Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/14/44. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in October 2014 and was accepted for publication in August 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mark Thursz has received fees for advisory boards and speaker engagements from Gilead, BMS, Abbvi, MSD, Jenssen and Abbott Laboratories. Paul Roderick has received grant support from Pfizer and is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Board. Michael Allison has received fees for advisory board engagements from Norgine and Luke Vale is a member of the Clinical Trials Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Thursz et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Aims

The primary objective of this study was to determine whether or not pentoxifylline (PTX) or corticosteroids reduce the mortality associated with severe alcoholic hepatitis (AH) and thereby to resolve the ongoing dilemma about the use of these two agents in clinical practice. In order to avoid the controversies caused by underpowered studies in this field, we aimed to conduct a well-powered, definitive study.

Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, sepsis and renal impairment have previously been exclusion criteria in many AH treatment studies but patients with these complications have the highest mortality risk and therefore have potentially most to gain. They were therefore included in the trial.

Early treatment benefits may subsequently be lost owing to an increased incidence of sepsis in the medium term or recidivism in the longer term. Mortality at 28 days, 90 days and 1 year after treatment was therefore assessed.

Virtually all trials of therapeutic interventions in AH have used Maddrey’s discriminant function (DF) to identify a group of patients with severe disease and an appreciable mortality risk. Recent research from the UK suggests that the Glasgow Alcoholic Hepatitis Score (GAHS) provides a more accurate prognosis. 1 In order to make this trial comparable to previous studies, we elected to keep the DF as an inclusion criterion, but we have compared the DF, GAHS, model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) and the Lille scores for their ability to predict mortality and/or response to therapy.

The effect of resumed alcohol abuse is thought to be one of the important predictors of mortality after the first month and we therefore aimed to collect data on recidivism and abstinence in order to assess the effect on patient outcomes.

Finally, we aimed to conduct within-trial and longer-term horizon economic evaluations of the two interventions.

Chapter 2 Background

Importance of the health problem to the NHS

Alcohol-related illness places an enormous burden on the NHS. It has been estimated by the Royal College of Physicians that the in-patient costs in 1998–9 arising from the consequences of alcohol misuse were as high as £2.9B. 2 Overall, alcohol-related deaths have more than doubled since 1979,3 and in Scotland, they increased by 236% between 1980 and 2002. 4 Throughout the UK, deaths from cirrhosis rose dramatically between 1987 and 1991. 5 Alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) accounts for the majority of alcohol-related deaths in the UK. 6 While many patients presenting with ALD will have cirrhosis, as many as 60% will have evidence of alcohol-related hepatitis. 7 AH is the most florid manifestation of ALD, but is potentially reversible. However, the short-term mortality of AH is particularly high among those with indicators of severe disease. The 28-day mortality of patients who have a DF ≥ 32 is 20–30% and historically up to 40%. 8–10 The 28-day mortality of patients who have a GAHS of ≥ 9 is approximately 60%1 (see Appendix 1 for description of DF and GAHS). AH affects a relatively young population (average age 50 years; patients may present in their twenties to thirties). Despite the increasing prevalence and the severity of this disease there is no consistency in its management. Considerable controversy exists, especially regarding the use of corticosteroids.

Summary of current evidence

Corticosteroids

Since 1971 there have been 13 randomised studies and four meta-analyses investigating the role of corticosteroid therapy for this condition. 11,12 Despite this apparent wealth of evidence, controversy persists. There remains deep division with regard to the use of corticosteroids. Advocates of the treatment cite significant improvement in the short- to medium-term mortality, while detractors cite the risks of sepsis and GI haemorrhage with corticosteroid therapy. Many of the published studies have been plagued by widely varying inclusion and exclusion criteria. The largest placebo-controlled study13 treated 90 patients and found no benefit with prednisolone compared with a similar placebo-treated group. This study was hampered by the inclusion of patients with both moderate and severe AH, as well as end-stage ALD. In the only study to require histological confirmation of AH in all patients, prednisolone was associated with a short-term improvement in mortality in patients, although this benefit was not apparent after 2 years. 14,15 On review of the published studies, none of these reached an adequate statistical power to make a statement with 80% confidence. The most recent meta-analysis of all of the available trials16 demonstrated that, although there was a trend of benefit with steroids, the results were not statistically significant (p = 0.2). However, a reanalysis of the three largest studies indicted a significant benefit from corticosteroids. 17 In this meta-analysis, patients with a DF ≥ 32 treated with prednisolone had 28-day mortality of 15%, compared with mortality of 35% among placebo-treated patients (p = 0.001).

Pentoxifylline

Pentoxifylline has also been studied in the treatment of AH. 18–20 It is believed to act, in part, by inhibiting the synthesis of the proinflammatory cytokine tumour necrosis factor alpha. 20 There has been one randomised controlled trial18 that showed significant benefit. In this study, 100 patients, all with a DF > 32, were enrolled. PTX was administered for 4 weeks, at a dose of 400 mg three times per day. In the PTX group, 12 of 49 patients (24.5%) died, compared with 24 of 52 (46.1%) in the placebo group during the index hospitalisation (p = 0.037). The principal benefit for the agent appeared to be a reduction in deaths attributed to hepatorenal syndrome. However, other studies found contrasting results and meta-analysis has failed to show any significant benefit of this drug. 19–21 Although published evidence for the use of PTX is inconclusive, the drug is widely used as an alternative to steroids, particularly in the USA, and further evaluation in a clinical trial is, therefore, clearly warranted. 22

Steroids and/or pentoxifylline

Combinations of steroids and PTX have been evaluated in clinical trials, using steroids alone as the control arm; however, the combination does not appear to have any benefit over steroids alone. 23,24 Three small studies25–27 have compared steroids directly with PTX but the results were inconsistent. One study28 explored the use of PTX as a rescue therapy once steroids had failed to improve liver function tests (LFTs) but this strategy did not influence survival.

Chapter 3 Trial design and methods

Study design

The clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of STeroids Or Pentoxifylline for Alcoholic Hepatitis (STOPAH) study was a pragmatic, multicentre, double-blind, factorial (2 × 2) trial to assess prednisolone and PTX in patients with severe AH. The factorial design meant that the two active treatments could be concurrently assessed when doubt exists over the efficacy of both medications.

The trial included an economic evaluation to assess which treatment is the most cost-effective, as well as the quality of life (QoL) and long-term prognosis in patients with AH (see Chapter 5). The main trial was also supplemented with a number of substudies (see Appendix 2). A description of the trial protocol has already been published. 29

Ethical approval and research governance

Ethical approval for the study was given by Wales Research Ethics Committee (REC) 3 (formerly REC for Wales) on 27 April 2010 (reference number 09/MRE09/59). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register under the reference number ISRCTN88782125.

Changes to original protocol

A summary of the changes made to the original protocol is given in Table 1.

| Change to protocol | REC approval |

|---|---|

| ‘4 weeks’ changed to ‘28 days’ | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Dosing instructions’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Patient target added – 1200 randomised patients | 19 July 2011 |

| Liver transplant added as secondary end point at 90 days | 19 July 2011 |

| Past medication substudy text clarified | 19 July 2011 |

| Informed consent process clarified. Time for consideration of study changed to < 24 hours if appropriate | 19 July 2011 |

| Clarification that consent should be sought from ‘incapacitated’ patient, once able | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘TENALEA account creation and registration’ sections added | 19 July 2011 |

| History of excess alcohol timeline added to ensure that patients have been drinking sufficiently heavily recently (to within 2 months of randomisation) | 19 July 2011 |

| Period of abstinence changed from ‘6 weeks’ to ‘> 2 months’ | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Clinically apparent’ jaundice added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘6-month’ timeline for previous use of study drugs changed to ‘6 weeks’ | 19 July 2011 |

| Treatment of patients with renal impairment, sepsis or GI bleed clarified | 19 July 2011 |

| Prohibited drugs clarified, i.e. N-acetylcysteine and ketorolac, plus prescription of study drugs during the treatment phase | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Start of treatment and treatment breaks’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Renal impairment dose reduction’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| IMP manufacture, labelling and storage procedures clarified, and IMP shipment process expanded | 19 July 2011 |

| IMP ‘temperature monitoring’ section added, to explain storage requirements and use of WarmMark Temp Tags (Tela Temp Inc., Anaheim, CA, USA) for transit | 19 July 2011 |

| IMP ‘documentation’, ‘dispensing procedures’ and ‘drug returns’ sections updated | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Patient adherence’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Screening assessments updated/corrected | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘EDTA sample for DNA analysis’ moved to baseline | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Central pathology review’ analysis section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Baseline assessments and timelines updated, including permitted 14-day window between screening and baseline visits | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Inflammatory markers in serum analysis’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Analysis of genetic causes of AH’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Monocyte study’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Treatment and follow-up assessments updated, including the permitted window around visits. Height removed from all assessments except screening | 19 July 2011 |

| WHO performance status added to all on treatment assessments | 19 July 2011 |

| Prior 48-hour window for blood samples at discharge added | 19 July 2011 |

| Details of day 28 telephone call added | 19 July 2011 |

| Only existing AEs to be followed up at day 90 and 1 year. No new AEs to be recorded after 4 weeks post IMP last dose | 19 July 2011 |

| Clarification of expected AEs and recording requirements for 4 weeks post IMP | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Exclusions to AE recording requirements’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Reporting of SAEs and SUSARs corrected, post-treatment SAE reporting and follow-up clarified, SUSAR causality assessment clarified, expedited SUSAR reporting clarified | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Patient loss from study’, ‘patients lost’, ‘patients not lost’ sections added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘National registries’ section added | 19 July 2011 |

| Other reasons for trial termination added | 19 July 2011 |

| ‘Quality of life in cirrhosis study’ section clarified | 19 July 2011 |

| CRF completion and return to SCTU procedures clarified | 19 July 2011 |

| Change from ‘minimum of 24 hours’ to ‘< 24 hours for study consideration’ for some patients | 19 July 2011 |

| Updated WHO performance status definitions added | 19 July 2011 |

| Parameters for standard gamble analysis added | 19 July 2011 |

Study setting and sample

Patients were identified, screened and recruited in the secondary care setting after admission with acute AH. A total of 66 hospitals across England, Wales and Scotland took part, although only 65 of these recruited patients to the study.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Clinical AH:

-

serum bilirubin level of > 80 µmol/l

-

history of excess alcohol (> 80 g/day for males and > 60 g/day for females) to within 2 months of randomisation.

-

-

Less than 4 weeks since admission to hospital.

-

DF of ≥ 32.

-

Informed consent.

Exclusion criteria

-

Abstinence of > 2 months prior to randomisation.

-

Duration of clinically apparent jaundice > 3 months.

-

Other causes of liver disease including:

-

evidence of chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis B or C)

-

biliary obstruction

-

hepatocellular carcinoma.

-

-

Evidence of current malignancy (except non-melanotic skin cancer).

-

Previous entry into the study, or use of either prednisolone or PTX within 6 weeks of admission.

-

aspartate aminotransferase (AST) level of > 500 IU or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level of > 300 IU (not compatible with AH).

-

Patients with a serum creatinine level of > 500 µmol/l or requiring renal support.

-

Patients dependent on inotropic support (adrenaline or noradrenaline). Terlipressin is allowed.

-

Active GI bleeding.

-

Untreated sepsis.

-

Patients with known hypersensitivity to PTX, other methylxanthines or any of the excipients.

-

Patients with cerebral haemorrhage, extensive retinal haemorrhage, acute myocardial infarction (within the last 6 weeks) or severe cardiac arrhythmias (not including atrial fibrillation).

-

Note that patients with evidence of sepsis, GI bleeding or renal failure may be treated for these conditions for up to 7 days and, if stable, the patients can then be rescreened for eligibility. Treatment can continue for > 7 days if they are stable. Patients who are not stable after 7 days of treatment will not be eligible for the study.

Study interventions

Patients were randomised to one of four arms:

-

arm A – placebo/placebo

-

arm B – placebo/prednisolone

-

arm C – PTX/placebo

-

arm D – PTX/prednisolone.

The Pharmacy Manufacturing Unit at the Royal Free Hospital in London manufactured the investigational medicinal product (IMP) by overencapsulating the active medication in gelatin capsules. Placebo preparations, which precisely matched the active medication in appearance, contained only microcrystalline cellulose. The IMP was provided in capsule form in two bottles (bottle A and bottle B). Bottle A contained PTX 400 mg or matched placebo and bottle B contained prednisolone 40 mg or matched placebo. Ideally, patients started their IMP within 48 hours of randomisation. It was administered for 28 days (bottle A one capsule daily and bottle B three times daily) and treatment breaks of up to 7 days were acceptable if required.

Concomitant medications may have been administered as medically indicated, including alcohol withdrawal therapy as required. All patients received supportive nutritional therapy. Nutritional supplements were offered but if the patient was unable to take these, enteral nutrition via a nasogastric tube was offered. The aim was to provide 35–40 kcal/kg/day non-protein energy with 1.5 g/kg/day of protein.

Study procedures

Recruitment

Site staff assessed patients admitted into secondary care with an acute episode of AH for potential eligibility for the trial.

Informed consent

Potentially eligible patients (or their legal representatives) were informed about the trial by one of the study team, and then given a patient information sheet to review. Patients were given a minimum of 24 hours in which to consider the study and ask questions, after which they (or their legal representatives) were asked to give written informed consent to participate, on the trial informed consent form.

For relevant patients, consent given by a legal representative was in place until the patient recovered capacity, at which point the patient was informed about the trial and asked to decide whether or not they wanted to continue in the trial. Consent to continue was then sought from the patients themselves.

Randomisation and concealment

Site staff registered patients onto the trial via Trans European Network for clinical trials services (TENALEA), a web-based registration and randomisation system, after written informed consent was obtained from the patient (or their legal representative). Subsequently, screening assessments took place to ascertain eligibility. Non-eligible patients were deemed screening failures, while eligible patients were then randomised by site staff, via the TENALEA, to one of four trial treatment arms. Treatment allocation was blinded to site staff and the patient by providing each patient with a unique four-digit patient pack number. The treatment arm was also concealed to investigators and researchers. Only the study statisticians were unblinded and this was for analysis purposes only.

