Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/31/02. The contractual start date was in February 2012. The draft report began editorial review in October 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Sniehotta is a co-applicant on a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Career Development Fellowship for Jean Adams, University of Newcastle (title: Financial incentives for health promoting behaviours). Professor Sniehotta is also a co-applicant on a related grant from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme [title: Parental incentives and quasi-mandatory schemes for increasing uptake of immunisations in pre-school children (September 2012–July 2014). J Adams, B Bateman, B Gardner Sood, S Michie, J Shucksmith, FF Sniehotta, T Cresswell, L Ternant. Value: £275,419.00]. Professor Linda Bauld is chief investigator on a NIHR HTA grant [title: Facilitators and barriers to smoking cessation in pregnancy (May 2013–April 2015). Bauld L, Graham H, Sinclair L, Flemming K, Naughton F, Tappin D, Gorman D. Value: £250,753.00]. Professor Bauld is also coprincipal investigator on a study funded by the Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, and the Glasgow Centre for Population Health and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde [title: Cessation in Pregnancy Incentives Trial (CPIT) (February 2011–December 2013). Tappin D, Bauld L, Briggs A and colleagues. Value: £850,000.00]. Professor David Tappin is co-applicant on a NIHR HTA grant [title: Facilitators and barriers to smoking cessation in pregnancy (May 2013–April 2015). Bauld L, Graham H, Sinclair L, Flemming K, Naughton F, Tappin D, Gorman D. Value: £250,753.00]. Professor Tappin is also coprincipal investigator on a study funded by the Chief Scientist Office, Scottish Government Health and Social Care Directorates, and the Glasgow Centre for Population Health and NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde [title: Cessation in Pregnancy Incentives Trial: The CPIT (February 2011–December 2013). Tappin D, Bauld L, Briggs A and colleagues. Value: £850,000.00].

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Morgan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

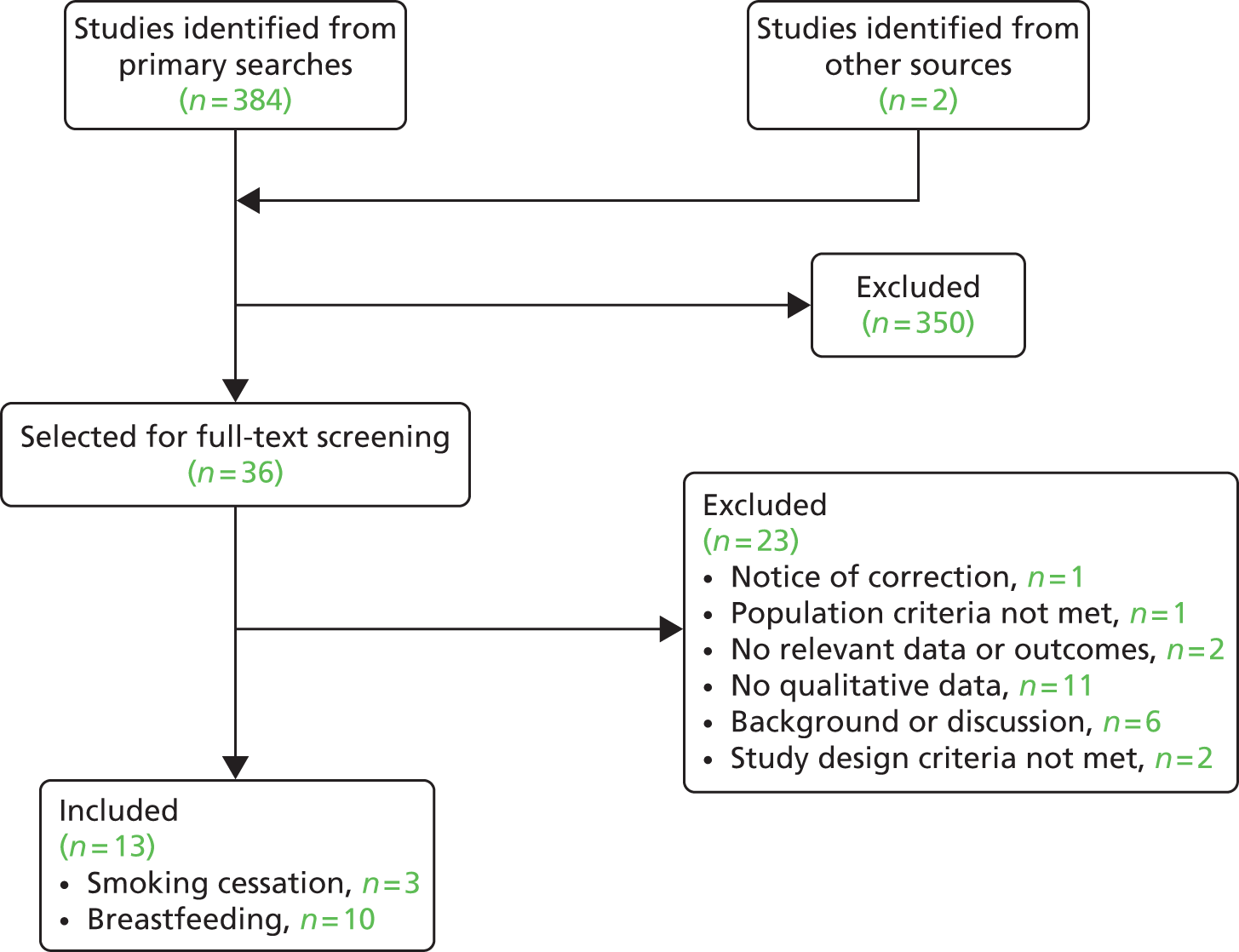

This monograph reports the findings of the Benefits of Incentives for Breastfeeding and Smoking cessation in pregnancy (BIBS) study. The BIBS study was funded to conduct evidence syntheses and primary qualitative and survey research, together with a discrete choice experiment (DCE), to develop an incentive taxonomy and to inform the design of an acceptable and feasible incentive intervention(s) with promise for improving smoking cessation in pregnancy and/or breastfeeding outcomes.

In this chapter we briefly describe what incentives are and how they are proposed to work to change behaviour. They are presented in the context of designing complex intervention trials to improve health outcomes. The health implications of smoking in pregnancy and breastfeeding are then considered with a brief history of incentives for these behaviours and the current policy context. The chapter concludes with the aims of the BIBS study and an overview of the chapters included in this report.

What are incentives and how do they work?

The Oxford English Dictionary1 defines an incentive as ‘a thing that motivates or encourages one to do something’. It is derived from the Latin word incentivum, ‘something that sets the tune or incites’, from incantare, ‘to chant or charm’. Incentives may be direct, as in a reward for attaining a goal, or indirect, for example reduced-price products or services. A financial incentive may also be a penalty imposed for not achieving a goal. Kane and colleagues2 argue that definitions of incentives often fail to distinguish their function and seldom consider the incentive within the larger environmental context. They propose that an incentive can function as a goal; as an external reinforcement of behaviour with the aim of increasing an individual’s internal motivation until it is sufficient; as reinforcement until learning is accomplished and a habit has formed; or as a way of focusing a person’s attention to a neglected area. For these reasons, we consider a broad definition of incentives delivered to and by a range of individuals and organisations in this study, as described later in this chapter.

Little is known about how incentives work in health care, how they might facilitate rather than erode informed choice and, crucially, how time and context modify effects. 3,4 In addition, new knowledge about behaviour, provided by neuroscience, is increasing rapidly and is beginning to inform theory. Incentive, motivation and behaviour theories are multitudinous, often overlap and are derived from a wide spectrum of disciplines besides health, including economics, psychology, sociology, education, law, business organisation and social policy. A review of these theories and of the neuroscience of incentives and rewards is beyond the scope of this study. Indeed, it has been asserted that there are too many theories of behaviour, with inherent problems around classification, labelling and the science underpinning the choice of theory. 5 In addition, Wise6 suggests that ‘Most writers have not come to grips with the problem of differentiating motivation from everything else’ (p. 161) with respect to human behaviour. This parallels the conclusion of Johnston and Dixon5 that there are gaps in the science of behaviour as applied to health. It is uncertain to what extent evidence and theories of incentives derived from non-health contexts are generalisable as this is a relatively new field of human behaviour research. Theories informing incentive interventions range from those targeting the individual only, which often stem from psychology and economics, to those that embrace the social network or apply a more ecological or systems approach to behaviour change. Economic theories focus on the values, costs and benefits of incentive interventions and can span all of these approaches. As many incentive interventions are multicomponent and complex,7 more than one theory of behaviour change from more than one discipline may explicitly or implicitly apply in an incentive programme.

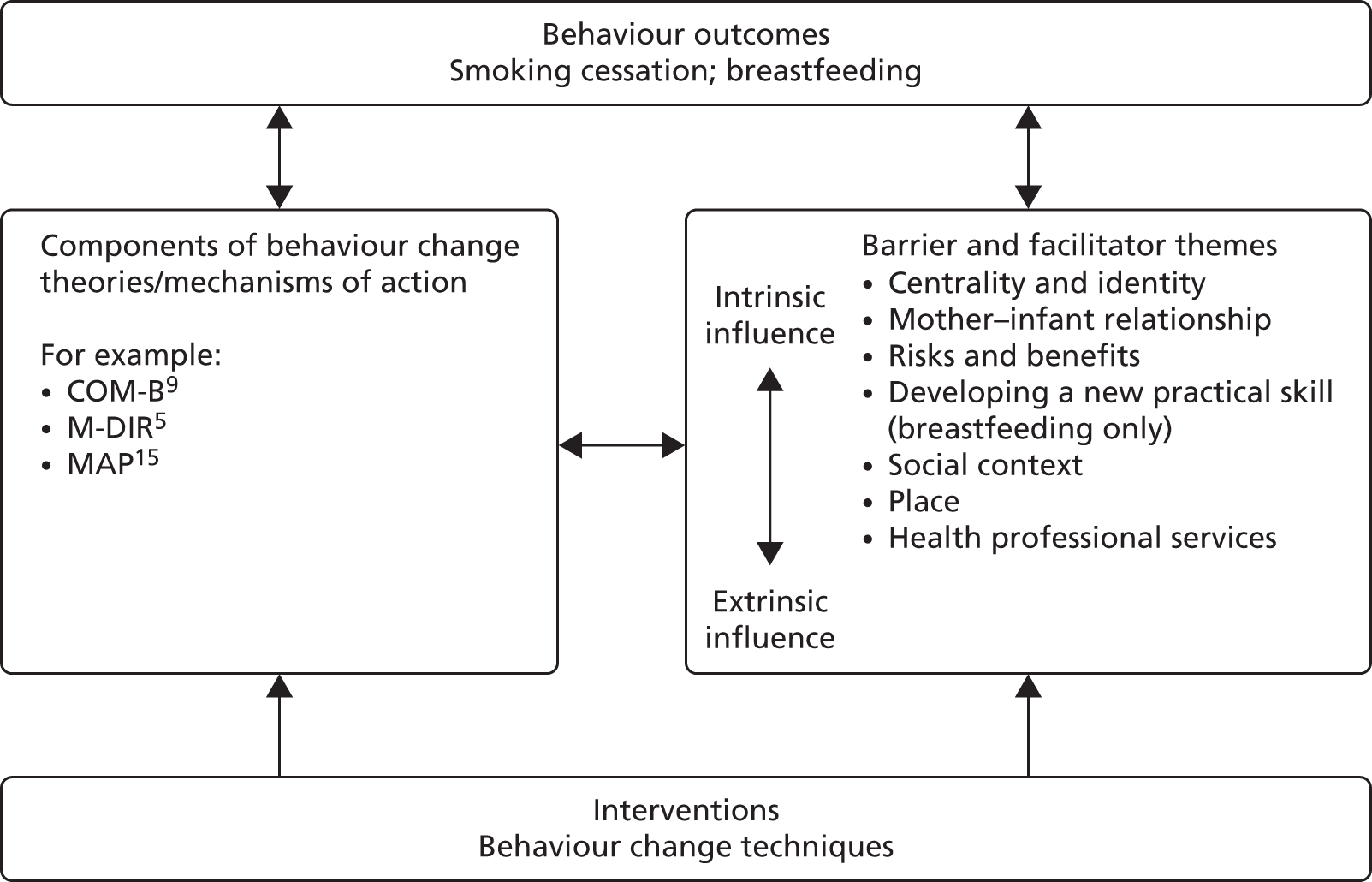

The following paragraphs provide a brief overview of theories selected by the research team because they were considered particularly relevant to the BIBS study of incentives for health behaviour change in relation to smoking cessation in pregnancy and breastfeeding. By definition, incentives serve as motivators. One motivational theory,6,8 discussed in the context of neuroscience research and substance misuse, describes three main variables for motivation: drive, incentive and reinforcement. This builds on the work of Skinner,9 who described the reinforcement of behaviours through rewards. A similar distinction between incentive and reinforcement is made by Michie and colleagues10 in a recent taxonomy of behaviour change techniques (BCTs). Drive and incentive precede behaviour and energise it; reinforcement follows the first enactment of behaviour to establish memory and other processes that strengthen and sustain it, for example pleasure. Intrinsic drive exerts a push effect on action and extrinsic factors such as incentives exert a pull effect on action. Consistent incentives, and their reinforcement, result in conditioned learned responses, which establish behaviour.

