Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/43/01. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The draft report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Cassell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sexually transmitted infections in the UK

Since 1998 there has been a substantial increase in reported cases of sexually transmitted infection (STI), most strikingly in the 16–24 years age group. 1 Across genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics in the UK in 2007, young people accounted for 65% of chlamydia cases, 50% of cases of genital warts and 50% of gonorrhoea infections. 1 Chlamydia is the most common STI in under-25s. Since 1998, the rate of diagnosed chlamydia has more than doubled in the 16–24 years age group (from 447 per 100,000 in 1998 to 1102 per 100,000 in 2007). This may be because of a combination of a higher proportion of young people testing, improved diagnostic methods and increased risk behaviour. 1 Chlamydia infection can frequently go undetected, particularly in women, as it is often asymptomatic. 1 If left untreated, chlamydia can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility in women. This highlights the importance of testing this higher-risk age group to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment.

It is estimated that 11–12% of 16- to 19-year-olds presenting at a GUM clinic with an acute STI will become reinfected within a year. 2 In order to minimise reinfection, preventative measures are required, including effective methods of notifying partners to ensure rapid diagnosis and treatment and reduce the likelihood of index patients being reinfected from the same source.

Current partner notification practice

Partner notification (PN) is an essential element of STI control. It supports patients by enabling diagnosis and treatment for their sexual partners and is an effective way of identifying at-risk and infected persons. PN has been defined as the spectrum of ‘public health activities in which sexual partners of individuals with STD are notified, informed of their exposure and offered treatment and support services’. 3

Treatment of partners remains important for three reasons:

-

to protect the original patient from reinfection and its health consequences

-

to prevent the further spread of infection by infected partner(s)

-

to reduce transmission of STIs (at a population level) by shortening the duration of infection, which is a key determinant of onward transmission rates. 4,5

In the UK, PN has been supported mainly by specialist health advisers (HAs) based in GUM clinics. However, as a result of the growth of the National Chlamydia Screening Programme (NCSP) in England, this role has also increasingly been taken on by local chlamydia screening offices (CSOs) in the community (including general practice surgery settings). 6

Patient referral, in which the patient contacts their sexual partner(s) to arrange testing and/or treatment, supported by the HA, is the most commonly used method of referral, as most partners prefer to contact their partners themselves. Moreover, this additional support is not available in some settings. 7 However, provider and contract referral are also used. 3 In provider referral, the HA offers to contact one or more of the index’s partners on their behalf; in contract referral, patients are asked to agree to a specialist HA informing their partner(s) if this has not been done after a verbally agreed period of time. These are important services to reach partners who might not otherwise be informed, for example casual or ex-partners. The extent to which patient referral is supplemented by health providers contacting partners on the patient’s behalf, and with their agreement (provider or contract referral), is variable. 8 There is, to date, no three-way comparison between patient referral alone, provider referral and contract referral. One trial, situated in a service with very high PN rates, suggested no advantage of contract referral over patient referral. In this study, contract referral achieved 1.15 partners tested per index case, versus 1.27 for patient referral. 9 However, in a setting with lower rates of successful PN, the offer of contract referral if partners did not present within 3 days achieved 0.62 partners tested per index case of gonorrhoea compared with 0.37 both for simple and for enhanced patient referral. 10 Most relevant to this trial is a study by Katz et al.,11 which achieved partner treatment of rates of 0.72 per index case for provider referral, and 0.22 and 0.18 for two differing forms of patient referral.

Partner notification in the primary care setting

Sexually transmitted infections are increasingly diagnosed and treated within the primary care setting,12,13 and around a third of patients presenting to GUM clinics first seek care from their general practice surgery. 14 Maximising the quality of care for patients seen in general practice with STIs has considerable potential for public health gain. However, clinical structure and process standards for PN remain poorly implemented in primary care. 15

Partner notification has been shown to present particular challenges to primary care practitioners. 16 There is historical evidence that only 30% of UK general practitioners would treat a partner,17 and as few as 13% of index patients have a documented attendance at a GUM clinic. 18 General practitioners (GPs) may overestimate how much PN they do,19 while patients treated by a GP are more likely to require retreatment than those treated in a GUM clinic at the outset. 20 This may be because of a lack of established processes for PN within many general practices.

The GP or practice nurse faces several specific challenges in PN compared with sexual health services. The sexual partners of index patients are often not registered at the practice, and general practice has no mechanism for enabling STI treatment in this situation, or for following up compliance. Even if partners are registered at the practice, the duty of confidentiality to individual patients presents difficulties in PN if the index patient declines to discuss their infection with the partner. Staff in general practice may not be confident in handling common issues with PN, which can be time-consuming and require training or support from a HA. 21 Patients diagnosed with a STI may be less willing to give frank information on number of partners, particularly casual or concurrent partners, to familiar staff than to a specialist STI service,21,22 although this has not been shown consistently. 7,23

Recognising these difficulties, guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommended that all patients with a STI, regardless of the setting of diagnosis, should be offered support in PN, which may be within the primary care setting or through referral to a PN specialist. 24 It did not, however, specify standards for content or delivery of this support. A high-quality randomised controlled trial (RCT) has demonstrated that specifically trained practice nurses can achieve PN outcomes equivalent to those achieved by referral to attend a GUM clinic. 7 This trial provided important evidence that PN in the form of patient referral can be undertaken within a highly motivated and specifically trained primary care setting. However, it does not provide an adequate model for a comparison between patient, provider and contract referral in a primary care setting, as it is unlikely that provider or contract referral could become routine work among all general practice surgeries in the foreseeable future, especially in those with no particular interest in sexual health.

The National Chlamydia Screening Programme

Evidence from a Department of Health-funded chlamydia screening pilot study of opportunistic screening in primary and secondary health-care settings demonstrated that it was feasible and acceptable to test women for chlamydia using urine samples using these services. 25 In a separate Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded programme, the Chlamydia Screening Studies (ClaSS) project,23 a cross-sectional study of 19,773 women and men aged 16–39 years, selected from general practice, invited participants to collect urine and vulvovaginal swab (for women) specimens at home and post to the laboratory for testing. These studies confirmed that the prevalence of chlamydia was highest amongst those aged under 25 years and was similar in both men and women. The urine and swab tests were also shown to be suitable samples for diagnostic testing with nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs).

The NCSP in England, which was established in 2003, is an opportunistic testing programme which has been rolled out over a number of years. The key objectives of the programme are to ‘prevent and control chlamydia through early detection and treatment of infection; and reduce onward transmission to sexual partners and prevent the consequences of untreated infection’. 26 Screening has come to contribute an increasing proportion of primary care STI diagnoses and must be considered as part of the relevant population when conducting any trial of PN in primary care.

There has been marked geographical variation in the mix of services contributing NCSP tests, and in positivity by setting, with positivity in educational settings as low as 3%. 27 By 2010, primary care was increasingly identified by NCSP as a key setting. In 2007/8, the highest percentage of tests was conducted within the community contraceptive services, at 25.9%; a further 17.9% were tested in youth services, 13.4% in education and 12.6% in general practice. 28 Coverage of the target 16- to 24-year-old population varied between 0% and 14% in different primary care trusts (PCTs), with local NHS targets set at 15% coverage. 29 In 2007, over 270,729 screens were performed, with 9.5% females and 8.4% of males testing positive. 1

The Department of Health Public Health Outcomes Framework 2013–16, published in 2012, now specifies the number of chlamydia diagnoses per unit population as a public health outcome target for England, replacing coverage targets. 30

The NCSP targets under-25s who are sexually active to test for chlamydia and offers sexual health promotion advice. Although the programme has a national co-ordination team, the organisation of each geographical area is determined at local level. In its early years, the NCSP encouraged the development of varying models of service provision including testing in outreach settings such as colleges, prisons, youth services and even shopping centres. Possible location categories for the treatment of index patients (as specified by the NCSP) are GUM, family planning, CSO, general practice, pharmacy and other.

The organisation of PN varies markedly, with GUM clinics providing this service in some areas, and community-based local chlamydia co-ordinators in others, while some high-volume areas have not made specified provision to support PN in primary care.

The commissioned research and its implementation

Given the increase in reported STIs over the last 10 years1 and variable management of PN in the UK,31 there was an evident need for further robust, evidence-based research on the effectiveness of different methods of PN. The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HTA programme therefore sought to commission a RCT to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different existing approaches to PN, specifically in primary care. The HTA tendered for a RCT comparing patient referral, provider referral and contract referral for patients diagnosed with a bacterial STI in the primary care setting. This study was commissioned as a full-scale RCT, and included health economics, mathematical modelling and patient factor components. It also included the building of a web-based referral tool that could both facilitate referral from primary care to specialist GUM services where HAs were based and collect summary outcome data on PN. It was envisaged that this web tool could subsequently have a role in NHS clinical care.

At the outset of the research, we undertook initial pilot work (phase 1) on the assumption that the RCT would scale up in the form in which it had been commissioned. However, it became clear that this was not likely to be feasible because of recruitment problems. We then undertook additional work aimed at improving recruitment. This included exploring potential for improvement in our existing recruitment strategy through literature review and consultation (phase 2), implementing the new recruitment strategy (phase 3) and, finally, implementing an additional novel recruitment strategy being used in a related study elsewhere (phase 4). Unfortunately, these efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, but they provide some interesting lessons relevant to the future planning of certain types of trial in primary care.

Phase 1 also identified some interesting conceptual and operational challenges to the planned comparison between the three proposed arms of this trial. As we sought to develop standardised approaches to provider referral and contract referral in consultation with practitioners, it emerged that practitioners found clear-cut distinctions between these approaches problematic. We explored and addressed this using qualitative methods.

Because of recruitment failure, we were unable to compare the costs of achieving our proposed outcomes. We are, however, able to present the costs of the intervention arms used in this study, and also of the intensive recruitment strategy used in phase 4, which may inform recruitment plans for other studies.

Unfortunately, because of insufficient recruitment, the patient factors and modelling work were not possible and they are not reported.

Outline of report

This report presents the various phases of recruitment, focusing on findings of relevance to other future studies in the fields of PN, sexual health in primary care or recruitment challenges. The four phases of recruitment mentioned above are presented, alongside methodological chapters exploring the practice of PN and the economic findings, and a chapter setting out the health landscape of chlamydia screening and its implications for research in sexual health.

