Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/35/01. The contractual start date was in August 2011. The draft report began editorial review in May 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Gilbody is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Clinical Evaluation and Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Richardson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Mental health difficulties in young people who offend

In England and Wales young people between the ages of 10 and 17 years committed 201,800 offences in 2009–10 and were responsible for 17% of all proven offending. 1 Problems linked to offending behaviour include educational underachievement, substance abuse and mental illness. With regard to mental illness, there is a lack of precise estimates of the prevalence and types of mental health difficulties experienced by young people who offend, but what evidence there is suggests prevalence figures substantially in excess of age-equivalent, general population rates. 2,3

The types of difficulties for which these rates are elevated cover a wide range of mental health problems, including depression, anxiety [particularly post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)], attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), psychotic-like symptoms and self-harm. 3,4 There is also some evidence that rates of learning disability and special educational needs may be high among this group. 5 The presence of mental health difficulties among young people who offend may increase the risk of a range of negative outcomes for both the young person and the wider community. The presence of mental health problems such as depression among this group may act as a risk factor for the persistence of offending behaviour into adulthood. 6 Additionally, conduct disorder in young people leads to a range of difficulties. For example, adults who had conduct disorder in adolescence are 70 times more likely to be imprisoned before the age of 25 years. 7 The cost of crime in England and Wales committed by adults who had conduct disorder as a child has been estimated at £2.25B. 8

Screening for mental health difficulties in young people who offend

Despite their prevalence and potential to increase the risk of negative outcomes, these difficulties remain under-identified and under-treated. 4,9 A number of screening methods have been used to identify young people with mental health problems, including those specifically tailored to young people who offend [e.g. Massachusetts Youth Screening Instrument – version 2 (MAYSI-2)10] and those developed in general settings.

Interventions for mental health difficulties in young people who offend

Screening, however, can be justified only if it results in a more effective treatment than would otherwise be the case and does so with a favourable ratio of costs to benefits. 11 There is substantial evidence from studies of young non-offender samples that effective psychological and pharmacological treatments exist for many of the mental health problems that are common in young people who offend, including treatments for depression,12 anxiety problems,13–15 ADHD16 and psychotic-like symptoms. 17 Evidence on the effectiveness of mental health interventions specifically for young people who offend appears to be very limited. One previous systematic review in this area cautiously concluded that treatments may be effective, although it suggested that larger, high-quality trials were needed. 18

Current UK policy and practice

In the UK, all young people who have offended are the responsibility of youth offending teams. The majority of young people are supervised in the community, but a smaller proportion is given a sentence that includes a custodial component, which is then followed by subsequent supervision in the community. A number of factors determine whether a young person is given a custodial sentence or is supervised in the community; these include the severity of the crime and the extent of any previous offending behaviour.

Those young people supervised in the community will typically receive either a referral order, if a first offence, or a youth rehabilitation order. These orders can vary in terms of both the level of supervision required and the additional conditions placed on the young person. For those people given a custodial sentence, the setting in which the person is placed will be determined by age and level of maturity. Secure children’s homes are typically for young people aged 10–15 years and young offender institutions are for those aged ≥ 16 years. There is also the option of a secure training centre for those aged 15 or 16 years.

There has been a focus in the UK in recent years on the prevention of offending by young people and the treatment of these young people. 19 As a result, there is substantial policy interest in screening for mental health problems in people who offend and access to appropriate mental health services for such people. The Criminal Justice Bill 2007 and Lord Bradley’s report20 set out a range of strategies to improve the situation, including youth rehabilitation orders. Department of Health guidelines21 have also made it clear that young people in secure settings should have appropriate access to mental health services. Such policy documents are supported by the recent national framework to improve mental health and well-being,22 which organises six high-level objectives of mental health strategy across all sectors of society.

Available evidence on practice suggests that the provision of adequate mental health screening and intervention remains patchy, with demand outstripping supply. 4 A joint initiative between the Youth Justice Board and the Department of Health has sought to improve the identification and assessment of health-related needs in children and young people in contact with the youth justice system, including mental health needs. This initiative has led to the Comprehensive Health Assessment Tool (CHAT),23 a bespoke, strategic toolkit that aims to identify and assess health-related needs of children and young people in contact with any part of the youth justice system. Within CHAT there are five areas of assessment:

-

part 1 assesses any immediate risk associated with physical health, mental health, substance misuse and safety

-

part 2 assesses physical health

-

part 3 assesses substance misuse

-

part 4 assesses mental health

-

part 5 assesses neurodevelopment disorders such as learning disability, autistic spectrum disorders and speech and language impairment, as well as any traumatic brain injury.

Versions of CHAT are available for the secure estate and community settings. For the secure estate, a reception health screen needs to be completed within 2 hours or before the first night of admission to identify any immediate risks or concerns, which may lead to the fast-tracking of a more detailed CHAT evaluation for any areas identified as important. All areas of the CHAT assessment should then be completed in the first 10 days of intake, with the mental health assessment being completed within the first 3 days. For community settings the health reception screen is not used.

It is intended that the information from an updated version of Asset,24 termed AssetPlus, will be made available to the professionals conducting the CHAT assessment in both incarcerated and community settings. Asset is an assessment tool that aims to identify those risk factors for the young person’s offending, including mental health difficulties. 24 It can be used, therefore, to identify potential mental health needs that may require further assessment and intervention. CHAT will replace previous mental health screening pathways, which, following a red flag on the Asset tool, involved further structured assessment with measures such as the Screening Interview for Adolescents (SIfA). 25

The Comprehensive Health Assessment Tool began to be rolled out in 2012. The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of this screening strategy has not yet been determined.

Summary

A wide range of mental health problems are common in young people who offend, and their presence is linked to a range of negative consequences both for the young person and for the wider society. There is currently substantial policy interest in screening for mental health problems in young people who offend, but the value of such screening is currently unknown.

Chapter 2 Description of the decision problem

The purpose of this research was to apply rigorous systematic review and evidence synthesis techniques to answer the question, ‘What would be the benefits of carrying out a screening assessment for treatable psychological and mental health conditions in young offenders and in which groups might it be cost-effective?’

Current UK policy provides guidance on screening for mental health problems in young people who offend,23 as described in the previous chapter, but the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the recommended screening pathways is largely unknown. There are, in fact, a number of ways in which screening pathways could be configured and a large number of uncertainties exist. The decision problem can be framed in terms of these uncertainties. A main aim of the review is to establish the extent to which existing evidence can reduce these uncertainties and to identify where future research should be targeted so that uncertainties can be further reduced.

Screening

One option for identifying mental health problems in young people who offend would be to offer this entire group a detailed diagnostic mental health assessment in the form of a gold standard interview conducted to internationally recognised criteria. 26,27 There are advantages to this: all who were offered treatment would be in need of it and all of those not given treatment would not require it. Although such an approach would give perfect precision, it may not be feasible because it may require substantial resources to implement.

The use of screening instruments, which trade a saving in resources for a reduction in precision, is the typical alternative to such a strategy. 11 Screening measures that have been used with young offenders can be divided into a number of broad categories: those that are designed to detect a specific mental health problem, such as major depression, and those that are designed to detect a general mental health problem or need. 28 Often this maps onto a division in young offender measures between those instruments that provide diagnostic test accuracy data and those that identify a mental health need but do not establish the accuracy against a gold standard diagnostic interview.

A further division is into those measures that are specifically designed for use with a young offender population (e.g. MAYSI-2,10 CHAT mental health screen23) and those that are used with young offenders but which were originally developed for use in the wider population. A potential advantage of measures designed specifically for young offenders is that they may consider expected characteristics of the population (e.g. limited literacy) and may be designed for use by youth justice personnel with no formal mental health training. However, a potential disadvantage is that they may not have received the same level of psychometric evaluation as some of the more widely used measures.

