Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/117/01. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The draft report began editorial review in June 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme commissioned this project following a bid by the authors, based at the Wessex Institute, University of Southampton. James Raftery is Professor of HTA at the Wessex Institute. He is a member of the HTA Editorial Board. Amanda Young has been employed by NETSCC since 2008. Louise Stanton was previously employed by NETSCC from 2008 to 2011. Ruairidh Milne is Director of the Wessex Institute and Head of NETSCC. He was employed by NETSCC from 2006 to 2012. Andrew Cook has been employed by NETSCC since 2006. David Turner was previously employed by the Wessex Institute from 2006 to 2011. Peter Davidson is a member of the HTA Editorial Board and has been Director of the HTA programme since 2006. As academics and professional researchers, the authors do not believe they have allowed bias to affect the design of the work, the analysis or the conclusions. Measures to prevent bias included an eminent advisory group and prospective specification of questions.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Raftery et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The Health Technology Assessment programme

The Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, established in 1993, recently celebrated its 20th birthday, part of which included an account of its history. 1 In brief, the programme funds assessments of health technologies with the aim of meeting the research needs of the NHS with scientifically robust evidence. These assessments take two forms: reviews of existing evidence and new research. The latter generally takes the form of clinical trials, most but not all of which are randomised. The overarching aim of the study is to assess the extent to which these trials contributed to meeting the needs of the NHS with scientifically robust evidence.

These randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are of interest for several reasons. First, although over 100 projects involving RCTs had been published by the end of 2011, no systematic compilation exists. Projects may include more than one trial. Some projects report on trials that either failed to recruit or had to depart from plans. As over 200 RCTs funded by the programme were in progress in 2011, a systematic list was required. Second, a small but growing literature studies RCTs. Reviewed below, this literature highlights the desirability of having standardised descriptions of key aspects of these trials.

The RCTs funded by the HTA programme are distinctive in being pragmatic, as opposed to explanatory or licensing trials. They aimed to evaluate the technology of interest in real-world conditions. Inclusion criteria were wide rather than narrow. Patient-related outcomes were preferred to intermediate or surrogate outcomes. Economic analysis was almost always included, sometimes along with qualitative studies. As most of the guidelines for the design, conduct and performance of clinical trials were designed for explanatory and licensing trials, their application to the pragmatic trials funded by the HTA programme may pose problems.

Studies of randomised controlled trials funded by the Health Technology Assessment programme

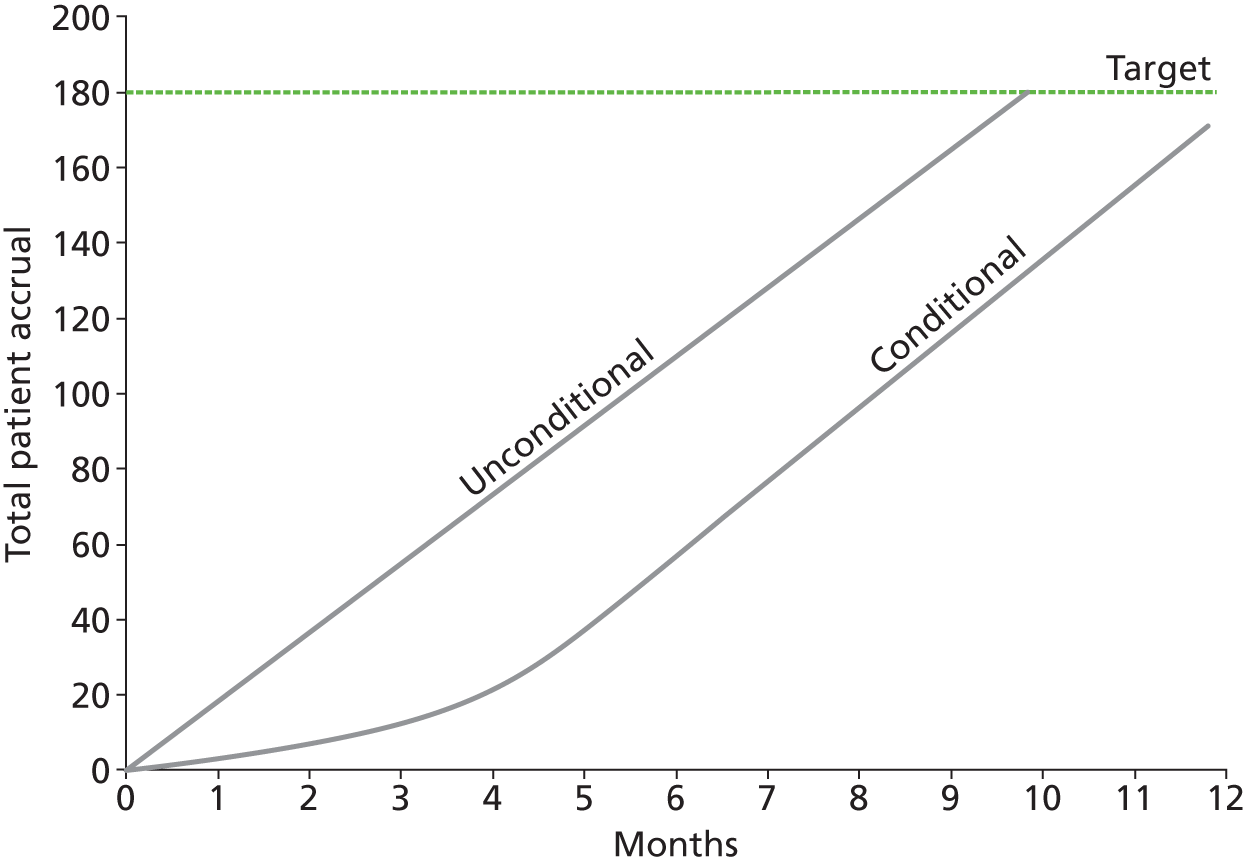

The Strategies for Trial Enrolment and Participation Study (STEPS),2 summarised in Chapter 6, reviewed recruitment in a cohort of trials funded by the HTA programme and the Medical Research Council (MRC) between 1994 and 2003, and showed that 80% failed to recruit 80% of planned patients.

A study of the impact of the HTA programme, published in 2007,3 reviewed all HTA-funded projects completed between 1993 and 2005, including many which did not include clinical trials, using Buxton and Haney’s payback method. 4 Data were drawn from HTA files and monograph reports supplemented by a survey of lead investigators and a random selection of case studies. It recommended collection of routine data on key headings from the payback approach (all peer-reviewed publications, data on other publications and presentations, capacity development linked to the project, etc.). The assessment of the impact of studies on policies was limited to the lead investigators’ views, which were explored in case studies.

One study considered how many trials funded by the programme showed a statistically significant difference in the primary outcome. 5 In the period 1993–2008 some two-thirds did not report such a difference. 5 This proportion was shown to be similar to other trial portfolios, notably that of National Institutes of Health (NIH) cancer trials. 6

Trials that fail to show such differences can make valuable contributions via their contributions to meta-analyses based on systematic reviews. Another study, which analysed one HTA trial and explored its contribution to the meta-analysis, showed that, although the question posed had been important at the time of commissioning the trial (large effect size, wide confidence interval), the reporting of six other trials in the interim meant that its eventual contribution to the meta-analyses was limited to narrowing the confidence intervals. 7 To follow up this work, one would need to know how many clinical trials funded by the HTA programme had both a relevant preceding and a subsequent meta-analysis.

