Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 08/56/02. The contractual start date was in August 2009. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in September 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Professor John R Stradling was an acting consultant for ResMed (UK) Ltd from April 2013. Professor Mary J Morrell received research funding from ResMed (UK) Ltd as an unrestricted education grant that was awarded to collaborator Professor AS Simonds, Royal Brompton Hospital and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by McMillan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overview of sleep apnoea

Obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) is caused by occlusion of the pharyngeal airway during sleep that results in a pause in breathing (apnoea). Each apnoea event or partial occlusion (hypopnoea) is associated with hypoxaemia, and is usually terminated by a brief arousal from sleep and an acute surge in blood pressure (BP). 1 The subsequent sleep disruption leads to symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness in some,2 but not all, people with OSA. 3 When OSA occurs with symptoms of excessive daytime sleepiness it is termed obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome (OSAS).

The long-term implications of severe4 OSAS are considerable in middle-aged people. Daytime sleepiness impairs function and increases accident risk,5,6 with OSAS patients being two to four times more likely to have road traffic accidents (RTAs) as a result of reduced alertness while driving. 7 OSAS patients are also more likely to experience mood changes8,9 and reduced quality of life,10,11 which is often attributed to reduced social functioning and vitality. 12 In addition, there is some evidence of reduced cognitive function,13–16 although the extent of the neurocognitive deficits in patients with OSA is currently debated. 17

The cardiovascular impact of OSAS has been established using epidemiological data to show that people with OSA have a threefold increased likelihood of developing hypertension over 4 years, independent of other risk factors. 18,19 In addition, treatment trials in patients with severe OSAS have produced a 2 mmHg to 3 mmHg reduction in BP. 20–22 Untreated severe OSAS may be associated with an increased risk of stroke,23,24 cardiovascular disease25–27 and death. 28–30 However, the close association between OSAS and obesity,31 as well as other disorders that predispose to vascular disease, makes it difficult to determine the risk factors associated with OSAS. 32 This is especially true in older people, who are more likely to have comorbidities.

Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in older people

The prevalence of OSAS was reported to be approximately 4% in males and 2% in females in a US cohort of 602 employed men and women (30–60 years). 33 However, more recent estimates from the same cohort predict that up to 14% of males and 5% of females have OSAS. 34,35 This represents a substantial increase since 1990, in part because of the increasing prevalence of obesity36 and the ageing population. Specifically, the prevalence of OSA (in the absence of daytime sleepiness) appears to increase with age, although there is some evidence to suggest that it plateaus or decreases in the population over the age of 65 years. 37 In a study that used similar criteria to define sleep apnoea in younger and older people, prevalence was eight times higher in community-dwelling older men (65–100 years) compared with 3% in a younger population (20–44 years). 38 Table 1 reviews in detail the prevalence of OSA and OSAS in older people. The wide variation in estimates is likely to reflect the definitions used to quantify the OSA or OSAS and the different health status of the older populations studied, for example relatively healthy community-dwelling individuals or nursing home residents with comorbidity.

| Reference | n | Female (%) | Age (years) | Population | Prevalence of OSA (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AHI (events/hour) ≥ 5 | AHI (events/hour) ≥ 10/≥ 15 | |||||

| Carskadon et al., 198139 | 40 | 55 | 62–86 | Community | 36 | – |

| Coleman et al., 198140 | 83 | 28 | 66 ± 5 | Sleep clinic | 39 | – |

| McGinty et al., 198241 | 26 | 0 | 64.4 ± 4.4 | Community | – | 62 |

| Roehrs et al., 198342 | 97 | 0 | 61–81 | Sleep clinic | 27 | – |

| Smallwood et al., 198343 | 30 | 20 | 50–80 | Community | 37 | – |

| Yesavage et al., 198544 | 41 | 0 | 69.5 ± 6.5 | Both | 73 | – |

| Hoch et al., 198645 | 56 | 52 | 69.3 ± 5.4 | Community | 5 | 4 |

| Knight et al., 198746 | 27 | NG | 75.8 ± 5.9 | Primary care | 37 | – |

| Mosko et al., 198847 | 46 | 65 | 68.7 ± 6.7 | Community | 28 | 16 |

| Ancoli-Israel et al., 198948 | 233 | 65 | 65–101 | Nursing home | 70 | – |

| Hoch and Reynolds 199049 | 105 | 53 | 60–91 | Community | 26 | 13 |

| Philips et al., 199250 | 92 | 52 | 64.2 ± 8.6 | Community | 15 | – |

| Ancoli-Israel et al., 199551 | 346 | 53 | 72.8 ± 6.1 | Community | – | 30 |

| 54 | 57 | 70.8 ± 6.2 | Community | – | 32 | |

| Bixler et al., 199852 | 75 | 0 | 65–100 | Community | 31 | 24 |

| Young et al., 200253 | 3448 | NG | 60–99 | Community | 54 | 20 |

| Endeshaw et al., 200454 | 58 | 76 | 77.7 ± 6.7 | Community | 56 | 19 |

| Haas et al., 200555 | 3643 | 52 | 70.2 ± 6.9 | Community | 46 | 20 |

| Hader et al., 200556 | 80 | 50 | 74.1 ± 6.3 | General clinic | 43 | 19 |

Aetiology of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in older people

The high prevalence of OSA in older people has led to debate regarding its causes and the consequences of the disease in this population. 57–59 In middle-aged people, pharyngeal occlusion occurs as a result of a reduction of pharyngeal dilator muscle tone during sleep60 coupled with excessive extraluminal pressure around the airway, produced by excessive adipose tissue. 61,62 In susceptible individuals these factors lead to airway collapse during sleep. Therefore, it is perhaps not surprising that neck circumference is a significant risk factor for OSA. 63,64 However, in older people, additional factors, such as an age-related reduction in pharyngeal muscle function65,66 and structural changes to the upper airway, increase the vulnerability to collapse. 67 Specifically, a decrease in the size of the upper airway lumen in older people,68 associated with an age-related lengthening of the pharyngeal airway in women69 and a descent of the hyoid bone,70 creates a predisposition to airway collapse.

Symptoms of obstructive sleep apnoea in older people

Older people report different levels of sleepiness and, compared with younger populations, rate their health differently for the same level of OSA severity. 71 This may be because older people have become habituated to the reduction in sleep quality that occurs as part of the normal ageing process. 72–74 Hence, older people may not suffer symptoms of daytime sleepiness as a result of the further sleep disruption caused by OSA. Alternatively, increased daytime sleepiness may be less debilitating in older people, who have different family and work demands and may have more time for daytime naps. In addition, older populations are more likely to have comorbidities which may cause sleep disruption75 and polypharmacy contributing to excessive daytime sleepiness. 76 Specifically, nocturia may disturb sleep, and there is some suggestion that OSA exacerbates nocturia. 77,78 Taken together, these factors could modify daytime sleepiness and obscure the symptoms of OSA. Therefore, although excessive sleepiness (regardless of its cause) is associated with increased all-cause mortality in older people,79 the proportion of sleepiness that is a result of OSA in older people, and hence could be modified by treatment, is unknown.

Both the ageing process80 and OSA14,15,81 are associated with a reduction in cognitive function. However, few studies have investigated the impact of OSA on cognitive function in older people. In those studies that have measured cognitive function in older people, cognitive impairment appears to be independently related to both OSA severity and increasing age, but the coexistence of these factors does not further increase dysfunction. 57,82,83 One explanation for the preservation of cognitive function in OSA patients is that neural compensation can overcome the cognitive deficits that are associated with the effects of intermittent hypoxia and/or sleep deprivation on the brain. 84 Whether or not the capacity for neural compensation is decreased in older people, who have less neural reserve, is unknown. 57 Recent data have shown that poorer sleep quality is associated with factors that may accelerate cognitive decline in older people and this finding requires further investigation. 85

With respect to the cardiovascular impact of OSA in older people, there are limited studies on the long-term consequences. Prospective observational data over 8 years86 showed that severe OSA in older people is associated with cardiovascular mortality, as it is in middle-aged people. Specifically, the cardiovascular risk in older people with untreated OSAS resulted from increased stroke and heart failure deaths. 23,25,86 However, a potential survival bias in people who have survived into older age means that they may be different in some way from younger people with OSAS. Alternatively, studies in older people with OSA may be selecting those who have developed OSA later in life.

Treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome

The evidence-based treatment of choice for moderate to severe OSAS in middle-aged patients is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy, which modifies the cardinal symptom of excessive daytime sleepiness20 and is cost-effective. 20,87

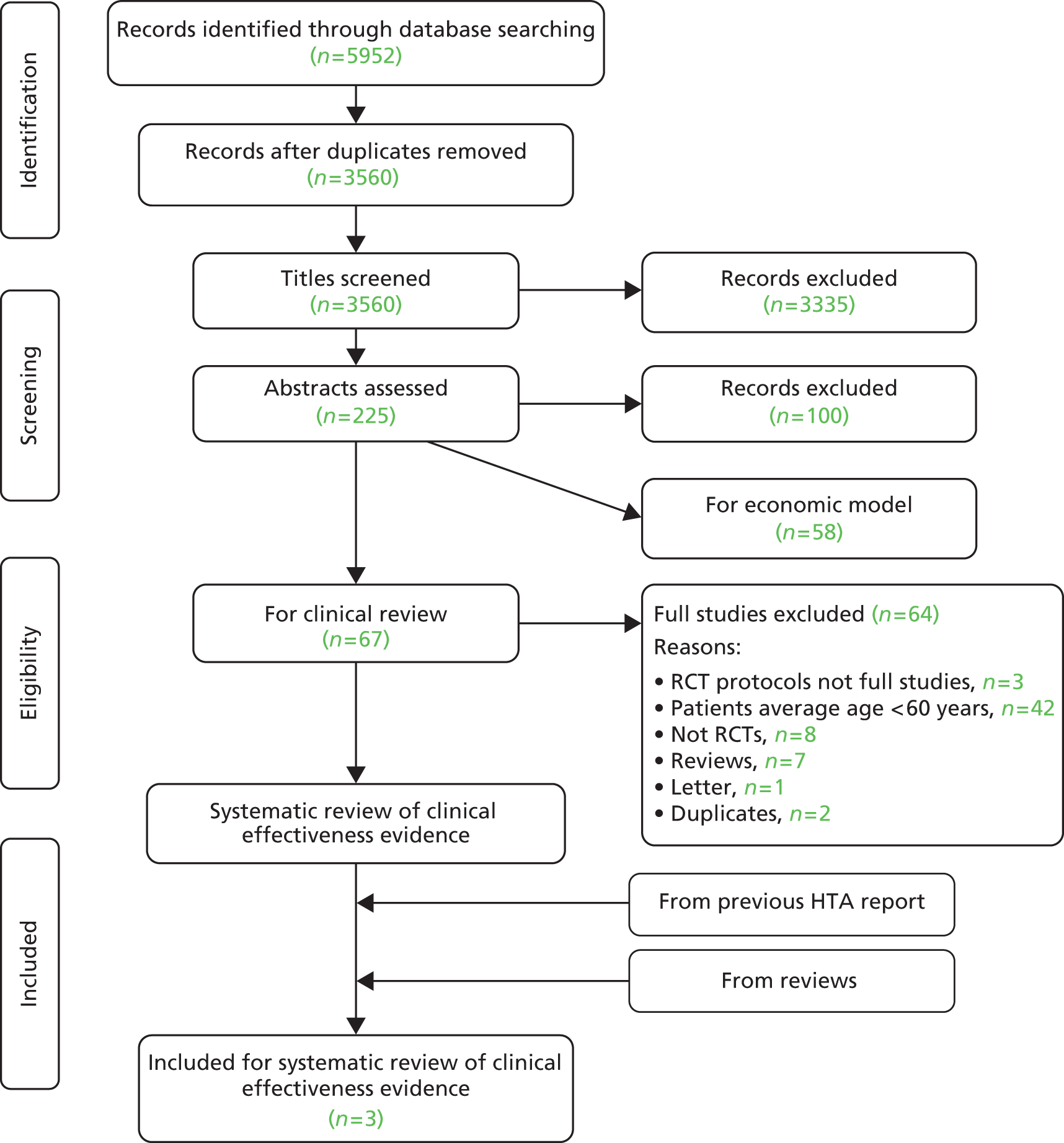

A literature search of the PubMed and The Cochrane Library databases to September 2013 (discussed in more detail in Chapter 4, Reviews for external evidence), without language restrictions, for full articles reporting randomised controlled trials (RCTs) assessing the efficacy of CPAP treatment in OSAS, in a population with an average age of 60 years or older and the capacity to give informed consent, identified only three studies which included patients with cardiovascular conditions and compared CPAP with sham CPAP88 or no CPAP. 89,90 None of the studies was conducted in the UK or in a secondary care setting. Furthermore, they did not collect generic measures of health utility. These studies were not generalisable to the overall patient population; consequently, these studies were not used to inform the cost-effectiveness estimates in the health economic model, and which were derived solely from the results of Positive Airway Pressure in Older People: a randomised controlled trial (PREDICT).

Multiple systematic reviews and meta-analyses have assessed the efficacy of CPAP therapy; the most recent and relevant to date being the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA) systematic review and economic analysis of CPAP devices for the treatment of OSAS. 20 This review concluded that CPAP is a clinically effective and cost-efficient treatment for moderate to severe OSA in well-defined middle-aged populations. It found that the majority of studies investigating the effect of CPAP treatment had enrolled patients between 44 and 58 years of age. However, it highlighted evidence gaps, with a need for trials in other patient groups, one such group being older people. It concluded that ‘clinical trials to define treatment effects at the extremes of age particularly in the elderly where cardiovascular comorbidity complicates assessment would be beneficial’. 20 Therefore, despite the high prevalence of OSA in older people, there is a paucity of evidence on the relative benefits or risks of CPAP treatment in older people. In addition, it cannot be assumed the benefits of CPAP treatment in younger populations will be replicated in older people.

Establishing the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of treatments for all common disease in older populations is a priority for health-care planners. PREDICT was an investigator-initiated project, funded by the HTA programme of the UK NIHR to address the evidence gap and enable the formulation of good-quality guidance on care for older people with OSAS.

Chapter 2 Methods

Trial design

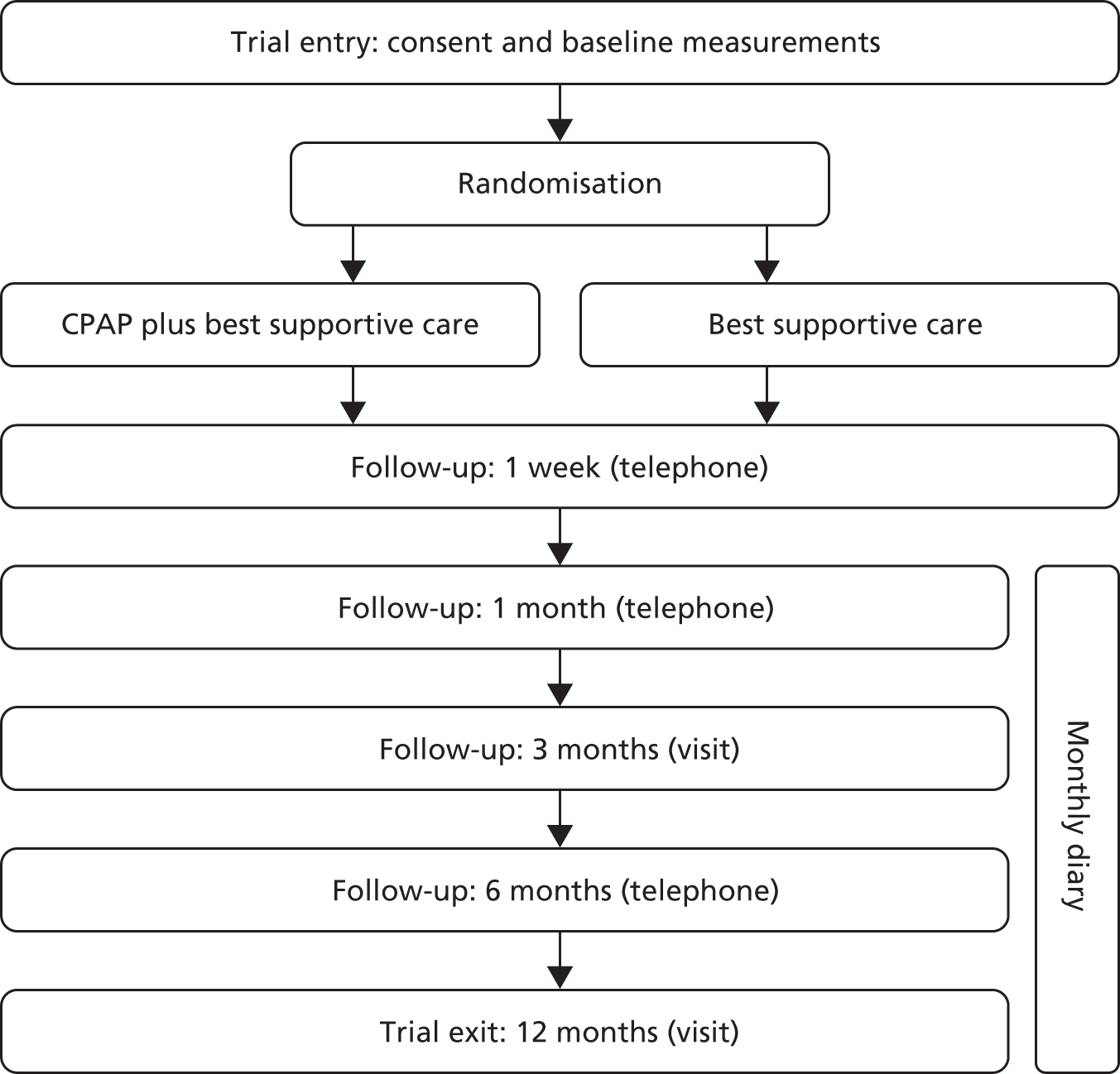

Positive Airway Pressure in Older People: a randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN90464927) was a pragmatic, single-blinded (investigator-blinded), parallel-group, multicentre RCT of 12 months’ duration (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial design.

All patients were randomised to receive CPAP plus best supportive care (BSC) or BSC only. The coprimary outcomes were the clinical effectiveness of CPAP in improving subjective sleepiness at 3 months and the cost-effectiveness of CPAP over the 12-month period.

Recruiting centres

Recruitment took place at secondary and tertiary care referral centres in England, Scotland and Wales, serving a variety of ethnic and social groups, and including both urban and rural areas.

At the start of the trial, patients were recruited through six secondary/tertiary care referral centres: Churchill Hospital (Oxford), Musgrove Park Hospital (Taunton), Royal Brompton Hospital (London), Royal Infirmary Edinburgh (Edinburgh), St James’s University Hospital (Leeds) and St Woolos Hospital (Newport). As the trial progressed, a further 18 centres requested to join via NIHR portfolio database; these centres were sent a feasibility questionnaire and subsequently nine further centres were opened, one of which was later closed because of recruitment difficulties. This left eight additional secondary care referral centres: Aintree Hospital (Liverpool), Blackpool Victoria Hospital (Blackpool), City General Hospital (Stoke-on-Trent), Freeman Hospital (Newcastle upon Tyne), Great Western Hospital (Swindon), Heartlands Hospital (Birmingham), New Cross Hospital (Wolverhampton) and Royal Berkshire Hospital (Reading). All centres had established sleep services where patients with OSAS are diagnosed and treated with CPAP therapy.

Ethical consideration

The trial was approved via the Integrated Research Application System (National Research Ethics Service/NHS/Health and Social Care Committees) (reference number 09/H0708/33). The trial was also approved by the local NHS Research and Development Office at each site.

Patients

Eligibility criteria

Patients were invited to participate if they were aged ≥ 65 years at the enrolment visit and had newly diagnosed OSAS. OSAS was defined as a oxygen desaturation index (ODI) at ≥ 4% desaturation threshold level for > 7.5 events/hour and an Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score of ≥ 9. Patients were not admitted to the trial if any of the following criteria applied:

-

previous exposure to CPAP therapy

-

arterial awake oxygen saturation < 90% on room air

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1)//forced vital capacity (FVC) ratio < 60%

-

substantial problems with sleepiness while driving (in those who are still driving)

-

currently using heavy goods vehicle or professional service vehicle driving licence

-

shift work

-

any very severe complication of OSAS such that CPAP therapy was mandatory

-

inability to give informed consent or comply with the protocol.

