Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/166/01. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The draft report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Fortnum et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Otitis media with effusion

Otitis media with effusion (OME) is the most common cause of impaired hearing in children of > 6 months of age. Treating the condition with insertion of grommets is the most common reason for surgical operations in children worldwide. OME is defined as the occurrence of thick sticky fluid behind the eardrum in the middle ear, without signs or symptoms of an ear infection, which leads to a variable and fluctuating hearing loss. The lack of infection distinguishes the condition from acute otitis media (AOM). 1 This build-up of sticky fluid has led to the adoption of the more commonly used term ‘glue ear’ among both clinicians and parents. In the short term, glue ear causes discomfort for the child and reduced auditory input. Hearing losses can be up to 35–40 dB, which, although mild, can lead in the longer term to delays in speech and language development; these have an even greater impact in children with co-existing learning and communication difficulties, such as children with Down syndrome. This can lead, in turn, to behavioural problems as both children and parents become frustrated. Optimising the management of communication disorders can therefore improve social integration and enhance quality of life for children and their families. Most cases of OME resolve spontaneously. Causes for concern are persistence of > 3 months and bilateral hearing loss of ≥ 25 dB.

(Note: throughout this report we will, when appropriate, use the term glue ear as synonymous with OME.)

Down syndrome

Down syndrome is the most common chromosomal disorder in the UK, with an incidence of 1 in 1000 live births. 2,3 Phenotypically, facial dysmorphism leading to ear and upper airway abnormalities,4,5 including stenotic ear canals6 and Eustachian tube dysfunction,7 combined with poor immune function, results in the development of upper airway obstruction, obstructive sleep apnoea, subglottic stenosis, ear infections and middle ear effusions. 8,9 OME is almost universal in children with Down syndrome, begins at a younger age and persists to older ages than in children without Down syndrome. It has been reported that between 55% and 93% of children with Down syndrome have a conductive hearing loss that is dependent on age, and the majority of these losses are caused by OME. 2,10–13 Developmental delay is associated with Down syndrome, affecting multiple areas that are important in any assessment of hearing function, including non-verbal cognition, language learning and social behaviour. 14 In addition, specific difficulties with speech and intelligibility, which are exacerbated by hearing loss, are associated with Down syndrome over and above delay. 15

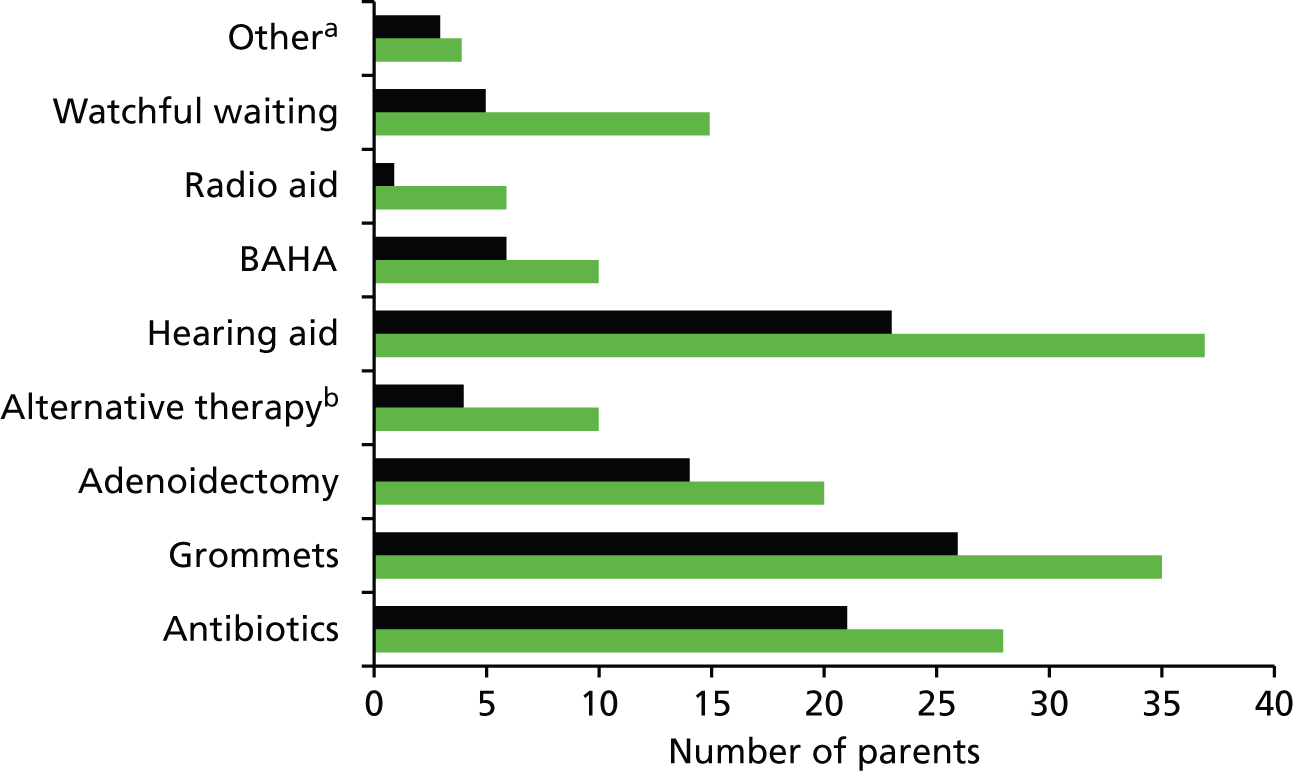

Interventions for otitis media with effusion

The commonest intervention to release the middle ear fluid is insertion of tympanostomy (T-tubes) or ventilation tubes more commonly known as grommets. Insertion of grommets is the commonest paediatric surgical procedure worldwide. However, grommet insertion can be difficult or sometimes impossible in children with Down syndrome, as the morphological features of Down syndrome lead to narrow ear canals. Forty per cent of cases can have stenotic external ear canals,16 making examination of the tympanic membrane impossible or difficult.

Amplification devices are alternative interventions to alleviate hearing losses consequent upon glue ear. Conventional behind-the-ear hearing aids (HAs) are often not tolerated by children with Down syndrome and pose hygiene problems if copresent acute or suppurative otitis media leads to eardrum rupture and discharge. Softband attachments for bone vibrators applied to the mastoid bone [bone-anchored hearing aid (BAHA) technology] are offered by some clinicians and may be tolerated better, although a controlled trial is lacking. Watchful waiting (WW) or active observation before determining definite need for intervention is now accepted to be good practice. Some patients have a period of aiding before having grommets, and some children choose aiding after previous grommet surgery.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines

Guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) published in 200817 reviewed the evidence for surgical management of OME in children and recommended guidelines for treatment in children with uncomplicated OME, and also in children with Down syndrome or cleft palate. The report found only limited studies of OME in children with Down syndrome, and reviewed just three studies in detail, concluding that existing studies evaluating effectiveness of interventions are of poor quality.

Two comparative studies of grommet insertion18,19 found poorer hearing thresholds and resolution rates in children with Down syndrome than in control children. In addition, grommets in children with Down syndrome were more likely to fall out and to be associated with complications. A case series using aggressive medical and surgical treatment16 suggested improvement in hearing thresholds in 98% of cases but that this efficacy was short lived owing to early extrusion of grommets. Shott et al. 16 suggest repeated grommet insertion, but this, in turn, may lead to eardrum perforations.

The NICE guidelines17 acknowledged that children with Down syndrome who have glue ear present particular problems of assessment and management because of the earlier age of onset, the prolonged course of the disease, the greater risk of complications and the potential treatment difficulties. The clinical recommendations, based on the evidence available, were for regular multidisciplinary assessments with expertise in assessing and treating children with Down syndrome, HAs to be offered as a first intervention, and consideration of the following before grommet insertion: severity of hearing difficulties, age, practicality of insertion, clinical risks and likelihood of early extrusion.

The NICE report17 recommended research and national audit projects to evaluate the acceptability, effectiveness and consequences of treatment strategies for children with Down syndrome who have glue ear. It is important to assess both the benefit and harm, and the resource costs and savings of all possible interventions. This would imply a randomised controlled trial (RCT) but, among other restrictions, any such trial requires not only the measurement of robust, relevant and measurable outcomes, but also, crucially, that parents and professionals would be willing to randomise the children. 20,21 The NICE report17 acknowledged that RCTs might not necessarily be the most cost-effective use of research resources and if proposed would need to be multicentre. It was recommended that ‘high-quality national audits with statistical control for baseline characteristics’ would provide data on natural history and the outcomes of varying clinical practices to inform best practice.

Measurement of effectiveness of interventions

Any definitive evaluation of intervention options requires identification of outcome measures of importance or concern to both parents and professionals. Testing hearing, and speech and language development requires particular expertise. For a population of children with delayed development, any assessment must be developmentally appropriate rather than age appropriate. 9 In terms of language learning, language comprehension is usually stronger than language production, and phonology and syntax is particularly challenging,22 making the results of speech tests difficult to assess. It is therefore important to consider other outcome measures for success of treatment. Karkanevatos and Lesser23 explored this issue with parents of children with Down syndrome and reported that symptoms such as earache, disturbed sleep, balance problems, general health, hearing difficulties and misunderstandings, behavioural problems and social skills, and speech and language development were considered to be important. In addition, clinical otological outcomes, such as ear infection and discharge, persistent perforation, scarring and cholesteatoma, are important to consider.

