Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/50/06. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Katherine O’Reilly and Athol Wells have previously been members of the InterMune advisory board for pirfenidone and received payment for research travel expenses only.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Loveman et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Description of underlying health problem

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) is a debilitating respiratory condition for which there is no cure. It is characterised by diffuse scarring (fibrosis) and mild inflammation of the lung tissue, leading to a gradual worsening of lung capacity. IPF is classed as an idiopathic interstitial pneumonia (IIP), which is a group of interstitial lung diseases (ILDs) also known as diffuse parenchymal lung disease. 1 IPF is the most common type of IIP, accounting for over 50% of this category of lung disease. 2

Initially believed to develop as a result of a chronic inflammatory process, the mechanism that results in IPF is now more widely thought to be due to fibrotic processes involving the epithelial alveolar cells. 3 The disease is thought to arise as a result of recurrent injury to epithelial alveolar cells. Many different cells types have been implicated in the development of IPF, including fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, alveolar macrophages and endothelial cells. IPF is a disease characterised by aberrant wound healing in which excessive (and perhaps abnormal) extracellular matrix is deposited in the lung, thereby distorting the architecture and disrupting function. This lung injury and scarring eventually leads to a decline in lung function, which culminates in respiratory failure and death. 4 Shortness of breath on exercise and a chronic dry cough are the prominent symptoms. 1

The natural history of IPF is not fully understood. It is a progressive chronic condition and was once thought to progress at a steady, predictable rate. However, this is often not the case, with many people deteriorating rapidly and others having periods of relative stability in their condition. 2,5 In some individuals, unexpected deterioration can occur with a sudden worsening of symptoms and resultant hypoxaemia (decreased partial pressure of oxygen in blood). 2,5 These episodes are usually without clinically apparent infection or other identifiable cause. Known as ‘acute exacerbations’, these are thought to occur in about 10–15% of cases and are often fatal episodes. 6

Distinguishing IPF from other IIPs can be difficult as presentation can be similar. International consensus statements published in 20007 and 20028 provided guidelines for the definition of IPF following the identification of a new subgroup of ILD, non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), which had a substantially better survival. 1 Prior to the identification of this group, some 20–35% of people diagnosed as IPF would have had NSIP,8 although in older populations the relative likelihood of NSIP may be lower. These guidelines also recognised that the term cryptogenic fibrosing alveolitis (CFA) was synonymous with IPF. 8 Prior to this, in the UK, the term CFA corresponded to a characteristic clinical presentation seen in IPF but common also to other IIPs. 9 In 2011, a joint statement from the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the European Respiratory Society (ERS), the Japanese Respiratory Society and the Latin-American Thoracic Society (hereafter referred to as the ATS/ERS 2011 guideline for ease of reference) provided updated guidance for the diagnosis of IPF (see Diagnosis). 10 No changes to the definition of IPF were made in the 2011 guideline (see below for discussion of diagnostic criteria).

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is known to affect males more than females and in particular affects those in middle age. The disease is uncommon in people < 50 years of age,2,11 and there is a peak prevalence in the eighth decade. Factors associated with the condition, for which there is no known cause, include cigarette smoking, environmental exposure, and possibly infective agents such as influenza, Epstein–Barr virus and hepatitis C. 7 Older age, male gender and smoking are all associated with shorter survival times (see Prognosis and progression). 12

Epidemiology

The epidemiology of IPF is uncertain. Most estimates in the literature are based on populations aged > 55 years and the number of incident cases of IPF appears to be increasing, although the reasons for this are unclear. 11,13 One particular difficulty with estimating the descriptive epidemiology of IPF is due to the use of different case definitions for IPF. Many studies may not use the currently used definition of IPF (based on ATS/ERS 2011 guidelines) and, as such, estimates may include people with other ILDs.

Large-scale population-based assessments of the epidemiology of IPF are limited; however, four published studies have been identified which provide estimates of the incidence and/or prevalence of IPF. Two of these are based on populations in the UK and two on populations in the USA.

Incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

In the UK, two studies have been published using data from The Health Improvement Network (THIN), which is a longitudinal primary care database recorded by general practitioners as part of routine clinical primary care. In the first of these studies, Gribbin and colleagues11 used data from 1991 to November 2004 from 255 general practices, which the authors state represented approximately 25% of general practices that were using the particular primary care software at that time. The study identified 920 people over the age of 40 years who had received their first diagnosis of IPF during the period of study. The study reports that participants with a clinical diagnosis of IPF were included but no definition was provided. The mean age at presentation was 71 years and 62% were male. As seen in Table 1, the overall crude incidence rate was 4.6 [95% confidence interval (CI) 4.3 to 4.9] per 100,000 person-years. Table 1 also shows that the incidence rates were generally higher in men than in women, and incidence also increased with increasing age.

| UK-based | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gribbin et al. 200611 | ||

| Population-based cohort study Population: from 255 general practices 1991 until November 2004 |

||

| Incidence of IPF (95% CI) per 100,000 person-years | ||

| Crude rate | 4.6 (4.3 to 4.9) | |

| Men | 5.69 (5.24 to 6.18) | |

| Women | 3.44 (3.10 to 3.82) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| < 55 | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.67) | |

| 55–64.9 | 7.30 (6.27 to 8.50) | |

| 65–74.9 | 17.06 (15.20 to 19.14) | |

| 75–84.9 | 25.37 (22.67 to 28.40) | |

| ≥ 85 | 22.37 (18.04 to 27.74) | |

| Navaratnam et al. 201113 | ||

| Population-based cohort study Population: from 446 general practices until July 2009 |

||

| Incidence of IPF (95% CI) per 100,000 person-years | ||

| Crude rate | 7.44 (7.12 to 7.77) | |

| Men | 9.46 (8.96 to 9.98) | |

| Women | 5.46 (5.07 to 5.86) | |

| Age (years) | ||

| ≤ 54 | 0.86 (0.75 to 1.00) | |

| 55–59 | 10.48 (9.06 to 12.13) | |

| 60–64 | 20.76 (18.34 to 23.50) | |

| 65–69 | 36.45 (32.99 to 40.27) | |

| 70–74 | 47.57 (43.26 to 52.32) | |

| 75–79 | 47.38 (42.76 to 52.49) | |

| 80–84 | 60.05 (52.47 to 68.73) | |

| > 85 | 34.82 (27.55 to 44.01) | |

| USA-based | ||

| Fernández Pérez et al. 201014 | Broad definitiona | Narrow definitiona |

| Population-based cohort study Population: 128,000 residents; 596 people initially thought to have IPF were screened from Olmsted County, MN, USA, between 1997 and 2005 |

||

| Incidence of IPF (95% CI) per 100,000 person-years | ||

| Age- and sex-adjusted, aged ≥ 50 years | 17.43 (12.42 to 22.44) | 8.8 (5.28 to 12.38) |

| Men, age-adjusted | 24.02 (14.84 to 33.20) | 13.38 (6.51 to 20.24) |

| Women, age-adjusted | 13.43 (7.50 to 19.37) | 6.08 (2.08 to 10.08) |

| Age, men (years) | ||

| 50–59 | 1.64 | 1.64 |

| 60–69 | 21.39 | 10.69 |

| 70–79 | 42.88 | 21.44 |

| ≥ 80 | 66.02 | 41.26 |

| Age, women (years) | ||

| 50–59 | 1.55 | 1.55 |

| 60–69 | 12.44 | 4.98 |

| 70–79 | 36.79 | 16.72 |

| > 80 | 11.78 | 3.93 |

| Raghu et al. 200615 | Broad definitionb | Narrow definitionb |

| Population-based cohort study Population: from US health plan covering 20 states and approximately 3 million people, between 1996 and 2000 |

||

| Incidence of IPF per 100,000 | ||

| Age- and sex-adjusted | 16.3 | 6.8 |

| Age, men (years) | ||

| 18–34 | 2.8 | 0.9 |

| 35–44 | 1.1 | 0.0 |

| 45–54 | 11.4 | 6.2 |

| 55–64 | 35.1 | 12.2 |

| 65–74 | 49.1 | 21.3 |

| ≥ 75 | 97.6 | 38.5 |

| Age, women (years) | ||

| 18–34 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| 35–44 | 5.4 | 4.5 |

| 45–54 | 10.9 | 5.4 |

| 55–64 | 22.6 | 9.9 |

| 65–74 | 36.0 | 16.6 |

| ≥ 75 | 62.2 | 19.5 |

In the most recent study using data from THIN’s database, Navaratnam and colleagues13 estimated incidence rates of IPF from all information available in the database up until July 2009 and including 446 practices. The definition of a diagnosis of IPF was not provided and although authors note that the diagnosis in the data sets has been validated, they also note that it is possible that some cases of other fibrotic lung diseases may be included. Crude annual incidence rates were calculated stratified by sex and age in 5-year age bands over the age of 55 years (see Table 1). After the exclusion of individuals with a variety of comorbidities, the study identified 2074 incident cases during the period of study. This equated to a crude overall incidence rate of 7.44 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 7.12 to 7.77). As in the Gribbin study,11 the authors found that the majority of incident cases were in men (63%) and that incidence also generally increased with age.

Fernández Pérez and colleagues14 undertook a population-based historical cohort study in Olmsted County, MN, USA, between 1997 and 2005. The study used the ATS/ERS 20028 consensus statement for the case definition of IPF, with incidence rates calculated as of the date the patient met the criteria. Two sets of criteria were used: a narrow criterion based on evidence of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) on surgical lung biopsy or a definite pattern on high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT), and a broad criterion based on surgical lung biopsy or a definite or possible pattern on HRCT. The age- and sex-adjusted incidence rate of IPF among residents aged ≥ 50 years using the narrow IPF criterion was 8.8 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 5.28 to 12.38 per 100,000 person-years). Using the broader criterion, the rates were estimated to be 17.43 cases per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 12.42 to 22.44 cases per 100,000 person-years). Incidence rates were directly adjusted for age, or age and sex, using the population structure of white persons in the USA in the year 2000. The incidence rates were seen to be higher in men than in women and also generally higher in the older age categories.

In a registry study using data from a large US health-care claims database (approximately 3 million people in 20 states), Raghu and colleagues15 also estimated incidence of IPF using a narrow and broad base criteria. The broad criteria included all people aged ≥ 18 years, who were eligible for health benefits, and had had at least one medical appointment with an International Classification of Diseases (ICD) code for IPF and no medical appointments with an ICD code for any other ILD. To meet the narrow case definition, the person was required to satisfy the broad criteria and have had at least one surgical lung biopsy. Data analysed were between 1996 and 2000 inclusive. Incidence rates were estimated by combining age- and sex-specific rates from the study with population weights from the US census. In this study, overall incidence rates for those diagnosed in 2000 were estimated to be 16.3 per 100,000 persons using the broad case definition, and 6.8 per 100,000 persons using the narrow case definition. The study demonstrated increasing incidence by age (see Table 1). Similar to other studies, incidence rates were also generally higher in men than in women.

Overall, the estimates suggest an incidence rate in the region of approximately 4.6 to 8.8 per 100,000, although this depends on the definitions of IPF used. 11,13–15

In the two UK-based studies, analyses confirmed that the incidence of IPF had increased over the two time periods studied. In the Gribbin and colleagues11 study, after adjusting for age and sex, the annual increase in incidence of IPF was estimated to be 11% (rate ratio 1.11, 95% CI 1.09 to 1.13; p < 0.0001). In the Navartnam and colleagues13 study, after adjustment for age, sex and health authority, the estimated annual increase in incidence was 5% (rate ratio 1.05, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.06).

