Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/109/04. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Linda Davies provided expert consultancy advice to the Home Office funded by grants to the University of Manchester (Drug Data Warehouse; planned evaluation of drug strategy).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Hayhurst et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Class A drugs

A range of drugs is included in the category of class A substances, which is a legal classification under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. 1 The Act identifies three classes of drugs (A, B and C). Those designated as class A carry the most severe legal penalties for possession or supply. Class A comprises a heterogeneous group of drugs, including (but not limited to):

-

powder cocaine

-

crack cocaine

-

ecstasy

-

LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide)

-

psilocybin

-

heroin

-

methadone.

Some of these (e.g. powder cocaine, ecstasy, LSD and psilocybin) are more commonly associated with a pattern of recreational use. Heroin, methadone and crack cocaine are more commonly associated with chronic and dependent use.

Prevalence of class A drug use

The Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW)2 provides estimates of the ‘past year’ prevalence of class A drug use. The CSEW is a survey of approximately 50,000 households in England and Wales. Estimates derived from the CSEW (2012/13) suggest that a total of 846,000 [95% confidence interval (CI) 763,000 to 930,000] individuals aged 16–59 years had consumed a class A drug in the previous year. Individuals who had used drugs such as powder cocaine (627,000 individuals, 95% CI 555,000 to 699,000 individuals); ecstasy (415,000 individuals, 95% CI 357,000 to 474,000 individuals); amphetamines (211,000 individuals, 95% CI 169,000 to 253,000 individuals) and hallucinogens (121,000 individuals 95% CI 90,000 to 153,000 individuals) accounted for the majority of drug use. The CSEW 2012/13 estimates the prevalence of opiate use as 38,000 individuals (95% CI 20,000 to 56,000 individuals) and crack use as 47,000 individuals (95% CI 27,000 to 67,000 individuals), in England and Wales. These estimates for use of opiates or crack cocaine are much lower than the 164,671 opiate and/or crack users known to have received treatment for substance misuse in England during 2011–12. 3 Surveys are unlikely to capture those marginal populations at high risk of dependent use of opiates/crack adequately, such as prisoners or the homeless. Estimates of the prevalence of opiate and/or crack cocaine use based on indirect estimation methods, not subject to the same biases as survey approaches, suggest that there were 298,752 (95% CI 294,858 to 307,225) opiate and/or crack cocaine users aged 15–64 years in England during 2010/11. 4 Combining the mid-point estimate with treatment figures suggests that around 58% of the opiate- and/or crack-using population were in receipt of drug treatment services during 2010–11. This proportion is higher than that estimated for most other European countries and comparable with that seen in Australia and the USA. 5 The use of crack or cocaine nationally increased from approximately 14% of treated drug users at the time of the National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS) in 19966 to at least 40% in 2010/11. 7 The largest proportion were treated crack users (72,000 treated crack users, with < 10,000 treated cocaine users).

There is considerable debate concerning the precise nature of the relationship between drug use and criminal behaviour. Regular, recent use of opiate drugs and/or crack cocaine is very common among UK samples of arrestees. Use is at rates that are very much greater than prevalence rates in the general population. 8 The bulk of those arrestees consider that they are dependent on these drugs. 9 Experience of class A drug use is also considerably higher among the prison, than the general, population. Across European countries, prisoners have a lifetime prevalence of 6–53% for cocaine use and 15–39% for heroin use. This compares with 0.3–10% and < 1%, respectively, in the general population. 10

Although the prevalence of other types of class A drug misuse is much greater, it is estimated that opiate and/or crack users account for 99% of the social and economic costs associated with class A drug use. 11 Opiate and/or crack users are the group primarily served by substance misuse treatment services. In the UK, they are the main focus of criminal justice system (CJS) diversion initiatives for drug misusers. Hence, it is the primary focus of the work described in this report.

Class A drug use and crime

Criminal justice system referral is an increasingly important route through which drug users access the treatment system. In 2010/11, 30% of clients starting new treatment journeys did so via a CJS referral. The Drug Interventions Programme (DIP) referrals accounted for 14% of referrals overall. 7 Nevertheless, arrest referral services were argued by some to do little to introduce ‘hidden’ client groups to treatment opportunities. 12 Offenders who misuse drugs often have more serious drug problems than the general population of drug users and they are potentially less responsive to treatment. 12–15

The pattern of offending differs somewhat between drug users and non-drug users. Samples of arrestees in England and Wales indicate that, for example, assault accounts for 29% of arrests yet just 4% of these were individuals reporting at least weekly use of heroin and/or crack. Conversely, shoplifting accounted for 10% of arrests yet 45% of these were problem drug users. 16,17 Indeed it has been estimated that over half of all such recorded acquisitive crime in the UK is drug related, motivated by the need to obtain income for drugs, rather than violence associated with pharmacological effects or drug markets. 18,19 However, the literature suggests a more complex association between drug misuse and acquisitive offending than a simple causal relationship. 20–23 Not all drug users commit acquisitive offences. Acquisitive crime often pre-dates problem drug use. 15,24 Drug use and criminality may develop in parallel,25 perhaps via a third factor such as socioeconomic deprivation. 23 The Drug Treatment Outcomes Research Study (DTORS)26 evaluation found that behavioural and demographic factors were stronger predictors of involvement in acquisitive crime than drug use expenditure. This suggests that the need to finance drug use is not necessarily the main factor driving acquisitive offending by drug users. 27

Use of cocaine, in particular crack cocaine, has been linked to acquisitive crime. In the Research Outcome Study in Ireland (ROSIE),28 people using cocaine/crack were more likely to report criminal activity than those not taking cocaine or crack. 29 In NTORS, predictors of acquisitive offending included regular use of cocaine (powder and/or crack). 15 Age may also predict criminal involvement: two-thirds of a 2009 class A drug-using offender cohort were aged < 35 years and arrestee surveys highlight the likelihood of acquisitive crime declining with increasing age among drug users. 16,30 Polysubstance-using offenders commit twice as many offences as those not reporting multiple drug use. 31 High levels of polydrug use are recorded among drug-using arrestees. 16

Policy context

The UK policy focus on reducing drug-related crime first emerged during the 1990s, most visibly with the publication of a series of reports by the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD). These considered responses to drug misuse within the CJS and highlighted the prevalence of class A drug misuse, particularly opiate use, among acquisitive offenders. 32

The issue gained political prominence in 1994 with the Labour Party stating, while in opposition, that a half of the £4B cost of recorded theft was attributable to drug misuse. This contrasted with the government estimate of between £58M and £864M for the cost of heroin-related acquisitive crime in England and Wales. 33 A subsequent, and independent, estimate suggests that the wider social and economic costs of problematic class A drug use in England and Wales was £12B (range £10.1B–17.4B) during 2000. Drug-related crime accounted for approximately 88% of that total. 34

Notwithstanding the accuracy of the above estimates, there was concern about the social consequences of problem drug use, particularly drug-related crime. This culminated in a strong emphasis on the potential for effective treatment to contain or reduce these consequences. The ACMD highlighted that,

. . . there is now an onus on these [drug treatment] agencies to take a broader view and develop their focus to incorporate community safety as well as care of the individual drug misuser.

ACMD32

The contemporary government drug strategy included the objective to, ‘reduce the incidence of drug-related crime’. 35 Although focusing primarily on law enforcement, the strategy recommended diversion of arrested drug misusers into treatment. A later review of drug misuse services36 concluded that contact with the CJS provided opportunities to engage problem drug users with treatment. In addition, the need to safeguard communities was reaffirmed within the subsequent government strategy for tackling drug misuse, which included the aim ‘to protect our communities from drug-related antisocial and criminal behaviour’. 37

In the latest government drug strategy document,38 covering England and Wales, CJS diversionary schemes continue to be a focus of contact with drug users. The coalition government expresses its desire to ‘. . . ensure that offenders are encouraged to seek treatment and recovery at every opportunity in their contact with the CJS’. 38 The 2010 strategy identified the importance of early intervention for young people and families to help those who may be at risk of involvement in crime and antisocial behaviour.

Current service provision

Drug treatment and rehabilitation services are commissioned and provided in four tiers. Tier 1 relates to primary-care services. Tier 2 provides open-access and non-structured drug treatment services; information, advice and harm-reduction services; screening for drug misuse and referral to specialist drugs services. Tier 3 provides structured community-based drug treatment and rehabilitation services. Services in tier 4 provide residential drug treatment and rehabilitation, aimed at individuals with a high level of presenting need. Tier 3 and 4 services account for around 70% of total drug treatment costs.

