Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 12/62/01. The protocol was agreed in June 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in January 2014 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Michael Fisher has received consultancy fees from Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Greenhalgh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Description of health problem

Acute coronary syndromes (ACSs) are life-threatening conditions associated with acute myocardial ischaemia with or without infarction. 1 These conditions usually result from a reduction in blood flow associated with a coronary artery becoming narrow or blocked through atherosclerosis (an accumulation of plaque containing fatty deposits or, less commonly, erosion of the endothelium) and atherothrombosis (a blood clot formed following the rupture of plaque). The classic symptom of ACS is chest pain or tightness, although many people (particularly women, the elderly and those with diabetes mellitus) may present with atypical pain or no pain at all. 2–4 Other symptoms may include breathlessness, sweating and nausea. 2–4

The underlying cause of ACS is build-up of atheroma within the wall of the coronary artery. This occurs over a number of years and is generally asymptomatic. 5 The risk factors for ACS are multifactorial and are the same as for cardiovascular (CV) disease. Among the non-modifiable risk factors are increasing age, sex (male) and a family history of premature coronary heart disease or premature menopause. Modifiable risk factors include smoking, diabetes mellitus (and impaired glucose tolerance), hypertension, dyslipidaemia, obesity and physical inactivity. 1,5 People with a history of myocardial infarction (MI) have an increased risk of recurrence or of other vascular events (e.g. stroke) when compared with the general population. 6

There are three main types of ACS diagnosed by clinical history, electrocardiography (ECG) and levels of cardiac enzymes: (1) ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), (2) non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and (3) unstable angina (UA). A diagnosis of STEMI indicates that the affected artery is completely occluded, resulting in progressive necrosis of the area of heart muscle dependent on its blood supply. 5,7 The most common cause of a STEMI is complete and persistent occlusion of a coronary artery by a blood clot (thrombus). 8 A diagnosis of NSTEMI indicates partial or temporary blocking of an artery with limited tissue damage. 5,7 In the case of UA, clinical history suggests cardiac ischaemia, but without tissue death. 5,7

Over time, any damage sustained by the heart muscle results in scar tissue. The degree of the damage impacts on the overall ability of the heart to pump blood, which in turn impacts on the patient’s longer-term survival. 8 The timely treatment of ACS is imperative as almost half of potentially salvageable heart muscle is lost within 1 hour of the coronary artery being occluded, and two-thirds is lost within 3 hours. 8 One treatment for ACS is percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), also known as coronary angioplasty. In PCI, the affected coronary artery is dilated using a balloon catheter and a stent is usually implanted to act as a scaffold and to hold open the artery wall. 9 All PCI procedures are accompanied by adjunctive treatment with antiplatelet drugs. These drugs are the focus of this review.

Treatment pathway

ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

The objective of treatment for patients with STEMI is rapid and sustained revascularisation. 10 The recommended treatment for people with confirmed STEMI is immediate (primary) PCI to the occluded artery. 9,11 Clinical guidelines produced by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (CG1678) recommend coronary angiography with follow-on PCI (if indicated) as the preferred treatment for acute STEMI if presentation is within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms and primary PCI can be delivered within 120 minutes. When PCI facilities are not immediately available, treatment with thrombolysis (pharmacological reperfusion achieved through the use of ‘clot-busting’ drugs) should be considered. 12 When STEMI persists despite thrombolytic treatment, PCI (rescue) in an appropriately equipped unit should be considered. 8

Unstable angina/non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction

The objective of treatment for patients with UA/NSTEMI is to alleviate pain and anxiety, prevent recurrences of ischaemia and prevent, or limit, progression to further acute MI. 1 NICE Clinical Guideline CG9413 recommends that people presenting with UA/NSTEMI are initially treated with aspirin and antithrombin therapy. Their risk of further cardiac events should then be assessed using a risk score measurement tool that predicts 6-month mortality, such as the Global Registry of Acute Cardiac Events (GRACE). 14 In addition to a GRACE14 score, additional factors should be considered, including full clinical history [age, previous MI, previous coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG)], physical examination (including measurement of blood pressure and heart rate), and resting 12-lead ECG and blood tests (troponin I or T, creatinine, glucose and haemoglobin). Table 1 is adapted from NICE CG9413 and describes the risk categories of future CV events assigned to risk scores.

| Predicted 6-month mortality | Risk of future adverse CV events |

|---|---|

| ≤ 1.5% | Lowest |

| > 1.5–3.0% | Low |

| > 3.0–6.0% | Intermediate |

| > 6.0–9.0% | High |

| > 9.0% | Highest |

Patients considered to be at intermediate to high risk should be offered coronary angiography and follow-on PCI (if appropriate) within 96 hours of admission. 15 Patients with UA/NSTEMI who are clinically unstable or at high ischaemic risk should be offered angiography as soon as possible. 13 Patients at low risk should be treated medically; however, if ischaemia is subsequently experienced or is demonstrated on ischaemia testing, coronary angiography and delayed PCI (if appropriate) should be offered. 13

Epidemiology

The Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project5 (MINAP) is a national clinical audit of the management of heart attack. All hospitals in England, Wales and Belfast that admit patients with STEMI or NSTEMI contribute data (with the exception of Scarborough Hospital).

The most recent audit report5 presents analyses for admissions between April 2012 and March 2013. The audit recorded 80,974 patients with a final diagnosis of MI; 40% (32,665) of cases were diagnosed as STEMI and 60% (48,309) were diagnosed as NSTEMI. The average age of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI was 65 years and 72 years, respectively. 5

The authors of the report5 emphasise that the audit records the majority of admissions for STEMI but that NSTEMI admissions are under-represented.

Of the total number of patient admissions for STEMI, MINAP5 recorded that 68% (20,990) had primary PCI. The remaining patients received thrombolytic treatment (3%), no reperfusion treatment or treatment that was unclear (29%). 5

The Assessment Group (AG) notes that the MINAP5 data set does not include data for patients with UA as this condition does not fall under the audit’s MI remit. However, the AG is aware that, in England in 2012 to 2013, there were 54,000 finished consultant episodes and 32,000 patient admissions for UA. 16

British Cardiovascular Intervention Society Audit Data

The British Cardiovascular Intervention Society (BCIS) continuously audits interventional activity in the UK and the results are published annually. The most recent audit returns are for the year 2012. 17 The audit shows that there are currently 99 NHS PCI centres in the UK, almost double the number recorded in 2002. In 2012, 91,000 PCI procedures (for all indications) were carried out in the UK NHS, 27.4% in STEMI patients and 36.9% in UA/NSTEMI patients; the remainder were rescue or facilitated PCIs. A total of 24,631 PCIs for STEMI were conducted, the majority of which (23,842) were primary PCIs. The number of PCIs for STEMI has increased over time while the number of PCIs for UA/NSTEMI has remained stable.

Of patients referred for PCI in the UK in 2012, 74% were male and the average age was 64.9 years. 17 Approximately 20% had diabetes mellitus and 27% had had a previous MI. 17 One-quarter were current smokers and the majority (92%) were European. 17 It should be noted that these data are for an overall population of patients treated with PCI and, therefore, include patients other than those with ACS.

There are 85 NHS PCI centres in England and four in Wales. The total number of PCIs (all indications) performed in the NHS in England and Wales in 2012 was 75,217 and 3850, respectively. Almost 21,000 PCI procedures in England and 1000 in Wales were primary PCI procedures.

The BCIS audit data17 show that the number of PCIs performed in England and Wales has increased annually, although the rate of increase has slowed. In 2002, fewer than 30,000 procedures were carried out and, in contrast, almost 80,000 PCIs were conducted in 2012. The BCIS data describe the use of the radial artery (guidewire inserted through the wrist) as the access point for PCI. Radial access has risen to 65% of PCIs conducted in 2012 from 10% in 2004.

Antiplatelet treatment

Treatment with antiplatelet therapy is an established adjunct to PCI both before and for up to 12 months after the procedure (NICE CG1678 and NICE CG94). 13 The purpose of antiplatelet treatment is to inhibit the aggregation of platelets that can lead to thrombus formation and further vascular events including stent thrombosis. Dual antiplatelet therapy, aspirin plus prasugrel (Efient®, Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd UK/Eli Lilly and Company Ltd), clopidogrel or ticagrelor (Brilique®, AstraZeneca), is the standard antiplatelet treatment in clinical practice in the UK.