Chapter 2 Summary and protocol for the randomised controlled trial as originally planned

Overview of the proposed randomised controlled trial

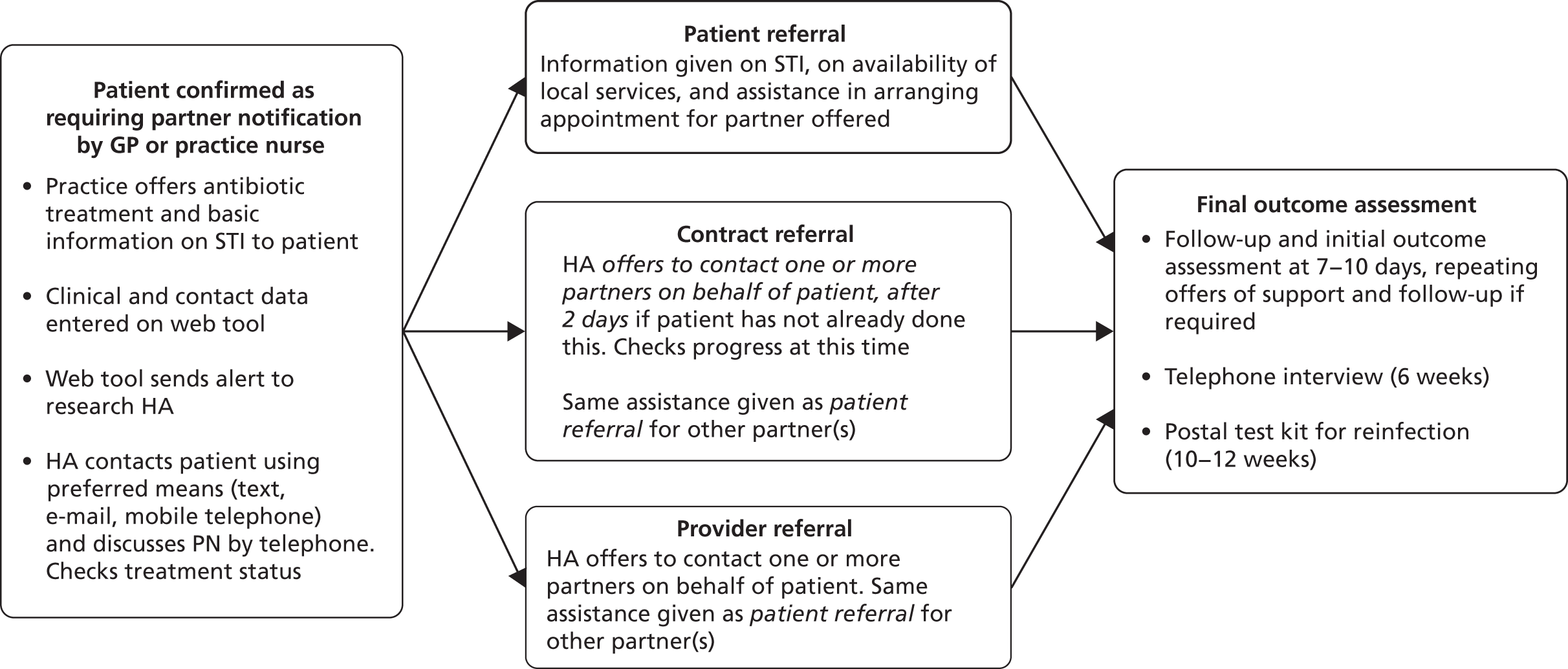

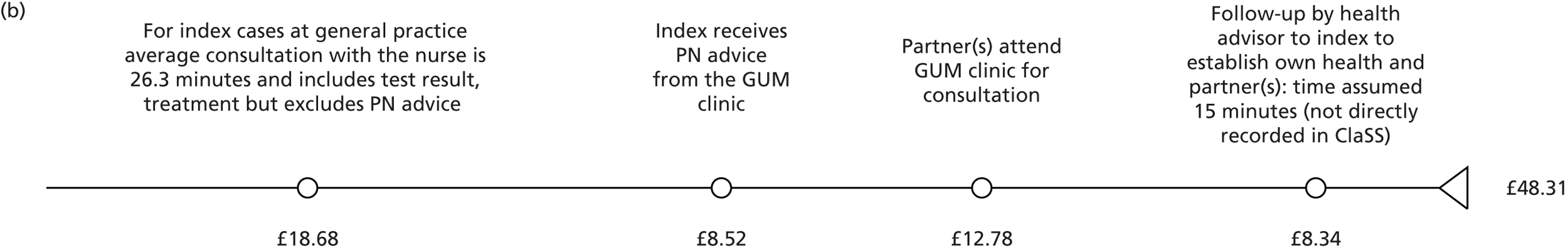

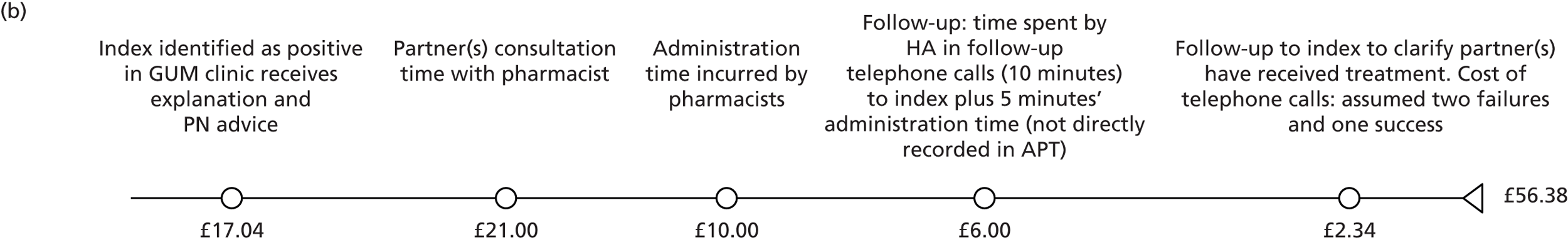

The technologies compared were three different interventions in PN (Figure 1):

-

PATIENT REFERRAL, where patients are given information about their infection and asked to tell their partner about the problem and the need to be treated.

-

PROVIDER REFERRAL, where, in addition to (i), patients are asked to agree to a specialist HA (contact tracing expert) contacting one or more of their partner(s) at the time of diagnosis.

-

CONTRACT REFERRAL, where, in addition to (i), patients are asked to agree to a specialist HA informing partner(s) if this has not been done after a verbally agreed period of time (usually no more than 7 days).

FIGURE 1.

Summary of PN interventions and outcome assessment.

The null hypothesis

Provider referral and contract referral offer no advantage over patient referral alone in PN for curable STIs in the primary care setting.

In order to answer the research question for the main trial, the following objectives and outcomes were established.

Objectives

-

To standardise, appropriate for the primary care setting, three contemporary and evidence-based models of PN for STIs (patient referral, provider referral and contract referral).

-

To compare the clinical effectiveness of these three models.

-

To compare the cost-effectiveness of these three models.

-

To determine the acceptability to patients of each approach to PN, and to identify means of improving PN rates for ‘highly connected’ partnerships.

-

To enhance the efficiency of the trial through mathematical modelling of the potential impact of each modality of PN on outcomes for different types of partner (main, casual and ex-partners) and for men who have sex with men (MSM).

-

To provide comprehensive, definitive evidence for policy-makers and public health practitioners on the implementation of clinically effective and cost-effective PN for patients diagnosed with STIs in the primary care setting.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes of the randomised controlled trial

-

Number of partners per index patient treated for chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea/non-specific urethritis/pelvic inflammatory disease.

-

Proportion of index patients testing negative for the relevant STI at 3 months.

Secondary outcomes of the randomised controlled trial

-

Number of partners per index patient presenting for treatment.

-

Proportion of index patients having at least one partner treated.

-

Number of main, casual and ex-partners per index patient tested for the relevant STI.

-

Number of main, casual and ex-partners testing positive for the relevant STI.

-

Number of current partners tested for a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection by 3 months.

-

Number of index patients tested for a HIV infection by 3 months.

-

Time to definitive treatment of index patient for the relevant STI.

-

Time to definitive treatment of current partner for the relevant STI.

-

Uptake by index patients of ‘contract’ and ‘provider’ referral for one or more partners, within the relevant randomised groups.

-

Patient-related factors impacting on PN or STI disclosure to main, casual and ex-partners.

Identification and recruitment of eligible individuals

Target population

The target population was as follows:

-

all 16- to 24-year-olds testing positive for chlamydia after chlamydia screening

-

all patients (aged ≥ 16 years) diagnosed with a curable STI following clinical presentation

-

all patients (aged ≥ 16 years) diagnosed elsewhere and attending the practice for antibiotic treatment.

Exclusion criteria

-

Any patient aged < 16 years.

-

Any patient unable to fully understand the trial information.

-

Any patient who required translation of trial information.

-

Any patient who required advocacy.

Setting

The setting of the trial was a diverse sample of primary care practices, both in specific localities [primary care research network (PCRN) practices in the South East region of England] and nationally [recruited via the Medical Research Council (MRC) General Practice Research Framework and the PCRN].

Patient and public involvement

A focus group of six sixth-form college students were consulted regarding their opinion on the participant information resources and recruitment methods. In addition, two University College London medical students who were members of the ‘Sexpression’ group (a network of student-led projects that teaches about relationships and sex education in local communities across the UK) agreed to sit on our Trial Steering Committee and advise on participant information resources and recruitment methods.