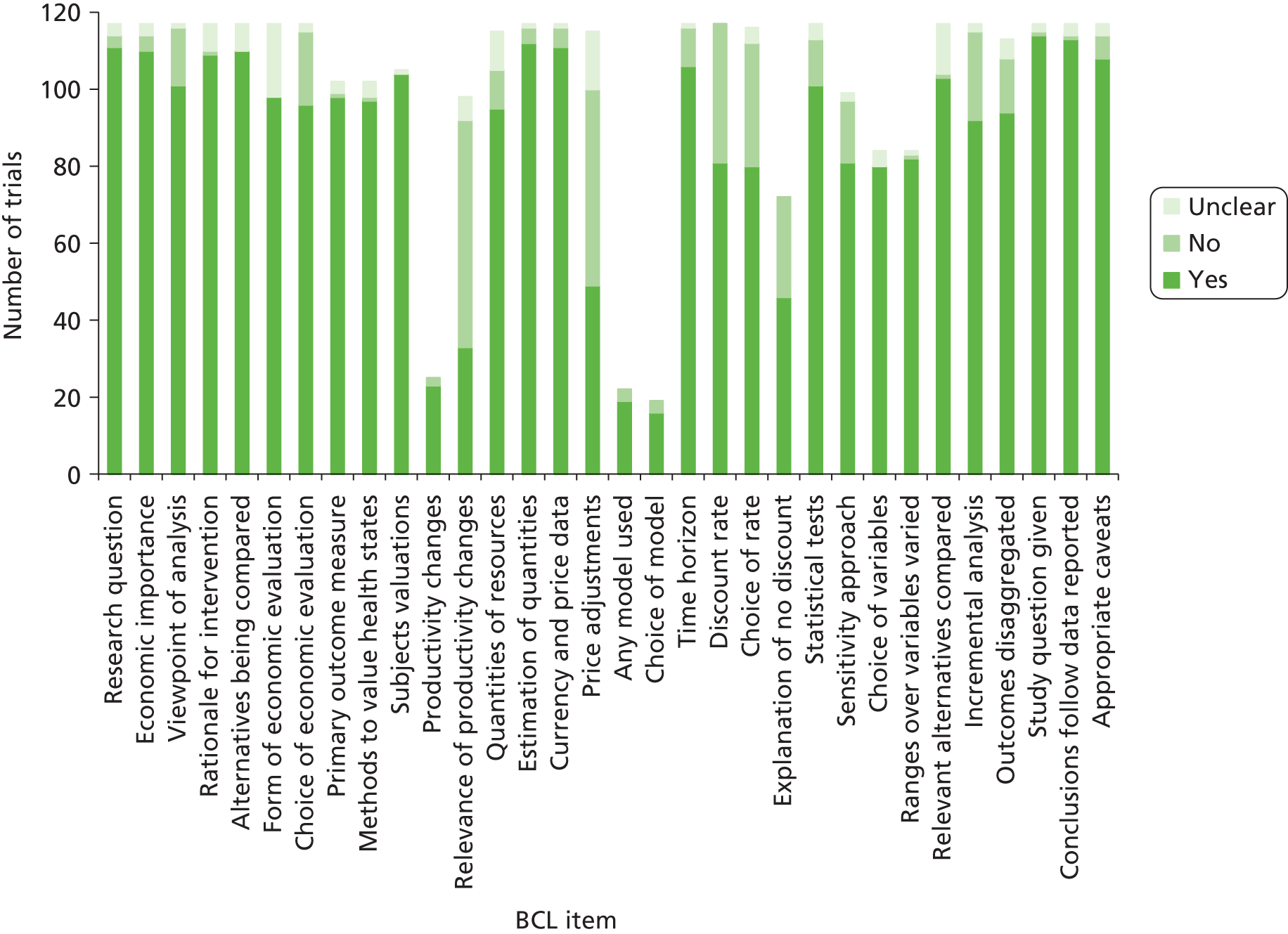

Finally, a review of economic analyses in HTA trials showed that economic analyses were generally included in trials funded by the HTA programme. 8

Metadata

Metadata is a term commonly used with regard to digital equipment such as cameras to refer to the data routinely recorded about each item, such as time and date. Additional data headings can be added, such as place and persons. Any document prepared using a standard word processing package contains metadata indicating date, person, computer, etc. Non-digital indexes such as a traditional library indexing system can also be described as metadata.

Some databases already contain metadata on clinical trials, such as the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) register (www.controlled-trials.com) and the US ClinGov register (https://clinicaltrials.gov). These registers, discussed more fully in Chapter 2, register trials under around 20 descriptive headings including title, start and planned completion dates, disease, intervention, primary outcomes, planned recruitment and contacts. No headings are specified for the reporting or analysis of results, or for the conduct or performance of the trial.

Aims

The aim of the project was to develop and pilot ‘metadata’ on clinical trials funded by the HTA programme. In exploring how to extend the metadata held in existing clinical trial registries, we considered two options. We could either aim to specify a comprehensive data set capable of answering all potential questions, or design a data set to answer particular questions. We pursued the latter option, starting with a set of themes and related questions that might plausibly be answered by such metadata.

We explored questions under six themes using classification systems in answering particular questions. Some classification systems were simple (yes/no) and some complex (16 headings for the European Medicines Agency guideline on handling missing data). Questions that had to do with whether or not analyses were as planned required not only classification of the planned and actual analyses, but also of their (dis)agreement. Data sources comprised both published and unpublished documents. Published sources were largely those in the HTA journal monograph series but also study protocols (most but not all published on the HTA website since 2006). Key unpublished sources included final application forms as well as vignettes, commissioning briefs and project protocol change forms.

The project explored the extent to which metadata could provide standardised data which would be useful not only in managing that portfolio but also in enabling assessment of the conduct, analysis and cost of those trials. Such assessment of the trials would require high-quality data, which had been subject to explicit quality assurance.

The four project objectives, as stated in the final application funded by the HTA programme, were:

-

to develop, pilot and validate metadata definitions and classification systems to answer specified questions within six themes

-

to extract data under these headings from published RCTs funded by the HTA programme

-

to analyse these data to answer specific questions grouped by theme

-

to consider further development and uses of the data set, including refinements of the metadata headings for their application to ongoing and future HTA trials.

The protocol stated that:

Metadata would provide standardised data about the portfolio of HTA trials. These data would enable assessment of questions such as how well the trials were conducted, and the extent to which their results were as expected. Some limited metadata are already publicly available; their extension as proposed here will require appropriate data headings (or classification systems), some of which would be developed in this project.

It also stated that:

The provision of such data would enable performance of the trial portfolio to be monitored over time. Such data would also indicate foci for improvement and help assess the contribution of the ‘needs-led’ and ‘value added’ scientific inputs. To the extent that similar data could be collated for other trials, these could be compared with the HTA trials.

Our research themes

The themes of most immediate interest was based around the composition and performance of the ‘portfolio’ of clinical trials funded by the HTA programme. The provision of such data was seen as enabling performance of the trial portfolio to be monitored over time. Such data would also indicate foci for improvement and help to assess the contribution of the ‘needs-led’ and ‘value-added’ elements of the programme.

The project proposal aimed to extend these trial registration metadata to include data required to answer questions under the following six broad themes:

-

How was the trial seen as meeting the needs of the NHS?

-

How well designed was the trial?

-

How well conducted was the trial?

-

Were the statistical analyses appropriate?

-

What, if any, kind of economic analysis was performed?

-

What was the cost of the trial?

Themes 1 (meeting the needs of the NHS) and 5 (economics) relate to the HTA programme’s overarching aim of meeting the needs of the NHS. Themes 2, 3 and 4 address the robustness of the scientific evidence. Theme 6, on the cost of trials, helps explore value for money.

