Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 09/22/136. The contractual start date was in January 2011. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in August 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

The authors have no current personal financial interests; the following non-financial interests are declared: Dr Hilton was a member of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Interventional Procedures Advisory Committee (2002–7); a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Evaluation, Trials and Studies Co-ordinating Centre (NETSCC) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Therapeutic Procedures Panel (2007–8) and the NETSCC-HTA Clinical Evaluations and Trials Prioritisation Group (2008–10); chair of the NICE development group for clinical guideline on urinary incontinence in women (2004–7); and a member of the James Lind Alliance Working Partnership on research priorities on urinary incontinence (2007–9). These last two groups identified the research question underlying this report as an important area for further research. Dr Lucas currently chairs the European Association of Urology Guidelines panel on Urinary Incontinence which has produced guidance on the use of urodynamics in clinical practice based on existing evidence. Professor McColl is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group although she was not involved in the editorial processes for this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Hilton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Prevalence of urinary incontinence

Urinary incontinence (UI), while rarely life-threatening, may seriously influence the physical, psychological and social well-being of affected individuals. 1–4 The impact on the families and carers may be profound and the resource implications for the health service considerable. 5 Prevalence figures for UI range from 5% to 69% in women aged 15 years and older, with most studies in the range 25–45%. 6 More severe UI is reported in 4–7% of women aged under 65 years, and around 5 million women over 20 years of age in England and Wales may be affected. 7

Although absolute prevalence rates vary widely, the distribution of UI subtypes appears more consistent, with stress UI (SUI) or mixed UI (MUI) accounting for 65–85% of cases. 8 Isolated SUI accounts for approximately half of all incontinence, with most studies reporting 10–39% prevalence; MUI is the next most common, with prevalence figures of 7.5–25.0%; isolated urgency UI appears to be relatively uncommon, with 1–7% prevalence. 6

Costs of urinary incontinence and investigation

A study of UI across 14 European countries reported the mean annual per capita UI-related costs to range from €359 in the UK/Ireland (for patients predominantly treated in primary care) to €515 in Germany and €655 in Spain (for patients treated by specialists). 9 A systematic review of the costs associated with UI and overactive bladder (OAB) similarly found the annual per capita costs to vary considerably between individual studies and countries, with the highest reported being in institutionalised individuals in the USA at US$9872. 10 A UK study using 1999/2000 prices estimated the annual cost to the NHS in England of treating clinically significant UI in women at £233M, with total annual service costs (including costs borne by individuals) of £411M. 11

Several methods are used in the assessment of UI to guide management decisions, and invasive urodynamic tests (IUTs) may form part of this. Essentially these investigations evaluate functional aspects of the lower urinary tract; cystometry, the most commonly used IUT, looks at the pressure/volume relationships during bladder filling, storage and emptying, with a view to defining a functional diagnosis as distinct from a purely symptomatic one. The costing report associated with the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence [now, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)] clinical guideline on UI used an estimated charge of £176 for each IUT (2006/7 English national tariff), and calculated the annual national cost of urodynamic investigations as over £22M. 12 From this, the potential saving from not undertaking urodynamic investigations before conservative treatment was estimated at approximately £3M. 12

Changes in available operative techniques and, in particular, the introduction of less invasive approaches such as mid-urethral tapes, have resulted in dramatic alterations to surgical practice in recent years. 13 Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) demonstrate a 50% increase in surgery for SUI in the 10 years following the introduction of mid-urethral tapes in 1997, with numbers apparently plateauing at 11,000–13,000 procedures annually in England between 2006/7 and 2012/13. 14 The NICE costing report estimated further savings of £321,000 from more rational use of IUTs before surgery, although this is perhaps a conservative estimate being based on ‘current use’ of 70% (the actual figure is probably closer to 100%) and ‘future use’ of 50%. 12 A more realistic estimate of annual savings based on 2012/13 national tariff costs (£403 per procedure for Healthcare Resource Group LB42Z)15 and HES activity data would be approximately £3.3M. There would also be an additional ‘opportunity cost’ saving from the alternative use of staff and equipment currently devoted to invasive urodynamic testing. It remains to be demonstrated, but should be recognised, that this saving may come at no detriment to health and with the avoidance of what some women undoubtedly see as unpleasant and embarrassing procedures.

Existing literature on clinical utility of invasive urodynamic tests prior to surgery

Urodynamic tests comprise a group of investigations used to evaluate function of the lower urinary tract; some of these are invasive (requiring catheterisation) and some are non-invasive. The tests are most often used for diagnosis, planning of appropriate intervention and prediction of treatment outcome, although they can also be used repeatedly to monitor the progress of disease over time or as outcome measures in clinical research. While cystometry is the most commonly used IUT, videocystometry and ambulatory bladder pressure monitoring are used by some. The current position of invasive urodynamic testing in the diagnostic pathway is not agreed and practices vary considerably: in a UK survey in 2002, only half of the units surveyed had guidelines on indications for the tests and 85% carried out cystometry in all women with incontinence. 16 Current guidance from NICE suggests that cystometry is not required prior to conservative treatments for UI, or prior to surgery where the diagnosis of SUI is clear on clinical grounds [i.e. where there are no symptoms of OAB or voiding dysfunction (VD), no anterior compartment prolapse and no previous surgery for SUI]. 17,18

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA), The Cochrane Collaboration and the International Consultation on Incontinence (ICI) have each recently undertaken systematic reviews on the subject of urodynamics and called for further high-quality primary research confirming clinical utility. 17,19–23 The specific aim of the current study is to assess the feasibility of a future large randomised controlled trial (RCT) to address a key research recommendation of the NICE and Cochrane reviews of the subject. The clinical utility of invasive urodynamic testing was also among the top prioritised uncertainties identified within the James Lind Alliance Urinary Incontinence Priority Setting Partnership in 2008. 24,25

A decision-analysis study from the USA failed to find support for invasive urodynamics before surgery in women likely to have SUI. 26 A similar economic assessment within the NICE report on UI, using assumptions more applicable to current NHS practice, found that for every 10,000 patients assessed there would be approximately 13 additional cures using invasive urodynamics, at an additional cost per cure of £26,125. With a ‘willingness-to-pay’ threshold of £20,000 per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), each cure would have to generate 1.3 QALYs for invasive urodynamics to be considered cost-effective. 17 Based on a gain of QALYs of 0.07 per annum for a woman cured compared with a woman not cured,27,28 this would require each cured woman to survive 19 years post treatment (assuming QALYs are not discounted); given that typical women undergoing surgical treatment for SUI are in their mid-40s (range 20s to 70s), their average life expectancy would be much greater than this, suggesting that invasive urodynamic testing may be cost-effective.

One small RCT showed no significant benefit from cystometry prior to conservative treatment, although interpretation is difficult, given that the control (not investigated) group in this study received both bladder retraining and pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT), whereas the intervention (cystometry) group received either bladder retraining or PFMT. 29 In a cohort study from the North Thames region, women were no more likely to benefit from incontinence surgery if they had undergone preoperative urodynamic testing,30 and a study of Medicare patients in the USA found that those who had preoperative testing appeared more likely to develop urge incontinence after their surgery. 31 A secondary analysis of data from a US randomised surgical trial found that preoperative investigation did not predict failure32 or postoperative VD. 33

Other studies ongoing during protocol development

Post funding, but during the refinement of the protocol for INVasive Evaluation before Surgical Treatment of Incontinence Gives Added Theraputic Effect? (INVESTIGATE-I), the investigators became aware of two other trials looking at the clinical utility of urodynamics in similar patient groups. One was from a multicentre group in the Netherlands [Value of Urodynamics prior to Stress Incontinence Surgery (VUSIS-1); www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/trial/385179/urodynamic], the other from the US Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network [Value of Urodynamic Evaluation (ValUE); www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/trial/472073/urodynamic]. 34 Both of these were full trials using a non-inferiority design. VUSIS-1 did not specifically define a non-inferiority margin, although the sample size was determined from a power of 70% using less than 5% difference between groups; this trial was terminated prematurely due to slow recruitment after achieving only 23% (59/260) of its planned accrual. 35 ValUE defined a non-inferiority margin of 11% (equivalent to a standardised difference of < 0.8), which we consider too high, that is we would look on a difference in outcome between groups of 11% as being clinically quite important and one that might potentially influence the decisions of both clinicians and patients. 36

In the ValUE study, women with a clinical diagnosis of SUI or stress predominant MUI, who also have clinically demonstrable stress leakage (i.e. a slightly different patient group from INVESTIGATE-I), were randomised to either no further assessment or to undergo urodynamic investigation (as in INVESTIGATE-I). In view of the recruitment difficulties with VUSIS-1, the Netherlands group proceeded to a further study of alternative design (VUSIS-2; www.controlled-trials.com/mrct/trial/474127/vierhout),37 in which all women underwent invasive urodynamic testing, and only those with discordant clinical and urodynamic findings were randomised between surgical treatment (as dictated by their clinical assessment) and individual treatment (dictated by the combination of clinical and urodynamic results); neither participants nor health-care professionals involved were blinded to the urodynamic results in either group.

