Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 07/41/05. The contractual start date was in December 2010. The draft report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Peckham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Smoking and severe mental illness

People with severe mental ill health (SMI), such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, are more likely to smoke1 and to smoke more heavily2 than the general population. The point prevalence of smoking among those with SMI has been estimated to be between 58% and 90%. 1,3 The presence of mental ill health is associated with an elevated risk of smoking by a factor of 2.7 [95% confidence interval (CI) 2.4 to 3.2]. 4 Smokers with SMI are more nicotine dependent, more likely to become medically ill and less likely to receive help in quitting, than the general population. 5 There are several reasons why people with SMI are more likely to smoke:

-

Compared with smokers without SMI, they smoke a greater number of cigarettes per day, and this is evident even before diagnosis. 6

-

They smoke each cigarette more intensely, extracting more nicotine per cigarette. 2,7

-

They are much less likely to receive advice to quit smoking from their general practitioner (GP)3 or mental health specialist. 8

People with SMI have a lot of time on their hands, and smoking is part of the ‘culture’ of mental health services (among both staff and patients). In addition, people with SMI often lack self-esteem and see the future as bleak; as a consequence, they may not be motivated to look after their physical health. 5 Many people with severe mental illness are also misinformed about the risks and benefits of smoking and those of nicotine dependence treatment. 9,10 They often fear and overestimate the medical risks of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT). 11 Many believe that smoking relieves depression and anxiety12 (although nicotine actually causes anxiety). Nicotine may also improve some aspects of cognitive dysfunction in schizophrenia, which could be a disincentive for patients to quit smoking. 13

Smoking contributes to the general poor physical health of those with SMI; in the UK the standardised mortality ratio (SMR) for all causes of death among people with schizophrenia has been reported to be 289 (95% CI 247 to 337), which means that people with schizophrenia have a mortality risk of just under three times that of the general population. 14 Although people with SMI are more likely than the general population to smoke, there is evidence that this is less likely to be recorded in primary care records or to be acted on for these patients than for the general population. 15 Burns and Cohen16 found that, although the annual general practice consultation rate is significantly higher among people with SMI (13–14 consultations a year) than in the general population (about three consultations per year), their health records are significantly less likely to include data relating to a variety of health promotion areas, including smoking advice. Recent studies show that people with mental health problems are just as likely to want to stop smoking as the general population – and are able to stop when offered evidence-based support. 17,18 However, research also shows that effective stop smoking treatment is not always offered to them. 19

It is within this context that a number of policy initiatives have emerged, which emphasise improving the physical care of those with SMI, including taking initiatives to facilitate smoking cessation and the promotion of smoke-free environments in secondary care services. 5,20 This has recently been the subject of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations about the provision of smoking cessation services for people with SMI in order to help address this health inequality. 21

Existing knowledge

Smokers most commonly cite stress relief and enjoyment as their main reasons for smoking,22 although the major cause is nicotine dependence. Nicotine acts in the midbrain, creating impulses to smoke in the face of stimuli associated with smoking,23 and producing what may be thought of as a kind of ‘nicotine hunger’ (a feeling of need to smoke) when blood nicotine concentrations are depleted. Smokers also experience nicotine withdrawal symptoms: unpleasant mood swings and physical symptoms that occur on abstinence and are relieved by smoking. 24 Nicotine dependence is the main reason that most unassisted quit attempts fail within a week. 25 Cochrane systematic reviews24–34 and evidence-supported guidance from NICE,35,36 highlight that the following smoking cessation interventions (including medications used as smoking cessation aids) are helpful in helping smokers reduce their tobacco intake and quit smoking.

Nicotine replacement therapy

Six different forms of NRT are available for use as smoking cessation aids: nicotine patch, gum, lozenge, inhaler, nasal spray and sublingual tablet (microtab). These provide a ‘clean’ alternative source of nicotine without the other 4000 toxic chemicals found in cigarette smoke. All deliver a lower dose of nicotine than would be received through smoking, with the only difference being differing absorption rates as a result of different methods of delivery. A meta-analysis of more than 100 randomised control trials (RCTs) shows that all forms of NRT are roughly equally effective in aiding long-term cessation [odds ratio (OR) 1.77; 95% CI 1.66 to 1.88)]. 25 For those not ready to stop smoking, but who are interested in cutting down, NRT prescription has been shown to reduce smoking and to facilitate quit rates later on (reduce to stop, or cut down to quit). 37

Antidepressants and nicotine receptor agonists

Two non-nicotine pharmacotherapies have been licensed as smoking cessation aids. These are varenicline, a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor partial agonist [Chantix® (USA), Champix® (EU and other countries), Pfizer], and bupropion, a noradenaline and dopamine reuptake inhibitor which was first introduced as an atypical antidepressant (Zyban,® GlaxoSmithKline). Varenicline is almost certainly the most effective treatment to date (OR for 12 months’ continuous abstinence for varenicline vs. placebo 3.22; 95% CI 2.43 to 4.27). It is more efficacious than bupropion (OR for varenicline vs. bupropion 1.66, 95% CI 1.28 to 2.16). 32 However, its use in people with SMI may be limited by case reports of worsening of depression or mental health in populations with a previous history of mental health difficulties.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) guidance on this matter states ‘some patients have reported changes in behaviour, agitation, depressed mood, suicidal thoughts or actions when attempting to quit smoking while taking varenicline or after stopping varenicline’. 38 It states that patients experiencing such changes should stop taking varenicline and contact their physician. A similar recommendation is made for bupropion. General recommendations are that these medications should be used in those whose mental state is stable. The association between varenicline use and exacerbation of mental illness, the frequency of which has yet to be ascertained, must be balanced against the very high risk of continued smoking. 39

Behavioural support

Advice, discussion and encouragement can be delivered via a range of means, from individual to group, open (rolling) or closed group, face to face, or over the telephone or internet. Meta-analyses of trials of multisession intensive behavioural support compared with brief advice found ORs of 1.56 (95% CI 1.32 to 1.84) for individual support and 2.04 (95% CI 1.60 to 2.60) for group support. 28,29 Regular support on the telephone is also effective. A meta-analysis of 10 trials of telephone support for people stopping smoking gave an OR of 1.64 (95 % CI 1.41 to 1.92). 34 There is some evidence to suggest that group support may be more effective in general than one-to-one support,40 and that it should involve multiple sessions. 40 There is also evidence that such sessions can be effective even if conducted over the telephone (OR 1.64, 95% CI 1.41 to 1.92). 34

The accumulated evidence for the use of current smoking cessation interventions has been distilled into clear recommendations for health-care professionals,41 and into a manual for those designing and delivering smoking cessation services. 42 In addition, guidance has been issued by the Royal Colleges of General Practitioners and Psychiatrists to guide the use of smoking cessation interventions for those with SMI. 43

Evidence on the effectiveness of smoking cessation strategies in SMI comes from a systematic review of randomised trials by Banham and Gilbody. 44 This review draws on the results of 10 RCTs of smoking cessation interventions among those with SMI and shows that combinations of behavioural support and pharmacotherapy (NRT and bupropion) are effective in facilitating smoking cessation. The evidence is strongest from bupropion, where the odds of quitting were improved fourfold [three trials; risk ratio (RR) 4.18, 95% CI 1.30 to 13.42]. The strongest evidence relates to NRT, where the addition of NRT tripled biochemically verified quit rates at 4 months (four trials; RR 2.77, 95% CI 1.48 to 5.16). There are, however, no trial-based data for varenicline.

Similar results were found following a recent Cochrane review assessing smoking cessation interventions in individuals with schizophrenia. 45 Smoking cessation rates were significantly higher among those taking bupropion than those taking placebo (seven trials; RR 2.78, 95% CI 1.02 to 7.58) with no report of serious adverse events (SAEs).

Rationale for the Smoking Cessation Intervention for Serious Mental Ill Health Trial

Despite the higher prevalence of smoking, a substantial proportion of people with SMI express a desire to quit. In a large population-based cohort, 30.5% of smokers with past-month mental illness had a self-reported ‘desire to quit’ (although this is lower than the rate of 42.5% among smokers without illness). 4 The introduction in 2004 of a new General Medical Services (GMS) contract46 created a policy impetus to improve the quality of primary care in priority areas. In terms of mental health, the new GMS contract specified that primary care is responsible for the provision of physical health care. Importantly, for smoking cessation initiatives, it ‘incentivises’ GPs to (1) produce a register of people with severe long-term mental health [Quality and Outcomes framework (QOF) indicator MH8 – the SMI register47] and (2) ensure that at least 90% of SMI patients have had a review that includes smoking status recorded within the previous 15 months (the QOF indicator MH9 – SMI health check48). This check includes patients seen in primary care, in secondary care and under shared care arrangements.

For those who are admitted to hospital, the introduction of smoke-free polices provides an opportunity to address smoking. This ban includes inpatient psychiatric units, although the complexities of the Mental Health Act49 have been interpreted by some hospitals as a requirement to provide smoking areas. The admission of an individual to hospital, while being stressful and occurring at a time of personal crisis, also provides a unique opportunity to provide general health advice and to engage individuals in interventions targeted at smoking reduction and cessation.

Recent guidance issued by NICE50 offers clear statements of purpose to make secondary care services (including mental health services) entirely smoke free and to promote a smoke-free culture among staff and users of services. Mental health services are highlighted as areas of priority and unmet need in relation to smoking cessation and there is clear guidance that services should be developed and implemented as a matter of some priority.

Smoking cessation services for people with SMI are not sufficiently evolved or embedded within the NHS. From the preceding discussion, we know ‘what works’ for smoking cessation in general; the purpose of the Smoking Cessation Intervention for Serious Mental Ill Health Trial (SCIMITAR) is to use enhancements of care to ensure that evidence-supported interventions are offered to (and taken up by) people with SMI and to see if smoking rates can be reduced. This technology represents a ‘complex health-care intervention’, and this study, therefore, uses the stepwise Medical Research Council complex interventions framework51 and the updated guidance52 to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, implementation and content of a bespoke smoking cessation (BSC) service for people with SMI.

Research objectives

-

To develop a BSC service based upon evidence-supported treatments for people with SMI.

-

To establish the acceptability and uptake of this BSC service by people with SMI in primary care and specialist mental health services.

-

To test the feasibility of recruitment and follow-up in a pilot trial of a BSC service among patients with SMI.

Chapter 2 Methods

Details of the methods used for the health economics can be found in Chapter 5 and details of the methods used in the qualitative substudy can be found in Chapter 6.

Study design

This study was a pragmatic, two-arm, parallel-group, pilot RCT. The setting was in primary care and specialist mental health services within three centres: York/Scarborough [principal investigator (PI) Professor Simon Gilbody), Manchester (Investigator Professor Helen Lester) and Hull (PI Professor Simon Gilbody). We recruited from both primary and secondary care settings. Given that this is a hard-to-reach population, several methods were used to try to identify and recruit eligible participants. A two-stage recruitment process was employed to check for eligibility, understanding of the study and to obtain consent. Participants were individually randomised to receive usual care or usual care plus a BSC service. Participants were followed up over the course 12 months, with data collected at 1 month, 6 months and 12 months post randomisation.

Approvals obtained

Ethical approval was sought and granted on 29 October 2010 by Leeds (East) Research Ethic Committee (10/H1306/72). Approval was also obtained from the relevant research and development departments (see Appendix 1).

Trial sites

The study was conducted in three sites in England. Sites recruited throughout the duration of the study.

Participant eligibility

Inclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion into this study participants needed to meet the following inclusion criteria:

-

aged 18 years and above

-

have SMI

-

are a smoker and express an interest in wanting to cut down smoking (though not necessarily quitting).

There is no agreed definition of SMI so we adopted a pragmatic definition of SMI,46,53 i.e. a documented diagnosis of schizophrenia or delusional/psychotic illness [International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10 F20.X & F22.X or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental disorders (DSM) equivalent] or bipolar disorder (ICD F31.X or DSM equivalent). This SMI-inclusive diagnosis needed to have been made by specialist psychiatric services and have been documented in either the GP or psychiatric notes.

Exclusion criteria

People who:

-

were pregnant or breastfeeding

-

had comorbid drug or alcohol problems (as ascertained by the GP or mental health worker)

-

were non-English speakers

-

lacked capacity to participate in the trial (guided by the 2005 Mental Capacity Act54).

