Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/116/97. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The draft report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Amar Rangan reports grants and personal fees from DePuy Ltd and grants from JRI Ltd; both are outside the submitted work. In addition, Professor Rangan has UK and European patent applications pending. Sarah Lamb is chairperson of the Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials and Evaluation Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Costa et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Fractures of the distal radius are extremely common injuries. In the Western world, 6% of women will have sustained such a fracture by the age of 80 years and 9% by the age of 90 years. 1 As the population continues to age, these figures are likely to increase further. The optimal management of fractures of the distal radius in adults remains controversial. There is a bimodal distribution in terms of age. Younger patients frequently sustain complicated high-energy injuries involving the wrist joint. However, fractures of the distal radius are also common in older patients, who are more likely to sustain low-energy fractures, often related to osteoporosis. 2 This study is designed to address both groups of patients, as the key management issues pertain to all patients with a fracture of the distal radius.

In general, fractures of the distal radius are treated non-operatively if the bone fragments are not displaced or the fragments can be held in a good anatomical alignment (reduction) by a plaster cast or orthotic. However, if this is not possible then operative fixation is required. This carries inherent risks for the patient and considerable cost implications for the NHS; much of this cost is related to the choice of fixation. 3

There are several operative options but the two most common in the UK are percutaneous Kirschner-wire (K-wire) fixation and volar locking-plate fixation using fixed-angle screws (locking plates). Each surgical method has its own advantages and disadvantages.

Kirschner-wire fixation is a long-standing and widely practised technique. During this procedure, smooth metal wires with a sharp point are passed across the fracture site through the skin. This is a relatively simple, quick and minimally invasive technique, which is cheap and requires limited operative hardware. However, as the fixation is not ‘rigid’ (the wires are inherently flexible) the wrist has to be immobilised in plaster cast; normally for 6 weeks or until the wires are removed. There is a risk of infection where the wires enter the skin. There is also a risk that the fracture will ‘collapse’ when the wires are removed, leading to deformity and loss of function. 4

Locking-plate fixation, in the distal radius and for other fractures, has been facilitated by recent advances in implant technology, which allow the screws to be ‘locked’ into the plate. This produces a ‘fixed-angle’ bone–plate construct, (previously, plate-and-screw constructs relied on friction alone to maintain their position on the bone). Although originally designed for use in osteoporotic bone specifically, the theoretical advantages of the locking plates may equally be applied to high-energy (often multifragmentary) fractures in younger patients. The technique has become increasingly popular in the UK and across the developed world over the last 5 years. The procedure requires an incision over the volar (palm) side of the wrist. The plate and screws are then applied to the bone fragments under direct vision. This produces a rigid construct,5 and, therefore, the patients can be permitted to mobilise their wrist more quickly, potentially reducing future stiffness. As the plate and screws can remain inside the patient permanently, the risk of later collapse of the fracture is also smaller. However, this technique takes longer than a K-wire fixation and there is a greater risk of serious intraoperative complications such as injury to a nerve or blood vessel. 5 There is also a risk of flexor and/or extensor tendon irritation and rupture. 6 The locking-plate hardware itself is specialised and considerably more expensive; a cost-analysis of the total cost of each intervention (Plant et al., University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust, 2009, unpublished data) suggested that the use of a locking plate increased the cost of the operation itself (total operating department cost) threefold.

In 2003, Handoll and Madhok7 summarised the results of a series of Cochrane reviews of randomised controlled trials of the treatment of fractures of the distal radius and ‘exposed the serious deficiency in the available evidence’. However, they were able to identify key areas for future research, including the area of ‘when and what type of surgery is indicated’. An influential group of academic trauma surgeons (AO UK Research Committee chaired by Professor Keith Willett) recently identified our specific research question as a ‘top priority’ for urgent investigation. 8

Relevance of project

The clinical management of any fracture depends on several factors including the severity of the fracture and the personal circumstances and comorbidity of the patient. These variables are generally out of the control of the treating surgeon. However, the type of operative intervention can be determined after the event. Although there will always be some variability in clinical practice, patients with a fracture of the distal radius may expect a reasonably consistent approach to the operative treatment of such a common fracture. However, for this particular injury there seems to be no consensus. 2 For fractures of the distal radius, perhaps more than any other fracture, the operative intervention varies enormously depending on the preference, training and experience of the treating surgeon and the policy, inventory and budget of the treating institution.

We recently performed a pilot study where the clinical details and radiological images of five patients with a displaced fracture of the distal radius were presented independently to 33 experienced trauma surgeons in the UK. The cases included younger patients with high-energy injuries and fragility fractures in older patients. The surgeons were asked to provide a treatment plan for each patient. There was < 50% agreement in the treatment regime for any individual patient. Across all of the cases, 44% of surgeons would use volar locking plates, 28% would use K-wire fixation, 7% would use volar non-locking plates, 5% would use external fixators and 15% would treat the patient with manipulation and a plaster cast alone. 9

We intend to provide high-level evidence to inform the future management of adult patients with a displaced fracture of the distal radius by directly comparing the results of K-wire fixation and locking-plate fixation in a multicentre randomised controlled clinical trial.

Null hypothesis

There is no difference in the Patient-Rated Wrist Evaluation© (PRWE) questionnaire score 12 months post injury between adult patients with a dorsally displaced fracture of the distal radius treated with locking-plate fixation versus K-wire fixation.

Objectives

The primary objective is to quantify and draw inferences on observed differences in the PRWE questionnaire score (a validated assessment of wrist function) between the trial treatment groups at 12 months post injury.

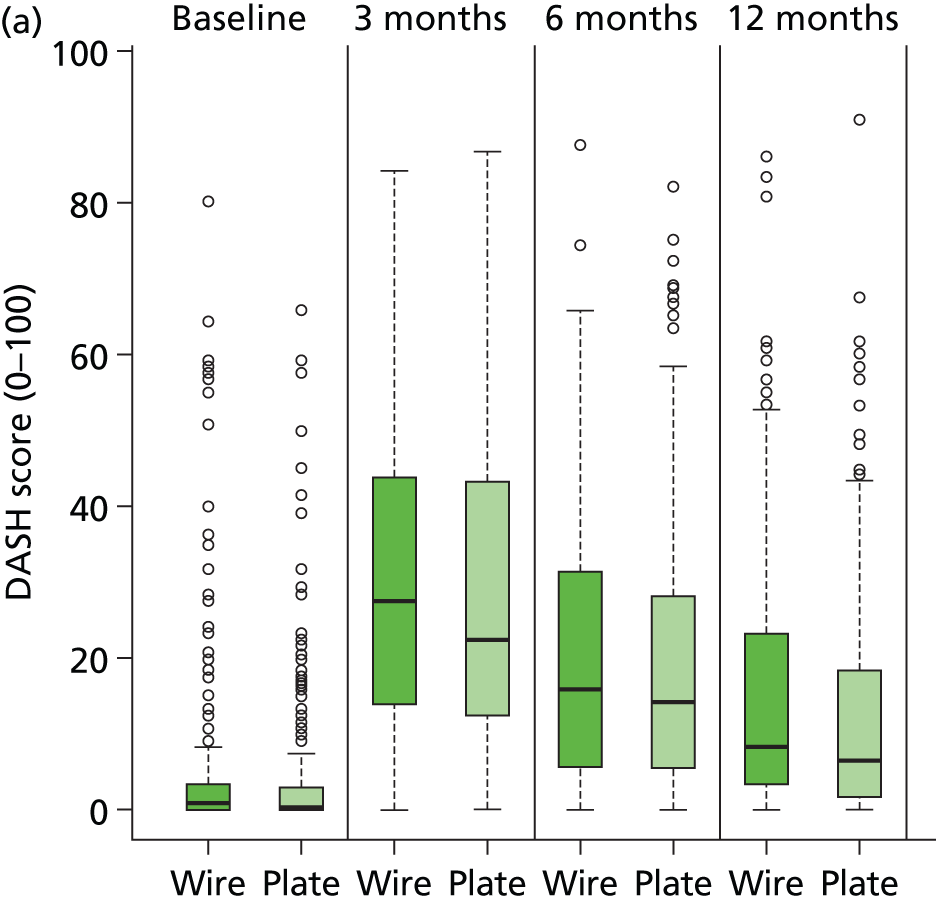

The secondary objectives are to quantify and draw inferences on observed differences in the Disabilities of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire score (a validated assessment of general upper-limb function) between the trial treatment groups at 12 months post injury; to determine the complication rate of K-wire fixation versus locking-plate fixation at 12 months post injury; and to investigate, using appropriate statistical and economic analysis methods, the resource use, and comparative cost-effectiveness, of K-wire fixation versus locking-plate fixation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

This was a multicentre, stratified (by centre, intra-articular extension of the fracture and age of the patient, with balanced randomisation 1 : 1) double-blind, controlled trial.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Patients were eligible for this study if:

-

They sustained a dorsally displaced fracture of the distal radius, which was defined as a fracture within 3 cm of the radiocarpal joint.

-

The treating consultant surgeon believed that they would benefit from operative fixation of the fracture.

-

They were over the age of 18 years and able to give informed consent.

-

The injury was < 2 weeks old.

Exclusion criteria

Patients were excluded from participation in this study if:

-

The fracture extended > 3 cm from radiocarpal joint.

-

The fracture was open with a Gustilo grading greater than 1. 10

-

The articular surface of the fracture could not be reduced by indirect techniques. (In a small number of fractures, the joint surface is so badly disrupted that the surgeon will have to open up the fracture in order to restore the anatomy under ‘direct’ vision.)

-

There were contraindications to anaesthetic.

-

There was evidence that the patient would be unable to adhere to trial procedures or complete questionnaires, such as cognitive impairment or intravenous drug abuse.

Patients who sustained other injuries, which could potentially affect the primary outcome measure at 1 year post injury, for example disruption of the carpal ligaments, were documented but included in the analysis.

Screening and recruitment

Patients were recruited from the emergency departments and fracture clinics at the trial centres. Any patient with a fracture of the distal radius who, in the opinion of the treating surgeon, required an operative intervention was referred to the local research associate for screening. The research associate then presented the eligible patient with the participant information sheet. Patients were given the opportunity to discuss any issues related to the trial with the research associate, as well as with members of their family and friends.

Consent

Informed consent was obtained by the local research associate. In general, patients who were admitted with a fracture of the distal radius had their surgery on the following day, so there was sufficient time for the patients to consider taking part in the trial. Any new information that arose during the trial that affected participants’ willingness to take part was reviewed by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC); if necessary this was communicated to all participants by the trial co-ordinator. A revised consent form was completed if necessary.

Settings and locations

The trial was run in 18 trauma centres across the UK (Box 1).

-

Addenbrooke’s Hospital.

-

Frenchay Hospital.

-

Ipswich Hospital.

-

James Cook University Hospital.

-

John Radcliffe Hospital.

-

Leicester General Hospital.

-

North Tyneside General Hospital.

-

Northampton General Hospital.

-

Peterborough City Hospital.

-

Poole Hospital.

-

Royal Blackburn Hospital.

-

Royal Victoria Infirmary.

-

St Thomas’ Hospital.

-

University Hospital Coventry & Warwickshire.

-

University Hospital North Staffordshire.

-

University Hospital of North Tees.

-

Wansbeck General Hospital.

-

Wexham Park Hospital.

Sample size

We performed an audit of the patients who had an operative fixation of their distal radius fracture at the University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire (UHCW) over a 4-month period in 2007. 11 This revealed that 32 patients had either a K-wire fixation or a locking-plate fixation at our hospital during this period. Therefore, we anticipated that there would be 90–100 eligible patients per year. As each of the recruiting centres served a similar catchment area (c. 500,000 patients) we expected that there would be approximately 900–1000 eligible patients within the trial centres each year. All of the centres chosen to take part in this study regularly performed both locking-plate fixation and K-wire fixation for patients with a fracture of the distal radius.

In previous trials performed at the lead centre, recruitment rates of between 70% and 90% were achieved for trials comparing different surgical treatments (both elective and trauma procedures). At a conservative estimate of 35–40% recruitment for a multicentre study, we were, therefore, confident of achieving the recruitment target of 390 patients in 12–18 months.

