Notes

Article history

This issue of Health Technology Assessment contains a project originally commissioned by the MRC but managed by the Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Programme. The EME programme was created as part of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and the Medical Research Council (MRC) coordinated strategy for clinical trials. The EME programme is funded by the MRC and NIHR, with contributions from the CSO in Scotland and NISCHR in Wales and the HSC R&D, Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland. It is managed by the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC) based at the University of Southampton.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from the material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Cathy Creswell was supported by a Medical Research Council Clinician Scientist Fellowship (G0601874).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Creswell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background

Anxiety disorders are among the most common psychological disorders in childhood, affecting 2.6–5.2% of children under the age of 12 years. 1,2 These disorders adversely affect children’s functioning in personal, social and academic domains,3,4 raise the risk for disorders in adolescence and adulthood,5 and carry a substantial health and social cost. 6 Following advances in the development of successful cognitive–behavioural therapies (CBTs) for adult anxiety disorders,7 CBT for child anxiety disorders has now been developed. Although there is still some uncertainty over the optimal form of such an intervention, recent systematic reviews of outcome research indicate that the general CBT approach produces significant therapeutic benefit in this patient group, with, on average, 59% of anxious children no longer meeting criteria for their primary anxiety disorder following CBT. 8 However, it is clear from these reviews, and from the individual treatment trials, that the outcome is highly variable, with a significant proportion (40.6%) of patients retaining their anxiety diagnoses following treatment. 8

Parental anxiety disorders are associated with poor treatment outcomes

One way of further improving children’s responses to treatment is to identify predictors of poor outcome which are amenable to therapeutic change. One of these is parental emotional distress, in particular parental anxiety disorder, which has been found to be associated with up to a 50% reduction in child recovery following treatment. 6,9–13 This is of great significance given that the rate of anxiety disorder among the parents of anxious children is raised. 14,15 Indeed, in a consecutive series of children referred for treatment of an anxiety disorder in our clinic, two-thirds of the mothers were found to have a current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)16 anxiety disorder (with no elevated rate of current disorder among the fathers), almost three times the base rate. 17

Two studies to date have examined whether or not targeting parental anxiety might benefit child treatment outcome. Cobham and colleagues9 found that supplementing child cognitive–behavioural therapy (CCBT) with parent anxiety management was associated with significantly improved diagnostic outcomes for children with anxiety disorders whose parents had elevated trait anxiety; however, this group did not maintain a specific benefit from the parent anxiety management treatment at a 3-year follow-up. 18 More recently, Hudson and colleagues19 used a similar design but classified groups according to parental anxiety disorder status. In this study, CCBT + parent anxiety management did not confer a significant benefit over CCBT post teatment or at a 6-month follow-up assessment. Notably, both studies administered brief treatments for parental anxiety which did not have an overall impact on parental anxiety symptoms or disorder. The question therefore remains open as to whether or not successful treatment of parental anxiety might benefit child outcome.

Other mechanisms associated with poor outcomes

An alternative possibility is that it might not be parental anxiety, per se, that is prognostically significant for child response to treatment but, rather, the parenting practices associated with high levels of parental anxiety that themselves reinforce or maintain the child disorder. Specific parenting responses have been implicated in the maintenance of child anxiety, in particular an overcontrolling and overprotective parental style, expressed anxiety when the child is faced with challenge, 20,21 and associated parental cognitions and expectations about child competence. 22 These behaviours are known to obtain significantly more in anxious than in non-anxious parents of children with anxiety disorder,23,24 as are associated cognitions characterised by elevated expectations that the child will be frightened and feel out of control in the face of a challenge. 23 Recent studies have suggested that targeting parental anxiety may be pertinent only insofar as it changes behaviours that are likely to interfere with the child’s treatment. 25 These studies suggest, therefore, that targeting parenting cognitions and behaviours, rather than parental anxiety, may be of most benefit in bringing about improvement in anxious children’s response to treatment in the context of parental anxiety disorders.

Implications for optimal treatment outcomes

Cognitive–behavioural therapy treatments of child anxiety disorder commonly require the day-to-day prosecution of treatment regimes to be managed by the parent (e.g. parents are typically required to model positive responses to fear provoking stimuli and to prompt and reinforce their child’s positive responses), so it is likely that the parent’s own anxiety and the associated disturbances in parenting responses may militate against optimal treatment delivery. Although the CBT treatments developed to date for the treatment of child anxiety do acknowledge the importance of both parental anxiety and parenting,26–29 there has been no systematic evaluation of an intervention in which both parental anxiety and parenting responses are specifically addressed. There is, therefore, a need for the development and evaluation of a CBT treatment for child anxiety disorder in which parental anxiety and associated patterns of parental responses to the child are systematically targeted.

Rationale for the research

The outcome from CBT for children with anxiety disorders is highly variable. Major factors contributing to this are likely to be the presence of parental anxiety and associated disturbances in how parents respond to their children when they are faced with challenges. Where parental anxiety has been addressed in treatment research,26–29 for several methodological reasons, it has been difficult to assess its contribution to child outcome. Two studies have systematically targeted parental anxiety in the treatment of child anxiety disorders. In one,9 child anxiety outcome was better where therapeutic measures to address parental anxiety symptoms were included, and in the other19 children’s outcomes were not improved. In both cases, as the treatment did not significantly alter levels of parental anxiety, it remains unclear what aspect of the treatment effected the clinical improvement in the children. Similarly, where therapeutic measures to address parenting responses have been included,30 it has not been possible to determine the specific role of such measures in the complex treatment package employed. A controlled trial in which both factors – treatment of parental anxiety and measures to alter parenting responses – are systematically varied, would produce data of both clinical utility and scientific importance. The study was determined on this basis, and there was no patient or public input at this stage.

Although paternal behaviours are likely to contribute to the maintenance of child anxiety disorder, this study focused on mothers for the following reasons: (i) it has been suggested that the parental responses that may promote anxiety among children differ for mothers and fathers;31 (ii) anxiety disorders are more common among women than men32 and, also, more common among mothers of children with anxiety disorders than fathers;17 (iii) mothers are most commonly the primary caregiving parent in the study region and are more likely to attend treatment sessions for their child (e.g. in a recent study in the same region, 98% of parents nominated as primary caregivers in order to attend treatment were mothers33).

Aims

The aim of the trial was to establish the relative clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of treatments of (i) maternal anxiety and (ii) key maternal parenting responses for children with anxiety disorders who have a mother with current anxiety disorder.

Research questions

In a randomised controlled trial (RCT) for child anxiety occurring in the context of maternal anxiety, the principal questions are:

-

Is the impact of CCBT enhanced by first providing CBT to the mother for her own anxiety?

-

Is the impact of CCBT enhanced by the addition of therapeutic measures designed to address potentially anxiogenic maternal parenting responses?

Secondary questions are:

-

Is sustained improvement in child anxiety significantly associated with a reduction in maternal anxiety?

-

Is sustained improvement in child anxiety significantly associated with improvements in maternal modelling, encouragement, overcontrolling/overprotective behaviour and associated cognitions?

Chapter 2 Trial design and methods

Study design

The trial was set up to evaluate the benefit of supplementing individual CCBT with either treatment of maternal anxiety disorder or treatment that targeted maternal responses when interacting with her child, for children with anxiety disorders whose mothers also had a current anxiety disorder. A three-arm trial was conducted in which children received individual CCBT in all three arms, supplemented by either CBT for the maternal anxiety disorder [CCBT + maternal cognitive–behavioural therapy (MCBT)] or a mother–child interaction (MCI) focused intervention. Non-specific interventions were also delivered in all treatment arms in order to balance therapist contact. The main trial was supplemented with an economic evaluation to consider the cost-effectiveness of the CCBT and MCI interventions.

Ethical approval and research governance

Ethical approval for the study was given by Berkshire Research Ethics Committee (07/H0505/156) and the University of Reading Research Ethics Committee (07/48). The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register under the reference number 19762288.

Participants

Participants were 211 children, aged 7–12 years [mean age 10.22 years, standard deviation (SD) 1.58], with a current anxiety disorder, together with their mothers. As noted above, the study focused on mothers as (i) intergenerational associations for anxiety disorders are most commonly found between mothers and their children;17 (ii) mothers are most commonly the primary caregivers in the study region; and (iii) paternal behaviours may have different associations with childhood anxiety. 34 Participants were all referred to Berkshire Child Anxiety Clinic, run jointly by Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and the University of Reading, by a health or educational professional. Participants were recruited between June 2008 and May 2011, with the last follow-up assessment in February 2013.

Inclusion criteria

Child

-

Age 7–12 years.

-

Primary diagnosis of DSM-IV generalised anxiety disorder (GAD), social phobia, separation anxiety disorder (SAD), panic disorder (PD)/agoraphobia or specific phobia (if comorbid with another anxiety disorder).

Mother

-

Primary carer.

-

Current maternal DSM-IV anxiety disorder.

Exclusion criteria

Participants were not eligible if any of the following criteria are met.

Child

-

Significant physical (where it would impede treatment delivery) or intellectual impairment (including autistic spectrum disorders) (determined by registration with local learning disability services).

-

Current prescription of psychotropic medication that had not been at a stable dose for at least 1 month and without agreement to maintain that dose throughout the study.

-

Previously received six or more sessions of systematically administered CBT for an anxiety disorder.

Mother

-

Significant intellectual impairment (determined by registration with local learning disability services).

-

Severe comorbid disorder (e.g. severe major depressive disorder, psychosis, substance/alcohol dependence that would interfere with the mothers ability to participate in treatment).

-

Prescription of psychotropic medication that had not been at a stable dose for at least 1 month and without agreement to maintain that dose throughout the study.

If participating mothers were having any ongoing treatment, this did not preclude them from participating in the trial, but ideally, any psychotherapeutic treatment should have finished prior to initiating this trial.

Six children were recruited to the trial (two in each treatment arm) who were assigned a primary diagnosis of anxiety disorder not otherwise specified. Following consultation with the trial management team it was decided to include these children as the anxiety disorder not otherwise specified diagnosis reflected a slight variation from meeting diagnostic criteria for GAD. One child was recruited to the trial (CCBT + MCI arm) on the basis of having a primary diagnosis of selective mutism; and in this case the trial management group agreed to inclusion as the selective mutism was comorbid with, and was considered to be a manifestation of, social anxiety disorder. Four children were outside the specified age range at the point of randomisation. One child was 6 years old but was due to turn the age of 7 years before initiating treatment (CCBT + MCI arm); three turned 13 years of age between the initial assessment and randomisation.