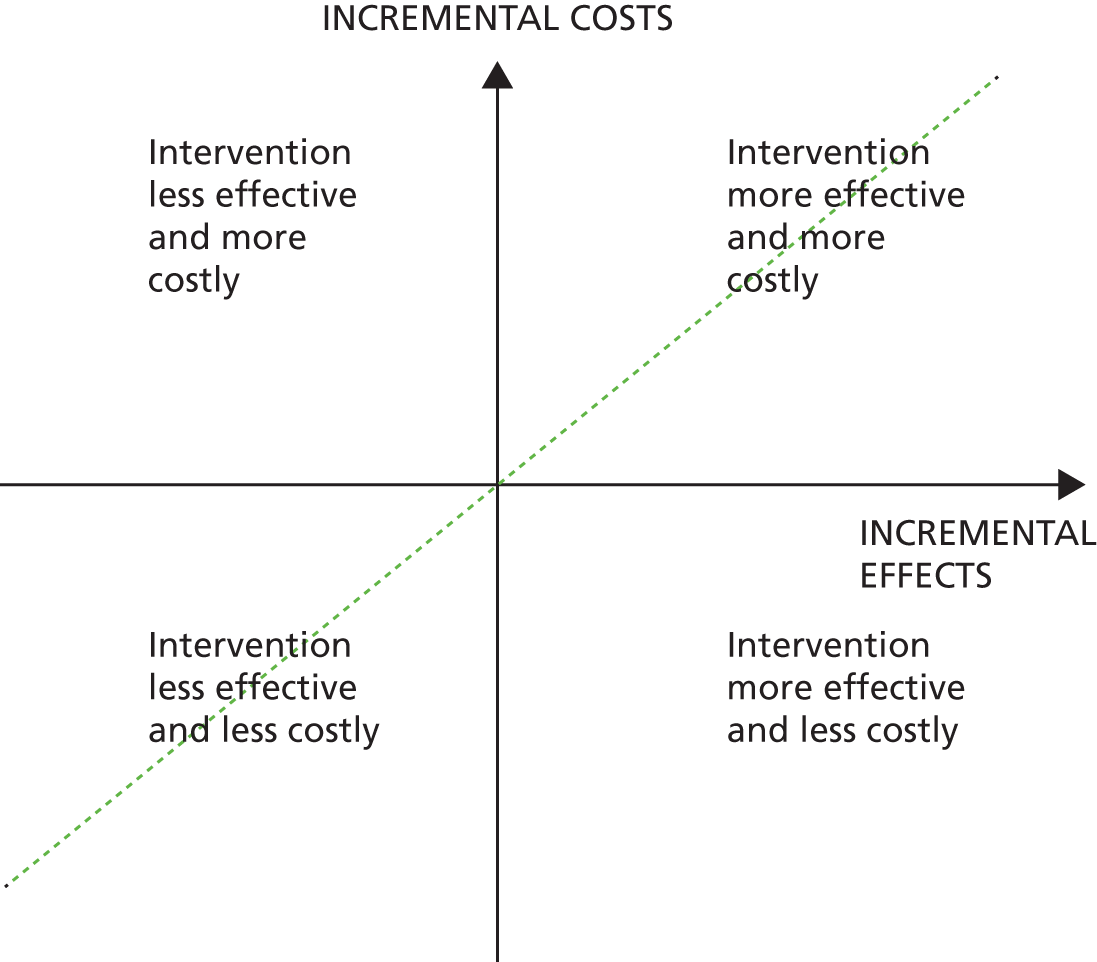

The choice of the above themes was that of the authors, guided by the literature and aiming to update or replicate previous studies. Four of the authors (JR, RM, PD and AC), having worked for the National Institute for Health Research Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) in a range of senior roles, identified these themes as of concern to the programme. Relevant published studies were updated where possible. As part of the first theme (the origin of the research question), an earlier paper by Chase et al. 9 was updated. For the second theme (design of trials), previous studies by Chan et al. 10 were drawn on. For performance (the third theme), STEPS,2 which examined the recruitment success of multicentre RCTs, was important. For the fourth theme (statistical analysis), besides Chan et al. 10 and Chan and Altman,11 the issues of concern were with the appropriate analysis of primary outcomes, including the congruence of planned and actual analyses. For economic analysis (the fifth theme), the widely used 1996 BMJ guideline12 provided a starting point. Few studies have been published on the costs of trials, mainly to do with commercial trials in the USA. Guidance from the UK Department of Health specified how non-commercial trials13 should be costed but its application had not been studied. This was the sixth theme. Each of these themes was operationalised into more specific questions and iterated against the data available (see Chapters 4–9).

Project team

Details of each authors' contributions are provided in Acknowledgements (p.113). An external advisory group, also detailed in Acknowledgements, provided valuable input for which we are grateful.

Structure of the report

The aims and objectives related to the development of the metadata were described in this chapter. Chapter 2 provides a review of the existing databases, Chapter 3 reports on methods and Chapters 4–9 report on each of the six themes. Chapters 10 and 11 provide a discussion of the main findings, draw conclusions for the overall project and discuss recommendations of the type of questions that are plausible for future use in the metadata database.

Chapter 2 Data quality and reporting in existing clinical trial registries: a review of existing databases

This chapter briefly reviews existing databases of clinical trials, including descriptions of the main databases and studies which have used them, based on a systematic literature search (detailed in Appendix 1).

Trial registries: the USA

The impetus for the US clinical trials database, ClinGov, came from legislation in 1997, against the background of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic, that mandated a registry of clinical trials for both federally and privately funded trials ‘of experimental treatments for serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions.’14 Patient groups had demanded ready access to information about clinical research studies so that they might be more fully informed about a range of potential treatment options, particularly for very serious diseases. The law emphasised that the information in such a registry must be easily accessible and available to patients, the public, health-care providers and researchers in a form that can be readily understood. 15

Previous attempts to establish clinical trials information systems had focused less on patient access than on clinician and researcher access and use. ClinGov had been concerned that if relevant data about trials were not published or are poorly reported, publication bias and, ultimately, poor care could result.

The design of ClinGov was guided by the following principles:

-

to ensure that design and implementation was guided by the needs of the primary intended audience, patients and other members of the public

-

to get broad agreement on a common set of data elements with a standard syntax and semantics

-

to acknowledge that requirements would evolve over time, implying a modular and extensible design.

A web-based system resulted, which aimed to be easy for novice users but which had extensive functionality. As all NIH-sponsored trials were to be included, ClinGov worked closely with the 21 NIH institutes, each of which had varying approaches to data management and collection and varying levels of technical expertise. The 21 institutes agreed on a common set of data elements for the clinical trials data. Just over a dozen required data elements and another dozen or so optional elements were agreed. The elements fell into several high-level categories: descriptive information such as titles and summaries; recruitment information to let patients know whether or not it is still possible to enrol in a trial; location and contact information to enable patients and their doctors to discuss with the persons who are actually conducting the trials; administrative data, such as trial sponsors and identification numbers; and optional supplementary information, such as literature references and keywords. Table 1 lists the 15 required and 12 optional data elements.

| Required data elements | Optional data elements |

|---|---|

| 1. Study identification number | 1. NIH grant or contract number |

| 2. Study sponsor | 2. Investigator |

| 3. Brief title | 3. Official title |

| 4. Brief summary | 4. Detailed description |

| 5. Location of trial | 5. Study start date |

| 6. Recruitment status | 6. Study completion date |

| 7. Contact information | 7. References for background citations |

| 8. Eligibility criteria | 8. References for completed studies |

| 9. Study type | 9. Results |

| 10. Study design | 10. Keywords |

| 11. Study phase | 11. Supplementary information |

| 12. Condition | 12. URL for trial information |

| 13. Intervention | |

| 14. Data provider | |

| 15. Date last modified |

The study sponsor was defined as the primary institute, agency or organisation responsible for conducting and funding the clinical study. Additional sponsors could be listed in the database. Investigator names were included at the discretion of the data provider. Data providers were asked to provide brief, readily understood titles and summaries, including why the study was being performed, what drugs or other interventions were being studied, which populations were being targeted, how participants were assigned to a treatment design and what primary and secondary outcomes were being examined for change (e.g. tumour size, weight gain, quality of life).

Location information included contact information and status of a clinical trial at specific locations. As many trials were being conducted at multiple locations, sometimes dozens of sites, contact information and recruitment status for all sites had to be accurate and current. Six categories of recruitment status applied: not yet recruiting (the investigators have designed the study but are not yet ready to recruit patients); recruiting (the study is ready to begin and is actively recruiting and enrolling subjects); no longer recruiting (the study is under way and has completed its recruiting and enrolment phase); completed (the study has ended and the results have been determined); suspended (the study has stopped recruiting or enrolling subjects, but may resume recruiting); and terminated (the study has stopped enrolling subjects and there is no potential to resume recruiting). Information about start and completion dates of the study were included, as was contact information including a name and a telephone number for further enquiries.

Eligibility criteria were defined as the conditions that an individual must meet to participate in a clinical study, based on inclusion and exclusion criteria and context.

Besides clinical trials designed to investigate new therapies, nine other study types were included: diagnostic, genetic, monitoring, natural history, prevention, screening, supportive care, training and treatment. Study design types included randomised and observational study designs as well as methods (e.g. double-blind method) and other descriptors (e.g. multicentre site).

ClinGov required certain items as separate data elements specifically to ensure optimal search capabilities. These included the study phase, the condition under study and the intervention being tested. The phase of the study was important information for patients who were considering enrolling in a particular trial. Data providers were requested to name the condition and intervention being studied using the medical subject headings (MeSH) of the Unified Medical Language System, if at all possible.

Optional information included references for publications that either led to the design of a study or reported on the study results. In these cases, data providers were asked to provide a MEDLINE unique identifier so that it could be linked directly to a MEDLINE citation record. A summary of the results could also be prepared specifically for inclusion in the database and the use of MeSH keywords was also encouraged. Supplementary information could include uniform resource locators (URLs) of websites related to the clinical trial.

The agreement of a common set of data elements was completed by the end of 1998. The next step was concerned with methods for receiving data for inclusion in a centralised database at the National Library of Medicine. Data were sent to ClinGov in Extensible Markup Language (XML) format according to a document type definition (DTD). Each clinical trial record was stored in a single XML document. A validator process performed checks on each record; each XML document was analysed and checked for adherence to the DTD. Adherence to the DTD helped identify structural errors in the document. Once the XML document was structurally correct, a Java object was created to facilitate content validation. Content validation could be performed on any data elements that did not contain free text.

Trial registries: World Health Organization clinical trials registry platform

Following the Declaration of Helsinki statement in 2000,16 the World Health Assembly vote to establish the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP)17 in 2004 and the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) 2004 declaration,18 the World Health Organization (WHO) established the ICTRP to facilitate the prospective registration of clinical trials. Trials could not be registered with WHO but with either a primary registry in the WHO Registry Network or with an ICMJE-approved registry. As regulatory, legal, ethical, funding and other requirements differ from country to country, the approved registries vary to some extent. WHO specified a 20-item minimum data set. This list was very similar to that of ClinGov but differed in several ways:

-

The WHO list included sources of funding, which was not explicitly included in ClinGov.

-

Primary and secondary outcomes were included by WHO but not ClinGov.

-

ClinGov used eligibility whereas WHO used inclusion/exclusion criteria.

-

WHO distinguished between public and scientific in both titles and contacts.

-

Different identification numbers were used (ISRCTN and ClinGov).

The WHO Registry Network comprises primary registries, partner registries and registries working towards becoming primary registries. Any registry that enters clinical trials into its database prospectively (that is, before the first participant is recruited), and that meets the WHO Registry Criteria or is working with ICTRP towards becoming a primary registry, can be part of the WHO Registry Network.

Primary registries in the WHO Registry Network meet specific criteria for content, quality and validity, accessibility, unique identification, technical capacity and administration. Primary registries meet the requirements of the ICMJE. The nine primary registries as at December 2011 are shown in Box 1.

Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry.

Brazilian Clinical Trials Registry.

Chinese Clinical Trial Registry.

Clinical Research Information Service, Republic of Korea.

Clinical Trials Registry, India.

Cuban Public Registry of Clinical Trials.

EU Clinical Trials Register.

German Clinical Trials Register.

Iranian Registry of Clinical Trials.

EU, European Union.

Partner registries meet the same criteria as primary registries in the WHO Registry Network (i.e. for content, quality and validity, etc.), except that they do not need to:

-

have a national or regional remit or the support of government

-

be managed by a not-for-profit agency

-

be open to all prospective registrants.

All partner registries must also be affiliated with either a primary registry in the WHO Registry Network or an ICMJE-approved registry. It is the responsibility of primary registries in the WHO Registry Network to ensure that their partner registries meet WHO Registry Criteria. Partner registries at the end of 2011 included the Clinical Trial Registry of the University Medical Center Freiburg, German Registry for Somatic Gene-Transfer Trials, the Centre for Clinical Trials, and Clinical Trials Registry – Chinese, University of Hong Kong.

The US registry, ClinGov, is not a partner of any kind in the WHO network. Two different realms thus exist in clinical registries: the USA and the rest of the world. Inevitably, the headings for trial registration, although broadly the same, differ. One striking difference is that the US register does not require data on the funding source of the trial, whereas this is required in the rest of the world. Another is that whereas the USA has moved towards requiring the registration of results of trials, the rest of the world has not.

Trial registries: the UK

The ISRCTN, a primary partner in the WHO platform, is run by Controlled Clinical Trials, which registers any clinical trial in the UK designed to assess the efficacy of a health-care intervention in humans. The ISRCTN collects the 20-point WHO list and makes this available on a trial-by-trial basis on the internet. The EU Clinical Trials Registry, a secondary partner in WHO, is confined to investigational drugs and includes the UK Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) as one of its data-providing agencies. It does not provide data on individual trials.

UK trials register mainly with ISRCTN but a proportion register with ClinGov. This appears to be partly for historical reasons (ClinGov came first), but also because registration is free in ClinGov but ISRCTN charges a small fee (£200 in 2012). Although this charge is met by the UK Department of Health for approved trials [those funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), research councils or UK charities], other trials which would have to pay may choose to register with ClinGov. A recent review of registration of UK non-commercial trials showed a rise in the proportion registering with ClinGov to around 30% in 2010. 19

Registries and reporting of results

An exploration of the issues raised by including reporting of the findings of clinical trials in databases under the aegis of WHO20–22 discussed issues to do with multiple outcomes and the importance of context in interpretation of results. It noted that, historically, access to the results of a trial had been achieved through publication in a peer-reviewed journal but that this publication model has its limitations, particularly in an environment where the end users of research information include health-care policy-makers, consumers, regulators and legislators who want rapid access to high-quality information in a ‘user-friendly’ format. It noted that in the future, researchers may be legally required to make their findings publicly available within a specific time frame (assuming any legislation created does not have escape clauses built in). In the USA, it noted that such legislation was already in place (available at www.fda.gov/oc/initiatives/HR3580.pdf).

Since the development of trial registration databases in 2000, research has been conducted to:

-

describe the characteristics of trials registered23

-

review the compliance and quality of entries in ClinGov,14 the WHO portal20–22 and several registers24

-

report on scientific leadership (ISRCTN and ClinGov)

-

compare planned and actual trial analyses, including analysis of primary outcomes in major journals27 and comparisons between protocols and registered entries to published reports. 28

Details of the literature searches on trial registration, uses and data quality are provided in Appendices 1–3. In summary, many trials registered were small, with 62% of interventional trials registered in ClinGov in 2007–10 enrolling fewer than 100 patients. The quality and compliance of registration was not good, with trials often registered late (whether defined as after recruitment had commenced or after the trial had been completed) and with missing registration data, specifically to do with contacts, primary outcomes and the processes of randomisation. Compliance was found to be improving, at least for the period 2005–7. 21 Around one-third of registered trials had not reported 24 months after completion, with worse performance for industry-funded trials.

Comparisons of planned and actual trial behaviour, summarised in Chapters 4–9, show that discrepancies between protocols or trial entries and trial reports were common.

Conclusions

This brief review of the literature indicates that:

-

Two main registry types have emerged – the US ClinGov and the WHO platform which provides an infrastructure for the rest of the world.

-

The data required differs between ClinGov and the WHO platform, with the latter including primary and secondary outcomes and source of financing. The former has more detail on patient eligibility and appears more patient oriented.

-

Prospective registration of planned RCTs has become common and mandatory in many countries.

-

In the UK, RCTs register mainly with the ISRCTN via Current Controlled Trials (CCT), but some register with ClinGov.

-

The quality of the data registered has been poor, with all studies indicating poor compliance.

-

Both the US and WHO registries are moving towards inclusion of results, with ClinGov further advanced owing to such reporting having become mandatory in the USA from 2006.

-

No studies were identified that went beyond the minimum data set for prospective registration to include conduct, performance, cost and results of trials.

Chapter 3 Methods

Introduction

This chapter outlines the target ‘population’, inclusion criteria, data sources and quality assurance methods used.

Population

The population of interest was completed RCTs funded by the HTA programme. The starting point was the published HTA monograph series which published the results of almost all funded projects. Projects were distinguished from trials, as projects can comprise several trials. Some trials were described as pilot or feasibility trials.

A RCT was defined for this study as:

An experiment in which two or more interventions, possibly including a control intervention or no intervention, are compared by being randomly allocated to participants. In most trials one intervention is assigned to each individual but sometimes assignment is to defined groups of individuals (for example, in a household) or interventions are assigned within individuals (for example, in different orders or to different parts of the body).

Reproduced with permission from www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/glossary?result_1655_result_page=R

Published HTA-funded projects which included a RCT were identified from the HTA monograph series (www.hta.ac.uk/). The title and the ISRCTN number for each published monograph were reviewed and cross-referenced with the HTA Management Information System (HTA MIS).

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were HTA-funded projects that had reported the results of at least one RCT and had been published as a HTA monograph by the end of February 2011. One project which included a clinical trial but failed to submit the draft final report and did not publish a HTA monograph was excluded on these grounds. One hundred and nine projects were included.

These criteria implied to the inclusion of pilot and feasibility studies. This mattered to varying degrees for the different themes. A full list of the RCTs included in the database is shown in Appendix 2.

Data sources

Data on each randomised clinical trial were extracted from seven sources:

-

the published HTA monograph (publicly available)

-

protocol changes form, if available (a confidential document submitted with the final report)

-

the final, most current version of the protocol (project protocols were not available for older HTA-funded trials)

-

the full proposal attached to the contract of agreement (confidential document)

-

the commissioning brief (publicly available)

-

the vignette (confidential document)

-

the HTA MIS (confidential).

As sources 2–6 above were mostly only available on paper, paper files were scanned to create electronic portable document format (PDF) copies, which were directly linked to the database.

As the HTA programme changed the format of these sources over time, a timeline was drawn within which each project was situated. These changes sometimes limited the data available for particular questions.

Quality control

Our approach to quality assurance was guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), which, although designed for systematic reviews, can be applied to the processes we used for data extraction. Out of the 27 PRISMA checklist items, 12 items are listed under ‘Methods’. Of these 12 statements, we used six items to help define the design of the project (eligibility criteria, information sources, search, study selection, data collection process and data items). PRISMA states: ‘Describe the method of data extraction from reports and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators’ (Liberati et al. 200929).

Data extraction forms were developed and piloted on five trials, leading to refinement. This led to the identification of five types of data field, each with a different process of quality assurance, as shown in Table 2 along with their relevance by theme.

| Type of data field | Description | Application to theme | Quality check |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. HTA MIS | Data fields obtained directly from the HTA MIS (read only) | 37 | Reasonableness, outliers |

| 2. Straightforward fields | Data fields relatively straightforward to extract and did not usually involve a judgement call (e.g. trial design, number of arms, details on project extensions, protocol changes) | 60 | Random sample checked against source documents |

| 3. Numeric | Data fields where the highest level of transcription errors (human error) were likely to occur (e.g. in conduct questions on number of patients recruited/randomised/followed up and number of centres) | 284 | All fields checked against source documents [with the exception of 58 fields for the health economics data, where a random sample was double-checked by the health economist (DT)]. The project statistician (LS) checked data extracted |

| 4. Judgement call fields | Data fields which involved a subjective judgement, for example whether or not the researchers had adequately specified the method of randomisation sequence generation, reported all CONSORT fields or the type of trial intervention | ||

| 5. Specialist data fields | Data fields which required specialised training or knowledge to understand and extract data accurately; these were likely to lead to the highest errors during data extraction (e.g. sample size calculation fields, planned method of statistical analysis, all health economics fields) |

Two members of the team went through discrepancies and queries relating to the complete extraction of data, came to an explicit agreement and amended the database accordingly. The level of checking for the 125 trials by the second team member varied; all data were checked for themes 1, 2, 3 and 4. A percentage of data checking was completed by DT for theme 5 [40% for the BMJ checklist (BCL)] and JR for theme 6 (40%).