Summary

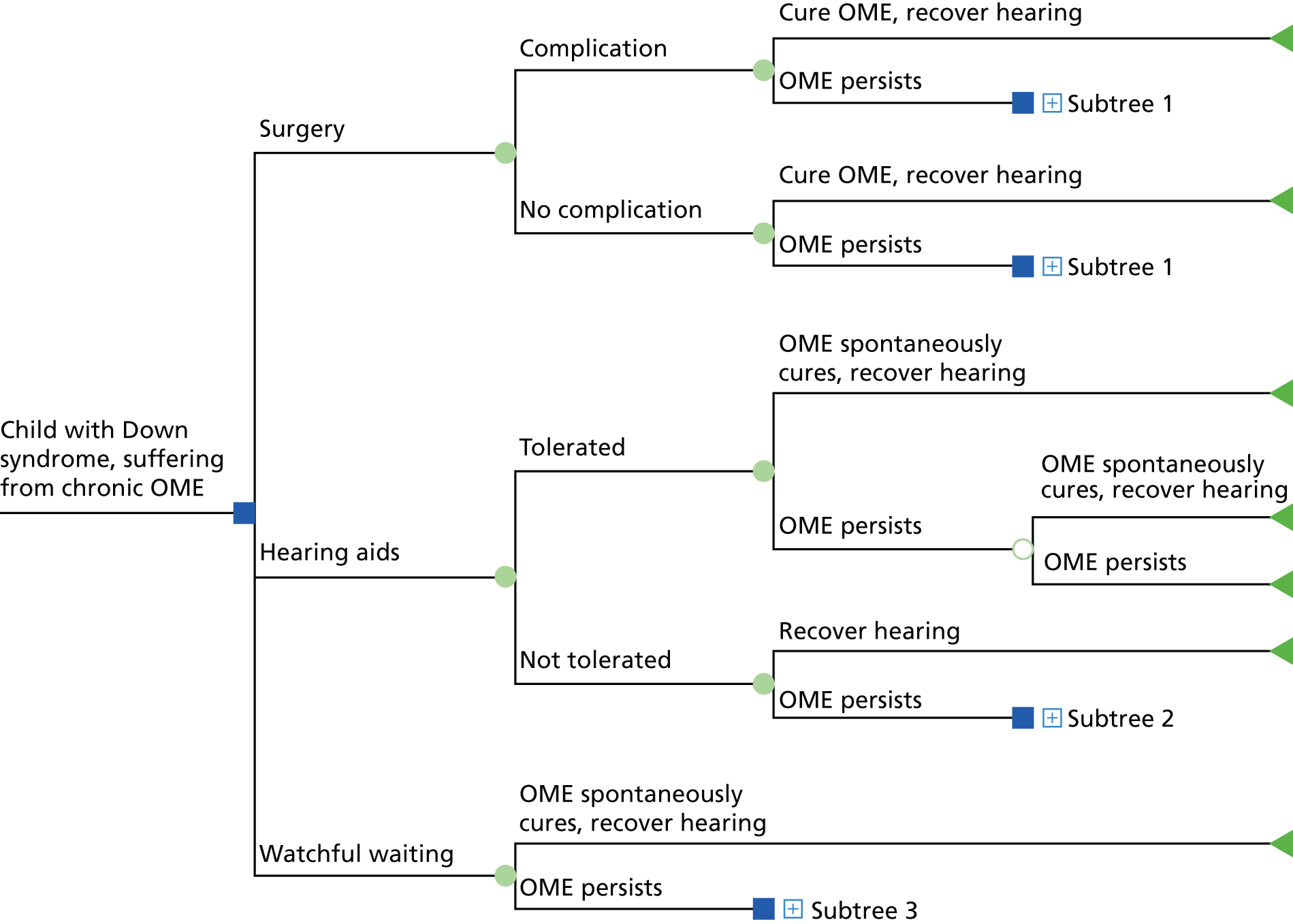

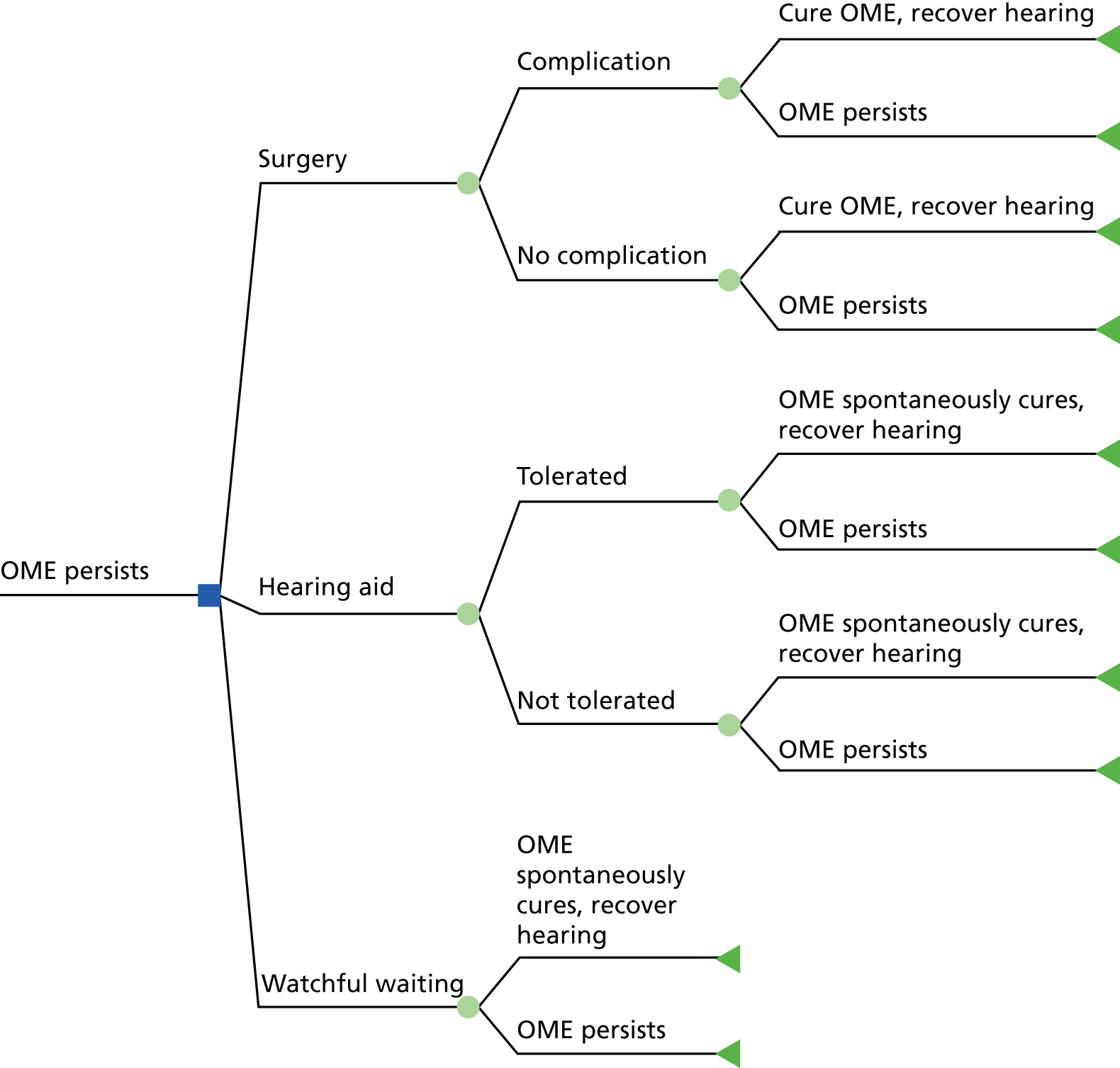

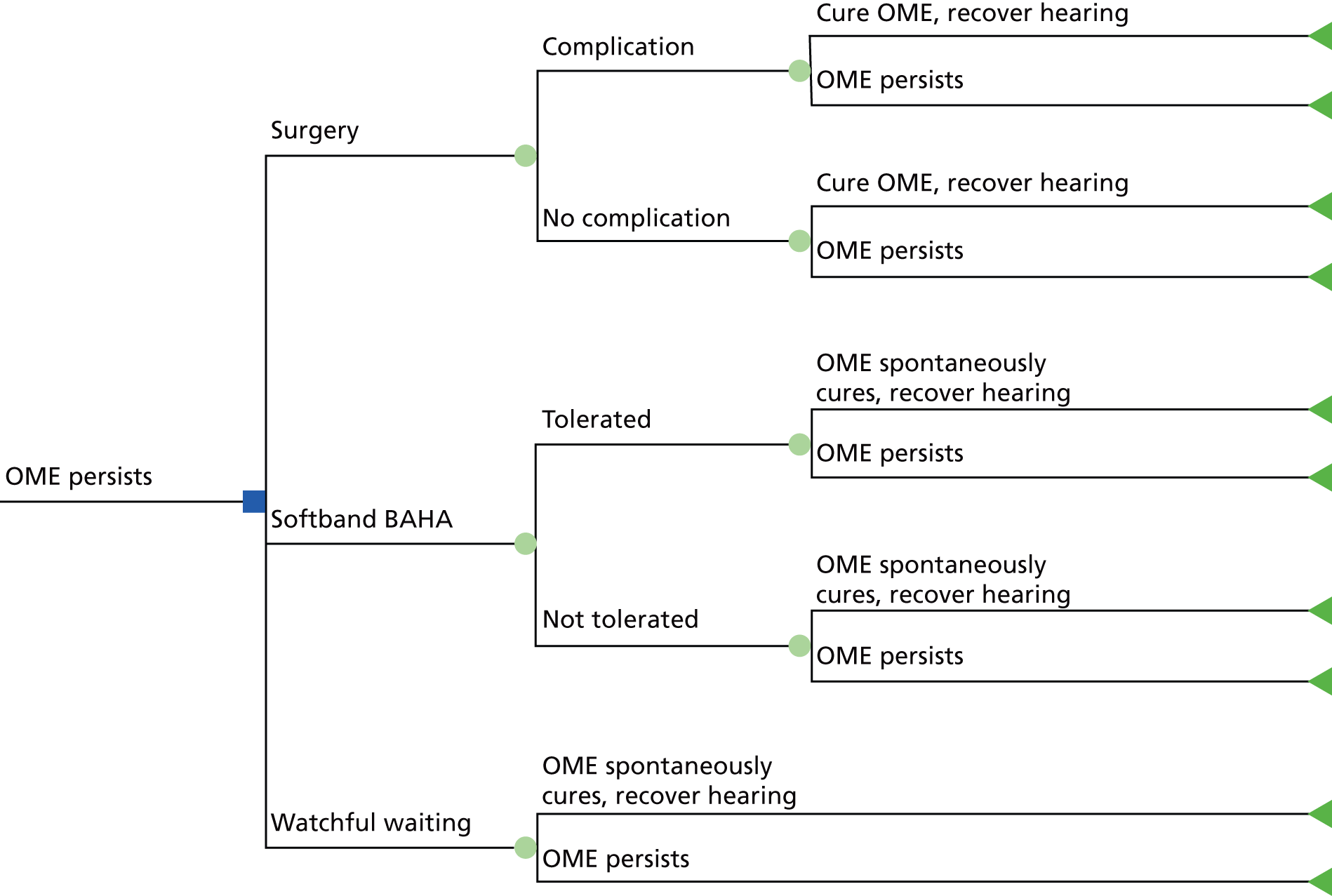

In summary there remains clinical uncertainty of the benefits and costs of different treatment options for children with Down syndrome who have glue ear. This feasibility study was designed to assess the extent of this lack of knowledge and determine if pursuing further information would be practical, beneficial and cost-effective. It assesses the clinical and economic value of, and the potential practical barriers to, undertaking a future RCT or multicentre prospective cohort study of children with Down syndrome who have glue ear. Such a future trial might compare active surgical treatment, i.e. grommet insertion with or without adenoidectomy, with provision of standard air conduction HAs, provision of soft-band bone conduction HAs or WW (active observation). This may not be straightforward and this report documents the findings of research to contribute information from several areas to any decision about the requirement for future research.

Objectives

-

To assess the level and practical effect of the current uncertainty around treatment options for children with Down syndrome and OME.

-

To assess the feasibility of studying the options for management of OME in children with Down syndrome via a RCT or multicentre prospective cohort study.

-

To evaluate the willingness of parents to agree to randomisation for their children.

-

To evaluate the willingness of clinicians to recruit participants to a definitive study.

-

-

To explore relevant and practically measurable outcome domains for use in a definitive study.

-

To assess the feasibility and practical requirements for collecting these outcome measures of the relevant type.

-

To undertake a value of information (VOI) analysis to assess the level and clinical impact of current uncertainty, and the likelihood of further research reducing that uncertainty and minimising the clinical impact of any uncertainty.

Structure of the report

The project comprised four elements to address the objectives.

-

A targeted review of the current literature to assess the level of current uncertainty around treatment options for children with Down syndrome and OME building on the review undertaken by NICE (objective 1) and to explore facilitators and barriers to participation in research (objective 2) (see Chapter 2).

-

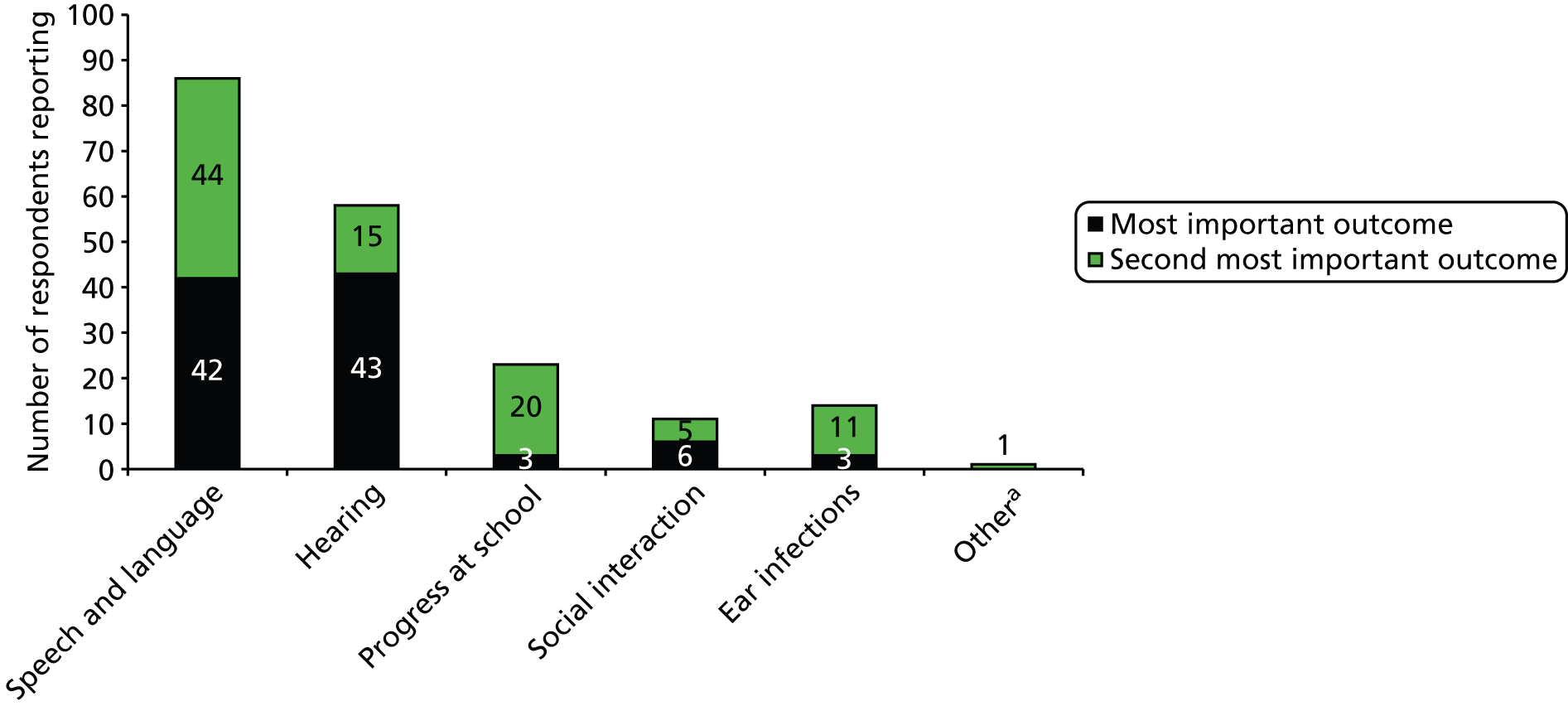

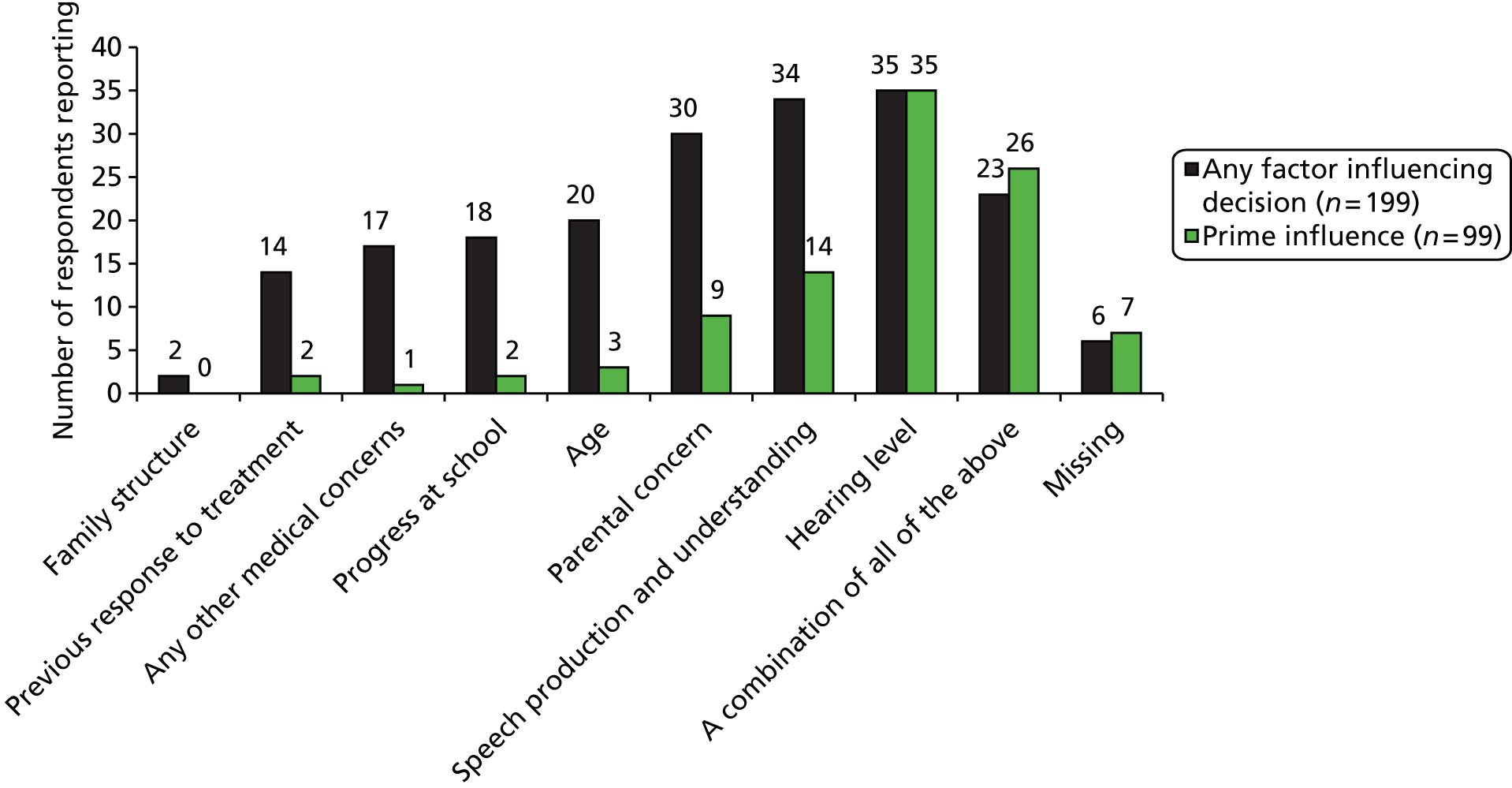

An exploration of the views and opinions of parents of children with Down syndrome (objectives 2i, 3 and 4) (see Chapter 3).