Randomisation

Those patients who consented to take part in the trial had their method of fixation allocated using a secure, centralised telephone randomisation service. The allocated treatment was then reported back to the research associate, who informed the patient and the treating surgeon. The surgeon then arranged the allocated surgery on the next available trauma operating list, as per standard practice at that institution. This ensured the integrity of the randomisation process.

Sequence generation

Randomisation was on a 1 : 1 basis, stratified by centre, intra-articular extension of the fracture and age of the patient (above or below 50 years).

Stratification by centre helped to ensure that any clustering effect related to the centre itself was equally distributed in the trial arms. The catchment area (the local population served by the hospital) was similar for all of the hospitals (c. 500,000), each hospital being a major orthopaedic unit dealing with these fractures on a daily basis. While it is possible that the surgeons at one centre may be more expert in one or other treatment than those at another centre, all of the recruiting hospitals were chosen on the basis that both techniques are currently routinely available at the centre, that is theatre staff and surgeons were already equally familiar with both forms of fixation. This could not eliminate the surgeon-specific effect of an individual at any one centre. 12 However, as the fixation of a fracture of the distal radius is a common procedure performed on routine trauma operating lists, many surgeons would be involved in the management of this group of patients: between 10 and 30 surgeons at each centre, including both consultants and trainees. Therefore, we expected that each individual surgeon would operate on only two or three patients enrolled in the trial, greatly reducing the risk of a surgeon-specific effect on the outcome in any one centre.

Stratification on the basis of intra-articular extension of the fracture (specifically involvement of the articular surface of the radiocarpal joint) eliminated a major potential confounder, since disruption of this articular surface may predispose to secondary osteoarthritis of the wrist. 13 Recent evidence14 suggests that other associated features of fractures of the distal radius which commonly appear in the classification systems, such as involvement of the ulna styloid process and distal radio-ulnar joint involvement, do not actually affect the functional outcome of the injury. Therefore, we did not include any other variables in the stratification of the randomisation sequence.

Stratification on the basis of age was used to discriminate between younger patients with normal bone quality sustaining high-energy fractures and older patients with low-energy (fragility) fractures related to osteoporosis. Empirically, both of these groups of patients could benefit from the fixed-angle stability provided by locking-plate fixation. However, the stratification would help to identify any effect related to the quality of the patient’s bone. The use of dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is widely regarded as the gold standard for the assessment of bone density. However, such an investigation may be expensive and not routinely available at all centres. Therefore, we used age as a surrogate for bone density. In a large study in Norway involving 7600 participants, it was demonstrated that forearm bone mineral density remains stable up until the age of 50 years. After the age of 50 years, bone mineral density in males decreased steadily, while in females there was an initial decline between the ages of 50 and 65, with a further decline in the age groups thereafter. 15 A recent study by Court-Brown and Caeser16 assessed over 1000 patients with a fracture of the distal radius. This study confirmed that there is a clear bimodal distribution for this type of fracture according to the age of the patient. The crossover of the two peaks of incidence was around 50 years of age. These studies provide strong evidence that patients over the age of 50 years become increasingly vulnerable to fragility fractures of the distal radius. Therefore, we chose the age of 50 years as the cut-off for this trial. Furthermore, the study by Court-Brown and Caeser16 demonstrated that in the UK approximately 60% of patients sustaining a fracture of the distal radius are over 50 years, while 40% are younger than 50 years. The number of patients above and below this stratification age would, therefore, be similar (see Statistical analysis).

Blinding

In this surgical trial, the patients could not be blinded to their treatment. The treating surgeons were, of course, not blind to the treatment, but took no part in the postoperative assessment of the patients. The statistical analyses were not performed blind.

Postrandomisation withdrawals

Participants could withdraw from the trial at any time without prejudice. If patients decided to have the treatment to which they were not randomised, they were followed up wherever possible and data collected as per the protocol until the end of the trial. The primary analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis with a secondary per-protocol analysis.

Interventions

All of the hospitals involved in this trial used both of the methods of fixation at the time of the trial and all of the surgeons involved were familiar with both techniques. Operative fixation of fractures of the distal radius usually took place under a general anaesthetic, but this decision was made by the attending anaesthetist. Patients undergoing surgical fixation for a fracture of the distal radius are placed in a supine (lying on their back) position with the affected arm on an ‘arm-board’ extension to the operating table, but the exact details of the positioning of the patient were left to the discretion of the treating surgeon. A copy of the ‘operating record’ formed part of the trial data set.

Each patient underwent the allocated surgery according to the preferred technique of the operating surgeon. Although the basic principles of percutaneous K-wire fixation and locking-plate fixation are inherent in the technique (see Kirschner-wire fixation and Volar locking plate), there are several different implant systems and several different options for the positioning of wires and screws. Similarly, each surgeon made minor modifications to their surgical technique according to preference and the specific pattern of each fracture. In this trial, the details of the surgery were left entirely to the discretion of the surgeon to ensure that the results of the trial could be generalised to as wide a group of patients as possible.

Although all of the surgeons in the trial were familiar with both techniques, it is possible that an individual surgeon may have had more experience with one technique than the other. We expect that the proficiency of an individual surgeon to perform the procedure may change over time, as the surgeon gains experience and expertise. The term ‘learning curve’ is often used to describe this process. It was important to monitor the learning curve for all surgeons throughout the trial. The operating time recorded on the operative record for each surgery was used as a proxy to measure the task efficiency of the surgeons (quality assurance of the clinical process), and the number of complications (e.g. infections) at 6 weeks after surgery was also recorded as a patient-based outcome. Given the number of centres and surgeons taking part in this trial, no individual surgeon was likely to perform more than a small number of the procedures. However, where data were available for individual surgeons, temporal variations in operation times and complications at 1 week were modelled for each surgeon using a power curve,12 for the trend with appropriate adjustment for confounding factors such as the age of the patients. In addition, as this study involved multiple surgeons, we expected that a more complex hierarchical model12 that fully accounted for the structure of the data might prove to be useful; therefore, we expected fitting models of this class in addition to the simpler models. Results from the learning curve analysis for each surgeon would inform inferences regarding overall treatment differences and if necessary guide recommendations for implementation and training.

Kirschner-wire fixation

The wires are passed through the skin over the dorsal aspect of the distal radius and into the bone in order to hold the fracture in the correct (anatomical) position. The size and number of wires, the insertion technique and the configuration of wires were left entirely to the discretion of the surgeon. A plaster cast was applied at the end of the procedure to supplement the wire fixation as per standard surgical practice. This cast holds the wrist still and is left on until the wires are removed at the 6-week follow-up appointment.

Volar locking plate

The locking plate is applied through an incision over the volar (palm) aspect of the wrist. Again, the details of the surgical approach, the type of plate, and the number and configuration of screws were left to the discretion of the surgeon. The screws in the distal portion of the bone were ‘fixed-angle’, that is screwed into the plate, but this is standard technique for the use of these plates. The type of proximal screw was left to the discretion of the surgeon; these may be locking or non-locking screws, as the bone in this area provides a much better purchase for the screws. Some surgeons used a temporary plaster cast to hold the patients’ wrist still but the fixed-angle stability provided by the locking plate was generally sufficient to allow early controlled range-of-movement exercises. The use of a cast or otherwise was again left to the discretion of the surgeon as per usual practice.

Radiographic evaluation

Patients were evaluated radiographically at presentation, and then at 6 weeks and 12 months post injury. The degree of palmar tilt, the ulnar variance and the presence of metaphyseal comminution were determined from the calibrated digital images of the posteroanterior and lateral radiographs using the OsiriX DICOM (Digital Imaging and Communications in Medicine) viewer (www.osirix-viewer.com).

The palmar tilt was measured as the angle between lines drawn perpendicular to the long axis and along the distal joint surface of the radius as described by Goldfarb et al. 17 and Mann et al. 18 (Figure 1). Dorsal angulation was denoted by a positive value and volar angulation by a negative value. 19

FIGURE 1.

Ulnar variance (the distance between the radial and ulnar articular surfaces).

The ulnar variance was determined using the method of perpendiculars described by Steyers and Blair20 Lines were drawn along the distal ulnar aspect of the radius and the distal cortical rim of the ulnar parallel to the perpendicular of the long axis of the radius20–22 (Figure 2). The distance between these lines measures the ulnar variance. 20

FIGURE 2.

Palmar tilt (the angle between the articular surface of the radius and the perpendicular of the long axis of the radius).

Rehabilitation

We ensured that all patients randomised into the two groups received standardised written physiotherapy advice detailing the exercises they needed to perform for rehabilitation following their injury. All of the patients in both groups were advised to move their shoulder, elbow and finger joints fully within the limits of their comfort. Those patients in the K-wire group were encouraged to perform range-of-movement exercises at the wrist as soon as their plaster cast was removed at the 6-week follow-up appointment. Those patients in the locking-plate group could begin the exercises immediately if they did not have a plaster cast or as soon as the cast was removed. In this pragmatic trial, any other rehabilitation input beyond the written information sheet (including a formal referral to physiotherapy) was left to the discretion of the treating surgeon. However, a record of any additional rehabilitation input (type of input and number of additional appointments) together with a record of any other investigations/interventions was requested as part of the 3-month, 6-month and 12-month postal follow-ups and this formed part of the trial data set.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure for this study was the PRWE questionnaire score. 23 The PRWE is a validated questionnaire which is self-reported (filled out by the patient). It consists of 15 items specifically related to the function of the wrist. These data were collected at baseline and 3, 6 and 12 months postoperatively. The PRWE questionnaire score is the most sensitive outcome measure for patients sustaining this specific injury. 24

The secondary outcome measures in this trial were:

-

DASH questionnaire score: the DASH outcome measure is a 30-item self-report questionnaire designed to provide a more general measure of physical function and symptoms in people with musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. 25

-

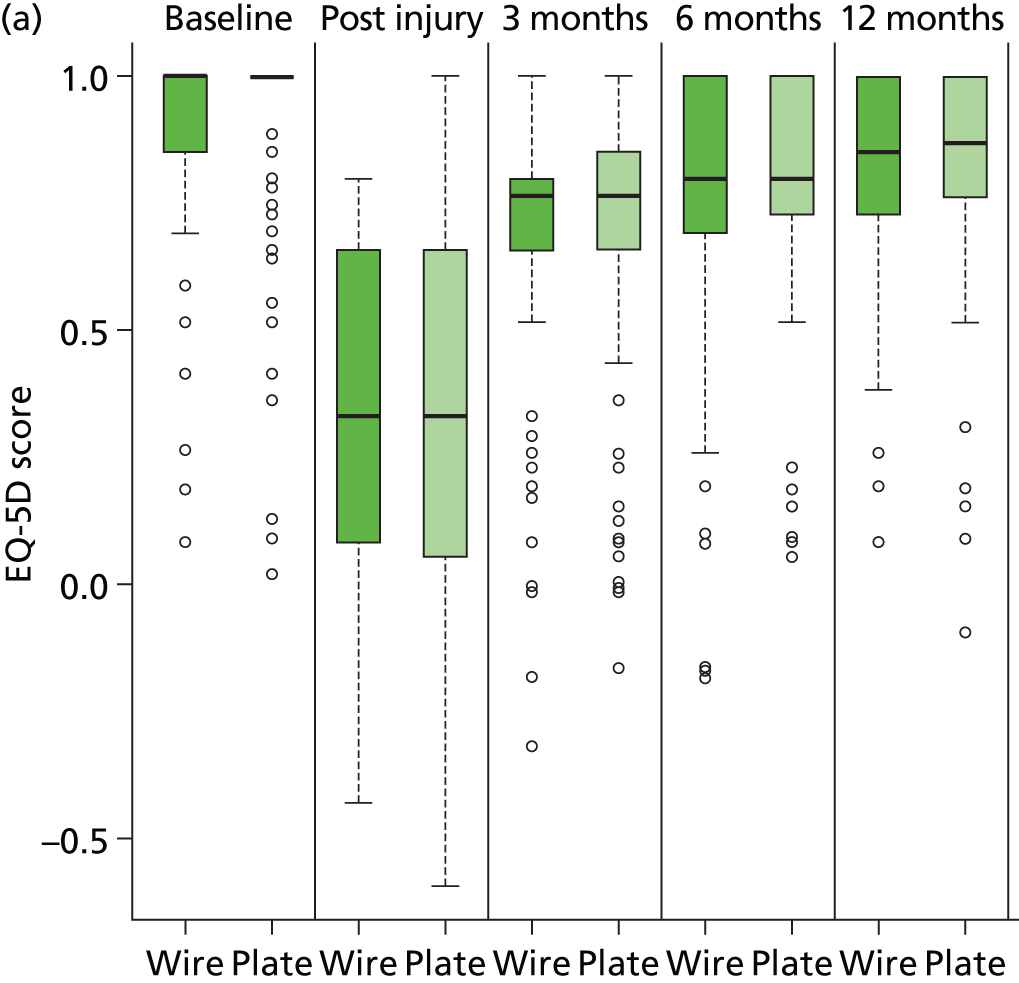

EuroQol – Five Dimensions (EQ-5D): the EQ-5D is a validated, generic, quality of life questionnaire consisting of five domains related to daily activities with a three-level answer possibility. The combination of answers leads to a health profile of five digits that can then be converted into a utility that represents the overall quality of life of the patient. 26

Complications: all complications were recorded.

