Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 10/108/01. The protocol was agreed in November 2012. The assessment report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

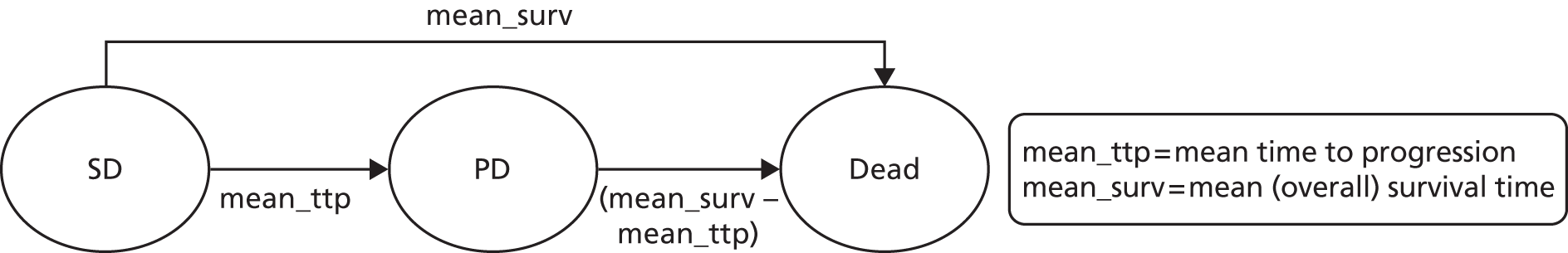

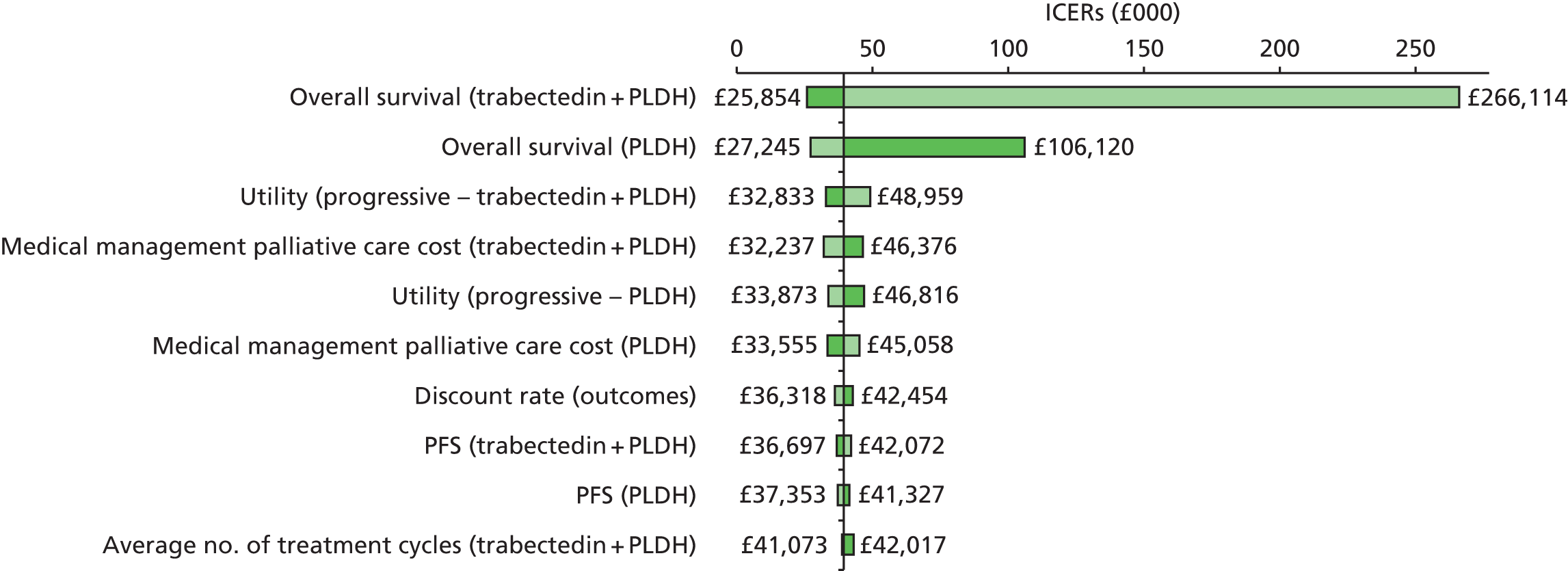

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Edwards et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Ovarian cancer is the fifth most common cancer in the UK, and is the fourth most common cause of cancer death. 1 Ovarian tumours are classified based on the cell type from which the tumour originates: surface epithelium, germ or stroma. Most ovarian malignancies are epithelial in origin, accounting for 80–90% of ovarian cancers. 1 Today, it is widely accepted that fallopian tube carcinoma and primary peritoneal carcinoma are, in general, histologically serous, and are considered to arise from the same pathophysiology as epithelial ovarian cancer. 2 Epithelial tumours can be further divided based on their histology (high-grade serous, low-grade serous, mucinous, endometrioid, clear cell, and undifferentiated or unclassifiable). The most common type of ovarian cancer in the UK is high-grade serous carcinoma. Other, rarer subtypes include germ cell tumours, which tend to occur in premenopausal women and are highly sensitive to chemotherapy (and therefore treatable), or borderline ovarian cancer. 1,3 Borderline ovarian cancers have low malignant potential and are usually considered separately as they do not usually require treatment with chemotherapy. It is thought that most histologies share common risk factors, with the probable exception of mucinous carcinomas. 1

Epidemiology

Incidence and prevalence

Ovarian cancer is predominantly a disease of older, postmenopausal women, with > 80% of cases being diagnosed in women of > 50 years of age. 1 The highest age-specific incidence rates are seen for women aged 80–84 years at diagnosis, with an incidence of 69 per 100,000, which drops to 64 per 100,000 in women aged ≥ 85 years. 1 However, for women with BRCA-deficient tumours, the age of diagnosis can be about 10 years earlier.

In 2008, around 6500 women were diagnosed with ovarian cancer in the UK, making it the second most common gynaecological cancer and the fifth most common cancer in women. 1 Focusing on England and Wales, in 2008, there were 5304 new cases in England and 400 in Wales, giving age-standardised rates per 100,000 of 15.8 [95% confidence Interval (CI) 15.4 to 16.2] and 19.6 (95% CI 17.7 to 21.5), respectively. 1 In 2010, 4295 deaths were attributed to ovarian cancer, accounting for 5.7% of all female deaths from cancer. 1 It has been estimated that the lifetime risk (adjusting for multiple primaries) of developing ovarian cancer is 1 in 54 for women in the UK (based on data from 2008). 1

Aetiology and pathology

Diagnosing ovarian cancer can be difficult. Patients typically present with subtle symptoms, such as difficulty eating, abdominal bloating and feeling ‘full’ quickly, all of which are suggestive of other, more minor conditions. As a result, many people (≈60%) are diagnosed with ovarian cancer when their disease is in an advanced stage. 4 Stage of ovarian cancer at diagnosis is based on the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) classification system. 2 The FIGO system is a scale of I–IV, where stage I represents early stage disease and stages III and IV represent advanced disease (summarised in Table 1).

| Stage | Criteria |

|---|---|

| I | Tumour confined to the ovaries |

| IIA |

|

| IIB | As for 1A, but tumour limited to both ovaries |

| IIC | Tumour limited to one or both ovaries, with any of the following:

|

| II | Tumour involves one or both ovaries with pelvic extension |

| IIA | Extension and/or metastases in the uterus and/or fallopian tubes but with no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| IIB | Extension to other pelvic organs but with no malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| IIC | Tumour staged either 2A or 2B with malignant cells in ascites or peritoneal washings |

| III | Tumour involves one or both ovaries with peritoneal metastasis outside the pelvis and/or regional lymph node metastasis Liver capsule metastasis equals stage 3 |

| IIIA | Microscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis |

| IIIB | Macroscopic peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis, none of which exceed 2 cm in greatest dimension |

| IIIC | Peritoneal metastasis beyond the pelvis, larger than 2 cm in greatest dimension and/or regional lymph node metastasis |

| IV | Distant metastasis (beyond the peritoneal cavity) |

The aetiology of ovarian cancer is not yet fully understood. Various factors have been linked with an increased risk of developing ovarian cancer, and, conversely, others have been proposed as having a ‘protective’ effect and reducing ovarian cancer risk. The strongest known risk factors associated with a higher risk of ovarian cancer are increasing age and the presence of a mutation in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, with the latter accounting for around 10% of cases. 1 The BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes are also associated with risk of breast cancer, and studies have shown a doubling in ovarian cancer risk for women with a previous breast cancer. Women who have a first-degree relative (i.e. parent, sibling or offspring) diagnosed with ovarian cancer have a three- to fourfold increased risk of developing the disease compared with women with no family history, although about only 10% of ovarian cancer cases occur in women with a family history. 1

Ovarian cancer risk tends to be reduced by factors that interrupt ovulation, such as pregnancy (with a dose–response relationship between increasing risk and a lower number of children), breastfeeding and oral contraceptive use. 1 Conversely, factors that prolong exposure to ovulation, such as nulliparity and infertility, increase risk. 1 It has been reported that 5 years’ use of oestrogen-only hormone replacement treatment (HRT) is associated with a 22% increase in the risk of ovarian cancer, which is considerably larger than the 10% risk increase identified with use of oestrogen–progestin HRT over the same time period. 1 It is estimated that about 50 cases of ovarian cancer in the UK in 2010 were linked with HRT, which is equivalent to about 1% of all ovarian cancers. 1 Past or short-term use of HRT is thought unlikely to increase the risk of ovarian cancer.

Risk of ovarian cancer seems to be higher in people who have some other gynaecological medical conditions. For example, studies have found that women with endometriosis have a 30–66% increased risk. 1 In addition, young women (15–29 years old) with ovarian cysts and functional cysts (harmless, short-lived cysts that are formed as a part of the menstrual cycle) have been found to have double the usual risk of ovarian cancer later in life, and women who had cysts surgically removed, or unilateral oophorectomy, have a ninefold risk increase. 1 Hysterectomy may reduce ovarian cancer risk, with case–control studies reporting a 30–40% risk reduction regardless of age at time of surgery, and a 50% risk reduction for women whose hysterectomy was 15 or more years before the study. 1

Lifestyle and environmental factors also affect risk of ovarian cancer, with both current and past smoking and high body mass index (BMI) being linked with increased risk. 1

Prognosis

Treatments for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer are given with curative intent. Primary treatment is determined by the stage and risk of disease at diagnosis. 1 Treatment options are surgery, or surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (most likely platinum based) or chemotherapy alone. Alternatively, if it is thought that removal of all the cancer during the initial surgery could be problematic because of tumour size, chemotherapy may be administered before surgery (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) to shrink the tumour, with additional adjuvant chemotherapy after surgery. Clinically complete remission is achieved in most newly diagnosed patients through a combination of cytoreductive surgery and chemotherapy.

Considering chemotherapy, up to 10% of patients might not respond to first-line chemotherapeutic treatment and, of those who do respond, between 55% and 75% of people will relapse within 2 years. 5 It is these latter populations, more specifically those people who have received prior platinum-based treatment, that are the focus of this systematic review. Diagnosis of recurrent disease varies in UK clinical practice, with diagnosis based on clinical examination, biochemical markers (CA125) or radiological confirmation, or any combination of these three. Clinical expert advice is that, typically, a patient is diagnosed as relapsed if they have a serial rise in CA125 or have developed clinical signs, such as ascites. Diagnosis is typically confirmed with radiological scans. If a patient has no clinical symptoms but does have a rise in CA125, although possibly classified as relapse, the patient might not start a new chemotherapeutic regimen until they go on to develop symptoms. Date of relapse by CA125 is likely to be about 4 months earlier than date of relapse based on radiological scans. A patient is considered to have relapsed if they have progressed after achieving complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), or after their disease has been stable for some time (typically 8–12 weeks).

Prognostic factors thought to influence outcome (i.e. response to treatment and survival) are:

-

the stage of the disease at diagnosis (FIGO stage)

-

age

-

patient’s general health (typically referred to as performance status) at the time of presentation

-

extent of residual disease after debulking surgery

-

tumour grade

-

tumour histology.

Of the prognostic factors listed, the stage of disease at diagnosis and extent of residual disease after debulking surgery are considered to be strong predictors of survival. Relative 5-year survival rate is > 90% for early stage disease but falls markedly to < 10% for later stages. 1,3

Based on age-standardised relative survival rates during 2005–9 in England, data indicate that 72.3% of women are expected to survive for at least 1 year, falling to 42.9% surviving for ≥ 5 years, and to 35.4% surviving for ≥ 10 years. 1 Relative survival for ovarian cancer is higher in younger women, even after taking account of the higher background mortality in older people;1 5-year relative survival rates for ovarian cancer in England during 2005–9 ranged from 87% in people aged 15–39 years to 16% in those aged 80–99 years. The higher survival rate in younger women is likely to be attributable to a combination of better general health, more effective response to treatment and earlier diagnosis in younger people. 1

As with most cancers, relative survival for ovarian cancer is improving. 1 Much of the increase occurred during the 1980s and 1990s, and appears to be levelling off in the 2000s (Table 2). 1 Increased use of platinum-based chemotherapy, wider access to optimal primary treatment and greater determination to treat recurrent disease are all thought to have contributed to the observed improvements in overall survival (OS) at 1 and 5 years. 1

| Time period | 1 year | 5 years |

|---|---|---|

| 1971–5 | 42.0 | 21.0 |

| 2005–9 | 72.3 | 42.9 |

Measurement of disease

Initially, an elevated level of CA125 (determined by a blood test) is used as an indicator in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. About 90% of people who have later stages of ovarian cancer have an elevated CA125 level, whereas about 50% of people with early-stage ovarian cancers have an elevated CA125 level; normal CA125 level is 0–35 U/ml. 6 However, CA125 is not specific to ovarian tumours, and other benign conditions of the womb and ovaries also result in elevated CA125 (e.g. endometriosis, fibroids and pelvic inflammatory disease). 1 Other non-gynaecological conditions that are associated with increased CA125 are liver cirrhosis and pleural effusions. If a person is found to have ovarian cancer that produces CA125 then this blood test can be used to monitor the clinical effectiveness of treatment. 1

As CA125 elevation is not specific to ovarian cancer, it is recommended that diagnosis of ovarian cancer be confirmed by an ultrasound scan of the abdomen and pelvis. 3 If the ultrasound, serum CA125 and clinical status suggest ovarian cancer, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the pelvis and abdomen is carried out to establish the extent of disease. Expert advice is that the ratio of CA125 to carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) may be a useful guide in assessing ovarian cancer. Research has suggested that a CA125–CEA ratio of < 25 may be suggestive of a non-ovarian malignancy. 7

Impact of health problem

Significance for patients in terms of ill-health (burden of disease)

As a result of the difficulties of diagnosing ovarian cancer, many women present with advanced disease (e.g. 60% of women are diagnosed with stage III or IV disease), having had subtle symptoms for months before presentation. 1,3 Only around 29% of women are diagnosed at FIGO stage I, 4% at stage II and 6% are unstaged. 1

Treatments for newly diagnosed ovarian cancer are given with curative intent; however, for women with advanced, recurrent disease, second- and subsequent-line chemotherapies are typically given with palliative rather than curative intent, with the aim of alleviating symptoms and prolonging survival. Thus, key considerations in the choice of treatment at these stages in the pathway are maintaining the patient’s quality of life (QoL) and adverse effects associated with the individual treatments.

A recent study by Hess and Stehman8 investigated health-related quality of life (HRQoL) for women with ovarian cancer before, during and after chemotherapy, via a systematic review. The review resulted in identification of a total of 139 unique studies of patients with ovarian cancer in which QoL data were collected. Within these studies, > 90 different measures of QoL were administered. The authors found that there was limited longitudinal data beyond the initial treatment and immediate follow-up which limited the understanding of the long-term impact upon QoL for ovarian cancer survivors.

Significance for the UK NHS

Patients with ovarian cancer require significant amounts of hospital resources, including surgery and multiple courses of chemotherapy. In 2011–12, ovarian cancer accounted for 36,690 finished consultant episodes, 34,376 admissions and totalling 66,003 bed-days, in England alone. 9

Current service provision

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance is available on the initial recognition and management of ovarian cancer,3 first-line chemotherapeutic treatments for ovarian cancer,5 and on the use of topotecan [Hycamtin®, GlaxoSmithKline (GSK)]; paclitaxel [Taxol®, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS)]; and pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride (PLDH; Caelyx®, Schering-Plough) as second-line or subsequent treatments of advanced ovarian cancer. 10

Initial management of ovarian cancer

After confirmation of a diagnosis of ovarian cancer, primary treatment is determined by the patient’s age and general health, in addition to the histology and grade of their cancer. Typically, surgery is the preferred initial treatment, the goal of which is to excise all macroscopic disease, irrespective of stage of disease.

For suspected early (stage I) ovarian cancer, NICE recommends optimal surgical staging, with no adjuvant chemotherapy for cancers identified as low-risk disease (grade 1 or 2, stage IA or IB). 3 For suspected early-stage disease that is considered high risk (grade 3 or stage IC), NICE recommends that surgery be followed by chemotherapy treatment comprising six cycles of carboplatin. 3

As noted earlier, most people are diagnosed with ovarian cancer when their disease has reached an advanced stage (stages II–IV). In such cases, complete excision of the tumour during surgery may be difficult and patients will typically require additional chemotherapeutic treatment. Chemotherapy may be administered prior to surgery (typically three cycles), with the objective of shrinking the tumour to facilitate excision and improve the probability of removal of all macroscopic disease. First-line chemotherapy is the first round of chemotherapeutic treatment a patient receives, whether it is as a neoadjuvant treatment before surgery, an adjuvant treatment to surgery or at some time in the longer term after surgery. Second- and subsequent-line treatment is for those who have either relapsed after first-line chemotherapeutic treatment or experienced progression of their disease while receiving chemotherapy.

Prior to offering cytotoxic chemotherapy to women with advanced ovarian cancer (stages II–IV), NICE recommends confirmation of tissue diagnosis with histology (or by cytology if histology is not appropriate). 3 For first-line chemotherapy, NICE recommends paclitaxel in combination with a platinum-based compound or platinum-based therapy alone (cisplatin or carboplatin). 5 NICE does not recommend the use of bevacizumab (Avastin®, Genentech) in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as a first-line chemotherapeutic treatment. 11

The NICE pathway for the management of advanced ovarian cancer is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Treatment pathway recommended by NICE for the management of patients with advanced (stages II–IV) ovarian cancer. 12 a, Do not offer intraperitoneal chemotherapy to women with ovarian cancer, except as part of a clinical trial.

Second- and subsequent-line chemotherapeutic treatment

Although first-line chemotherapeutic treatment achieves a response in approximately 70–80% of patients, most patients will eventually relapse and require second-line therapy. 13 Between 55% and 75% of those who respond to first-line therapy will relapse within 2 years of completing treatment. Second- and subsequent-line therapies are typically given with palliative rather than curative intent, with the aim of alleviating symptoms and prolonging survival. Thus, key considerations in the choice of treatment at these stages in the pathway are maintaining the patient’s QoL and adverse effects associated with the individual treatments.

A patient’s response to first-line platinum-based therapy is indicative of their response to second and subsequent lines of platinum-based treatment, with the length of the platinum-free interval (PFI) and the extent of relapse (site and number of tumours) particularly prognostic of response. However, most patients will develop resistance to platinum-based therapy over time, with decreasing length of PFI with increasing rounds of treatment. Platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (defined in Table 3) has a particularly poor prognosis, with a reported median OS of < 12 months. 14

| Categorisation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Platinum sensitive | Disease that responds to first-line platinum-based therapy but relapses at ≥ 6 months after completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy |

| PPS | Relapses between 6 and 12 months after completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy |

| FPS | Relapses at ≥ 12 months after completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Platinum resistant | Disease that relapses within 6 months of completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Platinum refractory | Disease that does not respond to initial platinum-based chemotherapy |

