Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 13/06/01. The protocol was agreed in June 2013. The assessment report began editorial review in December 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Sharma et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and definition of the decision problem(s)

Conditions and aetiologies

Brief statement describing the health problem

People with certain clinical conditions such as atrial fibrillation or heart valve disease are at high risk of thrombosis (blood clot). Untreated, these may lead to thromboembolism affecting the brain (causing a stroke), the lungs (pulmonary embolism) or other parts of the body. Many people with these conditions are required to take lifelong blood-thinning drugs (called vitamin K antagonists) to avoid the risks associated with thrombosis. Treatment using blood-thinning drugs is termed anticoagulant therapy and it is estimated that 1.4% of the population in the UK require anticoagulant therapy. 1

Warfarin is the most common vitamin K antagonist drug given to prevent clot formation and stroke. However, serious side effects including bleeding or stroke can result from people being on the wrong dose of warfarin (over- or underdosing). Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that people taking warfarin have ongoing monitoring of their blood coaguability.

Epidemiology and prevalence

There are increasing numbers of people with atrial fibrillation, heart valve replacement or other clinical conditions requiring long-term oral anticoagulation therapy (OAT). 2 As up to 60% of people with atrial fibrillation might be undiagnosed, screening programs have the potential to increase diagnoses and associated use of OAT. 3 The prevalence of atrial fibrillation has recently been described as ‘approaching epidemic proportions’4 and it has been predicted that, by 2050, more than 5.6 million adults in the USA will be diagnosed with atrial fibrillation, compared with 2.3 million in 2001. 5 Increased use of OAT has intensified pressure upon resources, with some haematology services becoming unable to cope. 6

Atrial fibrillation

In the USA, prevalence of atrial fibrillation has been reported as 0.1% in adults < 55 years of age and 9% in those ≥ 80 years old. 5 Over 6 million people in Europe have atrial fibrillation7 and a recent Swedish study reported prevalence of 2.9% in adults > 20 years. 8 Atrial fibrillation is the most common heart arrhythmia and affects around 800,000 people in the UK, or 1.3% of the population. 9 Prevalence increases with age, being 0.5% among people aged 50–59 years and approximately 5% to 8% among people aged > 65 years. 10,11 Atrial fibrillation is more likely to affect men than women and is more common in people with other conditions, for example high blood pressure, atherosclerosis, or other heart conditions such as heart valve problems. For people with atrial fibrillation, there is a five times higher risk of stroke and a three times higher risk of congestive heart failure. 12 One-fifth of all strokes are a result of atrial fibrillation. 7 An average proportion of 47% of people with atrial fibrillation currently receive anticoagulation therapy, such as warfarin. 1

Heart valve disease

Aortic stenosis is the most common type of heart valve disease. It affects 1 in 20 adults over the age of 65 years. 13,14 Data from the UK Heart Valve Registry indicate that approximately 0.2% of the UK population has prosthetic heart valves. 15 Around 6500 adult heart valve replacements (using mechanical or biological valves) are carried out each year, of which around 5000 are aortic valve replacements. 15,16

Impact of health problem: significance for the NHS and burden of disease

The blood coaguability of people taking warfarin is monitored by the use of the international normalised ratio (INR), which is a standardised unit for measuring the time it takes for blood to clot. INR monitoring can be delivered using various options in the NHS. The options include INR monitoring managed by health-care professionals in anticoagulant clinics based in hospitals using laboratory testing or managed in primary care (with or without the use of laboratory services). The use of a personal INR testing machine at home (known as a point-of-care test) allows people to perform self-testing (when people perform the test themselves and the results of the test are managed by health-care professionals) or self-management (when people perform the test and alter the dose of anticoagulation therapy themselves according to a personalised protocol). Self-testing and self-management are together referred to as self-monitoring. Self-monitoring is considered as one of the options for INR monitoring in the NHS, but there is limited evidence on the clinical effectiveness compared with other ways of delivering services.

The use of point-of-care coagulometers for self-monitoring may avoid unnecessary visits to hospitals while allowing regular INR monitoring and timely adjustment of warfarin dosing to avoid adverse events. For people requiring monitoring of their coagulation status, this may result in better quality of life. 17

Measurement of disease

The goal of anticoagulant therapy is to establish a balance between bleeding and clotting18 and it is desirable for people on warfarin to remain within a narrow INR therapeutic range, generally between 2.0 and 3.0. 19,20 If the dose of anticoagulation therapy is too low (underanticoagulation), the risk of thromboembolism increases, while if it is too high (overanticoagulation), the risk of haemorrhage increases. Individuals’ reactions to warfarin vary according to modifiable (e.g. diet) and non-modifiable factors (e.g. age, concomitant diseases). Adequate control of INR is necessary to avoid serious complications such as stroke. Therefore, repeated and regular measurements of INR are required to allow adjustments to size and/or frequency of dosage. 21

Description of technologies under assessment

Summary of point-of-care tests

Point-of-care devices for measuring coagulation status in people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy allow both self-testing and self-management, defined as follows:

-

Self-testing: point-of-care test carried out by the patient with test results managed by their health-care provider [e.g. general practitioner (GP), nurse, specialised clinic].

-

Self-management: point-of-care test carried out by trained patient, followed by interpretation of test result and adjustment of dosage of anticoagulant according to a predefined protocol.

Self-testing and self-management are together referred to as self-monitoring for the purposes of this report.

The purpose of this assessment was to appraise the current evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-monitoring (self-testing and self-management) using either the CoaguChek® system (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland), the INRatio2® PT/INR monitor, (Alere Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) or the ProTime Microcoagulation system® (International Technidyne Corporation, Nexus Dx, Edison, NJ, USA), compared with standard clinical monitoring in people with atrial fibrillation or heart valve disease for whom long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy is indicated.

All of these point-of-care devices, which are currently available for use in the NHS, are CE marked and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved. Point-of-care instruments work basically in the same way: a drop of capillary whole blood is obtained by a finger puncture device, applied to a test strip and inserted into a coagulometer. However, they differ in terms of methods of clot detection and general operational functions.

Summary of CoaguChek system

The CoaguChek system is a point-of-care testing device developed by Roche Diagnostics and measures prothrombin time and INR (the globally recommended unit for measuring thromboplastin time) in people on oral anticoagulation (vitamin K antagonist) therapy. A low INR indicates an increased risk of blood clots, while a high INR indicates an increased risk of bleeding events. CoaguChek S and CoaguChek XS devices are intended for patient self-monitoring. The CoaguChek XS model comprises a meter and specifically designed test strips for blood sample analysis (fresh capillary or untreated whole venous blood). The CoaguChek XS system purports to have the following advantages over the CoaguChek S: (1) the thromboplastin used in the prothrombin time test strips is a human recombinant thromboplastin, which is more sensitive and has a lower International Sensitivity Index (ISI) of 1.0 compared with 1.6; (2) test strips have onboard quality control that is automatically run with every test, rather than having to perform external quality control; (3) test strips do not have to be refrigerated; (4) a smaller blood sample can be used; and (5) the meter is smaller and lighter. The CoaguChek XS Plus model is aimed primarily at health-care professionals and possesses additional features to the XS system, including increased storage and connectivity for data management.

Summary of INRatio2 PT/INR monitor

The INRatio2 PT/INR monitor performs a modified version of the one-stage prothrombin time test using a recombinant human thromboplastin reagent. The clot formed in the reaction is detected by the change in the electrical impedance of the sample during the coagulation process. The system consists of a monitor and disposable test strips and the results for prothrombin time and INR are reported.

Summary of ProTime Microcoagulation system

The ProTime Microcoagulation system is designed for measuring prothrombin time and INR. The test is performed in a cuvette which contains the reagents. Two different cuvettes are available depending on the amount of blood that needs to be collected and tested: the standard ProTime cuvette and the ProTime3 cuvette.

Identification of important subgroups

There are a number of clinical conditions which require long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy to reduce the risk of thrombosis. These conditions include atrial fibrillation and heart valve disease.

Atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation results in unorganised atrial electrical activity associated with mechanically ineffective fibrillation, that contraction which can lead to blood stagnating in parts of the atria and as a result forming a clot. This clot may then move from the heart, causing thromboembolism, most commonly in the brain where it causes stroke. People with atrial fibrillation are at a five to six times greater risk of stroke, with 12,500 strokes directly attributable to atrial fibrillation every year in the UK. Treatment with warfarin reduces the risk by 50–70%. 1,22,23

Artificial heart valves

Valve disease can affect blood flow through the heart in two ways: valve stenosis, where the valve does not open fully, and valve regurgitation (or incompetence), where the valve does not close properly, allowing blood to leak backwards. The most effective treatment for many forms of valve disease is heart valve replacement. Replacement heart valves are either artificial (mechanical), or from humans or animals (tissue). The human valve could be from the same patient (autograft) when the native pulmonary valve is used in the aortic position (part of the Ross procedure); or from another patient (heterograft). People with mechanical heart valves generally require long-term anticoagulant treatment to prevent clotting related to the valve.

Current usage in the NHS

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guideline on atrial fibrillation24 recommends that self-monitoring of INR should be considered for people with atrial fibrillation receiving long-term anticoagulation, if they prefer this form of testing and if the following criteria are met:

-

the patient (or a designated carer) is both physically and cognitively able to perform the self-monitoring test

-

an adequate supportive educational programme is in place to train participants and/or carers

-

the patient’s ability to self-manage is regularly reviewed

-

the equipment for self-monitoring is regularly checked via a quality control programme.

Comparators

In UK clinical practice, INR monitoring is currently managed by a range of health-care professionals, including nurses, pharmacists and GPs. INR monitoring can be carried out in primary care and secondary care. Primary care anticoagulant clinics use point-of-care tests or laboratory analysers. In the latter, blood samples are sent to a central laboratory based at a hospital (‘shared provision’). In the case of secondary care, INR monitoring can be carried out in hospital-based anticoagulant clinics using point-of-care tests or laboratory analysers.

Care pathways

The clinical population considered for the purpose of this assessment includes people with atrial fibrillation or heart valve disease for whom long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy is intended. According to the NICE clinical guideline on atrial fibrillation and the Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network clinical guideline on antithrombotics,24,25 the most effective treatment considered for the treatment of atrial fibrillation is dose-adjusted warfarin, the most common vitamin K antagonist drug. Lifelong anticoagulation therapy with warfarin is also recommended in all people after artificial valve replacement. 26 Warfarin, especially if taken incorrectly, can cause severe bleeding (haemorrhages). Therefore, it is necessary to ensure that people taking warfarin have ongoing monitoring of their blood coaguability.

The routine monitoring of blood coagulation can take several configurations. The NICE anticoagulation commissioning guide1 states that UK anticoagulation therapy services can be delivered in a number of different ways, and that mixed models of provision may be required across a local health economy. This could include full service provision in primary or secondary care, shared provision, domiciliary provision or self-management.

This assessment focuses on the role of point-of-care tests (for the self-monitoring of INR by people at home) as an alternative to standard UK anticoagulation care.

Outcomes

Outcomes of interest for this review were as follows.

Clinical outcomes

-

Frequency of bleeds or blood clots.

-

Morbidity (e.g. thromboembolic and cerebrovascular events) and mortality from INR testing and vitamin K antagonist therapy.

-

Adverse events from INR testing, false test results, vitamin K antagonist therapy and sequelae.

Patient-reported outcomes

-

People‘s anxiety associated with waiting time for results and not knowing their current coagulation status and risk.

-

Acceptability of the tests.

-

Health-related quality of life.

Intermediate outcomes

-

Time and values in therapeutic range.

-

INR values.

-

Test failure rate.

-

Time to receive test result.

-

Patient compliance with testing and treatment.

-

Frequency of testing.

-

Frequency of visits to primary or secondary care clinics.

Overall aim and objectives of this assessment

The aim of this assessment was to appraise the current evidence for the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-monitoring (self-testing and self-management) using CoaguChek, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and ProTime Microcoagulation system point-of-care devices, compared with standard monitoring, in people with atrial fibrillation or heart valve disease receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy.

The specific objectives of this assessment were to:

-

systematically review evidence on the clinical-effectiveness of self-monitoring (self-testing and self-management) using CoaguChek, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and ProTime Microcoagulation system point-of-care devices, compared with standard monitoring practice, in people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy

-

systematically review existing economic evaluations on self-monitoring technologies for people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy

-

develop a de novo economic model to assess the cost-effectiveness of both self-testing and self-management (using CoaguChek XS system, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and ProTime Microcoagulation system as self-monitoring technologies) versus standard monitoring practice in people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy.

Chapter 2 Assessment of clinical effectiveness

Methods for standard systematic review of clinical effectiveness

An objective synthesis of the evidence for the clinical effectiveness of self-monitoring in people receiving long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy using either CoaguChek system, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor or ProTime Microcoagulation system compared with current standard monitoring practice has been conducted. The evidence synthesis has been carried out according to the general principles of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance for conducting reviews in health care,27 the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions28 and the indications of the NICE Diagnostics Assessment Programme Manual. 29 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses recommendations were followed for reporting. 30

Identification of studies

Comprehensive electronic searches were undertaken to identify relevant reports of published studies. Highly sensitive search strategies were designed using both appropriate subject headings and relevant text word terms, to retrieve randomised controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the point-of-care tests under consideration for the self-monitoring of anticoagulation therapy. A 2007 systematic review with similar objectives to those of the current assessment was identified in The Cochrane Library. 31 As extensive literature searches had already been undertaken for the preparation of this systematic review, the literature searches for the current assessment were run in May 2013 for the period ‘2007 to date’ to identify newly published reports. All RCTs included in the Cochrane review were obtained and included for full-text assessment. Searches were restricted to publications in English. MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, Bioscience Information Service, Science Citation Index and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) were searched for primary studies, while the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects and the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database were searched for reports of evidence syntheses.

Reference lists of all included studies were perused in order to identify additional potentially relevant reports. The expert panel provided details of any additional potentially relevant reports.

Searches for recent conference abstracts (2011–13) were also undertaken and included the annual conferences of the American Society of Haematology, the European Haematology Association and the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, as well as the proceedings of the 12th National Conference on Anticoagulant Therapy. Ongoing studies were identified through searching Current Controlled Trials, Clinical Trials, World Health Organization, International Clinical Trials Registry and NationaI Institutes of Health Reporter. Websites of professional organisations and health technology agencies were checked to identify additional reports. Full details of the search strategies used are presented in Appendix 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The initial scoping searches performed for this assessment identified a Cochrane review31 and a few technology assessment reports21,32,33 assessing different models of managing OAT. These publications focused on several RCTs, which reported relevant clinical outcomes. In particular, the Cochrane review included both the CoaguChek S and the CoaguChek XS devices. The CoaguChek XS system is the upgraded version of CoaguChek S and uses the same technology as its precursor. Details of the performance of the two CoaguChek models compared with standard INR monitoring are provided below (see Performance of point-of-care devices).

The studies fulfilling the following criteria were included in this assessment.

Population

People with atrial fibrillation or heart valve disease for whom long-term vitamin K antagonist therapy was required.

Setting

Self-INR monitoring supervised by primary or secondary care.

Interventions

The point-of-care devices considered in this assessment were:

-

CoaguChek system

-

INRatio2 PT/INR monitor

-

ProTime Microcoagulation system.

Comparators

The comparator considered in this assessment was standard practice, which consisted of INR monitoring managed by health-care professionals. INR monitoring can be carried out in primary care, in secondary care or in a ‘shared provision’ setting:

-

Primary care: INR monitoring can be carried out in primary care anticoagulant clinics using point-of-care tests or laboratory analysers. In the latter, blood samples are sent to a central laboratory based at a hospital (shared provision).

-

Secondary care: INR monitoring can be carried out in hospital-based anticoagulant clinics using point-of-care tests or laboratory analysers.

Outcomes

The following outcomes were considered.

Clinical outcomes

-

Frequency of bleeds or blood clots.

-

Morbidity (e.g. thromboembolic and cerebrovascular events) and mortality from INR testing and vitamin K antagonist therapy.

-

Adverse events from INR testing, false test results, vitamin K antagonist therapy and sequelae.

Patient-reported outcomes

-

People’s anxiety associated with waiting time for results and not knowing their current coagulation status and risk.

-

Acceptability of the tests.

-

Health-related quality of life.

Intermediate outcomes

-

Time and INR values in therapeutic range.

-

Test failure rate.

-

Time to receive test result.

-

Patient compliance with testing and treatment.

-

Frequency of testing.

-

Frequency of visits to primary or secondary care clinics.

Study design

We identified relevant RCTs assessing the effectiveness of the CoaguChek system, the INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and the ProTime Microcoagulation system. Therefore, non-randomised studies (including observational studies) were not considered for this assessment. Systematic reviews were used as source for identifying additional relevant studies.

Studies were excluded if they did not meet the prespecified inclusion criteria, and, in particular, the following types of report were not deemed suitable for inclusion:

-

biological studies

-

reviews, editorials and opinions

-

case reports

-

non-English-language reports

-

conference abstracts published before 2012.

Data extraction strategy

Two reviewers (PS and MB) independently screened the titles and abstracts of all citations identified by the search strategies. Full-text copies of all studies deemed to be potentially relevant were obtained and assessed independently by two reviewers for inclusion (PS and MC). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer (MB).

A data extraction form was designed and piloted for the purpose of this assessment (see Appendix 2). One reviewer (PS) extracted information on study design, characteristics of participants, settings, characteristics of interventions and comparators, and relevant outcome measures. A second reviewer (MC) cross-checked the details extracted by the first reviewer. There was no disagreement between reviewers.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

A single reviewer (PS) assessed the risk of bias of the included studies and findings were cross-checked by a second reviewer (MC). There were a few disagreements which were resolved by consensus or arbitration by a third reviewer (MB). The reviewers were not blinded to the names of studies’ investigators, institutions and journals. Studies were not included or excluded purely on the basis of their methodological quality. The risk of bias assessment for all included RCTs was performed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool (see Appendix 3). 28 Critical assessments were made separately for all main domains: selection bias (‘random sequence generation’, ‘allocation concealment’), detection bias (‘blinding of outcome assessor’), attrition bias (‘incomplete outcome data’) and reporting bias (‘selective reporting’). The ‘blinding of participants and personnel’ was not considered relevant for this assessment due to the nature of intervention being studied (i.e. patient performing the test themselves or under supervision of health-care professionals). However, we collected information related to the blinding of outcome assessors, which was considered relevant to the assessment of risk of bias.

We judged each included study as ‘low risk of bias’, ‘high risk of bias’ or as ‘unclear risk of bias’ according to the criteria for making judgments about risk of bias described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 28 Adequate sequence generation, allocation concealment and blinding of outcome assessor were identified as key domains for the assessment of the risk of bias of the included trials.

Data analysis

For dichotomous data (e.g. bleeding events, thromboembolic events, mortality), relative risk (RR) was calculated. For continuous data [e.g. time in therapeutic range (TTR)], weighted mean difference (WMD) was calculated. Where standard deviations (SDs) were not given, we calculated them using test statistics wherever possible. The RR and WMD effect sizes were meta-analysed as pooled summary effect sizes using the Mantel–Haenszel (M–H) method and the inverse-variance (IV) method, respectively. We also calculated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To estimate the summary effect sizes, both fixed-effect and random-effect models were used with RR and WMD. In the absence of clinical and/or statistical heterogeneity, the fixed-effects model was selected as the model of choice, while the random-effects model was used to cross-check the robustness of the fixed-effects model. However, in the presence of either clinical or statistical heterogeneity, the random-effects model was chosen as the preferred method for pooling the effect sizes, as in this latter situation, the fixed-effects method is not considered appropriate for combining the results of included studies. 28 Heterogeneity across studies was measured by means of the chi-squared statistic and also by the I2 statistic, which describes the percentage of variability in study effects that is explained by real heterogeneity rather than chance. It is worth noting that, for bleeding and thromboembolic events, we used the total number of participants who were actually analysed as denominator in the analyses. In contrast, for mortality, we used the total number of participants randomised as denominator because participants could have died due to any causes after randomisation but before entering the self-monitoring programme.

Apart from the prespecified subgroups analysis, according to the type of anticoagulation therapy management (self-testing and self-management), we performed a post-hoc subgroup analysis according to the type of the target clinical condition (i.e. atrial fibrillation, heart valve disease and mixed clinical indication) and one according to the type of service provision for anticoagulation management (i.e. primary care, secondary care and shared provision). Where trials had multiple arms contributing to different subgroups, the control group was subdivided into two groups to avoid a unit of analysis error.

Sensitivity analyses were planned in relation to some of the study design characteristics. The methodological quality (low/high risk of bias) and the different models of the CoaguChek system were identified at protocol stage as relevant aspects to explore in sensitivity analyses. In addition to those prespecified in the protocol, we performed a sensitivity analysis by excluding the studies conducted in the UK.

Review Manager software (Review Manager 5.2, 2012, The Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) was used for data management and all relevant statistical analyses for this assessment. Where it proved unfeasible to perform a quantative synthesis of the results of the included studies, outcomes were tabulated and described in a narrative way.