-

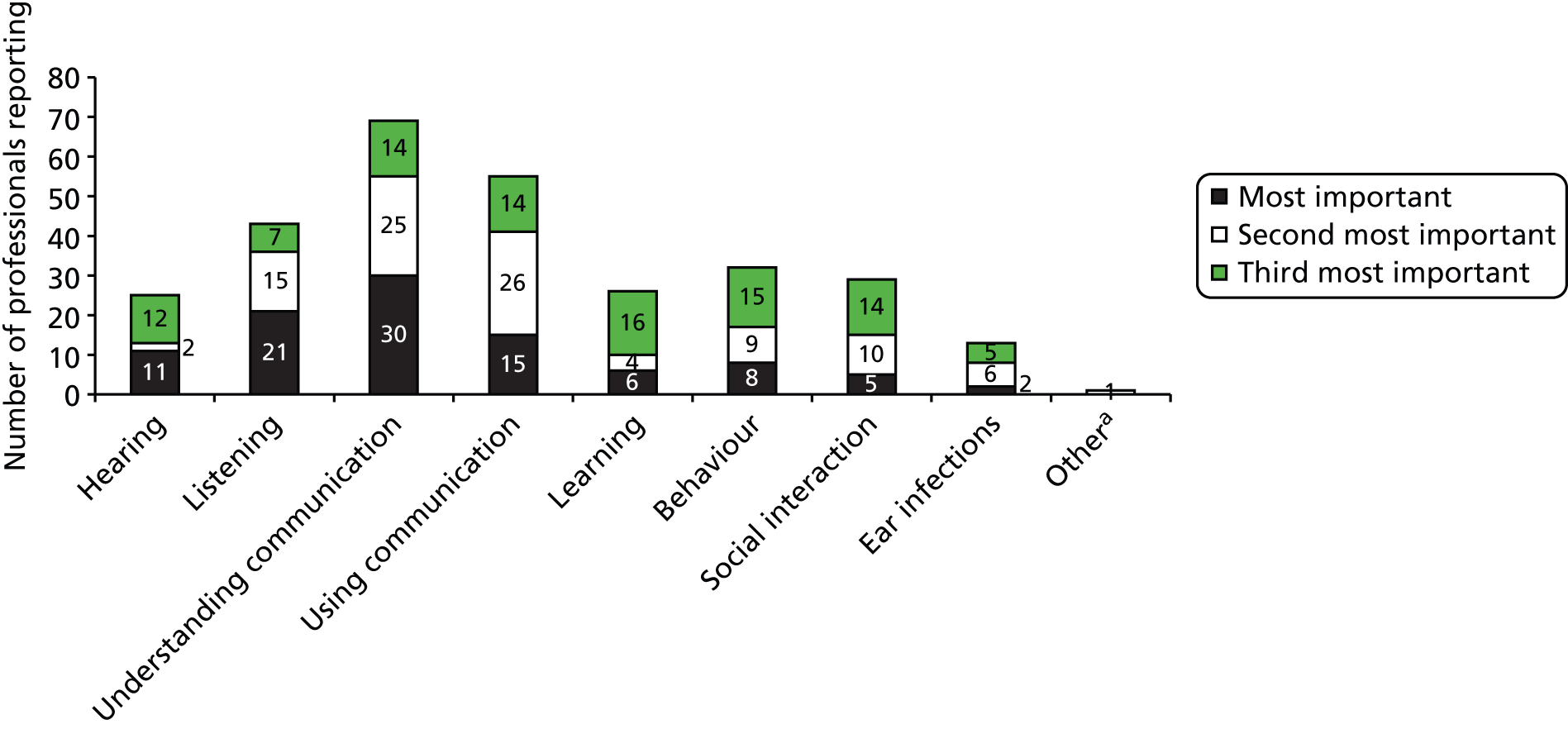

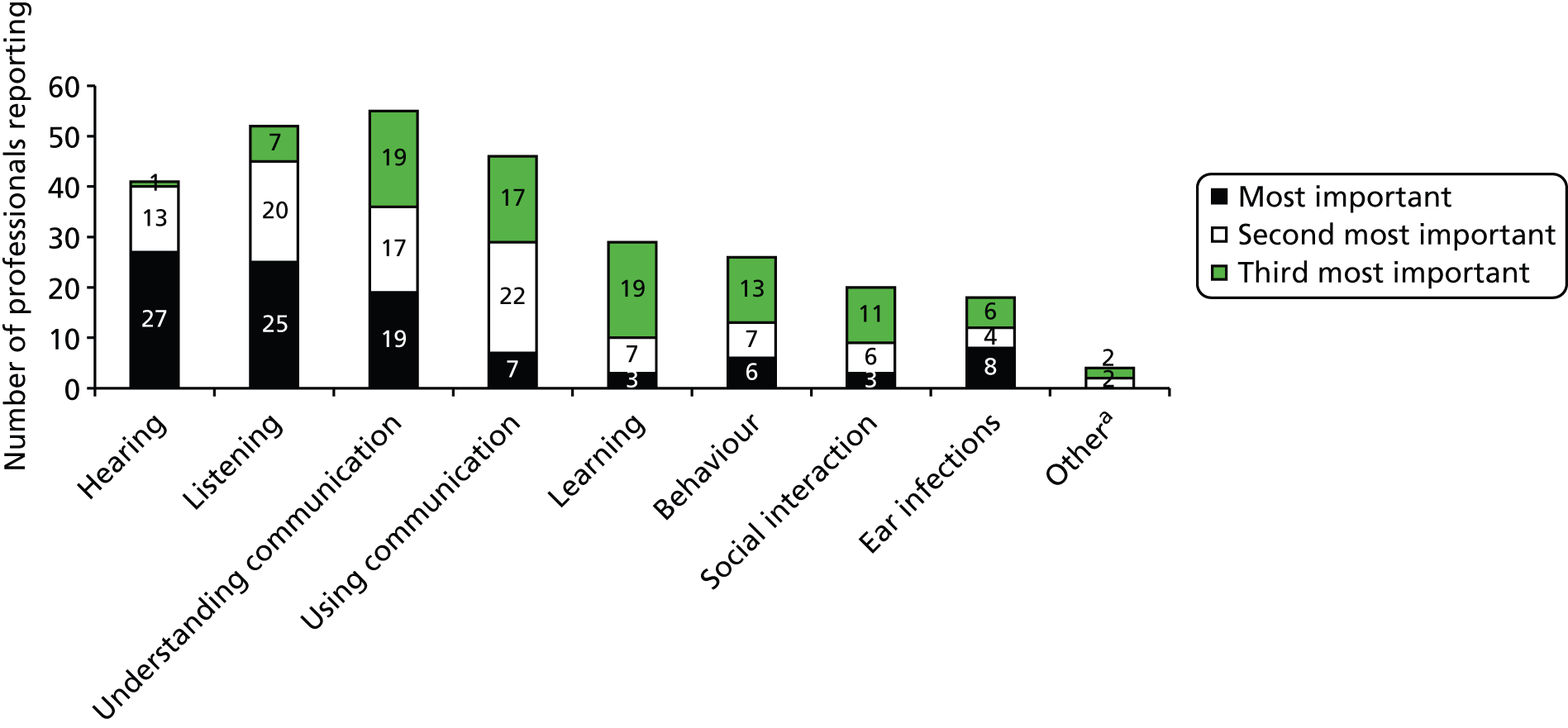

An exploration of the views and opinions of health-care professionals and teachers concerned with the care of children with Down syndrome (objectives 2ii, 3 and 4) (see Chapter 4).

-

A VOI analysis (objective 5) (see Chapter 5).

Each of the above elements is described in a separate chapter reporting objectives, methods, results and a summary. Finally, Chapter 6 includes the discussion for each element, including strengths and limitations, and recommendations for future research.

Patient and public involvement

To enhance the quality of the methodological approach to this project a multidisciplinary steering group was established at the start of the project. The group was chaired by a speech and language therapist (SLT), who is currently a registered intermediary with expertise in Down syndrome, and included representatives of the relevant professional disciplines, professional organisations, parent support associations, parents and the Down syndrome population (see Appendix 1 for the list of members of the steering group). At the initial meeting in January 2012 the group offered comment on drafts of the proposed questionnaires, information leaflets and consent documentation, and continued to contribute via e-mail as these documents were finalised. At the second meeting in January 2013, and subsequently by e-mail, the group offered comment on the interpretation of the results and presentation of the findings.

Research team

The research was undertaken by a multidisciplinary team of academics and clinicians based in the University of Nottingham and local UK NHS trusts in Nottingham.

Ethical approval

The initial project proposal and subsequent amendments received a favourable opinion from West Midlands – Staffordshire Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0874).

Chapter 2 Literature review

Objectives

To identify and assess the level and practical effect of current uncertainty around treatment options for children with Down syndrome and OME.

Methods

Given the recent NICE systematic review of the evidence for intervention in OME and the recognition that studies of OME in Down syndrome were very limited and of poor quality, this review was not designed to be a systematic review of all the evidence. Rather, the primary aim of this targeted review was to identify and assess the current state of literature regarding OME in children with Down syndrome to provide an informed background to the study and to contribute to the VOI analyses.

This review summarises the published research into glue ear in children with Down syndrome including the efficacy of interventions, cost-effectiveness and the barriers to recruitment and participation in health research, specifically in terms of studies incorporating RCT methodology.

Search strategy

The search strategy involved an electronic search of the following 15 electronic databases from inception through to June 2012:

-

The Cochrane Library

-

EconLit

-

Tufts Cost-Effectiveness Analysis (CEA) Registry

-

MEDLINE

-

PubMed

-

PsycINFO

-

EMBASE

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

-

Maternity and Infant Care

-

PsycARTICLES

-

Web of Science

-

Web of Knowledge (WoK)

-

British Psychological Society (BPS)

-

American Psychological Society (APS)

-

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD).

The search terms used included ‘children’, ‘Down* syndrome’, ‘otitis media with effusion’, ‘OME’, ‘glue ear’, ‘infant’, ‘research’. The terms were used in multiple combinations. Criteria for inclusion were (1) studies that were published in English; (2) studies that were published in peer-reviewed journals or government policy documentation; (3) studies that focused on children with Down syndrome who were experiencing OME; (4) studies that demonstrated the efficacy of treatments for OME (including surgical procedures such as grommets, adenoidectomy, HAs, antibiotics and any other appropriate treatments); and (5) RCTs that involved children with Down syndrome.

Criteria for exclusion were (1) studies that were focused on other forms of otitis media (unless specifically relevant) or other hearing problems (e.g. sensorineural hearing loss); (2) studies that were focused on Down syndrome in the general population, not affected by otitis media (e.g. studies of motor development); (3) studies of otitis media not in the Down syndrome population or other relevant populations (e.g. general population); (4) studies that were published in the grey literature or letters; and (5) studies that were focused on adults and not children.

Inclusion

Publications identified from the electronic search strategy were scrutinised by title and abstract to determine inclusion. Those reporting evidence that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved, and read by one reviewer for final decision on whether or not the data would contribute. The reference lists of included publications were searched to identify any further relevant studies.

Data extraction

A narrative synthesis was adopted. It was expected that included studies would be heterogeneous owing to the broad nature of the review. Relevant articles were reviewed to identify the topic of the article, the results and the methods used.

Results

The literature review confirmed the findings of the NICE report,17 in that there is a paucity of research/literature concerning the treatment options and effectiveness of such treatments for OME in children who have Down syndrome. No systematic reviews specifically concerning the efficacy of OME interventions in children with Down syndrome were identified. For example, Browning et al. 21 in their evaluation of RCTs on the efficacy of grommets (or ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with OME acknowledged the exclusion of Down syndrome from clinical trials, referring to participants with Down syndrome to note only how RCTs excluded them as a group.

Prevalence

Prevalence rates of glue ear at various ages have been reported as 59%,11 54.9%,12 77%,13 68%2 and 93%,2 as detailed below.

Schwartz and Schwartz11 investigated 39 non-institutionalised infants and children (mean age 3.1 years) with Down syndrome in the USA during the summer period and found that 59% showed evidence of ‘at least unilateral middle-ear effusion’.

In a survey using parent questionnaires and interviews in Australia to explore health problems and checks in 204 children with Down syndrome, Selikowitz12 reported that a glue ear diagnosis had been made in 112 children (54.9%).

Tomasevic13 reported a total population of 93 children, aged 18 months to 18 years, with Down syndrome, in Oxford, UK. Glue ear was diagnosed in 54 children (77%) and grommets were inserted in 29 children (54% of 54).

Barr et al. ,2 reporting findings from a prospective database set up since 2004 to capture the ear, nose and throat (ENT) health status of every preschool child with Down syndrome (aged 9 months to 6 years) in Greater Glasgow, accessing the community-based surveillance clinic, note that the prevalence of ENT problems is high in children with Down syndrome and that surgical treatment is frequently required. Between September 2004 and September 2008, data were available for 79 (91%) of the children. The prevalence of glue ear was 93% at 1 year old, although not all were symptomatic, dropping to 68% by 5 years old. During the time frame of the study, 37% of children were listed for surgery at some point, either adenotonsillectomy for obstructive symptoms or grommet insertion for OME. Barr et al. 2 recommend an active approach of regular ENT and audiology observation followed by early intervention, aimed at maximising long-term health and educational attainment.

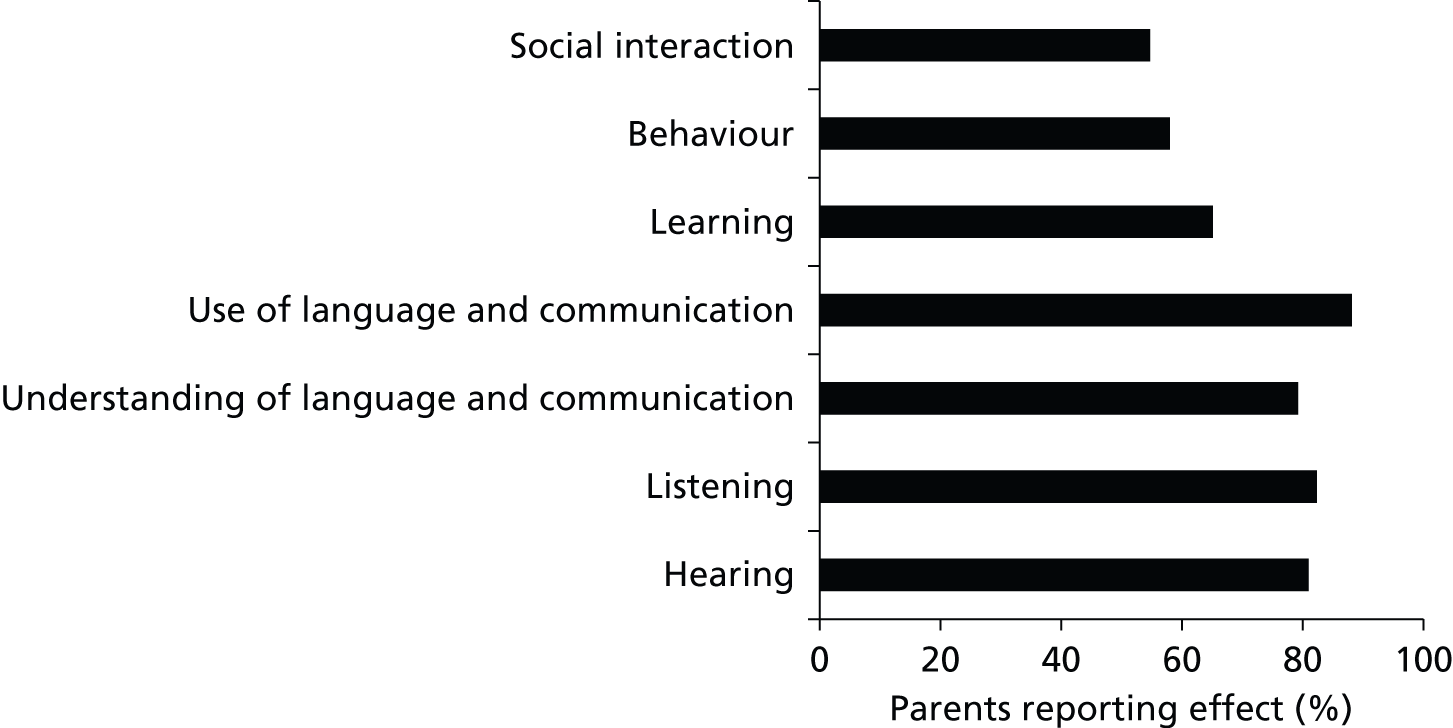

Outcomes

The hearing loss associated with glue ear in children who do not have Down syndrome mediates the emergence of difficulties in other areas. It may affect other developmental abilities in the long term and, for example, may hinder a child’s speech and language development, such that their understanding and production of language (fluency, grammar and syntax) are compromised. 24 Other cognitive and social abilities that may be negatively affected as a secondary consequence of glue ear are attention skills,25 behaviour,26,27 and learning and educational progress, particularly literacy and social interaction,28 with a consequent impact on quality of life. 29

Analyses of several unpublished large databases (OM8-30, Q-16, Eurotitis 2) provide valuable information regarding parental concerns for children with glue ear but without Down syndrome (M Haggard, University of Cambridge, February 2013, personal communication). The Q-16 database indicates that the concerns mentioned most frequently by parents and carers for children without the learning difficulties and medical problems associated with Down syndrome were hearing (20.8%) and school progress (20.1%) and five other categories each accounted for > 5%. However, it is not clear to what extent these findings would be altered for particular populations of children, such as those with Down syndrome.

