Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/44/01. The contractual start date was in March 2012. The draft report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dr Price reports grants from UK Medical Research Council, during the conduct of the study; Dr Turner reports grants from University of Birmingham/National Institute of Health Research (NIHR), during the conduct of the study; Dr Jordan, Professor Riley, Dr Moore, Professor Singh, Professor Adab, Professor Fitzmaurice, Dr Jowett and Professor Jolly report grants from the NIHR during the duration of the study; Professor Singh reports that the University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust holds the intellectual property for a self-management manual for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Jordan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: definition, prognosis and burden

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a long-term condition characterised by ‘persistent airflow limitation that is usually progressive and associated with an enhanced chronic inflammatory response in the airways and the lung to noxious particles and gases’. 1 The most important cause of COPD is cigarette smoking, although other risk factors are thought to be indoor and outdoor air pollution, occupational exposures and diet. 2 Over time, patients experience increasing breathlessness and more frequent exacerbations of respiratory symptoms, leading to increasing disability, reduced quality of life (QoL) and often repeated hospitalisations. 1

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease affects 5–10% of people worldwide,3 is rising in prevalence,4 and is a leading cause of death. 5 In the UK it is the second most common cause of emergency admissions,6 costing the NHS over £800M per year. 7 Increasing recognition of the importance of this disease8,9 culminated in a new National Clinical Outcomes Strategy in 2011. 6

Diagnosis and severity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

A diagnosis of COPD is suspected among people with breathlessness or cough and is supported by post-bronchodilator spirometry to confirm irreversible airflow obstruction. 10 Although definitions of airflow obstruction are inconsistent and controversial,11 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for COPD currently defines airflow obstruction when the ratio of forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) to forced vital capacity (FVC) is < 0.7 (i.e. FEV1/FVC < 0.7). 10 Despite the requirement for confirmation with spirometry, there are many people with a clinical diagnosis of COPD who do not meet these spirometric criteria. 12 Late-onset asthma, other comorbidities and difficulty obtaining spirometry data may contribute to misdiagnoses.

Severity of airflow obstruction in the UK is graded using categories of FEV1 as a percentage of predicted normal values of a healthy reference population (Table 1),10 although these definitions may vary across countries, and have changed over time.

| Category | FEV1% pred |

|---|---|

| Mild | > 80 |

| Moderate | 50–79 |

| Severe | 30–49 |

| Very severe | < 30 |

Severity of airflow obstruction does not necessarily reflect either the level of disability experienced or the frequency of exacerbation and composite measures to capture the global impact of the disease have been proposed. 1 However, they are not yet widely used as the basis for treatment decisions. Most research studies evaluating treatments use FEV1% pred (forced expiratory volume in 1 second percentage predicted) to select and describe patients. FEV1 is also often used as an outcome measure to describe prognosis of patients, as are clinical measures (such as dyspnoea and exacerbations), global measures such as health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and health service utilisation (e.g. hospital admissions).

Exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

Exacerbations or ‘flare-ups’ of COPD occur in approximately 50–60% of moderate/severe patients with COPD, per year, in published cohorts and trials13,14 and similar rates are also observed in primary care (unpublished data from the Birmingham COPD cohort study). They are a characteristic component of disease progression, often requiring hospitalisation1 and are associated with long-term poor outcome. Exacerbations are caused primarily by viral respiratory infections, particularly the common cold (associated with about two-thirds of exacerbations). 15 They result in worsening of a patient’s symptoms for several days, this being more frequent during winter months. 16

Approximately 15% of patients with COPD per year have exacerbations that are severe enough to lead to hospital admission,7 which contributes to over half of the total direct costs of COPD to the NHS. 7 Readmission for an exacerbation within 3 months is high at > 30%,17 as is 30-day mortality. Exacerbations are often not independent events, and there are a group of people who are frequent exacerbators. 18 Exacerbations are usually treated with an increase in usual medication, a course of antibiotics and/or steroids. 10

Management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

In early-stage disease patients may not display or recognise their symptoms but, as the disease progresses, varying degrees of cough, sputum, wheeze and dyspnoea1 may develop until eventually patients may require long-term oxygen therapy. 10 Other than the acute treatment of exacerbations, therapy is aimed at reducing progression and managing symptoms and is primarily based around smoking cessation, inhaled medications, pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) and, increasingly, more preventative disease management approaches [including self-management (SM)]. 10

Management of long-term conditions in the UK

More than 15 million people in England are living with long-term conditions such as COPD, diabetes, heart disease and asthma. 19 Long-term conditions represent > 70% of hospital bed-days and more than half of general practitioner (GP) consultations, and account for at least 70% of the total health and social care budget. 19 For patients, long-term conditions reduce QoL and ability to carry out daily tasks, as well as contributing to premature mortality. In the past, treatment of people with long-term conditions would have been more reactive. However, in 2004, the NHS Improvement Plan set out the plans for the future care of these patients by focusing on avoiding admissions and caring for patients at the primary care level, and encouraging patients to manage their own condition (SM). 20

Patients access health-care professionals relatively infrequently and, therefore, in order to optimise their health patients must be able to manage their own condition successfully on a daily basis. Support should be available to help patients (and their families/carers) manage their own condition and make healthier choices about their diet, physical activity and lifestyle. 20 Since the NHS Improvement Plan was published, this approach has been embedded in subsequent policy documents,21 which clearly emphasise the important role of SM. However, it is clear that clinicians are often reluctant to take this approach and, therefore, the support for patient SM is likely to be suboptimal. 19

Surveys indicate that > 90% of patients with long-term conditions would like to become more active self-managers, although in many conditions report insufficient knowledge or support to do so. 22

Self-management: definition and models

‘Self-management’ has been defined as the ability of a patient to deal with all that a chronic disease entails, including symptoms, treatment, physical and social consequences and lifestyle changes. 23 The exact nature of SM will vary from condition to condition and person to person. Indeed, there is debate about the interpretation of the goals of SM, which may differ between health-care professionals and patients, and between countries and health-care systems.

There are many factors that may affect a patient’s ability to self-manage (e.g. severity, presence of comorbidities, depression, education, psychological factors, ethnicity). 24–27 One behavioural model that describes SM is Patient Activation,28 which emphasises that patients should have the knowledge, skills and confidence to manage their own health and health care. Interventions to promote SM should aim to address each of these components.

Interventions to support self-management

Self-management support involves collaboration between the health-care professional and the patient so that the patient acquires and demonstrates the knowledge and skills required to manage his/her medical regimens, change their health behaviour, improve control of their disease and improve their well-being. 29 Patient education alone is not sufficient; monitoring and assessment of progress is also essential. SM interventions should teach skills that promote health behaviour modification with the aim of increasing self-efficacy (the belief that one can successfully execute particular behaviours), thus improving clinical outcomes, including adherence. 30 Strategies to promote self-efficacy include personal experience and practice, feedback and reinforcement, analysis of causes of failure and shared experience with successful peers. 30 Indeed, the established NHS Expert Patient Programme for managing chronic diseases is based on Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy. 31 Evaluations of SM programmes should therefore first assess patients’ self-efficacy, change in behaviour and then patient outcomes and health-care utilisation.

Self-management programmes can be delivered in a number of ways (e.g. series of workshops, written material, by telephone, internet or a mixture) by various professionals or lay personnel, and can have a range of components. Systematic reviews of SM programmes for long-term conditions have concluded that such programmes tend to lead to small improvements in some outcomes for some chronic diseases (but not all) and that further research is needed. 32,33 More recently there have been some unsuccessful high-profile trials in primary care settings,34–36 some of which suggest that only a subgroup of patients may be able to self-manage.

Self-management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: principles and current practice

Self-management for patients with COPD is complex and challenging. 10,25 It requires patients to be able to manage various facets of their condition on a daily basis, including understanding and taking their medications appropriately with good inhaler technique, early recognition of exacerbations of symptoms and early instigation of treatment during an exacerbation, receiving annual influenza vaccinations, managing their breathlessness (including stress management/relaxation) to allow them to undertake activities of daily living, bronchial clearance techniques, taking regular exercise to maintain their lung function and exercise capacity, quitting smoking and maintaining a healthy diet. 29,30,37

In reality, the true extent to which patients manage these aspects is not well described but it is likely to be suboptimal. A survey published in 2009 in Canada38 revealed that although patients felt that their knowledge about the disease was good, in reality their knowledge of the causes of COPD, the consequences of not adhering to their medication and how to manage exacerbations was inadequate. A small study in one GP practice in the UK in 200439 indicated that only 48% of patients with COPD had discussed levels of exercise with their GP/nurse and only 50% had spare antibiotics/steroids at home in case of exacerbations, although > 80% reported understanding their inhalers, knowing what to do if they had an exacerbation and having given up smoking.

Current self-management support for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the UK

Self-management support for COPD is less well developed than in other long-term conditions both in the UK and worldwide. NICE quality standards state that patients with COPD should have a comprehensive, up-to-date personalised management plan, including information/educational material about the condition and its management. 40 NICE guidance also emphasises that patients at risk of having an exacerbation of COPD should be given SM advice/treatment that encourages them to respond promptly to the symptoms of an exacerbation. 10 Other aspects of SM advice include promoting proactive behaviour change, such as smoking cessation and increased exercise. However, the evidence about the exact nature and the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of potential components of a SM package is acknowledged to be inadequate. 10

A variety of tools are available, such as the ‘Living Well with COPD’ programme developed by the Montreal Chest Institute and mentioned in the American Thoracic Society statement,30 materials provided by the British Lung Foundation,41 and materials developed by individual hospitals/universities or private health-care companies, but there is no one consistent recommended approach. 6,10 Limited evidence suggests that programmes are patchily provided and unlikely to be individualised. 42 Qualitative studies in the UK and elsewhere suggest that patients report a lack of SM support and a lack of understanding of their condition. 43,44

This heterogeneity is reflected in the literature describing trials of a wide variety of interventions. It is accepted, however, that the optimum package of care is not known,10 and this fact is one of the premises upon which this report is based.

There is considerable overlap between programmes that are defined as SM and other more complex supervised programmes, such pulmonary rehabilitation (PR). 37,45 PR is defined as ‘an evidence-based, multidisciplinary, and comprehensive intervention for patients with chronic respiratory diseases who are symptomatic and often have decreased daily life activities . . . programs involve patient assessment, exercise training, education, nutritional intervention, and psychosocial support’. 30 A continuum of support is now recognised, which should, ideally, be personalised to reflect an individual patient’s needs, including disease severity and other comorbidities. 37,45

For this reason, in the second study within our evidence report, we have included trials of a wide range of care packages including PR in order to identify which features of SM are most important, as long as they involve one or more of the specified components of SM.

Evidence for the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-management support for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: existing literature

Current literature on SM for COPD largely addresses the effectiveness of SM support when delivered to patients in a stable state. There are now many trials and overlapping systematic reviews of interventions (such as PR, integrated care), which include a SM component, although to varying degrees. 46–50 A Cochrane systematic review of SM education interventions48 (excluding studies on PR, updated in 2009) identified 14 randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that showed that SM interventions delivered to patients with COPD in the stable state could significantly reduce hospital admissions compared with usual care (UC) [odds ratio (OR) = 0.64, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.47 to 0.89], significantly improve some domains of QoL and effect a small improvement in dyspnoea. However, many of the other results were inconclusive, possibly because of the great heterogeneity in the populations studied, nature of the interventions, outcomes measured and length of follow-up. The authors concluded that ‘data were still insufficient to formulate clear recommendations regarding the form and contents of SM education programmes in COPD . . . with a need for more large RCTs with long-term follow-up’. 48

A systematic review of five trials on the effectiveness of action plans only (with only limited education) found that although patients were significantly more likely to recognise exacerbations and initiate treatment, there was no reduction in health-care utilisation, and they concluded that a more significant SM approach might be needed. 50 A further systematic review of COPD disease management programmes,49 including 10 trials and three before-and-after studies, indicated that such programmes (which often include SM components) may decrease hospital admission and improve QoL, although further exploration of the elements that bring the greatest benefit are needed.

A more recent systematic review of integrated disease management demonstrated a significant improvement in QoL and respiratory admissions,47 and there are other recent systematic reviews of breathing exercises,51 outreach nurses52 and exercise training. 53 These reviews are significantly overlapping in their inclusion but none of them comprehensively reviews all of the latest trials relating to SM interventions/components or attempts to delineate the relative effectiveness of the different components.

One important factor that varies among the trials already reviewed48 is the nature of the populations involved. It has been suggested that SM programmes should target those patients with more severe COPD and frequent exacerbations in order to be beneficial. 29,30 Patients who are admitted to hospital have a high risk of readmission within 90 days. 17 Thus a focus on patients who are currently hospitalised for COPD (or recently discharged) could have the most potential for health gain and reduction in resource use. Data on such interventions following hospitalisation (other than PR programmes) are limited. 54

Rationale for evidence review

Although there is a plethora of RCTs published and increasing numbers of systematic reviews on different aspects of SM support for COPD, results are conflicting about which of the many types of interventions, and particularly which components, are the most effective. 10 Furthermore, there remain significant unanswered questions about the timing and delivery of SM support, particularly whether SM support provided soon after discharge from hospital is effective or cost-effective.

In 2010, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme published a commissioning brief: supported SM for patients with moderate to severe COPD. It asked for a wide systematic review of the literature, particularly focusing on patients, around or soon after discharge, to answer: ‘What are the elements of supported SM that prevent readmission to hospital and adverse outcomes?’ We report a series of systematic reviews and an economic model to address this question.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