Recruitment procedure

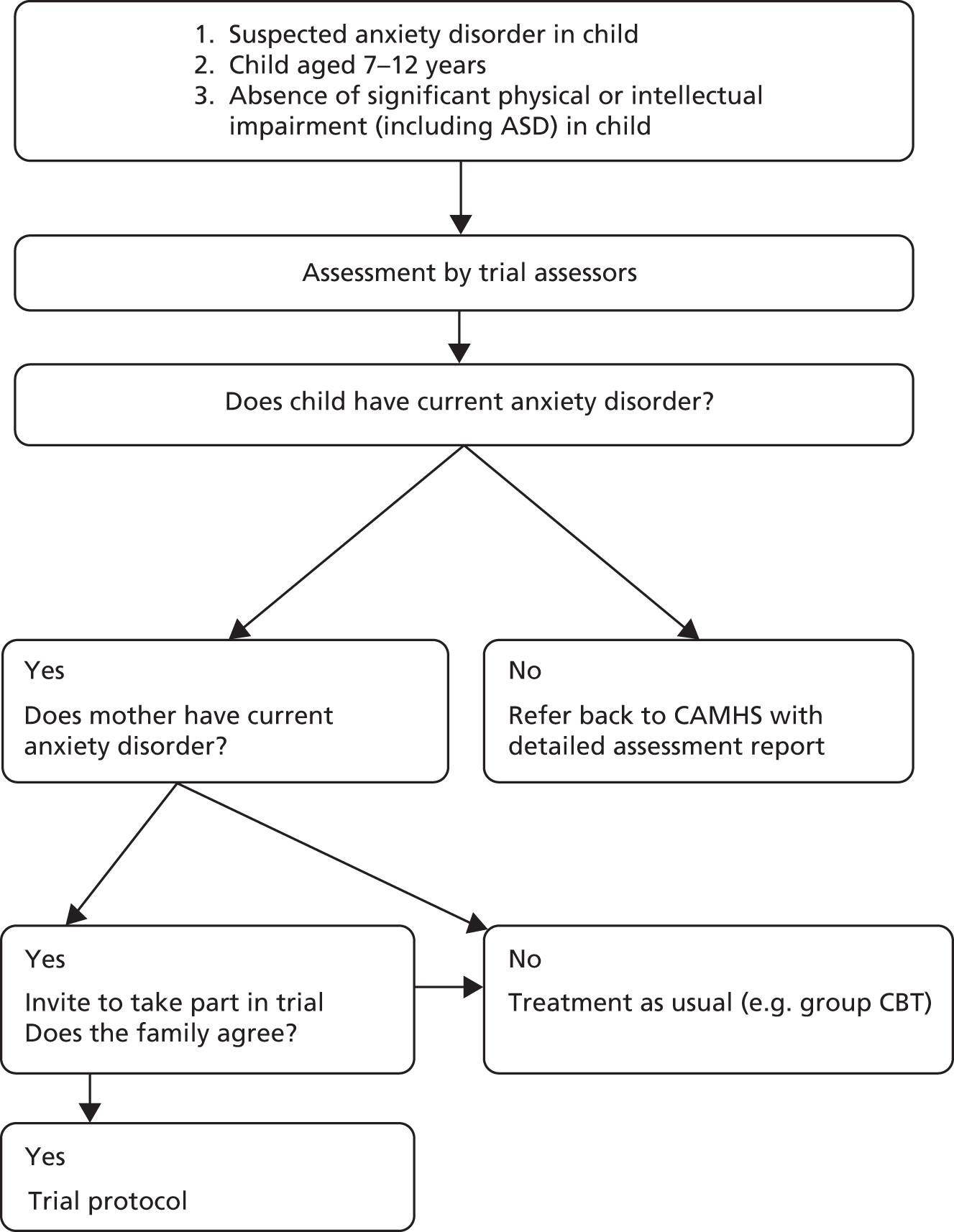

The recruitment schedule is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart outlining recruitment schedule. ASD, autistic spectrum disorder; CAMHS, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services.

Informed consent

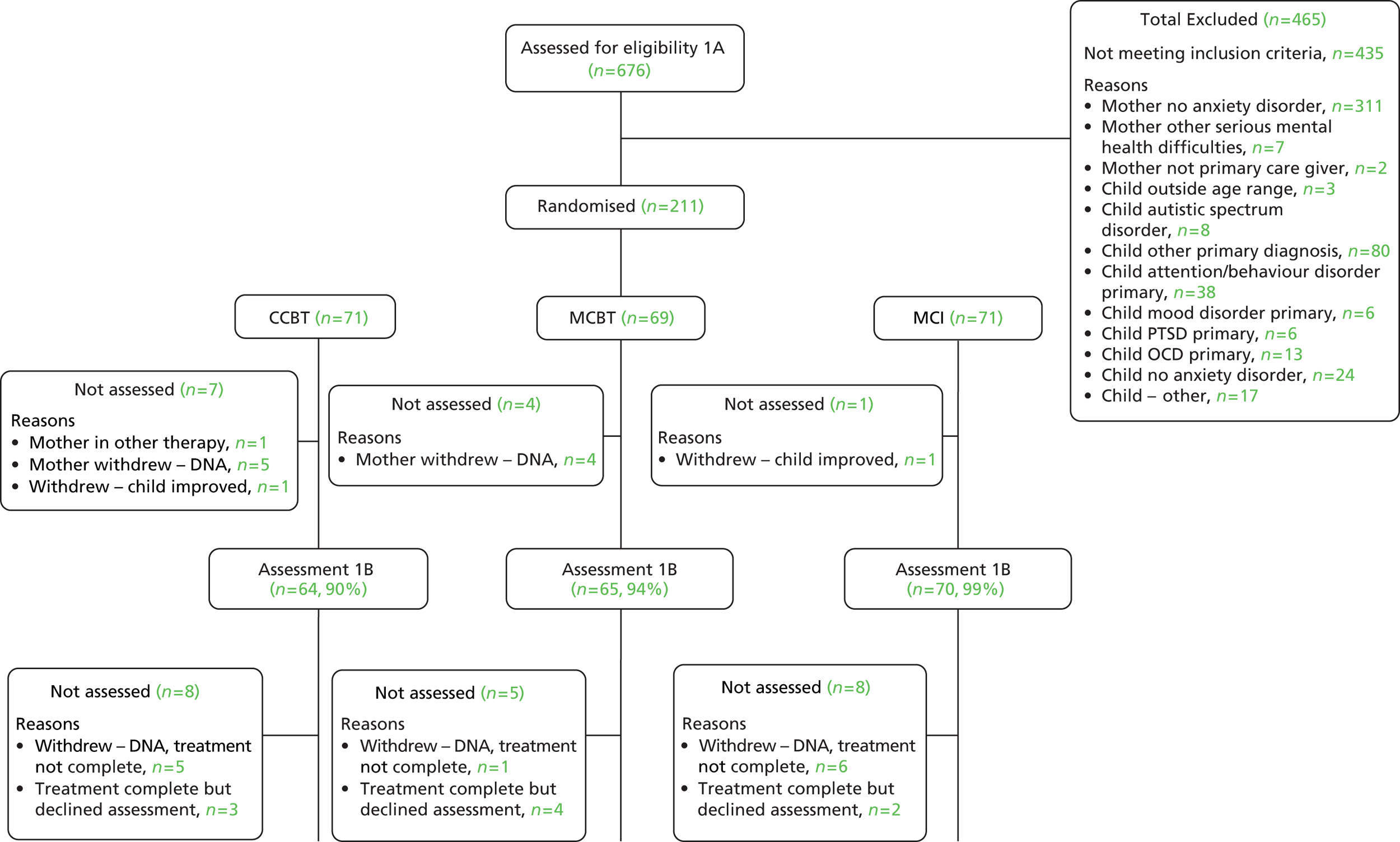

Participants were given a complete description of the study orally and in writing prior to written informed consent being obtained from participating mothers and assent from participating children. As shown in Figure 2, 676 children were referred and assessed for eligibility. A total of 435 families did not meet the inclusion criteria (24 children and 311 mothers because they did not meet criteria for a current anxiety disorder). Assent/consent was not given by 30 families.

FIGURE 2.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. A3, assessment 3; A4, assessment 4. DNA, did not attend; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Participants were randomised to one of three treatment conditions: (i) CCBT; (ii) CCBT plus CBT for maternal anxiety disorder (CCBT + MCBT); or (iii) CCBT plus treatment focused on the MCI (CCBT + MCI). Each of the three conditions included non-specific therapeutic interventions to balance the treatment arms for therapist contact with both children and mothers. These were non-directive counselling (NDC; for mothers not receiving MCBT, i.e. groups i and iii) and a family health (FH) intervention (for those not receiving MCI, i.e. groups i and ii), see Table 1.

Randomisation was performed externally at the Centre for Statistics in Medicine (University of Oxford, UK) on receipt of anonymised participant information by fax. Patients were randomised with a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio and minimisation was used to ensure balanced allocation across the treatment groups for child age, gender and type of child anxiety disorder, and baseline severity of the child’s and mother’s primary anxiety disorder. The trial manager was informed of randomisation and allocated participants to therapists for treatment. All assessors and coders remained blind to treatment group for the duration of the study.

Treatment group allocation

The order of treatment delivery is shown in Table 1. MCBT/NDC was delivered first, then the CCBT and MCI/FH interventions were delivered in parallel. Each phase of treatment (MCBT/NDC, CCBT, MCI/FH) was delivered by a different therapist.

| Condition | CCBT | CCBT + MCBT | CCBT + MCI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment 1: pre treatment | Diagnostic assessment (mother and child) + laboratory observation of MCI | ||

| Treatment 1 | NDC (8) | MCBT (8) | NDC (2) |

| Assessment 1B: mid-treatment (number of sessions) | Diagnostic assessment (mother and child) | ||

| Treatment 2 (number of sessions) | CCBT (8) + FH (mother: 2; child + mother: 2) | CCBT (8) + FH (mother: 2; child + mother: 2) | CCBT (8) + MCI (mother: 8; child + mother: 2) |

| Assessment 2: post treatment | Diagnostic assessment (mother and child) + laboratory observation of MCI | ||

| Assessment 3: 6 months post treatment | Diagnostic assessment (child) | ||

| Assessment 4: 12 months post treatment | Diagnostic assessment (child) | ||

| Total therapy sessions | Mother: 10 Child: 8 Child + mother: 2 |

Mother: 10 Child: 8 Child + mother: 2 |

Mother: 10 Child: 8 Child + mother: 2 |

Child cognitive–behavioural therapy

All children, in all treatment arms, received eight 1-hour weekly sessions of individual CBT delivered by 1 of 10 qualified clinical psychologists or cognitive–behaviour therapists (graduate therapists who held postgraduate certificates/diplomas in CBT), following a manual adapted from the widely used ‘Cool Kids’ programme35 to be used on an individual rather than group basis. Core components of the treatment include psychoeducation, identification and modification of anxious thoughts, and graded exposure to feared situations/stimuli. The adaptations involved reducing the number of sessions to eight (from nine) as the content could be covered more quickly on an individual basis, and altering exercises and practices so that they worked well on an individual basis using strategies from the ‘Coping Cat’ programme. 36 Sessions took place in the participants’ local Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS), at the University of Reading Child Anxiety Clinic or within the child’s home. The focus of treatment was on helping children to identify and challenge negative thinking styles, gradually increase exposure to feared stimuli and develop problem-solving skills. Mothers were included briefly in giving and receiving feedback at the beginning and end of each session (for approximately 5 minutes). To ensure therapist adherence to the CCBT treatment manual was equivalent across condition, 75 treatment sessions (25 from each condition) were rated for adherence to the manual (in terms of therapist stance, coverage of general and specific content) by blind raters (minimum Bachelor of Science psychology) trained to acceptable levels of reliability [therapist stance: intraclass correlation (ICC) = 0.76–76; general content: ICC = 0.73–0.82; specific content: ICC = 0.81–0.89]. Treatment adherence for CCBT did not differ across the three conditions [therapist stance: F(2,72) = 1.83, p = 0.17; general content: F(2,72) = 0.80, p = 0.92; specific content: F(2,72) = 0.23, p = 0.80].

Maternal cognitive–behavioural therapy

Maternal cognitive–behavioural therapy consisted of eight 1-hour weekly sessions delivered by one of seven clinical psychologists or cognitive–behaviour therapists (all supervised by a highly experienced clinical psychologist who was a British Association of Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies-accredited cognitive–behaviour therapist) following a manualised transdiagnostic treatment for adult anxiety disorders. 37 A transdiagnostic approach was applied on the basis that mothers presented with various anxiety disorders; the effectiveness of a transdiagnostic approach to anxiety disorders has been established in similar contexts. 38 This treatment used cognitive–behavioural methods to reverse the putative maintaining mechanisms identified through individual formulation. Treatment was delivered in the participants’ local CAMHS, at the University of Reading Child Anxiety Clinic or within the family’s home.

Groups that did not receive MCBT received a non-specific intervention (NDC), in which mothers received a supportive individual intervention that was not focused specifically on reducing symptoms of anxiety but involved supportive non-directive listening for clients to facilitate self-reflection and to clarify and focus on feelings within an accepting, non-judgemental, empathic environment, following the manual of Borkovec and Costello. 39 NDC was provided by one of five qualified counsellors (all accredited by the British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy), supervised by a highly experienced counsellor/psychotherapist with senior British Association for Counselling & Psychotherapy accreditation. 39 To ensure fidelity of the two treatments, the content of therapist utterances from 100 treatment sessions (50 MCBT, 50 NDC) was allocated by independent raters (psychology graduates), trained to a high level of reliability, to categories considered as allowed or not allowed within each treatment condition (reliability of proportion of allowable utterances, MCBT ICC = 0.73; NDC, ICC = 0.73). The proportion of MCBT allowable utterances was significantly higher in MCBT than in NDC [t(98) = 6.25; p < 0.001] and the proportion of NDC allowable utterances was significantly higher in NDC than in MCBT [t(98) = 4.40; p < 0.001], indicating that the content of the two treatments differed as intended. As shown in Table 1, MCBT and NDC were delivered first, before the delivery of CCBT.