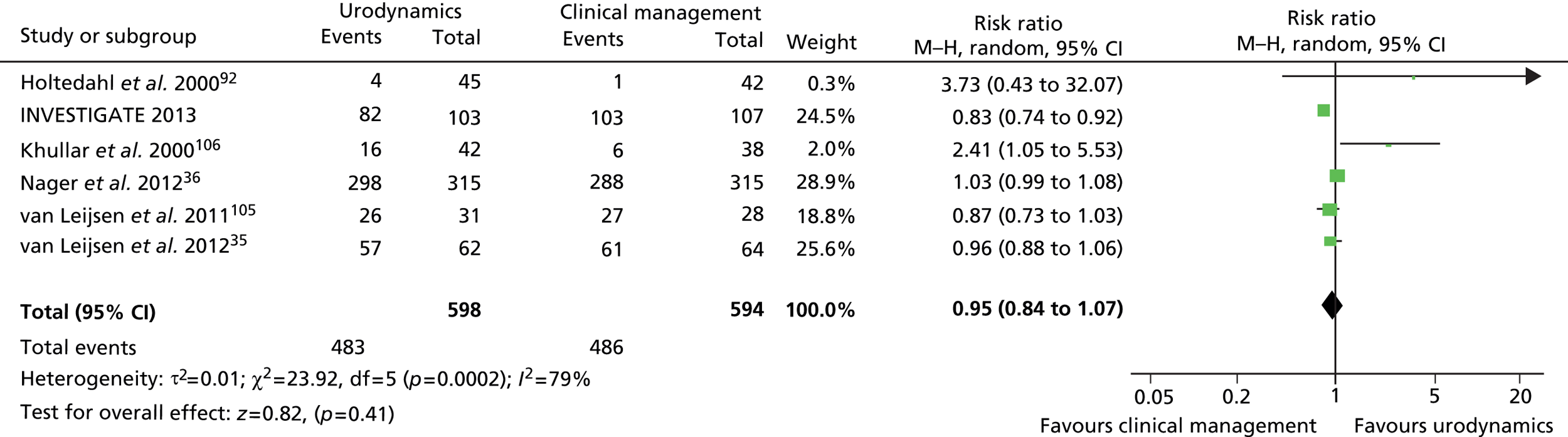

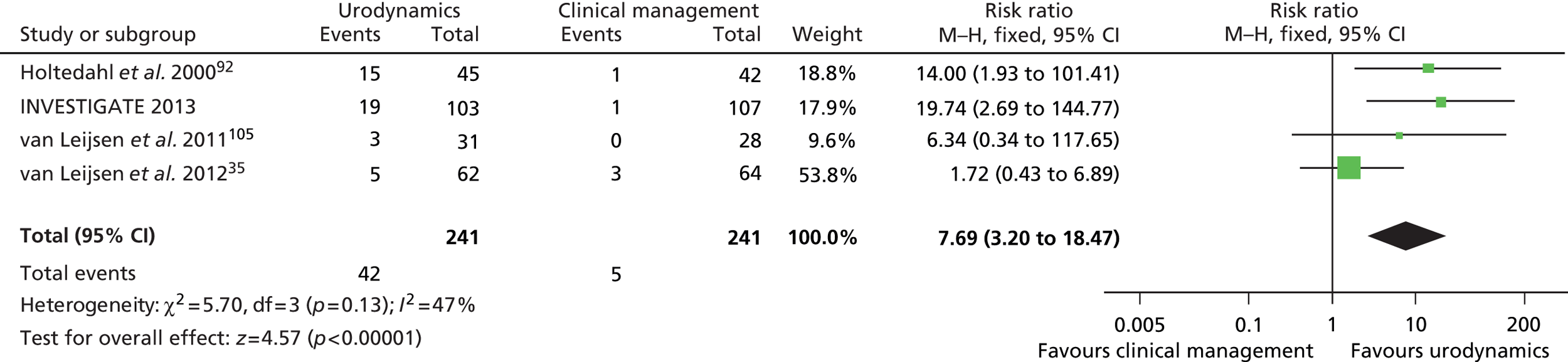

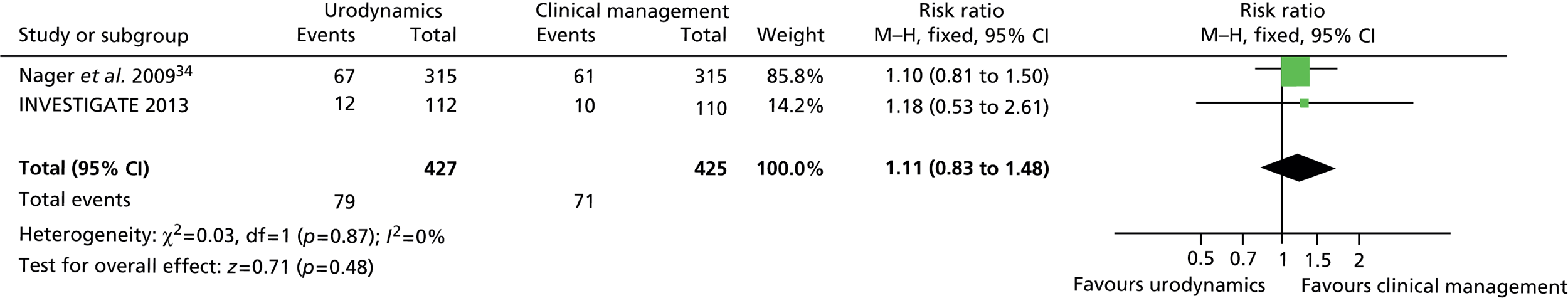

The primary outcome in ValUE and both VUSIS studies was based on the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) score at 12 months (ValUE used a 70% reduction in UDI along with a Patient Global Impression of Improvement score of ‘very much better’ or ‘much better’ as indicative of treatment success). Although we preferred the use of international standard outcomes as intended by the ICI Modular Questionnaire (ICIQ) as our primary outcome, we subsequently chose to include the UDI as an additional secondary outcome38 to facilitate easier comparison of results between these various studies and the incorporation of our results, even from this feasibility study, into a meta-analysis.

Each of these studies has been published during the period of recruitment and follow-up in INVESTIGATE-I;35,36,39 their results are discussed later in this report. How much they have already influenced clinical opinion and practice or will do so in the future is unclear, although a ‘point-counterpoint’ debate published after these studies (in 2013) makes it clear that there is still a question to be answered. 40,41 The most recent update of the Cochrane review of urodynamics for the management of UI in children and adults continues to emphasise the need for larger definitive trials, in which people are randomly allocated to management according to urodynamic findings or to standard management based on history and clinical examination. 42

Rationale for an initial feasibility study and pilot trial

Although NICE, NIHR HTA, The Cochrane Collaboration and the ICI have all called for large high-quality primary research to establish the clinical utility of invasive urodynamic investigations, there were several reasons to conduct a pilot trial and feasibility assessment before undertaking a definitive trial.

First, the sample size for a definitive trial was considered using estimates and assumptions from the modelling exercises cited above,17,26 and from a previous surgical trial. 43,44 However, such calculations are very sensitive to parameter values such as the proportion of recruits with SUI,26 the proportions of poor outcomes in the two arms and the effect size (target difference) of interest; currently available information is insufficient to plan a study that could be expected with reasonable certainty to produce robust results. Our own very preliminary sample size calculations gave figures between 1100 and 6700 per treatment arm. Since designing the feasibility study, the most recent Cochrane review of urodynamics in adults and children indicates that a similarly large sample size would be required to address this question. 42

Given the possible size of a definitive trial on this question therefore, a feasibility study was considered crucial to test assumptions made, give relevant estimates of key parameters and inform power calculations for the definitive trial.

Second, invasive urodynamic testing has been widely used in clinical practice over the last 30 years and, despite the lack of evidence of clinical utility, many clinicians look on cystometry as a mandatory part of the investigation of patients with UI, particularly prior to surgical treatment. 45–47 A survey of members of the British Society of Urogynaecology (BSUG) has shown a high level of disagreement with the NICE guidance in this respect,48 and others have questioned the safety of the recommendations. 49 We were aware that, although the ValUE study completed recruitment,36 the investigators encountered initial problems with lack of clinician equipoise (Peggy Norton, University of Utah Health Care, 2010, personal communication). Hence we needed to establish whether or not sufficient clinicians were in equipoise and willing to enrol and randomise patients within a definitive trial.

Finally, patients may not so easily see the importance of ‘testing a test’ in the same way as they might view testing a treatment. Indeed, they are willing and often keen to undergo investigation (even when this is invasive),50 in the belief that this will inevitably guide them and their clinicians towards appropriate treatment and away from inappropriate and possibly harmful interventions. Two HTA-funded trials of radiography for low-back pain were only able to recruit 23% and 51% of patients who were approached to enter the randomised arms. 51,52 The VUSIS-1 study was terminated prematurely when it had achieved only 23% of its planned recruitment. 35 Hence it was necessary to investigate patients’ willingness to take part in a RCT of this particular diagnostic test and to identify barriers to, and facilitators of, participation.

Overall, therefore, while we were encouraged that other researchers have similarly seen this topic as an important clinical uncertainty and have sought to undertake trials of similar design to that proposed in INVESTIGATE, we remained of the opinion that a feasibility study was an important step before embarking on a definitive trial using public funds.

It was recognised that a pilot RCT alone was probably inadequate to address the complexities of the determination of feasibility for a definitive trial in this aspect of health care. While most mixed-methods studies to date have been limited to combining qualitative methods and RCTs,53 we developed a protocol comprising a national survey of relevant clinicians, qualitative interviews with both trial participants (face to face) and clinicians (telephone), a randomised external pilot trial and a nested health economic analysis. Post hoc additions to the protocol included an update to the original clinician survey and a questionnaire to those identifying potential trial participants [research nurses and principal investigators (PIs)] regarding issues of screening sensitivity.

Chapter 2 Study components

Specific objectives

The objective of the proposed future definitive trial is to address the question of whether or not invasive urodynamic testing compared with basic clinical assessment with non-invasive testing alters treatment decisions and outcomes in women suitable for surgical treatment of SUI or stress predominant MUI. The outcome measures proposed would include the quantification of post-treatment urinary leakage, impact on general health and condition-specific quality of life (QoL), adverse effects from investigation or treatment and health economic outcomes. Thus, in a possible future definitive trial, it might be established whether or not invasive urodynamic testing should indeed be offered to all women prior to surgery.

The objective of the current feasibility study (INVESTIGATE-I) was to inform the decision whether or not to proceed to such a definitive RCT and whether or not any refinements to the design or conduct of that trial are warranted.

Study components

A mixed-methods approach was chosen to assess the feasibility of a future definitive RCT. There were five components to the study, each addressing different aspects of the overall determination of feasibility:

-

A pragmatic multicentre randomised pilot (external or rehearsal pilot) trial (see Chapter 3). This was designed to rehearse the methods and processes of a future definitive randomised trial. As such, it evaluated patient identification strategies, recruitment numbers and patients’ willingness to be randomised. The rate of retention within the study and the effectiveness of outcome measures in terms of response and completion rates were also evaluated. The pilot was also designed to provide outcome data to inform sample size calculations for a future definitive trial.

-

A full economic evaluation undertaken within the above pilot RCT (see Chapter 4). The pilot study rehearsed the data collection for the economic evaluation, which included health state utilities and costs to the NHS and patients. To inform the definitive economic analysis, the pilot study assessed consistency of resource use in administration of the IUT and other tests, surgical and non-surgical treatments, and the ease of access to information from hospital databases about resource use. It also piloted the use of data collection instruments.

-

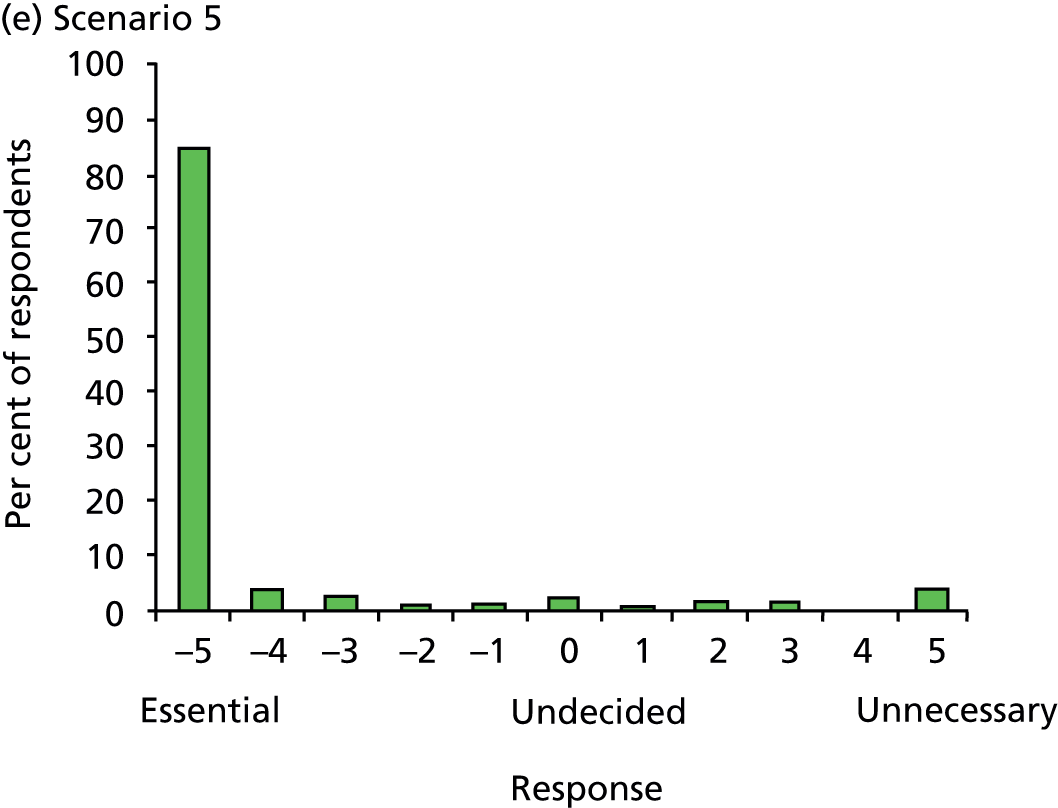

National online surveys of clinicians’ views about urodynamics (see Chapter 5). In order to assess the extent of ‘buy-in’ to a future definitive trial, the survey questionnaires explored surgeons’ views about the necessity for urodynamic investigations in a range of clinical scenarios and also their opinion about the importance of the research question underlying the INVESTIGATE studies. Since it was anticipated that a future robust trial would require a sample size very much larger than previous studies and seemed likely to need the involvement of a large number of units, clinicians’ workload in incontinence surgery and their willingness to randomise their own patients in a definitive trial was also assessed. A brief second survey was undertaken towards the end of the study to assess changes in clinical opinion over time as a result of other publications in the area. 35,36,39

-

Qualitative interviews with a subset of surgeons (see Chapter 6). The interview topic guide used here sought to illuminate the questionnaire responses from component 3 above. This complemented the results of the survey and explored further how clinicians use the results of IUTs to inform their decisions. The interview data were used to explore the differences between personal and community equipoise and the effect these may have on willingness to randomise patients into a future trial; they were also used to investigate some of the sociological aspects of diagnostic tests and, in particular, how clinicians approach a test that is widely used but lacking evidence of clinical utility.

