Notes

Article history

This issue of Health Technology Assessment contains a project originally commissioned by the MRC but managed by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The EME programme was created as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) coordinated strategy for clinical trials. The EME programme is funded by the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the CSO in Scotland and NISCHR in Wales and the HSC R&D, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. It is managed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) based at the University of Southampton. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from the material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Rogers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Despite advances in medical therapy and percutaneous coronary interventions (PCIs) there is good evidence that coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) offers superior survival and freedom from repeat intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease (CAD). 1–5 For example, in the published New York State registry of almost 60,000 patients, after risk stratification for cardiac and non-cardiac comorbidity, there was a significant reduction in mortality (absolute difference of 5%) and a sevenfold reduction in the need for repeat interventions at 3 years in patients undergoing CABG rather than PCI using stents. 2 Predictions that drug-eluting stents will significantly reduce the need for CABG are premature because, although these stents reduce the incidence of restenosis compared with bare metal stents, three large meta-analyses have shown that they do not improve survival or reduce the incidence of subsequent myocardial infarction (MI). 6–8 There are two reasons why CABG is likely to remain a superior treatment to PCI over the longer term: (1) CABG protects whole zones of proximal myocardium (as the graft is placed to the midcoronary vessel beyond all proximal disease);9 and (2) PCI frequently results in incomplete revascularisation, which adversely affects survival proportional to the incompleteness of revascularisation. 10 Currently around half a million patients worldwide undergo CABG each year. There is a real possibility that these numbers will increase with a growing elderly population, an increasing epidemic of diabetes and obesity which all predispose to the development of CAD, and an increasing realisation that PCI may merely delay definitive treatment.

Conventional CABG uses cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) (‘on-pump’) to support the circulation while the heart is temporarily stopped. CPB causes a systemic inflammatory response syndrome, which leads to multiorgan dysfunction, and, although mild and reversible in most, can contribute to mortality and overt morbidity, particularly in higher-risk patients. 11–19 Evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in low-risk populations shows that ‘off-pump’ CABG (OPCABG) is at least as safe as ‘on-pump’ CABG (ONCABG) in terms of mortality and that it reduces several aspects of morbidity but may lead to a higher need for subsequent reintervention. 11–14

However, the exclusion of high-risk patients from these RCTs is of key importance because there are consistent findings from large observational studies that OPCABG appears to reduce mortality and morbidity in such patients. 15–19 These studies, summarised in Table 1 , have used propensity scoring and/or logistic regression to take account of different baseline characteristics in the OPCABG and ONCABG groups but are still prone to all the limitations of non-randomised studies.

| Reference number | Effect measure | Number of patients | Mortality (%) | OPCABG risk reduction in mortality (%) | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ONCABG | OPCABG | ONCABG | OPCABG | ||||

| 15 | O/E ratio for death | 106,423 | 11,717 | 1.02 | 0.81 | 20 | 0.001 |

| 16 | O/E ratio for death | 10,631 | 1929 | 1.25 | 0.61 | 49 | 0.001 |

| 17 | Bayes’ risk based mortality | 5163 | 2223 | 2.9 | 1.4 | 52 | 0.001 |

| 18 | Death within 30 days among patients with a EuroSCORE of > 6 | 510 | 510 | 5.9 | 3.1 | 47 | 0.04 |

| 19 | Mortality in 422 very high-risk patients | 211 | 211 | 11 | 4 | 64 | < 0.05 |

Only 15–20% of all CABG in Europe and the USA are performed as OPCABG owing to concerns that it may result both in fewer grafts and in lower graft patency. The Prague-4 RCT of 400 patients in a single centre reported similar 30-day clinical outcomes but a reduction in 1-year saphenous vein graft patency (49% in OPACBG group vs. 59% in ONCABG group) in the OPCABG group. 20 In contrast, in the Surgical Management of Arterial Revascularisation Therapies trial, a single-centre, single-surgeon RCT of 197 patients, Puskas et al. 21 reported 1-year angiographic graft patencies of 94% for OPCABG (mean of 3.2 grafts) and 96% for ONCABG (mean of 3.4 grafts). In the Beating Heart Against Cardioplegic Arrest Studies,22 two single-surgeon RCTs of 401 patients in total, 7-year follow-up has shown graft patency of 86.2% and 85.4%, respectively.

Past research

Research published before commencement of the trial

When the Coronary artery bypass grafting in high-RISk patients randomised to off- or on-Pump surgery (CRISP) trial was conceived, there had been two meta-analyses11,12 and two consensus statements13,14 addressing the issue of OPCABG versus ONCABG. The key summary points of these, and of two other meta-analyses23,24 published before recruitment to CRISP began, are reproduced below. It should be noted that these papers report, in effect, analyses of the same primary data from RCTs. Two earlier meta-analyses,25,26 with fewer patients and listed in several publications, were statistically less rigorous and are not described.

Meta-analysis 1: Cheng et al. 200511

In this meta-analysis of 37 RCTs (3369 patients) of OPCABG versus ONCABG, no significant differences were found for 30-day mortality [odds ratio (OR) 1.02, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.58 to 1.80], MI (OR 0.77, 95% CI 0.48 to 1.26), stroke (OR 0.68, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.40), renal dysfunction (OR 0.58, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.33), intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) requirement, wound infection, rethoracotomy or reintervention. However, OPCABG significantly decreased atrial fibrillation (AF), transfusion, inotrope requirements, respiratory infections, ventilation time, intensive care unit stay and hospital stay. Patency and neurocognitive function results were inconclusive. In-hospital and 1-year direct costs were higher for ONCABG. Therefore, this meta-analysis demonstrates that mortality, stroke, MI and renal failure were not statistically significantly reduced in OPCABG; however, selected short- and mid-term clinical and resource outcomes were improved compared with ONCABG.

Meta-analysis 2: Wijeysundera et al. 200512

These authors carried out a meta-analysis of 37 RCTs (3449 patients) and 22 risk-adjusted (logistic regression or propensity score) observational studies (293,617 patients). In RCTs, OPCABG was associated with a reduced incidence of AF and trends towards reduced 30-day mortality (OR 0.91, 95% CI 0.45 to 1.83) and reduced incidence of stroke (OR 0.52, 95% CI 0.25 to 1.05) and MI (OR 0.79, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.25). Observational studies showed OPCAB to be associated with reduced 30-day mortality (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.78) and a reduced incidence of stroke (OR 0.62, 95% CI 0.55 to 0.69), MI (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.88) and AF (OR 0.78, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.82). At 1–2 years, OPCABG was associated with trends toward reduced mortality, but also increased repeat revascularisation (RCT: OR 1.75, 95% CI 0.78 to 3.94; observational: OR 1.35, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.39). The conclusions that can be drawn include that the RCTs did not find, aside from AF, the statistically significant reductions in short-term mortality and morbidity demonstrated by observational studies. 12 These discrepancies may be due to differing patient-selection and study methodology. Future studies must focus on improving research methodology, recruiting high-risk patients and collecting long-term data.

Meta-analysis 3: Sedrakyan et al. 200623

This was a meta-analysis of 41 RCTs (3996 patients) of OPCABG versus ONCABG. No statistically significant differences were found for mortality [relative risk (RR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.58 to 1.60], MI (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.19), renal failure (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.26 to 1.45), reintervention (RR 1.90, 95% CI 0.92 to 3.90) or recurrence of angina. However, OPCABG significantly decreased AF (RR 0.70, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.84), stroke (RR 0.52 95% CI 0.37 to 0.74) and wound infection.

Meta-analysis 4: Moller et al. 200824

In this meta-analysis of 66 RCTs (5537 patients) of OPCABG versus ONCABG, no significant differences were found for mortality (RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.44), MI (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.37), repeat revascularisation (RR 1.34, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.18) or stroke (RR 0.62, 95% CI 0.32 to 1.19); however, OPBCABG significantly decreased AF (RR 0.69, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.83). To increase the strength of evidence regarding which method to prefer, large RCTs with longer-term follow-up and blinded outcome assessment, recruiting consecutive high-risk patients, are needed.

American Heart Association scientific statement: Sellke et al. 200513

One of the most hotly debated and polarising issues in cardiac surgery has been whether CABG without the use of CPB or cardioplegia (OPCABG) is superior to that performed with the heart–lung machine and the heart chemically arrested (standard CABG). Various clinical trials are reviewed comparing the two surgical strategies, including several large retrospective analyses, meta-analyses and the randomised trials that address different aspects of standard CABG and OPCABG. 13 Although definitive conclusions about the relative merits of standard CABG and OPCABG are difficult to reach from these varied randomised and non-randomised studies, several generalisations may be possible. Nevertheless, there appear to be trends in most studies. These trends include less blood loss and need for transfusion after OPCABG, less myocardial enzyme release after OPCABG up to 24 hours, less early neurocognitive dysfunction after OPCABG and less renal insufficiency after OPCABG. Fewer grafts tend to be performed with OPCABG than with standard CABG. Length of hospital stay, mortality rate and long-term neurological function and cardiac outcome appear to be similar in the two groups. To answer definitively the remaining questions of whether either strategy is superior, and in which patients, a large-scale prospective randomised trial is required.

Recommendations of the National Heart, Lung, And Blood Institute working group on the future direction in cardiac surgery. Off-pump coronary artery bypass: Baumgartner et al. 200514

Although CPB may reduce the technical difficulty of performing CABG surgery, it also contributes to the risk of specific complications, such as perfusion-related embolisation, hypoperfusion, generalised inflammatory response and anaemia. Consequently, a number of surgeons perform OPCABG, in which CPB is avoided, in an effort to avoid perfusion-related complications. Definitive data establishing the superiority of one technique over the other are lacking. Retrospective reviews of large databases suggest that OPCABG is associated with a decrease in risk-adjusted mortality and morbidity. Smaller prospective, randomised clinical trials comparing OPCABG with pump-based CABG have produced varying results, even when only graft patency is examined. Such conflicting information has led to adoption of OPCABG in a haphazard manner that poorly serves the large patient population with CAD. Currently, fewer than 25% of coronary revascularisations are performed without CPB and this percentage of OPCABG procedures has not increased over the last 3 years. A large, multicentre, randomised clinical trial comparing OPCABG and CABG is needed to resolve uncertainty regarding their relative benefits.

Although these meta-analyses of RCTs showed clinically important effect sizes (similar to those in the observational studies), they were underpowered for statistical significance. The CRISP trial was set up to test the hypothesis that, in high-risk patients, OPCABG reduces mortality and morbidity without causing a higher risk of reintervention, with the aim of recruiting almost 50% more patients than included in the meta-analyses.

Research published after commencement of the trial

There have been eight further meta-analyses and a Cochrane systematic review published since 2009, when recruitment to the CRISP trial began. 27–35 Six of the meta-analyses were restricted to RCTs,27–30,33,35 one considered both RCTs and observational studies32 and the other was a meta-analysis of propensity score analyses. 31 The largest of these meta-analyses, which was similar in size to the Cochrane systematic review (86 RCTs, 9906 patients), examined the association between outcome and risk. 30 Superior results with OPCABG were reported in patients with a lower ejection fraction for mortality and the incidence of AF, but not for the incidence of stroke or MI. No effect modification was seen for age and sex.