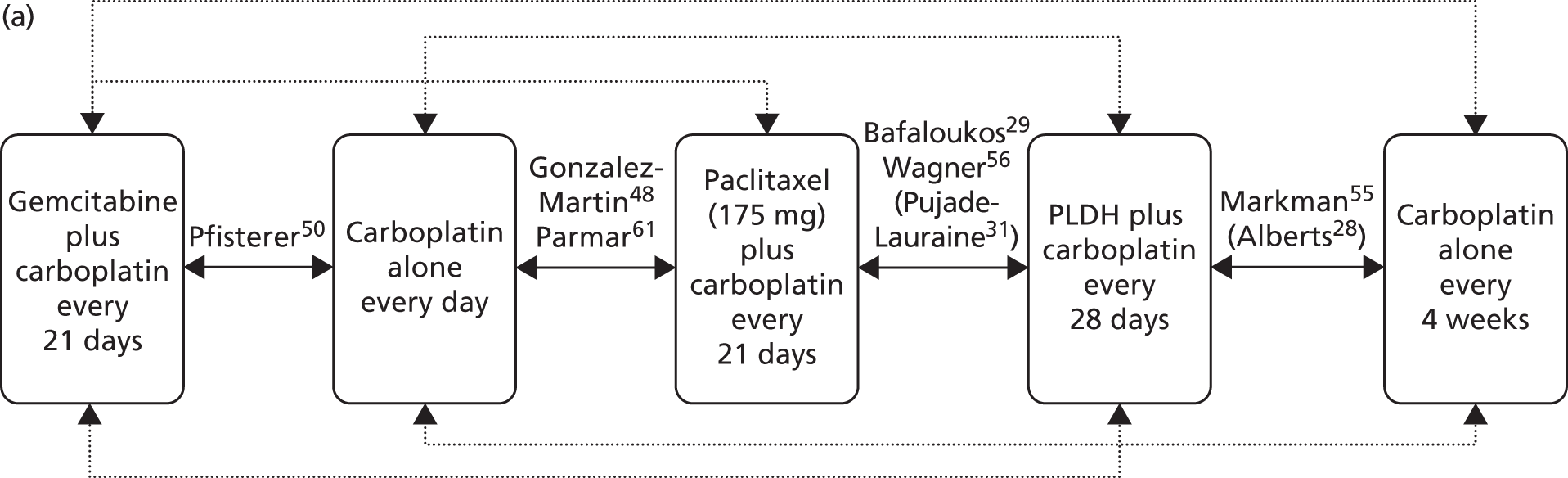

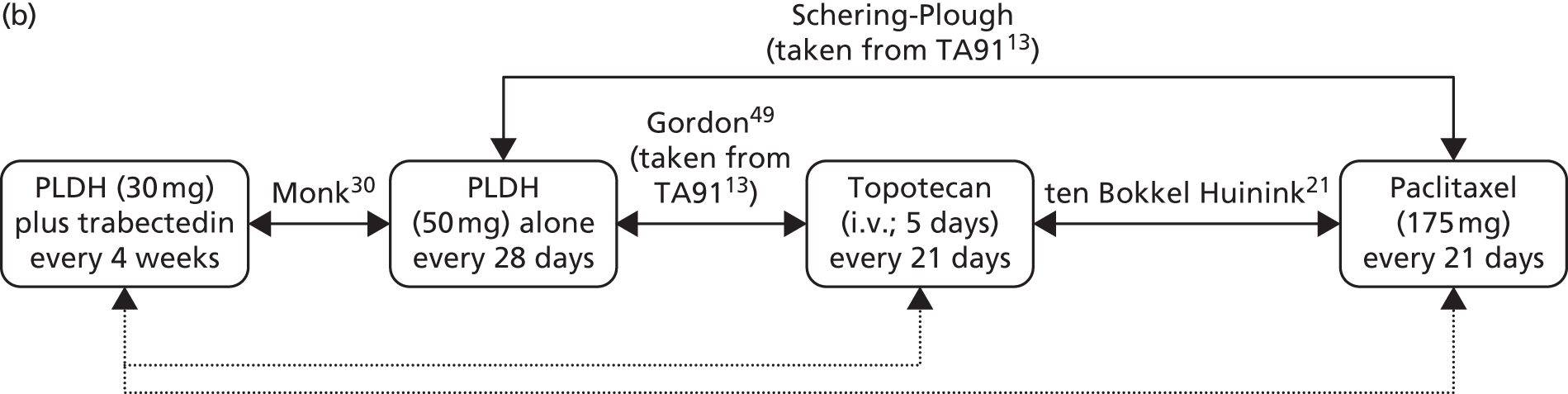

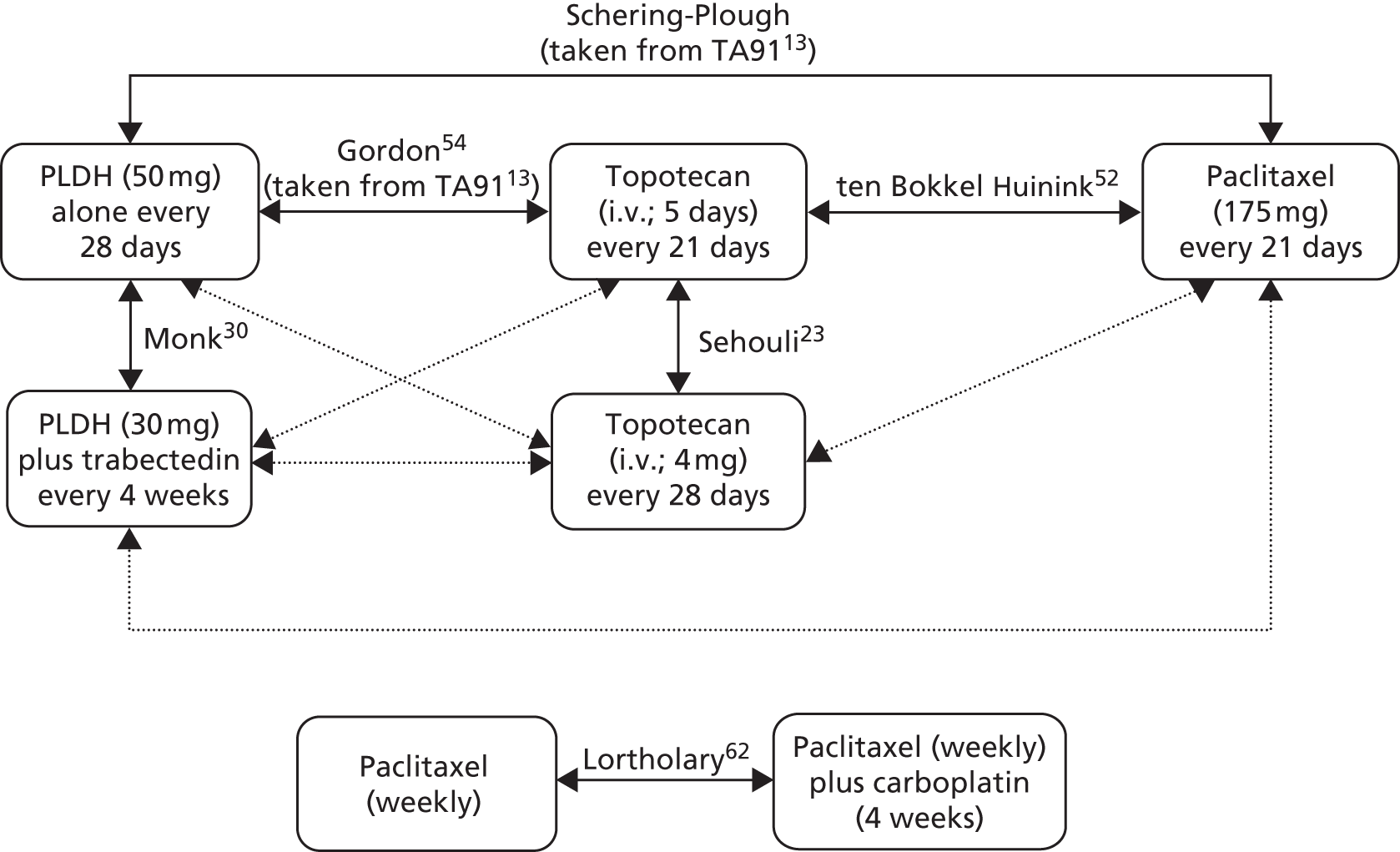

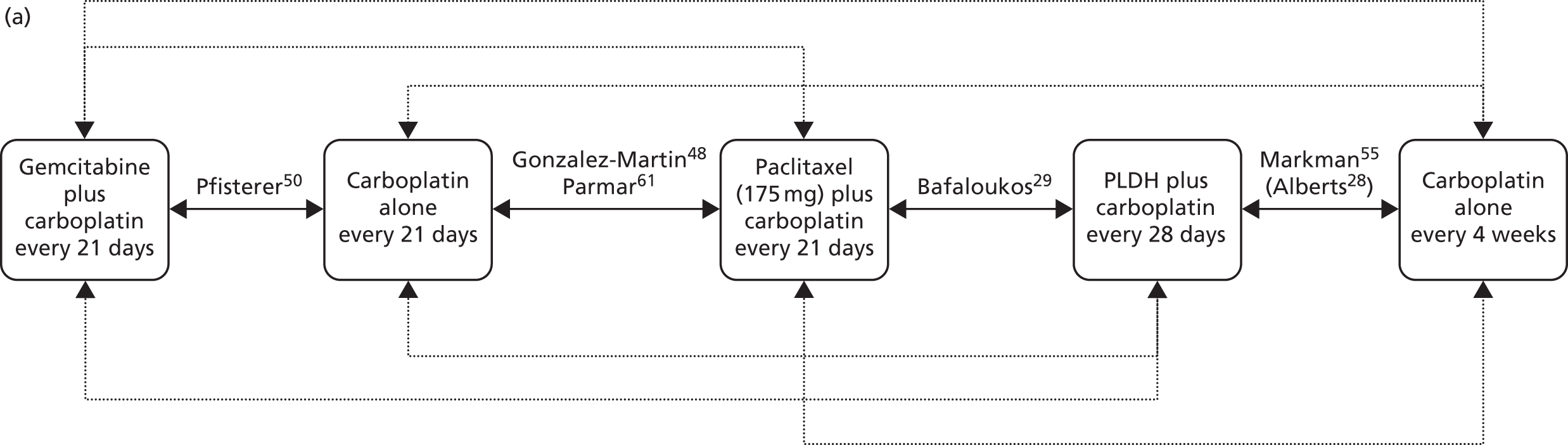

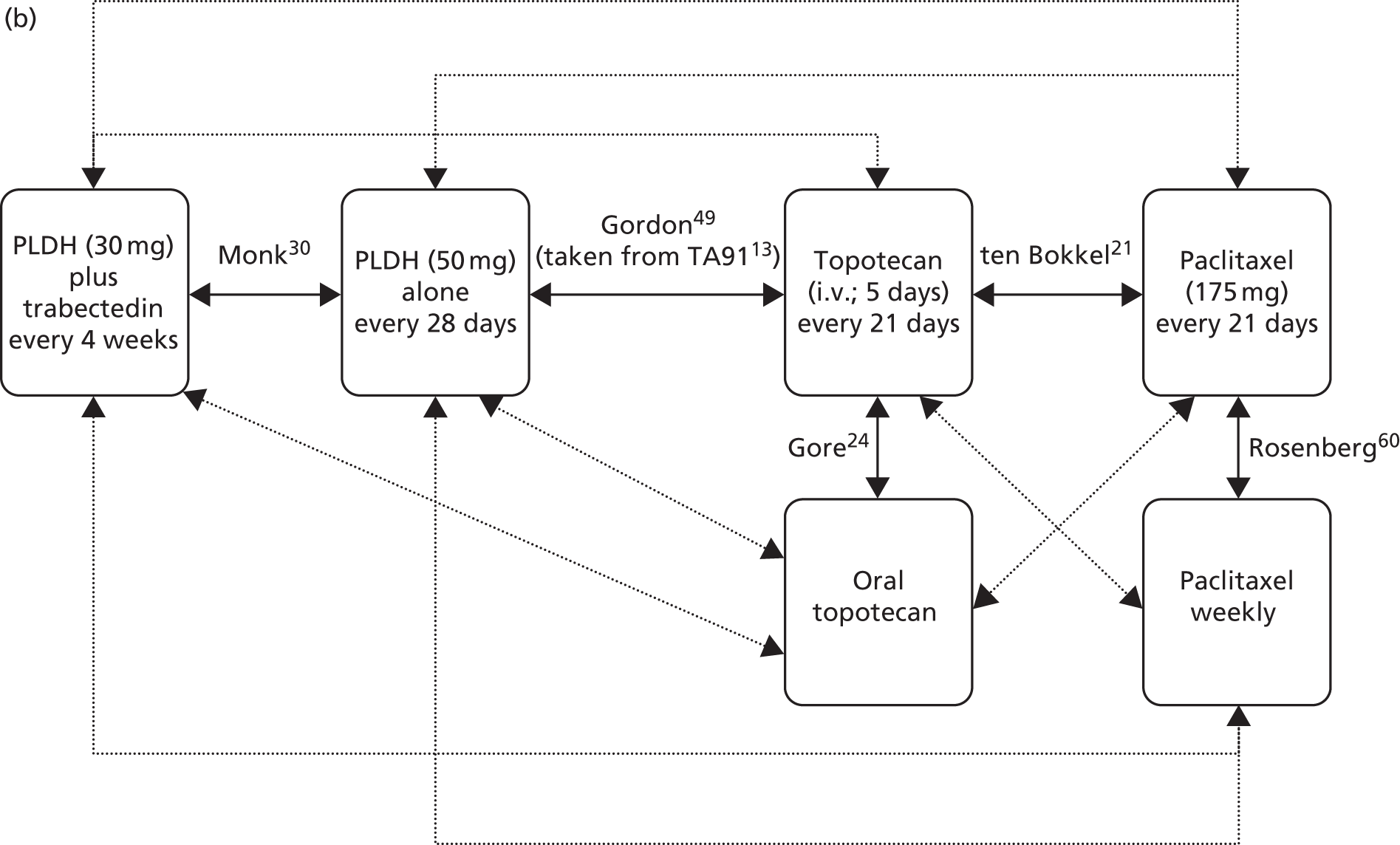

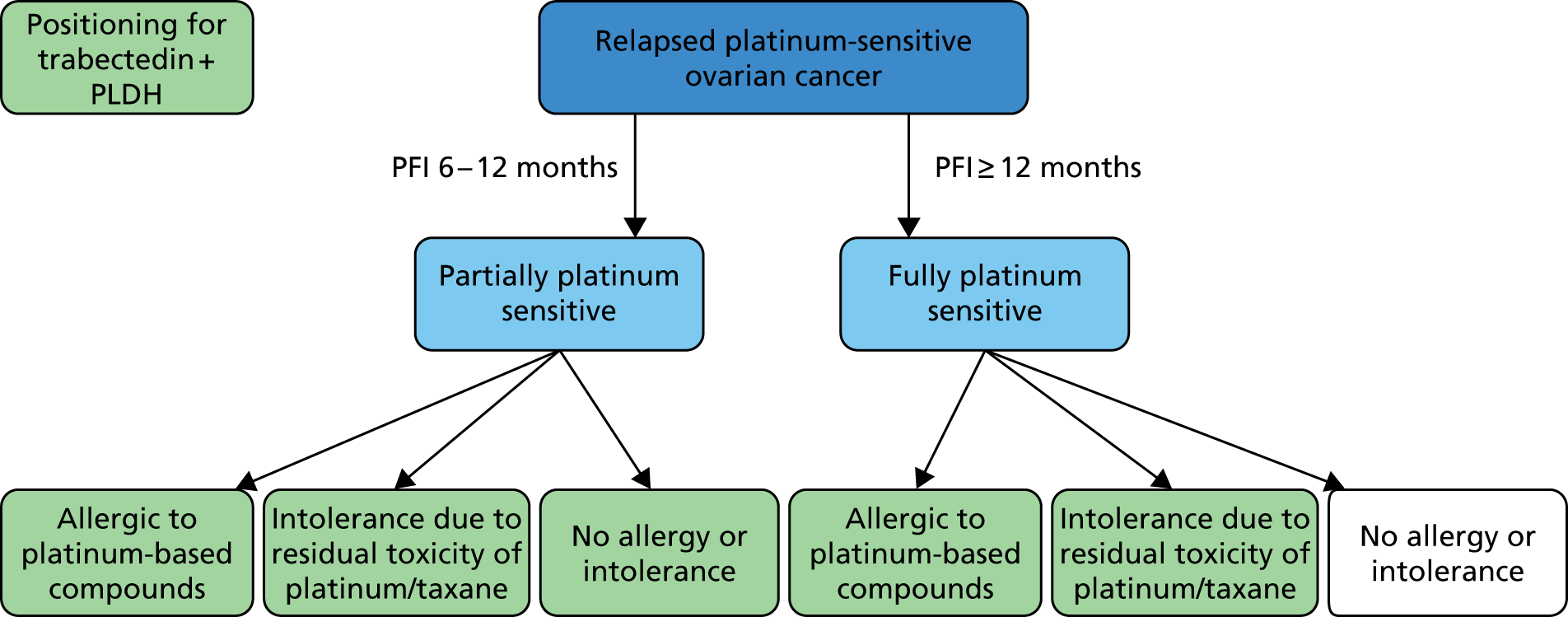

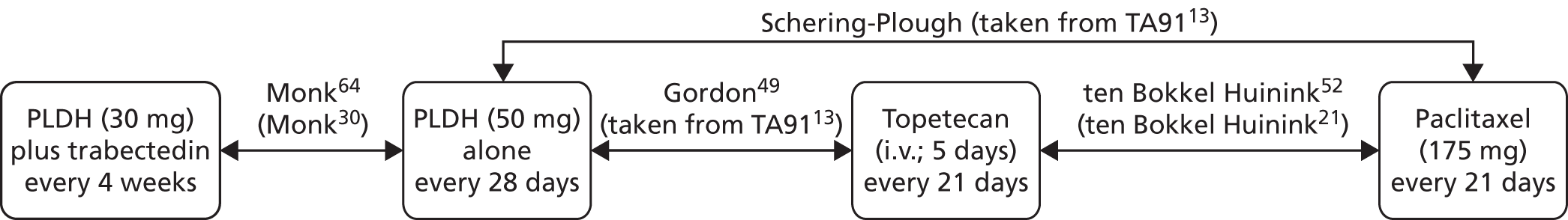

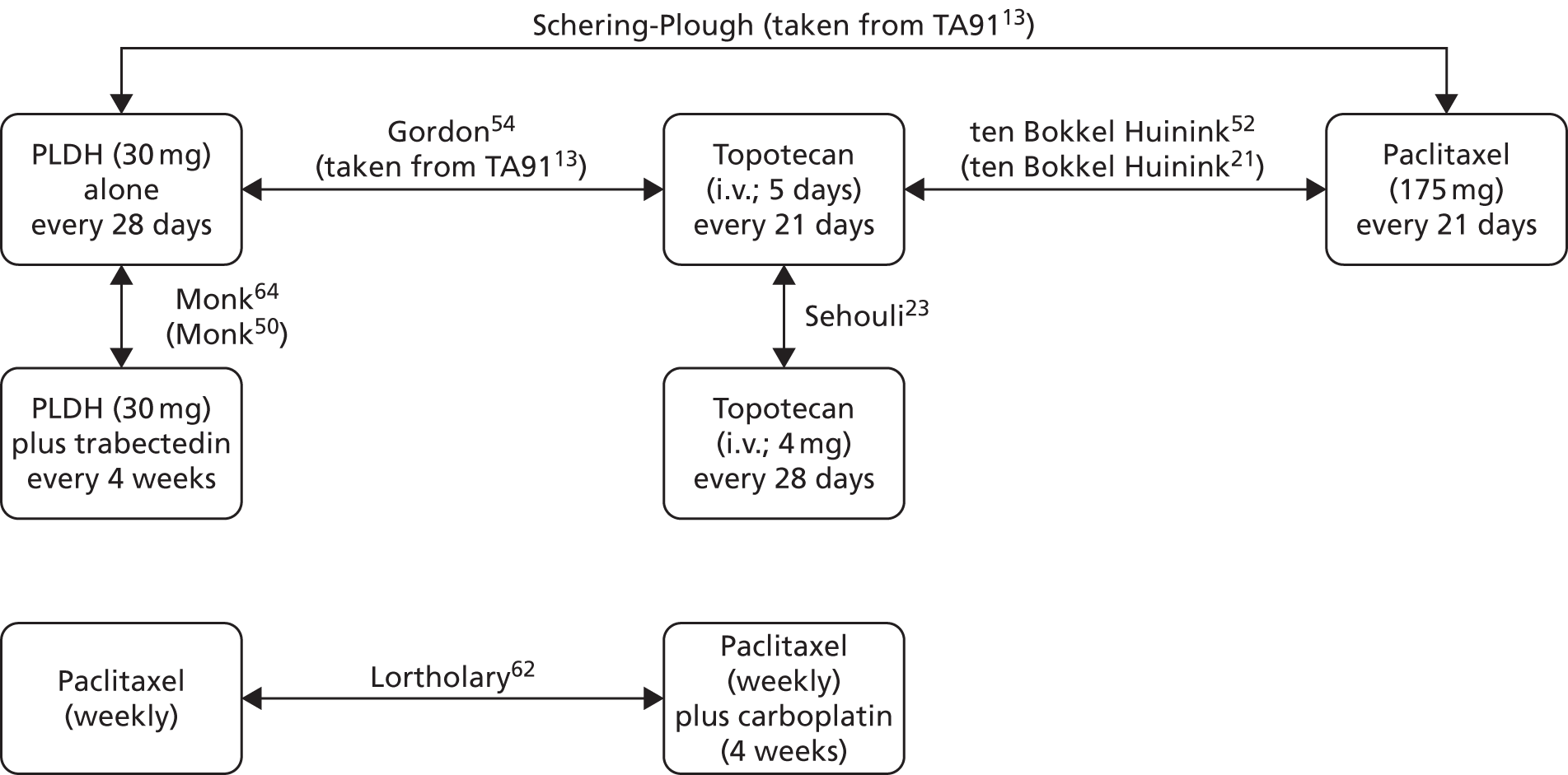

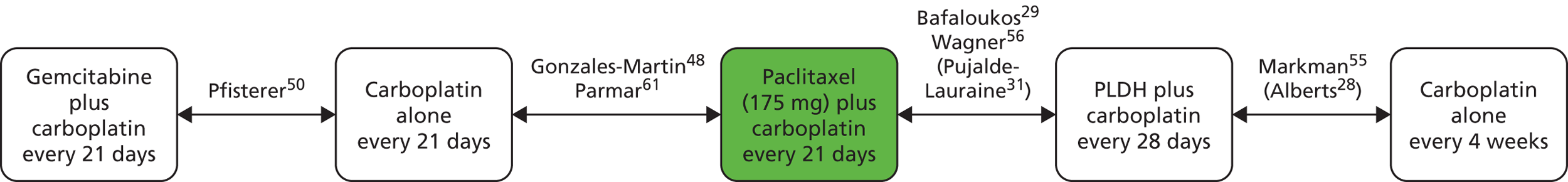

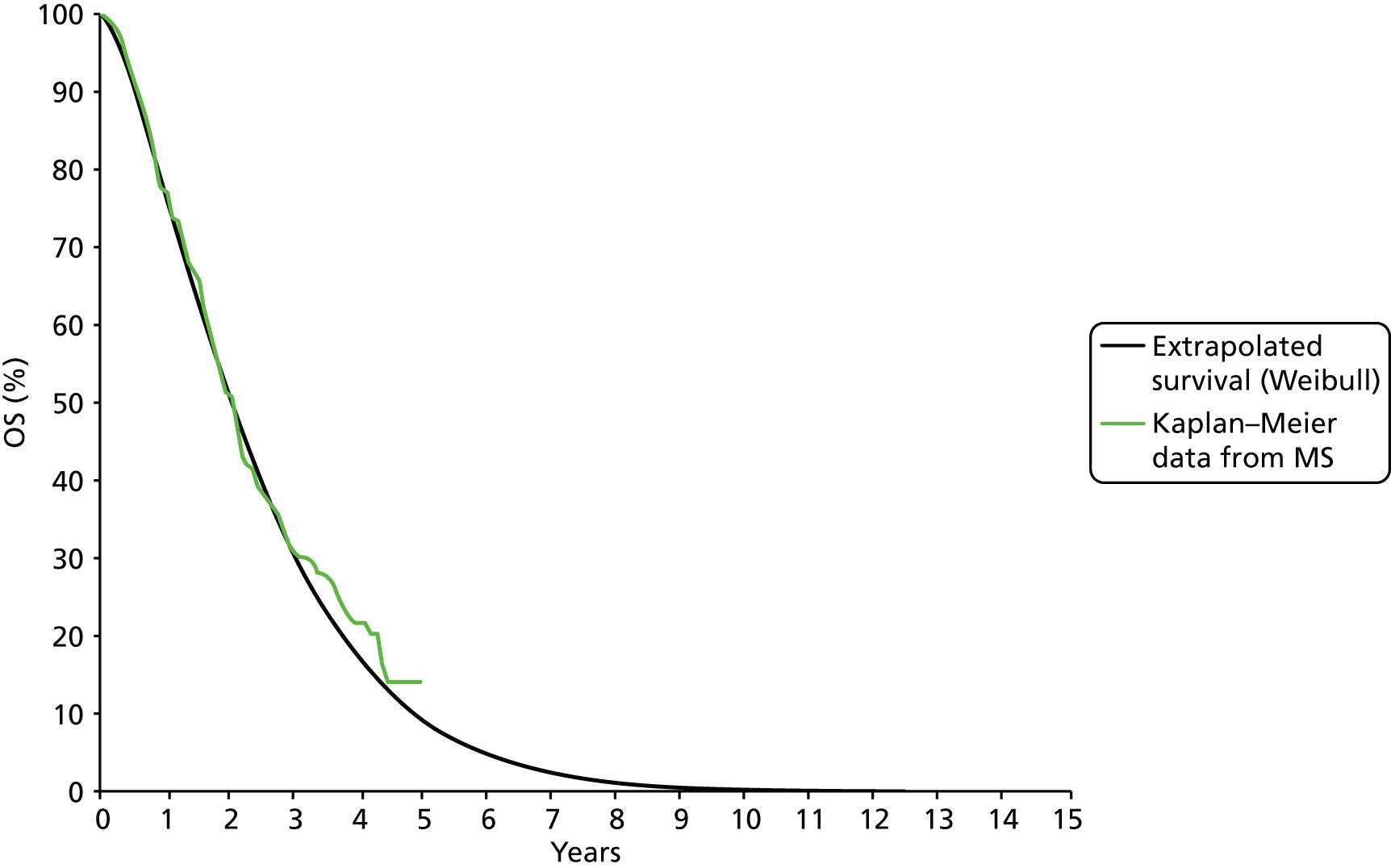

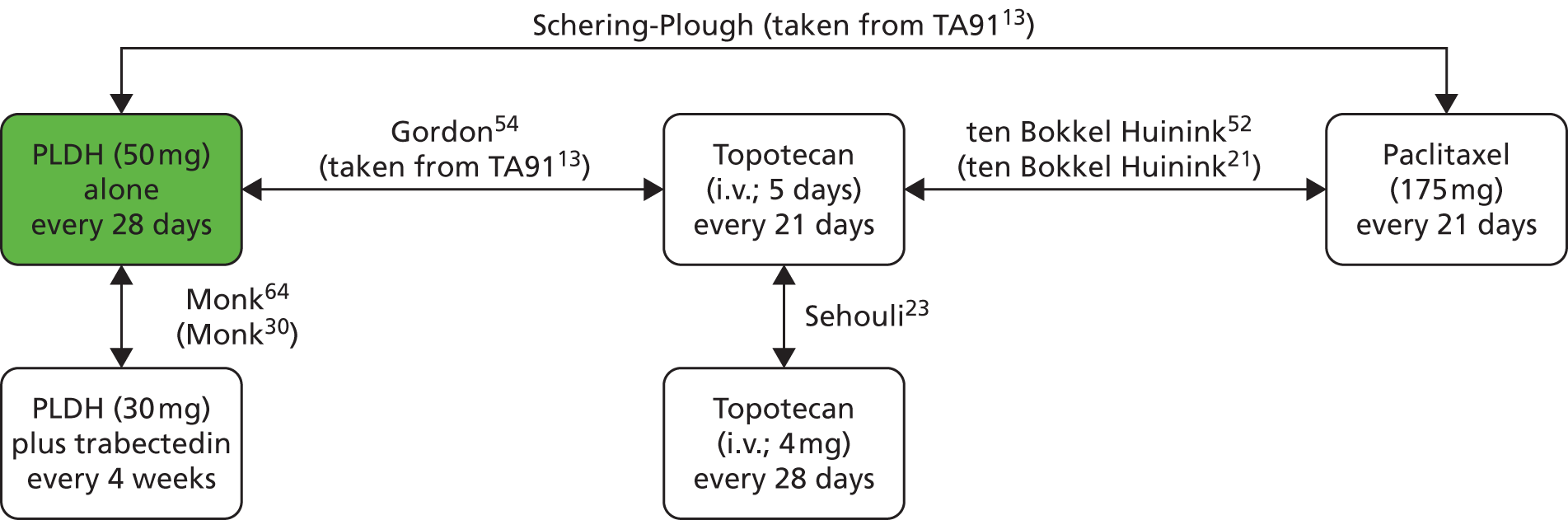

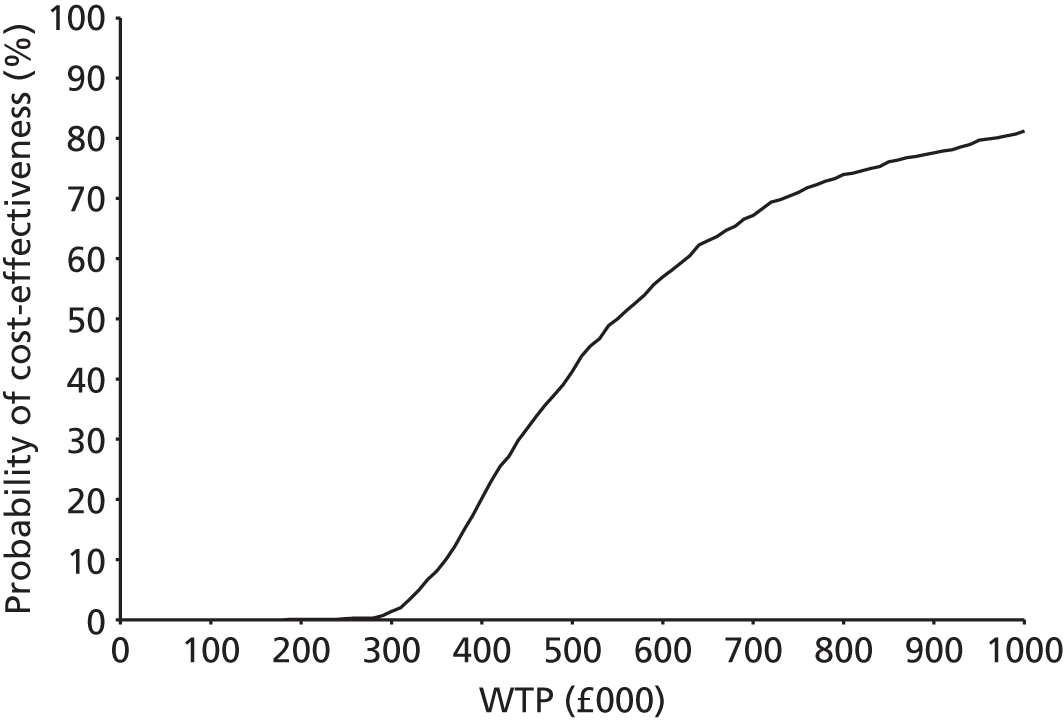

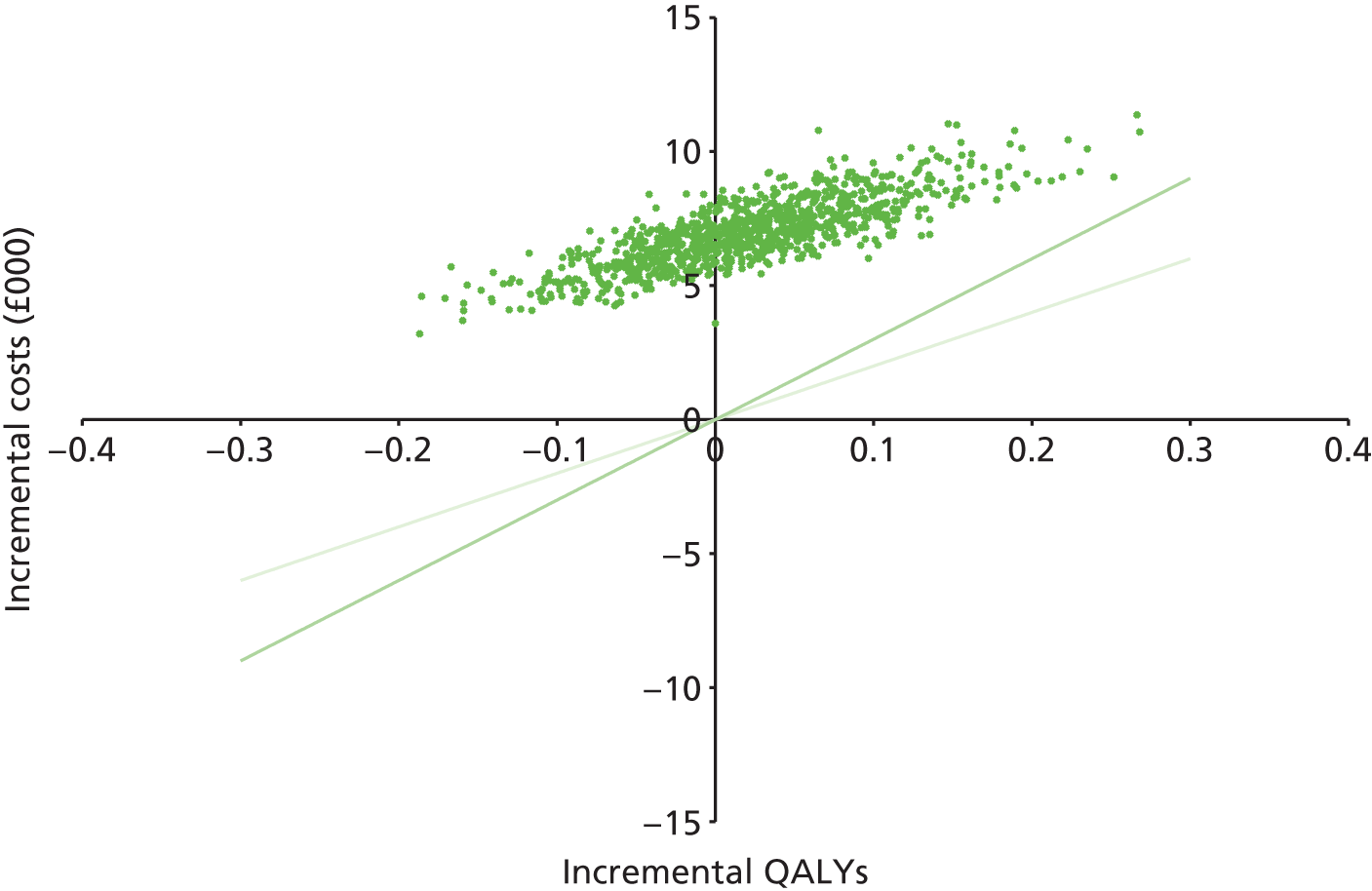

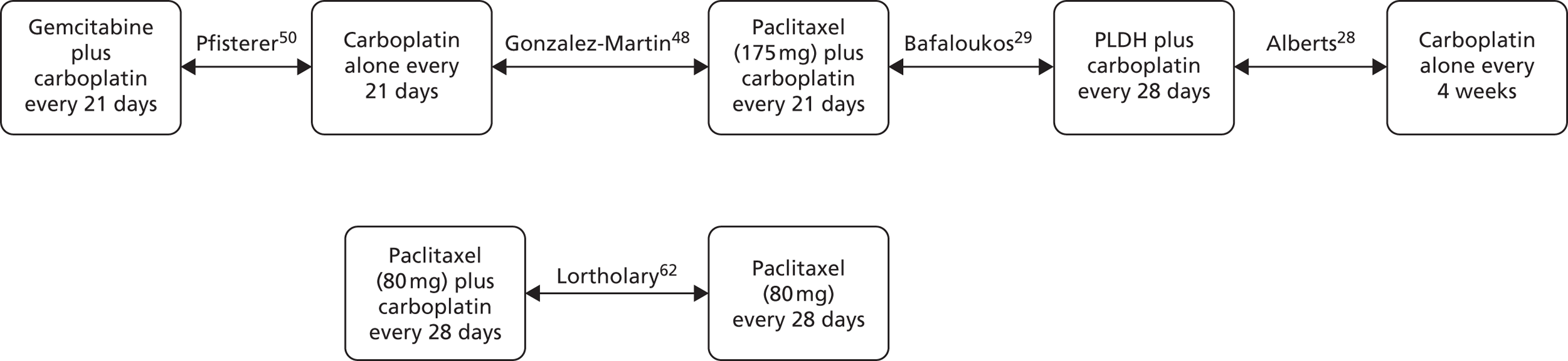

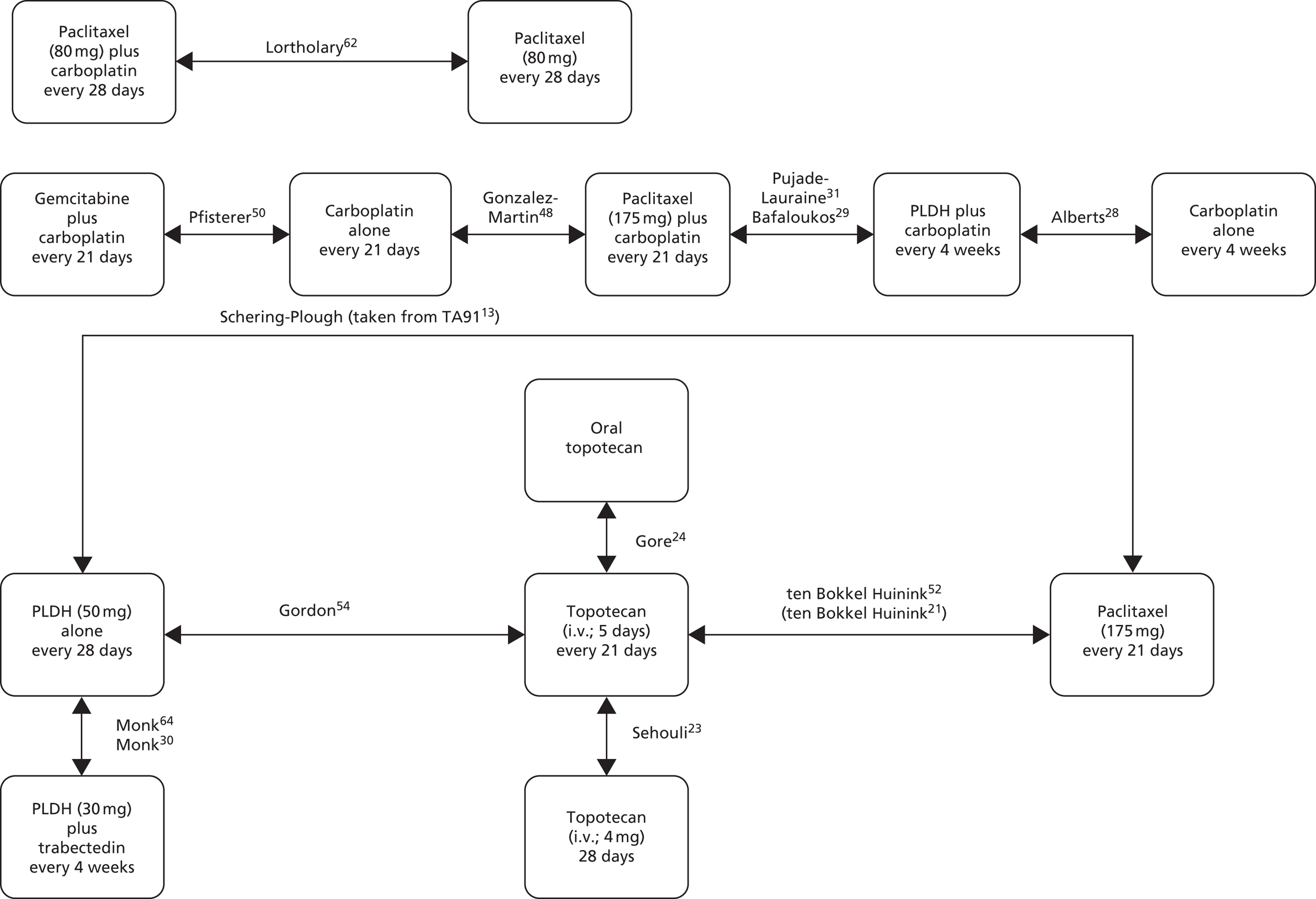

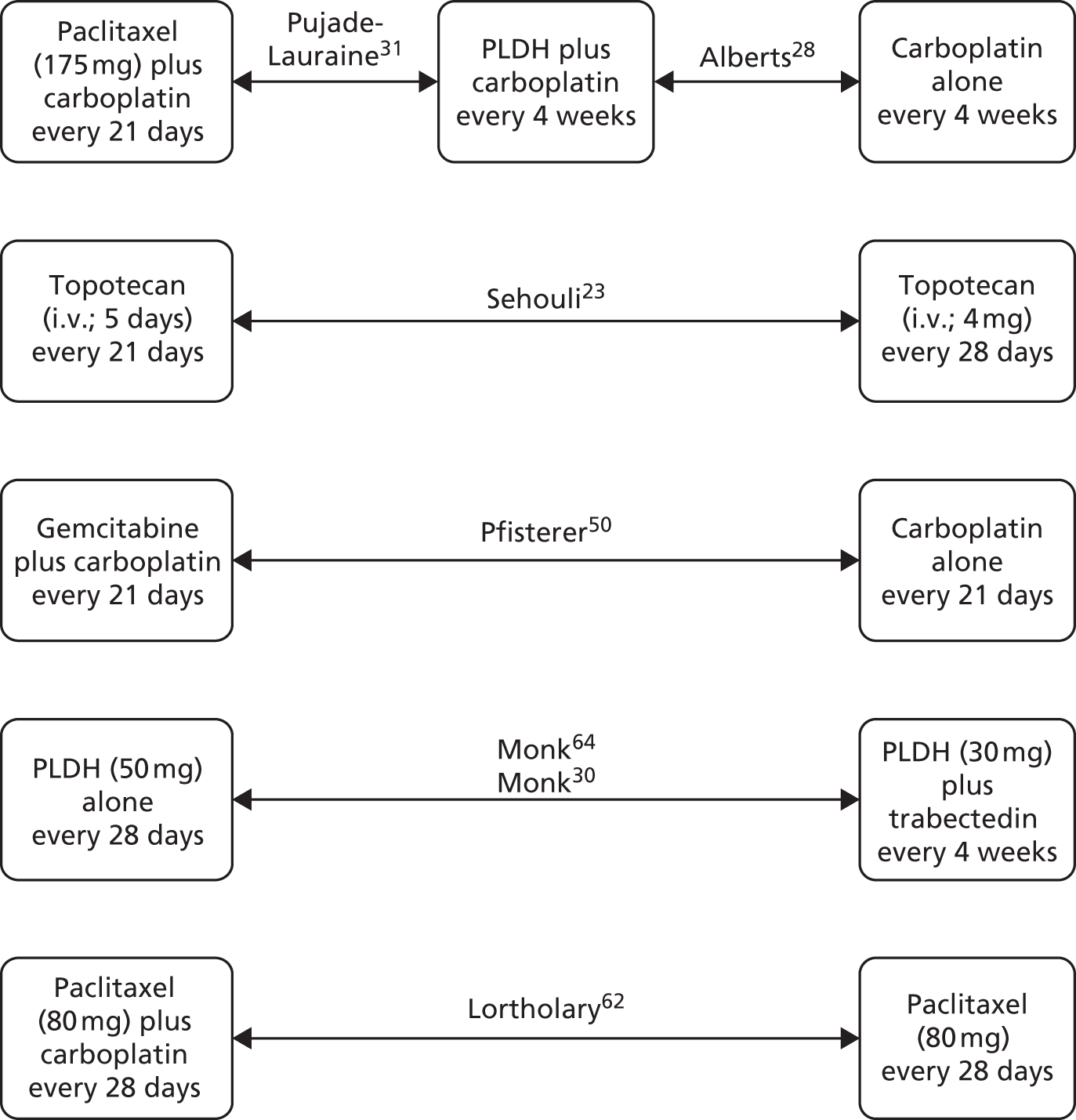

The choice of second and subsequent lines of treatment has long been based on a patient’s PFI, i.e. the period of time between the last treatment of one regimen and the first treatment of the next regimen. Current NICE guidance on second-line or subsequent treatment of advanced ovarian cancer is based on the duration of time since last platinum-based therapy, with treatment options of paclitaxel, either as a monotherapy or in combination with platinum-based (carboplatin or cisplatin) therapy, PLDH monotherapy and topotecan monotherapy. 10 Treatments options as recommended by NICE, based on degree of platinum sensitivity, are depicted in Figure 2. In recently completed technology appraisals (TAs), NICE did not recommend bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine (Gemzar®, Eli Lilly and Company) and carboplatin16 or trabectedin (Yondelis®, PharmaMar) plus PLDH17 for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer.

An important consideration in the choice of second-line treatment is the adverse effect of neurotoxicity, which is commonly associated with paclitaxel and also with carboplatin. Neurotoxicity can persist for up to 2 years after the end of treatment. 18 Patients who relapse after first-line treatment with paclitaxel–platinum combination therapy and are subsequently rechallenged with the same regimen within 12 months [i.e. those who are partially platinum sensitive (PPS)] are at an increased risk of developing neurotoxicity. 19 However, despite the associated increased risk of neurotoxicity, paclitaxel plus carboplatin is generally the preferred second-line treatment in UK practice in recurrent platinum-sensitive cancer, particularly for patients who relapse at > 12 months after completion of first-line chemotherapy. Carboplatin is chosen over cisplatin because of its more favourable adverse effect profile.

Current service cost

An analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics for 2006–8 of patients dying from prostate, breast, lung, upper gastrointestinal, colorectal or ovarian cancer indicates that patients with ovarian cancer and in their last year of life required 53,700 elective bed-days (at a cost of £14,274,623) and 216,723 emergency bed-days (at a cost of £58,606,527). 20 On a per-person basis, ovarian cancer had a longer elective stay and a longer emergency length of stay than the other cancers. 20 Ovarian cancer also had the highest overall cost, at £8000 per person. 20

Description of technologies under assessment

Topotecan

Topotecan is a semisynthetic, water-soluble derivative of camptothecin, a natural product isolated from the tree Camptotheca acuminate. 21 Topotecan elicits a chemotherapeutic effect through inhibition of the topoisomerase I enzyme, which has a crucial role in cell replication. Topoisomerase enzymes are involved in DNA replication, acting to relieve strain in the double-stranded DNA helix by ‘cutting’ one strand to release tension followed by reconnection of the two separate strands. Topotecan binds to the topoisomerase I–DNA complex, thus blocking the action of topoisomerase I and preventing re-formation of the DNA double helix.

Topotecan is licensed for the treatment of patients with metastatic carcinoma of the ovary after failure of at least one other treatment (i.e. topotecan is licensed as a second- and subsequent-line treatment). 22 The initial recommended dose of topotecan is 1.5 mg/m2 of body surface area (BSA), to be administered by intravenous (i.v.) infusion over 30 minutes for five consecutive days, with a 3-week interval between the start of each course. 22 It is recommended that topotecan be given for a minimum of four cycles. If well tolerated, treatment can be continued until disease progression. Topotecan should be administered under the supervision of a clinician experienced in the use of chemotherapy. Topotecan has also been evaluated in randomised controlled trials (RCTs) at an i.v. dose of 4.0 mg/m2 weekly,23 and as an oral treatment (dose of 2.3 mg/m2/day). 24 A dose for oral administration of topotecan has not been recommended for ovarian cancer.

Topotecan is contraindicated in patients who:22

-

have a history of severe hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients

-

are breastfeeding

-

already have severe bone marrow depression before starting the first course, as evidenced by baseline neutrophil count of < 1.5 × 109/l and/or a platelet count of < 100 × 109/l.

