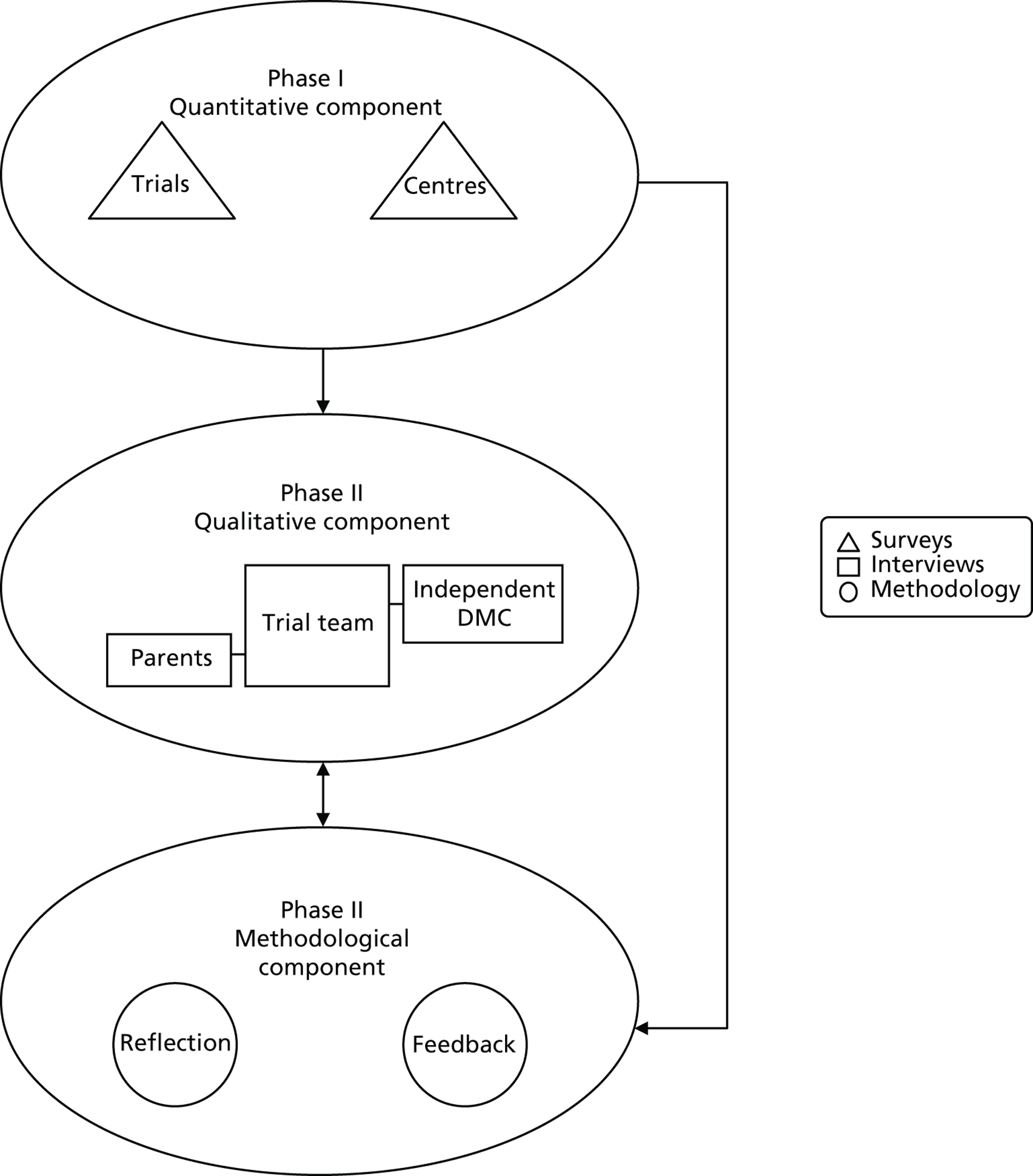

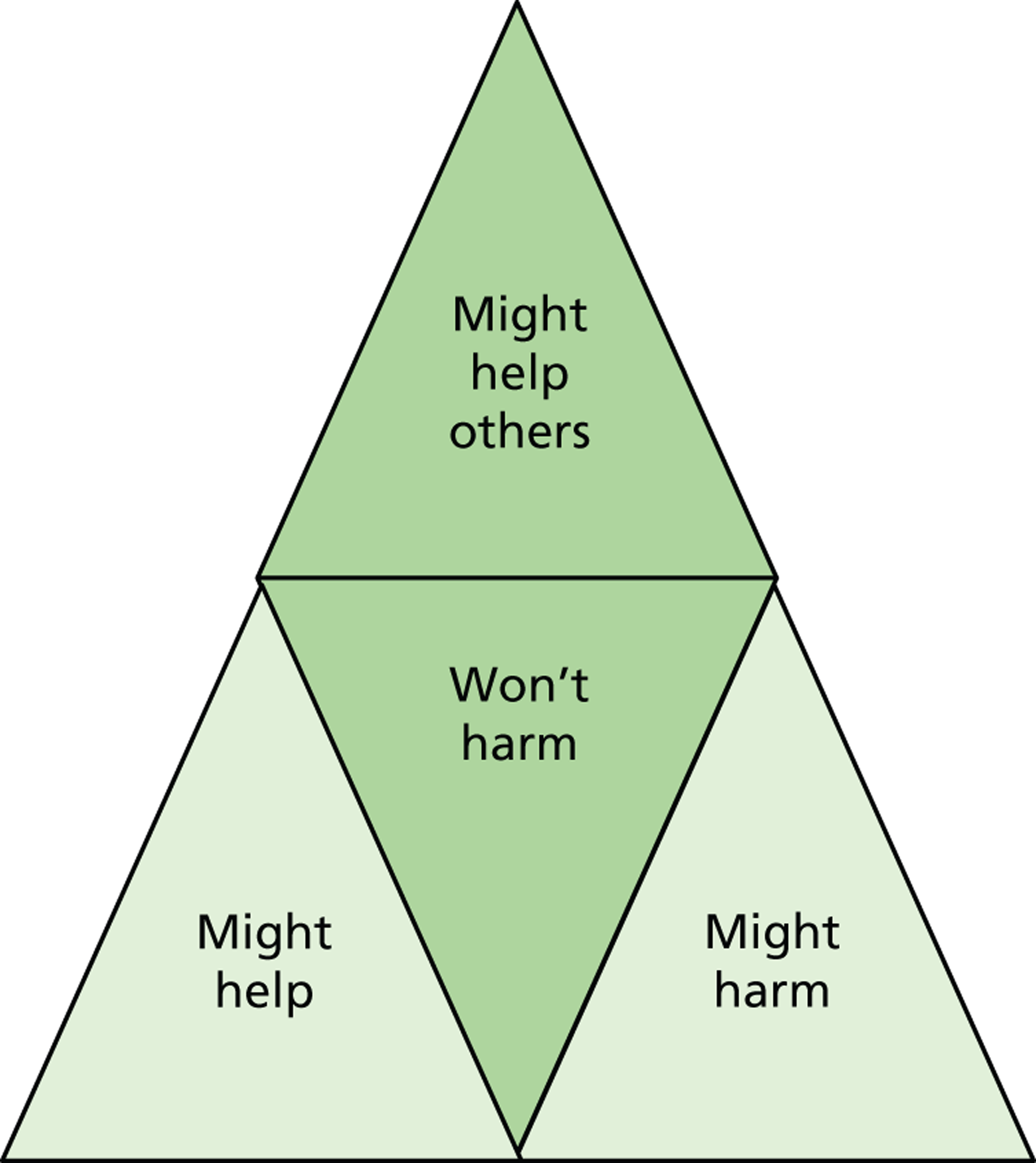

This two-phase, three-part structure uses multiple methods, which are described in Chapter 3 (Phase I – quantitative component), Chapter 4 (Phase II – qualitative component) and Chapter 11 (Phase II – methodological component). The overall structure is shown in Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3.

Structure of the BRACELET study.