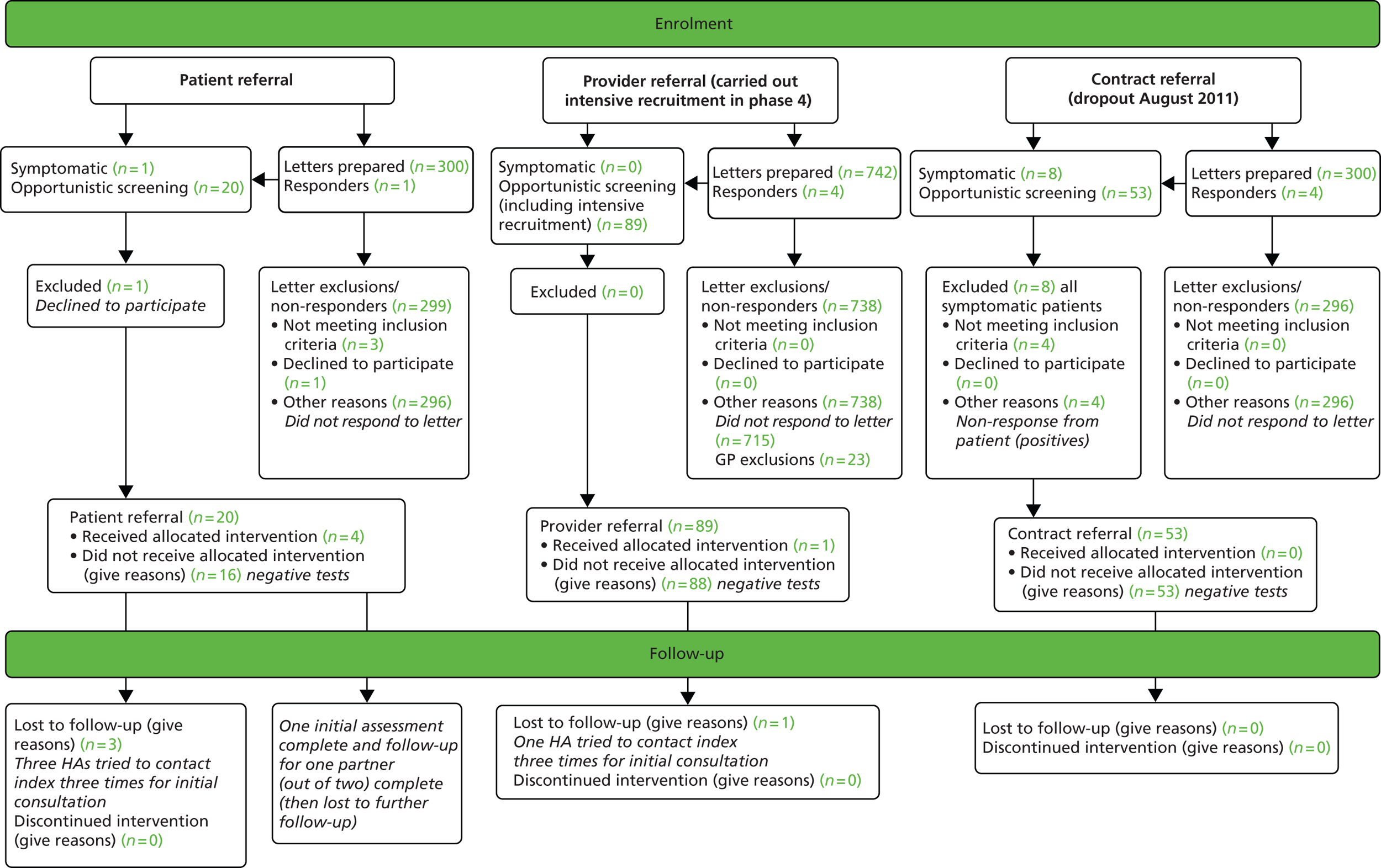

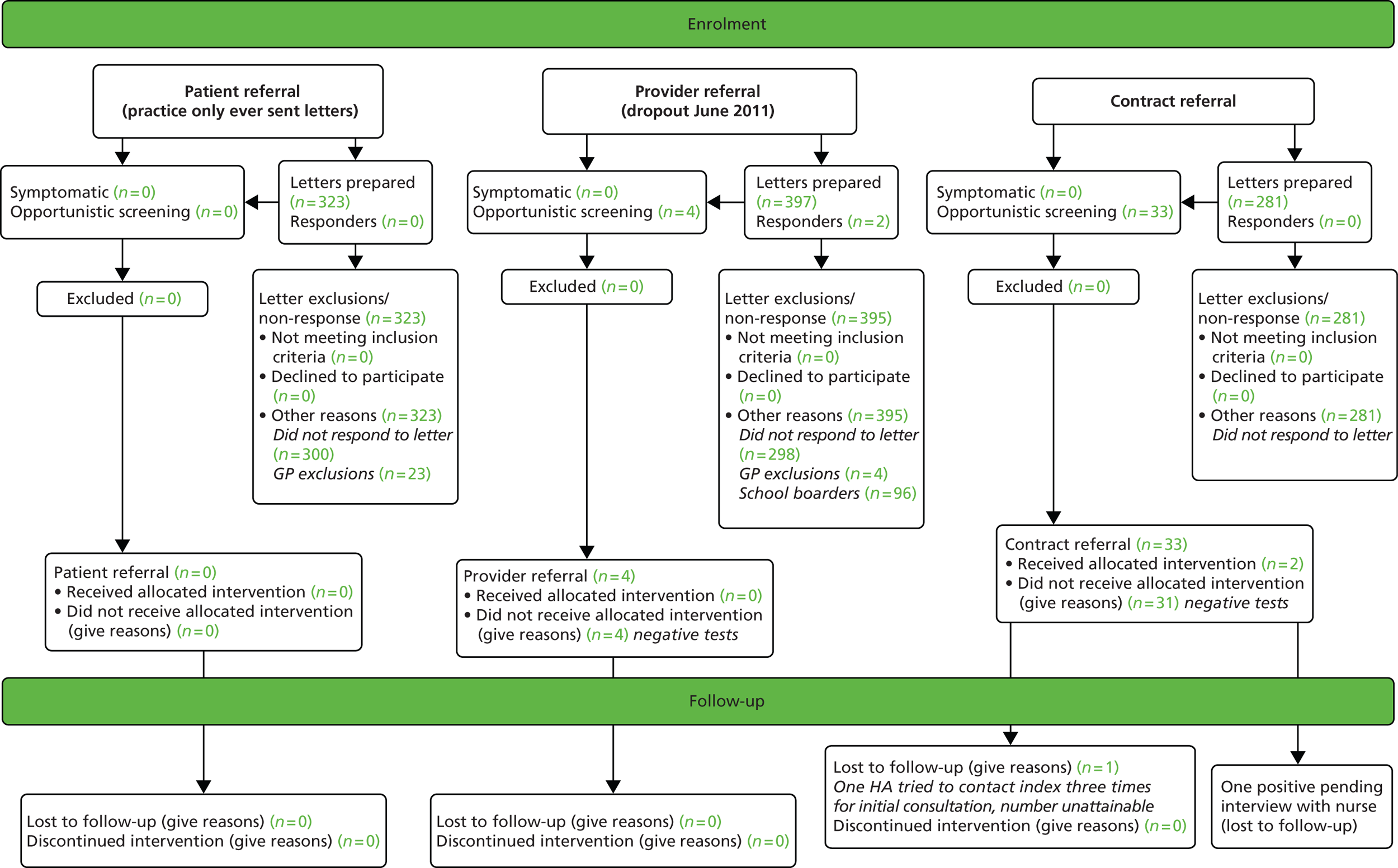

Approach to recruitment

Participants were to be recruited through letters of invitation, and personal invitation on attending the practice as follows:

-

Practices were asked to mail out letters to 300 randomly selected 16- to 24-year-olds at the beginning of the pilot (taken from the practice list), inviting them for a chlamydia test (as part of the NCSP). The invitation letter also mentioned the trial.

-

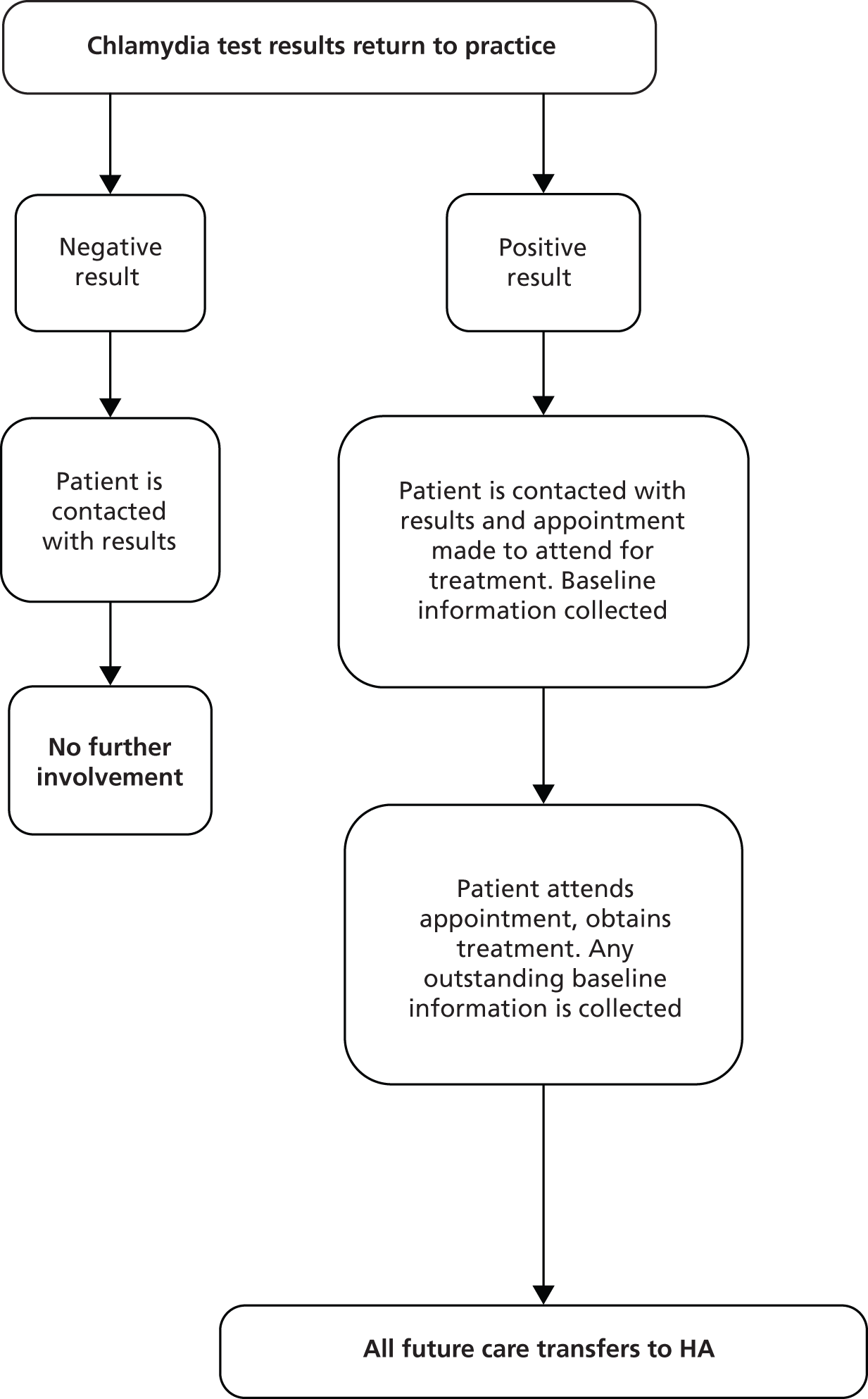

Clinical staff (usually practice nurses) approached potential participants, either (a) at the time of first attending the practice either with symptoms of a suspected or presumptive STI (symptomatic patients) or (b) at the time of chlamydia testing (asymptomatic patients, most of whom are tested as part of the NCSP) (Figure 2). The clinic staff were asked to explain that the practice was taking part in a study, as part of which additional assistance might be given to patients needing PN for a STI. It was explained that the practice had been randomly allocated to a group which would help either with providing care for STI patients up to the recommended national standard or with additional options for support. Patients were told the allocation of the practice. It was also explained that, should the patient be diagnosed with a STI, participation in the trial would mean, in all cases, that they would be contacted by an experienced HA. This HA would, depending on the trial allocation of the practice, assist them in their plans and actions to inform and obtain care for both current and ex-partners. Patients agreeing to be recruited at this stage provided personal contact details through which the study HA could communicate with them.