Special warnings and precautions for use of topotecan include haematological toxicity, severe myelosuppression, topotecan-induced neutropenia, development of interstitial lung disease and thrombocytopenia. 22

The most common adverse events (AEs) associated with topotecan (reported by at least 1 out of 10 patients) are infection; febrile neutropenia; neutropenia; thrombocytopenia; anaemia; leucopenia; anorexia (which may be severe); nausea; vomiting; diarrhoea; constipation; mucositis; abdominal pain; alopecia; pyrexia; asthenia; and fatigue. 22

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride

The active component in PLDH is doxorubicin hydrochloride, which is a member of the anthracycline class of antibiotics. Anthracyclines act by inhibiting synthesis, transcription and replication of DNA, and have potent antineoplastic (inhibits the growth and spread of cancerous cells) activity. 25 However, anthracyclines are also highly destructive to cellular membranes and are known to generate chemical species (oxygen-derived free radicals) that, as well as directly damaging DNA, are thought to damage the membranes of the heart, which may lead to congestive heart failure. 25 Cardiotoxic adverse effects of anthracyclines are irreversible and accumulative, and limit the clinical usefulness of this class of antibiotics.

Liposomes are minuscule spheres comprising a lipid bilayer, which can be used as vehicles for the administration of drugs. Coating the liposomes with methoxypolyethylene glycol (MPEG), a process known as pegylation, protects the liposome from detection by the body’s immune system. Encapsulation of doxorubicin hydrochloride in pegylated liposomes seems to increase the localisation and concentration of doxorubicin hydrochloride in cancerous cells, while simultaneously reducing the toxicity of doxorubicin hydrochloride to non-cancer tissues and cells, and, thereby, reducing the risk of severe adverse effects. 26

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride (2 mg doxorubicin hydrochloride in a pegylated liposomal formulation) is licensed for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in women who have failed a first-line platinum-based chemotherapy regimen. 27 The licensed dose of PLDH when given as a monotherapy is 50 mg/m2 given intravenously once every 4 weeks for as long as disease does not progress and the patient continues to tolerate treatment;27 clinical expert advice is that typical UK clinical practice is to administer PLDH at a dose of 40 mg/m2. It should not be administered as a bolus injection or undiluted solution. PLDH should be given under the supervision of a clinician who is qualified in the use of cytotoxic medicines. 27 Importantly, PLDH cannot be interchanged with other medicines containing doxorubicin hydrochloride.

Randomised controlled trials have also evaluated PLDH in combination with other agents, both platinum-based and non-platinum based. 28–31 No dose has been recommended for PLDH when used in combination treatment. Doses of PLDH evaluated in doublet chemotherapy were 30 mg/m2 in combination with trabectedin30 and with carboplatin,28,31 and 45 mg/m2 in combination with carboplatin. 29 In all RCTs, the interval between cycles was 4 weeks. Clinical experts fed back that PLDH would most likely be used at a dose of 30 mg/m2 in combination regimens.

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride is contraindicated in people with hypersensitivity to the active substance or to any of the excipients. 27 Special warnings and precautions for use of PLDH include cardiac toxicity, myelosuppression, and infusion-associated reactions. 27 It is recommended that all patients receiving PLDH routinely undergo frequent electrocardiogram (ECG) monitoring. 27

The most common undesirable adverse effect associated with PLDH (50 mg/m2 every 4 weeks) treatment in breast cancer and ovarian cancer RCTs was palmar–plantar erythrodysaesthesia (PPE), which is characterised by painful, macular, reddening skin eruptions. 27 The overall incidence of PPE was 44.0–46.1%. 27 These effects were reported to be predominantly mild, with severe (grade III) cases reported in 17–19.5% of patients. 27 The reported incidence of life-threatening (grade IV) cases was < 1%. 27

In patients with ovarian cancer, the most common adverse effects (reported by at least 1 out of 10 patients) associated with PLDH treatment were leucopenia; anaemia; neutropenia; thrombocytopenia; anorexia; constipation; diarrhoea; nausea; stomatitis; vomiting; PPE; alopecia; rash; asthenia; and mucous membrane disorder. Clinically significant laboratory abnormalities associated with PLDH included increases in total bilirubin (usually in patients with liver metastases) (5%) and serum creatinine levels (5%). 27

Paclitaxel

Paclitaxel is a taxane, a class of drugs isolated from the Pacific yew tree (Taxus brevifolia). 32 Paclitaxel targets a protein that is a key component of microtubules. Microtubules are important in various cellular processes, including the initiation of DNA synthesis. Unlike other taxanes, which inhibit microtubule assembly, paclitaxel stabilises the microtubule polymer, protecting the microtubule from disassembly and, therefore, further involvement in cellular processes.

