Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/97/01. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in December 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Perera et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and rationale

Cardiovascular disease: burden, causes and strategies for management

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) – comprising coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke and peripheral arterial disease – continues to be a major public health problem: it accounts for almost one-third of deaths in the UK, making it one of the leading causes of mortality,1–4 and it is responsible for one-fifth of all hospital admissions. 5 The cost implications of CVD are significant, with recent estimates of spending on cardiovascular care in the UK of approximately £12.5B: £9.6B on direct health-care cost, and £4.2B on informal care. 1

Importantly, a high proportion of CVD deaths are identified as premature (before the age of 75 years)1 and most may therefore be preventable. 4 Most CVD is caused by atheroma (or atherosclerotic plaques) in the arterial wall; these plaques develop progressively throughout life, and are often at an advanced stage before symptoms occur. 4,6 Three modifiable risk factors, smoking, blood pressure (BP) and cholesterol, particularly in combination, are thought to account for the majority of all premature CHD. 2,7

The number of deaths caused by CVD has gradually declined since reaching a peak in the 1970s. An estimated 60% of this decline is due to smoking cessation and reduction of other risk factors, with the other 40% resulting from improvements in treatment. 8 Strategies for CVD prevention therefore aim to address these risk factors. In the UK, there is currently a three-part strategy: a reduction in average levels of risk factors in the population; identifying those at a higher risk of CVD events; and reducing risk in people with established CVD through therapies to lower BP and lipid levels. 2,9,10

Lipid measurement and lipid-lowering treatments therefore play a vital role in CVD risk management: testing lipid levels provides a simple and safe way to identify those at increased risk of CVD, and enables the initiation and ongoing up-titration of therapies to lower lipid levels. Optimising the clinical strategy to identify dyslipidaemia for both primary and secondary CVD prevention is therefore of major importance; however, a number of key questions remain unanswered. There are several different cholesterol measures: total cholesterol (TC), low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, the ratios of these three measures, non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides (TGs), as well as more recent alternative measures such as apolipoprotein B (Apo B) and apolipoprotein A-I (Apo A-I). The utility of each of these measurements, including whether or not any meet the criteria for a screening test, is currently not known. Ideally, the selection of an optimal monitoring measure should take into account four different factors: (1) clinical validity, with the most useful tests being those strongly associated with the outcome and that give results early enough to allow action to be taken; (2) responsiveness to changes in therapy; (3) the ability to identify real changes from background measurement variability (short-term biological fluctuations and technical measurement error); and (4) practicalities such as affordability, accessibility, ease of testing and interpretation. 11

After an optimal monitoring test has been identified, translation to a monitoring strategy then requires further consideration of factors such as the frequency of testing, defining the clinical actions required if the target is out of range, evaluating the cost-effectiveness of the strategy, and ensuring that those implementing the strategy have adequate training and a quality assurance scheme is developed. 11 Cost-effectiveness is important because screening programmes need to produce a net benefit that should be achieved at a reasonable cost – accounting for savings from improved outcomes.

The factors for choosing an optimal monitoring measure and defining an optimal monitoring strategy have not been thoroughly addressed in the current guidelines that aim to help general practitioners (GPs) manage dyslipidaemia in primary and secondary populations with CVD. A recent systematic review12 examining the clarity and evidence base for such CVD prevention and treatment guidelines found that, of those with a section on lipids, only half recommended specific target levels or provided guidance on how to interpret initial measurements. The majority did not specify how or when to carry out subsequent monitoring, or provide management guidance when the target is out of range. Largely based upon consensus and expert opinion, the evidence base for an optimal monitoring interval is particularly weak.

This report forms part of a commissioned stream of work by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, and aims to provide evidence for an effective strategy for monitoring dyslipidaemia in both primary and secondary prevention populations. It has involved the development and use of new methods to determine an effective strategy for screening and monitoring of lipid levels in relation to primary and secondary CVD prevention. It includes drawing together (1) a systematic review of the literature to identify the predictive values of different lipid measures and help determine the optimal disease parameter for monitoring; (2) a systematic review of the literature to determine the effectiveness of lipid modification therapies and establish the effect size for treatment in both primary and secondary prevention populations; (3) individual patient data (IPD) analyses to derive parameters from repeated measurements to identify biological variability, measurement error and variation in the rate of change in specific lipid measurements over time; (4) simulation modelling to estimate the likelihood of false decisions with respect to treatment under different monitoring strategies; (5) IPD analyses to examine the potential impact of different approaches to lipid measurement have on CVD risk scores; and (6) health economics modelling, which takes into account individual variability in lipid progression, as well as the poor precision of tests, to determine the cost-effectiveness of different monitoring strategies. This introductory chapter reviews the clinical background for this work, summarising current lipid management guidance, particularly in the UK, and highlighting the key gaps in the evidence base that this report aims to address.

Lipid monitoring and statin therapy

Cholesterol is a lipid, essential for normal bodily function; however, high levels are associated with several health problems, in particular CVD. Lipid measurement is important for accurately assessing an individual’s overall risk of CVD and CHD: high TC and LDL cholesterol, and low HDL cholesterol predict an increased risk. 13 There is a clear log-linear relationship between cholesterol and cardiovascular events, with each mmol/l rise in TC associated with a 72% risk of a major coronary event. 7,14 Management of dyslipidaemia therefore plays an important role in the prevention of both primary and secondary cardiovascular events.

Statins are a group of medicines that can reduce serum LDL cholesterol through the inhibition of 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A (HMG-CoA) reductase, an enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of cholesterol, and the subsequent enhanced uptake of LDL from the bloodstream. 15,16 Since their introduction in the 1980s, they have made a dramatic difference in lipid management, with statin use reducing CHD mortality among those at both moderate and high risk of CHD. 17–25 Current guidelines in the UK2,9,10 propose their use for both primary and secondary prevention of CVD. Accordingly, UK statin expenditure has increased from approximately £20M in 199322 to £70M in 2004,26 and to > £800M in 2011. 27 Mirroring this treatment cost has been a large increase in lipid measurement. Lipid levels are measured both before and after the decision to initiate dietary or statin treatment. Our recent Oxfordshire-based study indicated a ≥ 15-fold rise in the overall number of lipid measurements over the past 20 years; although appropriate lipid testing has increased, and cholesterol levels appear to be lowered, there appears to be considerable, possibly unnecessary, repeat testing. 17

The objectives of lipid monitoring, which change over the course of treatment, can usefully be divided into the five phases described in Table 1. 11,28 Although individuals taking statins may require some monitoring of response to treatment or follow-up (phase 2: initial titration), most testing is likely to happen during screening (phase 1: pre-treatment) or long-term monitoring (phase 3: maintenance). This report focuses on the monitoring carried out in phases 1 and 3: screening and long-term monitoring.

| Phase | Monitoring objectives | Optimal interval |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Pre-treatment | Check need for treatment Establish a baseline for determining response and change |

Short – based on within person variability |

| 2. Initial titration | Assess individual response to treatment Assess immediate adverse effect Achieve control |

Medium – based on pharmacokinetics (e.g. drug half-life) and pharmacodynamics (physiological impact time) (wash-in) |

| 3. Maintenance | Detect drift from control limits Detect long-term harms |

Long – based on rate of random and systematic ‘drift’ |

| 4. Re-establish control | Bring level back within control limits | Medium – see (2) |

| 5. Cessation | Check safety of cessation | Medium – see (2) |

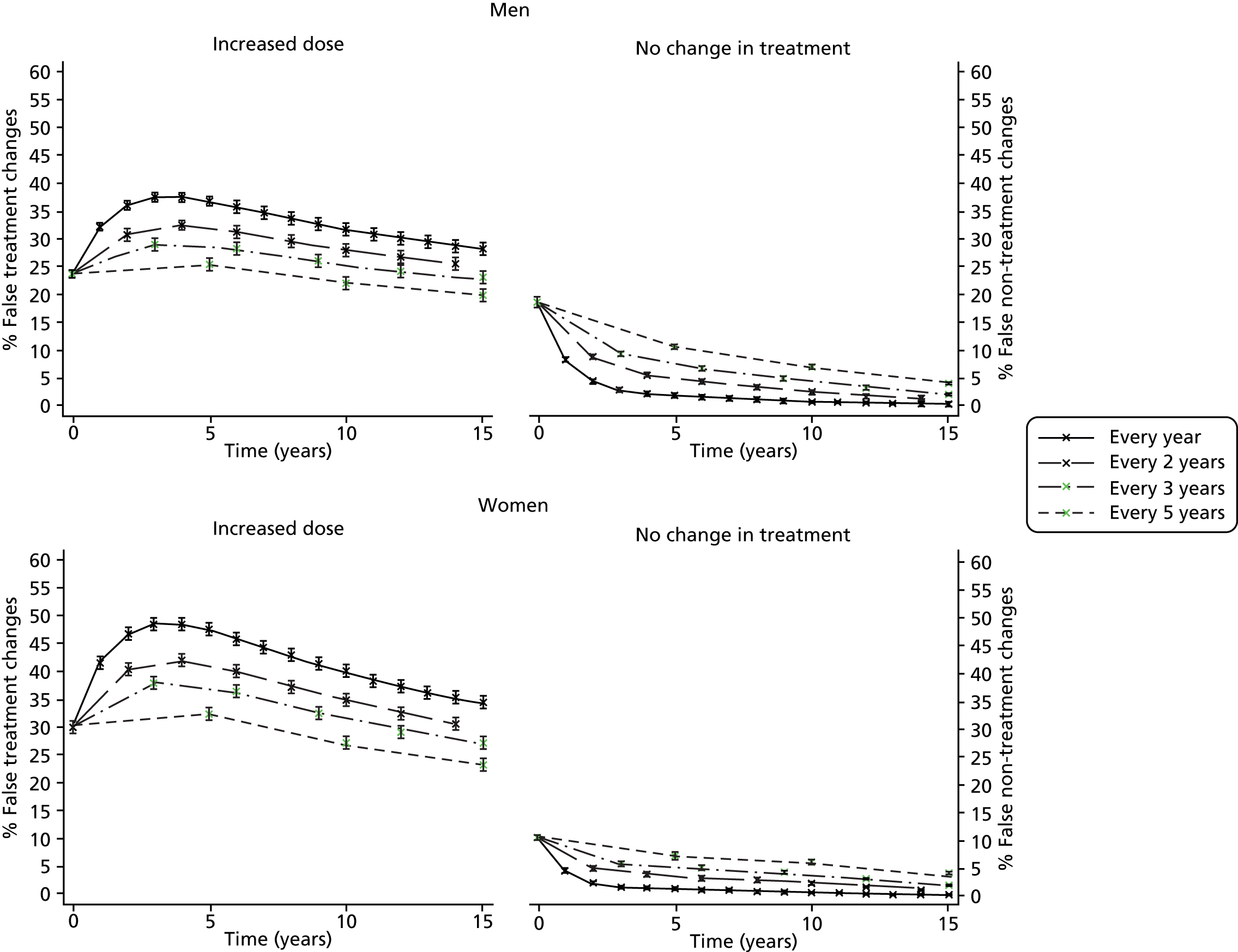

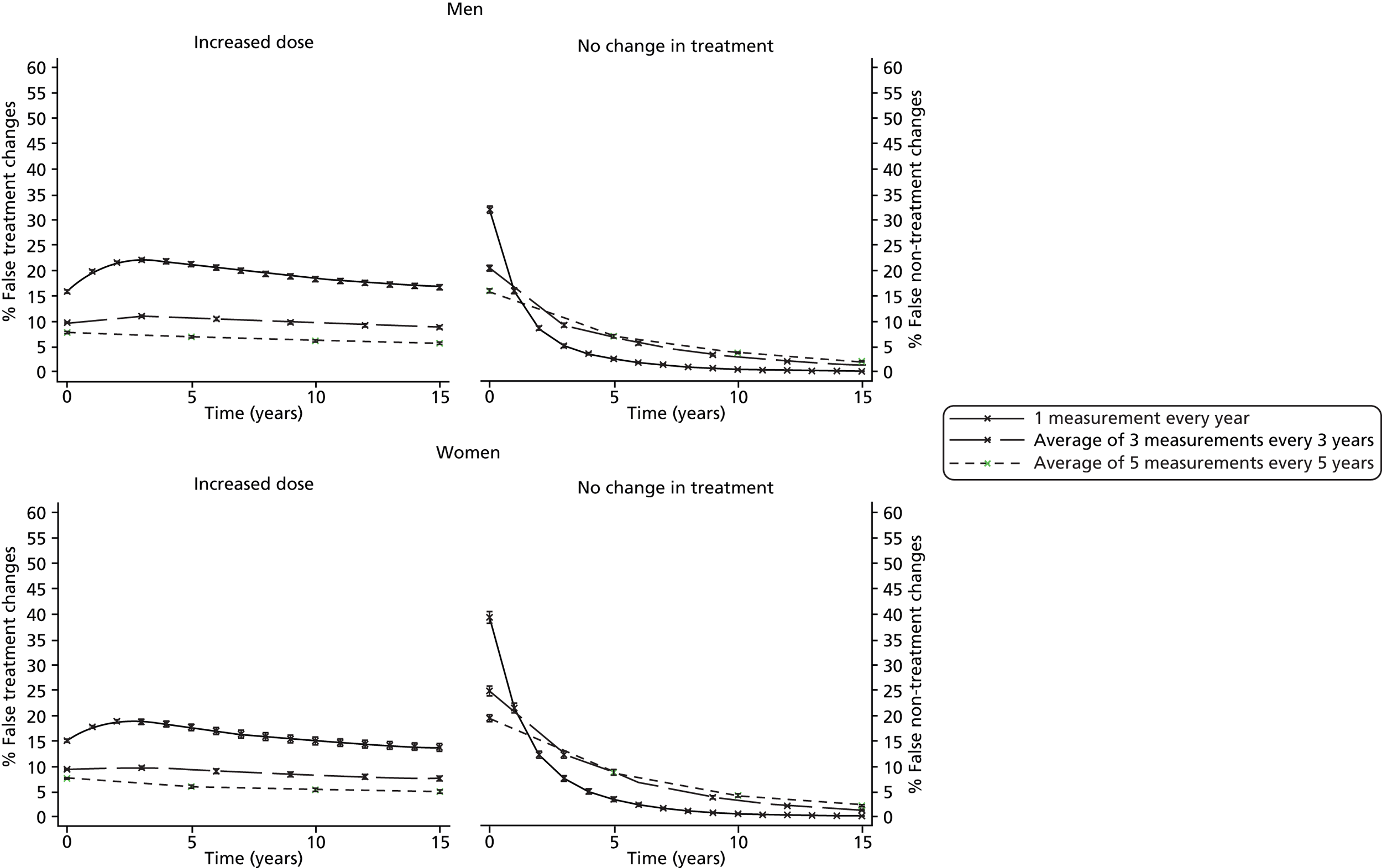

Screening and long-term monitoring of lipid levels requires interpretation of initial levels and also of the following sequential levels over time. 29 As part of this interpretation, it is necessary to consider both the short-term within-person variation (‘noise’) and the long-term variability among individuals in the population (‘signal’), illustrated in Figure 1. 30,31 At the time of writing, however, no published guidelines have considered either within-person or long-term variation in their re-screening strategies. 12 Recent evidence has suggested that, because of the weak signal–noise (SN) ratio of cholesterol level, frequent screening and/or monitoring – as part of long-term management – more often captures measurement error rather than true changes. 30–32 As clinical decisions on treatment are typically based upon these measurements, overly frequent monitoring may be detrimental to a patient’s health; therefore, less frequent testing of cholesterol, such as every 3–5 years, might be more appropriate.

FIGURE 1.

Variance of difference among individual cholesterol levels over 4 years.

Choice of lipid measure to monitor

Primary prevention

The seminal statin trials in the 1990s, such as 4S (Scandinavian simvastatin survival study),18 LIPID (The long-term intervention with pravastatin in ischaemic disease study),33 CARE (Cholesterol and current events trial)34 and WOSCOPS (West of Scotland coronary prevention study),19 focused on TC as the main lipid measurement for screening and monitoring. As a result, initial guidelines also focused on TC for screening, targets, and monitoring. 35,36 Although an important CVD risk factor, serum TC on its own is actually a relatively poor predictor of who will go on to have an event. 22,36 In practice, CVD can rarely be attributed to a single underlying risk factor; more commonly it is the additive and synergistic effect of several risk factors that lead to the atherosclerotic progression underlying most CVD. Thus, over time, there has been a shift towards assessment of absolute CVD risk, using CVD risk equations that include a combination of important risk factors. 37 For initial risk measurement, there is evidence from cohort studies38–40 and a meta-analysis41 to suggest that lipid ratios (TC/HDL cholesterol and LDL/HDL cholesterol) have greater independent predictive values for CHD than individual lipid levels. The better predictive ability, and ease of measuring TC compared with LDL, has led to the inclusion of TC/HDL cholesterol in many CVD risk equations,2,42 which, in turn, has meant a move to measuring and using a combination of TC and HDL for screening in primary prevention patients. Although TC and HDL, based upon cardiovascular risk, are the most commonly recommended lipids for screening, it is often suggested that LDL be either calculated using the Friedewald equation43 (requiring a fasting sample) or measured directly, even when guidelines do not specify what to do with the information. Additionally, most guidelines also recommend measuring TGs, although TGs play only a minor role in treatment choices.

Secondary prevention

For people with established CVD, statins reduce total mortality, cardiovascular mortality and morbidity, and are cost-effective, particularly for those with CHD. 16,44 However, substantial variation in the use of statins for secondary prevention combined with poor adherence to treatment, even in those who have experienced a CVD event,45–47 mean that in many instances serum cholesterol often remains at unacceptably high levels,48 and can be further improved with advice, support and treatment. Management of statins for the secondary prevention of CVD is usually based on controlling cholesterol levels to a target dose,2,49–51 but there is a lack of published evidence on the cost-effectiveness of treating to target compared with fixed doses of statins,2 and recommendations are based upon either economic simulation models or expert opinion.

When to monitor

Primary and secondary prevention

Information provided on the frequency of lipid monitoring in current CVD prevention guidelines differs greatly: some guidelines give vague references to testing lipids or assessing CVD risk at ‘regular intervals’, whereas others give specific intervals for specific groups of people, often with more frequent screening and measurement for those at higher risk or in secondary prevention groups. Most guidelines do not reference the evidence or level of evidence on which the recommendation was based, and, of those that do, most use only weak levels of evidence, consensus or expert opinion. 12

Screening and monitoring as part of primary cardiovascular prevention in the UK

The 2010 UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) lipid modification guidelines2 for the primary prevention of CVD recommend more active and systematic identification of those at high risk of CVD, but without full-scale (population wide) screening. 2 Based upon an economic analysis, the guidelines suggest the use of computerised GP records (with data on age, smoking, BP and, sometimes, serum lipids) to identify people aged between 40 and 74 years who are in need of a full CVD risk assessment. This full assessment would then include measurement of TC and HDL cholesterol (non-fasting samples would be adequate) and calculation of the patient’s 10-year risk of CVD using an appropriate CVD risk calculator, such as the QRisk2 equations from the QRESEARCH database,52 equations from the Framingham Heart Study,53 or the ASsessing cardiovascular risk using SIGN guidelines (ASSIGN) score. 54 Statin therapy is recommended as part of a management strategy for primary prevention people with a ≥ 20% 10-year risk of developing CVD. Although the economic analysis on which these guidelines were based allows for measurement error at a population level (through the incorporation of an error term based on published values for the coefficient of variation in TC and HDL cholesterol), individual variability in the progression of dyslipidaemia is not accounted for. Furthermore, only TC and HDL cholesterol measurement are considered, even although guidelines note that before offering lipid modification therapy, fasting levels of TC, HDL and TGs should be measured, and LDL should be calculated using the Friedewald equation. 43 The implication is that LDL cholesterol measurement is not required for risk assessment: complicated by the need for specialised assays to measure LDL cholesterol directly or a fasting sample to allow indirect calculation of LDL cholesterol.

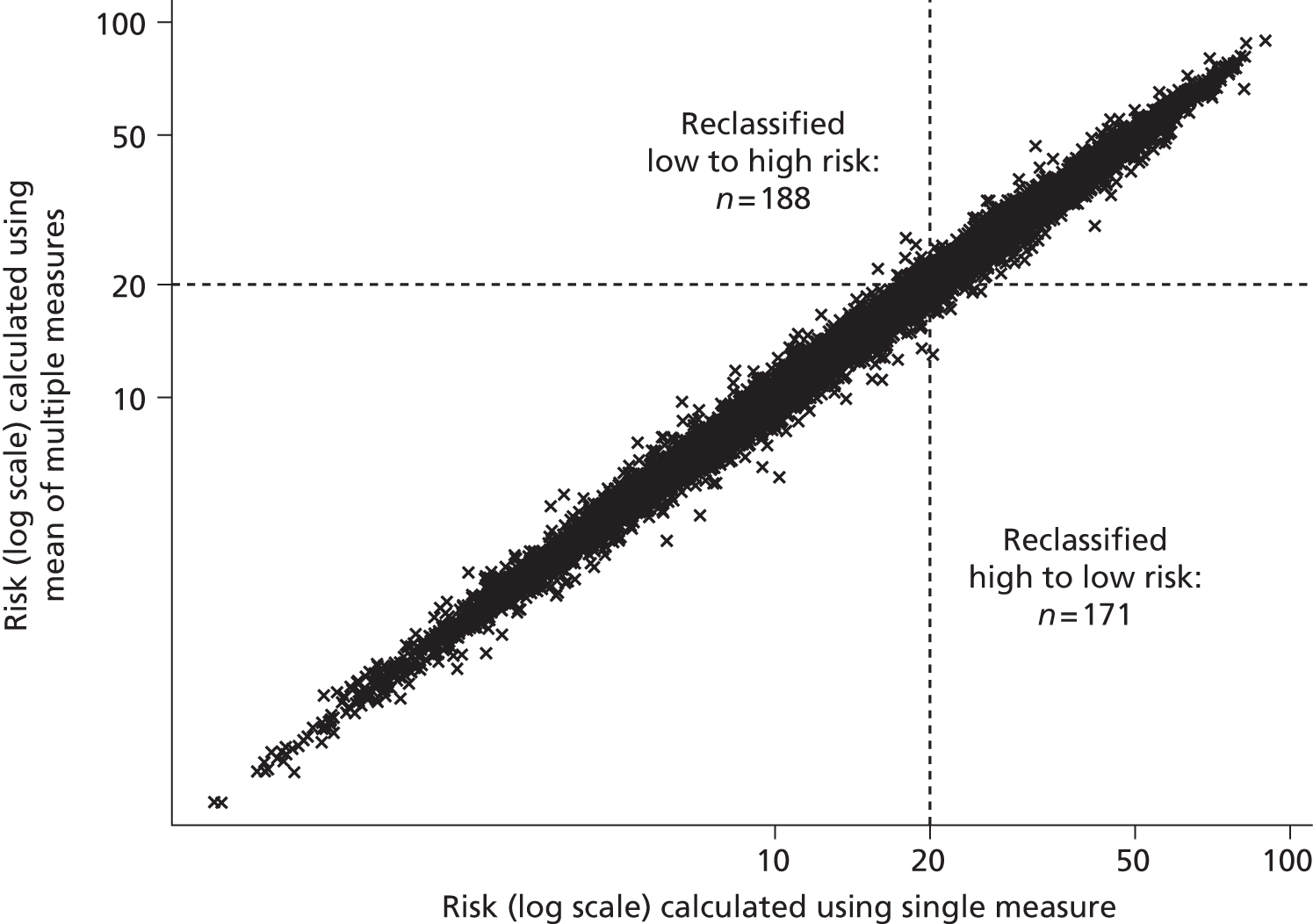

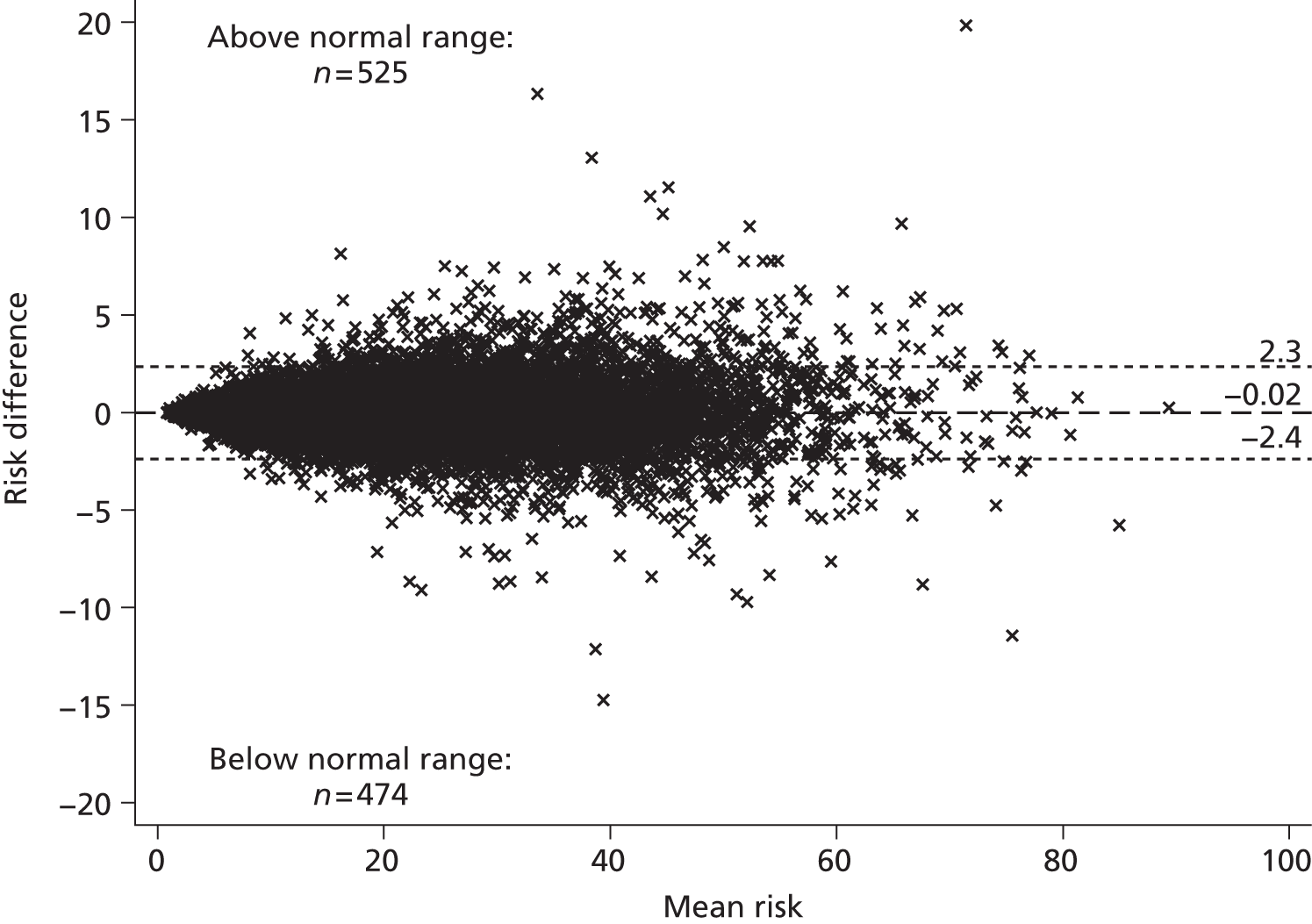

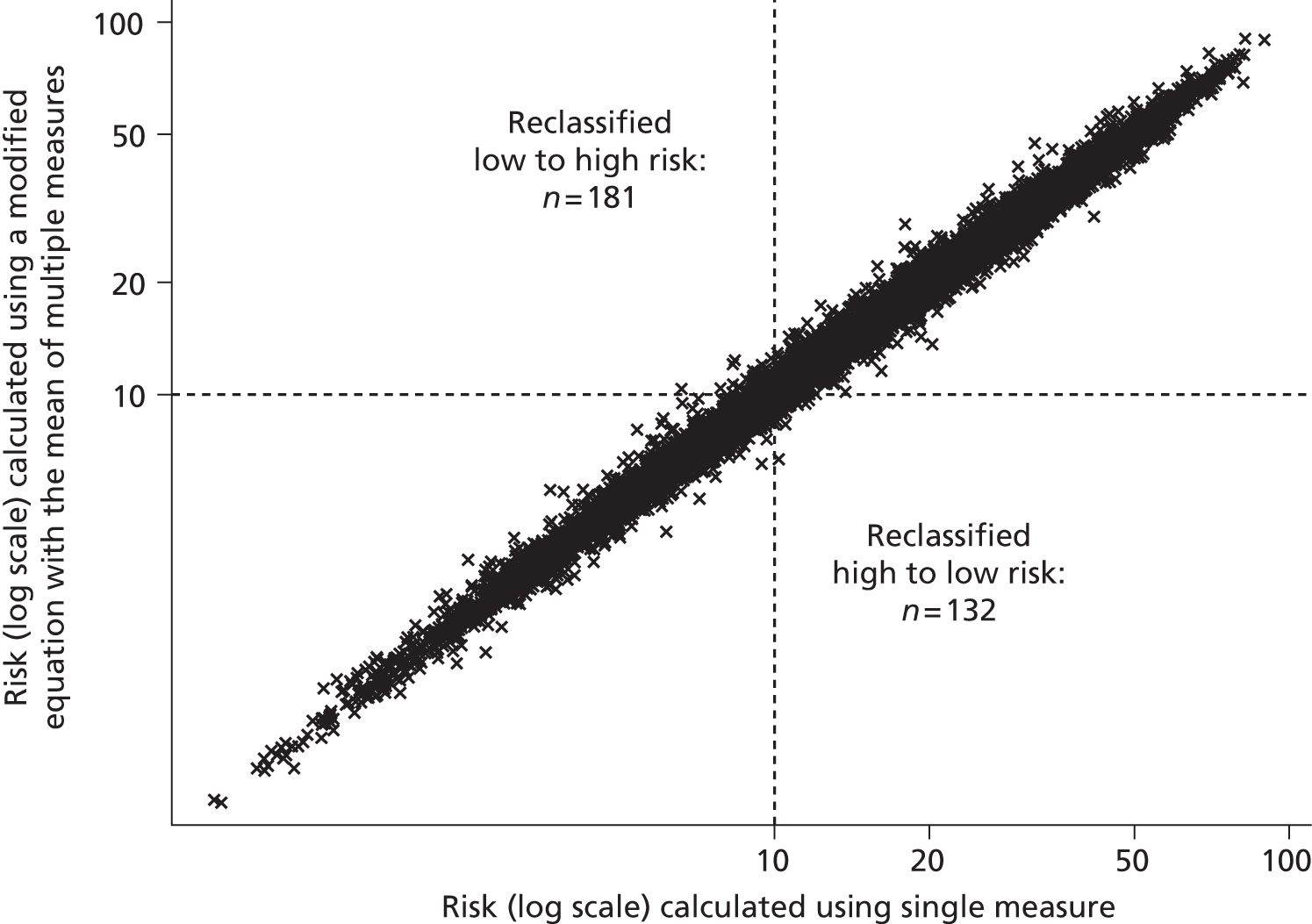

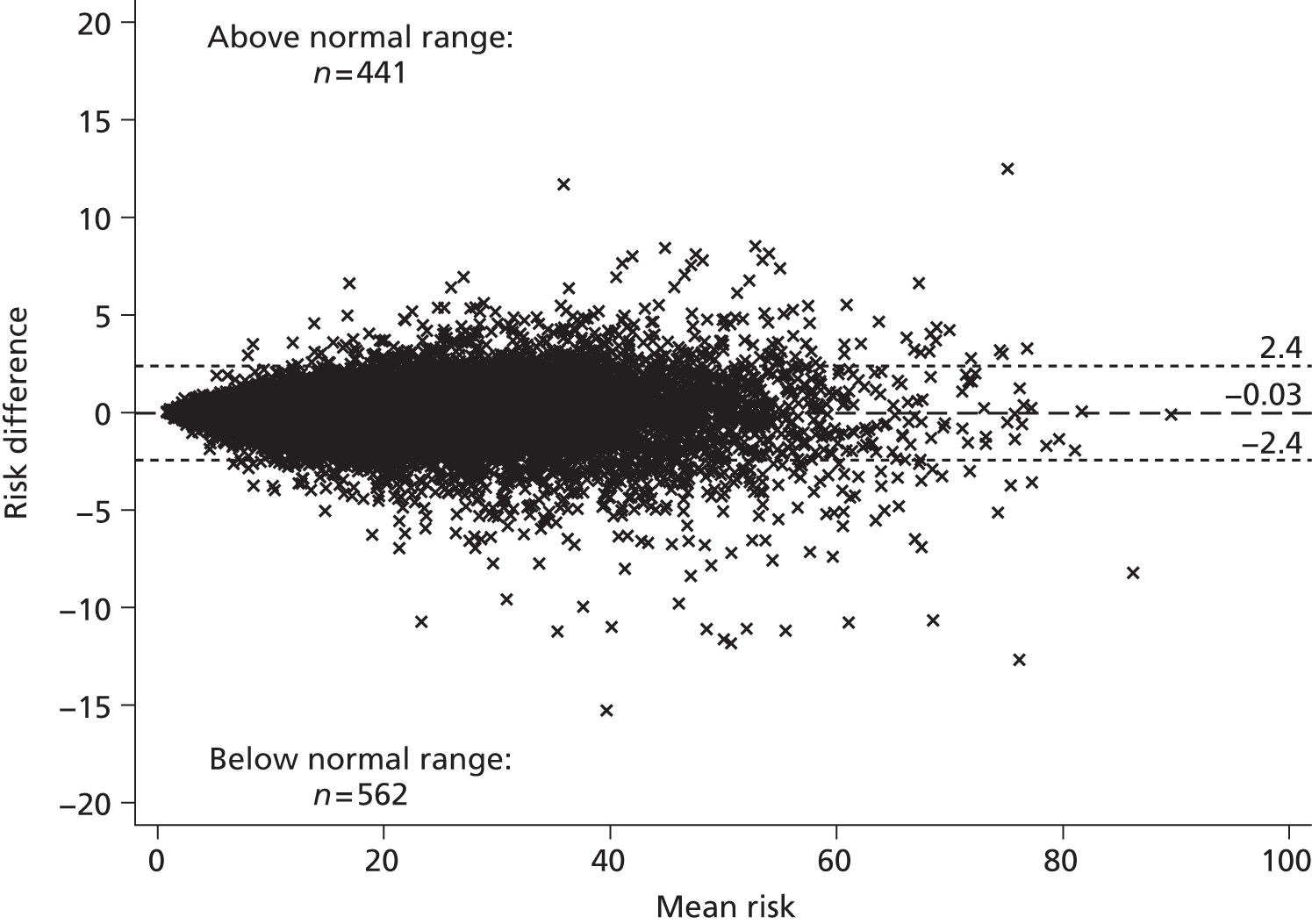

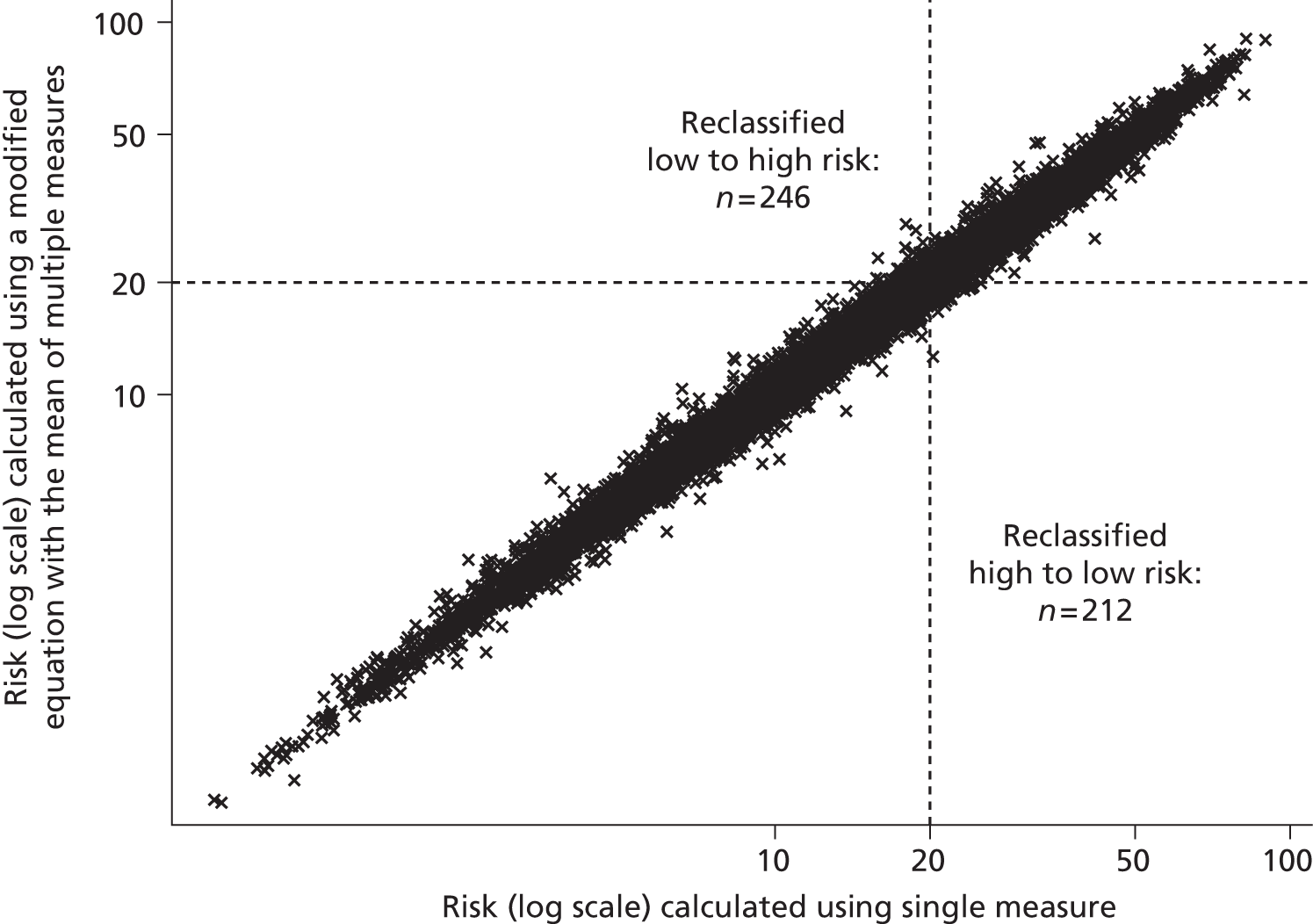

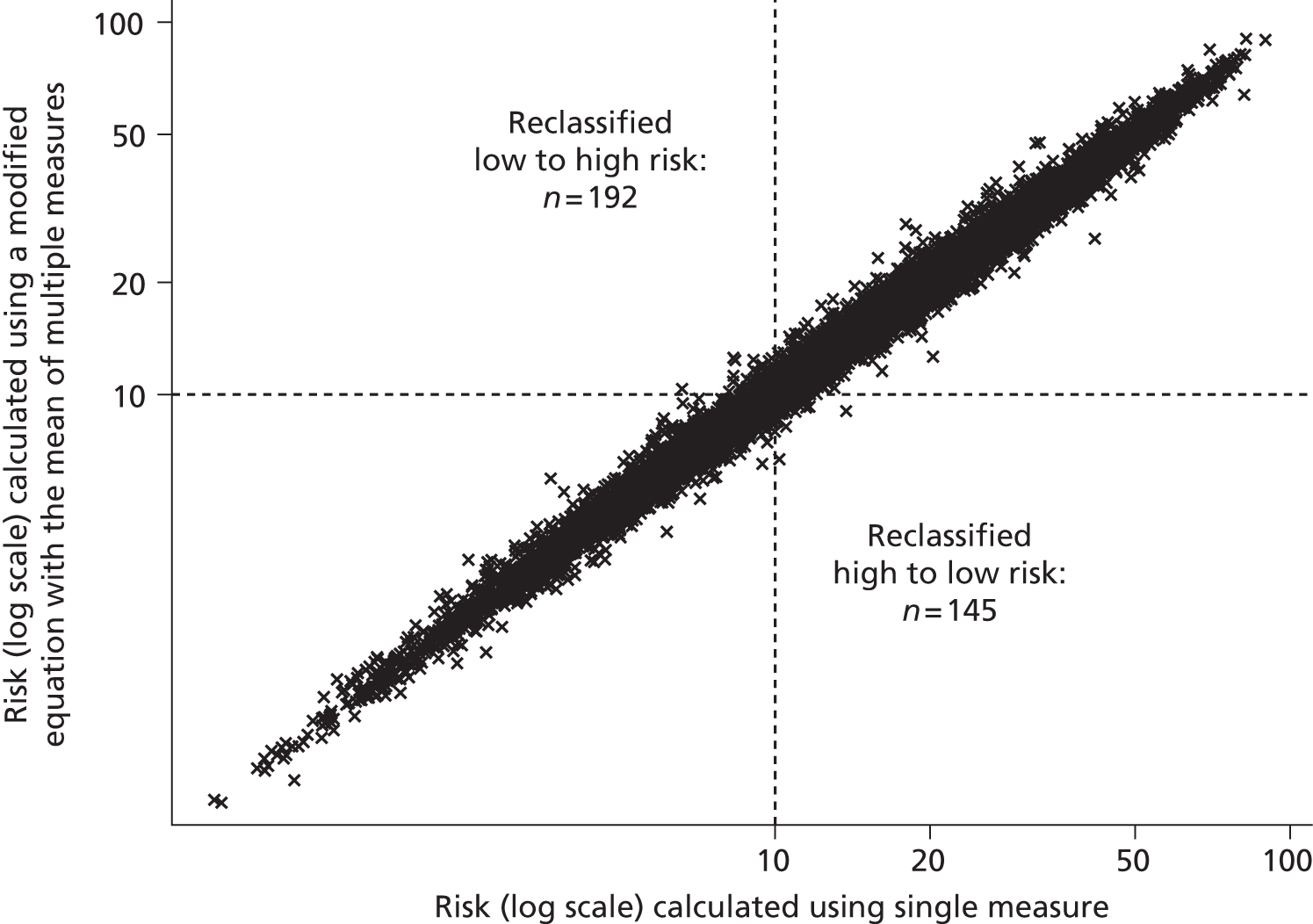

Although guidelines note that a patient’s CVD risk should be reviewed on an ongoing basis, a specific interval is not provided. Target lipid levels are not recommended and once a patient has started taking statins, no further monitoring of lipids is considered necessary: review of drug therapy should be guided by clinical judgement and patient preference. 2 This differs to many guidelines that have suggested close monitoring of those on treatment, and was suggested because of the lack of clinical trial evidence for treating to targets, which target to use, and the lack of cost-effectiveness studies on lipid measurement for risk assessment. 2 Although initially proposed over 10 years ago,37 the ‘fire and forget’ approach has been criticised because of the possibility of failing to identify non-response to treatment, whether or not biological or through non-adherence. 55 Despite the known inaccuracy of lipid measurements, NICE guidelines2 note that multiple measurements are impractical and risk delay, and thus recommend that treatment should be generally based on only one or two measurements. Using an average of several repeated measurements is likely to improve the estimate of an individual’s ‘true’ underlying lipid level but is also likely to have an impact on CVD risk prediction; this has not yet been investigated.

