Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 12/203/03. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The draft report began editorial review in September 2013 and was accepted for publication in November 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Frances Bunn and Daksha Trivedi are editors with the Cochrane Injuries Group, Phil Alderson is an employee of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and was employed by the UK Cochrane Centre (UKCC) from 1998 to 2004 and was seconded part time to the UKCC from May 2013 to March 2014, Frances Bunn, Daksha Trivedi, Phil Alderson and Steve Iliffe are all authors on Cochrane Reviews and Phil Alderson has also published papers about Cochrane Reviews.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Bunn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

In recent years there has been a growing emphasis on the use of evidence to inform decision-making in health care. 1–3 Improvements in the use of evidence have been seen as particularly relevant to commissioning in the English NHS because of the large financial commitments involved and because of the increasing complexity of health-care management decisions. 4 In addition, there has been a growing interest in the utilisation and impact of research. Researchers are increasingly expected to consider the contribution that their research might have made, not only to health-related outcomes but also to public policy, society, the economy, culture and quality of life. 5

The role of systematic reviews in evidence-informed decision-making

The development of methods for the synthesis of research has been a key driver in the move towards evidence-informed policy and practice. Although a number of terms have been used for such syntheses, the most widely used and understood is systematic review. Systematic reviews have several advantages over other types of research that have led to them being regarded as particularly important tools for decision-makers. Systematic reviews take precedence over other types of research in many hierarchies of evidence, as it inherently makes sense for decisions to be based on the totality of evidence rather than a single study. 6,7 Moreover, they can generally be conducted more quickly than new primary research and, as a result, may be attractive to policy-makers required to make a rapid response to a new policy issue. 8 Despite such arguments in favour of using systematic reviews to inform decision-making, it has been suggested that they have not had an impact on policy and practice in the way one might expect. Indeed, there is evidence to suggest that the diffusion and use of evidence across the NHS is generally poor. 4

Cochrane

One organisation involved in producing systematic reviews is Cochrane (www.cochrane.org/about-us). Established in the early 1990s, Cochrane is a global independent organisation that has the aim of promoting evidence-informed decision-making through the production of systematic reviews. Reviews are produced by Cochrane Review Groups (CRGs), which are made up of people who prepare, maintain and update the Cochrane Reviews and people who support them in this process. Each group has an editorial base, a small team of people that supports the production of Cochrane Reviews. Groups focus on a particular area of health, and review topics are identified by review authors or through prioritisation processes at editorial bases.

Cochrane is a not-for-profit organisation funded by a variety of sources including governments, universities, hospital trusts and charities. Cochrane systematic reviews should be well placed to influence policy-makers, practitioners and researchers, as they are generally acknowledged to be comprehensive and rigorous summaries of the best available evidence on a given topic. Moreover, they are periodically updated in the light of new evidence and there is increasing interest in the dissemination and impact of Cochrane Review findings. 9

Evidence-informed decision-making

It has long been recognised that the relationship between research and policy or practice is a complex one10 and that research may not always have the impact that researchers desire. 11 One reason for this is that research evidence is only one factor in shaping policy and practice. Decision-makers are subject to many different influences including political imperatives, the media, non-research evidence and powerful lobbying groups such as industry. 7,12 In addition, the usefulness of systematic reviews for aiding policy-makers in the decision-making process has come into question, with commentators suggesting a number of factors that might reduce their utility. These include a lack of good-quality primary research for synthesis, a tendency for reviewers to focus on randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled evaluations at the expense of other types of research, and inadequate evaluation of complex interventions with little recognition of the importance of contextual factors. 8,13,14 Moreover, there are significant challenges associated with conceptualising impact and identifying the extent to which systematic reviews are used to inform decision-making. 15

Defining research impact

A variety of terms have been used to describe the impact of research on policy and practice. These include research impact, influence, outcomes, benefit, payback, translation, transfer, uptake and utilisation. 16,17 Research can be used either directly in decision-making related to policy and practice or indirectly by contributing to the formulation of values, knowledge and debate. Commentators have pointed out that there is a key distinction to be made between conceptual use, which brings about changes in levels of understanding, knowledge and attitude, symbolic use which can lead to the mobilisation of support, and instrumental, or direct use, which results in changes in practice and policy making. 10,18–20 Indeed, ‘research impact forms a continuum, from raising awareness of findings, through knowledge and understanding of their implications, to changes in behaviour’. 21

Reason for conducting this study

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) systematic review programme currently supports 20 CRGs based in academic or health institutions in the UK. These groups cover a broad range of health-care areas and produce almost half of all Cochrane Reviews, publishing around 200 new reviews each year, as well as bringing a similar number of existing reviews up to date. 22 It is important that this funding represents value for money and that the reviews produced by these groups be useful for practitioners, policy-makers, service users and members of the public. One way in which their value might be judged is by the impact that the reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs have, or potentially have, on policy and practice, and on future research. However, although it is acknowledged that CRGs produce high-quality systematic reviews,23–25 to date there is a lack of information about the impacts of Cochrane Reviews. Moreover, it is important to understand how reviews are currently used in order to develop appropriate strategies for knowledge transfer and exchange. This study aimed to enhance our understanding of how Cochrane Reviews impact on policy and practice and to inform the development of methods for evaluating the impact of systematic reviews and future strategies for dissemination and knowledge transfer.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim was to identify the impacts and likely impacts on health care, patient outcomes and value for money of Cochrane Reviews published by NIHR-funded CRGs between the years 2007 and 2011 (time period set by funders). The research objectives were to identify and describe the impacts of Cochrane Reviews in terms of evidence of direct effect on clinical practice; their inclusion in, or use for, the preparation of national or international clinical guidance, such as guidance published by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE); their likely influence on clinical practice directly (i.e. without or before incorporation into national clinical guidance); and their identification of important gaps in knowledge and possible influence on the conduct of new primary research studies. The research questions are:

-

Have systematic reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs during 2007–11 had a direct effect on clinical practice?

-

Have systematic reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs during 2007–11 had a direct effect on NHS organisation and delivery?

-

To what extent have reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs during 2007–11 been included in clinical guidance, such as that produced by the NICE?

-

To what extent are reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs used in the preparation of NICE guidance?

-

What evidence is there that systematic reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs during 2007–11 are likely to change future clinical practice?

-

What influence have systematic reviews produced by NIHR-funded CRGs during 2007–11 had on the conduct of new primary research studies?

-

What are the barriers and facilitators to Cochrane systematic reviews impacting on policy, practice and future primary research?

Structure of the report

Chapter 1 describes the background and rationale for the study, Chapter 2 describes the conceptual approach adopted and the framework used to structure the evaluation and Chapter 3 details the methods used for the questionnaire surveys, bibliometrics and documentary review. The findings of the questionnaire surveys, bibliometrics and documentary review are presented in Chapters 4 and 5, with Chapter 4 including details of the findings relating to the overall impact of NIHR-funded CRGs and Chapter 5 focusing on the findings relating to the impacts of a representative sample of Cochrane Reviews produced by the NIHR-funded groups. Chapter 6 reports the methods and findings of the qualitative interviews. Chapter 7 summarises the study findings and looks at their implications. This includes a summary of the results of the impact evaluation, an analysis of how the results contribute to our knowledge of barriers and facilitators, a discussion of the strengths and limitations of the study and a consideration of the implications of the findings.

Chapter 2 Conceptual framework and approach

We undertook a mixed-methods approach which was informed by theories about research impact and guided by a framework for evaluating research impact that draws on previous work in this area. 26,27 There were two main work packages (WPs). The aim of the first WP (WP 1) was to obtain a general overview of the impact of the outputs produced by NIHR-funded CRGs between 2007 and 2011 and the aim of the second WP (WP 2) was to look in more detail at the impact of a sample of Cochrane Reviews. These WPs are described in more detail in Chapter 3. In this chapter we describe the approach we took to conceptualising and measuring research impact.

Many different terms have been used to define research impact. However, there is a consensus of opinion that several types of research impact exist,10,18,21,28 including instrumental or direct impact, conceptual impact and symbolic impact. The definitions of each type of impact are as follows:

-

Instrumental or direct impact – research findings drive practice decision- or policy-making.

-

Conceptual impact – research influences the concepts and language of policy and practice deliberations.

-

Symbolic impact – research is used to legitimate and sustain predetermined positions.

Although health benefits and broader economic benefits may be viewed as the real payback from health research, these are hard to measure, as it is difficult to attribute particular health gains to specific pieces of research. 29 Therefore, although we were able to make some inferences about health and economic benefits, these were largely beyond the remit of this evaluation. Instead we focused on impacts that are more easily assessed, such as clinical practice, service delivery, quality of patient care, policy and the targeting of future research. Our main focus was on instrumental or direct impact but we also considered examples of more indirect influence (e.g. conceptual or symbolic) and included both actual and potential impact. Examples of instrumental use of research might include direct impact on the behaviour of clinicians or the use of evidence to develop or update educational material, policy and guidelines. Likely, or potential, impact included examples where there was some evidence to suggest the review has had an impact but this is, at present, difficult to substantiate (e.g. when reviews might have impacted on policy and practice deliberations) or where the review is judged to have produced findings that clearly have the potential to impact on policy, service delivery or patient outcomes but there has been insufficient time since publication for impact to have occurred.