In the UK, paclitaxel is licensed as first-line chemotherapy in combination with cisplatin or carboplatin for ovarian cancer patients with advanced carcinoma of the ovary or with residual disease (> 1 cm) after initial laparotomy. 33 Paclitaxel is also licensed as a second-line chemotherapy for ovarian cancer after failure of standard, platinum-containing therapy. 33 The recommended dose for paclitaxel when used as a second- and subsequent-line treatment is 175 mg/m2 administered over a period of 3 hours, followed by a platinum-based compound, with a 3-week interval between courses of treatment. 33 Prior to treatment with paclitaxel, patients should undergo pre-treatment with corticosteroids, antihistamines and H2-receptor antagonists. 33

Paclitaxel is contraindicated during lactation and should not be used in patients with a baseline neutrophil count of < 1500/mm3. 33 Special warnings and precautions for use of paclitaxel include hypersensitivity reactions and bone marrow suppression (primarily neutropenia). 33 Patients with hepatic impairment may be at increased risk of toxicity, particularly grade 3 and grade 4 myelosuppression. 33

The most common adverse effects associated with paclitaxel (reported by at least 1 out of 10 patients) are infection (mainly urinary tract and upper respiratory tract infections); myelosuppression; neutropenia; anaemia; thrombocytopenia; leucopenia; bleeding; minor hypersensitivity reactions (mainly flushing and rash); neurotoxicity (mainly peripheral neuropathy); hypotension; diarrhoea; vomiting; nausea; mucosal inflammation; alopecia; arthralgia; and myalgia. 33

Trabectedin

Trabectedin is a synthetic antineoplastic drug, the structure of which is derived from a natural product originally extracted from the marine Caribbean tunicate (‘sea squirt’, a marine animal) Ecteinascidia turbinata. 34 Trabectedin binds to the minor groove of DNA, a process that triggers various events that affect multiple transcription factors, DNA binding proteins and DNA repair pathways, and ultimately results in disruption of the cell cycle.

Trabectedin in combination with PLDH is licensed for the treatment of patients with relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. 35 PLDH is administered first at a dose of 30 mg/m2, immediately followed by administration of trabectedin as a 3-hour infusion at a dose of 1.1 mg/m2. The recommended interval between treatment cycles is 3 weeks. To minimise the risk of PLDH infusion reactions, the initial dose of PLDH is administered at a rate of no greater than 1 mg/minute. 35 If no infusion reaction is observed, subsequent PLDH infusions may be administered over a 1-hour period.

All patients should be treated with corticosteroids 30 minutes before administration of PLDH (in combination therapy) or trabectedin (when used as a monotherapy). 35 Corticosteroids not only act as antiemetic prophylaxis, but also seem to afford hepatoprotective effects. 35

Trabectedin is contraindicated in:35

-

people who are hypersensitive to trabectedin or to any of the excipients

-

people who have concurrent serious or uncontrolled infection

-

people who are breastfeeding

-

concomitant combination with yellow fever vaccine.

Patients must meet specific criteria on hepatic function parameters before treatment (or re-treatment) with trabectedin can commence. 35 If patients do not meet the criteria listed below, treatment must be delayed for up to 3 weeks until the required levels are reached. Patients must have:

-

absolute neutrophil count of ≥ 1500/mm3

-

platelet count of ≥ 100,000/mm3

-

bilirubin level of less than or equal to the upper limit of normal (ULN)

-

alkaline phosphatase level of ≤ 2.5 × ULN

-

albumin level of ≥ 5 g/l

-

alanine transaminase and aspartate transaminase levels of ≤ 2.5 × ULN

-

creatinine clearance rate of ≥ 30 ml/minute (monotherapy), serum creatinine level of ≤ 1.5 mg/dl (≤ 132.6 µmol/l) or creatinine clearance rate of ≥ 60 ml/minute (combination therapy)

-

creatine phosphokinase level of ≤ 2.5 × ULN

-

haemoglobin level of ≥ 9 g/dl.

Additional special warnings and precautions for use of trabectedin include hepatic impairment; renal impairment; neutropenia; thrombocytopenia; nausea; vomiting; rhabdomyolysis; severe elevations of creatine phosphokinase level (> 5 × ULN); liver function test abnormalities; and injection site reactions. 35

The most common adverse effects associated with trabectedin (reported by at least 1 out of 10 patients) are neutropenia; leucopenia; anaemia; thrombocytopenia; anorexia; nausea; vomiting; constipation; stomatitis; diarrhoea; hyperbilirubinaemia; increase in alanine aminotransferase; increase in aspartate aminotransferase; increase in blood alkaline phosphatase; PPE syndrome; alopecia; fatigue; asthenia; mucosal inflammation; and pyrexia. 35

Gemcitabine

Gemcitabine is an analogue of the nucleoside deoxycytidine; in cells, nucleosides are modified enzymatically to produce nucleotides, which are the building blocks of RNA and DNA. As a nucleoside analogue, gemcitabine is a prodrug and, as such, once transported into a cell undergoes modification to produce the active form. 36 The activated form of gemcitabine replaces one of the nucleosides essential for DNA replication. Incorporation of the modified form of gemcitabine onto the growing DNA strand blocks further DNA synthesis and leads to apoptosis (cell death). 36

Gemcitabine is licensed for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic epithelial ovarian carcinoma, in combination with carboplatin, in patients with relapsed disease after a recurrence-free interval of at least 6 months after platinum-based, first-line therapy. 37 Gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin for the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer has not as yet been evaluated by NICE as part of the single technology appraisal (STA) process. When used as a treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer, it is recommended that gemcitabine be administered at a dose of 1000 mg/m2 as a 30-minute i.v. infusion on days 1 and 8 of each 21-day cycle. 37 Carboplatin should be administered after gemcitabine on day 1 of the cycle, and at a dose consistent with a target area under the curve (AUC) of 4.0 mg/ml/minute. Dosage reduction with each cycle or within a cycle may be applied based on the grade of toxicity experienced by the patient. 37

Gemcitabine is contraindicated in people who are hypersensitive to the active substance or to any of the excipients and in those who are breastfeeding. 37 Prolongation of the infusion time of gemcitabine and increased dosing frequency have been shown to increase toxicity. 37 Additional special warnings and precautions for use of gemcitabine include haematological toxicity, hepatic insufficiency, concomitant radiotherapy, use with concomitant live vaccinations (e.g. yellow fever), risk of cardiac and/or vascular disorders, pulmonary effects, renal effects, and effects on sodium levels.

The most common adverse effects (reported by at least 1 out of 10 patients) associated with gemcitabine treatment are leucopenia; bone marrow suppression (typically mild to moderate); thrombocytopenia; anaemia; dyspnoea (usually mild and passes rapidly without treatment); vomiting; nausea; elevation of liver transaminases and alkaline phosphatase; allergic skin rash; haematuria; mild proteinuria; influenza-like symptoms; and oedema/peripheral oedema. 37

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Population including subgroups

The population of interest is people with ovarian cancer that has recurred after first-line (or subsequent) platinum-based chemotherapy or that is refractory to platinum-based chemotherapy.

Subgroups of particular interest are:

-

people with platinum-sensitive recurrent ovarian cancer (i.e. relapse at ≥ 6 months after completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy), who will be divided further, evidence permitting, into those with partial (i.e. relapse within 6–12 months) and those with full platinum sensitivity (i.e. relapse at ≥ 12 months)

-

people with platinum-resistant (i.e. relapse within 6 months of completion of initial platinum-based chemotherapy) or platinum-refractory (i.e. disease that does not respond to initial platinum-based chemotherapy) recurrent ovarian cancer

-

those who are allergic to platinum-based treatment.

Interventions

The technology assessment report considers five interventions used within their licensed indication:

-

paclitaxel alone or in combination with platinum chemotherapy

-

PLDH alone or in combination with platinum chemotherapy

-

gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin

-

trabectedin in combination with PLDH

-

topotecan.

As per the final protocol,38 the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the five interventions of interest have been evaluated in the prespecified subgroups listed above (see Population including subgroups). Interventions of interest for the individual subgroups are presented in Table 4.

| Population | Interventions of interest |

|---|---|

| Platinum sensitive |

|

| Platinum resistant or platinum refractory |

|

| People who are allergic to platinum-based compounds |

|

Relevant comparators

As per the final protocol,38 the relevant comparators have been evaluated based on the prespecified subgroups listed above (see Population including subgroups). Comparators of interest listed by individual subgroup are presented in Table 5.

| Population | Comparators of interest |

|---|---|

| Platinum sensitive |

|

| Platinum resistant or platinum refractory |

|

| People who are allergic to platinum-based compounds |

|

In the final protocol, bevacizumab in platinum-containing chemotherapy was listed as a potential comparator of interest for platinum-sensitive patients subject to appraisal by NICE. 38 Subsequent to finalisation of the protocol, the outcome of the NICE STA was not to recommend bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and carboplatin for the treatment of first recurrence of platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. 16 Therefore, bevacizumab in platinum-containing chemotherapy has not been evaluated as a comparator in this group of patients.

Outcomes

The outcomes of interest considered for this review included:

-

OS

-

progression-free survival (PFS)

-

overall response rate (ORR)

-

adverse effects of treatment

-

HRQoL.

In addition to PFS, although not listed in the final protocol, time to progression (TTP) was also analysed in the evaluation of clinical effectiveness.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The purpose of this report is to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of paclitaxel (monotherapy or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy), PLDH (monotherapy or in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy), gemcitabine in combination with carboplatin, trabectedin in combination with PLDH, and topotecan as a monotherapy within their licensed indications for the treatment of advanced ovarian cancer that has relapsed after first-line treatment with a platinum-based regimen.

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Evidence for the clinical effectiveness of topotecan, PLDH, paclitaxel, trabectedin and gemcitabine was assessed by conducting a systematic review of published research evidence. The review was undertaken following the general principles published by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). 39 The protocol for the systematic review was registered on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42013003555).

Identification of studies

The literature search for this review was designed to update and expand the systematic search carried out in TA91, which evaluated the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of topotecan, PLDH and paclitaxel. 13 Medical subject heading (MeSH) and text terms for ovarian cancer, topotecan, PLDH and paclitaxel were taken from the search strategy presented in TA91, and text terms added for the interventions trabectedin and gemcitabine. To ensure the capture of all potentially relevant studies to inform a network meta-analysis (NMA), the decision was taken not to restrict the start date of the update search to the end date of the search (2004) reported in TA91.

As a result of the large number of studies retrieved from the scoping search, the decision was taken to implement search filters for RCT. Filters developed and validated by Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network were used. 40 The identified RCTs facilitated construction of three distinct networks for the outcomes of OS and PFS for both the platinum-sensitive (two networks) and platinum-resistant/-refractory (PRR) (one network) subgroups. In an attempt to identify a study to link the discrete networks for the platinum-sensitive subgroup, the retrieved abstracts were re-examined to consider interventions that were outside the scope of this review. Owing to time constraints, the decision was taken not to search for non-randomised trials. Bibliographies of previous reviews and retrieved articles were searched for additional studies. Clinical trial registries were also searched to identify planned, ongoing and finalised clinical trials of interest. In addition, clinical experts were contacted with a request for information on any additional studies of which they had knowledge. The manufacturer submissions (MSs) were assessed for unpublished data. Electronic databases searched were EMBASE, MEDLINE® and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Although the protocol stipulates that the Index of Scientific and Technical Proceedings would be searched to identify relevant conference proceedings, owing to time constraints this was not undertaken. However, based on the conference abstracts retrieved from the search of the prespecified electronic databases, the Technology Assessment Group (TAG) considers it likely that the key conference abstracts have been identified. Conference abstracts that were reviewed and found not to report additional results to those presented in the relevant full publication were excluded.

Electronic databases were initially searched on 18 January 2013 and results uploaded into Reference Manager version 11.0 (Thomson Research Soft, San Francisco, CA, USA) and deduplicated. An update search was carried out on 23 May 2013. No papers or abstracts published after this date were included in the review. Full details of the strategies are presented in Appendix 1.

Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were examined independently by two researchers (SB and TK) and screened for possible inclusion. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, or involvement of a third reviewer (SJE) in cases for which consensus could not be achieved. Full texts of potentially relevant studies were ordered. Full publications were assessed independently by two reviewers (SB and TK/AS) for inclusion or exclusion against prespecified criteria, with disagreements resolved by discussion or input from a third reviewer when consensus could not be achieved.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the review of clinical effectiveness, only RCTs were considered for inclusion in the review. Systematic reviews and non-randomised studies were excluded, as were studies that considered drugs administered as ‘maintenance therapy’ following directly on from first-line therapy without evidence of disease progression. Inclusion criteria were based on the decision problem outlined in Chapter 2 (see Decision problem) (presented as a whole in Table 6). No restrictions were imposed on language or date of publication. Reference lists of identified systematic reviews were used as a source of potential additional RCTs, as well as a resource to compare studies retrieved from the systematic literature search.

As in TA91,13 second-line chemotherapy was defined as the second chemotherapy regimen, administered either as a result of relapse after first-line therapy or immediately following on from first-line therapy in patients with progressive disease (PD) or stable disease (SD). The definition applied in cases where the second-line regimen comprised the same treatments as the first-line regimen.

For the purposes of this review, based on expert opinion, supportive care was defined as treatment for recurrent ovarian cancer that does not have an anti-tumour mode of action.

| PICO | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Study design | RCTs |

| Population | People with ovarian cancer that has recurred after first-line (or subsequent) platinum-based chemotherapy or is refractory to platinum-based chemotherapy |

| Interventions | For people with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer:

|

| Comparators | For people with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer:

|

Data abstraction strategy

Data pertaining to study design, methodology, baseline characteristics, and clinical outcomes efficacy were extracted by two reviewers (TK/AS) into a standardised data extraction form and validated by a second (SB). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion when necessary. Authors of reports published as meeting abstracts only, where insufficient methodological details were reported to allow critical appraisal of study quality were contacted with a request for additional information. If no additional information was obtained, the studies were excluded. Data abstraction forms for the included studies are provided in Appendix 2.

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality of the clinical effectiveness data was assessed by two independent reviewers (TK and SB) and checked for agreement. The study quality was assessed according to recommendations by the NHS CRD39 and Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions41 and recorded using the Cochrane risk of bias tool. 41

Methods of data synthesis

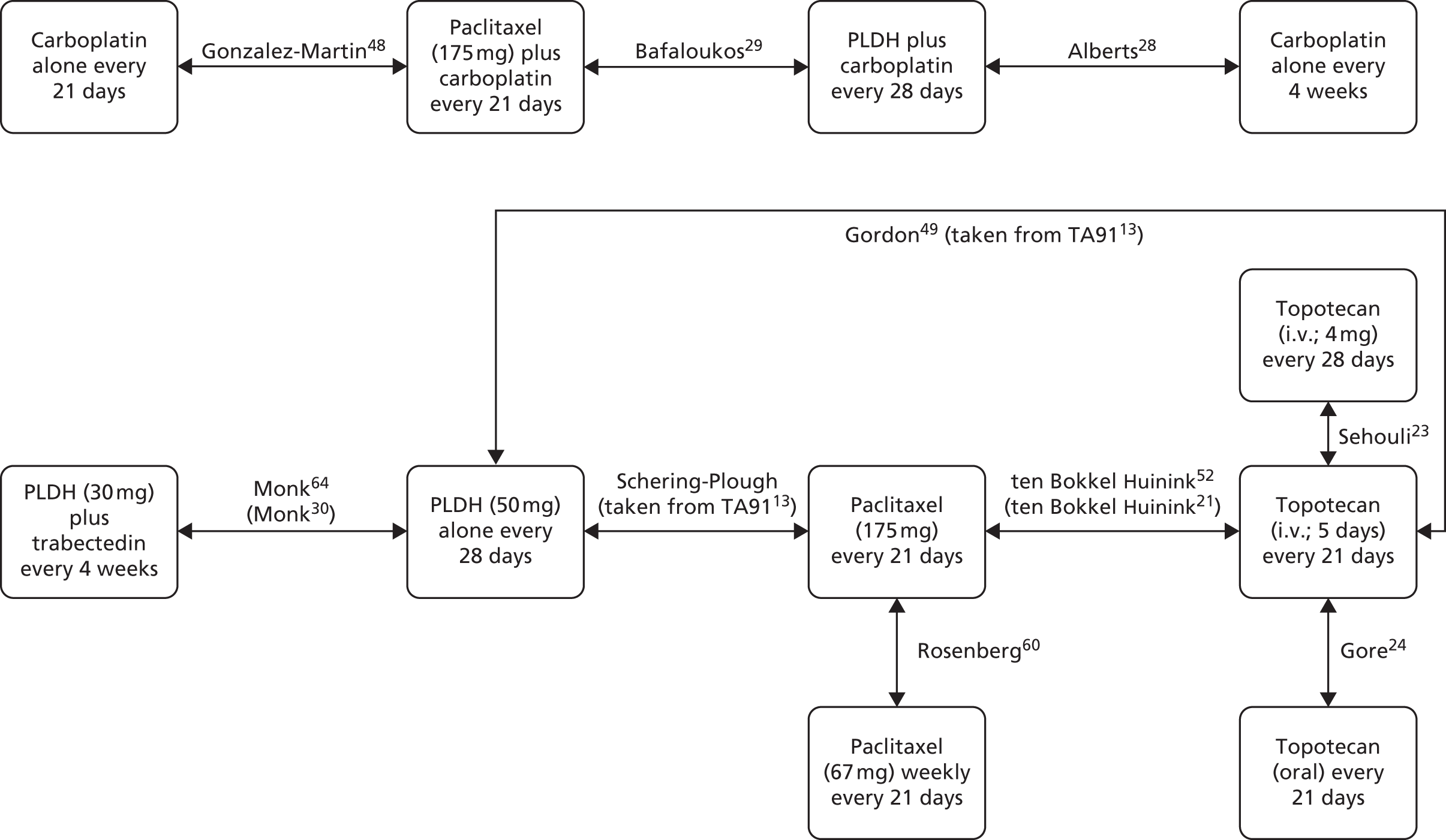

Details of results on clinical effectiveness and quality assessment for each included study are presented in structured tables and as a narrative summary. The possible effects of study quality on the clinical effectiveness data and review findings are discussed. The 16 RCTs identified evaluated 14 different pairwise comparisons. Therefore, there were insufficient data for most comparisons to carry out a standard pairwise meta-analysis. However, the TAG determined that the data identified were sufficiently homogeneous to investigate comparative effectiveness of interventions via a NMA. The methods used for the NMA followed the guidance described in the NICE Decisions Support Units (DSUs) Technical Support Documents (TSDs) for Evidence Synthesis. In essence, a NMA assumes that each trial included in the network could have potentially included all treatments of interest but that some of these treatments are missing completely at random (MCAR). To illustrate this further, in a simple indirect comparison of three treatments A, B and C, the trials of A compared with B and of B compared with C are assumed to have been potentially trials of A compared with B compared with C but where one arm from each trial is MCAR. In this example, an estimate of the relative treatment effect of A compared with C can be inferred using treatment B as a common comparator.

The TAG conducted a NMA for each network using a Bayesian Markov chain Monte Carlo simulation in WinBUGS version 1.43 (MRC Biostatistics Unit, Cambridge, UK). The following were implemented for each analysis:

-

Uninformed priors (also called ‘flat’ priors) were used.

-

All outcomes were considered independent. For example, although OS and PFS might be correlated in advanced ovarian cancer, the degree of correlation is unlikely to be derived from summary trial estimates provided in published papers. 42 As such, in the absence of individual patient data (IPD), the TAG took the pragmatic approach of assuming all efficacy and safety outcomes were independent.

-

Results for all efficacy outcomes analysed were based on 50,000 iterations after a ‘burn-in’ of 30,000 iterations. For safety outcomes all analyses had a ‘burn-in’ of 30,000 iterations, with results based on 100,000 iterations.

-

Summary effect estimates for OS and PFS were hazard ratios (HRs), whereas ORR and all safety outcomes used odds ratios (ORs) as summary effect estimates.

-

As a result of disparity in HRs reported in the identified trials, in terms of unadjusted HRs compared with adjusted HRs, together with variation in adjustment factors, for consistency the TAG used only unadjusted HRs in the NMA.

-

Any results taken forward into the economic model (see Chapter 4, Treatment effectiveness) used the posterior sampling to retain the correlation between parameter estimates caused by their joint estimation from a single data set. 43

However, the ability of the TAG to conduct NMAs was limited by the low number of trials identified (typically only one trial per treatment comparison). The constraints imposed by the limited number of trials available for analysis were:

-

Implementation of a fixed-effects model for all analyses. Although it was planned that fixed- and random-effects models would be explored and the model with the lowest deviance information criterion selected as the preferred model, the sparse number of trials available necessitated the use of a fixed-effects model. Using an uninformed prior for the between trial heterogeneity in a random-effects model ‘overwhelmed’ the influence of the available data for analysis with the posterior estimation of tau approximating the prior value used. Identification of an alternative source for the prior, for example from an existing systematic review, was explored but no suitable review was identified. 43 As such, despite the potential clinical heterogeneity from two studies, which are discussed in detail later (see Comparability of baseline characteristics), the TAG made the pragmatic decision to use a fixed-effects model in the absence of any reliable estimate available.

-

Disconnected networks identified for each outcome assessed. The trials identified in the clinical systematic review were unable to populate a single network for any of the outcomes assessed. A wider selection of treatments was assessed, as the systematic review was conducted in such a way as to identify all trials with at least one intervention of interest present. Unfortunately this did not uncover trials that could link the disconnected networks together. 44 In addition, the TAG’s clinical advisors did not consider any of the suggested assumptions to link the disconnected networks together to have face validity.

-

Heterogeneity and inconsistency. The networks constructed, typically ‘linear’ in nature, and the sparse number of trials available, typically only one per pairwise comparison, prevented the TAG from exploring any potential heterogeneity or inconsistency in each analysis.

The potential impact of these limitations is discussed where the results are reported.

Manufacturer submissions

All data submitted by the manufacturers were assessed. Data presented that met the inclusion criteria, and had not been identified in another published source, were extracted and quality assessed in accordance with the procedures outlined in this protocol. Economic evaluation included in the MSs, which complied with NICE’s advice on presentation, was assessed for clinical validity, reasonableness of assumptions and appropriateness of the data used in the economic model (see Description and critique of manufacturer submitted evidence).

Interpreting the results from the clinical trials

Clinical effectiveness

For the outcomes of OS and PFS/TTP, which are time-to-event outcomes, most trials identified evaluated comparative clinical effectiveness using a HR, which is the ratio of the hazard (e.g. death or progression) rate between two groups. Typically, a reported HR of < 1 indicates that the event of interest is occurring more slowly in the experimental group compared with the control group. In some trials identified, HR of > 1 (i.e. event occurs more frequently in the experimental group) is reported to favour a treatment. In these instances, the event recorded is not the hazard but the opposite event, i.e. survival or no progression over time. For the purposes of this review, PFS and TTP have been reported and evaluated under the outcome heading of PFS. Many trials identified also assess the extent to which a tumour shrinks compared with initial size, which is the response rate. Response rate is a dichotomous event (i.e. patients either respond or do not respond) and is reported as the proportion of patients achieving a response according to prespecified criteria.

Adverse effects

Many trials evaluating chemotherapeutic treatments categorise the severity of adverse effects based on criteria developed by the National Cancer Institute (NCI), one aim of which was to standardise reporting of adverse effects. 45 According to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC),46 adverse effects are graded from 0 to 5, with increasing grade indicating more severe adverse effects (Table 7). The NCI-CTC also provides a detailed list of adverse effects commonly occurring in oncology trials, together with clinical descriptions on grade of severity that are specific for each adverse reaction.

| Grade | Degree of severity |

|---|---|

| 1 | Mild; with no or mild symptoms; no interventions required |

| 2 | Moderate; minimal intervention indicated; some limitation of activities |

| 3 | Severe but not life-threatening; hospitalisation required; limitation of patient’s ability to care for him/herself |

| 4 | Life-threatening; urgent intervention required |

| 5 | Death related to AE |

Results

The RCTs meeting the inclusion criteria are discussed in the sections that follow. Initially, a summary of the quantity and quality of the evidence is provided, together with a table presenting an overview of the included trials. Additionally, a more detailed narrative description, together with an overview of trial quality, for each included trial is presented, including those trials previously identified in TA91. 13 A narrative description of population baseline characteristics and potential imbalances are discussed for each trial. Owing to the number of trials identified, baseline characteristics are not tabulated within the main body of the report but are provided within the data abstraction forms in Appendix 2. Instead, baseline characteristics for key prognostic factors in recurrent ovarian cancer (age, number of prior lines of chemotherapy, interval since last chemotherapy, and performance score) are presented for included trials in a summary table (see Table 10).