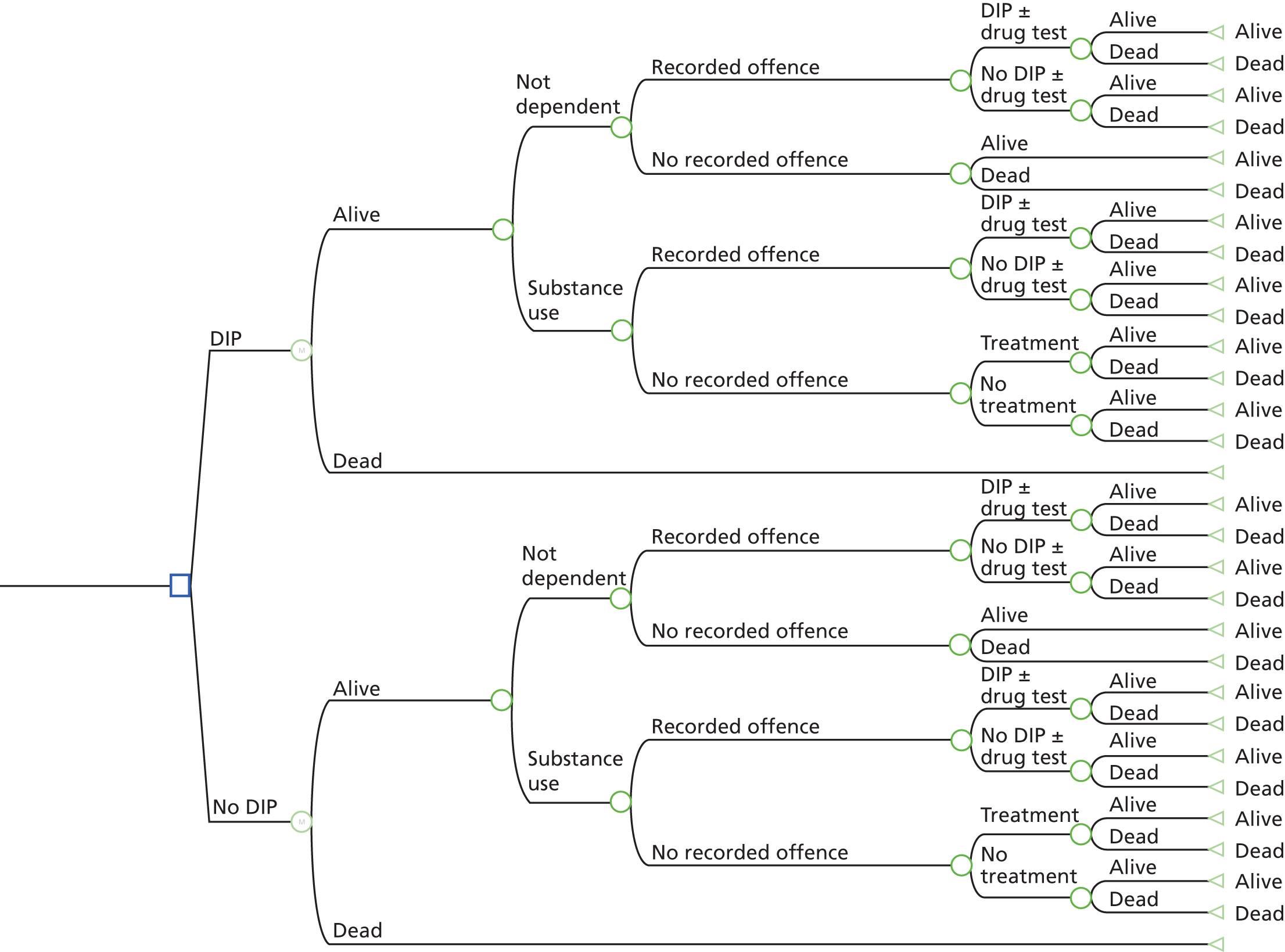

Following the introduction of arrest referral schemes14 the national DIP was introduced in 2003. DIP aimed to identify and work with drug-misusing offenders at each stage of their contact with the CJS from the custody suite through to community The core remit of DIP is to address drug misuse and offending to help individuals ‘get out of crime and into treatment and other support’. 39 The programme includes both custodial and community components, with voluntary and coercive elements. The bulk of provision, in terms of its diversionary component, centres on identification and appropriate treatment referral of drug-misusing offenders at the point of arrest or charge. Although the programme has evolved at various stages, its key components include:

-

identification of drug-misusing offenders – including, in some areas, drug testing (for opiate and cocaine metabolites) at the point of arrest (initially charge) for specific, acquisitive, ‘trigger’ offences (see Appendix 1) or at the discretion of a senior police officer

-

comprehensive and standard assessment of treatment and other support needs – assessment by a referral worker who is ‘embedded’ in the custody setting, latterly (from 2007), with new police powers for adults who test positive for drugs to be required to attend an assessment

-

case management designed to help break the (presumed) cycle of drugs and offending.

Rationale for this study

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme’s call for research in this field concluded that:

The evidence bases on effectiveness of diversion and aftercare are limited, with methodological problems and inconsistent costing methodology. The ways these two interventions are delivered remain poorly understood, with particularly limited evidence on aftercare. High quality research is required to determine effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such strategies.

NIHR HTA40

The DIP is the mainstay of CJS diversion for drug misusers in the UK. During 2012/13 central funding for DIP exceeded £91M. To set this figure in context, the economic and social costs of class A drug use for England and Wales in 2003/4 were estimated at £15B11 and the UK government’s Serious Organised Crime Agency currently estimates that drug trafficking to the UK costs £17.6B per year. 41

A number of previous studies suggest that drug treatment impacts favourably on reducing levels of offending. 34,42,43 Evaluation of DIP indicates that levels of offending are reduced following contact with the programme,44 although the evidence for this is weak.

The US Drug Abuse Treatment Outcome Study45 highlighted decreased crime costs following drug treatment in both residential and outpatient settings. 46 Drug treatment in ROSIE28 was associated with a significant decrease in acquisitive offending29 and 1-year follow-up in the UK NTORS observed a two-third reduction in the level of acquisitive offences compared with baseline. 47 A further UK analysis based on linking treatment data from the National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS) with the Police National Computer (PNC) points to levels of recorded offending falling after the initiation of substitute prescribing. 48 Although this study is subject to some ascertainment bias, the reduction in recorded offending was greatest in those with the longest period of substitute prescribing treatment.

Interviews with service providers in DTORS identified possible positive and negative impacts from increases in referrals from the CJS. Concern was expressed about the effectiveness of treatment if CJS referred clients demonstrated lower levels of motivation. 49 However, the same study found that referral through the CJS did not seem to impact on levels of motivation. 49 This supported findings from the quantitative component of DTORS, that CJS referral was not negatively associated with levels of motivation. 50

A number of evaluations of diversion schemes in the US conclude that there may be cost savings from the identification, assessment and referral of offenders into drug treatment services. 51–53 However, none of these studies provides a full economic evaluation and are primarily cost analyses. A systematic review concluded that there was uncertainty about the costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions for drug-using offenders. 54,55 Furthermore, the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of diversion schemes to identify and refer offenders who misuse drugs for treatment is unclear.

The use of the CJS as a means of referral into drug treatment has frequently been examined as a predictor of treatment success. Various studies have concluded that legal pressure either is, or is not, an effective means of achieving success in drug treatment. Within North America, several studies have concluded that legal pressure has a strong and positive impact on treatment entry and, subsequently, retention and positive outcomes. 56–59 Indeed, three of these studies suggest significantly improved performance for legally referred compared with voluntary clients However, it should be noted that they relate to either primary alcohol users,59 adolescents in specialist (CJS referral only) residential units58 or female offenders serving out alternatives to custody and/or child custody procedures. 56 Each of these represents a specific set of circumstances and motivational issues.

Other studies have concluded a negative impact of CJS compared with elective referral. 59–62 Again, the context of these studies varies and two of these59,60 were concerned with adolescents or primary alcohol users only. There is also literature that theorises the possible negative results of a policy of criminal justice referrals into treatment based on presumptions of need and non-empirical evidence bases. 63–65

The largest group of studies have found no statistically significant difference in the outcomes experienced by criminal justice referrals compared with referral through other routes. 57,65–75 Not all of these studies were designed specifically to examine the impact of legal pressure on outcomes. Even so, they generally show that clients sourced from the CJS experience outcomes that are not significantly different to other clients of treatment services. Indeed, both sets of clients (CJS and non-CJS) display statistically significant improvements after a set period of treatment. 66

Thus, the greater number of existing studies support the notion that CJS-referred clients can experience equal, or similar, advantages to treatment as non-CJS referrals but that these are not automatic. The majority of studies have focused on the effect of treatment provided as an alternative to sentencing, reflecting different practice and policy emphasis internationally. In England, CJS referral mechanisms are not homogenous and voluntary CJS initiated treatment engagement is much more common in the UK than in other settings such as North America.

The literature that concerns itself with treatment effectiveness reflects several permutations of formal and informal legal pressure, combined with different types of treatment intervention. The nature of the methods of diversion from CJS to treatment varies considerably. They include first, arrest referral schemes in England which provide a voluntary treatment referral system from within CJS settings to, in the main, community-based prescribing services; second, drug court referrals in the USA, dealing largely with individuals charged with drug-related offences and referring to abstinence-based residential programmes; and, finally, a host of European schemes that either provide, via a range of schemes, a choice of treatment or punishment or actually impose treatment-based sentences, such as in Austria, Germany or the Netherlands. 76

The current study systematically reviews the efficacy of diversion and aftercare programmes for offenders using class A drugs. In addition, it summarises and evaluates the economic evidence about the cost-effectiveness of diversion and aftercare for drug-using criminal offenders.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Population

-

Offenders, with or without a mental health problem, who are aged 18 years or older; and

-

using class A drugs; and

-

offered diversion and/or aftercare programmes (or as part of a control group in a study examining this type of intervention); and

-

study participants diverted to an intervention that has at least an element of treatment, which is specifically designed to treat and/or reduce substance misuse.

