Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/53/99. The contractual start date was in March 2011. The draft report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

during this study Steve Iliffe was Associate Director of the Dementia and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN), responsible for promoting primary care research; Barbara Stephens was CEO of Dementia UK at the time of the project; and Louise Robinson was Chair of the Primary Care Clinical Studies Group of DeNDRoN at the time of the research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Iliffe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

In the UK, dementia is a key government priority for reseach, as outlined in the Prime Minister’s challenge. 1 Improving the health and social care of older people is also a priority for health and social care policy. 2,3 Changing demographics will lead to an increase in the prevalence of age-related illnesses, such as dementia, which will in turn present considerable challenges for families and health and social care providers. This will particularly be the case for primary and social care services following the recommendations of the White Paper, Our Heath, Our Care, Our Say, which stipulated that care for older people, and for other people with long-term conditions, should be delivered as close to their homes as possible. 4

The scale of the problem

Dementia is one of the main causes of disability in later life; in terms of global burden of disease, it contributes 11.2% of all years lived with disability, which is higher than stroke (9.5%), musculoskeletal disorders (8.9%), heart disease (5%) and cancer (2.4%). 5 One in 14 people aged > 65 years has a form of dementia, rising to one in six of those aged > 85 years. 5 Currently, around 800,000 people in the UK have dementia;6 this is estimated to rise to 1 million by 2020 and 1.7 million by 2050, an increase of over 150%. 5 The current costs of caring for people with dementia in the UK have been estimated at around £23B a year,6 which is far greater than the corresponding costs for heart disease, stroke and cancer. 1 Around two-thirds of people with dementia currently live at home, with the majority of their care provided by family members, with support from primary and social care teams. 2,5 It is estimated that family caregiving saves public expenditure on dementia of around £8B each year. 6

The rising number of older people will lead to an increasing number of frail older people requiring complex care packages if they are to continue to live independently and postpone or avoid moving into care homes. This will present considerable challenges for primary and social care. People with dementia aged > 65 years occupy one-quarter of NHS beds at any one time. 6 There has been a significant increase in the number of people with dementia entering the acute hospital system, which is an area of concern,7 particularly with regard to care and assessment practice. 8 The NHS Operating Framework for 2012/13 in England9 has emphasised the need for greater provision of care and support in the community to reduce unnecessary hospital admissions for people with dementia.

Current evidence suggests that dementia care is in urgent need of improvement,1,5 with frequent failure to deliver services in a timely, integrated or cost-effective manner. 10 General practitioners (GPs) in primary care experience and describe difficulties in diagnosing and managing dementia. 10 In the UK, educational interventions in primary care have been implemented to try and improve dementia diagnosis and management rates; however, these interventions have not significantly affected diagnosis or clinical management. 11 In an attempt to address this issue within primary care, the NHS Commissioning Board has recently developed guidance for GP practices to implement an enhanced service for detecting dementia in people who may be at risk. 12 The aims of this service are to increase rates of early dementia diagnosis and improve the care of people with dementia (including provision of appropriate treatment and signposting). The National Audit Office report of 200710 encouraged the use of case management by Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs), believing it would reduce unnecessary hospital admissions of people with dementia.

Care co-ordination

Current national guidance13 on dementia care recommends the provision of co-ordinated health and social care, led by a single health or social care professional (often known as a ‘care manager’ in local authority adult services but as a ‘case manager’ in health care). This recommendation10,14 largely mirrors the views of people with dementia and their family carers. In NHS mental health services, case management is a particular type of collaborative care15 in which workers, known as ‘case managers’, systematically follow up patients under regular supervision and (usually) provide both brief psychological therapy and medication management. ‘Collaborative care’ has itself been variously defined to mean everything from collaboration between services, and ‘shared care’, to the more highly structured definition that is now becoming accepted internationally. 16

The components of a collaborative care model for depression are (1) a multiprofessional approach to patient care provided by a case manager working with the GP under supervision from specialist mental health medical and psychological therapies clinicians; (2) a structured management plan of medication support and brief psychological therapy; (3) scheduled patient follow-ups; and (4) enhanced interprofessional communication with patient-specific written feedback to GPs via electronic records and through personal contact. 17

In earlier studies of depression, mental health professionals provided the enhanced staff input to primary care settings and undertook a care co-ordinator role. 18,19 More recently, primary care nurses20,21 were used to fulfil the role of care co-ordinator. Most studies of collaborative care have taken place in the USA. In the UK, in one published study (carried out about 16 years ago) practice nurses undertook the care co-ordinator role but did not improve either patient antidepressant use or outcomes compared with usual GP care;21 however, more recently, Chew-Graham et al. 22 demonstrated an improvement in depression outcomes with the collaborative care approach and a flexible psychological intervention delivered by a mental health nurse. A systematic review of models of care for depression suggested that components that were found to significantly predict improvement were (1) the revision of professional roles; (2) the provision of a case manager who provided direct feedback and delivered a psychological therapy; and (3) an intervention that incorporated patient preferences into care. 23

The evidence base

A literature review24 published as part of the preliminary work for this study provided a commentary on case management interventions for people with dementia and a summary of its findings are provided here. The review set out to address (1) what are case managers and how do they relate to dementia care; (2) whether or not dementia care can be improved by case management; (3) what people with dementia and their carers want from a case manager and whether or not this can be provided; (4) whether or not we can measure the cost-effectiveness of case management; and (5) what direction research into case management needs to take.

A literature review,24 published as part of the preliminary work for the CARDEM study, provided a commentary on case management interventions for people with dementia and a summary of its findings are provided here. The review suggested that this diversity has led to difficulties in understanding the impact of the case manager role, who is most appropriate to undertake it, which populations may benefit most from it and what services should be offered as part of the case manager package. The review by Koch et al. 24 identified that many authors have suggested factors that may lead to a successful case manager approach. For example, Goodman et al. 25 proposed that successful case management requires:

-

a broad set of clinical skills

-

designated and protected time for case management

-

close involvement in multidisciplinary teamwork including a medical clinician and

-

having the mandate to undertake case management activities recognised by providers or commissioners or funders of services, especially if continuity of care and stability of services are to be assured.

Similarly, Minkman et al. 26 suggested that success factors for case management in dementia include the case manager having a wide knowledge base; working within a strong, local provider network that accepts case management; having effective multidisciplinary teams with medical input; and having a low threshold for accessing support services. Minkman et al. 26 also identified factors associated with failure, including a lack of investment, ill-defined patient inclusion criteria and an absence of involvement of primary care practitioners.

In addition to these findings, Verkade et al. 27 identified 44 essential components of case management and proposed that case management should be based on individual needs, should integrate management into the care chain, should offer a systematic active care approach and should provide information, support, co-ordination and monitoring roles. In our review24 we also reported the proposed theoretical framework of Connor et al. ,28 which identified 45 frequent case manager activities, which were further categorised into four main case management domains:

-

behaviour management

-

clinical strategies and caregiver support

-

community agency and

-

safety.

Connor et al. 28 commented that ad hoc but regular contact and the individualistic approach inherent in case management were responsible for the wide range of activities.

Impact of case management

Several empirical studies have illustrated the variety of roles that a case manager might undertake, including assessment, care planning, education, problem-solving, liaising, monitoring and counselling. 29–33 Overall, it was found that some studies showed positive results in the form of increased referrals to community services,29 fewer hospital and emergency admissions and less embarrassment, isolation and relationship strain,31 reduced stress30 and reduced risk of relocation to a care home,34 although few recorded a large effect. 24

The benefits associated with case management are variable and context specific. There is conflicting information about the duration of effects produced by case management, with some studies reporting a significant improvement in activities of daily living35 or reductions in relocation to care homes. 36 Additionally, our review24 found that case manager activities were being undertaken by a number of different professionals, to the extent that Newcomer et al. 37 concluded that there is currently no agreed choice of professional background for the role of case manager. Our review24 described how the level of heterogeneity of patients involved in case manager studies and the lack of subgroup analysis made it difficult to identify at what stage in the course of the illness patients and their carers would derive most benefit from a case management intervention.

Our review24 identified evidence that the needs of people with dementia and their caregivers revolve mainly around social networks, daytime activities, company and psychological distress,38,39 with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) and lack of social networks impacting indirectly on the person’s perceived quality of life. 38 These findings match the potential of aspects of various case management programmes well. As Mittelman et al. 40 suggested, there may be a direct association between quality of life and other measures such as time to institutionalisation, so that quality of life functions as an intermediate, early-changing, surrogate measurement for consequences that may take longer to appear. All this depends, of course, on regarding life in a care or nursing home as an undesirable outcome that leads to diminished quality of life, which may not always be the case.

Clinical and economic effectiveness

Verkade et al. 27 argued that, from the perspectives of clinical and economic effectiveness, there is little reason to promote case management programmes based on the current available evidence. Nevertheless, one could postulate that, because Mittelman et al. 40 – having followed participants for so long (17 years) – reported such convincing results, most of the trials described have failed to follow up participants for adequate periods of time to be able to demonstrate any outcome improvements or cost-effectiveness gains.

Our review24 suggested that the main limitation in these studies was the choice of outcome measures. It may be that aiming to delay a care home move may be an unrealistic or inappropriate goal, certainly in the short term, and the ambitions for case management therefore ought to be revisited. Most of the studies with positive findings report improvements in measures such as caregiver burden or stress,30,35,41 caregiver confidence,29 negative feelings about the patient,31 function35 and uptake of community services. 37,42 Moreover, in Mittelman’s study,40 spouse caregivers’ reactions to memory loss and challenging behaviour (BPSD), and satisfaction with social support, accounted for at least 30% of the effect of the intervention on nursing home admission. Reducing caregivers’ negative reactions to memory loss and BPSD accounted for 48.7% of the intervention’s impact, whereas depressive symptoms and frequency of BPSD were weaker (but still significant) mediators of the intervention effects. This subanalysis is pertinent as it seems to suggest that the intervention is more effective when it positively influences caregivers’ perceptions and reactions to the problems presented by dementia, rather than affecting any practical changes in their ability to manage the problems themselves. These findings corroborate the proposition that case management may affect the quality of life of both people with dementia and their carers.

The case management trials that we reviewed24 showed substantial heterogeneity in several domains: the number of activities or services offered, the length of the programme, the intensity of contact with the person with dementia or caregiver, and the personal and clinical characteristics of those individuals. Each of these could significantly affect the cost or cost-effectiveness of case management. Employing a case manager in primary care is likely to increase the use of other health and social care resources in the short term, which would need to be included in any economic evaluation. In many of the studies that attempted an economic evaluation and which concluded that using case management was too costly, the unfunded opportunity costs of caregivers’ and others’ inputs – whether for lost work time, lost leisure time or diminished caregiver health and well-being – were not considered. Case management should be costed from a societal perspective as well as the perspective of health and social care services if we are to understand its full impact and potential.

Our review24 suggested that case management does not need to reduce service costs to be cost-effective. It needs to demonstrate that any improvement in outcomes is worth any additional expenditure incurred. For example, Duru et al. 43 found that using internet-based case management software, developing a care plan and referring on to primary care and community agencies for specific treatment and care services were not cost-saving compared with standard care but were cost-effective because of improvements in patient and carer outcomes and because the quality of care of people with dementia was also significantly better. However, Pimouguet et al. 44 found only three randomised trials that included an explicit economic analysis and argued that no conclusion can be drawn about the economic impacts of case management. Nevertheless, some well-conducted long-term studies have demonstrated how case management can delay relocation to long-term care, with potentially important economic pay-offs. 40,45

Our review concluded by suggesting that there is a clear lack of UK-based research exploring the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alternative models of service delivery in dementia care. It proposed that a detailed specification of the sorts of activities to be included in case management was required, including developing a better understanding of how case managers might tailor their support to the needs of the person with dementia and their family. 24 The review recommended that further questions to be addressed include:

-

determining which skills are most appropriate to the role

-

where these may be located

-

which cohort of patients with dementia would benefit most from case management and

-

the type and intensity of contact required to successfully carry out case management for people with dementia in primary care.

We embarked on the CAREDEM study to explore these issues, following discussions within the Dementia and Neurodegerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN) Primary Care and Dementia Clinical Studies Groups. Our exploration began with an assessment of a successful case management trial conducted in the USA the PREVENT study. 30

Learning from the PREVENT study

The PREVENT study,30 a US-based trial of such a collaborative care model, led by a nurse practitioner working with a social worker in primary care, used evidence-based protocols to manage neuropsychiatric symptoms encountered by family carers of people with dementia. This study demonstrated significant improvements for both people with dementia (increased prescribing of cholinesterase medication, fewer behavioural and psychological symptoms) and their family carers (improved depression scores and higher carer satisfaction ratings). However, because of the limited follow-up period, effects on the rate of moves to long-term care facilities and cost-effectiveness could not be determined.