Screening

All patients potentially eligible to participate in the trial were identified from sleep and respiratory clinics predominantly by the principal investigator or nominated research staff member attending outpatient clinics and were initially assessed either by review of case notes or in person.

Once the diagnosis of OSAS was confirmed, based on the normal clinical practice in that centre, they were contacted by the principal investigator or nominated member of staff. Consecutively eligible patients were offered trial entry. Screening logs were kept documenting the number of patients assessed for eligibility and, if applicable, the reasons for non-inclusion.

Informed consent

Patients provided written informed consent at the enrolment visit.

Interventions

Patients were randomised to receive CPAP plus BSC or BSC alone.

Continuous positive airway pressure

Continuous positive airway pressure is the mainstay of medical treatment in middle-aged people with OSAS. CPAP machines are small electric pumps that deliver pressurised air to the upper airway via a hose and tightly fitting plastic mask that is worn over the nose and/or mouth during sleep. The air pressure acts as a pneumatic splint, opening up the airway, particularly at the pharyngeal level, thus preventing the soft tissue from collapsing. The pressure can be delivered as a fixed optimal pressure, which is usually manually set based on observation or titration during sleep. Alternatively, the pressure can be automatically adjusted, which is known as autotitrating CPAP. The autotitrating CPAP machines automatically increase and decrease the air pressure needed to maintain airway patency through the night, and hence they optimise OSA control. As the pressure delivered is adjusted by autotitrating machines, the mean pressure is often lower than that set on the fixed CPAP machines and therefore they are thought to reduce both the pressure required and associated side effects. However, it is important to note that no clinically important changes in adherence or other outcomes have been found using autotitrating CPAP versus fixed-level CPAP. 91 It has been proposed that autotitrating CPAP may benefit certain subgroups, although these have not yet been identified. 92 Serious side effects from CPAP are thought to be very rare.

There are many variations and adaptations to the delivery of CPAP therapy, such as humidification, which has been shown to prevent upper airway dryness associated with CPAP use,93 and various delivery interfaces (i.e. the type of mask). A recent systematic review94 highlighted the lack of research on the impact of different masks on adherence to treatment. Similarly, there is no evidence of increased adherence with humidified CPAP. 20

The recruitment centres were provided with identical autotitrating CPAP machines and humidification [AutoSet™, ResMed (UK) Ltd, Abingdon, Oxfordshire, UK] and a range of interfaces routinely used in clinical practice. They were asked to initiate CPAP treatment in keeping with their normal clinical practice by staff who were not involved in the trial outcome assessments or data analysis. Humidification and the choice of interface were made according to individual patient preference. At each follow-up visit, data on the hours of CPAP use, delivered pressure and any leaks were downloaded from the CPAP machine. All recruiting centres had established clinical expertise in the diagnosis and treatment of OSAS. The cost of the CPAP equipment will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Best supportive care

Best supportive care was defined as the provision of advice on minimising daytime sleepiness through sleep hygiene, using a nap/caffeine sleepiness management strategy and weight loss if appropriate. A booklet containing this information was compiled by the trial management team in conjunction with the Edinburgh and Oxford sleep centres and provided to all patients. This could also be supplemented with information routinely given at each centre.

Evidence for lifestyle modification as an efficacious treatment for OSAS is weak at present; however, lifestyle management is often recommended. 95,96 BSC was used as a comparator in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) HTA systematic review and economic analysis of CPAP machines for the treatment of OSAS. 20 This report showed that trials using BSC as a comparator produced results essentially identical to those from trials using subtherapeutic or sham CPAP as a comparator. Sham devices (CPAP machines that have been modified to deliver subtherapeutic pressure) have been validated as a placebo for CPAP; however, there is no consensus on the ideal comparator in sleep apnoea trials. Alternative comparators such as placebo pills or nasal dilator strips have been used, since it is argued that subtherapeutic CPAP may have an adverse impact on sleep quality. Two of our lead centres had substantial experience and expertise in using sham CPAP (Oxford and Edinburgh); however, these skills were not present across all recruiting centres and would have been difficult to establish widely. In addition, in a recent 6-month RCT, trial retention was lower in those allocated to sham CPAP. 15 BSC was, therefore, chosen as the trial comparator as it improved the simplicity of the trial delivery and was more appropriate for a multicentre design. The greater simplicity of BSC was also thought to be more suitable for a trial with a 12-month follow-up. Additionally, all patients were asked to continue with their normal medication and usual medical care for the duration of the trial.

Assessment

Both groups had identical visit schedules. Structured clinical assessments were performed at baseline and at 3 months and 12 months. Assessment visits were carried out at each local centre. Occasionally, research nurses agreed to see a patient in the patient’s own home if he/she was unable to attend the hospital. All patients received a telephone call from their centres at 1 week, 1 month and 6 months to record symptoms and side effects and to optimise CPAP adherence. Additionally, all patients completed monthly diaries recording their ESS score, functionality, quality of life, health-care usage, change in medication, caffeine and alcohol intake, frequency of exercise and any side effects.

All patients enrolled in the trial underwent a domiciliary overnight respiratory polygraphy (Embletta® GOLD™, Embla®, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) prior to treatment allocation, which was scored centrally. Domiciliary overnight pulse oximetry (Pulsox®–300i, Konica-Minolta Inc., Osaka, Japan) was performed at 3 and 12 months. Table 2 summarises the assessments completed at each time point.

| Assessment and measurement | Screening | Baseline | Week | Month | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |||

| Eligibility and exclusions | ✗ | ||||||||||||||

| Informed consent and enrolment | ✗ | ||||||||||||||

| Respiratory polygraphy | ✗ | ||||||||||||||

| Overnight pulse oximetry | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||||||||

| Clinical assessment visit | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Telephone call | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Patient diary returned via post | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||

| Demographics | ✗ | ||||||||||||||

| Subjective sleepiness (ESS score) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| Objective sleepiness (OSLER) test | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Quality of life (EQ-5D) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Generic quality of life (SF-36) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Disease-specific quality of life (SAQLI) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Mood (HADS) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Functionality (TDS) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Nocturia | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Mobility (TUG test) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Accidents | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||

| Cognitive function (MMSE, TMT–B, DSS test, RT) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Anthropometry | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| BP and resting pulse | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Fasting bloods | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Vascular events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| Health-care usage | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Change in medication | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Caffeine and alcohol intake | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Exercise | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CPAP compliance | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||||||

| CPAP side effects | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Adverse events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

Outcome measures

Coprimary outcomes

The first coprimary outcome was the change in subjective sleepiness from baseline to 3 months, which was measured by the mean ESS score at 3 and 4 months. The ESS is the most widely used subjective severity scale in clinical and research practice. It is a self-administered short questionnaire with eight questions that requires the patient to rate his or her tendency to fall asleep in eight everyday situations using a scale of 0–3 to represent the chance of dozing, where 0 is ‘none’, 1 is ‘slight’, 2 is ‘moderate’ or 3 is ‘high’. The score is the sum of the eight questions and can range from 0 to 24; a reduction in the score represents an improvement. 97 Patients completed the ESS themselves, without input from family of friends. A standard operating procedure was provided for the administration of the questionnaire. In addition, the ESS score was measured monthly throughout the trial.

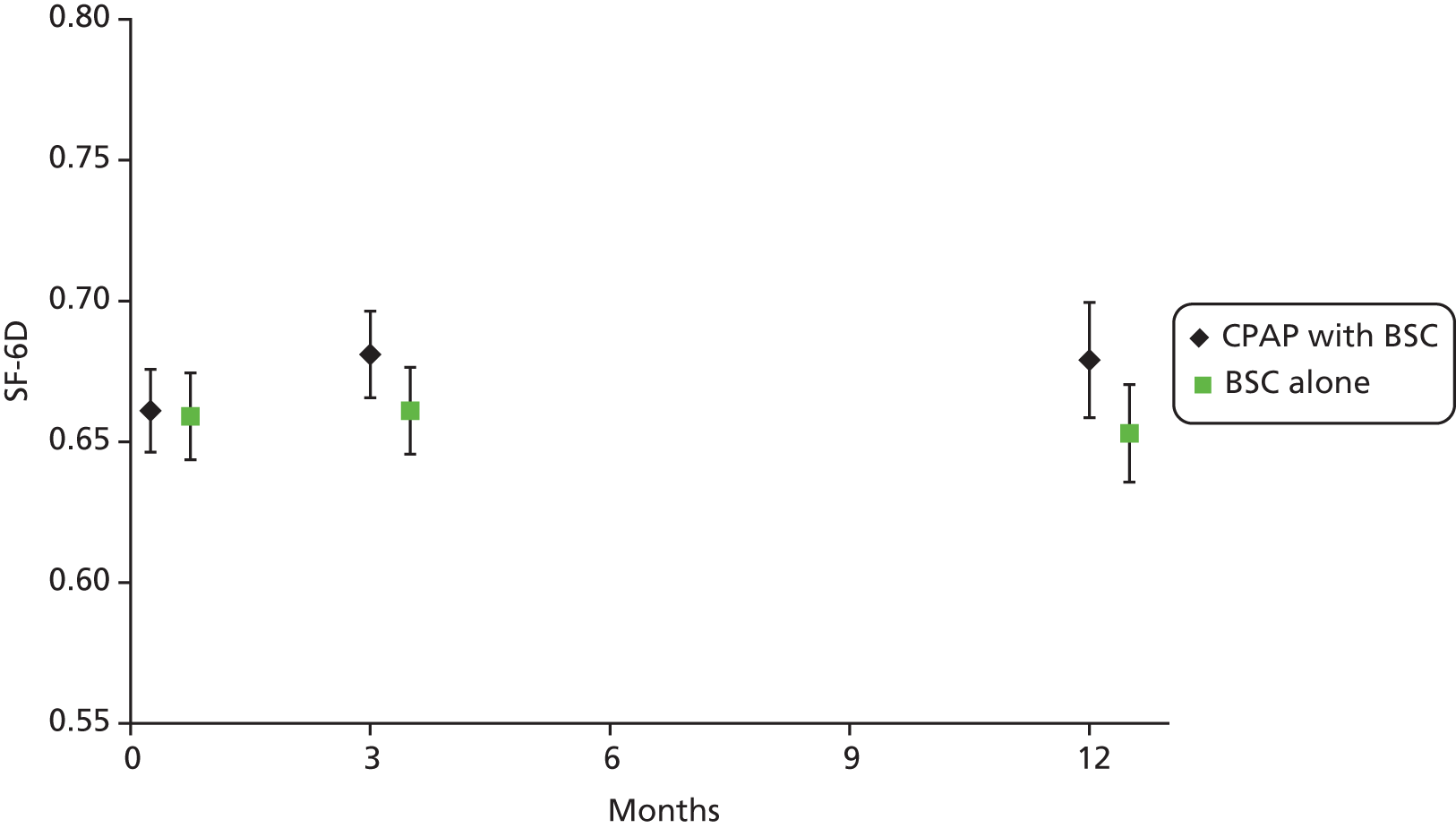

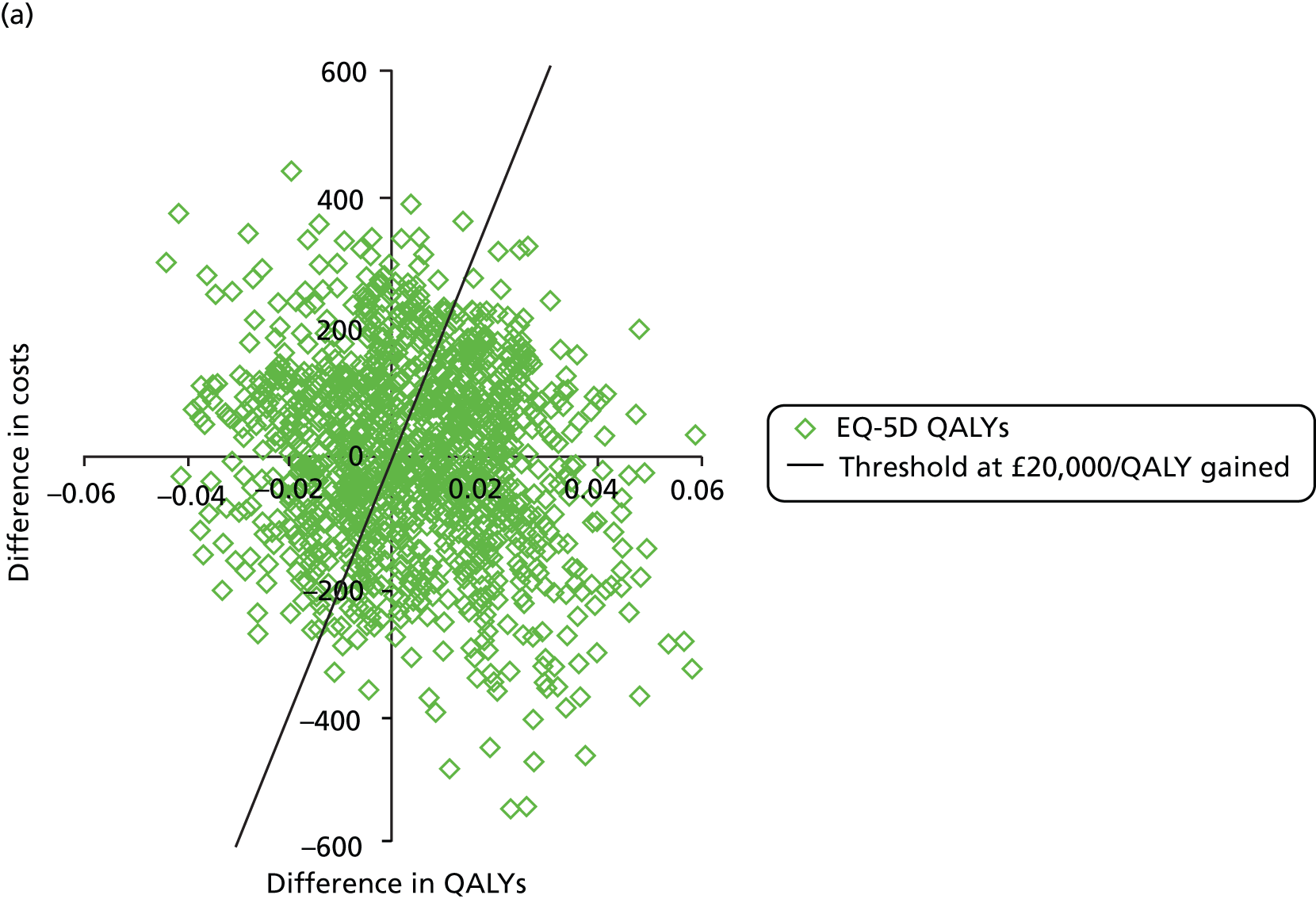

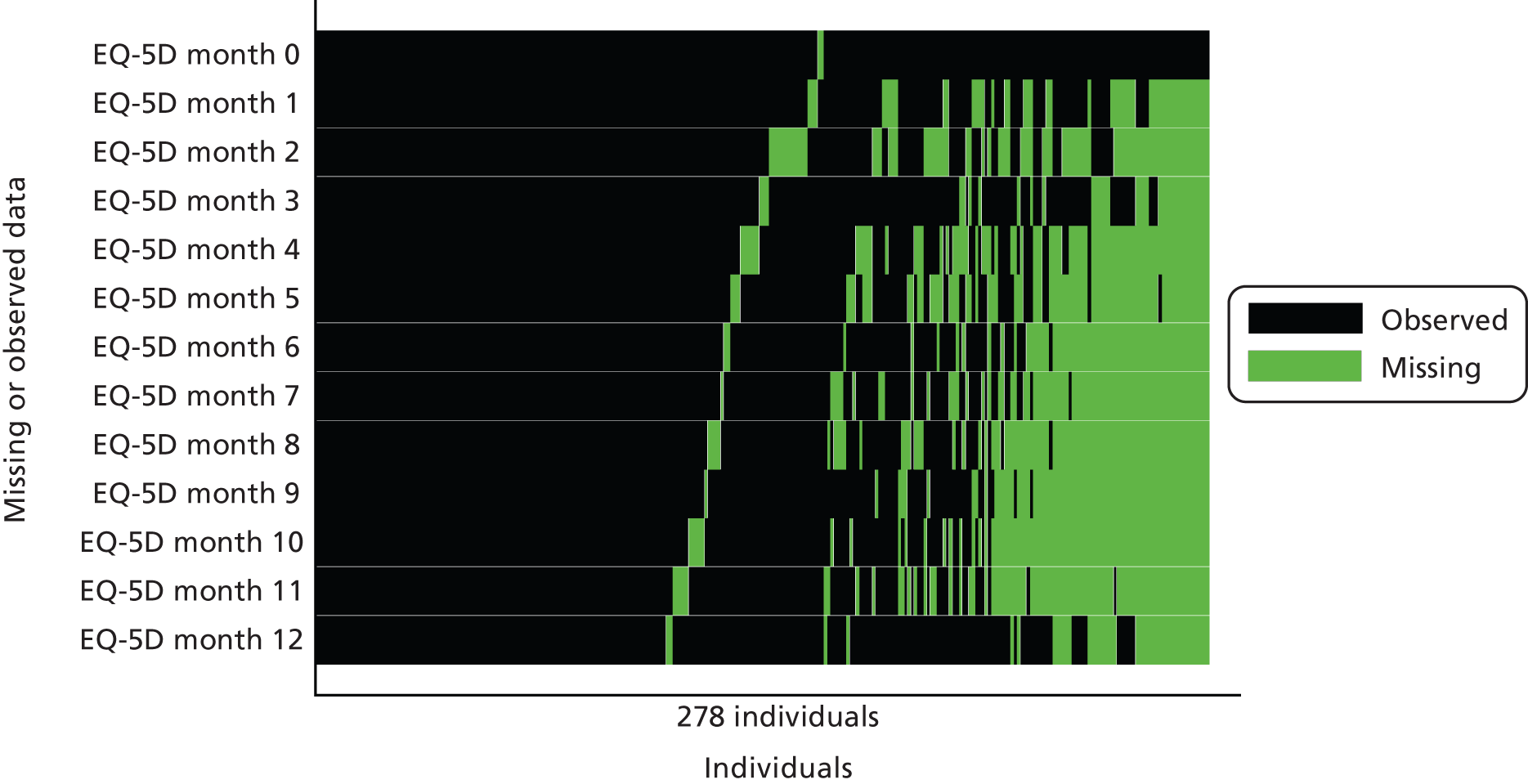

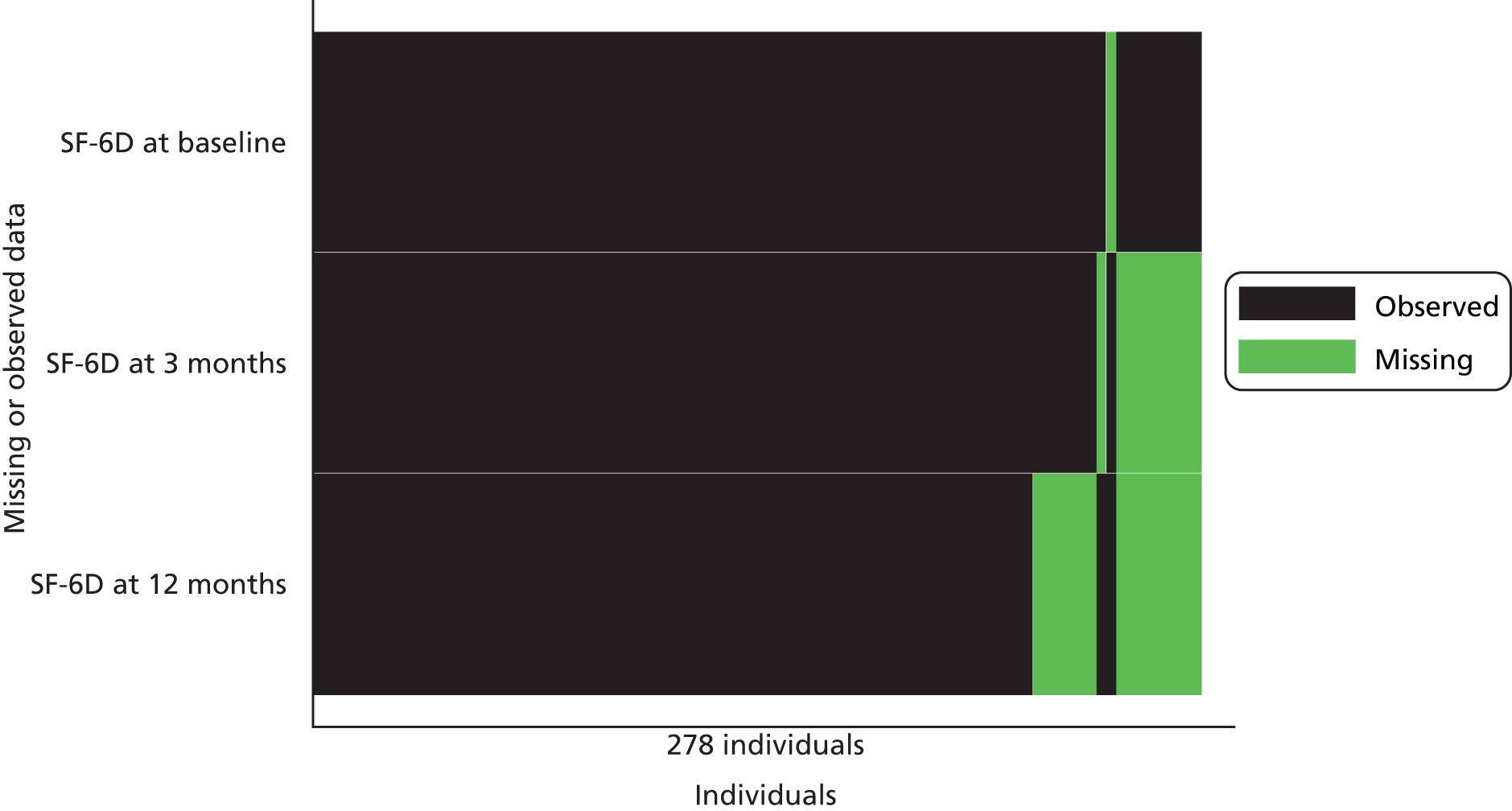

The other coprimary outcome was the cost-effectiveness and estimated health outcomes of providing CPAP plus BSC compared with BSC alone over 12 months. Health outcomes were expressed as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) using the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)98 and Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) derived from the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36)99 as an alternative scenario. Patients reported health-related quality of life (HRQoL) by filling in the EQ-5D questionnaire every month and the SF-36 at baseline, 3 and 12 months. The EQ-5D scores were valued using standard UK tariffs. Health-care resource use was recorded in the monthly diaries completed by the patients. Costs were evaluated in pounds sterling at 2012 prices from the UK NHS perspective. 100 The health economics analysis and results will be discussed in Chapter 4.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes included subjective sleepiness at 12 months, measured by the mean ESS score at months 10, 11 and 12, plus the following outcomes recorded at the 3- and 12-month assessments:

-

Objective sleepiness. This was measured by the Oxford Sleep Resistance (OSLER) test. The test measures the patient’s ability to resist sleep for up to 40 minutes. 101

-

Generic quality of life. This was assessed by the SF-36 questionnaires, which consist of 36 quality of life-related questions. Answers to questions are condensed into eight summary scores, which are further condensed into a mental component summary scale (MCS) score and a physical component summary scale (PCS) score. 102

-

Disease-specific quality of life. This was assessed using the Sleep Apnoea Quality of Life Index (SAQLI), a sleep apnoea questionnaire which included CPAP side effects. 103

-

Mood. This was assessed using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), a questionnaire with 14 questions, seven on each aspect. 104

-

Functionality. This was assessed by the Townsend Disability Scale (TDS), a nine-item questionnaire scored on a scale from 0 to 2 for each question (total 18). 105

-

Nocturia. The patients were asked if they had to pass urine and how many times per night on average.

-

Mobility. This was measured using the Timed Up and Go (TUG) test. This is the time taken in seconds to stand up from an armchair, walk 3 metres, turn, walk back to the chair and sit down. 106

-

Domestic accidents and RTAs. Domestic accidents were recorded in the case report forms (CRFs) and driving accidents were self-reported confidentially at each assessment.

-

Cognitive function was assessed using the following four tests:

-

Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE): a widely used screening tool that provides a measure of orientation, registration (immediate memory), short-term memory (but not long-term memory) and language functioning. It is scored out of 30; scores of 25–30 are considered normal. 107

-

Trail Making Test Part B (TMT–B): this gives information on visual search, scanning, speed of processing, mental flexibility and executive functions. It requires individuals to draw a line sequentially connecting 25 encircled numbers and letters on a piece of paper alternating between numbers and letters (e.g. 1, A, 2, B, 3, C, etc.). The score represents the amount of time required to complete the task, and performance decreases with increasing age and lower levels of education. 108

-

Digit Symbol Substitution (DSS) test: a coding exercise. At the top of a piece of paper is a code; each symbol in the code corresponds to a single-digit number. The individual is required to copy the code under rows of random numbers and complete as many as possible in 90 seconds. The score is the total number of correct answers completed in this time. 108

-

Simple and four-choice reaction time: a two-part test. The first part measures the time to react to a symbol appearing in a white box on a computer screen by pressing any button on a computer keyboard. The second part requires the individual to respond to the symbol appearing in any one of four white boxes at random. They have to respond using the allocated key on the keyboard, and the numbers of correct responses and errors are recorded.

-

-

Cardiovascular risk factors. These included systolic and diastolic office BP, fasting glucose, lipids and glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c).

-

New cardiovascular events. These included angina, newly diagnosed hypertension, atrial fibrillation, myocardial infarction (MI), heart failure, diabetes, stroke, transient ischaemic attack and peripheral vascular disease.

Tertiary outcomes

Treatment compliance was measured objectively by downloading data from a smart card located in the CPAP machine at the 3- and 12-month visits. The output was in a standardised, commercially available, format provided by the manufacturers of the CPAP machines. It contained data on hours and days used, pressure provided and estimated leaks. CPAP usage was recorded as the total hours used, divided by the numbers of days between the initiation of CPAP and the date of the 3- or 12-months visit. Non-users were defined as those who admitted to stopping CPAP therapy, had returned their machines or had no recorded usage data at their visits or who did not use CPAP at all in the month prior to their scheduled follow-up. Hours of usage was set to 0 hours per night in those with missing data and those who had subsequently stopped treatment.

Data collection and monitoring

Data generated by all centres were collected on CRFs, which were posted to the Oxford Respiratory Trials Unit (ORTU), the trial data co-ordinating centre, where they were entered on to a database that was created and maintained by the Medical Research Council Clinical Trials Unit (MRC CTU). The staff entering the data into the database had no part in the data collection, analysis or interpretation. All patients’ trial consent forms were reviewed and a 100% automated check was conducted for the ESS inclusion criteria. Automated data checks for consistency and date were completed for all CRFs. Data were also checked for inconsistencies in range and missing data. Missing or ambiguous data were queried with individual research nurses and resolved whenever possible. Quality control of CRF data entry was completed on a regular basis throughout the duration of the trial. Site initiation visits were organised for all sites prior to commencing recruitment and were conducted by the chief investigator, trial manager and clinical research fellow. Interim monitoring visits were completed for five centres and source data verification was completed during those visits. Eleven close-out visits were completed remotely and four centres were visited. All adverse events were reviewed by the Independent Data Monitoring Committee (IDMC).

Randomisation

Patients were randomised using a telephone computerised service provided by the MRC CTU. Allocation was physically carried out during working hours from Monday to Friday. The allocation group was indicated to the unblinded research nurse once the baseline data collection was completed.

The randomisation programme was created by the MRC CTU in accordance with its standard operating procedure and held on a secure server, access to which was confined to the CTU data manager. Allocation was on a 1 : 1 basis with a random element of 80% and stratified by disease severity (enrolment ESS score of > 13 vs. ≤ 13), functionality using the TDS score of > 1 versus ≤ 1 and recruitment centre. In the analysis, baseline ESS scores and TDS scores were entered into models as fixed-effects continuous variables. Recruiting centre was adjusted for using random effects in order to avoid dropping centres that may recruit only a single patient.

Blinding

As this was a physical device trial, the treatment allocation for the individual patients could not be concealed, although the treatment allocation could be concealed from a member of the research team completing follow-up assessments. Each centre was asked to identify a member of the research team who could be the blinded researcher and remain blinded to the treatment allocation throughout the trial. The CRFs were designed to collect blinded and unblinded data separately. Patients were discouraged from discussing their treatment allocation with the blinded research staff and the importance of maintaining blinding was highlighted in the patient information sheets (PISs). It was not possible to blind all trial staff, although the assessments were done blind wherever possible.

The trial manager and trial support staff at the co-ordinating centres in Oxford and London did not have contact with the patients. The trial statisticians analysed the results based on a treatment code, using an analysis plan that had been finalised prior to locking the database and prior to the blinded data analysis. Patients continued to see other health-care professionals unrelated to the trial for their usual medical care.

Sample size

The primary analysis was the difference between the two treatment groups in the mean change of ESS score from baseline to 3 months. The ESS is a scale from 0 to 24 and a 1-point change on the ESS is indicative of a shift in the symptom state in one domain which was considered to be the minimally clinically important difference. In the recent NICE/HTA appraisal of CPAP for OSAS in middle-aged patients,20 the effect of CPAP treatment on the difference in ESS score in middle-aged patients with mild OSA was –1.07 [standard deviation (SD) 2.4]. The inclusion criterion for this trial was in the range of moderate OSAS severity, but, since sleepiness may be less pronounced in older people, the power calculations were performed assuming a treatment response similar to that seen in mild OSAS in middle-aged patients. To detect a 1-point change in ESS score (SD of change 2.4) required 244 patients randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio with a 90% power at the two-sided 5% significance level. In shorter (less than 6 months’ duration) randomised trials with a similar design, the loss to follow-up rate was approximately 5%. Since PREDICT was of longer duration and undertaken in older people with comorbidity, it was conceivable that the loss to follow-up rate could be up to 10%. Therefore, the sample size for the trial was 270 patients (135 in each group).

Statistical methods

The statistical analysis plan was finalised and approved by the Trial Management Group (TMG). Statistical significance was tested at the 5% level for all analyses. All analyses were adjusted for the minimisation factors (enrolment ESS score of > 13 vs. ≤ 13, functionality using the TDS of > 1 vs. ≤ 1 and recruitment centre) to optimise power and reduce bias. In addition to the minimisation factors, age, sex, ODI and body mass index (BMI) were also adjusted for in an additional analysis of the primary outcome. All analyses were by intention to treat, incorporating all randomised patients who had complete data on the outcome of interest (complete-case analysis). No adjustments for multiple testing were made, but the statistical significance of the secondary outcomes was interpreted cautiously because of the large number of secondary analyses performed.

A secondary sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome was performed in order to establish proof of principle whereby patients who swapped from the BSC group to CPAP were excluded from the analysis. The effect of baseline ESS score, age, ODI and BMI and the effect of CPAP use on the primary outcome were also investigated.

All analyses and modelling were undertaken in Stata version 12.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Descriptive statistics

All baseline data were summarised by treatment groups. Only descriptive statistics were utilised; no formal statistical comparisons were undertaken, since any differences should be the result of chance rather than bias. Categorical variables were summarised by number (n) and percentage (%) and continuous variables were summarised by mean, SD or median, 25th and 75th percentiles as appropriate.

Coprimary outcomes analysis

Subjective sleepiness

Subjective sleepiness was assessed using the ESS. The mean of the 3- and 4-month ESS score was calculated for each patient and compared with baseline. The ESS score is the sum of its eight components and, therefore, if one of the components was missing, the ESS score was set to missing. If any non-integer values were given these were included in the sum and the final ESS score rounded up or down to the next integer. Any scores obtained outside the pre-specified window of 2 to 5 months after randomisation were excluded. If either the 3- or the 4-month score was missing, the single observed score was used. If both scores were missing or outside the required time frame, the patient was excluded from the primary analysis. The difference between the randomisation ESS score and follow-up ESS score was calculated for each patient and compared between groups using a multivariable linear regression model. The analysis was adjusted for the minimisation factors as outlined previously.

Cost-effectiveness

The cost-effectiveness analysis took the perspective of the UK NHS over a time horizon of 12 months. Health outcomes were expressed in QALYs using EQ-5D and SF-6D. The analysis incorporated health-care utilisation, including inpatient and outpatient hospital visits and general practitioner (GP) visits during the trial. The cost-effectiveness analysis will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 4.

Secondary outcome analyses

Subjective sleepiness at 12 months: the mean ESS score at 10, 11 and 12 months was calculated for each patient and was taken to be the 12 month score. The same principles described for primary analysis were used for calculating the mean ESS score at 12 months. The difference between the two groups in the change in subjective sleepiness at 12 months compared with baseline was analysed using a multivariable linear regression model adjusting for the minimisation factors as outlined previously.

In addition, the changes from baseline were compared at 3 and 12 months for the following outcomes between treatment groups.

Objective sleepiness

Objective sleepiness was measured by the OSLER test. Two tests were conducted at each visit (baseline, 3 months and 12 months) and the average time taken to fall asleep at each visit was used for the analysis. Kaplan–Meier plots were used to summarise the mean time taken to fall asleep (the event of interest) at baseline, 3 months and 12 months with log-rank tests used to compare survival curves. The change from baseline in the mean time taken to fall asleep at each follow-up visit was compared between treatment groups.

Generic quality of life

Generic quality of life was assessed by the SF-36. The MCS and PCS scores were calculated. If any of the 36 questions were not answered, the MCS and PCS were set to missing along with any of the eight summary scores dependent on the missing answers.

Disease-specific quality of life

Disease-specific quality of life was assessed by the SAQLI. The score is the average of 14 sleep-related questions and, if applicable, adjusted for side effects attributable to CPAP. If any of the answers were missing, the SAQLI was also set to missing.

Mood

Mood was assessed by the HADS. The anxiety and depression summary components of the score were reported. If any of the answers were missing the relevant summary component was also set to missing.

Functionality

Functionality was assessed by the TDS. Each of the nine items of the TDS is scored 0 (yes, with no difficulty), 1 (yes, with some difficulty) or 2 (no, need help). Items are then summed to give a total score out of 18. 109 If at least one of the components was missing, the TDI was also set to missing.

Nocturia

Nocturia was assessed by the self-reported average number of times that patients get up to pass urine at night.

Mobility

Mobility was assessed by the TUG test and was measured in seconds. There is no upper time limit and the time in seconds is rounded up or down to a whole second.

The number of road and domestic accidents

The proportion of patients experiencing any accidents was analysed adjusting accident history at baseline (whether or not they had an accident at home in the month before enrolment or while driving in the 3 months before enrolment).

Cognitive function

Cogitative function was assessed using the MMSE, TMT–B, the DSS test and the simple and four-choice reaction time test. The change in the score for each of the four tests was analysed.

Cardiovascular risk factors

Cardiovascular risk factors were assessed using systolic and diastolic BPs, fasting glucose, fasting lipids and HbA1c.

New adverse cardiovascular events

These were assessed as the proportion of patients reporting any new adverse cardiovascular event at the 3- and 12-month assessment. The analysis was adjusted for the proportion of patients with any cardiovascular event at baseline.

The continuous outcomes (SF-36, SAQLI, HADS, TDS, cognitive function tests, cardiovascular risk factors, mobility test and frequency of nocturia) were analysed using multivariable regression models and adjusted for their corresponding baseline score/measurement and the minimisation factors. Non-normal (skewed) data were not an issue and could be analysed using this method because of the implications of the central limit theorem that for a large sample size the mean will be approximately normally distributed.

For binary outcomes (accident and adverse cardiovascular events) the odds of experiencing the outcome were compared between treatment groups using logistic regression. All analyses were adjusted for the minimisation factors.

Tertiary outcomes analyses

Continuous positive airway pressure usage was taken to be the mean number of hours that CPAP was used per night during follow-up (total number of hours used divided by total number of days’ follow-up). CPAP use was summarised using the median and 25th and 75th percentiles. Patients who had stopped CPAP during follow-up and were missing adherence data were assumed to have 0 hours/night usage. The number of patients stopping CPAP or swapping to CPAP from BSC was summarised along with reasons at the 3- and 12-month time points.

Sensitivity analyses

Patients who were randomised to BSC alone and who subsequently started CPAP therapy during the follow-up potentially dilute the results of the ESS score comparisons. Sensitivity analyses of the primary and secondary ESS score outcomes were performed in which BSC patients who swapped to CPAP were excluded from the analysis if CPAP therapy had been started before the visit at which the observation was recorded.

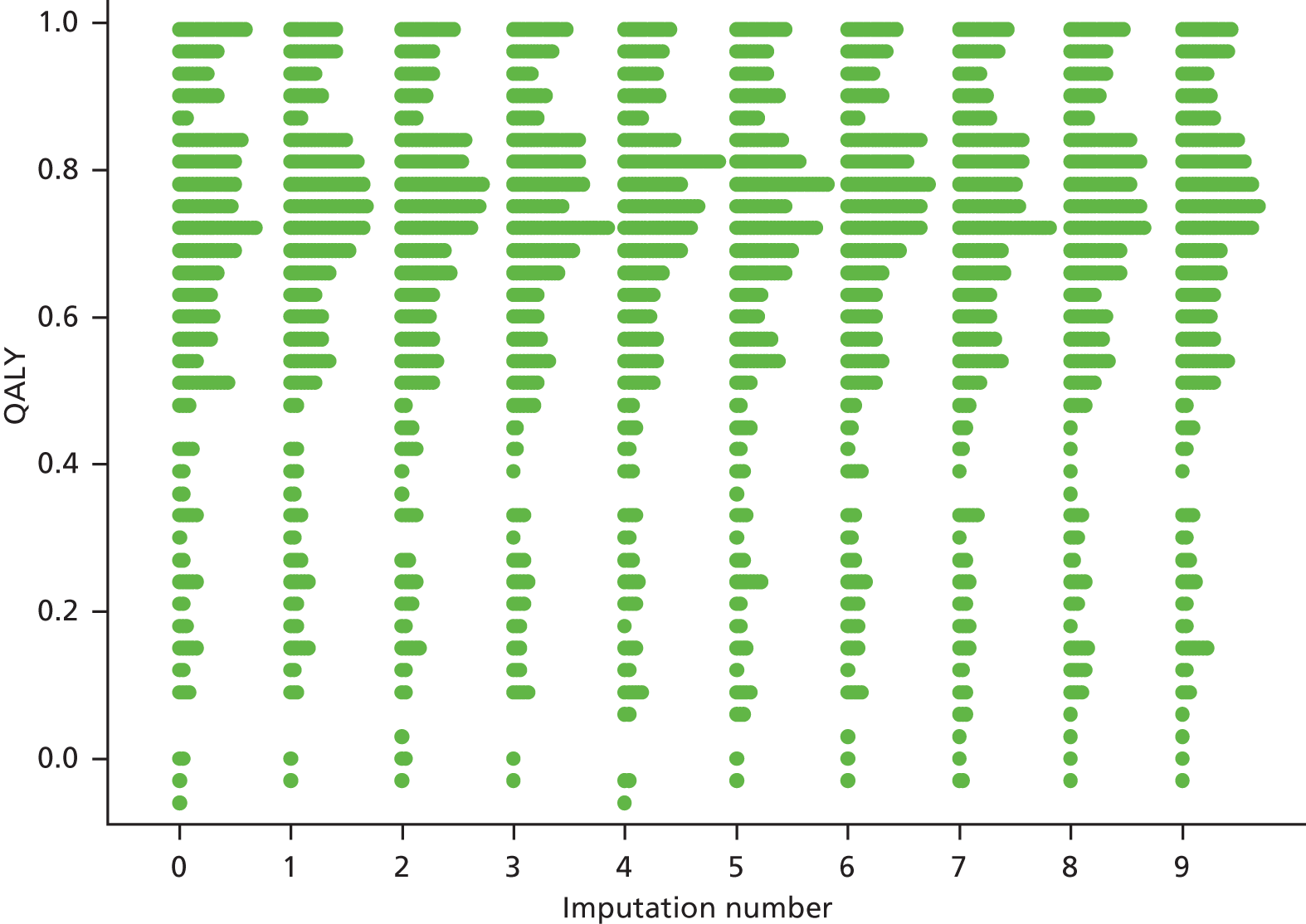

Multiple imputation analyses

Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to impute missing ESS scores over follow-up and produce an unbiased analysis under a missing at random assumption. Missing at random assumes that the probability of missing data depends only on the values of the observed data and not on the values of the missing data. The plausibility of the missing at random assumption was explored by comparing observed data in those patients with and without the outcome of interest.