Each screening instrument from these broad categories could be used in a number of ways to make a decision about a person’s mental health needs, including the need for treatment. Scores on a screening measure could be considered alone in making that decision, in combination with each other (e.g. a general screen for any mental health problem followed by a disorder-specific screen) or in combination with a gold standard (e.g. a general screen followed by gold standard interview for all those scoring positively on the screen).

Currently, there is uncertainty around which broad category of instrument is likely to be most effective (e.g. bespoke measures for young offenders vs. measures originally designed for use in the wider population) and within a category it is unclear if particular screening instruments are more accurate than others in identifying mental health problems. In addition, there is further uncertainty around whether a decision should be made on the basis of a single instrument or whether a combination should be used in a screening pathway.

Many screening instruments have a range of possible scores and so it is possible to identify different points along that range above which a person could be predicted by the screening instrument to have a mental health difficulty. As this cut-off point is varied, sensitivity and specificity will also change in a consistent way: as sensitivity increases, specificity will decrease (and vice versa). 11 (For an introduction to methods of quantifying diagnostic test accuracy, including concepts such as sensitivity and specificity, see Appendix 1.) There is, then, always a balance to be struck: if sensitivity is high, specificity is likely to be low; if specificity is high, sensitivity is likely to be low. A decision needs to be made about what balance between sensitivity and specificity is likely to be appropriate in a particular decision context. There are no definitive guidelines but, as a general rule, when the clinical context involves screening, high sensitivity is usually valued over high specificity. If sensitivity is high, this means that few people who have a condition will be missed, even if this is at the expense of somewhat lower specificity. Ensuring that few people with the condition are missed is often an aim of a screening strategy. However, in many decision contexts – including screening for mental health problems in young people who offend – it may not be possible to ensure very high sensitivity. Screening measures for mental health problems can have substantial inaccuracies when assessed against a gold standard, which means that very high sensitivity on such instruments is likely to be associated with low specificity. A consequence of low specificity is a high false-positive rate, which can be problematic in a number of ways. For example, if screening is used in the absence of a confirmatory gold standard diagnosis, treatment may be offered to many people who do not in fact require it. This may be potentially damaging to the recipients and can have substantial costs attached to it for services. Even if a screening measure is followed by a confirmatory diagnostic assessment, it may be inefficient and prohibitively costly to refer on for that further assessment all people who score positive to a screen if that number contains a large number of false positives. As a very broad guideline, then, a cut-off on a screening instrument may be required that gives sufficiently high sensitivity while retaining moderate specificity.

Studies of diagnostic test accuracy typically evaluate the screening measure against a gold standard categorisation of those with and without the mental health diagnosis, regardless of whether or not the true cases are already known to services or are previously unidentified cases. In this particular decision context, the screening for mental health problems in young people who offend, screening may be of value only for the identification of previously unidentified cases, because known cases may already be receiving treatment. There are a number of uncertainties related to this distinction between known and unidentified cases. It is unclear if the diagnostic performance of the test may differ if restricted to the identification of previously unknown cases. It is also unclear if the characteristics of the previously unidentified cases and the already identified cases differ, and this may be of relevance to understanding the likely performance characteristics of a test when restricted to the identification of new cases. For example, it is possible that already known cases will be more severe and therefore easily identifiable in the absence of screening, whereas unidentified cases may be less severe. This may have consequences for the need to offer treatment or the type of treatment offered. The prevalence of unidentified cases is also unclear, and this may have consequences for the balance between true positives and false positives at a particular cut-off point on an instrument. This in turn may affect the selection of an optimal cut-off point and the balance it offers between sensitivity and specificity.

Additional features of the decision problem relate to uncertainties about the behaviour of professionals in terms of screening. For example, it is unknown whether or not professionals find particular instruments acceptable and whether or not the results from a screening measure have an impact on professionals’ behaviour, such as making a referral for a particular type of treatment.

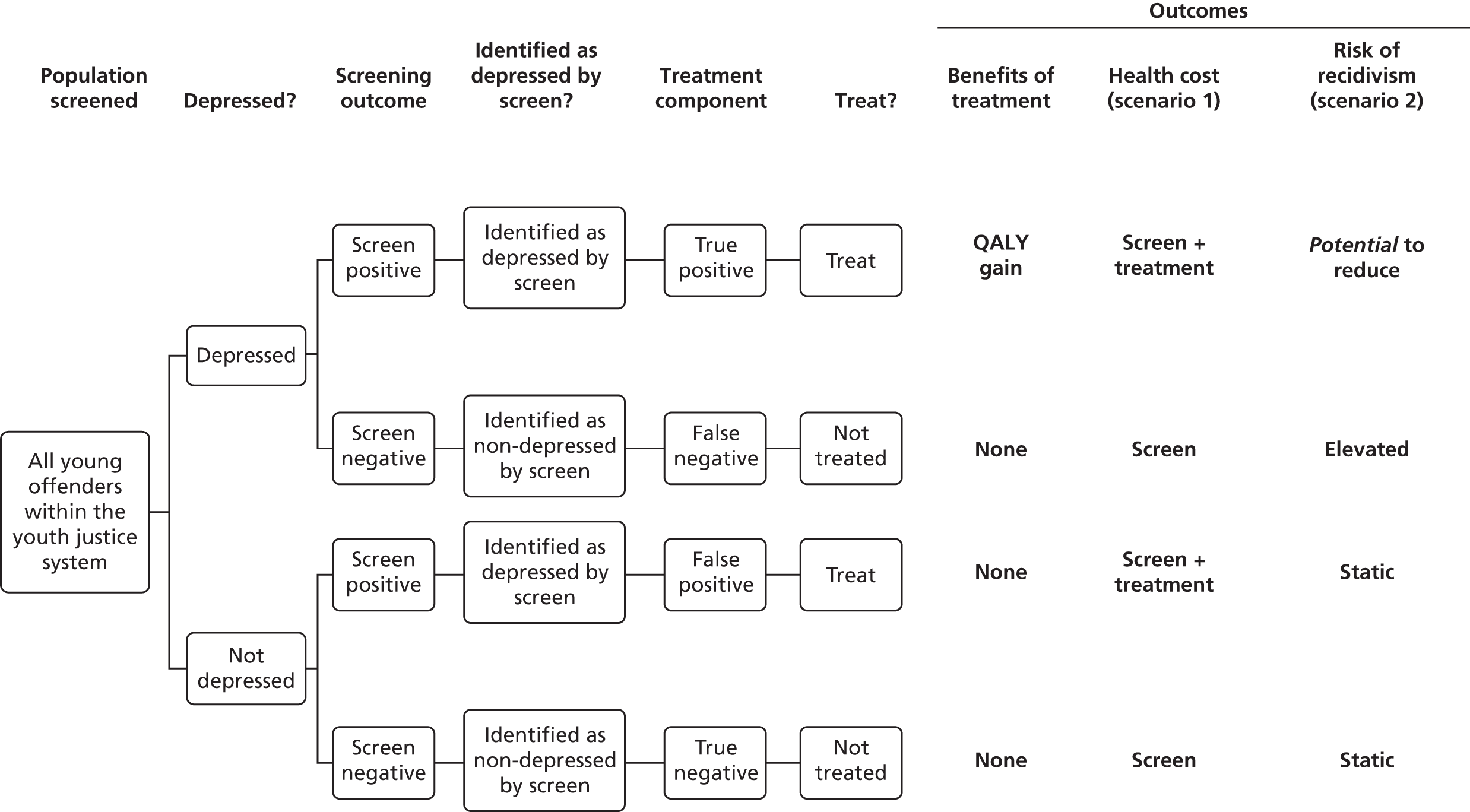

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

On the assumption that professional behaviour is altered by the results of a screening test, screening and referring are of use only if there is an effective and cost-effective treatment for the particular mental health problem. In terms of effectiveness there are a large number of uncertainties. These include whether or not interventions for mental health problems in young people who offend are clinically effective and cost-effective, whether or not improvements in mental health symptoms are related to changes in other outcomes, such as the likelihood of reoffending, whether or not the interventions are acceptable to this population and whether or not potentially effective interventions can be feasibly delivered in UK settings.