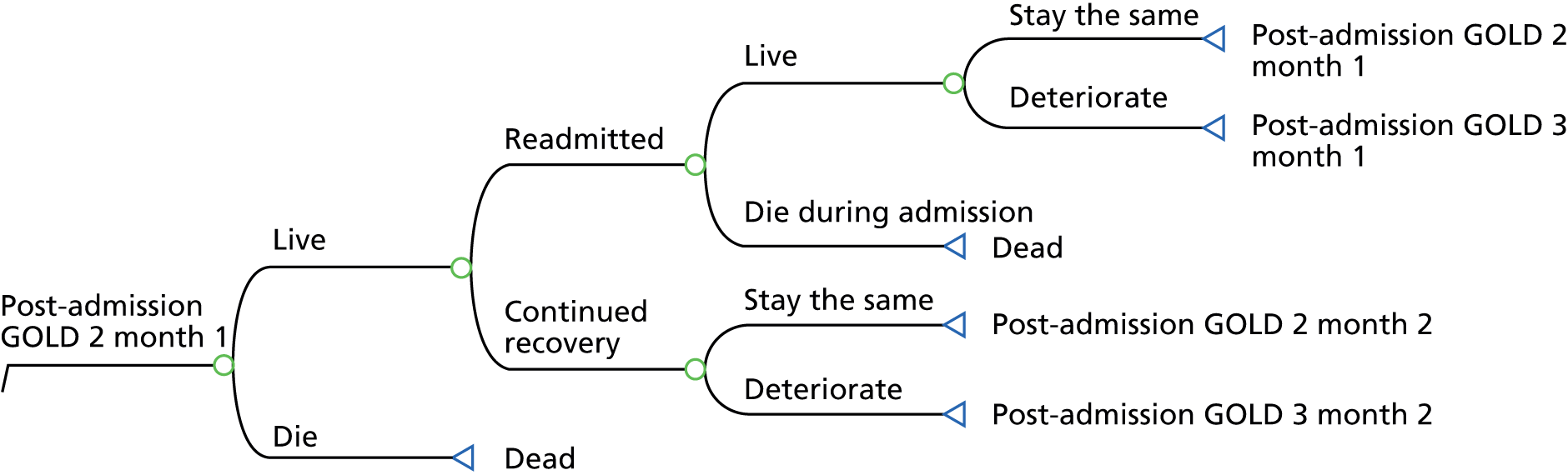

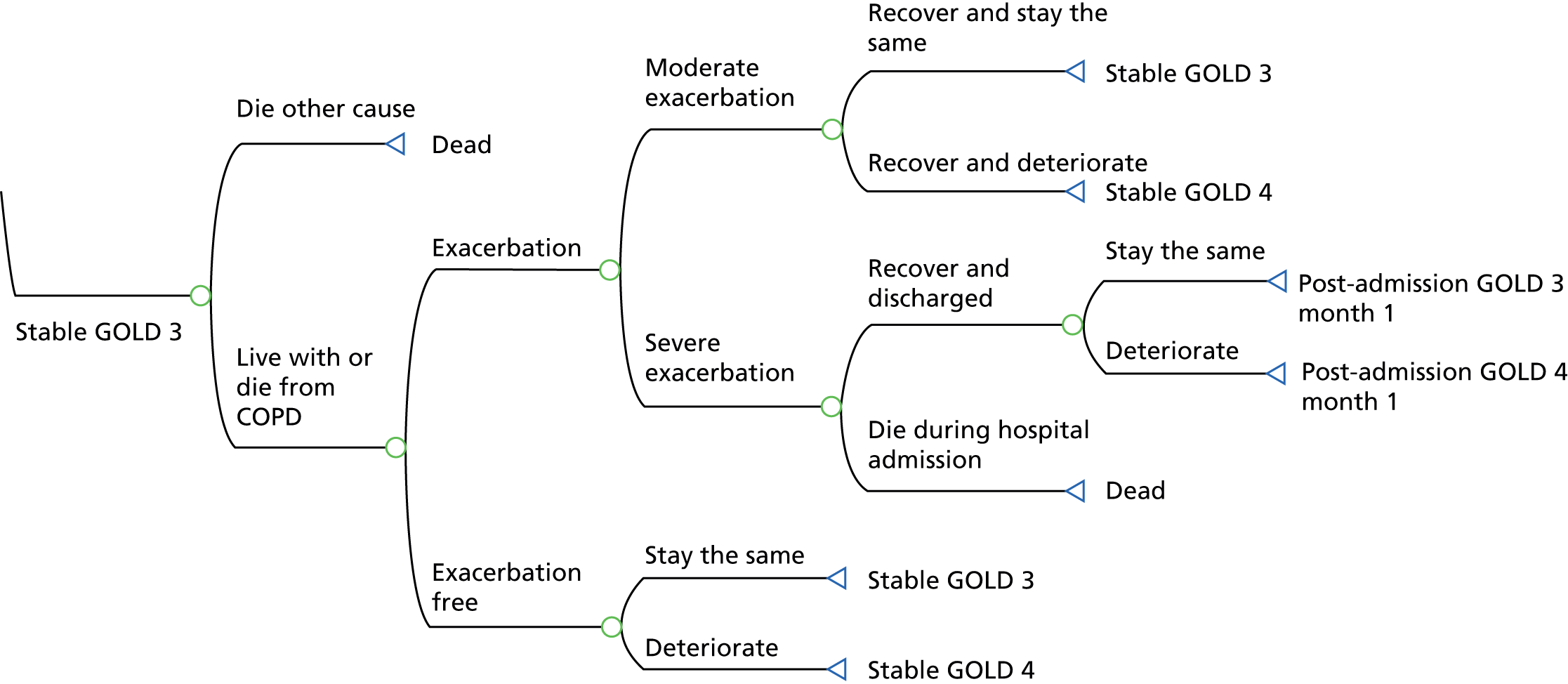

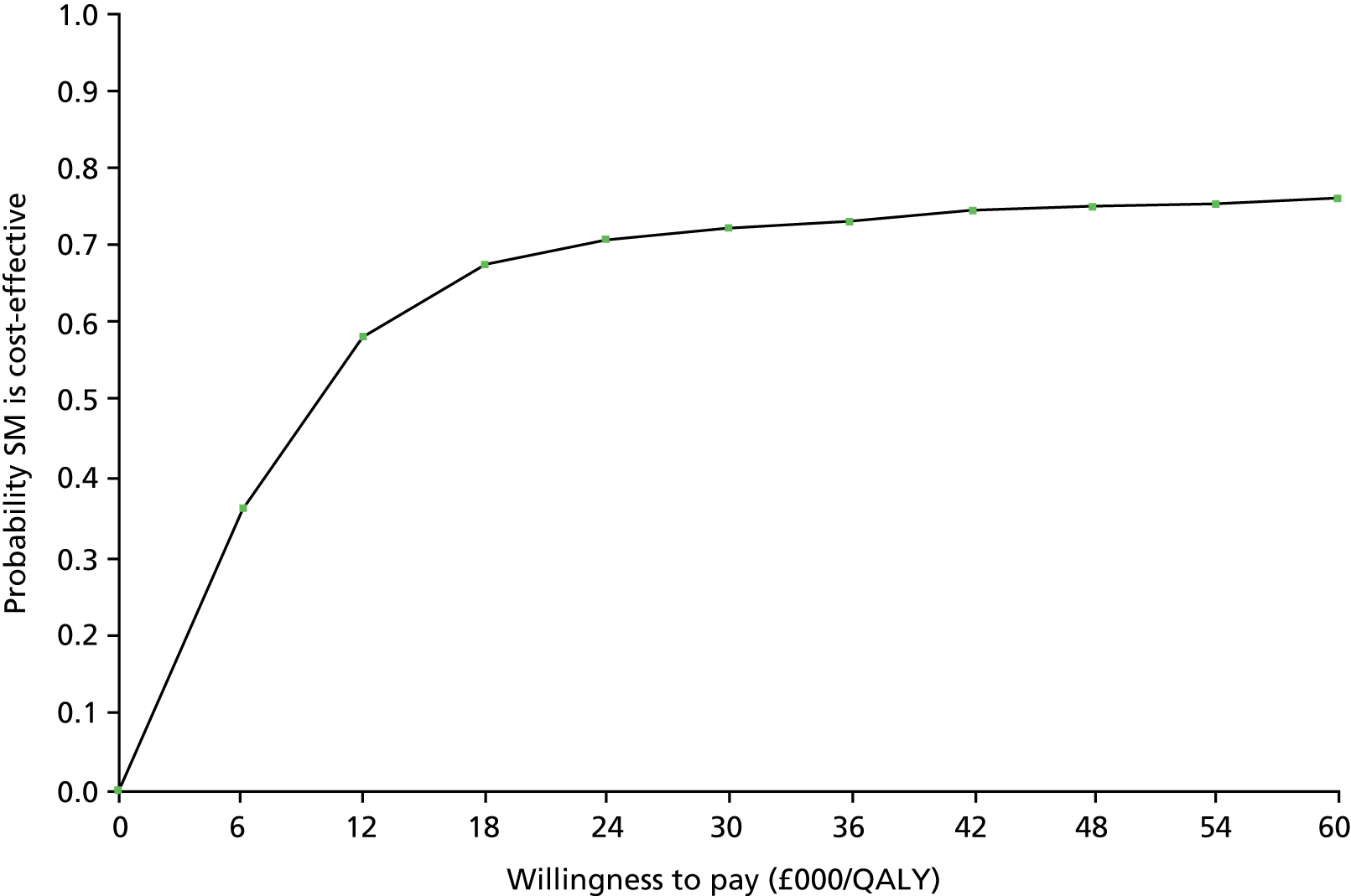

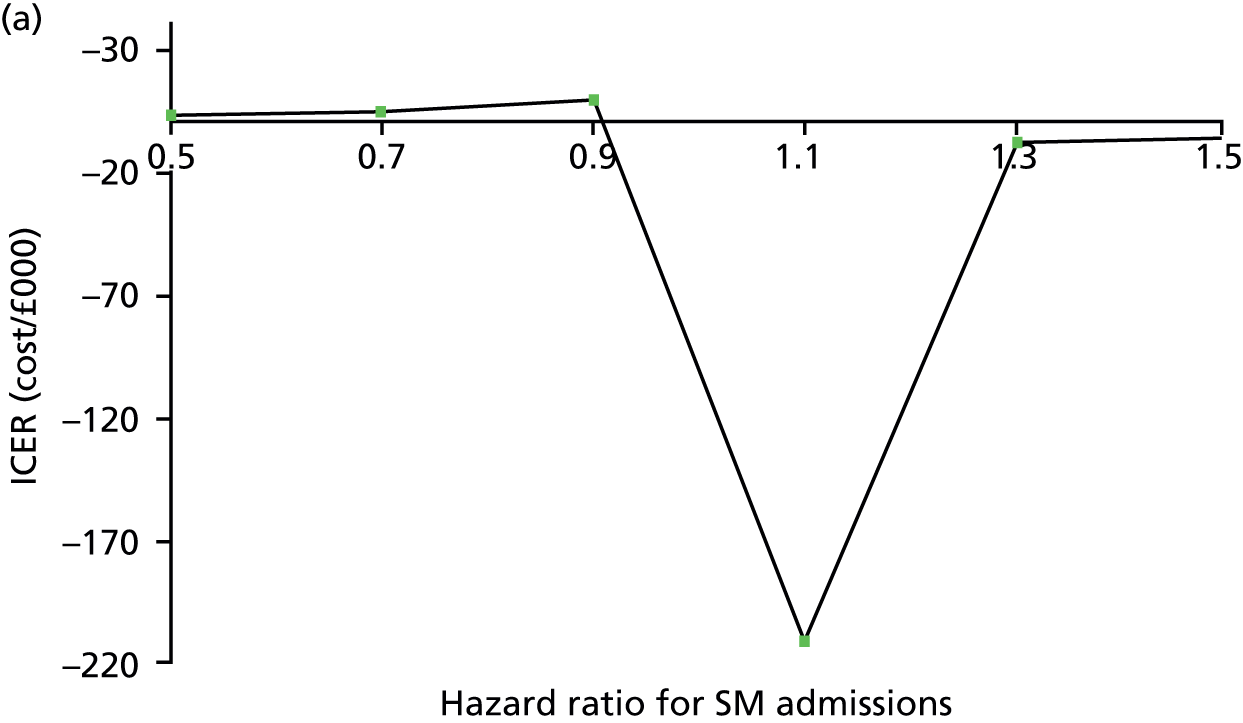

There were two main aims of this research project. The first was to undertake a systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of supported self-management among people with moderate to severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who had recently been discharged from hospital following an acute exacerbation of their condition, and to use this evidence to undertake a model-based cost-effectiveness analysis from the UK NHS perspective. With a wider systematic review, we also planned to identify the features and elements of self-management interventions that are most effective.

Each aim had specific objectives.

Aim 1

Among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at discharge, or recently discharged from hospital within the last 6 weeks, to undertake:

-

a systematic review of:

-

the evidence for the effectiveness of self-management support evaluating health behaviour change, self-efficacy, health service utilisation and patient-reported outcomes such as QoL (review 1)

-

the qualitative evidence about patient satisfaction, acceptance and barriers to self-management support (review 2)

-

the cost-effectiveness of self-management support (review 3)

-

-

a cost-effectiveness analysis and economic model of self-management support compared with usual care (economic model).

Aim 2 (review 4)

Among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, at any time point, to:

-

undertake a wider systematic review of the evidence of the effectiveness of self-management support [including interventions (such as pulmonary rehabilitation) for which there are significant components of self-management] in reducing exacerbations, hospital admissions/readmissions and improving QoL

-

describe the features and elements of self-management interventions in relation to their effectiveness by simple categorisation and tabulation

-

perform subgroup analysis and meta-regression to explore features such as the effect of study quality, population, setting and nature of intervention on the effectiveness of self-management interventions compared with usual care

-

use mixed-treatment comparison meta-analysis methods to explore which components or combinations of components are most effective.

Structure of the report

The following chapters report separately on:

-

Chapter 3: Aim 1 – clinical effectiveness review (review 1)

-

Chapter 4: Aim 1 – qualitative evidence review (review 2)

-

Chapter 5: Aim 1 – cost-effectiveness review (review 3)

-

Chapter 6: Aim 1 – economic model

-

Chapter 7: Aim 2 – review of effectiveness of components of self-management (review 4).

Each of the above chapters incorporates methods, results and discussion, and then, finally, Chapter 8 provides an overall summary.

Chapter 3 A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of supported self-management interventions delivered shortly after hospital discharge: review 1

The aim of this chapter is to present the findings of a systematic review of the evidence for the effectiveness of SM support evaluating health behaviour change, self-efficacy, health service utilisation and patient-reported outcomes, such as quality of life (QoL).

Methods

A systematic review of published evidence of the effectiveness of interventions to support self-management (SM) among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) who had recently been discharged from hospital.

Definition of self-management used for this review

‘Self-management’ has been defined as the ability of a patient to deal with all that a chronic disease entails, including symptoms, treatment, physical and social consequences and lifestyle changes. 23 SM interventions involve collaboration between the health-care professional and the patient so that the patient acquires and demonstrates the knowledge and skills required to manage their medical regimens, change their health behaviour, improve control of their disease and improve their well-being. 29 This definition of SM was used as a basis to devise a list of SM interventions/components that were considered for this review (Table 2). Because SM interventions are so heterogeneous, we specifically chose to include all possible aspects of SM to ensure completeness. However, we excluded interventions of smoking cessation alone, as there is already good evidence of the benefits of smoking cessation in general, and a large number of systematic reviews addressing the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions (currently 60 Cochrane systematic reviews alone). Most evidence of the effectiveness of smoking cessation relates to general populations, rather than people with a particular condition. Any study that included smoking cessation as one component of a multicomponent package in people with COPD was included. Similarly, there is already a systematic review of pulmonary rehabilitation (PR) at this time point;55 therefore, it was not considered necessary to repeat it but rather use it for comparison.

| Intervention/component | Included/excluded | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Adherence to medication | Include | Education about taking treatment correctly, promoting adherence |

| Ambulatory oxygen | Exclude | Unless it concerns education or support to take prescribed treatments such as ambulatory oxygen |

| Breathing techniques | Include | For example, pursed lip breathing |

| Bronchial hygiene techniques | Include | Mucus/airways clearance |

| Case management | Exclude | Unless elements of SM |

| Community matrons | Exclude | Unless elements of SM |

| Complementary therapies | Exclude | Exclude anything on acupuncture and massage, etc. |

| Early recognition of symptoms/action plans | Include | Must be self-monitoring, not external monitoring by external agency, unless there is a teaching/training element (e.g. patient being taught how to recognise the symptoms and act accordingly) |

| Education | Include | Any topics |

| Exercise | Include | Any type of exercise |

| Hospital at home | Exclude | Unless elements of SM |

| Inhaler technique | Include | Including assessment of inhaler technique |

| Integrated care | Exclude | Unless elements of SM |

| Nutritional programmes | Include | Include anything which encourages/helps people to maintain good nutrition or modify their diet; exclude anything to do with (proprietary) supplements, dietary programmes or trials of effectiveness |

| Patient empowerment | Include | As recommended by patient advisory group |

| Relaxation | Include | Any types |

| Respiratory muscle training | Include | Including both inspiratory and EMT |

| Smoking cessation | Exclude | Unless as a component of a larger package (not as a single active intervention) |

| Stress management | Include | Any types including counselling |

| Support groups | Include | As recommended by patient advisory group |

| Telecare | Include | Exclude if purely telemonitoring – not just about contact; include if there is an encouragement/support component, e.g. help to promote adherence to medication |

Search strategy for effectiveness studies

A comprehensive search strategy was designed and conducted by an experienced information specialist. The searches were kept broad to capture evidence to suit both aims.

Searches for relevant studies were conducted across the following bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations and EMBASE (via Ovid), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL – Wiley) and Science Citation Index (Institute of Scientific Information). Subject-specific databases were also searched: PEDro physiotherapy evidence database, PsycINFO (via Ovid) and the Cochrane Airways Group Register of Trials. Ongoing studies were sourced through the metaRegister of Current Controlled Trials, International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number database, World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform Portal and ClinicalTrials.gov. Specialist abstract and conference proceedings were sourced through the Institute of Science Information’s Conference Proceedings Citation Index and British Library’s Electronic Table of Contents (Zetoc). Hand-searching through European Respiratory Society, the American Thoracic Society and British Thoracic Society (BTS) conference proceedings from 2010 to 2012 was also undertaken, and selected websites were also examined. No language restrictions or methodological filters were applied to the searches. Electronic database searching was carried out from inception to May 2012, and no updated searches were undertaken beyond this time point. The search strategies used for electronic databases can be found in Appendix 1; terms for COPD were combined with those for SM and, where possible, utilised appropriate medical subject headings.

The citation lists of all included studies and any citations within relevant reviews were scanned for additional relevant studies. Consultations with experts in the field through the investigators identified additional relevant literature.

Reference Manager version 11 (Thomson ResearchSoft, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used to store and manage all search results.

Study selection process

After removal of duplicates, titles and abstracts of the remaining search results were independently reviewed by two reviewers. Full texts were obtained for papers meeting the inclusion criteria or when the abstract was unclear. Full texts were then independently reviewed by two reviewers using detailed and piloted selection criteria concerning study design, populations, interventions, comparators and outcomes for each review. Any discrepancies were resolved by a third reviewer. Any non-English language papers were assessed, based on titles and abstract, but when information was lacking or unclear, translators were used to decide final inclusion. A reviewer worked alongside translators to avoid misinterpretation of the selection criteria. During full-text screening, papers were categorised into their appropriate objectives or were excluded with reasons.

Selection criteria

The selection criteria for this review are summarised in Table 3.

| Study designs | RCTs |

|---|---|

| Population | Patients with moderate to severe COPD (defined clinically, with or without spirometry) recruited specifically at discharge or up to 6 weeks post discharge for an acute exacerbation of their condition (patients with mild or very severe COPD were included if they were a minority of the population group) Approximately 90% of patients in studies should have COPD The setting could be either hospital or community |

| Intervention | SM packages or important components of SM Excluding trials of smoking cessation and PR |

| Comparator | No intervention, UC, control/sham, other SM intervention |

| Primary outcomes | Any of: Health service outcomes and mortality Primary care consultations Hospital admissions Readmissions Duration of admissions Mortality Emergency department visits |

| Secondary outcomes | Any considered but to include: Behaviour change Self-efficacy Specific behaviours, e.g. increase in exercise/activity Patient-reported outcomes Exacerbations HRQoL Anxiety/depression Patient satisfaction Dyspnoea Other Lung function (FEV1 and FEV1/FVC) |

Only primary studies were included. Studies concerning patients with moderate to severe COPD were included, and those with patients with mild or very severe COPD were included only if the majority of the study population was moderate/severe. A COPD study population of approximately 90% was required for inclusion unless data on the subset of patients with COPD were provided separately. Studies were included if the intervention was set within either a hospital or a community. Studies of any SM intervention/package or components of SM interventions were included. For example, medication management, action plans, exercise, inhaler technique and stress management (see Table 2). Comparators consisting of usual care (UC), control/sham or other SM interventions were accepted.

Risk of bias assessment

All RCTs were assessed using the recommended and validated Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. 56 The following six domains were assessed: sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of personnel and participants (by outcome), incomplete outcome data (by outcome), selective outcome reporting and other potential threats to validity. Domains were judged as high risk of bias, low risk of bias and unclear risk of bias. For trials with multiple papers, information from all of the studies was used to judge risk of bias. After a piloting process, all studies were assessed by two independent reviewers with a third reviewer overseeing the process. The GRADE57 framework was used to denote overall quality of evidence across studies for each of the primary outcomes and also HRQoL, using a scoring system of 4 (high) to 1 (very low) quality. The findings were summarised in a table, incorporating the results but also aspects that led to the final judgement.

Data extraction and manipulation

Approach

Data were extracted into piloted tables by the first reviewer with a second reviewer checking the extraction and a third reviewer overseeing the process. The results of all studies were tabulated and described and considered for combination in meta-analyses. Authors of included studies were contacted to clarify details and provide additional data required for analyses.

Types of data extracted

The following types of data were extracted from all papers:

-

Study characteristics Including sample size, mean age, severity according to mean FEV1% pred, place of recruitment, descriptions of intervention and control groups, outcomes, length of intervention and length of follow-up. When multiple papers were derived from the same trial, study characteristics were obtained from the original paper.

-

Study results Summary results from baseline and all follow-up times were extracted, including treatment effects, p-values, confidence intervals (CIs), mean scores at follow-up and/or mean changes in each group, numbers of events, hazard ratios (HRs), rates, loss to follow-up, etc. If multiple interventions were considered in a study then data were extracted for each pair of interventions compared.

Data manipulation

In order to maximise and prepare the data for statistical analyses, a number of steps were taken:

-

Lengths of intervention and follow-up were converted to weeks as a proportion of a 52-week year and rounded to the nearest week.

-

For continuous outcomes, for example QoL, reported mean difference (MD) estimates and 95% CIs calculated from an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) were preferred, as this method adjusts for baseline imbalances. If not reported, the following methods were used in order of priority:

-

MDs reported from an analysis of change scores

-

MDs reported from an analysis of final scores

-

MDs calculated indirectly by ourselves from other information (e.g. mean change score for each group or the mean final score for each group).

-

If standard errors (SEs) were not reported directly, they were calculated from other information where available (such as p-values, 95% CIs, number in each group) at the end of follow-up, and the standard deviation (SD) of values in each group at the end of follow-up.

-

For effect estimates for numbers of events over time, for example number of admissions or exacerbations over follow-up, we preferentially used HRs (e.g. from a Cox regression analysis) because they compare the rate of events over the whole follow-up period and account for individuals lost to follow-up (censored). We used only first admissions, as it is not possible to combine different types of measures (e.g. with mean number of admissions per patient) without making very strong assumptions, and this was the most common measure. Where not reported, the following methods were used to estimate the HR and its 95% CI indirectly, used in this priority order:

-

Methods of Parmar et al. ,58 which allowed indirect estimation of the HR and its CI from the p-value, and the number of patients and outcomes in each group.

-

If numbers of events and sample size were available, the method of Perneger59 was used. Where there were zero cells then a continuity correction (1/sample size of the opposite group) was added to each cell to allow HRs to be calculable. 60

-

-

Where necessary, MD results and loge HRs presented on the same plots were multiplied by –1 to ensure that all estimates and intervals obtained related to the same direction of effect (e.g. that a MD in HRQoL of < 0 meant the same thing in each study).

-

To utilise more results on emergency department (ED) visits, reported mean numbers of visits during follow-up were converted to rate of ED visit by assuming that all patients not lost to follow-up were observed for the full duration of the trial.

Forest plots

Results for each outcome were presented, where relevant, on a forest plot. Interventions were heterogeneous across the studies so results were placed in subgroups most consistent with the intensity and duration of support provided:

-

more-supported SM package – six or more contacts or unspecified contacts but ≥ 6 weeks’ duration

-

less-supported SM package – fewer than six contacts or unspecified contacts and < 6 weeks’ duration

-

exercise-based intervention.

Within each of these subgroups, studies were displayed in order of length of follow-up except for QoL outcomes, which were also grouped by questionnaire [St George’s Respiratory Questionnaire (SGRQ), Chronic Respiratory (Disease) Questionnaire (CRQ), EuroQoL-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)]. As there were multiple follow-up points, it was decided that for each outcome, only data from the final follow-up period would be displayed in the forest plot and used in any subsequent meta-analysis. The subgroups were specified prior to inspection of the results to allow sensible exploration of the different types of interventions. Meta-regression was not possible owing to the limited number of studies.

Meta-analyses

General approach

For each outcome the core group met to discuss whether or not meta-analysis was appropriate. Meta-analysis was considered only when at least three studies were available.

All analyses were undertaken using Stata statistical software, version 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). When it was not appropriate to pool data, studies were displayed graphically in a forest plot but without pooling.

Meta-analysis methods

A random-effects meta-analysis model was used to synthesise effect estimates across trials61 to account for between-trial heterogeneity in intervention effects across the trials. MDs were pooled on the original scale, but HRs were pooled on the loge scale.

Heterogeneity across studies was summarised using the I2-statistic (which gives the percentage of the total variability in the data due to between-trial heterogeneity)62 and the tau-squared statistic (the between-trial variance). 61

When two or more interventions from the same study contributed to the same meta-analysis with the same control group, an adjustment was required:

-

For continuous outcomes, the SE of each estimate was inflated by first obtaining the pooled SD (assuming equal variances) using the estimates of SE and sample size in each group. An inflated SE was then calculated using the full sample size in the intervention group, and the sample size in the control group divided by the number of comparisons it contributed to within the meta-analysis.

-

For one study the same control group appeared twice or more in the analysis when using a HR outcome. As the HRs for this study had been calculated using two-by-two tables,59 adjustment was made by modifying the number of control events and the total sample size in the control group by dividing by the number of comparisons in which that control group was incorporated. The modified two-by-two tables were then used to calculate new HRs to be used in the meta-analyses where appropriate. 59

Assessing publication bias

This was not possible as there were fewer than 10 studies for each of the outcomes.