Following this positive US study, and the recommendations for primary care services from the World Alzheimer Report 2011,46 testing a case management approach for people with dementia in NHS primary care looked attractive. However, it quickly became apparent that there were grounds for being cautious. A recently completed critical review of nurse-led case management as a technique for supporting patients with complex needs warned against expecting substantial benefits from this approach. 25 Although a recent international systematic review of randomised controlled trials had identified studies of case management for people with dementia and their caregivers, with time to institutionalisation and cost as the main outcome variables, the authors of this study concluded that the evidence for the efficacy of case management in terms of cost and resource usage remains equivocal. 44 They highlighted that any further studies ought to consider which individuals might particularly benefit from case management. 44

Overview of the CAREDEM study

The CAREDEM study was a research and development project designed to (1) adapt the US-derived PREVENT intervention30 for use in English NHS contexts; (2) train primary care staff in the use of a culturally adapted intervention; and (3) test the acceptability and feasibility of this intervention in a pilot study in four general practices.

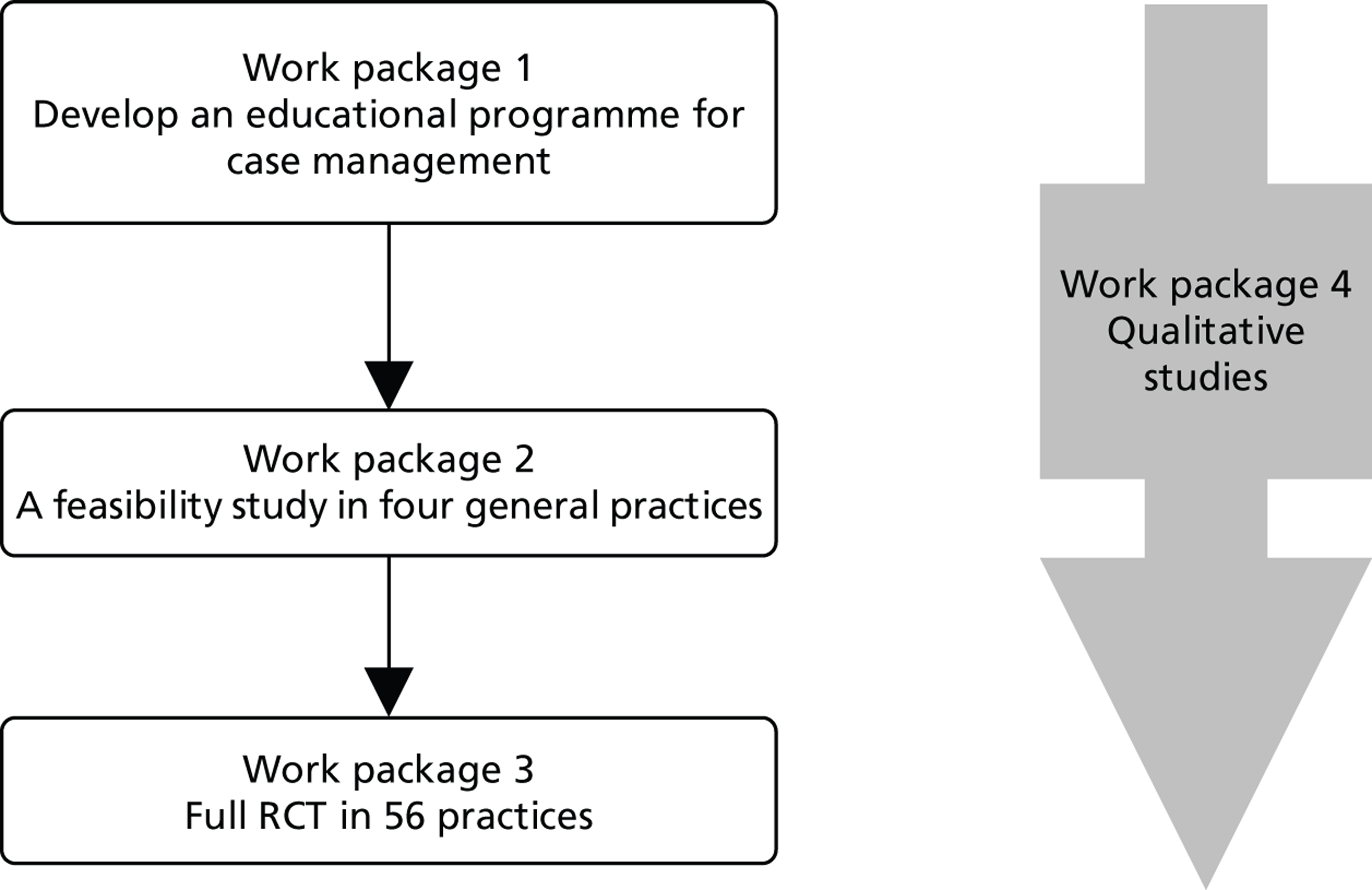

The full CAREDEM project as originally proposed consisted of four work packages; this report focuses on the pilot rehearsal trial and corresponding qualitative evaluation. The protocol for this study can be found at www.controlled-trials.com (ISRCTN74015152). Figure 1 shows the relationships between the work packages.

FIGURE 1.

Relationship between the four work packages of the CAREDEM study. RCT, randomised controlled trial.

The aim of the full CAREDEM trial was to develop a collaborative case management approach that can be embedded into primary care, to enable better management of common problems in dementia. Work package 1 (WP1) involved the development of case management protocols and evidence-based care pathways. Work package 2 (WP2) assessed the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention developed in WP1. The study design was such that, if WP2 demonstrated that the case management programme fitted into everyday primary care practice and also showed positive benefits, it would then be evaluated in a large-scale randomised controlled trial [work package 3 (WP3)]. Work package 4 (WP4) was designed to provide a qualitative evaluation of each stage to gain a comprehensive and systematic evaluation of this project.

Following the development of WP1 materials, the CAREDEM pilot (WP2) took place in general practice-based primary care in three areas; London, Norfolk and Newcastle. During the final months of the pilot study the researchers engaged with whole Practice Based Commissioning (Clinical Commissioning Groups since 1 April 2013) localities and consortia. Based on the outcome of WP2, it was intended that the main trial (WP3) would take place in general practice-based primary care. For the main trial we estimated a target equivalent to 56 medium-sized general practices (with average list sizes of around 6000 patients). It was anticipated that each practice would recruit 11 patients to the main trial (WP3), with six retained at the 18-month follow-up; these rates of recruitment and retention would be reviewed and, if necessary, revised based on data from the pilot study (WP2).

Our proposed case manager role was designed to be carried out by practitioners located within primary care and working in liaison with secondary care services, to provide a multiprofessional care co-ordination approach. We anticipated providing training in collaborative care and case management techniques to a range of primary care practitioners as determined by the local skill mix and by local commissioning needs and intentions. Scheduled patient follow-ups were designed to be included as part of the case management process, with the frequency and location of meetings being client led. Enhanced interprofessional communication and liaison using patient-specific written feedback to GPs via electronic records as well as personal (face-to-face or telephone) contact were designed to be an integral part of the case management method.

We envisaged that professionals undertaking the case management role could be already in post within a community-based organisation [individual GP-based primary care team, primary care trust (PCT), CMHT or social worker], depending on existing local arrangements, interest and expertise. We anticipated that practitioners interested in taking on the case manager role might be nurses with the level of experience found at band 7, working in district nursing, as community psychiatric nurses or as practice nurses. It was planned that they would be able to undertake additional training (developed in WP1 and tested in WP2), provided through the Admiral Nurse organisation Dementia UK, with an induction period, periodic refresher days, experiential learning and mentoring and formal on-site supervision by Admiral nurses in the three planned study centres. Training was to be delivered by a regional senior clinician from the project team and an Admiral nurse, with other clinicians or allied medical professionals delivering specific training as required. In the PREVENT model, training takes place over eight 2-hour sessions and this study anticipated that at least this amount of time would be necessary. In addition to individual training and mentoring, a meeting of case managers was convened during the project to allow an opportunity for group reflection on the case management task and the research project. Details of this can be found in Appendix 6.

Patient and public involvement

The CAREDEM proposal arose from discussions within the DeNDRoN Primary Care and Dementia Clinical Studies Groups, both of which have public and patient involvement (PPI) representatives who contributed to the discussion about the intervention and desirable outcomes. The chief executive of Dementia UK (Barbara Stephens) drew on the expertise of carers in this organisation. The director of the Social Care Workforce Research Unit at King’s College London (Professor Manthorpe) was responsible for PPI in the management of the trial, at the trial steering committee, at trial management and site management committee levels and also in the PPI forum. A PPI forum was held after WP1 to enable individuals to participate in debates about the development of the case management training, the content of the care pathways, the optimal ways to engage people with dementia and their carers in the trial, the interpretation of the findings and the planning of dissemination. The invitation to join this group was extended to a carer representative from a local Alzheimer’s Society, the Greater London Forum for Older People, other relevant bodies such as Age UK and Pensioner Forum volunteers. This meeting was held in February 2012 and 11 lay experts attended.

In addition, preliminary findings from the whole study were presented to a PPI group assembled by DeNDRoN in March 2013, to obtain insights into the project’s outcomes. See Appendix 7 for further details of this consultation.

Data handling, record keeping and confidentiality

Throughout each stage of the CAREDEM study, data collection and transfer in this trial complied with the National Research Ethics Service (NRES), Caldicott principles47 and the Data Protection Act 1998. 48 All study documentation was held in secure offices and the research team operated to a written and signed code of confidentiality. A clinical data management software package was used for data entry and processing, allowing a full audit trail of any alterations made to the data post entry. Identifiable data will be kept for the duration of the trial and thereafter destroyed. All study documentation will be archived and held for 10 years by the study sponsor.

Ethics committee approval

The conduct of this study has been in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly (Helsinki, Finland, 1964) and later revisions. Ethical approval was successfully sought from an appropriate research ethics committee before the commencement of the work packages. Separate protocols were prepared and separate ethics applications were made for WP1 (North West London Research Ethics Committee 10/H0722/50) and WP2 (NRES Wandsworth 11/LO/1555).

Chapter 2 Work package 1

Changing clinical practice is difficult. Although some new and effective treatments are adopted quickly and diffuse across health-care systems, many do not. 49 The variability of general practice is a problem for those seeking to change it, but may be an asset for patients because it favours personalisation and tailoring of care. As Miller et al. 50 put it: ‘Standardising care without identifying desirable variation or unique adaptations that take advantage of local opportunities or strengths misses an opportunity to identify and investigate unanticipated circumstances or locally adapted practice configurations associated with better health care outcomes’ (p. 874).

The adoption of new ways of working depends on both the characteristics of the new approaches themselves and the characteristics of the professionals and patients who use them. Diffusion science, as summarised by Berwick,49 underpinned the development processes in WP1. The characteristics of innovations that favour their uptake and diffusion through clinical practice51,52 are shown in Table 1.

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Compatibility | Innovations that are compatible with the values, norms and perceived needs of intended adopters will be more easily adopted and implemented |

| Complexity/ease of use | The degree to which the innovation is expected to be free of effort. Innovations that are perceived by key players as simple to use will be more easily adopted and implemented. The perceived complexity of an innovation can be reduced by practical experience and demonstration |

| Relative advantage | Innovations that have a clear, unambiguous advantage in terms of either effectiveness or cost-effectiveness will be more easily adopted and implemented. This advantage must be recognised and acknowledged by all key players. If a potential user sees no relative advantage in the innovation, he or she does not generally consider it further; in other words, relative advantage is a sine qua non for adoption. Relative advantage is a socially constructed phenomenon. In other words, even so-called ‘evidence-based’ innovations go through a lengthy period of negotiation amongst potential adopters, in which their meaning is discussed, contested and reframed; such discourse can either increase or decrease the perceived relative advantage of the innovation |

| Trialability | Innovations that can be experimented with by intended users on a limited basis will be more easily adopted and implemented. Such experimentation can be supported and encouraged through provision of ‘trialability space’ |

| Observability/result demonstrability | If the benefits of an innovation are visible to intended adopters, it will be more easily adopted and implemented. Initiatives to make the benefits of an innovation more visible (e.g. through demonstrations) increase the chances of successful adoption |

| Reinvention | If a potential adopter can adapt, refine or otherwise modify the innovation to suit his or her own needs, it will be more easily adopted and implemented. Reinvention is a particularly critical attribute for innovations that arise spontaneously as ‘good ideas in practice’ and which spread primarily through informal, decentralised, horizontal social networks |

| Image and visibility | The degree to which it is seen as adding to the user’s social approval and the degree to which the use of the innovation is seen by others |

| ‘Voluntariness’ | The degree to which use of the innovation is controlled by the potential user’s free will |

A full discussion of the development of WP1 has been published. 53 WP1 was designed to review, adapt and customise the PREVENT intervention30 for implementation in the CAREDEM study within NHS general practice. Development of WP1 took place in the area covered by Kent and Medway NHS and Social Care Partnership Trust. This location allowed for good facilitation of meetings and covered a diverse population and different organisational boundaries. As noted, ethical committee permission for this part of the study was obtained successfully (NW London Rec1 10/H0722/50) and local research governance permissions were also obtained.