Setting

Young people who have offended may be in the community or incarcerated. In terms of the decision problem outlined above, each of the considerations applies separately to these two settings. It is possible, for example, that a distinct screening pathway may be more appropriate in one setting than in another.

Objectives

On the basis of this decision problem we developed five objectives related to diagnostic test accuracy, the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of screening and (more broadly) the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions for mental health problems in young people who offend. These five objectives are to:

-

conduct a systematic review and evidence synthesis of the diagnostic properties and validity of existing screening measures for mental health problems in young people who offend

-

assess the clinical effectiveness of screening strategies in this population and (more broadly) the clinical effectiveness of interventions for mental health problems

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of screening strategies in this population and (more broadly) the cost-effectiveness of interventions for mental health problems, with specific reference to identifying in which groups they may be cost-effective

-

assess whether or not current screening strategies meet minimum criteria laid down by the UK National Screening Committee (NSC) in the light of this evidence synthesis

-

identify research priorities and the value of developing future research into screening strategies for young offenders with mental health problems.

Structure of the report

We carried out a single comprehensive search to identify the evidence needed for this research. This search is described in Chapter 3. We then conducted the research in a number of interlinked phases in which we summarised the available literature on screening assessments for treatable psychological and mental health conditions in young offenders.

At each stage of the review and in the production of the final report we adhered to the relevant guidelines for the conduct and reporting of systematic reviews. 29,30 The research is registered on the PROSPERO database (registration number CRD42011001466). A copy of the original protocol for the review is available alongside copies of this report on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) website (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/).

Stakeholder involvement

We established an expert advisory group and two stakeholder groups. The expert advisory group consisted of academics with methodological expertise in the conduct of systematic reviews and content expertise in the criminal justice system. Members of this group were approached at various stages of the project to offer advice on specific questions.

One stakeholder group consisted of professionals working within the justice system. We sought to include professionals working in both community settings and the secure estate. We met with members of this stakeholder group at various stages of the project. A specific role of this group was to help establish current UK practice in the screening and treatment of mental health problems in young people who offend and more generally to clarify the nature of the decision problem.

A second stakeholder group consisted of young people (age range 10–15 years) from the National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (Nacro). We held two meetings with these young people to gather their views on a range of subjects relevant to the review, including the acceptability of different potential screening pathways and different types of interventions. The older members of this group were asked to comment and help draft the plain English summary.

Appendix 2 provides a list of the stakeholders and professionals who provided advice during the review process.

Chapter 3 Literature search

Literature searches were undertaken to identify studies about the screening, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of psychological and mental health difficulties in young people who offend.

Search terms

The search strategies were devised using a combination of subject indexing terms, such as medical subject heading (MeSH) in MEDLINE, and free-text search terms in the title and abstract. The search terms were identified through discussion among the research team, through contact with members of the advisory group, by scanning background literature and by browsing database thesauri.

We considered two main approaches to searching the literature: a single comprehensive search to identify studies of relevance to each phase of the review (e.g. screening, clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness) and an alternative strategy of developing separate searches for each phase. We chose to use a single comprehensive search as the most effective and efficient means of identifying the relevant literature for each phase.

The search terms for each database covered three broad constructs:

-

age: terms to identify adolescents or young people

-

offenders: terms to identify people who had offended or who were in contact with the criminal justice system

-

mental health: terms to identify the range of mental health outcomes examined in the review.

Search terms for these three constructs were combined using the Boolean ‘AND’.

Our decision to use a single comprehensive search based on these three broad constructs had the advantage that the search was not reliant on specific terms for a particular phase, which may have limited sensitivity. For example, an alternative strategy for the diagnostic test accuracy phase would be to use methodological filters to identify test accuracy studies using terms such as ‘sensitivity’ and ‘specificity’. However, there is evidence that the inclusion of such filters in searches for such studies can lead to relevant studies being missed. 31 Another strategy would have been to list as search terms some of the more commonly used screening measures in practice and research in this area. However, this would have predetermined the type of screening measures that would be identified by the review and may have missed studies of other relevant screening measures.

The final set of search terms was developed through an iterative process. A series of pilot searches were run and the results examined and discussed by members of the research team. We considered the likely sensitivity of the search terms by establishing whether or not key citations that we knew were likely to meet inclusion criteria were retrieved by the search.

The searches were not limited by date range or language.

Databases and resources

A range of databases and resources was searched, including standard databases of predominantly peer-reviewed publications as well as resources for the identification of grey literature. The focus of the review spans the mental health literature and the criminal justice literature. We therefore specifically sought to examine databases that covered health and mental health as well as crime and social care. The following databases and resources were searched:

-

PsycINFO

-

MEDLINE

-

EMBASE

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL)

-

Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)

-

Criminal Justice Abstracts

-

National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS)

-

Social Policy & Practice

-

Social Services Abstracts

-

Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS) International

-

Science Citation Index (SCI)

-

Social Science Citation Index (SSCI)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S)

-

Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (CPCI-SSH)

-

Social Care Online

-

The Campbell Library

-

Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED)

-

OAIster

-

Index to THESES

-

Zetoc

-

Research Papers in Economics (RePEc).

The following organisation websites and conference proceedings were also searched:

-

Department of Health (www.dh.gov.uk/)

-

Department for Education (www.education.gov.uk/)

-

Home Office (www.homeoffice.gov.uk/)

-

Joseph Rowntree Foundation (www.jrf.org.uk/)

-

Royal College of Psychiatrists (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/)

-

Youth Justice Board (www.yjb.gov.uk/)

-

Policy Studies Institute (www.psi.org.uk/)

-

Mental Health Foundation (www.mentalhealth.org.uk/)

-

Young Minds (www.youngminds.org.uk/)

-

Nacro (www.nacro.org.uk/)

-

Revolving Doors (www.revolving-doors.org.uk/home/)

-

Prison Reform Trust (www.prisonreformtrust.org.uk)

-

Centre for Mental Health (www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/index.aspx)

-

British Society of Criminology (www.britsoccrim.org/)

-

American Society of Criminology (www.asc41.com/).

Searches were conducted in April 2011. Full details of the specific search strategies for PsycINFO, MEDLINE and EMBASE are given in Appendix 3.

Additional search strategies

In addition to the searches of databases and other resources, we used three additional methods to identify relevant citations:

-

Reverse citation search: we undertook reverse citation searches on all included papers using the Web of Science (WoS) Institute of Scientific Information (ISI) citation database.

-

Manual check of reference lists: we conducted a manual check of the reference list of all included studies and previous major relevant reviews.

-

Contact with experts: we contacted experts in the field to identify other potentially relevant papers and to request further information about included studies when necessary.

Deduplication

The number of databases searched and the use of several search strategies meant that some degree of duplication occurred. To manage this, the titles and abstracts of bibliographic records were downloaded and imported into EndNote X5 bibliographic management software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicate records were removed.

Screening of citations

Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts identified in the literature search for studies that were potentially eligible for any phase of the review. Full papers of potentially eligible studies were obtained and assessed for inclusion independently by two reviewers. At both stages (first sift – titles and abstracts; second sift – full papers), disagreements were resolved by consensus or deferred to a third party if necessary.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We developed detailed separate PICO criteria (population/patient problem, intervention, comparison, outcome) for the different phases of the review; these are summarised in each of the relevant review chapters. Guidance was given to coders to be inclusive at the first sift (titles and abstracts) if there was any uncertainty about a citation but to apply the PICO criteria rigorously at the second sift (full papers).

Overview of the literature search

Figure 1 summarises the literature searching process. The figure given for papers identified outside of the database searches includes papers identified by website searching as well as papers identified from other sources (e.g. contact with experts). The reasons for exclusion for the studies that passed the first sift (title and abstracts) but which did not meet second sift (full paper) inclusion criteria are given in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the literature search.