Relevant national guidelines

A quality standard for ACS has been referred for consideration to NICE and, at the time of writing, was expected to be published in September 2014. 18,19 A treatment pathway for patients with ACS is also available on the NICE website. 20

A number of NICE guidance documents and NICE guidelines are relevant to this review. These are described in Table 2.

| NICE documentation | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| TA18221 (2009): prasugrel for the treatment of ACSs with PCI | Prasugrel in combination with aspirin is recommended as an option for preventing atherothrombotic events in people with ACS having PCI, only when:

|

| CG9413 (2010): UA and NSTEMI: the early management of UA and NSTEMI | Offer a 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel to all patients with no contraindications who may undergo PCI within 24 hours of admission to hospital |

| In line with Prasugrel for the treatment of ACSs with PCI (TA182), prasugrel in combination with aspirin is an option for patients undergoing PCI who have diabetes or have had stent thrombosis with clopidogrel treatment | |

| It is recommended that treatment with clopidogrel in combination with low-dose aspirin should be continued for 12 months after the most recent acute episode of NSTEMI. Thereafter, standard care, including treatment with low-dose aspirin alone, is recommended | |

| TA23622 (2011): ticagrelor for the treatment of ACSs | Ticagrelor in combination with low-dose aspirin is recommended for up to 12 months as a treatment option in adults with ACS, that is, people:

|

| CG17223 (2013): secondary prevention in primary and secondary care for patients following a MI (CG172 is an update of CG48) | Aspirin should be offered to all people after a MI and continued indefinitely, unless individuals are aspirin intolerant or have an indication for anticoagulation |

| For patients with aspirin hypersensitivity, clopidogrel monotherapy should be considered as an alternative treatment | |

Clopidogrel is a treatment option for up to 12 months for:

|

|

| Ticagrelor is also recommended as per TA236 noted above | |

| Prasugrel for the treatment of ACS has not been incorporated in this guidance because this technology appraisal is currently scheduled for update | |

| There are special recommendations for antiplatelet therapy in people with an indication for anticoagulation | |

| CG1678 (2013): STEMI: the acute management of myocardial infarction with ST segment elevation | Following reperfusion therapy for STEMI, treatment with aspirin should be continued in line with CG48 MI secondary preventiona |

| The Guideline Development Group considered that treatment with clopidogrel is an established option in the pharmacological treatment of people with acute STEMI including people undergoing primary PCI. The Guideline Development Group were aware that a clopidogrel loading dose of 600 mg is not licensed in the UK, but is used widely in current practice, especially in people undergoing primary PCI | |

| Prasugrel was noted as a recommended treatment from TA182 and is the subject of this current appraisal | |

| Ticagrelor is recommended as in TA236 |

Description of technology under assessment

Intervention

The oral antiplatelet prasugrel, used within its licensed indication, is the focus of this review. The Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC) for prasugrel is available from the Electronic Medicines Compendium. 24

Prasugrel is a third-generation oral thienopyridine adenosine diphosphate receptor antagonist. It has a more rapid onset of action than clopidogrel as it requires only a single, relatively rapid metabolic step to produce the active agent (clopidogrel requires two steps). Prasugrel is prescribed as an adjunctive therapy to PCI to reduce platelet aggregation by irreversibly binding to P2Y12 receptors. It is available as 5-mg or 10-mg film-coated tablets. Prasugrel is given (with aspirin) as a single 60-mg loading dose and then continued at 10 mg daily for up to 12 months.

Prasugrel is licensed in Europe25 to be co-administered with aspirin, for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in patients with ACS (STEMI and UA/NSTEMI) undergoing primary or delayed PCI. As stated in the SPC, the use of prasugrel in patients with a history of stroke or transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is contraindicated, whereas in older (≥ 75 years) patients prasugrel is generally not recommended. For patients who weigh < 60 kg, the 60-mg loading dose of prasugrel should be used followed by a maintenance dose of 5 mg. 24 The SPC further states that, in patients with UA/NSTEMI in whom coronary angioplasty is performed within 48 hours after admission, the loading dose of prasugrel should be given only at the time of PCI.

NICE guidance (TA18221) limits the use of prasugrel (co-administered with aspirin) in the NHS to people with ACS having PCI only when:

-

immediate primary PCI for STEMI is necessary

-

stent thrombosis has occurred during clopidogrel treatment

-

the patient has diabetes mellitus.

In TA182,21 prasugrel was not recommended for patients with UA/NSTEMI who do not have diabetes mellitus or have not had a stent thrombosis following treatment with clopidogrel.

There is no patient access scheme in operation in the NHS for prasugrel.

The SPC for prasugrel highlights the increased bleeding risk for patients with ACS who are treated with prasugrel and aspirin. It is noted that the use of prasugrel in patients at increased risk of bleeding should be considered only when the benefits in terms of preventing ischaemic events are deemed to outweigh the risk of serious bleeding. 24

Current usage in the NHS

The decision paper26 presented to the Guidance Executive of NICE in June 2012 stated that the market share for prasugrel in terms of prescriptions had risen from 1% to 2% since 2011 and the monthly spend in the NHS had increased from approximately £400,000 to approximately £500,000. Data from the BCIS audit18 illustrate that prasugrel use has increased marginally between 2011 and 2012 (Table 3).

| Patient group | 2011 | 2012 |

|---|---|---|

| UA/NSTEMI | 1.5% | 2.6% |

| STEMI | 22% | 22.6% |

| UA/NSTEMI patients with diabetes mellitus | 1.7% | 2.8% |

The current British National Formulary (BNF)27 list price of prasugrel for both 5-mg and 10-mg tablets is £47.56 per pack of 28 tablets. The current Drug Tariff28 list price of aspirin 75 mg is 0.82 pence per pack of 28 tablets.

Comparators

The stated comparators to prasugrel in the final scope issued by NICE7 are clopidogrel (generic) and ticagrelor, both in combination with low-dose aspirin.

Clopidogrel

Clopidogrel is a thienopyridine and is available as a 300-mg and 75-mg film-coated tablet. The 300-mg tablet is intended as a loading dose for patients with ACS and treatment should be continued at 75 mg daily with aspirin (75–325 mg). Clopidogrel has a marketing authorisation for use in several patient groups relevant to this appraisal:

-

patients with MI (from a few days until < 35 days)

-

patients with STEMI in combination with aspirin who are eligible for thrombolytic therapy

-

patients with NSTEMI undergoing a stent placement following PCI, in combination with aspirin.

The AG notes that, according to its European Medicines Agency (EMA) licence, clopidogrel is not indicated for use in STEMI patients undergoing PCI. The patent for clopidogrel (Plavix, Sanofi) expired in 2010 and a number of generic versions are now licensed. This means that the cost of clopidogrel has substantially reduced since prasugrel was considered by NICE in 2009 (TA182). 21

In the SPC, increased bleeding risk with clopidogrel use is noted, as is a possible interaction with proton pump inhibitors. 29

The current Drug Tariff28 list price for clopidogrel is £1.71 per pack of 28 tablets.

Ticagrelor

Ticagrelor is a direct-acting P2Y12 receptor antagonist that has a different mechanism of action from the thienopyridines (prasugrel and clopidogrel). It has a rapid onset of action compared with clopidogrel and is a reversibly binding oral adenosine phosphate receptor antagonist. Ticagrelor is licensed in Europe30 (co-administered with aspirin) for the prevention of atherothrombotic events in adult patients with ACS (UA/NSTEMI or STEMI), including patients managed medically and those who are managed with PCI or CABG. Ticagrelor is administered as a 90-mg film-coated tablet. Treatment should be started with a single 180-mg loading dose (two 90-mg tablets) and then continued at 90 mg twice daily. The recommended use of ticagrelor is a single course of treatment up to 12 months with aspirin. 31

In the UK, NICE guidance (TA23622) recommends ticagrelor (with low-dose aspirin) for up to 12 months as a treatment option for adults with ACS:

-

with STEMI or

-

with NSTEMI or

-

patients admitted to hospital with UA.

The SPC31 for ticagrelor notes that patients treated with ticagrelor and aspirin are at increased risk of non-CABG major bleeding and are also more generally at risk of bleeds requiring medical attention but not fatal or life-threatening bleeds. Therefore, the SPC31 recommends that the use of ticagrelor in patients at known increased risk for bleeding should be balanced against the expected benefit in terms of prevention of atherothrombotic events. It is further noted that co-administration of ticagrelor with strong CYP3A4 inhibitors is contraindicated, as co-administration may lead to a substantial increase in exposure to ticagrelor. 31

Data from the 2012 BCIS audit report18 indicate that in 2012 ticagrelor was used in 3.74% of PCI procedures in patients with UA/NSTEMI and in 7.04% of PCI procedures in patients with STEMI. The current BNF price27 of ticagrelor is £54.60 per pack of 56 tablets.

