Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/13/24. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stephen Allen has carried out research in probiotics supported by Cultech, UK, has been an invited guest at the Yakult Probiotic Symposium, has received a speaker’s fee from Astellas, UK, and has received research funding from Yakult, UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Hood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overall introduction to the Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea study

The Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea (PAAD) study aimed to develop the platform for, and possibly implement, a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of probiotics administered with antibiotics to prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea (AAD). To justify a trial, we first needed an estimate of the magnitude of the AAD problem in care homes. We therefore set out to do a two-stage study. The purpose of PAAD stage 1 was to determine the prevalence of antibiotic prescribing and indication, the prevalence of AAD and to provide an indication of the prevalence of antibiotic-resistant organisms in the stool of care home residents. This would provide useful information in its own right to help guide care in this vulnerable population, in which infections are frequent and antibiotic prescribing is common and often not evidence based. It would also provide the basis for determining whether or not a RCT of probiotics to prevent AAD was justified and, if so, to generate data required for a sample size calculation for such a trial. The trial component of the study formed PAAD stage 2.

Antibiotic use in care homes

At least 4% of UK and US populations aged 65 years or over live in care homes. 1–3 Demand for long-term care in the UK is estimated to rise by up to 150% over the next 50 years. 4

Although data on infection prevalence in care homes are limited, point prevalence studies suggest that between 5% and 10% of residents in care homes will be prescribed antibiotics for a presumed infection at any one time. 5,6 This antibiotic use has consequences for residents’ quality of life (QoL) from both benefits and harms associated with antibiotic use, costs of care and increased risk that subsequent infections will be antibiotic resistant. 7–9 However, up to 40% of antibiotics prescribed in care homes might be inappropriate. 8–10 Accurate estimates of prescription rates by antibiotic class and indication are lacking.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

Antibiotic treatment disrupts the normal flora of the gut, sometimes causing diarrhoea. 11 The primary mechanism is thought to be disturbance in the metabolism of carbohydrates, short-chain fatty acids and bile acids, resulting in impaired resistance to pathogens. 12 While any antibiotic can cause AAD, clindamycin, cephalosporins, aminopenicillins and, more recently, fluoroquinolones have been directly linked with AAD, particularly in hospitalised patients. 13 Older patients with frequent hospitalisations and high comorbidity are at greatest risk. 13 Little is known about the frequency and type of antibiotics prescribed in care homes, or about the incidence and aetiology of AAD. AAD varies in incidence, is especially common in winter, and can occur in up to 39% of hospitalised patients receiving antibiotics. 14 A challenge to clinicians is to identify cases of AAD due to Clostridium difficile (Hall and O’Toole 1935) Prévot 1938 infection since this is the most commonly identified and treatable pathogen responsible and is also implicated in more severe cases of AAD. 11 C. difficile is implicated in 20–30% of AAD cases. 15

Clostridium difficile

Clostridium difficile is a Gram-positive, anaerobic, spore-forming bacteria that was identified in the late 1970s and has recently been highlighted as a potential deadly threat to hospitalised patients and residents of care homes. 13,16 The spores can survive for lengthy periods in the environment and gut; therefore, there is a high risk of cross-infection through direct patient-to-patient contact, via health-care staff or via a contaminated environment. The Health Protection Agency’s (HPA) data from voluntary surveillance of C. difficile in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 2006 described an overall increase in incidence, from 2005 to 2006, of 8% in England and 15% in Wales, with the highest incidence in the elderly. 17 Although there were some HPA data for positive stool samples originating in primary care, there are no data to indicate whether or not these are follow-up samples from hospitalised patients. We were not able to identify prospective UK data on C. difficile outside hospitals, nor were we able to identify studies that involved prospective, systematic sampling. The second study of Infectious Intestinal Disease (IID2) included the incidence of C. difficile among people living in the community but not in care homes. 18

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea (CDAD) is the most commonly identified cause of AAD, and is responsible for most cases of pseudomembranous colitis; it typically occurs in care homes, among other settings. 19 CDAD occurs most often as a consequence of disruption of the indigenous colonic microflora following broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment. C. difficile accounts for 20–30% of AAD,15 although some estimates are more conservative. 11 Although the majority of individuals recover fully, elderly and frail individuals in particular may suffer loss of dignity or become seriously ill with dehydration (as a consequence of the diarrhoea), and some may go on to develop pseudomembranous colitis.

Exposure to antibiotics within the previous 2 months is the most important risk factor for developing CDAD. 20 Cumulative antibiotic exposure appears to be associated with an increased risk of CDAD. 21 Other well-recognised risk factors include age [hospital patients aged over 65 years are four times more likely than general medical patients to develop CDAD (73.6 vs. 16 per 1000 admissions)], hospitalisation, severity of underlying illness, nasogastric tube and use of proton pump inhibitors or H2-agonists. 22–24

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea infection in care homes

There are few data regarding antibiotic use, AAD and CDAD in UK care homes. Most of the research to date has been carried out in hospital settings or in the USA. However, residents in care homes in the UK have many of the risk factors associated with developing AAD and CDAD (e.g. age over 65 years, frailty, multiple comorbidities and frequent antibiotic treatment).

Antibiotic use in US residential homes is common: estimations of single time point prevalence range from 8% to 17%, and in one study between 50% and 75% of residents received at least one antibiotic prescription over a 12-month period. 20 We conducted a prescribing audit of care homes in one health authority and found that 134 (7%) of 1901 residents were on an antibiotic in a single day. A study in care homes in Sweden found that 25% of residents were prescribed an antibiotic during a 3-month observation period. 25 However, considerably fewer antibiotics are prescribed in Sweden than in the UK. 26 It is not known how many of these residents developed AAD or how many had C. difficile in these studies. Providing reasonable estimates of these outcomes for the UK relate to the scientific importance of our study to the NHS. Diarrhoea within long-term care facilities (LTCFs) can cause fatalities and could become endemic.

Laffan et al. 27 retrospectively reviewed CDAD incidence and prevalence in a single 200-bed LTCF in Baltimore in the USA between July 2001 and December 2003. The incidence of CDAD ranged from 0 to 2.62 cases per 1000 resident-days. They found that CDAD in this LTCF occurred most often in patients who had recently been admitted to hospital. 27 US studies by Kutty et al. and Chang et al. found that over 90% of post-hospitalisation cases of CDAD occur within 30 days of discharge. 28,29

Riggs et al. , in the USA, found that over 50% of patients admitted to a LTCF during an outbreak were asymptomatic carriers of C. difficile (stool culture positive, but no diarrhoea). 30

A review of the diagnosis, management and prevention of C. difficile in LTCFs concluded that the epidemiology, risks and outcomes of C. difficile infection in older residents of LTCFs need to be better understood. 31 Better treatment modalities to reduce the risk of recurrent disease need to be developed and assessed, and measures such as antimicrobial stewardship should be introduced.

Probiotics to prevent antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

Probiotics are dietary supplements containing a single culture or mixed culture of live microorganisms such as bacteria or yeast which, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host by improving the properties of the indigenous microflora. 32 Probiotics have been proposed as a preventative intervention for AAD, including CDAD, as they reinforce the human intestinal barrier. 14,33–35 Probiotics’ likely mechanism of action is through secretion of antimicrobial factors, such as bacteriocins, and competition for adherence to the binding sites on mucins and epithelial cells, thereby preventing detrimental colonisation and contributing to barrier function. 36 Certain probiotic strains are resistant to digestion by enteric or pancreatic enzymes, gastric acid and bile, and prevent the adherence, establishment and/or replication of pathogens in the gastrointestinal tract. Probiotics are generally well tolerated and free of adverse effects although, theoretically, the introduction of live bacteria may carry the risk of introducing resistance genes and causing septicaemia. 37

A previous Cochrane review of probiotics as a treatment for presumed infectious diarrhoea included 23 studies with a total of 1917 participants and found that probiotics reduced the risk of diarrhoea at 3 days [relative risk (RR) 0.66, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.55 to 0.77, random-effects model; 15 studies] and the mean duration of diarrhoea by 30.48 hours (95% CI 18.51 to 42.46 hours, random-effects model; 12 studies). 35 A Cochrane review of probiotics for the prevention and treatment of AAD38 included 63 studies with a total of 11,811 participants and indicated a statistically significant association of probiotic administration with reduction in AAD [RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.68; p < 0.001; I2 = 54%; (risk difference –0.07, 95% CI –0.10 to –0.05) (number needed to treat 13, 95% CI 10.3 to 19.1)] in trials reporting on the number of patients with AAD. However, there is significant heterogeneity in the pooled results and the evidence is insufficient to determine whether this association varies systematically by population, antibiotic characteristic or probiotic preparation. The review concluded that probiotics are associated with a reduction in AAD; however, more research is required to determine which probiotics, patients and antibiotics are associated with the greater efficacy.

A recent Cochrane review of probiotics for the prevention of CDAD in adults and children included 23 studies with a total of 4213 participants and found that probiotics significantly reduce the risk of CDAD by 64%. 39 The incidence of CDAD was 2.0% in the probiotic group, compared with 5.5% in the placebo, no treatment, control group (RR 0.36, 95% CI 0.26 to 0.51). The review concluded that the moderate-quality evidence suggested that probiotics are both safe and effective for preventing CDAD.

A systematic review of six studies of paediatric patients found significant benefit to patients from using probiotics in per-protocol analyses compared with control patients (RR 0.43, 95% CI 0.25 to 0.75). However, no evidence for a difference was found in intention-to-treat analyses (RR 1.01, 95% CI 0.64 to 1.61). 40 Hickson et al. 41 randomised patients to receive either antibiotics and placebo (n = 66) or antibiotics and probiotics (n = 69) and found that 7 of 57 patients in the probiotic group, compared with 19 patients from 56 in the control group, developed AAD. However, only 135 of 1760 hospitalised patients taking antibiotics were randomised in this trial (randomisation rate 7.6%), which may limit the applicability of the findings. 41

Database searches

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE prior to starting this study, and our findings indicated that the evidence base for the use of probiotics is incomplete. In the light of our searches we have made recommendations about what should be done taking into consideration this uncertainty and about future research. 42 More specifically, we were not able to identify evidence for or against using probiotics to prevent AAD in people admitted to LTCF/care homes or in primary care. It is essential that research is carried out in the setting in which the evidence will be applied, the findings of hospital-based studies may not apply to the care home setting, as antibiotics, routes of administration and patient profiles differ between hospitals and care homes.

Conducting studies in care homes

There are 1203 care homes in Wales, of which 25% provide nursing care (300 homes). There are a total of 2607 care homes and 570 nursing homes in south-west England. Within these homes, there are approximately 427,000 beds across England and Wales, and it is understood that the number of beds will need to be increased in line with the projected rise in demand for long-term care. 1,2

Conducting studies in care homes, especially nursing homes, poses unique challenges. Care home research participants are more likely to be older, physically frail and cognitively impaired compared with other research settings. 43 Recruitment, consent, retention and data collection can be time-consuming and difficult and extra time and help should be provided to ensure that the staff in care homes have the ability to carry out the research procedures. 44 Care home staff are also more likely to move after short periods of employment.

Rationale for the Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea study

There are (incomplete) surveillance data from the USA and the UK, and UK clinical experience to suggest that AAD including CDAD is an important problem in care homes in the UK. There are strong grounds for evaluating probiotics in conjunction with antibiotic treatment to prevent AAD in care homes, but this strategy has never been properly evaluated in a clinical trial. However, before a trial is justified, the importance of the problem to the independent care home sector and NHS, a firm basis for sample size calculation and trial planning, needs to be more clearly established.

The introduction of probiotics in conjunction with antibiotic treatment in care homes could lead to a significant reduction in AAD, as antibiotic treatment is common in this group; spread is a particular risk, and patient frailty increases risk of acquisition and of complications. Diarrhoea in this group can lead to serious illness resulting in hospital admissions, cause illness in fellow care home residents, increase vulnerability through reduced nutrition and dehydration, result in ongoing incontinence, cause urinary tract infections (UTIs) and have a profoundly negative impact on dignity. Therefore, we proposed a two-stage study.

The PAAD study stage 1 would establish the descriptive data we needed to confirm both the magnitude of the problem and that our sample size calculation assumptions were correct. Knowing the amount and nature of antibiotics prescribed in care homes and describing AAD and CDAD would be useful in its own right and would help to guide future antibiotic prescribing decisions in this setting. To account for the known difficulties in conducting research in this setting, we also planned to pilot study procedures, model consent procedures, and develop training material to train care home staff in how to conduct the RCT and determine if cascading of the training to new colleagues would be possible.

If PAAD stage 1 confirmed a trial was justified, PAAD stage 2 would be a RCT to generate robust evidence that would fill an important gap in the evidence base about the use of probiotics, in conjunction with antibiotic treatment, in older people in care homes.

Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea study objectives

Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea stage 1: primary objectives

-

To conduct prospective systematic ascertainment of the incidence of AAD in care homes.

-

To allow an appraisal of the estimated sample size for a RCT in PAAD stage 2.

Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea stage 1: secondary objectives and auxiliary study objectives

-

To conduct prospective systematic ascertainment of antibiotic use in care homes.

-

To estimate the risk of AAD overall and from particular antibiotics in care home settings.

-

To identify barriers and implementation issues in conducting a trial of AAD prevention/amelioration in a care home setting.

-

To determine the prevalence of asymptomatic C. difficile carriage in residents within selected care homes.

The probiotic feasibility and acceptability study

-

To test the acceptability and feasibility of administering probiotic in a small number of care home residents.

-

To pilot and develop trial procedures including modelling consent procedures.

-

To develop a training package for care home personnel to implement the trial.

The qualitative study

-

To conduct focus groups and individual qualitative interviews with care home residents, their family, care home staff and general practitioners (GPs).