For children without Down syndrome there may be differences between the views of parents/carers, teachers and ENT surgeons concerning the relative importance of the impact of glue ear on different domains of development. A questionnaire study28 surveyed the perception of the impact of glue ear over four areas involving language and education, hearing, behaviour and balance between three groups involving parents, teachers and ENT consultants. The results indicated that teachers weighed language and education more highly than parents and ENT consultants, but that parents weighed hearing more highly than any other group. ENT professionals were least likely to weigh hearing as important. Differences attributed to the importance of different outcomes by stakeholders may influence the path that treatment takes.

Management of glue ear

There are a number of potential treatments for glue ear noted in the wider literature, but the evidence base is equivocal and only surgery and HAs are recommended by NICE guidelines. 17

Many reviews are available regarding the effectiveness of intervention for glue ear in children who do not have Down syndrome. These include a clinical evidence review of all interventions,30 and systematic reviews on the effectiveness of treatment of OME in the general population of grommet insertion,21,31 adenoidectomy,32 autoinflation,33 antibiotics,34 antihistamines and decongestants,35 oral and topical intranasal steroids36 and zinc supplements. 37 Most refer to participants with Down syndrome only to note that they were excluded from RCTs. Few studies16,18,19 and no reviews report the effectiveness of interventions for children with Down syndrome who have OME.

Surgical intervention

Grommets/ventilation tubes

Grommets [also known as ventilation tubes, pressure equalisation (PE) tubes and T-tubes] are tiny tubes that are inserted into the eardrum. They allow air to pass through the eardrum, between the outer and middle ear, which keeps the air pressure on either side equal. The surgeon makes a tiny hole in the eardrum and inserts the grommet or ventilation tube into the hole. It usually stays in place for 6–12 months and then falls out. This is typical and not considered to affect a child.

There are conflicting reports in the literature of grommet insertion being successful as an intervention,16 and not successful,18 for children with Down syndrome who have glue ear.

Rovers et al. 20 conducted an individual patient data (IPD) meta-analysis of grommets used for glue ear in order to identify subgroups of children who might benefit more than others from having ventilation tubes inserted. Rovers et al. 20 noted the following:

Subgroups that might benefit more from treatment with ventilation tubes include those with speech or language delays, behaviour and learning problems, Down’s syndrome, or children with cleft palate. These could not be studied in this IPD meta-analysis as these subgroups were excluded in individual trials. The experience of many clinicians that these subgroups of children benefit more from treatment with ventilation tubes has not yet been evidenced in RCTs. As the question whether to treat these children with ventilation tubes is very relevant for clinical practice, future trials studying these subgroups are justified.

Reproduced from [Archives of Disease in Childhood. Grommets in otitis media with effusion: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Rovers M, Black N, Browning G, Maw R, Zielhuis G, Haggard M. 90: 480–5, 2005.] with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd. p. 48420

Davies38 reports an early study of hearing and middle ear dysfunction in 100 children with Down syndrome and the findings are contrasted with those of previous studies. Normal hearing was indicated in only 16% of the study sample. Decongestants and antibiotics were established to be of limited use, with surgery frequently carried out. Davis reports a number of problems with surgery including (1) the anaesthetic risks posed by children because of respiratory problems or congenital heart disease; (2) the difficulty of surgery caused by stenosis of the ear canal; (3) the ineffectiveness of the results in the long term; and (4) a heightened risk of post-surgery middle ear infection. Davis reports that 32 children had to have grommets inserted on up to three occasions, with only two children showing continued improvement after 2 years.

Selikowitz18 examined the short-term efficacy of T-tubes or grommets for secretory otitis media (SOM) in 24 children with Down syndrome, aged 6–14 years. Children were tested with audiometry at 6–9 weeks after having T-tubes inserted for bilateral SOM. There was no hearing improvement in 40% of ears compared with only 9% of 21 age-matched control children who also presented with bilateral SOM. The paper concluded that T-tubes for SOM in children with Down syndrome have a pronounced short- and long-term failure rate and recommended that this should be clarified with the parents prior to insertion. It was suggested that management should involve making sure that adequate intervention was provided to allow patients to hear as much as possible. Continuing hearing loss may necessitate the use of HAs.

Iino et al. 19 recommend a conservative approach, suggesting that the use of ventilation tubes should be reserved for cases in which hearing loss, secondary to middle ear secretion, is severe or when there are physical changes to the tympanic membrane (e.g. atelectasis). This was one of the studies reviewed by the NICE report,17 and was a longitudinal observational study following 28 children with Down syndrome, up to at least 7 years of age, and 28 age-matched control children who had T-tubes inserted for > 2 years (n = 50 ears in each group). 19 Children were assessed every month for 6 months post surgery and then thereafter every 2 months. At the time of the last visit, 11 out of 50 ears in the Down syndrome group and 39 out of 50 ears in the control group had normal or retracted eardrums. The authors define this as cured. Complications such as atelectasis, permanent perforation and cholesteatoma were found in 15 of the children with Down syndrome and six of the control children. Improvements in hearing levels to < 25 dB at the last visit were recorded for 10 out of 50 ears in the children with Down syndrome and 40 out of 50 ears in the control children. Iino et al. 19 concluded that the insertion of T-tubes was much less effective in children with Down syndrome than in control children. They made the following recommendation:

For the treatment of OME in children with Down syndrome, we propose that conservative management should be the approach of first choice and that indications for the insertion of tympanostomy tubes should be limited only when hearing loss due to middle ear effusion is in a severe degree and when pathological changes of the eardrum, such as adhesion and deep retraction pocket formation, are going to occur.

Reproduced from [International Journal of Pediatric Otorhindaryngology. 49(2). Lino Y, Imamura Y, Harigai S, Tanaka Y. Efficacy of tympanostomy tube insertion for otitis media with effusion in children with Down Syndrome. 143–9 Copyright Elsevier Science Ireland Ltd (1999)]. with permission from Elsevier. p. 14819

In the more positive study reviewed in the NICE guidelines17 conducted in Cincinnati, USA, Shott et al. 16 advocate, prior to the age of 2 years, an early and aggressive medical and surgical treatment of OME, which can involve grommet insertion. 16 This 5-year longitudinal study followed 48 children with Down syndrome every 6 months. Forty of the children (83%) required insertion of PE tubes because of chronic otitis media, with 55% requiring between two and four sets of PE tubes. After treatment (PE tubes and/or antibiotics) 97.7% of the children had normal to borderline hearing levels (undefined).

In a retrospective review of 29 children with Down syndrome aged 1–10 years referred for common ENT problems to a paediatric otolaryngology clinic in New Mexico, 13 children had PE tubes inserted bilaterally and 7 out of 26 procedures led to a complication. 39

Complications of grommet insertion are more common in children with Down syndrome. Tomasevic,13 in a series of 93 children in Oxford, reported that insertion and retention of grommets was an issue, with a repeat insertion rate of 59%. Otitis externa was noted in 28% and residual tympanic membrane perforation in 10%.

Adenoidectomy

Adenoidectomy is surgical removal of the adenoid, which is a focus of lymphoid tissue located in the space at the back of the nose above the soft palate. Adenoid removal has been shown to increase the benefit from grommet insertion in certain groups of children without Down syndrome. 40 Adenoidectomy, often in combination with tonsillectomy, may be performed in children with Down syndrome to relieve upper airway obstruction. This surgery is not without complications, in particular bleeding, and often specialist postoperative care is required, depending on the size and age of the child and on the severity of their airway obstruction.

Casselbrant et al. ,41 in a study of children without Down syndrome, concluded that adenoidectomy with or without tube insertion, provided no advantage to children aged 2–4 years with chronic OME compared with tube insertion alone, and was not recommended as first-line surgical treatment. In the UK TARGET trial (Trial of Alternative Regimens for Glue Ear Treatment),40 adjuvant adenoidectomy was reported to double the benefit from short-stay grommets in children without Down syndrome, aged 3–6 years, with persistent glue ear.

A retrospective review of the outcomes of adenoidectomy operations compared 27 children with Down syndrome (age 1–15 years) with 53 age- and sex-matched control children in the USA. 42 Long-term follow-up data were collected by telephone interview. Children with Down syndrome had less improvement than control children in middle ear effusion (23.1% vs. 68.0%) and also in symptoms related to nasal obstruction. Children with Down syndrome were 7.7 times more likely than control children to suffer chronic ear drainage.

Device intervention

Behind-the-ear hearing aids

Air conduction aids comprise an ear mould (to hold the aid in place and deliver the amplified sound into the ear canal) and a behind-the-ear digital aid. They can be used for any type of hearing loss. It is necessary to have accurate hearing thresholds measured to ensure the amplification is set appropriately. For some children with Down syndrome the shape of their outer ear can make it difficult to get good-fitting, secure ear moulds, which makes it difficult to keep the HAs in place. Wearing ear moulds can also exacerbate ear infections in some children, which can mean they are unable to wear their HAs until the infection has cleared.

No studies were identified that specifically explored the use of conventional behind-the-ear HAs in children with Down syndrome.

Bone-anchored hearing aid technology, including soft band

Bone-anchored hearing aids are bone conduction aids that utilise a permanent titanium implant to route sounds directly through the skull to the inner ear. They are suitable for patients with any type of hearing loss and who have problems wearing air conduction HAs. For children who are too young for a permanent implant owing to the lack of sufficient thickness of skull bone to hold the device or whose conductive loss is likely to be temporary, the BAHA can be worn on a softband that holds the aid firmly against the child’s head. Skull thickness in very young children and the quality of the bone (it is too soft) means that surgical placement of a permanent fixture is usually delayed until the child is at least 4 years old. Although the softband is easy to wear and put on, some children dislike wearing anything around their heads and do not tolerate the sensation of the band well. Mostly this can be overcome by a slow, structured introduction to wearing the band but, in some cases, the child does not accept it and an alternative has to be found.

Ramakrishnan et al. 43 report a retrospective, anonymised, cross-sectional survey in the UK using two assessment measures: the Glasgow Benefit Inventory and the Listening Situations Questionnaire (parent version) which were completed at least 3 months after the device was fitted. Of the 109 patients (age 6 months to 26 years), 22 were children with syndromes (or ‘syndromic’ children), nine of whom were young people with Down syndrome. Of these nine, six were fitted with a softband BAHA and three had implanted devices. Improvements were seen in both outcome measures. Ramakrishnan et al. 43 conclude that using BAHAs and softband BAHAs leads to appreciable improvements in quality of life for hearing-impaired children and young people, including those with Down syndrome, and suggest that there is major underutilisation of BAHAs in children with ‘skull and congenital abnormalities’ (e.g. Down syndrome).

Kunst et al. 44 report a series from the Netherlands of 22 patients (7–73 years) with moderate ‘mental retardation’, 12 of who had Down syndrome, fitted with implanted BAHAs. They also demonstrated improvements in domains assessed by the Glasgow Children’s Benefit Inventory (GCBI) and in learning and listening assessed by the Listening Inventory for Education.

McDermott et al. 45 report a study of 15 children with Down syndrome (aged 2–15 years) who were implanted with a BAHA over a 15-year period. All were long-term users, and benefits were also demonstrated in scores on the GCBI.

A survey46 of the 81 centres performing BAHA surgery in the UK in 2005 reported that 18 had provided BAHAs to patients with Down syndrome. Forty patients aged < 30 years were included and all received implantable devices. There was a high rate of complications (58%) but the authors concluded that BAHA was an effective option in patients with Down syndrome whose HAs or ventilation tubes had been unsuccessful. Softband BAHAs were not assessed in any of these last three studies. 44–46

Active observation/watchful waiting

A NHS Quality Improvement Scotland review47 suggested that WW, compared with immediate grommet insertion, does not lead to disruption in the development of language, behaviour or social interaction for children with persistent bilateral glue ear diagnosed before 3 years of age and with no other disabling health conditions. However, the Scotland review47 notes that it is unclear whether or not the ‘safe use of WW’ can be applied to other children who have already presented with language and behavioural difficulties at diagnosis. As children with Down syndrome are characterised as having development that is delayed (at the outset), it might be argued that the use of WW as a management strategy for glue ear in this group might indeed be problematic.

Antibiotics

Although glue ear is defined as being non-infective, in a number of cases bacteria are identifiable in the middle ear fluid. In such cases, antibiotics could be hypothesised to be effective. A Cochrane review34 concluded that the benefits were seen only after long-term administration of antibiotics, and that these benefits did not outweigh the risks of resistance. Studies of children with Down syndrome were specifically excluded.

Other treatments for glue ear

The sections above looked at studies that investigate the effectiveness of treatment options commonly used in health-care settings. There is little research concerning the benefits of these management options in children with Down syndrome. The limited empirical studies there are appear to focus mostly on surgical treatments in this group. However, there are other options that have been used to help manage glue ear in children without Down syndrome. These include autoinflation,33,48 decongestants/antihistamines,38 vaccines,49–51 topical intranasal steroids36,52 and zinc supplements. 37

Barriers to research

Of particular interest to this feasibility study are the views and opinions of parents and professionals concerning participation of children with Down syndrome in any future health research, particularly that involving a RCT design.

Most of the literature is concerned with recruitment to RCTs in a general population although one study did consider participation of people with learning disabilities. 53

Barriers identified by professionals

In the particular situation explored in this feasibility study, some professional groups (such as ENT surgeons) would be more often responsible for directly recruiting to a trial involving surgical intervention. However, professionals within other disciplines (such as paediatricians, audiologists and SLTs) may also influence the decision of a parent or carer as to whether or not their child should participate in a research trial. Although an individual’s experience of recruitment may vary, research suggests that there are a number of factors that may be important in deciding to recruit to a trial or encouraging a parent to agree to their child taking part.

A systematic review of 78 studies54,55 reported barriers to professionals recruiting to RCTs as lack of time, lack of training, concern about doctor–patient relationships, concern for patients, loss of professional autonomy, difficulties with the consent procedure, lack of reward and recognition, and the research asking a question that was not sufficiently interesting. Spaar et al. ,56 in a postal survey of 55 physicians in Switzerland, involved in a trial of rehabilitation options for patients with chronic obstructive airways disease, again highlighted time constraints as the most challenging barrier to recruitment, and the only other factor reported was difficulties with actually including eligible patients because the patient did not want to be randomised to a non-attractive treatment option or saw the process as too complex.