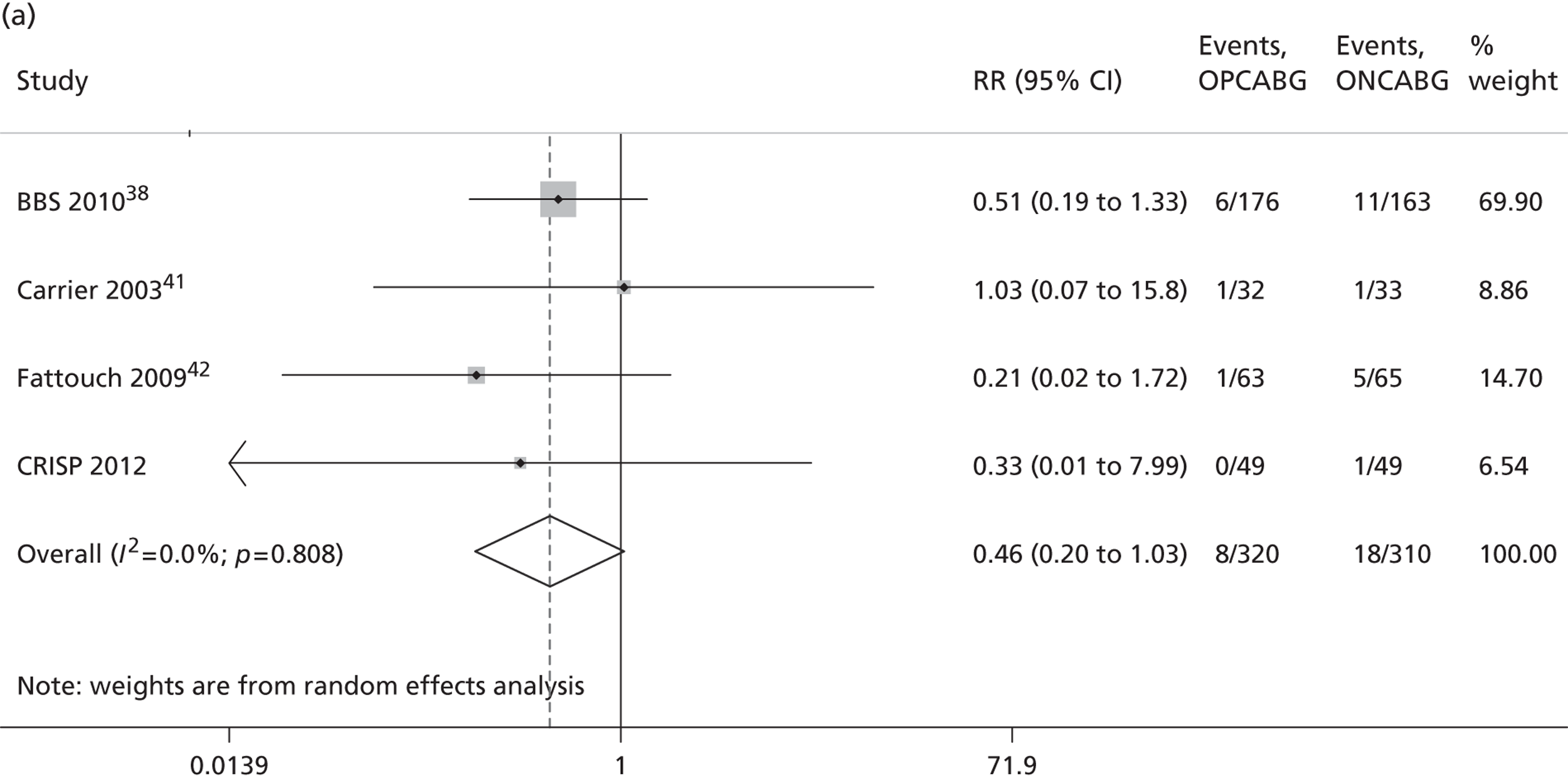

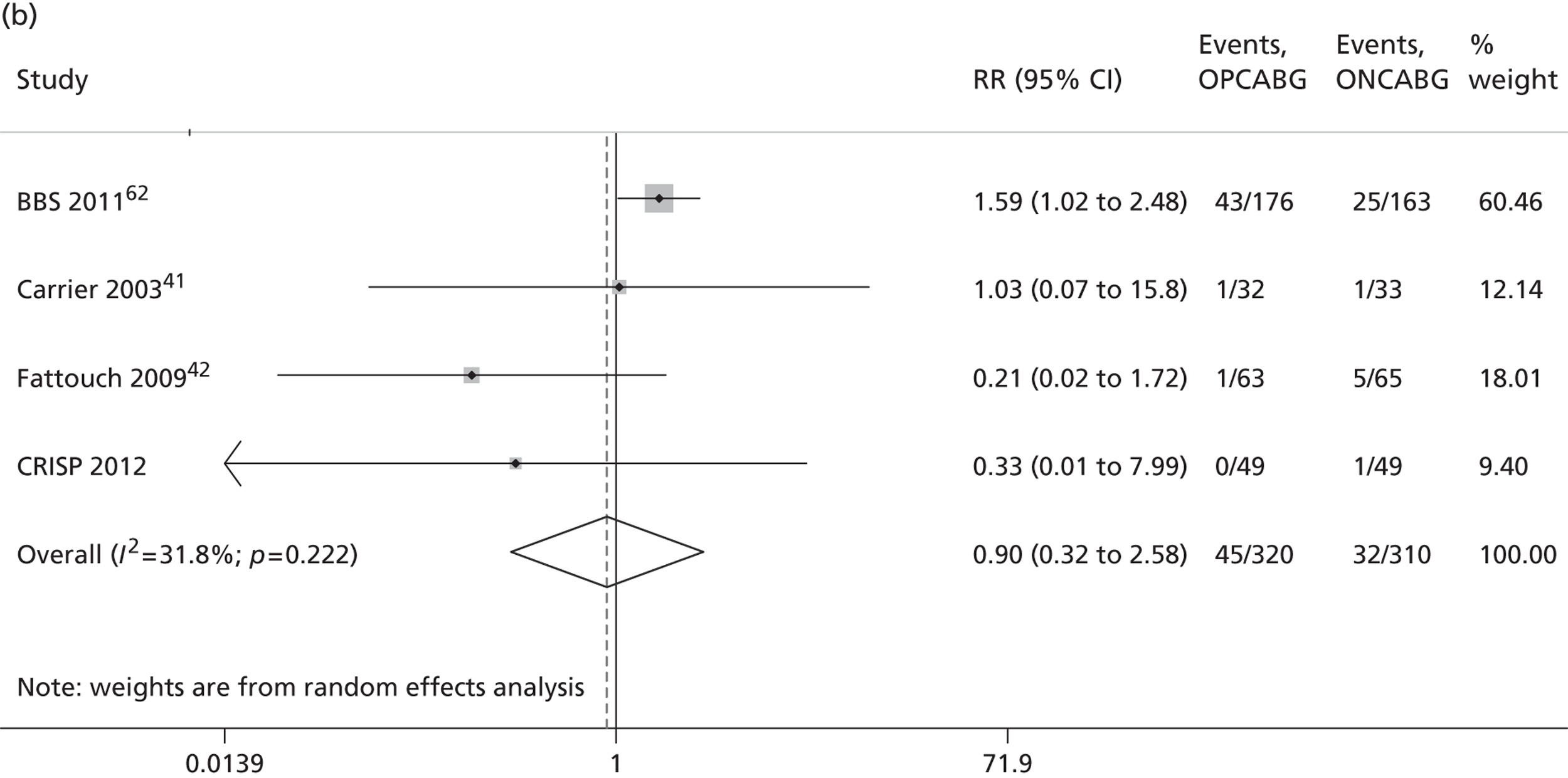

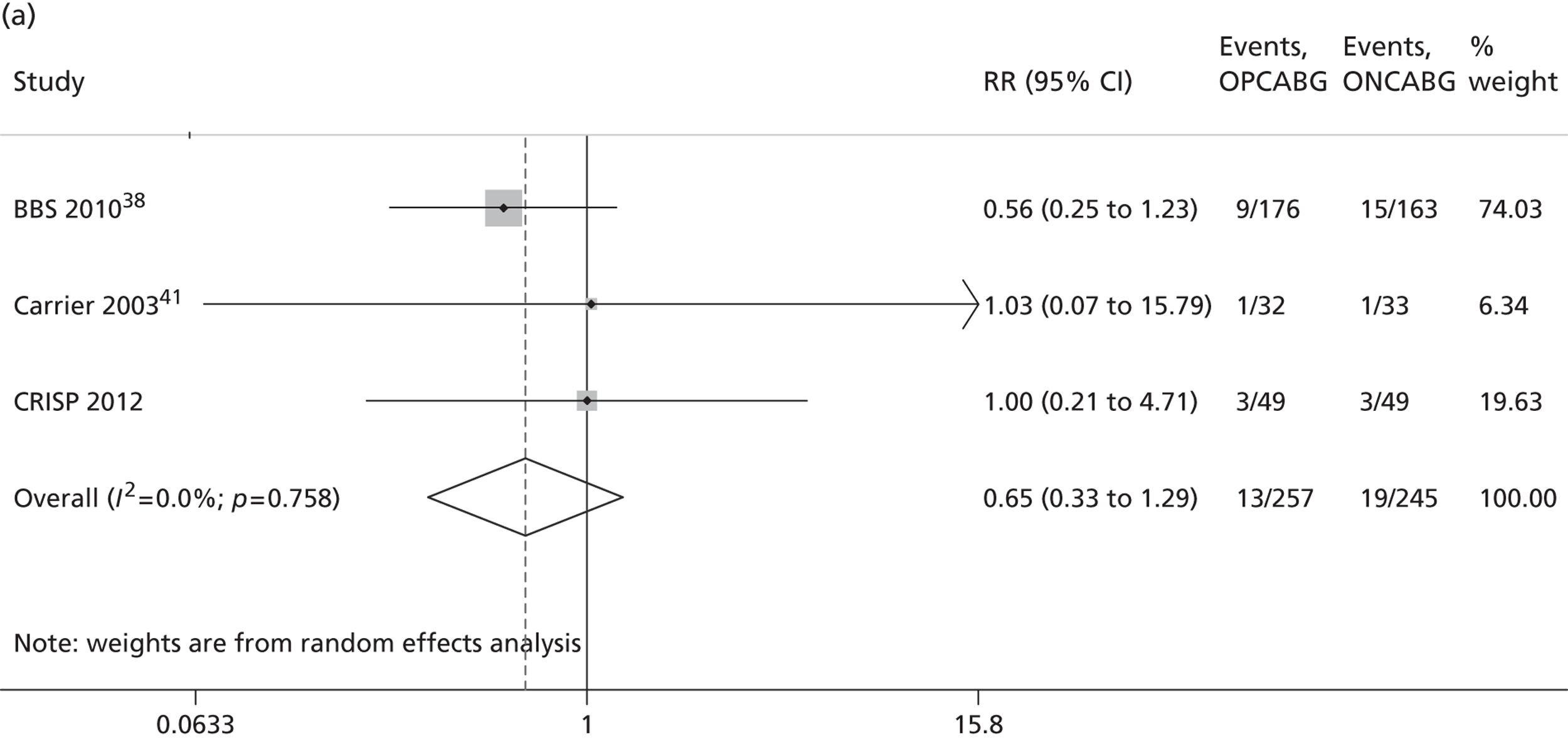

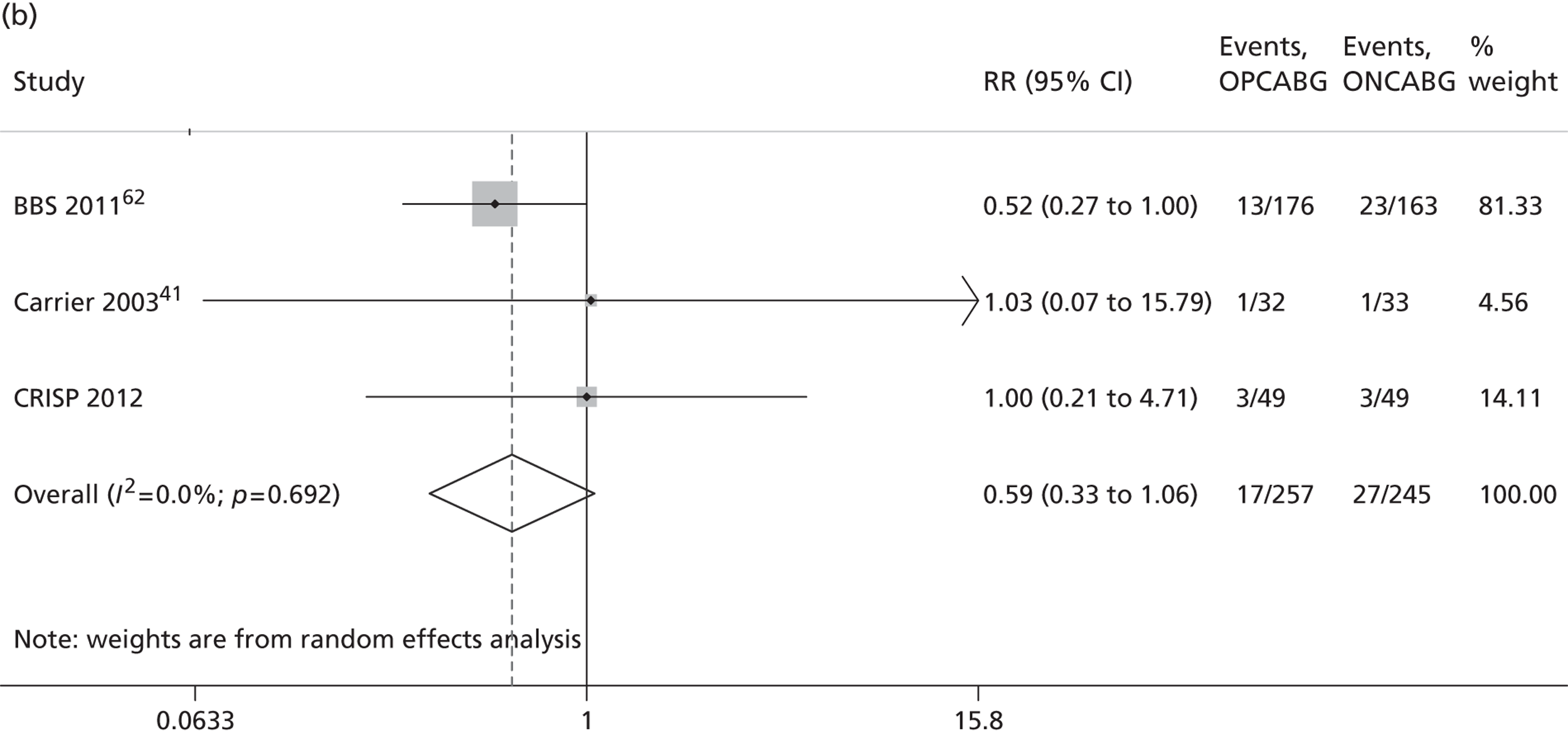

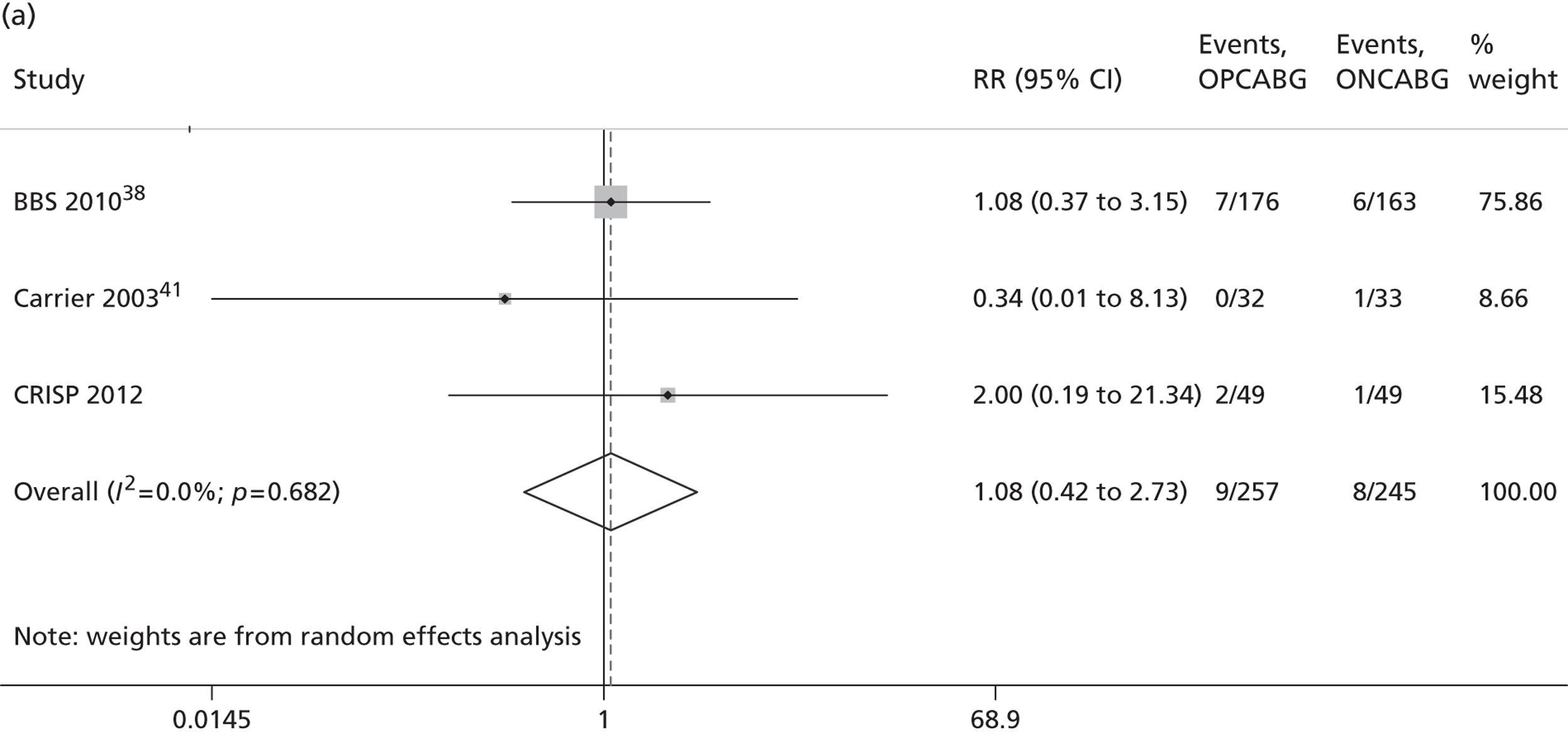

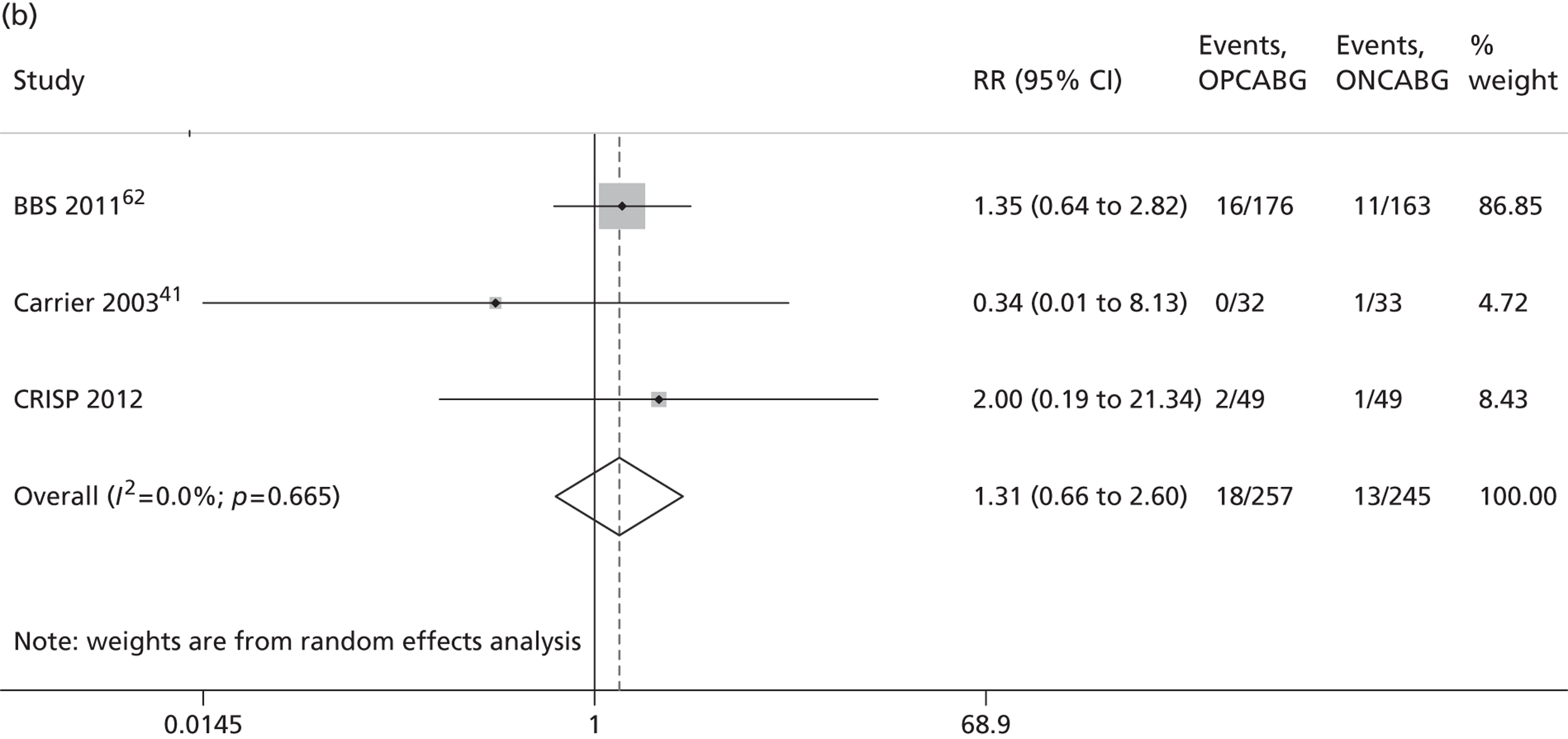

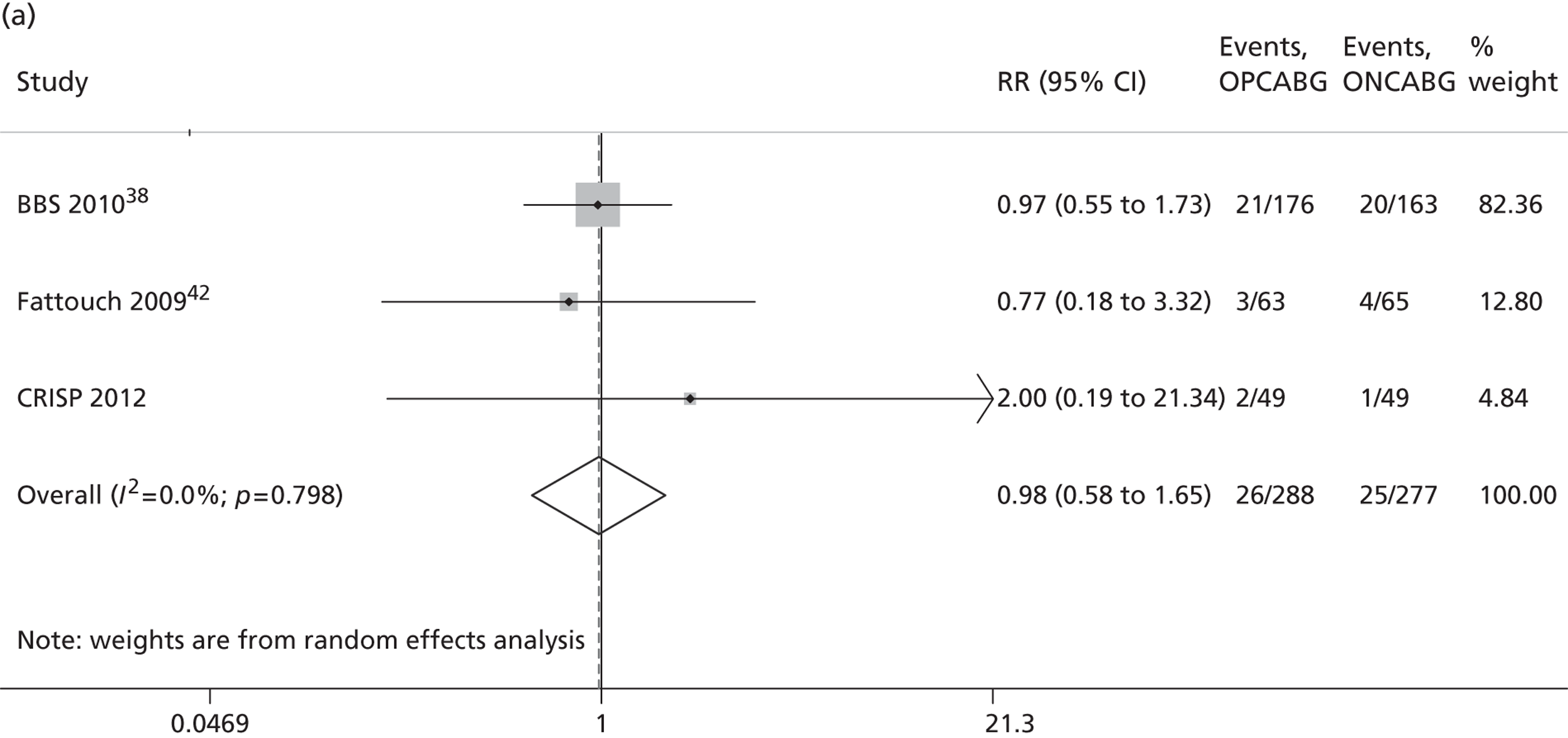

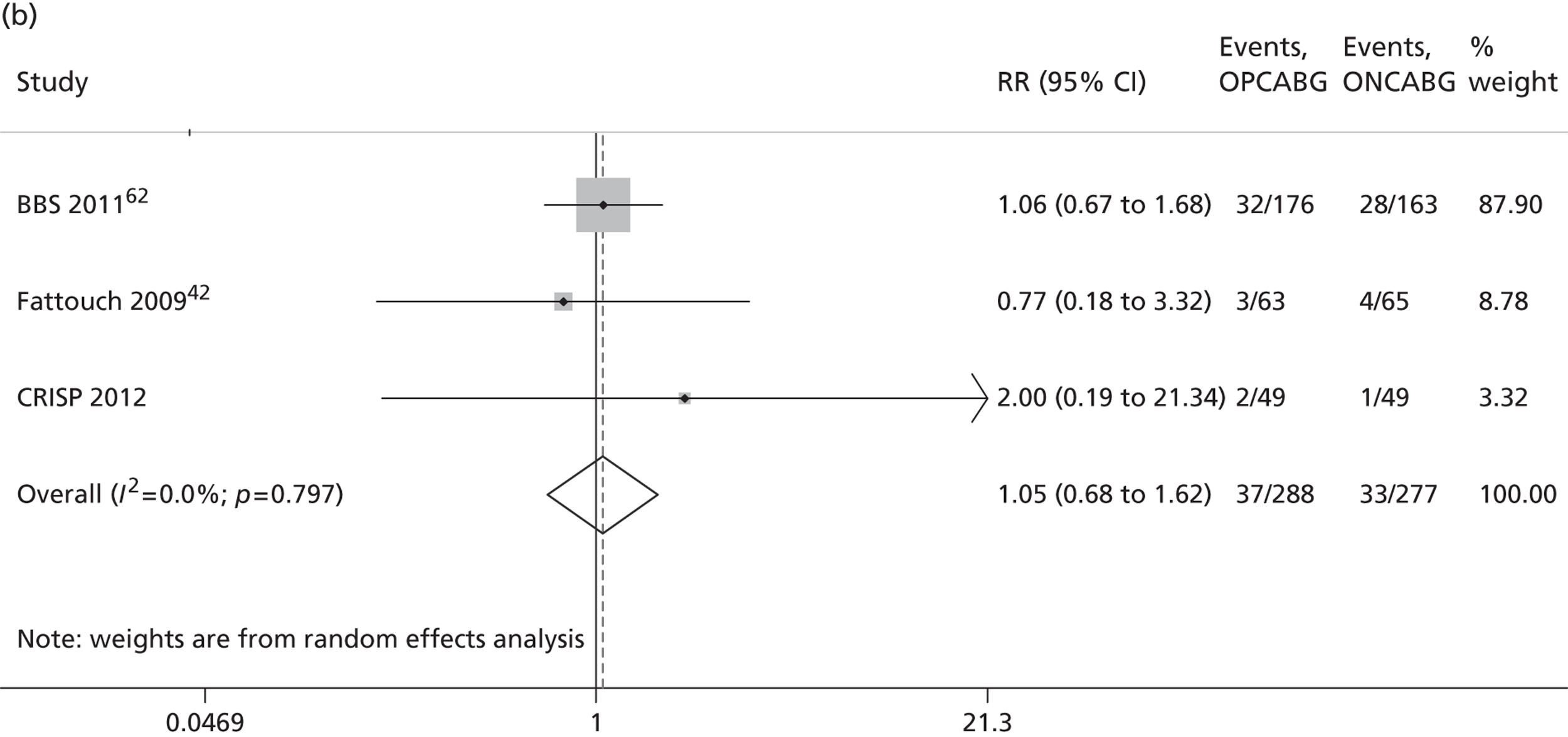

The Cochrane review published in 201234 includes 86 RCTs (10,716 patients). It includes results from four large trials (> 300 participants) published since the previous meta-analysis by the same group:24 the Medicine angioplasty or surgery study,36 the Randomised On/Off BYpass (ROOBY) trial,37 the Best Bypass Surgery (BBS) trial38 and the Danish On-pump Off-pump Randomisation Study (DOORS; published in abstract form only). 39 The review does not include the more recently published CABG off- or on-pump revascularisation (CORONARY) trial. 40 All-cause mortality to 30 days (death within 30 days of surgery) favoured OPCABG, but not significantly so (RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.33 to 1.20). However, when including follow up beyond 30 days, a significantly increased risk of death with OPCABG was found (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.01 to 1.53). There was no difference with respect to MI, either in the first 30 days (RR 1.16, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.64) or overall (RR 1.00, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.26). In contrast, the risk of stroke in the first 30 days was reduced (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.99) but, again, a difference in overall risk was not found (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.06). OPCABG conferred a non-significantly increased risk of coronary reintervention (RR 1.25, 95% CI 0.94 to 1.65) and a significantly reduced risk of postoperative AF (RR 0.78, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.96); the incidence of renal insufficiency was similar (RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.20). On average, OPCABG patients had fewer distal anastomoses (−0.28, 95% CI −0.40 to −0.16). The authors acknowledged that mainly patients with low risk of postoperative complications were enrolled and patients with three-vessel coronary disease and impaired left ventricular (LV) function were under-represented. The majority of trials were assessed as having a high risk of bias owing to the open-label design. There was no heterogeneity in all-cause mortality between trials with a low risk of bias. Within this subgroup of trials, both single-surgeon, single-centre and multicentre trials were represented. The review did not consider subgroups of patients because the trials did not report results of subgroups and included only three trials focusing on high-risk patients. 38,41,42 The authors concluded that ONCABG should be the standard treatment but that OPCABG should be considered for patients with contraindications to aortic cannulation and cardiac arrest. They also suggested that large high-quality RCTs recruiting experienced surgeons and focusing on patients with impaired ventricular function and in whom ONCABG is contraindicated are needed.