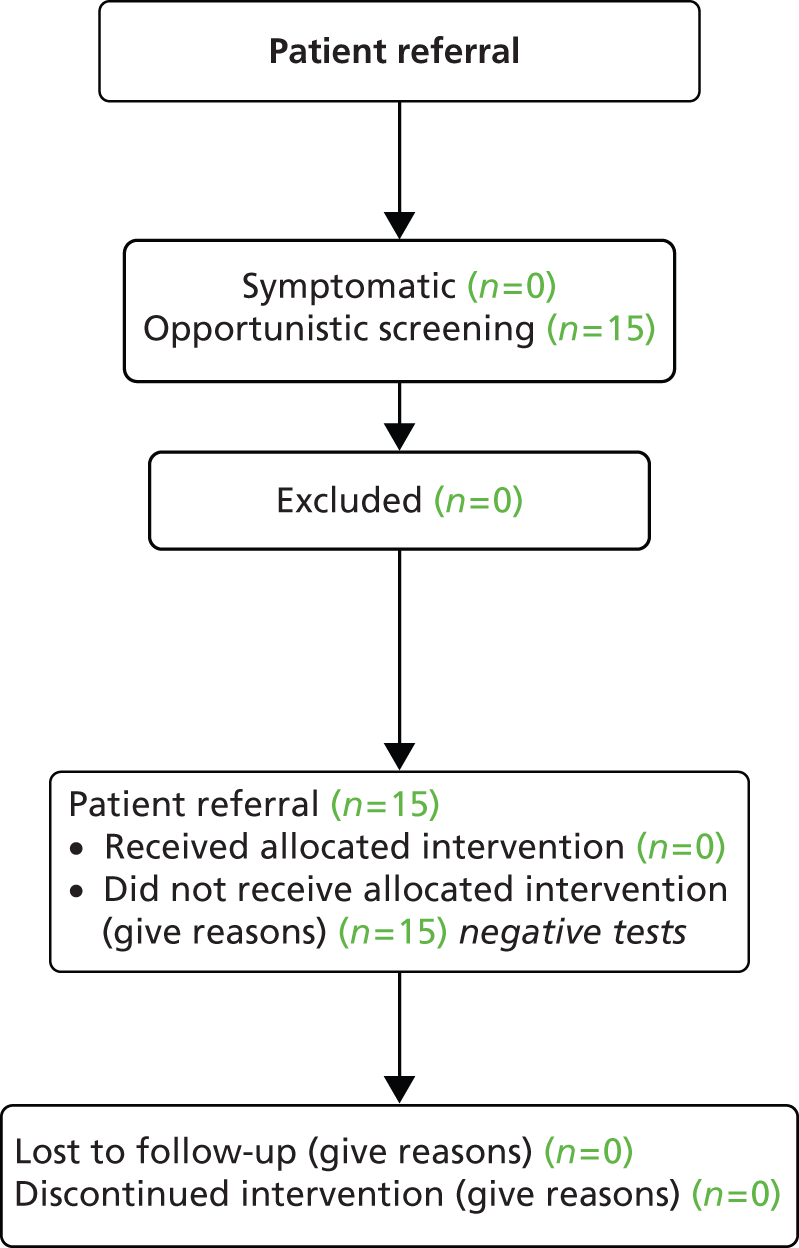

FIGURE 2.

Process of enrolling a participant.

Randomisation

Cluster randomisation at practice level was chosen for two reasons. First, there was a strong likelihood that clinical practice would be influenced by participation in the trial – with randomisation at patient level, practitioners who considered that ‘provider referral’ or ‘contract referral’ had advantages might more readily suggest that patients randomised to ‘patient referral’ attended a specialist clinic. Second, randomisation of patients who attend unpredictably in the middle of a busy surgery is more challenging than randomisation of patients with chronic disorders, while practice randomisation reduces this difficulty.

Consent at time of test versus consent at time of diagnosis

Two approaches to consent were piloted: consent at time of test (CAT) and consent at time of positive diagnosis (CAD). It was anticipated that CAD would reduce the workload for the health professional. However, a previous failed trial demonstrated the difficulty of achieving recruitment at the same time as a positive diagnosis is communicated to the patient. 32

We obtained written informed consent from all adults (aged ≥ 16 years). Where written informed consent was not possible (i.e. the patient had been tested for chlamydia, but no researcher was immediately available to take consent), consent was taken over the telephone soon after the patient had taken the test. In this case, potential participants were asked to agree to a researcher calling them to take consent. A ‘reason-for-test’ form included information on why patients were testing, whether or not they were interested in participating in the trial, contact information and signature (if they were happy for consent to be taken over the telephone).

Partner notification process

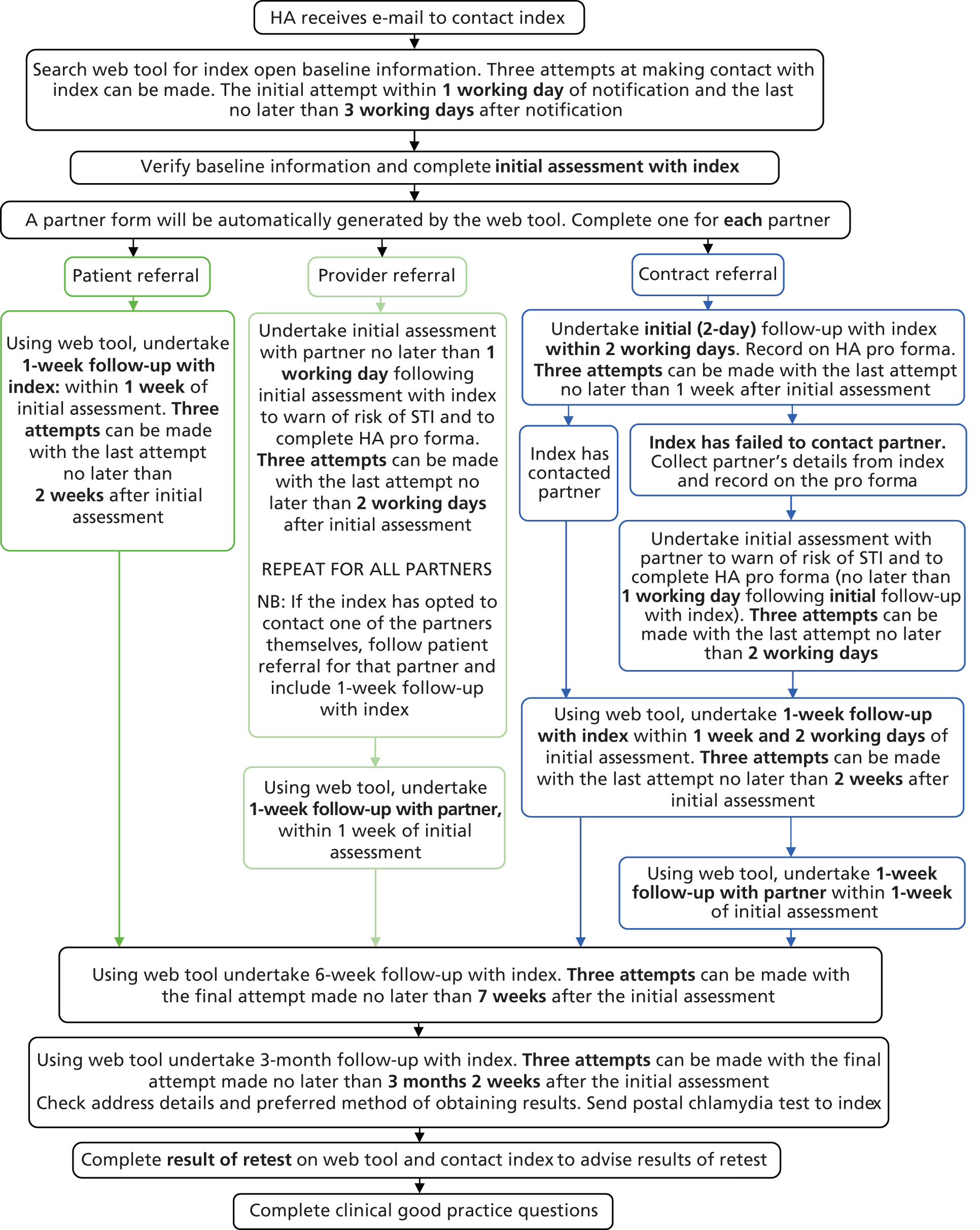

Following the diagnosis of a STI in general practice surgeries, patients were identified as in need of antibiotic treatment and PN (see Figure 1). The practice offered antibiotic treatment and basic information on STIs to the patient. Minimal clinical and contact data were then recorded on the web tool (see Chapter 8 for details). If the patient received a definite STI diagnosis, practice staff entered this information on the web tool, which automatically sent the research study HAs the basic contact information needed to contact and manage the patient, and information on the randomisation status of the practice (Figure 3). The HA then contacted the patient using their preferred means of contact (e.g. text, e-mail or mobile phone call). During the initial consultation the HA discussed PN with the patient and checked their treatment status. The patient was then followed up at 1 week, 6 weeks and 3 months for their PN outcome assessment (Box 1). The HA sent test kits for patients to be tested for reinfection at the 3-month period (testing with a NAAT). The patient then returned the tests to the HA based at Barts Health NHS Trust Sexual Health Services at The Royal London Hospital (Barts) for them to send to the laboratory, which subsequently returned the results to the HA (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3.

Initial management of infection and referral to HA.

HA records additional index details and baseline information for partner(s).