Resource use was monitored for the economic analysis. Patients retrospectively reported use of primary, secondary and community health-care use, medications and aids/instruments as well as social care, informal care, out-of-pocket expenses and lost productivity via a short questionnaire which was administered at 3, 6 and 12 months post surgery. Patient self-reported information on service use has been shown to be accurate in terms of the intensity of use of different services. 27,28

Follow-up measures

We used techniques common in long-term cohort studies to ensure minimum loss to follow-up, such as collection of multiple contact addresses and telephone numbers, mobile telephone numbers and e-mail addresses. Considerable efforts were made by the trial team to keep in touch with patients throughout the trial by means of newsletters, etc. Data were collected at baseline and at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months post surgery (Table 1).

| Time point | Data collection |

|---|---|

| Baseline | PRWE and DASH pre injury, EQ-5D pre injury and contemporary, radiographs |

| 6 weeks | Complication records, radiographs and operative record |

| 3 months | PRWE, DASH, EQ-5D, record of complications/rehabilitation or other interventions and economics questionnaire |

| 6 months | PRWE, DASH, EQ-5D, record of complications/rehabilitation or other interventions and economics questionnaire |

| 12 months | PRWE, DASH, EQ-5D, radiographs, record of complications/rehabilitation or other interventions and economics questionnaire |

The PRWE23 is a 15-item questionnaire, designed specifically for assessment of distal radial fractures and wrist injuries, that rates wrist function using a range of questions in two (equally weighted) sections concerning the patient’s experience of pain and disability. Scoring for all the questions is via a 10-point ordered categorical scale ranging from ‘no pain’ or ‘no difficulty’ (0) to ‘worst possible pain’ or ‘unable to do’ (10). Five questions relate to a patient’s experience of pain and 10 relate to function and disability; the scores for the 10 function items are summed and divided by 2 and added to the scores of the five pain items to give a total score out of 100 (best score = 0 and worst score = 100).

We performed a retrospective pilot study29 that obtained PRWE questionnaire scores for 84 patients (42 each receiving either a volar locking-plate fixation or a manipulation under anaesthetic and K-wire fixation) at 12 months after surgery. The mean PRWE questionnaire scores for the K-wire and locking-plate groups at 12 months were 33.2 and 27.5, respectively, with a pooled standard deviation (SD) of 19. The SD for the PRWE questionnaire score is similar to that reported for other studies of pain and disability after fracture of the distal radius,30 which was in the range of 17–23 points.

We assumed a normal distribution for the PRWE questionnaire scores, which seemed appropriate given that our pilot study indicated that the 12-month group mean PRWE questionnaire score would be expected to be approximately 30 with a SD of 20. An appropriate sample size for detecting a six-point difference between groups at the 5% level with 80% power was, therefore, 175 patients in each group (power and sample size software, available at http://medipe.psu.ac.th/episoft/pssamplesize/). A six-point difference between groups equates to a standardised effect size of 0.3, for an assumed SD of 20 points. MacDermid et al. 24 found that the PRWE questionnaire is sensitive enough to detect subtle but clinically relevant changes in wrist function of this order of magnitude in patients sustaining a fracture of the distal radius, for example changes between 3 and 6 months (effect size 0.5). At the individual level, a change in the PRWE questionnaire score of 6 points reflects the difference between turning a doorknob or cutting a loaf of bread with mild pain versus no pain. We believed that such an improvement would be important to patients on an individual level and at population level and could lead to a change in clinical practice in the UK.

However, it is also helpful to consider the effect of choosing two alternative minimal clinically important difference (MCID) values of 5 and 7 points on the PRWE questionnaire score scale on the required sample size for 80% power at the 5% level (Table 2).

| MCID | Standardised effect size | Sample size per group |

|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0.25 | 252 |

| 6 | 0.30 | 175 |

| 7 | 0.35 | 129 |

In summary, this study used the PRWE questionnaire score at 12 months after surgery as the primary outcome measure. The total number of patients required to obtain a power of 80% to detect a six-point difference between groups for the primary outcome measure was 350, that is 175 patients were required in each treatment group. In trials run previously at our institution comparing two different surgical techniques, we experienced a ≈5% loss to follow-up. With an allowance for a conservative 10% loss to follow-up, we planned to recruit a minimum of 390 patients.

If recruitment proceeded at a faster rate than expected, for example if there were particularly adverse winter weather, which is known to be a primary causative factor for distal radius fractures, then there was the possibility of increasing the overall trial sample size within the defined recruitment period. Increasing the sample size would provide an increase in the power to detect a six-point difference between groups for the primary outcome measure above the set level of 80%. Recruitment was monitored and discussed at monthly Trial Management Group (TMG) meetings and, where appropriate, recruitment projections were undertaken to assess this possibility. See Appendix 1 for details of recruitment projections and new sample sizes for increasing power.

Adverse event management

Adverse events are defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a clinical trial subject and which do not necessarily have a causal relationship with the treatment. All adverse events were listed on the appropriate case report form for routine return to the Distal Radius Acute Fracture Fixation Trial (DRAFFT) central office.

Serious adverse events (SAEs) were defined as any untoward and unexpected medical occurrence that:

-

results in death

-

is life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatients’ hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity

-

is a congenital anomaly or birth defect

or any other important medical condition which, although not included in the above, may require medical or surgical intervention to prevent one of the outcomes listed.

All SAEs were entered onto the serious adverse event reporting form and given to the DRAFFT central office within 24 hours of the investigator becoming aware of them. Once this was received, causality and expectedness were determined by the chief investigator. SAEs that were deemed to be unexpected and related to the trial were notified to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) within 15 days for a non-life-threatening event and within 7 days for a life-threatening event. All such events were reported to the TSC and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) at their next meetings. SAEs that were expected as part of the surgical interventions, and that did not need to be reported to the main REC, were complications of anaesthesia or surgery (e.g. wound infection, delayed wound healing and thromboembolic events). All participants experiencing SAEs were followed up as per protocol until the end of the trial.

Risks and benefits

The risks associated with this study were predominantly the risks associated with the surgery: infection, bleeding and damage to the adjacent structures such as nerves, blood vessels and tendons. Participants in both groups underwent surgery and were potentially at risk from any/all of these complications. The application of the locking plates requires a surgical incision over the volar aspect of the wrist, which, empirically, may lead to a higher risk of injury to the adjacent structures. However, the evidence available to quantify this risk was limited. 13 Late attrition and rupture of the extensor tendons have been associated with volar locking plates,31 but, equally, late collapse and secondary deformity have been associated with K-wire fixation. 19 The risk of secondary (as a result of the injury) osteoarthritis of the wrist joint, particularly in those patients with intra-articular extensions of the fracture, is well recognised,13 but there were no data to suggest what that risk is or that the risk is greater in one group or another. We believed that the overall risk profile was similar for the two interventions but an assessment of the number of complications in each group was a secondary objective of this trial.

Statistical analysis

Analysis plan

The statistical analysis plan was agreed with the DMC at the start of the study. Any subsequent amendments to this initial plan are clearly stated and justified. Interim analyses were performed only where directed by the DMC. The trial registration details were updated soon after the start of the trial; this was not a change to the statistical analysis plan, but merely the inclusion of extra detail in the registration document, which was added at the suggestion of the DMC.

Software

The routine statistical analysis was carried out using R version 3.0.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, www.r-project.org/). When any analyses were required, data were retrieved from the trial database by the trial statistician. The statistician imported data directly into the statistical package R for analysis and reporting. The version numbers of all software used, data files and all R scripts were made available to the DMC on request at any stage of the trial. Statistical results were reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) guidelines (www.consort-statement.org/).

Data validation

Prior to formal analysis, data were checked for outliers and missing values and validated using the defined score ranges for all outcome measures. Queries were reported to the trial co-ordinator and investigated. Standard statistical summaries (e.g. medians and ranges or means and variances, dependent on the distribution of the outcome) and graphical plots showing correlations were presented for the primary outcome measure and all secondary outcome measures. Baseline data were summarised to check comparability between treatment arms, and to highlight any characteristic differences between those individuals in the study, those ineligible for the study, and those eligible but withholding consent.

Missing data

As seemed likely at the outset, some data were not available because of the voluntary withdrawal of patients, lack of completion of individual data items or general loss to follow-up. Where possible, the reasons for data ‘missingness’ were ascertained and reported. Although missing data were not expected to be a problem for this study, the nature and pattern of the missingness were carefully considered – including, in particular, if data could be treated as missing completely at random (MCAR). If judged appropriate, we planned to impute missing data using the multiple imputation facilities (mice package) available in R. Any imputation methods used for scores and other derived variables were carefully considered and justified. We planned that if the degree of missingness was relatively low, as expected, the primary analysis would be based on complete cases only (complete case analysis), with analysis of imputed data sets used to assess the sensitivity of the analysis to the missing data. Reasons for ineligibility, non-compliance, withdrawal or other protocol violations would be stated and any patterns summarised. More formal analysis, for example using logistic regression with ‘protocol violation’ as a response, was also considered if appropriate and if it aided interpretation.

Interim analyses

Interim analyses were performed only where directed by the DMC. Any interim analyses would follow the same procedure as the final analyses.

Final statistical analyses

Null hypothesis

We considered that, while it may be of interest to the patient to know the time from surgery to returning to ‘normal’ function, our previous experience of collecting data related to this outcome has been very difficult. In addition, there is no clear formal definition of when a fracture can be considered to have fully healed and the patient is able to return to normal activity. This would be necessary if the time to this event were potentially to be used as the primary outcome measure in this trial. Therefore, for these reasons and as the practical difficulties and cost implications for a time-to-event analysis would be considerable, the main analysis investigated differences in the primary outcome measure, the PRWE questionnaire score at 12 months after surgery, between the two treatment groups (K-wire fixation and locking-plate fixation) on an intention-to-treat basis.

Null hypothesis: there is no difference in the PRWE questionnaire score 12 months post injury between adult patients with a dorsally displaced fracture of the distal radius treated with locking-plate fixation and those treated with K-wire fixation.

In addition to the analysis at 12 months post injury, early functional status was also assessed and reported at 3 months and 6 months.

Multilevel model

Differences between treatment groups were assessed, based on a normal approximation for the PRWE questionnaire score, at 12 months postoperatively, and at interim occasions. Tests were two-sided and considered to provide evidence for a significant difference if p-values are < 0.05 (5% significance level). Estimates of treatment effects were presented with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The stratified randomisation procedure should have ensured a balance in age, intra-articular extension and the recruiting centre between test treatments. Although generally we had no reason to expect that the clustering effects would be important for this study, in reality the data were likely to be hierarchical in nature, with patients naturally clustered into groups by recruiting centre and surgeon. Therefore, we proposed to account for this by generalising the conventional linear (fixed-effects) regression approach to a more general multilevel modelling approach; where patients are naturally grouped by surgeons and, likewise, surgeons are grouped by recruiting centres. This model would formally incorporate terms that allowed for possible heterogeneity in responses for patients owing to the recruiting centre and the surgeon, in addition to the fixed effects of the treatment groups, patient age and intra-articular extension. As discussed earlier, we expected that each individual surgeon would operate on only a small number (two or three) of the patients enrolled in the trial, which would greatly reduce the likelihood of a surgeon-specific effect on the outcome. Therefore, although we considered formally constructing a model with two levels of clustering (recruiting centre and surgeon), we expected that, if there were sparse data on individual surgeon effects, the final model would be simplified and consist of single random effect accounting for the recruiting centre only.

