Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/141/02. The contractual start date was in February 2012. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor Bhui is Director of Master of Science programmes in mental health including transcultural mental health care. Professor Weich is a member of the commissioning panel for the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Bhui et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The challenges faced by people from a black and minority ethnic (BME) group when they come into contact with psychiatric services are well documented. 1,2 Research reviews and evidence-based policies highlight ethnic inequalities in both experiences and outcomes. Indeed, in relation to BME people (relative to the white population), there are concerns about their worse record of patient safety, the disproportionate number of admissions and detentions in psychiatric hospitals, greater conflict with carers and staff, fear of services, lack of engagement with or poor access to effective services, fears about contact with the criminal justice system (principally the police), poorer access to psychological therapies and ethnic variations in the use of drug treatments. Recent data support differences in compulsory treatment, compulsory admissions, entry into primary care services, income and employment by ethnic groups. 3–5 Although BME is often used as a shorthand to represent minority ethnic groups in the UK owing to common linkages between histories of oppression, exclusion, vulnerability to psychiatric disorders and inequalities in outcomes and experiences,6 there are many subgroups and much heterogeneity within any ethnic group. 7 Furthermore, the over-representation of specific ethnic groups in specialist psychiatric services contrasts with their lesser use of primary care and public health interventions. Although this calls for a wider analysis, this report focuses on specialist psychiatric services only, irrespective of the disciplinary origins of staff in these services, given this has been the area generating most concern in previous policy reviews. 1,2

Culture and communication

The ability of mental health service staff to communicate effectively with any particular patient, and in a manner appropriate to that person’s culture, underpins successful diagnosis and therapy. The proposed value of understanding and evaluating communications is that they improve therapeutic outcomes through multiple mechanisms, hence the term therapeutic communications (TCs). For example, patients with a mental illness who cannot speak good (or perhaps any) English are likely to experience anxiety and uncertainty during assessment; moreover, diagnosis and clinical decision-making will be hampered. The use of family or friends as interpreters to address this issue is often inappropriate, and may undermine the clinical assessment. Instead, the use of bilingual professionals or interpreters with expertise in mental health is recommended. 8–10 Problems arise from language differences and the interconnection between language and concepts of health and illness (often called explanatory models or illness perceptions) that are used to communicate distress. These explanatory models vary across cultures, and this makes it difficult for the patient and professional to gather the same understanding of their cultural origins, and therefore concepts of health and illness, differ. These concepts may be expressed through particular idioms or metaphors, and these may differ across languages. The use of professional interpreters or other forms of formal language support is rare, but when the spoken word is the primary source of information for diagnosis and also the format of some forms of therapy, these cultural and linguistic influences on communication have a significant impact. 11,12 It is necessary to ensure that both aspects of diversity – language and culture – are addressed. 13 However, dissatisfaction and inequalities are also prominent among anglophone migrants and other people from BME groups who speak English. 9,10 There are wider issues of communication beyond translation and interpretation, and it is these that we focus on in this review.

Overall, BME groups are more likely than the white British population to report dissatisfaction with care, to fail to engage with services, to decline treatment and to have fears for their own safety while in treatment. This may be explained not only by inherent communication problems, but also by different (cultural) assumptions about the causes and treatments of mental and emotional distress. 14 Ineffective communication because of these differences may then lead to a feeling of not being understood, omissions of important information from the clinical assessment, conflict with staff, disengagement and/or a failure to take up interventions14,15 – sometimes termed failed negotiation. This may lead to more severe and more frequent episodes of illness and, in turn, the use of coercion, which is itself associated with a higher rate of adverse incidents. Such a cycle undermines the therapeutic potential of established care practices and processes, and further burdens BME users of mental health of services. Thus, improving TCs may permit maximum benefits to be realised from existing care and services, improve safety and avoid adverse incidents in care.

Effective communication is central to psychiatric assessment, diagnosis, engagement and treatment, and, ultimately, recovery. 14,15 Effective communication has proven more difficult to achieve where there are differences in culture or language between those delivering and receiving care. 6 Of course, communication difficulties might arise in any encounter between a patient and professional owing to differences in age, gender, social status or perceived power. However, cultural differences between patient and professional increase the challenges. For example, when attending to a patient from a different culture, the following abilities of a professional will be reduced:

-

the ability to identify with and empathise with the patient, and to assess that patient’s emotion accurately16–20

-

the ability to understand symbolic and metaphorical language, as this varies greatly across cultures21

-

the ability to understand the patient’s expectations of the health-care professional, as professional roles differ widely across countries and cultures (e.g. authoritarian versus egalitarian approaches and the preferential use of medication as opposed to ‘talking therapies’ to try to resolve emotional issues)22,23

-

the ability to appreciate the differences in illness perceptions and explanatory models of the illness. 14,24

Cultural factors amplify the limitations of TCs, and are of importance because they have the potential to compound inequalities in the social determinants of illness and to perpetuate inequalities in health-care outcomes following contact with health systems. 23,25,26 Conversely, good TC can reduce the inequalities. For example, Lorenz and Chillingerian27 argued that the use of visual supports to improve communication helps to address inequalities and gender disadvantage by introducing a more ‘fair process’ of assessment. They defined a fair process as one that involves patients in a collaborative approach to the exploration of diagnostic issues and treatments, explains the rationale for decisions, sets expectations about roles and responsibilities, and implements a core plan and ongoing evaluation. Fair process opens the door to bringing patient expertise into the clinical setting and the work of developing health-care goals and strategies. Although improved TC is at the heart of fair process, the evidence base to support its professional use is scattered across a number of disciplines, each of which uses a different theoretical model. There is therefore a need to pull together the evidence on interventions that improve TCs, appraise its quality and identify the components of effective interventions.

Cultural competency

One proposed solution to the problems stemming from poor communication between mental health services and their BME patients is the training of the professional in ‘cultural competency’. 28 A review of the international literature on cultural competency suggests that it is best conceptualised as a systemic and deep-seated process of change in both organisations and professional practice. 29 It often requires a change in the attitudes of staff, and a change in the way they assess, diagnose and treat people whose expectations and perceptions of both illness and recovery differ from their own. At an organisational level, the changes required include developing values that are more welcoming of culturally diverse populations and changes in management styles and human resource practices that reflect an understanding of the influence of culture on communication. Alongside these macro-level interventions, educational solutions have included training to address the attitudes and stereotypes held by individual members of staff. However, the introduction of long-term change at an individual and organisational level has not been widely achieved in the UK, perhaps because of the complexity of the task. Short-term educational solutions have been more popular and, therefore, more widely reported in the literature. These have varied in quality and focus, with some attending to communication; some to clinical skills and practices; some to the attitudes of practitioners and their cultural biases; and some to specific groups, such as faith groups, refugees, migrants, gypsies or other racialised groups. The lack of long-term programmes and the wide variability of the short-term interventions have made the development of a robust evidence base problematic.

Some cultural competency training has included information on race equality and compliance with recruitment legislation. The Department of Health rolled out a ‘race equality and cultural competency framework’ to address stigma, race equality and cultural factors. 30 This highlighted some of the communication issues that arise with BME patients and the need for sensitivity to stereotypes according to race and culture, but had rather little to say about clinical assessment, diagnosis or specific treatment strategies. Bennett and Keating28 mapped cultural competency training and its content in the UK and concluded there was insufficient attention to clinical interventions and to racial issues; they suggested instead that non-TC issues were more often reported. A systematic review of the international literature on cultural competency interventions in mental health settings similarly found few evaluations and none of these reported patient outcomes. 29 A systematic review of TCs with BME patients is necessary to synthesise the findings across the many approaches tried, and to identify lessons for policy, practice and research. Inevitably, such a systematic review will require characterisation of a wide range of interventions in diverse contexts and for diverse populations, rather than a meta-analysis of trials of a single intervention as there appears to be no single intervention that is known to be of superior efficacy.

