Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/27/16. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elizabeth Taylor Buck and Chris Wood are registered art therapists with the Health Care Professions Council. Kim Dent-Brown is a registered arts therapist with the Health Care Professions Council.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Uttley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the underlying health problem

Definition and prevalence of non-psychotic mental disorders

Among people under 65 years, nearly half of all ill health is mental illness, which accounts for 38% of all morbidity in the UK burden of disease. 1 Mental ill health is the largest single cause of disability in our society. 2 Mental disorders can be broadly categorised as either psychotic or non-psychotic, with non-psychotic disorders accounting for most (94%) mental health morbidity in adults. 1,3 Non-psychotic mental disorders include anxiety disorders such as phobias and obsessive–compulsive disorder, mood disorders such as depression and major depressive disorder, and other conditions such as eating disorders and personality disorders. Depression alone accounts for the greatest burden of disease among all mental health problems. 4,5 In addition, nearly one-third of all people with long-term physical conditions have a comorbid mental health problem such as depression or anxiety disorders, indicating an interaction between physical and mental illness. 6–8 Figures for mental illness quoted in the London School of Economics and Political Science report do not include dementia and alcohol and substance misuse, which are also important issues in their own right, and account for part of the outlay in mental health services in the UK NHS. 1

Costs to the NHS

Mental health receives a 13% share of the NHS expenditure despite mental health accounting for 23% in the burden of disease. 1 The largest part of this expenditure is on psychotic disorders, but these disorders account for less than 6% of people suffering with mental illness. One-quarter of all those with mental health problems are in treatment, compared with the vast majority of those with physical illnesses. 1 Research indicates that the costs of psychological therapy are low compared with general care admissions,9,10 and recovery rates are high. 11 Unlike most long-term physical conditions, much mental illness is curable. 11 For depression and anxiety the number needed to treat is estimated to be under 3. 1 Moreover, the same research used data from relevant National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance compiled by the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health and posits that ‘more expenditure on the most common mental disorders would almost certainly cost the NHS nothing’ because ‘when people with physical symptoms receive psychological therapy, the average improvement in physical symptoms is so great that the resulting savings on NHS physical care outweigh the cost of the psychological therapy’. 1

The NHS is under increasing pressure to provide cost-effective treatments to service users in a timely manner. The UK government initiative for Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) for depression and anxiety disorders within the NHS offers evidence-based psychological therapies that are recommended by NICE. However, IAPT is facing increasing criticism that it is too limited to handle the mental health problems of people with long-term physical conditions or medically unexplained symptoms. 1 Recent evidence also suggests that only one-quarter of people with a mental illness receive treatment for it and that mental health is seriously undervalued, under-recognised and underfunded in the NHS. 1 It may be that more mental health treatment options are needed, which vary according to the type and severity of mental disorder, rather than a one-size-fits-all approach across professions. In addition, recent evidence suggests that psychological treatment may be a preferred treatment option over pharmacological treatment for many who are undergoing treatment for a psychiatric disorder. 12,13 Moreover, patient preference for treatment may impact on adherence and treatment outcome. 14,15 Therefore, evaluation of forms of psychological therapy other than cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) need to be conducted in addition to the evaluation of specific pathways within those psychological therapies, in order to create a strategic framework of pathways for managing the burden of mental health morbidity.

Evaluation of psychological therapies such as art therapy is therefore critical in order to inform future recommendations for its use. There is a small body of evidence to support the claim that art therapy is effective in treating a variety of symptoms and disorders in patients of different ages. 16 However, to date a full systematic review of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy for non-psychotic mental disorders has not been undertaken. This project aimed to evaluate the current evidence for art therapy for people with non-psychotic mental disorders in order to inform researchers and commissioners about the value of future use of art therapy in the NHS.

Art therapy

Description of intervention

The intervention of interest is art therapy as might be delivered in the NHS. Art therapy involves using painting, clay work and other creative visual art-making (including creative digital media) as a form of non-verbal expression, in conjunction with other modes of communication within a therapeutic relationship in an appropriate therapeutic setting. Art therapy is a specific branch of treatment under the umbrella term ‘arts therapies’ used by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) which includes drama therapy and music therapy. Dance movement therapy is also described as one of the arts therapies but is not yet regulated. For the purpose of this technology assessment these other forms of arts therapies, which do not centre on the creation of a sustainable physical piece of visual art, are excluded.

Despite art therapy being an established and practised form of psychological therapy for decades, only more recently have researchers in the field of art therapy addressed the need to integrate art therapy into a model of evidence-based practice. Therefore, an abundance of literature exists consisting of single case studies or theoretical concepts in art therapy. Proponents of art therapy17–19 and of the arts therapies20,21 only relatively recently have come to realise that randomised controlled studies of art therapy are needed in order to create a pluralistic body of evidence. As a consequence there has been limited formal synthesis of evidence16,22 for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of art therapy in order to assess its relevance as a treatment for the most common mental disorders in the NHS.

Current use of art therapy in NHS

Currently, CBT is the most widely recommended psychological therapy for most mental health problems. However, NICE has identified that the arts therapies (including art therapy) may have specific benefits for people with psychosis and schizophrenia and, therefore, recommends art therapy to be considered for these patients, above counselling and supportive psychological therapy. 23 There are a number of non-psychotic mental health problems that are typified by service users’ reluctance or inability to communicate their feelings verbally. Art therapy is currently being used in the NHS for many non-psychotic mental disorders. For example, arts therapies are included in the autistic spectrum disorder (ASD) Strategic Plan for Wales20 as an accessible and appropriate form of psychotherapy for those with ASD. For these and other service users, it may be that art therapy is a more appropriate treatment than standard talking therapies, but the evidence base for the use and acceptability of art therapy in non-psychotic mental disorders has yet to be formally evaluated. There are clinical guidelines by art therapists for working with elderly people,24 working with prisoners,25 working with children, adolescents and families,26 and working with people with a diagnosis of personality disorder,27 indicating movement in the profession towards more specific systematic practice and research. There are currently no national guidelines in the UK specifically for the use of art therapy for non-psychotic mental disorders.

Art therapy is a widely used psychological therapy which has HCPC approval, higher education Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education subject benchmarks and a professional organisation for its practitioners – the British Association of Art Therapists (BAAT). While testimonials and case studies occupied much of the evidence for art therapy in the past, there has been less focus on producing rigorous randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of art therapy. The purpose of this review is to assess systematically the evidence that is relevant to whether or not art therapy is effective, how it may be clinically effective and whether or not it is cost-effective in people with non-psychotic mental health disorders.

The results of the 2014 BAAT Workforce Survey represented one-third of members from the professional association; with 70 responses from Scotland and 567 responses from England, Wales and Northern Ireland. The survey results suggested that:

-

In England, Wales and Northern Ireland, the NHS employs around half of art therapists who responded. Other large employers are third-sector organisations (charities, voluntary and independent organisations), educational institutions, private practices and local authorities.

-

Over half of art therapists who responded use generic skills in their work, such as assessments and key working, possibly reflecting a change towards delivering other services in addition to providing art therapy.

-

The majority of client groups served are adults, children and young people. Elderly people and families account for smaller proportions.

-

The range of mental health difficulties dealt with by art therapists who responded includes complex trauma and abuse, learning disabilities, alcohol and substance use, forensic mental health, criminal justice, elderly people and palliative care.

There are likely to be regional variations in the availability and practice of art therapy in the UK not captured by this survey.

There is no definitive criterion for who is routinely referred for art therapy, and at what point in their care pathway. 28 The only standardised guidelines for its use are in relation to schizophrenia. 29 However, discernible clusters of people undergo art therapy according to published literature, including people who have been abused and traumatised, who are on the autistic spectrum, who have addictions, dementia, eating disorders or learning difficulties, who are offenders, who are in palliative care, who have depression or personality disorders or who were displaced as a result of political violence. Therefore, adults are referred from a broad range of diagnostic categories, but they tend not to be referred on the basis of diagnosis alone. They may be referred on the basis of behavioural problems, including problems with engaging with services or problems with putting distress into words, for which talking therapies would not be the preferred option. Other clinicians making referrals to art therapy are often looking to widen the range of treatment options for people who, in addition to having complex, severe and enduring mental health problems, face emotional and socioeconomic deprivation. As seen in the use of art therapy for service users in palliative care, people facing the emotional consequences of serious physical health may also be referred.

Defining the use of art therapy for children and adolescents is also problematic. This is because children’s problems tend to be grouped as ‘emotional’ or ‘behavioural’ in the absence of diagnosed disorders. 30 Published outcome data are scarcer for children and adolescents, with more qualitative descriptions of art therapy occurring in the literature. However, BAAT reports that, in November 2010, of the approximately 1800 full members of BAAT, 878 described themselves as working with children, young people and/or families. Seemingly, therefore, art therapy is currently being widely practised with children and young people and should be duly considered in this review.

The art therapist’s role in the mental health service pathway

In service contexts where art therapists are working more briefly with service users, they may also refer on to other services. This is particularly important for clients who have long-term conditions, as it leaves the way open for clients to return for more art therapy at a later stage. Accordingly, art therapists have a professional responsibility to consider carefully referrals that they receive and that they make. Figure 1 indicates the mental health service pathway open to art therapists who are working in a multiagency context. This diagram is adapted from a presentation at the BAAT annual general meeting in 2010,31 in which a two-way bridge was highlighted as a potentially important relationship for art therapists who are working, clinically, with service users for relatively short periods of time.

FIGURE 1.

Mental health service pathway for art therapists working in a multiagency context.

Adapting the research to the research question

The protocol for this research project was designed by the research team in consultation with a project steering group consisting of external health professionals and service users (see Appendix 1). The steering group was made up of consultant psychiatrists with experience of referring to art therapy and service users who had been referred to art therapy. The purpose of the steering group was to ensure that the research team’s proposed research design was open to the views of stakeholders. In addition, the protocol was also publicly available online and the project was registered on the PROSPERO database of systematic reviews (registration no. CRD4201300395732).