The main analyses were conducted using specialist multilevel modelling functions available in the software package R. PRWE questionnaire data were assumed to be normally distributed, although we considered the possibility of appropriate variance-stabilising transformation. The primary focus was the comparison of the two treatment groups of patients, and this was reflected in the analysis, which was reported together with appropriate diagnostic plots that check the underlying model assumptions. Although baseline PRWE questionnaire scores were recorded using a retrospective assessment by each patient post injury, these were not considered to be sufficiently reliable for formal baseline adjustment in the multilevel model. Mean baseline PRWE questionnaire scores together with other patient demographic data (e.g. age and gender) were reported for each treatment group to assess population comparability post randomisation.

The interactions between the stratifying variables (age and intra-articular extension) and the main treatment effect were not expected to be large; therefore, for practical reasons, the study was not powered with subgroup analysis in mind, as this would require a substantial and unrealistic increase in overall sample size. However, analyses were planned for each of the stratifying variables, particularly for participants aged over 50 years, who constitute a sizeable and important subgroup within the full study population. Formal tests of interaction between each stratifying variable and the treatment factor were reported together with appropriate 95% CIs and p-values. Significant results from this analysis were interpreted with due caution and reported as such, in line with recommendations for subgroup analysis made elsewhere. 32

Complications

The temporal patterns of any complications were presented graphically and if appropriate a time-to-event analysis (Kaplan–Meier survival analysis) was considered to assess the overall risk and risk within individual classes of complications (e.g. infection). This was to be the primary analysis for complications. However, if multiple complications proved to be widely reported then a Poisson regression model (or zero-inflated Poisson regression model) was planned to assess overall differences in counts of events between groups, adjusting for potential confounding factors such as age and gender. Multiple complications were defined as two or more independent events, that is, not continuations of a previous complication, in the same patient and were identified only after discussion with the clinical team.

Reporting

Wherever possible, the results of all analyses were presented in a simple and easy-to-follow manner and related any observed differences to their clinical importance, so that they could be clearly understood by those with only rudimentary statistical knowledge. Open and confidential reports of the statistical analyses were planned, as required, by the trial statistician and, where appropriate, results were to be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and local mechanisms.

Health economic analysis plan

Objectives

The economic evaluation was designed to estimate costs of distal radial fractures treated by locking-plate fixation and by K-wire fixation. If appropriate, the primary objective was to evaluate the incremental cost-effectiveness of distal radial fractures treated by locking-plate fixation versus K-wire fixation.

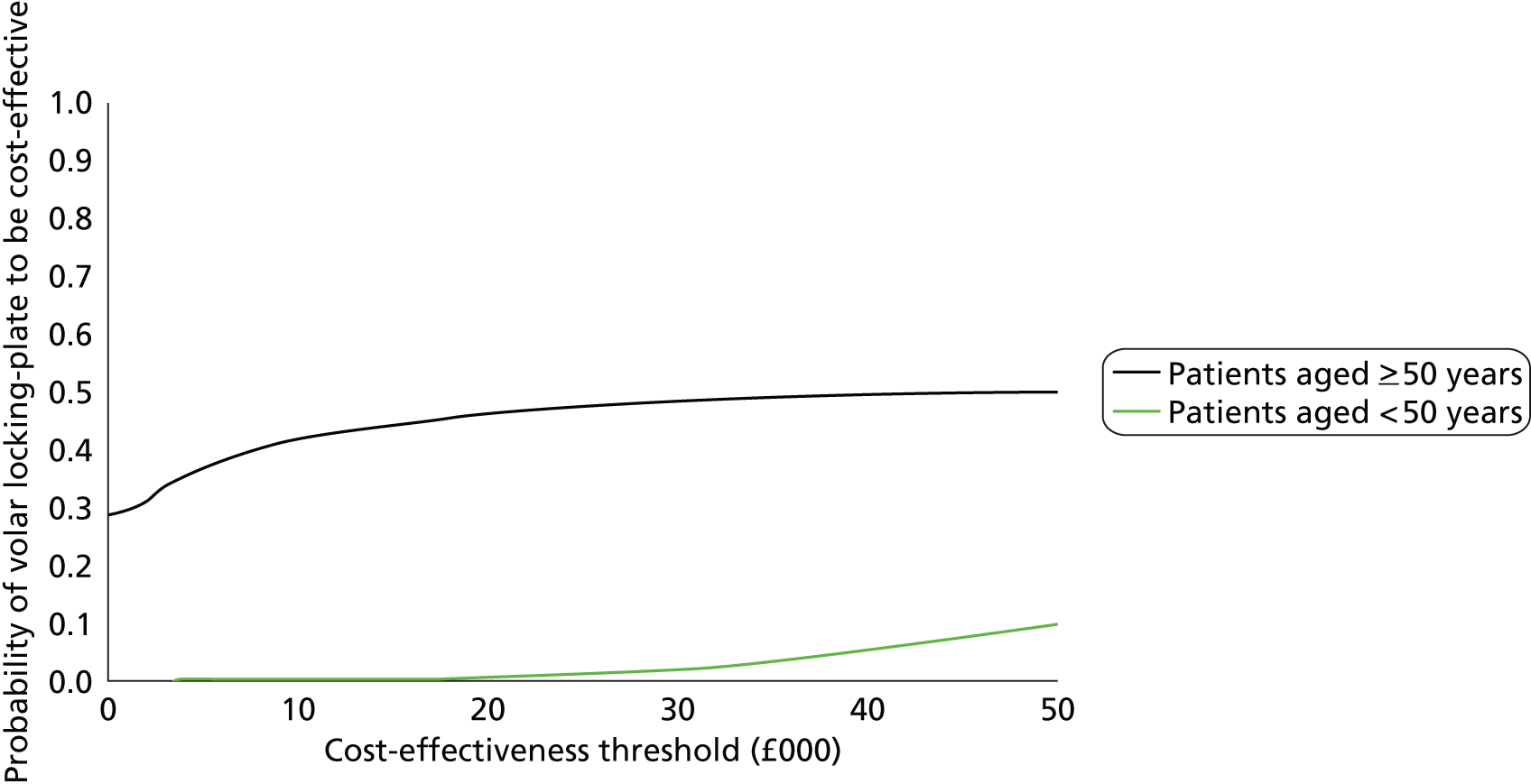

A within-trial analysis comparing the outcomes and costs up to 12 months’ follow-up using trial data was undertaken for two age groups: (1) patients < 50 years of age and (2) patients ≥ 50 years of age.

The evaluation followed the reference case guidance for technology appraisals set out by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 33

In the longer term, we will develop a cost-effectiveness analysis modelling outcomes and costs up to 10 years post surgery. The methods for this second analysis will be presented in due course. However, the results for this analysis are not presented in the present report; this will require longer follow-up data, which are not currently available.

Measurement of outcomes

The economic analysis used quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) to measure health outcomes. Health-related quality of life was estimated using responses from the EuroQol – Five Dimensions 3 Level. 26 Patients completed the EQ-5D questionnaire at baseline, 3 months, 6 months and 12 months after randomisation as secondary outcomes of the trial. Standard UK tariff values were applied to these responses at each time point to obtain utility. QALYs were calculated as an ‘area under the curve’ and formed the main outcome measure of the study. In addition, patients self-completed EQ-5D assessing their pre-injury quality of life retrospectively.

Measurement of costs

Patient-reported data on resource usage were collected within the trial at 3 months, 6 months and 12 months. For the 3-month data, the recall period was since discharge from hospital. For the other cases, it was since the last questionnaire was due to be completed. The questionnaires included number of further inpatient stays following the initial operation (including specialty and length of stay), number of outpatient, primary and community care visits, use of aids and adaptations, and medication use. Patients also reported the use of personal social services related to their treatment, as well as private costs such as treatments within private settings and time off work. Personal social services included number of weeks of frozen/hot meals on wheels, laundry services and number of visits of carers and social workers.

Costs were estimated combining patient-reported resource usage with unit cost data obtained from national databases such as the British National Formulary (BNF) and Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU) Costs of Health and Social Care. 34 Any unit cost that was not available was estimated in consultation with the UHCW finance department.

The analyses initially took the perspective of the NHS including the costs of health and social care. Subsequent analyses adopted a societal perspective taking into account productivity costs (time away from work) and out-of-pocket expenditures incurred by patients in relation with their treatment. The currency used is pounds sterling (£).

Missing data

Although missing data were not expected to be a problem in this study, the economic analyses followed the nature and pattern of the missingness reported by the statisticians. This was illustrated as MCAR, missing at random or not missing at random.

A base-case analysis of the complete data set was conducted including only patients with complete cost and QALY data.

We then explored the use of the last observation carried forward (LOCF) approach to deal with missing values. Costs and EQ-5D values were carried forward for only one successive missing observation.

Finally, we imputed missing data through multiple imputations. 35,36 This method, assuming that data are missing at random, replaces the missing values with plausible substitutes based on the distribution of observed data and, by using iterative multivariable regression techniques, includes randomness to reflect uncertainty. All baseline variables were used to impute missing data. This approach is recommended for economic analyses alongside clinical trials, as it reflects the uncertainty inherent in replacing missing data. 12 We considered the impact on the cost-effectiveness results using both imputation methods in the sensitivity analyses.

Within-trial analysis

Main characteristics of the analysis

The within-trial analysis aimed to determine the intervention that would maximise health outcomes (1) within the limited NHS budget and (2) within a societal perspective over the 12-month trial follow-up.

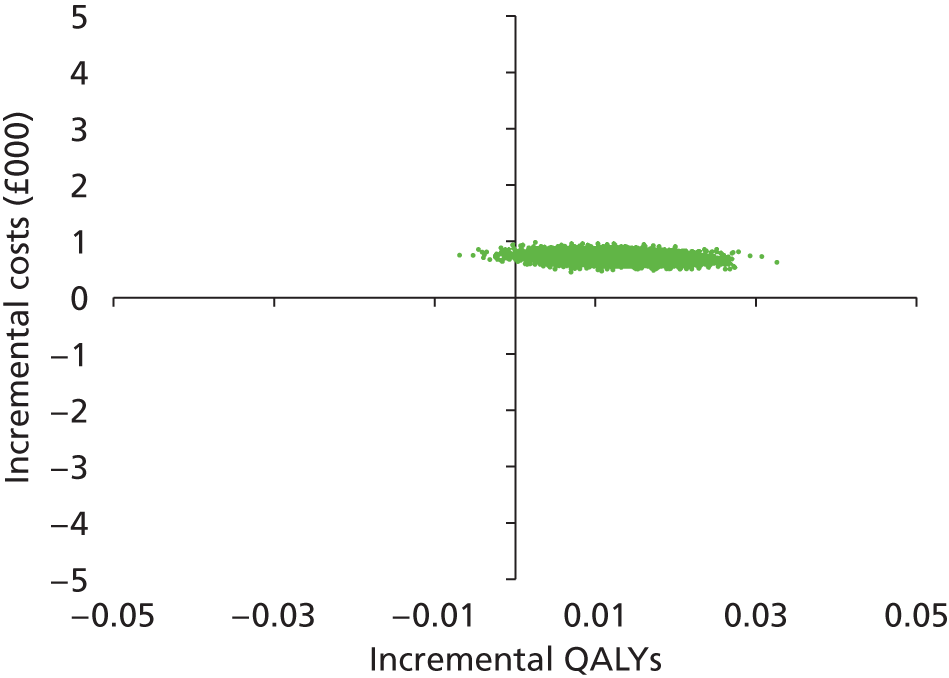

It adopted an intention-to-treat perspective and consisted of a cost–utility analysis over 12 months examining the cost per QALY gained for all patients. As the analysis uses a 1-year time horizon, discounting for the future cost and health outcome is not necessary in this analysis. We calculated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratios by dividing the average difference in cost between the two arms by the average difference in QALYs between the two arms as follows:

The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) represents the additional cost per unit of outcome gained. This indicates the trade-off between total cost and effectiveness when choosing between volar locking-plate fixation and K-wire fixation. When compared against the marginal trade-off for the NHS as a whole – the cost-effectiveness threshold – this gives an indication of whether or not spending additional money on volar locking-plate fixation appears efficient. As a guideline rule, we used the NICE implicit cost per QALY threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY to determine cost-effectiveness. NICE accepts an intervention with an ICER of less than £20,000 per QALY as cost-effective and generally states that an intervention costing more than £30,000 per QALY is not considered cost-effective. The more expensive intervention was considered cost-effective as long as its ICER is within or below the £20,000–30,000 per QALY range.