Updated guidelines were published by NICE in 2014;56 Table 2 summarises key differences in monitoring strategies between the 2010 and the 2014 guidelines. Based upon economic analyses, the update recommends that, although TC and HDL will remain the lipid measurements for screening, the treatment eligibility threshold for people with no history of CVD will be lowered to a 10-year CVD risk of 10%, and that this should be calculated using the QRisk252 assessment tool. As QRisk252 has been validated for people aged up to 85 years of age, people aged 75–84 years will also become eligible for screening. Moreover, a fasting sample prior to initiating statin therapy is no longer needed; instead TC, HDL cholesterol, and TG concentrations should be measured and non-HDL cholesterol calculated (through the subtraction of HDL cholesterol from TC), when a non-fasting sample is considered sufficient. More detailed follow-up monitoring is suggested, with measurement of TC and HDL cholesterol, and calculation of non-HDL cholesterol at 3 months, with a target reduction of at least 40% in non-HDL cholesterol. This recommendation is based upon an evidence review of statin efficacy, and it is noted that there are wide confidence intervals (CIs) around this 40% estimated reduction. It is not clear whether or not further lipid measurements after another 3 months are recommended for those who did not meet these goals. As with previous economic analyses, individual variability is not accounted for.

| Aspect of guideline | NICE Clinical Guideline | |

|---|---|---|

| 2010: Clinical Guideline 672 | 2014: Clinical Guideline 18156 | |

| Lipid measurements required | TC/HDL cholesterol measurements initially, followed by a full fasting panel pre treatment | Before starting lipid modification therapy for the primary prevention of CVD, take at least one lipid sample to measure a full lipid profile. This should include measurement of TC, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, and TG concentrations. A fasting sample is not needed |

| CVD risk score(s) | QRisk252 Framingham 199153 ASSIGN54 |

QRisk252 |

| CVD risk threshold for statin treatment | 20% | 10% |

| Initial statin treatment recommendation | Simvastatin 40 mg | Atorvastatin 20 mg |

| Follow-up recommendation | Once a person has been started on a statin . . . repeat lipid measurement is unnecessary. Clinical judgement and patient preference should guide the review of drug therapy and whether or not to review the lipid profile | Measure cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol in people who have been started on high-intensity statin treatment (atorvastatin, any dose) after 3 months of treatment and aim for a > 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol |

| Follow-up action | Target for TC or LDL cholesterol is not recommended for people who are treated with a statin for primary prevention of CVD | If a > 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol is not achieved:

|

Monitoring as part of secondary cardiovascular prevention in the UK

In 2010, NICE’s lipid modification guidelines for the secondary prevention of CVD2 recommend initiation with simvastatin 40 mg (except if contraindicated), and that if TC levels of < 4 mmol/l or LDL cholesterol levels of < 2 mmol/l are not achieved on the initial dose then the dose can be increased to simvastatin 80 mg or a statin of similar potency and acquisition cost. These recommendations were based upon economic analyses, as a systematic literature search identified no studies on the cost-effectiveness of treating to target compared with a fixed dose of statin. 2 These analyses do not consider individual variability in lipid levels or the frequency at which to monitor. Since 2010, a drug safety update from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA),57 based upon results from the SEARCH study (Study of the effectiveness of additional reductions in cholesterol and homocysteine),58 recommended that simvastatin 80 mg should be considered only in patients with severe hypercholesterolaemia and a high risk of cardiovascular complications; furthermore, the UK patent for atorvastatin expired in 2012, and now that generic versions are available, this is considered a preferred choice of statin by some local authorities,59,60 and an updated analysis is clearly needed.

As noted above, these guidelines have been under review since 2011. 61,62 Updated recommendations from 201456 are compared with those from 20102 in Table 3, and suggest initiating therapy with a 80-mg dose of atorvastatin for people with established CVD62 and the replacement of general target levels for TC and LDL cholesterol with an individual target of a 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol after 3 months’ treatment. Potential actions for those not achieving this target include optimising adherence to statin therapy, diet and lifestyle measures and the timing of the dose (i.e. taken at night). In addition, people already taking a different statin/dose could be switched to atorvastatin 80 mg. These suggestions are, again, based upon economic analysis that does not account for individual variability in lipids or the frequency at which to monitor within a framework including both statins and the prevention of CVD.

| Aspect of guideline | NICE Clinical Guideline | |

|---|---|---|

| 2010: Clinical Guideline 672 | 2014: Clinical Guideline 18156 | |

| Initial treatment recommendation | A drug with a low acquisition cost, such as simvastatin 40 mg | Atorvastatin 80 mg |

| Lipids required for monitoring | TC and LDL cholesterol | Measure cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and non-HDL cholesterol in people who have been started on high-intensity statin treatment (atorvastatin any dose) after 3 months |

| Lipid thresholds or follow-up recommendation | 4 mmol/l for TC or 2 mmol/l for LDL cholesterol | Aim for a > 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol at 3 months since statin initiation |

| Follow-up action | Consider increasing to simvastatin 80 mg or a drug of similar efficacy and acquisition cost of TC of < 4 mmol/l or LDL of < 2 mmol/l is not attained An ‘audit’ level of TC of 5 mmol/l should be used to assess progress in populations or groups of people with CVD, in recognition that more than half of patients will not achieve a TC of < 4 mmol/l or LDL of < 2 mmol/l |

If a greater than 40% reduction in non-HDL cholesterol is not achieved:

|

No specific monitoring intervals are given and the frequency of the monitoring is not discussed. In contrast, until 2014, the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF),63 a voluntary incentive-based scheme for GP practices in the UK, effectively recommends annual monitoring of TC levels in secondary prevention patients, as there was an indicator for the proportion of patients with CHD whose TC level, measured in the preceding 12 months, was ≤ 5 mmol/l. Updates for 2014–15 expect practices to continue to monitor TC/HDL cholesterol but targets have been removed,64 providing evidence to support that this decision may help to minimise the persistence of over-monitoring. Previous research has suggested that, as a result of measurement error, such frequent monitoring is just as likely to mislead when trying to decide whether or not changes in treatment are needed. 65

Aims and objectives

As described in this introductory chapter, screening and monitoring of lipid levels to aid treatment decisions provides a key method for reducing the risk of CVD; however, the optimal lipid measure, monitoring strategy and interval remain unclear. A large number of guidelines do not include clear information on what, when and how to monitor lipids, and, of those that do, the evidence base, for monitoring frequency in particular, is weak; moreover, within-person and long-term variation are not addressed in their re-screening strategies. 12 Therefore, the aim of the research reported in this monograph, and set out in the original protocol (see www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/hta/109701), is to develop a clinical and economic model of dyslipidaemia and use this to determine an effective strategy for screening and monitoring of lipid levels in relation to primary and secondary CVD prevention, including current practice.

Our specific objectives are to:

-

identify the relative ability of different lipid measures (single or combination) to detect important changes in lipid status

-

estimate the incremental gains and costs of different strategies (lipid measurements and intervals) for risk assessment and monitoring of lipid levels in patients at risk of, or with, CVD

-

develop and populate an economic model of lipid monitoring

-

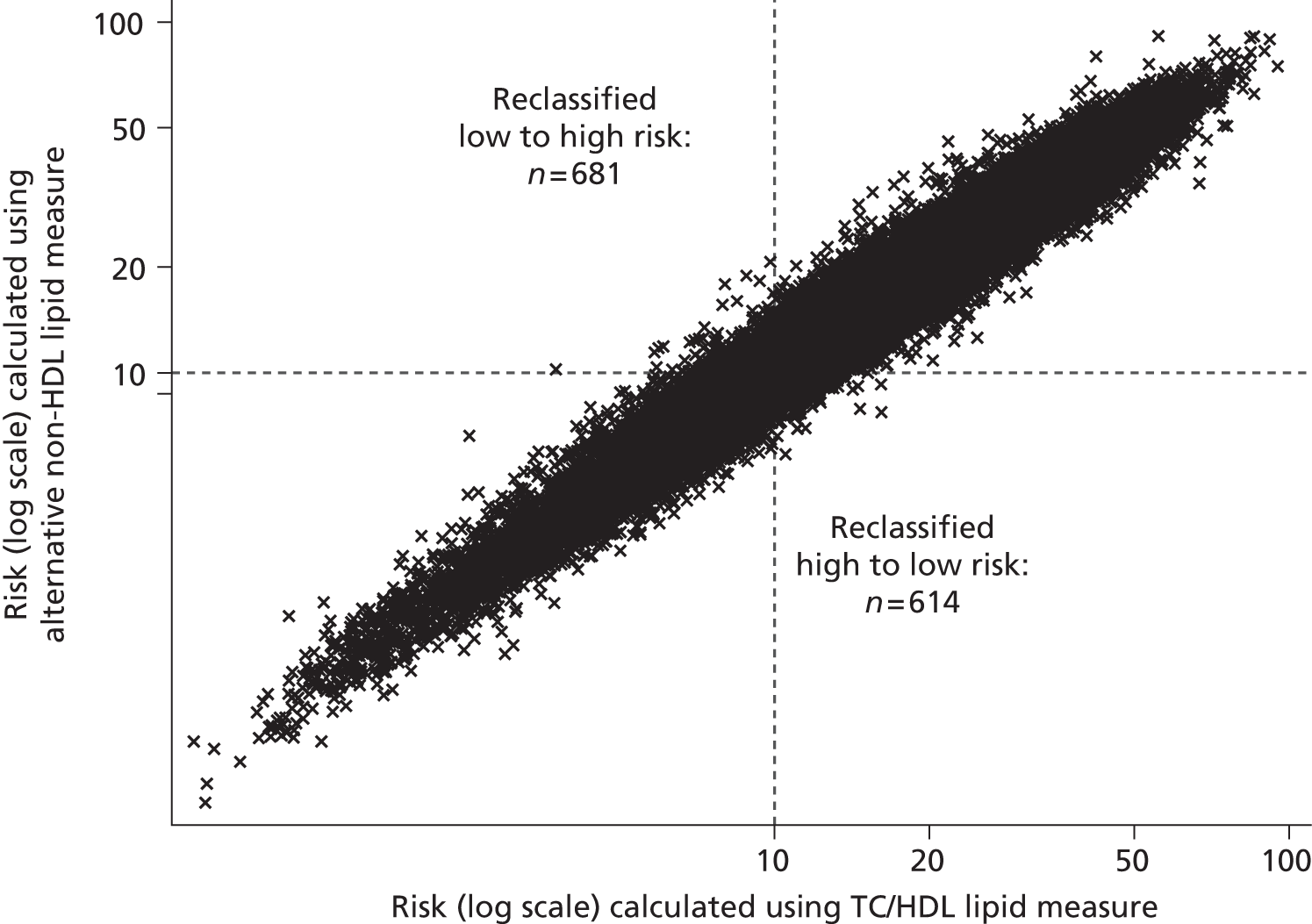

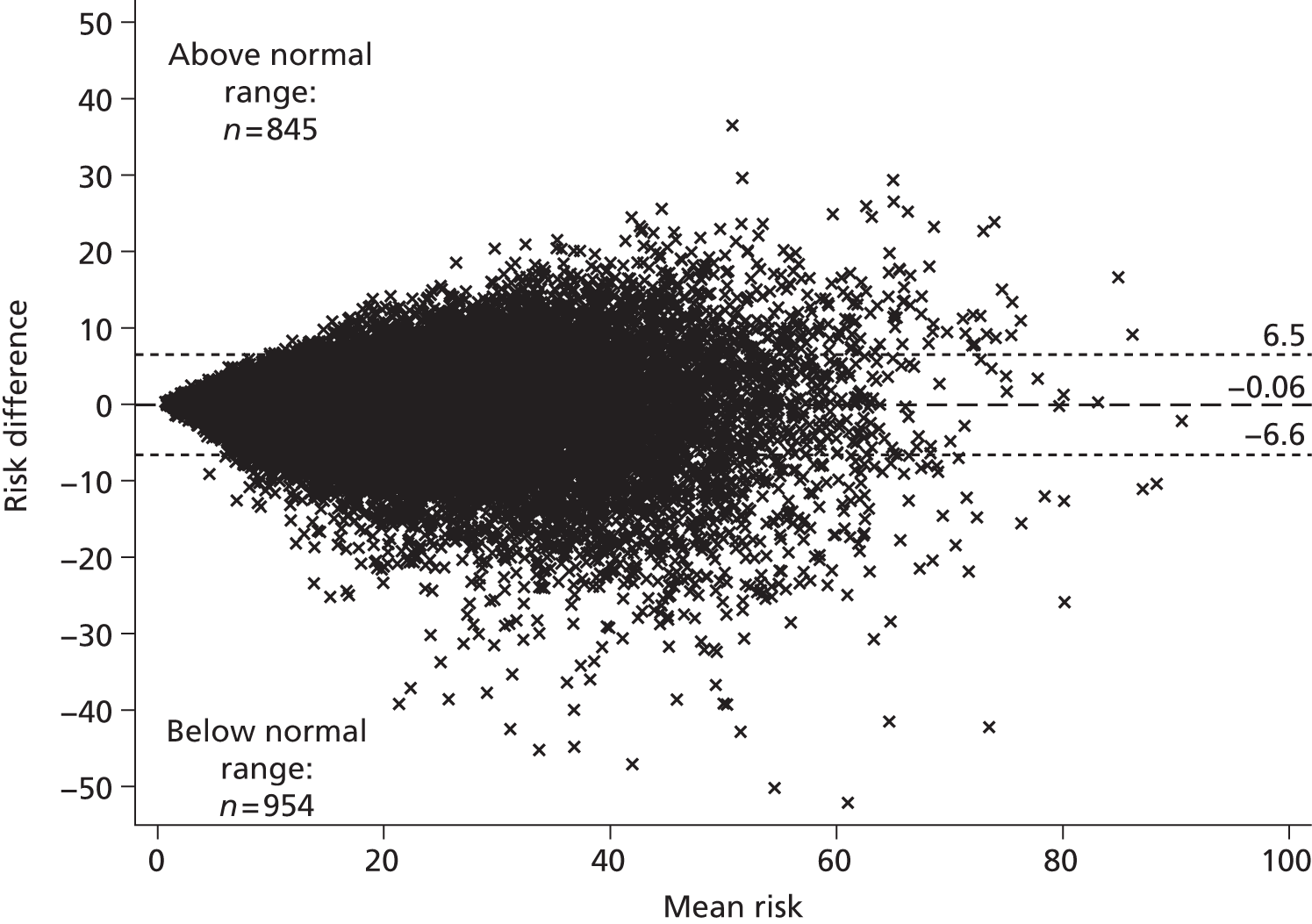

explore how the choice of lipid measure impacts on risk assessment of CVD compared with original risk scores

-

disseminate the impact of our findings on CVD risk assessment.

Modifications to the original protocol are listed in Appendix 2.

Overview of report structure

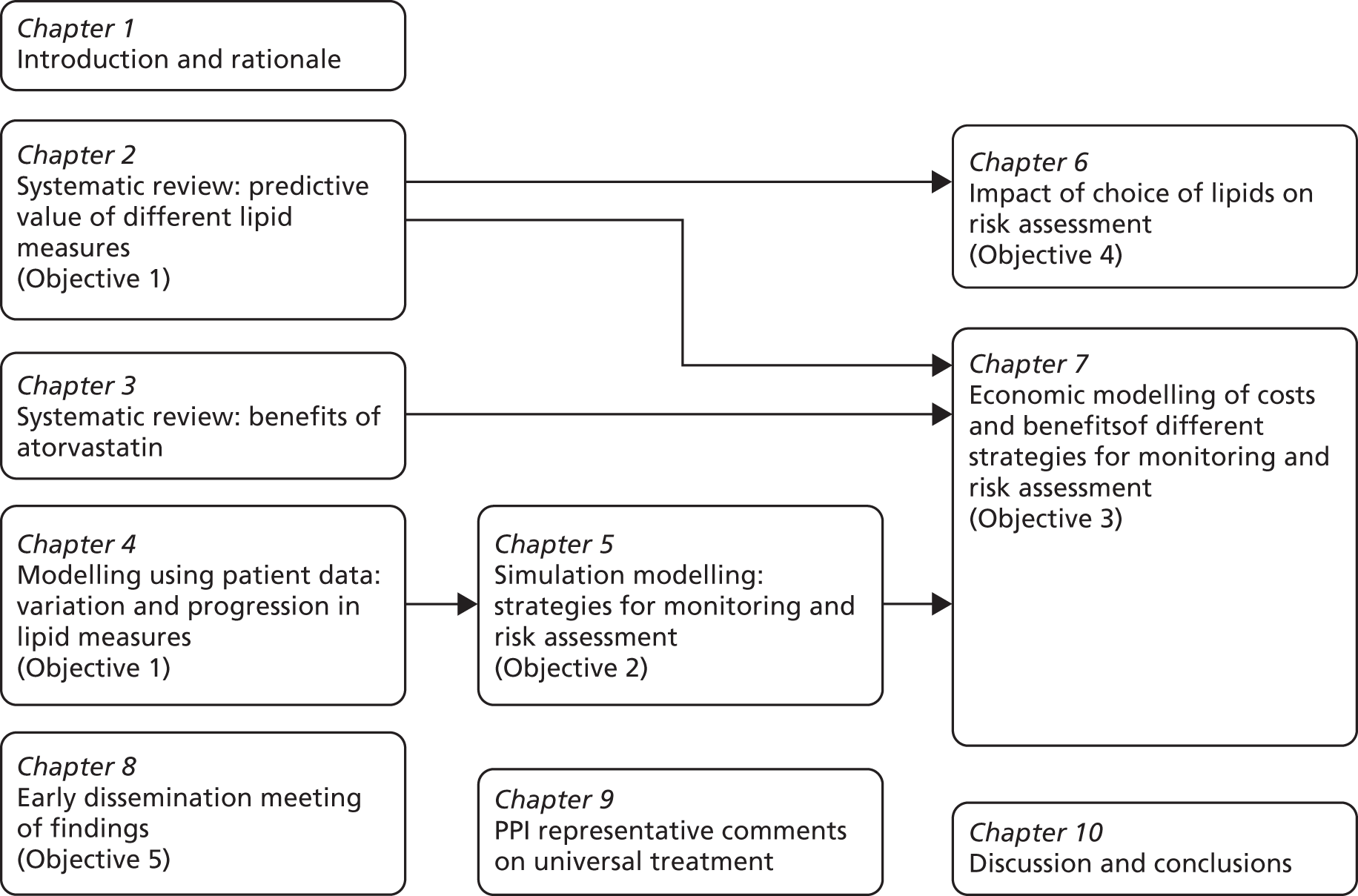

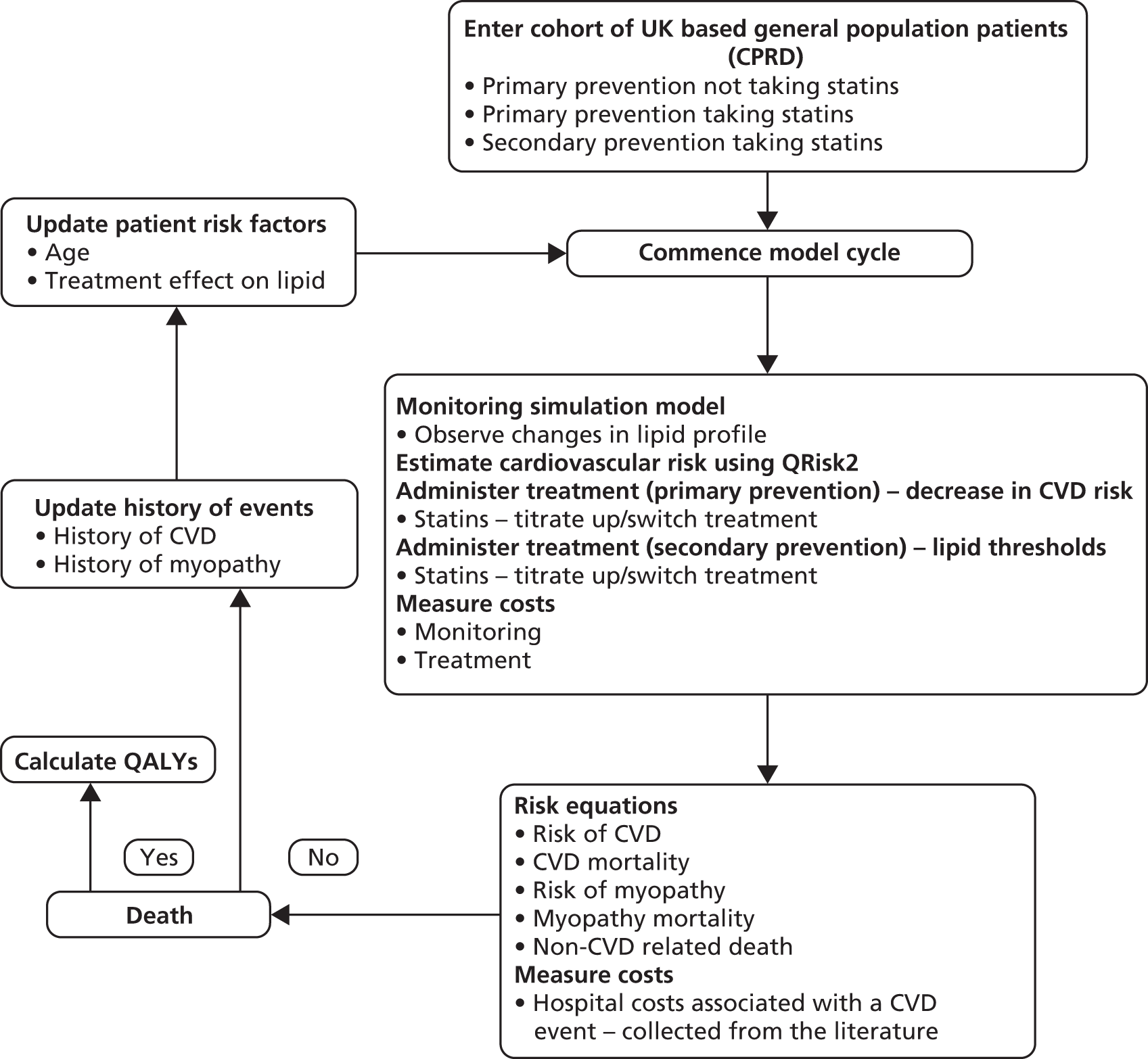

The scientific summary provides a brief overview of our main findings. The subsequent chapters (see Chapters 2–10) give full details of methods and comprehensive reporting of results. An outline of the content of each chapter and its relation to the objectives listed above is presented below. The report uses the following structure: systematic reviews, statistical modelling, health-economic modelling, and other chapters. Figure 2 shows the dependencies between chapters and the objectives.

FIGURE 2.

Dependencies between chapters and the objectives. PPI, patient and public involvement.

In Chapter 2, the predictive ability of different lipid measures for CVD events and all-cause mortality are compared in the systematic review of prognostic studies, addressing Objective 1 through secondary analyses of the literature.