Narratives, ethnography and diagnosis

The meaning a person assigns to an illness may be quite different from that assigned by the health professional. 31 This issue is not confined to the UK, and it reflects fundamental differences across national, cultural, ethnic and religious groups in the way mental distress and illness are understood and defined, and is related to expectations of recovery and treatment. 32,33 If psychiatric professionals have a good appreciation of a patient’s beliefs and expectations, then that can only be beneficial. Some pioneering services have sought to facilitate such an appreciation through, for example, the use of ‘patient narratives’ (the account of how the patient came to present to the professional, and what this might mean for the formulation of the treatment plan), what has been termed ‘ethnography’ (an understanding of, and sensitivity to, a patient’s ethnic background), and negotiations of meaning (the elucidation of the patient’s beliefs concerning the cause and likely outcome of the illness and, again, the account taken to inform the diagnosis and treatment plan).

Canales25 describes ‘narrative interaction’ – that is, the sharing of personal stories – as a form of TC that permits the inequalities by gender to be addressed in nursing practice. 25 Narratives and story-telling as part of assessment and treatment have a long history in cross-cultural psychology. 34 Narratives are ways of expressing and exploring personal identity, group histories and securing group cohesion35 that can influence the onset and course of psychiatric disorders. Assessing narratives in practice and research brings together idiographic and ethnographic methods of assessment and research. 36 Narrative methods are also valuable in addressing inequalities by engaging socially excluded groups, for example teenage mothers, so that they can receive nursing interventions,37 and in understanding challenges to the implementation of policy and practice. 38,39

A more detailed assessment of patients’ illness models is advocated by some medical anthropologists as a way of improving assessment; for example, ‘mini-ethnography’ has been used in the clinical assessment. 40 Studies of this approach have demonstrated improvements in diagnostic precision, diagnostic depth and care plans. Attempts to introduce ‘ethnography’ into the diagnostic process (i.e. to increase its ethnic sensitivity) have led to support for a ‘cultural formulation’, and indeed this has been highlighted in a previous and the most recent edition of the diagnostic manual produced by the American Psychiatric Association [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders–Fifth Edition (DSM-V)]. 41–43 This advocates that assessment includes ethnography and narrative, by the psychiatrist asking questions about cultural identity and explanatory models. Explanatory models in the anthropology literature are similar to illness perceptions reported in the psychology literature, as both refer to concepts about what causes illness, what it is called, who might help in recovery and what expectations there are of potential carers. 44 In addition, the cultural formulation covers psychosocial factors, and brings the clinician’s perspective into play by openly seeking the clinician’s reflections on interpersonal interactions before reaching an overall diagnosis and narrative about the problem and its resolution (also called a formulation). Although a cultural formulation has been reported to be helpful in clinical practice, the published papers have been mainly qualitative and descriptive, such as case reports; evaluative studies seem to appear only in the grey literature, although perhaps now just emerging in the scientific literature that tests effectiveness.

Other developments in the UK have included conflict resolution and mediation45 and a cultural consultation service (CCS) that is collecting pilot data on cultural competency and organisational narratives of care and communication with BME patients. 39

Chapter 2 Objectives

We conducted a systematic review and synthesis of the research evidence on interventions designed to improve TC between BME patients receiving specialist psychiatric care and the professionals who deliver that care.

Within this overall aim, our specific objectives were:

-

to review the published evidence as well as the unpublished grey literature and unreported research in order to identify promising interventions to improve TC for BME patients receiving specialist psychiatric care

-

to report evidence on the effectiveness, quality and cost-effectiveness of such interventions, using the following measures: patient-reported outcomes, symptoms, (dis)engagement with care, cost, safety and rates of adverse incidents (including the use of compulsion, such as being detained in hospital under the powers of the Mental Health Act (Mental Health Act 1983, www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1983/20/contents; Mental Health Act Amendment 2007, www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2007/12/contents), and treated compulsorily, including physical restraint)

-

to identify and describe the elements of interventions that show evidence of effectiveness, and list those that do not have a supportive evidence base

-

to produce recommendations for practitioners and policy-makers for different service contexts, patient groups and illnesses

-

to identify key gaps in the evidence and to highlight future primary research that would address these.

Chapter 3 Methods

Participants

We were interested in all studies that provide evidence on how to improve TC with BME psychiatric patients in the setting of specialist psychiatric care. Specialist psychiatric care is delivered by many professional disciplines. We adopt the term psychiatric services rather than mental health services as the latter is a very broad term that includes public health and social interventions in the community, for example housing and other services, that were not within the scope of the commissioned review.

Key populations included all age groups (young people, adults and the elderly) and all ethnic groups known to be prominent in health-care settings in the UK, i.e. people from Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, Sri Lankan, black Caribbean, black British, black African, Irish and Chinese backgrounds. We used these terms in the search strategy but complemented them with other terms in order to identify the broadest literature of relevance to the UK. Although commissioned as a review of BME groups, our analysis specifies the groups of importance to the UK setting and reveals the ethnic and cultural specificity of interventions.

Although originally commissioned to include only UK studies of the larger ethnic groups, we amended this aspect of the protocol during the study wherever relevant as useful information might otherwise be overlooked, for example if a study included a diaspora population of relevance to the UK (e.g. east Europeans) or if an intervention was judged to be transferable to the UK (e.g. an intervention for African Americans). However, we included such studies only where the other inclusion criteria were met.

During the review we came across some studies located at the interface of specialist psychiatric care and other sectors of care, but requiring specialist input; we included those studies in the review.

Interventions

At the outset, we defined TC as:

[A]ny conversation (face-to-face or technology-assisted) that is undertaken using a pre-defined model that seeks to improve understanding, engagement and therapeutic outcomes. For communication in health care to be therapeutic, it must involve a relationship and exchange of ideas between a patient and professional helper, be patient centred and engaging in order to influence the patient’s emotional world, and directed by the professional using expertise and skill. Therapeutic communications include all interactions that enable people in distress to resolve conflicts, divergent expectations, traumatic histories and adverse life events, and to take up and to overcome distress and also take up offers of help.

Bhui et al. 46

In this review we were specifically interested in all interventions seeking to improve TC with BME patients receiving psychiatric care, and expected a broad range of such interventions, for example conflict resolution, cultural consultancy, cultural competence and others as yet undefined.

These interventions might be aimed at either individuals or populations.

Care could be delivered by psychiatrists, general practitioners (GPs), psychologists, nurses or any other professional as long as it was located in specialist psychiatric settings.

From existing knowledge of this field, interventions to promote TC include those that:

-

employ mediation to enhance mutual understanding and to improve engagement with care

-

seek to manage divergent views, conflict and differing explanatory models and illness perceptions through negotiation and mediation

-

include narrative-based interventions (i.e. that place the service user and patient perspectives at the heart of consultation, assessment and treatment)

-

employ cultural consultation as a process of gathering narratives

-

apply cultural competence interventions focused on communication

-

any other new method or process for improving TCs that is not captured by the above, but is suited for BME populations in psychiatric care.

Any of the above processes could be delivered face to face or through two-way real-time communication technologies (e.g. NHS Direct or other support systems, telemedicine or e-mail).

We did not review the literature on interventions that are considered to be (generic) TCs themselves, such as psychological therapies or music therapies, unless the research evidence focused on interventions that might improve TCs with the specified target group(s), while meeting the other inclusion criteria (see Box 2).

Furthermore, given the evidence base already available,13 we did not include studies that were purely testing models of translation or interpretation as an intervention. The reasons for this were twofold. First, there is already a concurrent enquiry into interpretation, translation and language support (ITALS) in mental health care;12 and, second, without a control group who are denied access to an interpreter (which itself would be deemed unethical), it is difficult to determine any effect on outcome that is produced by the interpretation as distinct from the effect of the psychiatric intervention of which the interpretation is a component.

