Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HTA programme as project number 10/140/02. The contractual start date was in May 2012. The draft report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ken Stein is chair of the NIHR HTA Editorial Board and a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board.

Disclaimer

This report contains quotations from transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Richardson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

What is attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder?

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by age-inappropriate levels of inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity. 1 The current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fifth Edition (DSM-5) categorises particular constellations of symptoms into three presentations of ADHD. These are (1) predominantly inattentive; (2) predominantly hyperactive/impulsive; and (3) combined, where symptoms of both inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity criteria are present.

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for ADHD, published in May 2013, increased the age by which some symptoms must have been present from 7 to 12 years of age. 1 Another potentially key change in DSM-5 relates to the level of impairment; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)2 required clear evidence of clinically significant impairment for diagnosis, whereas DSM-5 requires only interference or a reduction in functioning. DSM-5 also requires clinicians to specify the severity level of a diagnosis: mild, moderate or severe. Given the recent publication of DSM-5 and the retrospective nature of evidence synthesis, the studies included in this review refer to diagnoses made according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Third Edition (DSM-III) or DSM-IV criteria. 2,3

The International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) classifies core ADHD symptoms as hyperkinetic disorder. 4 The diagnosis for hyperkinetic disorder is more restrictive, whereby inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity must all be present. Thus, the ICD-10 diagnosis represents a subsample of the DSM-5 ‘combined presentation’ of severe ADHD. In Europe, ‘ADHD’ has become the diagnostic phrase most commonly used in practice, even when the narrower ICD-10 criteria are being used.

The aetiology of ADHD is complex and may be most clearly understood as involving the interplay of biological, psychological and social factors. 5 Several causal factors have been suggested to contribute to the onset and maintenance of ADHD. These include genetic factors, psychosocial factors, complications in pregnancy and delivery and environmental factors such as high lead exposure, head injury and diet. 6–9 Heritability is a major factor and appears to contribute approximately 75% of the aetiology of ADHD. 6 Although no large single gene effect has been isolated, the DRD2, DRD4 and DRD5 dopamine receptors appear to be involved. 10 Although the current DSM-5 diagnostic criteria continue to weigh heavily on core symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, some research suggests that deficits in self-regulation and executive functioning could explain many of the problems of the condition and its impairments. 8 More recently, leading experts have argued for deficits in emotional self-regulation as a core feature of ADHD,9 but this has received relatively little research attention compared with the core symptoms of ADHD,11 and problems in emotional self-regulation are now the basis of a new category in DSM-5, ‘disruptive mood dysregulation disorder’, which may be associated with ADHD. 12

Prevalence

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is one of the most common disorders to present to child and adolescent mental health services; however, findings from studies that ascertain prevalence vary. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD is estimated at 2–5% for children aged < 18 years,13 with 3–16% of children displaying difficulties that do not reach the diagnostic threshold. Numerous studies have shown increases in the prevalence of clinical ADHD diagnoses and prescriptions for stimulant medication over recent decades, for instance, a 33% increase in prevalence of diagnosis from 5.69% in 1997–9 to 7.57% in 2006–8 according to US survey data. 14 Prevalence in the UK was found to be 3.62% for boys and 0.85% for girls, for a sample of over 10,000 children aged from 5 to 15 years in 1999. 15 Although a systematic review of research between 1978 and 2005 found no differences between European and US rates of ADHD,13 more recent studies sampling parent reports found that in the USA between 2008 and 2010, 6.3% of all children aged 5–9 years were reported by parents as having an ADHD diagnosis,16 whereas in the UK between 2007 and 2009, only 1.4% of children aged 6–8 years held ADHD diagnoses according to parent reports. 17

Although boys are more commonly diagnosed with ADHD than girls, the ratio varies between two and nine boys to one girl, depending on the category of ADHD presentation2 and whether prevalence is based on clinical or epidemiological populations. 18 Girls with ADHD may be less likely to be seen in clinics. 19 Younger childhood and low socioeconomic status have also been shown to be positively associated with prevalence. 20,21 Although prevalence appears to decline with age, a 2013 prospective study reported that ADHD persisted into adulthood for nearly a third of young people. 22 Despite the increasing clinical recognition in the UK, ADHD remains underdiagnosed in certain populations, including adults,23 children with intellectual difficulties24 and those with inattentive symptoms. 25 Differences in findings about prevalence are suggested to result from different study approaches to identification. 17 Differences in clinical practice,26 expression of symptoms and behaviour according to cultural, social and developmental contexts27,28 are argued to be additional contributing factors both within and between countries.

Co-existing issues

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder frequently co-exists with other mental health disorders, particularly antisocial and oppositional behaviour, but also tic disorders, specific learning difficulties, autistic spectrum disorders (ASDs), anxiety and depression. 11,29–31 As many as two-thirds of all children with ADHD in the general population are reported to have at least one other co-existing condition. 32 Many children with ADHD also have difficulties with social interaction and low self-esteem that affect their relationships with their parents, relatives and friends, as well as practitioners at school. 33 Often, these problems are at least as important as ADHD in contributing to the longer-term outcome in the individual child. 34 In addition, ADHD has also been linked with lower than average intellectual potential and academic underachievement across the developmental spectrum, from preschoolers to adults. 14 Inattentive symptoms and their related executive functioning deficits have been particularly associated with learning difficulties. 7 In the longer term, those with ADHD are less likely to be employed full-time, and more likely to have a lower household income than age and gender matched controls. 18

Controversy

Despite the breadth of research relating to prevalence, the diagnosis of ADHD has stimulated considerable debate and sometimes strong and conflicting views. 35 ADHD remains a contested disorder; for instance, in 2009 O’Regan found that 50% of general practitioners and 20% of special educational needs (SEN) co-ordinators in the UK did not believe that ADHD was a ‘real neurological condition’ (p. 4). 36 Bailey discusses the contested aetiology of ADHD and the issues that acceptance of a biological basis for ADHD can raise,37 which include concern over the use of medication for long periods of time in young children38 and the belief that the core symptoms of ADHD, inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity, are traits seen in many children, especially the very young. 39 It has been shown that higher percentages of diagnosis of ADHD may occur for the youngest children in school year groups, which has led some to suggest that behavioural differences attributed to ADHD may be due at least in part to immaturity. 40 The labelling of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention as ADHD when these behaviours interfere with expectations for correct classroom behaviour has been criticised by those who believe ADHD is a constructed response to the demands of modern academic education. 41 Timimi and Taylor argue that ADHD is best understood as a cultural construct, given the variability in prevalence internationally and rise in diagnosis rates in Western culture. 42

By contrast, other studies suggest that solely biological understandings of ADHD can be adopted by educational staff and/or parents and others as a means to transform ‘multifaceted problems into organic dysfunctions’ (p. 1). 43 The recently documented increase in diagnosis of, and medication for, ADHD has been linked to reduction in educational funding and restricted classroom discipline policies. 44 It has been suggested that pressures on health and educational institutions for higher attainment and rapid improvement mean that there is often a focus on short-term solutions provided by medication at the expense of more intensive, long-term educational support, such as that provided by non-pharmacological interventions. 45 Thus, polarised views of either cultural or biological origins continue to be reported in the literature, despite repeated research findings that suggest ADHD is a transaction between biological, environmental and psychosocial factors. 6,8–10

Interventions for children with or at risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical practice guidelines recommend that for school-age children and young people with severe ADHD, medication should be offered as the first-line treatment. 46 Parents should also be offered a group-based parent training/education programme. If the child or young person with ADHD has moderate levels of impairment, the parents or carers should first be offered referral to a group parent training/education programme, either on its own or together with a group treatment programme [such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) or social skills training] for the child or young person. Pharmacological treatment may then be added to the management plan if symptoms do not sufficiently respond to this approach. Teachers who have received training about ADHD and its management should provide behavioural interventions in the classroom to help children and young people with ADHD. Medication for children and young people with ADHD should always form part of a comprehensive treatment plan that includes psychological, behavioural and educational advice and interventions. Use of both medication and psychosocial treatment for ADHD varies widely within and across nations. 47 At present, the most common approaches to the treatment of ADHD are medication and/or psychological or behavioural interventions.