Prevalence

The two studies undertaken in the USA also reported estimated prevalence rates. Age- and sex-adjusted prevalence rates among people aged ≥ 50 years in the study undertaken in Olmsted county14 was 27.9 (95% CI 10.4 to 45.4) cases per 100,000 people using the narrow criteria for IPF. For the broad criteria, the estimated prevalence was 63 (95% CI 36.4 to 89.6) cases per 100,000. In the Raghu study,15 using data from a health-care claims database, the prevalence of IPF was estimated to be 42.7 per 100,000 persons using the broad definition, and 14.0 per 100,00 persons using the narrow definition. The prevalence was also seen to increase with age and was generally higher in men than in women in this study. Overall estimates suggest prevalence of between 14 and 30 per 100,000 persons when using a narrow definition for IPF. 14,15

Mortality

Mortality rates were presented from the two UK studies using data from THIN’s primary care database. 11,13 In the Navaratnam and colleagues13 study, data were also analysed from routine mortality data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) derived from death certificates in England and Wales between 1968 and 2008 and applied to the 2008 population. In the database cohort, the crude mortality rate was 228.8 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 193.8 to 216.7 per 1000 person-years). From the routine mortality data, the overall mortality rate standardised to the 2008 UK population over this period of time was 2.54 per 100,000 person-years (95% CI 2.52 to 2.56 per 100,000 person-years). In the Gribbin study,11 the crude mortality rate for people with IPF in THIN’s database cohort was 180 per 1000 person-years (95% CI 164 to 198 per 1000 person-years). In both studies mortality rates were higher in men and in older populations.

Prognosis and progression

The prognosis for individuals with IPF is poor. 2 Mean survival with IPF is generally estimated to be between 2 and 5 years from diagnosis. 1,16 In the study by Navaratnam and colleagues,13 median survival was estimated to be 3.03 years, with an estimated 5-year survival of 37%. The Gribbin and colleagues11 study showed the 3- and 5-year survival to be 57% and 43%, respectively.

The prognosis for an individual patient remains difficult to define and can be highly variable. 17 Pulmonary assessments can be useful to predict the course of the disease and which patients have a higher likelihood of death within the next year. 16 A decline in per cent predicted forced vital capacity (FVC) of at least 10% in a 6-month period is associated with a nearly fivefold increase in the risk of mortality. 18 From a single time point other pulmonary function tests, such as the diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO), and exercise tests such as the 6-minute walk test (6MWT), have also been shown to be useful prognostic determinants in some studies. 18

Acute exacerbations of IPF are also known to have an impact on the prognosis of IPF. These periods of rapid deterioration of IPF without infection, pulmonary embolism or heart failure have an impact on the overall survival of patients with IPF, with mortality possibly being as high as 75%. 1,17,19 Although the evidence on the incidence and risk factors of acute exacerbation of IPF is limited, and varies between studies, the incidence is thought to be in the region of 10–15%. 1,6,17,19 Risk factors for acute exacerbations include a low FVC, DLCO total lung capacity (TLC), and never having smoked. 17

The presence of other comorbidities may also have an impact on the prognosis of IPF. Some evidence supports the view that coexisting emphysema leads to a poorer prognosis. 12,20 Although the coexistence of emphysema leads to a preserved lung volume, it also leads to an impaired diffusion capacity, and results of studies suggest that the fibrosis is the dominant prognostic factor. 20 Rates of coexisting emphysema may be as high as 30% in IPF. 12 Pulmonary hypertension has also been shown to be an important determinant of disease outcomes in IPF. 1,21 Pulmonary hypertension is characterised by increased pressure in the pulmonary arteries, and most patients with end-stage disease have this.

While there is no optimal marker for disease severity, recent evidence supports the view that the per cent predicted FVC can be useful to categorise people into three severity groups: mild, moderate and severe. Caution is required in using these cut-offs because they do not take into account other patient factors such as the existence of comorbidities; however, a crude categorisation is normal FVC (> 80% predicted), mild (≥ 70%), moderate (55–69%), and severe (< 55%). 22,23

Impact of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

Presentation of an individual with IPF is often as a result of a gradual onset of shortness of breath on exertion. This non-specific symptom can be wrongly attributed to the ageing process, emphysema, heart disease or a respiratory tract infection, and therefore diagnosis can often be made some time after initial presentation. 1,5 In others, IPF is an incidental finding on a routine chest examination. Key symptoms of IPF include breathlessness (dyspnoea), a non-productive (dry) cough, which can be paroxysmal (spasmodic) in nature, reduced exercise tolerance and anxiety. In a retrospective review of 45 case notes of deceased patients, > 90% suffered from breathlessness and 60% from cough. 24 Other, less frequently documented symptoms were fatigue, depression/anxiety and chest pain. 24 Clark and colleagues25 described a high prevalence of nocturnal hypoxaemia with decreased energy levels and impaired daytime social and physical functioning.

Symptoms become progressively worse over time. 1 The irritating dry cough associated with IPF has a significant impact on a patient’s life, leading to a reduced quality of life (QoL). 4 Finger clubbing is found in approximately 50% of patients. 1 A progressive worsening of these symptoms, and deterioration in lung function, increasingly limits normal physical activity, and the individual becomes more debilitated and disabled. 3,18 The result of this is often an incremental shift to becoming housebound, dependent on others for completion of normal activities, and dependent on oxygen therapy. 2 This leads to death from respiratory failure or a complicating comorbidity. 2

Breathlessness is one of the main distressing symptoms; however, no treatments aiming to modify the disease process have been shown to improve breathlessness in IPF. 26 Therefore, symptomatic treatment is essential. Some IPF patients may need only short-burst oxygen initially for episodic breathlessness, but many will need long-term oxygen therapy and ambulatory oxygen to maximise their QoL. 27 IPF is recognised as a clinical indication for referral for home oxygen. 27 If breathlessness continues to burden a patient, opioids and benzodiazepines, often in combination, can be prescribed as for other patients with breathlessness in advanced disease. 28

In a retrospective review of ILD patients, Bajwah and colleagues24 noted that, beyond symptoms, there was a lack of documentation of spiritual needs and little documentation of assessment for depression and anxiety, or documentation of preferred place of care or preferred place of death. The authors commented that it is likely that these issues occur in these patients. 24

Many patients with IPF are admitted to hospital and hospices, although accurate data are scarce. Many studies have small sample sizes and data available predominantly relate to hospitals. One recent study undertaken in the USA followed 168 patients over a 76-week period and found that 23% of these were hospitalised for respiratory-related illnesses on a total of 57 occasions. 29 The mean number of days stay in hospital was 15 days, with the most common reason for hospitalisation being suspected infection. Data from the UK suggest that in 2008–9 there were 9500 finished consultant episodes for people categorised as ‘other interstitial pulmonary diseases with fibrosis’, with around 600 hospital admissions. 30 The mean length of stay for these people was 9 days.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is a difficult condition to manage, particularly in the later stages. Early and accurate diagnosis is important to maximise the potential for a better outcome.

Diagnosis

The 2011 ATS/ERS consensus statement for IPF10 states that ‘IPF should be considered in all adult patients with unexplained slowly progressing exertional dyspnoea, and commonly presents with cough, bibasilar inspiratory crackles, and finger clubbing’ (p. 792). Treatments for IPF predominantly aim to reduce the decline in lung function and therefore early diagnosis is important to improve prognosis. Despite this, in many cases, a diagnosis is made at the point where lung function abnormalities are more severe, with the individual often having had asymptomatic disease progression for some years before. 2 One reason for this is that the diagnosis of IPF is a challenge because there are no specific abnormalities on laboratory tests. Tests which suggest an inflammatory response in an individual, such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and rheumatoid factor, may be abnormal, but these are not specific to IPF. For the general practitioner, the tests available, and the symptoms shown by the patient, could be indicative of a number of other conditions. Guidelines for the diagnosis of IPF have, however, recently been produced in the UK by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 31

The gold-standard diagnosis of IPF requires precision and a multidisciplinary approach involving ILD specialists, radiologists and pathologists. 1,2,31 Correlation of the clinical, radiological and histopathological features increases the accuracy of an IPF diagnosis and is often made on an individual basis. Clinical symptoms, findings on HRCT, and results of lung biopsy are taken in context with one another, especially as results on each factor can sometimes be discordant. Although surgical lung biopsy is recommended to confirm all suspected cases of IPF, in some settings surgical lung biopsy may not be required and the diagnosis is made on clinical and HRCT findings alone. 1 This is especially likely when the risks of a surgical procedure are weighed up with the potential delay in diagnosis while awaiting a surgical lung biopsy. 2 If surgical lung biopsy is used, biopsies from two locations are usually taken.

High-resolution computed tomography allows a detailed examination of the pulmonary parenchyma, and estimates of diagnostic accuracy are thought to be high (specificity exceeding 90%). The primary role of HRCT is to discriminate between typical IPF and other HRCT appearances, which may be indicative of other ILDs but may also represent IPF with atypical HRCT appearances. 1

In the recent guidelines,10,31 the recommendation for diagnosis requires exclusion of other known causes of ILD (e.g. domestic and occupational environmental exposures, connective tissue disorders and drug toxicity); the presence of a UIP pattern on HRCT in patients not undergoing surgical lung biopsy; and specific combinations of HRCT and surgical lung biopsy pattern in patients undergoing surgical lung biopsy. 10

The ATS/ERS consensus guideline provides details of the criteria for UIP based on HRCT and histopathology (from surgical lung biopsy) in tabular form. The details for a definite UIP pattern on HRCT include subpleural, basal predominance; reticular abnormality; honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis. Findings for a judgement of ‘possible UIP pattern’ and an ‘inconsistent with UIP pattern’ are also presented. Histopathological criteria for UIP pattern include evidence of marked fibrosis; presence of patchy involvement of lung parenchyma by fibrosis; and presence of fibroblast foci. Findings for a judgement of ‘probably UIP pattern’, ‘possible UIP pattern’ and ‘inconsistent with UIP pattern’ are also presented. In addition, the guideline presents the specific combinations of HRCT and surgical lung biopsy patterns expected to make a diagnosis of IPF, using the criteria set out for each method as summarised above. These criteria are presented in Table 2.

| HRCT pattern | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UIP | Possible UIP | Inconsistent with UIP | ||||

| Surgical lung biopsy pattern (if performed) | ||||||

| UIP, probable UIP, possible UIP, nonclassifiable fibrosisa | Not UIP | UIP, probable UIP | Possible UIP, nonclassifiable fibrosisa | Not UIP | UIP | Probable UIP, possible UIP, nonclassifiable fibrosis,a not UIP |

| Diagnosis of IPF | ||||||

| Yes | No | Yes | Probableb | No | Possibleb | No |

Current service provision

As discussed above, IPF is often misdiagnosed because the early manifestations of the disease are non-specific. This can lead to significant delays between symptom presentation and the correct diagnosis in a disease where diagnosing IPF at an early stage is important to maximise the potential for treatment. 32,33 In addition, the incorrect diagnosis can lead to initiation of ineffective or potentially harmful treatments and delay the opportunity for possible lung transplant (discussed in Lung transplant, below). 33 In some cases, the delay to diagnosis may be patient related, where individuals can be reluctant to acknowledge the symptoms that they have and to seek help. 34

Evidence suggests that longer delays in accessing specialist care in IPF are associated with a higher risk of death. 34 A US-based cohort study of 418 adults referred to a tertiary centre found that a median delay from symptoms to initial evaluation at the centre was 2.2 years. 34 Longer delay was associated with an increased risk of death, independent of age, sex and baseline FVC per cent predicted, with an adjusted hazard ratio (HR) per doubling of delay to access of 1.3 (95% CI 1.03 to 1.6). Results of a survey of 1251 IPF patients and 197 caregivers conducted in the USA found that 55% reported at least a 1-year delay between initial presentation and diagnosis, with some 38% having been seen by three or more physicians. 35 Incorrect diagnoses included bronchitis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), emphysema and heart disease. The study also found that 64% of responders agreed that there was a lack of information and/or resources on IPF when they were diagnosed. Only half felt generally, or well, informed about the treatment options available to them.