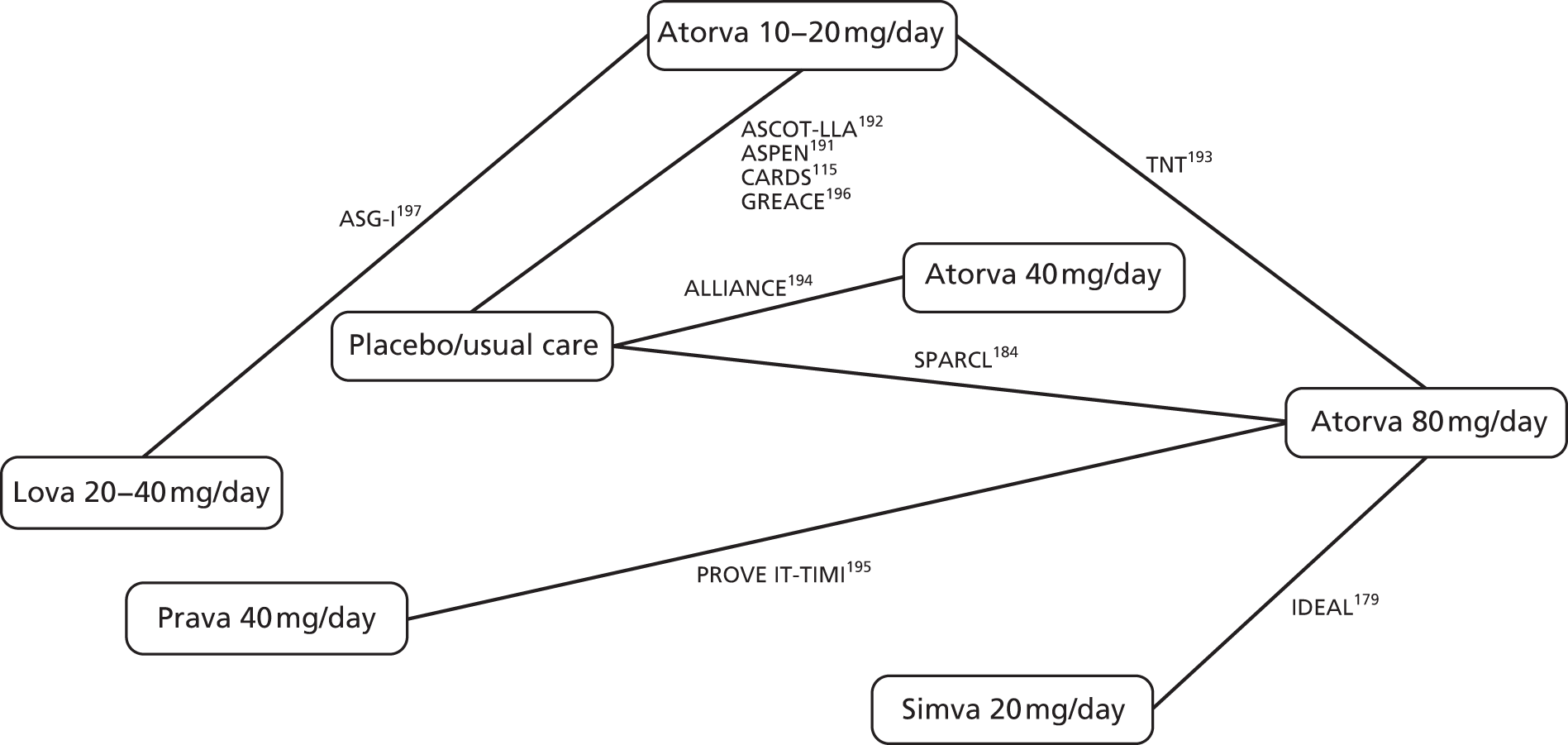

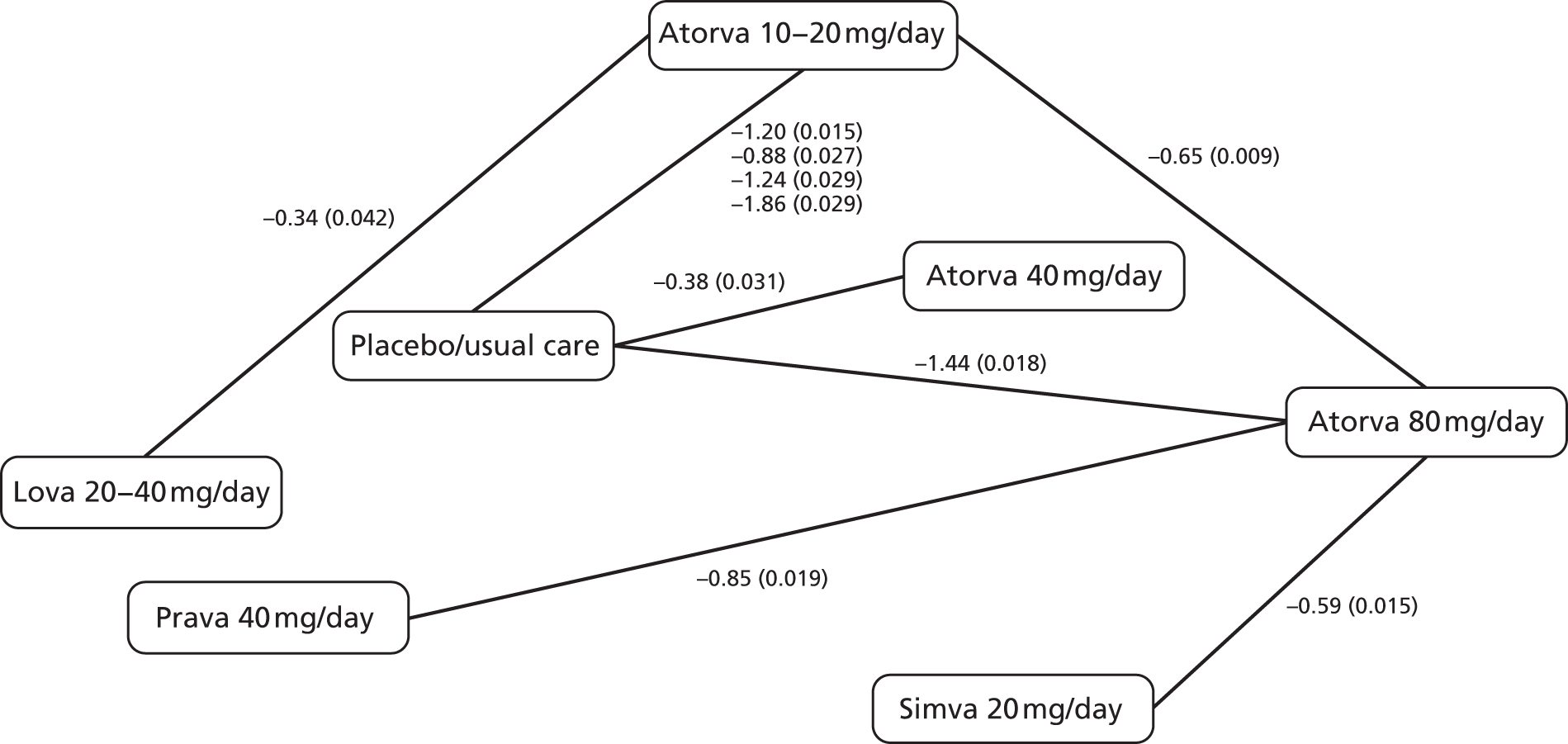

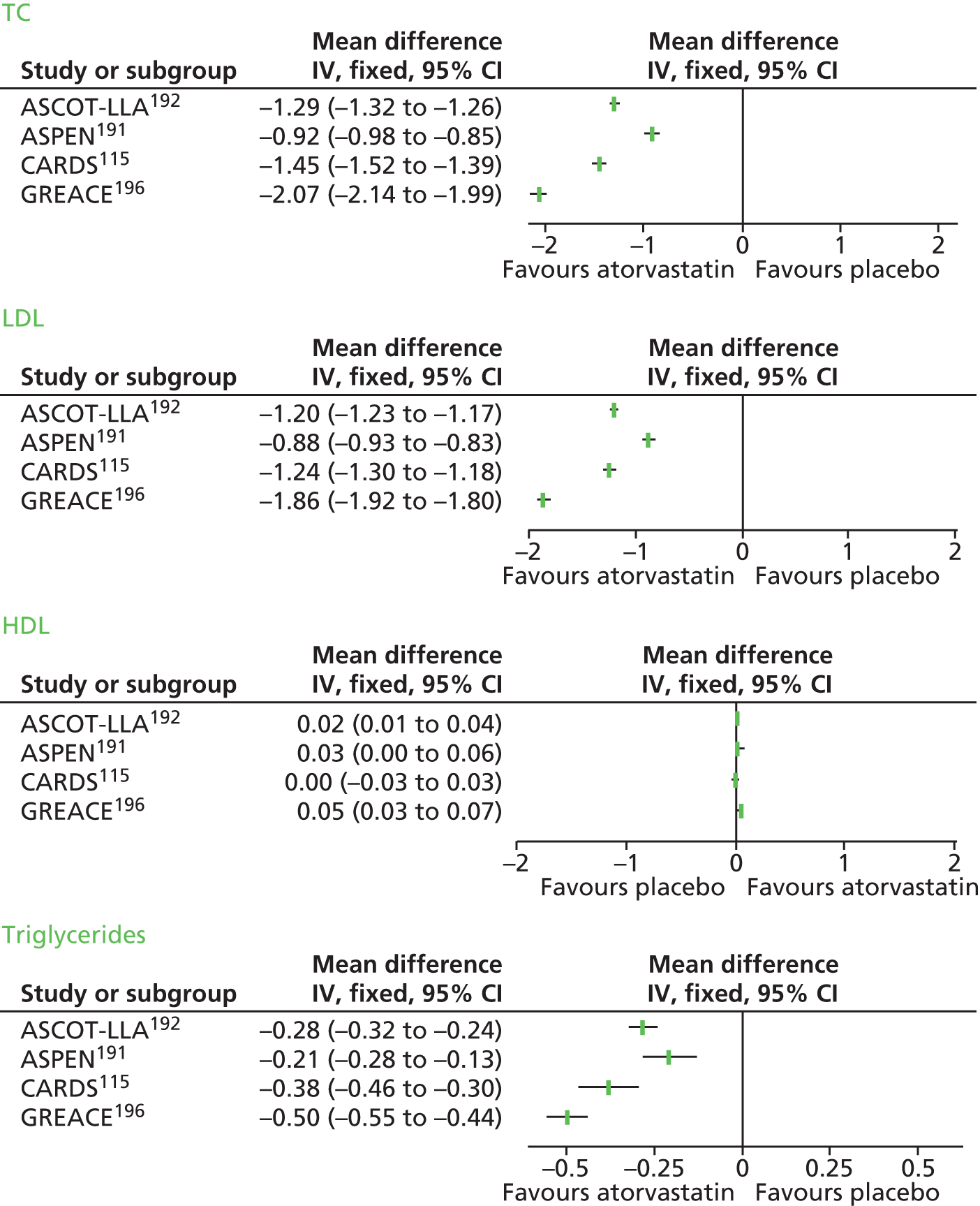

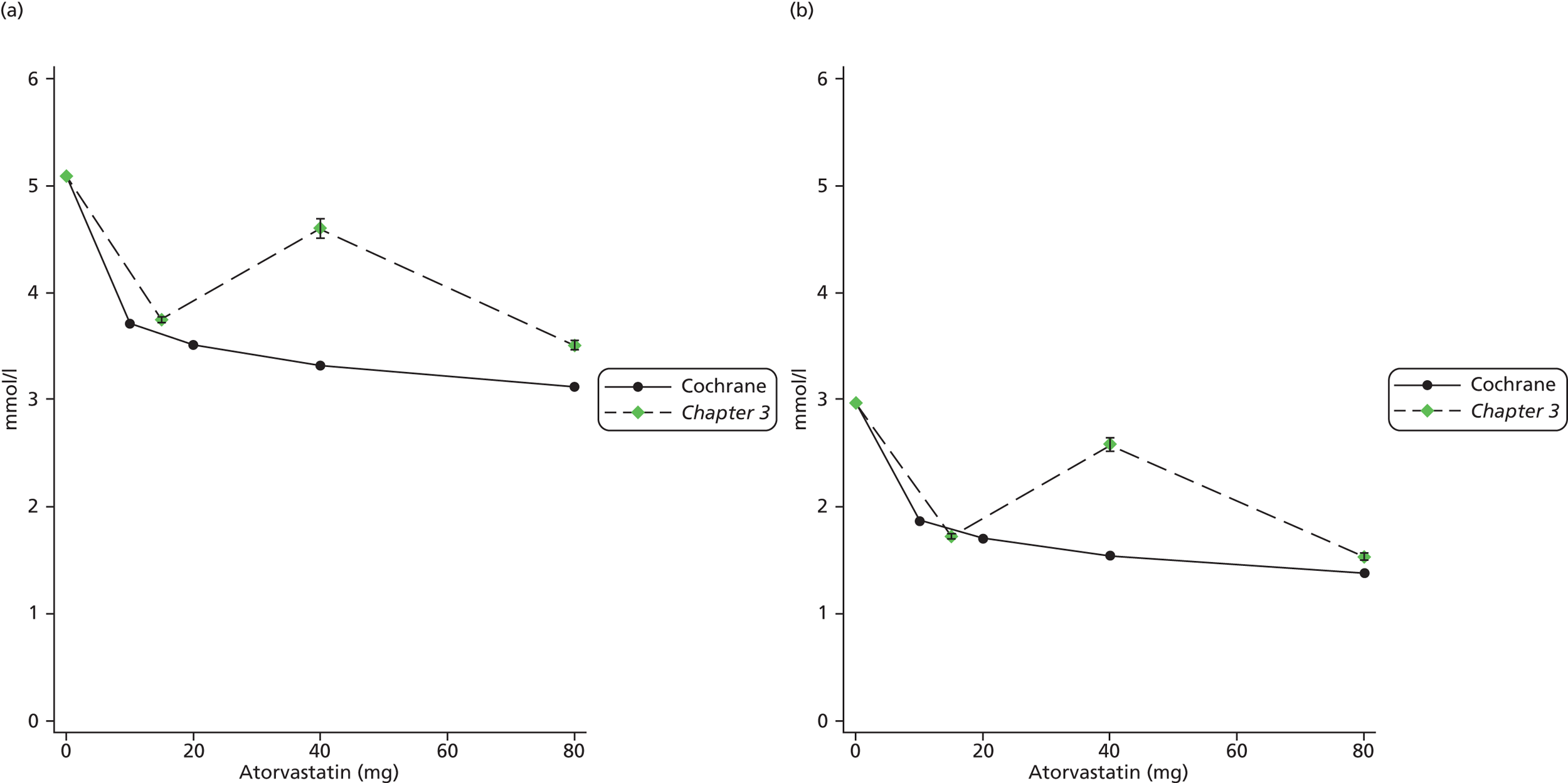

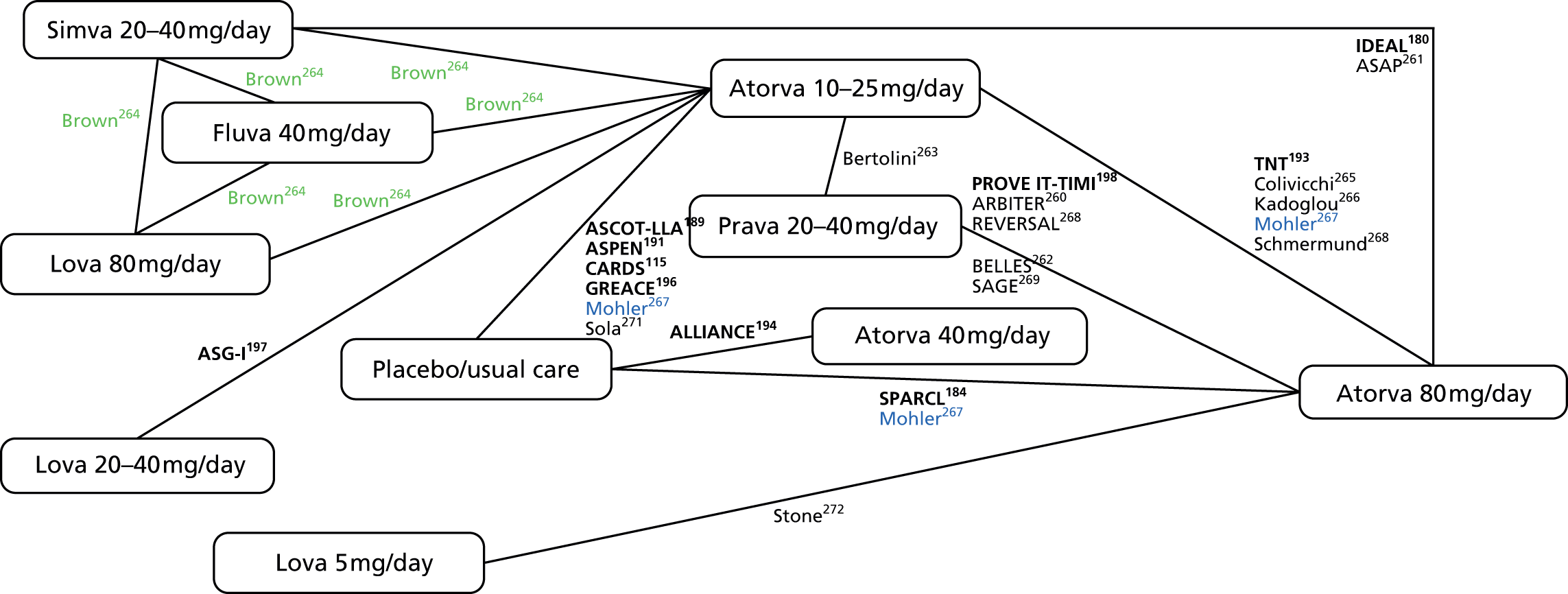

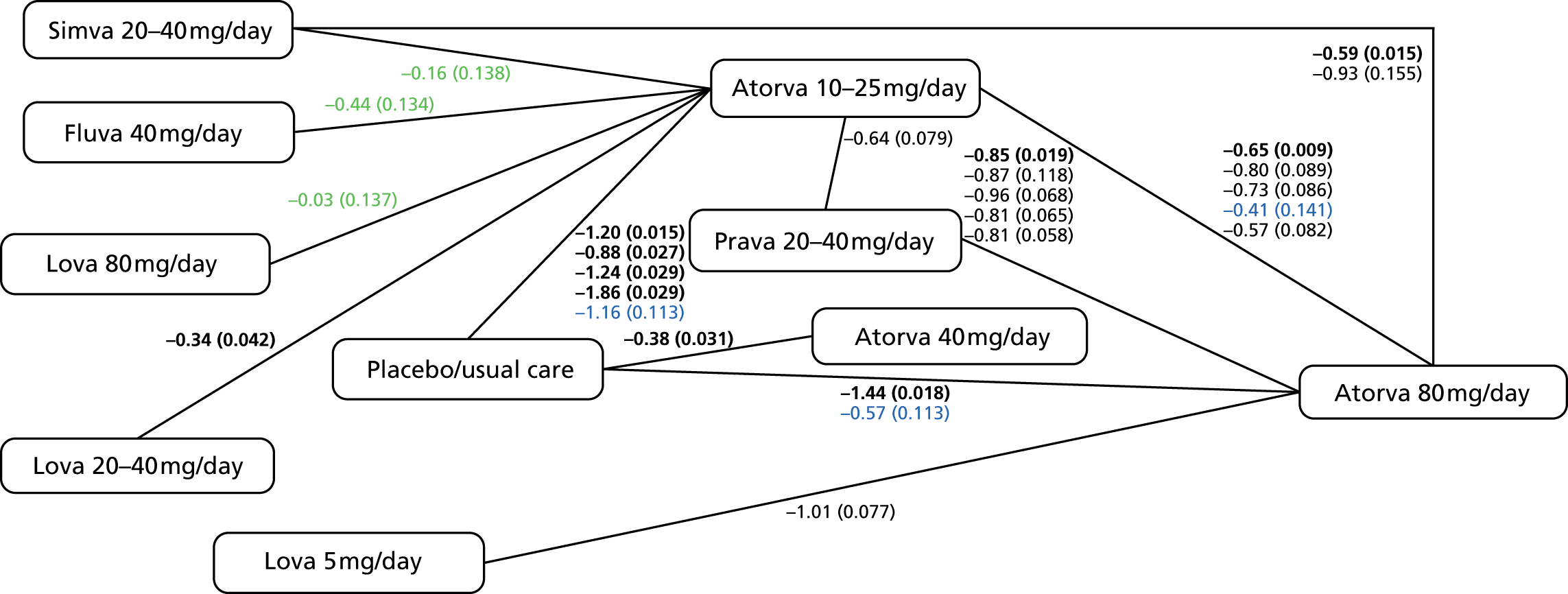

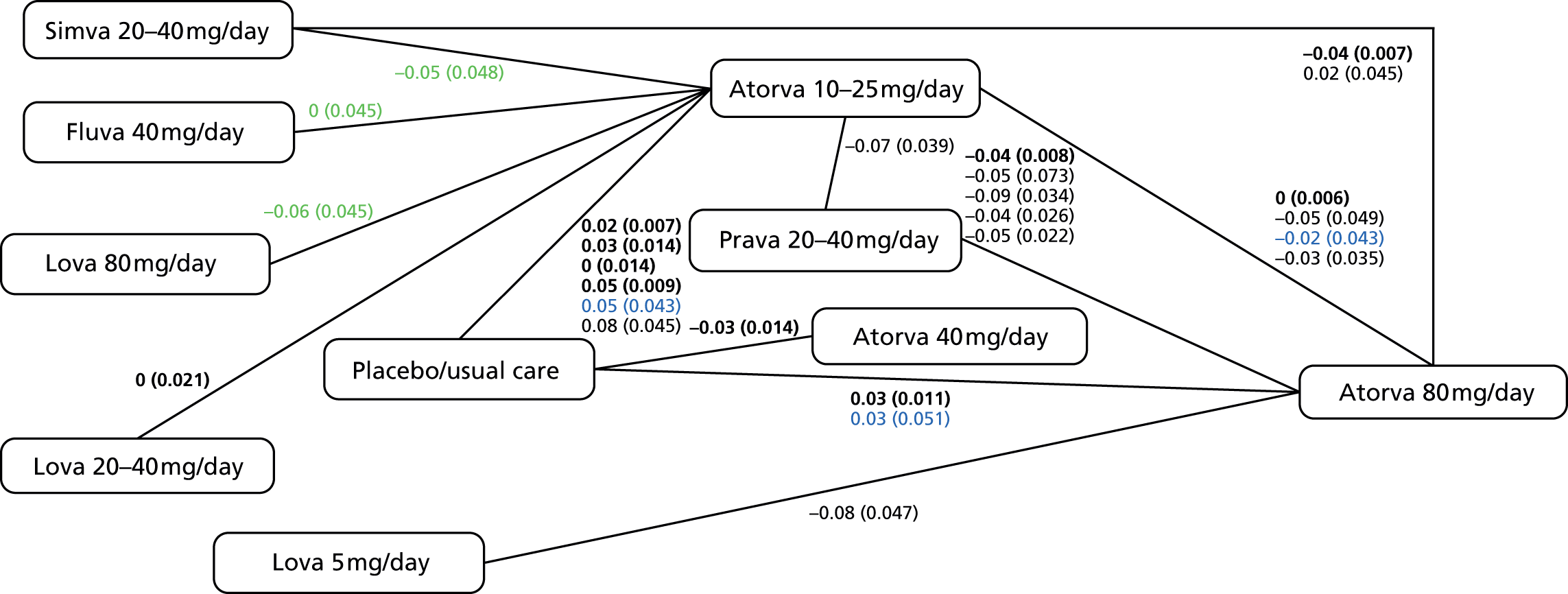

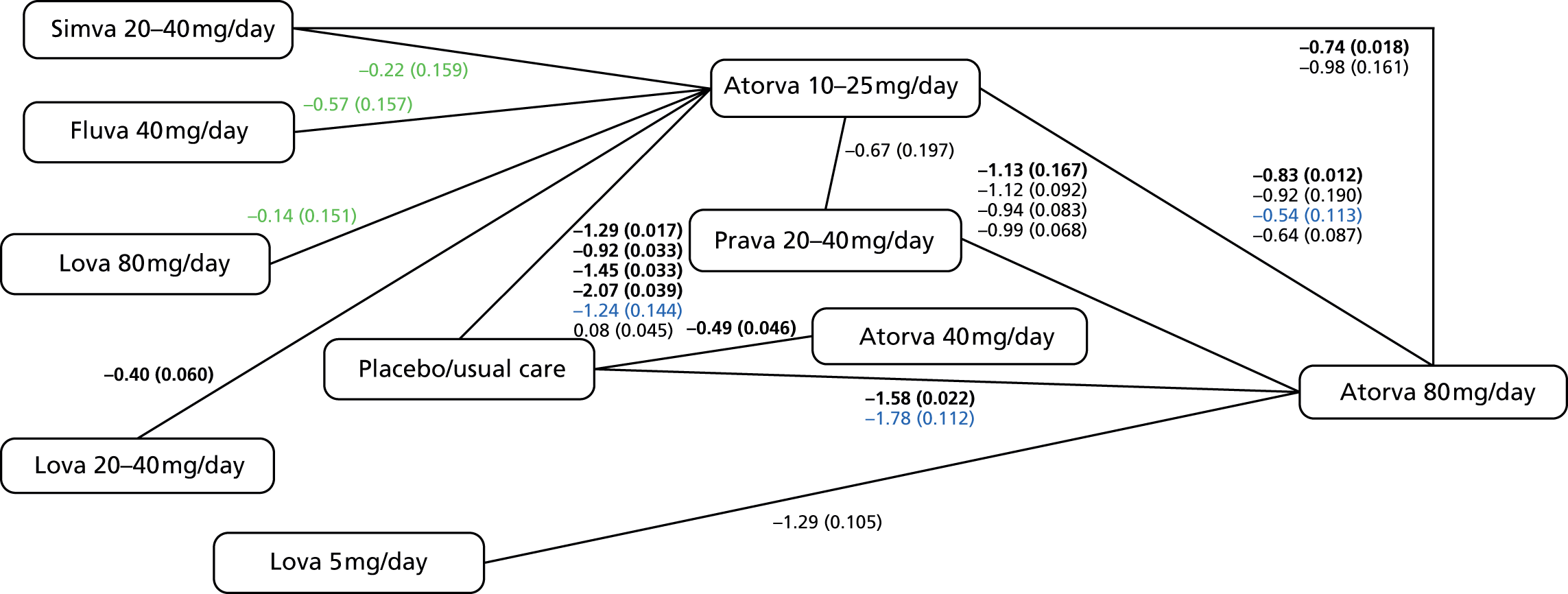

In Chapter 3, we review the randomised controlled trial (RCT) evidence for atorvastatin, with particular emphasis on dose effects, because this is now the recommended statin in UK guidelines and as a prerequisite for Chapter 7.

In Chapter 4, we quantify the degree of variability (noise) in different lipid measures, and compare this to the rate of progression (SN ratio), as a measure of the ability of different lipid measures to detect real versus apparent changes in lipid status, addressing Objective 1 through analyses of patient-level data.

We address Objective 2 by extending the results of Chapter 4 into a computer model of lipid monitoring. In Chapter 5 this model is used to compare different intervals for lipid-monitoring strategies (Objective 2), and in Chapter 6 it is used to consider the use of different lipid measures in CVD risk estimation (Objective 4). In Chapter 7 the computer model is extended into an economic model (Objective 3) of lipid monitoring.

Chapter 8 describes a meeting with key researchers and stakeholders as part of our dissemination strategy (Objective 5), and Chapter 9 summarises a subsequent consultation with our patient and public involvement (PPI) representative. The concluding Chapter 10 contains the discussion of our overall findings.

Chapter 2 Systematic review of association between lipid measures and cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality

Background

As noted in Chapter 1, there are a number of different lipids that could be measured as part of a strategy for the prevention of primary or secondary CVD. However, at the time of writing, there is no consensus on which lipid is the optimal target for monitoring. One key criterion for a monitoring target is the ability to predict clinically significant events,11 preferably at a stage early enough to allow preventative action to be taken.

The Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration66 has extensively examined the safety and efficacy of statins for lowering LDL cholesterol but, to date, has not compared the predictive ability of different lipid measures for CVD events or mortality. A number of previous reviews and meta-analyses have compared the association of different lipid measures with CVD outcomes, all of which have examined subjects who are not taking statins separately to those who are. The reasons for this are not clear, and are potentially historical.

To date, five reviews41,67–71 have assessed studies with subjects not taking statins. Their key features and findings are summarised in Tables 4 and 5, respectively. Three of these studies obtained IPD,41,67,69,70 whereas the other two analysed trial-level data. 68,71 All support an association between lipid measures and the cardiovascular outcomes examined; however, as each focuses on a different subset of lipid measures and/or a different cardiovascular outcome, their conclusions for the lipid most strongly predictive of CVD varied, and comparisons are difficult.

| Review name: number of studies – type | Review characteristics | Statistical methods and assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| APSC 2005:67 32 studies – IPD | No searches completed Studies included by invitation (subject to certain criteria) Studies included only if reported results for TC, HDL cholesterol and TGs at baseline Studies excluded if no events in follow-up Some subgroup analysis by gender and age and comments on heterogeneity of data because of regional differences, but essentially no quality assessment |

Prevention groups not stated Outcomes were analysed in equal quartiles (as assessed at baseline) and summarised through HRs Further analysis by use of likelihood ratio chi-squared statistic to compare models (results not shown) |

| Thompson and Danesh 2006:68 23 studies – published data | Searches up to October 2005 Extensive search, but no strategy provided Studies only included if reported results for Apo B, Apo A-I, Apo B/Apo A-I at baseline No table of excluded studies No quality assessment of studies, although subgroup analysis by quality factors; however, no conclusions drawn from these results Grading system for adjustment of data; however, all date pooled whether unadjusted or adjusted Outcome included various definitions of CHD, subgroup analysis to examine this, but no conclusions drawn |

Mixed primary and secondary populations Point estimates extracted and standardised ORs, RRs and HRs were assumed to be an approximate measure for relative risk Results displayed as meta-analysis (bottom vs. top-third baseline values) |

| PSC 2007:41 not stated – IPD | Search appears to be comprehensive but no search strategy available, no reference to language and search dates not published Screening not described No table of excluded studies Limited quality assessment Comprehensive analysis plan Results calculated only for participants with complete data for all four measures (TC, HDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, TC/HDL cholesterol) |

Primary prevention Age-specific HRs estimated by Cox regression (gender specific too in the original review) Results presented in this review as inverse of the published results to allow comparison Unreliable measurements excluded HRs are presented in unit measures approximately proportional to 1 SD (0.33 mmol/l HDL cholesterol, 1 mmol/l non-HDL cholesterol, 1.33 mmol/l TC/HDL cholesterol) |

| ERFC 2009,69 2012:70 112 – IPD | Extended work by APSC and PSC Original search up to August 2007, subsequent search dates not given. No search strategy provided Full search completed, except databases searched not stated, nor language or publication restrictions No statement about screening process Studies only included if reported results for TC, HDL, TGs, non-HDL cholesterol and several conventional risk factors at baseline Quality assessment was completed through a variety of subgroup and sensitivity analyses |

Primary prevention HRs calculated using coproportional regression models stratified by gender Four matched nested case–control studies provided ORs which were considered to approximate HRs HRs adjusted for age, gender, systolic BP, smoking, BMI, history of diabetes |

| Sniderman et al. 2011:71 107 – published data | Search based on previous reviews and PubMed search from 2005 until unstated date. No search strategy provided Previous reviews and experts contacted but no reference to publication or language restrictions Inclusion/exclusion criteria not stated Studies included only if reported relative risks for Apo B, non-HDL cholesterol and LDL cholesterol No statement about screening process No table of excluded studies Assessment of assay quality and degree of data adjustment, but no further quality assessment Outcome definition varied, sensitivity analysis completed to account for this |

Primary prevention RRR per 1 SD increment All ORs and HRs converted to RRRs Random-effects meta-analysis |

| Review name [summary measure used] | Number of studies | Outcome | Lipid measure | Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| APSC 200567 [HR per 1 SD increase] Note: HDL cholesterol as 1 SD decrease |

17 | CVD mortality | TC | 1.09 (1.05 to 1.14) |

| TG | 1.17 (log) (1.06 to 1.28) | |||

| HDL cholesterol | 1.16 (1.04 to 1.30) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.21 (1.11 to 1.32) | |||

| TC/HDL cholesterol | 1.23 (log) (1.12 to 1.36) | |||

| TG/HDL cholesterol | 1.21 (log) (1.09 to 1.34) | |||

| CHD mortality | LDL cholesterol | 1.35 (1.13 to 1.61) | ||

| Thompson and Danesh 200668 [RR] Note: Apo A-I reported as inverse |

21 | CHD | Apo A-I | 1.62 (1.43 to 1.83) |

| Apo B | 1.99 (1.65 to 2.39) | |||

| Apo B/Apo A-I | 1.86 (1.55 to 2.22) | |||

| PSC 200741 [age-specific HR] | 61 | CHD mortality | TC 80–89 years | 1.18 (1.12 to 122) |

| TC 70–79 years | 1.22 (1.18 to 1.25) | |||

| TC 60–69 years | 1.39 (1.35 to 1.45) | |||

| TC 50–59 years | 1.72 (1.64 to 1.76) | |||

| TC 40–49 years | 2.27 (2.08 to 2.38) | |||

| 23 | HDL cholesterol 70–89 years | 0.74 (0.67 to 0.82) | ||

| HDL cholesterol 60–69 years | 0.55 (0.49 to 0.61) | |||

| HDL cholesterol 40–59 years | 0.61 (0.54 to 0.69) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol 70–89 years | 1.37 (1.27 to 1.49) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol 60–69 years | 1.52 (1.41 to 1.64) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol 60–69 years | 1.75 (1.61 to 1.92) | |||

| TC/HDL cholesterol 70–89 years | 1.45 (1.35 to 1.59) | |||

| TC/HDL cholesterol 60–69 years | 1.67 (1.56 to 1.79) | |||

| TC/HDL cholesterol 40–59 years | 1.79 (1.67 to 1.96) | |||

| ERFC 2009,69 201270 [HR per 1 SD increase/decrease] | 68 (2009) | CHD and stroke | TG | 1.37 (1.31 to 1.42) |

| HDL cholesterol | 0.71 (0.68 to 0.75) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.56 (1.47 to 1.66) | |||

| 8 (2009) | CHD | LDL | 1.41 (1.11 to 1.81) | |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.49 (1.20 to 1.86) | |||

| 22 (2009) | CHD and stroke | Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.55 (1.34 to 1.80) | |

| Apo B | 1.61 (1.44 to 1.80) | |||

| HDL cholesterol | 0.71 (0.65 to 0.79) | |||

| Apo A-I | 0.81 (0.74 to 0.88) | |||

| Non-HDL cholesterol/HDL cholesterol | 1.52 (1.37 to 1.68) | |||

| Apo B/Apo A-I | 1.51 (1.39 to 1.63) | |||

| 26 (2012) | CVD | Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.27 (1.22 to 1.33) | |

| Apo B | 1.24 (1.19 to 1.29) | |||

| Apo A-I | 0.87 (0.84 to 0.90) | |||

| TC/HDL cholesterol | 1.32 (1.24 to 1.39) | |||

| Apo B/Apo A-I | 1.3 (1.24 to 1.36) | |||

| Sniderman et al. 201171 [geometric mean RRR] | 12 | CHD | LDL cholesterol | 1.25 (1.18 to 1.33) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.34 (1.24 to 1.44) | |||

| Apo B | 1.43 (1.35 to 1.51) |

Two recent systematic reviews have considered the predictive value of a limited selection of lipid measures in people taking statins. 72,73 Tables 6 and 7 summarise their characteristics and some key results; however, as each review used different methodology, and only one reported hazard ratios (HRs), it is hard to make a direct comparison. There was some indication that non-HDL cholesterol outperformed the other lipids examined; however, this was outcome dependent and differences were modest. Both reviews72,73 considered only RCTs for inclusion and, other than a sensitivity analyses in one review, examine primary and secondary prevention groups together, hence making the unverified assumption that lipid measures are similarly predictive of CVD events in populations both with, and without, a history of CVD.

| Review name: number of studies – type | Review characteristics | Statistical methods and assumptions |

|---|---|---|

| Robinson 2012:73 32 studies – Published articles and data from Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration | Search from 1966 to 1 December 2010. No strategy published. Plus reference lists and previous reviews. No comment on publication or language restrictions Screening process thorough and clearly stated Clear inclusion/exclusion criteria and definitions provided Studies included only if reported results for Apo B, TC, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol at baseline and one time point in follow-up No table of excluded studies No quality assessment of included studies |

Mixed primary and secondary populations Statin randomised control trials. Control arms either placebo or lower-dosage statin Changes in lipid measures were calculated as the difference between two treatment groups over the same time period Study specific crude relative risk and SE was estimated for each lipid measure for CVD Random-effects meta-analysis completed Results for Apo B presented. No further information on the impact of reduction of other lipid measures published |

| Boekholdt et al. 2012:72 29 studies – IPD | Authors followed PRISMA Search up to December 2011. No search strategy provided. Search restricted to PubMed and English-language publications only. No comment on grey literature, reference lists, etc. Studies included only if reported results for TC, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, TGs, and Apo B, Apo A-I at baseline and follow-up over 2 years No table of excluded studies Full assessment of quality using Delphi score A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) indicates a high-quality review, meeting all aspects of the assessment albeit some areas were not fully met |

Mixed primary and secondary populations HRs calculated using Cox proportional models Analyses were adjusted for gender, age, smoking, DM, systolic BP, and trial |

| Review name [summary measure used] | Number of studies | Outcome | Lipid measure | Estimate (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson et al. 201273 [percentage relative risk decrease = 10-mg/dl decrease in lipid measure] | 12 | CVD | Apo B | 11.60 (3.5 to 20.5) |

| Boekholdt et al. 201272 [HR per 1 SD increase] | 8 | CVD | LDL | 1.13 (1.10 to 1.17) |

| Non-HDL cholesterol | 1.16 (1.12 to 1.19) | |||

| Apo B | 1.14 (1.11 to 1.18) |

Thus, although a number of previous reviews have examined the predictive ability of different lipid measures for cardiovascular events, all have focused on a subset of lipids, a specific population or a specific cardiovascular outcome. In this chapter we therefore aim to evaluate the available evidence for the strength of association between each lipid measure and cardiovascular outcomes, including CVD events, CVD mortality and all-cause mortality, in both primary and secondary prevention populations.

Methods

Search methods for identification of studies

We reviewed all published systematic reviews since 2007 using the Montori systematic review filter74 for MEDLINE and the Wilczynki filter75 for EMBASE (both 75% sensitivity). Based on this overview, we opted to stratify results by statin use: populations taking statins and populations not taking statins. Consequently, two separate searches were carried out and two sets of results are presented, although the general methods remained the same for both groups. Dates for the searches were staggered, as the review was broken down into manageable tasks based on statin usage and existing reviews.

Searches were conducted in the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, EMBASE, the Clinical Trials Register, the Current Controlled Trials register, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) to identify relevant studies.

All trials included in identified reviews were considered for inclusion, along with any trials identified by the work of the Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. 66

Populations not taking statins A search was conducted (unrestricted for study design) from 1 September 2007 to 18 June 2013. This updated/extended the search carried out by the Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration (ERFC). 76 The search was restricted to English language only and did not include conference abstracts (see Appendix 3).

Populations taking statins Two strategies were used, based on study design type. For non-randomised controlled trials (non-RCTs) a search was completed for all publications up to 4 December 2012, with no restriction on language or publication type. For RCTs, all studies were included from previous reviews,72,73 plus a search was conducted to extend these review’s searches up to 9 April 2013. In line with these reviews, the strategy was for English language-only publications (both strategies are presented in Appendix 4). An additional search was conducted within the international Clinical Trials Registry and ClinicalTrials.gov for any studies in progress from 2010 to April 2013.

The title and abstract of each paper identified in the searches was reviewed by two reviewers to identify potentially relevant references. The full text of potentially relevant studies was then obtained, and two reviewers independently selected studies to be included in the review using predetermined inclusion criteria. In all cases, disagreements about study inclusion were resolved by consensus and a third reviewer was consulted if disagreements persisted. Flow charts were constructed to show the selection process.

Study selection criteria

We included all prognostic cohort studies of any design (univariable or multivariable) that measured lipids in humans. Studies from any setting regardless of statin treatment were included. RCTs with adequate follow-up were treated as cohorts providing evidence to a specific study group [e.g. a statin vs. placebo RCT would provide evidence for both populations taking statins (statin arm) and not taking statins (placebo arm) separately].

Consistent with previous reviews in this area, we included studies where at least 1000 relevant participants were recruited per cohort/intervention arm and a minimum 2-year average follow-up duration. 66,72 There was no restriction on gender. We included studies with only two or more lipid measures assessed at baseline/relevant time point, as the focus of the review was to compare predictive performance across different lipid measures.

Target group in PECO (Population, Exposure, Comparator, Outcome) format:

-

P Population with or without existing CVD.

-

E Measurement of lipid measures at baseline/relevant time point. Ten lipids measures were studied including TC, HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, non-HDL cholesterol, TGs, Apo B, Apo A-I, plus combinations of these measures as ratios TC/HDL cholesterol, LDL/HDL cholesterol and Apo B/Apo A-I.

-

C Control or comparator may or may not be present.

-

O Outcomes included cardiovascular events, cardiovascular mortality and all-cause mortality. Strokes were excluded if they were the sole outcome (included if treated as part of composite outcome with other CVD events).

In addition, we considered all studies from previous reviews for inclusion irrespective of whether or not they met the 1000-participant, minimum two lipid measures at baseline or 2-year follow-up thresholds to maximise comparability of our results with those published in previous reviews.

Included studies provided quantitative results for one or more of the following outcomes:

-

cardiovascular events [CHD, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, angina attack, other CVD, coronary bypass]

-

cardiovascular mortality (fatal MI, sudden cardiac death, stroke, congestive heart failure, other fatal CVD)

-

all-cause mortality.

Outcome definition was based on that reported in the included studies.

Data extraction and management

For all included studies, two reviewers independently carried out data extraction. Details extracted included study name and year, cohort numbers, baseline age, gender, prevention group, statin usage and dose if applicable, follow-up period, blood sample details and lipid data. When several follow-up periods were reported then data for the longest follow-up were extracted. Disagreements were resolved by consensus with a third reviewer being consulted when required.

The methodological quality of included studies was assessed using the Quality in Prognostic Studies (QUIPS) assessment tool. 77 Quality of studies with populations taking statins was independently assessed by two reviewers and the level of agreement tested by the kappa statistic (κ). For studies of populations not taking statins, quality was assessed by one reviewer. Quality was assessed in six bias domains, with emphasis placed on prognostic factors and attrition:

-

Study participants No quality bias was anticipated in this area, as all populations were included in the review. Studies were categorised by prevention group, which provided inception cohorts.

-

Study attrition There is no clear guidance for the assessment of attrition rates in prognostic studies. Previous prognostic reviews have considered attrition rates of 10–20% as low risk of quality bias, but these have been based on small populations with relatively rare conditions and short follow-up periods. 78,79 As the new cohorts in this review have > 1000 participants with long follow-ups, we anticipated that dropout could be higher. Risk of study attrition bias was considered to be low – if it was documented – and < 25%, moderate if 25–40% or not reported, and high risk if > 40%.

-

Prognostic factor Lipid measures were considered to be at low risk of quality bias if all tests were processed by a central accredited laboratory and procedures for different measures were described. Risk was assessed as moderate if a central laboratory was used but no further information given, and high risk of bias when no information was provided.

-

Outcome measure This dimension was not considered to be significant, as it was a necessary requirement in the study entry criteria. However, outcome bias could have been introduced owing to clarity of outcome definitions; this was explicitly addressed in sensitivity analyses.

-

Study confounding This too was not considered to be a significant concern, as study confounders were specially accounted for in the data analysis of each study: studies were divided into unadjusted and adjusted data.

-

Statistical analysis As most of the included studies were not designed to report the outcome data required for this review, we did not assess the quality of the study in relation to how the study data were analysed; instead we addressed this issue separately by carrying out a sensitivity analysis considering the type of analysis used in the original study.

Data analysis

Data were sought from the included studies for predictive outcomes as follows:

-

Direct estimates for one standard deviation (SD) incremental change either as HRs, odds ratios (OR) or risk ratios (RRs) and their variances. These ratios were assumed to approximate the same measure of risk. This assumption was tested in a sample of studies with the highest event rates and the ratios showed little variation.

-

Data in an alternative format to incremental change by one SD were converted where possible.

-

Univariable and multivariable models (unadjusted and adjusted). Multivariable analyses included any studies with adjustment for one or more of the following covariates: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), smoking, etc. Where a study produced more than one multivariable model then the most advanced model was selected for data inclusion. However, we specifically excluded any model that adjusted for any other lipid measure.

-

IPD were not actively sought, but used when available.

-

When no direct estimates were reported, alternative indirect methods for estimation were used. 80,81 Additionally, two further alternative indirect methods for estimation were used based on (1) generalised least squares for trend82,83 and (2) simulation methods. A brief description of these can be found in Appendix 5.

The primary analysis estimated the predictive strength (HR) for each lipid measure by each of the three outcomes. Outcomes are reported separately and stratified by unadjusted/adjusted estimates. Analyses were subgrouped by prevention group (primary or secondary prevention). Studies were considered to be only primary or secondary prevention if > 95% of the participants fell in that category; otherwise studies were considered as mixed. Numbers of studies, participants and study characteristics are presented in tables.

For each lipid measure, random effect meta-analyses were carried out to obtain summary HRs (by one SD) using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.2 (The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and results were displayed as forest plots. A random-effects model was selected because high heterogeneity was anticipated in both populations. Any risk of small study bias should be reduced by the majority of included studies having > 1000 participants. Overall summary plots presenting pooled estimates for all lipid measures (HDL and Apo A-I as inverse associations to allow clear comparisons with other measures) by outcome and by unadjusted/adjusted models were produced. Although pooling of data for lipid measures with only three or fewer studies could be potentially misleading, the figures were included in the summary plots as an indication of potential trends had there been more study data.

Heterogeneity was summarised using the I2 and chi-squared statistics. Potential sources of any heterogeneity (clinical or statistical) were explored using subgroup and sensitivity analyses.

Subgroup analyses, where possible, were conducted by:

-

pre-existing condition (e.g. diabetes)

-

study type [prospective (including RCTs) or retrospective cohorts]

-

age (threshold of median 40 years at inception).

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to determine the impact of study quality and data extraction on outcome. Focus was placed on consistency of overall results with those obtained in better-quality studies. When sufficient studies were available, sensitivity analyses were carried out by omitting:

-

studies in which the predictive outcomes were defined by CHD, a surrogate measure of CVD

-

studies assessed to have a higher/moderate risk of quality bias (based on prognostic factors and attrition quality domains)

-

studies in which the majority of the lipid tests were not completed in a central laboratory (yes/no)

-

studies in which summary data were extracted indirectly

-

within the populations not taking statins, studies that confirmed the use of lipid modification therapy.

The search aimed to be as broad as possible to include as many studies as possible. However, it is acknowledged that there is considerable publication bias in prognostic studies that is difficult to characterise;84 therefore we did not carry an analysis for potential publication bias.

A post hoc analysis was conducted as recommended by the external peer reviewer with the aim of exploring sources of potential heterogeneity. A meta-regression was completed to examine the associations between variables considered in the subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Meta-regression was completed, where possible, for those outcomes and variables with sufficient study data.

Amendments to protocol

The original protocol was registered with International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO, 2013: CRD42013003727). A number of changes were made to the protocol. Originally, the search strategy specified that all studies would be considered for inclusion in this review. However, it proved necessary to modify the strategy to take into account three reviews published in 2012 and the scale of the review. All studies from the three existing reviews were included, and the new search strategy extended the search beyond the search date of these reviews. Exclusion criteria were introduced to reduce the number of smaller studies (minimum participant numbers, length of follow-up and baseline lipids).

The method for data extraction was amended once the data were examined. Two additional indirect methods for data extraction were used (see Appendix 5) to ensure that the maximum number of data could be obtained for analysis. In the analysis, all outcome data for each lipid measure were pooled; however, it was acknowledged that only those summary estimates including three or more sets of data would be used to draw conclusions. Quality assessment of included studies was amended from an adapted Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies tool (QUADAS2) to a more recent tool77 specifically designed for prognostic reviews – QUIPS.

Results

We present the results grouped as studies based on populations (1) not taking statins and (2) taking statins.

All study names appear as abbreviations and the full study names are shown in Appendices 6 and 7.