Pharmacological interventions

The most frequently used pharmacological treatments, and those with the largest evidence base, are the stimulant medications, methylphenidate and dexamfetamine,48 but their use remains controversial among some people who work with children. 49,50 The Care Quality Commission revealed in 2013 that the prescribing of methylphenidate for ADHD in the UK had risen by 56% in primary care from 420,421 in 2007 to 657,358 in 2012. 51 Meta-analyses of stimulant medications have shown them to be effective at decreasing the symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention, although their effectiveness on cognition and achievement are more modest. 52 However, any positive effects do not appear to persist once stimulants are no longer used53 and as many as 30% of children do not respond to stimulants. 54 The potential adverse effects of treatment with stimulants include decreased appetite, weight loss, insomnia, stomach ache, headache and irritability. 55

Several studies of the cost-effectiveness of pharmacological ADHD interventions have been undertaken. In 2001 in the UK, Gilmore and Milne examined the cost-effectiveness of different medications from the perspective of the NHS, finding methylphenidate to offer the best value for money. 56 NICE estimated the cost per quality-adjusted life-year gained by methylphenidate at £9200 to £14,600. 57 Cost-effectiveness studies have compared medication to behavioural treatment and combined treatments, often finding in favour of medication alone. 58

Non-pharmacological intervention

Non-pharmacological interventions target behaviour directly or indirectly through cognitive and affective processes and typically target children, teachers and parents. Interventions that target teachers and parents usually involve training for delivery of interventions that target the children. An early meta-analysis compared a range of treatments for ADHD including both pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions and found larger effects from all interventions on behavioural (d = 0.56) rather than educational outcomes (d = 0.28). 59 These overall effects were larger for medical interventions (d = 0.45) than for educational (d = 0.39), psychosocial (d = 0.39), or parent training interventions (d = 0.31). However, the effects on educational outcomes were greater for educational interventions (d = 0.58) than for other types of psychosocial intervention. There was little support for the influence of any reduction in behavioural problems on educational outcomes across studies. Although it is widely accepted that intervention in ADHD should be based on multimodal treatment,55 some research has suggested that adding psychosocial interventions to medication does not improve outcomes significantly. 60,61

Several reviews point to the effectiveness of behavioural interventions, particularly behavioural parent training (BPT) and behavioural classroom management. 62–64 For example, Pelham and Fabiano examined three types of interventions, including behavioural modification in classroom settings (BMC) that consisted of ‘contingency management’ based on ‘social learning theory’, BPT and behavioural peer intervention (BPI). 64 Results were synthesised across a range of constructs related to ADHD (including behavioural observations, family functioning, academic productivity, peer relationships and cognitive functioning), informants (e.g. parents, teachers, children and clinicians), and intervention type. Average effects by study design indicated that methodologically weaker single- and within-subject (treatment group received multiple treatments over time in a crossover fashion) designs generally reported larger effects than controlled trials. For the comparison of treatment with waitlist/no treatment Cohen’s d ranged from –0.03 to 0.44 for BMC; –0.02 to 0.70 for BPT; and 0.29 to 0.63 for BPI. Cohen’s classification for interpreting effect sizes distinguished between ‘small’ (d = 0.20), ‘medium’ (d = 0.50) and ‘large’ (d = 0.80) sizes, with very small findings < 0.20 having the least clinical impact. 65 Although these findings include evidence for the effectiveness of these interventions, the wide range of reported effects does not clarify their size and consistency. Pelham and Fabiano suggested a range of potential moderating variables that could have influenced the treatment outcomes, which included recipient gender, age, comorbidity, socioeconomic status, therapist characteristics and treatment characteristics such as intensity and adherence. 64

Fabiano et al. conducted meta-analyses to evaluate the effectiveness of behavioural interventions that included parent training, child training and classroom-based behavioural interventions. 63 Effects were synthesised across intervention type; constructs related to ADHD (including two observational behavioural measures; ADHD symptoms, externalising symptoms, impairment productivity and achievement); intervention context (school and clinic); and informant types. As was found by Pelham et al. ,66 average effects by study design indicated that methodologically weaker single-subject, within-subject (treatment group received multiple treatments over time in a crossover fashion) and pre–post (treatment groups assessed pre and post intervention) designs reported larger effects than controlled trials. For the 20 controlled trials, the average weighted effect size was 0.67 with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) from 0.54 to 0.80. Significant reported heterogeneity across studies was perhaps due in part to the collapsing of data across different settings, outcomes and informants. 63

There is less evidence for the effectiveness of neurofeedback on ADHD. For example, Willis et al. conducted a systematic review of 14 empirical reports of neurofeedback treatment for children with ADHD and reported that neurofeedback is not well supported as an intervention for this disorder. 67 Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of neurofeedback has been called into question. 68 Social skills training, summer treatment programmes and academic modifications have some support in the treatment of a range of ADHD symptoms and related impairments. 69 However, Barkley reports that social skills training shows less benefit for teenagers with ADHD compared with younger children, which suggests that age may be an important moderator of the effectiveness of social skills interventions. 70

In 2013 Sonuga-Barke et al. published a systematic review of peer-reviewed randomised controlled trials (RCTs) investigating the efficacy of non-pharmacological interventions delivered in various contexts (including home, school and clinic settings). 62 Statistically significant treatment effects were found for all the non-pharmacological interventions when the person rating the outcome used was the closest to the intervention setting (e.g. teacher ratings for interventions in school settings). 62 This was the case for all dietary [standardised mean difference (SMD) ranged from 0.21 to 0.48] and psychological treatments (SMD ranged from 0.40 to 0.64) that included cognitive training, neurofeedback and behavioural interventions. However, these treatment effects were not statistically significant for all psychological interventions when raters were blinded to the treatment participants were receiving. 62

School-based interventions

The education system has a front-line role in the management of ADHD. Results from the 2004 British Child Mental Health Survey showed that more families of children with ADHD had sought support from education in the past year than from professionals in specialist health services (74% vs. 51%). 71 Few systematic reviews and meta-syntheses have examined the effectiveness of non-drug interventions in school settings independently of those delivered entirely in home and clinical contexts. One exception is DuPaul et al. who updated a previous meta-analysis to provide a quantitative review of school-based ADHD intervention research that had been conducted between 1996 and 2010. 72 The authors examined the effects of three intervention types labelled as ‘academic’, ‘contingency management’ and ‘cognitive–behavioural’. ‘Academic’ involved study skills training and modification of academic instruction; ‘contingency management’ involved the application of techniques grounded in operant conditioning (such as rewards and punishments) and ‘cognitive–behavioural’ encompassed the development of self-control skills including self-instruction and problem-solving strategies. For the behavioural outcome comprising symptoms related to ADHD, statistically significant positive effects were identified for the within-subjects group (treatment groups assessed pre and post intervention) and single-subject designs but not for the controlled trials (d+ = 0.18, 95% CI –0.62 to 0.98). Similarly, all mean effect sizes were positive for the academic outcome and statistically significant results were reported for single-subject designs but not for controlled trials (d+ = 0.43, 95% CI –0.36 to 1.21) and within-subjects designs. However, analyses for the controlled trials were severely limited by the small number of studies included (n = 3).

Although stimulant medication and behaviour modification typically target and have proven to be effective interventions to increase on task, and reduce disruptive behaviour among children with ADHD within the classroom, a literature review conducted in 2006 which focused on academic interventions for ADHD concluded that the manipulation of antecedent conditions, such as academic instruction or materials, often improved both behavioural and academic outcomes. 73 However, in 2007 Trout et al. 74 systematically reviewed non-pharmacological interventions that targeted academic outcomes using single-subject and within-group (treatment groups assessed pre and post intervention) study designs. They categorised interventions as ‘antecedent’ (interventions that target children prior to an academic task); ‘consequence’ [interventions that targeted children post performance of the target behaviour(s)]; ‘peer-mediated’ (intervention that were delivered in part by peers); ‘parent-mediated’ (interventions that were delivered in part by parents); ‘self-regulation’ (interventions that targeted self-regulation of cognition and behaviours); and other interventions that used a combination of treatments. The authors suggested that peer tutoring and self-regulation show some evidence of effectiveness. Nonetheless, the authors reported that there were few systematic lines of research and reached few firm conclusions regarding the effectiveness of behavioural interventions that target children with ADHD. In an earlier review conducted in 2005, Reid et al. 75 reported beneficial effects for interventions based on ‘self-monitoring’ related to ‘self-regulation’ in their review of symptom and scholastic outcomes, providing further support of the beneficial effect of self-monitoring. However, as single-subject and within-group designs were the focus of this review, it is yet to be established if these effects are observed in controlled trials.