Results

Performance of point-of-care devices

A formal evaluation of the performance of the CoaguChek, INRatio and ProTime point-of-care systems with regard to INR measurement was outside the scope of this assessment. An objective ‘true’ INR remains to be defined and usually the calculation of INR measurement is based on different assumptions. INR determined in the laboratory is regarded as the gold standard with which all other measurement methods should be compared. 34 Information on the precision and accuracy of these point-of-care devices was gathered from the available literature. Normally, the precision or reproducibility of point-of-care devices is expressed by means of the coefficient of variation (CV) of the variability, while the accuracy is the level of agreement between the result of one measurement and the true value and is expressed as correlation coefficient. 35 Table 1 summarises the performance of the target point-of-care devices according to the FDA self-test documentation and relevant published papers.

| Device | Precision | Accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) INR | CV (%) | Correlation (r) | |||

| Patient | Professional | Patient | Professional | ||

| CoaguChek S36 | 2.42 (0.68) | NR | NR | NR | 0.95a |

| CoaguChek XS37 | 2.57 (0.13) | 2.52 (0.13) | 5.13 | 5.36 | 0.93 |

| INRatio 238 | 2.70 (0.153) | 2.93 (0.180) | 5.68 | 6.16 | 0.93 |

| ProTime 339 | 4.0 (0.19)b | NR | NR | NR | 0.95 |

A systematic review published by Christensen and Larsen in 201235 assessed the precision and accuracy of current available point-of-care coagulometers including CoaguChek XS, INRatio and ProTime/ProTime3. The authors found that the precision of CoaguChek XS varied from a CV of 1.4% to one of 5.9% based on data from 14 studies, while the precision of INRatio and ProTime varied from 5.4% to 8.4% based on data from six studies. The coefficient of correlation for CoaguChek XS varied from 0.81 to 0.98, while that for INRatio and ProTime varied from 0.73 to 0.95. They concluded that the precision and accuracy of point-of-care coagulometers were generally acceptable, compared with conventional laboratory-based clinical testing. The same conclusions were drawn by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health report published in 2012 on point-of-care testing. 41 Similarly, the international guidelines prepared in 2005 by the International Self-Monitoring Association for oral Anticoagulation stated that ‘Point-of-care instruments have been tested in a number of different clinical settings and their accuracy and precision are considered to be more than adequate for the monitoring of OAT in both adults and children’ (p. 40). 42

CoaguChek XS versus CoaguChek S

The CoaguChek S monitor was replaced in 2006 by the XS monitor, which offers a number of new technical features such as the use of a recombinant human thromboplastin with a lower ISI and internal quality control included on the test strip. The safety and reliability of CoaguChek S and CoaguChek XS have been demonstrated in several studies in both adults and children. 43–50 A number of studies have also compared the performance of CoaguChek S with that of CoaguChek XS in relation to conventional INR measurement. Even though a good agreement between the two CoaguChek models and conventional laboratory-based results has been demonstrated, CoaguChek XS has shown more accurate and precise results than its precursor in both adults and children, especially for higher INR values (> 3.5). 34,36,51–54

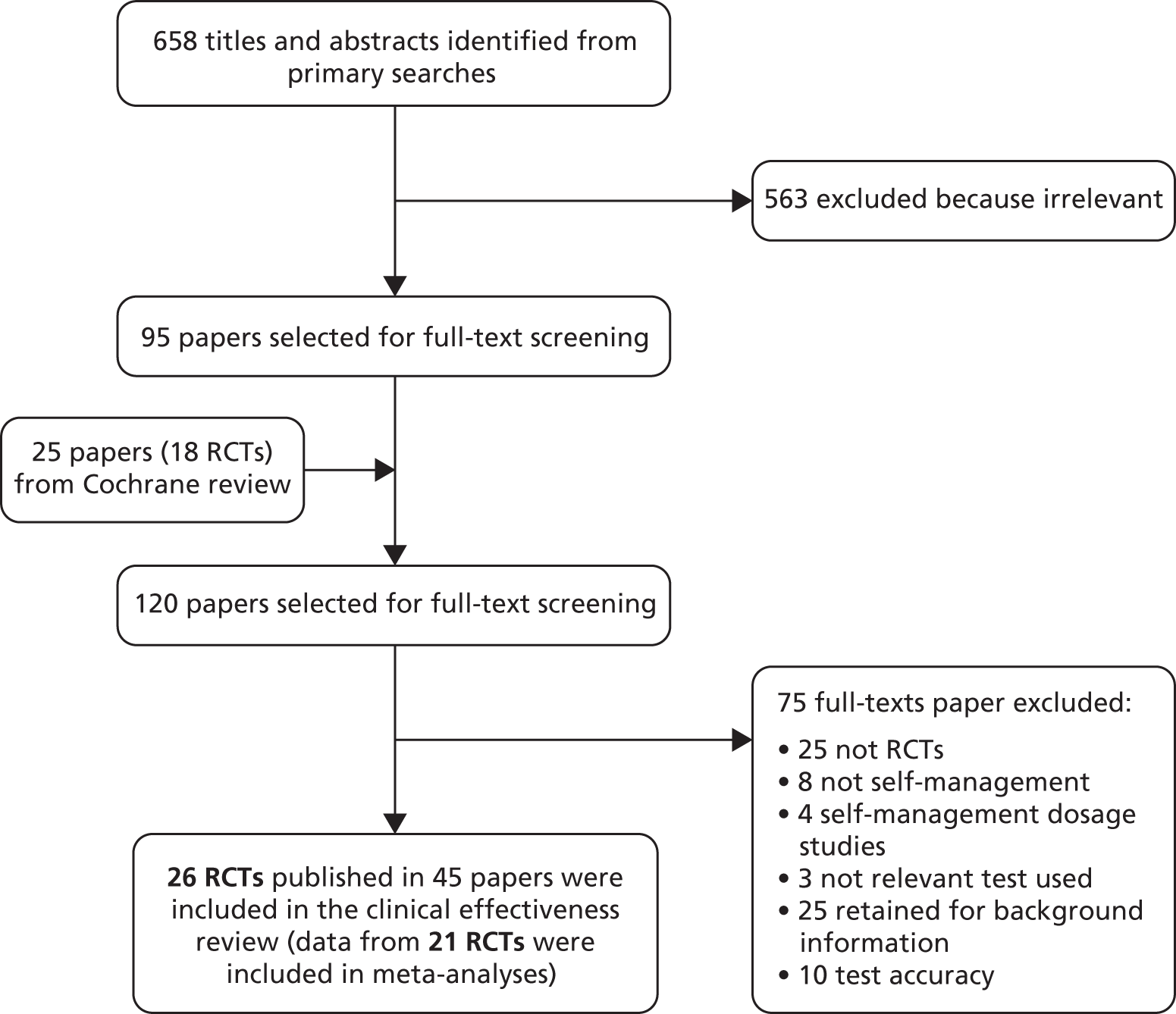

Quantity of available evidence

A total of 658 records were retrieved for the assessment of the clinical effectiveness of the point-of-care tests under investigation. After screening titles and abstracts, 563 were excluded and full-text reports of 120 potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment, including 25 full-text papers from the 18 trials included in the Cochrane systematic review published by Garcia-Alamino and colleagues. 31 In total, 26 RCTs (published in 45 papers) met the inclusion criteria and were included in the clinical effectiveness section of this assessment. Three of the 26 included studies were randomised crossover trials,32–34 while the remaining studies were parallel-group RCTs.

We based the primary analyses on data from 21 out of the 26 included studies relevant to the comparisons and outcomes of interest (Table 2 provides further details).

| Study ID | Comparisons | Reason for exclusion from meta-analyses | Reason for inclusion in this assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bauman 201055 | Compares PSM with PST group (PST was the usual care provided in the study context) | Lack of data on SC group where people received OAT are generally managed by the primary or secondary care | Only RCT that reported acceptability outcomes on the relevant subgroup of interventions for children |

| Gardiner 200545 | Compares PST with standard care | The data collected by the participants were not used for the analysis. Instead, monthly data collected by the health-care professionals were used | Reports patient acceptability of self-testing as secondary outcome |

| Gardiner 200656 | Compares PST with PSM and then historically compares the included subgroups with the standard care they received for last 6 months before their enrolment in the study | Lack of randomised data on SC group where participants receiving OAT are usually managed by the primary or secondary care | Provide relevant data on TTR on the subgroup of interventions that were of interest |

| Hemkens 200857 | Compares PSM with standard laboratory monitoring | Do not provide data on any relevant clinical outcomes or intermediate outcomes | Reports patient satisfaction of self-management as secondary outcome |

| Rasmussen 201258 | Compares PSM with standard care | Do not provide any relevant clinical outcomes. Data provided for TTR was in median (25th to 75th percentile) which was not possible to be converted into mean (SD) | Provide data on TTR |

Of these 21 trials which provided data for statistical analyses, 15 trials were the same as those included in the Cochrane systematic review by Garcia-Alamino and colleagues31 and six were newly identified trials, published in or after 2008.

Figure 1 shows a flow diagram of the study selection process. The list of 26 included RCTs (and other linked reports) is given in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram outlining the selection process.

Number and type of studies excluded

Appendix 5 lists the number of studies excluded after full-text assessment and the reasons for their exclusion.

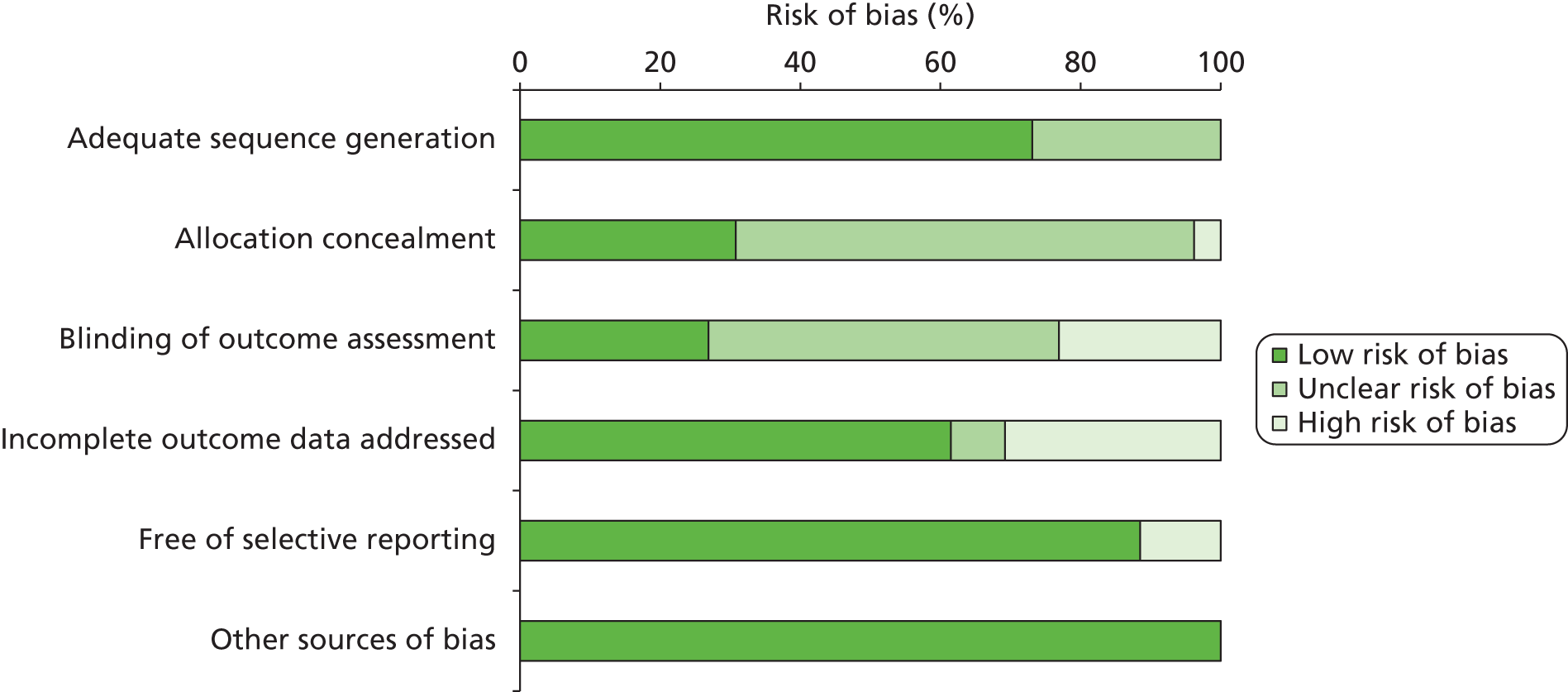

Quality of research available

Figure 2 illustrates a summary of the risk of bias assessment for all included studies. The majority of trials were judged at ‘unclear’ or ‘high’ risk of bias. One trial was only reported in abstract and hence did not allow for an adequate assessment of the risk of bias. 59 Similarly, one trial was discontinued before the end of the prespecified follow-up due to difficulties in the recruitment process. 60 Overall, only four trials were assessed to have adequate sequence generation, concealed allocation and blinded outcome assessment and, therefore, were judged at low risk of bias. 55,61–63 Three of these trials used either the CoaguChek model ‘S’61,63 or the model ‘XS’62 for INR measurement, while the other trial used CoaguChek XS to measure INR in children receiving anticoagulation therapy. 55 Appendix 6 provides details of the risk of bias assessment for each individual study. Main findings of the risk of bias assessment for all included studies are described in detail below.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of risk of bias of all included studies.

Selection bias

Of the 26 included trials, only seven trials reported adequate details on both generation of the randomisation sequence generation and concealment of allocation. 55,57,61–65 In 11 trials, the randomisation process proved to be adequate but no information was provided on the way in which participants were allocated to the study interventions. 58,60,66–74 One trial75 reported adequate details about the generation of the random sequence but failed to conceal the allocation of participants to study interventions. In contrast, another trial76 reported adequate information on allocation concealment but failed to provide details on the randomisation process. In six trials, both the randomisation process and the allocation concealment were judged as ‘unclear’ due to the lack of adequate information. 45,56,59,77–79

Attrition bias

Seventeen trials were judged to be at low risk of attrition bias. Six of them had limited missing data with similar reasons for discontinuation across intervention groups. 59,69,72,74,76,79 Seven trials relied on an intention-to-treat approach and all dropouts were fully accounted for in the statistical analyses,55,61,63–65,71,75 while the other four reported no missing data. 58,60,62,78 Eight of the 26 included trials were at high risk of attrition bias, with more than 5% dropout rate and with missing data not appropriately tackled. 45,56,57,66–68,73,77 In the Early Self-Controlled Anticoagulation Trial,70 the problem of incomplete outcome data was addressed for the first 600 participants but not for all included participants.

Performance and detection bias

Owing to the nature of the interventions being studied (use of point-of-care devices), blinding of participants or personnel was not feasible. Seven trials blinded the outcomes assessor (statistician or clinical outcome assessor). 55,58,61–63,72,77 In six trials, neither the participants nor the personnel involved in delivering the interventions were blinded. 60,65,66,71,74,75 One trial70 was described as ‘double blinded’ but no further information was given. Another trial68 reported that one of the two standard care groups studied (the untrained routine group) was blinded. In addition, this trial revealed that the nurses involved in transferring data on dosing as well as the dosing physicians were blinded. The remaining of the included trials did not provide information on blinding.

Reporting bias

With the exception of three trials,58,76,79 the outcomes reported in the trials were prespecified in the analysis section and reporting bias was not obvious in the published papers.

Other sources of biases

No other sources of biases were obvious in the included trials.

Characteristics of the included studies

Table 3 summarises the main characteristics of the 26 included RCTs. The baseline characteristics of all included trials are described below and tabulated in Appendix 7 (see Tables 31 and 32).

| Study characteristics | CoaguChek XS | CoaguChek S/CoaguChek | CoaguChek Plus | CoaguChek + INRatio | ProTime |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. of studies | 4 | 17 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Self-monitoring | |||||

| PSM | 2 | 14 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| PST | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| PSM and PST | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Standard care | |||||

| AC clinic | 4 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| GP/physician | 0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| AC clinic or GP/physician | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Country | |||||

| UK | 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-UK | 4 | 12 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Clinical indication | |||||

| AF only | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| AHV only | 0 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Mixed only (AF + AHV + others) | 4 | 12 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Total sample size | 414 | 3910 | 1155 | 222 | 3062 |

Study details

The majority of included trials were conducted in Europe: six trials were conducted in Germany,57,59,60,70,72,78 six in the UK,45,56,64,67,69,73 three in Denmark,58,66,75 three in the Netherlands,68,76,79 one in Ireland,62 one in Austria,63 one in France77 and one in Spain. 61 Three trials were conducted in Canada55,65,74 and one in the USA. 71 Of the 26 included trials, seven were multicentred,60,63,64,67,68,71,72 while the remaining 19 were conducted in a single centre.

The length of follow-up ranged from 14 weeks57 to more than 4 years. 63,71 Nine trials reported follow-ups ≥ 12 months. 55,61,63,64,70,71,73,78,79 One trial, which was originally supposed to run for 2 years, was discontinued prematurely due to the small number of recruited participants. 60

Nine of the included trials were funded independently by professional organisations or national/governmental agencies55,57–59,64–66,69,75 while 13 trials were fully or partly funded by industry. In the case of the remaining four trials, the source of funding was not reported. 70,76,78,79

Participants

Most of the included trials (15 out of 26) included participants with mixed indications of which atrial fibrillation, artificial heart valves (AHVs) and venous thromboembolism were the most common clinical indications,45,55–57,61–63,65,66,68,71,72,74–76 while six trials enrolled exclusively participants with AHVs59,70,73,77–79 and two trials limited inclusion to participants with atrial fibrillation. 60,69 Seven trials provided information on risk factors, comorbidity, and/or previous bleeding and thromboembolic events but did not report significant baseline differences between participants in self-monitoring and those in standard care (see Appendix 7, Table 32). 61,63,64,71,72,75,77

The mean sample size among the included trials was 337 participants (range 1639–292,271 participants). Fifteen trials performed a power analysis and a sample size calculation,58,60–66,68,69,71,72,74–76 two trials, with very small sample sizes, did not power their studies55,57 and the remaining trials did not provide information on how the sample size was determined. 45,56,59,67,70,73,77–79 The age of adult participants ranged from 16 to 91 years. 62 The only trial which assessed children reported a median age of 10 years. 55

Warfarin was the choice of vitamin K antagonist therapy in half of the included trials. 45,55,56,58,62,64–67,69,71,73,74,78 In seven trials, participants were taking phenprocoumon and/or acenocoumarol and/or fluindione57,61,63,68,72,76,77 and, in one trial, participants received either warfarin or phenprocoumon. 75 In the remaining four trials, the type of vitamin K antagonist therapy was not reported. 59,60,70,79 In nearly half of the included trials (12 out of 26), participants had been on OAT for at least 3 months before randomisation. 45,55,56,61,64,66–69,74–76 Three trials included vitamin K antagonist-naive participants for whom long-term OAT was recently indicated but who had not been on anticoagulation therapy before. 58,63,70 In the largest trial, The Home International Normalised Ratio Study (THINRS),71 randomisation was stratified according to the duration of anticoagulation but no significant differences were found between participants who had started anticoagulation therapy within the previous 3 months and those who had received anticoagulation therapy for > 3 months. In the two remaining trials, the included participants received OAT for < 3 months (1–2 months) before randomisation. 62,65

Point-of-care tests used for international normalised ratio measurement

CoaguChek system for INR monitoring was used in 22 of the 26 included trials. Nine trials used the S model,45,56,58,61,63,64,67,75,78 four used the XS model,55,62,66,74 one70 used the CoaguChek Plus model and two trials used the first model of the CoaguChek series, which was simply referred to as ‘CoaguChek’. 68,72 In six trials, it was unclear whether the CoaguChek device was the first model or its later versions. 59,60,69,73,76,79 Either the INRatio or the CoaguChek S was used for INR measurement in two trials (but results were not separated according to the type of the point-of-care device),57,77 and the ProTime system was used in other two trials. 65,71 In all six trials based in the UK, CoaguChek system (either CoaguChek or version S) was used for the INR measurement.

In 11 trials, in order to assure accuracy of the point-of-care devices being used, INR results measured directly by participants were compared with those measured in a laboratory. 45,55–58,64–67,69,77

Eight trials’ investigators who did not specify the model of the CoaguChek device (S or XS) used for INR measurement were contacted for further details. 60,68,69,72,73,76,77,79 Five of the them provided further information on the model of the CoaguChek point-of-care device. 58,68,72,77,79

Standard anticoagulant management

The type of standard care varied across trials. In 13 trials, INR was measured by professionals in anticoagulant or hospital outpatient clinics,45,57,58,61,62,64,66,68,69,71,74,76,79 by a physician or a GP in a primary care setting in six trials,59,60,65,67,70,78 and either by a physician/GP in a primary care setting or by professionals in anticoagulant/outpatient hospital clinics in five trials. 63,72,73,75,77 In two trials, comparing self-testing with self-management,55,56 self-testing within anticoagulant clinics was considered as standard care. In the majority of the included trials (17 out of 26), the anticoagulant clinic was led by a clinician (general or specialist),58–61,63,65,66,68–73,75,77–79 by a nurse in five trials, (three conducted in the UK,45,48,64 one in Canada55 and one in Germany57) and by a pharmacist in two trials, conducted in Canada74 and in Ireland. 62

International normalised ratio measurement was carried out in a laboratory in all but two trials, where CoaguChek S67 or another coagulometer75 was used instead.

Self-monitoring

The majority of the included trials (17 out of 26) compared self-management (participants performed the test and adjusted the dose of anticoagulation therapy themselves) with standard care,57–61,63–65,67,70,72–76,78,79 six assessed self-testing (participants performed the test themselves with the results managed by health-care professionals)45,62,66,69,71,77 and one evaluated both self-testing and self-management versus either trained or untrained routine care (four arms). 68 It is worth noting that for the subgroup meta-analysis according to type of OAT management, this four-arm trial contributed to two studies: one on self-testing and one on self-management. The two standard care groups (trained and untrained routine care) were initially combined to produce an overall control group and subsequently subdivided into two groups for the purpose of the subgroup analysis, which was undertaken to assess the effects of self-testing versus self-management.

The remaining two trials compared self-testing with self-management (without standard care as a comparator). 55,56 One of these two trials enrolled exclusively a population of children55 while the other provided a non-randomised comparison of participants in self-testing and self-management with those receiving standard care for a period of 6 months before study enrolment. 56 We deemed these two trials suitable for inclusion as they provide relevant outcomes for participants in both self-testing and self-management.