In October 2013, AstraZeneca32 reported that it had received a demand from the US Department of Justice, Civil Division, seeking documents and information regarding the PLATO (PLATelet inhibition and patient Outcomes)33 trial, the pivotal trial that led to the regulatory authorisation of ticagrelor both in the US and in Europe. The AG is aware34 that the EMA has also contacted AstraZeneca requesting further information about the PLATO33 trial.

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

Decision problem

The remit of this appraisal is to review and update (if necessary) the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evidence base described in TA182. 21 The key elements of the decision problem issued by NICE in the final scope7 for this appraisal are set out in Table 4.

| Interventions | Prasugrel in combination with aspirin |

| Population | Patients with ACS undergoing primary or delayed PCI |

| Comparators | Clopidogrel in combination with low-dose aspirin |

| Ticagrelor in combination with low-dose aspirin | |

| Outcomes | The outcome measures to be considered include:

|

| Economic analysis | The reference case stipulates that the cost-effectiveness of treatments should be expressed in terms of incremental cost per QALY gained |

| The reference case stipulates that the time horizon for estimating clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness should be sufficiently long to reflect any differences in costs or outcomes between the technologies being compared | |

| Costs should be considered from a NHS and Personal Social Services perspective | |

| Other considerations | If the evidence allows, the following subgroups will be considered: people with STEMI, UA/NSTEMI, people with diabetes mellitus |

| Guidance will be issued only in accordance with the marketing authorisation | |

| The availability of any patient access schemes for the interventions and comparators should be taken into account in the analysis |

Within this report, reference to the use of prasugrel, clopidogrel or ticagrelor indicates that these treatments are given concomitantly with low-dose aspirin as per their licensed indications.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The remit of this review is to appraise the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prasugrel within its licensed indication for the treatment of ACS with PCI (review of NICE technology appraisal TA182). 21

Chapter 3 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for reviewing the clinical effectiveness evidence are described in this chapter. The methods for reviewing the cost-effectiveness evidence are described in Chapter 6.

Methods for reviewing effectiveness

In addition to searching the manufacturer’s submission for relevant references, the following databases were searched for studies of prasugrel:

-

EMBASE (Ovid) 1974 to 18 June 2013.

-

MEDLINE (Ovid) 1946 to Week 1 June 2013.

-

The Cochrane Library June 2013.

-

PubMed January 2010 to April 2013.

The results were entered into an EndNote X5 (Thomas Reuters, CA, USA) library and the references were deduplicated. Full details of the search strategies used are presented in Appendix 1.

The reference lists of included trials were searched for relevant trials. Information on trials in progress was sought from cardiology conference databases (European Society for Cardiology and the American College of Cardiology). The website clinicaltrials.gov was also searched for ongoing trials. In addition, advice was sought from the clinical advisor to the review.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Two reviewers (JG and NF) independently screened all titles and abstracts identified via searching and obtained full-paper manuscripts that were considered relevant by either reviewer (stage 1). The relevance of each study was assessed (JG/NF) according to the criteria set out below (stage 2), and studies that did not meet the criteria were excluded and their bibliographic details were listed alongside reasons for their exclusion. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, when necessary, a third reviewer (AB) was consulted.

Study design

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the assessment of clinical effectiveness.

Interventions and comparators

The effectiveness of prasugrel within its licensed indication was assessed. Studies that compared prasugrel with clopidogrel or ticagrelor were considered for inclusion in the review.

Patient populations

Patients with ACSs who were to be treated with primary or delayed PCI constituted the relevant population.

Outcomes

Data on any of the following outcomes were included in the assessment of clinical effectiveness: non-fatal and fatal CV events, mortality from any cause, atherothrombotic events, incidence of revascularisation procedures, adverse effects of treatment (including bleeding events) and health-related quality of life (HRQoL).

Data extraction strategy

Data relating to both study design and quality were extracted by two reviewers (JG and KD) into an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel 2010; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The two reviewers cross-checked each other’s data extraction and, when multiple publications of the same study were identified, data were extracted and reported as a single study.

Quality assessment strategy

The quality of the clinical effectiveness studies was assessed independently by two reviewers (JG and KD) according to the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at the University of York’s suggested criteria. 35 All relevant information is tabulated and summarised within the text of the report. Full details and results of the quality assessment strategy for clinical effectiveness studies are reported in Appendix 2.

Methods of data synthesis

The results of the clinical data extraction and clinical study quality assessment are summarised in structured tables and as a narrative description. An indirect treatment comparison of prasugrel with ticagrelor was planned.

Results

Quantity and quality of research available

A total of 1940 titles and abstracts were screened for inclusion in the review of clinical effectiveness evidence. The process of study selection is shown in Figure 1. Titles excluded at stage 2 (n = 111) are listed in Appendix 3 along with reasons for their exclusion. The AG identified the pivotal trial (TRITON-TIMI 3836) discussed in TA18221 but did not identify any new trials for inclusion in the review.

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow chart.

At stage 2, the AG excluded four clinical trials. 37–40 One of the trials37 compared prasugrel with clopidogrel in a population of Asian patients with ACS undergoing PCI. This was excluded as it was considered to be a dose-ranging trial with a clopidogrel control. The trial recruited 719 patients and randomised them to one of three dosing regimens of prasugrel or standard clopidogrel according to patient weight and age (< 60 kg and > 70 years or vice versa). The primary outcome was platelet aggregation at 4 hours after the loading dose. Secondary outcomes included major adverse cardiac events and CABG and non-CABG thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) bleeding at 30 days and 90 days. The study was not powered to detect differences between treatments on the secondary outcomes. The JUMBO-TIMI (Joint Utilization of Medications to Block Platelets Optimally – Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction 26)38 trial was similarly excluded. In this trial, patients (n = 904) undergoing PCI were randomised to one of three prasugrel dosing regimens or to clopidogrel and followed up for 30 days.

Two further excluded trials39,40 included relevant comparators and patient populations but had pharmacodynamic (platelet aggregation) parameters. The AG considered that the trial populations were too small and the length of follow-up too short (5 days and 1 hour) to provide data relevant to this review.

Assessment of clinical effectiveness

The AG’s systematic search of clinical effectiveness evidence yielded one relevant RCT (TRITON-TIMI 3836) for inclusion in the review. This trial was the pivotal trial discussed in TA18221 and the key elements of this RCT are summarised in Table 5. The TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial included 13,608 patients and was conducted in 30 countries. Patients received a loading dose of either prasugrel or clopidogrel (60 mg or 300 mg, respectively) followed by daily maintenance doses of 10 mg or 75 mg, respectively.

| Design | Intervention | Inclusion criteria (main) | Exclusion criteria (main) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| International (30 countries) multicentre, Phase III double-blind, double-dummy RCT comparing prasugrel with clopidogrel in patients undergoing PCI. Patients (n = 13,608) were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio and stratified according to presentation [i.e. UA/NSTEMI (n = 10,074) or STEMI (n = 3534)]. Duration of study: 15 months (median). A total of 73 patients were recruited from the UK | Prasugrel (LD 60 mg/MD 10 mg). Clopidogrel (LD 300 mg/MD 75 mg). Loading dose administered before, during or after PCI. Maintenance dose was continued for a median period of 14.5 months | Moderate- to high-risk UA or NSTEMI patients: ischaemic symptoms of 10 minutes or longer within 72 hours of randomisation. TIMI risk score of ≥ 3 and either ST segment deviation of ≥ 1 mm or an elevated cardiac biomarker of necrosis. Patients with STEMI could be enrolled within 12 hours of symptom onset if primary PCI was planned or within 14 days if delayed PCI was planned following initial pharmacotherapy for STEMI | Patients at increased risk of bleeding: anaemia, thrombocytopenia, intracranial pathology including TIA or stroke (within the last 3 months), severe hepatic dysfunction, oral anticoagulants, chronic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, or use of any thienopyridine within 5 days | Primary: composite of CV death, non-fatal MI or non-fatal stroke during follow-up period. Secondary: composite of death from CV causes, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, rehospitalisation owing to cardiac ischaemic event. Composite of all-cause death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, stent thrombosis. At 30 days and 90 days: primary composite end point, composite of CV death, non-fatal MI, UTVR. Safety: non-CABG-related bleeding, TIMI life-threatening bleeding, TIMI major or minor bleeding |

The results of the AG’s quality assessment of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial are presented in Appendix 2. Overall, the AG considers that the trial was robustly designed and of strong methodological quality.