All 12 ESS follow-up scores were entered into an imputation model along with the minimisation variables and the previously listed covariates (age, sex, ODI and BMI). Imputations were performed separately within treatment groups. CPAP compliance at the 3- and 12-month visits were also included in the imputation model for the CPAP group. For each treatment group, 50 imputation models were created using the ‘ice’ command in Stata. In analyses secondary to those described previously, the primary and secondary ESS score outcomes were reanalysed on the imputed data sets and the results combined using Rubin’s rules.

The missing at random assumption is untestable and may be inappropriate; therefore, the probability that ‘missing data could depend on values of the missing data’ (missing not at random) was considered. The ESS score outcomes were reanalysed on all randomised individuals under a range of ‘missing not at random’ scenarios. The aim of this technique was to determine how sensitive the observed results were to different assumptions on the unobserved outcomes in the two groups.

Exploratory analyses

Effect of continuous positive airway pressure adherence on the Epworth Sleepiness Scale score

Patients who were randomised to the CPAP group were split into tertiles by their average CPAP use in the last month of follow-up prior to the 3-month visit. Each group was compared with the BSC group in a single model on the change in the primary ESS score outcome. The minimisation variables were adjusted and a global test was used to determine whether or not the treatment effect in each of the three CPAP groups differed. A similar analysis was conducted on the secondary ESS score outcome at 12 months, splitting patients into tertiles by their average CPAP use in the last 3 months of follow-up before the 12-month visit. The effect of CPAP usage on ESS score at each time point was also modelled using multivariable fractional polynomial (FP) models110 adjusting for the minimisation variables. Since the BSC group had no compliance data, the mean change in ESS score in this group was displayed on a FP plot.

Interaction analyses

The variation of the effect of CPAP therapy compared with BSC on the primary ESS score outcome was investigated over age, BMI, ODI and ESS score at baseline. FPs were used to model the interaction between the treatment effect and each covariate, using either one or two FP transformations of the covariate of interest, whichever had the lower Akaike information criterion. 110 The minimisation variables were also adjusted for in each model with continuous variables centred about their mean. A continuous plot of the treatment effect over the original, untransformed baseline covariate was then produced with 95% confidence interval (CI). To check the plausibility of the interaction curve, the covariate was categorised at its quartiles and the treatment effect in each subgroup was estimated. These treatment effects were then plotted against the subgroup means over the continuous plot. Consistency between the results of the two analyses increases the plausibility and evidence of any treatment interaction. Disagreement between the two models may be an indicator of an erroneous FP model or a type I error of the FP approach, in which case the results of the subgroup analysis were interpreted with caution.

Analysis of monthly diaries

A longitudinal analysis of the effect of CPAP compared with BSC over the whole follow-up period was performed using the ESS scores from the monthly diaries. A multilevel model for repeated measures was used with ESS score as the response variable and patient- and month-specific random effects. A treatment-by-month interaction was added to the model to test whether or not the effect of CPAP varied over the course of follow-up. This model makes the assumption that all trial visits and monthly diaries are completed on the expected dates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used. Month was treated as a categorical variable. From the model a plot of the treatment effect and its 95% CI at each month was constructed.

Summary of changes to the protocol

The changes to the trial documents following National Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval in October 2009 are summarised below; a copy of the Statistical and health economic analysis plans is given in Appendix 1.

-

Substantial amendment SA01 (approved by the REC on 4 November 2009). Changed the version number of the PIS mentioned in the consent form to match the PIS version 2.0 already approved.

-

Substantial amendment SA02 (approved by the REC on 2 December 2009). Changed contact details, updated staff details, minor editing and formatting of the sleep diaries and added information regarding data transfer in the PIS. Clarified which ESS score measurements would be used in the analysis, quantified what was meant by a clinical diagnosis of OSAS, corrected a mistake in one of the exclusion criteria, added sections explaining the blinding in more detail and the delivery of CPAP/service provision and clarified the procedure for returning the driving questionnaire.

-

Substantial amendment SA03 (approved by the REC on 10 May 2010). Updated staff/committee details, minor editing and administrative changes. Further information added to the PIS. Standard letters inviting patients to attend their 3- and 12-month visits were introduced at the request of the participating centres. The sleep diaries were updated and information regarding Sibutramine was removed from the BSC booklet. Clarifications were required for the blinding procedure, one of the exclusion criterion, the minimisation criteria, the trial treatment, loss to follow-up and the procedure for assessing safety, quality control and adverse events section.

-

Non-substantial amendment NA04 (acknowledged by the REC on 14 May 2010). One of the minimisation criterion had been changed in error and was corrected.

-

Substantial amendment SA05 (approved by the REC on 24 February 2011). Updated staff/committee membership and contact details. Clarified that the results of the Embletta test done prior to trial enrolment were acceptable as long as they were done not more than 3 months before randomisation. Amended the coenrolment guidelines and listed the blood tests. Updated the monitoring, amendments and safety-reporting section so that it referred to a device trial rather than an investigational medicinal product trial.

-

Substantial amendment SA06 (approved by the REC on 20 June 2011). Clarified the primary and secondary outcomes, selection of centres and patients and treatment data collection. Updated the follow-up section. Corrected the sample size calculation and added information regarding the role of the IDMC and TMG.

-

Substantial amendment SA07 (approved by the REC on 8 June 2012). Clarification of how the cardiovascular risk is measured, the ESS score calculations and the analysis plan. Corrections of the statistical calculations, update of the trial manager’s details and administrative corrections.

All amendments were implemented prior to breaking of the treatment allocation code and prior to finalising the analysis plan.

Trial conduct

Trial organisation

The trial was managed and co-ordinated from the National Heart and Lung Institute, Imperial College London, Royal Brompton Hospital, London, UK (Professor Mary Morrell and Dr Alison McMillan) and the ORTU (Magda Laskawiec-Szkonter). The ORTU was also responsible for data collection and management. Statistical analysis was overseen by Professor Andrew Nunn and Daniel Bratton and conducted at the MRC CTU in London.

The Trial Steering Committee (TSC) carried overall responsibility for the safe delivery of the trial. It initially met every 6 months until it was satisfied that trial recruitment was achievable, and thereafter it met annually to provide overall supervision of the trial. The TMG was responsible for the management of the trial and met frequently. An IDMC was also appointed. Memberships of the TMG, TSC and IDMC are listed at the end of the report. A full list of the PREDICT investigators is included in Appendix 2.

Patient involvement

Two patient representatives participated in the PREDICT management; in particular, Mr Frank Govan from Oxford acted as the patient representative. He attended the TSC meetings and his feedback was very helpful in progressing the trial. For example, he raised awareness of the study to the Sleep Apnoea Trust Association, which in turn, publicised the study with their members. The protocol was discussed with Sleep Apnoea Trust Association members at their annual meeting in 2012, and we were invited to present the results at their 2014 meeting (www.sleep-apnoea-trust.org/user/image/sm52.pdf).

Members of the Welsh Sleep Apnoea Society have also supported the PREDICT study by providing publicity for the trial. In 2011, Professor Morrell was made an honorary member of the society in recognition of the research that the team was carrying out (www.welshsas.org).

Mr Govan and other patients regularly discussed the rigours of participating in research studies with the TMG. These comments have been taken into account in designing subsequent trails. Mr Govern also voted at TSC meetings, and his independent views were sought when discussing topics such as opening new trial sites, through to trial authorship.

The patients who participated in PREDICT from the London centre were invited to an annual patient and public involvement event at the Royal Brompton Hospital (once their direct involvement in the trial was over) to provide feedback on their experiences. This feedback was collated and has been used to improve the study facilities at the site, as well as trial logistics, for example increased time for travel between sites.

Trial finances

Positive Airway Pressure in Older People: a randomised controlled trial was funded by the UK NIHR HTA (project number 08/56/02). Subcontracts were established between Imperial College London, ORTU, York University or Edinburgh University and each of the recruitment centres. Trial patients’ travel expenses were paid.

Trial insurance and indemnity

The usual NHS indemnity arrangements for negligent harm were applied to the trial. Imperial College London acted as sponsor for the trial and had third-party liability insurance in accordance with all local legal requirements. The CPAP machines in the trial were covered by product warranty.

Working with industry

Continuous positive airway pressure is delivered by a specialised but widely used medical device otherwise known as a CPAP machine. For a detailed description of the type of CPAP machine used see Continuous positive airway pressure. The CPAP machine and associated equipment (masks, tubing, filters and humidification units) were supplied by ResMed (UK) Ltd, which also provided on loan the sleep diagnostic equipment (Embletta GOLD). The consumables were purchased. At the start of the trial, ResMed (UK) Ltd provided information regarding the logistics of ordering and delivering equipment to multiple centres but it had no involvement in the trial design, data collection, analysis or interpretation. At the end of the trial, ResMed (UK) provided a small financial contribution to a second joint research study day (and a trial investigators meeting), which helped cover the cost of venue hire.

At the end of the trial, any unused CPAP machines or loaned equipment were purchased or returned to ResMed (UK) Ltd. Any patients established on the autotitrating CPAP who wished to continue using it were allowed to keep the machine as a goodwill gesture from ResMed (UK) Ltd.

Positive Airway Pressure in Older People: a randomised controlled trial offers numerous examples of good practice in the industry, in which the needs of the trial are put foremost. During the first 6 months of the trial, the number of failed home respiratory polygraphy sleep studies (performed on the Embletta GOLD equipment) was higher than expected. This issue was addressed with the help of the industry and in collaborative meetings with staff at the co-ordinating centres. It became apparent there had been a technical problem in the equipment that was supplied for use in the trial. This was identified quickly and addressed by ResMed (UK) Ltd, which provided its expertise, operational and delivery infrastructure for free.

The estimated cost saving for the trial by the provision of CPAP machines and associated equipment was £122,896.00. The loan of Embletta GOLD equipment and software was approximately £103,485.00, generating a total cost saving of £226,381.00.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment

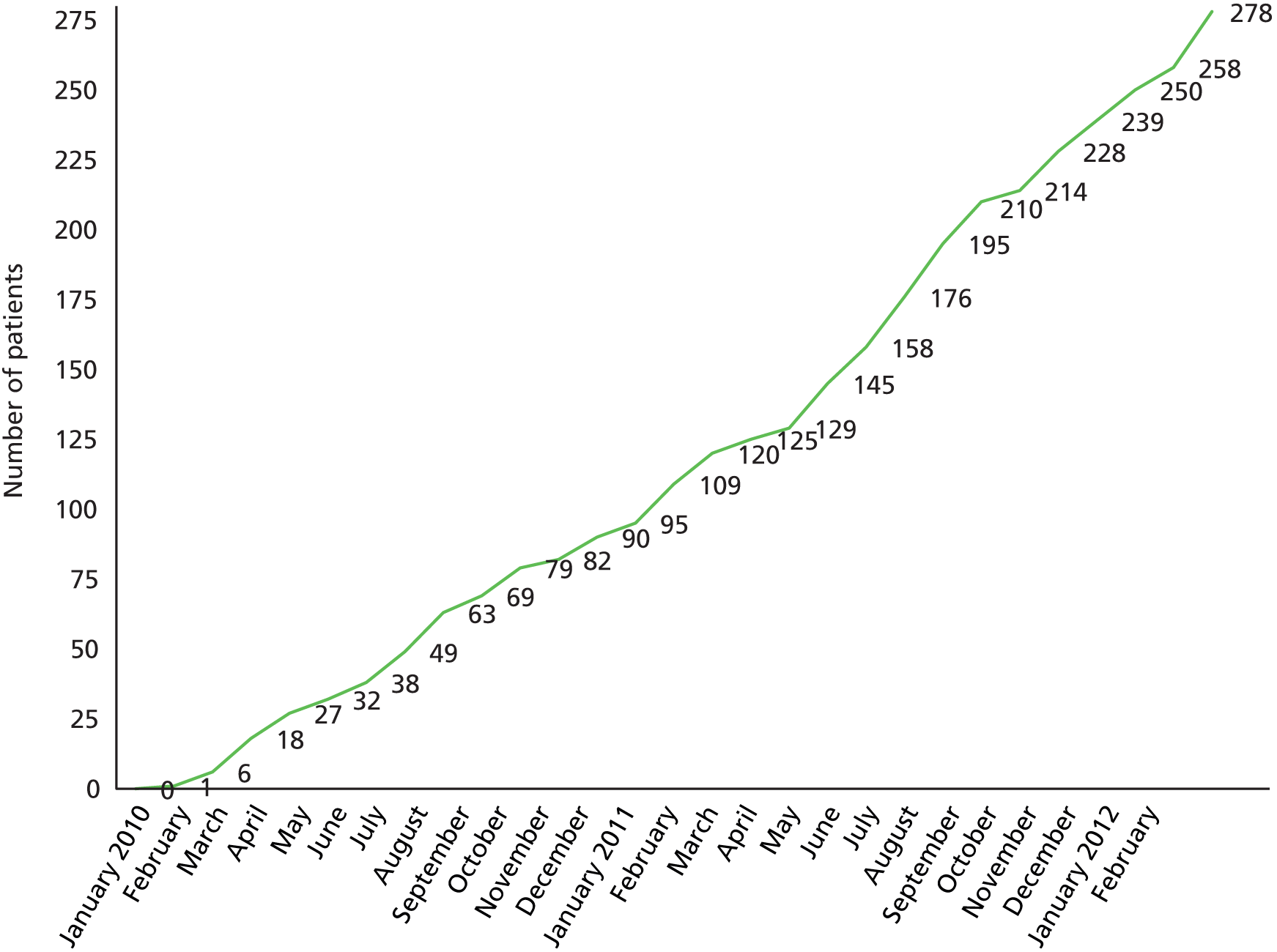

Recruitment took place between February 2010 and May 2012. The overall recruitment rate is shown in Figure 2. All the 12-month visits and trial exit were completed by May 2013. Although the trial was powered for 270 patients, 278 were recruited. This occurred because when approaching the target number a randomisation stop date was announced to coincidence with the end of a calendar month. Eight additional patients had completed their enrolment visit and randomisation prior to the official stop date. The TMG agreed the additional patients should be included.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative recruitment.

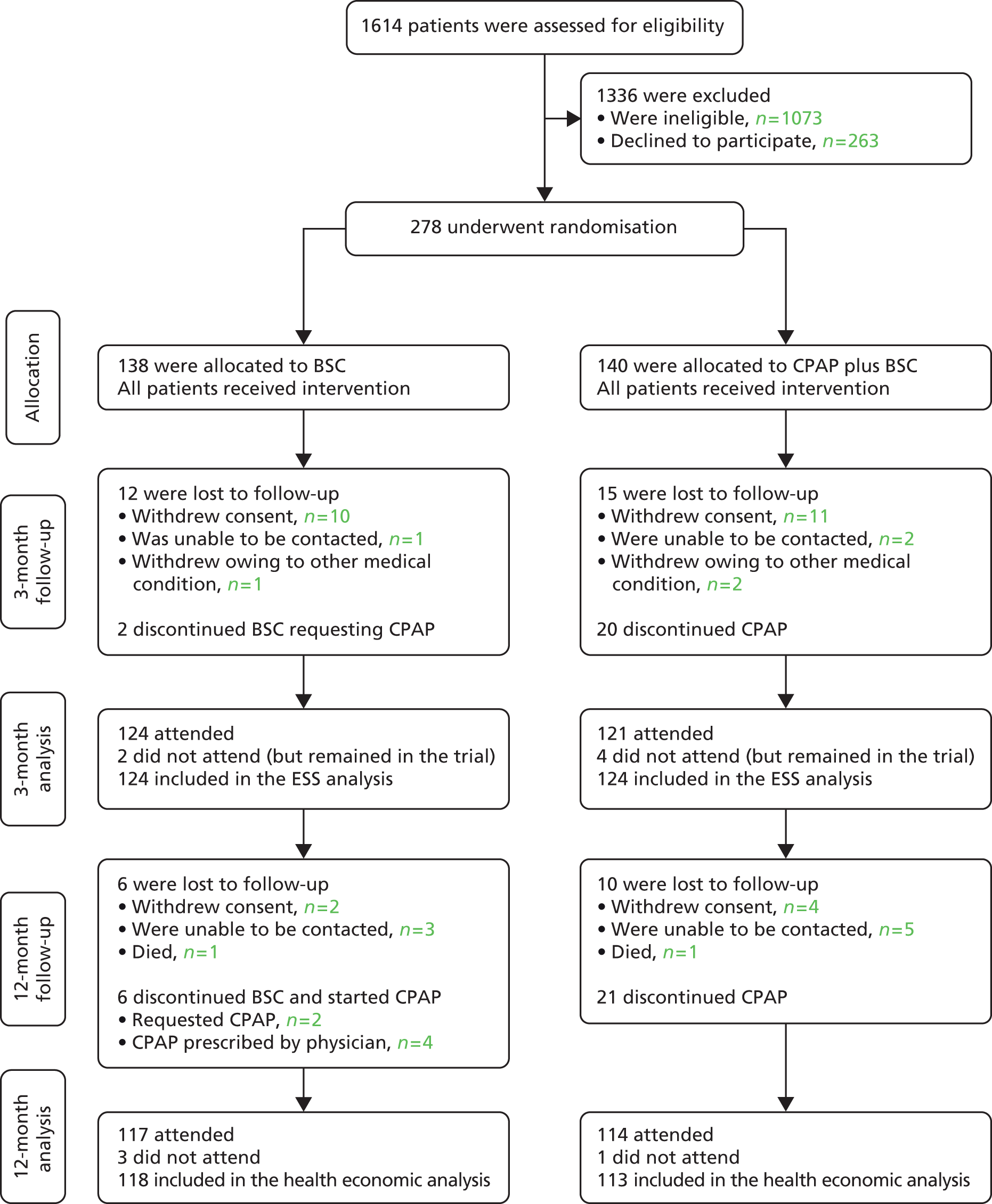

The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram shows the flow of patients through the trial (Figure 3). ‘Withdrew consent’ implies the patients withdrew from the treatment and trial, and ‘discontinued treatment’ implies the patient stopped their allocated treatment but remained in the trial. In total, 1614 individuals were screened as potential patients: of these 541 (34%) were eligible and subsequently 278 (51%) were randomised. 245 (88%) completed their 3-month follow-up and 231 (83%) completed their 12-month follow-up and the trial.

FIGURE 3.

Trial screening, enrolment, randomisation and follow-up.

Data collected on the screening logs enabled the 1073 ineligible patients to be grouped into the following categories:

-

not meeting inclusion ODI or ESS criteria, n = 442 (41%)

-

previous exposure to CPAP, n = 79 (7%)

-

awake oxygen saturations < 90% on air or FEV1/FVC < 60%, n = 171 (16%)

-

being a professional driver, reporting sleepiness while driving, shift work or any severe symptom of OSAS for which the referring physician felt CPAP was mandatory, n = 216 (20%)

-

no information or incomplete data, n = 165 (15%).