One of the major challenges in delivering the research lay in tailoring the research methodology to fit with the research question. The research question can be regarded as non-standard in that it centres on the intervention rather than the population. This health technology assessment can therefore be regarded as an evidence portfolio for art therapy. The population under review is patients with non-psychotic mental disorders. Psychosis is not a precise mental health condition but is a symptom that can feature in several mental health disorders; for example, conditions such as bipolar disorder and depression can occur with or without psychotic symptoms. Conversely, schizophrenia is perhaps one of the few mental health conditions that is characterised by psychosis, along with delusional disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorder, schizoaffective disorder, non-organic psychotic disorder and organic psychotic disorder. These are, therefore, some of the few mental health conditions that can be regarded as falling outside the population for this research.

Art therapy as a clinical intervention: definition

Although art therapy is a HCPC-approved form of psychological therapy in the UK, there is currently a lack of a clear single definition of art therapy. The BAAT describes art therapy as a form of psychological therapy that uses the art-making process as its primary mode of communication and can therefore be particularly helpful to people who find it hard to express their thoughts and feelings verbally. Clients who are referred to an art therapist do not need to have previous experience or skill in art, and the overall aim of its practitioners is to enable the client to explore and express their feelings in a safe and facilitating environment. Art therapy can be regarded as a three-way process between the client, the therapist and the image or artefact. 33

The concept of art therapy may sometimes be confused with creative arts movements or strategies designed to improve well-being through art (often called ‘arts in health’ approaches) which, although potentially beneficial, are not specific formal therapeutic interventions to target mental health conditions in individual service users. In order to distinguish the psychotherapeutic use of art therapy as is under investigation in this research question, a criterion to define art therapy as a form of psychological therapy has been formulated. This pragmatic definition was developed as a screening tool and a guide for assessing papers for inclusion into the systematic review. It is not intended to be an exhaustive definition and needed to be sufficiently flexible to include practices in the UK and abroad.

Definition of art therapy in this review:

-

The procedure includes establishing therapeutic boundaries appropriate for art therapy interventions (such as clarity about the start and finish of therapy and the frequency and length of sessions).

-

The intervention takes places in the presence of a therapist with whom there is an appropriate therapeutic relationship.

-

The intervention includes the therapeutic use of art materials.

-

The description of art therapy is appropriate to the cultural and service context.

Art therapy as a complex intervention

Non-pharmacological treatments such as psychotherapies are often considered to be complex interventions. The key features of complex interventions have been described (Craig et al. 200834) as:

-

having a number of interacting components

-

having a number and difficulty of behaviours required by those delivering or receiving the intervention

-

having a number of groups or organisational levels targeted by the intervention

-

having a number and variability of outcomes

-

requiring a degree of flexibility or tailoring of the intervention permitted (non-standardisation/reproducibility).

Art therapy can be regarded as a complex intervention according to each of these features for the following reasons:

-

Art therapy may often be used in service users with complex clinical presentations who may or may not have responded to several other treatments in mental health services. It is frequently delivered as part of a wider package of treatment and sometimes as a last resort when other treatments have failed.

-

Art therapy is not delivered for any one specific health condition or symptom. It is used in a variety of patient populations. In addition, art therapy is not alone in lacking a clear single definition; psychological therapy more generally is open to heterogeneity through its delivery by different individuals.

-

Art therapy is frequently used in service users with comorbid physical long-term conditions which may actually be their primary health diagnosis. There is no set clinical pathway for who should receive art therapy and at what stage of treatment. Therefore, it is difficult to define or exhaustively list comparators for art therapy.

-

There is currently no standard outcome measure for defining ‘successful’ treatment through art therapy in clinical practice.

-

Art therapists do not offer a set package but tend to tailor the course of treatment, as well as each individual session, to the client.

Thus, confidence in building a coherent network of evidence for a mixed treatment comparison that would contain all possible comparators, comparable study designs and homogeneous participants was low. The use of substantial resources to construct a comparison with potentially low internal validity, in terms of the relative dearth of relevant art therapy evidence, was not deemed appropriate.

Non-psychotic mental health population: definition

The population under consideration is people undergoing treatment for mental health symptoms that do not include psychosis. However, one of the complexities of this population is that not everyone who is being treated for mental health symptoms has a mental health diagnosis. The target population can be described as:

-

Mainstream mental health clinical samples with or without formal diagnoses.

The primary health diagnosis for many people who are service users in mental health may be for a long-term physical health condition or illness that impacts on their mental health. A second group who are also relevant to the research question can be defined as the study population:

-

b(i) Reversible or fluctuating physical conditions where the treatment goals of art therapy include reduction of mental health symptoms (such as depression, anxiety or trauma) as demonstrated by the outcome measures used.

In addition, service users may be in receipt of mental health services for conditions where the primary goal of treatment cannot be considered solely as ‘recovery’ from symptoms, but may be to cope with the symptoms of chronic conditions such as dementia. Therefore, a third group which can also be regarded as relevant to the research question can be defined as the study population:

-

b(ii) Irreversible AND/OR deteriorating physical conditions for which mental health outcomes (such as reduction in depression, anxiety or trauma symptoms) were explicitly targeted and measured.

The use of a more flexible definition for the population, while unconventional in the majority of health technology assessments, is employed here in order to ensure that, while adhering to the research question, the review is also providing a complete picture of the literature relevant to the research question.

Positive outcomes and ‘success’ in mental health treatment

In the field of mental health there is a movement to accept the term ‘recovery’ rather than ‘cure’. This is because recovery can be seen as an ongoing experience which may not be comparable to end points in pharmacological trials. The term ‘recovery’ accommodates the concept that the journey of transitioning from a negative mental health state may be non-linear and may include setbacks as well as progress. 21,35 Essential elements of the recovery approach are reported to be those that facilitate the rebuilding of a meaningful life despite the continuing presence of mental health problems. 36

In addition, the measurement of recovery from a mental health disorder requires the use of a user-validated outcome measure. 37,38 In this sense, the majority of service users would need to agree that the measure makes sense and evaluates human factors that are important to them. Crucially, the outcome measure selected to evaluate treatment needs to be valid, reliable and sensitive to change over time. Mental health disorders can be chronic, recurring and multistage, and it is important that formal evaluation of mental health states is able to capture these complexities.

Time points for measuring recovery should also receive consideration. Individual differences may account for some variation in response to treatment but programmes of psychological treatment themselves vary in duration and frequency. Interventions may or may not be tailored to the individual service user according to service provision. Measurement of patient response to treatment using long-term follow-up, as well as within the time period of the intervention, are essential to determine sustained benefit of psychological interventions.

Research questions addressed in this review

-

What is the evidence that art therapy is clinically effective in people with non-psychotic mental health disorders?

