Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/53/15. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Campbell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and review of current literature

Demands on UK primary care are increasing. The introduction of a new General Medical Services contract in 20041 was followed by an estimated 25% increase in primary care workload. 2 For many practices and staff, addressing this increase in workload has involved an exploration of alternative ways of managing patients, in an attempt to respond to government and societal expectations while continuing to deliver safe, high-quality care.

The introduction of UK NHS walk-in centres, the 24-hour nurse-led telephone advice service NHS Direct and the more recent NHS 111 service, the increased diversity of staff skill mix and the use of remote consultations in primary care all represent organisational responses aimed at increasing the range of services available to patients and improving access to primary health care. When combined with telephone consultation, telephone triage is believed to provide rapid access to health-care advice for patients while freeing up opportunities for face-to-face consultation. Previous research3 has demonstrated the utility of nurse-led telephone triage (NT) of patients requesting same-day appointments in UK general practice. An ‘average’ practice (7000 patients) might be expected to manage around 20 patients each day requesting a same-day appointment request, representing around 35% of general practitioner (GP) workload. 4

Some research evidence exists regarding the feasibility, workload implications and cost of telephone triage, and patient experience of care, safety and health status following telephone triage. Most evidence derives from models involving nurse triage; less research has been carried out to address the impact of GP telephone triage to date. There have been no large-scale multipractice studies examining the potential value of general practitioner-led telephone triage (GPT) or NT of patients requesting same-day consultations.

Feasibility of telephone triage

Previous studies suggest that around 50% of nurse triage calls in out-of-hours primary care settings may be handled by telephone advice alone. 5–8 However, such studies have been small or focused solely on out-of-hours primary care. Use of telephones (fixed or mobile) is now almost universal in the UK,9 and recent years have seen a near quadrupling in the proportion of GP consultations conducted on the telephone. 10

Primary care workload

In the short term, telephone triage, whether by doctor or nurse, appears to reduce GP contacts by around 40%,3,11 but it could be that this shifting of GP workload may result in the work undertaken by GPs comprising the more complex cases. 12 The reduction also appears to be associated with an increase in later return consultations of a roughly similar magnitude (30%,3 50%13 between 2 and 4 weeks following a same-day appointment request), in effect smoothing out the peaks and troughs of GP workload that are associated with same-day appointment requests. Although this level of return consultations following triage may raise concerns regarding patient safety, convenience of care and cost-effectiveness, it has been suggested that a proportion of return consultations may be planned routine appointments, resulting from a downgrading of urgency following triage.

Cost

Equivocal results on costs of telephone triage and associated resource service use have been reported across three trials. NHS Direct nurse triage was more expensive than practice nurse triage of patients making same-day consultation requests14 but similar costs have been reported elsewhere between standard management and practice NT of same-day consultation requests. 3 NT in out-of-hours primary care may reduce long-term NHS costs but may not be cost-effective at all times of the day. 15,16

Patient experience of care

Equivocal results on patient acceptability and satisfaction have been derived from small studies. One study13 reported no difference in satisfaction between telephone and face-to-face consultations. Jiwa et al. 11 reported that 80% of patients were satisfied with GP telephone management of same-day consultation requests, and Brown and Armstrong17 have suggested that patients who elect to use GP telephone consultations may do so as an alternative to face-to-face consultations in primary care.

Patient safety

Telephone consultation appears safe and effective. 18,19 A UK equivalence trial (in which death within 7 days of contact was the primary outcome) established the safety of out-of-hours primary care NT by experienced nurses using computerised decision support software (CDSS) in comparison with usual care (UC). 5 This is supported by work in the UK by the Richards et al. 20 study, in which audio tapes of nurse triage consultations to assess decision-making revealed that decision-making was rated by GP or nurse practitioner review to be mostly good, with minimal risk from poor nurse triage decisions. However, one Swedish study19,21 noted that nurses often used self-care advice and also over-rode software-determined recommendations on management. A recent Dutch study22 highlighted concerns regarding information-gathering in telephone triage when delivered without the use of CDSS, relying only on clinical protocols. Studies8,21,23,24 have highlighted the importance of training in the use of CDSS to address patient safety issues. Nurse telephone triage delivered within a framework of national guidelines (but not with CDSS) was judged to be efficient, although some concerns were raised with respect to patient safety. 25 One study,3 adopting a triage system involving ‘computerised management protocols developed by the practice’ identified a substantial increase in accident and emergency (A&E) attendance, although actual numbers were small. Although computerised, such a system did not provide CDSS (DA Richards, Institute of Health Research, University of Exeter Medical School, 2008, personal communication) such as is now available within a number of NHS primary care computer systems, and which we propose to examine in this study. 26 The other trial by Richards et al. 14 used CDSS for NHS Direct triage nurses, but not for nurses acting in primary care. A systematic review27 of nine studies of telephone consultation and triage noted that it is unclear if telephone management simply delays visits and thus also the provision of definitive care.

Patient health status

Several randomised studies (but none involving telephone triage) have compared the health status of primary care patients following consultations with a doctor or a nurse by patients with minor problems or after a same-day consultation request. One study28 identified no difference in health status [Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) scores] between the intervention groups when followed up after 2 weeks. Similar findings have been reported with respect to resolution of patients’ symptoms and concerns after 2 weeks,29 or in the proportion of patients reporting themselves as ‘cured’ or ‘improved’ 2 weeks after a consultation with either a doctor or a nurse. 30

Rationale for the research

The four UK-based trials3,5,11,13 of primary care telephone consultation and triage have been conducted in relatively small populations and/or in limited numbers of practice settings (i.e. urban, rural), and most studies examining NT without the use of CDSS, although research undertaken by Lattimer et al. 5 did involve out-of-hours primary care nurse telephone consultations using the CDSS ‘Odyssey TeleAssess’, provided by Plain Healthcare Ltd. Despite uncertainty about the benefits and costs, many practices operate GPT or NT systems as a way of providing fast access to care for patients and in order to manage practice workload, as demonstrated by the almost fourfold increase in proportion of consultations conducted over the telephone. 10 As an example, in 2008, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement31 promoted a model of GPT – the Stour Access system – within which GPs triage all patient requests for care by telephone but without any robust evidence about benefits. We therefore proposed to address this important agenda in a large-scale experimental study of two forms of triage currently being promoted by the NHS for use in UK primary care. Our findings may be generalisable to other health settings, especially those with strong primary care-based health-care systems.

Aims and objectives

The overarching aim of this trial was to assess, in comparison with UC, the impact of NT and GPT mechanisms on primary care workload and cost, patient experience of care, and patient safety and health status for patients requesting same-day consultations in general practice.

The specific research objectives were as follows:

Pilot and feasibility study To undertake an external pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) in six practices to:

-

confirm the ability of practices to implement the GPT and NT systems

-

confirm the proposed process for recruitment of practices

-

review the assumed level of clustering of outcomes

-

check data collection systems, and

-

identify potential difficulties in implementing the triage systems.

Main trial To undertake a three-arm pragmatic cluster RCT comparing, for patients requesting a same-day consultation in general practice, the effects on primary care workload and cost, and on patient experience of care, safety and health status of:

-

GPT compared with UC

-

NT compared with UC

-

GPT compared with NT.

The funding arrangements for this trial through the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme involved the delivery of the 1-year pilot study and satisfying a number of key stopping rules (see Appendix 1), before progression to the main trial phase.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

Consistent with the Medical Research Council framework for evaluating complex interventions,32 a two-stage mixed-methods study was conducted, comprising an external pilot trial, followed by a definitive cluster RCT. The ESTEEM trial was designed as a pragmatic three-arm, multicentre cluster RCT. Practices were randomised 1 : 1 : 1 to receive GPT, NT or UC as comparators. The main trial included a parallel economic evaluation to examine the cost-effectiveness of the two triage interventions and a process evaluation to assess the intervention acceptability from the perspectives of patients and practice staff.

Pilot study

A 12-month, external pilot cluster RCT and parallel process evaluation was undertaken in six practices across Devon and Bristol. This work informed aspects of the main trial protocol published in 2013. 33 We present the methods implemented within the main trial, relating to the triage interventions, practice and patient inclusion and exclusion, practice and patient recruitment, randomisation, and the outcome measures and sample size. A full account of the changes made to the main trial methods can be found in Appendix 2.

Ethical and governance arrangements

Multicentre ethical approval for the study was obtained from South West 2 NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) in October 2009 (reference 09/H0202/53). Local NHS research governance approvals were obtained from the primary care trusts (PCTs) in Devon, Somerset, North Somerset, Bath and North East Somerset, Bristol, South Gloucestershire, Warwickshire, Coventry, Norfolk, Suffolk and Great Yarmouth, and Waveney. At the time this work was undertaken, PCTs were the main unit of administration of primary care, with a total of 152 PCTs in England, each covering an average population of around 330,000 individuals. PCTs were abolished under major changes to the NHS, introduced in 2012, with clinical commissioning groups taking over former PCT functions. The Research Management & Governance Unit, Devon PCT, acted as the study sponsor. A Trial Management Group and an independent Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) ensured that the study was conducted within appropriate NHS and professional ethical guidelines. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) Register (reference 20687662).

Patient and Public Involvement

The Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) group supporting ESTEEM initially met to review the study protocol and methods. Practice service users (nurses, GPs, managers and administrative staff) were also consulted to inform the trial design. It was planned that patient service users would be involved at all stages of the pilot study and main trial. Patient representatives were recruited through an existing GP practice patient group local to the Exeter site (not an ESTEEM trial practice). Eleven patient representatives were recruited and were invited to contribute to some or all of the various tasks as they preferred. Although our intention was to recruit representatives on the basis of their demographic characteristics, to reflect variations in the people most likely to be requesting same-day consultations in general practice (e.g. parents of young children, retired people) the majority of the patient representatives were of retirement age.

There were a number of PPI tasks, as listed below, and not all patient representatives wished to contribute to every task over the duration of the study.

-

Most of the patient representatives contributed to the development of study materials in preparation for ethical review before the pilot study began, and then again at the end of the pilot study for use in the main trial. This involved helping to design the patient information sheets, consent forms, topic guides for patient interviews, and patient questionnaire. Comments were obtained through a combination of face-to-face meetings and via e-mail and post.

-

Advice was also sought on ways to improve patient participation in interviews for the process evaluation. This led to the introduction of an option for telephone interviews during the main trial.

-

(The same) two patient representatives sat on the Trial Steering Committee for the whole period of the trial and one, if not both, attended every meeting.

-

A small number of patient representatives contributed to the process of analysing qualitative data from the process evaluation during the pilot study.

-

A small number of patient representatives attended meetings and received postal material during the running of the trial in order to be kept informed of study progress.

-

All patient representatives were invited to contribute to the dissemination of the study results at the end of the project, by way of providing input to the plain English summary of the trial findings.

Health technologies assessed

Triage interventions

The GPT and NT interventions were complex interventions that involved staff training (clinical and technology based); CDSS to support the delivery of NT; process and organisational change in practices regarding reception activity and appointment system management; and accommodation of patient expectations. Some core elements of triage delivery were common to, and adopted by, all practices in both intervention arms. However, some organisational flexibility was permitted because of the complex nature of the intervention. Full details of the interventions are available from the research team.

Core triage processes

All patients contacting the practice initially spoke to a receptionist. Once the receptionist established that the patient (or a proxy asking on their behalf) was requesting a same-day, face-to-face appointment with a GP, the patient was asked to provide a contact telephone number and was advised that the clinician (GP or nurse, according to the practice’s allocation) would call them back within around 1–2 hours. This timescale was suggested as a guide for practices but was not considered mandatory.

On telephoning the patient (‘index consultation’), the clinician discussed the presenting condition and had a range of management options at their disposal:

-

give the patient self-care advice

-

book the patient into a ‘triage-bookable’ face-to-face or telephone appointment with the relevant health professional later the same day

-

book the patient into a ‘triage-bookable’ face-to-face or telephone appointment with the relevant health professional on another day

-

book the patient into any routine appointment available

-

refer the patient to other NHS services where appropriate, including those outside the practice.

Practices kept a number of ‘triage-bookable’ appointments with GPs and nurses, reserved exclusively for triaging clinicians to book. When patients required face-to-face appointments, they could be triaged to any available, appropriately timed, triage-bookable appointment slot; this may or may not have been with the patient’s usual doctor (at the discretion of the practice) or on the same day as the patient’s index consultation.