As this report is an update of TA182,21 the AG has reproduced the original summary information for TRITON-TIMI 3836 in Appendix 4. The summary information presented includes:

-

patient baseline characteristics (overall trial population)

-

primary and secondary end point analyses (overall trial population)

-

prespecified subgroup analyses for diagnosis, sex, age, diabetic status, type of stent implanted, use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa receptor agonist, renal function (overall trial population)

-

outcomes for STEMI patients (overall trial population)

-

primary outcome for UA/NSTEMI, STEMI, all ACSs, patients with diabetes mellitus, patients with stents (overall trial population)

-

outcomes for people with history of stroke/TIA

-

outcomes for people > 70 years or weighing < 60 kg

-

analyses of recurrent events following PCI (overall trial population).

A number of subgroup analyses relating to TRITON-TIMI 3836 have been published; the key publications are listed, along with a brief description, in Table 6. A more comprehensive list of associated publications is presented in Appendix 5 of this report. The paper by Wiviott (2011),42 which is directly relevant to this appraisal, focuses on a sub-population of patients from the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial who are described as the ‘core clinical cohort’. This sub-population is discussed in TA18221 as the ‘target population’. The core clinical cohort comprises patients for whom prasugrel is licensed and who may be treated with the full recommended dose of prasugrel (60-mg loading dose followed by 10 mg daily). These patients have no history of stroke or TIA, are younger than 75 years and weigh more than 60 kg. The AG focuses on the clinical evidence relevant to this subgroup. The rationale for this focus is presented in Appendix 6.

| Reference | Title | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Wiviott et al. 200641 | Evaluation of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with ACSs: design and rationale for the TRITON-TIMI 38 | Paper describing the design of the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial |

| Wiviott et al. 200736 | Prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in patients with ACSs | Primary publication of TRITON-TIMI 38 trial |

| Wiviott et al. 201142 | Efficacy and safety of intensive antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel from TRITON-TIMI 38 in a core clinical cohort defined by worldwide regulatory agencies | Paper describing outcomes of core clinical cohort of patients from TRITON-TIMI 38 trial: patients have no known history of stroke or TIA, are aged below 75 years and weigh more than 60 kg. The core clinical cohort represents 10,804 of the 13,608 patients included in the overall trial cohort |

The core clinical cohort42 comprised 10,804 patients (79%) from the randomised population of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. The characteristics of the patients in the core clinical cohort and the overall trial population are described in Table 7. The proportions of patients quoted in Table 7 (taken from Wiviott et al. 42) are not presented by trial arm. However, Wiviott et al. 42 states that patients in the core clinical cohort randomised to prasugrel and clopidogrel were well matched and that 50% of the core clinical cohort was randomised to prasugrel. 42 The AG notes that the patients in the overall trial population and the core clinical cohort appear to be similar in terms of baseline characteristics. In TA182,21 the overall trial population of TRITON-TIMI 3836 was considered to be younger and less likely to have experienced a prior MI than patients in clinical practice in England and Wales.

| Characteristic | Core clinical cohort, % (n = 10,804) | Overall trial population, % (n = 13,608) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (median) | NS | 61 years (median) |

| UA/NSTEMI | 73 | 74 |

| Male | 79 | 74 |

| White | 93 | 93 |

| Region | ||

| North America | 32 | 32 |

| South America | 4 | 4 |

| Western Europe | 25 | 26 |

| Eastern Europe | 25 | 25 |

| Africa/Asia/Middle East | 14 | 14 |

| Medical history | ||

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 56 | 56 |

| Hypertension | 62 | 64 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 22 | 23 |

| Previous MI | 17 | 18 |

| Previous CABG | 7 | 8 |

| Creatinine clearance < 60 ml/minute | 4 | 12 |

| Multivessel coronary intervention | 14 | 14 |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor | 56 | 55 |

| ACE/ARB | 75 | 76 |

| Beta-blocker | 89 | 88 |

| Statin | 93 | 92 |

| CCB | 16 | 18 |

| ASA | 100 | 99 |

Clinical efficacy in the core clinical cohort

The manufacturer submission (MS; Daiichi Sankyo Company Ltd/Eli Lilly and Company Ltd, 2013) and the Wiviott et al. 42 paper report the clinical outcomes for the core clinical cohort of patients from the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. It is emphasised by Wiviott et al. 42 that the core clinical cohort was identified in a post-hoc fashion defined by regulatory (EMA and the US Food and Drug Agency) criteria and should be considered as hypothesis generating.

The clinical efficacy outcomes for the core clinical cohort are presented in Table 8. For the primary composite end point of death from CV causes, non-fatal MI or non-fatal stroke, statistically significantly fewer events were recorded in the prasugrel arm (8.3%) than in the clopidogrel arm (11%) [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.74; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.66 to 0.84; p < 0.0001]. Similarly, for the secondary composite end point (death from any cause, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or non-CABG-related non-fatal TIMI major bleeding) statistically significantly fewer events were recorded in the prasugrel arm (10.2%) than in the clopidogrel arm (12.5%) (HR = 0.80; 95% CI 0.71 to 0.89; p < 0.001). The AG notes that the efficacy for both composite outcomes appears to be driven by the number of non-fatal MIs.

| End point | Clopidogrel, n/N (%) | Prasugrel, n/N (%) | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | ||||

| Death from CV causes, non-fatal MI or non-fatal stroke | 569/5383 (11)a | 433/5421 (8.3)a | 0.74 (0.66 to 0.84) | < 0.001 |

| Secondary | ||||

| Death from any cause, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, or non-CABG-related non-fatal TIMI major bleeding (net clinical benefit) | 641/5383 (12.5)a | 522/5421 (10.2)a | 0.80 (0.71 to 0.89) | < 0.001 |

| CV death or MI | 10.2% | 7.7% | 0.75 (0.66 to 0.85) | < 0.10 |

| CV death | 1.4% | 1.4% | 1.05 (0.75 to 1.46) | 0.78 |

| Death | 2.0% | 2.1% | 1.03 (0.78 to 1.37) | 0.82 |

| MI | 9.4% | 6.7% | 0.71 (0.62 to 0.81) | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 1.0% | 0.8% | 0.75 (0.49 to1.15) | 0.19 |

| Stent thrombosis: definite | 2.0% | 0.8% | 0.41 (0.29 to 0.60) | < 0.001 |

| Stent thrombosis: definite/probable | 2.3% | 1.0% | 0.44 (0.31 to 0.62) | < 0.001 |

Statistically significant differences in favour of prasugrel were also reported for the outcomes of definite stent thrombosis (HR = 0.41, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.60; p < 0.001) and definite or probable stent thrombosis (HR = 0.44; 95% CI 0.31 to 0.62; p < 0.001). There were also statistically significantly fewer MIs in the prasugrel arm (6.7%) than in the clopidogrel arm (9.4%) (HR = 0.71, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.81; p < 0.001).