In early incentive studies, for example that by Higgins and colleagues,11 individual learning theory and operant conditioning theory are applied whereby the behaviour is influenced or controlled by the consequences. Learning theories assume that incentives will increase the target behaviour and that withdrawing the incentives should result in the behaviour stopping. They are rooted in social cognitive theories, such as social learning theory12 and the theory of planned behaviour,13 and hypothesise that people deliberately consider the balance of anticipated positive and negative consequences of their behaviour. From this perspective, incentives might tip the balance towards a desirable behaviour. In addition, incentives can also be explained by expectancy-value models, in which an individual forms beliefs about the consequences of a behaviour, attributes a value to these beliefs and incentives can change the value and the likelihood of the behaviour occurring. Social cognition models, like the theory of planned behaviour, are developments of expectancy-value models. 13

It is important to understand the fit of incentives and rewards with more general theories of behaviour, such as dual process models, which have proposed that behaviour is underpinned by two separate, but interacting, systems: the cognitive, rational and reflective system as well as an impulsive, emotional, automatic system. 14,15 Although the relative importance of these two systems is often contested, incentives may exert their effects through either of these two behavioural systems. More specifically, Dixon and Johnston16 have recently proposed a cognitive route MAP (i.e. Motivation development, Action on motivation or Prompted/cued behaviour) to behaviour change. Whereas the motivation and action routes can be allocated to the reflective system of dual process models, the prompted route is akin to the automatic system. MAP has been used to inform interventions by organising 89 BCTs as affecting behaviour through either of these three proposed MAP routes. 16 Rewards delivered contingent on the behaviour are thereby considered to act via the prompted route, which bypasses the reflective system. Incentives, on the other hand, in which the actor is aware that a reward will be delivered contingent on a target behaviour or goal, were not considered in MAP, yet incentives have the potential to develop and to influence behaviour via the motivational route. The most recent taxonomy of BCTs17 lists 93 hierarchically clustered techniques agreed through expert consensus methods and includes both incentives (i.e. informing someone that future rewards or removal of future punishment will be contingent on performance of the behaviour) and rewards (i.e. arranging the delivery of a reward if there has been effort and/or progress towards performing the behaviour).

In a recent review of behaviour change intervention development frameworks, Michie and colleagues10 have systematically integrated psychological theory (in line with aspects of dual processing models and MAP) together with intervention functions (including BCTs) and policy categories. At the heart of the wheel is the COM-B system, which refers to three proposed essential conditions of a Behaviour system: Capability, Opportunity and Motivation. The outer layer of the wheel contains nine intervention functions, one of which is incentives. The intervention functions address deficits in the COM-B system and an outer ring of seven policy categories is outlined as a way to draw in specific intervention functions. Applying the behaviour change wheel to incentives highlights the complexity of incentive intervention development, both in terms of the mechanisms of action as well as from a policy perspective. Thus, to develop a successful incentive-based intervention, it is paramount to take into account which sources of behaviour (or route to behaviour within the MAP framework) are being targeted as well as how the intervention can be stimulated from a policy perspective to integrate evidence-based behaviour change practice into routine care.

It can be argued that wider systems and ecological theory are relevant to understanding incentive interventions as occurring within a complex sociocultural milieu. Such approaches view incentives as having multiple interactions at different levels: between personal attributes, situations and the local and distal features of place, including their structural attributes, cultures and meanings. 18,19 Individual and national economic milieu, media influences and local incentive cultures within schools, workplaces and shops are all likely to impact on incentive outcomes. For example, in a study by Allen and colleagues,20 it was found that a central reason for disengagement in a smoking cessation incentive programme was the change in the contractual relationship between the pharmacist and the client. Some participants associated attending the pharmacy with attending for methadone distribution, which pharmacists supervise, and were concerned about the potential stigma involved, which enhanced feelings of failure, guilt and shame.

In addition to the proposed mechanisms of action for the incentives described above, there are effect moderators operating through incentive delivery processes. These usually include a variety of associated activities and relationships, for example to establish behavioural targets, agree to a commitment contract, monitor performance or provide additional BCTs. 21 Incentives are unlikely to be similarly effective across all types of behaviour or in all contexts. Within health, differences would certainly be anticipated when comparing incentives for habitual behaviour change, in particular when overcoming a physiological addiction (such as smoking), and incentives for the establishment of a new skilled, performing behaviour (such as breastfeeding). Tversky and Kahneman22 propose that changes in behaviour may be more likely to be triggered to avoid losses than to realise rewards, and Deci and Ryan23 consider intrinsic motivation to be as important a factor in explaining human behaviour as extrinsic motivators such as economic incentives. Indeed, there are some surprising findings from studies that demonstrate changes of behaviour despite only a small proportion of the incentives offered actually being redeemed. 2 This suggests that mechanisms other than the actual incentive are responsible, for example triggering a socially desirable response, yet this has been relatively underexplored. Deci and colleagues24 argue that incentives can actually inhibit intrinsic motivation, with associated perceptions of ‘paternalism’ interfering with effectiveness. This complexity is compounded by the fact that these behaviours are socially, culturally and environmentally situated and have different meanings, which can change rapidly for the actors involved.

From the perspective of economic theory, financial incentives are used to change the behaviour of health-care consumers and providers to induce an optimal level of supply. The use of incentives increases the benefits associated with activities that require greater levels of effort, and so changes the costs and benefit balance associated with choices. By increasing benefits through the introduction of explicit incentives, policy-makers can increase the likelihood that behaviour changes in the desired direction, providing the benefits are perceived as exceeding the costs of the new behaviour. Behavioural economic theory acknowledges that people’s preferences may depend on timing, with more immediate desirable and certain outcomes (e.g. pleasure) valued more highly than distant and uncertain outcomes (e.g. potential health consequences). Such future uncertain benefits are valued less highly than those enjoyed immediately and with certainty, a process known as discounting. The costs of health-promoting behaviour (whether it is associated with additional financial costs or greater personal effort), on the other hand, are felt immediately. A measure of delayed discounting, which Yoon and colleagues25 equate to impulsivity, has shown that the greater discounting (impulsivity) of rewards predicts post partum smoking and substance misuse relapse. However, as Marteau and colleagues4 point out, many people do not act in the way that they retrospectively would have preferred to act, and much of our behaviour is triggered automatically by situations and environments. 26 Changes to the ‘choice architecture’ within an organisation or system can facilitate behaviour change and immediately associating incentives with a desired behaviour might therefore tip the balance. 27 There is strong evidence that financial penalty incentives, for example increased taxes, change behaviour. 28,29 Incentives as a means to redistribute resources to address health inequalities have recently gained popularity in low- and middle-income countries.

Evidence, complex intervention design and incentives

The BIBS study, reported in this monograph, provides an incentive evidence platform that takes theory, service-user, health professional and general public perspectives into account to inform the design of incentive intervention trials. It represents Phase I of the framework for the design of complex interventions as recommended by the Medical Research Council (MRC)30 and draws on the less linear development published in 2008. 31 A generic linear causal model for applying behaviour change theory to intervention design is described by Hardeman and colleagues32 and specifies techniques and measures for each step in a causal pathway. Another approach that we apply in this study is to develop a logic model, to understand the theory, intervention components, activities, processes and outcomes involved in a programme, as recommended by Armstrong and colleagues. 33

An important consideration was to define the target population for receipt of incentive interventions. In this study, the effectiveness of incentives delivered to consumers and to health-care providers is considered in Chapters 3 and 5. The focus is to change health behaviour outcomes. However, an alternative outcome of redistribution is apparent in some incentives literature, in which incentives are targeted to low-income populations. Health inequalities are increasing in the UK, with one in four children born into poverty. 34

Universalism, proportionate universalism35 or specific targeting is an important consideration for intervention design. Targeting can cause stigma and is unpopular with some, yet unhealthy lifestyle behaviours are socially patterned and health inequalities could be increased by universal incentive provision. Targeting has been used mostly in developing countries, for example conditional cash transfer or coresponsibility payments for pregnant women and families who attend antenatal, vaccination and child-care appointments have improved child health outcomes. 36 Such projects have been implemented in > 40 countries worldwide and aim to address poverty by providing cash to help families deal with their most urgent needs and use incentives to promote behaviours that aim to improve the well-being of children. However, their success and sustainability is questioned because of supply-side concerns in countries with weak health and education service infrastructure and shortages of service providers. 37,38

An example of targeting in the UK demonstrates the risks of incentivising a proxy outcome rather than the actual behaviour. The UK government’s Educational Maintenance Allowance programme was rolled out nationally in 2004 and was subsequently discontinued. This was a means-tested cash payment scheme conditional on attendance at post-compulsory education rather than achievements and had mixed outcomes. 39 The risk of implementing incentive schemes ahead of the evidence can be demonstrated by the example of the ‘smoke-free class’ competition for young people. This was widely implemented across some parts of Europe; however, a Cochrane review found no evidence that it had prevented young people from starting to smoke in the medium to long term. 40

Smoking in pregnancy: epidemiology, health impact and intervention effectiveness

Maternal smoking in pregnancy causes substantial harm, increasing the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, prematurity, low birth weight, perinatal morbidity and mortality, neonatal or sudden infant death, asthma, attention deficit disorder, learning difficulties, obesity and diabetes. 41–50 Annual costs to the NHS of adverse events related to smoking in pregnancy have been estimated at between £8M and £64M for maternal outcomes and between £12M and £24M for infant outcomes. 51 Pregnancy is an opportunity to help women stop smoking before their own health is permanently compromised, which can significantly reduce rates of spontaneous preterm birth, small for gestational age babies and complicated pregnancies compared with those of non-smokers. 52

The 2010 UK Infant Feeding Survey found that at least 12% of mothers continued to smoke throughout their pregnancy, down from 17% in 2005. 53 Of survey respondents, 28% reported that they lived with at least one other person who smoked during their pregnancy and, in these situations, 30% continued to smoke compared with only 5% of mothers who did not live with any other smokers. 53 Of mothers who smoked in the year before or during their pregnancy, 54% gave up at some point before the birth.