A 2010 questionnaire study of first-grade teachers76 points to the fact that interventions of the type reviewed in the studies cited above may not always match the interventions that teachers report using for children with ADHD difficulties. Teachers reported using environmental modifications, assignment modifications and behaviour modification strategies more frequently with inattentive students than with other students. Although some of the interventions mentioned by teachers, such as reward systems and time out, are considered evidence-based treatments for children with ADHD,64 other strategies the teachers reported using, such as preferential seating and additional time, are less often researched.

Reported effectiveness of school-based interventions may vary depending on the outcome of interest. In their 2005 review, Pelham et al. 66 compared a contingency management intervention to methylphenidate or the use of both treatments and reported effect sizes that were four to five times greater for the effectiveness of the educational intervention for classroom rule violations than for teacher ratings of ADHD behaviours. Although school-based behavioural interventions can improve targeted behaviours in the short term, they have been found less useful in reducing the core symptoms of ADHD. 60

Because of its prevalence and at times refractory course, childhood ADHD results in considerable costs for society, particularly to the educational system. In 2013, Telford et al. 77 considered the wider education, health and social care costs of adolescents with ADHD in the UK. The mean cost per adolescent for NHS, social care and education resources used in a 12-month period related to ADHD was £5493 in 2010 prices and the median was £2327. Education resources accounted for approximately three times the cost of health-care costs. The total annual cost of adolescents with ADHD in the UK is estimated to be £670M. 77

Methodological considerations

Reviews of quantitative research in school settings have frequently evaluated the preponderance of within-subject group and single-subject designs, which, although valuable, are more prone to bias than RCTs, which are the scientific ‘gold standard’ for evaluating treatment effects. 78 Many of the findings are difficult to interpret, as they combine results across different contexts (e.g. school, clinical and home), interventions, outcomes and informants. Tests of statistical significance and CIs are often not reported, which makes the findings difficult to interpret, and there are no standardised guidelines for interpreting effect sizes for within-subject group and single-subject designs and comparing these effects with those found in other study designs such as between-group designs where Cohen’s d is often reported. There are differences in the types of outcome measures used across study designs with most single-subject design studies employing proximal outcome measures such as curriculum-based measurements or direct observations of classroom behaviour. 72 In contrast, most controlled trials and within-subject group design studies used more distal measures such as teacher ratings or report card grades. 72

Sociopolitical aspects of educational research in the UK may contribute to a lack of research employing the most rigorous experimental designs. RCTs provide general information about interventions that are particularly useful to policy-makers. In contrast, educational researchers and/or practitioners may be more concerned about knowledge about the application of information to specific cases79,80 or be concerned about aspects of education that are not represented by straightforwardly measurable outcomes,81 for example those who suggest that education involves norms, values and processes of judgement that cannot be separated from extrinsic variables. 82 This may lead them to prefer approaches like case studies and action research. Educators may also be sensitive to moves towards a more central control of education, which some may associate with calls for evidence-based practice. 81

The measurement of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and outcomes

A range of constructs have been used to evaluate the effectiveness of treatments that target children with or at risk of ADHD in school settings. These constructs can be categorised into three higher-order groups: (1) core ADHD diagnostic symptom categories (including inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, ADHD combined); (2) symptoms commonly associated with ADHD (including externalising symptoms, internalising symptoms, social skills); and (3) scholastic behaviours and achievement (including ‘perceptions of scholastic adjustment’, ‘standardised achievement’ and ‘curriculum’-based achievement). Core ADHD diagnostic symptom categories include the three diagnostic presentations of ADHD as specified in DSM-5: age-inappropriate ‘inattention’; ‘hyperactivity/impulsivity’; and ‘combined’ inattention and hyperactivity/impulsivity. The second category of ADHD-related symptoms encompass difficulties that frequently coexist with the core symptoms of ADHD and complicate its management, but are not relevant to diagnosis. Scholastic behaviours and achievement encompass perceived adjustment to school such as achievement, motivation, academic skills and abilities. These three higher-order constructs have been assessed by a range of behavioural measures, which include ratings and observations, as well as more relatively objective neurocognitive assessments and tests of scholastic achievement with objective performance criteria.

Assessments

When measuring the effectiveness of school-based interventions, the child’s core ADHD symptoms, ADHD-related symptoms and scholastic behaviours and outcomes are typically assessed by teacher and parent perception-based measures [e.g. Conners’ Rating Scale (CRS)],83 although independent observers (who have had no previous relationship with the study participant) are sometimes used (e.g. observer-based assessments of on-task behaviour). Neurocognitive assessments such as the test of variables of attention (TOVA)84 have also been employed to assess ‘inattention’ and ‘hyperactivity/impulsivity’ and a range of standardised achievement tests are used to measure academic outcomes (e.g. Wide Range Achievement Test). 85 Most studies include a range of outcomes assessed by a number of raters or informants.

Sonuga-Barke et al. ’s 2013 systematic review of non-pharmacological interventions found significant treatment effects for all of the non-pharmacological interventions when the person rating the outcome used was the closest to the intervention setting (e.g. teacher ratings for interventions in school settings). 62 However, these treatment effects were not statistically significant for all psychological interventions when using the most methodologically rigorous blinded assessments, which indicates the potential for bias in outcomes from raters who are involved in intervention delivery and/or expect the intervention to be successful. Blinding, however, was sometimes inferred from the study design rather than taken from the reported use of blinding. Moreover, findings were limited to a composite outcome combining core ADHD symptom measures and delivery settings, which may mask important effects and account for some of the significant heterogeneity in findings across the primary studies. 62 In addition, there may plausibly be limited generalisation of the impact of an intervention in one setting to perceptions of the child’s behaviour in another setting. Nonetheless, Sonuga-Barke et al. 62 highlight the importance of methodological evaluation alongside evidence synthesis of interventions that target children with or at risk of children with ADHD.

Triangulation of data in quantitative versus qualitative research

Mixed methods in primary studies are considered to enable additional grounds for inference owing to triangulation of data, methods and analysis. 86 The benefits of mixed-methods systematic review are similar. 87 However, triangulation of data, when defined as the additional confirmation of a finding through repetition from different studies, can be problematic in qualitative studies. Unlike experimental evaluations, where repetition increases finding strength, an interpretive approach does not seek a true answer; rather, it explores the meanings people make of their experiences. 88 In interpretive studies it is expected that different people will make sense of things in different ways. By contrast, similar sense of a topic made by different people is not taken as additional evidence of truth, but rather that the participants are drawing from a similar cultural ideology to make sense of their experiences. 89 Therefore, an isolated finding may be more important than repeated findings, for example because it illuminates a previously implicit and overlooked meaning. 88,90 In interpretive research, triangulation of data can be understood as the compilation of multiple perspectives, where the resulting representation of complexity of perspective and depth of meaning is a sign of study rigour. 91

Rationale

The research questions of a systematic review guide the criteria for included studies. 87,92 Our research questions ask about effectiveness of ADHD interventions in schools, factors that enhance or limit the delivery of school interventions for ADHD, and the experience of ADHD in schools. We were unable to locate any systematic reviews of either the experience of non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD, or the experience of ADHD more generally; therefore the synthesis of qualitative primary studies holds important potential to contribute new information on this topic. In this systematic review, we synthesise qualitative research in addition to experimental evaluation studies in order to explore attitudes, experiences and factors that may help explain how or why interventions for ADHD in school settings are or are not effective. Through the overarching synthesis of both quantitative and qualitative reviews, we will explore similarities, contradictions and gaps between these syntheses, further informing the research questions and implications for further research. 87

This review also holds the potential to contribute important new information about the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD in schools. A range of non-pharmacological interventions have been developed and delivered in school settings by parents, teachers or other professionals. As outlined above, few published reviews have considered the effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in school settings independently of those delivered predominantly in other settings such as at home and in clinics. Therefore, a gap remains for a systematic review that considers the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such non-pharmacological interventions that are delivered primarily in school settings.

The reviews reported have typically taken a narrow focus in terms of the interventions and outcomes included and few have distinguished between different types of informants (see Fabiano et al. 63 for exception). Moreover, the focus has been on single-subject and within-group designs rather than on controlled trials, which compromises evidence synthesis as study design, intervention type, delivery context, outcomes and informant type may produce important differential effects. 62 Despite the current clinical recommendation for non-pharmacological ADHD interventions,46 there is a lack of clarity regarding their effectiveness and in particular their effectiveness in school settings. Moreover, their cost-effectiveness has not been systematically reviewed.