Studies based on populations not taking statins

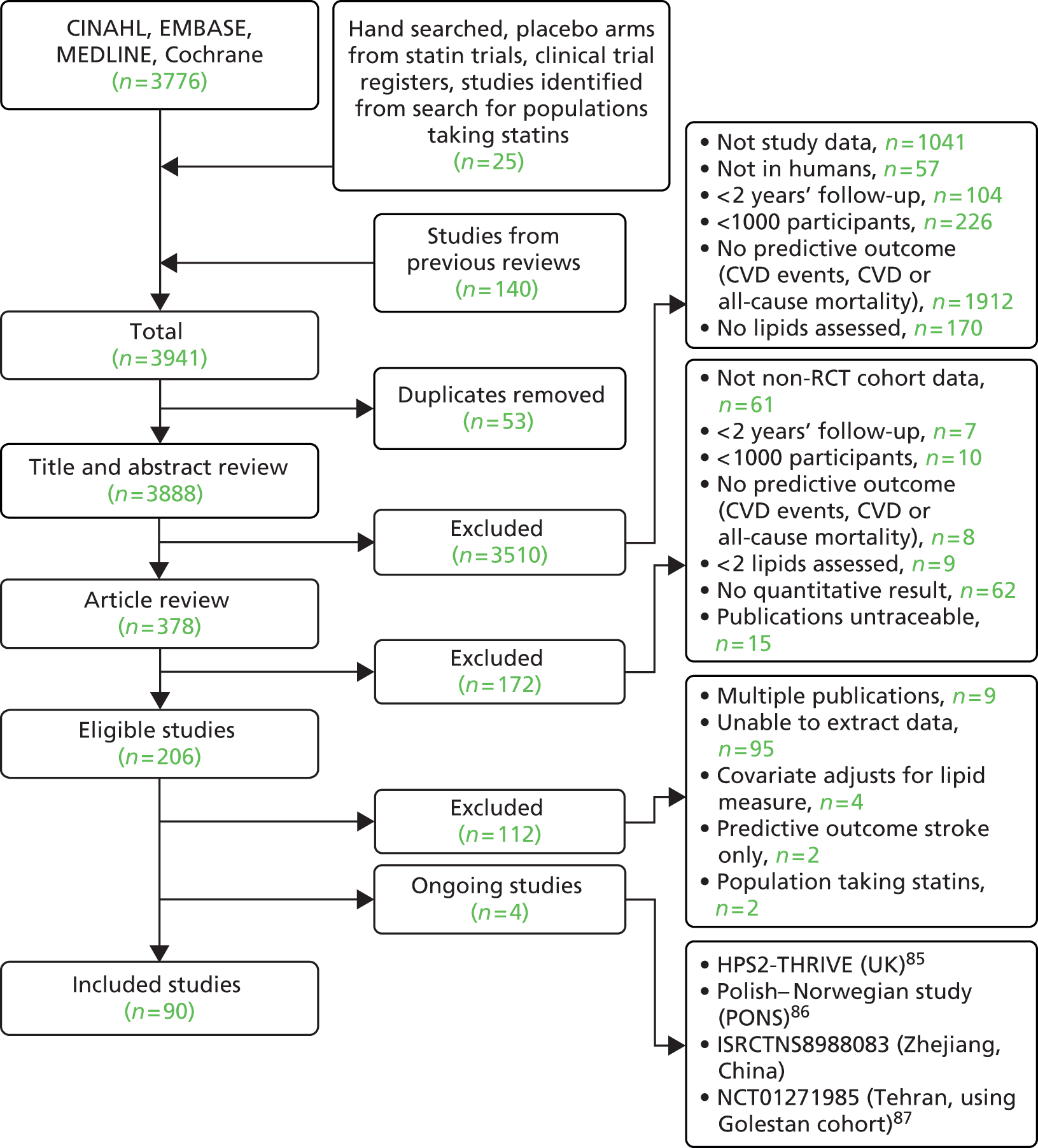

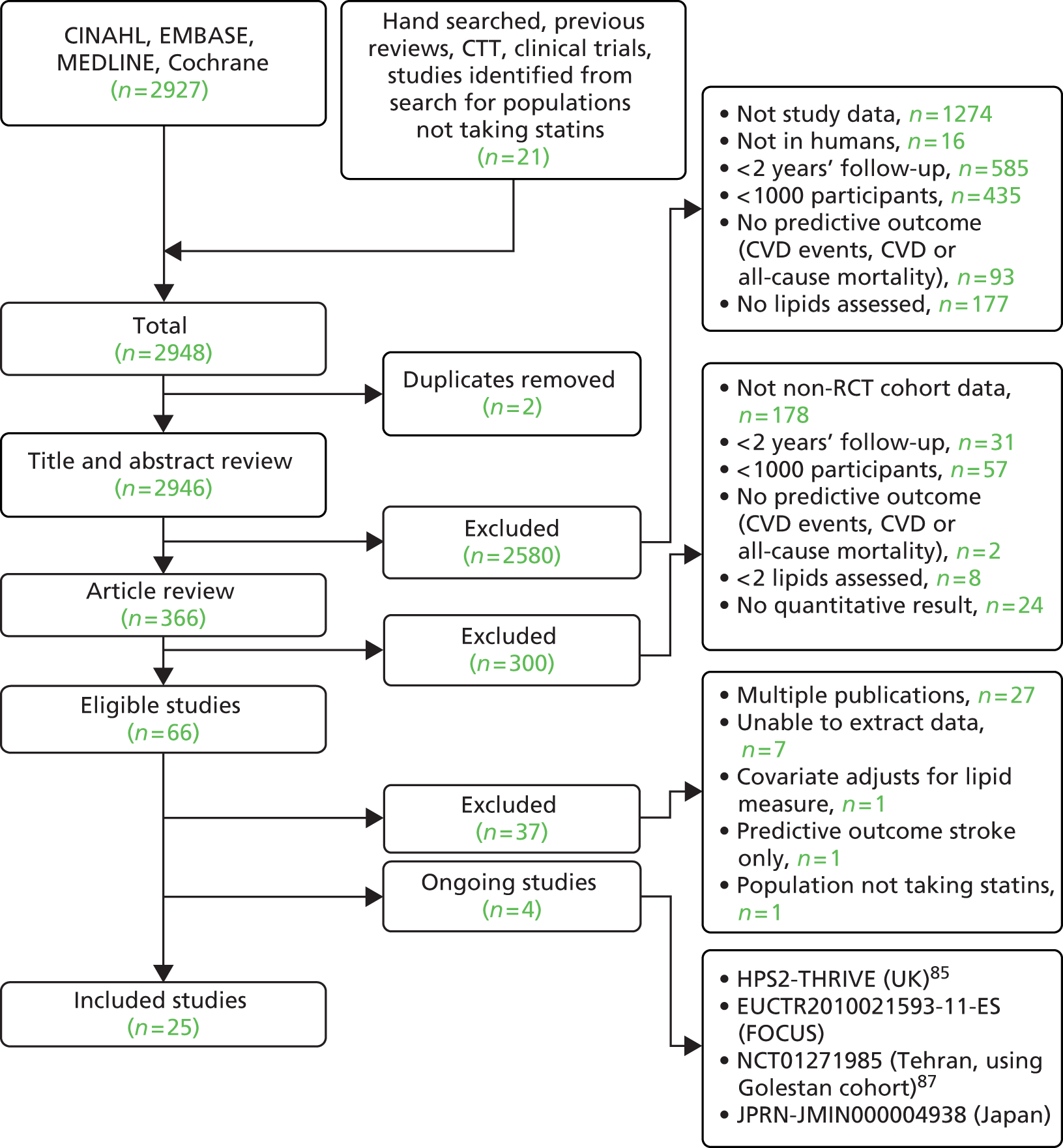

Figure 3 summarises the selection process; 3776 publications were screened from the search, with a further 165 potential studies identified from existing reviews and hand searching. Of these, 90 studies met the inclusion criteria and provided results (see Appendix 8), with 16 studies providing two or more sets of data; this resulted in a total of 110 sets of data. Twelve studies divided the data by gender [TLGS,88 Yao City,89 AMORIS,90 CB project,91 Copenhagen City,92 DUBBO,93 Framingham Offspring,40 IKNS (Yao),94 MONICA,95 Northwick Park I,96 Reykjavik,97 Rotterdam98]. Two studies divided the data by gender and then further by ethnicity (Charleston99) or presence of metabolic syndrome [European Prospective Investigation of Cancer (EPIC) – Norfolk study (EPIC-Norfolk)100] so providing four data sets each. Puerto Rico101 divided the data by rural and urban populations, and MRFIT102 by black and white men.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of study inclusion for populations not taking statins.

Full details of the characteristics of the 90 included studies are shown in Table 8. Of the included studies 73% were prospective cohorts and 17% were placebo arms of RCTs. The remaining nine studies were two retrospective cohorts (Swedish NDR;164 Juntendo, Japan134), three RCTs (of non-lipid modifying interventions) for which both arms were included in this review (SHEP,159 TREAT,167 Women’s Health172) and four nested case–control studies (BUPA,113 GLOSTRUP Population,124 Nurses’ Health,147 Physicians’ Health150). Studies provided data for between 1 and 10 lipid measures. Two studies provided data for all of the 10 lipid measures (FIELD,121 Women’s Health172). Data details for all studies are shown in Appendix 8. Table 9 shows the number of studies and participants by the 10 lipid measures. Numbers are also shown for three additional measures (Apo B/HDL cholesterol, TG/HDL cholesterol/HDL cholesterol/TC) that were revealed by the review; however, data were available from only one study for one outcome for each measure and therefore no pooled estimates were obtained.

| Study name | Study type | Maximum number of participantsa | Age (years: mean unless indicated) | Gender (% female) | Underlying condition for total population | Primary prevention (%) | Lipid-lowering drugs (%) | Fasting assay | Central laboratory | Direct or estimated LDL (N/A if no LDL measure) | Follow-up (years; mean unless indicated) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 Countries (Greece)103 | Prospective cohort | 1215 | 49 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | NS | N/A | 25 |

| 7 Countries (Italy)103 | Prospective cohort | 1712 | 49 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | NS | N/A | 25 |

| 7 Countries (Netherlands)104 | Prospective cohort | 885 | 71 | 0 | NS | 100 | 3 | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 25 |

| 7 Countries (Serbia)105 | Prospective cohort | 1563 | 40–59 range | 0 | NS | 99 | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 25 |

| AF/TexCAPS106 | RCT | 3301 | 58 | 15 | No | 100 | N | NS | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5.2 |

| ALERT107 | RCT | 1052 | 50 | 35 | Renal or combined renal and pancreas transplants > 6 months and stable graft function | 97 | N | F | Y | NS | 5.1 |

| AMORIS90 | Prospective cohort | 149,121 | 49+ | 44 | NS | 100 | NS | F/NF (fasting reported for 62% for Apos) | Y (accredited) | Estimated | 11.8 |

| ANHF108 | Prospective cohort | 8662 | 43 | 52 | None | 100 | NS | NS | NS | N/A | 15 |

| ASCOT-LLA109 | RCT | 1274 | 64 | 24 | Diabetes (II) | 100 | N | NF | Y | NS | 3.3 |

| AURORA110 | RCT | 1384 | 64 | 37 | End-stage renal failure/haemodialysis for 3 months | 28.2 | N | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 3.2 |

| BRHS111 | Prospective cohort | 7735 | 40–59 range | 0 | NS | 75 | NS | NF | NS | N/A | 7.5 |

| Bruneck112 | Prospective cohort | 765 (previous review) | 61–70 mean range | 50 | NS | 90 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 10 |

| BUPA113 | Nested case control | 1374 | 53 | 0 | NS | NS | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5+ |

| Caerphilly114 | Prospective cohort | 2225 | 45–59 range | 0 | NS | 69 | NS | F | Y | Estimated (Friedewald) | 9 |

| CARDS115 | RCT | 1410 | 62 | 32 | Diabetes (II) | 100 | N | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 3.9 median |

| CARE34 | RCT | 2078 | 59 | 14 | None | 0 | N | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5 median |

| Casale Monferrato116 | Prospective cohort | 982 | 69 | 57 | Diabetes II | 76 | NS | F | Y | Estimated (Friedewald, except for 3%) | 11 |

| CB project91 | Prospective cohort | 49,018 | 39 | 52 | NS | NS | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 11.8 |

| Charleston99 | Prospective cohort | 2181 | 50 | 55 | NS | NS | NS | F | NS | N/A | 30 |

| Chinese veterans117 | Prospective cohort | 1268 | 55+ | 0 | NS | 70 | NS | NS | NS | N/A | up to 18 years |

| CHS118 | Prospective cohort | 4885 | 73 | 60 | NS | 84 | ≤ 5.7 | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 7.5 |

| Copenhagen City92 | Prospective cohort | 9035 | 59 | 57 | NS | 99.50 | 0.5 | NF | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 14 |

| CORONA119 | RCT | 2497 | 73 | 24 | None | 0 | N | NF | Y | NS | 2.7 median |

| DAI120 | Prospective cohort | 2788 | 66–69 mean range | 43 | Diabetes (II) | 0 | 24–31.2 | F | N | NS | 4 |

| DUBBO93 | Prospective cohort | 2805 | 70 | 56 | NS | 75 | NS | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5.2 median |

| EPIC-Norfolk100 | Prospective cohort | 21,448 | 59 | 56 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | Y | Estimated (Friedewald) | 11 |

| FIELD121 | RCT | 4900 | 62 | 37 | Diabetes (II) | 78 | N | F | Two central labs – both accredited | NS | 5 median |

| FINRISK ‘92122 | Prospective cohort | 2378 | 54 | 52 | NS | 94 | NS | F | Y | N/A | 6.6 median |

| Framingham Offspring40 | Prospective cohort | 3322 | 51 | 53 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 14.8 |

| GISSI123 | RCT (stopped early) | 2133 | 60 | 14 | No | 0 | N | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 2 |

| GLOSTRUP Population124 | Nested case control | 264 | NS | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 8 |

| GOH125 | Prospective cohort | 1745 | 53 | 0 | NS | 90 | NS | F | Y (accredited) | N/A | 18 |

| GRIPS126 | Prospective cohort | 4368 | 40–59.9 range | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Direct | 10 |

| Hamaguchi 2007127 | Prospective cohort | 1221 | 47–49 mean range | 39 | None | 100 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 5.8 |

| Honolulu Heart128 | Prospective cohort | 3741 | 71–79 range | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | Y | N/A | 3–5 years |

| Hoorn study129 | Prospective cohort | 1817 | 61 | 52 | NS | 90 | N | F | NS | N/A | 10 |

| HPFS130 | Prospective cohort | 746 | 65 | 0 | Diabetes (II) | 100 | 9 | F (50%) | Y | Direct | 6 |

| HPS24 | RCT | 10,267 | 64 | 18 | None | 20.8 | N | NF | Y | Direct | 5 |

| IKNS (Yao)94 | Prospective cohort | 12,187 | 40–69 range | 66 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 8.9 |

| InCHIANTI131 | Prospective cohort | 1013 | 65+ | 56 | None | 95 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 6 |

| Israeli Ischaemic Heart132 | Prospective cohort | 10,059 | 40+ | 0 | NS | NS | NS | NF | Y | N/A | 23 |

| IwateKENCO133 | Prospective cohort | 24,566 | 60+ | 65 | NS | 100 | N | F/NF | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 2.7 |

| Juntendo, Japan134 | Retrospective cohort | 1074 | 59–60 mean range | 16 | All complete revascularisation/excluded those on haemodialysis | 0 | 7–10.5 | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 10.6 |

| KIHD135 | Prospective cohort | 1931 | 42–60 range | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Direct | 3 |

| Lan 2007136 | Prospective cohort | 2086 | 72 | 37 | None | 95 | NS | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 8.2 |

| LIFE (subanalysis)137 | Prospective cohort | 8243 | 67 | 53 | NS | 75.3 | 7.1 in full LIFE trial | NS | Y | N/A | 4.8 |

| LIPID138 | RCT | 4502 | 62 | 17 | No | 0 | N | F | Y | Estimated (Friedewald) | 6.1 |

| Livermore139 | Prospective cohort | 40 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | NS | NS | 53.2 | |

| LRC prevalence140 | Prospective cohort | 3678 | 35–74 range | 47 at 8-year follow-up | NS | 100 | N | F | NS | Estimated | 12.2 |

| MEGA141 | RCT | 3966 | 58 | 69 | N | 100 | 23 use by study end | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5.3 |

| MESA142 | Prospective cohort | 6693 | 62 | 53 | NS | 100 | 16.10 | F | Y | NS | 4.62 |

| MHS143 | Prospective cohort | 11,060 | 62 | 44 | Diabetic | NS | 32.60 | NS | NS | NS | 4.62 |

| MONICA95 | Prospective cohort | 2850 | 50 | 50 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | NS | N/A | 13 median |

| MRFIT102 | Prospective cohort | 6257 | 46 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | NS | 7 |

| NHANES III144 | Prospective cohort | 7594 | 45 | 50 | NS | NS | NS | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 10.3 median |

| NIPPON 80145 | Prospective cohort | 9216 | 50 | 56 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 17.3 |

| Northwick Park I96 | Prospective cohort | 3108 | 48 | 30 | NS | 97 | NS | NF | NS | N/A | 29 median |

| Northwick Park II146 | Prospective cohort | 2508 | 56 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | NS | Estimated (Wallduis) | 6 |

| Nurses’ Health147 | Nested case control | 683 (previous review) | 61 | 100 | NS | 100 | N | F | Y (accredited) | Direct | 8 |

| Palma 2007148 | Prospective cohort | 2848 | 53 | 53 | Surgical patients (various) | NS | NS | F | Y | N/A | 6 |

| PARIS149 | Prospective cohort | 6999 | 43–53 range | 0 | NS | 98 | NS | F | NS | N/A | 11.4 |

| Physicians’ Health150 | Nested case control | 492 (previous review) | 59 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 7 |

| PreCIS151 | Prospective cohort | 3098 | 54–55 mean range | 43 | NS | 53 | 41 (statins) | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 7.6 |

| PREVEND152 | Prospective cohort | 6948 | 48 | 52 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 7.9 |

| PROCAM153 | Prospective cohort | 5389 | 40–65 range | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 6 |

| Progetto Cuore154 | Prospective cohort | 20,447 | 50 | 64 | NS | NS | NS | NS | NS | N/A | 10.4 |

| PROSPER155 | RCT | 2913 | 75 | 52 | None | 30 | N | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 3.2 |

| Puerto Rico101 | Prospective cohort | 6205 | 45–64 range | 0 | NS | 94 | NS | NF | Y | N/A | 12 |

| Quebec Cardiovascular156 | Prospective cohort | 2177 | 57 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5 |

| Rancho Bernardo157 | Prospective cohort | 2227 | 69 | 59 | NS | 100 | N | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 9.6 |

| Reykjavik97 | Prospective cohort | 18,569 | 53 | 48 | NS | 95 | NS | F | NS | N/A | 17.4 |

| RIFLE158 | Prospective cohort | 20,386 | 30–69 range | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | N | N/A | 6 |

| Rotterdam98 | Prospective cohort | 6006 | 55+ | 59 | NS | 96 | 2.90 | F/NF (both F and NF stated) | NS | N/A | 4.2 |

| SHEP159 | Prospective cohort(both arms of RCT) | 4736 | ≥ 60 | 57 | NS | 93 | NS | F (60%) | Y | Estimated | 4.5 |

| SHS160 | Prospective cohort | 2108 | 57 | 63 | Diabetes (II) | 100 | NS | F | Y | Direct | 9 |

| SLVHS161 | Prospective cohort | 1682 | 52–55 mean range | 56 | no | 100 | 3 at baseline | F | NS | N/A | 9.3 |

| Stanek 2007162 | Prospective cohort | 30,348 | 66 | 45 | NS | 65 | NS | NS | NS | NS | 2.25 |

| Stockholm County163 | prospective cohort | 3502 | 60 | 54 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 11 |

| Swedish NDR164 | Retrospective cohort | 18,673 | 60 | 40 | Diabetes (II) | 86.6 | 42 | NS | N | Estimated (Friedewald) | 4.8 |

| Thrombo165 | Prospective cohort | 1045 | 48 | 24 | None | 0 | 38 | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 26 |

| Ting 2010166 | Prospective cohort | 4521 | 54+ median | 54 | Diabetic | 92 | 23 by study end | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 4.9 |

| TLGS88 | Prospective cohort | 6834 | 45+ | 56 | NS | 97 | ≤ 5 | F | Y | Estimated (Friedewald) | 9.3 |

| TREAT167 | Prospective cohort (both arms of RCT) | 4038 | 68 | 57 | NS | 63 | 15% in 1000 subgroup | NS | NS | N/A | 2.4 median |

| Turku Elderly168 | Prospective cohort | 1032 | 70 | 64 | NS | 0 | < 1% | F | Y | Estimated (Friedewald) | 12 |

| ULSAM169 | Prospective cohort | 1108 | 50 | 0 | NS | 100 | NS | F | NS | Estimated (Friedewald) | 28.7 |

| VA-HIT170 | RCT | 1267 | 64 | 0 | NS | 0 | N | F | Y (accredited) | Estimated (Friedewald) | 5.1 |

| Whitehall I171 | Prospective cohort | 17,718 | 40–64 range | 0 | NS | NS | NS | NF | Y | N/A | 18 |

| Women’s Health172 | Prospective cohort (both arms of RCT) | 15,632 | 54 | 100 | NS | NS | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | Direct | 10 |

| WOSCOPS19 | RCT | 3293 | 55 | 0 | N | 100 | N | F | Y (accredited) | NS | 4.9 |

| Yao City89 | Prospective cohort | 11,977 | 21–89 range | 32 | NS | 100 | NS | NF | Y (accredited) | N/A | 4.8 |

| Lipid measure | Outcome | Number of primary prevention studies | Number of secondary prevention studies | Overall number of studies | Number of participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LDL | CVD events | 15 | 7 | 28 | 110,021 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 17 | 1 | 22 | 286,038 | |

| CVD mortality | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4691 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 3 | 1 | 6 | 161,581 | |

| All-cause mortality | 2 | 0 | 7 | 13,958 | |

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 4 | 32,136 | |

| TC | CVD events | 16 | 5 | 27 | 110,304 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 28 | 1 | 39 | 256,259 | |

| CVD mortality | 6 | 0 | 14 | 36,514 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 9 | 1 | 19 | 234,018 | |

| All-cause mortality | 3 | 0 | 15 | 25,215 | |

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 8 | 0 | 19 | 128,446 | |

| HDL | CVD events | 18 | 7 | 33 | 129,205 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 29 | 1 | 39 | 323,111 | |

| CVD mortality | 4 | 0 | 6 | 19,421 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 5 | 1 | 10 | 179,359 | |

| All-cause mortality | 2 | 0 | 9 | 62,497 | |

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 1 | 0 | 5 | 29,372 | |

| TGs | CVD events | 13 | 6 | 25 | 100,441 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 9 | 1 | 14 | 128,055 | |

| CVD mortality | 4 | 0 | 5 | 11,837 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 4 | 1 | 5 | 159,421 | |

| All-cause mortality | 2 | 0 | 8 | 16,168 | |

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 3 | 0 | 5 | 17,274 | |

| Non-HDL | CVD events | 4 | 0 | 6 | 22,292 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 14 | 0 | 19 | 253,110 | |

| CVD mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8243 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 3 | 1 | 4 | 152,422 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| Apo B | CVD events | 7 | 2 | 10 | 26,528 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 17 | 1 | 21 | 207,994 | |

| CVD mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1145 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 1 | 0 | 3 | 158,280 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7594 | |

| Apo A | CVD events | 5 | 2 | 8 | 23,773 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 15 | 1 | 19 | 204,372 | |

| CVD mortality | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1145 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 1 | 0 | 3 | 158,280 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7594 | |

| Apo B/Apo-I | CVD events | 3 | 1 | 4 | 16,192 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 14 | 0 | 16 | 195,445 | |

| CVD mortality | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 156,715 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7594 | |

| TC/HDL cholesterol and non-HDL/HDL merged | CVD events | 5 | 1 | 7 | 17,659 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 17 | 1 | 23 | 258,011 | |

| CVD mortality | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3678 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 3 | 0 | 5 | 164,197 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 2 | 12,849 | |

| LDL/HDL cholesterol | CVD events | 3 | 0 | 3 | 8499 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 8 | 0 | 11 | 194,177 | |

| CVD mortality | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3678 | |

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | 1 | 1 | 3 | 157,789 | |

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7594 | |

| Additional lipid measures (ratios) revealed in included studies but not included in this review (insufficient data to analyse) | |||||

| Apo B/HDL | CVD events | 1 | 0 | 1 | 683 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 15,632 | |

| CVD mortality | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| TG/HDL | CVD events | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3678 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| HDL/TC | CVD events | 1 | 0 | 1 | 710 |

| CVD events (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality | No data | ||||

| CVD mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality | No data | ||||

| All-cause mortality (adjusted) | No data | ||||

Outcome data were available for CVD events, CVD mortality and all-cause mortality. Data were further divided into unadjusted (CVD events, CVD mortality, all-cause mortality) and adjusted data [CVD events (adjusted), CVD mortality (adjusted), all-cause mortality (adjusted)] and then by lipid measure. Meta-analyses were not possible for all combinations of outcomes and lipid measures. Outcome data for all lipid measures were pooled for CVD events (except LDL/HDL cholesterol) and CVD events (adjusted). For CVD mortality, outcome data were available only for nine lipid measures (no studies examined the ratio Apo B/Apo A-I) and only HDL cholesterol, TGs and TC had sufficient (more than three studies) to pool data. Outcome data were available for all 10 lipid measures for CVD mortality (adjusted), but Apo A-I, LDL/HDL cholesterol, Apo B and Apo B/Apo A-I data could not be pooled due to an insufficient number of studies. Data were available for four lipid measures for all-cause mortality (LDL, HDL, TC, TGs), all of which had sufficient studies to pool data. Finally, for all lipid measures bar non-HDL cholesterol, outcome data for all-cause mortality (adjusted) were provided, although only HDL cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, TC and TGs could be pooled as a result of insufficient studies.

Low-density lipoprotein measurement

Of the 59 studies that provided data for LDL, seven measured it directly [HPS,24 GRIPS,126 Health Professionals Follow-up Study (HPFS),130 KIHD,135 Nurses’ Health,147 SHS,160 Women’s Health172]; 34 studies (59%) estimated LDL cholesterol, of which 26 used the Friedewald formula,43 three studies stated that the measure was estimated but with no further information (SHEP,159 AMORIS,90 LRC prevalence140) and Northwick Park II146 estimated LDL using the Wallduis formula;173 the remaining 17 studies did not report whether or not LDL was measured or estimated.

Heterogeneity

Heterogeneity was generally high across all prevention groups, outcome data and lipid measures with few exceptions. For CVD events, both adjusted and unadjusted, the overall heterogeneity was considerable (I2 > 73%) for all lipid measures except Apo A-I in the unadjusted data (56%) and LDL/HDL cholesterol (55%) in the adjusted data where it was moderate. When further examined, the unadjusted CVD event data for primary prevention groups is considerably heterogeneous (77–97%) for all lipid measures except Apo A-I (5% based on five studies) and Apo B/Apo A-I (59% based on three studies). For adjusted CVD events outcome data in the primary prevention populations the heterogeneity is large (92–98%) for all lipid measures except LDL/HDL cholesterol were it is low (27%); though this is based on eight data sets, these were obtained from only three studies. There were insufficient data to examine heterogeneity in any of the lipid measures in the secondary prevention populations for CVD events adjusted outcome data. However, for these populations, in the unadjusted CVD events outcome data the heterogeneity was measurable in five out of the nine lipid measures and varied: LDL cholesterol was considerable (76%), TC, HDL cholesterol and TGs were moderate (34%, 52% and 63%) and for Apo B and Apo A-I there was no heterogeneity (0%). This was for the same two studies each (LIPID,138 Thrombo165). Heterogeneity for CVD mortality outcome data (unadjusted and adjusted) was substantial for all pooled lipid measures (67–91%). There was no heterogeneity statistic for secondary prevention populations owing to insufficient data. For the primary prevention groups in these data the heterogeneity ranged from 40% to 89%. Few lipid measures provided sufficient data for all-cause mortality and therefore assessment of heterogeneity was limited. For those that did, LDL cholesterol, TC, HDL cholesterol, TGs, heterogeneity for the summary estimate was moderate to considerable (52–95%), there were insufficient data to assess secondary prevention groups. All-cause mortality unadjusted data for primary prevention groups varied between two measures (LDL cholesterol, TC) showing considerable heterogeneity (> 95%) and two measures (HDL cholesterol and TGs) showing no heterogeneity (0%). Data from only two studies were available for each of these last two measures: of the two studies reporting HDL data, one study had 44,457 participants (AMORIS90) and the other 1013 (InCHIANTI131); for TGs, the participant numbers were 1013 (InCHIANTI131) and 2086 (Lan 2007136). Forest plots of all of these results appear in Appendix 9.