Patient advisory group

A patient advisory group was established from local patients with COPD, chaired by Mr Michael Darby. Meetings were held at the University of Birmingham, and the group provided advice on how COPD affected their lives, their understanding of the importance of SM and different components, and their experiences of SM programmes. This assisted in the development of the definition of SM for the inclusion criteria of this review. For example, they suggested the need for including peer support groups as an essential component. They also commented on the plain English summary.

Results

Search results

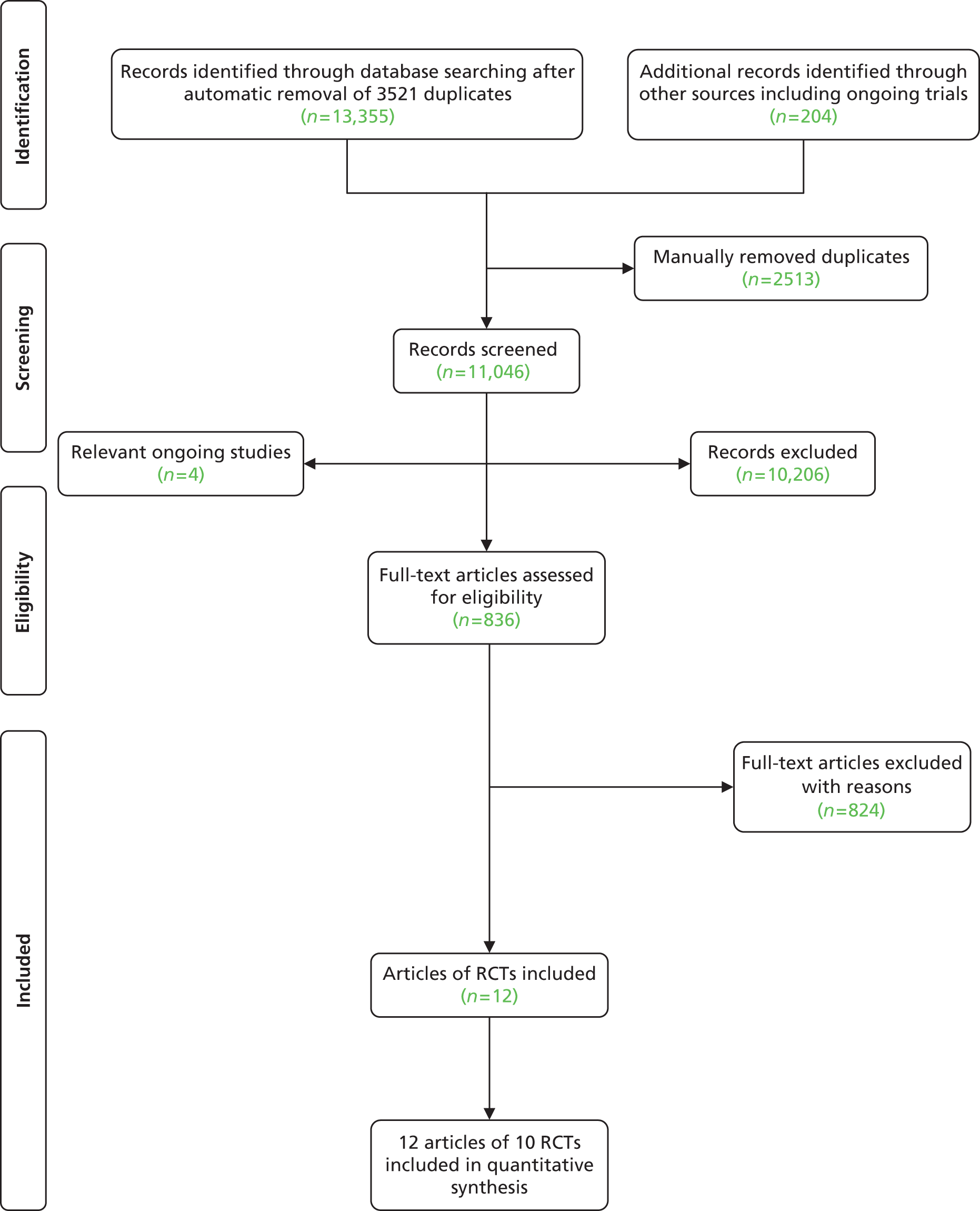

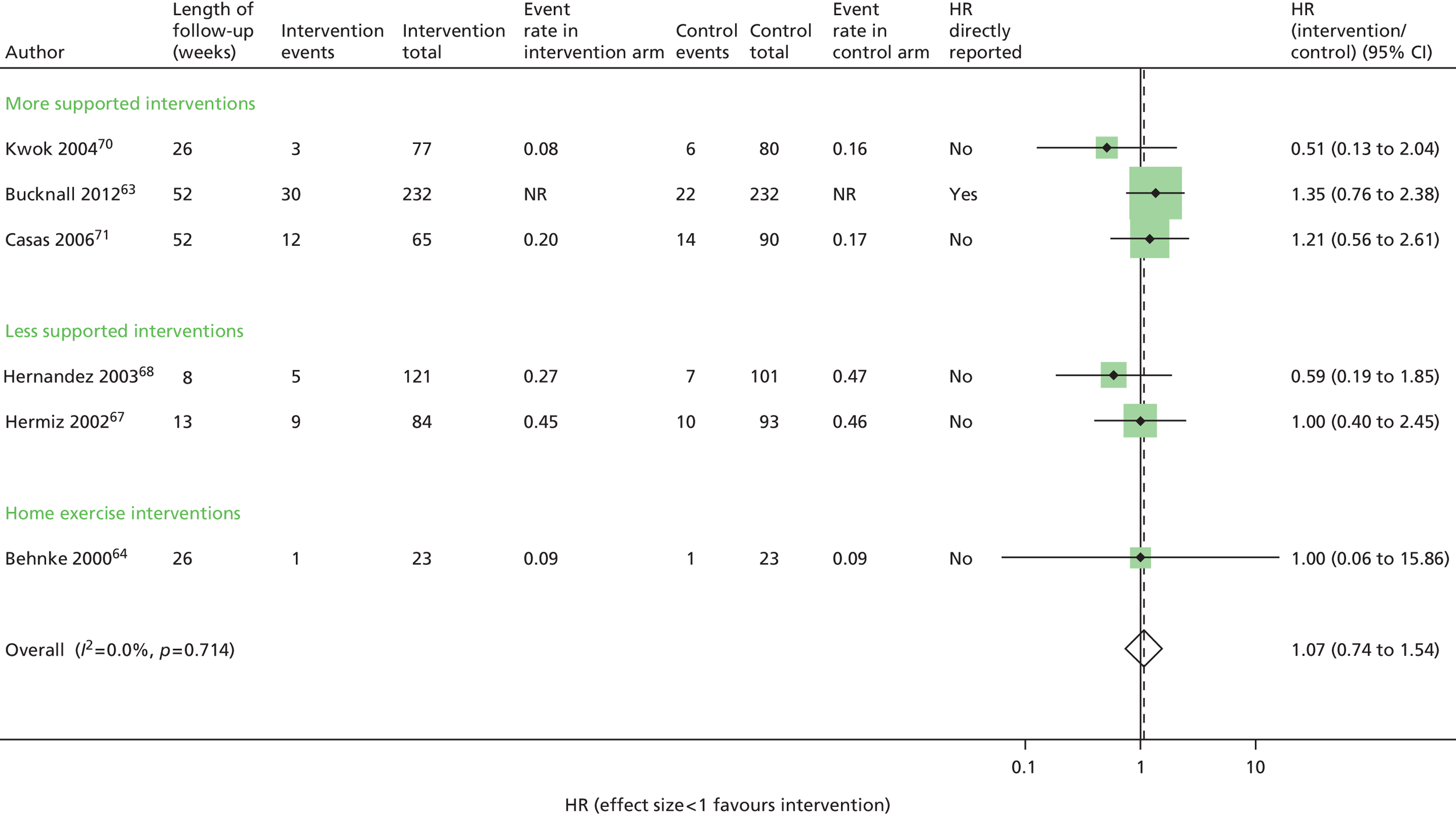

Study identification and flow chart

Initial database searches identified 13,355 records, of which 836 remained after scanning titles and abstracts using the inclusion/exclusion criteria (Figure 1). After the same criteria were applied to the full papers, 12 papers reporting 10 trials were finally included in the review. 63–74 Appendix 2 details the reasons for exclusion at each stage. These were largely because patients were not recruited at the appropriate time point during/after discharge. Overall, 5% of all full texts required arbitration by a third reviewer.

FIGURE 1.

The selection process for clinical effectiveness studies.

The inclusion of two trials was particularly difficult to assess. 68,75 Both were comparing ‘hospital at home’ with UC and had substantial SM components. One trial75 was excluded because all patients were seen in the ED then randomised to home compared with hospital (and therefore patients were not admitted at all unless in the control group). In the second study,68 although patients were assessed in the ED, a substantial proportion of patients in both arms were initially admitted and then discharged from hospital. The difference between the two arms was (a) the proportion of patients requiring admissions and (b) the intervention arm had ongoing SM support at home, whereas, once discharged, the control group had usual primary care support. Thus, this trial was included. 68

Conference abstracts meeting the inclusion criteria for this review are listed in Appendix 3. There were a further four trials that were ongoing at the time of the search end date (see Appendix 4).

Characteristics of included studies

There were 10 RCTs (from 12 papers). 63–74 One study69 had a limited qualitative element referring to patient satisfaction, which will be discussed in the following chapter (see Chapter 4), and one study68 included a cost analysis, which is presented in Chapter 5. Table 4 details the characteristics of the RCTs.

| Author, year, country, study design | Population inclusion criteria | Participants | Intervention (n) | Comparator (n) | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behnke, 2000,64 Germany, RCT | Inclusion: Severe COPD; patients admitted owing to acute exacerbation Exclusion: Unstable cardiac disease, cor pulmonale or other comorbidities preventing exercise participation, e.g. orthopaedic inabilities or peripheral vascular disease |

N = 46 Recruited in hospital 4–7 days post hospital admission Of 30 completers: Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 64.0 (1.9) Cont: 68.0 (2.2) Sex (male) n (%): Int: 12 (80.0) Cont: 11 (73.3) Mean FEV1% pred (SD): Int: 34.1 (7.4) Cont: 37.5 (6.6) |

TRAINING (n = 23) Usual medication and 30 minutes daily breathing exercises Ten-day hospital-based training including daily 6-minute treadmill and five self-controlled walking sessions Followed by 6 months individually tailored home-based walking programme, three times a day Diaries of exercise Two-weekly visits for 3 months then monthly telephone calls for 3 months |

CONTROL (n = 23) Usual medication and 30 minutes’ daily breathing exercises Ten-day hospital-based training, including daily 6-minute treadmill and five self-controlled walking sessions Advised to perform exercise at home without specific instruction |

Mortality (6 months) QoL – CRQ (3 and 6 months) Exercise capacity: 6-MWT treadmill (1, 2, 3 and 6 months) Dyspnoea: Baseline/Transitional Dyspnoea Index (every visit post discharge) Lung function: FEV1, FVC, TLC, ITGV, DLCO, RV (days 0 and 11, 3 and 6 months) Blood gas analysis, BP, heart rate (days 1 and 11, and 6 months) |

| Behnke, 2003,65 Germany, RCT | Inclusion: Severe COPD; patients admitted due to acute exacerbation Exclusion: Unstable cardiac disease, cor pulmonale or other comorbidities preventing exercise participation, e.g. orthopaedic inabilities or peripheral vascular disease |

N = 46 Follow-up of 26 of 30 patients who had participated in the Behnke et al.64 6-month trial Of 26 completers: Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 64.0 (7.5) Cont: 69.0 (6.9) Sex (male) n (%): Int: 11 (76) Cont: 9 (75) FEV1% pred (SD): Int: 34.9 (7.1) Cont: 37.5 (6.9) |

TRAINING (n = 23) Usual medication and 30 minutes’ daily breathing exercises Ten-day hospital-based training, including daily 6-minute treadmill and five self-controlled walking sessions Eighteen-month home-based training programme, three times a day for 15 minutes based on 125% of 6-MWT for 3 months and then advised to continue regular exercise Diaries of exercise Two-weekly visits for 3 months then monthly telephone calls for 3 months |

CONTROL (n = 23) Usual medication and 30 minutes’ daily breathing exercises No exercise training instructions in hospital or home No visits, but did receive monthly telephone calls |

QoL: CRQ (6, 12, 18 months) Exercise capacity: 6-MWT treadmill (6, 12, 18 months) Dyspnoea: Borg Scale at rest; Baseline/Transitional Dyspnoea Index (6, 12, 18 months) Lung function: FEV1, VC, TLC, ITGV, DLCO, RV (6, 12, 18 months) Hospital admissions (6-month periods for 18 months) Activity data (training group only) (each month) Inhaler and medications use |

| Lee, 2002,66 Hong Kong, cluster RCT | Inclusion: COPD; aged 65+ years; present residents of participating nursing home; at least one admission in previous 6 months Exclusion: Terminal illness (not expected to survive > 6 months) Communication problems |

N = 45 nursing homes N = 112 patients Patients recruited from the geriatric units of two hospitals with main diagnosis of COPD and soon to be discharged Of 89 completers: Mean (SD) age (years): Int: 81.08 ± 6.03 Cont: 79.68 ± 6.53 Sex (male) n (%): Int: 27 (56.3) Cont: 20 (48.8) Mean FEV1% pred (SD): Int: 30.64 (10.12) Cont: 31.08 (13.25) Severity n (%):

|

CARE SUPPORT TO NURSING HOME (n = 48 completers) Support to nursing home staff provided by community nurses Visit 1: Within 1 week of discharge:

Monthly visits by same nurse to provide ongoing support and education to the staff Between visits and as necessary community nurse would additionally provide advice via:

This may include advice on need for ED visit or admission If readmitted, protocol and visits recommenced on discharge back to the home |

CONTROL (n = 41 completers) Usual community nursing, e.g. wound/catheter management |

Hospitalisation (6 months)

Respiratory status (6 months): FEV1% pred Psychological status (6 months): GHQ: total and subscales Patient satisfaction (6 months): Thirteen-item Likert scale; not administered to control arm Nursing health staff satisfaction (1 month): Eleven-item Likert scale; not administered to control arm |

| Egan 2002,69 Australia, RCT plus qualitative element (n = 18) | Inclusion: COPD; ≥ 18 years; history of chronic bronchitis (with infection), emphysema, chronic obstruction, chronic asthma, or combination; admission to respiratory unit bed within 72 hours of hospital admission Exclusion: Cognitive function insufficient to complete questionnaire |

N = 66 Patients admitted with COPD to a major private hospital; recruited during admission Mean age (years): Int: 67.8 Cont: 67.2 Sex (male) n (%): Int: 12 (36) Cont: 20 (60) FEV1% pred: NR Severe (FEV1 < 35% pred) Int: 19 (57.6%) Cont: 19 (57.6%) Mild/moderate (FEV1 35–50% pred) Int: 14 (42.4) Cont: 14 (42.4) |

CASE MANAGEMENT (n = 33) Nursing assessment and review: comprehensive – to identify physical, psychological, social, spiritual, resource needs; standardised clinical pathway of care during hospital admission Coordination between medical, nursing and allied health personnel by case manager Coordinated case management with patient and carer education on managing the disease, medication, rehabilitation, available community services and arranged discharge planning Regular telephone calls to patient and carer at 1 week and 6 weeks |

UC (n = 33) Nursing assessment (not clear); standardised clinical pathway of care during hospital admission No contact with case manager, no case conferences and no post-discharge follow-up |

Hospital readmission: 3 months QoL: SGRQ and Subjective Well-Being Scale: 1 and 3 months Social support survey: 1 and 3 months Anxiety and depression: HADS (1 and 3 months) Patient satisfaction: qualitative semistructured interview with 18 participants, 3 months |

| Hermiz, 2002,67 Australia, RCT | Inclusion: COPD; 30–80 years; patients attending hospital ED or admitted with COPD Exclusion: Resided outside region; insufficient English skills; resident in nursing home; confused or demented |

N = 177 Patients attending hospital ED or admitted with COPD; not clear exactly when recruited but visit 1 occurred 1 week after discharge Mean age (years): Int: 67.1 Cont: 66.7 Sex (male), n (%): Int: 41 (48.8) Cont: 43 (46.2) FEV1% pred: NR |

HOME VISITS (n = 84) Two home visits (community nurse) Visit 1: Within 1 week of discharge

Progress review Patient encouraged to refer to education booklet for guidance |

UC (n = 93) UC (GP) |

Mortality (3 months) Readmissions or ED visits (3 months) GP consultations or nurse home visits (3 months) GP prescribed drugs GP arranged follow-up GP provided patient with education GP provided carer with education QoL: SGRQ (3 months) Behaviour change (3 months)

|

| Dheda, 2004,73 UK, RCT | Inclusion: Diagnosis of COPD; first admission of COPD Exclusion: Another dominant medical condition; mandatory reason for hospital follow-up, e.g. suspected cancer; already under outpatient follow-up; refused consent |

N = 33 First admission of COPD Not clear when recruited but implies at discharge (data may be completers only – not clear): Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 68.4 (5.8) Cont: 71.3 (8.4) Sex (male) n (%): NR Mean FEV1% pred (SD): Int: 44.7 (21.8) Cont: 39 (11.9) Disease severity (BTS guidelines) Int: 20% mild, 20% moderate, 60% severe Cont: 20% mild, 27% moderate, 53% severe |

HOSPITAL OUTPATIENT FOLLOW-UP (n = 15) Visit to respiratory nurse and/or chest physician: (n = 4+) over 6-month period (3, 6, 8, 12 or 16 weeks)

|

PRIMARY CARE FOLLOW-UP (n = 18) Visit primary care teams as required |

Hospital admissions (6 months) Exacerbations (two or more) (6 months) QoL: SGRQ, SF-36 (6 months) Lung function: FEV1 Oxygen saturation Pharmacological prescriptions: oxygen, nebuliser, theophylline, bronchodilators |

| Hernandez, 2003,68 Spain, RCT | Inclusion: COPD exacerbation; absence of any criteria for imperative hospitalisation as stated by the BTS guidelines Exclusion: Not living in the area or admitted from a nursing home, lung cancer and other advanced neoplasm, extremely poor social conditions, severe neurological or cardiac comorbidities, illiteracy, no telephone |

N = 222 Patients with COPD exacerbation. Recruited at emergency room of two tertiary hospitals Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 71 (9.9) Cont: 70.5 (9.4) Sex (male)%: Int: 96.7 Cont: 97 Mean (SD) FEV1 l (% pred): NR at baseline |

HOME-BASED HOSPITALISATION (n = 121) Assessed by specialised team in emergency room At discharge Standard pharmacological treatment was used in accordance with national guidelines Non-pharmacological treatment, 2 hour, including:

Duration of home hospitalisation determined by nurse; up to five visits permitted during 8-week period, but no limit of telephone contact; action plan revisited and education reinforced Failure was based on referral to emergency room or more than five nurse visits required |

UC (n = 101) Standard assessment by physician in emergency room Standard pharmacological treatment No post-discharge follow-up |

Mortality (2 months) Readmissions or ED visits (2 months) Hospitalisation: hospital days (2 months) QoL: SGRQ and SF-12 scale (2 months) Lung function: FEV1, FVC (2 months) Patient satisfaction (2 months) Disease knowledge (2 months) Inhaler technique (2 months) Medication prescriptions and home rehabilitation (2 months) Costs (2 months) |

| Kwok, 2004,70 Hong Kong, RCT | Inclusion: CLD (89% had COPD); 60+ years; having at least one hospital admission for CLD in the 6 months before index admission Exclusion: Resided outside region; communication difficulties; no family caregiver; resident in institutional care; terminal disease with life expectancy < 6 months |

N = 157 Hospitalised patients with principal diagnosis of CLD recruited from medical wards of two hospitals within 3 days of admission Of 149 completers: Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 75.3 ± 7 Cont: 74.2 ± 5.7 Sex (male) n (%): Int: 56 (73) Cont: 55 (69) Mean FEV1: NR |

INTERVENTION (n = 77) A community nurse Visit 1: Before discharge:

|

UC (n = 80) Routine follow-up by same medical teams Some patients received home visit if referred |

Hospital readmissions (4 weeks, 6 months) Period of hospitalisation (bed-days) ED visits (6 months) Psychosocial scores: London Handicap Scale, GHQ score, Multidimensional Health Locus of Control Scales (6 months) Exercise capacity: 6-MWT (6 months) Mortality (6 months) Care burden (6 months): Cost of Care Index |

| Wong, 2005,74 Hong Kong, RCT | Inclusion: Diagnosis of COPD; alert and orientated; contactable by telephone Exclusion: Discharged to an old-age home; serious alcohol or drug abuse or psychiatric disease; diagnosed with IHD, musculoskeletal disorders or other disabling diseases that may limit rehabilitation; dying and/or unable to provide informed consent |