Framework

The use of a framework for structuring assessments of impact has been recommended, as it can help organise inquiry30 and allow for easier comparison across reviews. 31 We structured our data collection and analysis using a framework that combined elements from two existing frameworks, the Health Economics Research Group (HERG) framework for assessing health research payback26,32,33 and The Research Impact Framework developed by Kuruvilla et al. 27 The HERG framework consists of a multidimensional categorisation of the benefits, or payback, from health research33 and includes five main categories: (1) knowledge production; (2) research targeting; (3) capacity building and absorption; (4) informing policy and product development; and (5) health benefits and broader economic benefits. The rationale for using this framework is that it is the most commonly used framework in the evaluation of health research impact,34 it is well described in the literature and there are a number of publications detailing suggested methods for conducting evaluations. In addition, although it was not developed specifically for systematic reviews, it has been used to assess their impact. 35

As previously stated, health benefits and broader economic benefits of research are hard to measure and are largely beyond the remit of this evaluation. 29 Therefore, we used a framework that combines elements of the HERG framework (knowledge production, research targeting, informing policy and product development) with elements (impact on practice/services) from The Research Impact Framework developed by Kuruvilla et al. 27 The latter is a conceptual framework that uses a standardised way of describing a wide range of potential areas of health research impact. 27,36 It was created by identifying potential areas of health research impact and draws on a number of other models including the payback model of health research benefits previously described26 and Lavis’s knowledge transfer approach to assessing the impact of research. 37 The framework we used for this evaluation, including main and subcategories, can be seen in Table 1.

| Main category | Subcategories | Further details |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge production | Impact within research community | Number of times review is cited |

| Stimulating debate in research community | ||

| Methodological developments | ||

| Other methods of dissemination | Press coverage | |

| Number of mentions in media | ||

| 2. Research targeting | Influence on other research | Identification of gaps in knowledge |

| Follow-on research | ||

| 3. Informing policy development (includes actual and potential) | Impact on national or government policy | For example, NICE guidance |

| Impact on international policy | For example, WHO guidance or international professional bodies | |

| Policies agreed at national or local level in the form of clinical or local guidelines | For example, guidance produced by local trusts | |

| Policies developed by those responsible for training and education | Local or national | |

| 4. Impact on practice/services (includes actual and potential) | Evidence-based practice | The use of research evidence by different groups involved in clinical decision-making |

| Adoption of research findings and health technologies by health-service providers | ||

| Adherence to research-informed policies and guidelines | ||

| Addressing barriers to evidence-based practice (e.g. training) | ||

| Quality of care | Efficacy of health services | |

| Availability, accessibility and acceptability of services | ||

| Utilisation and coverage | ||

| Cost containment and cost-effectiveness | Research-related changes in health systems in terms of expenditure or health outcomes | |

| Services management and organisation | Management of health-service procurement and provisioning (public and private) |

Measuring research impact

There is no single standard approach to measuring impact, and a variety of evaluative methods exist including bibliometrics, documentary analysis, semistructured interviews, case studies, panel review, surveys and network analysis. 17,34 The methods most frequently suggested for analysing the impact of research are bibliometrics, documentary review and interviews. 17,39 There are advantages and disadvantages of each method and it is generally recommended that a variety of sources be used in evaluations of research impact. 29,37 In the light of these considerations we used a mixture of bibliometrics, documentary analysis, questionnaire surveys and interviews. These methods are chosen because they were considered appropriate for determining and comparing the impact of reviews published by 20 CRGs on a variety of topics and over a 5-year period. They also enabled richer data to be gathered and allowed for triangulation. Moreover, these methods enabled us to track backwards from policy documents (WP 1) and track forward from specific systematic reviews (WP 2). These methods are discussed in greater detail in the sections following.

Questionnaires and interviews

We sent questionnaires to CRG editorial staff (WP 1) and review authors (WP 2) in order to obtain their views on the impacts, and likely impacts, of Cochrane Reviews included in our analyses. This enabled us to get the views of those people most closely associated with the reviews, otherwise known as the insider account. 34 The questionnaires were based on previous questionnaires for evaluating research impact40–43 and draw on our framework. In addition to the questionnaires, we undertook semistructured interviews with guideline developers (GDs) to gain further insight into how Cochrane Reviews have contributed to the development and preparation of guidance.

Documentary analysis

Documentary analysis allows for the ‘exploration and interpretation of existing documents and can elicit quantitative or qualitative findings’. 17 This might include identifying key citing papers and relevant clinical guidelines,39 or policy statements, articles in professional journals or website resources. Benefits of this technique are that it can be applied to a range of sources, provides contextual understanding and is cost-effective. 17

Bibliometrics

A common method for analysing research impact is to employ bibliometric methods which employ quantitative analyses to measure patterns of scientific publication and citation. One of the most important of these is citation analysis. This technique, which essentially involves counting the number of times a research paper is cited, works on the assumption that influential researchers and important works will be cited more frequently than others. 44 Advantages of using this technique are that citation rates are seen as an objective quantitative indicator for scientific success,45 they are robust and transparent and they are relatively simple and cost-effective to perform. However, citation analyses have been criticised, as they measure the number of research outputs rather than research outcomes. 17 In order to overcome this criticism we used the citation analyses in WP 2 to trace the flow of knowledge and look for any evidence that the reviews have had an impact on the research, practice and policy communities. For example, in line with objective 2, we checked citations in Web of Science (WoS) and Google Scholar™ (Google, CA, USA) to see if reviews had been cited in guidelines or policy documents.

We undertook citation analyses in WoS, Scopus (Elsevier) and Google Scholar, as, owing to the strengths and weaknesses of the different databases, the use of multiple sources is generally recommended. 44,46 Traditionally the Thomson Scientific Institute for Scientific Information (ISI) citation databases have been the main tool for citation analyses. However, in 2004, Scopus from Elsevier and Google Scholar from Google emerged to challenge the monopoly of the ISI citation index. 44,46 These bibliographic databases include additional document types such as books, chapters in books and conference proceedings that are not indexed in the ISI citation databases. Google Scholar may be of particular importance to citation analyses for Cochrane Reviews, as previous work47,48 suggests that citation counts for Cochrane Reviews are artificially low in ISI databases and Scopus because citing authors have incorrectly referenced Cochrane Reviews. Google Scholar is a research-orientated search engine that accesses conventional print material and web-based material. It also extracts citation information and can be used as a citation index as well as a search engine. However, Google Scholar needs to be used with some caution, as there is a lack of transparency about the sources and selection criteria49,50 and the citation information can be flawed or inadequate. 51

Chapter 3 Research plan and methods

Introduction

There were three WPs, with WPs 1 and 2 being conducted in parallel. The aim of WP 1 was to obtain a general overview of the impact of CRG outputs and the aim of WP 2 was to undertake a more detailed exploration of the impacts of a representative sample of Cochrane Reviews published by the NIHR-funded CRGs. In WP 3 we synthesised the findings from WPs 1 and 2.

There are currently 20 CRGs that receive support from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment programme. They are the following: Airways; Bone Joint and Muscle Trauma; Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders; Dementia and Cognitive Improvement; Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis; Ear, Nose and Throat; Epilepsy; Eyes and Vision; Gynaecological Cancer; Heart; Incontinence; Injuries; Neuromuscular; Oral Health; Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care; Pregnancy and Childbirth; Schizophrenia; Skin; Tobacco Addiction; and Wounds. The evaluation focused on outputs, in the form of systematic reviews, published by the CRGs between 2007 and 2011. This time frame was stipulated by NIHR in the original project brief. We included reviews that had either been first published or updated during 2007–11. To ensure that the analyses focused on outputs published during the specified years, review titles were crosschecked against details in The Cochrane Library and a master list of reviews provided by Wiley, the publisher of The Cochrane Library. These data from Wiley included details of the year and issue of The Cochrane Library when reviews were first published and any subsequent updates.