Additional assessment for provider/contract referral patients:

HA advises partner of contact with STI, and the need for testing and treatment.

Index can remain anonymous or be identifiable to partner.

1-week follow-upHA verifies via index: whether partner(s) have been notified, screened and treated.

Additional assessment for provider/contract referral patients:

HA verifies via partner(s): outcomes of partner(s) testing and treatment.

Targeted STI risk reduction with partner.

6-week follow-upHA verifies via index: adherence to treatment for both index and partner.

3-month follow-up (all arms)HA prompts index to test for reinfection using a self-taken postal chlamydia testing kit.

HA checks for additional STI/HIV screening and gives sexual health risk reduction information.

FIGURE 4.

Health adviser flow chart.

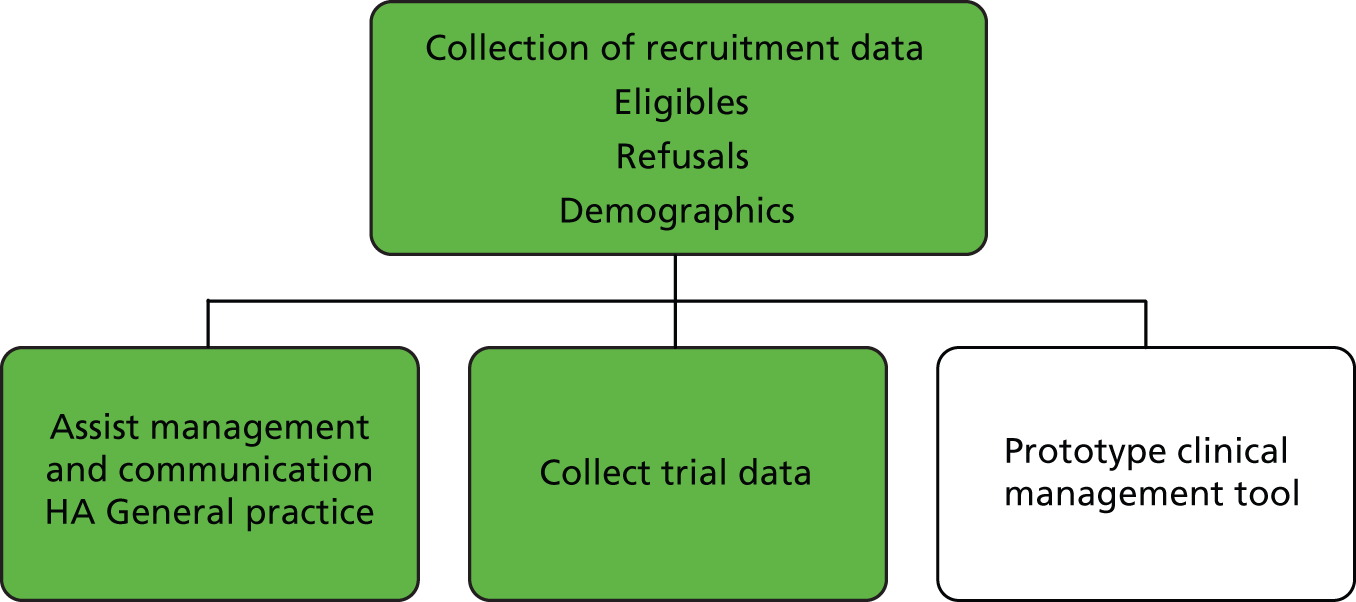

Development and implementation of a web tool for clinical referral and outcome measurements

A key aspect of the trial was the development of a web-based referral system, the ‘web tool’. This system enabled us to collect the recruitment and trial data and assist with the management and communication between the HA and general practice. It was also envisaged that this referral tool could be used in a number of settings where PN can be carried out remotely by a professional (Figure 5). We report further on the development of this system in Chapter 8.

FIGURE 5.

Web tool functions.

Data collection

There were a number of data collection points and Table 1 summarises the data captured from each stage of the research process. The data specification was adapted from the accelerated partner therapy (APT) trial specification in order to allow for direct comparison between trials. 33

| Study component | Purpose |

|---|---|

| Tests/diagnosis at practice | Test dates and results |

| Baseline data collected by nurse at practice | Additional information on patients diagnosed with a STI (treatment information and contact details) |

| Initial assessment by HA | Number of partners and individual partner details (can be anonymous) |

| 1-week follow-up with index or contact (by HA) | Partner tested/treated/diagnosed |

| 6-week follow-up with index (by HA) | Follow-up of partners, new partners, treatment adherence |

| 3-month follow-up with index (by HA) | Test for a HIV infection (index and current partner), details of previously undisclosed partners, test for reinfection |

Substudies

Three substudies were included in the PN programme to enhance the trial. We proposed to explore patient-related determinants of PN with a view to advising on targeting different approaches of PN. The economic evaluation proposed to determine the cost-effectiveness of alternative methods of PN, and the mathematical modelling study proposed to address the problem of the right skew in the number (and nature) of sexual partnerships.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: pilot of randomised controlled trial as originally planned

Introduction

As there was no existing or required commissioned pilot, we proposed to run a pilot before scaling up to a full-scale trial. The aim of the first phase of this research was to ascertain the feasibility and acceptability of the proposed trial. 34

Phase 1 was initially planned to run for 3 months but was extended to 4 months from November 2010 to February 2011. We also addressed emerging challenges in operationalising different approaches to PN, which are separately reported in Chapter 9.

We used an evaluation framework recommended by Thabane et al. 35 to assess the key elements of phase 1: process, resources, management and scientific assessment. Key performance indicators, results and actions are summarised in Table 2.

| Evaluation | Key assessment criteria | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Process: assessment of the feasibility and acceptability of the processes key to the success of the trial | ||

|

|

|

| Action | Investigate barriers to screening and establish new strategies to improve recruitment. Revise and improve trial materials | |

| Resources: assessment of the time and resource problems | ||

|

|

|

| Action | Investigate NCSP lab processes. Establish strategies for initial approach to patients to be made before appointment | |

| Management: assessment of potential human and data management problems | ||

|

|

|

| Action | Interrogate NCSP screening and diagnosis rates. Establish attendance rates of 16- to 24-year-olds. Use trial posters instead of NCSP posters Establish strategies to promote the trial to the wider practice team and improve practice engagement with the trial |

|

| Scientific: assessment of the intervention as intended | ||

|

|

|

| Action | Make a request to funders that the trial be reduced to two arms, and recalculate sample size accordingly Organise a dummy run of patients through the PN pathway |

|

Objectives of phase 1

-

To establish the current processes for chlamydia testing, treatment and PN in general practice.

-

To monitor the impact of recruiting at time of test versus time of diagnosis.

-

To assess the feasibility of our proposed approach to recruitment.

-

To monitor the numbers of eligible, tested, consented and diagnosed patients.

-

To assess any time and resource problems.

-

To assess potential human and data management problems.

-

To assess the intervention as intended.

Setting

Six pilot practices, accounting for approximately 10% of the sites required for the main trial, were recruited to take part in the pilot. These practices were identified through the MRC General Practice Research Framework register and PCRN South East as having a sufficient population of young people in the target population. Three practices were from the South East, one was from Yorkshire and Humberside, one was from the East Midlands and one was from the South West. The three practices piloting each approach were randomised to patient, provider and contract referral arms. In addition, two approaches to consent were piloted: CAT and CAD.

Target recruitment

Based on the original sample size calculations for the main trial we aimed to recruit 25 patients per year per practice. It was, therefore, estimated that it should be feasible to recruit 5–10 patients per practice over 3 months. This would require writing invitations to 300 patients in each practice. Each practice sent invitations to approximately 300 16- to 24-year-olds, who were selected at random from the practice register.

Patients were invited by letter to take a chlamydia test at the practice and the trial was mentioned in the invitation letter. Sixteen- to 24-year olds who were attending the practices for other reasons were to be invited to test opportunistically, as were patients who were aged ≥ 16 years who presented with a symptomatic STI or had been diagnosed elsewhere and were attending the practice for treatment.

Results of the evaluation

Process

Current process in practice

During the trial, practices were asked to ensure that all test results came back to the practice and that all results and treatment of patients diagnosed with a STI be dealt with by the practice. Before the trial started we established the practice’s current processes. The pre-trial testing and treatment procedures in the pilot practices were as follows:

-

Three practices offered in-house STI services ‘quite often’ and three practices offered them ‘occasionally’.

-

All the practices were registered as NCSP practices.

-

In five of the six practices the chlamydia test results went directly to the local NCSP CSO.

-

In five practices antibiotics for positive chlamydia patients aged 15–24 years were given by the local NCSP chlamydia co-ordinator.

-

One practice gave antibiotics directly to chlamydia patients diagnosed with a STI.

-

In five practices patients paid for their prescription if they were diagnosed with a STI or STI symptoms; in the other practice patients did not pay for this treatment.

Approaches to recruitment: letter versus opportunistic recruitment

The response to invitation letters was exceptionally poor, with only 11 out of 2218 of 16- to 24-year-olds having a test in response to the letter (0.5%). Nine tests were generated from CAD practices and two tests from CAT practices. Overall, during the 4-month period (November 2010 to February 2011) 30 tests were conducted in total (Table 3), 11 generated by letter and 19 through opportunistic recruitment in the six pilot practices. This amounted to less than two tests per month per practice.

| Recruitment data | Phase 1 |

|---|---|

| Dates (inclusive) | November 2010–February 2011 |

| Total number of chlamydia testsa | 31 |

| Number of positive chlamydia tests | 1 |

| Total number of active practicesb | 6 |

| Phase 1 practices activeb | 6 |

| Phase 3 practices activeb | – |

| Phase 4 practices activeb | – |

Feedback from practices showed that they had focused effort exclusively on sending out the letters and waiting for a response, and had not proactively approached 16- to 24-year-olds when they came into the surgery for another reason.

Approaches to consent: consent at test versus consent at diagnosis

Consent at test practices

All patients who took a chlamydia test were asked to take part in the trial and agreed (Table 4).

| Patient referral practice | Provider referral practice | Contract referral practice |

|---|---|---|

| No patients tested (this practice was unable to recruit patients opportunistically or symptomatically) | Two patients tested, results negative | Five patients tested, results negative |

Consent at diagnosis practices

Recruitment at the time of diagnosis was problematic (Table 5).

| Patient referral practice | Provider referral practice | Contract referral practice |

|---|---|---|

| One patient tested, result negative. One patient recruited when presented with a symptomatic STI | Five patients tested, results negative (an additional 440 letters, which were different from the trial letters, were sent to fulfil the practice's contract with NCSP) | 17 patients tested, all results negative. Six patients presented to the practice with a symptomatic STI, three were not eligible and three could not be contacted for consent |

Trial processes

Trial materials were reported by practice staff to be of a high standard and well designed and the trial name ‘Spread the Word’ was popular. However, using separate patient information leaflets and reason-for-test forms for opportunistic versus symptomatic patients was found confusing.

