Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 11/22/03. The contractual start date was in June 2012. The draft report began editorial review in April 2014 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ann S Le Couteur is one of the authors of the Autism Diagnostic Interview but receives no royalties; Elaine M McColl is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by McConachie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 MeASURe: systematic review of tools to measure outcomes for young children with autism spectrum disorder

Introduction

Autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) are neurodevelopmental, lifelong conditions diagnosed using a set of behavioural criteria. 1 ASD is known to affect at least 1% of the child and adult population. 2–4 There is wide variation in the progress made by individuals with ASD, so that many individuals have significant lifelong needs for support. The burden and cost to the individual, family and broader society are very high, with the economic costs in the UK estimated to be £28B per year. 5

In light of increased awareness about the prevalence of ASD, and the emphasis on early identification and diagnosis, it is important that health, education and social-care services provide evidence-based interventions and early support for individuals with ASD, and their families, carers and teachers. In the past decade there has been an increase in ASD intervention research, with recent improvement in the quality of studies. 6,7 The ASD early intervention literature is largely focused on promotion of social communication skills, with less emphasis on interventions for restricted and repetitive behaviours (RRBs). It also includes interventions focused on the high rates of co-occurring behaviours and problems (e.g. sleep, faddiness about food, aggression to others, toileting difficulties). 8,9 One problem for the interpretation of research findings is the multitude of different measurement tools that have been used in collecting evidence of progress and outcomes. Furthermore, longitudinal studies highlight the variation in individual developmental pathways. 10–12 The changes in prevalence are due, in part, to earlier recognition of ASD in children in the average range of ability, with likely effects on the pattern of outcomes. 13 The literature thus presents a large set of measures, inconsistently used, of varying relevance and with variable or indeed no evidence of their psychometric properties.

What should be measured?

There are several ways to consider the question of what to measure, including what government departments need in order to measure progress and outcomes, what matters to parents and individuals with ASD, and the theoretical basis of ASD, which has implications regarding important domains to measure.

The UK Chief Medical Officer’s 2012 report focused on Child Health,14 and discussed the poor educational, health and employment outcomes for children with neurodisability. In recent years, there has been consultation about the UK National Health Service Outcomes Framework 2011/12,15 part of a strategy that aims to deliver ‘the outcomes that matter most to people’, using patient-reported outcome measures. The Kennedy report ‘Getting It Right for Children and Young People’16 highlighted the need to identify a common vision between families and professionals for what services are seeking to achieve for children. Measuring outcomes that are valued by families is central to that vision, which, in turn, will influence what services are provided and how, and potentially what services and interventions are prioritised for research evaluation. A recent National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) study has reported agreement on what are the valued outcomes of care for children with neurodisability,17 but it is not clear whether or not these would be the same if a set of core outcomes were sought specifically for children with ASD.

The aims of our MeASURe (Measurement in Autism Spectrum disorder Under Review) review are to identify the validity of tools and outcome measures used in measuring and monitoring young children with ASD, and to consider how well these reflect and measure issues of importance for patients and carers (see Appendix 1). To achieve this we have:

-

identified the tools reported in literature on quantitative research involving children of up to approximately 6 years of age with ASD (see Chapter 3)

-

conducted a detailed systematic review of the measurement properties of tools within the major domains of development and functioning (see Chapter 4)

-

synthesised evidence regarding the most robust and useful tools in these different domains (see Chapter 5)

-

identified gaps in measurement of outcomes and made research recommendations.

An important part of the strategy has been to identify what people on the autism spectrum, and parents of children with ASD, think should be measured. As these stakeholders were involved at various stages throughout the project, there is no single section on ‘patient and public involvement’ in the report. Instead, parents and people on the autism spectrum have contributed particularly to Chapters 2, 5 and 6. In Chapter 2, we address the issue of what outcomes should be measured.

Chapter 2 Development of the conceptual framework

Introduction

Within the MeASURe project, we carried out a series of consultations with stakeholders, including professionals, parents of children with ASD and people on the autism spectrum, and a scoping review of qualitative literature. The aim was to identify (1) what outcomes should be measured when monitoring the progress of young children with ASD and (2) whether there is agreement between parents and professionals about the relative importance of what to measure. The review of how to measure those outcomes in order to progress towards an agreed battery of tools is presented in later chapters. The chapter is structured to incorporate:

-

general considerations for developing a conceptual framework in ASD for the review

-

findings from scoping relevant qualitative research with families

-

consultation with people who are on the autism spectrum

-

survey consultation with professionals

-

consultation with parents

-

consultation with multiple stakeholders at a Discussion Day.

Valued outcomes

There exist recommended procedures for agreeing what should be a core set of outcomes in various fields of health care. As Williamson et al. 18 note, ‘insufficient attention has been paid to the outcomes measured in clinical trials’. Consistency and interpretation will be improved if researchers always collect and report on core outcomes. The Core Outcome Measures in Effectiveness Trials (COMET) initiative funded by the Medical Research Council Network of Hubs for Trials Methodology Research aims to develop a set of evidence-based procedures for developing a core outcome set. The suggested steps involve:

-

Step 1 Agree the scope of the area of health care.

-

Step 2 Identify existing knowledge about outcomes.

-

Step 3 Involve key stakeholders, including patients and health-care providers.

-

Step 4 Develop consensus about what to measure. Techniques for doing this in an inclusive and objective way are outlined in Williamson et al.,18 including how to determine when consensus has been achieved.

A systematic review of studies that aimed to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials in children concluded that in most specialties no research had been undertaken. 19

The scope for this review was determined in the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) commissioning brief (i.e. COMET step 1) and includes a potentially broader use of outcomes than only in trials. This chapter presents the work undertaken on steps 2 and 3, i.e. to identify priorities for child outcomes as valued by parents and professionals, and as explored in qualitative literature. Because of the complexity of ASD as a disorder, and the developmental context of measuring outcomes up to the age of 6 years, the MeASURe review adopted a further step of placing the findings of the consultation stages in a conceptual framework to guide the full review of tools for measurement. This framework also guided further consultation with stakeholders about the relative importance of outcomes to measure. MeASURe did not undertake a further formal process to develop consensus (step 4 above). It may be that ‘consensus’ would be hard to achieve but it would require further procedures. In principle, the choice of outcomes to focus upon depends on the specific research question being asked, and on what is important to particular groups of stakeholders.

Considerations for developing a conceptual framework in autism spectrum disorder

One important potential basis for a conceptual framework for valued outcomes for children with ASD is the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health for Children and Youth (ICF-CY),20 so that what is measured can be ‘mapped’ against domains of functioning (e.g. Learning, Communication, Self-Care) and participation (e.g. Relationships, Community Life).

The conceptual framework should also be influenced by an understanding of ASD. The behavioural characteristics of ASD are underpinned by genetic, brain structure and neuropsychological differences from typical development. 21 The conclusions of many studies have led to the revision of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) published in May 2013, such that the impairments in ASD are best considered within two groupings: social/communication difficulties and restricted/repetitive interests and behaviours, including hypo- or hyper-responsiveness to sensory stimuli. The aetiological underpinnings for each of these broad domains of impairments may be different, and both may be targets for interventions targeting ‘core’ features of autism.

Another aspect of complexity in the understanding of ASD is that its measurement is affected by developmental considerations, i.e. children’s profile of skills and difficulties may look very different over time, and those trajectories will also be affected by levels of ability. As an obvious example, we cannot measure children’s social ability to make and keep friendships with validity until they are of an age at which that might be expected in typical development. However, there is some recent agreement on the core early impairments that may be observed. By the age of 2 years, differences in the development of children with ASD (from typically developing children and those with developmental delay) are evident in behaviours such as fearfulness, frustration and lack of co-operation, quick mood changes, and fine and gross motor skills. 22 This knowledge has been enhanced by recent studies of the early development of baby siblings of children with autism (who have an increased chance of themselves developing ASD); for example, Zwaigenbaum et al. 23,24 reported unusual eye contact, a lack of visual attention, orientating to name, imitation, social interest and emotional affect, and heightened sensory-orientated behaviours. These combinations of deficits have consequences for development of relationships, early language and play, and, in turn, for the content and targets of early intervention.