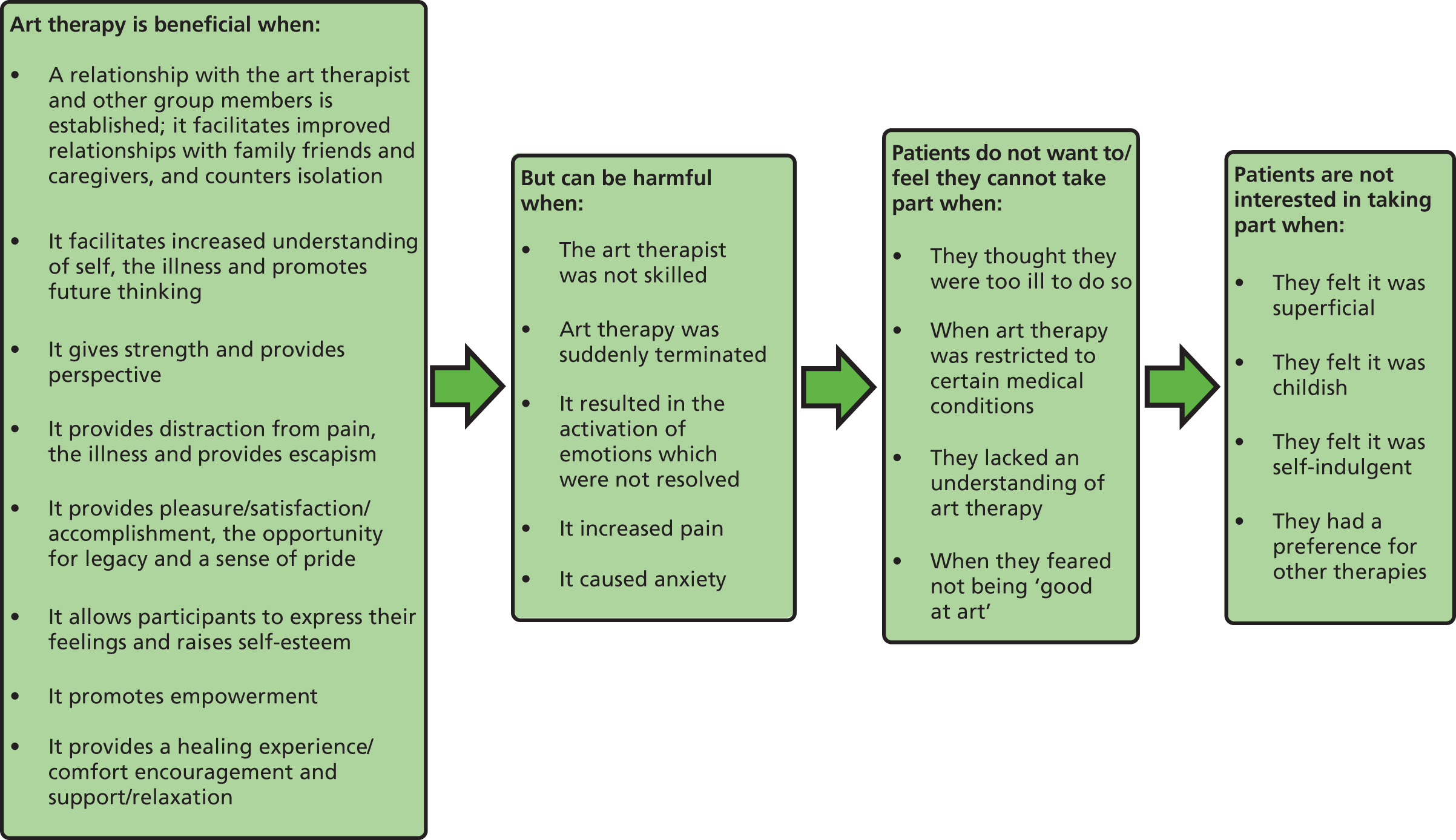

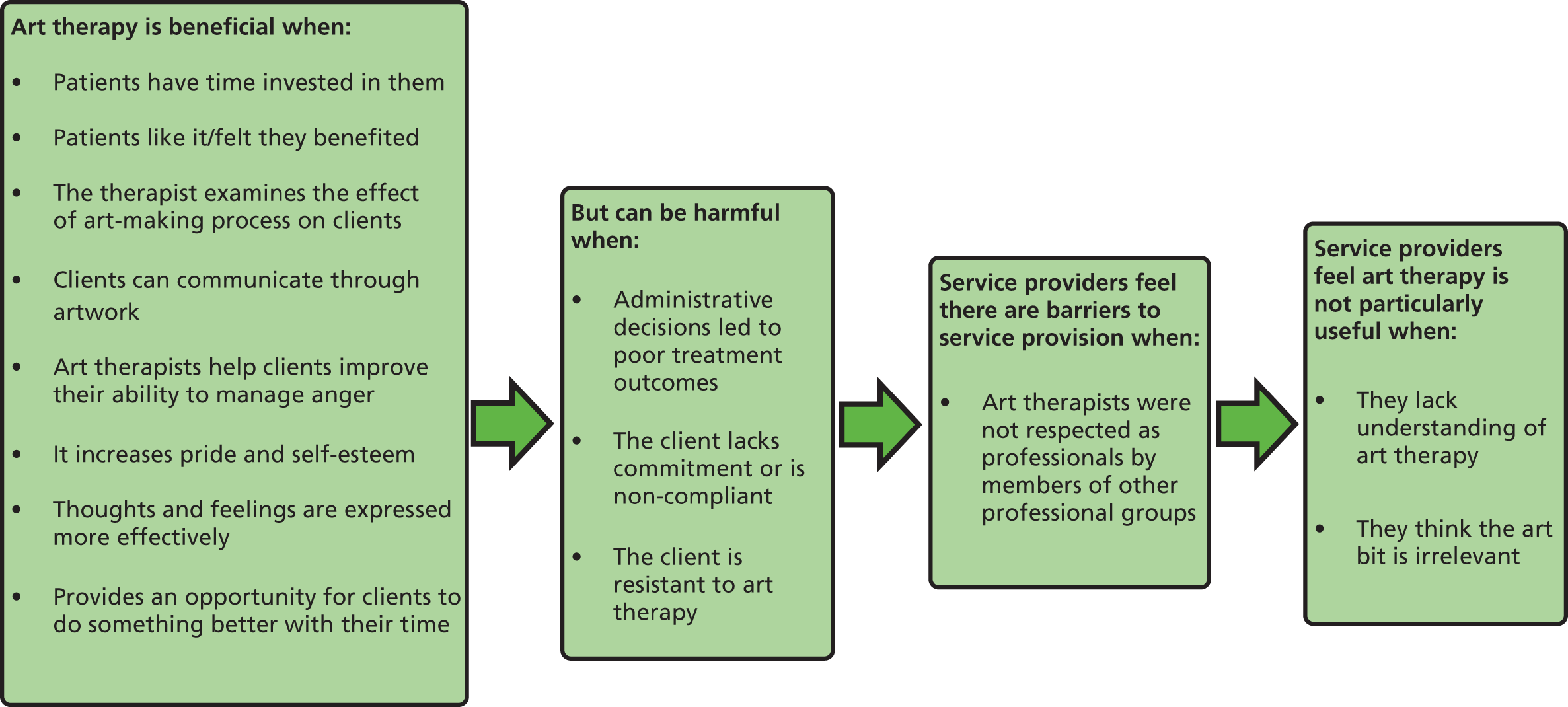

-

What are the user and service provider perspectives on the acceptability and relative benefits and potential harms of art therapy for people with non-psychotic mental disorders?

-

What is the evidence that art therapy is cost-effective in people with non-psychotic mental health disorders?

Chapter 2 Clinical effectiveness of art therapy: quantitative systematic review

This chapter aims to provide an overview of the evidence examining the clinical effectiveness of art therapy in people with non-psychotic mental health disorders.

Literature search methods

Bibliographic database searching

Comprehensive literature searches were used to inform the quantitative, qualitative and cost-effectiveness reviews. A search strategy was developed to identify reviews, RCTs, economic evaluations, qualitative research and all other study types relating to art therapy. Methodological search filters were applied where appropriate. No other search limitations were used and all databases were searched from inception to present. Searches were conducted from May to July 2013. The full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

To ensure that the full breadth of literature for the non-psychotic population was included, it was pragmatic to search for all art therapy studies and then subsequently exclude studies manually (through the sifting process) that were conducted in people with a psychotic disorder or a disorder in which symptoms of psychosis were reported. It is therefore possible for the reviewer to view all potentially relevant records available and manually exclude studies of samples with psychotic disorders. This method of searching through the literature is in contrast to an approach that uses a search strategy listing all possible mental health disorders that are considered to be ‘non-psychotic’ in the search terms. The latter method may not retrieve all relevant studies from populations that are not indexed under the named mental health disorders.

In addition to the range of conditions covered by the population, the evidence from the studies being generated was frequently not a clear-cut diagnosed ‘mental health disorder’ and the populations retrieved were not the clinical populations of common mental health problems that were first anticipated. At this point in the study identification process it would have been easy to exclude any study that did not include patients with a clinically diagnosed mental health disorder. If this approach had been taken, there would have been three studies in the quantitative review. Instead a pragmatic approach was taken by identifying, including and describing the populations that art therapy is being studied in, with reference to targeting mental health symptoms (see Chapter 1, Non-psychotic mental health population: definition).

Databases searched

-

MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed citations (OvidSP).

-

EMBASE (OvidSP).

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (The Cochrane Library).

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library).

-

Database of Abstracts of Review of Effects (The Cochrane Library).

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (The Cochrane Library).

-

Health Technology Assessment Database (The Cochrane Library).

-

Science Citation Index (Web of Science via Web of Knowledge).

-

Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science via Web of Knowledge).

-

CINAHL: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (EBSCOhost).

-

PsycINFO (OvidSP).

-

AMED: Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (OvidSP).

-

ASSIA: Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest).

Sensitive keyword strategies using free-text and, where available, thesaurus terms using Boolean operators and database-specific syntax were developed to search the electronic databases. Date limits or language restrictions were not used on any database. All resources were searched from inception to May 2013.

Grey literature searching

A number of sources were searched to identify any relevant grey literature. Relevant grey literature or unpublished evidence would include reports and dissertations that report sufficient details of the methods and results of the study to permit quality assessment. Conference proceedings without a corresponding final report (published or unpublished) would not qualify for inclusion, as they are unlikely to contain sufficient information to permit quality assessment and can often be different to results published in the final report. 39,40

Sources searched

-

NHS Evidence (Guidelines): www.evidence.nhs.uk/.

-

The BAAT: www.baat.org/index.html.

-

UK Clinical Research Network Portfolio Database: public.ukcrn.org.uk/Search/Portfolio.aspx.

-

National Research Register Archive: www.nihr.ac.uk/Pages/NRRArchive.aspx.

-

Current Controlled Trials: www.controlled-trials.com/.

-

OpenGrey: www.opengrey.eu/.

-

Google Scholar: scholar.google.co.uk/.

-

Mind: www.mind.org.uk/.

-

International Art Therapy Organisation: www.internationalarttherapy.org/.

-

National Coalition of Arts Therapies Associations: www.nccata.org/.

Additional search methods

A hand search of the International Journal of Art Therapy (formerly Inscape) was conducted. The additional search methods of reference list checking and citation searching of the included studies were utilised. Other complementary search methods were considered such as pearl growing; however, because the search method employed was considered to be very inclusive, such additional methods were unlikely to generate additional relevant records.

Review methods

Screening and eligibility

The operational sifting criteria (eligibility criteria) were defined and verified by two reviewers (LU and AS). Titles and abstracts of all records generated from the searches were scrutinised by one assessor and checked by a second assessor to identify studies for possible inclusion into the quantitative review. All studies identified for inclusion at abstract stage were obtained in full text for more detailed appraisal. Non-English studies were translated and included if relevant. For conference abstracts or clinical trial records without study data, authors were contacted via e-mail; however, no additional data were retrieved by contacting study authors. There was no exclusion on the basis of quality. If closer assessment of studies at full text indicated that eligible studies were not RCTs, then the studies were excluded. Agreement on inclusion, for 20% of the total search results (n = 2015), was calculated at title/abstract sift demonstrating 0.93 agreement using the kappa statistic. If there was uncertainty regarding the inclusion of a study, the reviewers sought the opinion of the team members with the relevant clinical, methodological or subject expertise to guide the decision.

Accumulation of results

All references were accumulated in a database using Reference Manager Version 12 (Thomson Reuters, Philadelphia, PA, USA), enabling studies to be retrieved in categories by keyword searches and duplicates to be removed.

