Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 13/12/01. The contractual start date was in July 2013. The draft report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Cooper et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Premature ejaculation (PE) is a form of male sexual dysfunction. It is also referred to as early ejaculation, rapid ejaculation, rapid climax, premature climax and (historically) ejaculation praecox. Official definitions of PE have been set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition-Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR)1 and in the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10). 2 The DSM-IV-TR defines the condition as persistent or recurrent ejaculation with minimal sexual stimulation before, on or shortly after penetration and before the person wishes it. 1 Other definitions have also been proposed by the Second International Consultation on Sexual and Erectile Dysfunction3 and the International Society for Sexual Medicine (ISSM). 4 All four definitions consider time to ejaculation, inability to control or delay ejaculation and negative consequences of PE. However, there is no current consensus on quantification of the time to ejaculation, which is usually described by intravaginal ejaculatory latency time (IELT), i.e. the time taken by a man to ejaculate during vaginal penetration. 5

Aetiology, pathology and prognosis

According to the European Association of Urology (EAU), the aetiology of PE is unknown, with few data to support suggested biological and psychological hypotheses, including anxiety, penile hypersensitivity and 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) receptor dysfunction, and the pathophysiology of PE is largely unknown. 6 PE can be either lifelong (primary) or acquired (secondary). 7 Lifelong PE is that which has been present since the person’s first sexual experiences, while acquired PE is that which begins later following normal ejaculation experiences. PE can occur secondary to another condition such as erectile dysfunction or prostatitis, in which case guidelines recommend treating the underlying condition first or concomitantly. 6,8 PE cannot be cured, but can be managed with behavioural and/or pharmacological treatment.

Epidemiology and prevalence

Epidemiological surveys in the USA and other countries suggest that PE as defined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)9 is the most common male sexual dysfunction, with prevalence rates of 20–30%. 3,10,11 The highest prevalence, 31% (among men aged 18–59 years), was found by the USA National Health and Social Life Survey study. 11 In a five-country European observational study, which included the UK, the prevalence of PE was 18%. 12

Impact of health problem

Men with PE are more likely to report lower levels of sexual functioning and satisfaction, and higher levels of personal distress and interpersonal difficulty, than men without PE. 5 They may also rate their overall quality of life lower than that of men without PE. 5 In addition, the partner’s satisfaction with the sexual relationship has been reported to decrease with increasing severity of the condition. 13

Measurement of disease

Diagnosis of PE is based on the patient’s medical and sexual history. 14,15 IELT can be either self-assessed or stopwatch measured. The EAU 2013 Guidelines on Male Sexual Dysfunction6 state that the use of IELT alone is not sufficient to define PE, and the need to assess PE objectively has led to the development of several questionnaires, including two questionnaires that can discriminate between patients who have PE and those who do not. These are the Premature Ejaculation Diagnostic Tool (PEDT)16,17 and the Arabic Index of Premature Ejaculation (AIPE). 18 Other questionnaires used to characterise PE and determine treatment effects include the Premature Ejaculation Profile (PEP),19 the Index of Premature Ejaculation (IPE)20 and the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire Ejaculatory Dysfunction. 21

Current service provision

Relevant national guidelines

Guidelines on PE include the EAU 2013 Guidelines on Male Sexual Dysfunction6 and the British Recommendations for the Management of Premature Ejaculation, 2006. 8

Management of the condition

The treatment of PE should attempt to alleviate concern about the condition as well as increase sexual satisfaction for the patient and the partner. 8 Descriptions of a recommended treatment pathway for the condition are varied. The British Association of Urological Surgeons suggest that counselling may help men with less troublesome PE but, for most men, the mainstay of long-term treatment is drugs. 22 The British Association for Sexual Health and HIV, Special Interest Group for Sexual Dysfunction, suggests that management of patients should be decided on a case-by-case basis that considers behavioural, local and systemic pharmacological treatments. 8 The EAU presents a definitive treatment pathway based on clinical diagnosis of the condition and treatment of PE based on whether or not the condition is either lifelong or acquired. There is currently no published literature that identifies a clinically significant threshold response to interventions for PE. 23

Description of technology under assessment

Summary of interventions

Treatments include behavioural techniques, anaesthetic creams and sprays, tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil, analgesics such as tramadol (Zydol SR®, Grünenthal) and other drug and non-drug interventions. 6,8 One antidepressant [dapoxetine (Priligy®, Menarini), a SSRI] has received approval for the treatment of PE in the UK. 24 To date, no other drug has been approved for PE in Europe or the USA and other medical treatments prescribed for PE are ‘off-label’ (the practice of prescribing treatments for an unapproved indication).

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

Population and subgroups

The relevant population comprised all men aged ≥ 18 years with PE, both lifelong and acquired PE. Studies focusing specifically on men with PE secondary to another condition (such as erectile dysfunction or prostate conditions) were excluded if possible; however, this information was often not reported.

Interventions assessed

Treatment modalities included behavioural techniques, topical therapies, systemic therapies and other therapies.

Relevant comparators

Comparators included other interventions, waiting list control, placebo or no treatment.

Key outcomes

The key outcomes for this review were IELT, sexual satisfaction, control over ejaculation, relationship satisfaction, self-esteem and quality of life. As these outcomes in PE are assessed in the literature using different methods, and there is a lack of core validated outcome measures, any assessment methods were permitted for these outcomes.

Overall aim and objective of assessment

The aim and objective of this assessment were to systematically review the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of interventions for management of PE, in the form of a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) short report.

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

A systematic review of the literature was undertaken to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of interventions for men with PE. A review of the evidence was undertaken in accordance with the general principles recommended in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 25 The completed PRISMA checklist is presented in Appendix 1.

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

Identification of studies

The following electronic databases were searched from inception to 6 August 2013 for published and unpublished research evidence: MEDLINE; EMBASE; Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL); The Cochrane Library including the Cochrane Systematic Reviews Database; Cochrane Controlled Trials Register (CCRT); Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and the HTA database; ISI Web of Science, including Science Citation Index, and the Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Science; The US Food and Drug Administration website and the European Medicines Agency website were also searched. All citations were imported into Reference Manager Software (version 12, Thomson ResearchSoft, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and any duplicates deleted.

Search terms were included a combination of medical subject headings (MeSHs) and free-text searches for terms around ‘premature ejaculation’. These included:

-

MeSHs: Ejaculation; Premature ejaculation.

-

Free-text search terms: premature$adj3 ejaculat$; early adj3 ejaculat$; rapid adj3 ejaculat$; rapid adj3 climax$; premature$adj3 climax$; ejaculat$adj3 pr?ecox.

Search filters (study design filters) were used to restrict the searches to randomised controlled trials (RCTs), reviews and guidelines. These were:

-

the RCT filter available from the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network26

-

the reviews filter available from the York Centre for Reviews and Dissemination27

-

the filter for guidelines available from the Health Evidence Bulletins Wales resource. 28

Details of the MEDLINE strategy are presented in Appendix 2. Existing reviews identified by the searches were obtained and examined for relevant RCT data. However, all bibliographic data sources were searched from inception; thus, existing reviews were not relied upon as the only source for identifying relevant RCTs.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Population

The relevant population included all men aged ≥ 18 years with PE, including both lifelong and acquired PE. Studies focusing specifically on men with PE secondary to another condition (such as erectile dysfunction or prostate conditions) were excluded; however, this information was often not reported.

As some formal definitions of PE have only recently been developed, studies were included whether or not they used a standard definition and all definitions used were recorded. Common definitions of PE include the following:

Included interventions

Behavioural interventions included psychological or psychosocial interventions to develop sexual management strategies that were either validated or described by investigators as being a treatment for PE treatment. Examples include:

-

‘Stop–start’ programme developed by Semans:16 the man or his partner stimulates the penis until he feels the urge to ejaculate, then stops until the sensation passes; this is repeated a few times before allowing ejaculation to occur. The aim is to learn to recognise the feelings of arousal in order to improve control over ejaculation.

-

‘Squeeze’ technique, proposed by Masters and Johnson:17 the man’s partner stimulates the penis until he feels the urge to ejaculate, then squeezes the glans of the penis until the sensation passes; this is repeated before allowing ejaculation to occur.

-

Sensate focus or sensate focusing:4 the man and his partner begin by focusing on touch which excludes breasts, genitals and intercourse, to encourage body awareness while reducing performance anxiety; this is followed by gradual reintroduction of genital touching and then full intercourse.

Topical treatments included:

-

Lidocaine–prilocaine, eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics (EMLA®, AstraZeneca), topical eutectic mixture for PE [(TEMPE), a combination of two medicines – lidocaine and prilocaine], dyclonine or lidocaine. These can be in the form of either a cream or an aerosol vehicle or a gel containing a local anaesthetic (Instillagel®, CliniMed).

Systemic treatments included:

-

SSRIs [e.g. fluoxetine, sertraline, citalopram (Cipramil®, Lundbeck), paroxetine, fluvoxamine and dapoxetine]. Dapoxetine is a short-acting SSRI that can be taken a few hours preintercourse rather than as a daily dose and is the only drug currently licensed for PE in the UK.

-

Serotonin–noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) [e.g. duloxetine (Cymbalta®, Eli Lilly & Co Ltd), venlafaxine].

-

TCAs (e.g. clomipramine).

-

PDE5 inhibitors [e.g. sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra®, Bayer), tadalafil (Cialis®, Eli Lilly & Co Ltd)].

-

Alpha-blockers [e.g. terazosin (Hytrin®, AMCO), alfuzosin].

-

Opioid analgesics (e.g. tramadol).

Other therapies included:

-

acupuncture

-

Chinese medicine

-

delay device/desensitising band: a small device which the man can use together with stop–start and squeeze techniques to gradually improve control over ejaculation

-

yoga.

Combinations of therapies included drug plus behavioural therapies or combinations of drug therapies.

Excluded interventions

The following interventions not considered relevant to the UK setting were excluded:

-

Severance Secret cream (SS cream: a topical plant-based preparation comprising extracts of nine plants). Not currently available within the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, Porterbrook Clinic, 2013, personal communication).

-

Antiepileptic drugs (e.g. gabapentin). Not currently included in the UK30 or European6 guidelines and not currently used in clinical practice in the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, personal communication).

-

Antipsychotics [e.g. thioridazine (Melleril, Novartis, withdrawn worldwide in 2005), perphenazine (Trilafon, Merck Sharp & Dohme), levosulpiride]. Not currently included in the UK30 or European6 guidelines and not currently used in clinical practice in the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, personal communication).

-

Antiemetics (e.g. metoclopramide). Not currently included in the UK30 or European6 guidelines and not currently used in clinical practice in the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, personal communication).

-

Barbiturates (e.g. Atrium 300). Not currently included in the UK30 or European6 guidelines and not currently used in clinical practice in the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, personal communication).

-

Beta-blockers (e.g. propranolol). Not currently included in the UK30 or European6 guidelines and not currently used in clinical practice in the UK (Professor Kevan Wylie, personal communication).

Comparators

Comparators included other interventions, waiting list control, placebo or no treatment.

Outcomes

The key outcomes for this review were:

-

IELT: studies that do not report this outcome objectively, but assess the outcome via another subjective measure such as a questionnaire, were included. Studies that assess ejaculation latency time in a laboratory setting, i.e. not intravaginally, were excluded.

-

Sexual satisfaction.

-

Control over ejaculation.

-

Relationship satisfaction.

-

Self-esteem.

Other outcomes included:

-

Quality of life.

-

Treatment acceptability.

-

Adverse events (AEs).

Included study types

Included study designs were restricted to RCTs, if available. If no RCT evidence was identified for a particular intervention, other study types (non-RCT) were considered. Owing to the time constraints of this short report, if RCTs were included in existing reviews, data were extracted from the review and not from the original RCT publication. RCTs not captured by existing reviews and those published subsequently to existing reviews were identified via the literature search and data were extracted directly from the RCT publication. RCTs reported in abstract form only were eligible for inclusion, provided adequate information was presented in the abstract. Studies using quasi-randomisation were excluded, providing other RCT evidence for the treatment of interest was available.

Non-English-language studies were excluded unless sufficient data could be extracted (from English-language abstracts and/or tables). Dissertations and theses were excluded.

Data abstraction strategy

Titles and abstracts of citations identified by the searches were screened for potentially relevant studies by one reviewer and a subset checked by a second reviewer (and a check for consistency undertaken). Full texts were screened by two reviewers. Details of studies identified for inclusion were extracted using a data extraction sheet. One reviewer performed data extraction of each included study. All numerical data were then checked against the original article by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved by a third reviewer. When studies comprised duplicate reports (parallel publications), all associated reports were used to extract information.

Methods of data synthesis

When possible, data were pooled in a meta-analysis from RCTs reported in the existing reviews along with data extracted from additional RCTs not captured by the existing reviews. Meta-analysis of outcome data from all RCTs was then undertaken using Cochrane RevMan software (version 5.2, The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). Outcomes reported as continuous data were estimated using a mean difference (MD) with 95% confidence interval (CI). Outcomes reported as dichotomous were estimated as relative risks (RRs) with associated 95% CI. When RCTs reported AEs in sufficient detail (e.g. the number of participants who experienced at least one AE), these were analysed as dichotomous data. Data from single-arm randomised crossover design studies were considered separately in the analysis to avoid a unit-of-analysis error. 31

Clinical heterogeneity across RCTs (the degree to which RCTs appear different in terms of participants, intervention type and duration and outcome type) and statistical heterogeneity were considered prior to data pooling. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the chi-squared test (p-value < 0.10 was considered to indicate statistically significant heterogeneity) in conjunction with the I-squared statistic. 32 For comparisons in which there was little apparent clinical heterogeneity and the I2-value was ≤ 40%, a fixed-effects model was applied. When there was little apparent clinical heterogeneity and the I2-value was > 40%, a random-effects model was applied. Effect estimates (estimated in RevMan as z-values) were considered significant at p < 0.05. Data were not pooled across RCTs for which heterogeneity was very high (I2-values of ≥ 75%).