Mother–child interaction treatment

The MCI intervention consisted of 10 sessions delivered over 8 weeks by one of seven qualified clinical psychologists or cognitive–behaviour therapists (supervised by an experienced clinical psychologist): eight sessions were with the mother alone and two were with the mother and child together. This was a novel intervention designed to target potentially anxiogenic maternal parenting behaviours. Specifically, it aimed to enhance maternal autonomy promoting cognitions (such as confidence in her child’s ability to face challenge) and behaviours and reduce potentially anxiogenic behaviours. This was achieved through a combination of specific strategies from existing family interventions for childhood anxiety,30,35 with the addition of video-feedback techniques developed and piloted by the trial investigators. 40,41 Sessions took place in the participants’ local CAMHS, at the University of Reading Child Anxiety Clinic or within the family’s home. The two mother and child sessions were conducted within the laboratory at the University of Reading, as these involved the mother and child completing structured tasks which were video-recorded for feedback purposes.

To balance therapist contact, those groups that did not receive the MCI intervention received sessions that focused on the promotion of a healthy lifestyle (see Table 1). A manual was developed for this intervention that principally focused on following a healthy diet and participating in regular exercise using a number of worksheets, games and activities based on existing interventions applied within school settings (FH). 42–54 The FH intervention was delivered by 1 of 10 therapists [qualified clinical psychologists, cognitive–behaviour therapists and one psychology graduate (Bachelor of Science) with extensive experience of delivering behavioural interventions, under supervision of an experienced clinical psychologist (LW)].

Mother–child interaction/FH were delivered in parallel with CCBT for all participants. To ensure treatment fidelity, raters who were blind to treatment condition rated audio-recordings of 40 therapy sessions on the degree to which session content focused on the MCI or FH. Inter-rater reliability was excellent (ICC = 0.98). MCI sessions were rated significantly higher than FH sessions on the degree to which sessions focused on MCI (Mann–Whitney U-test = 6.01; p < 0.0001), and FH sessions were rated significantly higher on the degree to which session focused on FH (Mann–Whitney U-test = 5.90; p < 0.0001) indicating that the content of the two treatments differed as intended.

Data collection and management

Trial data were entered into an International Business Machine Corporation Statistical Package for the Social Sciences database (IBM SPSS, version 17; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) and monitoring and tracking information was entered onto a Microsoft Access 2003 database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A range of data validation checks were carried out in Access, SPSS and Stata Software Release 12 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) to minimise erroneous or missing data.

Assessments of maternal anxiety disorder and parenting were made before and immediately following the interventions. Assessments of child anxiety disorder status and severity were conducted before and following treatment, as well as at 6 and 12 months after treatment. All assessors were blind to treatment group allocation throughout the trial.

Baseline assessment

Baseline assessment for the trial comprised diagnostic interviews conducted with children and their mothers to ascertain whether or not both the child and his/her mother met diagnostic criteria for a current anxiety disorder. All of the follow-up measures were also administered at baseline. All baseline assessments were conducted between May 2008 and May 2011.

Follow-up

As shown in Table 1, follow-up data collection was scheduled to take place ‘mid-treatment’ [i.e. after the initial maternal intervention, MCBT/NDC (assessment 1B)], then ‘post treatment’ [i.e. after the CCBT and MCI/FH intervention (assessment 2)], and 6 and 12 months from the post-treatment assessment. Diagnostic assessments were conducted to establish whether or not interventions had successfully altered maternal anxiety at the ‘mid-treatment’ (1B) and ‘post-treatment’ (2) assessments. To establish whether or not the interventions had successfully altered maternal responses, observational and parent-reported measures were administered at the ‘post-treatment’ assessment. Child diagnostic and symptom outcomes were assessed at all time points.

All follow-up data were collected between September 2008 and February 2013. A flow chart showing all recruitment and retention is given in Figure 2.

Measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes were (i) the status of the child’s primary anxiety disorder and (ii) the extent of child improvement at the post-treatment assessment. This second primary outcome was added to the primary outcomes identified in the original protocol following its inclusion as the primary outcome in a recent major multicentre trial for the treatment of anxiety disorders,55 with approval from the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Structured diagnostic interviews with children and parents

Children were assigned diagnoses on the basis of the Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule for DSM-IV for children, child and parent versions (Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule – child and parent report; ADIS-C/P). 56 For the ADIS-C/P, as is standard, overall diagnoses and clinical severity ratings (CSRs) were assigned if the child met diagnostic criteria on the basis of either the child or parent report, and the higher CSR of the two was taken. Following convention, only those with a CSR of ≥ 4 (moderate psychopathology) on a scale from 0 (complete absence of psychopathology) to 8 (severe psychopathology) were considered to meet diagnostic criteria. The assessors, all psychology graduates, were trained to administer and score the ADIS-C/P through verbal instruction, listening to assessment audio-recordings, role-play and participating in diagnostic consensus discussions. Each of the assessor’s first 20 interviews were discussed with a consensus team, led by a consultant clinical psychologist (LW). The assessor and the consensus team independently allocated diagnoses and CSRs. Once assessors achieved reliability of at least 0.85, they discussed one in six interviews with the consensus team (to prevent rater drift). Reliability for presence or absence of child diagnosis on the ADIS-C/P was κ = 0.98 (child report) and κ = 0.98 (mother report), and CSR ICC = 0.99 (child report) and CSR ICC = 0.99 (mother report).

Clinical Global Impression – Improvement scale57

Overall improvement in child anxiety was assessed using the Clinical Global Impression – Improvement (CGI-I) scale, a 7-point scale from 1 = very much improved to 7 = very much worse; scores of 1 and 2 are accepted to represent treatment success. Inter-rater reliability was established using the same procedures as for the ADIS-C/P. Overall mean inter-rater reliability for the assessment team was high (ICC = 0.96).

Secondary outcomes

Maternal anxiety and maternal interactive responses were assessed to establish whether or not MCI and MCBT effectively changed these factors. Secondary outcomes included (i) the severity of the child’s primary anxiety diagnosis; (ii) if the child was or was not free of all of their anxiety diagnoses (as assessed by the ADIS-C/P above); (iii) child- and mother-reported child anxiety symptoms and impact and comorbid difficulties; and (iv) teacher-reported symptoms of anxiety and adjustment to school at the post-treatment assessment. Finally, outcomes included all of the primary and secondary measures at the 6- and 12-month follow-up assessments.

Maternal anxiety disorder

The presence or absence of a current maternal anxiety disorder was assigned on the basis of the ADIS-IV,58 a structured diagnostic assessment designed to assess the presence and severity of DSM-IV anxiety, mood and somatoform disorders. CSRs for each disorder present are made and range from 0 (not at all severe) to 8 (extremely severe/distressing). A rating of 4 is considered to be the cut-off for a clinically significant disorder. Procedures for training assessors and ensuring inter-rater reliability followed those of the ADIS-C/P. Reliability for presence or absence of maternal diagnosis on the ADIS-IV was κ = 0.97; and for the CSR ICC = 0.99.

Maternal symptoms of anxiety and depression

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21)59 was administered to all participating mothers to assess self-reported symptoms. The DASS-21 has demonstrated good internal consistency and concurrent validity. 60 Maternal symptoms of worry were assessed using the Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ),61 a 16-item self-report inventory designed to assess the pathological worry characteristic of GAD. Maternal symptoms of social anxiety were also measured using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS) and the Social Phobia Scale (SPS). 62 The SIAS is a 20-item self-report inventory designed to assess anxiety experienced while interacting with others. The SPS is a 20-item self-report inventory designed to assess fear of scrutiny when performing a task or being observed by others. Internal reliability for the scales was good across assessment time points (DASS-21 anxiety α = 0.80–0.87; DASS-21 depression α = 0.90–0.92; PSWQ α = 0.92–0.93; SIAS α = 0.92–0.93; SPS α = 0.91–0.94).

Maternal parenting and parental expectations

Maternal behaviours in interaction with the child was assessed by laboratory observation under conditions of mild social, performance and physical threat. 23 The social threat task involved the child preparing and delivering a speech to a research assistant with a hand-held video camera with their mother’s support. The performance task involved the child attempting difficult tangram puzzles following the procedure of Hudson and Rapee. 63 The physical threat task required children to investigate the content of four chambers within a mysterious ‘black box’. To account for prior experience, the assessment was modified at the post-treatment assessment point; for social stress the child was required to present to a panel rather than a single research assistant, the tangram puzzles were more difficult and the black box was accompanied by sound effects (e.g. rustling/scratching).

Observers who were blind to treatment condition coded parental behaviours on scales developed by Murray and colleagues64 and adapted by Creswell and colleagues23 to be suitable for children aged 7–12 years and for the specific tasks. Ratings were given for each minute of the interaction on 5-point scales (1 = none, 5 = pervasive/strong). As interactions varied somewhat in duration, mean scores for each task were summed to give total scores across the full range of tasks. For the current study the following behaviours were considered: maternal expressed anxiety; control (overprotection and intrusiveness); positivity (warmth and encouragement); promotion of avoidance; and the general quality of the relationship. See Table 2 for a description of each type of parenting behaviour. For each coder, in each task, a second coder independently scored a random sample of 25 videotapes. ICCs showed good agreement across all indices (range 0.60–1.00; mean 72). The constructs of encouragement and warmth overlap and these scales correlated highly (p = 0.56–0.58) so were combined to form as single measure of ‘positive behaviours’.

| Negative behaviour | |

|---|---|

| Expressed anxiety | Modelling of anxiety: anxiety in facial expression (e.g. fearful expression, biting lip), body movements (e.g. rigid posture, wringing hands), and speech (e.g. rapid, nervous, or inhibited) |

| Overprotection | Initiates emotional and/or practical support that is not required (stroking/kissing/offering unnecessary help while child manages independently) |

| Intrusiveness | Interferes, verbally or physically, cutting across child behaviour, attempts to take over and impose own agenda |

| Promotion of avoidance | Actively encourages/supports child avoidance of task (e.g. saying ‘you don’t have to do it’) |

| Positive behaviour | |

| Encouragement (autonomy–promotion) | Provides positive motivation to child to engage in the task, showing enthusiasm regarding both task and child capacity/efforts |

| Warmth | Affectionate, expresses positive regard for child, both verbally and physically |

| Quality of relationship | Sense of relatedness and mutual engagement between mother and child (e.g. talking, listening, laughing and joking with each other) |

Mothers also completed the parental overprotection measure (OP)65 to assess parenting behaviours that restrict a child’s exposure to perceived threat or harm (e.g. ‘when playing in the park I keep my child within a close distance of me’). This parent-reported measure has been found to correlate significantly with observations of parent behaviours,65,66 and has been found to be reliable and valid for children aged 7–12 years. 66 Internal consistency was good across the assessment time points (α = 0.87–0.89).

Maternal expectations were assessed before initiating the challenge tasks. Immediately after receiving the instructions for each task, mothers were taken to a separate room where they were asked to provide ratings regarding their child’s response. 23 In the current study we were interested in their responses regarding (a) how their child would feel about doing the task (0 not scared at all, 10 extremely scared); (b) how they would feel while their child was doing the task (0 not anxious at all, 10 extremely anxious); (c) how much their child could do about how the task went (0 nothing at all, 10 a lot); and (d) how much they could do about their child’s feelings and behaviours during the task (0 nothing at all, 10 a lot). Ratings were combined across the three tasks to represent their expectations across a range of challenge contexts.