A co-design method was implemented to gain insight from a diverse range of experienced practitioners and carers54 (it was unfortunately not possible to recruit a person with dementia to this group). Following the development group meetings, the materials produced were reviewed and critiqued by two separate review groups, one a virtual group of practitioners and the other a forum of carers and older people with experience of using health and social care services. The virtual professional group responded to the output from the design group in a cyclic process, in which a series of prototypes were refined until the development group felt confident that it had produced a version of materials worth field-testing in WP2. Potential participants in the carers’ and older people‘s forum who were unable to attend a meeting were invited to contribute their comments by post or e-mail.

Development group

The research team invited an expert group of stakeholders including family carers as well as health and social care practitioners from the NHS, local authority and voluntary sectors to participate in the development group. Twelve people from a variety of backgrounds, including occupational therapy, social work, Admiral nursing, psychiatry, general practice and community mental health nursing, volunteered to join this core multidisciplinary development group. A family carer, an outreach worker from the local branch of the Alzheimer’s Society and an Age UK manager also joined the development group to ensure that a full range of perspectives were included during this process.

The group met six times (each meeting lasted half a day) with members of the research team (SI, JM and CF) from April 2010 to June 2011 to carry out the following tasks:

-

adapt the PREVENT intervention to meet service and cultural expectations in England

-

devise a job description and a list of desirable and essential attributes for a case manager

-

agree the contents of an educational needs assessment that would inform training and mentoring

-

produce written information designed to be used by the case managers with carers and people with dementia.

Review groups

The co-design process was extended by two further groups offering their comments on the materials produced by the development group. The research team recruited 10 professionals from different parts of England to provide comments by e-mail and, as noted earlier, also arranged a PPI forum of 11 older people with substantial experience of using health and social care services, including current and former carers of people with dementia. This was a diverse group including people from different ethnic and sociodemographic backgrounds and who held a variety of caregiving relationships (e.g. spouse/partner carers and adult/child carers). The forum membership was drawn from different locations from the development group to reflect a broader range of current service arrangements. During the forum a presentation was given on the objectives, activities and outputs of WP1 and the group was asked specific questions and for their general views. This forum served as a useful validation step, as participants’ comments helped to provide some assurance that the materials produced by the development group were suitable for other parts of England and for people with different experiences and circumstances.

Results/outputs

The development group agreed on the tasks that a case manager would carry out. That list of tasks was used to create a case manager job description (see Appendix 1), a person specification (see Appendix 2) and an educational needs assessment tool (see Appendix 3) to assist with recruitment, induction to the role and mentoring. A case management ‘manual’ (see Appendix 4) was also created (modified from materials used in the PREVENT study30). This manual included accessible leaflets for people with dementia and their carers, which could be used as an opportunity for information-giving and as talking points between case managers and their clients (both carers and people with dementia).

Job description and person specification

The development group was mindful to ensure that the job description and person specification did not overlap with existing roles. The group agreed that nurses would be a first obvious choice for this role (as in the PREVENT trial) but that other allied health and social care professionals might also be suitable. Therefore, the development of the job description focused on skills rather than specifying professional qualifications. The group was mindful that some professionals, for example doctors, were expensive and, therefore, possibly unaffordable. Important themes raised in the discussions included:

-

Interaction. Case managers would benefit from sharing knowledge and experiences with each other on a regular basis.

-

Mapping resources. Case managers would need to be proactive, ready to identify current resources to support people with dementia and their carers and able to identify gaps in the provision of services and the accessibility of resources.

-

Managing the risk of overload. There was a risk that the role might overwhelm the case manager (physically or emotionally) and the feasibility study (WP2) needed to highlight any such overload. This risk could be mitigated by developing close working relationships with specialist teams.

Educational needs assessment

The challenge for those seeking to change clinical performance is to find ways of working with the grain of professional knowledge and practice. One approach to working with the grain is to use educational needs assessments. 55 Assessment of educational needs has the potential to accommodate variations in individual understanding and competence, learning preferences and skill mix. Such tailoring of an educational ‘intervention’ to the specific identified needs of practitioners also draws on diffusion theory (as mentioned earlier) in that the ‘intervention’ itself can be modified in such a way as to make it more likely to be adopted. The educational needs assessment was constructed to take into account practitioners’ knowledge of the local health and social care systems, to reflect the complexity of the potential care processes for people with dementia, and to acknowledge the complexity of the disease process itself. 56 It was intended to foster reflection, allow practitioners to create time and space to plan changes and enable them to tolerate tension and discomfort. 57

During the development of the educational needs assessment, the group discussed case management tasks, competencies required or desirable for them, risks to minimise and tools required to undertake the case management role successfully. These conversations resulted in the production of a ‘task matrix’, which informed the job description (see Appendix 1) and person specification (see Appendix 2) as well as the educational needs assessment tool (see Appendix 3). This matrix was designed to be work in progress, with the expectation that some further risks and tools might emerge in WP2.

The overarching topics considered most important by the group were how existing competencies of case managers should be assessed in meeting the emotional needs of a person with dementia and their carers, and how to develop the skills of the case manager in areas where these could be improved. This was seen as important as each case manager was likely to bring different experiences and attributes and an adult learning approach would build on these and not assume that a common training package would suit all.

The competencies, risks and tools identified in the task matrix were used as the basis for an educational needs assessment tool. This mapped competencies onto the dementia disease trajectory under five headings:

-

supporting patients at the time of diagnosis

-

managing breakdown of support systems

-

managing acute illness and hospital admission

-

supporting decisions about relocation

-

supporting the person with dementia and his or her family at the end of life.

Subheadings were agreed for each of the five main headings (see Appendix 3). This educational needs assessment was designed not only to be used in the case manager induction process but also as a topic guide for mentoring during active case management.

The group viewed mentoring as essential to the introduction of case management approaches in primary care, as the new case managers would be learning through the experience of working with a diverse patient and carer group. The task of the mentor was to support the case manager in ‘absorbing’ the needs of people with dementia and their carers, ‘digesting’ these needs to understand what was tractable and needed solution and ‘providing’ where possible for unmet needs. 58

The manual

The manual focused on topics such as communication with the person with dementia, behaviour problems, mobility, personal care, sleep, legal and financial issues, physical health, depression and anxiety and how to respond to psychotic or distressing symptoms.

Rules were implemented in the adaptation of the PREVENT manual, to systematically alter the language and tone of the US version. These included:

-

Removal of all references to the person with dementia as the ‘loved one’ and replacement of this term with ‘relative’.

-

Use of words such as ‘try’, ‘consider’ and ‘may’ to make the manual less directive and prescriptive and deletion of phrases such as ‘instruct the carer’.

-

Replacement of phrases with a negative tone (advising carers not to do things) with more positive actions or things to try. Here the group added explanations for why the person with dementia might behave in a certain way and tried to make the manual more person centred by explaining that symptoms and difficulties were likely to vary from time to time and from person to person.

Information about local NHS and social care services and about the Alzheimer’s Society and local support organisations was added to the manual. Suggestions that the carer should speak to the case manager were included to make the manual more interactive. ‘Key points’ boxes and subheadings were added and the order of the contents was changed to provide a more coherent structure. Images were removed when these were inappropriate for the English context and distracted from the content. The development group felt that the manual required some additional sections and so it added an introduction and contents page; it also developed pages on asking for help, looking after yourself, physical health, aggression and agitation, depression and anxiety, and planning for the future.

Chapter 3 Work package 2

This chapter describes the second work package (WP2) in the CAREDEM study, in which the previously developed case management programme (WP1) was tested in a feasibility trial. The primary objective for this pilot phase was to ensure that case management skills and the collaborative care model would be easy to acquire and implement in routine practice. The secondary objectives were to determine whether or not practices could recruit 11 patients into the study (depending on practice size), that nine could be contacted at 6 months and that stakeholders would find the brief intervention procedures acceptable and feasible within routine NHS practice. The researchers intended to check assumptions about practice and patient recruitment and retention and to ensure the feasibility (data yield and quality) of outcome measures; if necessary, the sample size calculation for WP3 would be adjusted based on these data. Practices that took part in the pilot study would not be able to participate in the main trial. Approval for WP2 was obtained from Wandsworth NRES (11/LO/1555).

Recruitment of practices and case managers

Practices were recruited from each site as detailed in the following sections. Data were obtained on practice population size, number of GPs and deprivation score. The average deprivation score in England is 21.5, with a higher value indicating greater deprivation.

London

In December 2011, the researchers wrote to 26 GP practices in Camden and Islington, inviting them to take part in the CAREDEM pilot study. Eight practices contacted the research team requesting more information; however, seven of these practices declined participation. Reasons given for declining participation were concerns about time, resources and current commitments, meaning that they were already very busy. One of these eight practices invited the researchers to present the proposed study at its practice meeting. After this meeting the practice agreed to participate in the study on the condition that the research team could guarantee Service Support Costs for a practice nurse, to backfill their time whilst working on CAREDEM.

Additionally, in January 2012 the researchers made contact with the North Central London Research Consortium (NoCLoR), which put them in touch with two further GP practices from NoCLoR’s local research clusters. One of these practices agreed to the researchers presenting the proposed study at its practice meeting in January 2012 and this practice subsequently agreed to take part in the research. At this point, as it was not possible to guarantee the Service Support funding, the practice that wished to take part unconditionally was recruited. During this process the researchers were further assisted by NoCLoR, whose staff negotiated with local commissioners on the study’s behalf to obtain Service Support funding for the CAREDEM study in London. This process facilitated engagement with the local research network and the researchers have retained the details of four GP practices who were interested in taking part in the main trial or in further research in this area but who could not commit to the pilot study. The list size of the recruited practice is 15,510 patients and the practice is served by 8.5 whole-time equivalent (WTE) GPs. The practice serves a population spread across two London boroughs, with deprivation scores of 21.5 and 27.

Norfolk

In Norfolk, 30 practices were contacted through the primary care research network and the DeNDRoN local research network and 12 expressed an interest in participating in the study. Practices were visited and the first to confirm involvement was recruited. The practice recruited covers a mainly rural setting with one large market town at the main practice and two satellite practices. The main practice was located adjacent to a community hospital. The practice had a list size of 14,400 patients and is served by 4.5 WTE GPs. Its deprivation score is 18.77.

Newcastle

Two GP practices were approached by the site lead and agreed to participate in the study. Adult services in one local authority were approached to assist with recruitment of the case manager and offered a seconded role of a full-time case manager to provide the intervention across the two GP practices. Funding for the role was brokered by the locality PCT. A social worker with considerable experience of working with people with dementia and their families was initially recruited but accepted another post at the beginning of the recruitment screening. A second experienced social worker with knowledge of dementia took over the role. Recipients of case management were unaffected by the change in personnel. The social worker was primarily located at the larger practice but also spent a significant proportion of time in adult services, which afforded access to social work systems.

Patients were recruited across the two sites. One was a large, two-centred practice with a central and a satellite practice covering the city centre plus a broad radius of suburbs; the other was a smaller practice covering one area of the city. The larger practice had a list size of 28,396 patients served by 15 WTE GPs, and the practice’s deprivation score was 27.8 (putting this practice in the fourth most deprived centile). The smaller practice had a list size of 6501 patients served by 4.25 WTE GPs, and its deprivation score was 29.7. Recruitment was more successful in the larger practice.

Recruitment of patient and carer dyads

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The target patient population for the CAREDEM WP2 study was people of any age with a diagnosis of any type of dementia (confirmed by secondary care assessment). Potential participants had to be living in the community at the point of recruitment and to have a carer (spouse, close relative, friend or other informal carer) who maintained regular contact. Those resident in care homes or being seen regularly by specialist dementia services were deemed to be being case managed already and were therefore excluded. Those unable to read English language information sheets about the study were also excluded.

Delays in achieving approval from local PCT research and development departments meant that recruitment of patients could not begin before July 2012. Practices recruited people with dementia and their carers over a 6-month period between July and December 2012 and followed them up for 5 months, the last interview being on 31 May 2013.