N = 60 At discharge from medical department of acute care hospital Mean age (years) (SD): 73.6 (7.8) Sex (male) n (%): 47 (78.3) FEV1% pred: NR |

TELEPHONE FOLLOW-UP (n = 30) Structured, individualised educational and supportive telephone follow-up programme delivered by a respiratory nurse Based on Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy31

|

ROUTINE CARE (n = 30) UC |

Health service utilisation: ED, outpatient, admissions (1, 3 months) Self-efficacy: Modified Chinese COPD Self-Efficacy Scale for dyspnoea (day 35) |

| Casas, 2006,71 Spain, RCT | Inclusion: COPD; hospital admission > 48 hours due to exacerbation Exclusion: Not living in health-care area; severe comorbid conditions; logistical limitations due to poor social conditions, e.g. no telephone access; admitted to nursing home |

N = 155 (n = 113, Barcelona; n = 42, Leuven) Recruited immediately after hospital discharge from two tertiary hospitals (Barcelona, Leuven) Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 70 (9) Cont: 72 (9) Sex (male) n (%): Int: 50 (77) Cont: 79 (78) Mean FEV1% pred (SD): Int: 43 (20) Cont: 41 (15) |

INTEGRATED CARE (n = 65) Four-part integrated care:

|

UC (n = 90) UC: Hospital physician decided on outpatient control regime. Standard protocol for pharmacological prescription and in-hospital treatment Physician visit every 6 months |

Mortality (6, 12 months) Hospital admissions (12 months) Health-care resource utilisation (12 months): includes GP consultations |

| Garcia-Aymerich, 2007,72 Spain (subset of Casas et al.71), RCT | Inclusion: COPD; admitted because of an episode of exacerbation requiring hospitalisation for > 48 hours Exclusion: Not living in the health-care area or living in a nursing home; lung cancer or other advanced malignancies; logistic limitations due to poor social conditions, illiteracy or no telephone access; extremely severe neurological or cardiovascular comorbidities |

N = 113 Recruited immediately after discharge from one tertiary hospital Of 62 completers: Mean age (years) (SD): Int: 72 (10) Cont: 73 (9) Sex (male) n (%): Int: 16 (80.0) Cont: 37 (90) FEV1% pred: NR Described as ‘severe’ |

INTEGRATED CARE (n = 44) Four-part integrated care:

|

UC (n = 69) UC |

Mortality (6 and 12 months) QoL: SGRQ, EQ-5D (6 and 12 months) Dyspnoea: MRC (6 and 12 months) Treatment adherence and inhaler technique: Medication Adherence Scale, Inhaler Adherence Scale and observation; medication use (6 and 12 months) Medications and oxygen therapy (6 and 12 months) Lung function – FEV1, FVC, PaO2, PaCO2 (6 and 12 months) Vaccination uptake (influenza, pneumococcal): 6 and 12 months Patient satisfaction (6 and 12 months) Smoking (6 and 12 months) Exercise (6 and 12 months) Knowledge: about disease and identification/treatment of exacerbations BMI |

| Bucknall, 2012,63 UK, RCT | Inclusion: Patients with COPD admitted to hospital with acute exacerbation; FEV1 < 70% pred and FEV1/FVC < 0.7 Exclusion: History of asthma or left ventricular failure; active malignant disease; evidence of confusion or poor memory |

N = 464 During or shortly after hospital admission; six acute hospitals and contributing hospitals with eligible patients; augmented by review of patients attending PR and checking for evidence of hospital admission Mean age (years) (SD): 69.1 (9.3) Sex (male) n (%): 170 (37%) Mean FEV1% pred (SD): 40.5 (13.6) |

SUPPORTED SM (n = 232) Long-term treatment optimised, inhaler techniques checked, offered appropriate smoking cessation advice and PR Symptom daily diaries Supported SM by nurses trained in ‘self-regulation theory’; this aims to empower patients to manage COPD by improved knowledge and understanding of the disease and skills to monitor symptoms and carry out appropriate actions, such as altering treatment early in early stages of an exacerbation SM material based on ‘Living Well with COPD programme’ Content included:

|

UC (n = 232) Long-term treatment optimised, inhaler techniques checked, offered appropriate smoking cessation advice and PR Symptom daily diaries UC: continuing management by GP, hospital clinicians or both |

Mortality (12 months) Hospital admission with exacerbation of COPD (12 months) Successful SM (initiating treatment during exacerbation) (12 months) QoL: SGRQ, EQ-5D (6 and 12 months) Anxiety/depression – HADS (6 and 12 months) Self-efficacy – COPD Self Efficacy Scale (6 and 12 months) |

Characteristics of included randomised controlled trials

Size, setting, recruitment

Randomised controlled trials ranged in size from 3373 to 46463 total participants. One66 was a cluster RCT, based in 45 nursing homes. One paper was the 18-month follow-up of the original study,64,65 and one paper72 referred to the Spanish centre of a European study. 71

Participants were largely recruited in hospital during an exacerbation of COPD or at (or immediately after) discharge. Two papers67,68 also included patients recruited at the ED who may not have been admitted to hospital.

The definition of COPD for inclusion was generally based on a clinical diagnosis (except for Bucknall et al. ,63 which also required patients to meet the spirometric criteria for airflow obstruction). One study70 included a mixed population of patients with chronic lung disease, although 89% had COPD.

Patient exclusion from trials was usually based on inability to provide consent; terminal illness or extreme comorbidities preventing inclusion in rehabilitation/exercise; or social conditions/lack of access to a telephone. All of the studies were set among patients living at home except for the cluster RCT, which was specifically based in nursing homes. 66

Description of included patients

Mean age of participants was similar across the included RCTs (66–74 years), except in the cluster RCT based in nursing homes,66 where the mean age was approximately 80 years. Sex distribution, however, was variable across studies (ranging from 37% to 97% males). Where reported, severity of disease was similar with mean FEV1 ranging from approximately 31% to 42% of predicted values. Most patients were described as having moderate or severe COPD.

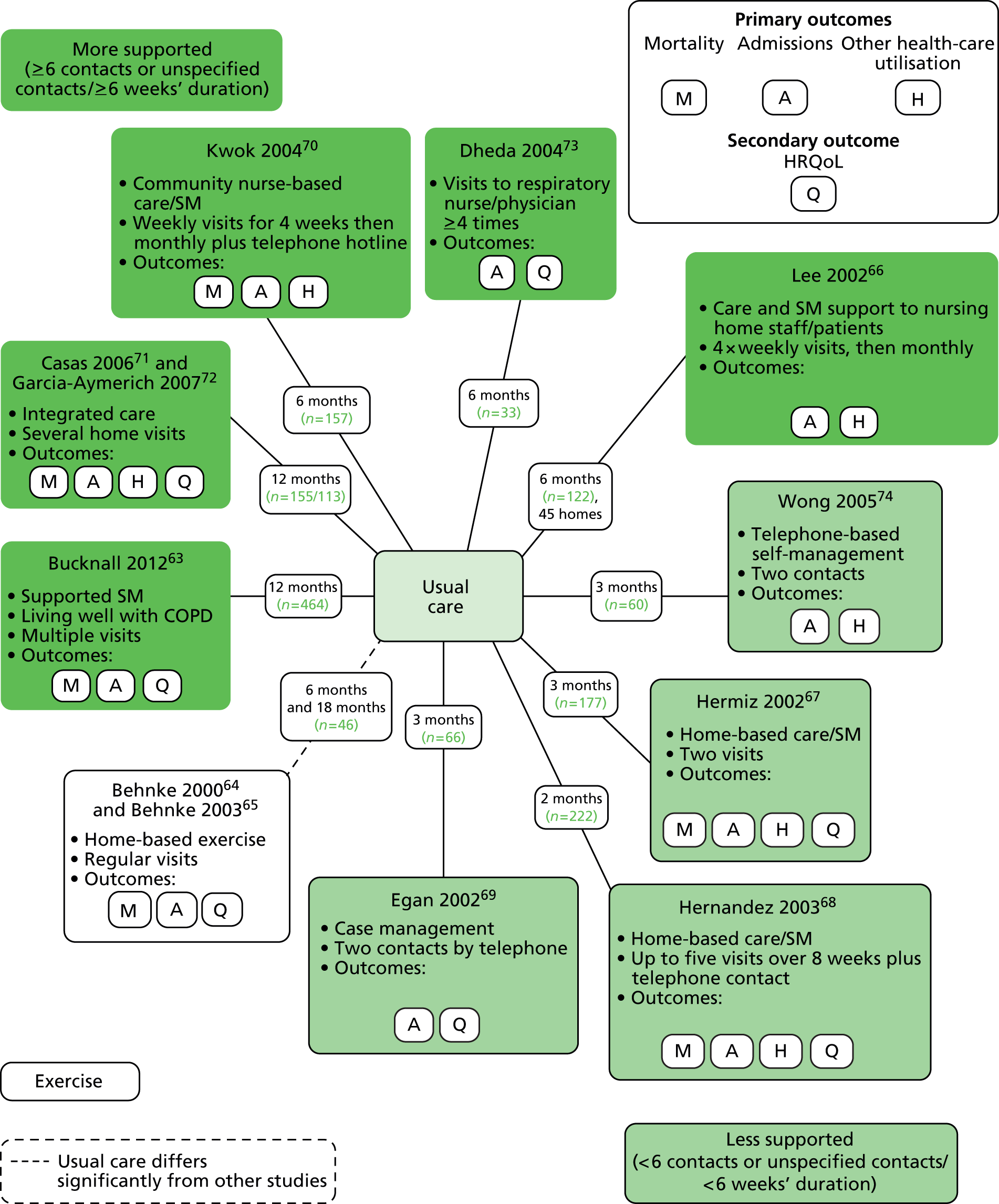

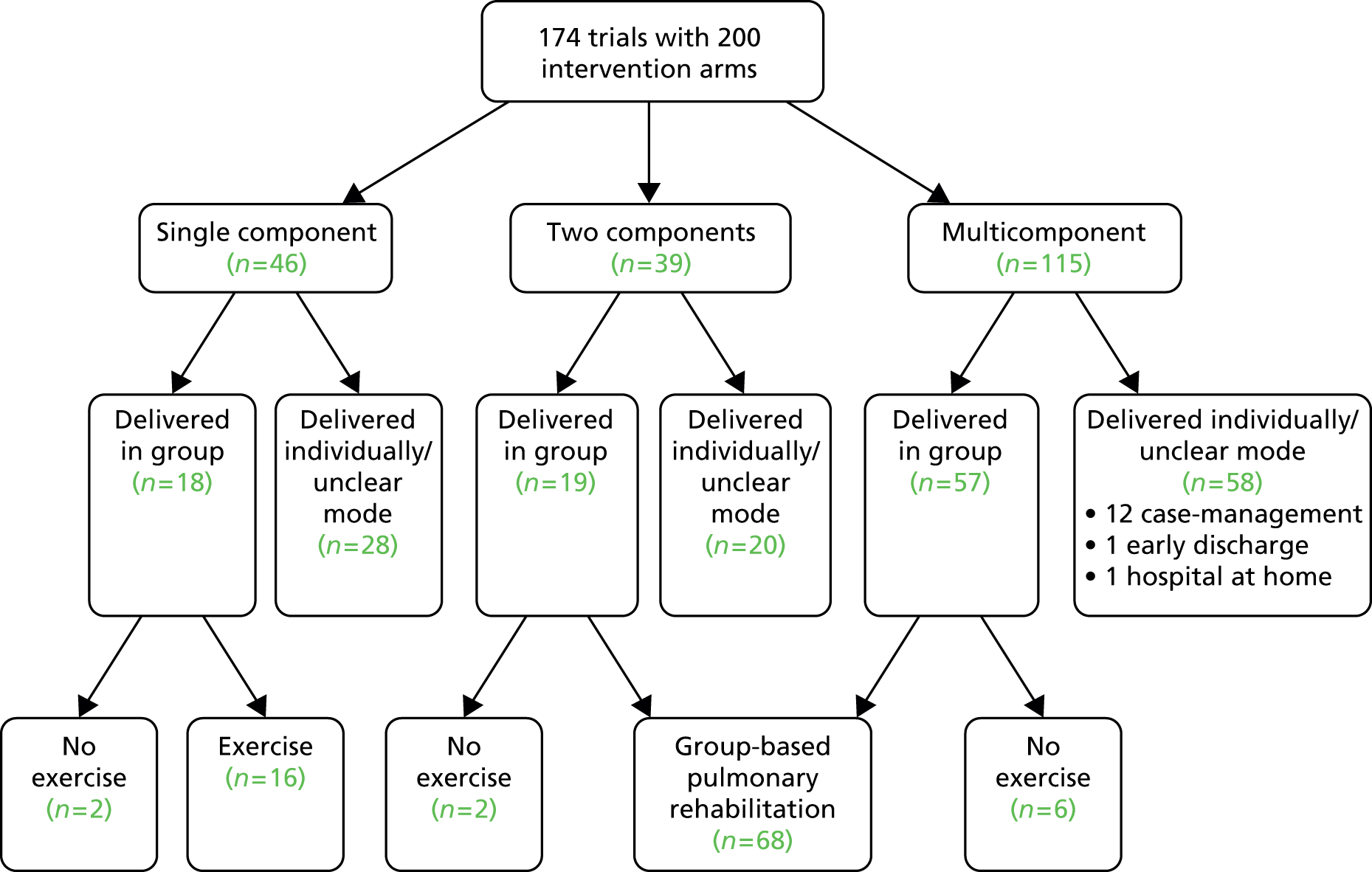

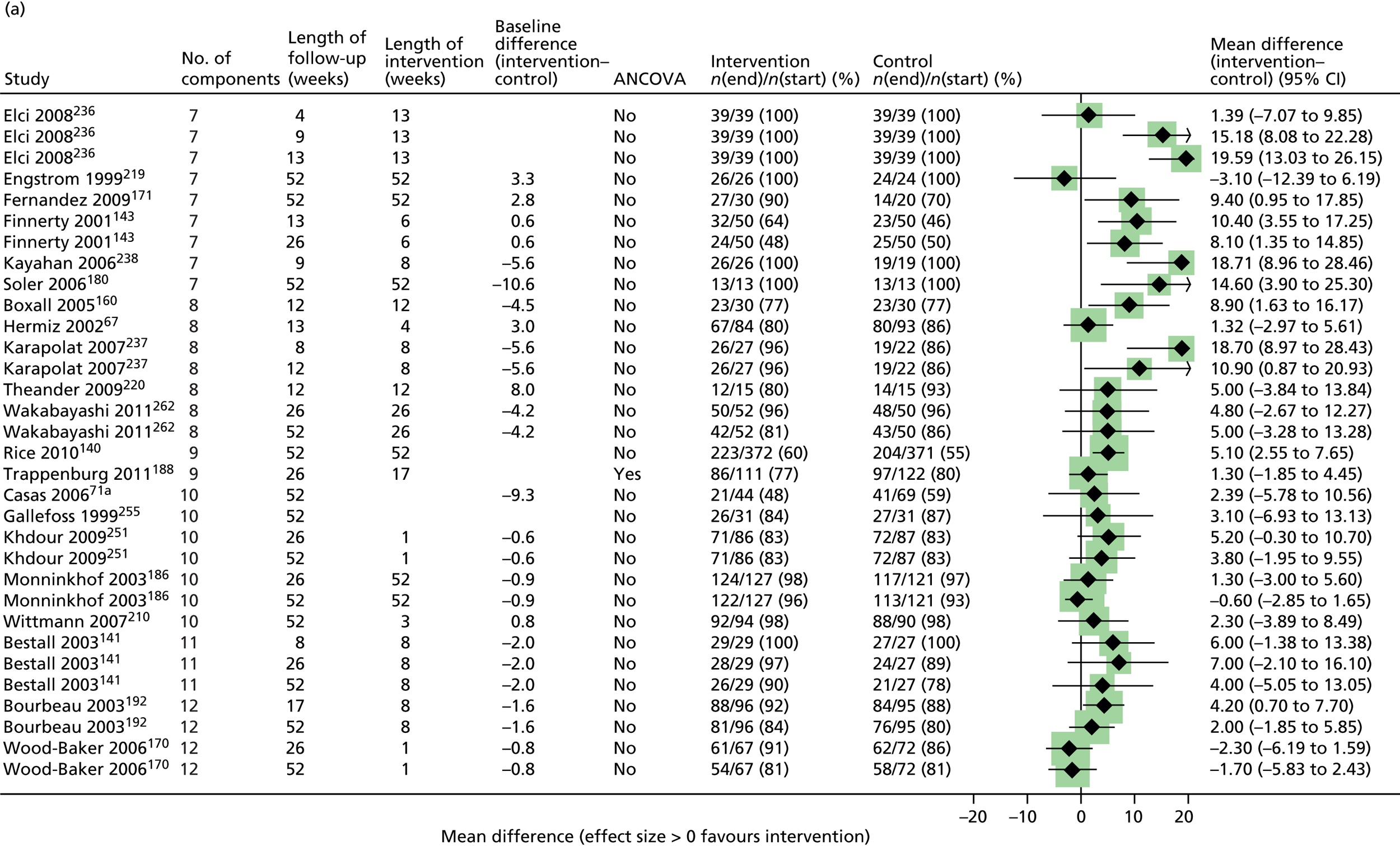

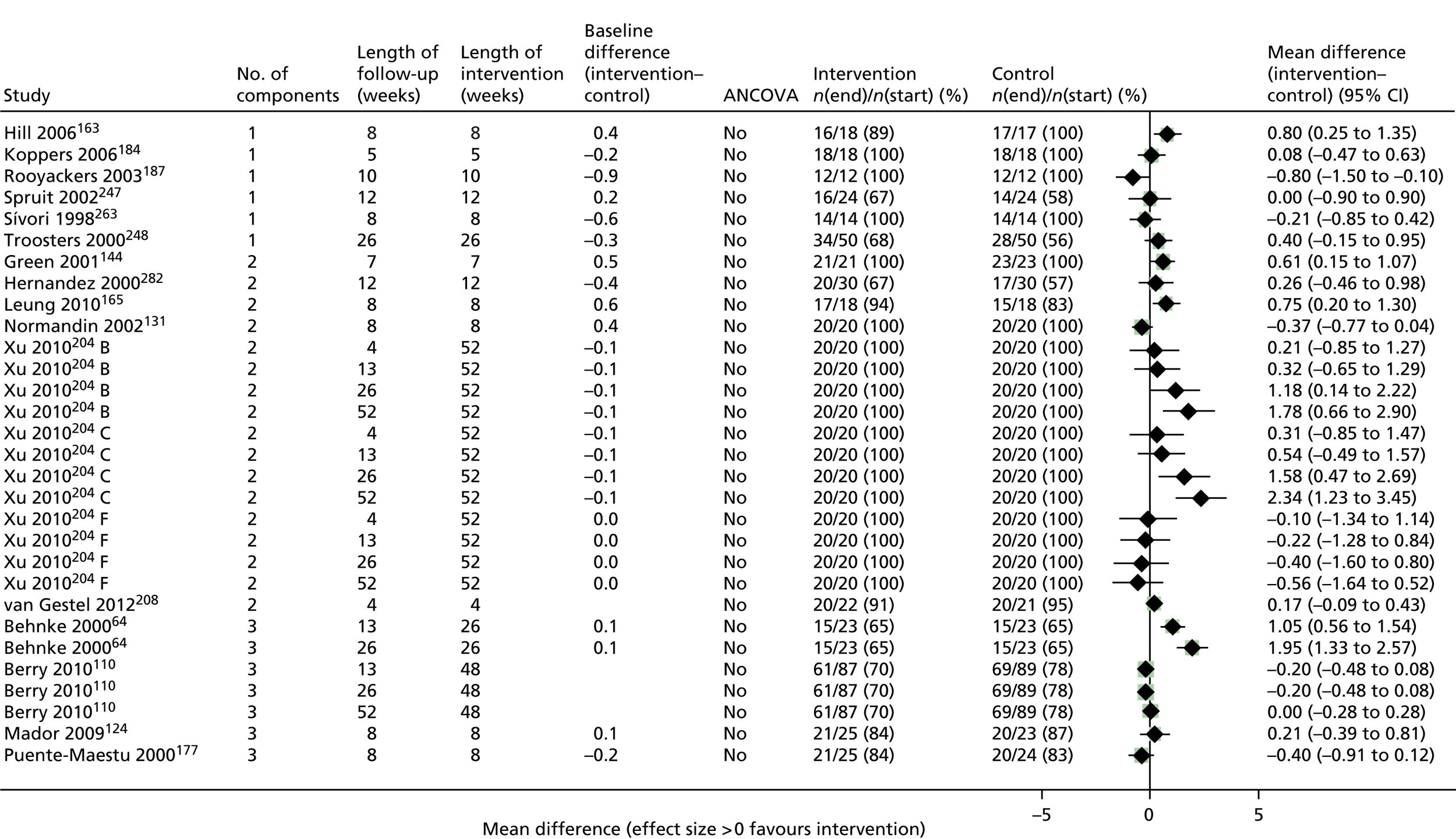

Description of self-management interventions and comparators

Interventions were varied and have been described in full in Table 4. Figure 2 provides a summary diagram of the included RCTs, with interventions grouped into three categories:

FIGURE 2.