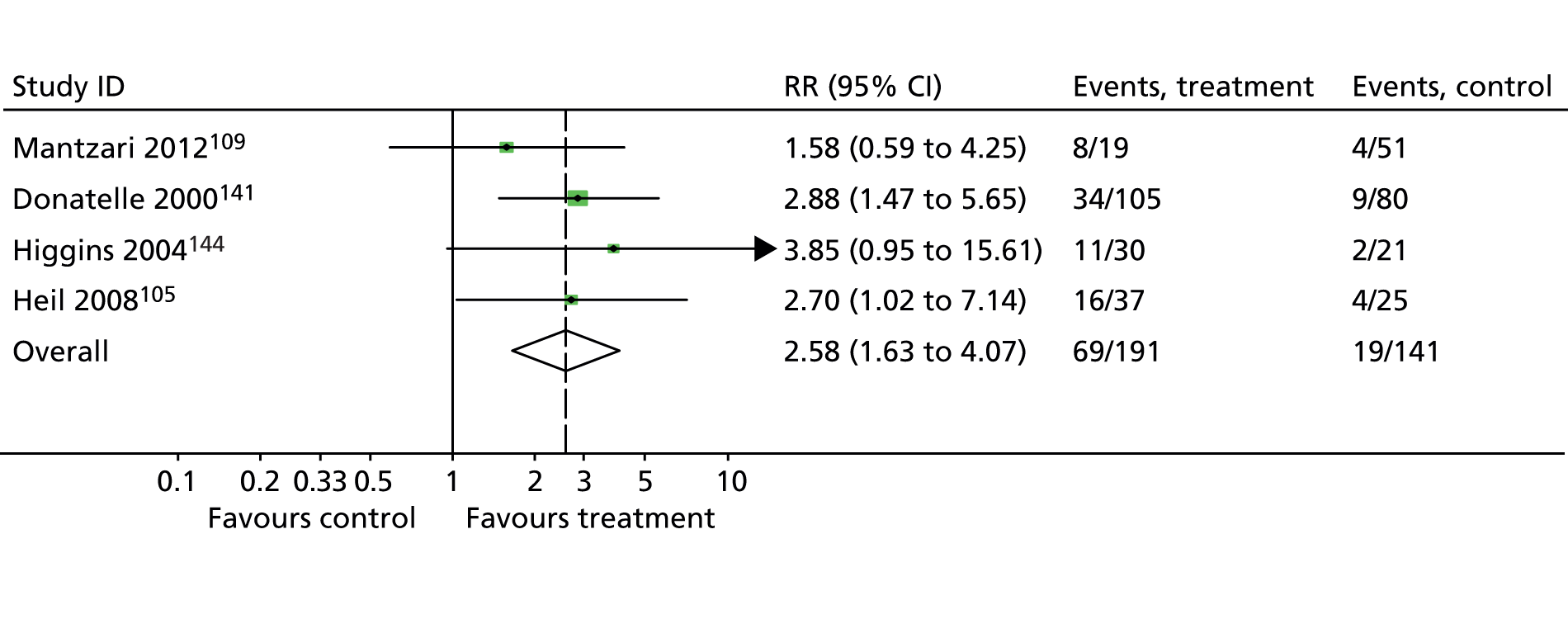

The most recent Cochrane review of smoking cessation interventions for pregnant women found that those used in early pregnancy can reduce smoking in later pregnancy by around 6%. Cognitive–behavioural approaches were found to be effective and financial incentives were the single most effective intervention, but this latter finding was based on just four trials from the USA. 54 Nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) is licensed for use in pregnancy; however, adding a nicotine patch (15 mg per 16 hours) to behavioural support did not significantly increase the rate of abstinence from smoking until delivery or decrease the risk of adverse pregnancy or birth outcomes in one large UK trial. 55 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines in the UK state that all pregnant women who smoke should be offered support to quit. 56 Self-help interventions have also been shown to be effective; however, the UK evidence for this is limited and may not be directly applicable. 57 In the UK, NHS stop smoking services are available for pregnant women, employing cognitive–behavioural approaches to cessation delivered by a trained adviser and including the offer of NRT when appropriate. 58 This follows the 2010 NICE guidance on smoking cessation interventions in pregnancy and following childbirth. 41 However, one challenge is that very few pregnant smokers access NHS support. In Scotland in 2006, for example, < 10% of pregnant smokers set a quit date with NHS services, suggesting that there is a need for new approaches that will encourage women to access support, potentially including the use of financial incentives. 59

Breastfeeding: epidemiology, health impact and intervention effectiveness

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding (with no other liquids or solids) until the age of 6 months. 60 This policy is supported by the UK government; however, < 1% of UK women currently breastfeed until 6 months. 53 In 2010, only 46% of UK women exclusively provided breast milk to their infant at 1 week and 23% did so at 6 weeks. 53 In the UK, data from a 5-yearly Infant Feeding Survey show a steady increase in breastfeeding initiation, from 62% in 1990 to 76% in 2005 and 81% in 2010; however, increases in the duration of breastfeeding have been disappointing. For women who initiate breastfeeding, 19% stop breastfeeding before 2 weeks and 85% of these women report that they would have liked to have breastfed for longer, and 32% stop before 6 weeks. 53 When women were asked, one in five responded that more guidance and support from hospital staff, midwives and family would have helped them to continue breastfeeding for longer. Mothers express dissatisfaction with breastfeeding care61,62 and 30% report feeding problems in the early weeks. 53

There is good-quality evidence on the short- and long-term health benefits of breastfeeding for both mothers and infants. 63 Babies who are breastfed are at a lower risk of respiratory and gastrointestinal infections and hospitalisations for these conditions, allergies and leukaemia. Premature infants who are breastfed are at decreased risk of necrotising enterocolitis and suboptimal neurological development, with lower longer-term risks in adolescence of raised blood pressure and cholesterol levels. 63 Mothers who breastfeed are at reduced risk of breast cancer, ovarian cancer and type 2 diabetes. A recent health economic analysis estimated that, if 45% of women exclusively breastfed at 4 months and 75% of infants in neonatal units were breastfed while in hospital, over £17M of treatment costs could be saved in terms of gastrointestinal infections, lower respiratory infections, otitis media and necrotising enterocolitis, as well as there being gains in maternal breast cancer-related quality-adjusted life-years. 64

Systematic review evidence on interventions to increase the initiation and duration of breastfeeding suggests that increased professional and lay support are effective, particularly if this spans pregnancy and postnatal care, with multifaceted interventions reported as more likely to be effective. 65 However, the generalisability of these findings is uncertain as nine UK trials providing additional support since 2000 have not reported significant improvements in breastfeeding outcomes. 66 Qualitative studies suggest that current UK NHS support is not meeting women’s needs, particularly in the early weeks following birth,62 and qualitative evidence synthesis recommends a woman-centred approach. 67

Smoking and breastfeeding behaviour around childbirth

Smoking cessation and breastfeeding have a long history of being researched independently; however, recent studies suggest correlations and possibly causal relationships between the two. 68–70 Women who quit smoking in pregnancy and who breastfeed are more likely to abstain from smoking post partum for up to 12 months,69,70 and data from incentive intervention studies suggest a causal relationship between stopping smoking and increased breastfeeding duration. 68 UK data (2009/10) report that 41.5% of non-smoking mothers exclusively breastfed their babies at 10–14 days compared with 13.6% of mothers who smoked, with a similar pattern observed for partial breastfeeding rates and across maternal age groups and deprivation categories. 53 Considerable health inequalities are evidenced for both smoking in pregnancy and breastfeeding behaviours. Pregnant mothers aged ≤ 20 years are more than five times less likely to be breastfeeding at 4 months,71 are three times more likely to smoke before or during pregnancy and are less likely to quit smoking than mothers aged ≥ 35 years. 53 The breastfeeding initiation rate was 90% for mothers in managerial and professional occupations compared with 74% for mothers in routine and manual occupations, with a fourfold difference in smoking before or during pregnancy (14% and 40% respectively). 53 Mothers in routine and manual occupations are also less likely to attend parentcraft education classes or engage in health services that support behavioural change.

Incentives for smoking cessation and breastfeeding: the policy context

Given the health burden and considerable health inequalities observed for smoking in pregnancy and not breastfeeding, together with the limited reach and effectiveness of interventions to date, new innovative approaches to change these behaviours, such as incentives, seem attractive. UK governments are adopting a broader approach than the previous focus on individual behaviour change interventions, with reducing health inequalities as a priority. 35,72 In 2010, the UK government set up the Cabinet Office Behavioural Insight Unit, or ‘Nudge’ Unit, to consider how to encourage people to act in their own longer-term interests, as well as those of society, informed by behavioural economics theory. 27 Strategies that act at a population level, with a wider systems approach, and which can complement individually tailored brief interventions are suggested. Patient-centred care and self-care, which encourage individuals to take responsibility for their health, is a strong policy theme. 7,73

The 2010 public health White Paper in England73 compares providing incentives to local communities to forge partnerships to deliver better health outcomes and reduce health inequalities with incentivising individuals or health service providers, and considers the former more feasible. Local community development incentive schemes can have benefits beyond individual behaviour change, by increasing social capital in disadvantaged communities, fitting the current UK government’s vision of a ‘Big Society’. 74

Until recently, disincentives through increasing taxes on tobacco products or restricting where people can smoke (through smoke-free legislation) have been the dominant policy approach in the UK. However, such initiatives have commanded media attention. Some of these have included local financial incentive schemes for smoking cessation in pregnancy and grey literature on some of these schemes is included in our review. In addition, at least one incentive programme for the general adult population has been conducted in the UK. This is the Quit4U programme in Scotland that offers supermarket vouchers of £12.50 (2013 prices) per week to people living in disadvantaged areas of Tayside. 75 The Quit4U evaluation showed that the incentives helped to engage smokers and increased short-term quit rates; however, success rates at 12 months were only slightly higher than for other, existing smoking cessation services76 and some adverse impacts on client–professional relationships were reported, which impacted on engagement with services. 20 Concern has been expressed by others about the change in professional–patient relationships when financial incentives to either party are involved, particularly around mutual trust. 77

Incentives for feeding babies have a long history in the UK, dating back to when Winston Churchill introduced free national dried milk in 1942 to improve the health of children, famously saying ‘There is no finer investment for any community than putting milk into babies’. 78 The Welfare Food Scheme operated from 1942 until 2006 and removed a financial barrier to formula milk purchase. Indeed, it can be argued that this acted as a disincentive to breastfeed. On the other hand, breastfeeding has been perceived as cost free, but other costs for nursing bras, pumps and pads, and crucially the mother’s time, are incurred but rarely calculated in public policy. Until 2006, lower-income mothers were entitled to 900 g of formula milk a week for every child aged < 1 year and this was distributed through health centres. This scheme was replaced in 2006 by the current Healthy Start scheme,79 which provides vouchers to low-income families that include a pregnant woman or children aged < 4 years that can be exchanged for infant formula, liquid cow’s milk and fresh or frozen fruit and vegetables. The scheme does not offer any extra incentive to breastfeed. The NHS endorses the WHO International Code of Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes;80 however, commercial formula milk samples, discount vouchers of < £90.00, cuddly toys and children’s clothes are available in the UK through mother-and-baby magazines, supermarket loyalty incentive schemes and websites.

Aims of the Benefits of Incentives for Breastfeeding and Smoking cessation in pregnancy study