Section A

Chapter 3 Quantitative survey of trials and clinical centres

Methods

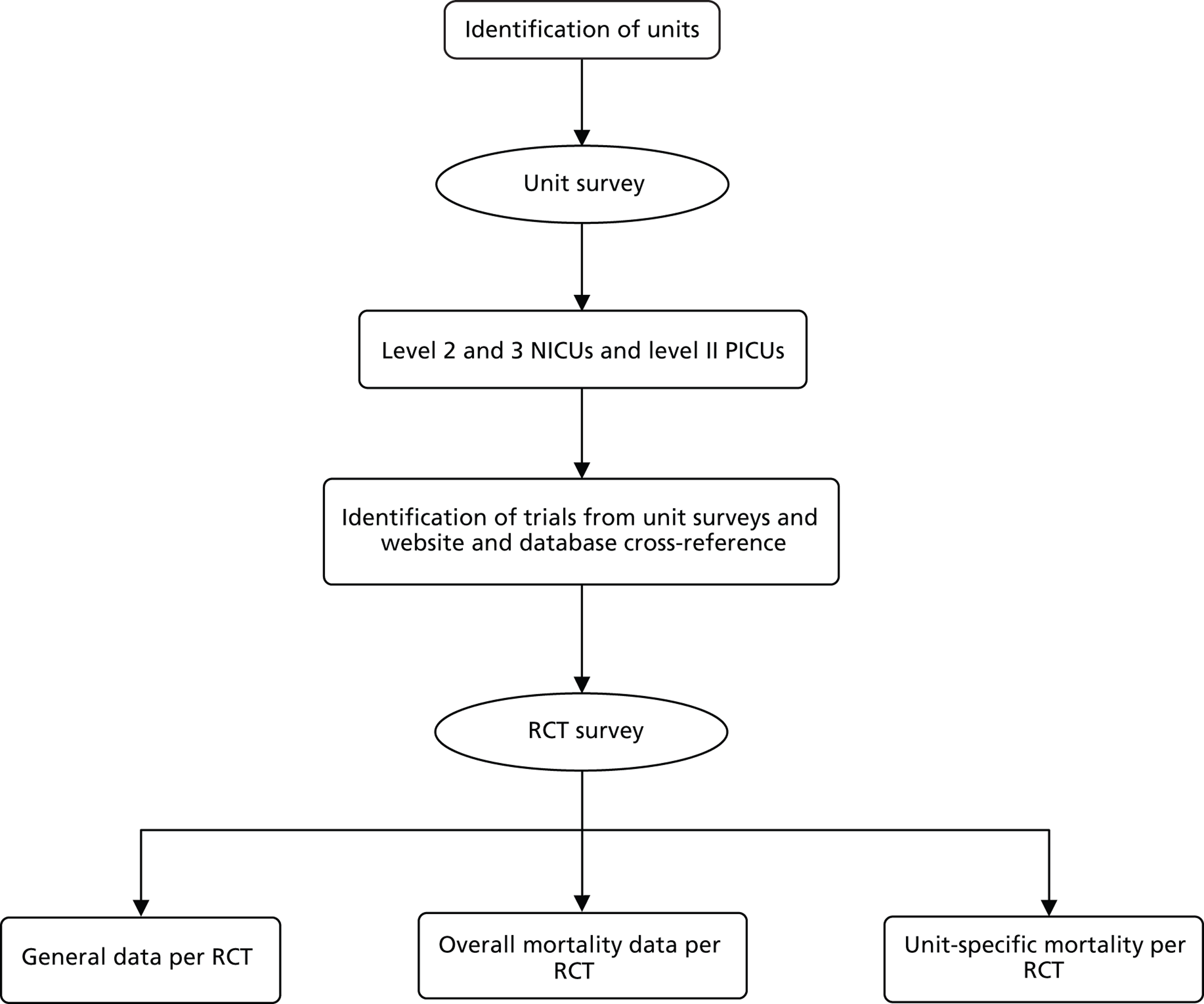

Phase I involved two linked surveys, which aimed to identify all NIC and PIC trials open to recruitment in the UK from 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2006, and to map where and in what sorts of trials deaths occurred, in what numbers and proportions. RCT activity was determined by conducting a survey of all UK NICUs and PICUs to determine their involvement in trials, followed by a survey of the trials identified to determine the number and proportion of deaths of babies and children in their samples. The structure is shown in Figure 4 and explained further below.

FIGURE 4.

Structure of BRACELET study surveys strategies to support the survey response rate.

Unit surveys

In order to carry out the two surveys, appropriate sampling frames were developed.

Neonatal intensive care unit sampling frame

In 2005, researchers at the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (NPEU) had reported that there were 218 neonatal units in the UK in 2004–5. 77 To ensure accuracy for 2007, units listed in the Directory of Critical Care78 and on the British Association of Perinatal Medicine (BAPM) website79 were cross-checked with data provided by the NPEU80 and an ongoing study also developing a sampling frame for neonatal units. 81 From this, 220 neonatal units including neonatal surgical units, were identified in the UK (183 in England, 17 in Scotland, 13 in Wales, and seven in Northern Ireland).

Neonatal units are categorised by ‘levels of care’, as described in the BAPM Standards for Hospitals Providing Neonatal Intensive and High Dependency Care (second edition) published in 200182 ( Table 1 ). Given the focus of BRACELET, we aimed to survey only Level 2 and Level 3 NICUs, which would have higher mortality rates than Level 1 units.

| Level of care | Criteria |

|---|---|

| 1 | Provides special care but does not aim to provide any continuing high-dependency care or intensive care. This term includes units with or without resident medical staff |

| 2 | Provides high-dependency care and some short-term intensive care as agreed within the network |

| 3 | Provides the whole range of medical neonatal care but not necessarily all specialist services, such as neonatal surgery |

Designated level of care is not a fixed status, and so for some NICUs this changes over time. Also, for some neonatal units, this information was missing in the source data for the sampling frame. All 220 units were therefore sent a questionnaire developed for the survey (see below for further details), which asked the respondent to indicate his/her unit’s designation at the time of completing the questionnaire, based on the BAPM guidelines and as agreed by the local network. Level 1 units were not asked to complete the rest of the questionnaire but simply to return it with confirmation of their designated level of care. Only representatives of Level 2 and 3 units were asked to go on to complete the rest of the survey questionnaire.

Designation of care as Level 2 or 3 was confirmed for 149 NICUs.

Paediatric intensive care unit sampling frame

As for the NICU survey, the BRACELET focus on deaths meant that the PICU survey concentrated on those units likely to have higher mortality rates. PICUs are classified based on the criteria described in the Paediatric Intensive Care Society (PICS) Standards Document83 ( Table 2 ).

| Level of care | Nurse to patient ratio | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| 1: high-dependency care | 0.5 : 1 | Close monitoring and observation required but not requiring acute mechanical ventilation |

| 2: intensive care | 1 : 1 | Requires continuous nursing supervision, usually intubated and ventilated; also includes unstable non-intubated or recently extubated child |

| 3: intensive care | 1.5 : 1 | Requires intensive supervision at all times and needs additional complex therapeutic procedures and nursing, e.g. unstable ventilated child on vasoactive drugs and inotropic support with multiple organ failure |

| 4: intensive care | 2 : 1 | Requires most the intensive interventions such as unstable or Level 3 children managed in a cubicle. Includes those on ECMO and children undergoing renal replacement therapy |

The PICU sampling frame for BRACELET therefore comprised PICUs with a paediatric intensivist in post, providing Level 2 intensive care and above. A database of UK PICUs was constructed using data provided by the Paediatric Intensive Care Audit Network (PICANet)84 and by checking the Directory of Critical Care 2006. 78 Thirty-two PICUs that fulfilled the above criteria were identified. It was unnecessary to first check the designation with a PICU representative as these level of care categories were more stable over time than for NICUs. Data were therefore requested from all PICUs with a paediatric intensivist in post, which provided at least Level 2 intensive care.

Unit questionnaire: development and mail-out

Given that neonatal and paediatric intensive care have different criteria to describe the level of care that units provide, two versions of a questionnaire were developed for the survey: one for NICUs and one for PICUs (see Appendices 2 and 3 ). The questionnaires were piloted in two NICUs and two PICUs. In this pilot phase, clinicians were asked to complete the questionnaire and provide feedback, including the clarity of instructions, the length of time that it took to complete, any sections that were difficult to complete, general layout, etc. Only minor revisions were required following the pilot surveys and it was not necessary to ask the pilot units to complete another questionnaire.

Representatives at the 149 Level 2 or 3 NICUs and at the 32 Level 3 PICUs were asked to complete the revised questionnaire in April 2007. In most cases this was the clinical lead or the person presumed to be the clinical lead for the unit. All unit representatives had been given prior notification of the survey by letter briefly describing the BRACELET study and the purpose of the survey (see Appendix 4 ). A survey pack was dispatched to units about 1 week after the pre-notification letter. The pack included the survey questionnaire, a study information leaflet (see Appendix 5 ), a prepaid, pre-addressed return envelope and a covering letter (see Appendix 6 ) explaining the purpose of the survey. Given that a short time cue can be effective in stimulating responses and specification of a deadline may increase the speed of the response,85 recipients were asked to respond within 2 weeks. Approximately 1 week after the deadline date had passed, a reminder letter was sent either via e-mail or mail. Again, recipients were asked to respond within 2 weeks. A second reminder was sent about 2 weeks after the second deadline had passed. The final reminder included a shortened version of the questionnaire containing a list of the multicentre RCTs that had been identified at that point (see Appendix 7 ). Telephone reminders were used where appropriate, and the questionnaire was also made available to clinicians in electronic form and placed on the study website (www.bracelet-study.org.uk) for download to facilitate returns.

Recipients were asked to indicate which RCTs (single- and multicentre) they had enrolled babies or children into during the period 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2006. All RCTs were eligible, regardless of size, intervention and outcome. International multicentre RCTs run from outside of the UK were also included. The questionnaires asked for brief details of all these RCTs.

The clinical lead for each unit was asked to indicate for each RCT listed in the questionnaire whether they would grant permission for the BRACELET study team to request their unit-specific, anonymised mortality data from the trial CI. We also asked about the provision of bereavement care for their unit, including the availability of a bereavement counsellor and other sources of emotional support for bereaved parents.

In addition to the questionnaire reminder process outlined above, a number of strategies were used to ensure a good response rate for the unit survey.

The BRACELET study was adopted by the MCRN and the study team worked very closely with the LRN managers and clinical research nurse practitioners who provided assistance with following-up non-responders. Members of the BRACELET team also spoke with clinicians from non-responding units in person at relevant meetings and conferences, and contact was made with some clinicians by e-mail or by calling their unit directly to encourage return of the questionnaires.

Clinicians could also be directed to the study website (www.bracelet-study.org.uk) for further documentation.