Serious mental illness patients who smoke while concurrently abusing substances may require additional medication or specialist advice, which was beyond the brief of the mental health smoking cessation practitioner (MHSCP) and this trial. Similarly, smoking cessation in pregnancy also requires specialist knowledge. It was planned that any participant who became pregnant during the course of the trial would be removed from the study and referred to local smoking cessation services specific to pregnancy.

Identifying participants

We used four methods to recruit participants: direct GP referral or following database screening, primary care referral following annual health check, secondary care recruitment – Care Programme Approach (CPA) and via Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) – and patient self-referral.

Direct general practitioner referral or following database screening

General practitioners are encouraged to offer opportunistic advice and information about smoking cessation services to all patients who smoke whenever they consult in primary care. GPs taking part in this study were provided with patient study information packs to give to patients with SMI who were receptive to participating in the trial. GPs then completed and faxed a referral form and patients’ consent to be contacted form to the SCIMITAR researchers, who approached the patient for recruitment.

General practitioner surgeries were also asked to consult their patient databases and SMI register, if available, to screen for potentially eligible participants. Patient information packs were sent from the GP practice inviting patients willing to take part in the study to return a completed consent to be contacted form to the SCIMITAR researchers, who then approached the patients to ascertain eligibility and recruitment. Following a database search, GPs were asked to provide details of the number of packs they had sent out to allow a return rate to be calculated.

Primary care referral following annual health check

At the time of the trial, annual primary care health checks for people with SMI55 (MH9) represented an opportunity to address smoking behaviour and to offer enhanced smoking cessation services within the context of a trial. Health checks are generally conducted by practice nurses, and we encouraged all primary care staff to make SMI smokers aware of the trial when they received their annual primary care health check. Patient information packs were given to interested and potentially eligible patients during their health check. Similar to GP referrals, practice nurses were instructed to complete referral forms and to fax the patients’ completed consent to be contacted form to the SCIMITAR researchers, who then approached the patients for eligibility and recruitment.

Secondary care recruitment – Care Programme Approach and via Community Mental Health Teams

A substantial proportion of people with SMI will be in receipt of the CPA, and will receive an annual review of their psychological, social and health-care needs. Study researchers worked with care co-ordinators and consultants to screen their entire caseloads for potentially eligible participants who matched the inclusion criteria. Participants identified as potentially suitable for the SCIMITAR trial were given a copy of the patient information pack by their care co-ordinator. The patient information pack contained a consent to be contacted form for potential participants to return to the research assistant giving permission for the researcher to contact them by telephone or letter, or in person to discuss the trial further.

Members of the CMHT were also invited to directly refer eligible patients to the research team, following a similar pathway as GP referrals.

Patient self-referral

Poster advertisements of the SCIMITAR trial and BSC service were displayed in venues where patients in secondary care often congregated (e.g. clozapine clinics, outpatient departments, day centres, etc.). The posters invited patients to contact study researchers if they were interested in participating in the study. The introduction of smoking bans in inpatient hospital services raised an ideal opportunity to offer smoking cessation services to patients who were interested in addressing their smoking behaviour. Therefore, we also advertised the BSC service in inpatient mental health settings. Interested participants contacted a SCIMITAR researcher, who sent out a patient information pack, including a consent to be contacted form.

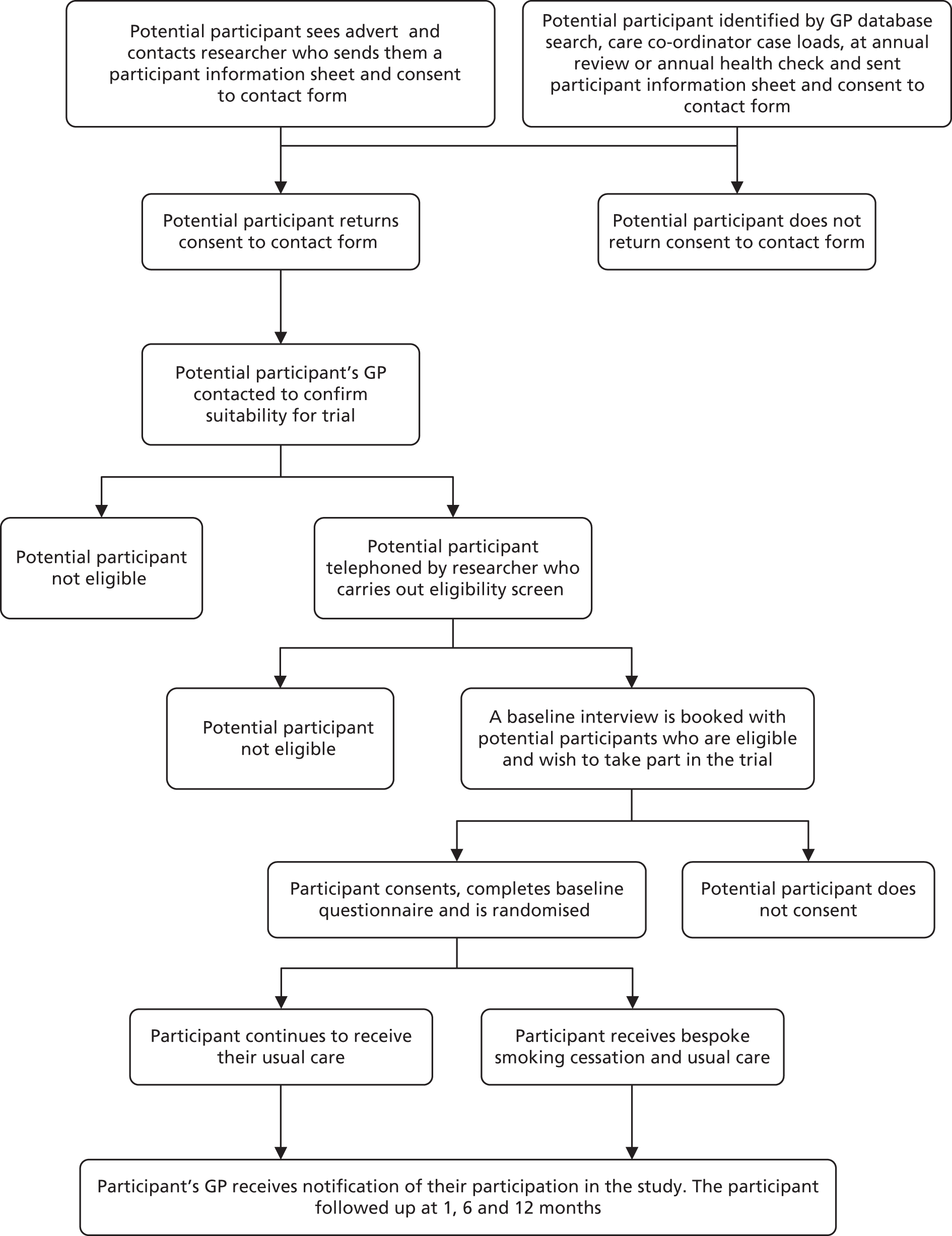

Screening for eligibility

Potential participants identified by database screening or self-referral

Once a potential participant returned their consent to contact form the participant’s GP was contacted to check for exclusion criteria (pregnancy or known drug/alcohol problems) and their judgement on the appropriateness of the patient’s inclusion into the study. Once the GP had confirmed that it was appropriate for the participant to take part in the trial the participant was contacted by a trial researcher.

Potential participants referred by general practitioner or other health-care professional

If the patient was referred, the health-care professional giving them the information pack (GP, mental health specialist, practice nurse, CPA co-ordinator) explained the trial, assessed the patient for eligibility and screened for the given exclusion criteria. On receipt of a faxed referral form and signed consent to be contacted form, patients were contacted by a trial researcher.

The SCIMITAR researcher first approached the potential participant by telephone. After briefly explaining the trial, the researcher enquired about the patient’s smoking habits, specifically: (1) Do you smoke? (2) How much do you smoke? and (3) Would you seriously consider quitting or cutting down with a view to quitting within the next 6 months? These ensured that the patient currently smoked but was seriously contemplating quitting. The researcher also asked screening questions about pregnancy and breastfeeding, drug and alcohol use, which led to exclusion if present. The researcher then arranged a meeting at a mutually convenient time and venue.

Consenting participants

Potential participants who met with the SCIMITAR researcher were given the opportunity to clarify any points they did not understand and ask any questions. A full oral explanation of the trial was given by the SCIMITAR researcher. It was emphasised that the participants may withdraw their consent to participate at any time without loss of benefits to which they otherwise would be entitled. Participants were also informed that, by consenting, they agreed to their GP being informed of their participation in the trial and that their medical records may be inspected by regulatory authorities, but that their name would not be disclosed. Written informed consent was then obtained, with both the participant and the researcher signing and dating the consent forms prior to the patient being randomised.

Baseline assessment

Once participants had consented to take part in the trial, they completed the baseline questionnaires. In addition, height and weight measurements were taken in order to calculate the patient’s body mass index (BMI) and an exhaled breath carbon monoxide (CO) reading was taken. These made up the participants’ baseline data set. The participant was randomised on completion of this data set.

Randomisation

Simple randomisation was used following a computer-generated random number sequence. The SCIMITAR researcher contacted a secure randomisation line run by the York Trials Unit and, once given the details of the patient’s allocation, immediately informed the patient of his or her allocation and set up the first appointment with the MHSCP (if so allocated). A letter was sent to the GP and mental health specialist to be included in the patient’s records and to advise them on subsequent smoking cessation management. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants, GPs, researchers or the MHSCPs to the treatment allocation.

Ineligible and non-consenting participants

All ineligible and non-consenting participants were referred back to their GP practice so that any general health-care advice on the importance of stopping smoking could be provided by the patients’ GP or community nurses.

Sample size

This pilot trial aimed to recruit 100 patients with SMI to obtain preliminary estimates of the effect size of the BSC service. Using the following assumptions (1) primary care QOF registers were assumed to give prevalence data for SMI of 0.5%; (2) an average of 2.5 whole-time equivalent GPs were assumed to work in each practice each with a list size of 1600 patients (4000 per practice); and (3) at least 80% of people with SMI smoke. If we were to recruit 25% of eligible patients in primary care, around 20 practices would enable us to recruit 100 patients over a 12-month period. This was a conservative assessment which did not allow for recruitment from secondary care, where recruitment is less easy to plan but was in addition to primary care.

Description of interventions

Trial intervention

This service intervention consisted of a mental health professional trained in smoking cessation interventions (MHSCP) who worked in conjunction with the patient and the patient’s GP or mental health specialist to provide a smoking cessation service individually tailored to each patient with SMI. The intervention was delivered in accordance the Smoking Cessation Manual: A Guide for Counsellors and Practitioners,42 which forms the basis of smoking cessation interventions in the NHS via the National Centre for Smoking Cessation Training (www.ncsct.co.uk).

This service was in line with current NICE guidelines for smoking cessation services56 and included support sessions specifically adapted for patients with SMI run by the MHSCP and GP-prescribed pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation (NRTs, bupropion or varenicline either separately or in combination, as decided by the GP), in addition to regular follow-up by the MHSCP. Examples of specific adaptations to the needs of those with SMI are (1) the need to make several assessments prior to setting a quit date; (2) recognising the purpose of smoking in the context of their mental illness, such as the use of smoking to relieve side effects from antipsychotic medication (and how this will be managed during a cessation attempt); (3) the need to involve other members of the multidisciplinary team in planning a successful quit attempt for those with complex care needs and multiagency programmes of care; (4) a greater need for home visits, rather than planned visits in GP surgeries; (5) providing additional face-to-face support following an unsuccessful quit attempt or relapse; and (6) informing the GP and psychiatrist of a successful quit attempt, such that they can review antipsychotic medication doses if metabolism changes. 57

Pharmacotherapies were provided as long as was deemed necessary, in line with NICE guidance, and were determined by the GP without the influence of the SCIMITAR trial team. In line with NICE recommendations, the MHSCP offered advice on the range of treatments options available to patients under the NHS (including medication, counselling and follow-up). It was not the remit of the trial to assess specific smoking cessation pharmacotherapies or treatments per se, although data on frequency of their usage were collected.