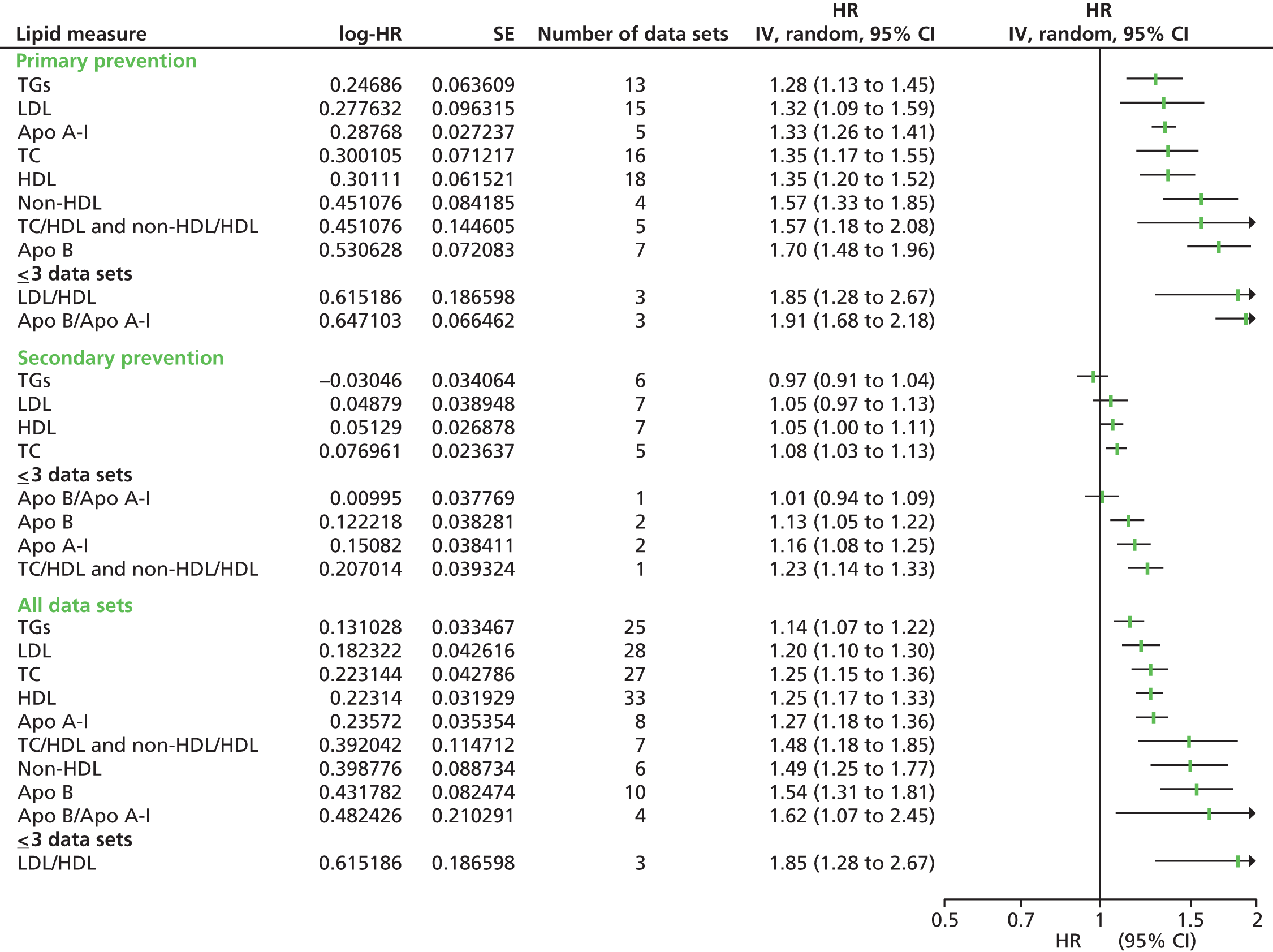

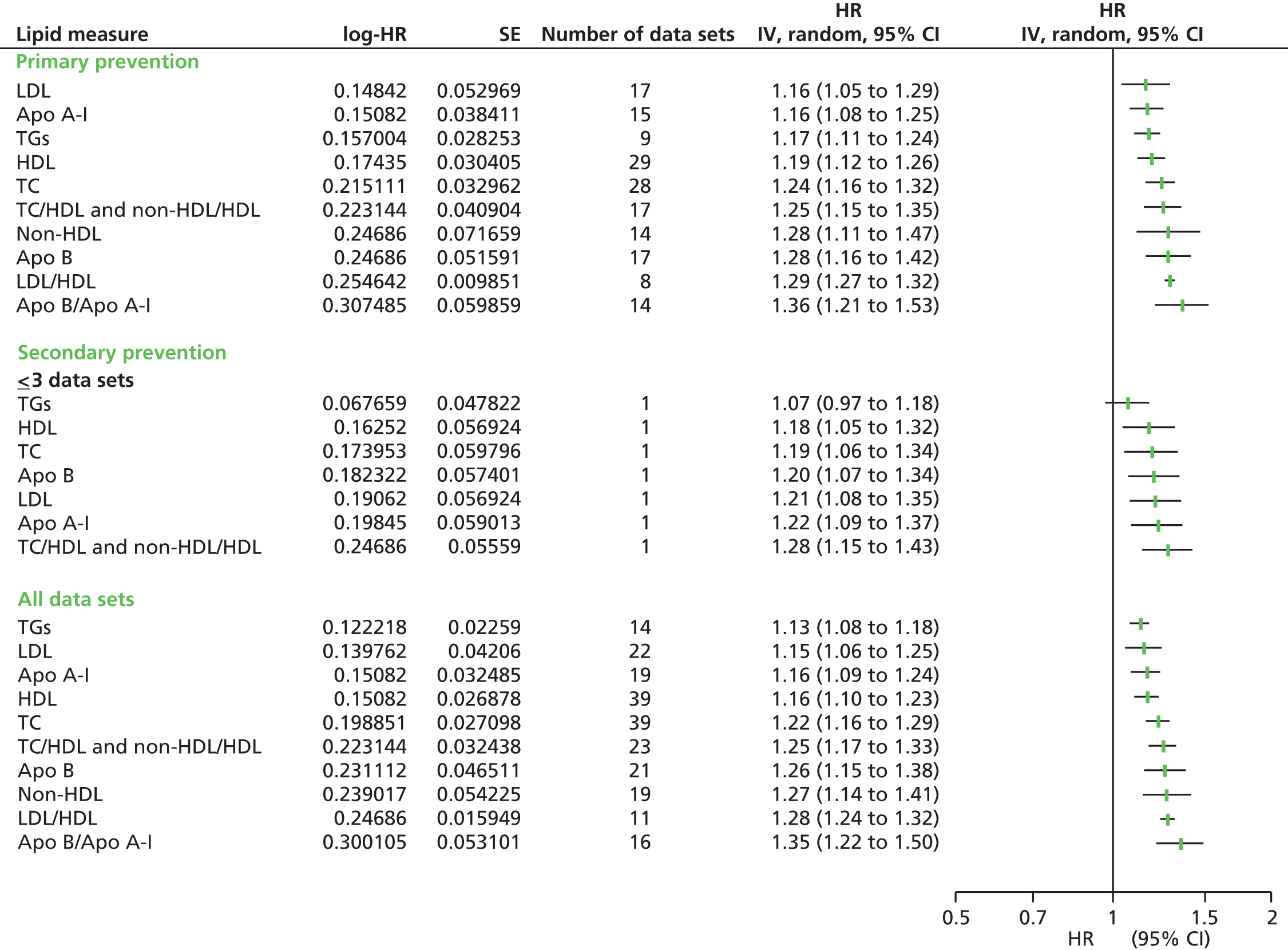

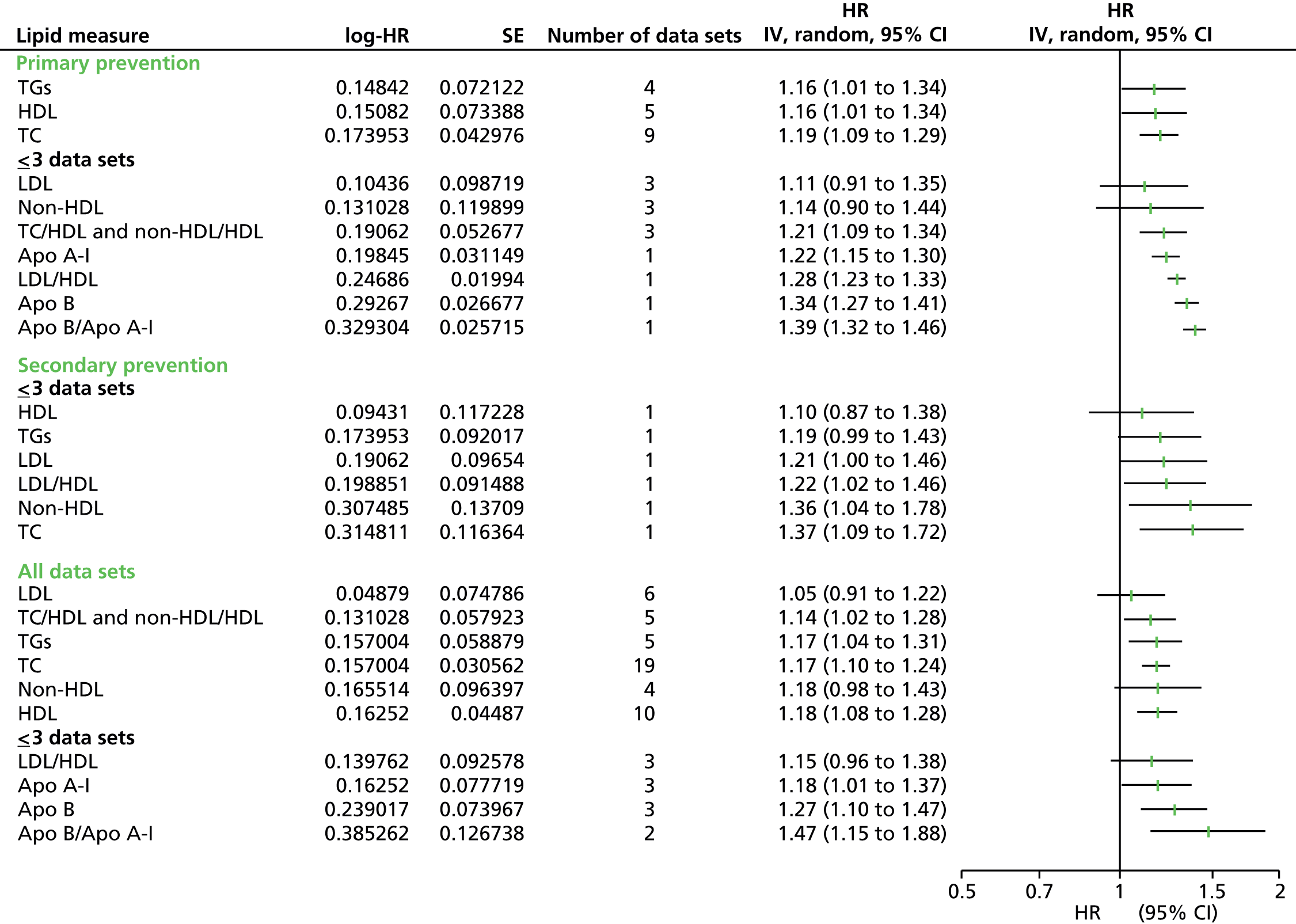

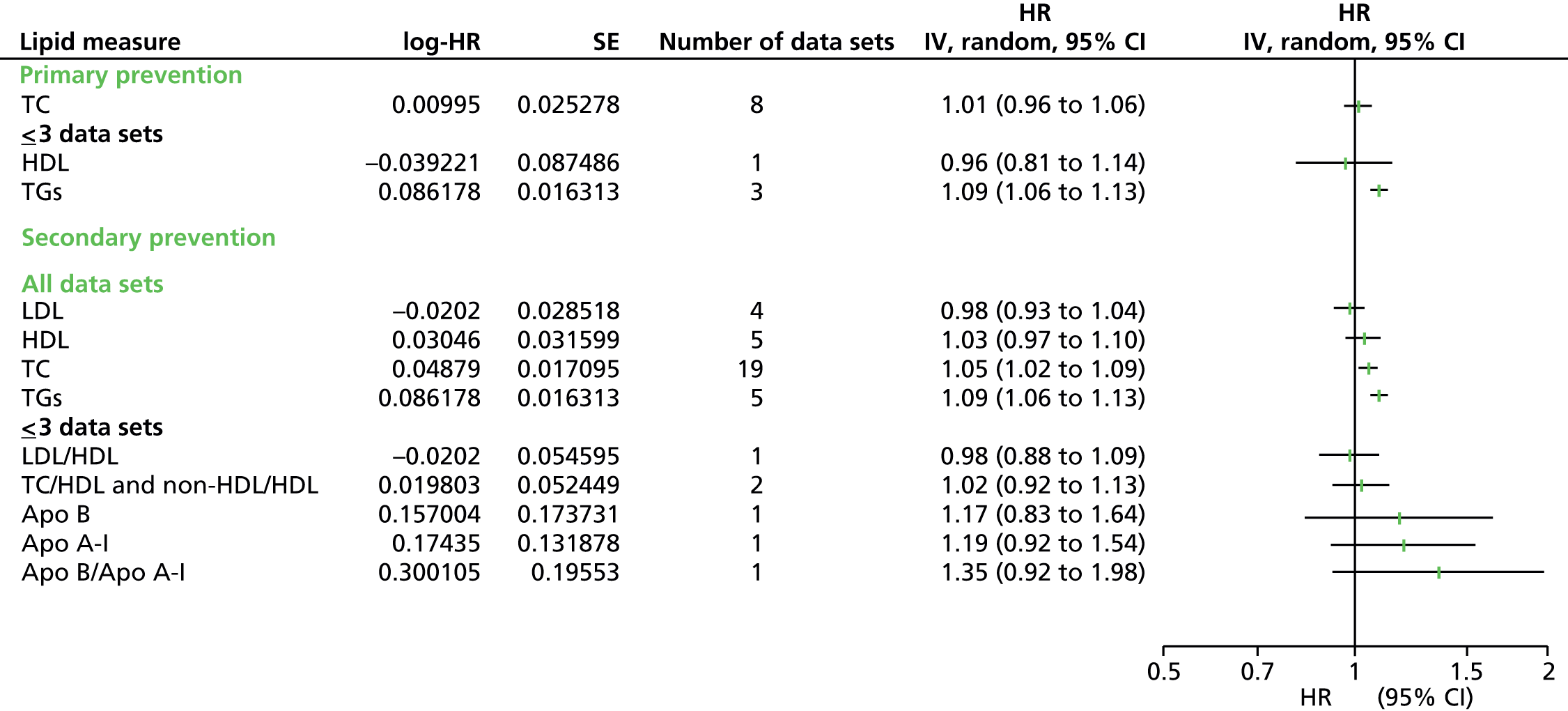

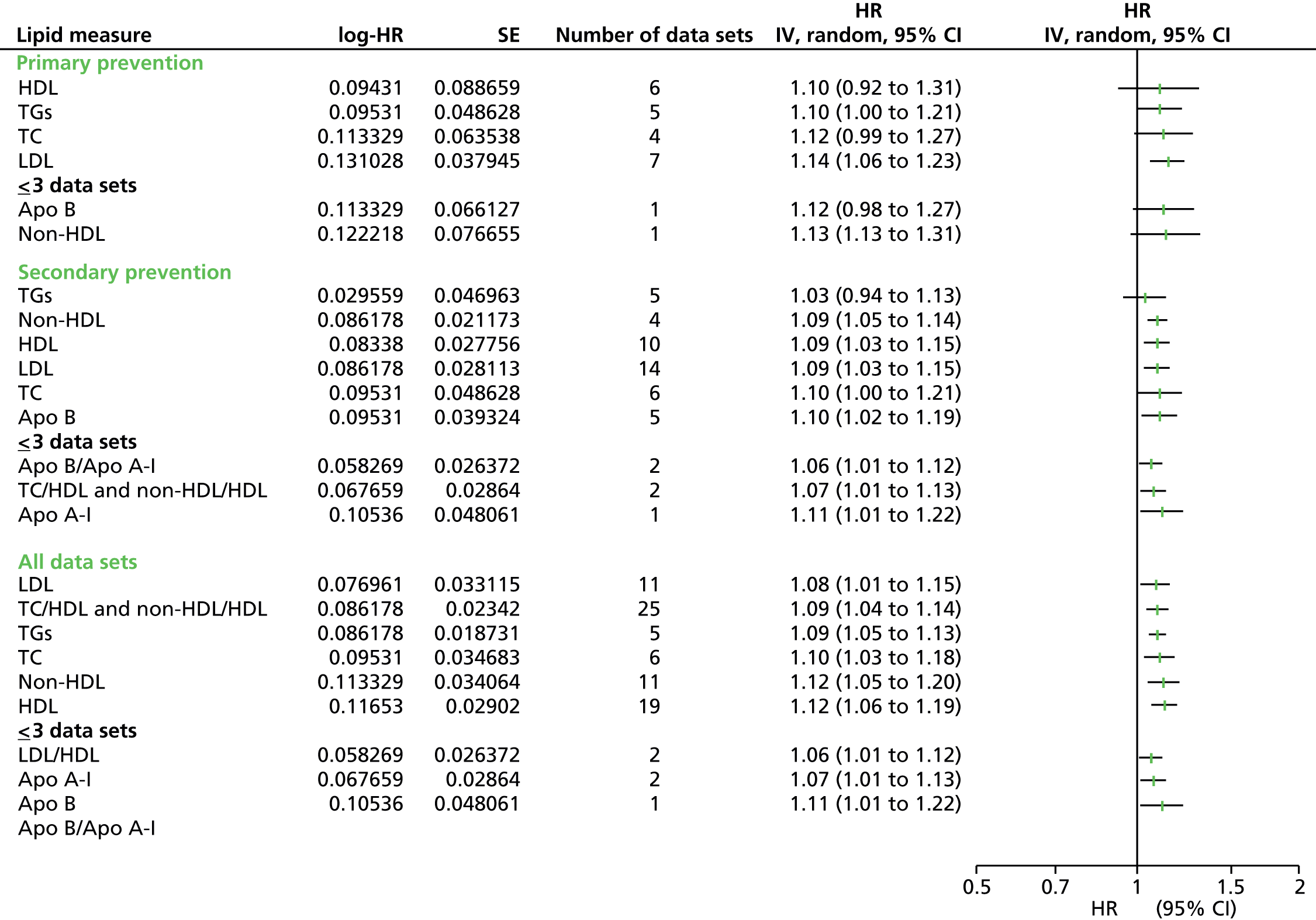

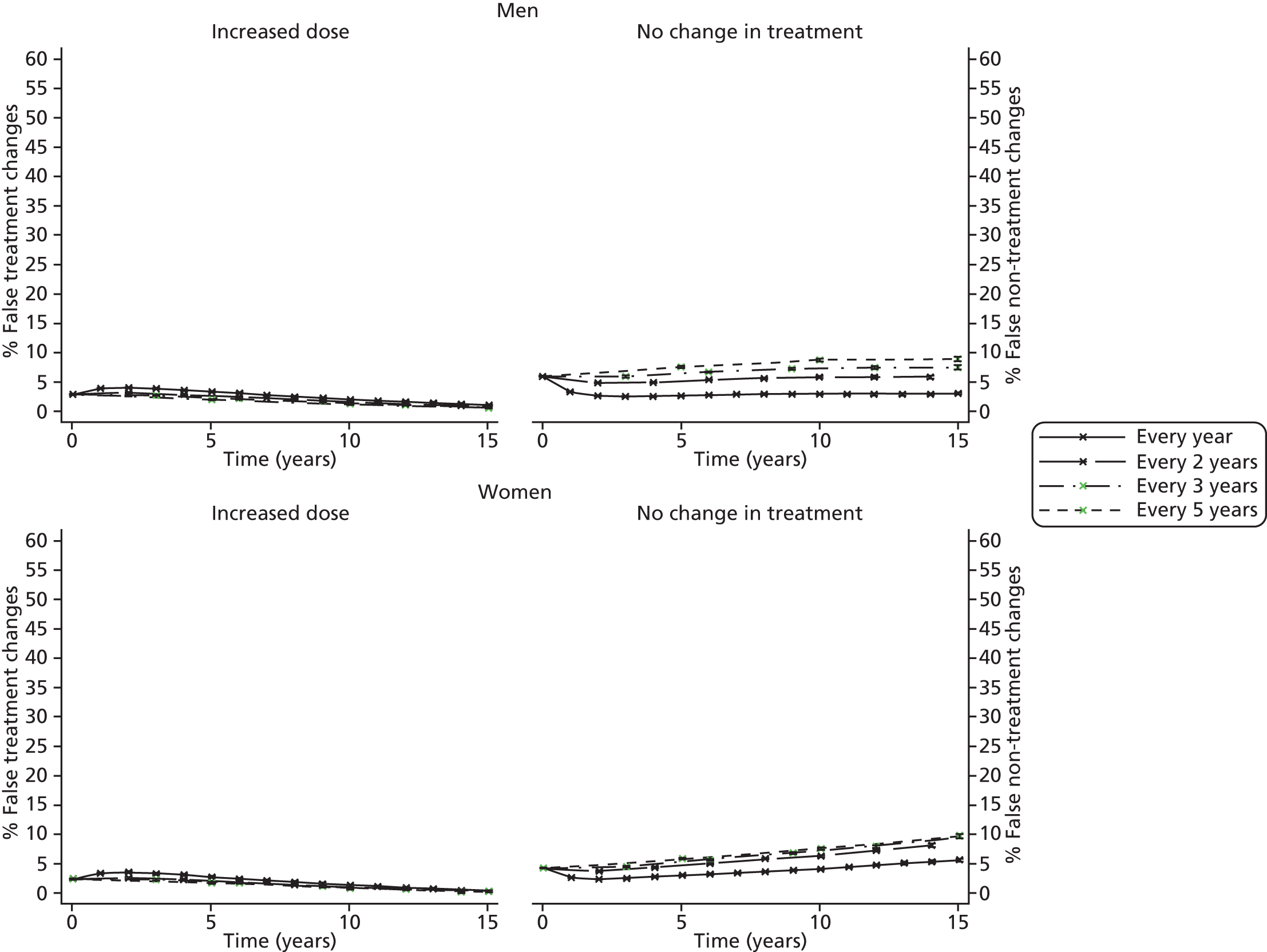

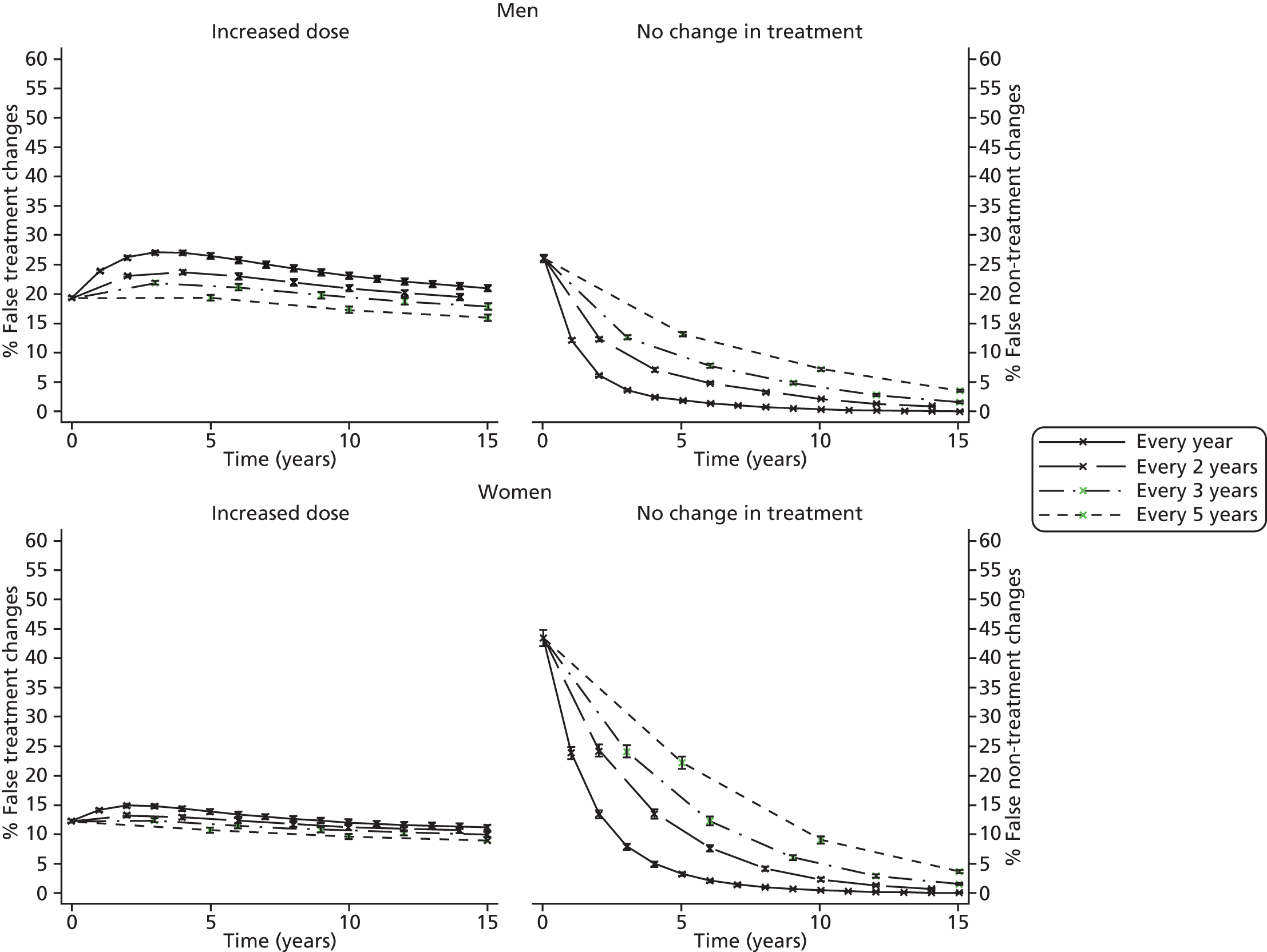

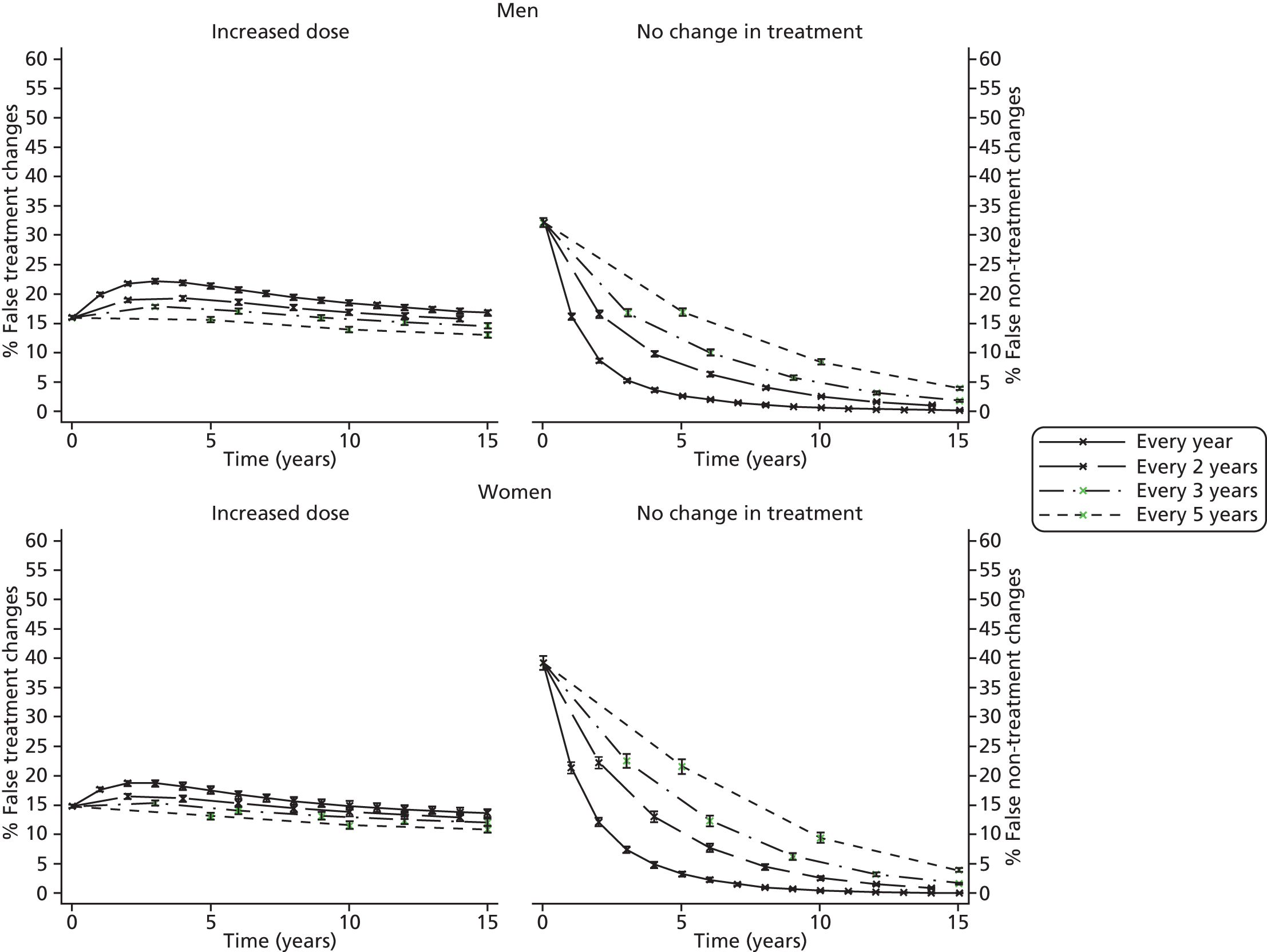

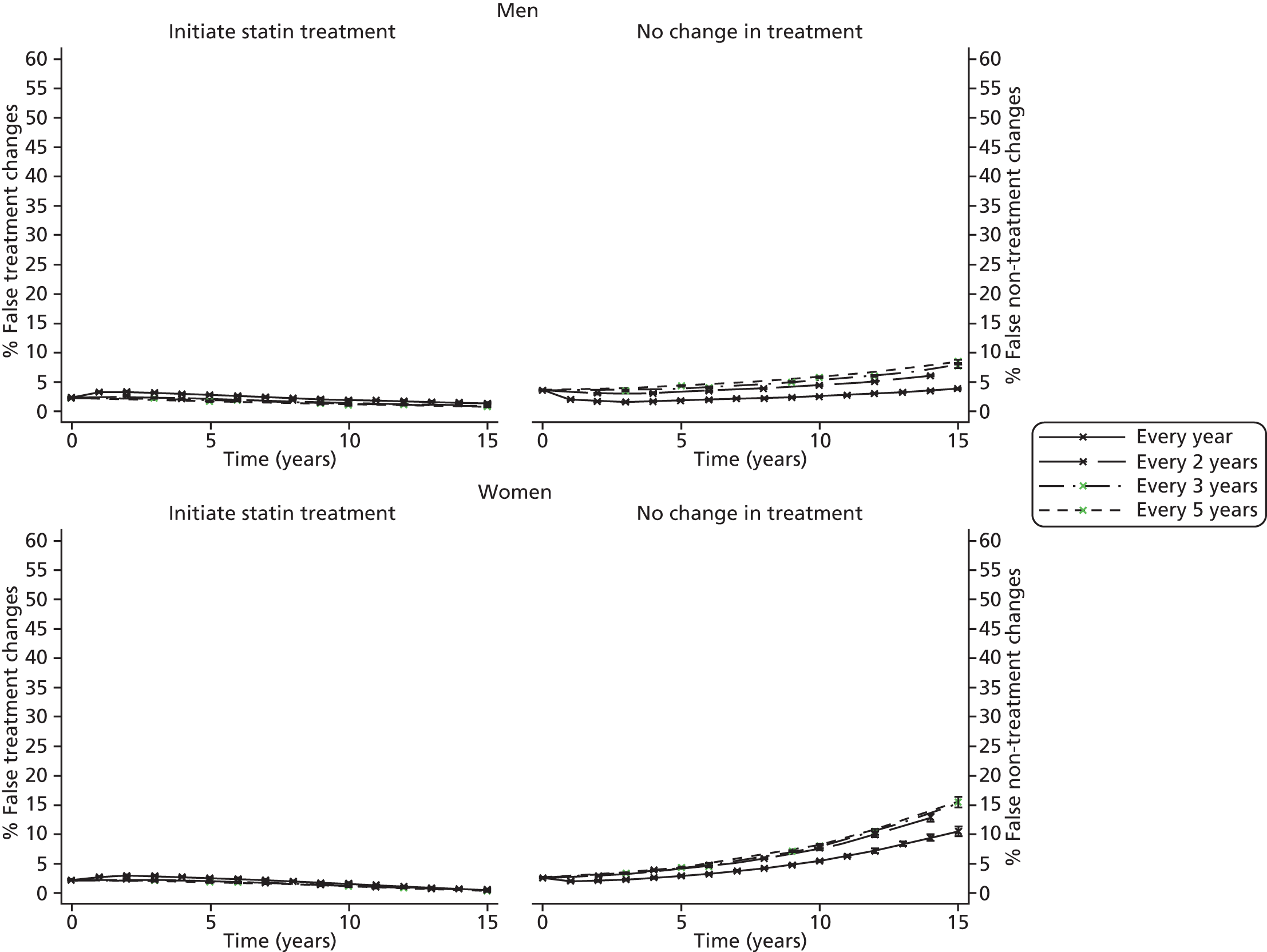

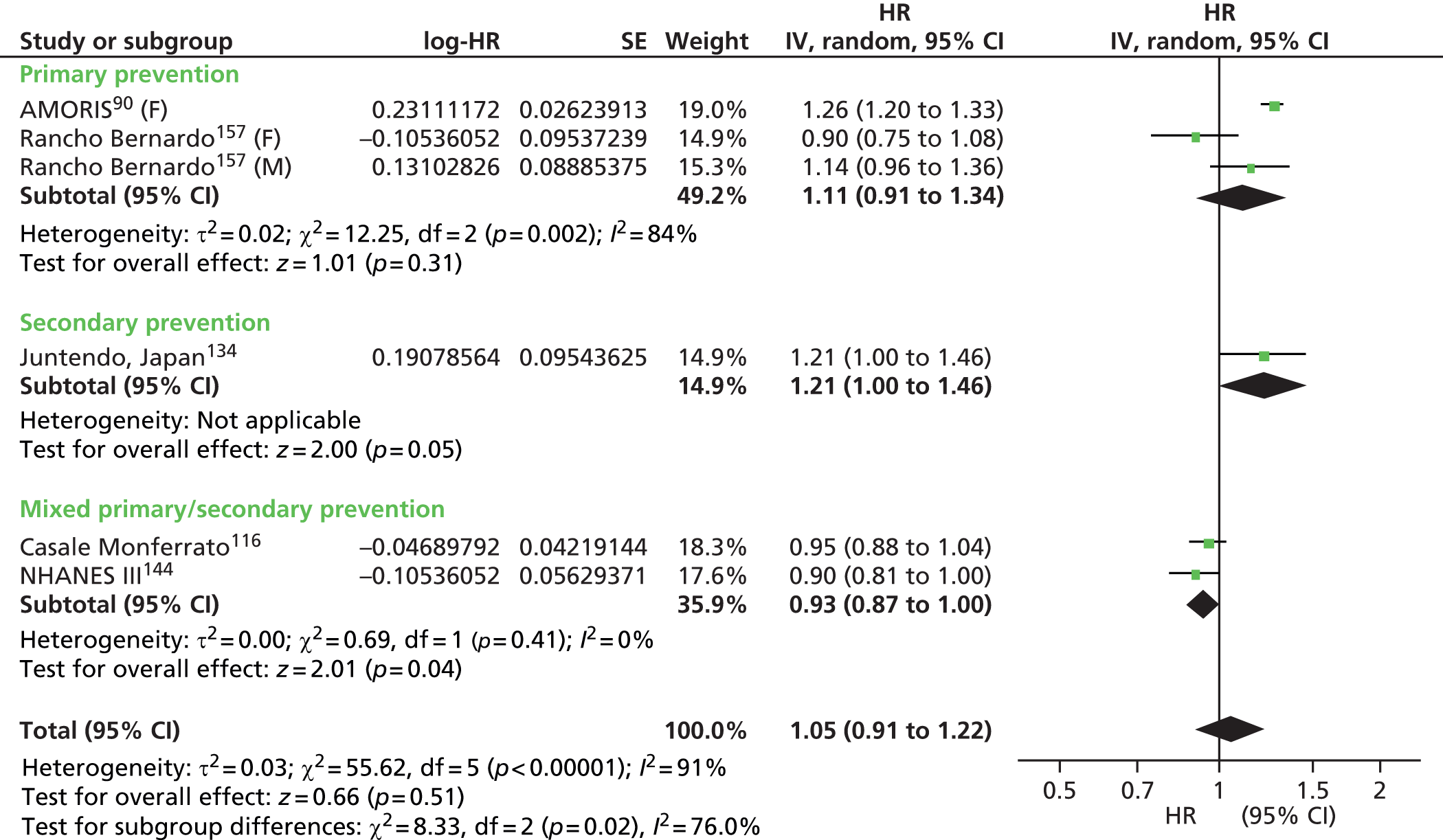

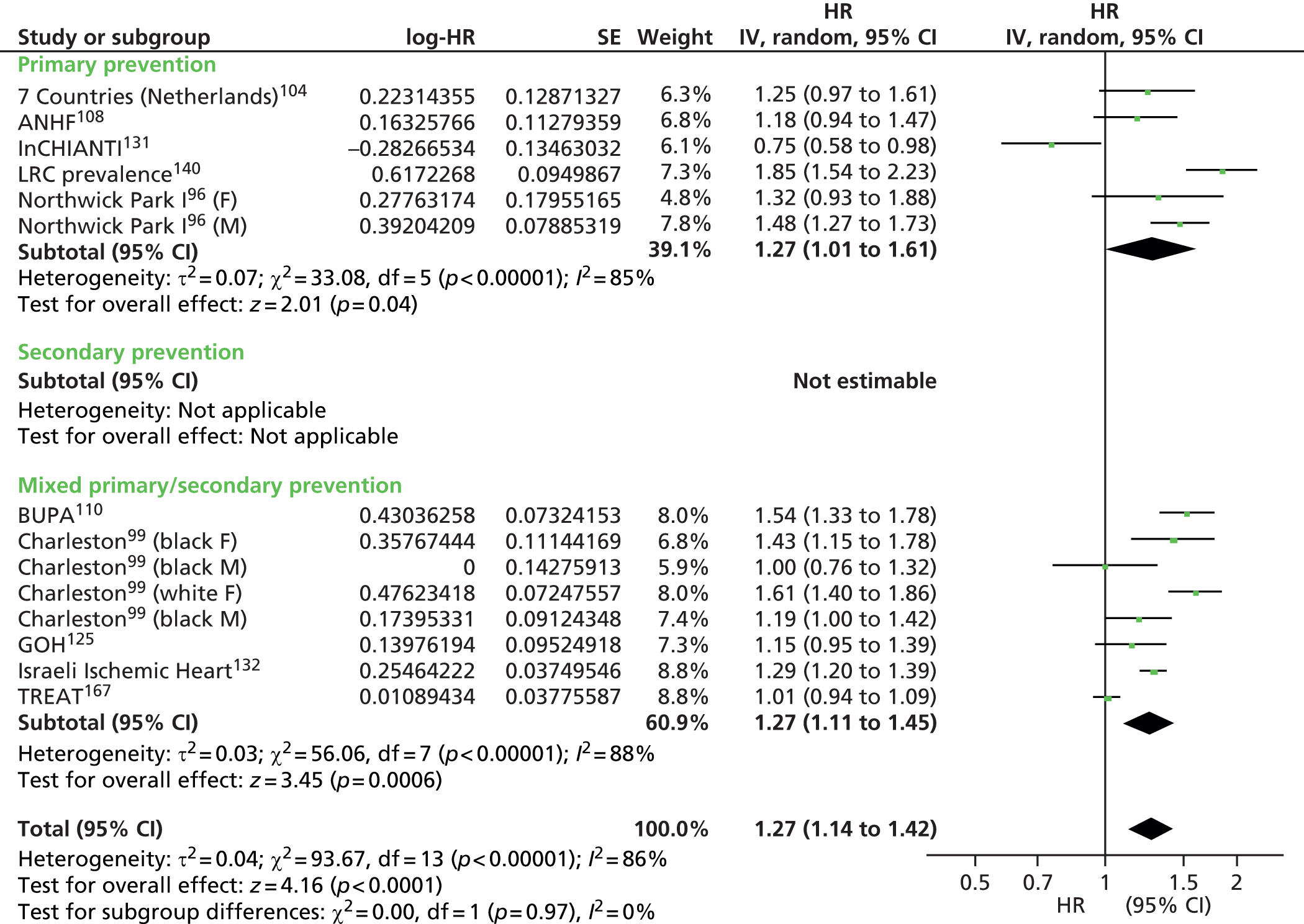

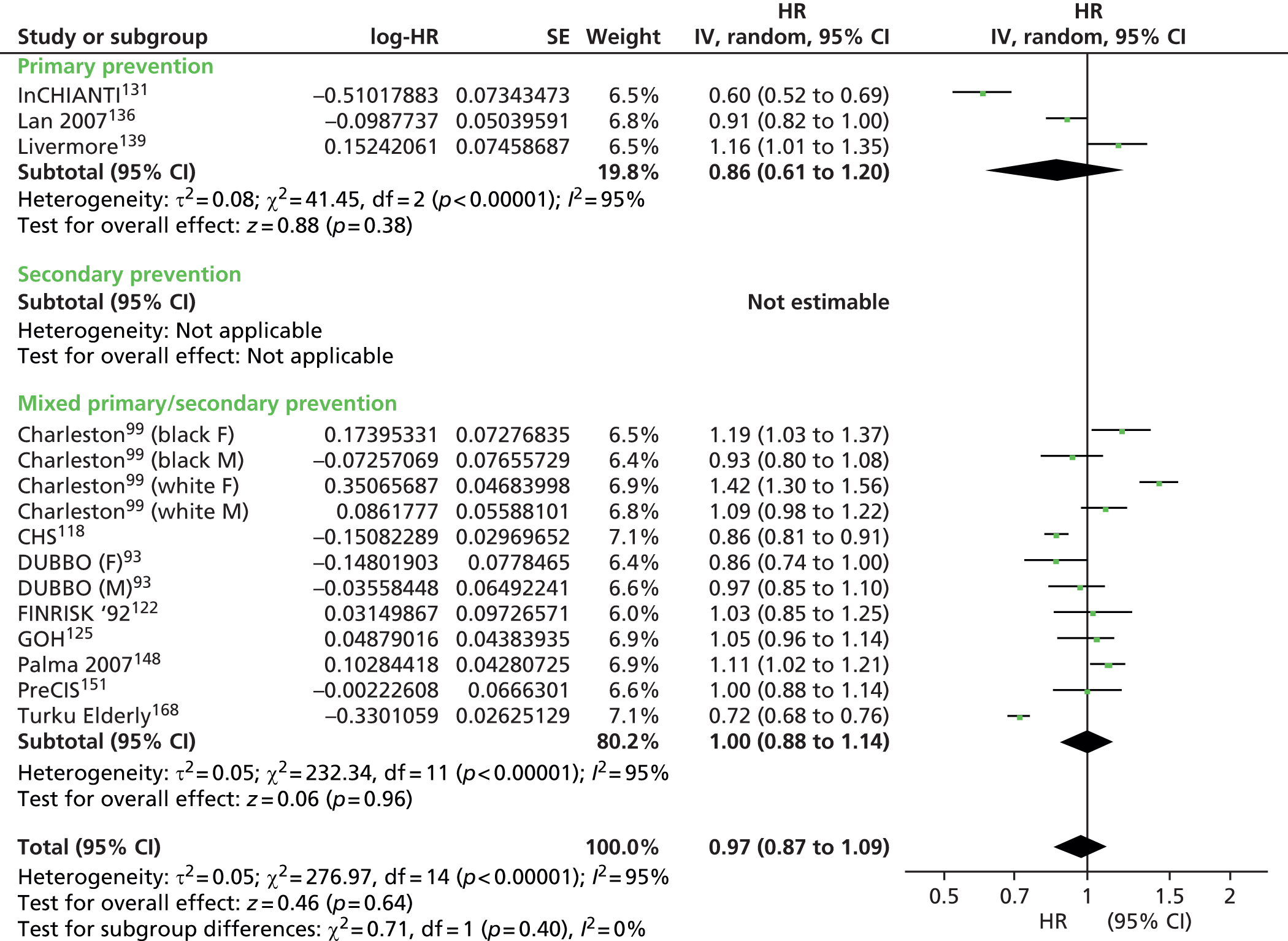

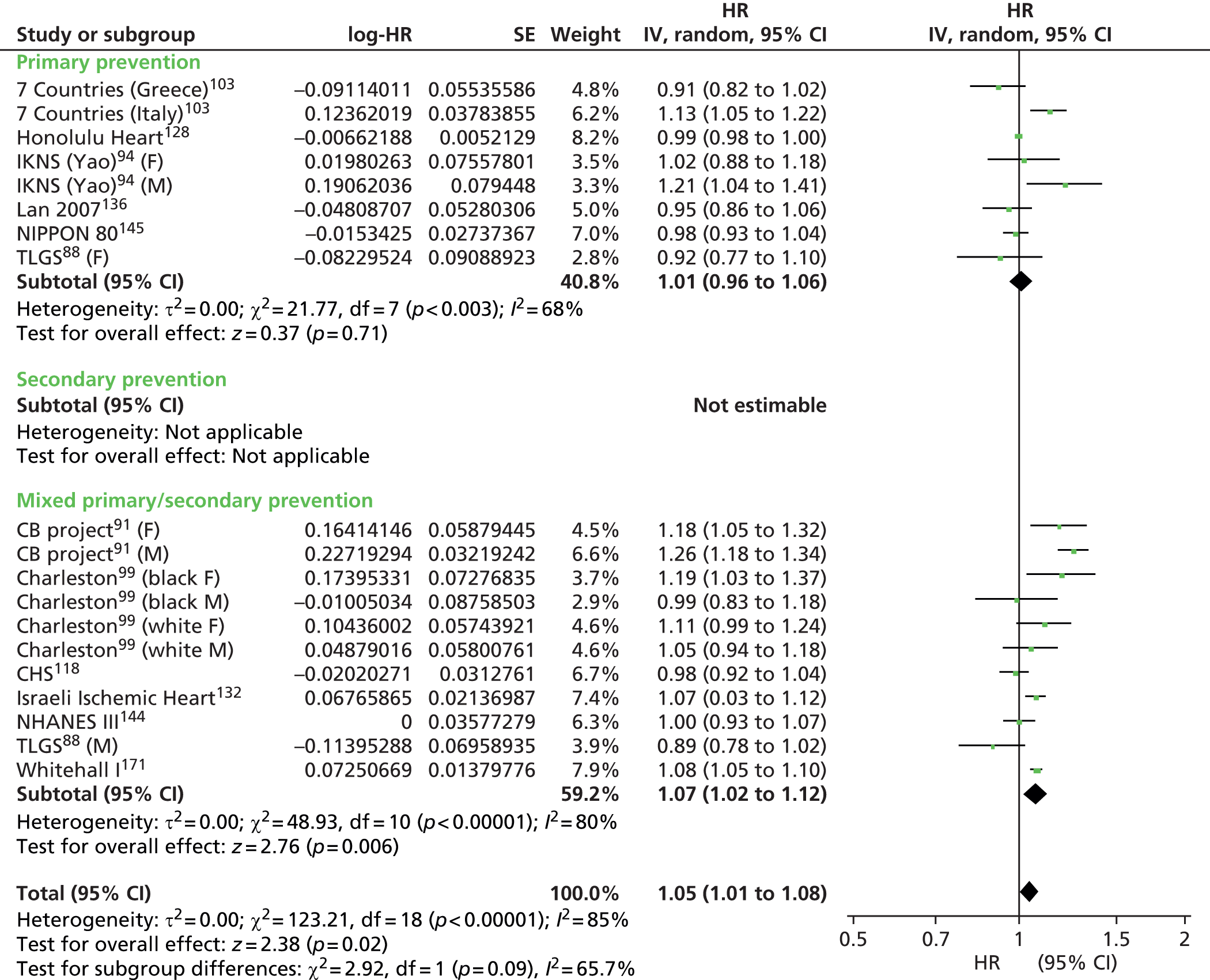