-

To explore the ethical and practical issues of consent and assent, particularly the topic of advanced consent, for elderly residents who may/may not have capacity to consent.

Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea stage 2 objectives

The primary objective was to:

-

assess the effectiveness of probiotics taken in conjunction with antibiotic treatment in reducing the incidence of AAD.

The secondary objectives were to:

-

assess the effectiveness of probiotics taken in conjunction with antibiotic treatment in reducing the incidence of CDAD

-

evaluate the impact of probiotics in conjunction with antibiotic treatment on the functional status and QoL

-

evaluate the cost-effectiveness of probiotics in conjunction with antibiotic treatment in reducing AAD.

Changes to objectives

The originally planned feasibility study, to test the acceptability and practicability of administering probiotic in a small number of residents, was not undertaken for two reasons. First, on discussion with the pharmaceutical company (Actiel), it was confirmed that the VSL#3 powder could be dissolved in as little as 25–50 ml of liquid or sprinkled on food; therefore, the initial concern over drinking a large volume of liquid (100 ml) was appeased. Second, it was considered resource and time intensive to conduct alongside the main observation study.

Summary

In summary, PAAD stage 1 aimed to identify the rates of antibiotic prescribing and AAD in care homes, to determine the prevalence of C. difficile in baseline stool samples and to provide reliable incidence data and confirm the basis of our sample size calculation for the RCT in PAAD stage 2.

If PAAD stage 1 indicated that AAD is a rare, unimportant problem, then, based on explicit stopping rules, we would not progress to PAAD stage 2.

In addition, work was planned in PAAD stage 1 to allow us anticipate and address challenges in the PAAD stage 2 trial design and implementation. In particular, we were keen to explore the acceptability of advanced consent procedures in a possible trial of probiotics to prevent AAD.

Chapter 2 Probiotics for Antibiotic-Associated Diarrhoea stage 1: a prospective observational study of antibiotic prescribing and antibiotic-associated diarrhoea in care home residents

Methods

Study design

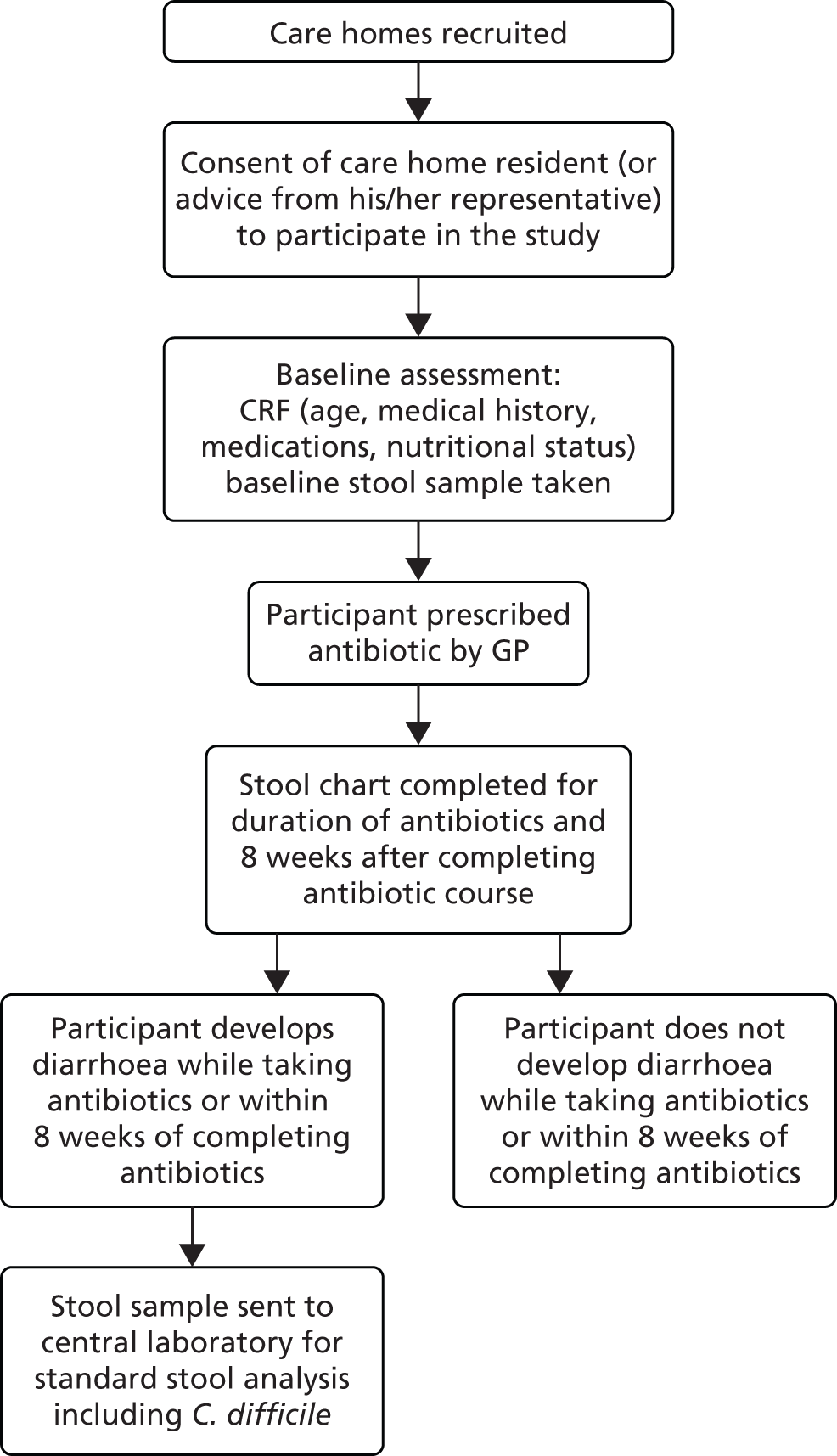

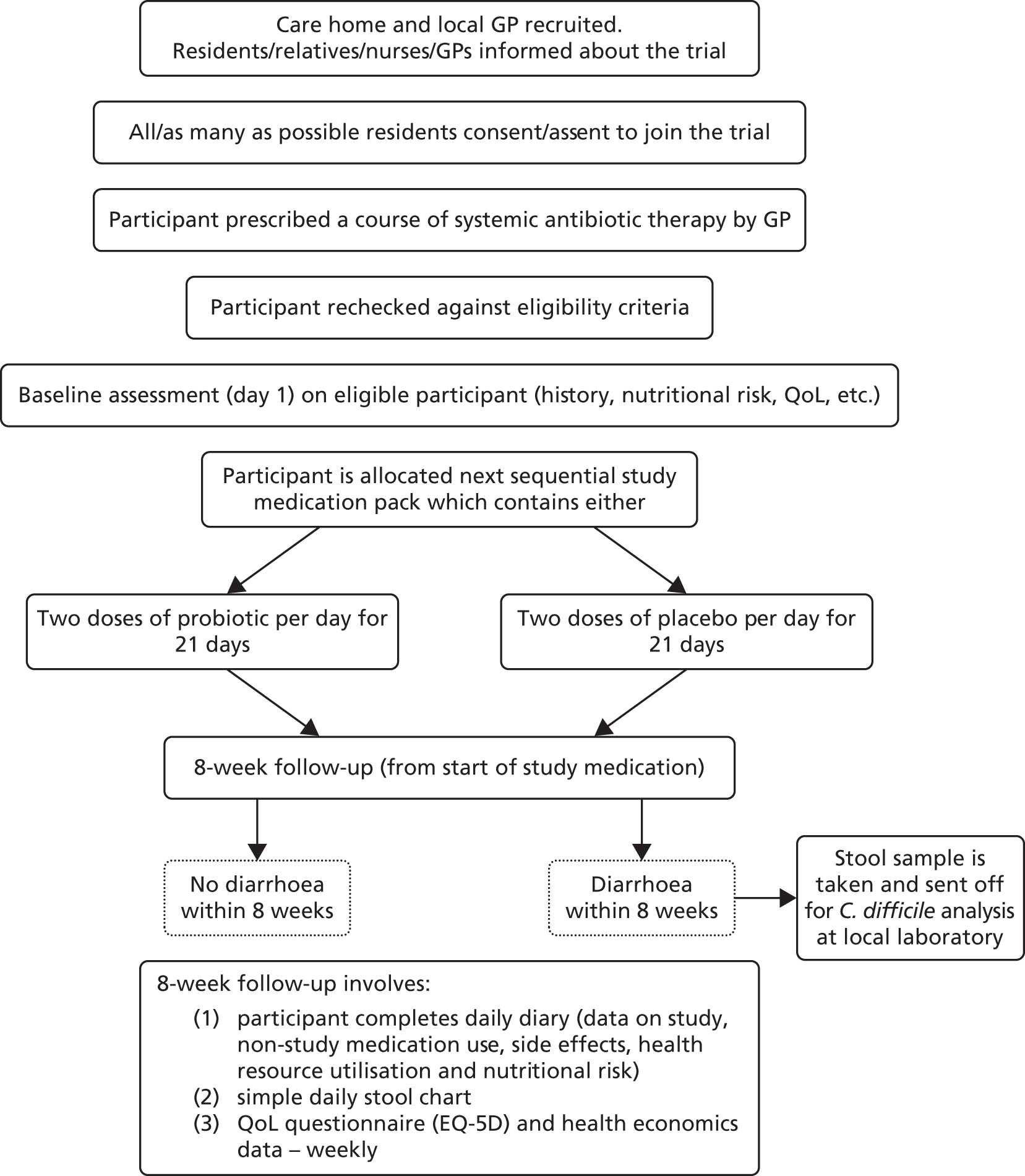

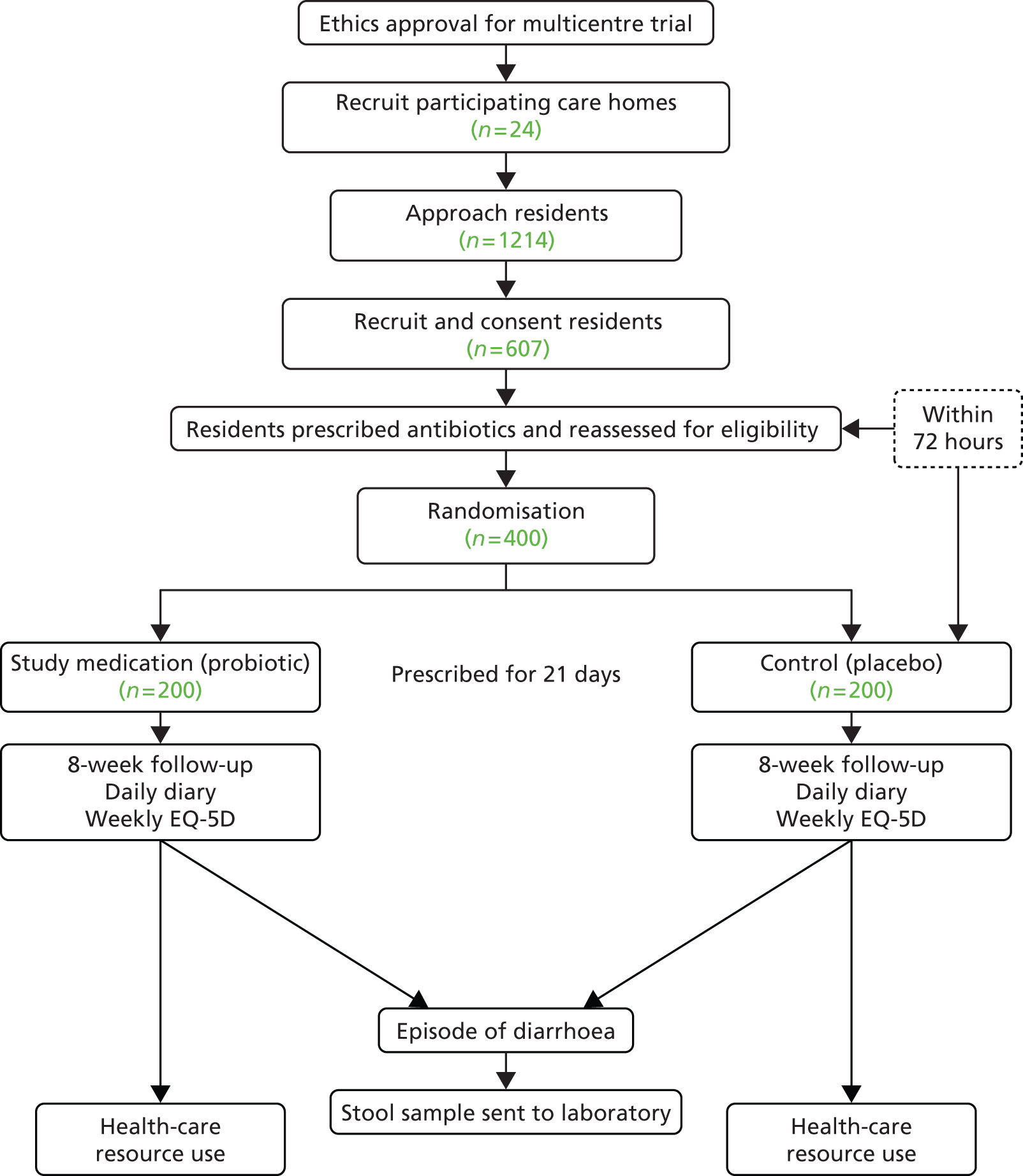

The PAAD study stage 1 was a prospective observational cohort study of antibiotic prescribing and associated AAD in care home residents (Figure 1). The study was conducted between November 2010 and March 2012 in care homes in South Wales. We aimed to recruit a total of 270 care home residents and follow up each resident for 12 months. The South East Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) approved the study (10/WSE03/31). Agreement to conduct the study at the care homes was either given by the care home manager, regional manager or care homeowner (if privately owned) or given by the local authority (LA).