Baseline data

In total, 278 patients were randomised; 140 to the CPAP with BSC and 138 to BSC alone. All 278 patients completed the baseline enrolment visit. The majority of patients were male (82%), with a mean age of 70 years, ranging from 65 to 89 years, and had on average moderate OSAS: ESS mean score (SD) of 11.6 (SD 3.7) and ODI 28.7 (SD 19.1) events/hour. The majority of patients were white (96%) and obese and had on average 11 years of education and normal MMSE. A total of 228 (82%) were current drivers, and 146 (53%) slept alone. Baselines demographic are shown in Table 3, clinical characteristics in Table 4, sleep characteristics in Table 5 and sleep measurements in Table 6. None of the baseline data between groups were considered different to any important degree.

| Characteristic or descriptor | BSC | CPAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 138 | 140 | |

| Age (years), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 70.3 (68.0–73.8) | 69.5 (67.1–74.1) | |

| Male sex, n (%) | 109 (79) | 120 (86) | |

| Education (years), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 11 (10–14) | 11 (10–15) | |

| MMSE, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 29 (28–30) | 29 (27–30) | |

| Current drivers, n (%) | 111 (80) | 117 (84) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White | 134 (97) | 133 (95) |

| Asian | 3 (2) | 5 (4) | |

| Other | 1 (1) | 2 (1) | |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 33.6 (6.4) | 33.9 (5.7) | |

| Neck circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 42.6 (4.0) | 44.0 (4.4) | |

| Waist size (cm), mean (SD) | 114.1 (15.5) | 115.3 (13.6) | |

| Hip size (cm), mean (SD) | 115.7 (12.8) | 116.6 (12.1) | |

| Waist-to-hip ratio, mean (SD) | 1.0 (0.1) | 1.0 (0.1) | |

| Smoking status, n (%) | Never | 45 (33) | 42 (30) |

| Ex | 86 (62) | 92 (66) | |

| Current | 7 (5) | 6 (4) | |

| Caffeinated drinks/day, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.6) | |

| Alcoholic drinks/week, median (25th–75th percentiles) | Beer (pints) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2.3) |

| Wine (glasses) | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | |

| Spirits (measure) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | |

| Exercise frequency (defined as lasting over 10 minutes), n (%) | 5–7 times/week | 67 (49) | 69 (49) |

| 2–4 times/week | 37 (27) | 37 (26) | |

| Once/week | 9 (7) | 10 (7) | |

| < once/week | 5 (4) | 8 (6) | |

| None | 19 (14) | 16 (11) | |

| Characteristic | BSC | CPAP |

|---|---|---|

| n | 138 | 140 |

| Asthma/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 34 (25) | 31 (22) |

| Other chronic lung diseases, n (%) | 13 (9) | 9 (6) |

| Ischaemic heart disease, n (%) | 49 (36) | 42 (30) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 104 (75) | 98 (70) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 43 (31) | 40 (29) |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 32 (23) | 26 (19) |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 41 (30) | 28 (20) |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 11 (8) | 7 (5) |

| Cerebral vascular disease, n (%) | 19 (14) | 16 (11) |

| Systolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 140.4 (20.0) | 137.7 (17.7) |

| Diastolic BP (mmHg), mean (SD) | 77.6 (12.4) | 77.7 (10.2) |

| FEV1, % predicted, mean (SD) | 84.5 (19.9) | 86.5 (19.4) |

| FVC, % predicted, mean (SD) | 5.1 (2.7) | 5.2 (2.6) |

| FEV1/FVC, mean (SD) | 83.6 (13.4) | 82.4 (12.8) |

| Nocturia (no. of times/night), mean (SD) | 2.1 (1.3) | 1.9 (1.3) |

| Incontinent overnight, n (%) | 8 (6) | 10 (7) |

| TDS, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 2.5 (1–7) | 2.5 (1–5) |

| Characteristic | BSC | CPAP | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 138 | 140 | |

| ESS score, mean (SD) | 11.6 (3.9) | 11.6 (3.4) | |

| OSLER (minutes), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 20.3 (9.4–37.5) | 22.4 (13.3–40.0) | |

| SAQLI, mean (SD) | 4.7 (1.2) | 4.8 (1.2) | |

| Self-reported sleep duration (hours), mean (SD) | 8.7 (1.4) | 8.5 (1.4) | |

| Sleep alone, n (%) | 71 (51) | 75 (54) | |

| Daytime nap, n (%) | 104 (75) | 107 (76) | |

| Number of naps/week, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 7 (3–7) | 7 (3–7) | |

| Duration of each nap (minutes), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 38 (25–60) | 30 (15–60) | |

| Snoring, n (%) | Yes | 127 (92) | 127 (91) |

| No | 7 (5) | 8 (6) | |

| Unknown | 4 (3) | 5 (4) | |

| Nocturnal choking, n (%) | Yes | 67 (49) | 68 (49) |

| No | 62 (45) | 55 (39) | |

| Unknown | 9 (7) | 17 (12) | |

| Witnessed apnoea, n (%) | Yes | 97 (70) | 105 (75) |

| No | 25 (18) | 19 (14) | |

| Unknown | 16 (12) | 16 (11) | |

| Measurements | BSC | CPAP |

|---|---|---|

| n | 138 | 140 |

| Time in bed (hours), mean (SD) | 8.7 (1.4) | 8.5 (1.4) |

| Apnoea Index (events/hour in bed), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 7.4 (2.7–17.3) | 7.1 (1.7–17.4) |

| Obstructive, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 6.5 (1.9–15.7) | 6.0 (1.4–15.5) |

| Central, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 0 (0–0.1) | 0 (0–0) |

| Mixed, median (25th–75th percentiles) | 0 (0–0.5) | 0 (0–0.2) |

| Hypopnea index (per hour in bed), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 18.6 (12.4–25.7) | 17.8 (11.6–28.4) |

| Total (per hour in bed), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 29.4 (18.9–46.0) | 28.1 (16.3–47.7) |

| Mean overnight O2 saturation (%), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 92.6 (90.9–93.7) | 92.6 (91.0–93.7) |

| Lowest O2 saturation (%), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 79 (73–83) | 79 (73–83) |

| Average desaturation (%), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 6.3 (5.3–7.5) | 6.3 (5.4–7.8) |

| Saturation < 90% (% of total sleep time), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 8.8 (3.3–26.3) | 8.6 (2.8–26.7) |

| ODI (> 4% events/hour), median (25th–75th percentiles) | 24.4 (15.2–39.2) | 28.1 (13.3–46.0) |

Coprimary outcomes

Subjective sleepiness

The primary outcome, the change in subjective sleepiness between groups at 3 months, is shown in Table 7. CPAP resulted in a mean change [standard error (SE)] of –3.8 (0.4) from an average (SD) of 11.5 (3.3) at baseline to 7.7 (4.0) at 3 months. BSC showed a mean change (SE) of –1.6 (0.3) from a baseline average (SD) of 11.4 (4.2) to 9.8 (4.3) at 3 months. The adjusted treatment effect at 3 months was –2.1 (95% CI –3.0 to –1.3) in favour of CPAP, which is statistically significant (p < 0.001). An additional analysis adjusting for age, sex, BMI and baseline ODI did not alter this result.

| Time assessed | BSC | CPAP |

|---|---|---|

| n randomised | 138 | 140 |

| n analysed | 124 | 124 |

| Baseline (at randomisation), mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.2) | 11.5 (3.3) |

| Month 3, mean (SD) | 9.8 (4.7) | 7.7 (4.1) |

| Month 4, mean (SD) | 9.7 (4.2) | 7.7 (4.3) |

| Mean of months 3 and 4 (SD) | 9.8 (4.3) | 7.7 (4.0) |

| Mean change from baseline (SE) | –1.6 (0.3) | –3.8 (0.4) |

| Treatment effect (95% CI), p-value | –2.1 (–3.0 to –1.3), p < 0.001 | |

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed (1) excluding two patients who swapped from BSC to CPAP prior to the 3-month assessment and (2) including all randomised patients by replacing missing values using multiple imputation. Excluding the two patients who swapped from BSC to CPAP prior to the 3-month visit resulted in a treatment effect of –2.1 (95% CI –3.0 to –1.3), p < 0.001, in favour of CPAP, identical to the primary analysis.

Results from the imputation analyses, calculating the effect of the incomplete ESS score data reported by 14 patients, estimated a change of –2.0 (95% CI –2.8 to –1.2) in favour of CPAP (p < 0.001). Once again this showed the primary result to be robust. The imputation analysis assumes missing outcomes are similar to the observed outcomes in patients with similar characteristics, but this may not be true, as missing outcomes may be better or worse than those observed. The assumption can be varied to see how sensitive the observed results are to the missing data. Figure 4 shows that observed results are not sensitive and that extreme assumptions about the missing data are needed to make any significant change to the primary analysis (i.e. a 5-point difference between missing and observed values) so any sensible assumptions about the missing data do not change the results.

FIGURE 4.

Sensitivity analysis of the primary outcome to missing data. Missing outcomes are imputed under the assumption that the average of the missing outcomes differ to the mean of the observed outcomes by an amount corresponding to each point of the x-axis. Imputation is performed for each treatment group separately.

Planned exploratory analysis

Exploratory analysis were planned to investigate the effect of CPAP use and age, BMI, ESS score and ODI at baseline on the primary ESS score outcome. Patients were split into tertiles by their average CPAP use in the last month of follow-up prior to their 3-month visit. The analysis by CPAP use is shown in Table 8. The change in ESS score between baseline and 3 months in those who used CPAP the most (third tertile) was 11.4 at baseline and 6.1 at 3 months. This resulted in a treatment effect of –3.7 (95% CI –4.8 to –2.6), p < 0.001, compared with BSC.

| Time assessed | BSC | CPAP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | ||

| n | 124 | 38 | 37 | 41 |

| Mean usage (hours/night), (minimum–maximum) | – | 0 (0–0) | 1.9 (0.001–4.6) | 6.4 (4.6–8.6) |

| Baseline ESS score, mean (SD) | 11.4 (4.2) | 10.6 (3.0) | 12.0 (3.9) | 11.4 (2.7) |

| ESS score month 3, mean (SD) | 9.8 (4.3) | 8.0 (3.9) | 9.0 (4.5) | 6.1 (2.7) |

| Change, mean (SD) | –1.6 (2.9) | –2.6 (3.9) | –3.1 (4.3) | –5.3 (3.4) |

| Treatment effect (95% CI) | – | –1.3 (–2.4 to 0.1) | –1.3 (–2.4 to –0.1) | –3.7 (–4.8 to –2.6) |

| p-value | – | 0.032 | 0.034 | < 0.001 |

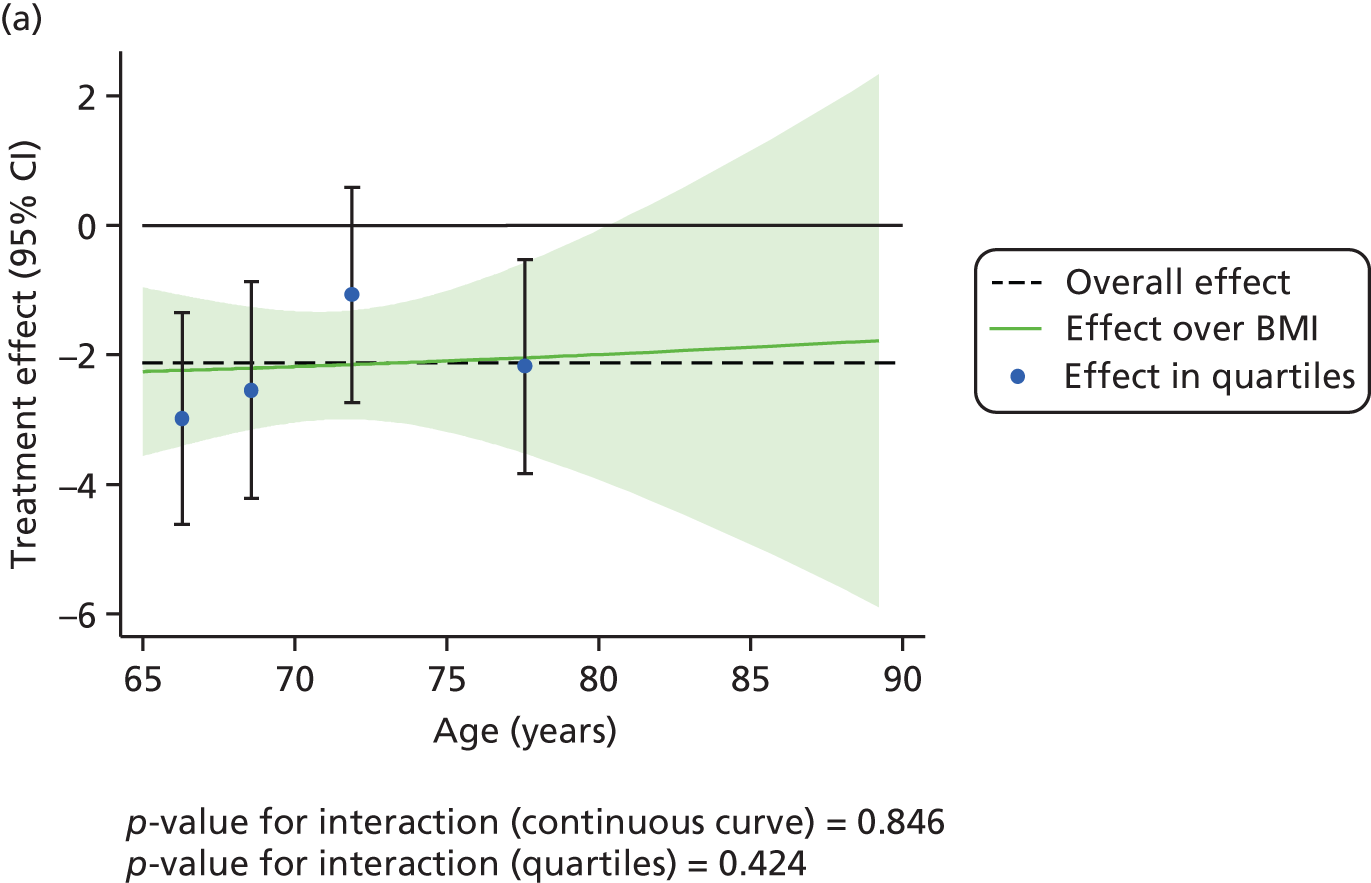

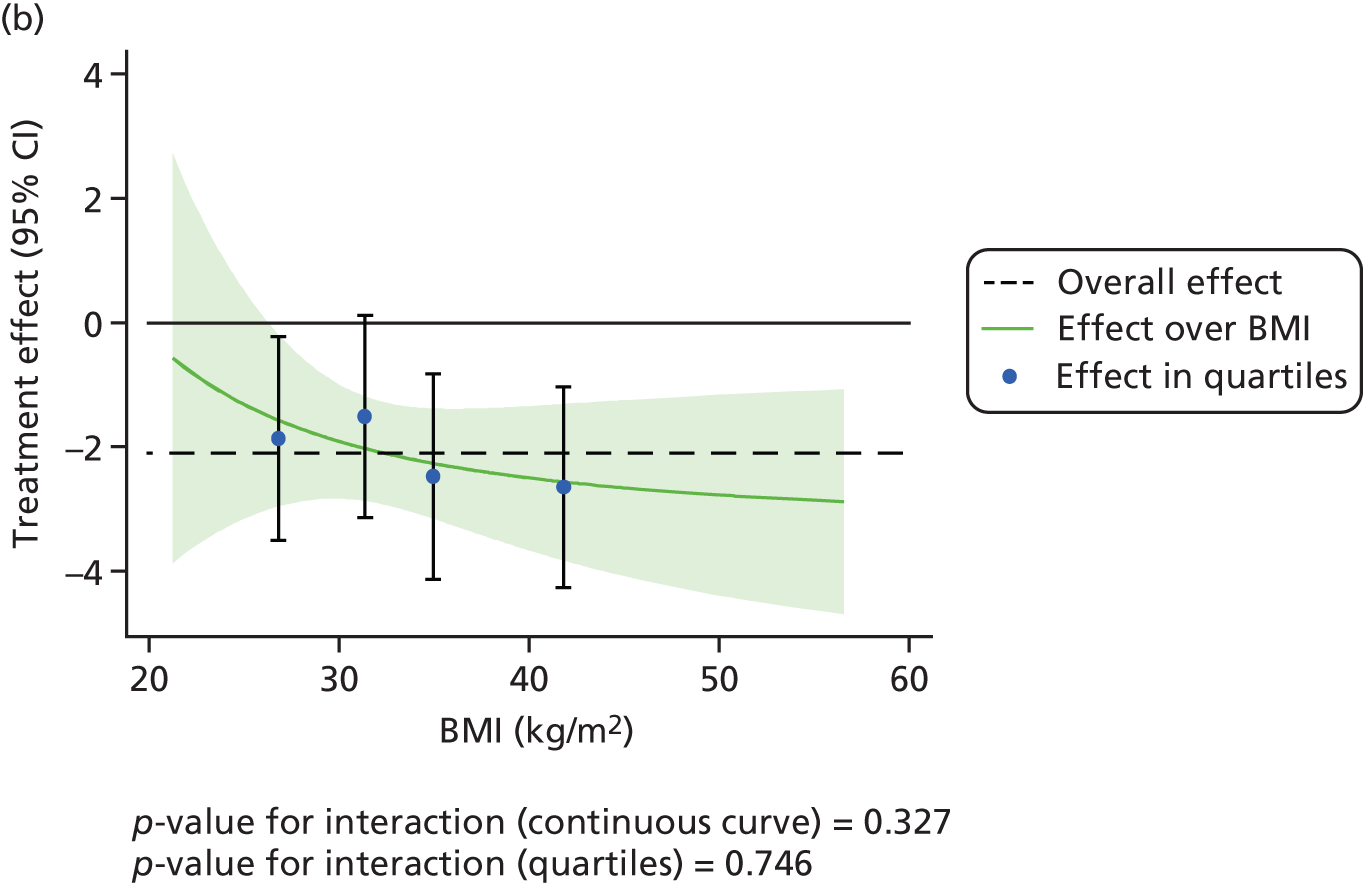

The effect of CPAP therapy compared with BSC on the primary ESS score outcome was also assessed separately over age, BMI, ESS score and ODI at baseline using FPs and is shown in Figure 5. The treatment effect was larger in patients with higher ESS score at baseline (p < 0.001).

FIGURE 5.

Interactions between primary treatment effect on ESS score and age, BMI, baseline ESS score and ODI. (a) Treatment effect over age; (b) treatment effect over BMI; (c) treatment effect over baseline ESS score; and (d) treatment effect over ODI.