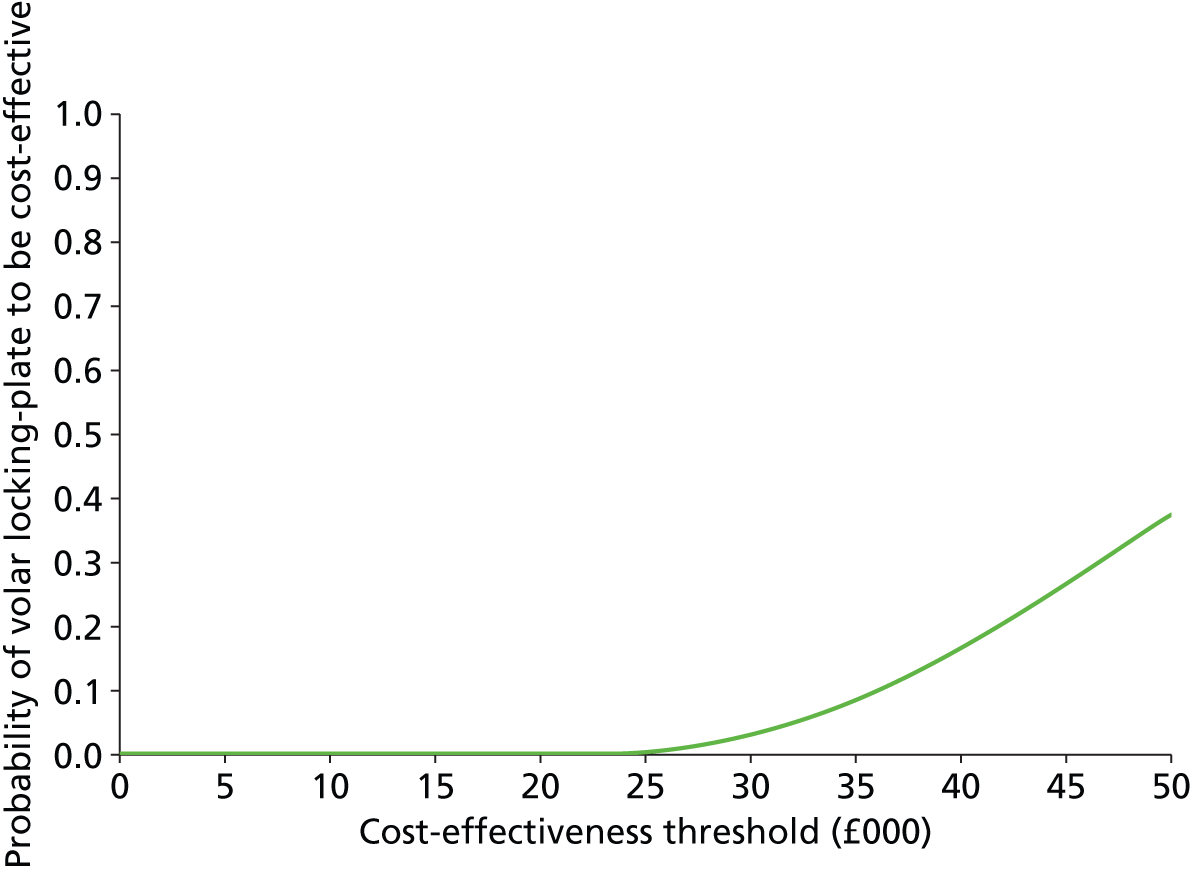

Uncertainty

The non-parametric bootstrapping approach was used to determine the level of sampling uncertainty around the ICER by generating 10,000 estimates of incremental costs and benefits. We planned to present cost-effectiveness scatter plots illustrating the uncertainty surrounding the cost-effectiveness estimates. The cost-effectiveness acceptability curves (CEACs) were derived by plotting the bootstrapped estimates. The bootstrap approach is a non-parametric method that considers the original sample as though it were the population and draws multiple random samples from the original sample. The CEACs illustrated the probability that a treatment is cost-effective in relation to a comparator, as a function of the threshold willingness to pay (WTP). 12 These were constructed using the net benefit approach. The standard non-parametric method for constructing CEACs is to bootstrap 10,000 samples from the original data, in order to plot the proportion of times each treatment represents the maximum average net benefit for a range of values of WTP values. Net monetary benefit (NMB) is calculated for each bootstrap estimate for a range of ceiling ratios as follows:

where λ is the value a decision-maker would be willing to pay.

The intervention with NMB > 0 should be adopted taking into account the NHS WTP threshold. A series of net benefits were calculated for relevant λ values ranging from £0 to £50,000 (£5000 increments) to incorporate the £20,000–30,000 per QALY gain threshold range currently specified for NICE decision-making in England and Wales. 32

Mean incremental net benefits between the two arms were reported, with 95% bootstrap CIs calculated using the bias-corrected method. 37

Sensitivity

We planned to undertake univariate sensitivity analyses to explore key uncertainties in the scenarios considered.

The results for complete cost and quality of life data (i.e. those with no missing data) as well as a strict per-protocol analysis of the data were provided to identify the impact of missing data on the analysis and any sensitivity to protocol violations.

As patients might also recover function within the first 3 months (rather than continuously to 3 months), a quicker initial recovery was explored in QALY calculations, where each patient’s quality of life was assumed to reach its observed 3-month level at 6 weeks postoperatively.

The cost assumptions in the analysis were modified if relevant (e.g. least expensive implant).

Sensitivity analyses were also planned to consider stratified analyses by factors such as age, gender, trial centre, baseline PRWE and DASH questionnaire scores, and intra-articular extension, if this was found to affect quality of life within the trial period.

Longer-term analysis

For the longer term, we will use decision-analytic modelling to compare locking-plate fixation and K-wire fixation for distal radial fractures over a longer time frame. We will use a 10-year Markov decision model based upon within clinical trial results to estimate the long-term effectiveness of fixations and the proportional hazards of complications and also revision in both people < 50 years of age and people ≥ 50 years of age.

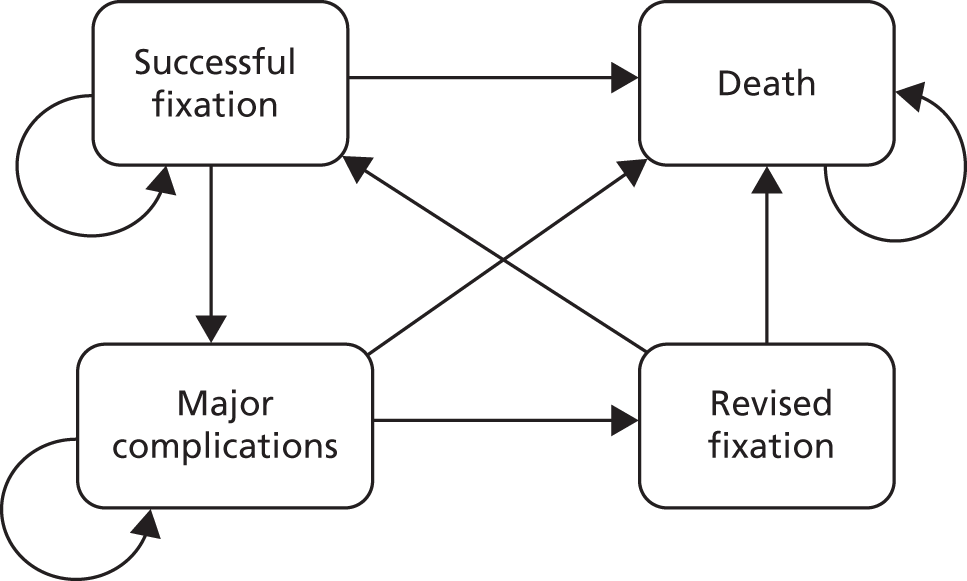

The model will include four possible states: (1) successful fixation; (2) complications; (3) revised fixation/surgery; and (4) death and its structure (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

States and allowable state transitions corresponding to use of a distal radius acute fracture fixation.

The impact of complications and subsequent revision surgery will be assessed using information from various sources: the extrapolation of within-trial data and the longer complication follow-up data which is currently ongoing, the published literature and/or expert opinions to create the most accurate model to compare locking-plate fixation and K-wire fixation for distal radial fractures. We will conduct a systematic review of cost-effectiveness models in the treatment distal radius fracture. This will act as the main resource of transition probabilities for the model. Where possible, transition probabilities will be based on the latest UK studies reflecting current care pathways and associated expectations relating to long-term patient functioning.

Two different base case scenarios will be considered, < 50 years of age cohort and ≥ 50 years of age cohort, both followed for 10 years.

Following the NICE reference case,33 costs and benefits will be discounted at 3.5% and a NHS perspective adopted.

Deterministic one-way sensitivity analysis will be performed to check the results over a plausible range of prior distributions placed on the time-varying model parameters. Multiway deterministic sensitivity analyses will be undertaken by modelling optimistic (‘best case’) and pessimistic (‘worse case’) scenarios. 38

Reporting

The results of the within-trial analyses are presented such that people with basic cost-effectiveness analysis knowledge can understand it.

It was planned that results would be disseminated through peer-reviewed journals, conference presentations and other types of research work dissemination. We expected to provide the within-trial analysis results for the trial main paper and we aimed at producing one extra paper focusing on the full health economics analysis with more mature data in the longer term.

Ethical approval and monitoring

Standard NHS cover for negligent harm was in place. There was no cover for non-negligent harm.

Ethics committee approval

The DRAFFT trial was approved by the Coventry Research Ethics Committee in February 2010 (REC reference 10/H1210/10) and by the research and development department of each participating centre. The final approved study protocol has been published.

Trial management group

The day-to-day management of the trial was the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator, based at Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (CTU) and supported by the CTU administrative staff. This was overseen by the TMG, which met monthly to assess progress. It was also the responsibility of the trial co-ordinator to undertake training of the research associates at each of the trial centres. The trial statistician and health economist were closely involved in the setting up of data capture systems and the design of databases and clinical reporting forms.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was responsible for monitoring and supervising the progress of the DRAFFT trial. The TSC consisted of four independent experts, a lay member and leading members of the TMG. Membership of the TSC is given in Acknowledgements.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was independent of the trial and was tasked with monitoring ethical, safety and data integrity. The trial statistician provided data and analyses requested by the DMC at each of the meetings. Membership of the DMC is given in Acknowledgements.