FIGURE 1.

Study design. CRF, case report form.

Study objectives

Primary objectives

-

To conduct prospective systematic ascertainment of the incidence of AAD in care homes.

-

To allow an appraisal of the estimated sample size for a RCT in stage 2.

The aim was to use this information to identify the scale of the AAD problem in care homes, provide reliable incidence data and confirm the basis of our sample size calculation for a RCT of probiotics in PAAD stage 2.

Secondary objectives

-

To conduct prospective systematic ascertainment of antibiotic use in care homes.

-

To estimate the risk of AAD overall and from particular antibiotics in care home settings.

-

To identify barriers and implementation issues in conducting a trial of AAD prevention/amelioration in a care home setting.

-

To determine the prevalence of asymptomatic C. difficile carriage in residents within selected care homes.

The aim was to use this information, in conjunction with AAD incidence, to estimate the risk of AAD overall, from antibiotics overall, and from particular antibiotics in care home settings. Additionally, the observational study would serve as an opportunity to ascertain the practicalities of conducting a RCT in a care home environment.

We planned an interim analysis at 8 months after commencing recruitment of residents, which would include follow-up data from residents recruited within the first 6 months, to assess the scale of the AAD problem in care homes. The results of the interim analysis, in relation to the explicit stopping rules defined by the research team, would determine whether or not progression to the PAAD stage 2 RCT was warranted.

Participants and recruitment

Care home recruitment

The research team identified all care homes in South Wales, stratified them based on the type of care they provided (nursing, residential or dual registered, i.e. providing both nursing and residential care), randomly ordered them within their stratum and approached the care homes sequentially by telephone to arrange a meeting with the manager of the care home to discuss the study further.

During this meeting, the aims and objectives of the study were explained in more detail and an informal questionnaire was used to prompt the team to gather data about the home in order to assess the feasibility and practicality of carrying out the study at that care home.

Care homes were recruited when the relevant manager and care home owner agreed for PAAD stage 1 to go ahead at their site and at least three staff at the site were willing to take responsibility for conducting the study in their care home. Reimbursement was offered for the time staff dedicated to the study or additional time spent over their contracted hours and additional research nurse or research officer support was provided by the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research – Clinical Research Centre (NISCHR CRC) where needed.

Once the essential governance documents were completed, signed and returned to the research team, the care home was provided with all the information, training and equipment necessary to carry out resident recruitment and study procedures.

Participant recruitment

Residents were eligible for the study if they met all of the PAAD stage 1 inclusion criteria (Table 1).

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Resident admitted to the care home for > 24 hours | There were no exclusion criteria for the PAAD stage 1 observational study |

| Planned admission to care home of 1 month or more (excludes short term respite care) | |

| Written confirmed consent/assent provided |

There were two categories of eligible residents: those who had capacity to consent and those unable to consent for themselves. Therefore, consent procedures differed depending on whether or not residents had capacity at the time the resident was approached and recruited into the study.

Senior care home/nursing staff were asked to identify residents who were eligible to join the study. Where staff members were unsure of the mental capacity status of an eligible resident, mental capacity was assessed during the consent procedure to determine capacity to consent. Study information was given using written information available in several forms (either the full information sheet or a more visually accessible information sheet in large print and a pictorial information sheet) to ensure that residents were given a full opportunity to consent for themselves. Residents with mental capacity and willing to participate were asked to provide written consent or verbal consent (for those unable to write). This was witnessed by two senior staff members. Where residents lacked capacity, senior care home/nursing staff were asked to identify representatives, herein referred to as ‘consultee’, for each resident (e.g. next of kin, those who visit most regularly). Consultees were provided with the study information sheet accompanied with a verbal explanation when they came into the care home or, if this was not possible, by post and then followed up with a telephone call. The consultees of the residents were explicitly asked, either in writing or verbally, to consider whether or not they believed the resident would want to join the study. Consultees who believed their relative would have wanted to participate in the study were asked to sign a consent form to document their decision.

For residents who did not have an available consultee, the plan was to contact Age UK for advice or request that the residents’ GP nominate an appropriate person or act on the resident’s behalf. Both of these options are suggested in the 2005 Mental Capacity Act (MCA). 45 However, this situation did not arise during the course of the study.

During the recruitment process, residents and their consultees were given as much time as needed to consider the information and the opportunity to question the care home staff, their GP or other independent parties to decide whether or not they were willing to participate in the study. All consent, written or verbal, and assessment of mental capacity was undertaken by study-trained senior care home staff/nursing staff. All residents and consultees were advised that they could withdraw participation in the study at any time without it affecting their care.

Study procedures

Study training

The research team aimed to deliver bespoke study training to staff at each individual care home because of the heterogeneity of the recruited care homes, in terms of both size and type of resident care. Core standardised training modules included the fundamentals of good clinical practice (GCP) as well as study-specific training on how to approach residents/consultees about the study, assessing capacity, taking informed consent, interpreting and using the Malnutrition Universal Assessment Tool (MUST), reporting serious adverse events (SAEs), interpreting the Bristol Stool Chart (BSC), taking and sending stool samples and data collection.

Initial training was provided before the start of the study, before recruitment, once the study began and continuously after that point with specific staff groups to refresh their memory. As much flexibility as possible was given to the time (i.e. evenings, weekends) and number of training sessions in order to provide training to as many senior staff members and registered nurses as possible without disrupting the usual routines in the homes. Owing to the need to retain adequate staffing levels at the homes, it was often not possible for all of the care assistants to attend training; therefore, we requested that the training be cascaded from those who had attended training to more junior members of staff.

Monthly teleconference calls were set up with key staff in each of the care homes to be used as a forum to update care home status, share challenges, find solutions and generally maintain engagement and enthusiasm for the study. Incentives, in terms of both monetary (vouchers) and non-monetary (certificates, specialised training courses, cake for site of the month, etc.) value were also provided.

Throughout the course of the study the research team organised three workshops with the aim of promoting engagement with the study and to provide ongoing training. Workshops were held in Cardiff city centre and were designed to help care home staff discuss procedures to obtain consent or maximise accurate case report form (CRF) completion.

Data collection

Prior to the recruitment of residents, care home staff were asked to complete a care home information CRF. The purpose of this CRF was to elicit summary information about the care home characteristics and, to that end, it incorporated questions asking about the number of beds, number of residents, staffing levels and whether or not there was an infection control policy in place. A further CRF was completed at the end of the study to provide a measure of change in number of residents and staffing levels over the study period.

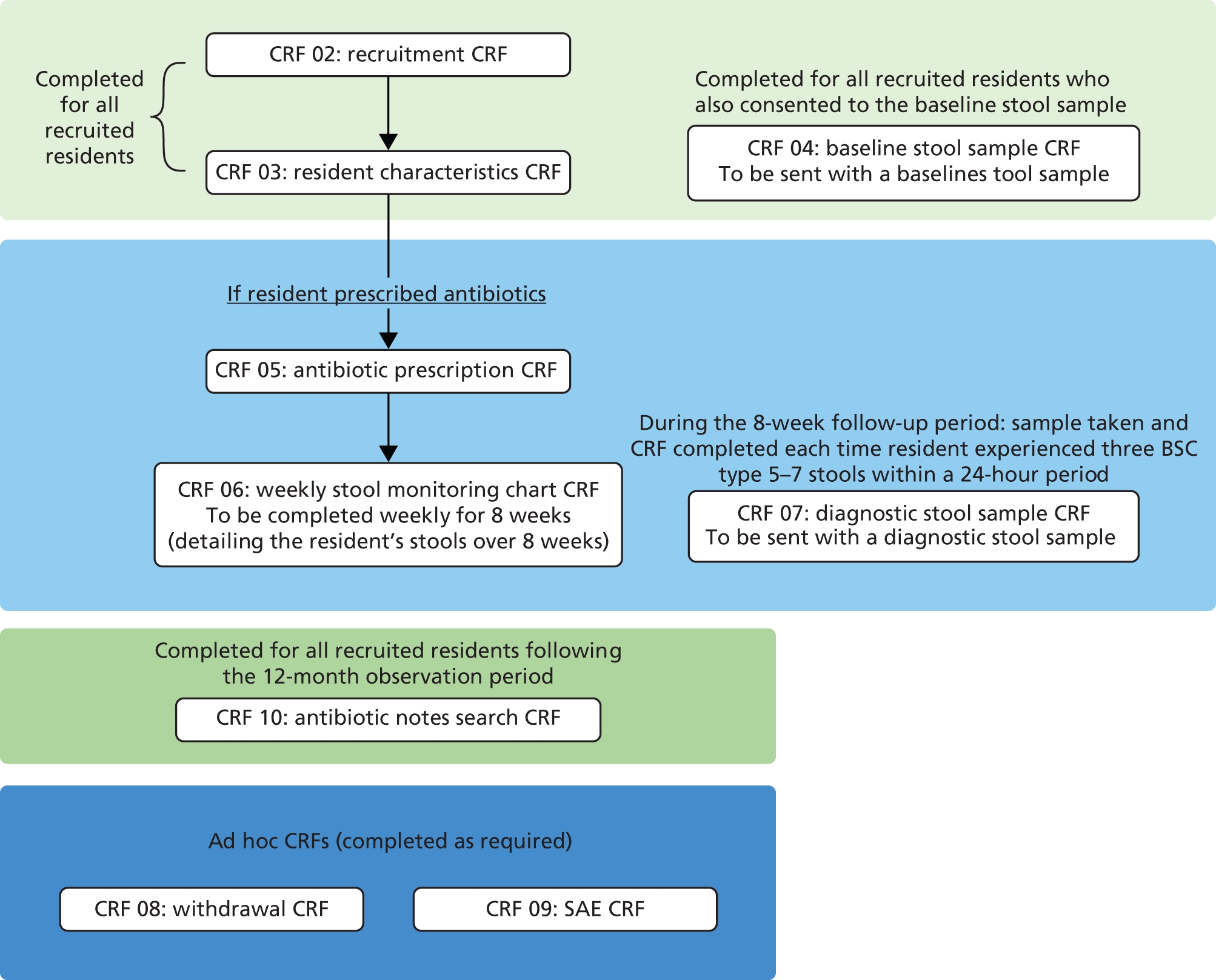

Data about residents participating in the observational study were collected in two phases (1) ‘baseline’ data were collected as soon as possible following consent and (2) ‘follow-up’ data were collected when a resident recruited into the study was prescribed antibiotics at any point during the 12 months following recruitment (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Data flow of recruited residents.

Serious adverse event reporting was undertaken for all recruited residents regardless of whether or not they were prescribed antibiotics during the 12-month observational period. The CRFs included standard screening and assessment tools (among other questions devised by the research team) (Table 2).

| Tool | Description of tool | When recorded |

|---|---|---|

| MUST | MUST is a five-step screening tool used to assess nutritional risk. The algorithm requires information about current body mass index, weight loss and current health status in order to provide the health professional with a score used to guide nutritional management of the patient46 | When recruited into the study (CRF 03) Each time the resident was prescribed an antibiotic (CRF 05) |

| Clinical Frailty Scale | The Clinical Frailty Scale is a visual aid used to assess a person’s perceived frailty. It has been used as a predictor of death or need for entry into care facility. The tool uses nine pictures, each with brief descriptions, on a Likert-type scale in which options vary between very fit and very severely frail or terminally ill47 | When recruited into the study (CRF 03) |

| BSC | The BSC is a visual aid used by health professionals as a diagnostic marker of digestive health. The scale depicts seven pictures of human faeces in various forms, ranging from faeces described as type 1 (separate hard lumps, like nuts; hard to pass) to type 7 (watery, no solid pieces, i.e. entirely liquid) | On the CRFs that accompanied the baseline stool sample (CRF 04) When a stool bowel movement was recorded following an antibiotic prescription (CRF 06) and/or diagnostic stool sample(s) (CRF 07) |

Table 3 details, for each PAAD study CRF, time point for data collection, a brief description of the type of data collected and who had overall responsibility for collecting the data. The research team requested that the original CRF should be sent to the PAAD study trial manager and a copy kept in the site file in each care home.

| CRF | Data collected | Time point | Collected by |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRF 01 – care home information | Type, size, occupancy of home. Staffing levels and infection control training | Prior to commencing recruitment | Care home staff |

| CRF 02 – recruitment | Eligibility confirmation, age, gender, capacity status | Immediately post consent | Care home staff |

| CRF 03 – resident characteristics | Medical history, recent hospitalisation, recent antibiotic use | Immediately post consent | Care home staff |

| CRF 04 – baseline stool sample | Date and time of stool collection. Consistency of stool | Within 1 week from consent | Care home staff |

| CRF 05 – antibiotic prescription | Name, dose, route, frequency, duration and indication of antibiotic | Day of commencement of antibiotic treatment until duration end date | Care home staff/NISCHR CRC research officers |

| CRF 06 – weekly stool monitoring chart | Time and consistency of bowel movements. Whether or not a stool sample was taken | Day of commencement of antibiotic treatment, every day for duration of antibiotic + 8 weeks | Care home staff/NISCHR CRC research officers |

| CRF 07 – diagnostic stool sample | Date and time of stool collection. Consistency of stool | When participant develops diarrhoea within the 8-week follow-up period following antibiotics | Care home staff |

| CRF 08 – withdrawal | Date and reason for withdrawal | Following a withdrawal | Care home staff/NISCHR CRC research officers |

| CRF 09 – SAE reporting | Details of adverse event (outcome, description, seriousness, expectedness and causality) | Following any SAE | Care home staff/NISCHR CRC research officers |

| CRF 10 – antibiotic notes search | Name, dose, route, frequency, duration and indication of antibiotics prescribed in the 3 months prior to study entry | At the end of the recruitment period at the care home | Care home staff/NISCHR CRC research officers |

Data collected following antibiotic prescription

For each antibiotic prescribed during the study period, care home staff recorded the medical indication, name, route, dose, day and duration of prescription on the antibiotic CRF (05). Immediately following an antibiotic prescription for the duration of and up until 8 weeks after the end of the antibiotic course, the care home staff collected data on the resident’s daily stools (including the time the stool was passed and the BSC type of the stool), using the stool monitoring CRF (06), reported on a weekly basis.