In 19 out of 26 included trials, participants received training and education in order to perform self-testing and self-management (see Appendix 7, Table 33). 45,55,56,61,62,64–67,69,72–77,79–81 In most of these trials (11 out of 19), the training was provided in group sessions which lasted for around 1–2 hours55,61,62,68,69,72,76,77,81 up to a maximum of 3 hours. 73,74 The training was usually administered by a single member of staff, either a nurse, a practitioner/physician45,56,61,64,69 or a pharmacist. 74 In a few trials, the training was provided by a team of professionals, such as a specialist physician together with paramedical personnel,80 a research pharmacist coupled with an haematologist62 or a physician assisted by a nurse. 63,72 In five trials, the personnel responsible for delivering the training was reported to be trained specifically on self-testing and self-management. 56,61,63,64,72

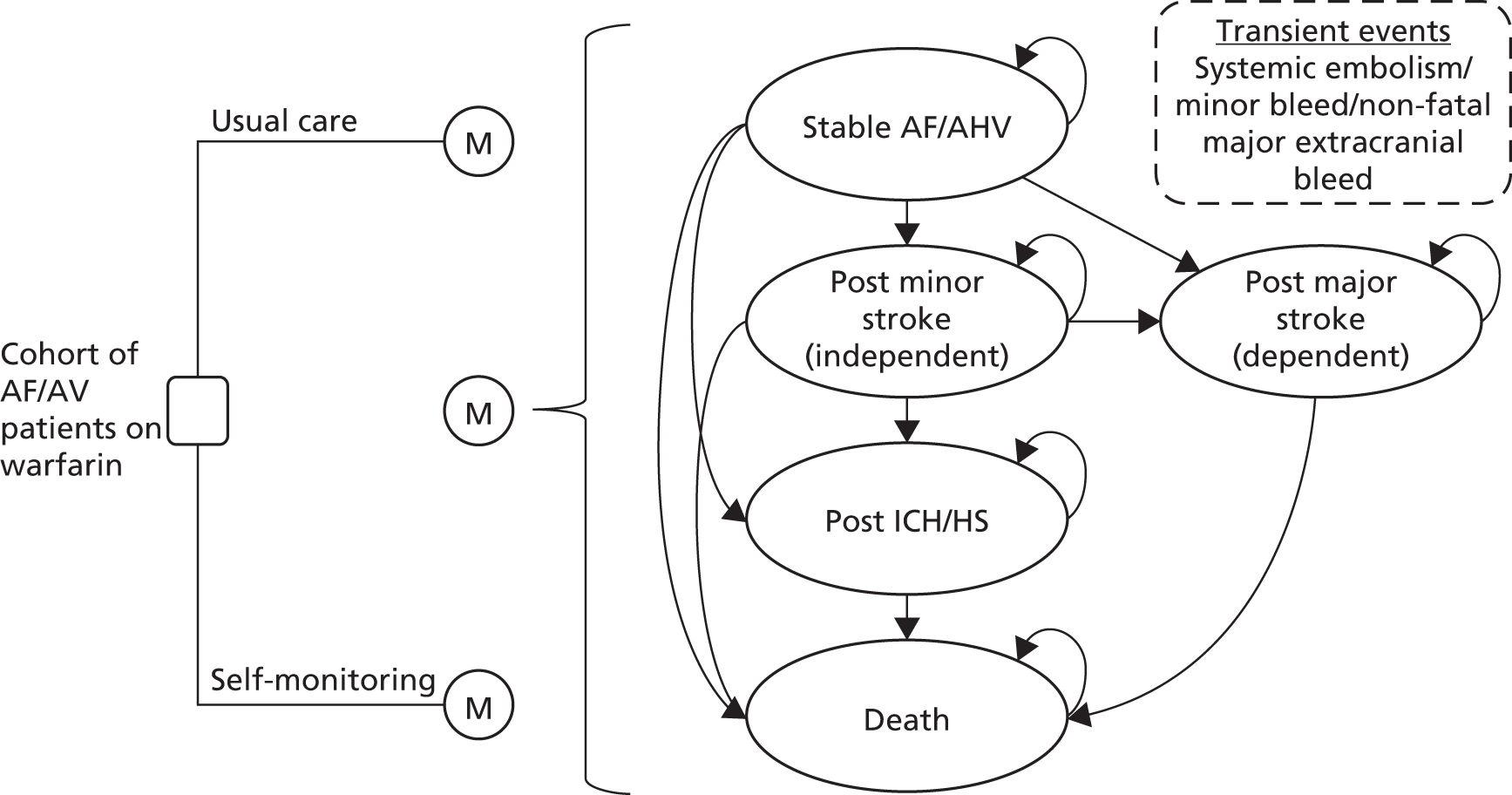

Clinical effectiveness results

Overview

This section provides evidence from 26 included trials on the clinical effectiveness of self-monitoring using CoaguChek system, INRatio2 PT/INR monitor and ProTime Microcoagulation system, compared with standard practice (see Figures 3–14; Tables 4–6; Appendix 8). For clarity, the results are reported under the broad headings of ‘clinical outcomes’, ‘intermediate outcomes’ and ‘patient-reported outcomes’. The summary effects of relevant clinical outcomes such as bleeding events, thromboembolic events and mortality have been described separately within the ‘clinical outcomes’ section. Tables 4 and 5 show the main findings of the five trials conducted in the UK and of the four trials using CoaguChek XS. The results of the sensitivity analyses for each point-of-care test are displayed in Table 6.

| Study ID | Type of SM | Type of SC | Clinical condition | Sample sizea | Bleeding events | Thromboembolic events | Mortality | TTR, % (95% CI) | Frequency of self-testing, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | |||||

| Fitzmaurice 200267 | PSM | GP | Mixed | 23 | 26 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 74 (67 to 81) | 77 (67 to 86) | 1.6 weeks |

| Fitzmaurice 200564 | PSM | Hospital- or practice-based AC clinic | Mixed | 337 | 280 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | b70 (68.1 to 72.4) | b68 (65.2 to 70.6) | 12.4 |

| Gardiner 200656 | PSM and PST | PST within AC was the SC | Mixed | 55/49 | – | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | PSM: 69.9 (60.8 to 76.7) PST: 71.8 (64.9 to 80.1) |

NR | |

| Khan 200469 | PST | AC clinic | AHV | 44 (40) | 41 (39) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | NR | NR | c71.1 (14.5) | c70.4 (24.5) | NR |

| Sidhu 200173 | PSM | GP or AC clinic | AHV | 51 (41) | 49 (48) | 3 | 2 | 10 | 10 | 0 | 4 | 76.5 | 63.8 | NR |

| Study ID | Country | Type of SM | Type of SC | Sample sizea | Bleeding events | Thromboembolic events | Mortality | TTR, % (95% CI) | Frequency of self-testing, mean (SD) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | PSM/PST | SC | |||||

| Bauman 201055 (child population) | Canada | PSM and PST | PST within AC was the SC | 14/14 | – | 0/0 | – | 0/0 | – | NR | – | b83/83.9 | – | NR |

| Christensen 201166 | Denmark | PST | AC clinic, hospital outpatient or GP | OW: 51 (46) TW: 40 (37) |

49 (40) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | OW: 79.7 (79 to 80) TW: 80.2 (79.4 to 80.9) |

72.7 (71.9 to 73.4) | OW: 7.4 (2.7) TW: 4.1 (1.8) |

| Ryan 200962 | Ireland | PST | AC clinic | 72 | 60 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 1 | NR | NR | b74 (64.6–81) | b58.6 (45.6–73.1) | 4.6 (0.8) |

| Verret 201274 | Canada | PSM | AC clinic | 58 | 56 | 26 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | c80 (13.5) | c75.5 (24.7) | NR |

| Outcomes | Main analyses | Sensitivity analyses | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All included trials | CoaguChek System | CoaguChek XS | ProTime | CoaguChek/INRatioa | |||||||||||

| RR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of trials | RR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of trials | RR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of trials | RR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of trials | RR (95% CI) | p-value | No. of trials | |

| Bleeding | 0.95 (0.74 to 1.21) | 0.66 | 22 | 0.90 (0.67 to 1.23) | 0.52 | 19 | 1.07 (0.70 to 1.62) | 0.77 | 3 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29) | 0.01 | 2 | 0.93 (0.70 to 1.23) | 0.60 | 20 |

| PSM | 0.94 (0.68 to 1.30) | 0.69 | 15 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | 0.75 | 14 | 1.09 (0.71 to 1.67) | 0.69 | 1 | 0.34 (0.01 to 8.16) | 0.50 | 1 | 0.95 (0.68 to 1.32) | 0.75 | 14 |

| PST | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.28) | 0.02 | 7 | 0.58 (0.22 to 1.47) | 0.25 | 5 | 0.28 (0.01 to 6.71) | 0.43 | 2 | 1.15 (1.03 to 1.29) | 0.01 | 1 | 0.97 (0.59 to 1.61) | 0.91 | 6 |

| Thromboembolic events | 0.58 (0.40 to 0.84) | 0.004 | 22 | 0.52 (0.38 to 0.71) | < 0.0001 | 19 | 1.67 (0.15 to 17.93) | 0.67 | 3 | 0.94 (0.48 to 1.84) | 0.86 | 2 | 0.51 (0.38 to 0.70) | < 0.0001 | 20 |

| PSM | 0.51 (0.37 to 0.69) | < 0.0001 | 15 | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.72) | 0.0001 | 14 | Not estimable | 1 | 0.20 (0.01 to 4.15) | 0.30 | 1 | 0.51 (0.36 to 0.72) | 0.0001 | 14 | |

| PST | 0.99 (0.75 to 1.31) | 0.95 | 7 | 0.71 (0.14 to 3.63) | 0.68 | 5 | 1.67 (0.15 to 17.93) | 0.67 | 2 | 1.01 (0.77 to 1.34) | 0.92 | 1 | 0.55 (0.13 to 2.31) | 0.41 | 6 |

| Mortality | 0.83 (0.63 to 1.10) | 0.20 | 13 | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 11 | Not estimable | Not estimable | 2 | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.19) | 0.71 | 1 | 0.69 (0.48 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 12 |

| PSM | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 10 | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 10 | Not estimable | Not estimable | 1 | Not estimable | Not estimable | Not estimable | 0.68 (0.46 to 1.01) | 0.06 | 10 |

| PST | 0.97 (0.78 to 1.19) | 0.74 | 3 | Not estimable | Not estimable | 1 | Not estimable | Not estimable | 1 | 0.96 (0.78 to 1.19) | 0.71 | 1 | 3.00 (0.48 to 1.01) | 0.50 | 2 |

| TTR | WMD 2.82 (0.44 to 5.21) | 0.02 | 11 | WMD 2.82 (–0.69 to 6.33) | 0.12 | 8 | WMD 7.18 (6.24 to 8.12) | < 0.00001 | 2 | WMD 3.83 (2.69 to 4.96) | < 0.00001 | 2 | WMD 3.21 (0.04 to 6.37) | 0.05 | 9 |

| PSM | WMD 0.47 (–1.40 to 2.34) | 0.62 | 6 | WMD 0.93 (–1.18 to 3.03) | 0.39 | 5 | WMD 4.50 (6.85 to 15.85) | 0.44 | 1 | WMD 8.60 (–7.07 to 24.27) | 0.28 | 1 | WMD 0.93 (–1.18 to 3.03) | 0.39 | 5 |

| PST | WMD 4.44 (1.71 to 7.18) | 0.001 | 5 | WMD 5.41 (1.85 to 8.97) | 0.003 | 3 | WMD 7.20 (6.25 to 8.15) | < 0.00001 | 1 | WMD 3.80 (2.69 to 4.96) | < 0.00001 | 1 | WMD 6.23 (4.10 to 8.36) | < 0.00001 | 4 |