Quality assessment of included studies

The methodological quality of systematic reviews used as a source of RCT data were assessed using the Assessing Methodological Quality of Systematic Reviews (AMSTAR) checklist. 33 This checklist consists of 11 items and has good face and content validity for measuring the methodological quality of systematic reviews. 33 Domain items with a ‘yes’ response are scored one point. ‘No’, ‘not applicable’ and ‘unclear’ responses score a zero. An overall score was estimated for each review by summing the total number of points. It was not possible to undertake quality assessment for RCTs for which data were extracted from existing reviews. Methodological quality of further RCTs identified from the literature search was assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration risk of bias assessment criteria. This tool addresses specific domains, namely sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting. 34 We classified RCTs as being at overall ‘low risk’ of bias if they were rated as ‘low’ for each of three key domains – allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment and completeness of outcome data. RCTs judged as being at ‘high risk’ of bias for any of these domains were judged at overall ‘high risk’. Similarly, RCTs judged as being at ‘unclear risk’ of bias for any of these domains were judged at overall ‘unclear risk’.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

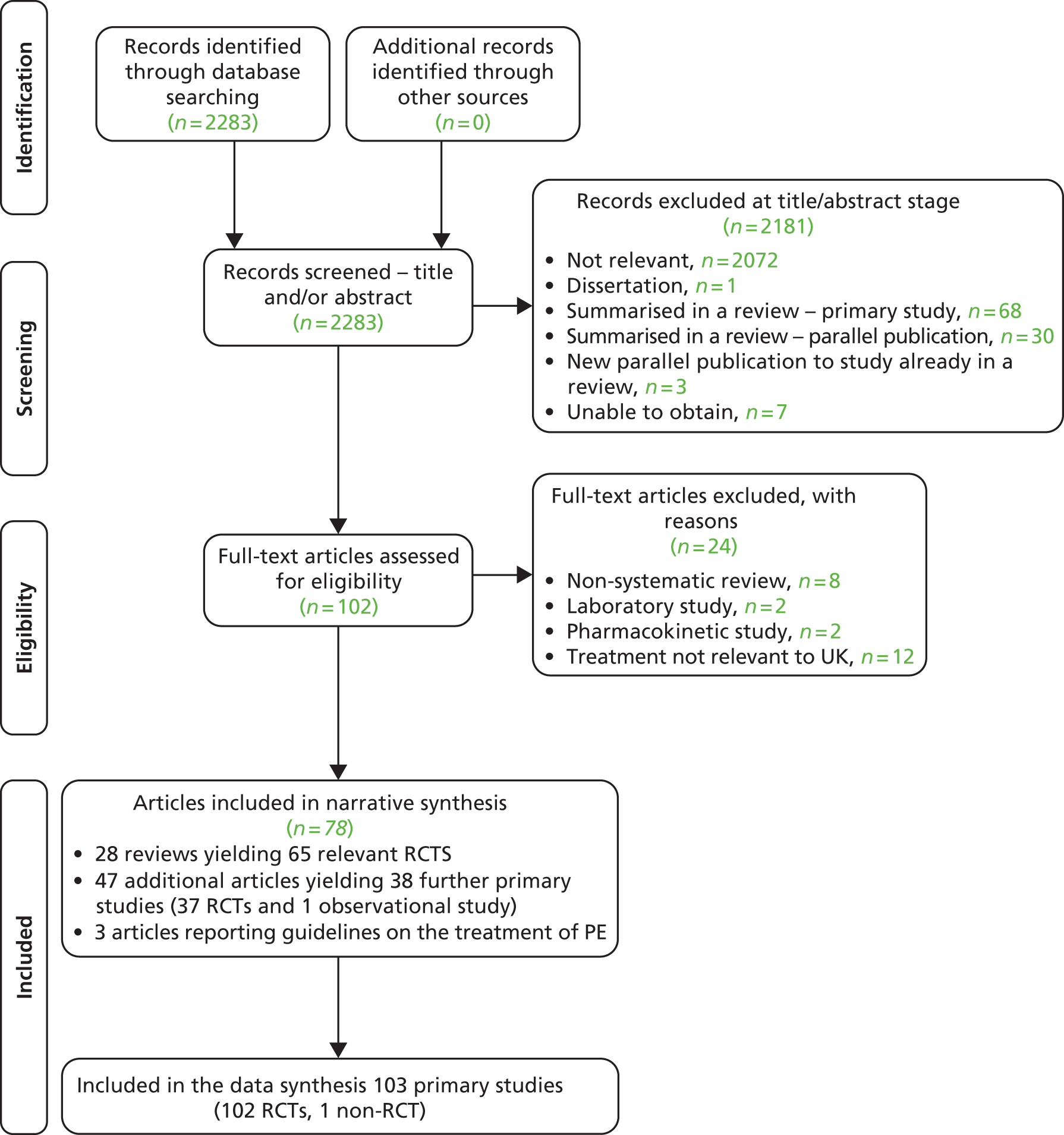

The searches identified 2283 citations. Of these, 2181 citations were excluded, 2174 based on title and/or abstract information and seven that we were unable to obtain. One hundred and three (103) full-text articles were obtained as potentially relevant. Of these, 24 were excluded: eight were non-systematic reviews or treatment overviews, two were laboratory-based assessments, two were pharmacokinetic assessment studies and 12 were studies evaluating treatments not relevant to the UK setting. Details of the 24 excluded studies are presented in Appendix 3. In total, 78 articles from the searches were included in this assessment report comprising: 28 reviews, 47 primary study articles (relating to 38 studies) and three guideline articles (relating to two guidelines) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study selection process: PRISMA flow diagram.

From these publications, a total of 103 primary studies (102 RCTs) are summarised in this review (Table 1). Sixty-five RCTs were extracted from existing reviews and 38 further studies from the literature search (see Table 1). All 65 RCTs reported in existing reviews were also captured by the searches for this assessment report. RCT evidence was available for all of the treatments of interest for this review, bar yoga. For yoga, one observational study was included (a non-RCT). Details of the AMSTAR33 quality assessment of included reviews and Cochrane risk of bias assessment34 for the RCTs not included by reviews are presented in Appendix 4.

| Intervention type | No. of reviews | No. of RCTs (extracted from reviews) | Further RCTs (not in reviews) | RCTs (total) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioural therapies | 435–38 | 939–47 | 348–50 | 12 |

| Topical anaesthetics | 451–54 | 755–61 | 262,63 | 9 |

| SSRIs other than dapoxetine | 7: | 26: | 16: | 42: |

|

||||

|

|

|||

|

||||

|

|

|

||

|

||||

|

||||

| Dapoxetine | 8: | 885,113–119 (one non-licensed doses; data not included here115) | 1120 | 9 (8 for licensed doses) |

| SNRIs | 168 | 1 (duloxetine)121 | 2 (venlafaxine)122,123 | 3 |

| TCAs (clomipramine) | 352,68,69 | 1039,76,124–131 | 3107,132,133 | 13 |

| PDE5 | 537,134–137 | 1039,55,138–145 | 2101,120 | 12 |

| Alpha-blockers | 2 (various treatments)52,69 | 1146 | 1107 | 2 |

| Opioid analgesics (tramadol) | 3147–149 | 546,150–153 | 2154,155 | 7 |

| Acupuncture | 0 | 0 | 2156,157 | 2 |

| Chinese medicine | 0 | 0 | 5158–162 | 5 |

| Delay device | 0 | 0 | 1163 | 1 |

| Yoga | 0 | 0 | 1164 (non-RCT) | 1 (non-RCT) |

As titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion by one reviewer, a check for consistency was undertaken. A second reviewer screened approximately 10% of the references (n = 250) during the initial screening stage. At this stage, references tagged as potentially relevant by reviewer 1 included 5 out of 194 (3%) references excluded by reviewer 2, and references tagged as potentially relevant by reviewer 2 included 22 out of 211 (10%) references excluded by reviewer 1. This gave a kappa statistic of 0.65, generally classed as good agreement. The discrepancies appeared to be due to the very broad inclusion criteria (in terms of study type and intervention type) that were applied at the time of initial screening. The references for which there was a discrepancy related to article types such as comment articles, news articles and uncontrolled studies that were initially tagged as potentially relevant. However, later examination revealed that none of these articles were relevant for inclusion in the final review.

Assessment of effectiveness

Overall summary of results

An overall results summary from this assessment report for outcomes of IELT, sexual satisfaction, control over ejaculation and other secondary outcomes, plus AEs, following treatment with behavioural techniques anaesthetic creams and sprays, TCAs, SSRIs including dapoxetine, PDE5 inhibitors, analgesics (tramadol) and other interventions in the management of PE is provided in Table 2. A detailed assessment of the effectiveness for each treatment type then follows.

| Treatment | Better than | On outcomes of | Between-group difference significant | AEs with treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behavioural therapies | ||||

| Behavioural therapy | Waiting list control | Duration of intercourse, sexual satisfaction, desire, self-confidence | Yes | No AE data available for behavioural therapies |

| Behavioural therapy plus pharmacotherapy | Pharmacotherapy alone | IELT, ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction, sexual anxiety | Yes | |

| Behavioural therapy plus pharmacotherapy | Behavioural therapy alone | IELT, ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction, sexual anxiety | Yes | |

| Pharmacotherapy alone | Behavioural therapy alone | IELT, sexual satisfaction | Yes | Various AEs associated with pharmacotherapy (nausea, vomiting, dry mouth, dizziness, flushing, diarrhoea) |

| Topical anaesthetics | ||||

| EMLA cream | Placebo | IELT | Yes | Loss of sensation, irritation and loss of erection (application ≥ 20 minutes) |

| TEMPE spray | Placebo | IELT ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and distress | Yes | |

| SSRIs currently not licensed for PE | ||||

| Citalopram | Placebo or no therapy | IELT, sexual satisfaction and measures of clinical improvement | Yes | |

| Escitalopram (Cipralex®, Lundbeck) | Placebo | IELT, sexual satisfaction | Yes | Nausea, headache, insomnia, dry mouth, diarrhoea, drowsiness, dizziness, somnolence, decreased libido and anejaculation |

| Fluoxetine | ||||

| Paroxetine | ||||

| Sertraline | Placebo | IELT, ejaculation control | Yes | |

| Clomipramine | Paroxetine | IELT | Yes | Similar to SSRIs |

| Fluvoxamine | Placebo | IELT | No | Not significant between fluvoxamine, fluoxetine, paroxetine and sertraline |

| SSRIs licensed for PE (dapoxetine) | ||||

| Dapoxetine 30 mg or 60 mg | Placebo | IELT, ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction, patients reporting change | Yes | Similar to other SSRIs |

| Dapoxetine 60 mg | Dapoxetine 30 mg | Yes | ||

| SNRIs | ||||

| Duloxetine | Placebo | IELT | Yes | Dry mouth and nausea; more AEs with venlafaxine than placebo |

| Venlafaxine | Placebo | IELT | No | Significantly more treatment-related side effects than placebo |

| TCAs | ||||

| Clomipramine: oral | Placebo | IELT | Yes | More AEs with clomipramine than fluoxetine or sertraline |

| Clomipramine: nasal (4 mg) | Yes | Local irritation associated with nasal administration | ||

| PDE5 inhibitors | ||||

| PDE5 inhibitors | Placebo | IELT | Vardenafil or tadalafil, yes; sildenafil, no | Flushing, headache and palpitations |

| PDE5 inhibitors | SSRIs | Sertraline, yes; fluoxetine, no | ||

| PDE5 inhibitors plus SSRIs | SSRIs alone | Yes | ||

| PDE5 inhibitors | Behavioural therapy | Yes | ||

| Alpha-blockers | ||||

| Terazosin | Placebo | Ejaculation control | Yes | Headache, hypotension, drowsiness, ejaculation disorder |

| Opioid analgesics | ||||

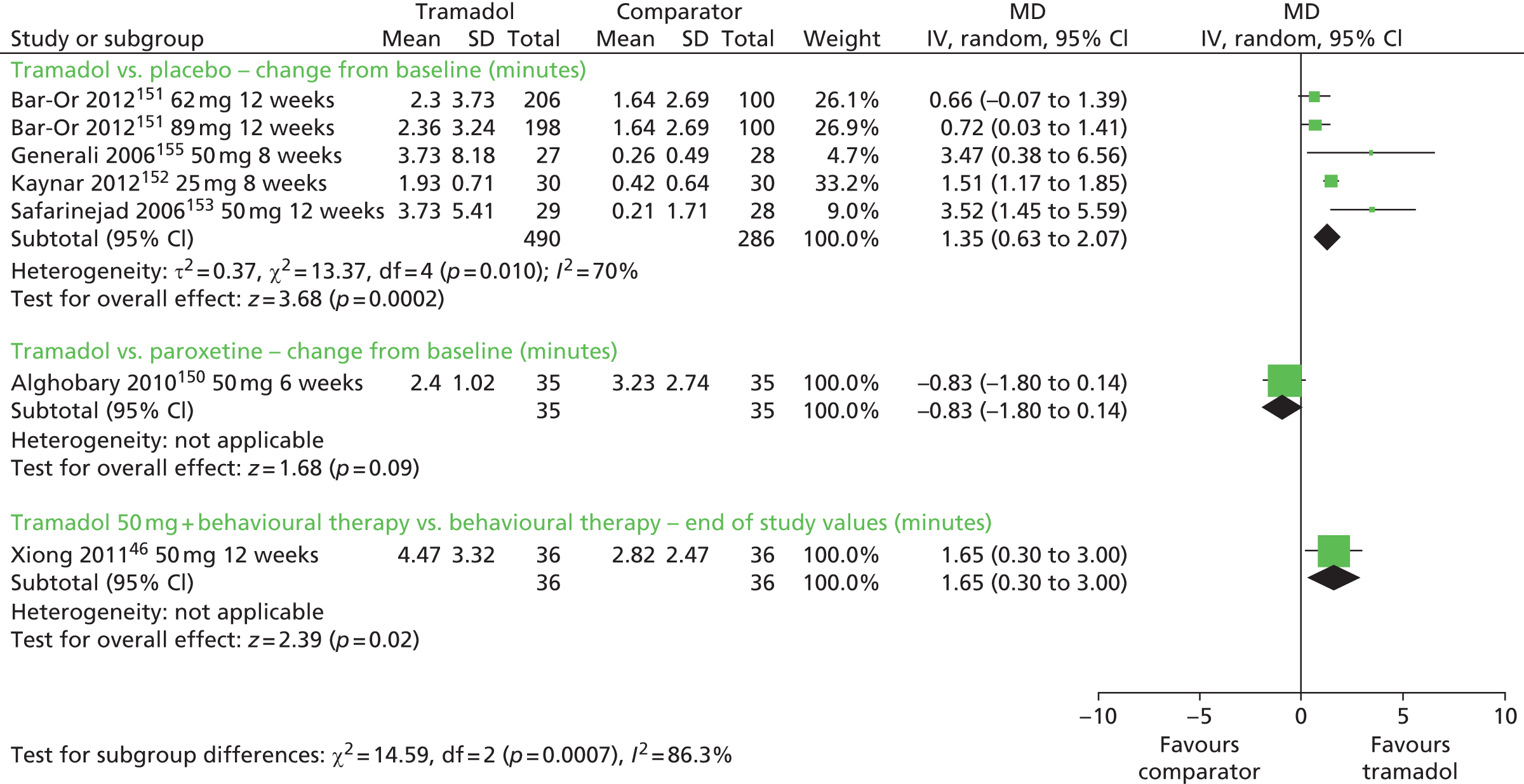

| Tramadol | Placebo | IELT, various patient-reported outcomes, including sexual satisfaction | Yes | Erectile dysfunction, constipation, nausea, headache, somnolence, dry mouth, dizziness, pruritus, vomiting |