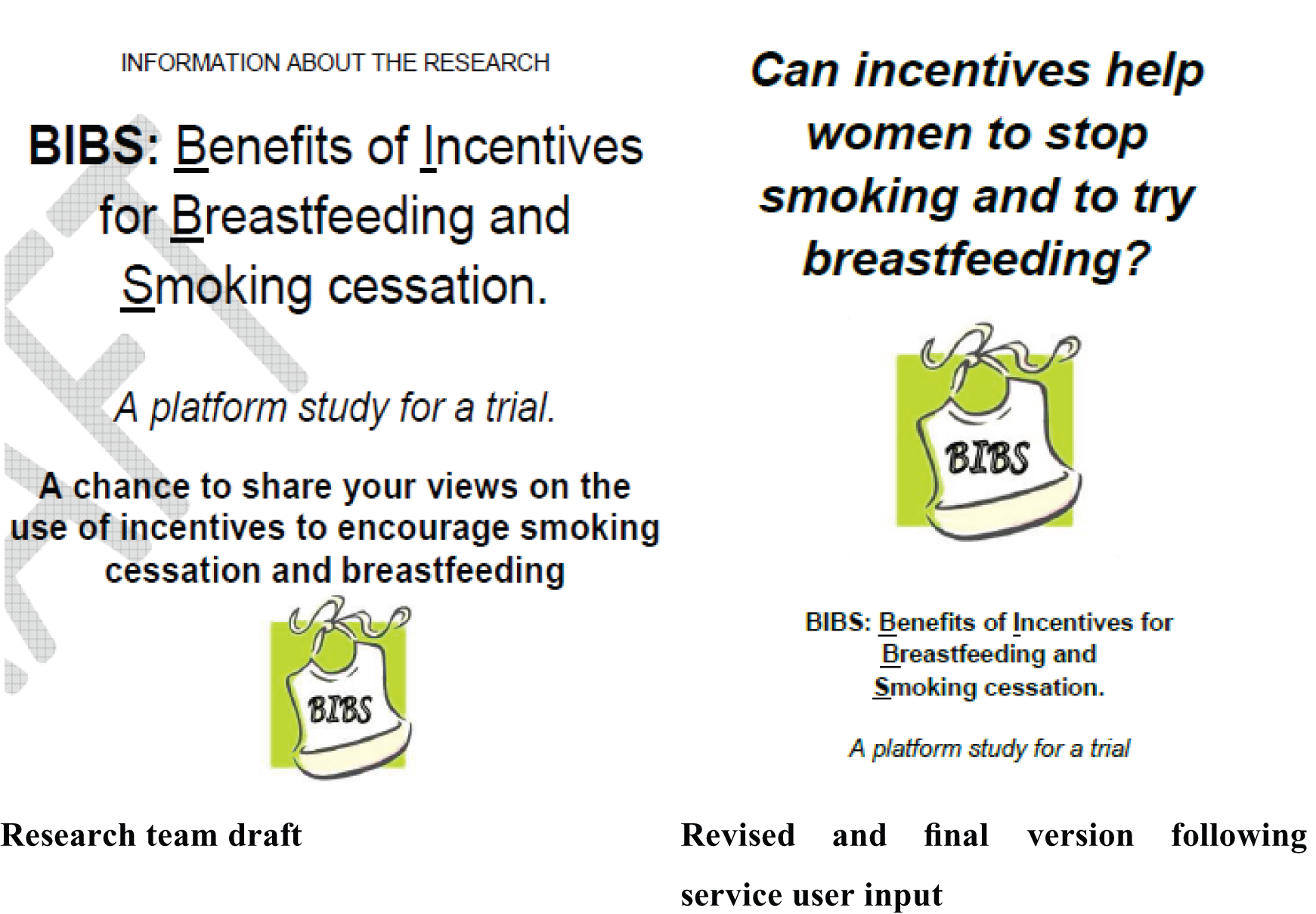

The overarching aims of the BIBS study were to conduct evidence syntheses and primary qualitative and survey research, together with a DCE, to develop an incentive taxonomy and to inform the design of an acceptable and feasible incentive intervention(s) with promise for improving smoking cessation in pregnancy and/or breastfeeding outcomes. Aberdeenshire, Glasgow and Lancashire were purposively selected as the settings for primary data collection because of their diverse sociodemographic characteristics and their different incentive cultures for smoking cessation in pregnancy and breastfeeding (Box 1). A multiphase mixed-methods design87 with sequential stages was considered the most appropriate design to address the commissioning brief (see Appendix 1). The quantitative and qualitative methods converged (Figures 1 and 2) and integration of the findings occurred iteratively throughout the study to address both the a priori and emergent research questions. The Cessation in Pregnancy Incentives Trial (CPIT)88 was running concurrently with the BIBS study and the CPIT qualitative process evaluation data were incorporated into the BIBS analysis towards the end of the BIBS study. An overview of the CPIT is provided in Box 2.

Aberdeenshire has a mixed urban/town/rural population, with partners absent for long spells working offshore or in the fishing industry and oil industries, and there are pockets of affluence and deprivation. In Grampian in 2012, 14.5% of women were reported as current smokers at antenatal booking and 13.5% were reported as smoking at 10–14 days after birth. 81 In 2011/2, 58.4% of babies were being given some breast milk at 10–14 days, with 45.4% still receiving some breast milk at 6–8 weeks after birth. 81

Incentive culture: Aberdeenshire has the highest proportion in Scotland (71%) of smoking cessation services for pregnant women delivered through community pharmacists, who receive payments per person registering for smoking cessation support and for data collection. 53 In discussions between PH and providers in primary care and maternity services, many managers and practitioners are resistant to providing financial incentives to patients following adverse media publicity about a smoking cessation incentive scheme in neighbouring Tayside, which our collaborator Susan MacAskill evaluated. Our co-applicant mother-and-baby group is an example of a partnership community development project that has raised money from local businesses to provide non-financial incentives (a crèche and subsidised café).

GlasgowGlasgow has an urban multicultural population with a wide sociodemographic range from affluence to large areas of extreme disadvantage. A total of 50% of households are in areas of the highest material deprivation compared with 20% for Scotland as a whole. In 2012, 18.3% of women living in Greater Glasgow and Clyde were reported as current smokers at antenatal booking, with 15.3% smoking at 10–14 days after birth. 82 In 2011/2, 43.4% of babies were being given some breast milk at 10–14 days, with 33.9% still receiving some breast milk at 6–8 weeks after birth. 83

Incentive culture: The CPIT started in June 2011 and includes a qualitative element examining how incentives are perceived by recipients and providers. This Phase II randomised controlled trial is summarised in Box 2.

LancashireLancashire has a mixed urban, small town and rural population with a wide sociodemographic range. For 2007 Indices of Deprivation,84 six local districts (including Blackpool) are ranked within the top 50 in England and in some towns up to 35% of births are to women of South Asian origin. Blackpool has one of the highest rates of teenage pregnancy, one of the lowest breastfeeding initiation rates (56% compared with 74% for England) and one of the lowest rates for babies still breastfed at 6–8 weeks (24% compared with 47% for England). 85 Although smoking rates vary across the region, Blackpool has the highest overall rate with 30% of women smoking at the time of delivery in 2011/12, which is over twice the national average for England (13%). 86

Incentive culture: Lancashire is an innovative area for breastfeeding incentive schemes. The Be a Star campaign started in Lancashire in 2008 and promotes breastfeeding among 16- to 25-year-old mothers (see www.beastar.org.uk/archives/tag/be-a-star-adverts-lancashire). It originated as a partnership between one of the primary care trusts, the Little Angels breastfeeding peer support organisation and The Hub social marketing agency. Be a Star transforms local breastfeeding mums to look like models, celebrities, singers and actresses, making breastfeeding glamorous, sexy and appealing, and provides breastfeeding support. Be a Star has been rolled out across 15 primary care trusts in England with encouraging results. The strategic health authority provided funds to three areas in the North West (one of which is NHS Blackpool Primary Care Trust) to run incentive schemes with the aim of increasing breastfeeding duration at 6–8 weeks in 2011 by 5%. The community Star Buddies Breastfeeding Peer Supporters who are delivering the incentive scheme in Blackpool operate out of St Cuthbert’s and Palatine Children’s Centre (our co-applicant base).

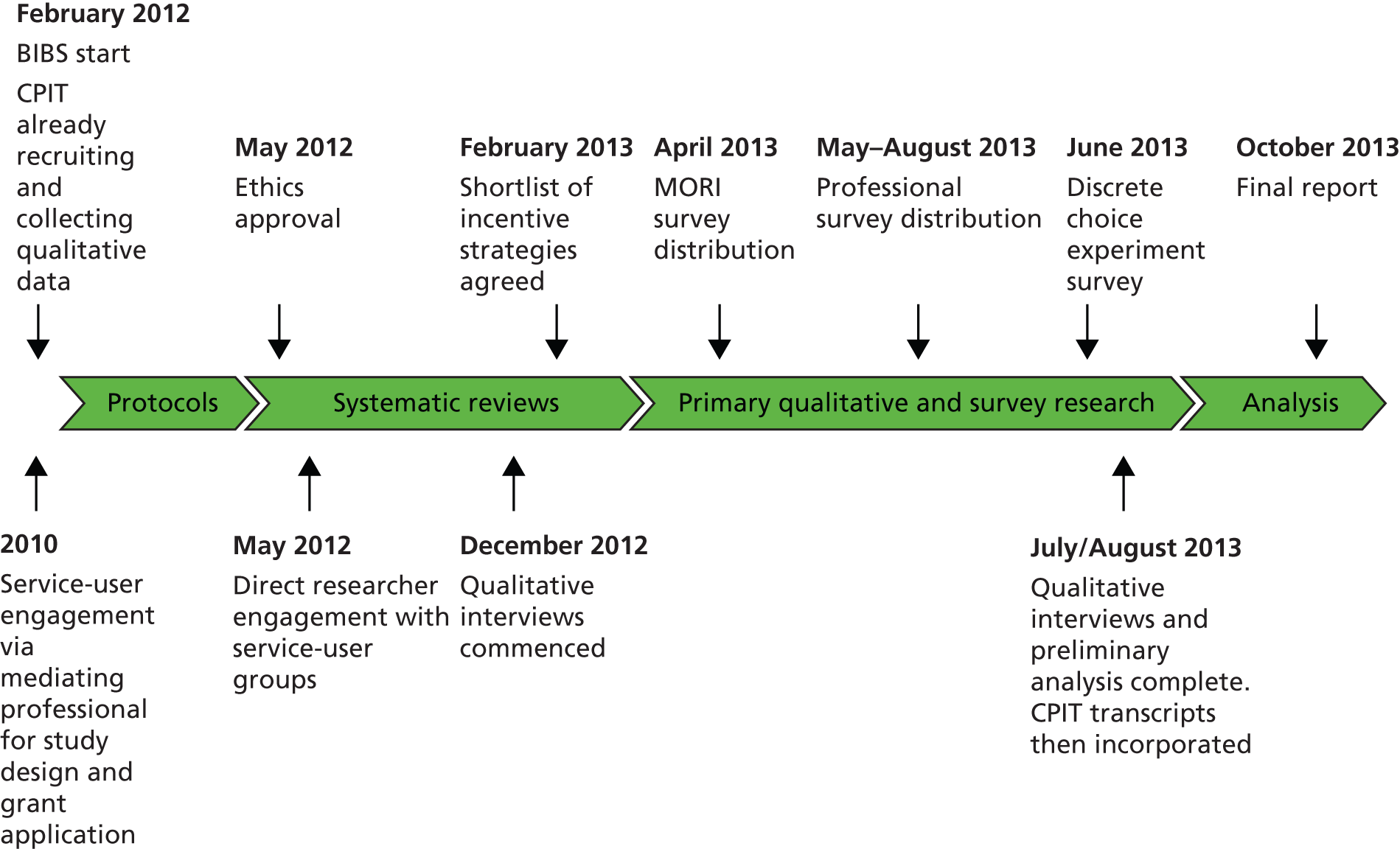

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the BIBS study.

FIGURE 2.

Timeline of the multiphased mixed-methods approach. MORI, Market & Opinion Research International (Ipsos MORI).

Pregnancy is an opportunity for most young women to stop smoking before their own health is irreparably compromised. Quitting will protect their infants from miscarriage, stillbirth, low birth weight, sudden infant death syndrome, asthma, attention deficit disorder and adult cardiovascular disease. The NICE guideline Quitting Smoking in Pregnancy and Following Childbirth41 highlights the lack of evidence and recommends a research question: ‘Within a UK context, are incentives an acceptable, effective and cost-effective way to help pregnant women who smoke to quit?’. A Phase II exploratory trial was therefore run from June 2011 to December 2013 aimed at establishing a workable trial design based on individual randomisation; a generalisable regimen of intervention delivery; a primary biochemically verified outcome measure; methods to document cost-effectiveness; and a process evaluation to explore women’s’ and professionals’ views.

SettingMaternity services, Glasgow, UK.

PopulationPregnant women who self-reported as smokers at maternity booking, who had an expired carbon monoxide level of ≥ 7 parts per million (p.p.m.), who were at least 16 years of age, who could speak English and who were < 24 weeks’ gestation at maternity booking.

RecruitmentAll women in Glasgow are asked routinely at the maternity booking appointment if they are current smokers and all have a carbon monoxide breath test. Self-reported smokers and all who have a carbon monoxide level of ≥ 5 p.p.m. are automatically referred to the Stop Smoking Service, which attempts to contact all to discuss smoking and possible cessation.

The trial was discussed with women who satisfied the eligibility criteria outlined above when contact was successful, either by telephone or at the booking clinic (walk-ins). If interested, women were given an information sheet and asked for permission for their contact details to be passed to the research team. They were then contacted by the research team for formal telephone consent. Concealed randomisation followed.