Overview of the research plan

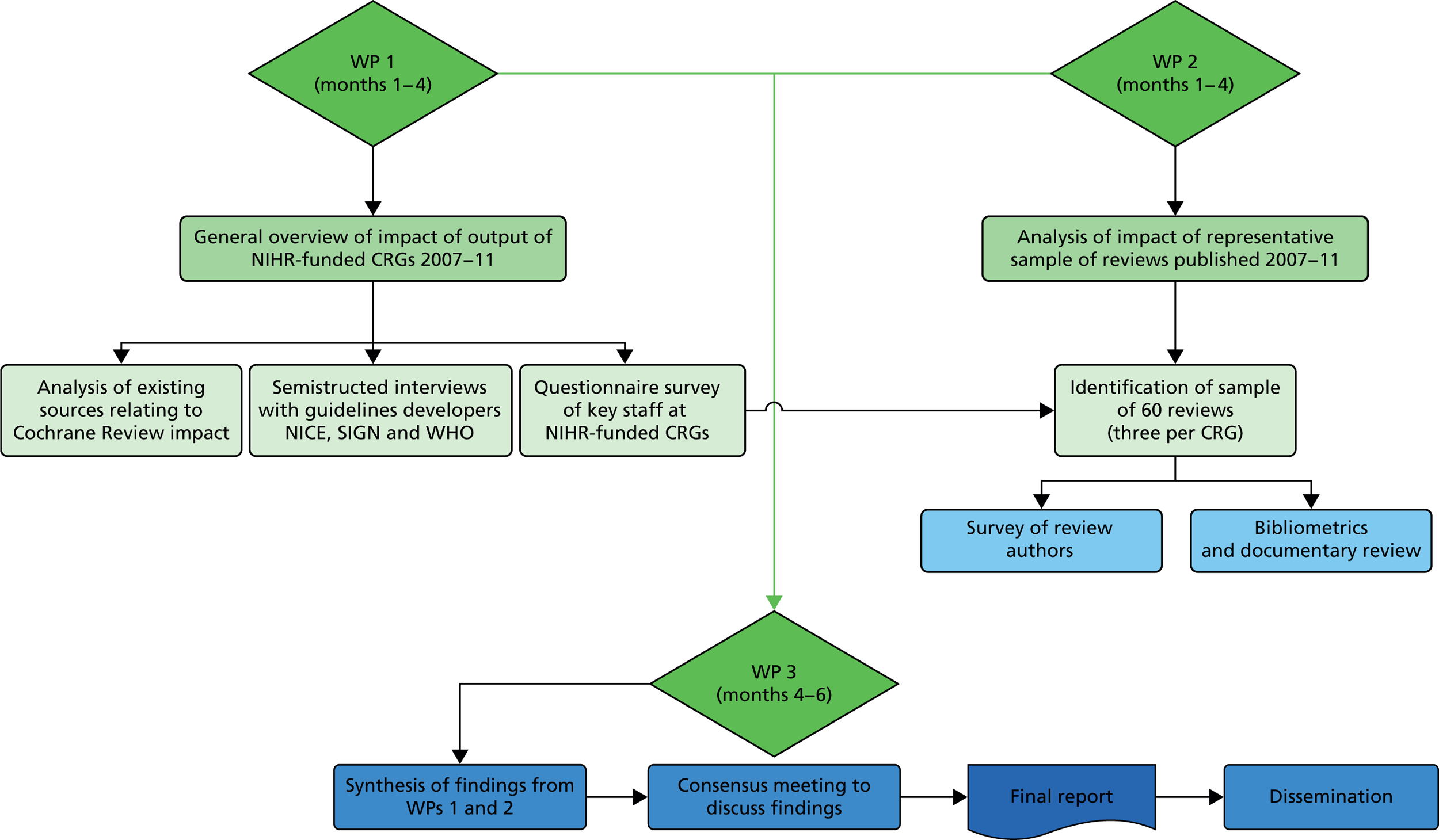

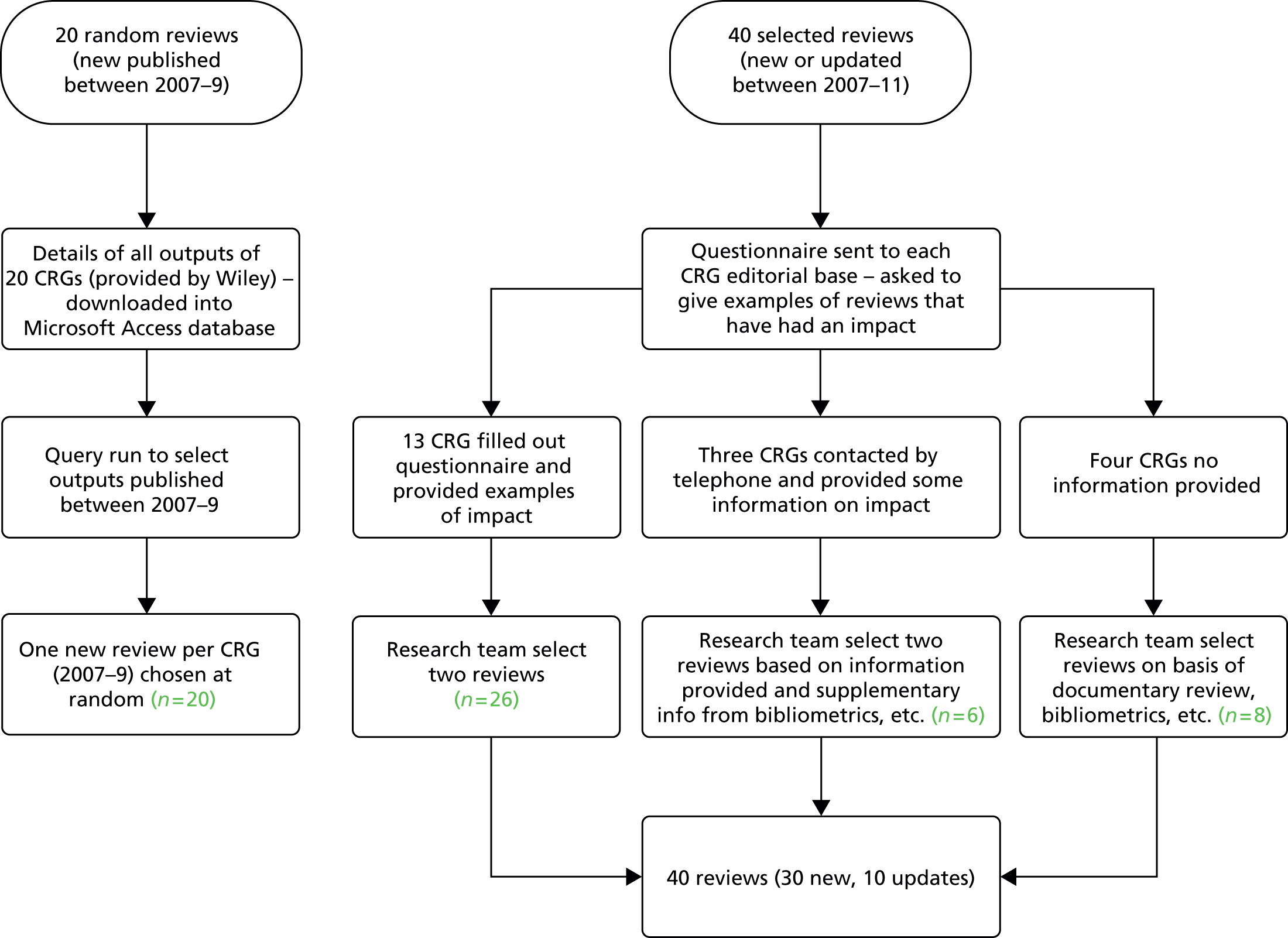

The methods are outlined here and then described in more detail later in the chapter. For details of the methods used for the semistructured interviews, see Chapter 6. A diagrammatic summary of the study can be seen in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Diagrammatic summary of methods. SIGN, Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network; WHO, World Health Organization.

Work package 1 (general overview)

We undertook the following:

-

sent a questionnaire survey to key staff at the 20 NIHR-funded CRG editorial bases to identify examples of impact and to help prioritise reviews for further analysis

-

analysed data on outputs and impact of reviews compiled by CRGs as part of the annual reports they submit to NIHR

-

analysed existing sources relating to Cochrane Review impact, for example data compiled by the UK Cochrane Centre (UKCC) on the use of Cochrane Reviews in NICE and Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) guidelines

-

performed general internet searches using keywords on the following websites:

-

World Health Organization (WHO) (www.who.int/rhl)

-

NHS evidence (www.evidence.nhs.uk/)

-

Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) (www.evidence.nhs.uk/qipp) – NICE quality and productivity Cochrane topics

-

-

conducted semistructured interviews with key personnel at NICE, SIGN and WHO involved in the development of guidelines (see Chapter 6).

Work package 2 (explore impact of sample of Cochrane Reviews)

We undertook the following:

-

identified a representative sample of 60 reviews (three per CRG)

-

sent a questionnaire survey to the first authors of the 60 reviews

-

performed citation analysis in WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar

-

conducted documentary analysis of existing sources to identify impact or likely impact, for example data compiled by the publisher of The Cochrane Library (Wiley) on the impact of Cochrane Reviews (e.g. downloads, media mentions)

-

performed internet searches of NHS Evidence, Turning Research into Practice (TRIP) and Google.

Work package 3 (synthesis and interpretation of findings)

In WP 3 we:

-

synthesised the findings from WPs 1 and 2

-

held a consensus meeting to discuss findings.

Methods for overview of impact of Cochrane Review Group outputs (2007–11)

Questionnaire survey of Cochrane Review Group editorial bases

Cochrane Review Groups currently compile data on outputs and review impacts as part of the annual reports that they submit to NIHR. However, although data on outputs are available for the whole 5-year period, data on review impacts are available only for 2009 onwards and in some instances these data are limited to citation in guidelines. Therefore, we supplemented data from the annual reports with a questionnaire survey to CRG editorial bases. The aim of this was to get an idea of the range and type of likely impact and to prioritise reviews for further analysis.