If care home staff observed loose stools (BSC score 5–7) in a participating resident during the stool monitoring follow-up period, a stool sample was taken on the second episode of loose stools to ensure that samples were collected whenever an episode of AAD might have occurred. This sample was sent to the laboratory along with a diagnostic stool sample CRF (07) which stated the stool’s consistency and time of sample collection.

Samples were sent to a central reference laboratory specialist antimicrobial chemotherapy unit for C. difficile culture and screening for the carriage of antibiotic-resistant organisms. Staff at care homes were also encouraged to also send a stool sample to their local laboratory as per their routine procedure.

Medication data

The care home staff or NISCHR CRC research officers were also asked to take a photocopy of the medication administration record (MAR) from the care plan of each consented resident. To maintain anonymity, residents’ names were replaced by their participant identifier (PID). The photocopy of the MAR was requested as soon as possible following consent, each time an antibiotic was prescribed and for the entire month of March 2012. The intention of the 1-month review was to inform an audit of the effectiveness of care home reporting of antibiotics. The purpose of the request following consent and following an antibiotic prescription was to determine whether or not there were any trends between certain medications and AAD or CDAD.

Serious adverse event reporting, withdrawals and loss to follow-up

When care home staff became aware that a participating resident had experienced a SAE, they were asked to complete a SAE CRF within 24 hours on becoming aware of the event.

The research team was notified of study withdrawals and deaths via the withdrawal CRF. Participating residents who were admitted to hospital were not considered lost to follow-up unless they stayed in hospital for the remainder of their time in the study.

Data management

Participant tracking

Residents were ‘tracked’ throughout their time in the study using the completed CRFs (and the dates on the CRFs) that were sent from care homes. Data were added on to the PAAD stage 1 database when these CRFs were received at the South East Wales Trials Unit (SEWTU). The data manager was able to search for each recruited resident in the database using the resident’s PID to determine which CRFs had been completed for each individual and, hence, what stage the resident was at in the study.

Clinical data

Receipt of CRFs was logged in the database. CRFs were first visually checked, then processed using Cardiff TeleForm, an optical mark recognition system, and stored in Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) data sets (SPSS version 20; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Missing/invalid data, identified during any of the above points and using data validation checks in SPSS, were queried at site using source data from care notes. Data corrections were undertaken prior to scanning in TeleForm, or via syntax in SPSS.

Stool data

Stool sample results were collated and stored electronically at the Public Health Wales laboratory. Care home staff were asked to fax or send the research team at SEWTU a copy of the completed diagnostic stool sample CRF (07) so that the research team could maintain a record of when stools samples had been sent to the laboratory.

Stool sampling

All care homes were provided with a protocol on the stool sampling procedure in order to promote standardisation when collecting and sending stool samples. The research team provided all care homes with disposable bowl inserts for commode pots, sample tubes, adhesive tube labels and spatulas as well as a fridge for storing samples that could not be immediately sent to the laboratory. Stool samples were taken either from stool passed into commode inserts or from the resident’s incontinence pad and placed into a sample tube. The research team requested that the sample [with the diagnostic stool sample CRF (07)] should be labelled with the resident’s PID and initials and sent to the central reference laboratory using Post OfficeTM-approved SafeboxesTM.

Stool sample analysis

The stool samples were cultured, including for C. difficile, and then stored at −70 °C. Cultured C. difficile isolates were then ribotyped, toxin tested and subjected to antimicrobial sensitivity testing as well as screened for carriage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. As the results of the loose stool study samples were used for research purposes only and were not fully analysed in real time, they were not sent back to the care homes or GPs.

Statistical methods

Care home sampling frame

Care homes in South-East Wales were split into three strata, based on the type of care home: nursing, residential or dual registered. The team intended to purposively recruit three care homes from each stratum, making a total sample of nine care homes. The aim of this method of sampling was to gain an insight into the amount of variability between and within different types of care homes (in terms of both the homes themselves and their residents).

Resident sample size justification

We predicted that nine care homes would generate a sample of approximately 270 residents. Previous literature indicated that 40% of care home residents would be likely to be prescribed antibiotics over a 12-month period. This figure would enable the research team to fit a 95% CI to an AAD rate of 25% ± 10%.

Interim analysis

A planned interim analysis was carried out evaluating data collected during the initial 3 months of the study, together with 2 additional months of data for AAD follow-up. The interim analysis would provide estimates of recruitment, antibiotic prescriptions and episodes of AAD. The duration and severity of AAD were also assessed. These estimates would provide a scientific and medical justification for a trial of probiotics to prevent/ameliorate AAD in care home residents, allow an understanding of the feasibility of recruiting in this setting and give a firm basis for sample size calculation for the RCT.

Owing to the descriptive nature of the interim analysis, no adjustments were made to the final analyses to correct for the fact that an interim analysis had been performed.

Progression/stopping criteria

Specific criteria related to recruitment, antibiotic prescribing and AAD were defined a priori. Specifically, it was deemed infeasible to continue to a RCT if the percentage of residents recruited from those approached was less than 60%. To justify a scientific and medical need for a RCT of probiotics in care homes to reduce AAD, we felt that at least 27% of residents needed to have been prescribed at least one course of antibiotics at the interim time point and at least 18% of prescriptions would have to result in at least one episode of AAD. Should our AAD progression criteria not be met, we planned to also take the severity of AAD into account when determining whether or not to progress to a trial.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for each care home type and overall using means (standard deviations), medians [interquartile ranges (IQRs)] and proportions, as appropriate.

All incidence rates were calculated as per care home resident-year. Clustering of antibiotic prescriptions and AAD by resident was explored and estimates were appropriately inflated.

The probability of residents being prescribed antibiotics was estimated by fitting a logistic regression model, with results presented as odds ratios (ORs), 95% CIs, and p-values.

We used logistic regression models to compare samples with and without antibiotic-resistant bacteria for identified risk factors. Results are presented as ORs, 95% CIs and p-values.

To estimate the risk of developing AAD, a two-level logistic regression model was fitted with stool-monitoring periods nested within care home residents. Results are presented as ORs, 95% CIs and p-values. The time from antibiotic prescription to first episode of AAD was similarly estimated by fitting a two-level Cox proportional hazards model. Results are presented as hazard ratios (HRs) with associated 95% CIs and p-values.

All regression models were entered in the following blocks: stool monitoring characteristics (for the AAD models only), resident characteristics and care home characteristics. Explanatory variables were included if they were associated with their outcome at the 20% level in a univariable analysis, with variables removed from the final multivariable regression models if they were not significant at the 5% level and were of marginal significance (p-value > 0.1) in the univariable analysis. All relevant modelling assumptions were checked prior to reporting. Estimates from the regression models are presented from each stage of the multivariable model, with corresponding univariable estimates.

The two-level Cox proportional hazards model was implemented using Stata version 10.0.18 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All other analyses were performed using IBM SPSS.

Substantial changes to study protocol

Over the course of the study a number of changes were made to the PAAD stage 1 protocol. Initially, the intention was to include a sample of care homes of differing sizes from those with 20 beds or fewer to those with 100 beds or more. However, there were very few nursing and dual-registered care homes with 20 beds or fewer in the South-East Wales region. As the most important factor in the care home sample was care home type (nursing, residential and dual registered) it was decided to recruit three care homes of each type regardless of size.

Several changes were made to improve recruitment and data collection. These included allowing verbal consent (with witnesses present) to be provided if the resident or consultee was unable to sign the consent form and enabling the research team to take copies of recruited residents’ MAR sheets at specific time points to ensure the collection of valid concomitant medication data. It also came to light that many of the residents and their consultees were frustrated that they were unable to give consent at the time they were approached (i.e. directly after reading and digesting the information on the participant information sheet) because the protocol stated a mandatory 24-hour ‘consideration’ time before they could join the study. As a result of this the protocol was amended (with REC approval) to allow residents/consultees an opportunity to provide consent at the time of their choosing.

Antibiotic prescribing and associated diarrhoea: findings from a prospective observational cohort study of care home residents

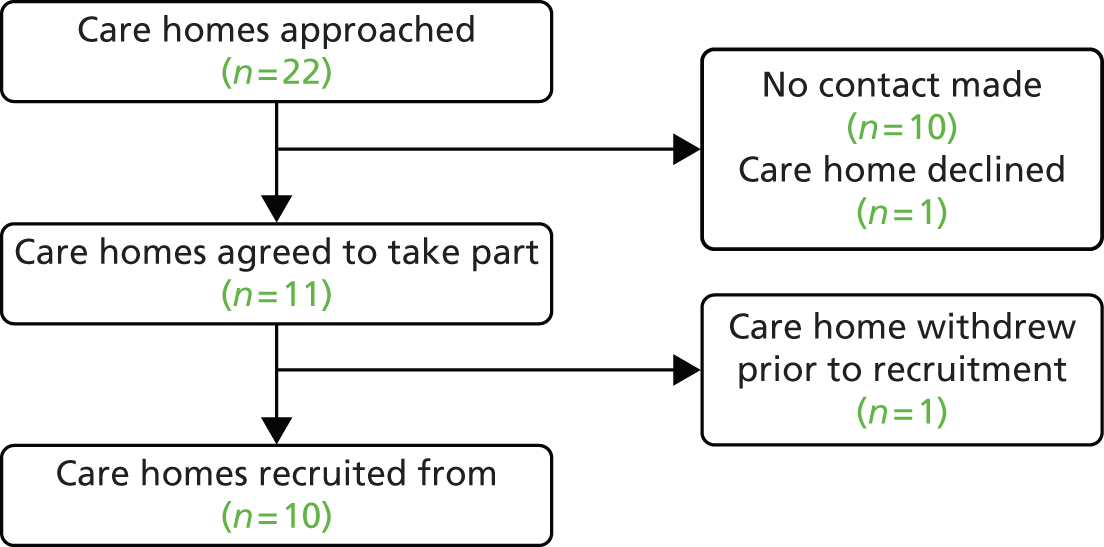

Care homes

Eleven care homes were recruited to the study. However, one withdrew before any residents were recruited. Residents were therefore recruited from 10 care homes: four nursing, four residential and two dual-registered homes. Nine homes were privately managed and one was managed by a LA. The median number of beds was 39.5 (IQR 31.0–50.0) and the median number of residents at the time of recruitment was 33.0 (IQR 28.0–50.0). The median number of staff working in a care home over a typical 24-hour period was 16.0 (IQR 14.0–25.0), with 20.5% (n = 41) categorised as short-term staff members (i.e. employed for less than 12 months) (Table 4 and Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Care home flow diagram.

| Care home type | Care home information | Accommodation details | Staffing details | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of care homes | Privately managed, n (%) | Total number of beds, median (IQR) | Total number of residents, median (IQR) | Total number of staff working in the last 24 hours, median (IQR) | Short-term staff working in the last 24 hours,a median (IQR) | |

| Nursing | 4 | 4 (100.0) | 36.0 (30.5–45.5) | 30.0 (27.5– 41.0) | 15.0 (13.0–20.5) | 3.0 (1.5–4.5) |

| Residential | 4 | 3 (75.0) | 35.5 (28.0–39.5) | 31.5 (26.5–37.0) | 15.5 (13.0–16.5) | 2.5 (1.0–3.5) |

| Dual registered | 2 | 2 (100.0) | 70.0 (54.0–86.0) | 66.5 (50.0–83.0) | 37.0 (29.0–45.0) | 10.0 (0.0–20.0) |

| Overall | 10 | 9 (90.0) | 39.5 (31.0–50.0) | 33.0 (28.0–50.0) | 16.0 (14.0–25.0) | 2.5 (1.0–4.0) |