Review procedures and processes

A systematic review was carried out in accordance with the methods outlined in guidance issued by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. The full peer-reviewed protocol submitted in the funding application has been published in an open access journal for scrutiny. 46 During the course of the review, the original protocol was changed in two ways, as indicated in Participants. First, we included studies from other countries of interventions that showed evidence of transferability to the UK and the ethnic groups were relevant to the UK (e.g. by being from the same diaspora), if other inclusion and exclusion criteria were met. Second, we discovered many studies that seemed not to include evaluations but only to describe an intervention; these were assessed more carefully for evaluative statements and conclusions to create a category of near misses (A– rather than A+).

Data sources and search strategy for published literature

The following databases were searched: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, The Campbell Collaboration, ACP (American College of Physicians) Journal Club, The Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Methodology Register, Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), British Nursing Index, Health Management Information Consortium, Social Science Citation Index (SSCI), Social Care Online (www.scie-socialcareonline.org.uk) and NHS Evidence collection on ethnicity and health. We also searched university databases for Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) theses (ProQuest assisted) and Master of Science theses from specialist centres on ethnicity and health.

The terms provided by Anderson et al. 47 to understand culturally competent care were adapted as a framework from which to generate search terms that might help identify publications on the effectiveness of interventions. Search strategies were constructed around BME groups using search terms refined through a number of systematic reviews29,48,49 and terms related to key descriptors of TCs: (1) aspect of TC; (2) types of mental disorder; (3) the professionals involved; and (4) aspects of clinical success.

These terms were tested and then applied to the electronic databases from database inception to 4 April 2012. All searches were rerun in early January and February 2013. The search strategy was designed to identify a broad range of literature on TC with BME patients and staff working in specialist psychiatric services (see Appendix 1 for the final search strategy). This strategy evolved as it was iteratively tested using a range of keywords and refined during pilot searches to provide a maximum yield.

The remit of the current systematic review is necessarily very broad: interventions for improving TC might be direct (i.e. between patient and professional) or indirect (through structural modifications to services to create more space for conflict to be resolved). Studies in both community and institutional settings were eligible. Studies of interventions designed to improve TC in our target population might not have been explicitly labelled as studies of TC. Indeed, relevant studies could be classified in many ways, for example as studies of communication, cultural competence or awareness, or just training to improve outcomes in ethnically diverse areas. Therefore, an inclusive strategy was felt most appropriate to capture all potentially relevant literature; specificity was sacrificed to maximise sensitivity.

The search strategy was iteratively developed to test its sensitivity to capture gold standard papers that were known to the research team. The final search strategy was settled following further discussion with the review management group (all investigators, listed as authors of this review) and carer representatives (Patrick Vernon/Afiya Trust). The complexity of the concept of TCs and the range of BME groups that might be relevant required us to develop this block search approach to ensure we captured all possible papers. The initial search strategy was trialled on different databases to assess the number of hits and relevant papers generated. We found a separate search strategy was needed to identify papers that included dementia, as these seemed not to be picked up by the generic search strategy. An example of the blocks of terms entered is shown in Box 1.

-

(BME or black ethnic minorit* or black minorit* ethnic*).mp.

-

asylum seeker*.ab,ti.

-

(migrant* or immigrant*).ab,ti.

-

race*.mp. or racial.ab,ti. [mp = title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, protocol supplementary concept, rare disease supplementary concept, unique identifier]

-

cultur*.ab,ti.

-

(multicultural or multi-cultural).ab,ti.

-

(cross-cultural or crosscultural).ab,ti.

-

(trans-cultural or transcultural).ab,ti.

-

(multi-rac* or multirac*).ab,ti.

-

(multiethnic or multi-ethnic).ab,ti.

-

refugee*.ab,ti.

-

(multi-lingu* or multilingu*).ab,ti.

-

(ethno-cultur* or ethnocultur*).ab,ti.

-

(socio-cultural or sociocultural).ab,ti.

-

(divers* or diverse population* or cultural diversity).ab,ti.

-

(south asian* or bangladeshi* or pakistani* or indian* or sri lankan*).mp.

-

(asian* or east asian* or chinese or taiwanese or vietnamese or korean* or japanese).mp.

-

(afro-caribbean* or african-caribbean* or caribbean or african* or black* or afro*).mp.

-

(islam* or hindu* or Sikh* or buddhis* or muslim* or moslem* or christian* or catholic* or jew*).ab,ti.

-

ethnic group*.mp.

-

((ethnic or linguistic) adj diversity).ab,ti.

-

(transient adj (group* or population*)).ab,ti.

-

acculturation.ab,ti.

-

(faith* or belief* or religion*).ab,ti.

-

ethnic minorit*.ab,ti.

-

minority ethnic.ab,ti.

-

hispanic.ab,ti.

-

(deprivation or low income).ab,ti.

-

or/1–28

-

mental disorders.mp. or exp Mental Disorders/

-

(psychosis or Psychotic or schizophr* or schizoaffective or delusional or depress* or dysthymi* or bipolar or cyclothymi* or panic or agoraphobia or phobia or “obsessive compulsive disorder” or “post-traumatic stress disorder” or stress or anxiety or dementia or ADHD or “attention deficit”).ab,ti.

-

30 or 31

-

Communication barriers.mp. or communication barriers/

-

(communicat* or talk* or interact* or “expressed emotion” or conversat* or discourse* or dialogue* or relationship* or alliance* or narrative* or “peer support”).ab,ti.

-

33 or 34

-

(adher* or complian* or concordan* or nonadher* or noncomplian* or persistence or “treatment usage”).ab,ti.

-

(attend* or engag* or “rejection of therapy”).ab,ti.

-

(“drop out” or “medication possession ratio”).ab,ti.

-

(service use* or pyschosocial intervention*).ab,ti.

-

(diagnosis or misdiagnosis).ab,ti.

-

36 or 37 or 38 or 39 or 40

-

Mental health services.mp. or exp Mental Health Services/

-

(psychiatr* or “mental health nurs* OR psychiatric nurs*” or “social work*” or psycholog* or “care coodinator*” or Counsel* or therapist* or “support work*” or “employment coach*” or “nurse practitioner*” or “case manager*” or “vocational rehab* specialist*” or “psych* tech*” or physician* or provider* or practitioner* or psychogeriatrician*).ab,ti.

-

42 or 43

-

29 and 32 and 35 and 41 and 44

-

limit 45 to (English language and humans)

Hand searches of the following journals were completed for the time period April 2007 to May 2012: Transcultural Psychiatry; Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry; International Journal of Social Psychiatry; Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology; Ethnicity and Health; Ethnicity and Disease; and Diversity in Health & Care. In addition, two special issues of journals were also screened:

Grey literature: data sources and search strategy

An important body of relevant evidence was expected in the grey literature: unpublished reports and papers containing practice and community-based information on interventions. For this material, standard database searches were replaced by a variety of strategies: hand-searching more recent issues of journals on ethnicity and health (those that had appeared in the last 10 years), and journals on communications; cascade-searching; and searching specialist collections at the Centre for Evidence in Ethnicity, Health and Diversity, The King’s Fund, the NHS library on ethnicity and health, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)’s Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), the Royal College of Psychiatrists and the Medical Foundation for the Care of Victims of Torture. We also made use of various web-based resources [e.g. Google (Google Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), NHS Evidence, JISCMail] to search for reports that were not published in conventional research or professional journals and research in progress.

Search strategies for these grey literature databases were also derived by an information scientist and researcher. They built on the terms used for searching the published literature (see Appendix 1). An initial stage consisted of testing several key terms and search strategies, followed by filtering by eye and then iterative refinement of the original searches.

Doctor of Philosophy or Doctor of Medicine theses

A search was undertaken of all dissertations and theses accepted for higher degrees by universities in Europe and North America up to February 2013. Examination of titles and abstracts (where available) identified six documents of potential importance. All were ordered; however, three had been lost by the originator universities52–54 and could not be assessed further. The other three were obtained,44,55,56 but the studies did not meet the criteria for inclusion (see Appendix 2 for details).