The Canadian-led CORONARY trial recruited 4752 patients from 79 centres in 19 countries. 40 The trial had a coprimary composite outcome of death, non-fatal stroke, non-fatal MI or new renal failure requiring dialysis at 30 days after randomisation. There was no significant difference in the rate of this primary composite outcome [hazard ratio (HR) 0.95, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.14] or in any of its individual components. OPCABG significantly reduced the rates of blood transfusion (RR 0.80, 95% CI 0.75 to 0.85), reoperation for bleeding (RR 0.61, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.93), acute kidney injury (AKI) (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.96) and respiratory complications (RR 0.79, 95% CI 0.63 to 0.98) but increased the rate of early repeat revascularisations (HR 4.01, 95% CI 1.34 to 12.0).

Aims and objectives

The CRISP trial was set up to address the limitations highlighted in the meta-analyses, namely to test the hypothesis that OPCABG in high-risk patients reduces mortality and morbidity, without causing a higher risk of reintervention. It complemented the CORONARY trial, which recruited predominantly lower-risk patients. Overall, 5.6% of CORONARY trial participants had impaired LV function (impairment was defined as LV function < 35%) and only 17.7% had a European system for cardiac operative risk evaluation (EuroSCORE) of > 5. 40

This report describes the results of the CRISP trial. The trial closed early, on the grounds of futility, after less than 2% of the target sample size had been reached. The challenges faced and the outcomes for the small cohort of patients recruited are described.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

The CRISP trial was a designed as an international, multicentre, open, parallel-group RCT of isolated OPCABG versus ONCABG in high-risk patients with an additive EuroSCORE of ≥ 5. The study received research ethics approval (reference 08/MRE00/58) and was registered (reference ISRCTN29161170).

The preferred method of randomisation when CRISP was set up was expertise based, i.e. patients were randomised to surgery carried out by an experienced off-pump surgeon or by an experienced on-pump surgeon. Evaluating surgical interventions using an expertise-based trial design was first proposed in 1980,43 but was rarely used until more recently. 44 The advantages of an expertise-based design have been discussed in detail by Devereaux et al. ,45 Cook46 and in the orthopaedic setting by Scholtes et al. 47 The rationale for choosing an expertise-based design for the CRISP trial was as follows: individual surgeons, because of their training and experience, are generally more proficient in a particular technique and so are likely to use primarily a single surgical approach. This could compromise the validity of a conventional RCT as the surgical expertise may be skewed toward the technique which is best established, most widely used or easiest to perform; a conventional RCT also has limited applicability since, by design, only surgeons experienced in OPCABG can take part. Surgical procedures that require a ‘learning curve’ are clearly disadvantaged as a minimum number of cases need to be performed and considerable experience is needed before a surgeon feels at ease with both techniques. Unless participating surgeons have expertise in both procedures, there is also a potential for differential crossover in the two arms of the trial (i.e. more crossovers in one direction than the other). OPCABG is less frequently performed than ONCABG, technically more demanding and may have a more prolonged ‘learning curve’. Previous conventional RCTs have been criticised for recruiting ‘inexperienced’ OPCABG surgeons, resulting in poor OPCABG results with an excess of graft occlusion and not the best ONCABG surgeons. 48 Expertise-based randomisation was chosen to avoid these problems. The surgeon eligibility criteria for participation in the CRISP trial are described in Settings.

Changes to trial design after commencement of the trial

After CRISP had been recruiting for 10 months, the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), in reviewing the recruitment challenges CRISP was experiencing at the time (see Chapter 3, Barriers to recruitment for further detail), agreed that the randomisation method should be relaxed and that both expertise-based and within-surgeon randomisation should be permitted, but with expertise-based randomisation remaining the preferred option when staff availability and logistics permitted its use. The CRISP randomisation system was then updated to record prospectively which allocation method, expertise based or within surgeon, was intended to be used for each patient recruited.

Participants

Eligibility criteria

Patients having isolated CABG surgery were eligible if they satisfied the following criteria:

-

additive EuroSCORE of ≥ 549

-

non-emergency surgery

-

operation to be carried out via a median sternotomy

-

written informed patient consent.

Patients with an additive EuroSCORE of five or more are at higher risk of mortality and morbidity. The EuroSCORE is made up of 17 components:

-

Age (one additive EuroSCORE point per 5 years from age 60 years).

-

Sex (one additive EuroSCORE point if female).

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (one additive EuroSCORE point if on bronchodilators or steroids for lung disease).

-

Extracardiac arteriopathy (two additive EuroSCORE points if claudication, carotid stenosis > 50%, previous or planned surgery of the abdominal aorta, limb artery or carotid).

-

Neurological dysfunction (two additive EuroSCORE points if disease severely affects ambulation or day-to-day function).

-

Previous cardiac surgery (three additive EuroSCORE points if pericardium opened previously).

-

Creatinine (two additive EuroSCORE points if > 200 µmol/l).

-

Active endocarditis (three additive EuroSCORE points if on antibiotics for endocarditis).

-

Critical preoperative state [three additive EuroSCORE points if on inotropes, IABP, acute renal failure (oliguria < 10 ml/hour), aborted sudden death, intermittent positive-pressure ventilation, ventricular tachycardia (VT), ventricular fibrillation (VF)].

-

Unstable angina (two additive EuroSCORE points if on intravenous nitrates until arrival in operating theatre).

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction (one additive EuroSCORE point if between 30% and 50%, three additive EuroSCORE points if < 30%).

-

Recent MI (two additive EuroSCORE points if MI < 90 days before surgery).

-

Pulmonary hypertension (two additive EuroSCORE points if systolic pulmonary artery pressure > 60 mmHg).

-

Emergency surgery required (two additive EuroSCORE points).

-

Not isolated CABG (two additive EuroSCORE points if major cardiac procedure with or without CABG).

-

Surgery on the thoracic aorta (three additive EuroSCORE points if ascending, arch or descending aorta).

-

Post-MI ventricular septal defect (four additive EuroSCORE points).

Note that the last four components are exclusion criteria from the trial and, therefore, patients would not accrue any EuroSCORE points from these components.

Patients having isolated CABG surgery were not eligible if they satisfied any of the following criteria:

-

additive EuroSCORE of < 5

-

emergency operation (immediate revascularisation for haemodynamic instability)

-

concomitant cardiac procedure with CABG

-

operation to be carried out via an incision other than a median sternotomy (e.g. anterolateral left thoracotomy)

-

known contraindication to ONCABG or OPCABG (e.g. calcified aorta, calcified coronaries, small target vessels).

Changes to trial eligibility criteria after commencement of the trial

Following the first CRISP investigators meeting, held in November 2009, participant age of < 70 years was removed as an exclusion criterion. This change was implemented from January 2010.

Settings

Patients were recruited to the CRISP trial from specialist cardiac surgery centres in the UK and Kolkata, India.

The preferred method of randomisation for CRISP was expertise-based randomisation (see Study design). Surgeons at participating centres using this preferred method were eligible to join CRISP if they had a stated preference for either OPCABG or ONCABG and were approved by the TSC as being sufficiently experienced in their preferred technique (i.e. at least 100 operations).

If, after detailed discussion with the research team, it was agreed that expertise-based randomisation was not possible at a centre, stratified within-surgeon randomisation was used. Centres and surgeons that planned to use within-surgeon randomisation required approval from the TSC (prior to the randomisation criteria being relaxed part-way through the trial; see Study design). The surgeons concerned were required to provide evidence that they have expertise in both techniques (at least 100 operations carried out using each method) and that they used both techniques with similar frequency.

Interventions

Trial patients were randomised to

-

CABG without CPB, i.e. OPCABG on the beating heart, via a median sternotomy incision, or

-

CABG with CPB, i.e. ONCABG on a chemically arrested heart, via a median sternotomy incision.

The anaesthetic technique and method of myocardial protection used were in accordance with established local protocols. These aspects were not specified in the trial protocol as there is a consistent 30-day mortality of around 2% for CABG across most UK centres, suggesting that minor differences in anaesthetic technique and methods of myocardial protection do not have a major influence on perioperative mortality. Surgical details were recorded on the case report form (CRF).

The only requirement was that the centre/surgeon followed the randomisation allocation. If it proved necessary to convert from OPCABG to ONCABG during the operation, this was recorded on the CRF.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a composite end point of death or serious morbidity (CRISPSw) within 30 days of surgery (i.e. up to and including day 30). The components were (1) all-cause death after Cardiac surgery, (2) new onset Renal failure, (3) MI, (4) Stroke, (5) Prolonged initial ventilation and (6) Sternal wound dehiscence.

New-onset renal failure was defined as a postoperative creatinine value of > 200 µmol/l, a percentage increase from preoperative creatinine of ≥ 40% and the need for renal replacement therapy (RRT). Dialysis/haemofiltration during CPB only did not constitute a requirement for RRT, and any patient who received RRT in the month prior to surgery was not eligible for this end point. The highest creatinine prior to any RRT was measured, along with preoperative and day 2 postoperative creatinine measurements for all patients.

Myocardial infarction was defined by (1) troponin I level of > 0.5 µg/l or troponin T level of > 0.2 µg/l and new pathological Q-waves with documented new wall motion abnormalities except in the septum, (2) creatine kinase MB isozyme (CK-MB) level of ≥ 10 upper limit of normal (non-Q MI), or (3) electrocardiographic (ECG) changes consistent with infarction (new significant Q-waves ≥ 0.04 cm or a reduction in R-waves of > 25%, in at least two contiguous leads). It was originally intended that if blood results did not indicate a MI but ECG suggested a MI had occurred, then the results would be adjudicated by an independent committee masked to the randomised allocation. However, after a blinded review of the data, it was decided that blood results and preoperative and postoperative ECGs for all patients would be adjudicated in this manner and MI defined on consensus of the adjudicators. ECG and blood samples (troponin T or troponin I, when possible; CK-MB was only used only if these tests were not available) were taken for the assessment of cardiac markers on day 5 postoperatively and all tests were redone if there was any indication of a suspected MI at any other time.

Stroke was defined as new acute focal neurological deficit thought to be of vascular origin, with signs or symptoms lasting longer than 24 hours and confirmed by a neurologist. Imaging was encouraged to further delineate between an ischaemic or haemorrhagic event.

Prolonged ventilation was defined as 96 hours or more, excluding any periods of reintubation following the initial extubation.

Sternal wound dehiscence was defined as requiring non-pharmacological intervention (e.g. vacuum-assisted closure dressing or reoperation). Any component events that occurred either prior to surgery or > 30 days after surgery were recorded but not included in the 30-day composite outcome.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were:

-

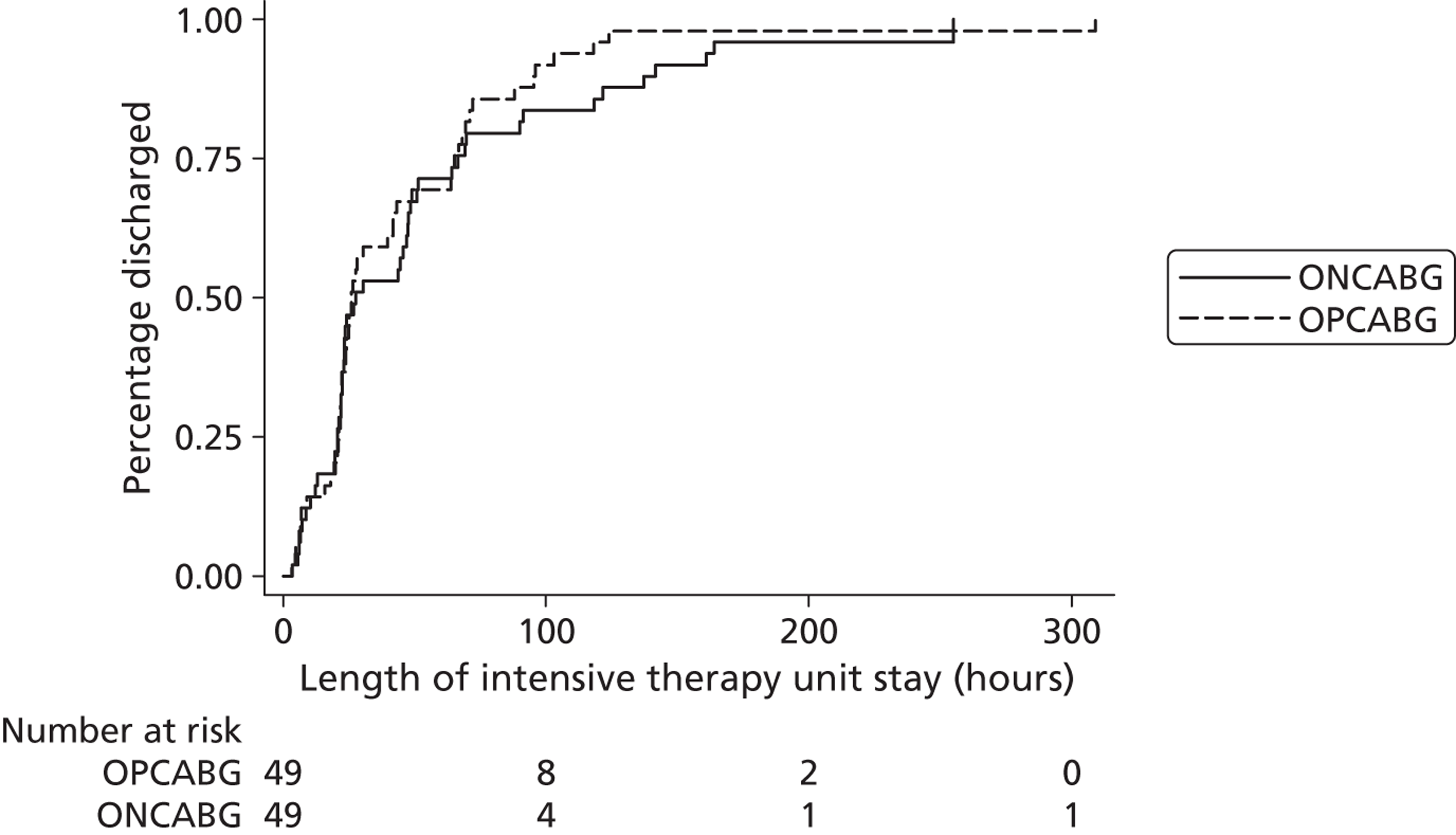

duration of cardiac intensive care unit (CICU) stay during the index hospital admission (excluding any periods when the patient was returned to CICU after initial discharge), calculated as the time from operation end to initial discharge from CICU