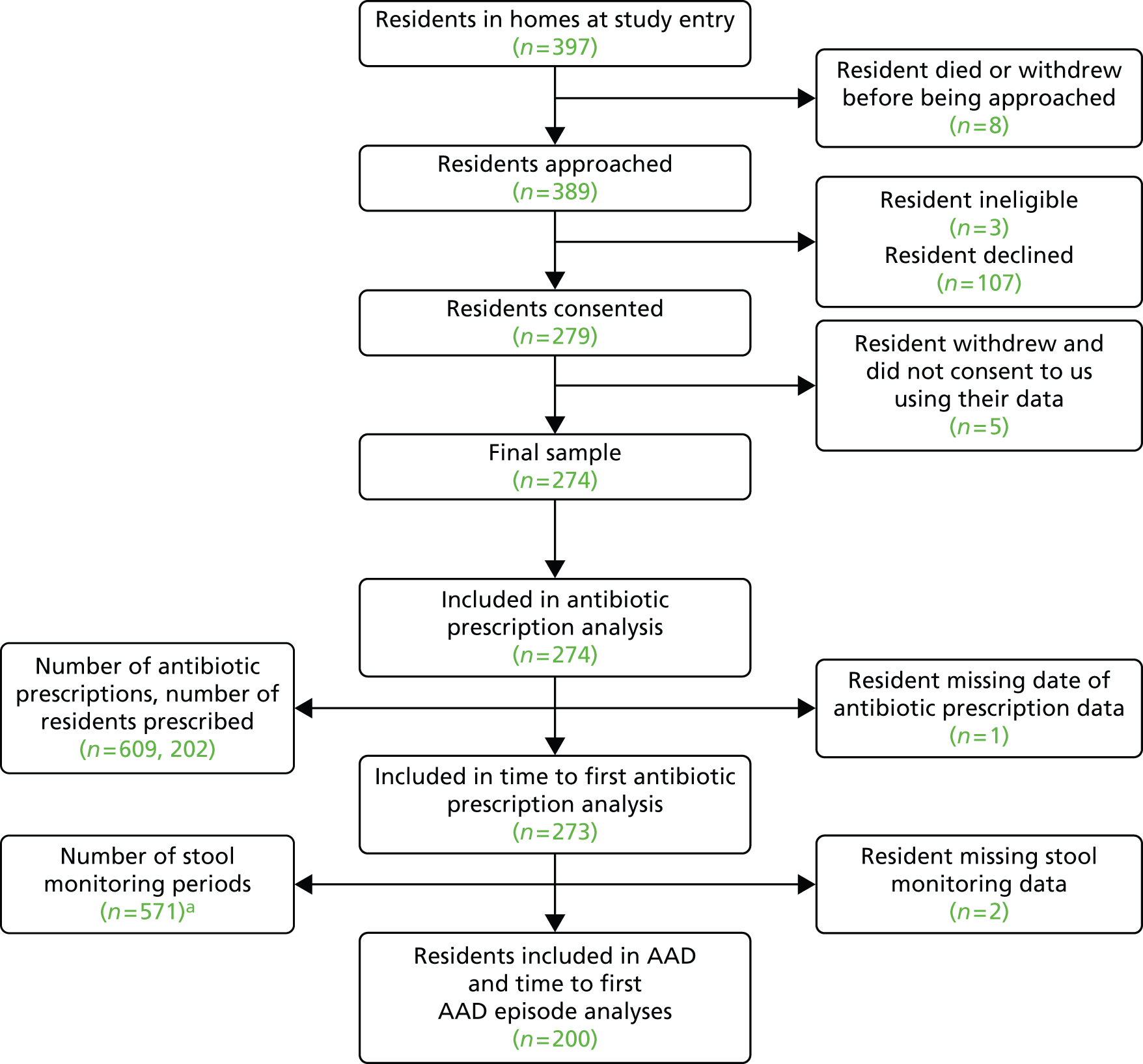

Participants

Three of the 389 residents (or consultees) approached were ineligible and 107 declined participation. A total of 279 residents were therefore recruited (71.7%). Of those recruited, 19 withdrew, 16 (84%) because they moved to a non-participating care home. Five of the 19 residents who withdrew from the study also withdrew permission for data already collected to be used; therefore, our analyses are based on a maximum of 274 residents (Figure 4). There were 81 hospitalisations reported during the study period, with at least one hospitalisation reported for 58 (21.2%) residents (incidence rate of 0.14 hospitalisations per resident-year, 95% CI 0.09 to 0.20 hospitalisations). In total, 64 residents died during the study period. No deaths were deemed study related. Residents were observed for a median of 310 days (IQR 230–364 days).

FIGURE 4.

Resident flow diagram. a, Some prescriptions overlapped in time and so did the stool monitoring periods in these instances.

Descriptive data

Residents had a median age of 86 years (IQR 82–90 years), with 20.4% (n = 56) < 80 years old, 57.7% (n = 158) between 80 and 90 years old and 21.9% (n = 60) older than 90 years. The majority of residents (75.9%) were female. Overall, 28.5% (n = 78) had capacity to provide informed consent for themselves. Few residents had any of the prespecified relevant serious medical conditions. At baseline, 7.7% (n = 21) had faecal incontinence with loose stools, 1.8% (n = 5) had diarrhoea and 66.8% (n = 183) routinely used incontinence pads. A ‘very fit to managing well’ classification was attributed to 13.5% (n = 37) of residents, 51.1% (n = 140) were classed as ‘vulnerable to moderately frail’ and 35.4% (n = 97) as ‘severely frail to terminally ill’. Nursing homes had more frail residents than residential homes. At baseline, 63.0% (n = 172) were classified as having a low nutritional risk status, 14.3% (n = 39) as medium risk and 22.7% (n = 62) as high risk. In the 4 weeks prior to recruitment, 6.9% (n = 19) had been admitted to hospital and 20.8% (n = 57) of residents were prescribed antibiotics (Table 5).

| Care home type (number of residents) | Age, median (IQR) | Gender (male), n (%) | Capacity to provide informed consent for study, n (%) | Admitted to hospital in last 4 weeks, n (%) | Prescribed antibiotics in last 4 weeks, n (%) | Routinely wear incontinence pads, n (%)a | MUST: low risk, n (%)b | MUST: medium risk, n (%)b | MUST: high risk, n (%)b | Clinical Frailty Score of 1–3, n (%)c | Clinical Frailty Score of 4–6, n (%)c | Clinical Frailty Score of 7–9, n (%)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing (n = 87) | 87.0 (83.0–91.5) | 26 (29.9) | 25 (28.7) | 11 (12.6) | 17 (19.5) | 66 (75.9) | 55 (64.0) | 9 (10.5) | 22 (25.6) | 2 (2.3) | 42 (48.3) | 43 (49.4) |

| Residential (n = 87) | 85.0 (76.5–89.0) | 19 (21.8) | 33 (37.9) | 6 (6.9) | 18 (20.7) | 39 (44.8) | 58 (66.7) | 14 (16.1) | 15 (17.2) | 22 (25.3) | 47 (54.0) | 18 (20.7) |

| Dual registered (n = 100) | 85.0 (82.0–90.0) | 21 (21.0) | 20 (20.0) | 2 (2.0) | 22 (22.0) | 78 (78.0) | 59 (59.0) | 16 (16.0) | 25 (25.0) | 13 (13.0) | 51 (51.0) | 36 (36.0) |

| Overall (n = 274) | 86.0 (82.0–90.0) | 66 (24.1) | 78 (28.5) | 19 (6.9) | 57 (20.8) | 183 (66.8) | 172 (63.0) | 39 (14.3) | 62 (22.7) | 37 (13.5) | 140 (51.1) | 97 (35.4) |

Interim analysis

At the interim time point, we had approached 363 care home residents and recruited 260, giving a recruitment rate of 72% (95% CI 67% to 77%). We recorded at least one antibiotic prescription for 119 residents, giving an antibiotic prescribing rate of 46% (95% CI 40% to 52%). There were 152 antibiotic prescriptions recorded at the interim time point, 51 of which with a corresponding episode of AAD, giving an AAD rate of 34% (95% CI 25% to 42%). As all criteria had been met, we were permitted to begin designing a RCT of probiotics to prevent/ameliorate AAD in care home residents (Table 6).

| Outcome | Stop if | Estimate | Result (proceed/stop) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Recruitment | The proportion of residents recruited is less than 60% of those approached | 260/363 = 72% (95% CI 67% to 77%) | Proceed |

| Antibiotic prescribing | The proportion of recruited residents prescribed at least one course of antibiotics is < 27% | 119/260 = 46% (95% CI 40% to 52%) | Proceed |

| AAD | The proportion of antibiotic prescriptions (with follow-up data) resulting in at least one episode of AAD is < 18% | 51/152 = 34% (95% CI 25% to 42%)a | Proceed |

| Severe AADb | The proportion of antibiotic prescriptions resulting in at least one episode of AAD < 18% and the proportion of AAD episodes classed as severe is low | There were no episodes of AAD lasting longer than 2 weeks. Of the 34 diagnostic stool samples received and analysed, eight (24%) were found to contain C. difficile. There were no episodes of AAD that resulted in hospitalisation or death | Proceed |

Antibiotic prescriptions

There were 609 antibiotic prescriptions recorded over the study period, with 73.7% (n = 202) of residents being prescribed at least one antibiotic course. We found an incidence of 2.16 antibiotic prescriptions per care home resident-year (95% CI 1.90 to 2.46 prescriptions).

Antibiotics were prescribed for a median of 7.0 days (IQR 6.0–7.0 days), with 14.7% (n = 88) prescribed for less than 5 days, 74.9% (n = 447) prescribed for between 5 and 7 days, 6.7% (n = 40) prescribed for between 8 and 10 days and 3.7% (n = 22) prescribed for more than 10 days.