The complexity of understanding ASD is made even greater when considering the interaction between domains of development, and how deficits in one may impact upon another; for example, visual sensory overload may lead to avoidance, which reduces opportunities for visual learning and social experience, leading to poor social skills. Furthermore, there is evidence that pragmatic skills (such as social timing in interaction) are closely associated with particular types of behavioural profiles. 25,26 Thus the conceptual framework for a review of outcome tools should consider both measurement of individual areas of functioning, which are likely to change over time, and also tools that bring together these separate areas into a more holistic assessment. It is particularly important to be able to create profiles for children with ASD, who often have difficulties in generalising learning between areas of skill and also generalising skills from one setting to another.

It is also important to detail other associated difficulties that are not unique to ASD but which, nevertheless, can play a major part in children’s development and the burden of care for families. These commonly include feeding and eating difficulties (resistance to certain food textures, faddiness about types and colours of food, etc.), behaviour and sleeping problems. Children who lack adequate nutrition and sleep are likely to be bad tempered and even more rigid in their thinking and behaviour. Furthermore, adaptive functioning may be more impaired in children with ASD than would be expected from their level of ability. Finally, as young children’s development is intimately affected by their environment, including the health, skills and resilience of parents and carers, it is important to include consideration of the impact on the family.

Although the conceptual framework developed over the process of consultation, and was informed by the separate activities described below, it is presented first for brevity and clarity (Table 1). The framework adopted was informed by discussion within the project team, and inspection of other relevant frameworks such as groupings of target symptoms/skills from interventions studies in ASD,20,27 education outcomes,28 grouping of interventions by Research Autism (http://researchautism.net/pages/autism.treatments.therapies.interventions/) and compilation of measures for children with developmental disabilities. 29 One area discussed was how to categorise quality of life, which is essentially a construct separate from the ICF-CY. The decision was made to include it in the participation domain, as it implies how an individual interacts with their environment. 30 For the MeASURe conceptual framework, there are four primary domains, with subdomains in each.

| Domains | Subdomains | Constructs of interest |

|---|---|---|

| Body Functions and Structures/Impairments | Symptom severity | Change in diagnostic category; autism severity; diagnostic scores used as measures of outcome |

| Social awareness | Joint attention skills; imitation; social attention | |

| Restricted, repetitive behaviour | Repetitive, stereotyped movements; repetitive use of objects; repetitive use of language; attention to detail; insistence on sameness | |

| Sensory processing | Hypersensitivity; hyposensitivity | |

| Language | Expressive language; receptive language; gestures | |

| Cognitive ability | IQ/developmental quotient; non-verbal ability; verbal ability/reasoning | |

| Attention | Distractibility; impulsivity; hyperactivity | |

| Emotional regulation | Happiness; irritability; distress; anxiety | |

| Physical skills | Poor co-ordination/gross motor skills; fine motor skills | |

| Physical indicators | Tics; gut/bowel symptoms; nutritional status; height and weight (growth); effectiveness of medication; adverse effects of medication; vaccination rates | |

| Activity-Level Indicators | Social communication | Frequency/quality of initiations; pragmatics |

| Social functioning | Attachment; interaction skills with other children; awareness of others’ emotions | |

| Play | Levels of play (exploratory to symbolic); organises own time/activities | |

| Behaviour | Maladaptive behaviour; tantrums/meltdowns; aggression; self-injury | |

| Habit problems | Sleep latency and waking; eating problems; toileting problems | |

| Learning | School readiness; early literacy; early numeracy | |

| Daily living skills | Feeding self using cutlery; dressing self | |

| Global measure of function | ||

| Global measure of outcome | ||

| Participation | Social relations | Sibling relationship; friendships; attending family events; attending birthday parties |

| Subjective well-being (quality of life) | Coping/resilience; self-esteem | |

| Social inclusion | Social participation; social exclusion; difficulty with attending appointments; awareness of danger | |

| Family Measures | Interaction style | Synchrony; shared attention |

| Parenting | Parent firm and fair; parent warmth to child | |

| Parent stress | Parent stress; parent coping style; parent anxiety and depression | |

| Family quality of life | Impact on family; family cohesion |

Scoping review of qualitative literature (BB, NL, CM)

Question

What child- and/or family-specific outcomes do parents of children with ASD perceive as important?

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted (7 June 2012) using:

-

MEDLINE: 1948 to current

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): 1937 to current

-

PsycINFO: 1806 to current.

Blocks of search terms were assembled for ASD (block 1) and Qualitative Study Designs (block 2), tailored to each database (see Appendix 2).

Papers were selected if they identified themes concerning parents’ aspirations or desired outcomes for their children, experience of assessment of their children, and their priorities for intervention for, and education of, their children. Papers were excluded if (1) ASD was not outlined in the paper as a specific focus (e.g. if ‘developmental disabilities’ were the conditions of interest); (2) they did not involve parents (e.g. a paper interviewing parents and teachers would be included; a paper interviewing just teachers was excluded); (3) the focus was on parents’ views and hopes for their adult children with ASD (e.g. focus must be on parents/carers of young children); and (4) the paper was not in English.

Abstracts and titles of references retrieved by the electronic searches were screened for relevance by one reviewer only (NL); two reviewers (BB, CM) then screened these titles and abstracts, and retrieved full texts for included papers.

Data synthesis

In order to present an overview to the parent advisory groups and the research team, key findings (including illustrative quotes) and analytical frameworks from each paper were extracted and tabulated, and themes identified.

Results

Searches identified 102 relevant papers. Fourteen studies were selected as sufficiently relevant to obtain a full text of the paper. Three of these were excluded because they did not collect qualitative data on outcomes; four were excluded because they contained no data on outcomes. Seven articles remained.

It was clear from an initial inspection of these articles that the quality of data was variable and ranged in focus/topic. Three articles reported data relevant to only parent outcomes,31–33 including process outcomes. Three articles reported data relevant to child outcomes only34–36 and one reported both. 37 One study included data collected directly from children and young people with ASD,34 although original quotes from children were not presented.

The age range of children represented in these studies was 0–21 years. Just two studies31,33 focused specifically on younger children (3–6 years;31 up to 5 years33). The diagnoses represented in the studies typically relied on parental reports. Two studies35,37 focused on particular diagnostic groups (Asperger syndrome;37 ASD with no functional communication35) and others were defined in terms of use of a particular service (speech-and-language therapy;31 assessment and diagnosis;32 preschool educational intervention33).

Data collection methods included focus groups, individual face-to-face interviews and open-ended/free-text questions within postal and web-based surveys.

Although we did not appraise quality of studies formally (using any standard checklist), the quality of reporting sampling and recruitment, data collection methods and data analysis processes was extremely variable.

Given the significant limitations, in terms of quality and relevance, a ‘light touch’ data extraction was undertaken to identify outcomes and themes (see Appendix 2).

In terms of child outcomes, it was notable that some aspects deemed ‘fundamental’ by parents may not be regularly assessed (such as ‘safety’),34 and certainly not as an outcome of an early intervention trial. ‘Awareness of danger’ was added to the conceptual framework (subdomain Social inclusion) as a fundamental issue of safety. The parents’ and young people’s emphasis on participation outcomes (such as being ‘isolated from peers’ or ‘live a normal life’) may also not be reflected in what is usually measured. Constructs concerning child and parent stress, and positive mental health36,37 were supported as important to include as outcome constructs in the conceptual framework.

In addition, parents often highlighted the processes of interaction with professionals, and the utility of information from assessments. Parents expected the service to provide them with information and research literature; to involve them in decision-making processes; and to teach parents how to deliver therapies at home. 31 Braiden et al. 32 reported that parents ‘desired information relevant and applicable to their child to assist them in understanding and making sense of their own child’s presentation’. They also mentioned wanting to have positive times with their child: ‘when he is behaving well and not gearing up for a fight, he’s a very happy and pleasant child’. 37 Such parent priorities have informed the conclusions of the MeASURe project.

Consultation with people on the autism spectrum (DG, GJ)

Questions

Outcomes

What do you think it is useful for health professionals and teachers to measure in young children (up to the age of 6 years) with autism?

Process

What is the best way of assessing these skills? (observation; asking parents; testing the child; asking the child questions)

Where is the best place for observation to take place? (home; school; clinic; other)

What is it important for professionals to know about children with autism before they start to test them?