A European qualitative study of 45 IPF patients from five European countries found that the median reported time from initial presentation with symptoms to diagnosis of IPF was 1.5 years. 36 This ranged from < 1 week to 12 years, and in 58% of cases the delay was > 1 year. Similar to the larger US-based survey, a proportion of patients had consulted more than three physicians; in this study the rate was 55%. The study also investigated feelings of satisfaction with medical care and information about IPF, and found this was highest in those who received care at centres of excellence.

While these figures are based on studies which have small samples, and may not have participants who are generalisable to those seen in the UK, the results suggest that a large proportion of patients experience delays in obtaining a diagnosis, and it is not anticipated that these are significantly different from what is experienced in the UK.

The 2013 clinical guideline produced by NICE31 outlines the key clinical features to be used in primary care to identify and assess possible IPF. The guideline recognises the fact that the initial assessment of these individuals needs to be improved, to reduce the risk of delays in diagnosis and initiation of treatments, including monitoring and best supportive care (BSC). The clinical features may include age > 45 years, persistent breathlessness on exertion, persistent cough, bilateral inspiratory crackles and finger clubbing. Spirometry may or may not be impaired. In cases of suspected IPF, people can then be referred to secondary care for diagnosis and clinical management. The guideline states that the diagnosis should be multidisciplinary at each stage of the diagnostic care pathway to include a consultant respiratory physician, consultant radiologist and ILD specialist nurse. All patients should be given BSC from the point of diagnosis, which includes information and support, symptom relief, management of comorbidities, withdrawal of ineffective therapies and end-of-life care. In addition, individuals should be assessed for pulmonary rehabilitation, if appropriate, and have a clinical nurse specialist available to them. The guideline also recommends that lung transplantation in those without contraindications should be considered between 3 and 6 months after diagnosis (or sooner if indicated clinically), with referral to regional transplant units for assessment if appropriate.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Individuals with ILD experience many of the same symptoms as those with COPD, commonly shortness of breath, fatigue and reduced exercise tolerance. It would, therefore, seem a priority to address these symptoms. Pulmonary rehabilitation is an established evidence-based intervention for individuals with COPD, with the precise aims of reducing the physical and emotional impact of the disease on the individual. 37 It is well documented that rehabilitation improves exercise capacity, dyspnoea and QoL. 37 The delivery of rehabilitation to individuals with COPD is advocated in national guidelines; however, until the 2013 NICE guidelines this had not been extended to IPF. 31 Many individuals are, therefore, currently not offered pulmonary rehabilitation. Further details about the intervention itself can be found in Description of technologies under assessment.

The referral to rehabilitation can be instigated by primary or secondary care physicians; in most cases, this would be after a detailed assessment and optimisation of treatment from a physician with a special interest in IPF. Prior to commencing a course of rehabilitation, medical management should be optimised; this may include the provision of supplemental oxygen. The most advantageous time to refer is unclear in the evidence, although it is anticipated that a prompt referral is more likely to be beneficial before an individual is too disabled by the disease.

Lung transplant

Lung transplantation is the only treatment that has been shown to improve survival in patients with IPF. The 5-year survival of IPF patients post transplant is in the region of 40–50%, which compares with an overall 52% 5-year survival rate. 38 As indicated in the NICE guidelines,31 treating clinicians should carefully consider whether or not their patient might be eligible and refer potentially suitable patients to a recognised transplant centre for a full evaluation. IPF is the most common ILD referred for lung transplantation throughout the world. Data from the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT) collected from 1 January 2011 to 30 June 2012 show IPF to be the third most common diagnosis leading to lung transplant throughout Europe, representing 17% of all lung transplants. 38 Data from the NHS Blood and Transplant service reveals that 17% (numbering between 23 and 33 patients per year) of all lung transplants in the UK between April 2009 and March 2013 were for fibrosing lung disease (NHS Blood and Transplant, 26 February 2013, personal communication). It is anticipated that the majority of patients in this category had IPF. This differs significantly from the current experience in the USA, where IPF is now the most common indication for lung transplantation (35% of transplants). 39 In the USA, the allocation of organs is governed by the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) system which calculates a lung allocation score (LAS). This calculates a post-transplant survival score and a waitlist survival score to give an overall LAS. Patients with a higher score are prioritised on the basis of urgency.

As IPF is a disease of older adults, many patients may not be considered for lung transplantation on the basis of their age. Most centres use age > 65 years as a relative, but not an absolute, contraindication to lung transplant. Data from ISHLT from 2011 to the first half of 2012 reveals that, worldwide, 15.4% of patients who received a transplant were > 65 years of age. 38 However, again, there was a considerable difference between European and American practice, with 4.4% of European recipients being > 65 years, compared with 25.3% of North American recipients. Recent data from the USA suggest that post-transplant mortality is no higher in patients > 70 years when compared with those in the 60- to 69-year-old age group. 40

People considered for transplant referral should be free of malignancy for at least 2 years and have no evidence of significant coronary artery disease, heart failure or any significant disease in a vital organ. They should be not be infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), chronic hepatitis B or C infection or be dependent on tobacco and other substances. Similarly, a lack of social support and significant psychological problems are contraindications to lung transplant. Poor nutritional status and being significantly overweight [body mass index (BMI) > 30 kg/m2] or underweight is another important contraindication. 41

Data from the UNOS show that overall mortality post lung transplant is 22% higher in patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m2. 42 Low-dose prednisolone use (< 0.3 mg/kg/day) is not considered a contraindication.

In patients who have no contraindications to lung transplant, the following specific criteria have been proposed to guide a timely referral in IPF:41

-

radiological or pathological evidence of UIP

-

diffusion capacity/transfer factor for carbon monoxide < 40% predicted

-

a reduction of 10% in the FVC over a 6-month follow-up period

-

a reduction in oxygen saturation below 88% on 6MWT

-

the presence of honeycombing on a HRCT scan (fibrosis score > 2). 43

However, as more patients with IPF than any other condition die on lung transplant waiting lists, the clinician should have a low threshold to refer a deteriorating patient even if they do not yet meet the above criteria. 44 Similarly, many experts would advocate early referral for a deteriorating patient even if the radiological and/or pathological findings are not entirely consistent with a UIP pattern, as evidence of deterioration is a powerful marker of a poor prognosis.

Traditionally, single-lung transplant has been preferred over double-lung transplant in IPF, with the latter being preferred for patients with cystic fibrosis or conditions associated with chronic infections. Some centres have suggested that long-term survival may be better post double-lung transplant,38,45 while others report little difference. 46,47 This remains a point of considerable debate and given the lack of availability of organs for donation it is likely that single-lung transplant will continue to be widely used. Exceptions to this may be in younger patients or those with a nidus of infection in the native lung.

Palliative care

As stated, patients with IPF have a poor prognosis, although determining individual prognosis is more difficult than in, for instance, lung cancer, and treatment options are limited. 27,48 Lee and colleagues49 describe three ‘pillars’ of care: disease-centred management, symptom-centred management, and education and self-management.

American Thoracic Society guidelines suggest that palliative care principles should be initiated when a patient with respiratory disease becomes symptomatic. 48 This may be particularly helpful in IPF as diagnosis can be variable and there may be rapid and unexpected deterioration resulting in death. 27 The guideline of the British Thoracic Society recommends that BSC should be considered a specific and important treatment strategy in all patients with IPF. 50 The recent NICE guideline31 states that BSC should be initiated at the point of diagnosis. Best supportive, or palliative, care is a proactive approach to symptomatic treatment and may include oxygen therapy, pulmonary rehabilitation, opiates, antireflux therapy, the withdrawal of steroids and other immunosuppressants, early recognition of terminal decline and liaison with palliative care specialists. 50 This should also allow patients with IPF the opportunity to consider their expectations, goals and preferences, but there is a reluctance of professionals to broach these difficult topics. 27 This might be one explanation as to why the majority of IPF patients in a recent study had no palliative care input in their last year of life, despite these recommendations regarding the early integration of palliative care. 24

The NICE 2013 guideline suggests that if a patient with IPF has breathlessness on exertion, ambulatory oxygen should be considered. 31 Where there is breathlessness at rest, consideration should also be given to benzodiazepines and/or opioid therapy.

Description of technologies under assessment

There is no universally accepted best treatment for IPF, with several treatment options available to clinicians. Disease-modifying treatments include immunosuppressants, antifibrotics and antioxidants, alone or in combination. Symptomatic treatments available include oxygen therapy, opioids, corticosteroids, antireflux therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation. Other treatments may be used to treat specific symptoms such as intractable cough or pulmonary hypertension. Finally, in some cases, lung transplantation is considered.

Disease-modifying treatments

Cyclophosphamide and azathioprine are immunosuppressant treatments which may also suppress inflammation and have been used in some patients with IPF. Both cyclophosphamide and azathioprine are used, in some cases in combination with the corticosteroid prednisolone. The ATS/ERS 2011 consensus guidance suggests that these are not used routinely in IPF. 10 The NICE guideline states that where the combination of azathioprine and prednisolone is already being used, there should be consideration of gradual withdrawal of these treatments. 31 In the UK, the use of cyclophosphamide and prednisolone is mostly restricted to the treatment of acute exacerbations, although not widely used.

N-acetylcysteine (NAC) is a precursor to the antioxidant glutathione, which may be reduced in the lungs of patients with IPF. It is an antioxidant therapy that does not have specific marketing authorisation for use in IPF, and it is readily available in health-food shops and over the internet. It can be used alone or, as has been done in the past, in combination with prednisolone and azathioprine (referred to as triple therapy). The ATS/ERS 2011 consensus guidance10 suggests that NAC (alone or in triple therapy) is not used in the majority of patients but it may be a reasonable choice in a minority. The 2013 NICE guideline31 suggests that it may be used alone after discussion of the risks of the treatment, and that if used in combination with azathioprine and prednisolone, these latter two treatments should be gradually withdrawn.

Pirfenidone is an orally bioavailable synthetic molecule with antifibrotic and anti-inflammatory properties. The mechanism of action at the molecular level is not fully understood; however, pirfenidone has marketing authorisation for use in mild to moderate IPF in Europe. Pirfenidone was not included in the scope of the NICE 2013 clinical guideline;31 however, it has been assessed by NICE under the technology appraisals programme. Final guidance to the NHS issued in 201323 states that pirfenidone is recommended as an option where an individual patient has a FVC between 50% and 80% predicted. This is the case only if the manufacturer of pirfenidone provides the treatment at a previously agreed (undisclosed) discount price.

Symptomatic treatments

Prednisolone is a corticosteroid which can be used to reduce inflammation. Most widely used in the past before the nature of IPF was fully understood and the diagnosis more specific, prednisolone is now used predominantly for symptom control, including for acute exacerbations. 10

Pulmonary rehabilitation is conventionally offered as a package of supervised exercise and education over a 6- to 8-week period by a multidisciplinary team. The ATS/ERS 2011 consensus guidance10 suggests that this is used in the majority of patients but this may not be a reasonable choice for some. In the UK, the clinical guideline from NICE31 recommends that individuals should be assessed for pulmonary rehabilitation where appropriate.

Most experience with pulmonary rehabilitation comes from treating COPD, although the adoption of pulmonary rehabilitation in the UK for IPF is becoming more widespread. The process of rehabilitation commences with a detailed assessment; it is most likely that a detailed study of lung function will have already characterised the patient. The rehabilitation assessment should include an evaluation of health-related quality of life (HRQoL), levels of anxiety and depression, and exercise capacity as a minimum. Additional measures that might be considered could be measures of peripheral muscle strength, self-efficacy and physical activity, but these are not widely reported for IPF. HRQoL measures are those commonly employed for individuals with COPD, for example the St George’s Hospital Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ)51 or the chronic respiratory disease questionnaire. 52 The exercise test is usually conducted outside the laboratory and in the UK is commonly the 6MWT53 or the incremental shuttle walking test. 54 During and immediately after an exercise test it is important to record levels of oxygen saturation, and, in discussion with the patient, make a decision about the use of supplemental oxygen while exercising. Repeat testing with oxygen might be expected to correct the desaturation to some degree and/or improve the level of perceived breathlessness.