To build evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of ADHD in school settings, knowledge of the effectiveness of interventions is required. However, heterogeneity among findings across studies of intervention effectiveness is a common conclusion for many reviews that assess non-pharmacological interventions that target children with or at risk of ADHD. 62,63,72,74 Although average, weighted, effect sizes may help to establish the importance of non-pharmacological interventions in improving outcomes for children with or at risk of ADHD, it is critical that the components linked with the most successful interventions are identified so that the design, implementation and replication of future interventions can make the best use of scarce resources.

Repeated calls have been made for precise specification of what makes one behaviour change intervention more effective than another and how this can be understood theoretically (e.g. Rothman93). A range of programme features have been highlighted as potentially moderating the effectiveness of interventions that target children with or at risk of ADHD; these include characteristics of the child participant (e.g. age, medication status, sex), characteristics of the intervention (i.e. the change techniques constituting intervention content) and characteristics related to the delivery of the intervention (e.g. intensity of the intervention, fidelity of delivery). 64 The identification of programme features that are necessary for effective intervention implementation in school contexts will facilitate links between particular intervention components and effectiveness, and in turn could help resources to be used more efficiently and benefit children displaying ADHD symptoms, their carers and service providers.

Through the consideration of relevant qualitative research alongside the synthesis of quantitative studies this review has the potential to provide explanations of why particular interventions are effective and what factors operate as catalysts and barriers to effectiveness. The review will also identify any significant areas of uncertainty with regard to school-based interventions for ADHD and recommend any future research needed to address them.

Aim and research questions

The broad aim of this series of systematic reviews and their overarching synthesis is to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions delivered in school settings for children with, or at risk of, ADHD and to explore the factors that may enhance, or limit, the delivery of such interventions.

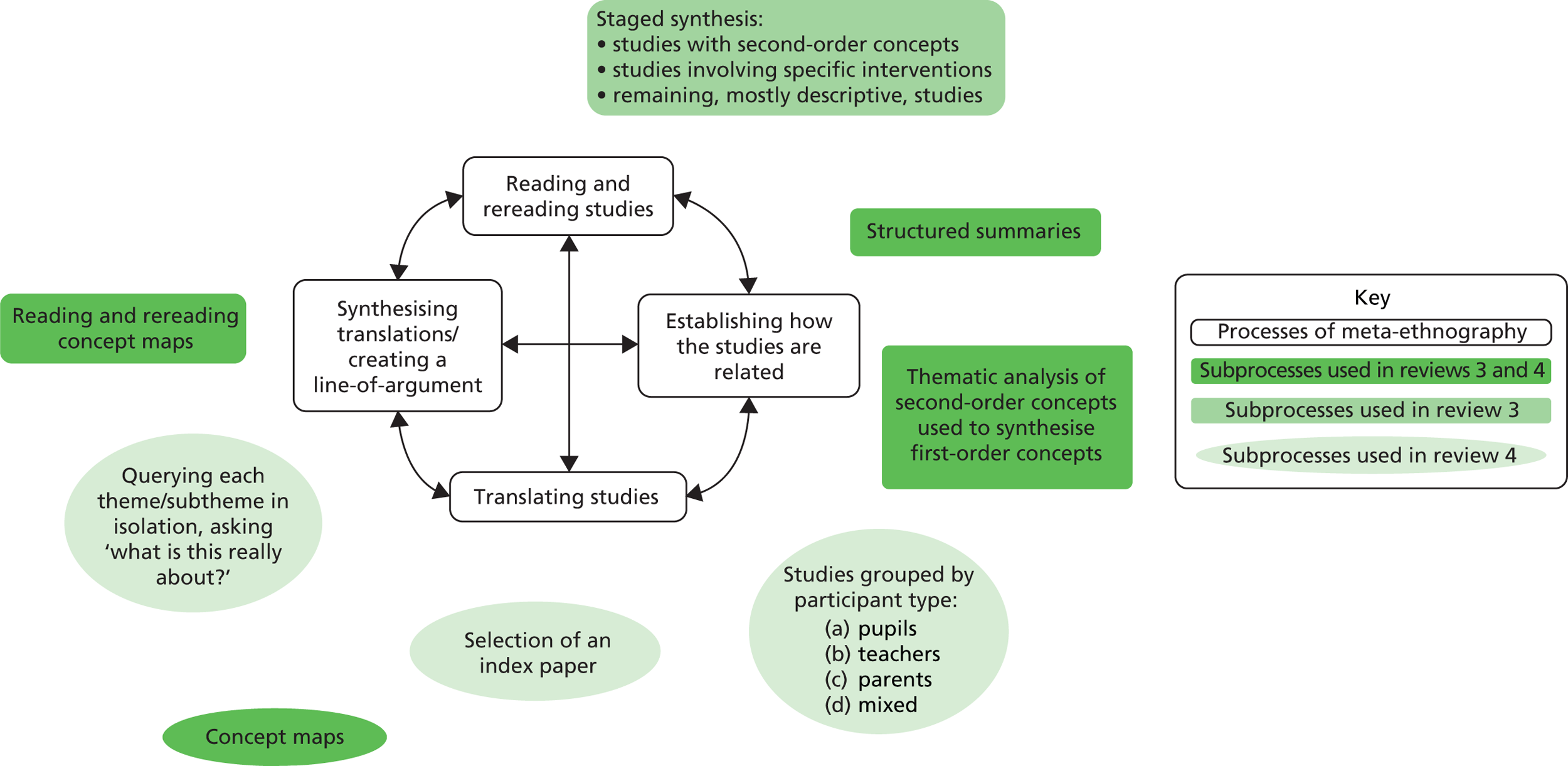

Four reviews were conducted. Review 1 (see Chapter 2) synthesises the effectiveness and the cost-effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions delivered in school settings for children with or at risk of ADHD. Review 2 (see Chapter 3) considers quantitative studies that explore attitudes towards school-based non-pharmacological interventions for pupils with ADHD. Review 3 (see Chapter 5) synthesises the attitudes and experiences of children, teachers, parents and others using ADHD interventions in school settings. Review 4 (see Chapter 6) explores the experience of ADHD in school among children, their parents and teachers more generally. The four reviews are subsequently brought together in an overarching synthesis (see Chapter 7). Each review addresses particular research questions as outlined below.

Review 1

-

Are non-pharmacological interventions delivered in school settings for children with or at risk of ADHD effective in improving:

-

Core ADHD symptoms (inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, ADHD combined)?

-

ADHD-related symptoms (externalising symptoms, internalising symptoms, social skills)?

-

Scholastic behaviours and outcomes (perceptions of school adjustment, curriculum achievement, standardised achievement)?

-

-

Is effectiveness moderated by particular programme features?

-

Have such interventions been shown to be cost-effective?

Review 2

-

What attitudes do educators, children with or at risk of ADHD, their peers and their parents hold towards non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD used in school settings?

-

Which school-based non-pharmacological interventions for ADHD are preferred and how do attitudes towards these interventions compare to non-school interventions including pharmacological ones?

-

What factors affect attitudes held towards these non-pharmacological interventions (including children’s ADHD subtype and teacher experience)?

Review 3

-

What are the experiences of and attitudes towards ADHD interventions in school settings?

Review 4

-

What are the school-related experiences and perceptions of pupils diagnosed with or at risk of ADHD, their teachers, parents and peers?

Overarching synthesis

The aim of the overarching synthesis is to synthesise findings from reviews 1–4.

Chapter 2 Review 1: effectiveness of non-pharmacological interventions in school settings for children with or at risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Research questions

This chapter describes systematic review 1 and addresses the following three research questions:

-

Are non-pharmacological interventions delivered in school settings for children with, or at risk of, ADHD effective in improving:

-

Core ADHD symptoms (inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, ADHD combined)?

-

ADHD-related symptoms (externalising symptoms, internalising symptoms, social skills)?

-

Scholastic behaviours and outcomes (perceptions of school adjustment, curriculum achievement, standardised achievement)?

-

-

Is effectiveness moderated by particular programme features?

-

Have such interventions been shown to be cost-effective?