Chapter 4 Systematic review of diagnostic accuracy

If we are to establish whether or not screening for mental health problems in young people who offend is of benefit, a first step is to establish how accurate available screening assessments are in this population. This chapter examines the available evidence for the accuracy of different screening methods for a range of mental health problems in young people who offend. It also provides a summary of the available information on the prevalence of mental health problems according to the screening instruments identified by the review and the gold standard methods of establishing a diagnosis of a mental health problem.

Methods to assess diagnostic test accuracy

As described in Chapter 2, sensitivity and specificity are central concepts in understanding diagnostic test accuracy and are described in detail in Appendix 1, along with further information on methods of quantifying diagnostic performance.

Assessing the validity of mental health needs measures

In recognition of the argument that the presence of a diagnosis does not necessarily equate with the level of need in young people who offend,28 we reviewed studies of screening measures designed to establish the presence of a mental health need. For these types of studies it is not possible to apply the standard strategies of assessing diagnostic accuracy because there is no gold standard of ‘mental health need’ against which the identification of the mental health need screening instrument can be assessed. It is impossible, therefore, to create a 2 × 2 table and summarise the performance of the screening instrument in terms of characteristics such as sensitivity and specificity.

For these studies we assessed the extent to which the assessments of mental health need had established criterion-related validity. Validity refers to the extent to which an instrument measures what it is intended to measure. 32 As applied to the question here, validity refers to whether or not a measure of mental health need in young people who offend does in fact measure the mental health needs of this group. Criterion-related validity assesses the validity of a measure by examining the extent to which it relates in ways we would expect it to relate to other measures of the same or different constructs. For example, if a mental health needs assessment is in fact a valid measure, we would expect it to relate to other indicators of mental health need, such as subsequent use of mental health services.

Rather than exclude all studies of mental health needs assessments that did not report the agreement of the measure against a gold standard diagnosis, for instruments for which we could not identify diagnostic test accuracy data we sought to include reports of validation studies that established the criterion-related validity of the mental health needs assessments.

Methods

This first phase of the review sought to answer two main questions:

-

For those screening measures reporting diagnostic status, what is their diagnostic accuracy?

-

For those screening measures identifying level of need, what evidence is there that these measures are valid indicators of mental health need?

In addition, we summarised the prevalence of mental health problems as identified by the screening instruments in these studies.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Two reviewers screened the titles and abstracts identified in the literature search for studies that were potentially eligible to be included in this phase of the review. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or deferred to a third party if necessary.

The PICO criteria for this stage of the review were:

-

Population and setting: young people (aged 10–21 years) who have offended and who are in contact with the criminal justice system.

-

Intervention: screening measures designed to identify one or more mental health diagnoses (see Diagnostic categories). Also included were measures that reported the presence of a mental health need. These can be brief screening measures or longer instruments. These types of measures were not diagnosis specific.

-

Reference: for studies reporting diagnostic accuracy, a standardised diagnostic interview conducted to internationally recognised criteria [e.g. ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders26 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)27]. For studies reporting the assessment of mental health needs, some form of validation needs to have been performed. This would typically take the form of examining the association or level of agreement between the assessment of mental health needs and one or more other indicators of mental health need.

-

Outcome: details of the prevalence of one of the specific mental health diagnoses or mental health needs, details of the diagnostic accuracy of the measure or details of validity data for those measures reporting mental health need rather than diagnosis.

-

Study design: cross-sectional, case–control and cohort studies and randomised controlled trials (when screening measure was used as a method of recruitment).

When citations met the inclusion criteria but reported data on samples that overlapped with those in other included studies, we examined the citations to establish whether different information on diagnostic test accuracy was reported. If so, more than one citation was included, although this was treated as a single data set. In cases in which no additional data were reported, we retained the citation reporting the largest sample size.

Diagnostic categories

For the diagnostic accuracy studies we sought evidence for a range of diagnoses, which we broadly grouped into mood disorders (e.g. major depression, bipolar disorder), anxiety disorders (e.g. generalised anxiety, panic disorder, PTSD), behavioural disruptive disorders [ADHD, conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)] and a miscellaneous ‘other’ category that included psychotic disorder, autistic spectrum disorder and self-harm/suicide.

Although self-harm and suicidal behaviour are not diagnoses, we sought evidence of the accuracy of screening measures for these because they are important mental health outcomes with an increased prevalence in young people who offend. Unlike the diagnostic categories, for which the gold standard is typically a structured clinical interview to establish the presence of a diagnosis, for self-harm/suicide we included studies that provided details of the accuracy of the self-harm/suicide screen in terms of future self-harm or suicidal behaviour. Studies that assessed the screening instrument against other outcomes, such as suicidal intent, were therefore excluded.

As described earlier, we also included measures that reported the presence of a mental health need.

Although particular measures developed in the UK are recommended as screening measures, we did not presuppose that these should be prioritised in the review.

Data extraction

All data were extracted independently by two reviewers using an agreed data extraction sheet. As with the detailed PICO criteria, the data extraction sheet was first piloted on full papers and refined through an iterative process.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the QUADAS-2 tool (Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies – version 2). 33 This tool examines four domains: patient selection, index test, reference standard, and flow and timing. The risk of bias is assessed for each of these domains. The first three of these also examine concerns about the applicability of the study to the review question.

The developers of the QUADAS-2 tool recommend that it is tailored to a review through the development of review-specific guidance. This may involve removing questions that are not applicable, adding additional questions that may be important quality assessment criteria for the specific subject area and providing details of how each criterion should be assessed and coded. In line with these recommendations, we developed a detailed guidance document for this review, which is given in full in Appendix 5.

We retained all of the risk of bias signalling questions and applicability questions. For the signalling question ‘Is the reference standard likely to correctly classify the target condition?’, we operationalised this as whether or not the researchers who conducted the gold standard interview had received appropriate training, had had their performance satisfactorily benchmarked or had rated well on inter-rater reliability tests. For the signalling question ‘Was there an appropriate interval between the index test and the reference standard?’, we defined an appropriate interval as < 2 weeks, in keeping with how this item has been applied in the evaluation of diagnostic test accuracy studies of mental health outcomes in previous versions of the QUADAS tool. 34

The risk of bias in each domain was assessed as ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’. Concerns regarding applicability in the first three domains were also assessed as ‘high’, ‘low’ or ‘unclear’.

Two reviewers independently rated the quality of the studies using the review-specific guidance. Disagreement was resolved by consensus and deferred to a third party when necessary.

Data synthesis

We produced a narrative synthesis of both the diagnostic accuracy studies and the assessment of the extent to which mental health needs screening measures are valid indicators of mental health needs in this population.

We summarised the results of the diagnostic studies in a descriptive manner. For studies that reported sufficient details to calculate 2 × 2 tables, we calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive likelihood ratios, negative likelihood ratios and diagnostic odds ratios (DORs) and their associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), with the diagti user-written command. For studies that reported information on diagnostic accuracy but which provided insufficient information to calculate a 2 × 2 table, we relied on the reports of sensitivity and specificity given in the study. There was an insufficient number of studies using the same screening measure for the same class of mental health outcomes to conduct a bivariate diagnostic meta-analysis.