Sample and data collection

We sent a questionnaire survey to the managing editor (n = 20) at each NIHR-funded CRG, copied to co-ordinating editors. The questionnaires were sent via e-mail with a personalised covering letter explaining that the evaluation had been commissioned by the NIHR Health Technology Assessment systematic reviews programme and would inform the quinquennial review. Respondents were given the choice to fill out a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) version of the questionnaire or an electronic version through Bristol Online Survey. 52 Questionnaires were sent out in April 2013. The questionnaire sent to CRGs can be seen in Appendix 1.

The survey included questions about general impact of the CRG output between 2007 and 2011 and the responses were mainly qualitative in nature. CRGs were informed that they did not need to provide information already included in the annual reports they had previously submitted to NIHR. Questions were guided by our evaluation framework and covered areas such as knowledge production, contribution to research training and further research and possible impact of the review on health policy and practice. Respondents were asked to focus on reviews first published, or updated, in the 5-year period between 2007 and 2011 and were asked, where possible, to provide supporting evidence of impact. Evidence of impact might include inclusion in clinical guidelines, impact on clinical practice, such as changes to clinicians’ behaviour or changes to service organisation and delivery, or influence on future primary research. CRGs were asked to identify reviews published (or updated) between 2007 and 2011 that they considered to have had the most influence on policy and practice. Where provided, this information was used to inform the selection process in WP 2. Non-responders were followed up by repeat e-mails and telephone.

Analysis

All data from the questionnaires were imported into Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA) for analysis. Researchers scrutinised the responses and extracted any examples of actual or potential impact from the information provided by the CRGs. Data were recorded on a specially designed form that included the categories from our framework. As there was a danger that CRGs might have inflated the impact of their work the research team critically assessed information provided and, where possible, sought evidence to verify it. For instance, when respondents said that a review had led to further research studies, we searched for a study protocol or final report to check whether or not the review had been cited (e.g. in the background as justification for the research). Where guidelines were said to have been informed by a Cochrane Review, we downloaded a copy and searched it using the word ‘Cochrane’. This enabled us to verify which reviews were cited and whether or not they had been published between 2007 and 2011. We excluded examples for which no supporting evidence was available.

Documentary review and analysis of existing sources

We undertook analysis of existing material relating to the impact of Cochrane Reviews that had been published (or updated) by the 20 NIHR-funded CRGs during the period of 2007–11. We began by hand searching the annual reports that CRGs had provided to the NIHR for the years 2007–12. These reports include information on outputs, training activities, prioritisation processes for review topics, dissemination and inclusion of reviews in guidelines. We also reviewed data on the use of Cochrane Reviews in NICE and SIGN guidance compiled by the UKCC. In addition to this documentary analysis we undertook keyword searches on a number of electronic databases and websites including Google, NHS Evidence, the WHO and QIPP (Cochrane quality and productivity topics). We searched the QIPP database via NHS Evidence in July 2013.

Data extraction and analysis

Data relating to impact were extracted from the annual reports and recorded on a specially designed form that was structured to reflect the domains on our framework. This includes knowledge production (citations and other outputs such as media mentions), research targeting (such as any follow-on studies), policy impact (e.g. inclusion in guidelines or use for the development of guidelines) and impact on practice/services (e.g. impact on clinical behaviour). Data relating to guidelines were collated in a separate Microsoft Excel spreadsheet which we stratified by CRG; this included the guideline title, details of the Cochrane Reviews cited in the guidance and the level of the guidance (e.g. local, national, international). Verification processes were the same as those previously described. Results are presented narratively and as tabular and graphical summaries structured to reflect the domains of the framework.

Methods for evaluation of impact of representative sample of Cochrane Reviews (2007–11)

In WP 2 we undertook further analysis on a representative sample of Cochrane Reviews published in the last 5 years.

Selection criteria

We had initially proposed to select a sample of 40 reviews. The rationale for choosing 40 reviews was that it allowed us to choose two reviews per group and was considered feasible in the time available. However, concerns about a potentially low response rate from authors meant that we increased the sample to 60 reviews, three from each CRG. As our intention was to select a representative sample of reviews, one review per CRG was chosen randomly and two were chosen from those identified as likely to have had an impact.

A master list of published outputs (2007–11) was provided by Wiley. Outputs for the 20 CRGs were entered into a Microsoft Access 2010 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and one review was randomly selected for each CRG. As there generally needs to be sufficient time after the research was completed for change to have occurred, we weighted our sample towards those reviews published between 2007 and 2010. In the questionnaires, CRGs were asked to give examples of reviews and updates (published between 2007 and 2011) that they thought had had an impact in some way. Where provided, the research team used this information to select two reviews for further analysis. Decisions on which of the reviews were chosen were based on year of publication and strength of the evidence of impact provided. However, in some cases CRGs did not provide this information, or provided this information too late, and we used data from our bibliometric and documentary analyses (e.g. citation counts or data on downloads) to guide our selection. In order to avoid a conflict of interest or bias the researchers excluded any reviews on which they are an author. A flow chart of the selection process can be seen in Appendix 2.

Questionnaire survey with systematic review authors

Sample, data collection and analysis

We sent a questionnaire survey to the first authors of all 60 reviews. Contact details for lead authors were taken from The Cochrane Library and checked for accuracy using Google. Questionnaires were sent out between May and June 2013 and were accompanied by a personalised covering letter specifying which review the questionnaire concerned. The questionnaire can be seen in Appendix 3. Where possible, the research team sought supporting evidence to substantiate claims of impact. Non-responders were followed up by a second mailing from the researchers. For those that did not respond to the second e-mail we contacted the managing editors at CRG editorial bases to ask them if they would be willing to contact the authors on our behalf. A number of CRGs agreed to do this and this resulted in several more questionnaires being returned. Data were imported into Microsoft Excel for analysis. For qualitative data, researchers scrutinised the responses and extracted examples of impact onto a specially designed form. We stratified data by CRG and by review.

Documentary and bibliometric analysis

We also undertook a range of bibliometric and documentary analyses to look for evidence of impact. We undertook citation analysis in WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar to see how many times the reviews had been cited; searches were undertaken in May and June 2013. As Cochrane Reviews are regularly updated there was often more than one published version of a review, each with a number of citations attached to it. In such instances we combined citation counts for each version as long as the publication date was between 2007 and 2011. For updated reviews we counted citations for only versions of the review published after 2007. In order to trace the flow of knowledge we screened the first five pages of results of the citation analysis in Google Scholar to see whether or not the citations related to policy documents such as guidelines. Previous studies15,48 suggest that the most relevant records in searches of Google and Google Scholar will be in the first five pages. Results of the citation analysis in WoS were imported into EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA), at which point we performed keyword searches using the words ‘guidance’ and ‘guidelines’.

It may, however, take several months or even years for a work to be first cited. Moreover, the dissemination channels for research have broadened to include a variety of social media. Therefore, in addition to the citation counts previously described we used an alternative metric measure to calculate an alternative metric score for each of the 60 reviews (the score measures the quantity and quality of the attention an article has received). The Altmetric Bookmarklet (Altmetric LLP, London; www.altmetric.com) provides article-level metrics which give an indication of the impact of a publication by looking at activity surrounding the publication on social media sites (e.g. Twitter, Facebook), newspapers and policy documents. Articles for which no mentions have been recorded score 0. The searches were conducted in July 2013.

In addition, we undertook searches on Google, NHS Evidence and TRIP using review author and title keywords. Searches were undertaken between May and July 2013. We also drew on data from the publishers of The Cochrane Library (Wiley) on the impact of Cochrane Reviews. This included data on the number of downloads of reviews (abstract only or full text) and the number of media mentions for Cochrane Reviews that had been press released. Reviews that are published in conjunction with a podcast are accompanied by a press release and Wiley collects press data for these reviews. Data are collected by Wiley through advanced keyword searches of Vocus (a paid-for clipping service; Cision, Beltsville, MD, USA) and searches on Google.

Analysis

Results were entered into a Microsoft Access database by one researcher (AM) and checked by a second (FB).

Methods for synthesis of work packages 1 and 2 and consensus meeting (work package 3)

In WP 3 we synthesised findings from WPs 1 and 2. Synthesis was guided by our overarching framework and took into consideration ideas relating to types of impact (e.g. instrumental/conceptual/symbolic). Preliminary findings were discussed at a consensus meeting involving the research team, a representative from the National Clinical Guideline Centre at the Royal College Physicians and members of the University of Hertfordshire Public Involvement in Research Group (PIRG). The purpose of this meeting was to assist in the process of conceptualising and identifying impact and to help make judgements about impacts. Examples of impact, including a review synopsis and any evidence relating to impact, were used as a basis for discussion. This process was considered important in order that we made appropriate judgements about potential or likely impacts and to ensure that impact was not overstated.