Conference papers

Conference papers were identified through key term searches of the ProQuest Conference Papers Index from June 2004 to February 2013. A total of 138 conference papers were identified and, following examination, 16 were selected as potentially relevant (see Appendix 3 for details). None of these papers, however, was included in the review after the full text had been read.

Bibliographies

Bibliographies of peer-reviewed articles short-listed for the main review were searched to identify any grey literature references. In total, 50 grey literature references were identified via this route; following examination, 32 were selected as likely to be relevant and a further 19 as possibly relevant (see Appendix 4 for details), but on testing against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, none was included in the review.

Websites and other electronic sources

Various electronic sources were searched using predefined search terms. Search strategies followed particular threads iteratively. A broad range of websites was searched systematically using key terms (see Appendix 5). Items identified were examined and short-listed by two reviewers. UK material was separated from non-UK material. A total of 97 items were short-listed: 86 from the UK and 11 from elsewhere (see Appendix 6). None was included in the final review.

Two further electronic sources were examined:

-

NHS Evidence: 380 items were identified; 34 were short-listed as relevant (see Appendix 7).

-

JISCMail archive: 29 items were identified and five were short-listed as relevant (see Appendix 8).

None of these entered the review after examination of the full text.

Other grey literature databases were considered but not searched, including the System for Information on Grey Literature (SIGLE), which was last updated in 2005, and the British National Bibliography for Report Literature, which ceased in 1998.

Research databases

Websites of research funding bodies were searched to identify projects in progress or those that had been completed. Intervention trials were distinguished from other studies. Potential items were examined and short-listed by two reviewers. This produced the following items for further examination:

-

UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) Study Portfolio: 15 projects of potential interest were short-listed; these include seven intervention trials, two of which focused on effective patient–clinician communication, but these specifically excluded non-English speakers (see Appendix 9).

-

NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC): 15 projects of potential interest were short-listed (see Appendix 9).

-

Research councils: no studies were identified on the Medical Research Council (MRC) website but five projects were short-listed from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) website (see Appendix 9).

Following assessment of the full text, these searches did not yield studies beyond those identified in the published literature. Any completed project was tracked to identify outputs.

Economic literature

A series of systematic MEDLINE searches was undertaken by the information scientist to identify economic materials that were potentially relevant to interventions (see Appendix 10). Abstracts, were assessed and a total of 21 items were short-listed for full examination (see Appendix 10), as a result of which two studies with economic data were entered into the review; however, both had already been identified, one from the published literature search57 and one from the grey literature search. 58

Survey of experts

We consulted with experts, both those who are known in the field and those identified by asking service users about who they consider to have expertise in this area. We identified key researchers who had studied TCs. The applicants and collaborators drew on their networks in the UK, the European Union (EU) and beyond. Community groups and charities were also contacted to identify materials in community-based collections. All individuals so identified were invited to comment on omissions in the searches and to put forward candidate papers and to volunteer research work that was unpublished or in progress.

An online questionnaire59 was developed and a personal invitation sent to 37 experts in the field and to 75 organisations for circulation to their members (for list see Appendix 11). The questionnaire aimed to identify any additional grey literature, such as reports on projects, research in progress and resources or toolkits for mental health professionals (see Appendix 12). A reminder was sent to all non-responders after 2 weeks. This resulted in a total of 60 replies, of which 30 provided details of available materials. Finally, a request was posted on the ‘Minority-Ethnic-Health’ JISCMail discussion group with apologies for any cross-posting. This generated a further 10 replies, but no additional materials were identified. In total, these 70 respondents identified 30 separate grey literature items; 12 items were identified as relevant (see Appendix 13) but, after reading the full text, none was deemed to report sufficient evidence to meet our inclusion criteria.

Selecting appropriate sources

All databases searched (and number of hits retrieved from each) are shown in Table 1.

| Date of original search | Original search | Original results to 31 March 2012 (number of references) | Date of updated search | New search results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 April 2012 | MEDLINE: THERACOM 030412 – group 2. Expanded communication set | 597 | 4 February 2013 | 47 |

| 3 April 2012 | MEDLINE: THERACOM 030412 – group 3. Group 4 adapted | 538 | 4 February 2013 | 42 |

| 3 April 2012 | MEDLINE– THERACOM 030412 – group 5 | 1302 | 4 February 2013 | 119 |

| 3 April 2012 | ASSIA | 15 | 4 February 2013 | 1 |

| 3 April 2012 | The Cochrane Library | 111 | 4 February 2013 | 12 |

| 3 April 2012 | SSCI | 26 | 4 February 2013 | 3 |

| 3 April 2012 | AMED | 15 | 4 February 2013 | 0 |

| 3 April 2012 | PsycINFO | 238 | 4 February 2013 | 9 |

| 3 April 2012 | Dissertations and theses | 14 | 4 February 2013 | 0 |

| 3 April 2012 | Social Care Online | 7 | 4 February 2013 | 1 |

| 3 April 2012 | CINAHL | 20 | 4 February 2013 | 2 |

| 3 April 2012 | EMBASE | 515 | 4 February 2013 | 80 |

| 3 April 2012 | The Campbell Collaboration | 14 | 4 February 2013 | 12 |

Citations in the scientific literature were downloaded into an EndNote (version X5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) library. The relevance of all papers was assessed against the pre determined inclusion and exclusion criteria (Box 2) by two researchers, who inspected all the titles and abstracts. Each reviewer worked independently. Forward and backward citation tracking complemented the database searches.

Studies that report evaluations of:

-

models of TC designed to improve assessment, diagnosis, clinical decision-making, treatment and treatment adherence for BME patients

-

other aspects of direct communication, for example consensual/participatory activities, including participatory aspects of cultural consultation, conflict resolution, cultural competence, consent issues, complaints and grievances, drawing up care plans and crisis plans

-

teleconsultation services (e.g. NHS Direct, telemedicine, e-mail consultations, etc.)

-

psychiatric care which involved outreach or referral into services

-

service user interventions if they assisted with TCs in specialist mental health care.

-

Articles that simply report on translation or interpreter use in clinical assessment.

-

Studies of services for populations speaking diverse languages.

-

Studies that implemented a construct of TC without adapting it to local needs or conditions.

-

Evaluations of actual TCs (e.g. psychological therapies) rather than interventions that might improve TCs.

-

Articles in which ethnic minorities or ethnicity were ‘mentioned in passing’ and were not a significant focus.

-

Evaluations with no specific focus on interventions to improve TC with patients receiving psychiatric care.

-

Studies in settings or of groups not appropriate or not relevant to ethnic minorities in the UK. During the review we also decided to exclude alcohol-related treatments and treatments for drug misuse, as separate evidence reviews for these had been undertaken previously, and the nature of the interventions and the settings would not match our inclusion criteria.

-

The interventions were for the management of chronic diseases associated with mental distress or disorder, rather than the mental distress or disorder itself, such as attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection or smoking cessation.

-

Studies in which no intervention was evaluated, but analysis of routine data led to an inference that modifiable characteristics showing an association with a measure of TC or a proxy could be used as an intervention; for example, studies of ethnic matching as a derived variable in routine data were not included, whereas studies prospectively matching on an ethnic (or other) characteristic and testing the impact on the outcome were eligible for entry.

Full-text manuscripts of any titles/abstracts were obtained if these met the inclusion criteria or if there was uncertainty when reviewing the title and abstract. Any discrepancies were resolved by consensus and, if necessary, a third reviewer was consulted. The papers were classified into one of three groups: A+, A– and B. Only A+ papers entered the review.

The A+ papers met the original inclusion criteria and were entered into the review.

The A– papers:

-

Were descriptions of an intervention or elements of an intervention with no evaluation data.

-

Reported on studies that included patients from a group not relevant to the UK and held no immediate lessons for UK ethnic groups, for example they examined issues stemming from aboriginality or indigenousness. Transferability of the intervention to the UK context was a consideration.