-

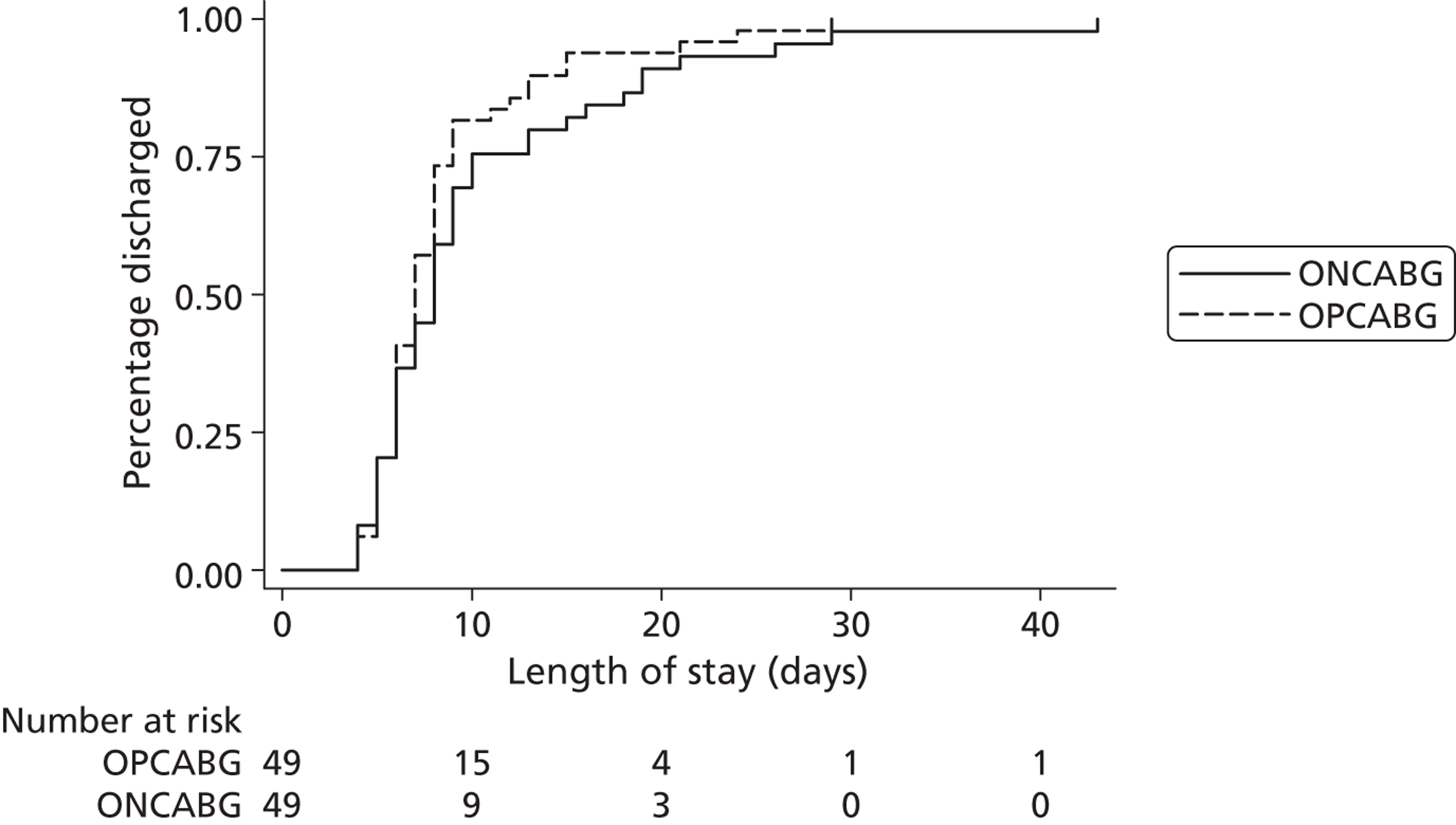

duration of hospital stay during index hospital admission, calculated as the time from operation to discharge from the cardiac unit

-

quality-of-life (QoL) assessment at recruitment and 4–8 weeks after surgery, measured using Rose Angina Questionnaire (short),50 Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) angina class,51 European QoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)52 and Coronary Revascularisation Outcome Questionnaire (CROQ)53

-

resource utilisation, determined by hospital resources during index admission

-

cost-effectiveness, determined by within-trial cost per CRISPSw event averted, extrapolated cost per life-year gained and per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained.

In addition, UK centres were randomised such that all patients operated at that centre received one of three different EQ-5D questionnaires: (1) the standard EQ-5D three-level questionnaire, (2) an extended five-level version with descriptors for all five levels, (3) an extended five-level version with descriptors for just the three original levels54 (see Appendix 2 ). An intended substudy of CRISP was to compare patient responses using the three scoring systems in patients undergoing coronary surgery.

Adverse events

Expected events were specified in the CRISP protocol (see Appendix 3 ). The protocol states that events listed are expected in the period from surgery and discharge from hospital after the operation. Any event outside this window is considered unexpected. Expected events were captured through purpose-designed CRFs (see Appendix 4 ). Unexpected events were captured in free-text format.

Changes to trial outcomes after commencement of the trial

Some small changes were made after the trial commenced at the recommendation of the Data Monitoring and Safety Committee (DMSC). First, the need to independently adjudicate blood test and ECG results for inconsistencies in the reporting of the MI primary outcome element was added. Second, in order to reduce any possible systematic bias, the definition of the new onset renal failure primary outcome element was changed from the need for RRT alone to the need for RRT and the fulfilment of clinical creatinine criteria. Finally, the collection of patient-reported CCS angina class was added to complement the Rose angina class also being collected.

The original intention of the trial was to follow-up patients for 1 year post surgery, but this was reduced to 4–8 weeks owing to the premature termination of the trial. Amendments were required to secondary outcomes to accommodate this: (1) all QoL outcomes were changed from assessment at recruitment, 4–8 weeks and 1 year post surgery to recruitment and 4–8 weeks alone; (2) resource use was changed from during 1 year to during the index hospital admission and (3) intended secondary outcomes of survival free from death or serious morbidity at 1 year and survival at 3 months were removed.

Sample size

The study sample size was set at 5418 patients (2709 per group). Pooled data collected from Bristol and Oxford cardiac databases were used to inform the sample size calculation. The data suggested an expected incidence of the composite primary outcome of 9.3% for patients with a preoperative EuroSCORE of ≥ 5. As all patients randomised to a given surgeon under expertise-based randomisation will have had their operations using the same technique, they cannot be regarded as independent of each other. Assuming that 80 surgeons would take part in the trial, the resultant intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was estimated from data from Bristol and Oxford cardiac databases to be 0.005. Using these assumptions, a sample size of 5418 patients had 90% power to detect a 30% reduction in RR with 5% significance (two tailed).

The DMSC periodically reviewed the safety data. At the start of the trial, two interim analyses of clinical outcomes were proposed: (1) when 50% of participants had been followed up to 30 days and (2) when 50% of participants had completed the trial (i.e. had been followed up for 12 months after surgery, the end of follow-up according to the original trial design). It was proposed that the trial should continue as planned unless there was a statistically significant difference between the two surgical approaches, with p ≤ 0.001. These interim analyses were not undertaken owing to the premature termination of the trial (see Chapter 3, Decision to close the trial early).

Randomisation

Randomised treatment allocations were internet based and generated by Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK. 55 Allocations were stratified by centre and cohort-minimisation used to minimise imbalance of key prognostic factors (age, sex, urgency of operation, poor LV function, impaired renal function, previous stroke, redo CABG and significant pulmonary disease) across the OPCABG and ONCABG groups. Patients were randomly assigned in a 1 : 1 ratio.

Using an internet-based randomisation system ensured that allocations were concealed until all data that could uniquely identify the patient, confirm eligibility and establish stratification and cohort minimisation groups were entered. Access to the system was password protected and only available for designated site staff. Randomisation was carried out after the trial co-ordinator or research nurse had obtained written informed patient consent. The timing of expertise-based randomisation was carefully chosen to leave enough time to schedule the surgery, but also to minimise the time between randomisation and surgery and, therefore, reduce the possibility of outcome events or cancellation of surgery occurring in this period. Within-surgeon randomisation was usually carried out as close as possible to surgery. Any patients who were unexpectedly rescheduled retained their study numbers and randomised allocation and every effort was taken to ensure the rescheduled operation was carried out by an appropriate surgeon participating in the trial, according to the randomisation method used and the assigned allocation.

Blinding

It was not possible to blind the surgeons or those involved in the postoperative care of the patients. However, at most centres, postoperative care follows strict protocols that are not ONCABG or OPCABG specific. Patients were not explicitly informed of their allocation and the external signs of surgery were similar for both groups. The careful choice of objective, clinically defined primary outcome components should minimise bias. In addition, the individuals undertaking the adjudication of MI data were masked to the treatment allocation.

Data collection

Data collection was performed both while the patient was under the care of the cardiac unit and again at their standard 4–8 week postoperative outpatients appointment to identify any elements of the primary outcome and/or adverse events (AEs). Data were collected from clinical records by research nurses and/or clinical trial co-ordinators. Purpose-designed CRFs were used to record data at each stage of a patient’s journey through the trial (see Appendix 4 ), with the key data collection points being pre surgery, the period from surgery to discharge and the routine 4–8-week follow-up appointment. Completed CRFs were then entered into the trial database via a password-protected web–based interface.

A bespoke trial database was designed using SQL server (2008). The database was intended to act as both a data storage facility and a trial management resource. For example, the database issued reminders when 4–8 week postoperative assessments were due, managed payment schedules to sites and provided facilities for tracking the progress of serious adverse event (SAE) reporting. Owing to the intended large sample size, a considerable amount of data validation was applied to the database. The validation rules were determined as a result of detailed discussions between clinical trial co-ordinators, research nurses, statisticians and database developers working on the study and were refined following any feedback from sites. Validation broadly included rules such as (1) the correct ordering of any dates and times, e.g. the date and time of CICU, high-dependency unit (HDU) or ward admission must be after the operation end date and time but prior to hospital discharge; (2) agreement of data on postoperative complications between the study CRFs and SAE forms for sponsor reporting, e.g. if there is an AE classified as serious on the CRFs an SAE form should be completed; (3) patient details (e.g. sex, age) and stratification/cohort minimisation data entered on the study CRFs should match that entered on the internet-based randomisation system; and (4) miscellaneous validation of related data recorded on different CRF pages, e.g. if the patient is recorded as being reintubated twice, there should be two reintubation and re-extubation dates and times entered on the relevant CRF. See Appendix 4 , Figure 1 , for an example of a message to the user if validation rules were not met.

Statistical methods

Analyses of the primary and secondary outcomes were carried out on the basis of intention to treat (ITT). The analysis (ITT) population consisted of all randomised patients excluding patients who died prior to surgery, patients who withdrew prior to surgery as it was decided not to perform surgery and patients who withdrew at any time and were unwilling for any data collected to be used. Continuous variables were summarised using the mean and standard deviation (SD) [or median and interquartile range (IQR) if the distribution was skewed] and categorical data were summarised as a number and percentage. All treatment comparisons are presented as effect sizes with 95% CIs, and p-values of < 0.05 from likelihood-ratio tests have been considered statistically significant. However, as the trial was stopped early, it was very underpowered to detect clinically important differences.

It was intended to adjust all formal comparisons of OPCABG versus ONCABG for surgeon and the factors used in the cohort minimisation. However, owing to the reduced sample size and resultant low event rates of some of the cohort minimisation factors, all models were adjusted for age, sex and operative priority as fixed effects and surgeon as a random effect. All underlying model assumptions were checked using standard methods (e.g. residual plots, tests for normality or for proportional hazards). Outlying observations that meant models did not fit the data adequately were excluded from analyses and are indicated in table footnotes.

The primary analysis is the proportion of patients experiencing the composite outcome of death or major morbidity (CRISPSw) up to 30 days and has been analysed using logistic regression with the treatment effect reported as an OR. Component events have been presented separately by occurrence pre or post hospital discharge. The duration of CICU stay and hospital stay were analysed as time to event outcomes, with patients who die prior to CICU/hospital discharge censored at the time of their death. Comparisons were performed using Cox proportional hazards models and treatment comparisons are presented as HRs. The validity of the assumption of proportional hazards was tested and, if violated, a model with a time-dependent covariate (the interaction term between the treatment and the survival time) was used. Random effects terms were fitted via the use of shared frailty terms. 56

For all QoL data, standard rules have been used to derive outcome measures. Rose angina and CCS angina class both result in ordinal outcomes ranging from no angina symptoms to ordered grades of angina symptoms. EQ-5D data are in two sections, the first consisting of five ordinal questions (which, for the patients who used the standard EQ-5D questionnaire, is converted into an EQ-5D single summary index) and the second a visual analogue scale. Finally, data from CROQ questionnaires are used to derive seven continuous scores, including an overall ‘core total’ score.

Rose and CCS angina class data at 4–8 weeks post surgery have been dichotomised into any angina symptoms versus no angina symptoms. Treatment groups have been compared using logistic regression, adjusting for the appropriate preoperative angina class as a categorical outcome, with treatment effects reported as ORs. Formal statistical comparisons of treatment effects have been performed only if > 10 patients in total experience the angina outcome (with at least one event in each treatment group). Responses to the five EQ-5D ordinal questions have been tabulated but no formal analyses undertaken (see Appendix 2 , Table 21 ). EQ-5D single summary index and visual analogue scale data and the CROQ core total score have been analysed using linear mixed effects methodology. Pre and postoperative values were modelled jointly to avoid the necessity to either exclude cases with missing preoperative measures or to impute missing preoperative values. Multivariate normal models were fitted incorporating separate parameter estimates for the mean baseline response and for each treatment at the 4–8 week time point (i.e. saturated model with time fitted as a categorical variable).