Methods

People on the autism spectrum in Birmingham and Newcastle were approached for their opinions by a person they knew well. In Birmingham, six adults were known to the University and responded by e-mail; 10 children were approached by a member of the Autism Outreach Team and were selected on the basis that they were thought able to give their views on the questions. In Newcastle, two children attending a National Autistic Society social group responded in person and, likewise, two young adults attending a social inclusion group. Responses to the questions were thus received from 12 young people aged 9–15 years, and from eight adults aged 22–43 years. Each respondent was given a shopping voucher in acknowledgement of their contribution. The verbatim responses were collated and common themes extracted.

Results

Outcomes

Responses showed that young people had a good knowledge of the areas that were likely to be affected in autism (e.g. eye contact, social skills and communication) and those likely to be measured (e.g. intellectual level). However, some of the respondents emphasised outcomes that may not usually be prioritised by professionals or researchers (the subdomains into which these suggestions fit are shown within parentheses):

-

How they respond to change in their lives (Restricted, repetitive behaviour); whether they are unhappy in a room because it might be dirty (Restricted, repetitive behaviour; Sensory processing); ability to sit still – if fidgety (Attention); whether they get angry easily (Emotional regulation); whether they like talking to people (Social functioning); how long it takes for information to stick (Learning); ability to make friends (Social relations); do they hang around with popular kids so that they are popular? (Social inclusion).

Areas that were mentioned most often by the adults as important to assess included special interests and sensory issues, and social interaction to a lesser extent. Some respondents stressed the importance of trying to understand the rationale for a young child’s repetitive actions or special interests.

Process

Many of the respondents emphasised the need to observe children, and for that observation to take place in more than one setting, as behaviour may be very different in different places. Tests (i.e. series of standard tasks) might be ‘alright’ if they are interesting, and given in manageable-length sessions. Some adults on the autism spectrum were concerned that the use of normed tests or checking against typical milestones leads to negative conclusions, because developmental trajectories of children on the autism spectrum may be atypical and strengths may be missed. Respondents suggested that those administering tests should not assume instructions are clear and have the same meaning for a child with ASD, and that testing should happen in a place where the child is comfortable.

Respondents expressed the view that people who do assessments should find out about children before assessing them. One child said: ‘Ask the child to show them what they like to do, e.g. jigsaws, lego’. They also felt that parents and support staff should be asked about special interests, motivators, sensory issues, and so on, and also about any events that have happened recently which may be affecting the child. One adult emphasised the need to be mindful of a child’s self-esteem: ‘So much of the time assessment is done in terms of measuring deficits against a supposed “normal” or “ideal” . . . I had a feeling of being ‘different’ or ‘wrong’ from approximately the age of 3 years’.

Survey of professionals working with early years children with autism spectrum disorder (GJ, JRP)

Question

What constructs are most often measured by early years professionals in monitoring children’s progress?

Methods

A survey was undertaken in autumn 2012 through the British Academy of Childhood Disability database of 240 UK Child Development Teams. Professionals were sent an electronic link to a web-based survey that took 10 minutes to complete. In parallel, education professionals received the survey via (1) ‘4 Children’, a national charity and UK Government strategic partner for early years and child care, through their database of 15,000 Early Years providers across England; (2) the database of an independent specialist centre for early years children with ASD; and (3) 150 practitioners undertaking the Birmingham University School of Education Autism Programme residential weekend.

The survey had five sections. Respondents were asked:

-

About their profession, and the setting in which they work.

-

‘Do you regularly work with children on the autism spectrum (this includes any activity that aims to improve/change an area of functioning)?’ and ‘Do you ever measure the progress or outcomes of children on the autism spectrum (i.e. more than just seeing the child once for assessment)?’. Those who indicated ‘yes’ were given access to the rest of the questions.

-

To identify all areas in which they formally measure or informally make judgements about progress or outcomes for children on the autism spectrum whom they see more than once, and who are aged ≤ 6 years. The 68 outcome constructs included were taken from the conceptual framework.

-

To indicate how frequently (on a six-point scale) they used different types of tool: standardised measures of progress or outcome (with manual and comparative age-related information); non-standardised measures (either published or created locally); informal judgements.

-

To give the three areas in which they most frequently measure progress over time, or outcome, with which of the three types of tools.

Results

The 836 respondents included 167 health professionals (paediatricians, speech-and-language therapists, clinical psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, dietitians, health visitors, social workers and educational psychologists), 353 education professionals (teachers, special educational needs co-ordinators, autism education advisors, teaching assistants, intervention practitioners), 125 nursery nurses and 191 other professionals, many of whom were childminders. Professionals worked in a variety of settings. Many health professionals worked in child development centres or hospitals but some were based mainly in educational settings. Education staff were from mainstream and specialist schools or early years settings.

Five hundred and thirty-seven professionals monitored the progress or outcome of children who were seen more than once, and were able to access the remainder of the survey.

Professionals were more likely to measure characteristics such as amount of speech (76%), social interaction (90%) and attention (79%) than life or adaptive skills (measuring for, or trying on, clothes 6%, difficulties with appointments, e.g. hairdresser, dentist 16%, use of knife and fork 29%), features related to ‘quality of life’ for the child (quality of life 21%, happiness 42%) or the family (nature of sibling relationship 18%, family quality of life 22%, impact on the family 33%).

Professionals were more likely to use their ‘own informal judgement in discussion with parents or other professionals’ than standardised measures to rate improvements (442 respondents agreed with ‘used often’, ‘most of the time’ or ‘always’ compared with 253 who checked ‘never’, ‘rarely’ or ‘sometimes’). The specific types of measures used varied very widely due to the broad range of professional respondents. However, consistently across the questions, around one-third of respondents replied that they used standardised measures, and half said that they were most likely to use parent or professional impression to gauge progress or outcome. (The standardised tools identified as used most frequently were later included in searches in Chapter 4.)

In conclusion, this survey found that professionals are most likely to measure features related to core impairment subdomains of autism, rather than aspects of daily living, family functioning, and child well-being and happiness.

Consultation with parents (DG, PG, AS le C, CM)

Question

What outcomes do parents consider as important to be assessed?

Methods

Parent advisory groups were recruited at three sites (Exeter, South London, Newcastle). In Exeter, the Peninsula Cerebra Research Unit involves families of disabled children as partners in research through a Family Faculty. 38 Parents of children with ASD were e-mailed and invited to volunteer: 12 expressed interest and seven participated in one or more meetings. In London, the Newcomen Neurodisability Team involves families of children with ASD in giving advice on an ad hoc basis; for MeASURe, 10 parents were invited by e-mail and six participated in one or more meetings. In Newcastle, parents of children with ASD aged ≤ 10 years were invited by e-mail; four participated in one or more meetings. Thus a total of 17 parents were involved in discussion meetings. Parents were given a financial acknowledgement in addition to travel expenses, to recognise their time and expertise at each attendance. Meetings were held at three points during the MeASURe project.

Early meeting To explore parents’ priorities and experiences of assessment and identify what outcomes parents saw as important, especially for monitoring their young child with ASD over time. This session involved an explanation of the aims of the project and open discussion, led by a member of the project team and a parent involvement co-ordinator.

Mid-point meeting To undertake a Q-sort of constructs emerging from the conceptual framework. Two members of the MeASURe project team (NL, GM) created ‘lay wording’ versions of the constructs. Sixty-two constructs were presented on cards in a jumbled order (i.e. not including symptom severity, physical indicators, global measure of function, global measure of outcome). The way in which the constructs had been chosen was introduced by the project team member. Through discussion within the parent group, the constructs were sorted on to a ‘forced-choice’ grid in a pyramid shape on a large piece of paper. Columns on the grid were rated for levels of importance (from ‘more’ to ‘less’ on an 11-point scale), i.e. ‘the importance of various things which could be measured when tracking the progress of children with autism aged up to 6 years, or in measuring the outcome of a specific preschool intervention’. It was stressed that none of the constructs was considered unimportant.