Quality assessment

Core quality criteria

Different quality assessment tools had to be used because there were multiple research designs in the studies selected for review. Particular core criteria, though, were assessed for all studies. These were (1) the clarity with which the intervention was described as improving TC directly, by inference only, or not at all; (2) whether or not the outcomes (e.g. alliance, reduced conflict, greater trust) of a change in TC were directly measured using a reliable and valid scale; and (3) whether or not the ethnic groups would be of relevance to the UK and described in a manner consistent with a specific classification scheme for ethnicity (not just ‘race’). The last criterion was later relaxed where studies were of minorities and there were lessons that could be applied to ethnic minority groups in the UK. Core criteria scores ranged from 2 to 12 [scores of 0 on the intervention to improve TCs (1 above) and on outcome (2 above) would have led to exclusion of the study].

If there was an economic evaluation within a trial, this was separately scored. In addition, a quality-rating schema suited to different study types was used. This schema covered randomised controlled trials, case–control studies, observational quantitative studies, case studies and case series, and qualitative studies. The sources of our scoring scheme are presented in the following six sections. Copies of the full scoring scheme are presented in Appendix 14.

Quality criteria for randomised controlled trials

Through a brief review of the literature, Moncrieff et al. 76 developed a tool to assess the design of randomised controlled trials. Fifteen items could score 0, 1 or 2 (range of total score 0–30). Checklist items relate to the appropriateness and adequate description of the hypotheses, study design, intervention, main outcomes and methods of analysis. The checklist demonstrated good inter-rater reliability, and correlations between the three raters in the validation paper were high (r = 0.75–0.86).

Quality criteria for non-randomised observational quantitative studies

For the quality assessment of case–control or cohort studies, we used the evaluation of non-randomised observational studies by Deeks et al. 77 From the recommended scales, we selected that created by Reisch et al. 78 because it considers important confounding factors and differences between groups prior to the intervention, it has a good case-mix adjustment and it is a validated numeric scale (scores 0–34).

Quality criteria for case series

Through a brief literature review, we identified the NICE criteria for the assessment of case series. 79 However, with this quality assessment tool alone it was very difficult to discriminate between two studies that were similar in design or execution but that differed in the importance of the findings and their implications for practice. Furthermore, important characteristics that might better reflect quality in a case series – like length of follow-up and loss of clients over time – are not mentioned.

A previous HTA report indicated how difficult it is to use a specific system of quality ratings for case series, given that so little methodological research on quality ratings has taken place. 80 Consequently, we adopted the scoring system developed by the Canadian Institute of Health Economics (IHE). 81 This comprehensive 18-item checklist is based on quality criteria for assessment of case series from the Centre for Review and Dissemination. The inter-rater reliability of the checklist was based on the three reviewers, and has high kappa values. The IHE Delphi panel did not develop a scoring system for the checklist. According to the report, the quality of a study was assessed by counting the number of ‘yes’ responses to different criteria in the checklist. A study with 14 or more ‘yes’ responses was considered of acceptable quality. We decided to add the scoring system to the checklist; hence, a ‘yes’ to a criterion in the checklist would qualify for a score of 1 and ‘no’ would score 0 (scores range from 0 to 38).

Quality criteria for case studies, qualitative studies and studies from the grey literature

We chose the National Centre for Social Research (NATCEN) quality assessment criteria. 82 These criteria not only concentrate on the methodological quality of qualitative studies, but also highlight its conceptual quality. The NATCEN tool was based on 29 sets of previously suggested assessment criteria and consists of 18 appraisal questions underpinned by four guiding principles. We allocated a mark for each question asked and each of the items that might be endorsed to indicate quality and so the scale offers a range from 0 to 87.

Economic studies

These were rated 1–4 on the basis of the type of economic analysis. Cost-effectiveness studies scored 4, impact of interventions and cost–benefit studies scored 3, an intervention being costed scored 1, or the benefits being considered in terms of finances scored 1. A 0 was scored if there was no economic evaluation.

Overall quality score

The approach taken to quality rating was to use the core criteria and add the specialised criteria according to study design, and for the trials to include the economic score. For all other study types, the core and specialised criteria were used. The scores were summed and presented as percentages of the maximum score for each of the core items, the aggregated score of the specialised items and then as a total overall quality score. These were then categorised into low, medium or high quality on the basis of percentage of the maximum score (i.e. < 33% low, 33–66% medium and > 66% high). These are presented in Tables 2–5 to give an overall visual impression of the quality ratings according to study design, including how key elements of quality were rated, rather than relying only on a single total score. In undertaking the scoring, details about the methodological and design issues were evaluated using the scoring schedules. Specific methodological strengths or weaknesses were considered in the synthesis.

The B papers were:

-

reviews with no primary data

-

descriptions of potential interventions on theoretical grounds, but without an evaluation; often these were case studies for teaching purposes, without an evaluative and critical element or conclusion.

| Study | Does intervention improve TC? (1–4) | Outcome as a measure of TC (1–3) | Ethnic groups (0–5) | Quality of RCT (0–30) | Economic evaluation (0–4) | Total score (0–46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rathod et al., 201361 | 75 | 66.67 | 100 | 67.13 | 0 | 80.43a |

| Acosta, 198360 | 75 | 66.67 | 40 | 40.00 | 0 | 41.30b |

| Afuwape et al., 201057 | 100 | 66.67 | 100 | 56.67 | 75 | 67.39a |

| Alvidrez et al., 200966 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 50.00 | 0 | 45.65b |

| Chong and Moreno, 201265 | 50 | 100.00 | 20 | 53.33 | 0 | 47.83b |

| Grote et al., 200967 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 46.67 | 0 | 43.48b |

| Kanter et al., 201068 | 50 | 33.33 | 0 | 40.00 | 0 | 32.61c |

| Hinton et al., 200464 | 75 | 66.67 | 60 | 53.33 | 0 | 52.17b |

| Hinton et al., 200563 | 75 | 66.67 | 60 | 70.00 | 0 | 63.04b |

| Lambert and Lambert, 198469 | 50 | 66.67 | 0 | 26.67 | 0 | 26.09c |

| Tom, 198952 | 50 | 66.67 | 20 | 70.00 | 0 | 56.52b |

| Wissow et al., 200862 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 83.33 | 0 | 67.39a |

| Study | Does intervention improve TC? (1–4) | Outcome of TC (1–3) | Ethnic groups (0–5) | Quality assessment of quantitative studies (0–34) | Total score (0–46) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alvidrez et al., 200571 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 26.47 | 32.61a |

| Kohn et al., 200270 | 75 | 66.67 | 60 | 29.65 | 19.57a |

| Study | Does intervention improve TC? (1–4) | Outcome of TC (1–3) | Ethnic groups (0–5) | Quality assessment for case series (0–38) | Total score (0–50) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirmayer et al., 200315 | 75 | 33.33 | 0 | 60.53 | 54a |

| Palinski et al., 201258 | 100 | 100 | 100.00 | 86.84 | 90b |

| Chow et al., 201072 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 78.95 | 72b |

| Study | Does intervention improve TC? (1–4) | Outcome of TC (1–3) | Ethnic groups (0–5) | Case study quality score (0–87) | Total score (0–99) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bhui and Bhugra, 200414 | 75 | 33.33 | 100 | 63.22 | 64.65a |

| Chu et al., 201274 | 50 | 33.33 | 60 | 77.01 | 73.74b |

| Schouler-Ocak et al., 200875 | 50 | 33.33 | 60 | 50.57 | 50.51a |

| Grote et al., 200740 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 52.87 | 52.53a |