Caldwell et al. ,57 exploring the recruitment of children to RCTs with paediatricians in Australia in a qualitative study, conclude that balancing risk and benefit often resulted in clinician non-participation. Many paediatricians saw RCTs as a hindrance rather than a help to the doctor–patient relationship, which they valued highly, because they had to explain the concept of clinical equipoise. Negative elements were again more work, less money and lack of control. Paediatricians recognised that the health status of the child was an important influence for themselves and for parents. If the child has a poor prognosis or the parents are desperate for help, they may be less likely to accept randomisation that involved a placebo or ‘do nothing’ arm. Equally, even if there is genuine clinical equipoise, clinicians are reluctant to lose control of the intervention offered. Poor communication with researchers and lack of detailed information and feedback were seen as barriers to participation.

Barriers identified by parents

Prescott et al. ’s review54 identified uncertainty, additional demands, patient preference and concern about information and consent as barriers to patient participation.

Caldwell et al. ,57 exploring parents’ attitudes to children’s participation in RCTs in Australia, report that the perceived benefits include an offer of hope, the opportunity for better access to new treatments, professionals and information, meeting with parents in a similar situation and helping others. Perceived risks included side effects, being randomised to an ineffective treatment and inconvenience. Agreement to participation would be influenced by factors to do with the parents themselves (knowledge, beliefs and emotional response), with their children (health status, child preference), with the trial (the use of placebos) and with the clinician (recommendation, communication of information). The authors concluded that in order to increase parents’ willingness to agree to participation of their child there is a need to educate parents about trials, improve communication between researchers, clinicians and parents, increase incentives and decrease inconvenience.

The special position of parents as givers of proxy consent for their child is addressed by Shilling and Young. 58 This special position results in a dilemma for many parents between wanting to do the best for their child while also protecting them from any potential adverse events.

Nabulsi et al. 59 report data from a study of parents in Lebanon, defined as a developing country, exploring differences with the developed world literature. Findings were in fact similar, demonstrating that a parent is a parent regardless of the development status of their country. Facilitators in this study were reported to be direct benefit to the child, trust in the doctor or the institution, financial gain and positive previous experience. Barriers were lack of understanding of randomisation and complex consent forms.

A study by Robotham and Hassiotis53 addressed participation by people with learning disabilities and emphasised the importance of including people who were representative of the study population in the design stage of the research.