InterventionThe control group received standard Stop Smoking Service care for pregnant women. This included the offer of a face-to-face appointment to discuss cessation and setting a quit date with telephone follow-up at 4 weeks after the quit date and the offer of telephone support for up to 12 weeks post quit date. Those who set a quit date were offered free NRT provided by pharmacy services for up to 16 weeks following their quit date.

Women in the intervention group were offered the routine service plus a £50.00 voucher if they attended their face-to-face appointment and set a quit date and a further £50.00 voucher if they had quit at the 4-week follow-up, which required a home visit to corroborate self-reported quitting by means of a carbon monoxide breath test (< 10 p.p.m.). Those who had quit at 4 weeks were contacted at 12 weeks and if they were still quit and this was corroborated by another carbon monoxide breath test carried out during a home visit they received a further £100.00 voucher. At a random time between 34 and 38 weeks’ gestation all participants were contacted to ascertain their current smoking status. Those who self-reported as having quit smoking were visited at home for corroboration of quit status using a carbon monoxide breath test and urine/saliva cotinine assays. Intervention participants who were confirmed to have quit by carbon monoxide breath test were sent a final voucher for £200.00. In total, £400.00 of voucher incentives were offered.

OutcomesThe primary outcome was self-reported quit at 34–38 weeks’ gestation, corroborated by either saliva (< 14.2 ng/ml) or urine (< 44.7 ng/ml) cotinine assay. A £25.00 voucher was given to all participants who provided primary outcome information.

Secondary outcomes were the proportion who set a quit date, birthweight and costs and benefits of the incentives intervention.

ResultsIn total, 612 women were enrolled over 15 months from December 2011 to March 2013, with two participants opting out of the control group. By May 2013, 480/610 (79%) participants had reached the primary outcome stage; 39 (16.2%) were lost to follow-up in the control group compared with 38 (15.9%) in the intervention group. In total, 49/241(20.3%) were cotinine-validated quit in the incentives group compared with 19/239 (7.9%) in the control group. Sensitivity analysis showed a significant improvement in the cotinine-validated quit rate whether those lost to follow-up were treated as all smokers or all non-smokers. This control group quit rate is similar to that seen in the Smoking, Nicotine and Pregnancy (SNAP) trial in Nottingham (7.6%),89 giving credibility to the intervention being generalisable to other geographical areas of the UK. The process evaluation found that the intervention was acceptable to pregnant women and professionals and that the trial was feasible to deliver, informing a future Phase III study.

ConclusionsThis Phase II trial has established a workable pragmatic trial design, for example the optimal sample size, which will reduce the risks associated with a future definitive Phase III multicentre randomised controlled trial. Stakeholder views about incentive payments for smoking cessation in pregnancy have been examined. A cost-effectiveness approach has been developed to inform data collection for a future definitive trial.

Trial registrationCurrent Controlled Trials ISRCTN87508788.

ReferenceTappin DM, Bauld L, Tannahill C, de Caestecker L, Radley A, McConnachie A, et al. The Cessation in Pregnancy Incentives Trial (CPIT): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2012;13:113.

Tappin D, Bauld L, Sinclair L, Boyd K, McKell J, Macaskill S, et al. Financial incentives for smoking cessation in pregnancy: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2015;350. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h134

Specific objectives were to:

-

Investigate the evidence for the effectiveness of incentive interventions delivered within or outside the NHS to (a) individuals and families or (b) organisations that aim to increase and sustain smoking cessation and breastfeeding.

-

Investigate the evidence for effective incentive delivery processes and how they work to increase and sustain smoking cessation and breastfeeding, including their acceptability and how they fit with existing barriers, facilitators and intrinsic and extrinsic motivators to behaviour change.

-

Systematically search for and identify incentive interventions in systematic reviews from other areas of health improvement, particularly for women of childbearing age to (a) assess fit with our evidence synthesis, (b) inform the primary research questions to investigate a shortlist of incentive strategies, and (c) identify research gaps where effective incentives for other behaviours have not been tested for smoking cessation and breastfeeding.

-

Investigate the acceptability and feasibility of a shortlist of promising incentive strategies and potential harms or adverse consequences from the perspectives of (a) women and partners; (b) health professionals, managers, policy-makers, research funders, ethics committee members, academics and other relevant stakeholders; and (c) the general public.

-

Develop an incentive taxonomy from the four objectives listed above.

-

Design a feasible trial: identify the target population, the active components and mechanisms of action of the intervention, the control group, the recruitment and delivery strategy, monitoring and outcome measurement and the effect size.

Definitions

The research team became aware early on that disciplines in applied health sciences use different terminologies that have multiple meanings and functions, which, as our service-user co-applicants pointed out, also have common usage or lay definitions. For terms that we identified as problematic in this respect, we referred to the Oxford English Dictionary1 for a common working definition; these are listed below:

-

Incentives include financial (positive or negative) and non-financial tangible incentives or rewards. By tangible, we mean free or reduced-cost items that have a monetary value or an exchange value, such as refreshments, baby products or services such as childcare or ironing (any setting). Our definition excludes intangible incentives such as supportive, motivational or persuasive relationships with professionals or peers. Incentives may be delivered directly or indirectly at a local, regional or national level by NHS or non-NHS organisations.

-

Incentive taxonomy – a classification of incentive characteristics in relation to behavioural change techniques.

-

Incentive typology – a classification of incentive types related to their meanings.

-

Incentive intervention logic model – a hypothetical description of a complex intervention and process whereby an incentive is delivered to a target population with the aim of sustaining or changing behaviour.

-

Incentive recipients may be women, families (collectively referred to in the report as consumers or service users) and/or NHS or non-NHS providers at the local, regional or national level. Incentive packages may benefit more than one group, for example local communities and parents.

-

Providers is an umbrella term referring to people, individually, in groups or in organisations, working in the NHS, government, voluntary sector or other organisations, who help women to stop smoking and/or to breastfeed. Providers also deliver incentive interventions and/or they may receive them.

When referring to human behaviour:

-

Intrinsic is a broad adjective referring to anything internal (states such as motivation, anxiety, pleasure; personal characteristics, for example age; thought processes such as planning; the senses; personal history) that is wholly within an individual, some of which can change over time. This definition of intrinsic is equivalent to the word internal and the two terms could be used interchangeably. The Oxford English Dictionary also describes another meaning in which intrinsic is the innate nature, or constitutional. Our interpretation is that this secondary definition implies a meaning of intrinsic as fixed rather than dynamic, which we do not wish to imply.

-

Extrinsic is used as an adjective in its broadest sense to refer to anything external to the individual (objects; other people; environments local to distal; cultures), some of which can change over time. This definition of extrinsic is equivalent to the word external and the two terms could be used interchangeably.

-

Influence is the capacity to have an effect on the character, development or behaviour of someone or something. We are using this term as an umbrella term rather than in a strict statistical sense and instead of using the more precise mediator or moderator terms that are sometimes used in relation to intervention design.

Our rationale for including incentives to providers is that a whole-systems approach is likely to be required. Changing recipients’ behaviour is likely to be less effective if there are barriers to the provision of support and thus changing provider behaviour may be more effective than individual incentives and the context in which incentives are delivered is likely to be important. The effect of incentivising both recipients and providers may be less than, the same as or greater than the sum of the two.