Study characteristics of the included RCTs.

-

‘More supported’ Six or more contacts or ≥ 6 weeks’ duration if contacts not specified. This category included:

-

– large RCT in the UK of supported SM (based on the Living Well with COPD materials) for 12 months, compared with UC63

-

– RCT in Spain/The Netherlands of integrated care including supported SM for 12 months,71,72 compared with UC

-

– RCT in Hong Kong70 of a community nurse-supported discharge programme, including SM support, with weekly visits for 4 weeks and then monthly, with additional telephone hotline and a total follow-up of 6 months, compared with UC

-

– small RCT in the UK73 of hospital outpatient visit-based SM support over 16 weeks with total 6 months’ follow-up, compared with UC

-

– cluster RCT in Hong Kong66 of support by community nurses to nursing home staff and patients with a supported SM component, weekly visits for 1 month and thereafter monthly visits for a total of 6 months, compared with UC.

-

-

‘Less supported’ Fewer than six contacts or < 6 weeks’ duration if contacts not specified. Including:

-

– RCT in China of telephone-based SM (based on Bandura’s theories of self-efficacy31), with two telephone calls before week three and total follow-up for 3 months, compared with UC74

-

– RCT in Australia of SM support provided by two visits after 1 week and 1 month, with total 3 months’ follow-up, compared with UC67

-

– RCT in Spain of home-based hospitalisation, including SM education and action plans, reinforced during up to five home-visits and telephone contacts over an 8-week period, compared with UC68

-

– RCT in Australia of case management with SM support with review and two telephone calls and follow-up for 3 months in total, compared with UC. 69

-

-

‘Exercise-only intervention’ Home-based exercise-only interventions:

Description of comparators

Comparators were ‘UC’ [often with little description but focused on usual GP management] except for the exercise trials,64,65 for which the control group had some initial exercise training in hospital and were then advised to perform exercise at home.

Range of outcomes reported

All included trials measured at least one of the primary outcomes. Mortality was reported in six trials;63,64,67,68,70–72 hospital admissions (measured in multiple ways) in all 10 trials;63–74 and other health-care utilisation in six trials. 66–68,70–72,74

Of the secondary outcomes, HRQoL was assessed in seven trials63–68,71–73 and was provided as an overall score as well as subdomains. The most common score was the SGRQ.

Exacerbations were reported in only one trial. 73 Self-efficacy was measured in two trials;63,74 behaviour change in four trials;63,67,68,72 anxiety/depression in five trials;63,66,69,70 exercise capacity in two trials;64,65,70 dyspnoea in two trials;64,65,72 and lung function in five trials. 64–66,68,72,73

Patient satisfaction with the intervention was described in five trials,66–68,72 one of which is described in full in the next chapter, as it involved qualitative interviews. 69 Costs were described in one trial,68 but no trials described days lost from work.

Quality of included randomised controlled trials

Risk of bias evaluations are presented in Table 5 and are described as high, low or unclear risk for each aspect of potential bias.

| Sources of bias | aBehnke 200064 | aBehnke 200365 | Egan 200269 | Hermiz 200267 | Lee 200266 | Hernandez 200368 | Dheda 200473 | Kwok 200470 | Wong 200574 | bCasas 200671 | bGarcia-Aymerich 200772 | Bucknall 201263 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Sequence generation | Unclear: Randomly allocated but method not described |

Unclear: Randomly allocated but method not described |

Low: Stratified and then random number tables |

Unclear: ‘Simple randomisation’ at one site and permutated block at another |

Unclear: Intervention and control nursing homes matched by readmission rates and stratified into high, medium, low risk. Randomised in pairs but details not given |

Low: Computer-generated random numbers in 1 : 1 or 2 : 1 ratio |

Unclear: Randomly allocated but method not described |

Low: ‘Random number table’ |

Low: ‘Research randomiser’ |

Low: Computer-generated random numbers |

Low: Computer-generated random numbers |

Low: Computer-generated sequence using permuted blocks and minimisation |

| 2. Allocation concealment | Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear Although described as ‘blindly assigned to groups’ |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Insufficient information |

Unclear: Although described as ‘blindly assigned to groups’ |

Unclear: Although described as ‘blindly assigned to groups’ |

Low: Treatment group allocation were obtained by telephone after baseline assessment had been made |

| 3. Blinding of outcomes | ||||||||||||

| a. Hospital admissions | n/a | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | n/a | Low |

| b. ED visits | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Low | Low | n/a | Low | Low | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| c. Primary care consultations | n/a | n/a | n/a | Low Available from GP |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Low | n/a | n/a |

| d. Mortality | Low | n/a | n/a | Low | n/a | Low | n/a | Low | n/a | Low | Low | Low |

| e. Patient-reported outcomes | HRQoL: high Dyspnoea: high Patient not blinded |

HRQoL: high Patient not blinded |

HRQoL: high Anxiety and depression: high Patient not blinded |

HRQoL: high Behaviour change: high Patient satisfaction: high Patient not blinded |

Psychological status: high Patient satisfaction: high Patients not blinded |

HRQoL: high Patient satisfaction: high Investigator administrating questionnaire blinded but patient not blinded |

HRQoL: high Patients not blinded |

GHQ score: high Patients not blinded |

Self-efficacy: high Patients not blinded although assessors blinded |

n/a | High HRQoL; dyspnoea; treatment adherence/inhaler technique; vaccine uptake; patient satisfaction; smoking; exercise; knowledge |

High HRQoL; anxiety and depression; self-efficacy Patients not blinded |

| f. Other outcomes of interest | Lung function: unclear No information provided but interviews conducted by the physicians managing the care so unlikely to be blind Exercise capacity: low risk because assessor gave no encouragement |

Lung function: unclear No information provided, but interviews conducted by the physicians managing the care so unlikely to be blind Exercise capacity: low risk because assessor gave no encouragement |

n/a | n/a | Lung function: unclear Not known whether or not assessors were blinded |

Lung function: unclear Not known whether or not assessors were blinded |

Lung function: unclear Not known whether or not assessors were blinded Exacerbations: unclear No information |

Exercise capacity: low Assessors were blinded |

n/a | Unclear Lung function No information provided on blinding |

n/a | |

| 4. Incomplete outcome data | Outcomes only provided on completers 14/23 (61%) in intervention arm 12/23 (52%) in control arm |

Ignoring deaths, 11% loss to follow-up, although reasons not provided for withdrawals | Outcomes only provided on completers (79.5% overall) Insufficient reporting of attrition/exclusions |

Implies that the only attrition during 8-week period was due to death | Most outcomes only provided on completers (89%) | Low: all participants accounted for, 3.3% dropout; missing values replaced by group mean | ||||||

| a. Hospital admissions | n/a | High | Unclear | Low 89% followed up |

High | Unclear | Unclear: Unclear follow-up rate |

Low: 89% followed up |

Low: 97% followed up |

Low | n/a | Low |

| b. ED visits | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | High | Unclear | Low 89% followed up |

Low 97% followed up |

n/a | n/a | n/a | |

| c.Primary care consultations | n/a | n/a | n/a | Low: 89% followed up |

n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a | Low: 97% followed up |

Low: Withdrawals reported; other than deaths < 10% lost |

n/a | n/a |

| d. Mortality | Low | n/a | n/a | Low: 100% followed up |

Low | n/a | Low | n/a | Low | Low | Low | |

| e. Other | High: Withdrawals reported; outcomes provided only on completers (65% in each arm) |

High |

High: Other than deaths, 12% loss to-follow-up, although reasons/characteristics not provided for withdrawals Data not provided for all participants |

Low: 89% followed up |

HRQoL: unclear | HRQoL: high Lung function: high 66.7% followed up in intervention arm and 83.3% followed up in control arm Withdrawals reported but no information on characteristics reported and, not accounted for in analysis |

Exercise capacity: high 77% took part due to loss to follow-up and mobility problems |

Low: 97% followed up |

n/a | High: High loss to follow-up (other than deaths, 14.2% lost) Reasons for withdrawals reported but analyses undertaken only on completers Lost to follow-up appeared more severely affected than completers |

High: HRQoL; self-efficacy; anxiety and depression high loss to follow-up; only 61% completed questionnaires at 6 months Non-completers had greater morbidity and worse baseline self-efficacy, and more likely to be in the control arm |

|

| 5.Selective outcome reporting | Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear Protocol not identified Mention of collection of GP consultations and exacerbations, but not reported |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

High: Data not available for HRQoL |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

Unclear: Protocol not identified |

| Other comments | Methodology of lung function measurement not given Table of characteristics provided only on completers |

Baseline differences for age, CRQ, lung function and 6-MWT Table of characteristics only provided on completers |

Clear imbalance of gender at baseline, and possibly other characteristics Outcome data very difficult to interpret as change provided between interim time points only |

Study design problematic Although a cluster design analysis does not take this into account Unknown validity of satisfaction questionnaire Methodology of FEV1 measurement not given |

Baseline differences with respect to smokers, oxygen therapy, although comparable to disease severity (FEV1% pred) Short follow-up period Outcome assessment not clear; percentage not always correct Lung function analyses not adjusted for baseline |

Very small study Methods of outcome assessment not described Numerical data not available for lung function Rather limited information provided throughout One patient excluded from analysis owing to visiting GP (not ITT) No table of characteristics Confusion over SEM or SD |

Three subjects in control were undergoing PR | Change in sample size calculation External validity of Chinese Self-Efficacy Scale Gender may not be very well balanced across arms |

Differences in text and Table 2 for differences in rate of admissions Not well balanced on previous hospitalisations, and receipt of influenza vaccination |

No description of lung function test methods Intervention arm seemed to have higher number of admissions in the previous year and possibly worse SGRQ score |

In general, the quality of reporting and conduct of the included studies was low, with some very small, poorly conducted studies. 64,65,73 Out of the 10 RCTs,63–74 appropriate methods of randomisation (e.g. computer random number generator) were used in six trials63,68–72,74 suggesting a low risk of bias, although methods were unclear in the remaining four. 64–67,73 Allocation concealment was insufficiently described in all except the largest most recent trial,63 which used a central telephone method of allocation to reduce the risk of bias.

Blinding of patients and health-care personnel would not have been appropriate for this type of SM and similar such interventions; therefore, the results of any patient-reported outcomes or non-blinded, investigator-assessed outcomes would be potentially subject to bias. In this review, the important patient-reported outcomes were consistently judged to be subject to high risk of bias across all of the trials, including HRQoL, dyspnoea, anxiety and depression, self-efficacy, patient satisfaction and behaviour change.

Measurements of lung function and exercise capacity both rely on assessors’ encouragement and could be subject to bias if not blinded. It was usually unclear whether or not investigators were blind to treatment when assessing lung function, although when measured, exercise capacity was judged to have low risk of bias because either the assessors were blind70 or it was explicitly stated that they did not provide encouragement. 64,65 In general, conduct of outcome measurement were frequently poorly described, with standards and conduct of lung function testing particularly unclear. 64,65,68,72

However, assessment of hospital admissions, other health-care utilisation and mortality would be likely to have a low risk of bias (either self-reported or obtained from records), as concluded for most of the included trials.

The most obvious flaw in the conduct of some of the included studies was the lack of completeness in follow-up, which was considerably < 70% in some trial arms and would be likely to bias most clinical measures and HRQoL (and other questionnaire) outcomes in particular,63–65,73 and any other questionnaire/clinical measures. This was even discussed by the authors of the largest, most recent trial with only 61% of randomised patients with HRQoL reported at follow-up,63 who concluded that the data were therefore unreliable. Several of the studies64,65 reported characteristics of only the completing participants rather than all randomised participants, or gave no table of characteristics at all. 73 This weakens any attempt to assess baseline imbalance and any bias introduced at this stage.

As is usual, it was difficult to assess selective outcome reporting without availability of protocols. In addition, outcome data were unclearly analysed in several studies,64–66,69,73 and the older studies (pre 2005) were often limited in their description of methods in general. There were signs of baseline imbalance between arms in some studies, which was not addressed in the analyses. 65 The best conducted and reported trials tended to be the most recent. 63,70–72,74