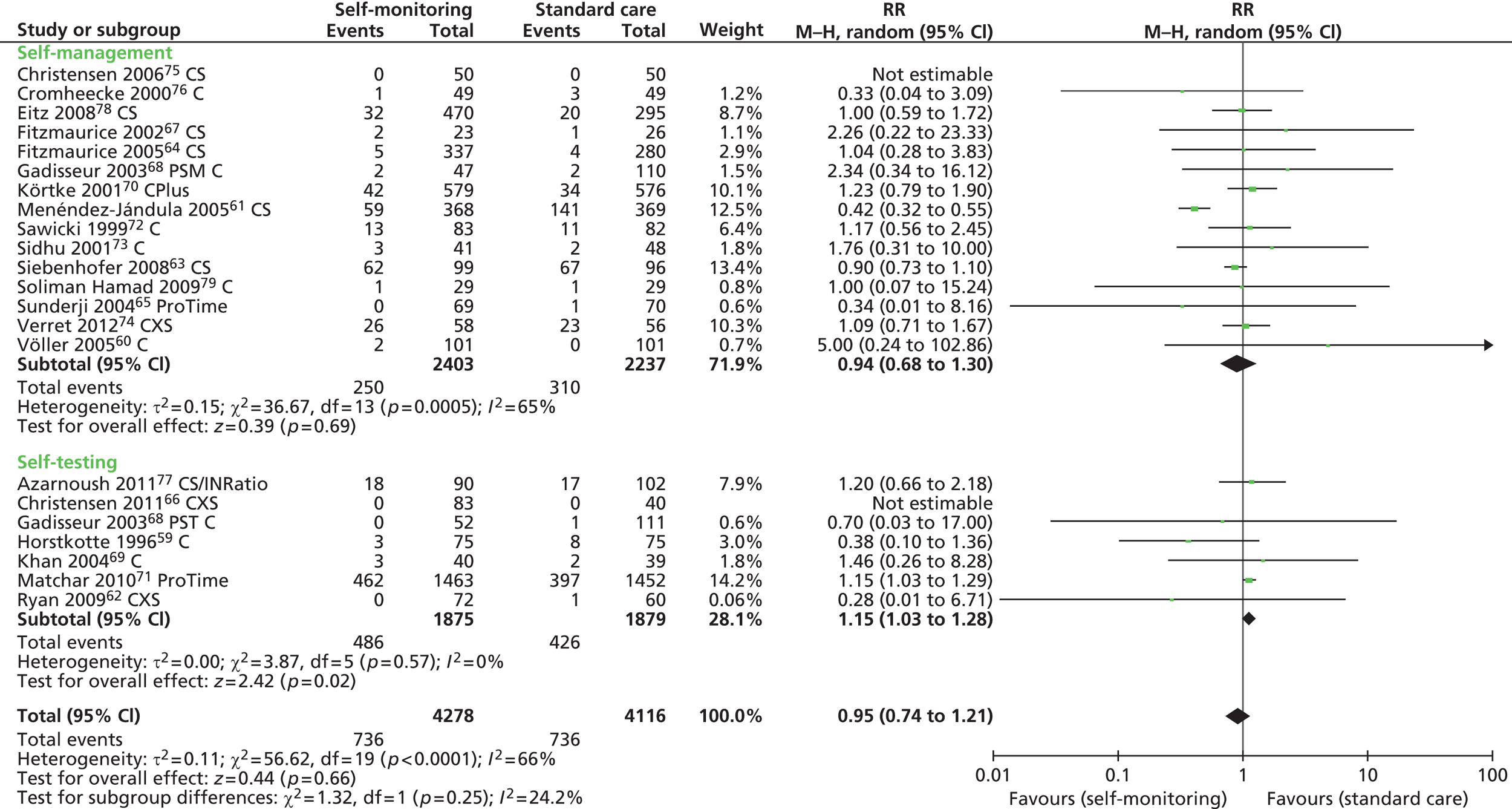

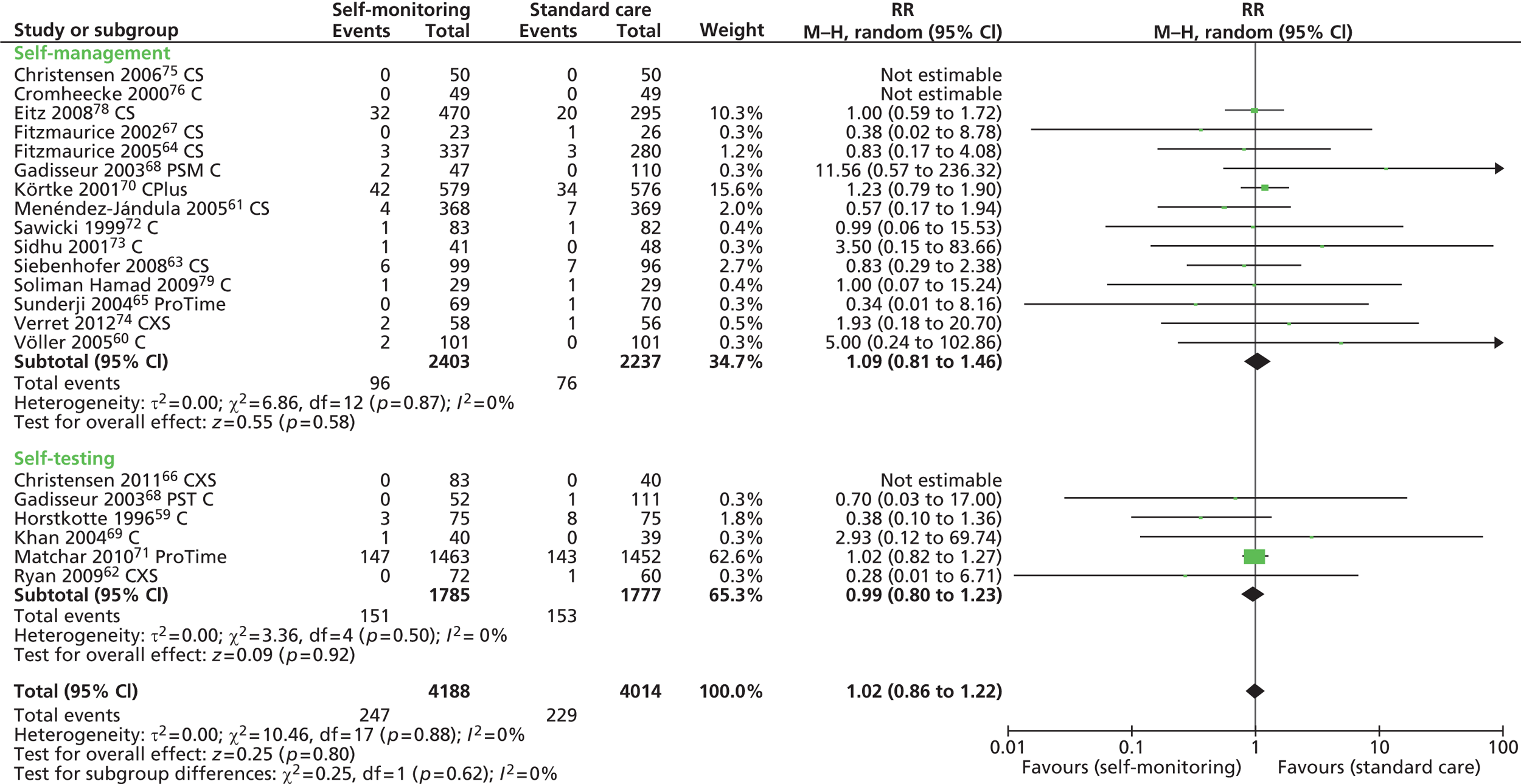

Clinical outcomes

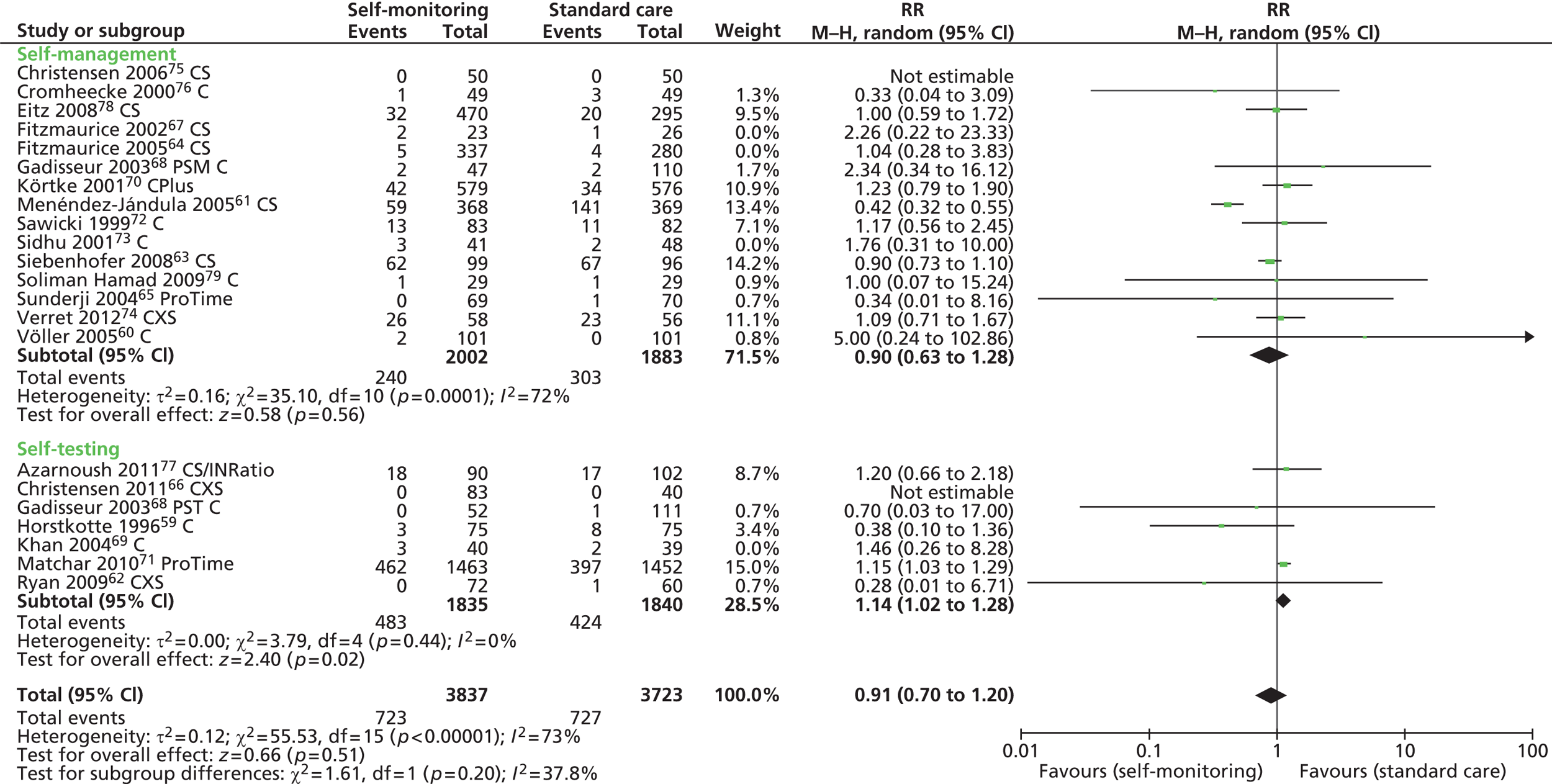

Bleeding

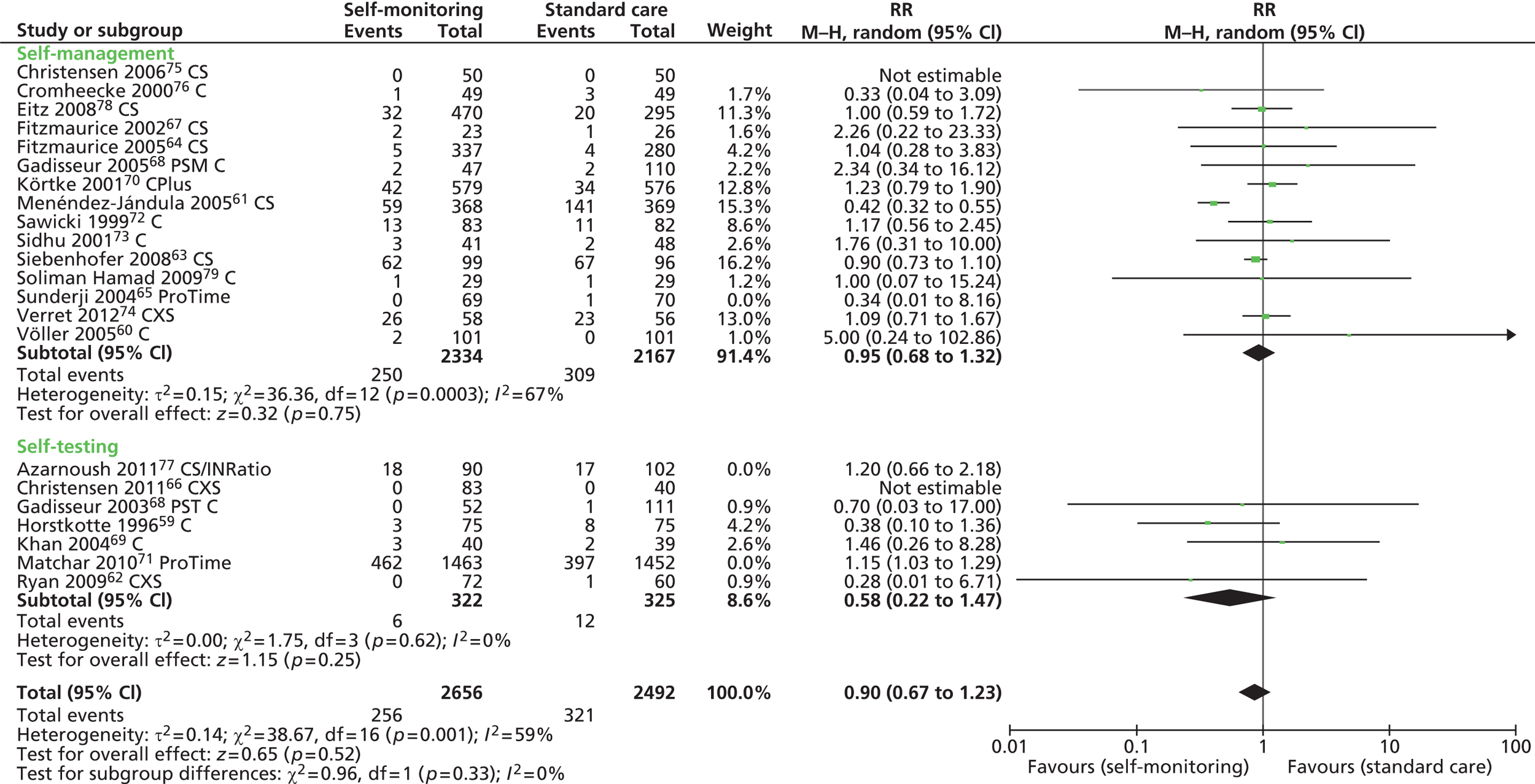

Twenty-one trials reported a total of 1472 major and minor bleeding events involving 8394 participants. 59–79 Two trials reported that there were no bleeding events and hence did not contribute to the overall effect size in the related meta-analysis. 66,75 Twenty-one trials reported 476 major bleeding events in a total of 8202 participants,59–65,67–74,77–79 while 13 trials reported 994 estimable minor bleeding events in a total of 5425 participants. 61,63,64,67,69,71–74,76,77 No statistically significant differences were observed between self-monitoring participants (self-testing and self-management) and those in standard care for any bleeding events (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.21; p = 0.66) (Figure 3), major bleeding events (RR 1.02, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.22; p = 0.80) (Figure 4) and minor bleeding events (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.34; p = 0.73) (Figure 5). The results were not affected by the removal of the UK-based trials (see Appendix 8) or by the removal of the trials assessing ProTime and/or INRatio (see Table 6 and Appendix 8). Similarly, sensitivity analyses restricted to CoaguChek XS trials demonstrated no differences from the all-trials results (see Table 6 and Appendix 8). A sensitivity analysis restricted to trials at low risk of bias slightly changed the estimate of effect but did not significantly impact on the findings (RR 0.59, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.30; p = 0.19) (see Appendix 8).

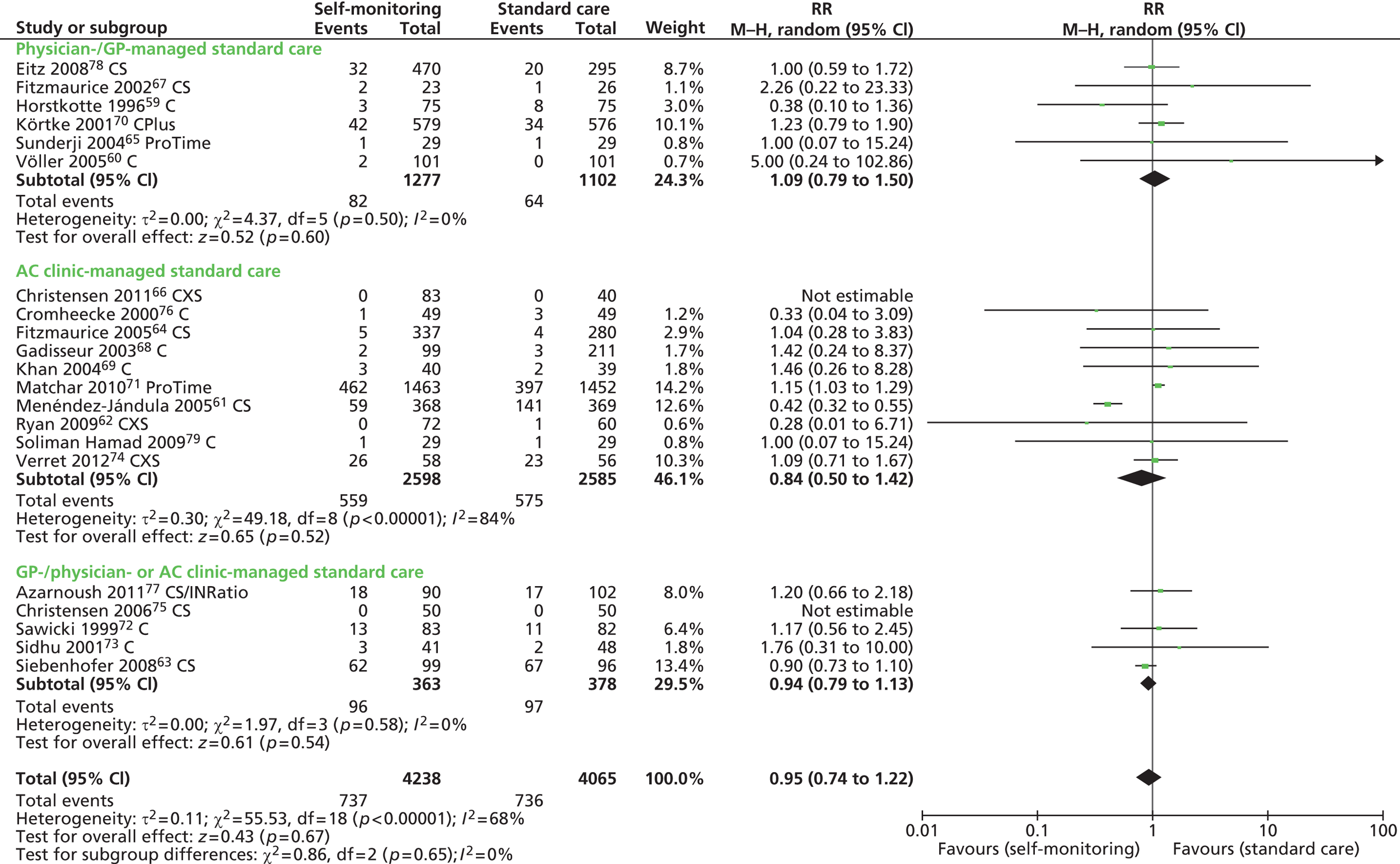

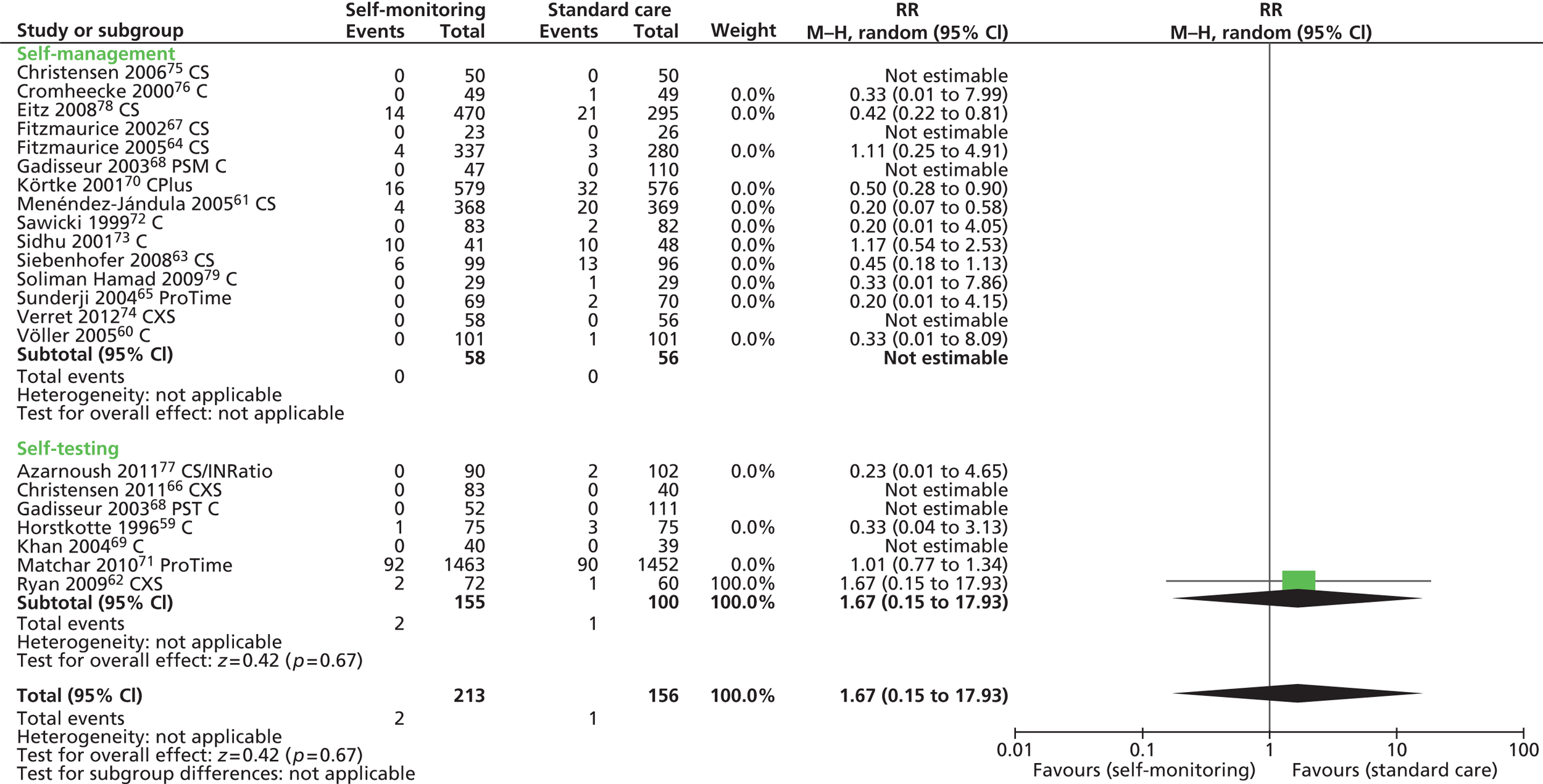

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of comparison: any bleeding events. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus; PSM, patient self-management; PST, patient self-testing.

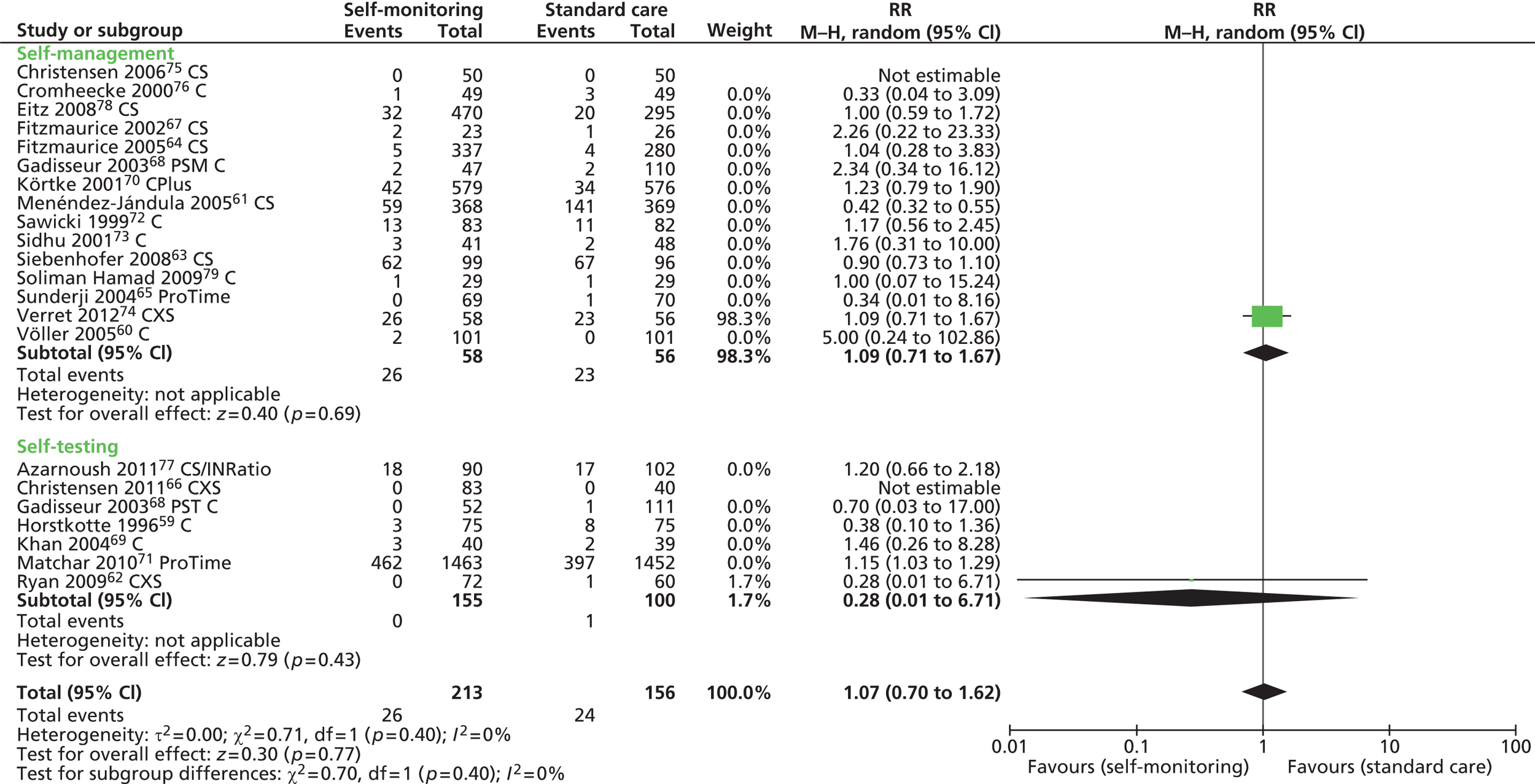

FIGURE 4.

Forest plot of comparison: major bleeding events. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus; PSM, patient self-management; PST, patient self-testing.

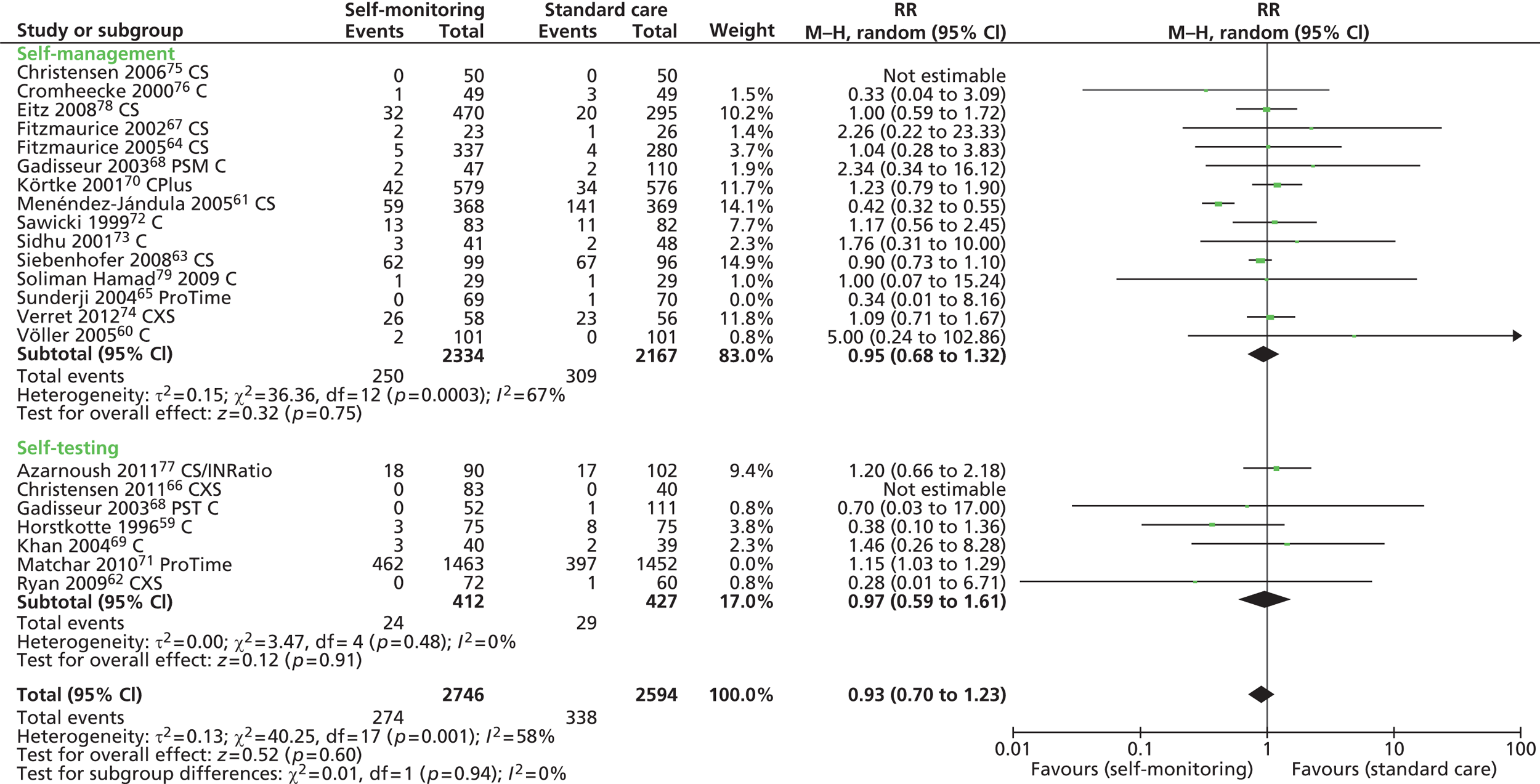

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot of comparison: minor bleeding events. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

The subgroup analysis by type of anticoagulant management therapy did not show any difference between self-management and standard care for any bleeding events (RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.68 to 1.30; p = 0.69) but revealed a significant higher risk in self-testing participants than in those receiving standard care (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.28; p = 0.02) (see Figure 3). When trials assessing ProTime and INRatio were removed from the analysis, a non-significant trend was observed in favour of self-testing (0.58, 95% CI 0.22 to 1.47; p = 0.25) (see Table 6 and Appendix 8). No significant differences in the risk of major bleeding were observed between self-management (RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.46; p = 0.58) and self-testing (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.23) versus standard care (see Figure 4). When only minor bleeding events were assessed (see Figure 5), a significant increased risk was observed in self-testing participants (23%), compared with those in standard care (RR 1.23, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.42; p = 0.005), but not in those who were self-managed (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.53 to 1.35; p = 0.47). Two trials enrolled participants with atrial fibrillation, six trials enrolled participants with AHVs and 13 trials enrolled participants with mixed indication. No statistically significant subgroup differences were found for bleeding events according to the type of clinical indication (Figure 6). Similarly, for bleeding events, no significant differences were detected when trials were grouped according to the type of control care (anticoagulant clinic care RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.50 to 1.42; p = 0.52; GP/physician RR 1.09, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.50; p = 0.60; mixed care RR 0.94, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.13; p = 0.54) (Figure 7).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot of comparison: any bleeding events – clinical indication. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot of comparison: any bleeding events – type of standard care. AC, anticoagulant; C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguCchek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