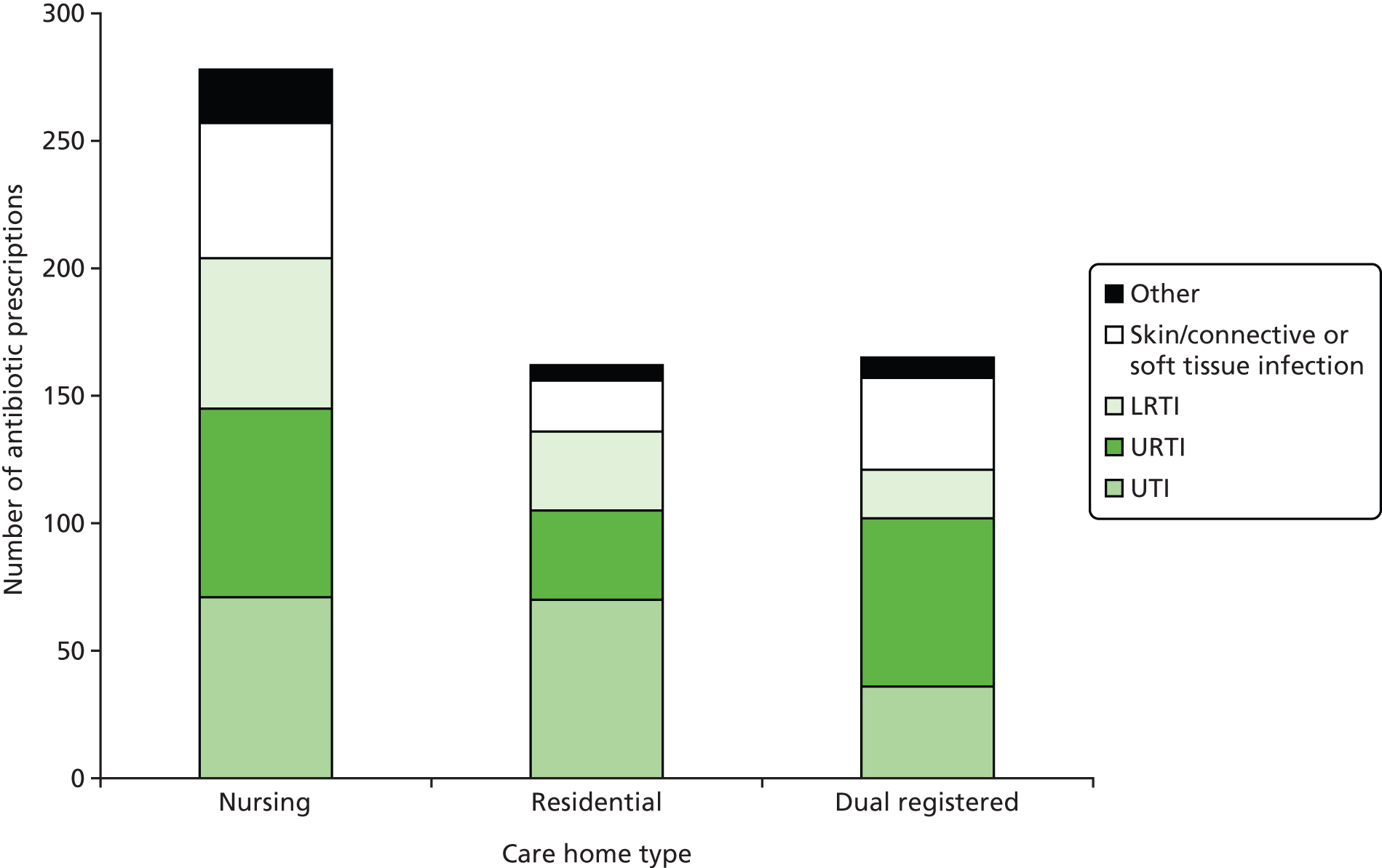

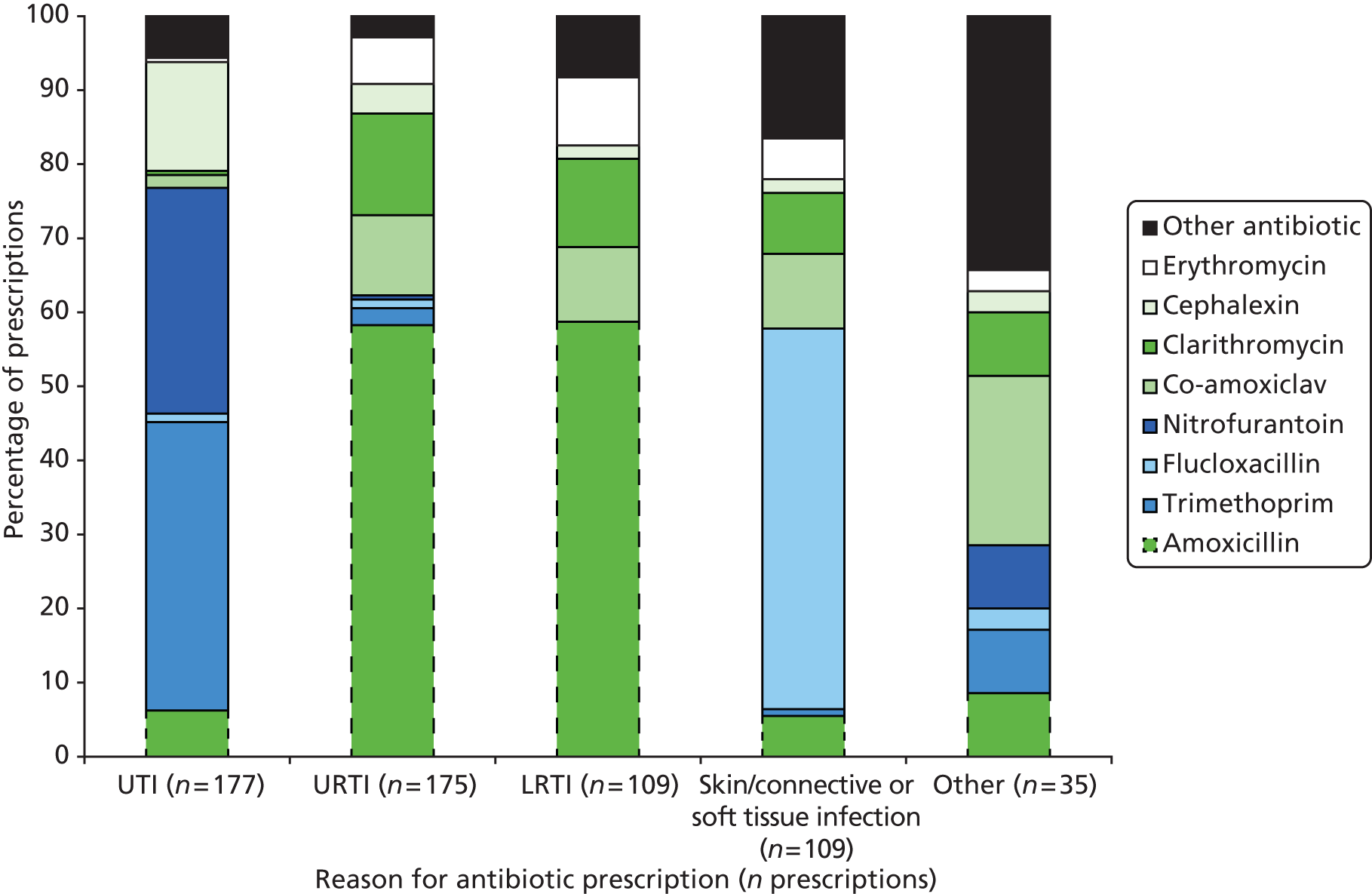

Antibiotics were most commonly prescribed for UTIs [29.3% (n = 177) of all antibiotic prescriptions], followed by URTIs [28.8% (n = 174)], skin/connective/soft tissue infections [18.2% (n = 110)] and lower respiratory tract infections (LRTIs) [18.0% (n = 109)]. The proportion of antibiotics prescribed for each indication varied by care home type. For example, prescriptions for UTIs accounted for 25.4% (n = 71) of all prescriptions in nursing homes, 43.5% (n = 70) in residential homes and 21.8% (n = 36) in dual-registered homes (Figure 5). The five most commonly prescribed antibiotics were amoxicillin [30.6% (n = 186) of all prescriptions], trimethoprim [12.7% (n = 77)], flucloxacillin [10.4% (n = 63)], nitrofurantoin [9.5% (n = 58)] and co-amoxiclav [8.7% (n = 53)]. A wide range of antibiotics were prescribed for each indication (Figure 6). The fluoroquinolone ciprofloxacin, previously implicated in CDAD, was prescribed relatively uncommonly, accounting for 3.0% (n = 18) of all antibiotic prescriptions recorded during the study period. Prescriptions of ciprofloxacin were primarily given for UTIs [44.4% (n = 8) of ciprofloxacin prescriptions] and skin/connective or soft tissue infections [27.8% (n = 5)]. Ciprofloxacin was also prescribed for LRTIs in two cases, for one UTI, for one gastrointestinal infection and also in one instance as prophylaxis.

FIGURE 5.

Reason for antibiotic prescriptions by care home type.

FIGURE 6.

Type of antibiotic prescribed by indication.

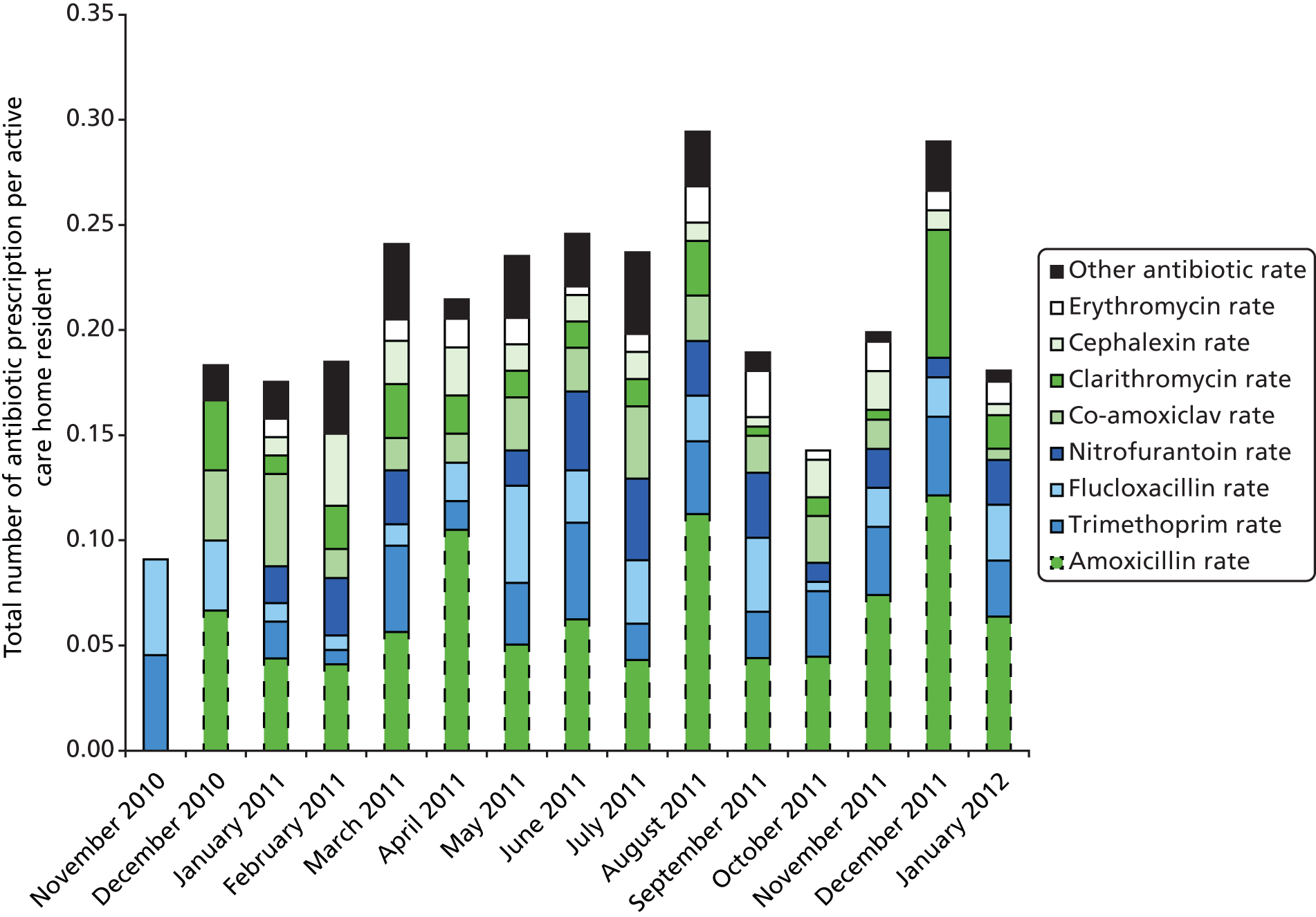

While the total number of antibiotic prescriptions each month varied considerably (range 0.09–0.29 prescriptions and average 0.21 prescriptions per resident), there was no obvious marked seasonal variation (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Antibiotic prescription rate by study month (stacked by antibiotic type). The height of each bar represents the total antibiotic prescribing rate per resident for the corresponding study month.

Compared with nursing home residents, those residents from dual-registered care homes had a significantly lower chance of being prescribed antibiotics during the study period (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.18 to 0.79; p = 0.009). The odds of being prescribed an antibiotic during the study period were 2.64 times higher for residents who had been prescribed antibiotics in the 4 weeks before study entry (95% CI 1.17 to 5.99; p = 0.020). Exposure to antibiotics was similar in residents who were vulnerable to moderately frail or severely frail to terminally ill and those who were very fit to managing well (Table 7).

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident characteristics | With care home characteristics | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Clinical frailty: very fit to managing well | Reference category for clinical frailty | |||||

| Clinical frailty: vulnerable to moderately frail | 2.14 (0.99 to 4.65) | 0.054 | 2.15 (0.98 to 4.71) | 0.057 | 1.88 (0.84 to 4.23) | 0.127 |

| Clinical frailty: severely frail to terminally ill | 1.58 (0.71 to 3.51) | 0.263 | 1.67 (0.74 to 3.75) | 0.218 | 1.33 (0.56 to 3.16) | 0.525 |

| Prescribed antibiotics 4 weeks prior to study entry | 2.56 (1.15 to 5.72) | 0.022 | 2.55 (1.14 to 5.72) | 0.023 | 2.64 (1.17 to 5.99) | 0.020 |

| Care home type: nursing | Reference category for care home type | |||||

| Care home type: residential | 0.48 (0.23 to 0.99) | 0.048 | – | – | 0.49 (0.22 to 1.09) | 0.080 |

| Care home type: dual registered | 0.39 (0.19 to 0.79) | 0.009 | – | – | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.79) | 0.009 |

Antibiotic-associated diarrhoea

Three antibiotic prescriptions (from two residents) provided no corresponding stool monitoring data. From the remaining 606 antibiotic prescriptions there were 571 stool monitoring periods, ranging between 1 and 11 weeks. The discrepancy between the number of prescriptions and monitoring periods arose because residents could be prescribed multiple antibiotics in the same week (hence, there was only one ongoing monitoring period). There were 447 unique episodes of AAD reported, with 43.5% (n = 87) of residents who were prescribed antibiotics experiencing at least one episode of AAD during the study period. There were 0.57 episodes of AAD per care home resident-year for those prescribed antibiotics (95% CI 0.41 to 0.81 episodes).

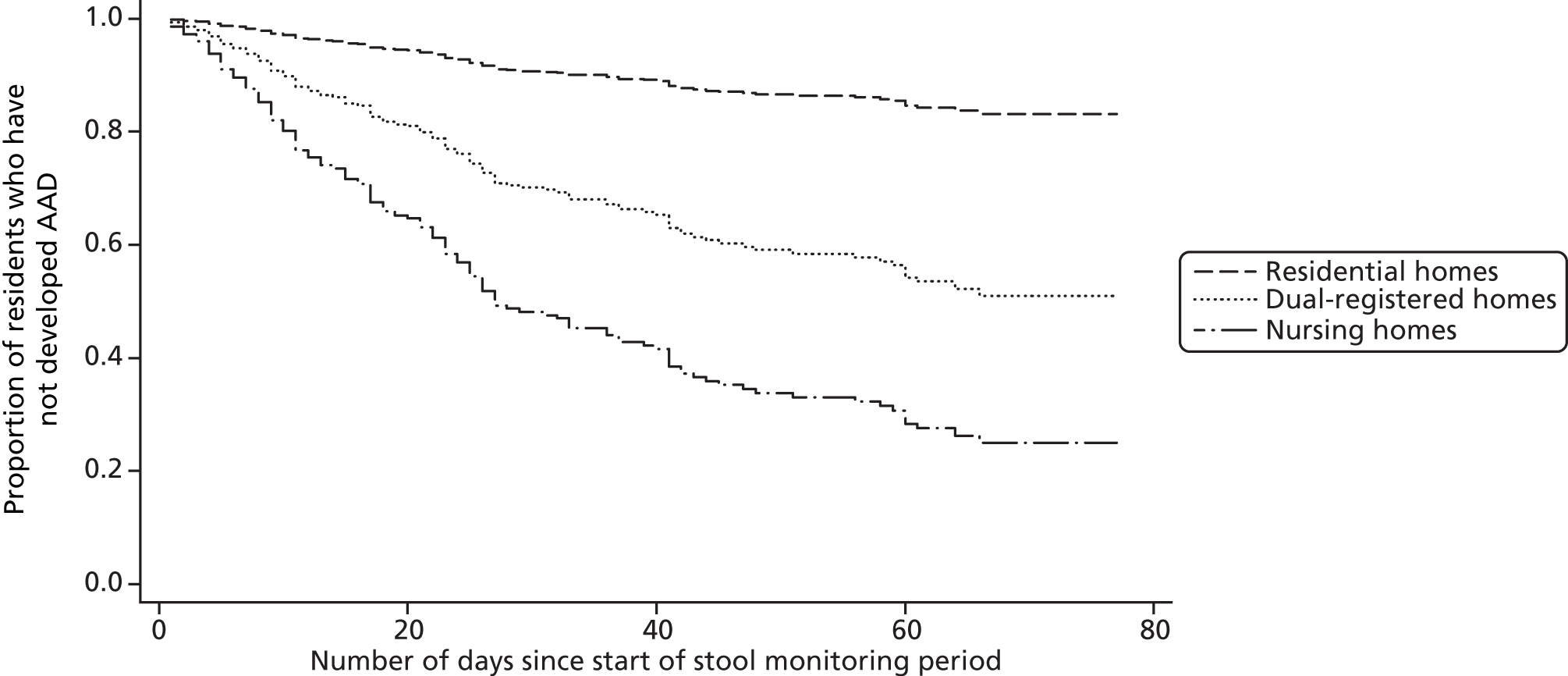

After controlling for length of stool-monitoring period, the odds of developing AAD during a stool monitoring period were more than twice as high in residents who were prescribed co-amoxiclav (OR compared with no co-amoxiclav prescription 2.19, 95% CI 1.06 to 4.52; p = 0.033), with the first AAD episode also occurring sooner (median time to first AAD episode for residents who were and were not prescribed co-amoxiclav was 23 days compared with 28 days, respectively; HR 2.08, 95% CI 1.18 to 3.66; p = 0.011). Time to first AAD episode was also shorter for residents who routinely used incontinence pads than for residents who did not (median 26 vs. 42 days, respectively; HR 2.54, 95% CI 1.26 to 5.13; p = 0.009). Compared with residents in nursing homes, those in residential homes were significantly less likely to develop AAD during the study period (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.27; p < 0.001) (Table 8) and experienced a slower time to first AAD episode (median for residents in residential homes 56 days, median for residents in nursing homes 21 days; HR 0.14, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.32; p < 0.001) (Table 9 and Figure 8).