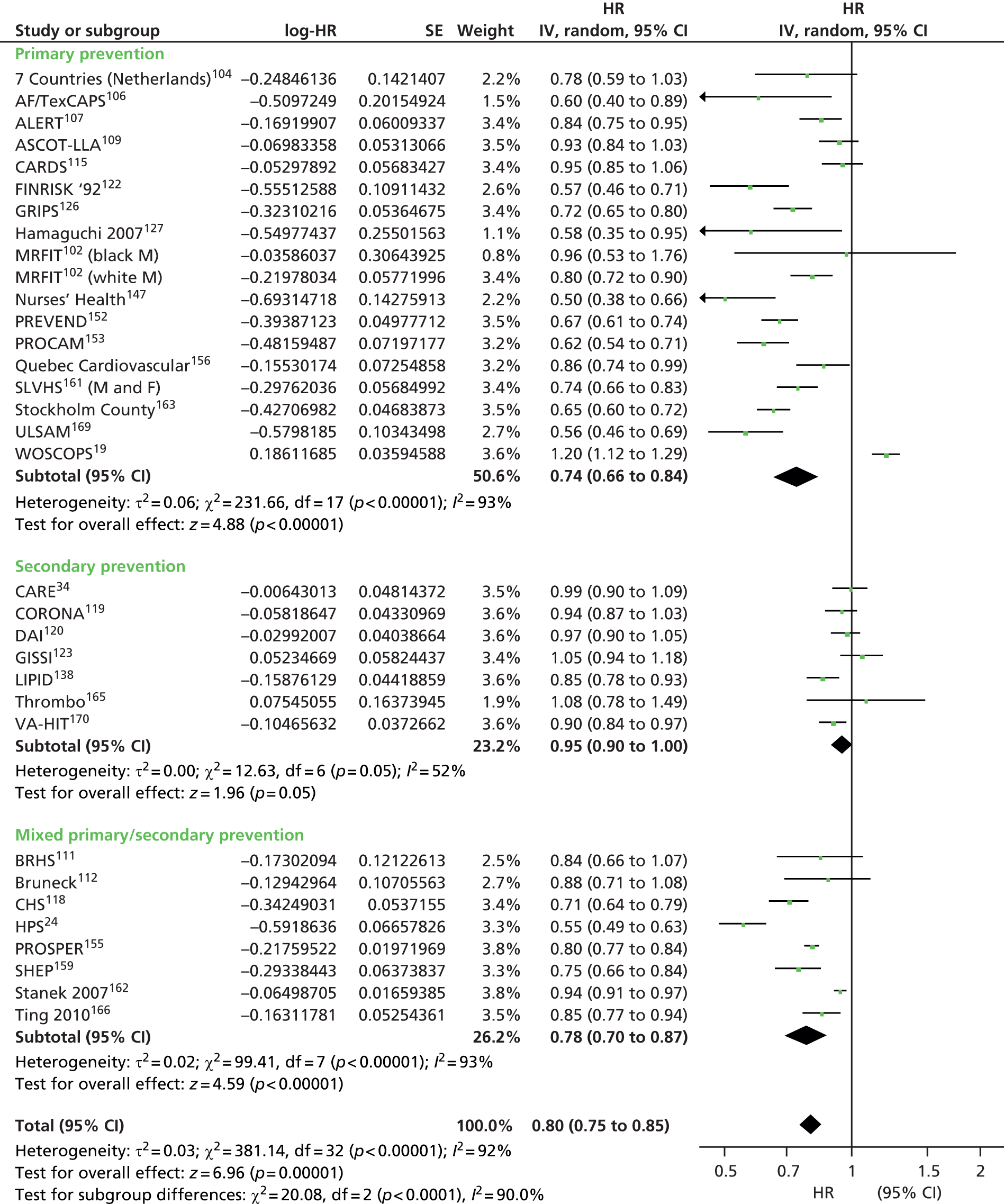

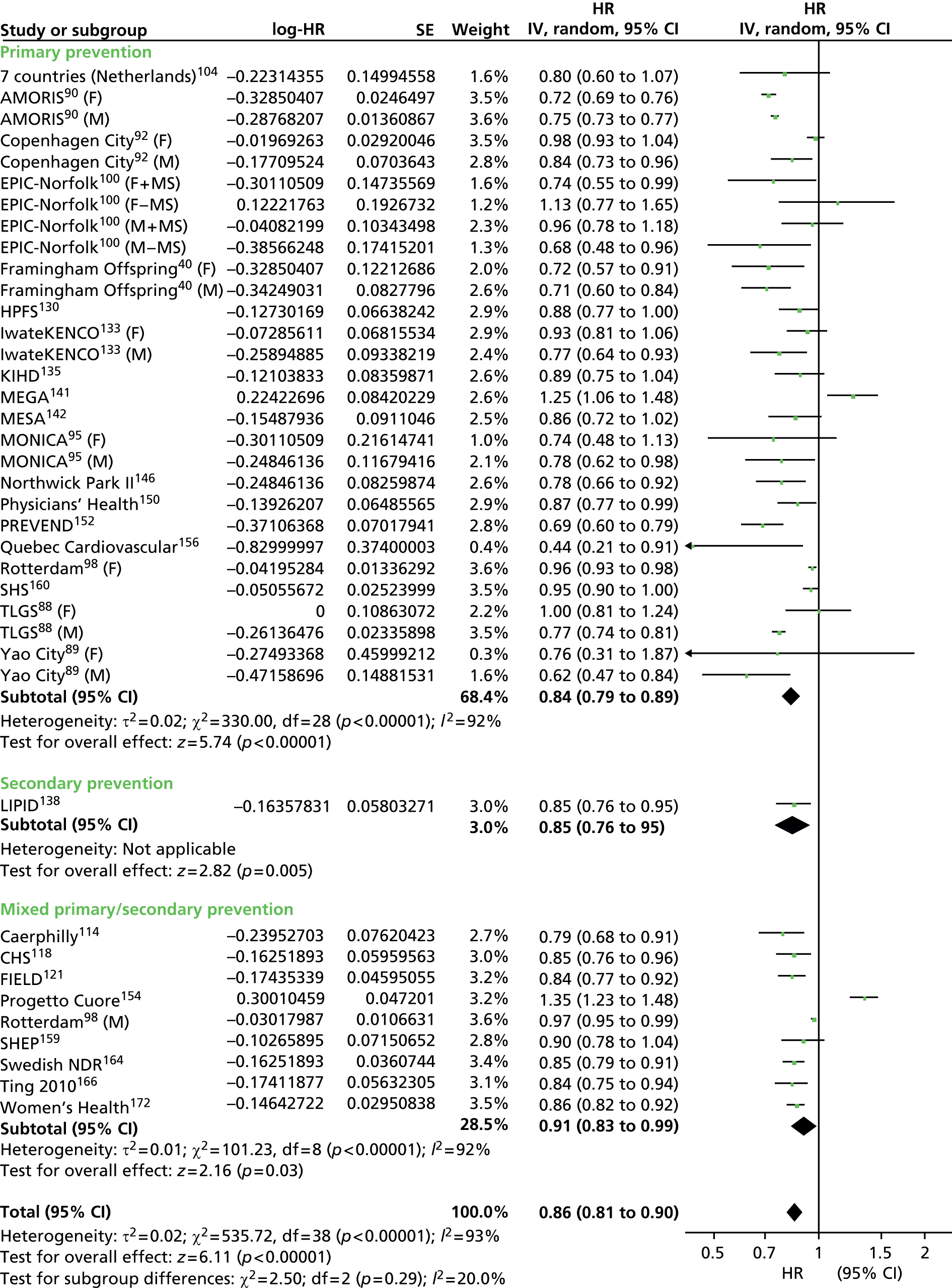

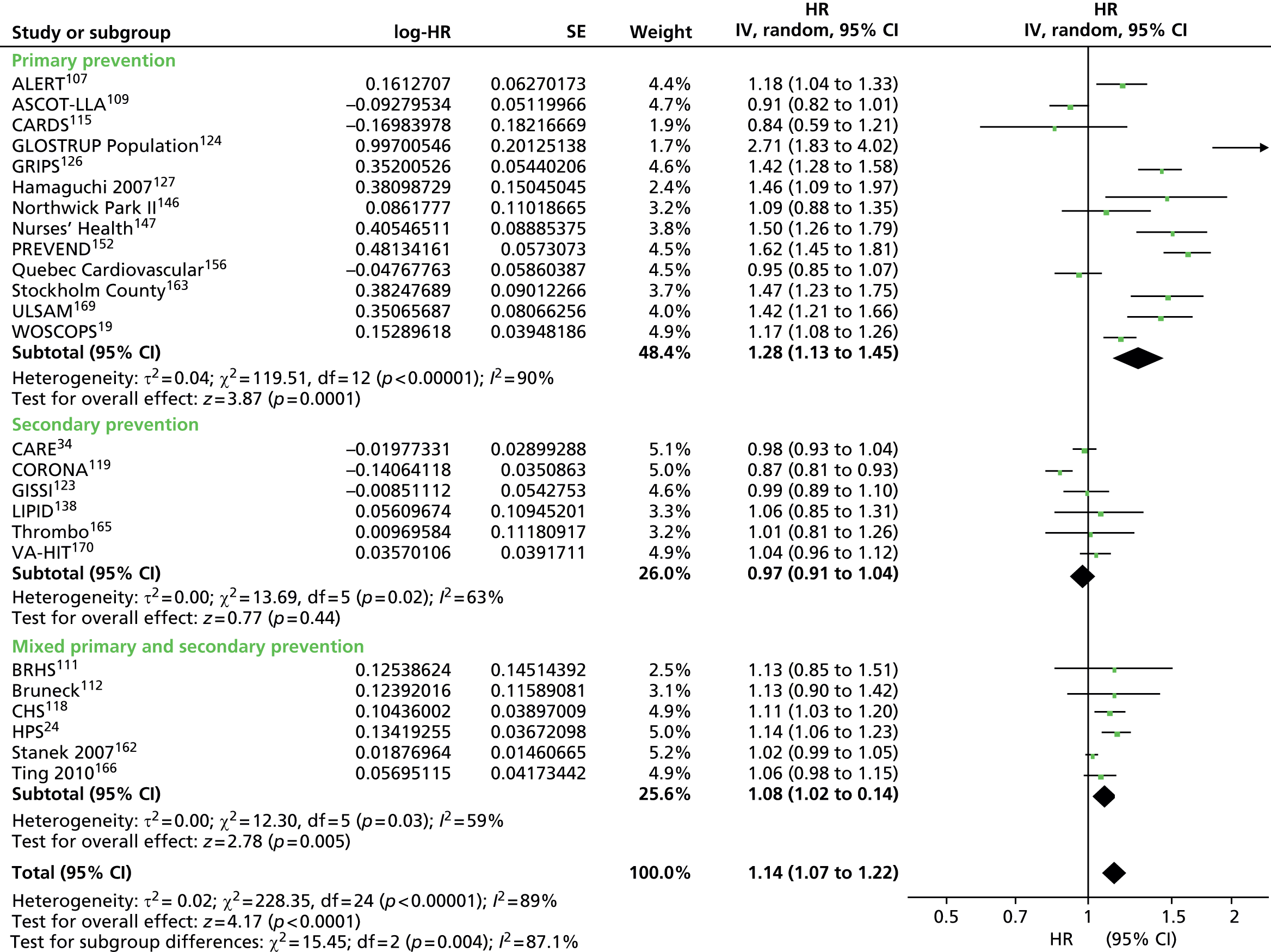

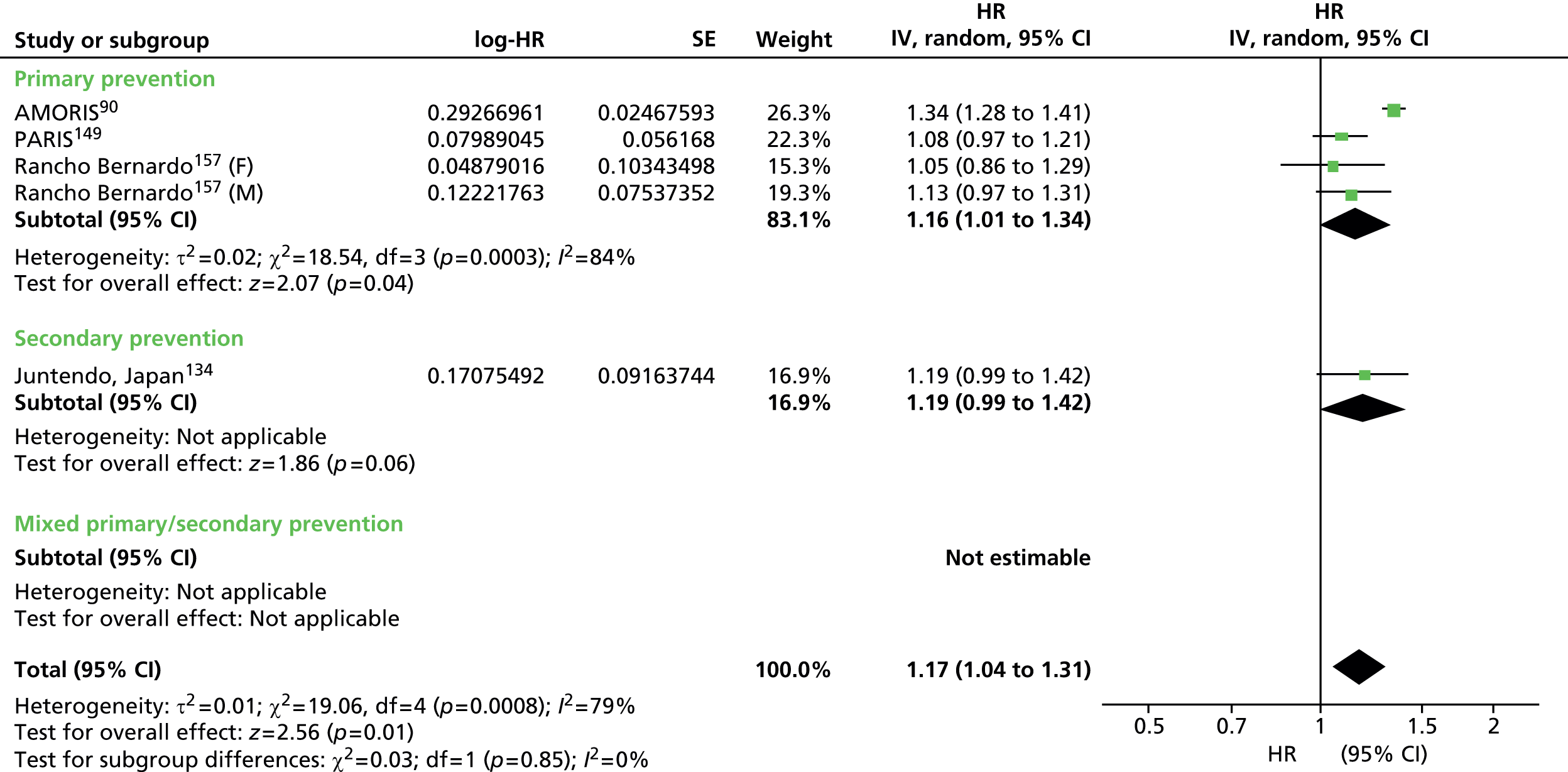

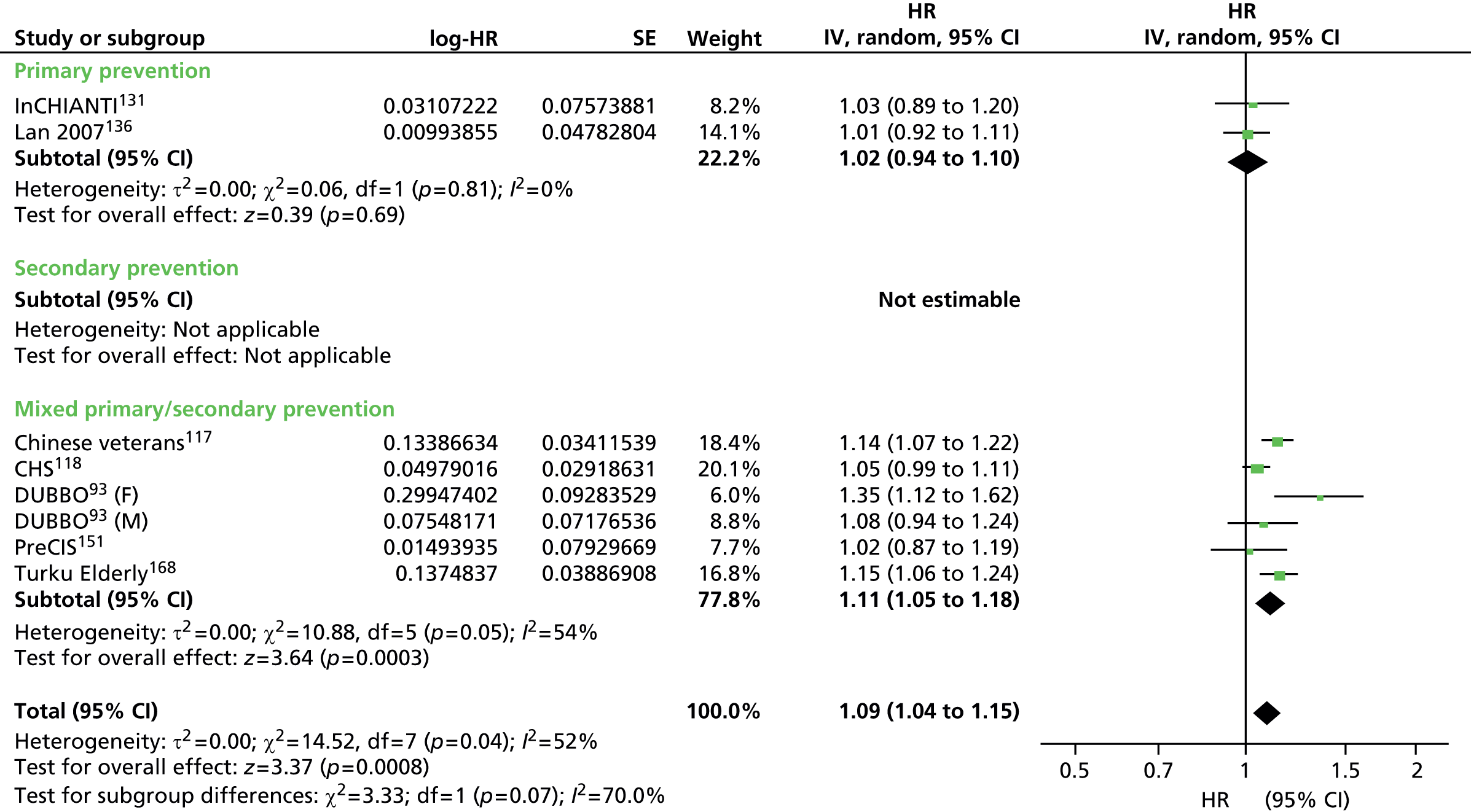

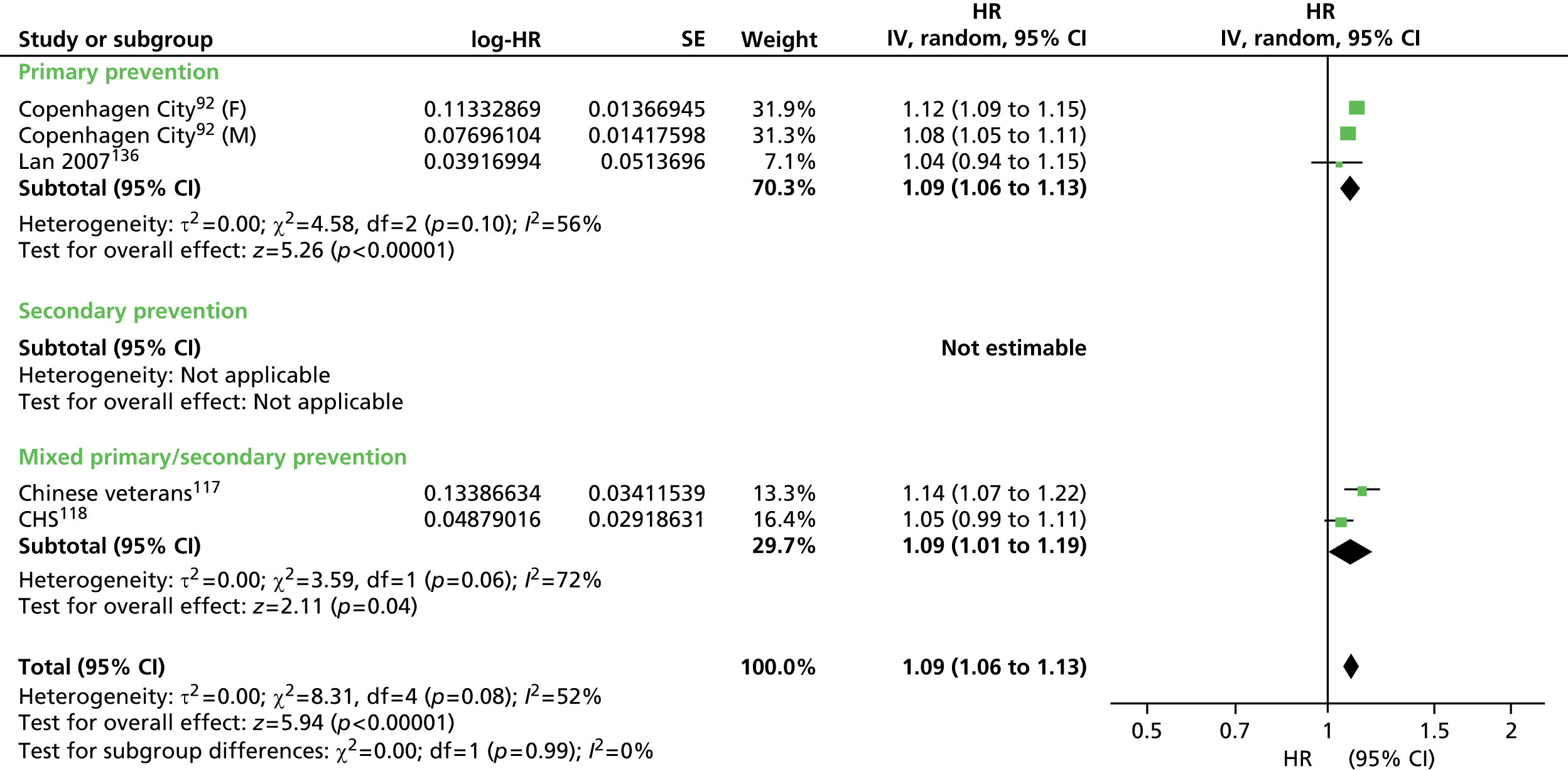

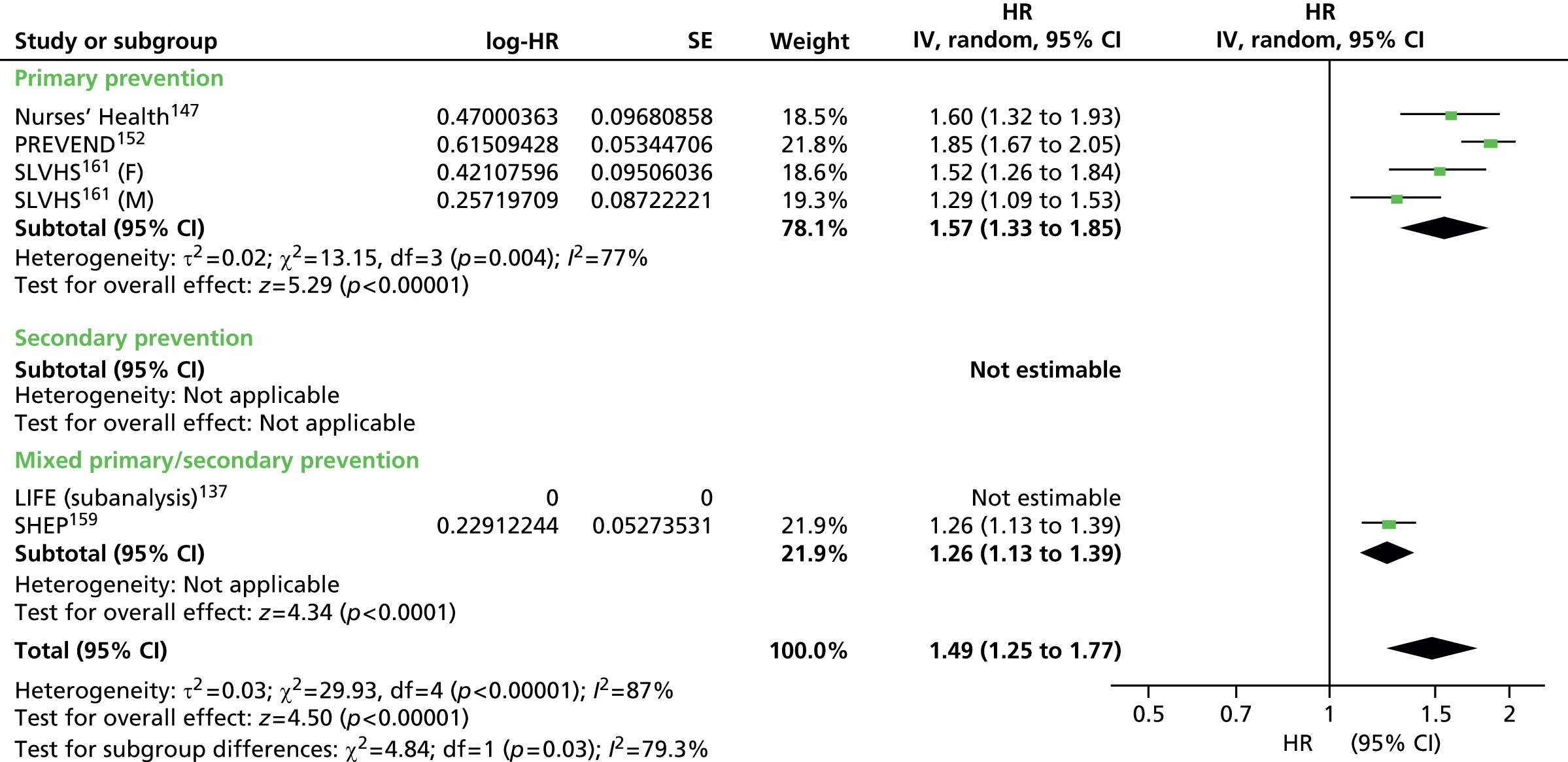

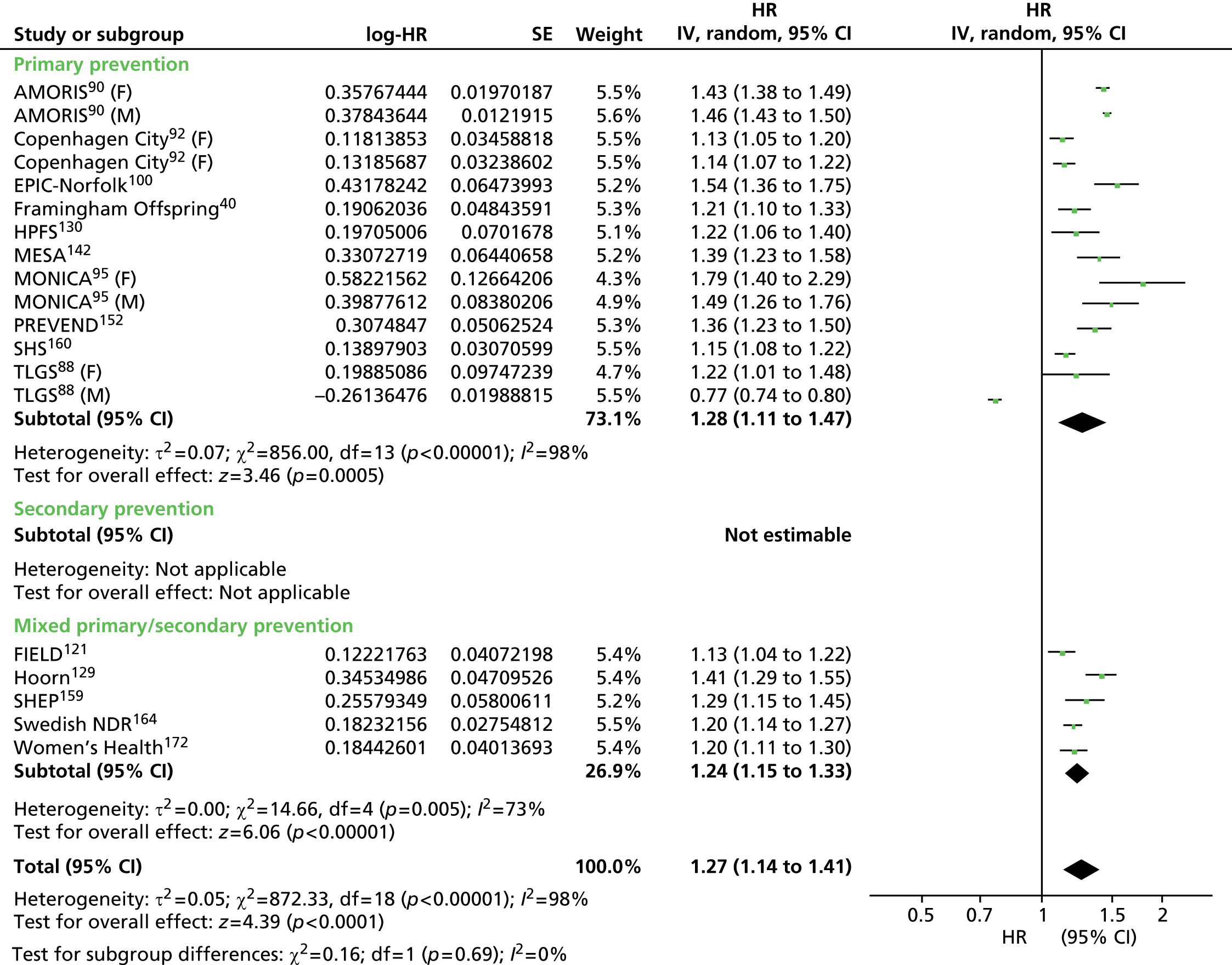

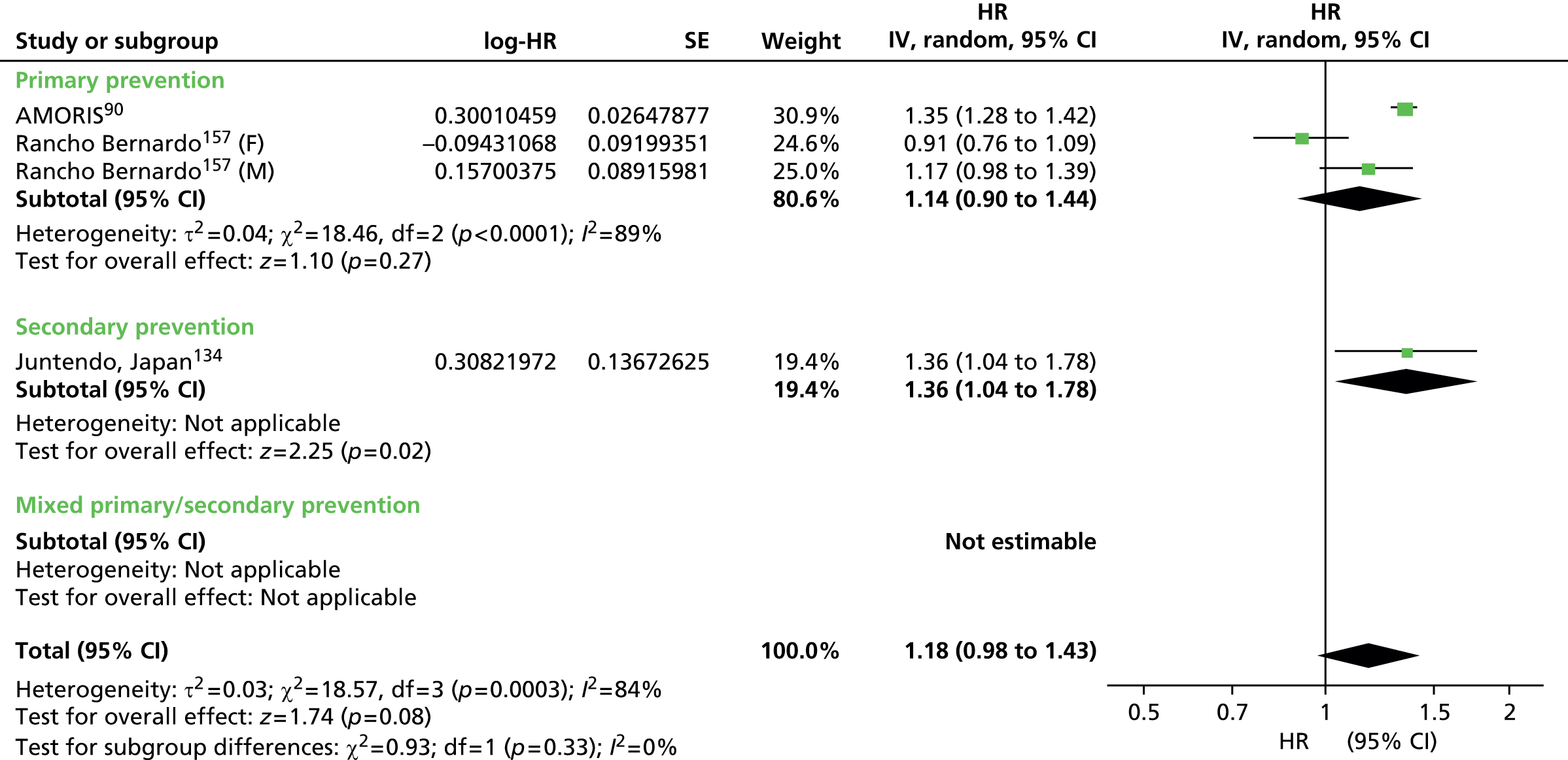

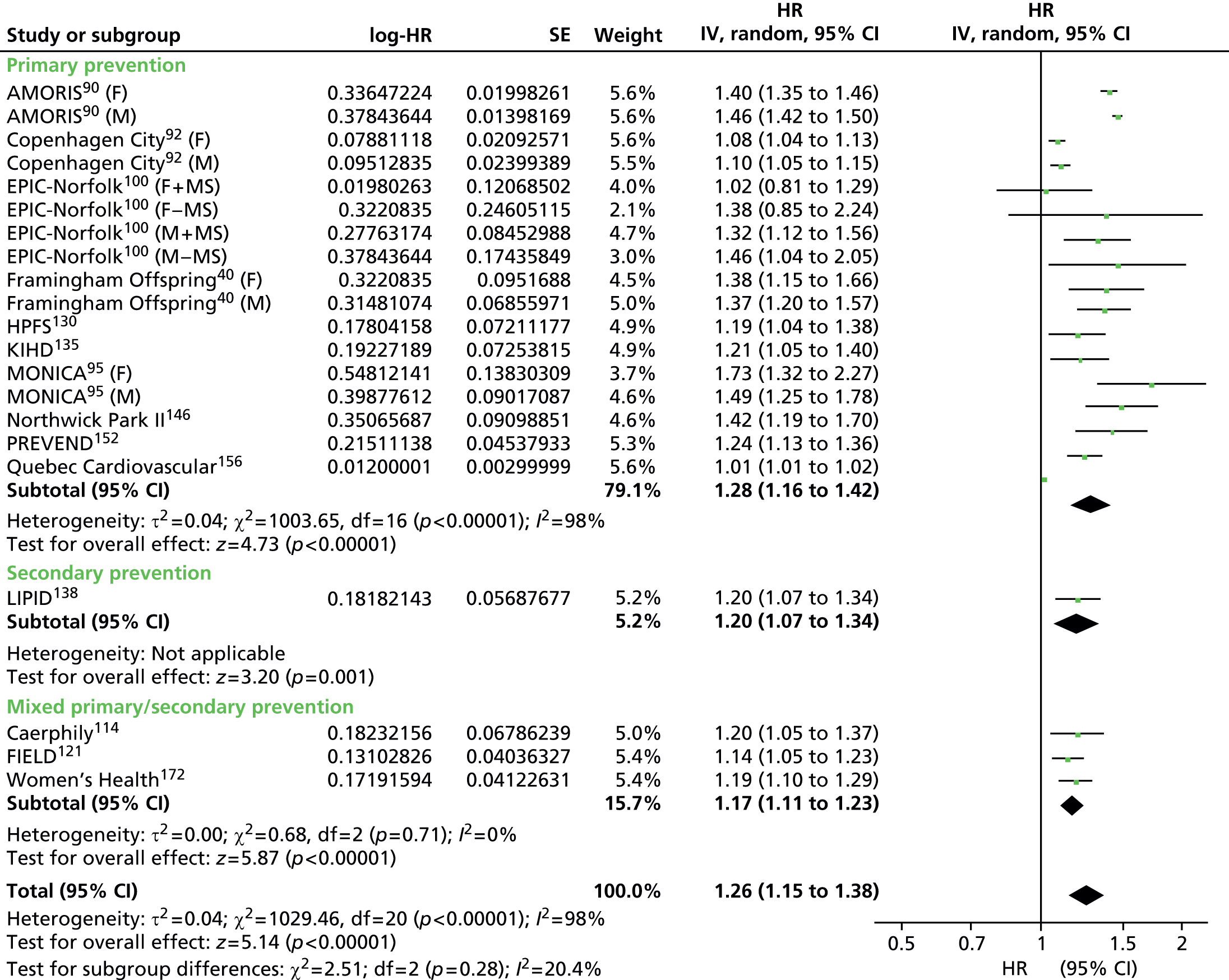

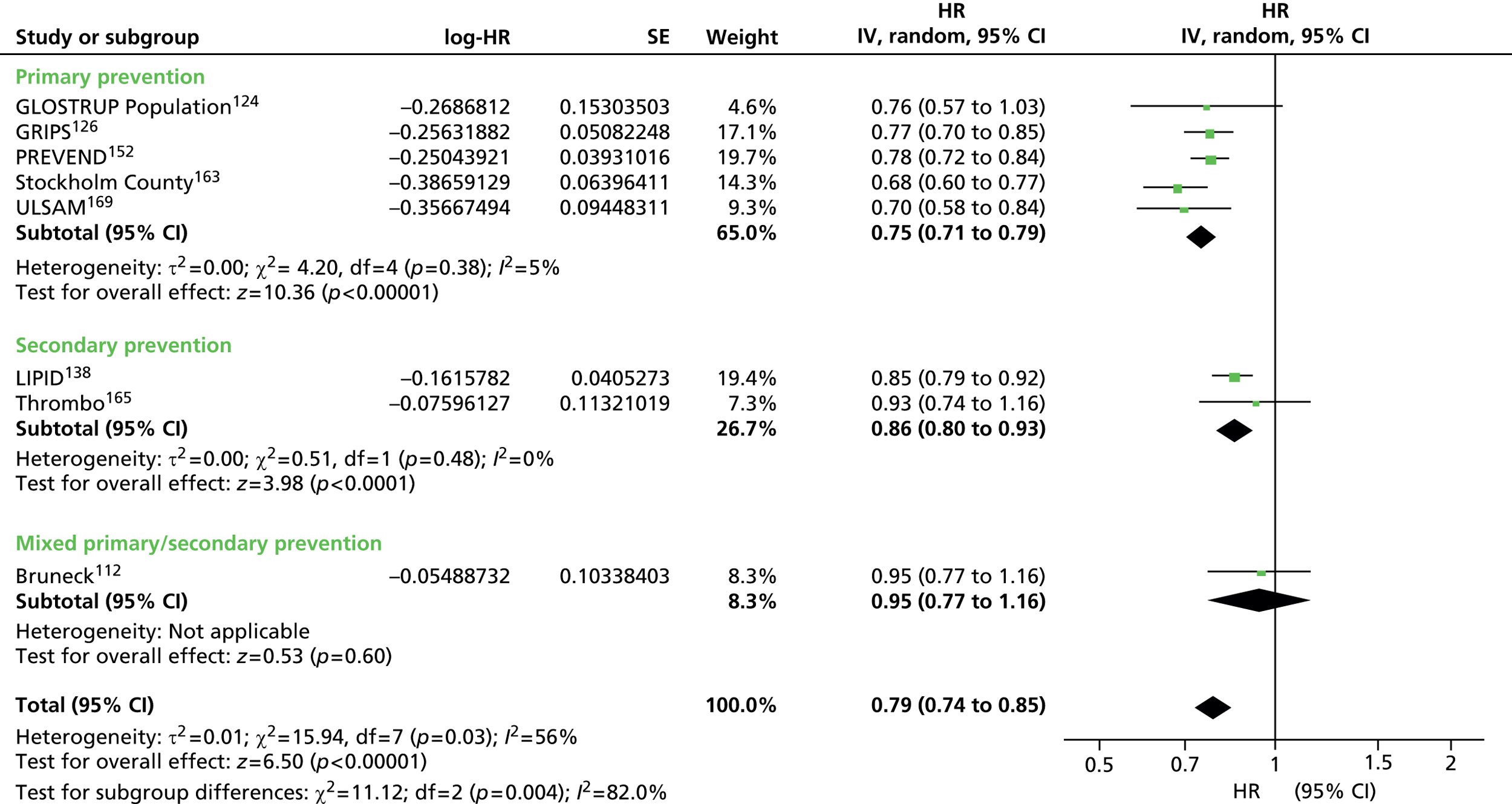

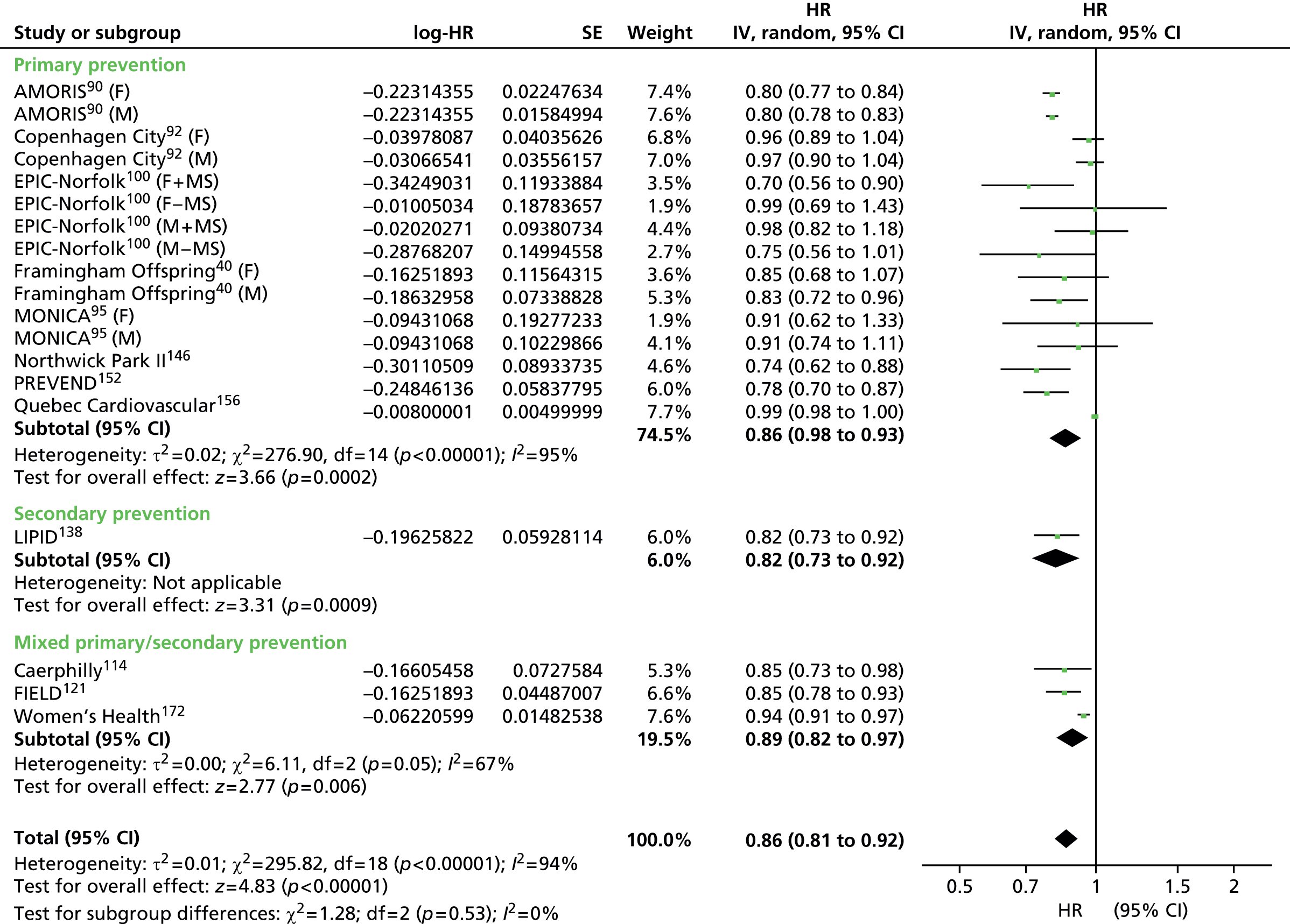

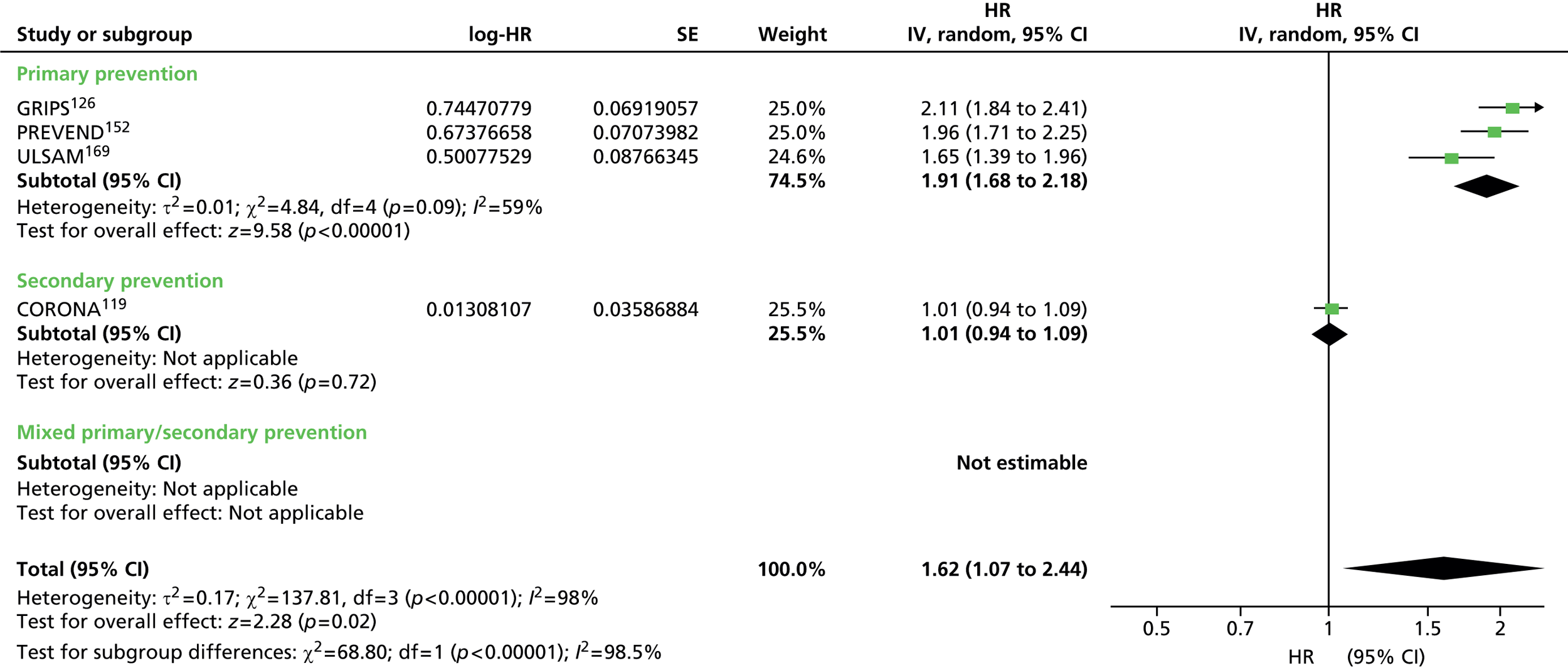