The usual format of rehabilitation is one of educational and supervised exercise. The groups are not specifically designed for individuals with IPF and, therefore, the education sessions may not all be entirely appropriate. Generally, the educational topics include medicines management, disease pathology, chest clearance techniques, breathing control, healthy eating, travelling with a lung disease, inhaler techniques, relaxation, stress management and energy conservation. The exercise programme is a combination of strength and aerobic exercises, prescribed and progressed on an individual basis. Bouts of purposeful exercise should also be completed at home, to accumulate five sessions per week of aerobic activity. On completion of a course of rehabilitation, it is recommended that a repeat assessment be conducted to reinforce the benefits of rehabilitation.

Maintaining the benefit of rehabilitation is challenging; however, there are opportunities to continue with regular supervised exercise in the community with exercise specialists trained to manage participants with chronic respiratory disease.

Oxygen therapy can either be used as a long-term therapy or be taken as a supplement after exertion. The ATS/ERS 2011 consensus guideline10 suggests that long-term oxygen therapy is used in patients with IPF and clinically significant resting hypoxaemia, and the NICE 2013 guideline31 also refers to the use of oxygen for breathlessness on exertion as discussed above.

Palliative care/BSC should be considered from the outset as an adjunct to disease-focused care. This may include corticosteroids, oxygen therapy, treatments for other symptoms such as cough, advanced directives and end-of-life care issues including hospice care.

Treatments for specific symptoms

Sildenafil is a phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitor with marketing authorisation for use in pulmonary hypertension and it has been used as a treatment for IPF. There are currently no recommendations from the ATS/ERS consensus committee of the 2011 guidance10 and in the NICE guideline sildenafil was not recommended as a treatment for modifying IPF owing to uncertainty around both benefits and harms. 31

Bosentan is a dual endothelin receptor A and B antagonist that has marketing authorisation for pulmonary hypertension. Endothelin is a vasoconstrictor and growth factor that is involved in the pathogenesis of pulmonary hypertension. The 2011 ATS/ERS10 consensus guidance suggests that these are not used based on the potential risks and costs of therapy. The NICE clinical guideline concurs with this. 31

Thalidomide is a potent immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic drug, and may be a potential therapy in IPF for cough. 55 Thalidomide does not have a UK marketing authorisation for IPF; however, the NICE clinical guideline31 states that thalidomide may be considered in a patient with intractable cough.

Treatments undergoing assessment in UK participants

BIBF 1120 or nintedanib is an intracellular inhibitor of tyrosine kinases and is currently under evaluation in phase III randomised controlled trials (RCTs) as a potential therapy for IPF. It has received orphan status from the European Medicines Agency in 2013 (orphan status provides some favourable marketing incentives to manufacturers). 56

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

This project will evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the different treatment strategies used within the NHS for IPF. It will review systematically the evidence on those interventions that are currently available and used to treat IPF. It will construct a new economic model relevant to the UK setting to estimate the cost-effectiveness of the different treatments. Deficiencies in current knowledge will be identified and recommendations for future research generated.

Chapter 2 Methods for the systematic review of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol, which was sent to our expert advisory group for comment. Although helpful comments were received relating to the general content of the research protocol, there were none that identified specific problems with the methodology of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Identification of studies

A comprehensive search strategy was developed, tested and refined by an experienced information scientist. Separate searches were conducted to identify studies of clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, QoL and epidemiology. Sources of information and search terms are provided in Appendix 1. The most recent searches were undertaken in July 2013.

Literature was sourced from 11 electronic databases, the bibliographies of articles, and grey literature sources, and our expert advisory group were contacted to identify any additional studies. All databases were searched from inception with no language restrictions. The following electronic databases were searched: MEDLINE (Ovid); MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations; EMBASE; The Cochrane Library including Central Register of Controlled Trials and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) including Health Technology Assessment Database, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and NHS Economic Evaluation Database; Web of Science (Science Citation Index Expanded) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index; and Bioscience Information Service Previews. A comprehensive database of relevant published and unpublished articles was constructed using Reference Manager software (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA). Research-in-progress databases (UK Clinical Research Network website, Current Controlled Trials and Clinical trials.gov, World Health Organization-International Clinical Trials Registry Platform) were searched for any ongoing studies of relevance.

In addition, professional society websites and conferences were searched for recent abstracts and ongoing studies (see Appendix 1).

Study selection and data extraction

Studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness through a two-stage process using predefined and explicit criteria (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria). Titles and abstracts from the literature search results were independently screened by two reviewers to identify all citations that possibly met the inclusion criteria. Full papers of relevant studies were retrieved and assessed by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer using a standardised eligibility form. As far as possible, full papers or abstracts describing the same study were linked together, with the article reporting key outcomes designated as the primary publication.

A two-stage approach was used to establish the relevance of each individual treatment for inclusion in the evidence synthesis. The advisory group individually and independently commented on the relevance of each treatment. The outcomes from this exercise were tabulated and those with complete consensus were either included or excluded as appropriate. Where consensus on any particular intervention was not reached, these were sent to the advisory group for a second time. At this stage, either consensus was confirmed or a decision was taken to include treatments where at least one expert had indicated that the treatment was used in their clinical practice.

Titles and abstracts identified by the search strategy for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness and HRQoL were assessed for potential eligibility by two reviewers using predetermined inclusion criteria (see Inclusion and exclusion criteria). Full papers were formally assessed for inclusion by one health economist with respect to their potential relevance to the research question and this was checked by one reviewer.

Data were extracted by one reviewer using a standard data extraction form (see Appendix 2) and checked by a second reviewer. At each stage, any disagreements between reviewers were resolved by consensus or, if necessary, by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Critical appraisal strategy

The methodological quality and the quality of reporting of the included clinical effectiveness studies were assessed using criteria based on those recommended by the CRD57 and the Cochrane Collaboration58 (see Appendix 2). The risk of bias within each study was summarised according to the risk of selection bias. Quality criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, with any differences in opinion resolved by consensus or by arbitration by a third reviewer.

Quality assessment for the systematic review of cost-effectiveness was based on a checklist for economic evaluation publications59 and guidelines for good practice in decision-analytic modelling in health technology assessment. 60

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Participants

-

People with a confirmed diagnosis of IPF.

As there have been changes in the diagnostic criteria for IPF, particular attention was paid to the inclusion criteria used by studies to ensure that the results were not influenced by mixed populations with differing prognoses. Studies of mixed populations were included only if the study reported outcomes for those with IPF separately.

Where the definition of IPF was uncertain, this was checked by our advisory group. Any studies remaining uncertain would have been included but discussed separately; no such instances occurred.

The presence of pulmonary hypertension in participants in included studies was not a reason for exclusion. Any included studies with known participants with pulmonary hypertension are discussed as appropriate in the results.

Interventions

-

Any available and currently used (in the NHS) interventions which aim to manage symptoms or modify IPF were eligible.

As described above, clinical experts and the expert advisory group for the review were asked to identify the current treatments used in the UK to ensure that the key treatments in use were included in the review. For discussion of the included interventions see Chapter 3.

Comparators

-

Any of the included interventions.

-

BSC.

-

Placebo interventions.

Outcomes

-

Measures of survival.

-

Measures of symptoms (breathlessness, cough).

-

QoL/HRQoL.

-

Lung function/capacity.

-

Exercise performance.

-

Adverse events.

-

Costs and cost-effectiveness.

Patient-assessed subjective outcome measures were included if assessed by validated tools (for descriptions see Chapter 3 and Appendix 3).

A variety of surrogate end points have been used in trials of interventions for IPF. Appendix 3 describes the key outcomes used, including evidence of the relationship between these and the final patient outcome.

Design

-

RCTs.

-

Where no RCTs were identified for a particular intervention, controlled clinical trials (CCTs) with a concurrent control group were eligible.

-

Economic evaluations (i.e. costs and consequences), including cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analyses.

Studies published as abstracts or conference presentations were included only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

Systematic reviews identified by the search were used as a source for identifying primary studies and are summarised in Chapter 3 (see Existing systematic reviews).

Method of data synthesis

Studies of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of results of included studies.