Results

A total of nine studies including eight independent samples met our inclusion criteria. 35–43 Two of the included studies38,43 reported data on samples that had some although not complete overlap with each other. The smaller of the two studies38 reported additional details of diagnostic accuracy not reported in the larger study. 43 Specifically, Hayes et al. 38 reported data on the performance of a voice-administered MAYSI-2, whereas the larger study by Wasserman et al. 43 study reported data on a paper and pencil version alone. We therefore report the results of both studies, the larger study because of its greater size and the smaller study because of the additional information it contains on the performance of the voice-administered version of the MAYSI-2. An additional citation44 provided a summary of the results of the included Wasserman et al. study. 43 All of the information contained in it was also included in the original report and so this citation was excluded. A further citation45 reported data on a subset of a sample reported in the included Kerig et al. study. 39 It did not contain additional information on diagnostic test accuracy and so was also excluded in favour of the larger data set reported in Kerig et al. 39

Eight of the nine studies reported data on the diagnostic test accuracy of one or more screening instrument. 35,36,38–43 The remaining study reported data on the validity of a mental health needs assessment, which will be discussed separately. 37

Diagnostic test accuracy results

Characteristics of the included studies

A summary of the characteristics of the eight diagnostic accuracy studies is given in Table 1.

| Study | Setting and sample | Screening instrument | Gold standard | Type of mental health diagnosis examined |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashel 199835 | Setting: correctional facility, USA Age (years), mean (SD): 16.0 (1.0) % male: 100 Ethnicity: 46.5% African American, 26.3% white, 23.2% Hispanic American, 4.0% other n = 99 |

Instrument: MMPI-A Completion time (minutes): 90 Literacy level: seventh grade or higher (audio-administration for grades 3–6) |

K-SADS-III-R (DSM-III-R) | Major depression, generalised anxiety, ADHD, conduct disorder |

| Grubin 200236 | Setting: young offender institutions, UK Age (years), range: 18–21 % male: 100 Ethnicity: not stated n = 30 |

Instrument: Prison Reception Health Screen Completion time (minutes): 5–10 Literacy level: not stated |

SADS-L (RDC) | Any condition |

| Hayes 200538 | Setting: adjudicated youth, USA Age (years), mean (SD): 15.7 (1.1) % male: 52.8 Ethnicity: 56.9% African American, 39.8% white, 1.6% Hispanic, 1.6% other n = 123 |

Instrument: voice and paper MAYSI-2 Completion time (minutes): 10 Literacy level: not stated |

Voice DISC (DSM-IV) | Mood disorder cluster, anxiety disorder cluster, disruptive disorder cluster |

| Kerig 201139 | Setting: county juvenile detention centres, USA Age (years), mean: 15.5 % male: 73.7 Ethnicity: 67% European American, 23% African American, 3% Hispanic, 3% multiracial, 1% American Indian/Pacific Islander and 0.5% Asian n = 498 |

Instrument: MAYSI-2 Completion time (minutes): not stated Literacy level: not stated |

UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent version (DSM-IV) | Full or partial PTSD |

| Kuo 200540 | Setting: secure facility for delinquent youth, USA Age (years), range: 13–17 % male: 74.6 Ethnicity: 51% Caucasian 34% African American n = 50 |

Instrument: MAYSI-2, MFQ, Short MFQ Completion time (minutes): 8–12 MAYSI-2; 5–7 MFQ; 2–3 Short MFQ Literacy level: not stated |

Voice DISC (DSM-IV) | Depression |

| McReynolds 200741 | Setting: juvenile justice setting, USA Age (years), mean (SD): 15.7 (1.1) % male: 55.4 Ethnicity: 55.9% African American, 40.5% white, 2.1% Hispanic, 1.5% other n = 195 |

Instrument: DISC predictive scales Completion time (minutes): 15 Literacy level: third-grade oral comprehension |

Voice DISC (DSM-IV) | Mood disorder cluster, anxiety disorder cluster, disruptive disorder cluster |

| Vreugdenhil 200642 | Setting: youth detention centres, the Netherlands Age (years), mean (SD): 16.4 (1.2) % male: 100 Ethnicity: 25% Dutch, 24% Surinamese, 21% Moroccan, 7% Turkish, 4% Antillean, 18% other, 2% unknown n = 196 |

Instrument: YSR Completion time (minutes): not stated Literacy level: not stated |

DISC (DSM-IV) | ADHD, ODD |

| Wasserman 200443 | Setting: correctional youth setting, USA Age (years), mean (SD): 16.7 (1.5) % male: 79.7 Ethnicity: 58.2% African American, 28.3% white, 11.1% Hispanic, 2.5% other n = 325 |

Instrument: MAYSI-2 Completion time (minutes): not stated Literacy level: not stated |

Voice DISC-IV (DSM-IV) | Mood disorder cluster, anxiety disorder cluster, disruptive disorder cluster |

Setting and sample

The majority of the studies were conducted in the USA; other studies were conducted in the UK (n = 136) and the Netherlands (n = 142). Studies took place in a range of criminal justice settings.

Although the inclusion criteria for the review permitted samples aged between 10 and 21 years, most of the studies had a mean age of between 15 and 16 years old, with a narrow standard deviation. There was, then, a lack of representation of the diagnostic accuracy of screening instruments in the younger age group. Three of the eight studies reported data on an entirely male sample,35,36,42 in two studies the male-to-female ratio was approximately even38,41 and in three studies the male-to-female ratio was approximately 3 : 1. 39,40,43 Although two of the studies used overlapping samples,38,43 the male-to-female ratio was approximately 1 : 1 in one study38 and 3 : 1 in the other. 43 In the US studies the majority of the samples were made up of young people from a Caucasian or African American background. Ethnicity was not reported in the UK study. 36 In the Dutch study the sample was made up of those from a range of ethnic backgrounds. 42

Screening measures used in included studies

Four studies, including three independent samples, used the MAYSI-2 as the screening instrument. 38–40,43 Kuo et al. 40 also examined the Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ) and a short version of the MFQ46 in addition to the MAYSI-2. The remaining four studies each used a different screening instrument. A brief description of the screening measures used in the included studies is given below:

-

MAYSI-2. The MAYSI-2 tool is a screening tool designed to assist juvenile justice staff in the identification of young people aged 12–17 years who may have mental health problems. 10 The tool consists of a self-report inventory of 52 questions and produces seven separate scales that focus on different areas of concern (e.g. depressed, anxious, suicidal ideation). Youths circle ‘yes’ or ‘no’ concerning whether or not each item has been true for them ‘within the past few months’ on six of the scales and ‘ever in your whole life’ on one scale. Youths can read the items themselves (the tool has a fifth-grade reading level) and circle the answers or questions can be read aloud by juvenile justice staff. A further method of administration is via a CD-ROM on a computer; youths listen to the questions using headphones and answer the questions using the keyboard or a mouse. Administration and scoring takes about 10–15 minutes.

-

Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (DISC) Predictive Scales (DPS). The DPS are brief self-report measures designed to identify young people who are at increased risk of meeting diagnostic criteria for mental health difficulties. 47 The scales are derived from the DISC,48 described in more detail in the following section, which is based on DSM criteria. 27 The scales consist of 56 items and enquire about difficulties over the last 12 months.

-

Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory – Adolescent version (MMPI-A). The MMPI-A is a self-report measure derived from the MMPI designed for adults. 49 The objective of the measure is to identify psychopathology in adolescents. The adolescent version consists of 478 items and takes approximately 90 minutes to complete. The number of items and time taken for completion mean that such a measure is unlikely to be used as a screening instrument. However, we retained the study here for two reasons. First, we did not specify a maximum completion time as part of the inclusion criteria. Second, the MMPI consists of a number of subscales, which in principle could be used as screening instruments.

-

MFQ. The MFQ is a 33-item self-report measure based on DSM criteria27 and designed to assess depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. 46 Items concern symptoms over the last 2 weeks and are rated as ‘not true’, ‘sometimes true’ and ‘true’. The short form of the questionnaire (Short MFQ) consists of 13 items from the full scale. 46

-

Prison Reception Health Screen. The Prison Reception Health Screen is a 15-item measure designed to be used at intake to detect physical health, mental health and substance use disorders. 36 Slightly different versions of the scale are used for males and females, and for young people an additional item is added to identify whether or not they have experienced a recent bereavement. The instrument is designed to be administered by prison health-care staff.

-

Youth Self-Report scale (YSR). The YSR is a standardised self-report measure for adolescents that is part of the family of measures developed by Achenbach,50 with other measures designed for completion by parents and teachers. The scale was developed for completion by adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years. It is scored on scale from 0 (‘not true’) to 2 (‘very true’) and provides a summary of a young person’s emotional and behavioural problems over the last 6 months. The scale has eight syndrome scales (e.g. anxiety and depression, somatic complaints, social problems), with a ninth scale (self-destructive/identity problems) scored for boys only and three broad problem scales (internalising, externalising, total problem score).