| Chow et al., 201072 | 75 | 66.67 | 20 | 64.37 | 72.73b |

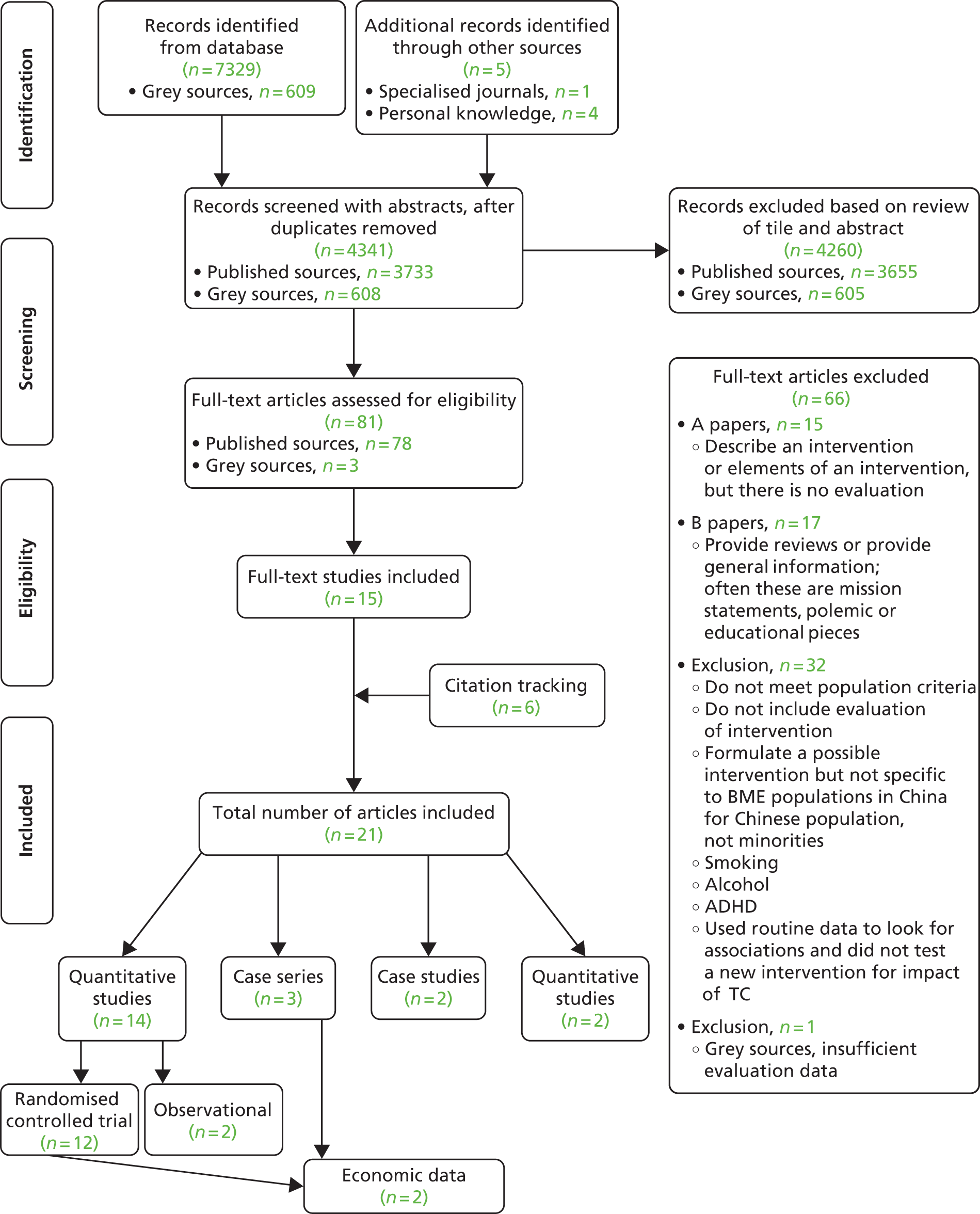

Studies included

The database searches yielded 7329 hits, and 3733 records were found to be potentially relevant after removing duplicates. An extensive search for grey literature yielded 608 sources, including six PhD theses, two of which could not be located from the original universities. Figure 1 shows the selection of papers at each stage of the review.

FIGURE 1.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram showing selection of papers at each stage.

A total of 21 publications were deemed to be relevant and met all the inclusion criteria. These comprised 12 trials52,57,60–69 one of which was from the grey literature,52 two observational studies,70,71 three case series58,72,73 (one of which was from the grey literature58 and one of which had a qualitative component that was separately extracted72), two qualitative studies40,74 (which included a case study in each) and two pure case studies. 14,75

Methods of analysis and synthesis

The findings are presented below in two groups (trials and non-trials) given that within the hierarchies of evidence it is the trials that provide the most definitive evidence of effectiveness. 83 We set out the interventions, study design, ethnic groups and service setting, and outcomes. Given the diversity of study settings, interventions and outcomes, the studies were not suitable for a meta-analysis and thus the data were subjected to a narrative synthesis. Popay et al. 84 define narrative synthesis as:

[A]n approach to the systematic review and synthesis of findings from multiple studies that relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis. Whilst narrative synthesis can involve the manipulation of statistical data, the defining characteristic is that it adopts a textual approach to the process of synthesis to ‘tell the story’ of the findings from the included studies. As used here ‘narrative synthesis’ refers to a process of synthesis that can be used in systematic reviews focusing on a wide range of questions, not only those relating to the effectiveness of a particular intervention.

It is part of a larger review process that includes a systematic approach to searching for and quality[-]appraising research[-]based evidence as well as the synthesis of this evidence. 84

Narrative synthesis includes the following elements: textual description, tabulation, grouping and thematic analysis. We undertook this process and by thematic analysis contrasted, within- and non-trial designs, elements of intervention, the outcomes used in studies, and direct or indirect measures of effectiveness, taking account of the elements contributing to the quality score and the perspectives of patients and carers who reviewed the emergent evidence (see Patients’ and carers’ views).

Data extraction

Quantitative studies

An electronic version of a quantitative data extraction form was circulated to all members of the review group for comments and revision as appropriate. The two main reviewers used an Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreedsheet to help ensure the consistency of the extracted data by allowing only certain types of options to be entered in any one field, thus ensuring that all data were categorised in a similar way. In the first stage, detailed information relating to study methods was extracted concerning the interventions (e.g. whether the effect of the change in TC was inferred or directly measured), size of the population, ethnic group, setting, timeline of intervention and of follow-up, and the outcomes that were measured (including the tool used to measure each outcome).

The second stage involved more detailed extraction of appropriate numerical data for all studies categorised as either randomised trials or quasi-experimental designs. This too was recorded in an Excel spreadsheet. The effect sizes of the various studies were extracted to judge whether or not a meta-analysis could be performed.

Qualitative studies

A similar pattern was followed with the qualitative studies. Data were extracted into a summary table in Excel. Data extracted comprised the concepts identified and evaluation methods of studies and narrative findings.

Patients’ and carers’ views

A key element of the study was to ascertain user views from the outset; in the design and operation of the literature review, as well as in the evaluation of the interventions and themes identified as having potential to improve TC. In other words, we asked service users and their carers what they regarded (or would regard) as TC and what they would see as better practice. The involvement of minority ethnic users (i.e. BME people currently using health services for mental health needs, or significantly involved as carers of such patients) was operationalised by a collaboration with the national charity The Afiya Trust (www.afiya-trust.org) and its links to the National Black Carers Workers Network (NWBCN), CatchAFiya, and the National Survivor User Network, which support and enable the voices of such individuals through a panel of users who have had basic training in self-representation and some experience of supporting similar research and service development.

The Afiya Trust circulated a call for expressions of interest and selected a panel of eight people who had relevant experience and covered a range of ethnicities and mental health needs. The panel members, chaired by an Afiya Trustee, then worked closely with the research team in advising on the literature search, considering the emergent themes and assisting with the rating, validation and dissemination of the emergent models of good practice.

The core user panel comprised two men and six women. Three self-identified as being of African/Caribbean/black British origin and five were of South Asian background, with Hindu, Sikh, Muslim and other religious affiliations, and from a variety of the major South Asian national/linguistic groups. Three had experience as carers of mental health service users (some having also been patients themselves) and most had also some experience of working with community-based third-sector support groups.