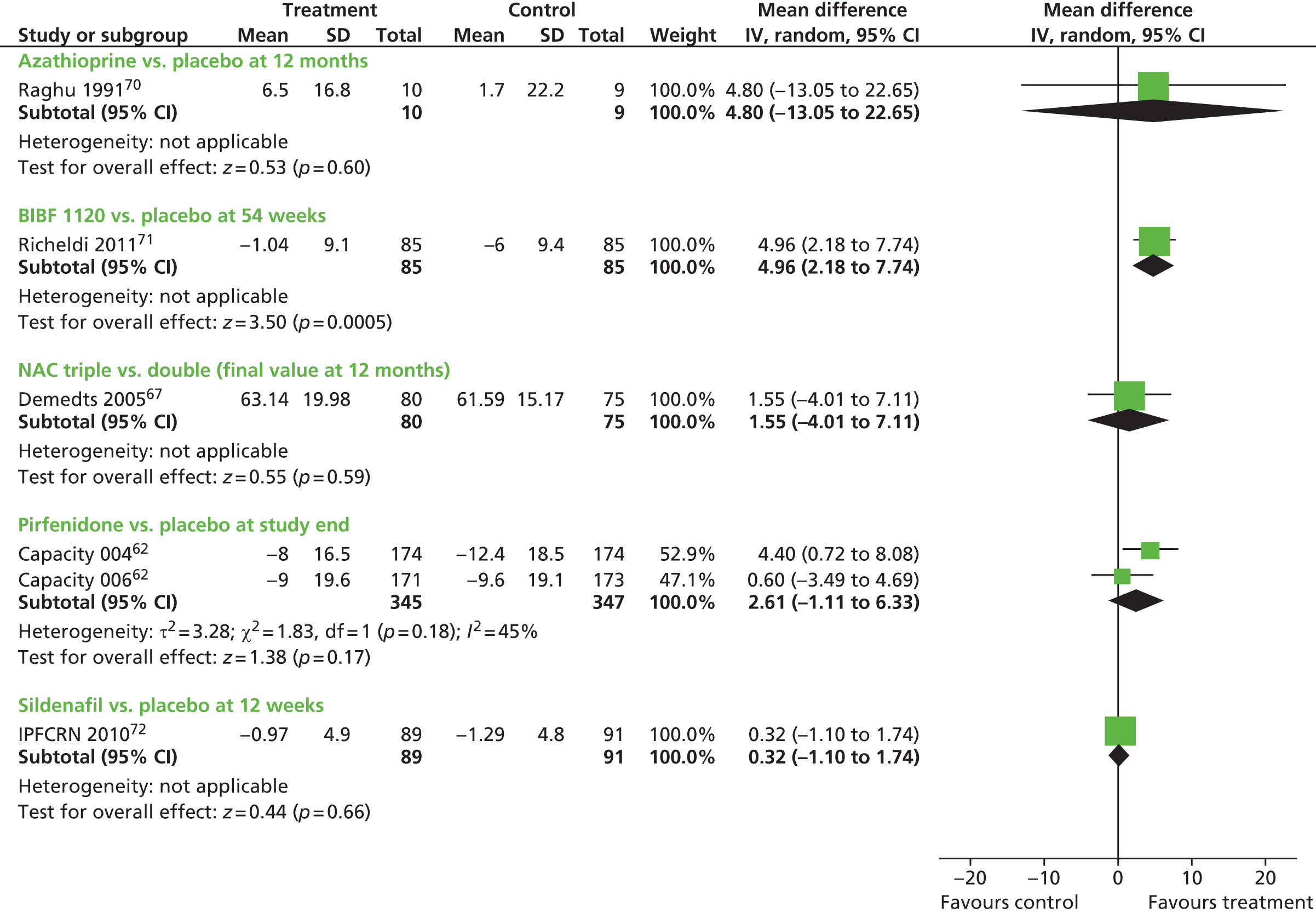

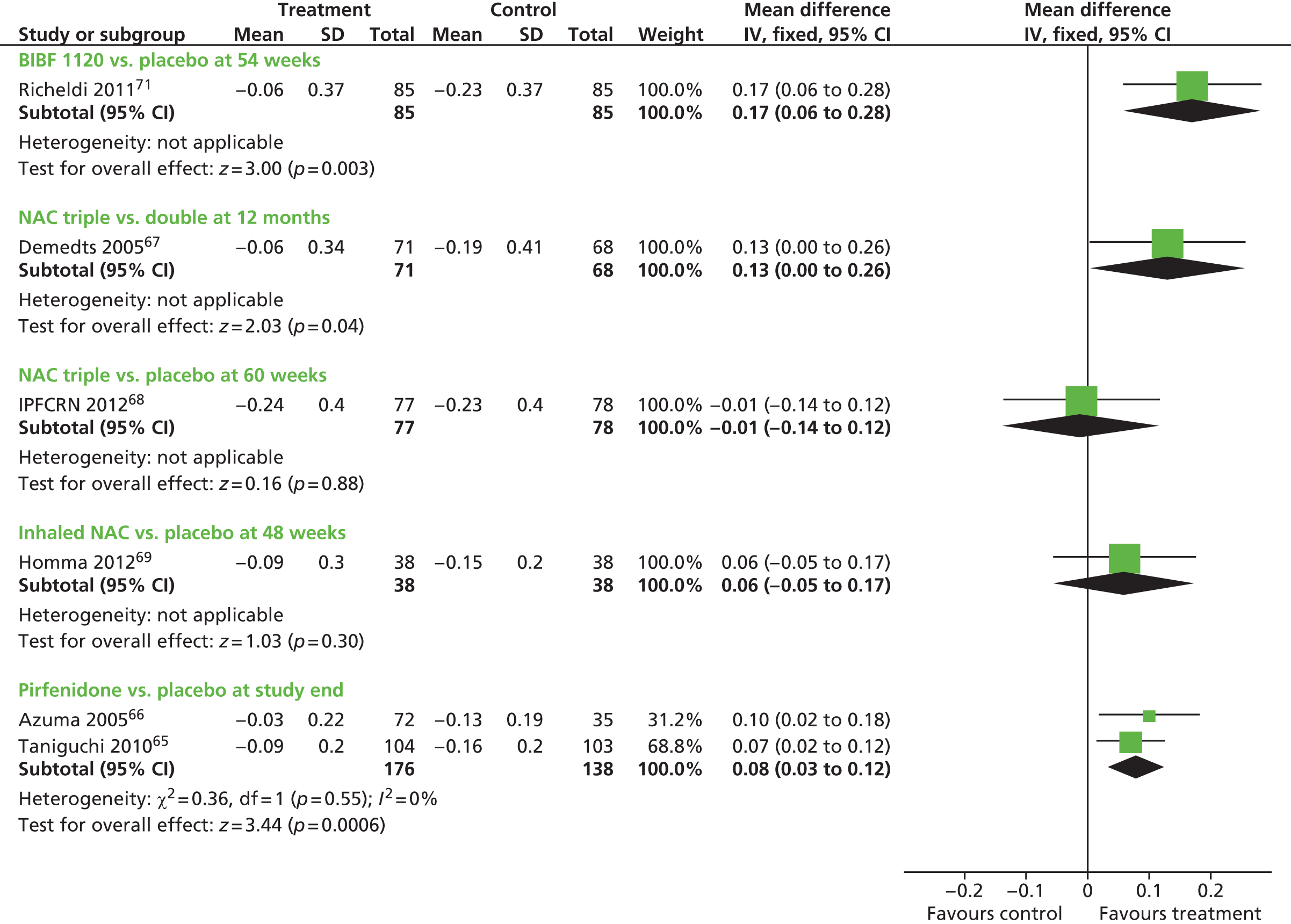

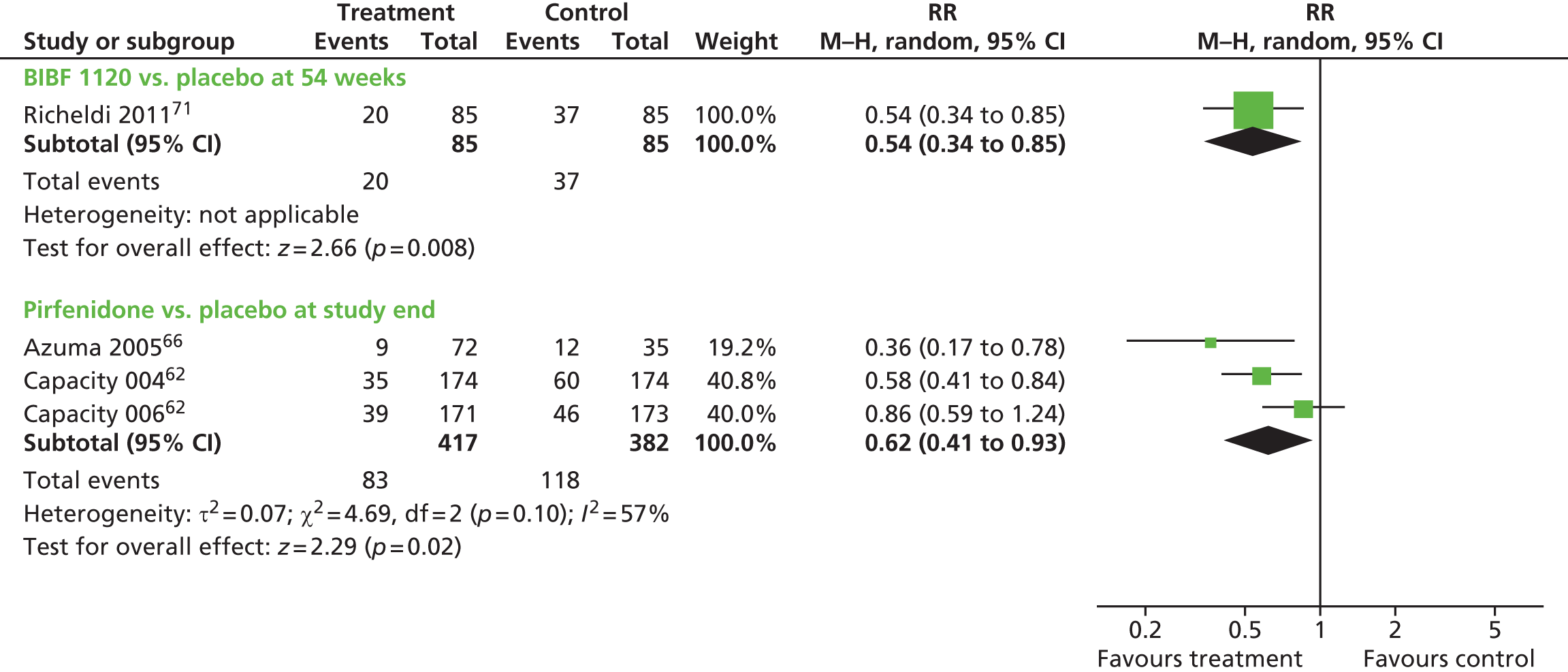

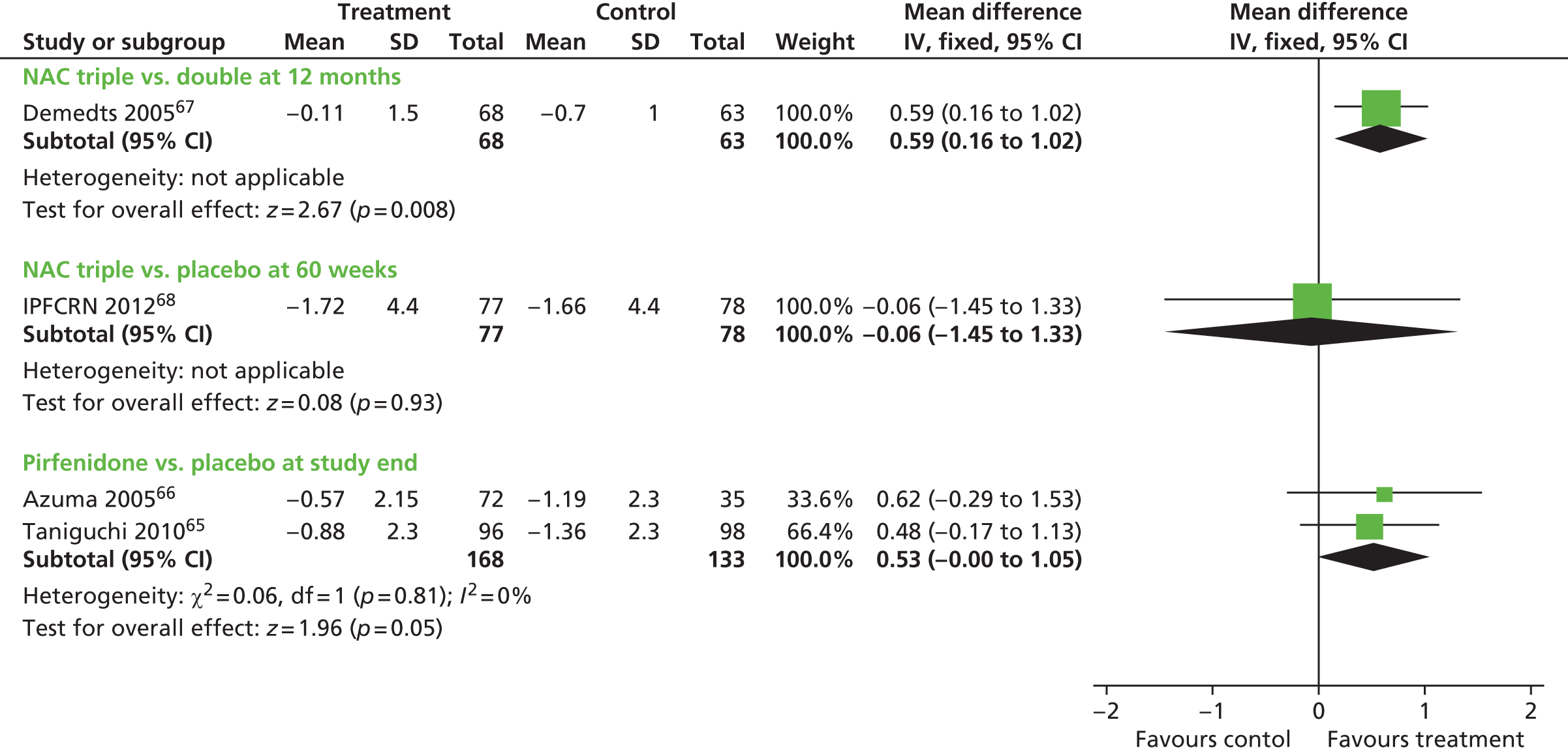

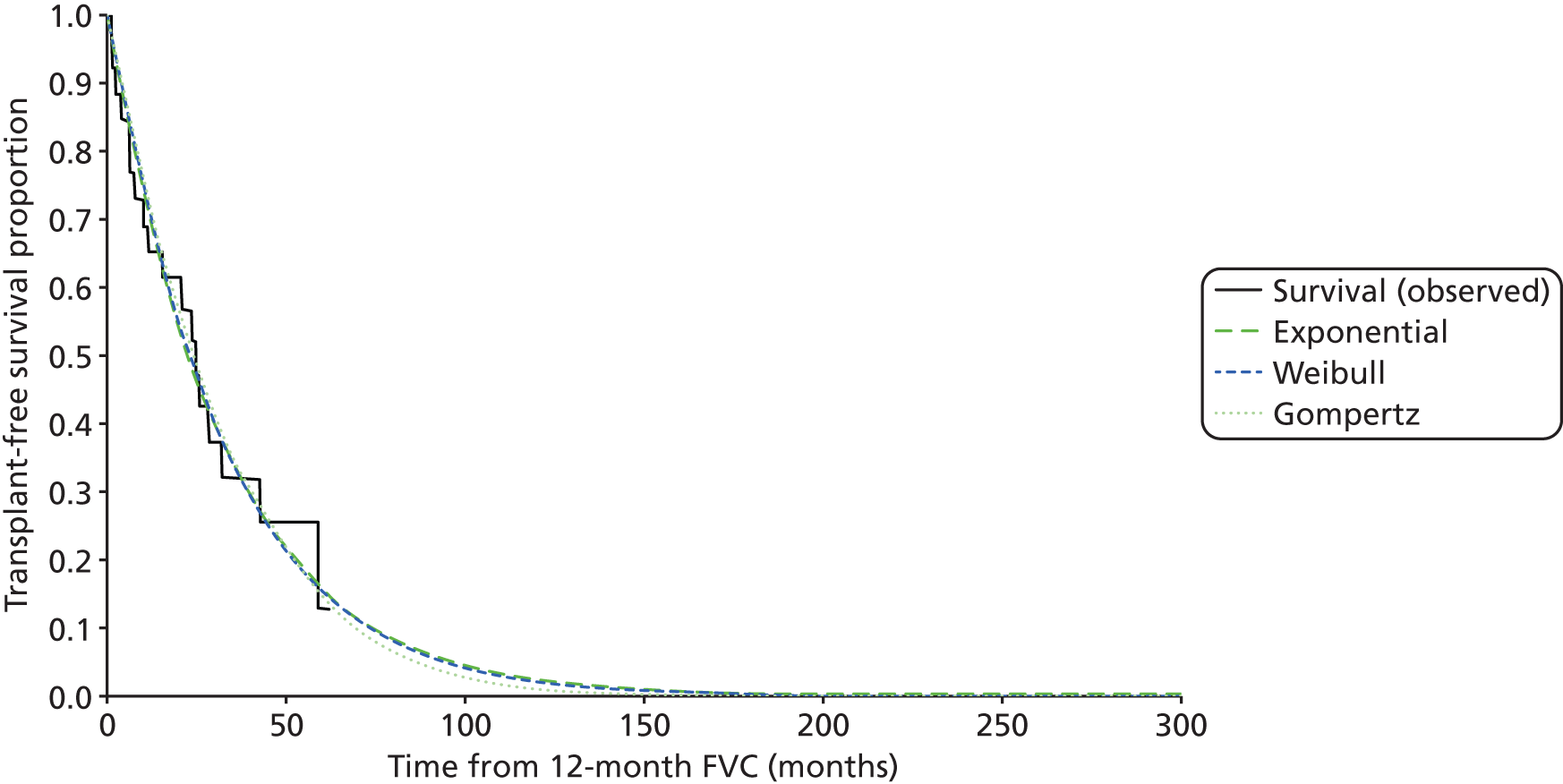

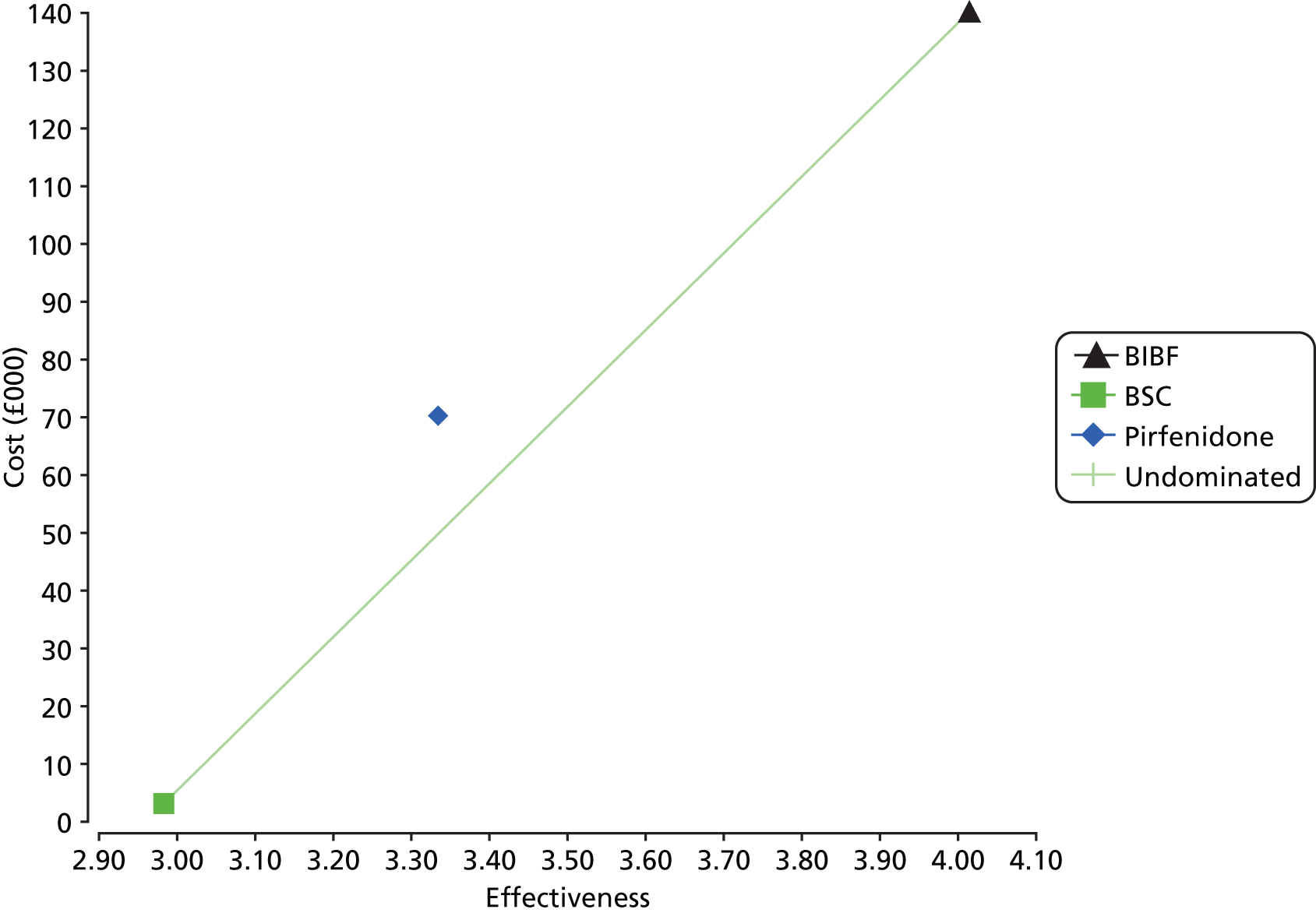

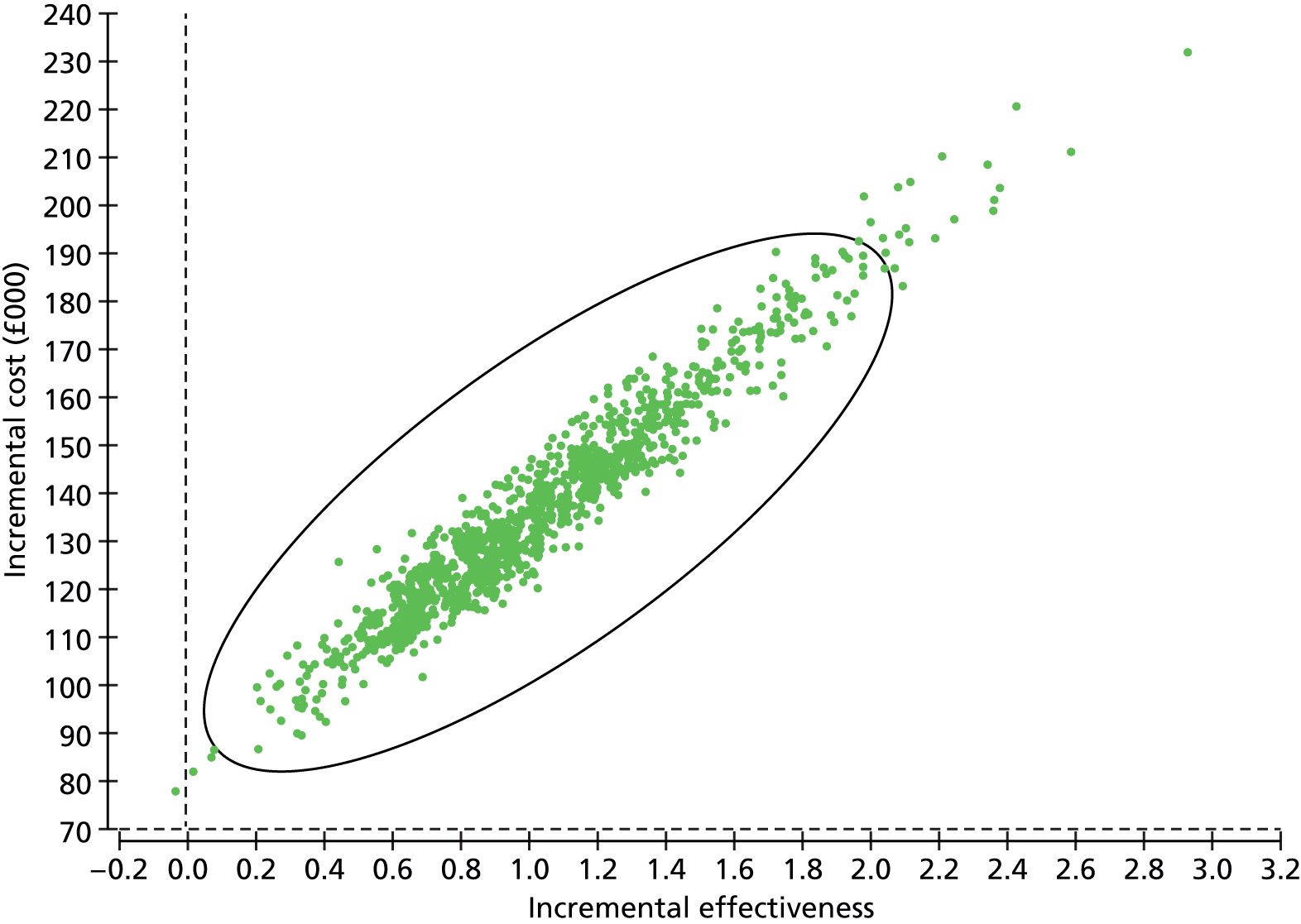

Where data were of sufficient quality and homogeneity, meta-analyses of the clinical effectiveness studies were performed to estimate the mean difference (for continuous data) and risk ratio (RR) (for dichotomous data) with 95% CIs. The random-effects method was used where statistical heterogeneity was observed. The standardised mean difference was used to combine per cent predicted FVC/VC and mean change in FVC/vital capacity (VC) in a meta-analysis. The standardised mean difference converts all outcomes to a common scale. It is the difference in means between the treatment arms divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD) of outcomes from all participants in each trial. Meta-analysis was performed by using Cochrane Review Manager 5 (RevMan, The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) and statistical heterogeneity was assessed using chi-squared test and the I2 statistic. 58 Where SDs were not presented in the published papers, these were calculated from the available statistics (CIs, standard errors or p-values).

In addition, a network meta-analysis (NMA) was undertaken to allow ranking of the effectiveness of the range of treatments being evaluated. NMA is an extension of traditional, pairwise meta-analysis where a statistical analysis of the network of trial evidence is used to produce comparable estimates of benefits and harms for a range of treatments. The NMA was conducted using current guidance on good practice (for further details see Chapter 3, Network meta-analysis).