| Tramadol plus behavioural therapy | Behavioural therapy | Yes | ||

| Paroxetine | Tramadol | IELT | No | |

| Other therapies | ||||

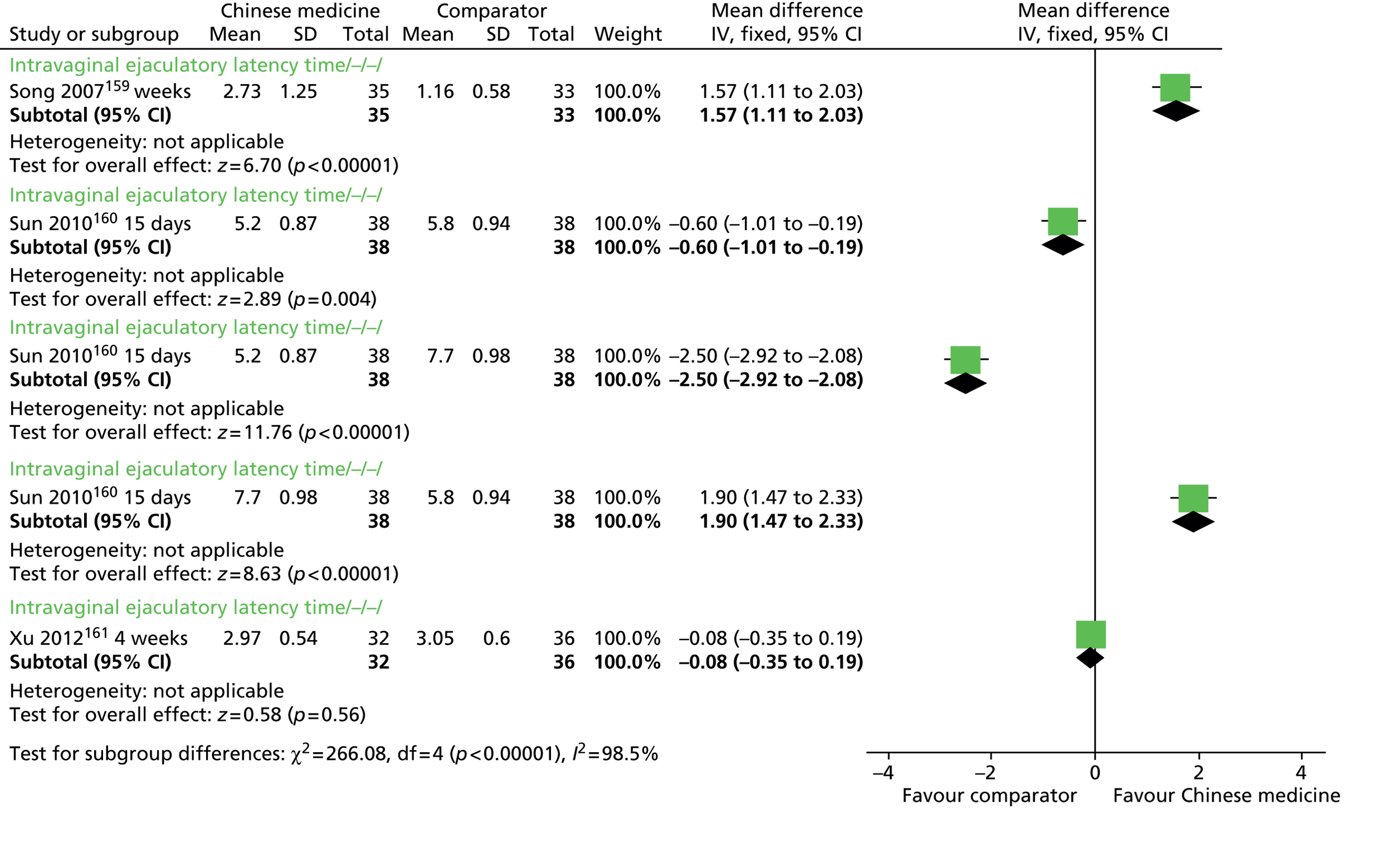

| Acupuncture | Sham acupuncture | IELT | Yes | No AE, data available for acupuncture, Chinese medicine or yoga |

| Chinese medicine | Treatment as usual | Yes | ||

| Yoga (observational study) | Baseline | IELT | Yes | |

| Fluoxetine | Yoga | Yes | ||

| Desensitising band plus stop–start technique | Stop–start technique | IELT | Yes | Appear minimal when device used as directed |

Behavioural therapies

Characteristics of included studies: behavioural therapies

Behavioural therapies were evaluated by one Cochrane review35 and two further systematic reviews of behavioural therapies. 36,38 Nine RCTs evaluating behavioural therapies were identified from these and other reviews of pharmacological therapies. 39–47 A further three RCTs of behavioural therapy were identified by the literature search:48–50 one evaluated pelvic floor exercises compared with dapoxetine,48 one evaluated a multicomponent behavioural therapy intervention compared with paroxetine alone or in combination with the behavioural intervention49 and one evaluated an internet-based behavioural intervention compared with waiting list control. 50

The Cochrane review by Melnik et al. 35 and the systematic review by Melnik et al. 38 were conducted in Brazil. The review by Berner and Gunzler36 was undertaken in Germany. The Cochrane review by Melnik et al. 35 was awarded an overall AMSTAR quality score 7 out of 11. The systematic reviews by Berner and Gunzler36 and Melnik et al. 38 were awarded 6 and 3 out of 11, respectively. Details of the review type, the databases searched and dates, relevant included RCTs and the AMSTAR points awarded to these reviews is presented in Table 3. Full details of the AMSTAR assessment for these and all other include reviews are presented in Appendix 4.

| Author (country) review type | Databases searched and dates | Included RCTs relevant to this section | AMSTAR review quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Berner and Gunzler, 201236 (Germany) systematic review | CENTRAL, MEDLINE, CINAHL, Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO, PubMed and PSYNDEX between 1985 and 2009 | de Carufel and Trudel 2006,40 Oguzhanoglu et al. 2005,43 Trudel and Proulx 198745 | AMSTAR score, 6/11: |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Melnik et al. 200938 (Brazil) systematic review | MEDLINE by PubMed (1966–2009), PsycINFO (1974–2009), EMBASE (1980–2009), Latin America and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature (1982–2009) and CENTRAL (The Cochrane Library, 2009, issue 1) | Abdel-Hamid et al. 2001,39 de Carufel and Trudel 2006,40 Li et al. 2006,42 Tang et al. 2004,44 Trudel and Proulx 1987,45 Yuan et al. 200847 | AMSTAR score, 3/11: |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

| Melnik et al. 201135 (Brazil) Cochrane review | MEDLINE, 1966–2010; PsycINFO, 1974–2010; EMBASE, 1980–2010; Latin America and Caribbean Health Sciences Literature, 1982–2010; and The Cochrane Library, 2010 | Abdel-Hamid et al. 2001,39 de Carufel and Trudel 2006,40 Li et al. 2006,42 Yuan et al. 200847 | AMSTAR score, 7/11: |

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

|

All reviews varied in terms of which RCTs they included. In total, nine RCTs of behavioural therapies39–47 (total n = 505) were included in at least one systematic review. The method of IELT assessment (stopwatch) was reported for only five RCTs. 39,40,44,46,48 The duration of the RCTs included in the reviews ranged from 2 to 12 weeks. The behavioural therapies that were evaluated included the squeeze technique,39 functional–sexological treatment involving movement of the body, speed of sexual activity and education regarding sensuality,40 the stop–start technique plus squeeze technique,40 behavioural psychotherapy,42 stop–start technique alone,43 behavioural psychotherapy,44 ‘Bibliotherapy’ (consisting of introduction to PE, descriptions of squeeze technique, pause technique and sensate focusing), and sexual therapy for couples (sensate focus, stop–start technique and communication exercises). 45 The type of behavioural intervention was not specified for one RCT. 47

In addition to the RCTs captured in reviews of behavioural therapy, one RCT evaluating the stop–start technique compared with fluoxetine or placebo41 was captured in reviews of SSRIs (see Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors currently not licensed for premature ejaculation) and one RCT evaluating a behavioural therapy that intervention was not specified compared with tramadol46 was captured in another review of pharmacological agents (see Opioid analgesics). Details of the RCTs extracted from reviews are presented in Table 4. All RCTs in reviews were captured by the search strategy for this assessment report.

| RCTs extracted from reviews | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT (source) | Duration | Treatments | PE definition | Lifelong/acquired | IELT assessment | Other outcomes |

| Abdel-Hamid et al. 200139 (references to review in which the publication is included35,37,38,52,69,134,135,137,165) | Single-arm crossover. 5 × 4-week phases each with 2-week washout | Sildenafil 50 mg 1 hour precoitus | IELT ≤ 2 minutes | Lifelong | Stopwatch | Modified Erectile Dysfunction Inventory of Treatment Satisfaction, Arabic Anxiety Inventory (scale 0–30) |

| Clomipramine 25 mg 3–5 hours precoitus | ||||||

| Sertraline 50 mg 3–5 hours precoitus | ||||||

| Paroxetine 20 mg 3–5 hours precoitus | ||||||

| Squeeze technique | ||||||

| (Total n = 31) | ||||||

| de Carufel and Trudel 200640 (reviews35,36,38) | NR | Functional-sexological treatment (education on sensuality, body movements, speed of sexual activity) | IELT < 2 minutes | NR | Stopwatch | Perception of duration of intercourse, sexual satisfaction |

| Behavioural therapy (squeeze and stop–start techniques) | ||||||

| Waiting list control | ||||||

| (Total n = 36 couples) | ||||||

| Kolomaznik et al. 200241 (reviews52) | 8 weeks | Stop–start technique | NR | NR | IELT not assessed | Duration of coitus, subject report |

| Fluoxetine (dose NR) | ||||||

| Placebo | ||||||

| (Total n = 93) | ||||||

| Li et al. 200642 (reviews35,38) | 6 weeks | Behavioural therapy + chlorpromazine 50 mg/day (n = 45) | IELT < 1 minute | NR | Method NR | Self-Rating Anxiety Scale |

| Chlorpromazine 50 mg/day (n = 45) | Chinese Index Premature Ejaculation | |||||

| Oguzhanoglu et al. 200543 (review36) | 8 weeks | Stop–start technique (n = 16) | Ejaculation before or within several minutes | NR | Method NR | Anxiety |

| Fluoxetine 20 mg/day (n = 16) | Satisfaction with treatment | |||||

| Tang et al. 200444 (reviews35,37,38,134) | 6 weeks | Behavioural psychotherapy (n = 30) | NR | NR | Stopwatch | Patient/partner sexual satisfaction (0–5-point Likert scale) |

| Sildenafil 50 mg + behavioural psychotherapy (n = 30) | ||||||

| Trudel and Proulx 198749 (reviews36,38) | 12 weeks | Bibliotherapy (book on behavioural techniques) | IELT ≤ 5 minutes | NR | Method NR | NR |

| Bibliotherapy with therapist contact by phone | ||||||

| Sexual therapy for couples (sensate focus, stop–start, communication) | ||||||

| Waiting list control | ||||||

| (Total n = 25 couples) | ||||||

| Xiong et al. 201146 (reviews148,149) | 12 weeks | Behavioural modification alone (not reported which) (n = 36) | IELT ≤ 2 minutes | Lifelong | Stopwatch | IIEF |

| Tramadol 50 mg 2 hours preintercourse with behavioural modification (n = 36) | ||||||

| Yuan et al. 200847 (reviews35,38) | 2 weeks | Behavioural therapy (n = 32) | NR | NR | Method NR | Sexual satisfaction |

| Citalopram 20 mg/day (n = 32) | ||||||

| Behavioural therapy plus citalopram (n = 32) | ||||||

| Further RCTs identified by searches (not captured in reviews) | ||||||

| RCT (country), risk of bias | Duration | Treatments, numbers analysed/randomised (%) | PE definition | Lifelong/acquired | IELT assessment | Other outcomes |

| Pastore et al. 201248 (Italy), unclear | RCT 12 weeks | Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation and electrical stimulation, three sessions/week (n = 19) | ISSM definition of PE | Lifelong | Stopwatch | None |

| Dapoxetine 30 mg or 60 mg on demand (n = 21) | ||||||

| Pelvic floor musclerehabilitation, 17/19 (89%); dapoxetine, 15/21 (71%) | ||||||

| Shao and Li 200849 (China), unclear | RCT 8 weeks | Paroxetine 10 mg/day (for first 4 weeks only) and behavioural therapy (n = 40) | NR | NR | CIPE5 | CIPE5 |

| Paroxetine 20 mg/day (n = 40) | ||||||

| Behavioural therapy (squeeze technique, sensate, focus, Qigong, acupoint tapping) (n = 40) | ||||||

| Paroxetine + behavioural therapy, 40/40 (100%); paroxetine, 40/40 (100%); behavioural therapy, 40/40 (100%) | ||||||

| van Lankveld et al. 200950 (the Netherlands), unclear | RCT 3 months | Internet-based sex therapy (sensate focus) (n = 22) | NR | NR | GRISS PE subscale | IIEF sexual desire, overall satisfaction, erectile dysfunction |

| Waiting list control (n = 18) | SEAR self-confidence | |||||

| Internet-based sex therapy, 21/22 (95%); waiting list control, 16/18 (89%) | Global Endpoint Question improvement/impairment of sexual functioning | |||||

The RCT by Pastore et al. 48 was conducted in Italy. Forty patients were randomised to pelvic floor muscle physiokinesitherapy (awareness of muscle contraction), comprising electrical stimulation of perineal floor, three 60-minute sessions per week, or to dapoxetine (30 mg or 60 mg on demand). IELT was assessed with a stopwatch. The duration was 12 weeks. The authors reported that 34 out of 40 (85%) patients completed the trial and IELT was stopwatch assessed. The RCT by Shao and Li49 was conducted in China. A total of 120 patients were randomised to paroxetine 10 mg per day (for the first 4 weeks) combined with behavioural therapy comprising the Masters and Johnson squeeze technique,17 sensate focus and Chinese traditional Qigong treatment (penis swinging and acupoint tapping), to paroxetine 20 mg per day, or to behavioural therapy only. The duration was 8 weeks. No objective assessment of IELT was reported. All patients (100%) were reported as completing the intervention. In the RCT by van Lankveld et al. ,50 an internet-based sex therapy based on the Masters and Johnson sensate focus technique was compared with waiting list control and 40 patients were randomised. The number and frequency of therapeutic contacts was left to the judgement of the therapist and the participant. No objective assessment of IELT was reported. The authors reported that 37 out of 40 (93%) patients completed the 3-month treatment programme. All three RCTs107,132,133 were considered to be at overall unclear risk of bias. 34

Details of the treatments evaluated, definition of PE, IELT assessment method, other outcomes assessed, study duration, along with the study country for the further RCTs not in reviews and the overall study quality assessment (AMSTAR33 for reviews and Cochrane risk of bias assessment34 for the RCTs not included by reviews) are presented in Table 4.

Assessment of effectiveness: behavioural therapies – intravaginal ejaculatory latency time outcomes

The reporting of IELT outcomes for RCTs included in the reviews was varied in terms of the treatment comparisons, the reporting of the assessment method, the outcome metric that was reported and the reporting of variance estimates and p-values. With the exception of the crossover study by Abdel-Hamid et al. 39 and the RCT by Xiong et al. ,46 no data were suitable to either estimate between-group differences for individual trial or pool data across studies in RevMan for this assessment report.

Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time: behavioural therapy compared with waiting list control

No variance estimates were reported for this outcome in the review by Berner and Gunzler. 36 Melnik et al. 35 reported that both functional sexological treatment and behavioural therapy significantly increased duration of intercourse compared with waiting list controls (functional sexological therapy: MD 6.87 minutes, 95% CI 5.10 to 8.64 minutes; behavioural therapy: MD 6.80 minutes, 95% CI 5.04 to 8.56 minutes) for one RCT. 40 p-values for the between-group differences were not reported. Summary results for these and across all other behavioural intervention trials are presented in Table 5.

| Comparison | Outcome | No. of RCTsa | No. of participants | Meta-analysis | Effect estimate (95% CI) | Favours | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IELT | ||||||||

| BT compared with waiting list control | IELT (minutes) | 240,45 | 36 | N/A | MD (two types BT vs. WL), 6.80, 6.87 (both significant)35,40 | BT | NR | |

| 25 | MD (three types BT vs. WL), 7.29, 8.84, 9.1136,45 | BT | NR | |||||

| BT with pharmacotherapy compared with pharmacotherapy alone | IELT | 142 | 90 | N/A | MD 1.11 (0.82 to 1.40)35 | BT + chlorpromazine | NR | |

| 147 | 96 | NR | BT + citalopram | NR | ||||

| CIPE5 ejaculatory latency score | 149 | 80 | N/A | MD 0.40 (0.18 to 0.62) | BT + paroxetine | 0.0003 | ||

| BT with pharmacotherapy compared with BT alone | IELT | 144 | 32 | N/A | MD 1.81 (NR) | BT + sildenafil | < 0.001 | |

| 146 | 72 | MD 1.65 (0.30 to 3.00) | BT + tramadol | 0.02 | ||||

| CIPE5 ejaculatory latency score | 149 | 80 | N/A | MD 0.60 (0.40 to 0.80) | BT + paroxetine | < 0.00001 | ||

| BT compared with pharmacotherapy | IELT | 148 | 32 | N/A | MD 1.22 (0.79 to 1.65) | Dapoxetine | < 0.00001 | |

| 147 | 96 | RR 0.52 (0.34 to 0.78)35 | Citalopram35 | NR35 | ||||

| 139 crossover | 31 | NS for clomipramine, sertraline and paroxetine | Sildenafil; NS for clomipramine, sertraline, paroxetine | < 0.00001; NS | ||||

| CIPE5 ejaculatory latency score | 149 | 80 | N/A | MD 0.20 (0.00 to 0.40) | Paroxetine | 0.05 | ||

| Other outcomes | ||||||||

| BT vs. waiting list control | Sexual satisfaction, desire, self-confidence | 240,50 | Varies | N/A | BT | < 0.0540,50 | ||

| BT with pharmacotherapy vs. pharmacotherapy alone | Ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and sexual anxiety | 442,44,47,49 | Varies | N/A | BT with pharmacotherapy (citalopram, chlorpromazine, sildenafil, paroxetine49) | < 0.0149; others NR | ||

| BT with pharmacotherapy vs. BT alone | Ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and sexual anxiety | 246,49 | Varies | N/A | BT with pharmacotherapy (paroxetine,49 tramadol46) | < 0.01;49 < 0.0546 | ||

| BT vs. pharmacotherapy | Ejaculatory control | 149 | 80 | N/A | Paroxetine49 | < 0.0149 | ||

| Sexual satisfaction | 149 | 80 | BT49 | < 0.0149 | ||||

| 147 | 96 | Citalopram | NR | |||||

Mean ejaculatory latency (minutes) post treatment in one trial45 was reported by Berner and Gunzler36 as follows: bibliotherapy without therapist contact, 11.05 minutes (change from baseline, p < 0.01); bibliotherapy with therapist contact by phone, 9.23 minutes (change from baseline, p < 0.01); sexual therapy for couples, 10.78 minutes (change from baseline, p < 0.01); and waiting list control, 1.94 minutes (improvement not significant, p-value not reported).

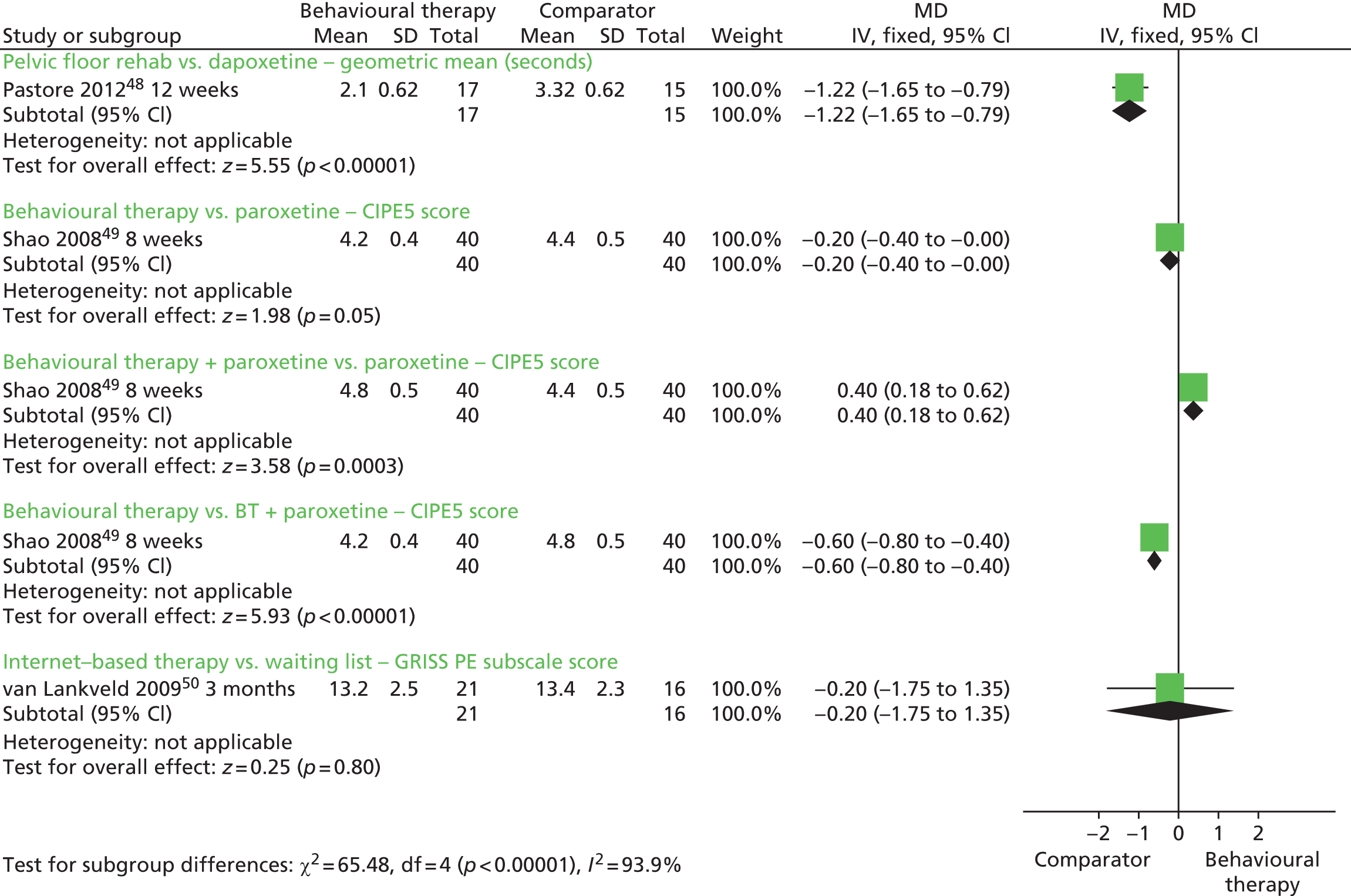

The between-group MD in the Golombok Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS) PE subscale score at 3 months based on one RCT50 (n = 37) was –0.20 minutes (fixed effect; 95% CI –1.75 to 1.35 minutes; p = 0.80) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Behavioural therapies compared with comparator: forest plot of IELT outcomes. CIPE5, Chinese Index of Premature Ejaculation 5 premature ejaculation-related items; df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time: behavioural therapy with pharmacotherapy compared with pharmacotherapy alone

Melnik et al. 35 reported that behavioural therapy plus chlorpromazine was superior to chlorpromazine alone in increasing IELT (minutes) after treatment in one RCT42 (MD 1.11 minutes, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.40 minutes). A p-value for the between-group difference was not reported.

Melnik et al. 35 reported that, in one trial,47 citalopram combined with behavioural therapy compared with citalopram alone favoured the combined approach therapy (no data reported). p-values were not reported.

The between-group difference in the Chinese Index of Premature Ejaculation 5 PE-related items (CIPE5) ejaculatory latency score at 8 weeks based on one RCT49 (n = 80) was 0.40 minutes in favour of behavioural therapy combined with paroxetine 20 mg compared with paroxetine 20 mg alone [MD (fixed effect), 95% CI 0.18 to 0.62 minutes; p = 0.0003] (see Figure 2).

Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time: behavioural therapy with pharmacotherapy compared with behavioural therapy alone

Mean values (minutes) at week 6 for one trial44 were reported as 3.63 minutes for cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) plus sildenafil compared with 1.82 minutes for behavioural therapy alone. The p-value for between-group difference was reported as p < 0.001 in favour of behavioural therapy with sildenafil.

The between-group difference in mean IELT (minutes) at 12 weeks, based on one RCT46 (n = 72), was 1.65 minutes, significantly favouring tramadol with behavioural therapy compared with behavioural therapy alone (95% CI 0.30 to 3.00 minutes; p = 0.02). The forest plot for this analysis is presented as Figure 18 in the Opioid analgesics section of this assessment report.

The between-group difference in the CIPE5 ejaculatory latency score at 8 weeks based on one RCT49 (n = 80) was 0.60 minutes in favour of behavioural therapy combined with paroxetine 20 mg compared with behavioural therapy alone [MD (fixed effect), 95% CI 0.40 to 0.80 minutes; p < 0.00001] (see Figure 2).

Intravaginal ejaculatory latency time: behavioural therapy compared with pharmacotherapy

The between-group difference in geometric mean IELT (minutes) at 12 weeks based on one RCT48 (n = 32) was 1.22 minutes in favour of dapoxetine 30 mg or 60 mg compared with pelvic floor rehabilitation [MD (fixed effect) 95% CI 0.79 to 1.65 minutes; p < 0.0001] (see Figure 2).

Melnik et al. 35 reported that, in one trial,47 citalopram significantly improved IELT compared with behavioural therapy (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.78). p-values were not reported.

The review by Berner and Gunzler36 reported that no outcome data were available for the one RCT evaluating this treatment comparison. 43

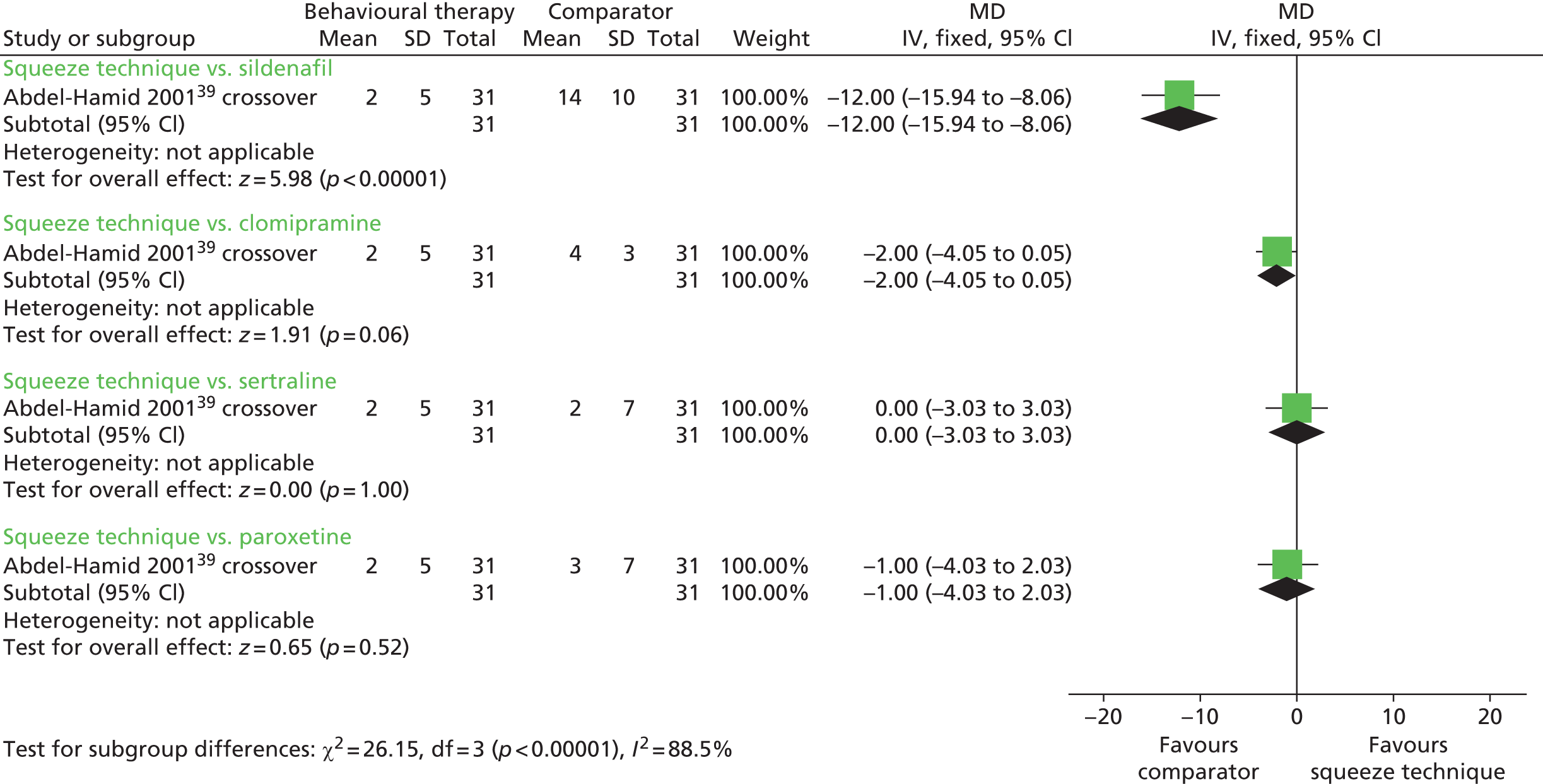

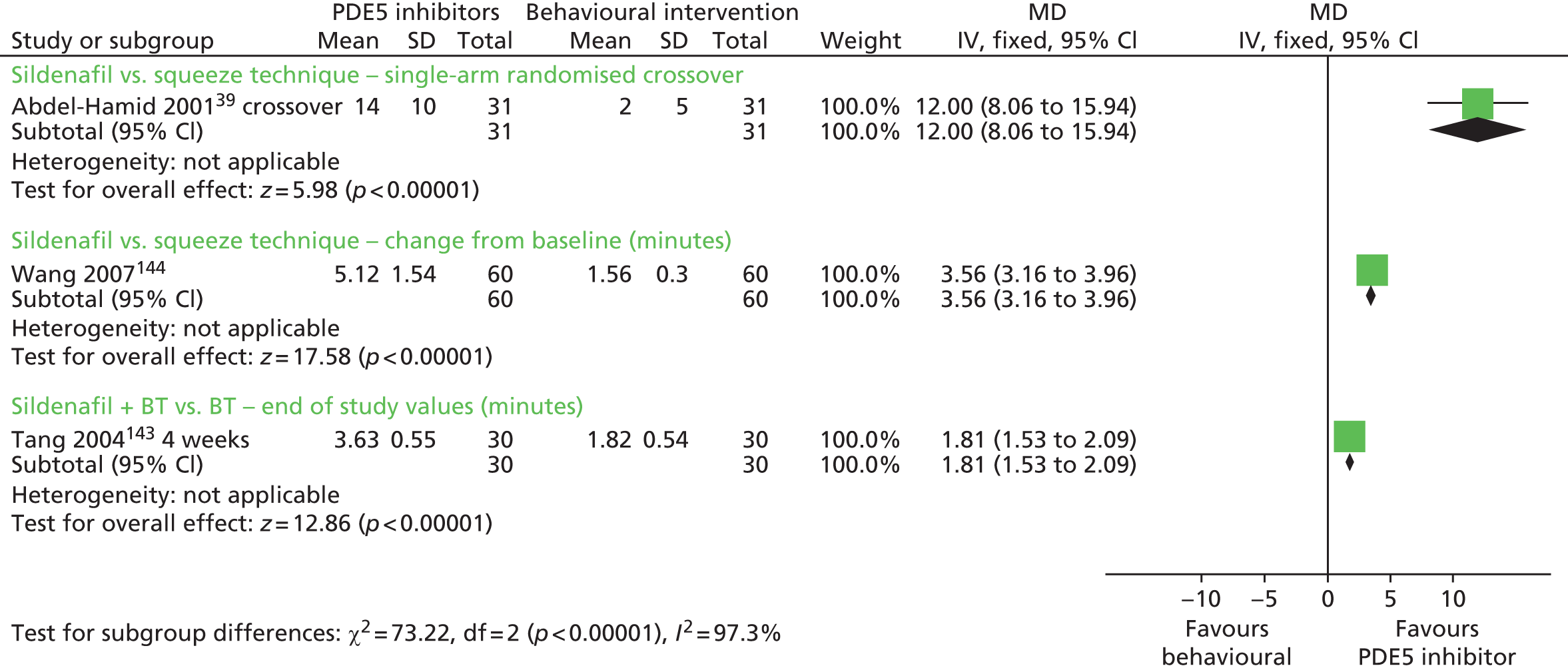

The between-group difference in mean IELT change (minutes) following a 4-week randomised crossover comparison39 was 12.00 minutes in favour of sildenafil compared with squeeze technique [MD (fixed effect) 95% CI 8.06 to 15.94 minutes; p < 0.00001]. Comparisons of squeeze technique with clomipramine, sertraline and paroxetine were not significant (Figure 3). A paired analysis could not be undertaken for approximation purposes for this study. Data from this trial were not pooled with other RCTs in any meta-analysis in this assessment report.

