Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/06. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The draft report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Livingston et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

The frequency of dementia will rise dramatically over the next 20 years because of increased longevity. In the UK, 700,000 people currently have dementia (> 1% of the entire UK population), and this figure is projected to reach over 1 million by 2020 and double again in the 20 years after that. 1,2 Dementia affects the person with the illness, his or her family and society through increasing dependence and challenging behaviour. In the UK, dementia care is currently estimated to cost £23B per year and costs are projected to treble in the next 30 years as the number of older people increases;2,3 for comparison, the entire NHS budget is currently £96B per year. England’s National Dementia Strategy4 emphasises that ‘Family carers are the most important resource available for people with dementia’ (p. 12). Families and individuals bear the biggest financial burden; two-thirds of people with dementia live at home, receiving most of their care from family carers, who save the public purse more than £6B per year. 2

About 40% of family carers of people with dementia have clinically significant depression or anxiety, while others have significant psychological symptoms. 5,6 These symptoms are more common when the family carer is older, a woman, living with the person with dementia and reports greater carer burden and behavioural symptoms of dementia. 5,6 This impacts on the NHS as well as on patients and families, as carer psychological morbidity, in particular depression, predicts care breakdown and, therefore, institutionalisation,7,8 as well as elder abuse. 9 However, a recent report shows that levels of services and support for people with dementia and families are inadequate. 2 Specialist, individually tailored, psychological support to people with dementia and their family carers has been shown to reduce the rate of, although not necessarily the time to, care home admission in the USA, although there is no evidence in the UK. 10,11 Only multicomponent interventions have been shown to be effective in preventing institutionalisation. 11,12 Nationally, a reduction in care home placements would have huge benefits for society, because most older people want to continue living at home, and those who do live at home report higher quality of life (QoL) than those placed in care homes. 13 There are also economic benefits, for example, in reduced use of health services by carers suffering from psychological symptoms and, in particular, in reduced use of care homes, which are a very expensive resource.

Evidence for a coping-based psychological therapy for carers

In our team’s earlier systematic review of interventions to improve the mental health of carers, we identified, prior to starting this study, 62 references which met our inclusion criteria. 10 We found that behavioural management and coping strategy-based interventions had been efficacious, that interventions targeting individuals tended to work better than group interventions and that the minimum number of sessions of individual behaviour management which had been shown to be efficacious was six. Education about dementia by itself, group behavioural therapy and supportive therapy were not effective carer interventions. An earlier review had suggested that interventions which required active participation of the carers were more effective. 14 In a further systematic review of evidence about treating dementia carer anxiety, we found that cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and other therapies developed primarily to target depression did not effectively treat anxiety. 5 Preliminary evidence suggested that an intervention might be effective if it included relaxation techniques and other strategies to help carers actively find ways to manage caring demands rather than reducing demands by reducing contact and avoidance. Overall, while evidence is promising, it is scant and of low quality, and further randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of interventions for carer psychological health in dementia are required. 15

The Coping with Caregiving programme

The Coping with Caregiving programme16,17 was developed in the USA as a group intervention. It is a manual-based, psychological intervention delivered in weekly group sessions. It was comprehensibly evaluated in the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health project, which recruited carers from a range of clinical and community sources in the USA; depression scores were significantly decreased in treatment groups compared with controls in all of the studies16–19 and self-efficacy scores were increased. 18 Although the impact of this therapy programme on rates of institutionalisation has not been tested, a recent systematic review finds that there is some evidence that carer support can reduce institutionalisation and that therapies such as the Coping with Caregiving programme, which include problem-solving strategies and offer carers a choice of support strategies which can be tailored to their individual needs, are most effective. 11

Delivery of therapy

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recognises that psychological therapy for dementia family carers should be a key component of high-quality dementia care:20 ‘Carers of people with dementia who experience psychological distress and negative psychological impact should be offered psychological therapy, including cognitive–behavioural therapy, conducted by a specialist practitioner’ (p. 40). However, the report noted the paucity of evidence in this area, and recommended that research is needed to address the question: ‘For carers of people with dementia, is a psychological intervention cost-effective when compared with usual care?’ (p. 45). Our team’s systematic review found only one study of the cost-effectiveness of a therapeutic approach [similar to the StrAtegies for RelaTives (START) intervention] for supporting carers. 20,21 It examined the cost-effectiveness of a modular, multicomponent intervention delivered in carers’ homes, in three sessions by telephone, supplemented by five group sessions (five or six carers in each) delivered by telephone. Focusing on hours of caregiving, the authors found a significant difference over the 6-month study period, with carers in the intervention group having more time to dedicate to activities unrelated to caregiving, which has potentially positive impacts on emotional well-being and QoL. 22,23 Therefore, more evidence is needed of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions for supporting caregivers.

Rationale for new therapy in the NHS

Although the efficacy trials discussed above have shown promising reductions in family carer morbidity, there are no manual-based therapies currently available for dementia carers in the NHS, nor is there an evidence base to demonstrate whether or not such standardised psychological interventions can be realistically, effectively and economically delivered to family carers within NHS services. A therapy which is needed by many NHS consumers that can be effectively implemented only by clinical psychologists is unlikely to be economically viable. However, too little professional training is unlikely to be helpful; a recent unstructured, non-manual-based befriending programme delivered by ex-carers was ineffective in reducing anxiety or depression. 24

The UK national agenda is to have a stepped care approach to improve access to psychological therapies in which less intensive therapy is delivered by psychology graduates supervised by clinical psychologists. 25 In this study, we used similar delivery infrastructure; we anticipated that a psychological therapy specifically tailored to the emotional, practical and information needs of carers could have significant population benefits, including greater carer and care recipient well-being and decreased statutory care costs. Our therapy was delivered by psychology graduates, trained and supervised by the coapplicant experts in psychology, carer involvement, nursing and psychiatry, all of whom work in the NHS. Our intervention was as suggested by the evidence: individual, manualised, with different elements, required active participation, incorporated relaxation and was based on the US Coping with Caregiving programme.

Through our clinical and personal involvement in caring for people with dementia, we are aware that it can be difficult for carers to attend groups held outside their home at one specific time because of their caring commitments. There is evidence from systematic reviews that therapies individualised to the carer receiving them are most effective in delaying institutionalisation,11 and that individual behavioural therapies are more effective than group interventions in reducing carer morbidity. 10 Therefore, with the authors’ agreement, we adapted Coping with Caregiving for NHS use as an individual therapy. As a result, sessions were quicker to deliver because, in groups, time is needed for all group members’ problems to be discussed; thus, the number of weekly sessions required decreased from 13 to 8 after piloting.

Chapter 2 Objectives

We carried out this RCT to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the manual-based individual therapy for dementia carers delivered by psychology graduates compared with treatment as usual (TAU) in the short (up to 8 months)26,27 and longer term (up to 2 years).

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial registration

This trial is registered as ISCTRN70017938. The full protocol is available online.

Trial design

The study is a randomised, parallel-group superiority trial, with blinded outcome assessment, recruiting participants 2 : 1 to intervention and TAU to allow for therapist clustering.

Patient and public involvement

Shirley Nurock, a former family carer working with the Alzheimer’s Society, contributed to the design of the study at the application stage and commented on the study as part of the Trial Management Group throughout, including the information sheet. Lynne Ramsey, a family carer, who was then in a Dementias and Neurodegenerative Disease Research Network (DeNDRoN) group, was a member of the steering group and helped to make decisions about the study. U Hla Htay, a family carer, who we initially met as a University College London MSc student, contributed to the Data Monitoring Committee.

Participants

Eligibility criteria for participants

We included family carers of patients with dementia referred in the previous year who:

-

provided emotional or practical support at least weekly

-

identified themselves as the primary carer of someone with dementia not living in 24-hour care.

We excluded family carers who:

-

were unable to give informed consent to the trial

-

were currently taking part in a RCT in their capacity as a family carer (not just as an informant)

-

lived more than 1.5 hours’ travelling time from the researchers’ base.

To help identify these potential participants, we completed the Mini Mental State Examination28 in carers aged ≥ 60 years. Participants who scored < 24 out of 30 were discussed with the investigators GL or CC to determine if the low score was related to cognition, mood or education. If carers were judged to have dementia, they were not included in the study and the referring clinician was informed. This occurred only once in the study.

Settings and locations where the data were collected

Participants were recruited through three mental health trusts: Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust (CIFT), North Essex Partnership Foundation Trust (NEPFT) and North East London and Essex Foundation Trust (NELFT) Admiral Nurse Service. We also recruited from a neurology clinic at University College London (UCL) called the Dementia Research Centre (DRC), a tertiary service whose referrals include a high rate of people with young-onset dementia. Although we had planned to recruit from Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health Trust, the trust refused to provide extra treatment costs and we did not recruit from there. The sampling frame encompassed urban, suburban and rural areas and ethnic and social class diversity. Recruitment was assisted by North Thames DeNDRoN.

Referrals and recruitment procedure

Prospective participants were initially approached by a clinician they knew and given or sent an information sheet. Those interested in participating were then referred to the research team. The referral gave the name, sex and relationship of the carer to the patient, as well as the patient’s sex. The researchers were divided into two teams (A and B). The team that was to carry out blinded assessments for this client (e.g. A) telephoned the client 24 hours or more after they received the information sheet. The team member answered any questions and then arranged to meet those who thought they wished to take part, to obtain their informed consent and complete the baseline assessment before randomisation. Recruitment of carers to the trial commenced on 4 November 2009 and finished on 8 June 2011. The first 4-month follow-up took place on 4 March 2010, with the final 8-month follow-up on 7 February 2012 and the final 24-month follow-up on 7 June 2013.

Randomisation

The assessing team member gave the details of those enrolled to the trial manager, who entered them into the online randomisation system. Randomisation to intervention or TAU was carried out using an online computer-generated randomisation system. Randomisation was stratified by trust using random permuted blocks. An allocation ratio of 2 : 1 (intervention to TAU) was used to allow for potential clustering effects by therapist in the intervention arm. 29 It was set up and maintained by an independent Clinical Trials Unit at the Institute of Psychiatry, King’s College London, and accessed only by the START trial manager and supervising clinical psychologist.

Blinding

Outcome assessors were blinded to randomisation status, but it was not possible to blind study participants. The researchers worked in two teams, each assessing outcomes for approximately half the participants and providing therapy to those allocated to treatment in the half of participants they were not assessing. These teams were in different rooms and had supervision separately so as to remain blinded. Assessors asked participants at the beginning of each interview not to disclose their allocation group.

The trial manager told the intervention team (B if the assessment team was A or vice versa) the result, but the assessment team was not informed of the outcome of randomisation. The participant was then telephoned by a member of the intervention team and informed that they had been allocated either to TAU and would be contacted for a 4-month follow-up (by the assessment team A, if the therapy team was A or vice versa) or to the intervention. If allocation was to therapy, an appointment was made for the first session of the therapy to start. Allocation within the individual team was according to workload.

Intervention

See Appendix 3 for the START manual.

Location of interventions

Participants were usually seen for assessment and for intervention in their own homes, although, if participants so requested, they were seen in other settings. In the intervention group, most participants were seen at home, but a minority were seen at UCL (n = 7) or the NHS trust’s offices (n = 13). One carer was seen both at work and at a local restaurant and another both at home and in the trust.

Development of the intervention manual

Dolores Gallagher-Thompson gave us permission to adapt the ‘Coping with Caregiving’ manual, a 13-session group therapy. We therefore used it to develop the START manual, an eight-session manual-based individual therapy programme adapted for UK use with individual family carers. The therapy was adapted by the project team, GL, PR, CC and DL, by considering UK usage of language and culture, brevity, and the fact that we were addressing individuals rather than a group.

We began by familiarising ourselves with the structure and content of the manual, which made use of the stress appraisal and coping response model. In this, stress is seen as the mismatch between primary appraisal (perceived demand) and secondary appraisal (perceived ability to cope and available resources and options, and principles from CBT).

Why change from group to individual intervention?

Carers face difficulties in attending a group intervention, as it can be impossible to make alternative care arrangements for their relative and to be available at a prespecified time. Individual therapy also has the advantage that it can be tailored to the specific problems faced by the carer, and our previous systematic review found that therapies worked better with individuals rather than groups. Individual therapies are quicker to deliver, as, in groups, time is needed for all group members’ problems to be discussed and, so, the number of sessions was decreased.

Reducing the number of sessions

We identified the key components of the intervention and began reducing the 13 sessions to eight shorter sessions. This was a collaborative process. At this early stage, care was taken to adapt the language and tone of the American manual to ensure that the language of the revised manual was suitable for its target audience and to ensure that it was written in a clear and accessible style. Although the content of sessions varied, each session followed a broadly similar structure: an introduction, a review of a homework task from the previous session (from session 2 onwards), one or more specific topics including worked examples and space for carers to identify their own examples, a stress reduction technique, a session summary and a homework task (e.g. keeping a diary of challenging behaviours for the following week).

In the original manual, the sessions were (1) stress and well-being, (2) target behaviours, (3) strategies for changing behaviour, (4) refining our behaviour plans, (5) behaviours and thoughts, (6) changing unhelpful thoughts, (7) communication styles, (8) communication and memory problems, (9) planning for the future, (10) more planning for the future, (11) pleasant events, (12) refining your pleasant events and (13) review and conclusion.

Having initially produced the eight-session manual, the team revised each session to ensure that the content was written in appropriate UK English, was without jargon, was comprehensive and included both theoretical components and exercises for the participants to work through their own examples and experiences. Attention was given to ensuring a balance between information provision and interactive exercises inviting the carer to reflect on their own resources and strategies for coping, as well as relaxation exercises. In the original manual, ‘planning for the future’ emphasised end-of-life care, but, as most of our participants were expected to be seen soon after diagnosis, ‘planning for the future’ also encompassed getting support from other relatives, increasing community services, considering power of attorney and planning for a care home. The carer could then identify priorities and work through the information which they felt would be most useful. We piloted the manual by the research assistants trying it with PR, GL, CC, DL and each other, and altered it whenever it did not flow, or was unclear or repetitive. The research assistants met in groups, practised delivering the sessions and provided oral and written feedback on how to improve the sessions and increase the accessibility and clarity of the session content.

This process was repeated until the researchers and therapists agreed that the sessions were ready for use. Sessions were practised with each other to ensure that all researchers had the same understanding of how to deliver the therapy. Two separate versions of the manual were written: one for the carer to keep and one for the therapist to use, which included additional prompts and guidance to the therapist. In addition to the text, pictures and images were included to make the manual more user-friendly.

At this point, the sessions were piloted by PR with a carer who would have met the criteria for inclusion in the study. After each session, the clinical psychologist provided feedback to the team on how both the process and content was received by the carer, including the ease of delivery and timing of the sessions and adjustments were made accordingly. Final versions of both the therapist and carer versions of the manual were then produced for use within the study.

The therapy took place in the carers’ preferred location, usually their home, without the patient in the room and at a time convenient to them. It was individually tailored to address the particular problems the carer was experiencing with the person for whom they cared. The therapy was carried out with an interpreter if the carer did not speak English fluently. Four participants needed translation, three of whom were randomised to the therapy sessions. The languages were Bengali (two carers), Farsi and Turkish (one each).

The eight sessions covered:

1. Psychoeducation about dementia, carer stress and understanding behaviours of the person cared for. This session discussed what dementia was and identified the difficulties faced by the carer. If the carer did not have any, we had examples of common problems. It introduced the idea of stress and how carers could recognise when they felt stressed.

2–5. Discussion of behaviours or situations that the carer finds difficult, incorporating behavioural management techniques including functional analysis; skills to take better care of themselves, including identifying and changing unhelpful thoughts; assertive communication; effective communication with people with dementia and promoting emotion-focused coping strategies and acceptance; and where to get emotional support and positive reframing.

6. Future needs of the patient, with information about care and legal planning specifically adapted to the UK. We discussed what they wanted to plan and who else they wanted to consult. We gave the carers information leaflets about making common decisions as individually appropriate. 30

7. Planning pleasant activities. This incorporated aspects of behavioural activation and reflected that many previous pleasant activities were impractical but that there may be many small enjoyable activities which still could be incorporated and the carer could add them to the day for either themselves or the person with dementia.

8. Maintaining the skills learned over time. This encompassed discussing which techniques and ideas the carer had found useful and making a written plan of what they would use in the future.

Each session ended with a different stress reduction technique session. Carers were given homework tasks to complete between sessions, including relaxation, identifying triggers and reactions to challenging behaviours, and identifying and challenging negative thoughts. The therapist and the family carer both had a manual, and carers filled in and kept their own manual. Our group audio-recorded relaxation exercises for use in these sessions and gave them to carers on a compact disc (CD). The relaxation techniques used were signal breath, focused breathing, physical grounding, guided imagery (three different versions), meditation and stretching.

We defined adherence to therapy after consulting with our clinical psychologist supervisor, on clinical grounds, as participating in five or more sessions.

Training and delivery

We employed and trained psychology graduates with no clinical training to deliver the intervention. Researchers in the two groups carried out assessments on carers having received training in taking informed consent, good clinical practice and all the assessment tools being administered. There was a strong practical focus in the training programme on how to deliver the therapy, potential clinical dilemmas, working with interpreters, empathic listening skills, effective use of supervision, safe working practice and when to ask for help. Throughout the training, a strong emphasis was placed upon the researchers guiding carers to where they themselves could get answers to their concerns or questions rather than feeling the need to provide specialised advice themselves within the session. We trained therapists to adhere to the manual and required them to demonstrate, by role-play, competence in delivering each session of the intervention.

Monitoring fidelity to the manualised intervention

Therapists recorded one therapy session per participant. We (PR, CC, DL and GL) devised a fidelity checklist for each session by considering the most important components of the session. The session to be recorded was selected at random by the trial manager using a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) formula before any interventions were carried out. This session was rated for fidelity to the manual by a therapist in the same team who was not involved in that participant’s intervention using the standard checklist. An overall fidelity score for each session was then given by the rater considering whether or not the therapist was ‘keeping the carer focused on the manual’. Possible scores ranged from 1, meaning ‘not at all’, to 5, meaning ‘very focused’. We planned to have two researchers rate independently initially while inter-rater reliability was established. Ratings were out of a possible five points. If fidelity scores were not high, the supervising clinical psychologist addressed this in supervision. This was the case for 7 out of the 131 recorded sessions, and often it was because carers had refused to participate in a particular aspect of a session.