Symptoms of child anxiety

The Spence Child Anxiety Scale (SCAS)29,67 assessed child- and parent-reported child anxiety symptoms. The child version [Spence Child Anxiety Scale – child report (SCAS-c)] requires children to rate how often they experience each of 38 anxiety symptoms, presented alongside six positive filler items. The SCAS-c and Spence Child Anxiety Scale – parent report (SCAS-p) have demonstrated high internal reliability and concurrent validity with other well-known anxiety measures. 29,67

Impact of child anxiety

The Child Anxiety Impact Scale (CAIS) was used to measure the extent to which anxiety interferes in a child’s life. 68 The Child Anxiety Impact Scale – child report (CAIS-c) and Child Anxiety Impact Scale – parent report (CAIS-p) covers three psychosocial domains (school, social activities and family functioning) and consists of 34 items, each rated on a 4-point scale to indicate how much anxiety has caused problems (not at all, just a little, pretty much, very much). The CAIS-c and CAIS-p have demonstrated good reliability and validity. 68,69

Symptoms of child comorbid difficulties

The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire (SMFQ)70 assessed child- and parent-reported symptoms of child low mood. The Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire – child report (SMFQ-c) and Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire – parent report (SMFQ-p) are brief, 13-item measures which require children or parents to report how often in the past 2 weeks they have experienced a number of symptoms. The SMFQ-c has demonstrated high internal reliability and concurrent validity with other well-known measures of symptoms of depression. 70 The conduct problems scale from the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)71 was used to assess child- and parent-reported behavioural disturbance. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire – child report (SDQ-c) and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire – parent report (SDQ-p) are known to have good psychometric properties and scores correlate highly with other well-known scales. 71

Internal reliability for all these scales was good across assessment time points (SCAS-c α = 0.92–0.94; SCAS-p α = 0.88–0.93; CAIS-p α = 0.69–0.91; SMFQ-c α = 0.89–0.94; SMFQ-p α = 0.90–0.93), with the exception of the SDQ conduct scales where internal reliability was marginal (SDQ-p α = 0.54–0.68; SDQ-c α = 0.55–0.69), although this may reflect the relatively low number of items, and the CAIS-c at the initial assessment (α = 0.52), although for this scale internal reliability was higher at subsequent assessments (α = 0.88–0.96).

Teacher-reported child symptoms and adjustment

Teacher reports were collected in an attempt to provide an objective assessment of child adjustment in the school domain before and after treatment. To assess teacher perceptions of child anxiety symptoms they completed an adapted version of the SCAS (Spence Child Anxiety Scale – teacher report; SCAS-t). This comprised the 30 items that it was felt that teachers would be in a position to comment on (i.e. removing items about, for example, sleep, heights, animal fears). Teachers also completed the conduct scale of the parent/teacher report form of the SDQ (Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire – teacher report; SDQ-t)71 which comprised five items. Finally, teachers completed a new measure of the child’s adjustment to school (Child Adjustment to School – teacher report; CAS-t), which focused on avoidance or worry about common school-based activities, such as showing things to the class, participating in group activities, speaking to the teacher. This comprised eight items that were rated on a 3-point scale from 0 (not true) to 2 (certainly true), see Appendix 4. Internal reliability for all these scales was acceptable across assessment time points (SCAS-t α = 0.91–0.96; SDQ-t α = 0.64–0.78; CAS-t α = 0.89–0.92).

Sample size

The study was powered to provide 90% power at the 5% (two-sided) significance level to detect a 30% difference in the proportion of children who recovered from their primary anxiety disorder post treatment in the CCBT + MCI or CCBT + MCBT conditions compared with the CCBT condition, with an estimated remission rate for the CCBT group of 40%. 9 Although the effects of the non-specific treatment on child outcomes were not clear, using the 40% remission rate from Cobham and colleagues9 was considered reasonable to account for the effect of CCBT plus any non-specific intervention, given the substantially briefer form of CCBT delivered in the current trial.

A difference of 30% in the proportion of anxiety-free children following completion of the treatment was considered to be the minimum that would be clinically worthwhile taking into account the increased resources required and change to service delivery that would be required if either of these interventions were found to be effective and implemented in practice. The required sample size of 56 children per group was increased to allow for an estimated 20% loss to follow-up. The sample size was estimated as if two independent trials were conducted, with no adjustment for multiple testing, as recommended by Machin and colleagues. 72

Statistical analysis

A comprehensive statistical analysis plan was prepared before embarking on the analysis. All primary and secondary analyses, apart from the per-protocol (PP) sensitivity analyses, were conducted on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. The primary end points (recovery from primary diagnosis and overall improvement in anxiety (CGI-I ratings) at post treatment and other binary end points were analysed using a modified Poisson regression approach with robust error variance adjusting for the minimisation factors [child age, child gender, type of child anxiety disorder (GAD, social phobia, SAD, other)], baseline severity of the child’s and the mother’s primary anxiety disorder (ADIS-IV CSR). The modified Poisson regression approach described by Zou73 is an alternative to logistic regression which allows for estimation of risks ratios (RRs) rather than odds ratios. Sensitivity analyses of the primary end points included (i) no adjustment for minimisation criteria; (ii) PP population (this included those participants who had received at least half of the treatment sessions and had data for the post-treatment assessments, with the exception of one mother in the MCBT condition who also received the MCI intervention in error, rather than the FH control; data from this family was also removed for the PP analyses); and (iii) multiple imputation analysis. Missing data for the primary end points were multiply imputed by chained equations methods. 74 All results from sensitivity analyses were very similar to the primary results. Interim analyses were conducted by the trial statistician when 156 participants had been recruited following a request from the funders. The interim results were kept confidential from the trial manager, all assessors, therapists and their supervisors.

Questionnaire scores, maternal behaviours and maternal cognitions were modelled using linear regression models with the change from baseline as the dependent variable, adjusted for baseline score and minimisation factors. There were outliers present in some of the regression models; however, these were reviewed and were not considered to be due to incorrect completion of the questionnaires. Furthermore, their removal did not change the conclusions from the regression.

All analyses were conducted using Stata software.

Chapter 3 Trial results

Patient flow and numbers analysed

Patient flow is shown in Figure 2. The number of available participants for each treatment arm were as follows:

-

post treatment: CCBT n = 56 (79%), CCBT + MCBT n = 60 (87%), CCBT + MCI n = 62 (87%)

-

6 months post treatment: CCBT n = 49 (69%), CCBT + MCBT n = 53 (77%), CCBT + MCI n = 51 (72%)

-

12 months post treatment: CCBT n = 43 (61%), CCBT + MCBT n = 50 (70%), CCBT + MCI n = 46 (65%).

Baseline data

Baseline characteristics were well balanced across treatment groups (Table 3).

| Baseline characteristic | Category | CCBT, n (%) | CCBT + MCBT, n (%) | CCBT + MCI, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child ethnicity | White British | 67 (94.4) | 58 (84.1) | 55 (77.5) |

| White Irish | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Any other white background | 5 (7.2) | 7 (9.9) | ||

| White and black Caribbean | 1 (1.4) | |||

| White and black African | 1 (1.4) | |||

| White and Asian | 2 (2.9) | |||

| Any other mixed background | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Indian | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Pakistani | 2 (2.9) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Any other Asian background | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Caribbean | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Any other ethnic group | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Did not wish to state ethnicity | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Not recorded | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Child gender | Male | 34 (47.9) | 35 (50.7) | 32 (45.1) |

| Female | 37 (52.1) | 34 (49.3) | 39 (54.9) | |

| Martial status | Single, never married | 2 (2.8) | 5 (7.2) | 5 (7.0) |

| Married (first time) | 28 (39.4) | 41 (59.4) | 38 (53.5) | |

| Remarried | 8 (11.3) | 3 (4.3) | 5 (7.0) | |

| Divorce/separated | 21 (29.6) | 11 (15.9) | 12 (16.9) | |

| Living with partner | 11 (15.5) | 9 (13.0) | 8 (11.3) | |

| Not recorded | 1 (1.4) | 3 (4.2) | ||

| Employment mother | Unemployed | 21 (29.6) | 23 (33.3) | 18 (25.4) |

| Part time | 33 (46.5) | 33 (47.8) | 37 (52.1) | |

| Full time | 14 (19.7) | 8 (11.6) | 13 (18.3) | |

| Not recorded | 3 (4.2) | 5 (7.2) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Employment father | Unemployed | 1 (1.4) | 6 (8.7) | 5 (7.0) |

| Part time | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Full time | 50 (70.4) | 50 (72.5) | 53 (74.6) | |

| NA | 5 (7.0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Not recorded | 15 (21.1) | 11 (15.9) | 11 (15.5) | |

| Overall SES | Higher professional | 29 (40.8) | 39 (56.5) | 38 (53.5) |

| Other employed | 29 (40.8) | 16 (23.2) | 26 (36.6) | |

| Unemployed | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Not recorded | 11 (15.5) | 14 (20.3) | 6 (8.5) | |

| Mother education | School completion | 21 (31.3) | 11 (17.7) | 22 (33.9) |

| Further education | 34 (50.8) | 32 (51.6) | 27 (41.5) | |

| Higher education | 7 (10.5) | 12 (19.4) | 12 (18.5) | |

| Postgraduate qualification | 5 (7.5) | 7 (11.3) | 4 (6.2) | |

| Father education | School completion | 17 (34.7) | 12 (22.6) | 23 (39.7) |

| Further education | 17 (34.7) | 20 (37.7) | 20 (34.5) | |

| Higher education | 9 (18.4) | 15 (28.3) | 11 (19.0) | |

| Postgraduate qualification | 6 (12.2) | 6 (11.3) | 4 (6.9) | |

| Child ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis | SAD | 19 (26.8) | 16 (23.2) | 21 (29.6) |

| Social phobia | 16 (22.5) | 18 (26.1) | 14 (19.7) | |

| GAD | 22 (31.0) | 20 (29.0) | 24 (33.8) | |

| Other | 14 (19.7) | 15 (21.7) | 12 (16.9) | |

| Specific phobia | 8 (11.3) | 11 (15.8) | 5 (7.0) | |

| PD without agoraphobia | 1 (1.4) | |||

| PD with agoraphobia | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Agoraphobia without PD | 3 (4.2) | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Selective mutism | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Anxiety disorder not otherwise specified | 2 (2.8) | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.8) | |

| Child ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis CSR | Moderate 4 | 6 (8.5) | 5 (7.2) | 5 (7.0) |

| Moderate 5 | 21 (29.6) | 19 (27.5) | 19 (26.8) | |

| Severe 6 | 36 (50.7) | 37 (53.6) | 40 (56.3) | |

| Severe 7 | 8 (11.3) | 8 (11.6) | 7 (9.9) | |

| Child mood disorder (major depressive disorder/dysthymia) | No diagnosis | 62 (87.3) | 62 (89.9) | 67 (94.4) |

| Diagnosis | 9 (12.7) | 7 (10.1) | 4 (5.6) | |

| Child age (years) | 6 | 1 (1.4) | ||

| 7 | 4 (5.6) | 5 (7.2) | 7 (9.9) | |

| 8 | 12 (16.9) | 7 (10.1) | 13 (18.3) | |

| 9 | 9 (12.7) | 12 (17.4) | 12 (16.9) | |

| 10 | 17 (23.9) | 17 (24.6) | 13 (18.3) | |

| 11 | 18 (25.4) | 16 (23.2) | 13 (18.3) | |

| 12 | 10 (14.1) | 11 (15.9) | 11 (15.5) | |

| 13 | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | ||

| Mother’s ADIS-IV primary disorder | Specific phobia | 12 (16.9) | 17 (24.6) | 9 (12.7) |

| GAD | 37 (52.1) | 35 (50.7) | 40 (56.3) | |

| Social phobia | 9 (12.7) | 14 (20.3) | 11 (15.5) | |

| PD | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | ||

| Agoraphobia | 2 (2.8) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.8) | |

| OCD | 1 (1.4) | |||

| PTSD | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Major depressive disorder | 5 (7.0) | |||

| Hypochondriasis | 2 (2.8) | |||

| Anxiety disorder not otherwise specified | 1 (1.4) | 2 (2.9) | 8 (11.3) | |

| Mother ADIS-IV CSR of primary disorder | Moderate 4 | 20 (28.2) | 18 (26.1) | 18 (25.4) |

| Moderate 5 | 22 (31.0) | 25 (36.2) | 21 (29.6) | |

| Severe 6 | 22 (31.0) | 22 (31.9) | 24 (33.8) | |

| Severe 7 | 6 (8.5) | 4 (5.8) | 8 (11.3) | |

| Very severe 8 | 1 (1.4) | |||

| Mother mood disorder (major depressive disorder/dysthymia) | No diagnosis | 57 (80.3) | 58 (84.1) | 56 (78.9) |

| Diagnosis | 14 (19.7) | 11 (15.9) | 15 (21.1) |

Manipulation checks: effects of the interventions on maternal anxiety and responses

Manipulation checks were conducted to evaluate whether or not the MCBT and MCI interventions successfully altered maternal anxiety and maternal responses, respectively.