The BRACELET study addresses a sensitive topic and there was some concern among the team that perhaps units might be reluctant to take part in a study exploring issues relating to mortality in the context of their RCTs. During the data collection process the team did receive some feedback in which clinicians expressed discomfort over release of their mortality data. A letter was therefore sent from the then-director of the NPEU (also a BRACELET study investigator – PB) addressing these potential concerns, stressing the importance of BRACELET and providing reassurance about the confidentiality of the data (see Appendix 8 ).

Data collection was concluded in May 2008.

Trials survey

Trials sampling frame

Although new trials are increasingly being registered, especially those involving new medicinal products, there is no single repository of trials through which all trials conducted in the UK over specified time periods and particular specialties can be identified. The unit survey generated a list of trials, and this was supplemented by searches of relevant specialised databases and websites, including the UK Department of Health National Research Register [replaced by the UK Clinical Research Network (CRN) database]; the UK Department of Health Research Findings Register (replaced by the UK CRN database); PubMed; the NPEU website; the PICS website; the BAPM website; and the European Society of Paediatric and Neonatal Intensive Care websites.

For all RCTs identified as being potentially eligible for the trials survey, the trial CI, trial manager or other relevant contact was asked to confirm that the RCT fulfilled the eligibility criteria below.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Randomised controlled trials were eligible for inclusion if:

-

allocation was randomised

-

the trial was enrolling babies or children during the period 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2006

-

the intervention was delivered to the baby or child within the NICU or PICU setting (or, if it was initiated outside of the unit, it was delivered by, or under the auspices of, a neonatologist or paediatric intensivist leading to admission to the unit for ongoing care)

-

the intervention was delivered to the parent(s) but was designed to impact the baby or child’s ‘outcome’.

Randomised controlled trials were excluded if the intervention was delivered to unit staff or was delivered at a unit level and did not require informed consent from individual parents of babies or children.

Trials questionnaire

A pilot questionnaire was completed by trial managers for two multicentre RCTs and a CI for a single-centre RCT. Minor revisions were made to the questionnaire following their feedback.

Once eligibility had been confirmed, trial investigators were asked to complete the revised trial questionnaire. A questionnaire was dispatched to the trial investigators in May 2007, which sought information for the 5-year study period in relation to two areas. Part 1 sought general information about the RCT, including start and end dates of recruitment, numbers enrolled, aims/hypotheses, inclusion and exclusion criteria, primary and secondary outcomes, sample size, source(s) of funding, details of participating units and collection of post-mortem data (see Appendix 9 ). Part 2 sought the total numbers of UK survivors and non-survivors before discharge from hospital for the RCT overall, irrespective of randomised allocation (overall mortality data), and the numbers of survivors and non-survivors before discharge from hospital, irrespective of randomised allocation, for every participating unit that had given permission for these data to be released to the BRACELET study team (unit-specific mortality data) (see Appendix 10 ). The questionnaire information was supplemented by data from published papers, relevant websites and personal communication, where appropriate.

Respondents were also asked to provide copies of their protocol, parent information leaflets, information leaflets relating to bereavement, letters sent to bereaved parents or any other relevant documents.

Categorisation of randomised controlled trials

Based on the eligibility criteria and the types of units that took part, RCTs were categorised as being NIC or PIC RCTs. They were further categorised as follows:

-

Single-centre Participants were recruited from one unit only in the UK.

-

Multicentre Participants were recruited from two or more units in the UK only. This included RCTs that were conducted in two or more units within the same NHS Trust.

-

International Participants were recruited from two or more units, of which at least one was in the UK.

Analysis

Descriptive data are presented as proportions and ranges, as appropriate. Analysis used the statistical package Stata 10 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Variations in the denominators for some of the numbers reported in the Results section reflect different response rates for the unit survey and the trials survey, and incomplete release of mortality data by some units and some trials.

Results

Neonatal intensive care unit and paediatric intensive care unit survey

Overall, of the 220 NICUs surveyed, responses were received from 191 (86.8%), of which 149 were eligible units – 82 providing Level 2 care and 67 providing Level 3 care ( Table 3 ).

| Unit | Total | Responded, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| NICU: | ||

| Level 1 | 42 | 42 (100.0) |

| Level 2a | 96 | 82 (84.4) |

| Level 3b | 80 | 67 (83.8) |

| Not known | 2 | 0 (0.0) |

| Total | 220 | 191 (86.8) |

| Total NICU: Levels 2 and 3 | 176 | 149 (84.7) |

| PICU (≥ Level 2) | 32 | 28 (87.5) |

| Overall NICU and PICU | 252 | 219 (86.9) |

In most cases (n = 142, 95.3%) a member of the unit staff filled in the questionnaire. A small number of questionnaires were completed either via MCRN contact with unit staff (n = 3), via MCRN contact with the hospital’s Research and Development (R&D) department (n = 3) or via one of the study investigators telephone contact with unit staff (n = 1).

Of the 32 PICUs providing Level 2 intensive care and above, responses were received from 28 (87.5%) (see Table 3 ). Of these, one questionnaire was filled in via MCRN contact with the hospital’s R&D department. The remaining questionnaires were filled in by a member of the unit staff.

Fifty RCTs (36 NIC and 14 PIC trials) were identified as having enrolled babies or children during the 5-year period 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2006.

Randomised controlled trial survey

For the trials survey, a response to Part 1 of the RCT survey, which collected general information about the RCT, was received for 43 (32 NIC and 11 PIC) of the 50 RCTs.

Overall UK mortality data (i.e. data for the whole trial) up to discharge from hospital were released for Part 2 of the RCT survey for 37 trials (28 neonatal, nine paediatric). Unit-specific mortality data up to discharge from hospital were released by 33 trials (24 neonatal, nine paediatric) for those ICUs that had permitted release of their data to BRACELET in the unit survey.

Findings of the surveys

Characteristics of randomised controlled trials

Of the 36 NIC trials, 10 were international, 14 UK multicentre, and 12 single centre. Of the 14 PIC trials, nine were international, and five single centre. Of the 10 international NIC RCTs, six were run from the UK, two from the USA and two from Canada. Of the nine international PIC RCTs, two were run from the UK, two from Canada, two from the US, and one each from Australia, the Netherlands and France – i.e. 32 out of 36 (88.9%) NIC RCTs and 7 out of 14 (50.0%) PIC RCTs were UK led.

Further characteristics of the 50 RCTs by type (NIC or PIC) are reported in Table 4 . The source(s) of funding for the trial was reported by a trial representative in the questionnaire or was obtained from the published papers for 37 (74.0%) RCTs. Most RCTs were funded by public sector or charitable organisations. For nine RCTs, funding was from two or more sources. Investigators for one single-centre RCT and one multicentre RCT (with two participating units) reported that they received no direct funding. In both NIC and PIC RCTs, the interventions that were most frequently evaluated were either drugs and food (including nutritional supplements and feeding regimens) or non-medicines interventions, which included temperature regulation, mechanical ventilation and surgical procedures.

| Characteristics of RCTs | NIC (N = 36), n (%) | PIC (N = 14), n (%) | Total (N = 50), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundinga | |||

| Public sector | 11 (30.6) | 4 (28.6) | 14 (28.0) |

| Charity | 8 (22.2) | 6 (42.9) | 14 (28.0) |

| Commercial – academic led | 5 (13.9) | 1 (7.1) | 6 (12.0) |

| Commercial – company led | 2 (5.6) | 1 (7.1) | 3 (6.0) |

| None | 2 (5.6) | – | 2 (4.0) |

| Not reported | 4 (11.1) | 1 (7.1) | 5 (10.0) |

| Non-responder | 5 (13.9) | 3 (21.4) | 8 (16.0) |

| Types of intervention | |||

| Drugs and foods (including blood products, anaesthesia, oxygen and food supplements) | 19 (52.8) | 7 (50.0) | 26 (52.0) |

| Physical therapies (including cooling, heating, mechanical ventilation, surgery) | 15 (41.7) | 7 (50.0) | 22 (44.0) |

| Monitoring | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Psychosocial (including parenting support) | 1 (2.8) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.0) |

| Mortalityb | |||

| Primary – sole outcome | 2 (5.6) | 2 (14.3) | 4 (8.0) |

| Part of composite – primary outcome | 7 (19.4) | 3 (21.4) | 10 (20.0) |

| Secondary outcome | 10 (27.8) | 4 (28.6) | 14 (28.0) |

| Not reported as an outcome | 13 (36.1) | 5 (35.7) | 18 (36.0) |

| Non-responder | 8 (22.2) | 3 (21.4) | 11 (22.0) |

Information about primary outcomes was obtained from either a BRACELET questionnaire (n = 6), the trial protocol (n = 26) or the published paper (n = 7), and so these data were available for 39 RCTs. Eighteen of the RCTs (46.2%) did not specify mortality as an outcome in either a BRACELET questionnaire (n = 3), or the trial protocol (n = 11), or the published paper (n = 4). Of the remaining 21 RCTs, 14 measured mortality as a primary outcome (four as sole primary and 10 as part of a composite) and 14 had mortality as a secondary outcome (including some with mortality as one component of a composite primary outcome).