Intervention

The effectiveness and economic reviews included studies that reported evaluation of diversion and/or aftercare programmes. For the purposes of the reviews, the following definitions of diversion and aftercare were used:

-

Diversion is a process whereby offenders who use class A drugs are identified as having a drug problem at any point in the CJS. This then results in subsequent criminal justice interventions comprising wholly, or partly, of specific treatment, rehabilitation or education requirements for drug abuse. These are either voluntary, mandated by the court, and/or monitored by probation, or drug, services.

-

Aftercare is the treatment or intervention activity following any relevant diversion event, as per review inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Evaluation of aftercare interventions comprised studies which examined care following the diversion process, not care following prison or another intervention. In addition, studies which sought to evaluate prison-based interventions were not included.

Control

For the purpose of this review the following definitions of control group were used:

-

matched to characteristics of experimental group, but receives nothing

-

matched to characteristics of experimental group and receives placebo/pseudo-intervention

-

matched to characteristics of experimental group and receives treatment as usual (TAU)

-

not matched to characteristics of experimental group and receives nothing

-

not matched to characteristics of experimental group and receives placebo/pseudo-intervention

-

not matched to characteristics of experimental group and receives TAU.

Outcomes

The review of effectiveness focused on studies that reported one or more of the following outcomes: reoffending/rearrest/recidivism/reincarceration; reduction or increase in drug use; health, risk and service variables, such as hospital admission; and mortality data.

Aims and objectives

-

To review systematically the efficacy of diversion and aftercare programmes for offenders using class A drugs.

-

Based on a systematic review of the data, to model the impact of diversion and aftercare programmes for offenders using class A drugs.

-

To summarise and evaluate the economic evidence about the cost-effectiveness of diversion and aftercare for drug-using criminal offenders.

-

To identify and explore the consequences of potential characteristics of diversion and aftercare interventions that may have most impact on the cost-effectiveness of the programmes.

-

To estimate probability, cost and outcome data, relevant to the UK setting, to populate an economic model.

-

To integrate the findings from the above objectives and make recommendations for the design of high-quality primary research studies to further inform future HTA research.

See commissioning brief in Appendix 2.

Chapter 3 Review of effectiveness

Methods

Advisory panel

The project team included clinicians, commissioners/service providers and experts in the field. The full project team had input into the methods and design of the reviews. The role of this panel was to inform the choice of population, interventions and outcomes to define the initial search strategy and inclusion criteria and to help identify the relevant databases to be searched. The group was also asked to comment on the draft report.

Search strategy

The design of the systematic effectiveness review followed guidelines set out in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 77 Sources included both medical and social science databases chosen in consultation with the project team and with systematic review experts. Sources were chosen to provide a balance between the health, social science and criminal justice literature and to include material derived from both mainstream and ‘grey’ literature sources.

The following databases provided a comprehensive search of the literature: MEDLINE; PsycINFO; Web of Science; Wiley Online Library; JSTOR; EMBASE; Ingenta; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; Criminal Justice Abstracts; Wilson Social Science Abstracts; Social Sciences Index; Campbell Collaboration Social, Psychological, Education, and Criminological Trials Registry; Informa Healthcare; Sage; Science Direct; HighWire; ProQuest; Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; British Humanities Index; National Criminal Justice Reference Service; Social Services Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences; Sociological Abstracts; ProQuest Dissertations and Theses; SciVerse; Metapress; Scopus; Taylor and Francis Online; System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination Database; Allied and Complementary Medicine and TRIP (formerly known as Turning Research into Practice).

The project team developed a robust search string. The search strategy balanced sensitivity (to ensure that relevant material was identified) and specificity (to ensure that a reasonable proportion of the material was relevant). Medical subject heading terms and text words for inclusion in the search strategy were developed from terms relating to elements of the review question, namely: offenders, class A drugs, and diversion and aftercare programmes. Search strategy development was informed by the successive fractions approach. 78 This allows for objective testing of the productivity of main terms, restriction terms, and terms taken in combination, to optimise the balance between sensitivity and specificity.

Initial trials of the search strategy were carried out in MEDLINE and subsequently refined. Testing by proxy was used to select terms. A term was deemed sufficiently productive if at least 10% of citations were relevant to the review. Additional relevant search terms were identified by examining key papers and consulting experts. All new search terms were tested for retrieval of novel citations, i.e. those not previously identified by existing search terms. Sensitivity and specificity were tested by applying the search string to a ‘dummy database’, comprising known relevant and irrelevant citations. Subsequently, sensitivity was increased by the addition of further search terms. Specificity was improved by the addition of the Boolean term, ‘NOT’ which excluded irrelevant material. Final evaluation of the search string included testing against a control list of papers referenced by previous reviews and a cardinal list of key papers in the field. The final search strategy is listed in Appendix 3.

Databases were searched between 2 November 2011 and 6 January 2012. Electronic database searches were limited to papers published in English between January 1985 and January 2012. It was decided not to update the search prior to publication of this report. This was based on the paucity of evidence identified for the review from the original search. Given changes in the organisation and provision of the NHS and social care that also affect services for addiction it was felt that swift publication was of greater importance. Libraries of retrieved studies were exported into EndNote citation manager software (EndNote X6, Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and deduplicated. The reference lists of all full-text articles retrieved, including grey literature, were hand-searched for additional material.

Inclusion criteria

Population criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Class A drug users or reporting of class A drug user subsample.

-

Contact with any part of the CJS.

-

In any country.

Where eligibility for age or class A drug use was not specified or unclear the authors were contacted for additional information.

Diversion intervention criteria

Diversion was defined as a criminal sanction that is, or contains an element of, treatment which is specifically designed to treat and/or reduce drug. The intervention might, or might not, be accompanied by a reduction in disposal severity and/or sentence length for treatment compliance.

Diversion intervention included individuals who:

-

receive drug treatment and testing orders (DTTOs) as a community sentence, or have drug treatment requirements as a sentence alone or alongside other probation orders (e.g. specific programme or course)

-

were sent to prison initially but then released with a drug treatment requirement as a condition of parole

-

people who receive drug treatment via specialist court/probation programme in lieu of imprisonment

-

receive drug treatment via specialist court, or probation programme in lieu of reduced charges, or reduced sentence

-

were receiving treatment in any form of community-based treatment setting, for example specialist prescribing, residential detoxification, day centre attendees, counselling, cognitive–behavioural therapy and therapeutic communities.

Relevant outcomes

These included treatment completion; reduction or increase in drug use; health service contact; mental and, or physical illness; health risk behaviour, i.e. injecting; mortality; social functioning, i.e. employment, training, education, homelessness, family and/or social support; and CJS contact for any offence type, i.e. rearrest, recidivism and imprisonment. Studies reporting only predictors of drug treatment completion were not included.

Exclusion criteria

Exclusion criteria were:

-

participants were in prison at the time of the intervention

-

participants were not in contact with the CJS

-

participants were not diverted

-

participants were probationers and intervention or treatment was part of probation case management

-

participants were aged under 18 years

-

the sample contained mixed drug use with no class A drug primary or subanalysis

-

there were no relevant outcomes reported

-

there were no relevant outcomes for class A drug users only predictor analyses.