Efficacy across subgroups within the core clinical cohort

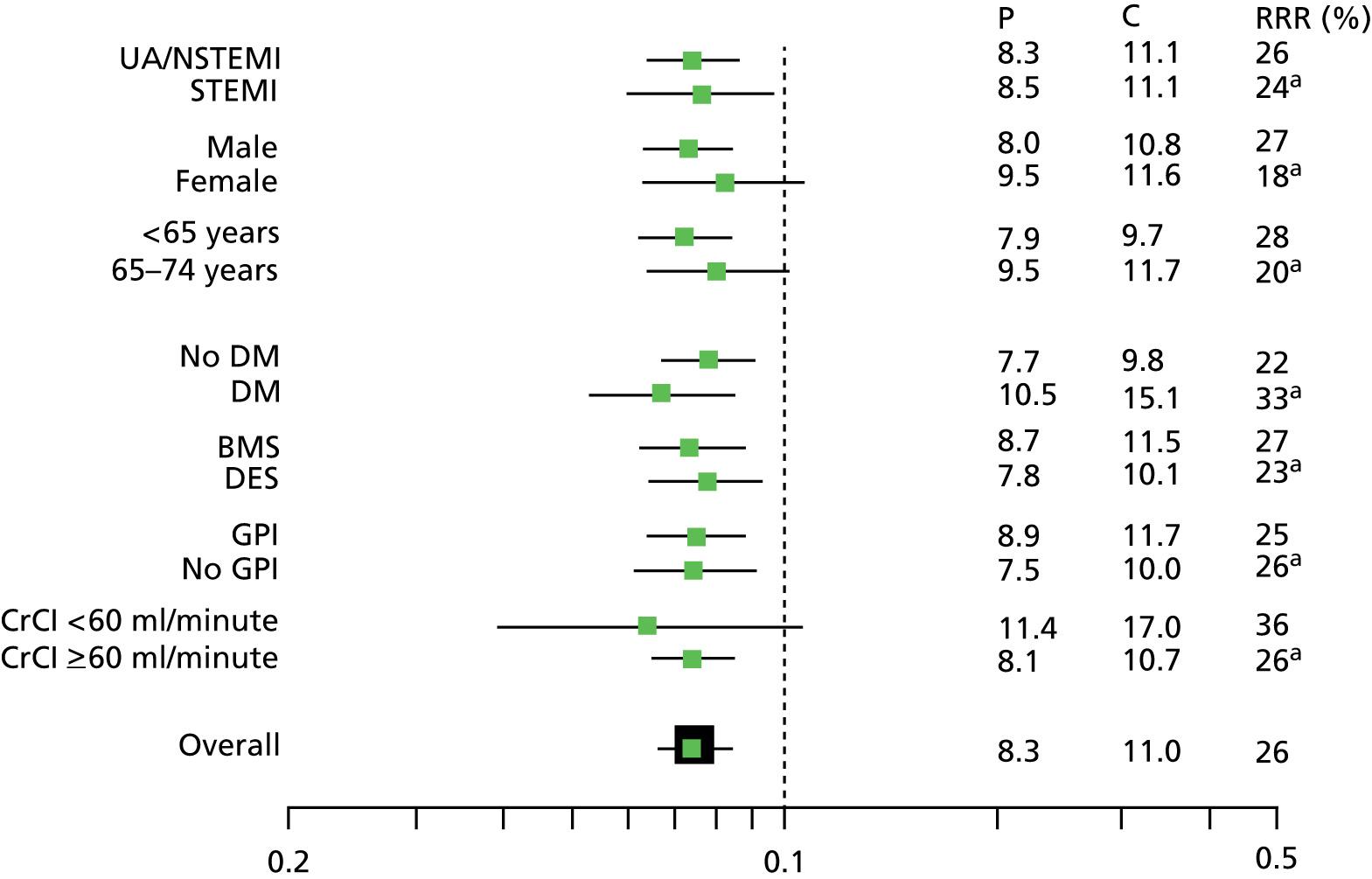

Wiviott et al. 42 present a forest plot that displays the relative effectiveness of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel across a range of subgroups within the core clinical cohort, including diagnostic group (UA/NSTEMI or STEMI), sex, age and diabetic status. The published forest plot is reproduced in Figure 2. The clinical effectiveness of prasugrel appears to be consistent across subgroups.

FIGURE 2.

Key subgroups for primary efficacy end point (core clinical cohort). BMS, bare metal stent; CrCI, creatinine clearance; DES, drug-eluting stent; DM, diabetes mellitus; GPI, glycoprotein inhibitor; RRR, relative risk reduction. a, p-value was not significant. Reprinted from Am J Cardiol, vol. 108, Wiviott SD, Desai N, Murphy SA, Musumeci G, Ragosta M, Antman EM, et al. , Efficacy and safety of intensive antiplatelet therapy with prasugrel from TRITON-TIMI 38 in a core clinical cohort defined by worldwide regulatory agencies, pp. 905–11, 2011, with permission from Elsevier.

Efficacy across time in the core clinical cohort

It is noted in Wiviott et al. 42 that, in the core clinical cohort, prasugrel was more effective than clopidogrel for the primary end point at 30 days as well as at the 15-month follow-up (Table 9).

| End point | Clopidogrel (n = 5383) | Prasugrel (n = 5421) | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary: death from CV causes, non-fatal MI or non-fatal stroke | ||||

| 30 days | 7.0% | 5.0% | 0.70 (0.60 to 0.82) | < 0.0001 |

| 30 days to 15 months | 4.5% | 3.6% | 0.80 (0.65 to 0.97) | 0.027 |

Safety in the core clinical cohort

The key safety end point in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial was the rate of non-CABG-related TIMI major bleeding in the overall trial cohort at 15 months. The data for the safety end points at 15 months in the core clinical cohort are presented in Table 10. No statistically significant difference in non-CABG-related TIMI major bleeding was noted between patients in the prasugrel and clopidogrel arms; however, there was a significant difference in favour of clopidogrel when major and minor bleeding events were combined (3.0% vs. 3.9%) (HR = 1.26, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.57; p = 0.03).

| End point | Clopidogrel, n/N (%) | Prasugrel, n/N (%) | HR (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-CABG-related TIMI major bleeding | 73/5337 (1.5) | 91/5390 (1.9) | 1.24 (0.91 to 1.69) | 0.17 |

| TIMI major or minor bleed | 3.0% | 3.9% | 1.26 (1.02 to 1.57) | 0.03 |

| Fatal TIMI major | 0.1% | 0.2% | 2.65 (0.70 to 9.97) | 0.14 |

| Intracranial haemorrhage | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.69 (0.30 to 1.62) | 0.39 |

| TIMI major or minor bleeding | ||||

| 30 days | 1.6% | 1.9% | 1.21 (0.91 to 1.62) | 0.19 |

| 30 days to 15 months | 1.5% | 2.1% | 1.31 (0.95 to 1.79) | 0.97 |

Net clinical benefit

The analysis of the net clinical benefit outcome (death from any cause, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke or non-CABG-related non-fatal TIMI major bleeding) favoured the use of prasugrel in the core clinical cohort (12.5% in the clopidogrel group vs. 10.2% in the prasugrel group; HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.89; p < 0.001).

Health-related quality of life

Data relevant to HRQoL are available only for the TRITON-TIMI 3836 overall trial population and are not specific to the core clinical cohort. The HRQoL substudy was open to all TRITON-TIMI 3836 patients at participating sites in eight countries: the USA, Australia, Canada, Germany, Italy, Spain, the UK and France. HRQoL was evaluated using three instruments: (1) the Angina Frequency and Physical Limitations scales of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire; (2) the London School of Hygiene Dyspnoea Questionnaire; and (3) the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) self-report questionnaire and the European Quality visual analogue scale. Assessments were taken at baseline and at days 30, 180, 360 and 450 (or last visit).

The HRQoL study recruited a much smaller sample than was initially planned (475 patients, compared with 3000 patients), and in TA18221 the representativeness of the substudy sample was considered to be unclear, as was the clinical utility of the results. Therefore, the AG was unable to draw any conclusions as to the HRQoL of patients treated with prasugrel or clopidogrel in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. The results from the HRQoL study are presented in the MS.

Data relevant to key patient groups of the core clinical cohort

Specific clinical data relating to patients with STEMI, NSTEMI or diabetes mellitus in the core clinical cohort were not available from the MS. The AG notes from the forest plot in Figure 2 that the clinical effectiveness of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel was in evidence across the range of subgroups including STEMI, UA/NSTEMI and patients with and without diabetes. The manufacturer’s model enabled economic data pertaining to these patient groups to be extracted.

Overall summary of findings

All of the outcomes listed in the final scope issued by NICE were reported in the MS.

The clinical outcomes for the core clinical cohort of the TRITON-TIMI 3842 trial demonstrate statistically significant differences in favour of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel across a range of outcomes and clinical subgroups. In terms of safety (bleeding events), one statistically significant difference between prasugrel and clopidogrel was noted. The exception was for the combined outcome of TIMI major and minor bleeding, for which significantly more events occurred with prasugrel than with clopidogrel. No conclusions regarding HRQoL could be drawn owing to lack of data.

Clinical discussion points from TA182

It is noted in this report that the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial was a well-designed trial. However, three key areas of uncertainty were raised at the time of TA18221 by the Appraisal Committee (AC) in respect of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. The AC was concerned that the results of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial may not be generalisable to patients in England and Wales for the following reasons:

-

The loading dose of clopidogrel administered in the trial was 300 mg whereas a loading dose of 600 mg may be administered in clinical practice in England and Wales.

-

The majority of patients (74%) in the trial received the clopidogrel loading dose during the PCI procedure. In clinical practice in England and Wales, patients undergoing planned PCI receive the clopidogrel loading dose before the PCI procedure.

-

Clinical efficacy in the trial was largely driven by statistically significant differences in non-fatal MIs. Non-fatal MIs included both clinical MIs (symptoms) and non-clinical MIs (biomarkers and ECG readings). If only the incidence of clinical MIs were compared between treatment arms, there may be no differences in outcomes between the arms.

Clopidogrel loading dose: size

Manufacturer comments

The difference in size of the clopidogrel loading dose given to patients in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial (300 mg) and the dose (600 mg) most often used in clinical practice in England and Wales is addressed in the MS. The manufacturer acknowledges that there is variation in UK clinical practice as to whether 300 mg or 600 mg of clopidogrel is used in PCI treatment.