Study appraisal

Two reviewers (LU and AS) performed data extraction independently for all included papers and discrepancies were resolved by discussion between reviewers. When necessary, authors of the studies were contacted for further information. Data were input into a data extraction template using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which was designed for the purpose of this review and verified by two reviewers. Information related to study population, sample size, intervention, comparators, potential biases in the conduct of the trial, outcomes including adverse events, follow-up and methods of statistical analysis was abstracted from the published papers directly into the electronic data extraction spreadsheet.

The evidence generated from the comprehensive searches highlighted that the majority of research in art therapy is conducted by or with art therapists. This indicates potential researcher allegiance towards the intervention in that art therapists are likely to have a vested interest in the output of the study. For this reason it was deemed important to focus on the highest quality evidence available from the study literature. Trials that were non-randomised (i.e. in which the researcher was able to select and allocate participants to treatment arms) were considered to be too low in methodological rigour to be included in this review. The consequence of including data from non-randomised studies into the review is that the resulting data are biased and therefore not robust or sufficient to inform and contribute to the evidence base. 41,42 The inclusion and exclusion criteria for the quantitative review are shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Eligibility criteria for the quantitative review.

Setting

Studies could be conducted in any setting, including primary, secondary, community based or inpatient.

Sessions

Study selection was not limited by the number of sessions, and studies that provided the intervention in a single session were included.

Timing of outcome assessment

Post-treatment outcomes and outcomes at reported follow-up points were extracted and summarised when reported.

Quality assessment strategy

Quality assessment of included RCTs was performed for all studies independently by two reviewers using quality assessment criteria adapted from the Cochrane risk of bias,44 Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidance45 and Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP)46 checklists to develop a modified tool for the purpose of this review. The modified tool was developed to incorporate relevant elements across several tools to allow comprehensive and relevant quality assessment for the included trials. Judgements and corresponding reasons for judgements for each quality criterion for all studies were stated explicitly and recorded. Risk of bias was assessed to be low, high or unclear. Where insufficient details were reported to make a judgement, risk of bias was stated to be unclear and authors were not contacted for further details. Discrepancies in judgements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers.

Results of the quantitative review

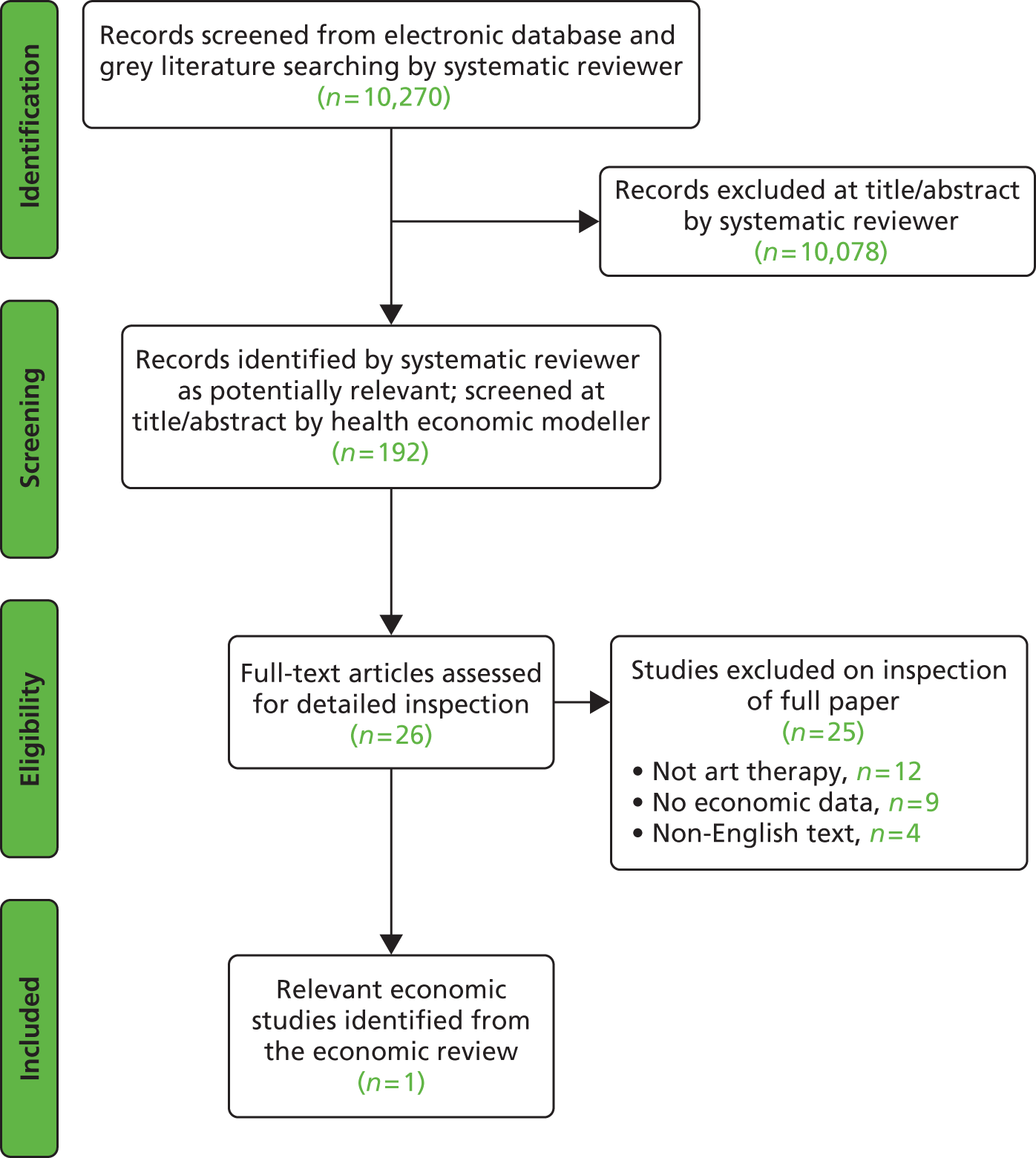

The total number of published articles yielded from electronic database searches after duplicates were removed was 10,073 (see Figure 3). An additional 197 records were identified from supplementary searches, resulting in a total of 10,270 records for screening. Of these, 10,221 records were excluded at title/abstract screening. Common reasons for exclusion from the review can be seen in Table 1. A full list of the studies excluded from the quantitative review at full text stage (with reasons for exclusion) can be found in Appendix 3.

FIGURE 3.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram of studies included in the quantitative review.

| Common reasons for exclusion | Examples |

|---|---|

| Not art therapy | Arts-based initiatives not adhering to art therapy definition (see Art therapy as a clinical intervention: definition), antiretroviral therapy |

| Not a RCT | Before-and-after study, no control group, no randomisation |

| Psychotic disorder | Patients with schizophrenia or psychosis |

| Arts therapies | Combination of therapies without individual results for art therapy |

| No study data | Abstract without data and no response from author contact, studies which focused on the artwork itself and did not measure health outcomes |

The grey literature searches yielded very few potentially relevant records that were not generated by the electronic searches. One record appeared highly relevant to the research question and related to a clinical trial record of and RCT of art therapy in personality disorder (CREATe) for which the status was ‘ongoing’. However, e-mail contact with the primary investigator of this trial confirmed that the trial had been terminated because of poor recruitment.

Included studies: quantitative review

Fifteen RCTs were identified for inclusion into the review which were reported in 18 sources (see Table 2). For clarity in this comparison, where a study with multiple sources is discussed only one of the sources has been noted.

| Study author and year | Journal/publication | Country | n | Patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target population | ||||

| Chapman et al. 200149 | Art therapy | USA | 85a | Children with PTSD |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 | Art therapy | USA | 29 | Adolescents with PTSD |

| Thyme et al. 200747 | Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy | Sweden | 39 | Depressed female adults |

| Study population | ||||

| Beebe et al. 201058 | Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology | USA | 22 | Children with asthma |

| Broome et al. 200150 | Journal of National Black Nurses’ Association | USA | 97a | Children (n = 65) and adolescents (n = 32) with sickle cell disease |

| Gussak 200759 | International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology | USA | 44a | Incarcerated males |

| Hattori et al. 201151 | Geriatrics and Gerontology International | Japan | 39 | Patients with Alzheimer’s disease |

| Kim 201352 | The Arts in Psychotherapy | Korea | 50 | Non-clinical older adults (no formal mental health diagnosis) |

| McCaffrey et al. 201153 | Research in Gerontological Nursing | USA | 39 | Older adults |

| Monti and Peterson 200460 | Psychiatric Times | USA | 111a | Women with cancer |

| Monti et al. 200661 | Psycho-Oncology | |||

| Monti et al. 201254 | Stress and Health | USA | 18 | Women with breast cancer (no clinical mental health problem) |

| Puig et al. 200655 | The Arts in Psychotherapy | USA | 39 | Women with breast cancer |

| Rao et al. 200956 | AIDS Care | USA | 79a | Adults with HIV/AIDS |

| Rusted et al. 200657 | Group Analysis | UK | 45a | Patients with dementia |

| Thyme et al. 200962 | Palliative and Supportive Care | Sweden | 41 | Women with breast cancer |

| Svensk et al. 200963 | European Journal of Cancer Care | |||

| Oster et al. 200664 | Palliative and Supportive Care | |||

Ten out of the 15 included studies were conducted in the USA, while only one study was conducted in the UK (see Tables 2 and 3). Eleven of the studies were conducted in adults (who are the primary focus of this review) and four were conducted in children. All trials had small final sample sizes with the number of participants reported to be included in each study ranging between 18 and 111. The mean sample size was 52.

| Study type | Comparator | Study | Control group description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-active control | Treatment as usual | Chapman et al. 200149 | Standard hospital careb |

| Gussak 200759 | No treatment | ||

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | No art therapy | ||

| Wait-list | Beebe et al. 201058 | Crossover not reported | |

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | Control offered crossover at 9 weeks | ||

| Puig et al. 200655 | Control offered crossover at 4 weeks | ||

| Active control | Attention placebo | aBroome et al. 200150 | Fun activities |

| Hattori et al. 201151 | Simple calculations | ||

| Kim 201352 | Regular programme activities | ||

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 | Arts and craft activities | ||

| McCaffrey et al. 201153 | Guided garden walking | ||

| Monti et al. 201254 | Educational support group | ||

| Rao et al. 200956 | Video tape on use of art therapy | ||

| Rusted et al. 200657 | Activity group | ||

| Psychological therapy | aBroome et al. 200150 | CBT relation for pain | |

| Thyme et al. 200947 | Verbal dynamic psychotherapy |

Three studies are of patients from the target population of people with non-psychotic mental disorders. 47–49 Of these three studies, only one was conducted in adults. 47

In the remaining 12 studies, the study population comprised individuals without a formal mental health diagnosis. 49–59,61,62 The populations in these studies are, therefore, mainly people with long-term medical conditions which are not reported to be accompanied by a mental health diagnosis; however, outcomes targeted in these studies were mental health symptoms.