Supervision

Following the recruitment and training of the psychology graduates the process of formal clinical supervision began. Our clinical psychologist, PR, met with each of the two teams (of three or four psychology assistants) for 1.5 hours of group supervision a fortnight. In addition to this group supervision, she was available for individual supervision, which either was requested by the psychology graduates on an ad hoc basis or, on occasion, was initiated by the investigators. Additionally, weekly team meetings with DL, GL and PR were held for the entire team, during which both procedural and clinical issues were addressed. The psychology graduates could approach one of the research team at any time if they had concerns or questions relating to their clients, for example if risk issues arose during a session.

A group supervision format was adopted as it was seen as the most effective use of available resources, with psychology graduates benefiting from both the professional expertise of their supervisor and the clinical experiences of their peers. It was hoped that the group format would maximise peer support both within and outside the supervision sessions and facilitate effective teamworking. The supervision format was tailored to reflect the specific needs of the START research project. During the course of the project, supervision performed a number of functions including case management, clinical skills development, monitoring the fidelity to the manualised intervention and ensuring safe practice with clients and staff support. Each of these functions is explored in turn below.

Case management

Once recruitment was under way and psychology graduates were fully trained, they held a caseload of approximately 4–6 clients for intervention. An important function of supervision was to ensure that all of these interventions were being managed effectively and appropriately. Therefore, in every group supervision session, each psychology graduate provided a brief update of his or her caseload, ensuring that clients and any related issues or concerns did not get overlooked, for example if there was a repeated pattern of cancellation or non-attendance that the psychology graduate had not identified. This aspect of supervision was extremely important as the psychology graduates had varied levels of experience and skill in managing their own caseloads and they were juggling delivering the intervention with offering baseline and follow-up assessments. This process also encouraged psychology graduates to be transparent about their work and to recognise when apparently simple or straightforward cases were more complex than initially perceived. As the cases for intervention were allocated and managed within the team, it was useful for psychology graduates to be aware of who their colleagues were seeing and who had space to take on new clients, developing a sense of shared responsibility.

Clinical skills development

Group and individual supervision sessions provided psychology graduates with the opportunity to develop their clinical skills via a range of approaches. In addition to a brief summary of their caseloads, at the start of every supervision session the group would agree an agenda and psychology graduates would identify a clinical challenge or dilemma that they wished to explore in more detail. Generally, each psychology graduate would talk in detail about one client; however, this very much depended on their present caseload. If there was a large agenda, psychology graduates were encouraged to prioritise and negotiate in terms of urgency among themselves. Although the intervention was manualised and psychology graduates were expected to strictly adhere to the manual, there was great variety in the dilemmas that they encountered in delivering the intervention. Often, the challenge for the psychology graduates was how to respond to their clients and overcome difficulties continuing to be empathic while sticking to the prescribed intervention, for example when carers would repeatedly ask them for solutions or direct advice.

For the more in-depth clinical discussions, PR encouraged the psychology graduates to identify a particular focus or question which they wanted to address rather than simply talking about a client in an unfocused way. These clinical discussions encompassed what the psychology graduates thought had worked well and what they had already tried, as well as what they felt that they could have done differently. In addition to offering advice and potential solutions to the psychology graduates, she encouraged them to share ideas and experiences with their peers and to make connections and identify themes across cases so that supervision was a positive learning experience regardless of whether or not their own cases were being discussed. As many of the psychology graduates hoped to develop a career in either clinical or academic psychology, they were keen within supervision sessions to link their practice and experiences to wider psychological theory. Various themes tended to emerge within their discussions of clinical cases, for example around grief and loss, or managing the therapeutic relationship, and the group would choose academic papers and book chapters to read for supervision sessions to extend their learning and understanding and to connect back to their cases.

In addition to using therapy tapes to monitor the fidelity to the intervention manual, listening to tapes of sessions provided the opportunity to reflect upon and develop clinical skills. All of the psychology graduates had the opportunity to play extracts from their taped sessions focusing on both general skills and the specific challenges that they faced in delivering the intervention to carers, for example how to manage sessions where the carer was extremely talkative, or how to respond when carers were unable to identify examples of challenging behaviours or possible coping strategies. Listening to the tapes was often combined with role-playing sections of intervention sessions to experiment with different ways to deliver the manual. Although role-play and listening to tapes can be anxiety provoking, because the psychology graduates were used to listening to and rating each other’s tapes outside supervision, they were more comfortable using these methods within supervision.

Ensuring safe practice with clients

An important aspect of supervision was to identify and respond to any risks identified during the course of assessment or intervention. The psychology graduates were provided with specific training in how to respond to any risks disclosed by carers, in relation to harm to both themselves and the person they were caring for. Psychology graduates would speak to one of the lead investigators if the abuse Modified Conflict Tactic Score (MCTS) was in the possibly abusive range (≥ 2) or if they had any concerns about potential abuse. Similarly, if carers reported high levels of depression or anxiety, this was discussed with the lead investigators. If concerns were raised, a plan was made with one of the lead investigators about how to manage the risk and information was shared with the local clinical teams.

Within supervision, psychology graduates were encouraged to identify any concerns about risk and prioritise these for discussion. As noted above, asking the psychology graduates to talk about their entire caseload at each session was an important way of ensuring that any concerns were identified. By talking about examples of good practice as well as difficulties and ensuring that there was an opportunity for individual supervision on request and a senior member of the team was always available, it was hoped that a culture of transparency developed and that the psychology graduates would always raise concerns about their clients. Time was also taken within supervision to highlight the importance of behaving ethically and safely in all aspects of clinical work, for example reflecting on maintaining clear boundaries clinically and how to practise safely when working alone in people’s homes.

Staff support

In offering therapeutic interventions to carers of people with dementia, the psychology graduates, who had limited direct clinical experience, were frequently faced with the often distressing day-to-day lives of the carers and their relatives with dementia. An important dimension of clinical supervision was to provide a supportive context for the psychology graduates to develop self-reflexivity, exploring and making sense of their own responses to the people and situations that they were working with clinically. The combination of group and individual supervision meant that the psychology graduates benefited from the support of their peers and felt that their experiences were validated by their shared experiences.

Treatment as usual

As several teaching trusts were involved, we expected the TAU to be similar to good TAU throughout the UK and based on the NICE guidelines. 31 Services are based around the person with dementia. Treatment is medical, psychological and social. Thus, it consisted of assessment, diagnosis and information, drug treatment, cognitive stimulation therapy, practical support, treatment of neuropsychiatric and cognitive symptoms and carer support. We have described TAU by trust below.

Camden and Islington NHS Foundation Trust

Patients and carers in this service were referred by a general practitioner (GP) to the Memory Service for assessment and diagnosis, assessed at home with family carer and, after investigations, offered a diagnostic appointment. Medication was prescribed as was appropriate and, if on anti-dementia medication, followed up by memory clinic nurses. Information and education in dementia was offered initially by nurses but then by dementia advisors situated in offices in and managed by the Alzheimer’s Society. Patients were offered cognitive stimulation therapy. Risk assessments were carried out and risk plans put in place, for example telecare, driving information to the Driver and Vehicle Registry Agency (DVLA), medical identification (ID) bracelets, advice regarding power of attorney and capacity assessment, and social services referral for personal care, day centre and financial advice. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients were assessed and managed.

North East London Foundation Trust

We recruited from NELFT’s Admiral Nurse Service. Admiral Nurses are mental health nurses who specialise in dementia and work with family carers and people with dementia in the community and other settings. Family carers are referred to the Admiral Nursing Service through self-referral, directly from the GP, or from community mental health teams and the Memory Service. They assess the needs of both the carer and the person with dementia, and provide information, education and advice about caring for someone with dementia. Admiral Nurses focus on the needs of the family carer and provide emotional and psychological support to families through the transitional phases of the illness, such as diagnosis, when the condition advances, care home placement and end-of-life care. Referrals may be made to other services and they liaise with other health and social care professionals on behalf of the family.

North Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust

Patients and carers in this service were referred by a GP to the Memory Service for assessment and diagnosis, assessed at home with family carer and, after investigations, offered a diagnostic appointment. The diagnosis was given in the clinic with a doctor or at home with nurses. Other interventions included medication as appropriate and, if on antidementia medication, follow-up by memory clinic nurses; risk assessment with a risk plan put in place, for example telecare and driving information to the DVLA; medical ID bracelet; and social services referral for personal care or day centre. Information and education in dementia was offered initially by nurses but thereafter by dementia advisors. Neuropsychiatric symptoms were assessed and managed. Patients were referred to dementia advisors situated in the Alzheimer’s Society and carers were offered support groups.

University College London Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Patients were referred by their local GP, memory clinic or specialist to this cognitive disorders clinic. They were assessed in the clinic, with investigations completed during the visit. They were admitted as day case for cerebrospinal fluid examination or for other investigations. A few weeks later they had a diagnostic appointment with a neurologist, when they received the results of any tests, and on the same day saw a nurse consultant for discussion. In this discussion they were given information, education around legal and financial implications and a risk assessment was carried out. All patients were offered the opportunity to take part in clinical trials and other research. Available patient support groups were highlighted to them. This was followed up by telephone consultations. If appropriate, patients returned to the nurse-led therapeutics clinic for medication. Complex cases were followed up in the clinic and all others signposted back to their local services.

Barnet, Enfield and Haringey Mental Health Trust

We did not recruit participants from this trust as they did not agree to extra treatment costs.

Chapter 4 Outcomes

Assessments

Carers were interviewed at baseline and 4, 8, 12 and 24 months after randomisation, usually in their own home, unless they preferred to come to the research team base in UCL. We continued to follow up carers, asking them to remain in the study for 2 years, even if the person they were looking after went into a care home or died. They continued to give us data about themselves and their own use of services and, if the care recipient was in a care home, about the recipient’s use of services. Information collected at baseline consisted of sociodemographic details about the carer and the person with dementia, and clinical and resource use items. Collection of clinical and resource use information was repeated at all follow-up data collection time points.

Sociodemographic details obtained at baseline included age, sex, ethnicity, relationship to the patient (e.g. spouse or child), level of education, last occupation and living situation.

Other assessments include:

-

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS)32 is a self-complete scale, and is validated for all age groups and settings, in people who are physically well or ill, and in Asian and African ethnic groups. 33 The scale is summarised as HADS-depression (HADS-D) and HADS-anxiety (HADS-A), with scores ranging from 0 to 21, and as a HADS-total score (HADS-T), with scores ranging from 0 to 42 (higher scores indicating more symptoms). The HADS-T is our chosen primary outcome as it has better sensitivity and positive predictive value than either of the individual scales in identifying depression when compared with International Classification of Diseases (ICD) criteria. 34 The anxiety and depression scores were also dichotomised as ‘case’ and ‘non-case’, with a cut-off point of 8 or 9. 33

-

The Zarit Burden Interview is a 22-item self-report questionnaire and is the most consistently used measure of carer burden;35 scores range from 0 to 88, with higher scores indicating more burden. We used it to adjust for the baseline burden on carers as those who have more burden may be expected to be more stressed.

-

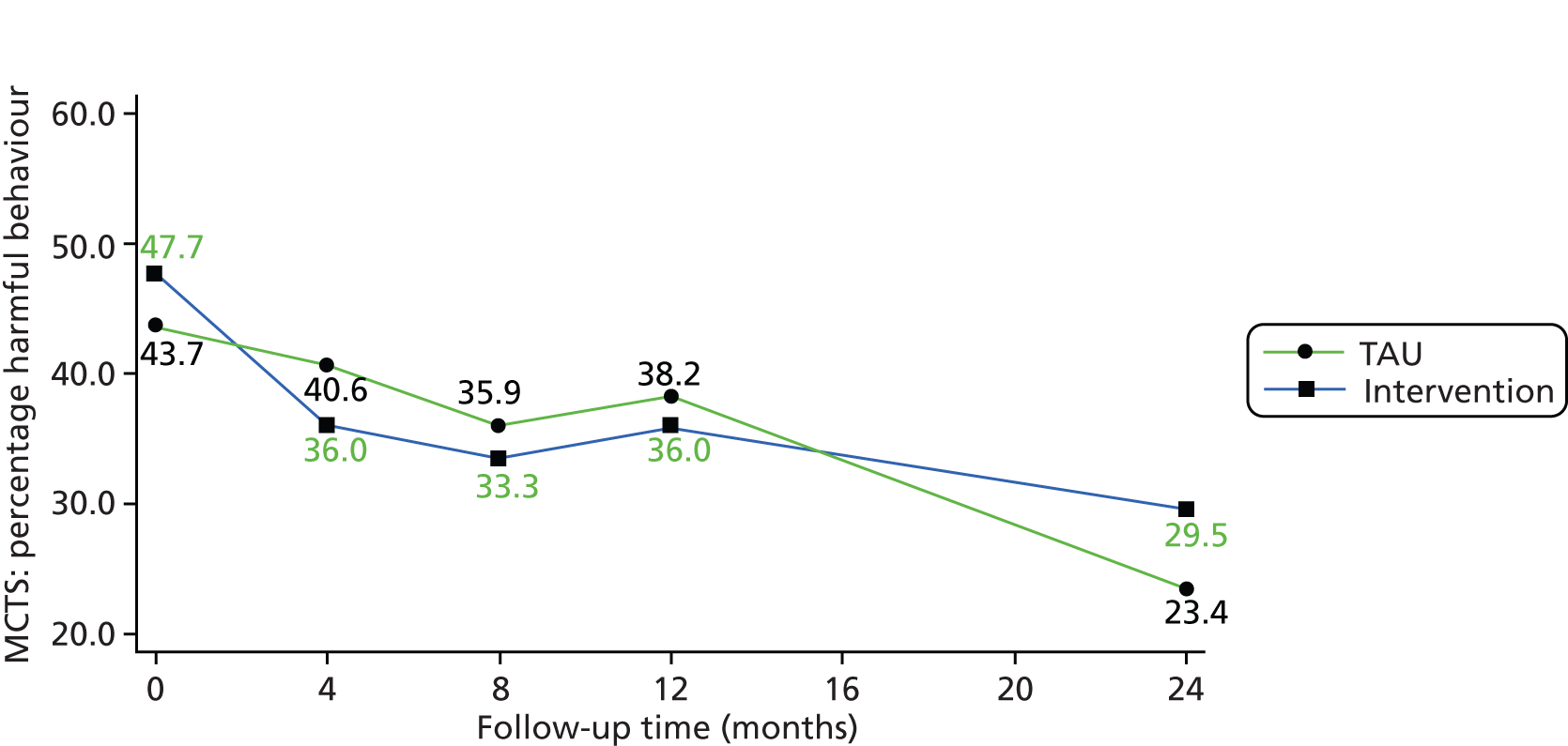

The MCTS is a self-completed measure of potentially abusive behaviour by the carers towards those for whom they care. 36 Ten behaviours are scored on whether or not, during the previous 3 months, these have occurred never (0), almost never (1), sometimes (2), most of the time (3) or all of the time (4), and these items can be added to make a score. These behaviours range from shouting, through threatening, to shaking or slapping. A score of 2 or more on any one of the items is classified as an abusive behaviour. If participants scored this on any item, the score was discussed with a supervising clinician and, if it was judged that the person with dementia was at risk, permission was asked to inform the clinical team so that the carer and patient could have appropriate help. This scale has been validated for use in family carers of people with dementia. 37

-

The Health Status Questionnaire (HSQ)38 mental health domain measures health-related QoL throughout the age range, is sensitive to change and has been validated in older and younger people. It is summarised as a continuous score, ranging from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better outcome.

-

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)39,40 is a standardised measure of health status which provides a simple descriptive profile and a single index value for health status. The EQ-5D descriptive system comprises five dimensions: mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain or discomfort, and anxiety or depression. Each dimension has three levels: no problems, some problems and severe problems. The respondent is asked to indicate his or her health state by ticking (or placing a cross) in the box against the most appropriate statement in each of the five dimensions. The digits for the five dimensions can be combined in a five-digit number describing the respondent’s health state.

-

The Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)41 comprehensively covers services, including (but not limited to) inpatient stays, outpatient attendances, day hospital treatment, visits to social clubs, meals at lunch clubs, day care visits, and hours spent in contact with community-based professionals such as community teams for older people, community psychologists, community psychiatrists, GPs, nurses (either practice, district or community psychiatric), social workers, occupational therapists, paid home help or care workers, and physiotherapists.

At all time points, carers were also asked for information about the person with dementia using:

-

The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI). 42 The NPI is a validated instrument with 12 symptom domains that are scored for their severity and frequency and summarised as a single continuous score (higher scores indicating worse symptoms). This was included as neuropsychiatric symptoms have been shown to be associated with carer psychological morbidity. Possible scores range from 0 to 144, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms.

-

Quality of Life-Alzheimer’s disease (QoL-AD). 43 The QoL-AD is an instrument used to rate the QoL of people with dementia and can be observer rated. It was rated by the family carer to assess the patient’s overall QoL. The total score ranges from 13 to 52, with higher scores indicating better outcome.

-

Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR). The CDR, which we used as an informant instrument, grades the level of impairment of someone with dementia [categories: healthy (0), very mild (0.5), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3)]. 44

Changes to trial outcome after trial commenced

After the trial commenced, the team began to think further about the clinical relevance of this trial and concluded that the appropriate clinical questions were ‘does the intervention work?’ and, if it works, ‘does it keep working and show more effect over time or does the effect wear off?’. As the intervention targets coping strategies, in theory, over time there may be a larger separation between those who use ‘good’ strategies and those who do not when dealing with the intractable problem of somebody with dementia. On the other hand, people may revert to their previous tactics and usefulness may be lost over time. In the last case, we might consider whether or not a ‘top up’ would be appropriate. We therefore proposed to our steering group, data management group and the National Institute of Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme that we split the follow-up period into short- and long-term follow-up.

We agreed with all of them that our primary short-term outcome would be repeated measures of the HADS at 4 and 8 months and our long-term outcome would be repeated measures of the HADS at 1 and 2 years. Our original proposal was inconsistent whether we would use the HADS-A or HADS-D score as a primary outcome. There are three validation studies in community samples (as opposed to solely, for example, people with cancer). The largest of these included 6163 participants, more than five times the sum of the other validation studies and includes random samples of adults throughout the age group and groups of people with psychiatric and physical illnesses. 34 Although the HADS is usually used to generate scores and caseness for the two subscales of clinically significant anxiety and depression separately, this study found that HADS-T had better sensitivity and positive predictive value than either of the individual scales in identifying cases when validated against standardised clinical criteria. The authors comment that their results are in line with those of previous smaller studies. We therefore concluded that the HADS-T was the best measure to use.

In addition, we requested and received a 5-year no-cost extension to the trial. We wished to follow up the participants every 6 months to examine carer mental health and care recipient admission to 24-hour care settings (homes and continuing care beds) over the longer term or until death at home. This is because changes in the rate of admissions may become more apparent over a longer time.