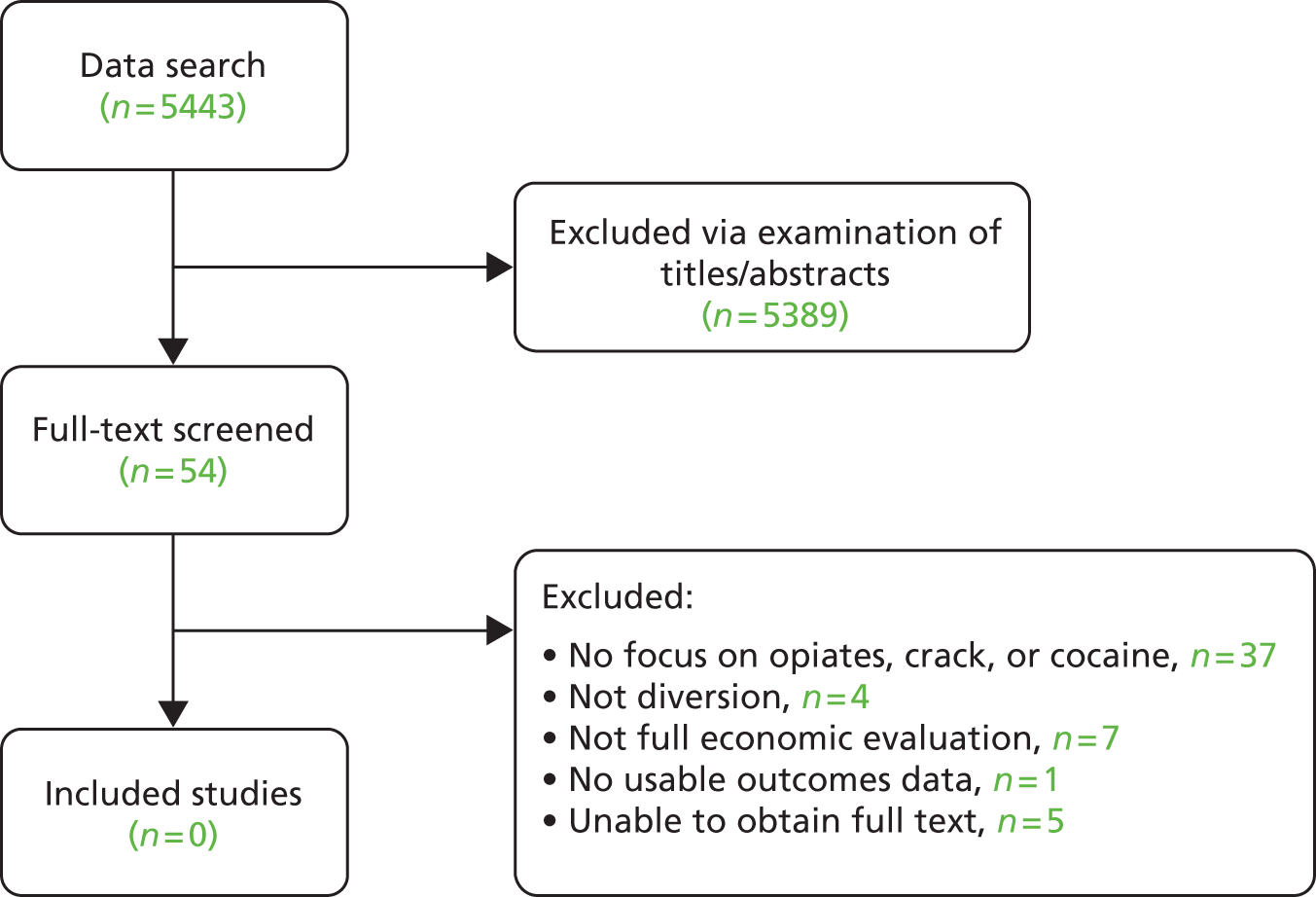

These inclusion/exclusion criteria were applied to the titles and/or abstracts of studies identified by the search strategy (see Appendix 4). A second reviewer independently screened 50% of identified studies following the establishment of an acceptable level of inter-rater reliability (κ = 0.7). References in the following formats, books, conference proceedings, dissertations, or theses, were excluded. Potentially relevant references were copied into a separate file and the full text of the article obtained. Two reviewers independently assessed each study for inclusion with any disagreement resolved by consensus and a third reviewer, if necessary. Reasons for exclusion of full-text references were documented (see Figure 1).

Quality assessment

There are a large number of available instruments for the objective evaluation of study quality. However, few of these have been adequately validated79 and the vast majority are directly applicable only to randomised controlled trials (RCTs). RCTs remain a rarity in the field of criminal justice research and none of the studies meeting our inclusion criteria followed this methodology, although one study80 derived its data from a previously conducted RCT.

Objective quality assessment scales that directly address the type of ‘real-world’ approach, which is the natural methodology of drug diversion research, are virtually non-existent. One exception to this general rule is the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods81 summarised in Appendix 6. This scale was developed specifically to address the constraints of research in the criminal justice setting and is currently the most widely utilised quality evaluation scale in this context. The scale considers both broad aspects of research design (e.g. controls and randomisation) but, more importantly in this context, considers also in greater detail threats to internal validity.

Data extraction

Data extraction (see Appendix 5) was carried out independently by at least two reviewers. Data pertaining to study design, intervention, sample demographic characteristics, relevant outcomes and any relevant statistical analyses were extracted and inputted into Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS), version 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA; 2011). Any disagreements were resolved by consensus and a third reviewer, if necessary.

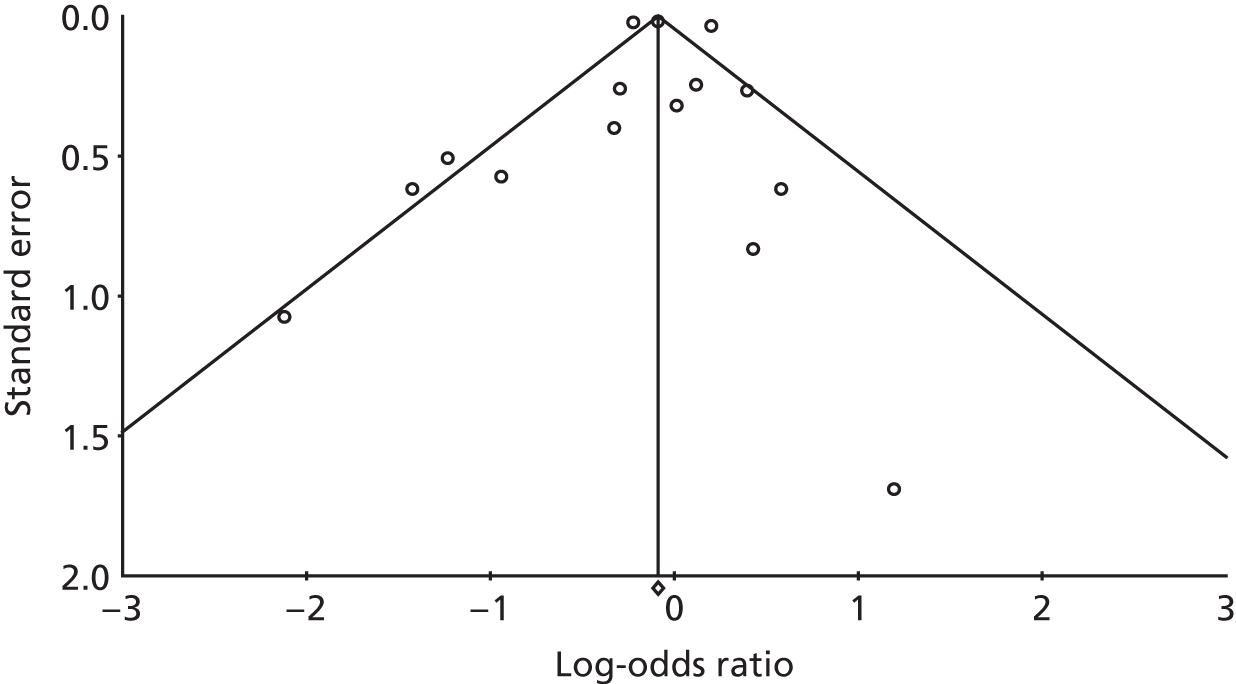

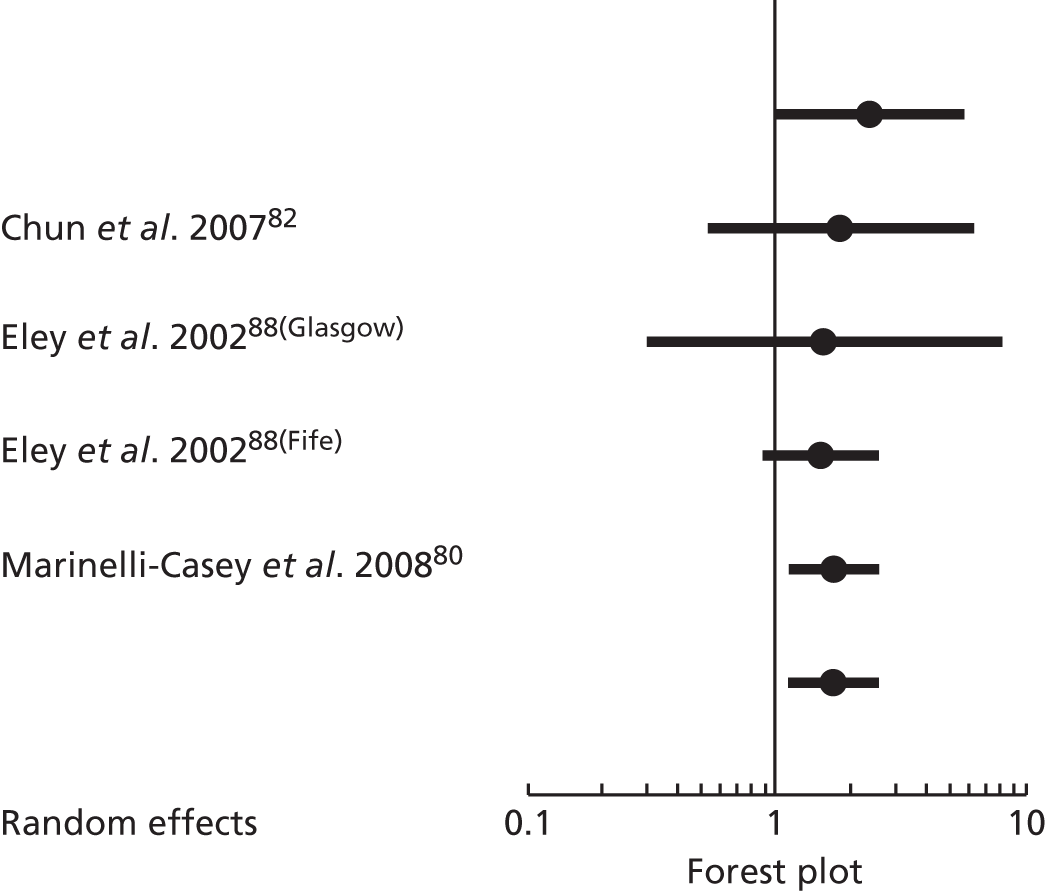

Data synthesis

An initial narrative synthesis of the available material was used to explore and outline the extent, nature and quality of the available evidence in this area. This qualitative assessment of the available data also explored observed heterogeneity in study and participant characteristics, study designs and study outcomes. It was used to inform the structure of subsequent quantitative synthesis of the data, including the choice of comparisons to be made and the outcome measures amenable to quantitative treatments. A bivariate analysis of outcomes explored the potential associations between study and participant characteristics and outcomes identified via narrative review. Outcomes suited to meta-analysis were then converted to odds ratios (ORs) and data from individual studies combined to provide a quantitative evaluation of heterogeneity. Where studies evaluating a particular outcome (e.g. reduction in primary drug use) were identified as both statistically and conceptually amenable to combined analysis, meta-analytic models were developed to identify a pooled effect size. Meta-analysis was also used to explore publication bias.