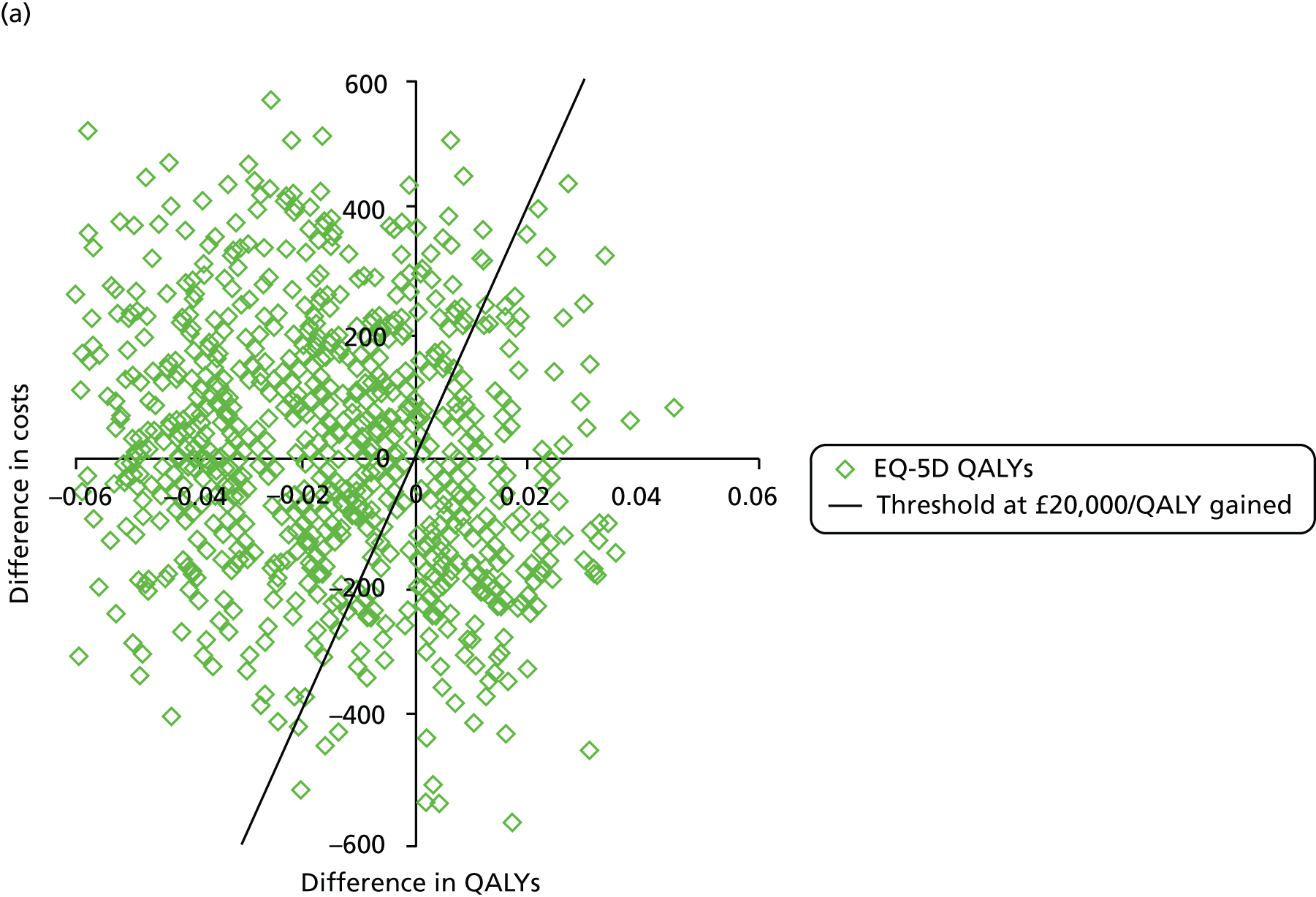

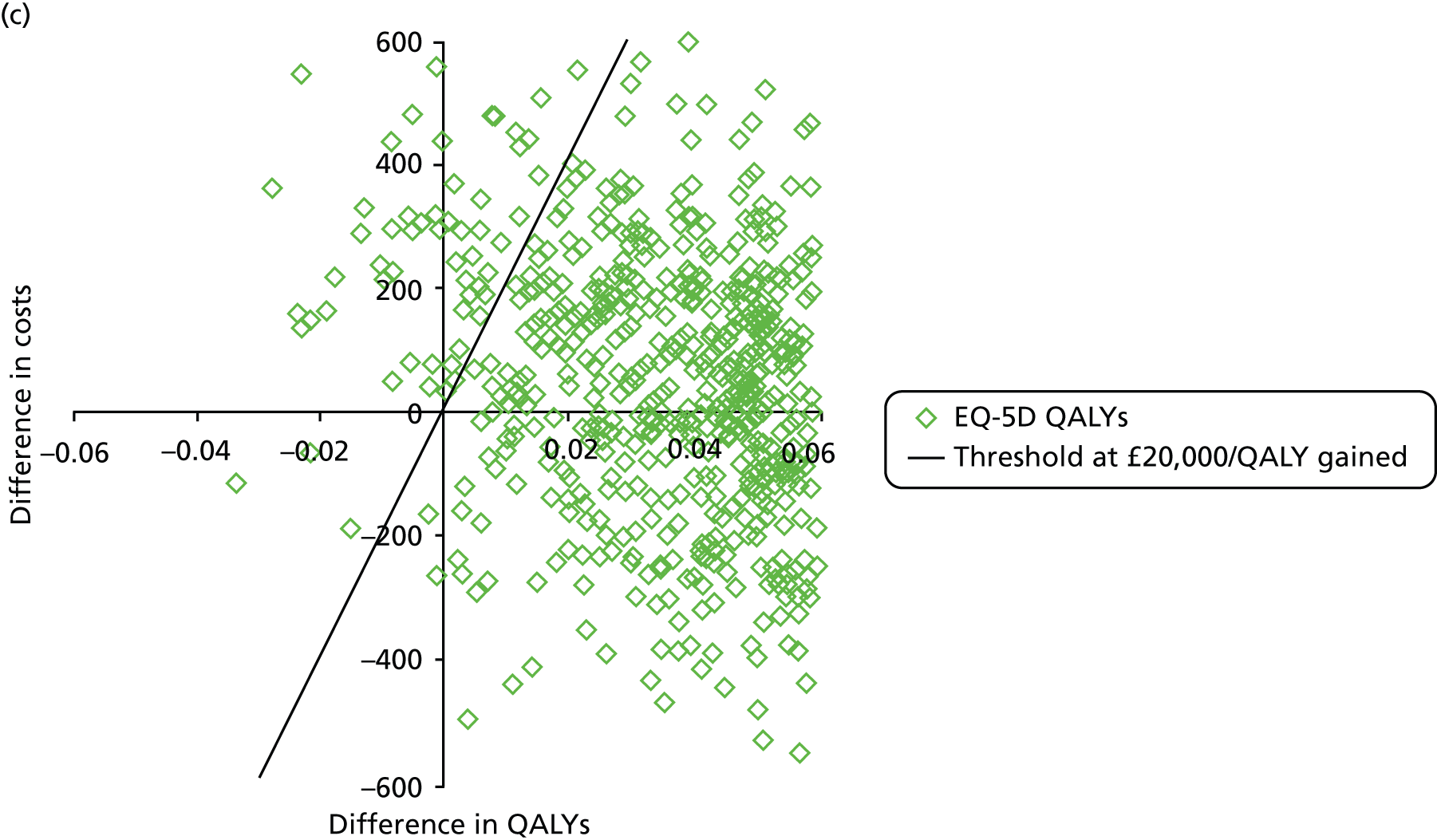

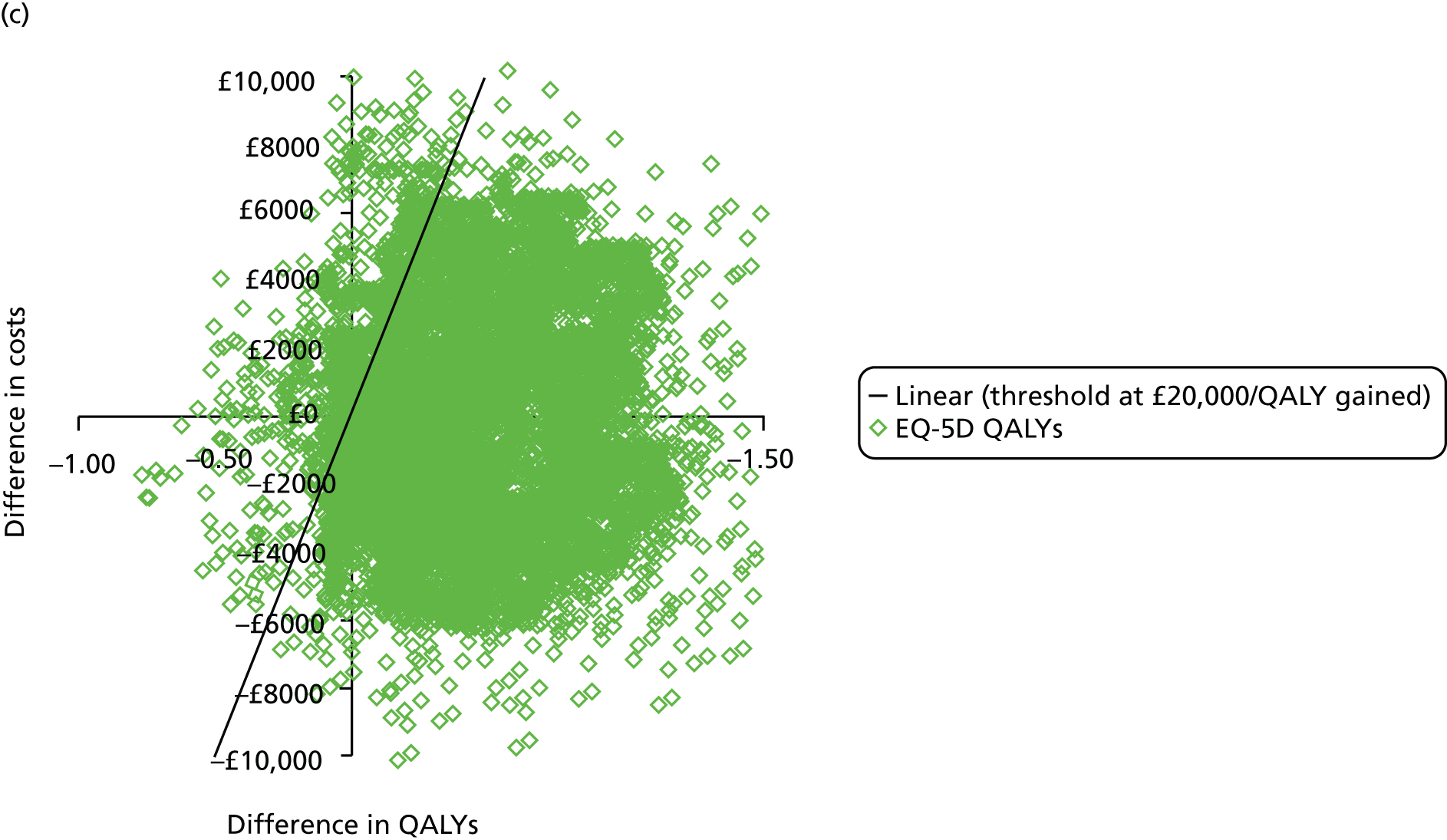

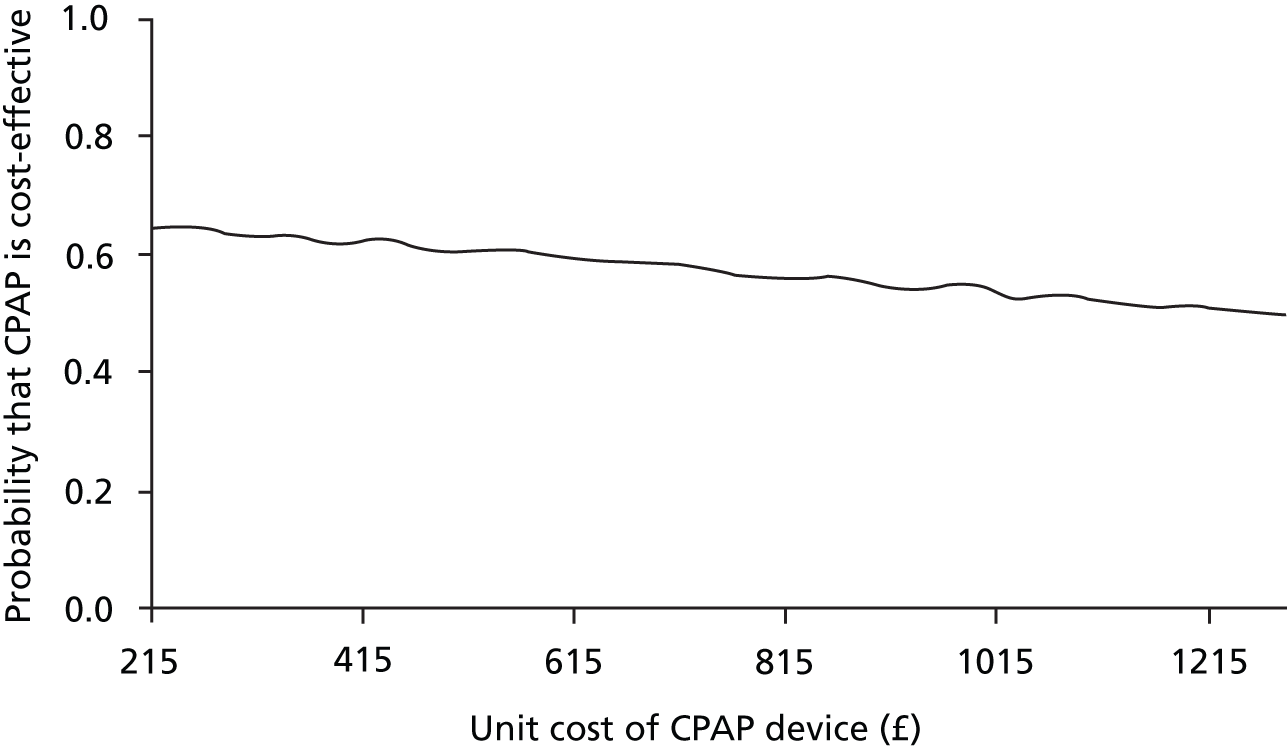

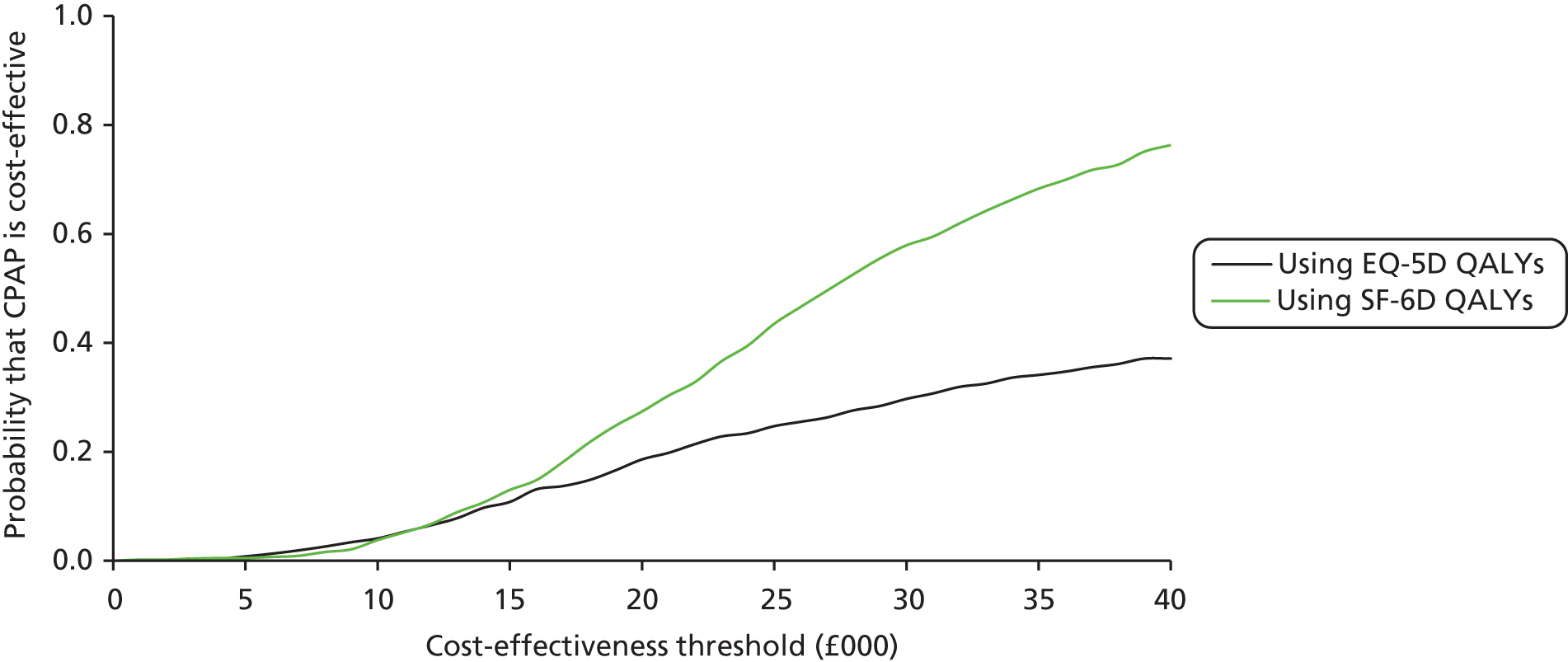

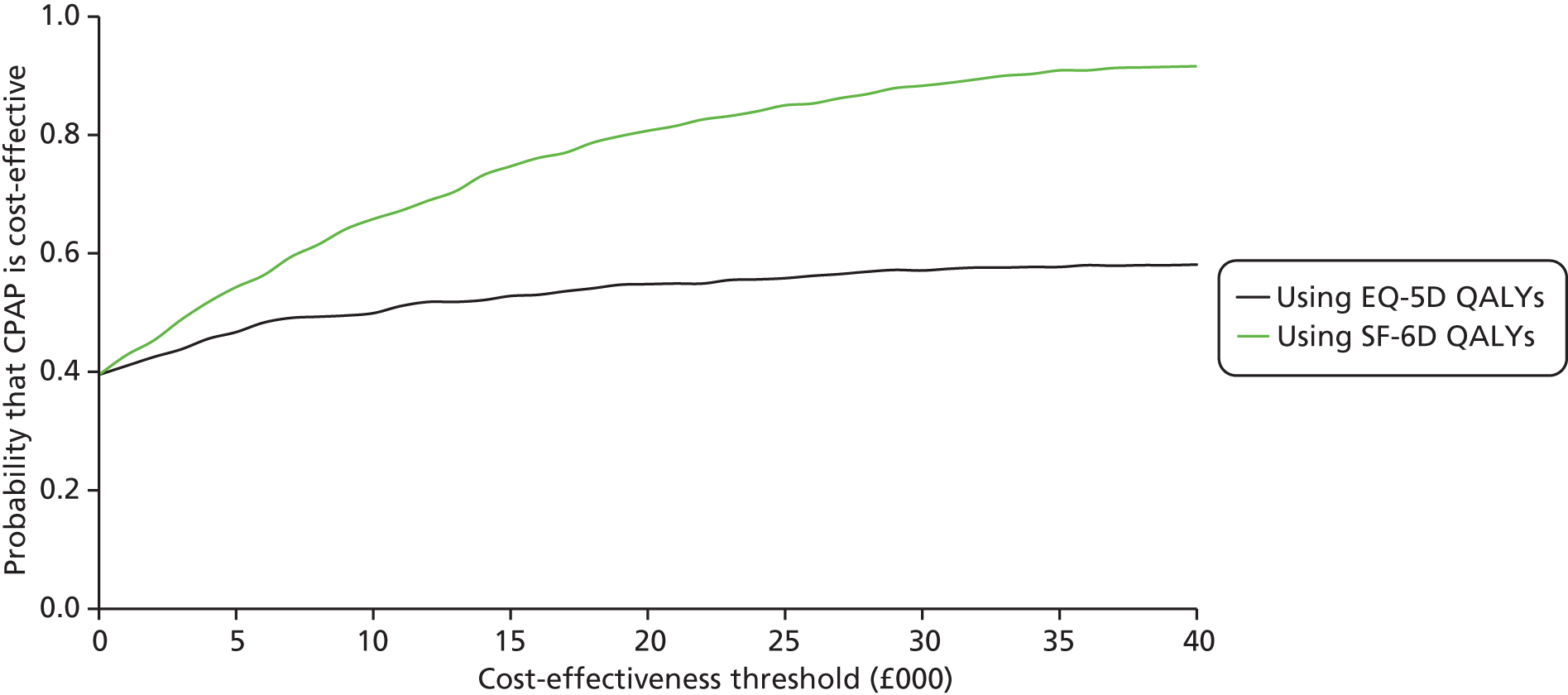

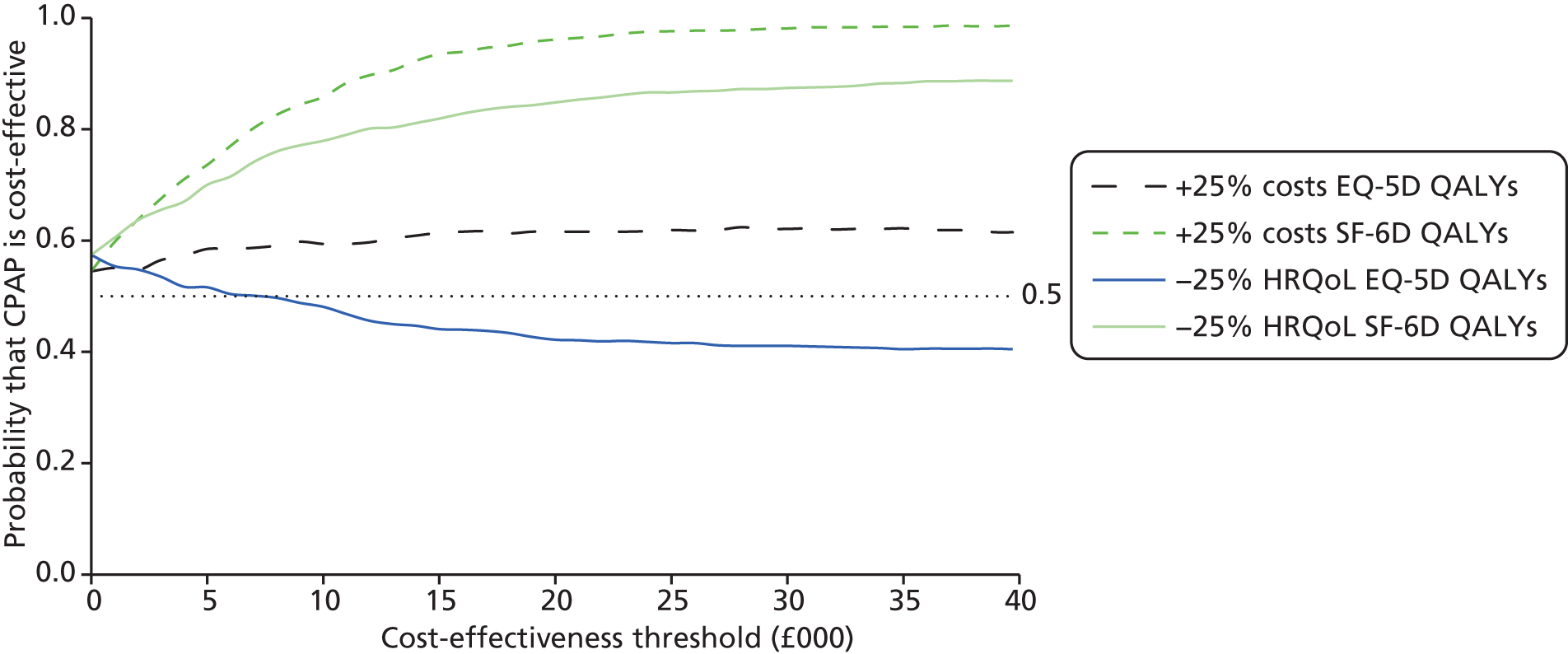

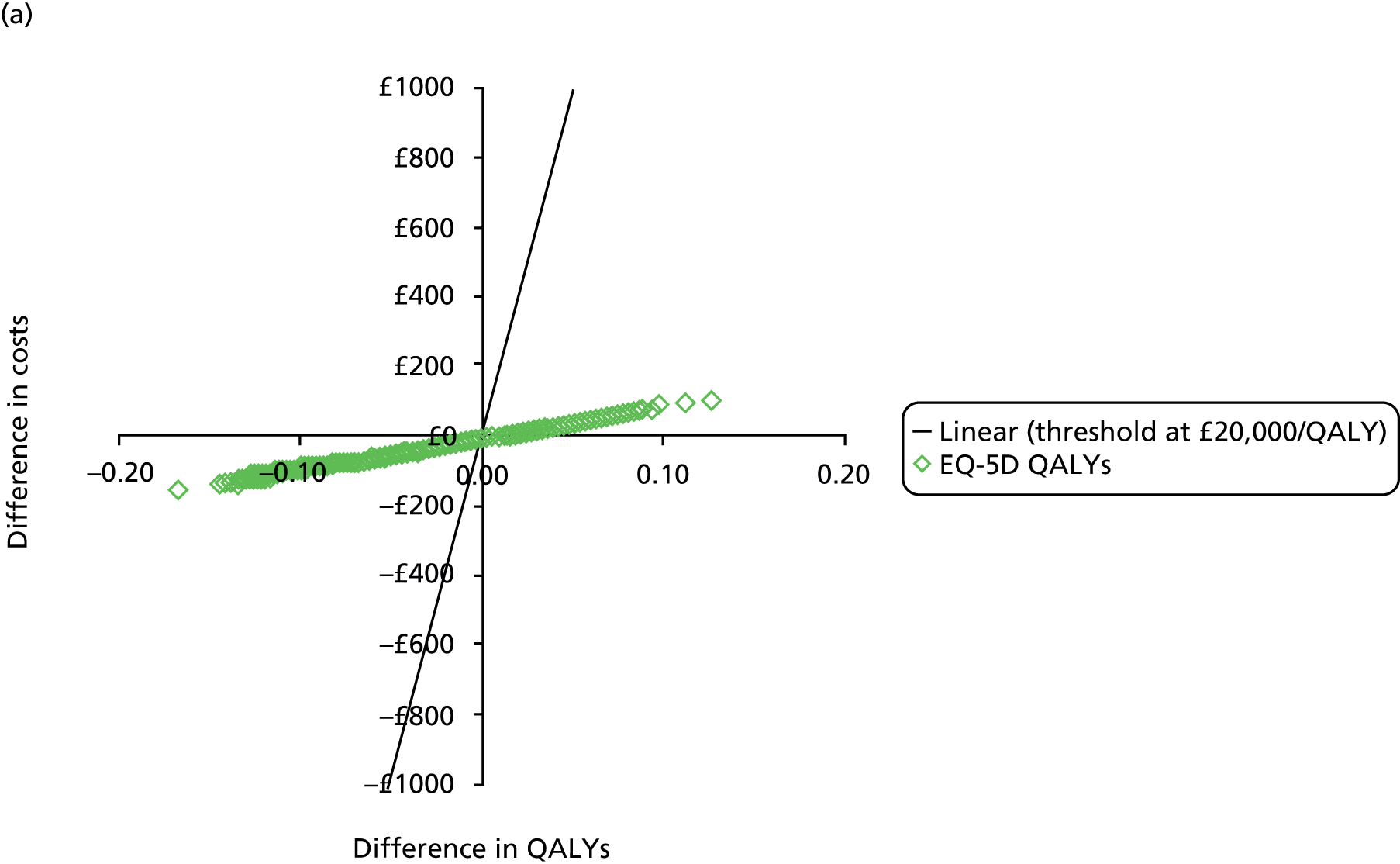

Cost-effectiveness

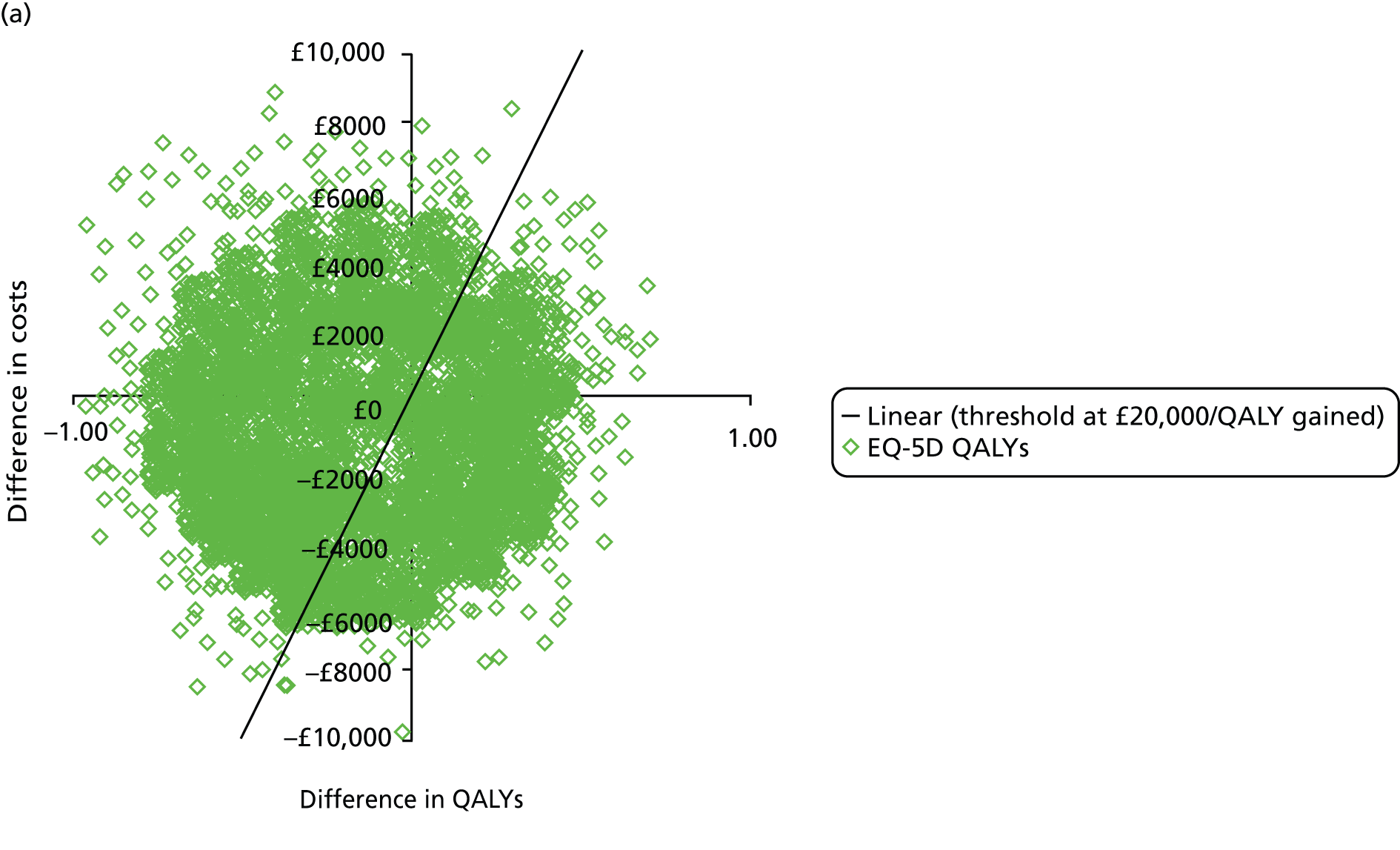

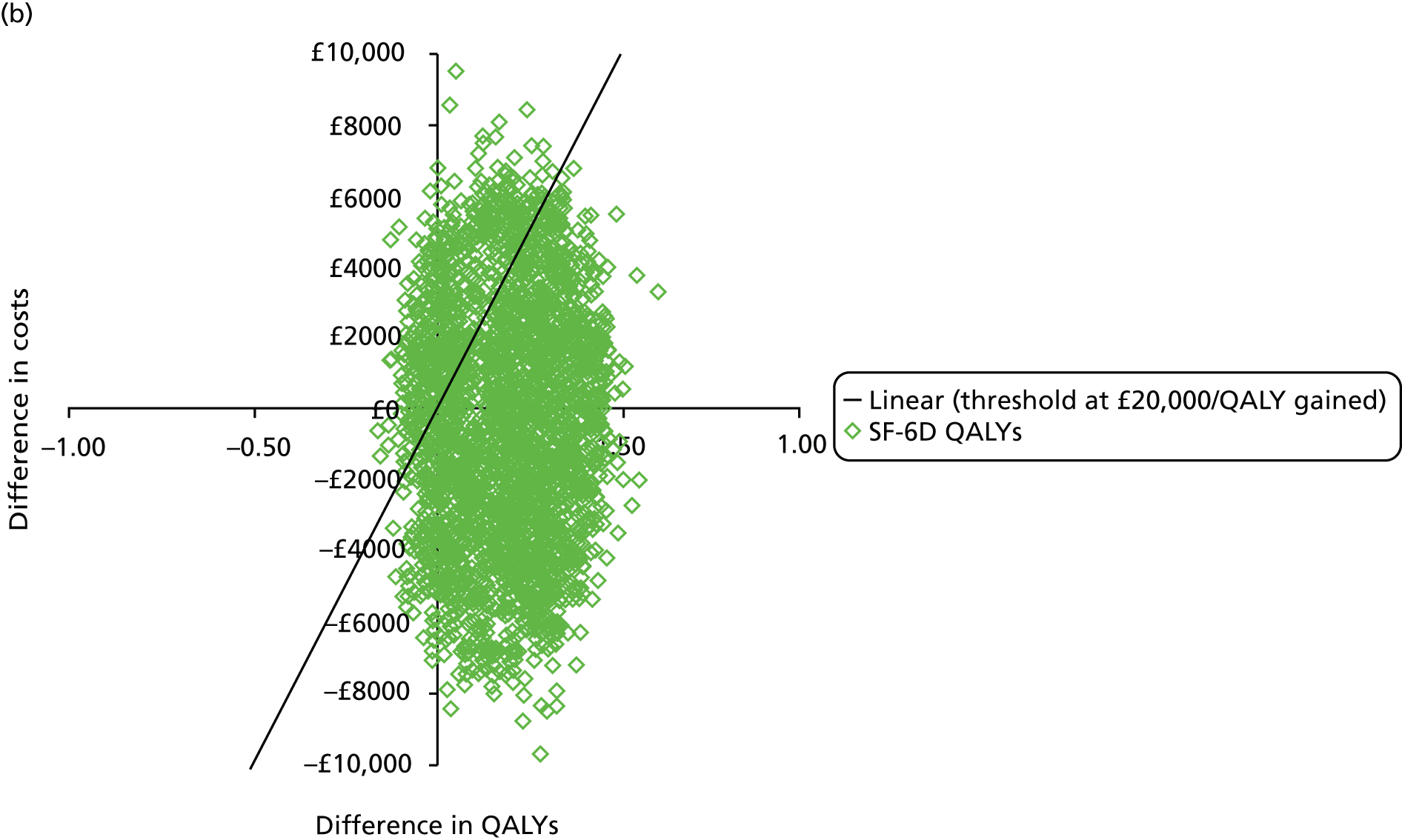

The primary outcome of cost-effectiveness is shown in Table 9. There was small difference between those treated with CPAP and those treated with BSC. The average cost per patient was £1363 (95% CI £1121 to £1606) for those allocated to CPAP and £1389 (95% CI £1116 to £1662) for those receiving BSC. Overall, the cost accrued by the CPAP group was, on average, £35 (95% CI –£390 to £321) lower than in the BSC group, a difference which was not statistically significant. The results were not sensitive to different assumptions regarding the missing data. However, the results were sensitive to the assumptions used to cost CPAP treatment. This is discussed in Chapter 4.