Neonatal intensive care unit and paediatric intensive care unit randomised controlled trial activity

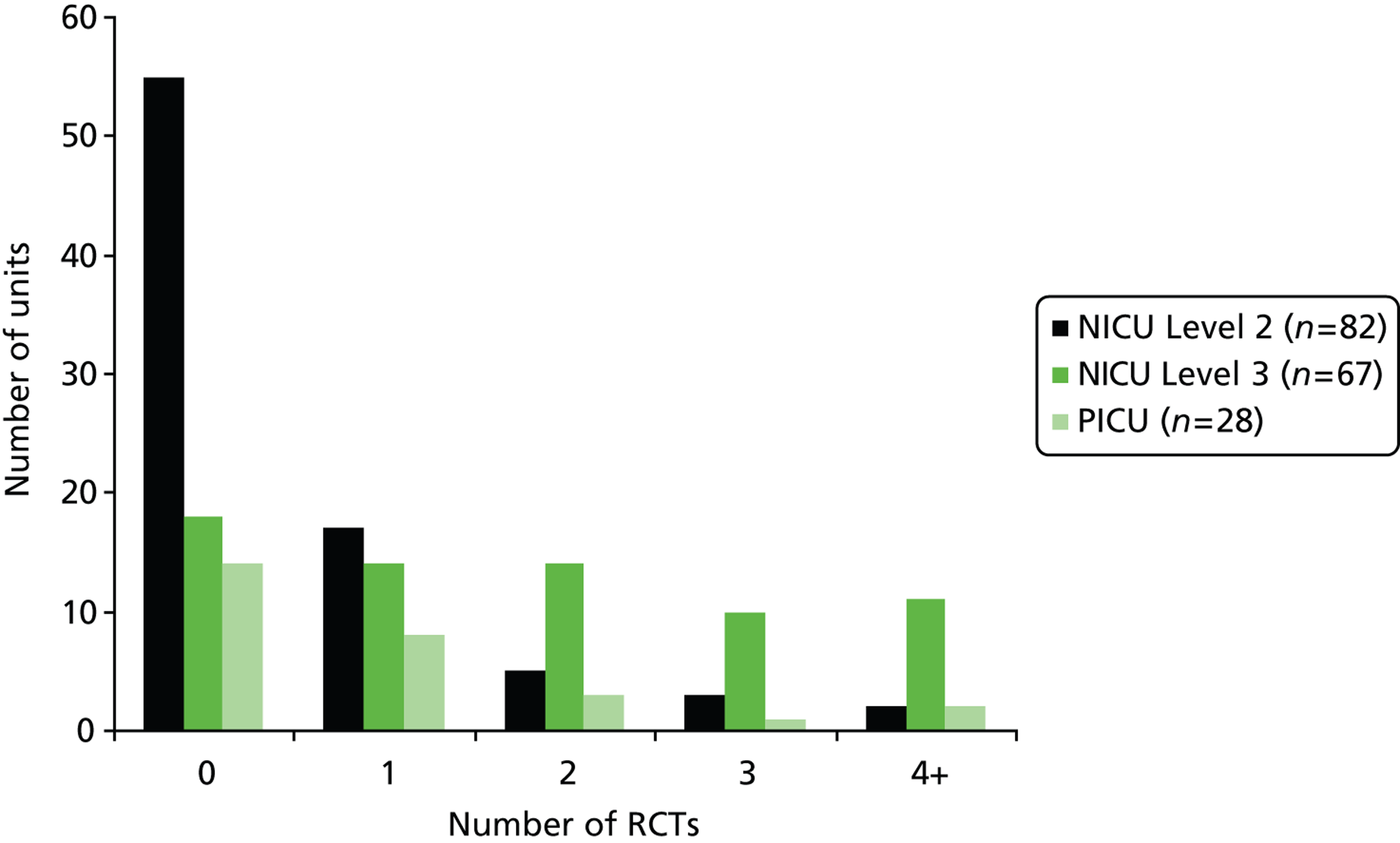

Randomised controlled trial activity was determined by whether a NICU or PICU had enrolled at least one baby or child into a RCT during the period 1 January 2002 to 31 December 2006 (this was confirmed by the trial CI or trial manager in the trials survey). Half of the units enrolled one or more participants in one or more trials during the 5-year study period [76/149 NICUs (51.0%), 14/28 PICUs (50.0%)]. Participation in RCTs was higher in the Level 3 NICUs; 73.1% reported having enrolled babies into one or more trials compared with 32.9% of Level 2 NICUs. Of the 28 PICUs for which questionnaire information was available, 50.0% had enrolled at least one child into one or more RCTs ( Table 5 and Figure 5 ).

| No. RCTs | NICUs | PICUs, N = 28, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2, N = 82, n (%) | Level 3, N = 67, n (%) | Total, N = 149, n (%) | ||

| 0 | 55 (67.1) | 18 (26.9) | 73 (49.3) | 14 (50.0) |

| 1 | 17 (20.7) | 14 (20.9) | 31 (20.8) | 8 (28.6) |

| 2 | 5 (6.1) | 14 (20.9) | 19 (12.8) | 3 (10.7) |

| 3 | 3 (3.7) | 10 (14.9) | 13 (8.7) | 1 (3.6) |

| ≥ 4 | 2 (2.4) | 11 (16.4) | 13 (8.7) | 2 (7.1) |

| ≥ 1 RCT | 27 (32.9) | 49 (73.1) | 76 (51.0) | 14 (50.0) |

FIGURE 5.

Participation in RCTs: by type of NICU and by PICU.

Most of the NICUs and PICUs participated in international RCTs (n = 77) or UK multicentre RCTs (n = 39). A small number of Level 3 NICUs (n = 9; 13.4%) and PICUs (n = 5; 17.9%) reported having conducted single-centre RCTs. This was more common for PICUs for which 5 of the 14 responding paediatric units ran single-centre trials (17.9% of units) compared with 9 of the 149 NICUs (6% of units). Notably all neonatal single-centre trials were conducted in Level 3 units ( Table 6 ).

| Type of RCT | NICUs | PICUs, n = 28, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 2, N = 82, n (%) | Level 3, N = 67, n (%) | All, N = 149, n (%) | ||

| International | 23 (28.0) | 45 (67.2) | 68 (45.6) | 9 (32.1)a |

| Multicentre | 11 (13.4) | 27 (40.3) | 38 (25.5) | 1 (3.6)b |

| Single centre | 0 (0.0) | 9 (13.4) | 9 (6.0) | 5 (17.9) |

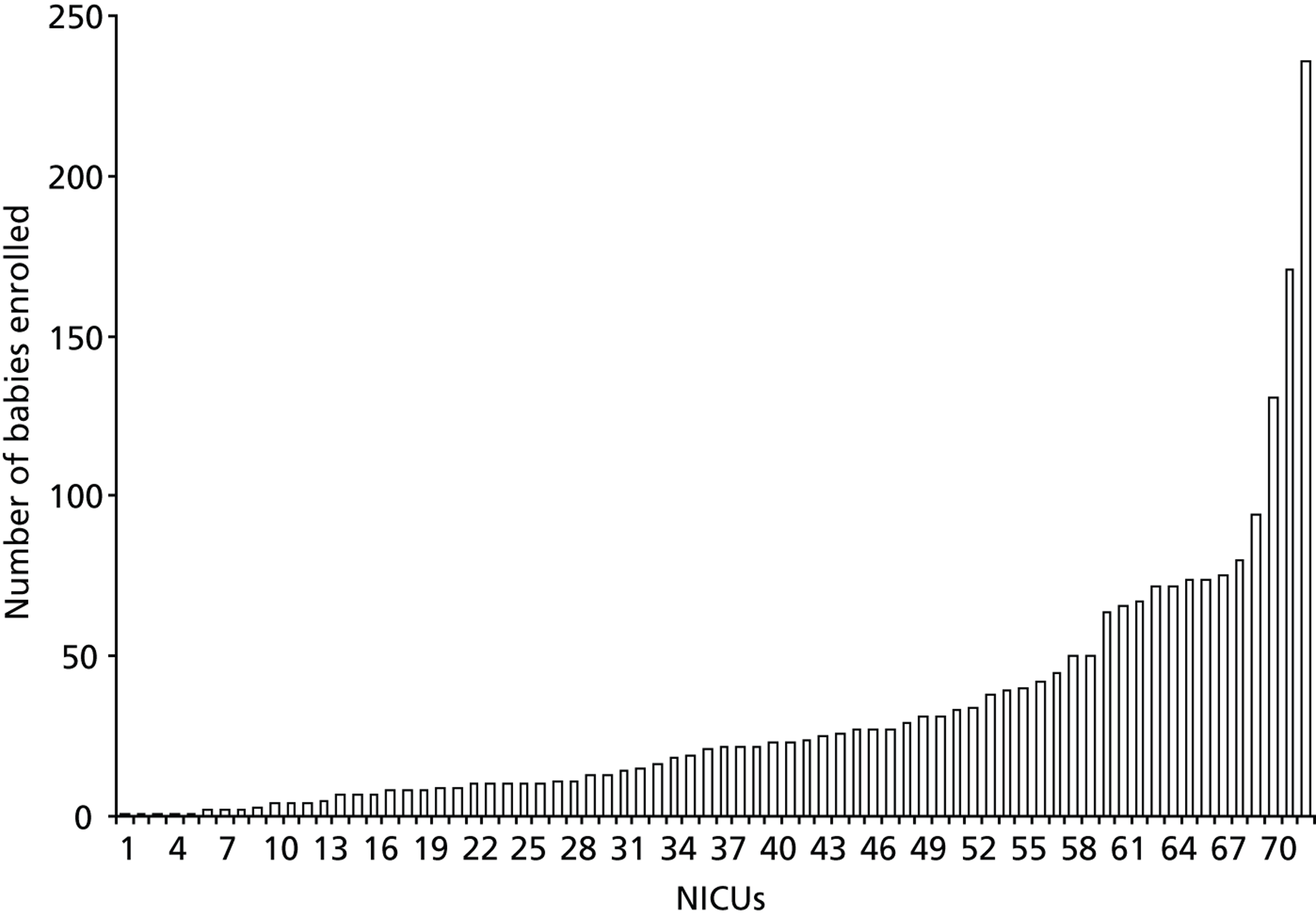

Numbers of babies and children enrolled into randomised controlled trials

Of the 76 NICUs that enrolled to a trial, 72 provided details of the number of babies enrolled. A total of 3117 babies were enrolled by these neonatal units into the 29 neonatal trials for which some enrolment data for the 5-year study period were available ( Table 7 ). The number of babies enrolled per neonatal unit ranged from 1 to 236 [median 22, interquartile range (IQR) 8–40] ( Figure 6 ). Most of those enrolled were being treated in Level 3 NICUs.