Results

Study flow

Database and bibliography searches identified 28,408 potentially relevant studies. Screening of titles and/or abstracts led to the exclusion of 27,110 studies, with 1328 articles proceeding to an examination of the full text. Full-text review led to the exclusion of a further 1284 articles and 14 papers, relating to 16 studies, were included in the quantitative synthesis. This process is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of included studies.

Selection of included studies

Data analysis for 15 of the 16 studies was based on secondary data drawn from available published reports; complete raw data were available for one study,82 with partial raw data available for one study in which a part of the sample met our inclusion criteria. 83 Reasons for exclusion of the studies not included in the review are listed in Figure 1 and a comparison between included and excluded studies is provided in Appendix 6.

Profile of included studies

Publication date

The review covered the period January 1985 to January 2012. However, the bulk of relevant studies identified (n = 14, 87.5%) were published post 2000. The focus of the relevant literature on drug courts, first established in 1989, accounts for this.

Publication type

All of the included studies were published studies. Over half were published in academic, peer-reviewed journals, with the majority of the remainder being publicly available government reports and one study52 was a university publication (see Table 1).

Country of origin

Included studies primarily (62.5%) provide information regarding the US situation. The small number of UK-based studies (n = 2, reports with a combined total of four studies; 25% of studies in total) focused on interventions which are, effectively, the UK equivalent of drug courts – DTTOs. The two remaining studies52,84 reported outcomes from a Toronto drug treatment court and an Australian early court intervention pilot, again both equivalents of the US drug court model (see Table 1).

Table 1 sets out descriptive summaries of each of the included studies. Note that Eley et al. 88 is an ‘umbrella’ study addressing the roll-out of a programme in two locations. The report of this study divides into three substudies, two outlining outcomes for each location and the third providing additional outcomes for a sample drawn from the combined data. In order to clarify which substudy is being discussed the individual substudies will be included in the citation [Eley et al. 88(Fife) for the Fife substudy, Eley et al. 88(Glasgow) for the Glasgow substudy and Eley et al. 88(combined) for the analysis of both the Fife and Glasgow substudies combined].

| Study | Country | Study description | Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anglin et al., 200785 | USA | Comparison of treatment outcomes (primarily recidivism) for SACPA-referred methamphetamine users and SACPA-referred users of other drugs. Journal article | Concurrent group comparison |

| Brecht and Urada, 201186 | USA | Evaluation of treatment performance and outcome indicators for Proposition 36 (SACPA)-referred methamphetamine users, comparing outcomes with similar groups either not referred via Proposition 36 or not using methamphetamine. Journal article | Concurrent group comparison |

| Brewster, 200187 | USA | Evaluation of the Chester County Drug Court Programme, comparing recidivism and drug use outcomes for clients on the programme, with outcomes for a group of clients on probation prior to the programme’s introduction who would have been eligible for inclusion had the programme existed previously. Journal article | Cross-sectional group comparison |

| Chun et al., 200782 | USA | Evaluates treatment outcomes (CJS involvement and drug use) for opioid dependent clients. Comparisons drawn between treated (therapeutic community plus methadone maintenance) and untreated (therapeutic community but no methadone maintenance) clients and between treated and untreated clients on probation and treated and untreated clients referred via Proposition 36 (SACPA). Journal article (raw data provided by author) | Concurrent group comparison |

| Eley et al., 200288(Fife) | UK (Scotland) | Programme and outcome evaluation of pilot DTTO programmes in Glasgow and Fife. Government report | Longitudinal follow-up |

| Eley et al., 200288(Glasgow) | UK (Scotland) | Programme and outcome evaluation of pilot DTTO programmes in Glasgow and Fife. Government report | Longitudinal follow-up |

| Eley et al., 200288(combined) | UK (Scotland) | Programme and outcome evaluation of pilot DTTO programmes in Glasgow and Fife. Government report | Case series |

| Hartley and Phillips, 200189 | USA | Analysis of drug court case files to evaluate factors potentially contributing to likelihood of successful ‘graduation’. Journal article | Correlational |

| Hevesi, 199990 | USA | Evaluation of probation case records for crack/cocaine users to determine if drug treatment programmes contributed to reduced recidivism based on arrests for misdemeanours, drug-related crime and violent and non-violent felony. Government report | Correlational |

| Longshore et al., 200791 | USA | Evaluation of treatment completion and outcome indicators for clients referred through Proposition 36 (SACPA) either via probation or while on parole, with outcomes for those referred either via the CJS but not through SACPA or referred through non-CJS routes. Government report | Cross-sectional group comparison |

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | USA | Evaluation of drug court treatment outcomes comparing methamphetamine users receiving outpatient treatment under drug court supervision with a similar group of methamphetamine users not under drug court supervision. Journal article | Concurrent group comparison |

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | Canada | Evaluation of participant intake and treatment compliance as predictors of treatment completion in a Toronto drug treatment court focused on non-violent crack/cocaine and opiate users. Journal article | Concurrent group comparison |

| Passey et al., 200352 | Australia | Evaluation of the Lismore MERIT pilot programme, designed to promote early referral into treatment for drug-using offenders. Other (university publication) | Concurrent group comparison |

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | USA | An evaluation of whether or not a history of violent offending is significantly related to the likelihood of recidivism following referral to treatment via a drug court. Journal article | Before-and-after comparison |

| Turnbull and Webster, 200793 | UK | Process and outcome evaluation of DTTOs for crack-using offenders in a London borough. Government report | Correlational |

| Van Stelle et al., 199483 | USA | Evaluation of recidivism following referral of substance-using offenders to the Wisconsin TAP, a treatment programme based on the TASC model. Journal article (raw data provided by author) | Longitudinal follow-up |

Quality assessment

The evaluation of study quality relates to each study taken as a whole. For a number of studies (see Appendix 6) only a subgroup of participants met our inclusion criteria and subsequent analyses of outcomes are therefore based only on outcomes for these individuals. However, to evaluate the extent to which outcomes can be relied on, it is the overall study design which provides the best indicator of research ‘quality’.

Table 2 sets out the design profiles of included studies, indicating study design, sample size, allocation of participants, length of follow-up and attrition and details in line with the Maryland Scale of Scientific Methods criteria. Table 2 highlights the fact that included studies were not of a rigorously high methodological standard. Designs were, in the main, retrospective and/or correlational; sample sizes tended to be modest and there was no, or limited, follow-up beyond the intervention end point. None of the studies used random selection or random allocation of participants or was able to blind raters, where more than one group was available for analysis.

| Study | Data collection | Power calculation | Sample size: N (n used in analyses) | Group allocation; comparison group (n) | Control variables; variable measurements | Attrition % lost; control for any attrition | Length of follow-up (days) | Statistical tests/effect sizes | Core level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglin et al., 200785 | Retrospective | No | 36,132 (29,757) | Post hoc; 3 | 5; 3 | 17.7%; 2 | 730–1095 (varied) | Yes | 4 |

| Brecht and Urada, 201186 | Prospective | No | 145,947 (73,805) | Post hoc; 3 | 5; 3 | 55.5%; 2 | 0 (main outcomes measured only at discharge) | Yes | 4 |

| Brewster, 200187 | Retrospective | No | 235 (235) | Post hoc; 3 | 1; 3 | 0.0% | 365 | Yes | 2 |

| Chun et al., 200782 | Prospective | No | 85 (18–85) | Post hoc; 4 | 5; 3 | 78.8%; 2 | Unclear | Yes | 4 |

| Eley et al., 200288(Fife) | Prospective | No | 49 (unclear) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 4 | Unclear | Unclear | No | 2 |

| Eley et al., 200288(Glasgow) | Prospective | No | 47 (unclear) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 4 | Unclear | Unclear | No | 2 |

| Eley et al., 200288(combined) | Prospective | No | 10 (10) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 1 | 0.0% | 0 | No | 2 |

| Hartley and Phillips, 200189 | Retrospective | No | 196 (196) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); NA (focus on treatment completion) | 0.0% | Not stated | Yes | 1 |

| Hevesi, 199990 | Retrospective | No | 154 (147) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 1 | 0.0% | 1460, but intervention length unclear | Yes | 2 |

| Longshore et al., 200791 | Mixed | No | 492,966 (unclear) | Post hoc; 3 | 3; 3 | 12.7%; 2 | 900 for year 1 intake; 365 for years 2 and 3, varied on participant | Yes | 2 |