-

Qualitative interviews with a subset of women eligible for the pilot trial to assess their experiences of the study (see Chapter 7). By approaching those who did and did not agree to participate, we sought to define the reasons behind these decisions. The interview topic guide was designed to facilitate exploration of patients’ experiences of being approached to take part in the trial, their perceptions of the study information sheets and the burden associated with study outcome questionnaires.

The methods employed, results obtained and key messages from these different study components are described separately in Chapters 3–7; discussion is combined in Chapter 8, and the overall consideration of feasibility is presented in Chapter 9. The latest version of the protocol is available on the NIHR Journals Library website. The report is made in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement;54 the CONSORT diagram for the randomised pilot trial is given as Figure 5; the CONSORT checklist is shown in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Randomised external pilot trial

Methods

This was a pragmatic multicentre randomised external (rehearsal) pilot trial to assess patient recruitment and willingness to be randomised, rehearse trial methods and processes, and provide outcome data to inform sample size calculations for a future definitive trial. All of these were considered important elements of the determination of feasibility.

Units recruiting to the trial

Recruitment to the pilot trial was initially limited to six specified units; these were a mix of specialist urogynaecology (Newcastle upon Tyne and Leicester) and female urology (Sheffield and Swansea) departments in university teaching hospitals providing secondary- and tertiary-level care, and general gynaecology units in district general hospitals providing secondary care services (Wansbeck Hospital, Northumberland and Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Gateshead).

In order to improve adherence with recruitment targets and to test the processes for possible future use, two Patient Identification Centre (PIC) sites (Sunderland Royal Hospital and South Tyneside District General Hospital) and one additional full recruiting site (South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) were introduced during 2012.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for the pilot trial (and currently anticipated inclusion criteria for the future definitive trial) were as follows:

Women were required to fulfil ALL criteria to be eligible:

-

Clinical diagnosis of SUI or stress predominant MUI.

-

Women must state that their family is complete.

-

Women should have undergone a course of PFMT (± other non-surgical treatments for their urge symptoms) with inadequate resolution of their symptoms.

-

Both the woman herself and her treating clinician should agree that surgery is an appropriate and acceptable next line of treatment.

Exclusion criteria

For the pilot trial (and currently anticipated for a future definitive trial), the following situations excluded eligibility:

-

Symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse requiring treatment.

-

Previous surgery for UI or pelvic organ prolapse (POP).

-

Urodynamic investigation within the last 3 years.

-

Neurological disease causing UI.

-

Current involvement in competing research studies (e.g. studies of investigation or treatment of UI).

-

Unable to give competent informed consent.

Withdrawal options

There were two trial withdrawal options:

-

Withdrawing completely, that is withdrawal from the allocated investigation protocol and provision of follow-up data. Consent would be sought to retain data collected up to the point of withdrawal and to complete an ‘end of study’ visit at the time of withdrawal.

-

Withdrawing partially, that is withdrawal from the allocated investigation protocol (including a request to move to the alternative investigation arm) but continuing to provide follow-up data by attending clinic and completing questionnaires.

Participants’ reasons for withdrawal were recorded where possible, as the information might be relevant to the protocol for a future definitive study.

Recruitment

Potential trial recruits were identified by the study research nurses prior to attending new or follow-up appointments for SUI or MUI in the clinics run by the unit clinical leads. The Patient Information Sheet (PIS) was available in two forms: a short (one-page) introduction to the study and a more detailed (six-page) description of the trial and the implications of involvement (see Appendix 5 and 6). The short PIS was sent out along with a letter of invitation (see Appendix 2), with new appointments or with a reminder letter to attend follow-up appointments; this allowed any questions that the woman may have about the study to be addressed at the one visit; the full PIS was provided on request. Those declining to take part underwent further investigation and/or treatment as appropriate at the same visit. Those agreeing to take part signed a study consent form (see Appendix 10); with the patient’s agreement, the general practitioner (GP) was notified of their involvement in the trial (see Appendix 3).

Where other potential recruits became apparent only at the time of a clinic visit, they were invited to take part in the study and given verbal and written information. After a period of at least 24 hours to read, consider and discuss the information with family and/or friends, the research nurse contacted the patient by telephone to respond to any further outstanding questions and review their decision regarding involvement.

Patient and public involvement

In order to ensure that issues of importance to women undergoing IUTs would be addressed by a future definitive trial, advice and opinions were sought from patients and patient advocates at all stages of the INVESTIGATE-I study, particularly at the time of its conception, design and initiation. One of the trial grant holders (BSB), a clinical researcher, was the past chair of the Bladder and Bowel Foundation (B&BF), a patient-led support and advocacy organisation. B&BF members, staff and trustees were involved at the early stages of trial development in co-ordinating the involvement of patients in reviewing the protocol, materials and grant applications. The B&BF was also involved in identifying patient members for the Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Incontinence is a sensitive issue that is seldom discussed or acknowledged in public, so identifying women who were willing to participate in this capacity was less straightforward than may be the case in other areas of health care.

A particular challenge for the trial was the design of materials such as the PISs. In addition to explaining clearly the trial’s purpose and what involvement would mean for participants, these had to address two issues specific to the trial that are not common to many studies.

First, a diagnostic test that is routinely used, even an invasive test, is often accepted without question by patients in the belief that it will serve to inform treatment decisions. In this context, explaining the absence of good evidence of its value and the equipoise that exists between a diagnostic test and no test is more challenging than explaining equipoise between two treatments. It was important that participants understood that they were not being denied an effective element of the care process.

Second, a feasibility study may not be perceived to be as important as a definitive trial by potential participants. The PIS had to outline the potential importance of a feasibility study in making best use of public funds by informing the design of a definitive trial that could ultimately result in less invasive but equally effective patient care pathways.

Lay members of the TSC and a previous service user (trial participant) were involved in reviewing the plain English summary.

In a future definitive trial, a broader spread of patient and public representation could be sought. This might include, women’s network members from professional organisations or research support structures (e.g. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists and Research Design Services); ex-patients; and, ex-trial participants. A Patient Advisory Group facilitated by one of the research team could serve to increase the level of engagement from patient and public representatives. As a result of our experiences in these feasibility studies, it would be intended to extend patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the whole development and implementation of a definitive trial, including, design of the research (through contribution to proposal and protocol development); formulation of patient information materials (through consultation with PPI representatives); and, trial management (through membership of TSC), reporting and dissemination (through contribution to trial publication and presentation to lay audiences).

Randomisation

To ensure concealment of allocation, randomisation was undertaken by an internet-accessed computer randomisation system held by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU); randomisation between intervention and control was 1 : 1 and was stratified by centre using random block length. The recruiter logged into the system by password and site identification code and then entered the date of birth and initials of the patient they were randomising. The system responded with a unique randomisation number and the trial arm to which the patient had been randomised. This was viewed on the screen and backed up with an e-mail confirmation to the individual carrying out the randomisation and also copied to the central trial office.

Sample size

The sample size for the external pilot trial was determined pragmatically, using the recommended minimum of 30 participants per arm. 55 We aimed to recruit 60 participants per trial arm to investigate both the distribution and key parameters of the outcome measures. Previous trials in the area of pelvic floor dysfunction, including investigation,29 surgical44,56,57 and non-surgical treatments58 suggested average attrition rates of 13% (7–20%) between identification and randomisation, 16% (6–20%) between randomisation and treatment, and 13% (9–20%) between treatment and follow-up at 6 months. Taking the more pessimistic figure in each case, we estimated that a total of 240 eligible patients should be approached allowing for 50% overall attrition. The recruiting units collectively undertook 540 relevant procedures per year; therefore, identifying 240 eligible women within the originally planned 9-month recruitment period should not have presented undue difficulty.

Blinding

It was neither feasible nor appropriate to blind participants or clinicians (investigating and operating) as to the allocation of investigation strategy.

Interventions

Patients were randomised [documented on case report form (CRF) – ‘visit 1′ – see Appendix 19c] to receive either:

-

no IUT: basic clinical assessment supplemented by non-invasive tests as directed by the clinician; these included frequency/volume charting or bladder diary, mid-stream urine culture, urine flow rate and residual urine volume measurement (by ultrasound), or

-

IUT: basic clinical and non-invasive tests as above, plus invasive urodynamic testing. Dual-channel subtracted cystometry with simultaneous pressure/flow voiding studies is the most commonly applied technique in the evaluation of patients prior to surgery for SUI in most centres. Videourodynamics and ambulatory bladder pressure monitoring are used as alternative or additional invasive tests in some units; these tests were also permissible within the pilot trial, at the discretion of the clinician.

Given the pragmatic nature of the pilot trial, we were not prescriptive about which tests were carried out, nor indeed about exactly how they were carried out, save for the expectation that they would conform to good urodynamic practices. 59,60 For this reason, we do not feel it appropriate to give a detailed description of the interventions in accordance with the TIDieR guidelines. 61 Readers wishing to understand more about the interventions might refer to standard texts,62,63 or to standardisation documents. 59,60

Further investigation was undertaken, where appropriate, at the same visit or a later one, as per local custom, and the treatment plan formulated.

Outcome measures

In INVESTIGATE-I, we were primarily concerned with determining the number of eligible patients in each unit, and the rates of patient recruitment, randomisation, retention and response. We also piloted the collection of the outcome measures for a future definitive trial, to assess data yield (e.g. percentage of recruited participants returning completed questionnaires) and quality (e.g. completeness and consistency of responses within returned questionnaires). This information was collected to guide the choice and mode of administration of questionnaires and data collection tools in a future definitive trial.