Practices reported that the NCSP testing and laboratory processes were different from the everyday process used in practice for general laboratory requests, and organising for NCSP results to be returned to the practice was time-consuming and not straightforward. In one practice this had demoralised the practice nurse to the extent that she did not want to continue in the trial.

Staff did not feel comfortable approaching patients to screen opportunistically and believed that patients would be embarrassed if they were asked to take a chlamydia test.

The web tool processes were straightforward and the web tool was considered to be simple and easy to use.

Partner notification pathway

One patient was diagnosed and consented into the trial. The HA initially spoke to the patient and was asked to call back; however, the HA was unable to make contact with this patient again.

Resources

Practices reported that the training session was well organised and training materials were comprehensive and easy to use. The web tool was felt to be simple and easy to use, and we did not experience any problems with incorrect data input from practices. However, staff did report that they often forgot to invite patients to screen and that there was insufficient time to approach patients during appointments, in addition to the reluctance described above.

Management

Five out of six practices reported very little interaction with the local NCSP staff and office. They were not aware of NCSP targets and there was some misapprehension that the trial team were part of the NCSP.

Practice nurses reported that it was difficult to engage their colleagues in the trial and to promote chlamydia screening throughout the practice and that often they were working alone. They reported that very few 16- to 24-year-old patients were seen in their practices, and that they did not see many chlamydia cases.

We were unable to assess the web tool as a PN management tool, as we did not have sufficient numbers of diagnosed patients to be managed through the pathway.

Scientific

In developing manuals in consultation with the HAs who would provide PN, it became apparent that it was hard to define a process of contract referral in a way that was clearly distinct from provider referral. HAs described their practice as a process of negotiation with the patient, leading towards the choice of a mode of PN.

Because insufficient numbers of patients were diagnosed with chlamydia we were unable to assess the PN pathway.

Summary

The small number of tests conducted coupled with the low positivity rate meant we did not have a sufficient number of patients diagnosed with a STI come through the trial to test all trial procedures.

It was agreed by the trial team and Trial Steering Committee that we needed to explore the barriers to testing and identify improved recruitment strategies in practice in order to boost recruitment if the trial was to be scaled up successfully.

Chapter 4 Phase 2: identifying improvements

Introduction

From our experience in phase 1 (see Chapter 1), it was evident that the major challenge we faced was to identify and implement effective means of increasing the number of STI cases diagnosed in each practice, in order to recruit an adequate number of patients into the trial.

Phase 2 of the pilot ran from March 2011 to June 2011. Our overall aim was to identify solutions to our recruitment challenges. We also addressed challenges in operationalising different approaches to PN, which are separately reported in Chapter 9.

The objectives for phase 2 were:

-

to undertake a review of literature relevant to improving uptake of chlamydia testing within general practice

-

to explore in detail existing chlamydia testing rates in general practice, with a view to optimising recruitment of additional practices

-

to explore the potential for use of incentives to boost recruitment

-

to interview primary care practice staff involved in phase 1 to identify barriers to recruitment, potential facilitators and challenges in managing the trial

-

to maintain and enhance recruitment in existing practices.

Literature review

Methods

Since our application for funding, the NCSP had moved on in its policy and practice. Given the degree of local variation in its implementation, we were keen to identify novel and effective approaches to increasing testing rates. We therefore undertook a literature review, aimed at identifying alternative approaches to increasing STI testing in general practice and generally optimising our approach to recruitment.

Based on our experiences in phase 1, the review focused particularly on interventions that could improve chlamydia testing/screening rates for young people up to 24 years old in general practice or similar settings; the use of incentives (for patients or health-care staff) to improve testing rates and/or recruitment in the field of sexual health; clinical pathways used to organise the testing of young people for STIs in general practice or similar settings; general practice staff experiences, behaviour and attitudes to STI testing; and the use of general practice by young people.

Three broad sources of evidence were reviewed, of which the findings are presented in Table 6. The review was targeted, but did not take the form of a formal systematic review.

First, we studied a review published in 2006, which summarised evidence for various elements of chlamydia screening and testing programmes relevant to the UK health system. 5 Second, we searched PubMed for peer-reviewed publications since 2005 on chlamydia testing and screening, using relevant search terms derived from the review in order to identify recently published settings. We reviewed full-text versions of original research relating to the UK and settings where general practice has a broadly similar role (e.g. Australia). Third, we reviewed policy documents, newsletters and conference abstracts focused on England, which described the implementation of chlamydia screening and testing in the general practice setting and included evaluation of effectiveness. The studies we identified are summarised in Table 6.

Findings

| Author | Chlamydia screening intervention | Conclusion | Relevance and implications for the PN trial |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al., 200636 | Opportunistic sampling of general practice surgery lists in Birmingham and Bristol, 16- to 24-year-olds. Postal invitation to collect urine or swab sample at home | Proactive postal screening may have more impact than opportunistic. Convenience and privacy of home sampling welcomed by those who did respond. Non-responders did not understand purpose, felt low personal risk (especially men), did not want responsibility | Perception of low risk and lack of awareness about infection are barriers. Find methods to increase awareness amongst target population, plus need for regular checks |

| Pimenta et al., 200325 | Women opportunistically invited in variety of health-care settings | Study may overestimate enthusiasm for home sampling. No examples of negative responses. Reported some dissatisfaction with being offered information leaflets by reception staff (too indiscreet). Respondents attending ‘sexually related services’ were most comfortable with offer | Focus attention towards approaches at clinics in general practice surgeries that are sexually related, e.g. contraception clinics Ensure opportunistic approaches are discreet |

| Santer et al., 200337 | Sampling at eight Edinburgh general practice surgeries. Women < 20 years having contraceptive consultations or pregnancy testing; women < 35 years having smear tests. Offered urine testing. Purposive sampling based on test result, age, reason for attendance | Age range 15–31 years Knowledge: women showed lack of awareness of chlamydia in general, and understanding that asymptomatic infections can cause problems. Experience of screening: all glad to have been screened; recognised risk of infertility, benefits of treatment; appreciated ease of testing; would advise friends to be tested; felt all sexually active women should be offered testing but given choice |

Raise awareness among both genders through information on asymptomatic nature and possible long-term risks in leaflet on chlamydia Ensure testing and study recruitment is a simple process Ensure patients are aware of the support available afterwards |

| Perkins et al., 200338 | General practice surgery staff, GUM and family planning clinics in Wirral and Portsmouth. Opportunistic of all women 16–24 years attending regardless of reason. Self-collected urine samples | HCP views of receptionists: waiting room inappropriate to offer leaflet; offer of test causes embarrassment and offence; too busy to offer to all women; problem of multiple offers of tests to same person Of GPs and nurses: impact on workload (extra 2–3 minutes on consultation if information leaflet already given, 10 minutes if not); reluctance to manage positive results in practice; problem targeting women only; remuneration important Conclusion: chlamydia screening in general practice should be by call–recall |

Education and feedback to practice staff on the nature of the study and screening benefit to younger patients Consider boosting opportunistic offers with research staff days Consider offers are made in private where possible Maintain regular feedback on progress and where practice is placed within league of screening practices in study Emphasise support available to all staff from research team during study Consider buying out some receptionist time to help target when reminders should pop up for relevant staff |

| Bilardi et al., 201041 | Cluster randomised trial testing the effect of a small financial incentive on chlamydia testing rates in Australian general practice | A small financial incentive did not increase testing. Staff described other barriers to testing | Financial incentives to GPs are unlikely alone to suffice to increase testing |

| McNulty et al., 201039 | HCW opportunistic screening invitation behaviour. High, medium and low screening practices invited to focus groups | In all screening programme areas the majority of practices screened fewer than 5% of 16- to 24-year-old patients Men tend not to be asked QOF measure for chlamydia screening would help with auditing offers made |

Support and pro-screening attitudes of practice staff as a whole team are essential in raising screening rates Willingness to approach patients regardless of reason for visit is essential |

| Walker et al., 201140 | Longitudinal strategies to maintain participants in study | Patients recruited by non-clinic staff in private. Every female in target age group approached in general practice surgeries. Small incentives, regular contact with research team and contact detail-checking helped sustain high level of engagement in 12-month study | Recruitment face-to-face in surgeries worked well Incentive to stay in the study to the end may be necessary for participants |

Potential for testing young people through postal and in-practice approaches

In a study of consultations by young adults in general practice, Salisbury et al. 42 compared opportunistic and systematic postal chlamydia screening methods using 27 general practice surgeries around Bristol and Birmingham, reporting on patients aged 16 to 24 years. They estimated that, on their own, each method (face-to-face through the general practice surgery when attending at least once over a 12-month period, or being sent a test kit via post) would fail to contact a substantial minority of the target group. Of nearly 13,000 eligible patients, an estimated 21% of patients would not attend their practice during the 12-month period but would be reached by postal screening, 9% would not receive a postal invitation (e.g. because the wrong address was held by their general practice surgery) but would attend their general practice surgery, and 11% would be missed by both methods.

Andersen et al. 43 compared in-home screening with usual care practices for chlamydial infection with nearly 30,500 21- to 23-year-olds in Aarhus County, Denmark, between October 1997 and February 1998. The authors had previously shown this age group to have the highest infection rates, of 23.7% (men aged 21 years) and 8.7% (women aged 22 years). Patients were randomly assigned to one of three groups. Group 1 (n = 4500) were sent a home sampling kit to their centrally registered home address; group 2 (n = 4500) were sent a reply card (pre-stamped and addressed to the study centre) to their home address with which a home sampling kit could be ordered; and group 3 (n = 21,439), as well as groups 1 and 2, had access to their usual care of swab sampling at their general practice surgery. The invitation contained a letter describing the outreach programme and a leaflet about the infection. The test was a urine capture for men, and a saline pipette vaginal flush for women, which were posted directly back to the test lab at Aarhus hospital (pre-paid postal packaging was included in the kit). Results could be sent to any address or their doctor. Although only 1.4% of men and 19.4% of women in the usual care-only control group received any test during the year, this was substantially increased by the two mailing options. For males, options 1 and 2 were equal, with overall coverage around 17%. In females, 39% in group 1 and 33% in group 2 received a test. Although in women an equal number of infections was detected in groups 1 and 2, among men more infections were detected when the kit was posted to them than when they were invited to request a test kit. 43 In all three arms, about 9% of women and only 0.5–1.4% of males received a conventional test in the practice.