Randomisation was stratified and performed using the following two stratification factors:

-

geographic region (28 in total)

-

risk group – either ‘high’ or ‘intermediate’ risk (‘high’ risk was defined as either sepsis or history of GI bleeding in the previous 7 days or creatinine level of > 150 µmol/l, or any combination of the these; ‘intermediate’ risk was defined as no sepsis and no history of GI bleeding in the previous 7 days and creatinine ≤ 150 µmol/l).

Unblinding service

The Emergency Scientific and Medical Services at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust provided a 24-hour unblinding service for the trial. The Emergency Scientific and Medical Services held a copy of the study randomisation list and were able to perform emergency unblinding if the enquirer considered the medical management of the patient to be dependent on knowing their treatment allocation.

Data collection and management

Sites entered trial-specific data, as specified in the protocol, onto paper case report forms (CRFs). Completed paper CRFs were sent to the Southampton Clinical Trials Unit (SCTU) that was responsible for the data management of the trial. Data were transcribed from paper CRFs into an InForm database (InForm version 5.0, ORACLE, Redwood Shoves, CA, USA) at the SCTU. A range of data validation checks was carried out within both InForm and SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) to minimise incorrect or missing data.

Source data verification was undertaken during site monitoring visits, in accordance with the SCTU’s trial monitoring plan. For sites that recruited ≥ 15 patients a planned monitoring visit was scheduled. In total, 29 planned monitoring visits and two triggered monitoring visits took place.

Baseline

At baseline, a number of characteristics were collected to determine the patient’s prognosis at the beginning of the trial. The outcomes collected at this time point included the following: vital signs, World Health Organization performance status, concomitant medication, LFTs, prothrombin time (PT), full blood count (FBC), urea, creatinine, GI bleed or sepsis since screening and time since admission to hospital. Prognostic scores at baseline (DF, MELD score, GAHS and Lille score) were derived using baseline data with the exception of the Lille score, which also uses data from day 7. Demographic data were captured at screening.

Follow-up

Patients who were being treated as in-patients were followed-up every 7 days from the start of treatment until the end of treatment (day 28). If the patient was discharged from hospital during the treatment phase, then the 28-day follow-up visit was conducted by phone, when possible, in order to gather treatment information. All patients were scheduled for a follow-up hospital visit at 90 days and 1 year from start of treatment, at which time details of the patients’ alcohol consumption and attendance at alcohol counselling were collected. There were also repeated measurements of outcomes recorded at baseline (see Baseline) as well as if patients had experienced an occurrence of GI bleed or sepsis since their last visit. Finally, for the 1-year follow-up visit only, demographic data were collected on the patients’ marital status, employment status and housing status.

All patients were asked to consent to information about their health status being held and maintained by the Health and Social Care Information Centre and the NHS Central Register to enable long-term follow-up. In January 2013, the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment (funding body) awarded a no-cost extension to recruitment (from the end of December 2012 to the end of February 2014), but with follow-up reduced to a minimum of 28 days (to the end of March 2014), so that primary outcome data could be collected for all randomised patients.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was 28-day mortality. This was chosen as this time point represents the end of the peak period of mortality for AH. Also, this is consistent with other AH trials, which allows a comparison to be made. Patient mortality at day 28 was treated as a binary outcome (1 = dead, 0 = alive).

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes at day 90 and 1 year

Mortality or liver transplant at day 90 and 1 year were considered as secondary outcome measures. These were calculated in a similar fashion to the primary outcome; the main difference being that these also included the incidence of liver transplantation.

Overall survival (OS) was also evaluated, for which an event was defined as any death occurring during 1-year post-treatment start. The OS time was defined as the following:

-

if the date of death was < 1-year post-treatment start, then the OS time was the difference between the treatment start date and death date

-

if the date of death was > 1-year follow-up, then patients were censored with an OS time of 365 days

-

if no date of death was received, then patients were censored with an OS time of 365 days, if they were known to be alive at 1 year, or the difference between treatment start and date last known alive.

Outcomes of recidivism in patient’s alcohol intake were collected at day 90 and 1 year. This included whether or not patients had attended any alcohol counselling sessions. Development of renal failure, sepsis and GI bleed at day 90 and 1 year were also assessed.

Prognostic scores and predictors of mortality

The outcomes of 28-day, 90-day and 1-year mortality were considered in relation to the GAHS at baseline. Other scores considered were DF, MELD score and the Lille score (see Appendix 1).

Other baseline measures were evaluated to see whether or not they were predictors of mortality, including: pyrexia (temperature > 37.2 °C), hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 100 mmHg), tachycardia (pulse > 100 beats per minute), alcohol intake (units/week), albumin (g/l), alkaline phosphatase (ALP) (U/l), bilirubin (µmol/l), hepatic encephalopathy (presence vs. absence), PT ratio or international normalised ratio (INR), age (years), white blood cell (WBC) count (109 WBC/l), urea (mmol/l) and creatinine (µg/dl).

Safety

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were measured during the treatment period using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 4.0.

Health-related quality of life

Hospital readmission rates for liver- or non-liver related events (including access to other health services) and incremental NHS costs and QoL data [using the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) score], were collected at day 90 and 1-year follow-up visits.

Duration of hospitalisation, type of hospital, time of initial presentation and time of admission to treating hospital (if a tertiary referral) were evaluated.

Sample size

The sample size was performed in nQuery Advisor version 2.0 (Statistical Solutions, Boston, MA, USA) using a two-group continuity-corrected chi-squared test and the following parameters:

-

power = 90% (to allow for secondary outcomes)

-

two-sided significance level of 5%.

Estimated 28-day mortality rate in each treatment arm is given in Table 2.

| PTX | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Prednisolone | |||

| No | 35% (placebo/placebo) | 25% (PTX/placebo) | 30% |

| Yes | 25% (placebo/prednisolone) | 17%a (prednisolone/PTX) | 21% |

| Total | 30% | 21% | – |

Based on a reduction in the 28-day mortality rate at the margins from 30% to 21%, a sample size of 513 per group of single agent versus no single agent was required. Thus, in total, the trial required 1026 patients. We allowed for an approximate 10% dropout rate up to day 28 and therefore aimed to randomise 1200 patients to the study, with an equal treatment group allocation.

The sample size for this trial was not powered to assess for any observed treatment interaction and, in fact, assumed that there was no interaction between the two treatments (i.e. that receiving prednisolone in addition to PTX does not change the effect of PTX and vice versa). Assessing the size of any interaction was not of primary interest, as it was assumed to be small or non-existent and would require a fourfold increase in the sample size, so it was deemed appropriate not to power for assessing an interaction.

Stopping guidelines

Prior to this trial, the benefits and harms of PTX in this patient population were unknown, as only limited data were available, and prednisolone had a significant, although uncertain, evidence base. In addition, there was huge uncertainty about whether or not the combination of PTX and prednisolone would be harmful or beneficial, and whether or not there would be a treatment interaction. It was therefore important to conduct interim analyses with predefined criteria to assess both for harm and benefit.

Prespecified stopping guidelines were developed based on the Peto–Haybittle rule, as recommended by Pocock. 30 The guidelines recommended that certain treatment arms were stopped if a two-sided (i.e. for harm or benefit) p-value of < 0.001 was found in group comparisons of day-28 mortality using logistic regression analysis. Pocock30 states this p-value ties in well with the concept of proof beyond reasonable doubt. This p-value was used for both stopping guidelines of harm and benefit, as the treatments were not new and were already in use in practice. Also, should evidence of harm or benefit arise, evidence needed to be sufficiently convincing to ensure that others would believe it and change their practice accordingly. No adjustment in the significance of the p-value for the final analysis was made, owing to the p-value of 0.001 being considered sufficiently small.

The Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee met to review cumulative safety and efficacy data at three time points during the trial. The following interim stopping guideline assessments were made:

-

Primary end-point data from 200 patients: only stopping guidelines for harm were assessed. No treatment arms were stopped for harm at this interim assessment.

-

Primary end-point data from 400 patients: stopping guidelines for harm and benefit were assessed. No treatment arms were stopped for harm or benefit at this interim assessment.

-

Primary end-point data from 800 patients: stopping guidelines for harm and benefit were assessed. No treatment arms were stopped for harm or benefit at this interim assessment.

Statistical analysis

All trial analyses and reporting were carried out following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines. Statistical analysis was carried out in SAS version 9.2 and/or 9.3 following a predefined statistical analysis plan, which was approved by the Data Monitoring and Ethic Committee. Some subsequent analyses were carried out that were not predefined; these will be highlighted in the relevant sections of this report (see Chapter 3, Secondary Outcomes).

Analyses were carried out with respect to the factorial design for which:

-

the prednisolone-treated group (arms B and D) was compared with the prednisolone control group (arms A and C)

-

the PTX-treated group (arms C and D) was compared with the PTX control group (arms B and D).

If a significant interaction (at the 5% significance level) was found then the comparison of interest was individual treatment arm. All descriptive tables were presented by treatment arm.

All analyses were adjusted for risk group and factorial design unless otherwise stated, and were assessed at the two-sided 5% significance level.

Analysis populations

All summaries and analyses were carried out on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population unless otherwise specified. The ITT population included all patients who were randomised regardless of treatment adherence. For analyses at a certain time point, the ITT population was modified to include only patients who were known to be alive at the specified time point or had died prior to the time point, that is, for primary analysis, this included all randomised patients for whom we knew that they were alive at day 28 or who died prior to or on day 28.

A per-protocol population was defined as:

-

treatment adherence ≥ 75%

-

patients who reached day 28 needed to have had taken at least 75% of treatment (> 21 days) to be included in the per-protocol population

-

patients who withdrew or died before day 28 needed to have had a minimum of 7 days of treatment and taken at least 75% of treatment up until they withdrew/died

-

-

patients who had no major protocol violations.

The primary end-point analysis was repeated for the per-protocol population.

Preliminary analyses

Summary statistics were produced for a selection of key clinical and demographic characteristics at baseline to assess baseline comparability between the four treatment arms. Any significant differences were reported.

Primary analyses

The primary outcome of 28-day mortality was analysed using logistic regression. Although the trial was not powered to detect a treatment interaction, this was tested using a secondary logistic regression model in order to test the underlying model assumptions surrounding factorial design.

Secondary analyses

The primary outcome analysis method was repeated for the 90-day and 1-year mortality or liver transplant outcomes. For OS, comparisons were made using Cox proportional hazards regression and Kaplan–Meier curves.

A number of analyses were carried out on the DF, GAHS, MELD and Lille prognostic scores. First, to assess the predictive power of the scores on 28-day, 90-day and 1-year mortality, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was carried out. Graphical representation of the ROC curves was produced along with area under the curve statistics. Further ROC curve analysis was carried out on the Lille score comparing the two prednisolone-treated groups (not predefined). Univariate logistic regression analysis was also carried out to look at the relationship between the scores and outcome.

Univariate logistic regression analysis was carried out to assess the relationship between baseline prognostic factors and 28-day, 90-day and 1-year mortality. The prognostic factors included in this analysis were as follows: pyrexia, hypotension, tachycardia, alcohol intake, albumin, ALP, bilirubin, encephalopathy, PT ratio/INR, age, WBCs, urea and creatinine. Odds ratios with a 95% confidence interval (CI) and corresponding p-value were produced for each model fitted. Any factors that were significant in the univariate analysis were added to a multivariate model, which also included the treatment indicators for prednisolone and PTX. Backward elimination was then applied to produce adjusted odds ratios for the effects of prednisolone and PTX. Please note that the use of backward elimination was not predefined in the statistical analysis plan.

Descriptive summaries of the following were produced: causes of death, SAEs, alcohol behaviour and alcohol counselling attendance.

Finally, the effect of drinking habits on 1-year mortality was explored by fitting a logistic regression model with abstinence as the reference event. This was compared with the other three alcohol consumption statuses (reduced drinking to below government defined safety limits, reduced drinking but still above safety limits and not reduced). Please note that this analysis was not predefined.

For all regression models applied, the assumptions underlying these models were checked using appropriate methods; the Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test for assessing logistic regression modelling and the proportional hazards assumption for Cox proportional hazards modelling. Covariates used in logistic regression modelling were assessed for outliers. Subsequently, outliers were excluded during a sensitivity analysis to allow for any differences in results to be examined.

Sensitivity analyses

A sensitivity analysis of the primary end-point outcome was produced by excluding any patients who were randomised and followed-up but were later found to be ineligible through central monitoring of baseline characteristics. Patients were excluded if they had any of the following characteristics at baseline:

-

< 18 years old

-

bilirubin level of < 80 µmol/l

-

maximum alcohol consumption in past 2 months < 70 units/week for a male

-

maximum alcohol consumption in past 2 months < 52.5 units/week for a female

-

time between initial admission and screening date > 4 weeks

-

DF of < 32

-

AST level of > 500 IU/l

-

ALT level of > 300 U/l

-

creatinine level of > 500 µmol/l

-

unresolved sepsis

-

unresolved GI bleed.

Please note that this sensitivity analysis was not predefined.

Subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses were performed to further explore whether or not particular subsets of the patient population were at more benefit to treatment and prolongation of survival. The subgroups considered were the prognostic scores (DF, GAHS, MELD and Lille score) and risk at baseline. These analyses looked at 28-day, 90-day and 1-year mortality using logistic regression analysis methods as described in Statistical analysis. Please note that these subgroup analyses were not predefined.

Patient and public involvement

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was delighted to recruit Mr Colin Stanfield as a patient representative. He attended the majority of TMG meetings during the set up and running of the STOPAH trial. His input from a patient perspective was valuable in terms of the design of the patient information sheet and consent form. He also provided guidance on a number of occasions about patient behaviour and acceptability of interventions, and data collection.