Participants were encouraged to (1) reduce smoking to quit,37 (2) set their own quit dates and (3) make several attempts to quit if their initial attempt failed. It is generally recommended that patients wait a few months after a failed quit attempt before trying again. This was not strictly enforced in this population and was left to the discretion of the MHSCP. All patients remained under the care of their GP and continued to receive their usual NHS treatment.

Bespoke smoking cessation interventions were in line with best practice guidance relevant to the provision of all NHS stop smoking interventions (including for those with mental illness). It sets out fundamental quality principles for the delivery of services and stop smoking support – stipulated in the Department of Health’s NHS Stop Smoking Services: Service and Monitoring Guide 2009/10. 3,58

In training our MHSCPs, we also paid attention to the content of the intervention to ensure that evidence-supported behaviour change techniques (BCTs) were incorporated. We followed contemporary best practice and incorporated evidence-supported BCTs59,60 in the following way:

-

During the design phase of SCIMITAR we reviewed existing trial data in this area (published in a systematic review by Banham and Gilbody). 44

-

We contacted the first authors of all existing SMI smoking cessation trials to obtain their smoking cessation manuals (10 manuals were obtained).

-

We classified the behavioural content of all existing mental health smoking cessation manuals using the taxonomy of BCTs developed by Abraham and Michie. 59

Finally, we identified those BCTs which were associated with a positive trial result (OR > 1.5) and incorporated these into our manualised SCIMITAR intervention.The specific evidence-supported mental health BCTs are summarised in Box 1.

-

Identify reasons for wanting and not wanting to stop smoking.

-

Measure CO.

-

Facilitate barrier identification and problem solving.

-

Facilitate relapse prevention and coping.

-

Facilitate action planning/know how to help identify relapse triggers.

-

Facilitate goal setting.

-

Advise on conserving mental resources.

-

Advise on stop-smoking medication.

-

Give options for additional and later support.

-

Assess current and past smoking behaviour.

-

Assess current readiness and ability to quit.

-

Assess nicotine dependence.

-

Assess physiological and mental functioning.

-

Elicit client views.

-

Monitor psychiatric medication levels and side effects throughout the quit attempt.

Control intervention

This was a usual-care control group in which participants were encouraged to consult with their GP or local NHS quit smoking services. GPs were given advice to follow current NICE guidelines for smoking cessation, without the additional support of a bespoke MHSCP. Usual care could include pharmacotherapies to aid smoking cessation (NRTs, bupropion or varenicline either separately or in combination), access to self-help materials and referral to local NHS stop smoking clinics (which would not be specifically tailored for the needs of those with SMI). Patients were encouraged to reduce smoking to quit and set their own quit dates, but were managed solely by their own GP or mental health specialist and, crucially, did not receive regular visits from a MHSCP. Details of NRT that control participants received were gathered by accessing patients’ GP notes and details of any smoking cessation management were requested from participants in the follow-up questionnaires.

Follow-up

Participants were followed up 1 month, 6 months and 12 months after randomisation.

Baseline assessments and 12-month follow-up were carried out face to face, while 1- and 6-month follow-ups were carried out by telephone interview, using paper questionnaires or via online questionnaires. If it was not possible to meet the participant for a face-to-face 12-month follow-up, a systematic approach was used to explore other avenues to collect data (self-report data only). Follow-up was carried out by researchers who were not blind to treatment allocation; however, the objective nature of the primary outcome eliminated any potential bias.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome was whether patients had stopped or reduced smoking when assessed at 12 months post recruitment. This was determined by CO measurement, where abstinence is defined as CO < 10 p.p.m. In the absence of a CO measurement, self-reported smoking cessation was used.

Secondary outcomes

-

Self-reported number of cigarettes smoked per day.

-

Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND). 61

-

Motivation to quit (MTQ) questionnaire.

-

Self-reported number of attempts to quit and period of cessation.

-

Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9). 62

-

Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12). 63

-

Service utilisation.

-

Self-reported drug substitution (specifically cannabis use).

Table 1 gives details of the measures collected and the time points at which they were collected. Copies of the questionnaires can be found in Appendix 2.

| Assessment | Timeline (months post randomisation) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 1 | 6 | 12 | |

| Eligibility and consent | ||||

| Eligibility | ✓ | |||

| Consent | ✓ | |||

| Background and follow-up | ||||

| Personal details | ✓ | |||

| Body mass index | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Mental health details | ||||

| Mental health history | ✓ | |||

| Self-reported current mental health status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Current medications | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Referrals to mental health services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Admissions to hospital related to mental health | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Smoking details | ||||

| Smoking history | ✓ | |||

| Current smoking status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Use of smoking cessation services | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CO measurement | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Adverse event reporting | Ongoing collection | |||

| Questionnaires | ||||

| FTND questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| MTQ questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PHQ-9 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health-related quality of Life (SF-12) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health state utility (EQ-5D) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Health economics/service utilisation questionnaire | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

Participant engagement

Participant engagement was measured using the proportion of intervention participants who engaged with (1) contacts which were offered from a MHSCP; (2) medication when this was offered by their GP (as measured by the number of filled prescriptions issued by the GP); or (3) compliance with CO monitoring by MHSCPs. Smoking status at baseline and (where possible) follow-up were verified by exhaled CO. Readings < 10 p.p.m. confirmed that participants had not smoked recently (i.e. within 12 hours). Measurements above 10 p.p.m. indicated that the patient has not ceased smoking. At least two CO readings were taken; if participants claimed to have stopped but their CO readings were above 10 p.p.m., they were asked when they had last smoked and whether or not they had any minor relapses during their quit attempt.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat basis, including all randomised patients in the groups to which they were randomised. Analyses were conducted in STATA version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Baseline data

The baseline data were summarised by treatment group and described descriptively. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken. Continuous measures were reported using means and standard deviations (SDs; median and range were also included where appropriate), whereas categorical data were reported using counts and percentages.

Primary analysis

The primary outcome was cessation of smoking at 12 months as measured by the breath CO test and self-reported smoking cessation in the absence of a breath measurement. The two treatment groups were compared using logistic regression with adjustment for prognostic variables: sex, age, number of cigarettes smoked at baseline and alcohol consumption. ORs and corresponding 95% CIs were obtained from this model.

Secondary analyses

The 1-, 6- and 12-month secondary outcomes analysed were self-reported smoking cessation, number of cigarettes smoked per day, dependence on smoking as assessed by the FTND questionnaire, level of motivation as assessed by the MTQ questionnaire, length of cessation of smoking, PHQ-9, BMI, SF-12 physical component score and SF-12 mental component score. Secondary outcomes were summarised descriptively, with no formal statistical comparisons undertaken. Continuous measures were reported using means and SDs (median and range was also included where appropriate), whereas categorical data were reported using counts and percentages.

Missing data

The numbers of patients analysed were reported for the primary and secondary outcomes for each treatment group. For the primary outcome, analysis was performed on complete cases only and cases without a CO measure or a self-reported smoking cessation result at 12 months were excluded from analysis. In a full trial, multiple imputation and mixed modelling would be considered in the presence of missing outcome data.

Qualitative substudy

We explored specific issues of acceptability and adherence of smoking cessation interventions among those with SMI and those who referred to and delivered the intervention. Full details of the qualitative substudy are given in Chapter 6.

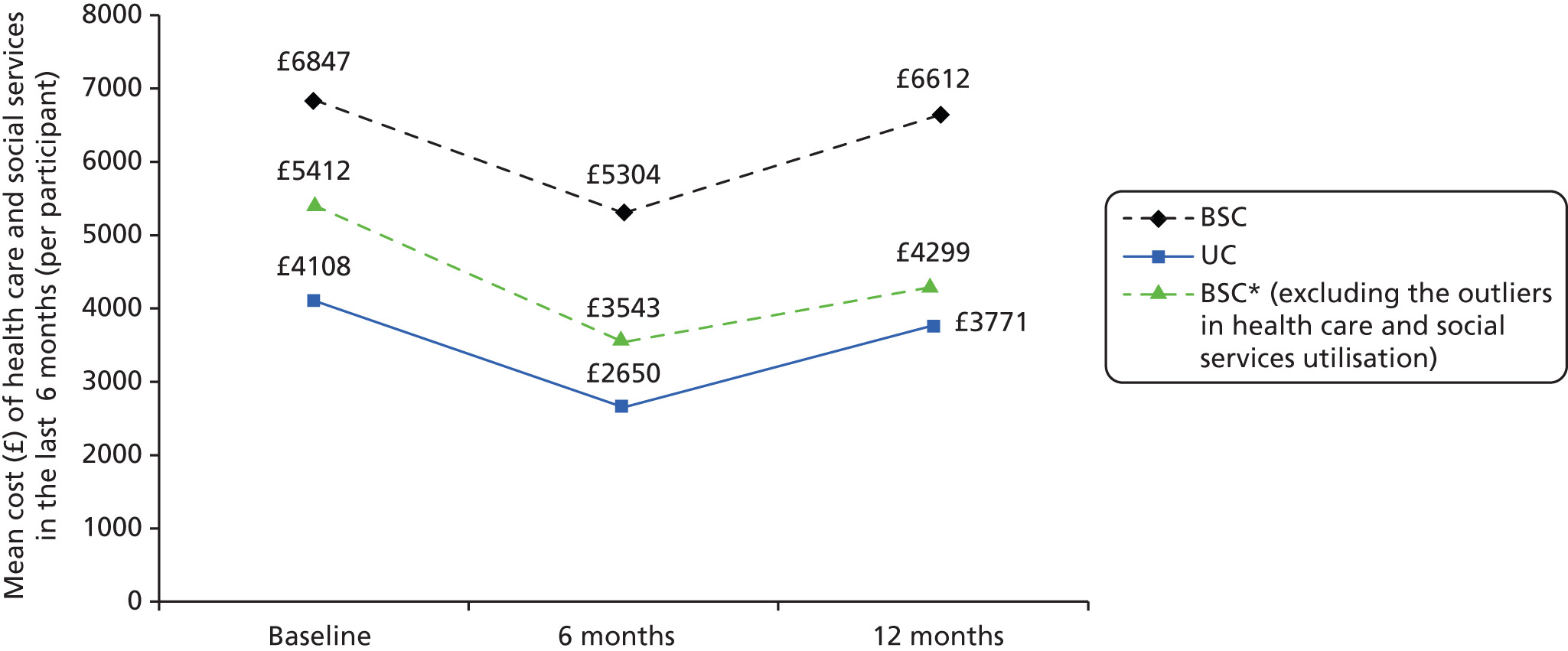

Cost assessment

A cost assessment was carried out to estimate the cost of the alternative treatment strategies. A costing methodology was carried out in two steps. The first step was to measure resource use by trial patients in physical units. Health-care and community services resource use information was collected using an adapted health economic/service utilisation questionnaire included in the baseline and follow-up questionnaire (see Appendix 3). For medication use, the participating GP surgeries were asked to extract prescription information of participants during the trial period from their records at the end of the trial. Owing to the huge variety of medication that could be prescribed to participants, a list of antipsychotic medication was used to reduce the burden of data collection upon the GP surgeries (Table 2). Therefore, only the information on antipsychotic medication and prescriptions related to pharmacotherapy for stop smoking was collected from GP surgeries. The pharmacotherapy for stop smoking included NRT products, varenicline and bupropion. While the prescriptions of pharmacotherapy were collected from GP records, the usage of pharmacotherapy was also collected using the trial questionnaire, covering both prescription and over-the-counter purchases. The second step was to calculate the cost of resources used by applying market prices or national average unit costs. Costs were assessed from a NHS and Personal Social Service perspective. Intervention costs were based on delivery costs within the trial and included staff, equipment, supervision and appropriate annuitised capital costs. Missing data were estimated by using the average value among the same group at the same follow-up point.

| Chemical name | |

|---|---|

| Citalopram hydrobromide | |

| Clozapine | |

| Fluoxetine hydrochloride | |

| Flupentixol decanoate | |

| Fluphenazine decanoate | |

| Haloperidol decanoate | |

| Lithium carbonate | |

| Olanzapine | |

| Paroxetine hydrochloride | |

| Prochlorperazine maleate | |

| Procyclidine hydrochloride | |

| Quetiapine | |

| Risperidone | |

| Trihexyphenidyl hydrochloride | |

| Zuclopenthixol |

A cost-effectiveness analysis was undertaken at 12 months comparing resource use in the BSC group with resource use in the usual-care group using the incremental quit rate for the intervention over and above usual care. This cost-effectiveness analysis is undertaken to demonstrate the analysis that would be undertaken in a full trial. This is a pilot trial and results should be interpreted with extreme caution because of the small sample size. We do not conduct a full cost–utility analysis because of the very small sample size.