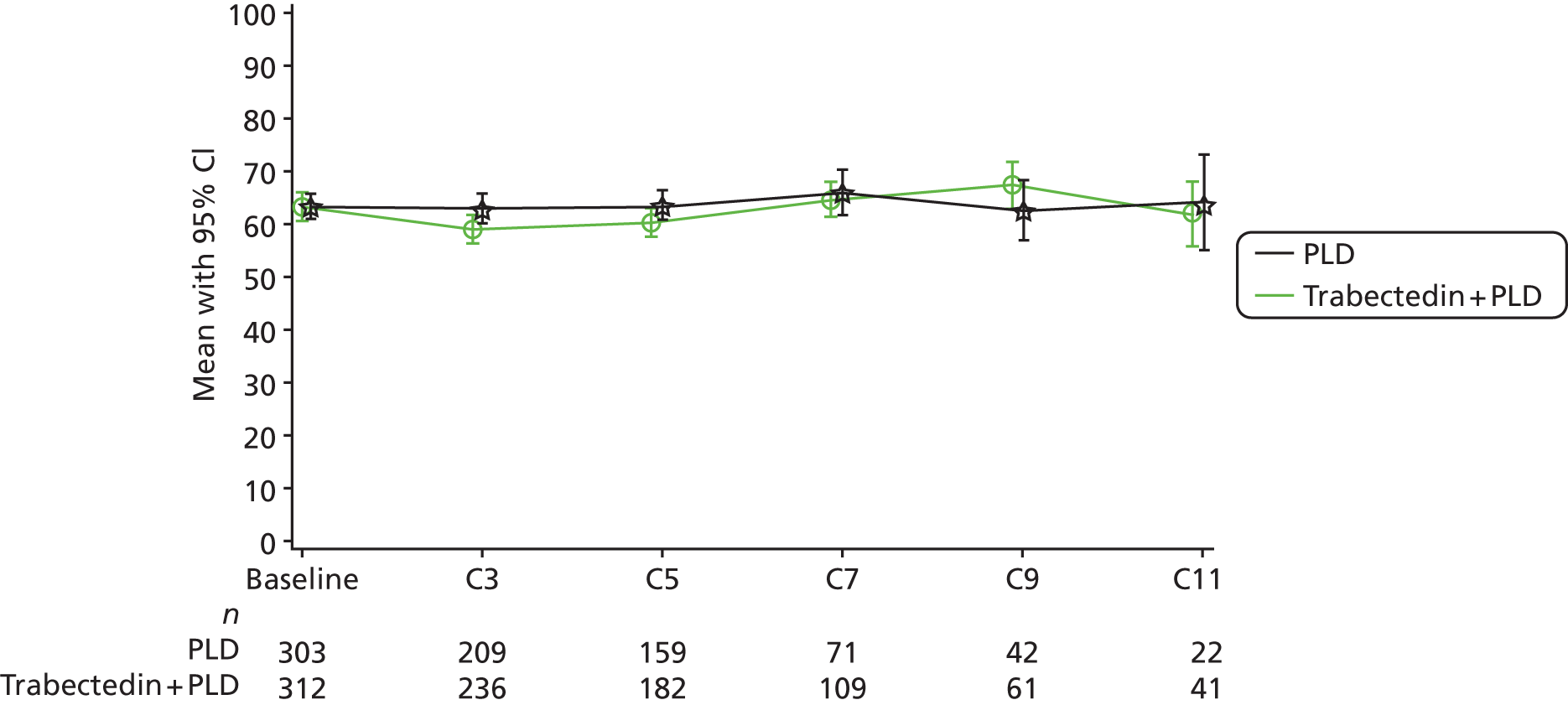

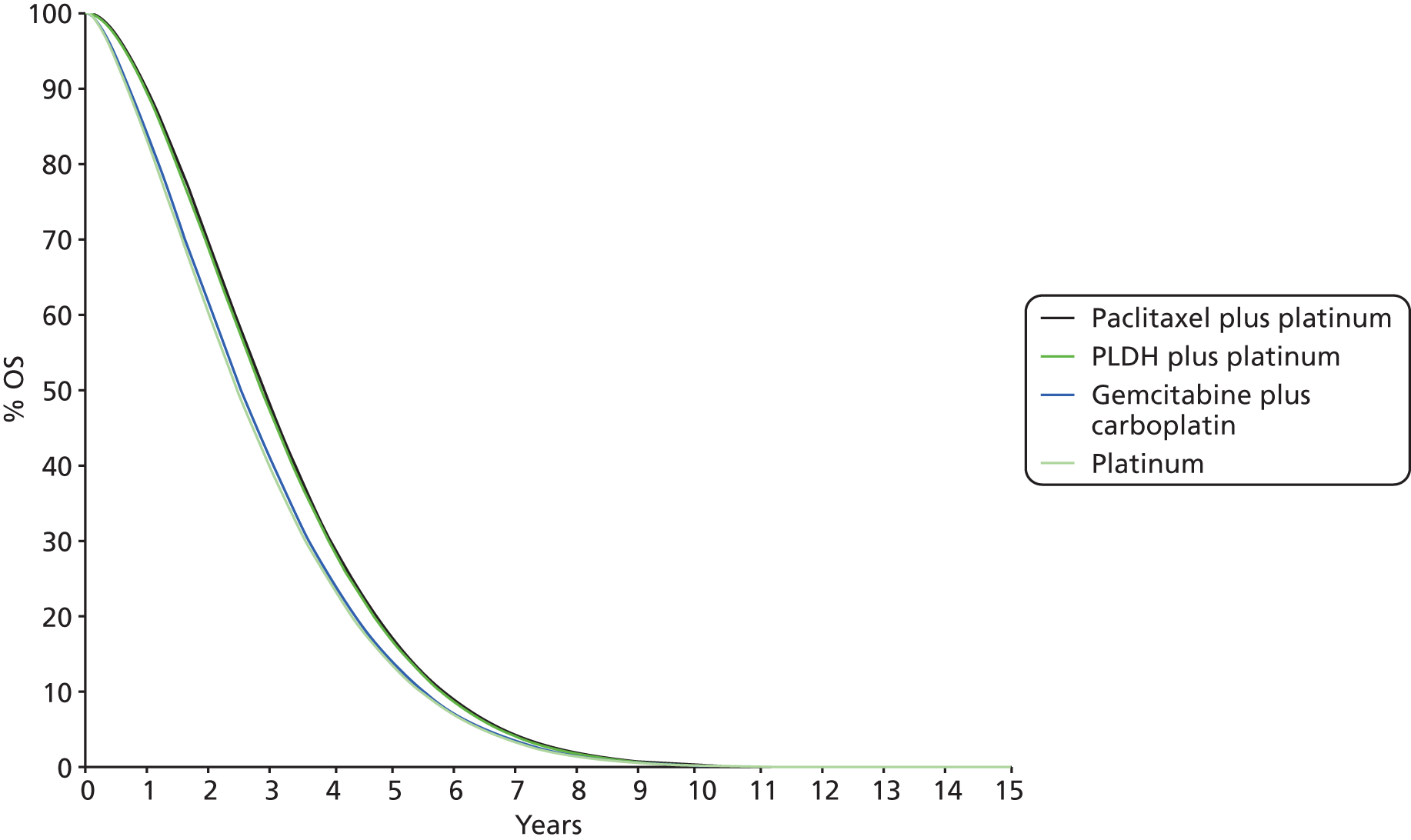

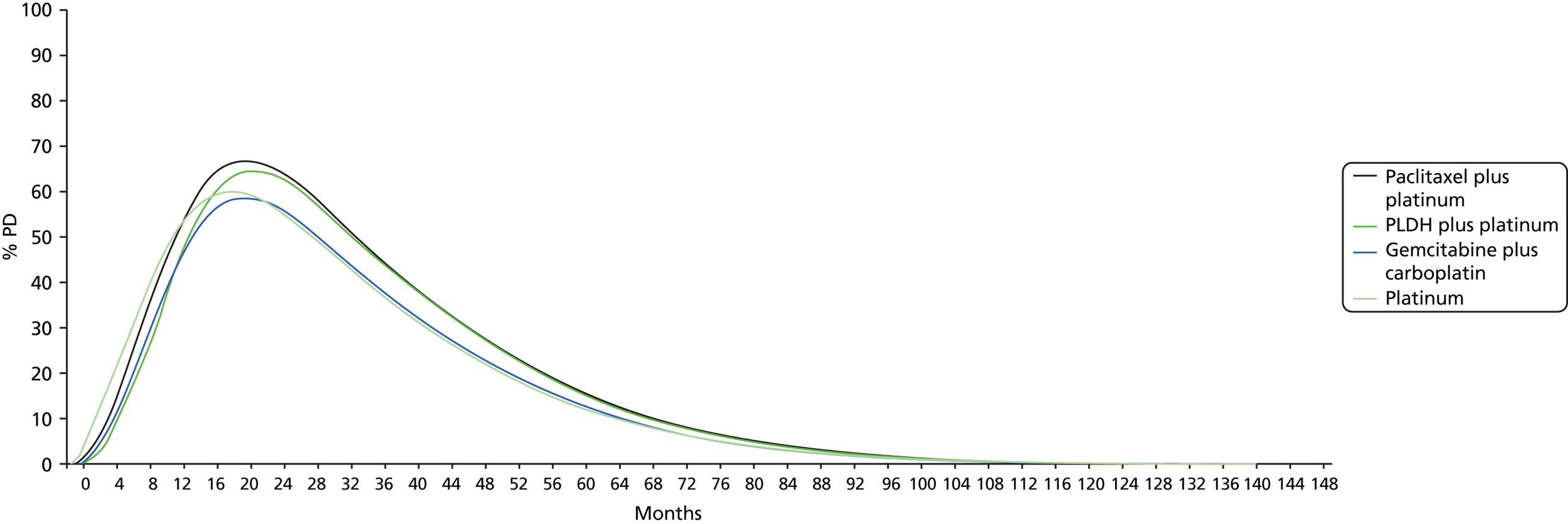

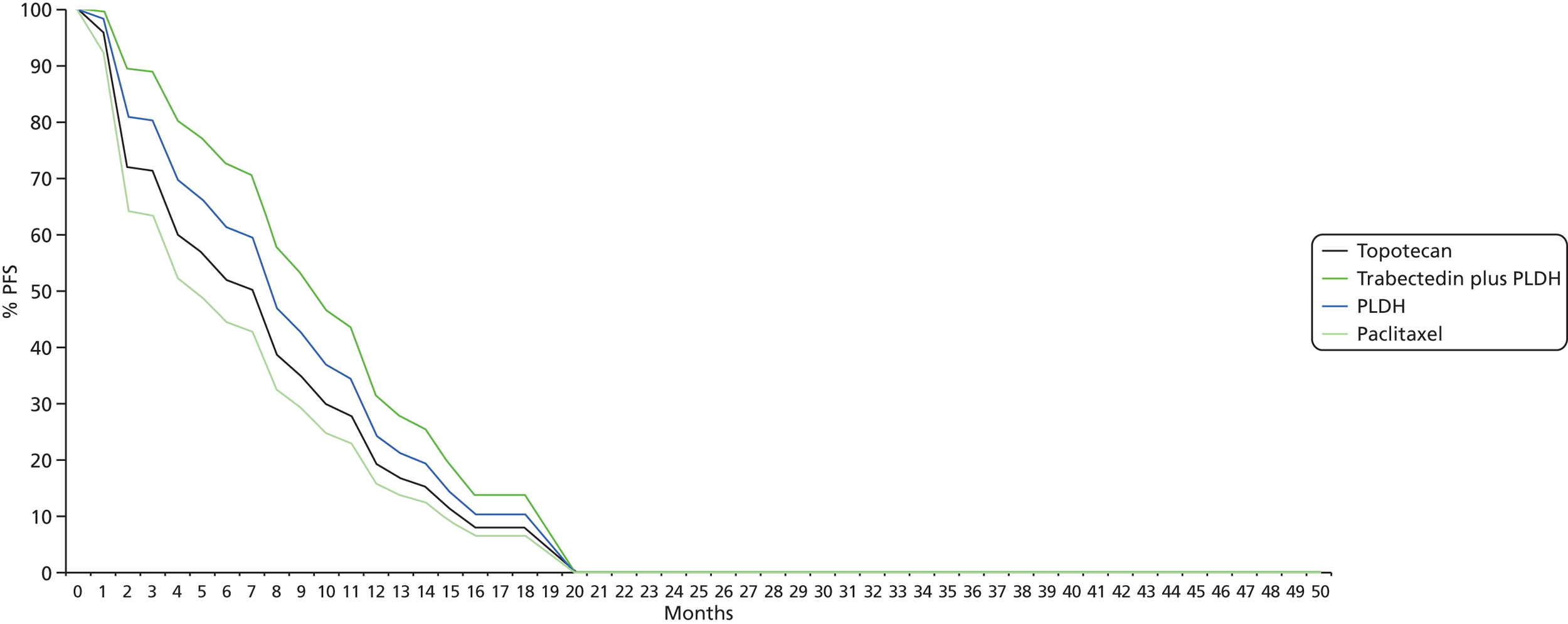

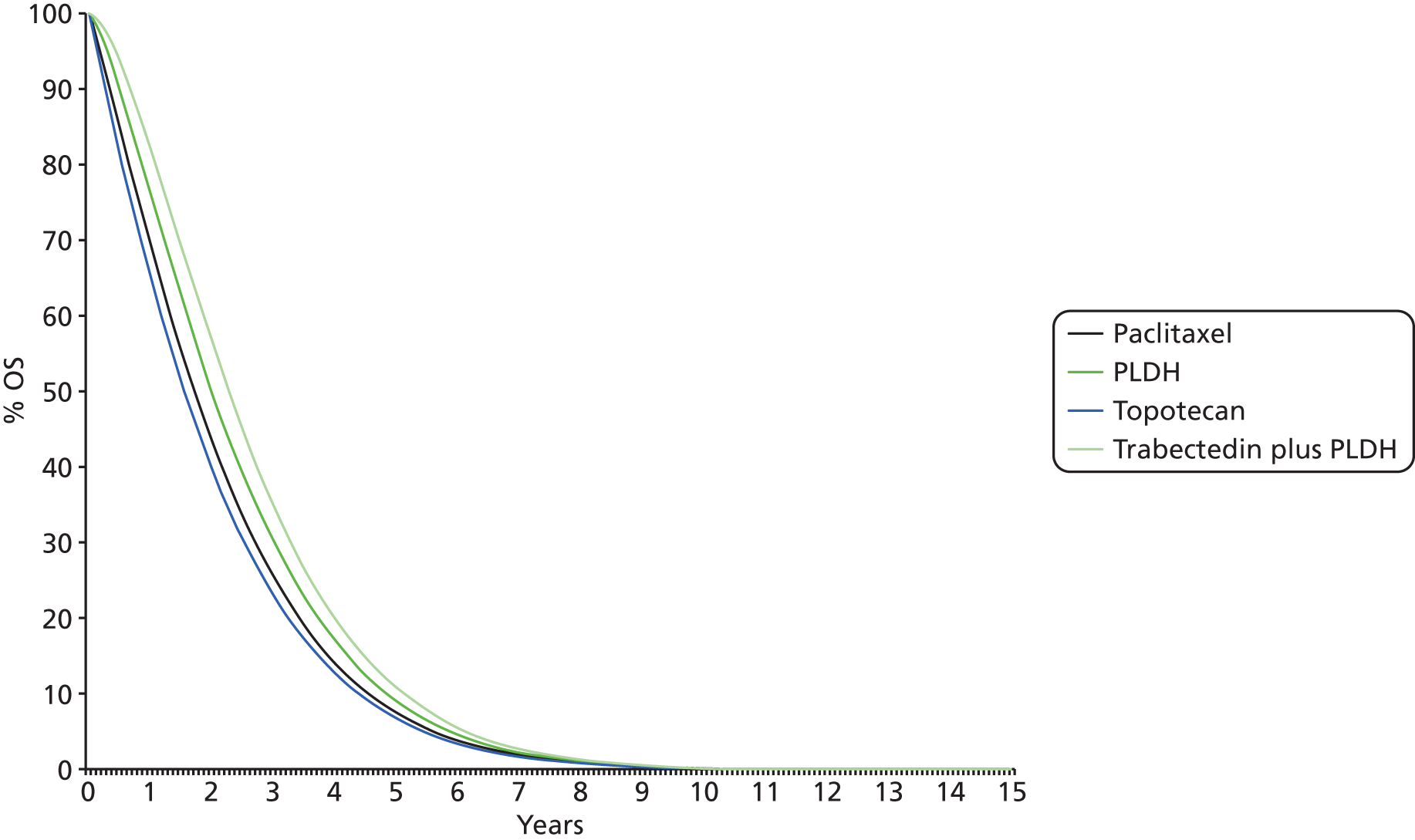

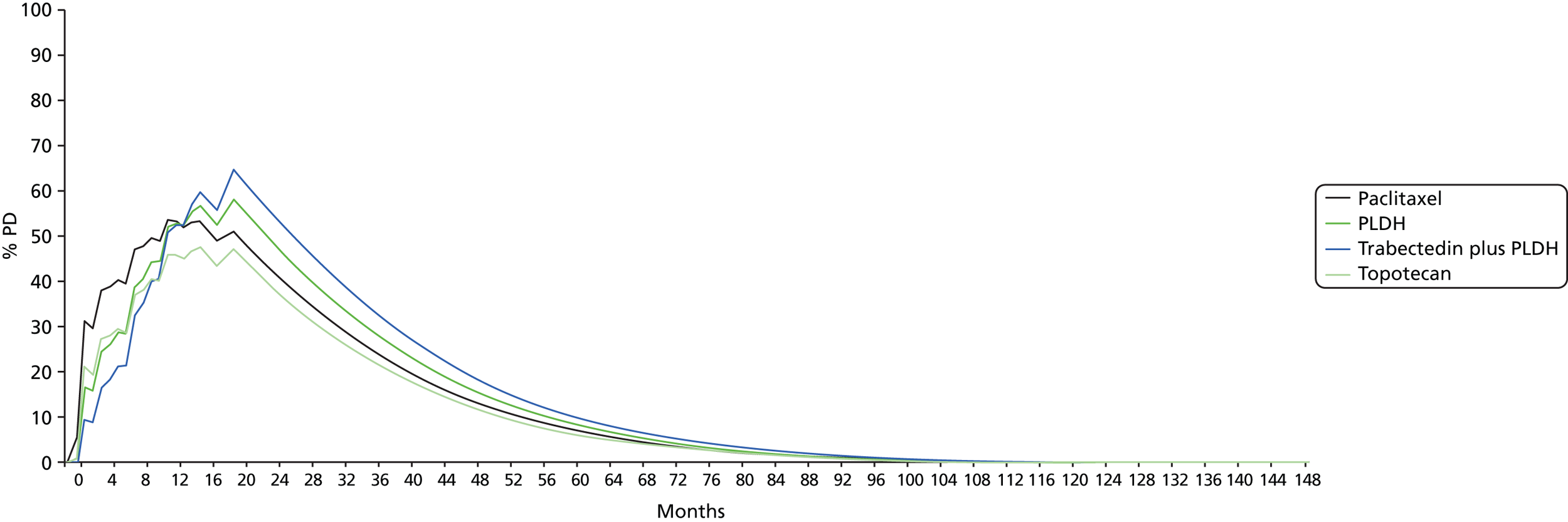

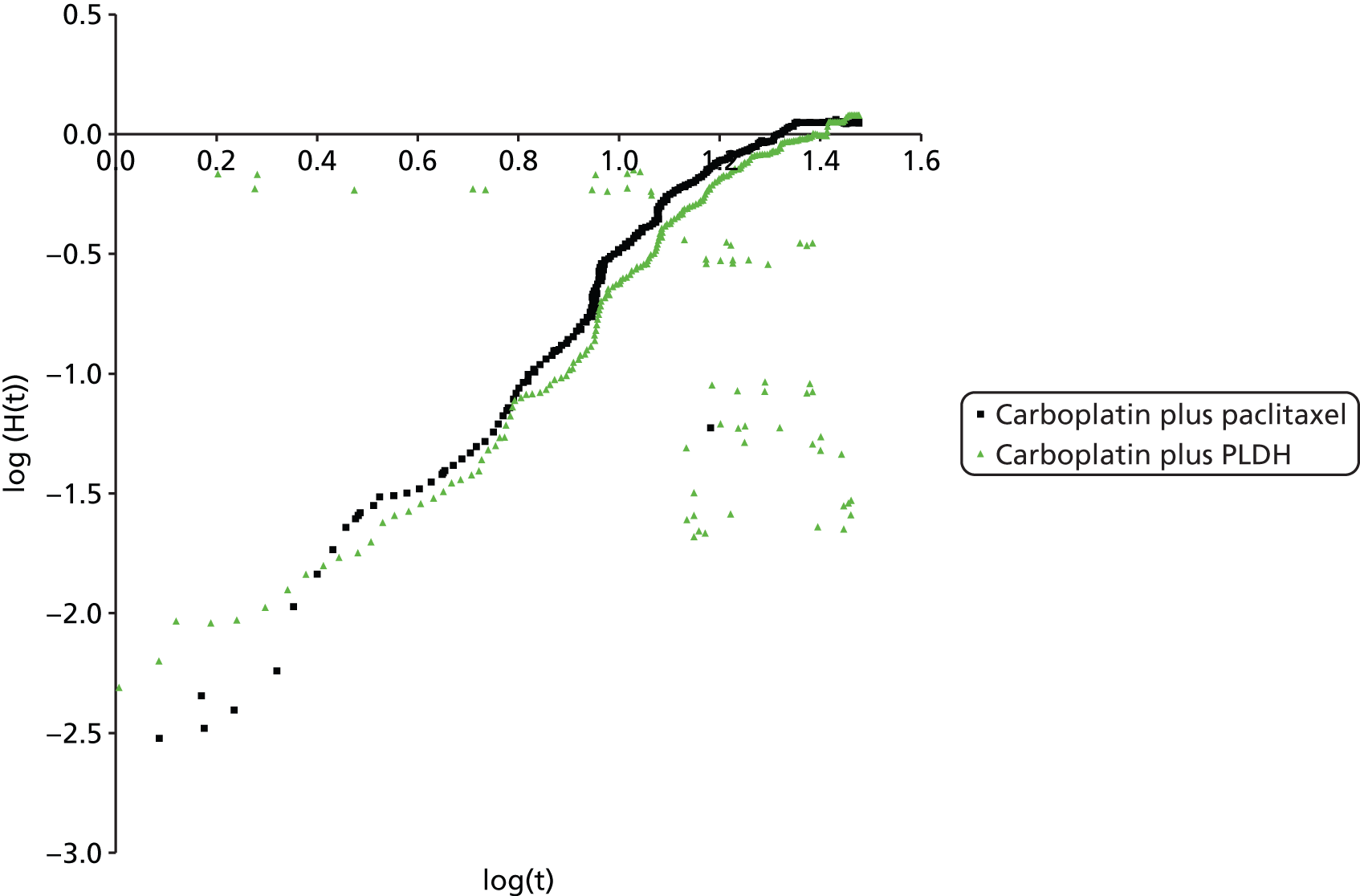

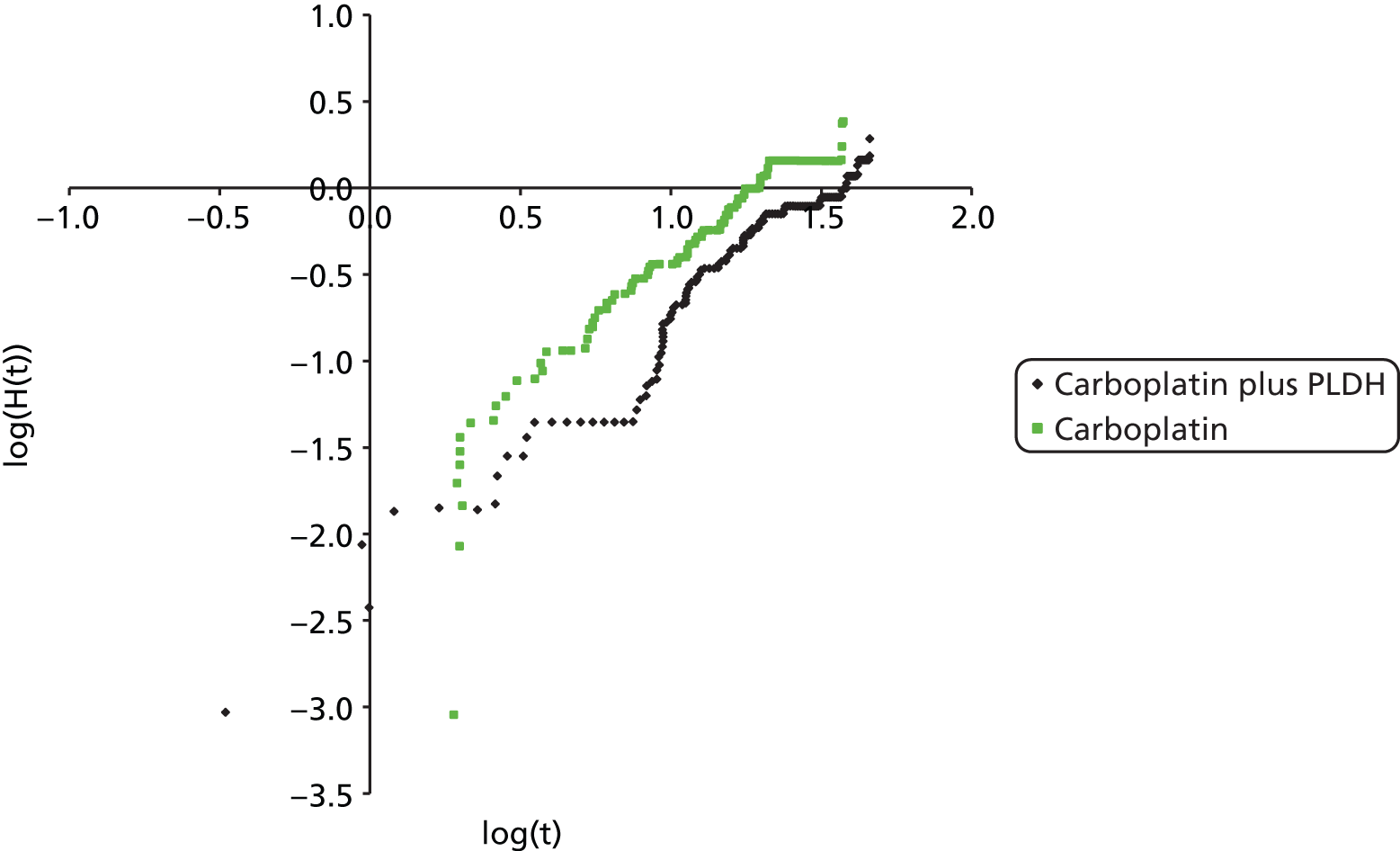

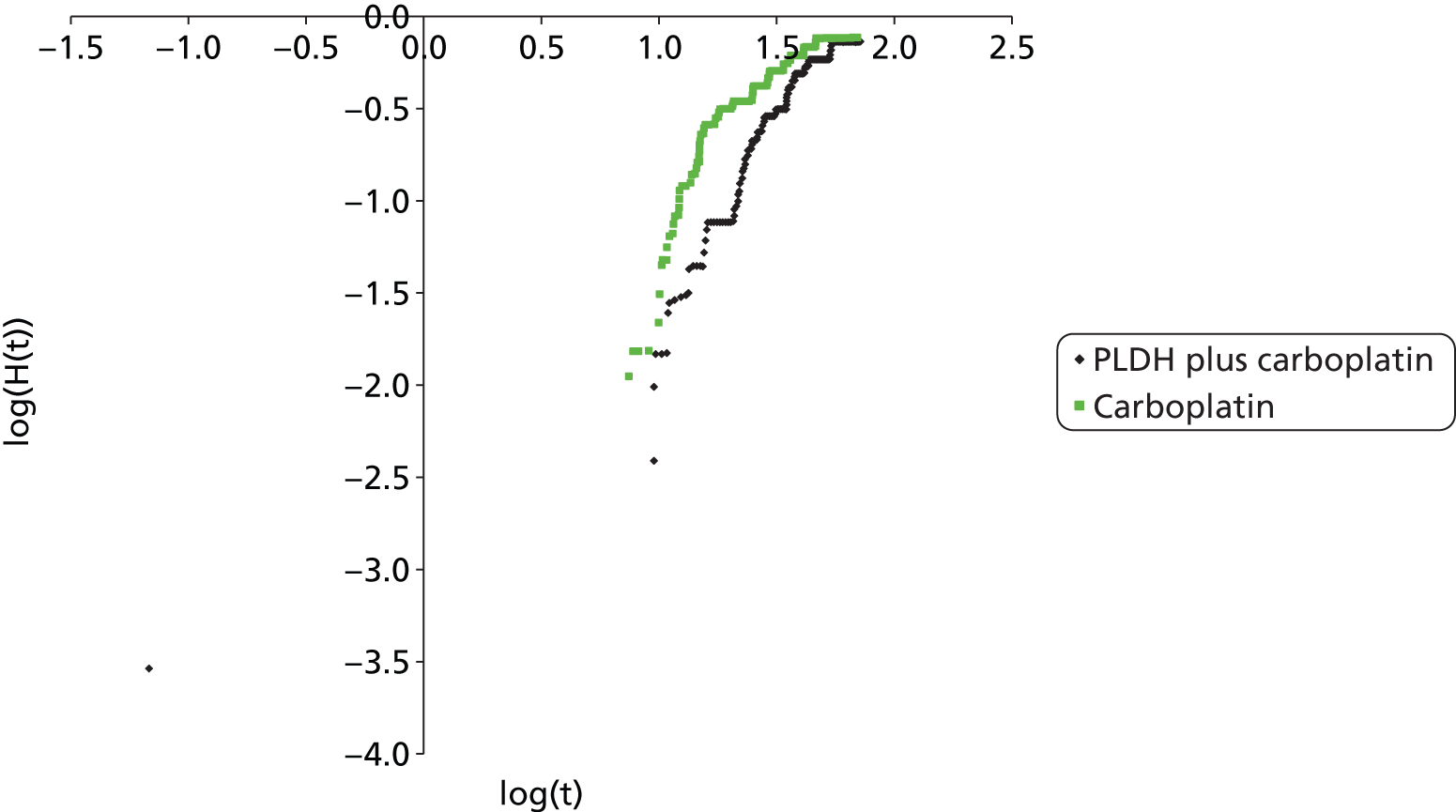

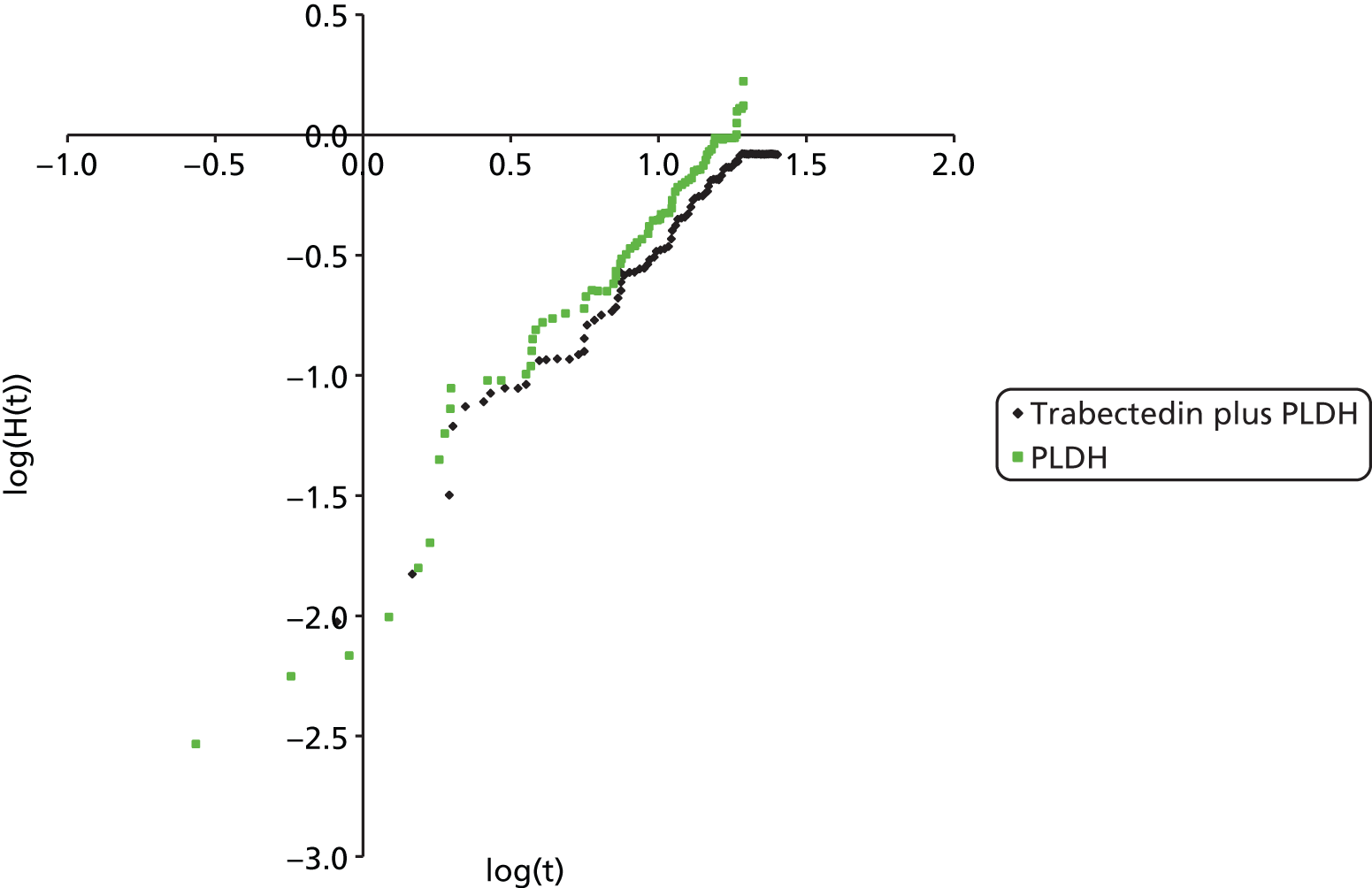

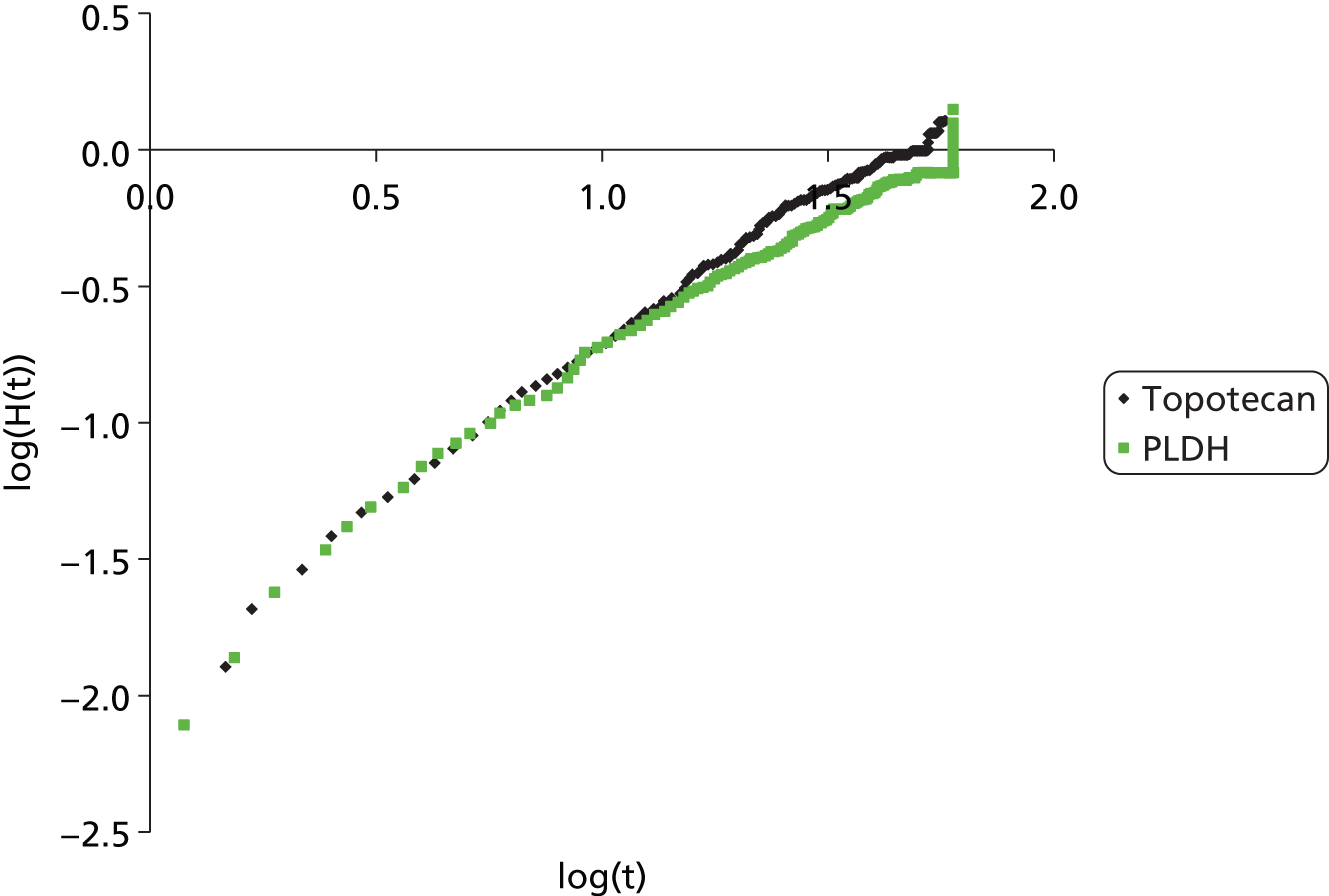

Clinical effectiveness results are reported by outcome (OS, PFS, ORR, QoL and adverse effects). Within the efficacy outcomes of OS, PFS and ORR, results are presented separately based on platinum sensitivity. Results by population are ordered: platinum sensitive, which is broken down further to fully platinum sensitive (FPS) and PPS, when data are available; PRR; and the overall population (when trial includes patients with platinum-sensitive