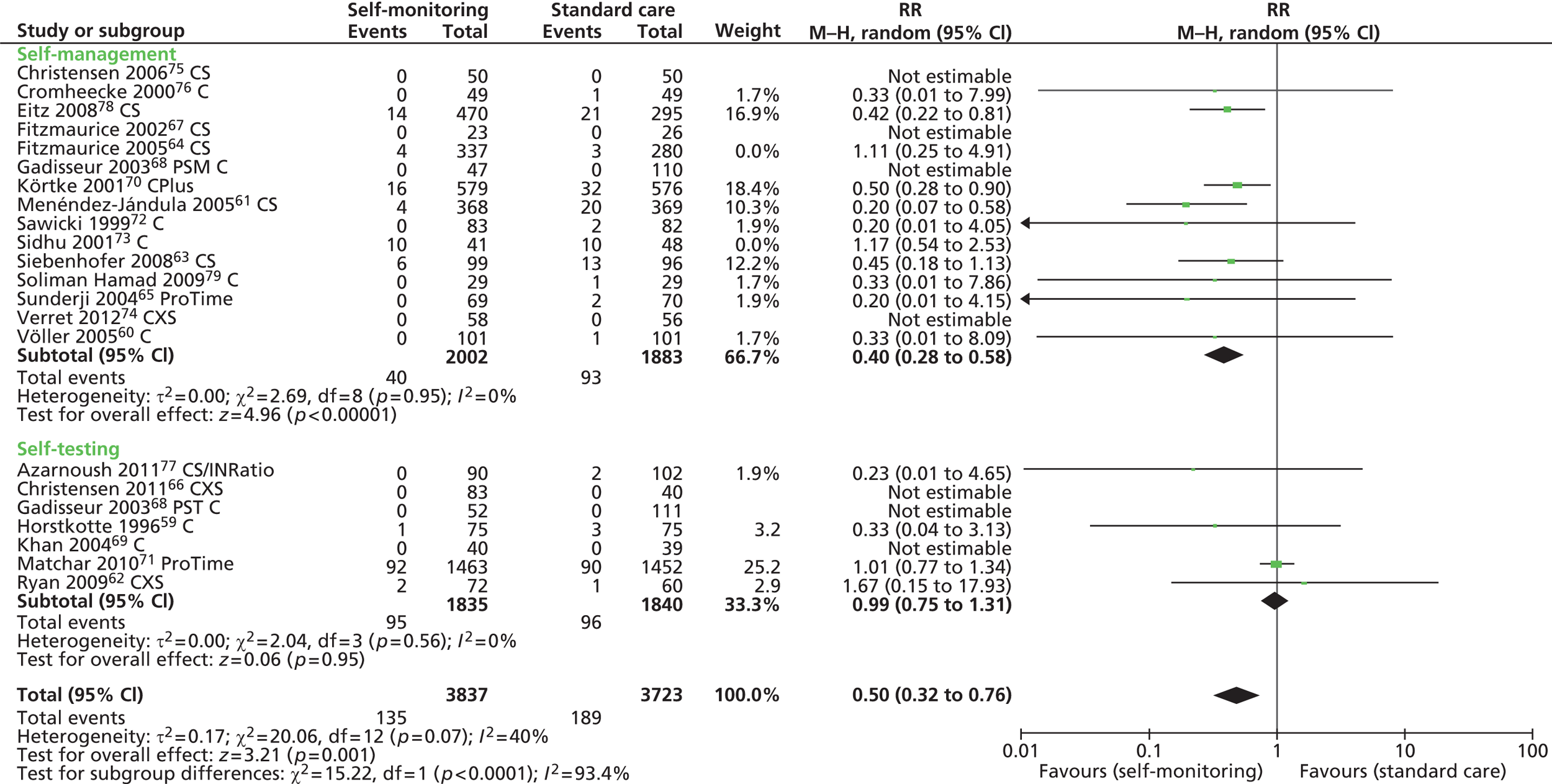

Thromboembolic events

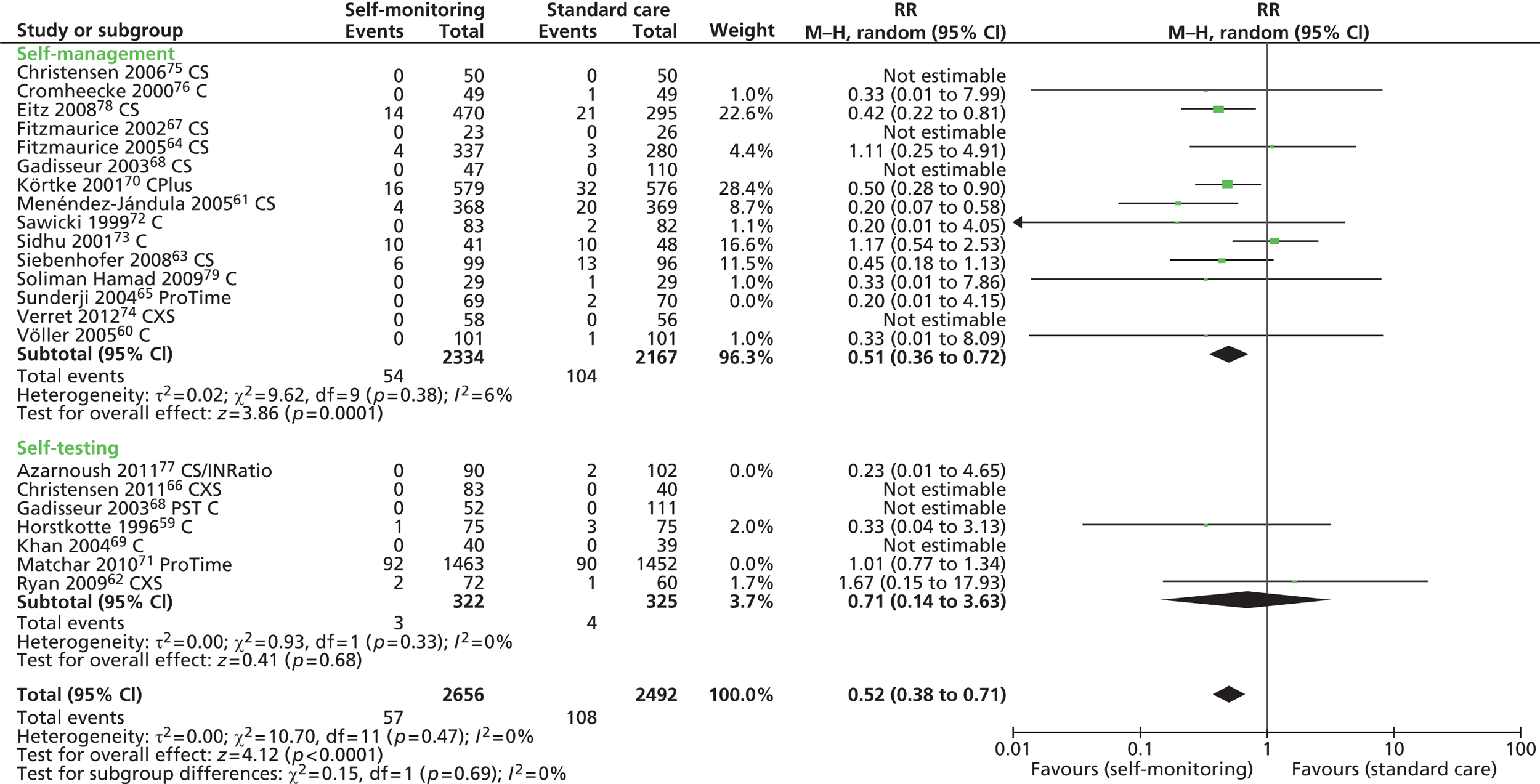

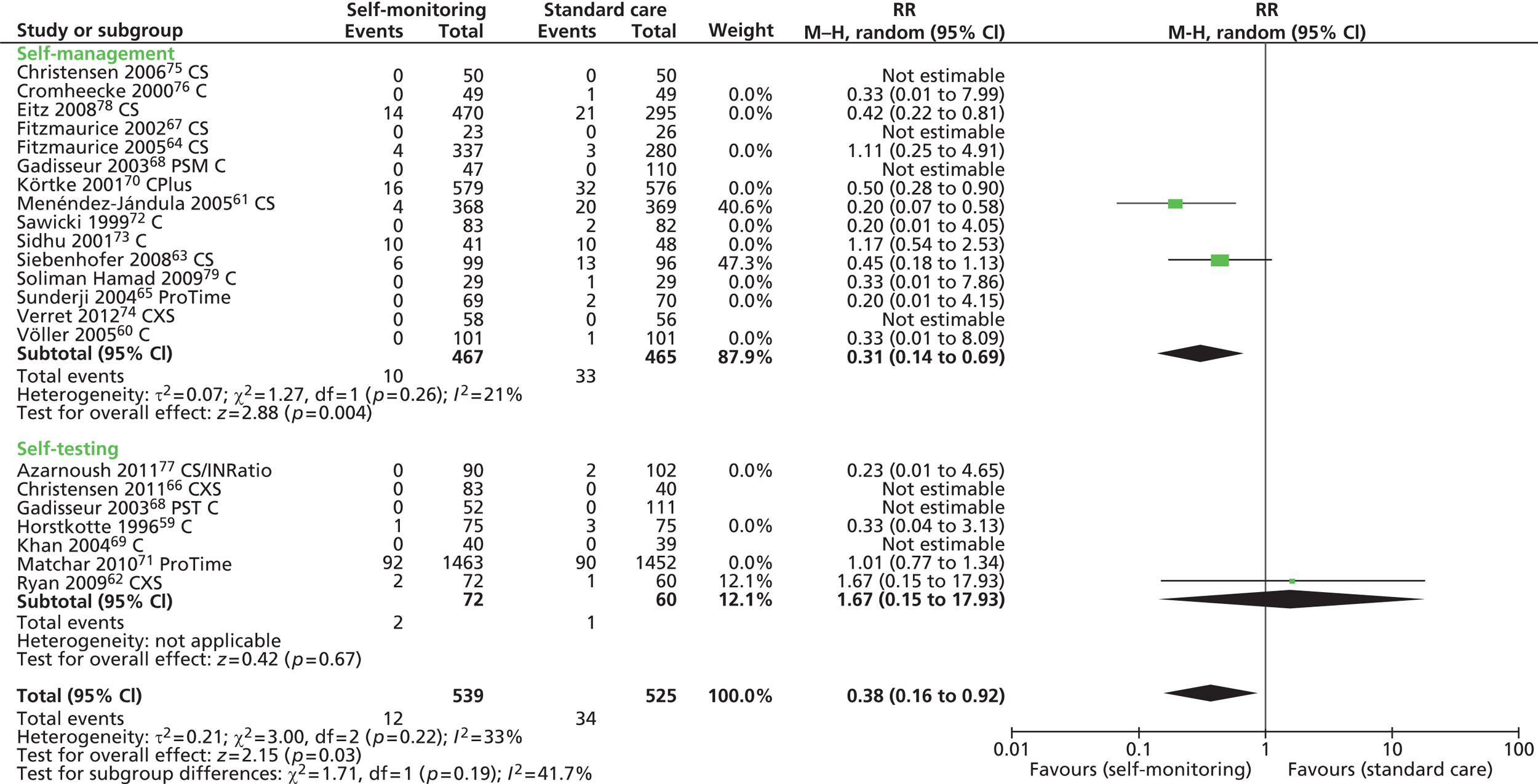

Twenty-one trials reported 351 major and minor thromboembolic events in a total of 8394 participants. 59–79 Six of these trials did not contribute to the overall estimate of effect as they reported ‘zero’ events in both groups. 66–69,74,75 Self-monitoring (self-testing and self-management) showed a statistically significant reduction in the risk of thromboembolic events by 42% (RR 0.58, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.84; p = 0.004), compared with standard care (Figure 8). The risk reduction further increased to 48% when only major thromboembolic events were considered (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.34 to 0.80; p = 0.003) (Figure 9). The risk of thromboembolic events significantly decreased when the analyses were restricted to non-UK trials (RR 0.50, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.76; p = 0.001); to CoaguChek trials (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.71; p < 0.0001); and to trials at low risk of bias (RR 0.38, 95% CI 0.16 to 0.92; p = 0.03) (see Appendix 8).

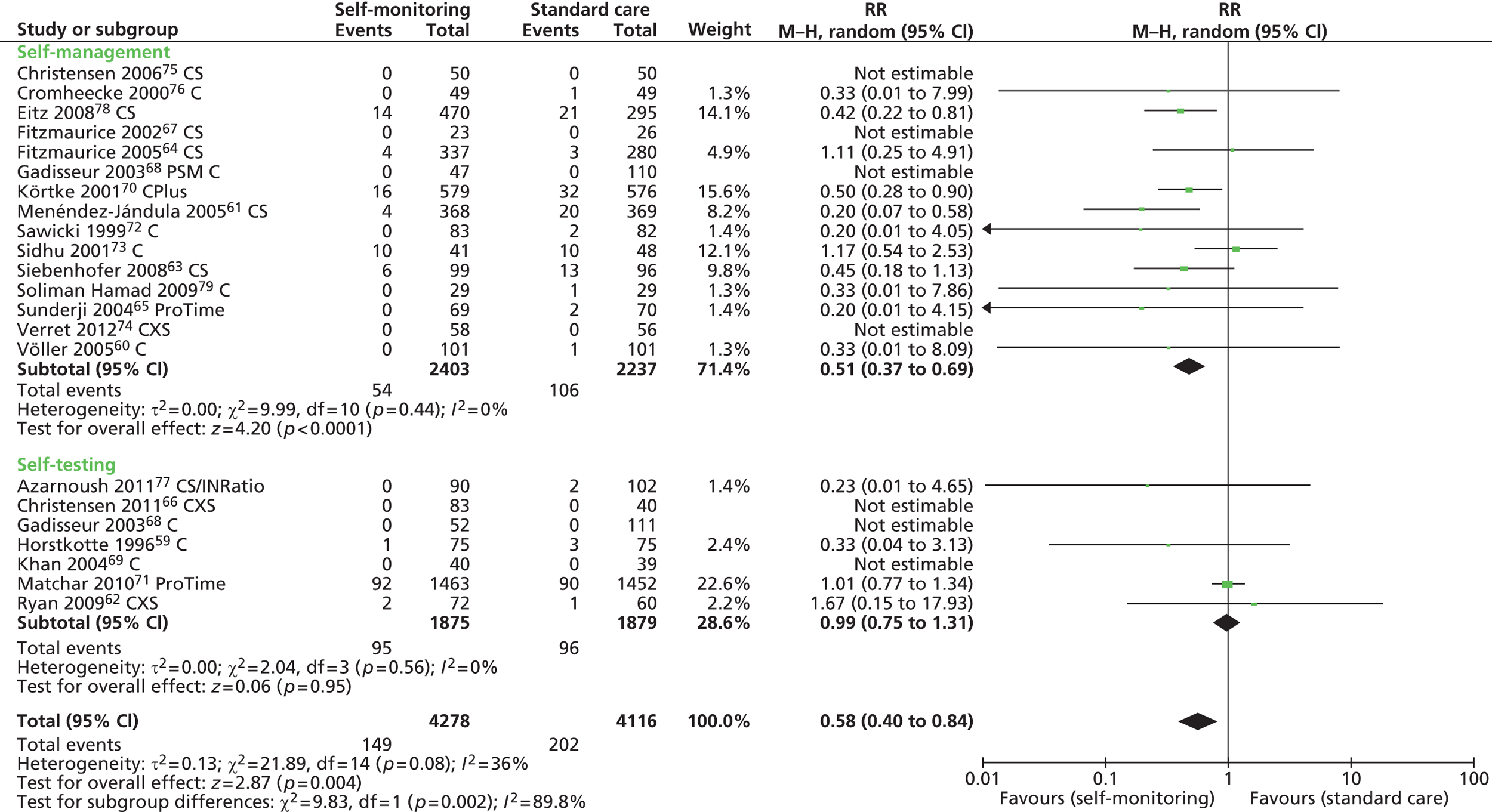

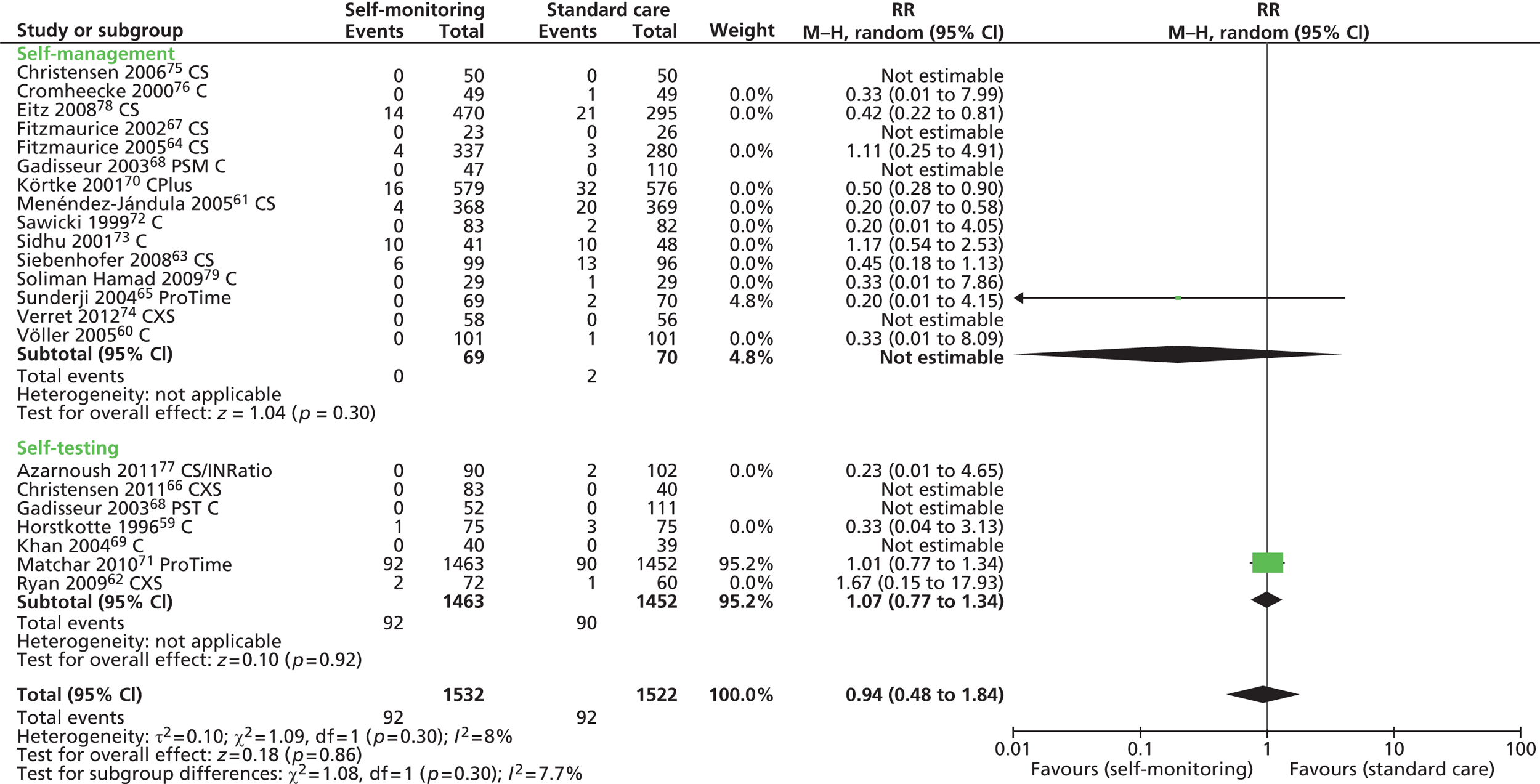

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot of comparison: thromboembolic events. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus; PSM, patient self-management; PST, patient self-testing.

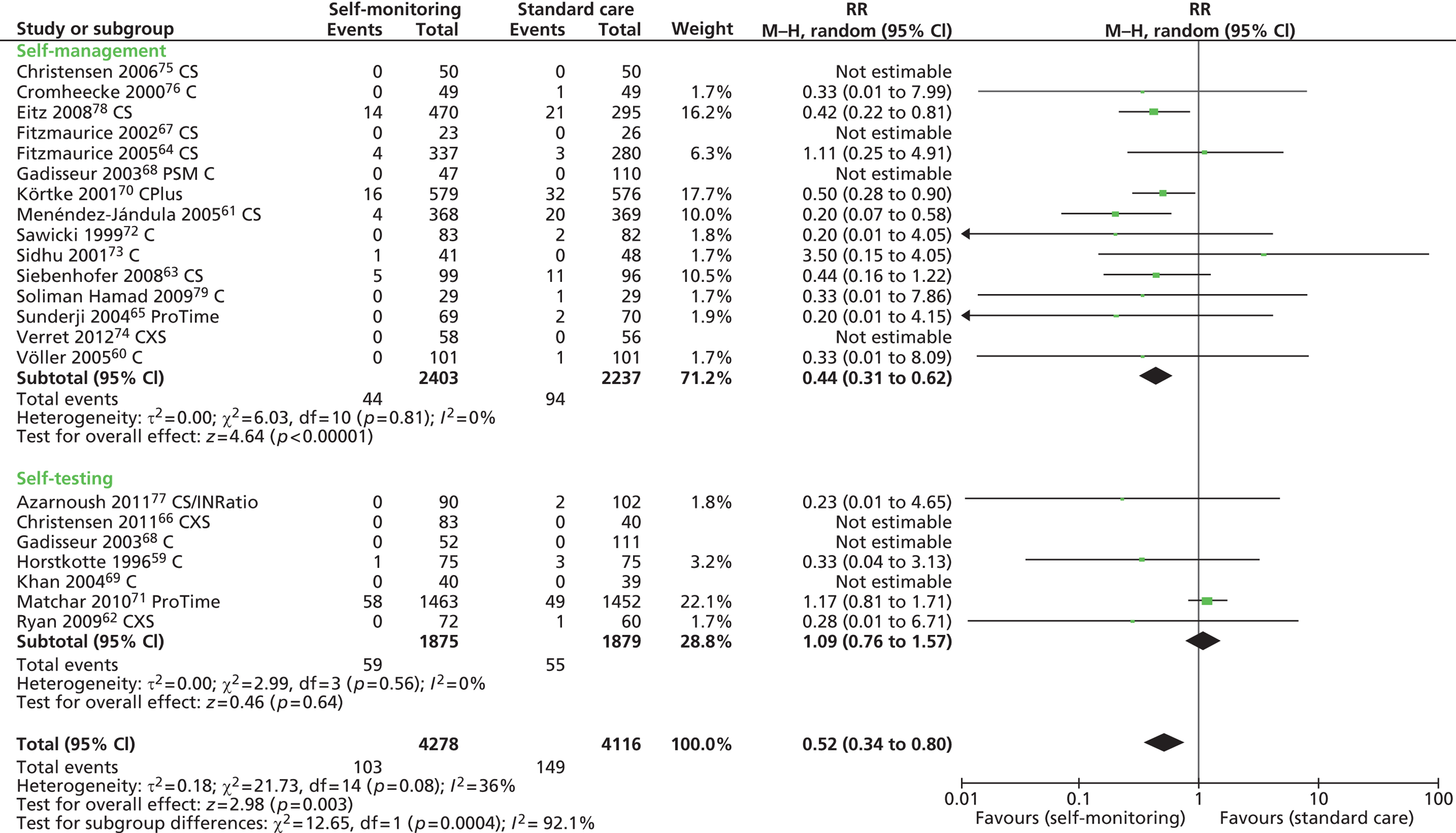

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot of comparison: major thromboembolic events. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus; PSM, patient self-management.