We submitted all of these agreed changes as major amendments to National Research Ethics Committee and appropriate research and development departments and they were agreed.

Short-term primary outcome (up to 8 months’ follow-up)

Long-term main outcomes (12 to 24 months’ follow-up)

-

Carer HADS-T score.

-

Cost-effectiveness: costs using the CSRI alongside the carer QALYs calculated from the EQ-5D by applying societal weights.

Seven-year follow-ups

Time to entry to 24-hour care (this was added after funding and is not in this report, which covers the 2 years post recruitment).

Sample size

This was calculated to test our main hypotheses that HADS-T score will be significantly lower in the intervention group than in the TAU group.

This study was originally powered for a primary outcome of HADS-A score based on data from a cross-sectional pilot study of family carers. Mean HADS-A scores for this group were 7.2 with a standard deviation (SD) of 4. A decrease of 2 points in mean score and a 0.5 change in SD was considered to be clinically significant (expert consensus). To detect such a difference, with 90% power at 5% significance level, 75 participants per group were required. To account for therapist clustering, a design effect of 1.87 was used for the intervention group, assuming an average of 30 carers per therapist and an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC) of 0.03. 46 Based on these calculations and inflating for 20% attrition, we planned to recruit 90 participants in the TAU group (no clustering) and 168 participants in the intervention group (clustering).

For the reasons given above, it was agreed that the primary outcome should be changed to HADS-T score. As recruitment was complete, the sample size available for analysis was fixed with achieved numbers of 87 in the TAU group and 173 in the intervention group. The following power calculation justified that this achieved sample size was adequate to address the new primary objectives based on the HADS-T outcomes at 4 and 8 months.

This power calculation considers the short-term primary analysis of HADS-T score using repeated measurements at 4 and 8 months, with an adjustment (using analysis of covariance) for baseline score. We calculated that the sample size available (87 carers in the control group and 173 in the intervention group) would be sufficient to detect a clinically important difference of at least 2.4 points on the HADS-T.

The calculations assumed a HADS-T SD of 7.4 (as given from our cross-sectional pilot study data), correlation between baseline and follow-up scores of 0.5 and a correlation between repeated follow-up measurements of 0.7 (both chosen as conservative estimates). Based on these values, with the available sample size we have 80% power to detect a difference of 2.4 points on the HADS-T and 90% power to detect a 2.7-point difference, both consistent with differences considered to be clinically important. This calculation has factored in adjustments for 10% dropout and a design effect of 1.4 for clustering in the intervention arm (calculated using the known average cluster size, 15 carers per therapist and an assumed ICC of 0.03). 46

Statistical methods

Scoring questionnaires

The relevant outcome scores were calculated from the individual items for each instrument according to standard algorithms. Where individual items were missing, standard procedures (where available) for the calculation of these outcome scores were used. Single missing data items on the HADS were imputed using the subscale mean, but cases with more than one missing item in any given subscale were excluded as invalid. 47 Missing cells on the Brief COPE scale were imputed using the carer’s own mean score for that particular subscale if there was one item missing (Charles Carver, University of Miami, 2011, personal communication). For the QoL-AD, if one or two items were missing, the mean of the completed items was used to impute the missing items. For all other outcomes, scores were calculated only where all relevant items had been completed.

Clinical outcomes

Separate regression analyses were used to estimate group differences in HADS-T score over the short term (using 4- and 8-month follow-ups) and the longer term (using 12- and 24-month follow-ups). In both cases, random-effects models accounted for repeated measurements and therapist clustering in the intervention arm. Adjustments were made for baseline HADS-T scores and centre (on which randomisation was stratified), and also on factors believed from the literature to affect affective symptoms (carer age, sex, carer burden and care recipient neuropsychiatric symptoms). All analyses were carried out by intention to treat, but we excluded. in the short term. carers who had data missing at both 4- and 8-month follow-up and, in the longer term, those with data missing at the 12- and 24-month follow-up. If an individual’s data were available at 4 months but not at 8 months, or vice versa, their partial data were used in the short-term analysis, and similarly with the 12- and 24-month data for the long-term modelling.

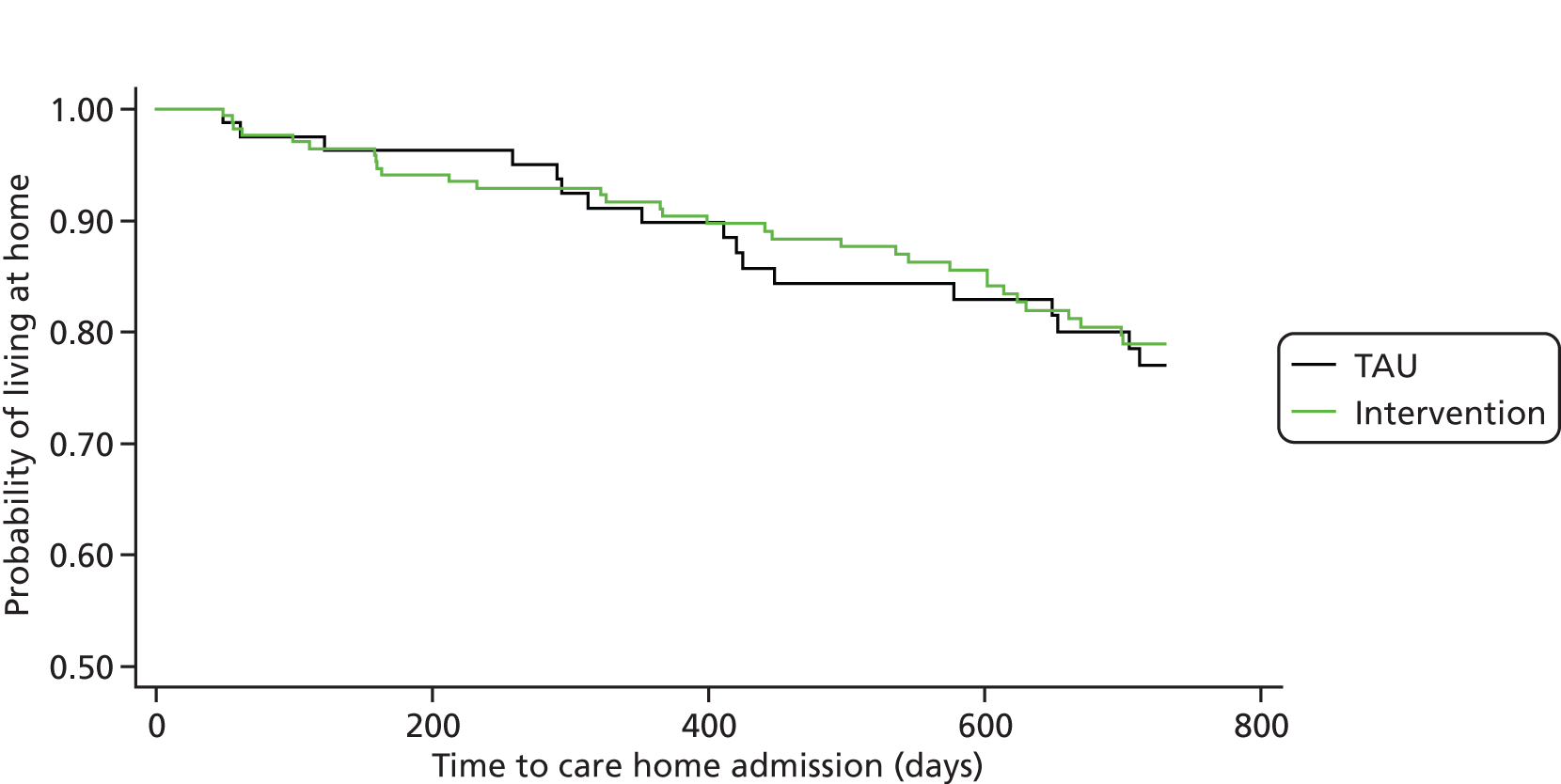

Similar approaches were taken for analyses of the secondary outcomes. Random-effects logistic regression was used for binary outcomes. In the short term, entry of the person with dementia to 24-hour care was compared between groups using a simple comparison of proportions (not allowing for clustering) because of small numbers. For the long-term analyses, the effect of the intervention on the time until institutionalisation was examined using parametric shared frailty models to allow for clustering in the intervention arm and adjustment for baseline factors. (The models fitted had a gamma distribution for the shared frailty and a Weibull survival distribution for time until institutionalisation.)

Model assumptions were examined by checking the normality of the residuals and also plotting the residuals compared with the fitted values both at the individual and therapist cluster level. To quantify therapist clustering, unadjusted ICCs at each follow-up within the intervention group were estimated with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Sensitivity analyses were used to reanalyse the outcomes in various ways to assess robustness of our conclusions. These analyses considered adjustment for imbalances in baseline characteristics between the randomised groups and the differential effects of treatment over time (treatment by time interaction). In considering missing data, we examined the extent to which missing outcome varied by baseline characteristics using logistic regression. In these analyses, for each outcome a binary variable was created according to whether or not it was missing (1 = missing score, 0 = valid score). This binary outcome was used in logistic regression to determine associations with baseline factors. In a sensitivity analysis, the main analyses for each outcome were repeated adjusting for those factors found to be associated with missingness, thus making missing at random assumptions more plausible. In the longer-term analyses, we also fitted models incorporating all repeated measurements (at 4, 8, 12 and 24 months) and examined the interaction between treatment group and long-/short-term follow-up.