Adverse events

Clear guidance on the prescription of antismoking medications in the presence of SMI (including safety considerations) have been published and were made available to all GPs to help inform their prescribing decisions. A key feature of the SCIMITAR trial was to ensure that GPs manage antismoking medications within this framework and with their prior knowledge of the patient and their concomitant use of medication. This was with the aim of replicating real-life practice of the use of antismoking medications in primary care. The medication profile of the individual participants was reviewed by their GP or mental health specialist to assess any potential safety issues (in line with the latest practice guidance on the provision of smoking cessation interventions in the NHS). An important aspect of the design of this study was that the SCIMITAR team had no direct influence over prescribing decisions made by GPs since this was not a drug trial or an investigation of a medicinal product(s).

A standard operating procedure for detecting and reporting adverse events (AEs) was implemented. An AE was defined as any unexpected effect or untoward clinical event affecting the participant. It could be directly related, possibly related or completely unrelated to the intervention. It was also classed according to severity, either as a non-serious AE (including discomfort or slight worsening of symptoms) or as a SAE (which could be particularly harmful, dangerous or required hospitalisation).

The participant’s MHSCP, GP and mental health specialist were requested to inform the research team of any serious or non-serious AEs. In addition, participant responses to questions in the follow-up questionnaire relating to hospital admissions, attendance at accident and emergency, use of the emergency services or if the participant volunteered information which could potentially be classed as an AE or SAE, were followed up by the research team.

All AEs and SAEs were independently reviewed by a clinician and reported to the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee and Trial Steering Committee. Any SAEs that were deemed to be related to the intervention and unexpected were reported to the Research Ethics Committee and sponsor within 7 days of notification.

Suicide protocol

A protocol for identifying and reporting suicide risk was implemented (see Appendix 6 for protocol). Question 9 on the PHQ-9, which asks if the patient ‘have you had thoughts that you would be better off dead or hurting yourself in some way?’, was used to identify any suicide risk.

If the participant indicated a response of 3 for this item, then the suicide protocol was implemented and the patient asked if he or she had talked to a GP, psychiatrist or care co-ordinator/community psychiatric nurse about these feelings. If the patient had not sought help, consent was sought to to inform the patient’s GP of the situation. If the patient refused, the relevant designated psychiatrist/health professional was contacted. If the patient agreed, the patient’s GP or psychiatrist was contacted immediately. A suicidal intent form was also completed and, where applicable, a ‘suicidal intent form: psychiatrist/health professional’ was completed. These forms were stored with the patient’s trial records.

Chapter 3 Changes to the protocol

Online questionnaires

In the original proposal participants would complete paper questionnaires and the answers would be manually entered into the database by the researcher. However, the possibility of participants completing the questionnaires online became available. As some participants may find this preferable to completing a paper questionnaire, they were given the additional option of completing questionnaires online via a secure website held on the university server.

Extension to end of study date

Owing to recruitment taking longer than anticipated an extension was requested and granted. It was originally planned that the study would end in May 2013. This was extended to November 2013. The extension was to allow sufficient time for the study team to collect all outstanding follow-up data from participants.

Twelve-month follow-up

In the original protocol, all 12-month follow-ups were to be carried out face to face. It became apparent because of the nature of the patient population being studied that this would not always be possible. To collect data from as many participants as possible, we decided that if a participant could not be met face to face, attempts would be made to collect 12-month data via a telephone interview or postal questionnaire. In these cases smoking abstinence or reduction would not be verified by CO measurements; however, self-reported quit rates would still be collected.

Gift vouchers

The SCIMITAR Trial management group offered participants taking part in the qualitative substudy a £10 gift voucher as a goodwill gesture and token of thanks for their time.

Chapter 4 Results

Recruitment

Recruitment started in May 2011 and ended in May 2012. Over the course of the trial, 45 GP surgeries in Manchester, York/Scarborough and Hull mailed out recruitment packs. Recruitment of at least one trial participant occurred in 25 of the 45 GP surgeries which mailed out packs. Twenty-nine CMHTs were enlisted to recruit participants, along with 21 other secondary care organisations and 14 tertiary care organisations. Four participants were recruited through direct referral, having seen a poster advertising the study.

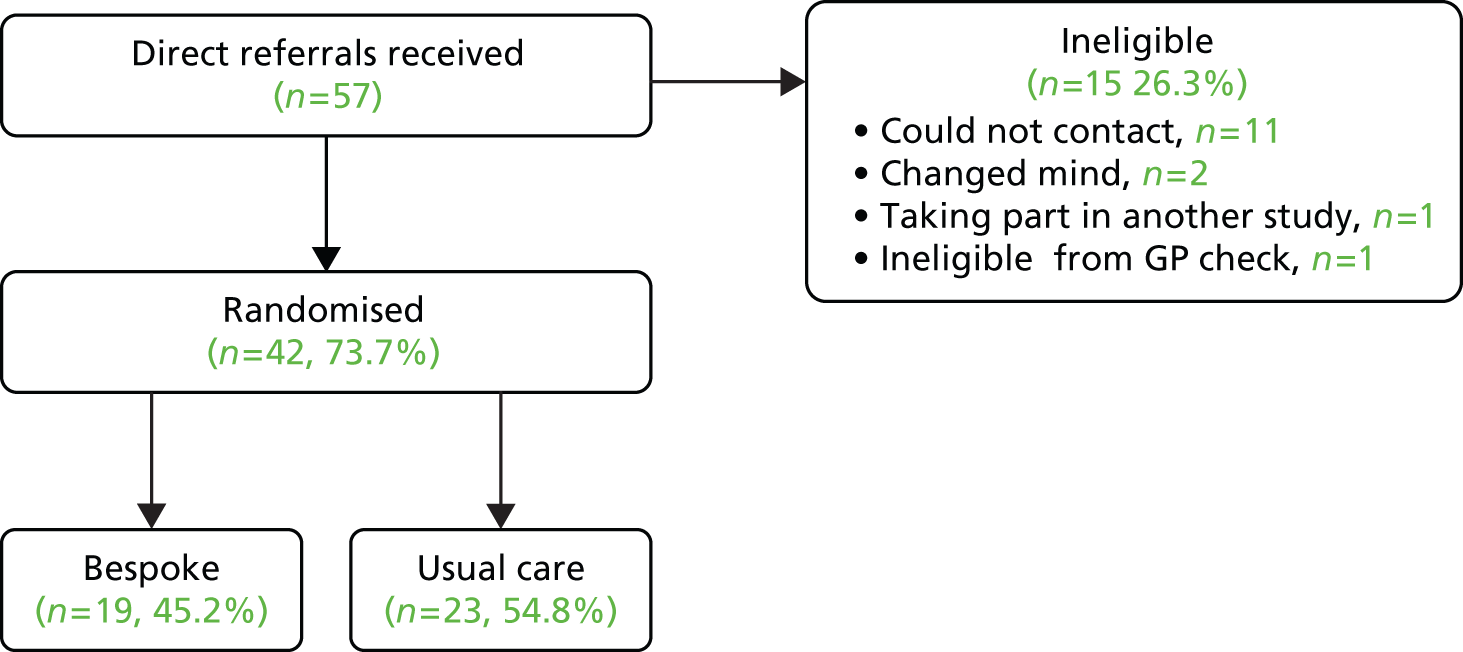

In primary care, 1036 recruitment packs were mailed out by GP surgeries which resulted in 64 consent to contact forms being returned (a response rate of 6.2%). Of these, 51 people were recruited into the study. From secondary care 57 direct referrals were received, of which 42 were recruited and randomised (a rate of 74%); however, it was not possible to determine how many packs were given out by CMHTs and other secondary and tertiary care organisations.

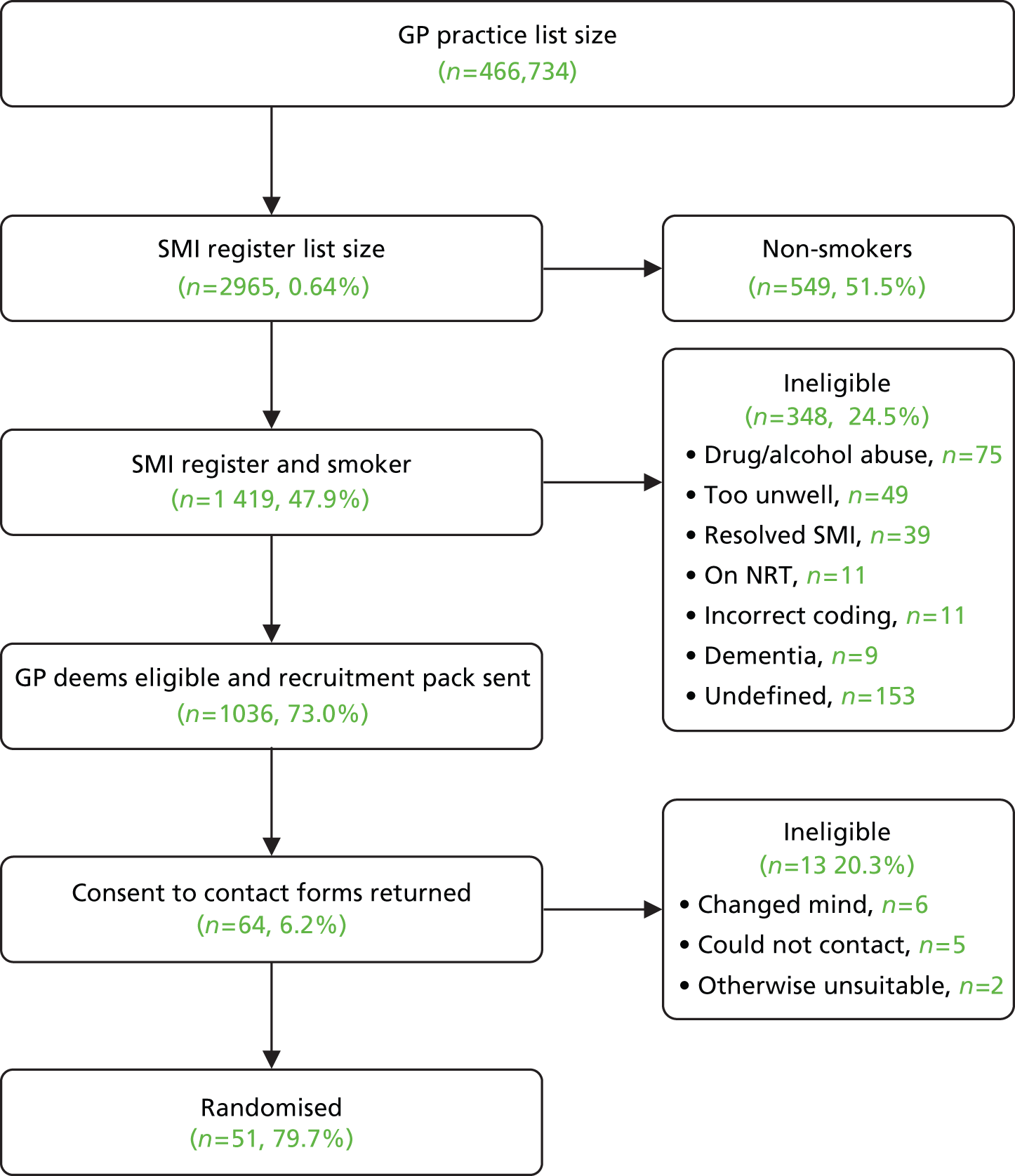

A total of 97 patients were recruited to the trial. The rate of recruitment is shown in Figure 1. Recruitment occurred at three sites (York/Scarborough, Manchester and Hull) and was evenly distributed between primary and secondary care (Table 3). Table 4 shows how many people were recruited from each of the different secondary care organisations. Participant flow through the trial is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram (Figure 2). The conversion rates of each stage of the recruitment process in primary care are shown in Figure 3 and the conversion rate of each stage of the secondary care recruitment process is shown in Figure 4. It can be seen that a total GP list size of 466,734 led to 51 randomisations.

FIGURE 1.