| Cost-effectiveness | BSC | CPAP |

|---|---|---|

| Costs of CPAP treatment | 0 | £201 |

| Costs of health-care resource use, mean (SE) | £1389 (£139) | £1363 (£123) |

| EQ-5D QALYs, mean (SE) | 0.666 (0.020) | 0.680 (0.021) |

| SF-6D QALYs, mean (SE) | 0.658 (0.008) | 0.678 (0.007) |

| CPAP versus BSC | ||

| Difference in costs, mean (SE, 95% CI) | –£35 (£180, –£390 to £321) | |

| Difference in EQ-5D QALYs, mean (SE, 95% CI) | 0.005 (0.020, –0.034 to 0.044) | |

| Difference in SF-6D QALYs, mean (SE, 95% CI) | 0.018 (0.008, 0.003 to 0.034) | |

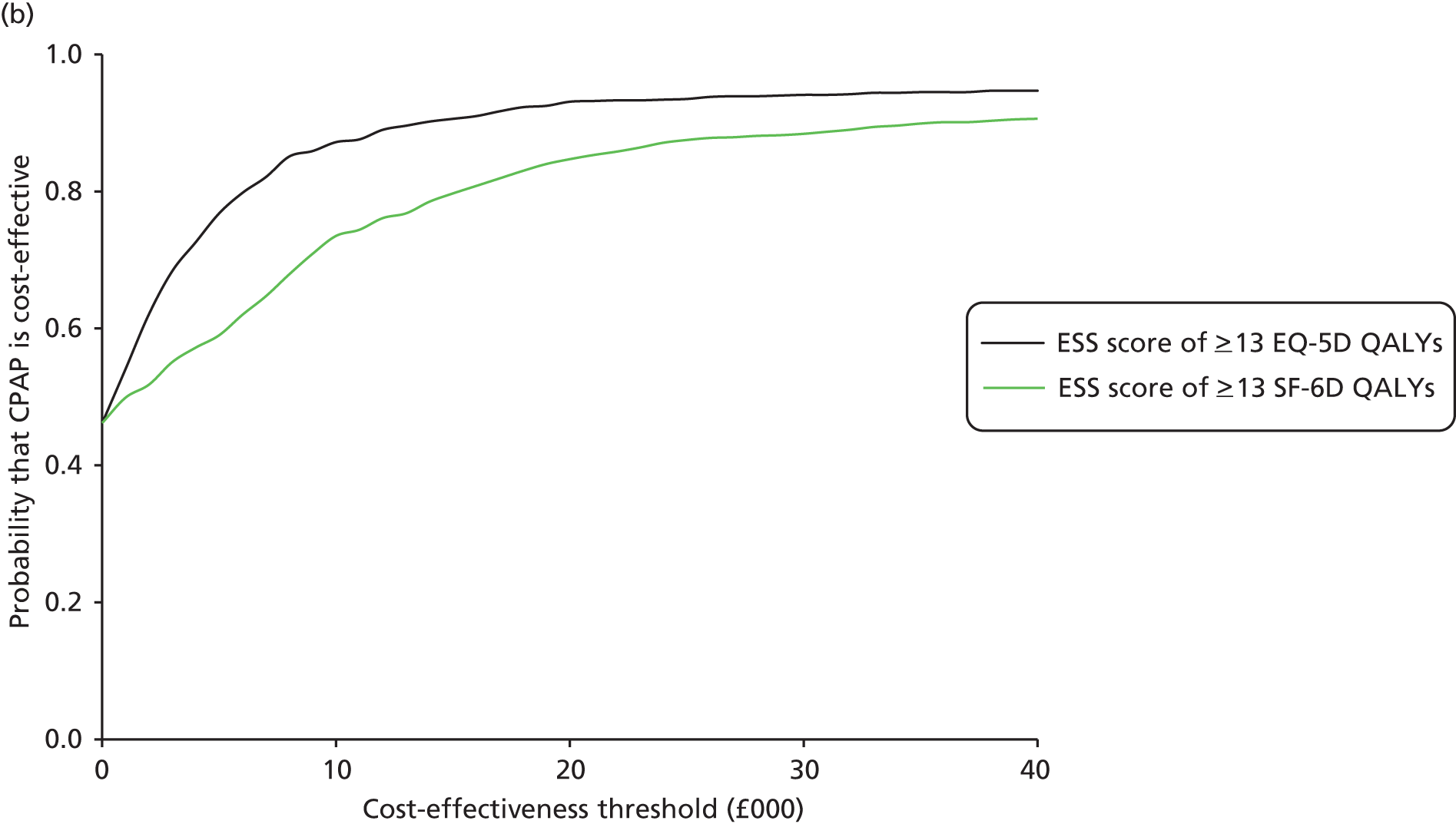

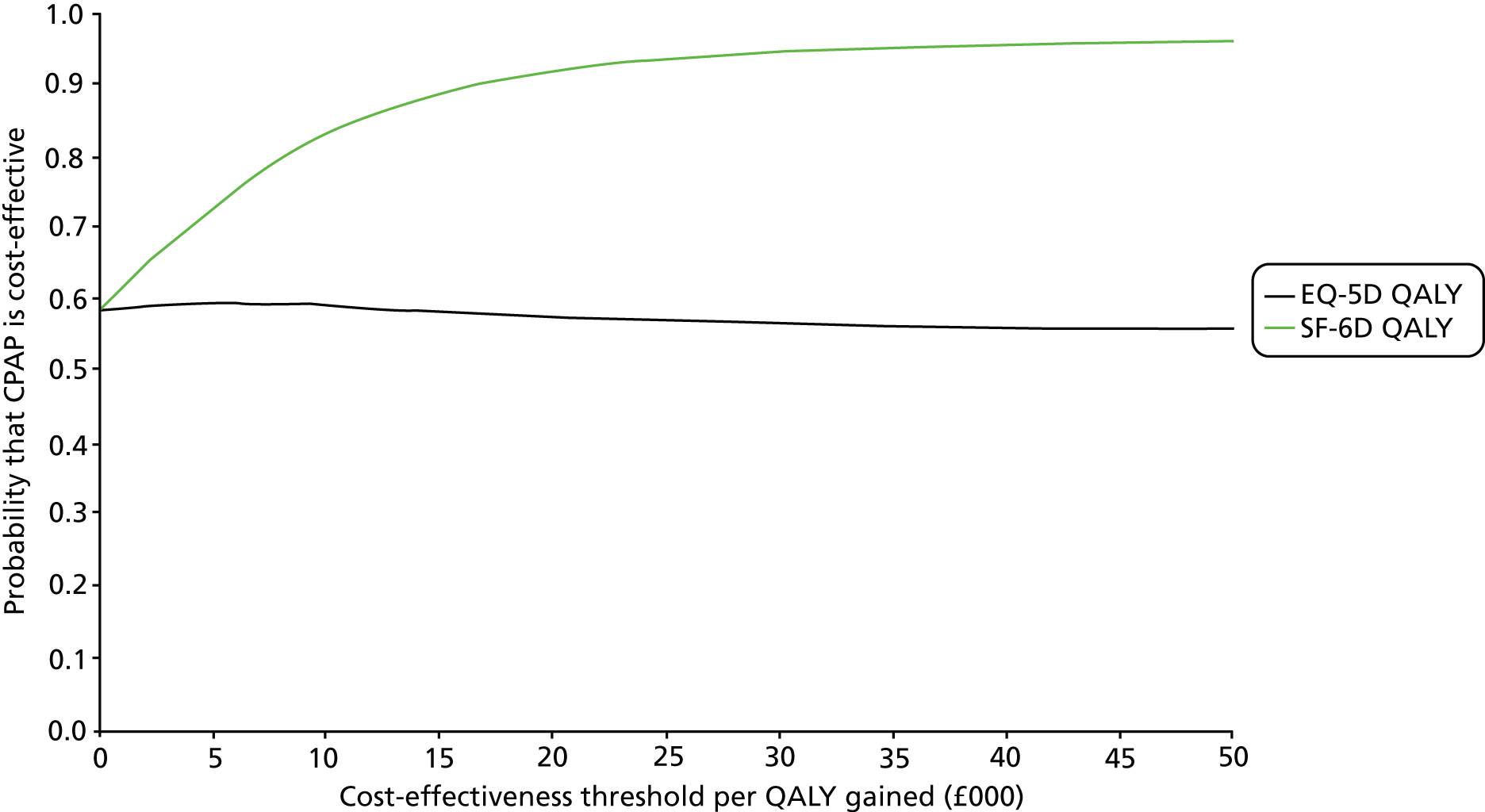

During the trial follow-up, the BSC group gained 0.666 (95% CI 0.627 to 0.705) QALYs using EQ-5D and 0.658 (95% CI 0.643 to 0.673) QALYs using SF-6D; the CPAP group gained 0.680 (95% CI 0.638 to 0.722) QALYs using EQ-5D and 0.678 (95% CI 0.664 to 0.691) QALYs using SF-6D. The QALY difference between the CPAP and the BSC groups was 0.005 (95% CI –0.034 to 0.044) QALYs using the EQ-5D and 0.018 (95% CI 0.003 to 0.034) QALYs using the SF-6D.