Quality assurance by type of data (Table 2) was applied as follows. With a few exceptions, fields relating to the design of the trial, conduct of the trial, statistical analysis and Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) were classified as type 3, 4 or 5 in Table 2. All health economics fields were classified as type 5, the cost of trials fields were classified as type 4 and the NHS need fields were classified as type 2.

Errors noted in the data extracted were corrected and the data changed were recorded in a central Microsoft Office Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. If the change needed further discussion it was noted in the spreadsheet and discussed with AY and/or other members of the steering group.

These quality assurance processes were carried out weekly to ensure issues with fields could be spotted quickly. Monthly reports were provided to the project steering group.

Most of the fields in the database were either numeric or categorical. For categorical fields, the possible categories for data entry were listed as a drop-down menu and locked to these codes to prevent errors.

Data extraction

Data extraction specification forms were developed for each question (see Appendix 3). Free-text entries were allowed only when no classification system could be employed. Classification systems were used to specify the forms, showing for each item the data to be extracted, the type of field and, if categorical, the classification we planned to use. Existing classifications from the published literature were used where possible. Where there were two competing classifications we used both, and if there was no published classification, we used either the HTA MIS (if applicable) or, in extremis, a simple hierarchical system (yes/no, if yes, then detail).

The forms were developed by the research fellow and statistician in conjunction with the research lead for each theme and reviewed by the steering group. The project advisory group was sent a full list of the data fields that were planned to be included in the metadata database for comment. The data items finally included in the metadata database were based on consensus.

Projects and trials included in the database

This section reports on the number of trials that met the eligibility criteria along with problems encountered.

From its start date in 1997 to the end of February 2011, the HTA programme published 574 projects in the HTA monograph series (in 15 annual volumes). The executive summary for each report was independently reviewed by two members of the steering group to assess whether or not the monograph included the results of a RCT. One hundred and twelve projects were identified as potentially including a RCT. From screening, three of the projects were excluded and full data were extracted from 109 monographs (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded RCTs and monographs.

The three excluded projects were:

-

one report originally funded as a RCT on paramedic training for serious trauma, which failed to randomise and went on as a non-randomised study (1998, Volume 2, Number 17)

-

one economic evaluation of pre-existing RCT data, which was not funded by the HTA programme (1999, Volume 3, Number 23)

-

one report of the long-term outcomes of patients in 10 RCTs of cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) conducted between 1985 and 2001 (2005, Volume 9, Number 42).

Narrowly included projects

One trial was narrowly included, in which participants were randomly assigned to be offered two different types of hearing aids. This study of a screening programme included a small RCT, the results of which were reported in the monograph.

Pilot and feasibility studies

Four monographs reported pilot or feasibility studies:

-

The feasibility of a RCT of treatments for localised prostate cancer (2003, Volume 7, Number 14) (trial ID15).

-

A two-centre, three-arm pilot conducted to assess the acceptability of a RCT for comparing arthroscopic lavage with a placebo surgical procedure (2010, Volume 14, Number 5) (trial ID97).

-

A pilot study conducted to assess the safety and efficacy of reducing blood pressure with two types of medication for patients with hypertension. The pressor phase of the trial was terminated owing to poor recruitment (2009, Volume 13, Number 9) (trial ID78 and ID110).

-

A pilot study on impact of early inhaled corticosteroids prophylaxis, conducted to assess recruitment rates and project protocol, pilot assessment tools and refine the sample size calculation for a definitive study (2000, Volume 4, Number 28) (trial ID121).

From the 109 included projects, 125 RCTs were identified and constituted the cohort of trials included in this study. Eleven monographs included the results of more than one RCT. Five of these included three RCTs and six included two RCTs.

Unique trial identification number

Each project funded by the HTA programme had a unique reference number (e.g. 10/07/99) given when the outline proposal was submitted. We used this to link records in the database to the HTA Management Information System. For the 11 projects that included more than a single RCT, we developed an additional identifier. A free-text field was included in the database to identify the specific clinical trial. Fields were also included in the database showing the number of trials in the monograph, listing the trial ID numbers for those trials reported in the same monograph. For example, the HTA-funded project 96/15/05, ‘Which anaesthetic agents and techniques are cost-effective in day surgery? Literature review, national survey of practice and randomised controlled trial’, contained two RCTs, a two-arm trial for the paediatric population and a four-arm trial for the adult population. This project has a single ISRCTN number (87609400). We created one unique ID for each RCT: ID13 for the adult study and ID14 for the paediatric study.

Completeness of data sources

Data extraction took place from 6 August 2010 to 8 November 2011. Table 3 shows the completeness of the sources of information used for data extraction.

| Document | Number available for data extraction (%) |

|---|---|

| Vignette | 99/109 (90.8) |

| Commissioning brief | 99/109 (90.8) |

| Application form (proposal) | 106/109 (97.2) |

| Protocol | 58/109 (53.2) |

| Monograph | 109/109 (100) |

| Protocol change form | 78/109 (71.6) |

| Progress reports/extension requests | Multiple documents per trial available; too many to count |

| Total number of monographs | 109 |

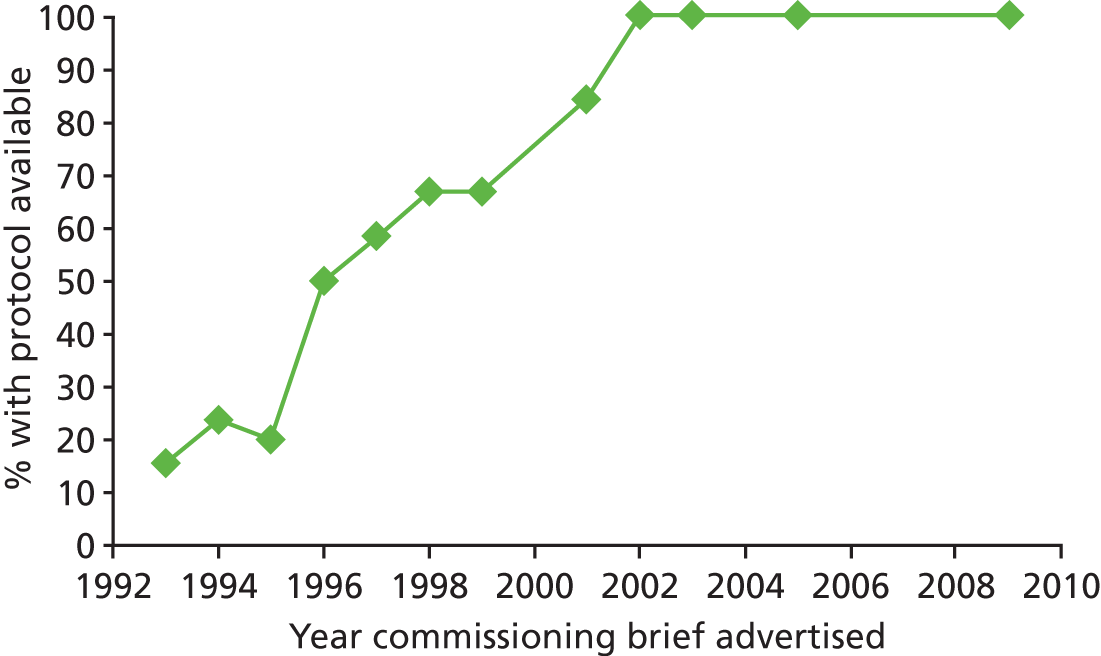

The least complete category of documents retrieved was the project protocols (65/125, or 53%). Only 30 out of the 65 were available in the public domain (via the HTA programme website, www.hta.ac.uk/). These were mainly linked to monographs published after 2009. Twenty-six protocols were extracted directly from the HTA project paper folders; these were not in the public domain and were treated as confidential. For the 60 trials lacking a protocol, we contacted the chief investigator (a) to see if a project protocol existed; (b) if one did exist, to request a copy of the document to include in the database; and (c) to seek permission to forward the protocol to the HTA programme. We succeeded in contacting 59 chief investigators and were unable to find current contact details for one. Of the 59 chief investigators contacted, 35 responded (59.3%), leading to retrieval of an additional nine project protocols.

Vignettes and commissioning briefs were located for 99 projects (90.8%). Out of 109 projects, 106 application forms were retrieved. Seventy-eight projects produced a protocol changes form which only applied to those that required such a change (for two trials, a non-standard form was used, which was included in these figures).

Database

Data for each trial were stored in a Microsoft Access 2003 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database. Each clinical trial entered had a unique ID number which linked data to every table and form.

Relevant direct website links were included to assist in data entry. A hyperlink to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (Theme 2) (http://apps.who.int/classifications/icd10/browse/2010/en) led to a drop-down menu for the disease chapters. Other hyperlinks included the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC), Health Research Classification System (HRCS) for interventions (www.hrcsonline.net/rac/overview),30 CONSORT (www.consort-statement.org/), International Conference on Harmonisation of Technical Requirements for Registration of Pharmaceuticals for Human Use (ICH) (www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/guidances/ucm122049.htm) and BMJ health economics checklist (www.bmj.com/content/313/7052/275.full).