FIGURE 6.

Total numbers of babies enrolled across NICUs. Figure excludes 4 out of the 76 NICUs that participated in RCTs but for which numbers of babies enrolled were not obtained.

| Trials | No. enrolled from neonatal units | No. enrolled from paediatric units | Total no. enrolled |

|---|---|---|---|

| Neonatal trials | |||

| No. of trials | 29 | 2 | 29a |

| No. of units | 36 | 2 | 38 |

| No. of babies enrolled | 3117 | 20 | 3137 |

| No. of babies enrolled per recruiting unit; median (IQR) | 1–236; 222 (8 to 40) | 4 and 16b | 1–236; 20 (8 to 39) |

| No. of babies enrolled per trial; median (IQR) | 1–1322; 40 (14 to 104) | 4 and 16b | 5–1326; 40 (15 to 104) |

| Paediatric trials | |||

| No. of trials | 9 | 9 | |

| No. of units | 11 | 11 | |

| No. of children enrolled | 210 | 210 | |

| No. of children enrolled per recruiting unit; median (IQR) | 1–53 | 1–53; 11.5 (2 to 34) | |

| No. of children enrolled per trial; median (IQR) | 2–53 | 2–53; 11 (6 to 39) | |

| All neonatal/paediatric trials | |||

| No. of babies/children enrolled | 3117 | 230 | 3347 |

| No. of trials | 29 | 11 | 38a |

An additional 20 babies were recruited into two multicentre NIC RCTs by two PICUs, bringing the total enrolled in NIC trials to 3137 babies. Of these, 480 (15.3%) were recruited into single-centre trials and 2657 (84.7%) into multicentre trials (UK and international) (see Table 8 ).

Of the 14 PICUs that enrolled into a paediatric trial, 11 provided details of the number enrolled. A total of 210 children were enrolled by these paediatric units into nine PIC trials for which some enrolment data for the 5-year study period were available. The number of children enrolled per paediatric unit into PIC trials ranged from 1 to 53 (median 7, IQR 2–34). Of these, 94 (44.8%) were enrolled into single-centre trials and 116 (55.2%) to multicentre trials (all of which were international) (see Table 8 ).

Mortality* following enrolment into a randomised controlled trial

(*Mortality data refer to deaths before discharge from hospital.)

Overall UK mortality data were available for 28 NIC and nine PIC RCTs. In total, 534/3288 (16.2%) children died before leaving hospital following enrolment in the 37 trials.

The numbers of babies who did and did not survive to leave hospital following enrolment into a NIC RCT are presented in Table 8 by type of RCT. These figures are based on data provided by the trial investigators or reported in the published papers. The 28 NIC trials enrolled 3088 babies, of whom 522 (16.9%) died. Mortality was higher for babies enrolled into international trials (21.3%) than multicentre (11.4%) and single-centre trials (9.8%).

| Type of RCT | Total enrolled, n | Survived, n (%) | Died, n (%) | N/K, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International, n = 7a | 1800 | 1415 (78.6) | 383 (21.3) | 2 |

| Multicentre – UK, n = 10b | 808 | 716 (88.6) | 92 (11.4) | 0 |

| Single centre, n = 11 | 480 | 433 (90.2) | 47 (9.8) | 0 |

| Overall, n = 28c | 3088 | 2564 (83.0) | 522 (16.9) | 2 |

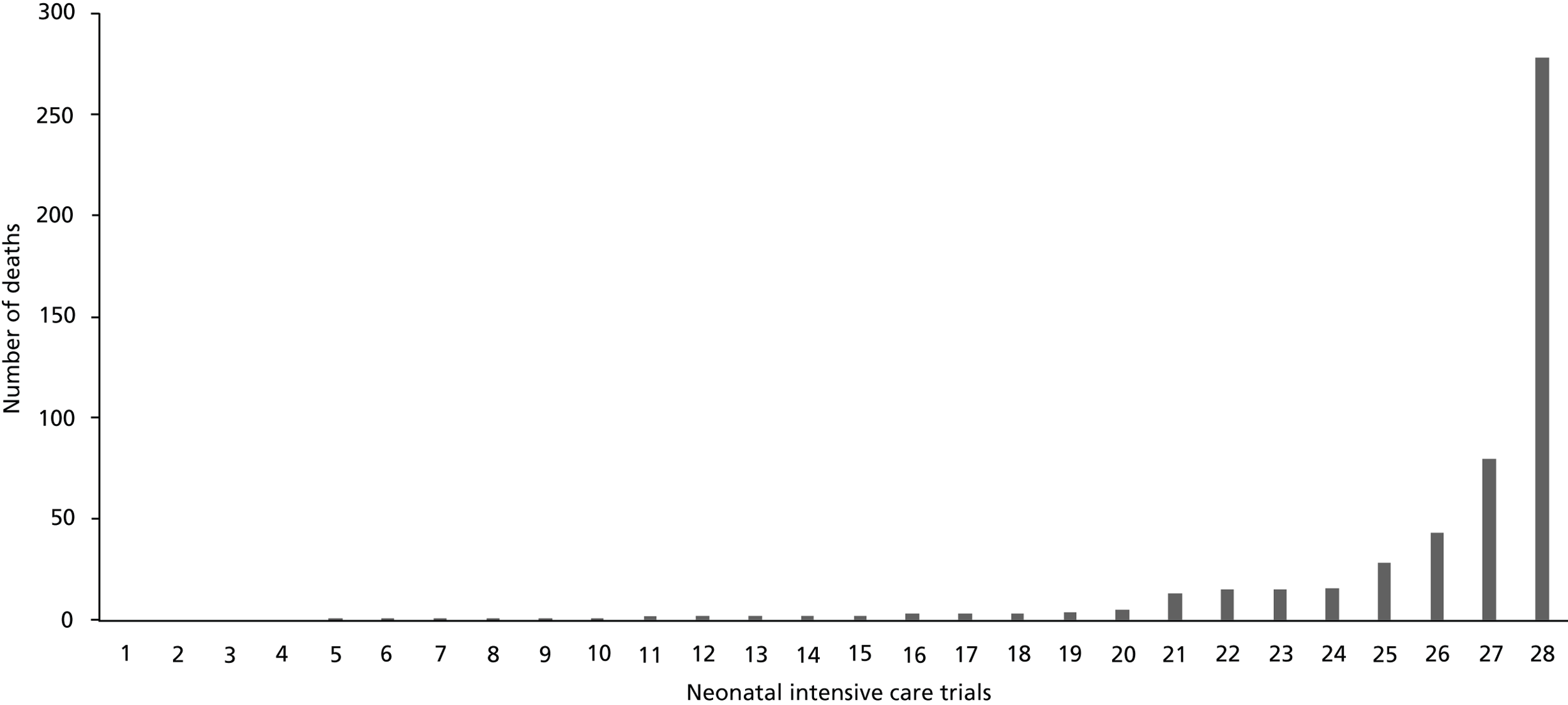

The number of deaths per neonatal trial ranged from 0 to 278 (median 2, IQR, 1–15) ( Figure 7 ). Of the 28 neonatal trials, 24 had at least one death. The highest mortality rate among these trials was 29% (80 deaths). Most reported small numbers of deaths, with only eight trials reporting more than 10 deaths. The majority of deaths [429/522 (82.2%)] occurred in four trials, three of which were multicentre (n = 278 + 80 + 43 deaths) and one single centre (n = 28 deaths). Single-centre trials reported fewer deaths and a lower death rate (47/480, 9.8%) than multicentre trials (475/2608, 18.2%).

FIGURE 7.

Variation in numbers of deaths across neonatal trials. (The high number of deaths in some of these trials is likely to be due to the numbers recruited, the severity of their condition and the types of interventions in these trials.)

In the nine PIC trials for which mortality data were available, 12 (6.0%) out of 200 children died following enrolment into a trial ( Table 9 ). Six of the nine trials had a least one death, with the number of deaths ranging from 0 to 4. Very few deaths occurred in single-centre PIC trials (2/94, 2.1%) compared with those in the single-centre NIC trials (47/480, 9.8%) and the multicentre PIC trials 10/106 (9.4%).

| Type of RCT, n | Total enrolled, n | Survived, n (%) | Died, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| International, 6 | 106 | 96 (90.6) | 10 (9.4) |

| Multicentre UK, 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Single centre, 3 | 94 | 92 (97.9) | 2 (2.1) |

| All RCTs, 9 | 200 | 188 (94.0) | 12 (6.0) |

Overall, mortality rates were lower for all types of PIC RCTs than for NIC RCTs. However, there appeared to be a similar pattern of higher mortality for children enrolled into international RCTs (10.0%) than for those enrolled into a multicentre (6.2%) or single-centre RCTs (2.1%). There may be many reasons for this, for example the ‘severity’ of the condition being studied in the trial.