End-point meeting Parent groups met again to consider a summary of the findings of the literature reviews and early consultations. This included a question about the reasons for differences between what parents consider important to be measured and what professionals most often measure. The main activity was to examine five questionnaires that had been rated positively in the systematic reviews. Parents were asked to compare and contrast two questionnaires about parent stress, two questionnaires about children’s behaviour problems, and one questionnaire designed as a global measure of outcome. The issues raised were then taken by parent representatives to the MeASURe project Discussion Day on 14 February 2014 (see Chapter 2, Consultation with multiple stakeholders).

Results

Early meeting

Parents expected that professionals would focus on assessment of core features of autism, such as communication and social interaction. However, they suggested that the child’s skills should be acknowledged and more attention be paid to unusual behaviours that the child is exhibiting, as well as measuring what the child is not achieving. For parents, priority areas for measurement included habit behaviours (such as sleep, diet and food-related behaviours, sensory processing issues, toileting) and also challenging behaviours and ‘meltdowns’ (such as self-harm, hitting out, anxiety, stress, happiness, tics). Parents endorsed the importance of social communication and social functioning (interacting, playing with others, playing alone, understanding and communicating) and, furthermore, the building blocks of learning, independence and life skills (reading and academic achievements, hobbies and sport, imagination and creativity, self-care, preparing food, getting dressed, time management, vulnerability and danger). They also stated that they recognised that some activities/skills may not seem that important or be seen as relevant for this young age range but become a more significant priority later on in development and as their child progresses through school. Parents also mentioned difficulties they had with taking children to appointments for health care (vaccination, dental care, shoes, eyes and hearing). These constructs influenced the conceptual framework, and the content of the survey for professionals.

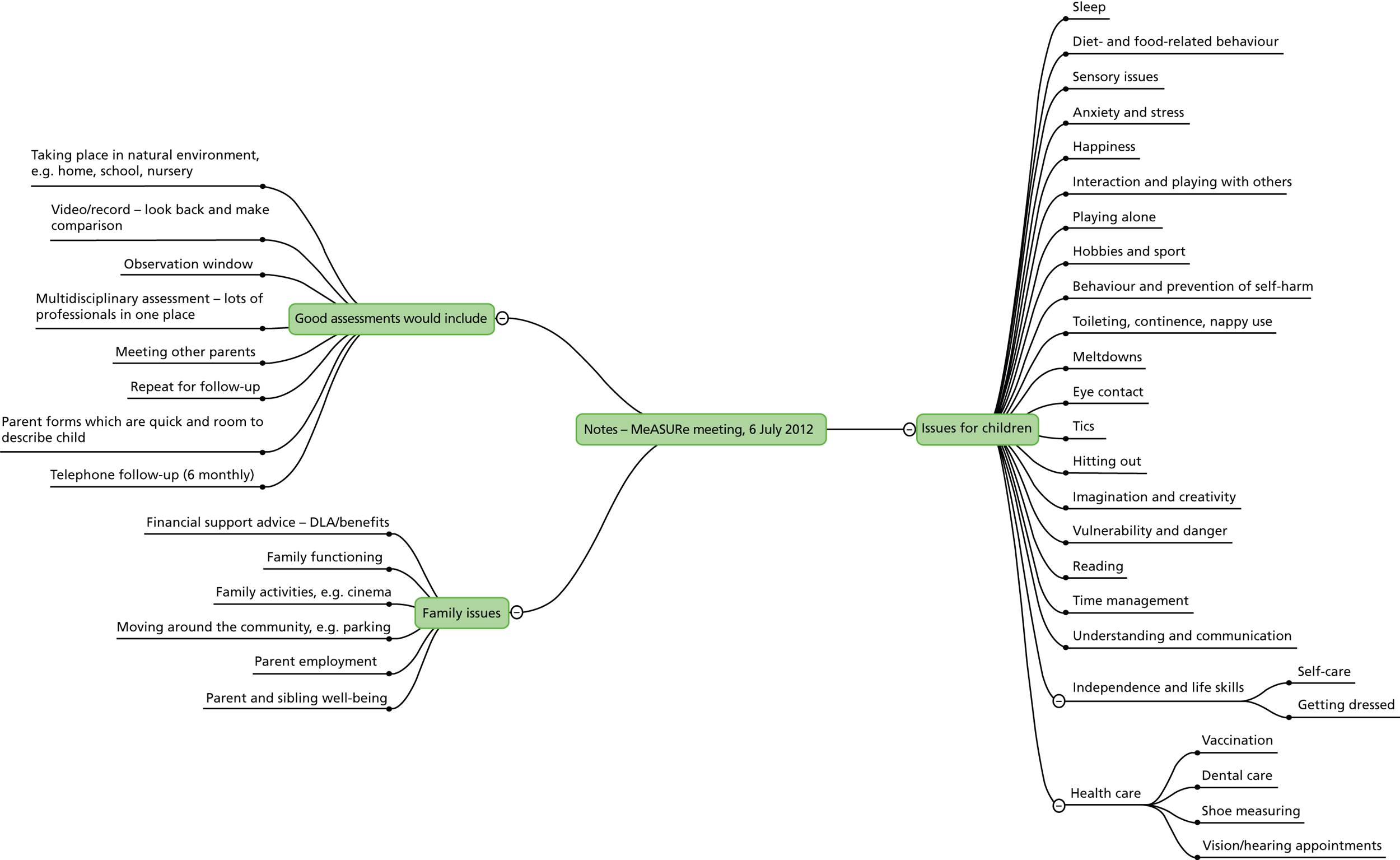

Parents also commented on aspects of the process of assessment. They recommended the use of video in relaxed environments, so that professionals may watch for changes. They stressed the value of information gathered in a range of settings (suggesting use of video to rate change over time and between different settings). Figure 1 illustrates the themes arising from one of the parent group meetings.

FIGURE 1.

Themes from Exeter parent group discussion. DLA, Disability Living Allowance.

Mid-point meetings to undertake the Q-sort

There were four groups that completed this task (two in London to accommodate parents’ availability). Taking an average of the Q-sort ratings from all sites, the items rated on average as ‘more important’ can be grouped as:

-

Body functions/impairments Hypersensitivity, anxiety, unusual fears, distress, non-verbal ability, expressive and receptive language.

-

Activity level indicators Aggression, sleep problems, school readiness.

-

Participation Happiness, self-esteem, relationships with brothers and sisters, being bullied/rejected, no awareness of danger.

-

Families Parent stress.

The highest level of consistency in rating these constructs across groups was for aggression and sleep problems. Parents rated happiness as important for all young children but one group did not agree that this could be considered an ASD-specific measurable outcome. In discussion parents mentioned that they had had to learn about autism, and so had not understood at the start of assessments of their child why skills such as ‘joint attention’ were of importance.

End-point meetings

In London it was not possible to arrange an end-point meeting; there were a number of barriers for parents’ attendance including ‘travel time’, ‘difficulties getting child care’ and ‘need to battle the new school statementing system’. In Exeter, a preliminary meeting was held to discuss with parents how to assess the strengths and weaknesses of tools used in assessment (i.e. explanations of terms such as reliability, validity and sensitivity to change).

Within the preliminary report, the ratings on importance by parents were compared with the constructs most often measured by professionals (Table 2), and parents were asked to reflect on the differences.

| Professionals: areas regularly measured | Parents: important areas to measure (rank) |

|---|---|

| 90% social interaction with children | Happiness (1) |

| 84% play skills | Anxiety, unusual fears (2) |

| 79% attention | Positive views of self (self-esteem) (3) |

| 76% amount of speech | Distress (4) |

| 75% understanding of language | Non-verbal ability (5) |

| 73% expressive communication skills | Relationships with brothers and sisters (6) |

| 72% pretend play | Parent stress (7) |

| 70% fine motor skills | Fighting, hitting others (8) |

| 68% participation in activities | Sleep problems (9) |

| 68% challenging behaviour | Being rejected by others (10) |

The only area of overlap between parents and professionals was ‘challenging behaviour’/’fighting, hitting others’. Parents in Newcastle highlighted that they believed that parents tend to focus on broader outcomes than professionals, as they see their children everyday in different environments. Anxieties and distress were emphasised; parents remarked that it is emotional needs that impact on the child’s and family’s quality of life. Parents also believe that professionals tend to be unaware of these important difficulties before a child enters the social environment of education.