Areas of flexibility

Although the core triage processes were specified, practices had some areas of flexibility in implementing triage interventions, in order to accommodate the complexities of individual practice organisation. These models used were informed by individual practices’ audits of appointment requests, GP and nurse capacity information, and guidance and training given to practices prior to starting the trial (see Training practices in the two triage systems). Flexibility was allowed in terms of the triaging clinician, triage availability, the triaging of babies, and same-day requests for nurse practitioner consultations.

Triaging clinician

Three alternative staffing models emerged regarding which clinician (GP or nurse) delivered the triage: (1) one clinician (GP or nurse) at a time conducted a triage session (on a rotating basis); (2) a number of clinicians (GPs or nurses) conducted triage sessions on the day (on a rotating basis); or (3) in GPT practices only, all of the GPs conducted triage each day, with GPs triaging their own patients to triage-bookable appointments.

Triage availability

Practices were asked to triage all consecutive eligible patients during opening hours to ensure the least disruption and shortest time of trial data collection possible. In the event that limited staff resources prevented triage of all eligible patients each day, practices were permitted to operate triage within specific agreed sessions (‘research window’), amounting to no less than 50% of the week, encompassing all five working days and both mornings and afternoons. These arrangements were agreed with the research team in advance. Practices were advised of the importance of all eligible patients being triaged during an entire session, as opposed to receptionists booking in a set number of triage patients within a session and then ‘closing’ the triage once the allocated slots were taken. Practices operating triage within ‘research windows’ had their data collection period extended until the patient recruitment target was reached.

Triaging babies

Practices were advised that babies (i.e. ≤ 2 years of age) were eligible for trial entry according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with the parent or guardian identified as the individual who participated in the triage call. As some practices routinely see babies as soon as possible on the same day of the appointment request, it was expected that some practices would opt to book these patients in for a face-to-face appointment rather than add them to a triage list. Although all of the intervention practices were encouraged to offer triage to babies during intervention training, some practices elected to offer face-to-face appointments in line with their existing practice policy. When this happened, the babies were still included in the trial analysis on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis.

Requests for same-day, face-to-face nurse practitioner consultations

Some practices operated a nurse practitioner-led clinic for acute or minor illnesses, for which the nurse typically managed same-day consultation requests. This request was deemed equivalent to a same-day GP appointment request, as the patient would see a GP if the nurse practitioner was unavailable. Such patients were deemed eligible for trial entry and managed as per the treatment arm allocation.

Training practices in the two triage systems

Role of commercial providers in triage training

To prepare GPT and NT practices for incorporating telephone triage within their appointment systems, we worked with Productive Primary Care Ltd, a Leicestershire-based, NHS-focused commercial organisation that works nationally across the UK with NHS organisations. Plain Healthcare’s ‘Odyssey PatientAssess’ (derived for general practice use from ‘Odyssey TeleAssess’ or ‘TAS’) CDSS was used to support the nurses in NT practices. Plain Healthcare, then part of the Avia Health Informatics PLC group, supplies the NHS with CDSS systems (e.g. out-of-hours primary care services). Plain Healthcare liaised directly with NT practices to discuss IT and training requirements for the installation of the software. Following a ‘site initiation call’ between Plain Healthcare and each practice, installation and testing took place over a 6-week period. The CDSS was fully embedded within the Egton Medical Information System (EMIS, Yeadon, Leeds) ‘PCS’ and ‘LV’, and installed as a separate ‘stand-alone’ window tab to the clinical notes within all other types of practice IT system [e.g. Microtest Evolution (Microtest, Bodmin, Cornwall), Vision (In Practice Systems Ltd, Battersea, London), SystmOne (The Phoenix Partnership, Horsforth)].

Nurses received CDSS training and training in telephone consultation skills. Following this, there was a pretrial period of 1 month during which nurses practised using CDSS in simulated patient scenarios during their daily work. Towards the end of this period, the nurses’ use of the system was assessed by Plain Healthcare trainers, with all nurses needing to demonstrate proficiency in its use before being recruited into the trial. It is also important to note that the CDSS is designed to support the nurses’ clinical decision-making; there was no requirement in the trial that the recommended advice the CDSS generated had to be followed.

Computer decision support in nurse triage

Odyssey PatientAssess [www.advancedcomputersoftware.com/ahc/products/odyssey-patient-assess.php (accessed 5 November 2014)] is a UK product, developed to support nurses and paramedics to assess the clinical needs of patients. It is already being used by several out-of-hours primary care and NHS walk-in services, and is also the subject of the Department of Health-funded SAFER1 trial focusing on the care of older people who have called the 999 service following a fall, and the HTA-funded SAFER3 trial focusing on the care of adults who have called the 999 services and are not in need of transfer to an emergency department. 34

Odyssey PatientAssess has been evaluated in a number of other RCTs, and its clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness in settings other than in-hours general practice is already established. For instance, it has been demonstrated to be safe and cost saving in the long term in one study5,16 involving a co-investigator compared with GP telephone triage in a trial of out-of-hours primary care consultations. That study remains the largest trial of nurse telephone triage to date. 5,16 Furthermore, in excess of 60% of PCTs currently commission out-of-hours primary care services that use nurses to triage patients by telephone, supported by Odyssey PatientAssess (Chris Coyne, Plain Healthcare, 2008, personal communication). However, the findings and experience of out-of-hours primary care (providing care for around 10.8 million contacts per year in UK) cannot necessarily be generalised to the very different system providing in-hours primary care and experiencing around 1 million contacts per working day.

Odyssey PatientAssess provides the user with a network of assessment prompts and guided responses relating to over 465 presenting complaints. It allows for multiple symptoms to be evaluated simultaneously, supported by evidence-based frameworks for referral and self-care, with all assessment data remaining visible at all times. It supports the clinician’s judgement and expertise through enhancing normal consultation processes. The clinical database comprises several hundred assessment and examination guidelines and protocols, each linked to triage, treatment and advice guidelines, differential diagnoses, patient information and education. These are maintained by an in-house clinical development team, which reviews the entire clinical content at least annually to ensure that it reflects current best practice, including National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance.

The assessment screens include drop-down menus that provide regularly updated referenced information on differential diagnoses and rationales for lines of enquiry for each type of presentation – so reminding the user about the importance of different lines of enquiry. For the purposes of the ESTEEM trial, Odyssey PatientAssess was either embedded within GP computing systems (EMIS and SystmOne) or installed to run in parallel alongside all other systems (Synergy, Microtest, Vision). Odyssey PatientAssess guides and stores documented records of the assessment, advice and/or referral of each patient producing a fully auditable record. Based on the data elicited during the telephone assessment, Odyssey PatientAssess suggests an appropriate care plan (e.g. patient advice, same-day appointment, home visit, routine appointment, 999 referral).

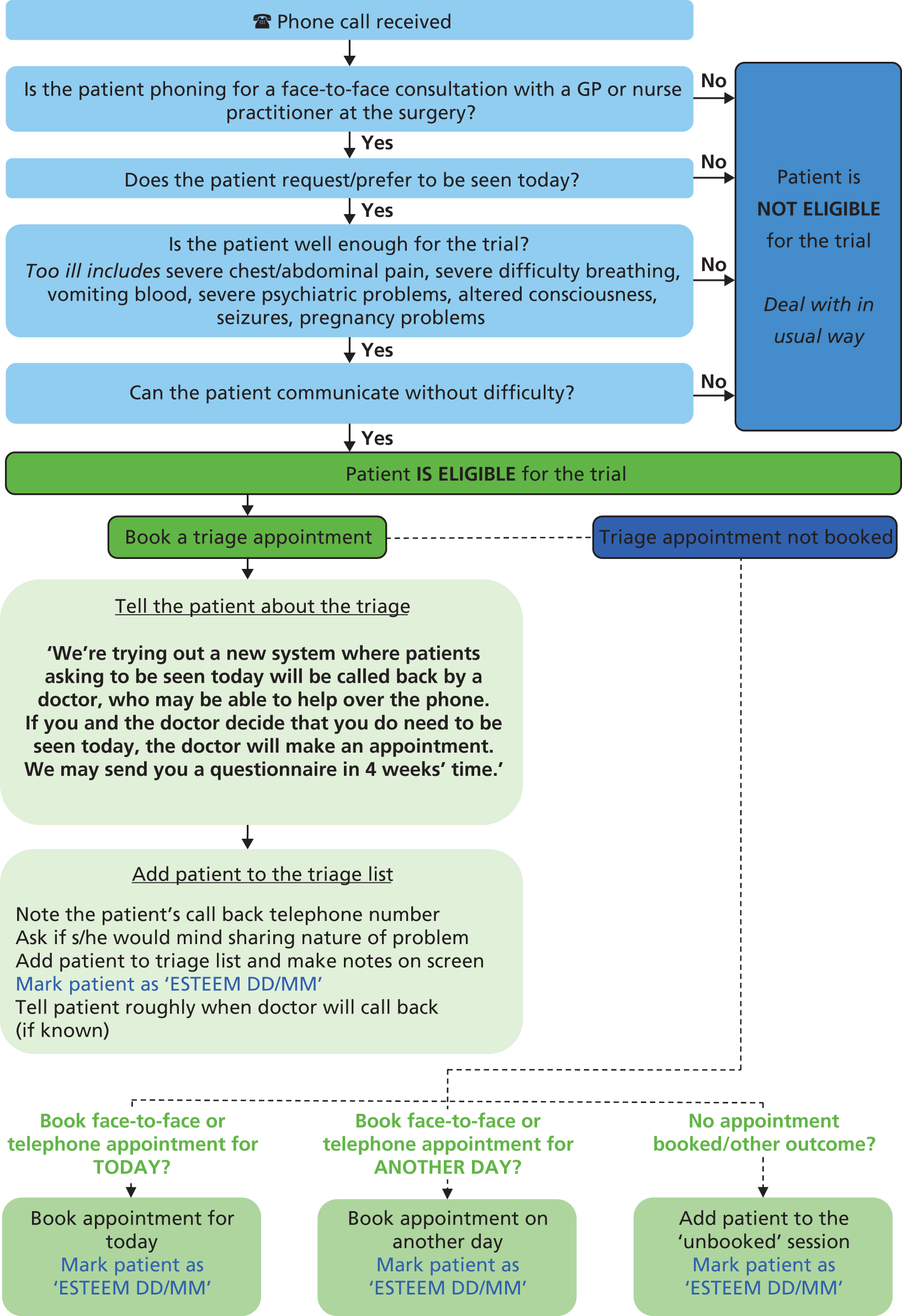

Overview of practice training

Practices were trained in research procedures and the delivery of triage interventions, following a model (Figure 1) devised during the pilot study. Training was delivered in six stages, and by a combination of Productive Primary Care (GPT and NT only), Plain Healthcare (NT only) and trial researchers (all arms). ‘Triage training’ workshops were organised for GPT and NT practices (training components 3–5, described below) and delivered as a package to staff from a number of practices at a central location in each of the recruitment areas. If practices were unable to attend a central training event, the various components were delivered on site at the practice.