Trial recruitment rate.

| Recruitment site | Recruitment method | Recruiting sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| York/Scarborough | Hull | Manchester | Total | ||

| Primary care | Database search | 25 | 9 | 15 | 49 |

| Self-referral | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | |

| Secondary care | Direct referral | 12 | 2 | 29 | 43 |

| Self-referral | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | |

| Total | 38 | 13 | 46 | 97 | |

| Centre | CMHT | Clozapine/depot clinic | Assertive outreach | Assisted housing | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| York/Scarborough | 7 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 3 |

| Manchester | 14 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 10 |

| Hull | 8 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Total | 29 | 5 | 5 | 12 | 13 |

FIGURE 2.

A CONSORT diagram showing participant flow through the trial.

FIGURE 3.

Primary care randomisations from GP database searches.

FIGURE 4.

Secondary care randomisations.

Of the 97 participants, 51 were randomised to usual GP care and 46 participants were randomised to BSC (Table 5).

| Group | Recruiting sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| York/Scarborough | Hull | Manchester | Total | |

| Usual GP care | 18 | 6 | 27 | 51 |

| BSC | 20 | 7 | 19 | 46 |

| Total | 38 | 13 | 46 | 97 |

Baseline data

The baseline characteristics of participants are summarised in Tables 6–10. Table 6 summarises participants by the prespecified prognostic factors. There were more male than female participants (59.8% vs. 40.2% respectively) and a greater proportion of men in the BSC group (69.6%) than in the usual GP care group (51.0%). There was some imbalance between the treatment groups with respect to alcohol consumption, with more alcohol consumption in the usual GP care group (62.7%) than in the BSC group (50.0%). The mean age of participants was 47 years, with a range from 19.1 to 73.3 years.

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Female, n (%) | 25 (49.0) | 14 (30.4) | 39 (40.2) |

| Male, n (%) | 26 (51.0) | 32 (69.6) | 58 (59.8) |

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.9 (12.8) | 47.8 (12.4) | 46.8 (12.6) |

| Median (range) | 46.4 (22.2–71.5) | 47.3 (19.1–73.3) | 47.2 (19.1–73.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Alcohol consumption at baseline | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 32 (62.7) | 23 (50.0) | 55 (56.7) |

| No, n (%) | 19 (37.3) | 23 (50.0) | 42 (43.3) |

| Number of cigarettes | |||

| Mean (SD) | 22.8 (13.2) | 25.8 (11.6) | 24.2 (12.5) |

| Median (range) | 20 (5–60) | 22.5 (5–60) | 20 (5–60) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) |

Table 7 summarises the general health of participants. Almost half of participants reported moderate health (48%) over the past year and a mean of 5.5 consultations with a GP in the last 12 months (range 0–40 consultations). The majority of participants (86%) felt that smoking had affected their health, and 63% of participants had been advised to stop smoking by their GP. The mean BMI of participants was 28.6 kg/m2 (range 17.9–43.1 kg/m2), which is categorised as overweight (normal weight BMI range is 18.5–25 kg/m2). Fifteen per cent of participants reported taking recreational drugs.

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health over the past year, n (%) | |||

| Excellent | 4 (8.0) | 2 (4.3) | 6 (6.3) |

| Good | 11 (22.0) | 12 (26.1) | 23 (24.0) |

| Moderate | 24 (48.0) | 22 (47.8) | 46 (47.9) |

| Poor | 9 (18.0) | 6 (13.0) | 15 (15.6) |

| Very poor | 2 (4.0) | 4 (8.7) | 6 (6.3) |

| Number of times consulted GP in the last 12 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 5.4 (7.1) | 5.7 (6.2) | 5.5 (6.7) |

| Median (range) | 3 (0–40) | 3.5 (0–24) | 3 (0–40) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Smoking has affected the state of your health, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 43 (84.3) | 40 (87.0) | 83 (85.6) |

| No | 8 (15.7) | 6 (13.0) | 14 (14.4) |

| GP or doctor advised you to quit smoking, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 30 (58.8) | 31 (67.4) | 61 (62.9) |

| No | 21 (41.2) | 15 (32.6) | 36 (37.1) |

| Recreational drugs at baseline, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 10 (19.6) | 5 (10.9) | 15 (15.5) |

| No | 41 (80.4) | 41 (89.1) | 82 (84.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 29.1 (5.8) | 28.1 (5.7) | 28.6 (5.7) |

| Median (range) | 29.3 (18.5–43.1) | 27.3 (17.9–41.5) | 28.6 (17.9–43.1) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

Table 8 summarises the sociodemographic data of participants and Table 9 summarises their employment status. The majority of participants (87%) were white British and the next largest ethnic group was black or black British-Caribbean (5%). About 20% of the participants had General Certificates of Secondary Education (GCSEs)/O-levels as their highest educational qualification. Over half of participants (56%) were not employed but not seeking work because of ill health and 75% of those unemployed had not been employed for over 5 years. Over half of participants were single (57%), 20% were married or living with a partner and 19% were divorced or separated.

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White – British | 41 (80.4) | 42 (93.3) | 83 (86.5) |

| White – Irish | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Any other white background | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Mixed – white and black Caribbean | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Any other mixed background | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Asian or Asian British – Pakistani | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Black or black British – Caribbean | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (5.2) |

| Black or black British – African | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Chinese | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 32 (62.7) | 24 (52.2) | 56 (57.7) |

| Married | 4 (7.8) | 7 (15.2) | 11 (11.3) |

| Living with a partner/cohabiting | 5 (9.8) | 3 (6.5) | 8 (8.2) |

| Divorced/separated | 9 (17.6) | 9 (19.6) | 18 (18.6) |

| Widowed | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Never married | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Highest educational qualification | |||

| GCSE/O-level | 10 (19.6) | 9 (19.6) | 19 (19.6) |

| GCE A/AS-level or Scottish Higher | 1 (2.0) | 4 (8.7) | 5 (5.2) |

| NVQ/SVQ levels 1–3 | 6 (11.8) | 3 (6.5) | 9 (9.3) |

| BTEC certificate | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| BTEC diploma | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Qualified teacher status | 1 (2.0) | 2 (4.3) | 3 (3.1) |

| Degree (first degree/ordinary degree) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Postgraduate certificate | 7 (13.7) | 2 (4.3) | 9 (9.3) |

| Postgraduate diploma | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| PhD | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Other | 15 (29.4) | 15 (32.6) | 30 (30.9) |

| Don’t know/no response | 6 (11.8) | 7 (15.2) | 13 (13.4) |

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Employed full-time | 4 (7.8) | 3 (6.5) | 7 (7.2) |

| Employed part-time | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.3) | 4 (4.1) |

| Self-employed | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Retired | 5 (9.8) | 7 (15.2) | 12 (12.4) |

| Looking after family or home | 2 (3.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (2.1) |

| Student | 3 (5.9) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (3.1) |

| Voluntary worker | 6 (11.8) | 3 (6.5) | 9 (9.3) |

| Not employed but seeking work | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Not employed, but not seeking work because of ill health | 25 (49.0) | 29 (63.0) | 54 (55.7) |

| Not employed, but not seeking work for some other reason | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| If unemployed, length of unemployment, n (%) | |||

| 4–12 months | 2 (7.4) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) |

| 1–2 years | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.6) | 1 (1.8) |

| 2–5 years | 3 (11.1) | 5 (17.9) | 8 (14.5) |

| > 5 years | 20 (74.1) | 21 (75.0) | 41 (74.5) |

| Don’t know/no response | 2 (7.4) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (5.5) |

Table 10 summarises baseline mental health status. The most common severe mental health problems were schizophrenia or other psychotic illness (n = 57, 59%), schizoaffective disorder (n = 10, 10%) and bipolar disorder (n = 30, 31%). Over half of the participants (56%) had a CPA co-ordinator and 60% were under the care of a CMHT. On average, participants had twice (mean) in the last 10 years required psychiatric treatment in hospital, with a range of 1 to 15 periods of hospital treatment. Eighty per cent of participants described their condition as ‘stable’ and 8% described their condition as ‘unstable’ (though each participant had been judged to be stable from the point of view of their condition by either their GP or a responsible mental health professional). Almost all participants (99% of those who responded to the question) were taking a medication, the most common being olanzapine (23%) and clozapine (8%).

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51), n (%) | BSC (N = 46), n (%) | Overall (N = 97), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do you have a CPA co-ordinator? | |||

| Yes | 25 (51.0) | 26 (61.9) | 51 (56.0) |

| No | 24 (49.0) | 16 (38.1) | 40 (44.0) |

| Do you have a CMHT? | |||

| Yes | 28 (58.3) | 27 (62.8) | 55 (60.4) |

| No | 20 (41.7) | 16 (37.2) | 36 (39.6) |

| Number of times needed psychiatric treatment in hospital in last 10 years | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.7 (1.6) | 2.3 (3.1) | 2 (2.4) |

| Median (range) | 1 (0–6) | 1 (0–15) | 1 (0–15) |

| Missing | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Would you describe your condition as | |||

| Stable | 40 (80.0) | 37 (80.4) | 77 (80.2) |

| Unstable | 4 (8.0) | 4 (8.7) | 8 (8.3) |

| Unsure | 6 (12.0) | 5 (10.9) | 11 (11.5) |

| Do you take any medications? | |||

| Yes | 41 (100.0) | 34 (97.1) | 75 (98.7) |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) | 1 (1.3) |

| Missing | 10 (19.6) | 11 (23.9) | 21 (21.6) |

| If yes, do you take the following medications | |||

| Haloperidol | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Fluphenazine | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) |

| Clozapine | 4 (7.8) | 4 (8.7) | 8 (8.2) |

| Olanzapine | 11 (21.6) | 11 (23.9) | 22 (22.7) |

| Fluvoxamine | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Duloxetine | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Propranolol | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Insulin | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Theophylline | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Cimetidine | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Flecainide | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