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool monitoring period characteristics | With resident characteristics | With care home characteristics | ||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Stools monitored for ≤ 4 weeks | Reference category for length of stool-monitoring period | |||||||

| Stools monitored for 5–8 weeks | 3.59 (2.01 to 6.41) | < 0.001 | 3.48 (1.95 to 6.23) | < 0.001 | 3.61 (1.99 to 6.55) | < 0.001 | 3.65 (1.96 to 6.82) | < 0.001 |

| Stools monitored for > 8 weeks | 2.99 (1.80 to 4.97) | < 0.001 | 3.04 (1.82 to 5.08) | < 0.001 | 3.27 (1.94 to 5.52) | < 0.001 | 3.40 (1.96 to 5.89) | < 0.001 |

| Prescribed co-amoxiclav | 2.31 (1.23 to 4.31) | 0.009 | 2.30 (1.19 to 4.46) | 0.014 | 2.05 (1.05 to 4.01) | 0.035 | 2.19 (1.06 to 4.52) | 0.033 |

| Resident had capacity to provide informed consent for study | 0.56 (0.29 to 1.08) | 0.084 | 0.72 (0.35 to 1.49) | 0.374 | 0.76 (0.36 to 1.62) | 0.472 | ||

| Resident frequently used incontinence pads at study entry | 2.84 (1.52 to 5.30) | 0.001 | 2.59 (1.30 to 5.15) | 0.007 | 1.90 (0.94 to 3.82) | 0.073 | ||

| Clinical frailty: very fit to managing well | Reference category for clinical frailty | |||||||

| Clinical frailty: vulnerable to moderately frail | 2.38 (0.95 to 6.01) | 0.066 | 2.43 (0.94 to 6.28) | 0.067 | 1.69 (0.59 to 0.45) | 0.328 | ||

| Clinical frailty: severely frail to terminally ill | 2.87 (1.10 to 7.44) | 0.031 | 2.30 (0.83 to 6.37) | 0.108 | 1.40 (0.43 to 4.56) | 0.575 | ||

| Care home type: nursing | Reference category for care home type | |||||||

| Care home type: residential | 0.11 (0.05 to 0.24) | < 0.001 | 0.12 (0.05 to 0.27) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Care home type: dual registered | 0.69 (0.36 to 1.35) | 0.278 | 0.60 (0.27 to 1.32) | 0.199 | ||||

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stool monitoring period characteristics | With resident characteristics | With care home characteristics | ||||||

| HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | HR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Prescribed co-amoxiclav | 2.13 (1.20 to 3.78) | 0.010 | 2.13 (1.20 to 3.78) | 0.010 | 1.96 (1.11 to 3.47) | 0.020 | 2.08 (1.18 to 3.66) | 0.011 |

| Resident frequently used incontinence pads at study entry | 4.04 (2.04 to 7.99) | < 0.001 | – | – | 3.80 (1.87 to 7.70) | < 0.001 | 2.54 (1.26 to 5.13) | 0.009 |

| Clinical frailty: very fit to managing well | Reference category for clinical frailty | |||||||

| Clinical frailty: vulnerable to moderately frail | 4.60 (1.50 to 14.07) | 0.007 | – | – | 3.76 (1.19 to 11.85) | 0.024 | 2.49 (0.78 to 7.94) | 0.124 |

| Clinical frailty: severely frail to terminally ill | 4.58 (1.44 to 14.50) | 0.010 | – | – | 2.98 (0.91 to 9.78) | 0.071 | 1.75 (0.50 to 6.09) | 0.381 |

| Care home type: nursing | Reference category for care home type | |||||||

| Care home type: residential | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.23) | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.32) | < 0.001 |

| Care home type: dual registered | 0.80 (0.44 to 1.47) | 0.476 | – | – | – | – | 0.82 (0.43 to 1.57) | 0.547 |

FIGURE 8.

Survival curves illustrating the association between care home type and time to first AAD episode.

Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhoea

Of the 447 unique episodes of AAD, corresponding microbiological data from stool samples were available for only 55. C. difficile was cultured from eight of the sample. C. difficile was also detected in a further five stool samples taken after residents experienced loose stools (i.e. BSC type 5–7 stools) although the frequency of stools did not meet our definition of AAD. The 13 samples were obtained from nine residents in the same care home. In total, 12 samples were toxin B positive and there were nine different ribotypes (005, 010, 014, 020, 026, 027, 106, 160 and 193). No ribotype was found in more than one resident (Table 10).

| Anonymised unique participant ID | Date sample taken | Ribotype | Toxin B | CDAD according to our definition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 March 2011 | 193 | Positive | Yes |

| 1 | 8 May 2011 | 193 | Positive | Yes |

| 2 | 10 May 2011 | 160 | Positive | Yes |

| 3 | 24 April 2011 | 010 | Negative | No |

| 4 | 4 January 2012 | 020 | Positive | Yes |

| 5 | 12 April 2011 | 106 | Positive | Yes |

| 5 | 24 April 2011 | 106 | Positive | Yes |

| 6 | 7 June 2011 | 014 | Positive | No |

| 6 | 20 July 2011 | 014 | Positive | No |

| 7 | 23 April 2011 | 026 | Positive | Yes |

| 7 | 23 April 2011 | 026 | Positive | Yes |

| 8 | 30 April 2011 | 027 | Positive | No |

| 9 | 12 June 2011 | 005 | Positive | No |

Prevalence and risk factors for bowel carriage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and Clostridium difficile in care home residents

Participant flow and recruitment

Of the 274 residents recruited, 80.7% (n = 221) provided a stool sample at study entry. Samples were collected from all 10 participating care homes, with collection rates between care homes varying from 66.7% to 96.4% (Table 11). Participants who provided samples had a median age of 86.0 years (IQR 82.0–90.0 years) and 78.3% (n = 173) were women. Over one-fifth (n = 49) had been prescribed antibiotics in the 4 weeks prior to study entry and 7.2% (n = 16) of participants had been admitted to hospital in this time frame. There were no statistically significant differences between participants who did and did not provide samples (Table 12).

| Care home type | Care home | Number of participants recruited | Stool sample collection rate, % (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | A | 21 | 61.9 (13) |

| B | 42 | 83.3 (35) | |

| D | 11 | 90.9 (10) | |

| I | 13 | 69.2 (9) | |

| Residential/EMI | E | 18 | 66.7 (12) |

| F | 17 | 82.4 (14) | |

| H | 24 | 83.3 (20) | |

| J | 28 | 96.4 (27) | |

| Dual registered | C | 59 | 74.6 (44) |

| G | 41 | 90.2 (37) | |

| Overall | 274 | 80.7 (221) | |

| Variable | Provided stool sample data (N = 221) | Did not provide stool sample data (N = 53) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age of resident (years), median (IQR) | 86.0 (82.0–90.0) | 85.0 (82.0–90.0) | 0.915 |

| Age of resident < 80 years, % (n/N) | 21.7 (48/221) | 15.1 (8/53) | 0.283 |

| Age of resident ≥ 80 years, % (n/N) | 78.3 (173/221) | 84.9 (45/53) | |

| Gender (female), % (n/N) | 78.3 (173/221) | 66.0 (35/53) | 0.061 |

| Capacity to provide informed consent for study, % (n/N) | 28.1 (62/221) | 30.2 (16/53) | 0.757 |

| Clinical frailty: very fit to managing well, % (n/N) | 12.2 (27/221) | 18.9 (10/53) | 0.216 |

| Clinical frailty: vulnerable to moderately frail, % (n/N) | 50.2 (111/221) | 54.7 (29/53) | |

| Clinical frailty: severely frail to terminally ill, % (n/N) | 37.6 (83/221) | 26.4 (14/53) | |

| MUST: low risk, % (n/N) | 62.3 (137/220) | 66.0 (35/53) | 0.528 |

| MUST medium risk, % (n/N) | 15.5 (34/220) | 9.4 (5/53) | |

| MUST: high risk, % (n/N) | 22.3 (49/220) | 24.5 (13/53) | |

| Prescribed antibiotics in last 4 weeks, % (n/N) | 22.2 (49/221) | 15.1 (8/53) | 0.254 |

| Admitted to hospital in last 4 weeks, % (n/N) | 7.2 (16/221) | 5.7 (3/53) | 0.684 |

Baseline data

Stool type

There was wide variation in the consistency of stool samples. Samples were most often described as a BSC type 4, but over one-quarter of samples (n = 58) were described as a types 5–7 (Table 13).

| Stool typea | Samples, % (n) |

|---|---|

| 1 | 5.4 (12) |

| 2 | 14.0 (31) |

| 3 | 14.9 (33) |

| 4 | 37.6 (83) |

| 5 | 15.4 (34) |

| 6 | 8.6 (19) |

| 7 | 2.3 (5) |

| Missing stool type | 1.8 (4) |

| Overall | 100.0 (221) |

Outcomes and estimates

Isolates cultured

In total, 478 isolates were cultured from the 221 collected stool samples (approximately 2.2 isolates cultured per sample) (Table 14). The three most commonly cultured isolates were E. coli [88.2% (n = 195) of samples], Enterococcus spp. (ex Thiercelin and Jouhaud 1903) Schleifer and Kilpper-Bälz 1984 [54.3% (n = 120)] and Pseudomonas spp. Migula 1894 [25.3% (n = 56)]. The number of isolates cultured varied among care homes, as did the number of different isolates found in their stool samples (Table 15). In terms of total bacterial load, the total Columbia blood agar count was most commonly in the region of 107–108 per 10-μl loop of faeces.

| Care home type | Care home | Number of samples/participants | Total number of isolates cultured | Average number isolates/participant | Average number isolates/participant |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | A | 13 | 28 | 2.2 | 2.2 |

| B | 35 | 75 | 2.1 | ||

| D | 10 | 23 | 2.3 | ||

| I | 9 | 21 | 2.3 | ||

| Residential/EMI | E | 12 | 24 | 2.0 | 2.1 |

| F | 14 | 27 | 1.9 | ||

| H | 20 | 44 | 2.2 | ||

| J | 27 | 55 | 2.0 | ||

| Dual registered | C | 44 | 91 | 2.1 | 2.2 |

| G | 37 | 90 | 2.4 | ||

| Overall | 221 | 478 | 2.2 | 2.2 | |

| Isolate | Care home type | Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | Residential/EMI | Dual registered | ||||||

| % (n) | Range (%)a | % (n) | Range (%)a | % (n) | Range (%)a | % (n) | Range (%)a | |

| E. coli | 89.6 (60) | 85.7–100.0 | 90.4 (66) | 83.3–96.3 | 85.2 (69) | 84.1–86.5 | 88.2 (195) | 83.3–100.0 |

| Enterococcus spp. | 59.7 (40) | 48.6–90.0 | 50.7 (37) | 40.7–65.0 | 53.1 (43) | 45.5–62.2 | 54.3 (120) | 40.7–90.0 |

| Pseudomonas spp. | 22.4 (15) | 10.0–44.4 | 23.3 (17) | 10.0–33.3 | 29.6 (24) | 22.7–37.8 | 25.3 (56) | 10.0–44.4 |

| Klebsiella b /Enterobacter c /Serratia d | 16.4 (11) | 7.7–20.0 | 17.8 (13) | 0.0–25.0 | 17.3 (14) | 16.2–18.2 | 17.2 (38) | 0.0–25.0 |

| Other | 16.4 (11) | 7.7–22.9 | 12.3 (9) | 0.0–25.0 | 18.5 (15) | 16.2–20.5 | 15.8 (35) | 0.0–25.0 |

| Proteus spp. | 14.9 (10) | 0.0–23.1 | 11.0 (8) | 7.1–20.0 | 19.8 (16) | 15.9–24.3 | 15.4 (34) | 0.0–24.3 |

| Number of samples/participants | 100.0 (67) | 100.0 (73) | 100.0 (81) | 100.0 (221) | ||||