The manufacturer points out the inconsistency between clinical guidelines as to the recommended loading dose of clopidogrel (300 mg or 600 mg). For example, in NICE CG94,13 published in 2010, NICE recommends 300 mg while acknowledging that evidence exists to support the use of 600 mg. The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN)43 guidelines recommend the use of a 300-mg loading dose, whereas the European Society for Cardiology (ESC) advocates both 300-mg and 600-mg loading doses. 10,11,44

The manufacturer states that the case for the additional benefit of 600 mg rather than 300 mg is not proven and cites the results of the CURRENT-OASIS (Clopidogrel and Aspirin Optimal Dose Usage to Reduce Recurrent Events–Seventh Organization to Assess Strategies in Ischemic Syndromes 7)45 trial, published in 2010. In this trial, patients with ACS (n = 25,806) who were scheduled for early angiography and PCI were randomised to receive a loading dose of 300 mg or 600 mg of clopidogrel and either high- or low-dose aspirin. The patients who received a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel and had a PCI continued with 150 mg of clopidogrel for the first 7 days and on day 8 received the standard 75-mg maintenance dose. Patients who received the 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel and had a PCI continued on 75 mg of clopidogrel following the PCI procedure. The MS reports that in the overall trial population (which also includes the patients who did not undergo the scheduled PCI), the primary composite end point of death from CV causes, MI or stroke at 30 days was not statistically significantly different between the 600-mg arm (4.2%) and the 300-mg arm (4.4%) (HR = 0.94, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.06; p < 0.61); however, there was a statistically significant increase in bleeding events in the 600-mg arm (2.5%) compared with the 300-mg arm (2.0%) (HR = 1.24, 95% CI: 1.05 to 1.46; p < 0.01). This finding was consistent for subgroups of patients regardless of diagnosis (STEMI or NSTEMI).

The outcomes for the 69% of patients randomised to the CURRENT-OASIS 746 trial and who received PCI treatment after randomisation only are also reported in the MS. A statistically significant difference in the occurrence of the primary composite end point in favour of the 600-mg arm (3.9%) compared with the 300-mg arm (4.5%) is noted (HR 0.86, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.99; p = 0.039). However, the MS states that no statistical differences were noted for either the STEMI subgroup (HR 0.83, 95% CI 0.66 to 1.05; p < 0.117) or NSTEMI subgroup (HR 0.87, 95% CI 0.72 to 1.06; p < 0.167).

The manufacturer concludes that the results of the overall CURRENT-OASIS45 trial do not demonstrate any clear benefit associated with the use of a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel compared with a 300-mg dose and thus it is unlikely that the use of 600 mg of clopidogrel in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial would have changed the efficacy results, although it may have resulted in an increase in the number of bleeding events in the clopidogrel arm.

Assessment Group comments

The AG is aware that the licensed loading dose of clopidogrel is 300 mg and that this was the established loading dose in routine clinical practice in the USA when the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial commenced. The AG notes that, in TA182,21 the manufacturer supported the case for the use of 300 mg of clopidogrel in the UK by reporting data from the Eli Lilly-sponsored AntiPlatelet Treatment Observational Registry47 and the IMS Health Acute Cardiovascular Analyser study. 48,49 These data indicated that, in 2007, 60–79% of ACS patients in the UK received the 300 mg licensed dose. Clinical advice to the AG is that clinical practice differs between PCI centres as to the loading dose of clopidogrel.

The AG agrees with the manufacturer that there are differences in the stated recommendations in the available clinical guidelines. The manufacturer correctly states that that the SIGN43 guidelines recommend a 300-mg loading dose of clopidogrel whereas the ESC10,11,44 guidelines recommend both 300 mg and 600 mg.

The most recent NICE guidelines for UA/NSTEMI (CG9413) state that most people admitted with UA/NSTEMI should be treated with a loading dose of 300 mg of clopidogrel. However, the guidelines further state that, if very early (< 24 hours) invasive intervention is planned, a higher loading dose should be considered, particularly in cases for which the procedure will be carried out within 6 hours. The guideline development group (GDG) responsible for CG9413 has stated in the guideline that as they were not able to formally review all the evidence for a 600-mg loading dose, they were not able to recommend this at the time of publication.

The recently published (July 2013) NICE guidelines CG1678 for patients with STEMI simply state that treatment with clopidogrel is an established option in the pharmacological treatment of people with acute STEMI, including people undergoing primary PCI. The GDG for CG1678 noted that a clopidogrel loading dose of 600 mg is not licensed in the UK but is used widely in current practice, especially in people undergoing PCI.

The AG agrees with the manufacturer’s conclusion that the results from the overall population of the CURRENT-OASIS 745 trial do not appear to support the use of a 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel over a 300-mg dose. However, the AG considers that the results of the subgroup analysis45 of the 69% (17,263) of patients treated with PCI suggest that the trial protocol clopidogrel regimen of a 600-mg loading dose followed by 7 days at 150 mg and then 75 mg daily statistically significantly reduces CV events (including stent thrombosis) when compared with a loading dose of 300 mg followed by 75 mg daily. However, the AG also notes that the prevalence of bleeding events was statistically significantly greater in the 600-mg arm than in the 300-mg arm. In addition, the trial follow-up was for a period of 30 days and, therefore, longer-term outcomes are unknown. The AG notes that the findings of the PCI subgroup analysis of the CURRENT-OASIS 746 trial are based on subgroup analyses that are subject to statistical caveats; however, the findings are consistent with those of a meta-analysis comprising trials with PCI-treated patients. 50

In summary, the AG considers that the loading dose of clopidogrel given in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial may be inconsistent with the majority of clinical practice in England and Wales. Data to determine whether or not there is any difference in clinical efficacy between a 300-mg and 600-mg loading dose of clopidogrel are limited.

Timing of the clopidogrel loading dose

Manufacturer comments

In the MS, the manufacturer notes that the timing of the clopidogrel loading dose administered to patients in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial (79% of patients received treatment at the time of PCI) is different to the timing of the loading dose in clinical practice (clopidogrel is given prior to PCI whenever possible) in England and Wales. 21 However, the manufacturer also points out, citing data from the MINAP report,5 that door-to-treatment time in the UK is decreasing annually, thereby reducing the opportunity for preloading with clopidogrel.

The manufacturer restates the arguments put forward in their MS for TA18221 that changing the timing of the loading dose of clopidogrel in the trial would not have greatly impacted on the clinical efficacy outcomes of the trial. The manufacturer cites numerous sources of evidence derived from the analysis of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial to support their argument:

-

The effects of prasugrel were consistent over time. For the overall study period, the HR (0.81, 95% CI 0.73 to 0.90) is similar to the HR for the 0–3 days time period (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.96) and the period from 3 days to the end of the study period (HR 0.80, 95% CI 0.70 to 0.93). An additional landmark analysis examining occurrence of MI, stent thrombosis and urgent target vessel revascularisation (UTVR) at 0–3 days and beyond 3 days confirmed sustained benefit over time.

-

In the case of patients treated with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors, there was no evidence that the relative benefit of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel was reduced or that there was an excess need for bail-out glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor use during PCI in those patients randomised to clopidogrel in the study.

-

A group of patients received pretreatment up to 24 hours before PCI. The percentage of patients in this pretreated subgroup reaching the composite end point of CV death, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke from randomisation through study end was 9.94% and 11.29% (unadjusted crude event rates) for patients pretreated with prasugrel and clopidogrel, respectively. Although the difference is not statistically significant for this subgroup, the difference supports the theory that, to a large extent, the timing of the loading dose did not influence overall efficacy.

Assessment Group comments

The AG considers that the evidence to support or refute the benefits of preloading with clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel at the time of PCI is equivocal; this means that whether or not patients in the trial would benefit more from clopidogrel compared with patients in the NHS in England and Wales remains unclear.

Clinical compared with non-clinical myocardial infarctions

Manufacturer’s comments

A point of discussion during the previous appraisal21 of prasugrel was that the definition of MI used in TRITON-TIMI 3836 included non-clinically detected MIs. The manufacturer states that the definition of MI in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial was based on the American College of Cardiology Task Force on Clinical Data Standards published in 2001. 51 This definition was prespecified and agreed with the regulatory agencies [United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and EMA] prior to the start of the trial. The AC and the Evidence Review Group (ERG) were concerned that, if the non-clinical MIs were excluded from the analyses, the resultant clinical difference in non-fatal MIs alone may not be statistically significant when comparing prasugrel with clopidogrel. In response, the manufacturer cited evidence from a reanalysis52 of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial MI (n = 1218 MIs). These MIs were reassessed according to the 2007 criteria of the Universal Definition of Myocardial Infarction (Table 11) developed by the European Society of Cardiology, the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the World Heart Federation Task Force. 53 Reviewers, who were blinded to treatment allocation, assessed the size and timing of all MIs and whether or not the MI was STEMI or NSTEMI. Of the 1218 MIs considered, 1163 had biomarker data to indicate the size. In the MS, the manufacturer reports that, when analysed according to non-clinical and clinical MIs, compared with clopidogrel, prasugrel demonstrated a significant reduction in MIs that was consistent across the spectrum of MIs of varying type, size and timing.