Change in maternal anxiety

Recovery from maternal primary diagnosis at assessment 1B

As shown in Table 4, from the CCBT group eight mothers had missing data for their primary ADIS-IV diagnosis at the mid-treatment assessment (assessment 1B, i.e. after the MCBT intervention), for the CCBT + MCBT group this was four mothers and for CCBT + MCI this was one mother.

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 8 (11.3) | 23 (32.4) | 40 (56.3) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 4 (5.8) | 38 (55.1) | 27 (39.1) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1 (1.4) | 30 (42.3) | 40 (56.3) | 71 |

| Total | 13 | 91 | 107 | 211 |

As shown in Table 5, at assessment 1B, 23 mothers (37%) in the control group had recovered from their primary diagnosis. In the CCBT + MCBT group 38 mothers (59%) had recovered and in the CCBT + MCI group 30 mothers (43%) had recovered.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 23 (36.5) | 40 (63.5) | 63 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 38 (58.5) | 27 (41.5) | 65 |

| CCBT + MCI | 30 (42.9) | 40 (57.1) | 70 |

| Total | 91 | 107 | 198 |

Mothers in the CCBT + MCBT group were 1.63 times more likely to recover from their ADIS-IV primary diagnosis by assessment 1B than those in the CCBT group [adjusted RR 1.63, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13 to 2.36; p = 0.009]. The adjusted RR for CCBT + MCI versus CCBT is 1.22 (95% CI 0.83 to 1.81; p = 0.314) (Table 6).

| Parameter | Adjusted RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.63 | 1.13 to 2.36 | 0.009 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.22 | 0.83 to 1.81 | 0.314 | |

Recovery from all anxiety diagnoses at assessment 1B

As shown in Table 7, the CCBT group had the largest per cent of missing data for mothers at assessment 1B with 13%, the CCBT + MCBT group had 6% and the CCBT + MCI group had 1%.

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 9 (12.7) | 10 (14.1) | 52 (73.2) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 4 (5.8) | 25 (36.2) | 40 (58.0) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1 (1.4) | 22 (31.0) | 48 (67.6) | 71 |

| Total | 14 | 57 | 140 | 211 |

As shown in Table 8, in the CCBT group 10 mothers (16%) had recovered from all anxiety diagnoses by assessment 1B. However, in the CCBT + MCBT group there were 25 recovered mothers (39%) and in the CCBT + MCI group there were 22 recovered mothers (31%).

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 10 (16.1) | 52 (83.9) | 62 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 25 (38.5) | 40 (61.5) | 65 |

| CCBT + MCI | 22 (31.4) | 48 (68.6) | 70 |

| Total | 57 | 140 | 197 |

Mothers receiving CCBT + MCBT or CCBT + MCI were more than twice as likely to have recovered from all anxiety diagnoses by assessment 1B than mothers in the control group CCBT + MCBT (RR 2.51, 95% CI 1.43 to 4.40; p = 0.001) and CCBT + MCI (RR 2.15, 95% CI 1.21 to 3.81; p = 0.009) (Table 9).

| Parameter | RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 2.51 | 1.43 to 4.40 | 0.001 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 2.15 | 1.21 to 3.81 | 0.009 | |

Change in maternal self-reported symptoms at assessment 1B

Table 10 shows the results of analyses looking at the change from baseline to assessment 1B scores of questionnaires completed by mothers about themselves. There were no significant differences between treatment groups. Summary scores are shown in Appendix 5, Table 123.

| Questionnaire | Treatment | n | Adjusteda mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSWQ total score | CCBT | 40 | –2.91 (–5.91 to 0.10) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 42 | –4.96 (–7.90 to –2.01) | –2.05 (–6.31 to 2.21) | 0.342 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 44 | –3.72 (–6.59 to –0.84) | –0.81 (–5.03 to 3.40) | 0.704 | |

| SIAS total score | CCBT | 41 | –0.86 (–3.37 to 1.66) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 44 | –1.24 (–3.67 to 1.18) | –0.39 (–3.92 to 3.15) | 0.829 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 47 | –0.49 (–2.84 to 1.86) | 0.37 (–3.12 to 3.85) | 0.835 | |

| SPS total score | CCBT | 41 | –0.77 (–3.19 to 1.64) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –0.21 (–2.52 to 2.10) | 0.56 (–2.81 to 3.94) | 0.742 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 | 0.07 (–2.22 to 2.36) | 0.84 (–2.53 to 4.22) | 0.622 | |

| DASS-21 depression subscale | CCBT | 38 | –1.54 (–3.28 to 0.21) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 43 | –2.11 (–3.74 to –0.49) | –0.58 (–3.00 to 1.85) | 0.638 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 45 | –1.70 (–3.30 to –0.11) | –0.17 (–2.57 to 2.23) | 0.890 | |

| DASS-21 anxiety subscale | CCBT | 38 | –0.38 (–2.36 to 1.60) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 44 | –1.95 (–3.79 to –0.11) | –1.57 (–4.32 to 1.18) | 0.259 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 45 | –1.99 (–3.81 to –0.18) | –1.61 (–4.34 to 1.10) | 0.243 | |

| DASS-21 stress subscale | CCBT | 41 | –0.90 (–2.88 to 1.08) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –1.76 (–3.65 to 0.13) | –0.86 (–3.63 to 1.91) | 0.539 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 45 | –1.28 (–3.18 to 0.61) | –0.38 (–3.16 to 2.40) | 0.786 |

Recovery from maternal primary diagnosis at assessment 2 (end of all treatment)

As shown in Table 11, missing data was similar at the end of treatment (assessment 2) for mothers in the CCBT and CCBT + MCBT groups (24% and 20%, respectively). In the CCBT + MCI group it was 13%.

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 17 (23.9) | 28 (39.4) | 26 (36.6) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 14 (20.3) | 36 (52.2) | 19 (27.5) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 9 (12.7) | 41 (57.8) | 21 (29.6) | 71 |

| Total | 40 | 105 | 66 | 211 |

As shown in Table 12, there were 36 mothers (66%) in the MCBT group and 41 mothers (66%) in the CCBT + MCI group who recovered from their primary diagnosis by assessment 2 compared with 28 mothers (52%) from the CCBT group.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 28 (51.9) | 26 (48.1) | 54 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 36 (65.5) | 19 (34.5) | 55 |

| CCBT + MCI | 41 (66.1) | 21 (33.9) | 62 |

| Total | 105 | 66 | 171 |

The results from log-linear regression of the mothers’ recovery from their primary ADIS-IV diagnosis by assessment 2, adjusted for minimisation factors, are shown in Table 13. There were no significant differences between CCBT + MCBT and CCBT or between CCBT + MCI and CCBT. The adjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCBT on recovery from maternal primary diagnosis was 1.23 (95% CI 0.90 to 1.68; p = 0.201). Similarly, the adjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCI on recovery was 1.27 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.74; p = 0.126).

| Parameter | Adjusted RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.23 | 0.90 to 1.68 | 0.201 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.27 | 0.93 to 1.74 | 0.126 | |

Recovery from all anxiety diagnoses at assessment 2

Missing data was similar at assessment 2 for mothers in the CCBT and CCBT + MCBT groups (24% and 20%, respectively). In the CCBT + MCI group it was 13% (Table 14).

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 17 (23.9) | 19 (26.8) | 35 (49.3) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 14 (20.3) | 26 (37.7) | 29 (42.0) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 9 (12.7) | 29 (40.9) | 33 (46.5) | 71 |

| Total | 40 | 74 | 97 | 211 |

As can be seen in Table 15, 29 mothers (47%) in the CCBT + MCI group had recovered from all ADIS-IV anxiety diagnoses at assessment 2 and 26 (47%) from the CCBT + MCBT group. Nineteen mothers (35%) had fully recovered from the CCBT group.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 19 (35.2) | 35 (64.8) | 54 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 26 (47.3) | 29 (52.7) | 55 |

| CCBT + MCI | 29 (46.8) | 33 (53.2) | 62 |

| Total | 74 | 97 | 171 |

Table 16 shows the results from log-binomial regression of the mothers’ recovery from all ADIS-IV anxiety diagnoses adjusted for minimisation factors. There were no significant improvements for the CCBT + MCBT group (RR 1.32, 95% CI 0.85 to 2.04; p = 0.210) or the CCBT + MCI group (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.87 to 2.10; p = 0.179).

| Parameter | RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.30 | 0.84 to 2.01 | 0.244 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.35 | 0.87 to 2.10 | 0.180 | |

Change in maternal self-reported symptoms at assessment 2

The regression results from the change in mothers’ self-report questionnaires can be seen in Table 17. There were no significant differences between the CCBT + MCBT and CCBT groups or between the CCBT + MCI and CCBT groups.

| Questionnaire | Treatment | n | Adjusteda mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSWQ total score | CCBT | 35 | –7.14 (–10.67 to –3.60) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 41 | –6.71 (–10.00 to –3.42) | 0.43 (–4.47 to 5.32) | 0.863 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 35 | –6.43 (–10.01 to –2.86) | 0.70 (–4.40 to 5.81) | 0.785 | |

| SIAS total score | CCBT | 34 | –3.52 (–6.77 to –0.27) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 40 | –4.80 (–7.82 to –1.79) | –1.28 (–5.79 to 3.22) | 0.574 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 36 | –4.75 (–7.93 to –1.58) | –1.23 (–5.84 to 3.37) | 0.597 | |

| SPS total score | CCBT | 35 | –3.91 (–6.15 to –1.67) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 41 | –4.03 (–6.12 to –1.94) | –0.12 (–3.24 to 2.99) | 0.937 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 36 | –2.20 (–4.65 to –2.16) | 1.71 (–1.49 to 4.91) | 0.291 | |

| DASS-21 depression subscale | CCBT | 32 | –2.83 (–5.11 to –0.55) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 36 | –3.89 (–6.05 to –1.73) | –1.06 (–4.24 to 2.13) | 0.511 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 33 | –2.59 (–4.87 to –0.31) | 0.24 (–3.05 to 3.54) | 0.884 | |

| DASS-21 anxiety subscale | CCBT | 32 | –0.62 (–2.80 to 1.57) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 36 | –2.75 (–4.85 to –0.65) | –2.13 (–5.21 to 0.94) | 0.171 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 33 | –2.40 (–4.61 to –0.19) | –1.79 (–4.95 to 1.38) | 0.266 | |

| DASS-21 stress subscale | CCBT | 34 | –3.60 (–5.82 to –1.39) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 41 | –2.45 (–4.48 to –0.42) | 1.15 (–1.88. 4.19) | 0.453 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 35 | –2.77 (–4.98 to –0.56) | 0.83 (–2.36 to 4.02) | 0.606 |

Change in parenting responses

Parenting behaviours

Change in maternal parenting behaviours was analysed using linear regression. Analysis in Table 18 shows the adjusted mean change from baseline to assessment 2, for each of the seven areas in each treatment group. The mean score over three tasks is used for each parenting behaviour. The adjusted mean difference compares the CCBT + MCBT group with CCBT and also the CCBT + MCI group with CCBT. A summary of scores is given in Appendix 5, Table 122.