Chapter 4 Trial results

Recruitment and randomisation

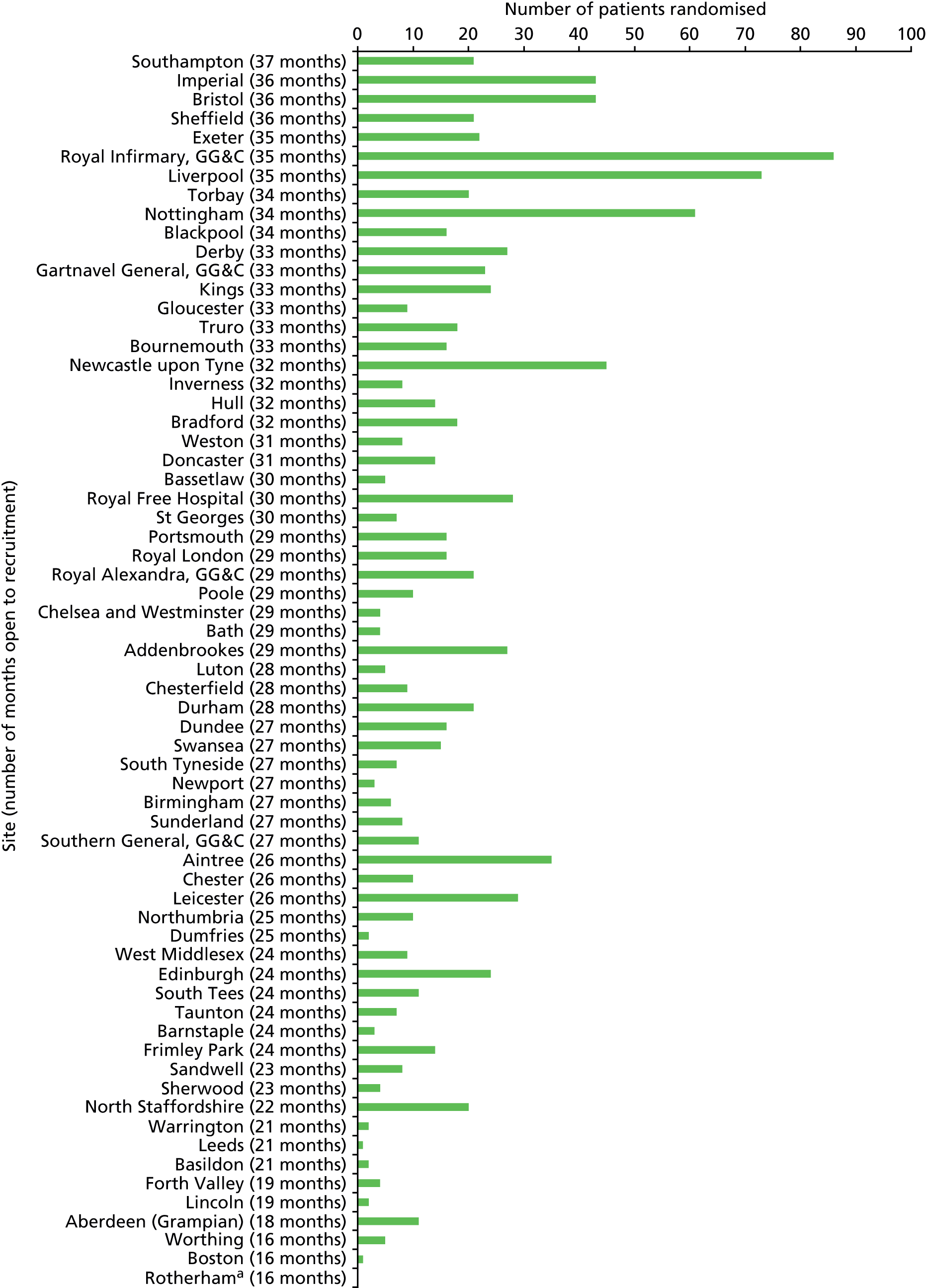

The SCTU site staff performed initiation visits between October 2010 and August 2012. In total, 66 trial sites were opened but subsequently one site was closed after failing to recruit any patients. The details of recruitment by site are given in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Number of patients randomised by site, ordered by number of months open to recruitment. a, All sites closed to recruitment on 28 February 2014 with the exception of Rotherham, which closed on 19 October 2012, after 16 months open, owing to poor recruitment activity. GG&C, Greater Glasgow and Clyde.

A total of 5234 patients were screened for the trial, and after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria, 1103 were randomised and evenly allocated to the four treatment arms. Analysis of screening logs indicates that the trial recruited 85% of eligible patients; disease severity being too mild was the most common reason for patients not being recruited. There were a total of 50 dropouts prior to the primary end-point time point at 28 days. A total of 168 patients died between 28 days and the next time point at 90 days, and 221 patients dropped out of the study between 90 days and 1 year. We were unable to follow-up 228 patients recruited during the last 9 months of the trial as the study was closed. Details of the patient flow are provided in the CONSORT diagram (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart. HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus. a, No usage of data allowed – patient withdrew consent and would not allow any data collection to be used; b, withdrew – patient withdrew consent but allowed use of data collection up to point of withdrawal; and c, early cessation of follow-up – recruitment extended to end of February 2014, but follow-up for all patients ceased end March 2013, so that primary end-point data could be collected for all patients.

As detailed in the sample size and power calculation in Chapter 3, Sample size, the trial aimed to recruit 1200 patients in order to be confident of having primary end-point data on 1026 patients. Although the final number of patients recruited fell short of the target number, the trial exceeded the number needed for the trial power to be maintained in the primary end-point analysis.

Flow of participants through the trial

See Figure 2 for CONSORT flow diagram.

Unblinding of patients

Requests for unblinding were received for a small number of patients. In all cases there were reasonable clinical justifications for the unblinding (detailed in Table 3), which were judged to be acceptable by the trial chief investigator (ChI). In view of the hard trial end points and the small number of unblinding events these are not thought to have any impact on the trial result.

| Treatment allocation | Reason for unblinding |

|---|---|

| Placebo/prednisolone | Research nurse requested unblinding of patient who had had surgery following bowel perforation previous night. Treating medical/surgical team wanted to know if patient had received steroids |

| PTX/placebo | Patient’s clinical condition had deteriorated. Responsible clinician has discussed this with ChI who has authorised unblinding |

| PTX/placebo | Due to forthcoming inquest into patient’s death, ChI requested unblinding via Hull RI research nurse |

| Placebo/placebo | Patient has been in ICU for 5–6 days following complications during an investigative procedure. Admitted to ICU 6 days after starting trial drug(s) and these ceased on admission. Patients condition ‘stable but critical’. Patient put on hydrocortisone when admitted to ICU and needs to stop [prednisolone]. Caller insists decision to stop hydrocortisone dependent on knowledge of study treatment so they can decide to stop immediately or taper drug off |

| PTX/prednisolone | Patient admitted to West Middlesex Hospital with sepsis and pneumonia. Condition developing and worsening over last 2 days |

| Placebo/prednisolone | Patient is very poorly on ITU and the his/her medical management is dependent on knowing if he/she is receiving active or placebo drug |

| PTX/placebo | Unblinding request from ChI (no further details available) |

| Placebo/prednisolone | The patient died and the treatment allocation information would be useful for the post-mortem |

| PTX/placebo | ChI agreed to unblinding as patient developed severe psychosis |

| Placebo/prednisolone | Patient had persistent jaundice since November – caller would like to know what treatment the patient was receiving when taking trial medication. The patient finished treatment on 20/12/2012 |

| PTX/placebo | Patient due to stop trial tomorrow (15/06/2013) but has been deteriorating. Consultant treating patient would like to start steroids, but only if patient hasn’t already been on steroids in the study |

| Placebo/prednisolone | First call at 23.50 – patient on GI ward with suspected perforation. Dr wants to administer IV hydrocortisone and would like to know treatment that the patient is on. Second call at 00.12 – confirming that the Dr would like to unblind as the patient has an actual perforation and sepsis. No further details on patient’s condition as caller is the on-call pharmacist |

| Placebo/prednisolone | Caller has been asked by the PI to find out what arm the patient was on. They finished the trial over 3 weeks ago and have been hospitalised with deranged LFTs. The caller has spoken to the ChI and they have confirmed that this subject can be unblinded |

| Placebo/placebo | Caller has a patient with severe VT and torsade and requires tertiary cardiac HDU care. The patient was enrolled on to the trial on 31/07/2013 and completed a month’s supply of IMP. The patient was transported from their local hospital for tertiary cardiac HDU care from the cardiologist. Local PI has received confirmation to unblind from ChI |

| PTX/prednisolone | Caller requested unblinding of a patient that has died, stating that they needed to know the treatment allocation for the coroner’s report. They think the patient died of necrotising pancreatitis and peritonitis |

Characteristics of the study sample

The baseline characteristics of the patients are typical of those seen in other studies in this population of patients. In particular, disease severity scores (DF, MELD, GAHS and Lille) were consistent with those seen in other publications. 23,31 Details of the clinical and laboratory values are provided in Table 4. There were no significant differences in laboratory values or prognostic scores between the four treatment arms except for ALP and Lille score, which were significant at the 1% level, and PT, which was significant at the 5% level.

| Baseline characteristics | Placebo/placebo (N = 272) | Prednisolone/placebo (N = 274) | Placebo/PTX (N = 273) | Prednisolone/PTX (N = 273) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | ||||

| Male | 162 (60) | 177 (65) | 164 (60) | 182 (67) |

| White | 259 (95) | 262 (96) | 264 (97) | 261 (96) |

| WHO performance status | ||||

| 0 – asymptomatic | 14 (5) | 24 (9) | 21 (8) | 26 (10) |

| 1 – symptomatic but completely ambulatory | 75 (28) | 84 (31) | 90 (33) | 77 (28) |

| 2 – symptomatic < 50% in bed | 91 (33) | 77 (28) | 69 (25) | 77 (28) |

| 3 – symptomatic > 50% in bed | 66 (24) | 69 (25) | 74 (27) | 67 (25) |

| 4 – bedbound | 22 (8) | 17 (6) | 15 (5) | 17 (6) |

| Encephalopathy | ||||

| None | 191 (70) | 205 (75) | 211 (77) | 190 (70) |

| Grade I | 46 (17) | 38 (14) | 33 (12) | 48 (18) |

| Grade II | 19 (7) | 19 (7) | 16 (6) | 12 (4) |

| Grade III | 5 (2) | 1 (< 0.5) | 5 (2) | 7 (3) |

| Grade IV | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Sepsis on admission | 31 (11) | 27 (10) | 23 (8) | 29 (11) |

| Renal failure on admission | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 |

| GI bleeding on admission | 16 (6) | 21 (8) | 15 (5) | 15 (5) |

| Pyrexia | 42 (15) | 28 (10) | 32 (12) | 34 (12) |

| Hypotension | 49 (18) | 46 (17) | 45 (16) | 52 (19) |

| Tachycardia | 47 (17) | 46 (17) | 56 (21) | 52 (19) |

| Mean (SD) | ||||

| Age (years) | 48.8 (10.28) | 49.3 (10.57) | 47.9 (10.23) | 48.6 (9.81) |

| Alcohol consumption (g/day) | ||||

| Female | 153.7 (98.54) | 141.7 (75.42) | 145.7 (93.11) | 157.0 (143.77) |

| Male | 195.4 (126.53) | 209.9 (117.67) | 192.4 (129.81) | 201.7 (127.28) |

| Time from admission to treatment (days) | 6.1 (3.82) | 6.5 (3.85) | 6.7 (4.16) | 6.5 (4.40) |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | 305.9 (157.94) | 297.5 (155.19) | 292.6 (144.62) | 306.1 (163.09) |

| Albumin (g/l) | 25.6 (6.26) | 25.2 (6.22) | 25.1 (5.37) | 25.3 (6.01) |

| AST (IU/l) | 143.7 (69.53) | 133.6 (64.78) | 134.3 (73.24) | 143.4 (77.19) |

| ALP (U/l)a | 184.7 (86.36) | 207.7 (113.06) | 182.4 (85.09) | 196.1 (98.52) |

| Creatinine (µmol/l) | 73.4 (38.33) | 79.8 (46.31) | 78.5 (49.08) | 81.5 (51.65) |

| WBC (× 109/l) | 10.1 (5.56) | 10.6 (8.13) | 9.9 (5.42) | 9.8 (4.94) |

| Neutrophils (× 109/l) | 7.6 (5.20) | 7.7 (5.24) | 7.4 (4.92) | 7.3 (4.51) |

| PT (seconds)a | 21.1 (5.27) | 20.8 (5.26) | 22.1 (6.79) | 21.1 (5.17) |

| Prognostic scores | ||||

| DF | 61.9 (25.66) | 60.7 (25.34) | 65.6 (31.64) | 62.4 (25.62) |

| GAHS | 8.2 (1.18) | 8.3 (1.27) | 8.3 (1.19) | 8.3 (1.32) |

| MELD | 20.7 (5.54) | 21.2 (6.19) | 21.4 (6.32) | 21.5 (6.84) |

| Lille scorea,b | 0.5 (0.32) | 0.4 (0.33) | 0.5 (0.34) | 0.4 (0.34) |

Allocation of treatments

Allocation to treatment arms is detailed in Table 5. Overall, 22% of patients were categorised in the high-risk classification at randomisation, although a small number of these were inappropriately classified and were correctly defined for the primary end-point analysis.