FIGURE 3.

Behavioural therapies, squeeze technique vs. SSRIs or TCAs – forest plot of IELT outcomes. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

The between-group difference in the CIPE5 ejaculatory latency score at 8 weeks based on one RCT49 (n = 80) was 0.20 in favour of paroxetine 20 mg compared with behavioural therapy [MD (fixed effect), 95% CI 0.00 to 0.40 minutes; p = 0.05] (see Figure 2).

Assessment of effectiveness – behavioural therapies: other outcomes

With the exception of the RCTs by Pastore et al. 48 and Trudel and Proulx45 all of the included trials were reported as evaluating one or more other outcomes. However, these were diverse across the included trials and were often not reported in sufficient detail to permit any pooling across trials (Table 6).

| RCT, duration | Treatment | Outcome measure | Results | Between-group difference reported as significant | AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BT compared with waiting list control | |||||

| de Carufel and Trudel 2006,40 NR | Functional sexological treatment | Perception of duration of intercourse | Perception of duration of intercourse improved significantly in both treatments, but not in the waiting-list group (p < 0.05) | Yes | NR |

| BT | Couples’ sexual satisfaction | Both treatment groups had significant improvements over waiting list for couples’ sexual satisfaction | Yes | ||

| Waiting list control | |||||

| (Total n = 36 couples) | |||||

| Trudel and Proulx 1987,45 12 weeks | Bibliotherapy | NR | NR | NR | Different and high dropout rates across groups. No further data reported |

| Bibliotherapy with therapist contact | |||||

| Sexual therapy for couples | |||||

| Waiting list control | |||||

| (Total n = 25 couples) | |||||

| van Lankveld et al. 2009,50 treatment duration was 3 months, follow-up at 3 and 6 months post treatment | Internet-based sex therapy (n = 22) | IIEF sexual desire, overall satisfaction, erectile dysfunction | IIEF overall satisfaction and IIEF sexual desire: p-values for change from baseline for internet-based sex therapy of p < 0.05 | Yes (from baseline) | NR |

| Waiting list control (n = 18) | SEAR self-confidence | SEAR self-confidence score: p-value of 0.05 for change from 3-month to 6-month follow-up | Yes (at one time point) | ||

| GEQ improvement/impairment of sexual functioning | GEQ: no significant between-group difference (p > 0.05) | No | |||

| Combined therapies compared with monotherapy | |||||

| Li et al. 2006,42 6 weeks | BT + chlorpromazine (n = 45) | Self-Rating Anxiety Scale | Chlorpromazine + BT was superior to chlorpromazine alone for Self-Rating Anxiety Scale and for some CIPE questions (‘anxiety in sexual activity’, ‘partner sexual satisfaction’, ‘patient sexual satisfaction’, ‘control ejaculatory reflex’ and ‘ejaculatory latency’) | Yes | NR |

| Chlorpromazine (n = 45) | CIPE | ||||

| Shao and Li 2008,49 8 weeks | BT + paroxetine (n = 40) | CIPE5 | Ejaculation control: BT + paroxetine better than paroxetine, p < 0.01; or BT, p < 0.01; paroxetine better than BT, p < 0.01 | Yes | Four AEs (10%) in the paroxetine + BT group and 16 (40%) in the paroxetine group. No further details reported |

| Paroxetine 20 mg per day (n = 40) | Patient satisfaction: BT + paroxetine better than paroxetine, p < 0.01; or BT, p < 0.05; BT better than paroxetine, p < 0.01 | ||||

| BT (n = 40) | Partner satisfaction: BT + paroxetine better than paroxetine, p < 0.01; or BT, p < 0.05; BT better than paroxetine, p < 0.01 | ||||

| Sexual anxiety: BT + paroxetine better than paroxetine, p < 0.01; or BT, p < 0.01; BT vs. paroxetine, NS | |||||

| Tang et al. 2004,44 6 weeks | BT (n = 30) | Patient/partner sexual satisfaction (0–5-point Likert scale) | BT, 19/30 ‘satisfied’; BT + sildenafil, 26/30 ‘satisfied’. NR what point(s) of scale = ‘satisfied’. p-value for between-group difference, NR | Unclear | NR |

| Sildenafil + BT (n = 30) | |||||

| Combined therapies compared with monotherapy | |||||

| Xiong et al. 2011,46 12 weeks | Behaviour modification (n = 36) | IIEF | Tramadol + behaviour modification: mean change 4 | Yes | Any AE:

|

| Tramadol + behaviour modification (n = 36) | Behaviour modification alone: mean change 2 | ||||

| Between-groups p < 0.05 | |||||

| Yuan et al. 2008,47 2 weeks | Behavioural – therapy (n = 32) | Sexual satisfaction | Citalopram significantly improved the number of couples satisfied with their sex life vs. BT | Yes | NR |

| Citalopram (n = 32) | Citalopram + BT vs. citalopram favoured combined approach for satisfaction with sex life | ||||

| BT plus citalopram (n = 32) | |||||

| BT compared with pharmacotherapy | |||||

| Abdel-Hamid et al. 2001,39 5 × 4 week phases each separated by a 2-week washout | Squeeze technique | Erectile Dysfunction Inventory of Treatment Satisfaction scale 0–5: sexual satisfaction score | Clomipramine, 11; sertraline, 11; sildenafil, 30; paroxetine, 9; squeeze technique, 6 | NR | Headache, flushing, and nasal congestion: sildenafil, 18% |

| Sildenafil 50 mg – Clomipramine | Arabic Anxiety Inventory (scale 0–30) | Clomipramine, 11; sertraline, 10; sildenafil, 15; paroxetine, 12; squeeze technique, 3 | NR | The incidence of side effects was similar among groups (numbers NR) | |

| Sertraline | (Unclear if means or medians; no SD or p-values reported) | ||||

| Paroxetine | |||||

| (Total n = 31) | |||||

| Kolomaznik et al. 2002,41 8 weeks | Stop–start technique | Duration of coitus, subject report | NR | NR | NR |

| Fluoxetine | |||||

| Placebo | |||||

| Total n = 93 | |||||

| BT compared with pharmacotherapy | |||||

| Oguzhanoglu et al. 2005,43 8 weeks | Stop–start technique (n = 16) | Anxiety | State Anxiety change from baseline:

|

No | NR |

| Fluoxetine (n = 16) | No | ||||

Trait Anxiety change from baseline:

|

|||||

| Satisfaction with treatment | Satisfaction with treatment: p > 0.05 between groups | ||||

| Pastore et al. 2012,48 12 weeks | Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation (n = 19) | None | – | – | Pelvic floor muscle rehabilitation, no side effects |

| Dapoxetine 30 or 60 mg (n = 21) | Dapoxetine: 30 mg nausea 1/8 (12.5%); 60 mg nausea, 2/7 (28.5%), diarrhoea 1/7 (14.0%) | ||||

| No severe AEs, no discontinuations due to AEs | |||||

Male perceptions of the duration of intercourse and couples’ sexual satisfaction were significantly improved with either functional sexological treatment (sensual education) or behavioural therapy (stop–start technique and squeeze technique) compared with waiting list control in one RCT. 40 One RCT50 reported a significant increase from baseline in International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF) measures of sexual satisfaction and desire, and on a measure of self-confidence associated with internet-based sex therapy based on a sensate focus technique compared with waiting list control. No difference was evident on an improvement/impairment of sexual functioning measure.

Behavioural psychotherapy combined with chlorpromazine was reported by one RCT as being more effective than chlorpromazine alone on a self-rated measure of anxiety and Chinese Index of Premature Ejaculation (CIPE) measures of sexual anxiety, sexual satisfaction and ejaculatory control. 42 Shao et al. 49 reported that CIPE measures of ejaculation control, patient/partner satisfaction and sexual anxiety were all significantly improved following treatment with behavioural therapy comprising squeeze technique, sensate focus and Chinese traditional treatment plus paroxetine compared with paroxetine alone. Yuan et al. 47 reported that behavioural therapy combined with citalopram was more effective at improving sexual satisfaction than citalopram alone.

Shao et al. 49 reported that CIPE measures of ejaculation control, patient/partner satisfaction and sexual anxiety were all significantly improved following treatment with behavioural therapy comprising squeeze technique, sensate focus and Chinese traditional treatment plus paroxetine compared with behavioural therapy alone. In one RCT,44 more patients receiving behavioural therapy plus sildenafil than patients receiving behavioural therapy alone reported ‘satisfied’ on a measure of sexual satisfaction. Xiong et al. 46 reported a between-group difference at 8 weeks of p < 0.05 on the IIEF favouring the tramadol plus behavioural therapy group compared with behavioural therapy alone.

Shao et al. 49 reported that paroxetine was significantly better than behavioural therapy on CIPE assessed ejaculation control. However, patient/partner satisfaction was significantly better following behavioural therapy than following paroxetine. No significant between-group difference was observed for sexual anxiety. Yuan et al. 47 reported that citalopram significantly increased the number of couples satisfied with their sex life compared with behavioural therapy alone. Oguzhanoglu et al. 43 reported no statistically significant between-group difference in satisfaction with treatment for stop–start technique compared with fluoxetine.

Assessment of safety: behavioural therapies – adverse events

Adverse event data were available for only 4 of the 12 included RCTs. Abdel-Hamid et al. 39 reported that the incidence of side effects was similar among groups and included headache, flushing and nasal congestion in 18% of the patients who received sildenafil. Pastore et al. 48 reported that dapoxetine was associated with nausea and diarrhoea whereas no AEs were reported for the pelvic floor rehabilitation group. In the RCT by Shao et al. ,49 the incidence of AEs was reported in the paroxetine group and the behavioural therapy combined with paroxetine group. However, the types of AEs were not reported. AEs for the behavioural therapy-only group were not reported. For one RCT,46 the between-group difference in relative risk (RR) at 12 weeks was 21.00 experiencing AEs [RR (random effects), 95% CI 1.28 to 345.41; p = 0.03] in favour of behavioural therapy alone compared with tramadol (lower risk). The forest plot for this analysis is presented as Figure 20 in the Opioid analgesics section of this assessment report.

Assessment of effectiveness: behavioural therapies – evidence summary

The current evidence base for behavioural therapy in the treatment of PE comprises 12 RCTs, nine captured in three low to good methodological quality systematic reviews and three further RCTs which are at overall unclear risk of bias. The quality of IELT outcome reporting across these trials is limited and does not facilitate any meaningful pooling across trials to be undertaken. However, individual trial results suggest that behavioural therapies are better than waiting list control in improving IELT, that behavioural therapies combined with pharmacological therapies are better than pharmacological agents alone (chlorpromazine, citalopram or paroxetine) and that behavioural therapies combined with pharmacological therapies (sildenafil, paroxetine or tramadol) are better than behavioural therapy alone in improving IELT in men with PE.

Various assessment methods in terms of ejaculation control, patients’/partners’ sexual satisfaction, anxiety and other patient-reported outcomes have been used across RCTs to measure the effectiveness of behavioural therapies. There is, however, some evidence to suggest that behavioural therapies combined with pharmacological therapies (paroxetine or tramadol) are better than behavioural therapy alone and that behavioural therapies combined with pharmacological therapies are better than pharmacotherapy alone (paroxetine, chlorpromazine, sildenafil or citalopram) in improving outcomes other than IELT. AE reporting across RCTs evaluating behavioural interventions is limited and AEs are often reported only for an adjuvant pharmacological agent or a pharmacological comparator. Adjuvant therapies to behavioural interventions that include SSRIs (dapoxetine, paroxetine) and PDE5 inhibitors (sildenafil) are reported to be associated with headache, flushing, nausea and diarrhoea.

Behavioural therapy alone appears to be more effective than no treatment in the treatment of PE. Behavioural therapy combined with pharmacological therapy appears more effective than behavioural therapy or pharmacological therapy alone. Comparisons between behavioural therapy and pharmacological therapies generally favour the pharmacological intervention for improvement in IELT, but are uncertain for other outcomes. AEs may be associated with adjuvant pharmacotherapy. The long-term efficacy of behavioural therapy in the treatment of PE is not evaluated in the current evidence base.

Topical anaesthetics

Characteristics of included studies: topical anaesthetics

Topical anaesthetics were evaluated by two systematic reviews51,53 and one ‘mini review’. 54 Two of these systematic reviews pooled data in a meta-analysis. 51,53 Trials of topical treatments were also included in one other review of pharmacological therapies. 52 A further two RCTs were identified, one of which evaluated EMLA (lidocaine and prilocaine) cream compared with electrical stimulation or placebo,62 while the other evaluated a lidocaine spray (Premjact, Boots Pharmaceuticals) compared with paroxetine. 63

One of the reviews of topical anaesthetics was conducted in the USA. 54 The two systematic reviews that pooled data in a meta-analysis were both undertaken in China. 51,53 The overall AMSTAR quality score of one of the reviews was 1 out of 11. 54 The two systematic reviews with a meta-analysis were scored as 4 out of 1151 and 5 out of 11. 53 Details of the review type, the databases searched and dates, relevant included RCTs and the AMSTAR points awarded to these reviews are presented in Table 7. Full details of the AMSTAR assessment for these and all other include reviews are presented in Appendix 4. The search methodology and inclusion criteria varied across these reviews. Pu et al. 51 pooled secondary outcome data from different domains of the same instrument in an overall summary effect estimate, in effect counting participants twice in the analysis. In the review by Xia et al. ,53 the authors pooled IELT effect estimates across studies using a standardised MD.

| Author (country), review type | Databases searched and dates | Included RCTs relevant to this section | AMSTAR review quality assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Morales et al. 200754 (USA), mini-review | MEDLINE 1966 to January 2004 | Atan et al. 2006,55 Atikeler et al. 2002,56 Busato and Galindo 2004,57 Dinsmore et al. 2007,59 Gittelman et al. 200661 | AMSTAR score, 1/11:

|

| Pu et al. 201351 (China), systematic and meta-analysis | Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, PubMed (from 1980 to June 2012), and EMBASE (from 1980 to June 2012) | Atan et al. 2006,55 Atikeler et al. 2002,56 Busato and Galindo 2004,57 Carson et al. 2010,58 Dinsmore et al. 2007,59 Dinsmore and Wyllie 200960 | AMSTAR score, 4/11:

|

| Xia et al. 201353 (China), systematic and meta-analysis | The Cochrane Library, PubMed and EMBASE to October 2012 | Atikeler et al. 2002,56 Busato and Galindo 2004,57 Carson et al. 2010,58 Dinsmore et al. 2007,59 Dinsmore and Wyllie 200960 | AMSTAR score, 5/11:

|

The reviews above varied in terms of which RCTs they included. In total, seven RCTs (total n = 675) were included in at least one of these reviews. 55–61 IELT was reported as being assessed using a stopwatch in four RCTs57–60 and by patient self-report in one RCT. 56 The method of IELT assessment was not reported for two RCTs. 55,61 With the exception of the RCTs by Atikeler et al. 56 that evaluated the effects after more than five applications of treatment, and one trial reported as a crossover RCT,61 duration across trials ranged from 4 to 12 weeks. The topical anaesthetics evaluated included EMLA cream, TEMPE spray (containing lidocaine and prilocaine) and other topical anaesthetic creams (dyclonine cream and alprostadil cream). All of the RCTs compared topical anaesthetics with placebo. In addition, one RCT was identified that compared EMLA cream with sildenafil or EMLA cream combined with sildenafil. 55 This RCT is also evaluated in the section Phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors of this assessment report. All RCTs in reviews were captured by the search strategy for this assessment report.