Report structure

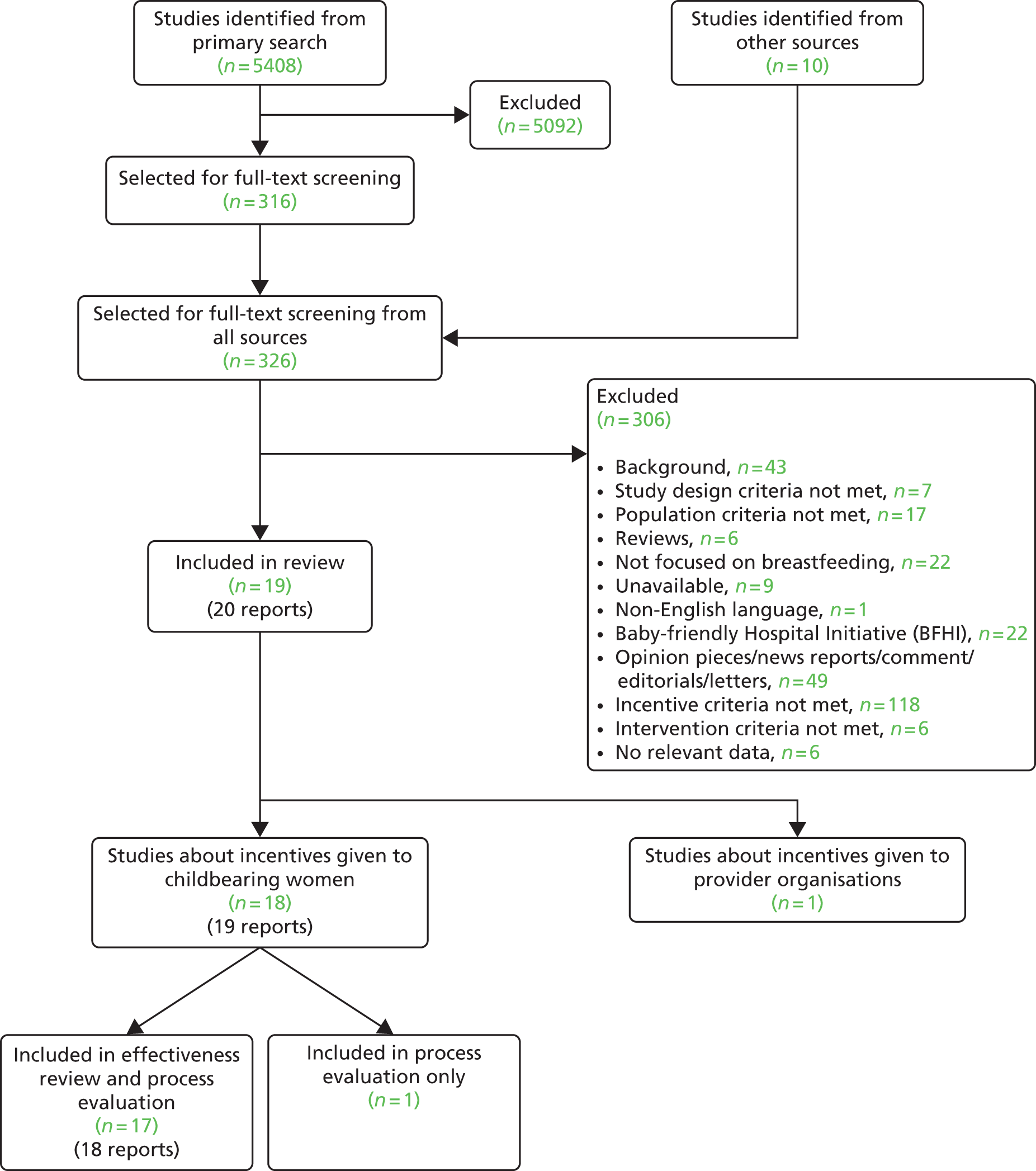

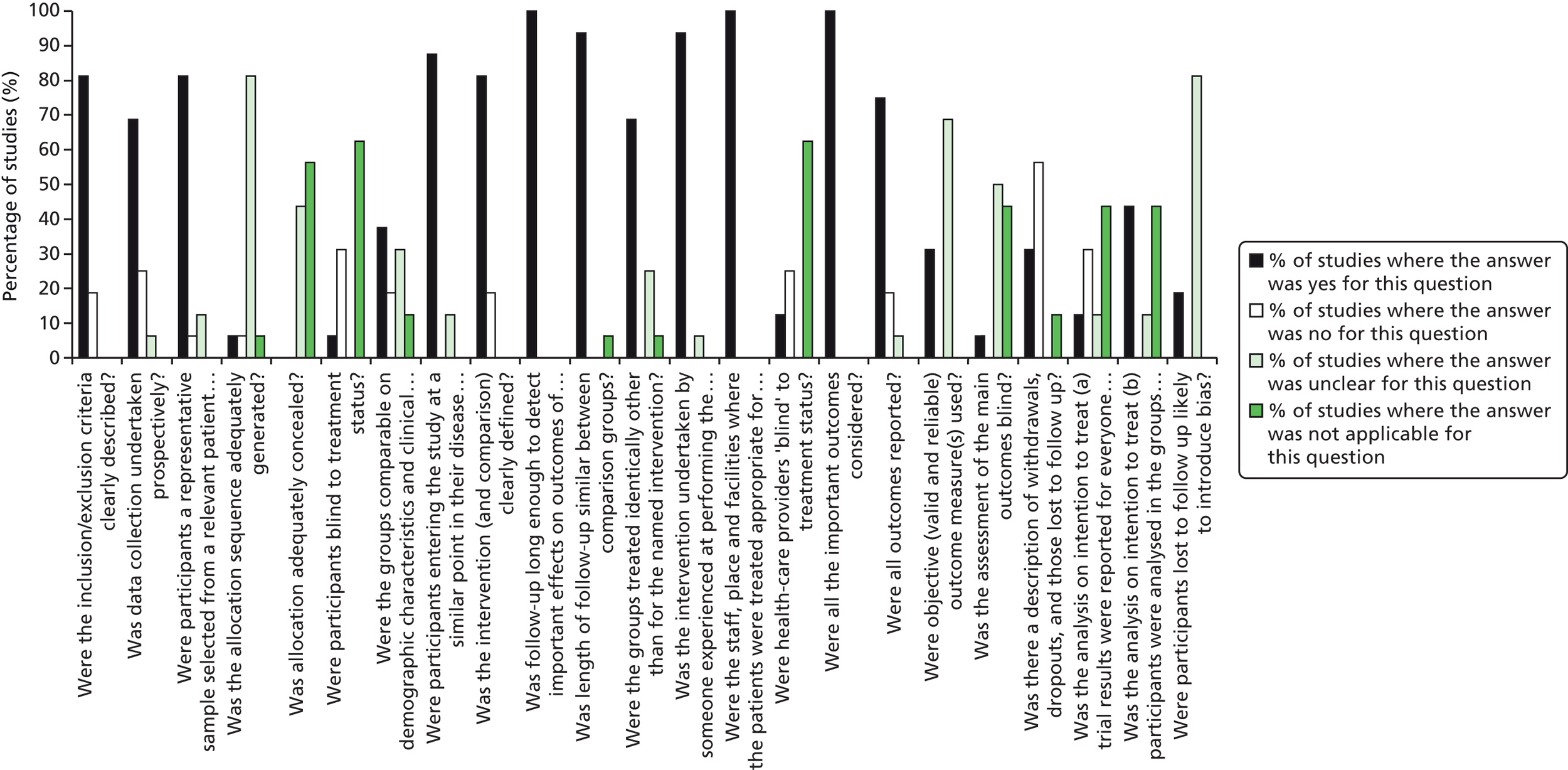

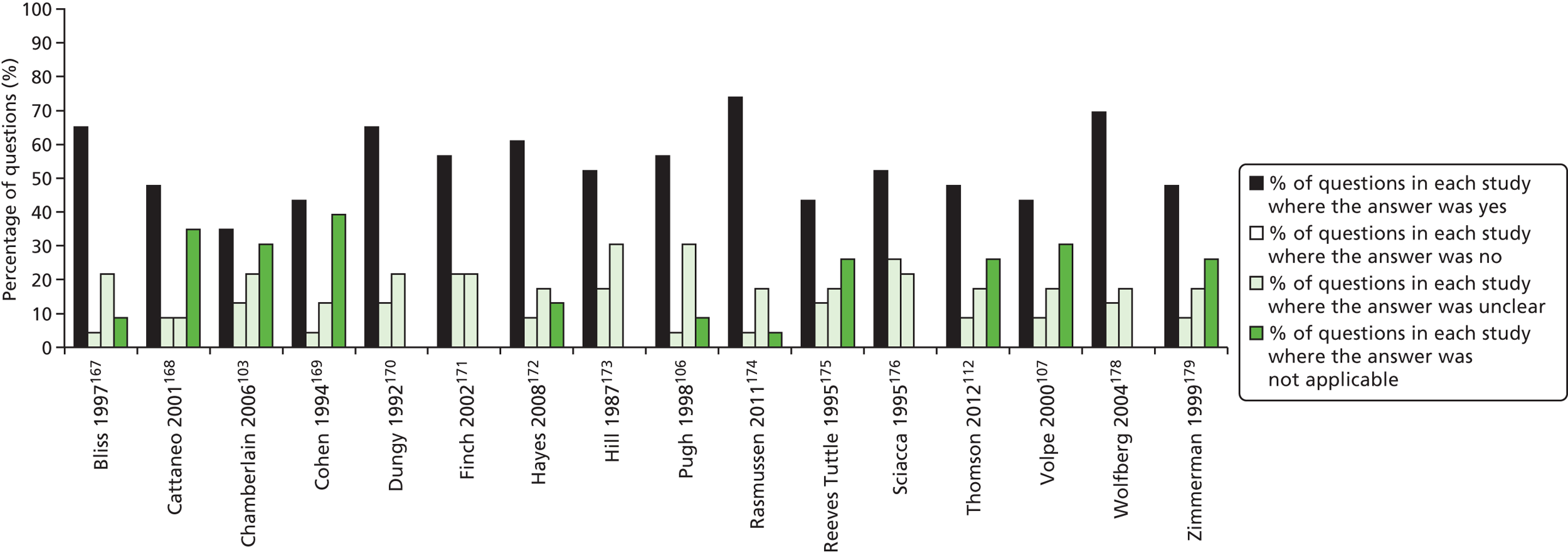

This report is in two parts. Part 1 presents the evidence syntheses (stage 1 in Figure 1) and part 2 presents the primary qualitative, survey and DCE research (stages 2 and 3 in Figure 1). At the end of each part the findings are discussed together with the strengths and limitations. Each chapter concludes with the implications for the relevant outcomes described in Figure 1.

In part 1:

-

Chapter 2 describes how our co-applicant mother-and-baby groups contributed service-user perspectives throughout the study.

-

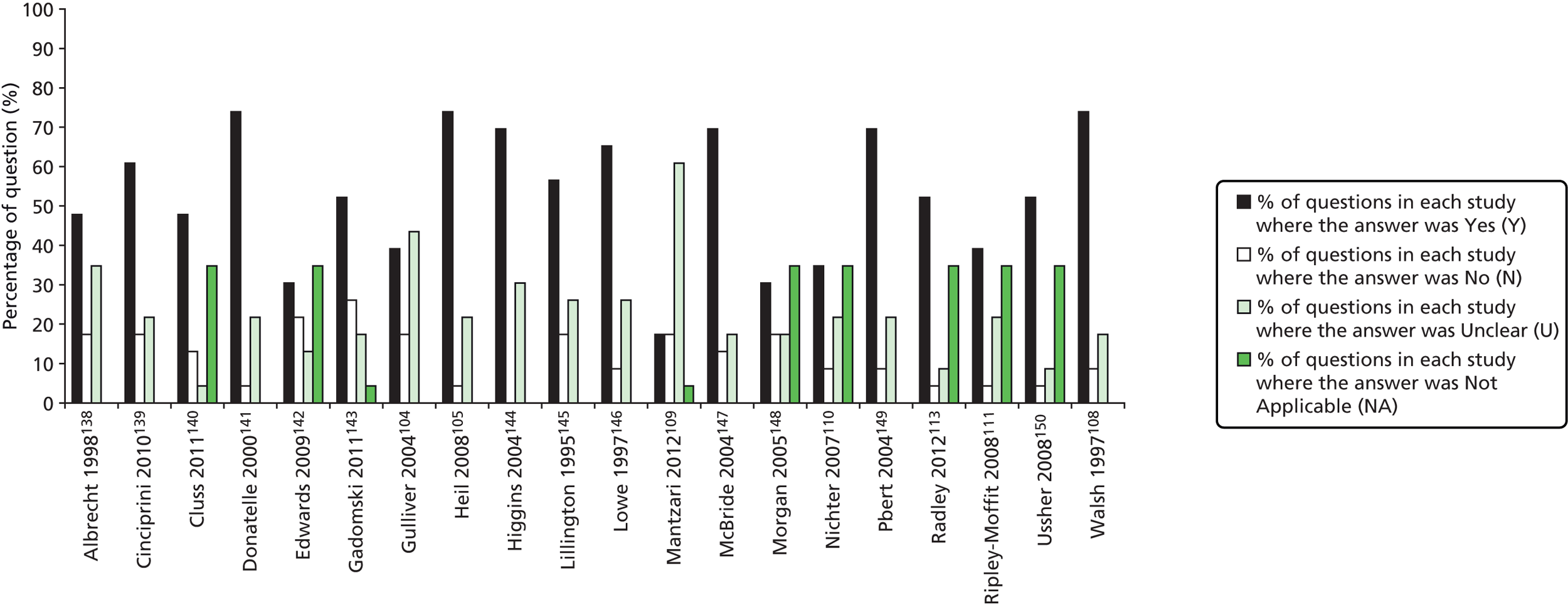

Chapter 3 presents a quantitative and qualitative evidence synthesis of the effectiveness and delivery processes of incentives to promote smoking cessation and breastfeeding in pregnancy. The review assesses incentive strategies at an individual recipient level as well as at provider and organisation levels. It develops an incentive taxonomy and the beginnings of an incentive typology, which are further developed and incorporated into an incentive logic model in Chapter 6. It concludes by considering the implications for a shortlist of incentive strategies, which is then refined by the findings presented in each of the subsequent chapters.

-

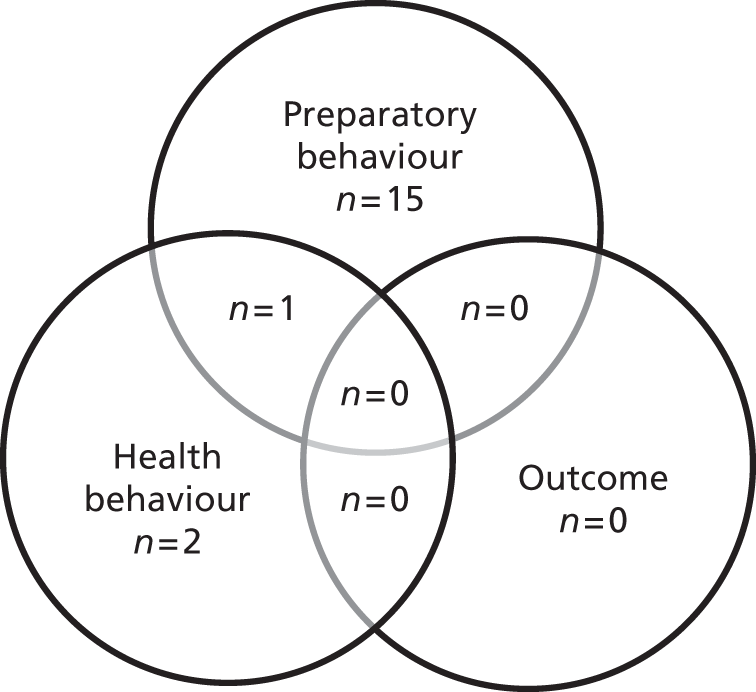

Chapter 4 presents a systematic narrative review of qualitative syntheses and a logic model to describe women’s perspectives on smoking in pregnancy and breastfeeding. This assists in understanding the barriers and facilitators, together with the overall balance of existing intrinsic and extrinsic motivators or demotivators for pregnant women and new mothers, for either initiating or sustaining smoking cessation or breastfeeding. The chapter concludes by considering how the findings inform the incentive taxonomy and the shortlist of incentive strategies.

-

Chapter 5 presents a scoping review of systematic reviews that have assessed the effectiveness of incentives for complex lifestyle behaviours relevant to women of childbearing age. The review identifies evidence of effective incentive strategies that support the findings presented in Chapter 2, as well as identifying knowledge gaps and incentive strategies that have not yet been evaluated for smoking cessation in pregnancy or breastfeeding. This review therefore triangulates findings from the earlier chapters and informs the shortlist of incentive strategies to take forward for further investigation in the primary qualitative and survey research.