Chapter 3 Results

Screening

Overall

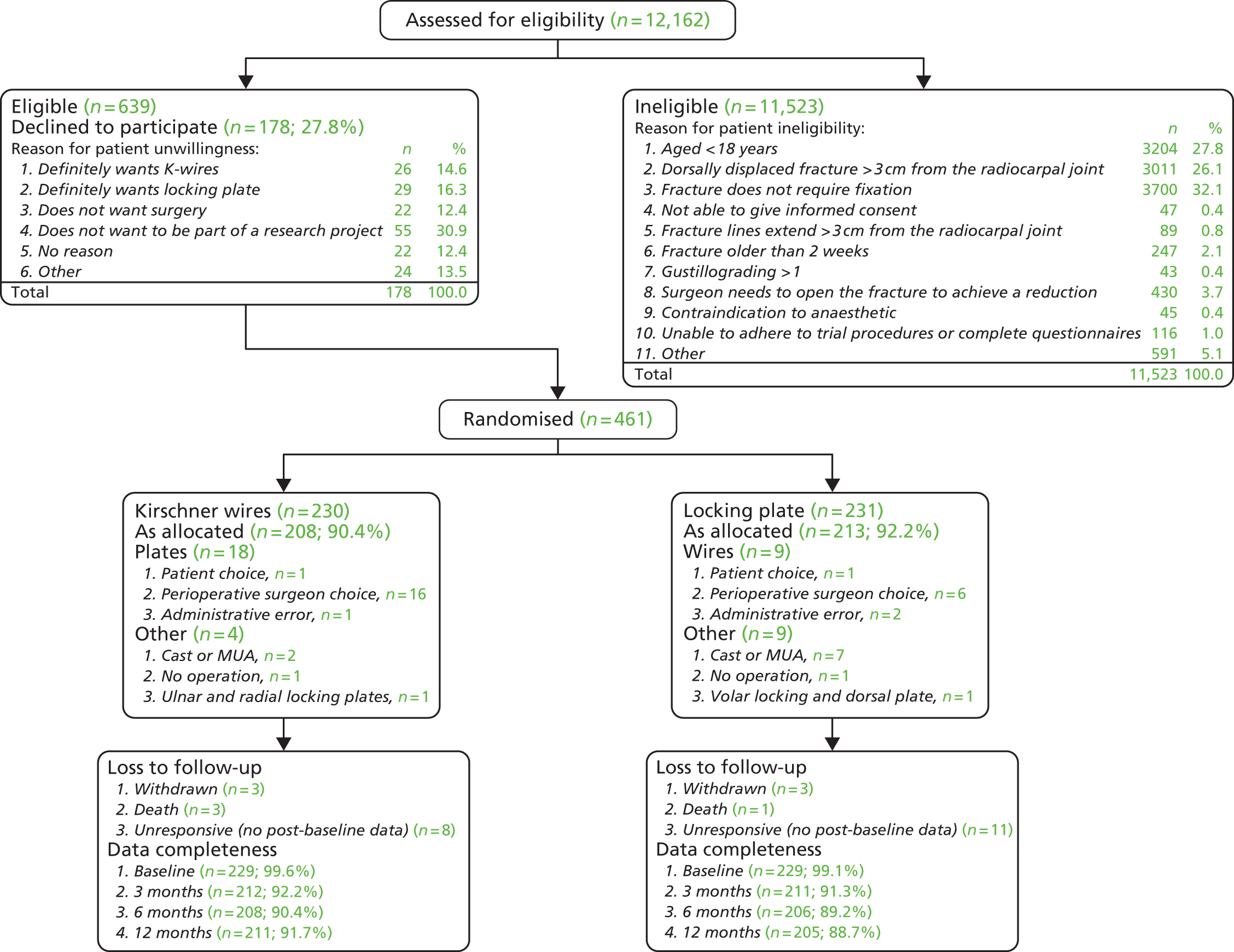

The overall flow of patients in the trial is shown in Figure 4. The total number of patients screened was 12,162; Table 3 shows the age and gender split.

FIGURE 4.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) plot: overall flow of patients in the study. MUA, manipulation under anaesthetic.

| Gender | Age group (years) | Total, n (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|

| < 50, n (%) | ≥ 50, n (%) | ||

| Female | 2317 (21.6) | 4806 (44.7) | 7123 (66.3) |

| Male | 2798 (26.0) | 830 (7.7) | 3628 (33.7) |

| Total | 5115 (47.6) | 5636 (52.4) | 10,751 (100.0) |

The overall median age of screened patients, where data were available, was 53 years [interquartile range (IQR) 18–72 years]; for females it was 63 years (IQR 39–77 years) and for males 23 years (IQR 12–48 years).

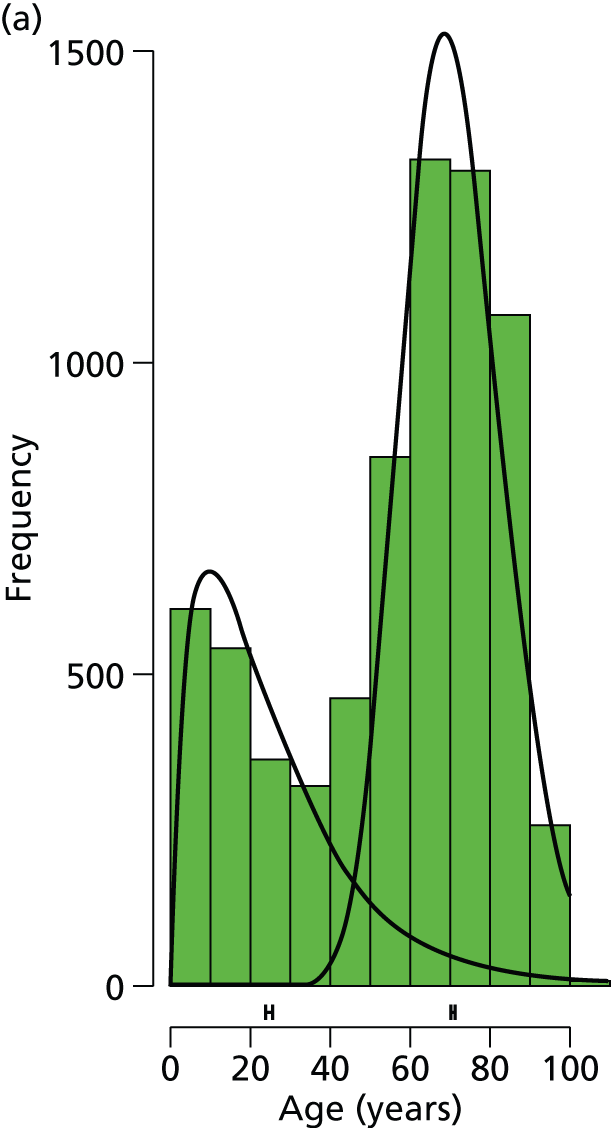

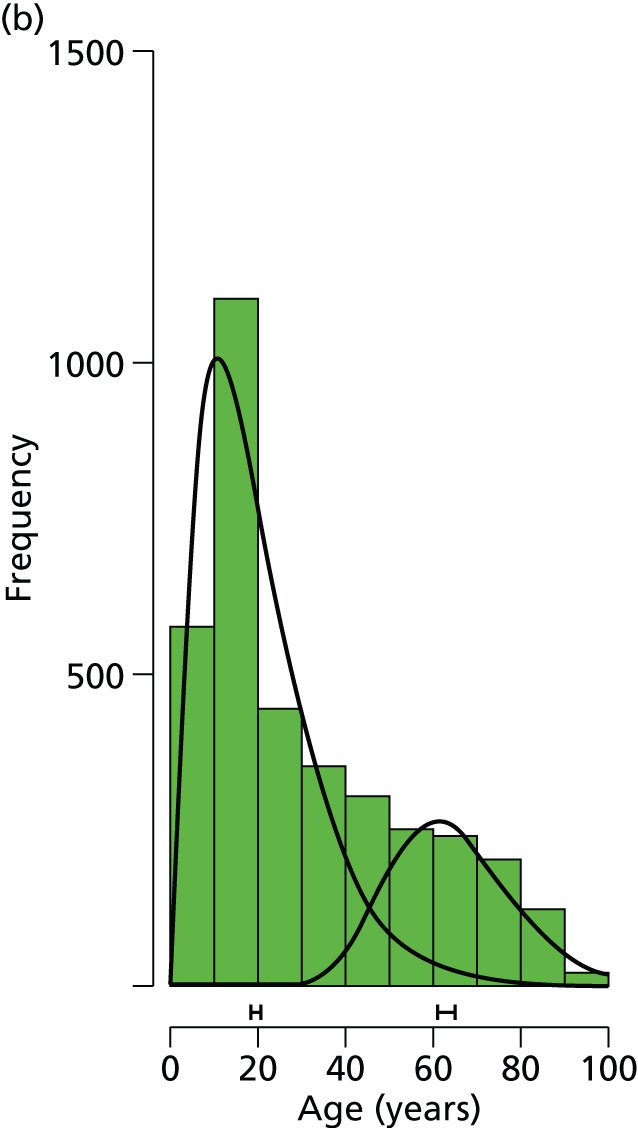

There was clear bimodality in the age distributions for each gender (Figure 5), particularly for females. A Gamma mixture model, gammamixEM function in R package mixtools, was fitted to data from each gender to estimate the proportionate split and median ages in each group; bootstrapping (n = 100) was used to estimate 95% CIs for these statistics.

FIGURE 5.

Age distribution of screened patient bars and fitted distributions for (a) females (n = 7123) and (b) males (n = 3628).

The modelling suggests that, for females, the ‘young’ group has a median age of 25.1 years (95% CI 24.1 to 25.8 years) and the ‘old’ group has a median age of 71.1 years (95% CI 70.6 to 71.5 years), with the split by group (young : old) given by 32.3% : 67.7% (95% CI 30.8 to 33.5). For males, the ‘young’ group has a median age of 19.7 years (95% CI 18.3 to 20.6 years) and the ‘old’ group has a median age of 63.7 years (95% CI 61.3 to 65.1 years), with the split by group (young : old) given by 73.5% : 26.5% (95% CI 69.3 to 76.0).

A recent study by Court-Brown and Caeser16 assessed over 1000 patients with a fracture of the distal radius. This study suggested that there is a clear bimodal distribution for this type of fracture according to the age of the patient; with a crossover of the two peaks of incidence at around 50 years of age. This was also the case for our data, for both males and females, with Figure 5 showing that the approximate division between the two age groups was also at around 50 years. Stratification on the basis of age was used to discriminate between younger patients with normal bone quality sustaining high-energy fractures and older patients with low-energy (fragility) fractures related to osteoporosis.

Eligibility

Figure 4 shows that the total number eligible for the study was 639, that is the total number screened (12,162) minus the total number ineligible (11,523). The main reasons for patient ineligibility were that the fracture did not require fixation (32.1%), the fracture was dorsally displaced > 3 cm from the radiocarpal joint (26.1%) and the patient was aged < 18 years (27.8%).

Willingness

Of the 639 eligible patients, 461 (72.1%) were willing and 178 were unwilling to take part in the trial. The main reason for being unwilling to participate was a simple unwillingness to be part of a research project (55 patients; 30.9%). Of those patients who expressed a preference, there was a balance between the treatment groups, with 26 patients stating a preference for wires (14.6%) and 29 stating a preference for a plate (16.3%).

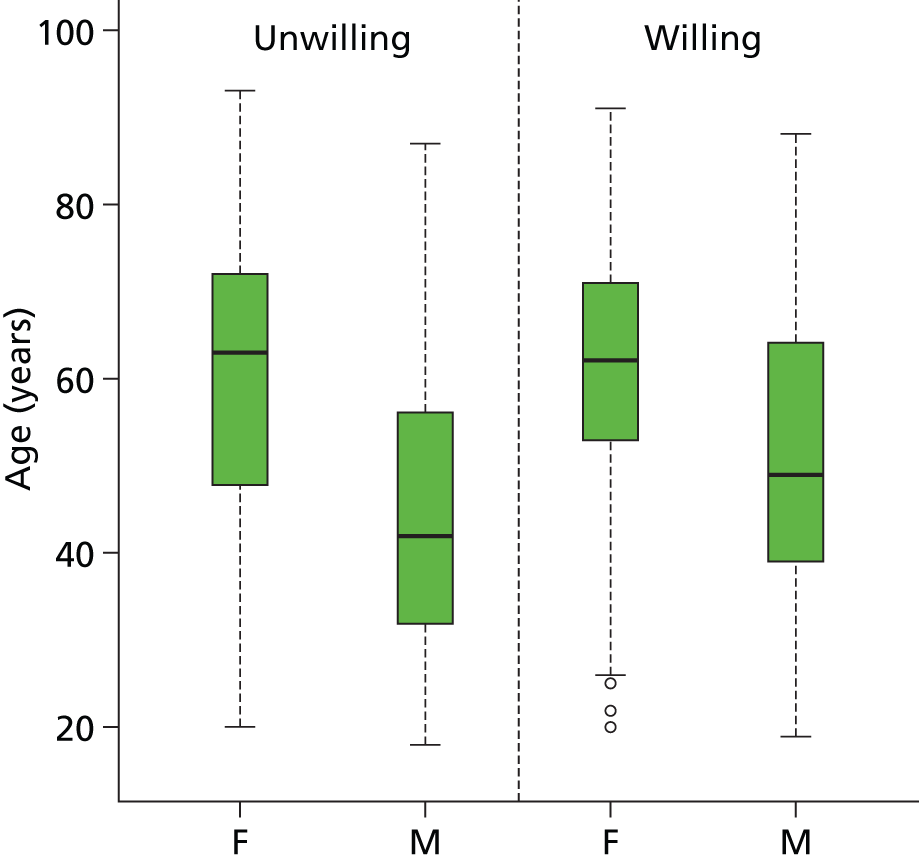

In total, 461 patients were willing to participate in the DRAFFT study. The gender and age of the individuals who were willing and unwilling to participate in the study are shown in Table 4 and the distribution of ages by gender and group in Figure 6.

| Characteristic | Willing (n = 461) | Unwilling (n = 178) |

|---|---|---|

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 58.8 (15.9) | 56.1 (18.8) |

| Gender (% female) | 83.0 | 79.1 |

FIGURE 6.