The WP2 protocol stated that patients would be invited to take part by their GP; however, in the London and Norfolk practices this was not realistic and eligible patients were screened and invited to take part by the practice nurse working in the case manager role, with the agreement of their GP. In the Newcastle practices the invitations were offered by the patients’ GPs and followed up by the research team.

The case manager or GP sent the patient and carer an information sheet, an opt-in form and a prepaid envelope and followed this up with a telephone call. Once the opt-in form or verbal consent form had been received, the research team was informed and contacted potential participants to answer any questions that they may have had. If the patient and carer were happy to proceed, the researcher arranged a visit at home or in another place specified by them to obtain informed consent and collect the baseline data. At the end of the baseline interview the researcher explained the next stages of the process and agreed with the participants that they would contact them for a follow-up appointment.

Directly after the baseline appointment the researcher informed the local case manager that the baseline assessment had been completed so that they could commence the intervention and completed a reflection log on the informed consent form process. Mentoring was provided by an Admiral nurse seconded to the project from Dementia UK, who visited the practices, carried out joint assessments with the case managers, communicated by telephone and e-mail with case managers on a regular basis and used the educational needs assessment and task matrix as the framework for discussing the case management role. Patients were followed up at 5 months (instead of 6 months as specified in the protocol) to allow completion of the study.

Quantitative data collection methods

Following the process of informed consent, interviews were conducted with the carer and the person with dementia individually, unless either person preferred the interview to take place with their relative in the room.

Demographic details, including date of birth, gender, marital status, level of education, employment status, ethnicity and relationship to care recipient, were obtained from participants at the baseline interview.

The carer completed the following assessments:

-

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI)59 (on which the current sample size calculations are based). This is a validated instrument with 12 domains, completed in an interview with a carer to assess the prevalence of behavioural and psychological symptoms experienced by the person with dementia he or she is supporting.

-

The Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale (BADLS)60 was used to assess the functional impairment of the person with dementia.

-

The 28-item General Health Questionnaire (GHQ-28)61 was used to provide a measure of the carers’ mood and quality of life.

-

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) (see www.euroqol.org/about-eq-5d.html; accessed 23 June 2014) was used to assess carer quality of life and to generate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs).

-

The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)62 captures service utilisation data for the carer and the patient (including institutionalisation, extra patient care during therapy), unpaid carer support and other aspects relevant to health economics. The rates and dates of entry into institutional care are recorded.

The person with dementia was assessed in the following ways:

-

The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)63 was used as a measure of cognitive function.

-

The Dementia Quality of Life (DEMQOL) scale33 was completed if the patient scored ≥ 11 on the MMSE, in line with guidance. The DEMQOL scale is a generic measure from which it is possible to generate QALYs.

Discontinued measures

The decision was taken before recruitment of participants to remove two of the measures included in the original protocol. The scale measuring quality of life in Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD)64 was removed as we were already measuring quality of life with the EQ-5D and the DEMQOL scale; the researchers felt that the extra measure was excessive and therefore unnecessary. Similarly, the 12-item Health Status Questionnaire (HSQ-12)65 was removed and the GHQ-28 was retained.

Adverse events

The numbers and details of adverse events (e.g. emergency admission to hospital) or serious adverse events (e.g. deaths) were recorded.

Qualitative data collection

In-depth qualitative interviews were conducted with members of a range of stakeholder groups to explore different perspectives on case management. Those interviewed included people with dementia (patients), carers, case managers, the case manager mentor (hereafter ‘mentor’), health and social care professionals and members of the research team. Separate interview topic guides were developed for each stakeholder group to reflect different levels of engagement with case management. During data collection, interview topic guides for all stakeholder groups were adapted through an iterative process in light of low levels of intervention delivered in practice and emerging themes.

Interviews were conducted by members of the research team at various stages of the feasibility study to capture processes and experiences of case management at different time points and to capture key events such as case manager training. The majority of interviews were conducted face to face with individuals; however, when this was not practically feasible, a small number of interviews were conducted with two or three participants in a group or by telephone.

Patient and carer interviews

A purposive sample of patients and carers was invited to participate in a single in-depth qualitative interview to explore their experiences and views of case management (Table 2). Some interviews with patients and carers were carried out jointly at the request of the participants; however, when possible, interviews were conducted separately to enable exploration of potentially differing carer and patient experiences.

Case manager and mentor interviews

In total, there were four case managers throughout the pilot study. The views of the mentor were also sought through interview. Case managers and the mentor participated in several interviews throughout the study to explore changing expectations, the development of the role, training and supervision, the implementation of case management in practice and their views on the value of the case management approach. In total, 13 interviews were conducted (four with the mentor, two with each of three case managers and three with one case manager).

Research team interviews

Two members of the research team were interviewed and informal discussions were conducted with a further member of the team. These interviews/discussions explored the induction process, expectations of case management, barriers to implementation and their views on the value of the case management approach.

Health and social care professional interviews

In total, 18 in-depth interviews were conducted with a range of health and social care professionals (Table 3). Some practitioners reported direct interactions with the case managers whereas others gave a more theoretical perspective on case management (e.g. one of the commissioners). These are reported in Chapter 7.

| Profession | No. of participants |

|---|---|

| GP | 6 |

| Administrative practice staff | 5 |

| CMHT | 2 |

| Voluntary sector worker | 3 |

| Commissioner | 2 |

| Total | 18 |

Qualitative data management and analysis

All interviews were audio recorded, transcribed, checked and anonymised. In the initial stage of analysis individual team members (CB, KB, MP and LR) read and reread a number of transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data and identify preliminary themes. A series of data workshops were then held in which team members discussed these preliminary themes and developed a draft coding frame. This was then applied to a small number of transcripts and the findings were discussed in subsequent data workshops. Following a series of iterations, and informed by the theoretical domains framework,66 a final coding frame was agreed. All transcripts were coded in NVivo (version 9; QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate data management using the final coding frame. In the next stage of analysis, the output for different stakeholder groups was reviewed. This led to the combination of some codes, the identification of new subcodes and the production of a narrative summarising the key themes for each group. These narratives were then compared and overarching themes identified across the stakeholder groups.

Confidentiality

Although we recruited both male and female case managers, to avoid identification we have referred to all case managers as female and we have not attributed quotes to individual case managers. By virtue of her role, the mentor was identifiable and she has reviewed and agreed to the use of all quotes attributed to her. Quotes from patient and carer interviews are identified by site (A, B or C) and unique identifier within each site.

The findings from WP2 are presented in the following four chapters:

-

Chapter 4 – recruitment to the study of practices and patient–carer dyads

-

Chapter 5 – implementation of the study including recruitment processes, acceptability and feasibility of outcome measures, patient and carer views on study participation and case manager and mentor views on study procedures

-

Chapter 6 – capturing what the case managers did during case management

-

Chapter 7 – stakeholder perceptions of case management for people with dementia.

Chapter 4 Recruitment to the study and characteristics of participants at baseline and follow-up

This chapter describes the recruitment and follow-up of study participants, by site, and provides a baseline description of participants’ characteristics as well as baseline and follow-up values for the following outcome measures: the NPI, the EQ-5D visual analogue scale, the BADLS, the GHQ-28 (total and domain scores), the MMSE and the DEMQOL scale (total and selected domain scores). We present the data primarily to characterise the sample and document the extent of follow-up. Finally, serious adverse events occurring during the study are described.

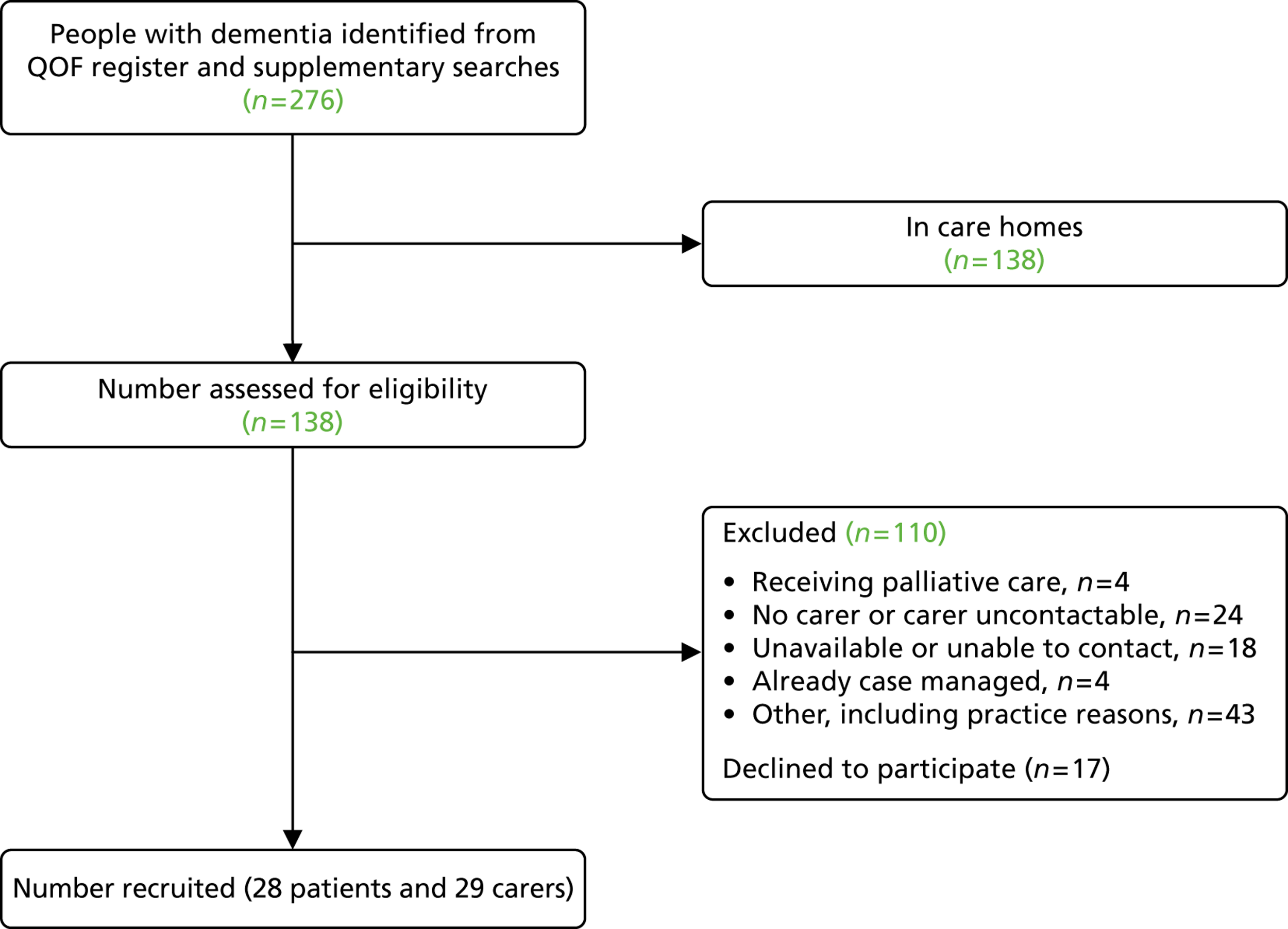

Recruitment

The recruitment target was 44 dyads (person with dementia plus a carer), 11 from each practice. The number of dyads recruited was 29; 14 were recruited from the two north-east practices, nine from the Norfolk practice and six from the London practice. Recruitment was halted at the Norfolk practice to deal with a backlog of case management work and this practice would probably have achieved its target had more time been available to the nurse case manager. Case identification using the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) dementia register was supplemented by searches of electronic medical records to identify those taking cholinesterase inhibitors who were not on the QOF dementia register. Additional searches for patients with symptoms suggesting possible dementia (memory loss, confusion) allowed medical records to be checked for evidence that a formal diagnosis had been made but had not been added to the patient record. Figure 2 shows the derivation of the participant sample for the feasibility study.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment flow diagram.

Of those patients not living in care homes, 45 [33%, 95% confidence interval (CI) 29% to 48%] met all of the criteria for inclusion in the study apart from providing informed consent. In total, 28 of these (62%, 95% CI 46% to 76%) agreed to participate.

Recruitment and follow-up by site

In London, six participant dyads (12 participants – six people with dementia and their main carer) were recruited between 17 August 2012 and 18 December 2012. Three potential participants agreed to speak with the researcher but declined to participate in the study. Reasons provided for this were not having the time to participate (two people) and not wanting their relative with dementia exposed to research questioning (one person). In London, a female patient was referred to the study and agreed to meet one of the researchers but it became apparent that she was unlikely to have dementia. The researcher checked with the surgery, which had placed her on the QOF dementia register without a diagnosis of dementia confirmed by secondary assessment. The researcher wrote to her to thank her for her time and withdrew her from the study. Follow-up appointments for the recruited participants in London were completed at 5 months. Six dyads were successfully contacted and follow-up data were collected.