Initially, a series of three user workshops were held, to elicit key themes and to discuss perspectives on TC as a process and what issues were seen as likely to be of concern. The panel’s views were then compared and contrasted with those emerging from the review of the published scientific literature and the grey literature. This background exploration was important for the patients and carers in order to prepare themselves to consider the outputs from the review, so that they were more active in deliberating the value of the interventions identified in the review.

The interventions or other solutions identified by the literature review were grouped and presented as model responses, using a technique of vignettes that included quotes from the publications and a brief description of key elements. A series of Delphi technique consultation rounds were engaged in using e-mail and workshops to highlight the most significant issues and to draw up a list of priorities for desired changes or best practice, as well as a list of issues of concern, responding to the research team’s initial questions and planned recommendations. Although overall agreement did emerge, there was a degree of variation between panel members, and many of the model interventions were ranked as ‘most desirable’ by some members but ‘least important’ by one or more others, illustrating the heterogeneity of need and the requirement for a variety of options to be available to service providers and users.

The patient and carers commented on the proposed interventions and ranked them as high or low priority, and these judgements were included in the synthesis alongside the quality of design and methodological issues, and the strength of the findings.

Chapter 4 Results and synthesis

A total of 21 publications were deemed to be relevant and met all the inclusion criteria. These comprised 12 trials52,57,60–69 (one of which was from the grey literature52), two observational studies,70,71 three case series58,72,73 (one of which was from the grey literature58 and one of which had a qualitative component that was separately extracted72), two qualitative studies (which included a case study in each)40,74 and two pure case studies. 14,75 Two studies included economic information (see Figure 1). 57,58 The data from extractions were tabulated separately for trials and the more varied non-trial designs. The findings for trials were stratified by the quality banding (upper, middle, lower third). Within each group, we first describe the intervention and its components, and the outcomes assessed in these studies. We then synthesise the findings and conclude with a summary of that synthesis. The purpose of the groups by which the results are presented is that due weight can be given to the trials over other designs, and specifically the high-quality trials. We did not wish to overlook potential interventions that did not fall within this high-quality trials group, and so have included all trials and non-trials with evidence of effectiveness on any proxy measure. This synthesis takes account of methodological insights during the extraction and analysis process, the broad quality bandings and, where significant, particular elements contributing to quality scores.

The trials

For trials Table 6 includes details of the study authors, title, intervention and the country, ethnic groups and sample sizes, diagnostic groups and service settings, and details on the professionals involved and the outcome measures used. The findings of the trials are presented in Table 7, which gives both the statistical details against each of the main outcomes used and a narrative summary of the findings for each study.

| Study | Title | Country | Intervention | Study design | Sample size (number of individuals) and ethnic groups | Diagnostic groups | Service setting | Professional groups | Outcome measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rathod et al., 201361 | Cognitive–behaviour therapy for psychosis can be adapted for minority ethnic groups: a RCT | UK | CaCBTp. Tseng’s framework of philosophical, practical, technical and theoretical adaptation | RCT in two centres. Thirty-five participants with a diagnosis from schizophrenia group of disorders. CaCBTp participants were offered 16 sessions of CaCBTp with a trained therapist and compared with standard treatment | African Caribbean: CaCBTp = 5, TAU = 4, Black African: CaCBTp = 1, TAU = 4 Mixed race: CaCBTp = 4, TAU = 6 Pakistani: CaCBTp = 3, TAU = 3 Bangladesh: CaCBTp = 2, TAU = 0 Other (Iranian): CaCBTp = 1, TAU = 0 |

Schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder or delusional disorders (ICD-10 criteriaa) | Inpatient forensic: CaCBTp = 3, TAU = 4 Rehabilitation: CaCBTp = 1, TAU = 0 Assertive outreach: CaCBTp = 1, TAU = 0 EIP: CaCBTp = 7, TAU = 4 CMHT: CaCBTp = 4, TAU = 8 Other (immigration centre) CaCBTp = 0, TAU = 1 |

Psychotherapists registered with BABCP; all therapists received ongoing supervision | Primary outcome: CPRS. Several subscales were derived and analysed: MADRAS, SCS, BRAINS Secondary outcome: Insight in Psychosis scale, PEQ, medication |

| Wissow et al., 200862 | Improving child and parent mental health in primary care: a cluster randomised trial of communication skills training | USA | Brief communication training of three, 1-hour discussions structured around video examples of family/provider communication. Each was followed by practice with standardised patients and self-evaluation. Skills encouraged were eliciting parent and child concerns, partnering with families, and increasing expectations that treatment would help. Psychiatrists training primary care professionals to work with family, negotiate treatment choice and expectations of treatment | Cluster randomised trial. The training was tested with providers at 13 sites. Children (5–16 years of age) on a routine visit were enrolled if they screened ‘possible’ or ’probable’ for mental disorders on a questionnaire, or if their provider said they were likely to have an emotional or behavioural problem | 418 children: 54% were white, 30% black, 12% Latino and 4% other ethnicities | On the basis of SDQ 39% had possible or probable disorder related to hyperactivity, 51% conduct difficulties and 31% emotional difficulties | Participating rural sites (n = 7) included a solo paediatric practice, a hospital-based, multimember, paediatric practice, four freestanding multispecialty offices and a practice staffed by two family nurse practitioners. Urban sites (n = 6) included three community medical centres (two multispecialty and one paediatric), a private paediatric practice, a hospital-based family practice and a community centre serving Latino immigrants | Paediatric primary care, no site had formal arrangements with psychiatrists or psychologists. Providers had practised for an average of 15 years since obtaining their degree (range 2–40 years; median 13 years); 85% had been at their site for 1 year, and 60% were female. Sixty per cent were trained in paediatrics, and 38% in family practice. Eighty-three per cent were physicians, 16% were nurse practitioners and one was a physician’s assistant. Twenty-one per cent had additional training in child behaviour | Parent mental health symptoms – rated on GHQ-28. Child symptoms and functional impairment-computed total symptom (range 0–40) and impairment (range 0–10) scores from the parent-rated SDQ |

| Afuwape et al., 201057 | The Cares of Life Project (CoLP): an exploratory RCT of a community-based intervention for black people with common mental disorders | UK | Needs-led stepped-care approach by six community health workers with a more experienced therapist. Practical advice, assistance, advocacy for social needs, health education, mentoring, brief therapies based on CBT and brief work focused on solutions. CBT with ethnically matched therapists (black African and black Caribbean origin), delivered through multiple social sites with significant flexibility | RCT: individuals were randomised to a needs-led package of care (rapid access) or to a 3-month waiting list control with information on local mental health services (standard access). The needs-led package involved practical advice and assistance, advocacy for social needs, health education and mentoring as well as one-to-one brief therapies based on principles of CBT and brief solution by ethnically matched therapists | 40 individuals of black African origin (black African individuals born in sub-Saharan Africa or born in the UK with at least one parent of sub-Saharan descent) and of black Caribbean origin (black patients born in the Caribbean or born in the UK with at least one parent of Caribbean descent) | WHO diagnostic criteriaa for anxiety (generalised anxiety, panic, social disorder or agoraphobia) and/or depression | Separate service at the interface between statutory agencies and the local black community organisations. Community, referrals for service users, services, and self-referral or referral by friend (37%) | Community health workers (psychology graduates with a minimum of 2-months’ training in the delivery of the intervention). There was backup of a more experienced therapist with access to a psychiatrist for individuals with more complex needs | Primary outcome: At 3 months, GHQ-28 total scores. Secondary outcome: transformed sub-scales of the GHQ-28; Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional, Mental Health, Experience of a severe difficulty from the Life Events and Difficulty. General psychosocial functioning using the GAF; eight transformed scales of the SF-36 and the Mental and Physical component summary scores; ‘fresh start’ events and cost of service use |