Chapter 4 Overview of impact of Cochrane Review Group outputs (2007–11)

Between 2007 and 2011, 3187 new and updated reviews were published on the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Of those, 1502 (47%) were produced by the 20 CRGs funded by the NIHR (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

New and updated reviews published by each CRG between 2007 and 2011. BJM, Bone, Joint and Muscle trauma; DAN, Depression, Anxiety and Neurosis; ENT, Ear, Nose and Throat; PaPaS, Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care. This figure has been reproduced from figure 2 © Bunn et al. The impact of Cochrane Systematic Reviews: a mixed method evaluation of outputs from Cochrane Review Groups supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Syst Rev 2014;3:125,38 under Creative Commons Licence 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Results of Cochrane Review Group questionnaires

In total, 17 of the 20 CRGs returned the questionnaire, although not all had completed all sections. Reasons for not completing all sections of the questionnaire were because the CRG did not have any examples for that section, because it did not have any additional information to that already provided in their annual reports and because it did not have time to fill out all sections. Three declined to fill out the questionnaire. Reasons for not returning the questionnaire included the following: the group felt that the evaluation should be done externally without input from them, the group did not have time to fill out the questionnaire and the group felt there was no additional information to add to that already provided to NIHR in their annual reports. More details can be seen in Table 2.

| Questionnaire status | Number | Name of CRG |

|---|---|---|

| Returned questionnaire and information provided | 13 | Airways; BJM; Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders; Depression Anxiety and Neurosis; ENT; Incontinence; Injuries; Neuromuscular; Oral Health; Pregnancy and Childbirth; Skin; Tobacco Addiction; and Wounds |

| Returned questionnaire but not all sections completed | 4 | Epilepsy; PaPaS; Gynaecological Cancer; Heart |

| Did not fill out questionnaire but provided some information by telephone (e.g. some info on which reviews might have had impact) | 3 | Eyes and Vision; Dementia and Cognitive Improvement; Schizophrenia |

Research targeting

Cochrane Review Groups were asked if they were aware of any reviews first published by their group between 2007 and 2011 that had generated subsequent research (e.g. contributed to successful grant applications for future primary research). Of the 13 groups that responded to this question, 12 (92%) said yes and one (8%) said no. Of the groups that said yes, 12 provided some form of supporting evidence (some of them providing several examples) and 11 gave details of who had funded the research. All of the 11 groups that gave details of the funding body cited at least one primary study funded by NIHR. Other funders included government organisations in other countries, local funders and charities. A summary of all data on the impact on primary research can be seen in Table 3. Data in Table 3 are collated from CRG and author questionnaires and documentary review.

| CRG | Number of reviews | Type and number follow-on research | Review is citeda | Type of funder |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Airways | 1 | RCT | Yes | Not known |

| BJM | 2 | 2 RCTs | Yes | 2 government (1 UK, 1 Australia) |

| Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders | 5 | 5 RCTs | Yes | 3 government (UK), 2 not known |

| DAN | 2 | 1 RCT, 1 not known | 1 yes, 1 not known | 1 government (UK), 1 not known |

| Eyes and Vision | 1 | 1 not known | Yes | 1 charity |

| Incontinence | 3 | 3 RCTs | 2 yes, 1 not known | 3 government (UK) |

| Injuries | 7 | 9 RCTs | 7 yes, 2 not known | 7 government (3 Australia, 3 UK, 1 Denmark), 1 industry, 1 charity |

| Neuromuscular | 4 | 3 RCTs, 1 not known | 2 yes, 2 not known | 2 government (1 USA, 1 France), 1 charity, 1 not known |

| Oral Health | 1 | RCT | Yes | 1 government (UK) |

| Pregnancy and Childbirth | 1 | Qualitative | Yes | Not known |

| Schizophrenia | 1 | 1 RCT, 2 not known | Not known | Not known |

| Skin | 5 | 5 RCTs, 1 not known | 4 yes, 2 not known | 3 government (UK), 2 charity (1 UK, 1 USA) |

| Tobacco Addiction | 2 | 3 RCTs | Yes (all) | 2 government (UK), 1 not known |

Informing policy development

Seventeen groups provided us with information about potential impacts on policy, mostly in the form of guidelines which cited a review produced by their CRG. Additional information on inclusion in guidelines was collated from the CRG annual reports, from data compiled by the UKCC, and from documentary review and database searches. All of the CRGs had produced reviews which had affected policy-making in the form of guidelines or guidance. Across the 20 CRGs there were 722 citations in 248 guidelines, with 481 systematic reviews being cited at least once. Cochrane Reviews produced by 13 CRGs had been cited in 30 different NICE guidelines, and reviews from 12 CRGs had been cited in 23 sets of guidance developed by SIGN. Information on inclusion in guidelines (by CRG) is summarised in Table 4. This shows the total number of reviews cited in guidance, the number of guidelines and the level of the policy. The level of policy is categorised as international, national and local, with national meaning guidance produced by a national body in any country (not just the UK) (Table 5 has further details). A full list of guidelines and a list by CRG is available on request.

| CRG | Total number of citations | Number of reviews cited in guidelines/guidance | Total number of guidelines | Level of guideline | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International | National | Local | ||||

| Airways | 54 | 45 | 16 | 3 | 13 | 0 |

| BJM | 18 | 12 | 9 | 0 | 8 | 1 |

| Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders | 16 | 15 | 13 | 3 | 9 | 1 |

| DAN | 84 | 52 | 26 | 10 | 16 | 0 |

| Dementia and Cognitive Improvement | 14 | 14 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 0 |

| ENT | 33 | 21 | 17 | 3 | 14 | 0 |

| Epilepsy | 8 | 7 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Eyes and Vision | 8 | 6 | 6 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Gynaecological Cancer | 7 | 7 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Heart | 37 | 19 | 26 | 5 | 21 | 0 |

| Incontinence | 29 | 22 | 9 | 1 | 8 | 0 |

| Injuries | 42 | 29 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 0 |

| Neuromuscular | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| Oral Health | 47 | 17 | 25 | 1 | 20 | 4 |

| PaPaS | 48 | 33 | 20 | 4 | 15 | 1 |

| Pregnancy and Childbirth | 129 | 85 | 33 | 15 | 18 | 0 |

| Schizophrenia | 57 | 43 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 0 |

| Skin | 20 | 14 | 14 | 3 | 11 | 0 |

| Tobacco Addiction | 22 | 18 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 |

| Wounds | 41 | 25 | 11 | 1 | 10 | 0 |

| Level | Number | Further details |

|---|---|---|

| International | 62 | Global 35, Europe 21, Australasia 4, Scandinavia 1, USA/Canada 1 |

| National | 176 | USA 48, UK 87, Australia 13, Canada 12, Netherlands 2, Ireland 2, Germany 4; Taiwan, Sweden, Singapore, Saudi Arabia, Norway, South Korea, France and Belgium 1 |

| Local | 10 | North East NHS, UK 3; North East London, UK 1; North England, UK 1; Berkshire, UK 1; Ontario, Canada 1; New South Wales, Australia 1; Melbourne, Australia 1; private health-care provider, USA 1 |

Nature of policy impact

The conceptual approach adopted for this evaluation includes an assessment of the nature of the policy impact based on the categories devised by Weiss. 53 This attempts to distinguish between instrumental or direct impact and conceptual or symbolic use. In this case there was evidence that a number of Cochrane Reviews had some direct or instrumental impact in that they were used to inform practice guidelines. However, in this part of the evaluation we assessed only whether or not the reviews were cited by guidelines and did not look in detail at how reviews were used or if guidelines included recommendations that were in agreement with the Cochrane Review conclusions. In addition, most guidelines are based on a number of different publications and it is not easy to determine the contribution of individual reviews. For a further exploration of how GDs use Cochrane Reviews, see Chapter 6.

Impact on practice and services

In the questionnaire we asked CRGs if they were able to give us examples of ways in which reviews produced by their CRGs had influenced practice and services. Eight groups provided examples of changes to behaviour and six gave examples of how their reviews had led to health, health-service or economic benefits. Impacts on behaviour included changes through the use of evidence-based guidance and impacts on prescribing behaviour or the use of new technologies. Benefits to the health service included safer prescribing, a reduction in inappropriate prescribing and the identification of new effective drugs or treatments. We discounted some of the examples we were given, either because the impact was judged to be outside the time frame for this evaluation or because no supporting evidence was provided and we were unable to verify the impact in any way.

Examples of impact judged to relate to reviews first published or updated between the years 2007 and 2011 include the following:

-

A review on support surfaces for pressure ulcer prevention54 was used to inform guidance on purchasing within the NHS. 55

-

Reviews on long-acting beta-antagonists in asthma56–58 may have led to safer prescribing of these drugs for people with asthma (www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm200776.htm).

-

A review on colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation59,60 may have influenced calls to stop starch use within the NHS, a decision that has the potential to save both lives and money. 61

-

An updated review on antiviral treatment for Bell’s palsy62 may have contributed to changes in practice and a reduction of prescriptions of antiviral drugs for Bell’s palsy (http://cks.nice.org.uk/bells-palsy).

-

A review on antifibrinolytic drugs for trauma patients63,64 led to follow-on research which influenced the decision by the Medicines Innovation Scheme to fast-track tranexamic acid for use in the NHS. Ambulance crews throughout the NHS now administer tranexamic acid to bleeding trauma patients (www.swast.nhs.uk/txa.htm).