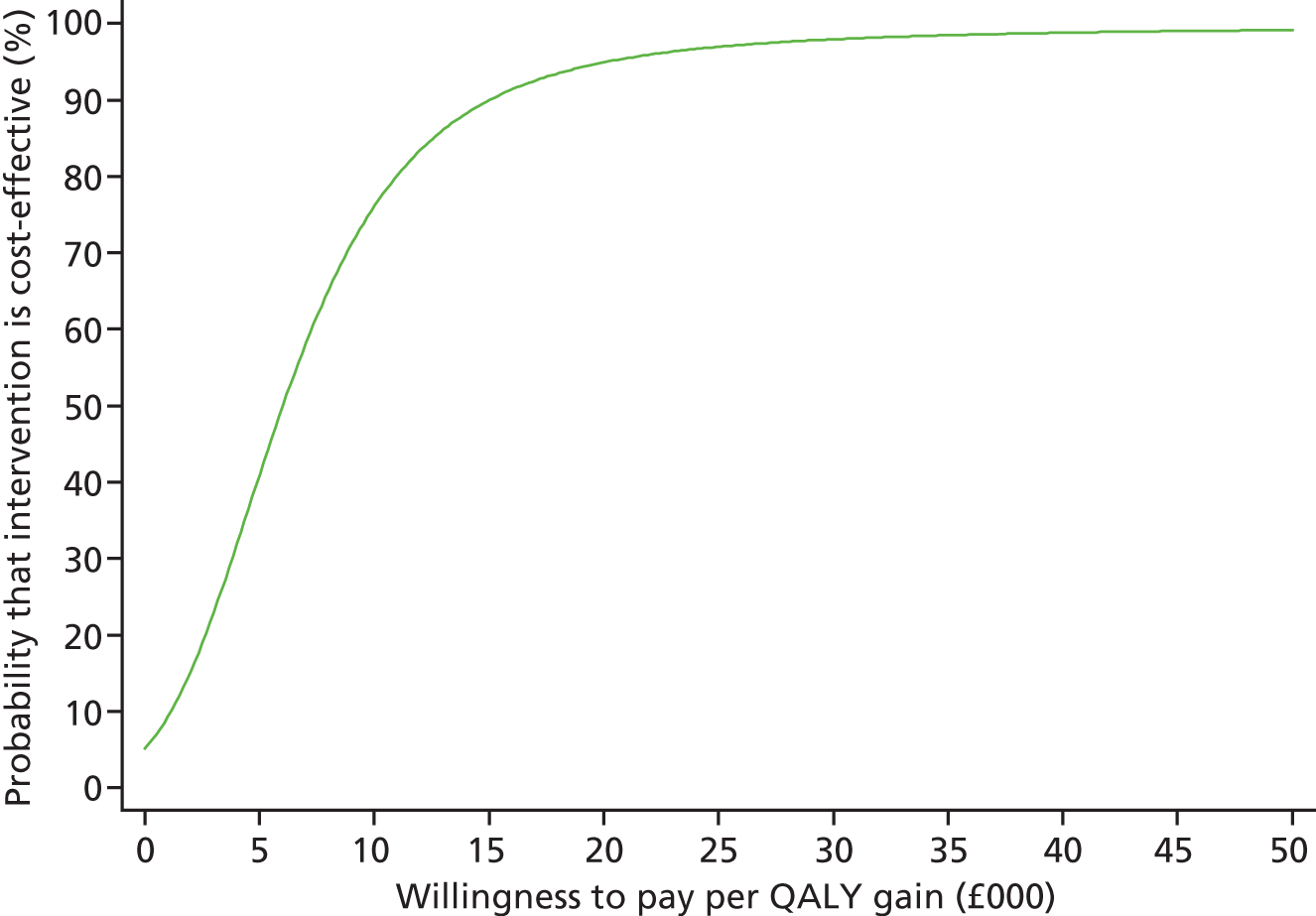

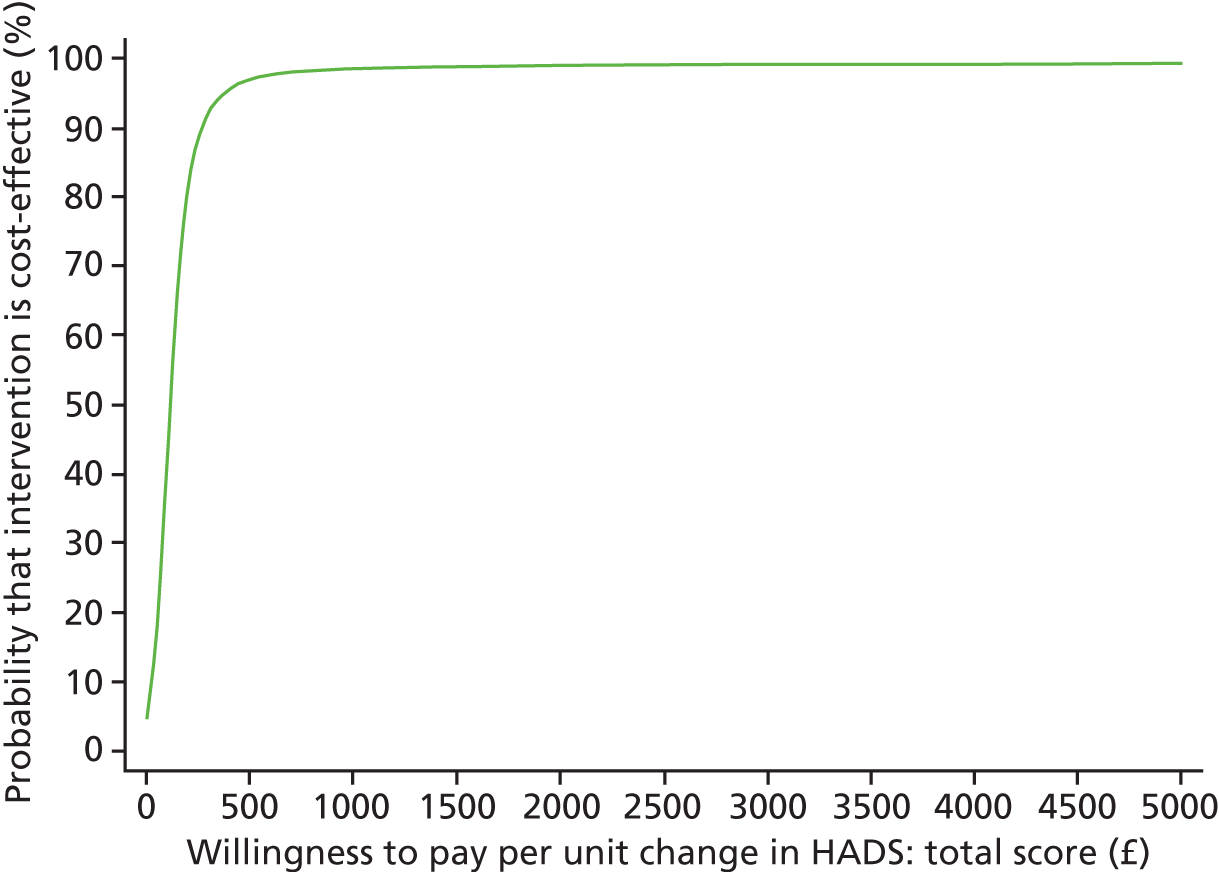

Cost-effectiveness

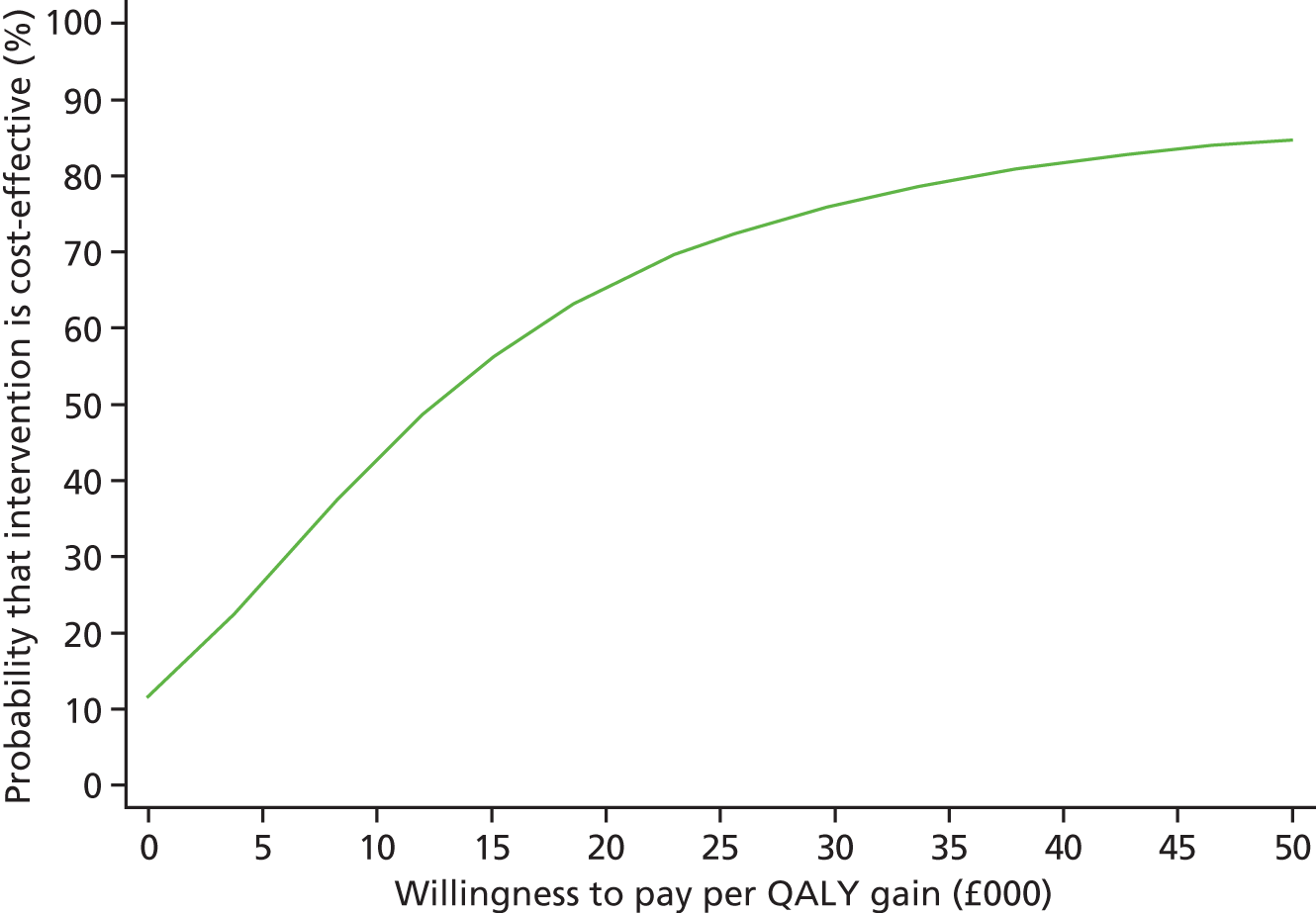

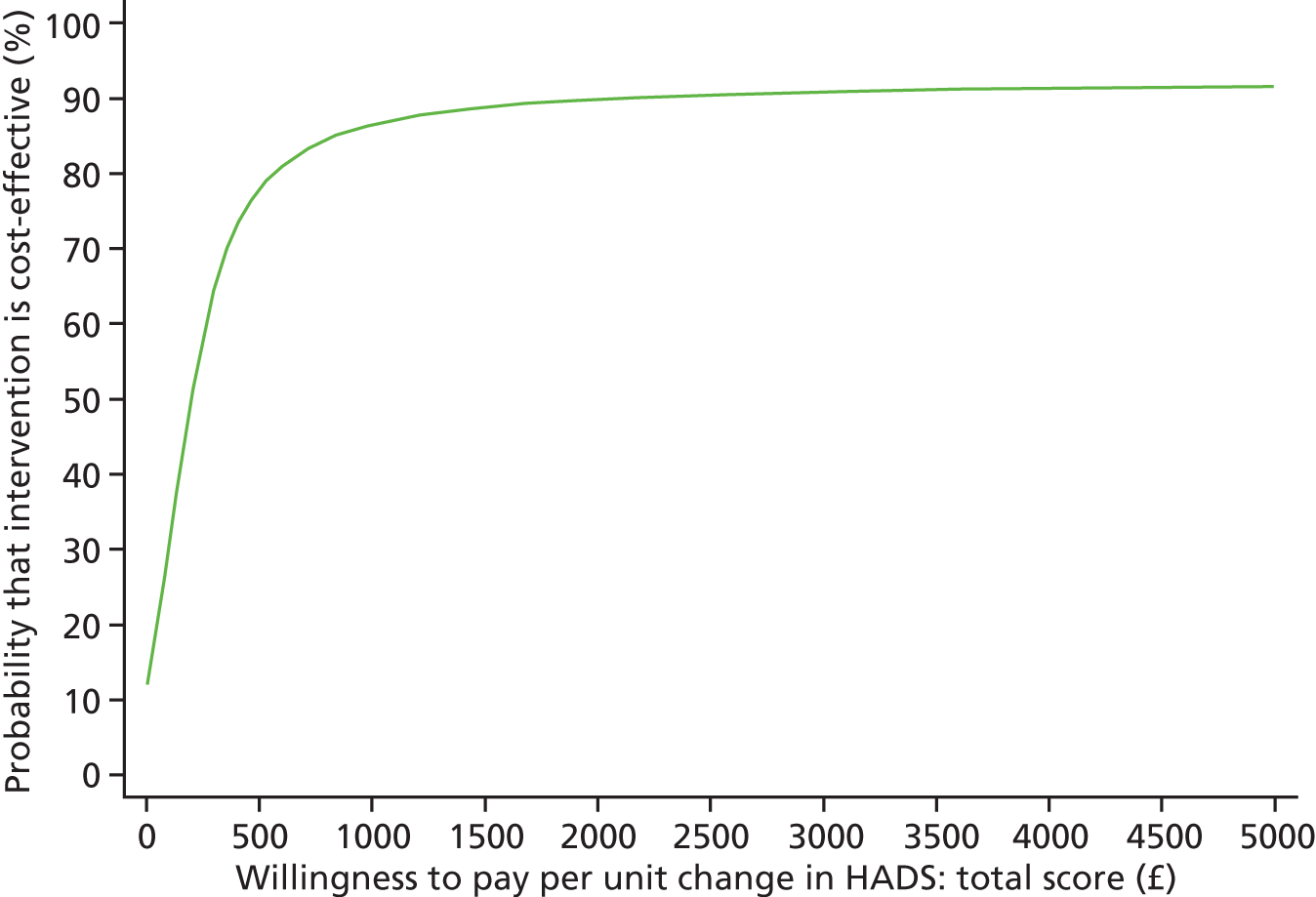

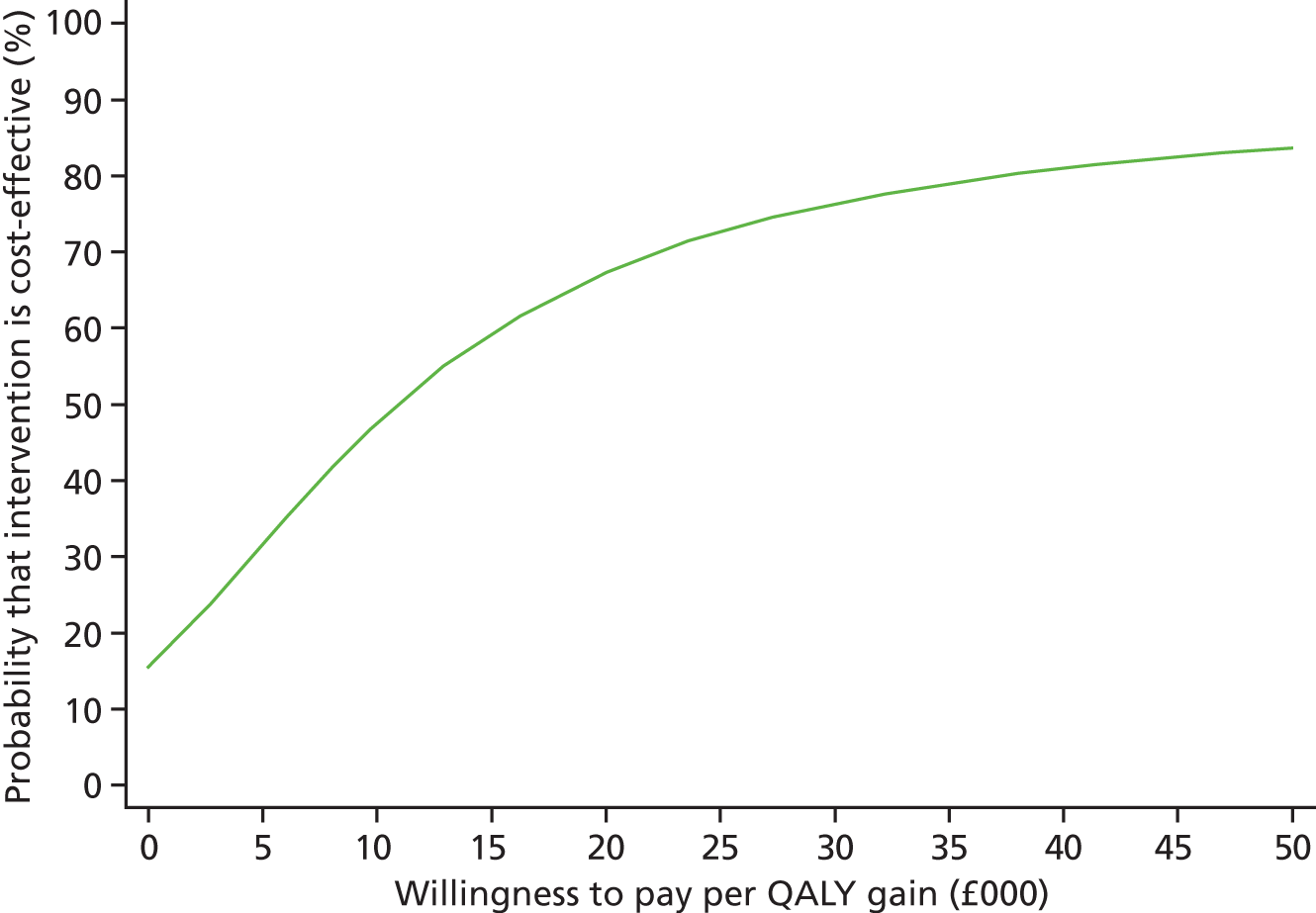

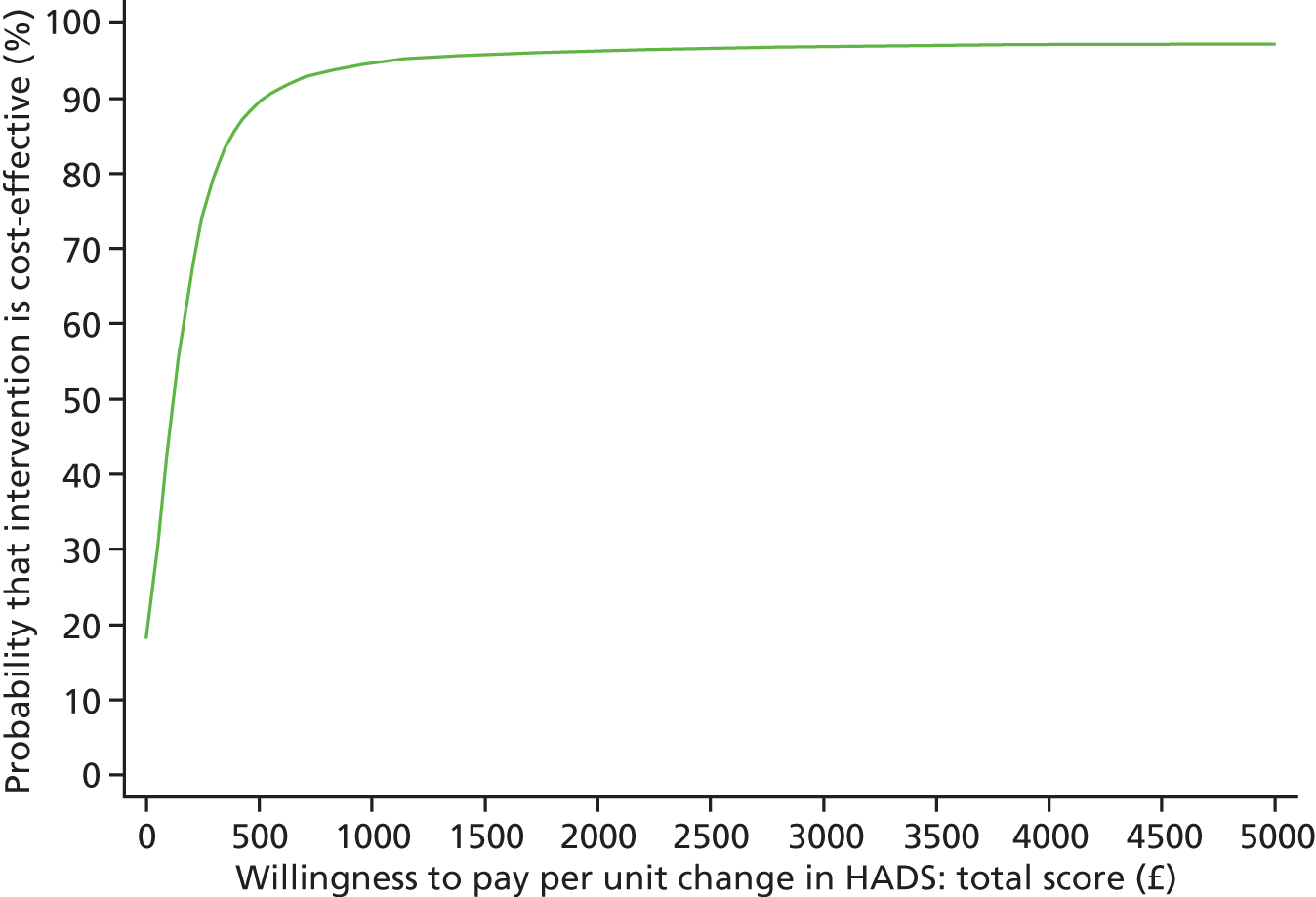

The primary economic evaluation was a cost-effectiveness analysis comparing differences in treatment costs for carers receiving the START intervention with QALYs computed from the EQ-5D40 and societal weights48 over 1–8 months’ and then 1–24 months’ follow-up. In a secondary analysis, differences in treatment costs were compared with changes in in HADS-T score over the same time periods. Both the primary and secondary economic evaluations were undertaken from the perspective of health and social care agencies.

Data on services used and support received by the carer and the person with dementia were collected using an adapted version of the CSRI as above at baseline (randomisation) and at 4, 8, 12 and 24 months. On each occasion, the carer was asked to report service use over the previous 4 months. For the primary economic analyses over 1–8 months and then 1–24 months, our focus was on service use by the carer.

Total carer-related costs were derived by combining health and social care service use data with estimated unit costs. Costs were calculated for the periods 1–8 months and 1–24 months. We did not collect service use data during the period between the 12- and 21-month data collection time points (on average 8 months). Costs during this period were interpolated from the 12- and 24-month data.

Unit costs were obtained from publicly available sources and set at 2009–10 prices: Department of Health National Schedule of Reference Costs 2008–949 for inpatient (accident and emergency) and outpatient attendances; the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) unit cost compendium50 for some inpatient services such as acute adult inpatient services; most other community-based health and social care professional services; and voluntary organisation services for a small number of services used by a few carers. Unit costs of services are listed in Appendix 1.

The cost of the START intervention was calculated using data on time spent by therapists in training and supervision with a clinical psychologist and contacts that therapists had with carers in delivering the intervention. Cost per hour of contact for therapists and supervising clinical psychologist were based on figures in the PSSRU compendium,50 taking the mid-point of the relevant scales and including employer costs (national insurance and superannuation contributions) and appropriate overheads (capital, administration and managerial, including recruitment costs). We added costs for the relaxation CDs based on the market rates for copying and delivering.

We analysed HADS-T and QALY differences between START and TAU interventions using a multilevel, mixed-effects model to account for therapist clustering in the intervention arm and repeated measures at 4, 8, 12 and 24 months. For the HADS-T analysis, we adjusted for baseline HADS-T score, centre and carer age and sex, carer burden (Zarit) and neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI) of the person with dementia. For the QALY analyses, we adjusted for the same baseline variables, except substituting QALY for HADS-T.

Differences in total health and social care cost between the START and TAU interventions were regressed on treatment allocation, baseline costs, centre, carer age and sex, carer burden (Zarit) and care recipient neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPI). We used a linear multilevel regression model to account for therapist clustering in the intervention arm and repeated measures for each individual. Non-parametric bootstrapping was used to estimate 95% CIs for mean costs. Significance (p < 0.05) was judged where the bias-corrected 95% CIs of between-group change score excluded zero.

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis; carers were excluded if data were missing at both 4 and 8 months for the 1–8-month economic analysis, and, for the 1–24-month economic analysis, carers were excluded if data were missing at 4, 8 and 24 months. Because the estimation of QALYs requires data at each time point, only complete cases were included in the cost-effectiveness analysis. No imputation was conducted.