Methods

Search strategy

Electronic database search

A database search strategy was developed which combined three elements: ADHD plus synonyms and derivatives; terms related to a school context; and intervention terms. The database search strategies used a mixture of subject headings (controlled vocabulary) and free-text terms. Searches were restricted to years from 1980 onwards. Twenty electronic databases were searched {Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA)/ProQuest, MEDLINE/OvidSP, EMBASE/OvidSP, PsycINFO/OvidSP, British Education Index/ProQuest, Australian Education Index/ProQuest, Education Research Complete/EBSCOhost, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC)/ProQuest, The Cochrane Library [Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Methodology Register (CMR), Health Technology Assessment (HTA), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED)], The Campbell Library, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC)/OvidSP, Social Policy and Practice/OvidSP, Social Sciences Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (via ISI Web of Science)}, from 16 to 28 May 2012. Searches were updated between 11 and 18 February 2013. An example search strategy used for the PsycINFO/OvidSP database is shown in Appendix 1. No language or geographical limitations were applied. Titles and abstracts returned by the search strategy were exported into EndNote v.X5 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and independently screened by two of six researchers (MR, DM, TND, RW, MRo and RA) using the predefined criteria specified below. All disagreements were resolved by discussion between MR and DM. Where it was not possible to decide on exclusion of a paper based on the information in the title and abstract, the full text was retrieved. Two researchers (MR and DM) examined these independently for inclusion or exclusion using modified predefined criteria (specified below). Again, all disagreements were resolved through discussion. Where full-text papers were not easily retrievable (locally or from The British Library) authors were contacted. The same methods were applied to identify additional unique records from an updated search of the electronic databases conducted in February 2013.

Supplemental search strategies

Backward (searching the references of included articles) and forward (searching articles citing included articles using Web of Knowledge) searches were conducted by two researchers (MRo and DR) to locate further primary articles of potential relevance. In addition, DR searched websites (see Appendix 2 for a list of websites searched) and hand-searched five key journals published between 2008 and 2012: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry; British Educational Research Journal; Journal of School Psychology; Journal of Attention Disorders; and Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The screening of potentially relevant articles was carried out in two stages: at stage 1, predefined criteria were applied to titles and abstracts and at stage 2, these criteria were modified and applied to the screening of full-text articles. The criteria are detailed in Table 1 and parentheses indicate where they were applied at stage 2 only (for full-text screening).

| Criteria | Specification |

|---|---|

| Population | Inclusion:

|

| Intervention | Inclusion:

|

| Outcomes | Inclusion: Child outcomes including ADHD symptoms (i.e. inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity); ADHD-related symptoms (i.e. externalising, internalising and social skills) and scholastic behaviours (i.e. perception of scholastic adjustment, standardised achievement and curriculum achievement)

|

| Study design | Inclusion:

|

| Comparators | Inclusion:

|

| Other | Exclusion:

|

Data extraction

Methodological information

A form was developed with reference to existing coding frames94,95 and modified after pilot testing to extract the relevant programme features of the included studies, which included bibliographic and study details, participant characteristics, outcome assessments, intervention package(s) and characteristics relating to the delivery of the intervention package(s). The typology of information extracted is reported in Table 2.

| Programme feature | Information extracted |

|---|---|

| Bibliographic and study details |

|

| Child participant characteristics |

|

| Outcome assessment(s) |

|

| Intervention package(s) |

|

| Characteristics relating to the delivery of the intervention package(s) |

|

Conceptual synthesis: mapping measures onto child-related constructs that assessed aspects of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Owing to the heterogeneity in assessment of child outcome measures, a classification system that mapped the measures reported in included studies onto nine commonly assessed child-related constructs assessing aspects of the condition was developed by MR and checked by DM. The classification system was developed by reading and rereading descriptions of the measures and items located in the primary papers and other online resources, and mapping them to definitions of the constructs. This tool was then used by MR to map outcome assessment instruments reported in the primary papers onto nine commonly assessed child-related constructs assessing aspects of ADHD. The labels and definitions of these constructs, as well as the measures and informants (parents, teachers, children and observers), are reported in Table 3.

| Construct label and definition | Measures (subscales italicised in parentheses where relevant) | Informant(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Construct label: inattention Construct definition: inability to focus and pay attention appropriate to task and context. For example, inattention, easy distractibility, disorganisation, procrastination and forgetfulness |

BASC-II (inattention)96 | Parent |

| SKAMP (cognitive impairment attention)97 | Teacher | |

| CRS;98 CRS-R (inattention/passivity, cognitive problems/inattention, daydream/attention problems, DSM-IV inattention)98 | Parent and teacher | |

| DBD (inattention)99 | Parent and teacher | |

| CBCL (attention)100 | Parent and teacher | |

| ADHD (inattention)2 | Parent and teacher | |

| VADTRS; VADPRS (inattention)101 | Parent and teacher | |

| d2 test of attention9 | Child | |

| BRIEF102 | Child | |

| MFFT (number of errors)103 | Child | |

| TOVA (visual and auditory omission)84 | Child | |

| Per cent on/off task104 | Observer | |

| Construct label: hyperactivity/impulsivity Construct definition: inability to manage activity levels appropriate to task and context. Fidgets, interrupts others, constantly in motion, inability to stay seated without excessive movement, restlessness, excessive talking, inability to engage in tasks quietly, impatience and inability to regulate emotions |

VADTRS; VADPRS (hyperactivity/impulsivity)101 | Parent |

| APRS (impulse control)105 | Teacher | |

| IOWA Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale (hyperactivity)106 | Teacher | |

| SCRS107 | Teacher | |

| ADHD (hyperactivity/impulsivity subtype)2 | Parent and teacher | |

| CRS;98 CRS-R (hyperactivity, DSM-IV hyperactivity/impulsivity)98 | Parent and teacher | |

| DBD (hyperactivity. impulsivity)99 | Parent and teacher | |

| Gordon’s Vigilance Task (impulsivity)108 | Child | |

| MFFT (commission)103 | Child | |

| TOVA (visual and auditory commission)84 | Child | |

| Construct label: ADHD combined type Construct definition: inability to focus and pay attention and to manage activity levels appropriate to task and context |

CSI-IV (ADHD)109 | Teacher |

| DBD (ADHD)99 | Teacher | |

| ADHD Rating Scale2 | Parent and teacher | |

| CBCL (ADHD)110 | Parent and teacher | |

| CRS;98 CRS-R (ADHD index, DSM-IV total)98 | Parent and teacher | |

| Construct label: externalising symptoms Construct definition: emotional and behavioural symptoms that are undercontrolled and externalised, for example fighting, bullying, defiance |

BASC-I (externalising composite score; aggression, conduct)111 | Parent |

| DBD (oppositional defiant, conduct disorder)99 | Teacher | |

| IOWA Conners’ Teacher Rating Scale (aggression)106 | Teacher | |

| SSQ112 | Teacher | |

| SSRS (problem behaviour subscale)113 | Teacher | |

| CBCL (delinquent, aggression, external)114,115 | Parent and teacher | |

| CRS;98 CRS-R (oppositional, conduct problems)98 | Parent and teacher | |

| ODD2 | Parent and teacher | |

| Pianta Conflict Scale116 | Parent and teacher | |

| Construct label: internalising symptoms Construct definition: emotional and behavioural symptoms that are overcontrolled and internalised, for example shyness, anxiety, withdrawal from social situations |

The Scale of Behavioural Problems (internalisation, anxiety)117 | Parent |

| CBCL (withdrawal, anxiety, depression, internalising)115,118 | Parent and teacher | |

| CRS;98 CRS-R98 (anxious/passive, emotional indulgent, perfectionism, anxiety)119 | Parent and teacher | |

| Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (anxiety)120 | Child | |

| Construct label: social skills Construct definition: capacity to communicate and interact with others effectively (including peers, siblings, teachers and parents) and appropriate to context |

Scale of Behavioural Problems (social adjustment)117 | Teacher |

| Merrell School Social Behaviour Scale (interpersonal skills)121 | Teacher | |

| Walker–McConnell Scale of Social Competence and School Adjustment122 | Teacher | |

| CBCL (social problems)110 | Parent and teacher | |

| CRS-R98 (asocial)98 | Parent and teacher | |

| IRS (social skills)123 | Parent and teacher | |

| SSRS (co-operation)113 | Parent and teacher | |

| Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (popularity)120 | Child | |

| Self-Esteem Inventory (social self subscale)124 | Child | |

| Construct label: school adjustment Construct definition: perceptions of scholastic behaviours encompassing adjustment to school. For example, achievement, motivation, productivity, and study skills (including time management and organisation) |