The methods for the economic model are described in Chapter 4 (see Methods for economic analysis).

Chapter 3 Clinical effectiveness

Research identified and included

Searches identified a total of 905 references after deduplication, and full texts of 64 references were retrieved after screening titles and abstracts. Initial screening of the full texts identified 47 publications of possible relevance. The interventions and comparators used in these 47 studies were tabulated and sent to the advisory group to determine their relevance. The final list of included interventions can be seen in Table 3. One new treatment, BIBF 1120 (nintedanib), was included as it will possibly be used in future practice. After this exercise, 13 RCTs and one CCT61 were included (two of the RCTs were reported in one publication). 62

| Treatment | Decision |

|---|---|

| Ambrisentan | Exclude |

| Azathioprine and prednisolone a | Include |

| BIBF 1120 (nintedanib) | Include as possible future use |

| Bosentan | Include if pulmonary hypertension present |

| Bromhexine hydrochloride | Exclude |

| Colchicine | Exclude |

| Colchicine and prednisolone | Exclude |

| Colchicine and d-penicillamine | Exclude |

| Colchicine and cyclophosphamide | Exclude |

| Cyclophosphamide and prednisolone | Include if used for acute exacerbations |

| Ciclosporin | Exclude |

| Disease management programmes | Include |

| Etanercept | Exclude |

| Everolimus | Exclude |

| Iloprost | Exclude |

| Imatinib | Exclude |

| Interferon-γ–1b | Exclude |

| Interferon-γ–1b and prednisolone | Exclude |

| Macitentan | Exclude |

| Methylprednisolone | Include if used for acute exacerbations |

| NAC | Include |

| NAC (inhaled) | Include |

| NAC, azathioprine, prednisolone | Include |

| Pirfenidone | Include |

| Pulmonary rehabilitation | Include |

| Prednisone (prednisolone) | Include |

| Prednisone and d-pencillamine | Exclude |

| Prednisone, d-pencillamine, colchicine | Exclude |

| Prednisone and warfarin | Exclude |

| Prednisone and methylprednisolone | Include if used for acute exacerbations |

| Septrin | Include |

| Sildenafil | Include if pulmonary hypertension present or in severe IPF |

| Thalidomide | Include if for cough |

One non-English (Polish) publication was considered to be eligible for inclusion. 61 The publication contained an English translation of the abstract and results tables. A translation of the methods was requested from the author; however, no response was received. The methods were translated using Google Translate (http://translate.google.com) and results were extracted from the tables but not the text to avoid error.

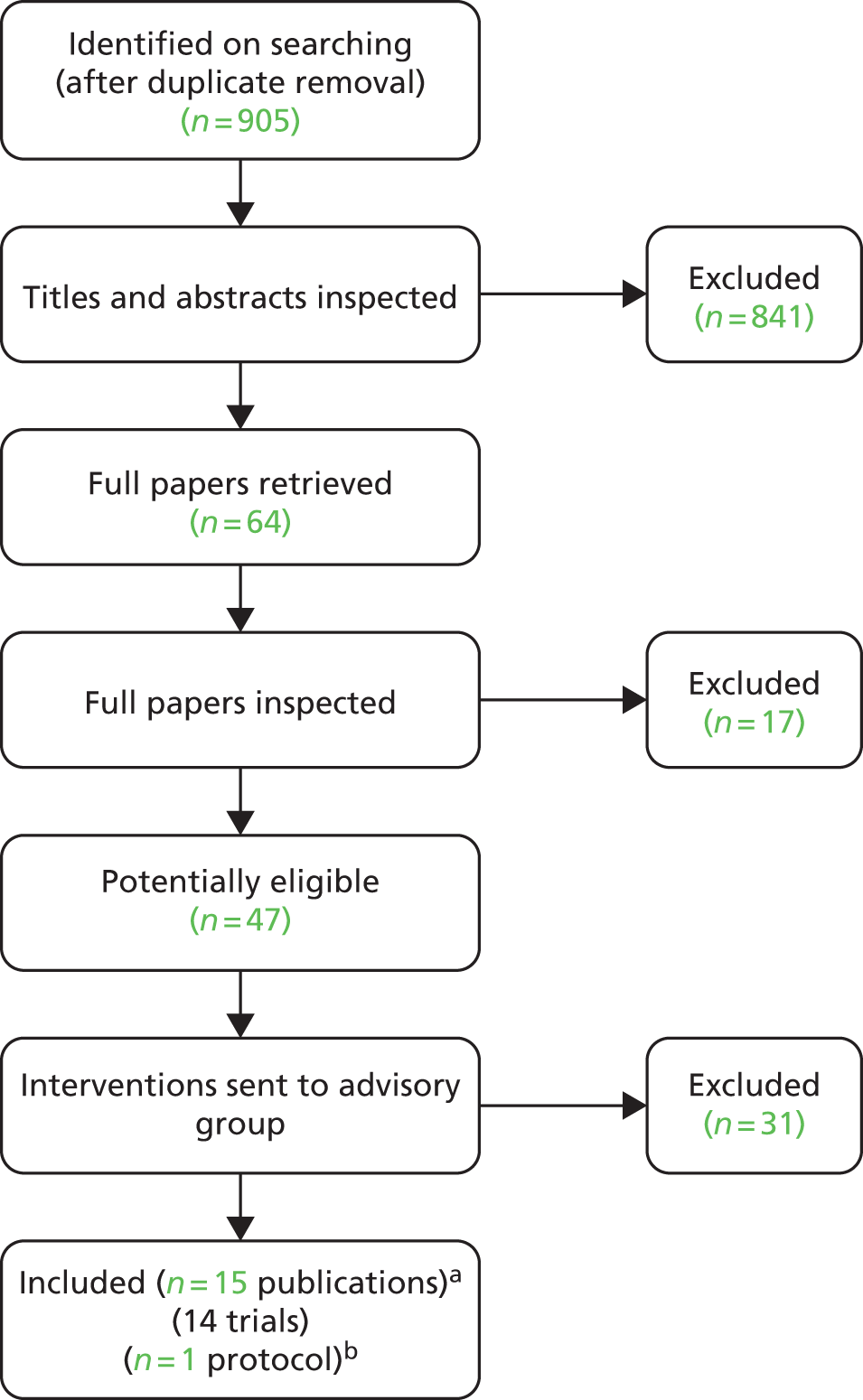

The number of references excluded at each stage of the systematic review is shown in Figure 1. References that were retrieved as full papers but subsequently excluded are listed in Appendix 4, with reasons for exclusion. Seventeen references were excluded owing to participants (eight studies), study design (seven studies) or irrelevant outcomes (three studies), with one study being excluded for more than one reason. Thirty-one studies were eligible in the first full-paper screen but were then excluded as the interventions were not considered relevant by the advisory group. The level of agreement between reviewers for screening was high, although this was not formally assessed.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart for the identification of studies. a, two RCTs were reported in one publication; two further trials each had two linked publication; b, one trial was published as a protocol only:63 see Ongoing randomised controlled trials.

Searches identified 25 relevant ongoing studies, a summary of which can be seen later in this chapter (see Ongoing randomised controlled trials). One conference abstract was also identified but the abstract did not present sufficient information for the study to be formally assessed for inclusion. This study was a CCT of a 12-week pulmonary rehabilitation compared with a control group (undefined). 64 No full publication for this study has been identified on updated searches.

Four RCTs evaluated the use of pirfenidone,62,65,66 three the use of NAC (alone or in combination),67–69 one azathioprine,70 one BIBF 1120,71 one sildenafil (in severe IPF),72 one thalidomide,55 one a pulmonary rehabilitation programme,73 and one a disease management programme. 74 In addition, one CCT of pulmonary rehabilitation was included. 61 No studies of bosentan, cyclophosphamide and prednisolone, methyprednisolone (alone or in combination with prednisolone) or co-trimoxazole (Septrin®, Aspen) were included because studies of these interventions had ineligible comparator treatments. No studies of palliative care interventions were identified that met the inclusion criteria.

Description of included studies

Eleven of the included RCTs investigated the use of pharmacological interventions for IPF. One was a single-centre randomised crossover trial,55 and the rest were multicentre trials, with the number of centres ranging from two70 to 110. 62 The majority of centres were in either the USA or European countries, although some included countries such as Mexico and Republic of Korea, and three studies were undertaken solely in Japan. 65,66,69 Sample sizes ranged from 2455 to 435,62 although all except two trials55,70 had sample sizes of 100 or more participants. Nine of the 11 trials investigating pharmaceutical agents received some funding from the drug manufacturer. Across the 11 trials, participants would likely be classified as mild to moderate in 10, with one study looking at participants in the more severe stages of IPF. 72 In the three studies investigating non-pharmacological interventions, one RCT was undertaken in Japan and investigated a pulmonary rehabilitation programme,73 one CCT was undertaken in Poland and investigated inspiratory muscle training in addition to pulmonary rehabilitation,61 and the other RCT investigated a disease management programme in the USA. 74 These trials were single-centre studies and funding was from public or charitable funds where data were available. The sample size was 30 in both of the pulmonary rehabilitation programme studies,61,73 and 21 in the disease management programme trial. 74 The populations in these trials were at the more moderate to severe end of the spectrum of IPF. Further detail of the characteristics of these studies and their participants can be found in subsections below and in Table 4, which summarises the key attributes of the fourteen included studies, and Table 5, which summarises the key participant characteristics.

| Study | Intervention details | Key eligibility criteriaa | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological agents | |||

| Azathioprine | |||

| Raghu et al. 199170 Country: USA Design: RCT Number of centres: two Funding: Grant from Virginia Mason Research Centre, Seattle, WA, USA |

1. Prednisone and placebo, n = 13 2. Prednisone and azathioprine, n = 14 Dose details: prednisolone decreased from 1.5 mg/kg/day (not to exceed 100 mg/day) for 2 weeks, decrease of 20 mg/day until a dose of 40 mg/day was reached for 2 weeks, decrease of 5 or 10 mg/day every 2 weeks according to patient tolerance. Maintenance dose of ≤ 20 mg/day Azathioprine 3 mg/kg/day (not to exceed 200 mg/day) to the nearest 25-mg dose increment for the duration Duration of treatment: assume 112 months |

Inclusion criteria: a diagnosis of IPF supported by lung biopsy. Previously untreated and available for routine follow-up. Fulfilled criteria for progressive clinical disease [one or more of (1) progressive dyspnoea from day of onset, (2) progressive roentgenographic parenchymal abnormality, (3) ≥ 10% decrease in FVC or TLC compared with previous values, (4) ≥ 20% reduction in DLCO compared with previous values] Excluded: collagen vascular disease, hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pneumoconiosis, drug-induced diffuse pulmonary injury, or irradiation fibrosis |

Primary outcomes: not stated as primary or secondary – measurable change in lung function (FVC, DLCO, PA – aO2) at 12 months; survival Length of follow-up: 12 months |

| BIBF 1120 | |||

| Richeldi et al. 201171 Country: 25 countries including Italy, Mexico, Germany, USA, Republic of Korea, UK, France Design: RCT (dose-finding phase II study) Number of centres: 92 Funding: supported by Boehringer Ingelheim |

1. BIBF 1120 50 mg/day, n = 86 2. BIBF 1120 50 mg twice per day (100 mg/day), n = 86 3. BIBF 1120 100 mg twice per day (200 mg/day), n = 86 4. BIBF 1120 150 mg twice per day (300 mg/day), n = 85 5. Placebo, n = 85 Dose details: a group-wise dose escalation was used with stepwise increases in dose for serial cohorts Duration of treatment: 52 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: ≥ 40 years, IPF consistent with the ATS/ERS 2000 criteria, diagnosis < 5 years, HRCT < 1 year, FVC that was ≥ 50% predicted, DLCO 30–79% predicted, and PaO2 when breathing ambient air ≥ 55 mmHg at altitudes up to 1500 m, or ≥ 50 mmHg at altitudes above 1500 m Excluded: medical conditions or concomitant medications that might interfere with the performance of the study, other diseases that might interfere with testing procedures (stated), continuous oxygen supplementation, predisposition to bleeding or thrombosis, concomitant anticoagulation medication, elevated liver enzymes, likelihood of lung transplantation during the study or life expectancy < 2.5 years for a disease other than IPF |