| Stratification factors | Placebo/placebo (N = 272) | Prednisolone/placebo (N = 274) | Placebo/PTX (N = 273) | Prednisolone/PTX (N = 273) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk used in randomisation,a n (%) | ||||

| Intermediate | 212 (78) | 214 (78) | 216 (79) | 214 (78) |

| Highb | 60 (22) | 60 (22) | 57 (21) | 59 (22) |

| Actual risk at baseline,c n (%) | ||||

| Intermediate | 216 (79) | 219 (80) | 222 (81) | 213 (78) |

| Highb | 56 (21) | 55 (20) | 51 (19) | 60 (22) |

| IMP centre, n (%) | ||||

| Aberdeen | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Addenbrookes | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 7 (3) | 6 (2) |

| Basildon | 0 | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 |

| Blackpool | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Bradford | 4 (1) | 5 (2) | 5 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Bristol | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) | 18 (7) |

| Derby | 17 (6) | 18 (7) | 17 (6) | 18 (7) |

| Dumfries | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 |

| Dundee | 3 (1) | 5 (2) | 4 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Edinburgh | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) | 6 (2) |

| Forth Valley | 2 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 |

| Frimley Park | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) |

| Hull | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Imperial | 23 (8) | 23 (8) | 22 (8) | 23 (8) |

| Inverness | 2 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) | 3 (1) | 2 (1) |

| King’s | 9 (3) | 8 (3) | 8 (3) | 8 (3) |

| Leeds | 0 | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Liverpool | 30 (11) | 29 (11) | 30 (11) | 29 (11) |

| Luton | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 2 (1) |

| Newcastle upon Tyne | 26 (10) | 25 (9) | 24 (9) | 26 (10) |

| Nottingham | 23 (8) | 23 (8) | 25 (9) | 25 (9) |

| Plymouth | 20 (7) | 21 (8) | 21 (8) | 21 (8) |

| Glasgow Royal Infirmary | 34 (13) | 36 (13) | 34 (12) | 35 (13) |

| Sheffield | 9 (3) | 10 (4) | 11 (4) | 10 (4) |

| Southampton | 16 (6) | 16 (6) | 16 (6) | 15 (5) |

| St Georges | 2 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (< 0.5) | 2 (1) |

| Swansea | 4 (1) | 4 (1) | 3 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Worthing | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 1 (< 0.5) | 2 (1) |

Treatment adherence

The predefined per-protocol analysis depended on measurement of treatment adherence as defined in Chapter 3, Analysis population. Per-protocol analysis required patients to have taken at least 75% of prescribed medication and that they had no protocol violations. Data on treatment adherence were poorly documented, so it was difficult to define a sufficiently sized ‘per-protocol’ population for analysis.

Primary outcome

Table 6 documents the primary outcome at 28 days. At day 28, 45 of 269 (16.7%) patients in the placebo/placebo arm had died, 50 of 258 (19.4%) patients in the PTX/placebo arm had died, 38 of 266 (14.3%) patients in the prednisolone/placebo arm had died and 35 of 260 (13.5%) patients in the PTX/prednisolone arm had died. Therefore, in the prednisolone-treated group, 13.9% of patients died compared with 18.0% in the group who did not receive prednisolone (odds ratio 0.72, 95% CI 0.52 to 1.01; p = 0.056). In the PTX-treated group, 16.5% of patients died compared with 15.5% in the group who did not receive PTX (odds ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.49; p = 0.686). There was no interaction between the effects of prednisolone and PTX (p = 0.407) (Table 7).

| PTX | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Prednisolone | |||

| No | 16.7% (45/269) (placebo/placebo) | 19.4% (50/258) (placebo/PTX) | 18.0% (95/527) |

| Yes | 14.3% (38/266) (prednisolone/placebo) | 13.5% (35/260) (prednisolone/PTX) | 13.9% (73/526) |

| Total | 15.5% (83/535) | 16.5% (85/518) | 16.0% (168/1053) |

| Prednisolone | No prednisolone | PTX | No PTX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 28-day mortality (n/N) | 13.9% (73/526) | 18.0% (95/527) | 16.4% (85/518) | 15.5% (83/535) |

| Adjusted odds ratiob (95% CI) | 0.72 (0.52 to 1.01) | 1.07 (0.77 to 1.49) | ||

| p-value | 0.056 | 0.686 | ||

Secondary outcomes

Day 90, year 1 and overall survival

Table 8 documents the secondary outcomes at day 90. At day 90, there had been 139 deaths out of 478 participants (29.1%) deaths in the PTX group compared with 146 deaths out of 490 participants (29.8%) deaths in the group not treated with PTX (odds ratio 0.97, 95% CI 0.73 to 1.28; p = 0.807). There had been 144 of 484 (29.8%) deaths in the prednisolone group compared with 141 of 484 (29.1%) deaths in the group not treated with prednisolone (odds ratio 1.02, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.35; p = 0.875) (Table 9).

| PTX | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Prednisolone | |||

| No | 26.5% (66/249) (placebo/placebo) | 31.9% (75/235) (placebo/PTX) | 29.1% (141/484) |

| Yes | 33.2% (80/241) (prednisolone/placebo) | 26.3% (64/243) (prednisolone/PTX) | 29.8% (144/484) |

| Total | 29.8% (146/490) | 29.1% (139/478) | 29.4% (285/968) |

| Prednisolone | No prednisolone | PTX | No PTX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-day mortality/liver transplant | 29.8% (144/484) | 29.1% (141/484) | 29.1% (139/478) | 29.8% (146/490) |

| Odds ratio (95% CI)b | 1.02 (0.77 to 1.35) | 0.97 (0.73 to 1.28) | ||

| p-value | 0.875 | 0.807 | ||

At 1 year there had been 205 of 365 (56.2%) deaths in the PTX group, compared with 216 of 382 (56.5%) deaths in the group not treated with PTX (odds ratio 0.99, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.33; p = 0.972). There had been 210 of 371 (29.8%) deaths in the prednisolone group, compared with 211 of 376 (56.1%) deaths in the group not treated with prednisolone (odds ratio 1.01, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.35; p = 0.937) (Tables 10 and 11).

| PTX | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||

| Prednisolone | |||

| No | 55.2% (106/192) (placebo/placebo) | 57.1% (105/184) (placebo/PTX) | 56.1% (211/376) |

| Yes | 57.9% (110/190) (prednisolone/placebo) | 55.2% (100/181) (prednisolone/PTX) | 56.6% (210/371) |

| Total | 56.5% (216/382) | 56.2% (205/365) | 56.4% (421/747) |

| Prednisolone | No prednisolone | PTX | No PTX | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-year mortality/liver transplant, % (n/N) | 56.6% (210/371) | 56.1% (211/376) | 56.2% (205/365) | 56.5% (216/382) |

| Adjusted odds ratiob (95% CI) | 1.01 (0.76 to 1.35) | 0.99 (0.74 to 1.33) | ||

| p-value | 0.937 | 0.972 | ||

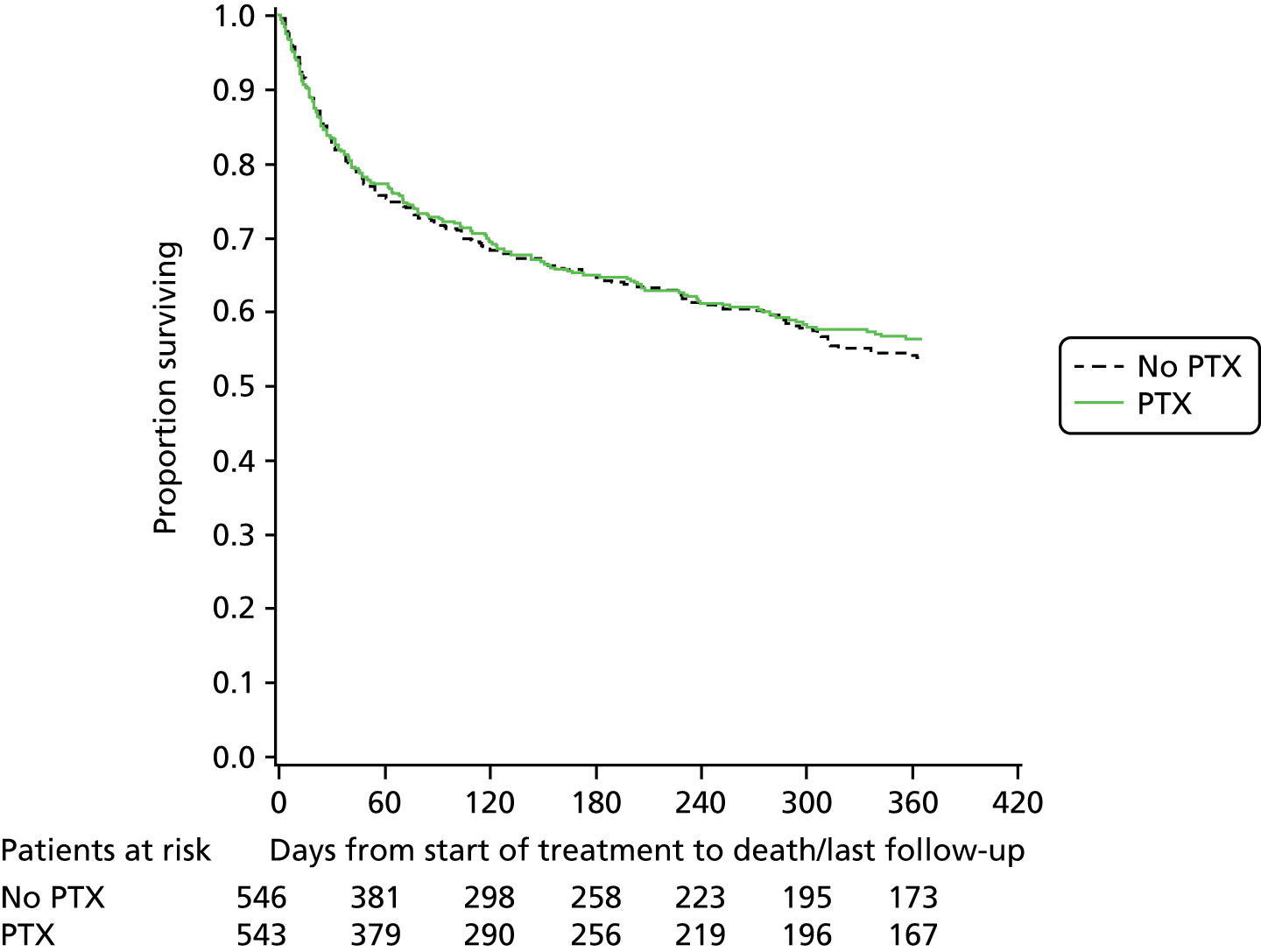

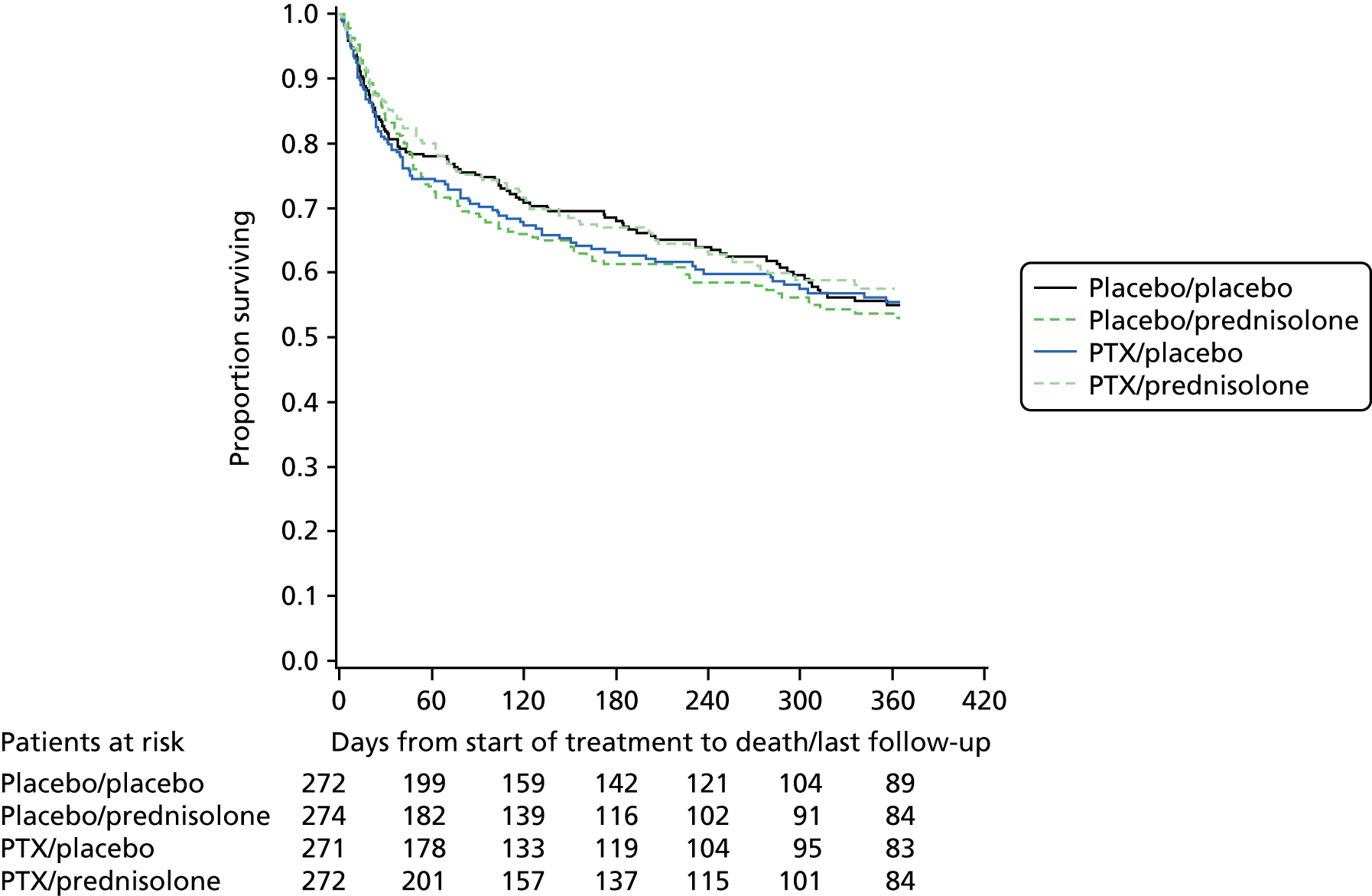

Neither prednisolone nor PTX appear to influence all-cause survival after 28 days (Figures 3–5). Analysis of the causes of mortality as recorded by the investigators indicate that most patients died from liver-related causes, and in many cases this included a contribution from sepsis. The 28-day mortality in this trial was appreciably less than that seen in other studies in this patient group. However, the overall mortality at 1 year is 56%, illustrating the extent to which ALD contributes to the alarming rise in liver disease mortality in the UK.