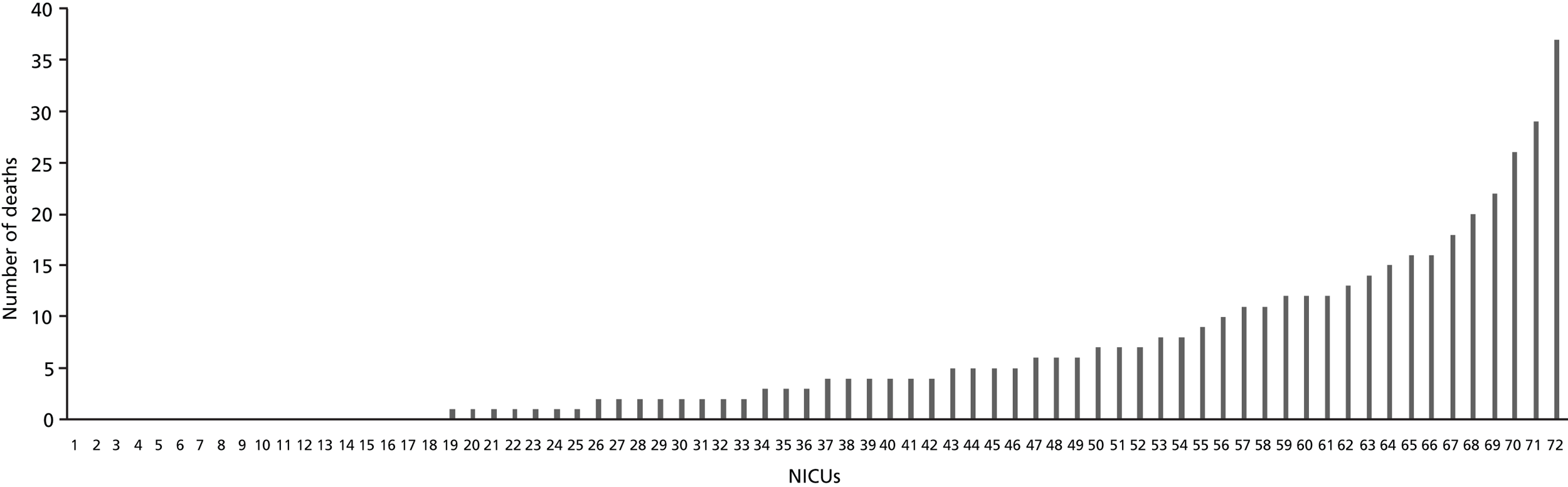

Variation in mortality across units (unit-specific mortality)

Unit-specific mortality data on 434 deaths were released by 24 neonatal trials for 72 NICUs with the permission of the units in question. The number of deaths per unit ranged from 0 to 37 (median 4, IQR 0–9) ( Figure 8 ). Although 54 units saw at least one death following enrolment in a trial, more than half (42/72, 58.3%) saw fewer than five deaths over this 5-year period ( Table 10 ). Five Level 3 NICUs had larger numbers (n = 37, 29, 26, 22 and 20) and 30.9% of all deaths recorded by the units occurred in these five units. In around half of the units, the proportion of babies who died following trial enrolment was 20% or more ( Table 11 ).

FIGURE 8.

Variation in numbers of deaths across NICUs. (The high number of deaths in some of these NICUs is likely to be due to the numbers recruited, and the severity of the condition of the babies in these units.)

| No. of deaths | NICUs | PICUs |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of units (n = 72) | No.a of units (n = 12b) | |

| None | 18 (25) | 6 |

| 1–4 | 24 (33) | 5 |

| 5–9 | 13 (18) | 1 |

| 10–14 | 8 (11) | 0 |

| 15–19 | 4 (6) | 0 |

| ≥ 20 | 5 (7) | 0 |

| Total no. of deaths in these units | 434 | 14 |

| No. (%) of units seeing at least one death | 54 (75) | 6 (43) |

| Proportion of deaths | NICUs | PICUs |

|---|---|---|

| No. (%) of units (n = 72) | No. of unitsa (n = 12b) | |

| 0 | 18 (25) | 6 |

| > 0–0.1 | 10 (14) | 3 |

| > 0.1–0.2 | 14 (19) | 3 |

| > 0.2–0.3 | 16 (22) | |

| > 0.3–0.4 | 7 (10) | |

| > 0.4–0.5 | 5 (7) | |

| ≥ 0.5 | 2 (3) |

Nine PIC trials released unit specific mortality data for 14 PICUs. The number of deaths per unit ranged from 0 to 7 (median 1, IQR 0–2), with six units witnessing at least one death (see Table 10 ). In all of these units, the proportion of children who died following trial enrolment was under 20% (see Table 11 ).

Trials survey: practices after the death of a child

Collection of post-mortem data

For the 36 NIC RCTs, 23 trial investigators reported whether they had collected post-mortem data for the trial. All reported that collection of post-mortem data was not part of the trial protocol. For nearly half (47.8%) this was because these data were not considered necessary. Nine trial investigators reported that although they did not specifically request post-mortem examinations to be conducted on their behalf, they did request to see post-mortem reports if they were available ( Table 12 ).

| Reason for not collecting post-mortem data | N | Requested copies of post-mortem reports if available? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n | No, n | Not reported, n | ||

| Not necessary | 11 | 2 | 7 | 2 |

| Desirable but unlikely to be successfully obtained | 5 | 4 | 1 | |

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| No reason given | 6 | 3 | 3 | |

| Total | 23 | 9 | 9 | 5 |

For the 14 PIC RCTs, nine trial investigators reported whether they had collected post-mortem data for the trial. All reported that collection of post-mortem data was not part of the trial protocol mainly because it was not necessary. None of the trial investigators had requested to see post-mortem reports if they were available ( Table 13 ).

| Reason for not collecting post-mortem data | N | Requested copies of post-mortem reports if available? | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes, n | No, n | Not reported, n | ||

| Not necessary | 6 | 5 | 1 | |

| Desirable but unlikely to be successfully obtained | 1 | 1 | ||

| Other | 1 | 1 | ||

| No reason given | 1 | |||

| Total | 9 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

Contact with bereaved parents from the trial team

Of the 50 RCTs, investigators for just over half (n = 27) provided a copy of the full trial protocol. None of the protocols documented a policy relating to the care of parents bereaved following enrolment of their child into the RCT.

Parent information leaflets were provided for 29 of the 50 trials. These were generally of a standard format that included information about the purpose of the trial, details of the investigators organising the trial, what taking part would involve, the benefits and risks of taking part, what would happen if the parents declined their baby or child taking part, what would happen if something went wrong, the rights of the parents to withdraw their baby or child from the trial at any time, and confidentiality. Some also referred to the publication of the trial results, and whether and when these would be available to parents. [For those trials in which parents were told – when their baby was alive at enrolment – that they would be sent the results of the trial, there could be a clash between this expectation having been set up if, later, bereaved parents were not asked when permission was sought to send the results (e.g. at discharge from hospital or at follow-up)].

Of the 50 RCTs, investigators for two NIC trials (one multicentre and one UK-led international RCT) had produced an information leaflet specifically for bereaved parents. Both leaflets were produced from the same CTU and were of the same format as follows.

The trial investigators started by offering their sincere condolences to the parents and thanked them for allowing their baby to participate in the trial. They expressed their hope that the parents would find some consolation in the fact that their baby’s contribution to the trial would play an important part in future decisions about the best way to care for babies with similar medical conditions. They offered reassurances that all the information collected would be stored safely and confidentially, and would be used in the analysis at the end of the trial. Information about organisations, such as SANDS (the Stillbirth and Neonatal Death Charity: www.uk-sands.org) and BLISS (the National Charity for the Newborn: www.bliss.org.uk) were provided, including telephone helpline numbers. The leaflet ended by offering the parents the opportunity, if they wished, to ask questions about the trial, either relating to their baby or more generally, by contacting either the doctor or nurse who cared for their baby or by contacting a named person at the trial co-ordinating centre.

One clinical trial investigator for a single-centre NIC trial reported having a policy on contact with bereaved parents but took a different approach. Three deaths occurred following enrolment into this trial and the investigator had sent a personal letter to each set of parents to thank them for allowing their child to take part in the trial and to offer contact should they wish to discuss the trial or the continued use for their child’s data in the trial.