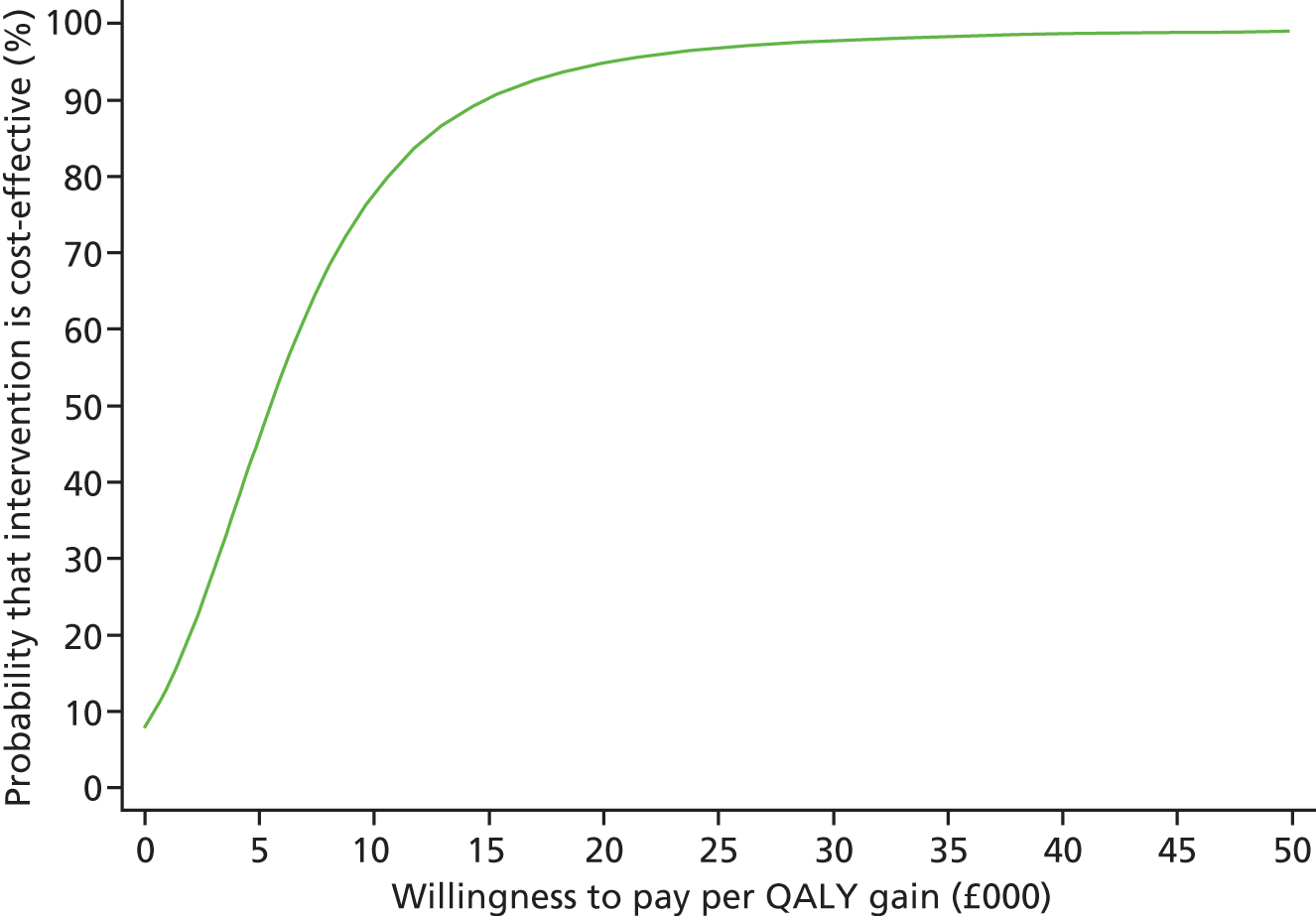

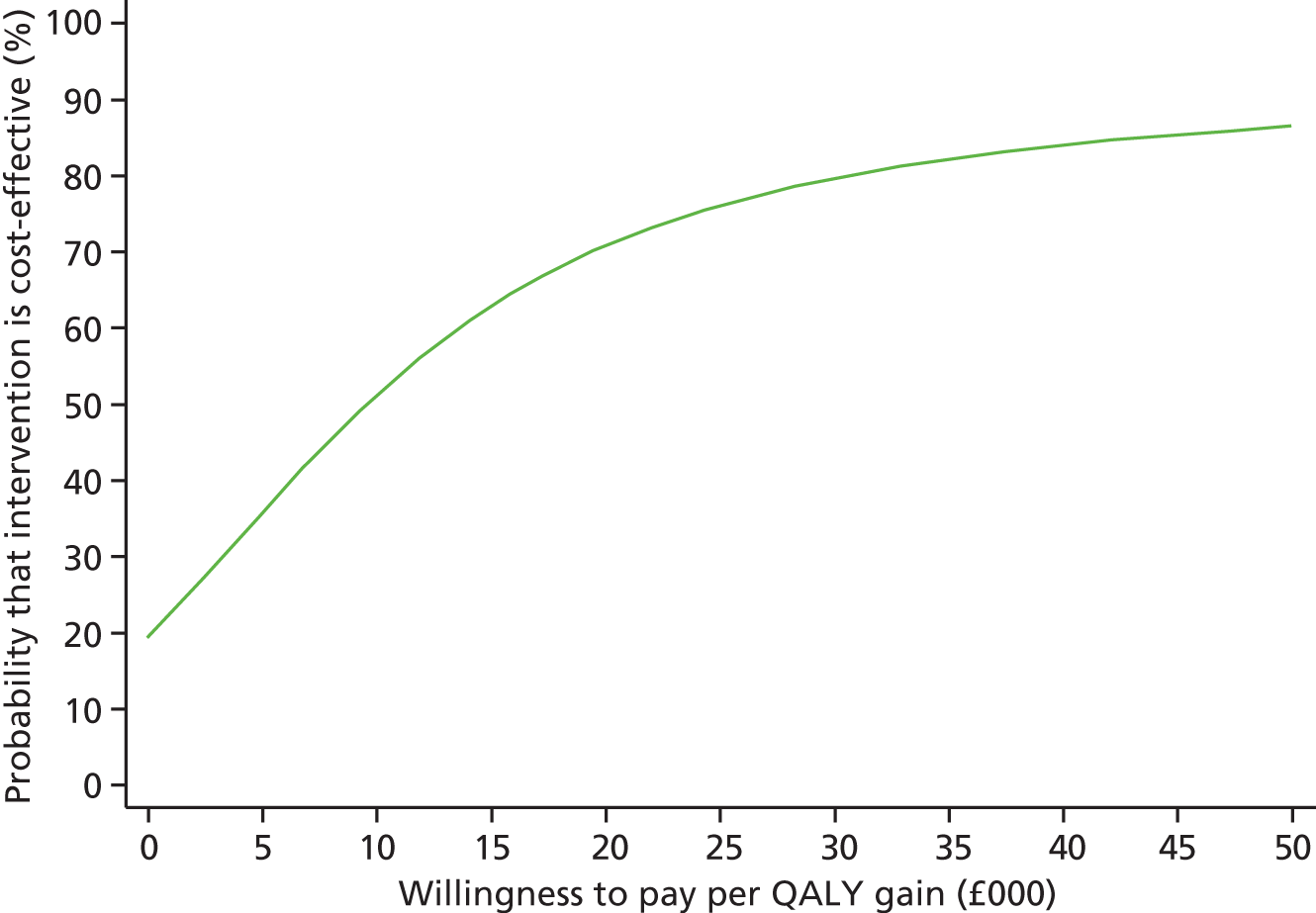

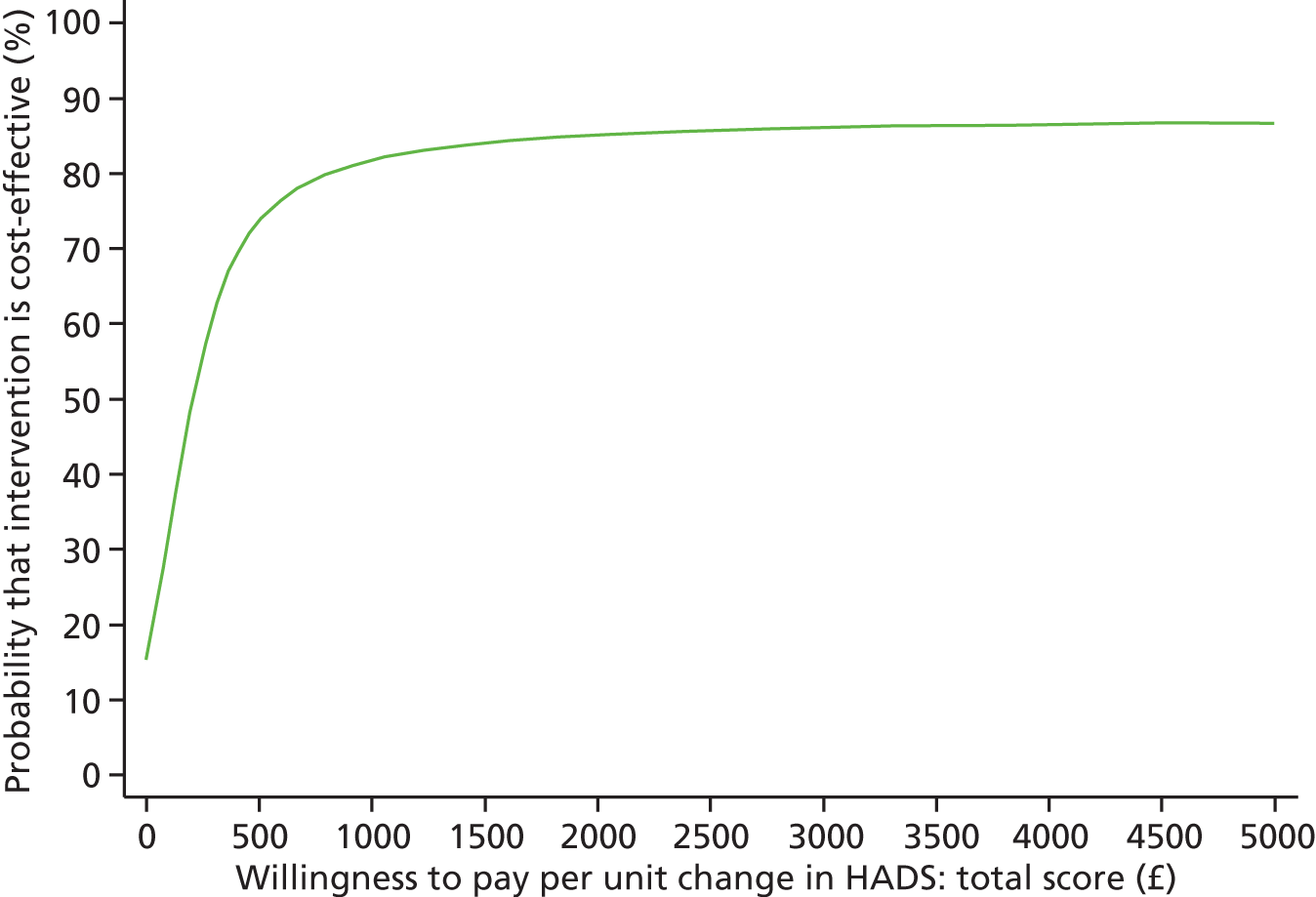

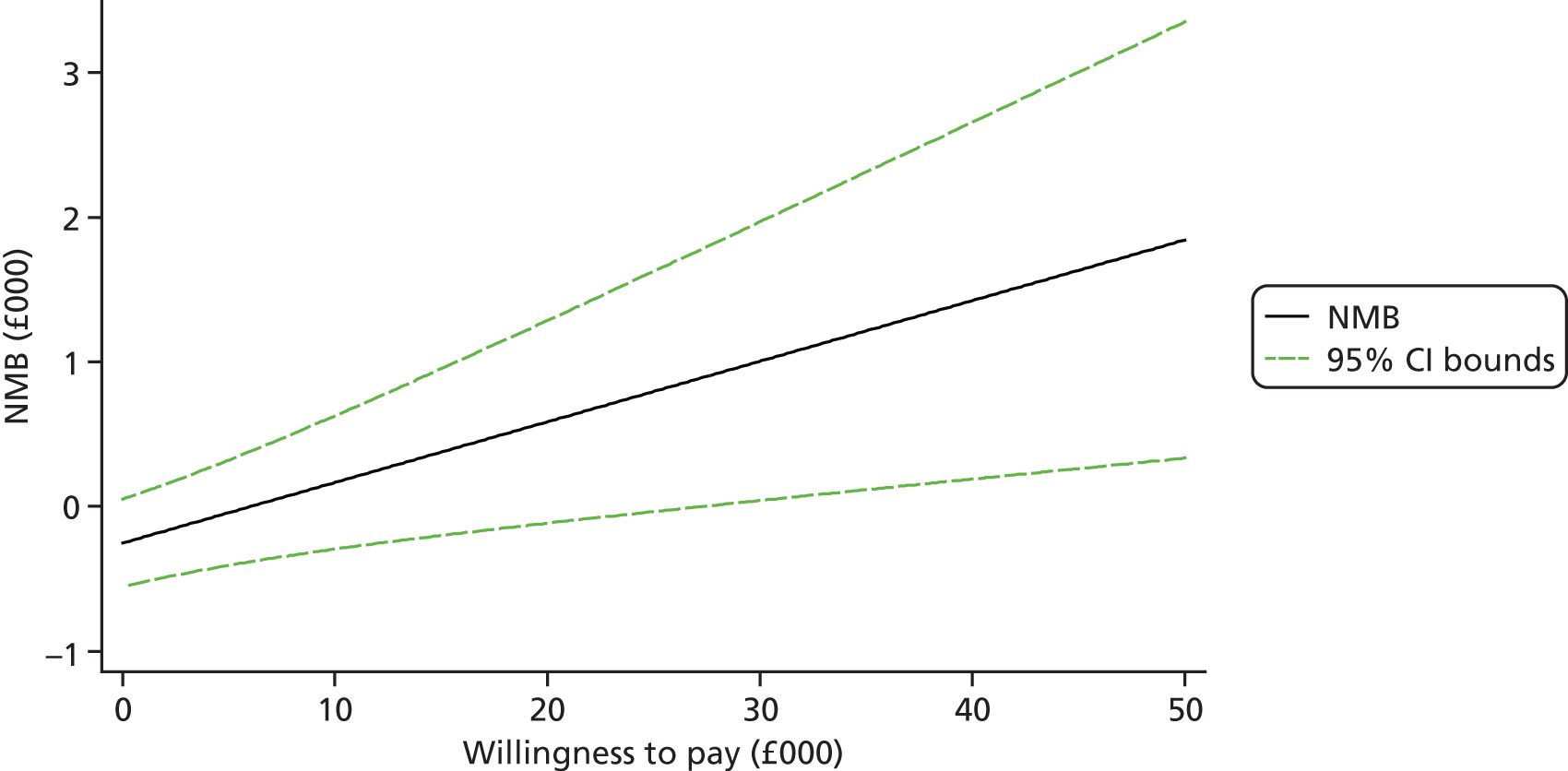

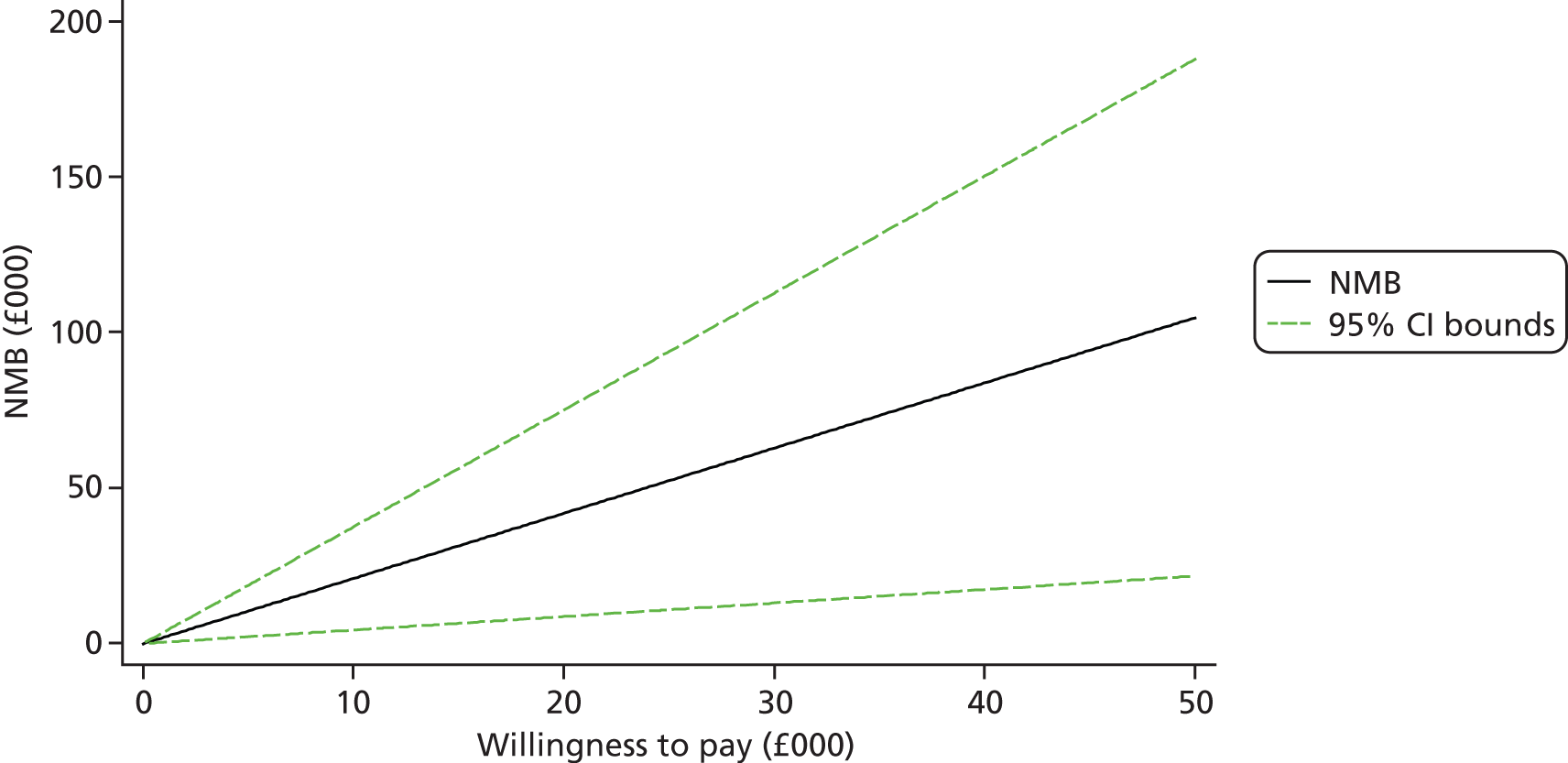

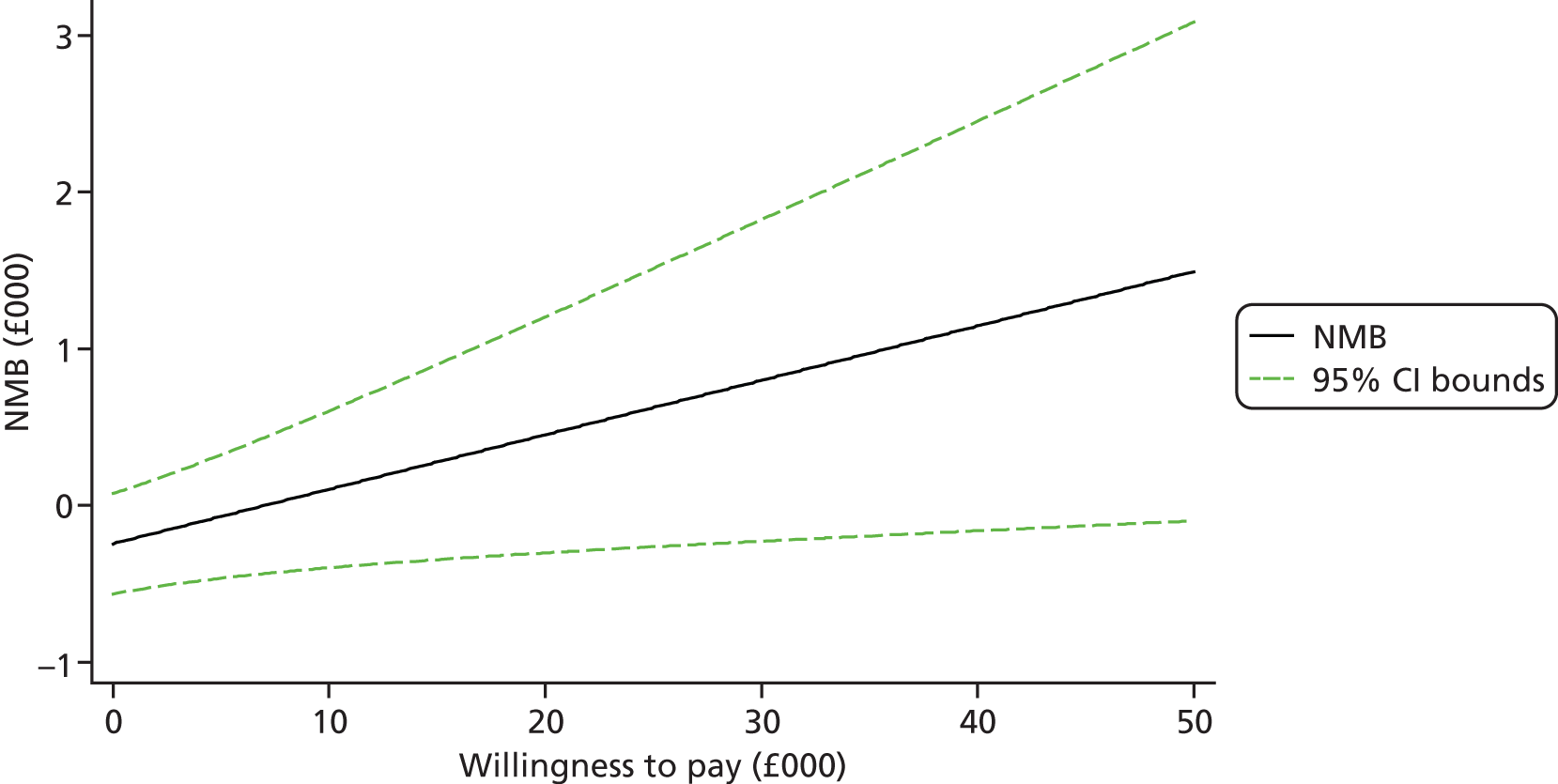

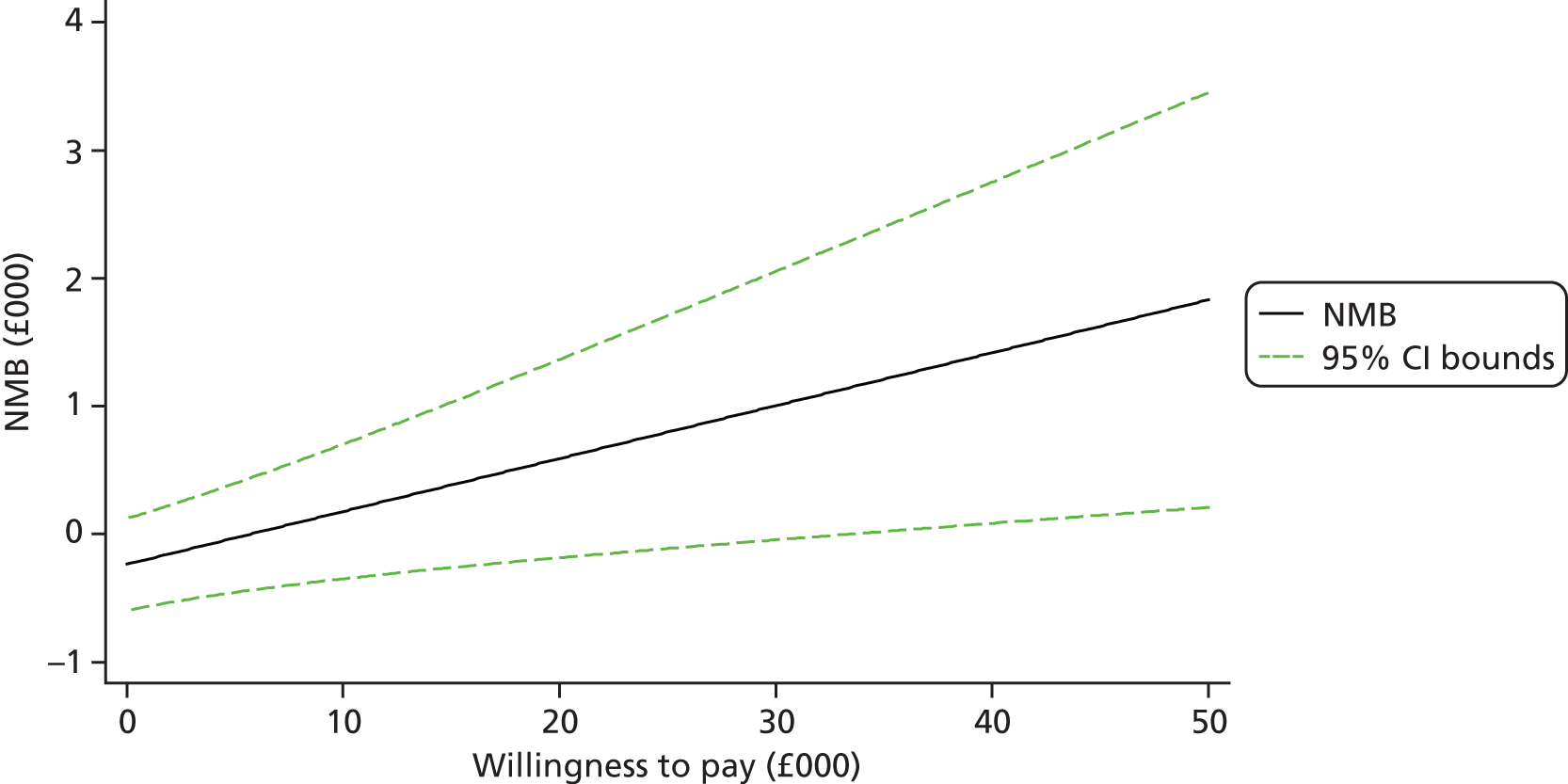

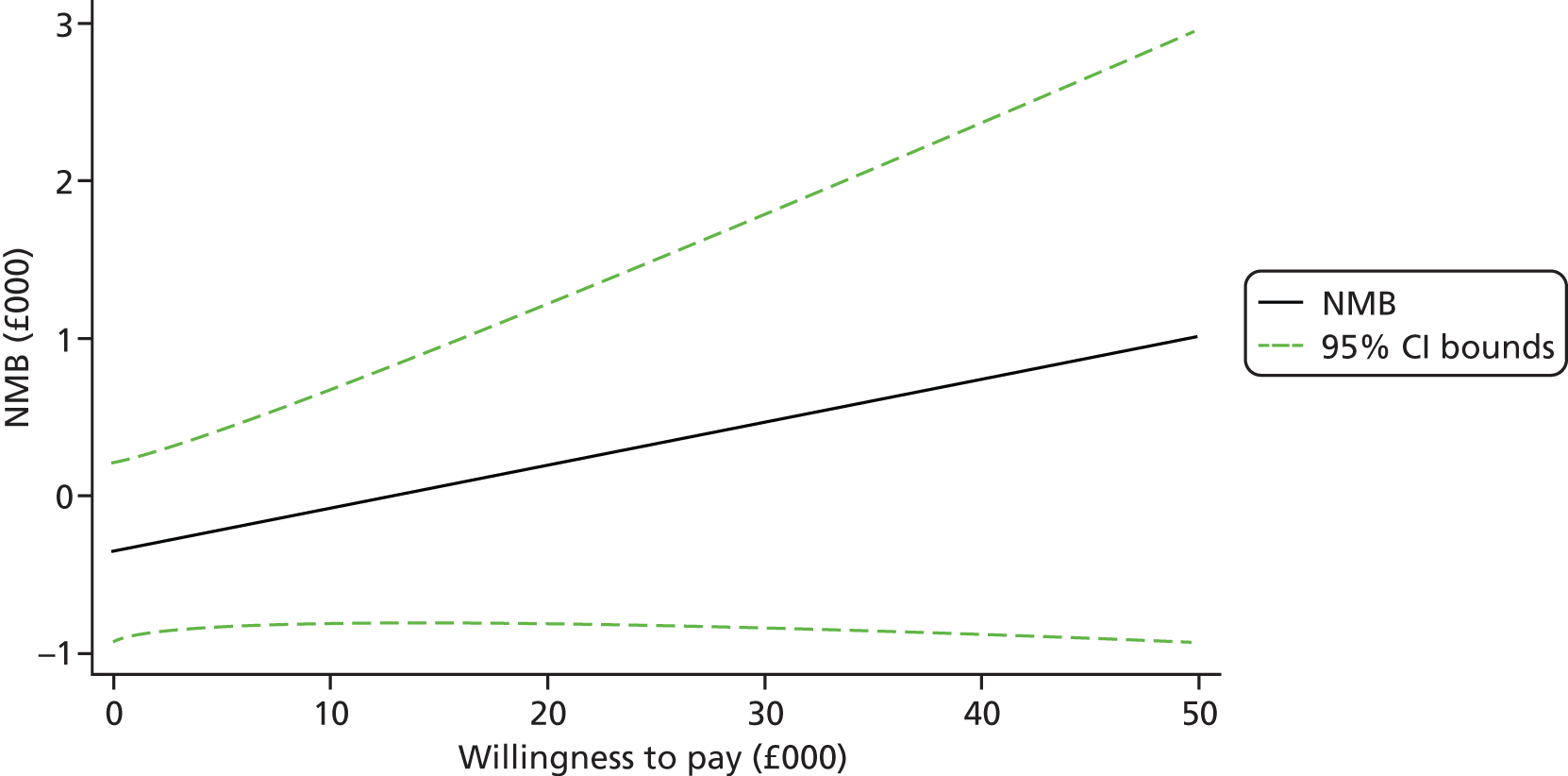

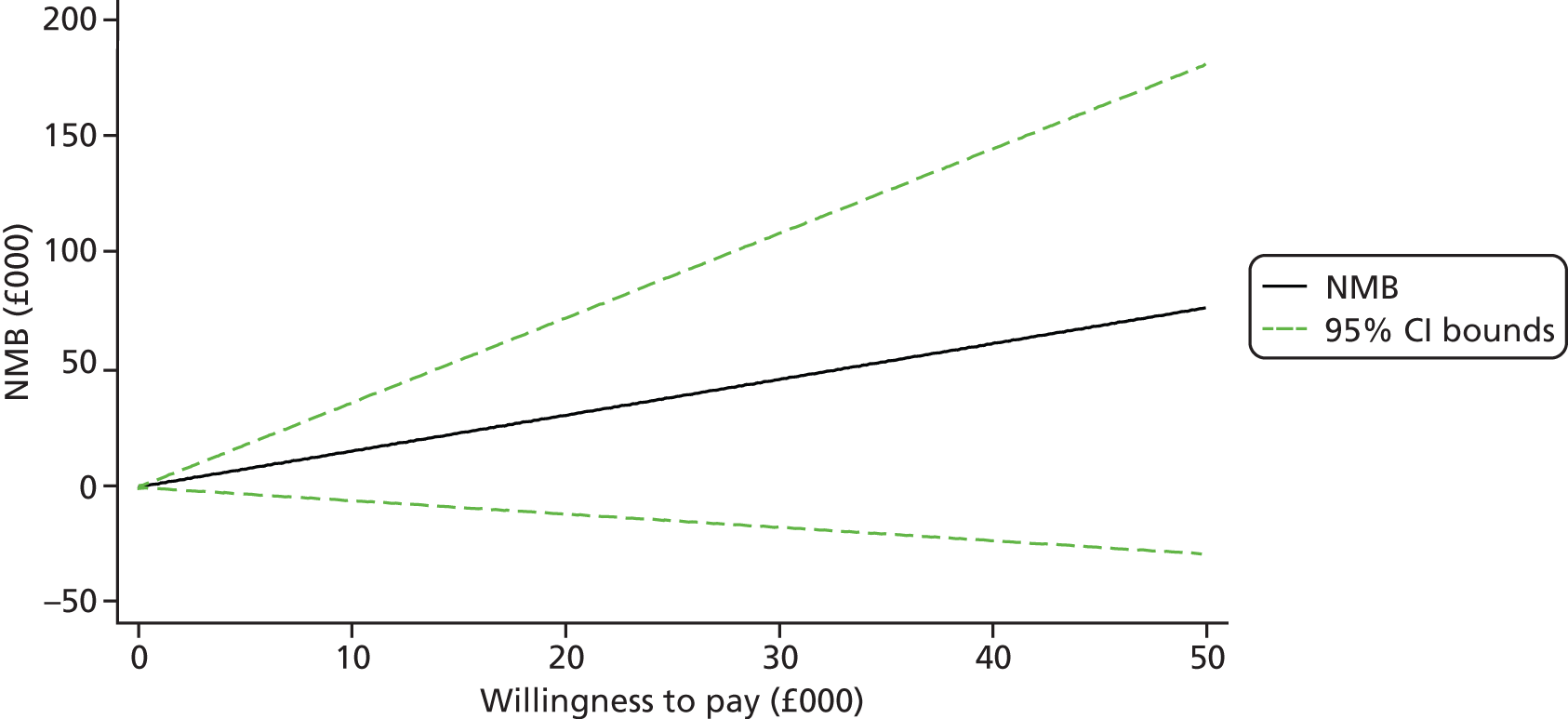

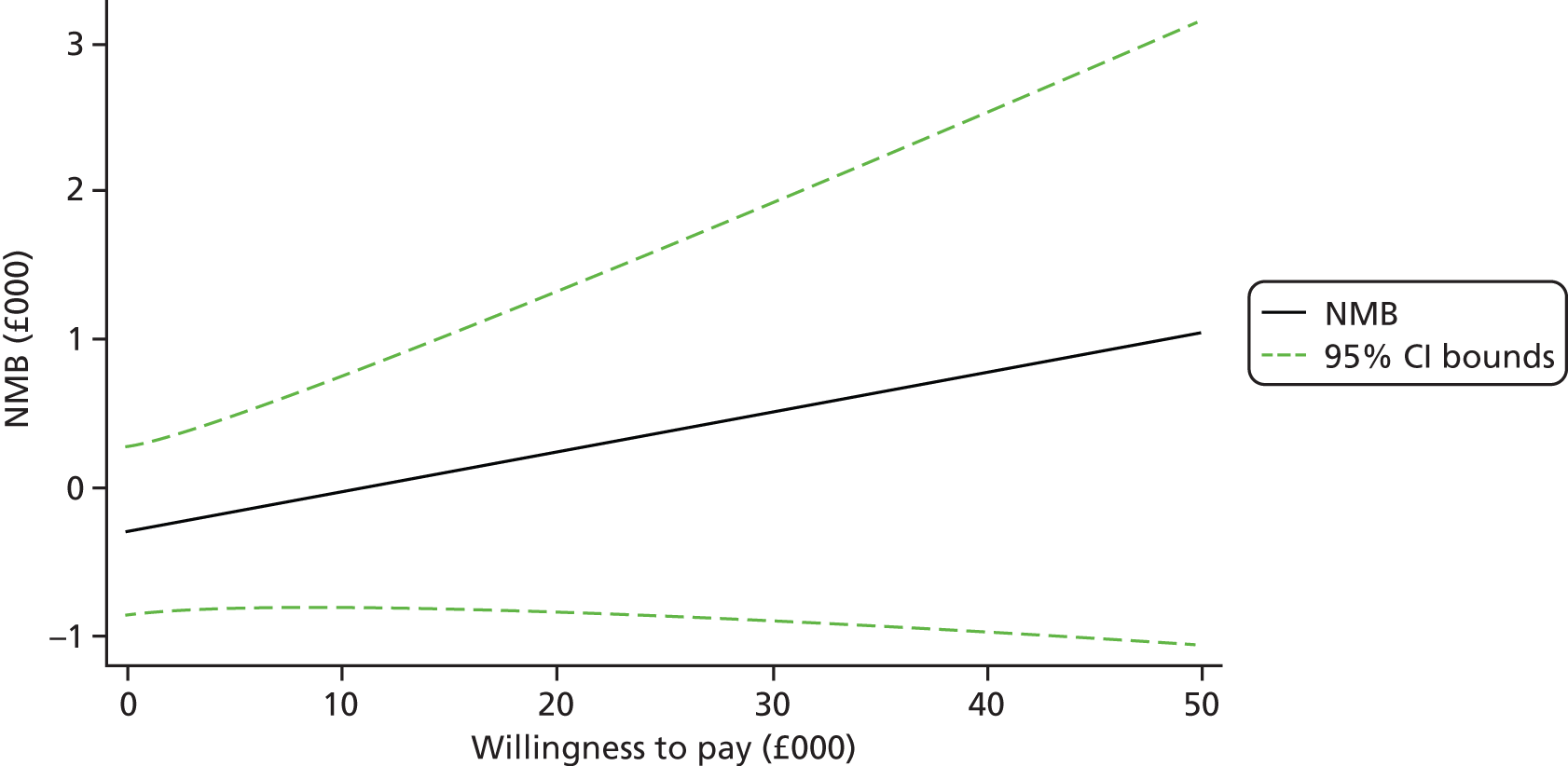

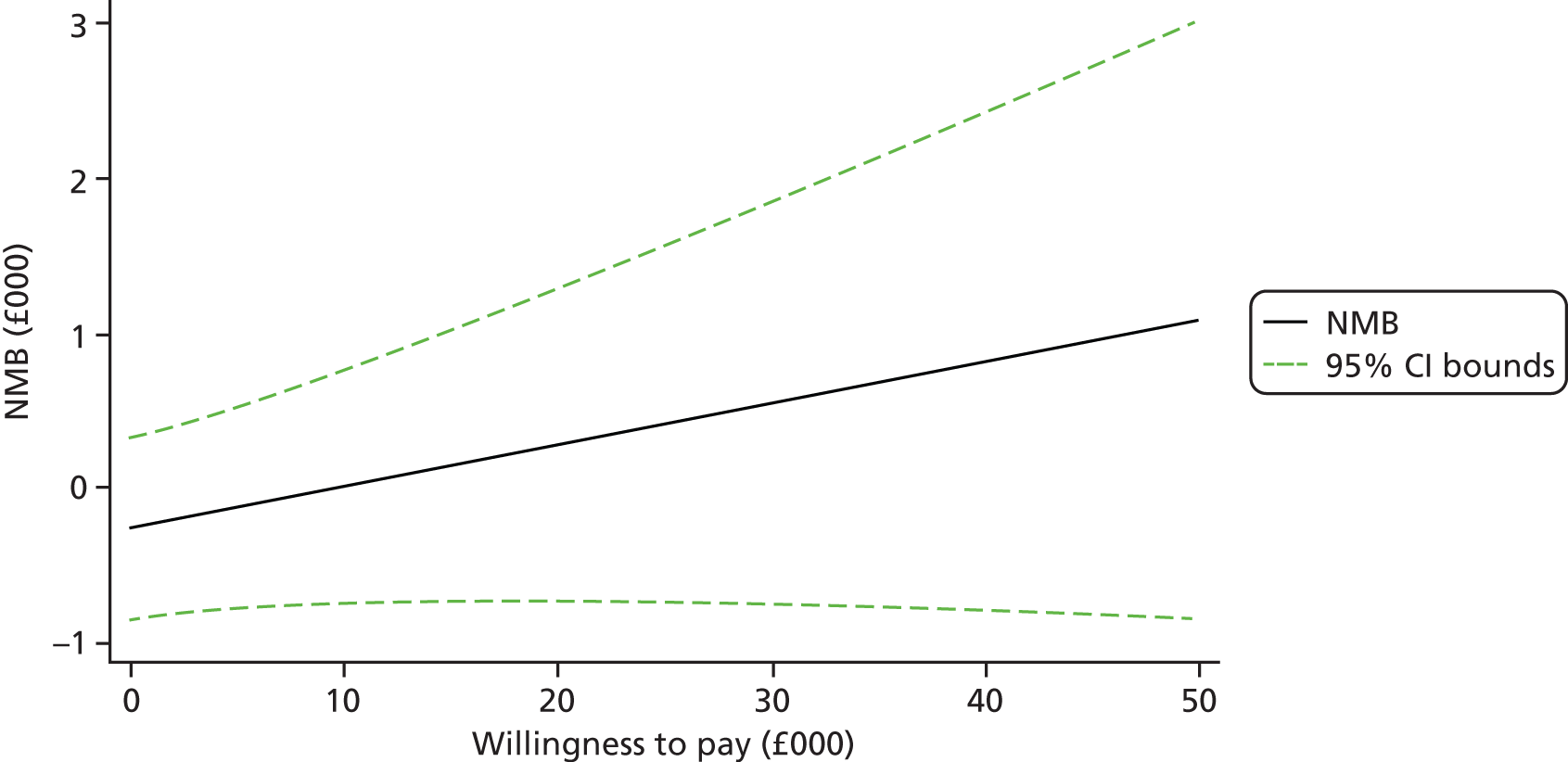

Each incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated as the difference in the cost of the START and TAU interventions divided by the difference in outcome (measured by HADS-T score or QALYs). Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were plotted to locate the findings of the economic evaluation in their wider decision-making context. The CEAC illustrates the probability that the START intervention would be seen as cost-effective compared with TAU across a range of hypothesised values placed on incremental outcome improvements (willingness to pay by health and social care system decision-makers). Each CEAC was derived using a net benefit approach. Monetary values of incremental effects and incremental costs for each case were combined and net monetary benefit (NMB) derived as:

where NMB was net monetary benefit, λ is willingness to pay for a 1-point difference in the outcome measure (HADS-T score or QALYs) and subscripts a and b denote the TAU and START interventions, respectively. We explored a range of λ values for each outcome. We were able to account for sampling uncertainty and make adjustments as necessary in the primary analyses and sensitivity analyses.

For the cost-effectiveness analyses carried out at 24 months’ follow-up, costs and outcomes in the second year were discounted at a rate of 3.5%, as recommended by NICE. 51 The discount rate was varied from 0% to 6% to assess the impact changing the NICE-recommended rate had on costs, outcome and the ICER.

Two sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of our results. The first sensitivity analysis adjusted for those variables which predicted missing outcomes, HADS-T score and QALYs, and was investigated separately for each outcome using logistic regression. The first step was to model a binary variable (missing vs. not missing) in bivariate logistic regression with each baseline demographic variable. Those variables identified as significantly associated with missing were then used in multivariate logistic regression to determine which remained significant. The main analyses were then repeated, adjusting for those factors which were found to be associated with ‘missingness’ on each outcome. For the analysis of HADS-T scores, the variables found to be associated with ‘missingness’ were patient living with carer, relationship to carer, carer having children at home, patient ethnicity and COPE dysfunction score. For the QALY outcome, the carer’s work situation (employed vs. unemployed) and ethnicity were associated with ‘missingness’.

A second sensitivity analysis adjusted for imbalances in baseline characteristics between the treatment groups that occurred despite randomisation [i.e. adjusting for carers’ work situation, relationship to patient, and patients’ and carers’ education and living situation (coresident or living separately)]. These analyses were chosen so as to be consistent with those used in the effectiveness analysis. 41

We also plotted the CIs around the NMB to estimate the impact of uncertainty.

All economic analyses were carried out using Stata, version 12 (StataCorp LP, Chicago, IL, USA).

Chapter 5 Results

Participant flow and recruitment

Two hundred and sixty (55%) of the 472 carers referred were randomised (CIFT = 182, NELFT = 16, DRC = 35, NEPFT = 27) to the trial. The others declined to participate (n = 181; 38%), did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 22; 5%) or were uncontactable (n = 9; 2%).

Short-term clinical results (over 8 months)

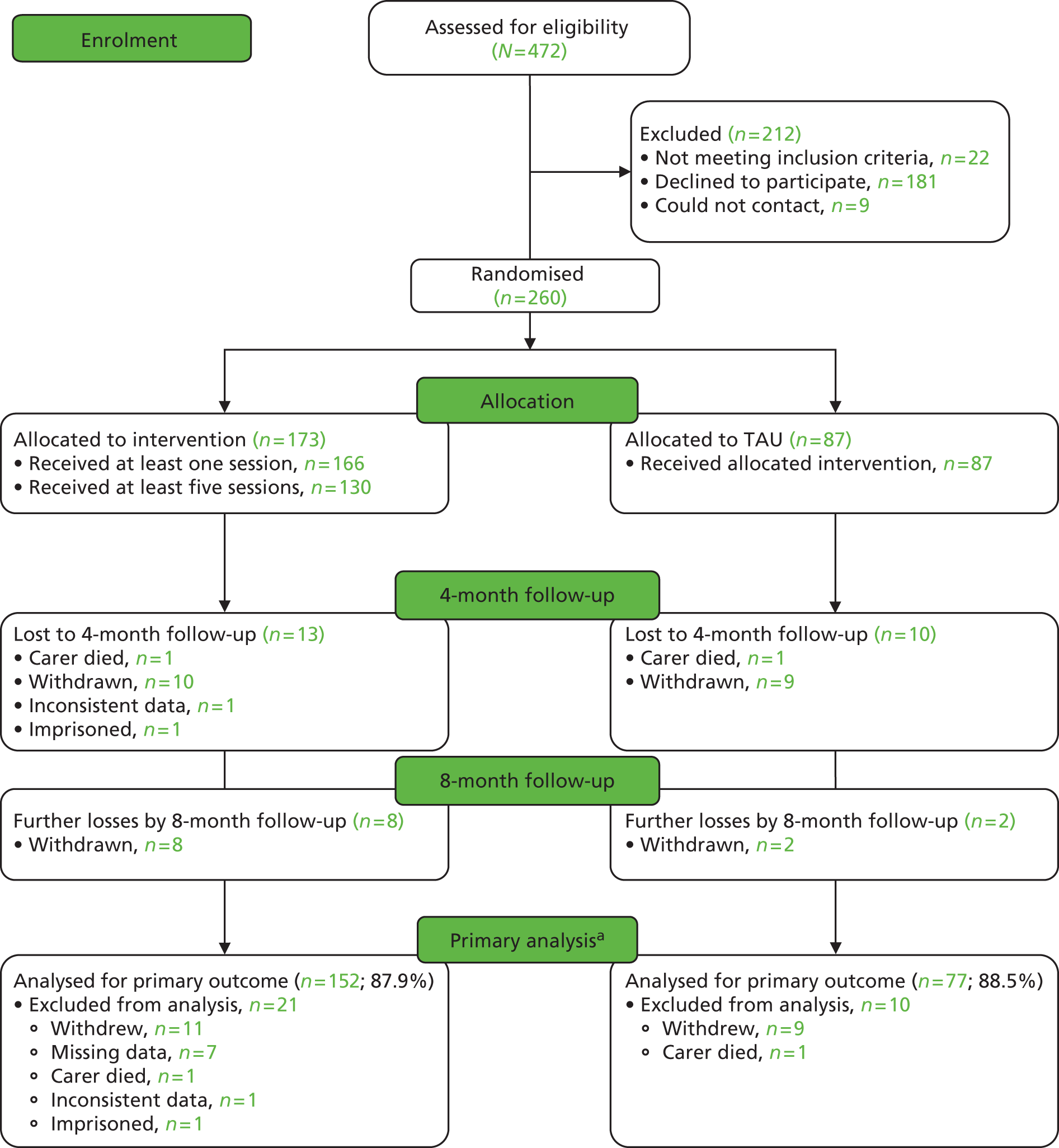

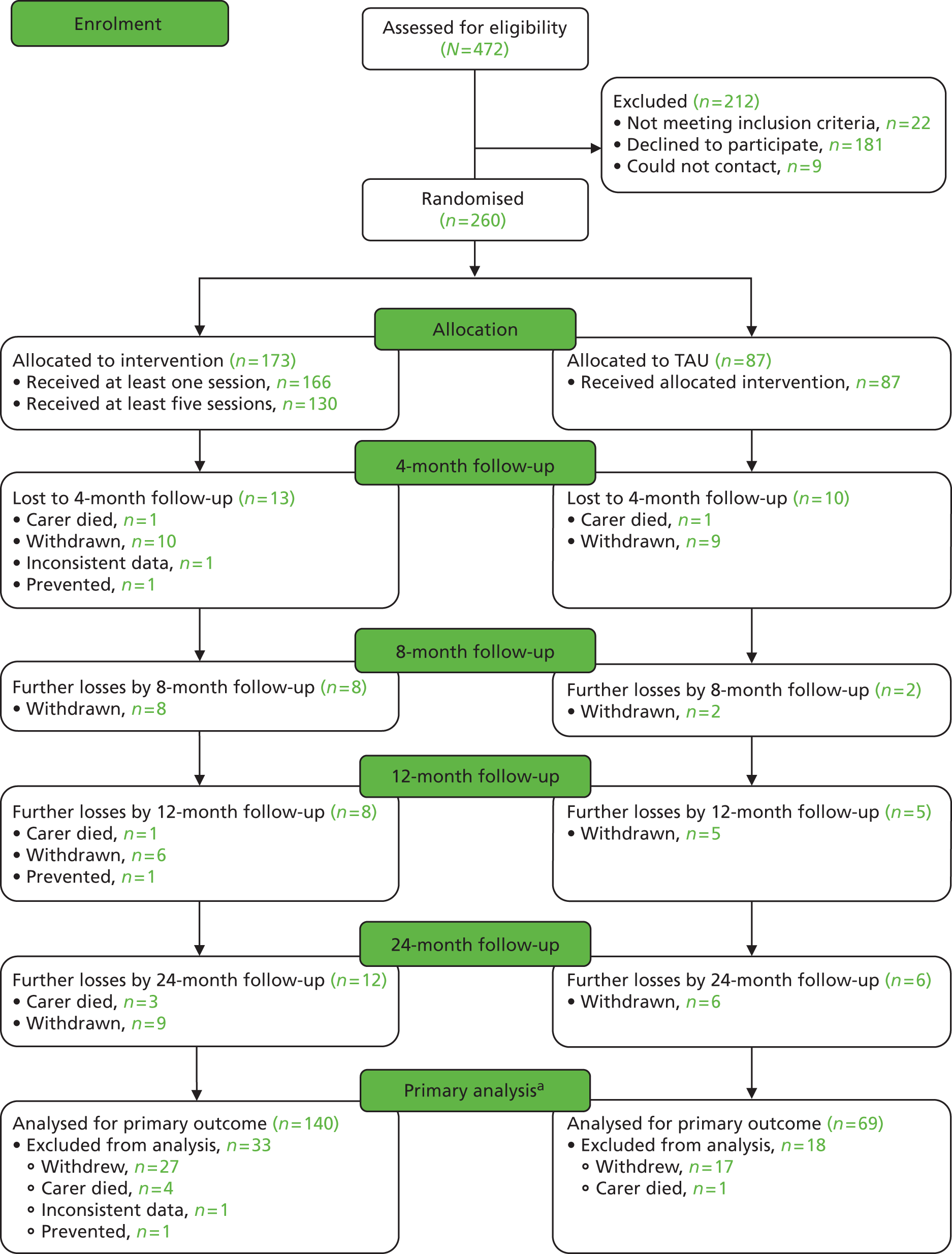

The flow through the study to the short-term (8-month) outcome is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram (short-term analysis). a, To be included in the primary short-term analysis, the individual must have at least one score available for the HADS at 4 or 8 months. Those excluded have no measurements for either.

Participant flow through study

Over the 8-month follow-up, 12 carers from the control group and 21 from the intervention group withdrew or were lost to follow-up (see Figure 1). These included two who died (one from each group). In the intervention group, one carer gave inconsistent data and was withdrawn by the team and one was in prison. The participants gave the following reasons for withdrawal: wanted treatment but not allocated to it (four in TAU group), did not feel the intervention was for them (three in intervention group), too busy (four in intervention group, one in TAU group), disliked talking about care recipient when they were not there (one in TAU group, one in intervention group), other family member wanted them to withdraw (one in TAU group), unwell (one in intervention group), care recipient died (one in TAU group) and trial too upsetting (one in intervention group). Six gave no reason (five in intervention group, one in TAU group). Three others did not participate and were not contactable at the 4- or 8-month follow-up, but have since come back to the study.

External validity

Table 1 compares the known demographic details of those who consented and those who did not and shows that the study sample had good external validity. Those who consented were, however, slightly more likely to be married to the care recipient than those who did not consent.

| Demographics | Carers eligible but not randomised (n = 190) | Carers randomised (n = 260) |

|---|---|---|

| Carer sex | ||

| Male | 56 (29%) | 82 (32%) |

| Patient sex | ||

| Male | 75 (39%) | 108 (42%) |

| Patient relationship to carer | ||

| Spouse/partner | 65 (34%) | 109 (42%) |

| Child | 90 (47%) | 113 (43%) |

| Friend | 8 (4%) | 6 (2%) |

| Daughter’s/son’s partner | 4 (2%) | 12 (5%) |

| Nephew/niece | 8 (4%) | 8 (3%) |

| Grandchild | 4 (2%) | 6 (2%) |

| Sibling | 5 (3%) | 4 (2%) |

| Other | 6 (3%) | 2 (1%) |

Baseline data

One hundred and seventy-three (66.5%) participants were randomised to the intervention group and 87 were randomised to TAU. Details are shown in Table 2. In general, randomisation achieved good balance for patient and baseline carer demographic and clinical characteristics between the randomised groups (Tables 2 and 3).

| Demographics | Carer | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU | Intervention | TAU | Intervention | |

| Mean (SD), minimum, maximum | Mean (SD), minimum, maximum | |||

| Age (years) | 56.1 (12.3), 27, 89 (n = 87) | 62.0 (14.6), 18, 88 (n = 172) | 78.0 (9.9), 53, 96 (n = 87) | 79.9 (8.3), 55, 95 (n = 173) |

| n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 62 (71.3%) | 116 (67.1%) | 50 (57.5%) | 102 (59.0%) |

| Male | 25 (28.7%) | 57 (32.9%) | 37 (42.5%) | 71 (41.0%) |

| Total | 87 | 173 | 87 | 173 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White UK | 65 (74.7%) | 131 (76.2%) | 61 (70.1%) | 126 (72.8%) |

| White other | 5 (5.7%) | 10 (5.8%) | 6 (6.9%) | 14 (8.1%) |

| Black and minority | 17 (19.5%) | 31 (18.0%) | 20 (23.0%) | 33 (19.1%) |

| Total | 87 | 172a | 87 | 173 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Not currently married | 25 (28.7%) | 61 (35.3%) | 47 (54.0%) | 92 (53.2%) |

| Married/common law | 62 (71.3%) | 112 (64.7%) | 40 (46.0%) | 81 (46.8%) |

| Total | 87 | 173 | 87 | 173 |

| Education | ||||

| No qualifications | 18 (20.7%) | 45 (26.0%) | 44 (51.2%) | 73 (44.5%) |

| School-level qualification | 33 (37.9%) | 51 (29.5%) | 16 (18.6%) | 28 (17.1%) |

| Further education | 36 (41.4%) | 77 (44.5%) | 26 (30.2%) | 63 (38.4%) |

| Total | 87 | 173 | 86 | 164 |

| Work situation | ||||

| Full-time | 28 (32.2%) | 36 (20.8%) | N/A | N/A |

| Part-time | 20 (23.0%) | 27 (15.6%) | N/A | N/A |

| Retired | 23 (26.4%) | 80 (46.2%) | N/A | N/A |

| Not working | 16 (18.4%) | 30 (17.3%) | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 87 | 173 | N/A | N/A |

| Living with carer | ||||

| Yes | N/A | N/A | 50 (57.5%) | 113 (65.3%) |

| Total | N/A | N/A | 87 | 173 |

| Scale | Carer | Patient | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU | Intervention | TAU | Intervention | |

| HADS-T scoresa | 14.8 (7.4) (n = 87) | 13.5 (7.3) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

| HADS-A scoresa | 9.3 (4.3) (n = 87) | 8.1 (4.4) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

| HADS-D scoresa | 5.5 (3.9) (n = 87) | 5.4 (3.8) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

| QoL-AD scoresa | N/A | N/A | 29.9 (6.9) (n = 87) | 30.2 (6.9) (n = 170) |

| HSQ mental health scoresa | 58.2 (21.7) (n = 87) | 58.3 (22.4) (n=171) | N/A | N/A |

| MCTS total scoresa | 2.7 (3.1) (n = 87) | 2.5 (2.9) (n=172) | N/A | N/A |

| Zarit total scoresa | 38.1 (17.0) (n = 84) | 35.3 (18.4) (n = 165) | N/A | N/A |

| NPI total scoresa | N/A | N/A | 26.6 (20.1) (n = 86) | 24.0 (19.0) (n = 171) |

| CDR overall scoreb | N/A | N/A | (n = 87) | (n = 171) |

| Score 0.5 | N/A | N/A | 12 (13.8%) | 30 (17.5%) |

| Score 1 | N/A | N/A | 43 (49.4%) | 91 (53.2%) |

| Score 2 | N/A | N/A | 30 (34.5%) | 48 (28.1%) |

| Score 3 | N/A | N/A | 2 (2.3%) | 2 (1.2%) |

| HADS-A case (score of ≥ 9)b | 48 (55.2%) (n = 87) | 85 (49.4%) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

| HADS-D case (score of ≥ 9)b | 17 (19.5%) (n = 87) | 36 (20.9%) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

| MCTS (at least one item with score of ≥ 2)b | 38 (43.7%) (n = 87) | 82 (47.7%) (n = 172) | N/A | N/A |