The total number of patients in the included studies is 777. Nine studies compared art therapy with an active control group and six studies compared art therapy with a wait-list control or treatment as usual.

Two studies were reported to be conducted in an inpatient setting48,49 and one study was conducted in prison. 59 The majority of studies were conducted in community/outpatient setting, although the precise setting for conducting the intervention was not reported in six studies. 50,52,54–56,61

Brief descriptions of the art therapy interventions are provided in Tables 4 and 5.

| Study | Age (years), range (mean) | Duration and type | Art therapy description | Control description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broome et al. 200150 | 6–18 (child, 9.2; adolescent, 15.3) | 4 weeks; group | Opportunity to express feelings about pain and develop social skills through interactions with others using art as a focal point | CBT relaxation for pain; or attention control (fun activities e.g. picnic, museum) for children group only |

| Hattori et al. 201151 | 73–83 (74) | 12 weeks; group (approximately n = 5) session | Primary task to colour abstract patterns, which are unclear before colouring. Encouraged to draw familiar objects based on memories or favourite seasons | Simple calculations (additions and multiplications of one- or two-digit numbers). No preset target; patients completed as many as they could in session |

| Kim 201352 | 69–87 (78) | 4 weeks; group | Introductory 10–15 minutes ‘unfreezing’ phase, followed by 35–40 minutes for individual art-making, 15–20 minutes for group discussion | Regular programme activities such as reading books, playing board games and watching television |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 | 13–17 (15) | 16 weeks; group (approximately n = 2 to 5) session | Completion of 13 > collages or drawings to express a ‘life story’ narrative. Encouraged but not required to discuss dreams, memories and feelings related to their trauma | ‘Treatment as usual’ – arts and craft making activity group |

| McCaffrey et al. 201153 | 65–NR (74) | 6 weeks; NR | Drawing self-portraits; presented to group; create new drawings; display and discuss (art therapy was reported as the control) | The two intervention groups were individual (n = 13) or guided (n = 13) garden walking in the Morikami Museum and Japanese Gardens in Delray Beach |

| Monti et al. 201254 | 52–77 (54) | 8 weeks; group | Mindfulness-based art therapy. Art-making paired with meditation and ways of expressing emotional information in a personally meaningful manner | Educational support group: control given equal time and provided with support and resources to maximise quality of life including expert speakers on topics and time for sharing and supportive exchanges |

| Rao et al. 200956 | 18–NR (42) | Brief (1 session); individual | Art therapist learns about patient and then offers art materials and assures patient they can use them in any way. Therapist helped participant process the meaning of the work and then discussed thoughts and feelings elicited | Viewed a video tape on the uses of art therapy |

| Rusted et al. 200657 | 67–92 (82) | 40 weeks; group (approximately n = 6) | Group-interactive psychodynamic approach | Activity groups: a selection of recreational activities from different centres in the locality |

| Thyme et al. 200947 | 19–35 (34) | 10 weeks; NR | Psychodynamic art therapy. Painting and reflective dialogue between the participant and the therapist | Verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy |

| Study | Age (years), range (mean) | Duration and type | Art therapy description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beebe et al. 201058 | 7–14 (NR) | 7 weeks; group | Included an opening activity; discussion of the weekly topic and art intervention; art-making; opportunity for the parents to share their feelings related to the art they created; and the closing activity |

| Chapman et al. 200149 | 7–17 (10.7) | NR; individual | Chapman Art Therapy Treatment Intervention including drawing; verbal narrative and encouragement to express trauma-specific fears |

| Gussak 200759 | 21–59 (NR) | 8 weeks; group | Asked to draw person picking an apple from a tree and other similar art therapy tasks |

| Monti and Peterson 200460 Monti et al. 200661 |

26–82 (54) | 8 weeks; group | Mindfulness-based art therapy multimodal programme including a standardised mindfulness-based stress reduction curriculum; art therapy tasks and supportive group therapy |

| Puig et al. 200655 | 18-NR (51) | 4 weeks; individual | Semistructured creative experiences using art creation. Creative freedom encouraged in order to facilitate and explore emotional expression, spirituality and psychological well-being state |

| Thyme et al. 200962 Svensk et al. 200963 Oster et al. 200664 |

37–69 (median: 59 and 55) | 5 weeks; individual | Art-making with an art therapist including reflection and expression using verbal and non-verbal methods. Aimed at triggering a chain of feelings and thoughts an important object for communication. Basic idea was to use the participant’s picture as the new mode of expression, followed by a reflective dialogue |

Study duration ranged between the 15 studies from 1 session to 40 sessions, with a mean number of nine sessions (see Tables 4 and 5). Most studies with an active control group were of ‘group’ art therapy. One study which was a ‘brief’ intervention consisting of one individual session per participant. 56 Two studies did not state explicitly if sessions were in a group or individual. 47,53 Three studies with no active control were group art therapy58,59,61 and three studies were individual art therapy. 49,55,62

The symptoms or outcome domains under investigation and associated outcome measures are reported in Table 6.

| Study author and year | Outcome domains investigated | Outcome measures | Time points |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | |||

| Gussak 200759 | Depression | BDI-II | Exact time point post test NR |

| Hattori et al. 201151 | Mood; vitality; behavioural impairment; QoL; ADL; cognitive function | MMSE, WMS-R, GDS; Apathy Scale (Japanese version) SF-8 – Physical and Mental components; Barthel Index; DBD; Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview | 12 weeks |

| Kim et al. 201352 | Positive/negative affect; state-trait anxiety; self-esteem | PANAS; STAI; RSES | NR: assume 4 weeks |

| McCaffrey et al. 201153 | Depression | GDS | 6 weeks |

| Monti 200660,61 | Symptoms of distress including depression, anxiety and quality of life | SCL-90-R, GSI; SF-36 | 8 and 16 weeks |

| Monti et al. 201254 | Correlation of CBF on fMRI with experimental condition | fMRI; CBF; correlation with anxiety using SCL-90-R | Within 2 weeks of end of 8-week programme |

| Puig et al. 200655 | Mood symptoms including depression and anxiety | POMS; EACS | 4 weeks |

| Rao et al. 200956 | Physical symptoms including pain etc.; anxiety | ESAS; STAI | Immediately following session |

| Rusted et al. 200657 | Depression; mood; sociability and physical involvement | CSDD; MOSES; MMSE; RBMIT; TEA; Benton Fluency Task | 10, 20 and 40 weeks during trial then 44-week and 56-week follow-up |

| Thyme et al. 200747 | Stress reactions after a range of traumatic events; mental health symptoms; depression | IES; SCL-90; BDI; HRSD | 10 weeks and 3 month follow-up |

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | Depression; anxiety; somatic and general symptoms; QoL Coping methods | SASB; GSI; SCL-90; WHOQOL-BREF; EORTC QoL Questionnaire-BR23; CRI | 2 and 6 months |

| Children and adolescents | |||

| Beebe et al. 201058 | QoL; behavioural and emotional adaptation | PedsQL; Asthma module Beck Youth Inventories – Second Edition | 7 weeks and 6 months |

| Broome et al. 200150 | Coping and health care utilisation | SCSI; A-COPE; ER visits; clinic visits; hospital admissions | 4 weeks and 12 months |

| Chapman et al. 200149 | PTSD symptoms | Children’s PTSD-I | 1 week, 1 month and 6 months after discharge |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 | PTSD symptoms | University of California, Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV Child Version; Milieu behavioural measures, e.g. use of restraints | NR: reports (n) for 2 years. Study is ongoing in a further 15 patients |