disease or PRR disease). Results for QoL and adverse effects are presented for the overall population, irrespective of sensitivity to platinum. Within the outcome, results are initially presented separately for each trial reporting data, and are supplemented with the findings from the NMA, including a description of assumptions made and potential bias across the trials included in the network.

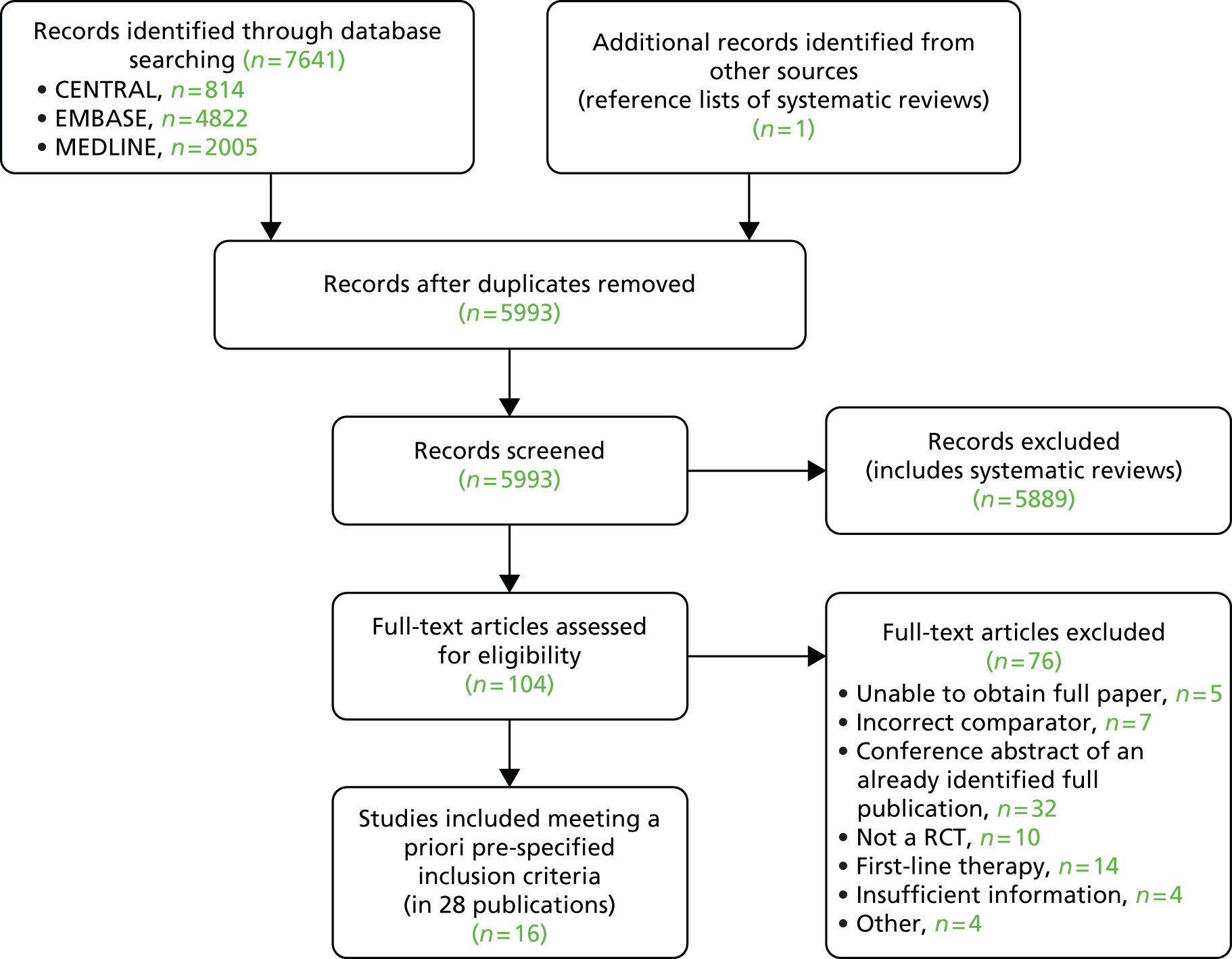

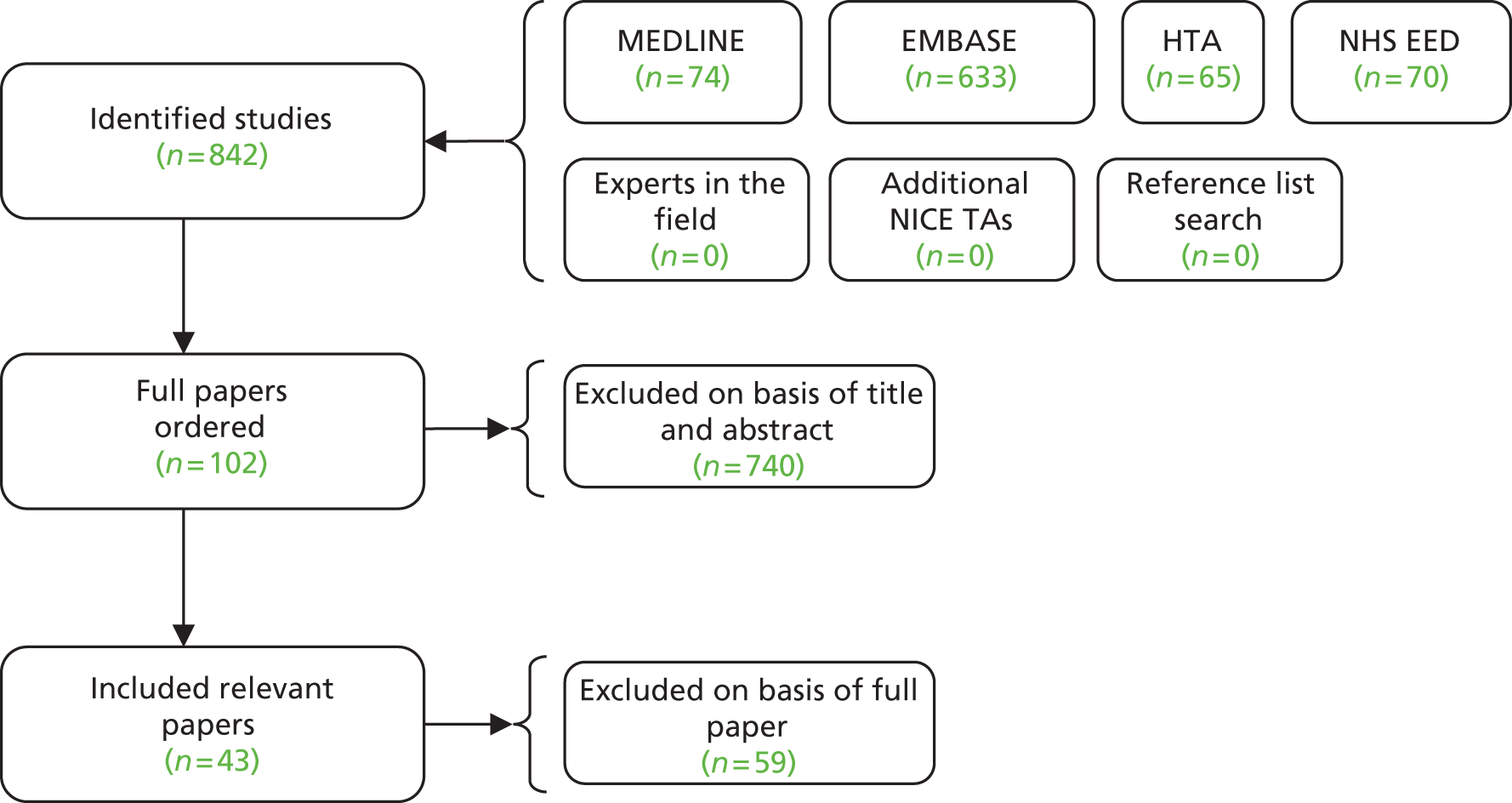

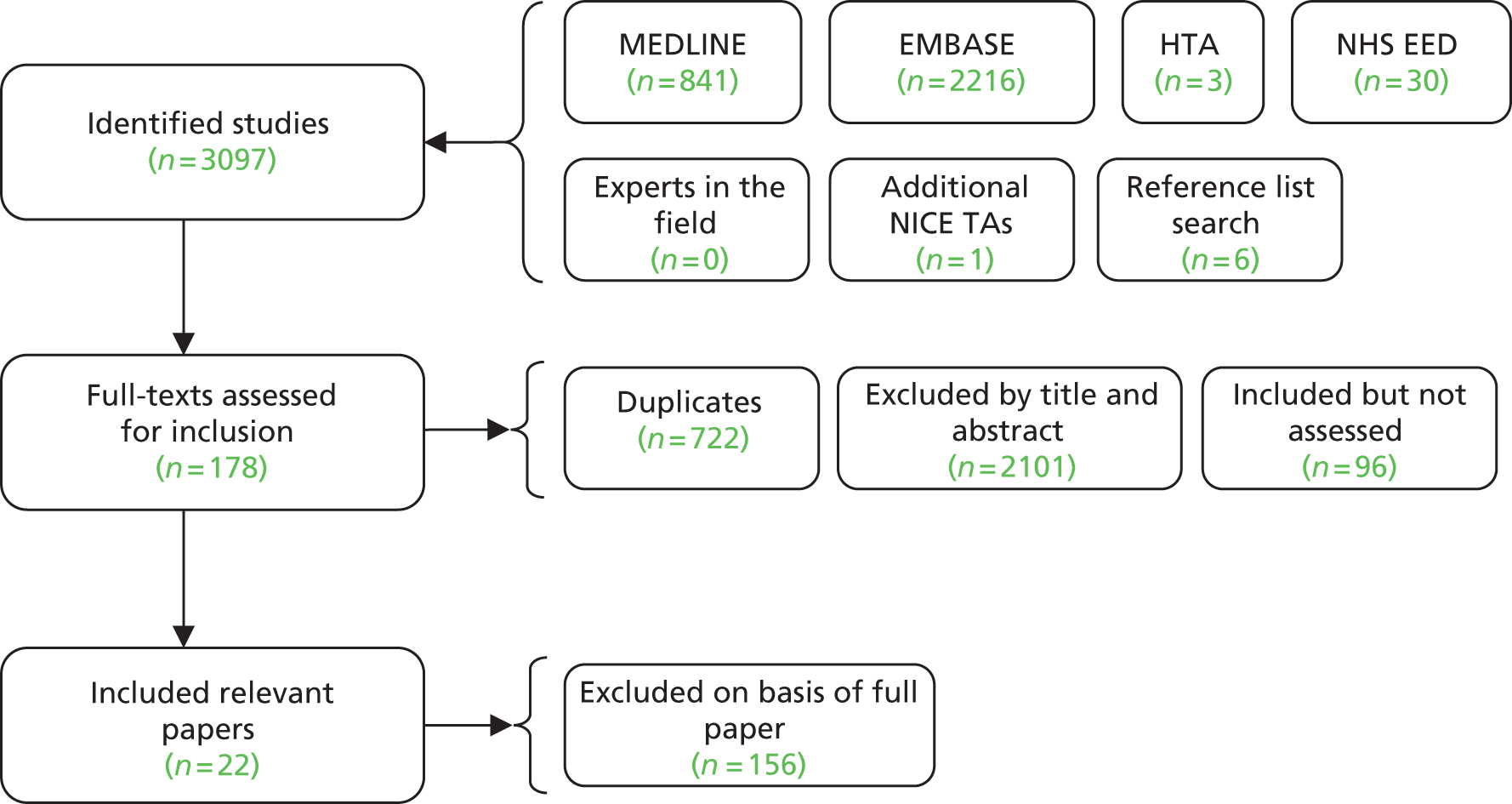

Quantity and quality of research available

The searches retrieved a total of 5993 records (post deduplication) that were of possible relevance to the review (Figure 3). These were screened and 104 full references were ordered. Of these, five had to be cancelled because they were unobtainable. Of the full references evaluated, 28 papers describing 16 studies were included in the review.