Provision of bereavement support in neonatal intensive care units and paediatric intensive care units

Of the 149 NICU respondents, 110 (75%) provided information about bereavement care. Of these, 41 (37%) reported that there was a specific bereavement counsellor for their unit. Of the 69 (63%) NICUs that did not have a specific bereavement counsellor, most reported other sources of support, but two respondents reported that there were no other sources of support for bereaved parents ( Table 14 ).

| NICU | Bereavement counsellora | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |

| NICU Level 2, n = 61 | 23 (37.7) | 38 (62.3) |

| Other sources of support: | ||

| Yes | 18 | 38 |

| No | 3 | – |

| Not reported | 2 | – |

| NICU Level 3, n = 49 | 18 (36.7) | 31 (63.3) |

| Other sources of support: | ||

| Yes | 16 | 28 |

| No | 2 | 2 |

| Not reported | – | 1 |

| All NICUs, n = 110 | 41 (37.3) | 69 (62.7) |

| Other sources of support: | ||

| Yes | 34 | 66 |

| No | 5 | 2 |

| Not reported | 2 | 1 |

Of the 28 PICU respondents, 21 (75%) provided information about bereavement care. Of these, 13 (62%) reported that there was a specific bereavement counsellor for their unit. Nearly all respondents reported that other sources of support were available as well. Of the eight (38%) PICUs without a specific bereavement counsellor, three respondents did not report whether other sources of support for bereaved parents were available ( Table 15 ).

| PICU | Bereavement counsellora | |

|---|---|---|

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | |

| PICUs, n = 21 | 13 (61.9) | 8 (38.1) |

| Other sources of support | ||

| Yes | 11 | 5 |

| No | 2 | – |

| Not reported | – | 3 |

The most frequently reported source of support for bereaved parents was the hospital chaplaincy service. Unit-led support was usually from midwives or nurses in the NICU or PICU who were trained counsellors ( Table 16 ).

| Other sources of support | NICUs, N = 100, n (%) | PICUs, N = 21, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Chaplaincy services | 89 (89.0) | 12 (57.1) |

| Unit-led support | 23 (23.0) | 9 (42.9) |

| Hospital or department counselling/support services | 18 (18.0) | 8 (38.1) |

| Local support group | 7 (7.0) | 3 (14.3) |

| Social workers | 3 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Discussion

The BRACELET study is currently the only study to investigate RCT activity in UK NICUs and PICUs, to report the numbers of babies and children enrolled into these trials, and to determine the extent and distribution of mortality involved. The study showed that in a 5-year period (2002–6), approximately 50% of the NICUs and PICUs from which a response was received participated in one or more of 50 RCTs, enrolling over 3000 babies and children. However, most of the RCTs were conducted in a much smaller number of units. Less than 20% of NICUs and around 10% of PICUs had taken part in three or more RCTs during the 5-year period. For the majority of international and multicentre RCTs very low numbers of UK units took part. For example, fewer than five UK units took part in six out of nine international RCTs and in 8 out of 11 multicentre RCTs conducted in NIC for which this information was available. Level 3 NICUs were more likely than Level 2 NICUs to have participated in RCTs, including conducting their own single-centre RCTs. This is probably because the types of interventions being evaluated in a RCT, especially those aimed at the sickest babies and children, are more likely to delivered in these Level 3 units. Such units also tend to be located within teaching hospitals where there are more doctors and nurses with academic appointments and better resources for research activity.

In both NIC and PIC trials, the interventions that were most frequently evaluated were drugs but only a very small number of RCTs received funding from commercial organisations. There is widespread concern that most medicines used in the field of paediatrics are unlicensed or off-label. 2,86 It has been suggested that the pharmaceutical industry has been reluctant to conduct clinical trials of medicines because of the small market for the sale of drugs for babies and children, making investment in expensive research less attractive. Other reasons may include concerns about the ethics of conducting research in children, difficulties with blood sampling and recruiting sufficient numbers. 2

Nearly three-quarters of the RCTs identified involved NIC. This is perhaps not surprising given that PIC is a relatively new specialty and that there are only a small number of PICUs in the UK, reflecting the smaller numbers of children needing intensive care. The majority of RCTs in both NICs and PICs were multicentre (whether in the UK only or international). NIC RCTs were more likely to have been UK led than PIC RCTs, with the majority (72.2%) of NIC trials having been conducted within the UK only. There were more multicentre than single-centre NIC RCTs, of which most were collaborations between two or three NICUs. Of the international RCTs conducted within NIC, 60% were led from the UK.

Although PICUs were clearly taking part in collaborative research, the lack of UK-based multicentre RCTs over the period of this survey suggests that collaborative networks within the UK still needed to be established. Since then, three UK-based multicentre PIC trials were funded by HTA: SLEEPS: Safety profiLe, Efficacy and Equivalence in Paediatric intensive care Sedation (www.hta.ac.uk/1613); CATheter infections in CHildren – the CATCH trial (www.hta.ac.uk/1867); and Control of Hyperglycaemia In Paediatric intensive care trial – the CHIP trial (www.hta.ac.uk/project/1533.asp).

For over half of the RCTs for which the information was available, mortality was either a primary and/or secondary outcome measure. Although for other RCTs, mortality was not an end point, these data were still being recorded as trial investigators were able to provide numbers of hospital survivors and non-survivors for the BRACELET study. Over 500 deaths (around 16% of the total enrolled) were reported, predominantly in the neonatal context. The causes of the deaths were usually based on clinical, rather than pathologist reports, as there has been a general decline in neonatal and paediatric autopsy rates over the last 20 years. 87–89 It is not surprising therefore that all of the trial investigators who completed the section of the questionnaire about post-mortem data reported that these data were not specifically collected as part of the trial protocol. Most PIC investigators (66.7%) reported that post-mortem data were unnecessary compared with less than half (47.8%) of NIC investigators. None of the PIC investigators requested to see post-mortem reports, whereas 39.0% of NIC investigators reported that they had.

Whatever the cause of deaths, the variation in the distribution of the deaths identified in the survey suggests that a complex relationship exists between mortality, RCTs and units. For instance, in both NIC and PIC RCTs, higher proportions of babies and children died following enrolment into international RCTs than those enrolled into multicentre or single-centre RCTs. This could be because international RCTs were studying sicker populations, or needed to be international to accrue the larger numbers of units and babies or children to assess mortality differences, but there were also cases where there was such high mortality (e.g. owing to the severity of the condition at trial entry) that the necessary numbers could be enrolled in UK-only trials.

The most obvious division, however, is between the NIC and the PIC contexts. Although the same proportion of NICUs and PICUs took part in at least one trial, the numbers of deaths and the mortality rates that were identified were very different (n = 522 vs. n = 14 and 16.9% vs. 6.4%, respectively), and less than half of the PICUs that enrolled children into one or more RCTs witnessed a death following enrolment. Only one PICU reported more than one death. This is not surprising, as PIC mortality is generally lower in PIC (4.2% in 2009) than in NIC. 90 As death is a ‘rare event’, it is seldom used as a primary outcome measure in PIC RCTs. Rather the focus is other end points such as ‘ventilator-free days at 30 days after randomisation’91 or ‘nosocomial infection rate’. 92 This may mean that for the PIC specialty overall, death following RCT enrolment may not be a particularly salient issue, although for individual trials in the future that involve critically ill populations and those involving interventions that aim to improve survival, it will still be a potentially important consideration.

In contrast, a high proportion of NICUs (71.1%) that enrolled babies into at least one RCT witnessed one or more deaths following enrolment. The number and proportion of deaths in the NIC setting do suggest the salience of the issue both for the specialty and for the NIC research community. The degree of salience might well differ, however, across NICUs given the uneven distribution of deaths. Given that Level 3 NICUs enrolled more babies into RCTs than Level 2 NICUs, it is not surprising that the total number of deaths was also higher in these units. Even so, the proportion of babies who died overall was similar for the two types of units. There was however, a marked difference in the proportion of babies who died following enrolment into a multicentre RCT. Mortality was higher in the Level 3 units than in the Level 2 units but this is probably because more of the Level 3 NICUs took part in a large multicentre RCT that was enrolling much sicker babies.

Some NICUs did not participate in any trials and some that did, did not record any deaths. The majority of the reported deaths occurred in small numbers per unit; over half of the units that recruited to a trial reported five or fewer cases in the study period and so saw one or fewer cases per year. There was, however, a group of particularly research-active NICUs with much greater experience of death in this context. Five units witnessed 20 or more deaths in the study period, the highest number being 37, and one-quarter of the deaths for the neonatal sample as a whole (134/520) occurred in these units. All five were Level 3 units, which had high recruitment rates to RCTs with high mortality rates, and to RCTs with lower mortality rates but large samples. The RCTs to which these five units recruited were a mix of international, multicentre and single-centre RCTs.

The overall mortality figures for the NIC RCTs themselves were also variable, but with a far wider range and a far more skewed distribution than was seen for individual units. Again, some trials reported no or very small numbers of deaths, but the vast majority (82%) of reported deaths were concentrated in only four RCTs and more than half occurred in one high-recruiting RCT. This RCT reported 278 deaths before discharge from hospital in the 5-year period in the UK and a 21% mortality rate. [This trial has since been published,93 with a total of 579 deaths before discharge (16.6%), although these were not all in the UK and spanned more than the 5-year period covered by BRACELET.]

As further RCTs are initiated and accrue more participants, the population of parents bereaved after agreeing to enrol their child in a trial will accumulate; it is already sufficiently sizeable to warrant attention, but whether and how to respond to this population are complex questions.