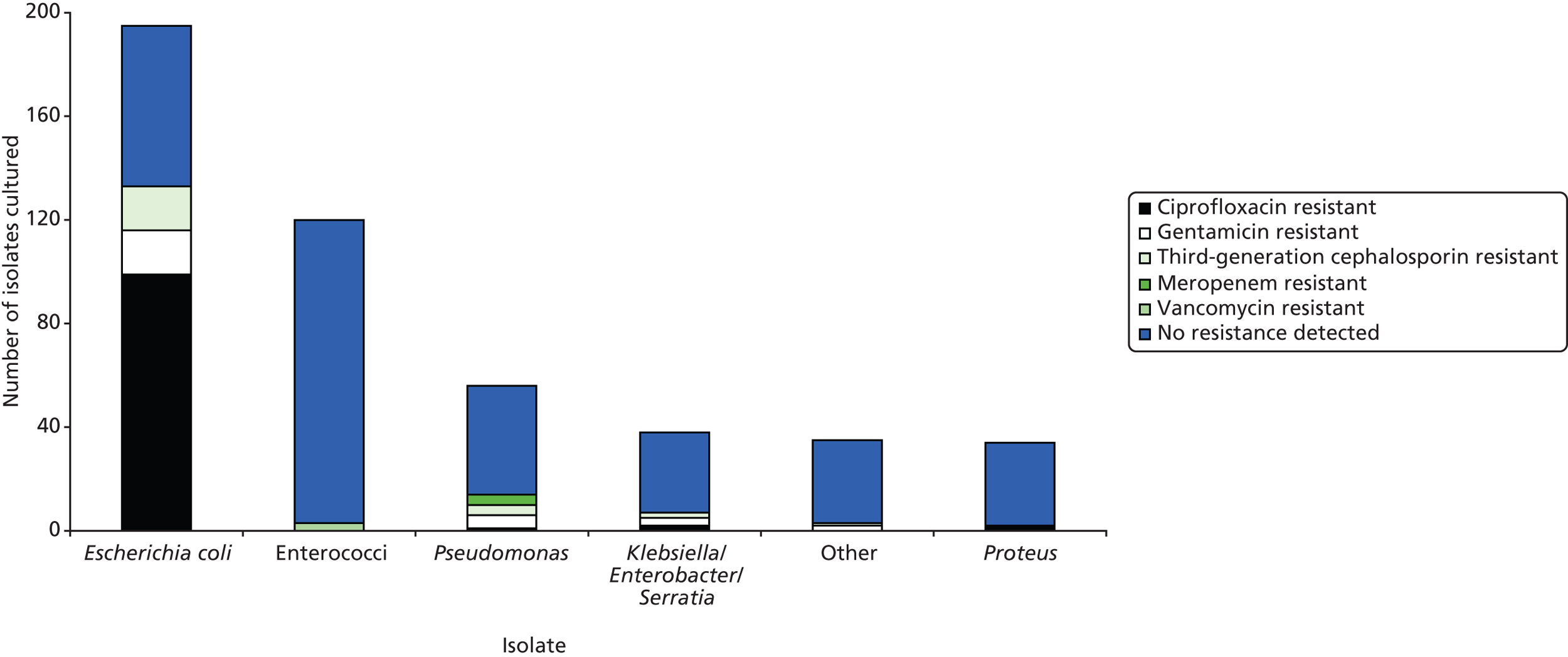

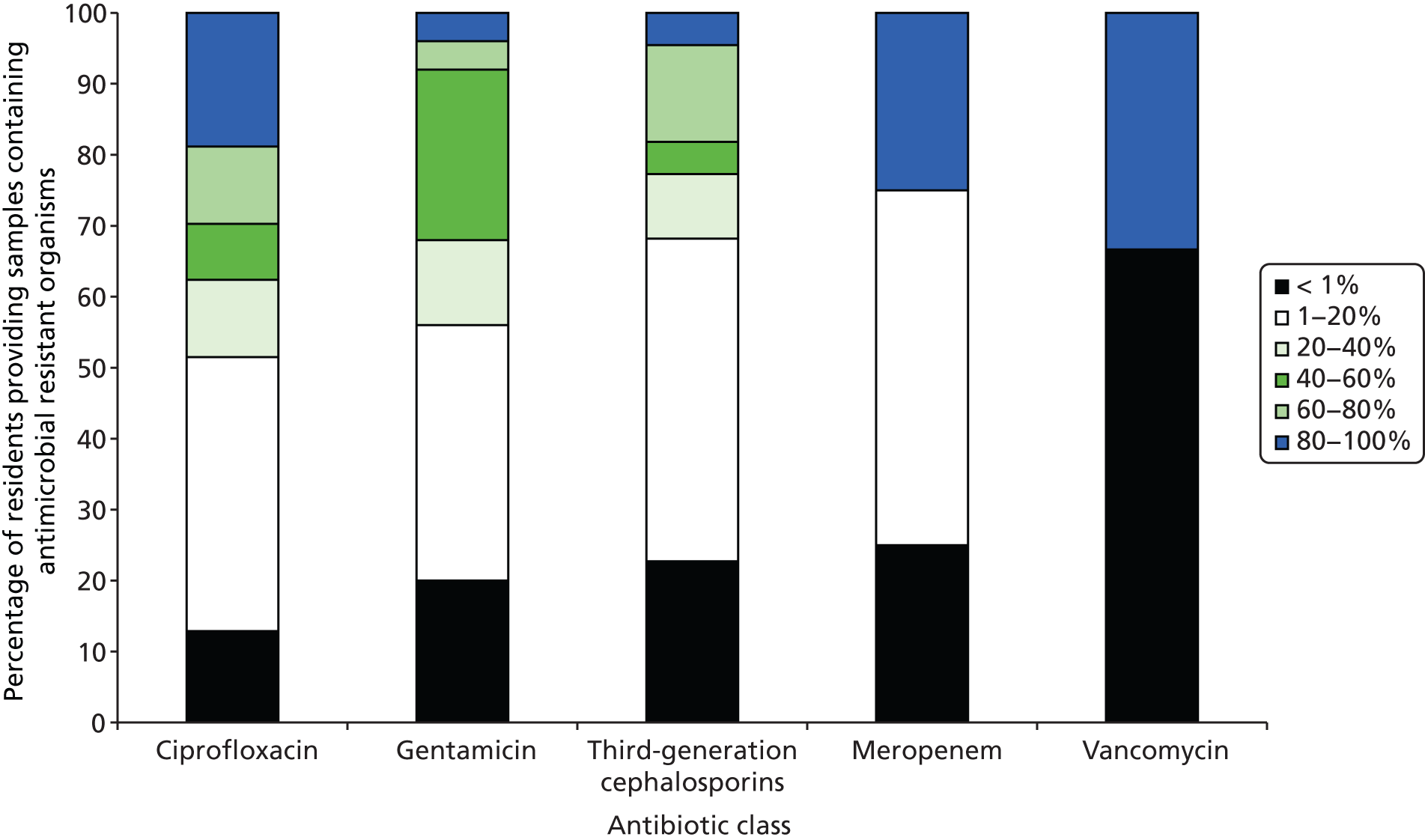

Antibiotic resistance

Organisms which were resistant to one or more of the tested antibiotics were found in 51.6% (n = 114) of participants. Enterobacteriaceae resistant to ciprofloxacin were found in 47.1% (n = 104) of participants, to gentamicin in 12.2% (n = 27), to third-generation cephalosporins in 10.9% (n = 24), to meropenem in 1.9% (n = 4) and to vancomycin in 1.4% (n = 3). There was wide variation in the proportion of participants providing stool samples containing bacteria resistant to various antibiotics in different types of care homes, with care home-level intracluster correlations (ICCs) ranging from 0.00 for meropenem and vancomycin to 0.16 for gentamicin (Table 16). Of the four residents who provided samples containing meropenem-resistant isolates, one was prescribed an antibiotic (amoxicillin) and none had been hospitalised in the 4 weeks prior to study entry. Although resistance to ciprofloxacin, gentamicin and third-generation cephalosporins was mainly found in E. coli [95.2% (n = 99), 63.0% (n = 17) and 73.9% (n = 17), respectively], resistance to meropenem was exclusively found in Pseudomonas spp. (Figure 9). Resistant bacterial load, expressed as a percentage of total bacterial load, varied between antibiotic classes (Figure 10). For example, where isolates resistant to ciprofloxacin were found in stool samples, ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates accounted for less than 1% of the total quantity of isolates cultured in samples 12.8% of the time.

| Care home type | Antibiotic/antibiotic class | Number of samples | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin | Gentamicin | Ceftazidime/cefotaxime (third-generation cephalosporins) | Meropenem | Vancomycin | ||

| Nursing | 62.7 (42) | 16.4 (11) | 10.4 (7) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) | 67 |

| Residential | 35.6 (26) | 6.8 (5) | 8.2 (6) | 2.7 (2) | 2.7 (2) | 73 |

| Dual registered | 44.4 (36) | 13.6 (11) | 13.6 (11) | 2.5 (2) | 1.2 (1) | 81 |

| Overall | 47.1 (104) | 12.2 (27) | 10.9 (24) | 1.8 (4) | 1.4 (3) | 221 |

| Care home ICCa | 0.06 | 0.16 | 0.10 | 0.0 | 0.0 | – |

FIGURE 9.

Cultured isolates and their resistance to antibiotics.

FIGURE 10.

Percentage of resistant bacterial load by antibiotic class.

Factors associated with carriage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria

The odds of participants carrying antibiotic-resistant bacteria in their stools significantly increased with age (OR for 80 years or older 2.54, 95% CI 1.23 to 5.26; p = 0.012) and previous antibiotic use in the 4 weeks prior to study entry (OR 2.21, 95% CI 1.11 to 4.43; p = 0.025). The odds of carrying antibiotic-resistant bacteria were significantly lower for participants in residential homes than for those in nursing homes (OR 0.44, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.91; p = 0.028). After controlling for the age of the resident, clinical frailty status was not significantly associated with carriage of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (Table 17).

| Variable | Univariable | Multivariable | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resident characteristics | With care home characteristics | |||||

| OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | OR (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Age of resident < 80 years | Reference category for age of resident | |||||

| Age of resident ≥ 80 years | 2.94 (1.49 to 5.81) | 0.002 | 2.67 (1.30 to 5.49) | 0.007 | 2.54 (1.23 to 5.26) | 0.012 |

| Clinical frailty: very fit to managing well | Reference category for clinical frailty | |||||

| Clinical frailty: vulnerable to moderately frail | 2.48 (1.03 to 6.00) | 0.044 | 2.11 (0.82 to 5.40) | 0.122 | 1.78 (0.68 to 4.65) | 0.243 |

| Clinical frailty: severely frail to terminally ill | 2.21 (0.89 to 5.48) | 0.089 | 1.74 (0.64 to 4.69) | 0.275 | 1.35 (0.46 to 3.78) | 0.614 |

| Prescribed antibiotics 4 weeks prior to study entry | 2.07 (1.07 to 4.00) | 0.031 | 2.10 (1.06 to 4.17) | 0.034 | 2.13 (1.06 to 4.26) | 0.033 |

| Care home type: nursing | Reference category for care home type | |||||

| Care home type: residential | 0.39 (0.20 to 0.77) | 0.007 | – | – | 0.44 (0.21 to 0.93) | 0.030 |

| Care home type: dual registered | 0.57 (0.30 to 1.11) | 0.099 | – | – | 0.58 (0.29 to 1.16) | 0.123 |

Prevalence of Clostridium difficile

Clostridium difficile was cultured in 7.2% (n = 16) of stool samples. The prevalence varied between care homes, from no C. difficile detected in four care homes to C. difficile being detected in 19.4% (n = 7) of samples from a single home.

One of the 16 samples from which C. difficile was cultured was toxin B negative, with the remaining 15 being toxin B positive. There were 11 different ribotypes (001, 002, 005, 015, 021, 027, 062, 103, 106, 160 and 193). In the majority of cases, ribotypes were unique to each home, with one instance of a ribotype occurring within the same home twice (n = 106). The care home level ICC was 0.29 (Table 18).

| Care home type | Care home | Number of samples | C. difficile cultured, % (n) | Ribotypesa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nursing | A | 13 | 15.4 (2) | 015, 027 |

| B | 36 | 19.4 (7) | 005, 027, 103, 106 (×2), 160, 193 | |

| D | 10 | 0.0 (0) | N/A | |

| I | 9 | 22.2 (2) | 001, 005 | |

| Residential/EMI | E | 12 | 0.0 (0) | N/A |

| F | 14 | 0.0 (0) | N/A | |

| H | 20 | 15.0 (3) | 002, 005, 027 | |

| J | 27 | 0.0 (0) | N/A | |

| Dual registered | C | 43 | 2.3 (1) | 021 |

| G | 37 | 2.7 (1) | 062 | |

| Overall | 221 | 7.2 (16) | 001, 002, 005 (×3), 015, 021, 027 (×3), 062, 103, 106 (×2), 160, 193 | |

Barriers and implementation issues identified and lessons learned

Research experience

Very few of the 10 sites had any experience of participating in research. Care homes are a unique research environment since 24-hour care is provided to residents and, within any 1 day, care home staff have to deal with many unpredictable daily events that need an immediate response. Careful consideration and a flexible approach were needed to embed a study into this busy environment. We worked closely with our lay representative and care home staff ahead of study commencement and throughout the study to ensure implementation of PAAD stage 1 went as smoothly as possible and that all valuable and essential lessons learned from PAAD stage 1 could be applied to PAAD stage 2. The most important factors we identified for successfully delivering research of this kind in care home included the following.

Timing of approach to care homes

The time of year for approaching the care homes was critical, i.e. care homes are significantly affected by winter pressures. Thus, training, embedding study procedures and commencing recruitment proved difficult and, as a result, many care homes did not start recruitment until late winter or spring. Approaching care homes and ensuring the study was up and running well ahead of the winter period was pivotal when it came to setting up PAAD stage 2.

Care home set-up and training

A significant amount of time at the beginning was spent engaging with the care home staff and building up their understanding, as well as setting up the processes, documentation and training for all staff. Initial half-day training sessions were delivered and short (1 hour), tailored training sessions concentrating on each staff member’s role and responsibility for the shift (day, night and weekend) were also designed. Realistic time frames need to be set for approaching and bringing on board care homes. In addition, we found that staggering care home set-up and ensuring recruitment has commenced before focusing on another care home was likely to increase compliance with the Protocol and dedication of care home staff to study procedures.

Staff engagement and motivation

Care home staff had little understanding of what it meant to carry out research; as a result they felt overwhelmed by the tasks required of them, and not all staff understood the protocol. Half-day workshops were also offered to care home staff to meet the study team and principal investigators (PIs) to discuss issues and successes for the site, as well as focusing on topics such as how to improve recruitment or resolve quality of data. Additional monetary and non-monetary incentives, such as providing opportunities for continuing professional development (CPD) (e.g. GCP training) or personal incentives for staff working on specific aspects of the protocol (e.g. gift vouchers), increased the level of interest in the study by junior staff and return of completed stool-monitoring CRFs.

Communication