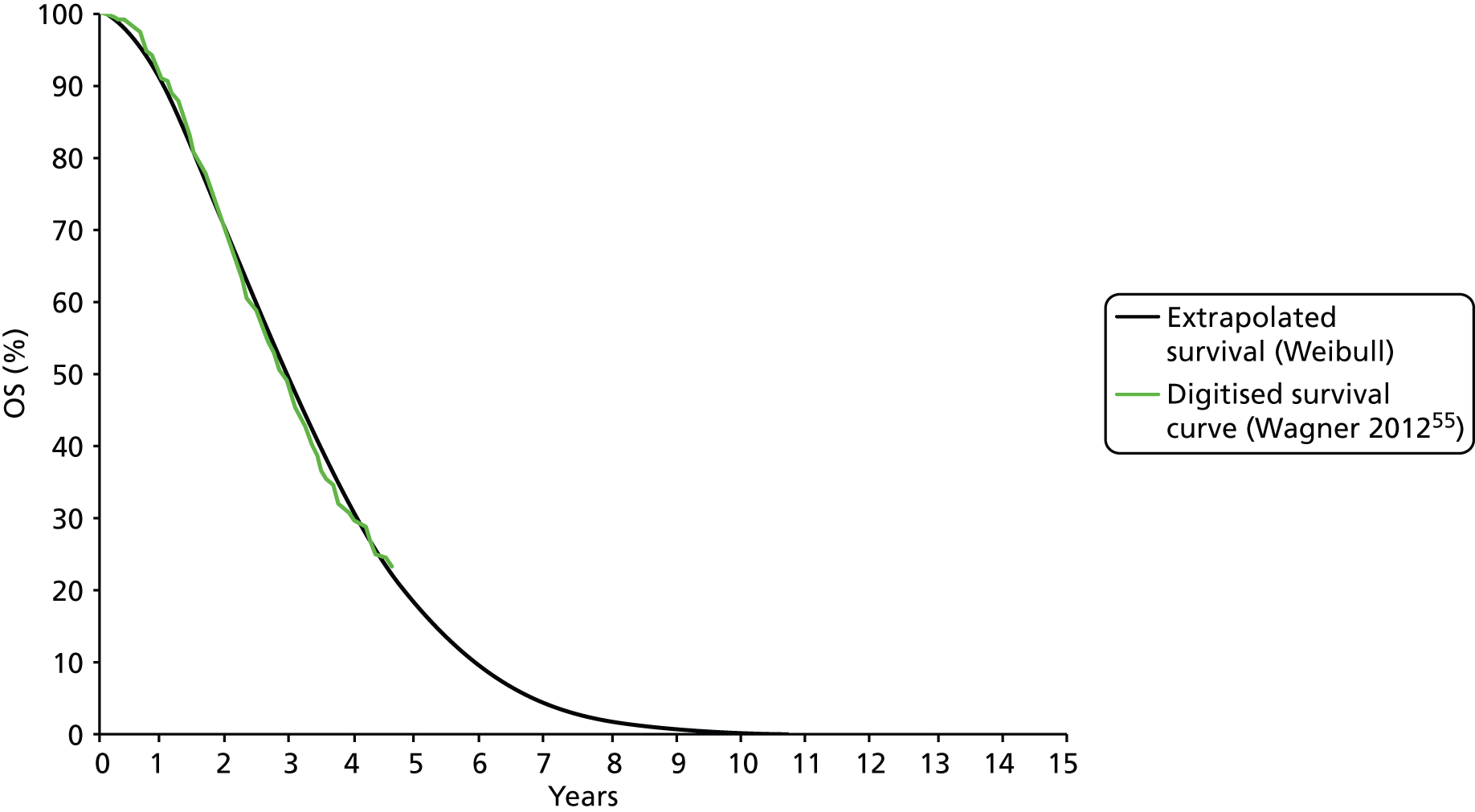

FIGURE 3.

A PRISMA flow diagram for studies included and excluded from the clinical effectiveness review.

The full list of studies included in the review is given below (see Table 8), whereas a list of the papers screened but subsequently excluded (with reasons for exclusion) from the review is presented in Appendix 3.

Included studies

Sixteen RCTs reported in 15 primary publications, with 13 accompanying publications, were included in the review. One RCT from TA9113 was included, which was identified in the literature search only as an abstract and the results of which have not been published in full elsewhere (referred to hereafter as Trial 30–57). 47 An overview of the identified trials is provided in Table 8. Of the 16 RCTs identified, five evaluated the intervention and comparator within their licensed indication, and dose and route of administration. 13,21,48–50 The remaining 11 RCTs evaluated the intervention or comparator outside the parameters specified in the licence, in terms of, for example, dose or route of administration. No RCT identified evaluated interventions specifically in a population who were allergic or intolerant to platinum-based treatments. Of the nine RCTs identified in TA91, only one RCT51 has been excluded from this update. Cantu et al. 51 evaluated paclitaxel alone compared with a combination of cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin and cisplatin (CAP). Doxorubicin administered in the trial is the non-pegylated formulation and is outside the scope of this review, which specifies PLDH as the intervention of interest.

Two manufacturers [Eli Lilly and Company (gemcitabine); PharmaMar (trabectedin)] submitted clinical evidence for consideration for this multiple technology appraisal (MTA).

Eli Lilly (gemcitabine) did not carry out a systematic review of the literature; instead, the manufacturer reported clinical data from three studies:

-

a Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus carboplatin with carboplatin monotherapy in patients with platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer (study JHQJ)

-

a single-arm, Phase II study of gemcitabine plus carboplatin in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer (study JHRW)

-

a single-arm, Phase I/II dose-finding study of gemcitabine plus carboplatin in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer (study SO026).

The data provided by the manufacturer for JHQJ, the Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus carboplatin with carboplatin monotherapy, are reported in the full publication of the trial,50 which was identified and included as part of the systematic review of the literature on clinical effectiveness (see Results, above).

The two additional studies (JHRW and SO026) are single-arm trials and as such do not meet the criteria for inclusion in the review (see Results, above).

PharmaMar (trabectedin) carried out a systematic search of the literature. Specifically, the manufacturer updated the review carried out for the STA TA222,15 which evaluated the use of trabectedin plus PLDH in the treatment of platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. The manufacturer searched the following databases: EMBASE; MEDLINE; MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; and The Cochrane Library. Studies were included if:

-

the study type was a RCT

-

the population of interest was relapsed platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer

-

outcome data for PFS, OS or AEs were included

-

the interventions and comparators of interest included at least one of trabectedin, PLDH, paclitaxel, topotecan, etoposide, or best supportive care.

The manufacturer limited the comparators within searches to the comparators outlined in the NICE pathway for patients who are unsuitable for platinum-based chemotherapy; this represents the target population for the MS.

The manufacturer identified two additional relevant studies relating to OVA-301,30 which were identified as part of the review of the clinical effectiveness literature and are discussed in a subsequent section (see subsequent text).

| Study and principal citation | Trial design | Population (n) | PFI | Randomised treatments | Supplementary publications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Comparator | |||||

| Both intervention and comparator used within licensed indication and at licensed dose | ||||||

| ten Bokkel Huinink et al.21 | Phase III, multicentre, open-label RCT | 235 | Disease that recurred or progressed after first-line platinum based therapy (no minimum PFI specified) | Topotecan (1.5 mg/m2 as a 30-minute i.v. infusion) for five consecutive days every 21 days | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as a 3-hour i.v. infusion) every 21 days | ten Bokkel Huinink et al.52 Gore et al.53 |

| Gordon et al.49 | Phase III, multicentre, open-label RCT | 474 | Disease that recurred after, or failed, first-line platinum-based chemotherapy (no minimum PFI specified) | PLDH (50 mg/m2 as a 1-hour i.v. infusion) every 28 days | Topotecan (1.5 mg/m2 as a 30-minute infusion) for five consecutive days every 21 days | Gordon et al.54 |

| Trial 30–57; data taken from TA9113 | Phase III, multicentre, open-label RCT | 216 | Disease that recurred after, or failed, one platinum-based first-line regimen (no minimum PFI specified) | PLDH (50 mg/m2) every 28 days | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) every 21 days | One conference abstract (O’Byrne et al.47) |

| Gonzalez-Martin et al.48 | Phase II, ‘pick the winner’ design, multicentre RCT; level of masking unclear | 81 | Progression > 6 months after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as a 3-hour i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 3 weeks | Carboplatin alone (AUC 5) every 3 weeks | None identified |

| Pfisterer et al.50 | Phase III, multicentre, international, open-label RCT | 356 | Disease recurrence at least 6 months after completion of first-line, platinum-based therapy | Gemcitabine (1000 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 4) every 21 days | Carboplatin alone (AUC 5) every 21 days | None identified |

| Intervention or comparator used outside licensed indication or dose | ||||||

| Gore et al.24 | Multicentre, open-label RCT (phase not clear) | 266 | Disease progression on first-line platinum-based chemotherapy or relapse within 12 months of completion of first-line platinum-based treatment | Oral topotecan (2.3 mg/m2) given daily | Intravenous topotecan (1.5 mg/m2) for five consecutive days every 21 days | None identified |

| Sehouli et al.23 | Phase II, multicentre RCT | 194 | Disease that had recurred after radical surgery and at least one platinum-based chemotherapy with recurrence at < 6 months after cessation of platinum-based treatment | Topotecan (4.0 mg/m2 as a 30-minute i.v. infusion on days 1, 8 and 15) weekly every 28 days | Topotecan (1.25 mg/m2 as a 30-minute i.v. infusion) for five consecutive days every 21 days | None identified |

| Alberts et al.28 | Phase II RCT; level of masking unclear | 61 | Disease that recurred within 6–24 months of completing platinum-based chemotherapy | PLDH (30 mg/m2 as a 1-hour i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 4 weeks | Carboplatin alone (AUC 5) every 4 weeks | Markman et al.55 |

| Bafaloukos et al.29 | Phase II RCT; level of masking unclear | 204 | Recurrence at > 6 months after completion of platinum-based chemotherapy | PLDH (45 mg/m2 as a 90-minute i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 4 weeks | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as a 3-hour i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 21 days | None identified |

| CALYPSO ; Pujade-Lauraine et al.31 | Phase III, non-inferiority, multicentre, international, open-label RCT | 976 | Disease that had recurred/progressed > 6 months after first- or second-line platinum-based chemotherapy | PLDH (30 mg/m2 as an i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 28 days | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as an i.v. infusion) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 21 days | Wagner et al.,56 Gladieff et al.,57 Kurtz et al.,58 Brundage et al.59 |

| Rosenberg et al.60 | Multicentre RCT (phase not clear) | 208 | Disease that recurred or progressed after first-line platinum-based therapy (no minimum PFI specified) | Paclitaxel (67 mg/m2) weekly | Paclitaxel (200 mg/m2) every 21 days | None identified |

| ICON4/AGO-OVAR 2.2; Parmar et al.61 | Phase III, multicentre, international RCT (three parallel RCTs, each with its own protocol) | 802 | Disease that had been treatment free for > 6 months | Paclitaxel (175 or 185 mg/m2) plus carboplatin or cisplatin every 21 days | Carboplatin or cisplatin alone every 21 days | None identified |

| CARTAXHY; Lortholary et al.62 | Phase II, multicentre, open-label, three-armed RCTa | 165 | Disease progression during or relapse within 6 months of completing platinum-based chemotherapy | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15) weekly plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 28 days | Paclitaxel (80 mg/m2 on days 1, 8 and 15) weekly every 28 days | None identified |

| Piccart et al.63 | Phase II, open-label, multicentre RCT | 86 | Disease that progressed or stabilised after prior platinum-based treatment; for those experiencing relapse, relapse was to have occurred within 12 months of last platinum-based therapy | Paclitaxel (175 mg/m2 as a 3-hour infusion) every 21 days | Oxaliplatin (130 mg/m2 as a 2-hour infusion) every 21 days | None identified |

| OVA-301; Monk et al.30 | Phase III, open-label, multicentre, international RCT | 672 | Disease that was persistent, recurrent or progressing on current treatment | Trabectedin (1.1 mg/m2 as a 3-hour infusion) plus PLDH (30 mg/m2 as a 90-minute infusion) every 21 days | PLDH (50 mg/m2 as a 90-minute infusion) every 28 days | Monk et al.,64 Poveda et al.,65 Kaye et al.,66 Krasner et al.67 |

| Omura et al.68 | Phase III, multicentre RCT | 372 | Histologically confirmed ovarian cancer treated with no more than one prior platinum-based regimen and no prior taxane | Paclitaxel 250 mg/m2 (24-hour infusion) every 21 days (patients in this group also randomised to filgrastim (Neupogen®, Amgen) 5 or 10 µg/kg subcutaneously) | Paclitaxel 175 mg/m2 (24-hour infusion) every 21 days | None identified |

Study characteristics

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride plus carboplatin compared with paclitaxel plus carboplatin

Two RCTs29,31 were identified for this comparison. The RCTs were of similar design but one was a Phase II RCT29 and one was a Phase III RCT. 31 In addition, the dose of PLDH evaluated differed between the trials, with 45 mg/m2 and 30 mg/m2 used by Bafaloukos et al. 29 and Pujade-Lauraine et al. ,31 respectively. The licence for PLDH does not recommend a dose of PLDH for use in combination with platinum-based chemotherapy. Bafaloukos et al. 29 note in the discussion that, at the time of initiation of the trial, limited information was available on the optimal dose for PLDH in combination with carboplatin. As highlighted by Bafaloukos et al. ,29 retrospective analyses suggest that lower dose intensities of PLDH (30–40 mg/m2) are as clinically effective but with improved tolerance. Clinical experts have fed back that, in UK clinical practice, PLDH would most likely be used at a dose of 30 mg/m2 when combined with carboplatin.

Bafaloukos et al. 29 report the results of a randomised study in which 204 patients with histologically confirmed recurrent ovarian cancer were randomised to either PLDH (45 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 28 days or paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 21 days. Patients recruited had disease that had recurred at least 6 months after platinum-based chemotherapy, i.e. women with platinum-sensitive disease. Women with only elevated CA125 levels (twice the ULN or more) as an indicator of disease were also included.

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the comparative clinical effectiveness of the two treatment regimens in terms of response rate and toxicity in women with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer relapsing after first-line platinum-based therapy. OS and TTP were analysed as secondary outcomes. Subsequent to randomisation, 15 patients were found to be ineligible (reasons provided). Therefore, analyses presented are based on data from 189 eligible patients (96 in the paclitaxel plus carboplatin group vs. 93 in the PLDH plus carboplatin group). The reported power calculation indicates that 201 patients were needed to identify a 20% difference in response rate between the groups. The study might have been underpowered to detect a difference between groups in response rate.

Randomisation (1 : 1) was performed at the central Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group (HeCOG) Data Office in Athens but details on the method of randomisation were not reported. Stratification criteria were not applied at randomisation. Tumour response was evaluated using World Health Organization (WHO) criteria for patients with measurable disease and CA125 based on Rustin’s criteria for patients without measurable disease. Median duration of follow-up was reported as 43.6 months (95% CI 0.1 to 74.8 months), but the range of follow-up was not reported either for the full trial population or for the individual treatment groups.

All patients received standard premedication of dexamethasone, diphenhydramine and ranitidine (Zantac®, GSK) prior to paclitaxel. In the group receiving paclitaxel, premedication was administered twice, orally 12 hours before and again intravenously 30 minutes before paclitaxel infusion. In the group receiving PLDH, premedication was administered only intravenously prior to PLDH infusion. Six cycles of chemotherapy were administered, unless disease progression or unacceptable toxicity occurred. A maximum of 2 weeks’ delay was allowed for toxicity and treatment was discontinued if longer toxicity-related delays occurred. For grade 3 and grade 4 thrombocytopenia, a 25% and a 50% dose reduction, respectively, was recommended for all drugs.

A median of six cycles of paclitaxel plus carboplatin (range 1–9) and six cycles of PLDH plus carboplatin (range 1–8) were administered. Most patients in each group completed the planned treatment (68% in paclitaxel plus carboplatin and 70% in PLDH plus carboplatin).

In the second RCT identified for this comparison, Pujade-Lauraine et al. 31 report the results of a randomised international, multicentre, open-label, Phase III non-inferiority trial (CALYPSO) in which 976 patients with platinum-sensitive (disease progression > 6 months after prior treatment) relapsed/recurrent ovarian cancer received a combination of PLDH plus carboplatin (n = 467) or carboplatin plus paclitaxel (n = 509). Prior treatment must have included a taxane and no more than two previous platinum-based regimens (i.e. patients had failed first- or second-line treatment). Patients with measurable [according to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours (RECIST)] and CA125 assessable [according to Gynecologic Cancer Intergroup (GCIG)] criteria were eligible.

The primary publication presents results on PFS. Accompanying publications were identified that present results on mature OS data,56 clinical effectiveness results in the subgroup of patients with PPS ovarian cancer (relapse at between 6 and 12 months since receipt of last cycle of chemotherapy)57 and QoL. 59

The trial was of a non-inferiority design with the aim of determining whether PLDH (30 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) every 4 weeks was non-inferior to the standard treatment of paclitaxel (175 mg/m2) plus carboplatin every 3 weeks. 31 The goal was to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of the treatments in terms of efficacy and toxicity. The primary outcome of the trial was PFS, with OS, QoL and toxicity as prespecified secondary outcome measures. Determination of disease progression was based on RECIST and GCIG criteria modifications, and included any of the following: occurrence (clinically or by imaging) of any new lesion; increase in measurable and/or non-measurable tumour defined by RECIST; CA125 elevation defined by GCIG criteria; health status deterioration attributable to disease; and death from any cause before progression was diagnosed. Assessments were independently reviewed. All patients were observed for at least 5 years from random assignment to assess OS.

Randomisation was in permuted blocks of six in a 1 : 1 ratio, and patients were stratified based on therapy-free interval from last chemotherapy (6–12 months vs. 12 months), measurable disease (yes vs. no) and centre. Despite randomisation, an imbalance in treatment allocation was noted (467 randomised to PLDH plus carboplatin vs. 509 randomised to paclitaxel plus carboplatin).

All patients received antiemetics, including a serotonin antagonist and corticosteroid. Patients randomly assigned to paclitaxel plus carboplatin received premedication to prevent hypersensitivity reactions. Dose delay and dose reduction were allowed for haematological and non-haematological toxicity. In the absence of unacceptable toxicity or disease progression, patients were treated for a total of six courses of therapy; if SD or PR was achieved after six courses of therapy, patients were allowed to remain on therapy until progression.

To assert non-inferiority of PLDH plus carboplatin, it was estimated that a sample size of 898 evaluable patients (estimate of 745 progression) would be required. 31 The calculation was based on non-inferiority margin with a HR of 1.23 at 15 months or a 7.9% absolute difference at 12 months (90% power and a one-sided CI of 95%).

Median follow-up was 22 months; median follow-up in the individual treatment groups not reported. 31 The median number of cycles was six in each treatment group, with a range of cycles from 1 to 14 in the PLDH plus carboplatin group and 1 to 12 in the paclitaxel plus carboplatin group. A significantly larger proportion of patients in the PLDH plus carboplatin group completed at least six cycles of treatment (85% vs. 77%; p < 0.001).

Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin hydrochloride plus carboplatin compared with carboplatin alone

Alberts et al. 28 reported the results of a randomised study in which 61 patients from the USA with recurrent stage III or i.v. epithelial or peritoneal ovarian carcinoma were randomised to PLDH (i.v. infusion of 30 mg/m2) plus carboplatin (AUC 5) once every 4 weeks (31 patients) or carboplatin (AUC 5) alone once every 4 weeks (30 patients). A follow-up study reporting final OS results was also identified. 55

To be eligible for enrolment, patients had to have histologically diagnosed stage III or IV disease that was determined to be progressive based on RECIST or GCIG CA125 criteria. Patients also had to have a progression-free interval and a PFI of 6–24 months after first-line platinum-based chemotherapy, which indicates that the study focused on women with platinum-sensitive disease. Patients were excluded if Zubrod performance status was > 1. Prior treatment with up to 12 courses of a non-platinum containing consolidation treatment during the 6- to 24-month PFI was allowed on the proviso that treatment had been completed at least 28 days prior to registration.