FIGURE 3.

Prednisolone vs. no prednisolone.

FIGURE 4.

Pentoxifylline vs. no PTX.

FIGURE 5.

Individual treatment arms.

Prognostic scores

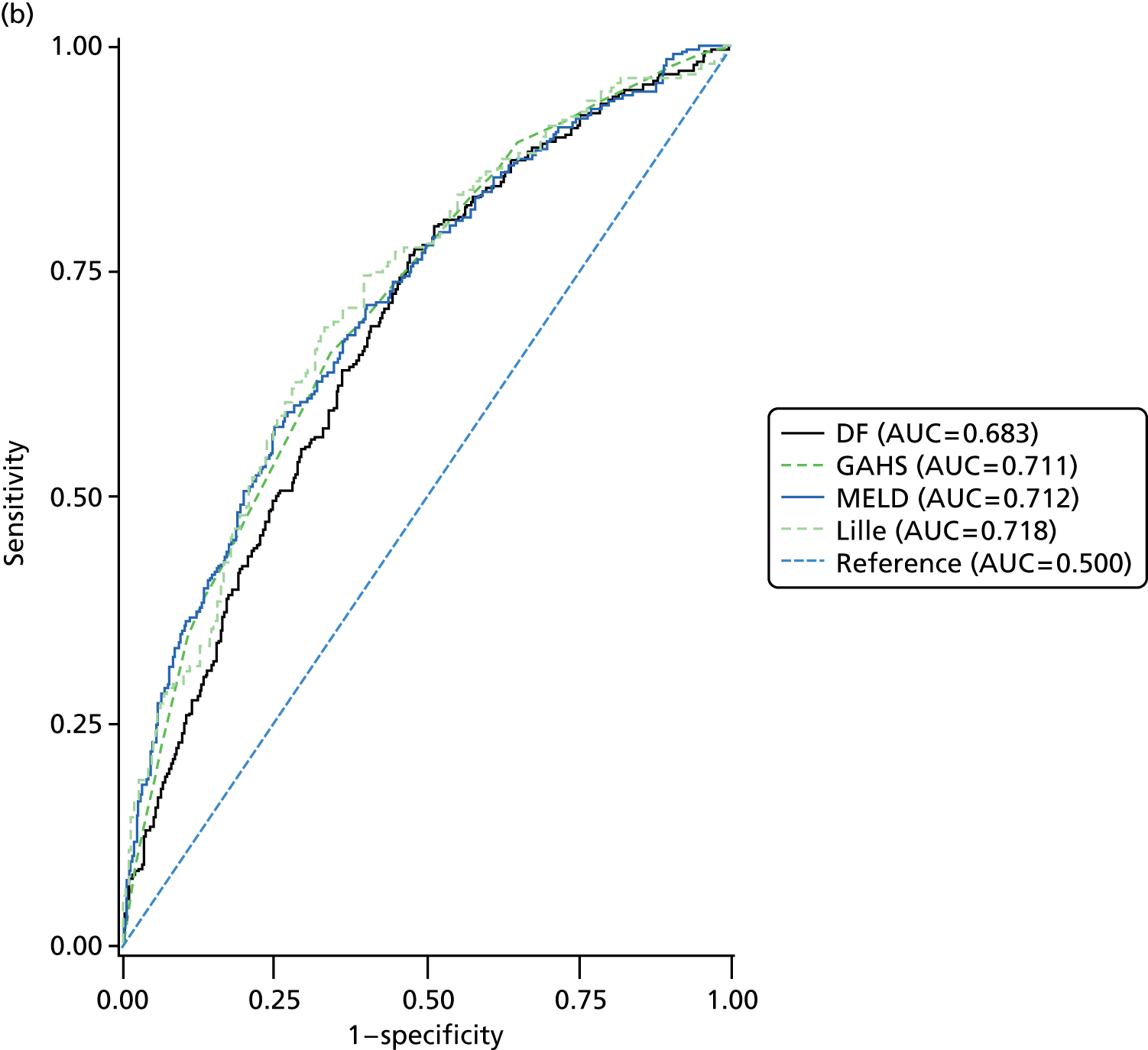

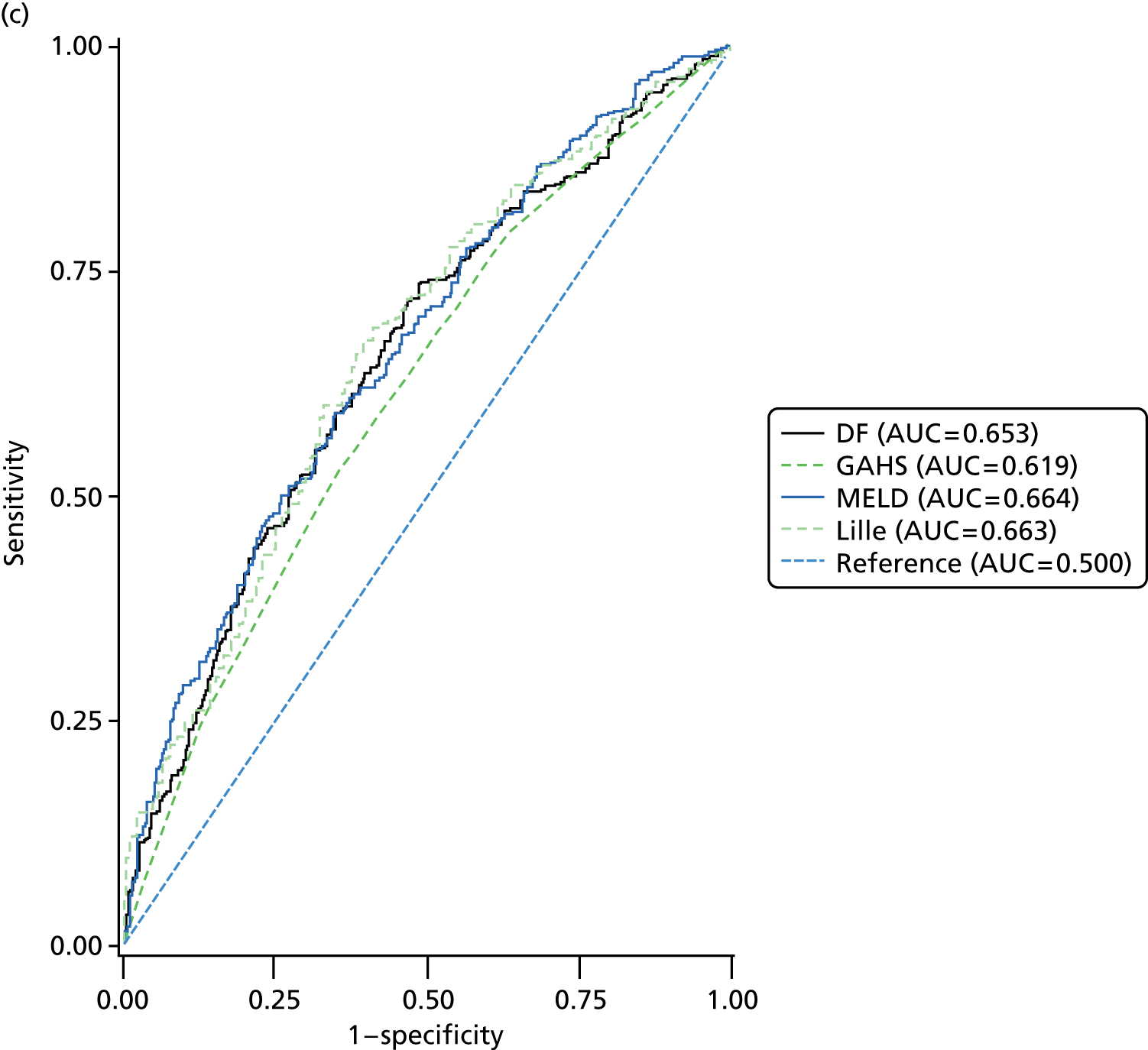

Four scoring systems have been described for use in providing prognostic information in patients with AH. DF, GAHS and MELD are derived from clinical and laboratory parameters at baseline whereas the Lille score also incorporated the response to 1 week of prednisolone therapy, determined by the change in bilirubin level at 7 days. Although each of the scores were highly significantly associated with mortality (Table 12) at each time point, the diagnostic performance was not considered to be adequate at a threshold for the area under the ROC curve of 0.75 (Table 13 and Figure 6). Inevitably the prognostic value of the scores diminished with increasing duration of follow-up.

| Prognostic score | 28-day mortalitya | 90-day mortalityb | 1-year mortalityc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| DF | 1049 | 1.021 | 1.016 to 1.027 | < 0.001 | 965 | 1.022 | 1.017 to 1.028 | < 0.001 | 744 | 1.022 | 1.015 to 1.028 | < 0.001 |

| GAHS | 930 | 2.128 | 1.789 to 2.532 | < 0.001 | 855 | 1.956 | 1.698 to 2.253 | < 0.001 | 650 | 1.406 | 1.239 to 1.595 | < 0.001 |

| MELD | 1008 | 1.147 | 1.116 to 1.179 | < 0.001 | 925 | 1.138 | 1.109 to 1.168 | < 0.001 | 715 | 1.105 | 1.076 to 1.136 | < 0.001 |

| Lilled | 697 | 1.027 | 1.019 to 1.034 | < 0.001 | 637 | 1.024 | 1.019 to 1.030 | < 0.001 | 498 | 1.017 | 1.012 to 1.023 | < 0.001 |

| Prognostic score | 28-day mortalitya | 90-day mortalityb | 1-year mortalityc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AUC | 95% CI | n | AUC | 95% CI | n | AUC | 95% CI | |

| DF | 1049 | 0.688 | 0.646 to 0.730 | 965 | 0.683 | 0.647 to 0.720 | 744 | 0.653 | 0.614 to 0.693 |

| GAHS | 930 | 0.733 | 0.689 to 0.778 | 855 | 0.711 | 0.673 to 0.748 | 650 | 0.619 | 0.577 to 0.660 |

| MELD | 1008 | 0.741 | 0.699 to 0.783 | 925 | 0.712 | 0.676 to 0.749 | 715 | 0.664 | 0.624 to 0.704 |

| Lille | 697 | 0.735 | 0.682 to 0.789 | 637 | 0.718 | 0.675 to 0.761 | 498 | 0.663 | 0.616 to 0.711 |

FIGURE 6.

Receiver operating characteristics curves for prognostic scores. (a) 28-day mortality; (b) 90-day mortality; and (c) 1-year mortality. AUC, area under the curve.

The impact of prognostic scores on the response to prednisolone was explored by stratifying patients by the magnitude of the prognostic score value or by their risk category (Table 14). These data suggest that the risk group (high vs. intermediate) has no impact on the effect of prednisolone on mortality. Based on the odds ratios, patients with a low DF and low GAHS appear to derive more benefit from prednisolone. However, in contrast, patients may benefit from prednisolone when they have a higher MELD score. These results appear contradictory and will need to be explored in further studies.

| Risk | Day 28 | Day 90 | 1 year | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | n | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| High | 218 | 0.72 (0.39 to 1.33) | 0.291 | 203 | 0.86 (0.49 to 1.52) | 0.603 | 151 | 0.82 (0.42 to 1.61) | 0.561 |

| Intermediate | 835 | 0.72 (0.48 to 1.07) | 0.105 | 765 | 1.08 (0.79 to 1.49) | 0.631 | 596 | 1.07 (0.78 to 1.48) | 0.665 |