The Exeter parents had a rather different way of viewing the table. They suggested that professionals measured aspects that were intermediate outcomes, which facilitate what parents rate as important. For example, they suggested that parents’ identification of ‘fighting, hitting others’, ‘distress’, ‘happiness’ and even ‘parent stress’ could be mapped from what the professionals highlighted as ‘challenging behaviour’. Similarly, when parents highlighted ‘relationships with brothers and sisters’, these benefited from adequate ‘speech’ and ‘understanding of language’. So, despite the different labels, there was general support from parents for what professionals measure, and parents had noticed their children making progress in these areas.

Consultation with multiple stakeholders

Question

What outcomes is it important to assess when monitoring the progress and outcomes for children with ASD up to the age of 6 years?

Methods

A Discussion Day was held in London on 14 February 2014. Twenty-five participants were invited: four parents of children with autism; three young people with autism, two of those with staff who support them in education; eight speech-and-language therapists, occupational therapists, paediatricians or psychologists; and two researchers working with children with autism; six MeASURe project researchers who work in health or education services also attended.

As one activity, groups of similar background carried out a further Q-sort to rate the importance of constructs, and ascertain similarities or differences between what parents, professionals and researchers consider most important. The set of 21 constructs for the parents and for the young people was drawn primarily from those reported as most often assessed by the early years professionals in the survey. The set for the professionals and the researchers included the 10 rated as most important by the parent groups, and the 10 most often measured by professionals as reported in the survey. Both sets were completed with added constructs to represent a wide span of subdomains.

We hypothesised that:

-

The young people and parents might well agree on the top 10 constructs.

-

The professionals might also agree with parents, even although what they actually measure is not in accordance.

-

The researchers might choose a different set (more based on intervention elements, symptoms and everyday function).

-

We had no expectation about parents’ views on the order of importance of what professionals tend to measure.

Results

Adverse weather conditions and train cancellations prevented several participants joining the Discussion Day, including two young people on the autism spectrum. However, four groups of four people each considered the constructs.

One young adult on the autism spectrum joined the parent group; his/her ranking showed a high level of agreement with the averaged ranking of constructs undertaken previously by parent groups (Spearman rank correlation rs = 0.618). Fine motor skills were rated higher than previously because of the experiences of the young adult as a child. ‘Friendships’ was rated higher than previously, reflecting on the precursor skills needed by the child early on that will lead later to being able to make friendships. Aspects that affect the emotional state of the child, including sensory processing, continued to be rated highly. ‘Participates in mainstream activities’ was rated low: the group thought ‘this means the ASD child has to adapt to the mainstream world rather than ‘mainstream’ adapting/understanding/respecting ASD needs’. They also gave a low rating to ‘not cooperating, throwing, spitting, won’t sit (challenging behaviour)’, as they considered it the role of adults (parents, education and care staff) to try to make the environment right for the child so his/her autism was less ‘disabling’.

The two multidisciplinary groups of health and education professionals, and the group of ASD researchers, had low agreement with the averaged ratings of the parent groups (rs = –0.268, 0.131 and –0.063, respectively). The health and education professionals commented that they measure what they can (in the setting, given the available tools) and what they traditionally have done. They emphasised as ‘important’ what they see as most urgent to try to change, such as challenging behaviour and communication skills. In contrast, although acknowledging the importance of the construct ‘positive views of self (self-esteem)’, they gave it a lower rating because of the developmental stage of children up to 6 years; researchers similarly rated self-esteem as low because of the lack of a suitable measurement tool. The researchers had rated highest ‘not cooperating, throwing, spitting, won’t sit (challenging behaviour)’ on the basis of its impact on others and on the child’s experience. Both groups of health and education professionals identified a range of additional constructs that they would consider it important to measure, including communicative competence, problems with food, functional adaptive behaviour, etc. They also mentioned the importance of identifying the skill set of support staff, and parent confidence in managing their child’s needs and behaviours.

When all groups came together, the discussion highlighted differences in perspective, in summary a ‘social’ model and a ‘medical’ model. The parents and the young adult on the autism spectrum argued that it is important to focus on what children can do, to see autism as a ‘difference’ rather than always use a ‘deficit’ model, and to focus more on how to enable children through improving their environments. Parents were encouraged that the clinicians had mentioned including assessment of the skills of care and education staff. The clinicians reflected that their approach to assessment and intervention is based on a more ‘medical’ model: early identification of specific impairments, treatment, prevention of secondary impairment, and so on. The measurement of outcomes and tools available reflect this framework, with an emphasis on problems and deficits. For the researchers, the model of intervention and outcome assessment was also primarily embedded in a ‘deficit’ model of autism, with an emphasis on treating and measuring core features of autism. Research outcomes such as helping parents manage better and understand more are seen as ‘soft outcomes’, and not given the same importance as changing children’s characteristics. A certain contradiction was pointed out between the recognition that publicly funded research must now be informed by good patient and public involvement, and yet the priority research questions, commissioning briefs and frameworks for judgement of what is good science do not necessarily value the social model of understanding a condition such as ASD.

Overall conclusions

The MeASURe project took a multifaceted approach to consultation. We aimed to identify (1) what outcomes should be measured when monitoring the progress of young children with ASD and (2) whether there is agreement between parents and people with ASD on the one hand, and professionals on the other hand, about the relative importance of what to measure. The initial stages of the review of qualitative literature, and the early parent advisory groups, added to the conceptual framework developed to guide the project. That framework of four domains and 26 subdomains appears to cover the constructs valued by various stakeholders, and enabled similarities and differences in perspective to be elicited.

We found a striking difference between the constructs rated important by parents and the constructs most frequently measured by health and education professionals. In discussion it became clear why this would be likely. Parents’ experience with their children leads them to emphasise emotional well-being as affecting the whole family. Professionals measure what they have the tools for, and acknowledge that their practice is influenced by an emphasis on the core impairments in autism and the behaviour of the individual child, rather than necessarily seeing the broader picture of how the child is affected by their environment. Thus the consultation has highlighted the need to include information from multiple sources to reflect the complementary perspectives of the different stakeholders. This greater awareness of contrasting perspectives has enriched the discussion of available tools (see Chapter 5). Furthermore, parents and young people highlighted critical points about the process of assessment and monitoring of young children with ASD which also contributed to the evidence synthesis.

Chapter 3 Systematic search of observational and intervention literature

Introduction

In preparation for the MeASURe project, an initial scoping search of published systematic reviews of intervention in ASD was conducted (in May/June 2011 by NL); this identified eight Cochrane Collaboration reviews and 13 recent journal papers. The scoping search enabled us to gather information regarding tools that are commonly used to measure outcomes, and to identify theoretically important gaps in the domains measured. This scoping search was not limited to children up to 6 years of age. Seventy-nine tools were reported in the reviews, including 23 assessing adaptive and maladaptive behaviour; 17, language/communication; 13, ability; eight, sensory; nine, ASD specific; four, impact on family; two, social interaction; one, motor skills; and two, summary scales.

Many of the reviews failed to discuss the relevance of the outcome domains, and the strengths and weakness of the included tools – those that did were relatively consistent in their recommendations for improvement. The domain most commonly cited by review authors as missing was ‘quality of life’. 39–41 Other missing outcomes included ‘school readiness’, ‘independence and daily living skills’39 and ‘behavioural outcomes’ such as sleep disturbance, self-mutilation, attention and concentration problems. 40 Also mentioned was the need for qualitative research to determine which outcomes are ‘useful and relevant to consumers, clinicians and service providers’. 41

A key limitation mentioned in the reviews concerned ASD-specific tools, developed to aid diagnostic assessment, but used to monitor change, even although not designed and validated for this purpose. 40–42 Similarly, intelligence quotient (IQ) has been used as a measure of change although designed to measure a ‘stable’ construct. 43 Two further unresolved questions are first how parents (and other stakeholders) define an important change, and, second, what magnitude of change should be considered clinically relevant (and therefore used as the target difference in intervention studies). 40–42

Several review teams commented that included studies had measured outcomes using unpublished or non-standardised measures. 8,43,44 Some reviews included studies focusing on anecdotal reports or ad hoc questionnaires created by the researchers for that specific study45 and not adequately validated.