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Type 1 | Spontaneous MI caused by a primary coronary event, such as a plaque rupture in a coronary artery with less blood then flowing to the muscle |

| Type 2 | Secondary MI owing to either increased oxygen demand or decreased supply owing to other conditions such as spasm of the coronary artery or low blood oxygen from anaemia |

| Type 3 | Sudden cardiac death with evidence of MI but occurring before blood samples could be obtained or before the appearance of cardiac biomarkers in the blood |

| Type 4 | MI related to a PCI |

| Type 4a | MI associated with a PCI procedure |

| Type 4b | MI associated with stent thrombosis as documented by an angiography or at autopsy |

| Type 5 | MI associated with CABG |

The manufacturer also points to a further analysis54 of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 data in which the rate of CV death within 180 days was compared in people who had experienced a new MI and those who had not. Among patients who experienced a new MI of any type, the rate of CV death was significantly higher (6.5% vs. 1.3%; p < 0.001). This was the case even after adjustment for other risk factors (adjusted HR 5.2, 95% CI 3.8 to 7.1; p = 0.001). The manufacturer argues that these findings suggest that all MIs have prognostic implications.

In summary, the manufacturer claims that the results of the reanalysis52,54 of the MIs from the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial demonstrate that treatment with prasugrel significantly reduces the risk of all MIs when compared with clopidogrel. The manufacturer also states that further evidence suggests that any type of MI is associated with a significantly increased risk of CV death, with a consistent relationship across all MI types as defined53 by the universal classification system.

Assessment Group comments

The AG considers that the manufacturer has provided a convincing case to support the hypothesis that prasugrel is effective across all types of MI when compared with clopidogrel. The AG also notes the finding that the reductions in MIs associated with small enzyme releases were not significantly different in the prasugrel-treated and clopidogrel-treated arms of the trial. This suggests that the clinical efficacy results were unlikely to have been driven by reductions in non-clinical MIs.

In summary, of the three key issues raised in TA18221 and discussed in this section, the AG considers that the size and timing of the loading dose of clopidogrel and the impact these factors have on the primary outcome of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial remain unclear. However, the reanalysis52,54 of the MIs by the manufacturer demonstrates that prasugrel was more effective than clopidogrel in preventing occurrence of MIs.

Stent thrombosis

In TA182,21 prasugrel is recommended for patients who have had a stent thrombosis during the course of treatment with clopidogrel. In the MS for the present review, the manufacturer describes the outcomes of related research conducted in collaboration with Professor Gershlick (Consultant Cardiologist, University Hospital of Leicester, Leicester, UK). The purpose of the research is to develop a method to identify patients at risk of stent thrombosis. The manufacturer reports that 20 risk factors for stent thrombosis have been identified, nine relating to patient factors, three relating to the lesion and eight relating to the PCI. These risk factors are presented in table 26 of the MS. The risk scores have subsequently been validated by the manufacturer using data from patients in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. It is suggested in the MS that the risk scores could be used in clinical practice to identify patients at risk of stent thrombosis and thereby guide treatment decisions.

Comparison of prasugrel with ticagrelor

At the time of TA182,21 the standard comparator to prasugrel was clopidogrel. However, in 2010, NICE approved the use of ticagrelor as an antiplatelet treatment for patients with ACS (TA236). 22 The pivotal clinical trial assessing ticagrelor is the PLATO33 trial, in which ticagrelor is compared with clopidogrel in a population of ACS patients. Further information pertaining to the PLATO33 trial is presented in Appendix 7. In the MS (for ticagrelor), the manufacturer of ticagrelor (AstraZeneca) put forward a convincing case that a formal indirect treatment comparison between the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials would be inappropriate. The manufacturer’s case was accepted by both the ERG and the AC at the time of the ticagrelor appraisal (TA236). 22

Since the appraisal of ticagrelor, no new relevant RCTs have been conducted with either prasugrel or ticagrelor, nor is there any new direct evidence comparing prasugrel with ticagrelor. However, a number of authors have published indirect treatment comparisons using data from the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials. The AG considers that any comparison of the results of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials is both problematic and inappropriate. Consequently, the AG has not conducted an indirect treatment comparison in this update of TA182. 21 The AG is of the opinion that the issues that mitigate against conducting such an indirect comparison remain unchanged from those presented and accepted during TA236 (ticagrelor). 22 Specifically, these refer to differences in the target populations, the usage of clopidogrel (loading dose and timing of administration) and differences in MI assessment. The AG notes that there is no indirect comparison presented in the MS and that the manufacturer agreed with the AC and the ERG in TA236 (ticagrelor)22 that such an indirect comparison would be inappropriate.

Problems with an indirect comparison of the TRITON-TIMI 38

The key features of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials are described in Table 12 (reproduced from the MS for TA236). 22 Both trials were conducted in an ACS population, use clopidogrel as a comparator and report the same primary composite efficacy end point (death from CV causes, non-fatal MI, or non-fatal stroke during the follow-up period).

| Characteristic | TRITON-TIMI 38 | PLATO |

|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 13,608 | 18,624 |

| Patient population | Patients with early invasively managed ACS scheduled for PCI (including STEMI and NSTEMI patients undergoing same admission PCI). Symptom onset within 72 hours | Broad ACS population (including STEMI). Symptom onset within 24 hours |

| Prior clopidogrel | Excluded | Allowed (including in-hospital prior to randomisation) |

| % STEMI | Capped at 26% (18% undergoing primary PCI) | 40.5% (all intended for primary PCI) |

| Clopidogrel load | Only 300 mg allowed | 300 mg or 600 mg |

| Timing of randomisation | Later: after angiography; after decision to perform PCI | Earlier: usually before angiography (if done) |

| Randomisation | Prasugrel 60-mg load and 10 mg once daily or clopidogrel 300-mg load and 75 mg once daily | Ticagrelor 180-mg load and 90 mg twice daily or clopidogrel 300- to 600-mg load and 75 mg once daily |

| Administration of study drug | Started in the time interval from randomisation up to 1 hour after PCI | Started immediately after randomisation |

| Primary efficacy end point | CV death/MI/stroke | CV death/MI/stroke |

| Primary safety end point | Non-CABG TIMI major bleeding | PLATO major bleeding |

| PCI | 99% (all at randomisation) | 61% (49% within 24 hours of randomisation) |

| CABG | 3.2% (0.35% on primary admission) | 10.2% (4.5% on primary admission) |

| Medical management only | 1.1% | 34% |

| Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa use | 54% | 27% |

| Follow-up | Up to 15 months | Up to 12 months |

Differences in the target population

The TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial recruited patients with ACS who were intended to be managed with PCI and were randomised just prior to the PCI. A more diverse range of patients was randomised to the PLATO33 trial; patients in PLATO33 were randomised at presentation and then investigators decided whether patients were to receive revascularisation treatment or medical therapy.

A TRITON-TIMI trial publication55 describes the results of a subgroup of patients with STEMI; however, this group included patients who were treated with primary or planned PCI. In the PLATO33 trial, all patients with STEMI were treated with primary PCI.

A subgroup analysis56 of the PLATO33 trial has also been published. This analysis describes the results of ACS patients who were intended for invasive treatment. However, as only 77% of this cohort actually underwent PCI it cannot be considered as a PCI-only cohort.

Differences in clopidogrel loading

The two trials33,36 differed as to the dosing and timing of administration of clopidogrel (the common comparator). The loading dose of clopidogrel administered in the TRITON-TIMI 38 trial36 was 300 mg, but, in the PLATO trial,33 loading doses of 300 mg or 600 mg were allowed. A total of 19.6% of clopidogrel-treated patients in the overall PLATO33 cohort, 26.8% in the cohort intended for invasive management and 38.6% in the STEMI cohort received 600 mg of clopidogrel.

In the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial, most patients received their loading dose of clopidogrel in the time interval between the insertion of the guidewire for PCI up to 1 hour after the procedure, whereas, in the PLATO33 trial, most patients received their loading dose of clopidogrel before randomisation.

The issue of the size of loading dose and timing of administration of clopidogrel was discussed in detail earlier in this report (see Clinical discussion points from TA182). The AG is of the opinion that the differences in clopidogrel usage across the two trials must be considered problematic. The AG remains convinced that, for the reasons previously outlined, there are no reliable clinical data to permit a robust comparison of prasugrel with ticagrelor.