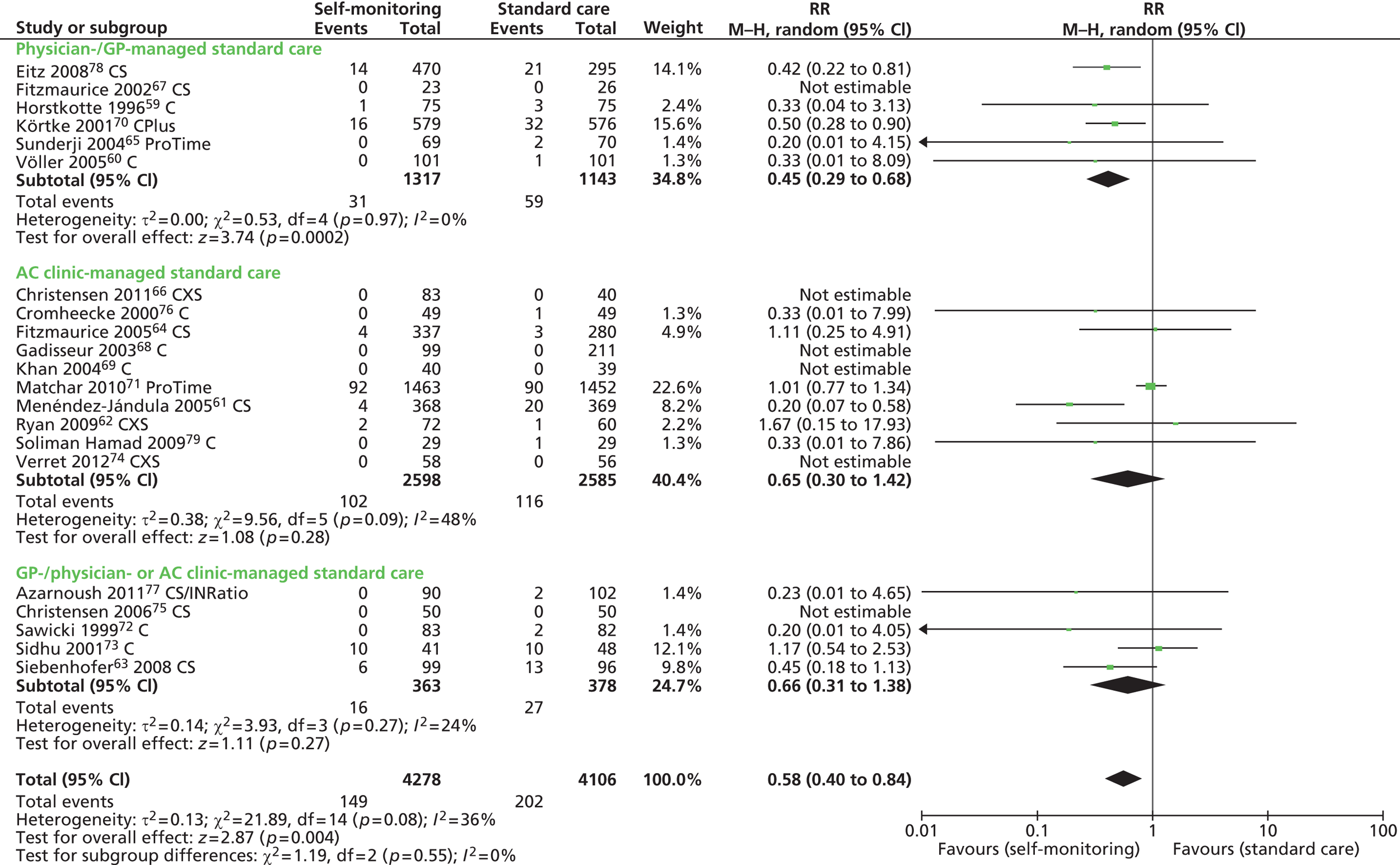

Self-management compared with standard care halved the risk of thromboembolic events (RR 0.51, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.69; p < 0.0001). In contrast, for self-testing participants59,62,71,77 no significant risk reduction was observed compared with those in standard care (RR 0.99, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.31; p = 0.95) (see Figure 8). The subgroup difference between self-management and self-testing was statistically significant (p = 0.002). When trials assessing the ProTime system were removed from the analysis, the risk reduction increased from 1% to 45% but the summary estimate of effect was not statistically different from the all-trials summary estimate (RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.13 to 2.31; p = 0.41) (see Table 6 and Appendix 8). Self-monitoring participants with AHVs showed a significant reduction in the number of thromboembolic events, compared with those in standard care (RR 0.56, 95% CI 0.38 to 0.82; p = 0.003). Among participants with mixed clinical indication (atrial fibrillation, AHVs or other conditions), the effect was larger but not statistically significant than that observed in participants receiving standard care (RR 0.57, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.09; p = 0.09) (Figure 10). The risk of thromboembolic events reduced in self-monitoring participants by 55% when routine anticoagulation control was managed by a GP or physician (RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.29 to 0.68; p = 0.0002). In contrast, even though fewer thromboembolic events were observed in participants who self-monitored their therapy than in those managed in specialised anticoagulation clinics (RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.30 to 1.42; p = 0.28) or those in mixed provision managed by either a physician/GP or a specialist (RR 0.66, 95% CI 0.31 to 1.38; p = 0.27), no significant subgroup differences were detected (Figure 11).

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot of comparison: any thromboembolic events – clinical indication. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

FIGURE 11.

Forest plot of comparison: any thromboembolic events – type of standard care. AC, anticoagulation; C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

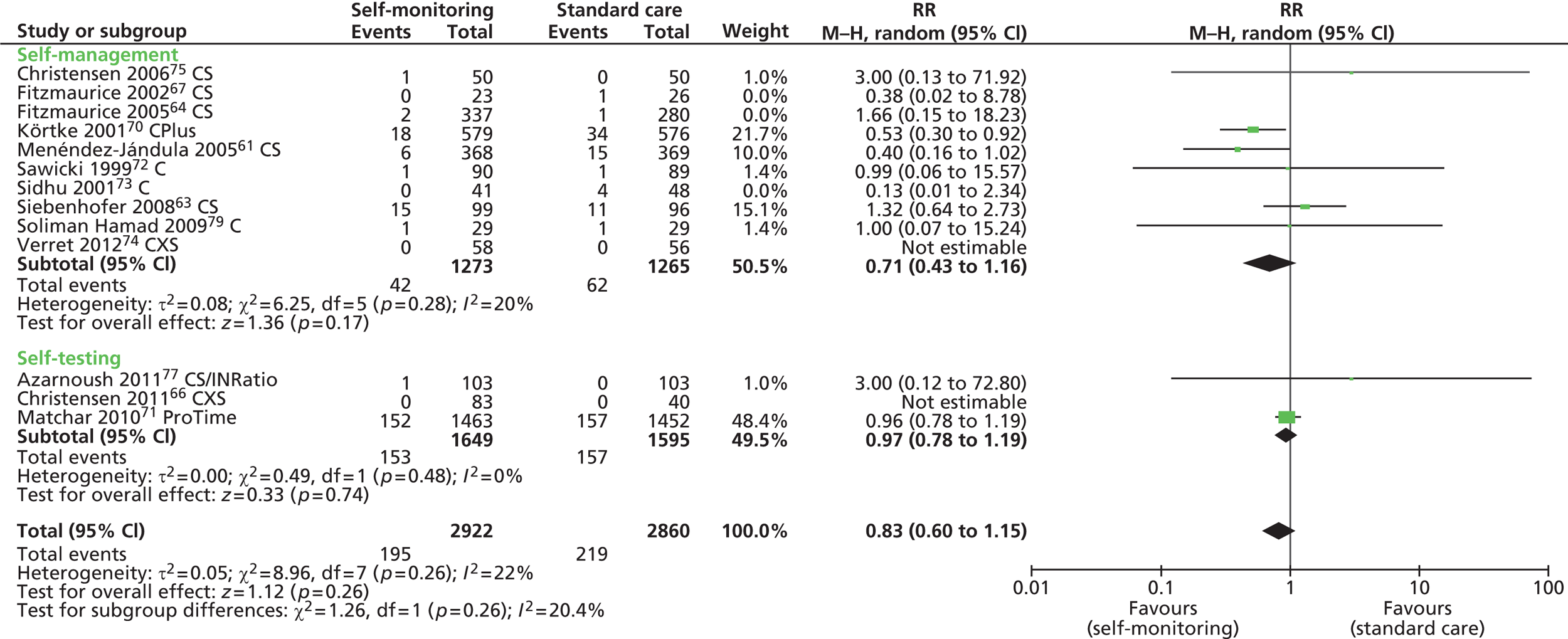

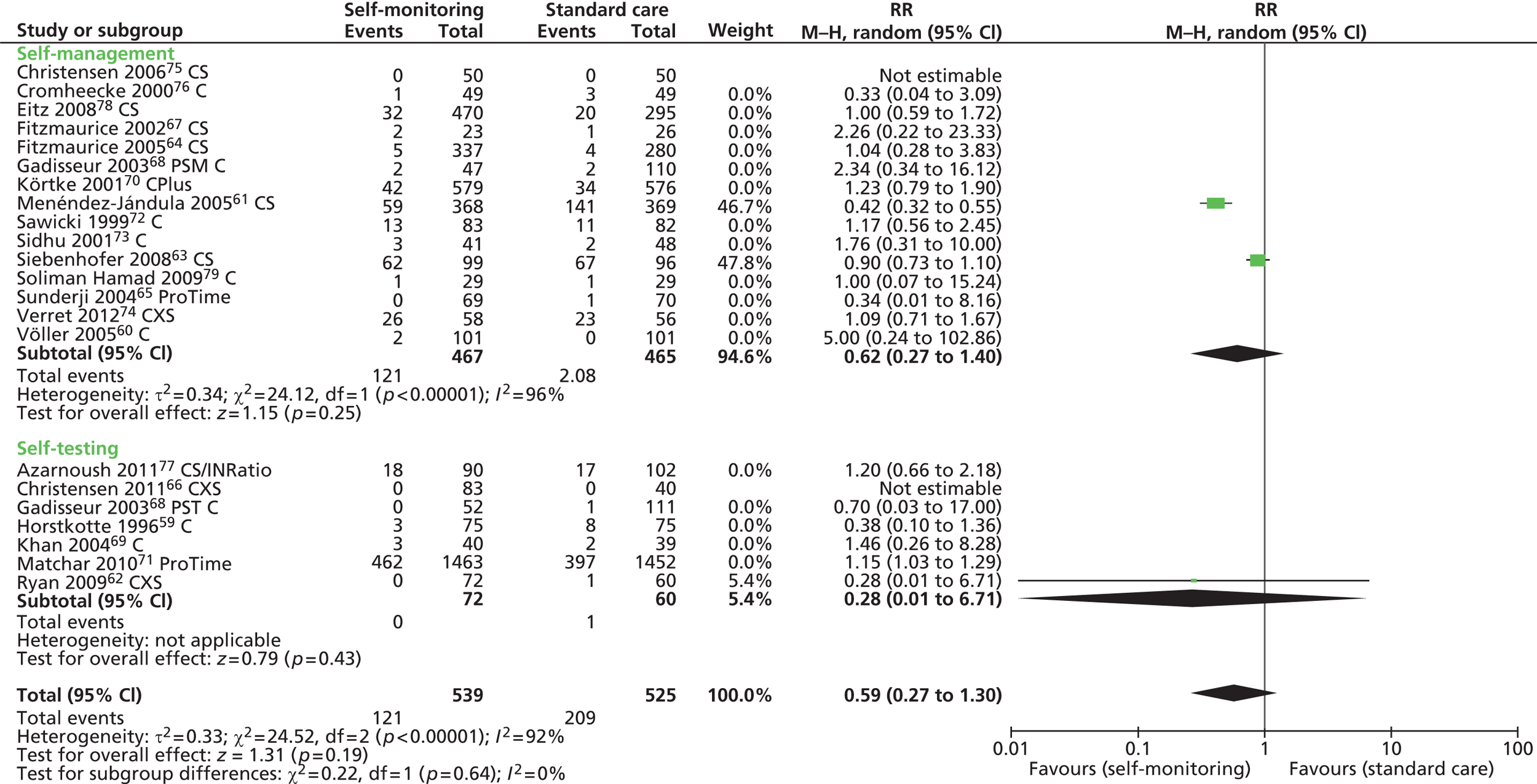

Mortality

Thirteen trials reported 422 deaths due to all-cause mortality in a total of 6537 participants. 61,63,64,66,67,70–75,77,79 Two trials with zero fatal cases did not contribute to the overall estimate of effect. 66,74 One trial of 1200 participants70 reported overall mortality data without separating the results for participants self-managed and for those receiving standard care. We contacted the corresponding author of this trial for further information but we did not receive any reply. Therefore, for mortality data, for this particular trial, we relied on the estimates published in the previous meta-analysis by Garcia-Alamino and colleagues31 and in the HTA by Connock and colleagues,21 which were based on individual patients’ data.

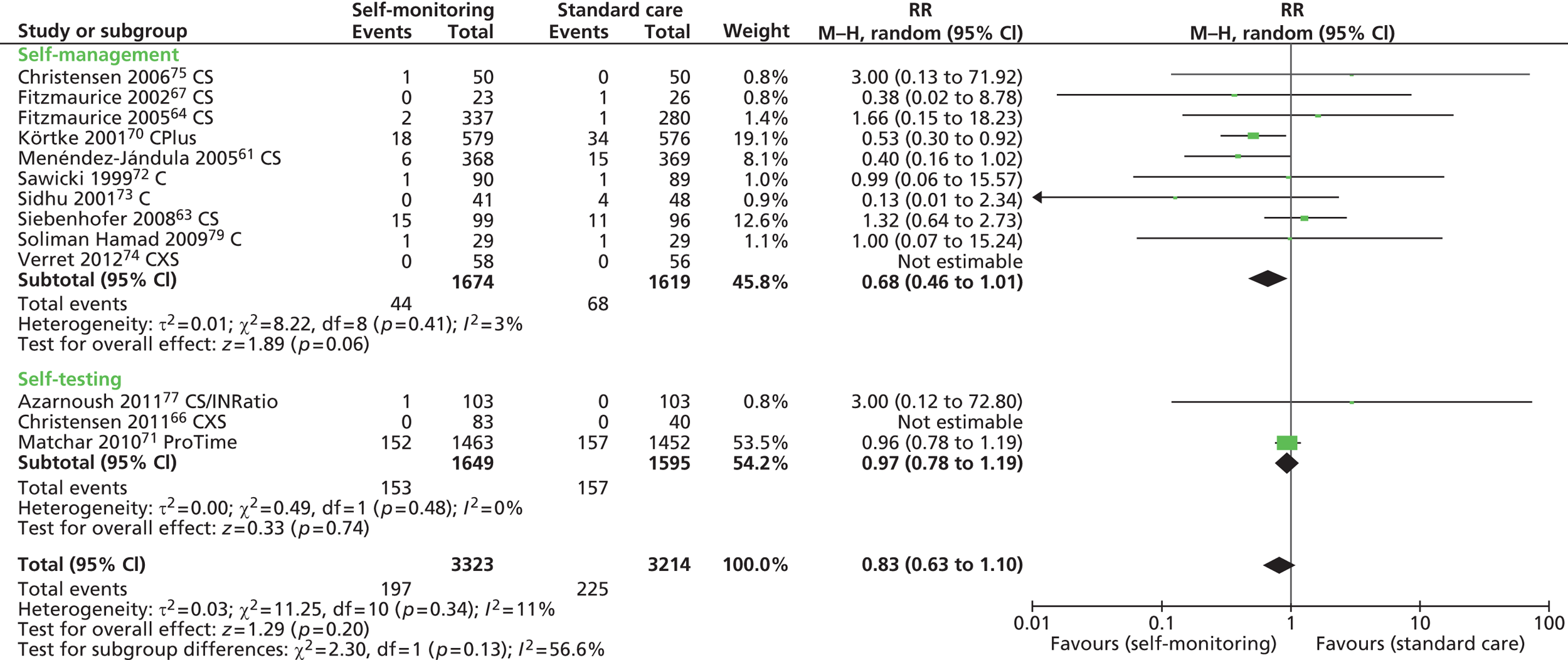

The risk reduction for all-cause mortality was not statistically significant different between self-monitoring (self-testing and self-management) and standard care (RR 0.83, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.10; p = 0.20) (Figure 12). The results were not affected by the removal of the UK-based trials or by the removal of trials at high or unclear risk of bias. When the analysis was restricted to trials that used the CoaguChek system, the summary estimate for self-monitoring was not different from the all-trials estimate (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.01, p = 0.06) (see Table 6 and Appendix 8). Two trials reported six deaths out of a total of 932 participants, related to vitamin K antagonist therapy. 61,63

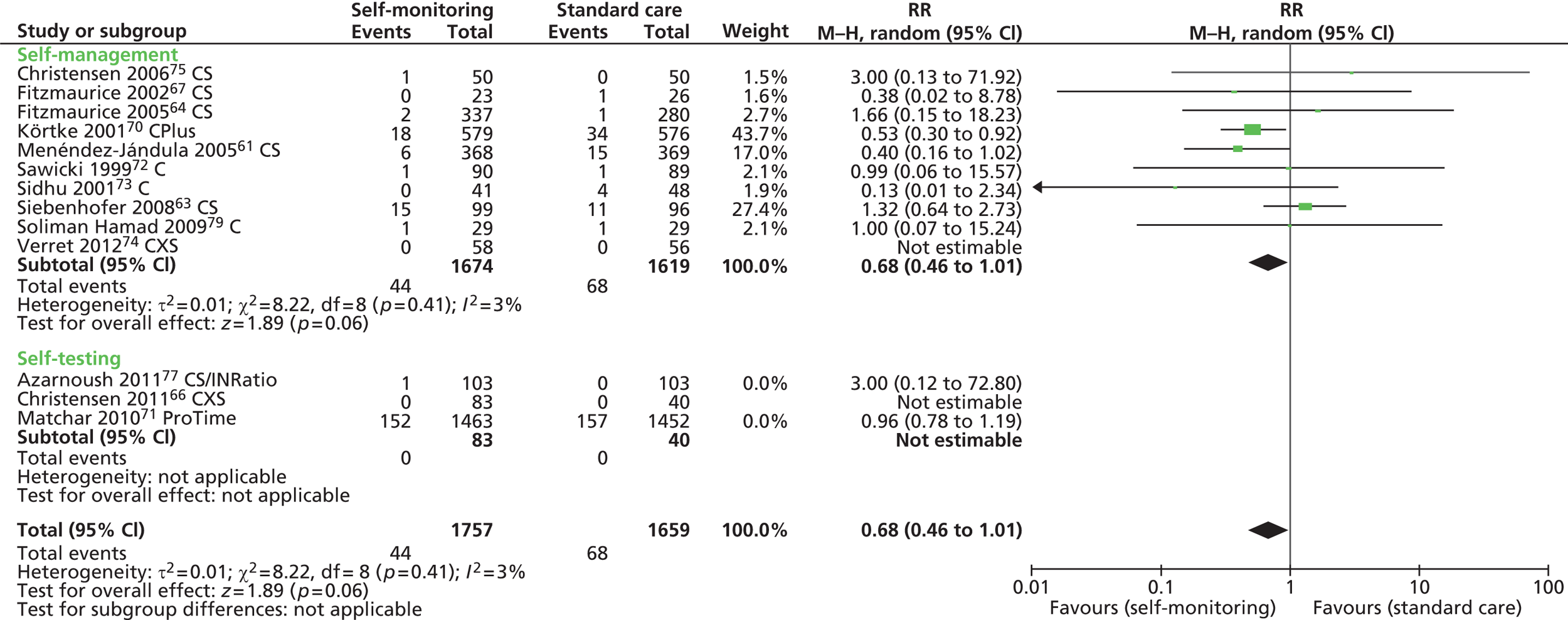

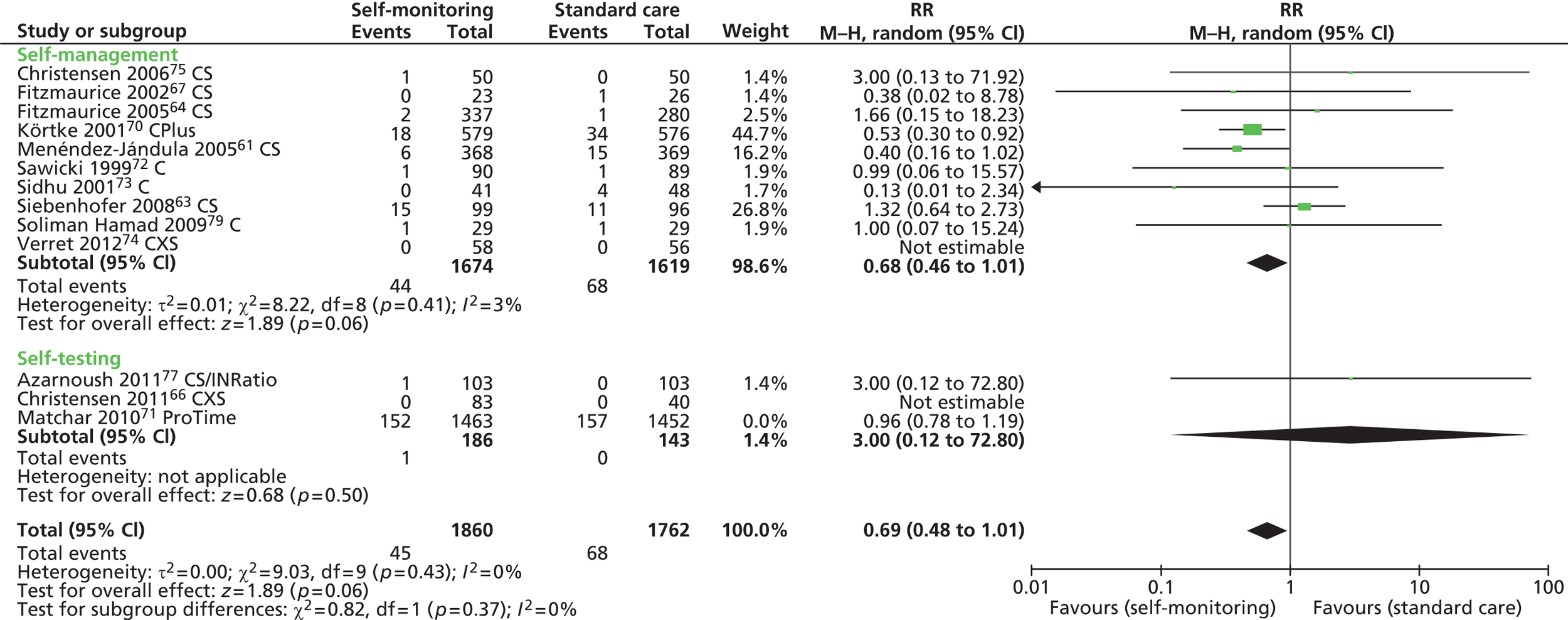

FIGURE 12.