In Norfolk, nine participant dyads (18 participants – nine people with dementia and their main carer) were recruited between 7 August 2012 and 24 September 2012. Three patients who were invited to participate returned the opt-in form stating that they would not be interested in taking part but gave no details about why they were declining participation. In Norfolk, all 18 participants recruited into the study completed a follow-up appointment at 5 months.

Thirteen dyads plus one carer-only participant were recruited in the north-east. Ten dyads were recruited through the larger practice. Recruitment took place between 30 July 2012 and 27 November 2012. Only one patient returned the opt-in form stating that she was not interested in participation.

A further four participants were agreeable to their details being passed to the researcher; however, either the patient or the nominated carer declined participation when approached by the researcher. Reasons for declining participation included patient illness/hospital admission and other family or care commitments. Despite multiple attempts, the researcher was unable to contact an additional two patients who had expressed an interest in participation through the GP contact. Table 4 shows the derivation of the denominator for outcome assessment at all sites.

| Area | Dyads recruited | Follow-up at 5 months | Denominator for outcome and quality of life data at 5 months | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Rate (%) | 95% CI (%) | |||

| London | 6 | 6 | 100 | 54 to 100 | 4a |

| Norfolk | 9 | 9 | 100 | 66 to 100 | 9 |

| North-east | 13 | 10b | 77 | 46 to 95 | 4c |

| Total | 28 | 25 | 89 | 71 to 98 | 16 |

Baseline data collection

Baseline data were collected from all dyads (nine from Norfolk, six from London and 13 dyads and one carer from the north-east). All nine dyads from Norfolk and all six from London were followed up at 5 months, with complete data collection. Ten of the 13 dyads from the north-east were successfully followed up at 5 months (outcome data were collected from four and the other six indicated that they were willing to provide it). Two dyads in the north-east indicated that they were not willing to provide outcome data (one patient had moved into residential care and her carer felt that the patient was not capable of participating; one patient did not receive the intervention and the carer felt that data collection would be too upsetting for the patient) and one further patient was lost to follow-up.

Demographics of participants at baseline

Tables 5 and 6 show the characteristics at baseline of the carers and the people with dementia, respectively.

| Demographic | Centre | All (n = 29) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfolk (n = 9) | London (n = 6) | North-east (n = 14) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 71.2 (14.0) | 62.7 (13.6) | 64.1 (13.7) | 66.0 (13.8) |

| Gender female, n (%) | 5 (56) | 4 (67) | 10 (71) | 19 (66) |

| Marital status: married/partnered, n (%) | 6 (67) | 2 (33) | 10 (71) | 18 (62) |

| Level of education: no qualifications, n (%) | 3 (33) | 0 (0) | 6 (43) | 9 (31) |

| Work: retired, n (%) | 7 (78) | 3 (50) | 8 (57) | 18 (62) |

| Children at home, n (%) | 1 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (7) | 2 (7) |

| Ethnicity: white British, n (%) | 9 (100) | 3 (50) | 14 (100) | 26 (90) |

| Demographic | Centre | All (n = 28) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfolk (n = 9) | London (n = 6) | North-east (n = 13) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 81.1 (3.5) | 79.8 (6.6) | 79.8 (11.6) | 80.2 (8.5) |

| Gender female, n (%) | 6 (67) | 5 (83) | 9 (69) | 20 (71) |

| Relationship to carer | ||||

| Cared for by a spouse/partner, n (%) | 7 (78) | 2 (33) | 6 (46) | 15 (54) |

| Cared for by a son or daughter, n (%) | 2 (22) | 3 (50) | 7 (54) | 12 (43) |

| Marital status: married, n (%) | 7 (78) | 2 (33) | 5 (38) | 14 (50) |

| Level of education: no qualifications, n (%) | 4 (44) | 3 (50) | 9 (69) | 16 (57) |

| Ethnicity: white British, n (%) | 9 (100) | 4 (67) | 13 (100) | 26 (93) |

Outcome measures

For each variable we provide an indication of the distribution of responses at baseline, usually in the form of a box and whiskers plot. Additionally, we present descriptive statistics for each of the measures of outcome and quality of life used in the pilot study. The purpose behind this is to facilitate the planning of any future studies. In particular, measures of variability are likely to inform sample size calculations; it is not intended that the data be used to make comparisons between the particular sites that participated in this study.

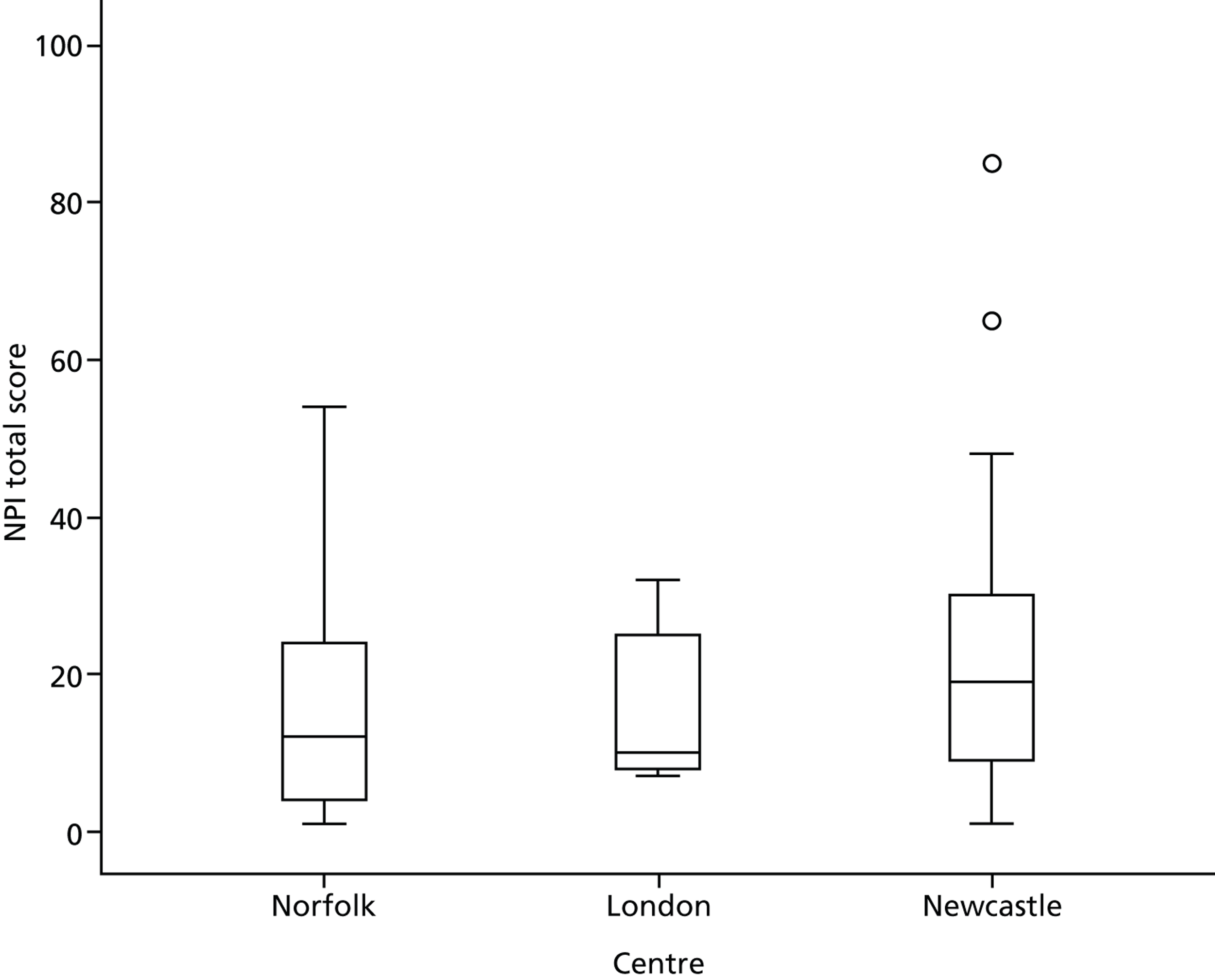

Neuropsychiatric Inventory

The NPI was chosen as the likely primary outcome measure for a definitive trial. The NPI assesses 10 behavioural disturbances occurring in dementia patients: delusions, hallucinations, dysphoria, anxiety, agitation/aggression, euphoria, disinhibition, irritability or emotional lability, apathy and aberrant motor activity. Higher scores suggest higher levels of disturbance. The distribution of total scores for the patients recruited to the feasibility study is provided in Table 7 and Figure 3.

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 9 | 1 | 54 | 12.0 | 16.00 | 16.64 |

| London | 6 | 7 | 32 | 10.0 | 15.33 | 10.58 | |

| North-east | 14 | 1 | 85 | 19.0 | 25.43 | 24.63 | |

| Total | 29 | 1 | 85 | 13.0 | 20.41 | 20.13 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 8 | 5 | 40 | 20.0 | 19.62 | 11.33 |

| London | 4 | 2 | 13 | 8.5 | 8.00 | 4.97 | |

| North-east | 4 | 4 | 29 | 13.0 | 14.75 | 11.18 | |

| Total | 16 | 2 | 40 | 13.5 | 15.50 | 10.68 |

FIGURE 3.

Neuropsychiatric Inventory total scores: box and whiskers plot of baseline values.

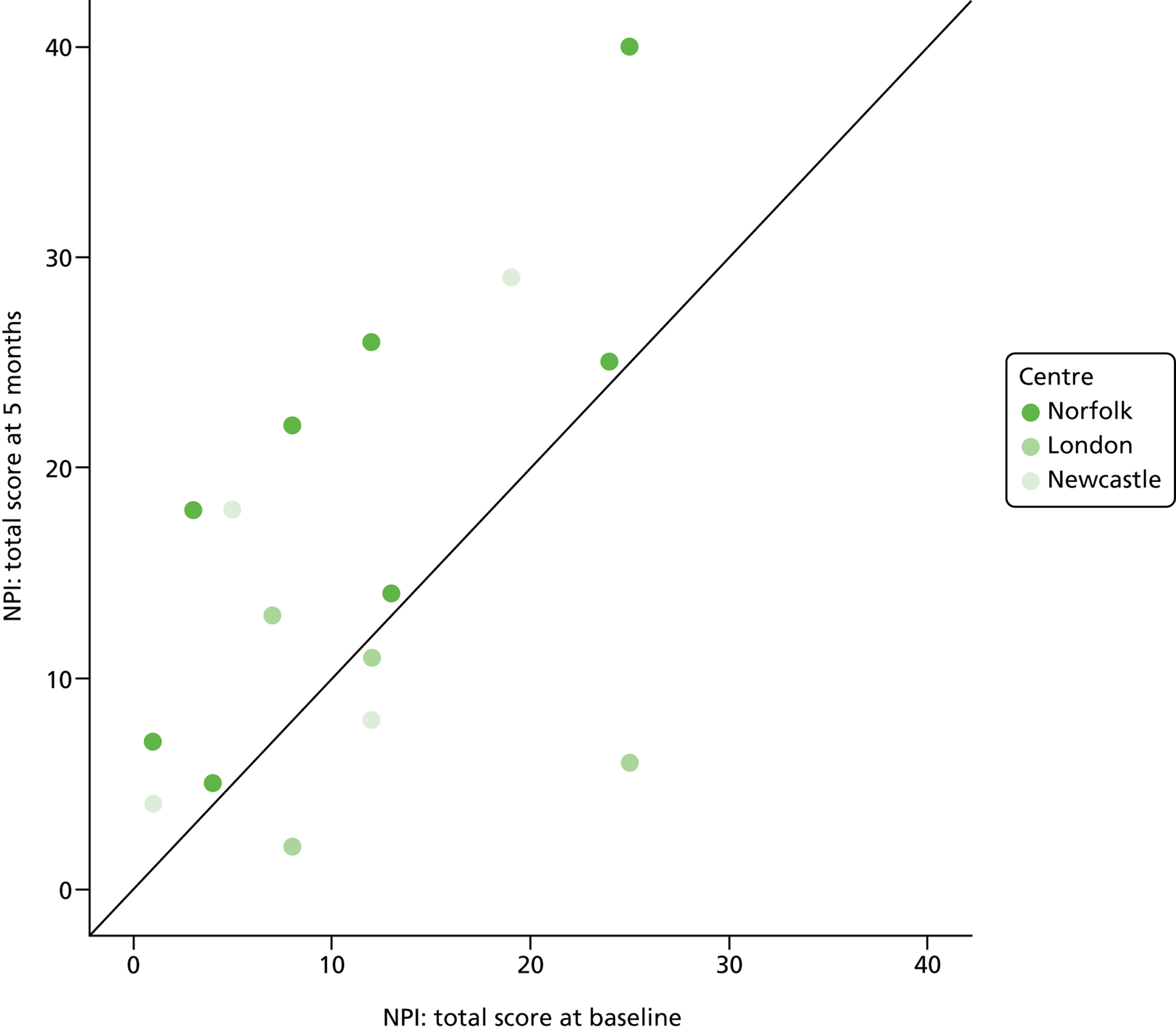

In Figure 3 (and subsequent box and whiskers plots), the horizontal line within each box corresponds to the median value, the lower and upper edges of the box correspond to the 25th and 75th percentiles and the whiskers indicate the range, except for any outlying values, which are indicated by circles and or stars. Figure 4 plots the NPI scores at 5 months against the baseline scores.