Homework Problem Checklist125 | Parent |

| Scale of Behavioural Problems (school problems)117 | Parent | |

| APRS (academic skills, productivity)105 | Teacher | |

| SSRS (academics)113 | Teacher | |

| IRS (classroom and academics)123 | Parent and teacher | |

| Children’s Organisational Skills (maladjustments)126 | Parent and teacher | |

| BASC-I (school maladjustment)111 | Child | |

| Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (intellectual, school status)120 | Child | |

| Self-Esteem Inventory (school, academics)124 | Child | |

| Dimensions of Self-Concept (academic interest, satisfaction)127 | Child | |

| Construct label: standardised achievement Construct definition: achievement in scholastic tasks as assessed by standardised intelligence and achievement tests |

CPM128 | Child |

| DIBELS (maths, reading)129 | Child | |

| Gates–MacGinitie Reading Tests (vocabulary, comprehension)130 | Child | |

| Gray Oral Reading Test (comprehension, fluency)131 | Child | |

| IOWA Test of Basic Skills (language)132 | Child | |

| Process Assessment of the Learner (reading, writing)133 | Child | |

| Wechsler Individual Achievement Test, Second Edition (numerical operations, maths fluency)134 | Child | |

| Wide Range Achievement Test, Third Edition (spelling, word reading)85 | Child | |

| Woodcock–Johnson Psychoeducational Test Battery135 | Child | |

| Construct label: curriculum achievement Construct definition: scholastic attainment on school-based curriculum tests and coursework |

School curriculum-based tests | Child |

| GPA | Child |

Conceptual synthesis: developing a classification system of interventions

As there was also a great deal of heterogeneity across interventions, MR developed a classification system of intervention content by reading and rereading descriptions of interventions (reported in the study papers and extracted as part of the data extraction phase) and identified (inductively) discrete ‘packages’ of interventions. Although some interventions target a combination of recipients including teacher, parents and children, we focused on the intervention packages that targeted the children alone. This process led to the identification of 15 ‘packages’ of techniques. The labels and definitions of these packages are reported in Table 4 and were developed using the descriptions of interventions in the included studies and reference to previous general classifications of behaviour change interventions. 136,137 These packages of interventions were categorised based on the similarity of active ingredients: (1) reward and punishment; (2) skills training and self-management; (3) creative-based therapies; and (4) physical treatments. Two packages (‘adaptations to learning environment’ and ‘information only’) could not be grouped into a higher-order category and were, therefore, categorised as ‘other’ packages. Packages in the ‘reward and punishment’ group are broadly based on the concepts of ‘rewards’ and ‘punishments’ originating from conditioning theories. 138 Self-management is more explicit in the ‘skills training and self-management’ group (as characterised by the skills training element) and can be broadly traced to self-regulation theories. 139 ‘Creative-based therapies’ include music and drama-based treatments, whereas ‘physical treatments’ target psychological processes indirectly via the physical body. ‘Information only’ refers to the provision of education only (independent of any further intervention), whereas ‘adaptations to learning environment’ refers to physical (e.g. change of seating arrangements in a classroom setting) and/or social adaptations (groups vs. one-to-one teaching format) implemented to enhance performance of the wanted behaviour(s) and/or a reduction in unwanted behaviour(s). The classification system was scrutinised conceptually by the other team members and subsequently used by MR (and checked by DM) to classify the text relating to the intervention(s) reported in the primary papers. The few disagreements were resolved through discussion between MR and DM. Teachers, parents and carers trained in managing children with ADHD were categorised as intervention providers and are detailed in Intervention delivery characteristics.

| Intervention | Definition |

|---|---|

| Reward and punishment | |

| 1. Contingency management | Systematic use of rewards and/or punishments to change, alter or redirect the child’s behaviour(s) |

| 2. DRC with contingency management | A method used in collaboration with a child to set goal(s) and monitor progress towards them. Rewards and/or punishments are then used in response to the child’s progress towards their goals in order to reinforce the wanted behaviour(s) or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour(s) |

| Skills training and self-management | |

| 3. Motivational beliefs | Encourage or facilitate the adoption of beliefs that facilitate self-motivation towards obtaining the focal behaviour(s) (e.g. the attribution of success at school to hard work and effort) |

| 4. Cognitive–behavioural self-regulation training | Establish methods for the child to self-monitor and record their behaviour(s). Includes analysing the factors that lead to problem behaviour(s) and identifying solutions to overcome them (‘problem solving’) and self-instruction on how to perform the behaviour(s) |

| 5. Cognitive retraining | Training and practice in the use of cognitive processes related to executive functioning (e.g. attention and working memory) |

| 6. Academic and study skills training | Training and practice in academic skills (e.g. reading and writing strategies) and general study strategies (e.g. note taking, test taking, organisation and time management) |

| 7. Social skills training | Training and practice in effective social interaction |

| 8. Emotional skills training | Training and practice in learning to recognise and control emotions (e.g. relaxation training and/or enhancing positive emotion) |

| 9. Biofeedback | Feedback about physiological or biochemical activity (e.g. heart rate and brain waves) using an external monitoring device to enhance self-control of wanted behaviour(s) |

| Creative-based therapy | |

| 10. Music therapy | Music used in a prescribed way to modify or alter thoughts, emotions and behaviours |

| 11. Play therapy | Play used in a prescribed way to modify or alter thoughts, emotions and behaviours |

| Physical treatment | |

| 12. Massage | Applying pressure to parts of the body (e.g. rubbing or kneading) in a prescribed way to modify or alter thoughts, emotions and behaviours |

| 13. Structured physical activity | Planned physical activity with the aim of increasing energy expenditure and improved physical fitness and health |

| Other packages | |

| 14. Adaptations to learning environment | Alteration to the environment (physical and social) where learning takes place and/or learning materials in order to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour or create barriers to the unwanted behaviour (e.g. adapt teaching methods, tasks and classroom) |

| 15. Information | Provide information about focal behaviour(s) (e.g. information about positive peer relationships, communication skills) |

Statistical information

A data extraction form was developed to record the relevant statistical information for each trial meeting the inclusion criteria of review 1. For each relevant outcome/informant combination, post-test means, standard deviations (SDs) and sample sizes (or statistics that could be used to derive these) were extracted for the relevant treatment and control groups where available.

Effect size was calculated using the SMD, that is, the difference between the means in each of two groups divided by their pooled SD (Cohen’s d) with Hedges’ correction. 140 For continuous outcomes, the SMD and 95% CIs were calculated using the mean, SD and the sample size for intervention and control groups or, if these were not reported or were not available from the study authors, statistics that could be used to derive these (e.g. t statistic). For three studies that reported proportions rather than continuous data,141–143 the log-odds ratio was converted into a SMD [for formula see URL: www.campbellcollaboration.org/artman2/uploads/1/2_D_Wilson__Calculating_ES.pdf (accessed 16 December 2014)]. 144 For one study reporting change scores, the SMD was estimated by dividing the difference between the gain scores in each trial arm by the pooled SD while taking account of the pre–post correlations within each arm. The above calculations were performed using the online calculator at www.campbellcollaboration.org/escalc/html/EffectSizeCalculator-SMD1.php (accessed 16 December 2014). 144 For seven studies where the relevant empirical data were not reported or available from the study authors, only narrative synthesis was conducted. 141,162,180,186,191,192,198 All data were extracted by MR and checked by DM with all disagreements resolved successfully through discussion.

Quality appraisal was conducted simultaneously with data extraction using criteria adapted from the Cochrane risk of bias tool145 and an appraisal tool developed by Miller and Wilbourne. 146 The criteria assessed, reported in Table 5, consider selection bias (randomisation and allocation concealment for RCTs only); detection bias (blinding of outcome assessors); attrition bias [intention to treat (ITT) and response rate]; and use and length of follow-up(s). A trial was defined as meeting the ITT criteria when all participants remained in the intervention groups to which they were randomised and where data for all randomised participants were included in the analysis. 145 Quality appraisal decisions were made independently by two reviewers (DM and MR) and disagreements were resolved through discussion by these reviewers. The appraisals were used to evaluate study quality and were not used to exclude papers.

| Criteria | Coding |

|---|---|

| RCTs only | |

| What was the unit of randomisation? | Individual; cluster |

| Was the method used to generate randomisation specified? | Yes/no/partial |

| Was allocation concealment of randomisation reported? | Yes/no |

| Was ITT employed? | Yes/no |

| RCTs and non-RCTs | |

| Was blinding of assessor reported for one or more outcomes? | Yes/no |

| Was the response rate adequate? | 85–100%; 70–84%; < 70%; NR146 |

| Were follow-ups assessed? | Yes/no |

| Was the longest follow-up ≥ 6 months? | Yes/no |

Analytic strategy

Characteristics of the studies were summarised using means and SDs for continuous variables and percentages for categorical variables. Separate meta-analyses were conducted for each construct/informant combination (where data permitted). Tests of interaction using meta-regression were carried out to investigate whether or not study characteristics modified the effect of the interventions.