In part 2:

-

Chapter 6 presents the findings of the qualitative research, in which interviews and focus groups were undertaken with pregnant and post partum women, partners, health professionals, experts, decision-makers and other key informants. The chapter begins with an incentive intervention logic model, which was developed during the course of the study according to our study data and applies the metaphor of a ‘ladder’ to understand how key components of incentive programmes (rungs) are perceived in relation to the life course and context facilitators of (rungs) and barriers to (missing or damaged rungs) smoking cessation in pregnancy and breastfeeding. A typology of incentive types and meanings expands the incentive taxonomy developed in Chapter 3 and is integrated into the logic model. Findings relevant to incentive intervention components and delivery processes for the shortlist of promising incentive strategies are described. Finally, we present participants’ views on potential unintended consequences of incentive interventions and issues relating to research studies.

-

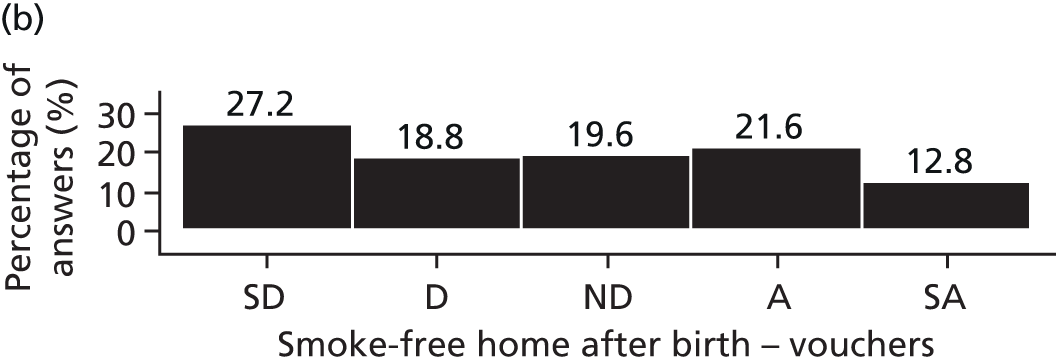

Chapter 7 presents the findings of a survey to assess the acceptability of the shortlist of incentive strategies. We report findings from a Market & Opinion Research International (MORI) survey of the general public and a survey of health professionals who work with pregnant women, infants or new parents across Scotland and North West England.

-

Chapter 8 reports the findings from a DCE to inform the design of the most promising incentive strategy from the shortlist, which addresses incentives to improve smoking cessation outcomes in pregnancy.

-

Chapter 9 discusses the overall findings from the study. The most promising incentive trial design to emerge, together with other promising incentive strategies that require further development and research, are presented. The acceptability and feasibility of incentive interventions are considered, and the potential utility of the incentive logic model is discussed.

-

Chapter 10 summarises the main conclusions and implications for research.

Part 1

Chapter 2 Service-user engagement

For this project, a novel approach was adopted and we recruited two mother-and-baby groups, located in disadvantaged areas, as co-applicants. This chapter describes how we engaged service users through their groups, how they informed the research process and some reflections on collaborative approaches.

Background

Although there is a need to include patient and public involvement (PPI) in health research, which is a statutory requirement by virtue of the Health and Social Care Act 2001,90 and there is guidance and a growing pool of resources available on how this might be achieved,91 there is no ‘gold standard’ in terms of what constitutes best practice in PPI. The ways in which research teams approach PPI vary. 92 However, new strategies are being developed to actively and effectively involve the public to make PPI more meaningful. 93

The benefits of PPI include enhanced depth, credibility and applicability of findings, improved clarity of final reports and recommendations and an immediate link between practice-based evidence and evidence-based methodology. 94–96 Although it is recognised that PPI in research should begin at the earliest stage possible, in practice it is not easily achievable. Constraints on time, funding, ethics approvals and the availability of appropriate representatives often mean that PPI is not included until research is fairly well advanced. This is particularly so in studies such as BIBS, where the grant application was submitted in response to a commissioned National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme funding call. Involving patients or the public at a later stage, however, jeopardises and compromises one aim of PPI: to ensure that research is being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them. It can marginalise them during the crucial project scoping and design phases, although the NIHR/HTA programme boards have PPI representation when deciding whether to commission research. Innovatively, we actively engaged in our project, from its inception, groups of service users who had not previously been involved in research, and who were untrained, by working with them as co-applicants.

Our aim was to foster a partnership approach97–99 to understand service-user perspectives on engaging in research, rather than imposing an unequal ‘researcher-dominant’ agenda. In the following sections we use a traditional structure to describe the process of service-user engagement, that is, using the headings of Methods and Findings, although it could be argued that this is inappropriate for such a categorisation, as the collaborative approach was dynamic and flexible, rather than fixed a priori. Service-user engagement was therefore conceived as an iterative, loosely structured process that was emergent and sensitive to the views and preferences of the service users involved. PH had the original idea based on her experience as a member of maternity service liaison committees; she had used action research methods successfully in a previous study100 and had conducted a longitudinal qualitative study with families recruited from disadvantaged areas to inform the design of interventions to improve breastfeeding outcomes. 62 NC, PH, HM and GT have extensive experience in conducting qualitative interviews with service users, including those living in disadvantaged areas.

Methods

Engaging service-user groups

At the grant application stage, service-user engagement was initiated by approaching maternity services, primary care and children’s centre managers to select two thriving, but diverse, groups operating in areas of high deprivation in Aberdeen and Lancashire. Managers identified group representatives to negotiate involvement with the study: a health visitor – Wendy Ratcliffe (Aberdeen) – and a community centre worker – Helen Cook (Blackpool) – both named in the grant application. Areas of high deprivation were considered most likely to be able to provide insights from service users who had experience of the target behaviours for change: smoking in pregnancy and formula feeding. 53 Moreover, the selected groups were considered to be particularly well suited to collaboration on the BIBS project: the Aberdeen group is user led, is successful in generating some funding and provides a café and crèche as incentives to attend; the Blackpool group is located in a local authority-run children’s centre. The settings for these groups were summarised in Chapter 1 (see Box 1) and the group profiles are summarised in Table 1.

| Group | Location | Distance for researcher to travel | Setting | Average attendance | Meetings | Purpose and structure | Funder |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mastrick Café Crèche, Aberdeen | One of the most disadvantaged areas of Aberdeen | Approximately 10-minute walk | One room within a larger family centre including a separate crèche room. Sofas, play area adjacent, toys, kitchen area, dining area, unobtrusive site manager in room nearby | Approximately seven mothers (two mothers left the group and two new mothers joined) and their babies, two (grandmothers fairly regular group membership) | Weekly, Wednesdays 1200–1400 (except during school holidays), plus some additional social/fundraising events | Set format: the café is facilitated by mothers who make and sell a cheap, healthy lunch costing £2.00 (subsidised through fundraising) to mothers and babies during the first hour, when, until early 2013, a health visitor was present to provide support. During the second hour the babies go into the crèche and the mothers enjoy a coffee and a catch-up or participate in training activities/listen to external speakers | Established through a partnership project between Aberdeen City Council, Homestart (see www.home-start.org.uk/) and NHS Grampian. The café crèche is now independent and self-funding |

| St Cuthbert’s and Palatine Children’s Centre, Blackpool | Covers a disadvantaged area of Blackpool | 18-mile drive | One room within a larger community centre with toys, books and soft-play facilities and seating for parents. A café is also located in this room for parents to purchase drinks and food | 16–20 families (discontinuous participation) | Weekly | Unstructured format. Mother-and-baby/toddler group in an informal setting where parents can drop in and out to interact with and receive support from children’s centre staff members and engage with peers. Children’s centre staff member in attendance throughout the session | Local government |

The group representatives were sent drafts of the grant proposal to discuss with the groups and they provided feedback during the planning stages. They negotiated reimbursement for their group’s refreshments and crèche costs as part of the grant application. Although the service-user collaborators were independent or local government representatives, rather than NHS groups, we considered it preferable to gain ethics committee approval before active engagement, particularly because the groups had not been involved in research before. When the study started (February 2012), service users assisted in developing the protocol and study information materials through feedback to the group representatives (HC and WR). Once ethics approval had been obtained (May 2012), the group representatives made the introductions between the service users and the fieldwork researchers. Researchers HM and GT attended 15 meetings between May 2012 and September 2013 to engage the service users by discussing study progress, gaining feedback and thus informing the research strategy. Reflecting on researcher perspectives is important and so reflexive diaries were kept and researcher observations were shared with the research team throughout.

Negotiating meeting frequency and types of visits

In Aberdeen, initial contact was made through the health visitor (WR); however, the researcher was able to exchange contact details with group members at her second visit and so the gatekeeper role shifted to the group’s treasurer, who shared it with one of the grandmothers who was responsible for organising meetings and events. This allowed for much less formal communication, good rapport building and thus intermittently ‘dropping in’ for informal lunch visits, as well as the more directed research sessions. The group met at a facility within walking distance of the university (approximately 10 minutes); this made visits easy to schedule and undertake. These circumstances were also fortunate in that, a few months into the project (September 2012), WR was relocated by her NHS employer and her replacement assumed a less prominent role within the group. In fact, after some further months (February/March 2013), health visitor support for the group was withdrawn altogether. However, this did not adversely affect engaging these service users and possibly strengthened a direct partnership between the researcher (HM) and the group. By contrast, in Blackpool, contact was initiated and continued through the community centre worker and therefore only formal research meetings were undertaken. The distance of travel for the researcher (18 miles by car) was a barrier to informal contacts. For both groups, long school holidays coincided with crucial research stages and were thus inopportune for our research schedule. For example, the final qualitative data analysis overlapped with the school summer holidays, although we were able to conduct an exercise involving our key qualitative findings with both groups (September 2013).

The Aberdeen group used Facebook (see www.facebook.com) as its primary communication mode; however, despite gaining ethical approval, the research team decided against engaging with the group using this social medium. Several concerns were discussed around maintaining appropriate boundaries, the best use of researcher time and a lack of published guidance. Using e-mail/telephone/text only did not appear to prevent or diminish engagement. Informal contacts and balancing communication traffic presented a challenge to the researcher (HM), who was confronted with some pressure for full group membership, such as being proactively invited to additional/extra activities: to assist at fundraising events and fêtes, to wear fancy dress to group seasonal parties and to attend mothers’ social evenings. The requirements of a researcher to remain objective and maintain a distance compared with a more anthropological approach to fieldwork were discussed with the research team. Of the six informal social events that took place during the course of this research, HM attended three to show goodwill. Researcher participation can therefore be considered as ‘active’101 as HM was able to gain insight into the cultural codes and rules for behaviour of the group.

Including service-user perspectives

Participatory approaches were employed and initially consisted of building good rapports with both groups by attending their meetings, informally socialising and observing in an unobtrusive manner to acknowledge the researchers’ roles as visitors to an established group. 101 This began with standing passively on the periphery, waiting to be invited in, eventually sitting comfortably on the sofas and even on the floor, and led to more active engagement, such as being asked to console crying babies. Once rapports were established, the researchers initiated requests for more directed sessions to gather feedback and data on important stages in the study.

Directed data-gathering sessions with the service users occurred after information was provided in advance and on an agreed date. HM and GT sought informed consent to audio record discussions. Researchers involved the groups in the design, editing and presentation of intervention vignettes derived from a diverse sample of promising studies identified in the systematic reviews (see Appendix 2). The study vignettes were then used in interviews and focus groups to gain participants’ perspectives of incentive interventions and to assist with shortlisting promising incentive strategies. Pilot focus groups were undertaken to contribute to interview topic guide refinement. We were able to generate data that contributed to the qualitative analysis from five of those sessions [two individual interviews and three focus groups (see Chapter 6)]. In addition, group members piloted the DCE as the majority had a smoking history, constructed their own intervention ‘ladders’ using the logic model that we developed (see Chapter 6), commented on the lay summary and advised on future dissemination of study findings. Our co-applicant groups also assisted us in identifying and actively engaging ‘hard-to-reach’ women, who seldom access health services and participate in PPI initiatives even less often. Although they contributed to the development work leading to the shortlist of incentive strategies asked about in the MORI survey of the general public (see Chapter 7), a separate sample of independent general public participants was sought to pilot this to minimise the ‘group think’ that may occur through repeated discussion of a topic. 102

Findings

Collaborative approaches to incorporating service-user perspectives

The Aberdeen group environment, cohesiveness and set structure suited a directed format, that is, focused activities, to address research issues. Women in this group were used to undertaking training (e.g. food preparation, child first aid) and had regularly welcomed external speakers in the second hour of their weekly 2-hour meetings. During this time, women sat on comfortable sofas around a large coffee table or leaned in over the kitchen counter if they were making the tea/coffee. Meanwhile, their children were occupied in the crèche, which meant that the researcher (HM) could interact with women informally as well as undertaking researcher-led whole-group data collection sessions, with minimal issues around audio recording and using interactive materials, such as the intervention vignettes. Although computing/projector facilities were not available, whiteboard and printed copies were used and worked fairly well. The vignettes helped the group to become focused and positively engaged with the study in a more concrete and tangible way. On one occasion, however, internal politics caused tension because the session was led by the organiser, who was upset that day and prevented any research activities taking place because she was ‘telling off’ members of the group about rota duties and fulfilling their responsibilities (e.g. washing up and cleaning the carpets).