In many instances there was a lack of specific evidence to support the claims made in the CRG questionnaires. Even with the additional searches carried out by the research team it was often difficult to verify these claims and find a clear link between a review and an outcome. Moreover, attributing particular behaviour changes, health benefits or costs saving to a particular systematic review (or reviews) is difficult. Generally, new research adds to an existing pool of knowledge65 and many research projects may lie behind a specific advance in health care. 66 Therefore, many of the examples we were given by CRGs have to be considered likely or potential impacts rather than proven impacts.

Despite difficulties verifiying impacts, it is apparent that many Cochrane Reviews have the potential to affect practice and policy and that some produce findings that could potentially lead to cost savings and health-service benefits. Some of these potential benefits are highlighted in the Cochrane quality and productivity topics. These documents are developed as part of the NICE QIPP. They are based on the ‘implications for practice’ section in Cochrane systematic reviews and focus on interventions that lack evidence of change, those with strong evidence for ineffectiveness and those in which risks outweigh benefits. Topics are evaluated only if they reflect a current gap in NICE guidance. 67 We found 19 relevant quality and productivity reports based on reviews from nine different CRGs. Potential benefits identified by NICE included economic benefits through cash savings or the release of cash, improvements in clinical quality, reduction in the use of unproven or unnecessary procedures, and improvements in patient and carer experiences. Table 6 has details of the reviews on which these are based and the potential cost savings and health-service benefits.

| Review title | CRG | Year of Cochrane Review used | Potential savings | Other potential impacts |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tailored interventions based on exhaled nitric oxide versus clinical symptoms for asthma in children and adults | Airways | 2009 | Real cash savings | Increase in patient safety in children |

| Inhaled corticosteroids for cystic fibrosis | Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders | 2009 | Cash savings through reduced expenditure on drug budgets and fewer adverse events | Better outcome for patients by avoiding side effects of Inhaled corticosteroids |

| Statins for the treatment of dementia | Dementia and Cognitive Improvement | 2010 | Cash releasing, although may be limited as patients may continue to take statins for other reasons | |

| Antigen-specific active immunotherapy for ovarian cancer | Gynaecological Cancer | 2010 | Mixture of cash savings and improved productivity | Improved clinical quality due to reduction in use of unproven therapies |

| Improved patient safety due to decreased risk of adverse events | ||||

| High-dose rate versus low-dose rate intracavity brachytherapy for locally advanced uterine cervix cancer | Gynaecological Cancer | 2010 | Cash savings | Improved clinical quality, better outcomes for patients |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy plus surgery versus surgery for cervical cancer | Gynaecological Cancer | 2010 | Cash savings | Improved clinical quality due to reduction in use of unproven therapies |

| Improved patient safety due to decreased risk of adverse events | ||||

| Behavioural and cognitive interventions with or without other treatments for the management of faecal incontinence in children | Incontinence | 2011 | Cash releasing | Better clinical outcomes for patients, improved patient safety and experience |

| Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients (also a proven case study but it cites the 2012 update) | Injuries | 2011 | Cash releasing | Improved patient safety due to decreased risk of adverse events |

| Pharmacological interventions for the prevention of allergic and febrile non-haemolytic transfusion reactions | Injuries | 2010 | Real cash savings | Improved clinical quality due to reduction in use of unproven therapies |

| Non-pharmacological interventions for breathlessness in advanced stages of malignant and non-malignant diseases | Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care | 2008 | Cash releasing | Concentrating resources in providing services supported by evidence likely to have beneficial impact on patient and carer experience |

| Single-dose oral codeine, as a single agent, for acute postoperative pain in adults | Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care | 2010 | Possible real cash savings | Improved clinical quality |

| Single-dose oral gabapentin for established acute postoperative pain in adults | Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care | 2010 | Real cash savings | Likely to improve quality of patient care |

| Antenatal interventions for fetomaternal alloimmune thrombocytopenia | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2011 | Real cash savings | Improved clinical quality due to reduction in use of unproven therapies |

| Enemas during labour | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2007 | Cash releasing | Improved patient and carer experience |

| Fetal and umbilical Doppler ultrasound in normal pregnancy | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2010 | Cash releasing | Improved patient and carer experience |

| Intra-amniotic surfactant for women at risk of preterm birth for preventing respiratory distress in newborns | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2010 | Real cash savings and improved productivity | Improved clinical quality due to reduction in use of unproven therapies and unnecessary procedures |

| Repeat digital cervical assessment in pregnancy for identifying women at risk of preterm labour | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2010 | Minimal impact on cash but improved productivity | Improved clinical quality, patient safety and patient experience |

| Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour | Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2010 | No impact on cash | Improved clinical quality and patient experience by reducing unnecessary practice |

| Relapse prevention interventions for smoking cessation | Tobacco Addiction | 2009 | Cash releasing | Improved clinical quality, better patient outcomes, improved patient experience |

Chapter 5 Impact of a representative sample of Cochrane Systematic Reviews

Results of author questionnaire

Three reviews per CRG were selected for further evaluation. One review per group was chosen randomly (n = 20) and two on the basis that they were more likely to have had an impact (n = 40). Where possible, the latter were selected from examples provided by the CRGs. Four CRGs did not provide information on impact and reviews for these CRGs were selected by the researchers. Nine reviews were updates and the rest were new reviews. Thirteen were published in 2007, 23 in 2008, 12 in 2009 and six each in 2010 and 2011. Details of these reviews, including citation, country of first author and whether they were a new review or an updated review, can be seen in Appendix 4. In a couple of instances the review initially selected had to be changed for a different review. This was either because the review had subsequently been allocated to a different CRG68 or because the review had been withdrawn from The Cochrane Library. 69

In total, 29 out of 60 authors (48%) returned their questionnaire; 16 were returned after the initial mailing, five after a reminder from the research team and a further eight after they were contacted by the managing editor of the CRG concerned. Thirteen questionnaires were returned by authors based in the UK (out of a possible 34) and 16 (out of a possible 26) from authors outside the UK. The numbers of questionnaires returned for each CRG can be seen in Table 7.

| CRG | Returned (out of three) | Country of first author returned questionnaires |

|---|---|---|

| Airways | 1 | 1 USA |

| BJM | 2 | 1 New Zealand, 1 Australia |

| Cystic Fibrosis and Genetic Disorders | 2 | 2 UK |

| Dementia and Cognitive Improvement | 0 | NA |

| DAN | 1 | 1 Brazil |

| ENT | 2 | 2 UK |

| Epilepsy | 0 | NA |

| Eyes and Vision | 3 | 1 Brazil, 1 UK, 1 Italy |

| Gynaecological Cancer | 1 | 1 Lebanon |

| Heart | 1 | 1 UK |

| Incontinence | 0 | NA |

| Injuries | 3 | 2 UK, 1 Canada |

| Neuromuscular | 1 | 1 Japan |

| Oral Health | 0 | NA |

| PaPaS | 2 | 2 UK |

| Pregnancy and Childbirth | 2 | 1 USA, 1 Ireland |

| Schizophrenia | 2 | 1 Australia, 1 Canada |

| Skin | 3 | 1 UK, 1 Australia, 1 Taiwan |

| Tobacco Addiction | 1 | 1 UK |

| Wounds | 2 | 1 UK, 1 Australia |

| Total | 29 (48%) | – |

Research targeting

Authors were asked if their review had informed the development of future research, either by any of the review authors themselves or by other researchers. The responses can be seen in Table 8. Supporting evidence included information such as a reference to the study, the name of the funding body or the name of the study. Where the funder was not provided, we undertook internet searches for further details. Research had been funded by a variety of organisations in the UK and elsewhere; this included governmental bodies such as NIHR, charities, universities and industry.

| Question | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) | No response (%) | Supporting evidence provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Has the review generated subsequent research by any of the review authors? | 14 (48.25) | 14 (48.25) | 0 (0.00) | 1 (3.50) | 15a |

| Are you aware of any ways in which your review has contributed to further research conducted by others? | 7 (24.10) | 4 (13.80) | 18 (62.10) | 0 (0.00) | 7 |

Informing policy development

Authors were asked if they thought their review had influenced health policy- or decision-making at any level of the health service, including international, national, regional, local trust or unit, professional, administrative or managerial. They were also asked if they were aware of any potential future impact, for example if the review was being used in guidelines currently under development. Results can be seen in Table 9. In general, the supporting evidence provided related to the review having been cited in or used to develop some form of clinical or practice guideline.

| Question | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) | No response | Supporting evidence provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Have review findings impacted on policy-/decision-making? | 23 (79.3) | 1 (3.5) | 5 (17.2) | 0 | 20 |

| Are there any reasons for expecting the findings to be used for future policy-/decision-making? | 14 (48.3) | 2 (6.9) | 13 (44.8) | 0 | 5 |

Impact on practice and health services

Authors were asked if they thought the findings from their review had already led to changes, either directly or through the application of research-informed policies in the behaviour of health-care professionals or providers, health-care managers, health-service users or the wider public. Responses can be seen in Table 10. More respondents gave examples of changes to the behaviour of health professionals (37.9%) than changes to the behaviour of health-care managers (20.7%).