Differences in myocardial infarction assessment

The assessment of MIs across the two trials requires consideration. It was noted in TA23622 that determining whether or not a patient has a non-clinical MI during the angioplasty procedure is difficult, as any enzymatic changes observed may be wholly due to the original MI that triggered the procedure. A more definitive assessment can be made if multiple measurements of cardiac enzymes are taken between the initial event and the PCI procedure as it is then possible to differentiate a gradually falling pattern of enzymes and a subsequent rise after the PCI (consistent with a further MI having occurred at the time of the procedure). It was further noted in TA23622 that, in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial (with the exception of the STEMI primary PCI cohort), there was time for at least two preprocedure enzyme measurements to be taken, whereas, in the PLATO33 trial, only one preprocedure enzyme measurement was taken and any elevated enzymes could not be reliably attributed to either the index event or a new MI. The impact of the differences in MI assessment means that in the PLATO33 trial the majority of MIs included in the primary end point were clinical MIs, whereas almost half of those included in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial results were non-clinical only.

Differences in duration of trials

There was a difference in the length of follow-up of the two trials. The PLATO33 trial involved a median follow-up of 9 months, whereas the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial followed patients for a median of 15 months. The AG is of the opinion that it is not appropriate to indirectly compare outcomes at 9 months with those at 15 months as the proportion of participants experiencing CV death, MI or stroke is likely to increase as the length of follow-up increases.

Differences in the primary analysis of the trials

The two trials33,36 also used different measures for the primary analysis. In anticipation of a lack of proportionality of hazards in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial, assessment of the primary outcome was made using the Gehan–Wilcoxon test for the primary analysis rather than the log-rank test. (The Gehan–Wilcoxon test assigns greater weight to earlier time points than the log-rank test.) The log-rank test was then used in a prespecified sensitivity analysis. In contrast, the Cox proportional hazards model was used for the primary analysis in the PLATO trial. 33 The AG is concerned about the impact that the different assumptions stated in these trials would have on the results of an indirect comparison.

Summary and critique of published indirect comparisons of prasugrel and ticagrelor

Four published indirect comparisons57–60 of prasugrel compared with ticagrelor were identified by the AG and the manufacturer during searching; the key features of these studies are described in Appendix 8. The quality of the four published indirect comparisons57–60 identified by the AG (and the manufacturer) was assessed using the assessment of multiple systematic reviews (AMSTAR)61 tool. The results are presented in Appendix 9.

The published indirect comparison of ticagrelor and prasugrel in patients with ACS conducted by Biondi-Zoccai et al. 57,62 was based on the results of the PLATO33 and TRITON-TIMI 3836 trials as well as on data from a 12-week dose-ranging trial that compared ticagrelor with clopidogrel in 990 patients with NSTEMI [Dose confIrmation Study assessing anti-Platelet Effects of AZD6140 vs. clopidogRel in non-ST segment Elevation myocardial infarction 2 (DISPERSE 2)]. 63 The total number of patients in the indirect comparison was 32,893. The results of the indirect comparison of prasugrel and ticagrelor demonstrated no statistically significant differences in overall death, non-fatal MI, non-fatal stroke, or their composite. 57 Prasugrel was associated with a significantly lower risk of stent thrombosis, and ticagrelor was associated with a significantly lower risk of any major bleeding and major bleeding associated with cardiac surgery. However, the risk of non-CABG-related major bleeding was similar for prasugrel and ticagrelor. The authors concluded that prasugrel and ticagrelor are superior to clopidogrel for ACS. The results of the indirect comparison suggest similar efficacy and safety of prasugrel compared with ticagrelor, whereas prasugrel appears more protective of stent thrombosis but causes more bleeding.

The AG’s main criticism of the indirect comparison in Biondi-Zoccai et al. 57 is that the findings are largely based on the outcomes of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials. The substantial differences between the two trials (see Problems with an indirect comparison of TRITON-TIMI 38) render the results of the indirect comparison unreliable. The AG considers that results from the dose-ranging DISPERSE-263 trial make a negligible contribution to the results presented by Biondi-Zoccai et al. 57 as the length of follow-up was very short. The AG also notes that the published indirect comparison considered overall death (not CV death) as part of the primary composite end point.

The publication by Passaro et al. 59 presented a simplified network meta-analysis graph to improve the communicative value of the analysis undertaken by Biondi-Zoccai et al. 57 The analysis excluded the dose-ranging DISPERSE-263 trial and instead included the outcomes from the Clopidogrel in Unstable angina to prevent Recurrent Events (CURE)64 trial in which clopidogrel was compared with placebo in 12,562 patients with NSTEMI who were largely managed medically (only 21% of patients were treated with PCI). No rationale was given for the inclusion of the CURE64 trial. The AG assumes that the reason for inclusion was to enable the authors to expand the treatment network. The conclusions of this analysis concurred with those of Biondi-Zoccai et al. ,57 with the exception that no difference in major bleeding between prasugrel and ticagrelor was indicated. 59

As stated previously, the AG does not consider it appropriate to compare the results of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials owing to their inherent differences.

The meta-analysis conducted by Chatterjee et al. 58 was intended to compare prasugrel and ticagrelor in patients with ACS or those undergoing coronary intervention for the same, or for significant coronary artery disease, by conducting a network meta-analysis. 58 Four studies, comprising a total of 34,126 patients, were included: PLATO,33 TRITON-TIMI 38,36 DISPERSE-263 and JUMBO-TIMI 26. 38 The JUMBO-TIMI 2638 trial was a dose-ranging Phase II trial comparing prasugrel with clopidogrel in 900 patients intended for PCI. The follow-up was limited to 30 days. Chatterjee et al. 58 found no difference in CV mortality or rates of MI among patients undergoing PCI but stated that CABG-related bleeding was lower with prasugrel than with ticagrelor. The authors concluded that prasugrel may be more effective than ticagrelor for preventing stent thrombosis and recurrent ischaemic events and warn that the credibility of any indirect comparison hinges on the similarity of the included trials and point to the differences in the patient populations included in the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials (randomised at presentation for PCI and randomised at presentation to the treatment centre, respectively). The authors acknowledge that this increases the likelihood of heterogeneity and recommend that a head-to-head trial of prasugrel and ticagrelor should be carried out.

The AG is of the opinion that the results of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials have made a major contribution to the Chatterjee et al. 58 analysis and do not consider it appropriate to compare these two trials. The AG also considers that the length of follow-up of the DISPERSE-238 and JUMBO-TIMI 2638 trials was too short to provide data relevant to the current appraisal.

The work published by Steiner et al. 60 was intended to indirectly compare prasugrel, ticagrelor, high-dose clopidogrel and standard-dose clopidogrel in patients scheduled for PCI by undertaking a network meta-analysis from 14 eligible studies (48,982 patients). All studies are described in Appendix 7. The three largest studies are TRITON-TIMI 38,36 a substudy from the PLATO trial (PLATO-INVASIVE56) and CURRENT-OASIS 7 PCI. 45 These trials included patients with ACS and contributed almost 90% of patients in the analysis, whereas the other studies included stable or mixed study populations. A subgroup analysis was conducted on patients with ACS and treated with PCI using data from five studies: TRITON-TIMI 38,36 PLATO,33 CURRENT-OASIS 7,45 Han et al. 65 and DOSER. 66 This subgroup analysis corroborated the overall findings of the review which were that, for the majority of outcomes, there was no superiority of either prasugrel or ticagrelor and that prasugrel was associated with a significantly lower risk than ticagrelor for stent thrombosis but an increased risk of major or minor bleeding.

The AG is of the opinion that the overall network meta-analysis is not relevant to this review as the majority of included trials comprise stable or mixed study populations and are of short duration with primarily pharmacodynamics outcomes. The results of the ACS PCI subgroup are largely based on the comparison of the TRITON-TIMI 3836 and PLATO33 trials; the AG has previously stated this comparison to be inappropriate. The three other trials included in the subgroup analysis (CURRENT-OASIS 7,46 Han et al. 65 and DOSER66) compare high-dose clopidogrel with standard-dose clopidogrel and are of too short a duration to be of relevance to the current appraisal.

Discussion

One relevant RCT was identified for inclusion in this review, namely the TRITON-TIMI 3836 trial. This was an international, double-blind trial that recruited a large number of patients. The trial was robustly designed to demonstrate the clinical efficacy of prasugrel compared with clopidogrel in a population of patients with ACS who were treated with PCI. The outcomes for the core clinical cohort were considered relevant to this appraisal. Although the core clinical cohort comprised 79% of the overall trial population, this subgroup analysis was not prespecified in the original trial protocol42 and should, therefore, be considered as exploratory and hypothesis generating. Searching did not identify any trials of prasugrel compared with ticagrelor.