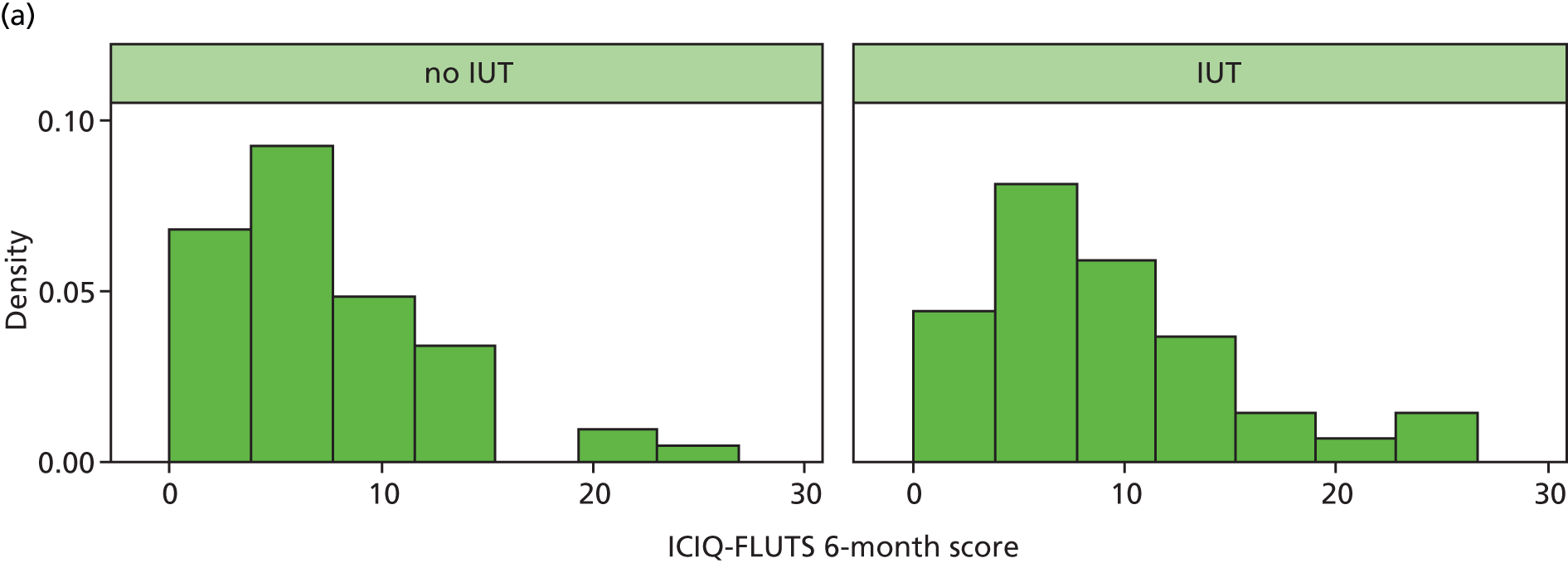

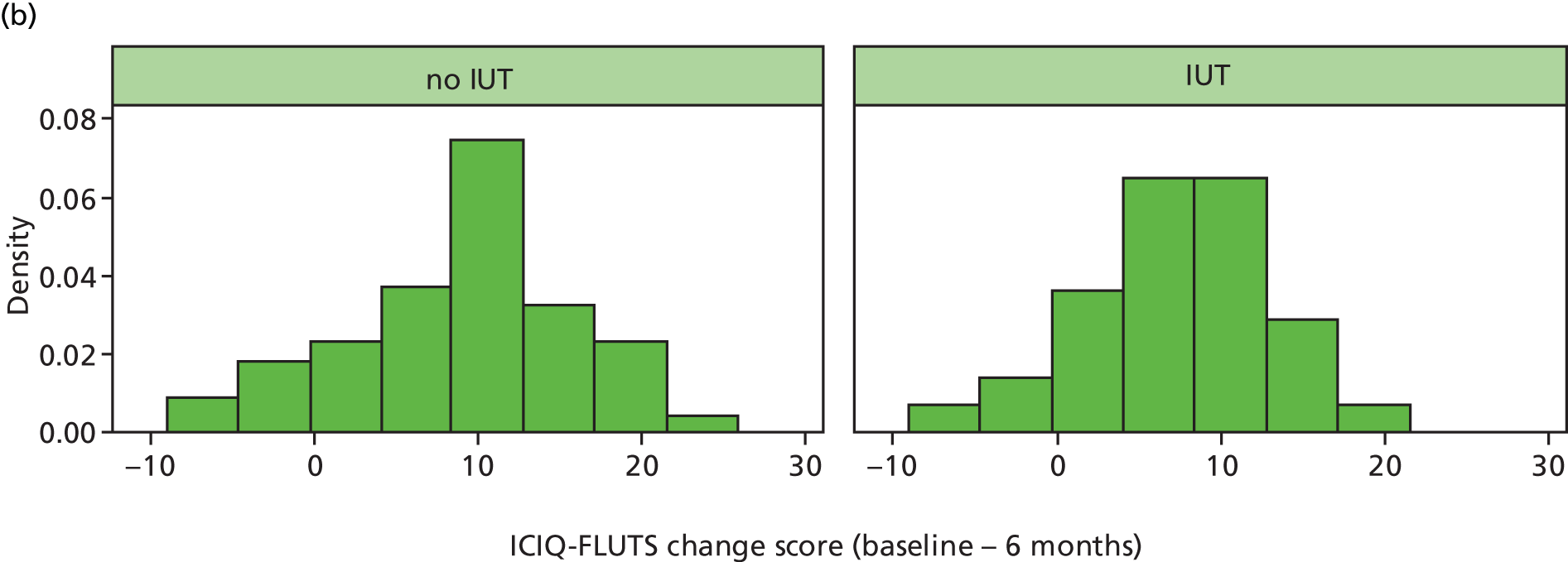

In a definitive trial, we would intend to use patient reported outcome measures as opposed to the more traditional methods for the quantification of leakage as the primary outcome. Our preferred primary outcome, rehearsed in the pilot trial, was:

-

the combined symptom score of the ICIQ Female Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms (ICIQ-FLUTS) questionnaire at 6 months after treatment. 43

Secondary outcomes for the future trial, also rehearsed in the pilot, comprise:

-

general health questionnaire [Short Form 12 version 2 (SF-12v2) © Health Survey 1994, 2002; QualityMetric Incorporated and Medical Outcomes Trust]. 64

-

quantification of urinary leakage [3-day bladder diary and ICIQ Urinary Incontinence Short Form (ICIQ-UI SF)]. 65

-

prevalence of symptomatic ‘de novo’ functional abnormalities including VD and detrusor overactivity (DO) (using subscales in ICIQ-FLUTS,43 with cystometric investigation in symptomatic patients).

-

the impact of urinary symptoms on QoL [ICIQ Lower Urinary Tract Symptoms Quality of Life (ICIQ-LUTSqol) questionnaire and UDI]. 38,66

-

EuroQol-5D (EQ-5D)-3 Level (EQ-5D-3L). 67

-

utility values from the EQ-5D-3L and from Short Form 6D (SF-6D) [the latter derived from responses to the Short Form 12 (SF-12)]. 68

-

costs to the NHS.

-

QALYs derived from both EQ-5D-3L and the SF-6D.

-

incremental cost per QALY with QALYs based on both EQ-5D-3L and SF-6D data.

Further details of the scoring systems applied to the ICIQs and UDI are given in Appendix 16.

Thus, within INVESTIGATE-I, we piloted the collection of the above outcome measures, to assess data yield (e.g. percentage of recruited participants returning completed questionnaires) and quality (e.g. completeness and consistency of responses within returned questionnaires). This information can then be used to guide the choice and mode of administration of questionnaires and data collection tools in a future definitive trial.

Baseline assessment of study outcomes

Following consent and randomisation, patients were given a pack of baseline study outcome questionnaires; these were presented in the order ICIQ-FLUTS, ICIQ-LUTSqol, ICIQ-UI SF, UDI, EQ-5D and SF-12 (see Appendix 17). Participants were asked to complete the questionnaires at home, within 2 weeks of receipt, and to post their responses, using the addressed prepaid envelope provided, to the Trial Manager at the NCTU.

Subsequent treatment within the trial

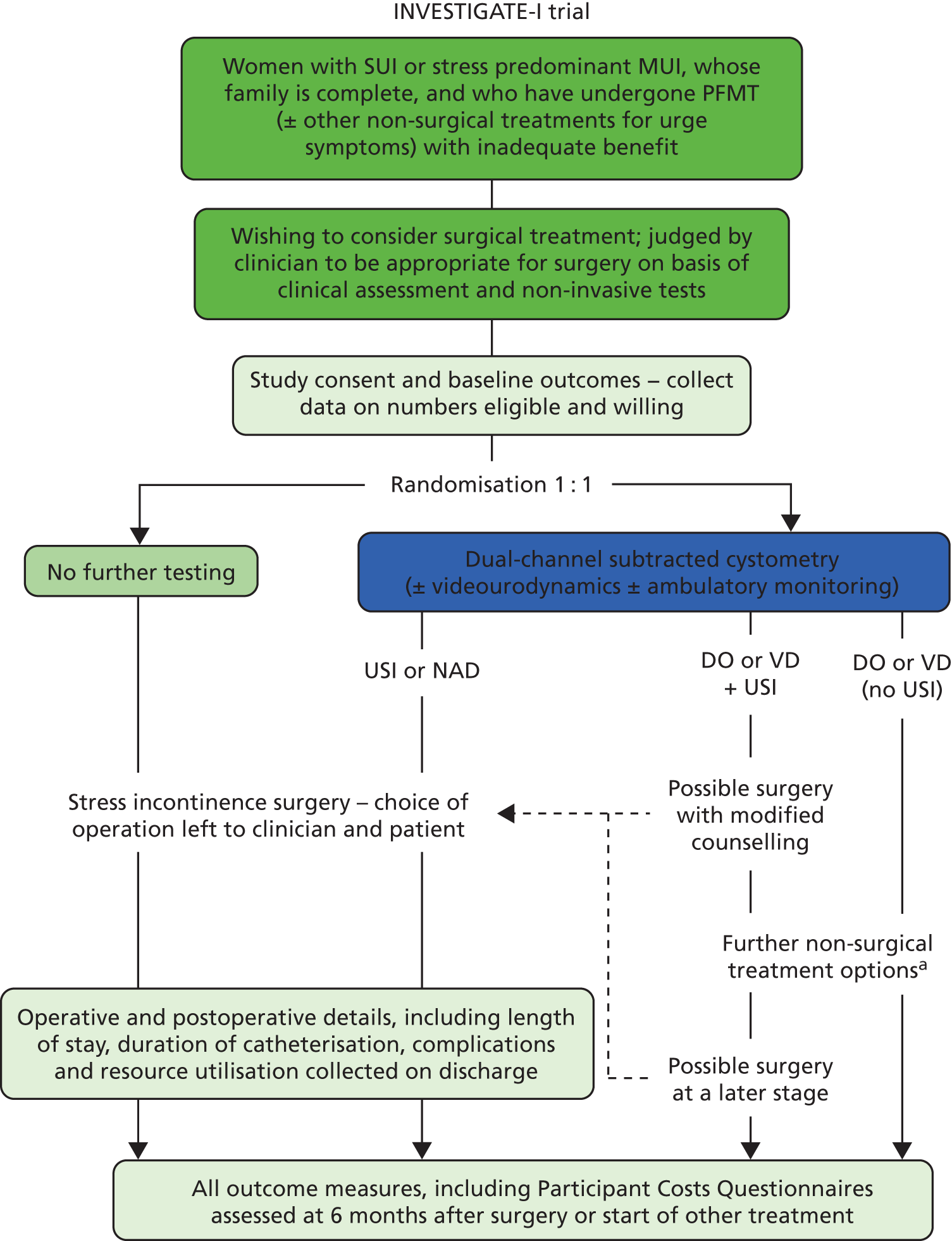

Following investigation, it would be expected that women randomised to the control (no IUT) arm of the study, i.e. those treated on the basis of clinical assessment and non-invasive tests (documented on CRF – ‘visit 2’ – see Appendix 19e), would undergo surgical treatment (documented on CRF – ‘visit 4′ – see Appendix 19g) (Figure 1). Given the pragmatic nature of the study, the choice of operation was left to the individual surgeon and patient; as only primary cases were included, it was anticipated that this would be either a retropubic or transobturator foramen mid-urethral tape procedure in most cases. Those randomised to the intervention (IUT) arm, i.e. undergoing invasive urodynamic testing (documented on CRF – ‘visit 3′ – see Appendix 19f), had similar surgical treatment when urodynamic stress incontinence (USI) was confirmed (documented on CRF – ‘visit 4’). Where other diagnoses were identified following investigation, alternative treatments might be offered (documented on CRF – ‘visit 5′ – see Appendix 19i); these included bladder retraining, anti-muscarinic drug treatments, neuromodulation, botulinum toxin injections (where DO was diagnosed), or clean intermittent self-catheterisation (where a VD was identified). Exactly which of these interventions was chosen depended on what conservative treatments had been used before entry into the trial; for example, if a woman had tried PFMT plus bladder retraining before entry, she was likely to be offered anti-muscarinic drug treatment if DO was shown on invasive urodynamic testing. In all centres the treatment algorithm employed was in keeping with the then current NICE recommendations (2006). 17 In some cases where mixed abnormalities were reported, women would first undergo one or more of these interventions (to stabilise bladder overactivity, or improve voiding efficiency) and then proceed to surgery for SUI. After the participant entered the study the clinician remained free to recommend alternative investigation or treatment to that specified in the protocol at any stage if they felt it to be in the participant’s best interest. In these cases the participant remained in the study for the purposes of follow-up and data analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of the study design and the flow of participants. a, The choice of non-surgical treatments is left to the clinician and patient, but may include bladder retraining, drugs, neuromodulation, botulinum toxin injections, and clean intermittent catheterisation, depending on IUT results, local protocols and previous trials of therapy. NAD, no abnormality detected; USI, urodynamic stress incontinence.