Recruitment and retention of young people in sexual health intervention studies

A longitudinal investigation was conducted in Australia (CIRIS – Chlamydia Incidence and Reinfection Rates Study) by Walker et al. 40 to investigate retention in a chlamydia screening study in women between 16 and 25 years old recruited to primary health-care clinics. Follow-up was by post at 3-monthly intervals plus the return of questionnaires and self-collected vaginal swabs. To maximise retention, the team used recruiting staff who were independent of clinic staff, patients were recruited in private, patients regularly communicated with study staff and follow-up was made as easy as possible including incentives and small gifts to patients (of gift vouchers – AUS$10 voucher at 3 months, AUS$25 at 6 and 9 months, and AUS$50 at 12 months plus small gifts with each follow-up test kit, e.g. tampons, cosmetics, confectionery, as agreed by the local ethics committee) to maintain good will. At the start, information on the study was presented with STI information, some condoms and lubricant. Female research assistants were placed in each clinic for up to 6 months and approached every 16- to 25-year-old woman presenting for a consultation. They recruited 66% of eligible women, 79% of whom were retained to the end of the 12-month study. Sixty-six per cent of the total were recruited from general practice clinics.

Walker et al. 40 reported that loss to follow-up was associated with lower education level, recruitment from a sexual health centre rather than a general practice and previously testing positive for chlamydia. Other factors, including age and number of sexual partners, were not associated with loss to follow-up. They believe face-to-face recruitment was a strong factor in its success. Intensive communication strategies with patients through a variety of means and prompting for contact detail updates before sending out the next follow-up pack were associated with good retention in this and other studies (Atherton et al. , 2010, cited by Walker et al. 40).

The experiences, attitudes and behaviours of general practice staff

In a recent study, McNulty et al. 39 interviewed practice staff to explore attitudes and testing behaviours within the NCSP. The focus was on the opportunistic screening habits of practice staff with 16- to 24-year-olds who attended their practice for any reason. Twenty-five focus groups were held from late 2005 to early 2007, comprising 72 GPs, 46 nurses, 23 administrators and receptionists, eight practice managers and seven other staff. Interviews with two low-screening practices were conducted later.

The range of practice chlamydia screening rates was 0% to > 30%, and in all screening programme areas the majority of practices had screened fewer than 5% of their 16- to 24-year-old patients.

McNulty and colleagues found stark differences between staff attitudes to opportunistic screening for chlamydia in low- and high-screening practices. Low-screeners tended to have low belief in the success of screening in this way, and tended to only have a single champion within the practice. In contrast, high-screening practices’ staff held strong beliefs in the utility of opportunistic screening of the target group. All practices reported low numbers of offers to men and felt motivation would be increased with regular reminders at practice meetings, screening training and feedback to practices on successful detection rates from NCSP. In all practices, clinicians’ (GPs, nurses and health-care assistants) self-belief in raising the screening regardless of the patient’s reason for attending was a key factor to their frequency of approach. A whole-team positive view on the value of chlamydia screening was identified as being crucial to the practice’s screening rates. There was no Quality and Outcomes Framework measure associated with chlamydia screening, which also had the effect of decreasing the perceived priority of the NCSP’s campaign. Auditing of offers and acceptance rates is problematic whilst there is no Read code to record this information. The authors conclude that their results are likely to be generalisable across England, but raise the issue of a lack of short- and long-term intervention studies to assess whether or not the methods used by high-screening practices can transform attitudes about opportunistic screening and offers within the teams of low-screening practices.

The authors noted that high screening practices had:

-

a screening champion (not necessarily the GP)

-

normalised screening, so all at-risk patients were offered opportunistic screening whenever they attended

-

facilitated screening using a variety of time-saving methods including computer prompts, test kits in the reception area, youth clinics and receptionist involvement

-

sustained screening through frequent reminders to practices via newsletters from the CSO with feedback on their performance and those of their neighbours

-

advertised screening to the ‘at-risk’ population

-

undertaken training prior to registration as a screening site. 44

The guidance, during the time of our phase 1 pilot, on chlamydia screening to providers and commissioners from NCSP was:

that PCTs build their programmes around the existing core services of Reproductive and Sexual Health (RSH) Services, community pharmacy, general practice, and termination of pregnancy services – and then consider other measures to increase access and target specific ‘at risk’ groups such as websites, outreach etc. 45

Incentives for practices to test young people for chlamydia

In England’s pilot chlamydia screening studies, where general practice surgeries were paid to test, they achieved a 33% screening rate for women in the 16–24 years age group who were invited while attending their general practice surgery for any reason. An average of 80% of women in the 16–24 years age group accepted screening at their general practice surgery when asked, with acceptance lower in younger women. 25 In this first large-scale opportunistic chlamydia screening study in England, the research covered settings including general practice, family planning, GUM clinics, adolescent sexual health clinics, termination of pregnancy clinics and women’s services in hospitals (antenatal, colposcopy, gynaecology and infertility clinics) in two health authorities (Wirral, and Portsmouth and South East Hampshire). Pimenta et al. 25 also reported in this study that major factors influencing women’s decision to accept screening were the non-invasive nature of the urine test method and treatment, desire to protect future fertility and the experimental nature of the screening programme.

Investigators on the Australian Chlamydia Control Effectiveness Pilot (ACCEPt) research study, currently ongoing, explored in a pilot stage the use of incentives to GPs for opportunistic chlamydia testing of young women between 16 and 24 years. 41 Of 145 general practices approached, 12 practices were recruited and assigned to receive either a small payment (AUS$5) or no payment for testing a patient for chlamydia. Forty-five GPs participated between May 2008 and January 2009. GPs were advised to use first-pass urine, self-collected vaginal swabs or endocervical swabs. Practices were provided with screening posters and leaflets for waiting rooms, and a DVD of the education session for GPs unable to attend their training session. Chlamydia testing increased from 6.2% to 8.8% in the control group and from 11.5% to 13.4% in the intervention group, a non-significant increase. The GPs reported that the major barriers to increased chlamydia testing included lack of time, difficulty in remembering to offer a test and lack of patient awareness around testing. The authors believe the lack of test-rate feedback and payment made at the end of the 6-month period to the intervention group GPs were both limiting factors, as many GPs appeared to forget they were in a trial. They also believe the control group’s testing increase was partly due to the educational components of the study. They note there is insufficient research on the use of reminders and incentives to determine what an appropriate level is to raise screening rates by GPs (Professor J Hocking, Melbourne School of Population and Global Health, 2011, personal communication).

We also reviewed a recent example from a chlamydia screening programme which was local to one of the pilot practices (Jason May and Suzy Dion, Northamptonshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust, 2011, personal communication and unpublished report). This district had used incentives for GPs to encourage each practice to meet a 10% screening target, as recommended by the NCSP. For every month that a practice opportunistically screened 10% of their 16- to 24-year-old cohort, a £50 gift voucher was paid. We were advised that this had resulted in an increase in screening rates, although only 27% reached their 10% target at least once over the period, but we were not able to identify a formal evaluation.

Incentives

Expert advice from a marketing specialist

As a result of the literature review and poor uptake of testing in phase 1 of the trial, we felt we should explore the possibility of using incentives for the trial. In addition to the literature review summarised above, we spoke to a marketing specialist with substantial experience in running national campaigns, marketing and public relation projects. He suggested that we consider incentives for both the patients and practice staff as described in the sections following (Harvey Atkinson, University of Brighton Students’ Union, 2011, personal communication).

Patient incentives

We were advised that it was felt that for our target age group (16–24 years) we would need to have incentives and that those incentives would need to have an immediate gain for the individual. It was suggested that this could be an inexpensive incentive which could be reinforced by a substantial deferred reward, such as a raffle for an iPod. The marketing specialist also speculated that this age group might be more likely to engage if approached by someone of their own age group, by using volunteers to approach individuals.

Practice incentives

For the practice, incentives could be given to the group and/or the individual. For individual incentives, the team would need to ascertain how each individual could be motivated. The motivations of the reception staff, for example, might be different from the motivation of nurses. It was suggested that there needed to be a practice champion who would act as the change agent and have ownership of the study. The team would need to consider by whom the different staff types are influenced, and whoever this is would need to deliver the message of why screening is important. The marketing specialist also emphasised that screening needed to be embedded into practice behaviour, making it normal practice, and that all parties needed to be engaged.

For group incentives at practice level, a deferred reward must be attractive to all involved (there should be a consensus amongst the group). It was suggested that it could be beneficial for the team to attend a practice meeting, along with the contraception and sexual health nurse and local chlamydia screening officers. This meeting would include explaining why screening is so important, clearly stating how much money can be earned by improving screening numbers and what the incentives are for individuals at the practice.

It was recommended that an outline for a poster could be provided to the practice for the practice manager to tailor to practice requirements. Furthermore, weekly and/or monthly updates should be sent to the practice on screening rates and highlighting numbers screened. It was proposed that competitions could be set up between practices (e.g. practice of the month), encouraging increased testing.

The marketing specialist suggested we discover what works best for the practice and give them various options for running the screening, allowing them to tailor the screening process to fit in with their own procedures (e.g. manual or electronic check-in system).

Survey of young people

We also conducted a short survey over a 2-week period by snowball recruitment using a social networking site, members of a youth group, and members of a sexual health-oriented group (Sexpression) to explore incentives for young people. A short questionnaire, consisting of nine questions, was posted online for young people aged 16–24 years to access and respond to anonymously (a hard copy was also made available).

One hundred and seventy-three young people took part, the majority of whom were in full-time education (74%, n = 128). Twenty per cent were not in any form of education or training (n = 34) and 6% were in part-time education (n = 11).

A large majority of respondents (83%, n = 144) said that they would take a chlamydia test if a doctor or nurse asked them to during a routine appointment. This was more than those who said they would if the receptionist asked them to test (61%, n = 105) or if self-test kits were available in the reception (66%, n = 115). Of the 17% (n = 29) who would not take a test, 38% (n = 11) said they would change their mind if offered an incentive. One participant who would not take the test or take part in the study was concerned that sexual health issues would appear on their medical record and they also expressed concern that ‘you don’t get paid to see a doctor so why get paid for this?’ This response demonstrated potential barriers to using incentives.