The RCT by Mallat et al. 62 was conducted in Tunisia. Patients were randomised, 30 per group, to EMLA, electrical stimulation or placebo. The trial was reported in abstract form only and the full details each treatment were not reported. The authors reported that 90 out of 90 (100%) patients completed the 12-week follow-up. The assessment method of IELT was not reported. The RCT by Steggall et al. 63 was conducted in the UK. Sixty patients were recruited to the trial and were randomised to either a lidocaine spray (Premjact) 10 minutes preintercourse or paroxetine 20 mg daily. Treatment duration was 2 months and the authors reported that 44 out of 60 (70%) patients completed the intervention. Both of these trials were considered to be at overall unclear risk of bias.

Details of the treatments evaluated, definition of PE, IELT assessment method, other outcomes assessed, study duration, along with the study country for the further RCTs not in reviews, and the overall study quality assessment (AMSTAR33 for reviews and Cochrane risk of bias assessment34 for the RCTs not included by reviews) are presented in Table 8.

| RCTs extracted from reviews | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCT (source) | Duration | Treatments | PE definition | Lifelong/acquired | IELT assessment | Other outcomes | ||||||

| Atan et al. 200655 (reviews51,54) | 8 weeks | EMLA 15 minutes precoitus (n = 22) | DSM-IV | NR | IELT not assessed | NR | ||||||

| Sildenafil 50 mg 45 minutes precoitus (n = 20) | ||||||||||||

| EMLA + sildenafil (n = 22) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo (n = 20) | ||||||||||||

| All patients analysed | ||||||||||||

| Atikeler et al. 200256 (reviews152–154) | ≥ 5 applications | EMLA 2.5 g with condom: | IELT < 1 minute | Lifelong | Subject report | NR | ||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Placebo (n = 10) | ||||||||||||

| Busato and Galindo 200457 (reviews51,53,54) | 4–8 weeks | EMLA 2.5 g with condom 10–20 minutes precoitus (n = 24) | DSM-IV | Lifelong and acquired | Stopwatch | Sexual satisfaction (method NR) | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 18) | ||||||||||||

| (16 and 13 completed) | ||||||||||||

| Carson and Wyllie 201058 (reviews51,53) | 12 weeks | TEMPE spray 3 actuations (each 7.5 mg lidocaine, 2.5 mg prilocaine) 5 minutes precoitus (n = 167) | DSM-IV and ISSM | Lifelong and acquired | Stopwatch | IPE | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 82) | PEP | |||||||||||

| Dinsmore et al. 200759 (reviews51,53,54) | 4 weeks | TEMPE 3 actuations (each 7.5 mg lidocaine, 2.5 mg prilocaine) 15 minutes precoitus (n = 27) | DSM-IV | Lifelong | Stopwatch | IEC | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 28) | SQoL | |||||||||||

| (20 and 23 analysed) | ||||||||||||

| Dinsmore and Wyllie 200960 (reviews51,53) | 12 weeks | TEMPE 3 actuations (each 7.5 mg lidocaine, 2.5 mg prilocaine) 5 minutes precoitus (n = 200) | DSM-IV and ISSM | Lifelong and acquired | Stopwatch | IPE | ||||||

| Placebo (n = 100) | PEP | |||||||||||

| (191 and 99 analysed) | ||||||||||||

| Gittelman et al. 200661 (reviews54) | Single–arm crossover: duration NR | 5–20 minutes preintercourse: | NR | NR | Method NR | Sexual satisfaction – yes or no in ‘PSQ diary’a | ||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| (Total n = 30) | ||||||||||||

| Further RCTs identified by searches (not captured in reviews) | ||||||||||||

| RCT (country), risk of bias | Duration | Treatments, numbers analysed/randomised (%) | PE definition | Lifelong/acquired | IELT assessment | Other outcomes | ||||||

| Mallat et al. 201262 (Tunisia), unclear | 12 weeks | EMLA (n = 30) | NR | NR | Method NR | IIEF | ||||||

| Electric stimulation (n = 30) | ||||||||||||

| Placebo (n = 30) | ||||||||||||

| No details of treatments reported | ||||||||||||

| All groups (100%) | ||||||||||||

| Steggall et al. 200863 (UK), unclear | 2 months | Lidocaine 3–8 sprays 10 minutes precoitus | DSM-IV diagnosis plus IELT ≤ 3 minutes | Lifelong and acquired | Stopwatch | IIEF number of acts of coitus per week | ||||||

| Paroxetine 20 mg per day | IIEF intercourse satisfaction | |||||||||||

| (Total n = 60) | ||||||||||||

| Total n 44/60 (70%), n per group NR | ||||||||||||

Assessment of effectiveness: topical anaesthetics – intravaginal ejaculatory latency time outcomes

With the exception of the RCT by Atan et al. ,55 IELT outcomes were reported for all of the RCTs identified from existing reviews. The review by Morales et al. 54 reported that there was no statistical advantage in adding sildenafil to topical prilocaine-lidocaine treatment in the RCT by Atan et al. 55 No data or p-value were reported. The two further RCTs identified for inclusion in this assessment report both reported IELT outcomes, but without any variance estimates. Mallat et al. 62 reported a p-value for IELT of p < 0.001, but it was unclear if this was across or between groups, or whether this was for end of study values or change from baseline. Steggall et al. 63 reported a p-value for median IELT change from baseline of p = 0.038 for lidocaine spray and p < 0.0005 for paroxetine. These trials were therefore not included in any IELT meta-analysis in this assessment report.

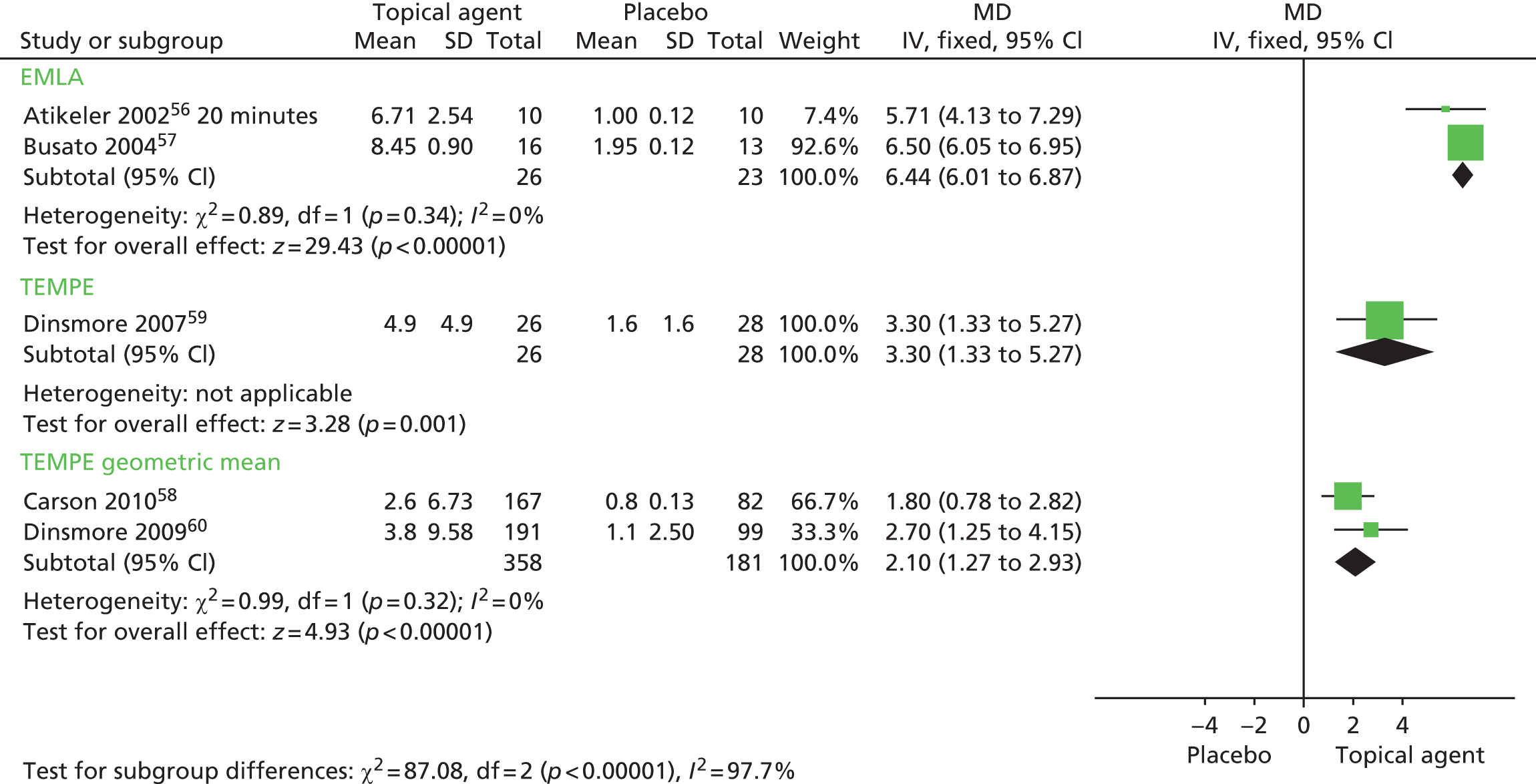

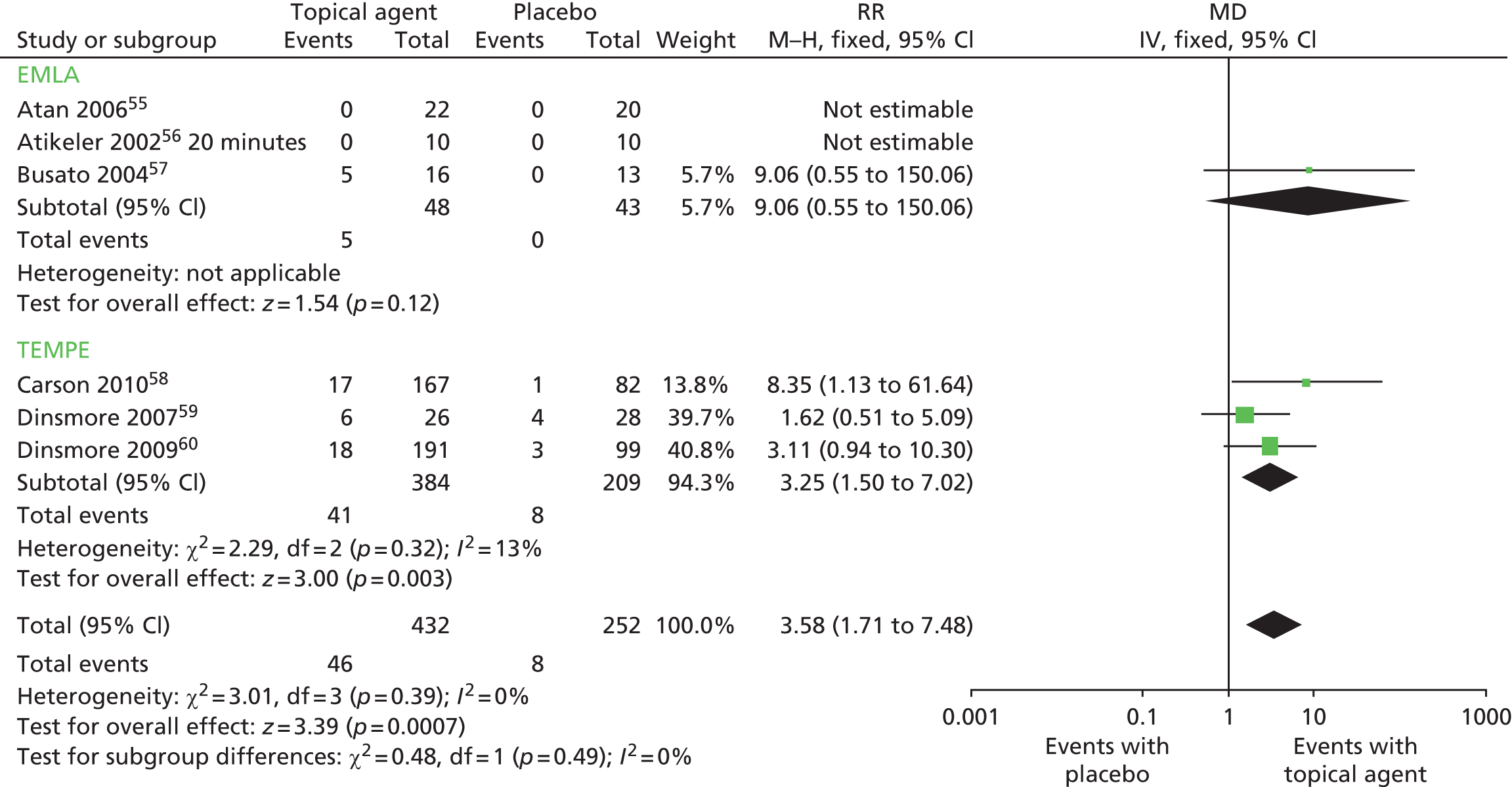

Meta-analysis of mean IELT (minutes) following an application of EMLA cream < 20 minutes preintercourse, based on two RCT study group comparisons (n = 49), displayed low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The pooled MD in IELT was 6.44 minutes, significantly favouring EMLA [MD (fixed effect); 95% CI 6.01 to 6.87 minutes; p < 0.00001]. The forest plot for this analysis is presented in Figure 4. Summary results for these and all other meta-analyses are presented in Table 9.

FIGURE 4.