Classification systems

Data for each question were structured and entered into a classification system. The classification systems generated during the development of the data extraction specification forms were entered into the tables as value lists (source type). For example, trials type was classified as 1;‘Superiority’;2;‘Non-inferiority’;3;‘Equivalence’. Data fields sharing the same classification system were set up in an Access table. For example, data extraction for treatment of missing data was required for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis of the trial, with 14 options to choose from. Instead of replicating these in each of the data fields, an Access table was generated.

Data collection and management

The data extraction specification forms defined the metadata database, using Access forms. The database was designed to directly link to the HTA programme’s MIS (also Access) so that relevant fields in the HTA MIS could be included in the metadata database and automatically updated. The metadata database was linked to the HTA MIS using either the project number (number given at the time of the outline proposal, which stays with the project until publication) or priority area number (number given at the time of commissioning).

The database was designed to be comprehensive, storing all data items and queries raised during data extraction and decisions made in relation to these. As it linked directly to the information sources for each trial, the database is a repository for all documents about included trials. Further, as suggested by a member of the advisory group, the source and page number of relevant data fields were incorporated into the database. These measures also mean that future researchers can use the links and page numbers to check on the accuracy of data previously extracted, indicate if there are any disagreements and include their own comments.

An escalation process was set up to deal with uncertainty and to resolve any disagreements. The research fellow extracted all data and recorded it in the database, with problems logged under the trial’s additional comments section. Regular meetings were held between the research fellow and statistician to resolve queries logged under each trial. If they could not resolve the issue, the research fellow was to discuss it with the relevant research lead, with escalation to the steering group if necessary. Most queries were resolved at early stages and none were escalated to the steering group.

The metadata database

The Access metadata database included 429 data fields on the 125 trials (Table 4).

| Theme | Actual number of data fields | Source of information |

|---|---|---|

| Core trial information | 48 | Monograph |

| Theme 1: meeting the needs of the NHS | 22 | Vignette, commissioning brief, monograph and HTA MIS |

| Theme 2: design and adherence to protocol | 72 | Protocol or proposal, monograph and HTA MIS |

| Theme 3: performance and delivery of the NIHR HTA programme-funded RCTs | 72 | Protocol or proposal, monograph, HTA MIS and protocol change form |

| Theme 4: statistical analyses appropriate and as planned | 97 | Protocol or proposal and monograph |

| Theme 5: economic analyses alongside clinical trials | 58 | Proposal, monograph and HTA MIS |

| Theme 6: cost of RCTs, trends and determinants | 60 | Protocol or proposal and monograph |

| Total | 429 |

Security, back up and confidentiality

The project had a dedicated research folder on the University of Southampton’s secure server. Access to the folder was only visible to the research team. Access to the folder was not possible without permission from AY.

Any documents containing sensitive data, such as named principal investigators or confidential information, were stored using a protected password; only two members of the project team had these. Other members of the research team were able to access these documents via these two people if deemed necessary.

The HTA programme policy for access to unpublished data requires signing a confidentiality agreement. That confidentiality agreement was signed by all members of the research team at the start of the project. We suggest below that the same rules, updated as appropriate, should govern future access to the database by other researchers.

Some data from older sources of information were deemed confidential, such as failed trials, the funding details of particular trials and problems with the conduct of the trials. Project protocols before 2007, which were often only in the form of proposals, might be seen as confidential as they are not in the public domain. Since 2007, the most current version of the project protocol has been published with researchers’ consent on the NETSCC HTA programme website.

This project assumed that protocols for trials funded before 2007 should be treated as confidential. All final proposals attached to the contract of agreement to the Department of Health were also treated as confidential, including the vignette.

For each trial record, a drop-down menu specified whether or not the source was confidential (not in the public domain). Data fields were positioned on the Access form based on where the information was extracted from and by theme. Page numbers and source of information boxes determined whether or not the data extracted were confidential.

Questions for which data should be extracted

This section outlines the method used to decide the questions for which data should be extracted.

Some questions under each theme were quickly shown as not feasible owing to lack of data or time required to extract data. These questions are discussed under each theme in the relevant chapters (see Chapters 4–9).

The questions deemed feasible were taken further by extracting data, entering it in the relevant classification systems and assessing it.

For each question, a judgement was made regarding whether it should be:

-

kept

-

amended

-

dropped.

These options were developed from those suggested by Thabane et al. 31 Three criteria were used to reach these judgements:

-

How complete were the data required?

-

Were changes recommended to the classification system?

-

What skills and resource (linked to data type and need for judgement) did the classification system require?

The completeness of the data was measured for each question. Whether or not changes were recommended to the classification system helped indicate if it should be amended. The final criterion, with regard to the skills and resources, was based on records kept by AY.

The criteria were applied hierarchically, with only those for which data were available being assessed against the other criteria. A threshold of 80% was set for data completeness on the basis of representativeness. However, instead of applying the criteria mechanically, the steering group retained the option to consider retaining any question that seemed particularly important.

Changes/deviations from the protocol for this study

Given that one of the questions explored in this project concerns protocol changes, this section discusses changes to the protocol for this study. We deviated from our protocol twice. These deviations were because of:

-

the number of trials included; we included 125 trials in the metadata database, more than the 120 maximum that we specified

-

planned quality assurance; we abandoned our plan to invite chief investigators to check our data extraction on the basis of the results of a small pilot study.

Further, the project was originally funded for 1 year to extract data on 63 RCTs. The piloting of data extraction showed that only around 40 RCTs, or around half the total published to mid-2009, could be done within that time scale. The steering and advisory groups agreed that the value of the database would increase with the number of trials included. The project steering group requested and received a 1-year extension.

None of these in our opinion was likely to have introduced bias.

Chapter 4 Theme 1: meeting the needs of the NHS

This chapter considers questions linked to the theme: ‘How was the trial seen as meeting the needs of the NHS by the HTA programme?’ After a brief review of the relevant literature, it summarises available data on how trials funded by the HTA programme could answer questions about meeting the needs of the NHS. It explores how topics of trials were generated and prioritised. It also explores the outcomes used and the time from prioritisation to publication of the findings. The methods used to answer each question are described and the results are followed by analysis and discussion.

Introduction

Several terms may usefully be defined. By commissioned research, we mean research where the topics to be researched are defined by the programme and not by the researchers who do the work. This implies that the programme is acting on behalf of the NHS and must have mechanisms for ‘knowing’ the needs of the NHS. This differs from both response-mode research (the traditional mode, with funders taking bids from expert teams of researchers) and researcher-led research (HTA’s term for the work stream introduced in 2006 where proposals are submitted by researchers but are rigorously assessed against NHS need). 1

To be relevant to decision-making in the NHS, any clinical trials would need to be pragmatic as opposed to explanatory. Pragmatic trials have been defined as those with broad inclusion criteria, carried out in many centres and with patient-relevant outcomes. 32

To employ a term given prominence in the Cooksey Report (2006),33 NHS-funded research had to be restricted to public interest or market failure research, that is, work that the private sector would not be interested in carrying out. This is often due to the inability to patent that which is being tested (difficult outside new drugs or, in particular, interventions made up of services rather than tightly defined products).

As the HTA programme is a commissioned programme, one might expect it to prioritise research focused on the needs of the NHS. A substantial literature discusses methods for research prioritisation but there is much less on how potential topics should be identified, or on assessments of whether or not prioritised research is indeed ‘needs-led’. 9,34–37

Since its inception, the NHS research and development (R&D) has focused on identifying gaps in research relevant to the NHS and prioritising them. Setting priorities is difficult and complex, partly because there is ‘no agreed upon definition for successful priority setting, so . . . no way of knowing if an organisation achieves it’. 38

Different methods have been suggested, such as multidisciplinary involvement, public and patient involvement, the use of scoring systems, the Delphi process and information specialist involvement. Economic impact approaches include the payback approach or expected value of information models. Priority setting means an allocation of limited resources, which can be highly political and controversial. Developing a structured topic prioritisation process helps address this challenge.

Chase et al. 9 described the different sources used by the HTA programme in 1998 to identify potential priorities. Overall, there were 1100 suggestions for the programme from four main sources: (1) a widespread consultation of health-care commissioners, providers and patients; (2) research recommendations from systematic reviews; (3) reconsideration of previous research priorities; and (4) horizon scanning. Nearly half (46%) of final programme priorities were from the widespread consultation, with 20% from systematic reviews and 10% from each of the other two areas. (The remainder came simultaneously from more than one source.) Chase et al. 9 concluded that there was value in having a mix of sources. One of the aims of this chapter was to apply the approach of Chase et al. 9 to all the RCTs published to mid-2011.

A small literature discussed the patient relevance of outcomes in publications, through surveys of trials published in a particular disease area. There are three notable examples:

-

Gandhi et al. 39 looked at diabetes trials and found that primary outcomes were patient important in only 78 of 436 RCTs (18%).