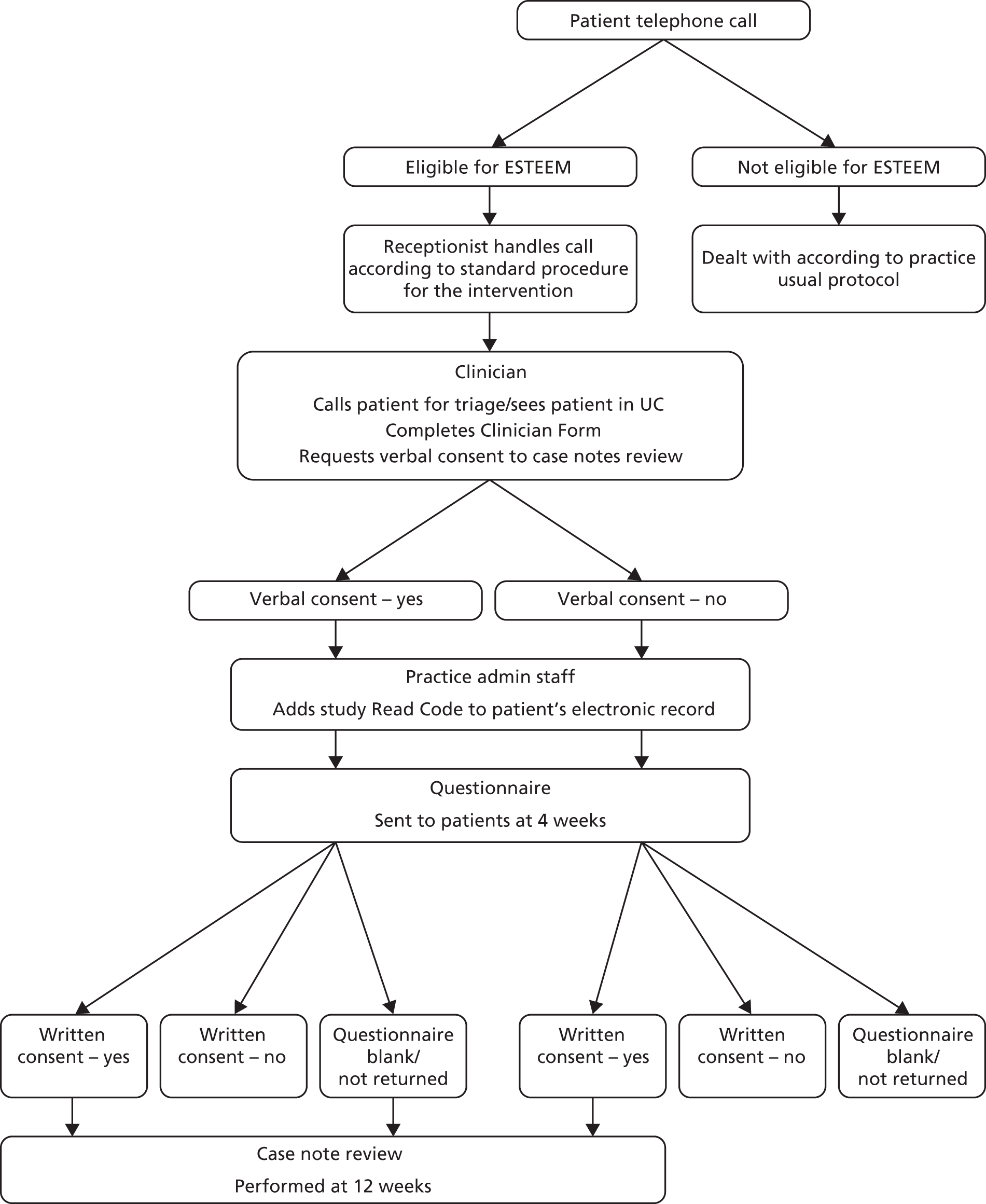

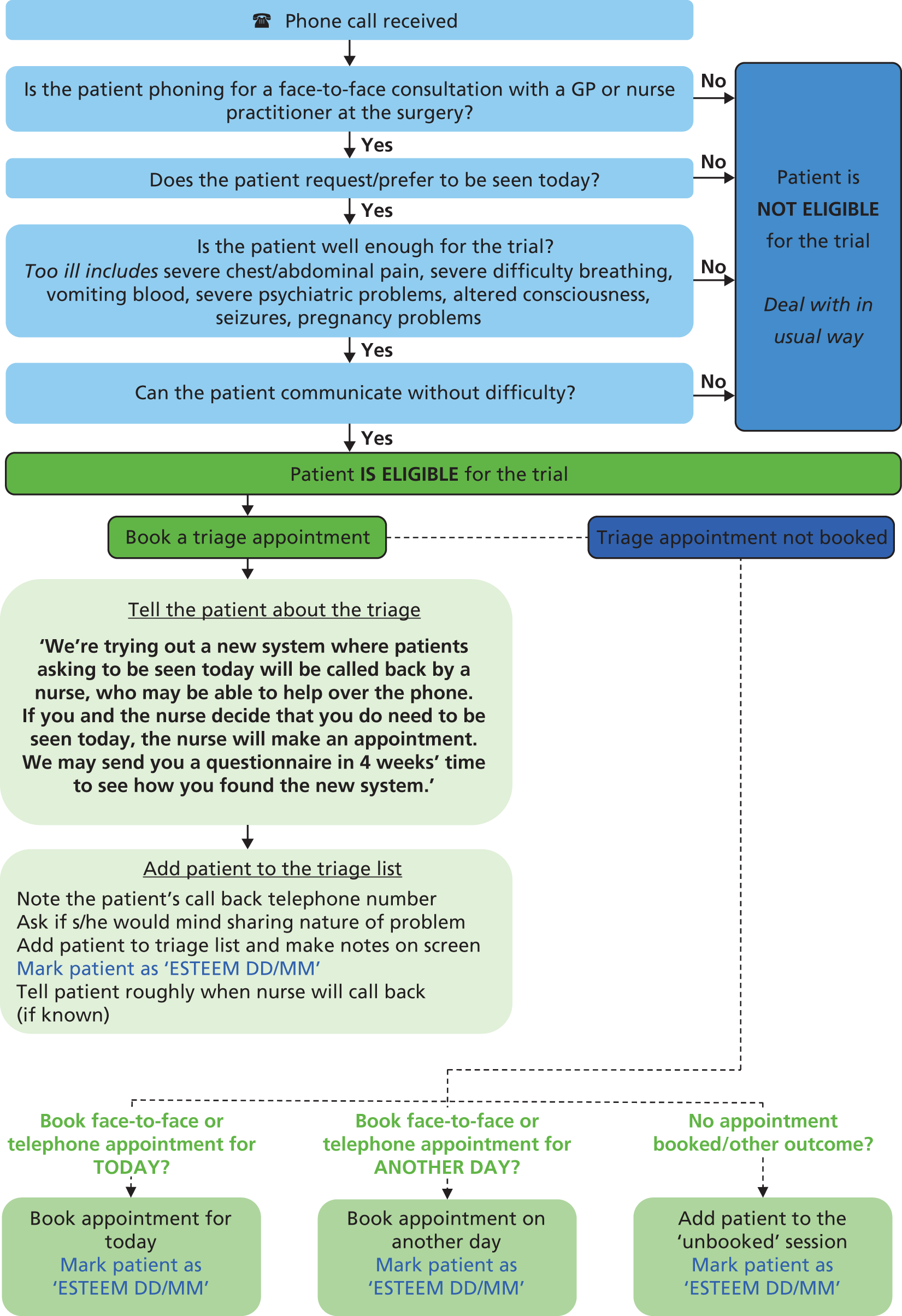

FIGURE 1.

Practice training structure.

-

Inception meeting An initial whole-practice meeting with the trial researcher was held to outline the trial, staff group involvement and timeline of training. The meeting was convened for the practice manager, at least three receptionists, at least two GPs – to include the two GPs identified as clinical leads for the trial – and up to four nurses (NT only).

-

Appointment request audit To assess patient demand for same-day and prebookable appointments, a 1-week audit was conducted by the practice reception team. Capacity information was collated relating to the number of GP and nurse sessions provided per week and the number and typical duration of appointments offered within each session (including the proportion reserved for same-day and prebookable use). The trial researcher provided the reception team with Audit Log Sheets (see Appendix 3) and asked them to record all incoming calls each day for a week (Monday to Friday), indicating whether each call was a same-day or prebookable appointment request. The researcher maintained contact with the practice during the first day or two of the audit to ensure that the procedure was followed appropriately.

-

Organisational training and guidance in organising the triage system Productive Primary Care trained the practice manager, at least two receptionists, at least two GPs (GPT) and up to four nurses and one GP (NT). The training incorporated advice for the reception teams on how to communicate the introduction of the triage system to patients. Practical guidance on setting up the appointment system to incorporate triage consultation slots and face-to-face appointment slots for the use of the triaging clinician was also given. Using the data collected during the appointment request audit, Productive Primary Care used a spreadsheet (the Appointment Redesign Tool) to estimate the number of appointments that the practice needed to provide and the proportion that should be ‘triage bookable’ based on their previous experience of working with a range of practices. The details of the calculations for these estimates are the intellectual property of Productive Primary Care.

-

GP triage skills In GPT practices, Productive Primary Care delivered training to GPs on how to communicate the operation of the new triage system to patients, and general guidance for consulting over the telephone. At least two GPs at each practice were required to receive this training and were expected to disseminate the information to their other GP colleagues.

-

Professional issues and telephone consultation skills All nurses at each NT practice who would undertake triage were required to receive this training. A learning and development adviser from Plain Healthcare presented information and advice on the professional issues that may arise from nurses consulting over the telephone. Guidance on telephone consulting skills, including role-play scenarios, was provided. In addition, nurses received one-to-one remote training from an advisor while they practised using the CDSS on computerised simulated patient scenarios in the weeks leading up to the trial, culminating in a proficiency assessment.

-

Research procedures training Trial researchers provided briefing sessions to practice staff in data collection procedures. Staff groups included the reception team, practice manager, key IT and administrative staff and the GPs and nurses to be involved in triage or dealing with patients requesting same-day consultations.

-

Usual care comparator

Practices were asked to continue with their standard consultation management systems for handling same-day consultation requests. UC practices also (1) received training through the inception meeting; (2) performed the appointment request audit; and (3) received the standard research procedures training, as outlined for the intervention arms.

To describe the range of systems that constitute UC, all 42 practices were asked to complete a Practice Profile Questionnaire before randomisation to collect details on their current staffing and appointment system arrangements to manage same-day consultation requests, including the extent to which they already used triage of any sort.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Practices

Practices already implementing a documented triage system for routinely handling same-day GP consultation requests were excluded. We defined a documented triage system as a system involving telephone triage (by a GP or a nurse) managing > 75% of all same-day consultation requests received. This definition recognised that many GP practices already undertake some form of telephone triage. Practices also had to be willing to be randomised to one of the three trial arms.

Patients

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive patients making telephone requests for a same-day, face-to-face consultation with a GP during the data collection period were potentially eligible. When an individual patient had multiple same-day consultation requests during the recruitment period, only the first contact was included in the study to avoid confusion in following up the contact (although subsequent calls would be triaged in the same way, according to trial arm). All patients aged < 12 years and ≥ 16 years requesting eligible appointments were included with respect to the primary and secondary outcome measures. Parents or guardians of children aged < 12 years provided consent on behalf of the child.

Exclusion criteria

Temporary residents or young people aged 12.0–15.9 years were excluded, as the study involved receipt of a postal questionnaire along with written consent to review case notes. We believed that receipt of the questionnaire at the young person’s address may have inadvertently led to a breach of confidentiality should third parties have access to the young person’s mail. Although excluded from trial participation, both temporary residents and young people received the intervention as per trial allocation. Adults aged ≥ 16 years were included, unless the practice wished to screen out patients for whom they felt it would be inappropriate to send a questionnaire (e.g. patients with recent bereavement, vulnerable adults).

Patients seeking urgent or emergency care on account of the following conditions were excluded:30 too ill to participate (severe chest or abdominal pain or severe difficulty breathing; vomiting blood; altered consciousness; seizures; pregnancy-related problems; or severe psychiatric symptoms); unable to speak English or difficulties with communicating on the telephone (hearing or speech). Reception staff members were trained to refer to a standardised ‘Receptionist flow chart’ to ascertain patient eligibility (see Appendix 4).

Patients ringing on a second occasion were not included in the trial again (i.e. their point of entry into the trial was on the first occasion they rang the practice seeking a same-day consultation). However, in practice, receptionists would have recorded the patient as being eligible and sent their information to the research team. Our database would have flagged them as a duplicate and excluded them from being entered into the trial database again.