Any adverse events (AEs) or serious adverse events (SAEs) were documented in the CRF (see Appendices 20 and 21); SAE notification was faxed to the NCTU within 24 hours.

Follow-up

Clinicians arranged postoperative follow-up or other outpatient review, as per their normal practice and timing (documented on CRF – ‘visit 6’ – see Appendix 19h). Patients were sent a pack of follow-up study outcome questionnaires along with a prepaid envelope by the NCTU at 6 months after the start of treatment (i.e. 6 months after the date of surgery, or the start of any non-surgical intervention, or period of ‘watchful waiting’). This applied in all cases, even where surgery was undertaken as a secondary intervention in those women initially treated non-surgically. They were asked to complete the questionnaires at home and return them to the NCTU. Those failing to return questionnaires within 1 month of the initial request were contacted by the appropriate research nurse by telephone, to encourage responses. In the last 9 months of the study, the option of completing the questionnaire over the telephone with the research nurse was also given to participants during the reminder telephone call. If the questionnaires were not returned after the telephone reminder, a further copy of the questionnaires was mailed to the participant with a reminder letter. The patients withdrawal or completion of study follow-up was documented on CRF – ‘visit 7’ (see Appendix 19k).

Governance and regulatory arrangements

Ethics and research and development approval

The conduct of this study was in accordance with the ethical principles set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (2008)69 and the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care (second edition, 2005). 70 Application for ethical approval was made through the Integrated Research Application System, and a letter of favourable ethical opinion was obtained from Newcastle & North Tyneside 1 Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 6 January 2011 – reference number 10/H0906/76. Application for research and development (R&D) approval was made via the NIHR Co-ordinated System for gaining NHS Permissions (CSP) – reference number 62776. Global sign-off for R&D approval was received on 15 March 2011, with local R&D approvals of the protocol between 28 March 2011 and 9 August 2011.

Changes to the original protocol

Two amendments were made to the original protocol. The first (v1.1; dated 1 July 2011) added detail to the protocol on the collection of health economics outcomes from the study, and included the Participant Costs Questionnaire (PCQ) and the trial management plan as appendices. The second (v1.2; dated 12 September 2012) related to a change in the method for follow-up reminders; as in the original protocol, a telephone reminder would be undertaken by the local site research nurse if the questionnaire had not been returned after 4 weeks; in addition, if after the telephone reminder, the questionnaires were not returned within a further 2 weeks, a further copy of the questionnaires would be mailed to the participant with a reminder letter. Both amendments were approved by the study sponsor and by Newcastle & North Tyneside 1 REC.

Clinical trials agreements

Clinical trials agreements (CTAs), using the model for non-commercial research within the health service, were established for the various study sites with sponsor Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (NuTH) between 25 May and 15 August 2011. Site initiation visits took place between 30 March and 17 June 2011, with the start to recruitment permitted (‘green light’ to proceed) only after completion of all regulatory approvals and site initiation, between 14 June and 15 August 2011 (for the primary sites) (Table 1).

| Site | Type | R&D approval | CTA | Site initiation | Site open to recruitment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newcastle | Primary | Full | 28 March 2011 | 25 May 2011 | 17 June 2011 | 18 June 2011 |

| Gateshead | Primary | Full | 29 March 2011 | 14 June 2011 | 13 April 2011 | 15 June 2011 |

| Wansbeck | Primary | Full | 25 July 2011 | 28 July 2011 | 21 April 2011 | 29 July 2011 |

| Sheffield | Primary | Full | 7 July 2011 | 29 June 2011 | 28 April 2011 | 8 July 2011 |

| Swansea | Primary | Full | 23 June 2011 | 30 June 2011 | 8 April 2011 | 1 July 2011 |

| Leicester | Primary | Full | 9 August 2011 | 15 August 2011 | 30 March 2011 | 16 August 2011 |

| South Tees | Secondary | Full | 9 July 2012 | 17 July 2012 | 2 August 2012 | 3 August 2012 |

| South Tyneside | Secondary | PIC | 17 September 2012 | 23 August 2012 | 18 September 2012 | |

| Sunderland | Secondary | PIC | 30 May 2012 | 30 May 2012 | 31 May 2012 | |

Following approval of an extension to recruitment, one additional recruiting site and two PIC sites were approved.

Consent

Women were informed about the detail of the study with the brief and more detailed PIS, and by discussion with the local research nurse independently of the clinician responsible for ongoing care, and of staff undertaking investigations. Patients provided written informed consent. Separate written consent to take part in the qualitative patient interview substudy was sought, and it was made clear to trial participants that they were under no obligation to take part in the qualitative substudy (see Chapter 7).

To inform the design of a future definitive trial, those who declined to participate in the trial or who withdrew prematurely were asked for their reasons for withdrawal, but the right to refuse to participate without giving reasons was also respected.

Other regulatory arrangements

Other regulatory arrangements for the study, relating to confidentiality, indemnity, on-site monitoring and internal audit, day-to-day management by the Trial Management Group (TMG), and oversight by the TSC and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) are described in detail in the study protocol, the latest version of which is available on the NIHR Journals Library website.

Encouraging participant recruitment

It is unclear why some trials appear to recruit more easily to target than others. 71 Factors related to the research question itself (e.g. being a cancer or drug trial), related to trial organisation (e.g. having a dedicated trial manager) and related to treatment access (e.g. involving a treatment only available within the trial) have been shown to be associated with more successful recruitment. Other strategies have been employed to encourage recruitment for example, newsletters and mailshots, although it has not been shown unequivocally that these are causally linked to changes in recruitment. 72,73 One of the aims of a feasibility study is to investigate how well units are able to identify eligible trial participants and recruit them. A number of additional strategies were employed within INVESTIGATE-I, partly to encourage recruitment in the pilot itself, but more particularly to rehearse them as possible strategies within a future definitive trial. These included the establishment of additional study sites, and strategies to facilitate communication and staff engagement.

Additional study sites

Following approval by HTA of a 9-month extension to recruitment (initially 2 months, then a further 7 months), one additional full recruiting site (South Tees Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust) and two PIC sites (Sunderland Royal Hospital and South Tyneside District General Hospital) were established.

Communication and staff engagement

Study acronym and logo

The full study title incorporated the underlying clinical question addressed, the overall study methodology, and identified the trial element as having a randomised design. The short title (INVasive Evaluation before Surgical Treatment of Incontinence Gives Added Therapeutic Effect?), study acronym (INVESTIGATE-I), and logo (incorporating a graphic image of dripping and calmed water) did not simply provide a random selection of letters from the full title to give a snappier sound bite. They each serve to complement and ‘stand for’ the full title, add to the effectiveness and understanding of the message, by a representational name and image. They were used in all communications to trial staff, regulatory authorities, other clinicians, patients (other than when site specific stationery was appropriate) and the trial website, and as such provided a constant identity for the INVESTIGATE studies. The importance of such study ‘branding’ is emphasised in the STEPS study. 72

Basecamp

Basecamp© (developed by www.37signals.com, Chicago, IL, USA) is a web-based project management application; this was used for communication and document sharing between members of the TMG and between the TMG and other members of the research team, particularly those based outwith Newcastle.

Trial website

A trial website (www.investigate-trial.com) was developed early during the project as a means of increasing awareness of the INVESTIGATE studies within the research team, for other staff at the various study sites, for clinical colleagues who might be interested to learn more and perhaps to collaborate in a future trial, and for the general public. It includes information about the current study (INVESTIGATE-I), including the justification, methodology, and recruitment progress; reference is also made to a possible future definitive study; trial governance arrangements are included, with appropriate links; PISs and study newsletters (v.i.) are available for download, and there are links to open-access publications from the INVESTIGATE studies; contact details for the research team and site clinical staff are also provided. All sections are updated as necessary, and a ‘latest news’ section on the home page gives topical issues regarding trial progress and staff development (see Appendix 22).

Study newsletters

Study newsletters were circulated to the research team every 2 to 3 months during the trial period. These covered, information about the study, including protocol amendments; progress with the trial and interview studies; feedback from the TSC and DMEC meetings, and from the trial funder; details of study presentations and publications; personal news from the trial team (see Appendix 23). Progress with recruitment against target was included using the ‘Recruitment to Target’ (RtT) thermometer (©Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and Newcastle University) (v.i.).

Recruitment updates

At times when recruitment was a particularly acute concern, a weekly progress update was distributed to the research team. These were employed in particular during the 2-month provisional extension (during which 50% recruitment had to be completed in order to secure a further extension) and in the final weeks of recruitment. These updates were limited to information on recruitment, but showed this by centre, with a competitive edge to encourage peer rivalry; progress was illustrated in a variety of ways [e.g. using a ‘league table’; the RtT thermometer; black, red, amber, green (‘BRAG’) flag status (black = zero recruits, red = > 24% off target, amber = 15–24% off target, green = 0–14% off target); and countdown clock and filmstrip graphics (see Appendix 24)].

‘Recruitment to Target’ thermometer

During the construction of the study website, a graphic device described as the ‘RtT (Recruitment to Target) thermometer’ was developed to help trial staff visualise progress against recruitment target numbers and timing. This was initially formatted in Microsoft PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), as a simple graphic image illustrating actual recruitment against recruitment target (including a BRAG status pennant, colour-coded as above), and time expired of the available study recruiting time, in the form of a ‘maximum and minimum thermometer’. It was then converted into hypertext markup language (HTML) code that can easily be adapted for use in any trial, and added into a website (see Appendix 25). The use of the device was subsequently disseminated for use in other studies via the NCTU trial managers and Comprehensive Local Research Network (CLRN).

Statistical analysis

Given that this was a pilot trial, the statistical analysis was largely descriptive in nature and provided estimates of key trial parameters to inform the design of the future definitive trial. Screening and recruitment numbers were summarised in a CONSORT diagram. In addition, screening numbers were summarised by centre and recruitment numbers were summarised by month and centre. Results were reported at baseline and 6-month follow-up time points. Data analysis was by intention to treat.

Categorical variables were summarised as percentages per category by treatment arm. Questionnaire scale and subscale totals and continuous variables were summarised by mean and standard deviation (SD) and 5-number summaries [median, interquartile range (IQR) and range] by treatment arm and time point. The burden of missing data were summarised by response rates for each variable. No data imputation was attempted for any outcome [other than in the economic evaluation (see Chapter 4)]. The summary statistics for the primary outcome measure were combined with the target/minimum clinically important difference (MCID) and recruitment, retention and response rates to inform the sample size for a future definitive trial.

Results

Screening

Overall, 771 patients were identified by research nurses from clinic notes and correspondence as being potential recruits into the study, and were sent the PISs. Of those screened, 284 were deemed eligible for the trial, giving a ‘screen positive’ rate of 37%. The reasons for non-eligibility of screened patients are shown in Table 2; most commonly these were patients not having undergone supervised PFMT prior to referral (14%), urgency or urgency predominant MUI (12%), failure to attend clinic appointments (11%), patients not wishing to participate (8%), patients with prolapse requiring treatment (5%), or clinicians feeling that surgery was not appropriate (5%). Although the reasons for non-eligibility varied between centres, the overall figures were obviously heavily weighted by the centre screening the highest number of patients. In some units, patients not wishing to participate made up a larger proportion of screening failures; overall however, 78% of eligible women identified were recruited into the study.

| Code | Description | Newcastle | Gateshead | Wansbeck | Leicester | Swansea | South Tees | Sheffield | Total | Per cent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | Patient has not undergone a course of PFMT | 74 | 10 | 15 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 105 | 14 |

| 14 | Urge incontinence | 85 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 92 | 12 |

| 13 | Other (give details) | 52 | 5 | 17 | 8 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 86 | 11 |

| 15 | Did not attend clinic | 54 | 24 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 81 | 11 |

| 7 | Patient does not wish to participate, include reason if offered | 13 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 3 | 59 | 8 |

| 1 | Symptomatic uterovaginal prolapse requiring treatment | 22 | 0 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 40 | 5 |

| 8 | Clinician feels surgery inappropriate | 1 | 26 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 39 | 5 |

| 9 | Patient does not wish surgery | 5 | 11 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 21 | 3 |

| 2 | Previous surgery for UI or POP | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 1 |

| 3 | Urodynamic investigation within the last 3 days | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| 10 | Patient does not consider her family is complete | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 1 |

| 4 | Neurological disease causing UI | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 5 | Current involvement in a conflicting research study | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6 | Unable to give competent informed consent | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 | Study not discussed at clinic visit (please give reason) | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Recruited | 75 | 50 | 37 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 8 | 222 | 29 | |

| Total screened | 399 | 140 | 103 | 48 | 39 | 28 | 14 | 771 | 100 | |

| Per cent of screened women recruited | 19 | 36 | 36 | 42 | 44 | 54 | 57 | 29 | ||

| Per cent of eligible women recruited | 84 | 85 | 76 | 67 | 55 | 100 | 73 | 78 |

The numbers screened at individual centres varied between 14 and 399; the percentage of eligible women recruited varied between 55% and 100%, but did not show an obvious trend with the number screened (see Table 2). Although a single code was assigned to each patient, it is possible that codes were used variably in the different centres, and that there may have been some inconsistency or overlap in the use of codes. For example, it is possible that ‘patient does not wish to participate’ could overlap with ‘patient does not wish surgery’. While the centres screening larger numbers of women also recruited larger numbers (Figure 2), the conversion from screening to recruitment decreased as the screening number increased (Figure 3).