FIGURE 4.

Plot of NPI scores at 5 months against scores at baseline.

Most of the scores at 5 months are greater than the scores at baseline. There are four exceptions, three of which correspond to responses from London carers or patients. The mean increase in NPI total score is 4.3 (95% CI –0.31 to 8.56) (based on 50,000 bootstrap samples).

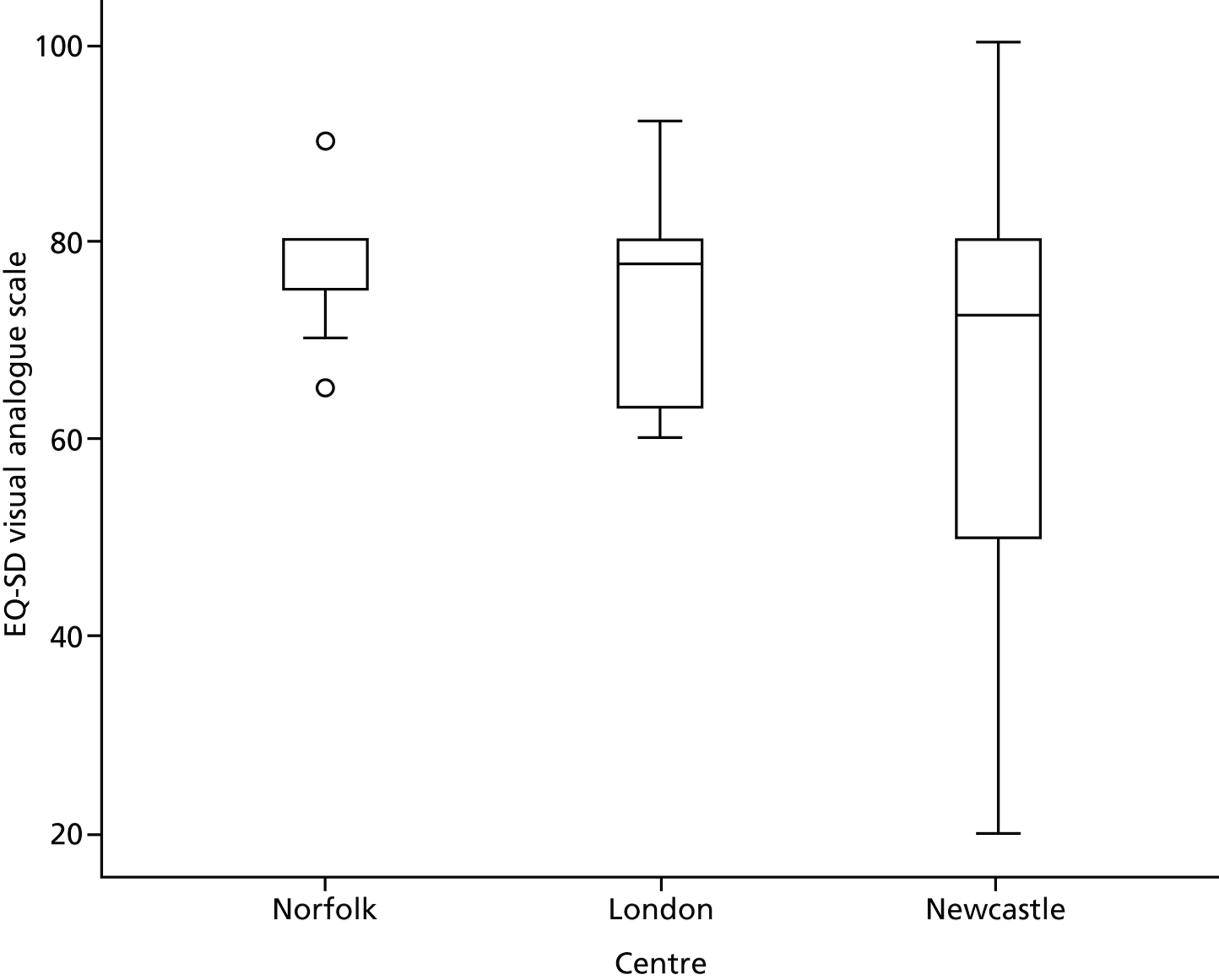

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions visual analogue scale

This general health rating scale (0–100) was completed by carers. Higher values suggest a higher quality of life. Table 8 shows the descriptive statistics for the EQ-5D visual analogue scale at baseline and at the 5-month follow-up and Figure 5 shows a box and whiskers plot of baseline values.

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 9 | 65 | 90 | 80.0 | 77.22 | 7.120 |

| London | 6 | 60 | 92 | 77.5 | 75.00 | 11.900 | |

| North-east | 14 | 20 | 100 | 72.5 | 68.57 | 21.700 | |

| Total | 29 | 20 | 100 | 75.0 | 72.59 | 16.571 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 9 | 40 | 95 | 75.0 | 72.78 | 18.047 |

| London | 4 | 40 | 80 | 69.5 | 64.75 | 17.231 | |

| North-east | 4 | 70 | 95 | 80.0 | 81.25 | 10.308 | |

| Total | 17 | 40 | 95 | 75.0 | 72.88 | 16.507 |

FIGURE 5.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions visual analogue scale: box and whiskers plot of baseline values.

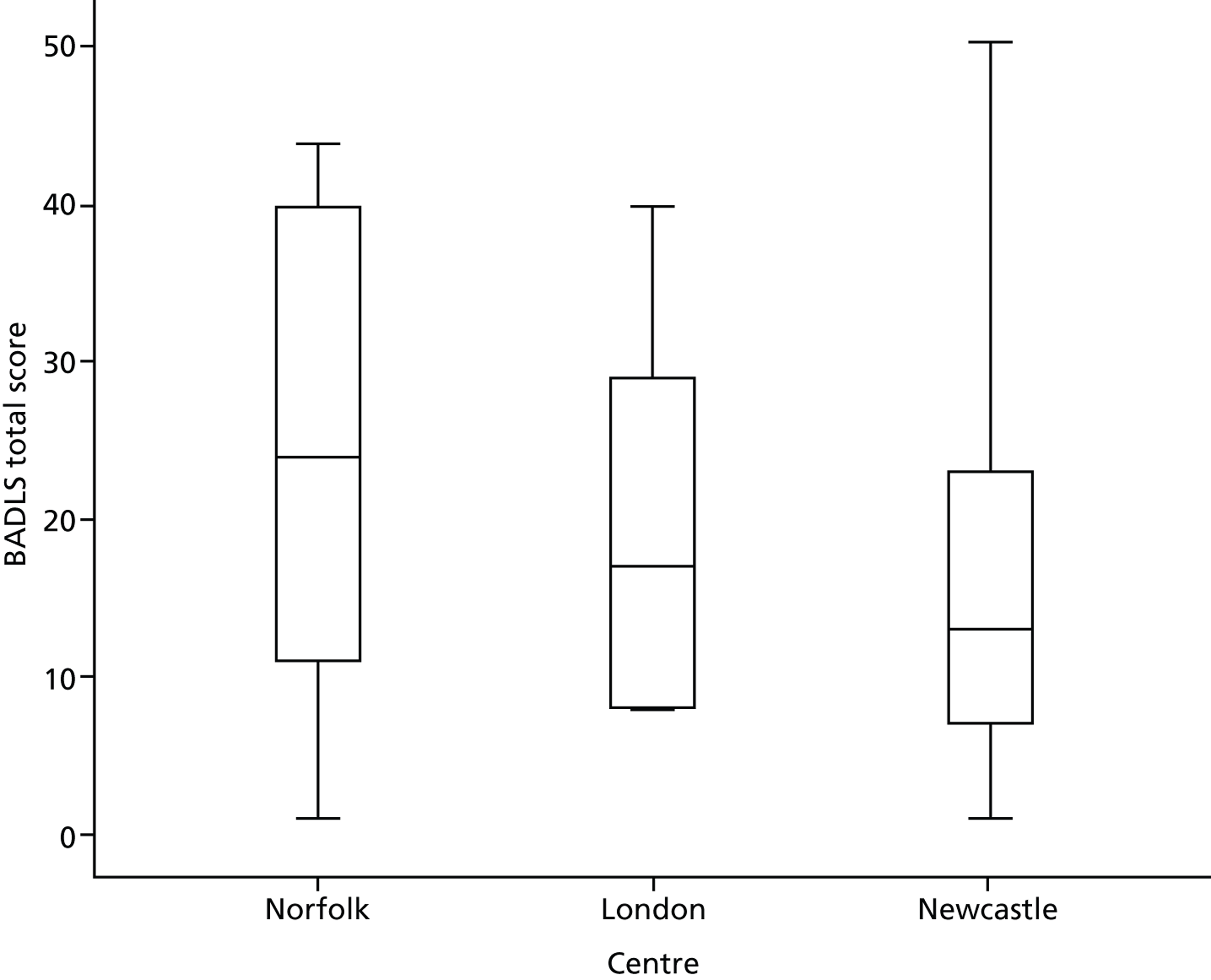

Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale

The BADLS was designed specifically for use in patients with dementia and assesses 20 daily living abilities. A score of 0 suggests total independence and a score of 60 suggests total dependence. Table 9 shows the BADLS scores at baseline and at 5 months’ follow-up and Figure 6 shows baseline values as a box and whiskers plot.

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 9 | 1 | 44 | 24.0 | 22.78 | 17.548 |

| London | 6 | 8 | 40 | 17.0 | 19.83 | 12.937 | |

| North-east | 14 | 1 | 32 | 13.0 | 15.00 | 10.720 | |

| Total | 29 | 1 | 44 | 15.0 | 18.41 | 13.550 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 8 | 4 | 48 | 23.0 | 24.00 | 15.381 |

| London | 4 | 8 | 30 | 14.5 | 16.75 | 10.372 | |

| North-east | 4 | 1 | 29 | 4.0 | 9.50 | 13.178 | |

| Total | 16 | 1 | 48 | 17.5 | 18.56 | 14.325 |

FIGURE 6.

Bristol Activities of Daily Living Scale total scores: box and whiskers plot of baseline values.