Safety data have been reported on the safety population, defined as all randomised patients excluding patients who withdrew prior to surgery, as it was decided not to perform surgery, and patients who withdrew at any time and were unwilling for any data collected to be used. Expected events (i.e. listed in the study protocol as expected prior to hospital discharge following cardiac surgery) and unexpected events (any event not listed in the protocol occurring before discharge and any event occurring after hospital discharge) have been tabulated separately (see Tables 15 – 17 ), with events that meet the criteria (prolonged an ongoing hospitalisation/resulted in hospitalisation, resulted in death, was life-threatening or resulted in persistent or significant disability/incapacity) of a SAE identified. Events have been presented and grouped by the treatment received, rather than the treatment allocated, and no formal comparisons between treatment groups have been made.

No formal corrections have been made for multiple testing, but the number of statistical comparisons has been limited and our interpretation of the results takes into account the magnitude and consistency of effect estimates. No subgroup or sensitivity analyses were performed. A planned subgroup analysis to compare the treatment effect in patients with an additive EuroSCORE of < 8 and ≥ 8 was planned but not performed owing to the early termination of the trial.

Missing data in all tables are indicated by footnotes. There were no missing data for the primary outcome or the time to event outcomes. Missing data for QoL outcomes were infrequent (< 5%) and, therefore, cases with missing postoperative values have been excluded from analyses. For cases with complete postoperative but missing preoperative data, the joint modelling of continuous data avoids the necessity to impute such data under the assumption that data are missing at random, but for categorical data the most common category across both treatment groups has been imputed. Owing to the low levels of missing data, it was judged that more complex missing data approaches (e.g. multiple imputation) would be unlikely to recover any additional information.

All statistical models were fitted in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All other analyses and data management were performed in SAS version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Health economics

Given the early cessation of the trial (see Chapter 3, Decision to close the trial early), unit cost estimates for valuing resource utilisation data had not yet been collected. This, plus the small sample sizes at trial cessation, precludes the calculation of the costs associated with each method of CABG, as well as estimates of cost-effectiveness. Resource utilisation data reported for each arm of the trial are, therefore, limited to key items consumed during the index hospital admission for surgery, including duration of operation, duration on ventilation, time in CICU, time in HDU and time on a ward.

Following general guidance issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, continuous data are presented using mean and SDs for each group. Differences between groups are presented using the mean difference (MD) and 95% (bootstrapped) CI for the difference.

Chapter 3 Results

Centres

The CRISP trial planned to recruit patients from 40 centres, 20 in the UK and 20 overseas. In the recruitment period from October 2009 to March 2011, patients were recruited from eight centres in the UK and one centre in India. A total of 39 surgeons participated: 19 ONCABG specialists and 20 OPCABG specialists. The number of surgeons at each centre ranged from two to nine ( Table 2 ). The proportion of consultant surgeons at a centre participating in CRISP ranged from 20% to 100%.

| Centre | Number of surgeons | |

|---|---|---|

| ONCABG surgeons | OPCABG surgeons | |

| Basildon | 1 | 2 |

| Blackpool | 2 | 3 |

| Bristol | 3 | 6 |

| King’s College | 3 | 1 |

| Oxford | 1 | 1 |

| Papworth | 1 | 1 |

| Sheffield | 2 | 1 |

| Wolverhampton | 4 | 2 |

| India | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 19 | 20 |

In addition to the nine participating centres, a further five UK centres (University College London; Sussex Cardiac Centre, Brighton; The Cardiothoracic Centre, Liverpool; Nottingham University Hospital; and South Tees Hospital, Middlesbrough) had the necessary approvals in place to start but had not recruited any trial participants before the study closed to recruitment in March 2011 at the request of the funder (see Decision to close the trial early). Two UK centres, in Edinburgh and Cardiff, and 10 overseas centres were at various stages of the research approvals process when the study closed (see Appendix 1 ).

Screened patients

A total of 787 patients were assessed for potential inclusion in the trial. Six hundred and eighty-one were excluded: 523 were ineligible, 82 were eligible but not approached, 74 were approached but did not consent and two were omitted for other reasons. The numbers of patients screened, found to be ineligible, not approached, did not consent and randomised are given by centre in Table 3 and demonstrate different proportions of ineligible patients between centres (range 0% to 76%). This reflects the fact that some centres did not screen all potential patients.

| Centre | Screened (n) | Excluded from study | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ineligible | Not approached | Did not consent | Other reason | Randomised | ||||

| n | %a | n | n | n | n | %a | ||

| Basildon | 13 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 6 | 46 |

| Blackpool | 44 | 17 | 39 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 21 | 48 |

| Bristol | 436 | 330 | 76 | 39 | 41 | 0 | 26 | 6 |

| King’s College | 64 | 40 | 63 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

| Oxford | 132 | 93 | 70 | 15 | 5 | 0 | 19 | 14 |

| Papworth | 48 | 22 | 46 | 12 | 9 | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Sheffield | 27 | 17 | 63 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 7 | 26 |

| Wolverhampton | 17 | 2 | 12 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 11 | 65 |

| India | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 100 |

| Total | 787 | 523 | 66 | 82 | 74 | 2 | 106 | 13 |

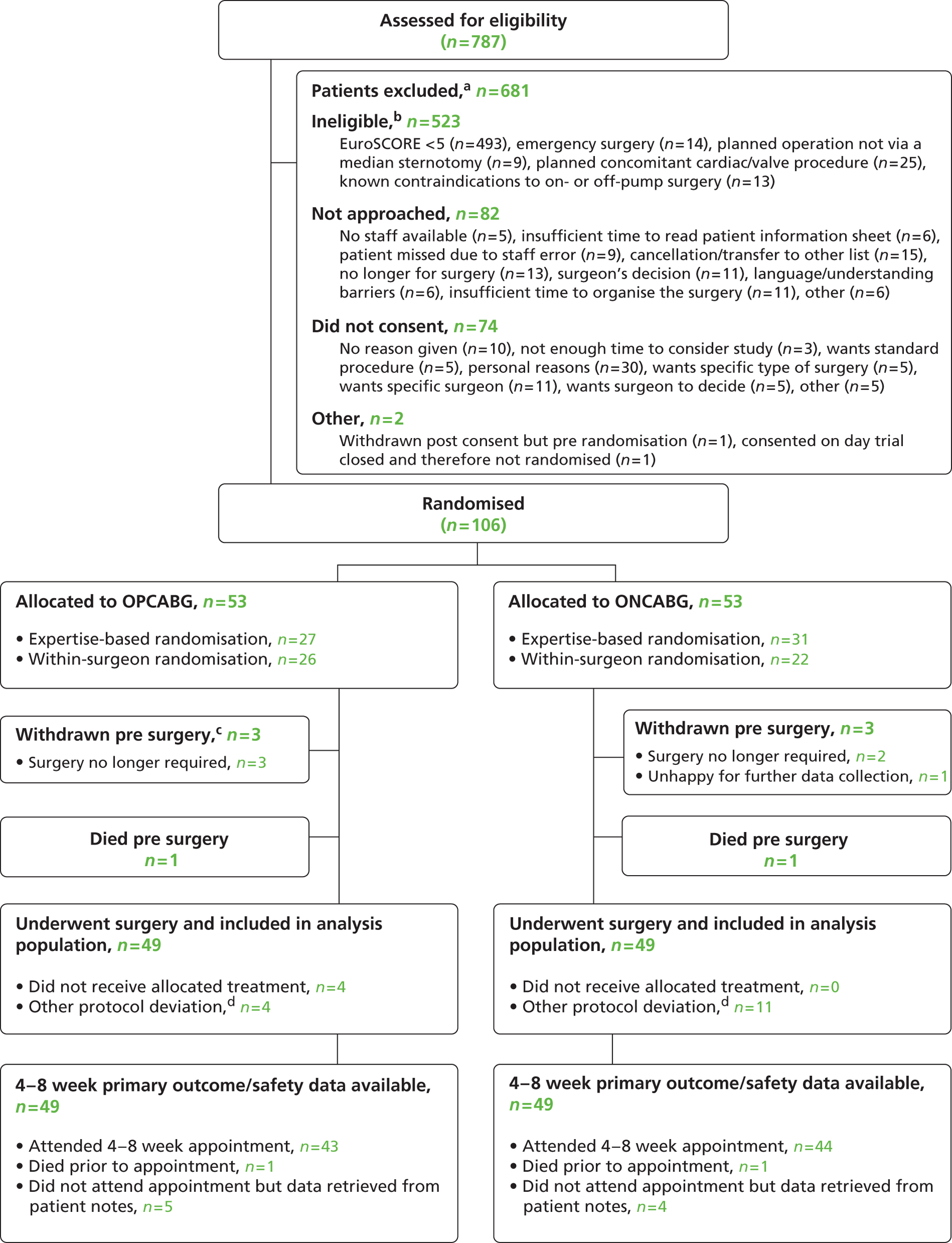

The majority of ineligible patients [493 out of 523 (94%)] had an additive EuroSCORE of < 5. Other reasons for ineligibility, non-approach and non-consent are given in Figure 1 . Reasons for eligible patients not being approached included (1) cancellations and transfers to another surgeon’s list, (2) a decision not to operate, (3) time constraints and (4) a surgeon’s decision.

FIGURE 1.

Flow of participants. a, The exclusions section is incomplete as not all sites have entered full screening data; b, some patients may be ineligible for more than one reason; c, one further patient (not included on flowchart) withdrew pre surgery but was happy for data collection to continue; therefore, the patient is included in all applicable analyses (for details of all withdrawals see Table 8 ); and d, for further details see Table 9 .

The main reason given for patients declining to take part was personal reasons, followed by the patient having a preference for a specific surgeon.

Even at the Bristol and Oxford centres, where the screening data were most complete, 75 and 39 eligible patients, respectively, were identified each year on average: significantly fewer than the average 300 eligible patients identified retrospectively from an institutional database of all cardiac procedures over the same period in Bristol. The main reasons for the deficit were (1) not all surgeons were participating in CRISP, (2) only willing OPCABG surgeons could participate if logistical problems (e.g. time constraints or surgeon unavailability) required a within-surgeon allocation, (3) other trials were recruiting from the same pool of patients in the same time period (although CRISP was prioritised over other trials in Bristol).

Recruitment

A total of 106 eligible patients were recruited into the study from October 2009 to March 2011. Patient follow-up was completed in June 2011. The study was closed to recruitment in March 2011 at the request of the funder (see Decision to close the trial early).

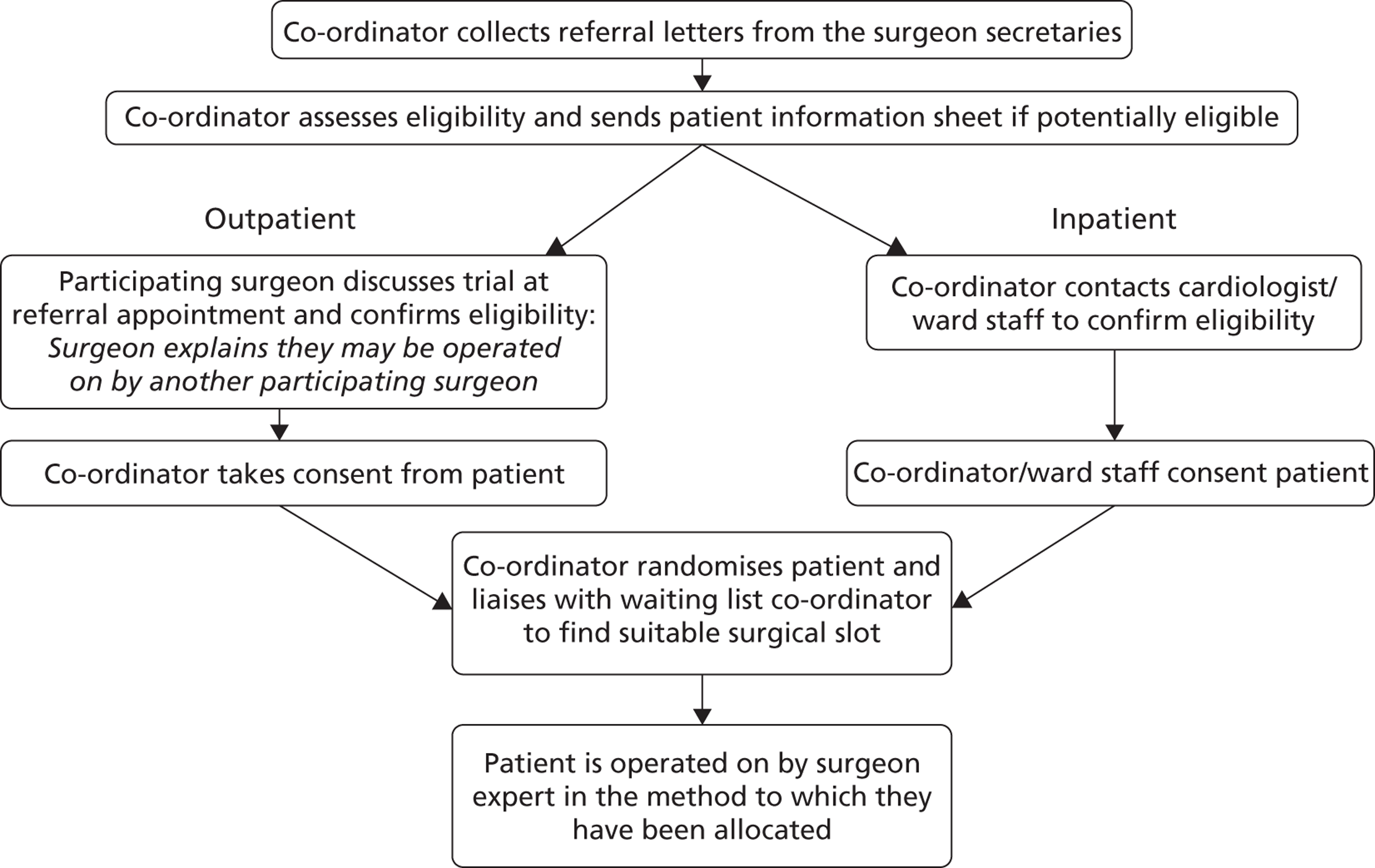

Recruitment pathway

The logistics of identifying eligible patients, recruiting them into the trial and organising the surgery within an expertise-based allocation framework was recognised as the key challenge for participating centres. It was acknowledged that the recruitment pathway could vary between centres in order for them to meet this challenge while continuing to work and operate within national and local protocols. The recruitment pathway envisaged before commencement of the trial, modelled on the recruitment pathway at the Bristol centre, is described in Figure 2 .