-

Montori et al. 40 also looked at diabetes trials and found that primary outcomes were patient important in only 42 of 199 RCTs (21%).

-

Rahimi et al. 41 looked at cardiovascular trials and found that primary outcomes were solely patient important (death, morbidity or patient-reported outcomes) in only 93 of 413 trials (23%).

Chalmers and Glasziou42 proposed a framework for considering avoidable waste in research, with four stages. The first concerned whether or not the questions addressed by research are relevant to clinicians and patients; if they are not, Chalmers and Glasziou42 argue that the research is wasted.

Although Chalmers and Glasziou42 give some examples of the ways in which research fails to address relevant questions, they provide no quantifiable measures of waste in this stage of the framework, unlike the other three stages (design, publication and useable report), for each of which empirical estimates of waste are provided.

The extent to which RCTs have been preceded by systematic reviews can indicate the source of the topic. A recent review of 48 trials funded by the HTA programme between 2006 and 2008 indicated that 80% had been preceded by a systematic review. 43

Questions addressed

The questions on which data were extracted are shown in Box 2.

-

T1.1. Type of commissioning work stream?

-

T1.2. Prior systematic review?

-

T1.3. The source for topic identification?

-

T1.4. Type of HTA advisory panel?

-

T1.5. What was the priority given by the programme to the research?

-

T1.6. Did the statement of need change?

-

T1.7. Frequency and accuracy of reporting the primary outcome?

-

T1.8. Adequate reporting of the proposed and published primary outcome?

-

T1.9. What was the time lag between prioritisation and publication of the monograph?

Methods

Nine questions were piloted in theme 1 (hereafter T1). One question (‘How was the relevance to the NHS assessed?’) was deemed not feasible owing to lack of data. However, data were available on the work stream (commissioned or researcher led) (T1.1), whether or not a prior systematic review existed (T1.2) and the source of the topic (T1.3). These are explored below.

Denominators

For questions T1.1, T1.3 and T1.4 the denominator was the number of priority areas (n = 100) which precede any call for a trial. (Note: ‘T’ refers to theme. Each of the six themes are numbered with additional numerals referring to questions within that theme.) One hundred research suggestions/priority areas made it through to the commissioning brief stage, which led to 107 projects being funded containing 123 RCTs. The denominator for questions T1.2 and T1.5–T1.9 was the total number of projects (n = 109) (107 projects via the commissioned work stream and two projects via direct commissioning).

Results

Question T1.1: type of commissioning work stream

Out of the 100 priority areas, 107 (98.2%) projects were funded through the commissioned work stream. The other two projects were ‘directly commissioned’ {09/94/01 [head-to-head comparison of two H1N1 swine influenza vaccines in children aged 6 months to 12 years] and 99/01/01 [conventional ventilatory support versus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for severe adult respiratory failure (CESAR)]}.

Question T1.2: prior systematic review

Of the 109 projects, 56% reported a prior systematic review in the published monograph.

Question T1.3: the source for topic identification

Of the four main sources of identification, ‘widespread consultation’ contributed 64 (66.7%) topics followed by systematic reviews (25%, 24/100) and the Horizon Scanning Centre (3%, 3/100).

The balance of these sources shifted over time. When the number of trials increased in 2001–2, the proportion of topics from systematic reviews rose to 65% (Table 5).

| Source of topic identification | 1993–4, n (%) | 1995–6, n (%) | 1997–8, n (%) | 1999–2000, n (%) | 2001–2, n (%) | 2003–4, n (%) | 2005–6, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widespread consultation | 17 (89.5) | 22 (84.6) | 11 (73.3) | 6 (66.7) | 3 (15.0) | 4 (66.7) | 1 (100) | 64 (66.7) |

| Systematic reviews | 2 (10.5) | 2 (7.7) | 3 (20.0) | 2 (22.2) | 13 (65.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 24 (25.0) |

| Horizon Scanning Centre | 0 | 1 (3.8) | 1 (6.7) | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 3 (3.1) |

| Reconsidered topics | 0 | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 3 (15.0) | 0 | 0 | 5 (5.2) |

| Total | 19 (19.8) | 26 (27.1) | 15 (15.6) | 9 (9.4) | 20 (20.8) | 6 (6.3) | 1 (1.0) | 96 (100.0) |

Question T1.4: type of Health Technology Assessment advisory panel

The source of topics varied by advisory panel (Table 6). Widespread consultation was the main commissioning source for two of the three panels (83.3%, 15/18 and 72.2%, 39/54, respectively). The exception was the pharmaceutical panel, where 50% (12/24) of the commissioned topics were from systematic reviews.

| Source of topic identification | Diagnostic and screening panel, n (%) | Pharmaceutical panel, n (%) | Therapeutic panel, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Widespread consultation | 15 (83.3) | 10 (41.7) | 39 (72.2) | 64 (66.7) |

| Systematic reviews | 2 (11.1) | 12 (50.0) | 10 (18.5) | 24 (25.0) |

| Horizon Scanning Centre | 0 | 1 (4.2) | 2 (3.7) | 3 (3.1) |

| Reconsidered topics | 1 (5.6) | 1 (4.2) | 3 (5.6) | 5 (5.2) |

| Total | 18 (18.8) | 24 (25.0) | 54 (56.3) | 96 (100.0) |

Question T1.5: what was the priority given by the programme to the research?

The programme prioritised 70% of projects in the top band. Of the 71 projects prioritised up to and including 1999, 50 (70.4%) were classified as A-list topics (‘recommended for commissioning – must commission’) and 18 (25.4%) were B-list topics (‘recommended for commissioning’ only). The HTA MIS database did not provide sufficient information for 4.2% of trials (3/71) (Table 7).

| Priority status and HTA advisory panel description | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Priority band (up to and including publication date 1999) | |

| Recommended for commissioning – must commission (A) | 50 (70.4) |

| Recommended for commissioning (B) | 18 (25.4) |

| Category unknown | 3 (4.2) |

| Total | 71 |

| HTA advisory panel | |

| Diagnostic and screening | 21 (19.3) |

| Pharmaceutical | 25 (22.9) |

| Therapeutic procedures | 61 (56.0) |

| Department of Health – Direct Project Commissioned | 2 (1.8) |

| Total | 109 |

Question T1.6: did the ‘statement of need’ change?

This question asked if researchers undertaking research drifted from the programme’s initial assessment of NHS need for the research. The statement of need did not change between the commissioning brief and the monograph in 101 trials (94.4%, 101/107). No data were available for the remaining six projects. For these six projects, we were unable to compare the information reported in the commissioning brief with that reported in the monograph for three trials (2.8%). The reasons were ‘No commissioning brief or vignette was available’ (trials ID121 and ID122) and ‘No commissioning brief or vignette was prepared. It was a fast track topic’ (trial ID106). For the final three projects, we were unclear about the reporting of the statement and whether or not it changed from the advertisement to the executive summary in the monograph (trials ID60, ID79 and ID86). Owing to the complexity of data extracted to answer this question, it was not possible to analyse the data further. In addition, it was agreed that all data fields related to the ‘statement of change’ question would be dropped from further analyses.

Question T1.7: frequency and accuracy of reporting the primary outcomes

The 109 funded projects included 125 clinical trials. The main primary outcome, defined as that used for sample size calculation, was reviewed independently by two researchers (RM and AY) for the 109 projects. Four projects lacked requisite information (the monograph did not clearly state what the main primary outcome was nor was it possible to determine what the main primary outcome was during the data extraction process). In this instance, consensus was reached by both researchers reviewing the monograph (specifically, the sample size calculation section reported in the methods chapter of the monograph) to determine the actual type of primary outcome. It was not possible to accurately identify what the main primary outcome was for one project (trial ID68).

Seventy-eight (73%) of the 107 projects in the commissioned work stream reported sufficiently on the proposed primary outcome. Twenty-one projects reported limited information. Eight commissioning briefs (7.5%) contained no information about what the primary outcome was.