We asked all participants which incentives would make them more likely to take a test and participate in the study. One hundred and seventy-one participants replied to this question, of whom 42% (n = 72) said that incentives would not make a difference. Of the remaining 99 participants, 88 (89%) said that a cash incentive would make them more likely to take a chlamydia test and be part of a study, 64 (65%) said that shopping vouchers would, and only 13 (13%) said that mobile phone credits would make a difference to their participation (respondents were able to select more than one option).

When asked the lowest value of incentive that would make them more likely to participate, 39% (n = 58) of 172 participants still responded that no amount would make a difference, although this was less than for the previous question. A £5 incentive was the most popular option among those who said that an incentive would make them more likely to participate, with 34% of participants choosing this response (n = 58). Seventeen per cent of participants replied that £10 would be the minimum they would accept (n = 29), 6% (n = 11) chose £2, and 4% chose £1 (n = 7). The majority of respondents (76% of 167, n = 127) stated that they would prefer all participants to receive the same incentive, rather than a small incentive to take part and the chance to win a much larger prize (lottery incentives).

In conclusion, over 40% of the sample stated that incentives would not make a difference to their decision whether or not to participate in the study, and more than 80% of respondents would participate if asked by their doctor or nurse. This suggests that incentives for patients may not be an effective way to boost testing and recruitment. It should be noted, however, that this group included a high percentage of students still in full-time education, which may have biased the results, as they may not be representative of all 16- to 24-year-olds.

Practice staff experiences and views on barriers and attitudes to recruitment

Practice interviews

During phase 2 of the pilot, members of the trial team visited every practice in the pilot to establish the practice staff’s experiences and views on barriers and attitudes to recruitment. The practice staff found the trial materials and web tool easy to use. However, there appeared to be a number of myths held by the practice staff which affected their ability to test for chlamydia. Most stated that they saw very few young people in their practice, and it was generally believed that chlamydia was not prevalent in their area. There also appeared to be no systematic way of identifying potential participants within the practice and some staff were unclear about the best way to approach young people to test for chlamydia and enter the trial.

Staff also reported having no time to recruit patients, and communication difficulties in approaching patients to test for chlamydia when they were attending for a completely different health matter.

Treatment issues

How patients diagnosed with a STI received their treatment varied considerably by practice and proved to be an additional barrier to the trial. The practices were told that they needed to have a structure in place to administer the treatment, either managing this under a Patient Group Direction/Patient Specific Direction (PGD/PSD) or using their normal processes. The drugs required for treatment had to be obtained through a suitable supply chain. It was agreed that the practices should be referred to a guideline established by the study team and should manage this process themselves. Treatment was administered via the practice, through the NCSP or via prescription.

Testing in practice and lab processes

It was also highlighted during the practice interviews that there was confusion over the laboratory processes. All practices were part of the NCSP and in the majority of practices’ results were previously being sent directly to the local CSO rather than coming back to the practice. However, during the time of the trial all test results were required to come back to the practice in order for patients diagnosed with a STI to be managed under the trial. As many practices were using the NCSP kits, we provided them with labels to place on the NCSP laboratory forms to redirect back to the practice, rather than on to the local CSO (the local CSO was made aware of this process). Test results requested on normal laboratory forms came back to the practice as normal. A system also had to be put in place for each practice to ensure that the research nurse received all the test results, since tests could be conducted by other members of the clinical team due to NCSP using a different laboratory from practice tests.

In some areas there was concern over who paid for the laboratory tests. We discovered that most PCTs had block contracts with laboratories covering a number of diagnostic tests (not just chlamydia). Some PCTs, however, used block contracts for NCSP tests or the CSOs negotiated separate contracts with the laboratories depending on their arrangements. This variation was an additional hurdle when setting up the practices.

Regional training nurse focus group

The research co-ordinator also ran a focus group with the General Practice Research Framework’s regional training nurses (RTNs) to discuss their views on the trial and recruitment. The key findings were that the RTNs also believed the myths (that people would not want to test and young people do not attend the practice). They were confused over the NCSP and how this could run in parallel with the trial. They also suggested asking young people what would encourage them to test.

Implications

Results of this focus group and the practice interviews suggested that the myths in practice needed to be addressed, that the NCSP involvement be clarified, that a systematic way to identify patients be established in each practice in the most effective and time-efficient way and that staff were clear on the best way to approach young people to screen and invite them into the trial.

Maintaining and enhancing ongoing recruitment

Recruitment report

This study had been funded on the assumption that a large number of chlamydia tests would be taken within general practice, in accordance with national data showing a large and growing proportion of all chlamydia tests taking place in this setting. However, the low number of tests we were experiencing was surprising. We therefore collaborated with the Health Protection Agency (HPA) to explore the distribution of chlamydia testing within practices in more detail, since these data were not publicly available.

The Chlamydia Vital Signs Indicator 2010/11 measures the proportion of the 15- to 24-year-old total population tested for chlamydia outside GUM clinics. The target set by the Department of Health was 35% for testing undertaken during the period 1 April 2010 to 31 March 2011. Data for monitoring the vital signs indicator are based on NCSP data returns and testing outside GUM not reported to the NCSP. In 2010–11, 25.2% of the population aged 15–24 years were tested for chlamydia (1,733,220 tests) based on data reported to the NCSP. 46

Data received from the NCSP reported 6319 participating NCSP practices across England, of which around one-third (n = 2895) registered no positive chlamydia test results between April and December 2010. The range of tests performed by these practices over this period was 1–176, with a mean of nine tests per practice. Only eight practices performed between 332 and 2336 tests, averaging 797, and obtained over 30 positive results.

This indicates that there were very few NCSP practices testing for chlamydia at the rate the trial required to conduct the planned study (Table 7). Positivity varied little by practice, and stood at 6% at the time of the study.

| Number of positive tests | Number of practices | Average number of tests (range) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2895 | 9 (1–176) |

| 1–5 | 3128 | 38 (1–474) |

| 6–10 | 236 | 102 (18–200) |

| 11–20 | 43 | 191 (52–1118) |

| 21–30 | 9 | 360 (172–1175) |

| > 30 | 8 | 797 (332–2336) |

What are the general practice consultation rates of young people?

Table 8 reports data from a QRESEARCH® (University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK) report showing the patient consultation rates with GPs and nurses of 15- to 19-year-olds and 20- to 24-year-olds over the period 1998–2009 in England. 47

| Incidence of consultations in general practice per registered person per year (2008/9) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Age (years) | Incidence |

| Male | 15–19 | 2.2 |

| 20–24 | 2.2 | |

| Female | 15–19 | 4.2 |

| 20–24 | 5.6 | |

Although measures of dispersion are not given in this report, the data indicate that a substantial majority of people within the 15–24 years age group are visiting their registered practice for a GP or nurse appointment at least once per year.

Summary of findings relevant to improving testing rates and recruitment through modification of our processes

Despite a wide range of innovative approaches in the NCSP, including incentives both for young people and for staff, we had identified little robust evaluation that could reliably inform our strategies to improve recruitment.

However, recently emerging peer-reviewed literature suggested that addressing practice organisation and culture could be useful. A team approach to recruitment, along with an identified ‘champion’ within a practice, appeared to be important, and a good understanding across all staff of the benefits of chlamydia testing appeared to be key. Newsletters and feedback on practice-level performance were also seen to be helpful and relevant to our study.

Embarrassment of practice staff about offering a chlamydia test in an unrelated consultation was consistently reported to be a challenge, and emerged in our practice interviews as a barrier. The peer-reviewed literature emphasised the need to normalise the offer of testing, an approach which was likely to be best addressed through training and a whole-practice approach. Published research reported that widespread advertising of chlamydia testing as a standard offer within the practice through posters and leaflets was widely used in practices with high testing rates. It also suggested that a highly organised and strategic approach using computer prompts and similar aides-memoires was necessary to identify young people. We concluded that it would be helpful to support practices in developing focused plans aimed at approaching, offering tests to and recruiting young people to the study (the latter particularly in ‘consent at test’ practices). We also planned to use newsletters and feedback on testing rates more proactively as a way of improving engagement.

The peer-reviewed literature (notably from the CLaSS study) suggested that mailed offers of chlamydia testing kits could yield uptake of up to a third of young people. However, in studies using this approach, the patient’s first encounter with the general practice was at the time of treatment. Our approach of inviting young people by letter, and additionally asking the practice to undertake opportunistic testing, had not yielded useful numbers of people attending the practice in order to have a test. Moreover, it seemed to have encouraged practices to ‘take their eye off the ball’ in taking advantage of young people’s attendance as an opportunity to test. Our commission was to evaluate different approaches to PN within primary care (taken to mean general practice for the purposes of this study), and we also noted that the current direction of Department of Health policy was to encourage chlamydia testing within general practice, as the major complement to sexual health settings. We therefore concluded that in order to focus the intervention on primary care we needed to focus wholly on the opportunistic approach which had been successful in the initial English pilots of chlamydia testing. 25,48

Our practice interviews were consonant with the peer-reviewed literature on barriers to testing. However, we identified three myths which emerged in many interviews and which were discouraging primary care staff from enthusiastic or strategic approaches to opportunistic testing. First, there was a widespread belief that very few young people attended the practice; second, it was generally thought that, even if common nationally, chlamydia was not common in their area; and, finally, many staff believed that young people would be unwilling to test in a practice setting. These findings suggested that we could use high-quality data from a number of domains to address these beliefs. The high-quality data on attendance rates in general practice that we consulted suggest that attendance – particularly of young men – is much higher than generally thought, while epidemiological data show that variation in chlamydia prevalence by geography is much lower than in many other STIs. Previous studies show high levels of acceptability for testing despite the initial concerns of staff. We concluded that active information campaigns could be used to counter these myths within participating practices.

The question of incentivisation was complex and challenging. Our opportunities for personal incentivisation of practice staff were limited by the internal structures of each practice, regulations on use of our research funding, and NHS research ethics approvals (including their likely view of any proposal to incentivise staff either for testing or for recruitment). This is likely to explain the paucity of evaluations of staff incentivisation. We did identify one NCSP location where vouchers had been offered to staff, but the evaluation was not sufficiently robust to ascribe effect to cause. On balance, we felt we were not in a position to offer direct staff recruitment. Nevertheless, we were able to pay NHS service support costs that fully covered research-related staff costs (including initial testing), and it was not clear to us how or whether the information on this practice-level incentive was being used. This had potential for improving practice engagement, through a ‘top-down’ approach, and we concluded that information on potential income ‘lost’ should be reported to practices in order to encourage effective planning for chlamydia testing.