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | Prospective | No | 287 (287) | Post hoc; 3 | 5; 4 | 0.0% | 365 | Yes | 4 |

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | Prospective | No | 365 (365) | Post hoc; 3 | 1; 2 | 0.0% | 730 | Yes | 1 |

| Passey et al., 200352 | Prospective | No | 266 (262) | Post hoc; 3 | 5; NA (focus on treatment completion) | 1.5%; 2 | Varied (average 270) | Yes | 1 |

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | Retrospective | No | 456 (452) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 3 | 0.9%; 2 | 1095 for 70% of participants | Yes | 2 |

| Turnbull and Webster, 200793 | Mixed | No | 70 (70) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 1 | 0.0% | 540 | No | 2 |

| Van Stelle et al., 199483 | Mixed | No | 259 (259) | NA (single group only) | NA (single group only); 1 | 0.0% | 540 (average) varied on participant | Yes | 2 |

Appendix 6 sets out additional characteristics that affect the plausibility and interpretability of studies. The likely reliability and validity of outcome measures was rarely addressed. The use of intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses was restricted to retrospectively collected data. Baseline differences between comparator groups were not always controlled for. More recent studies tended to be of a higher quality when the overall evaluation of study quality was taken into consideration (rho = 0.74; p < 0.001) but not when the more restricted set of Maryland criteria only were used to judge this (rho = 0.34; p = 0.20).

Studies were grouped into three broad categories based on quality. This is a relative measure of quality between the included studies only. As stated, all included studies were not of a high methodological standard.

Highest quality

-

Marinelli-Casey et al. :80 Maryland Scale level 4, concurrent group comparison, adequate sample size and follow-up, clear focus on choice of variables and control for effect modifiers.

-

Chun et al. :82 Maryland Scale level 4, prospective, concurrent group design with repeated measures, clear focus on choice of variables and control for effects modifiers, but small sample size.

-

Brecht and Urada:86 Maryland Scale level 4, prospective concurrent group design, control for effect modifiers, but high dropout and data collected via chart review.

-

Anglin et al. :85 Maryland Scale level 4, concurrent group design with a large sample size, long follow-up and good control for effect modifiers, but retrospective data collection.

Medium quality

-

Newton-Taylor et al. :84 prospective concurrent group design, adequate sample size with no attrition, longitudinal data, but Maryland Scale level 1.

-

Passey et al. :52 prospective concurrent group design, low attrition with adequate follow-up, control for modifier effects, but Maryland Scale level 1.

-

Saum and Hiller:92 before-and-after design with long follow-up, adequate sample size and low attrition, but retrospective data collection and Maryland Scale level 2.

Lower quality

-

Hevesi:90 retrospective correlational study, with data collected via chart review but long follow-up and Maryland Scale level 2.

-

Van Stelle et al. :83 longitudinal follow-up design with some prospective data collection and adequate sample size, Maryland Scale level 2, but authors make specific reference to difficulty of collecting reliable data.

-

Hartley and Phillips:89 retrospective correlational study, data collected via chart review, Maryland Scale level 1.

-

Brewster:87 cross-sectional group design, but with an historical control group, adequate sample size and length of follow-up, Maryland Scale level 2, but data collection retrospective and poor control for modifier effects.

-

Longshore et al. :91 cross-sectional group comparison, with some data collected prospectively, adequate follow-up and large sample size, Maryland Scale level 2 and some attention to controlling for effect modifiers, but authors note a lack of clarity regarding whether data collated from different sites referred to ‘episodes’ or ‘individuals’, hence sample size is estimated and may conflate people and treatment episodes.

-

Eley et al. :88 (three studies) longitudinal follow-up design, either single cohort or case series. Repeated measures and triangulation on main outcome measure, Maryland Scale level 2, but small sample size and length of follow-up and attrition not stated.

-

Turnbull and Webster:93 correlational study, with some prospectively collected data, but data collection primarily via chart review, Maryland Scale level 2, authors make specific reference to difficulty of collecting reliable data.

Study design

All 16 studies identified a potential cohort of participants, primarily via existing services (e.g. probation) or routine data sources, for example California Outcomes Measurement System (CalOMS) and California Alcohol and Drug Data System. These cohorts were used to compare outcomes for interventions. Where comparisons were drawn between experimental and (broadly defined) control groups (n = 8), allocation to groups was post hoc. Data collection in eight studies was either wholly or partly retrospective. None of the studies used either randomised selection or randomised allocation of participants. Although it was impossible to blind participants to the receipt of an active intervention, studies did not report any attempt to blind those analysing the data to participant allocation. Validation of key outcomes, such as continued drug use, via triangulation (e.g. use of self-report and other report), or via an evaluation of reliability (e.g. repeated assessment) or validity (e.g. comparison of self-report use with urine testing) was almost entirely lacking (Eley et al. 88 did compare self-report and urine screening).

Sample size

Sample size or power calculations were not reported in any of the included studies. It is unclear whether or not sample size or power calculations were used to estimate sample requirements for the analyses. Small sample size is likely to have impacted on the robustness of outcomes presented for a number of the studies. 82,88,93 Studies with large sample sizes85,86,91 and consequent statistical power, tended to be characterised by uncertainties about the reliability of data collected.

Length of follow-up

Ideally, length of follow-up would be measured to a point beyond the timescale occupied by the intervention itself. Length of follow-up, for a number of the studies reported here, referred either to time while in treatment,84,88(combined) or included an unspecified or individually variable length of time during which treatment was still taking place. 52,86,87,90,91,93 Some authors failed to clarify whether or not follow-up included time in treatment82,85 and three studies88(Fife),88(Glasgow),89 provided no information about length of follow-up. Only three studies80,83,92 explicitly set out a follow-up period which began at the point of treatment discharge. For these three studies, the mean length of post-discharge follow-up was 666 days, the shortest length of follow-up was 365 days. 80 These latter studies provide a strong indicator of the likely durability of the treatment modalities addressed.

Attrition

Dropout during the course of a study undermines faith in the reliability and generalisability of outcomes. Of those studies with some, or all, outcome data collected prospectively, five80,83,84,88(combined),93 reported no loss to follow-up. For the four studies with prospective or mixed data collection which reported some loss to follow-up, attrition ranged widely from 1.5%52 to 78.8%82 (the latter was subsequently excluded from analysis). Two studies had attrition at levels sufficient to substantially undermine outcomes. 82,86 Two further studies, both of which had substantive sample sizes, also suffered a significant loss to follow-up of 12.7%91 and 17.7%. 85

Analysis design

Intention to treat

In the absence of ITT analysis, it is unclear whether or not outcomes reflect treatment effectiveness on the sample who started treatment. Any observed positive impact could demonstrate efficacy only in those who fully engaged with, and completed, both the intervention and its evaluation. Four studies88(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),93 report no statistical analysis of outcomes and are consequently excluded from an evaluation of whether or not analyses are ITT. Of the remainder, five80,84,87,89,90 (41.7%) reported, or were identified by the review team, as carrying out all analyses on an ITT basis. Of these, four studies80,84,87,89 had experienced no attrition from their sample. The remaining study90 had experienced minimal sample attrition. The two studies85,86 identified as failing to carry out any of their analyses on an ITT basis both had substantive attrition. Of the remaining studies which carried out statistical analyses, three52,82,83 used ITT analysis for at least some of the analyses presented. In all three cases, the analyses which did not use an ITT approach were those for which data for the outcome analysed were missing.

Baseline equivalence

Eight of the included studies drew comparisons between different groups of participants. With regard to outcome measures, four of the eight group comparison studies52,80,82,84 did evaluate baseline equivalence for all relevant variables, using statistical analyses. Of the remainder, one used statistical analysis, but only for a subset of the outcome measures86 and three, although commenting on baseline characteristics for some or all of the measures, failed to carry out statistical evaluations to establish equivalence between groups. 85,87,91

Outcome focus

Treatment completion was the most commonly reported measure overall, with all but one study88(combined) reporting outcomes for this variable (Table 3). All but two studies52,85 provided data on drug use during, or subsequent to, the intervention. Of those studies reporting drug use, the most common measure used was self-reported drug use (n = 7, 50%). Urine tests, or other forms of drug screening,80,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),87,93 and drug-related arrests83,87,91–93 were variously reported in a number of studies. None of the studies reported drug-related convictions as an outcome. Four studies80,82,88(Fife),88(Glasgow) used a scale-based measure of drug use [Addiction Severity Index (ASI)].