Data synthesis

Heterogeneity of the included studies

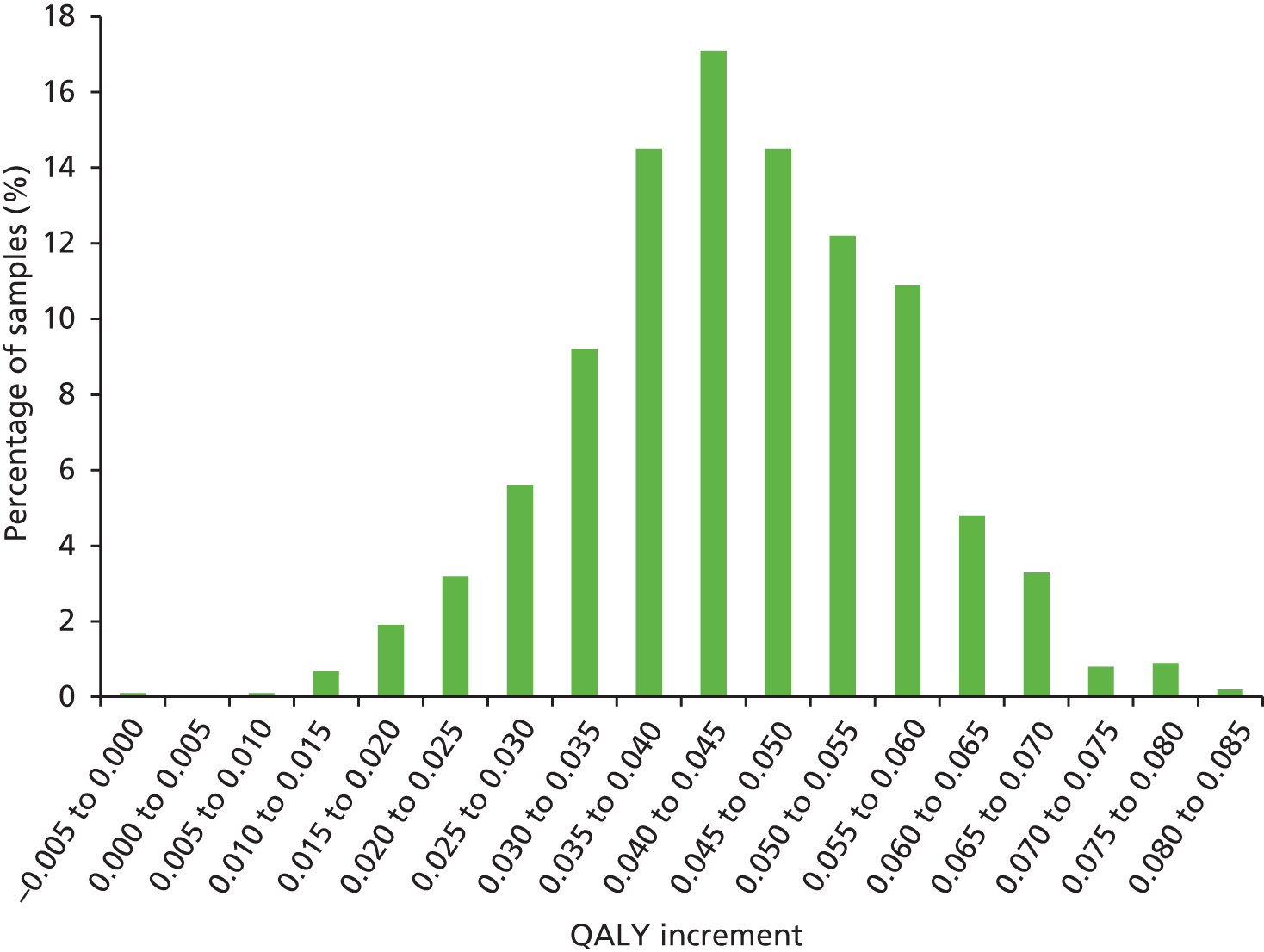

The study populations are heterogeneous (Figure 4), highlighting the wide application of art therapy in this small number of included RCTs but also demonstrating the difficulty in obtaining a pooled estimate of treatment effect. In this respect the clinical profile of patients can be regarded as a potential treatment effect modifier.

FIGURE 4.

Patient clinical profiles in the 15 included RCTs.

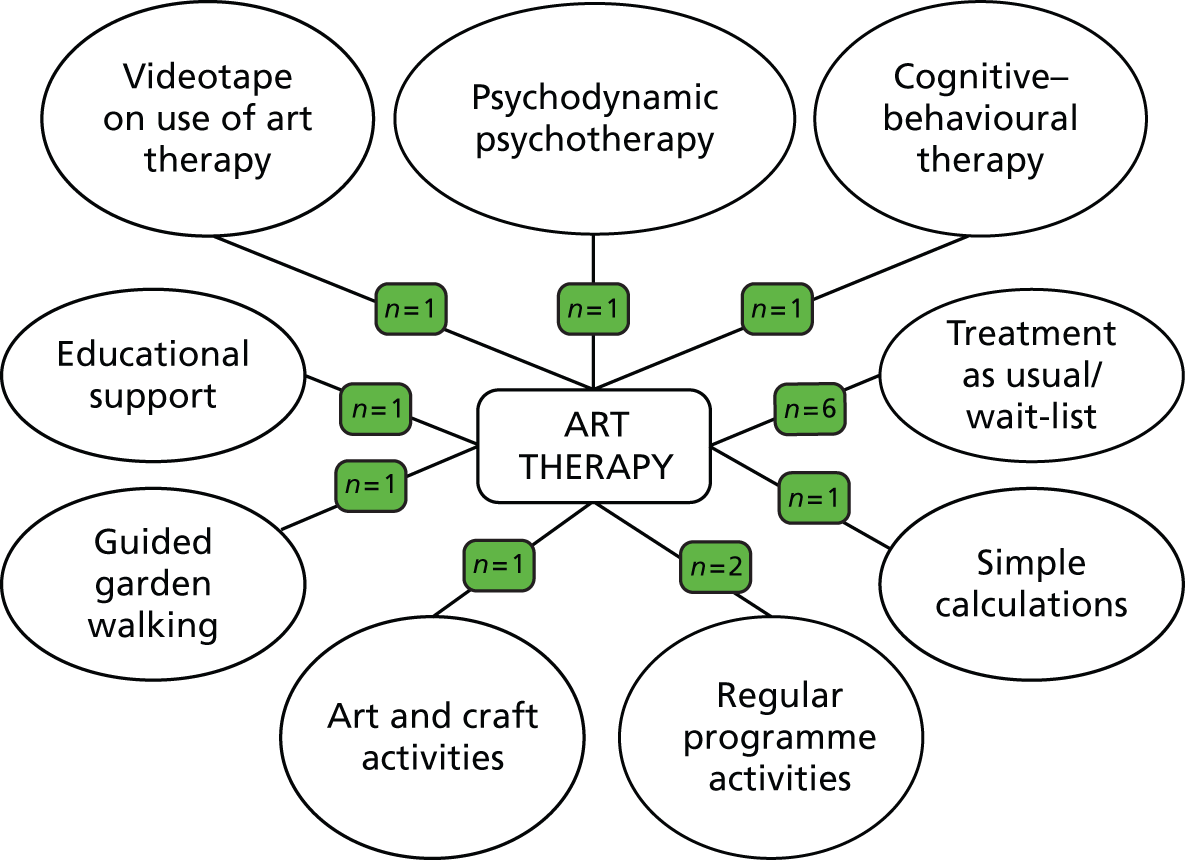

The control groups across the included studies are heterogeneous (Figure 5); therefore, there may be different estimates of treatment effects depending on what art therapy is compared against. Creating a network meta-analysis, which would incorporate all relevant evidence for all the comparators, for all non-psychotic mental health disorders, would be beyond the remit for this research project.

FIGURE 5.

Comparator arms in the 15 included RCTs.

In addition, despite common mental health symptoms being investigated across the included RCTs, the majority of studies were using different measurement scales to assess these outcomes (Table 7). Therefore, as there are insufficient comparable data on outcome measure across studies, it is not possible to perform a formal pooled analysis.

| Outcome measure | n studies | Study names |

|---|---|---|

| SCL-90-R | 4 | Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 |

| Monti et al. 201254 | ||

| Thyme et al. 200747 | ||

| Thyme et al. 200962 | ||

| GDS | 2 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| McCaffrey et al. 53 | ||

| GSI | 2 | Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 2006;61 aThyme et al. 200962 |

| STAI | 2 | Rao et al. 201156 |

| Kim 201352 | ||

| A-COPE | 1 | Broome et al. 200150 |

| Apathy Scale (Japanese version) | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| Barthel Index | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| BDI | 1 | Thyme et al. 200747 |

| BDI-II | 1 | Gussak 200759 |

| Beck Youth Inventories – Second Edition | 1 | Beebe et al. 201058 |

| Benton Fluency Task | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

| Children’s PTSD-I | 1 | Chapman et al. 200149 |

| CRI | 1 | aOster et al. 200664 |

| CSDD | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

| DBD | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| ESAS | 1 | Rao et al. 200956 |

| EORTC QoL Questionnaire-BR23 | 1 | aSvensk et al. 200963 |

| ER visits; clinic visits; hospital admissions | 1 | Broome et al. 50 |

| HRSD | 1 | Thyme et al. 200747 |

| IES | 1 | Thyme et al. 200747 |

| Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 | 1 | Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 |

| MMSE | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| MOSES | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

| PedsQL Asthma module | 1 | Beebe et al. 201058 |

| PANAS | 1 | Kim 201352 |

| POMS | 1 | Puig et al. 200655 |

| RBMIT | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

| RSES | 1 | Kim 201352 |

| SCSI | 1 | Broome et al. 200150 |

| SF-8 – Physical (PCS-8) and Mental (MCS-8) | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| SASB | 1 | aThyme et al. 200962 |

| TEA | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

| University of California, Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index for DSM-IV Child Version | 1 | Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 |

| WMS-R | 1 | Hattori et al. 201151 |

| WHOQOL-BREF | 1 | aSvensk et al. 200963 |

Potential treatment effect modifiers in the included studies

As well as the patient’s clinical profile, several other treatment effect modifiers can be identified from the included studies.

Experience/qualification of the art therapist

Twelve of the 15 included studies stated that the art therapy was delivered by one or more art therapists. One study was reported in three sources to use a ‘trained’ art therapist. 62–64 One study reported the art therapist as ‘licensed’. 56 Two studies reported using a ‘qualified’ art therapist. 48,57 Two studies reported using a ‘certified’ art therapist. 50,53 One study was reported in two sources as using a ‘registered’ art therapist. 60,61 One study reported using ‘experienced art psychotherapists’. 47 Four studies simply stated ‘art therapist’ without reference to accreditation. 49,52,58,59 One study stated that the sessions were run by one artist and two speech therapists. 51 One study stated that the sessions were run by two mental health counsellors. 55 One study did not state whether or not an art therapist was involved. 54 While there was considerable variability in the reporting of the accreditation of the therapist, most studies were conducted by a person who was considered to be qualified as an art therapist.

Individual versus group art therapy

The majority of RCTs are of group art therapy with only 4 of the 15 RCTs examining individual art therapy. 49,55,56,62

Gender

Five RCTs involved only women,47,54,55,61,62 and one RCT only men. 59 In the remaining nine RCTs the subjects were of mixed gender.