Finally, one prominent recommendation common to all reviews was the need for a core shared battery of baseline assessment and outcome measurement tools, although the challenge of developing a single battery was recognised, because of the heterogeneity of children’s difficulties, developmental ability and trajectory of developmental change. 46 Some reviewers proposed specific key domains that they felt should be considered, including intellectual ability, developmental abilities across domains, adaptive behaviour, communication skills, severity of autism, play, social skills, challenging behaviours, rigidity and other behaviours that are characteristic of children with autism. 40,47

Review of tools in use

The purpose of this systematic review was to identify the range of tools used to date in observational and intervention evaluation studies, and relate these tools to the subdomains of the conceptual framework adopted for the MeASURe project.

Review question

What tools are in use for measuring and monitoring developmental outcomes in young children with ASD?

Search strategy

We included studies published from 1992 to coincide with the publication of the international classifications, International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV). 48,49

Original searches were conducted in June and July 2012, and re-run in June and July 2013. The databases searched were:

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ProQuest) 1987 to present

-

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost) 1981 to present

-

The Cochrane Library [includes Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, HTA, Cochrane Central Register of controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Ovid)] inception to present

-

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (ProQuest) 1966 to present

-

MEDLINE (including In-Process and Other Non-Indexed citations) (Ovid) 1946 to present

-

EMBASE (Ovid) 1988 to present

-

PsycINFO (Ovid) 1987 to present

-

Sociological Abstracts (ProQuest) 1952 to present

-

Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts (ProQuest) 1973 to present

-

Health Management Information Consortium (Ovid) 1979 to present

-

PapersFirst [Online Computer Library Centre (OCLC)] inception to present

-

Proceedings (OCLC) inception to present

-

Scopus, inception to present

-

Social Services Abstracts (ProQuest) 1979 to present

-

Web of Science (Science Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index, Arts and Humanities Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index inception to present)

-

WorldCatDissertations (OCLC) inception to present.

Additionally, grey literature was searched via Digital Education Resource Archive, Oxford Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement database, Turning Research into Practice database, internet searches, and searching of selected websites (see Appendix 3). The National Research Register and UK Clinical Research Network were also searched for ongoing research.

A master search strategy was created and modified as needed for searching across the breadth of databases; a list of terms can be found in Appendix 3. Modifications included changes to syntax, fields searched and Medical Subject Heading/thesaurus terms. Full search strategies are available from the first author, and example search strategies for MEDLINE, ERIC and Web of Science are provided in Appendix 3. Searches were limited to English-language articles only. When possible, search filters were used to limit study types returned.

Inclusion criteria

We considered inclusion criteria based on types of studies, participants and types of measurement.

Types of studies

We included:

-

all relevant randomised and quasi-randomised trials of social, psychological and educational early interventions for children with a diagnosis of ASD

-

observational studies of children with ASD (cross-sectional and longitudinal)

-

case–control studies

-

cohort studies, including studies of baby siblings of children with autism, which provide information on tools to monitor developmental progress and follow early markers of ASD.

Types of participants

We reviewed all studies that included at least 50% of children with ASD. Child participants had a ‘best-estimate’ clinical diagnosis of an ASD, including autism, ASD, atypical autism, Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder – not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS), according to either ICD-10 or DSM-IV48,49 criteria. Use of a particular diagnostic tool such as the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) or the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) was not required. Children with ASD and another medical condition, and children with ASD and comorbid conditions were included.

All children were aged ≤ 6 years upon entering the study.

Types of measurement included

-

Direct assessment of child ASD symptoms by trained assessor.

-

Direct assessment of developmental skills, i.e. language, cognition, play skills, fine and gross motor skills, by trained assessor.

-

Observational coding of social interaction skills.

-

Interview or self-completed (parent, teacher or other professional) questionnaire report of child ASD symptoms.

-

Interview or self-completed questionnaire report of developmental skills, i.e. language (vocabulary), adaptive skills, with/by parent, teacher or other professional.

-

Interview or self-completed (parent, teacher or other professional) questionnaire report of associated problems, including behaviour that challenges, aggression, sleeping, eating, toileting, anxiety, hyperactivity and others identified through parent consultation.

-

Idiographic measures focused on particular behaviours (e.g. goal attainment scaling, target behaviours).

-

Measures of impact on parent or family.

Types of measurement not included

-

Economic impact on home and family.

-

Experimental tasks and measures, for example barrier tasks, reaction time.

-

Biophysical measures, medical investigations.

-

Process measures, for example fidelity, adherence, parent satisfaction with intervention.

Sifting

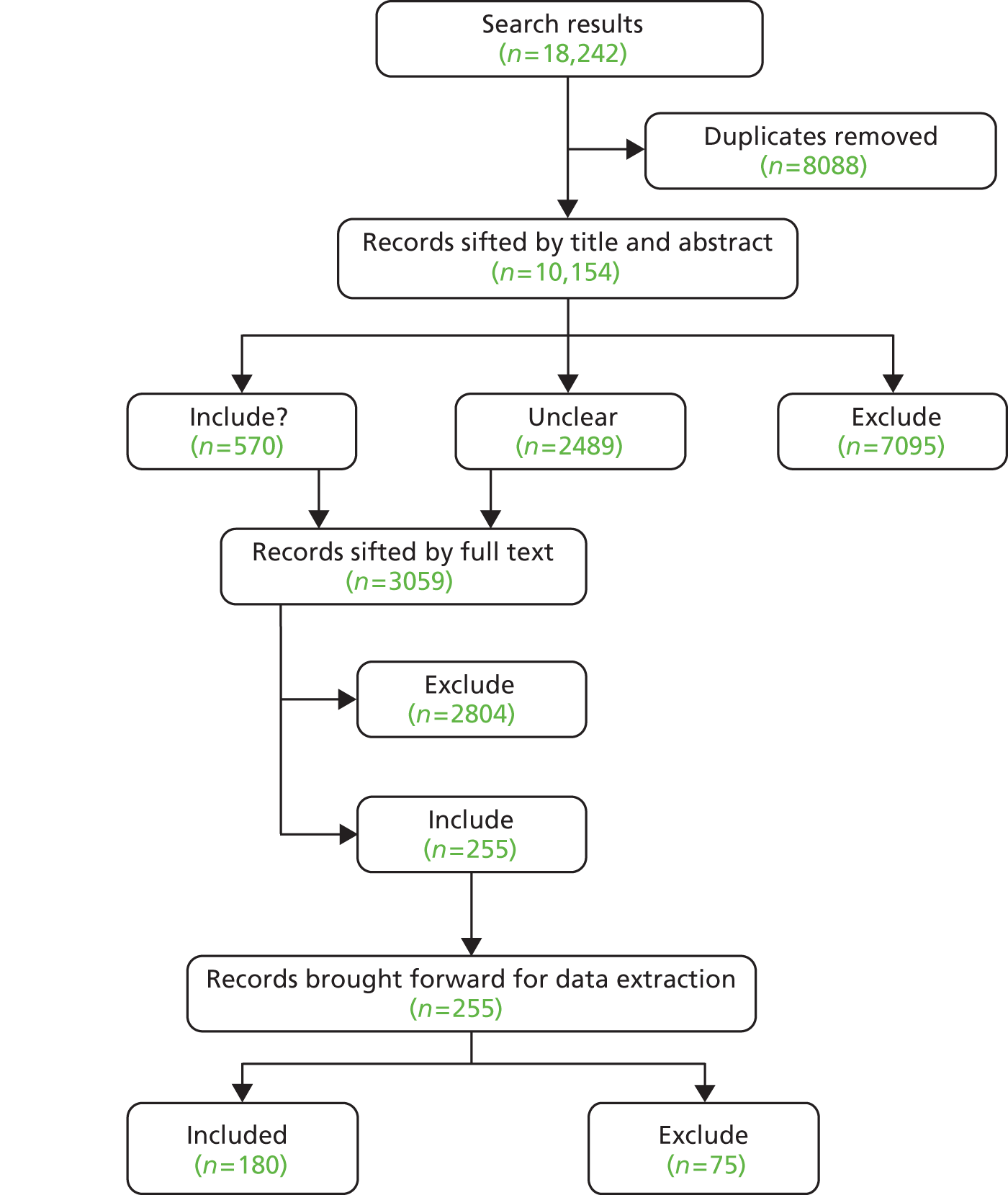

Papers were first sifted by title and abstract (Figure 2). The decision categories were ‘potentially include’, ‘exclude’, ‘consider for Chapter 4’ (assesses the measurement properties of a tool only) or ‘unclear’. The two reviewers (NL, IPO) cross-checked sets of 20 papers at a time until they reached a high level of agreement. Regular (at least weekly) discussion of decisions was held throughout the process to maintain consistency. Then 3059 papers were examined at full text. When decisions regarding inclusion were uncertain, a third reviewer (HMcC) made the final decision.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of searching and sifting. Search results up to date as of 17 July 2013 (original search and update combined). Sifting decisions up to date as of 13 August 2013. Final total for data extraction = 184 (with addition of records identified at stage 3).