The only significant difference was for CCBT + MCI versus CCBT in the ‘overprotection’ scores (p = 0.026). The difference between the CCBT + MCI and CCBT arms also approached significance for maternal self-report overprotection (p = 0.057).

| Questionnaire | Treatment | n | Adjusteda mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive behaviour (–) | CCBT | 42 | 0.042 (–0.058 to 0.141) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –0.009 (–0.104 to 0.086) | –0.050 (–0.190 to 0.090) | 0.478 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | 0.067 (–0.024 to 0.158) | 0.026 (–0.112 to 0.163) | 0.714 | |

| Over-protection (+) | CCBT | 42 | –0.016 (–0.036 to 0.005) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –0.035 (–0.055 to –0.016) | –0.020 (–0.048 to 0.009) | 0.174 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | –0.048 (–0.066 to –0.029) | –0.032 (–0.060 to –0.004) | 0.026 | |

| Promotion of avoidance (+) | CCBT | 42 | –0.019 (–0.045 to 0.007) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –0.024 (–0.049 to 0.001) | –0.004 (–0.041 to 0.033) | 0.813 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | –0.042 (–0.066 to –0.019) | –0.023 (–0.059 to 0.013) | 0.207 | |

| Intrusiveness (+) | CCBT | 42 | –0.058 (–0.163 to 0.046) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | 0.015 (–0.085 to 0.116) | 0.074 (–0.074 to 0.221) | 0.324 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | –0.108 (–0.205 to –0.012) | –0.050 (–0.195 to 0.195) | 0.499 | |

| Anxiety (+) | CCBT | 42 | –0.005 (–0.106 to 0.097) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | 0.034 (–0.063 to 0.132) | 0.039 (–0.103 to 0.182) | 0.589 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | –0.013 (–0.107 to 0.080) | –0.009 (–0.149 to 0.131) | 0.901 | |

| Quality of relationship (–) | CCBT | 42 | 0.023 (–0.074 to 0.121) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | 0.050 (–0.044 to 0.142) | 0.026 (–0.111 to 0.163) | 0.712 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 49 | 0.003 (–0.086 to 0.092) | –0.020 (–0.155 to 0.114) | 0.763 | |

| POI total score ( + ) | CCBT | 34 | –5.83 (–9.07 to –2.59) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 38 | –6.41 (–9.51 to –3.31) | –0.58 (–5.06 to 3.89) | 0.7974 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 34 | –10.32 (–13.60 to –7.04) | –4.49 (–9.12 to 0.14) | 0.0573 |

Parenting cognitions

Maternal expectations were assessed before the behavioural tasks. These ratings were recorded at baseline and at assessment 2. The following analysis, shown in Table 19, looks at the change scores from baseline to assessment 2, analysed using adjusted linear regression.

For the pre-task ‘scared’ rating and pre-task ‘child in control’ rating there were significant differences between CCBT + MCI and CCBT (p = 0.029 and p = 0.046, respectively). A summary of mean scores is provided in Appendix 5, Table 125.

| Questionnaire | Treatment | n | Adjusteda mean change (95% CI) | Adjusteda mean difference (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-task ‘child scared’ (+) | CCBT | 40 | –0.69 (–1.12 to –0.26) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –1.22 (–1.62 to –0.82) | –0.53 (–1.12 to 0.07) | 0.083 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 | –1.36 (–1.76 to –0.96) | –0.67 (–1.26 to –0.07) | 0.029 | |

| Pre-task ‘mother anxious’ (+) | CCBT | 40 | –0.87 (–1.32 to –0.42) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –1.43 (–1.85 to –1.01) | –0.56 (–1.18 to 0.07) | 0.079 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 | –1.43 (–1.85 to –1.02) | –0.56 (–1.18 to 0.06) | 0.077 | |

| Pre-task ‘child in control’ (–) | CCBT | 40 | 0.25 (–0.12 to 0.63) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | 0.75 (0.40 to 1.10) | 0.50 (–0.03 to 1.02) | 0.063 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 | 0.78 (0.44 to 1.13) | 0.53 (0.01 to 1.05) | 0.046 | |

| Pre-task ‘mother in control’ (+/–) | CCBT | 40 | –0.28 (–0.80 to 0.23) | Ref. | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 | –0.07 (–0.55 to 0.41) | 0.21 (–0.51 to 0.93) | 0.564 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 | –0.08 (–0.55 to 0.39) | 0.20 (–0.50 to 0.91) | 0.569 |

Primary outcomes

Missing data

Nine (13%) participants allocated to CCBT + MCBT and nine (13%) participants allocated to CCBT + MCI were not able to be measured for the primary end points. These rates of missing data were slightly lower than for participants allocated to CCBT (21%). Baseline characteristics of participants with or without missing primary outcomes are given in Tables 20–22.

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 15 (21.1) | 27 (38.0) | 29 (40.9) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 9 (13.0) | 35 (50.7) | 25 (36.2) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 9 (12.7) | 37 (52.1) | 25 (35.2) | 71 |

| Total | 33 | 99 | 79 | 211 |

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | Much/very much improved, n (%) | Not much/very much improved, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 15 (21.1) | 36 (50.7) | 20 (28.2) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 9 (13.0) | 48 (69.6) | 12 (17.4) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 9 (12.7) | 47 (66.2) | 15 (21.1) | 71 |

| Total | 33 | 131 | 47 | 211 |

| Baseline characteristic | Category | Assessment 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Completed, n (%) | Missing, n (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 84 (83.2) | 17 (16.8) |

| Female | 94 (85.5) | 16 (14.5) | |

| Marital status | Single, never married | 7 (58.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| Married (first time) | 90 (84.1) | 17 (15.9) | |

| Remarried | 13 (81.3) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Divorce/separated | 39 (88.6) | 5 (11.4) | |

| Living with partner | 25 (89.3) | 3 (10.7) | |

| Not recorded | 4 (100.0) | ||

| Employment mother | Unemployed | 48 (77.4) | 14 (22.6) |

| Part time | 89 (86.4) | 14 (13.6) | |

| Full time | 30 (85.7) | 5 (14.3) | |

| Not recorded | 11 (100.0) | ||

| Employment father | Unemployed | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) |

| Part time | 2 (100.0) | ||

| Full time | 128 (83.7) | 25 (16.3) | |

| NA | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | |

| Not recorded | 34 (91.9) | 3 (8.1) | |

| Overall SES | Higher professional | 93 (87.7) | 13 (12.3) |

| Other employed | 57 (80.3) | 14 (19.7) | |

| Unemployed | 3 (100.0) | ||

| Not recorded | 25 (80.6) | 6 (19.4) | |

| ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis (initial assessment) | SAD | 45 (80.4) | 11 (19.6) |

| Social phobia | 42 (87.5) | 6 (12.5) | |

| GAD | 51 (77.3) | 15 (22.7) | |

| Other | 40 (97.6) | 1 (2.4) | |

| ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis CSR (initial assessment) | Moderate 4 | 12 (75.0) | 4 (25.0) |

| Moderate 5 | 50 (84.7) | 9 (15.3) | |

| Severe 6 | 97 (85.8) | 16 (14.2) | |

| Severe 7 | 19 (82.6) | 4 (17.4) | |

| ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis CSR at assessment 1B | No diagnosis | 3 (100.0) | |

| Mild 3 | 6 (100.0) | ||

| Moderate 4 | 25 (92.6) | 2 (7.4) | |

| Moderate 5 | 52 (85.2) | 9 (14.8) | |

| Severe 6 | 86 (91.5) | 8 (8.5) | |

| Severe 7 | 5 (71.4) | 2 (28.6) | |

| Very severe 8 | 1 (100.0) | ||

| Not recorded | 12 (100.0) | ||

| Child age (years) | 6 | 1 (100.0) | |

| 7 | 11 (68.8) | 5 (31.3) | |

| 8 | 27 (84.4) | 5 (15.6) | |

| 9 | 28 (84.8) | 5 (15.2) | |

| 10 | 41 (87.2) | 6 (12.8) | |

| 11 | 43 (91.5) | 4 (8.5) | |

| 12 | 25 (78.1) | 7 (21.9) | |

| 13 | 3 (100.0) | ||

Unadjusted analyses: primary end points

As shown in Table 23 and Figure 3, 48% of the children in the CCBT arm were free of their primary diagnosis status at assessment 2 compared with 58% of children in the CCBT + MCBT and 60% of children in the CCBT + MCI arms.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 27 (48.2) | 29 (51.8) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 35 (58.3) | 25 (41.7) | 60 |

| CCBT + MCI | 37 (59.7) | 25 (40.3) | 62 |

| Total | 99 | 79 | 178 |

FIGURE 3.

Presence of pre-treatment ADIS-C/P child primary diagnosis.

The unadjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCBT versus CCBT on recovery from primary ADIS-C/P diagnosis by assessment 2 was 1.21 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.71; p = 0.280). This was very similar to the unadjusted estimate of the effect of CCBT + MCI versus CCBT, RR 1.24 (95% CI 0.88 to 1.74; p = 0.219).

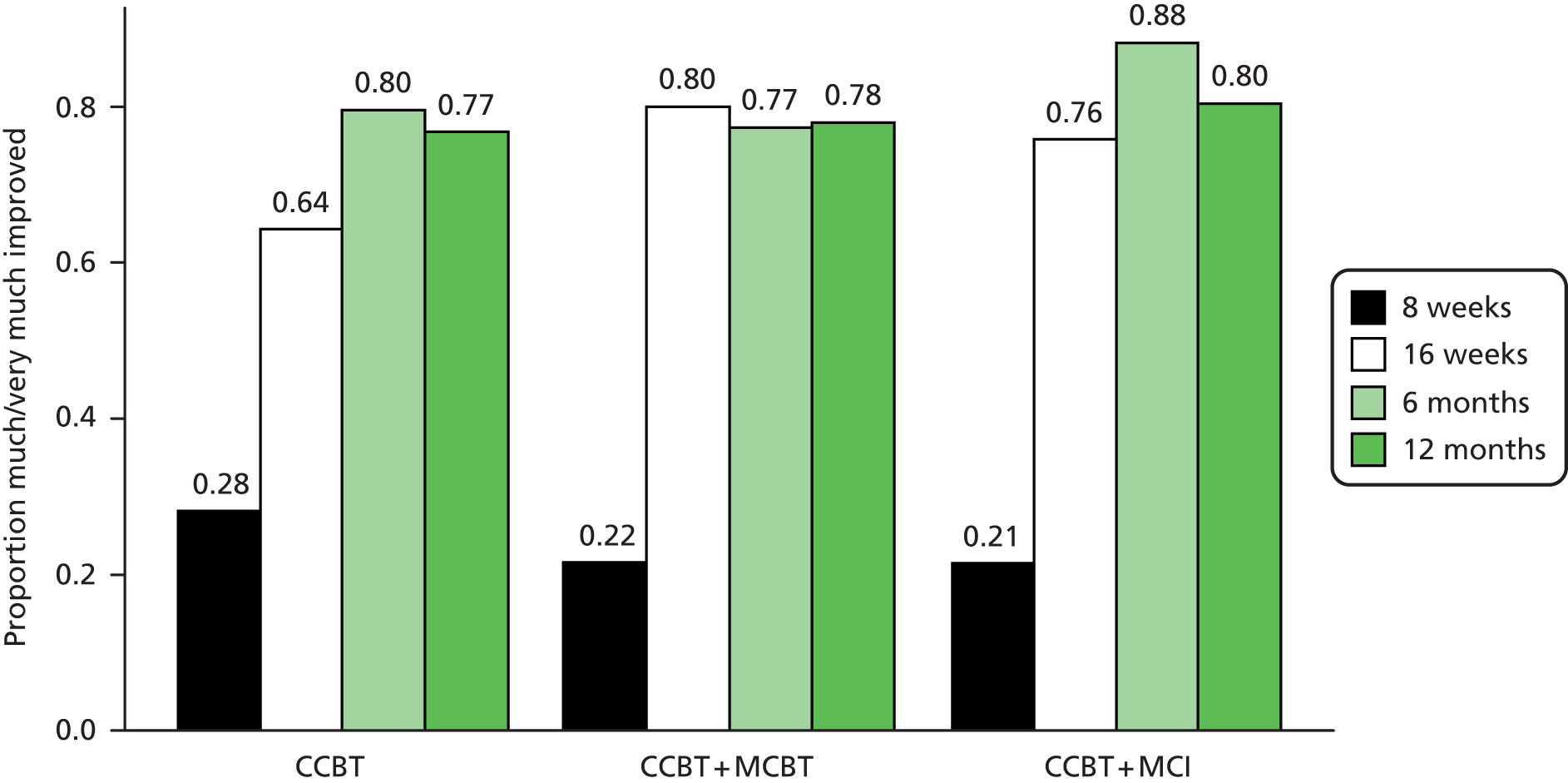

The unadjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCBT versus CCBT on CGI-I by assessment 2 was 1.24 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.57; p = 0.065) and for the effect of CCBT + MCI versus CCBT the RR was 1.18 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.50; p = 0.179). Frequencies are displayed in Table 24 and Figure 4.

| Treatment allocation | Much/very much improved, n (%) | Not much/very much improved, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 36 (64.3) | 20 (35.7) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 48 (80.0) | 12 (20.0) | 60 |

| CCBT + MCI | 47 (75.8) | 15 (24.2) | 62 |

| Total | 131 | 47 | 178 |

FIGURE 4.