Pre-existing physical condition

In nine studies patients had pre-existing physical conditions. 50,51,54–58,61,62 The remaining six studies involved people who were depressed,47,59 people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)48,49 or older people. 52,53

Other

Other potential treatment effect modifiers which are not fully explored in the included RCTs include duration of disease (mental or physical), underlying reason for mental health disorder and patient preference for art therapy.

Owing to the degree of clinical heterogeneity across the studies and the lack of comparable data on outcome measures, meta-analysis was not appropriate. Therefore, the synthesis of data is limited to a narrative review to analyse the robustness of the data, which includes trial summaries as well as tabulation of results.

Study summaries

This section provides short overviews of each study with reference to statistically significant differences between groups that were reported in each of the studies.

Beebe et al. 201058

This was a RCT in children (n = 22) with asthma of art therapy versus wait-list control. Sessions lasting 60 minutes were provided once a week for seven weeks. Outcomes were measured at baseline, immediately following completion of therapy and 6 months after the final session. Targeted variables were quality of life (QoL) and behavioural and emotional adaptation. Outcome measurement tools were the Paediatric QoL asthma module and Beck Youth Inventories. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Dunnett’s test. Compared with baseline scores, the intervention group showed a significant reduction in 4 out of 10 QoL items at 7 weeks and in 2 out of 10 QoL items at 6 months. Significant improvement relative to the control group was found in two out of five items of the Beck Youth Inventory at 7 weeks and in one out of five items at 6 months.

Broome et al. 200150

This was a three-arm RCT in children and adolescents (n = 97) with sickle cell disease of art therapy versus CBT (relaxation for pain) or attention control (fun activities). Group sessions were provided over 4 weeks. Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 4 weeks and 12 months. The targeted variable was coping and the authors hypothesised that coping strategies would increase after attending a self-care intervention. Outcome measures were the Schoolagers’ Coping Strategies Inventory and Adolescent Coping Orientation for Problem Experiences scores and numbers of emergency room visits, clinic visits and hospital admissions. The number of coping strategies used was analysed at three time points using Pearson’s correlations, independent t-tests and ANOVA. Coping strategies increased in children and adolescents in all three groups, but data regarding the difference between the intervention and control groups were not reported.

Chapman et al. 200149

This RCT of brief art therapy versus treatment as usual was carried out in children (n = 85) hospitalised with PTSD. A 1-hour individual session was provided but the number of sessions was not reported. Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 1 week, 1 month, and 6 and 12 months (in children who were still symptomatic). The targeted symptom was PTSD. The outcome measurement tool was Children’s Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Index (PTSD-I). The method of statistical analysis was not described. No significant differences were found between groups, but a non-significant trend towards greater reduction in PTSD-I scores was observed in the intervention group relative to the control group.

Gussak 200759

This was a RCT in incarcerated adult males (n = 44) of art therapy versus no treatment. Eight weekly group sessions were provided. Outcomes were measured pre- and post-test (exact time points not reported). The targeted symptom was depression. The outcome measure was the Beck Depression Inventory-Short Form (BDI-II). The change in BDI-II scores from pre-test to post test was calculated and differences between groups analysed using independent-samples t-tests. Depression was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group post test.

Hattori et al. 201151

This was a RCT in Alzheimer disease (n = 39) of art therapy versus a ‘simple calculation’ control group. Twelve 45-minute weekly sessions were provided (individual/group not reported). Outcomes were measured at baseline and at 12 weeks. Targeted variables were mood, vitality, behavioural impairment, QoL, activities of daily living and cognitive function. Outcome measures were the Mini Mental State Examination Score (MMSE), the Wechsler Memory Scale revised; the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS); the Apathy Scale (Japanese version); Short Form questionnaire-8 items (SF-8) – Physical (PCS-8) and Mental (MCS-8) components; the Barthel Index; the Dementia Behaviour Disturbance Scale; and the Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview. Outcomes were measured at baseline and 12 weeks. The percentage of responders who showed a 10% or greater improvement relative to baseline score before the intervention was compared between groups using a chi-squared test. A significant improvement in the intervention group was seen in MCS-8 subscale of the SF-8 and the Apathy Scale. The control group showed a significant improvement in MMSE relative to the intervention group. No significant differences between groups in other items were reported.

Kim 201352

This RCT in older adults (n = 50) compared art therapy with regular programme activities. Between 8 and 12 sessions lasting 60–75 minutes were provided over 4 weeks. Targeted variables were positive/negative affect, state–trait anxiety and self-esteem. Outcomes were measured using the Positive & Negative Affect Schedule, the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Time points for measurement were not reported (assumed 4 weeks). Independent group t-tests were performed to compare pre- and post-test scores between groups. Significant improvements in the intervention were seen in all three outcomes compared with the control group.

Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748

This RCT in adolescents (n = 29) with PTSD compared art therapy with arts and crafts activities. Sixteen weekly group sessions were provided. The targeted symptom was PTSD. Outcome measurement tools were the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) PTSD Reaction Index (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders – Fourth Edition, Child Version) (primary measure) and milieu behavioural measures (e.g. use of restraints). Measurement time points were not reported, but data at two years were provided. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using repeated-measures ANOVA. The intervention was significantly better than control at reducing PTSD symptoms, according to the UCLA PTSD Reaction Index.

McCaffrey et al. 201153

This was a RCT in older adults (n = 39) of art therapy versus garden walking (individual and group). Twelve 60-minute sessions (group/individual not reported) were provided over 6 weeks. The targeted symptom was depression. The outcome measurement tool was the GDS. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using repeated-measures ANOVA. Measurement was at baseline and 6 weeks. Depression significantly improved from baseline in all three groups with no significant differences between groups.

Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661

This RCT in women with cancer (n = 111) compared mindfulness-based art therapy with wait-list control. The trial was sized to have 80% power to detect a standardised effect size of 0.62. Eight 150-minute group sessions were provided over 8 weeks. Targeted variables were distress, depression, anxiety and QoL. Outcome measurement tools were the Symptom Checklist-90-Revised (SCL-90-R), the Global Severity Index (GSI) and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). Measurement was at baseline and at 8 weeks and 16 weeks. Pre-and post-test measures were compared between groups using mixed-effects repeated-measures ANOVA. A significant decrease in symptoms of distress and highly significant improvements in some areas of the QoL scale were observed in the intervention group compared with the control group.

Monti et al. 201254

This RCT of women with breast cancer (n = 18) compared mindfulness-based art therapy with educational support (control group). Eight 150-minute weekly group sessions were provided. The targeted symptom was anxiety but the authors were interested in whether or not cerebral blood flow (CBF) correlated with experimental condition. The primary outcome measurement was functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) CBF and the correlation with anxiety using SCL-90-R. Measurement was at baseline and within 2 weeks of the end of the 8-week programme. The method of statistical analysis was not described and the effectiveness of the intervention was not the primary outcome. Anxiety was reduced in the intervention group but not in the control group. CBF on fMRI changed in certain brain areas in the art therapy group only. It should be noted that patients with a confirmed diagnosis of a psychiatric disorder were excluded from this study.

Puig et al. 200655

This was a RCT in women with breast cancer (n = 39) of art therapy versus delayed treatment. Four 60-minute weekly sessions were provided. Targeted symptoms were anger, confusion, depression, fatigue, anxiety, activity and coping. The outcomes, the Profile of Mood States and the Emotional Approach Coping Scale (EACS) scores, were measured before and 2 weeks after the intervention. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using ANOVA. The intervention group showed significant improvements in the anger, confusion, depression and anxiety mood states but fatigue and activity were not significantly different between the groups. In the intervention group, EACS coping scores increased, but were not significantly different from those in the delayed treatment control group.

Rao et al. 200956

In this RCT in adults with HIV/AIDS (n = 79), the intervention group received brief art therapy while the controls watched a video tape on the uses of art therapy. Only one 60-minute session of individual art therapy was provided. Targeted symptoms were anxiety and physical symptoms, including pain. The outcome measures used were Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale (ESAS) scores (primary outcome) and STAI scores. Pre-and post-test scores were compared between groups using analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) and adjusted for age, gender and ethnicity. Measurements were recorded before and immediately after the intervention or control session. The intervention group experienced significant improvements in physical symptoms (ESAS) compared with the control group, but anxiety was not significantly different between the groups.

Rusted et al. 200657

In this RCT in adults with dementia (n = 45), art therapy was compared with an activity group control. Forty 60-minute weekly group sessions were provided. Targeted symptoms were depression, mood, sociability and physical involvement. Outcome measures were the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia the Multi Observational Scale for the Elderly, MMSE, The Rivermead Behavioural Memory Test, Tests of Everyday Attention and the Benton Fluency Task. Measurements were recorded at baseline, 10 weeks, 20 weeks, 40 weeks and at follow-up at 44 and 56 weeks. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using ANOVA with time of assessment as repeated measures. At 40 weeks, the intervention group was significantly more depressed than the control group, but this effect was reduced at follow-up. However, groups were not comparable at baseline, as the art therapy group were more depressed at the beginning of the study than the control group.

Thyme et al. 200747

This was a RCT in depressed female adults (n = 39) of psychodynamic art therapy versus verbal dynamic psychotherapy. Ten 60-minute weekly sessions (individual/group not reported) were provided. Targeted symptoms were stress reactions after a range of traumatic events, mental health symptoms and depression. Outcome measurements were Impact of Event Scale, Symptom-Checklist-90 (SCL-90), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) and Hamilton Rating Scale of Depression scores. Measurements were recorded at baseline, at 10 weeks and at a 3-month follow-up. All patients improved from baseline on all scales (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences between groups so art therapy was not significantly different to the comparator at either time point.

Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664

This RCT in women with breast cancer (n = 41) compared art therapy with treatment as usual as a control. Five 60-minute weekly individual session were provided. Targeted symptoms were depression, anxiety, somatic, general symptoms, QoL and coping methods. Outcome measure tools were the Structural Analysis of Social Behavior, the GSI, the SCL-90, the World Health Organization (WHO) QoL instrument – Swedish version, the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) QoL Questionnaire-BR23 and the Coping Resources Inventory (CRI). Measurements were recorded at baseline and at 2 months and 6 months. The intervention significantly improved depressive, anxiety, somatic and general symptoms compared with the control. Pre- and post-test scores were compared between groups using t-tests, ANOVA and linear regression. On the WHOQoL, scores on the overall, general health and environmental domains at 6 months were significantly higher in the intervention group than in the control group. There were no significant differences between groups on the EORTC. In the intervention group, the score on only the ‘social’ dimension of the CRI was increased relative to the control group.

Results

Findings of the included studies

The directions of statistically significant results from the 15 included RCTs are summarised in Table 8.

| Direction of significant findings | n | Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Significant positive effects in all outcome measurements investigated in the art therapy group compared with the control group | 1 | Kim 201352 |

| Significant positive effects in some, but not all, outcome measurements investigated in the art therapy group compared with the control group | 9 | Beebe et al. 201058 |

| Gussak 200759 | ||

| aHattori et al. 201151 | ||

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 | ||

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | ||

| Monti et al. 201254 | ||

| Puig et al. 200655 | ||

| Rao et al. 200956 | ||

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | ||

| Improvement from baseline but no significant difference between groups | 4 | Broome et al. 200150 |

| Chapman et al. 200149 | ||

| McCaffrey et al. 201153 | ||

| Thyme et al. 200747 | ||

| Art therapy worse than comparator at baseline and follow-up | 1 | Rusted et al. 200657 |

As can be seen in Table 8, in 14 of the 15 included studies there were improvements from baseline in some outcomes in the art therapy groups. However, both the intervention and the control groups improved from baseline in four studies, with no significant difference between the groups. 47,49,50,53 The control groups across these four studies were verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy,47 treatment as usual,49 CBT50 and garden walking,53 and verbal psychodynamic psychotherapy, respectively.

In eight studies, art therapy was significantly better than the control group for some but not all outcome measures. Table 9 shows the results according to the mean change from baseline between groups in these eight studies.

| Study and control description | Outcome measures | Mean CFB and ps |

|---|---|---|

| Beebe et al. 201058 Wait-list |

PedsQL Asthma module | Intervention positive reduction in 4 out of 10 QoL items at 7 weeks Between-group means at 7 weeks: QoL – parent total (6.167 vs. –13.091), p = 0.025; QoL – child total (9.727 vs. –13.364), p = 0.0123; QoL – parent worry (47.917 vs. –13.182), p = 0.0144; QoL – child worry (54.545 vs. –45.909), p = 0.0142 Intervention positive reduction in 2 out of 10 at 6 months Between-group means at 6 months: QoL – Parent worry (58.333 vs. –40.909), p = 0.024; QoL – child worry (79.545 vs. –25.000), p = 0.0279 |

| Beck Youth Inventories – Second Edition | Intervention significant reduction in 2 out of 5 items at 7 weeks compared with control Beck – Anxiety (–15.6 vs. 5.3), p = 0.0388, Beck – Self-concept (12.091 vs. –3.545), p = 0.0222 Intervention significant reduction 1/5 at 6 months: Beck – Anxiety (–14 vs. 0.545), p = 0.03 No significant differences for depression component of Beck youth inventory at 7 weeks (p = 0.21) or 6 months (p = 0.29) Baseline means NR |

|

| Gussak 200759 Treatment as usual |

BDI-II | Statistically significantly greater decrease in intervention compared with control: BDI Intervention mean CFB (–7.81) vs. control (+ 1.0), p < 0.05 |

| Hattori et al. 201151 Simple calculations |

SF-8 – PCS-8 and MCS-8 | Intervention significant improvement from baseline in MCS-8 subscale of SF-8 components: percentage of patients showing a ≥10% improvement was compared between groups by chi-squared test. MCS-8 (p = 0.038; odds ratio 5.54) |

| Apathy Scale (Japanese version) | Statistically significant improvement from baseline (p = 0.0014) in Apathy Scale but not significantly different to control: CFB Intervention (–3.2) vs. control (–1.1), p = 0.09 | |

| MMSE | Control group significant improvement in MMSE compared with art therapy intervention: CFB Intervention (–0.02) vs. control (+ 1.1), p < 0.01 | |

| WMS-R; GDS; Barthel Index; DBD; Zarit Caregiver Burden Interview | No significant differences in other items | |

| Lyshak-Stelzer et al. 200748 Arts and craft |

University of California, Los Angeles PTSD Reaction Index (DSM-IV Child Version) | Intervention significantly better at reducing trauma symptoms than control: CFB intervention (–20.8) vs. control (–2.5) p < 0.01 |

| Milieu behavioural measures (e.g. use of restraints) | No significant differences for behavioural milieu | |

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 Wait-list |

GSI | Intervention significantly decreased symptoms of distress and resulted in highly significant improvements in some QoL areas compared with control: intervention (–0.20) vs. control (–0.04), p < 0.001 |

| SCL-90-R | Anxiety, intervention (–0.26) vs. control (–0.10), p = 0.02; depression, intervention (–0.27) vs. control (–0.08), p = 0.01 | |

| Medical Outcomes Study SF-36 | SF-36: general health intervention (7.97) vs. control (–0.59), p = 0.008; mental health intervention (13.05) vs. control (2.16), p < 0.001 | |

| Monti et al. 201254 Educational support group |

SCL-90-R | Anxiety reduced in intervention but not control group: SCL-90-R decrease in intervention (p = 0.03) but not in control (p = 0.09) |

| fMRI CBF and correlation with anxiety using CBF | fMRI changed in certain brain areas in art therapy group only. No changes in control group | |

| Puig et al. 200655 Wait-list |

POMS | ANCOVA showed intervention had significantly decreased symptoms of:

|

| EACS | No significant differences for coping | |

| Rao et al. 200956 Video-tape on the uses of art therapy |

ESAS | Intervention significantly better for physical symptoms (ESAS) than control: adjusted ESAS total score (21.1 vs. 26.2), p < 0.05 |

| STAI | Not significantly different for anxiety | |

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 Treatment as usual |

General | Intervention significantly improved depressive, anxiety, somatic and general symptoms compared with no significant improvements in control |

| SCL-90 | Depression, intervention (–0.37) vs. control (–0.15), p = 0.002; anxiety, intervention (–0.26) vs. control (–0.09), p = 0.009 | |

| SASB | Intervention (–0.14) vs. control (–0.03), p = 0.049 | |

| GSI | Intervention (–0.16) vs. control (–0.05), p =0.005 | |

| WHOQOL-BREF | Intervention significantly improved WHOQoL overall and on the general health and environmental domains vs. control at 6 months WHOQoL CFB: overall Intervention (+10) vs. control (–5.12), p = 0.003; general health intervention (+ 13.75) vs. control (–4.52), p = 0.024; environment intervention (–0.35) vs. control (–2.1), p = 0.034 |

|

| CRI | Intervention significantly improved only the ‘social’ domain, out of five possible domains, for coping resources compared with control (p < 0.05 at 2 and 6 months) | |

| EORTC QoL Questionnaire-BR23 | No significant differences between groups |

In one study,52 all outcomes were significantly better in the art therapy intervention group than in the control group. Table 10 shows the results from the Kim52 study.

| Study and control description | Outcome measures | Results |

|---|---|---|

| Kim 201352 Regular programme activities |

General | Significant improvements in all three outcomes in the intervention group compared with control |

| PANAS | CFB: intervention (19.88) vs. control (–5.64), p < 0.01 | |

| STAI | CFB State: intervention (–13.17) vs. control (+3.08), p < 0.01 CFB Trait: intervention (–7.84) vs. control (+2.96), p < 0.01 |

|

| RSES | CFB: intervention (4.24) vs. control (–0.48), p < 0.01 |

In one study57 of a sample of people with dementia, outcomes were worse for the art therapy group than for the control group, which was an activity control group. An unusual pattern of results is presented, including a significant increase in anxious/depressed mood (p < 0.01) at 40 weeks which was not present at the 10- or 20-week time points and dissipated by 44 and 56 weeks. The authors discuss several reasons for this result including the high level of attrition; the reliance on observer ratings in the frail and elderly sample (and subsequent potential impact of observer bias); the increased depression as a response to the sessions ending; and the possibility that art therapy was contraindicated in this sample.

Narrative subgroup analysis of studies by mental health outcome domains

Table 11 presents the results for effectiveness of art therapy across relevant mental health outcome domains.

| Symptom/variable | Art therapy significantly better than control group | Improvement from baseline but no difference between groups | No improvement from baseline/control group better |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (n = 9 studies) | Gussak59 | aBeebe et al.58 | Rusted et al.57 |

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | Hattori et al.51 | ||

| Puig et al.55 | McCaffrey53 | ||

| Thyme et al. 200747 | Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | ||

| Anxiety (n = 7 studies) | aBeebe et al.58 | Rao et al.56 | |

| Kim52 | |||

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | |||

| Monti et al. 201254 | |||

| Puig et al.55 | |||

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | |||

| Mood (n = 4 studies) | Hattori et al.;51 Kim 2013;52 Puig et al.55 | Rusted et al.57 | |

| Trauma (n = 3 studies) | aChapman et al. 2001;49 aLyshak-Stelzer et al.;48 Thyme et al. 200747 | ||

| Distress (n = 3 studies) | Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | Thyme et al. 200747 | |

| Thyme et al. 2009;62 Svensk et al. 2009;63 Oster et al. 200664 | |||

| Quality of life (n = 4 studies) | aBeebe et al.58 | ||

| Hattori et al.51 | |||

| Monti and Peterson 2004;60 Monti et al. 200661 | |||