There was a further stage of sifting of records found during the search of papers about measurement properties of tools (see Chapter 4), with searches completed by 9 September 2013. Those searches revealed 118 records potentially relevant to Chapter 3. Once duplicates were removed (86), 32 additional records were sifted by full text (completed 8 December 2013): of these, 28 were excluded and four were added to the final total for data extraction.

Data extraction

A data extraction tool was created as a web-based instrument and piloted (see Appendix 4). The data extracted included study eligibility; type of study; participant characteristics; number of outcome tools (then for each tool: name, population for which designed, specific subscales, outcomes measured according to authors). Subsequently, two reviewers with expertise in ASD (JR, HMcC) reviewed each paper further and indicated which subdomains in the conceptual framework (see Table 1) were measured by each tool, including subscales.

Results

The data extracted from the 184 papers are presented in Appendix 5. All of the tools identified in the review as used to measure outcomes are presented in Table 3. In addition, there were a number of tools developed for use in particular studies; these were described as, for example, ‘Caregiver–child interaction’, ‘Coded observation of joint attention’, ‘Examiner ratings of social engagement’, ‘Naturalistic examiner–child play sample’, ‘Parent interview’, ‘Video recording of child in classroom activities’, ‘Sleep diaries’ and so on. Such tools could not be searched for in databases by name (see Chapter 4) to examine their measurement properties and so were not considered further (see Appendix 5). When tools had a generic-sounding name, information from the source reference was included in the searching. Other tools included below, but not considered further, were:

-

adaptations of tools for use in another language, or tools for which an alternative UK version exists

-

tools used only in outcome and monitoring studies published before 1995 (given different diagnostic definitions before 1994).

| Subdomains | Tools |

|---|---|

| Autism symptom severity | Autism Behavior Checklist |

| Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised | |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule | |

| Autism Observation Scale for Infants | |

| Baby and Infant Screen for Children with aUtIsm Traits-Part 1 | |

| Behavioral Summarized Evaluation Scale (also Revised) | |

| Childhood Autism Rating Scale | |

| Gilliam Autism Rating Scale | |

| Infant Behavioral Summarized Evaluation scale | |

| Modified Checklist for Autism in Toddlers | |

| Parent Observation of Early Markers Scale | |

| Pervasive Developmental Disorders Behavior Inventory | |

| Real Life Rating Scale (Ritvo–Freeman) | |

| Social Communication Questionnaire (originally known as Autism Screening Questionnaire) | |

| Social Responsiveness Scale | |

| Childhood Autism Rating Scale – Tokyo versiona | |

| Social awareness | Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (Behavior Sample) |

| Early Social Communication Scales | |

| Imitation Battery | |

| Imitation Disorders Evaluation scale | |

| Motor Imitation Scale | |

| Preschool Imitation and Praxis Scale | |

| Pre-Verbal Communication Schedule | |

| Social Communication Assessment for Toddlers with Autism | |

| Social Communication Behaviour Codes | |

| Restricted, repetitive behaviour | Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule | |

| Repetitive Behavior Scale (and Revised) | |

| Sensory processing | Infant/Toddler Sensory Profile |

| Sense and Self-Regulation Checklist | |

| Sensory Profile | |

| Short Sensory Profile | |

| Autism Screening Instrument for Educational Planning | |

| Battelle Developmental Inventory-Second Edition | |

| Language | British Picture Vocabulary Scale-II |

| Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals-Revised | |

| Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (Caregiver Questionnaire) | |

| Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language | |

| Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test | |

| Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities | |

| MacArthur–Bates Communicative Developmental Inventories | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | |

| Pragmatics Profile | |

| Preschool Language Scales | |

| Reynell Developmental Language Scales | |

| Sequenced Inventory of Communication-Revised | |

| Test for Auditory Comprehension of Language | |

| Test of Language Development | |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-Reviseda | |

| Differential Ability Scalesa | |

| Cognitive ability | Battelle Developmental Inventory |

| Bayley Scales of Infant Development | |

| Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function-Preschool Version | |

| British Ability Scales | |

| Cattell Infant Intelligence | |

| Developmental Profile | |

| Griffiths Mental Developmental Scales | |

| Leiter International Performance Scale-Revised | |

| Leiter Performance Scales (Arthur adaptation) | |

| McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities | |

| Merrill–Palmer Scale of Mental Tests | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | |

| Snijders–Oomen Non-Verbal Intelligence Test | |

| Stanford–Binet Intelligence Scale | |

| Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Revised | |

| Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised | |

| Differential Ability Scalesa | |

| Tanaka–Binet Intelligence Test (Japanese version of Stanford–Binet)a | |

| Kyoto Scale of Psychological Developmenta | |

| Snabbt Performance Test På Intelligence IQ IIa | |

| Attention | Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition |

| Child Behavior Scale | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | |

| Connors Rating Scales-Revised | |

| Emotional regulation | Baby and Infant Screen for Children with aUtIsm Traits-Part 2 |

| Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | |

| Children’s Global Assessment Scale | |

| Conners Rating Scales-Revised | |

| Developmental Behaviour Checklist | |

| Emotion Regulation Checklist | |

| Infant–Toddler Social–Emotional Assessment | |

| Toddler Behavior Assessment Questionnaire | |

| Physical skills | Annett’s Pegs |

| Beery Visual–Motor Integration Test | |

| Brunet–Lezine’s Oculomotor Coordination Subtest | |

| Functional Independence Measure for Children | |

| Infant Motor Maturity and Atypicality Coding Scales | |

| Mullen Scales of Early Learning | |

| Peabody Developmental Motor Scales | |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Physical indicators | – |

| Social communication | Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised |

| Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule | |

| Autism Screening Instrument for Educational Planning | |

| Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (Caregiver questionnaire) | |

| Early Social Communication Scales | |

| Pragmatic Profile | |

| Social Communication Assessment for Toddlers with Autism | |

| Social Communication Behavior Codes | |

| Social functioning | Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised |

| Child Behavior Scale | |

| Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Scales | |

| Social Behavior Rating Scale | |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Vineland Social Maturity Scale, Indian adaptationa | |

| Play | Communication and Symbolic Behavior Scales-Developmental Profile (Caregiver Questionnaire) |

| Developmental Play Assessment | |

| Structured Play Assessment | |

| Symbolic Play Test | |

| Test of Pretend Play | |

| Preschool Play Scalea | |

| Behaviour problems | Aberrant Behavior Checklist |

| Baby and Infant Screen for Children with aUtIsm Traits-Part 3 | |

| Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition | |

| Behavior Screening Questionnaire | |

| Child Behavior Checklist | |

| Child Behavior Scale | |

| Conners Rating Scales-Revised | |

| Developmental Behaviour Checklist | |

| Home Situations Questionnaire-Pervasive Developmental Disorders version | |

| Nisonger Child Behavior Rating Scales | |

| Parent Target Problems (or Parent Target Behaviours) | |

| Preschool Behaviour Checklist | |

| Behavior Style Questionnaire – Chinese versiona | |

| Habit problems | Child Behavior Checklist |

| Sense and Self-Regulation Checklist | |

| Learning | Autism Screening Instrument for Educational Planning |

| Extended Basic Academic Skills Assessment System | |

| Wechsler Individualised Achievement Test | |

| Daily living skills | Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Global measure of function | Ages and Stages Questionnaire |