Recruitment and randomisation procedures

Practices

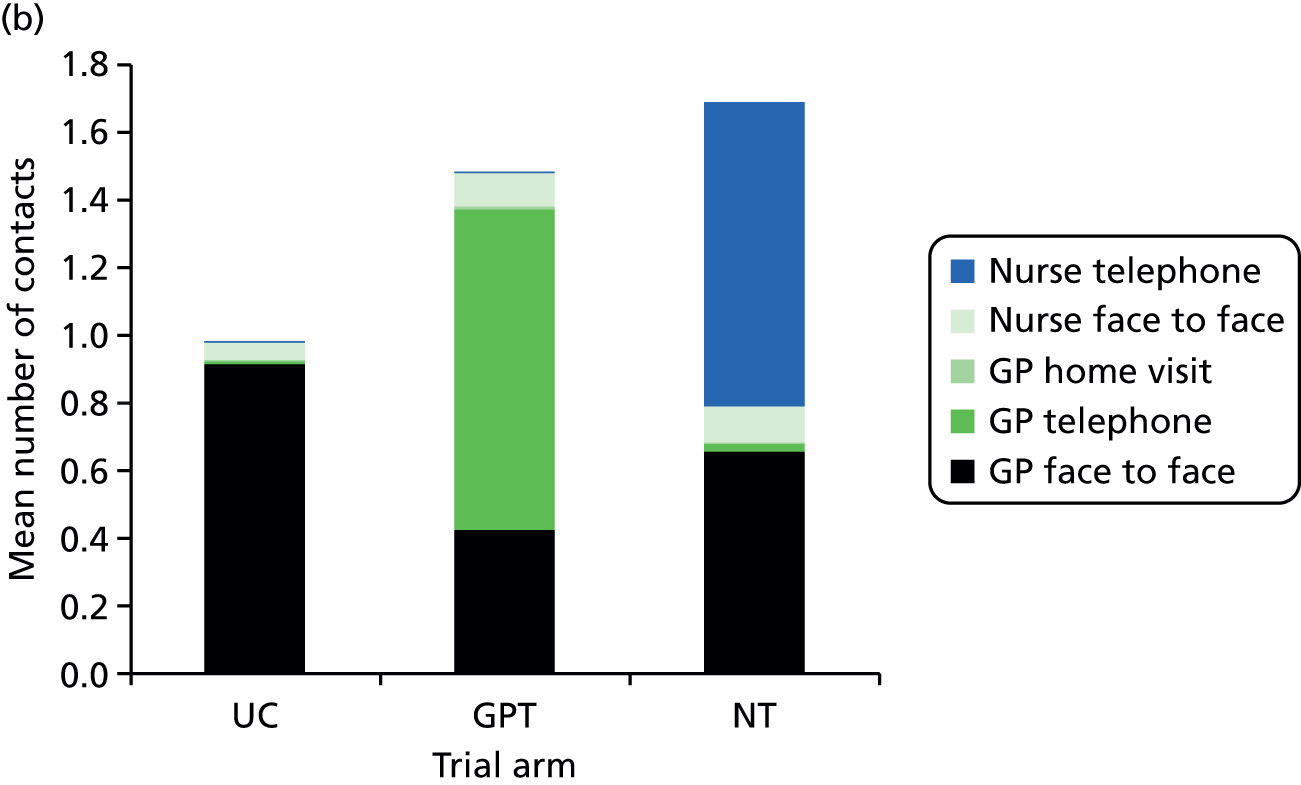

We approached all practices within our four participating centres (Devon, Bristol/Somerset, Warwickshire/Coventry and Norfolk/Suffolk). To maximise recruitment we ran the trial in conjunction with the NIHR Primary Care Research Network (PCRN), including the networks in the South West, West Midlands (South) and East of England. In recognition of the challenges of recruitment into large-scale clinical trials of complex interventions,35 a two-stage recruitment process was adopted (Figure 2). A written letter inviting participation was sent to all practices in the four geographical areas. This letter was co-signed by the trial Chief Investigator, the local principal investigator and local PCRN clinical lead. Practices expressing preliminary interest were sent an information pack and offered a practice visit by a researcher. At this recruitment meeting (for which the practices were remunerated), the trial design and methods were explained, and staff were given the opportunity to ask questions. We prioritised recruiting practices in workable proximity to recruitment centres (taking account of relevant sampling issues).

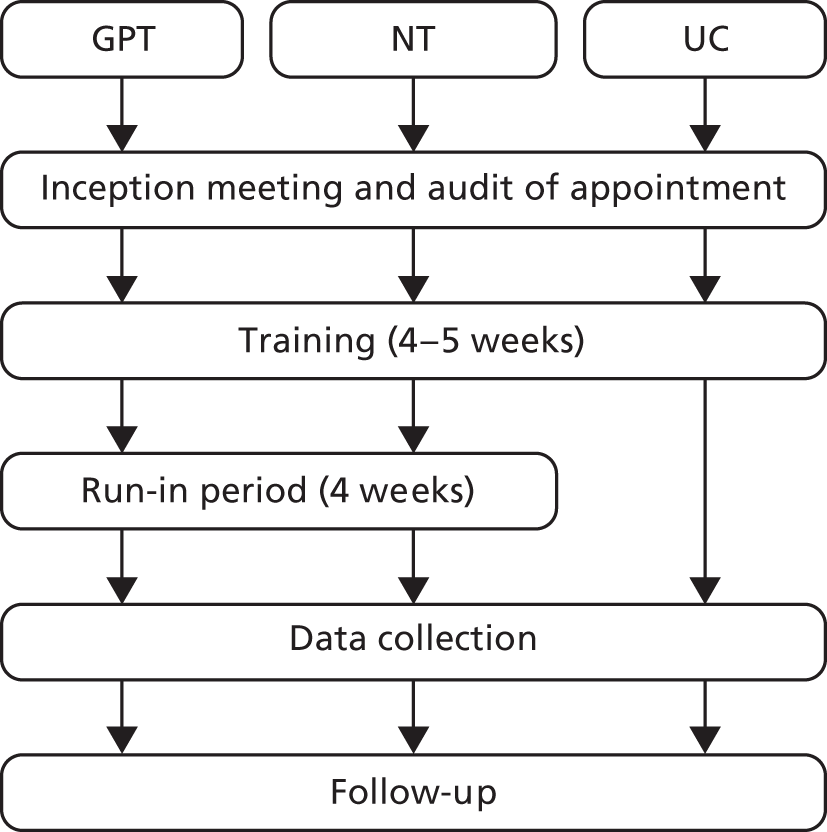

FIGURE 2.

Practice recruitment procedure.

Randomisation procedure

Individual patient-level randomisation was deemed impractical as it was unable to reflect the practice-level triage system implementation and was vulnerable to contamination. A cluster RCT design was adopted, with practices that agreed to take part subsequently randomised to one of the three trial intervention arms (GPT, NT, UC). 36 To manage the recruitment process, practices were randomised in three distinct ‘waves’. Wave 1 took place during spring and summer 2011, wave 2 during winter 2011/12 and wave 3 during spring and summer 2012.

The sequence of practice randomisation was computer generated and minimised for geographical location (Devon, Bristol, Norwich, Warwick), practice deprivation [based on the data provided by the Association of Public Health Observatories (APHO)37 at time of randomisation, practices were classed as ‘deprived’ (i.e. score is above the average for England) and ‘non-deprived’ (score is average or below average) and practice list size of ‘small’ (< 3500 patients), ‘medium’ (3500–8000 patients) and ‘large’ (> 8000 patients)]. A stochastic element was included within the minimisation algorithm to maintain concealment. Practice allocation was undertaken using a password-protected web portal (developed and validated by the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC)-accredited Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit) by a statistician who was independent from the trial statistical team. Allocation was communicated by e-mail to the trial manager who then informed the local researchers, who, in turn, informed practices of their allocation.

Replacing practices that withdrew post randomisation

To maintain balance between groups, practices that withdrew post randomisation were replaced with a practice from a waiting list in the same geographical area, and of a similar size and deprivation level, where possible. Owing to the limited number of waiting list practices, it was not possible to select a matched practice randomly. Instead, replacement practices were purposively allocated to a trial arm based on locality, practice size and deprivation index. However, other than knowing that the practice was matched for the above characteristics, the researcher making the practice selection was unaware of any other characteristics of that practice. Replacement practices were not aware of their potential allocation when the researcher checked that they were still willing to enter the trial. A questionnaire exploring reasons for withdrawal was sent to practice managers (see Appendix 5).

Patients

During the intervention period all practices were provided with a poster to be displayed in the practice to inform participants of the trial and its purpose, and some practices incorporated a voice message onto their telephone systems to explain that the triage system was being trialled. All incoming calls were received by a practice receptionist, who (referring to the ‘Receptionist flow chart’) ascertained whether the patient was requesting a same-day, face-to-face consultation with a GP at the surgery. Reception staff asked patients to briefly outline the nature of their problem in order to facilitate timely care (but patients did not have to disclose this information). If the patient was not requiring urgent or emergency care (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria), the receptionist informed the patient of the current practice consultation arrangements (according to trial arm) and managed the request following the standard operating procedure for that practice.