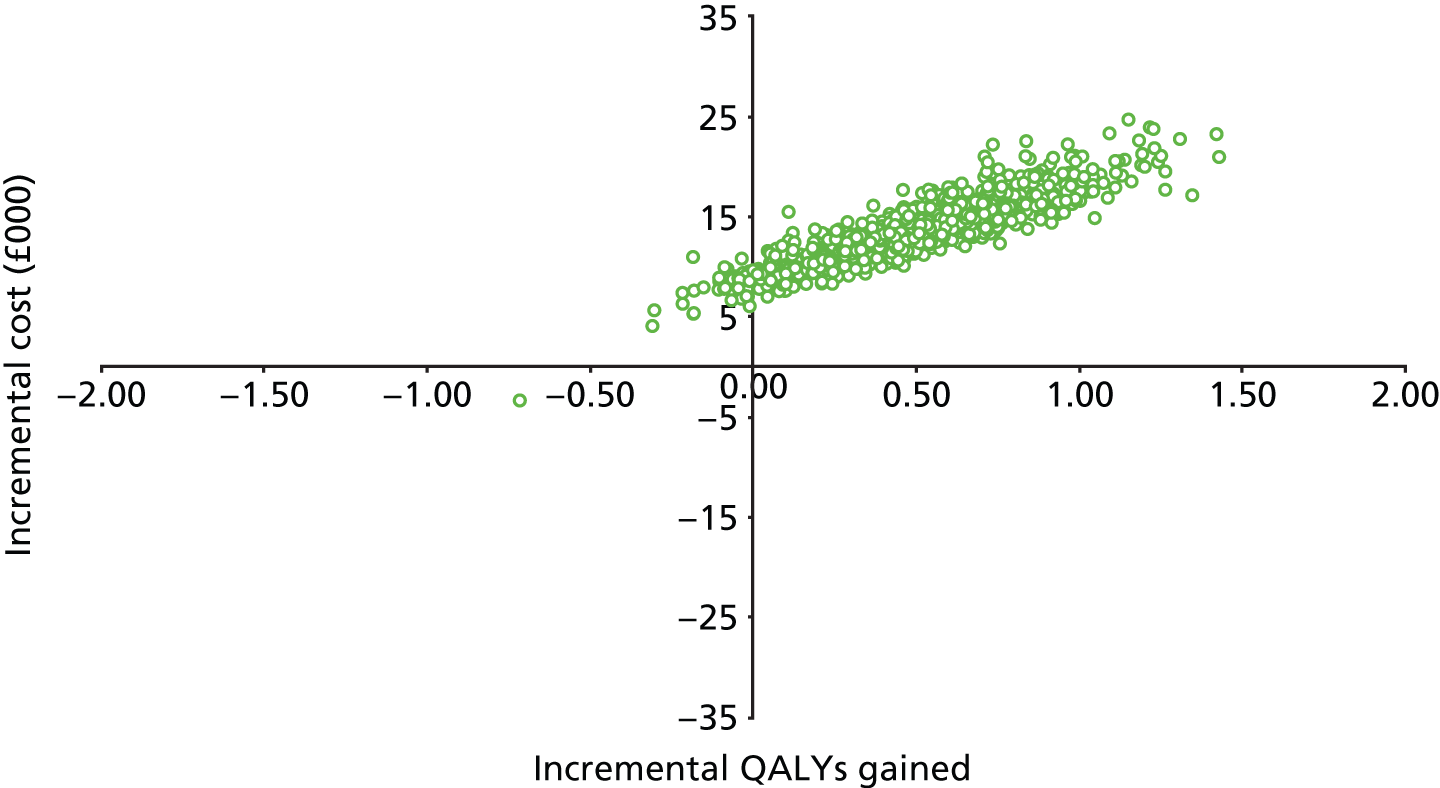

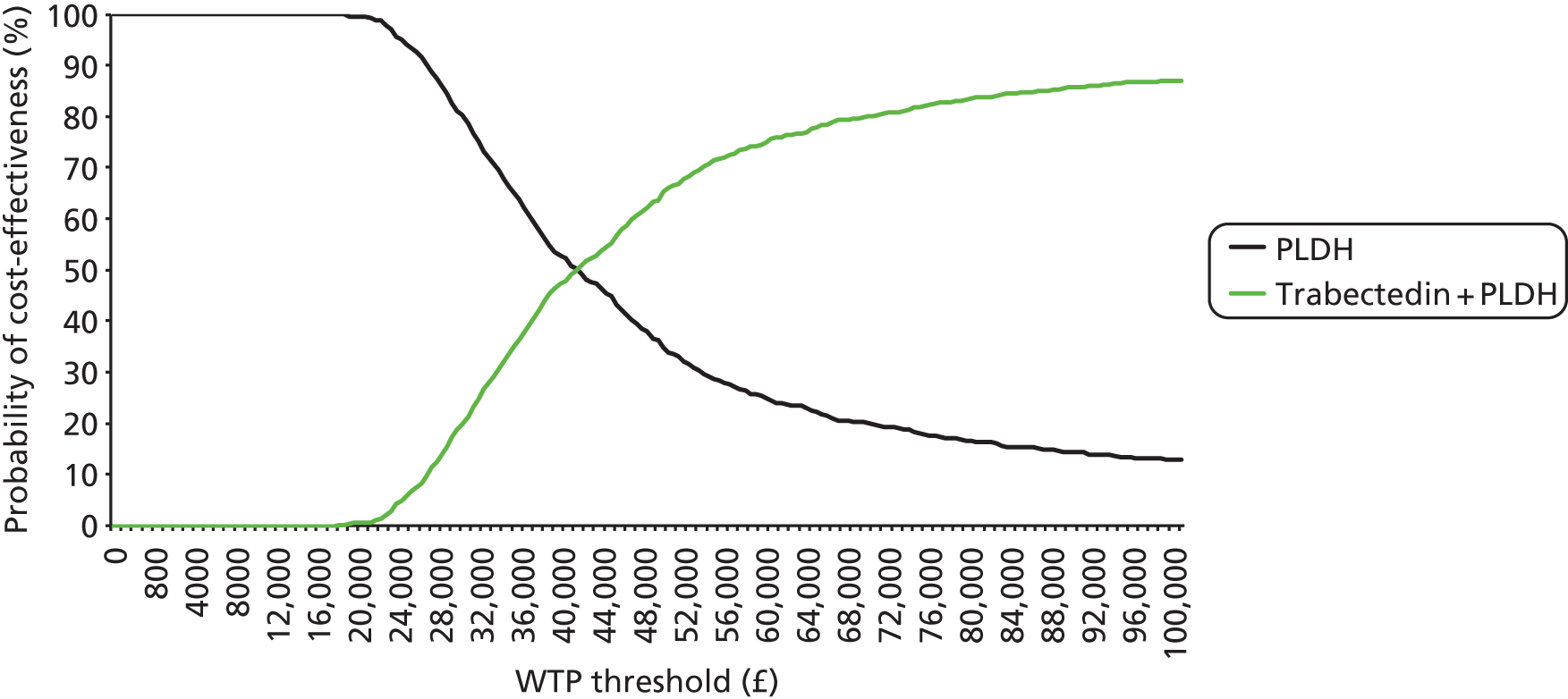

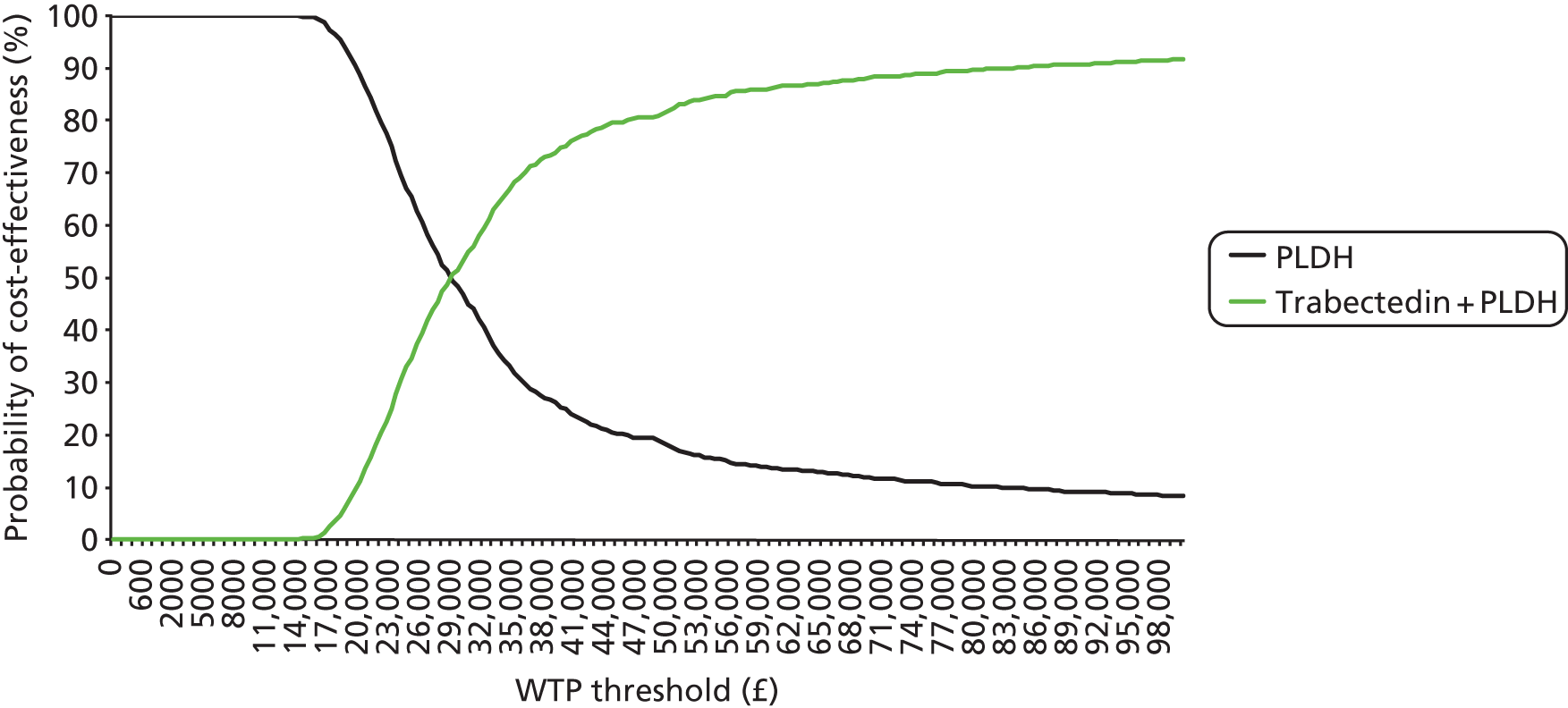

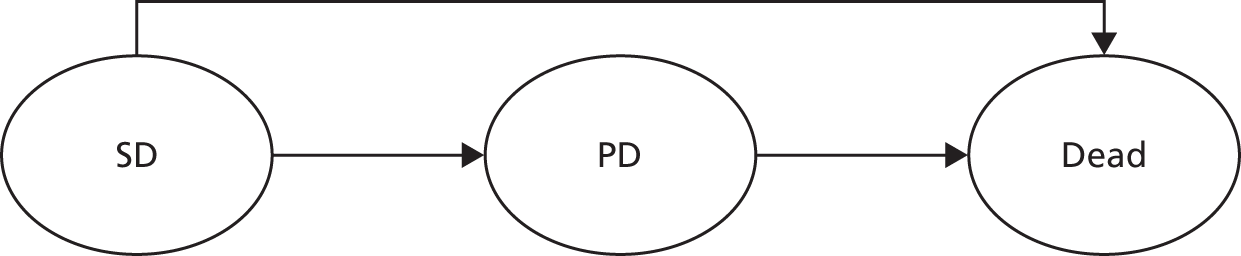

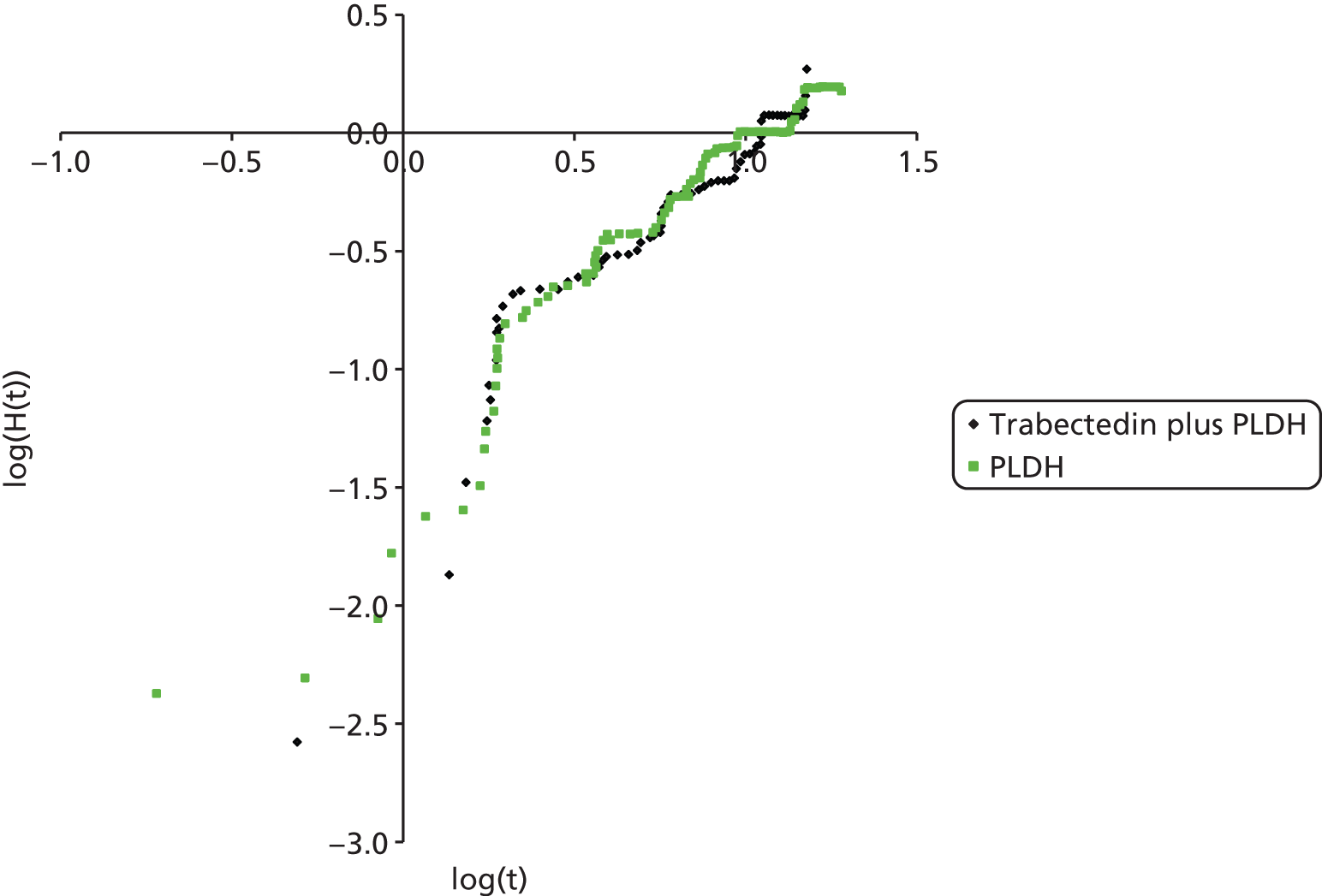

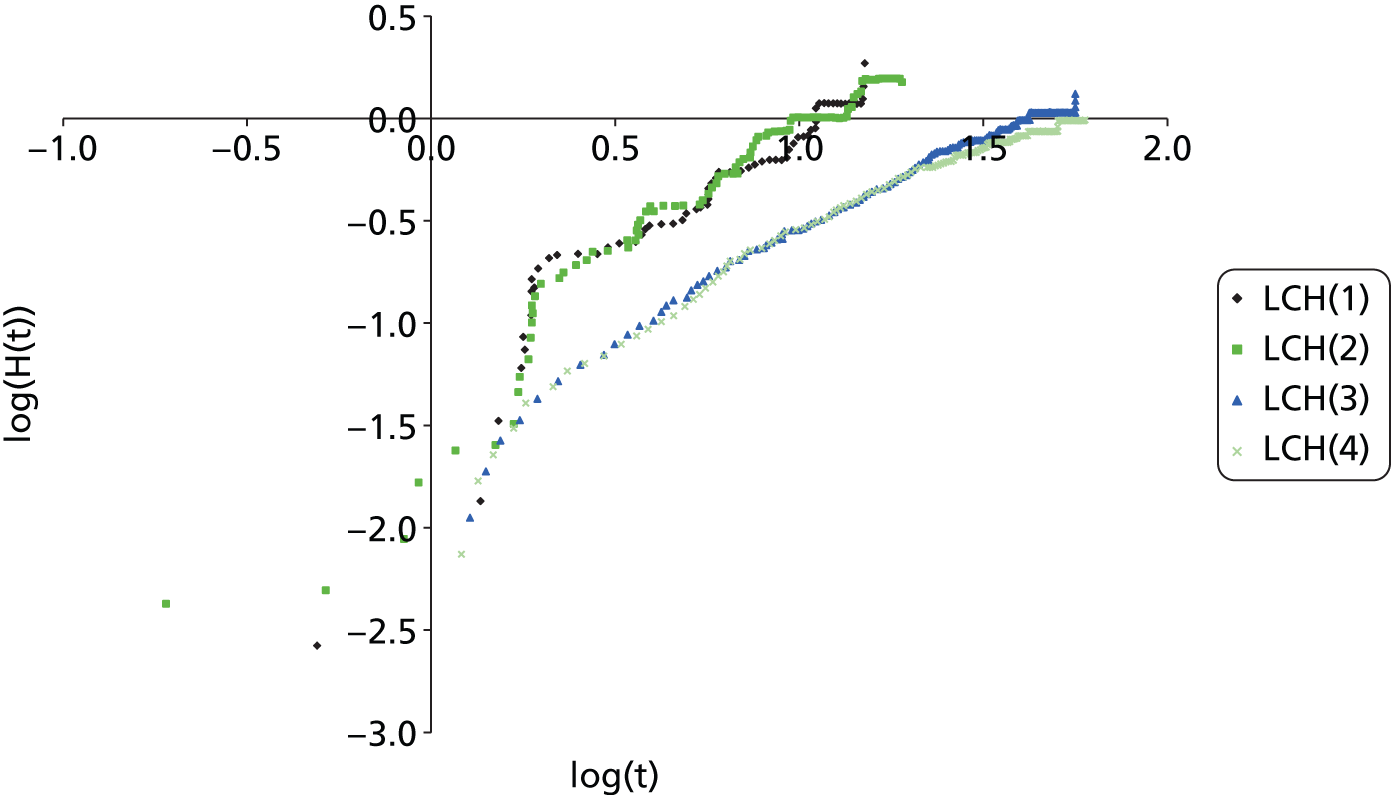

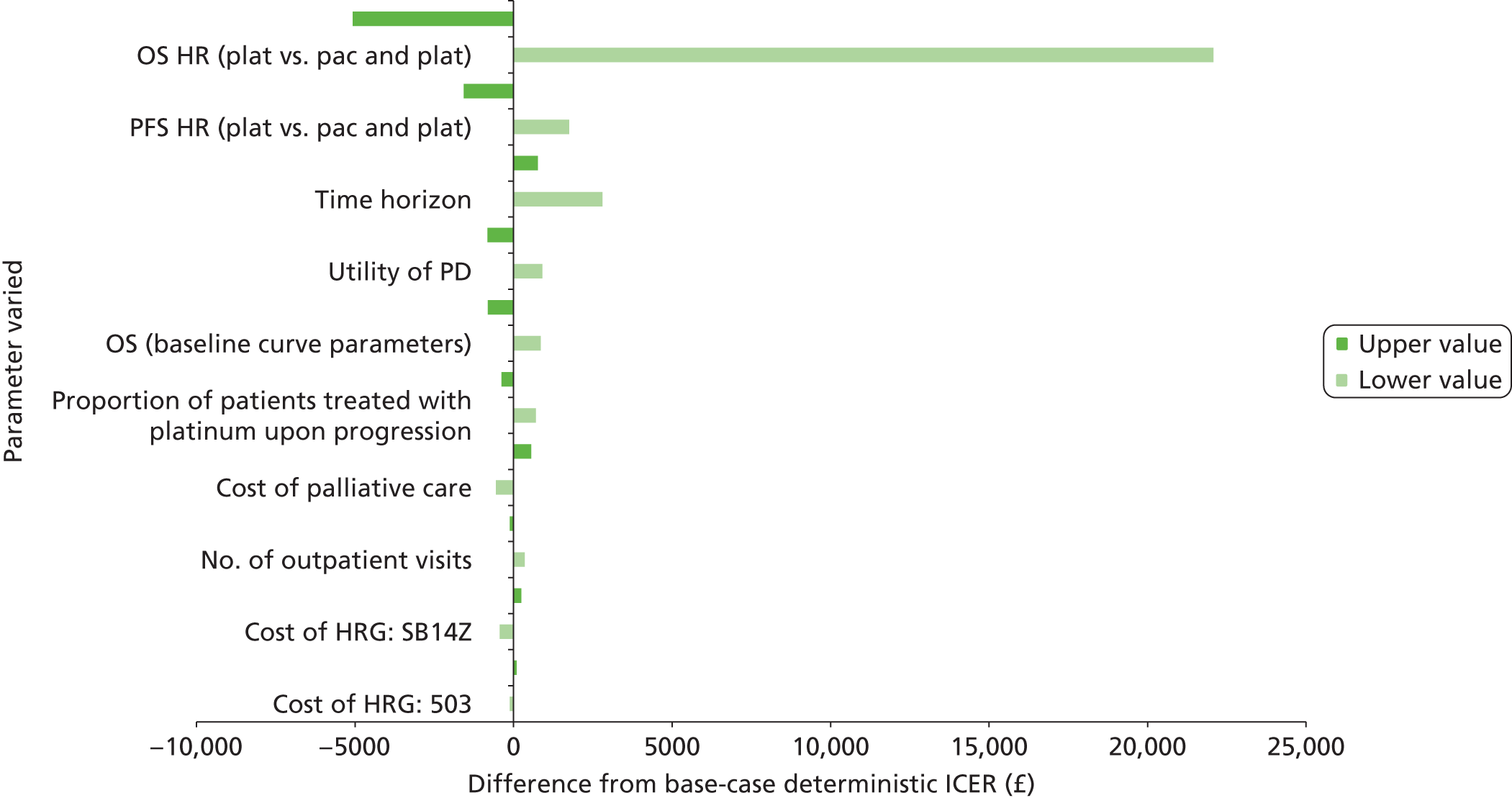

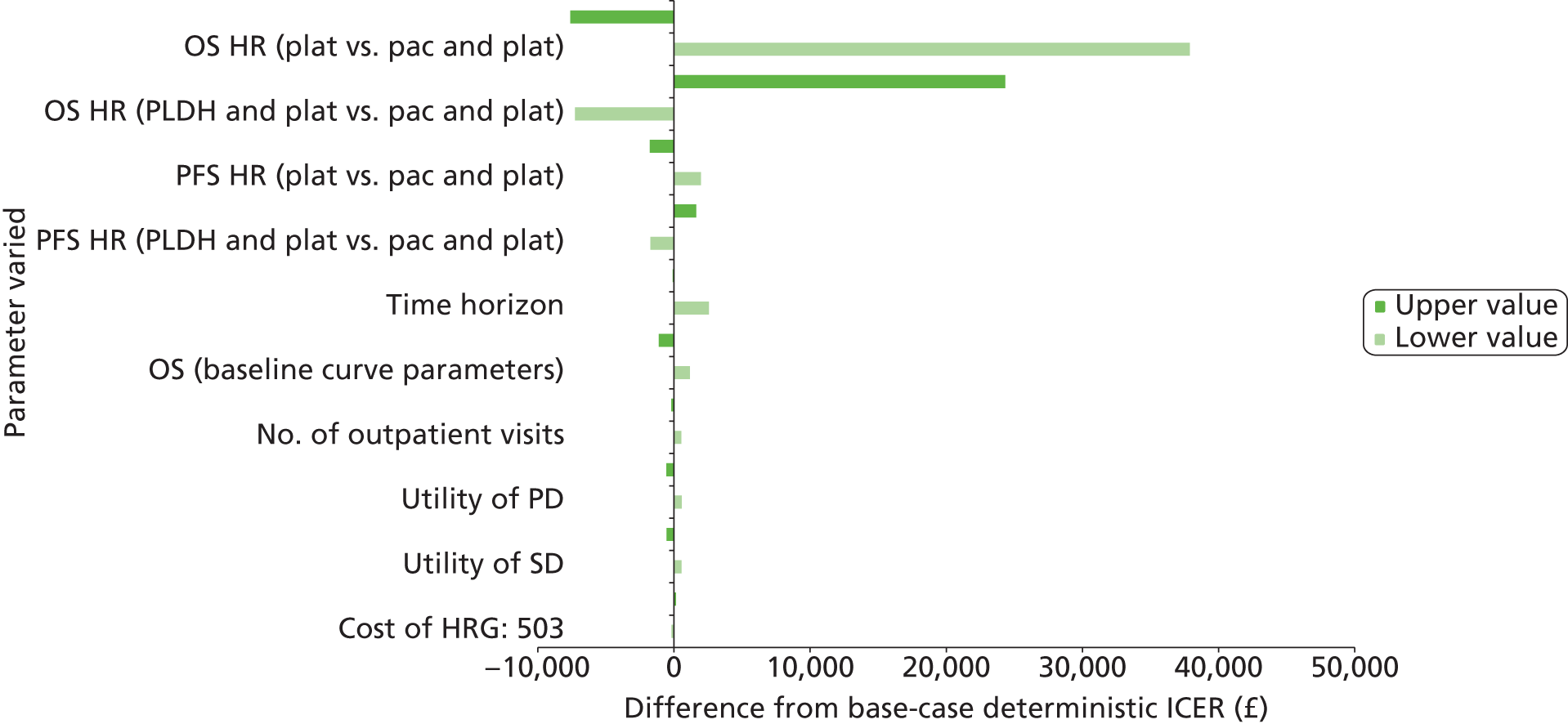

The primary aim of the study was to evaluate the comparative clinical effectiveness of the two treatment regimens in terms of OS in women with platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer. PFS, confirmed CR rate and time to treatment failure were analysed as secondary outcomes. Objective response and disease progression were defined according to standard RECIST criteria. 69 GCIG CA125 progression criteria were also implemented in defining disease progression. 70