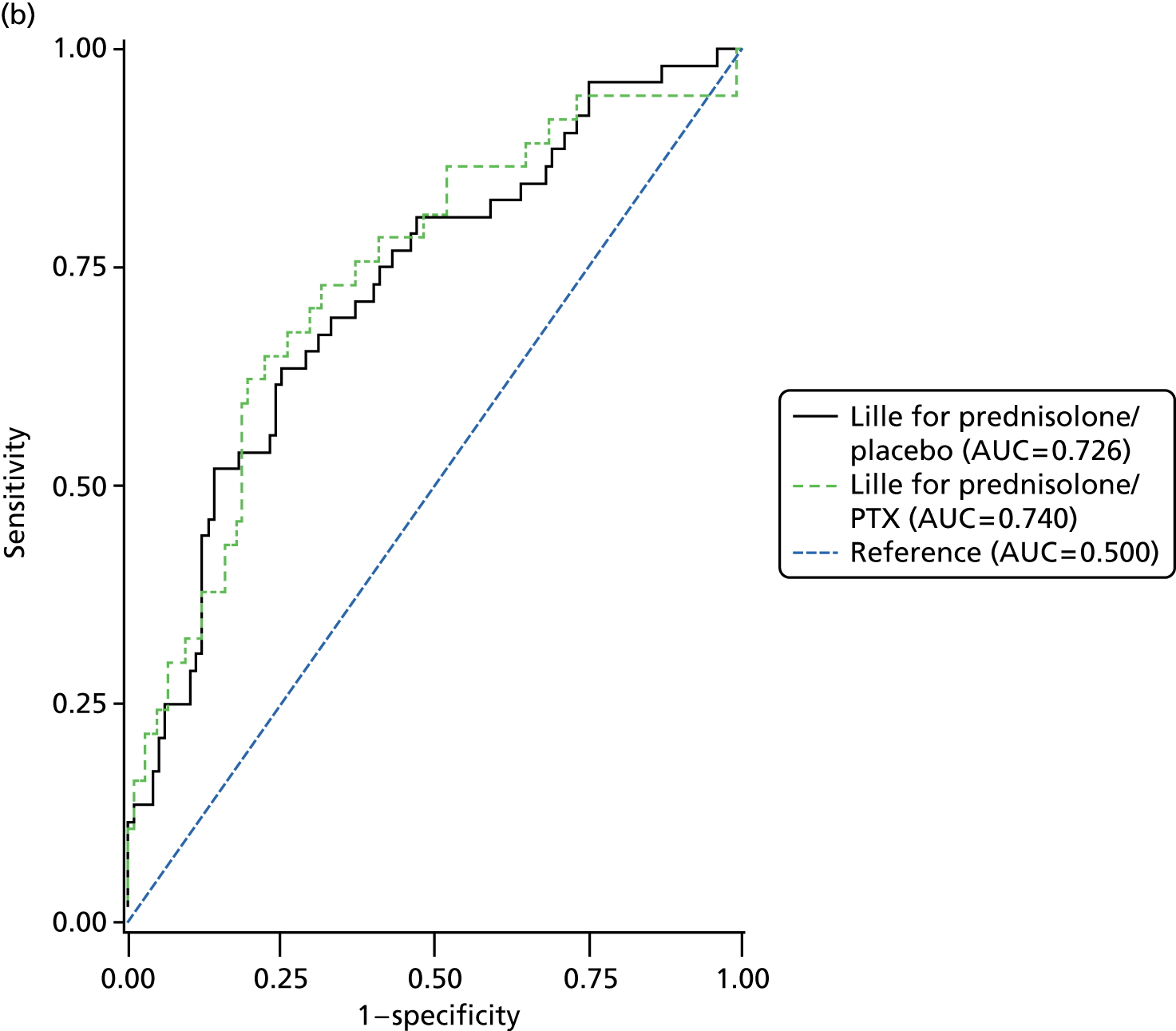

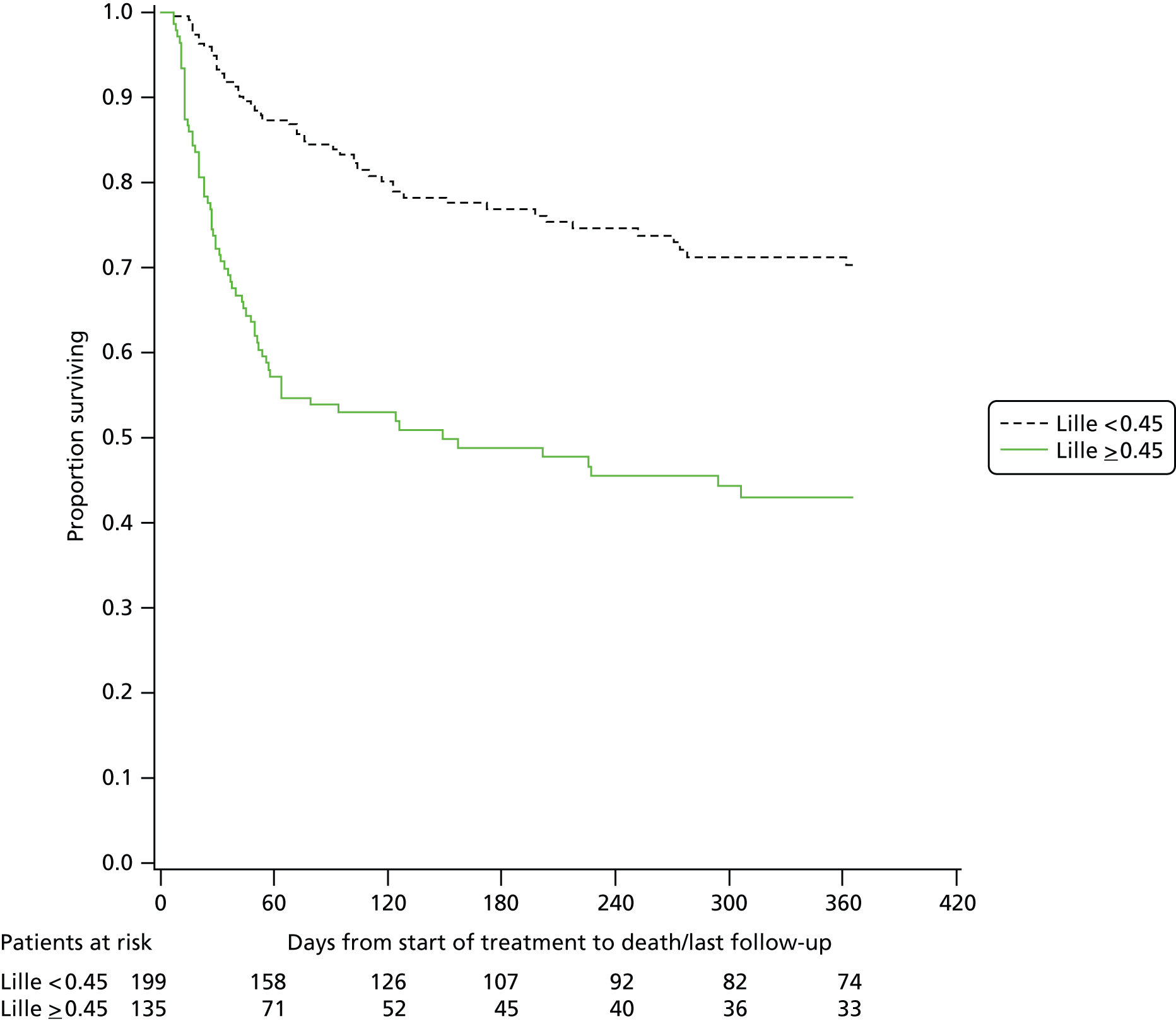

The Lille score was originally derived to predict mortality based on the response to prednisolone. When the analysis of Lille performance was restricted to only those patients who received prednisolone, the diagnostic performance improved (Table 15 and Figure 7). However, in the original description of the Lille score, a score ≥ 0.45 identified a population of patients who had an expected mortality of 75% by 6 months, whereas in our study a Lille score ≥ 0.45 was associated with around 50% survival at 6 months (Table 16 and Figure 8). At this survival rate the Lille score cannot be used to identify a population who may be suitable for liver transplantation as envisaged in the French pilot scheme.

| Lille score by treatment group | 28-day mortalitya | 90-day mortalityb | 1-year mortalityc | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | AUC | 95% CI | n | AUC | 95% CI | n | AUC | 95% CI | |

| Prednisolone/placebo | 168 | 0.765 | 0.661 to 0.870 | 152 | 0.726 | 0.640 to 0.812 | 116 | 0.650 | 0.549 to 0.751 |

| Prednisolone/PTX | 158 | 0.735 | 0.596 to 0.873 | 145 | 0.740 | 0.643 to 0.837 | 107 | 0.656 | 0.552 to 0.761 |

FIGURE 7.

Receiver operating characteristics curves to compare the Lille score (prednisolone-treated group only). (a) 28-day mortality; (b) 90-day mortality; and (c) 1-year mortality. AUC, area under the curve.

| Prednisolone group, Lille category ≥ 0.45 | Prednisolone group, Lille category < 0.45 | |

|---|---|---|

| 1-year mortality, (n/N) | 51.9% (70/135) | 24.6% (49/199) |

| Adjusted hazard ratiob (95% CI) | 2.80 (1.94 to 4.03) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

FIGURE 8.

Kaplan–Meier graph for over survival by Lille score (< 0.45 and > 0.45) (prednisolone-treated group only).

Other predictive factors of mortality

Factors that influenced mortality at 28 days, 90 days and 1 year were analysed in univariate and multivariate analyses using baseline clinical and laboratory characteristics. Table 17 summarises the findings from the univariate analysis. As expected, the variables significantly associated with mortality were encephalopathy, bilirubin, PT ratio, age, WBC count, creatinine and urea.

| Variable (baseline value) | 28-day mortalityb | 90-day mortalityc | 1-year mortalityd | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Pyrexia (temperature > 37.2 °C) | 1049 | 0.658 | 0.374 to 1.159 | 0.147 | 965 | 0.664 | 0.422 to 1.045 | 0.077 | 745 | 0.780 | 0.503 to 1.210 | 0.267 |

| Hypotension (SBP < 100mm/Hg) | 1048 | 1.200 | 0.789 to 1.826 | 0.394 | 965 | 0.981 | 0.680 to 1.414 | 0.917 | 745 | 1.134 | 0.768 to 1.673 | 0.527 |

| Tachycardia (pulse > 100 beats per minute) | 1048 | 1.085 | 0.715 to 1.646 | 0.702 | 965 | 1.024 | 0.719 to 1.459 | 0.894 | 745 | 0.941 | 0.648 to 1.366 | 0.748 |

| Alcohol intake (g/day) | 1032 | 0.999 | 0.998 to 1.001 | 0.371 | 949 | 0.999 | 0.998 to 1.000 | 0.055 | 733 | 0.999 | 0.998 to 1.000 | 0.066 |

| Albumin (g/l) | 1044 | 0.988 | 0.961 to 1.016 | 0.405 | 960 | 0.986 | 0.963 to 1.009 | 0.235 | 743 | 0.993 | 0.969 to 1.017 | 0.557 |

| ALP (U/l) | 1031 | 0.998 | 0.996 to 1.000 | 0.074 | 948 | 0.999 | 0.997 to 1.000 | 0.119 | 733 | 0.999 | 0.997 to 1.000 | 0.178 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | 1053 | 1.004 | 1.003 to 1.005 | < 0.001 | 968 | 1.003 | 1.002 to 1.004 | < 0.001 | 747 | 1.002e | 1.001 to 1.003 | 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (presence vs. absence) | 1009 | 3.700 | 2.587 to 5.292 | < 0.001 | 929 | 2.352 | 1.720 to 3.217 | < 0.001 | 717 | 2.191 | 1.539 to 3.118 | < 0.001 |

| PT ratio or INRe | 1046 | 1.379e | 1.101 to 1.727 | 0.005 | 962 | 1.909e | 1.456 to 2.504 | < 0.001 | 741 | 1.797 | 1.317 to 2.453 | < 0.001 |

| Age (years) | 1053 | 1.049 | 1.032 to 1.067 | < 0.001 | 968 | 1.050 | 1.035 to 1.065 | < 0.001 | 747 | 1.036 | 1.021 to 1.051 | < 0.001 |

| WBCs (109/l) | 1050 | 1.055 | 1.027 to 1.084 | < 0.001 | 965 | 1.045 | 1.019 to 1.071 | 0.001 | 744 | 1.017 | 0.991 to 1.043 | 0.200 |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 1041 | 1.140e | 1.099 to 1.182 | < 0.001 | 958 | 1.142e | 1.099 to 1.186 | < 0.001 | 740 | 1.124 | 1.072 to 1.178 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 1014 | 3.074e | 2.315 to 4.082 | < 0.001 | 930 | 3.070 | 2.266 to 4.161 | < 0.001 | 720 | 2.695e | 1.843 to 3.941 | < 0.001 |

Multivariate analysis was conducted by first including variables from the univariate analysis that were significant at the 5% level (Table 18). Variable selection was performed using backward elimination at the 5% significance level. The logistic regression analysis now demonstrated a clearly significant influence of prednisolone on 28-day mortality with an odds ratio of 0.609 (95% CI 0.409 to 0.909; p = 0.015). The odds ratio for 28-day mortality is adjusted for the following baseline factors: PT ratio or INR, bilirubin, age, WBC count, urea, creatinine and encephalopathy.

| Variable (baseline value) | 28-day mortalitya | 90-day mortalityb | 1-year mortalityc | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n d | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n d | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n d | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Prednisolone vs. no prednisolone | 954 | 0.609 | 0.409 to 0.909 | 0.015 | 915 | 0.995 | 0.728 to 1.361 | 0.976 | 686 | 1.012 | 0.737 to 1.390 | 0.942 |

| PTX vs. no PTX | 954 | 1.105 | 0.743 to 1.642 | 0.623 | 915 | 0.909 | 0.664 to 1.244 | 0.550 | 686 | 0.948 | 0.690 to 1.303 | 0.742 |

| PT ratio or INRe | 954 | 1.381 | 1.129 to 1.691 | 0.002 | 915 | 1.936 | 1.428 to 2.626 | < 0.001 | 686 | 1.643 | 1.171 to 2.305 | 0.004 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | 954 | 1.002 | 1.001 to 1.003 | 0.003 | 915 | 1.002 | 1.001 to 1.003 | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Age (years) | 954 | 1.050 | 1.029 to 1.071 | < 0.001 | 915 | 1.050 | 1.033 to 1.067 | < 0.001 | 686 | 1.030 | 1.014 to 1.047 | < 0.001 |

| WBCs (109/l) | 954 | 1.030 | 1.002 to 1.060 | 0.037 | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 954 | 1.065 | 1.015 to 1.118 | 0.011 | 915 | 1.088 | 1.047 to 1.130 | < 0.001 | – | – | – | – |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 954 | 1.564 | 1.048 to 2.332 | 0.028 | – | – | – | – | 686 | 2.127 | 1.452 to 3.117 | < 0.001 |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (presence vs. absence) | 954 | 3.073 | 2.050 to 4.605 | < 0.001 | 915 | 1.828 | 1.297 to 2.576 | 0.001 | 686 | 1.813 | 1.242 to 2.646 | 0.002 |

Further multivariate analysis was performed after the removal of patients who had outlying observations. A patient was classed as an outlier if they had a standardised residual with an absolute value of > 2 for the fitted variables. The results of this analysis (Table 19) show an important increase in the treatment effect of prednisolone (odds ratio 0.427, 95% CI 0.253 to 0.721); however, the treatment effect is confined to 28-day mortality with no impact on later time points.