Primary outcomes: annual rate of decline in FVC Secondary outcomes: per cent predicted FVC; DLCO; SpO2; TLC; 6MWT, SGRQ, decrease in FVC of > 10% or > 200 ml; SpO2 decrease of > 4%; acute exacerbations; survival; death from a respiratory cause; adverse events Length of follow-up: 54 weeks |

| NAC (alone or in combination) | |||

| Demedts et al. 200567 Country: Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Spain, the Netherlands Design: RCT Number of centres: 36 Funding: sponsored by the Zambon group |

1. NAC, prednisolone, azathioprine, n = 92 (80 analysed) 2. Placebo, prednisolone, azathioprine, n = 90 (75 analysed) Dose details: NAC at 600 mg three times per day. Azathioprine at 2 mg/kg per day. Prednisone dose decreases from 0.5 mg/kg body weight per day; 0.4 mg/kg per day at month 2; 0.3 mg/kg at month 3; until 10 mg per day in months 4–6 and then maintained until month 12 Duration of treatment: not stated, assume 12 months |

Inclusion criteria: 18–75 years, histological or radiologic pattern typical of UIP. HRCT suggestive or consistent with a probable diagnosis of UIP. Open or thoracoscopic lung biopsy in those aged < 50 years. In the absence of lung biopsy, a transbronchial biopsy was advocated to exclude alternative diagnoses. Duration > 3 months, bibasilar inspiratory crackles, dyspnoea score at least 2 on a scale of 0 (minimum) to 20 (maximum), VC ≤ 80% predicted or TLC < 90% predicted, and single-breath DLCO < 80% predicted Excluded: contraindication/intolerance to study treatments. Prednisone at least 0.5 mg/kg/day or azathioprine at least 2 mg/kg/day during the month before inclusion, treatment with NAC of >600 mg/day for > 3 months in the previous 3 years. Concomitant or pre-existing diseases, or treatments that interfere with IPF |

Primary outcomes: absolute changes in VC and DLCO at 12 months Secondary outcomes: per cent predicted VC, per cent predicted DLCO, alveolar volume change and per cent predicted, CRP score, dyspnoea score, maximum exercise indexes, HRCT outcomes, SGRQ, adverse events, withdrawals, and mortality Length of follow-up: 12 months |

| Raghu et al. IPFCRN 201268 Country: USA Design: RCT (PANTHER study) Number of centres: 25 Funding: grants from the NHLBI; the Cowlin Family fund. NAC and placebo donated by Zambon |

1. NAC and placebo (data not presented in article as ‘ongoing’ data collection), n = 81 2. NAC/prednisolone/azathioprine, n = 77 3. Placebo, n = 78 Dose details: NAC at 600 mg orally three times per day. Prednisone decreased from 0.5 mg/kg of ideal body weight to 0.15 mg/kg during 25 weeks. Azathioprine (maximum 150 mg/day) based on ideal weight, concurrent use of allopurinol, and thiopurine methyltransferase activity Duration of treatment: up to 60 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: IPF aged between 35–85 years with mild to moderate lung-function impairment (FVC ≥ 50% and DLCO ≥ 30% of predicted values), modified criteria of the ATS/ERS (2011) for diagnosis of IPF, received diagnosis on the basis of HRCT or biopsy ≤ 48 months before enrolment Excluded: FEV1–FVC ratio < 0.65; PaO2 on room air < 55 mmHg; residual volume > 120% predicted; evidence of active infection; significant bronchodilator response; post-bronchodilator FVC differing by > 11%; listed for lung transplantation; history of cardiac disease or hypertension; HIV or hepatitis C; liver cirrhosis and chronic active hepatitis |

Primary outcomes: change in FVC at 60 weeks Secondary outcomes: rate of death, time until death, frequency of acute exacerbation, frequency of maintained FVC response, time to disease progression, clinical and physiological measures including DLCO, 6MWT, CPI, UCSDSBQ, SGRQ, SF-36, EQ-5D. Adverse events Length of follow-up: 60 weeks in the planned analysis. The study was stopped early. The mean follow-up was 32 weeks |

| Homma et al. 201269 Country: Japan Design: RCT Number of centres: 27 Funding: grant from Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare |

1. NAC inhaled, n = 51 (38 analysed) 2. Control, n = 49 (38 analysed) Dose details: NAC inhalation of 352.4 mg diluted with saline to a total volume of 4 ml twice a day, using microair nebulisers and vibration mesh technology Control: states ‘no treatment or placebo’ Duration of treatment: 48 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: well-defined IPF (by ATS/ERS guidance and Japanese criteria). Histological evidence of UIP was not mandatory, but HRCT evidence was required as were presence of other typical clinical features. Aged between 50 and 79 years, severity of disease classified as stage I (partial O2 concentration ≥ 80 mmHg at rest), or stage II (partial O2 concentration 70–80 mmHg at rest), a lowest arterial oxygen saturation of > 90% during the 6MWT Excluded: an improvement in symptoms during the preceding 3 months; use of NAC, immunosuppressive agents, oral prednisolone or pirfenidone; clinical suspicion of IIP other than IPF |

Primary outcomes: absolute change in FVC at 48 weeks Secondary outcomes: changes in lowest arterial O2 saturation, 6MWT distance, PFT parameters (VC, per cent predicted VC, TLC, per cent predicted TLC, DLCO, predicted DLCO), serum markers of pneumocyte injury; disease progression as determined by HRCT; subjective changes in symptoms such as dyspnoea, adverse events Length of follow-up: 48 weeks |

| Pirfenidone | |||

| Noble et al. 201162 Capacity study 006 Country: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, UK, USA Design: RCT Number of centres: 110 centres Funding: InterMune |

1. Pirfenidone 2403 mg/day, n = 171 2. Placebo, n = 173 Dose details: the dose was increased to the full dose over 2 weeks Duration of treatment: 72 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: aged 40–80 years, diagnosis of IPF in the previous 48 months, no evidence of improvement in measures of disease severity over the preceding year. Predicted FVC of ≥ 50%, predicted DLCO of ≥ 35%, either predicted FVC or DLCO ≤ 90%, 6MWT distance of ≥ 150 m Excluded: obstructive airway disease, connective tissue disease, alternative explanation for ILD, those on a waiting list for a lung transplant |

Primary outcomes: change in per cent predicted FVC Secondary outcomes: categorical FVC (5-point scale), PFS, worsening IPF, dyspnoea, 6MWT distance, worst peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) during the 6MWT, per cent predicted DLCO, fibrosis, mortality Length of follow-up: 72 weeks from the date the last patient was enrolled |

| Noble et al. 201162 Capacity study 004 Country: Australia, Belgium, Canada, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Poland, Spain, Switzerland, UK, USA Design: RCT Number of centres: 110 centres Funding: InterMune |

1. Pirfenidone 2403 mg/day, n = 174 2. Pirfenidone 1197 mg/day, n = 87 3. Placebo, n = 174 Dose details: the dose was increased to the full dose over 2 weeks Duration of treatment: 72 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: aged 40–80 years, diagnosis of IPF in the previous 48 months, no evidence of improvement in measures of disease severity over the preceding year. Predicted FVC of ≥ 50%, predicted DLCO of ≥ 35%, either predicted FVC or DLCO ≤ 90%, 6MWT distance of ≥ 150 m Excluded: obstructive airway disease, connective tissue disease, alternative explanation for ILD, those on a waiting list for a lung transplant |

Primary outcomes: change in per cent predicted FVC Secondary outcomes: categorical FVC (5-point scale), PFS, worsening IPF, dyspnoea, 6MWT distance, worst peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2) during the 6MWT, per cent predicted DLCO, mortality Length of follow-up: 72 weeks from the date the last patient was enrolled |

| Taniguchi et al. 201065 Country: Japan Design: RCT Number of centres: 73 Funding: public sector grants. Drug and placebo from Shionogi & Co., Ltd |

1. Pirfenidone 1800 mg/day, n = 108 2. Pirfenidone 1200 mg/day, n = 55 3. Placebo, n = 104 Dose details: doses increased in a stepwise manner over 4 weeks Duration of treatment: 52 weeks |

Inclusion criteria: aged 20–75 years, IPF diagnosed using ATS/ERS and clinical diagnostic criteria guidelines for IIP in Japan. Independently evaluated HRCT scans. Probably UIP by surgical lung biopsy. Arterial oxygen saturation criteria of (1) oxygen desaturation of ≥ 5% difference between resting SpO2 and the lowest SpO2 during a 6MET; and (2) the lowest SpO2 during the 6MET of ≥ 85% while breathing air Excluded: decrease in symptoms (preceding 6 months); use of immune-suppressants and/or oral corticosteroids at a dose of > 10 mg/day–1 (preceding 3 months); clinical features of IIP other than IPF; coexisting lung conditions (stated) or severe respiratory infection |

Primary outcomes: change in VC to week 52 Secondary outcomes: PFS time, change in lowest SpO2 during the 6MET. PaO2, PA – aO2, TLC and DLCO, acute exacerbation, markers of interstitial pneumonias, symptoms Length of follow-up: 52 weeks |

| Azuma et al. 200566 Country: Japan Design: RCT Number of centres: 25 Funding: Shionogi & Co., Ltd |

1. Pirfenidone 1800 mg/day, n = 73 2. Placebo, n = 36 Dose details: doses increased in a stepwise manner over 1 week Duration of treatment: 9 months |

Inclusion criteria: histological evidence of UIP not mandatory, HRCT evidence of definite or probable UIP required. Presence of bibasilar inspiratory crackles, abnormal PFTs, and increased serum levels of damaged-pneumocyte markers. Aged 20–75 years with PaO2 ≥ 70 mmHg at rest and demonstrated SpO2 of ≤ 90% during exertion while breathing air, 1 month before enrolment Excluded: a decrease in symptoms (preceding 6 months), use of immunosuppressive and/or oral prednisolone > 10 mg/day (preceding 3 months), clinical suspicion of IIP other than IPF, coexisting lung conditions (defined); uncontrolled diabetes, comorbid conditions |

Primary outcomes: change in the lowest SpO2 during the 6MET Secondary outcomes: resting PFTs while breathing air (VC, TLC, DLCO PaO2), disease progression by HRCT patterns, acute exacerbation, serum markers of pneumocyte damage, QoL Length of follow-up: minimum of 9 months |

| Thalidomide | |||

| Horton et al. 201255,75 Country: USA Design: randomised crossover trial Number of centres: one Funding: Celgene Corporation |

1. Thalidomide, n = 23 2. Placebo, n = 23 Dose details: 50 mg oral daily, increased to 100 mg if no improvement in cough occurred after 2 weeks (21 of 22 receiving thalidomide and 23 of 23 receiving placebo) Duration of treatment: 12 weeks each treatment with a 2-week washout period between treatments |

Inclusion criteria: aged > 50 years, clinical history consistent with IPF (symptom duration ≥ 3 months and ≤ 5 years) and chronic cough (defined as > 8 weeks’ duration, that adversely affected QoL and not due to other identifiable causes). HRCT scans consistent with IPF or surgical lung biopsy demonstrating UIP, FVC between 40% and 90% predicted, TLC between 40% and 80% predicted, and DLCO between 30% and 90% predicted Exclusion criteria: pregnancy, female with childbearing potential, toxic or environmental exposure to respiratory irritants, collagen vascular disease, airflow obstruction, active narcotic antitussive use, peripheral vascular disease or neuropathy, inability to give informed consent, allergy or intolerance to thalidomide, life expectancy < 6 months (opinion of investigators) |