Forest plot of comparison: mortality. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

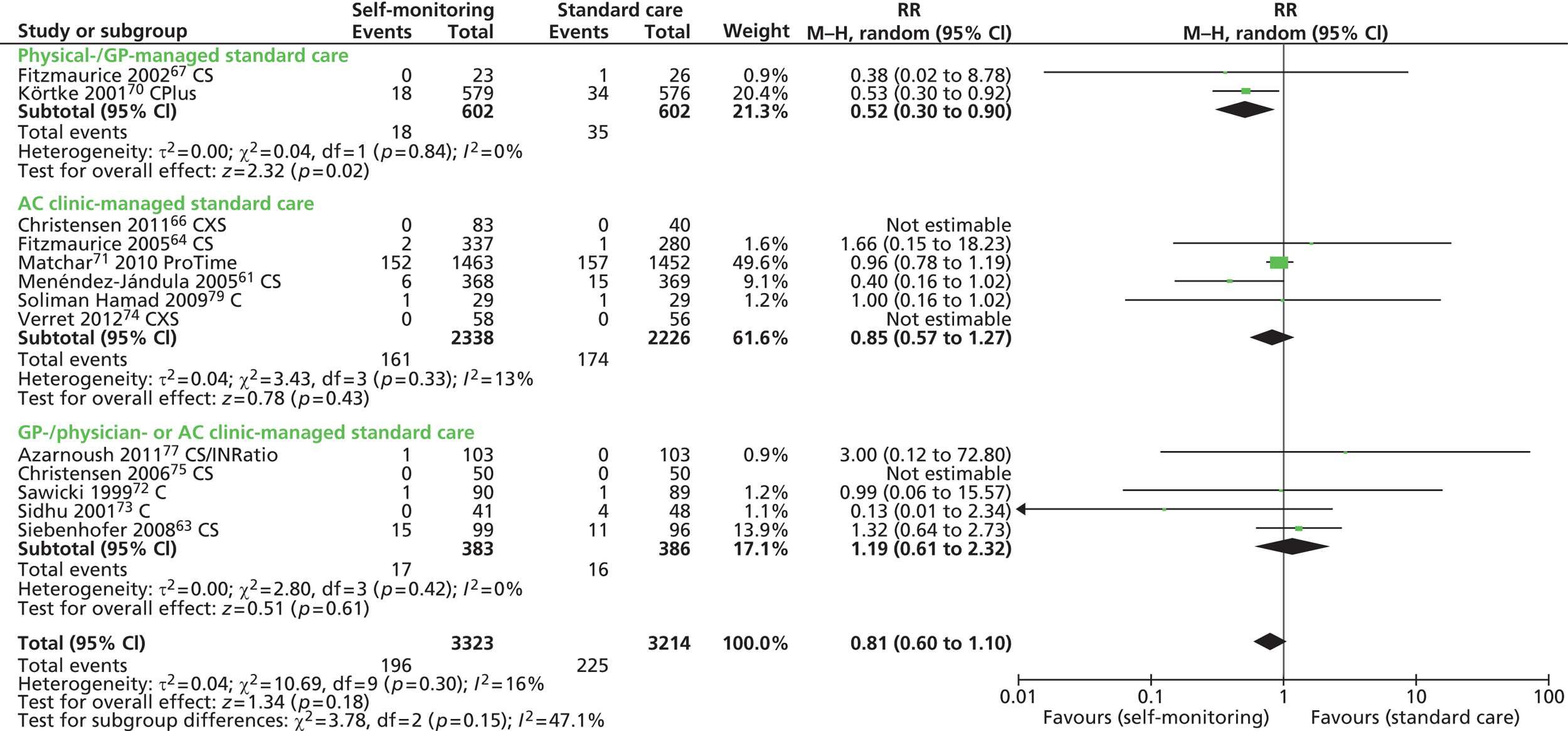

Risk of death reduced by 32% through self-management (RR 0.68, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.01; p = 0.06) but not through self-testing (RR 0.97, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.19; p = 0.74), even though the test for subgroup differences was not statistically significant (p = 0.13) (see Figure 12). Self-monitoring halved the risk of mortality in participants with AHVs (RR 0.54, 95% CI 0.32 to 0.92; p = 0.02) but not in those with mixed clinical indication for AOT (RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.78 to 1.16; p = 0.61) (Figure 13). The subgroup difference between participants with AHVs and those with mixed indication with regard to the number of deaths was statistically significant (p = 0.05). No data were available from trials that enrolled participants with atrial fibrillation. Significantly fewer deaths were recorded among participants who self-monitored their therapy than among those who were routinely managed by their GP/physician (RR 0.52, 95% CI 0.30 to 0.90; p = 0.02) (Figure 14).

FIGURE 13.

Forest plot of comparison: mortality – clinical indication. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

FIGURE 14.

Forest plot of comparison: mortality – type of standard care. AC, anticoagulation; C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’; CPlus, CoaguChek Plus.

Heterogeneity among trials

A significant statistical heterogeneity was observed for any bleeding outcomes (I2 = 66%, p < 0.0001). In contrast, there was no statistically significant heterogeneity across trials for thromboembolic outcomes (I2 = 36%, p = 0.08) or for mortality (I2 = 11%, p = 0.34). The summary estimates of effect were influenced considerably by five large trials: Eitz and colleagues,78 Körtke and colleagues,70 Fitzmaurice and colleagues64 and Menéndez-Jándula and colleagues61 for self-management, and Matchar and colleagues71 for self-testing. The trial by Matchar and colleagues,71 which was the largest trial on self-testing, did not show any significant difference between self-testing and standard care with regard to the incidence of major events. Standard care was provided by means of high-quality clinic testing in this trial (a designated, trained staff responsible for participants’ visits and follow-up; the use of a standard local procedure at each site for anticoagulation management; and the performance of regular INR testing about once a month). The estimated effect of self-testing versus standard care in the subgroup analysis was dominated by this large trial, and, therefore, interpretation of this finding requires caution.

Adverse events

No other adverse events from INR testing, false test results, vitamin K antagonist therapy and sequelae were reported in the included trials.

Intermediate results

Anticoagulation control: target range

Anticoagulation control can be measured as the time that INR is in the therapeutic range or as INR values in therapeutic range. Data on INR TTR were available from 18 trials. 55,56,58,60–69,71,73–75,77 However, there was variation in the measures used for reporting TTR. Seven trials comparing self-monitoring with standard care reported TTR as mean percentage;61,64,65,69,71,74,77 three as median percentage,58,62,75 five as overall percentage63,66–68,73 and one as cumulative number of days. 60 The two remaining trials, which compared patient self-management with patient self-testing, reported the TTR as mean percentage time (one trial)55 and overall percentage time (the other trial). 56 It proved impossible to convert median values into mean values due to the lack of information on the maximum or minimum value required by the conversion formula. Therefore, we were unable to pool the TTR results from the 18 trials which provided this information. The results of these trials are shown in Table 7.

| Type of point-of-care test | Study ID and country | Measure | INR TTR | INR value in target range | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM/PST | Control | Difference | p-value | Measure | PSM/PST | Control | Difference | p-value | |||

| CoaguChek XS | Bauman 2010,55 Canada (children only) | Mean % (95% CI) | PSM: 83 | PST: 83.9 | 1 (–7.7 to 9.7) | NR | |||||

| Christensen 2011,66 Denmark | aOverall days % (95% CI) (SD) | PST-OW: 79.7 (79 to 80.3) (2.3) PST-TW: 80.2 (79.4 to 80.9) (2.3) |

72.7 (71.9 to 73.4) (2.6) | 7 (6 to 7.9) (73% to 80%) | < 0.001 | % of INR values (95% CI) | PST-OW: 78.3 (76.5 to 80.1) PST-TW: 80.8 (79.3 to 82.1) |

67.2 (64.1 to 70.2) | < 0.001 | ||

| Ryan 2009,62 Ireland | Median % (IQR) | 74 (64.6–81) | 58.6 (45.6–73.1) | < 0.001 | NR | ||||||

| Verret 2012,74 Canada | Mean % (SD) | 80 (13.5) | 75.5 (24.7) | 0.79 | NR | ||||||

| CoaguChek S or CoaguChek | Christensen 2006,75 Denmark | Median % (95% CI) | 78.7 (69.2 to 81.0) | 68.9 (59.3 to 78.2) | 0.14 | NR | |||||

| Cromheecke 2000,76 Netherlands | Values NR | NS | % of INR values | 55 | 49 | OR 1.2 (95% CI 1.0 to 1.6) | 0.06 | ||||

| Eitz 2008,78 Germany | NR | % of INR values | 79 | 65 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Fitzmaurice 2002,67 UK | % (95% CI) (SD)a | 74 (67 to 81) (16.2) | 77 (67 to 86) (23.5) | NS | % of INR values (95% CI) | 66 (61 to 71) | 72 (65 to 80) | NS | |||

| Fitzmaurice 2005,64 UK | Mean % (95% CI) (SD)a | 70 (68.1 to 72.4) (20.1) | 68 (65.2 to 70.6) (23.0) | 2.4 (–1.2 to 6.0) | 0.18 | Mean % of individual (95% CI) | 70 (64.8 to 74.8) | 72 (66.3 to 77.1) | NS | ||

| Gadisseur 2003,68 Netherlands | % (95% CI) (SD)a | PSM: 68.6 (63.7 to 73.6) (16.8) PST: 66.9 (62.7 to 71.0) (14.9) |

67.9 (62.9 to 73.0) (19.5) | PST: 3.4 (–2.7 to 8.9) PSM: 5.1 (–1.1 to 11.3), p < 0.5 |

0.33 | % (95% CI) | 66.3 (61–71.5)/63.9 (59.8–68) |

61.3 (55–62.4)/58.7 | PST: + 5.2 (–1.7 to 12.1) PSM: + 7.6 (0.1 to 14), p < 0.5 |

0.14 | |

| Gardiner 2006,56 UK | % (95% CI) (SD) | PSM: 69.9 (60.8 to 76.7) (23.1) | PST: 71.8 (64.9 to 80.1) (22.1) | PSM + PST: (n = 77): 71 (64.7 to 76.4) (22.5) | 0.46 | NR | |||||

| Khan 2004,69 UK | Mean % (SD) | 71.1 (14.5) | 70.4 (24.5) | NS | NR | ||||||

| Horstkotte 1996,59 Germany | NR | % of INR values | 43.2 | 22.3 | < 0.001 | ||||||

| Menéndez-Jándula 2005,61 Spain | Mean % (SD) | 64.3 (14.3) | 64.9 (19.9) | 0.2 | Mean % of individual (SD) | 58.6 (14.3) | 55.6 (19.6) | 95% CI 0.4 to 5.4 | 0.02 | ||

| Rasmussen 2012,58 Denmark | Median (25th–75th percentile) % | 52 (33–65) | 55 (49–66) | NR | |||||||

| Sawicki 1999,72 Germany | NR | % of individual | 53 | 43.2 | 0.22 | ||||||

| Sidhu 2001,73 UK | % | 76.5 | 63.8 | < 0.0001 | NR | ||||||

| Siebenhofer 2008,63 Austria | % (IQR) 6/12 months | 70.6 (60.9–83.9)/75.4 (9.4–85.0) | 57.5 (34.2–80.3)/66.5 (47.1–81.5) | < 0.001/0.029 | NR | ||||||

| Soliman Hamad 2009,79 Netherlands | NR | Mean % per patient (SD) | 72.9 (11) | 53.9 (14) | 0.01 | ||||||

| Völler 2005,60 Germany | Mean cumulative days (SD) | 178.8 (126) | 155.9 (118.4) | NS | Mean % of INR values (SD) | 67.8 (17.6) | 58.5 (19.8) | 0.0061 | |||

| CoaguChek Plus | Körtke 2001,70 Germany | NR | % of INR values | 79.2 | 64.9 | < 0.001 | |||||

| CoaguChek/INRatio | Azarnoush 2011,77 France | Mean % (SD) | 61.5 (19.3) | 55.5 (19.9) | 0.0343 | NR | |||||

| Hemkens 2008, Germany57 | NR | NR | |||||||||

| ProTime | Matchar 2010,71 USA | Mean % (SD) | 66.2 (14.2) | 62.4 (17.1) | 3.8 (95% CI 2.7 to 5.0) | < 0.001 | NR | ||||

| Sunderji 2004,65 Canada | Mean % (SD) | 71.8 (45.69) | 63.2 (48.53) | 0.14 | NR | ||||||

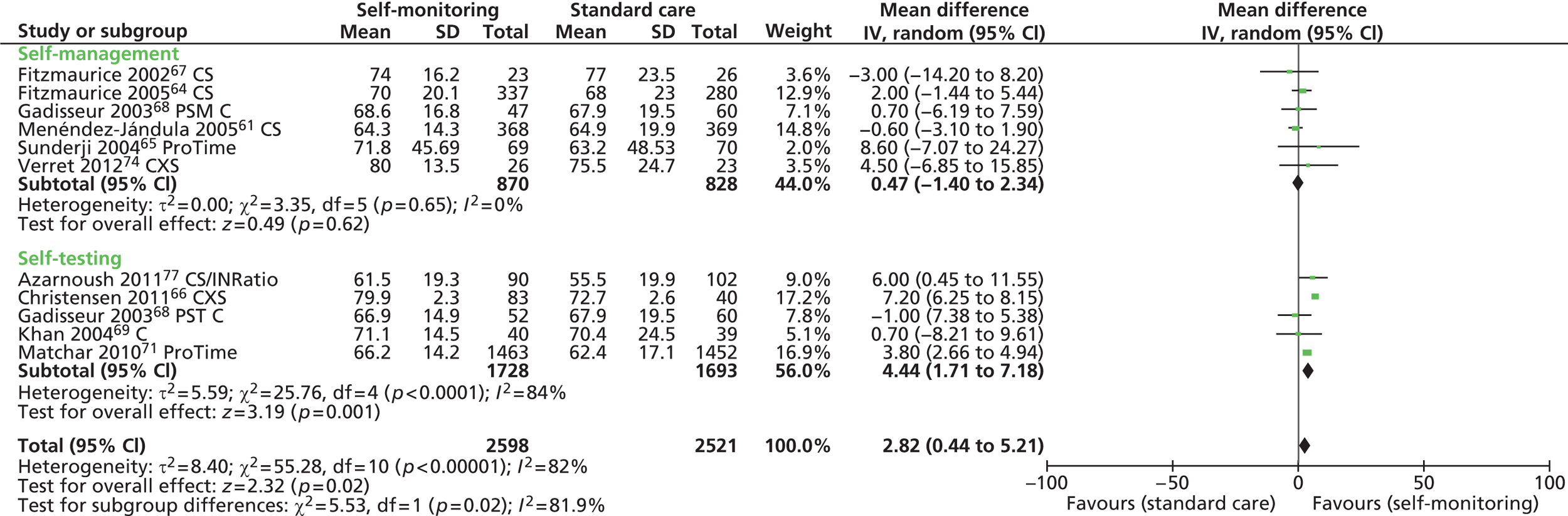

Time in therapeutic range ranged from 52%58 to 80%66,74 for self-monitoring and from 55%58 to 77%67 for standard care. In all but three trials,58,61,67 TTR was higher in self-monitoring participants than in those receiving standard care and, in five of these trials, the difference between intervention groups was statistically significant. 62,66,71,73,77 Three of the UK-based trials reported no significant differences between self-monitoring and standard care. 64,67,69 Pooling of results was possible for 10 trials that provided suitable data. 61,64–69,71,74,77 No statistically significant differences were found between self-management and standard care (RR 0.47, 95% CI –1.40 to 2.34; p = 0.62). A modest but significantly higher proportion of TTR was, however, found for participants assigned to self-testing than for those in control care (WMD 4.44, 95% CI 1.71 to 7.18; p = 0.001) (Figure 15). It is worth noting that the overall estimate of effect was dominated by the largest included trial on self-testing, THINRS. 71 In two trials, one using CoaguChek XS66 and the other using ProTime,71 the WMD between self-testing and standard care for TTR was significantly higher, indicating better anticoagulation control among self-testing participants.

FIGURE 15.

Forest plot of comparison: TTR. C, CoaguChek; CS, CoaguChek ‘S’; CXS, CoaguChek ‘XS’.

The INR values in therapeutic range were reported in 12 trials. 59–61,64,66–68,70,72,76,78,79 There was great variation between trials in the measures used to assess INR values in therapeutic range and, therefore, the pooling of data across trials proved unfeasible. In eight trials which reported the proportion of INR measurements in the therapeutic range,59,60,66–68,70,76,78 the values ranged from 43.2%59 to 80.8%66 for self-monitoring and from 22.3%59 to 72%67 for standard care. In four trials that reported the proportion of participants in the therapeutic range instead,61,64,72,79 the values ranged from 53%72 to 72.9%79 for self-monitoring and from 43.2%79 to 72%64 for standard care. With the exception of two UK-based trials,64,67 all trials reported higher proportion of INR measurements or larger proportions of participants in therapeutic range for self-monitoring than for standard care. Significant differences between interventions were detected in six of these trials. 60,61,66,70,78,79 The INR values in therapeutic range are summarised in Table 7.

Among participants with AHVs, self-monitoring resulted in a significantly higher INR TTR73,77 or INR values in therapeutic range59,70,78,79 than standard care. In two trials that included participants with atrial fibrillation,60,69 no TTR differences were found between self-monitoring and standard care.

Test failure rate

Only one trial45 reported one instrument defect and one test strip problem in the self-testing group. No other failures were mentioned in the remaining included trials.

Time to receive test result

One trial74 reported the time for each INR monitoring (i.e. time from INR measurement to test results) and the total time spent for anticoagulant management during the 4-month follow-up period. The time spent for each INR monitoring by self-managed participants was significantly lower (mean 5.3 minutes, SD 2.6 minutes) than the time spent by participants receiving standard care (mean 158 minutes, SD 67.8 minutes; p < 0.001). During the 4-month follow-up, the total time spent for anticoagulation monitoring by participants in standard care was significantly higher (mean 614.9 minutes, SD 308.8 minutes) than the total time spent by participants who self-managed their therapy (mean 99.6 minutes, SD 46.1 minutes; p < 0.0001).

Patient compliance with testing

Gardiner and colleagues45 reported > 98% compliance with self-testing and stated that participants were conscientious in performing and recording their weekly tests. Of those who did not comply with self-testing, two had difficulties performing the test or experienced disruption due to hospitalisation and one lost the CoaguChek meter. In the trial by Khan and colleagues,69 75% (30 out of 40) of participants did not report any problems with the use of the device and expressed willingness to continue with self-monitoring. On the other hand, participants who did not comply (25%) with the testing procedure reported difficulties with the technique or problems placing the fingertip blood drop on the right position on the test strip. This resulted in the need to use multiple strips to achieve a single reading.

Frequency of testing

Even though the frequency of self-testing was preplanned in 18 of the included trials,45,56,59,62–69,71–77 only 10 trials eventually reported it. 59,62–68,71,76 The frequency of self-testing ranged on average (mean) from every 4.6 days62 to every 12.4 days64 (Table 8).

| Study ID | Type of OAT management | Total number in SM | Number (%) attending training | Number (%) completing and starting SM | Number (%) adherence to SM or completing SM | Planned frequency of self-testing | Actual frequency of self-testing, mean (SD) days | Clinic visit per year | QA per year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Azarnoush 201177 | PST | 103 | NR | NR | 90 (87) | Once weekly | NR | NR | NR |

| Bauman 201055 | PSM vs. PST | PSM: 14 PST: 14 |

NR | NR | PSM: 12 (86) PST: 14 (100) |

NR | NR | NR | Once |

| Christensen 200675 | PSM | 50 | 50 (100) | 48 (96) | 47 (≈ 98) | Daily for first 3 weeks then once weekly | NR | NR | Once |

| Christensen 201166 | PST: once weekly/twice weekly | 51/40 | NR | NR | 46 (90)/37 (92) | Once weekly Twice weekly |