| Variable (baseline value) | 28-day mortalitya | 90-day mortalityb | 1-year mortalityc | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n removedd | n e | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n removedd | n e | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | n removedd | n e | Odds ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Prednisolone vs. no prednisolone | 42 | 912 | 0.427 | 0.253 to 0.721 | 0.001 | 17 | 897 | 0.988 | 0.707 to 1.381 | 0.944 | 4 | 702 | 1.017 | 0.737 to 1.402 | 0.920 |

| PTX vs. no PTX | 42 | 912 | 1.282 | 0.770 to 2.136 | 0.340 | 17 | 897 | 0.960 | 0.686 to 1.343 | 0.811 | 4 | 702 | 0.939 | 0.681 to 1.296 | 0.703 |

| PT ratio or INRf | 42 | 912 | 1.903 | 1.417 to 2.558 | < 0.001 | 17 | 897 | 3.627 | 2.566 to 5.126 | < 0.001 | 4 | 702 | 3.397 | 2.283 to 5.054 | < 0.001 |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | 42 | 912 | 1.003 | 1.001 to 1.005 | < 0.001 | 17 | 897 | 1.002 | 1.001 to 1.003 | < 0.001 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| Age (years) | 42 | 912 | 1.094 | 1.063 to 1.125 | < 0.001 | 17 | 897 | 1.068 | 1.049 to 1.087 | < 0.001 | 4 | 702 | 1.032 | 1.015 to 1.049 | < 0.001 |

| WBCs (109/l) | 42 | 912 | 1.069 | 1.022 to 1.118 | 0.004 | 17 | 897 | 1.039 | 1.005 to 1.074 | 0.024 | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| Urea (mmol/l) | 42 | 912 | 1.072 | 1.008 to 1.139 | 0.027 | 17 | 897 | 1.089 | 1.046 to 1.135 | < 0.001 | 4 | 702 | 1.106 | 1.049 to 1.167 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 42 | 912 | 2.070 | 1.276 to 3.360 | 0.003 | – | – | – | – | – | 4 | – | – | – | – |

| Hepatic encephalopathy (presence vs. absence) | 42 | 912 | 6.093 | 3.641 to 10.195 | < 0.001 | 17 | 897 | 1.987 | 1.381 to 2.859 | < 0.001 | 4 | 702 | 1.775 | 1.212 to 2.598 | 0.003 |

Serious adverse events and deaths

As expected in this patient population, there were numerous adverse events and fatalities. As shown in Table 20 the vast majority of deaths were liver related and include all the common complications of acute-on-chronic liver failure.

| Cause of death | Placebo/placebo (n = 272), n (%) | Prednisolone/placebo (n = 274), n (%) | Placebo/PTX (n = 273), n (%) | Prednisolone/PTX (n = 273), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of deaths (during follow-up period)a | 106 (39) | 110 (40) | 103 (38) | 99 (36) |

| Liver related | 92 (87) | 99 (90) | 93 (90) | 81 (82) |

| Cardiac arrest (in addition to liver-related causes) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Encephalopathy | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Gastric haemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hepatic failure | 39 (37) | 36 (33) | 40 (39) | 38 (38) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders (other, alcohol abuse) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Infection-related causes | 26 (25) | 26 (24) | 24 (23) | 20 (20) |

| Multiorgan failure | 10 (10) | 16 (15) | 9 (9) | 5 (5) |

| Oesophageal varices haemorrhage | 6 (6) | 2 (2) | 8 (8) | 4 (4) |

| Pulmonary oedema | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Renal failure-related causes | 3 (3) | 9 (8) | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Upper GI haemorrhage | 3 (3) | 7 (6) | 6 (6) | 5 (5) |

| Non-liver related | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 4 (4) |

| Cardiac arrest (with no liver-related causes) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Infection-related causes | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Nervous system disorders (other, hypoxic brain injury) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Both liver and non-liver related | 7 (7) | 10 (9) | 8 (8) | 6 (6) |

| Cardiac arrest (both liver-related and non-liver-related causes) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Duodenal haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| GI disorders (other, ruptured umbilical hernia) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hepatic failure | 1 (1) | 5 (5) | 3 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Infection-related causes | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications (other, intoxicated) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Multiorgan failure | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Nervous system disorders (other, traumatic brain injury) | 2 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Pulmonary oedema | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Renal failure-related causes | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stroke | 2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Thromboembolic event | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Unknown | 4 (4) | 0 | 2 (2) | 7 (7) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions (other, bleeding) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural causes | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Not available | 3 (3) | 0 | 2 (2) | 5 (5) |

| Upper GI haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

Serious adverse events are summarised in Table 21. Over 75% of SAEs were at Common Toxicity Criteria For Adverse Events grade 3 or above. SAEs resulted in mortality in 31% of cases. Details of the SAEs are given in Table 22 and the incidence of infection is shown in Table 23.

| SAEs reported | Placebo/placebo (n = 272), n (%) | Prednisolone/placebo (n = 274), n (%) | Placebo/PTX (n = 273), n (%) | Prednisolone/PTX (n = 273), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients experiencing at least one SAEa | 106 (39) | 128 (47) | 111 (41) | 116 (42) |

| Total number of SAEs | 136 | 184 | 145 | 159 |

| Number of SAEs/SARs/SUSARs per patienta | ||||

| 1 | 83 (31) | 90 (33) | 84 (31) | 87 (32) |

| 2 | 17 (6) | 25 (9) | 22 (8) | 19 (7) |

| 3 | 5 (2) | 11 (4) | 3 (1) | 6 (2) |

| 4 | 1 (< 0.5) | 0 | 2 (1) | 4 (1) |

| ≥ 5 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Principal investigator assessment (with reference to prednisolone/PTX)b | ||||

| SUSAR/SAE | 0 | 3 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| SAE/SAR | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 5 (3) | 0 |

| SAR/SAE | 5 (4) | 24 (13) | 13 (9) | 19 (12) |

| SAR/SAR | 4 (3) | 11 (6) | 4 (3) | 3 (2) |

| SAE (no IMP taken) | 3 (2) | 6 (3) | 3 (2) | 13 (8) |

| SAE/SAE | 123 (90) | 138 (75) | 120 (83) | 123 (77) |

| CTCAE gradeb | ||||

| 1 – mild | 4 (3) | 9 (5) | 7 (5) | 4 (3) |

| 2 – moderate | 28 (21) | 41 (22) | 30 (21) | 42 (26) |

| 3 – severe | 37 (27) | 49 (27) | 36 (25) | 41 (26) |

| 4 – life-threatening | 25 (18) | 28 (15) | 25 (17) | 31 (19) |

| 5 – death-related to SAE | 42 (31) | 57 (31) | 47 (32) | 41 (26) |

| Why the event was serious | ||||

| 1 – resulted in death | 45 (33) | 54 (29) | 47 (32) | 37 (23) |

| 2 – life-threatening | 21 (15) | 20 (11) | 19 (13) | 31 (19) |

| 3 – required hospitalisation or prolongation of existing hospitalisation | 68 (50) | 110 (60) | 75 (52) | 91 (57) |

| 4 – persistent or significant disability/incapacity | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| 5 – congenital anomaly/birth defect | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| 6 – medically significant event | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Action taken following prednisoloneb | ||||

| 0 – none | – | 131 (71) | – | 107 (67) |

| 1 – dose reduction | – | 0 | – | 0 |

| 2 – treatment delayed | – | 14 (8) | – | 13 (8) |

| 3 – treatment reduced and delayed | N/A | 0 | N/A | 0 |

| 4 – treatment stopped | – | 33 (18) | – | 26 (16) |

| No IMP given | – | 6 (3) | – | 13 (8) |

| Action taken following PXTb | ||||

| 0 – none | – | – | 77 (53) | 107 (67) |

| 1 – dose reduction | – | – | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| 2 – treatment delayed | – | – | 10 (7) | 12 (8) |

| 3 – treatment reduced and delayed | N/A | N/A | 1 (1) | 0 |

| 4 – treatment stopped | – | – | 52 (36) | 26 (16) |

| No IMP given | – | – | 3 (2) | 13 (8) |

| System organ class and CTCAE event | Placebo/placebo (n = 272), n (%) | Prednisolone/placebo (n = 274), n (%) | Placebo/PTX (n = 273), n (%) | Prednisolone/PTX (n = 273), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of SAEs | 136 | 184 | 145 | 159 |

| GI disorders | 31 (23) | 49 (27) | 56 (39) | 48 (30) |

| Ascites | 7 (5) | 13 (7) | 14 (10) | 13 (8) |

| Upper GI haemorrhage | 5 (4) | 12 (7) | 10 (7) | 18 (11) |

| Oesophageal varices haemorrhage | 7 (5) | 5 (3) | 7 (5) | 5 (3) |

| Abdominal pain | 6 (4) | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Pancreatitis | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Vomiting | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) |

| Abdominal distension | 0 | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Diarrhoea | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) |

| GI disorders: other | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Oesophageal haemorrhage | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Lower GI haemorrhage | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Colonic perforation | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Gastric haemorrhage | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| GI pain | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Nausea | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Rectal haemorrhage | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Colitis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Colonic obstruction | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Constipation | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Duodenal perforation | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Enterocolitis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Ileus | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 27 (20) | 44 (24) | 16 (11) | 30 (19) |

| Lung infectiona | 11 (8) | 20 (11) | 6 (4) | 18 (11) |

| Sepsis | 8 (6) | 11 (6) | 6 (4) | 3 (2) |

| Infections and infestations: other | 6 (4) | 9 (5) | 3 (2) | 3 (2) |

| Skin infection | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Hepatic infection | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Abdominal infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Endocarditis infective | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Joint infection | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 27 (20) | 27 (15) | 24 (17) | 23 (14) |

| Hepatic failure | 26 (19) | 27 (15) | 23 (16) | 22 (14) |

| Hepatobiliary disorders: other | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 10 (7) | 10 (5) | 13 (9) | 8 (5) |

| Acute kidney injury | 9 (7) | 5 (3) | 4 (3) | 5 (3) |

| Renal and urinary disorders: other | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 9 (6) | 3 (2) |

| Nervous system disorders | 12 (9) | 12 (7) | 6 (4) | 9 (6) |

| Encephalopathy | 8 (6) | 4 (2) | 4 (3) | 4 (3) |

| Seizure | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Syncope | 0 | 4 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Stroke | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Depressed level of consciousness | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Nervous system disorders: other | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 7 (5) | 12 (7) | 9 (6) | 11 (7) |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (1) | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 5 (3) |

| Dyspnoea | 2 (1) | 4 (2) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Adult respiratory distress syndrome | 0 | 0 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) |

| Pulmonary oedema | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 2 (1) |

| Pleural effusion | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders: other | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Aspiration | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bronchospasm | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Epistaxis | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hypoxia | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| General disorders and administration site conditions | 8 (6) | 6 (3) | 7 (5) | 9 (6) |

| Multiorgan failure | 6 (4) | 3 (2) | 6 (4) | 7 (4) |

| Malaise | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| General disorders and administration site conditions: other | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Non-cardiac chest pain | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Oedema limbs | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications | 5 (4) | 7 (4) | 3 (2) | 8 (5) |

| Fall | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Injury, poisoning and procedural complications: other | 0 | 4 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Fracture | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Arterial injury | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Hip fracture | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Seroma | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Psychiatric disorders | 4 (3) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) | 4 (3) |

| Confusion | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) |

| Hallucinations | 2 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psychosis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Psychiatric disorders: other | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Suicide attempt | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac disorders | 3 (2) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Cardiac arrest | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Chest pain – cardiac | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Myocardial infarction | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Ventricular tachycardia | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 5 (3) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Hyperglycaemia | 0 | 4 (2) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Dehydration | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Investigations | 0 | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Investigations: other | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Vascular disorders | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Hematoma | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Thromboembolic event | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (2) | 0 |

| Anaemia | 0 | 0 | 2 (1) | 0 |

| Haemolysis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Leucocytosis | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Back pain | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Muscle weakness lower limb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Myositis | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 0 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Skin ulceration | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Toxic epidermal necrosis | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Social circumstances | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Social circumstances: other | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Type of SAE and time point | Prednisolone (n = 551), n (%) | No prednisolone (n = 552), n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with an infection-related SAE | 71 (13) | 38 (7) |

| Before start of treatment | 3 (1) | 2 (< 0.5) |

| Day 1–28 | 50 (9) | 31 (6) |

| Day 29–56 | 16 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Multiple time points | 2 (< 0.5) | 2 (< 0.5) |

| Number of patients who died from an infection-related SAEa | 25 (35) | 12 (32) |