Gold standard instruments used in included studies

The DISC48 was used as the gold standard in five studies, including four independent samples. 38,40–43 Two studies35,36 used a version of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS)51 and one study39 used the University of California at Los Angeles Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder Reaction Index (UCLA PTSD RI) – Adolescent version. 52 These three diagnostic instruments are described in more detail below:

-

DISC. The DISC is a structured diagnostic interview to establish diagnoses for a range of mental health difficulties. 48 The interview uses a probe and follow-up format so that, if a young person answers positively to a probe question, further questions are asked to establish whether or not the person meets diagnostic criteria. The diagnoses identified by the DISC can be grouped into clusters (e.g. mood disorders, anxiety disorders, disruptive disorders). The interview takes approximately 60 minutes to complete but can be longer depending on the number of symptoms endorsed.

-

The interview can be delivered in a number of formats. In the standard format the interview is administered by a trained interviewer, a delivery format used in one of the included studies. 42 An alternative format is the Voice DISC in which the young person listens to pre-recorded questions on a headphone and gives his or her response to the spoken questions using a computer keyboard. Non-clinicians, with training in the interview and computer literacy, are able to administer the Voice DISC. Four of the included studies, including three independent samples, used this format. 38,40,41,43

-

In the included studies, the accuracy of the screening instruments was typically assessed against clusters of diagnoses as determined by the DISC, including mood disorders, anxiety disorders and disruptive behavioural disorders (including ADHD).

-

-

SADS. The SADS51 is a semistructured diagnostic interview for the diagnosis of affective and psychotic disorders in adults. Responses are rated on either a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘severe’) or a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 6 (‘extreme’). It was developed before the development of DSM-III criteria and is instead based on Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC); however, the degree of convergence between RDC and DSM diagnoses is high. The standard version asks about current mental health symptoms and the lifetime version (SADS-L) asks about previous episodes. The K-SADS-III-R (Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children) is a modified version of the SADS designed for use with children and adolescents (aged 6–18 years) and provides DSM-consistent diagnoses. 53 It uses the same 4-point and 6-point response format as the adult SADS.

-

UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent version. The UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent is a 48-item measure designed to assess DSM criteria for PTSD. 52 A DSM diagnosis of PTSD requires criterion A (presence of real or perceived threat to physical integrity), criterion B (re-experiencing of traumatic event), criterion C (avoidance) and criterion D (hyper-arousal) to be met. The UCLA PTSD RI follows this structure. The instrument can be used to determine whether a full or partial diagnosis of PTSD is likely; a full diagnosis requires each of criterion A, B, C and D to be met; a partial diagnosis requires criterion A to be met along with two out of three of criteria B, C and D. Although the UCLA PTSD RI does not provide a formal diagnosis, we included this as a gold standard measure because it maps closely onto a recognised diagnostic system (DSM) and has convergent validity with other established gold standard diagnostic systems such as the SADS.

Quality assessment of the included studies

Table 2 summarises the risk of bias individually for the eight included studies according to QUADAS-2 criteria and Table 3 summarises the applicability criteria individually for the eight studies. Figures 2 and 3 provide an overall summary of the risk of bias and applicability respectively.

| Study | Patient selection: consecutive or random sample | Patient selection: avoided case–control | Patient selection: avoided inappropriate exclusions | Patient selection: overall risk of bias | Index test: index test interpreted blind to reference test | Index test: threshold prespecified | Index test: overall risk of bias | Reference test: reference test correctly classifies target condition | Reference test: reference test interpreted blind to index test | Reference test: overall risk of bias | Flow/timing: interval of ≤ 2 weeks | Flow/timing: all participants receive a reference standard | Flow/timing: all participants receive same reference test | Flow/timing: all participants included in analysis | Flow/timing: overall risk of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashel 199835 | ? | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear | ✓ | ? | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear |

| Grubin 200236 | ? | ✓ | ✓ | Unclear | ✓ | ? | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

| Hayes 200538 | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | High | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | High |

| Kerig 201139 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ? | ✗ | High | ✓ | ? | Unclear | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low |

| Kuo 200540 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | High | ? | ✗ | High | ✓ | ? | Unclear | ? | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | High |

| McReynolds 200741 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | High |

| Vreugdenhil 200642 | ? | ✓ | ✗ | High | ? | ✓ | Unclear | ✓ | ? | Unclear | ? | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | High |

| Wasserman 200443 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | High | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ✓ | ✓ | Low | ? | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | High |

| Study | Patient selection: applicability | Index test: applicability | Reference test: applicability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cashel 199835 | Low | High | Low |

| Grubin 200236 | High | Low | Low |

| Hayes 200538 | Low | Low | Low |

| Kerig 201139 | Low | Low | Low |

| Kuo 200540 | Low | Low | Low |

| McReynolds 200741 | Low | Low | Low |

| Vreugdenhil 200642 | Low | Low | Low |

| Wasserman 200443 | Low | Low | Low |

FIGURE 2.

Overall risk of bias across QUADAS-2 domains for the included diagnostic test accuracy studies (n = 8).

FIGURE 3.

The QUADAS-2 applicability criteria for the included diagnostic test accuracy studies (n = 8).

Patient selection

The patient selection domain assesses if the way in which participants were selected may have introduced a bias. Four studies, consisting of three independent samples, were rated as being at high risk of bias for this domain;38,40,42,43 the risk of bias was rated as low for two studies39,41 and unclear for the remaining two studies. 35,36

Although all studies avoided a case–control design, some studies did not use random or consecutive sampling for recruiting participants and others were judged to have a high number of inappropriate exclusions. The absence of random or consecutive sampling could artificially either increase or decrease the observed performance of a screening instrument against a gold standard; the direction of the influence would be determined by the exact nature of the sampling procedure used. The same is true of the high number of inappropriate exclusions from the sample. Therefore, although there is some evidence of bias for the patient selection domain, it is unclear what effect this had on the observed diagnostic accuracy in the included studies.

Index test

The index test domain asks whether the conduct or interpretation of the screening test may have introduced a bias. The overall risk of bias for this domain was rated as high for two studies,39,40 unclear for three studies,35,36,42 and low for three studies, consisting of two independent samples. 38,41,43

For some studies it was unclear if the index test was interpreted blind to the reference standard. Blinding is essential to ensure that knowledge of the results does not influence the scoring of the reference standard, which may artificially inflate the observed diagnostic test accuracy of the screening test. Some studies also failed to use a prespecified cut-off point on the index test. The post hoc selection of the cut-off point can capitalise on a chance finding and artificially inflate observed diagnostic test accuracy.

Reference standard

The reference standard domain assesses whether the gold standard used or the conduct or interpretation of the gold standard test may have introduced bias. The overall risk of bias for the reference standard domain was considered low for five studies,35,36,38,41,43 consisting of four independent samples, and unclear for three studies. 39,40,42 The unclear ratings resulted from a lack of clear evidence that the diagnostic gold standard was conducted blind to the results of the index test. As with lack of blinding for the index test, this can also distort the observed diagnostic performance of the screening test.

Flow and timing

Six out of the eight studies,36,38,40–43 consisting of five independent samples, were rated as being at high risk of bias in terms of the flow and timing domain, which assesses whether or not the participant flow through a study and the timing of measurement may have introduced bias. The reasons for the rating of high risk for many of the studies were that not all participants received the reference standard and not all participants were included in the analysis. Participants included in the diagnostic test accuracy analysis may have differed in systematic ways from participants who were not included and this may distort the test accuracy.