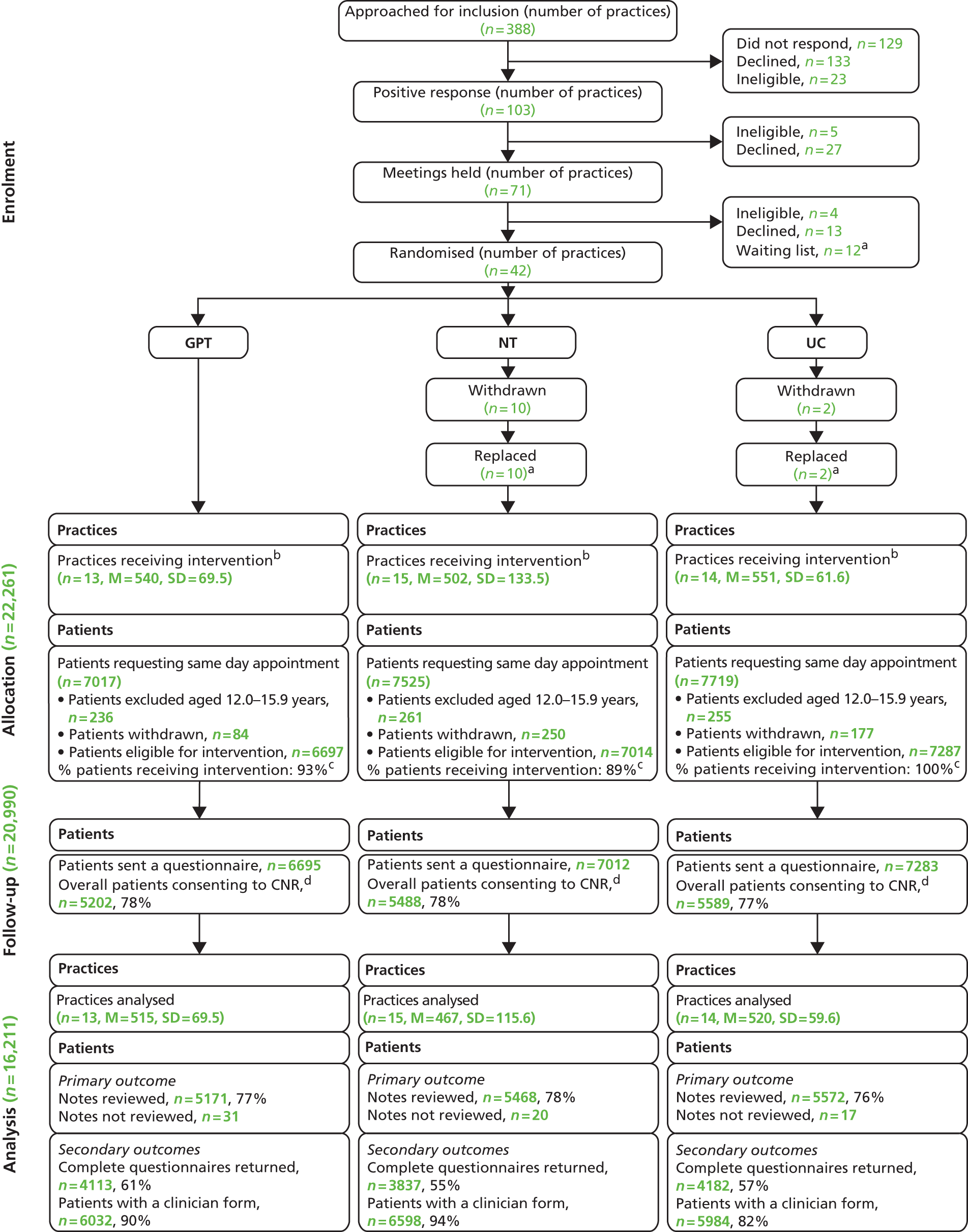

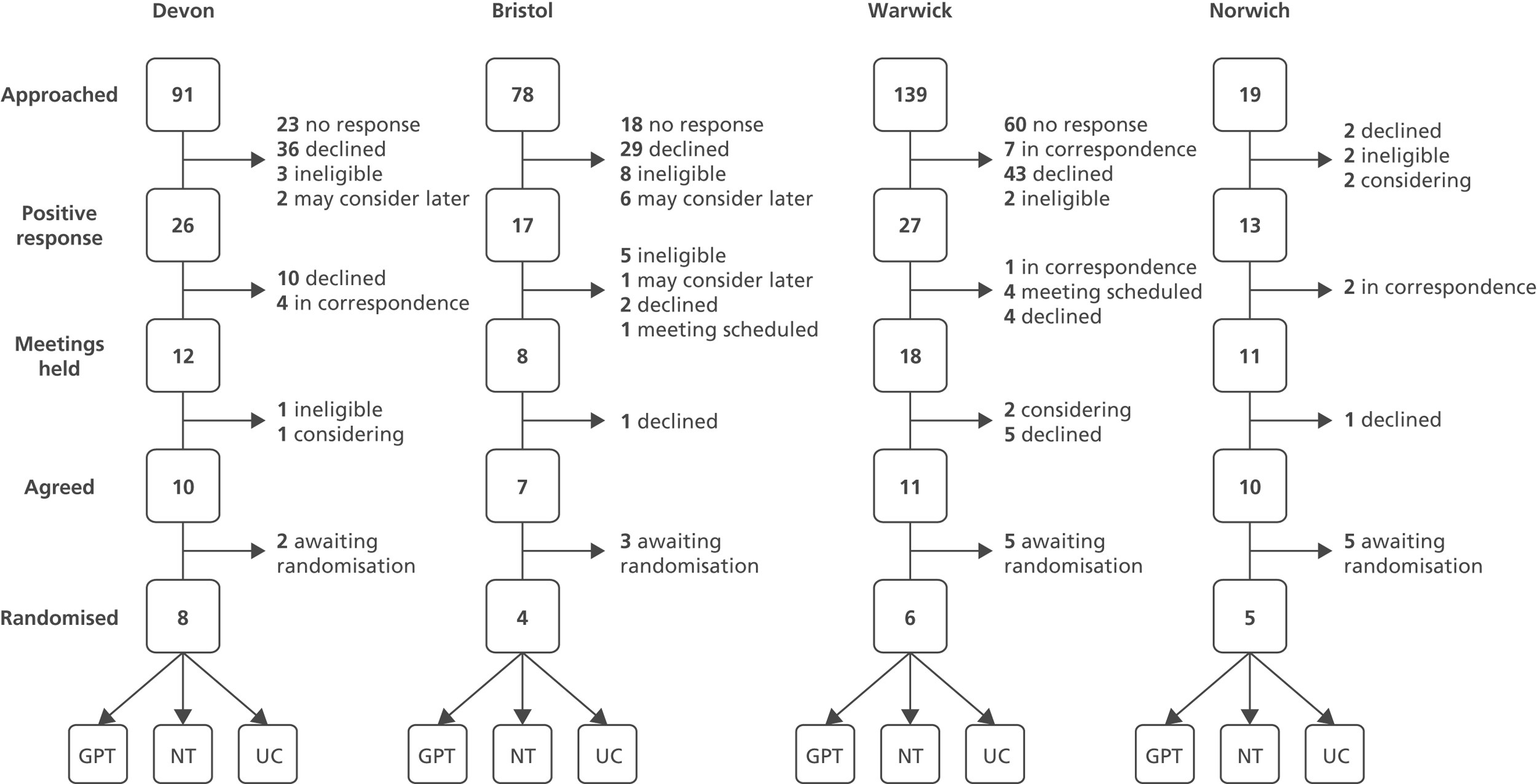

Patient consent

The patient recruitment and consent procedure is summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Patient recruitment and consent procedure.

Consent to trial participation

Consistent with the cluster RCT design, all of the eligible patients were managed according to the practice’s trial allocation. Patients were not asked to give individual consent on the basis that all UK practices are free to organise patient care to fit their circumstances. Reception staff simply explained the current consultation arrangements to patients, and informed patients that they would receive a postal questionnaire in 4 weeks’ time regarding their experience of care and that their completion of the questionnaire would be greatly appreciated.

Consent to the case note review

At the end of the clinical interaction during the index triage or UC consultation, the clinician reminded the patient that they may receive a questionnaire in 4 weeks’ time regarding their experience of care that day. The clinician referred to standard text, asking the patient for their initial verbal consent to the case note review aspect of the study. Twenty-eight days after the index consultation, patients were sent a questionnaire pack by the practice.

Each pack included a covering invitation letter (see Appendix 6), an information sheet describing the study (see Appendix 7), a questionnaire (see Appendix 8) and a prepaid return envelope. The pack also contained a flyer providing details of an incentive to return the questionnaire: entry to a prize draw to receive one of 20 prizes of £25 worth of shopping vouchers. Patients’ written consent to a case note review was sought on the final page of the questionnaire. Patients who had given initial verbal consent at the index consultation could opt out of the case note review at this stage if they wished, or opt in if they had initially declined, with written consent always taking priority over the previous verbal response. A name and contact details were provided if patients required any further information about the trial. Patients who did not wish to complete a questionnaire were encouraged to return a blank questionnaire in the prepaid envelope in order to receive no further contact in relation to the study. Non-responders after 2 weeks were sent a reminder questionnaire pack.

Capturing the patient sample

The receptionist flagged a triage or UC appointment as being allocated for a study participant by entering a free-text comment (‘ESTEEM’) and the date of the appointment request as a note on the appointment slot. Within a week, a dedicated member of the practice staff applied a study-specific Read Code to each ‘ESTEEM’-flagged patient, thus defining the eligible patient sample. This Read Code was dated as per the receptionist’s free-text comment, allowing the practice to run electronic searches to generate an ESTEEM patient list that was passed to the research team as the denominator for the study database.

In the triage practices, if for any reason an eligible patient was booked a face-to-face or any other type of appointment instead of triage (e.g. a patient being unable to receive a telephone call while at work), such patients were still captured as part of the eligible sample and followed up according to the study protocol. Similarly, if a patient was not booked into an appointment (of any type), despite having made an eligible request (e.g. a patient failed to complete the telephone call with the receptionist), the patient’s record was still flagged by reception staff as eligible and included within the study denominator.

It was not possible to routinely record eligibility for all patients telephoning the practice. However, on two occasions during run-in and once during data collection (see Integrity checks) receptionists logged all incoming calls and recorded patient eligibility, flagging those patients who were requesting same-day appointments and who were too unwell or could not communicate clearly (see Appendix 9). We used these data to estimate the proportion of patients making same-day requests who were ineligible for the trial. However, receptionists did not complete the log sheets as fully as we would have liked. For example, in some cases a call had been recorded, but there was no record of whether or not it was a same-day request. Additionally, for other patients recorded as requesting a same-day appointment but who were ineligible, the reason why was sometimes omitted.

Confidentiality

All personal information obtained about patients or staff for the purposes of recruitment or data collection (e.g. names, addresses, contact details, personal information) was kept confidential and held in accordance with the Data Protection Act. Each patient included in the trial was assigned a research number, and all data were encrypted and stored without the subject’s name or address. Electronic data were held on a secure database accessible by only members of the study team, and paper-based information was held in a locked filing cabinet in the research team office. Names and participant details were not passed on to any third parties and no named individuals have been included in the reports.

Regarding case note review, the clinical record was viewed only when patients had given verbal or written consent. Patient records were accessed by researchers holding relevant approvals and letters of access granted by PCT research governance units and NHS staff. Case note reviews took place in the practice and no patient records were removed from the premises. Any data extracted were identified by the research number; all other patient identifiers were removed. When data were temporarily stored on laptops, memory sticks or attached to e-mails prior to transfer to the research offices, these media were encrypted as per NHS security requirements. Researchers adhered to confidentiality agreements stipulated by the practices concerned.

Safety of participants

There were not thought to be any significant risks to patients or staff arising from the trial methods. Triage itself may carry risks but the approaches to triage in this trial were already in routine use in the NHS in other settings. Notwithstanding this, we identified two areas of potential minor risk, and developed systems to ensure that these were minimised.

Minimising risk of delays to care for emergency cases or inappropriate triaging

Eligible patients are those requesting same-day consultations at their practice. Consequently, some patients were likely to perceive themselves to have urgent or emergency health-care needs. Where emergencies were identified (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria), patients were to be dealt with according to the practice’s usual emergency protocol and excluded from trial participation.

Telephone triage means that some patients who might otherwise have been seen in person are managed over the telephone. It was essential that this did not lead to a patient’s care being delayed when same-day care was needed. The triage systems were designed to provide safeguards against inappropriate triaging. Both have been tested in previous studies and have been found to be safe (see Health technologies assessed), and are already used within some GP practices in the UK. Clinicians and receptionists received training in the system that they were using, and were provided with ongoing support from a clinical lead in the practice and from the system designers. The NT intervention, which relied on CDSS, required nurses to pass a proficiency test (see Training practices in the two triage systems). As the GPT intervention draws on clinical skills that are routinely offered by GPs, no proficiency test was required, although guidance in the practicalities of telephone triage were provided.

Minimising risk associated with unexpected software or triage problems

Steps were taken to minimise the risks associated with any unexpected CDSS or triaging problems. Each study practice identified two named clinical leads to be the first point of contact, and who were able to deal with any immediate problems and take corrective action. A form was established for use in practices to alert the clinical leads and the trial manager to any such problems arising. A run-in period of 4 weeks was also built in to allow the interventions to be properly set up, and to allow staff to begin operating the interventions ‘hands on’ before patient recruitment and data collection began. Finally, for NT practices, the CDSS was installed and thoroughly tested by Plain Healthcare before the trial began.

Outcome measures

The selection of relevant outcomes has been a contentious issue in previous evaluations of triage systems in primary care. 27 Most studies assessed primary care and hospital service use and workload. However, these outcomes may not fully capture the aim of triage and more broadly the aim of primary care. We proposed that the aim of a primary care consultation management system is to provide an administrative framework for practices to facilitate (1) the safe, timely and definitive (‘first pass’) management of patients and (2) the timely and efficient management of primary care consulting time resource. We collected descriptive data on practices and patients, and for the following outcome domains: (1) total primary care workload [primary outcome measure (POM), including out-of-hours primary care, A&E and walk-in centre attendance]; (2) patient safety; (3) NHS resource use and cost, and non-attendance rates in primary care; (4) patient health status and experience of care; and (5) case complexity.

Describing practices and patients

Practice-level descriptive data (e.g. list size, location, rural or urban nature, staffing) were collected on trial entry via the Practice Profile Questionnaire completed by the practice manager. This questionnaire also captured information on the typical management of patients before the trial began, providing a description of ‘UC’. Practice-level deprivation was collected from the APHO website. 37

We collected patient-level descriptive data (age, gender, deprivation) from practice records. Patient self-reported ethnicity, presence of long-standing health conditions and ease of taking time away from work (where relevant) were derived from the postal questionnaire.

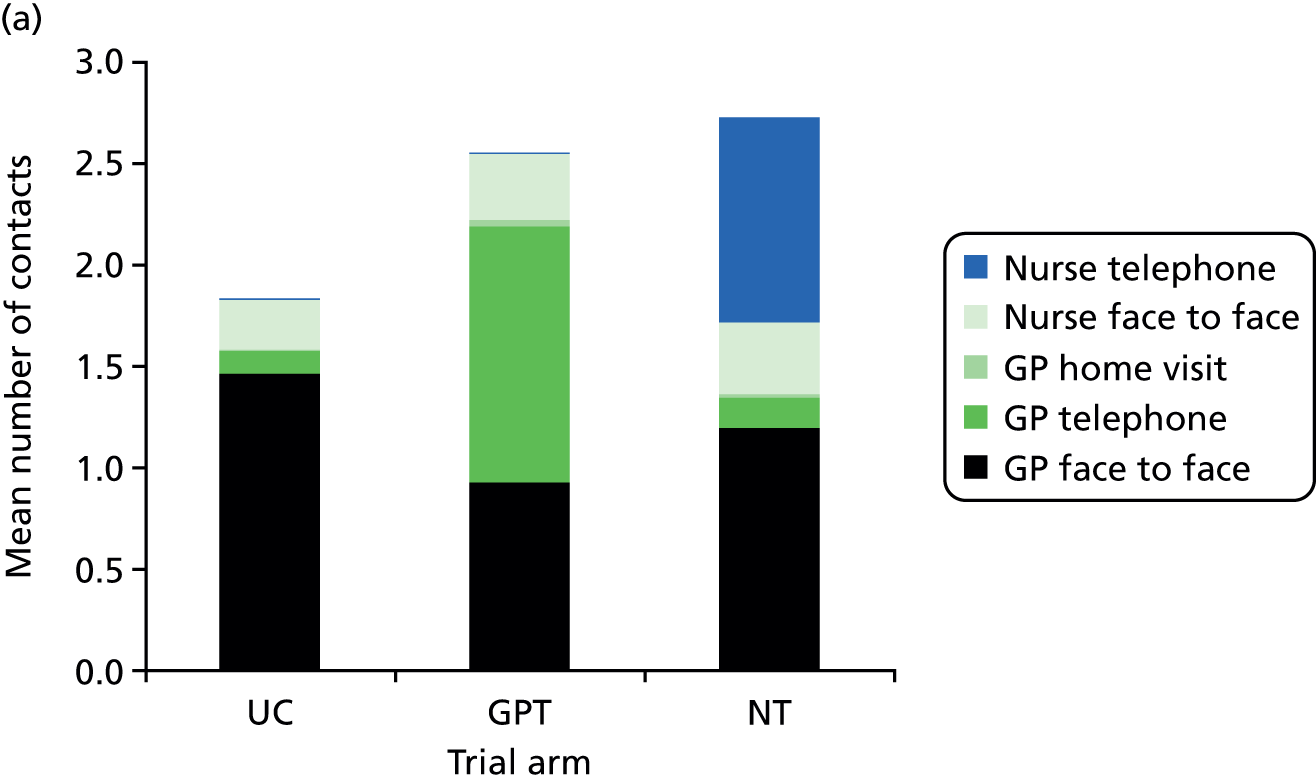

Primary outcome measure

The POM is the total number of NHS primary health-care contacts that took place in a 28-day period, commencing with the day of a patient’s index telephone request for a same-day consultation. This number includes the index consultation (initial health-care contact resulting from the index telephone call) and all subsequent NHS primary health-care contacts (as defined below) over the following 28 days, which may or may not be related to the nature of the index consultation. All POM data were collected via a case note review (see Data collection and management). The primary health-care contacts included in the POM were:

-

GP practice contacts:

-

GP face-to-face consultation (in surgery)

-

GP telephone consultation

-

GP home visit (within surgery hours)

-

GP unspecified

-

nurse face-to-face consultation (in surgery)

-

nurse telephone consultation

-

nurse home visit (within surgery hours)

-

nurse unspecified

-

general unspecified

-

-

out-of-hours primary care contacts:

-

GP face-to-face out-of-hours consultation

-

GP out-of-hours home visit

-

GP telephone out-of-hours consultation

-

nurse face-to-face out-of-hours consultation

-

nurse out-of-hours home visit

-

nurse out-of-hours telephone consultation

-

unspecified

-

-

walk-in centre contacts:

-

walk-in centre attendance (doctor)

-

walk-in centre attendance (nurse)

-

walk-in centre attendance (unspecified)

-

-

A&E contacts.

The focus of the trial is on primary care workload; however, it is recognised that changes in access to practice appointments may have a knock-on effect on A&E contacts and, therefore, these contacts were also included within the POM.

Secondary outcome measures

Patient safety

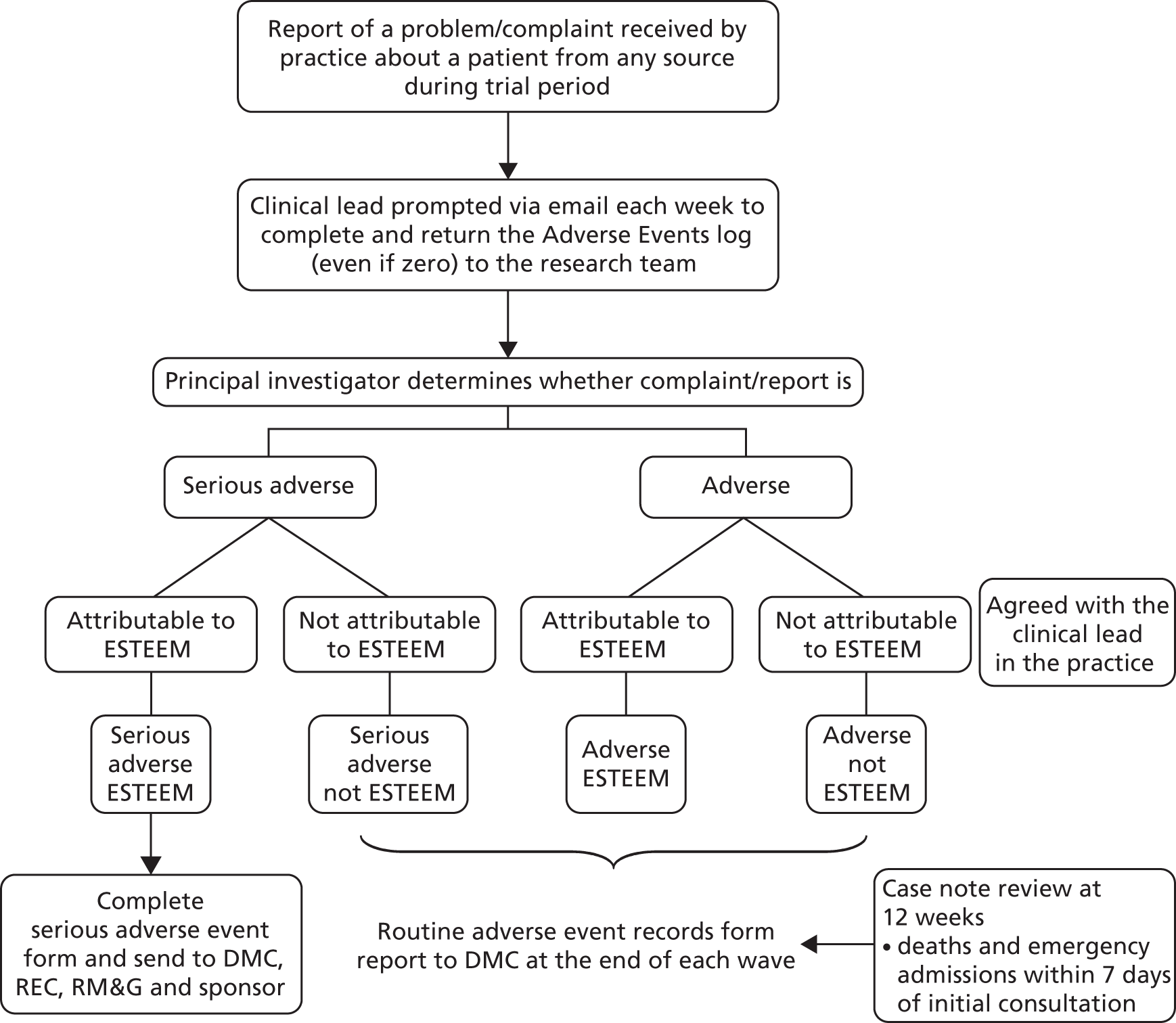

The number of deaths and unplanned ‘emergency’ hospital admissions (and associated number of bed-days) within 7 days, and A&E attendances within 28 days of the index consultation request were collected at case note review. An unplanned emergency hospital admission was defined when there was no evidence in the notes of advance planning, even on the day the admission occurred. The number of ‘planned’ hospital admissions was also collected. An ‘adverse events’ reporting procedure (see Appendix 10) was developed to monitor patient safety. The clinical lead(s) at each practice were contacted weekly by the trial researcher and asked to return a log sheet completed with any events arising during the intervention period, such as trial patient deaths, emergency hospital admissions or A&E attendances, as well as any problems with the triage system itself or patient complaints.

It became evident that the number of deaths recorded in the weekly log sheets of adverse events from practices did not always correspond to that identified at case note review. On discussion with the DMC, practices were asked to perform a search of their electronic records at the end of the trial to produce a report of all deaths occurring during the data collection period. This became the definitive source of data on patient deaths.

Patient management on the index day

A description of the management of patients on the index day of the same-day consultation request was based on patients’ first two primary care contacts collected for our POM.

NHS resource use

The NHS resources that were combined into the POM were also reported separately as secondary outcomes. Non-attendance rates for allocated appointments in the 28 days following the index request were also collected by case note review. It was not possible to capture patients’ contacts with NHS Direct from practice records. Patients’ use of NHS Direct during the 28-day follow-up period was assessed through self-report by postal questionnaire.

We collected actual consultation length for the index triage and UC (face to face or telephone) consultations on the Clinician Form (see Data collection and management). We also estimated the length of subsequent face-to-face consultations, for both ‘same-day’ and ‘28-day follow-up’ periods. The former was based on the recorded start and end times of a small sample of consultations captured over two randomly selected days in each practice during the intervention period. The latter was based on consultation length used in published unit costs reported within the NHS Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU38).

Patient-reported outcomes

All patient-reported outcomes were collected by the postal questionnaire.

Health status

Health status was assessed using the EuroQol Group European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D39) questionnaire, and a question on problem resolution28,29 (five-point Likert scale). We had originally intended to use the SF-36;40 however, piloting emphasised the need to shorten the overall length of the patient questionnaire for the main trial, and thus the shorter EQ-5D measure of health status was adopted (see Appendix 1).

Patient experience of care

Patient experience in the context of this trial relates to an episode of care delivered following a same-day consultation request, potentially involving multiple health-care contacts during the index day. Survey instruments suitable for use in a UK setting ask individuals to evaluate a specific consultation41,42 or aggregate (practice-based) care. As no validated instruments assessing the patient’s experience of an overall episode of care were identified, we used relevant questions from the national GP Patient Survey instrument,43 modifying the questions to focus on the patient’s recent experiences of care rather than over the last 6 months. Items selected included the responsiveness of the consultation management system (e.g. how quickly care was provided, overall satisfaction) and patient evaluations (using a five-point Likert scale)44,45 of the timeliness and convenience of the response46 to the same-day consultation request.

Case complexity

To define patient case mix, the clinician conducting the index consultation captured the complexity of the case (after Howie et al. )47 using an eight-point scoring schedule incorporated on the Clinician Form (see Data collection and management). Each consultation was scored as having either substantial (2 points), attributable (1 point) or no content (0 points) with respect to each of four domains: physical, social, psychological or ‘other’ (e.g. administrative) components to the consultation.

Sample size

Our sample size estimate was based on our POM, combined with a methodology for gaining patients’ consent to case note review that was not eventually operationalised in either pilot or main trials. A UK study comparing NT with standard practice for handling same-day consultation requests3 reported the number of NHS consultations based on general practice (GP and nurse), A&E and out-of-hours primary care contacts. We believed this to be a good proxy for our POM. Over the 28-day follow-up, that trial reported a mean number of NHS consultations of 1.02 [pooled standard deviation (SD) 0.78] in UC compared with 1.38 (pooled SD 1.79) in the NT arm. Using these data, we estimated trial sample size requirements under four scenarios shown in Table 1, based on 80% or 90% statistical power, and intracluster correlation coefficients (ICCs) of 0.01 or 0.05 (chosen from a range of ICCs reported from a survey across a basket of outcome measures collected in trials from primary care settings). 48

| n per groupa | ICC | Design factor | n patients per group | Final n patients per groupc | n practices per group |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 305a | 0.01 | 3.26 | 994 | 1867 | 4 |

| 305 a | 0.05 | 12.3 | 3751 | 7046 | 14 |

| 228b | 0.01 | 3.26 | 743 | 1396 | 3 |

| 228b | 0.05 | 12.3 | 2804 | 5267 | 10 |

Selecting the most conservative sample size scenario (i.e. 90% power, ICC 0.05) we required 3751 patients for analysis and 14 practices per group to detect a difference in means of 1.02 (SD 0.78) compared with 1.38 (SD 1.79) in our POM at follow-up between NT and UC arms. To inform the study power, and prior to undertaking the pilot study that would yield supporting data, we estimated that of all patients requesting a same-day consultation, 6%3,28,29 would be deemed ineligible, 10%14,29,30 would initially decline participation in the trial and/or follow-up of their notes when talking to the receptionist, and 30%28–30 would not respond to the request to return the questionnaire. Of those who did respond in the questionnaire survey, we estimated 10% (conservative) would decline notes review. Thus, a total of 7046 patients seeking same-day consultations across 14 practices over a 5-week period would be required in each of the three trial arms. In the absence of information about a minimum clinically important difference, we used the same sample size as outlined for the NT and UC comparison above for the comparison between GPT and UC. Therefore, we needed 21,138 patients in total (i.e. 7046 per arm) from 42 practices.