| Before start of treatment | 1 (1) | 2 (5) |

| Day 1–28 | 16 (23) | 10 (26) |

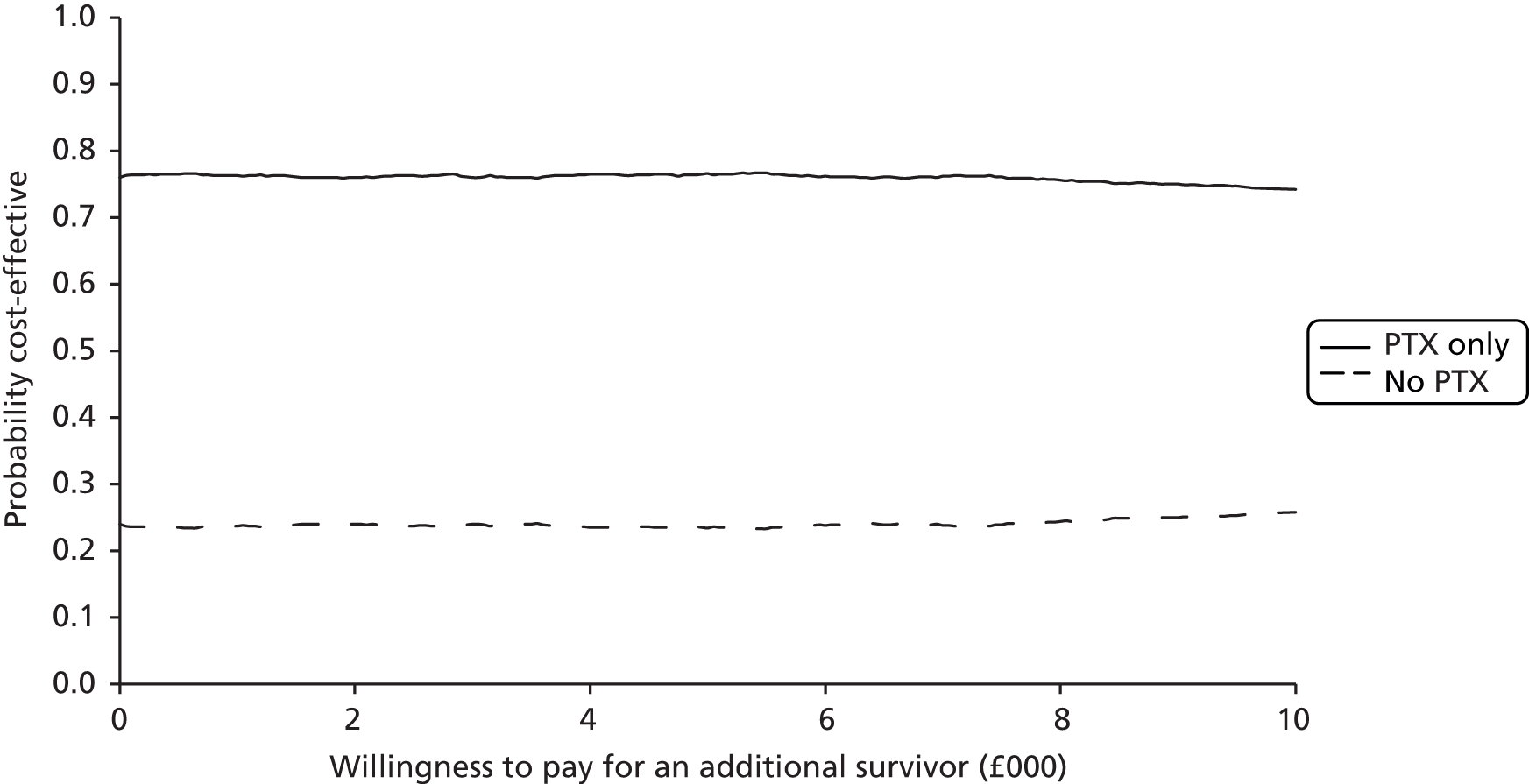

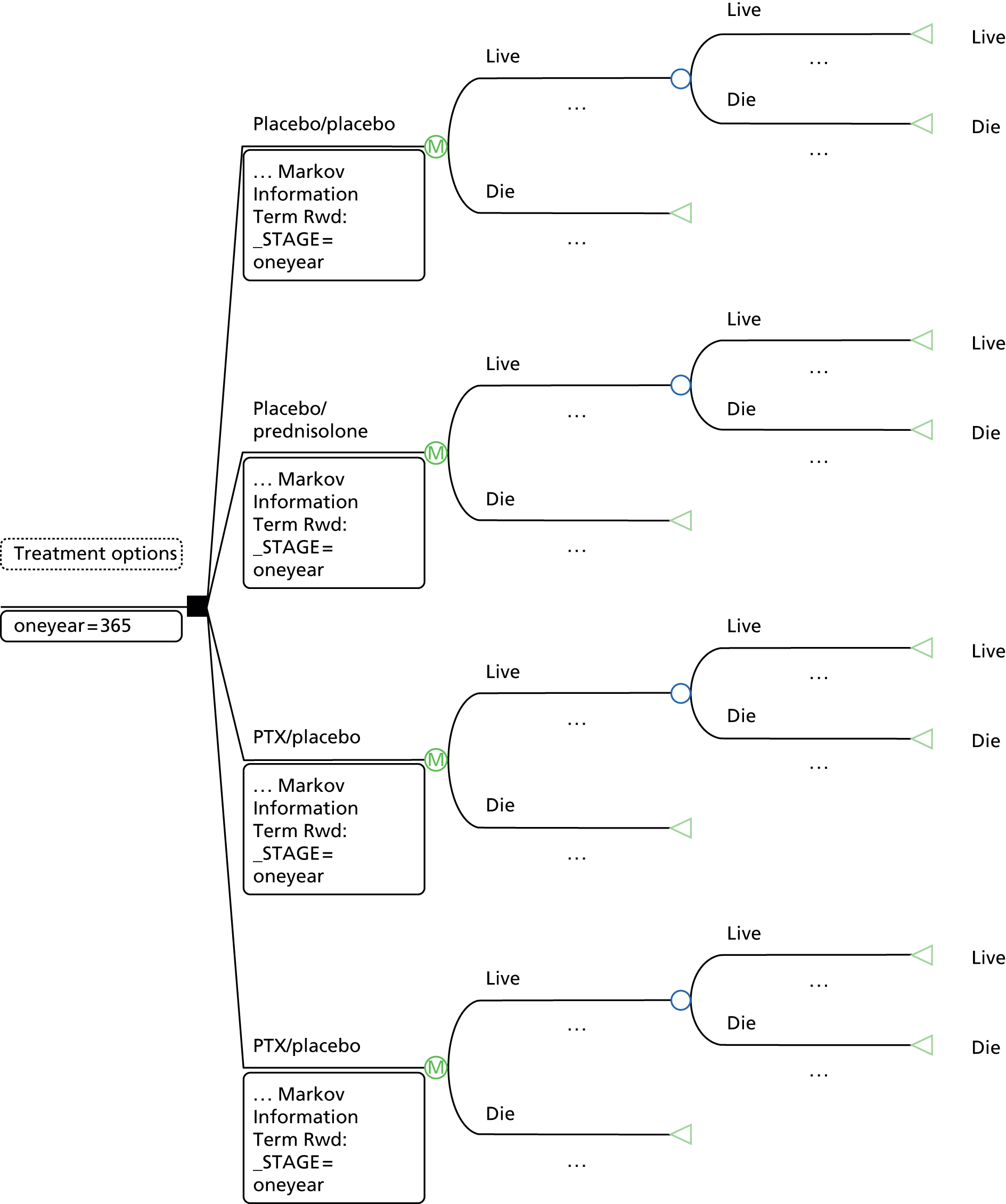

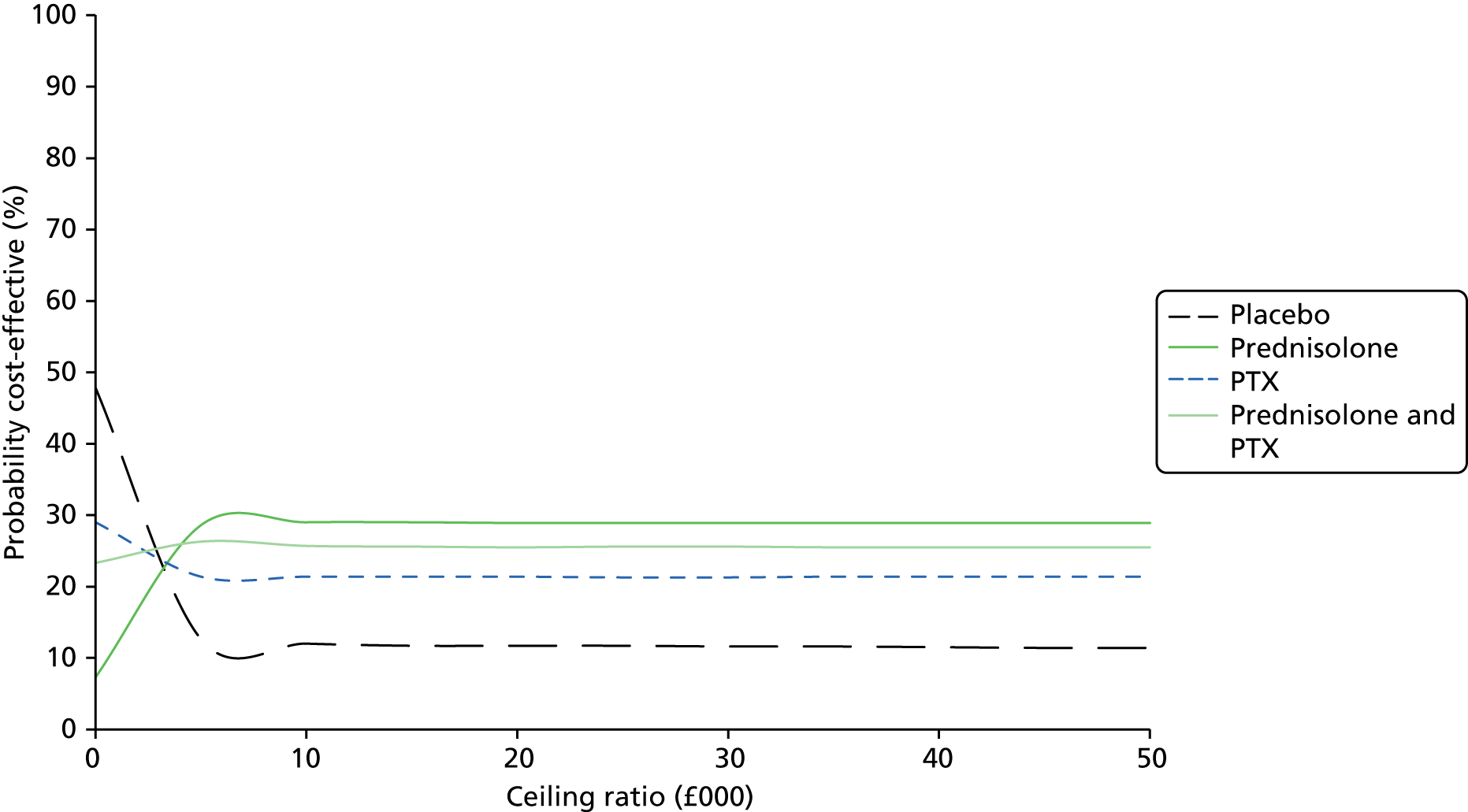

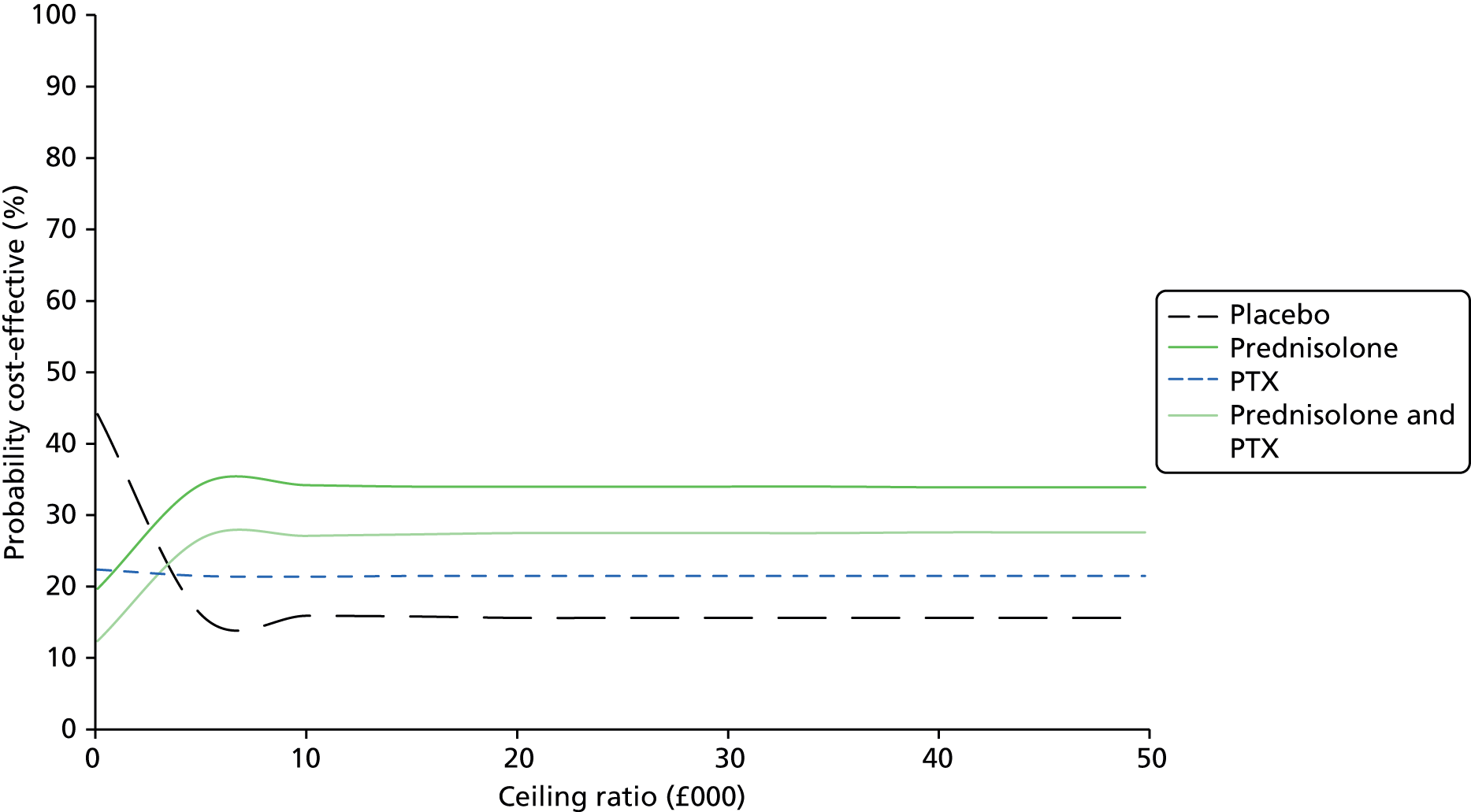

| Day 29–56 | 8 (11) | 0 |