Applicability criteria

Table 3 summarises by individual study the extent to which the QUADAS-2 applicability criteria are met and Figure 3 provides an overall summary. The applicability criteria were broadly met for the patient selection and index test domains and entirely met for the reference standard domain. One study did not meet the criterion for index test applicability. 35 As we describe earlier, this was because the study used the MMPI-A, a 458-item measure taking approximately 90 minutes to complete, which makes it unsuitable as a screening measure, although one or more subscales could feasibly be used to screen. One study did not meet the applicability criterion for patient selection. 36 This was because the study recruited from a variety of adult and young offender institutions, although it was possible to extract some data for the young offender population and the results discussed later for that study are based solely on the young offender subgroup.

Summary

With the exception of the reference standard domain, for which a majority of studies had a low risk of bias, the risk of bias was either high or unclear for the majority of studies in the other three QUADAS-2 domains. No study was rated as being at low risk for all four domains. In contrast, applicability criteria were broadly met across all studies. The identified studies are therefore largely relevant to the diagnostic test accuracy question that this review seeks to answer but some caution is needed in relying on the diagnostic accuracy data reported by these studies because the level of potential bias across many QUADAS-2 domains was often unclear or high.

Results by diagnostic clusters

This section presents the diagnostic test accuracy of the included studies organised by broad diagnostic clusters. It also provides detail on the prevalence of the mental health problems as established by the screening instruments and gold standards in those samples reporting data for both types of assessment. There was an insufficient number of studies to conduct a diagnostic meta-analysis of the results for any of the broad diagnostic clusters; a narrative summary is instead given for all clusters.

When studies reported diagnostic accuracy data for multiple subscales of a measure, we report here those subscales that measure the same or a similar construct as that assessed by the gold standard. For example, Hayes et al. 38 report diagnostic test accuracy data for a large number of subscales of the MAYSI-2 (alcohol/drug use, angry–irritable, depressed–anxious, somatic complaints, suicidal ideation, thought disturbance), each against mood, anxiety and disruptive clusters of the DISC. Rather than report each of the subscales against the mood disorder cluster, we report the depression–anxiety subscale because of its conceptual link with the gold standard diagnosis.

Mood disorders

Five studies, consisting of four independent samples, reported information on the diagnostic test accuracy of one or more screening instrument assessed against a gold standard diagnosis of a single mood disorder or a cluster of mood disorders. 35,38,40,41,43

Prevalence

Kuo et al. 40 used the MFQ and Short MFQ as a depression screen. The MFQ, using the literature standard cut-off point of 27, suggested a prevalence estimate of 24%; for the Short MFQ the figure was 42%. This compares with a prevalence figure of 14% for depression using the gold standard (Voice DISC).

McReynolds et al. 41 reported data on the DPS. The prevalence of any affective disorder using the DPS was 20%. A young person was classified as having an affective disorder if he or she scored positive on any of the affective predictive subscales. The prevalence for the gold standard (Voice DISC) was 11.8% for any affective disorder.

The MAYSI-2 subscales group mood and anxiety difficulties into a single subscale (depression–anxiety); therefore, it is not possible to estimate the prevalence of solely mood disorders according to standard literature cut-off points on this instrument. The figures for the depression–anxiety subscale, using the ‘caution’ cut-off point, are 39% for the voice-administered MAYSI-238 and 35.0% for the paper and pencil-administered version of the test. 43 The gold standard estimate of the prevalence of mood disorders according to the DISC affective disorder classification was 12.0% in Hayes et al. 38 and 10.5% in Wasserman et al. 43 Kuo et al. 40 provide data on the prevalence of depression according to what they report as the MAYSI-2 depression scale, although it is unclear if this in fact refers to the depression–anxiety subscale of the MAYSI-2.

Prevalence figures according to the MMPI used in Cashel et al. 35 are not given because of insufficient detail reported in that study.

Diagnostic test accuracy for mood disorders

Two studies reported diagnostic test accuracy data for major depression. 35,40 Table 4 summarises the performance of the screening measures in these studies. Limited data are presented in Table 4 and subsequent tables for Cashel et al. 35 because there was insufficient information reported in that study to calculate the 2 × 2 tables needed for the additional diagnostic test accuracy statistics.

| Study | Sample size | Depressed according to gold standard (%) | Gold standard | Index test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashel 199835 | 99 | Not reported | K-SADS-III-R | MMPI-A scales 2, 4 and 5 | 0.8a | 0.84a | –a | –a | –a |

| Kuo 200540 | 50 | 14 (n = 7) | Voice DISC | MAYSI-2: | |||||

| Cut-off: 3 | 0.71 (0.29 to 0.96) | 0.65 (0.49 to 0.79) | 2.05 (1.10 to 3.81) | 0.44 (0.13 to 1.44) | 4.67 (0.91 to –b) | ||||

| Cut-off: 4 | 0.71 (0.29 to 0.96) | 0.79 (0.64 to 0.9) | 3.41 (1.62 to 7.2) | 0.36 (0.11 to 1.18) | 9.44 (1.76 to 49.2) | ||||

| MFQ: | |||||||||

| Cut-off: 27 | 0.71 (0.29 to 0.96) | 0.84 (0.69 to 0.93) | 4.39 (1.92 to 10.0) | 0.34 (0.11 to 1.11) | 12.9 (2.31 to 69.6) | ||||

| Cut-off: 29 | 0.71 (0.29 to 0.96) | 0.93 (0.81 to 0.99) | 10.20 (3.12 to 33.6) | 0.31 (0.09 to 0.99) | 33.3 (4.95 to 225.0) | ||||

| Short MFQ: | |||||||||

| Cut-off: 8 | 1.0 (0.59 to 1.0) | 0.67 (0.52 to 0.81) | 3.07 (2.0 to 4.72) | –b | –b | ||||

| Cut-off: 10 | 1.0 (0.59 to 1.0) | 0.72 (0.56 to 0.85) | 3.58 (2.22 to 5.79) | –b | –b | ||||

Kuo et al. 40 reported literature standard cut-off points for the three screening measures examined in that study (MAYSI-2: 3; MFQ: 27; Short MFQ: 8) as well as a single alternative cut-off point for each measure. Some caution is needed in interpreting the alternative cut-off points because, unlike the literature standards that are predetermined, it is possible that the selection of these post hoc may capitalise on chance.

The sensitivity at the literature standard cut-off points for two of the instruments was in the range of 0.7–0.8, which may be unacceptably low for screening instruments because it would lead to a high proportion of people with major depression being missed. The results for the short form of the MFQ were more impressive, with a sensitivity of 1 and a specificity of approximately 0.7 at the two reported cut-off points. However, caution is needed in interpreting these results because of the small sample size and the low number of people with major depression, which means that any estimate of sensitivity is likely to be imprecise.

It is of note that, on the basis of the limited evidence presented here, the MAYSI-2, a measure designed specifically for use with young people who have offended, did not appear to have greater performance characteristics than more general measures. Although the cut-off point could be altered to increase sensitivity, this would further reduce specificity, which may lead to a high proportion of false positives. This would be problematic for the MAYSI-2, which already has low specificity at the ‘caution’ cut-off point; increasing sensitivity for this would further lower specificity and lead to a very high false positive rate.