It is important to note that our patient recruitment process was altered before conducting the main trial (see Appendix 1) in two ways that both impact on our original sample size estimate. First, we did not incorporate a stage at which patients could initially decline participation in the trial and/or follow-up of their notes when speaking to the receptionist (estimated 10%, above). Second, the pilot study also led to a change in method of patient consent to case note review from written consent only (obtained from completed patient questionnaires) to include initial verbal consent obtained from the treating clinician. As a result, we anticipated that, post pilot study, the proportion of patients agreeing to case note review would be around 78%, a much higher estimate than in our original pre-pilot estimate. The pilot study provided confirmation of our assumed ICC of 0.05 [i.e. mean 0.03, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.00 to 0.08].

Feasibility of patient recruitment

An average practice (7000 patients) accommodates around 714 consultations per week,49 approximately 142 consultations per day. Some have estimated4 that up to one-third of these are patients seeking same-day consultations; case definition is, however, important and we proposed a more conservative estimate of around 20 patients per day (100 per week, 14% of consultations). This figure was found by the pilot study to be realistic, confirming that to achieve our sample size for the main trial we would need to recruit patients for a 5-week period in each of the 42 practices.

Secondary outcomes

Patient health status and perception of access to care were to be collected by the postal questionnaire with an estimated response rate after one reminder of 70%;50–53 after piloting this process was altered to include two reminder packs in the main trial. The questionnaire pack also incorporated written consent for case note review, through which our POM is derived. Before the pilot study, we estimated that at 80% power and 5% alpha, our sample size of 7046 per group would allow us to detect an effect size of 0.18 of a SD at an ICC of 0.01, and an effect size of 0.34 of SD at an ICC of 0.05. Thus, the proposed sample size would allow us to be able to detect a small-to-moderate effect size in our patient-reported secondary outcomes.

Trial delivery in participating practices

Following standardised training, practice systems were allowed to stabilise during a run-in period prior to a period of ‘live’ data collection (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Timeline of interventions.

Run-in period

A minimum ‘run-in’ period of 2 weeks was required before ‘live’ trial data collection could proceed. During this time all triage and data collection activities were introduced and allowed to bed in. Practices remained in ‘run-in’ until their performance met predefined trial criteria indicating protocol compliance (see Integrity checks). UC practices required only a 2-week run-in period to familiarise themselves with research procedures. As triage practices used this period to adjust the number and distribution of triage slots and protected appointments for exclusive use by the triaging clinicians, most were in run-in for 4 weeks, although some took longer to demonstrate protocol compliance.

Data collection period

Data collection was planned to last approximately 5 weeks in each practice. Medium-sized practices (3500–8000 patients) were expected to recruit 500 unique patients, whereas small (< 3500 patients) and large practices (> 8000 patients) were expected to recruit 350 and 550 patients, respectively. Practices ceased data collection when the target number of unique patient records was entered into the study database; if the target was not reached within 5 weeks then data collection continued.

All GPT and NT practices were asked to revert to their UC arrangements on completing the data collection period for a minimum of 4 weeks. This was for the purpose of preventing differential continuation with a triage management system (should practices wish to continue using triage) by practices during the 28-day period in which we examined patients’ use of primary care services.

Data collection and management

The sources of outcome data and the timing of data collection are summarised in Table 2.

| Data | Timing of data collection | Source of data |

|---|---|---|

| Practice characteristics (list size, location, deprivation) | Prior to randomisation | List size and location derived from practice; deprivation derived from APHO websitea |

| Practice staffing and other clinical information | Prior to randomisation | Practice Profile Questionnaire |

| Patient age, gender | At entry to trial (i.e. on the day of index same-day request) | Practice records |

| Duration of first management/triage consultationb | Patient’s index contact during trial | Clinician Form |

| Case complexityb | Patient’s index contact during trial | Clinician Form |

| Duration of face-to-face contacts subsequent to index consultation requestc | Two randomly selected days during trial | Recording by GPs and nurses of durations of face-to-face appointments |

| Adverse events | During the data collection period of the trial | Practice staff weekly log |

| Patient deprivation data | During the data collection period of the trial | Patients’ residential postcode data provided by practices and mapped to dIMD 201054 via LSOA |

| Patient satisfaction outcomes | Approximately 28 days after date of index consultation request | Patient questionnaire |

| EQ-5D | Approximately 28 days after date of index consultation request | Patient questionnaire |

| Patient self-reported NHS direct use | Approximately 28 days after date of index consultation request | Patient questionnaire |

| Patient ethnicity, presence of a long-standing health condition, ease of taking time away from work (if relevant) | Approximately 28 days after date of index consultation request | Patient questionnaire |

| Patient contacts in a 28-day period; includes the date of the index consultation request, deaths and emergency hospital admissions within 7 days of the index consultation request | Approximately 12 weeks after the index consultation request (to allow time for contacts to be recorded at practice) | Case note review by researchers |

| Patient deaths within 7 days of the index consultation request | End of trial (i.e. following end of data collection period) | Practice records |

Clinician Form

A supply of Clinician Forms (see Appendix 11) was available in each consulting room for every day of the patient recruitment and data collection period. Clinicians completed this form at the time of the initial ‘index’ consultation following a patient’s same-day request. This index consultation was usually a telephone triage call in the NT or GPT arms, or a face-to-face consultation in the UC arm. The form captured consultation details, including which health professional had been consulted; whether the patient ‘did not attend’ (DNA); a measure of case mix; treatment and management options chosen (e.g. ordering of tests, recommending subsequent appointment or referral); and the start and end time of the consultation. The clinician also recorded whether the patient had verbally consented to case note review.

Patient questionnaire

Patients were sent a postal questionnaire 28 days after their index request (see Appendix 8). The questionnaire measured patient experience and health status, and use of NHS Direct during the 28-day follow-up period (see Secondary outcome measures). The questionnaire offered patients the opportunity to confirm their initial verbal consent to the case note review, or to withdrawal if they wished. Patients were asked to send back a blank questionnaire in a prepaid envelope if they did not wish to be contacted again. Patients who did not respond were sent two reminder letters with another copy of the questionnaire, at 2 and 4 weeks after the initial mail-out.

Case note review

Researchers undertook a review of patient’s medical records 12 weeks after patients’ index request, completing a case note review form (see Appendix 12). This delay was to allow time for patients’ medical records to be updated with any information on contacts with services outside the practice. The purpose of the review was to extract information regarding our POM (see Primary outcome measure) and safety data relating to hospital admissions (see Patient safety). A standardised operating procedure was developed to support the four researchers who were conducting these reviews.

The inter-rater reliability of the data extraction process was assessed at three time points during the trial. Any divergence between researchers was documented and the standardised procedure updated as appropriate. The inter-rater reliability was assessed by each researcher reviewing the same random set of 30 case notes. Case notes were selected from different practices, trial arms and practice IT systems (Vision, EMIS LV and SystmOne). The inter-rater reliability results are displayed in Table 3.

| Assessment | Location of practice | Trial arm of practices’ notes | Cohen’s kappa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-wave 1 | Devon | One UC and one NT, practice followed by one GPT practice | 0.64 followed by 0.92a |

| Pre-wave 2 | Warwick | One NT practice | 0.89 |

| Pre-wave 3 | Devon | One NT practice | 0.82 |

Blinding

Given the nature of interventions it was not possible to blind patients, clinicians or researchers (conducting case note reviews) to treatment allocation. However, data analysis was carried out by a statistician who was blind to treatment allocation.

Data entry

Electronic records were stored in a bespoke Microsoft SQL Server 2008 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), hosted on a restricted-access secure server maintained by Plymouth University. Data entry was performed via a website encrypted using Secure Sockets Layer (SSL).

Monitoring intervention fidelity

Integrity checks

Researchers monitored patient recruitment and adherence to research procedures during both the run-in and data collection periods. Receptionists kept a handwritten log (see Appendix 9) of all telephone calls received during three half-day sessions. Integrity checks were preplanned with practices, covering two morning sessions during the latter half of the run-in period and one morning session during the first week of data collection.

For each patient’s call that was recorded, the Receptionist Trial Log Sheet captured whether the patient was eligible for the trial, and, if eligible, selected one of the following disposition options:

-

triage or telephone appointment booked for today

-

face-to-face appointment booked for today

-

face-to-face or telephone appointment booked for another day

-

patient asked to call again another time (i.e. no appointment booked at all)

-

other outcome.

The integrity check documented the following performance indicators:

-

at least 75% of patients identified as eligible on the log sheet were subsequently added to that day’s triage list

-

at least 75% of eligible patients had the study Read Code added to their medical record

-

at least 75% of eligible patients had a completed Clinician Form.

Practices satisfying these performance indicators during the run-in period proceeded to data collection. Practices that failed any of the indicators remained in an extended run-in period until another integrity check could be arranged. When practices moved into the data collection period, they were required to undertake one final integrity check during the first week. A practice that failed this final check was permitted to continue with data collection but the trial researcher would have further communication with the relevant members of practice staff regarding the aspect of research procedures on which the integrity check had been failed. An overview of how practices performed at these checks can be found in Appendix 13.

In addition, we used the Receptionist Trial Log Sheet completed during the integrity checks to estimate the proportion of all incoming calls to reception which were received from individuals presenting a request for a same-day consultation. We used the same data set to estimate the proportion of individuals presenting same-day consultation requests who met our exclusion criteria (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria).

Use of computerised decision support software in nurse-led telephone triage practices

A further approach to monitoring intervention fidelity was put in place for NT practices. We assessed the nurses’ use and extent of use of CDSS during each triage consultation. Nurses were advised that the CDSS was intended to act as a support tool, and, although ESTEEM did not aim to evaluate the CDSS itself, as a minimum it should be opened for all triage consultations with ESTEEM patients. The information required for an assessment of use was extracted once the trial was completed by utilising reporting functions within the CDSS. Further details can be found in Appendix 14.

Statistical analysis

The methods and reporting of statistical analyses were in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines for cluster randomised trials and pragmatic trials. 55,56 The combined statistics and health economics plan33 was reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee and DMC in advance of the analyses.