Meta-analysis

Random-effects meta-analysis models were fitted based on the assumption that the studies are estimating different effects. We are therefore estimating the average of multiple effects but, for simplicity, we generally refer to a singular pooled effect. To avoid underestimation of the standard error of the pooled estimate, when two or more measures assessing the same construct were reported in a given study, the estimated effects were combined into a summary effect for that study, applying a method that uses the correlations among the conceptually similar measures to calculate the 95% standard error for the study-specific estimate. 140 The correlations were obtained from the study report itself or unrelated papers that administered the outcomes and reported the correlations. In studies with two relevant active intervention groups, the outcome was combined across intervention groups based on the group-specific means, SDs and sample sizes using the ttesti command in Stata v.12.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) prior to calculation of the SMD. Combining results across multiple treatment groups within studies before pooling avoids double counting participants in the control group and underestimating the standard error of the pooled effect size. 140

Final score means (adjusted for baseline where reported) were compared between groups; in three studies that reported comparisons at several time points over the duration of the intervention, effect sizes were calculated for each time point after the baseline observation and then averaged before entry into the meta-analyses. 159,160,197

Separate meta-analyses were conducted for RCTs and non-RCTs. Cohen’s65 guidelines were used to interpret effect sizes. Classifications for what are considered to be ‘small’, ‘medium’ and ‘large’ effect sizes are d+ = 0.20, d+ = 0.50 and d+ = 0.80, respectively.

Cochran’s (1954)147 test was used to assess evidence for heterogeneity, with a p-value < 0.05 taken to indicate evidence of heterogeneity. The I2 statistic (possible range 0–100%) was used to quantify the amount of between-study heterogeneity. 148 Values < 25% have been suggested to indicate low heterogeneity; values between 25% and 50% moderate heterogeneity; and values > 50% high heterogeneity. 148 Given that the Q test is sensitive to the number of included studies, the I2 statistic is our main method for identifying marked heterogeneity. 148

Publication bias was planned to be assessed by examining funnel plots for asymmetry using the metafunnel command in Stata v.12.1. 149 However, we were unable to assess funnel plots properly or use more advanced regression-based assessments to assess publication bias owing to the inadequate numbers of included trials and the substantial heterogeneity identified across studies. 150

Meta-regression analyses

Tests of interaction were performed using meta-regression to examine whether or not there was evidence that the pooled intervention effects differed across defined programme features. Planned analyses were conducted where there was evidence of heterogeneity (i.e. I2 values > 0%). 62 A range of programme features, including study details, participant characteristics, intervention package and intervention delivery elements were assessed.

Table 6 describes the potential moderators. Although a minimum of 10 studies is often cited as sufficient, there are no hard and fast rules, and, in light of the data collated, we adopted a lower threshold of eight studies. 140 For the dichotomised constructs, at least three studies were required to provide intervention effect data in each category of the potential moderator. Meta-regression models were fitted using the metareg command in Stata v.12.1. The Knapp and Hartung adjustment for multiple testing was adopted. 151 Adjusted R2, the proportion of between-cluster variability accounted for by the moderator variable, and I2, the proportion of residual between-study variation attributable to heterogeneity, were reported.

| Programme feature | Moderator |

|---|---|

| Study characteristic |

|

| Participant characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

| Intervention packages |

|

|

|

| Delivery characteristics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Empirical findings synthesised narratively

The findings from studies where meta-analysis was not appropriate or possible were summarised narratively.

Results

Number of studies included

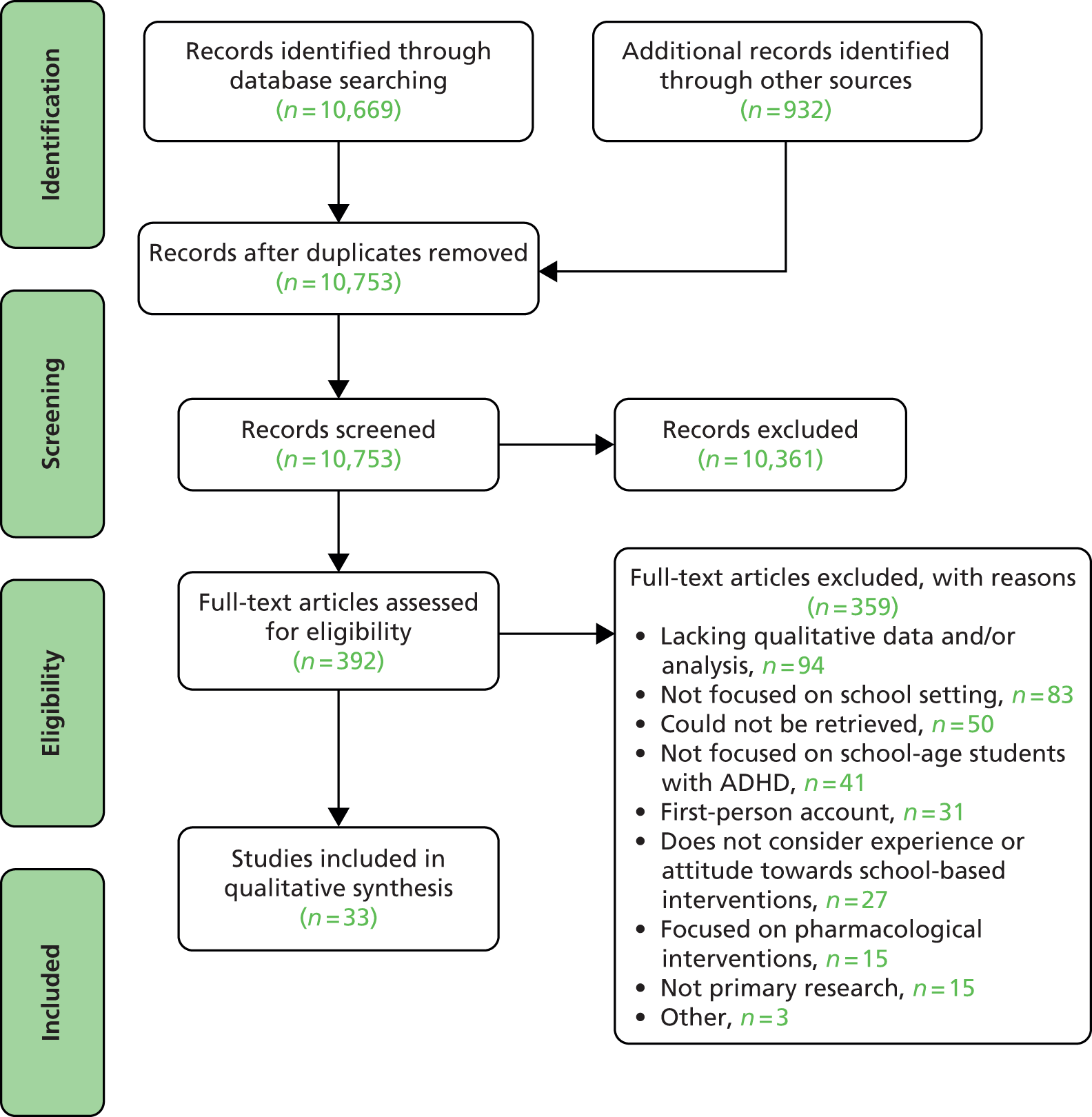

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram152 in Figure 1 summarises the search process.

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram showing search process and study selection for review 1.

After the removal of duplicates, a total of 15,481 records were screened at title and abstract stage and a total of 655 potentially relevant articles were identified for which full texts were required. Of these, 567 (87%) were successfully retrieved, and of those that were not obtainable, 24 were foreign-language papers.

Research questions 1 and 2: evaluations that assess child outcomes

Fifty-four English-language papers met our full-text screening criteria and were included in the synthesis. Of the seven foreign-language papers retrieved and translated by BG, AJ, AV, SI, HK, none met our inclusion criteria.