| Question | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) | No response (%) | Supporting evidence provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Led to changes in the behaviour of medical/allied health professionals/other providers | 11 (37.9) | 1 (3.5) | 17 (58.6) | 0 (0.0) | 8 |

| Led to changes in the behaviour of health-care managers | 6 (20.7) | 3 (10.3) | 19 (65.5) | 1 (3.5) | 4 |

| Led to changes in the behaviour of health-service users or the wider public | 3 (10.3) | 1 (3.5) | 24 (82.7) | 1 (3.5) | 2 |

Authors were also asked if they thought the findings from their review had led to any health, health-service or economic benefits. This included costs reductions in existing services, improvements in the process of service delivery, increased effectiveness of services (e.g. through increased health), greater equity (e.g. through the improved allocation of resources) or economic benefits arising from a healthier workforce. Responses can be seen in Table 11.

| Question | Yes (%) | No (%) | Don’t know (%) | Not applicable (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Led to cost reduction in the delivery of existing services | 4 (13.8) | 1 (3.5) | 20 (68.9) | 4 (13.8) |

| Led to qualitative improvements in the process of service delivery | 4 (13.8) | 1 (3.5) | 22 (75.9) | 2 (6.8) |

| Led to increased effectiveness of services, e.g. increased health | 3 (10.3) | 1 (3.5) | 22 (75.9) | 3 (10.3) |

| Led to greater equity, e.g. improved allocation of resources at district/hospital level, better targeting and accessibility | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.5) | 23 (79.2) | 4 (13.8) |

| Led to economic benefits from a healthier workforce and reduction in working-days lost | 1 (3.5) | 1 (3.5) | 20 (68.9) | 7 (24.1) |

The majority of respondents reported that they did not know if the review had led to health-service or economic benefits. For those who said yes, the examples of impact related to changes to practice (e.g. a reduction in treatments or technologies not proven to be beneficial) or cost savings through the health service no longer having to pay for a treatment not proven to be beneficial. However, in most cases the supporting evidence provided was anecdotal or difficult to substantiate.

Results of bibliometric analysis

Citation analysis

In order to obtain some understanding of the likely influence the reviews have had on the research and practice community, we undertook citation analyses in WoS, Scopus and Google Scholar. The numbers of citations ranged from 0 to 348 in WoS, from 0 to 467 in Scopus and from 5 to 737 in Google Scholar. Mean citations were higher for selected reviews than for random reviews. A summary of the citation analysis data, showing the total number, median and range of citations across the three different databases, can be seen in Table 12. This shows the difference in the number of citations between the three databases, suggesting that citation analyses in WoS and Scopus may underestimate the impact of Cochrane Reviews in comparison with Google Scholar.

| Citations | WoS | Scopus | Google Scholar |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of citations (all 60 reviews combined) | 2192 | 3562 | 8333 |

| Mean number of citations | 36.5 (R 19, S 45) | 59.3 (R 33, S 72) | 138.8 (R 62, S 177) |

| Median number of citations | 20 | 28.5 | 72 |

| Interquartile range | 7–51 | 11–80 | 25–168 |

| Variation in counts | 0–348 | 0–467 | 5–737 |

The average number of citations a paper receives may be affected by the type of specialty it represents and the length of time since publication. Therefore, it is not really appropriate to compare citation rates across the different CRGs; rather they should be considered against papers in a similar field. Moreover, we have looked at only three reviews for each CRG and this does not give us an idea of the impact of the total output of the groups.

Alternative metrics

According to the Altmetric website (www.altmetric.com/whatwedo.php#score), many articles currently score 0. The proportion varies but currently a mid-tier publication (definition not given) might expect 30–40% of the papers it publishes to be mentioned at least once (mentioned once would give a paper a score of 1). At the time we performed the searches, 36 (60%) of the reviews had a score of 1 or more, with 12 reviews having a score over 10 and four scoring over 50. This in itself is not perhaps very meaningful, as two-thirds of the reviews in our sample were chosen on the basis that they might have had an impact and, therefore, interest in these reviews might be expected to be higher than the average. Moreover, the score needs to be interpreted cautiously, as it may not accurately reflect interest in reviews published before 2011. Altmetric has been recording some activity (such as Twitter mentions) only for articles published since 2011. Mean Altmetric scores were higher for the selected reviews than the random reviews (2 vs. 25).

However, what the Altmetric scores do provide is some indication of the interest around a review, and the way Cochrane Reviews may have affected on knowledge production by stimulating discussion and debate. This includes discussion and debate amongst researchers and practitioners but also amongst service users and members of the general public. For example, a review on active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour70 had an Altmetric score of 37 (a score higher than 97% of its peers). Further breakdown of this score shows how the review has impacted on the research and practice community and stimulated debate. For full details of the citations counts and Altmetric scores for each review, see Appendix 4. Five of the 60 reviews had been accompanied by a podcast and press release on publication. 71–75 These had all been picked up in the press with the number of mentions ranging from 37 to 100.

Results of documentary review

Review downloads

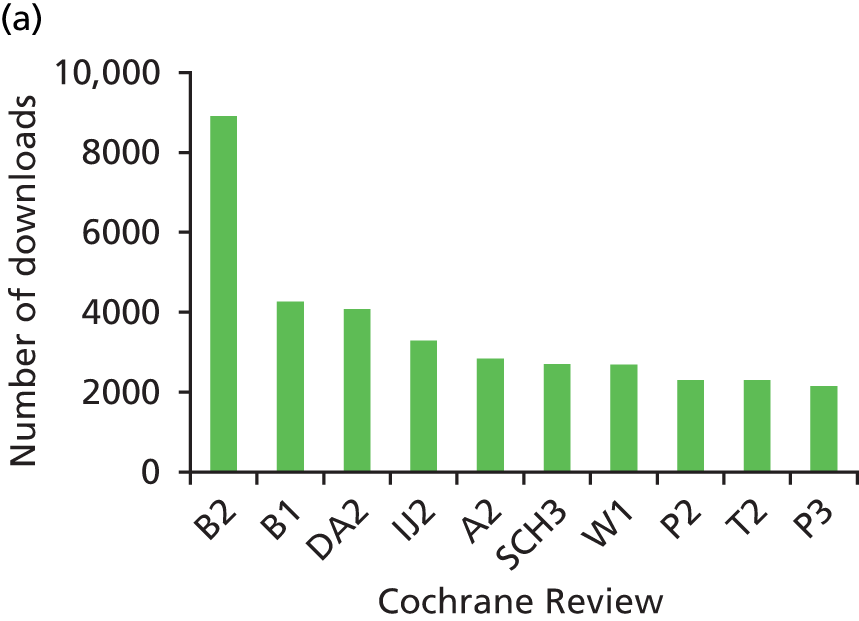

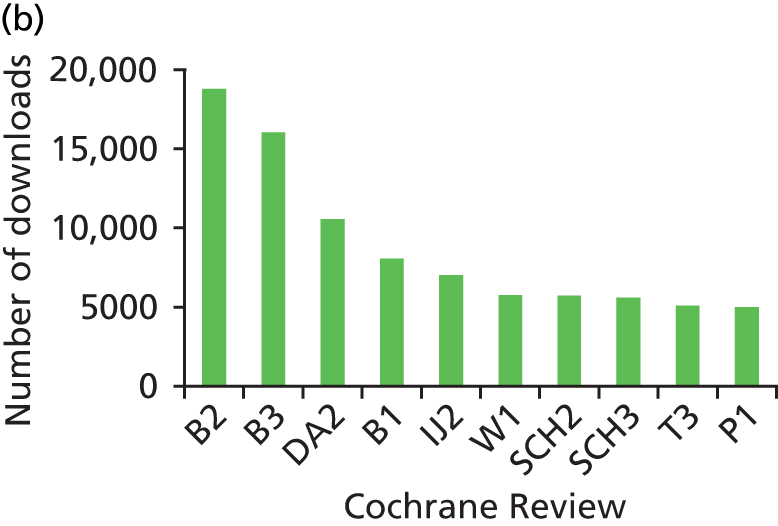

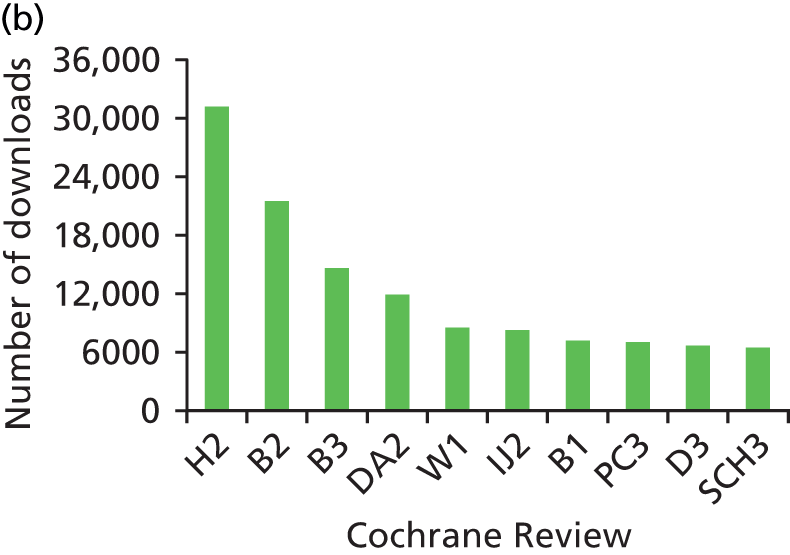

We looked at information on the number of times that the reviews were downloaded between 2007 and 2011. Data on the number of downloads was provided by Wiley, the publisher of The Cochrane Library. It was able to supply us with the number of full-text downloads for all years and abstract downloads for 2009–11. The number of downloads varied considerably between reviews. Of the sample of 60 reviews, the 10 that were downloaded most frequently (full text and abstract) can be seen in Figures 3–5. These figures give an indication of the impact of reviews within the research and practice communities and show how downloads for reviews have increased over the 5-year period.