7.4 (2.7)/4.1 (1.8) | Twice | Twice |

| Cromheecke 200076 | PSM | 50 | NR | NR | 49 (98) | Once weekly then once every 2 weeks | 8.6 | NR | NR |

| Eitz 200878 | PSM | 470 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Twice | NR |

| Fitzmaurice 200267 | PSM | 30 | 27 (90) | 26 (96) | 23 (88) | Every 2 weeks | 1.6 weeks | Four visits | Four in 6 months |

| Fitzmaurice 200564 | PSM | 337 | 327 (97) | 242 (74) | 193 (80) | Every 2 weeks | 12.4 (95% CI 11.9 to 12.9) | Four visits | Four |

| Gadisseur 200368 | PSM | Total 720 | 184 (25) | 180 (98) | NR | Once weekly | NR | NR | NR |

| Gardiner 200545 | PST | 44 | 43 (98) | 39 (91) | 31 (79) | Once weekly | NR | NR | Once |

| Gardiner 200656 | PST vs. PSM | PST: 55 PSM: 49 |

NR | NR | PSM: 41 (74) PST: 36 (73) |

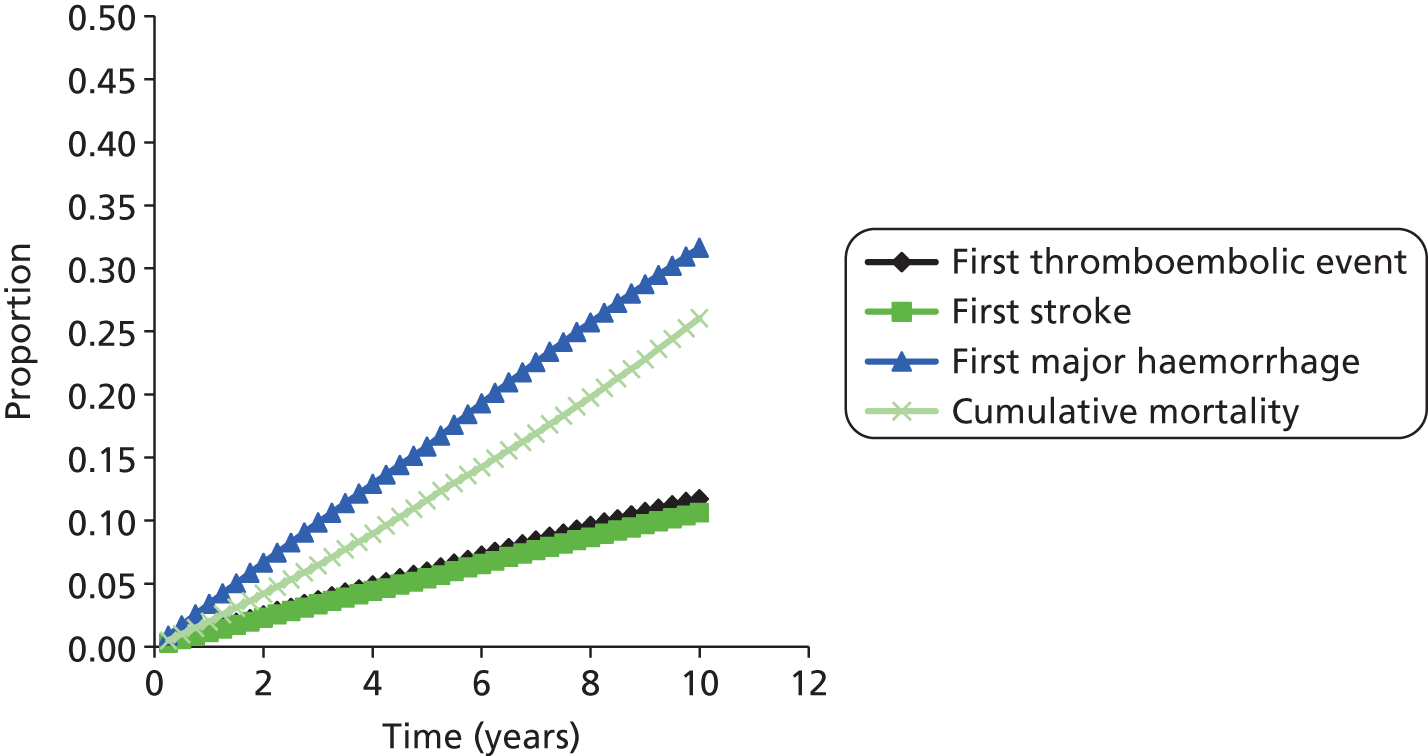

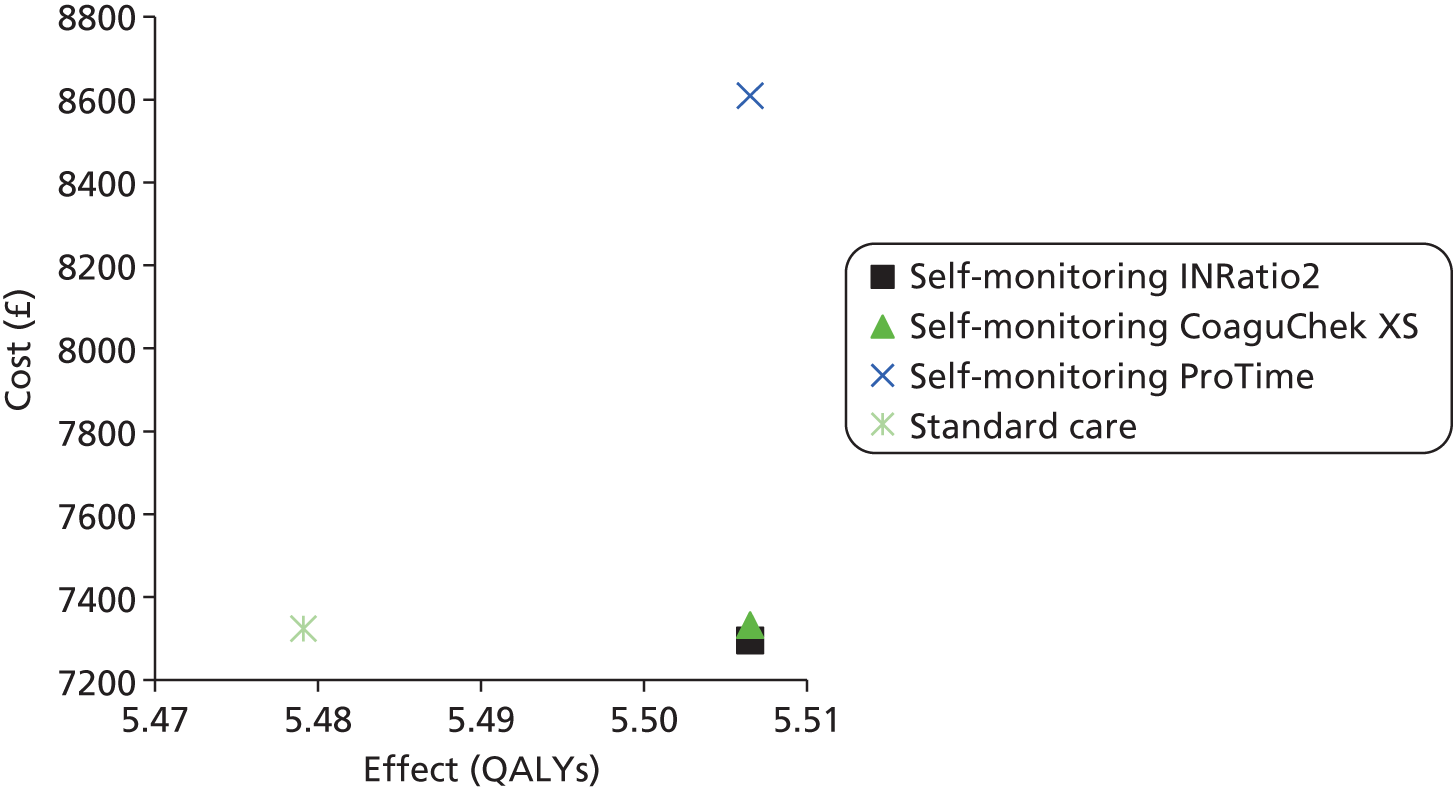

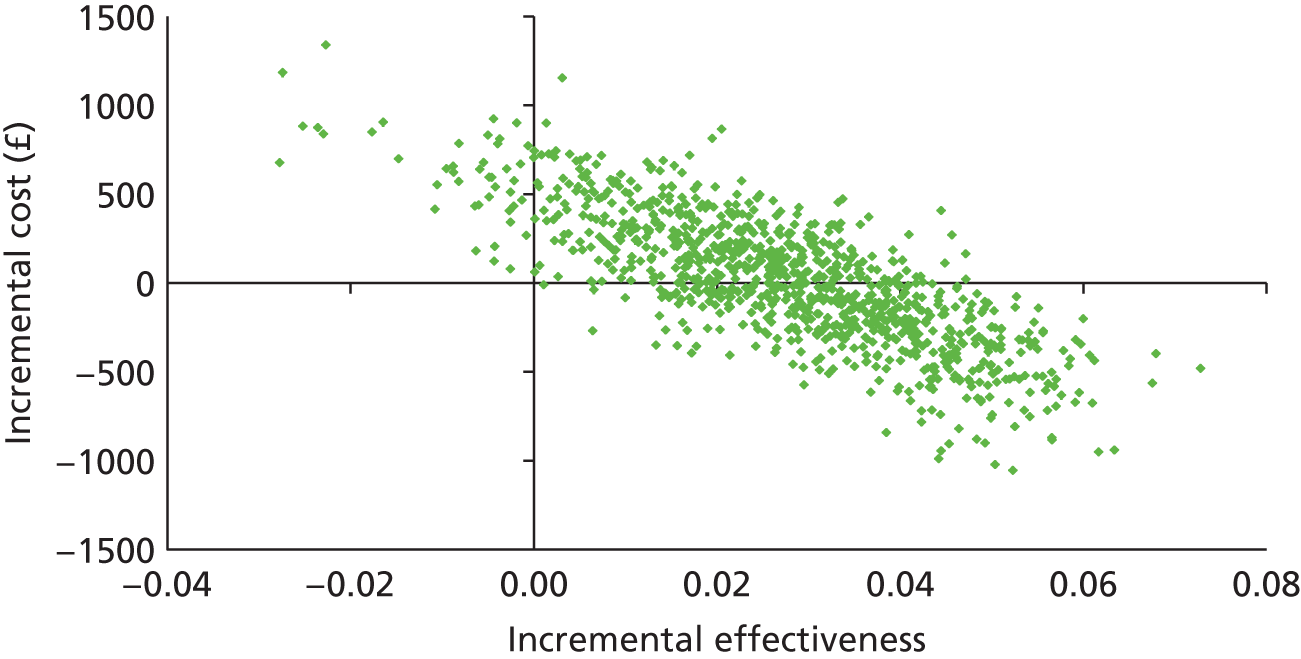

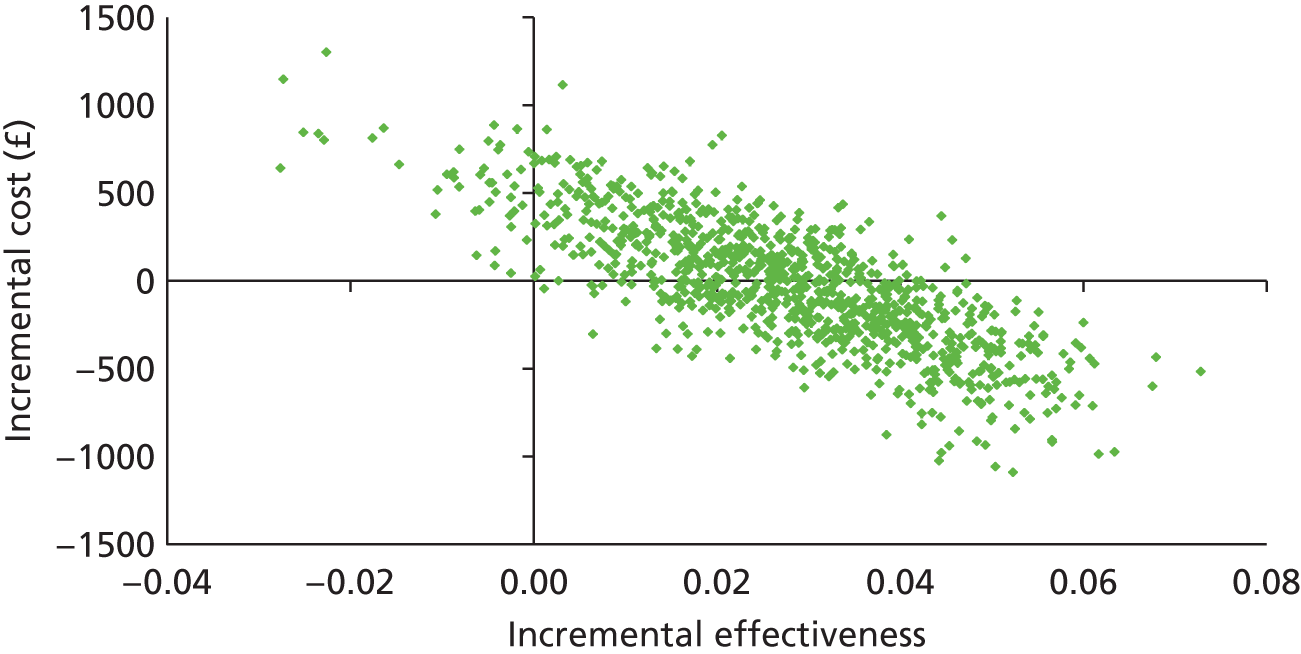

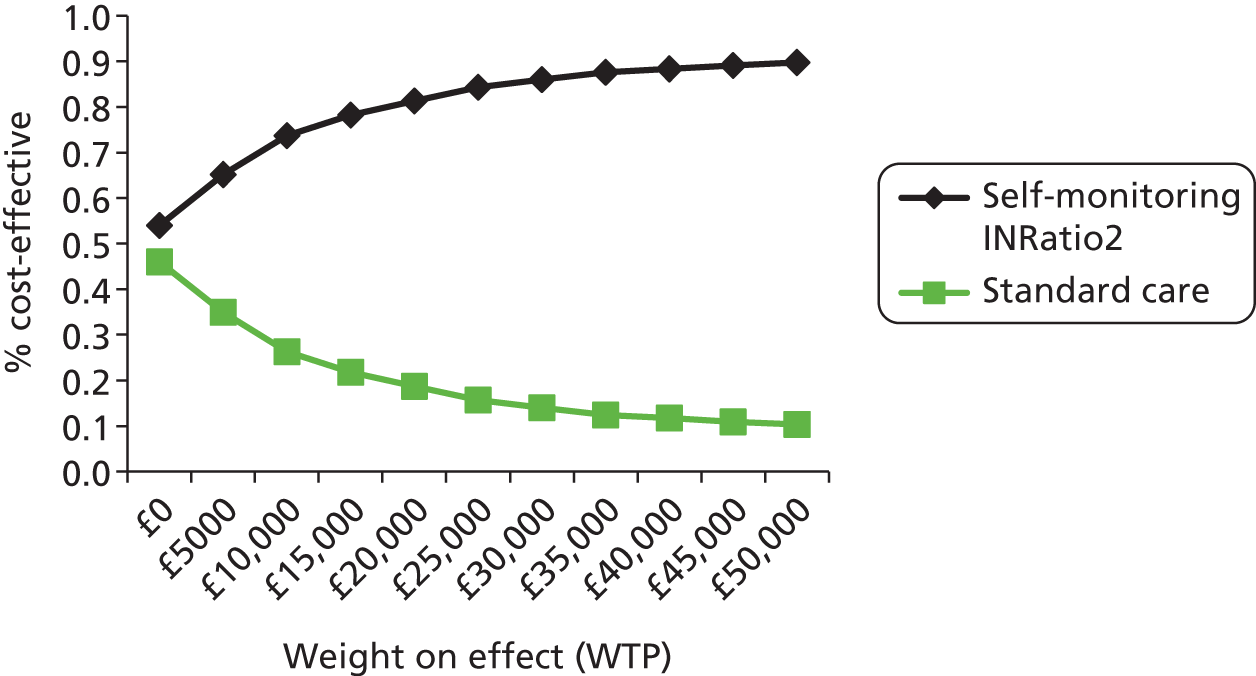

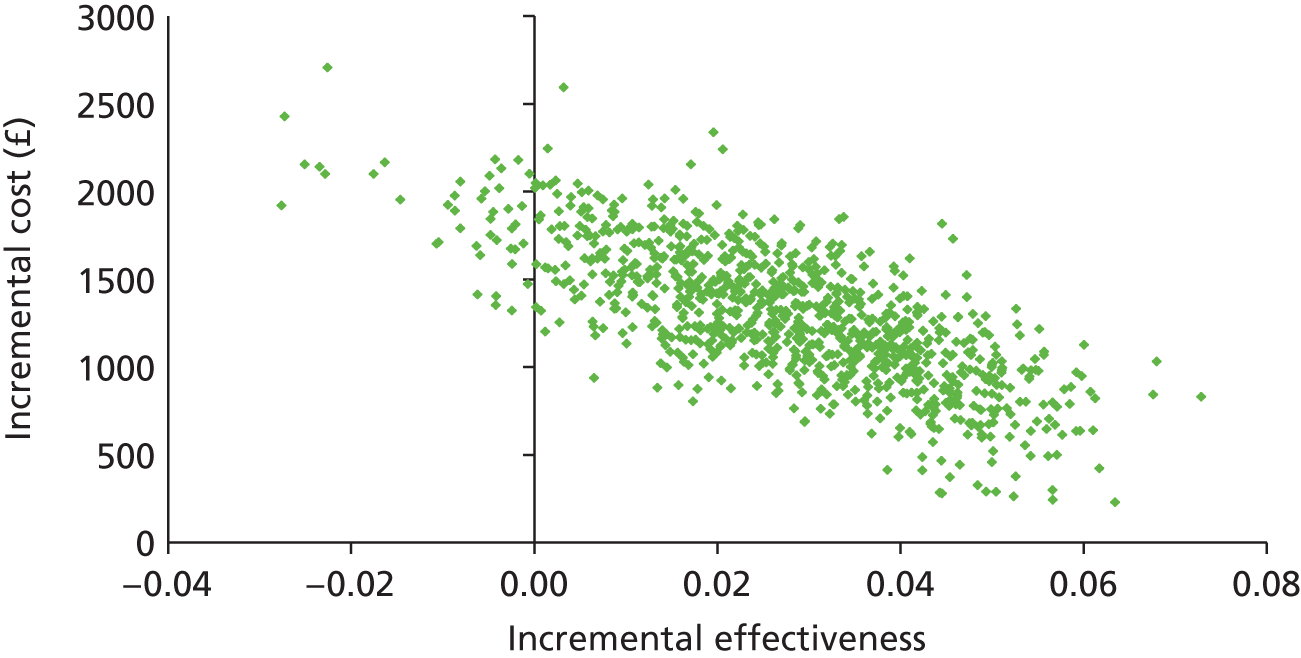

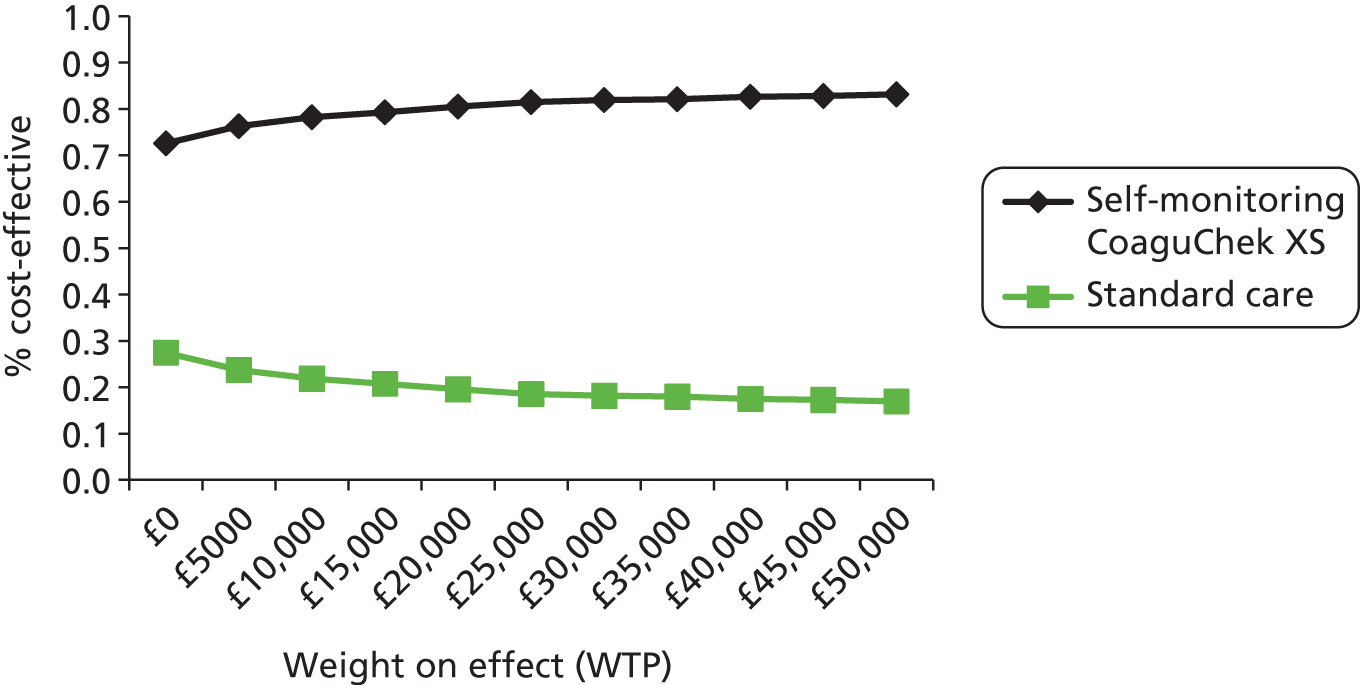

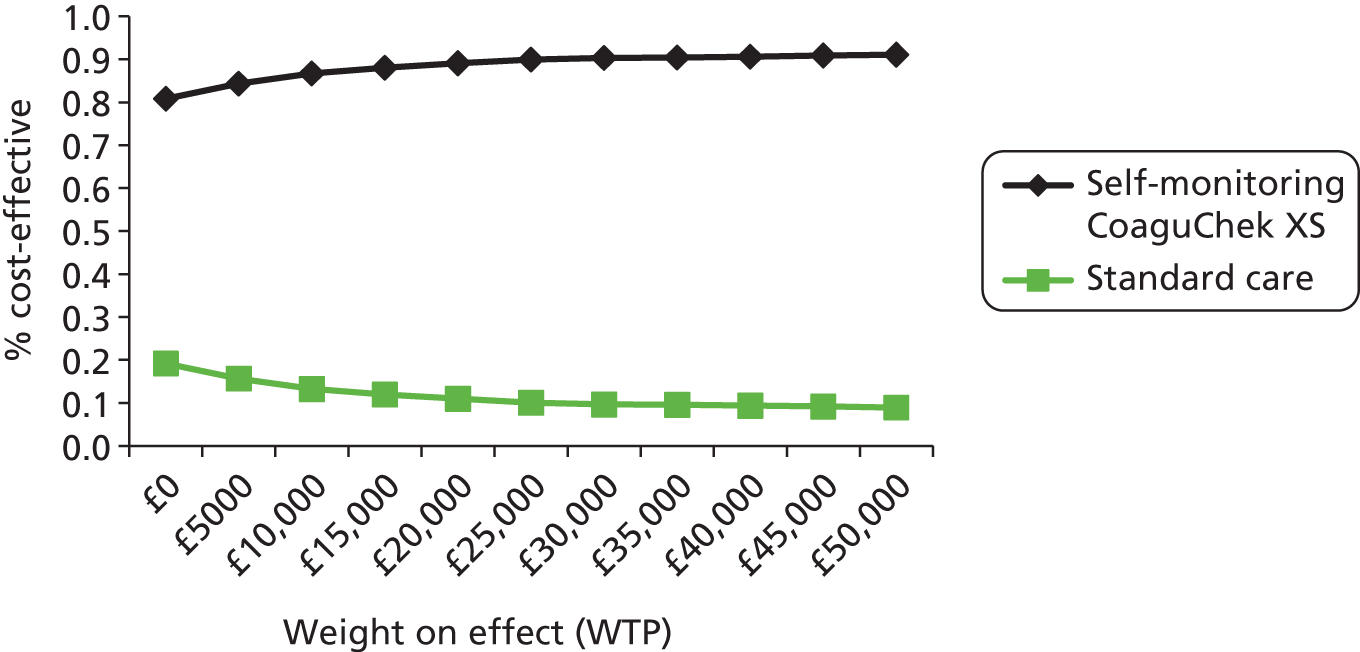

Every 2 weeks | NR | NR | Once |