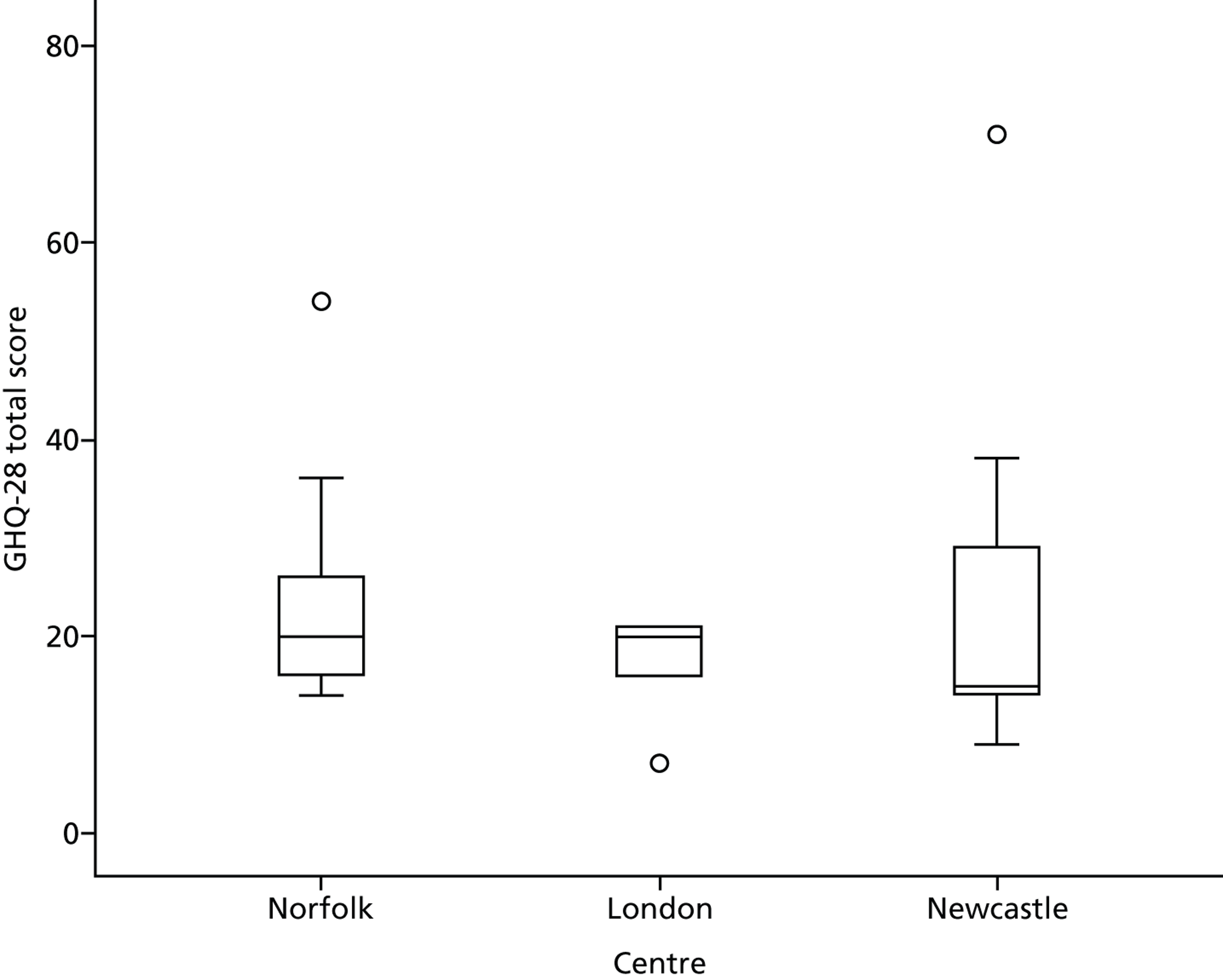

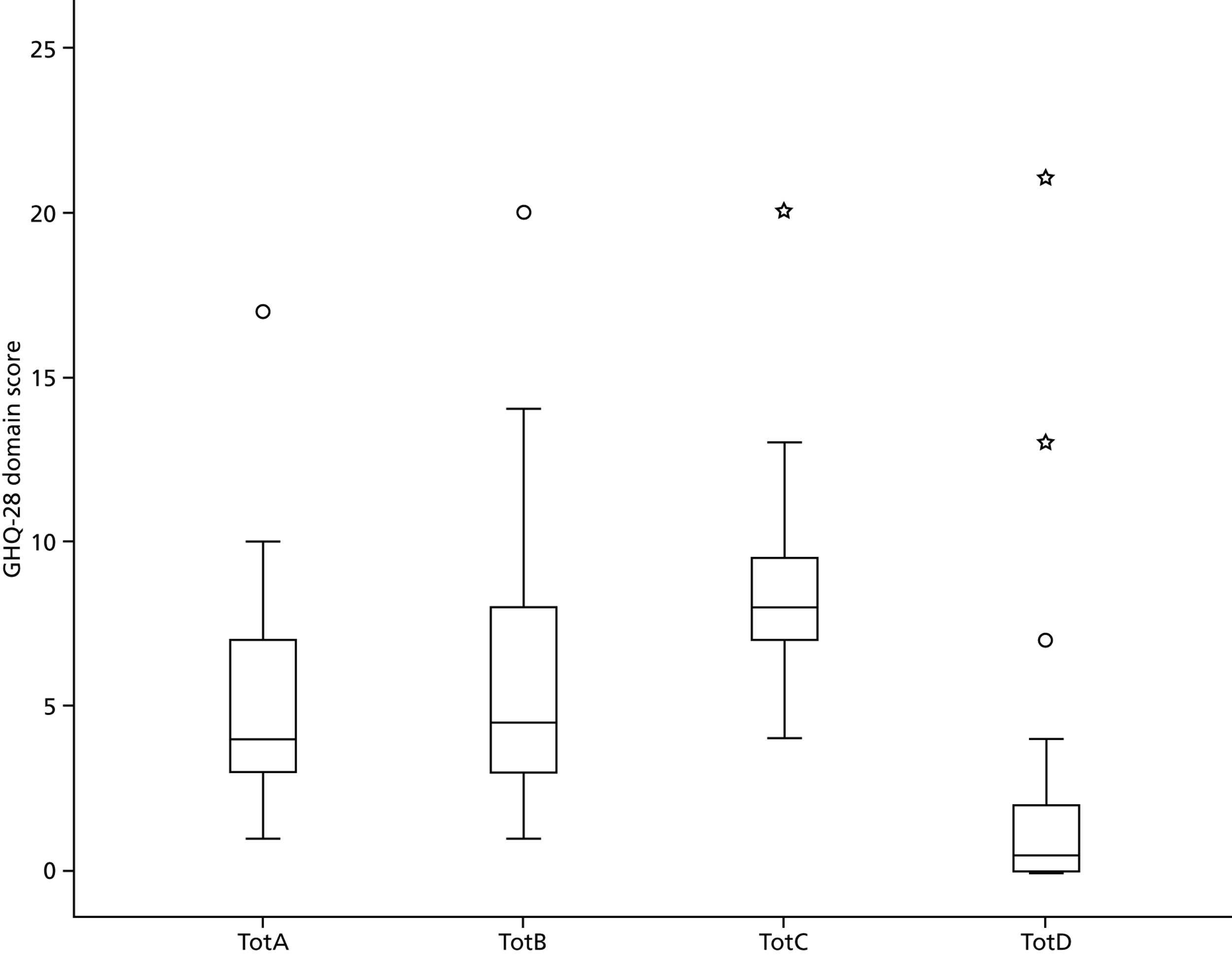

General Health Questionnaire

The GHQ-28 has possible scores across four domains in the range from 0 to 84, with higher scores suggesting higher levels of psychological disorder. The four domains are (A) somatic symptoms, (B) anxiety and insomnia, (C) social dysfunction and (D) severe depression. Table 10 shows the GHQ-28 total scores at baseline and at 5 months’ follow-up and Figure 7 shows the GHQ-28 total scores at baseline as a box and whiskers plot. Table 11 shows the domain scores at both time points and Figure 8 shows the baseline domain scores as a box and whiskers plot.

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 9 | 14 | 54 | 20.0 | 24.44 | 13.182 |

| London | 5 | 7 | 21 | 20.0 | 17.00 | 5.958 | |

| North-east | 14 | 9 | 71 | 15.0 | 23.00 | 16.530 | |

| Total | 28 | 7 | 71 | 17.5 | 22.39 | 13.974 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 7 | 8 | 45 | 18.0 | 21.00 | 12.728 |

| London | 3 | 11 | 32 | 16.0 | 19.67 | 10.970 | |

| North-east | 4 | 9 | 28 | 11.0 | 14.75 | 8.921 | |

| Total | 14 | 8 | 45 | 15.5 | 18.93 | 10.930 |

FIGURE 7.

General Health Questionnaire total scores: box and whiskers plot of baseline values.

| Time point | Centre | Section A | Section B | Section C | Section D | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | n | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

| Mean | 5.56 | 6.44 | 9.44 | 3.00 | ||

| SD | 2.455 | 3.712 | 4.157 | 4.416 | ||

| London | n | 5 | 5 | 5 | 5 | |

| Mean | 3.20 | 5.60 | 8.00 | 0.20 | ||

| SD | 1.789 | 2.510 | 2.915 | 0.447 | ||

| North-east | n | 14 | 14 | 14 | 14 | |

| Mean | 5.79 | 6.29 | 8.43 | 2.50 | ||

| SD | 4.264 | 5.902 | 2.503 | 5.460 | ||

| Total | n | 28 | 28 | 28 | 28 | |

| Mean | 5.25 | 6.21 | 8.68 | 2.25 | ||

| SD | 3.460 | 4.677 | 3.116 | 4.600 | ||

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | n | 9 | 7 | 9 | 8 |

| Mean | 7.22 | 6.57 | 7.22 | 2.13 | ||

| SD | 3.898 | 4.036 | 2.682 | 3.643 | ||

| London | n | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Mean | 4.33 | 6.67 | 8.00 | 0.67 | ||

| SD | 4.041 | 4.509 | 2.646 | 0.577 | ||

| North-east | n | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Mean | 3.25 | 4.75 | 6.75 | 0.00 | ||

| SD | 2.872 | 6.850 | 0.500 | 0.000 | ||

| Total | n | 16 | 14 | 16 | 15 | |

| Mean | 5.69 | 6.07 | 7.25 | 1.27 | ||

| SD | 3.911 | 4.714 | 2.236 | 2.764 | ||

FIGURE 8.

General Health Questionnaire domain scores: box and whiskers plot. A, somatic symptoms; B, anxiety and insomnia; C, social dysfunction; D, severe depression; and Tot, total.

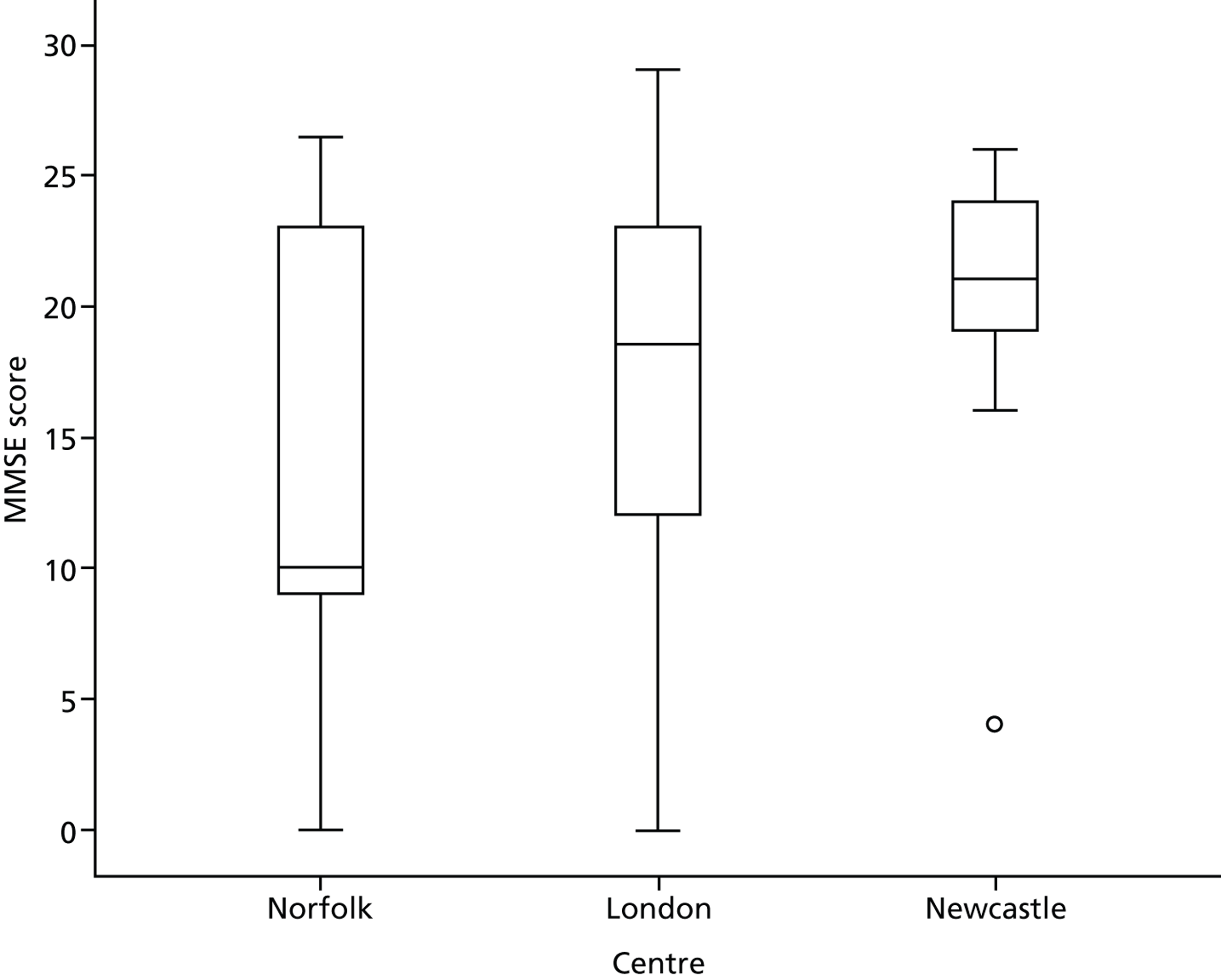

Mini Mental State Examination

The range of scores on the MMSE is from 0 to 30, with lower scores suggesting worse cognitive impairment. Table 12 shows the MMSE scores at baseline and at 5 months’ follow-up and Figure 9 shows the baseline MMSE scores as a box and whiskers plot. A MMSE score of < 10 suggests advanced dementia (Table 13).