| Hinton et al., 200563 | A RCT of CBT for Cambodian refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: a crossover design | USA | Culturally adapted CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks. Information about PTSD and PD, muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing, culturally appropriate visualisation, relaxation techniques/mindfulness; cognitive restructuring of fear networks; exposure to anxiety-related sensation alongside reassociation to positive images to treat panic attacks generated by sensation-activated fear networks. Exposure to, and narrativisation of, trauma-related memories. Teaching cognitive flexibility by lotus visualisation and enactment and by a flexibility protocol. Practice set shifting, during the emotional processing protocol: shifting from acknowledgement of trauma to self and other pity, to kindness and to mindfulness | RCT: individual CBT was offered across 11 weekly sessions. Vietnamese social workers and staff provided translation and cultural consultation | Cambodian refugees (n = 40): 20 patients in the IT condition and 20 in DT | PTSD and panic attacks | Two community-based outpatient clinics that provided specialised services to non-English speaking Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees | Therapist (fluent in Cambodian). All outcomes were measured by a Cambodian bicultural worker (D.C., V.P.) with over 2 years of mental health experience; blind to treatment condition |

|

| Hinton et al., 200464 | CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks: a pilot study | USA | Culturally adapted CBT for Vietnamese refugees with treatment-resistant PTSD and panic attacks. Eight core elements highlighted in the sessions: providing information about the nature of PTSD and panic disorder; training in muscle relaxation and diaphragmatic breathing procedures, including the use of applied relaxation techniques; instruction in a culturally appropriate visualisation; framing relaxation techniques as a form of mindfulness; cognitive restructuring of fear networks; exposure to sensations that induce panic; providing an emotional processing protocol; and exploring panic | Pilot of RCT: individual CBT was offered across 11 weekly sessions. Vietnamese social workers and staff provided translation and cultural consultation. Pilot RCT and cohort study | (n = 12) non-English speaking Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees | PTSD and panic attacks | Two community-based outpatient clinics that provided specialised services to non-English speaking Cambodian and Vietnamese refugees | Therapist | HTQ, translated and validated for the Vietnamese population HSCL-25, translated and validated for the Vietnamese population ASI, translated and validated for the Vietnamese population H-PASS O-PASS Outcomes from HTQ, HSCL-25 and ASI were measured (a) at pre-treatment (first assessment); (b) after group 1 had undergone 11 sessions of CBT (second assessment); and (c) after group 2 had undergone 11 sessions of CBT (third assessment). Outcomes from H-PASS and O-PASS were measured every 2 weeks |

| Chong and Moreno, 201265 | Feasibility and acceptability of clinic-based telepsychiatry for low-income Hispanic primary care patients | USA | Telepsychiatry intervention for Hispanic patients. Online meeting programme between Hispanic psychiatrists and Hispanic low-income primary care patients seeking consultation. Two Hispanic psychiatrists fluent in English and Spanish; organisational readiness concept; importance of mental health treatment accepted; payment not expected of either group. Patient and psychiatrists sit in front of respective PC using webcam | RCT: eligible subjects were randomly assigned to telepsychiatry using WEB or TAU. Those assigned to the WEB condition agreed to arrive for telepsychiatry sessions once a month for 6 months (1 hour for intake and six 30-minute follow-ups). Those assigned to TAU were told that their provider would be responsible for their mental health needs | 80 intervention and 89 TAU Hispanic patients | Depression | Primary care referred for telepsychiatry specialist consultation | Hispanic psychiatrists | PHQ-9: WEB – each session (for 6 months); TAU – baseline, 3 and 6 months post baseline MINI: only once for exclusion and inclusion ARSMA II SDS: patients baseline and 3 and 6 months post baseline. WEB – monthly. TAU – baseline and 3 and 6 months post baseline VSQ-9 was developed from Rand’s Medical Outcomes Study. The VSQ-9 was found to reflect patient–doctor communication if used immediately after the clinical visit Working Alliance Inventory Short Form rate questions regarding the working relationship between them and the clinician/therapist during the specific clinic visit. It measures three subscales of the alliance that are related to the goal, task, and client–therapist bond. VSQ-9 (doctor patient communication) satisfaction ratings, proportion of completed primary care appointments |

| Alvidrez et al., 200966 | Psychoeducation to address stigma in black adults referred for mental health treatment: a randomised pilot study | USA | Psychoeducation booklet to tackle stigma. Booklet based on peers’ experiences of services to reduce stigma – preparatory to treatment in mental health services/engagement. Getting Mental Health Treatment: Advice from People Who’ve Been There was a psychoeducation booklet developed from qualitative interviews revealing black patients’ experiences with mental health treatment and stigma. The booklet included information on what consumers wished they had before entering mental health treatment, challenges faced, getting or staying in treatment and the strategies to deal with challenges, and advice on making treatment work better | RCT: comparison with information in two existing brochures on local mental health services and the services in the outpatient clinic. Twenty-two of 42 participants assigned to psychoeducation and 20 to general information | 42 clients self-identified as black/African Americans, first time clients of the clinic | DSM-IV, diagnosis made by clinician. Depression, PSTD, stress and anxiety disorders were most common. Forty per cent co-occurring substance misuse, 40% had treatment previously in another setting | County hospital-based outpatient mental health service | Clinicians diagnosed conditions | Symptom severity based on Global Severity Score of Brief Symptom Inventory Perceived need for treatment. Treatment concerns. Diagnosis. Stigma-discrimination (devaluation-discrimination scale). Helpfulness of information (questionnaire). Treatment entry and attendance |

| Grote et al., 200967 (pilot data reported in 200740 and included in this paper) | A RCT of culturally relevant, brief interpersonal psychotherapy for perinatal depression | USA | Short, enhanced culturally relevant interpersonal therapy. IPT-B delivered as part of multicomponent care for antenatal depression; engagement sessions were followed by eight IPT-B sessions before the birth and maintenance IPT up to 6 months post partum. IPT was combined with motivational and ethnographic interviews taking account of social isolation, vulnerability and financial strain | RCT: 53 non-treatment seeking, pregnant African American and white patients receiving prenatal services were randomly assigned to receive either enhanced IPT-B (n = 25) or enhanced usual care (n = 28). Participants were assessed before and after treatment | 53 non-treatment seeking pregnant African American women (n = 33) and white counterparts (n = 20) | Depression on EPDS, score of > 12 | Obstetrics and gynaecology clinic in an urban setting | Therapists | Baseline, 3 months post baseline, 6 months post partum: depression diagnoses, symptoms (EPND scale for screening post-natal depression). Beck 21 item for depression diagnosis if cut off > 10; BAI-21 anxiety measure; social functioning on Social Adjustment Scale’s social and leisure domain |

| Acosta, 198360 | Preparing low-income Hispanic, black, and white patients for psychotherapy: evaluation of new orientation programme | USA | Audiovisual programme instructing patients about psychotherapy. The control patients saw a programme that was neutral with regard to psychotherapy. Orientation, role induction, management of expectations assuming knowledge is limiting factor. An audiovisual slide/cassette programme titled ‘Tell It Like It Is’ designed to inform patients from widely diverse ethnic, language and cultural backgrounds about verbal psychotherapy. Combined simple explanations of the therapy process with presentations of vignettes that model helpful patient behaviours such as self-disclosures and direct statements of patient expectations | RCT: patients in each of the three ethnic groups were assigned randomly to one of two experimental groups: (1) oriented or (2) not oriented. The study employed a 2 × 3 × 2 factorial design, with two levels of patient orientation (oriented and not oriented). Three levels of patient ethnicity (Hispanic, black and white) and two levels of patient sex (male and female) | 62 Hispanic, 51 black and 60 white participants (n = 173) | Most frequent diagnoses: Hispanics: 27.8% transient situational disturbance, black: 34.1% psychoses, white: 37% neuroses | Psychiatric outpatients | Adult psychiatric outpatient clinic | Attitude Towards Psychotherapy; questionnaire is an 8-item questionnaire on 6-point Likert-type scales that ranged from ‘agree strongly’ to ‘disagree strongly’. Knowledge Questionnaire, 10 items with multiple-choice questions |