Provision for bereavement is almost universally made within clinical centres but this body of parents, with potentially diverse experiences and needs, is largely scattered across a number of recruiting clinical centres; most deaths within trials occurred as relatively isolated cases and the majority of centres witnessed small numbers of deaths per year. This is likely to make it difficult for many of the clinical centres to develop, assess and sustain specialised responses to post-trial bereavement themselves. The patterns of mortality revealed by the BRACELET study also suggest, however, that there were pockets of NICUs and NIC trials with substantial numbers of deaths. In general, large units draw upon well-developed bereavement services,5 and research-active centres such as these may be appropriate candidates to develop and assess dedicated trial-related bereavement practices. In trials in which a substantial number of deaths is anticipated, it may also be possible to develop and assess trial-related bereavement practices. The BRACELET study showed that three trials had already developed a response to bereavement, such as preparing a bereavement leaflet for use in clinical centres or sending condolence letters directly to parents (for an example leaflet, see www.npeu.ox.ac.uk/down-loads/nest/NEST-Bereavement-Leaflet.pdf). What other forms that trial-related bereavement practices might take is unclear. This is discussed later in the monograph (see Chapter 9 ).

The BRACELET study has demonstrated that bereavement occurs in relation to RCTs of any size and type and with a range of clinical foci. The four trials that reported the majority of deaths in the 5-year period assessed very different interventions, from routine care practices to potentially life-saving technologies. They involved very different populations and were conducted in single-centre, multicentre and international contexts. This suggests that bereavement in a trial context may be an issue of broad relevance in specialties such as intensive care, and that it could be particularly appropriate for large trials – or trials focusing on high-risk situations – to plan for and assess their approach to bereavement with substantial research populations.

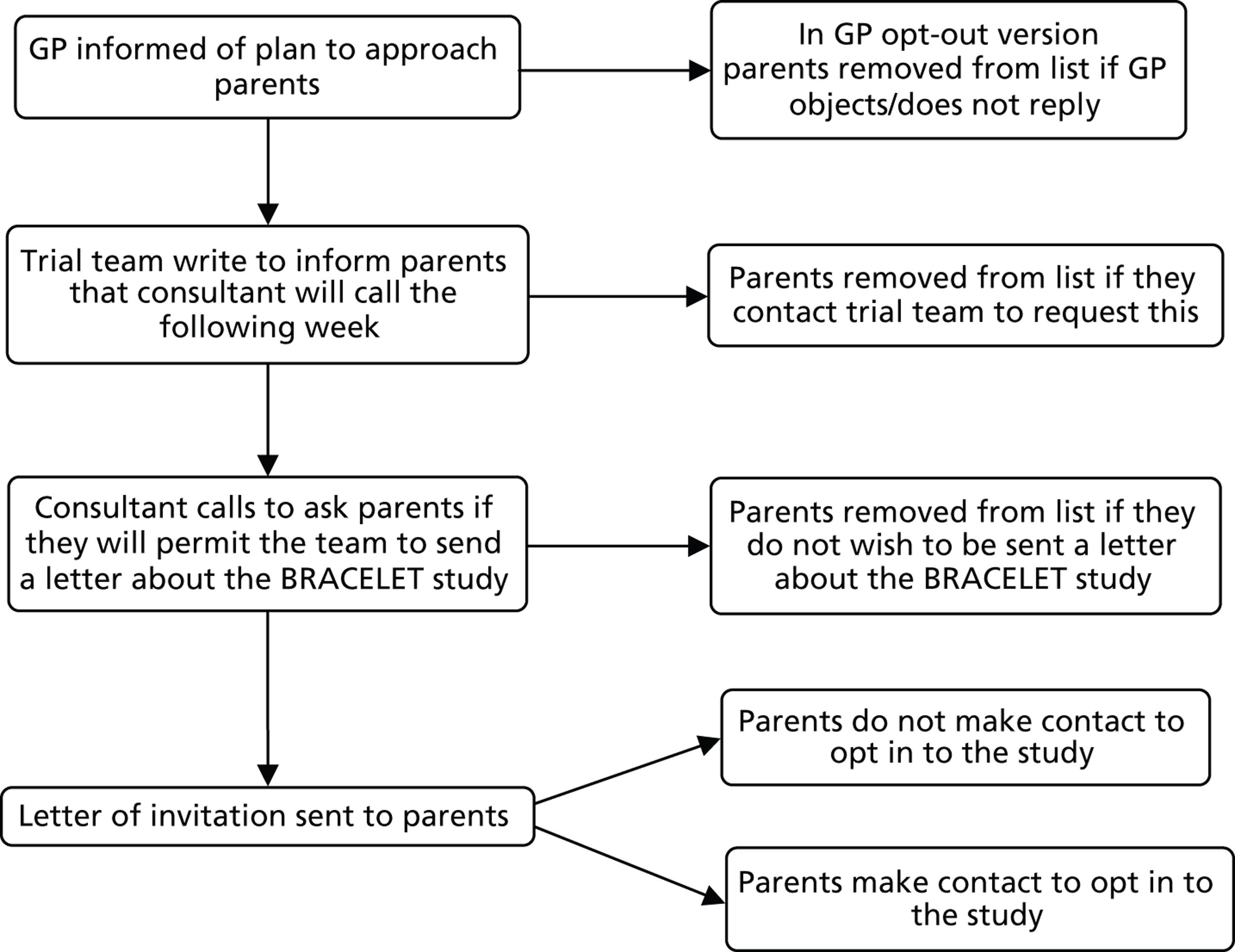

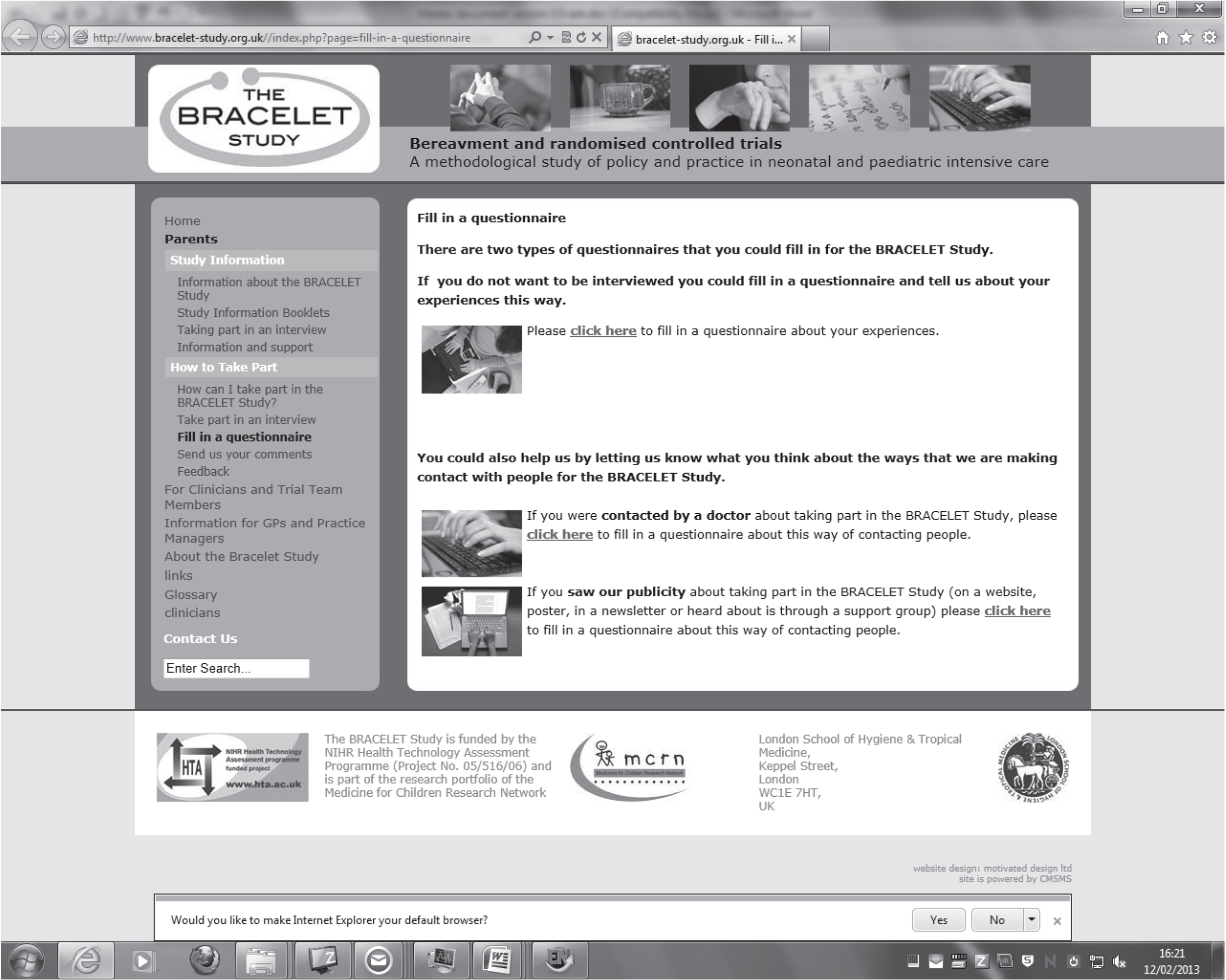

Trials are complex, highly collaborative endeavours between recruiting clinical centres and trial teams – groups that may feel a shared interest in and responsibility for parents bereaved in trials. Their collaboration might be exploited to good effect if experts within these fields take collective responsibility for the potential needs of the population identified here. If those trials and clinical centres with the greatest experience of post-trial bereavement develop effective approaches to care for and support bereaved parents, other smaller trials and centres may draw upon their recommendations and follow their lead. Even in the PIC context in which deaths occurred infrequently, PICUs were more likely than NICUs to have a dedicated bereavement counsellor, and individual trials may still involve severely compromised populations and so find that post-trial bereavement care is a salient issue.