Box plot showing age distribution by gender and willingness to participate in trial. F, female; M, male.

A t-test showed that ages did not differ significantly between groups (p = 0.088) and a chi-squared test showed no difference in gender split between groups (p = 0.301).

Recruitment

The trial planned to recruit as a minimum 390 patients in total. Formal recruitment started on 1 January 2011 and finished on 30 June 2012. Recruitment took place at 18 centres (Table 5).

| Centre | Code |

|---|---|

| 1. Addenbrookes Hospital | ADH |

| 2. Frenchay Hospital | FRH |

| 3. Ipswich Hospital | IPH |

| 4. James Cook University Hospital | JCH |

| 5. John Radcliffe Hospital | JRH |

| 6. Leicester General Hospital | LGH |

| 7. North Tyneside General Hospital | NTG |

| 8. Northampton General Hospital | NGH |

| 9. Peterborough City Hospital | PCH |

| 10. Poole Hospital | POH |

| 11. Royal Blackburn Hospital | BBH |

| 12. Royal Victoria Infirmary | RVI |

| 13. St Thomas’ Hospital | STH |

| 14. University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire | UHC |

| 15. University Hospital North Staffordshire | UNS |

| 16. University Hospital of North Tees | NTH |

| 17. Wansbeck General Hospital | WGH |

| 18. Wexham Park Hospital | WPH |

Overall

Overall trends in recruitment are shown in Figure 7; the final number of participants recruited to the study was 461 (Table 6).

FIGURE 7.

Overall DRAFFT recruitment (thick black line) and recruitment by centre (January 2011 to June 2012); logarithmic scale used to enhance detail for individual centres. Original target = 390 patients.

| Hospital | Treatment group | Total | Months open | Rate (per month) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wire | Locking plate | ||||

| UHC | 50 | 50 | 100 | 23 | 4.51 |

| RVI | 30 | 30 | 60 | 19 | 3.21 |

| WGH | 15 | 16 | 31 | 12 | 2.58 |

| FRH | 15 | 14 | 29 | 18 | 1.62 |

| BBH | 13 | 13 | 26 | 11 | 2.53 |

| ADH | 12 | 12 | 24 | 17 | 1.50 |

| JCH | 13 | 11 | 24 | 17 | 1.47 |

| IPH | 11 | 12 | 23 | 18 | 1.32 |

| JRH | 11 | 12 | 23 | 13 | 1.78 |

| UNS | 10 | 11 | 21 | 15 | 1.48 |

| NGH | 11 | 9 | 20 | 11 | 1.86 |

| POH | 9 | 11 | 20 | 13 | 1.58 |

| STH | 8 | 10 | 18 | 14 | 1.30 |

| LGH | 6 | 5 | 11 | 11 | 1.09 |

| PCH | 6 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 1.15 |

| WPH | 5 | 5 | 10 | 7 | 1.64 |

| NTH | 4 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 1.78 |

| NTG | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 4.68 |

| Average | – | – | – | 13.05 | 1.96 |

| Total | 230 | 231 | 461 | 235 | – |

The final number of recruited participants was above the initial target of 390.

Recruitment proceeded at a faster rate than expected; therefore, the decision was taken to allow the sample size to increase above the target of 390 patients.

Population characteristics

The randomisation was stratified by hospital, age group and intra-articular extension. Table 7 shows recruitment numbers by treatment group, age group and intra-articular extension.

| Age group, years | Intra-articular extension | Treatment | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wire | Locking plate | |||

| < 50 | No | 31 | 33 | 64 |

| Yes | 29 | 27 | 56 | |

| ≥ 50 | No | 91 | 89 | 180 |

| Yes | 79 | 82 | 161 | |

| Total | 230 | 231 | 461 | |

The breakdown by age, gender and treatment group is shown in Table 8.

| Age group, years | Gender | Treatment | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wire | Locking plate | |||

| < 50 | Female | 35 | 46 | 81 |

| Male | 25 | 14 | 39 | |

| ≥ 50 | Female | 156 | 148 | 304 |

| Male | 14 | 23 | 37 | |

| Total | 230 | 231 | 461 | |

The majority (304 out of 461) of patients recruited to the trial were female and ≥ 50 years of age, as expected.

Surgeons and operations

Before proceeding to analyse the outcomes, it is informative to look at the details of the surgical procedures.

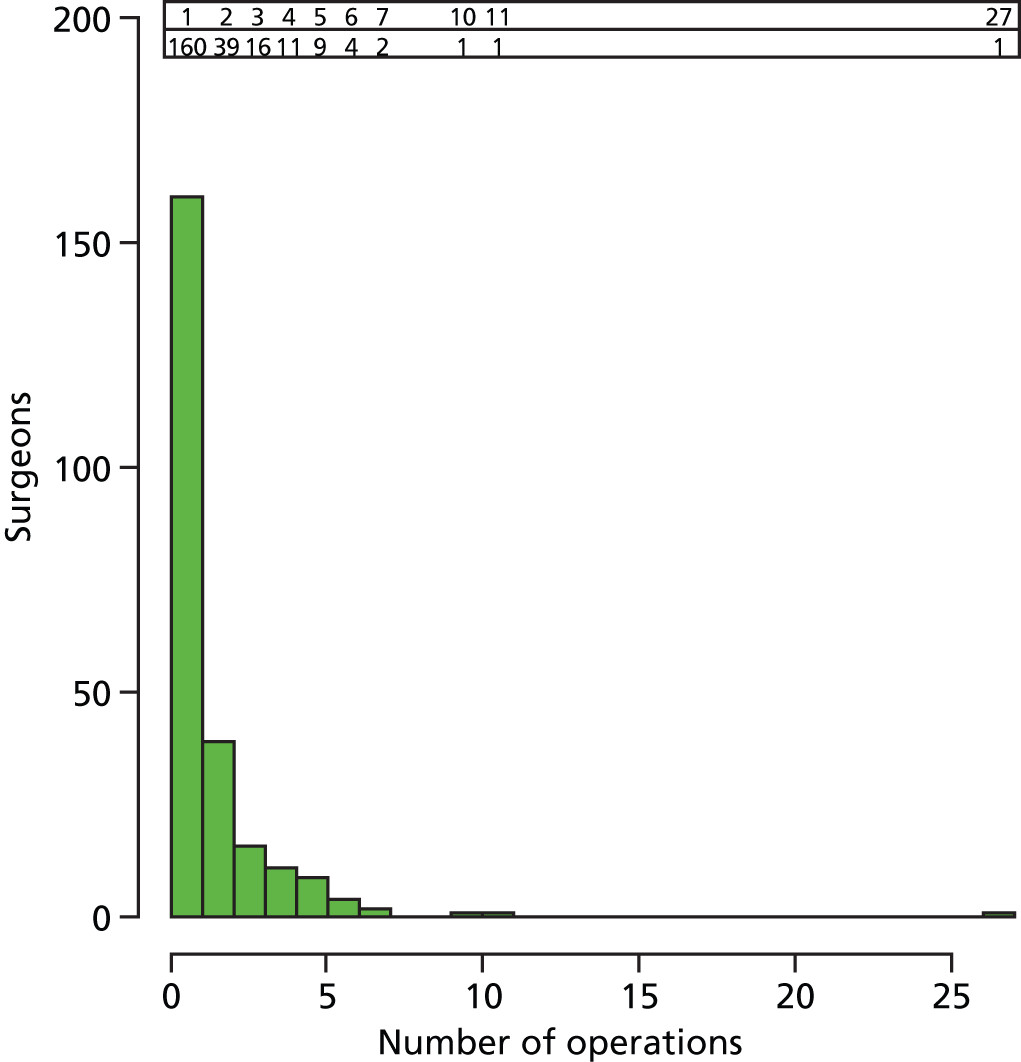

Surgeons

Treatments were undertaken by 244 different surgeons; the median number of operations per surgeon was 1 (IQR 1–2). Figure 8 shows a histogram of the number of procedures undertaken by each surgeon.

FIGURE 8.

Histogram of numbers of operation for each surgeon.

As expected, any individual surgeon operated only on a small number of patients (n = 2 or 3) enrolled in the study; 88% of surgeons (215 out of 244) treated fewer than three study participants. This greatly reduces the likelihood of a surgeon-specific effect on the outcome at any one centre, that is one particularly good or bad surgeon dominating the other surgeons in the study.

Operations

Details of the surgeon grade and experience and methods employed for each procedure are shown in Table 9 and operation times by surgeon grade are shown in Figure 9.

| Details of surgeons and surgery | K-wire (n = 230) | Locking plate (n = 231) |

|---|---|---|

| Perioperative antibiotic (no : yes) | 58 : 164 (71%) | 19 : 191 (83%) |

| Operated wrist (right : left) | 101 : 24 (54%) | 102 : 124 (54%) |

| Intraoperative problems (no : yes) | 222 : 4 (2%) | 219 : 4 (2%) |

| Surgeon grade, n (%)a | ||

| Consultant | 60 (26) | 71 (31) |

| Specialist trainee | 102 (44) | 106 (46) |

| Staff grade/associate specialist | 30 (13) | 29 (13) |

| Other | 34 (15) | 20 (9) |

| Surgeon experience (number of prior operations), n (%)a | ||

| 0 | 0 (0) | 1 (0) |

| < 5 | 11 (5) | 8 (3) |

| 5–10 | 16 (7) | 23 (10) |

| 11–20 | 25 (11) | 30 (13) |

| > 20 | 171 (74) | 158 (68) |

| Wires, n (%) | ||

| Number of wires useda | ||

| 1 | 1 (0) | – |

| 2 | 96 (42) | – |

| 3 | 105 (46) | – |

| > 3 | 5 (2) | – |

| Wire sizea | ||

| 1.6 mm | 187 (81) | – |

| 1.1 mm | 1 (0) | – |

| Other | 12 (5) | – |

| Techniquea | ||

| Kapandji | 54 (23) | – |

| Interfragmentary | 78 (34) | – |

| Mixed technique | 71 (31) | – |

| Plates, n (%) | ||

| Number of screws useda | ||

| 3 | – | 20 (9) |

| 4 | – | 62 (27) |

| 5 | – | 42 (18) |

| > 5 | – | 88 (38) |

| Proximal screwa | ||

| Locking | – | 103 (45) |

| Non-locking | – | 110 (48) |

| Operation time | ||

| Minutes | 31 | 66 |

| Median (IQR) | 24 (45) | 50 (85) |

| Mean (SD) | 37.2 (19.8) | 69.9 (27.7) |

| Length of stay | ||

| Days | 1 | 1 |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (1) | 0 (1) |

FIGURE 9.

Operation times by surgeon grade and procedure.

There was no evidence to suggest that operation times differed between surgeon grades.