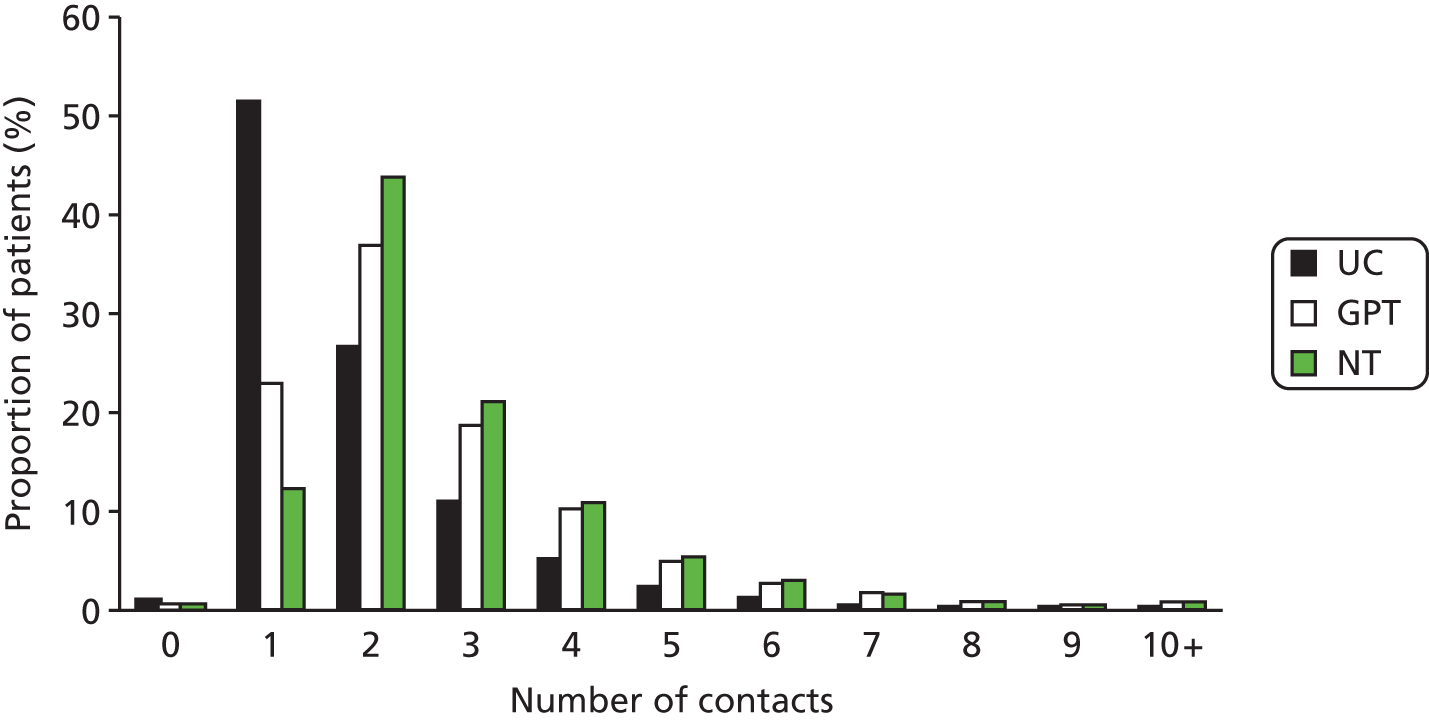

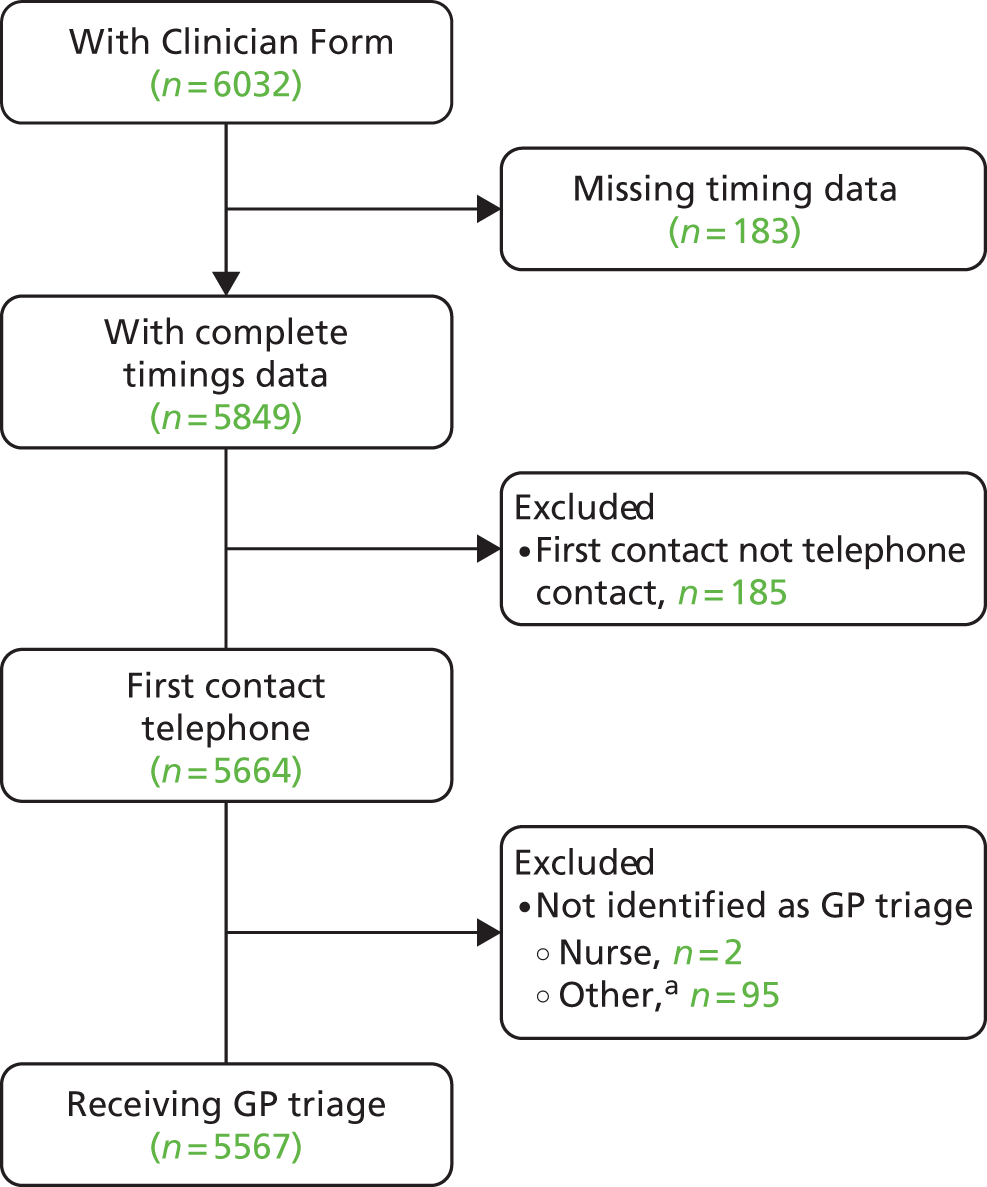

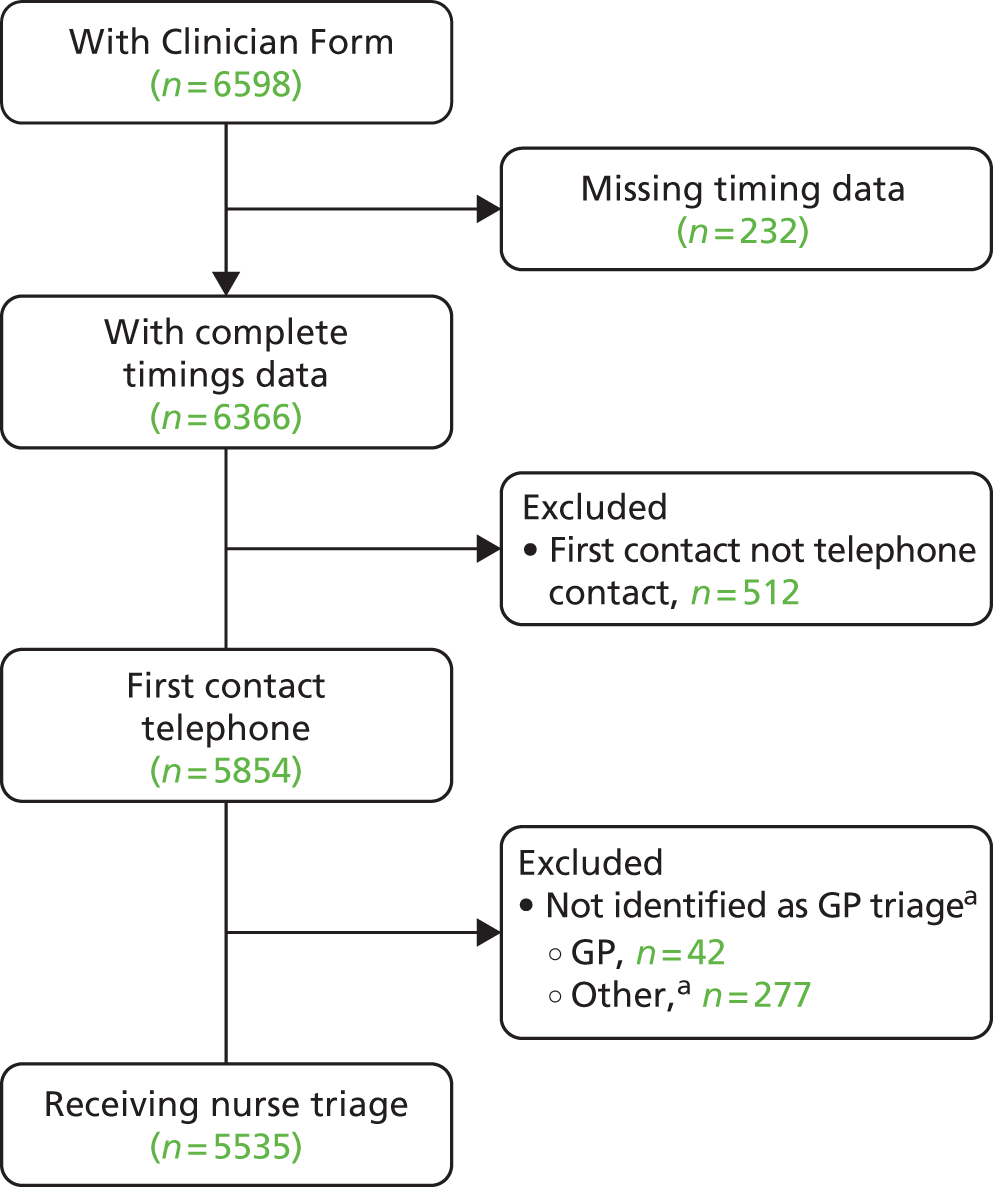

Practice and patient characteristics

The recruitment of trial practices and disposition of patients during the trial was summarised using a CONSORT flow diagram. Practice characteristics (location, list size and level of deprivation) were compared descriptively across the three trial arms. Practices that withdrew from the study at any point (following initial consent to participate) were scrutinised with regard to their key characteristics, as well as to the trial arm to which they were allocated. The stage of the trial at which they withdrew was recorded, as well as any specific reason for withdrawal (e.g. as the result of staff changes). The results of the baseline Practice Profile Questionnaire (see Appendix 15) were also reported descriptively.

Patient demographic characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity and deprivation) were reported descriptively by arm. Age was reported both as a continuous variable and divided into six categories for reporting of frequencies and for use in inferential analyses: 0–4 years; 5–11 years; 16–24 years; 25–59 years (reference category); 60–74 years; and ≥ 75 years. Patients’ deprivation status was based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 201054 score and rank of patients’ residential lower super output area (LSOA), obtained by mapping the patient’s residential postcode to the relevant LSOA.

Availability of patient information throughout the trial was reported descriptively, as was information regarding consent status and initial patient management (specifically, whether a patient in a triage arm was regarded as having been managed per protocol (see Appendix 16). Demographic differences between patients who did and did not have case note review performed, and did or did not return a completed questionnaire with at least one completed question (excluding the consent to case note review), were also explored. Potential associations between age, gender and deprivation status, and availability of case note review were described using logistic regression analyses; equivalent analyses were performed for availability of a completed questionnaire. Presence of a long-standing health condition and ease of taking time away from work, if relevant, were also reported descriptively by arm.

Primary outcome

The primary analysis was based on an ITT principle, i.e. analysis of all trial patients in practices according to random allocation. The primary analysis took the form of a regression analysis, using a hierarchical model to take account of the cluster allocation, utilising a random effect to adjust for potential clustering effect by practice, and allowing for adjustment for practice-level minimisation variables (geographical location, deprivation level and list size of practice). For all inferential analyses, patient demographic factors were adjusted for (in conjunction with minimisation variables) if baseline descriptive analyses indicated imbalance of demographic factors across arms. Models were performed twice, initially using the UC arm as reference and then using the GPT arm as reference, to derive comparison between the two triage arms.

A generalised linear model (GLM) was fitted with the appropriate choice of family and link function, according to the type of data and its properties. As the POM (and all secondary outcome measures based on number of patient contacts) was a count, the most appropriate model would be either a Poisson or a negative binomial model, depending on the degree of dispersion in the data. Cluster-level SDs were reported where appropriate, as this parameter approximates the coefficient of variation in underlying cluster rates in certain models. 57,58 To derive an ICC for the primary outcome, a linear hierarchical model was also fitted.

Additional analyses were conducted on the POM, and on secondary measures derived from the POM, using the hierarchical GLM methods above. Some of these analyses were determined a priori; others were determined post hoc following initial inspection of the data.

A priori analyses

-

A per-protocol analysis including only those patients in the triage arms who received a telephone triage contact by the appropriate clinician type on the index day (all patients in UC were considered to be per protocol).

-

Exclusion of data from two practices in GPT that did not revert to UC as requested following their period of implementing triage and recruiting patients to the trial.

-

Investigation of the effect of missing primary outcome data (due to lack of availability of a case note review) using multiple imputation methods,59 based on the assumption that missing case note review data were missing at random.

-

Analyses to investigate interactions between treatment arm and practice characteristics (deprivation, location and list size) on the POM, using interaction terms within the regression models. A series of models were fitted, each model investigating interactions between treatment arm and a specific covariate. Age (as a proxy for case complexity), gender and ethnicity (dichotomised into ‘White and other ethnic group’, comprising ‘Mixed or multiple ethnic groups’, ‘Asian’ or ‘Asian British’, ‘Black/African/Caribbean/black British’ and ‘Other ethnic group’) were also investigated for potential interaction with the treatment arm. A significance threshold of 0.01 was used for hypothesis tests for interaction terms. However, the trial was not powered to investigate subgroup interactions and results should be interpreted with caution.