Child CGI-I.

Multiple imputation analyses

Multiple imputations were used to account for missing data for the two primary end points. Twenty imputed data sets were developed using the Stata ‘ice’ function for multiple imputation with chained equations. Imputation models were developed using variables for treatment allocation, minimisation factors [child age, child gender, type of child anxiety disorder (GAD, social phobia, SAD, other), baseline severity (ADIS-C/P CSR) of the child’s primary anxiety disorder and baseline severity (ADIS-IV mother self-report) of the mother’s primary anxiety disorder] as well as assessment of ADIS-C/P CSR at assessment 1B, assessment of ADIS-C/P primary diagnosis at assessment 1B, CGI-I at assessment 1B and baseline mother’s depression (DASS-21 – depression), child depression symptoms (SMFQ-c), child behavioural problems (SDQ-conduct) and presence of child social phobia.

Results from multiple imputation analyses, which were the primary analyses, along with adjusted RRs are presented in Table 25. Adjusted analyses for log-binomial regression models did not converge (as is often the case), therefore the modified Poisson regression framework with robust error variance was used as specified in the analysis plan, which gives almost identical CIs.

Confidence intervals for all estimates remained similar regardless of the method of analysis.

| Assessment 2 | RRa | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADIS-C/P primary diagnostic status: child | |||

| Unadjusted | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.21 | 0.86 to 1.71 | 0.280 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.24 | 0.88 to 1.74 | 0.219 |

| Adjusteda | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.22 | 0.88 to 1.67 | 0.228 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.21 | 0.88 to 1.65 | 0.243 |

| Multiple imputationa | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.18 | 0.827 to 1.62 | 0.285 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.22 | 0.90 to 1.67 | 0.203 |

| CGI-I: child | |||

| Unadjusted | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.24 | 0.99 to 1.57 | 0.065 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.18 | 0.93 to 1.50 | 0.179 |

| Adjusteda | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.25 | 0.99 to 1.57 | 0.058 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.18 | 0.93 to 1.50 | 0.173 |

| Multiple imputationa | |||

| CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.26 | 1.00 to 1.59 | 0.054 |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.20 | 0.95 to 1.53 | 0.133 |

Per-protocol analysis of primary outcomes at assessment 2

The PP population is a subset of the ITT population and excludes from the analysis participants who were ineligible or had significant non-compliance.

The CCBT arm PP population contained 58 children, the CCBT + MCBT arm contained 60 children and the CCBT + MCI arm contained 64 children. This is a total of 182 children in the PP population, whereas the ITT population contains 211 children.

Table 26 shows for each treatment group the proportion of children who had recovered from their primary diagnosis by assessment 2; in both the CCBT + MCBT and CCBT + MCI arms this was 59% and in the CCBT arm it was 49%.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 27 (49.09) | 28 (50.91) | 55 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 33 (58.93) | 23 (41.07) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCI | 36 (59.02) | 25 (40.98) | 61 |

| Total | 96 | 76 | 172 |

As shown in Table 27, the adjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCBT versus CCBT on recovery from primary ADIS-IV diagnosis by assessment 2 was 1.17 (95% CI 0.85 to 1.62; p = 0.328). This was very similar to the adjusted estimate of the effect of CCBT + MCI versus CCBT, RR 1.19 (95% CI 0.86 to 1.64; p = 0.288).

| Parameter | Adjusted RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.17 | 0.85 to 1.62 | 0.328 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.19 | 0.86 to 1.64 | 0.288 | |

The proportion of patients where the CGI-I rating improved by assessment 2 is shown in Table 28; in the CCBT arm this was 64%, in the CCBT + MCBT arm it was 80% and in the CCBT + MCI arm it was 75%.

| Treatment allocation | Much/very much improved, n (%) | Not much/very much improved, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 35 (63.64) | 20 (36.36) | 55 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 45 (80.36) | 11 (19.64) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCI | 46 (75.41) | 15 (24.59) | 61 |

| Total | 126 | 46 | 172 |

As shown in Table 29, the adjusted RR for the effect of CCBT + MCBT versus CCBT on improvement in CGI-I by assessment 2 was 1.26 (95% CI 0.99 to 1.59); p = 0.056. The adjusted estimate of the effect of CCBT + MCI versus CCBT was RR 1.18 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.52; p = 0.170).

| Parameter | Adjusted RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.26 | 0.99 to 1.59 | 0.056 | |

| CCBT + MCI | 1.18 | 0.93 to 1.52 | 0.170 | |

Secondary outcomes

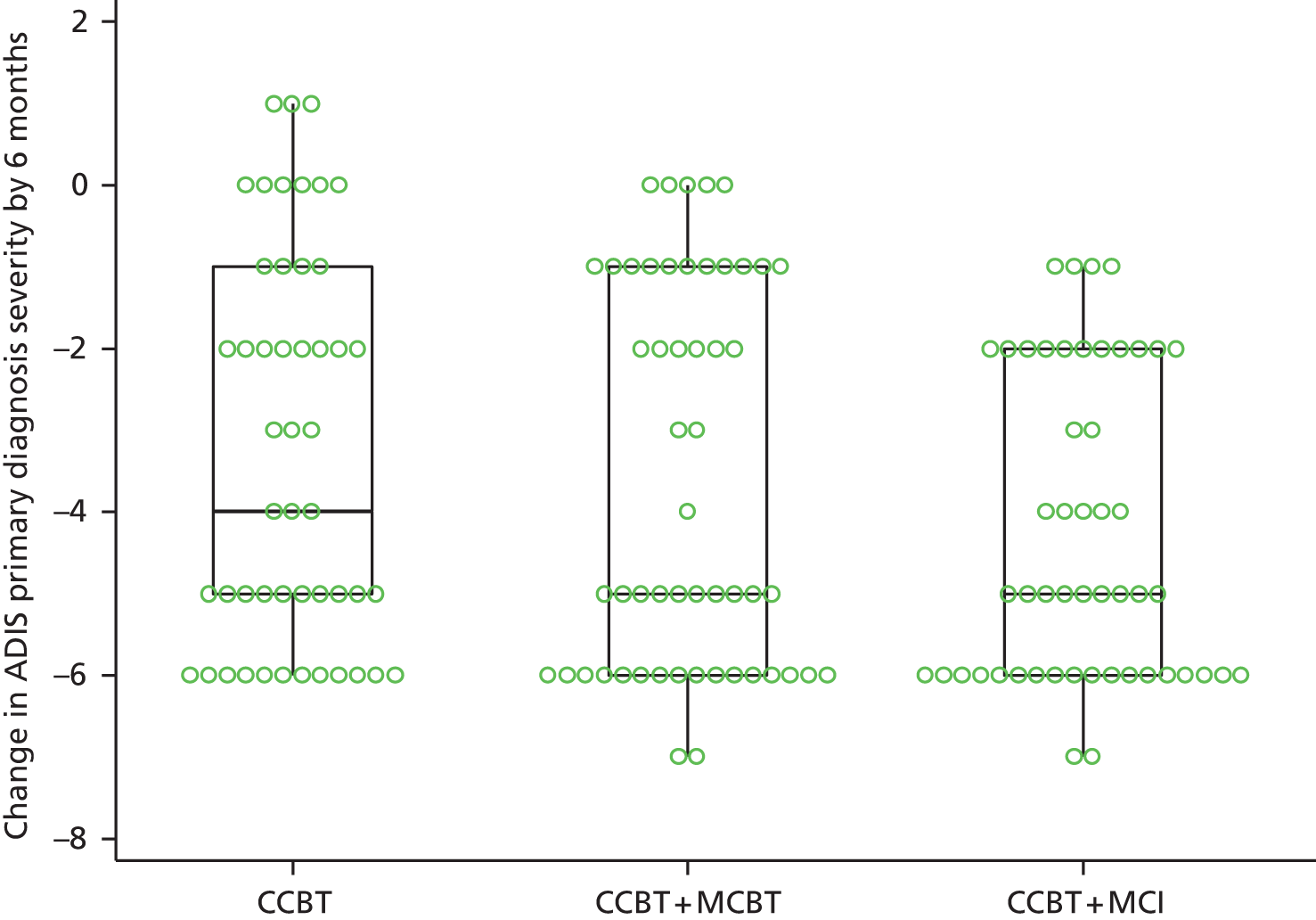

Severity of child’s primary Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule diagnosis at assessment 2

By assessment 2, 59% of the CCBT arm, 73% of the CCBT + MCBT arm and 73% of the CCBT + MCI arm children had seen an improvement of at least 2 points (Figure 5 and Tables 30 and 31).

There were no significant differences between CCBT + MCBT and CCBT or between CCBT + MCI and CCBT (p = 0.101 and 0.118, respectively).

FIGURE 5.

Box plot of change in severity of child’s primary ADIS-C/P diagnosis at assessment 2 by treatment group.

| Treatment | –7 | –6 | –5 | –4 | –3 | –2 | –1 | 0 | 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 1 (1.8) | 9 (16.1) | 11 (19.6) | 2 (3.6) | 4 (7.1) | 6 (10.7) | 13 (23.2) | 9 (16.1) | 1 (1.8) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 2 (3.3) | 14 (23.3) | 9 (15.0) | 4 (6.7) | 4 (6.7) | 11 (18.3) | 7 (11.7) | 8 (13.3) | 1 (1.7) | 60 |

| CCBT + MCI | 2 (3.2) | 17 (27.4) | 8 (12.9) | 4 (6.5) | 2 (3.2) | 12 (19.4) | 14 (22.6) | 3 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) | 62 |

| Total | 5 | 40 | 28 | 10 | 10 | 29 | 34 | 20 | 2 | 178 |

| Treatment | n | n (%) with a 2 or more point reduction | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 56 | 33 (58.9) | |

| CCBT + MCBT | 60 | 44 (73.3) | 0.101 |

| CCBT + MCI | 62 | 45 (72.6) | 0.118 |

Presence of any Anxiety Disorder Interview Schedule anxiety diagnosis in children at assessment 2

As shown in Table 32, the proportion of children with missing data was higher in the CCBT arm (21%); the CCBT + MCBT arm (13%) and the CCBT + MCI arms (13%) were fairly similar.

| Treatment allocation | Missing, n (%) | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 15 (21.1) | 16 (22.5) | 40 (56.3) | 71 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 9 (13.0) | 18 (26.1) | 42 (60.9) | 69 |

| CCBT + MCI | 9 (12.7) | 25 (35.2) | 37 (52.1) | 71 |

| Total | 33 | 59 | 119 | 211 |

As can be seen in Table 33, in the CCBT + MCBT and CCBT + MCI arms 18 and 25 children (30% and 40%), respectively, had recovered from all ADIS-C/P anxiety diagnoses at assessment 2. From the CCBT arm, 16 participants (29%) had fully recovered.