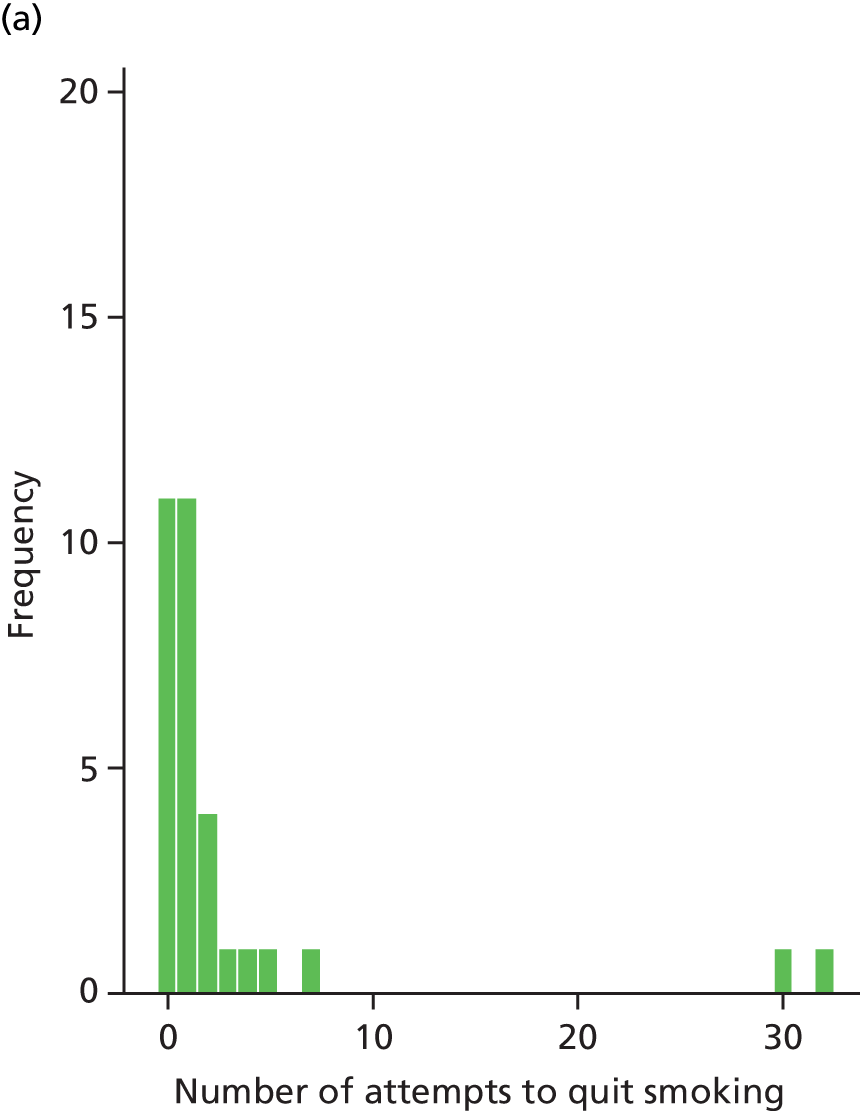

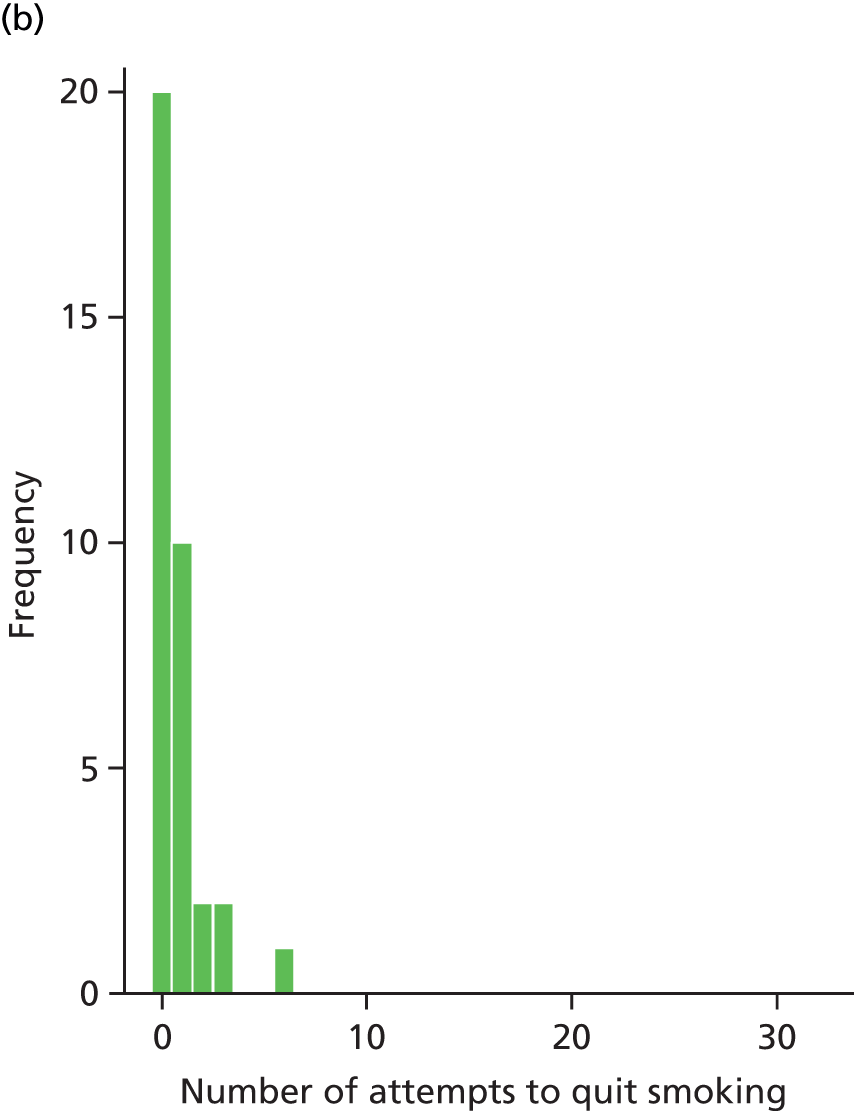

Table 11 summarises smoking history of participants. The mean length of smoking was 27 years, with a range from 3 years to 60 years. Most participants smoked packet (66%) or hand-rolled cigarettes (53%) (or both). The median number of attempts to quit was three, with a range of 0 to 150 attempts. The mean duration of reported longest quit attempt was 43 days (median 8.5 days), with a range of 0 to 832 days. The most common self-reported previous strategies used to stop smoking were ‘cold turkey’ (70%), followed by nicotine skin patches (68%), nicotine chewing gum (52%) and nicotine inhalator (47%).

| Characteristic | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length of time smoking (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 25.8 (12.2) | 28.5 (13.5) | 27.1 (12.9) |

| Median (range) | 25 (5–55) | 26.5 (3–60) | 25 (3–60) |

| Missing, (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Type of tobacco used, n (%) | |||

| Packet cigarettes | 38 (74.5) | 26 (56.5) | 64 (66.0) |

| Hand-rolled cigarettes | 26 (51.0) | 25 (54.3) | 51 (52.6) |

| Cigars | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) |

| Pipe | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) |

| Chewing tobacco | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Water pipe/Hookah/Sheesha pipe | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| If using roll-ups or pipe, amount of tobacco used per day (ounces) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.0 (6.7) | 9.1 (11.1) | 8.1 (9.2) |

| Median (range) | 7 (0–25) | 5.5 (0–50) | 7 (0–50) |

| n | 25 | 28 | 53 |

| Number of attempts to quit in the past | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (2.5) | 9.7 (25.7) | 6.3 (18.1) |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–12) | 3 (0–150) | 3 (0–150) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.0) |

| Longest quit attempt (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 47.5 (139.5) | 37.7 (64.2) | 42.8 (109.6) |

| Median (range) | 8 (0–832) | 9 (0–260) | 8.5 (0–832) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Previous methods used to stop smoking, n (%) | |||

| Nicotine chewing gum | 29 (56.9) | 21 (45.7) | 50 (51.5) |

| Nicotine skin patches | 32 (62.7) | 34 (73.9) | 66 (68.0) |

| Nicotine nasal spray | 7 (13.7) | 3 (6.5) | 10 (10.3) |

| Nicotine inhalator | 25 (49.0) | 21 (45.7) | 46 (47.4) |

| Nicotine microtab | 5 (9.8) | 5 (10.9) | 10 (10.3) |

| Nicotine lozenges | 5 (9.8) | 7 (15.2) | 12 (12.4) |

| Zyban | 2 (3.9) | 2 (4.3) | 4 (4.1) |

| Champix | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.5) | 6 (6.2) |

| ‘Cold turkey’ | 37 (72.5) | 31 (67.4) | 68 (70.1) |

| Hypnosis | 6 (11.8) | 6 (13.0) | 12 (12.4) |

| Acupuncture | 2 (3.9) | 4 (8.7) | 6 (6.2) |

| Other | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.2) |

The reasons for smoking and their importance are summarised in Table 12. The most important reason given for smoking was helping to cope with stress (65%), followed by helping to relax (47%).

| Reasons for smoking | Usual GP care (N = 51), n (%) | BSC (N = 46), n (%) | Overall (N = 97), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| It helps me relax | |||

| Very important | 22 (43.1) | 24 (52.2) | 46 (47.4) |

| Quite important | 26 (51.0) | 16 (34.8) | 42 (43.3) |

| Not important | 3 (5.9) | 6 (13.0) | 9 (9.3) |

| It helps break up my working time | |||

| Very important | 11 (21.6) | 12 (26.1) | 23 (23.7) |

| Quite important | 21 (41.2) | 13 (28.3) | 34 (35.1) |

| Not important | 19 (37.3) | 21 (45.7) | 40 (41.2) |

| It is something to do when I am bored | |||

| Very important | 14 (27.5) | 18 (39.1) | 32 (33.0) |

| Quite important | 28 (54.9) | 23 (50.0) | 51 (52.6) |

| Not important | 9 (17.6) | 5 (10.9) | 14 (14.4) |

| It helps me cope with stress | |||

| Very important | 34 (66.7) | 29 (63.0) | 63 (64.9) |

| Quite important | 14 (27.5) | 14 (30.4) | 28 (28.9) |

| Not important | 3 (5.9) | 3 (6.5) | 6 (6.2) |

| I enjoy it | |||

| Very important | 17 (33.3) | 18 (39.1) | 35 (36.1) |

| Quite important | 19 (37.3) | 16 (34.8) | 35 (36.1) |

| Not important | 15 (29.4) | 12 (26.1) | 27 (27.8) |

| It’s something I do with family and friends | |||

| Very important | 10 (19.6) | 7 (15.2) | 17 (17.5) |

| Quite important | 15 (29.4) | 17 (37.0) | 32 (33.0) |

| Not important | 26 (51.0) | 22 (47.8) | 48 (49.5) |

| It stops me putting on weight | |||

| Very important | 7 (13.7) | 8 (17.4) | 15 (15.5) |

| Quite important | 8 (15.7) | 6 (13.0) | 14 (14.4) |

| Not important | 36 (70.6) | 32 (69.6) | 68 (70.1) |

| It stops me getting withdrawal symptoms | |||

| Very important | 21 (41.2) | 17 (37.0) | 38 (39.2) |

| Quite important | 15 (29.4) | 19 (41.3) | 34 (35.1) |

| Not important | 15 (29.4) | 10 (21.7) | 25 (25.8) |

Table 13 summarises the reasons for giving up smoking. The most important reason cited for trying to give up smoking was that it is bad for health (86%).

| Reasons for giving up smoking | Usual GP care (N = 51), n (%) | BSC (N = 46), n (%) | Overall (N = 97), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| It is expensive | |||

| Very important | 35 (68.6) | 29 (63.0) | 64 (66.0) |

| Quite important | 13 (25.5) | 9 (19.6) | 22 (22.7) |

| Not important | 3 (5.9) | 8 (17.4) | 11 (11.3) |

| It is bad for my health | |||

| Very important | 44 (86.3) | 39 (84.8) | 83 (85.6) |

| Quite important | 5 (9.8) | 6 (13.0) | 11 (11.3) |

| Not important | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| I don’t like feeling dependent on cigarettes | |||

| Very important | 35 (68.6) | 31 (67.4) | 66 (68.0) |

| Quite important | 13 (25.5) | 10 (21.7) | 23 (23.7) |

| Not important | 3 (5.9) | 5 (10.9) | 8 (8.2) |

| It makes my clothes and breath smell | |||

| Very important | 22 (43.1) | 17 (37.0) | 39 (40.2) |

| Quite important | 18 (35.3) | 18 (39.1) | 36 (37.1) |

| Not important | 11 (21.6) | 11 (23.9) | 22 (22.7) |

| It is a bad example for children | |||

| Very important | 25 (49.0) | 26 (56.5) | 51 (52.6) |

| Quite important | 14 (27.5) | 12 (26.1) | 26 (26.8) |

| Not important | 12 (23.5) | 8 (17.4) | 20 (20.6) |

| It is unpleasant for people near me | |||

| Very important | 20 (39.2) | 22 (47.8) | 42 (43.3) |

| Quite important | 21 (41.2) | 14 (30.4) | 35 (36.1) |

| Not important | 10 (19.6) | 10 (21.7) | 20 (20.6) |

| It makes me less fit | |||

| Very important | 33 (64.7) | 34 (73.9) | 67 (69.1) |

| Quite important | 14 (27.5) | 11 (23.9) | 25 (25.8) |

| Not important | 4 (7.8) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (5.2) |

| People around me disapprove of my smoking | |||

| Very important | 17 (34.0) | 15 (32.6) | 32 (33.3) |

| Quite important | 16 (32.0) | 14 (30.4) | 30 (31.3) |

| Not important | 17 (34.0) | 17 (37.0) | 34 (35.4) |

| It is bad for the health of people near me | |||

| Very important | 26 (51.0) | 19 (41.3) | 45 (46.4) |

| Quite important | 17 (33.3) | 18 (39.1) | 35 (36.1) |

| Not important | 8 (15.7) | 9 (19.6) | 17 (17.5) |

Table 14 summarises the smoking behaviour of participants at baseline. Most of the participants smoked more than five cigarettes in the last week (96%). The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day is 25, with a range of 5 to 60. The mean CO reading is 24 p.p.m. with a range of 4 to 58 p.p.m. A CO reading > 20 p.p.m. indicates heavy smoking. The majority of participants (80%) said they smoke the same number of cigarettes every day. Table 15 summarises recent quit attempts. The median number of quit attempts in the last 6 months was three, with a range of 0 to 150 attempts. The mean length of the most recent quit attempt was 23 days, with a range of 0 to 180 days.