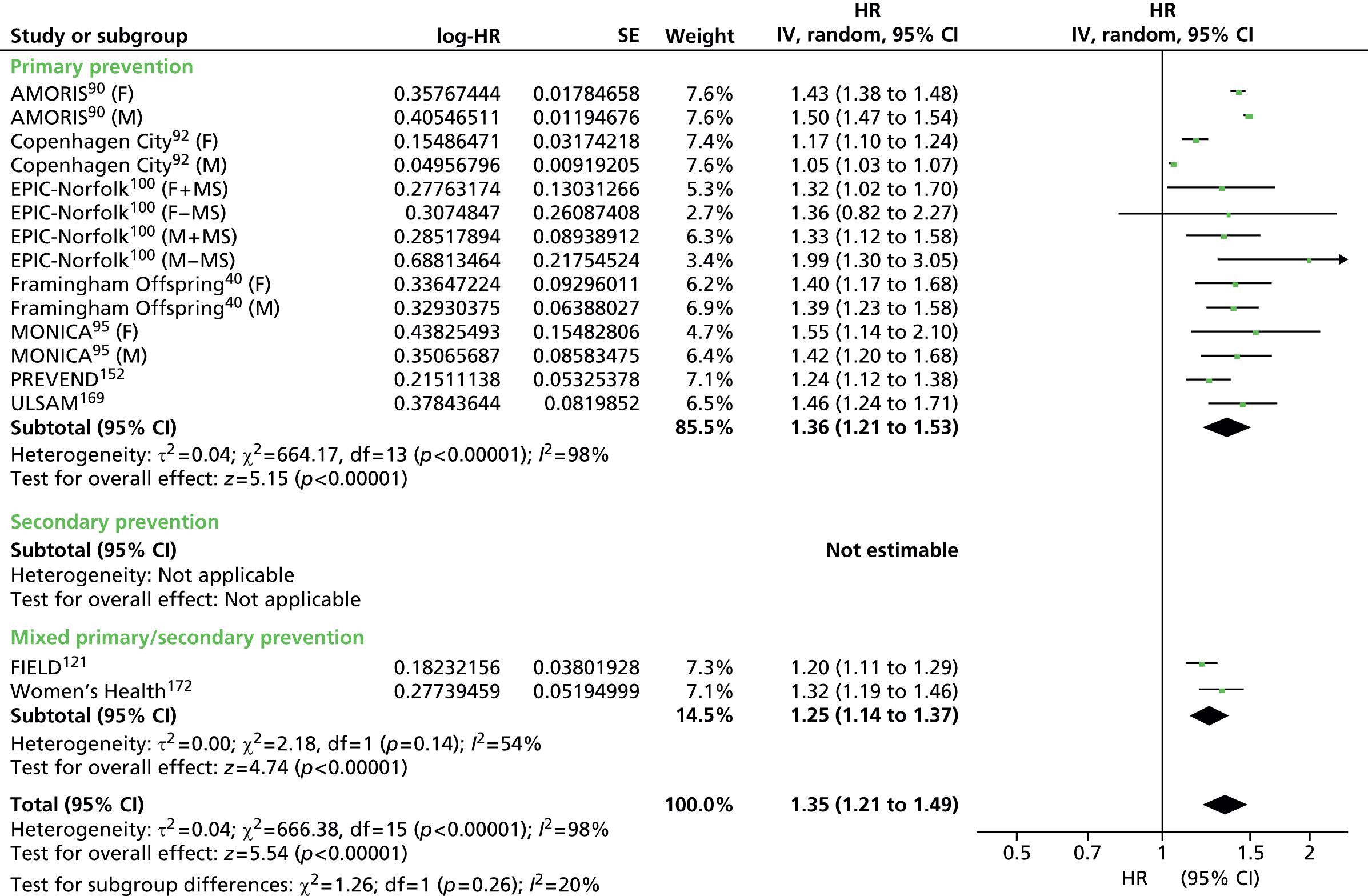

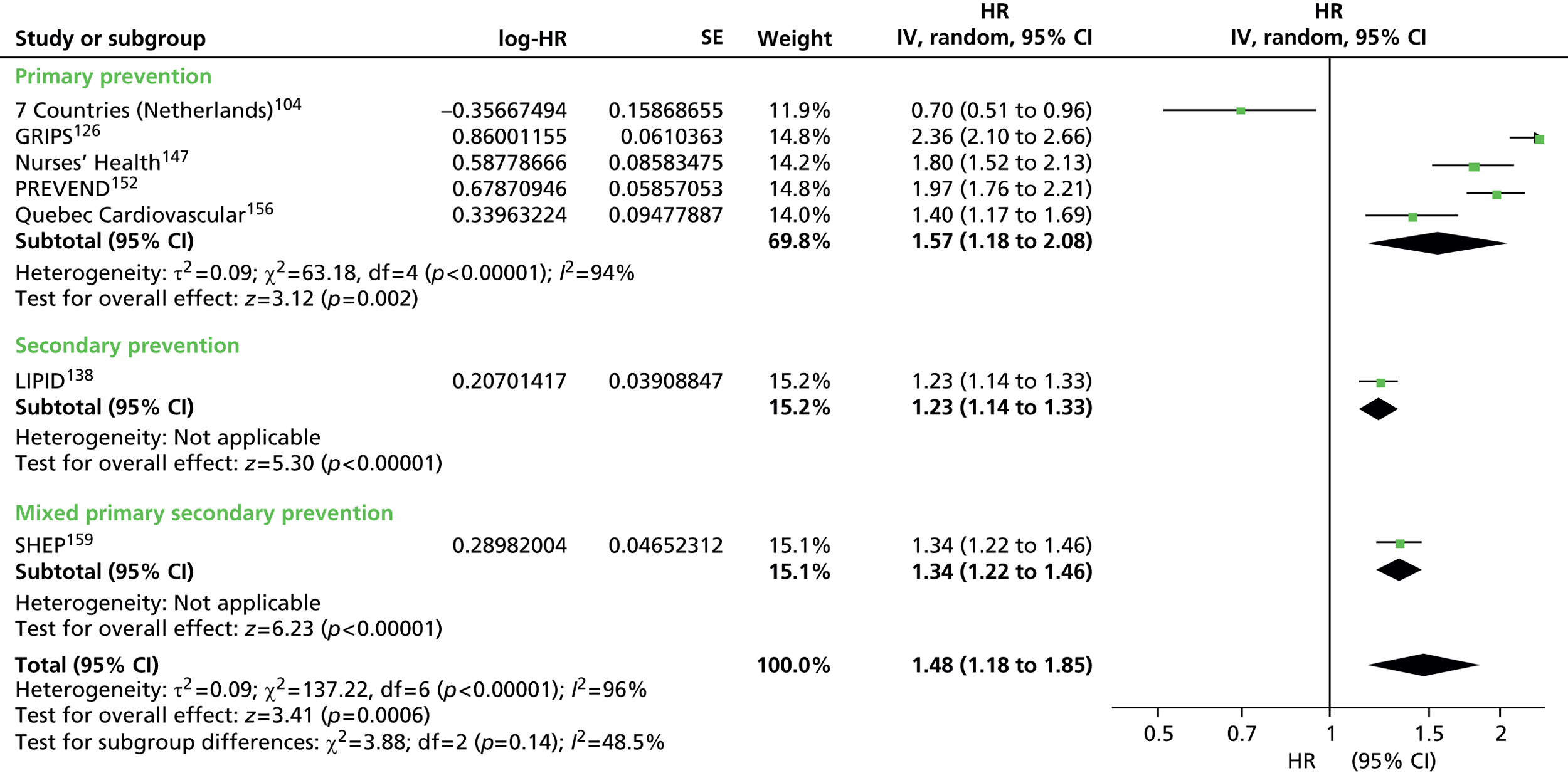

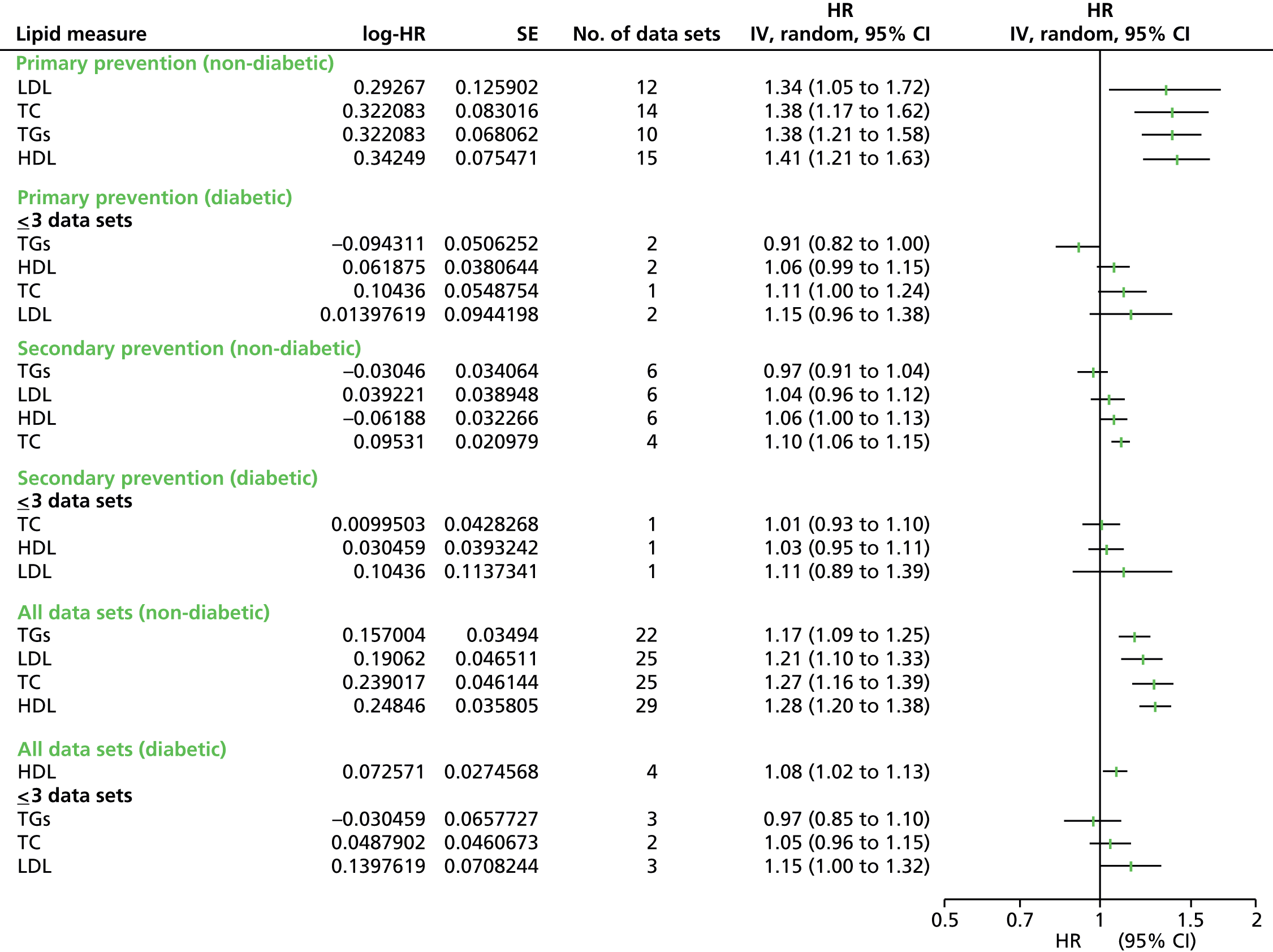

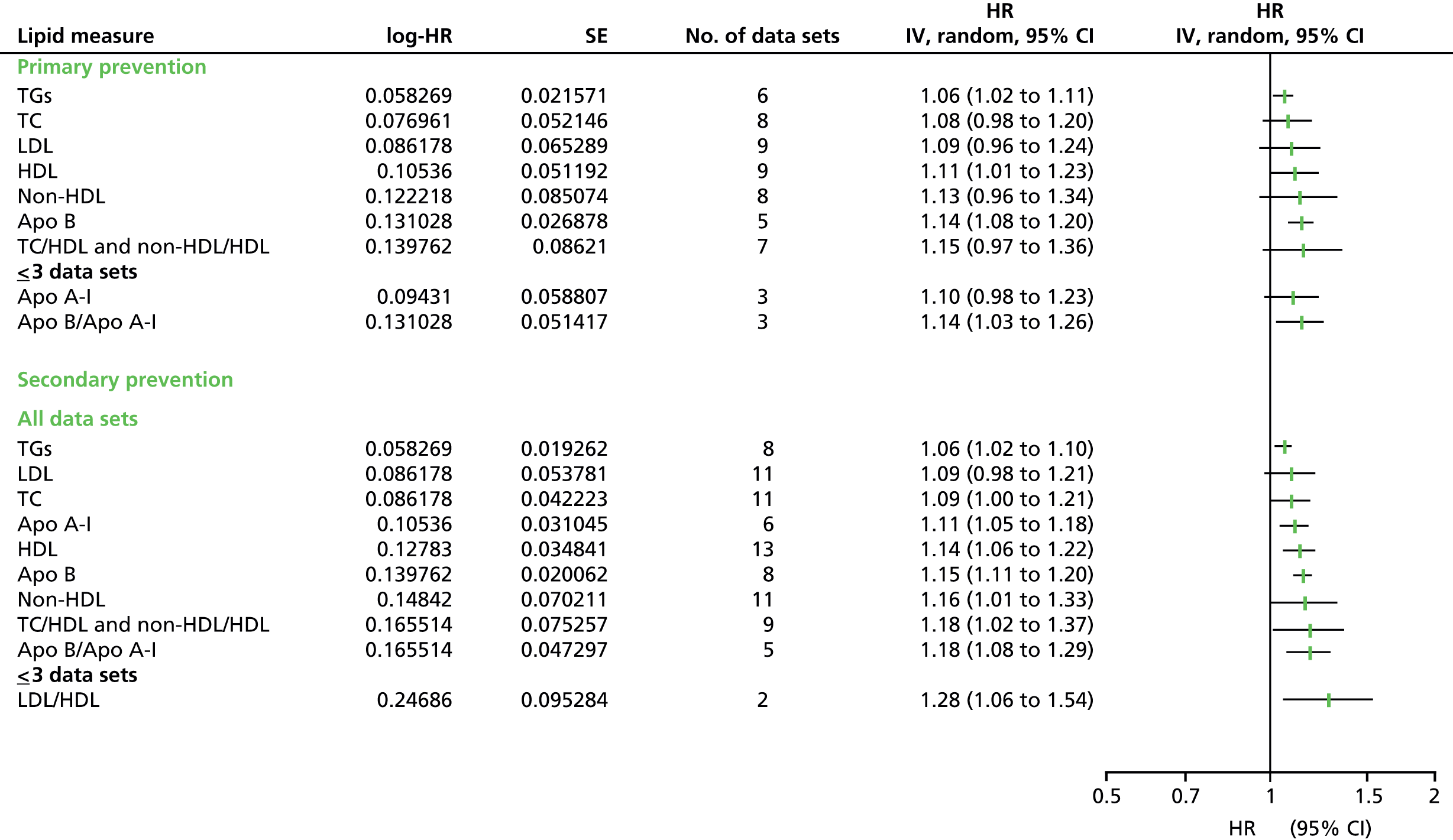

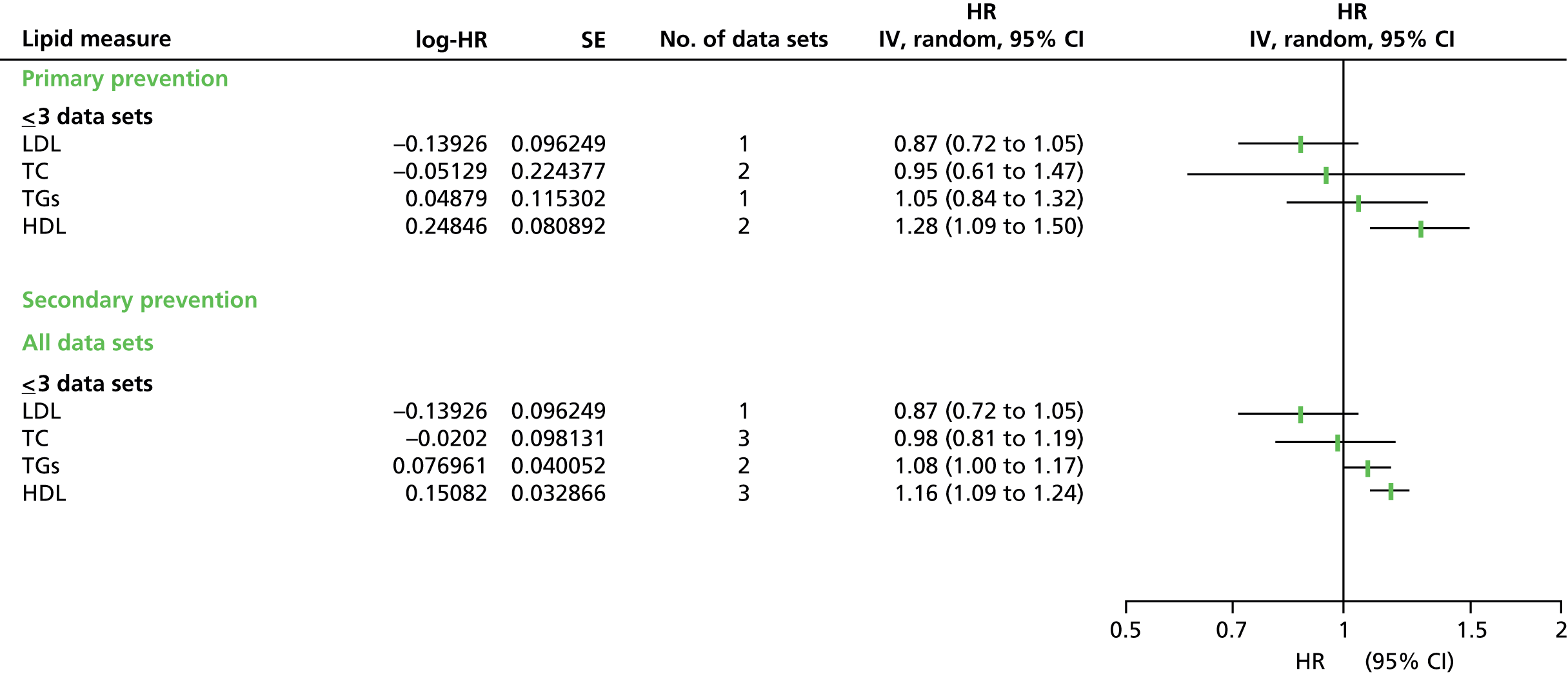

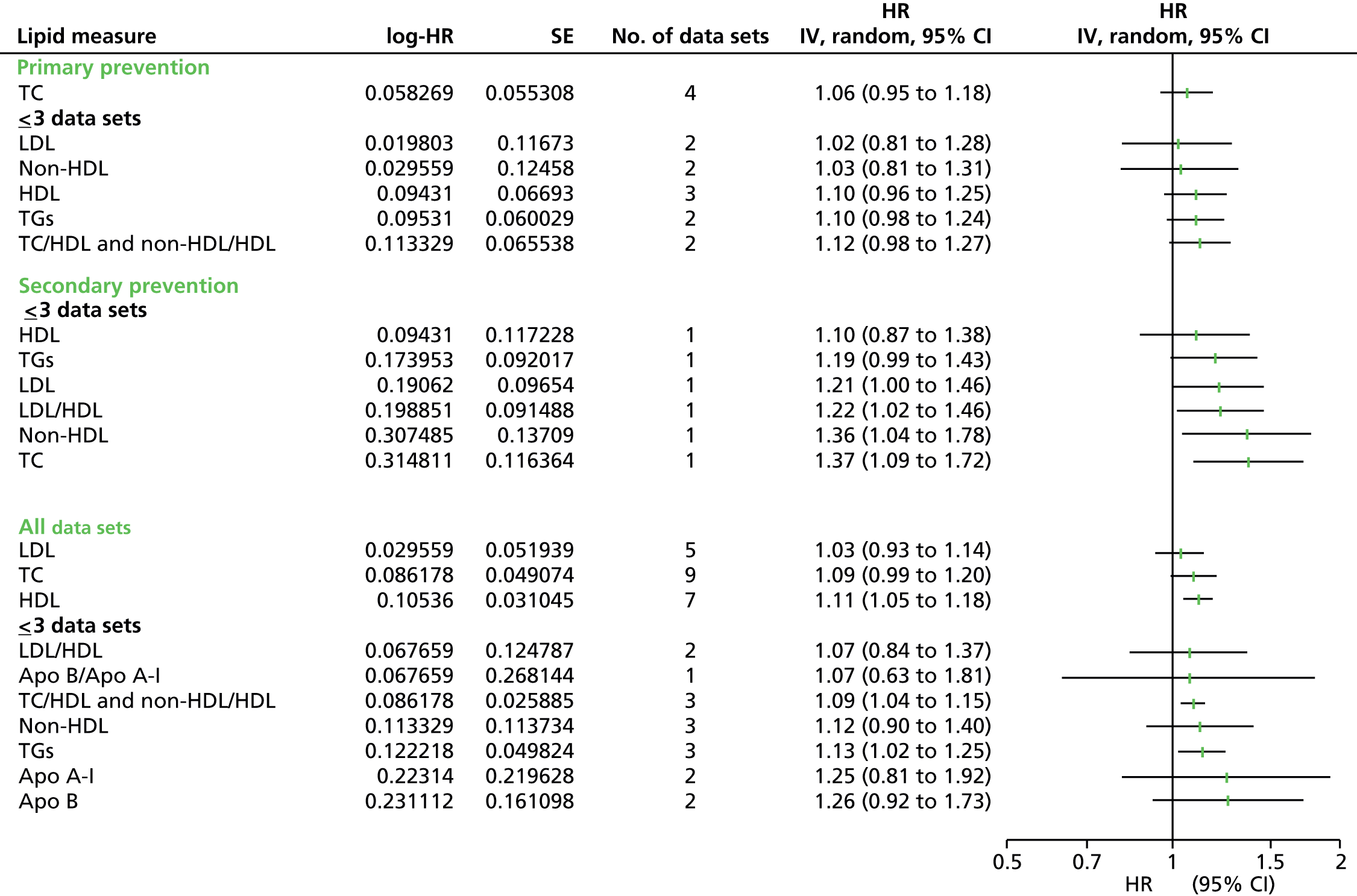

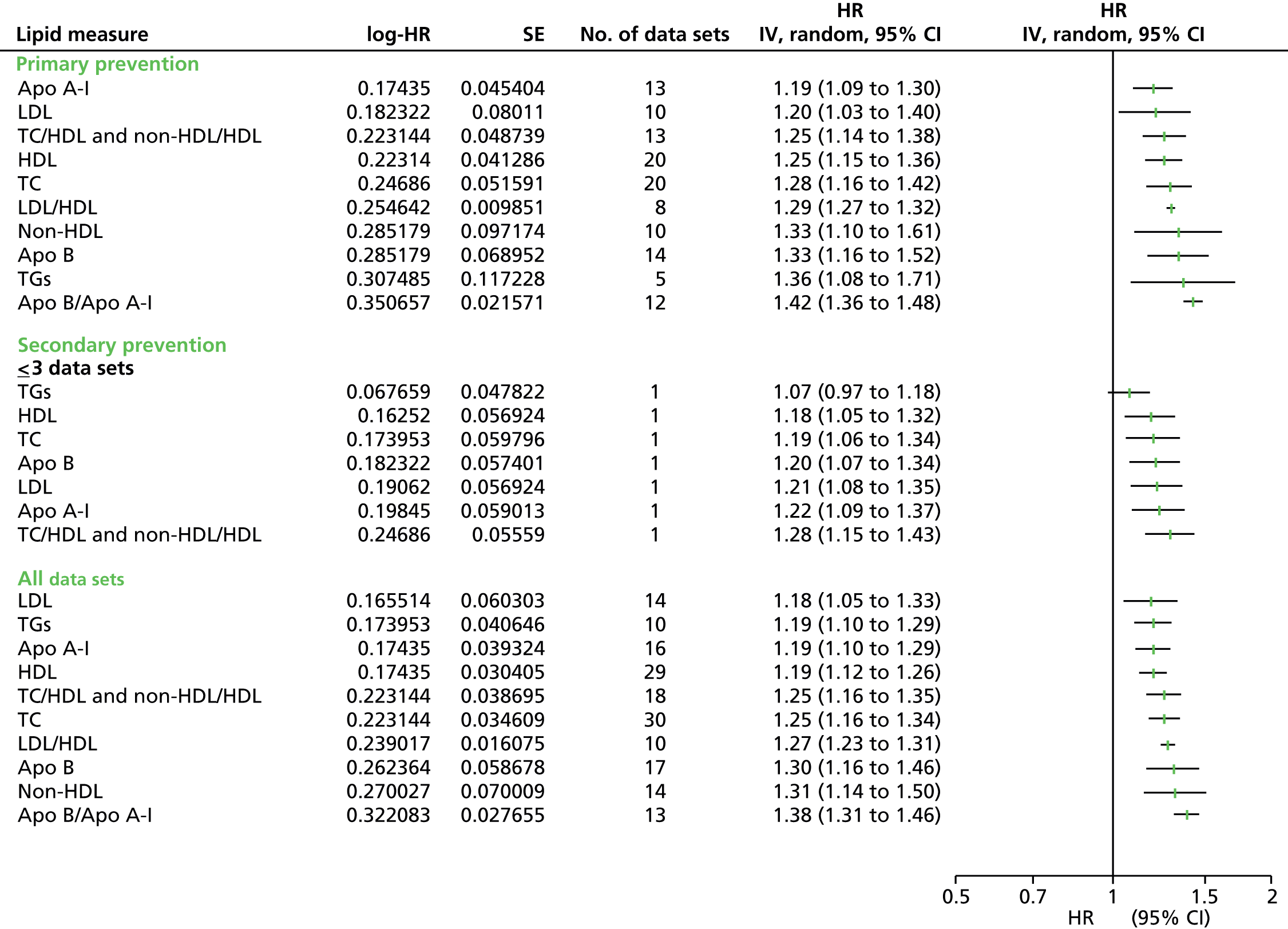

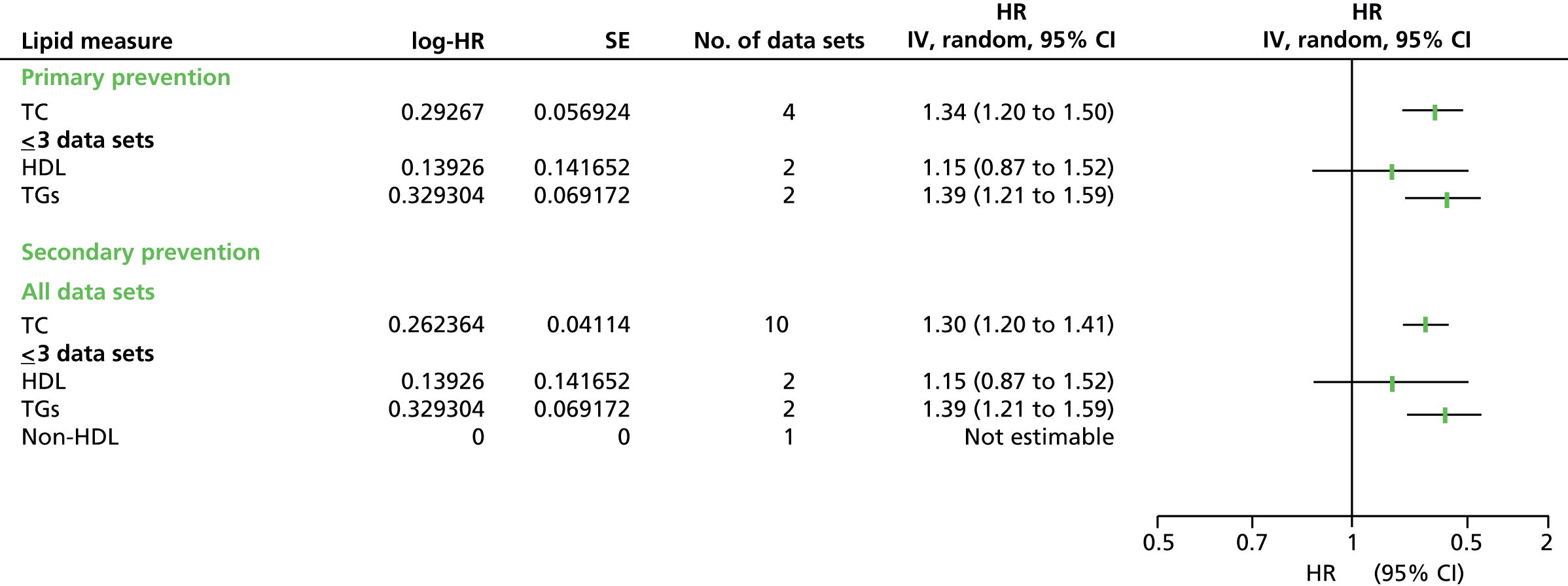

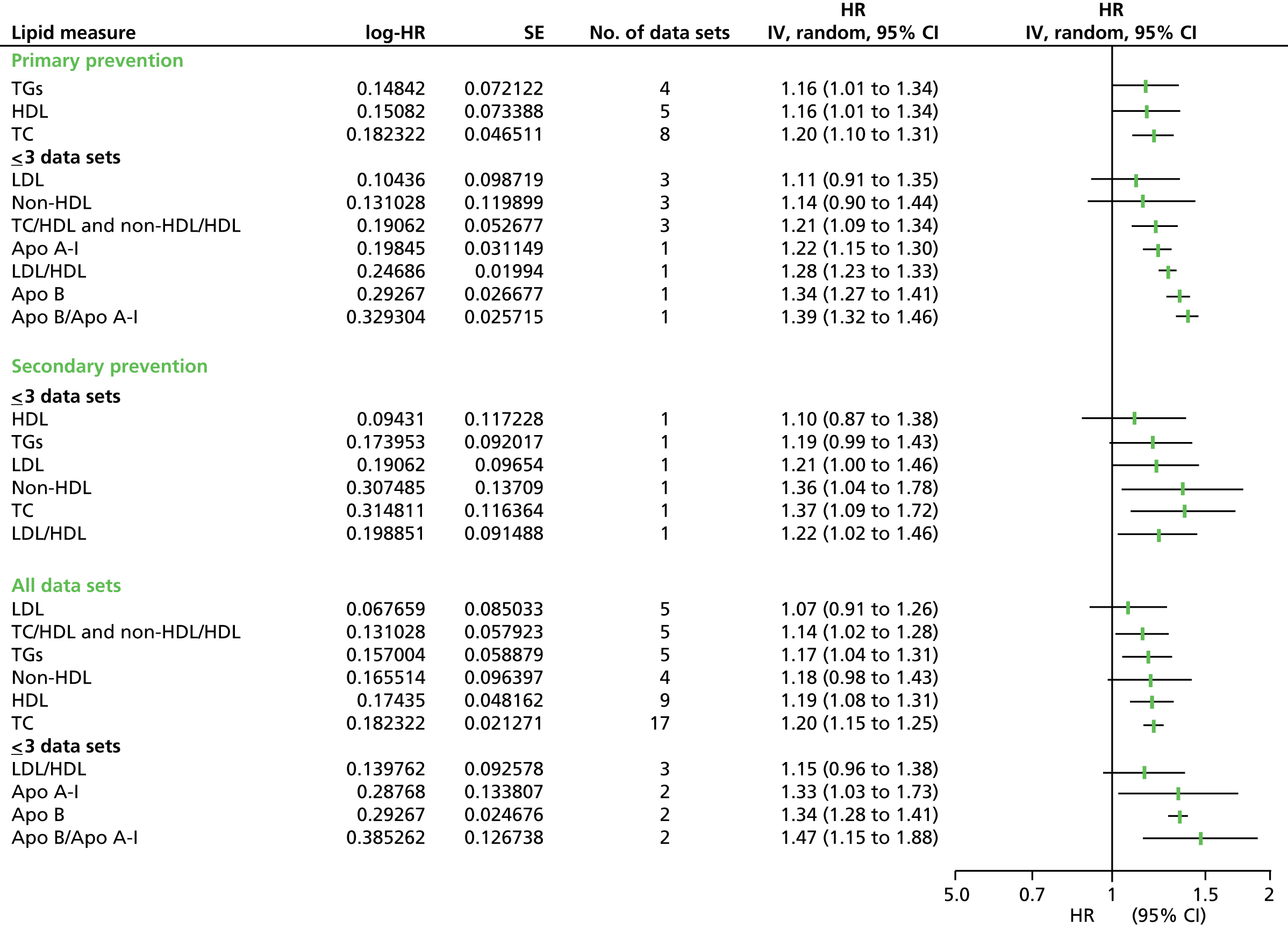

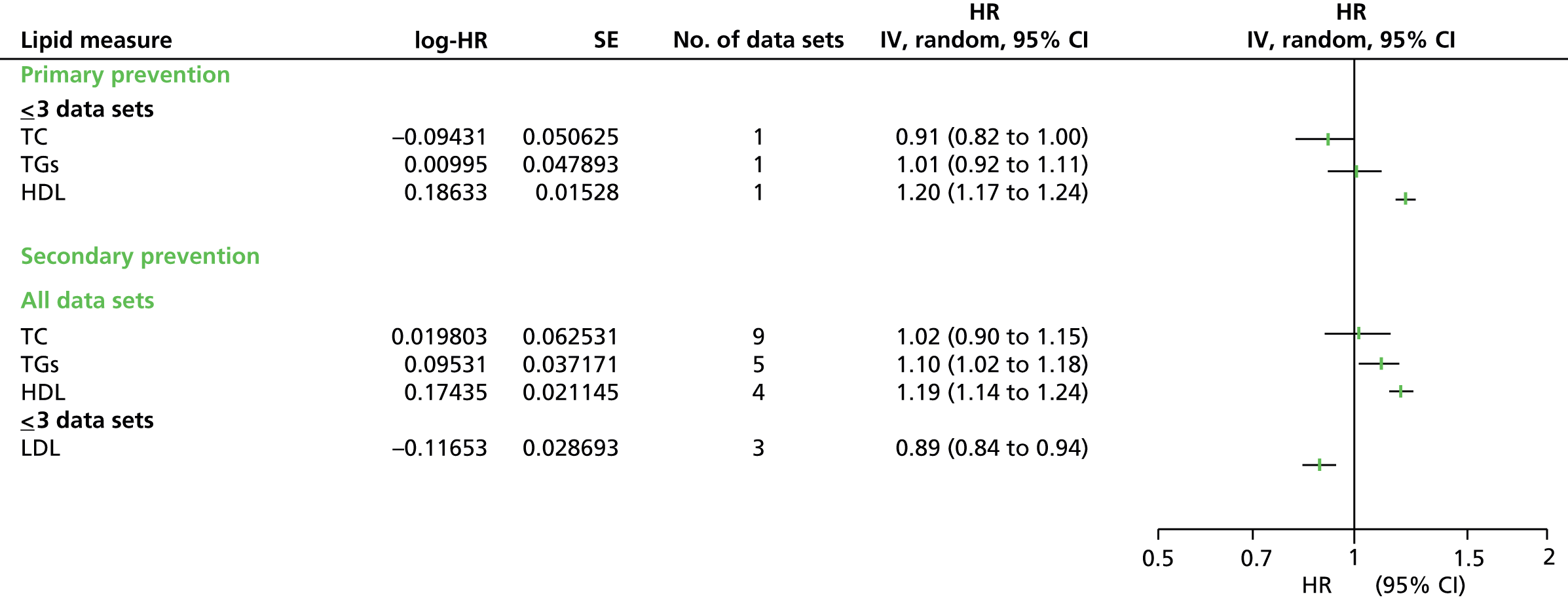

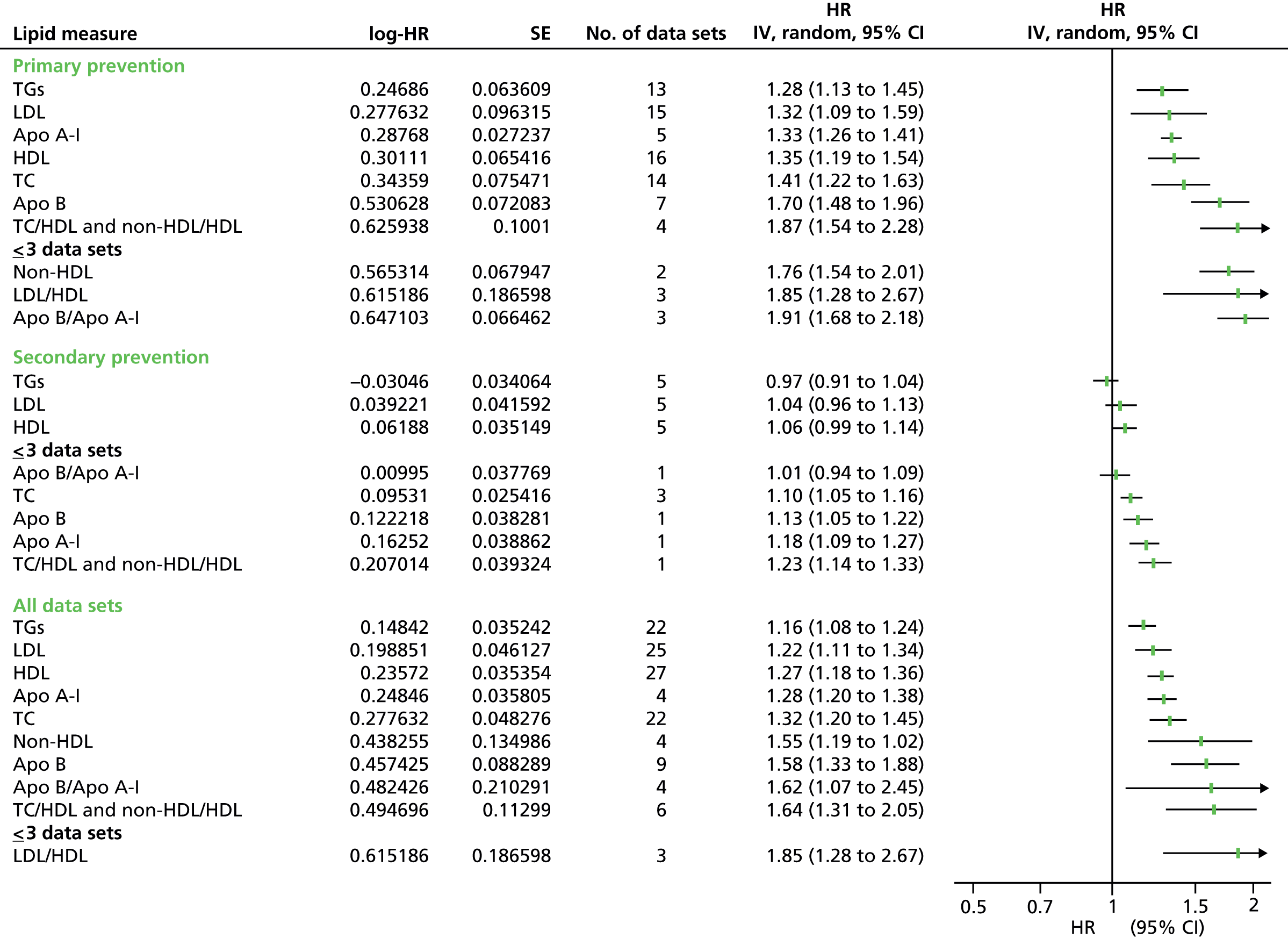

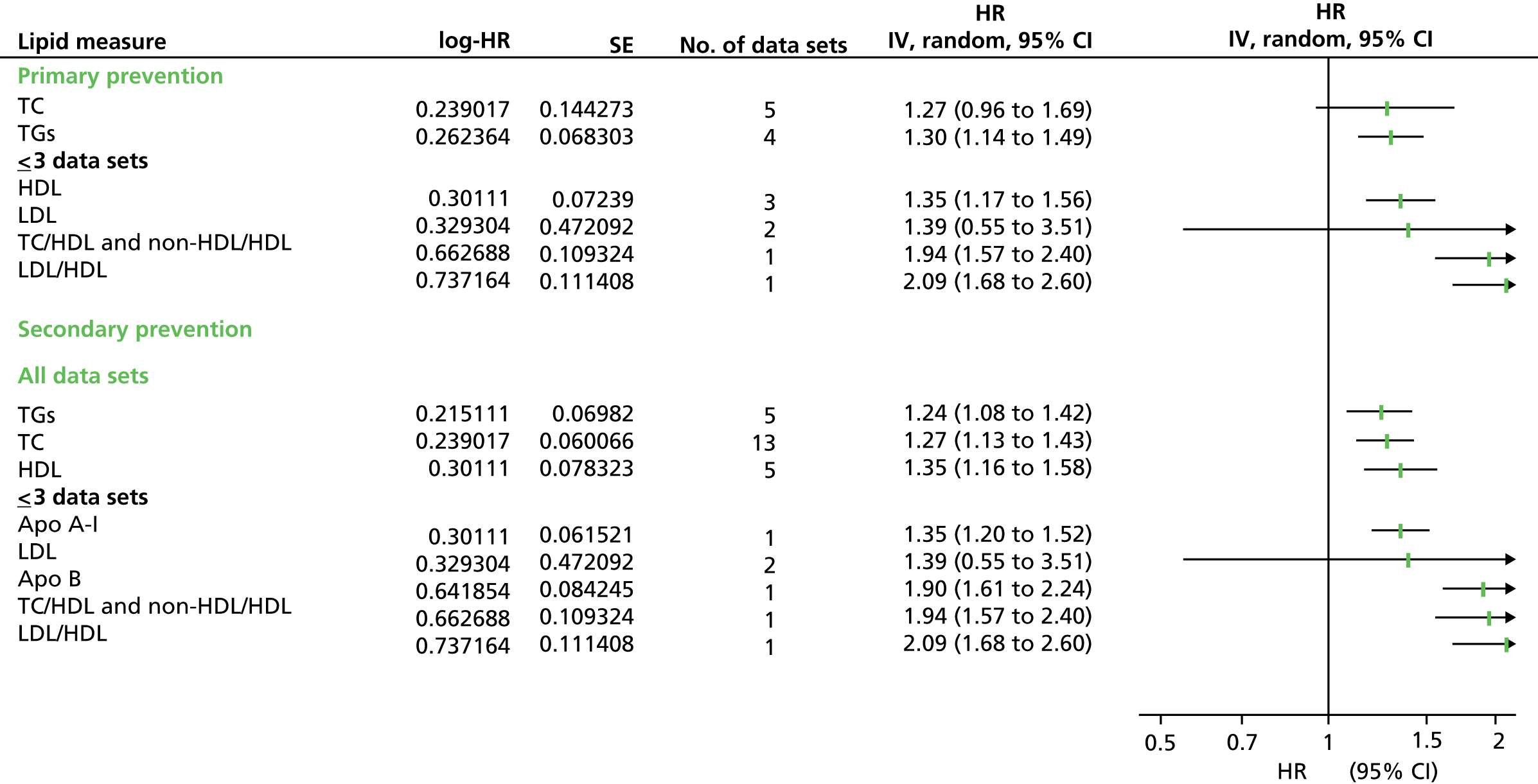

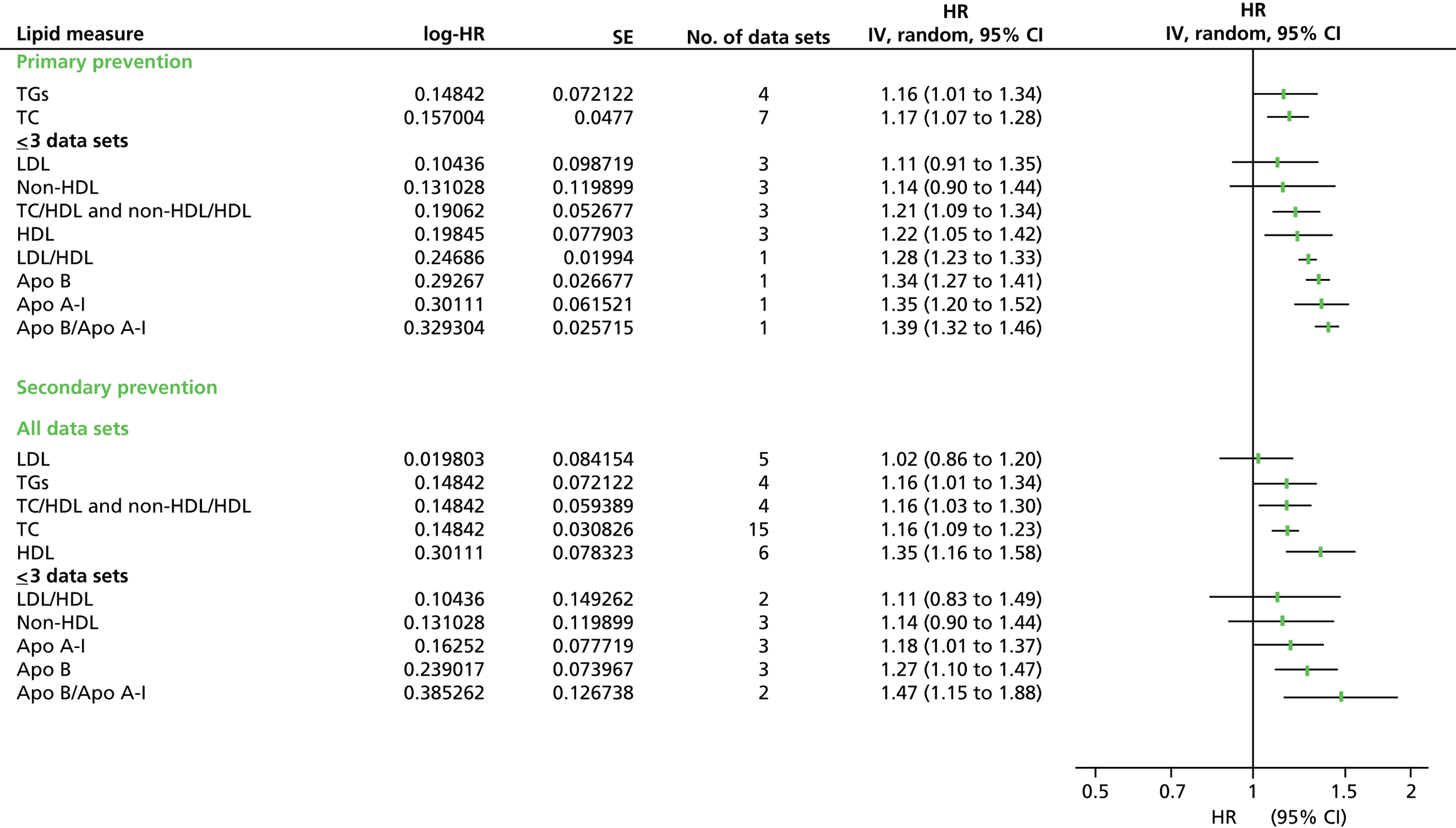