FIGURE 2.

Numbers screened and recruited at individual centres.

FIGURE 3.

Number and percentage recruited to trial by number screened (shown on log scale) at each centre. The graph plots the percentage and number of participants recruited. The number of participants is indicated by black filled circles and the percentage of participants by green open circles.

Quality assurance of screening processes

In view of the variations seen in screening and recruitment between centres, a quality assurance check was made with PIs and recruiting staff in each unit, confirming that all employed a similar practice in relation to screening; this was stated in the study protocol as follows:

Potential trial recruits will be identified by the study research nurses prior to attending new or follow-up appointments for SUI or MUI in the clinics run by the unit clinical leads. The Patient Information Sheet (PIS) will be sent out with new appointments or with a reminder letter to attend follow-up appointments; this will allow any questions that the woman may have about the study to be addressed at the one visit. Those declining to take part would undergo further investigation and or treatment as appropriate at the same visit. Those agreeing to take part will sign a study consent form.

If other potential recruits become apparent only at the time of a clinic visit, they will be invited to take part in the study, and will be given verbal and written information. After a period of at least 24 hours to read, consider and discuss the information with family and/or friends, the research nurse will contact the patient by telephone to respond to any further outstanding questions, and review their decision regarding involvement.

It is possible that women referred to the various centres were in some way different, although the workload and nature of the units would have made this unlikely. The number of women screened in individual centres would therefore be expected to be determined by the ease with which PIs or research nurses were able to identify eligible women from referral letters or hospital notes. It might also be a reflection of their individual position on the spectrum of sensitivity versus specificity, that is whether they perceived the priority as being only to screen those women who were very likely to be eligible, or saw the importance of ‘broadening the net’ to include all potential recruits. In view of the pragmatic intention of the pilot trial, we did not give a strict definition to the term ‘stress predominant MUI’, preferring to leave it to clinicians to determine this within their own practices. It is possible that individual screeners or PIs may have interpreted the term variably, such that this also could have contributed to variation in recruitment rates.

In order to explore these issues further, a series of 20 identical vignettes were distributed to screeners via the trial Basecamp site. These were mainly based on actual GP referral letters, although in some cases with modifications to cover the range of inclusion and exclusion criteria. Sixteen vignettes mentioned one or more definite inclusion criteria (SUI, stress predominant MUI, PFMT, family complete); the other four had possible inclusions (UI but not specified as to stress or urgency related; ‘wet all the time’; PFMT mentioned but level of supervision not specified). Four had definite exclusions (previous pelvic floor surgery; neurological disease; urgency predominant MUI) and 15 contained possible exclusions (unsupervised PFMT). The vignettes are shown in Appendix 26.

Each of the 11 screeners from the seven full recruiting units graded the vignettes independently, on the basis of the following instructions:

What we want to know is whether you would have considered each of the women described in the letters to be a potential recruit for the INVESTIGATE-I trial. In other words, if you had reviewed the letter at the time that we were looking for recruits into the trial would you, or would you not, have sent out a Patient Information Leaflet (PIL) to the woman described (please tick either ‘Yes’ or ‘No’ in the blue boxes on the score sheet). It would also be helpful to know whether you feel the decision is clear-cut, or borderline (by ticking in the appropriate green box), and something of why you made that decision (by ticking the orange boxes and adding comments as appropriate), on the score sheet provided.

The possible responses were, therefore, clear cut ‘Yes’ (Y); borderline ‘Yes’ (?Y); borderline ‘No’ (?N), or clear cut ‘No’ (N). Each screener’s grading for the various vignettes is shown in Table 3. For six vignettes, everyone agreed that the patient was eligible; for one, all agreed that the patient was not eligible; the grade breakdown for the remainder was mixed.

| Vignette no. | Centre and screener | % Yes | Grade breakdown | Majority grade | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WGH | RVI | LE | SHE | RVI | WGH | ST | SW | QEH | LE | SW | ||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | Y | ?Y | ?N | N | ||||

| 8 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 14 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ?Y | Y | Y | 100 | 10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 17 | Y | Y | Y | ?Y | Y | Y | ?Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | 9 | 2 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 4 | Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 100 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 7 | Y | Y | Y | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | 100 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 1 | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | Y | 100 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 0 | ?Y | Y |

| 3 | Y | Y | ?Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ?Y | ?N | 91 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 | Y | Y |

| 20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | 91 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Y | Y |

| 6 | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | ?N | 91 | 2 | 8 | 1 | 0 | ?Y | Y |

| 12 | ?Y | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | N | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | N | 82 | 1 | 8 | 0 | 2 | ?Y | Y |

| 16 | Y | ?Y | Y | ?Y | ?Y | N | ?N | ?Y | Y | N | Y | 73 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 2 | Y/?Y | Y |

| 9 | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?N | Y | ?Y | ?N | N | ?Y | ?Y | 73 | 1 | 7 | 2 | 1 | ?Y | Y |

| 2 | Y | ?Y | ?Y | ?Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | ?N | 64 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Y | Y |

| 11 | ?Y | ?Y | N | ?Y | ?Y | Y | N | ?Y | N | N | N | 55 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 5 | ?Y/N | Y |

| 5 | ?Y | N | ?Y | ?Y | ?N | ?N | Y | N | N | N | ?N | 36 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 4 | N | N |

| 18 | N | ?Y | N | N | N | ?N | ?Y | ?Y | N | ?Y | N | 36 | 0 | 4 | 1 | 6 | N | N |

| 19 | N | ?Y | N | ?N | ?Y | Y | Y | N | N | ?N | N | 36 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 5 | N | N |

| 10 | ?N | N | ?Y | ?N | ?N | N | N | N | N | ?N | ?N | 9 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 5 | ?N/N | N |

| 13 | ?Y | N | N | ?N | ?N | ?N | N | N | N | N | N | 9 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 7 | N | N |

| 15 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 | N | N |

| % Yes (Y or ?Y) | 80 | 80 | 75 | 75 | 70 | 65 | 65 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 45 | |||||||

| ‘Yes’ when majority ‘No’ | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |||||||

| ‘No’ when majority ‘Yes’ | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 5 | |||||||

| Total ‘disagreements’ | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 5 | |||||||

Assuming a majority decision was one in which the ‘%Yes’ grading was above or below 50% (irrespective of whether the decisions were considered to be clear-cut or borderline), in other words that the majority felt that the patient described in the vignette was (or was not) eligible for screening, then there were 34 occasions on which one or more individual screeners ‘disagreed’ with the majority. The number of ‘disagreements’ varied across the 11 screeners; this ranged from one screener who dissented from the majority decision for 1/20 vignettes to another who dissented in 7/20 vignettes. Table 3 reports these separately as occasions on which the screener said ‘Yes’ when the majority said ‘No’, and those on which the screener said ‘No’ when the majority said ‘Yes’. The former judgement would lead some patients being deemed eligible and sent the PIS when they might be found to be ineligible at a later appointment (i.e. erring on the side of over-inclusiveness at the screening stage). The latter judgement would lead to some potential recruits not being invited to take part in the trial when they would have been eligible. Given the difficulty in recruiting patients in some centres, it is the latter judgement that should be minimised within trials.

Free-text comments were sought to help clarify the screeners’ decisions. These included:

Vignette 2 (majority view – clear-cut ‘yes’) Four comments, all along the same line,that is the letter did not specifically mention PFMT; they appeared, therefore, to have taken the view that it had not been done rather than ‘might have been done’.

Vignette 3 (majority view – clear-cut ‘yes’) One comment: ‘Need to check notes and if documented that pt [patient] has stress incontinence and received PFMT then would be eligible but if it is only on patient’s say so then further investigations would be beneficial to give a diagnosis.’ The vignette did specifically state: ‘Complaining of stress incontinence. She denies any urgency and says that when she coughs and laughs she passes small amounts of urine.’ As well as: ‘She has tried pelvic floor exercises including an internal pelvic toner to no avail’.

Vignette 5 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) Five comments, essentially taking the view that the vaginal laxity was the greater problem and the incontinence less of an issue. Physiotherapy report (included with referral) states: ‘She has attended on 3 occasions in total and reports that her continence symptoms have become more manageable but not completely resolved’ and ‘on examination there was no significant vaginal or uterine vaginal or uterine descent’.

Vignette 6 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) One comment, essentially same as vignette 3 (same screener).

Vignette 9 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) Three comments, all along the same lines – no supervised physiotherapy, and best assess later.

Vignette 10 (majority view – borderline ‘no’) One comment, highlighted the patient had previous surgery and may not have done PFMT, but indicated ‘yes’ to screening.

Vignette 11 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) Four comments, indicating need for PFMT (this was not mentioned in the letter, although it did state that the patient wished to consider surgery); two also referred to young age and therefore uncertainty of family plans.

Vignette 12 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) Two comments, one relating to complaint of ‘dragging sensation’, one to need for PFMT (not mentioned in letter).

Vignette 13 (majority view – clear-cut ‘no’) One comment on definition of ‘repair operation’.

Vignette 16 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) Three comments both relating to the history of OAB. Letter states:

She has been treated in the past for urinary problems, and has had a number of medications, and says that she even had Botox injections to her bladder. Since these latter interventions her symptoms have changed somewhat; previously she reported both urge and stress incontinence, but now she is left with only the stress element, with leakage occurring particularly on coughing or sneezing, or when she is at the gym.

Vignette 18 (majority view – clear-cut ‘no’) Most referred to lack of supervised PFMT specifically indicated in letter. One commented that ‘Patient may feel she has done 6 months physio and it may be agreed that surgery is an appropriate treatment now’.

Vignette 19 (majority view – clear-cut ‘yes) One comment related to treatment for rectal (not uterovaginal) prolapse.

Vignette 20 (majority view – borderline ‘yes’) One comment referred to need for pad at night and that this could represent OAB or fistula.

Hence the majority of the explanatory comments related to missing information, most commonly whether or not PFMT had been undertaken at all, or whether or not it had been supervised. A number also related to reports of vaginal laxity or dragging sensation, although information about clinical findings in relation to POP either was not present or was negative. There were also uncertainties or misinterpretations of the significance of descriptions of rectal prolapse and repair surgery.

Differences between units were not clearly apparent and the relationship between disparity in screening categorisation in this exercise and screening to recruitment ratios in the trial itself was also not obvious.

In a future trial it would be appropriate to:

-

ensure that definitions in inclusion and exclusion criteria are clarified (e.g. prolapse symptoms vs. clinical findings vs. need for treatment; rectal vs. uterovaginal prolapse, etc.)

-

suggest that where information is missing from referral letters it is assumed the patient might be eligible, and therefore that the default action should be to send out the PIS, unless obvious exclusions are specified

-

arrange group training/standards setting sessions for PIs and research nurses to agree a consistent approach to the screening and recruitment process across sites.