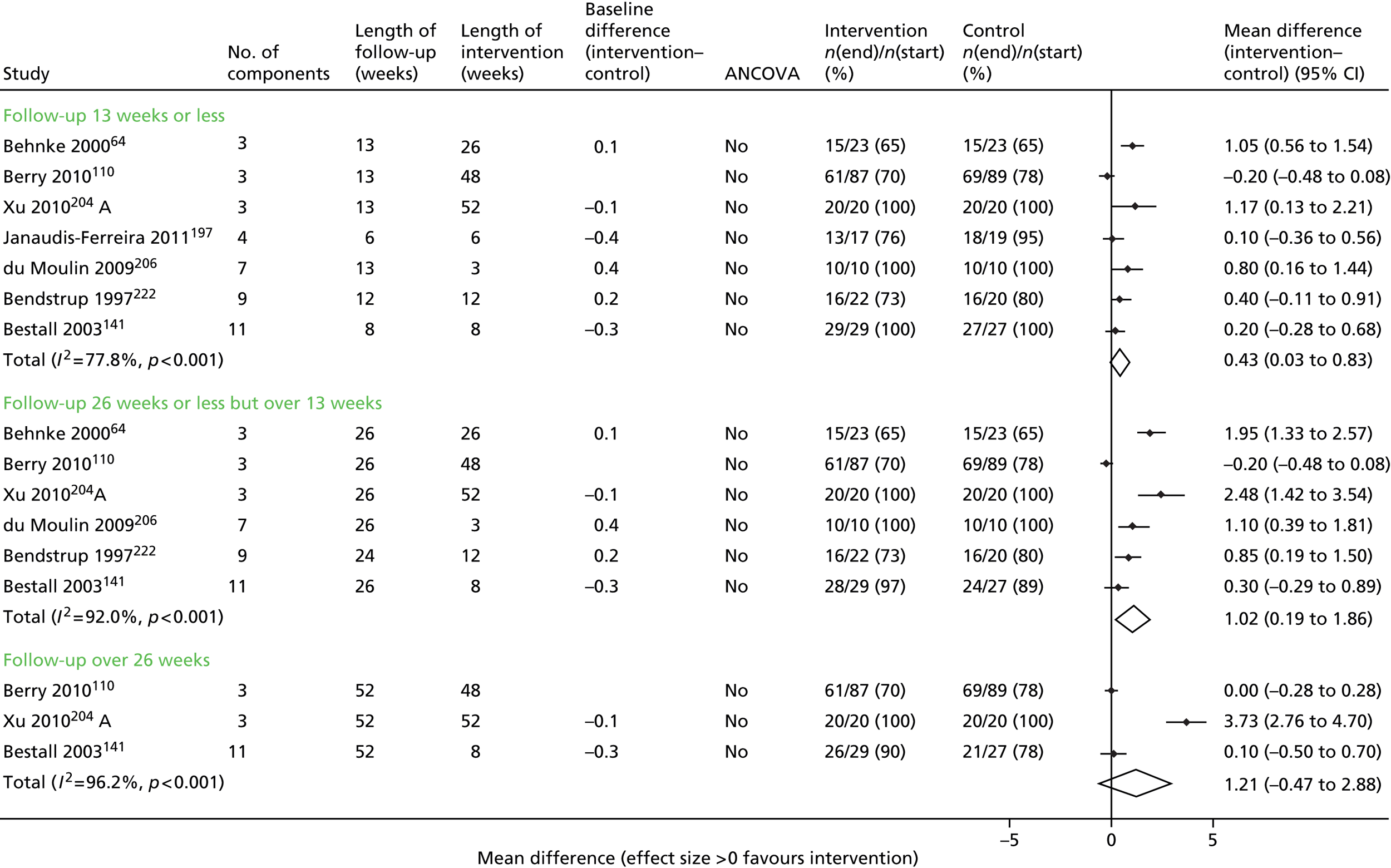

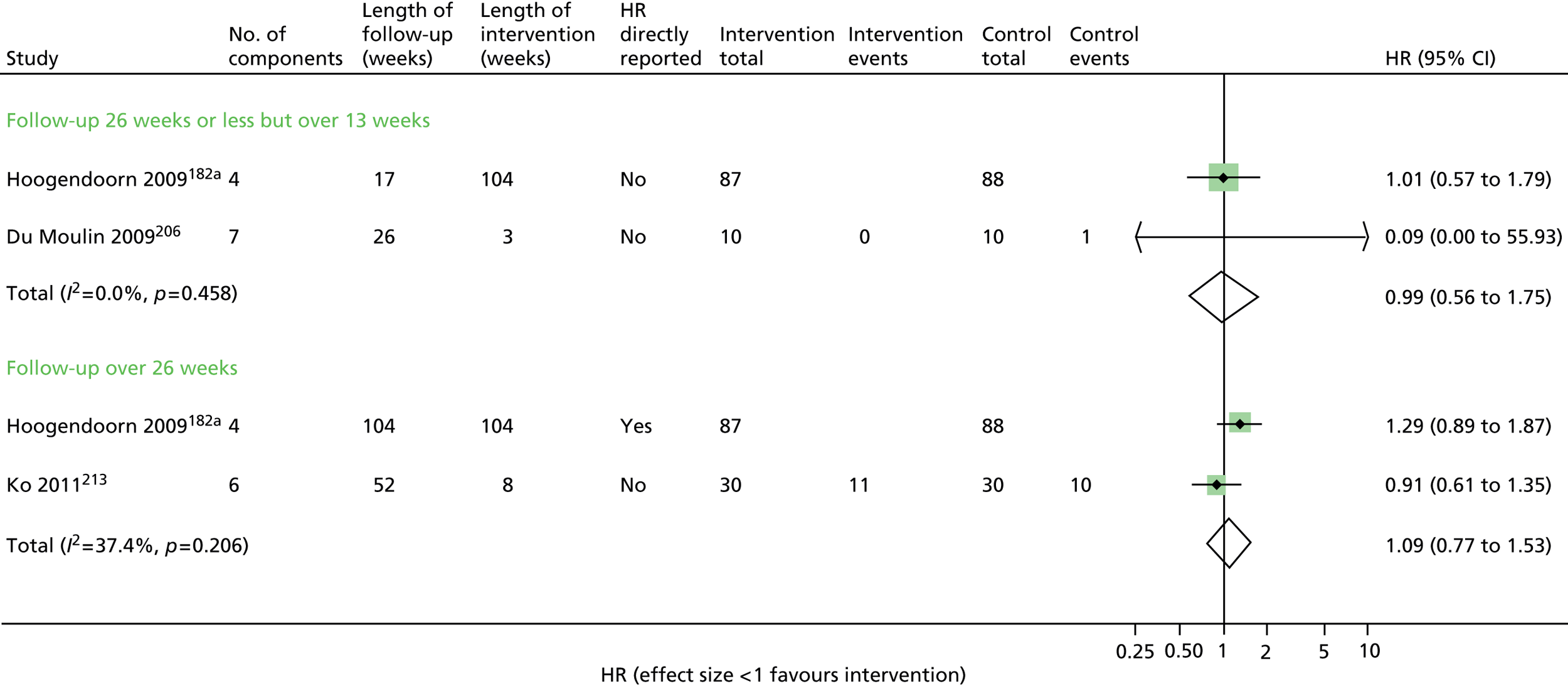

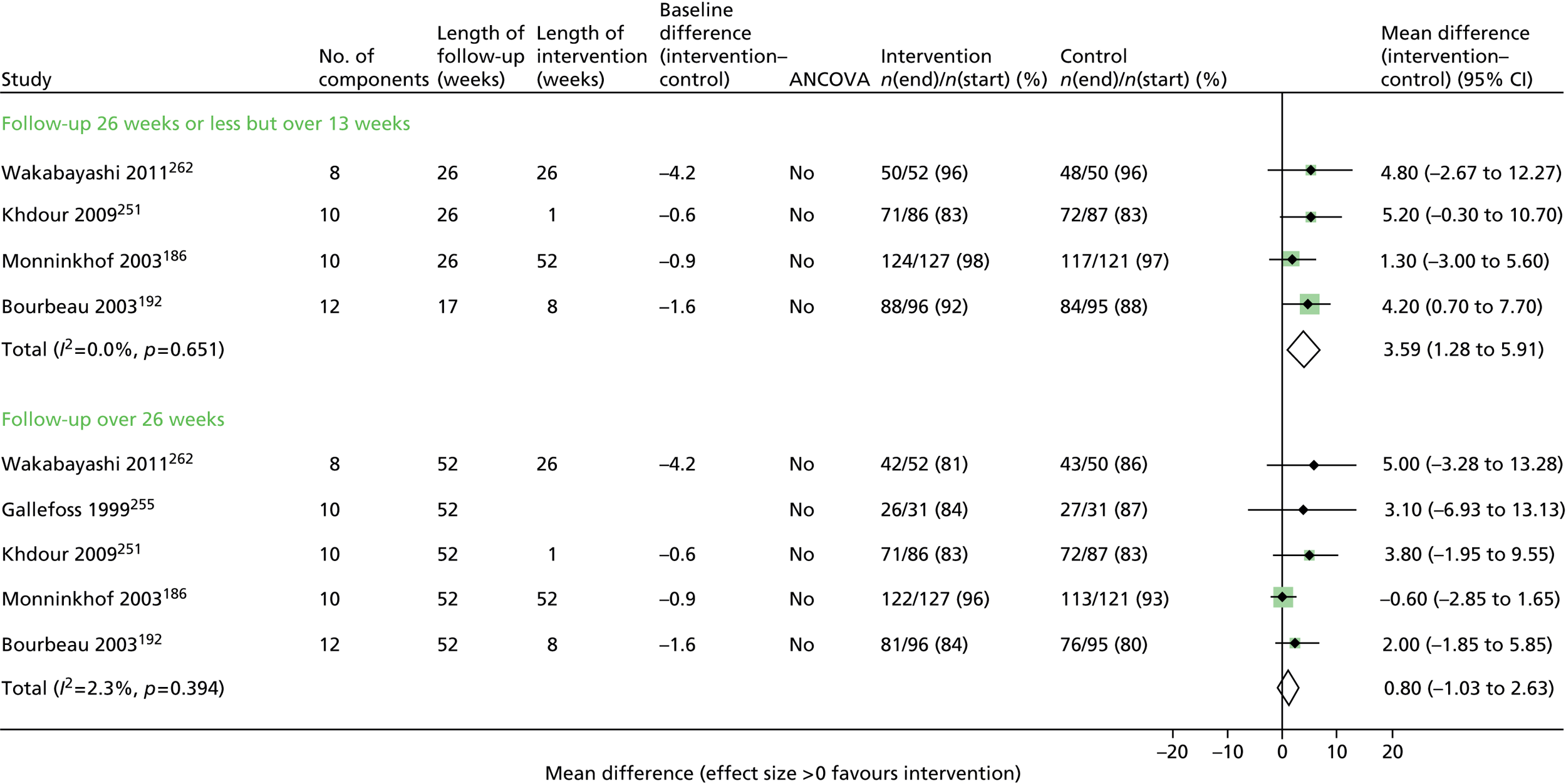

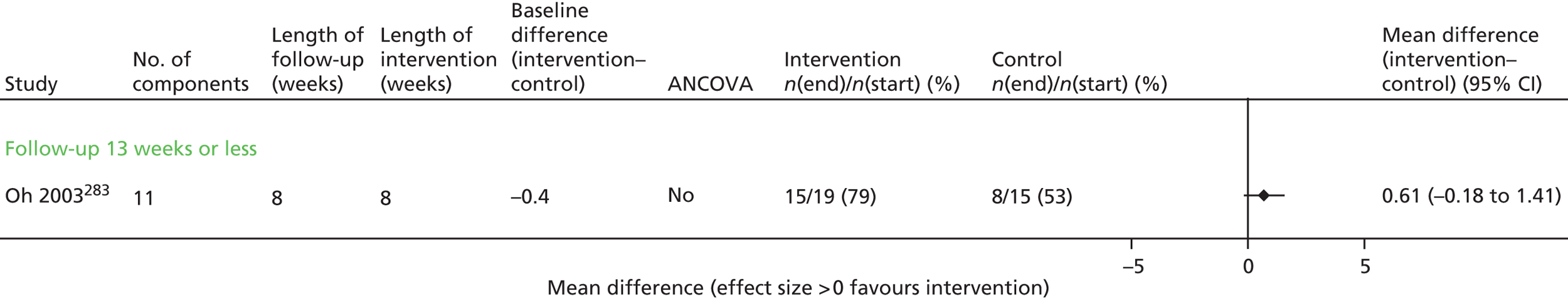

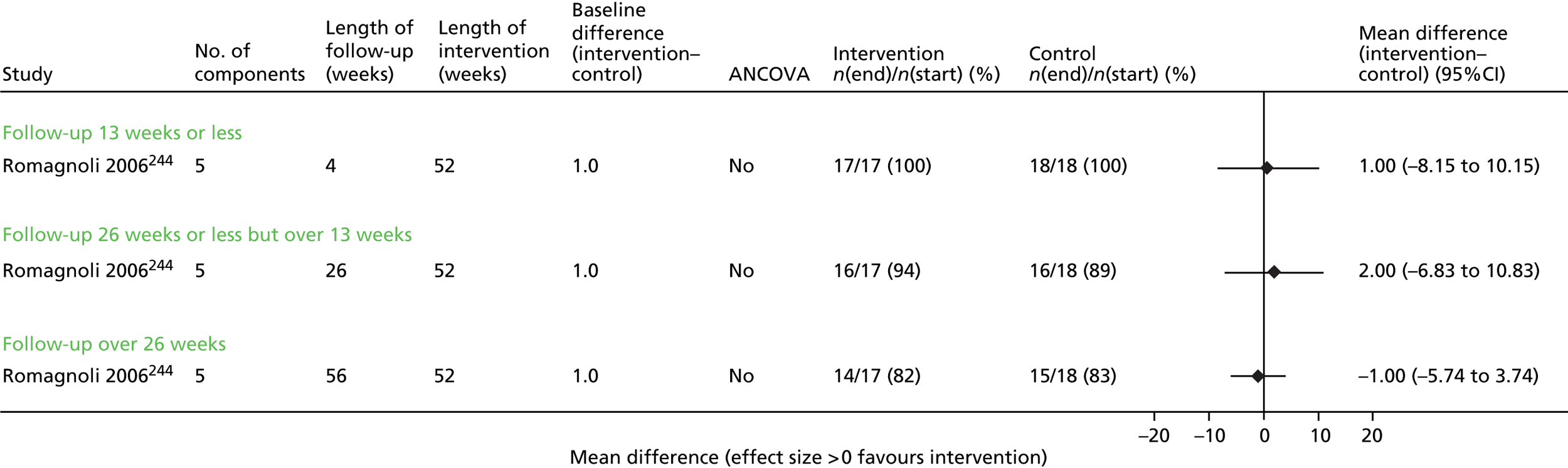

Primary outcomes

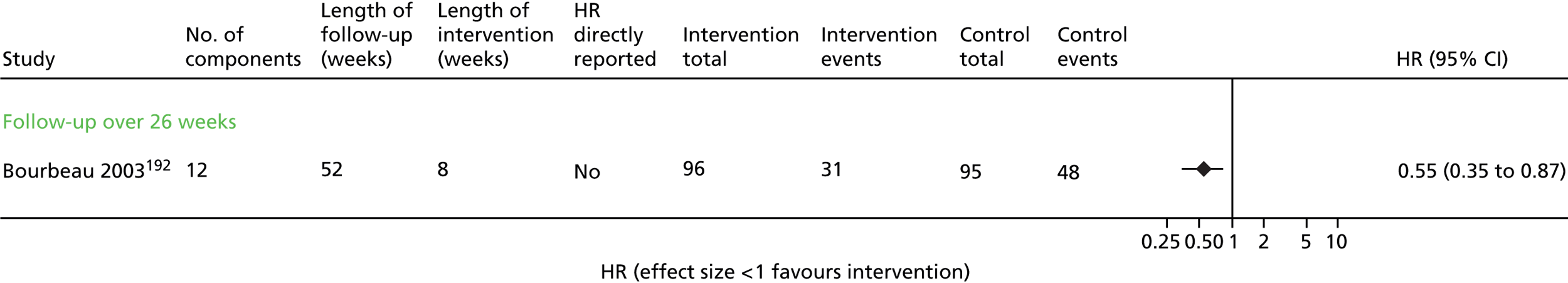

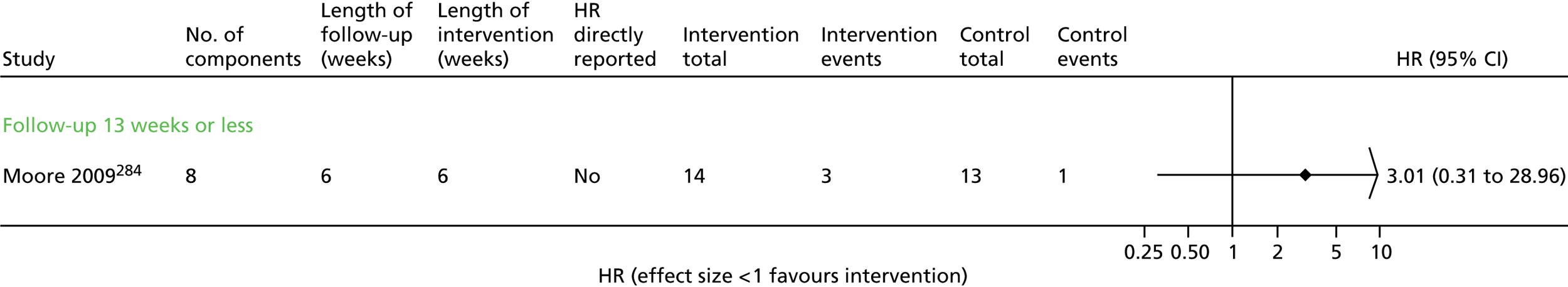

All-cause mortality: no evidence of effect

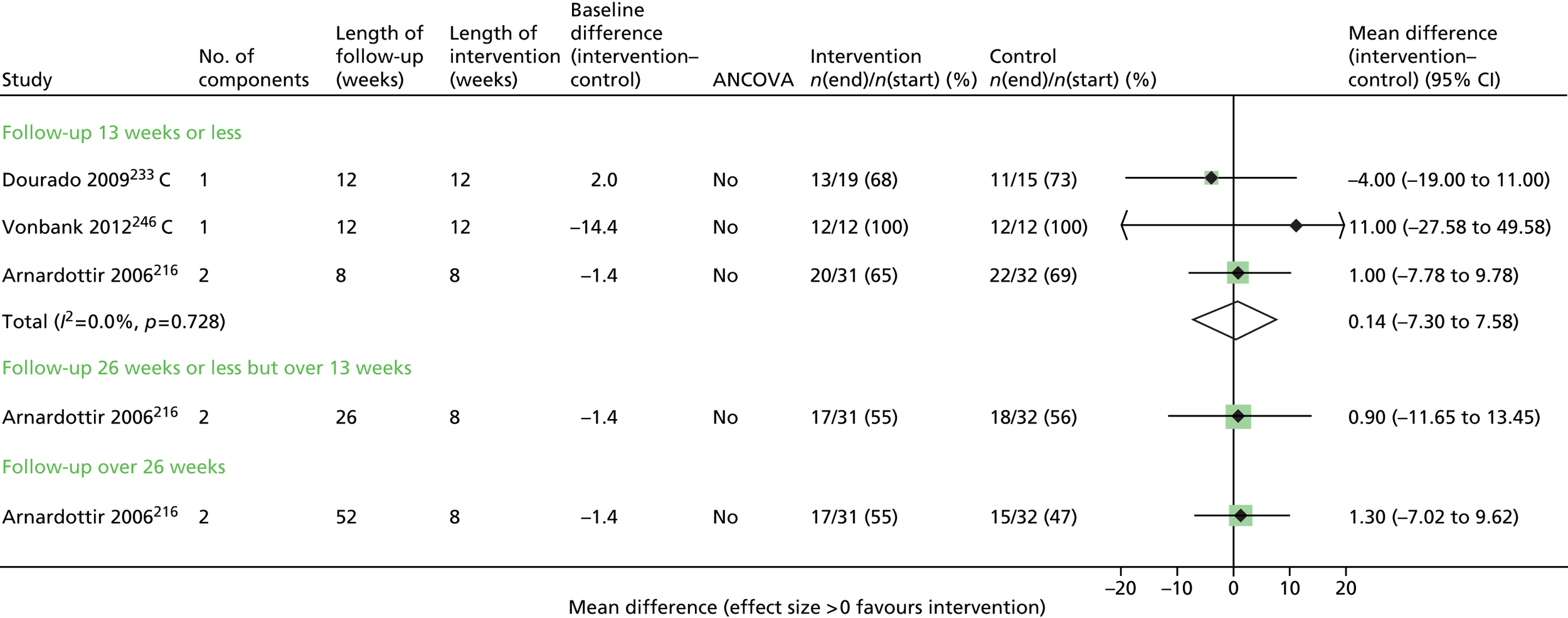

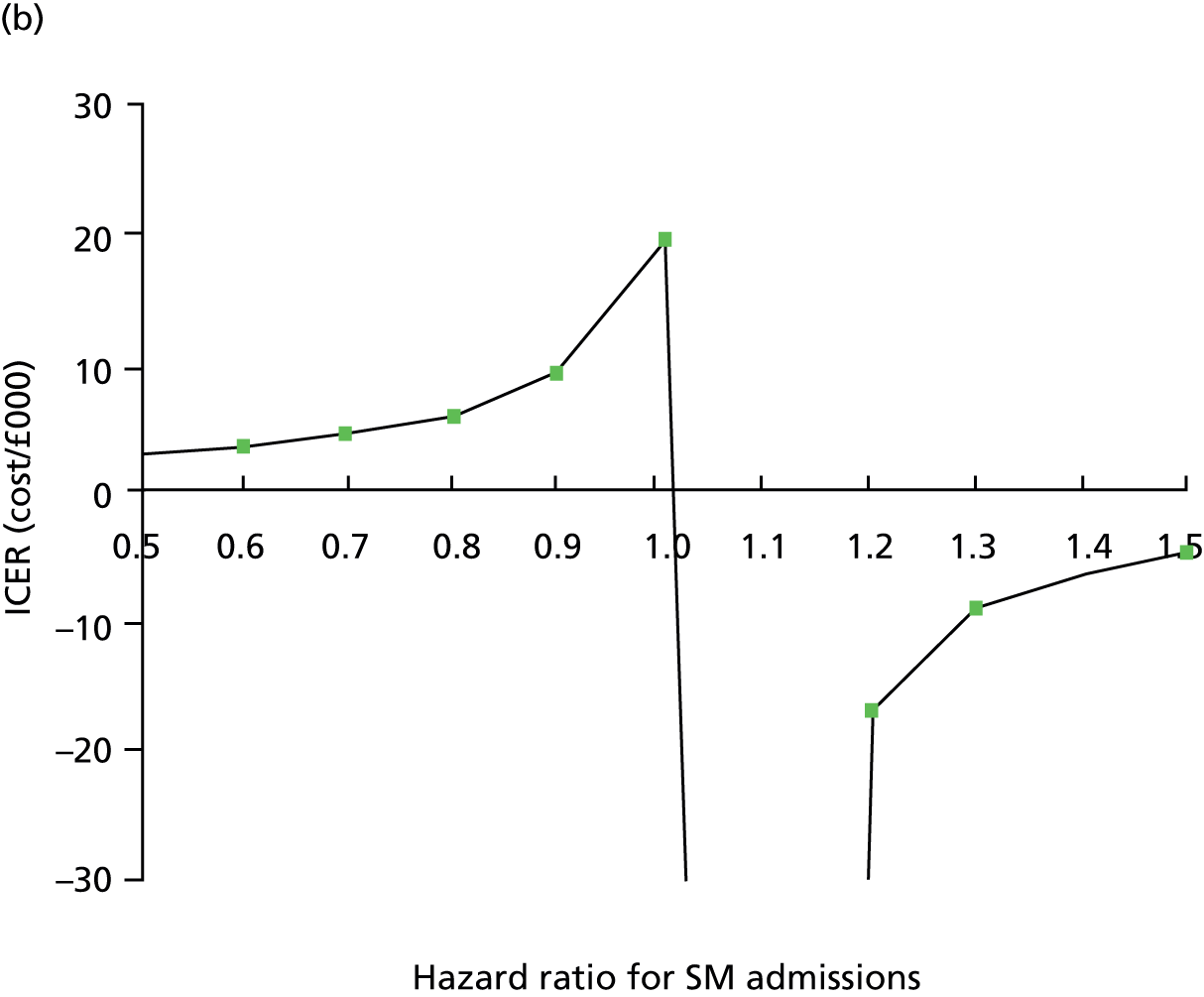

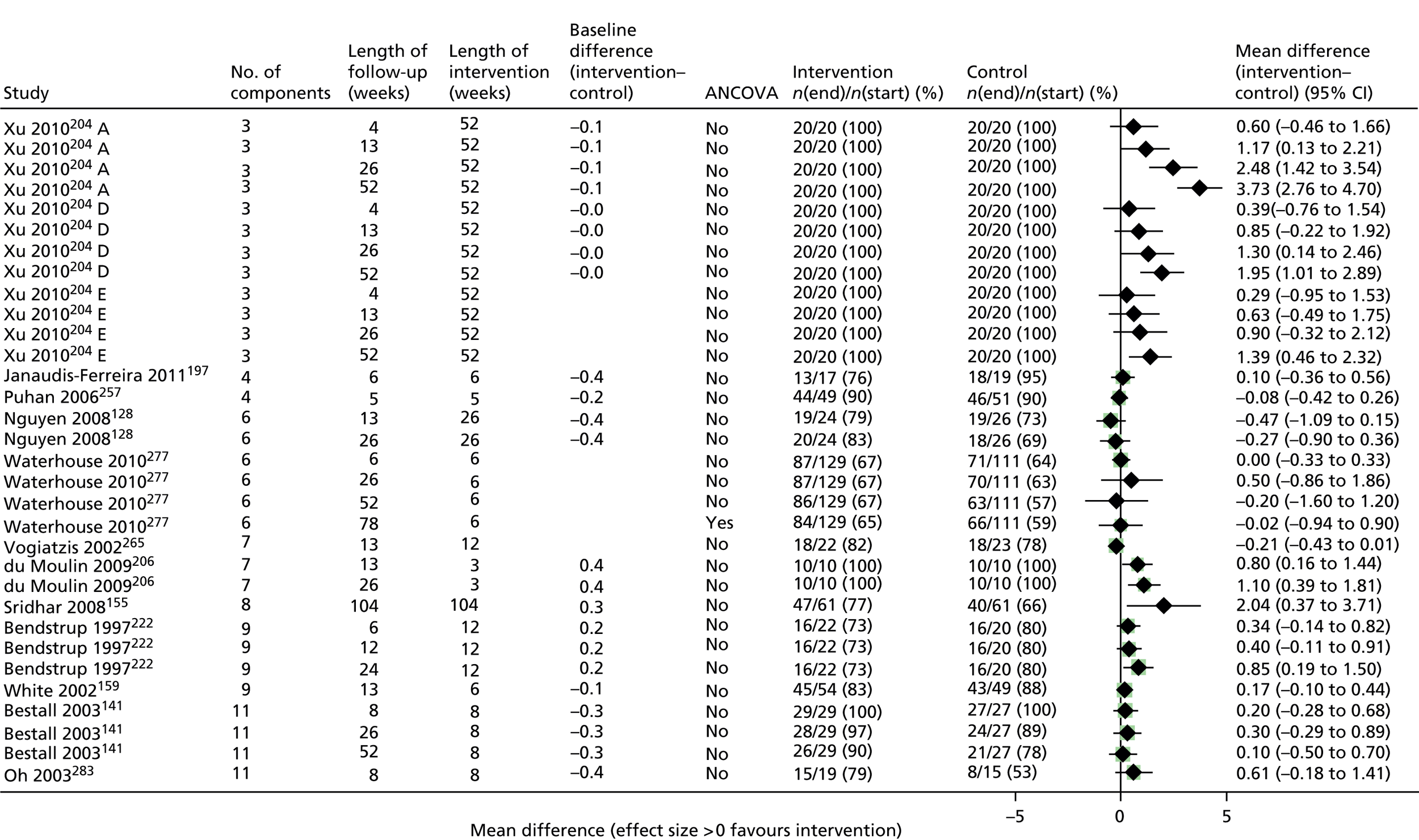

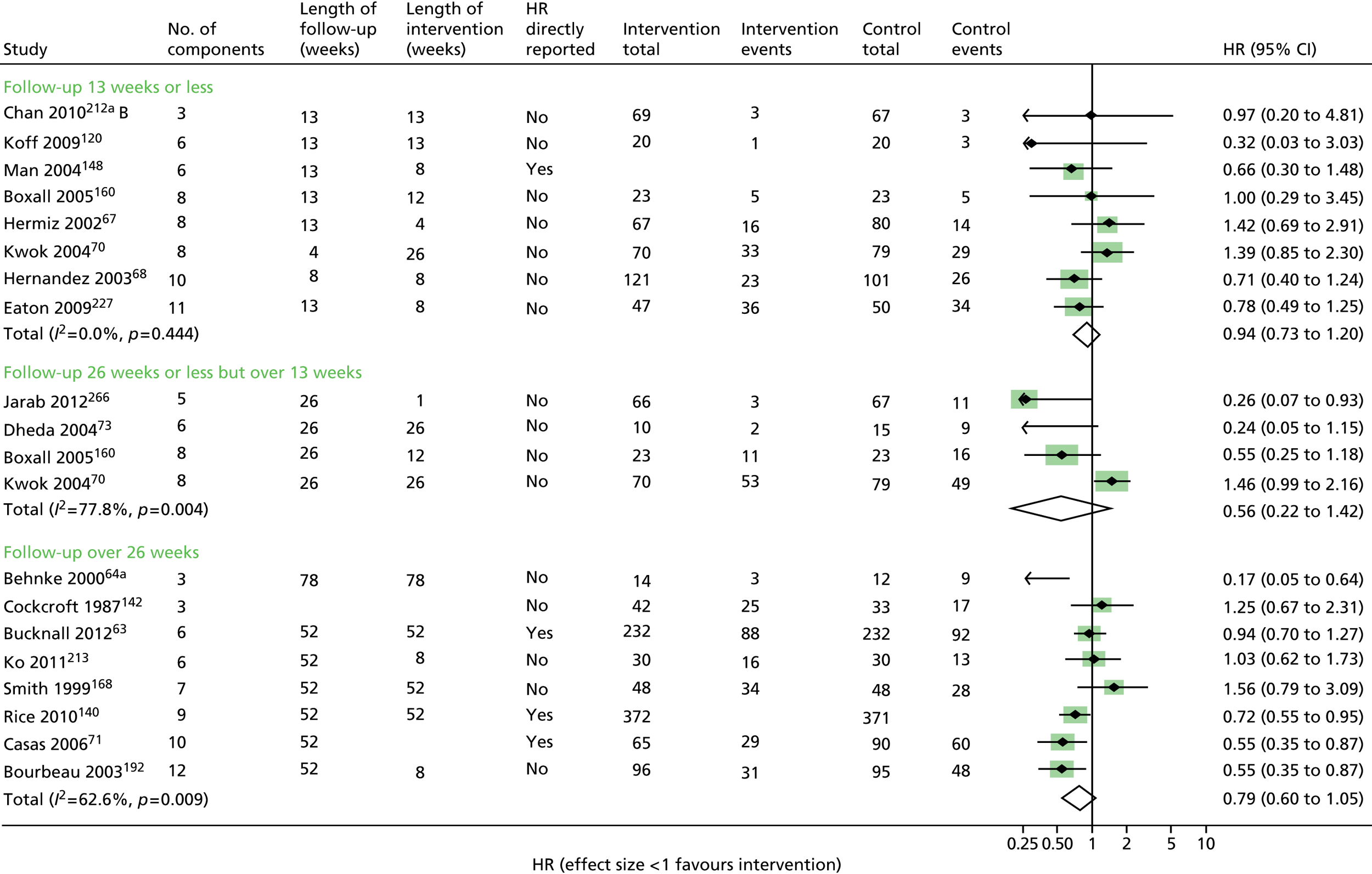

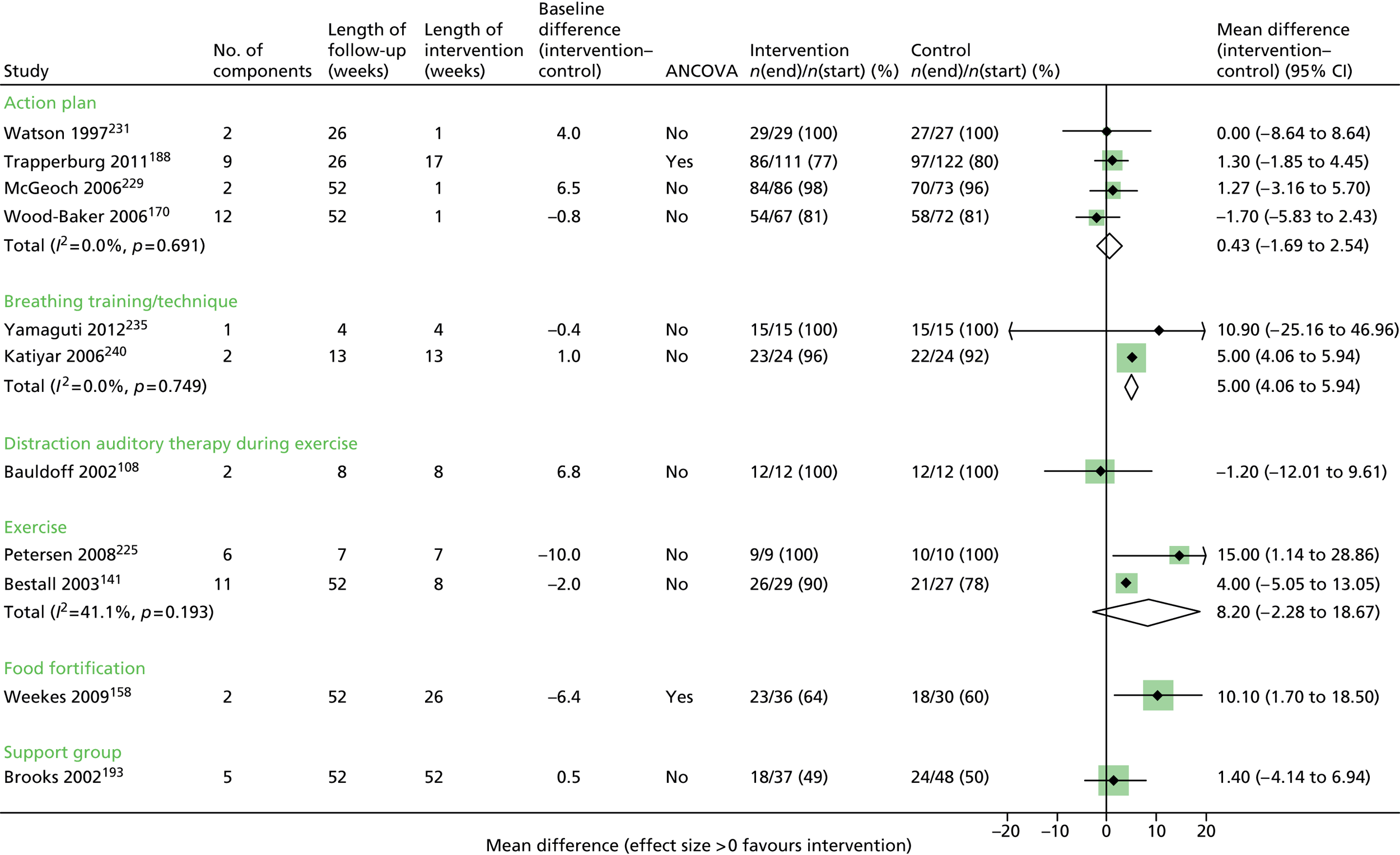

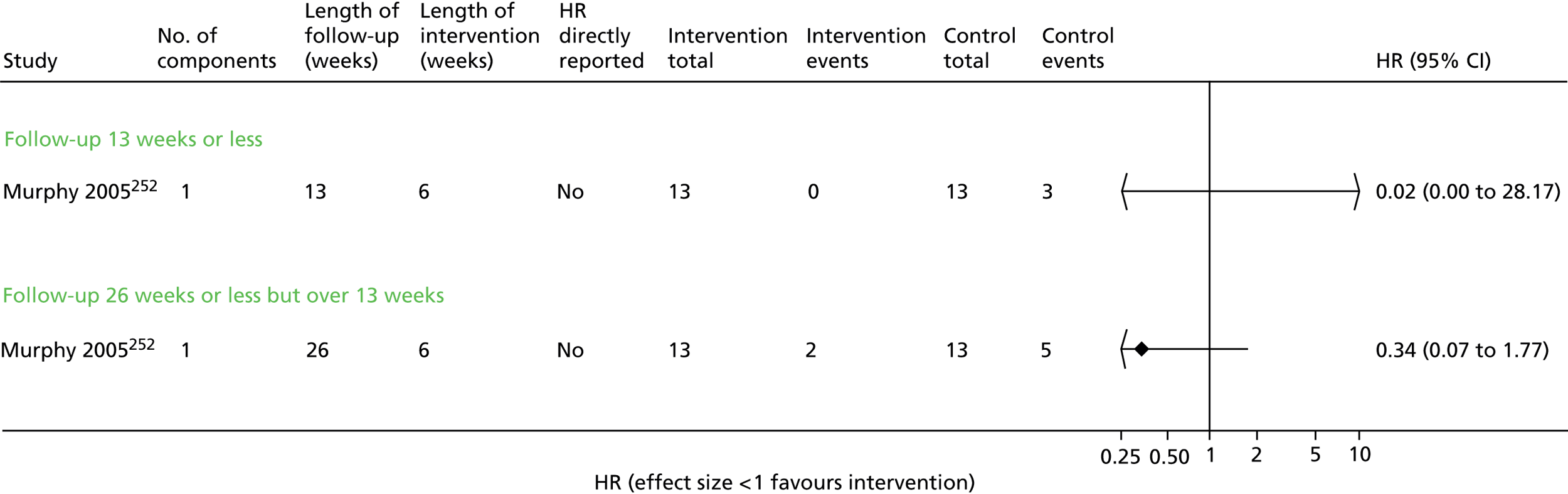

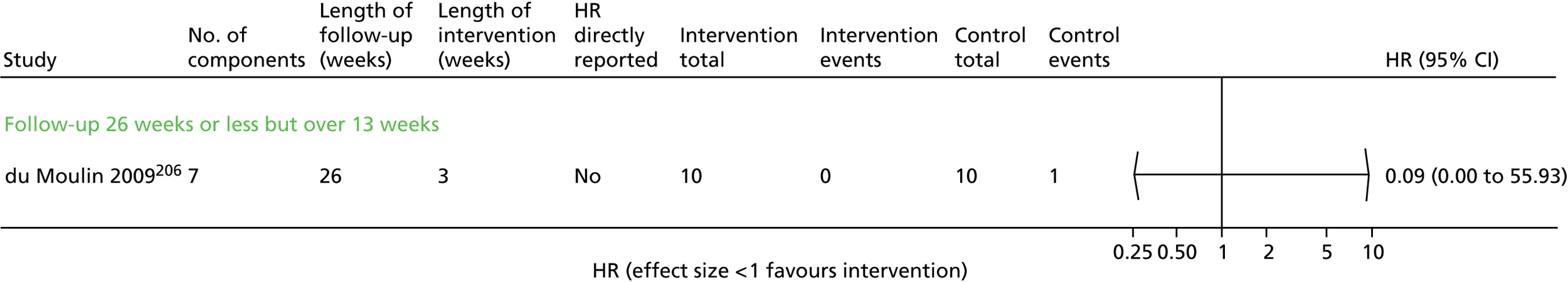

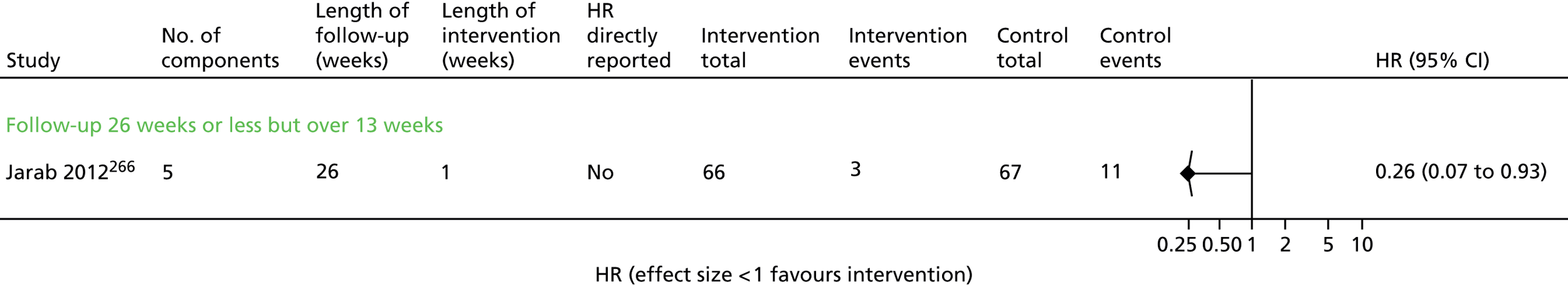

Six trials63,64,67,68,70–72 contributed mortality results (Figure 3 and Appendix 5). There was a wide range of event rates across the trials. Despite the general heterogeneity of interventions, there was no statistical heterogeneity and the overall results indicated that there was no evidence of effect on mortality (HR 1.07, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.54). Using the GRADE system, we would judge that this is moderate-quality evidence (Table 6).

FIGURE 3.

All-cause mortality. NR, not reported.

Hospital admissions: no evidence of effect

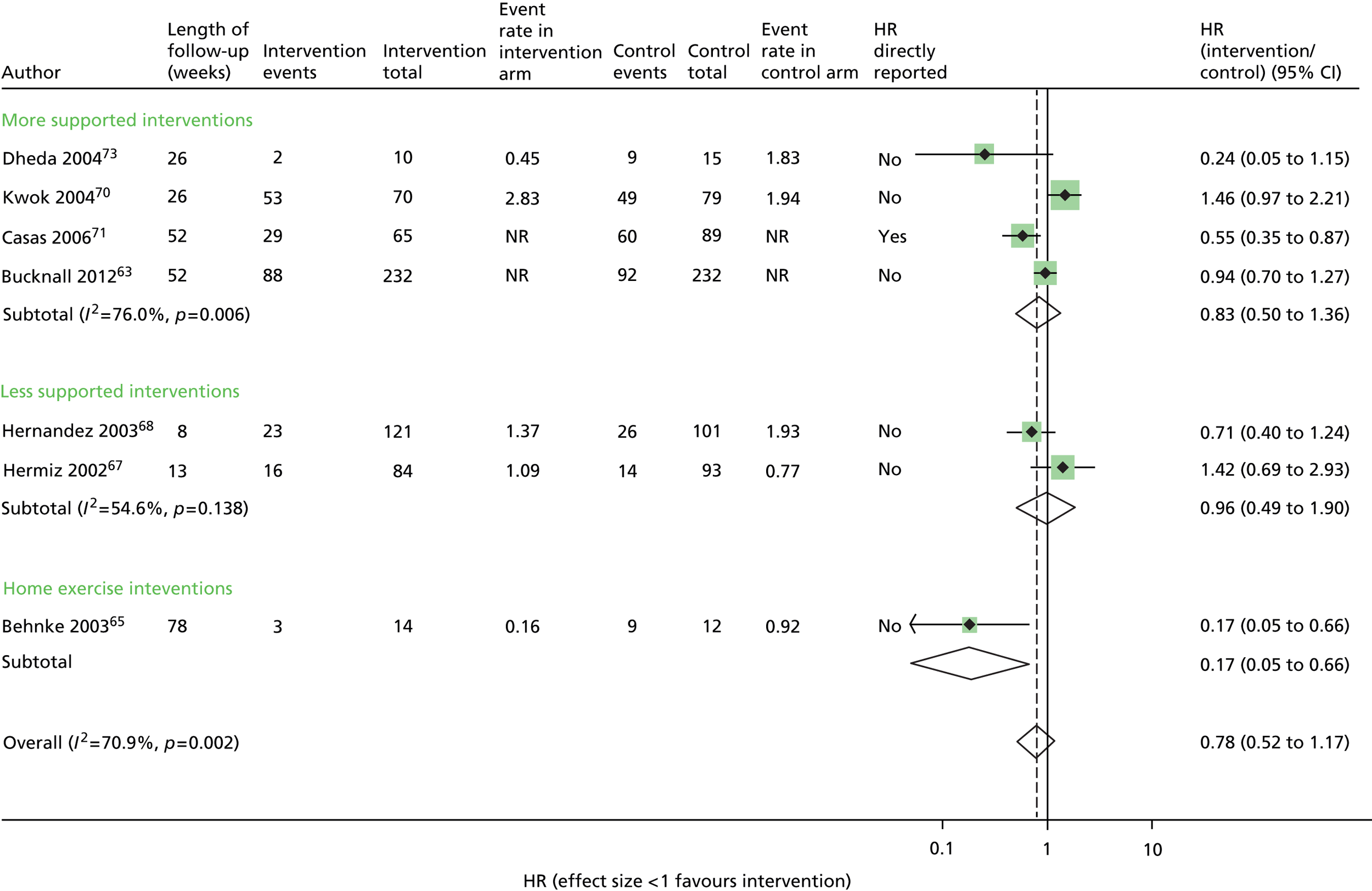

Seven trials63,65,67,68,70,71,73 contributed data to the admissions results (Figure 4 and Appendix 6). The results of three trials66,69,74 could not be included in the combined results because they reported mean number of admissions rather than first admission and one69 also did not provide sufficient information to calculate a SE.

FIGURE 4.

First hospital admission. NR, not reported.

Overall, statistical heterogeneity was high (I2 = 70.9%), and subdividing by level of support explained only a fraction of this. Estimates are provided by level of SM support, although there was no evidence of any effect for the non-exercise-based interventions and substantial remaining heterogeneity.

One of the studies that may have contributed to the remaining heterogeneity in the non-exercise-based studies is the small study of 33 participants by Dheda et al. ,73 which was poorly reported, had signs of inadequate randomisation and very high loss to follow-up, especially in the intervention arm. This study73 had the most extreme results in its category.

The trial of home-based exercise65 demonstrated a large relative reduction on the rate of first admission (HR 0.17, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.66), although this trial was very small and these results were based only on participants who completed the study (< 60% of those randomised), and thus would also be subject to high risk of bias. Furthermore, although subgrouping by intervention category was an a priori identified analysis, care must be taken in the interpretation of results due to multiple comparisons being performed. The evidence above was judged to be of low quality according to GRADE (see Table 6).