Three studies, consisting of two independent samples, reported data on the diagnostic accuracy of screening instruments compared with a gold standard diagnosis of any affective disorder. 38,41,43 All three used the DISC affective disorder cluster as the gold standard. Table 5 summarises the results for these studies. The level of sensitivity for the MAYSI-2 at the literature standard cut-off of 3 (the ‘caution’ cut-off) was again not as high as would be ideal for use as a screening measure. The sensitivity of the DPS was even lower at the reported cut-off point, although this was paired with a higher specificity. It is unclear if altering the cut-off point to increase the sensitivity of the DPS would retain a sufficiently high specificity to limit the number of false positives.

| Study | Sample size | Depressed according to gold standard (%) | Gold standard | Index test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayes 200538 | 123 | 12 (n = 16) | DISC affective cluster | MAYSI-2 Voice: depressed/anxious (cut-off: 3) | 0.75 (0.48 to 0.93) | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.79) | 2.59 (1.72 to 3.9) | 0.35 (0.15 to 0.83) | 7.35 (2.30 to 23.3) |

| McReynolds 200741 | 195 | 13.8 (n = 27) | DISC affective cluster | DPS: any affective | 0.57 (0.35 to 0.77) | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.9) | 3.74 (2.26 to 6.19) | 0.51 (0.32 to 0.82) | 7.3 (2.95 to 18.1) |

| Wasserman 200443 | 325 | 10.5 (n = 34) | DISC affective cluster | MAYSI-2 paper and pencil: depressed/anxious (cut-off: 3) | 0.74 (0.56 to 0.87) | 0.60 (0.54 to 0.66) | 1.84 (1.44 to 2.36) | 0.44 (0.25 to 0.78) | 4.19 (1.92 to 9.14) |

Summary

It is difficult to make any firm conclusions about the accuracy of screening instruments in identifying major depression or more broad affective disorder clusters as there were not enough studies estimating the accuracy of the same measures using the same cut-off points. However, on the basis of the available evidence, there is no clear indication that the performance of a measure designed specifically for use by young people who offend (MAYSI-2) is superior to that of more generic screening measures.

Anxiety disorders

Five studies, consisting of four independent samples, reported diagnostic test accuracy data on a single anxiety disorder or a cluster of anxiety disorders. 35,38,39,41,43

Prevalence

In terms of single anxiety disorders, Kerig et al. 39 report a range of cut-off points on the traumatic experience subscale of the MAYSI-2 separately for males and females. There is no established cut-off point on this scale but a score of ≥ 3 has been used for research purposes. The prevalence of PTSD symptoms according to a positive screen on the MAYSI-2 using this cut-off point was 34.4% for males and 39.1% for females. According to the UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent scale, which is treated here as the gold standard, the prevalence was in fact higher (males 49.8%; females 59.6%). There were insufficient data reported in Cashel et al. 35 to calculate prevalence estimates for generalised anxiety disorder according to the screening instrument or the gold standard instrument.

In the study by McReynolds et al. ,41 the prevalence of anxiety disorders according to a positive score on any of the anxiety DPS was 65.6%. For the gold standard measure (DISC), the prevalence of any anxiety disorder ranged from 21.2% to 27.6% (see Table 7).

Diagnostic test accuracy for anxiety disorders

Two studies reported data on the diagnostic performance of screening measures for a single anxiety disorder as established by a gold standard. Cashel et al. 35 report data for generalised anxiety and Kerig et al. 39 report data for full or partial PTSD. Table 6 summarises the results of these two studies. Cashel et al. 35 examined a number of MMPI-A scales as a screen for generalised anxiety disorder and reported a sensitivity of 0.73 and a specificity of 0.84. There were insufficient data reported in this study to extract a 2 × 2 table and so CIs and other diagnostic performance characteristics could not be calculated. As described earlier, there is no agreed cut-off point for the MAYSI-2 traumatic experience subscales, as used in Kerig et al. 39 At the cut-off point of 3, which has been used for research purposes, the MAYSI-2 traumatic experience subscale had modest sensitivity and good specificity for both the males and females in the sample (see Table 6).

| Study | Sample size | Anxiety disorder according to gold standard (%) | Gold standard diagnosis | Index test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cashel 199835 | 99 | Generalised anxiety: % not reported | K-SADS-III-R | MMPI-A scales 2, 4 and 6 | 0.73a | 0.84a | –a | –a | –a |

| Kerig 2011,39 male sample | 337 | Full or partial PTSD: 49.9 (n = 168) | UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent scale | MAYSI-2 traumatic subscale (cut-off: 3) | 0.54 (0.46 to 0.62) | 0.85 (0.79 to 0.90) | 3.66 (2.48 to 5.40) | 0.54 (0.45 to 0.64) | 6.81 (4.05 to 11.4) |

| Kerig 2011,39 female sample | 161 | Full or partial PTSD: 59.6 (n = 96) | UCLA PTSD RI – Adolescent scale | MAYSI-2 traumatic subscale (cut-off: 3) | 0.55 (0.44 to 0.65) | 0.85 (0.74 to 0.92) | 3.59 (1.97 to 6.53) | 0.53 (0.41 to 0.68) | 6.78 (3.12 to 14.7) |

The same three studies that reported data on the diagnostic accuracy of screening measures for any depressive disorder (including two independent samples) also assessed their accuracy against a gold standard measure of ‘any anxiety disorder’. 38,41,43 All three used the DISC anxiety disorder cluster as the gold standard. Table 7 summarises the results for these studies. The Hayes et al. 38 and Wasserman et al. 43 studies, which had overlapping samples, reported modest sensitivity for the MAYSI-2 at the literature standard cut-off points, combined with modest specificity. The McReynolds et al. 41 study used the DPS as the screening measure. Participants were scored positively if they scored above the cut-off on any of the anxiety scales. Sensitivity was very high (0.97, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.99) but this was combined with low specificity (0.44, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.52).

| Study | Sample size | Any anxiety disorder according to gold standard (%) | Gold standard | Index test | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) | Positive likelihood ratio (95% CI) | Negative likelihood ratio (95% CI) | DOR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hayes 200538 | 123 | 27.6 (n = 34) | DISC anxiety cluster | MAYSI-2 Voice: depressed/anxious (cut-off: 3) | 0.52 (0.35 to 0.7) | 0.73 (0.62 to 0.81) | 1.93 (1.22 to 3.05) | 0.65 (0.44 to 0.95) | 2.97 (1.32 to 6.66) |

| McReynolds 200741 | 195 | 22.6 (n = 44) | DISC anxiety cluster | DPS: any anxiety | 0.97 (0.88 to 0.99) | 0.44 (0.36 to 0.52) | 1.74 (1.50 to 2.01) | 0.05 (0.01 to 0.36) | 33.4 (5.65 to –a) |

| Wasserman 200443 | 325 | 21.2 (n = 69) | DISC anxiety cluster | MAYSI-2 paper and pencil: depressed/anxious (cut-off: 3) | 0.70 (0.57 to 0.8) | 0.64 (0.58 to 0.7) | 1.94 (1.54 to 2.43) | 0.48 (0.33 to 0.69) | 4.07 (2.31 to 7.19) |

Summary

There were too few studies to conduct a diagnostic meta-analysis or make firm conclusions about the diagnostic performance of any of the instruments in the identification of anxiety disorders among young people who offend. As with the results for depressive disorders, there is not a clear indication that the MAYSI-2, a test specifically designed for young people who have offended, has superior operating characteristics relative to other more general screening instruments.

Disruptive disorders

Five studies,35,38,41–43 consisting of four independent samples, reported data on the diagnostic accuracy of screening instruments for disruptive disorders.

Prevalence

In terms of specific disruptive disorders, prevalence estimates could not be calculated for the Cashel et al. 35 study because insufficient information was reported to carry out the calculations. The prevalence of ADHD according to the acceptable sensitivity cut-off point of the attention deficit hyperactivity (ADH) subscale of the YSR was 53.1% in Vreugdenhil et al. ;42 the prevalence according to the gold standard (DISC) was 8%. Vreugdenhil et al. 42 also report data on ODD. If the aggressive subscale of the YSR is used to estimate the prevalence of ODD it suggests a figure of 85.7%; when the externalising subscale is used the figure is 53.1%. The gold standard suggests a figure of 14%.

The prevalence of any disruptive disorder according to the angry–irritable subscale (cut-off 5) of the MAYSI-2 (voice version) was 44.7% according to Hayes et al. 38 For the paper and pencil version, the figure was 38.5%. 43 McReynolds et al. 41 used the DPS as the screening instrument; a positive score on any of the disruptive scales gave a prevalence estimate of any disruptive disorder of 51.3%. Gold standard estimates for the three studies, all of which used the DISC as the gold standard, ranged from 28.6%43 to 39%,38 although these two studies had overlapping samples.

Diagnostic test accuracy for disruptive disorders