| Treatment allocation | No diagnosis, n (%) | Diagnosis, n (%) | Total, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CCBT | 16 (28.6) | 40 (71.4) | 56 |

| CCBT + MCBT | 18 (30.0) | 42 (70.0) | 60 |

| CCBT + MCI | 25 (40.3) | 37 (59.7) | 62 |

| Total | 59 | 119 | 178 |

Table 34 shows the results from log-binomial regression of the children’s recovery from all ADIS-C/P anxiety diagnoses at assessment 2 adjusted for minimisation factors.

| Parameter | Adjusted RRa | 95% CI | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment | CCBT | Ref. | ||

| CCBT + MCBT | 1.06 | 0.63 to 1.78 | 0.816 | |

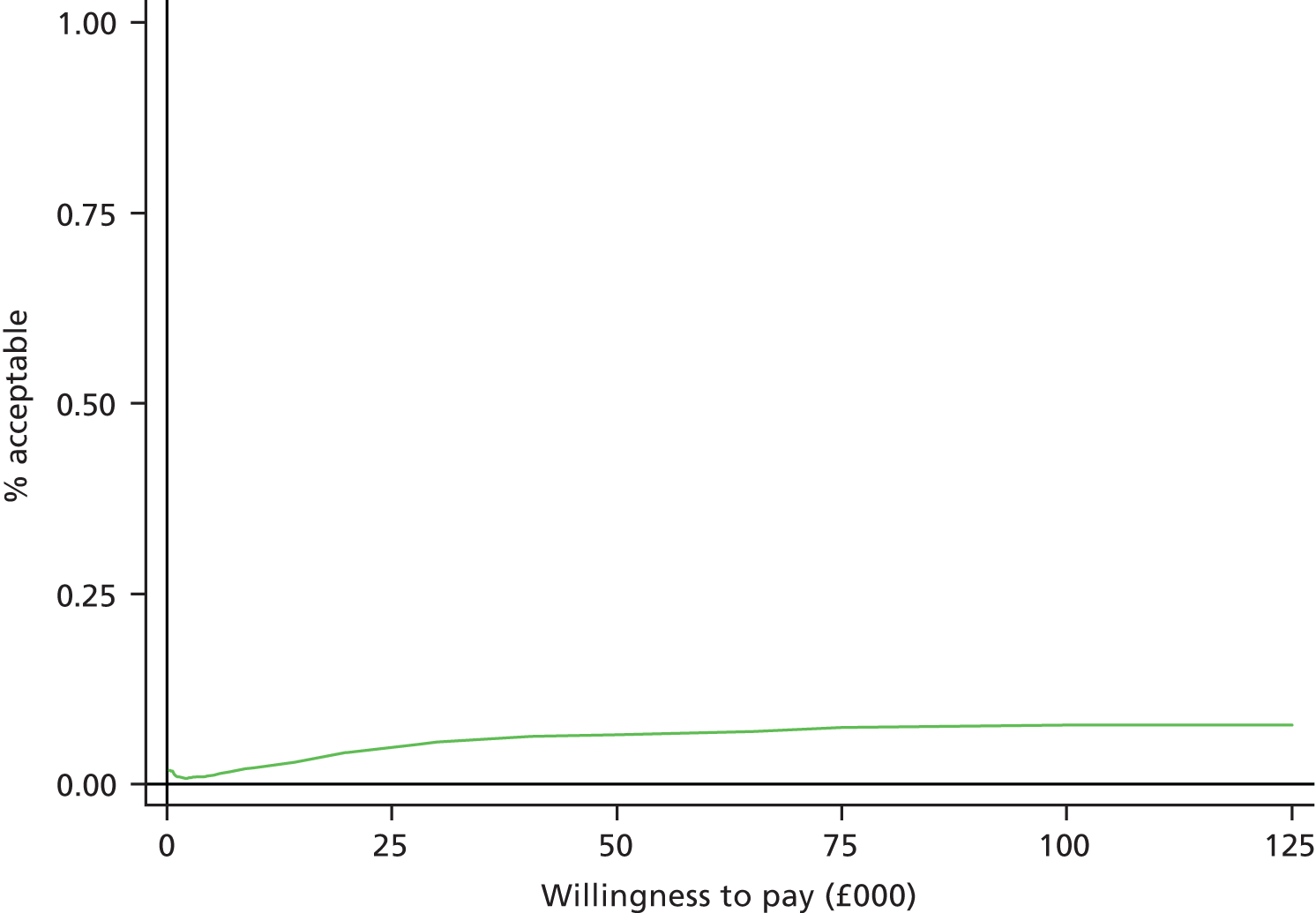

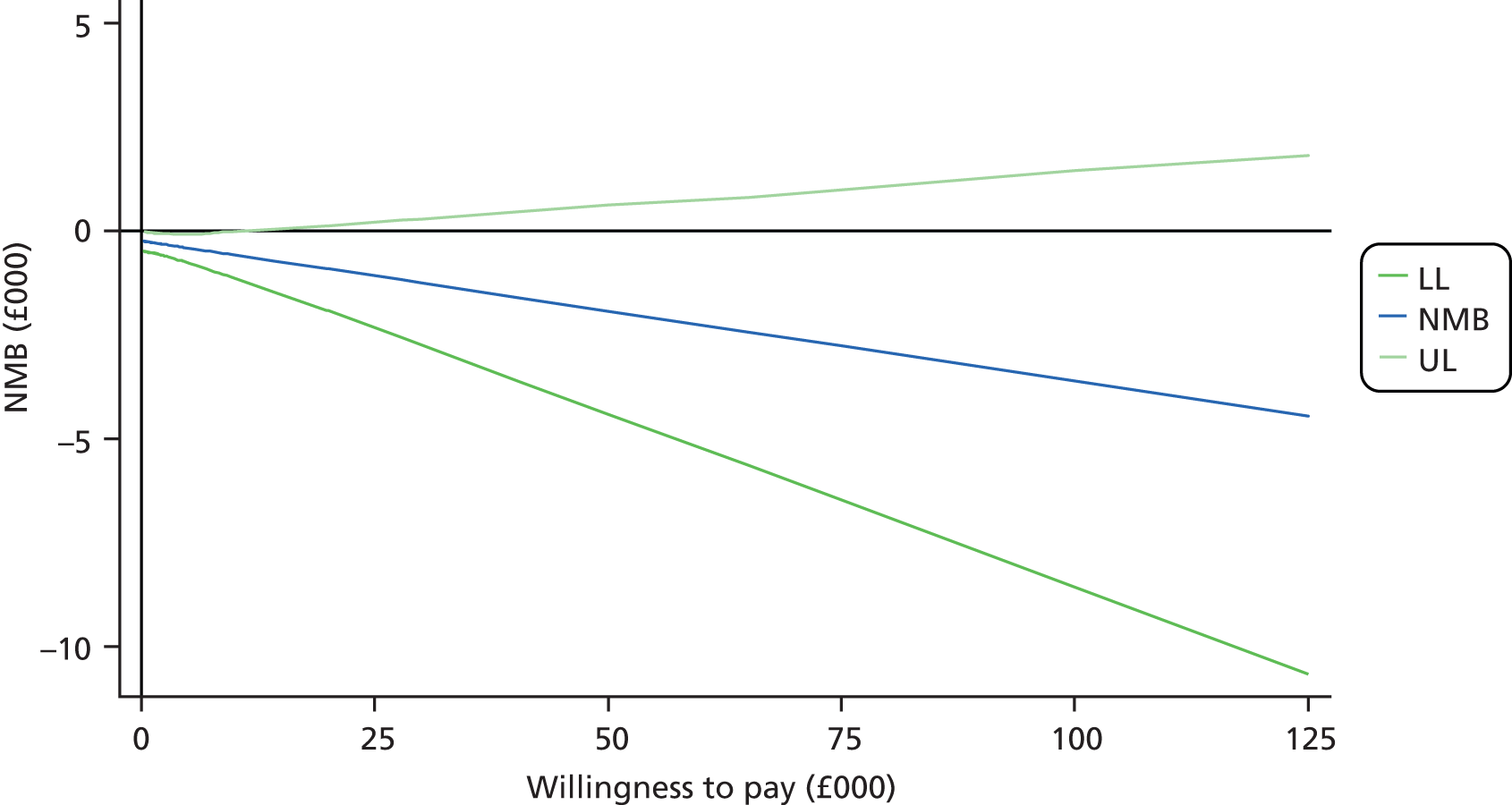

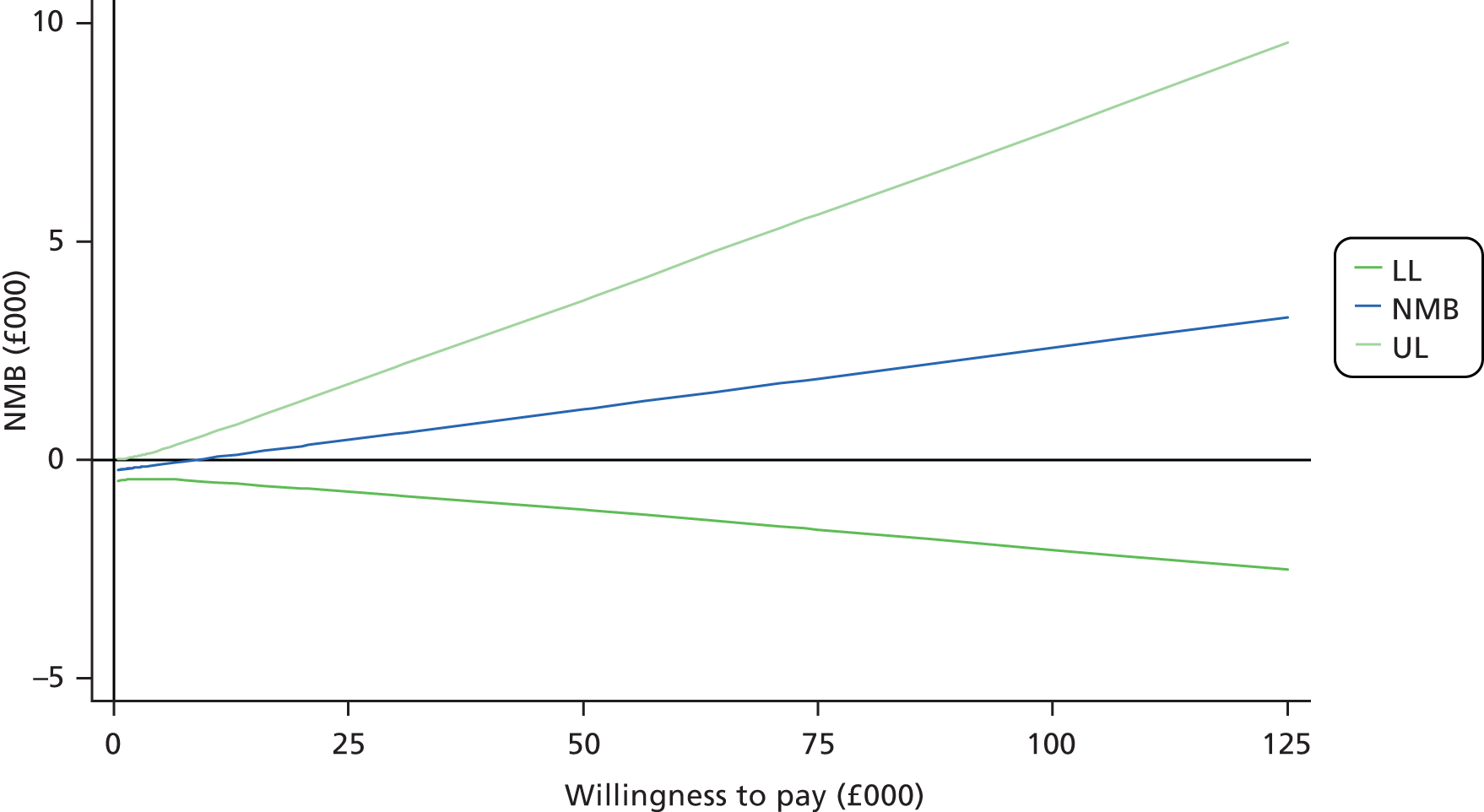

| CCBT + MCI | 1.48 | 0.92 to 2.37 | 0.102 | |