Topical anaesthetics, EMLA cream or TEMPE spray compared with placebo: forest plot of IELT outcomes. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

| Comparison | Outcome | No. of RCTsa | No. of participants | I 2 | Model | Effect estimate in minutes (95% CI) | Favours | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IELT | ||||||||

| EMLA cream vs. placebo | IELT (minutes) | 256,57 | 49 | 0% | Fixed effect | MD 6.44 (6.01 to 6.87) | EMLA cream | < 0.00001 |

| TEMPE spray vs. placebo | IELT (minutes) | 159 | 54 | N/A | N/A | MD 3.30 (1.33 to 5.27) | TEMPE spray | 0.001 |

| TEMPE spray vs. placebo – geometric mean | IELT (minutes) | 258,60 | 539 | 0% | Fixed effect | MD 2.10 (1.27 to 2.93) | TEMPE spray | < 0.00001 |

| Dyclonine cream vs. placebo | IELT (minutes) | 155 crossover | 60 | N/A | N/A | MD 0.87 (0.71 to 1.03) | Dyclonine cream | < 0.00001 |

| Alprostadil cream vs. placebo | IELT (minutes) | 155 crossover | 60 | N/A | N/A | MD 1.41 (1.24 to 1.58) | Alprostadil cream | < 0.00001 |

| Dyclonine/alprostadil cream vs. placebo | IELT (minutes) | 155 crossover | 60 | N/A | N/A | MD 1.74 (1.58 to 1.90) | Alprostadil cream | < 0.00001 |

| Other outcomes | ||||||||

| EMLA cream vs. placebo | Other outcomes (various) | 257,62 | 119 | Two RCTs reported significant differences at 12 weeks in IPE ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and distress, and in PEP scores.58,60 | ||||

| TEMPE spray vs. placebo | Other outcomes (various) | 358–60 | 594 | Two RCTs reported significant differences at 12 weeks in IPE ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and distress and in PEP scores.58,59 One RCT reported no significant differences in Index of Ejaculatory Control and SQoL at 4 weeks60 | ||||

| AEs | ||||||||

| Topical anaesthetics (EMLA or TEMPE) vs. placebo | AEs | 655–60 | 704 | 0% | Fixed effect | RR 3.58 (1.71 to 7.48) | Placebo (fewer AEs) | 0.0007 |

| EMLA cream (applied ≤ 20 minutes) vs. placebo | AEs | 355–57 | 111 | N/A | Fixed effect | RR 9.06 (0.55 to 150.06) | NS | 0.12 |

| TEMPE spray vs. placebo | AEs | 358–60 | 593 | 0% | Fixed effect | RR 3.25 (1.50 to 7.02) | Placebo (fewer AEs) | 0.003 |

The between-group difference in mean IELT (minutes) based on one RCT (n = 54) was 3.30 minutes, significantly favouring TEMPE spray [MD (fixed effect); 95% CI 1.33 to 5.27 minutes; p = 0.001]. Meta-analysis of geometric mean IELT (minutes), based on two RCT study group comparisons (n = 49), displayed low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). The pooled MD in IELT was 2.10 minutes, significantly favouring TEMPE spray [MD (fixed effect); 95% CI 1.27 to 2.93 minutes; p < 0.00001]. The forest plot for this analysis is presented in Figure 4.

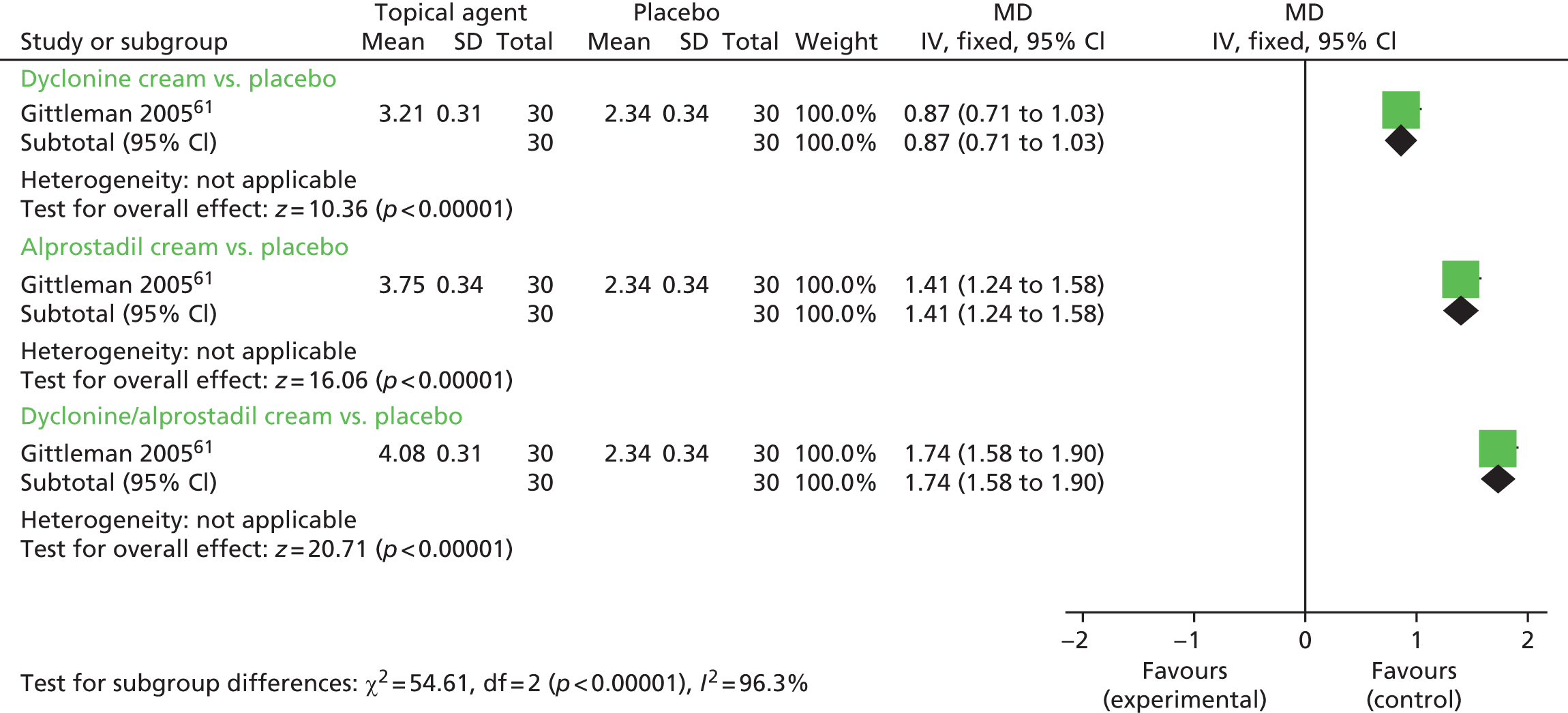

One single-arm randomised crossover trial (n = 30) evaluated three different topical anaesthetics. 61 The between-group differences in mean IELT (minutes) were 0.87 minutes in favour of dyclonine cream compared with placebo (95% CI 0.71 to 1.03 minutes; p < 0.00001); 1.41 minutes in favour of alprostadil cream compared with placebo (95% CI 1.24 to 1.58 minutes; p < 0.00001); and 1.74 minutes in favour of dyclonine/alprostadil cream compared with placebo (95% CI 1.58 to 1.90 minutes; p < 0.00001). The forest plot for this analysis is presented in Figure 5. A paired analysis could not be undertaken for approximation purposes for this study. Data from this trial were not pooled with other RCTs in any meta-analysis in this assessment report.

FIGURE 5.

Topical anaesthetics vs. placebo – forest plot of IELT outcomes. df, degrees of freedom; IV, inverse variance; SD, standard deviation.

Assessment of effectiveness: topical anaesthetics – other outcomes

Three RCTs did not report any effectiveness outcomes other than IELT. 55,56,63 Amongst the other RCTs, outcomes other than IELT were diverse across the included trials (Table 10).

| RCT, duration | Treatment | Outcome measure | Results | Between-group difference reported as significant | AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atan et al. 2006,55 8 weeks | EMLA (n = 22) | NR | NR | NR | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: EMLA, 0/22 (0%); placebo, 0/20 (0%) (sildenafil and sildenafil + EMLA arms NR) |

| Sildenafil (n = 20) | |||||

| EMLA + Sildenafil (n = 15) | |||||

| Placebo (n = 20) | |||||

| Atikeler et al. 2002,56 ≥ 5 applications | EMLA:

|

NR | NR | NR | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: EMLA 20 minutes, 0/10 (0%); placebo, 0/10 (0%). Erection loss or numbness: 30-minute group, 6/10; 45-minute group, 10/10 |

| Placebo (n = 10) | |||||

| Busato and Galindo 2004,57 4–8 weeks | EMLA (n = 21) | Sexual satisfaction (method NR) | Sexual satisfaction: EMLA, 8.7; placebo, 4; p = 0.001 | Yes | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: EMLA, 5/16 (34%); placebo, 0/13 (0%) |

| Placebo (n = 21) | n/N reporting ‘great’ or ‘excellent’ satisfaction: EMLA, 6/16; 5/16; placebo, 3/13; 0/13 | Yes | EMLA-associated AEs: men, 2/29 retarded ejaculation, 2/29 loss of sensitivity, 2/29 penile irritation; women 1/29 decreased sensitivity | ||

| Carson and Wyllie 2010,58 12 weeks | TEMPE spray (n = 167) | IPE | Ejaculatory control (IPE): TEMPE, 11.6; placebo, 6.5 | Yes | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: TEMPE, 17/167 (10%); placebo, 1/82 (< 1%) |

| Placebo (n = 82) | Sexual satisfaction (IPE): TEMPE, 13.4; placebo, 8.6 | Yes | |||

| Distress (IPE): TEMPE, 6.1; placebo, 3.7 | Yes | ||||

| PEP | PEP ≥ 1 point improvement: p < 0.0001 (unclear if between groups or baseline) | Yes | |||

| Dinsmore et al. 2007,59 4 weeks | TEMPE spray (n = 27) | IEC | Ejaculatory control (IEC) change: TEMPE, 6.7; placebo, 3.0; p = 0.12 | No | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: TEMPE, 6/26 (23%); placebo, 4/28 (14%) |

| Placebo (n = 28) | SQoL | SQoL change: TEMPE, men 7.0, women 3.3. Placebo, men 5.5, women 1.8. p-value men, 0.48; women, 0.56 | No | Assume with TEMPE: hypoaesthesia, 3/26; erectile dysfunction, 1/26. Women: mild burning 1/26 | |

| Dinsmore and Wyllie 2009,60 12 weeks | TEMPE spray (n = 191) | IPE | Ejaculatory control (IPE): TEMPE, 14.3; placebo, 7.4 | Yes | n/N (%) experiencing AEs: TEMPE, 18/191 (9%); placebo 3/99 (3%) |

| Placebo (n = 99) | Sexual satisfaction (IPE): TEMPE, 14.8; placebo, 9.1 | Yes | |||

| Distress (IPE): TEMPE, 7.1; placebo, 4.5 | Yes | ||||

| PEP | PEP ≥ 1 point improvement: p < 0.001 (unclear if between groups or baseline) | Yes | |||

| Gittelman et al. 2006,61 NR (crossover) | Dyclonine cream | Sexual satisfaction – yes or no in ‘PSQ diary’a | % reporting ‘yes’: dyclonine cream, 73.3%; alprostadil cream, 83.3%; dyclonine/alprostadil cream, 86.7%; placebo cream, 66.7% | Unclear | Proportion experiencing AEs: dyclonine cream, 17.5%; alprostadil cream, 20%; dyclonine/alprostadil cream, 17.5%; placebo cream, 5%. Type not reported |

| Alprostadil cream | |||||

| Dyclon/alpro cream | |||||

| Placebo cream | |||||

| (Total n = 30) | |||||

| Mallat et al. 2012,62 12 weeks | EMLA (n = 30) | Number of coitus per week | Number of coitus: EMLA, 1.4; electric stimulation, 2.3; placebo, 1.3 | Unclear | No withdrawals caused by AEs across all treatments, but more AEs were associated with EMLA. No further details reported |

| Electric stimulation (n = 30) | IIEF intercourse satisfaction | IIEF satisfaction: EMLA, 10; electric stimulation, 14; placebo, 10 | Unclear | ||

| Placebo (n = 30) | |||||

| Steggall et al. 2008,63 8 weeks | Lidocaine spray | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Paroxetine | |||||

| (Total n = 60) |

A statistically significant between-group difference in sexual satisfaction in favour of EMLA cream after 2 months was reported by Busato and Galindo. 57 There appeared to be no difference between EMLA cream and placebo on the IIEF. Number of coitus per week and sexual satisfaction values were reported by one RCT. 62