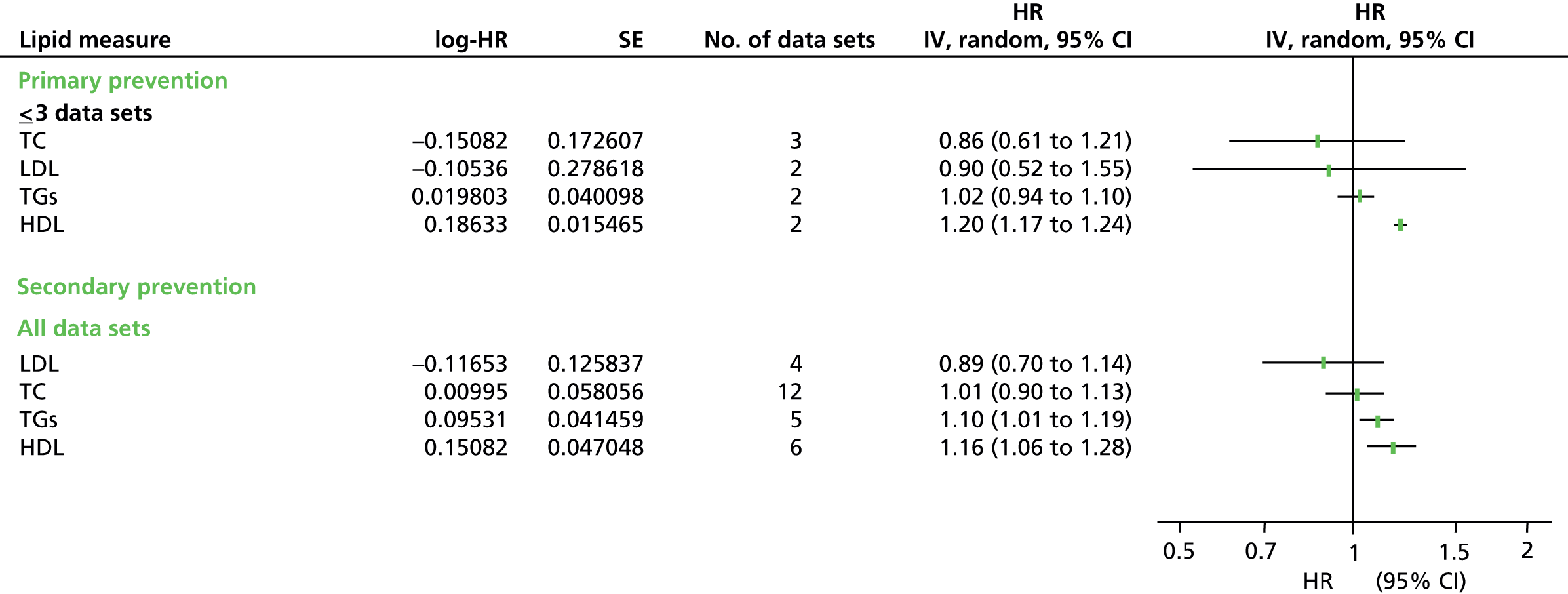

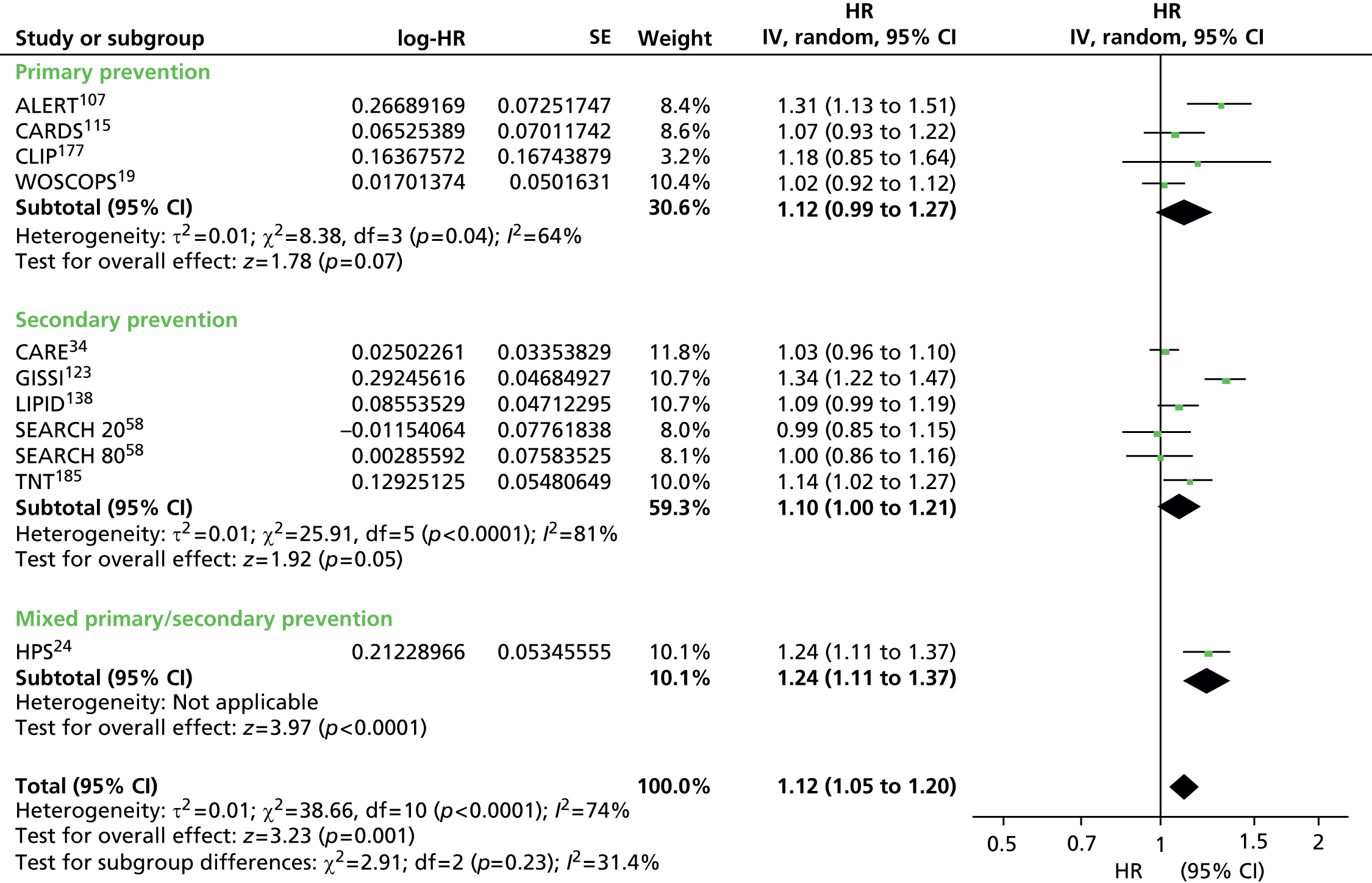

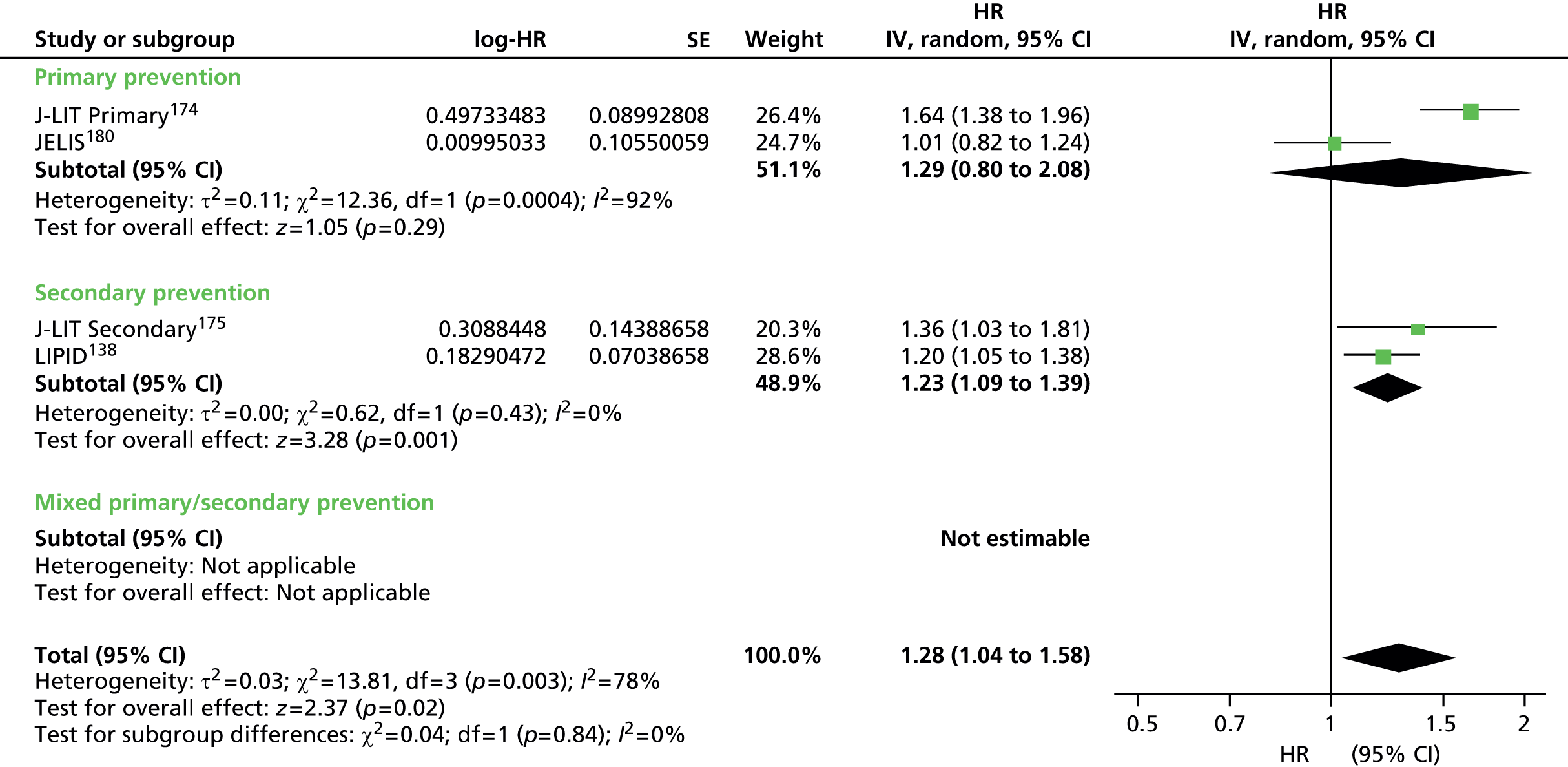

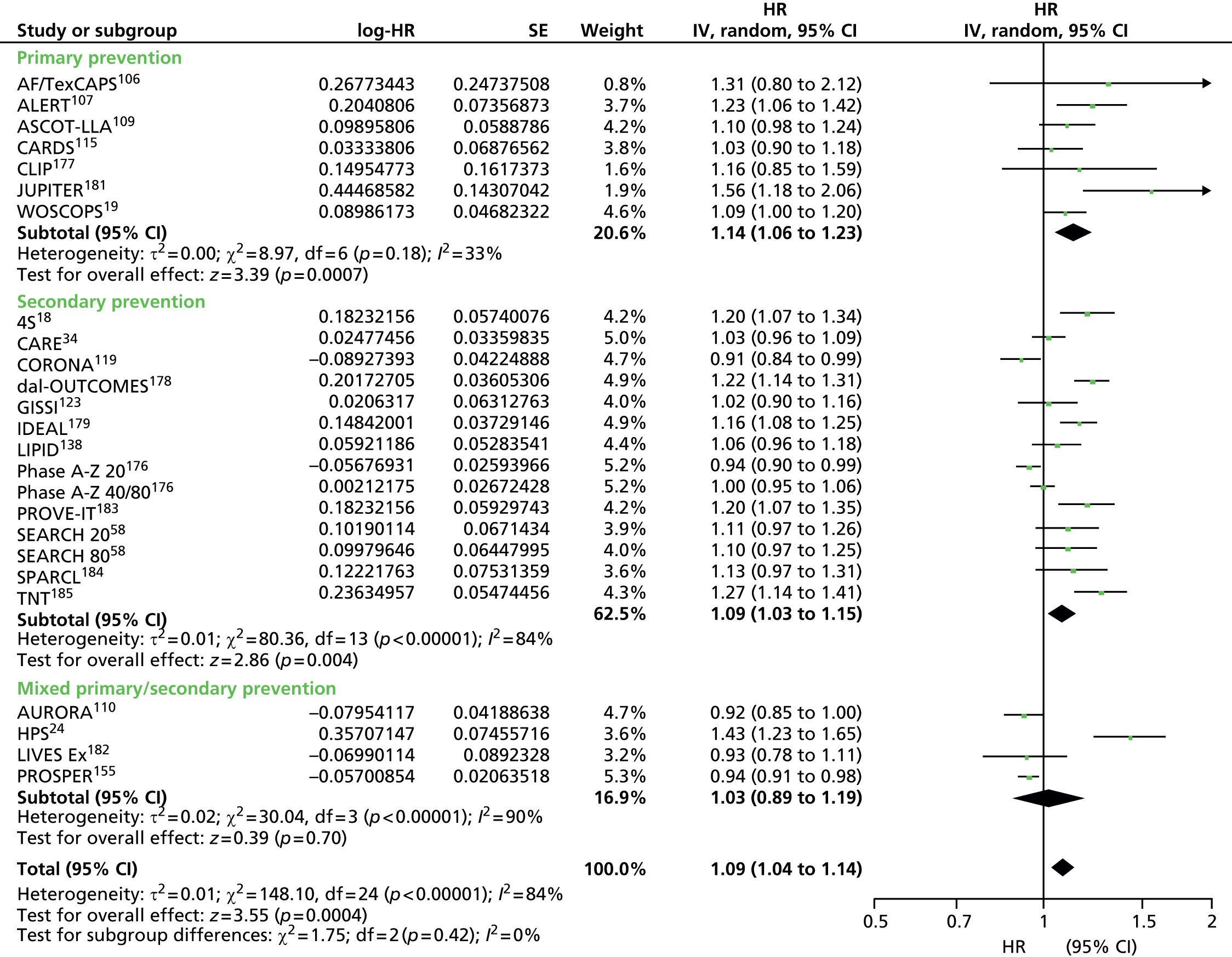

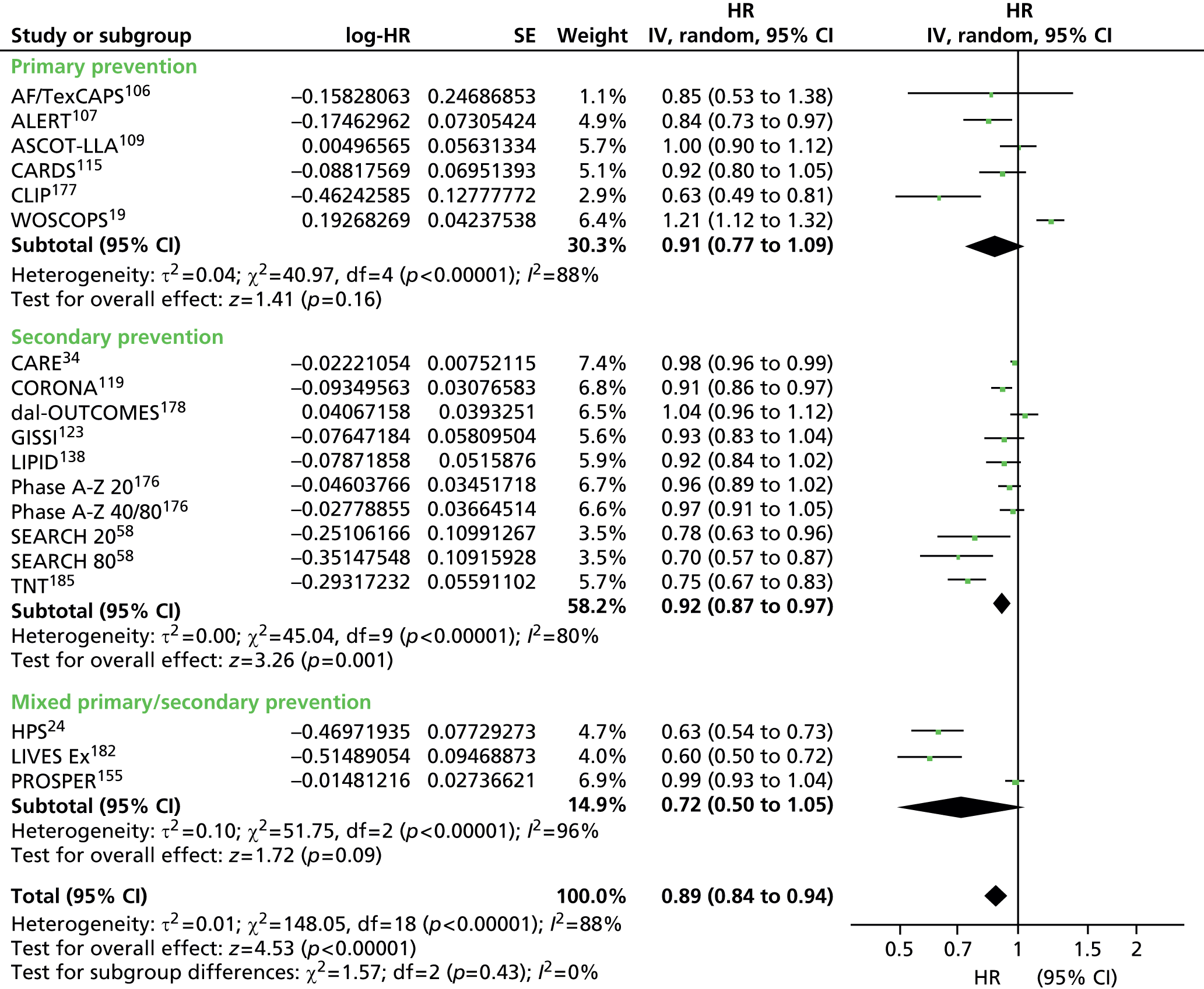

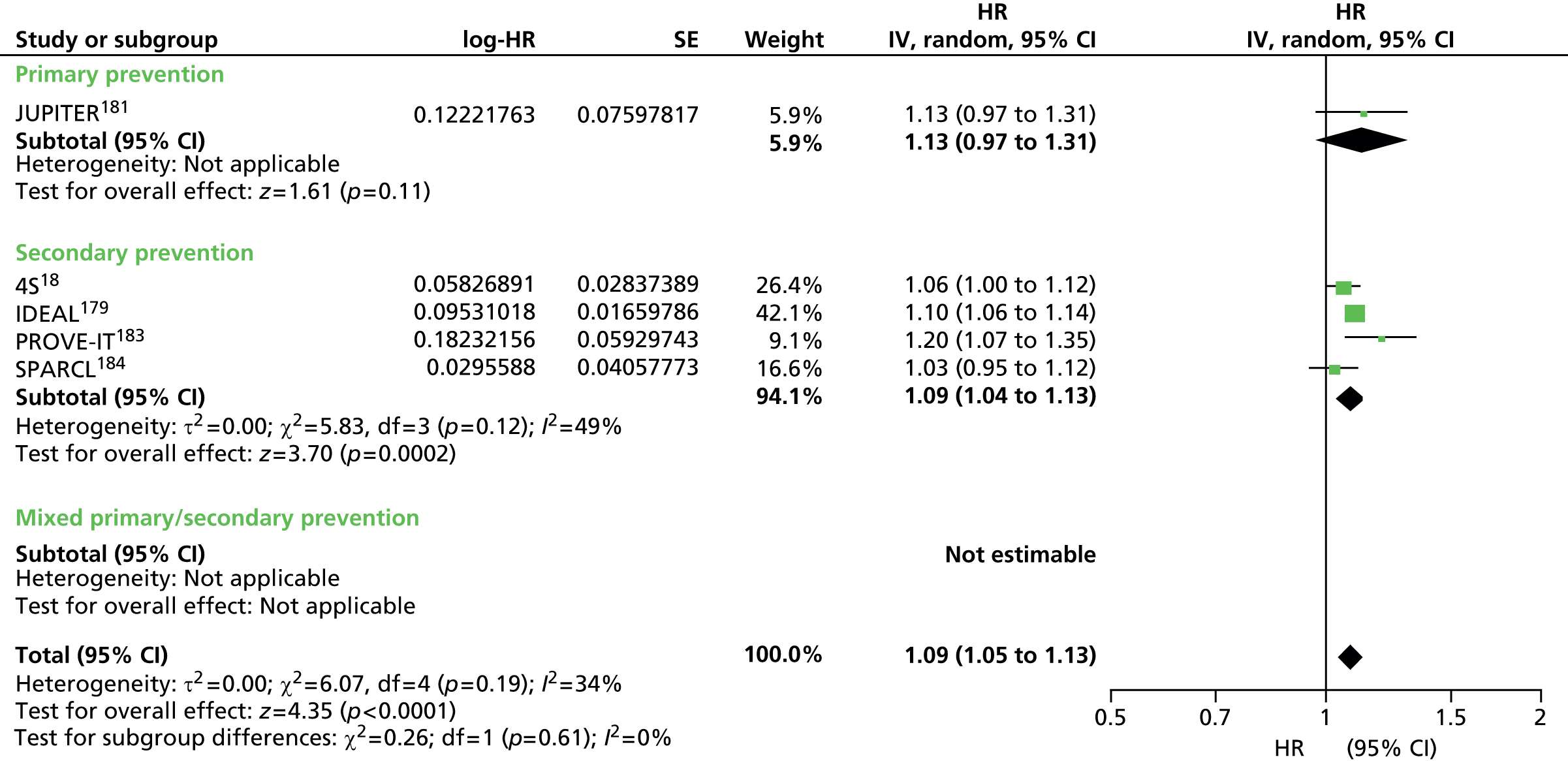

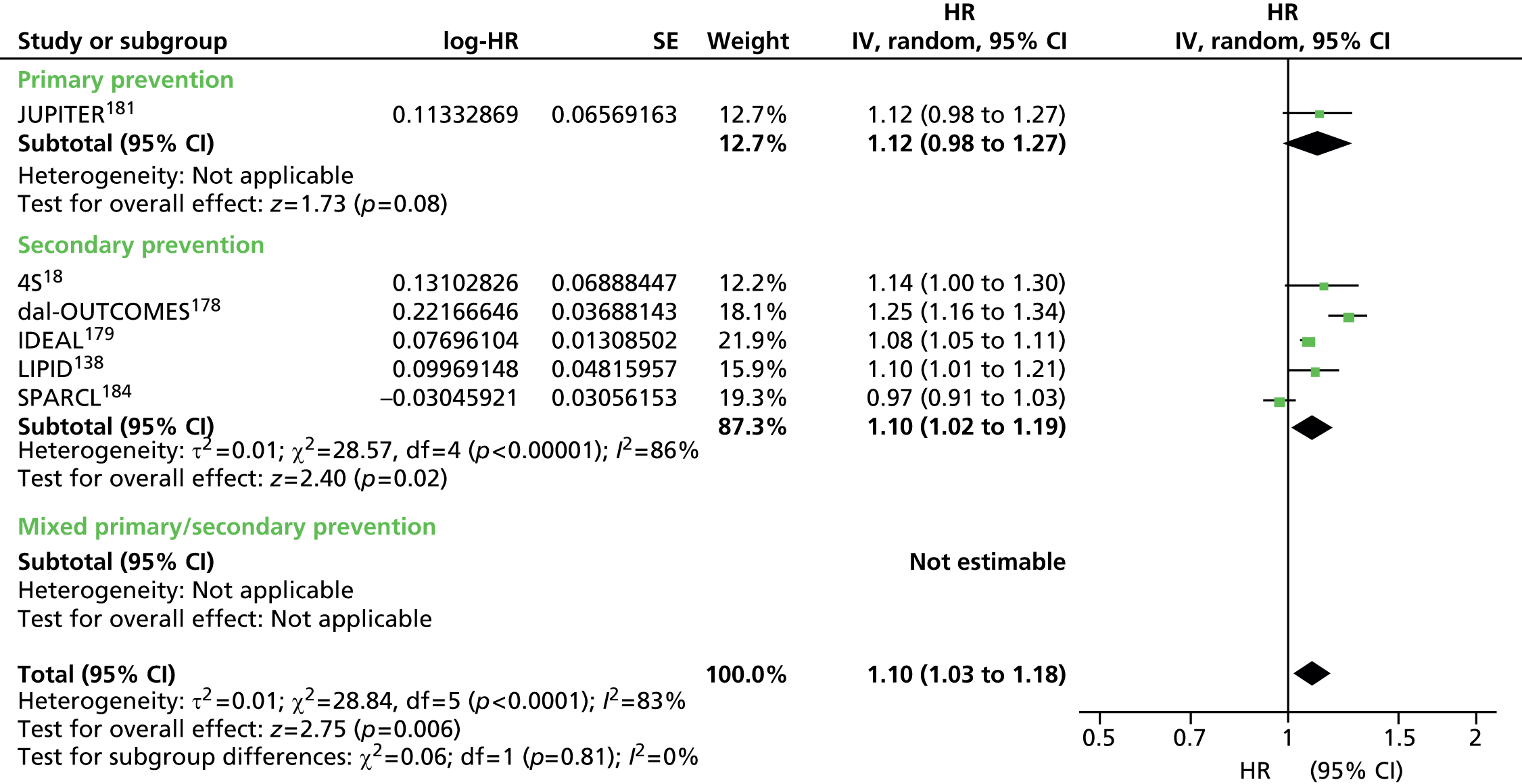

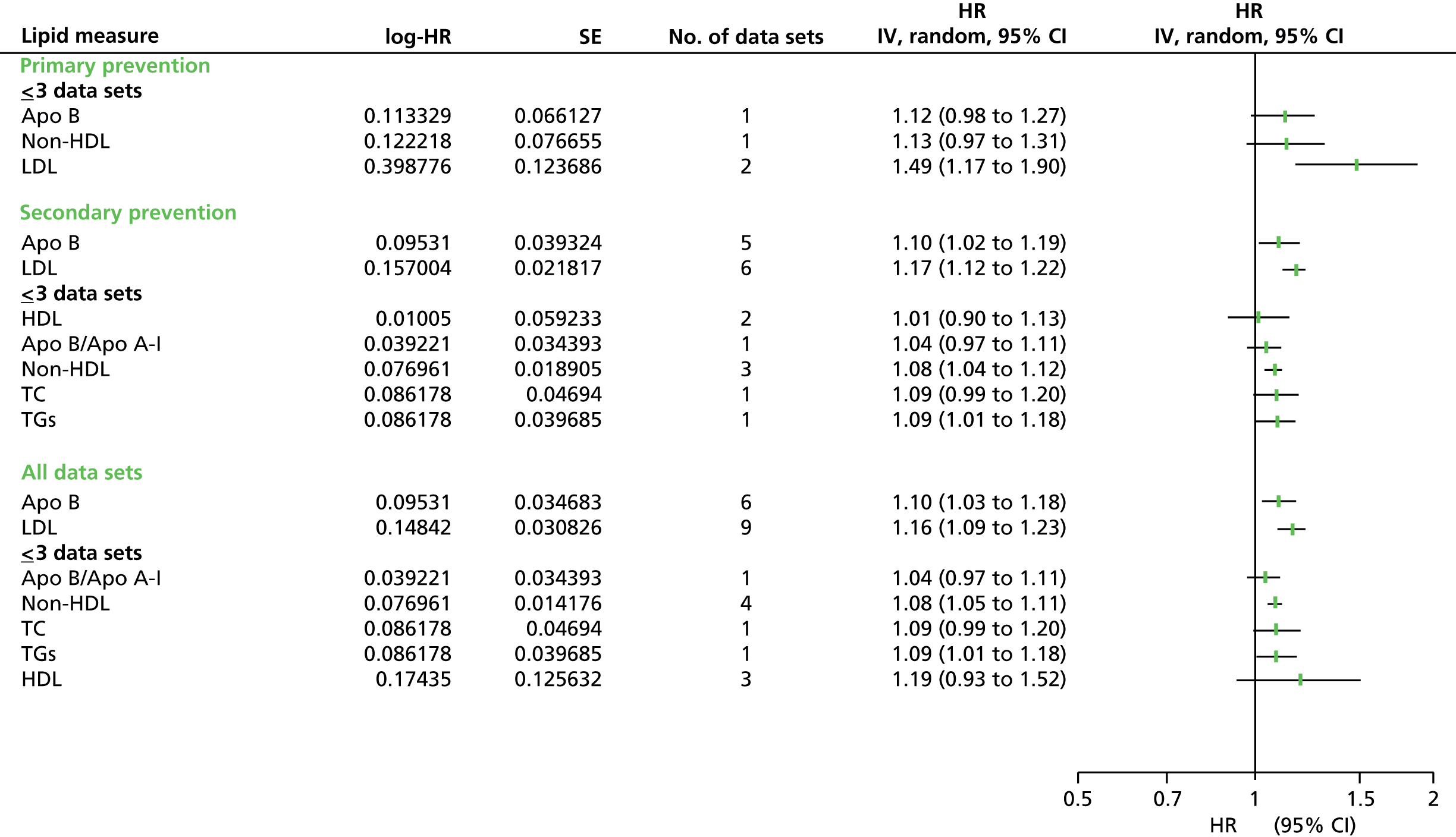

Figures 4–9 show the summaries of the overall results for all lipid measures for CVD events, CVD events (adjusted), CVD mortality, CVD mortality (adjusted), all-cause mortality and all-cause mortality (adjusted), respectively.

FIGURE 4.