Question T1.8: adequate reporting of the proposed and published primary outcome

All projects were analysed to compare the proposed primary outcomes with those published (n = 109). We were able to classify the proposed primary outcome for 97 projects (88.9%) and the published primary outcome for 108 projects (99.1%) (Table 8); little changed between these two stages. Patient-important outcomes were reported in more than half of the HTA-commissioned projects, at both the proposed and published stages of the project (67%, 73/109 and 73.4%, 80/109, respectively). A number of outcomes could not be classified using the Gandhi et al. 39 three main headings. Fourteen proposed primary outcomes and 18 published primary outcomes were categorised as ‘other’.

| Type of primary outcomes reported | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Type of primary outcome reported at the commissioning stagea | |

| Patient important (including others) | 75 (70.1) |

| Surrogate | 0 |

| Physiological/laboratory | 0 |

| Other | 3 (2.8) |

| Limited information reported in the commissioning brief | 21 (19.6) |

| No information available | 8 (7.5) |

| Total | 107 |

| Type of primary outcome reported in the proposal/protocol | |

| Patient important (including others) | 73 (67.0) |

| Surrogate | 8 (7.3) |

| Physiological/laboratory | 2 (1.8) |

| Other | 14 (12.8) |

| No information available | 12 (11.0) |

| Total | 109 |

| Type of primary outcome reported in the monograph | |

| Patient important (including others) | 80 (73.4) |

| Surrogate | 9 (8.3) |

| Physiological/laboratory | 1 (0.9) |

| Other | 18 (16.5) |

| No information available | 1 (0.9) |

| Total | 109 |

Thirteen projects (11.9%) had differences between the planned and actual type of primary outcome. These discrepancies were mainly due to a lack of information or having no information on the primary outcome in the planned documentation (proposal/protocol) (n = 12). The monograph was able to provide sufficient information for 10 of these projects to enable the primary outcome to be classified accordingly. Table 9 highlights where these discrepancies were between the planned and actual reporting of the primary outcome.

| Planned primary outcome as reported in the proposal/protocol | Actual primary outcome measure as reported in the monograph | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient important (including others), n (%) | Surrogate, n (%) | Physiological/laboratory, n (%) | Other, n (%) | No information available, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| Patient important (including others), n (%) | 72 (90.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.6) | 0 | 73 (67.0) |

| Surrogate, n (%) | 0 | 8 (88.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (7.3) |

| Physiological/laboratory, n (%) | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.8) |

| Other, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (77.8) | 0 | 14 (12.8) |

| No information available, n (%) | 7 (8.7) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 3 (16.7) | 1 (100.0) | 12 (11.0) |

| Total, n (%) | 80 (73.4) | 9 (8.3) | 1 (0.9) | 18 (16.5) | 1 (0.9) | 109 (100.0) |

When diagnostic and screening projects (n = 20) were excluded, patient-important outcomes increased from 67% (n = 73) to 73% (65/89).

Over the period 1993–2002, 82.7% (67/81) of reported primary outcomes were patient important (Table 10). The years 1993–2002 provide a more accurate report of the type of primary outcome reported in the monograph, as a number of projects funded during the period 2003–10 have not yet published.

| Type of primary outcome | 1993–4, n (%) | 1995–6, n (%) | 1997–8, n (%) | 1999–2000, n (%) | 2001–2, n (%) | 2003–4, n (%) | 2005–6, n (%) | 2007–8, n (%) | 2009–10, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient important (including others) | 16 (80.0) | 20 (83.4) | 12 (100.0) | 4 (66.7) | 15 (78.9) | 3 (75.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 0 | 71 (80.6) |

| Surrogate | 1 (5.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 3 (15.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 8 (9.1) |

| Physiological/laboratory | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (1.1) |

| Other | 3 (15.0) | 2 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 1 (25.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (8.0) |

| No information available | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) |

| Total | 20 (100.0) | 24 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) | 6 (100.0) | 19 (100.0) | 4 (100.0) | 1 (100.0) | 0 | 2 (100.0) | 88 (100.0) |

Question T1.9: what was the time lag between prioritisation and publication of the monograph?

This question asked about the time taken between the programme prioritising a topic and the monograph publishing the results. The interval was 8–10 years (Table 11). The average was 8 years for trials prioritised in 1993 and 9 years for those prioritised in 1999.

| Year of publication | PAR year | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993, n (%) | 1994, n (%) | 1995, n (%) | 1996, n (%) | 1997, n (%) | 1998, n (%) | 1999, n (%) | 2000, n (%) | 2001, n (%) | 2002, n (%) | 2003, n (%) | 2004, n (%) | 2005, n (%) | 2009, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

| 1999 | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| 2000 | 5 (41.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (5.5) |

| 2001 | 2 (16.7) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 (2.8) |

| 2002 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (10.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 (3.7) |

| 2003 | 1 (8.3) | 1 (7.1) | 1 (10.0) | 2 (10.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (5.5) |

| 2004 | 1 (8.3) | 3 (21.4) | 3 (30.0) | 4 (20.0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (10.1) |

| 2005 | 1 (8.3) | 5 (35.7) | 0 | 7 (35.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 14 (12.8) |

| 2006 | 0 | 0 | 2 (20.0) | 4 (20.0) | 4 (33.3) | 0 | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (10.1) |

| 2007 | 0 | 2 (14.3) | 2 (20.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (8.3) | 1 (33.3) | 3 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10 (9.1) |

| 2008 | 0 | 0 | 1 (10.0) | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 2 (12.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 (6.4) |

| 2009 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (16.7) | 1 (33.3) | 1 (11.1) | 0 | 10 (62.5) | 2 (50.0) | 2 (33.3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 18 (16.5) |

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.0) | 1 (8.3) | 0 | 3 (33.3) | 0 | 4 (25.0) | 2 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 0 | 0 | 1 (50.0) | 15 (13.9) |

| 2011 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (16.7) | 0 | 1 (100.0) | 1 (50.0) | 3 (2.7) |

| Range (years) | 6–12 | 6–13 | 7–13 | 6–14 | 6–13 | 9–11 | 7–11 | 0 | 7–9 | 7–8 | |||||

| Median (years) | 7.5 | 10.5 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 9.5 | 10.0 | 9.0 | 8.0 | 7.5 | ||||||

| Mean (years) | 8.25 | 10.07 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 9.92 | 10.0 | 9.22 | 8.13 | 7.5 | ||||||

| Total number of projects (%) | 12 (11.0) | 14 (12.8) | 10 (9.2) | 20 (18.3) | 12 (11.0) | 3 (2.8) | 9 (8.3) | 0 | 16 (14.7) | 4 (3.7) | 6 (5.5) | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 109 |

Analysis

In Chase et al. ’s9 review, 46% of programme priorities in 1998 came from the widespread consultation and 20% from systematic reviews. Our data show greater reliance on consultation but with variation from year to year. The key question concerns what can be inferred about the importance of the HTA projects to the NHS. It would be a mistake to equate widespread consultation with NHS relevance and systematic reviews with academic interest. There is no reason why this should be so. The processes the HTA programme had in place between the identification of topics and their advertisement as commissioning briefs means that the initial topic only served as a starter for the real work on NHS relevance.

Unsurprisingly, most projects that were funded had been prioritised; 70% had been given the top band (A) by the programme’s prioritisation processes. Band A, ‘recommended for commissioning – must commission’, meant that the programme would ‘go the extra mile’ to ensure that research was funded in that area. What to make of this 70% figure? The priority banding was the end of a process that started with the source of the topic, addressed in the previous question. This process involved detailed consideration of potential research priorities by panels of NHS experts (patients, clinicians, managers) as well as an overarching standing group on health technologies, meeting annually for 2 days. The priority band was a summary score produced by the whole process. The process was producing research proposals of which 70% were thought to be of high relevance to the NHS and so of a high priority.

By contrast with the finding by Jones et al. 43 that 80% of RCTs funded by the HTA programme and published between 2006 and 2008 were preceded by a systematic review, we found that 56% of all trial published to 2011 were preceded by a systematic review.

The finding that the statement of need did not change between the commissioning brief and that reported in the monograph in 101 out of 107 trials (94%) suggests no evidence of ‘drift’. Unfortunately, the data available in the database were not detailed enough to allow us to make further informative assessments in this area.

Primary outcomes tended to be patient relevant. Excluding those projects relating to ‘diagnostic technologies and screening’ increased these figures from 67% to 73%, much higher than previous studies (18% in Gandhi et al. ,39 21% in Montori et al. 40 and 23% in Rahimi et al. 41).

The lag between the programme prioritising a topic and publishing the results in the monograph series was 8–10 years. As this measures the time to publication in the HTA journal and not to publication in any journal, it overestimates to some extent. The key question is choice of benchmark: what is the right length of time against which 8–10 years should be compared?

Discussion

Question T1.9 on the 8- to 10-year time lag from topic identification to monograph publication was striking. However, we were unable to find any comparable estimate in the literature.

Although the answers to most questions were largely as expected, these questions only relate to meeting NHS need in an oblique and indirect way. Data availability limited the questions that could be asked regarding the core aim of the HTA programme, that is, how well the research it funds aims to meet the needs of the NHS. This is something that the programme should consider how best to address.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

Addressing this overall question based on NHS need was hampered more than other questions in this report by the limitations of the database before 2000. This is because so much of the needs-related information is captured at the very start of a project, rather than during or at its completion.

The strength of the work has been given a new focus by the work of Chalmers and Glasziou42 in highlighting avoidable waste in research. Their framework starts with posing questions that matter, something that is key to the HTA programme.

This project looked only at trials funded through the HTA programme’s commissioned work stream. Since 2006, the programme has developed a growing portfolio through its researcher-led work stream. Proposals for this work stream are also assessed in terms of NHS need.

Recommendations for future work

Any future work will need to take account of the data limitations on how the trials funded aimed to meet the needs of the NHS. Any future work should include seven of the questions explored in this chapter, five as is (T1.1, T1.3, T1.7, T1.8 and T1.9) and two to be amended (T1.2 and T1.4).

Unanswered questions and future research