| Assessment of Basic Language and Learning Skills | |

| Assessment, Evaluation and Programming System | |

| Behavior Assessment System for Children-Second Edition | |

| Brigance Diagnostic Inventory of Early Development-2 developmental profile | |

| Early Intervention Developmental Profile | |

| Early Learning Accomplishment Profile | |

| Functional and Emotional Developmental Questionnaire | |

| Learning Accomplishment Profile-Diagnostic, Third Edition | |

| Pediatric Daily Occupation Scale | |

| Preschool Developmental Profile | |

| Psychoeducational Profile-Revised | |

| Scales of Independent Behavior-Revised, Early Development Form | |

| Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales | |

| Social Adaptive Development Quotient Scalea | |

| Global measure of outcome | Autism Treatment Evaluation Checklist |

| Behavioral Summarized Evaluation scale (and Revision) | |

| Clinical Global Impression – Improvement Scale | |

| Infant Behavioral Summarized Evaluation scale | |

| Pervasive Developmental Disorders Behavior Inventory | |

| Social relations | – |

| Subjective well-being | Kiddie–Infant Descriptive Instrument for Emotional Statesa |

| Social inclusion | School Liking and Avoidance Questionnaire |

| Teacher Rating Scale of School Adjustment | |

| Interaction style | Functional Emotional Assessment Scale |

| NICHD Early Child Care Network scales | |

| Parent stress | Autism Parenting Stress Index |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | |

| Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Inventory | |

| General Health Questionnaire | |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale | |

| Parenting Sense of Competence | |

| Parenting Stress Index | |

| Positive and Negative Affect Schedule | |

| Questionnaire on Resources and Stress-Friedrich Short form | |

| Reaction to Diagnosis Interview | |

| Satisfaction with Life Scale | |

| Stress Arousal Checklist | |

| Symptom Checklist-90-Revised | |

| Family quality of life | Beach Family Quality of Life Questionnaire |

| Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scales II | |

| Family Assessment Device-General Functioning Scale | |

| Family Assessment Measure | |

| Family Empowerment Scale | |

| Family Support Scale | |

| Kansas Inventory of Parental Perceptions | |

| McMaster Family Assessment Device | |

| Parenting Alliance Inventory |

Conclusion

There were 131 tools to be taken forward, and their names (and acronyms) were used in searches to find papers on their measurement properties (described in Chapter 4). It is apparent that, as discussed in the introduction to this chapter, the tools used in research studies to measure outcomes include many which were designed for a different purpose, such as for screening or to enable conclusions to be drawn about an ASD diagnosis in children. However, the review has adopted a pragmatic, inclusive approach to the examination of the identified tools.

The planned data extraction in this chapter was to have included information about the reliability, validity and responsiveness to change of tools as described in the intervention evaluation and observational studies. However, when this extraction was piloted, it was found that most studies simply cited the reliability and validity of tools from their source references, irrespective of whether this had been tested with samples of children with ASD. Furthermore, it was not possible to interpret the evidence on responsiveness to change without considering whether the study was adequately powered to detect change, and whether the choice of outcome tool was appropriate to the nature of the intervention. If a significant intervention effect was not shown, there were a number of possible reasons, and the properties of the tool constituted only one of those reasons. For these reasons, the decision was taken to rely on the systematic assessment of measurement properties of tools described in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4 Systematic review of measurement properties of tools

Introduction

The searches reported in Chapter 3 revealed the varied range of tools used in the 184 papers from which data were extracted. The next stage of the MeASURe project examined the measurement properties of these tools. As an introduction, we summarise the many different types of tools currently in use, involving face-to-face assessment, observation or report.

Types of measurement in use

Standardised norm-referenced assessments all have to be administered by a trained professional. They have the advantage of comparison with children of the same age but for several reasons may be misleading when used for the assessment of young children with ASD. The abilities of the children may be underestimated by lack of co-operation with standardised testing, and they may have profiles that are dissimilar to typical development.

Direct observation includes both highly structured observational procedures (such as ADOS)50 and tools used primarily to measure social interaction in naturalistic settings, especially parent–child interaction. The former are a diagnostic assessment tool conducted by a trained assessor with subsequent rating of the child’s behaviours. The latter have the advantage of providing an in-depth understanding of patterns of responsiveness, which may have long-term effects on language and other development. 51,52 However, one major disadvantage of direct observation is the limited time frame with consequent questions of validity. Further, there are almost as many different coding schedules as studies, depending on the focus of interest.

Standardised semistructured interviews have been used in the characterisation of children’s early development and current ASD characteristics (e.g. the ADI-R),53 in the broad measurement of adaptive behaviour [e.g. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales (VABS)]54 and to gather information on additional difficulties, such as behaviour problems, anxiety and sleep. Problems of measurement include a paucity of tools focused on behaviour, which are specifically validated for ASD (e.g. the Autism Comorbidity Interview-Present and Lifetime Version is one such tool but is validated from only 5 years of age). 55

There are very many questionnaires used in studies of children with ASD, completed by parents, teachers and clinicians. However, as with the direct observation and assessment tools, many have not been specifically validated for use in ASD and contain assumptions about patterns of typical development (e.g. standard quality-of-life measures do not ask about children’s special skills and circumscribed interests).

Search strategies

Not all tools identified in Chapter 3 could be searched for by name. There were two main reasons. First, a number of tools had been developed for a particular study (such as a coding procedure for playground behaviour or parent–child interaction, with content related to a particular intervention approach). Second, some tools were translations or adaptations of tools for use in another country, or had been used only up to 1994. Thus papers relating to 131 tools could be searched for by name. Because of its particular relevance to the review, it was decided to add the Early Years Foundation Stage Profile, identified in our consultation with professionals in Chapter 2 as being widely used in nurseries.

Original searches for stage 3 were conducted in March and April 2013, with iterative searches run in August, September and November 2013. The databases searched were:

-

ERIC (ProQuest): 1966 to present

-

MEDLINE (Ovid): 1946 to present

-

EMBASE (Ovid): 1988 to present

-

CINAHL (EBSCOhost): 1981 to present

-

PsycINFO (Ovid): 1987 to present.

In order to search for papers describing studies of the measurement properties of tools, a search filter developed by the COnsensus-based Standards for the selection of health status Measurement INstruments (COSMIN) group was applied. 56 The COSMIN filter was originally designed for use in PubMed, and was translated for use in other databases by our information specialist (SR). The translation was tested in Ovid, and discrepancies were discussed with CBT (co-investigator, and part of the team who devised COSMIN). The sensitivity of the revised filters was tested continuously through the early part of data extraction, through inspection of references for ‘marker’ papers that should have been included, until the new filters were judged satisfactory. The translation can be found in Appendix 6.

Each search consisted of four components: autism terms, age group terms, COSMIN filter and tool name. A master search strategy was created and modified as needed for searching in various databases – a list of terms can be found in Appendix 6. Tool names required basic searches in their own right to determine variant spellings, variant names and to include acronyms. For example, numerous tools include the word ‘scale’, but this might have been reported as ‘scales’, ‘scale’, ‘score’ or ‘scores’ by the authors. Some databases, notably PsycInfo, include a field for tests and measures, and this was utilised if available, as this provides a standard way of identifying a tool regardless of how an author has reported the title.

Searches were limited to English-language papers only and papers published from 1992 to present. Measurement tool-only search strategies are available in Appendix 6.

Finally, the searches in Chapter 3 had identified 128 papers which were about measurement properties of tools rather than about monitoring progress or outcomes, and so these were also included in the stage 3 sifting (see Figure 3).

Inclusion criteria

-

Study was published as a ‘full text original article’.

-

The tool measured a domain of interest (see ‘conceptual framework’, Table 1).

-

A tool identified at stage 2 (i.e. used for monitoring and/or to measure outcome in a longitudinal or intervention study with children with ASD up to 6 years old) was the focus of the study. (When a paper reported the measurement properties of a ‘new’ relevant tool this was noted but not included.)

-

The study sample overlapped with the age range 0–6 years (e.g. a sample with age range from 6 to 18 years was judged eligible; one that included 8- to 15-year-olds was ineligible).

-

The study sample included at least 50% of children with ASD. Furthermore, the study sample could be individuals who were being monitored for ASD symptoms even if they had another primary diagnosis (e.g. a paper monitoring ASD symptoms in a Fragile X population could be eligible if exploring measurement properties of a tool used as an outcome).

-