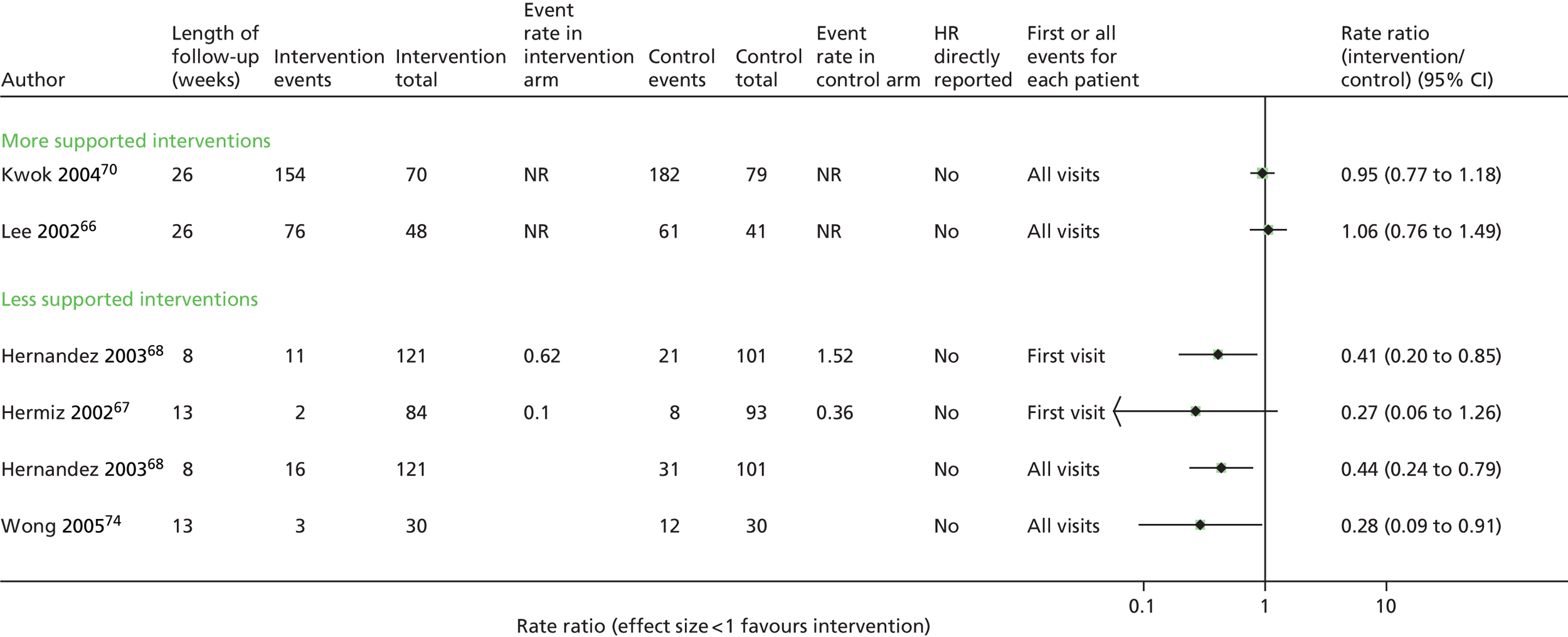

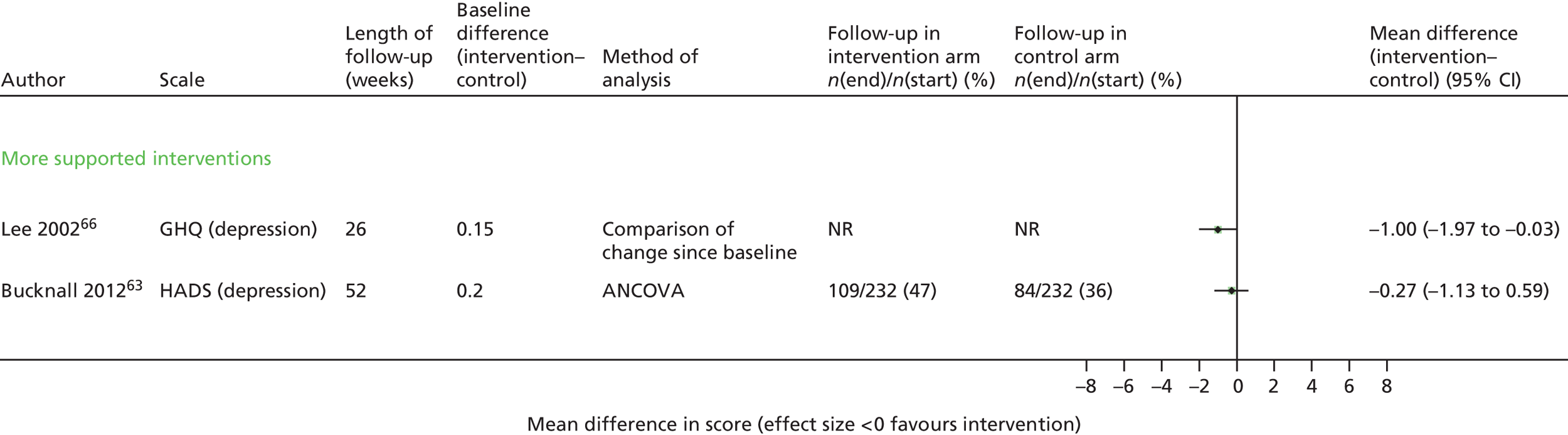

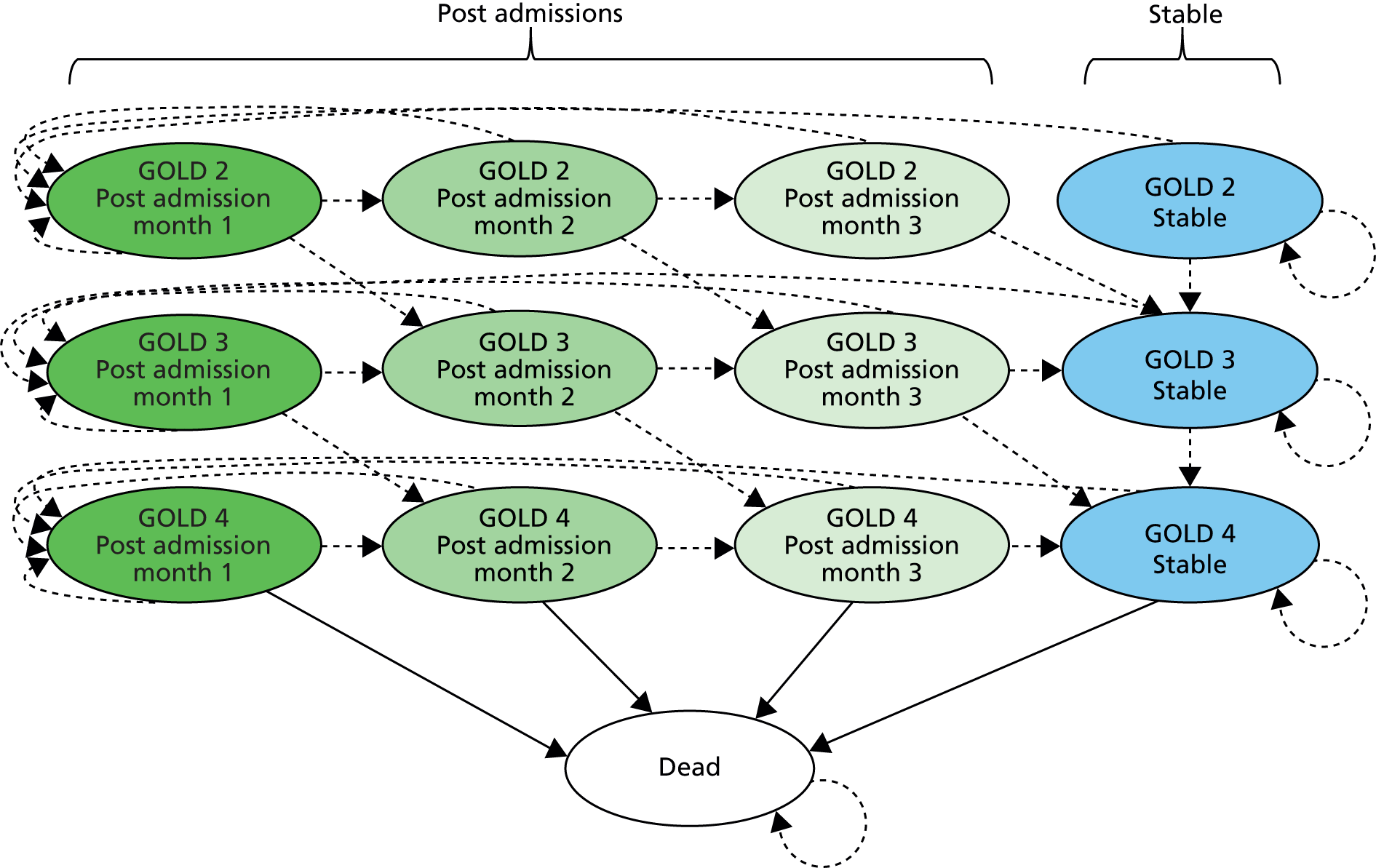

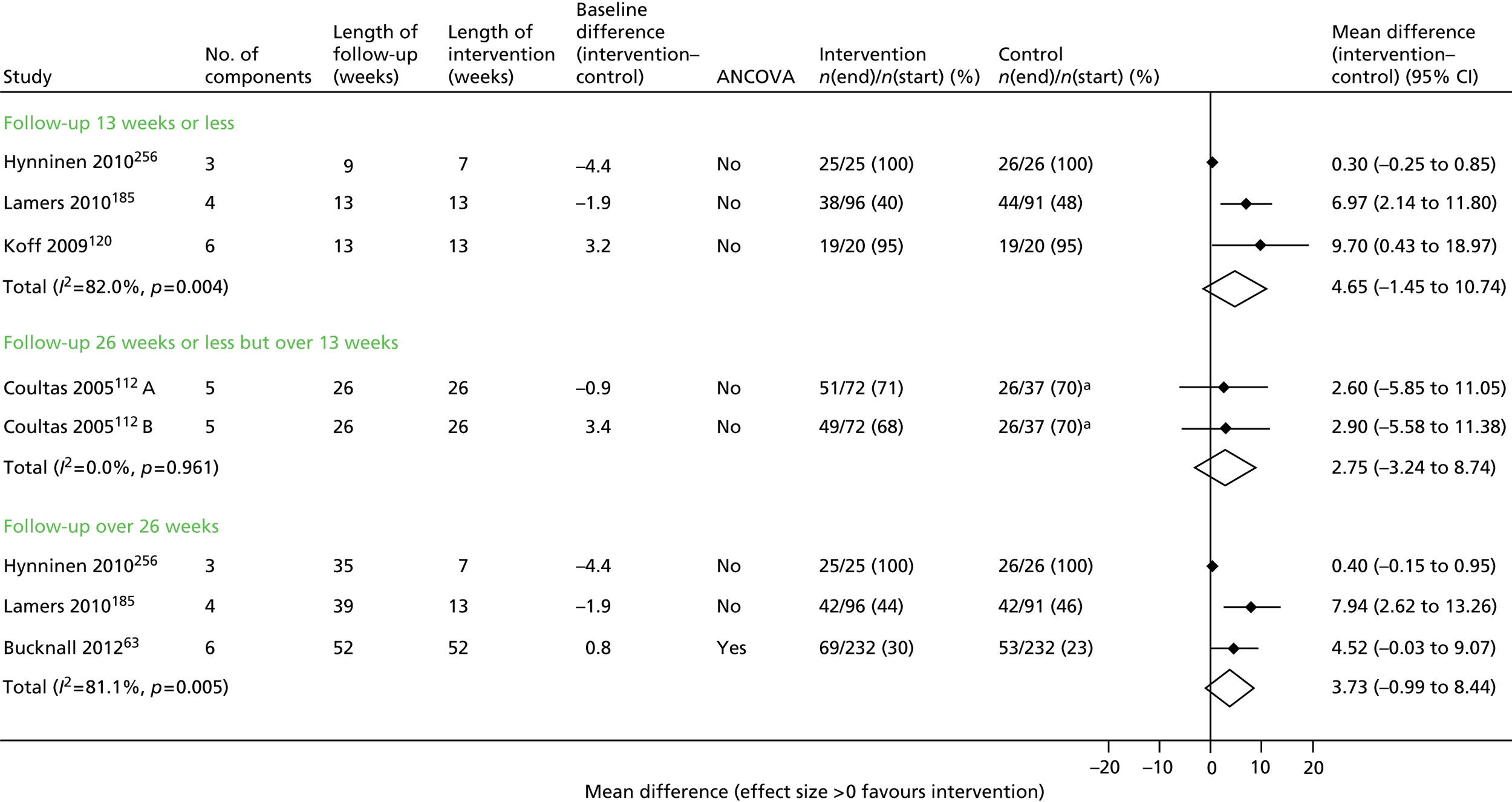

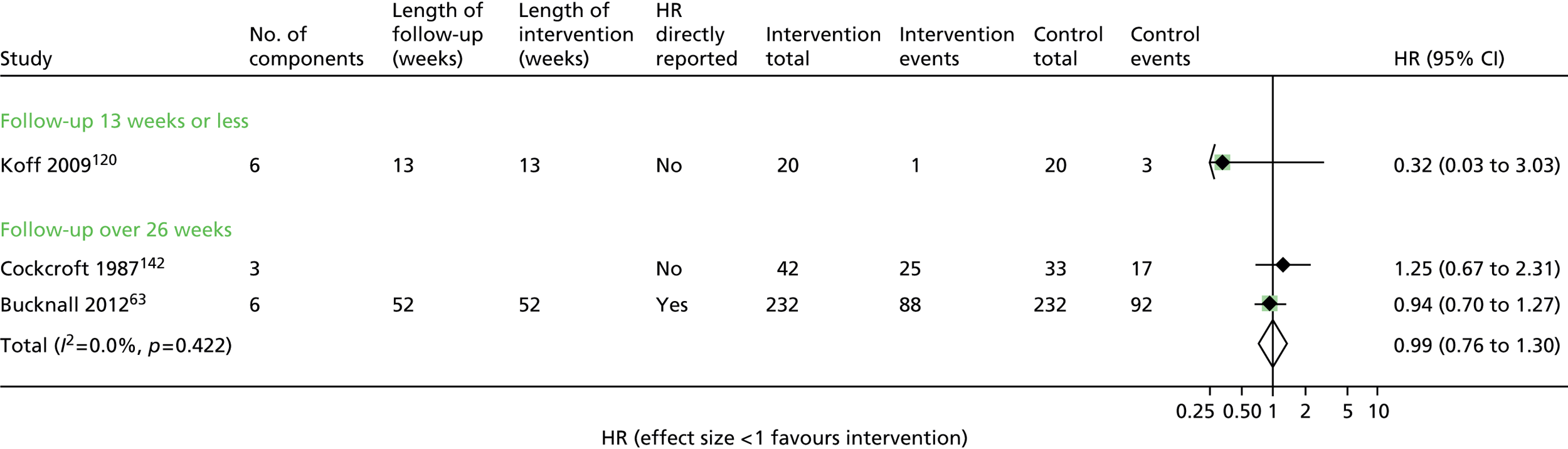

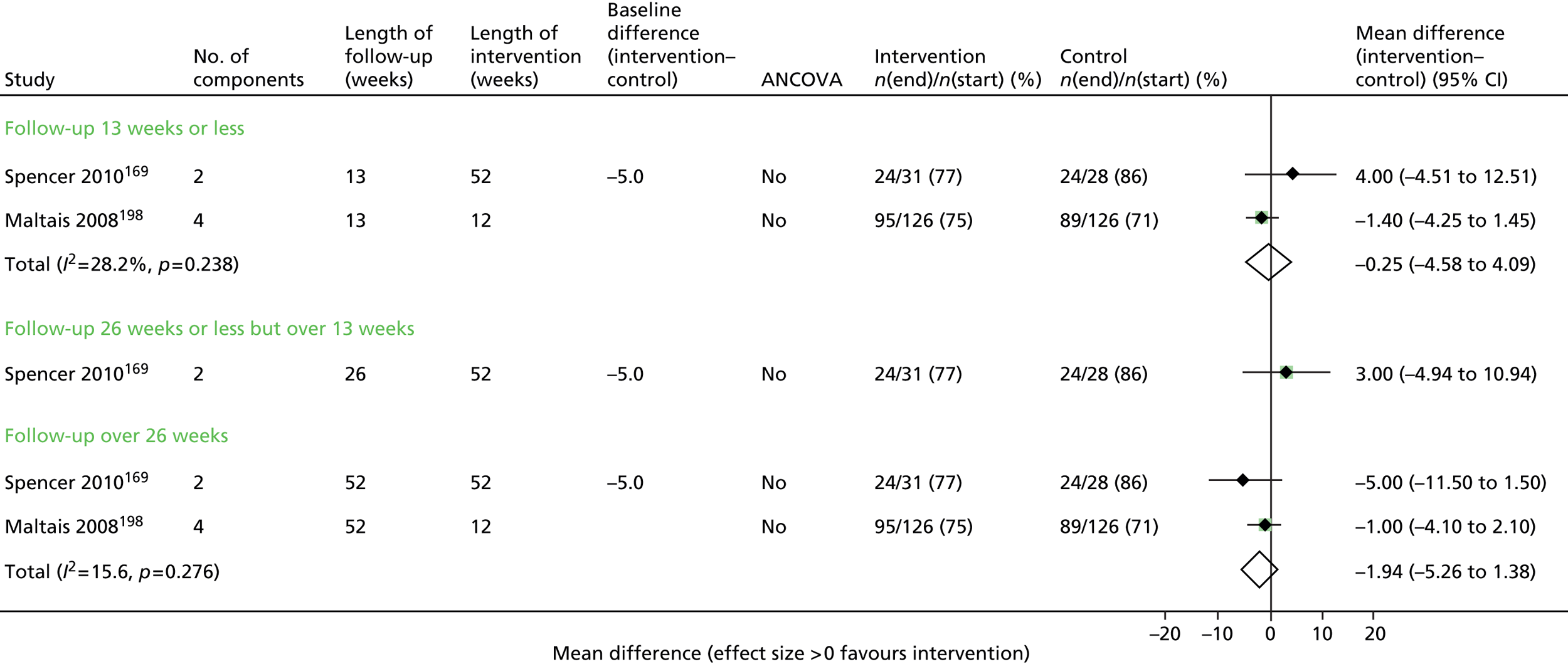

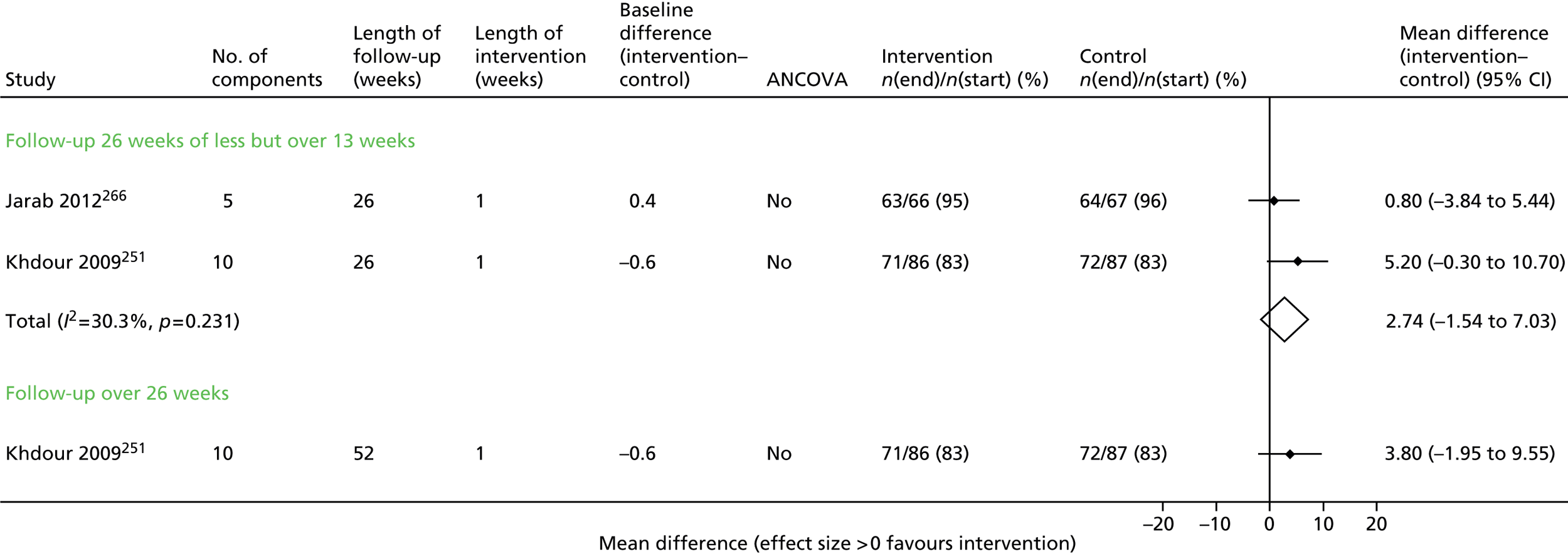

General practitioner consultations: no evidence of effect