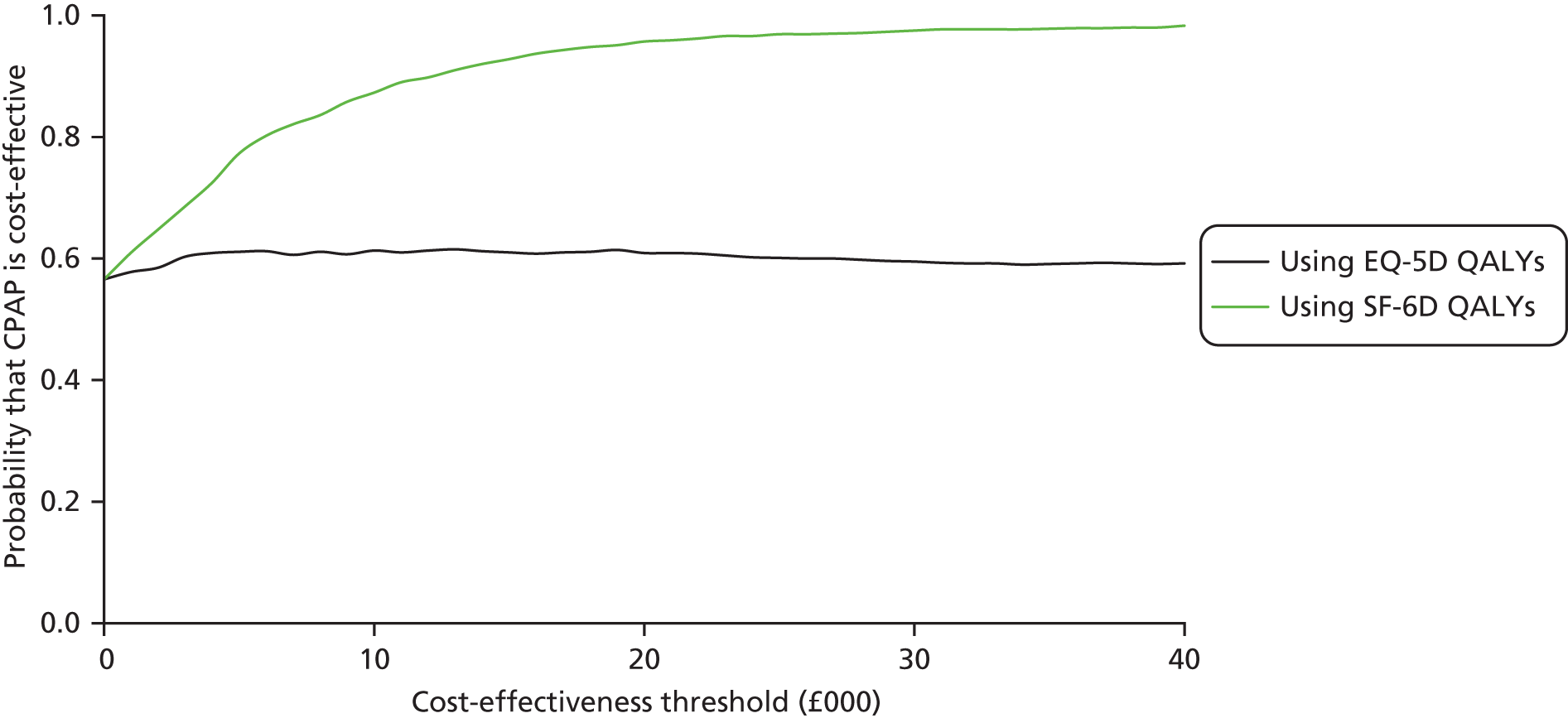

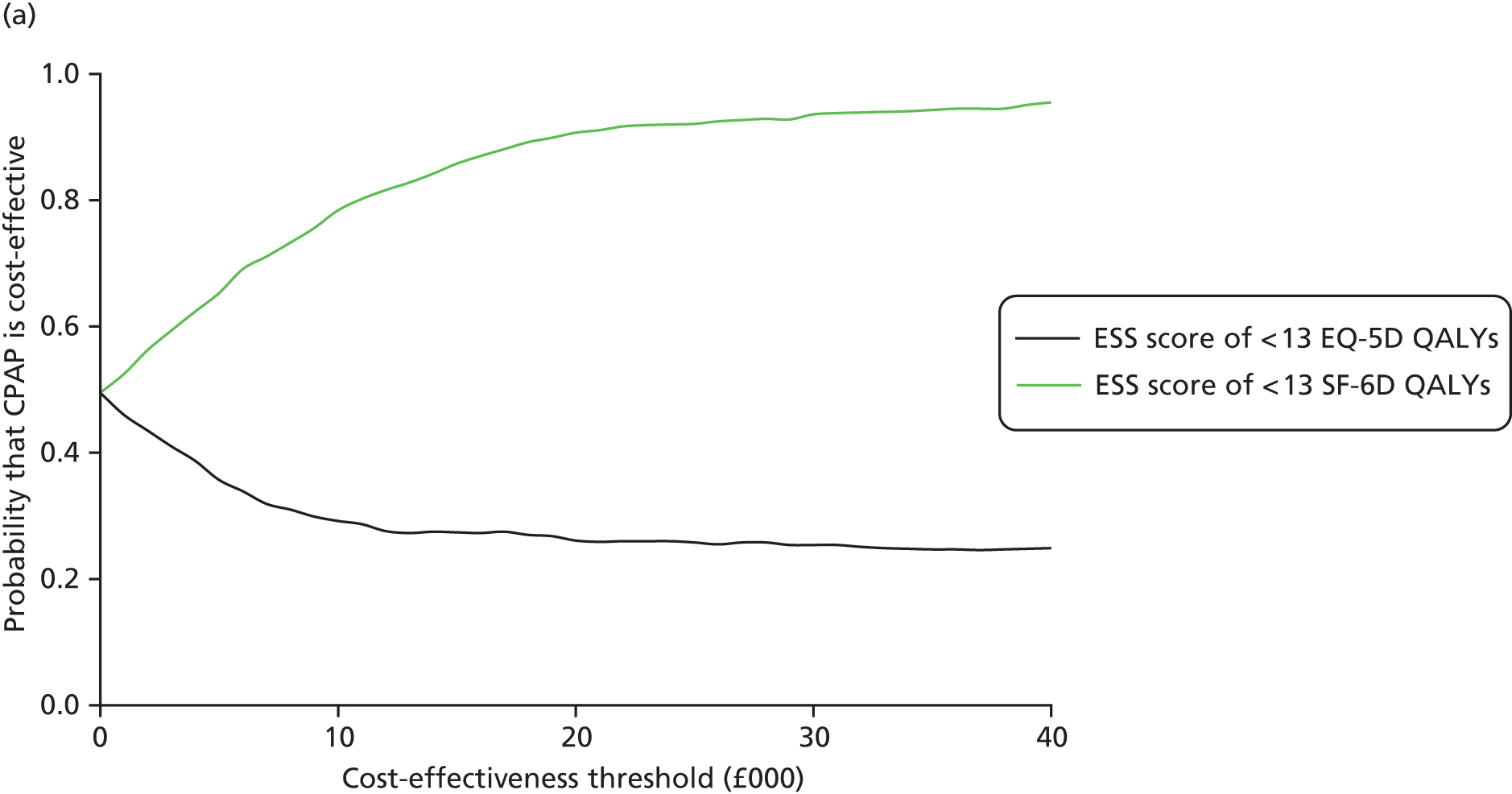

Overall, the probability that the intervention was cost-effective at the threshold conventionally used in the NHS of £20,000 per QALY gained was 0.61 using EQ-5D QALYs and 0.96 using SF-6D QALYs.

Secondary outcomes

Subjective sleepiness

The change in subjective sleepiness, as measured by the mean ESS score of months 10, 11 and 12, is shown in Table 10. CPAP resulted in a mean change (SD) of –4.2 (SD 4.1) in ESS score, from an average of 11.4 (SD 3.4) at baseline to 7.2 (SD 3.6) at 12 months. BSC showed a change of –2.1 (SD 3.6), from a baseline of 11.3 (SD 4.0) to 9.2 (SD 4.0) at 12 months. The difference between the two groups at 12 months was –2.0 (95% CI –2.8 to –1.2) in favour of CPAP, which was statistically significant (p < 0.001). A sensitivity analysis excluding eight patients who swapped from BSC to CPAP was performed but this did not alter the conclusion; the difference between the two groups was –2.1 (95% CI –3.0 to –1.3; p < 0.001), in favour of CPAP.

| Timed assessed | BSC | CPAP |

|---|---|---|

| n randomised | 138 | 140 |

| n analysed | 122 | 116 |

| ESS score baseline (at randomisation), mean (SD) | 11.3 (4.0) | 11.4 (3.4) |

| ESS score month 10, mean (SD) | 9.3 (4.3) | 7.3 (4.1) |

| ESS score month 11, mean (SD) | 9.6 (4.4) | 7.2 (4.1) |

| ESS score month 12, mean (SD) | 9.0 (4.1) | 7.0 (3.8) |

| Mean of months 10, 11 and 12, mean (SD) | 9.2 (4.0) | 7.2 (3.6) |

| Mean change from baseline (SD) | –2.1 (3.6) | –4.2 (4.1) |

| Treatment effect (95% CI), p-value | –2.0 (–2.8 to –1.2), p < 0.001 | |

Continuous positive airway pressure reduced subjective sleepiness at 3 months; the effect was maintained at 12 months and was statistically significant (p < 0.001). This is shown graphically in Figure 6. Similarly, the effect was larger in patients with greater CPAP use. The analysis by CPAP use is given in Table 11.

FIGURE 6.

The treatment effect of CPAP compared with BSC care on subjective sleepiness. Adjusted treatment effects of CPAP and BSC and their 95% CI on the mean ESS score of months 3 and 4 (coprimary outcome) and of months 10, 11 and 12 (secondary outcome). Lower scores indicate an improvement.

| Descriptor | BSC | CPAP | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First tertile | Second tertile | Third tertile | ||

| n | 122 | 52 | 30 | 30 |

| Mean usage (hours/night) (minimum–maximum) | – | 0 (0–0) | 2.3 (0.002–4.4) | 6.3 (4.5–8.9) |

| Baseline ESS score, mean (SD) | 11.3 (4.0) | 11.2 (3.5) | 11.4 (4.0) | 11.8 (2.6) |

| ESS score months 10,11 and 12, mean (SD) | 9.2 (4.0) | 8.1 (3.9) | 7.3 (3.5) | 5.6 (2.6) |

| Change, mean (SD) | –2.1 (3.6) | –3.0 (4.4) | –4.2 (3.4) | –6.2 (3.3) |

| Treatment effect (95% CI) | – | –1.0 (–2.0 to 0.1) | –2.0 (–3.2 to –0.7) | –3.6 (–4.9 to –2.4) |

| p-value | – | 0.063 | 0.002 | < 0.001 |

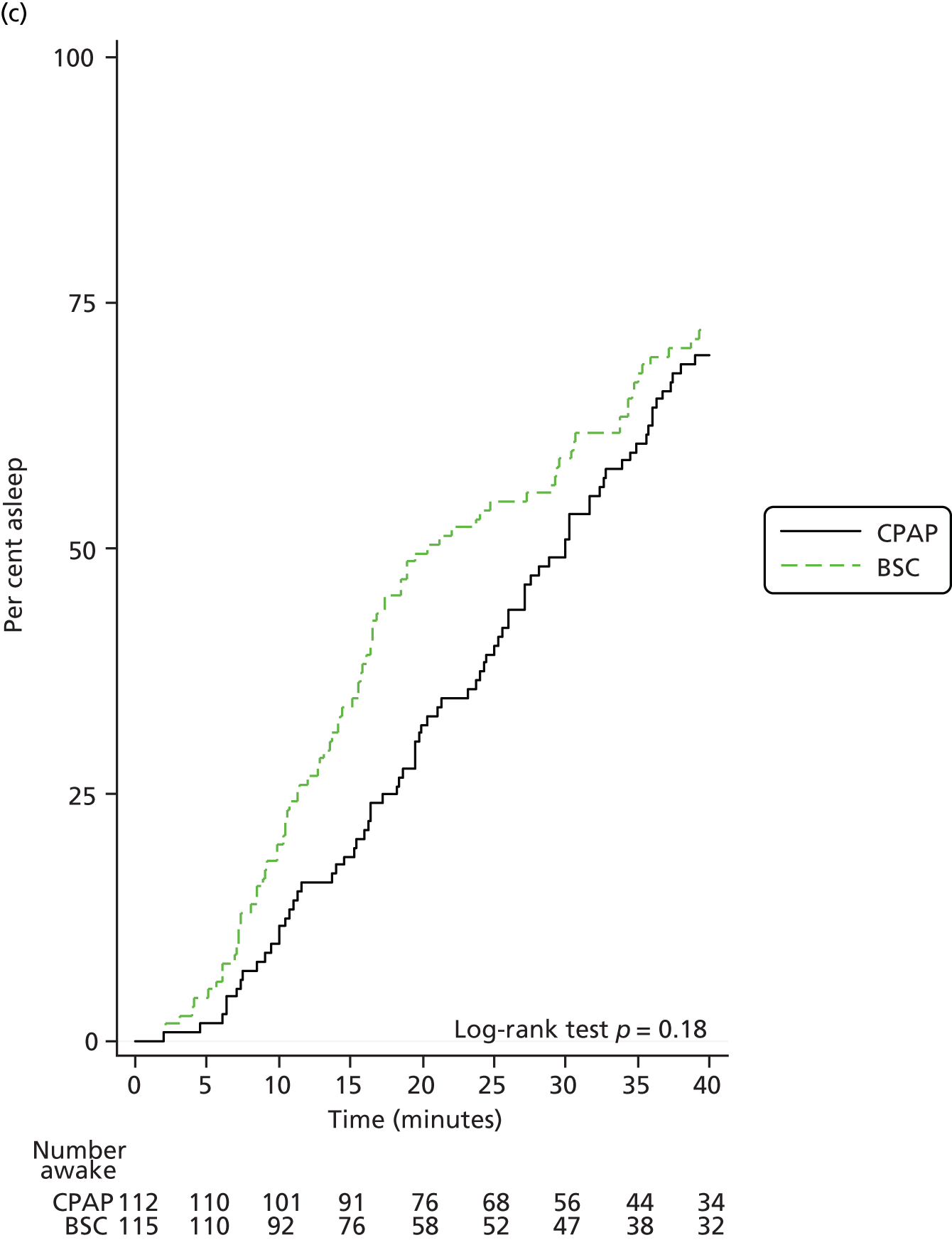

Objective sleepiness

Sleepiness was also measured objectively using the OSLER test at 3 and 12 months. The mean time to fall asleep is shown in Tables 12 and 13 (3 and 12 months, respectively). The difference between groups was statistically significant at 3 months (p = 0.024) in favour of CPAP but less so at 12 months (p = 0.058). The mean time for patients to fall asleep is also shown in Kaplan–Meier plots in Figure 7.

| Time assessed | BSC | CPAP | Treatment effect (minutes), (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 121 | 116 | 2.8 (0.4 to 5.2) | 0.024 |

| Baseline, mean time to sleep (minutes) (SD) | 21.5 (13.4) | 23.6 (12.7) | ||

| Month 3, mean time to sleep (minutes) (SD) | 22.8 (13.9) | 27.3 (12.4) | ||

| Mean change from baseline 3 months (SD) | 1.3 (10.8) | 3.6 (10.6) |

| Time assessed | BSC | CPAP | Treatment effect (minutes), (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 115 | 110 | 2.6 (–0.1 to 5.3) | 0.058 |

| Baseline, mean time to sleep (minutes) (SD) | 21.4 (13.3) | 24.5 (12.7) | ||

| Month 12, mean time to sleep (minutes) (SD) | 23.8 (13.4) | 27.8 (11.6) | ||

| Mean change from baseline at 12 months (SD) | 2.4 (11.9) | 3.3 (13.2) |

FIGURE 7.

Kaplan–Meier plot of average time taken to fall asleep for each patient at baseline, 3 months and 12 months. (a) Baseline; (b) 3-month visit; and (c) 12-month visit.

Quality of life and mood

Generic quality of life was assessed using the SF-36 (version 1) at 3 and 12 months. Raw scores were analysed with factor loadings obtained from Jenkinson et al. 102 The difference between groups in the energy/vitality domain was statistically significant at 3 months (p = 0.001) and 12 months (p = 0.004) in favour of CPAP. The MCS score was also statistically significant at 3 months (p = 0.046) but not at 12 months (p = 0.22). The physical functioning score was also statistically significant at 12 months (p = 0.033) in favour of CPAP but not at 3 months (p = 0.16). The difference between the two groups on each summary score at the 3- and 12-month visits is shown in Figure 8.

FIGURE 8.

Short Form questionnaire-36 items treatment effects at 3 and 12 months. Adjusted treatment effects and their 95% CI, CPAP versus BSC, on the MCS, the PCS and the eight individual components at 3 and 12 months. Higher score indicate an improvement.

Disease-specific quality of life was measured using the SAQLI, a sleep apnoea-specific questionnaire which also incorporates side effects associated with CPAP. Both groups showed an improvement but the effect was greater in the CPAP group at 3 months (p = 0.005) and 12 months (p = 0.001).

Mood was assessed using the HADS, which was summarised into an anxiety score and a depression score. Both groups showed a reduction in their score at 3 and 12 months but the difference between groups at either time point was not statistically significant.

The SF-36, SAQLI and HADS scores are shown in Tables 14 and 15 (3 and 12 months, respectively).

| Outcome | BSC | CPAP | Treatment effect (95% CI) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Baseline, mean (SD) | Month 3, mean (SD) | n | Baseline, mean (SD) | Month 3, mean (SD) | |||

| SF-36 | ||||||||

| Bodily pain | 125 | 59.9 (26.8) | 60.5 (26.4) | 123 | 61.9 (28.4) | 61.4 (26.9) | –0.7 (–5.6 to 4.2) | 0.78 |