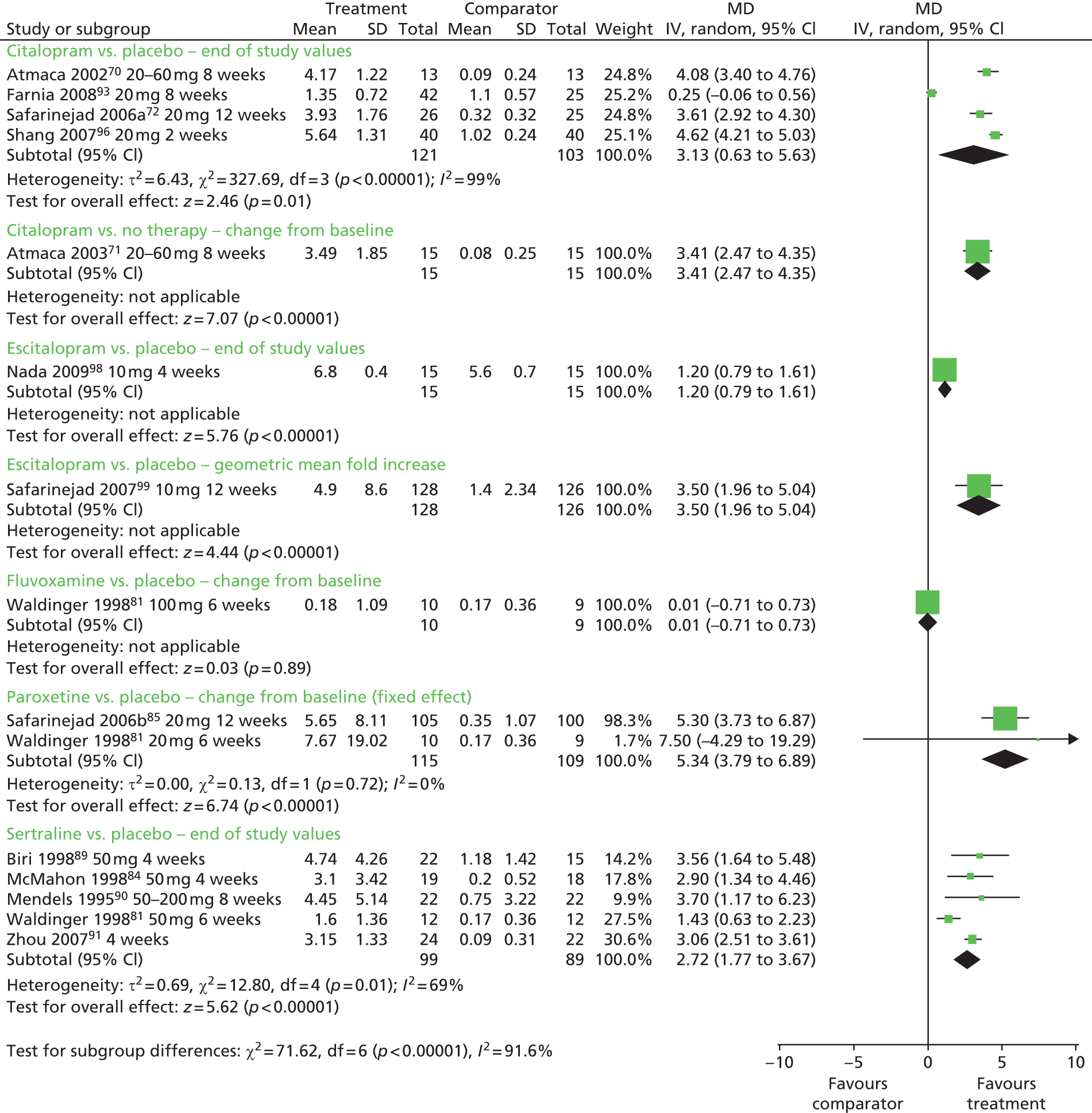

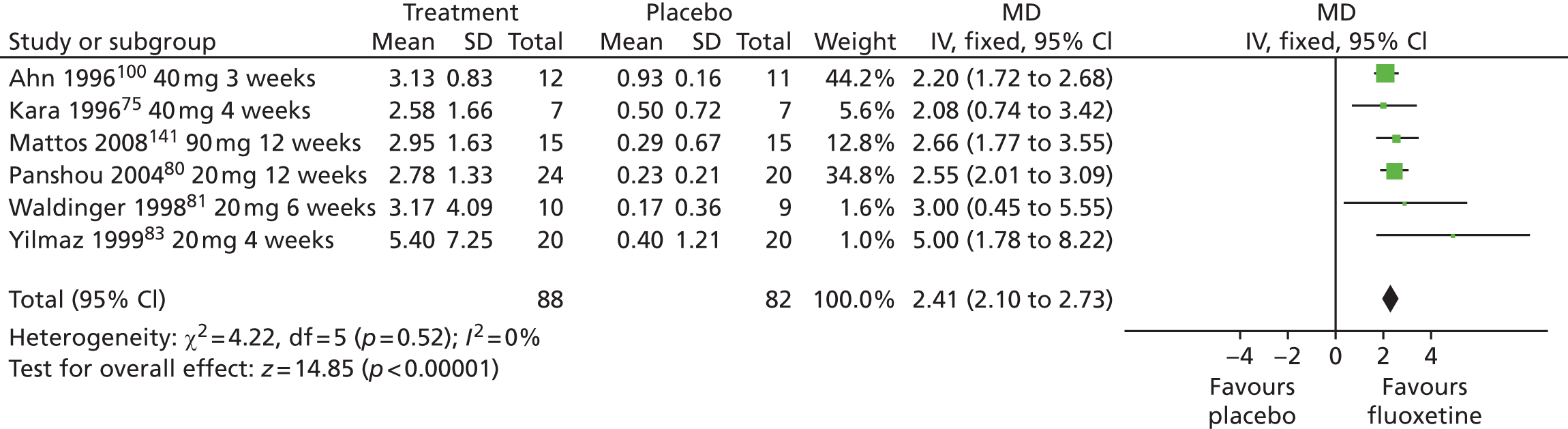

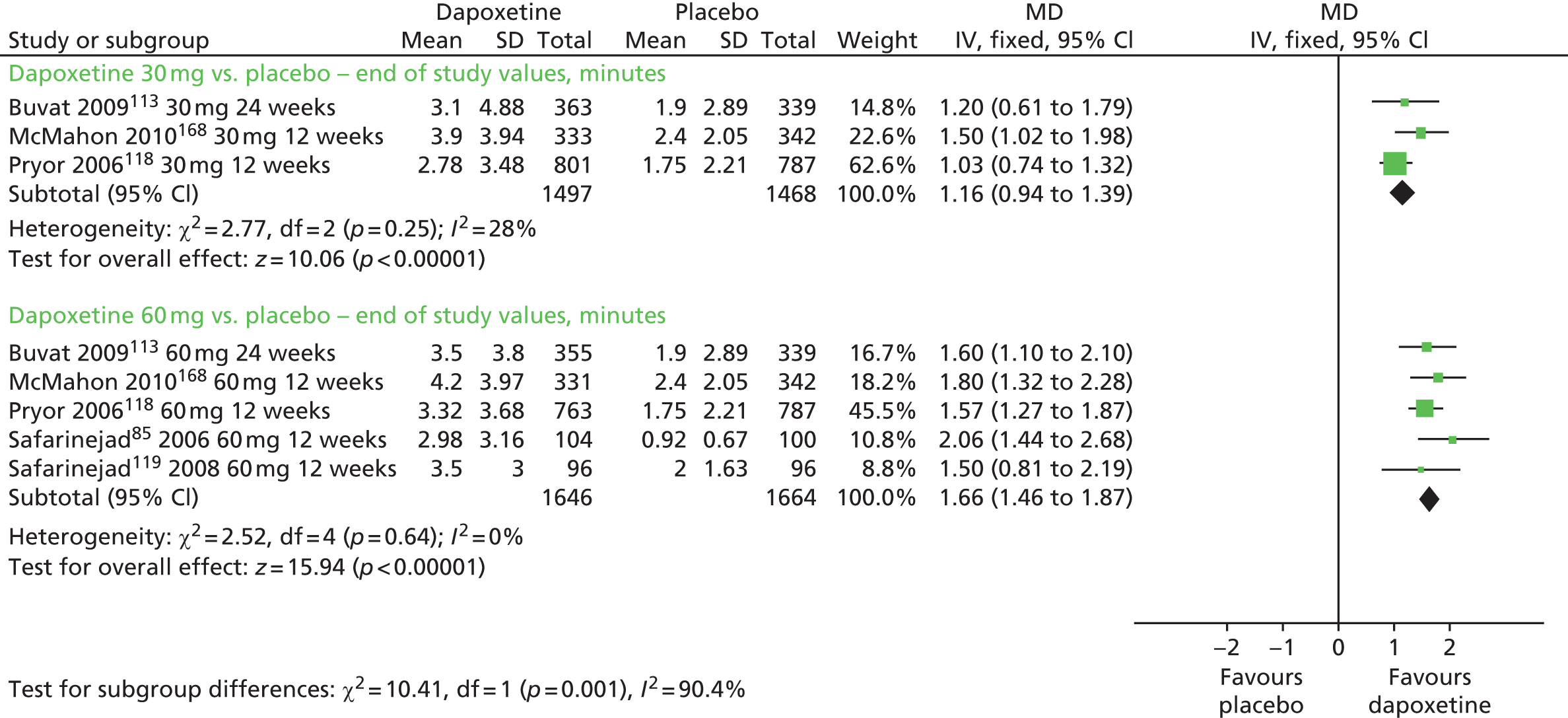

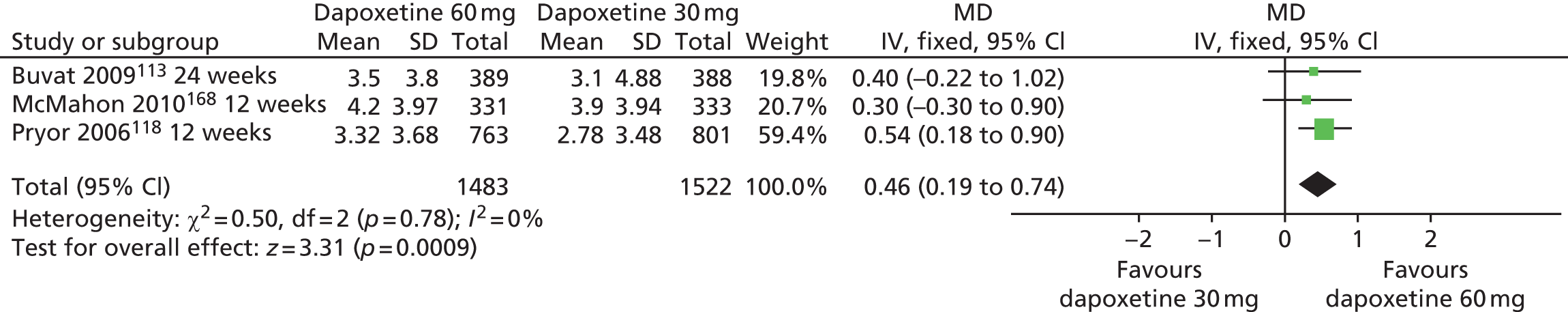

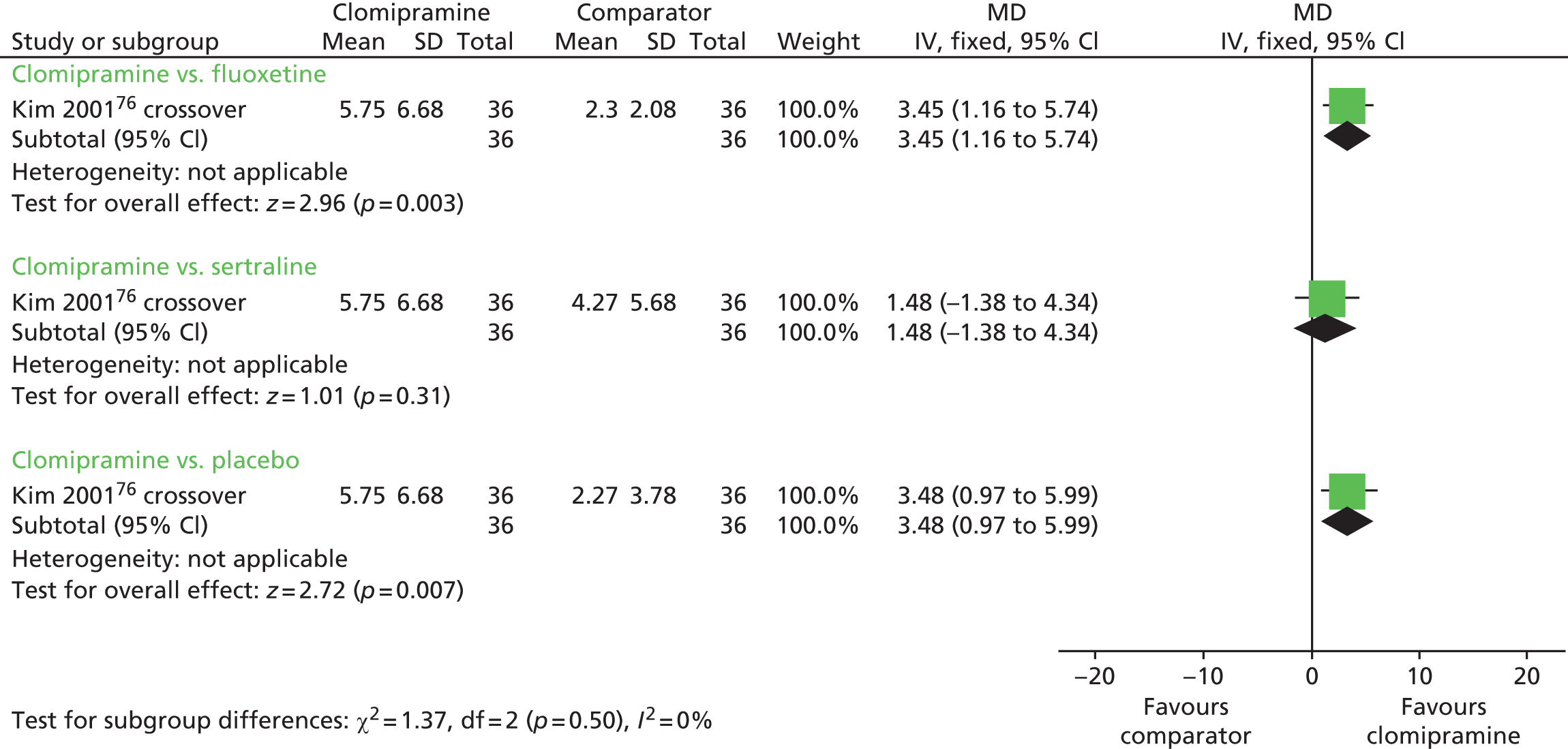

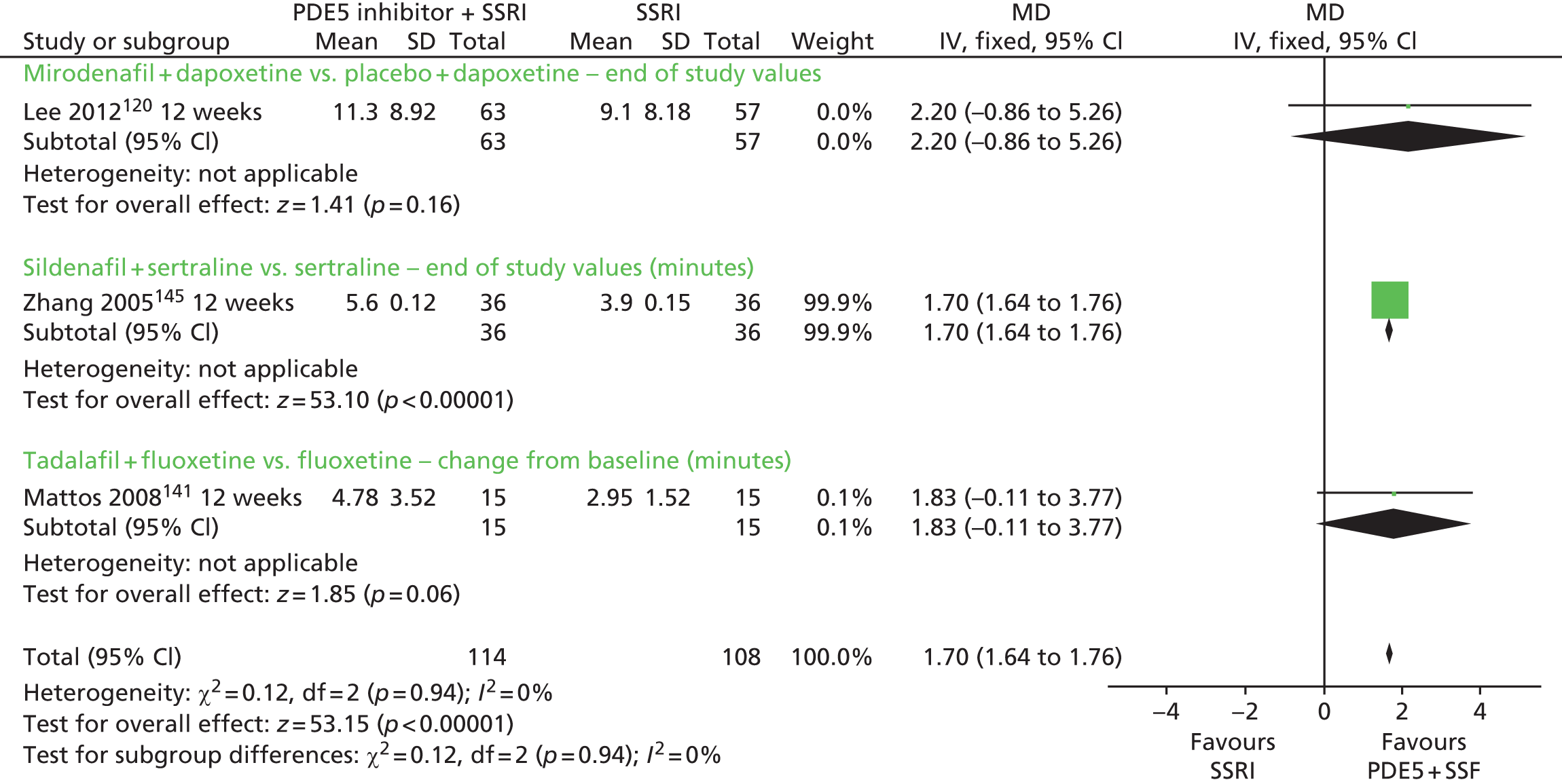

The between-group differences on the Index of Ejaculatory Control and Sexual Quality of Life for both men and women were reported as being not statistically significant at 4 weeks in one RCT. 59 However, two RCTs reported that TEMPE spray was significantly more effective than placebo at 12 weeks on the IPE measures including ejaculatory control, sexual satisfaction and distress and on the PEP. 58,60