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment pathway (Bristol model).

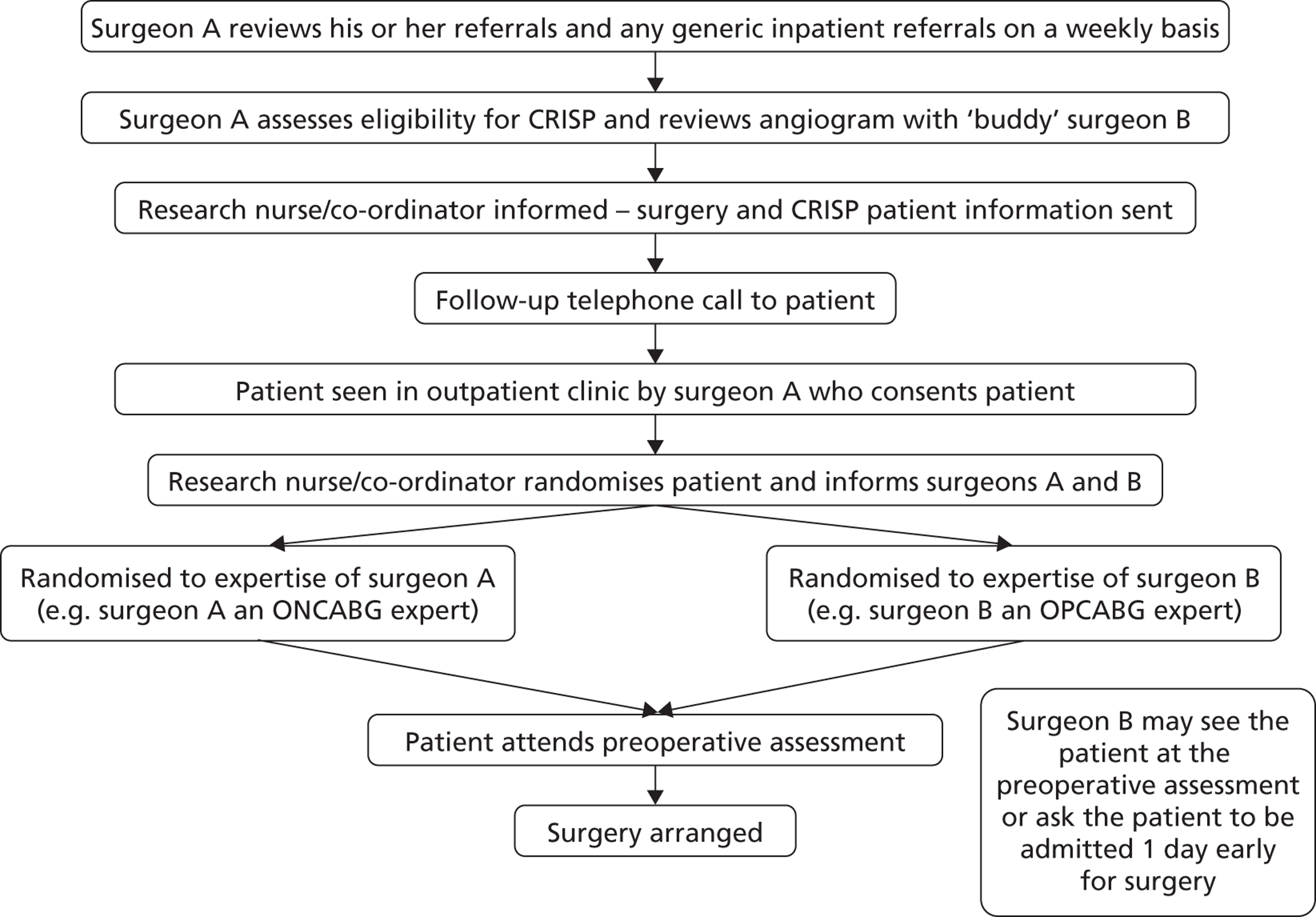

When presenting the study at site initiation visits it became apparent that this exact model would not be applicable at all centres. The model developed at Wolverhampton, where the majority of referrals are to a named surgeon, is shown in Figure 3 .

FIGURE 3.

Recruitment pathway (Wolverhampton model).

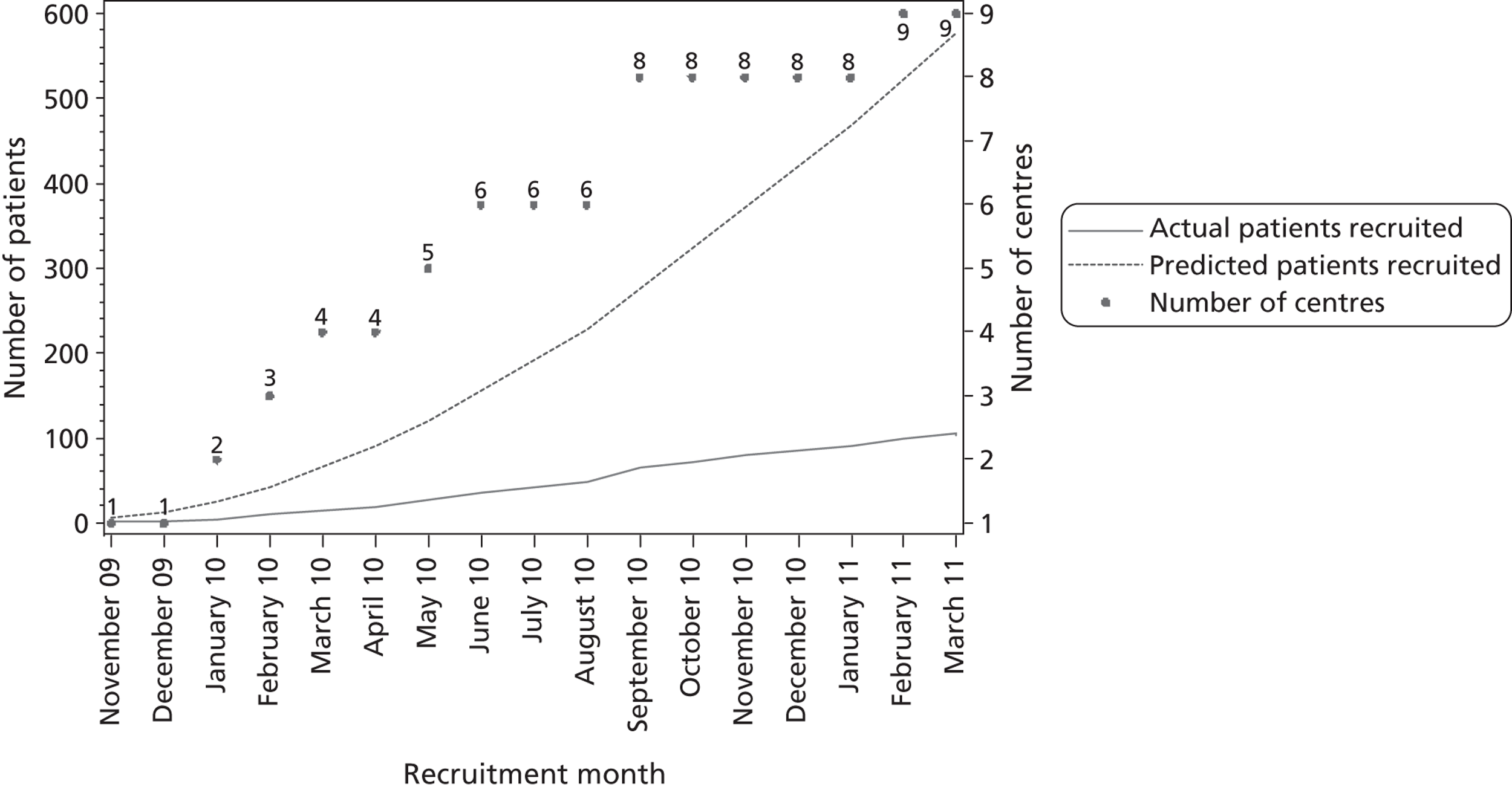

Recruitment rate

When the CRISP trial was designed, it was estimated that each centre would recruit at least six patients per month. This estimate was based on data from the Bristol and Oxford centres, where between 200 and 300 eligible patients underwent CABG each year. Based on previous trials, it was anticipated that 40% of eligible patients would be recruited,22 which would have resulted in an annual recruitment rate of between 80 and 120 patients per year. This target was not met at any participating centre. Two centres (Blackpool and Bristol) recruited five patients in 1 month and three centres (Blackpool, Wolverhampton and India) each recruited four patients in 1 month. The number of patients recruited by month and centre is shown in Table 4 and cumulative predicted and actual recruitment is shown in Figure 4 .

| Centre | Month of randomisation | Total | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | ||||||||||||||||

| November | December | January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | January | February | March | ||

| Basildon | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| Blackpool | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 21 |

| Bristol | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 26 |

| King’s College | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Oxford | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Papworth | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Sheffield | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| Wolverhampton | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| India | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 1 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 18 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 9 | 7 | 106 |

FIGURE 4.

Predicted and actual recruitment. The predicted number of patients assumes six patients recruited per centre per month (predictions in study protocol).

Barriers to recruitment

During study visits to centres and through a survey of the UK centres, we sought to gain information on the characteristics and key challenges of the recruitment process at each of the CRISP centres. The information provided by the UK study centres is summarised in Table 5 . The centres not listed did not respond. Five key barriers to recruitment emerged from the information gathered:

-

The number of participating surgeons. Recruitment using an expertise-based randomisation system was severely hampered if only two surgeons in a centre were taking part.

-

Access to potentially eligible patients. In some centres, urgent inpatients were transferred to the specialist cardiac centre several days before surgery, which provided sufficient time to gain the patient’s consent and organise the surgery. In other centres, patients were not transferred until late on the day before surgery and the time window for recruitment was invariably too short.

-

Referral system. Some centres operated a generic referral system for all patients (i.e. patients were placed in a pool) while, in other centres, there was a mixture of generic referrals and referrals to a named surgeon. In some centres, the vast majority were named referrals. Surgeons were reluctant to ‘share’ patients referred to them whom they had met in clinic, as they believed that the patients would want to stay with the surgeon they had met.

-

Targets. The need to meet referral-to-treatment targets and other performance targets imposed locally.

-

Insufficient information in the referral letter to determine eligibility. The EuroSCORE is made up of several components, and frequently the information provided on referral was inadequate to allow the score to be calculated accurately.

| Centre | Patient pool | Recruitment opportunities and key challenges | Participating surgeons |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basildon | Aimed to recruit from urgent patient pool because few (< 20%) of the elective patients would be eligible (EuroSCORE of ≥ 5) | Urgent inpatients referred for surgery are transferred to the cardiac centre at least 3 days prior to surgery. Patients would be recruited, randomised and the surgery arranged in this 3-day window | One ONCABG, two OPCABG |

| Blackpool | Approximately 200 operations in eligible patients per year. Aimed to recruit from urgent patient pool because elective patients are allocated to a surgeon on the basis of their ‘geographic patch’ and the centre was of the opinion that patients want to stay with the allocated surgeon they meet in clinic | Inpatients referred for surgery are transferred to the cardiac centre several days prior to surgery. Patients would be recruited, randomised and the surgery arranged in this window. Soon after recruitment started, the centre stopped screening elective patients for the trial | Two ONCABG, three OPCABG |

| Bristol | Approximately 200 to 300 operations in eligible patients per year. Aimed to recruit eligible patients from both the elective and urgent inpatient pool | Three ONCABG, six OPCABG | |

| King’s College | Aimed to recruit eligible patients primarily from the elective patient pool | Urgent inpatients waiting in a ‘feeder’ hospital are not transferred to the cardiac centre until the night before surgery, which does not give enough time for patients to be given trial information, make a decision and the surgery to be arranged according to an expertise-based allocation | Three ONCABG, one OPCABG |

| Oxford | Patients are referred to named surgeons. The centre was of the opinion that patients want to stay with the allocated surgeon they meet in clinic | With only two surgeons participating, patients can only be recruited and randomised using an expertise-based allocation when both surgeons are available to operate, otherwise national or local protocols could be breached | One ONCABG, one OPCABG |

| Papworth | With only two surgeons participating, patients can be recruited and randomised using an expertise-based allocation only when both surgeons are available to operate. Otherwise national or local protocols could be breached | One ONCABG, one OPCABG | |

| Sheffield | Aimed to recruit from urgent patient pool | Urgent inpatients referred for surgery are transferred to the cardiac centre a couple of days prior to surgery. Patients would be recruited, randomised and the surgery arranged in this window | Two ONCABG, one OPCABG |

| University College, Londona | No specific research nurse or trial co-ordinator support was available – the centre was dependent on secretarial staff to run the trial. The centre was encouraged to contact the CLRN for research support | ||

| Wolverhampton | The majority of patients are referred to a named surgeon | Established a buddy system to facilitate recruitment and the allocation within the expertise-based allocation framework | Four ONCABG, two OPCABG |

The trial team and the participating centres worked hard to try and overcome these challenges. Meetings with referring cardiologists were arranged to increase awareness of the trial and the importance of providing complete referral data. Despite the team providing purpose-designed stickers with tick-boxes that could be added to the referral letters, the quality of the referral data did not improve. Options for seeking consent from urgent inpatients before the transfer to the cardiac centre were explored in the centres with a policy of transferring urgent inpatients the night before surgery. However, this proved unsuccessful; for example, in the Bristol area, the lead research nurse for the comprehensive local research network (CLRN) was not comfortable with asking her team of local research nurses to explain and seek consent for a trial that was taking place in another hospital. The option of a research nurse from the cardiac centre visiting the feeder hospital was also explored, but, in the UK, this requires explicit research and development approval at the feeder hospital, the need to identify a local principal investigator at each feeder hospital and the agreement of the patient’s referring cardiologist. As there was no research funding available and no cardiac surgeon with an interest in the trial employed at the feeder hospitals, this proved impossible to achieve. The study had ethical approval to allow trial information to be faxed to a feeder hospital to allow potential participants time to consider the trial in advance any discussion with a surgeon and this approach was used at the Bristol centre. However, at other centres, e.g. Basildon, faxing patient information to feeder hospitals was not permitted.