FIGURE 3.

Top 10 downloads from The Cochrane Library in 2009. Identifying codes for reviews can be seen in Appendix 4. a, Top 10 full-text downloads from 2009. b, Top 10 abstract downloads from 2009. This figure has been reproduced from figure 3 © Bunn et al. The impact of Cochrane Systematic Reviews: a mixed method evaluation of outputs from Cochrane Review Groups supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Syst Rev 2014;3:125,38 under Creative Commons Licence 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FIGURE 4.

Top 10 downloads from The Cochrane Library in 2010. Identifying codes for reviews can be seen in Appendix 4. a, Top 10 full-text downloads from 2010. b, Top 10 abstract downloads from 2010. This figure has been reproduced from figure 3 © Bunn et al. The impact of Cochrane Systematic Reviews: a mixed method evaluation of outputs from Cochrane Review Groups supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Syst Rev 2014;3:125,38 under Creative Commons Licence 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

FIGURE 5.

Top 10 downloads from The Cochrane Library in 2011. Identifying codes for reviews can be seen in Appendix 4. a, Top 10 full-text downloads from 2011. b, Top 10 abstract downloads from 2011. This figure has been reproduced from figure 3 © Bunn et al. The impact of Cochrane Systematic Reviews: a mixed method evaluation of outputs from Cochrane Review Groups supported by the UK National Institute for Health Research Syst Rev 2014;3:125,38 under Creative Commons Licence 4.0, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Summary of impact

Overall, 40 of the 60 reviews had been cited in some form of clinical guidance and 15 had influenced further primary research. There were 12 examples of impact on practice or services but not all of these were verified. A summary of the main impacts can be seen in Appendix 5. The data in Appendix 5 are collated from the questionnaires, citation analyses, documentary review and internet searches and show the impact of the reviews in terms of knowledge production, research targeting, informing policy and impact on practice and services.

Chapter 6 Interviews with guideline developers

Introduction

Clinical guidelines have been defined as ‘an attempt to distil a large body of medical expertise into a convenient, readily usable format’76 and as ‘systematically developed statements to assist practitioner and patient decisions about appropriate health care for specific clinical circumstances’. 77 A number of potential health- and service-related benefits of clinical practice guidelines have been identified. 77 This includes improvement in the quality of health care, a reduction in variation in service delivery among different providers and geographical regions, better equity and improved efficiency. Although the methods and analyses described in previous chapters enabled us to ascertain if Cochrane Reviews have been cited in guidance, it did not necessarily tell us the role Cochrane Reviews play in the development of guidance, for example whether they are just used as supporting evidence or they were instrumental in informing guidance. Therefore, in order to gain a greater understanding of the role that Cochrane Reviews play in the development of guidance, we undertook semistructured telephone interviews with key informants at national and international bodies involved in the development of guidance.

Methods

Sample and data collection

We undertook telephone interviews with a purposive sample of GDs from NICE and NICE National Collaborating Centres, SIGN and WHO. In the first instance one of the authors (PA) identified potential participants, with further snowballing as required. Recruitment was stopped once we felt data saturation was reached. Our sample attempted to capture a range of experiences (both positive and negative) of using Cochrane Reviews in guideline development. The focus of the data collection was to identify the way Cochrane Reviews are used in the development of guidance and to identify barriers and facilitators to their use. We used a semistructured interview schedule which was guided by our evaluation framework and by previous literature on barriers to review impact. 78 Interviews were taped and transcribed in full and lasted between 20 and 40 minutes.

Analysis

Owing to time limitations, and because we had a relatively small number of transcripts for analysis, we undertook the qualitative data analysis by hand. In order to elicit key features of GDs’ experiences of using Cochrane Reviews, we used thematic content analysis. 79 To ensure a degree of inter-rater reliability and transparency, two authors (of AM, FB and DT) independently read and coded each transcript. From this a list of initial codes and themes were created which were then further refined after discussion with the wider project team. 80

Findings

Altogether we interviewed eight participants: four from NICE (or NICE collaborating centres), two from SIGN and two from WHO. Out of the eight participants, five were female and three were male. More details of the participants and their roles can be found in Table 13.

| Organisation | No. of participants | Role |

|---|---|---|

| NICE – internal | 2 | Technical analyst, clinical guidelines team × 2 |

| NICE – external collaborating centres | 2 | Senior systematic reviewer × 2 |

| SIGN | 2 | Evidence and information scientist × 1, programme manager × 1 |

| WHO | 2 | Senior manager × 2 |

Participants have been assigned a number, which is linked to any quotes in the text. In order to preserve interviewees’ anonymity these numbers were assigned randomly.

The analysis resulted in six overarching themes and a number of subthemes relating to the views and experiences of GDs and their use of Cochrane Reviews. The overarching themes are:

-

the process of using Cochrane Reviews in the development of guidance

-

the quality of Cochrane Reviews

-

culture and approaches

-

up-to-date evidence

-

methodological issues

-

collaboration and communication.

These themes and subthemes can be seen in Box 1, and are described in more detail in the text.

-

The process of using CR in the development of guidance.

-

Scope for guidelines set by guideline development group but CR may be used to inform guideline questions and assess potential strength of evidence base.

-

CRs used early in process/used in development phase.

-

Systematic reviews top of evidence hierarchy/priority over other forms of evidence.

-

GDs will use CR if available, but not always possible – CR may not be available/may not ‘fit’.

-

GDs may use whole CR or parts of CR (e.g. using evidence tables)/parts used vary.

-

CRs can save GD time (e.g. using existing searches/data).

-

GDs may build on work of Cochrane reviewers/existing reviews.

-

GDs may redo the review (depending on resources).

-

-

Quality of CRs.

-

Cochrane is a respected/trustworthy brand.

-

GDs look for CR first.

-

Transparent/easy to replicate.

-

Robust methods.

-

Variable quality (not all good).

-

Perception that quality may be poorer in older reviews.

-

-

Culture and approaches.

-

Cochrane and GDs have similar attitudes towards evaluating and appraising evidence.

-

Cochrane embedded in culture of guideline development.

-

Some differences in methods (e.g. CRs double data extraction but some GDs not).

-

Judgement part of guideline development process (but not part of CR process).

-

Cochrane and GDs may have different scopes/focus/drivers behind review questions.

-

Tensions between different perspectives and interests (e.g. academic/clinical/policy).

-

GDs sometimes need to be ‘pragmatic’.

-

Resources – different timeframes and sources of funding.

-

-

Up-to-date evidence.

-

CRs can be out of date (this limits their impact).

-

CRs become out of date quickly.

-

Some confusion around dates of updates.

-

Some GDs (e.g. WHO) work with CRGs to update reviews (they fund this).

-

Factors contributing to delay in updates unclear, but lack of resources, reviewer delay and slow editorial processes indicated.

-

-

Methodological issues.

-

Cochrane methods respected.

-

Newer is better (newer CRs seen as methodologically better).

-

May be statistical issues (wrong data/statistical methods – barrier to use).

-

Lack of clarity on which follow-up data used from papers.

-

Network meta-analysis, comparative analysis reviews.

-

GRADE (NICE has to use it, Cochrane does not).

-

Cochrane focuses on RCTs – not always appropriate, particularly for public health.

-

GDs want better facilities for sharing and reanalysing data from CRs.

-

-

Collaboration/communication.

-

Good communication improves use of review.

-

Timing of communication important.

-

Dialogue/clear communication/negotiation important with appropriate persons.

-

Collaboration and positive engagement might help to speed things up.

-

Close collaboration between WHO and certain Cochrane groups.

-

Formal links between CRG and GDs to promote use of CR.

-

GDs experience problems communicating with CRGs.

-

Issues of ownership/authorship – recognition and reward.

-

CR, Cochrane Review; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation.

Theme 1: the process of using a Cochrane Review in the development of guidance

It was clear that Cochrane Reviews were used at a number of different stages of the guideline development process. They were often used early in the process, for example to scope review questions and assess the strength of existing evidence.

Normally at the guideline group meetings I might present the findings [of Cochrane Review] . . . to give them an introduction into what kind of research is out there already.

Participant 4

All of the GDs we spoke to said that they would search for Cochrane Reviews as part of the guideline process, with searching for Cochrane Reviews often seen as a priority.

If you find a couple of good Cochrane Reviews you think oh thank heavens, you know Cochrane have done it. So we would use those first and foremost.

Participant 8

If suitable Cochrane Reviews existed they would be used as they were or built on and updated.