Outcomes

Treatment allocation

Table 10 shows the treatment allocation and the treatments received by treatment group. In the K-wire group 90.4% of participants received their allocated intervention and in the locking-plate group 92.2% received their allocated intervention.

| Received | Allocated | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| K-wire, n | Locking plate, n | Total, n | |

| K-wire | 208 | 9 | 217 |

| Locking plate | 18 | 213 | 231 |

| Other | 4 | 9 | 13 |

| Total | 230 | 231 | 461 |

Unless stated otherwise, all analyses reported here will be on an intention-to-treat basis, that is by allocated treatment.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics are well balanced between treatment groups (Table 11).

| Baseline characteristics | K-wire (n = 230) | Locking plate (n = 231) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (female : male) | 191 : 39 (17%) | 194 : 37 (15%) |

| Intra-articular extension (no : yes) | 122 : 108 (47%) | 122 : 109 (47%) |

| Age (years) | 59.7 (16.4) | 58.3 (14.9) |

| Injury side (right : left) | 101 : 123 (53%) | 101 : 124 (54%) |

| Handedness (right : left) | 196 : 32 (14%) | 202 : 26 (11%) |

| Previous problem on injured side (no : yes) | 197 : 33 (14%) | 191 : 39 (17%) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.8 (4.0) | 26.5 (5.3) |

| Osteoporosis (no : yes) | 208 : 22 (10%) | 211 : 20 (9%) |

| Regular analgesia (no : yes) | 160 : 70 (30%) | 169 : 61 (26%) |

| Smoker (no : yes) | 180 : 50 (22%) | 189 : 42 (18%) |

| Mechanism of injurya | ||

| Low-energy fall | 190 (83%) | 189 (82%) |

| High-energy fall | 36 (16%) | 36 (16%) |

| Road traffic collision | 1 (0%) | 4 (2%) |

| Crush | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 2 (1%) | 2 (1%) |

| Fracture classificationa,b | ||

| A1 : A2 : A3 | 0 (0%) : 73 (32%) : 84 (37%) | 0 (0%) : 71 (31%) : 78 (34%) |

| B1 : B2 : B3 | 1 (0%) : 1 (0%) : 1 (0%) | 4 (2%) : 1 (0%) : 0 (0%) |

| C1 : C2 : C3 | 33 (14%) : 26 (11%) : 7 (3%) | 30 (13%) : 34 (15%) : 11 (5%) |

| Alcohol consumption (per week)a | ||

| 0–7 units | 164 (71%) | 164 (71%) |

| 8–14 units | 39 (17%) | 45 (19%) |

| 15–21 units | 16 (7%) | 14 (6%) |

| > 21 units | 11 (5%) | 8 (3%) |

| Pre-injury scores (retrospectively) | ||

| PRWE | 2.6 (8.4) | 2.8 (8.7) |

| DASH | 5.4 (12.7) | 4.6 (10.8) |

| EQ-5D | 0.92 (0.17) | 0.94 (0.15) |

| Patient preference (after randomisation) | ||

| K-wire | 38 (17%) | 39 (17%) |

| Locking plate | 35 (15%) | 42 (18%) |

| No preference | 156 (68%) | 150 (65%) |

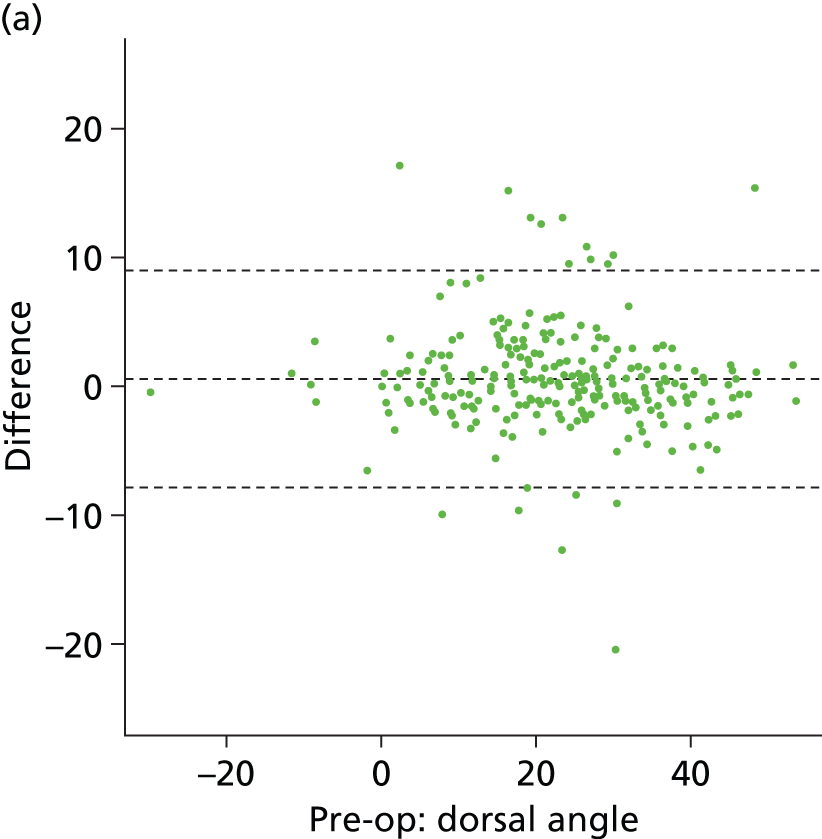

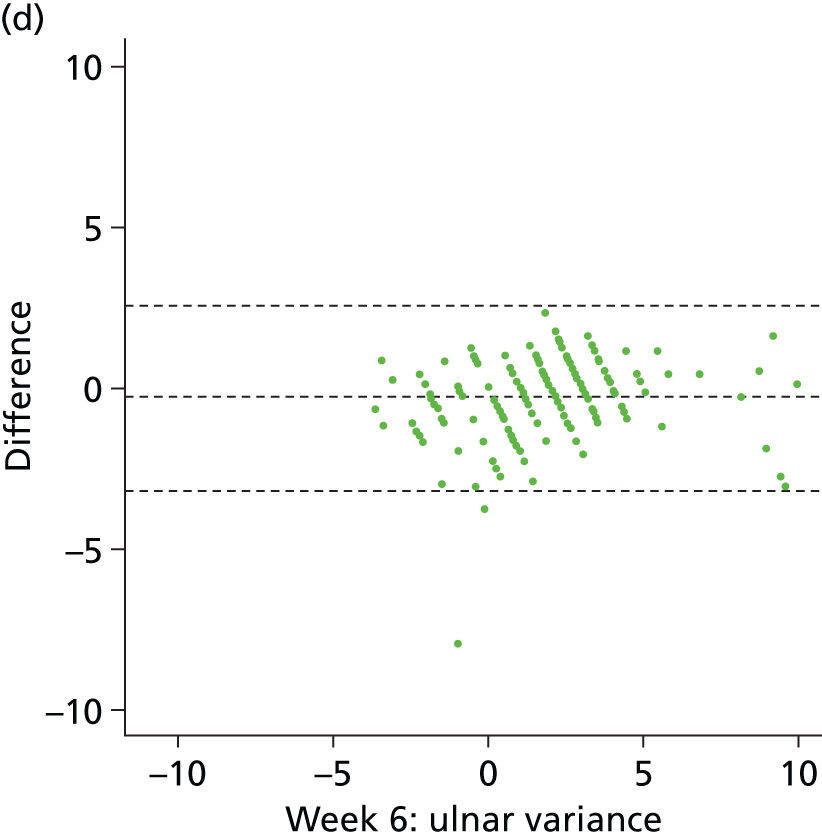

Imaging outcomes

Dorsal angle (°) and ulnar variance (mm) data were extracted from available images from all study participants before their operation (pre-op), and 6 weeks and 12 months postoperatively. In addition to the principal clinician extracting these images (assessor 1), an additional clinician (assessor 2) also assessed and extracted data independently. Table 12 shows estimates of intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), with 95% CIs based on 1000 bootstrapped samples, for dorsal angle and ulnar variance data at the preoperative assessment, and at 6 weeks and 12 months postoperatively. The ICC provides a measure of agreement between the two assessors and can be interpreted as follows: 0 to 0.2 poor, 0.2 to 0.4 fair, 0.4 to 0.6 moderate, 0.6 to 0.8 substantial and 0.8 to 1.0 almost perfect.

| Occasion | Measure | n | ICC | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | Dorsal angle (°) | 279 | 0.94 | 0.91 to 0.96 |

| Ulnar variance (mm) | 277 | 0.87 | 0.78 to 0.94 | |

| Week 6 | Dorsal angle (°) | 266 | 0.84 | 0.77 to 0.90 |

| Ulnar variance (mm) | 266 | 0.82 | 0.70 to 0.92 | |

| 12 months | Dorsal angle (°) | 208 | 0.87 | 0.81 to 0.91 |

| Ulnar variance (mm) | 209 | 0.89 | 0.82 to 0.93 |

It is clear from Table 12 that for both measures there was almost perfect agreement between both assessors. This is displayed visually by the Bland–Altman plots in Figure 10, where the difference between data from the two assessors is plotted against the mean with 95% CIs. We conclude from the analysis presented in Table 12 and Figure 10 that there was excellent agreement between assessors, indicating a high level of confidence in the measurements made by the principal assessor (assessor 1). The following comparative analysis (between intervention groups) is based purely on the data extracted from the images by this assessor.

FIGURE 10.

Bland–Altman plots showing agreement between assessors 1 and 2 for dorsal angle (°) preoperatively (a), 6 weeks (c) and 1 year (e); and for ulnar variance (mm) preoperatively (b), 6 weeks (d) and 1 year (f). Plots show differences plotted against mean data, with 95% CIs indicated by dashed lines.

Image data were available from all 461 study participants before their operation (pre-op), and 6 weeks and 12 months postoperatively. However, some data were not available for analysis because of lack of collection, corrupted data files (which could not be opened) and poor-quality images that could not be analysed. In summary, only six study participants (1%) had no image data available at any occasion.

Metaphyseal comminution was reported at the preoperative assessment, in addition to dorsal angle and ulnar variance, and appeared to be well balanced across intervention groups, with 70.0% (152 out of 217) and 70.1% (155 out of 221) of study participants being assessed affirmatively for this characteristic for the K-wire and locking-plate groups respectively. Table 13 shows the mean and SD for imaging outcomes at baseline, 6 weeks and 12 months postoperatively, and estimated treatment effects after adjustment at 6 weeks and 12 months. Adjusted effects were from mixed-effects regression analysis based on complete cases with treatment group, age group, sex and intra-articular extension as covariates (fixed effects) and recruiting centre as a random effect.

| Imaging outcome | K-wire | Locking plate | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Raw | Adjusteda | |||

| Dorsal angle (°) | Baseline | 23.10 (12.57) | 220 | 22.05 (13.85) | 225 | –1.05 | – | – |

| 6 weeks | –1.16 (11.00) | 215 | –4.31 (9.39) | 215 | –3.15 | –3.18 (–5.02 to –1.33) | < 0.001 | |

| 12 months | –0.49 (12.35) | 178 | –5.20 (8.24) | 173 | –4.70 | –4.64 (–6.76 to –2.53) | < 0.001 | |

| Ulnar variance (mm) | Baseline | 3.26 (2.62) | 219 | 3.55 (3.24) | 222 | 0.29 | – | – |

| 6 weeks | 1.95 (2.11) | 215 | 1.20 (2.18) | 215 | –0.75 | –0.75 (–1.15 to –0.35) | < 0.001 | |

| 12 months | 2.43 (2.31) | 179 | 1.32 (2.02) | 173 | –1.11 | –1.08 (–1.53 to –0.63) | < 0.001 | |

In summary, these results indicate that there was a significantly larger (more positive) dorsal angle in the K-wire group than the locking-plate group, at both 6 weeks and 12 months post operation. In addition, the variability in dorsal angle was significantly less in the locking-plate group than in the K-wire group at both 6 weeks and 12 months (F-test to compare the variances of two samples from normal populations; p = 0.020 and p < 0.001 and ratio of variances 0.73 and 0.45, at 6 weeks and 12 months, respectively). There was a significantly larger (more positive) ulnar variance in the K-wire group than in the locking-plate group, at both 6 weeks and 12 months post operation. However, there was no difference in variability between groups for ulnar variance at 6 weeks and 12 months (p = 0.615 and p = 0.081).

The image data are summarised further in the box plots of Figure 11, which clearly show the temporal trends in data and the difference in variance between dorsal angle data between groups at 12 months post operation.

FIGURE 11.

Box plots of baseline and postoperative scores and trends in means (filled circles) with 95% CIs for (a) dorsal angle and (b) ulnar variance.

Functional and quality of life outcomes

The primary outcome for this study is the PRWE questionnaire score23 at 12 months after surgery. Early functional status was also assessed and reported at 3 months and 6 months. The DASH questionnaire25 was used as a more general measure of physical function and symptoms in people with musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb. Quality of life was assessed using EQ-5D. Data are summarised for each outcome measure, at each assessment occasion, in Tables 14–16. Baseline data are retrospective measurements made by study participants to assess pre-injury function and quality of life at recruitment. For EQ-5D, participants also made a post-injury assessment.

| Treatment | Measure | Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 12 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| K-wire | n | 229 | 212 | 208 | 211 |