In the centres outside the UK, the main barriers that hampered the set-up were (1) obtaining approved translations and back-translations of all essential documents, (2) insurance/indemnity issues (some centres, particularly in North America, required additional insurance/indemnity, which had cost implications) and (3) the per-patient funding available, which several potential investigators felt was insufficient.

Actions taken to increase recruitment

In August 2010, the TSC agreed that the expertise randomisation was a significant barrier to recruitment and that to alleviate the logistical challenges and improve recruitment, a change to within-surgeon randomisation was needed. The TSC agreed that the study could still deliver important data with the revised design and was mindful that the CORONARY trial40 also began with an expertise-based design and changed to a within-surgeon allocation to alleviate recruitment difficulties (Professor David Taggart, University of Oxford, 2010, personal communication).

This TSC decision was communicated to CRISP centres via a study newsletter. Several OPCABG experts expressed their concerns about the decision. A significant number indicated that they would not be willing to operate ONCABG on high-risk patients and so they were effectively withdrawing from the trial. At a further meeting, held in October 2010, the TSC reviewed this feedback and agreed that a balance was needed, whereby recruitment could be improved through within-surgeon randomisation (thereby overcoming some logistical challenges by allowing late referrals to be included and recruitment to continue when the ONCABG expert is unavailable) and some expertise-based randomisation (to maintain the trial’s unique design and allow all participating surgeons to remain in the trial). They therefore agreed to allow both methods of randomisation within a centre and the randomisation database was changed to record prospectively the randomisation method to be used for each recruited patient.

In summer 2010, the study team asked the Research Ethics Committee (REC) to allow an amendment relaxing the time between a potential participant being provided with the patient information sheet and consent being requested. When REC approval was first sought, this time was set at a minimum of 24 hours. The REC agreed to this time restriction being removed to allow urgent cases identified at short notice to be included in the study, provided patients were given sufficient time to consider the information and ask any questions.

Proposals to increase recruitment

The CRISP study team, the DMSC and TSC were all mindful that, even after relaxing the randomisation criteria and removing the 24-hour ‘thinking time’ restriction, the target 5418 of patients recruited was unlikely to be achieved in a realistic time scale. In order to address this, other changes to the trial design were considered.

-

Widening the inclusion criteria. There was no support for this. It was agreed that the trial needed to focus on high-risk patients.

-

Changes to the primary outcome to reduce the study size (two alternative changes to the primary outcome were considered).

-

Replacing the composite end point with a new primary end point: time from surgery to ‘fitness for hospital discharge’. The definition of fitness was made up of six objective components, chosen to avoid the subjective non-clinical factors associated with hospital discharge that can bias open trials. The six components (precise definitions for each of the components were to be agreed) proposed were:

-

normal temperature

-

normal pulse

-

normal rate of respiration

-

normal oxygen saturation

-

bowels opened since surgery

-

ability to walk 70 m or a flight of stairs (or reach pre surgery level of fitness if unable to do this pre surgery).

-

-

Each component would be assessed on a daily basis from the medical notes, with the first day on which all the criteria were met being defined as day the patient was deemed ‘fit for discharge’. Sample size calculations suggested that a 2-day difference in median time to fitness (8 vs. 10 days) could be detected with a sample size of approximately 1000 patients (with 90% power).

-

The TSC felt that use of a fitness for discharge measure could demonstrate a material benefit, in terms of costs, as well as acting as a surrogate for the major clinical end point events included in the composite primary end point. However, the DMSC members were less convinced. The DMSC agreed that the end point should be changed in such a way that would allow a reduction in the sample size but was not in favour of a fitness for discharge measure on the grounds that it was not ‘major’ enough for such a large trial, that the scientific community would not value its clinical significance and that it favoured OPCABG.

-

Extending the composite 30-day outcome to include (1) reoperation for bleeding, (2) low cardiac output, (3) new onset of atrial arrhythmia and (4) replacing new-onset renal failure with the less severe AKI. It was estimated that this revised composite outcome would have had occurred in approximately 30% of patients and that this increased incidence would have reduced sample size from 5418 to 1094 patients (90% power to detect a 30% reduction in RR). This option was presented to the funder (see Decision to close the trial early).

-

-

Seeking REC approval to randomise eligible patients prior to consent – this was suggested by several investigators as a solution to the logistic challenges of expertise-based randomisation that would allow the patient to meet the allocated expert surgeon in clinic prior to surgery. It was not pursued for several reasons, (1) ethical concerns, (2) the potential for bias and the opportunity for the surgeon to influence the patient’s decision to participate or not and (3) potential for imbalance between the groups if the consent rates differed between those allocated to an ONCABG or OPCABG expert.

Decision to close the trial early

After the TSC meeting in August 2010, which was attended by representatives from the funder, the study team were asked to prepare a recovery plan. This plan, which included the following recommendations, was submitted to the funder in September 2010.

-

The original research question remained very important to surgeons, and to the NHS, and was substantially different from the question being addressed by the CORONARY trial.

-

The primary end point should be revised to reduce the study size, as it was anticipated that recruitment would need to be extended to the year 2015 in order to reach the original target study size. A revised protocol, with a change to the primary end point (see Proposals to increase recruitment), would have allowed the two main aspects of the research question: (1) efficacy of off- versus on-pump methods in high-risk patients and (2) the methods compared among both off- and on-pump surgeons, to be answered within a shorter time frame and with significant saving of research costs.

Following further discussions regarding the primary end point with the TSC and DMSC in October and November 2010, respectively, this was followed up with a detailed proposal for the revised primary end point, based on extending the composite end point to include (1) reoperation for bleeding, (2) low cardiac output, (3) new onset of atrial arrhythmia and (4) replacing new-onset renal failure with the less severe AKI (see Proposals to increase recruitment). Using this revised end point, with revised recruitment rates based on the CRISP experience (two to three patients per centre per month) and recruiting from 20 centres, rather than the original target of 40 centres, the trial team estimated that the revised target sample size could be achieved by December 2012, with a financial saving of approximately £500,000 owing to the reduced sample size.

This recovery plan was considered by the NIHR-EME Board in February 2011 and the trial team were informed in March 2011 that the CRISP trial was to close. The Board did not feel that it would have funded the trial with the proposed revised end point and also owing to the overlap with the US funded CORONARY trial. The last CRISP patient was randomised on 11 March 2011.

Recruited patients

Screening data are compared between ineligible, eligible but non-consenting and randomised patients in Table 6 . Ineligible patients were on average younger, less likely to be female and less likely to have preoperative conditions that result in higher additive EuroSCORE, e.g. chronic pulmonary disease, extracardiac arteriopathy, unstable angina or recent MI.

| Eligibility criteria | Ineligible (N = 523) | Eligible but non-consenting (N = 74) | Randomised (N = 106) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Urgent operation | 228 | 44 | 26 | 35 | 50 | 47 |

| EuroSCORE of ≥ 5 | 30 | 6 | 74 | 100 | 106 | 100 |

| EuroSCORE, median (IQR) | 3 (1–3) | – | 6 (5–8) | – | 6 (5–8) | – |

| Age | ||||||

| < 60 years (0 points) | 132 | 25 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 60–64 years (1 point) | 118 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| 65–69 years (2 points) | 109 | 21 | 6 | 8 | 11 | 10 |

| 70–74 years (3 points) | 115 | 22 | 19 | 26 | 18 | 17 |

| 75–79 years (4 points) | 42 | 8 | 31 | 42 | 34 | 32 |

| 80–84 years (5 points) | 4 | 1 | 15 | 20 | 31 | 29 |

| 85–89 years (6 points) | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 5 |

| 90–94 years (7 points) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≥ 95 years (8 points) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Female (1 point) | 70 | 13 | 24 | 32 | 25 | 24 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease (1 point) | 25 | 5 | 10 | 14 | 14 | 13 |

| Extracardiac arteriopathy (2 points) | 16 | 3 | 16 | 22 | 32 | 30 |

| Neurological dysfunction (2 points) | 2 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 |

| Previous cardiac surgery (3 points) | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Serum creatinine level > 200 µmol/l (2 points) | 10 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Active endocarditis (3 points) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Critical preoperative state (3 points) | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Unstable angina (2 points) | 6 | 1 | 7 | 9 | 11 | 10 |

| LV functiona | ||||||

| Good (> 50%) (0 points) | 371 | 81 | 47 | 66 | 60 | 57 |

| Moderate (30–50%) (1 point) | 71 | 16 | 17 | 24 | 41 | 39 |

| Poor (< 30%) (3 points) | 15 | 3 | 7 | 10 | 5 | 5 |

| Pulmonary hypertensionb (2 points) | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Recent MI (2 points) | 55 | 11 | 28 | 38 | 53 | 50 |

Differences in randomisation practices between centres are shown in Table 7 . There was wide variation in the proportion of patients randomised using expertise-based randomisation and the median times from randomisation to surgery, although the numbers of randomised patients per centre are small. Overall, patients were randomised earlier using expertise-based randomisation (median 17.5 days prior to surgery, IQR 7–42 days) than using within-surgeon randomisation (median 3.5 days, IQR 1–16 days).

| Centre | Randomised | Expertise-based randomisation | Time from randomisation to surgerya , b | Operative priority | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | n | %c | Median | IQR | Electived | Urgentd | |

| Basildon | 6 | 4 | 67 | 2 | 1–14 | 3 (1) | 3 (3) |

| Bristol | 26 | 15 | 58 | 35.5 | 2–43 | 16 (13) | 10 (2) |

| Blackpool | 21 | 17 | 81 | 10 | 8–17 | 1 (0) | 20 (17) |

| King’s College | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0–3 | 4 (0) | 1 (0) |

| Oxford | 19 | 12 | 63 | 5 | 1–34 | 15 (9) | 4 (3) |

| Papworth | 5 | 2 | 40 | 11 | 0–34 | 4 (2) | 1 (0) |

| Sheffield | 7 | 2 | 29 | 10 | 4–43 | 4 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Wolverhampton | 11 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 11–50 | 9 (0) | 2 (0) |

| India | 6 | 6 | 100 | 1 | 1–1 | 0 (0) | 6 (6) |

| Total | 106 | 58 | 55 | 10 | 2–37 | 56 (26) | 50 (32) |

The numbers of urgent and elective patients recruited varied across centres (see Table 7 ). In Blackpool and the centre in India, the patients were predominantly urgent cases (20 out of 21 in Blackpool and 6 out of 6 in India), while in Oxford and Wolverhampton the majority were elective (15 out of 19 and 9 out of 11, respectively). At the other centres, similar numbers of elective and urgent cases were recruited.

Patient withdrawals

Eight of the 106 randomised patients were excluded from the analysis population: six patients withdrew prior to surgery and two patients died prior to surgery. Therefore, 98 patients underwent surgery and have been included in the principal analysis population, 49 in the OPCABG group and 49 in the ONCABG group (see Figure 1 ).

Five patients were withdrawn because it was decided that surgery was no longer required and one patient withdrew on the day of randomisation with no further details given. A further patient (OPCABG group) also withdrew their consent preoperatively owing to anxiety that they were not randomised to ONCABG; however, they were happy to be followed-up and for their data to be used and so remained in the analysis cohort. Table 8 shows a summary of withdrawals; for full details, see Appendix 2 , Table 20 .

| Withdrawal | Randomised to OPCABG (N = 53) | Randomised to ONCABG (N = 53) | Overall (N = 106) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Any withdrawal | 4 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Decision taken by | ||||||

| Patient | 1 | – | 1 | – | 2 | – |

| Clinician | 3 | – | 2 | – | 5 | – |

| Reason for withdrawal | ||||||

| Surgery no longer required | 3 | – | 2 | – | 5 | – |

| Type of surgery allocated to | 0 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Patient did not give reason | 0 | – | 1 | – | 1 | – |

| Other reason | 1 | – | 1 | – | 2 | – |

Protocol deviations

There were 21 protocol deviations in 19 patients ( Table 9 ). Four patients randomised to OPCABG did not receive their allocation and there were no crossovers in the ONCABG group. Reasons for not receiving the allocated treatment were (1) development of ST segment on ECG during manipulation of the heart, (2) unplanned additional procedure required, (3) VF/VT arrest and (4) myocardial ischaemia with ST changes and low blood pressure. Other types of protocol deviations were (1) patient did not meet eligibility criteria (n = 4), (2) the operating surgeon was not on the approved list of trial surgeons (n = 6), (3) expertise-based randomisation was used but the surgeon was not an expert in the allocated surgery type (n = 6), and (4) within-surgeon randomisation was used with an ONCABG surgeon (n = 1). Data on all patients for whom there was a protocol deviation were included in the trial analyses on an intention-to-treat basis.

| Protocol deviation | Randomised to OPCABG (N = 49) | Randomised to ONCABG (N = 49) | Overall (N = 98) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Any protocol deviation | 8 | 16 | 11 | 22 | 19 | 19 |

| Did not receive allocated treatmenta | 4 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Did not meet eligibility criteriab | 3 | 6 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Surgeon not on list of trial surgeons – expertise-based randomisation | 0 | 0 | 6 | 12 | 6 | 6 |

| Surgeon not on list of trial surgeons – within-surgeon randomisation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Expertise-based randomisation used but the surgeon not an expert in allocated surgery type | 2 | 4 | 4 | 8 | 6 | 6 |

| Within-surgeon randomisation used with ONCABG surgeonc | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Patient follow-up

Follow-up data 4–8 weeks after surgery were obtained for all 98 patients in the principal analysis population: 87 patients attended their follow-up visit, two patients died prior to their visit and nine did not attend but data were retrieved from their clinical notes and/or general practitioners.

Numbers analysed

Ninety-eight patients in the principal analysis population were included in all tables of demographic and operative characteristics and analyses of the primary outcome and duration of CICU/hospital stay. Ninety-seven patients were included in QoL analyses: (1) 90 patients with both preoperative and 4–8 weeks postoperative data, (2) six patients with preoperative data only and (3) one patient with postoperative data only. One hundred patients were included in the safety analyses: the 98 patients in the principal analysis population plus the two patients who died prior to surgery.

Baseline data and operative characteristics