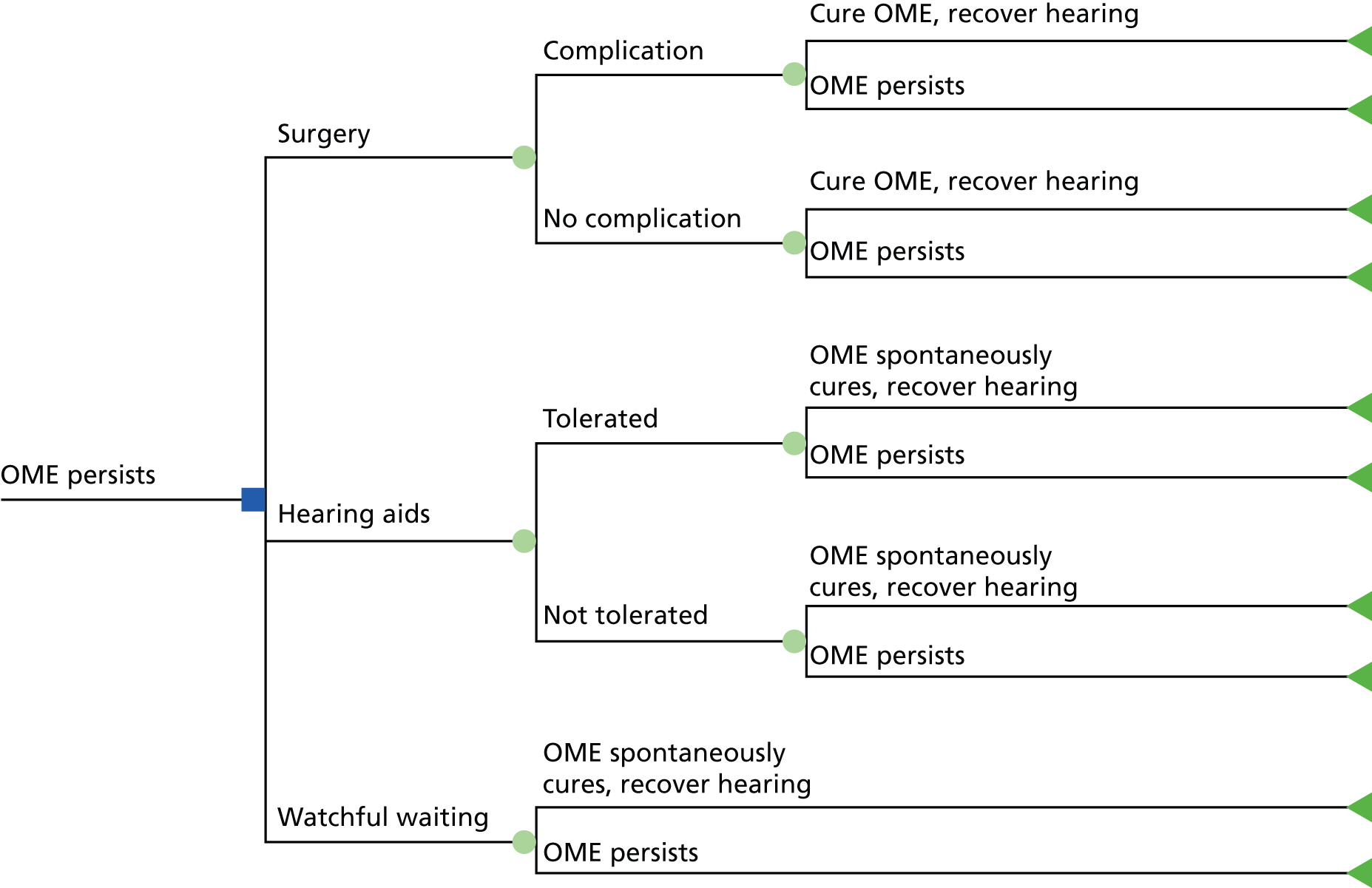

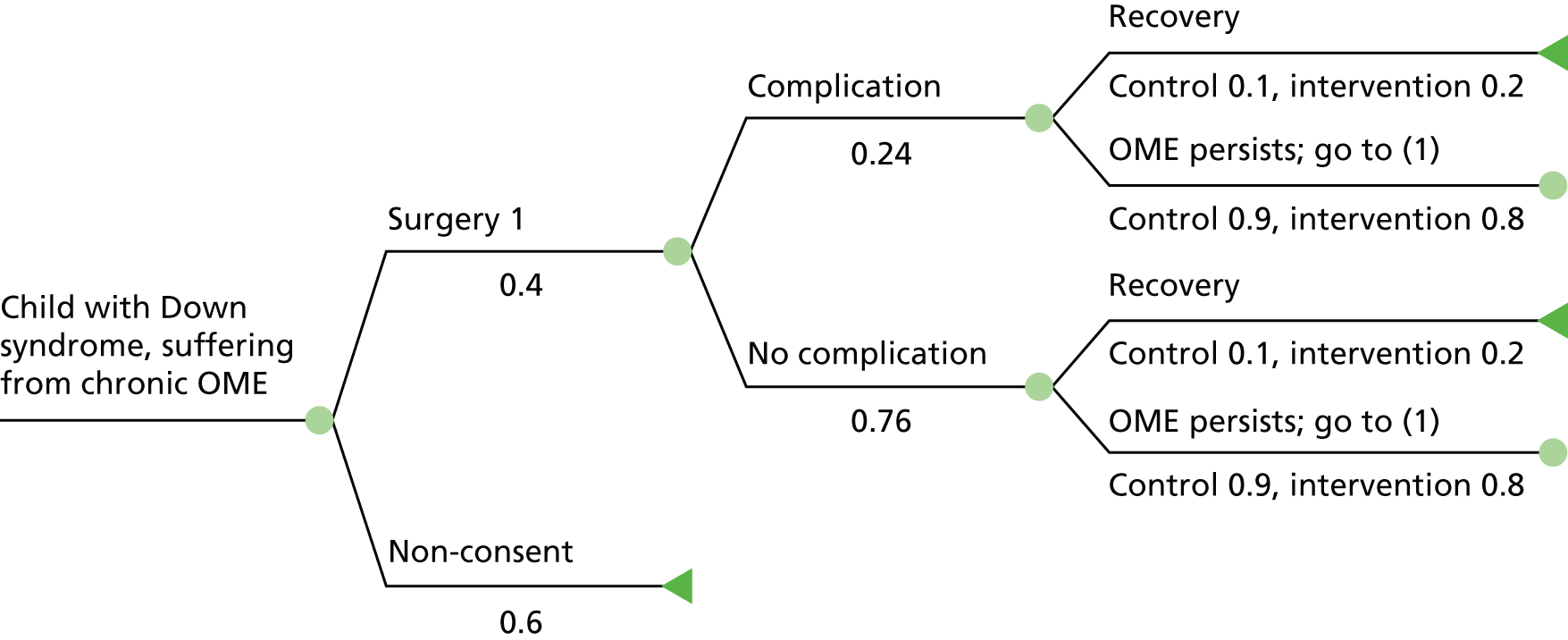

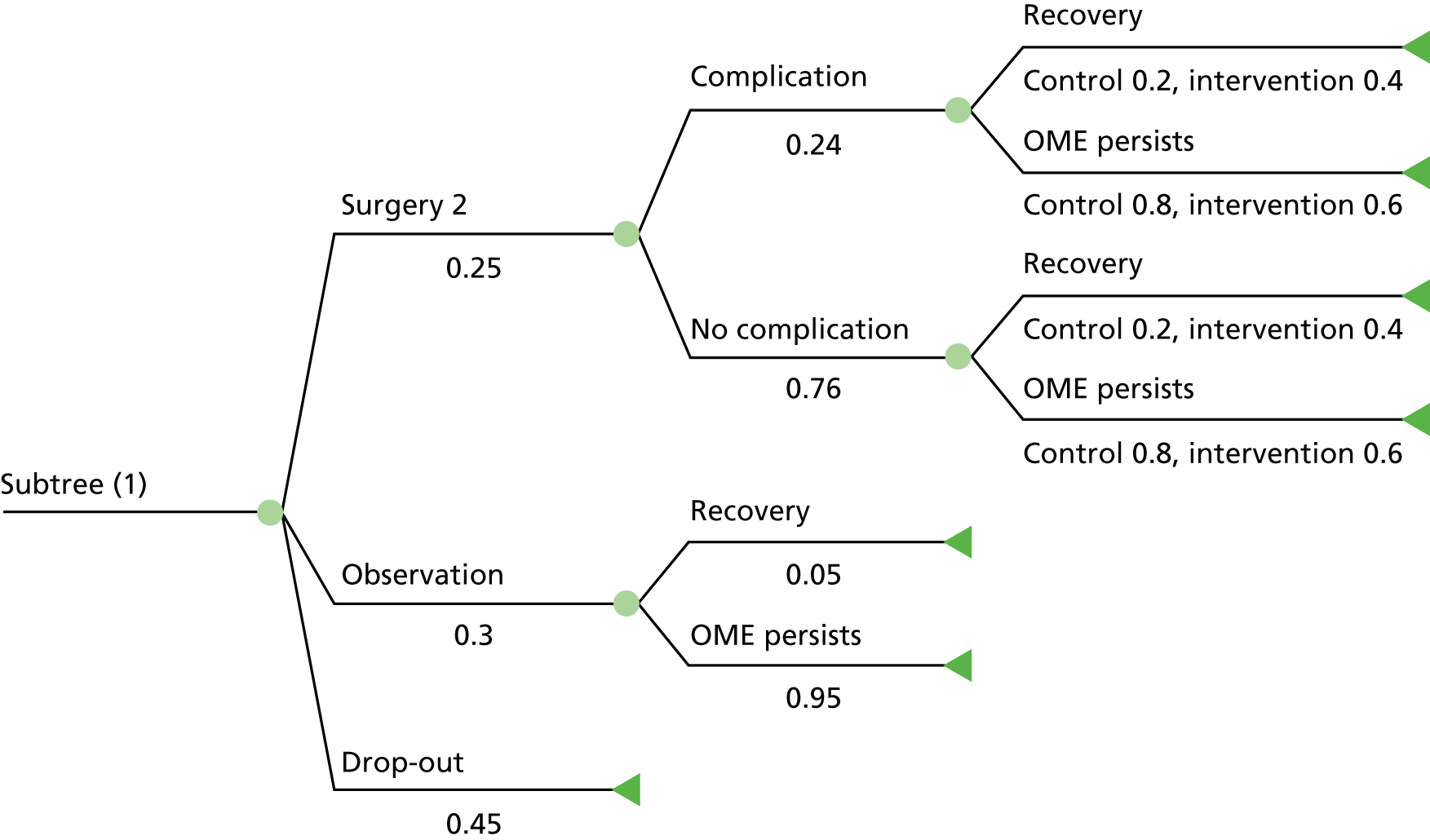

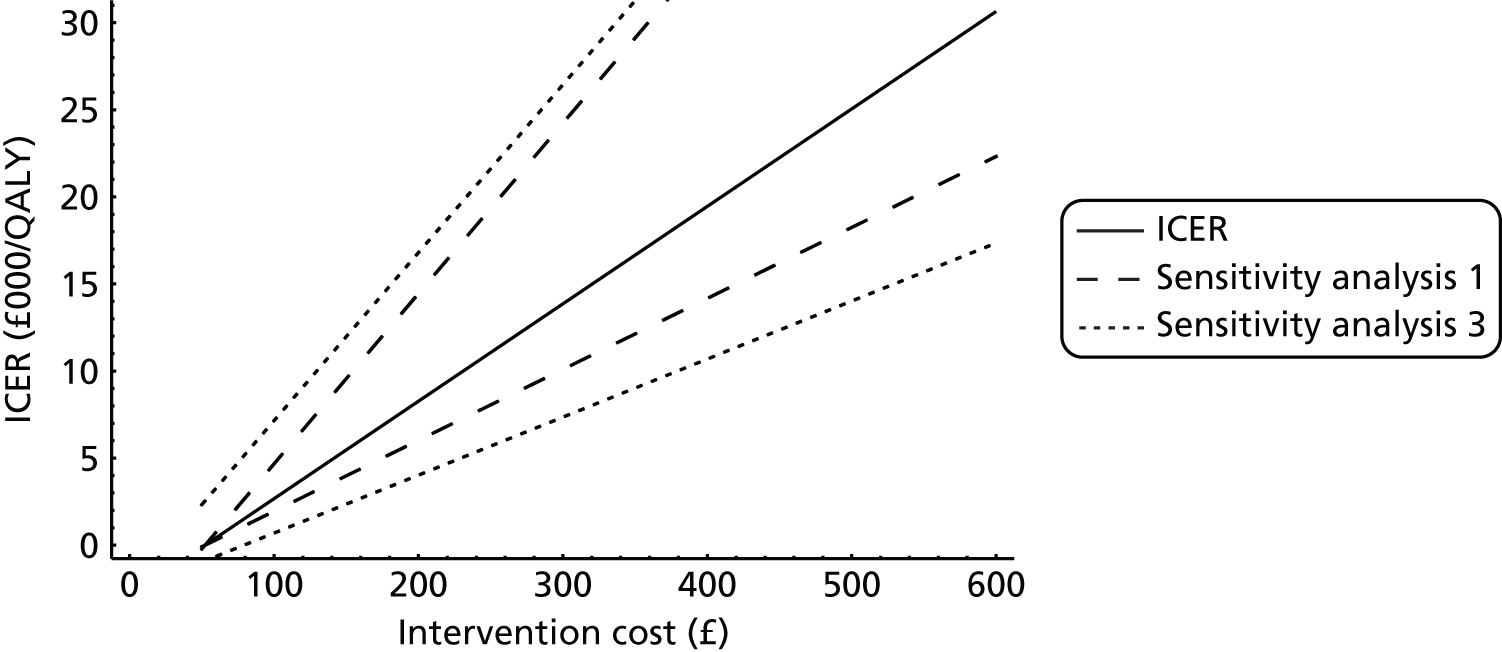

Cost-effectiveness

The literature search identified very little health economic literature on the subject. Ackerman et al. 60 constructed an economic model to estimate the costs associated with several childhood illnesses in children with Down syndrome. These were respiratory, gastrointestinal and related to the ears (otitis media and sinusitis). The estimated mean cost per episode of otitis media per child with Down syndrome was US$301 (in 1999). The study modelled the impact of a preschool intensive infection control programme. Before the intervention, the estimated cost of illness was US$1235 per child, which was reduced to US$615 per child after the intervention, giving cost savings of around US$620 per child. However, this cost savings estimate is spread over multiple conditions, only one of which is otitis media, therefore the cost savings attributable to a decline in otitis media are potentially less. Hellstrom et al. 61 reported that ventilation tubes were cost-effective; however, no details were given as to the economic analysis performed, and no incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was reported, giving no justification of this statement. Berman et al. 29 investigated a hypothetical case of a 13-month-old boy with bilateral middle ear effusion, using effectiveness data generated by a meta-analysis of clinical trials. The analysis was conducted from a private health insurance perspective, using 1992 Medicaid reimbursement rates to estimate costs. They estimated that the most cost-effective strategy was a corticosteroid plus antibiotic at 6 weeks after diagnosis, further antibiotics for non-responders at 9 weeks, and finally, ventilation tubes for non-responders at 12 weeks. It was estimated that this strategy cost US$600.91, increasing to US$1088.54 with a 6-month follow-up. The estimated difference in national expenditures between the most cost-effective strategy and sequential antibiotics was US$643.6M and the study recommended the implementation of the cost-effective strategy. However, from a UK perspective, this study is not particularly useful, as antibiotics are not a currently accepted method for treating OME, and therefore the results have little application to the UK. The only other model with relevance was the economic model developed for the NICE guidance. 17 This model estimated the cost-effectiveness of two surgical interventions – grommets and grommets plus adenoidectomy – against HAs and ‘do nothing’. The model used HAs as the base intervention, with zeroed benefits. The model allowed for repeated surgical interventions, with a child having up to three sets of grommets. However, once receiving a particular treatment, the child would always receive that one treatment – they would not be switched to another. The model estimated that HAs had an expected cost of £752, whereas the ‘do nothing’ cost was £187, the cost of ventilation tubes was £1208, and the cost of ventilation tubes plus adenoidectomy was £1354. HAs were dominated, as they had the same effectiveness as ‘do nothing’; meanwhile, when compared with the ‘do nothing’ intervention, grommets had an ICER of £16,041 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). This is below the general NICE threshold value of £20,000 per QALY, but the authors suggested caution when interpreting the results, as the ICERs rose to > £20,000 per QALY in the sensitivity analyses (SAs), in which the HAs were assumed to have some degree of effectiveness, and reported ICERs of approximately £13,500. The economic model developed for the guidance is applicable for only the general population, and the parameters and costs in the model reflect this. Therefore, the results of the economic model must be taken with a degree of caution when applying to the population with Down syndrome.

Summary

-

The evidence concerning effective and efficient treatment of glue ear specifically in children with Down syndrome is sparse.

-

Clinical decisions must currently be based on experience, and evidence in populations who do not have Down syndrome.

-

Other clinical and developmental problems in children with Down syndrome mean that standard interventions (grommets and HAs) are not necessarily the best management options or strategy.

-

There is a need for good-quality evidence to support intervention decisions in children with Down syndrome who have glue ear.

Chapter 3 Exploration of the views of parents

Objectives

To:

-

assess the feasibility of studying the options for management of OME (glue ear) in children with Down syndrome via a RCT or multicentre prospective cohort study

-

evaluate the willingness of parents to agree to randomisation for their children

-

determine relevant and practically measurable outcome domains for use in a definitive study

-

assess the feasibility and practical requirements for collecting these outcome measures.

Methods

Parents of children with Down syndrome aged 1–11 years were identified by paediatricians who were responsible for the health service provision to the children through lists held by the local children’s service.

Our catchment area included all three of the main centres of population in the East Midlands and south Yorkshire (Nottingham, Sheffield and Leicester). Inclusion of smaller services in Derby, Mansfield and Chesterfield provided complete geographic coverage of Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire. Areas were included on the basis of having a named person who had responsibility for children with Down syndrome and who had an accessible database of such children of the appropriate age. We accessed a total population known to community child health and/or hospital-based services in each area. All known families were initially identified but paediatricians did not contact families for whom they felt that circumstances were such that an approach would be distressing for the family, for instance if the child or another close family member was seriously or terminally ill.

We chose to invite participation from a general population rather than identifying families through a special interest association, such as the Down’s Syndrome Association, to enhance the generalisability of the results.

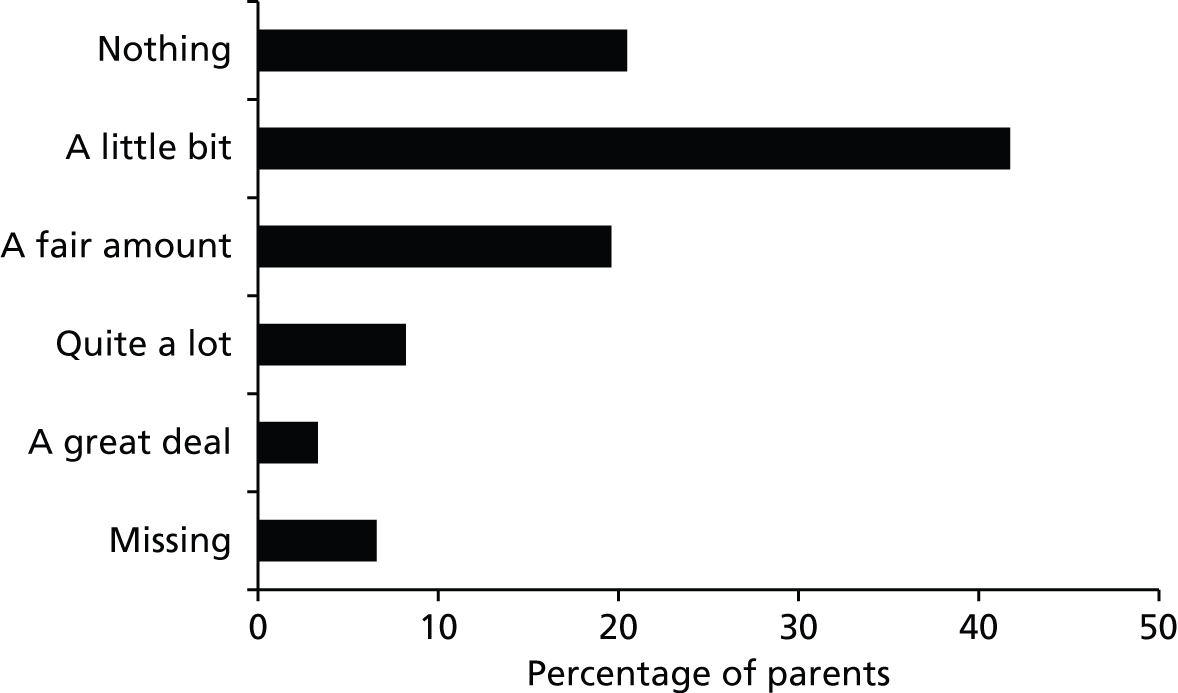

Questionnaires

The questionnaire for parents was developed with input from a number of sources, including databases developed from the TARGET trial (OM8-30, Q-16 and Eurotitis 2),40,62,63 existing OME literature,16,17 parent surveys from other areas of clinical/health research and feedback from the project steering/advisory group. The questions for the survey were also developed and refined via recursive feedback received from members of the multidisciplinary research team. These professionals had expertise in a number of disciplines, including speech and language therapy, paediatrics, epidemiology, psychology, audiology, ear, nose and throat surgery, and health services research. The information on the TARGET trial40 databases was obtained from Professor Mark Haggard, an advisor to the study. These databases are very important in the field and certainly relevant to any study on OME in children. They address issues of the relative importance of concerns expressed by parents. For example, in the Q-16 database (which looks at the impact of OME on children without Down syndrome), the concerns mentioned most frequently for children without the learning difficulties and medical problems associated with Down syndrome, were hearing (20.8%) and school progress (20.1%) and five other categories each accounted for > 5%. However, it is not clear how much this spectrum would be altered for children with Down syndrome.

The questionnaire for parents was piloted with two parents of children who have Down syndrome. These parents, who were members of the project steering group, were asked to give feedback concerning the design and scope of the questionnaire and their experiences of completing it. Feedback was generally positive, but one parent reported that certain sentences were ambiguous (owing to medical terminology or descriptions) and needed to be made clearer. Consequently, certain sentences were rewritten to aid clarity or were deleted. This improved the questionnaire’s accessibility. The questionnaire was also piloted with staff of the research unit who had children without Down syndrome but of an appropriate age.

The questionnaire (see Appendix 2) and a letter and information sheet explaining the project were sent to each family from a paediatrician known to them in May and June 2012 as a complete batch in all centres except Leicester, where the questionnaire distribution was staggered over several weeks. One reminder was sent to each family (unless they had returned the questionnaire and indicated their name and address) in June and July 2012. A poster advertising the existence of the project and offering families the opportunity to request a further questionnaire was sent to the consultant paediatricians in September 2012, together with a number of blank questionnaires. The paediatricians were asked to display the posters in clinical areas that children with Down syndrome were likely to attend. Some of the paediatricians also verbally reminded families about the project during consultations.

Questionnaires were returned directly to the research team and consent was implied and inferred by completion. Questionnaires were written in English and the front page included (in three locally common languages: Urdu, Punjabi and Polish) an offer to provide a translation of the questionnaire if required. Both closed, forced-choice questions and open-ended questions were included.

The questionnaire explored, for each respondent:

-

experience of glue ear and general health of their child

-

effects of glue ear experienced by their child

-

interventions and treatment received and his/her views on its effects

-

views on taking part in research and circumstances that would encourage or discourage participation

-

views on the importance of various outcome domains to them and for their children

-

demographic variables.

The fifth bullet point in the above list concerning the importance of various outcome domains was included to provide more detailed input into the design of any future trial.

The outcome measures we chose to explore covered a broad range of domains, and were relevant to children with Down syndrome, appropriate to the age range in which it would be practicable to conduct a trial, clear to non-professional respondents and describable by a label that is widely understood and of which the importance can be explicitly judged. Measurement of outcomes in a future trial would need to have the capacity to demonstrate reliable differences between treatment arms but more importantly to be seen as important to parents.

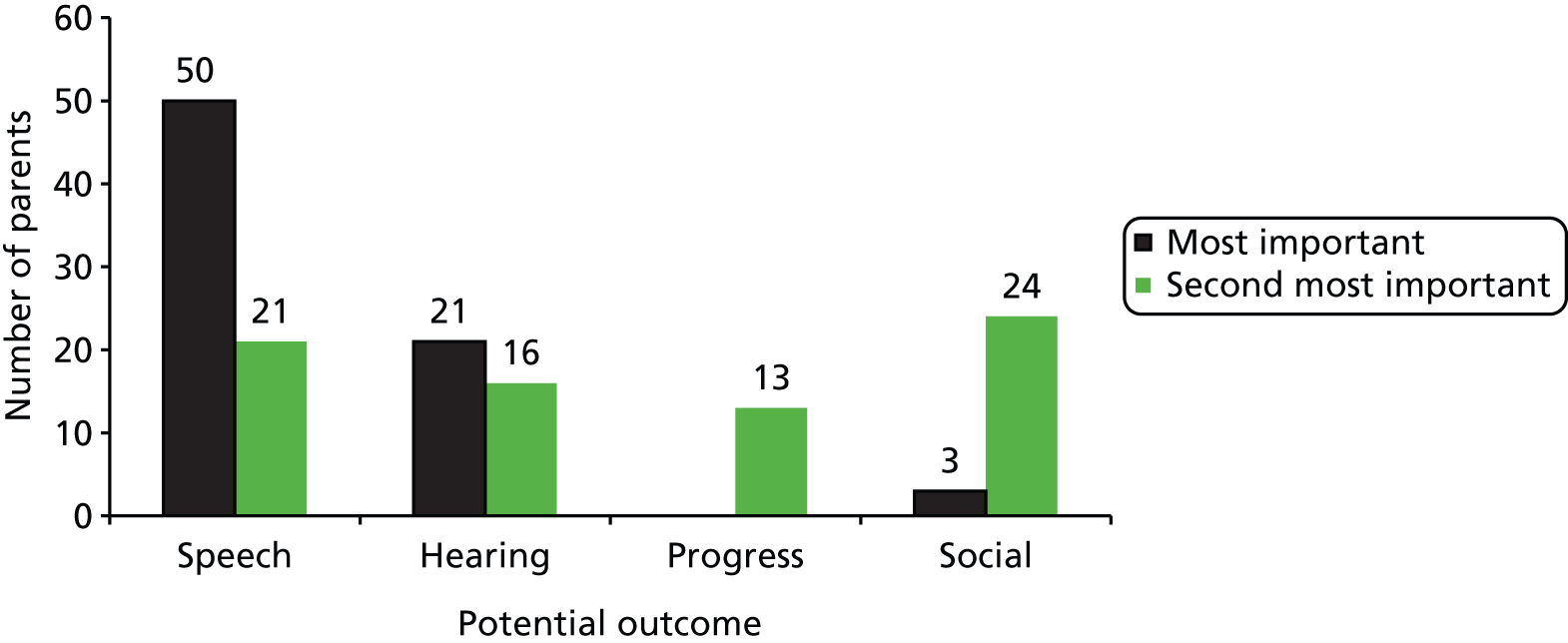

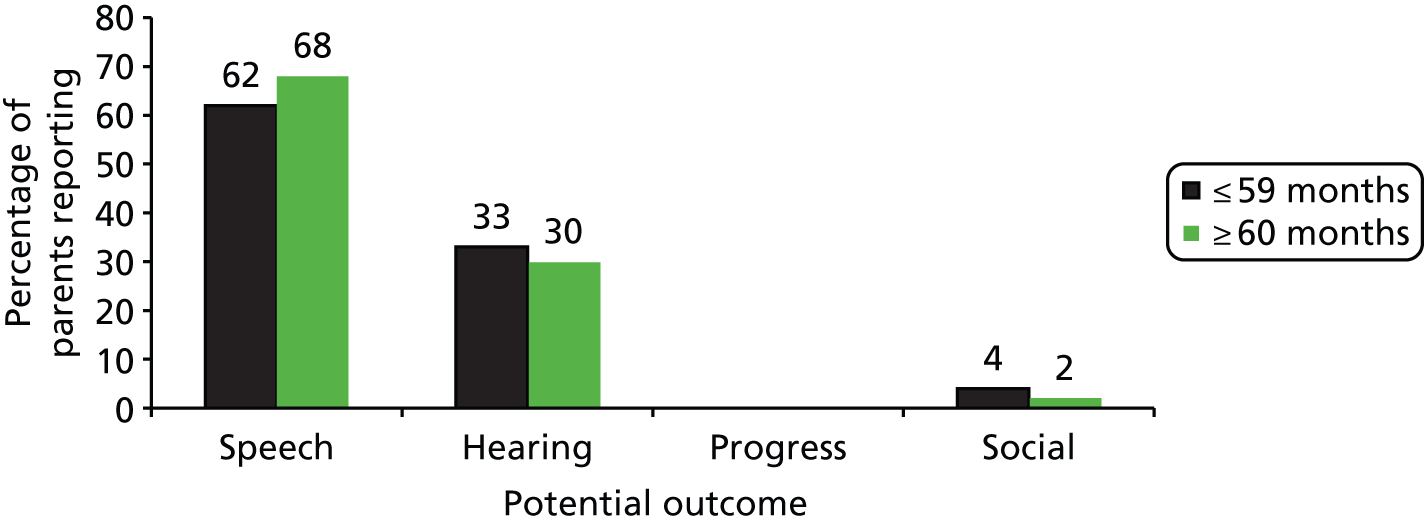

We offered a set of outcomes as a short forced-choice list, which was not comprehensive, but met the criteria above on the basis of general knowledge of the main effects of the disease in children without Down syndrome.