| Baseline smoking outcome | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Smoked in last week, n (%) | |||

| Not even a puff | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Yes, just a few puffs | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Yes, between one and five cigarettes | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| Yes, more than five cigarettes | 49 (96.1) | 44 (95.7) | 93 (95.9) |

| Number of cigarettes per day | |||

| Mean (SD) | 23.3 (13.2) | 26.5 (12.0) | 24.8 (12.7) |

| Median (range) | 20 (5–60) | 25 (5–60) | 20 (5–60) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (4) | 3 (6.5) | 5 (5.2) |

| Breath CO reading (p.p.m.) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 24.7 (14.1) | 22.9 (13.2) | 23.8 (13.6) |

| Median (range) | 22 (4–57) | 21 (6–58) | 22 (4–58) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Following statement best describes you, n (%) | |||

| I smoke the same number of cigarettes every day | 37 (72.5) | 41 (89.1) | 78 (80.4) |

| I have cut down the number of cigarettes I smoke | 13 (25.5) | 4 (8.7) | 17 (17.5) |

| I smoke cigarettes but not every day | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| I have stopped smoking completely | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| Baseline smoking outcome | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of quit attempts in last 6 months | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.2 (2.5) | 9.8 (25.7) | 6.3 (18.1) |

| Median (range) | 2 (0–12) | 3 (0–150) | 3 (0–150) |

| Missing, n (%) | 1 (2.0) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (2.1) |

| Length of most recent quit attempt (days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 38.1 (70.9) | 10.2 (29.9) | 23.4 (53.4) |

| Median (range) | 1 (0–180) | 0 (0–90) | 0 (0–180) |

| Denominator | 8 | 9 | 17 |

| FTND questionnaire score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.1 (2.2) | 6.0 (2.6) | 6.1 (2.4) |

| Median (range) | 6 (1–10) | 7 (0–10) | 6.5 (0–10) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (4.3) | 2 (2.1) |

| MTQ questionnaire score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.4 (2.4) | 14.3 (2.3) | 13.8 (2.4) |

| Median (range) | 14 (6–18) | 14 (10–19) | 14 (6–19) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

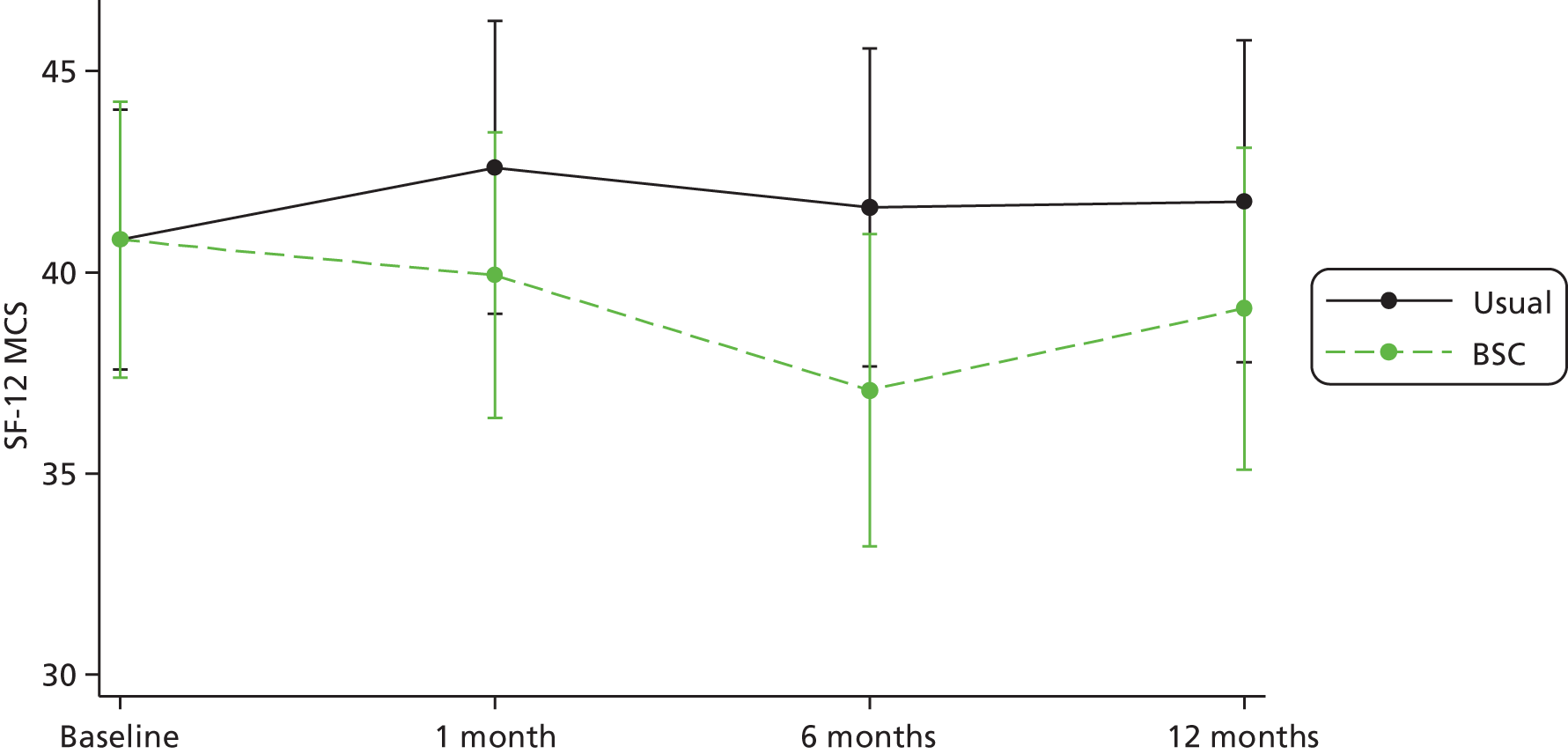

Table 16 gives a breakdown of the answers to the FTND questionnaire score at baseline. The mean FTND score at baseline was 6.6, indicating moderate nicotine dependence, with a range of 0 to 10. The mean MTQ questionnaire score at baseline was 13.8, with a range of 6 to 19. Table 17 summarises the PHQ-9 and SF-12 scores. The mean PHQ-9 score at baseline was 9.2, indicating moderate levels of low mood but below the threshold for case-level depression (indicated by a score ≥ 10). The mean SF-12 physical component score at baseline was 45, with a range of 15 to 67. This is lower than the mean of the general UK population, indicating worse physical health than the general population. The mean SF-12 mental component score was 41, with a range of 13 to 64. This is about one SD lower than the mean of the general UK population, indicating worse mental health than the general population.

| FTND question | Usual GP care (N = 51), n (%) | BSC (N = 46), n (%) | Overall (N = 97), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How soon after you wake up do you smoke your first cigarette? | |||

| ≤ 5 minutes | 26 (51.0) | 23 (50.0) | 49 (50.5) |

| 6–30 minutes | 23 (45.1) | 17 (37.0) | 40 (41.2) |

| > 30 minutes | 2 (3.9) | 6 (13.0) | 8 (8.2) |

| Do you find it difficult to stop smoking in no-smoking areas? | |||

| Yes | 23 (45.1) | 18 (39.1) | 41 (42.3) |

| No | 28 (54.9) | 28 (60.9) | 56 (57.7) |

| Which cigarette would you hate most to give up? | |||

| The first of the morning | 33 (64.7) | 35 (76.1) | 68 (70.1) |

| Other | 18 (35.3) | 11 (23.9) | 29 (29.9) |

| How many cigarettes per day do you usually smoke? | |||

| ≤ 10 | 10 (19.6) | 3 (6.7) | 13 (13.5) |

| 11–20 | 21 (41.2) | 17 (37.8) | 38 (39.6) |

| 21–30 | 7 (13.7) | 15 (33.3) | 22 (22.9) |

| ≥ 31 | 13 (25.5) | 10 (22.2) | 23 (24.0) |

| Do you smoke more frequently in the first hours after waking than during the rest of the day? | |||

| Yes | 33 (64.7) | 24 (52.2) | 57 (58.8) |

| No | 18 (35.3) | 22 (47.8) | 40 (41.2) |

| Do you smoke even if you are so ill that you are in bed most of the day? | |||

| Yes | 22 (43.1) | 20 (43.5) | 42 (43.3) |

| No | 29 (56.9) | 26 (56.5) | 55 (56.7) |

| Do you smoke hand-rolled cigarettes? | |||

| Yes | 25 (49.0) | 25 (55.6) | 50 (52.1) |

| No | 26 (51.0) | 20 (44.4) | 46 (47.9) |

| If yes, how many do you usually smoke per day? | |||

| Mean (SD) | 16.0 (10.9) | 29.1 (14.5) | 22.6 (14.3) |

| Median (range) | 15 (2–50) | 30 (6–60) | 20 (2–60) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | 4 (0.1) |

| How much tobacco do you usually use per day (g)? | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.9 (12.5) | 14.5 (11.7) | 13.1 (12.0) |

| Median (range) | 7 (1–56) | 12.5 (1–50) | 8.2 (1–56) |

| Missing (n%) | 4 (0.2) | 6 (0.2) | 10 (0.2) |

| Secondary outcome | Usual GP care (N = 51) | BSC (N = 46) | Overall (N = 97) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PHQ-9 score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 8.7 (6.6) | 9.8 (7.1) | 9.2 (6.8) |

| Median (range) | 9 (0–22) | 8 (0–27) | 8 (0–27) |

| Missing, n (%) | 2 (3.9) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (3.1) |

| SF-12 physical component score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 45.3 (10.9) | 45.0 (10.9) | 45.2 (10.8) |

| Median (range) | 46.1 (15.4–67.0) | 43.0 (19.1–63.5) | 45.1 (15.4–67.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

| SF-12 mental component score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 40.8 (11.8) | 40.8 (13.1) | 40.8 (12.4) |

| Median (range) | 43.4 (16.2–62.7) | 42.9 (13.1–63.7) | 42.9 (13.1–63.7) |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.0) |

Withdrawals

There were 15 participant withdrawals (15%) from the trial: five (10%) from the usual GP care group and 10 (22%) from the BSC group. A total of seven participants (7.2%) withdrew fully from the trial, while five participants (5.1%) withdrew from follow-up and three participants (3.1%) were too unwell to continue (Table 18). There are four categories of patient withdrawal:

-

Full withdrawal – participant withdrawn from the trial with regards completion of both postal questionnaires and collection of GP data.

-

Withdrawal from follow-up – participant has withdrawn from the completion of postal questionnaires, but agrees with the continuing collection of GP data.

-

Withdrawal from treatment – participant withdraws from trial intervention treatment, but agrees with continuing completion of postal questionnaires and collection of GP data.

-

Too unwell to continue – participant is deemed too unwell by medical staff to complete any questionnaires. This generally only occurs when a participant has been hospitalised.

| Withdrawal type | Usual GP care | BSC | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full withdrawal | 2 | 5 | 7 |

| Withdrawal from follow-up | 2 | 3 | 5 |

| Withdrawal from treatment | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Too unwell to continue | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Total | 5 | 10 | 15 |

Follow-up

Participants were given the option of providing data face to face, via the telephone or by postal questionnaire. Of those who returned follow-up data at 12 months only one person declined a face-to-face visit and completed the follow-up by telephone; all the other participants who completed a 12 month follow-up did so face to face. Participants did not use the option of completing questionnaires online.