Intervention

Therapists

We trained 10 psychology graduates with no further clinical training – seven women and three men – who were ethnically white British (eight) and black and minority ethnic (two) in the age range 23–33 years. They worked with between 11 and 32 participants each (mean 17.3 participants) (Table 4).

| Therapist | Number of carers (%) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 11 (6.4) |

| 2 | 21 (12.1) |

| 3 | 12 (6.9) |

| 4 | 19 (11.0) |

| 5 | 12 (6.9) |

| 6 | 11 (6.4) |

| 7 | 32 (18.5) |

| 8 | 21 (12.1) |

| 9 | 17 (9.8) |

| 10 | 17 (9.8) |

| Total | 173 (100.0) |

Adherence with therapy

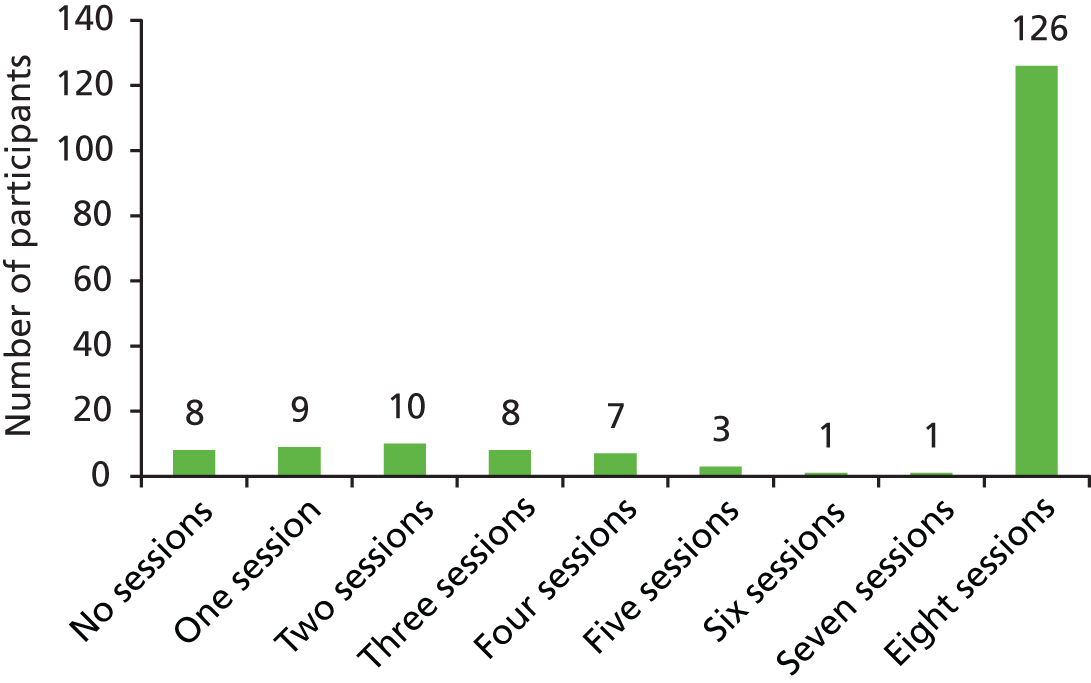

Of the eight therapy sessions offered, five or more were attended by 130 (75.1%) carers in the intervention group (Figure 2 shows details of number of sessions attended). Seven (4.0%) of those in the intervention group withdrew before taking part in any therapy sessions. Adherence (attending five or more sessions) was better in those of white ethnicity [110 (78.0%) vs. 19 (61.3%)] than in those of other ethnicity and slightly better for male carers [46 (80.7%) vs. 84 (72.4%) of female carers] and those with at least A-level education [56 (80.0%) vs. 74 (71.8%)]. Adherence was similar by age group [aged < 60–75 years (77.3%) vs. 55 years (73.3%)] and work situation [in paid work 49 (77.8%) vs. other 81 (73.6%)].

FIGURE 2.

Number of sessions completed by participants.

Fidelity

Double rating was carried out for the first 13 participants; these had a Cohen’s kappa value of 0.77, which is substantial agreement. 52 After this, we judged it was necessary to have only a single rating for the remaining participants. Fidelity rating was carried out for 128 (78%) of the 165 participants who received one or more intervention(s). The remaining 38 either refused to be audiotaped (10) or withdrew before carrying out the session which had been randomly selected for assessment (n = 28). For 100 (78%) participants fidelity was rated as 5, for 20 (16%) it was rated as 4, for five it was rated as 3 and for three it was rated as 2. Overall mean fidelity was calculated by adding each average rating (rating 1 plus rating 2, divided by 2) of the first 13 participants to the ratings of the remaining 105 participants, and dividing by the overall number of participants with available fidelity ratings. The mean fidelity score was 4.7 (SD 0.66).

Languages, translation and interpreters

Four eligible participants used translators at the recruitment stage, in Turkish (one), Bengali (two) and Farsi (one), and all four consented and were randomised: three to intervention and one to TAU. One participant allocated to intervention changed his or her mind and withdrew from intervention before session 1 but not follow-ups; one completed five sessions and one completed eight sessions.

Missing outcome data

The proportion of missing data for the main trial outcomes is given in Table 5 by group and follow-up time. The primary outcome (HADS-T score) was missing for 35 (13.5%) patients at 4 months and for 56 (21.5%) patients at 8 months, with a slightly higher proportion missing in the intervention group: 40 (23.0%) in the intervention group and 16 (18.0%) in the TAU group. Two hundred and twenty-nine (88.1%) had HADS-T data for at least one of the 4- and 8-month points and, so, could be included in the primary analyses. Using logistic regression models, we identified baseline factors that were associated with missing outcome data.

| Scale | Baseline | 4 months | 8 months | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TAU, % missing | Intervention, % missing | TAU, % missing | Intervention, % missing | TAU, % missing | Intervention, % missing | |

| HADS-A | 0.0 | 0.6 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 18.4 | 23.1 |

| HADS-D | 0.0 | 0.6 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 18.4 | 23.1 |

| HADS-T | 0.0 | 0.6 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 18.4 | 23.1 |

| Zarit total | 3.4 | 4.6 | 26.4 | 20.2 | 31.0 | 32.4 |

| MCTS total | 0.0 | 0.6 | 20.7 | 20.2 | 26.4 | 30.6 |

| HSQ mental health | 0.0 | 1.2 | 17.2 | 16.8 | 24.1 | 29.5 |

| QoL-AD total | 0.0 | 1.7 | 24.1 | 20.8 | 29.9 | 30.6 |

Missingness of HADS-T score at 4 months was associated with the patient living with carer (p = 0.007) and for the 8-month outcome with having dependent children at home (p = 0.003), patient ethnicity (p = 0.013), patient living with carer (p = 0.002), patient relationship to carer (p = 0.011) and the COPE dysfunction score (p = 0.004).

Clinical outcomes

Primary outcome

Analysis of HADS-T, adjusting for trust and baseline score and for factors related to outcome (carer age and sex, NPI and Zarit scores), showed a mean difference of –1.80 points (95% CI –3.29 to –0.31 points; p = 0.02) in favour of the intervention (Table 6). If the model did not include factors relating to outcome, then the results were similar, with an average decrease in score of –1.46 points (95% CI –2.89 to –0.03 points; p = 0.05). There was little therapist clustering: ICC at 4 months was 0.02 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.09) and at 8 months was 0.00 (95% CI 0.00 to 0.08).

| Measure | TAU | TAU | Intervention | Intervention | Adjusted for baseline score and centre, difference (95% CI) | Adjusted also for carers age, sex, NPI and Zarit, difference (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 months, mean (SD) | 8 months, mean (SD) | 4 months, mean (SD) | 8 months, mean (SD) | |||

| HADS-T scores | 14.3 (7.4) (n = 75) | 14.9 (8.0) (n = 71) | 12.4 (7.4) (n = 150) | 12.9 (7.9) (n = 133) | –1.46 (–2.89 to –0.03; p-value = 0.05) (n = 229) | –1.80 (–3.29 to –0.31; p-value = 0.02) (n = 220) |

| QoL-AD scores | 29.8 (5.8) (n = 66) | 29.7 (6.3) (n = 61) | 30.6 (6.4) (n = 136) | 30.2 (7.2) (n = 119) | 0.80 (–0.45 to 2.05) (n = 205) | 0.59 (–0.72 to 1.89) (n = 197) |

| HSQ mental health scores | 58.4 (18.0) (n = 72) | 58.2 (19.2) (n = 66) | 62.7 (20.8) (n = 144) | 58.6 (22.0) (n = 122) | 4.55 (0.92 to 8.17) (n = 219) | 4.09 (0.34 to 7.83) (n = 211) |

| HADS-A scores | 8.6 (4.2) (n = 75) | 8.8 (4.4) (n = 71) | 7.5 (4.2) (n = 150) | 7.6 (4.4) (n = 133) | –0.62 (–1.43 to 0.19) (n = 229) | –0.91 (–1.76 to –0.07) (n = 220) |

| HADS-D scores | 5.7 (4.0) (n = 75) | 6.1 (4.2) (n = 71) | 4.9 (3.9) (n = 150) | 5.3 (4.0) (n = 133) | –0.88 (–1.68 to –0.09) (n = 229) | –0.91 (–1.71 to –0.10) (n = 220) |

| HADS-A case (score of ≥ 9) | 36 (48.0%) (n = 75)a | 33 (46.5%) (n = 71)a | 54 (36.0%) (n = 150)a | 53 (39.9%) (n = 133)a | 0.35 (0.11 to 1.18) (n = 229)b | 0.30 (0.08 to 1.05) (n = 220)b |

| HADS-D case (score of ≥ 9) | 18 (24.0%) (n = 75)a | 23 (32.4%) (n = 71)a | 25 (16.7%) (n = 150)a | 28 (21.1%) (n = 133)a | 0.25 (0.08 to 0.81) (n = 229)b | 0.24 (0.07 to 0.76) (n = 220)b |

| MCTS (at least one item with score of ≥ 2) | 28 (40.6%) (n = 69)a | 23 (35.9%) (n = 64)a | 50 (36.0%) (n = 139)a | 40 (33.3%) (n = 120)a | 0.47 (0.18 to 1.23) (n = 214)b | 0.48 (0.18 to 1.27) (n = 206)b |

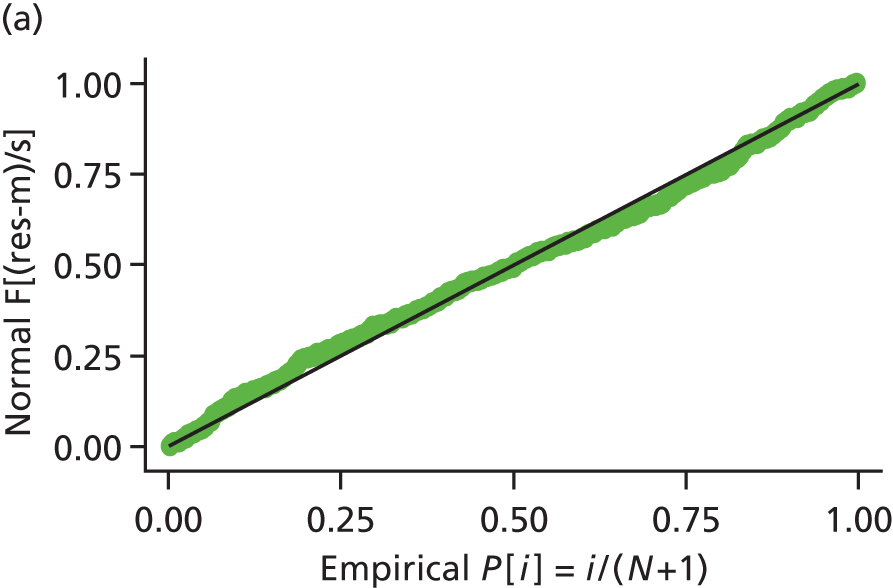

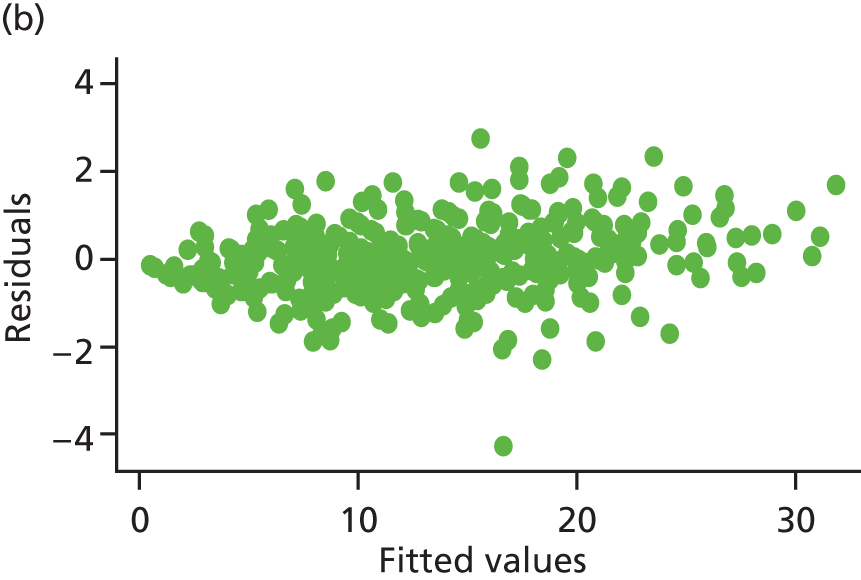

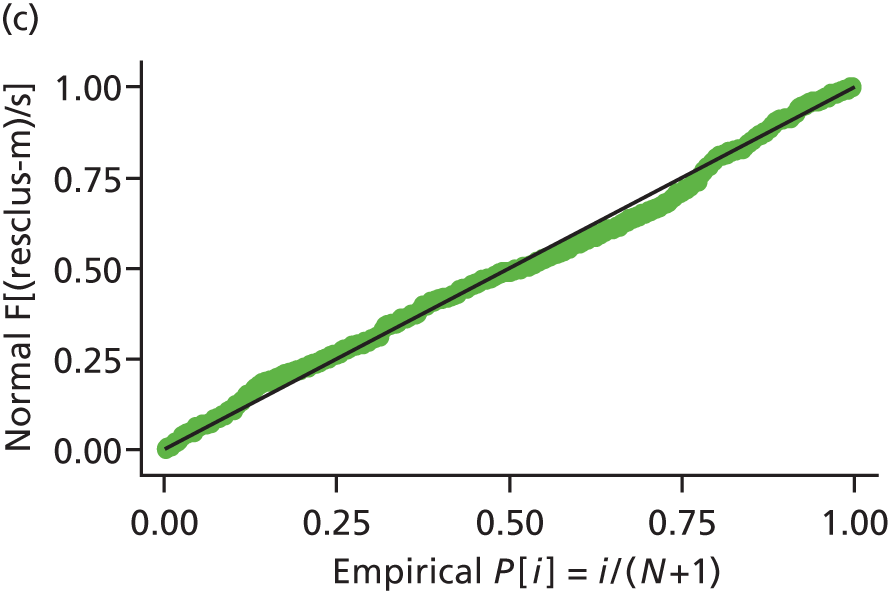

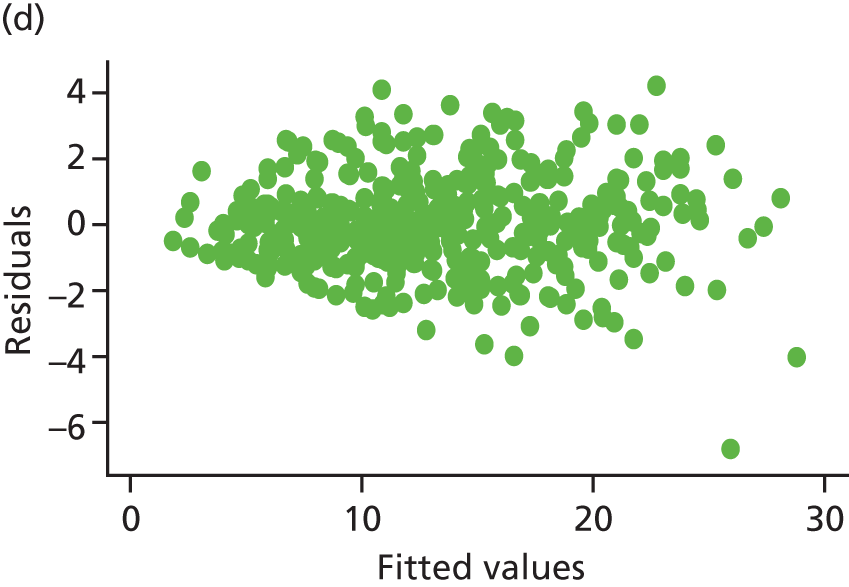

Model assumptions were examined by checking the normality of the residuals and also plotting the residuals compared with the fitted values. These were done at the individual and therapist cluster level. These plots are shown in Figure 3 and do not indicate concerns about the model fit.

FIGURE 3.

Checking model assumptions: residuals and fitted values from the models for HADS-T (based on the model-adjusted only for centre and baseline score). (a) Normality of residuals (individual level); (b) residuals vs. fitted values (individual level); (c) normality of residuals (cluster level); and (d) residuals vs. fitted values (cluster level).

Sensitivity analysis

For the sensitivity analysis we adjusted for baseline factors associated with missingness of the HADS-T outcome. Missingness of the 4-month HADS-T was associated with patient living with carer (p = 0.007) and for the 8-month outcome with having dependent children at home (p = 0.003), patient ethnicity (p = 0.01), patient living with carer (p = 0.002), patient relationship to carer (p = 0.010) and the COPE dysfunction score (p = 0.004). Refitting the main models adjusting for these significant predictors of missing values did not have a significant impact on the results (mean difference –1.53, 95% CI –2.96 to –0.10). We also carried out a sensitivity analysis to adjust for baseline imbalances, namely carer’s work situation, relationship to carer and patient and carer education and living situation, which again gave similar conclusions (mean difference –1.78, 95% CI –3.30 to –0.27). Models including an interaction with time showed no evidence of a differential effect of the intervention between the 4- and 8-month time points (p = 0.90).

Secondary outcomes

Depression and anxiety caseness on the HADS

There was a significant reduction in the odds of HADS-D cases in the intervention group compared with TAU, with an odds four times higher for the TAU group [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 0.24, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.76]. Similarly, there was some evidence for a reduction in odds of HADS-A caseness (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.08 to 1.05).