With these considerations in mind we decided to elicit judged importance for four domains: hearing, developmental/educational progress in nursery or school, speech/language and social participation. To elicit a little more information on the valuation hierarchy, we offered a first and second priority among the four.

The final question of the questionnaire asked if the family/parent was interested in taking part in an interview and/or focus group. If so, they were asked to provide contact details but, if not, the questionnaire could be returned anonymously.

Responses to closed or forced-choice questions are reported descriptively, and open textual responses have been coded via a thematic analysis and summarised.

Interviews

(See Appendix 3 for discussion areas for interviews.)

Greater depth and more detail about family experiences of treatment and attitudes towards future research were collected using qualitative, semistructured interviews. The rationale for questions asked in the interviews was informed by the ticked responses and written comments in returned questionnaires. To assess any difficulties with the questions asked (such as ethical concerns due to sensitivity of subject areas or problems with the recording equipment) the proposed questions and subject areas to be explored were piloted with a parent of a child with Down syndrome in the Nottinghamshire region in July 2012 at the research unit (NIHR Nottingham Hearing Biomedical Research Unit). This pilot interview lasted about 1 hour. On the basis of the pilot interviewee’s feedback, the interview duration, questions and subject areas were found to be appropriate both in terms of research aims and ethics. The recording equipment was found to be effective in recording a two-way conversation accurately enough to be transcribed without being intrusive in the context of the interview.

A selected sample of parents was identified from among those who indicated a willingness to participate further in the research. The sample included those with different experiences of treatment options, those with younger children and those with older children, those who were positive about future research, and those who were noting concerns about research. None of those expressing a willingness to take part in an interview requested an interpreter and all interviews were conducted in spoken English.

Parents were contacted by telephone by the researcher and an appointment for the interview was arranged. Each interview was undertaken on a single occasion, face to face, and all but one were conducted in the family’s home. Informed consent was confirmed at the beginning of the interview.

Questioning explored further the lines of enquiry in the questionnaire but offered greater scope for families to reflect in more detail upon their experiences. In addition, families were offered the opportunity to introduce and raise relevant topics that were not covered in the survey research. Views on randomisation and about the most appropriate domains for outcomes to be measured in any future trial were explored in detail. Interviews were conducted by a research fellow (LB) and audio-recorded with permission. Recordings were transcribed in full and data was handled using the NVivo computer package version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Focus groups

(See Appendix 4 for focus group discussion areas.)

Further qualitative data were collected during focus groups through which findings from both questionnaires and interviews were reviewed and refined. A second purposively selected sample of parents was drawn from those previously involved in the project (both questionnaire and interview stages). All parents previously interviewed who had indicated either ‘yes’ or ‘don’t know’ to an interest in taking part in a focus group (n = 18), and 15 parents who had not previously been interviewed but who had expressed an interest in taking part in a focus group, were invited by post or e-mail to do so and two dates were offered. Non-response was followed up by telephone.

Two focus groups were held on consecutive mornings at the research unit in Nottingham, each lasting 2–3 hours. Each focus group was led and facilitated by two members of the research team (PL and LB), audio-recorded with permission and transcribed in full. All parents taking part had an understanding of spoken English and interpreters were not requested. The descriptive statistics from the questionnaire survey and the analytic framework from the interviews acted as prompts for discussion during these groups. Parents were asked to further explore opinions and perspectives on treatment and on clinical research, including issues around randomisation, with the aim of determining a parental view on the design of any future study.

Parents taking part in interviews or focus groups received full details of the process when initially invited, and again from a member of the research team when the interviews or focus groups took place. All of those taking part in interviews or focus groups signed a consent form before taking part and consented to audio-recording.

Qualitative data analyses

Qualitative data were analysed to explore parents’ experiences of treatment, and to investigate their attitudes towards clinical research, including willingness to participate in clinical trials, strategies for recruiting participants and the acceptability of randomisation. These data may contribute to the generation of a tailored recruitment strategy for any future trial, and the development of bespoke information packs for trial participants that reflect parents’ understanding and concerns. Analysis followed the conventions of framework analysis,64–66 allowing each interview to be considered independently, and enabling the development and refinement of cross-cutting themes.

Framework analysis is a hierarchical, matrix-based method developed for applied or policy-relevant qualitative research. It is a highly structured, transparent and rigorous approach to qualitative data, which is well suited to research for which timescales are limited, and the goals of research are clearly defined at the outset (in this case supporting the development of a future trial). Broadly, framework analysis sees qualitative data mapped on to a thematic framework, from which it can then be interrogated to address information needs and research objectives. Through the process of building, revising and populating a thematic framework, findings can be generated that both directly address research objectives while also being strongly rooted in the responses of research participants.

In the present research, an initial thematic framework was constructed from the literature on clinical treatment and clinical trial recruitment, and the findings of the parent survey. It reflected the research objectives and contained several main themes: the challenges of Down syndrome and OME; diagnosis and treatment pathways; treatments – experiences and opinions; applied health research (AHR); and study design detail. Each main theme was subdivided into a number of topics. For example, theme 1 – The challenges of Down syndrome and OME – included three topics: symptoms, consequences and priorities for improvement. The adequacy of this framework was tested by coding a subset of the interview scripts and themes and subtopics were amended if, for example, they captured no data or an excess of data. New themes and topics were added if participants raised issues that were not otherwise evident in the analytic framework. For example, for theme 1, a topic of ‘Other un-categorised comments’ was added. Once the framework had been finalised, all interview data were mapped on to it – one table for each main theme, with topics as columns and individual cases as rows. The convention in framework analyses is to record summaries of original data rather than extensive chunks of text and this was adhered to in this analysis. Interview transcript page references were recorded to enable linkage to the original data (Table 1).

| Challenges of Down syndrome and OME (theme) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Symptoms (topic) | 1.2 Consequences (topic) | 1.3 Priorities for improvement (topic) | 1.4 Other uncategorised comments (topic) | |

| Int.1 |

|

etc. | etc. | etc. |

| Int.2 |

|

|||

| Int.3 |

|

|||

| etc. | ||||

Once all data had been ‘charted’ in this way it was assessed to address the research objectives. Broad summaries of themes (complete tables) and topics (individual columns) were generated and key experiences, opinions and attitudes were identified. Each key feature was marked as a subtopic and a final analytic framework constructed (see Appendix 5). Links to original data enable each theme, topic and subtopic to be developed more fully to illustrate a particular phenomenon or perspective.

Outcomes acceptability

One of the objectives of this project was to explore the relevant outcome domains for use in a future trial and whether or not the measurement of these outcomes would be practical and feasible for the relevant population.

The acceptability and value of measures of outcome within relevant areas were explored with parents (through questionnaires, interviews and focus groups) and with professionals (through a Delphi technique) (see Chapter 4) to inform the design of any future trial.

To assess outcomes in terms of communication and outcomes specifically related to glue ear we asked parents who had previously taken part in an interview and/or a focus group to review and assess three instruments designed to measure progress in outcomes. Two of these instruments were the MacArthur–Bates Communicative Development Inventories (CDIs) ‘Words and Sentences’ for older children and ‘Words and Gestures’ for younger children (available at www.brookespublishing.com/resource-centre/screening-and-assessment/cdi/). These instruments assess language and communication skills through parental report but are not designed specifically for children with learning difficulties or developmental delays. However, they assess a child’s understanding across a wide range of modalities and therefore could be useful with children with Down syndrome.

In terms of a tool to measure outcomes specifically related to glue ear, we invited parents to comment on the shorter OMQ-14 instrument (see Appendix 6), developed from the OM8–30 by Professor Haggard. This includes the items that best predicted quality of life in the TARGET study40 and is designed for children aged 3–9 years, but we felt that many of the questions were sufficiently generic that parents of younger children would be able to answer appropriately. An impartial review62 suggested that OM8–30 has the best psychometric properties overall of any instrument available, and it has a strong pathophysiological and developmental rationale and a growing set of applications (construct validity) plus a range of useful facilities. A particular attraction of the OM8–30 is that it has recently been mapped to the universal Utility Scale [via the standard Health Utilities Index Mark 3 (HUI3)] for generic quality of life. 63

The three instruments were sent to a sample of 17 parents who had taken part in either an interview or a focus group. They were asked to look through the instruments and answer three questions for each one:

-

Do you think the questions would apply to a child with Down syndrome?

-

Are there particular things about the questionnaires that would make it difficult to answer for a child with Down syndrome?

-

Are there things about the questionnaires that are particularly good for a child with Down syndrome?

Parent rating of importance

There is potential value, in terms of policy and dissemination, in documenting any large differences in the perceived importance of domains between OME in Down syndrome and OME in children without Down syndrome. To explore comparison between our data and the outcome measure instruments developed from the TARGET trial40 we engaged with Professor Haggard as a special adviser to the project. He provided analysis of the Eurotitis-2 database (∼2000 cases currently with OM8–30, approximately 900 in English and another 1100 in 15 other European languages) and of the open-ended response data from TARGET baseline on aspects of concern to parents within a category scoring system that showed high intercoder agreement. The latter were from > 1100 parents of children with uncomplicated but persistent OME and they establish adequate item coverage and good content validity for the measures of outcome used, as well as the weightings needed to combine facet scores into aggregates. To align the priority data between the two studies, we compared the relative weighting of necessary basic categories of outcome facets from our work with (1) the number of open-ended mentions of concern in uncomplicated glue ear and (2) the empirically optimal (regression coefficient) weights seen in the Dakin et al. mapping63 referred to above (see Outcomes acceptability).

Insofar as our qualitative research may show a similar list of facets to those seen in uncomplicated glue ear, a large body of research on glue ear, including the OM8–30 becomes applicable, perhaps with an altered set of weighting coefficients. If there is a considerable divergence of results, then the implication is that new measures would need to be developed to cover the outcome domains efficiently.

Results

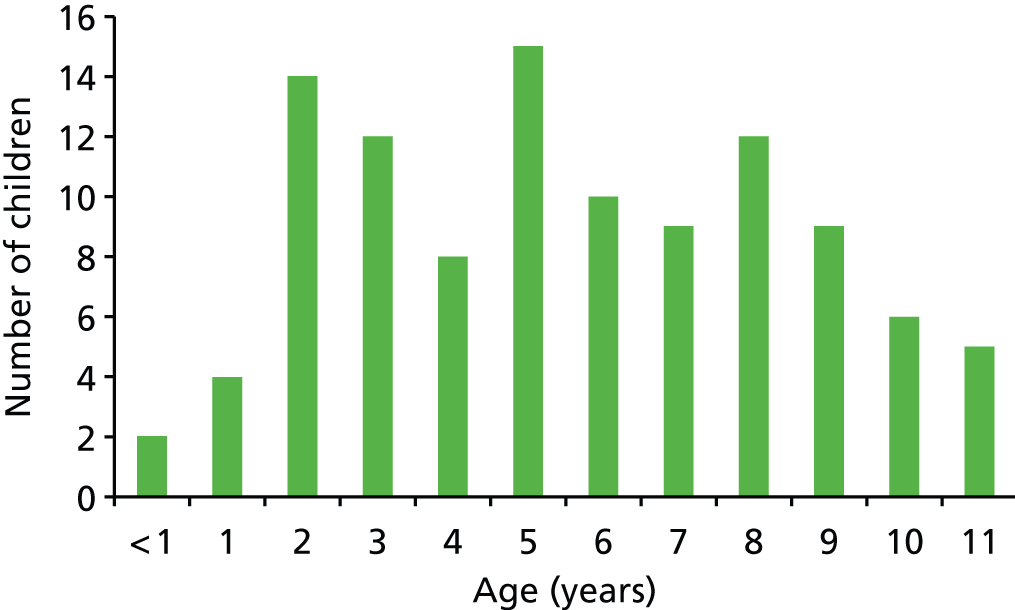

Representativeness

The population covered by this study is broadly based within the East Midlands (Nottingham, Derby, Mansfield, Chesterfield and Leicester) and Sheffield in south Yorkshire. For the purposes of assessing representativeness within the UK and the potential impact on a future study, it is appropriate to use the East Midlands as a basis for comparison. The population of the East Midlands is broadly representative of the diversity present in the wider UK population in terms of socioeconomic classification (Table 2),67 although there are some statistically significant differences in the classifications used here (Table 2).

| Socioeconomic classification | East Midlands (%) | UK (%) | Significance (p-value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Higher managerial and professional | 9.7 | 10.7 | NS |

| Lower managerial and professional | 21.6 | 22.2 | NS |

| Intermediate occupations | 9.3 | 10.0 | NS |

| Small employers and own account workers | 7.4 | 7.5 | NS |

| Lower supervisory and technical | 10.5 | 9.1 | 0.018 |

| Semiroutine occupations | 13.8 | 12.9 | NS |

| Routine occupations | 11.9 | 9.4 | 0.032 |

| Never worked, unemployed and not elsewhere classified | 15.7 | 18.1 | 0.002 |

In terms of ethnicity, Table 3 indicates a lower proportion of non-white individuals in the East Midlands than in England and Wales. All comparisons in the categories presented in Table 3 are statistically significant at the p < 0.05 level.

| Ethnicity | 2011 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| East Midlands (total 4,533,222) | England and Wales (total 56,075,912) | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| White: British, Irish, other white | 4,046,356 | 89.26 | 48,209,395 | 84.97 |

| Mixed: white and black African, white and black Caribbean, white and Asian, other mixed | 86,224 | 1.90 | 1,224,400 | 2.18 |

| Asian or Asian British: Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, other Asian | 293,423 | 6.47 | 4,213,531 | 7.51 |

| Black or black British: black Caribbean, black African, other black | 81,484 | 1.79 | 1,864,890 | 3.32 |

| Other ethnic group: Arab | 9746 | 0.21 | 230,600 | 0.41 |

| Other ethnic group: any other | 15,989 | 0.35 | 333,096 | 0.59 |

However, we consider these differences to be practically small and, given our initial selection of a total population sample, we are confident that the project design had the potential to provide information from a sufficiently diverse and representative population to be relevant in any consideration of the value of a future RCT.

For each of the following sections reporting questionnaire data, reference is made to the section of the questionnaire contributing the data (see Appendix 2).