In Blackpool, the group’s drop-in format presented the researcher (GT) with the practical challenge of having to move between members to involve them in ‘chance encounters’. Although the service users were keen to participate and engage in discussions, group membership was discontinuous and so GT was unable to engage with the same parents at each visit. Despite these limitations, a number of women were involved in various activities on more than one occasion, and an advantage was that a wider number of service users were engaged in total (n = 12) compared with the Aberdeen group (n = 8). Further challenges were faced when trying to engage parents and carers in meaningful conversations when their infants/children were in attendance. However, during piloting of the DCE, additional support was provided by children’s centre staff to ‘supervise’ the children to enable close reading and discussion of the online format of this tool. Furthermore, although the noise levels (children playing, shouting, etc.) compromised the digital recordings of the discussions, GT also kept handwritten notes and transcribed the session recordings herself as soon as possible to facilitate accurate and comprehensive data documentation.

Relationship with the wider research team

Engaging the mother-and-baby groups with the wider research team was problematic. Inviting and encouraging group members to attend regular weekly or formal research team meetings at the university (e.g. grant holders’ meetings) proved impossible at both sites. The health visitor group facilitator from Aberdeen (WR) attended one meeting (September 2012) and suggested that the women would have been very nervous had any of them attended because of the formality. Her successor was invited to a subsequent meeting and expressed an interest in the associated paperwork, which was e-mailed to her; however, she did not attend. It was not possible for Blackpool group members to attend because of the distance to travel and they did not accept an invitation to attend by telephone.

Other members of the research team were invited to join HM and GT for visits to the mother-and-baby groups. Highly sceptical comments such as ‘You’ll be lucky!’ were made by academic colleagues and administrative staff when considering the potential take-up of such an invitation. PH accepted on two occasions and attended an Aberdeen mother-and-baby group Christmas ‘drop-in’ (December 2012) and observed and took notes while HM facilitated a ‘ladders’ session (September 2013) (see Substantive contributions, Ladders). NC similarly observed and took notes while GT facilitated a ‘ladders’ session in Blackpool (September 2013).

The importance for the groups of researchers going into their territory to gain PPI input was evident. They took pride in hosting researcher visits, for example enthusiastically offering refreshments and home baking (Aberdeen) or computer facilities for directed sessions (Blackpool). In addition, researchers witnessed conversations that are seldom encountered in formal health or research settings. For example, some group members were adversarial towards health professionals, one group described complex and disruptive domestic relationships and highly charged personal opinions were expressed about health behaviours (smoking during pregnancy) and on one occasion someone left the room. In the presence of health service staff, such accounts would have been unlikely.

Substantive contributions

Designing participant materials

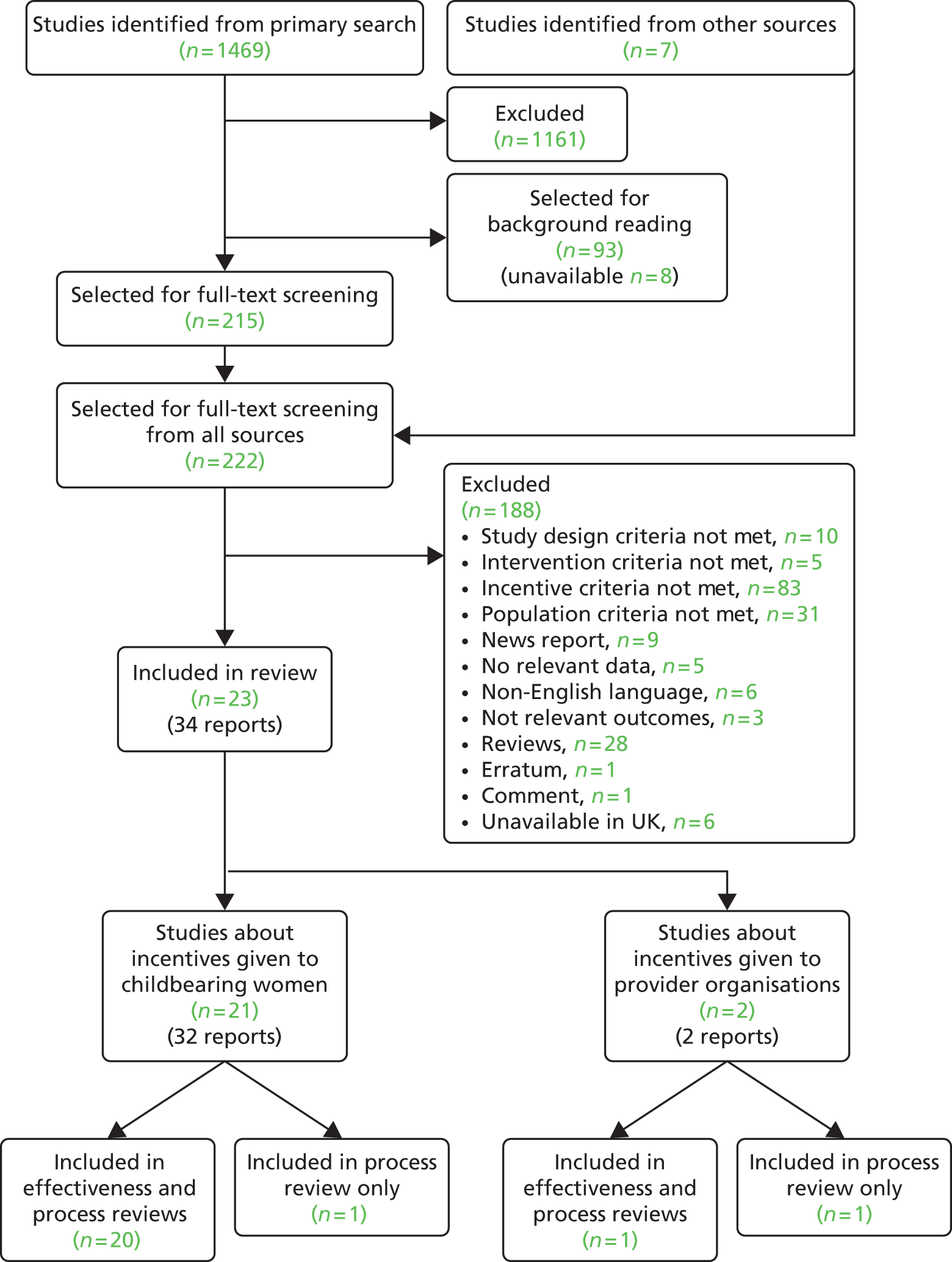

Through the group representatives as mediators, service users helped us to rephrase several sections of the information sheet for both readability and acceptability before gaining ethics approval and undertaking the primary qualitative research (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Comparison of the patient information leaflet before and following service-user input.

We revised the document to take account of the target participants’ style preferences, language and social and cultural contexts. In particular, they drew our attention to their unfamiliarity with the term ‘cessation’ and the predominance of formula feeding, either from their own personal experience or in their immediate family and social networks. Thus, they suggested that ‘help women to stop smoking’ and ‘try breastfeeding’ were more appropriate phrases, and they also pointed out that ‘encourage’ is persuasive, ‘smoking cessation’ is too technical and the word ‘breastfeeding’ alone implies a certainty. The last of these was a very important change as we noted that a mother in one of the groups disclosed that she was providing exclusive breast milk to her infant (on her information form) but pretended that she was formula feeding to other group members, using bottles of expressed breast milk that she allowed them to assume was formula by talking about preparing it. Breastfeeding was not a social norm and this woman anticipated that it could possibly be considered unacceptable by some.

Systematic review feedback and study vignettes

The mother-and-baby groups contributed to interpreting systematic review findings by providing feedback on a number of vignettes of studies included in the evidence syntheses, which were initially drafted by the researchers. Six vignettes were developed from studies that were selected either because they had statistically significant effects or because they involved an unusual or innovative approach. 103–108 Different vignette structures were tried out, for example presenting and discussing sections of the vignette sequentially compared with presenting the whole vignette. Presenting the vignette as a whole was the most popular format and this differed from the advice that we had received from our steering committee. Discussions around the vignettes assisted in talking interviewees through the interventions step by step and provided valuable insights into which incentives and programmes might be acceptable. This was particularly useful as very little detail around acceptability and processes is reported in the included studies (see Chapter 3), even when they are classified as using qualitative or mixed methods. 109–113

Piloting topic guides

We piloted draft interview topic guides in three focus groups with service-user mother-and-baby groups before recruiting participants. In Aberdeen, this involved trying a structured topic guide and the integration of study vignettes within the schedule and revisions. The final preferred version was unstructured with prompts for use if and when appropriate, for example opening with questions around what incentives were meant for women and using women’s conceptions of incentives to guide the interview.

The discrete choice experiment

The DCE was piloted with four mothers with a history of smoking from one group (Blackpool). When reading and answering each of the questions (using SurveyMonkey’s online format – see www.surveymonkey.com), the mothers were asked to use the ‘think aloud’ cognitive interviewing technique114 whereby they expressed their feelings and discussed any issues around the questions/process. This session was facilitated by GT, who audio recorded and transcribed the key points for team discussion. All participants in this session took the questionnaire seriously and engaged with the choices. Descriptions and explanations in the DCE were revised for better understanding and readability based on their comments.

‘Ladders’

In the final stages of the project, the ‘ladder’ logic model emerged through mixed-methods analysis of the BIBS study data and feedback from our mother-and-baby group co-applicants (see Chapter 6). This was taken to the groups in an interactive format so that women could engage and feed back on it before finalising it as a research output, but could also attempt to put together their own ‘ideal’ tailored interventions, using the components that either they or we identified. As researchers, we wanted to garner a sense of how the ladder might be communicated in lay terms and also to assess whether it could be used with potential trial participants as a tool to contribute to identifying important components and processes to optimise intervention codesign. This exercise proved popular and was successfully completed by participants in Aberdeen (n = 4; n = 3 reproduced with consent in Appendix 3) using a blank ladder and three envelopes labelled ‘life’, ‘incentive’ and ‘other’ rungs. Each envelope contained individual paper ‘rung’ cards with labels corresponding to barriers and facilitators, identified from study data, and some blank rungs for women’s own contributions (see Appendix 4). They then constructed their own smoking cessation or breastfeeding behaviour change programmes, applying star stickers to highlight those ‘rungs’ that they considered crucial. In retrospect, clarity could have been improved with separate ladders for barriers (damaged or missing rungs) and facilitators (rungs). However, women liked the simplicity of the ladder metaphor. They considered that it enabled them to set a clear goal and a direct means of reaching it while taking their personal circumstances and contexts into consideration and valuing their individual needs and preferences. Participants in this exercise commented that this model for intervention design would improve engagement as it felt personalised and suggested that it could work for other or multiple health behaviours. For example, some spontaneously talked about the implications of incentive rungs for other health behaviours, in particular healthy eating, which was considered too expensive to do. One woman commented that if she was ‘overhauling’ her health she might attempt to improve several aspects of her lifestyle, especially if she was being provided with incentives or rewards to help her do this. This suggests the relevance of incentives for addressing multiple health behaviours at this life stage. However, others expressed entrenched resistance to change; for example, when completing a ladder for stopping smoking, one woman responded to breastfeeding saying ‘no, no, no, no, no!’