Recruitment

Monthly recruitment by centre is shown in Table 4 and Figure 4, for the initial recruitment period (up to the end of March 2012) and for the period of extension (from April to December 2012). Regulatory requirements took approximately 3 months longer than anticipated and, as a result, recruitment targets were revised. Even once all approvals were in place, and all sites in a position to start recruitment, the rate of accrual was significantly less than required with some sites unable to identify any patients for some weeks after opening to recruitment. Although proposed in 2011,74 the NIHR 70-day benchmark for recruitment was not published until 2012 and was not a required of CLRNs until after 2013. 75 Nevertheless, several steps were introduced to improve recruitment, including the incorporation of additional clinicians on two of the existing sites and the establishment of an additional full recruiting site and two PIC sites. A request was made for a 9-month unfunded extension to the recruitment period.

| Year.Quarter | Period | Date | Predicted recruitment | Actual end of month recruitment by site | Totals | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original | First revised | Second revised | Newcastle | Gateshead | Wansbeck | South Tees | PIC sites | Leicester | Swansea | Sheffield | Monthly | Cumulative | |||

| 1.2 | Initial recruitment period | 1 April 2011 | 0 | ||||||||||||

| 1.2 | 1 May 2011 | 20 | |||||||||||||

| 1.2 | 1 June 2011 | 40 | |||||||||||||

| 1.3 | 1 July 2011 | 60 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||||||||

| 1.3 | 1 August 2011 | 90 | 20 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 7 | ||||||

| 1.3 | 1 September 2011 | 120 | 40 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 | 19 | ||||

| 1.4 | 1 October 2011 | 150 | 60 | 12 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 21 | ||||

| 1.4 | 1 November 2011 | 180 | 90 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 23 | ||||

| 1.4 | 1 December 2011 | 210 | 120 | 20 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 10 | 33 | ||||

| 2.1 | 1 January 2012 | 240 | 150 | 38 | 20 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 38 | |||

| 2.1 | 1 February 2012 | 180 | 54 | 23 | 13 | 8 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 19 | 57 | ||||

| 2.1 | 1 March 2012 | 210 | 70 | 26 | 18 | 12 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 17 | 74 | ||||

| 2.2 | 1 April 2012 | 240 | 87 | 26 | 24 | 16 | 13 | 6 | 2 | 13 | 87 | ||||

| 2.2 | +2 months | 1 May 2012 | 104 | 34 | 27 | 18 | 13 | 9 | 4 | 18 | 105 | ||||

| 2.2 | 1 June 2012 | 121 | 41 | 35 | 20 | 0 | 16 | 10 | 4 | 21 | 126 | ||||

| 2.3 | Extension period +7 months | 1 July 2012 | 138 | 47 | 35 | 21 | 0 | 18 | 10 | 4 | 9 | 135 | |||

| 2.3 | 1 August 2012 | 155 | 51 | 40 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 11 | 4 | 18 | 153 | |||

| 2.3 | 1 September 2012 | 172 | 55 | 41 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 19 | 13 | 4 | 7 | 160 | |||

| 2.4 | 1 October 2012 | 189 | 59 | 43 | 31 | 5 | 0 | 19 | 14 | 6 | 17 | 177 | |||

| 2.4 | 1 November 2012 | 206 | 62 | 45 | 31 | 10 | 0 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 11 | 188 | |||

| 2.4 | 1 December 2012 | 223 | 66 | 47 | 33 | 11 | 0 | 20 | 16 | 7 | 12 | 200 | |||

| 3.1 | 1 January 2013 | 240 | 75 | 50 | 37 | 15 | 0 | 20 | 17 | 8 | 22 | 222 | |||

FIGURE 4.

Monthly total recruitment numbers. The original and revised predictions of overall recruitment are shown as continuous and dashed lines, and actual recruitment in histogram; the overall ‘BRAG’ flag or ‘RtT’ status is also illustrated.

The number of participants recruited per recruiting month (i.e. between the completion of all site-specific regulatory requirements and the end of the study) varied between 0.4 and 3.9 per month at the original sites (mean 1.9); at the additional full recruiting site this figure was 2.5 per month; the PICs did not identify any potentially eligible patients for referral to a recruiting site in the 8 months that they were active.

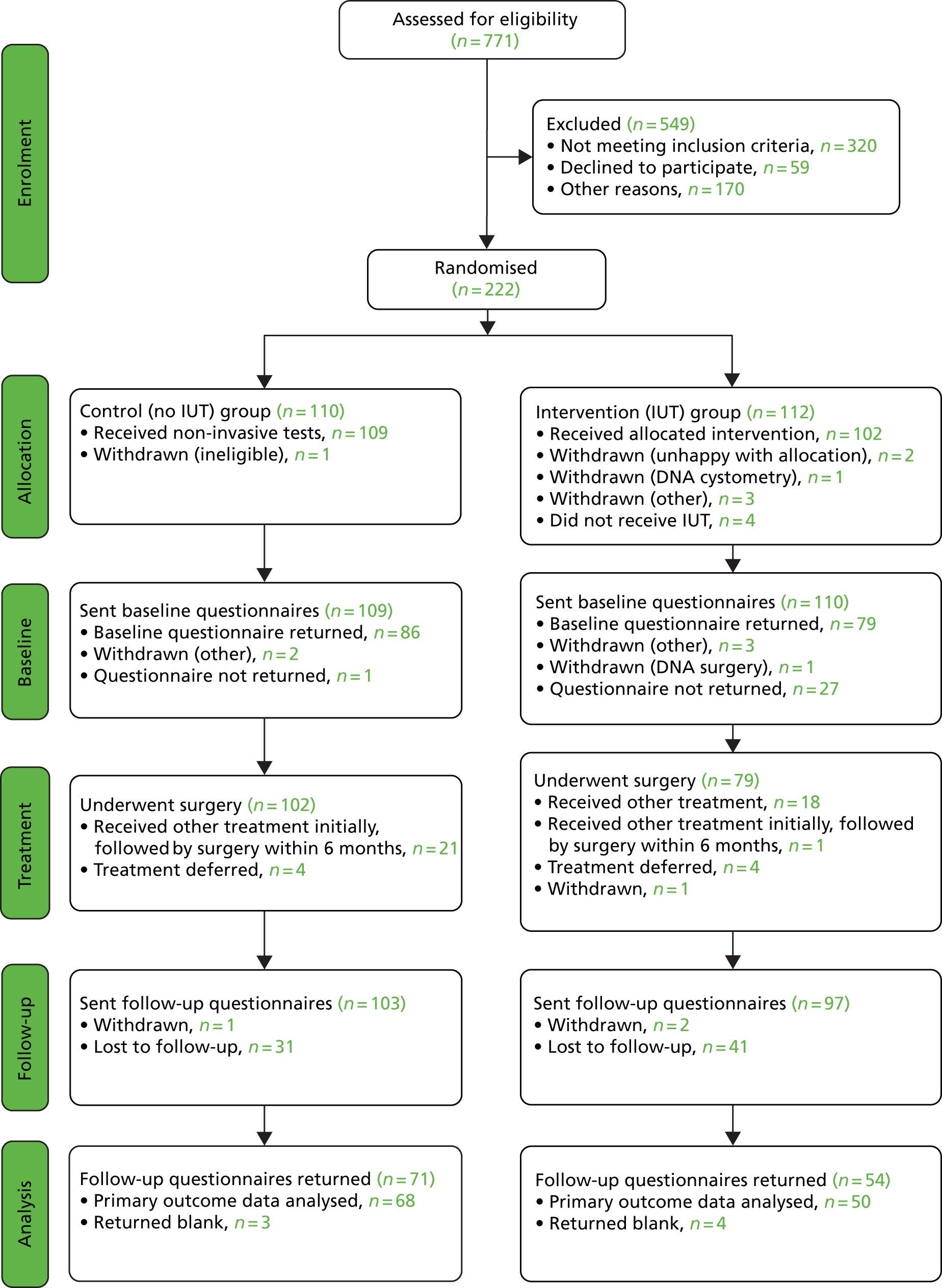

Randomisation

Of the 284 women screened positive, 222 agreed to randomisation into the trial, giving a trial consent rate of 78%. This recruitment total (222) represented 93% of the planned sample size (240) for the pilot trial. Overall, 110 women were randomised to the control or no IUT arm and 112 to the intervention or IUT arm. Immediately after randomisation it became apparent that one woman in the no arm was ineligible for the trial and she was withdrawn leaving a total of 221 eligible patients randomised (109 in the no IUT arm and 112 in the IUT arm).

The screening, recruitment, randomisation and trial follow-up are summarised in the CONSORT diagram shown as Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Trial CONSORT flow diagram. DNA, did not attend.

Retention

Demographic data and details of any subsequent treatment for incontinence were collected from hospital notes and CRFs (see Appendices 19a–k), and women were asked to complete questionnaires on clinical outcomes (see Appendix 17) and a 3-day bladder diary (see Appendix 18) at baseline and 6 months after the start of treatment (i.e. 6 months after the date of surgery, or the start of any non-surgical intervention, or period of ‘watchful waiting’). Baseline questionnaires were sent to 219 women and returned by 165; this represented a response rate of 75% overall, 72% in the IUT arm and 79% in the no IUT arm. At 6 months after treatment, questionnaires were returned by 63% (125/200) of those who were sent questionnaires at follow-up; 56% (54/97) in the IUT arm and 69% (71/103) in the no IUT arm.

Six women returned a completely blank questionnaire booklet (three in each study arm); one further woman in the IUT arm completed only the EQ-5D and SF-12 questionnaires, but for the purpose of return of primary outcomes this was categorised as returning a blank questionnaire, as the ICIQ-FLUTS was not completed. This information is summarised in the trial CONSORT diagram Figure 5. Six of the seven women who returned blank questionnaires reported ‘no significant urinary symptoms’ on the follow-up CRF (visit 6). The same six either annotated the front of their questionnaire or bladder diary, or in one case telephoned the NCTU indicating that they had not had urinary problems since their surgery. One of the women who returned a blank questionnaire reported ‘significant urinary symptoms’ on the follow-up CRF; she also annotated her diary to indicate that there had been little change in her urinary symptoms following her surgery, although she improved slightly with subsequent drug treatment.

The progress of recruitment and follow-up is shown in Figure 6. It also shows the anticipated follow-up at 6 months, although these predictions do not make allowance for individual centre waiting times for investigation and surgery; this was certainly an error that would require attention in planning a future definitive trial. The actual times at which follow-up questionnaires were posted out to participants (at 6 months after surgery or start of treatment) do reflect these waits, and illustrate an average additional delay to follow-up of approximately 4 months. Figure 6 also illustrates the actual rate at which follow-up questionnaires were received back at the NCTU. At the time of closure of the database for final analysis, 125 follow-up questionnaires had been received (exceeding the target of 120), although as per the CONSORT diagram, seven of these omitted primary outcome data – ICIQ-FLUTS total score.