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 7 | 9 | 27 | 19.00 | 17.57 | 7.786 |

| London | 5 | 12 | 29 | 23.00 | 20.20 | 7.050 | |

| North-east | 13 | 4 | 26 | 21.00 | 20.15 | 5.757 | |

| Total | 25 | 4 | 29 | 21.00 | 19.44 | 6.436 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 6 | 7 | 24 | 20.00 | 17.17 | 7.548 |

| London | 3 | 22 | 29 | 23.00 | 24.67 | 3.786 | |

| North-east | 4 | 15 | 27 | 20.00 | 20.50 | 5.196 | |

| Total | 13 | 7 | 29 | 22.00 | 19.92 | 6.512 |

FIGURE 9.

Mini Mental State Examination scores: box and whiskers plot.

| MMSE category | Centre | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Norfolk | London | North-east | ||

| ≥ 10 | 6 | 5 | 12 | 23 |

| < 10 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 |

| Total | 9 | 6 | 13 | 28 |

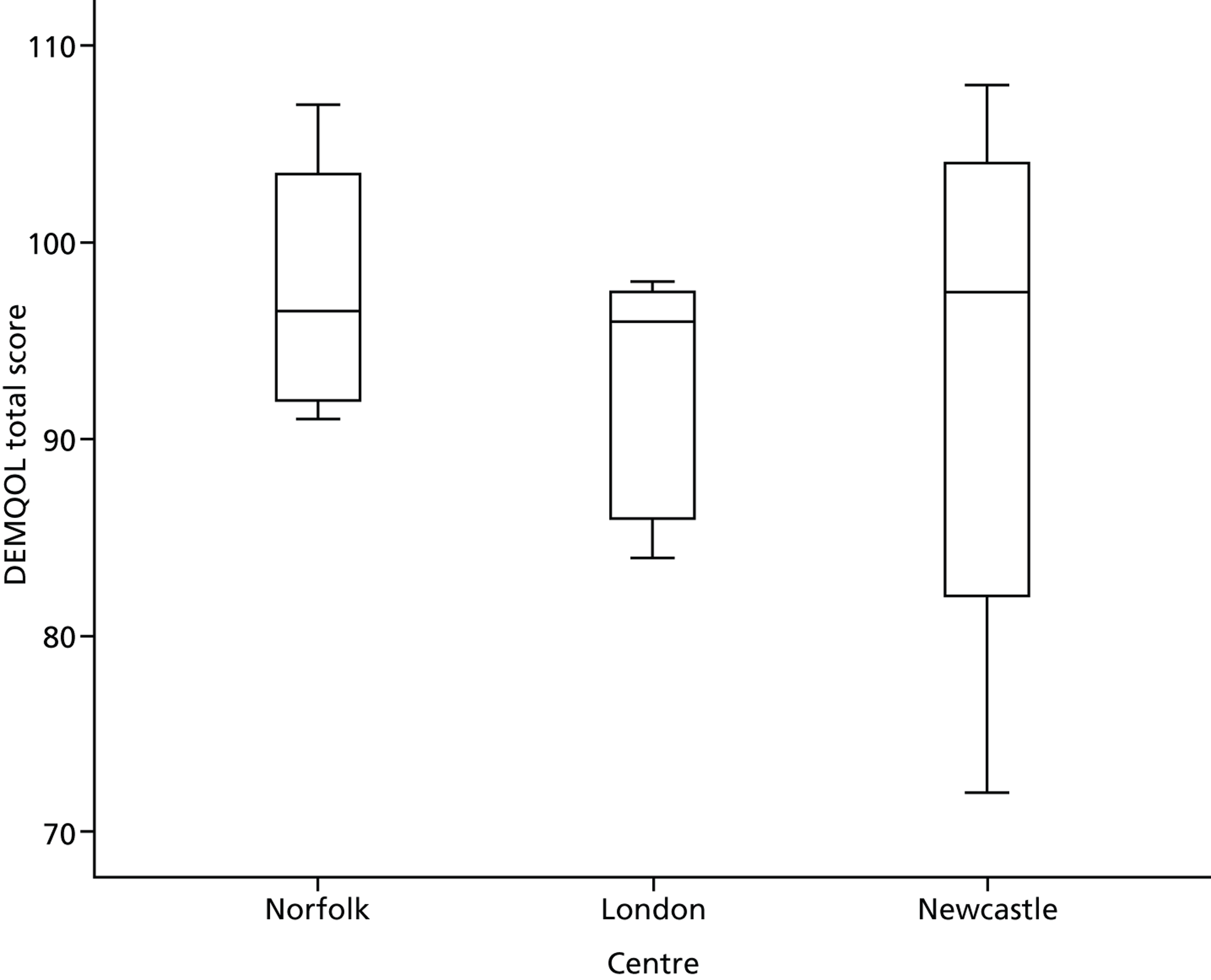

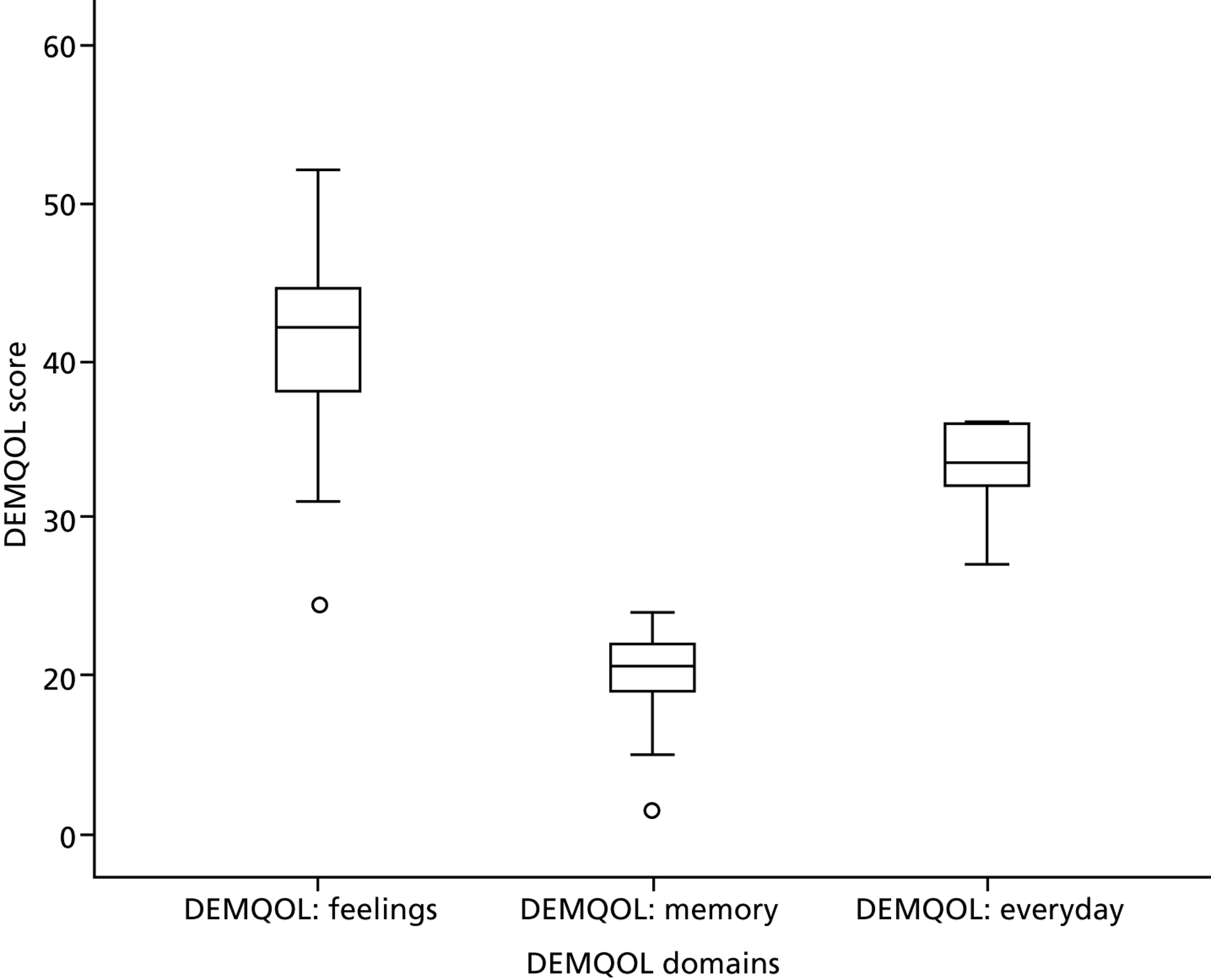

Dementia Quality of Life scale

The DEMQOL is a quality of life measure in which higher scores imply better quality of life. Participant total scores at baseline and at 5 months’ follow-up are shown in Table 14; Figure 10 displays baseline values as a box and whiskers plot. The DEMQOL scale includes five domains, three of which are reported in Table 15 (‘feelings’ = health and well-being; ‘memory’ = cognitive function; and ‘everyday’ = daily activities and looking after yourself). Baseline domain scores are provided in Figure 11 as a box and whiskers plot.

| Time point | Centre | n | Minimum | Maximum | Median | Mean | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | 4 | 91 | 107 | 96.50 | 97.75 | 7.274 |

| London | 4 | 84 | 98 | 96.00 | 93.50 | 6.455 | |

| North-east | 12 | 72 | 108 | 97.50 | 92.67 | 13.282 | |

| Total | 20 | 72 | 108 | 97.00 | 93.85 | 11.008 | |

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | 4 | 90 | 111 | 98.00 | 99.25 | 9.979 |

| London | 3 | 80 | 103 | 84.00 | 89.00 | 12.288 | |

| North-east | 4 | 75 | 111 | 92.50 | 92.75 | 17.017 | |

| Total | 11 | 75 | 111 | 92.00 | 94.09 | 12.888 |

FIGURE 10.

Dementia Quality of Life scale total scores: box and whiskers plot.

| Time point | Centre | DEMQOL: feelings | DEMQOL: memory | DEMQOL: everyday | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Norfolk | n | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 42.75 | 20.25 | 34.75 | ||

| SD | 6.397 | 1.500 | 1.500 | ||

| London | n | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Mean | 42.25 | 19.50 | 31.75 | ||

| SD | 1.708 | 3.109 | 3.686 | ||

| North-east | n | 12 | 12 | 12 | |

| Mean | 39.42 | 19.92 | 33.33 | ||

| SD | 8.372 | 3.848 | 2.674 | ||

| Total | n | 20 | 20 | 20 | |

| Mean | 40.65 | 19.90 | 33.30 | ||

| SD | 7.066 | 3.243 | 2.755 | ||

| 5-month follow-up | Norfolk | n | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | 44.00 | 20.00 | 35.25 | ||

| SD | 5.715 | 4.082 | 1.500 | ||

| London | n | 3 | 3 | 3 | |

| Mean | 38.67 | 17.67 | 32.67 | ||

| SD | 6.351 | 4.726 | 3.215 | ||

| North-east | n | 4 | 4 | 4 | |

| Mean | 38.75 | 21.00 | 33.00 | ||

| SD | 10.532 | 2.944 | 3.830 | ||

| Total | n | 11 | 11 | 11 | |

| Mean | 40.64 | 19.73 | 33.73 | ||

| SD | 7.632 | 3.744 | 2.936 | ||

FIGURE 11.

Dementia Quality of Life scale domain scores: box and whiskers plot.

Safety: serious adverse events

In London, two serious adverse events were reported. One involved a carer being admitted to hospital and one involved a patient (from a separate dyad) being admitted to hospital. These admissions were the result of falls and were unrelated to the study but were expected because of the nature of the patient and carer population. In the north-east, four serious adverse events were reported. One patient was hospitalised twice, both times because of a fall. Another patient suffered a fall and one patient was hospitalised with suspected pneumonia. Again, these serious adverse events were expected because of the age of the patients recruited. No serious adverse events were reported in Norfolk.

Costs

Case management salary costs for WP2 amounted to £52,890 across all sites. Training and mentoring by an Admiral nurse cost £5201 and £6273, respectively.

Chapter 5 Implementing the pilot study: review of processes and procedures

As part of the embedded qualitative study, data were collected on a number of aspects of study processes and procedures, including:

-