| Study | Outcome measure | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported drug use | Drug screening | Treatment completion | Scale-based outcomes | Drug-related arrests | General arrests | Arrests for violent offending | Incarceration | |

| Anglin et al., 200785 | Methamphetamine users less likely to complete treatment than alcohol or marijuana users, more likely to complete than cocaine users or opiate users | |||||||

| Brecht and Urada, 201186 | No significant differences between SACPA methamphetamine users and SACPA other-drug users for treatment completion rate or 90-day treatment retention rates | |||||||

| Brewster, 200187 | No statistically significant difference, by type of drug | |||||||

| Chun et al., 200782 | Significant reductions in self-reported alcohol, heroin, cocaine, other sedative use in last 30 days, but no significant group differences except for heroin use where ‘untreated, referred from probation’ group showed a greater reduction | No significant group differences for days’ retention in treatment | Significant reduction in ASI-measured alcohol and drug scores, employment and psychiatric scores The ‘untreated referred from probation’ group showed significantly lower mean reductions in ASI employment score |

No differences in proportion of participants arrested in last 30 days | No significant differences in days incarcerated in last 30 days | |||

| Hartley and Phillips, 200189 | No statistically significant differences, by referral methods | |||||||

| Hevesi et al., 199990 | Treatment completers significantly less likely to reoffend than non-completers | |||||||

| Longshore et al., 200791 | Heroin/opiate users less likely to complete treatment than users of other drugs. Women more likely to complete than men, older people than younger people, people from ethnic minorities less likely to complete than white groups, longer continuous drug use likely to increase likelihood of completion, frequent use decreased likelihood of completion, referral from parole decreased likelihood of completion in contrast to referral from probation | |||||||

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | Significant group differences in mean methamphetamine use at discharge, 6- and 12-month follow-ups for drug court participants | Drug court participants significantly more likely to remain abstinent/have more methamphetamine-free urine tests than non-drug court participants | Drug court participants more likely to remain in treatment > 30 days, more weeks retained in treatment and higher % completed treatment than non-drug court participants | Drug court participants significant reductions in ASI drug scores at 6 and 12 months compared with non-drug court participants | ||||

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | Significant group differences in self-reported substance abuse for graduated participants vs. expelled–engaged and expelled–non-engaged participants | Graduated and expelled–engaged participants significantly better treatment compliance than expelled–non-engaged participants | ||||||

| Passey et al., 200352 | Heroin users more likely to complete treatment vs. other drugs | |||||||

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | Increasing age significantly decreased likelihood of rearrest | No significant differences except that time at risk and lifetime charges increased likelihood of rearrest | Primary cocaine users more likely to be rearrested for any violent offence than participants using other drugs as their primary drug Time at risk and lifetime charges were increased likelihood of rearrest, increasing age reduced likelihood of rearrest |

|||||

Seven studies reported outcomes for general offending82,83,86,87,90–92 and five reported outcomes relating to arrests for violent offending. 83,87,90–92 None of the studies reported outcomes in respect of convictions for violent offending, although one study83 did report outcomes relating to convictions for general offending behaviour. In addition, five studies reported outcomes relating to incarceration82,83,86,87,93 and one study82 reported offending behaviour evaluated using the ASI.

A small number of studies considered other potential outcomes of an intervention. Three82,86,87 reported outcomes for employment or training; one86 reported on family and social support outcomes; and one84 reported on compliance with treatment programme and court conditions.

A noticeable absence from the list of outcomes reported was any assessment of the impact of an intervention on the physical or mental health of participants. None of the studies reported outcomes for either hospital admissions or mortality. One study only82 reported medical and psychiatric status, with outcomes based on the ASI.

Intervention characteristics

The level of detail provided about the interventions evaluated varied substantially, but overall few specific details (e.g. proportion of participants diverted to a particular treatment modality) were provided. Interventions were largely pragmatic and ad hoc (e.g. utilising services available in the local area) rather than tailor-made for a particular programme. Details of the diversion process (e.g. how decisions were made about which intervention might be most appropriate for particular individuals) were also few and far between. The lack of information regarding these key issues is problematic. It leaves outcomes open to wide interpretation regarding what aspect of treatment has or has not worked in a given context. This is notable where treatment options are diverse in focus or delivery as is the case for the majority of the included studies.

Type and focus of intervention

One study90 provided no details of the intervention evaluated, other than that a number of participants received a ‘drug treatment programme’ while the remainder were on probation with no such programme. Of the remaining fifteen studies, seven (43.7%)80,83,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),89,92 are best described as multifactorial day programmes, a further five (31.2%)52,85,86,91,93 as multifactorial day and residential programmes and one82 as a multifactorial residential programme. Details for the remaining two studies focus on expectations participants were required to satisfy, rather than on treatment received as such. In total, 80% of the interventions evaluated were multifactorial programmes, with the remaining 20% either not described at all or subject to broad interpretation.

Of the multifactorial interventions offering clients both day and residential options, three52,91,93 provide details of how the treatment options on offer were distributed between participants. Two studies,85,86 evaluating Substance Abuse and Crime Prevention Act (SACPA) interventions (SACPA-referred methamphetamine users compared with other groups given the same treatment options), set out a broad summary of treatment options. They gave no indication of the proportion of participants in experimental or comparator groups who were offered any given option. The options available to participants in both studies are broadly similar. Participants in Anglin et al. 85 were offered detoxification, methadone detoxification, methadone maintenance, outpatient non-methadone treatment and residential treatment/recovery. Participants in Brecht and Urada86 were offered outpatient treatment, residential treatment lasting either < 30 days or > 30 days, detoxification, Narcotic Treatment Programme (NTP) detoxification or NTP maintenance.

Of the seven studies80,83,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),89,92 evaluating multifactorial programmes offering only day (non-residential) treatment, one80 provides a detailed outline of the intervention received by participants. This study evaluates the matrix model of intervention offered by the Methamphetamine Treatment Project (MTP). It compared outcomes of this programme for methamphetamine users either under, or not under, drug court supervision. The remaining six studies within this category, provide accounts of the intervention being evaluated which vary in their level of detail. None of the studies provide a clear indication of the proportion of participants receiving a specific treatment option.

Setting/diversion

The main focus of included studies was on drug courts; participants in just over half (56.2%)82,84,85(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),87,89,92,93 of the studies were diverted to treatment ‘from court’. Participants in six other studies included participants diverted from a broader range of settings. 52,78,83,85,88,90,91 One study,86 fails to provide any details of the setting(s) from which participants were referred to treatment. In this study, for the SACPA group at least, this is likely to follow the ‘referred by court or recommended by probation or parole’ pattern identified for other studies evaluating the SACPA.

Level of intervention

The majority of studies (n = 9, 56.2%) indicated that components of the intervention(s) offered were based on both individual and group therapies. None of these studies, however, clarified the proportion of participants given either level of therapeutic intervention. Six studies82,84,85–87,90 are exceptions to this mixed pattern of intervention, which indicated that all interventions were given at the individual level only.

Prior treatment

Half of the included studies (n = 8, Table 4) failed to provide any details about the treatment history of their participants. These included prospective studies in which the researchers had at least some control over data collection. 84,88(Fife),88(combined) All studies providing details of treatment history52,80,82,85–88(Glasgow),91 identified that at least a proportion of participants had prior experience of drug treatment. This ranged from 2% (non-drug court comparator group)87 to 79% (SACPA participants). 82 Taking an average across the studies providing this information, just over half (50.4%) of the participants included had prior experience of drug treatment. Excluding figures for Brewster,87 which is a clear outlier in this context, 57.2%, on average, had prior experience.

| Study | Intervention(s) | Setting | Level | Treatment history | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Divert from | Divert to | ||||

| Anglin et al., 200785 | Multifactorial day and residential | Mixed settings | Mixed settings | Individual | Yes |

| Brecht et al., 201186 | Multifactorial day and residential | Not stated | Mixed settings | Individual | Yes |

| Brewster, 200187 | Drug court | Court | Community | Individual | Yes |

| Chun et al., 200782 | Multifactorial residential | Court | Residential therapeutic community | Individual | Yes |

| Eley et al., 200288(Fife) | Multifactorial day | Court | Community | Mixed | Not stated |

| Eley et al., 200288(Glasgow) | Multifactorial day | Court | Community | Mixed | Yes |

| Eley et al., 200288(combined) | Multifactorial day | Court | Community | Mixed | Not stated |

| Hartley and Phillips, 200189 | Multifactorial day | Court | Community | Mixed | Not stated |

| Hevesi, 199990 | Not stated | Mixed settings | Community | Individual | Not stated |

| Longshore et al., 200791 | Multifactorial day and residential | Mixed settings | Mixed settings | Unclear | Yes |

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | Multifactorial day | Mixed settings | Community | Mixed | Yes |

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | Harm reduction | Court | Community | Individual | Not stated |

| Passey et al., 200352 | Multifactorial day and residential | Mixed settings | Mixed settings | Mixed | Yes |

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | Multifactorial day | Court | Community | Mixed | Not stated |

| Turnbull and Webster, 200793 | Multifactorial day and residential | Court | Mixed Setting | Mixed | Not stated |

| Van Stelle et al., 199483 | Multifactorial day | Mixed settings | Community | Mixed | Not started |

The six group studies identifying prior treatment experience noted that both experimental and comparator group(s) included participants with experience of drug treatment. 80,82,85–87,91 Two of these studies80,82 carried out statistical analyses comparing the proportion of participants in each group previously engaged in treatment. Marinelli-Casey et al. 80 reports that drug court participants were significantly less likely to have had prior treatment than the comparator group of non-drug court participants (33.3% vs. 52.2%, χ2 = 6.49; p < 0.01). Details in Chun et al. 82 indicate that, while there were no statistically significant differences between SACPA and non-SACPA groups in respect of history of substance abuse treatment as measured by the Circumstances, Motivation and Readiness (CMR) scale, SACPA participants were more likely to already be in receipt of methadone treatment at baseline (p < 0.001).