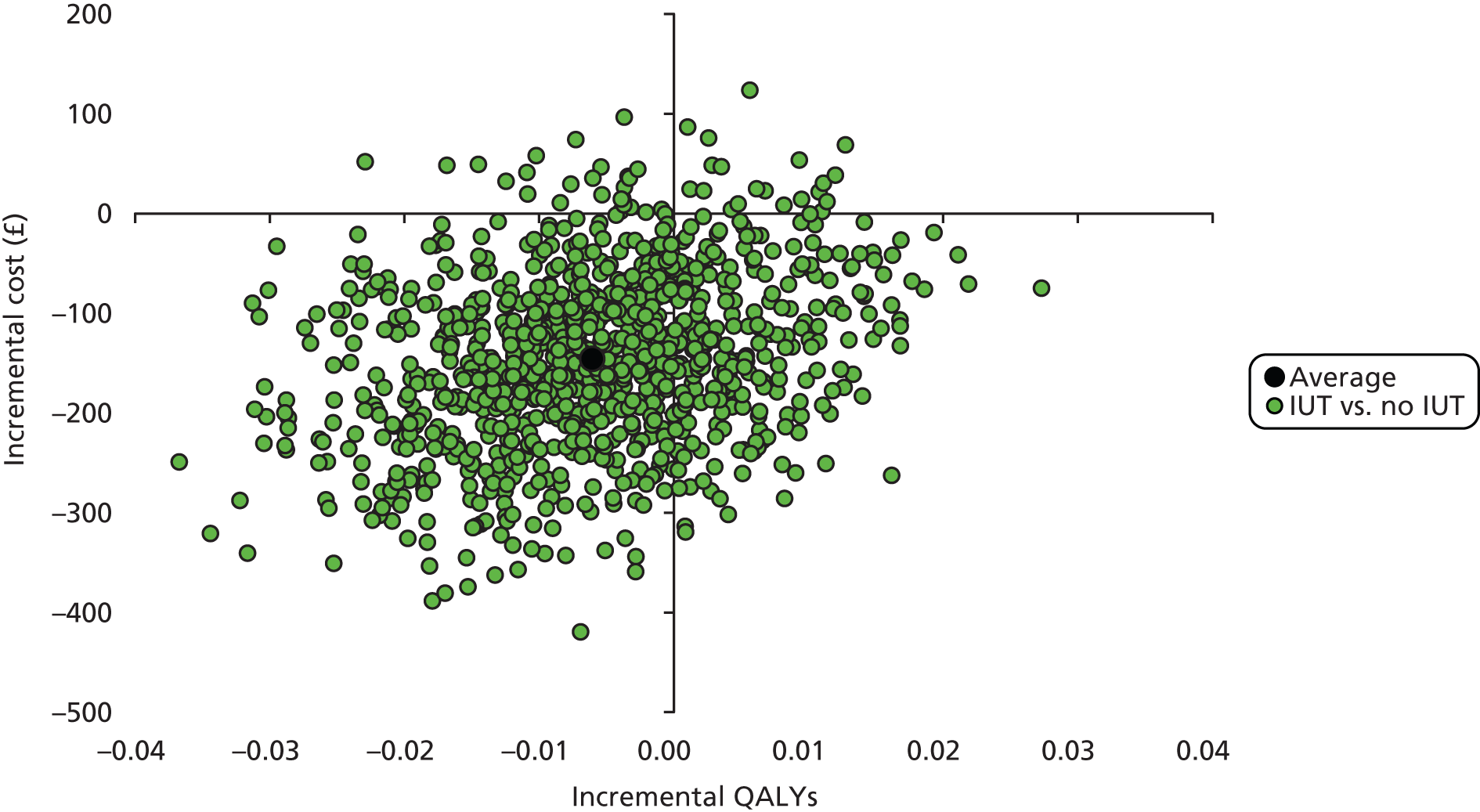

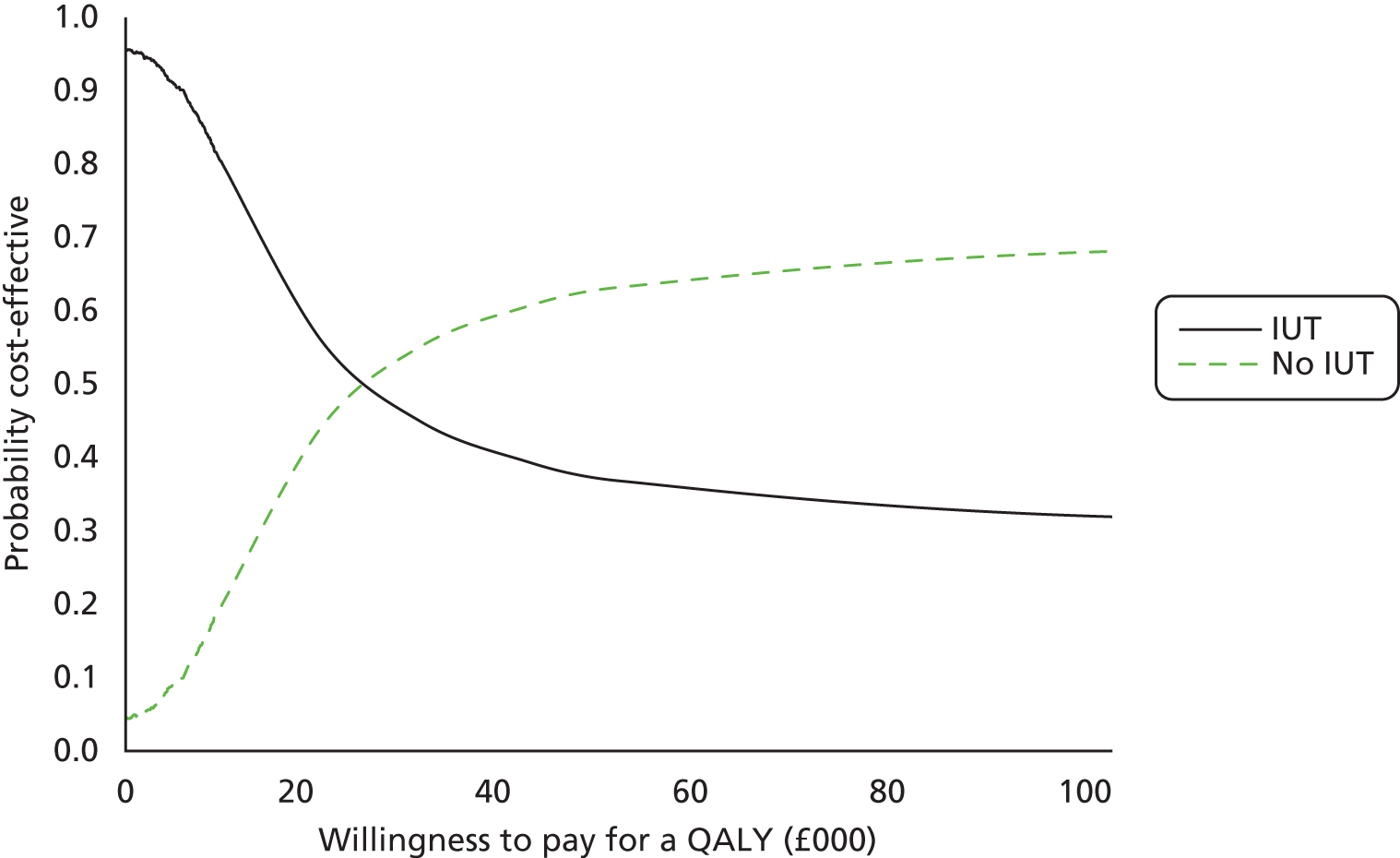

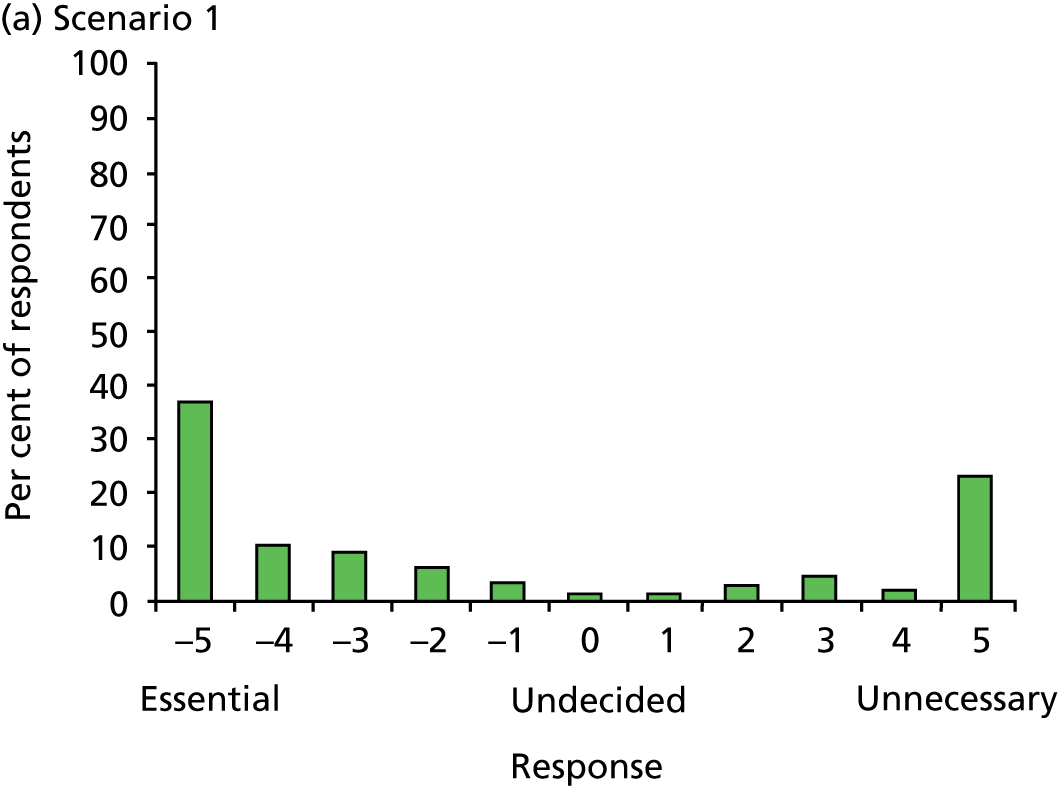

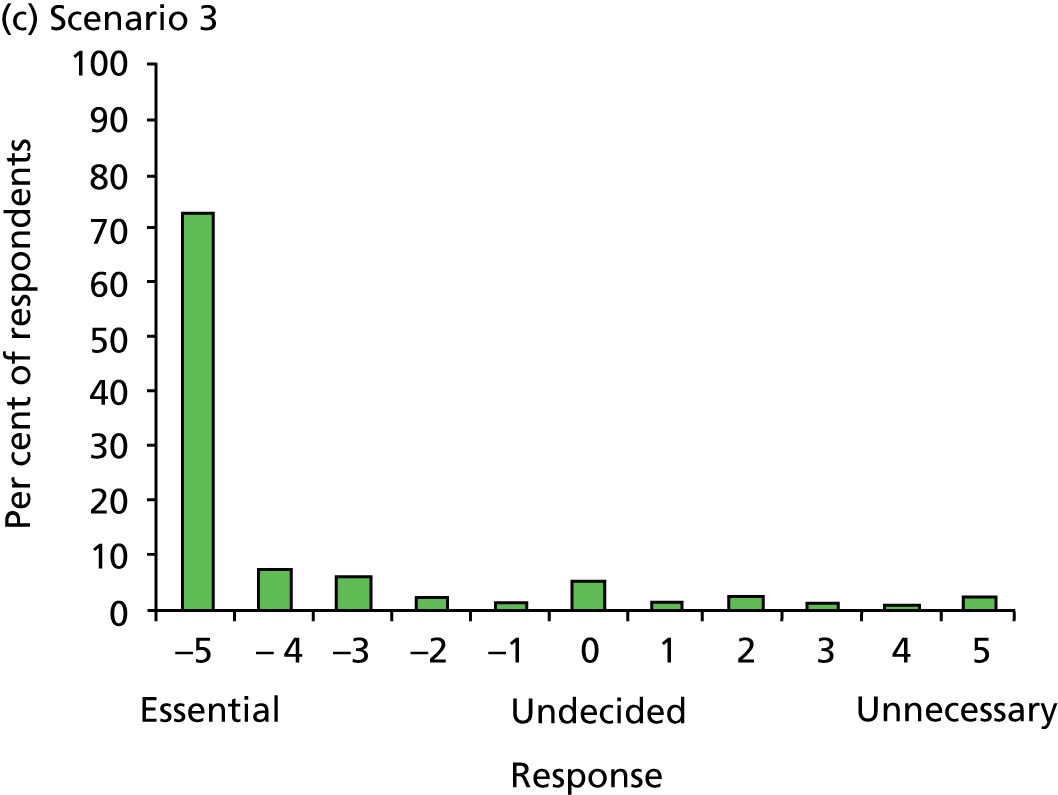

FIGURE 6.