Research question 3: evaluations that assess economic outcomes

Of the 54 studies that met the full-text screening criteria, there were no studies that included economic outcomes. Consequently, there are no further results in relation to research question 3 about the cost-effectiveness of interventions that target children with or at risk of ADHD in school settings.

Please refer to Appendix 3 for a complete list of reasons for the exclusion of 601 papers after full-text screening.

Descriptive statistics

Study and participant information: descriptive statistics

Fifty-four studies met the inclusion criteria, of which 39 were RCTs104,142,143,153–188 and 15 were non-RCTs. 141,189–202 Forty-seven contained data suitable for meta-analyses; seven studies141,162,180,186,191,192,198 included empirical data that could not be meta-analysed and that were, therefore, synthesised narratively. Three studies104,143,185 included some data that were meta-analysed and some data that were synthesised narratively. Tables 7 and 8 report on the study and participant characteristics for the RCTs (see Table 7) and non-RCTs (see Table 8). Ten studies155,153,163,169,178,184,186,192,198,202 were dissertations or theses (n = 10: 7 RCTs; 3 non-RCTs); the remaining were journal articles (n = 42:104,141–143,153,154,157–162,164–168,170,172–177,179–183,185,187–188,190,191,193–197,199–201 31 RCTs; 11 non-RCTs), a report (1 RCT)171 and a conference paper (1 non-RCT). 189 Studies were from North America (n = 44:104,141–143,153–169,171–176,178,179,181–184,188,189,191–194,197,198,200–202 33 RCTs; 11 non-RCTs); Europe (n = 6: 2 RCTs including one each from the Netherlands185 and Sweden;177 4 non-RCTs including 1 from Italy199 and 3 from Spain190,195,196); Asia (2 RCTs including 1 each from Iran170 and Jordan187); Africa (1 RCT)186 and New Zealand (1 RCT). 180 Forty-two studies104,141–143,153,155,156,159–168,170–173,177,180,182–187,189,190,192–202 included a treatment-as-usual or waitlist control (n = 42: 28 RCTs; 14 non-RCTs). Treatment as usual refers to a usual school routine and/or treatment obtained in the community relative to the participants in the study’s treatment arm. Eight RCTs154,157,158,174,175,176,181,188 and 1 non-RCT191 included comparators that were matched to the treatment group (i.e. irrelevant content, matched for time/contact). In the three studies169,178,179 where the control group included some but not all elements of the intervention, the unique components received by the treatment group were identified. Sample sizes were, on average, small and comprised fewer female than male students.

| First study author and year | Country | Publication status | Target(s) | Relevant treatment groups (n) | Type of control | Sample size | School level | Percentage of female participants | Percentage on medication for ADHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aBarkley 2000104 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 2 | TAU | 119 | Elementary/primary | 36 | 0 |

| bBloomquist 1991153 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 2 | WLC | 52 | Elementary/primary | 31 | 0 |

| bCassar 2010154 | North America (Canada) | Journal article | Core symptoms and related symptoms | 1 | EXP | 6 | Elementary/primary | 50 | NR |

| bChacona 2008155 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core symptoms | 1 | TAU | 60 | Elementary/primary | 30 | NR |

| bCloward 2003156 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core symptoms | 1 | TAU | 8 | Elementary/primary | 38 | NR |

| bDenkowski 1984157 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 2 | EXP | 45 | Elementary/primary | NR | NR |

| bDenkowski 1983158 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Academic/study skills | 1 | EXP | 48 | Middle school | 0 | 0 |

| aDunson 1994143 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms | 1 | TAU | 20 | Elementary/primary | 35 | Yes (% NR) |

| bEvans 2011159 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 49 | Middle school | 29 | 31 |

| bEvans 2007160 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 79 | Middle school | 23 | Yes (% NR) |

| bFabiano 2010161 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 63 | Elementary/primary | 14 | 52 |

| cFrame 2003162 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 65 | Elementary/primary | 30 | 83 |

| bHoover 1986163 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 70 | Elementary/primary | 43 | NR |

| bIseman 2011164 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 29 | Combination of school levels | 28 | 66 |

| bJurbergs 2010165 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 2 | TAU | 45 | Elementary/primary | 26% (of 43) | 23% (of 43) |

| bKhilnani 2003166 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms | 1 | WLC | 30 | Combination of school levels | 20 | NR |

| bLangberg 2012167 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | WLC | 47 | Middle school | 23 | 66 |

| bLangberg 2008168 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Academic/study skills | 1 | WLC | 37 | Elementary/primary | 16 | 43 |

| bLomas 2002169 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core and related symptoms | 1 | ADD | 33 | Elementary/primary | 18 | 67 |

| bLooyeh 2012170 | Asia (Iran) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | WLC | 14 | Elementary/primary | 100 | 0 |

| bMcGraw 2004171 | North America (USA) | Report | Academic/study skills | 1 | WLC | 53 | Middle school | 30 | NR |

| bMolina 2008172 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 23 | Middle school | 25 | 30 |

| bMurray 2008173 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 24 | Elementary/primary | 29 | 88 |

| bOmizo 1980174 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and academic/study skills | 1 | EXP | 56 | Middle school | 0 | 0 |

| bOmizo 1980175 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | EXP | 52 | Elementary/primary | 0 | 0 |

| bOmizo 1982176 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | EXP | 32 | Elementary/primary | 0 | NR |

| bOstberg 2012177 | Europe (Sweden) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms | 1 | TAU | 70 | Elementary/primary | 16% (of 61) | 82% (of 61) |

| bPoley 1996178 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core symptoms | 1 | ADD | 26 | Elementary/primary | 12 | 85 |

| bRabiner 2010142 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 2 | TAU | 77 | Elementary/primary | 31 | 7 |

| bReid 1987179 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | ADD | 77 | Elementary/primary | NR | 0 |

| cRickson 2003180 | Australasia (New Zealand) | Journal article | Related symptoms | 2 | WLC | 18 | High school/secondary | 0 | 50 |

| bRivera 1980181 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | EXP | 36 | Elementary/primary | 0 | 0 |

| bSeeley 2009182 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 42 | Elementary/primary | 7 | 10 |

| bSteiner 2011183 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 2 | WLC | 41 | Elementary/primary | 48 | 60 |

| bStorer 1994184 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core and related symptoms | 2 | TAU | 24 | High school/secondary | 25 | NR |

| avan Lier 2004185 | Europe (the Netherlands) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms | 1 | TAU | 92 (class I) | Elementary/primary | 22 | NR |

| cVan der Westhuizen 2007186 | Africa (South Africa) | Thesis | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | WLC | 12 | Elementary/primary | 17 | 8 |

| bZaghlawan 2007187 | Asia (Jordan) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | TAU | 60 | Elementary/primary | 45 | 0 |

| bZentall 2012188 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Academic/study skills | 1 | EXP | 17(ADHD) | Elementary/primary | 71 | NR |

| First study author and year | Country | Publication status | Target(s) | Relevant treatment groups (n) | Type of control | Sample size | Grade level | Percentage of female participants | Percentage on medication for ADHD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aAbikoff 1983189 | North America (USA) | Conference paper | Academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 20 | Elementary/primary | 0 | 100 |

| aBornas 1992190 | Europe (Spain) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 21 | Elementary/primary | 48 | NR |

| bEastman 1981191 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | EXP | 11 | Elementary/primary | NR | NR |

| bEvans 2005141 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 27 | Middle school | 22 | 81 |

| bHarper 1996192 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core and related symptoms | 2 | WLC | 33 | Elementary/primary | NR | 100 |

| aKapalka 2005193 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | TAU | 86 | Elementary/primary | 0% | Yes (% NR) |

| aKendrick 1995194 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 54 | Elementary/primary | 15 | Yes (% NR) |

| aMiranda 2006195 | Europe (Spain) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 33 | Elementary/primary | 12 | 0 |

| aMiranda 2002196 | Europe (Spain) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 50 | Elementary/primary | 16 | 0 |

| aOwens 2005197 | North America (USA) | Journal article | Core and related symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | WLC | 42 | Elementary/primary | 29 | 40 |

| bPoillion 1993198 | North America (USA) | Thesis | Core symptoms and academic/study skills | 1 | TAU | 106 | Elementary/primary | 39 | NR |

| aRe 2007199 | Europe (Italy) | Journal article | Core symptoms | 1 | TAU | 10 | Nursery/preschool | 50 | NR |