Response rate

Questionnaire

A nominated consultant paediatrician with responsibility for the care of children with Down syndrome in each of the NHS paediatric services in Chesterfield, Derby, Leicester, Mansfield, Nottingham and Sheffield identified parents of children with Down syndrome, aged 1–11 years, whom they considered met the inclusion criteria for the project. The number of families identified in each centre is shown in Table 4.

| Centre | Questionnaires distributed | Responses after 3 weeks | Responses as of November 2012 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | |||

| Chesterfielda | 10 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Derby | 63 | 5 | 13 | 20.6 |

| Leicester | 114 | 10 | 42 | 36.8 |

| Mansfield | 21 | 2 | 4 | 19.0 |

| Nottingham | 107 | 12 | 38 | 35.5 |

| Sheffield | 77 | 10 | 25 | 32.5 |

| TOTAL | 392 | 39 | 122 | 31.1 |

The total response was just > 30%, which is lower than the 50% that we anticipated, despite postal reminders, posters in clinics and personal reminders from the paediatricians. The response rate across centres varied from 0% (of 10 questionnaires sent from Chesterfield) to 36.8% (of 114 questionnaires sent from Leicester).

All parents completed the questionnaire in English. One parent requested the questionnaire to be translated into Punjabi but did not then return the translated version.

In Nottingham the responsible paediatrician was a member of the research team (EM) and agreed to gather some basic anonymised information from her clinical records on the families who had not responded. We returned to EM a list of 20 Nottingham responders who had given us their name and address. In addition, we provided details of the child’s age and gender, number of siblings, mother’s age and first three digits of the post code for the remaining 18 responders. From this information, EM was able to identify 35 of the 38 respondents and provide some anonymous general information on the remaining 72 families who were sent a questionnaire (this number of 72 includes the three respondents who could not be identified). Table 5 compares the responders and non-responders in Nottingham by age of the child, and indicates that there is no difference in the age of the children in the responding families compared with the non-responding families (Mann–Whitney U-test; p = 0.088). If aggregated into preschool age and school age there is still no significant difference (Fisher’s exact test; p = 0.139).

| Age of child (years) | Responders | Non-responders | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | %a | n | %a | |

| < 2 | 3 | 8.8 | 10 | 13.9 |

| 2 | 7 | 20.6 | 4 | 5.6 |

| 3 | 4 | 11.8 | 7 | 9.7 |

| 4 | 4 | 11.8 | 5 | 6.9 |

| 5 | 7 | 20.6 | 9 | 12.5 |

| 6 | 2 | 5.9 | 6 | 8.3 |

| 7 | 1 | 2.9 | 7 | 9.7 |

| 8 | 1 | 2.9 | 10 | 13.9 |

| 9 | 2 | 5.9 | 6 | 8.3 |

| 10 | 3 | 8.8 | 6 | 8.3 |

| 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2.8 |

| Aggregated age group | ||||

| Preschool age ≤ 4 years | 18 | 52.9 | 26 | 36.1 |

| School age ≥ 5 years | 16 | 47.1 | 46 | 63.9 |

| Missing | 4 | 0 | ||

| Total | 38 | 72 | ||

We did not specifically ask for the mother’s age in the questionnaire – rather we asked for ‘your age’ from the person filling in the questionnaire. We can only assume, based on clinical experience, that it is more commonly the mother who answers such questionnaires rather than the father, even if the answers are discussed within the family.

In the group of parents who responded, 4 of the 32 with a known parental age (12.5%) were < 30 years old when the child was born. EM reports that routinely collected data for the last few years indicate that approximately one-third of mothers of children with Down syndrome in Nottingham are < 30 years of age when the child is born. This suggests that the parents responding to this survey in Nottingham were older at the time of the birth.

Interviews

Sixty-four respondents to the questionnaire (53.3%) expressed an interest in taking part in an interview. Twenty-four parents were approached and invited to take part in an interview. Twenty-three parents from 21 families were interviewed. For two interviews both parents were present. Each interview was conducted over 1–2 hours on one occasion in the family’s home. The distribution of parents participating by site is shown in Table 6.

| Site | No. agreeing to interview (% of parents/families completing the questionnaire) | No. of families interviewed (% of parents/families agreeing to be interviewed) |

|---|---|---|

| Derby | 5 (41.7) | 2 (40.0) |

| Leicester | 20 (48.8) | 4 (20.0) |

| Mansfield | 1 (25.0) | 0 |

| Nottingham | 22 (57.9) | 8 (36.4) |

| Sheffield | 16 (64.0) | 7 (43.8) |

| Total | 64 (53.3) | 21 (32.8) |

Parents were selected to receive an invitation to an interview to try to achieve (1) a balance of parents with children of different ages and (2) a mix of parents who had differing levels of knowledge about research, and both positive and negative views on future research. This information was indicated by their response to questions, which asked if parents would agree to their child taking part in research involving a RCT and/or an observational approach (see Appendix 2) (Table 7).

| Age of child (years) | How much do you know about research in general? | Imagine if you were asked to agree to your child taking part in a RCT comparing different treatments for glue ear – would you agree? | Imagine if you were asked to agree to your child taking part in an observational study comparing different treatments for glue ear – would you agree? |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | Quite a lot | Don’t know | Yes |

| 2 | Nothing | Yes | Yes |

| 2.5 | A little bit | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | A little bit | Yes | Yes |

| 3 | Nothing | Don’t know | Don’t know |

| 4 | A fair amount | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | A fair amount | Don’t know | Yes |

| 5 | Quite a lot | No | Yes |

| 5 | A fair amount | Don’t know | Yes |

| 5 | A little bit | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Nothing | Don’t know | Yes |

| 6 | A little bit | No | Yes |

| 6 | Nothing | Yes | Yes |

| 7 | Nothing | Don’t know | Don’t know |

| 7 | A fair amount | Don’t know | Yes |

| 7 | A fair amount | Not answered | Yes |

| 8 | A fair amount | Don’t know | Yes |

| 8 | Quite a lot | No | No |

| 9 | Nothing | Yes | Yes |

| 9.5 | A little bit | No | Yes |

| 10 | A little bit | Yes | Yes |

Focus groups

Eighteen of the parents who had taken part in the interviews and indicated a willingness to take part in a focus group were invited to do so. Seven declined to be involved. Two parents were unavailable for either of the dates offered and two cancelled nearer the time owing to unforeseen circumstances (e.g. child’s ill health). Seven parents were available on the suggested dates and five parents from five families attended.

Of the 15 parents who had not taken part in interviews but had expressed a willingness to take part in a focus group, 10 parents initially indicated that they would be free to attend. Four of these parents cancelled attendance nearer the time owing to unforeseen circumstances (e.g. having to attend a child’s school review). Nine parents from six families attended the focus group.

Six parents (from five families) attended the first parent focus group (a.m. Thursday 4 October 2012) and eight parents (from six families) attended the second (a.m. Friday 5 October 2012).

The distribution of parents by site is shown in Table 8.

| Site | No. agreeing to focus group (% of parents/families completing the questionnaire) | No. of families attending focus group (% of parents/families agreeing to take part in a focus group) |

|---|---|---|

| Derby | 2 (16.7) | 0 |

| Leicester | 13 (31.7) | 4 (30.7) |

| Mansfield | 0 | 0 |

| Nottingham | 18 (47.4) | 5 (27.8) |

| Sheffield | 8 (32.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Total | 41 (34.2) | 11 (26.8) |

Table 9 presents data on the 11 families taking part in the focus groups in terms of the age of the child and their views on future research.

| Age of child (years) | Already been interviewed | Would take part in RCT | Would take part in observational study | Knowledge of research |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Focus group 1 | ||||

| 2.5 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A little bit |

| 4 | Yes | Don’t know | Yes | A fair amount |

| 4 | Yes | Yes | Yes | A fair amount |

| 6a | No | Yes | Yes | Nothing |

| 9.5 | Yes | No | Yes | A little bit |

| Focus group 2 | ||||

| 2.5a | No | Yes | Yes | A little bit |

| 4.5 | No | Yes | Yes | Not answered |

| 5 | No | Don’t know | Yes | A little bit |

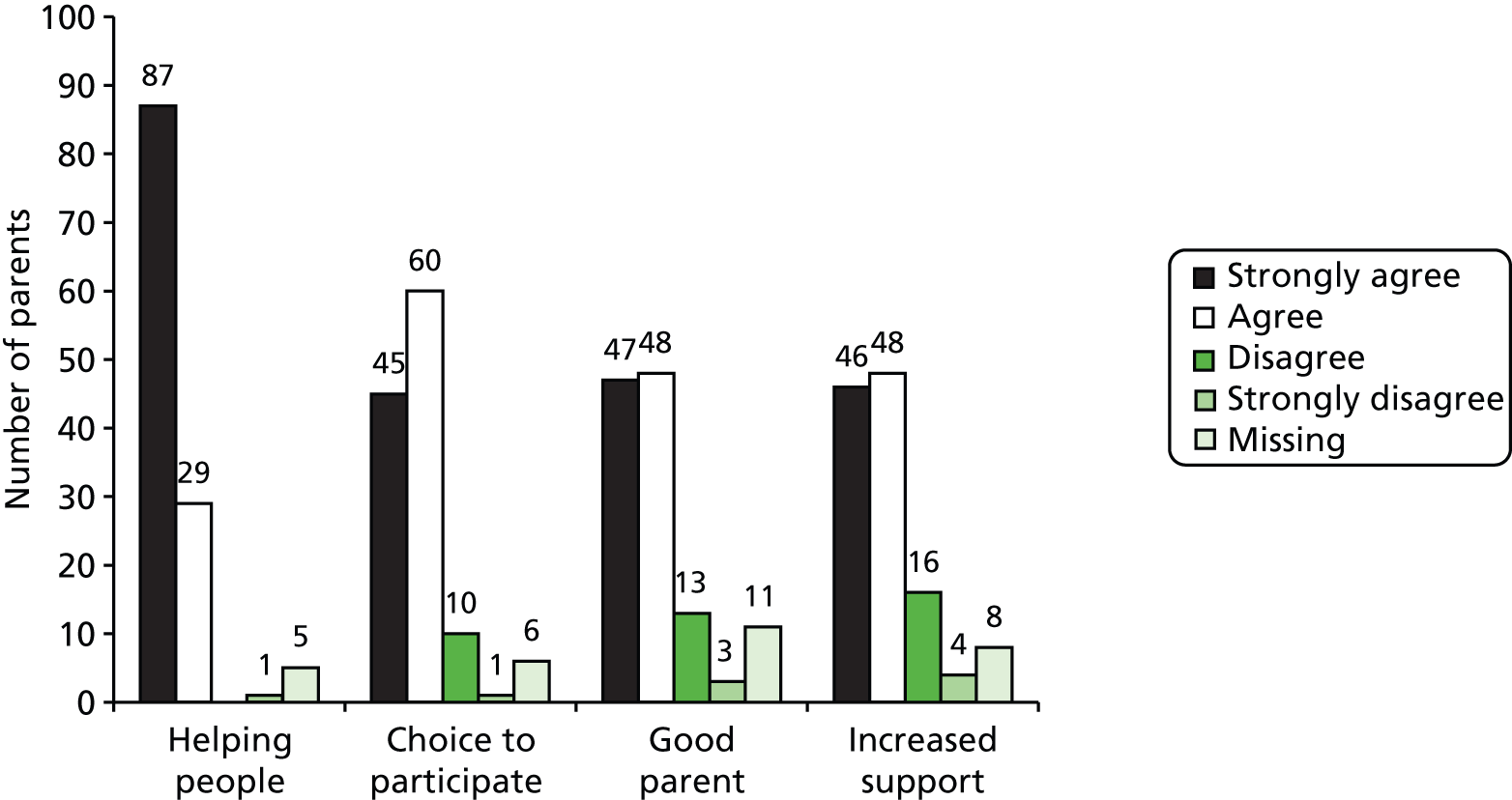

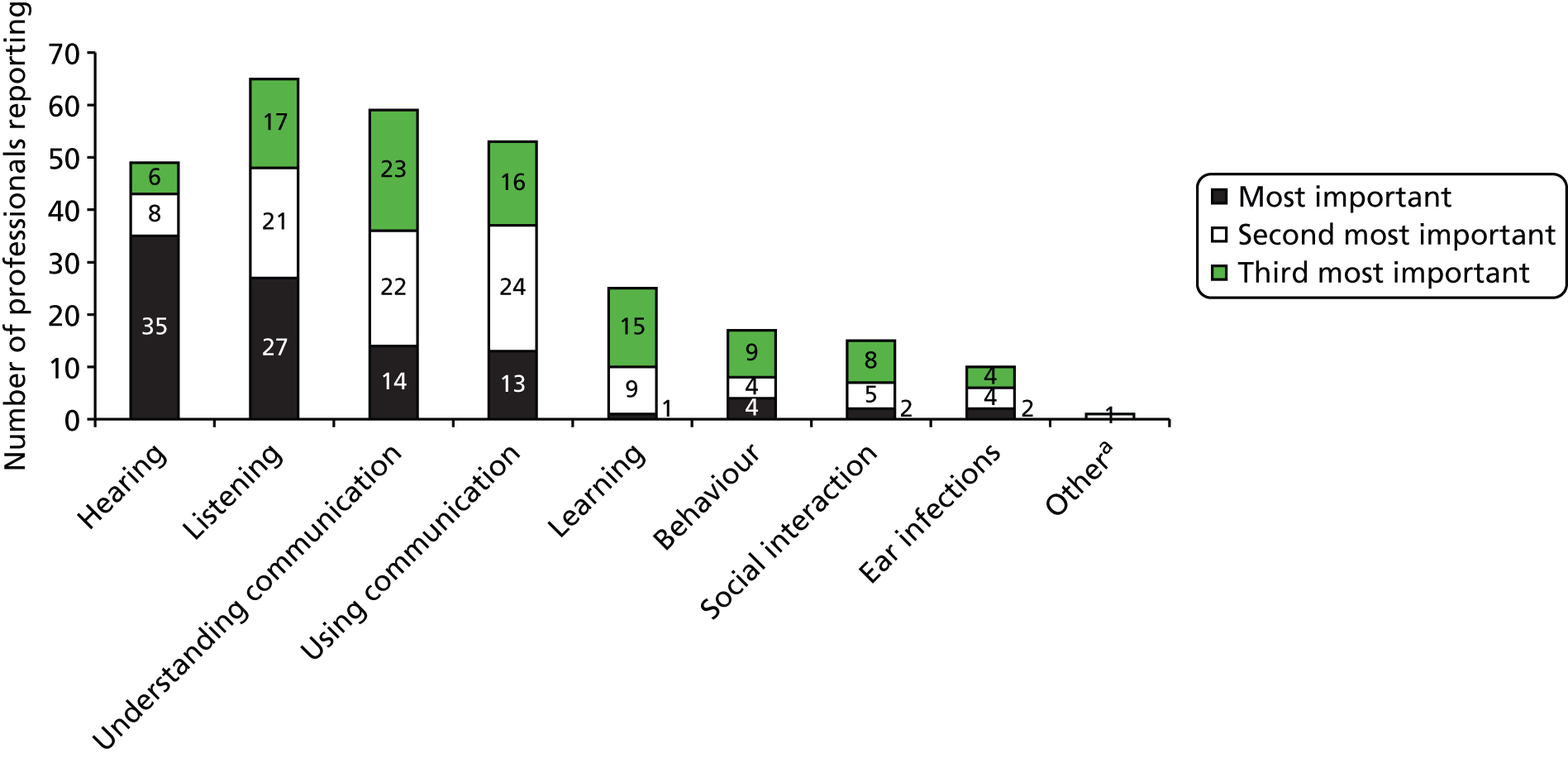

| 6 | No | Yes | Yes | A little bit |