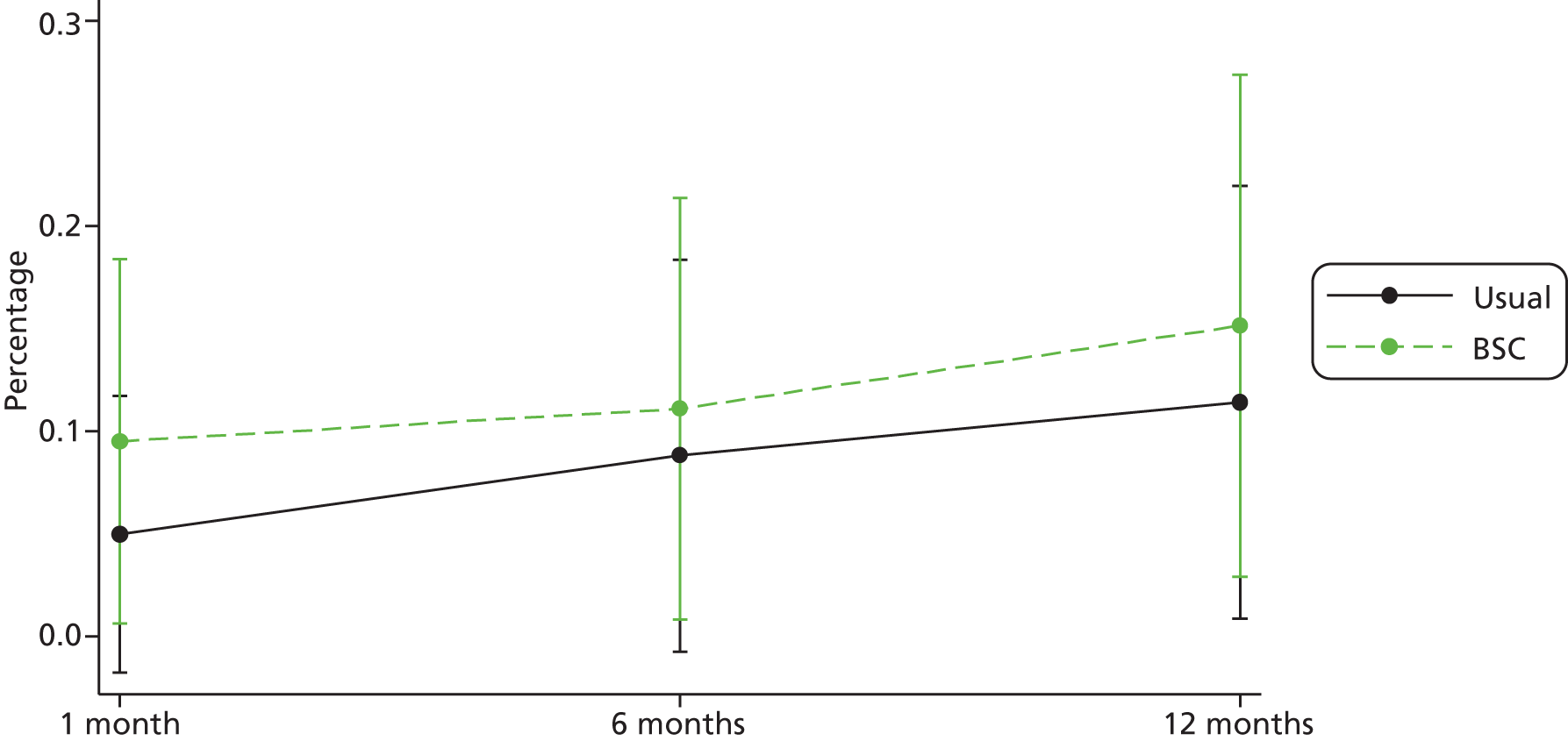

Primary outcome

Smoking cessation at 12 months was defined as a CO measure of < 10 p.p.m. or self-reported cessation if no CO measure was available. A CO measure of < 10 p.p.m. indicated no smoking in the last 8 hours and self-reported quit indicated no smoking within the last week. At 12 months, 64 participants had a CO measure and four participants had only a self-reported measure. Eight out of thirty-five participants (23%) had stopped smoking in the usual GP care arm and 12 out of 33 participants (36%) had stopped smoking in the BSC arm (Table 19).

| Primary outcome | Usual GP care (N = 51), n (%) | BSC (N = 46), n (%) | Overall (N = 97), n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number quit (CO verified) | 8 | 24.2a | 10 | 32.3a | 18 | 28.1a |

| Number with CO measure | 33 | 94.3a | 31 | 93.9a | 64 | 94.1a |

| Number quit (self-report only) | 0 | 0.0b | 2 | 100.0b | 2 | 50.0b |

| Number with self-report only | 2 | 5.7b | 2 | 6.1b | 4 | 5.9b |

| Total number quit | 8 | 22.9c | 12 | 36.4c | 20 | 29.4c |

| Total number with CO or self-reported measure | 35 | 100.0c | 33 | 100.0c | 68 | 100.0c |

A logistic regression of smoking cessation at 12 months on randomised group, adjusted for sex, age, number of cigarettes smoked at baseline and alcohol consumption at baseline, gave an OR of 2.9 (95% CI 0.8 to 10.5) for BSC compared with usual care (Table 20). This indicates that those randomised to BSC have greater odds of smoking cessation than those randomised to usual care, although this is not statistically significant. However, the analysis has been carried out on a small sample (complete cases, n = 65), so results should be interpreted with caution.

| Characteristic | OR | Standard error | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC vs. usual care | 2.94 | 1.91 | 0.83 to 10.50 | 0.10 |

| Age | 0.97 | 0.02 | 0.93 to 1.02 | 0.30 |

| Male | 0.78 | 0.54 | 0.20 to 3.04 | 0.72 |

| Number of cigarettes smoked per day | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.89 to 1.01 | 0.09 |

| Alcohol consumption | 1.23 | 0.80 | 0.35 to 4.38 | 0.75 |

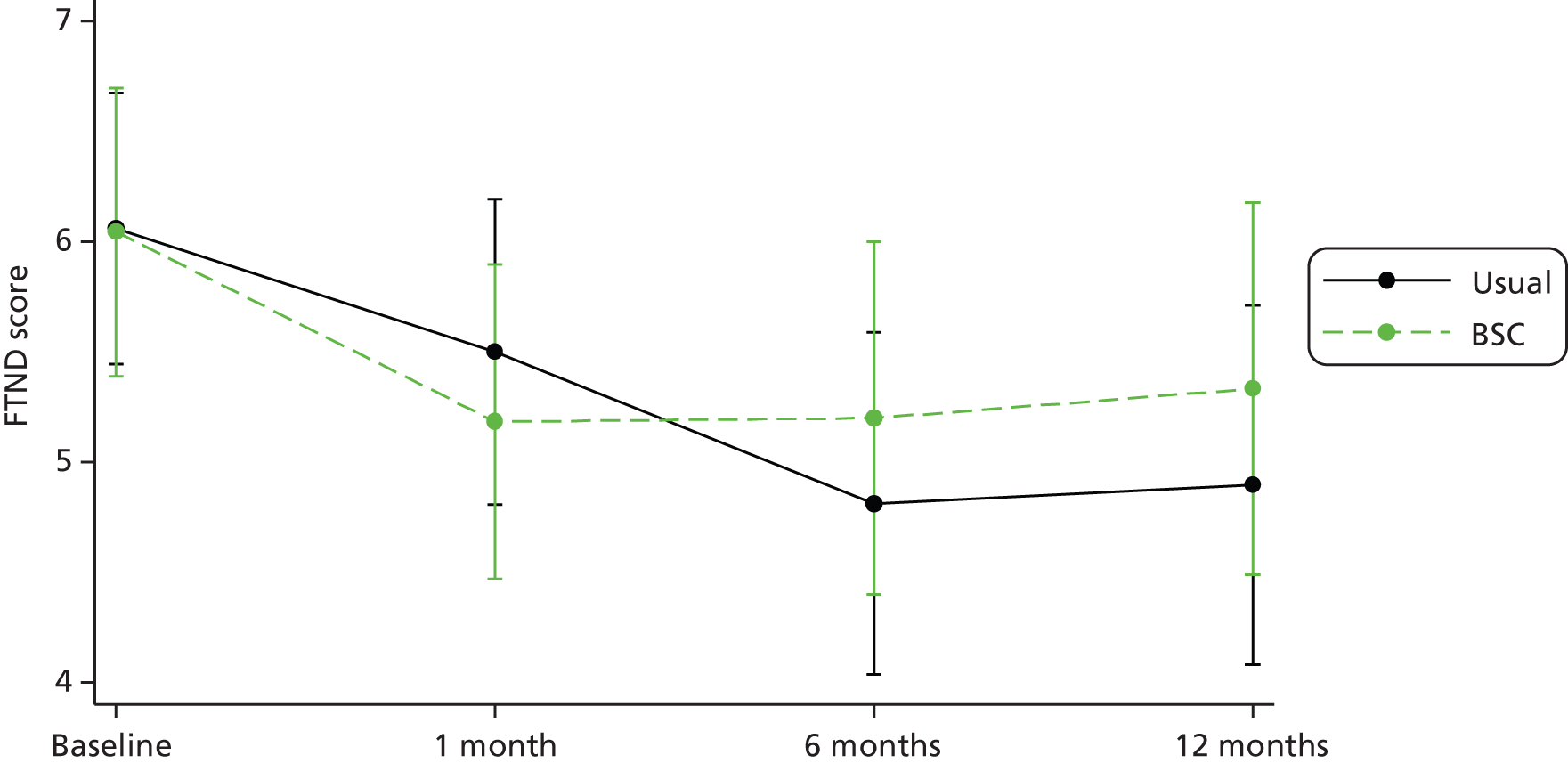

Secondary outcomes

A summary of the smoking-related secondary outcome is given in Table 21 and a summary of the non-smoking-related secondary outcomes is given in Table 22.

| Outcome | Usual care | BSC | Overall | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-reported quit | n a | Frequencyb | % | n a | Frequencyb | % | n a | Frequencyb | % |

| 1 month | 40 | 2 | 5.0 | 42 | 4 | 9.5 | 82 | 6 | 7.3 |

| 6 months | 34 | 3 | 8.8 | 36 | 4 | 11.1 | 70 | 7 | 10.0 |

| 12 months | 35 | 4 | 11.4 | 33 | 5 | 15.2 | 68 | 9 | 13.2 |

| Number of cigarettes | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 1 month | 37 | 19.4 (12.3) | 0–50 | 38 | 18.4 (9.6) | 4–60 | 75 | 18.9 (11.0) | 0–60 |

| 6 months | 30 | 17.1 (11.6) | 1–50 | 31 | 16.8 (9.6) | 1–40 | 61 | 16.9 (10.5) | 1–50 |

| 12 months | 30 | 18.4 (11.6) | 5–50 | 26 | 20.1 (10.6) | 2–40 | 56 | 19.2 (11.1) | 2–50 |

| Number quit attempts | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 1 month | 40 | 1.1 (1.8) | 0–10 | 41 | 1.4 (2.8) | 0–15 | 81 | 1.2 (2.3) | 0–15 |

| 6 months | 33 | 0.9 (1.1) | 0–4 | 34 | 1.1 (1.1) | 0–4 | 67 | 1.0 (1.1) | 0–4 |

| 12 months | 35 | 0.7 (1.2) | 0–6 | 32 | 3.1 (7.5) | 0–32 | 67 | 1.9 (5.3) | 0–32 |

| Length of cessation | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 1 month | 12 | 0.3 (0.9) | 0–3 | 10 | 1.0 (1.8) | 0–5 | 22 | 0.59 (1.4) | 0–5 |

| 6 months | 11 | 1.3 (2.8) | 0–7 | 10 | 46.5 (72.9) | 0–180 | 21 | 22.8 (54.2) | 0–180 |

| 12 months | 8 | 1.8 (2.4) | 0–7 | 8 | 21.1 (42.5) | 0–120 | 16 | 11.4 (30.7) | 0–120 |

| FTND score | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 1 month | 40 | 5.5 (2.4) | 0–10 | 38 | 5.2 (2.1) | 0–9 | 78 | 5.3 (2.3) | 0–10 |

| 6 months | 32 | 4.8 (2.1) | 0–9 | 30 | 5.2 (2.3) | 1–9 | 62 | 5.0 (2.2) | 0–9 |

| 12 months | 29 | 4.9 (2.2) | 0–9 | 27 | 5.3 (2.0) | 1–9 | 56 | 5.1 (2.1) | 0–9 |

| MTQ score | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range | n | Mean (SD) | Range |

| 1 month | 40 | 11.8 (2.4) | 7–17 | 41 | 14.2 (2.5) | 9–19 | 81 | 13.0 (2.7) | 7–19 |

| 6 months | 34 | 12.3 (3.1) | 4–19 | 33 | 12.6 (3.2) | 6–18 | 67 | 12.5 (3.1) | 4–19 |

| 12 months | 32 | 11.1 (3.1) | 4–18 | 33 | 12.1 (4.0) | 5–19 | 65 | 11.6 (3.6) | 4–19 |

| Secondary outcome | Usual care | BSC | Total | ||||||