Participant profile

Appendix 6 provides details of the participant profiles, which are summarised below.

Participant demographics

Details of participant demographics provided for a number of the studies do not map directly onto the samples used for study outcomes. Discrepancies are set out in Appendix 6. The extent of demographic information available (Table 5) varied substantially between studies. For studies where demographic data are presented separately for different groups,80,84,85–87,91 the values given are mean values taken from the individual values for all groups. Values for all demographic characteristics are baseline values and any statistically significant differences are detailed in the text.

| Study | Age (years), mean (range) | Gender, % male | Ethnicity, % white | Employment | Education |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anglin et al., 200785 | 33 (–) | 73.3 | 45.1 | Employed, 29.6% | Mean highest grade completed, 11.2 |

| aBrecht and Urada, 201186 | Not stated | 73.9 | 41.0 | Employed, 33.2% | High school or above, 60.9% |

| Brewster, 200187 | 28 (18–75) | 81.0 | 49.4 | Employed, 57.2% | High school graduate/GED or above, 33.5% |

| Chun et al., 200782 | 39 (20–62) | 63.5 | 54.1 | 70.6% lowest income category, further details not available | High school/GED, 47.1% |

| Eley et al., 200288(Fife) | 25 (19–34) | 93.9 | Not stated | Employment at DTTO, 0.0% | Not stated |

| Eley et al., 200288(Glasgow) | 30 (19–58) | 80.4 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Eley et al., 200288(combined) | Not stated | 100.0 | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated |

| Hartley and Phillips, 200189 | 34 (21–60) | 66.3 | 55.6 | Employed prior to programme, 67.3% | High school/GED, 63.3% |

| Hevesi, 199990 | – (19–29) | 100.0 | Not stated | Employed at time of arrest, 18.4% | Not stated |

| Longshore et al., 200791 | 33 (–) | 67.7 | 45.7 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | 32 (18–57) | 62.7 | 56.7 | Employed, 71.5% | High school graduate, 52.8% |

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | 35 (–) | 75.1 | Not stated | Employed, 22.0% | Secondary education or above, 90.5% |

| bPassey et al., 200352 | Not stated | 75.9 | Unclear | Employment, 7.1% | Tertiary, 6.6% |

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | 30 (18–59) | 78.5 | 27.2 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Turnbull and Webster, 200793 | 31c (20–46) | 93.0 | 57.1 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Van Stelle, 199483 | Not stated | 100.0 | Not stated | Majority employed full time | Majority high school diploma or less |

| Total sample | 31.8 | 80.7 | 47.9 |

Age

Mean age did not vary substantively between the included studies. Our inclusion criteria were set to age 18 years and above, but no upper age boundary was set. Few studies (n = 3, 18.7%) indicated that they had included any participants in the 60+ years age bracket. Given the mean ages for these studies (28 years,87 39 years82 and 34 years89), it is unlikely that substantive numbers from this older age group were included.

Of the eight group comparison studies,52,80,82,84–87,91 four carried out statistical analysis evaluating the relative age profiles of comparison groups. 80,82,84,86 Of these, no significant differences were identified for two studies,80,82 whereas one study implied that there were significant differences86 (i.e. methamphetamine users were younger than non-methamphetamine users) but presented no further information and one identified a clear distinction between the experimental and control groups (graduates were older than either of the expelled groups; F = 5.62, p = 0.004). 84

Gender

All included studies provided details regarding participant gender. Statistical analyses comparing the proportion of men and women in comparator groups are available for only three (37.5%)80,82,84 of the eight group comparison studies. 52,80,82,84–87,91 No statistically significant differences were found. All but three studies83,88(combined),90 included female participants. The average proportion of women in studies with both male and female participants was close to one-quarter (24.2%).

Ethnicity

Further details on non-white ethnicity are available in Appendix 6. Nearly one-third of studies (n = 5, 31.2%) made no reference to ethnicity,84,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),90 with a further three studies52,83,89 (18.7%) making reference only to the proportion of ethnic minority participants and providing either no further details,89 or providing a description of ethnicity which lacked clarity. 52,83 Statistical analyses of group differences in ethnicity are available for only two studies. 80,82 No statistically significant differences were identified for Chun et al. ,82 while in Marinelli-Casey et al. 80 there were statistically more Latino participants in the drug court experimental group than in the non-drug court comparator sample (chi-squared analysis, p < 0.05). Brecht and Urada86 reported that methamphetamine users were more likely to be white or Hispanic than non-methamphetamine users, but again no specific details of any statistical analysis are provided.

Employment status

Only two studies82,87 provided details of the proportion of participants in different income groups. The general profile set out is one of a largely unemployed group of participants on low or very low incomes. This having been said, there was substantial variation between studies reporting these data. For a minority of studies,80,89 full-time employment was the norm rather than the exception for participants. Statistical analyses to explore potential group differences in employment status were available for three studies. 80,82,84 None of the statistical analyses showed significant differences. Brecht and Urada86 reported that SACPA groups had higher rates of employment than non-SACPA groups, but no details of any statistical analysis are set out.

Educational level

Nine studies provided information about participants’ educational status (see Table 5). Overall, the profile presented is of a fairly poorly educated population of participants. However, as with the profile for employment status, there are notable exceptions to the rule. Nearly one-fifth of participants, for whom information is available, completed a comparatively high level of education. Three studies reporting statistical analysis of potential group differences80,82,84 found no evidence of a significant difference in educational status between their experimental and comparator groups. Brecht and Urada86 noted that ‘SACPA groups had a higher level of education than non-SACPA groups’, but again analyses specific to this distinction are not set out.

Mental and physical health

Participant mental and physical health status is summarised in Table 6. Fewer than half of the studies (43.7%)52,82,84,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),85,91 discussed participant mental health issues, and, of these, only five (31.2% of included studies)52,82,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),85 provided any figures for the proportion of participants with a mental health condition. No study provided any detailed breakdown of diagnoses. Details available in respect of participant physical health are even more limited. Slightly less than one-third of studies (31.2%)52,82,88(Fife),88(Glasgow),85 provided any information regarding the physical health of participants. The proportion of participants with a physical health problem was clearly set out in only three studies (18.7%). 52,82,85

| Study | Mental health | Physical health |

|---|---|---|

| Anglin et al., 200785 | 7.7% of methamphetamine users reported ever having chronic mental illness compared with average of 9.5% of other drug users | 10.0% of methamphetamine users reported a physical disability compared with an average of 11.7% of other drug users |

| Brecht and Urada, 201186 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Brewster, 200187 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Chun et al., 200782 | Mean ASI psychiatric score for the sample as a whole: 0.16, 41.2% of the participants had a score of 0 indicating no identified psychiatric problem | Mean ASI medical score for the sample as a whole: 0.31, 51.8% of the participants had a score of 0 indicating no identified medical problem |

| Eley et al., 200288(Fife) | Details from 55 initial assessments 15 (27.3%) referenced mental health concerns, including physical and emotional abuse, bereavement, memory impairment and blackouts | 48 of 55 assessments (87.3%) referenced physical health. Of these, health was reported as good in 11 cases (22.9%), problems reported related primarily to drug use, including hepatitis B and C, abscesses, deep-vein thrombosis and seizures |

| Eley et al., 200288(Glasgow) | ||

| Eley et al., 200288(combined) | Not stated | Not stated |

| Hartley, 200189 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Hevesi, 199990 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Longshore et al., 200791 | All three groups (both experimental and control) across all 3 years contained participants with diagnosed mental health disorders, these were described as mixed diagnoses, but no further details are givena | Not stated |

| Marinelli-Casey et al., 200880 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Newton-Taylor et al., 200984 | Participants not accepted onto the programme if they had mental health concerns that would interfere with their ability to participate fully | Not stated |

| Passey et al., 200352 | 39.1% of participants reported a mental health problem, 26.3% reported a previous suicide attempt | 74.8% of participants reported a chronic physical disease, 45.9% reported infection with hepatitis B or C |

| Saum and Hiller, 200892 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Turnbull and Webster, 200793 | Not stated | Not stated |

| Van Stelle et al., 199483 | Not stated | Not stated |

Drug use

Considering first a broad overview of the profiles set out (see Table 7), it is clear that the ‘bias’ of included studies towards US drug court evaluations and, particularly, evaluations of SACPA referral, has produced a parallel bias towards a focus on methamphetamine use. Three studies explicitly evaluate outcomes for methamphetamine users. 80,85,86 A further study,91 while not setting out to ‘recruit’ methamphetamine users, reports figures indicating that the single largest group of participants in the study are methamphetamine users. The four UK-based studies88(Fife),88(Glasgow),88(combined),93 show an equivalent bias resulting from the focus on evaluations of DTTO programmes, with all four studies evaluating outcomes for participants who are primary users of heroin or crack/cocaine.